User login

Some Thoughts on the Patient-Doctor Relationship

There is an inherent power differential in the patient-doctor relationship: The patient comes to the doctor as an authority on his/her physical or emotional state and is thus either intellectually or emotionally dependent on the doctor’s treatment plan and advice. It is therefore absolutely essential that the doctor respect the patient as an equal participant in the treatment. Although the doctor certainly has knowledge about how similar conditions were successfully treated in the past, hopefully a medical professional will display an attitude of respect and mutual collaboration with the patient to resolve his/her problem.

Listening is a key component of conveying an attitude of respect toward the patient. Nowadays practitioners are most often taking notes at their computers while speaking with the patient. This is certainly time-efficient and may in fact be necessary in order for a medical practice to remain solvent with the demands of Medicare and insurance companies. However, multitasking does not convey to the patient that they are connecting with the doctor. Listening is a complex action, which not only involves the ears, but the eyes, the kinesthetic responses of the whole body, and attention to the patient’s nonverbal communication.

Some of the key faux pas to avoid when listening to the patient include:

- Not centering oneself before engaging in a “crucial conversation”;

- Not listening because one is thinking ahead to his/her own response;

- Not maintaining eye contact;

- Not being aware of when one feels challenged and/or defensive;

- Discouraging the patient from contributing his/her own ideas;

- Not allowing the patient to give feedback on what s/he heard as instructions; and

- Taking phone calls or allowing interruptions during a consultation.

It is always helpful to give a patient clear, written instructions about medications, diet, exercise, etc., that result from the consultation. Some doctors send this report via secure email to the patient for review, which is an excellent technique.

The art of apology is another topic that greatly impacts the doctor-patient relationship, as well as the doctor’s relationship with the patient’s family members. This art is a process that has recently emerged in the medical and medical insurance industries. Kaiser Permanente’s director of medical-legal affairs has adopted the practice of asking permission to videotape the actual conversation in which a physician apologizes to a patient for a mistake in a procedure. These conversations are meant to help medical professionals learn how to admit mistakes and ask for forgiveness. Oftentimes patients are looking for just such a communication, which may allow them to put to rest feelings of resentment, bitterness, and regret.

Our patients’ well-being is our ideal goal. Knowing that they have been heard and their feelings understood may in the long run allow patients and their families to heal mind/body/soul more powerfully than we had ever thought. Of course, in our litigious society this may well be an art that remains to be developed over the long term.

There is an inherent power differential in the patient-doctor relationship: The patient comes to the doctor as an authority on his/her physical or emotional state and is thus either intellectually or emotionally dependent on the doctor’s treatment plan and advice. It is therefore absolutely essential that the doctor respect the patient as an equal participant in the treatment. Although the doctor certainly has knowledge about how similar conditions were successfully treated in the past, hopefully a medical professional will display an attitude of respect and mutual collaboration with the patient to resolve his/her problem.

Listening is a key component of conveying an attitude of respect toward the patient. Nowadays practitioners are most often taking notes at their computers while speaking with the patient. This is certainly time-efficient and may in fact be necessary in order for a medical practice to remain solvent with the demands of Medicare and insurance companies. However, multitasking does not convey to the patient that they are connecting with the doctor. Listening is a complex action, which not only involves the ears, but the eyes, the kinesthetic responses of the whole body, and attention to the patient’s nonverbal communication.

Some of the key faux pas to avoid when listening to the patient include:

- Not centering oneself before engaging in a “crucial conversation”;

- Not listening because one is thinking ahead to his/her own response;

- Not maintaining eye contact;

- Not being aware of when one feels challenged and/or defensive;

- Discouraging the patient from contributing his/her own ideas;

- Not allowing the patient to give feedback on what s/he heard as instructions; and

- Taking phone calls or allowing interruptions during a consultation.

It is always helpful to give a patient clear, written instructions about medications, diet, exercise, etc., that result from the consultation. Some doctors send this report via secure email to the patient for review, which is an excellent technique.

The art of apology is another topic that greatly impacts the doctor-patient relationship, as well as the doctor’s relationship with the patient’s family members. This art is a process that has recently emerged in the medical and medical insurance industries. Kaiser Permanente’s director of medical-legal affairs has adopted the practice of asking permission to videotape the actual conversation in which a physician apologizes to a patient for a mistake in a procedure. These conversations are meant to help medical professionals learn how to admit mistakes and ask for forgiveness. Oftentimes patients are looking for just such a communication, which may allow them to put to rest feelings of resentment, bitterness, and regret.

Our patients’ well-being is our ideal goal. Knowing that they have been heard and their feelings understood may in the long run allow patients and their families to heal mind/body/soul more powerfully than we had ever thought. Of course, in our litigious society this may well be an art that remains to be developed over the long term.

There is an inherent power differential in the patient-doctor relationship: The patient comes to the doctor as an authority on his/her physical or emotional state and is thus either intellectually or emotionally dependent on the doctor’s treatment plan and advice. It is therefore absolutely essential that the doctor respect the patient as an equal participant in the treatment. Although the doctor certainly has knowledge about how similar conditions were successfully treated in the past, hopefully a medical professional will display an attitude of respect and mutual collaboration with the patient to resolve his/her problem.

Listening is a key component of conveying an attitude of respect toward the patient. Nowadays practitioners are most often taking notes at their computers while speaking with the patient. This is certainly time-efficient and may in fact be necessary in order for a medical practice to remain solvent with the demands of Medicare and insurance companies. However, multitasking does not convey to the patient that they are connecting with the doctor. Listening is a complex action, which not only involves the ears, but the eyes, the kinesthetic responses of the whole body, and attention to the patient’s nonverbal communication.

Some of the key faux pas to avoid when listening to the patient include:

- Not centering oneself before engaging in a “crucial conversation”;

- Not listening because one is thinking ahead to his/her own response;

- Not maintaining eye contact;

- Not being aware of when one feels challenged and/or defensive;

- Discouraging the patient from contributing his/her own ideas;

- Not allowing the patient to give feedback on what s/he heard as instructions; and

- Taking phone calls or allowing interruptions during a consultation.

It is always helpful to give a patient clear, written instructions about medications, diet, exercise, etc., that result from the consultation. Some doctors send this report via secure email to the patient for review, which is an excellent technique.

The art of apology is another topic that greatly impacts the doctor-patient relationship, as well as the doctor’s relationship with the patient’s family members. This art is a process that has recently emerged in the medical and medical insurance industries. Kaiser Permanente’s director of medical-legal affairs has adopted the practice of asking permission to videotape the actual conversation in which a physician apologizes to a patient for a mistake in a procedure. These conversations are meant to help medical professionals learn how to admit mistakes and ask for forgiveness. Oftentimes patients are looking for just such a communication, which may allow them to put to rest feelings of resentment, bitterness, and regret.

Our patients’ well-being is our ideal goal. Knowing that they have been heard and their feelings understood may in the long run allow patients and their families to heal mind/body/soul more powerfully than we had ever thought. Of course, in our litigious society this may well be an art that remains to be developed over the long term.

