User login

Afghan-Born Hospitalist Gives Back through Free California Clinic

When Ahmad Nooristani, MD, became a physician, part of his motivation was to help his native country. “I wanted to become a physician so that I could give back,” says Dr. Nooristani, who emigrated to the U.S. from Afghanistan in 1981. He graduated medical school in 2008.

One way to address preventive care for the uninsured, he reasoned, was to open a free clinic. In 2009, in addition to his seven-on/seven-off duties as a hospitalist, Dr. Nooristani began work on establishing a clinic for uninsured patients in his new hometown. Almost three years and countless fundraising events later, the Noor Foundation Clinic opened its doors in October 2011, offering not just primary care but ophthalmologic examinations, nutrition counseling, physical therapy, and point-of-service testing, too. For now, the clinic is open Friday and Saturday afternoons; all care is free.

Dr. Nooristani has worked 20 hours a week on the project. He’s recruited 400 volunteers, ranging from high-level administrators from the county’s hospitals to community fundraisers to off-duty nurses and physician colleagues.

“He’s a hard-working guy and is always looking for ways to improve things,” says hospitalist colleague Christian Voge, MD, medical director and president of San Luis Hospitalists. “I think he saw a need and is trying to give back.”

A Gap to Fill

Located on the central coast of California, San Luis Obispo County has a population of 269,637, according to 2010 U.S. Census figures. County public health officer Penny A. Borenstein, MD, MPH, says that figures from such surveys as the California Health Interview Survey and the Census Bureau indicate that approximately 35,000 of the county’s residents had no health insurance at some point in the last 12 months. The number of those who are underinsured (i.e. who carry minimal catastrophic insurance with high deductibles) is harder to quantify.

——Christian Voge, MD, medical director and president, San Luis Hospitalists AMC

Although other clinic options exist in the county, through Medi-Cal and the County Medical Services Program, Dr. Borenstein believes that the Noor Foundation Clinic will help address gaps.

“Even a sliding scale fee [such as those charged by community health centers] can sometimes be a deterrent to people,” she notes. “I give [Dr. Nooristani] many kudos for taking the bull by the horn and saying, ‘Let’s at least try to put something together to help fill the gaps in a very imperfect healthcare system.’”

New Skills Acquired

During an interview just days after the clinic opened its doors, Dr. Nooristani voiced some amazement about the long permitting process. “The hoops you have to jump through—it’s unbelievable,” he said.

Subject to federal, state, and county regulations, the clinic had to be retrofitted with a $25,000 air filtration and ducting system, among other upgrades. As a result, the foundation was paying rent for two years before the clinic opened its doors. “I could have seen a few thousand patients,” Dr. Nooristani says. “I mean, think about the complications I could have prevented.”

Still, he’s philosophical about the process. “On the flipside, I’m glad I did it this way. As tedious and time-consuming as it was, it served the purpose of bringing the whole community together,” he says.

Fundraising events for the foundation, as well as private donations, raised a total of $80,000 in a two-year period. Just before the clinic opened, the San Luis Obispo County Board of Supervisors approved a $75,000 grant to the Noor Foundation to cover the annual costs of point-of-service testing. And a broad swath of the county’s office holders, healthcare administrators, and community leaders attended the clinic’s grand opening.

Geared to the Patient

Keeping in mind his patient population, Dr. Nooristani plans to incorporate patient education on managing chronic illnesses. An ophthalmologist has volunteered one day a month. A separate optometric examination room is outfitted with all the requisite equipment, and eyeglasses have been donated.

Furnished tastefully throughout, the clinic does not have the stark quality sometimes associated with free clinics. Dr. Nooristani also is respectful of patients’ time: “I don’t want anybody sitting in the waiting room for more than 30 minutes,” he says.

That’s why the appointment calendar is structured to accommodate future appointments, and he currently staffs each clinic day with two physicians and additional providers. He’s also savvy about his use of volunteers, limiting their hours to avoid burnout. (Listen to Dr. Nooristani talk about access to preventive care and starting free clinics.)

Catching Fire

Dr. Nooristani already has his sights set on more clinics, hopefully in his home country. In the meantime, though, he says, “people need care here.”

Like the meaning of the clinic name (“noor” means hope, and his name translates to “land of hope”), he hopes to inspire others to follow his lead. “Any community, big or small, can do this,” he says, enthusiasm in his voice. “You just have to keep your eyes on the prize.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

When Ahmad Nooristani, MD, became a physician, part of his motivation was to help his native country. “I wanted to become a physician so that I could give back,” says Dr. Nooristani, who emigrated to the U.S. from Afghanistan in 1981. He graduated medical school in 2008.

One way to address preventive care for the uninsured, he reasoned, was to open a free clinic. In 2009, in addition to his seven-on/seven-off duties as a hospitalist, Dr. Nooristani began work on establishing a clinic for uninsured patients in his new hometown. Almost three years and countless fundraising events later, the Noor Foundation Clinic opened its doors in October 2011, offering not just primary care but ophthalmologic examinations, nutrition counseling, physical therapy, and point-of-service testing, too. For now, the clinic is open Friday and Saturday afternoons; all care is free.

Dr. Nooristani has worked 20 hours a week on the project. He’s recruited 400 volunteers, ranging from high-level administrators from the county’s hospitals to community fundraisers to off-duty nurses and physician colleagues.

“He’s a hard-working guy and is always looking for ways to improve things,” says hospitalist colleague Christian Voge, MD, medical director and president of San Luis Hospitalists. “I think he saw a need and is trying to give back.”

A Gap to Fill

Located on the central coast of California, San Luis Obispo County has a population of 269,637, according to 2010 U.S. Census figures. County public health officer Penny A. Borenstein, MD, MPH, says that figures from such surveys as the California Health Interview Survey and the Census Bureau indicate that approximately 35,000 of the county’s residents had no health insurance at some point in the last 12 months. The number of those who are underinsured (i.e. who carry minimal catastrophic insurance with high deductibles) is harder to quantify.

——Christian Voge, MD, medical director and president, San Luis Hospitalists AMC

Although other clinic options exist in the county, through Medi-Cal and the County Medical Services Program, Dr. Borenstein believes that the Noor Foundation Clinic will help address gaps.

“Even a sliding scale fee [such as those charged by community health centers] can sometimes be a deterrent to people,” she notes. “I give [Dr. Nooristani] many kudos for taking the bull by the horn and saying, ‘Let’s at least try to put something together to help fill the gaps in a very imperfect healthcare system.’”

New Skills Acquired

During an interview just days after the clinic opened its doors, Dr. Nooristani voiced some amazement about the long permitting process. “The hoops you have to jump through—it’s unbelievable,” he said.

Subject to federal, state, and county regulations, the clinic had to be retrofitted with a $25,000 air filtration and ducting system, among other upgrades. As a result, the foundation was paying rent for two years before the clinic opened its doors. “I could have seen a few thousand patients,” Dr. Nooristani says. “I mean, think about the complications I could have prevented.”

Still, he’s philosophical about the process. “On the flipside, I’m glad I did it this way. As tedious and time-consuming as it was, it served the purpose of bringing the whole community together,” he says.

Fundraising events for the foundation, as well as private donations, raised a total of $80,000 in a two-year period. Just before the clinic opened, the San Luis Obispo County Board of Supervisors approved a $75,000 grant to the Noor Foundation to cover the annual costs of point-of-service testing. And a broad swath of the county’s office holders, healthcare administrators, and community leaders attended the clinic’s grand opening.

Geared to the Patient

Keeping in mind his patient population, Dr. Nooristani plans to incorporate patient education on managing chronic illnesses. An ophthalmologist has volunteered one day a month. A separate optometric examination room is outfitted with all the requisite equipment, and eyeglasses have been donated.

Furnished tastefully throughout, the clinic does not have the stark quality sometimes associated with free clinics. Dr. Nooristani also is respectful of patients’ time: “I don’t want anybody sitting in the waiting room for more than 30 minutes,” he says.

That’s why the appointment calendar is structured to accommodate future appointments, and he currently staffs each clinic day with two physicians and additional providers. He’s also savvy about his use of volunteers, limiting their hours to avoid burnout. (Listen to Dr. Nooristani talk about access to preventive care and starting free clinics.)

Catching Fire

Dr. Nooristani already has his sights set on more clinics, hopefully in his home country. In the meantime, though, he says, “people need care here.”

Like the meaning of the clinic name (“noor” means hope, and his name translates to “land of hope”), he hopes to inspire others to follow his lead. “Any community, big or small, can do this,” he says, enthusiasm in his voice. “You just have to keep your eyes on the prize.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

When Ahmad Nooristani, MD, became a physician, part of his motivation was to help his native country. “I wanted to become a physician so that I could give back,” says Dr. Nooristani, who emigrated to the U.S. from Afghanistan in 1981. He graduated medical school in 2008.