Coordinated Approach May Help in Caring for Hospitals’ Neediest Patients

To my way of thinking, a person’s diagnosis or pathophysiology is not as strong a predictor of needing inpatient hospital care as it might have been 10 or 20 years ago. Rather than the clinical diagnosis (e.g. pneumonia), it seems to me that frailty or social complexity often are the principal determinants of which patients are admitted to a hospital for medical conditions.

Some of these patients are admitted frequently but appear to realize little or no benefit from hospitalization. These patients typically have little or no social support, and they often have either significant mental health disorders or substance abuse, or both. Much has been written about these patients, and I recommend an article by Dr. Atul Gawande in the Jan. 24, 2011, issue of The New Yorker titled “The Hot Spotters: Can We Lower Medical Costs by Giving the Neediest Patients Better Care?”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Statistical Brief 354” on how health-care expenditures are allocated across the population reported that 1% of the population accounted for more than 22% of health-care spending in 2008. One in 5 of those were in that category again in 2009. Some of these patients would benefit from care plans.

The Role of Care Plans

It seems that there may be few effective inpatient interventions that will benefit these patients. After all, they have chronic issues that require ongoing relationships with outpatient providers, something that many of these patients lack. But for some (most?) of these patients, it seems clear that frequent hospitalizations don’t help and sometimes just perpetuate or worsen the patient’s dependence on the hospital at a high financial cost to society—and significant frustration and burnout on the part of hospital caregivers, including hospitalists.

For most hospitals, this problem is significant enough to require some sort of coordinated approach to the care of the dozens of types of patients in this category. Implementing whatever plan of care seems appropriate to the caregivers during each admission is frustrating, ensures lots of variation in care, and makes it easier for manipulative patients to abuse the hospital resources and personnel.

A better approach is to follow the same plan of care from one hospital visit to the next. You already knew that. But developing a care plan to follow during each ED visit and admission is time-consuming and often fraught with uncertainty about where boundaries should be set. So if you’re like me, you might just try to guide the patient to discharge this time and hope that whoever sees the patient on the next admission will take the initiative to develop the care plan. The result is that few such plans are developed.

Your Hospital Needs a Care Plan

Relying on individual doctors or nurses to take the initiative to develop care plans will almost always mean few plans are developed, they will vary in their effectiveness, and other providers may not be aware a plan exists. This was the case at the hospital where I practice until I heard Dr. Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, present on this topic at HM12 in San Diego.

Dr. Hilger led a multidisciplinary team to develop care plans (they call them “restriction care plans”) and found that they dramatically reduced the rate of hospital admissions and ED visits for these patients. Hearing about this experience served as a kick in the pants for me, so I did much the same thing at “my” hospital. We have now developed plans for more than 20 patients and found that they visit our ED and are admitted less often. And, anecdotally at least, hospitalists and other hospital staff find that the care plans reduce, at least a little, the stress of caring for these patients.

Unanswered Questions

Although it seems clear that care plans reduce visits to the hospital that develops them, I suspect that some of these patients aren’t consuming any fewer health-care resources. They may just seek care from a different hospital.

My home state of Washington is working to develop individual patient care plans available to all hospitals in the state. A system called the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) has been adopted by nearly all the hospitals in the state. It allows them to share information on ED visits and such things as care plans with one another. For example, through EDIE, each hospital could see the opiate dosing schedule and admission criteria agreed to by patient and primary-care physician.

So it seems that care plans and the technology to share them can make it more difficult for patients to harm themselves by visiting many hospitals to get excessive opiate prescriptions, for example. This should benefit the patient and lower ED and hospital expenditures for these patients. But we don’t know what portion of costs simply is shifted to other settings, so there is no easy way to know the net effect on health-care costs.

An important unanswered question is whether these care plans improve patient well-being. It seems clear they do in some cases, but it is hard to know whether some patients may be worse off because of the plan.

Conclusion

I think nearly every hospital would benefit from a care plan committee composed of at least one hospitalist, ED physician, a nursing representative, and potentially other disciplines (see “Care Plan Attributes,” above). Our committee includes our inpatient psychiatrist, a really valuable contributor.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

To my way of thinking, a person’s diagnosis or pathophysiology is not as strong a predictor of needing inpatient hospital care as it might have been 10 or 20 years ago. Rather than the clinical diagnosis (e.g. pneumonia), it seems to me that frailty or social complexity often are the principal determinants of which patients are admitted to a hospital for medical conditions.

Some of these patients are admitted frequently but appear to realize little or no benefit from hospitalization. These patients typically have little or no social support, and they often have either significant mental health disorders or substance abuse, or both. Much has been written about these patients, and I recommend an article by Dr. Atul Gawande in the Jan. 24, 2011, issue of The New Yorker titled “The Hot Spotters: Can We Lower Medical Costs by Giving the Neediest Patients Better Care?”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Statistical Brief 354” on how health-care expenditures are allocated across the population reported that 1% of the population accounted for more than 22% of health-care spending in 2008. One in 5 of those were in that category again in 2009. Some of these patients would benefit from care plans.

The Role of Care Plans

It seems that there may be few effective inpatient interventions that will benefit these patients. After all, they have chronic issues that require ongoing relationships with outpatient providers, something that many of these patients lack. But for some (most?) of these patients, it seems clear that frequent hospitalizations don’t help and sometimes just perpetuate or worsen the patient’s dependence on the hospital at a high financial cost to society—and significant frustration and burnout on the part of hospital caregivers, including hospitalists.

For most hospitals, this problem is significant enough to require some sort of coordinated approach to the care of the dozens of types of patients in this category. Implementing whatever plan of care seems appropriate to the caregivers during each admission is frustrating, ensures lots of variation in care, and makes it easier for manipulative patients to abuse the hospital resources and personnel.

A better approach is to follow the same plan of care from one hospital visit to the next. You already knew that. But developing a care plan to follow during each ED visit and admission is time-consuming and often fraught with uncertainty about where boundaries should be set. So if you’re like me, you might just try to guide the patient to discharge this time and hope that whoever sees the patient on the next admission will take the initiative to develop the care plan. The result is that few such plans are developed.

Your Hospital Needs a Care Plan

Relying on individual doctors or nurses to take the initiative to develop care plans will almost always mean few plans are developed, they will vary in their effectiveness, and other providers may not be aware a plan exists. This was the case at the hospital where I practice until I heard Dr. Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, present on this topic at HM12 in San Diego.

Dr. Hilger led a multidisciplinary team to develop care plans (they call them “restriction care plans”) and found that they dramatically reduced the rate of hospital admissions and ED visits for these patients. Hearing about this experience served as a kick in the pants for me, so I did much the same thing at “my” hospital. We have now developed plans for more than 20 patients and found that they visit our ED and are admitted less often. And, anecdotally at least, hospitalists and other hospital staff find that the care plans reduce, at least a little, the stress of caring for these patients.

Unanswered Questions

Although it seems clear that care plans reduce visits to the hospital that develops them, I suspect that some of these patients aren’t consuming any fewer health-care resources. They may just seek care from a different hospital.

My home state of Washington is working to develop individual patient care plans available to all hospitals in the state. A system called the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) has been adopted by nearly all the hospitals in the state. It allows them to share information on ED visits and such things as care plans with one another. For example, through EDIE, each hospital could see the opiate dosing schedule and admission criteria agreed to by patient and primary-care physician.