One way to address preventive care for the uninsured, he reasoned, was to open a free clinic. In 2009, in addition to his seven-on/seven-off duties as a hospitalist, Dr. Nooristani began work on establishing a clinic for uninsured patients in his new hometown. Almost three years and countless fundraising events later, the Noor Foundation Clinic opened its doors in October 2011, offering not just primary care but ophthalmologic examinations, nutrition counseling, physical therapy, and point-of-service testing, too. For now, the clinic is open Friday and Saturday afternoons; all care is free.

Dr. Nooristani has worked 20 hours a week on the project. He’s recruited 400 volunteers, ranging from high-level administrators from the county’s hospitals to community fundraisers to off-duty nurses and physician colleagues.

“He’s a hard-working guy and is always looking for ways to improve things,” says hospitalist colleague Christian Voge, MD, medical director and president of San Luis Hospitalists. “I think he saw a need and is trying to give back.”

A Gap to Fill

Located on the central coast of California, San Luis Obispo County has a population of 269,637, according to 2010 U.S. Census figures. County public health officer Penny A. Borenstein, MD, MPH, says that figures from such surveys as the California Health Interview Survey and the Census Bureau indicate that approximately 35,000 of the county’s residents had no health insurance at some point in the last 12 months. The number of those who are underinsured (i.e. who carry minimal catastrophic insurance with high deductibles) is harder to quantify.

——Christian Voge, MD, medical director and president, San Luis Hospitalists AMC

Although other clinic options exist in the county, through Medi-Cal and the County Medical Services Program, Dr. Borenstein believes that the Noor Foundation Clinic will help address gaps.

“Even a sliding scale fee [such as those charged by community health centers] can sometimes be a deterrent to people,” she notes. “I give [Dr. Nooristani] many kudos for taking the bull by the horn and saying, ‘Let’s at least try to put something together to help fill the gaps in a very imperfect healthcare system.’”

New Skills Acquired

During an interview just days after the clinic opened its doors, Dr. Nooristani voiced some amazement about the long permitting process. “The hoops you have to jump through—it’s unbelievable,” he said.

Subject to federal, state, and county regulations, the clinic had to be retrofitted with a $25,000 air filtration and ducting system, among other upgrades. As a result, the foundation was paying rent for two years before the clinic opened its doors. “I could have seen a few thousand patients,” Dr. Nooristani says. “I mean, think about the complications I could have prevented.”

Still, he’s philosophical about the process. “On the flipside, I’m glad I did it this way. As tedious and time-consuming as it was, it served the purpose of bringing the whole community together,” he says.

Fundraising events for the foundation, as well as private donations, raised a total of $80,000 in a two-year period. Just before the clinic opened, the San Luis Obispo County Board of Supervisors approved a $75,000 grant to the Noor Foundation to cover the annual costs of point-of-service testing. And a broad swath of the county’s office holders, healthcare administrators, and community leaders attended the clinic’s grand opening.

Geared to the Patient

Keeping in mind his patient population, Dr. Nooristani plans to incorporate patient education on managing chronic illnesses. An ophthalmologist has volunteered one day a month. A separate optometric examination room is outfitted with all the requisite equipment, and eyeglasses have been donated.

Furnished tastefully throughout, the clinic does not have the stark quality sometimes associated with free clinics. Dr. Nooristani also is respectful of patients’ time: “I don’t want anybody sitting in the waiting room for more than 30 minutes,” he says.

That’s why the appointment calendar is structured to accommodate future appointments, and he currently staffs each clinic day with two physicians and additional providers. He’s also savvy about his use of volunteers, limiting their hours to avoid burnout. (Listen to Dr. Nooristani talk about access to preventive care and starting free clinics.)

Catching Fire

Dr. Nooristani already has his sights set on more clinics, hopefully in his home country. In the meantime, though, he says, “people need care here.”

Like the meaning of the clinic name (“noor” means hope, and his name translates to “land of hope”), he hopes to inspire others to follow his lead. “Any community, big or small, can do this,” he says, enthusiasm in his voice. “You just have to keep your eyes on the prize.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

Online System Doesn’t Affect Pneumonia, Heart Attack Mortality Rates

A study released in the past week shows that Hospital Compare, Medicare's online system for patients to compare the efficacy of hospitals, had little or no impact on 30-day mortality rates for three common inpatient conditions. But a leading hospitalist says the findings should not detract from the value of transparency in medical performance.

"It's version 1.0 of public reporting," says Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass. "To expect that it's going to lower mortality rates in the first iteration, it's not a realistic expectation. ... It's the beginning of a very long journey. We have to take the long view."

The Health Affairs report, “Medicare's Public Reporting Initiatives on Hospital Quality Had Modest Or No Impact on Morality From Three Key Conditions," found that public reporting had no impact on the mortality rates for heart attacks and pneumonia and "minimal impact" on heart-failure cases. The authors, who analyzed Medicare claims data from 2000 to 2008, also suggested that Hospital Compare "did not result in patients being directed toward higher-quality hospitals."

Dr. Whitcomb says he's not surprised by the results, given other literature that has shown limited impacts from public reporting. But he sees an opportunity to build better reporting systems, via in-person, electronic, or mobile portals that are more focused on user interface. For example, he says, it takes about 22 minutes to review a single patient's file for reported measurements in a heart-failure case. Automating that process would give hospitalists and other physicians additional time to deal directly with patients.

"What the quality initiative movement has to figure out is how to spend more time on making care better and less time on measurement and reporting," Dr. Whitcomb says. "Often, the important work of changing care to make it more evidence-based ... doesn’t get the focus."

A study released in the past week shows that Hospital Compare, Medicare's online system for patients to compare the efficacy of hospitals, had little or no impact on 30-day mortality rates for three common inpatient conditions. But a leading hospitalist says the findings should not detract from the value of transparency in medical performance.

"It's version 1.0 of public reporting," says Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass. "To expect that it's going to lower mortality rates in the first iteration, it's not a realistic expectation. ... It's the beginning of a very long journey. We have to take the long view."

The Health Affairs report, “Medicare's Public Reporting Initiatives on Hospital Quality Had Modest Or No Impact on Morality From Three Key Conditions," found that public reporting had no impact on the mortality rates for heart attacks and pneumonia and "minimal impact" on heart-failure cases. The authors, who analyzed Medicare claims data from 2000 to 2008, also suggested that Hospital Compare "did not result in patients being directed toward higher-quality hospitals."

Dr. Whitcomb says he's not surprised by the results, given other literature that has shown limited impacts from public reporting. But he sees an opportunity to build better reporting systems, via in-person, electronic, or mobile portals that are more focused on user interface. For example, he says, it takes about 22 minutes to review a single patient's file for reported measurements in a heart-failure case. Automating that process would give hospitalists and other physicians additional time to deal directly with patients.

"What the quality initiative movement has to figure out is how to spend more time on making care better and less time on measurement and reporting," Dr. Whitcomb says. "Often, the important work of changing care to make it more evidence-based ... doesn’t get the focus."

A study released in the past week shows that Hospital Compare, Medicare's online system for patients to compare the efficacy of hospitals, had little or no impact on 30-day mortality rates for three common inpatient conditions. But a leading hospitalist says the findings should not detract from the value of transparency in medical performance.

"It's version 1.0 of public reporting," says Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass. "To expect that it's going to lower mortality rates in the first iteration, it's not a realistic expectation. ... It's the beginning of a very long journey. We have to take the long view."

The Health Affairs report, “Medicare's Public Reporting Initiatives on Hospital Quality Had Modest Or No Impact on Morality From Three Key Conditions," found that public reporting had no impact on the mortality rates for heart attacks and pneumonia and "minimal impact" on heart-failure cases. The authors, who analyzed Medicare claims data from 2000 to 2008, also suggested that Hospital Compare "did not result in patients being directed toward higher-quality hospitals."

Dr. Whitcomb says he's not surprised by the results, given other literature that has shown limited impacts from public reporting. But he sees an opportunity to build better reporting systems, via in-person, electronic, or mobile portals that are more focused on user interface. For example, he says, it takes about 22 minutes to review a single patient's file for reported measurements in a heart-failure case. Automating that process would give hospitalists and other physicians additional time to deal directly with patients.

"What the quality initiative movement has to figure out is how to spend more time on making care better and less time on measurement and reporting," Dr. Whitcomb says. "Often, the important work of changing care to make it more evidence-based ... doesn’t get the focus."

Pioneering Hospitalists Earn Masters of Hospital Medicine Designation

Three pioneering hospitalists will join seven distinguished colleagues at the pinnacle of recognition from their field when SHM inducts them as Masters of Hospital Medicine (MHM) at HM12 in San Diego in April, singling them out for what the society calls "the utmost demonstration of dedication to the field of hospital medicine through significant contributions to the development and maturation of the profession."

While the practice of hospital medicine can be personally satisfying, leadership positions are even more gratifying from developing "systems of care that affect not just my own patients but all patients in the hospital," says Patrick J. Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, CPE, FACP, FACHE, chief medical officer at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Medical Center in Charleston, where he is responsible for the quality and safety of all of its patient care programs and clinical service lines.

Dr. Cawley, one of this year's MHM honorees, is a past president of SHM. He founded an HM program at Duke University and later managed a private HM practice in Conway, S.C., before coming to MUSC.

Peter Lindenauer, MD, MSc, MHM, FACP, who now directs the Center for Quality of Care Research at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., is also being honored. Hired as a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco in July 1996, he was a founding SHM board member, then called the National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP).

Since moving to Baystate, Dr. Lindenauer has held leadership roles in quality improvement, clinical informatics, and research. His center studies the quality and outcomes of hospital care, the effectiveness of treatments and care strategies for patients with common medical conditions, and methods for translating evidence-based treatments into routine clinical practice.

The third honoree, Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, now leads one of the largest hospitalist practices in an academic setting, but he also founded one of the first hospitalist groups at an inner city public hospital, Grady Hospital in Atlanta, in 1998.

An inaugural fellow of hospital medicine, a past president of SHM, and founding editor-in-chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Williams has served on numerous SHM committees. He is the principal investigator of SHM's Project BOOST, and leads its new Hospitalist Program Peak Performance initiative. His published research focuses on quality improvement (QI), care transitions, teamwork and health literacy.

Three pioneering hospitalists will join seven distinguished colleagues at the pinnacle of recognition from their field when SHM inducts them as Masters of Hospital Medicine (MHM) at HM12 in San Diego in April, singling them out for what the society calls "the utmost demonstration of dedication to the field of hospital medicine through significant contributions to the development and maturation of the profession."

While the practice of hospital medicine can be personally satisfying, leadership positions are even more gratifying from developing "systems of care that affect not just my own patients but all patients in the hospital," says Patrick J. Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, CPE, FACP, FACHE, chief medical officer at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Medical Center in Charleston, where he is responsible for the quality and safety of all of its patient care programs and clinical service lines.

Dr. Cawley, one of this year's MHM honorees, is a past president of SHM. He founded an HM program at Duke University and later managed a private HM practice in Conway, S.C., before coming to MUSC.

Peter Lindenauer, MD, MSc, MHM, FACP, who now directs the Center for Quality of Care Research at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., is also being honored. Hired as a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco in July 1996, he was a founding SHM board member, then called the National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP).

Since moving to Baystate, Dr. Lindenauer has held leadership roles in quality improvement, clinical informatics, and research. His center studies the quality and outcomes of hospital care, the effectiveness of treatments and care strategies for patients with common medical conditions, and methods for translating evidence-based treatments into routine clinical practice.

The third honoree, Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, now leads one of the largest hospitalist practices in an academic setting, but he also founded one of the first hospitalist groups at an inner city public hospital, Grady Hospital in Atlanta, in 1998.

An inaugural fellow of hospital medicine, a past president of SHM, and founding editor-in-chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Williams has served on numerous SHM committees. He is the principal investigator of SHM's Project BOOST, and leads its new Hospitalist Program Peak Performance initiative. His published research focuses on quality improvement (QI), care transitions, teamwork and health literacy.

Three pioneering hospitalists will join seven distinguished colleagues at the pinnacle of recognition from their field when SHM inducts them as Masters of Hospital Medicine (MHM) at HM12 in San Diego in April, singling them out for what the society calls "the utmost demonstration of dedication to the field of hospital medicine through significant contributions to the development and maturation of the profession."

While the practice of hospital medicine can be personally satisfying, leadership positions are even more gratifying from developing "systems of care that affect not just my own patients but all patients in the hospital," says Patrick J. Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, CPE, FACP, FACHE, chief medical officer at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Medical Center in Charleston, where he is responsible for the quality and safety of all of its patient care programs and clinical service lines.

Dr. Cawley, one of this year's MHM honorees, is a past president of SHM. He founded an HM program at Duke University and later managed a private HM practice in Conway, S.C., before coming to MUSC.

Peter Lindenauer, MD, MSc, MHM, FACP, who now directs the Center for Quality of Care Research at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., is also being honored. Hired as a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco in July 1996, he was a founding SHM board member, then called the National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP).

Since moving to Baystate, Dr. Lindenauer has held leadership roles in quality improvement, clinical informatics, and research. His center studies the quality and outcomes of hospital care, the effectiveness of treatments and care strategies for patients with common medical conditions, and methods for translating evidence-based treatments into routine clinical practice.

The third honoree, Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, now leads one of the largest hospitalist practices in an academic setting, but he also founded one of the first hospitalist groups at an inner city public hospital, Grady Hospital in Atlanta, in 1998.

An inaugural fellow of hospital medicine, a past president of SHM, and founding editor-in-chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Williams has served on numerous SHM committees. He is the principal investigator of SHM's Project BOOST, and leads its new Hospitalist Program Peak Performance initiative. His published research focuses on quality improvement (QI), care transitions, teamwork and health literacy.

C. difficile Infections Hit All-Time High

Clostridium difficile infections have reached an all-time high in the United States, and 94% of these infections initiate with medical care, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. C. difficile–related deaths increased from 3,000 in 1999-2000 to 14,000 in 2006-2007, according to the CDC.

The data were published as a CDC Vital Signs report and were presented in a telebriefing on March 6.

C. difficile is "a formidable opponent," and a patient safety issue everywhere that medical care is provided, said Dr. Clifford McDonald, a CDC epidemiologist and the lead author of the report. CDC’s data show that 25% of C. difficile infections first appear in hospitalized patients, while 75% occur either in nursing home residents or in people recently treated in doctors’ offices or clinics. People most at risk are those who take antibiotics and receive care in an outpatient setting.

In general, the risk of developing C. difficile increases with age; although half of C. difficile infections occur in those younger than 65 years, 90% of C. difficile-related deaths occur in those aged 65 years and older, said Dr. McDonald.

He said that clinicians can help reduce C. difficile infections by following six steps:

• Prescribe antibiotics judiciously.

• Be proactive about testing patients for C. difficile if they develop diarrhea while taking antibiotics.

• Isolate patients with C. difficile.

• Wear gloves and gowns when treating C. difficile patients, even for short visits.

• Clean surfaces in exam and treatment rooms with bleach or other spore-killing products.

• When a patient transfers to another facility, notify the medical team about a C. difficile infection.

Also, be sure to order the appropriate cultures to determine whether antibiotics are really needed, Dr. McDonald suggested, and watch for signs that signal C. difficile. "Antibiotic-associated diarrhea is very common," but C. difficile accounts for only about one-third of that, he said.

However, certain clues suggest C. difficile, including more than three unformed stools in 24 hours, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea that continues once an antibiotic has been discontinued, or diarrhea that began only once an antibiotic was discontinued, he said.

If someone has been on antibiotics, think about C. difficile early and get them tested, whether they are patients in inpatient or outpatient facilities, Dr. McDonald emphasized.

To determine the current prevalence of C. difficile, CDC researchers reviewed data from their Emerging Infections Program, which conducted population-based surveillance from eight geographic areas, and the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). In 2010, a total of 10,342 cases of C. difficile infection were identified via the Emerging Infections Program in 2010, and a total of 42,157 incident laboratory-identified CDI events were reported via the NHSN.

On a positive note, early results from state-led programs in Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York showed that hospital collaboration can reduce C. difficile infections, Dr. McDonald said. The 71 hospitals in these states that participated in C. difficile–prevention programs reduced infection rates by 20% over 21 months. "These promising results follow similar efforts in England, a nation that dropped C. difficile infections by more than 50% during a recent 3-year period," the CDC researchers said in the full report (MMWR 2012;61:1-6).

For additional information about tracking HAIs infections, contact the Emerging Infections Program or the NHSN.

Dr. McDonald had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The recent alarm by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention which reports on the increasing incidence and burden of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) in the United States is drawing attention to a phenomenon which is already well- known to gastroenterologists and infectious Ddisease physicians worldwide. In fact, the sweeping changes in the epidemiology of CDI – with reports of increasing rates, outbreaks, and elevated morbidity and mortality since 2002 originally in parts of Canada and the United States – has now been described in almost every developed country which keeps statistics on this infection.

The only fact which is even more alarming in the CDC’s report is that there has not been any “leveling off” or abatement in this health care–associated complication in the U.S. Although GI and ID physicians, hospitalists, and many other health care providers around the globe have been aware of the disquieting rise in CDI since 2002, the hoped-for stabilization or reduction in its incidence due to aggressive infection prevention and control (IPC) techniques, as has been seen in the U.K., has not materialized in the U.S. and central Canada.