So it seems that care plans and the technology to share them can make it more difficult for patients to harm themselves by visiting many hospitals to get excessive opiate prescriptions, for example. This should benefit the patient and lower ED and hospital expenditures for these patients. But we don’t know what portion of costs simply is shifted to other settings, so there is no easy way to know the net effect on health-care costs.

An important unanswered question is whether these care plans improve patient well-being. It seems clear they do in some cases, but it is hard to know whether some patients may be worse off because of the plan.

Conclusion

I think nearly every hospital would benefit from a care plan committee composed of at least one hospitalist, ED physician, a nursing representative, and potentially other disciplines (see “Care Plan Attributes,” above). Our committee includes our inpatient psychiatrist, a really valuable contributor.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

To my way of thinking, a person’s diagnosis or pathophysiology is not as strong a predictor of needing inpatient hospital care as it might have been 10 or 20 years ago. Rather than the clinical diagnosis (e.g. pneumonia), it seems to me that frailty or social complexity often are the principal determinants of which patients are admitted to a hospital for medical conditions.

Some of these patients are admitted frequently but appear to realize little or no benefit from hospitalization. These patients typically have little or no social support, and they often have either significant mental health disorders or substance abuse, or both. Much has been written about these patients, and I recommend an article by Dr. Atul Gawande in the Jan. 24, 2011, issue of The New Yorker titled “The Hot Spotters: Can We Lower Medical Costs by Giving the Neediest Patients Better Care?”

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s “Statistical Brief 354” on how health-care expenditures are allocated across the population reported that 1% of the population accounted for more than 22% of health-care spending in 2008. One in 5 of those were in that category again in 2009. Some of these patients would benefit from care plans.

The Role of Care Plans

It seems that there may be few effective inpatient interventions that will benefit these patients. After all, they have chronic issues that require ongoing relationships with outpatient providers, something that many of these patients lack. But for some (most?) of these patients, it seems clear that frequent hospitalizations don’t help and sometimes just perpetuate or worsen the patient’s dependence on the hospital at a high financial cost to society—and significant frustration and burnout on the part of hospital caregivers, including hospitalists.

For most hospitals, this problem is significant enough to require some sort of coordinated approach to the care of the dozens of types of patients in this category. Implementing whatever plan of care seems appropriate to the caregivers during each admission is frustrating, ensures lots of variation in care, and makes it easier for manipulative patients to abuse the hospital resources and personnel.

A better approach is to follow the same plan of care from one hospital visit to the next. You already knew that. But developing a care plan to follow during each ED visit and admission is time-consuming and often fraught with uncertainty about where boundaries should be set. So if you’re like me, you might just try to guide the patient to discharge this time and hope that whoever sees the patient on the next admission will take the initiative to develop the care plan. The result is that few such plans are developed.

Your Hospital Needs a Care Plan

Relying on individual doctors or nurses to take the initiative to develop care plans will almost always mean few plans are developed, they will vary in their effectiveness, and other providers may not be aware a plan exists. This was the case at the hospital where I practice until I heard Dr. Rick Hilger, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, present on this topic at HM12 in San Diego.

Dr. Hilger led a multidisciplinary team to develop care plans (they call them “restriction care plans”) and found that they dramatically reduced the rate of hospital admissions and ED visits for these patients. Hearing about this experience served as a kick in the pants for me, so I did much the same thing at “my” hospital. We have now developed plans for more than 20 patients and found that they visit our ED and are admitted less often. And, anecdotally at least, hospitalists and other hospital staff find that the care plans reduce, at least a little, the stress of caring for these patients.

Unanswered Questions

Although it seems clear that care plans reduce visits to the hospital that develops them, I suspect that some of these patients aren’t consuming any fewer health-care resources. They may just seek care from a different hospital.

My home state of Washington is working to develop individual patient care plans available to all hospitals in the state. A system called the Emergency Department Information Exchange (EDIE) has been adopted by nearly all the hospitals in the state. It allows them to share information on ED visits and such things as care plans with one another. For example, through EDIE, each hospital could see the opiate dosing schedule and admission criteria agreed to by patient and primary-care physician.

So it seems that care plans and the technology to share them can make it more difficult for patients to harm themselves by visiting many hospitals to get excessive opiate prescriptions, for example. This should benefit the patient and lower ED and hospital expenditures for these patients. But we don’t know what portion of costs simply is shifted to other settings, so there is no easy way to know the net effect on health-care costs.

An important unanswered question is whether these care plans improve patient well-being. It seems clear they do in some cases, but it is hard to know whether some patients may be worse off because of the plan.

Conclusion

I think nearly every hospital would benefit from a care plan committee composed of at least one hospitalist, ED physician, a nursing representative, and potentially other disciplines (see “Care Plan Attributes,” above). Our committee includes our inpatient psychiatrist, a really valuable contributor.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at john.nelson@nelsonflores.com.

Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2012 Guidelines: Updates For the Hospitalist

Background

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome with systemic effects that can progress to severe sepsis and/or septic shock. The incidence of severe sepsis and septic shock is rising in the United States, and these syndromes are associated with significant morbidity and a mortality rate as high as 25% to 35%.1 In fact, sepsis is one of the 10 leading causes of death in the U.S., accounting for 2% of hospital admissions but 17% of in-hospital deaths.1

The main principles of effective treatment for severe sepsis and septic shock are timely recognition and early aggressive therapy. Launched in 2002, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) was the result of a collaboration of three professional societies. The goal of the SSC collaborative was to reduce mortality from severe sepsis and septic shock by 25%. To that end, the SSC convened representatives from several international societies to develop a set of evidence-based guidelines as a means of guiding clinicians in optimizing management of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Since the original publication of the SSC guidelines in 2004, there have been two updates—one in 2008 and one in February 2013.2

Guideline Updates

Quantitative, protocol-driven initial resuscitation in the first six hours for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock remains a high-level recommendation, but SSC has added normalization of the lactate level as a resuscitation goal. This new suggestion is based on two studies published since the 2008 SCC guidelines that showed noninferiority to previously established goals and absolute mortality benefit.3,4

There is a new focus on screening for sepsis and the use of hospital-based performance-improvement programs, which were not previously addressed in the 2008 SCC guidelines. Patients with suspected infections and who are seriously ill should be screened in order to identify sepsis early during the hospital course. Additionally, it is recommended that hospitals implement performance-improvement measures by which multidisciplinary teams can address treatment of sepsis by improving compliance with the SSC bundles, citing their own data as the model but ultimately leaving this recommendation as ungradable in regards to the quality of available supporting evidence.5

Cultures drawn before antibiotics and early imaging to confirm potential sources are still recommended, but the committee has added the use of one: 3 beta D-glucan and the mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibody assays when considering invasive candidiasis as your infective agent. They do note the known risk of false positive results with these assays and warn that they should be used with caution.

Early, broad-spectrum antibiotic administration within the first hour of presentation was upgraded for severe sepsis and downgraded for septic shock. The decision to initiate double coverage for suspected gram-negative infection is not recommended specifically but can be considered in situations when highly antibiotic resistant pathogens are potentially present. Daily assessment of the appropriate antibiotic regimen remains an important tenet, and the use of low procalcitonin levels as a tool to assist in the decision to discontinue antibiotics has been introduced. Source control is still strongly recommended in the first 12 hours of treatment.