Why is it so difficult to control CDI? Because it requires the accomplishment of multiple simultaneous aggressive IPC maneuvers – all of which must be done correctly -– in order to overcome this infection on an institutional level:

- Appropriate antimicrobial use and stewardship- Rapid testing, isolation, and treatment of any patient with diarrhea who has recently received antibiotics, while awaiting test results

- Rigorous hand-washing and appropriate use of personal protective equipment when in contact with suspected or confirmed cases

- Meticulous and frequent environmental cleaning with sporicidal agents which are tolerable to patients and personnel

- Attention to cleaning and disinfection of the innumerable shared pieces of medical equipment, like blood pressure cuffs, thermometers, bladder scanners, and the like

- High level of scrutiny for quickly detecting and treating recurrences, which occur in 15%-40% of CDI patients

- Real-time surveillance to detect outbreaks and effect heightened measures, when necessary.

The “new CDI” has demonstrated itself to be an unforgiving infection in health care facilities. Any lapse in one or more of the above IPC interventions is enough to cause a rise in the incidence or complication rate.

It is unclear exactly why the “new CDI” is behaving as it does. Certainly, the appearance of a new hyper-virulent strain with additional fluoroquinolone resistance (on top of C. difficile’s “usual” multi-drug resistance), a mutation in the toxin regulator gene, and a seemingly greater propensity to sporulate (and thus resist disinfection) appears to be the event which has coincided with the re-emergence of this disease during the past 10 years.

However, not all of the clinical aspects of this “new CDI” can be explained by these findings alone. For instance, the rapid progression from diarrhea to fulminant colitis in the elderly and the immunocompromised, the high recurrence rate (compared with historical controls) and the elevated morbidity (i.e., colectomy and need for intensive care) and mortality remain unnerving manifestations without a real explanation.

The number of scientific publications describing the new epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prophylactic or treatment options has risen impressively over the past several years in order to gain an understanding of this relentless bacterium.

Medical journals are not the only place for CDI-related news, however. The internet and social media sites are rife with stories of personal tragedies from this affliction. Typical stories like a healthy grandfather undergoing uncomplicated elective surgery but then dying from antibiotic-induced CDI during or soon after his hospitalization are too commonly detailed in surveillance data and in personal blogs.

Sites dedicated to and run by patients who have suffered from CDI compete with other sites established by the all-too-commonly depressed individuals who have had to undergo a therapeutic colectomy or who are suffering multiple recurrences of this disease and are searching for centers offering a fecal transplant.

There is no doubt that the true tragedy of CDI, a health care complication with an attributable mortality of almost 15% in the frail elderly over 85 years of age, is the fact that it is more likely to kill than the primary cause of hospitalization (such as a pneumonia, cellulitis, or hip fracture) in this population.

At a time when CDI is clearly overcoming our ability to control it in many parts of the world, it remains puzzling why the U.S. and many European countries do not yet have a true, real-time local and national CDI surveillance network for tracking the number of cases.

Using hospital discharge data or disease coding has been shown to be inaccurate and too late to be of immediate use. Real-time local, state, and national CDI surveillance is essential in telling us where we are, where we are going, and what we have to do to control this affliction. There is clearly a battle going on between health care providers and CDI in many countries, including the U.S. and Canada. We need to use as many tools and tricks as possible to gain control. This is one war we cannot afford to lose.

MARK MILLER, M.D., FRCPC, is Chief, Infectious Diseases, and Head, Infection Prevention and Control Unit, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal.

The recent alarm by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention which reports on the increasing incidence and burden of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) in the United States is drawing attention to a phenomenon which is already well- known to gastroenterologists and infectious Ddisease physicians worldwide. In fact, the sweeping changes in the epidemiology of CDI – with reports of increasing rates, outbreaks, and elevated morbidity and mortality since 2002 originally in parts of Canada and the United States – has now been described in almost every developed country which keeps statistics on this infection.

The only fact which is even more alarming in the CDC’s report is that there has not been any “leveling off” or abatement in this health care–associated complication in the U.S. Although GI and ID physicians, hospitalists, and many other health care providers around the globe have been aware of the disquieting rise in CDI since 2002, the hoped-for stabilization or reduction in its incidence due to aggressive infection prevention and control (IPC) techniques, as has been seen in the U.K., has not materialized in the U.S. and central Canada.

Why is it so difficult to control CDI? Because it requires the accomplishment of multiple simultaneous aggressive IPC maneuvers – all of which must be done correctly -– in order to overcome this infection on an institutional level:

- Appropriate antimicrobial use and stewardship- Rapid testing, isolation, and treatment of any patient with diarrhea who has recently received antibiotics, while awaiting test results

- Rigorous hand-washing and appropriate use of personal protective equipment when in contact with suspected or confirmed cases

- Meticulous and frequent environmental cleaning with sporicidal agents which are tolerable to patients and personnel

- Attention to cleaning and disinfection of the innumerable shared pieces of medical equipment, like blood pressure cuffs, thermometers, bladder scanners, and the like

- High level of scrutiny for quickly detecting and treating recurrences, which occur in 15%-40% of CDI patients

- Real-time surveillance to detect outbreaks and effect heightened measures, when necessary.

The “new CDI” has demonstrated itself to be an unforgiving infection in health care facilities. Any lapse in one or more of the above IPC interventions is enough to cause a rise in the incidence or complication rate.

It is unclear exactly why the “new CDI” is behaving as it does. Certainly, the appearance of a new hyper-virulent strain with additional fluoroquinolone resistance (on top of C. difficile’s “usual” multi-drug resistance), a mutation in the toxin regulator gene, and a seemingly greater propensity to sporulate (and thus resist disinfection) appears to be the event which has coincided with the re-emergence of this disease during the past 10 years.

However, not all of the clinical aspects of this “new CDI” can be explained by these findings alone. For instance, the rapid progression from diarrhea to fulminant colitis in the elderly and the immunocompromised, the high recurrence rate (compared with historical controls) and the elevated morbidity (i.e., colectomy and need for intensive care) and mortality remain unnerving manifestations without a real explanation.

The number of scientific publications describing the new epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prophylactic or treatment options has risen impressively over the past several years in order to gain an understanding of this relentless bacterium.

Medical journals are not the only place for CDI-related news, however. The internet and social media sites are rife with stories of personal tragedies from this affliction. Typical stories like a healthy grandfather undergoing uncomplicated elective surgery but then dying from antibiotic-induced CDI during or soon after his hospitalization are too commonly detailed in surveillance data and in personal blogs.

Sites dedicated to and run by patients who have suffered from CDI compete with other sites established by the all-too-commonly depressed individuals who have had to undergo a therapeutic colectomy or who are suffering multiple recurrences of this disease and are searching for centers offering a fecal transplant.

There is no doubt that the true tragedy of CDI, a health care complication with an attributable mortality of almost 15% in the frail elderly over 85 years of age, is the fact that it is more likely to kill than the primary cause of hospitalization (such as a pneumonia, cellulitis, or hip fracture) in this population.

At a time when CDI is clearly overcoming our ability to control it in many parts of the world, it remains puzzling why the U.S. and many European countries do not yet have a true, real-time local and national CDI surveillance network for tracking the number of cases.

Using hospital discharge data or disease coding has been shown to be inaccurate and too late to be of immediate use. Real-time local, state, and national CDI surveillance is essential in telling us where we are, where we are going, and what we have to do to control this affliction. There is clearly a battle going on between health care providers and CDI in many countries, including the U.S. and Canada. We need to use as many tools and tricks as possible to gain control. This is one war we cannot afford to lose.

MARK MILLER, M.D., FRCPC, is Chief, Infectious Diseases, and Head, Infection Prevention and Control Unit, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal.

The recent alarm by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention which reports on the increasing incidence and burden of Clostridium difficile infections (CDI) in the United States is drawing attention to a phenomenon which is already well- known to gastroenterologists and infectious Ddisease physicians worldwide. In fact, the sweeping changes in the epidemiology of CDI – with reports of increasing rates, outbreaks, and elevated morbidity and mortality since 2002 originally in parts of Canada and the United States – has now been described in almost every developed country which keeps statistics on this infection.

The only fact which is even more alarming in the CDC’s report is that there has not been any “leveling off” or abatement in this health care–associated complication in the U.S. Although GI and ID physicians, hospitalists, and many other health care providers around the globe have been aware of the disquieting rise in CDI since 2002, the hoped-for stabilization or reduction in its incidence due to aggressive infection prevention and control (IPC) techniques, as has been seen in the U.K., has not materialized in the U.S. and central Canada.

Why is it so difficult to control CDI? Because it requires the accomplishment of multiple simultaneous aggressive IPC maneuvers – all of which must be done correctly -– in order to overcome this infection on an institutional level:

- Appropriate antimicrobial use and stewardship- Rapid testing, isolation, and treatment of any patient with diarrhea who has recently received antibiotics, while awaiting test results

- Rigorous hand-washing and appropriate use of personal protective equipment when in contact with suspected or confirmed cases

- Meticulous and frequent environmental cleaning with sporicidal agents which are tolerable to patients and personnel

- Attention to cleaning and disinfection of the innumerable shared pieces of medical equipment, like blood pressure cuffs, thermometers, bladder scanners, and the like

- High level of scrutiny for quickly detecting and treating recurrences, which occur in 15%-40% of CDI patients

- Real-time surveillance to detect outbreaks and effect heightened measures, when necessary.

The “new CDI” has demonstrated itself to be an unforgiving infection in health care facilities. Any lapse in one or more of the above IPC interventions is enough to cause a rise in the incidence or complication rate.

It is unclear exactly why the “new CDI” is behaving as it does. Certainly, the appearance of a new hyper-virulent strain with additional fluoroquinolone resistance (on top of C. difficile’s “usual” multi-drug resistance), a mutation in the toxin regulator gene, and a seemingly greater propensity to sporulate (and thus resist disinfection) appears to be the event which has coincided with the re-emergence of this disease during the past 10 years.

However, not all of the clinical aspects of this “new CDI” can be explained by these findings alone. For instance, the rapid progression from diarrhea to fulminant colitis in the elderly and the immunocompromised, the high recurrence rate (compared with historical controls) and the elevated morbidity (i.e., colectomy and need for intensive care) and mortality remain unnerving manifestations without a real explanation.

The number of scientific publications describing the new epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prophylactic or treatment options has risen impressively over the past several years in order to gain an understanding of this relentless bacterium.

Medical journals are not the only place for CDI-related news, however. The internet and social media sites are rife with stories of personal tragedies from this affliction. Typical stories like a healthy grandfather undergoing uncomplicated elective surgery but then dying from antibiotic-induced CDI during or soon after his hospitalization are too commonly detailed in surveillance data and in personal blogs.

Sites dedicated to and run by patients who have suffered from CDI compete with other sites established by the all-too-commonly depressed individuals who have had to undergo a therapeutic colectomy or who are suffering multiple recurrences of this disease and are searching for centers offering a fecal transplant.

There is no doubt that the true tragedy of CDI, a health care complication with an attributable mortality of almost 15% in the frail elderly over 85 years of age, is the fact that it is more likely to kill than the primary cause of hospitalization (such as a pneumonia, cellulitis, or hip fracture) in this population.

At a time when CDI is clearly overcoming our ability to control it in many parts of the world, it remains puzzling why the U.S. and many European countries do not yet have a true, real-time local and national CDI surveillance network for tracking the number of cases.

Using hospital discharge data or disease coding has been shown to be inaccurate and too late to be of immediate use. Real-time local, state, and national CDI surveillance is essential in telling us where we are, where we are going, and what we have to do to control this affliction. There is clearly a battle going on between health care providers and CDI in many countries, including the U.S. and Canada. We need to use as many tools and tricks as possible to gain control. This is one war we cannot afford to lose.

MARK MILLER, M.D., FRCPC, is Chief, Infectious Diseases, and Head, Infection Prevention and Control Unit, Jewish General Hospital, Montreal.

Clostridium difficile infections have reached an all-time high in the United States, and 94% of these infections initiate with medical care, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. C. difficile–related deaths increased from 3,000 in 1999-2000 to 14,000 in 2006-2007, according to the CDC.

The data were published as a CDC Vital Signs report and were presented in a telebriefing on March 6.

C. difficile is "a formidable opponent," and a patient safety issue everywhere that medical care is provided, said Dr. Clifford McDonald, a CDC epidemiologist and the lead author of the report. CDC’s data show that 25% of C. difficile infections first appear in hospitalized patients, while 75% occur either in nursing home residents or in people recently treated in doctors’ offices or clinics. People most at risk are those who take antibiotics and receive care in an outpatient setting.

In general, the risk of developing C. difficile increases with age; although half of C. difficile infections occur in those younger than 65 years, 90% of C. difficile-related deaths occur in those aged 65 years and older, said Dr. McDonald.

He said that clinicians can help reduce C. difficile infections by following six steps:

• Prescribe antibiotics judiciously.

• Be proactive about testing patients for C. difficile if they develop diarrhea while taking antibiotics.

• Isolate patients with C. difficile.

• Wear gloves and gowns when treating C. difficile patients, even for short visits.

• Clean surfaces in exam and treatment rooms with bleach or other spore-killing products.

• When a patient transfers to another facility, notify the medical team about a C. difficile infection.

Also, be sure to order the appropriate cultures to determine whether antibiotics are really needed, Dr. McDonald suggested, and watch for signs that signal C. difficile. "Antibiotic-associated diarrhea is very common," but C. difficile accounts for only about one-third of that, he said.

However, certain clues suggest C. difficile, including more than three unformed stools in 24 hours, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea that continues once an antibiotic has been discontinued, or diarrhea that began only once an antibiotic was discontinued, he said.

If someone has been on antibiotics, think about C. difficile early and get them tested, whether they are patients in inpatient or outpatient facilities, Dr. McDonald emphasized.

To determine the current prevalence of C. difficile, CDC researchers reviewed data from their Emerging Infections Program, which conducted population-based surveillance from eight geographic areas, and the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). In 2010, a total of 10,342 cases of C. difficile infection were identified via the Emerging Infections Program in 2010, and a total of 42,157 incident laboratory-identified CDI events were reported via the NHSN.

On a positive note, early results from state-led programs in Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York showed that hospital collaboration can reduce C. difficile infections, Dr. McDonald said. The 71 hospitals in these states that participated in C. difficile–prevention programs reduced infection rates by 20% over 21 months. "These promising results follow similar efforts in England, a nation that dropped C. difficile infections by more than 50% during a recent 3-year period," the CDC researchers said in the full report (MMWR 2012;61:1-6).

For additional information about tracking HAIs infections, contact the Emerging Infections Program or the NHSN.

Dr. McDonald had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Clostridium difficile infections have reached an all-time high in the United States, and 94% of these infections initiate with medical care, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. C. difficile–related deaths increased from 3,000 in 1999-2000 to 14,000 in 2006-2007, according to the CDC.

The data were published as a CDC Vital Signs report and were presented in a telebriefing on March 6.

C. difficile is "a formidable opponent," and a patient safety issue everywhere that medical care is provided, said Dr. Clifford McDonald, a CDC epidemiologist and the lead author of the report. CDC’s data show that 25% of C. difficile infections first appear in hospitalized patients, while 75% occur either in nursing home residents or in people recently treated in doctors’ offices or clinics. People most at risk are those who take antibiotics and receive care in an outpatient setting.

In general, the risk of developing C. difficile increases with age; although half of C. difficile infections occur in those younger than 65 years, 90% of C. difficile-related deaths occur in those aged 65 years and older, said Dr. McDonald.

He said that clinicians can help reduce C. difficile infections by following six steps:

• Prescribe antibiotics judiciously.

• Be proactive about testing patients for C. difficile if they develop diarrhea while taking antibiotics.

• Isolate patients with C. difficile.

• Wear gloves and gowns when treating C. difficile patients, even for short visits.

• Clean surfaces in exam and treatment rooms with bleach or other spore-killing products.

• When a patient transfers to another facility, notify the medical team about a C. difficile infection.

Also, be sure to order the appropriate cultures to determine whether antibiotics are really needed, Dr. McDonald suggested, and watch for signs that signal C. difficile. "Antibiotic-associated diarrhea is very common," but C. difficile accounts for only about one-third of that, he said.

However, certain clues suggest C. difficile, including more than three unformed stools in 24 hours, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea that continues once an antibiotic has been discontinued, or diarrhea that began only once an antibiotic was discontinued, he said.

If someone has been on antibiotics, think about C. difficile early and get them tested, whether they are patients in inpatient or outpatient facilities, Dr. McDonald emphasized.

To determine the current prevalence of C. difficile, CDC researchers reviewed data from their Emerging Infections Program, which conducted population-based surveillance from eight geographic areas, and the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). In 2010, a total of 10,342 cases of C. difficile infection were identified via the Emerging Infections Program in 2010, and a total of 42,157 incident laboratory-identified CDI events were reported via the NHSN.

On a positive note, early results from state-led programs in Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York showed that hospital collaboration can reduce C. difficile infections, Dr. McDonald said. The 71 hospitals in these states that participated in C. difficile–prevention programs reduced infection rates by 20% over 21 months. "These promising results follow similar efforts in England, a nation that dropped C. difficile infections by more than 50% during a recent 3-year period," the CDC researchers said in the full report (MMWR 2012;61:1-6).