The SSC 2012 guidelines specifically address the rate of fluid administered and the type of fluid that should be used. It is now recommended that a fluid challenge of 30 mL/kg be used for initial resuscitation, but the guidelines leave it up to the clinician to give more fluid if needed. There is a strong push for use of crystalloids rather than colloids during initial resuscitation and thereafter. Disfavor for colloids stemmed from trials showing increased mortality when comparing resuscitation with hydroxyethyl starch versus crystalloid for patients in septic shock.6,7 Albumin, on the other hand, is recommended to resuscitate patients with severe sepsis and septic shock in cases for which large amounts of crystalloid are required.

The 2012 SSC guidelines recommend norepinephrine (NE) alone as the first-line vasopressor in sepsis and no longer include dopamine in this category. In fact, the use of dopamine in septic shock has been downgraded and should only to be considered in patients at low risk of tachyarrhythmia and in bradycardia syndromes. Epinephrine is now favored as the second agent or as a substitute to NE. Phenylephrine is no longer recommended unless there is contraindication to using NE, the patient has a high cardiac output, or it is used as a salvage therapy. Vasopressin is considered only an adjunctive agent to NE and should never be used alone.

Recommendations regarding corticosteroid therapy remain largely unchanged from 2008 SCC guidelines, which only support their use when adequate volume resuscitation and vasopressor support has failed to achieve hemodynamic stability. Glucose control is recommended but at the new target of achieving a level of <180 mg/dL, up from a previous target of <150 mg/dL.

Notably, recombinant human activated protein C was completely omitted from the 2012 guidelines, prompted by the voluntary removal of the drug by the manufacturer after failing to show benefit. Use of selenium and intravenous immunoglobulin received comment, but there is insufficient evidence supporting their benefit at the current time. They also encourage clinicians to incorporate goals of care and end-of-life issues into the treatment plan and discuss this with patients and/or surrogates early in treatment.

Guideline Analysis

Prior versions of the SSC guidelines have been met with a fair amount of skepticism.8 Much of the criticism is based on the industry sponsorship of the 2004 version, the lack of transparency regarding potential conflicts of interest of the committee members, and that the bundle recommendations largely were based on only one trial and, therefore, not evidenced-based.9 The 2012 SSC committee seems to have addressed these issues as the guidelines are free of commercial sponsorship in the 2008 and current versions. They also rigorously applied the GRADE system to methodically assess the strength and quality of supporting evidence. The result is a set of guidelines that are partially evidence-based and partially based on expert opinion, but this is clearly delineated in these newest guidelines. This provides clinicians with a clear and concise recommended approach to the patient with severe sepsis and septic shock.

The guidelines continue to place a heavy emphasis on three- and six-hour treatment bundles, and with the assistance of the Institute for Health Care Improvement efforts to improve implementation of the bundle, they are already are widespread with an eye to expand across the country. The components of the three-hour treatment bundle (lactate measurement, blood cultures prior to initiation of antibiotics, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and IV crystalloids for hypotension or for a lactate of >4 mmol/L) recommended by the SSC have not changed substantially since 2008. The one exception is the rate at which IV crystalloid should be administered of 30 mL/kg, which is up from 20 mL/kg. Only time will tell how this change will affect bundle compliance or reduce mortality. But this does pose a significant challenge to quality and performance improvement groups accustomed to tracking compliance with IV fluid administration under the old standard and the educational campaigns associated with a change.

It appears that the SSC is here to stay, now in its third iteration. The lasting legacy of the SSC guidelines might not rest with the content of the guidelines, per se, but in raising awareness of severe sepsis and septic shock in a way that had not previously been considered.

HM Takeaways

The revised 2012 SCC updates bring some new tools to the clinician for early recognition and effective management of patients with sepsis. The push for institutions to adopt screening and performance measures reflects a general trend in health care to create high-performance systems. As these new guidelines are put into practice, there are several changes that might require augmentation of quality metrics being tracked at institutions nationally and internationally.

Dr. Pendharker is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco and San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Gomez is assistant professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at UCSF and San Francisco General Hospital.

References

- Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, et al. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: a challenge for patients and hospitals. NCHS Data Brief. 2011:1-8.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Schoonderbeek FJ, et al. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:752-761.

- Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, et al. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:739-746.

- Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:367-374.

- Guidet B, Martinet O, Boulain T, et al. Assessment of hemodynamic efficacy and safety of 6% hydroxyethylstarch 130/0.4 vs. 0.9% NaCl fluid replacement in patients with severe sepsis: The CRYSTMAS study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R94.

- Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer’s acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:124-134.

- Marik PE. Surviving sepsis: going beyond the guidelines. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:17.

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368-1377.

Background

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome with systemic effects that can progress to severe sepsis and/or septic shock. The incidence of severe sepsis and septic shock is rising in the United States, and these syndromes are associated with significant morbidity and a mortality rate as high as 25% to 35%.1 In fact, sepsis is one of the 10 leading causes of death in the U.S., accounting for 2% of hospital admissions but 17% of in-hospital deaths.1

The main principles of effective treatment for severe sepsis and septic shock are timely recognition and early aggressive therapy. Launched in 2002, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) was the result of a collaboration of three professional societies. The goal of the SSC collaborative was to reduce mortality from severe sepsis and septic shock by 25%. To that end, the SSC convened representatives from several international societies to develop a set of evidence-based guidelines as a means of guiding clinicians in optimizing management of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Since the original publication of the SSC guidelines in 2004, there have been two updates—one in 2008 and one in February 2013.2

Guideline Updates

Quantitative, protocol-driven initial resuscitation in the first six hours for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock remains a high-level recommendation, but SSC has added normalization of the lactate level as a resuscitation goal. This new suggestion is based on two studies published since the 2008 SCC guidelines that showed noninferiority to previously established goals and absolute mortality benefit.3,4

There is a new focus on screening for sepsis and the use of hospital-based performance-improvement programs, which were not previously addressed in the 2008 SCC guidelines. Patients with suspected infections and who are seriously ill should be screened in order to identify sepsis early during the hospital course. Additionally, it is recommended that hospitals implement performance-improvement measures by which multidisciplinary teams can address treatment of sepsis by improving compliance with the SSC bundles, citing their own data as the model but ultimately leaving this recommendation as ungradable in regards to the quality of available supporting evidence.5

Cultures drawn before antibiotics and early imaging to confirm potential sources are still recommended, but the committee has added the use of one: 3 beta D-glucan and the mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibody assays when considering invasive candidiasis as your infective agent. They do note the known risk of false positive results with these assays and warn that they should be used with caution.

Early, broad-spectrum antibiotic administration within the first hour of presentation was upgraded for severe sepsis and downgraded for septic shock. The decision to initiate double coverage for suspected gram-negative infection is not recommended specifically but can be considered in situations when highly antibiotic resistant pathogens are potentially present. Daily assessment of the appropriate antibiotic regimen remains an important tenet, and the use of low procalcitonin levels as a tool to assist in the decision to discontinue antibiotics has been introduced. Source control is still strongly recommended in the first 12 hours of treatment.

The SSC 2012 guidelines specifically address the rate of fluid administered and the type of fluid that should be used. It is now recommended that a fluid challenge of 30 mL/kg be used for initial resuscitation, but the guidelines leave it up to the clinician to give more fluid if needed. There is a strong push for use of crystalloids rather than colloids during initial resuscitation and thereafter. Disfavor for colloids stemmed from trials showing increased mortality when comparing resuscitation with hydroxyethyl starch versus crystalloid for patients in septic shock.6,7 Albumin, on the other hand, is recommended to resuscitate patients with severe sepsis and septic shock in cases for which large amounts of crystalloid are required.

The 2012 SSC guidelines recommend norepinephrine (NE) alone as the first-line vasopressor in sepsis and no longer include dopamine in this category. In fact, the use of dopamine in septic shock has been downgraded and should only to be considered in patients at low risk of tachyarrhythmia and in bradycardia syndromes. Epinephrine is now favored as the second agent or as a substitute to NE. Phenylephrine is no longer recommended unless there is contraindication to using NE, the patient has a high cardiac output, or it is used as a salvage therapy. Vasopressin is considered only an adjunctive agent to NE and should never be used alone.

Recommendations regarding corticosteroid therapy remain largely unchanged from 2008 SCC guidelines, which only support their use when adequate volume resuscitation and vasopressor support has failed to achieve hemodynamic stability. Glucose control is recommended but at the new target of achieving a level of <180 mg/dL, up from a previous target of <150 mg/dL.

Notably, recombinant human activated protein C was completely omitted from the 2012 guidelines, prompted by the voluntary removal of the drug by the manufacturer after failing to show benefit. Use of selenium and intravenous immunoglobulin received comment, but there is insufficient evidence supporting their benefit at the current time. They also encourage clinicians to incorporate goals of care and end-of-life issues into the treatment plan and discuss this with patients and/or surrogates early in treatment.

Guideline Analysis

Prior versions of the SSC guidelines have been met with a fair amount of skepticism.8 Much of the criticism is based on the industry sponsorship of the 2004 version, the lack of transparency regarding potential conflicts of interest of the committee members, and that the bundle recommendations largely were based on only one trial and, therefore, not evidenced-based.9 The 2012 SSC committee seems to have addressed these issues as the guidelines are free of commercial sponsorship in the 2008 and current versions. They also rigorously applied the GRADE system to methodically assess the strength and quality of supporting evidence. The result is a set of guidelines that are partially evidence-based and partially based on expert opinion, but this is clearly delineated in these newest guidelines. This provides clinicians with a clear and concise recommended approach to the patient with severe sepsis and septic shock.

The guidelines continue to place a heavy emphasis on three- and six-hour treatment bundles, and with the assistance of the Institute for Health Care Improvement efforts to improve implementation of the bundle, they are already are widespread with an eye to expand across the country. The components of the three-hour treatment bundle (lactate measurement, blood cultures prior to initiation of antibiotics, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and IV crystalloids for hypotension or for a lactate of >4 mmol/L) recommended by the SSC have not changed substantially since 2008. The one exception is the rate at which IV crystalloid should be administered of 30 mL/kg, which is up from 20 mL/kg. Only time will tell how this change will affect bundle compliance or reduce mortality. But this does pose a significant challenge to quality and performance improvement groups accustomed to tracking compliance with IV fluid administration under the old standard and the educational campaigns associated with a change.

It appears that the SSC is here to stay, now in its third iteration. The lasting legacy of the SSC guidelines might not rest with the content of the guidelines, per se, but in raising awareness of severe sepsis and septic shock in a way that had not previously been considered.

HM Takeaways

The revised 2012 SCC updates bring some new tools to the clinician for early recognition and effective management of patients with sepsis. The push for institutions to adopt screening and performance measures reflects a general trend in health care to create high-performance systems. As these new guidelines are put into practice, there are several changes that might require augmentation of quality metrics being tracked at institutions nationally and internationally.

Dr. Pendharker is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco and San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Gomez is assistant professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at UCSF and San Francisco General Hospital.

References

- Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, et al. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: a challenge for patients and hospitals. NCHS Data Brief. 2011:1-8.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Schoonderbeek FJ, et al. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:752-761.

- Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, et al. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:739-746.

- Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:367-374.

- Guidet B, Martinet O, Boulain T, et al. Assessment of hemodynamic efficacy and safety of 6% hydroxyethylstarch 130/0.4 vs. 0.9% NaCl fluid replacement in patients with severe sepsis: The CRYSTMAS study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R94.

- Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer’s acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:124-134.

- Marik PE. Surviving sepsis: going beyond the guidelines. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:17.

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368-1377.

Background

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome with systemic effects that can progress to severe sepsis and/or septic shock. The incidence of severe sepsis and septic shock is rising in the United States, and these syndromes are associated with significant morbidity and a mortality rate as high as 25% to 35%.1 In fact, sepsis is one of the 10 leading causes of death in the U.S., accounting for 2% of hospital admissions but 17% of in-hospital deaths.1

The main principles of effective treatment for severe sepsis and septic shock are timely recognition and early aggressive therapy. Launched in 2002, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) was the result of a collaboration of three professional societies. The goal of the SSC collaborative was to reduce mortality from severe sepsis and septic shock by 25%. To that end, the SSC convened representatives from several international societies to develop a set of evidence-based guidelines as a means of guiding clinicians in optimizing management of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Since the original publication of the SSC guidelines in 2004, there have been two updates—one in 2008 and one in February 2013.2

Guideline Updates

Quantitative, protocol-driven initial resuscitation in the first six hours for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock remains a high-level recommendation, but SSC has added normalization of the lactate level as a resuscitation goal. This new suggestion is based on two studies published since the 2008 SCC guidelines that showed noninferiority to previously established goals and absolute mortality benefit.3,4

There is a new focus on screening for sepsis and the use of hospital-based performance-improvement programs, which were not previously addressed in the 2008 SCC guidelines. Patients with suspected infections and who are seriously ill should be screened in order to identify sepsis early during the hospital course. Additionally, it is recommended that hospitals implement performance-improvement measures by which multidisciplinary teams can address treatment of sepsis by improving compliance with the SSC bundles, citing their own data as the model but ultimately leaving this recommendation as ungradable in regards to the quality of available supporting evidence.5

Cultures drawn before antibiotics and early imaging to confirm potential sources are still recommended, but the committee has added the use of one: 3 beta D-glucan and the mannan antigen and anti-mannan antibody assays when considering invasive candidiasis as your infective agent. They do note the known risk of false positive results with these assays and warn that they should be used with caution.

Early, broad-spectrum antibiotic administration within the first hour of presentation was upgraded for severe sepsis and downgraded for septic shock. The decision to initiate double coverage for suspected gram-negative infection is not recommended specifically but can be considered in situations when highly antibiotic resistant pathogens are potentially present. Daily assessment of the appropriate antibiotic regimen remains an important tenet, and the use of low procalcitonin levels as a tool to assist in the decision to discontinue antibiotics has been introduced. Source control is still strongly recommended in the first 12 hours of treatment.