For additional information about tracking HAIs infections, contact the Emerging Infections Program or the NHSN.

Dr. McDonald had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Major Finding: C. difficile-related deaths increased from 3,000 in 1999-2000 to 14,000 in 2006-2007.

Data Source: The data were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Emerging Infections Program and the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN).

Disclosures: Dr. McDonald had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Different Strokes for Different Folks

A 35‐year‐old woman presented to her primary care physician complaining of left post‐auricular pain, swelling, and redness. She described the pain as 8 out of 10, constant, sharp, and nonradiating. She denied fever or chills. A presumptive diagnosis of cellulitis led to a prescription for oral trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. Left facial swelling worsened despite 4 days of antibiotics, so she came to the emergency department.

Noninfectious causes of this woman's symptoms include trauma, or an inflammatory condition such as polychondritis. Key infectious considerations are mastoiditis or a mastoid abscess. Herpes zoster with involvement of the pinna and auditory canal may also present with pain and redness. In the absence of findings suggestive of an infection arising from the auditory canal, cellulitis is a reasonable consideration. With the growing incidence of community‐acquired methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, an agent effective against this pathogen such as trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole may be used, usually in combination with an antibiotic that provides more reliable coverage for group A streptococcus.

Her past medical history included poorly controlled type II diabetes mellitus and asthma. She reported no previous surgical history. Her current medications were insulin, albuterol inhaler, and trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole, although she had a history of noncompliance with her insulin. She was married with 1 child and was unemployed. She smoked 1 pack of cigarettes daily, drank up to 6 beers daily, and denied use of illicit drugs.

Her history of diabetes increases her risk of malignant otitis externa. Both diabetes and excess alcohol consumption are risk factors for herpes zoster. Smoking has been shown to increase the risk of otitis media and carriage by S. pneumoniae, a common pathogen in ear infections.

She was ill‐appearing and in moderate respiratory distress. Her temperature was 39C, blood pressure 149/93 mmHg, pulse 95 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 26 times per minute, with an oxygen saturation of 96% while breathing ambient air. She had swelling of the left side of the face extending to the left forehead and lateral neck. Examination of the external ear and auditory canal were unremarkable. The swelling had no associated erythema, tenderness, or lymphadenopathy. She had no oropharyngeal or nasal ulcers present. Her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light and accommodation with normal sclera. Her trachea was midline; thyroid exam was normal. The heart sounds included normal S1 and S2 without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Her lung exam was remarkable for inspiratory stridor. The abdominal examination revealed no distention, tenderness, organomegaly, or masses. Cranial nerve testing revealed a left‐sided central seventh nerve palsy along with decreased visual acuity of the left eye. Strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes were normal.

While there are many causes of facial nerve palsy, distinguishing between a peripheral palsy (which causes paralysis of the entire ipsilateral side of the face) and a central palsy (which spares the musculature of the forehead) is important. The most common type of peripheral facial nerve palsy is Bell's palsy. Infections such as meningitis or tumors of the central nervous system can cause central facial nerve or other cranial nerve palsy. Important infections to consider in this case would be viral such as herpes zoster or simplex, or atypical bacteria such as Mycoplasma and Rickettsia, which may explain the neurologic but not all of the other clinical findings in this case. It is also critical to determine whether she has an isolated seventh cranial nerve palsy or if other cranial nerves are involved such as may occur with basilar meningitis, which has a myriad of infectious and noninfectious causes. The decreased visual acuity may be a result of corneal dryness and abrasions from inability to close the eye but may also represent optic nerve problems, so detailed ophthalmologic exam is essential. Her ill appearance coupled with facial and neck swelling leads me to at least consider Lemierre's syndrome with central nervous system involvement. Finally, facial swelling and the inspiratory stridor may represent angioedema, although one‐sided involvement of the face would be unusual.

The results of initial laboratory testing were as follows: sodium, 138 mmol/L; potassium, 3.4 mmol/L; chloride, 109 mmol/L; bicarbonate, 14 mmol/L; blood urea nitrogen level, 19 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.1 mg/dL; white cell count, 23,510/mm3; differential, 90% neutrophils, 1% bands, 7% lymphocytes, 2% monocytes; hemoglobin level, 12.5 g/dL; platelet count, 566,000/mm3; hemoglobin A1c, 11%; albumin, 1.6 g/dL; total protein, 6.2 g/dL; total bilirubin, 0.8 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 103 U/L; alanine aminotransferase level, 14 U/L; international normalized ratio of 1.2; partial thromboplastin time, 29 seconds (normal value, 2434 seconds); erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 121 mm/hr; creatine kinase, 561 U/L (normal value 25190). Arterial blood gas measurements with the patient breathing 50% oxygen revealed a pH of 7.34, a partial pressure of carbon dioxide of 28 mmHg, and a partial pressure of oxygen of 228 mmHg.

I am concerned that this patient has sepsis, likely due to an infectious trigger. With her clinical presentation localized to the head and neck, her history of diabetes, and the accelerated sedimentation rate, malignant otitis externa would explain many of her findings. Empiric anti‐infective therapy directed toward Pseudomonas aeruginosa should be initiated, and imaging of the head and ear should be undertaken.

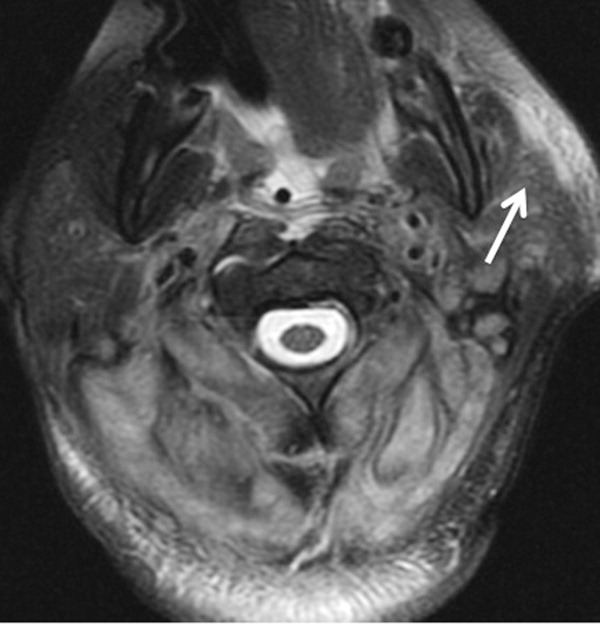

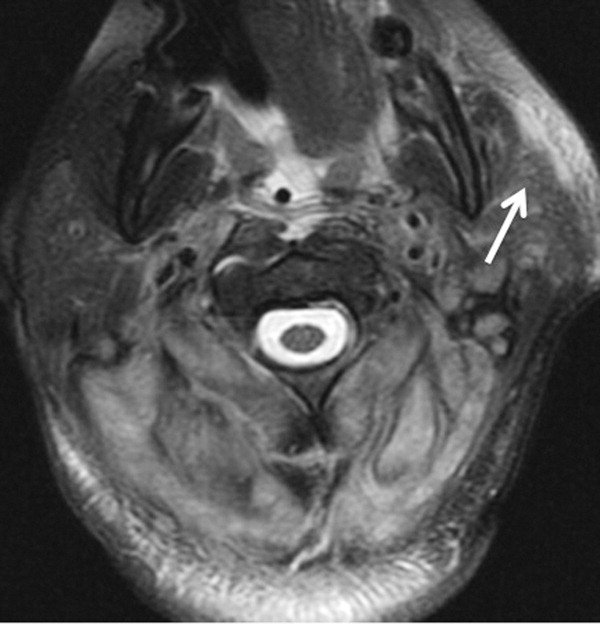

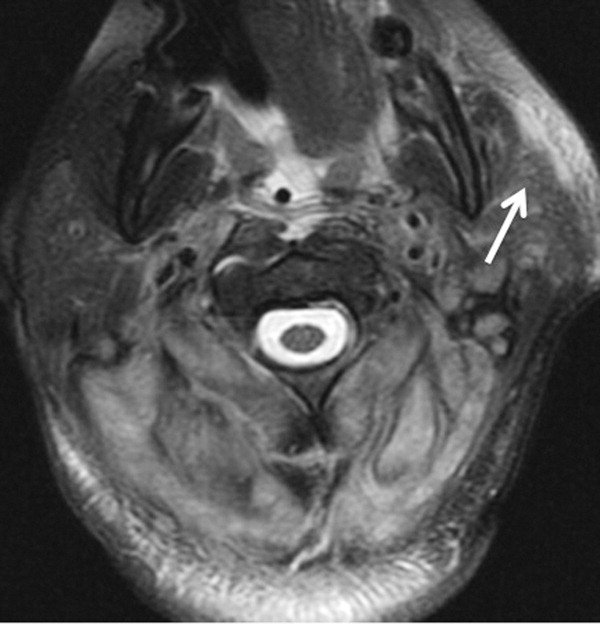

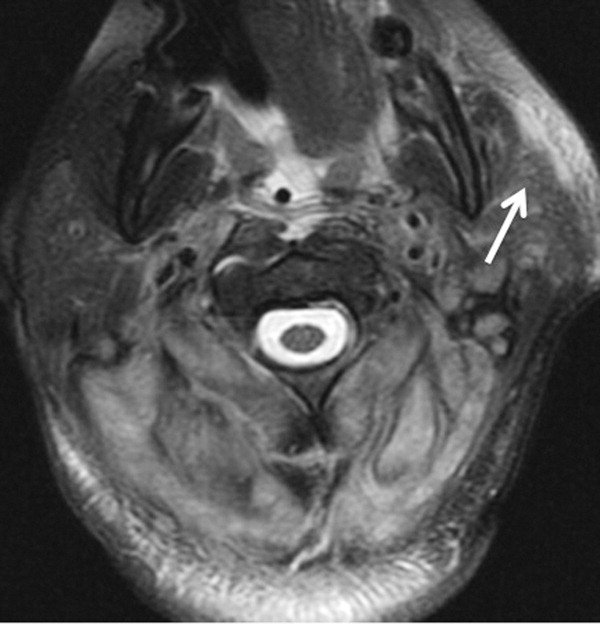

The patient required intubation due to increased respiratory distress and stridor. Her physicians used intravenous vancomycin, clindamycin, and piperacillin/tazobactam to treat presumed cellulitis. Her abnormal neurologic exam led to magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and MR angiography of her neck and brain, which showed evidence of multiple regions of ischemia in the left occipital and inferior parietal distributions, as well as bilateral cerebellar distributions and enhancement of the parotid gland and mastoid air cells (Figure 1). A cerebral angiogram revealed irregularity and caliber reduction in multiple cervical and intracranial arteries, associated with intraluminal thrombi within the left intracranial vertebral artery, consistent with either vasculitis or infectious angioinvasion (Figure 2).

The angioinvasive nature of the findings on imaging leads me to suspect fungal infection. The patient's history of diabetes mellitus and acidosis are risk factors for mucormycosis. Aspergillus and Fusarium may also be angioinvasive but would be much more likely in neutropenic or severely immunocompromised patients. S. aureus may cause septic emboli mimicking angioinvasion but should be readily detected in conventional blood cultures. At this point, I would empirically begin amphotericin B; tissue, however, is needed for definitive diagnosis and a surgical consult should be requested.

After reviewing her imaging studies, an investigation for vasculitis and hypercoagulable states including antinuclear antibody, anti‐deoxyribonucleic acid, anti‐Smith antibody, anti‐SSA antibody level, anti‐SSB level, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, activated protein C resistance level, factor VIII level, human immunodeficiency virus antibody, homocysteine level, cardiolipin antibody testing, lupus anticoagulant, prothrombin 20210 mutation, and protein C level was done, and all tests were normal. Protein S level was slightly low at 64% (normal value 65%140%). Given the enlarged parotid gland and the enhancement of the left parotid bed on magnetic resonance imaging, she underwent a parotid biopsy that revealed sialadenitis.

Systemic vasculitides can result in tissue damage, mediated by the release of endogenous cellular contents from dying cells, known as damage‐associated molecular patterns, sufficient to cause systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). This patient presented with acute symptoms but has negative laboratory studies for autoantibodies. The parotid biopsy also did not reveal evidence of vasculitis. All these findings make the diagnosis of vasculitis much less likely.

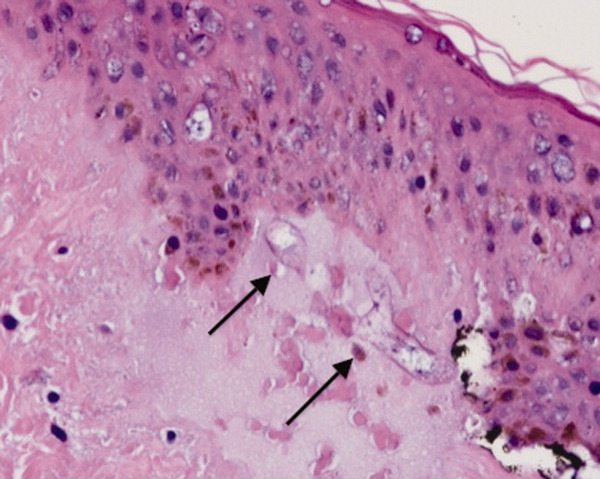

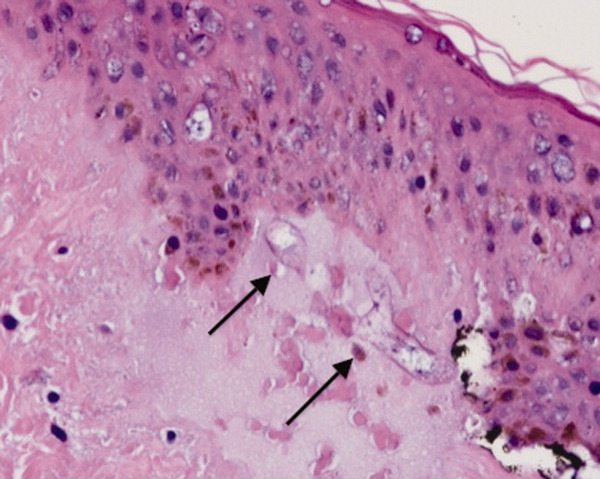

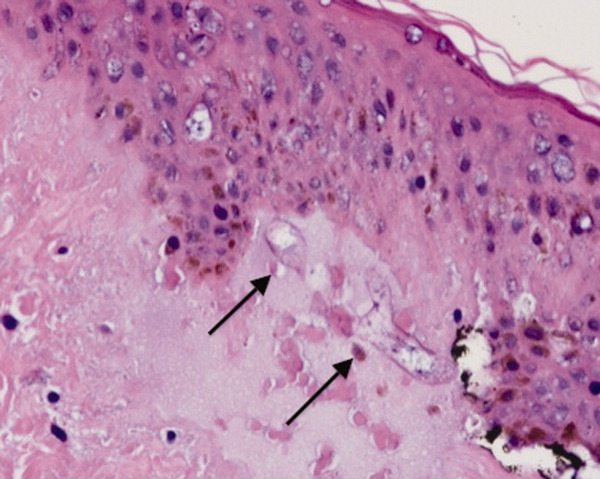

She remained in the medical intensive care unit on mechanical ventilation, with minimal symptomatic improvement. On hospital day 10, the patient developed necrosis of the left external ear. A punch biopsy of the necrotic area of her left pinna was performed; the pathology report read: Sections of punch biopsy of skin show an unremarkable epidermis. There is dermal necrosis involving the stroma and adnexal structures. Intravascular thrombi within the deep dermis are seen. Within superficial dermis there are broad, elongated, nonseptated hyaline structures reminiscent of Mucor. Special stains (periodic acid‐Schiff stain and Grocott Gomori methenamine silver stain [GMS]) performed with appropriately reactive controls fail to highlight these structures (Figure 3). The infectious disease team reviewed the pathology slides with the pathologist. As there was inconclusive evidence for zygomycosis, ie, only a few hyaline structures which failed to stain with GMS stain, the consultants recommended no change in the patient's management.

The gross and microscopic evidence of necrosis and areas of intravascular thrombi are nonspecific but compatible with a fungal infection in a patient with risk factors for zygomycosis. The GMS stain is a very sensitive stain for fungal structures, so a negative stain in this case is surprising, but additional testing such as immunohistochemistry should be pursued to confirm or refute this diagnosis. While Rhizopus species can be contaminants, the laboratory finding of these organisms in specimens from patients with risk factors for zygomycosis should not be ignored.