The SSC 2012 guidelines specifically address the rate of fluid administered and the type of fluid that should be used. It is now recommended that a fluid challenge of 30 mL/kg be used for initial resuscitation, but the guidelines leave it up to the clinician to give more fluid if needed. There is a strong push for use of crystalloids rather than colloids during initial resuscitation and thereafter. Disfavor for colloids stemmed from trials showing increased mortality when comparing resuscitation with hydroxyethyl starch versus crystalloid for patients in septic shock.6,7 Albumin, on the other hand, is recommended to resuscitate patients with severe sepsis and septic shock in cases for which large amounts of crystalloid are required.

The 2012 SSC guidelines recommend norepinephrine (NE) alone as the first-line vasopressor in sepsis and no longer include dopamine in this category. In fact, the use of dopamine in septic shock has been downgraded and should only to be considered in patients at low risk of tachyarrhythmia and in bradycardia syndromes. Epinephrine is now favored as the second agent or as a substitute to NE. Phenylephrine is no longer recommended unless there is contraindication to using NE, the patient has a high cardiac output, or it is used as a salvage therapy. Vasopressin is considered only an adjunctive agent to NE and should never be used alone.

Recommendations regarding corticosteroid therapy remain largely unchanged from 2008 SCC guidelines, which only support their use when adequate volume resuscitation and vasopressor support has failed to achieve hemodynamic stability. Glucose control is recommended but at the new target of achieving a level of <180 mg/dL, up from a previous target of <150 mg/dL.

Notably, recombinant human activated protein C was completely omitted from the 2012 guidelines, prompted by the voluntary removal of the drug by the manufacturer after failing to show benefit. Use of selenium and intravenous immunoglobulin received comment, but there is insufficient evidence supporting their benefit at the current time. They also encourage clinicians to incorporate goals of care and end-of-life issues into the treatment plan and discuss this with patients and/or surrogates early in treatment.

Guideline Analysis

Prior versions of the SSC guidelines have been met with a fair amount of skepticism.8 Much of the criticism is based on the industry sponsorship of the 2004 version, the lack of transparency regarding potential conflicts of interest of the committee members, and that the bundle recommendations largely were based on only one trial and, therefore, not evidenced-based.9 The 2012 SSC committee seems to have addressed these issues as the guidelines are free of commercial sponsorship in the 2008 and current versions. They also rigorously applied the GRADE system to methodically assess the strength and quality of supporting evidence. The result is a set of guidelines that are partially evidence-based and partially based on expert opinion, but this is clearly delineated in these newest guidelines. This provides clinicians with a clear and concise recommended approach to the patient with severe sepsis and septic shock.

The guidelines continue to place a heavy emphasis on three- and six-hour treatment bundles, and with the assistance of the Institute for Health Care Improvement efforts to improve implementation of the bundle, they are already are widespread with an eye to expand across the country. The components of the three-hour treatment bundle (lactate measurement, blood cultures prior to initiation of antibiotics, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and IV crystalloids for hypotension or for a lactate of >4 mmol/L) recommended by the SSC have not changed substantially since 2008. The one exception is the rate at which IV crystalloid should be administered of 30 mL/kg, which is up from 20 mL/kg. Only time will tell how this change will affect bundle compliance or reduce mortality. But this does pose a significant challenge to quality and performance improvement groups accustomed to tracking compliance with IV fluid administration under the old standard and the educational campaigns associated with a change.

It appears that the SSC is here to stay, now in its third iteration. The lasting legacy of the SSC guidelines might not rest with the content of the guidelines, per se, but in raising awareness of severe sepsis and septic shock in a way that had not previously been considered.

HM Takeaways

The revised 2012 SCC updates bring some new tools to the clinician for early recognition and effective management of patients with sepsis. The push for institutions to adopt screening and performance measures reflects a general trend in health care to create high-performance systems. As these new guidelines are put into practice, there are several changes that might require augmentation of quality metrics being tracked at institutions nationally and internationally.

Dr. Pendharker is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at the University of California San Francisco and San Francisco General Hospital. Dr. Gomez is assistant professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at UCSF and San Francisco General Hospital.

References

- Hall MJ, Williams SN, DeFrances CJ, et al. Inpatient care for septicemia or sepsis: a challenge for patients and hospitals. NCHS Data Brief. 2011:1-8.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580-637.

- Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Schoonderbeek FJ, et al. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:752-761.

- Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, et al. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:739-746.

- Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:367-374.

- Guidet B, Martinet O, Boulain T, et al. Assessment of hemodynamic efficacy and safety of 6% hydroxyethylstarch 130/0.4 vs. 0.9% NaCl fluid replacement in patients with severe sepsis: The CRYSTMAS study. Crit Care. 2012;16:R94.

- Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer’s acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:124-134.

- Marik PE. Surviving sepsis: going beyond the guidelines. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:17.

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368-1377.

How Should Common Symptoms at the End of Life be Managed?

Case

A 58-year-old male with colon cancer metastatic to the liver and lungs presents with vomiting, dyspnea, and abdominal pain. His disease has progressed through third-line chemotherapy and his care is now focused entirely on symptom management. He has not had a bowel movement in five days and he began vomiting two days ago.

Overview

The majority of patients in the United States die in acute-care hospitals. The Study to Understand Prognosis and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT), which evaluated the courses of close to 10,000 hospitalized patients with serious and life-limiting illnesses, illustrated that patients’ end-of-life (EOL) experiences often are characterized by poor symptom management and invasive care that is not congruent with the patients’ overall goals of care.1 Studies of factors identified as priorities in EOL care have consistently shown that excellent pain and symptom management are highly valued by patients and families. As the hospitalist movement continues to grow, hospitalists will play a large role in caring for patients at EOL and will need to know how to provide adequate pain and symptom management so that high-quality care can be achieved.

Pain: A Basic Tenet

A basic tenet of palliative medicine is to evaluate and treat all types of suffering.2 Physical pain at EOL is frequently accompanied by other types of pain, such as psychological, social, religious, or existential pain. However, this review will focus on the pharmacologic management of physical pain.

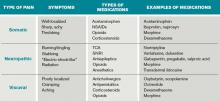

Pain management must begin with a thorough evaluation of the severity, location, and characteristics of the discomfort to assess which therapies are most likely to be beneficial (see Table 1).3 The consistent use of one scale of pain severity (such as 0-10, or mild/moderate/severe) assists in the choice of initial dose of pain medication, in determining the response to the medication, and in assessing the need for change in dose.4

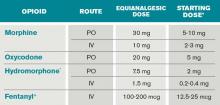

Opioids are the foundation of pain management in advanced diseases because they are available in a number of formulations and, when dosed appropriately, they are effective and safe. Starting doses and equianalgesic doses of common opioids are presented in Table 2. Guidelines recommend the use of short-acting opioids for dose titration to gain control of poorly controlled pain.3 If a patient is experiencing mild pain on a specific regimen, the medication dose can be increased up to 25%; by 25% to 50%, if pain is moderate; and 50% to 100%, if severe.5 When the pain is better-controlled, the total amount of pain medication used in 24 hours (24-hour dose) can be converted to a long-acting formulation for more consistent pain management. Because there is a constant component to most advanced pain syndromes, it is recommended that pain medication is given on a standing basis, with as-needed (prn) doses available for exacerbations of pain.3 Prn doses of short-acting medication (equivalent to approximately 10% of the 24-hour dose of medication) should be available at one- or two-hour intervals prn (longer if hepatic or renal impairment is present) for IV or PO medications, respectively.

Opioids often are categorized as low potency (i.e. codeine, hydrocodone) and high-potency (i.e. oxycodone, morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl). When given in “equianalgesic doses,” the analgesic effect and common side effects (nausea/vomiting, constipation, sedation, confusion, pruritis) of different opioids can vary in different patients. Due to differences in levels of expressed subtypes of opioid receptors, a given patient might be more sensitive to the analgesic effect or side effects of a specific medication. Therefore, if dose escalation of one opioid is inadequate to control pain and further increases in dose are limited by intolerable side effects, rotation to another opioid is recommended.4 Tables documenting equianalgesic doses of different opioids are based on only moderate evidence from equivalency trials performed in healthy volunteers.6 Due to interpatient differences in responses, it is recommended that the equianalgesic dose of the new medication be decreased by 25% to 50% for initial dosing.5

Certain treatments are indicated for specific pain syndromes. Bony metastases respond to NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, and radiation therapy in addition to opioid medications. As focal back pain is the first symptom of spinal cord compression, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for compression in any patient with malignancy and new back pain. Steroids and radiation therapy are considered emergent treatments for pain control and to prevent paralysis in this circumstance. Pain due to bowel obstruction is usually colicky in nature and responds well to octreotide as discussed in the section on nausea and vomiting. Steroids (such as dexamethasone 4 mg PO bid-tid) might be an effective adjuvant medication in bone pain, tumor pain, or inflammation.

*Half this dose should be used in renal or liver dysfunction and in the elderly.

Preferred in renal dysfunction.

SOURCES: Adapted from Assessment and treatment of physical pain associated with life-limiting illness. Hospice and Palliative Care Training for Physicians: UNIPAC. Vol 3. 3rd ed. Glenview, IL: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2008, and Evidence-based standards for cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(23):3879-3885.

Back to the Case

At home, the patient was taking 60 mg of extended-release morphine twice daily and six doses per day of 15-mg immediate-release morphine for breakthrough pain. This is the equivalent of 210 mg of oral morphine in 24 hours. His pain is severe on this regimen, but it is unclear how much of this medication he is absorbing due to his vomiting. Using the IV route of administration and a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) system will enable rapid dose titration and pain control. The equivalent of the 24-hour dose of 210 mg oral morphine is 70 mg IV morphine, which is equivalent to a drip basal rate of approximately 3 mg IV morphine per hour. This basal rate with a bolus dose of 7 mg (10% of the 24-hour dose) IV morphine q1 hour prn is reasonable as a starting point.

Review of the Data: Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting affect 40% to 70% of patients in a palliative setting.7 A thorough history and physical exam can enable one to determine the most likely causes, pathways, and receptors involved in the process of nausea and vomiting. It is important to review the timing, frequency, and triggers of vomiting. The oral, abdominal, neurologic, and rectal exams, in addition to a complete chemistry panel, offer helpful information. The most common etiologies and recommended medications are included in Table 3. It is worthwhile to note that serotonin-antagonists (i.e. ondansetron) are first-line therapies only for chemotherapy and radiation-therapy-induced emesis. If a 24-hour trial of one antiemetic therapy is ineffective, one should reassess the etiology and escalate the antiemetic dose, or add a second therapy with a different (pertinent) mechanism of action. Although most studies of antiemetic therapy are case series, there is good evidence for this mechanistic approach.8

*EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms

The various insults and pathways that can cause vomiting are quite complex. The medullary vomiting center (VC) receives vestibular, peripheral (via splanchnic and vagal nerves), and higher cortical inputs and is the final common pathway in the vomiting reflex. The chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) near the fourth ventricle receives input from the vagal and splanchnic nerves, and generates output to the VC.

General dietary recommendations are to avoid sweet, fatty, and highly salted or spiced foods. Small portions of bland foods without strong odors are best tolerated.7 Constipation commonly contributes to nausea and vomiting and should be managed with disimpaction, enemas, and laxatives as tolerated. Imaging may be required to make the important distinction between partial and complete bowel obstruction, as the treatments differ. Surgical procedures, such as colostomy or placement of a venting gastrostomy tube, can relieve pain and vomiting associated with complete bowel obstruction.

Back to the Case

The patient is found to have a fecal impaction on rectal exam, but vomiting persists after disimpaction and enema use. Imaging documents a complete bowel obstruction at the site of a palpable mass in the right upper quadrant and multiple large hepatic metastases. Octreotide is initiated to decrease intestinal secretions and peristalsis. Steroids are given to decrease tumor burden and associated inflammation in the intestine and liver, as well as to relieve distension of the hepatic capsule. Haloperidol is used in low doses to control episodes of nausea.

Review of the Data: Dyspnea

Dyspnea is a common symptom faced by patients at EOL. An estimated 50% of patients who are evaluated in acute-care hospitals seek treatment for the management of this often-crippling symptom.10 Unfortunately, as disease burden progresses, the incidence of dyspnea increases towards EOL, and the presence and severity of dyspnea is strongly correlated with mortality.

It is imperative for providers to appreciate that dyspnea is a subjective symptom, similar to pain. The presence and severity of dyspnea, therefore, depends on patient report. Given its subjective nature, the degree of dyspnea experienced by a patient might not correlate with objective laboratory findings or test results. In practice, the severity of dyspnea is commonly assessed with a numeric rating scale (0-10), verbal analogue scale, or with verbal descriptors (mild, moderate, severe). It is important to determine the underlying etiology of the dyspnea and, if possible, to target interventions to relieve the underlying cause. However, at the end of life, the burdens of invasive studies to determine the exact cause of dyspnea might outweigh the benefits, and invasive testing might not correlate with patients’ and families’ goals of care. In that instance, the goal of treatment should be aggressive symptom management and providers should use clinical judgment to tailor therapies based on the patient’s underlying illness, physical examination, and perhaps on noninvasive radiological or laboratory findings. Below are nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions that can be employed to help alleviate dyspnea in the actively dying patient.

Nonpharmacological Management

A handheld fan aimed near the patient’s face has been shown to reduce the sensation of dyspnea.11 This relatively safe and inexpensive intervention has no major side effects and can provide improvement in this distressing symptom.

Often, the first line of therapy in the hospital setting for a patient reporting dyspnea is the administration of oxygen therapy. However, recent evidence does not show superiority of oxygen over air inhalation via nasal prongs for dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer or heart failure.12,13

Pharmacological Management

Opioids are first-line therapy for alleviating dyspnea in patients at EOL. The administration of opioids has been shown in systematic reviews to provide effective management of dyspnea.14,15 Practice guidelines by leading expert groups advocate for the use of opioids in the management of dyspnea for patients with advanced malignant and noncancer diseases.10,16 Fear of causing unintended respiratory sedation with opioids limits the prescription of opioids for dyspnea. However, studies have not found a change in mortality with the use of opioids appropriately titrated to control dyspnea.17

Studies examining the role of benzodiazepines in dyspnea management are conflicting. Anecdotal clinical evidence in actively dying patients supports treating dyspnea with benzodiazepines in conjunction with opioid therapy. Benzodiazepines are most beneficial when there is an anxiety-related component to the dyspnea.

Many patients with advanced disease and evidence of airflow obstruction will benefit from nebulized bronchodilator therapy for dyspnea. Patients with dyspnea from fluid overload (i.e. end-stage congestive heart failure or renal disease) might benefit from systemic diuretics. An increasing number of trials are under way to evaluate the efficacy of nebulized furosemide in the symptomatic management of dyspnea.

Back to the Case

The patient’s clinical course decompensates, and he begins to report worsening dyspnea in addition to his underlying pain. He becomes increasingly anxious about what this new symptom means. In addition to having a discussion about disease progression and prognosis, you increase his PCA basal dose to morphine 4 mg/hour to help him with this new symptom. You also add low-dose lorazepam 0.5 mg IV q8 hours as an adjunct agent for his dyspnea. The patient reports improvement of his symptom burden.

Review of the Data: Secretions

Physiological changes occur as a patient enters the active phase of dying. Two such changes are the loss of the ability to swallow and a reduced cough reflex. These changes culminate in an inability to clear secretions, which pool in the oropharynx and the airways. As the patient breathes, air moves over the pooled secretions and produces a gurgling sound that is referred to as the “death rattle.” The onset of this clinical marker has been shown to have significant prognostic significance for predicting imminent death within a period of hours to days. Proposed treatments for the symptom are listed below.

Nonpharmacological Management

Nonpharmacological options include repositioning the patient in a manner that facilitates postural draining.18 Careful and gentle oral suctioning might help reduce secretions if they are salivary in origin. This will not help to clear deeper bronchial secretions. Suctioning of deeper secretions often causes more burden than benefit, as this can cause repeated trauma and possible bleeding.

Family and caregivers at the bedside can find the “death rattle” quite disturbing and often fear that their loved one is “drowning.” Education and counseling that this is not the case, and that the development of secretions is a natural part of the dying process, can help alleviate this concern. Explaining that pharmacological agents can be titrated to decrease secretions is also reassuring to caregivers.

Pharmacological Management

Pharmacological options for secretion management include utilizing anticholinergic medications to prevent the formation of further secretions. These medications are standard of care for managing the death rattle and have been found to be most efficacious if started earlier in the actively dying phase.19,20 Anticholinergic medications include glycopyrrolate (0.2 mg IV q8 hours), atropine sulfate ophthalmological drops (1% solution, 1-2 drops SL q6 hours), hyoscyamine (0.125 mg one to four times a day), and scopolamine (1.5 mg patch q72 hours). These medications all have possible side effects typical of anticholinergic agents, including delirium, constipation, blurred vision, and urinary retention.

Back to the Case

The patient becomes increasingly lethargic. You meet with his family and explain that he is actively dying. His family reiterates that the goals of medical care should focus on maximizing symptom management. His family is concerned about the “gurgly” sound they hear and want to know if that means he is suffering. You educate the family about expected changes that occur with the dying process and inform them that glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg IV q8 hour will be started to minimize further secretions.

Bottom Line

Pain, nausea, dyspnea, and secretions are common end-of-life symptoms that hospitalists should be competent in treating.

Dr. Litrivis is an associate director and assistant professor at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, and Dr. Neale is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

References

- The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve the care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591-1598.

- World Health Organization Definition of Palliative Care. World Health Organization website. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed April 12, 2012.

- NCCN Guidelines Version 2. 2011 Adult Cancer Pain. National Comprehensive Cancer Network website. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pain.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2012.

- Whitecar PS, Jonas AP, Clasen ME. Managing pain in the dying patient. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(3):755-764.

- Bial A, Levine S. Assessment and treatment of physical pain associated with life-limiting illness. Hospice and Palliative Care Training for Physicians: UNIPAC. Vol 3. 3rd ed. Glenview, IL: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2008.

- Sydney M, et al. Evidence-based standards for cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(23):3879-3885.

- Mannix KA. Gastrointestinal symptoms. In: Doyle D, Hanks G, Cherny N, Calman K, eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Tyler LS. Nausea and vomiting in palliative care. In: Lipman AG, Jackson KC, Tyler LS, eds. Evidence-Based Symptom Control in Palliative Care. New York, NY: The Hawthorn Press; 2000.

- Policzer JS, Sobel J. Management of Selected Nonpain Symptoms of Life-Limiting Illness. Hospice and Palliative Care Training for Physicians: UNIPAC. Vol 4. 3rd ed. Glenview, IL: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2008.

- Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(4): 435-452.

- Galbraith S, Fagan P, Perkins P, Lynch A, Booth S. Does the use of a handheld fan improve chronic dyspnea? A randomized controlled, crossover trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(5): 831-838.

- Philip J, Gold M, Milner A, Di Iulio J, Miller B, Spruyt O. A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial of the effect of oxygen on dyspnea in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(6):541-550.

- Cranston JM, Crockett A, Currow D. Oxygen therapy for dyspnea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD004769.

- Jennings AL, Davies AN, Higgins JP, Broadley K. Opioids for the palliation of breathlessness in terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(4):CD002066.

- Ben-Aharon I, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Leibovici, L, Stemmer, SM. Interventions for alleviating cancer-related dyspnea. A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(14): 2396-2404.

- Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, et al. Evidence-based interventions to improve the palliative care of pain, dyspnea, and depression at the end of life: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(2):141-146

- Booth S, Moosavi SH, Higginson IJ. The etiology and management of intractable breathlessness in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review of pharmacological therapy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5(2):90–100.

- Bickel K, Arnold R. EPERC Fast Facts Documents #109 Death Rattle and Oral Secretions, 2nd ed. Available at: http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_109.htm. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- Wildiers H, Dhaenekint C, Demeulenaere P, et al. Atropine, hyoscine butylbromide, or scopalamine are equally effective for the treatment of death rattle in terminal care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(1):124-133.

- Hugel H, Ellershaw J, Gambles M. Respiratory tract secretions in the dying patient: a comparison between glycopyrronium and hyoscine hydrobromide. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(2):279-285.

Case

A 58-year-old male with colon cancer metastatic to the liver and lungs presents with vomiting, dyspnea, and abdominal pain. His disease has progressed through third-line chemotherapy and his care is now focused entirely on symptom management. He has not had a bowel movement in five days and he began vomiting two days ago.

Overview

The majority of patients in the United States die in acute-care hospitals. The Study to Understand Prognosis and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT), which evaluated the courses of close to 10,000 hospitalized patients with serious and life-limiting illnesses, illustrated that patients’ end-of-life (EOL) experiences often are characterized by poor symptom management and invasive care that is not congruent with the patients’ overall goals of care.1 Studies of factors identified as priorities in EOL care have consistently shown that excellent pain and symptom management are highly valued by patients and families. As the hospitalist movement continues to grow, hospitalists will play a large role in caring for patients at EOL and will need to know how to provide adequate pain and symptom management so that high-quality care can be achieved.

Pain: A Basic Tenet