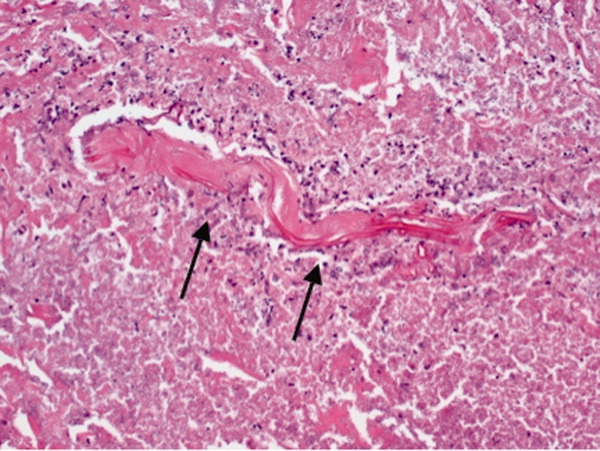

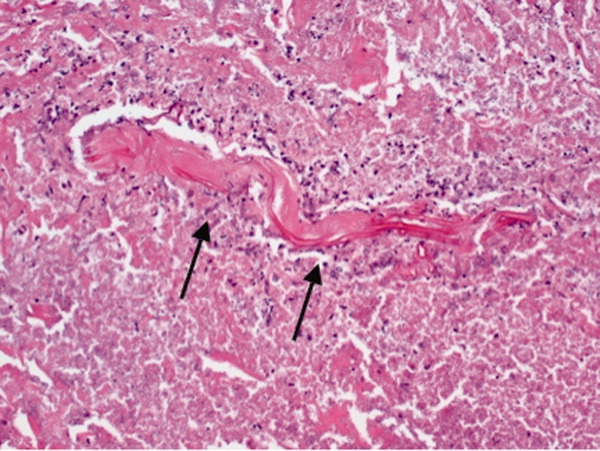

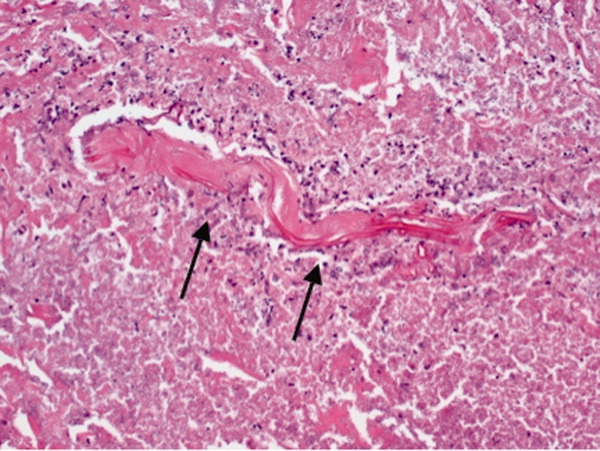

On hospital day 12, the patient was noted to have increased facial swelling. A computed tomographic (CT) angiogram of the neck revealed necrosis of the anterior and posterior paraspinal muscles from the skull base to C34, marked swelling of the left parotid gland, and left inferior parieto‐occipital enhancing lesion. An incisional parotid biopsy was performed. Special stains were positive for broad‐based fungal hyphae consistent with mucormycosis (Figure 4).

Given these findings, the patient should be started on amphotericin B immediately. Medical therapy alone generally does not suffice, and aggressive surgical debridement combined with intravenous antifungal therapy results in better outcomes. The longer the duration of symptoms and the greater the progression of disease, the less favorable the prognosis.

The patient was started on amphotericin B lipid complex and micafungin. However, after 16 days of therapy, repeat imaging of the neck showed worsening necrosis of the neck muscles. At this time, she underwent extensive debridement of face and neck, and posaconazole was added. After prolonged hospitalization, she was discharged to a rehabilitation facility on posaconazole. She resided in a nursing facility for 6 months. One year after her hospitalization, she is living at home and is able to ambulate independently, but requires feeding through a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube because she remains dysphagic.

COMMENTARY

Infections caused by the ubiquitous fungi of the class Zygomycetes typically take 1 of 5 forms: rhinocerebral, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, disseminated, and cutaneous. The presentation varies widely, ranging from plaques, skin swelling, pustules, cellulitis, blisters, nodules, ulcerations, and ecthyma gangrenosum‐like lesions to deeper infections such as necrotizing fasciitis, osteomyelitis, and disseminated infection.1 Infections typically occur in immunocompromised hosts, including transplant recipients and patients with hematologic malignancy, but also occur in patients with diabetes mellitus, intravenous drug users, and patients on deferoxamine therapy.2 Deferoxamine and other iron‐binding therapy is thought to predispose to zygomycetes infections because of improved iron uptake of the fungal species and, thus, stimulation of growth.3 Pulmonary and rhinocerebral infections are the most common clinically encountered forms, and 44% of cutaneous infections are complicated by deep extension or dissemination.4

The articles cited above describe the more typical presentations of this rare disease. However, this patient had an unusual presentation, as parotid involvement due to zygomycosis has only been described once previously.5 Her inflammatory vasculitis and ensuing strokes from involvement of the carotid artery are recognized complications of zygomycosis, and in 1 case series of 41 patients with rhinocerebral mucormycosis, carotid involvement was seen in 31% of patients.6 After the punch biopsy of the patient's pinna showing nonseptated hyphae reminiscent of Mucor, why did her physicians delay administering amphotericin?

There are 2 likely possibilities: anchoring bias or error in medical decision‐making due to inaccurate probability estimates. Anchoring bias describes a heuristic where the initial diagnosis or gestalt biases the physician's process for assigning a final diagnosis.7, 8 This bias creates cognitive errors by limiting creativity in diagnosis. In this case, the infectious disease team carefully weighed the information obtained from the first biopsy. Given their low pretest estimate of this virtually unreported presentation of a rare disease, they decided to evaluate further without beginning antifungal therapy. Of note, there were few hyaline structures, and those structures lacked uptake of GMS. Since they considered the diagnosis yet rejected the diagnosis due to insufficient evidence, it is unlikely that anchoring bias played a role.

Was there an error in medical decision‐making? The physicians in this case faced a very common medical dilemma: whether or not to start a toxic medication empirically or wait for diagnostic confirmation prior to treatment.9 To solve this dilemma, one can apply decision analysis. Moskowitz et al described 5 phases of medical decision analysis by which a probabilistic right answer to clinical scenarios can be deduced mathematically.10 To solve this problem, probabilities must be assigned to the risk of giving a drug to a patient without the disease versus the risk of not giving a drug to a patient with the disease. For example, amphotericin deoxycholate causes acute renal failure in 30% to 47% of patients. Newer formulations of amphotericin, such as liposomal amphotericin and lipid complex, result in lower rates of nephrotoxicity (27% vs 47%). The risk of not giving amphotericin to a patient with zygomycosis is death. Even in patients treated with amphotericin, the mortality rate has been shown to be 66%, and up to 100% in those with strokes related to zygomycosis.2, 6, 11 Simply looking at these probabilities, decision analysis would favor empiric treatment.

The physicians caring for this patient did not have the luxury of retrospective speculation. After looking at all of the data, the equivocal skin biopsy and rare clinical presentation, the question to ask would change: What is the risk of giving amphotericin empirically to someone who, based on available information, has a very low probability of having zygomycosis? When phrased in this manner, there is a 47% chance of nephrotoxicity with amphotericin versus the very small probability that you have diagnosed a case of zygomycosis that has only been described once in the literature. Mathematically andmore importantlyclinically, this question becomes more difficult to answer. However, no value can be placed on the possibility of death in suspected zygomycosis, and the risk of short‐term amphotericin use is much less than that of a course of treatment. As such, empiric therapy should always be given.

Physicians are not mathematicians, and dynamic clinical scenarios are not so easily made into static math problems. Disease presentations evolve over time towards a diagnosable clinical pattern, as was the case with this patient. Two days after the aforementioned biopsy, she worsened and in less time than it would have taken to isolate zygomycosis from the first biopsy, a second biopsy revealed the typical nonseptated hyphae demarcated with the GMS stain. Even appropriate diagnostic testing, thoughtful interpretation, and avoidance of certain cognitive errors can result in incorrect diagnoses and delayed treatment. It is monitoring the progression of disease and collecting additional data that allows physicians to mold a diagnosis and create a treatment plan.

The primary treatment of zygomycosis should include amphotericin. However, there are limited data to support combination therapy with an echinocandin in severe cases, as in this patient.12 Posaconazole is not recommended for monotherapy as an initial therapy, but there is data for its use as salvage therapy in zygomycosis.13 This case highlights the difficulties that physicians face in the diagnosis and treatment of rare diseases. Cerebral infarction in a hematologic malignancy, uncontrolled diabetes, or iron chelation therapy could be the initial presentation of rhinocerebral zygomycosis. There truly are different strokes for different folks. Recognizing this and similar presentations may lead to a more rapid diagnosis and treatment of zygomycosis.

TEACHING POINTS

-

Zygomycosis has a wide range of clinical presentations ranging from skin lesions to deep tissue infections. As it is an angioinvasive organism, it can also present as cerebral infarcts and brain abscesses.

-

Zygomycosis infections should be suspected in patients with uncontrolled diabetes, hematologic or oncologic malignancies, and patients on iron chelation therapy with a potentially compatible clinical picture.

-

If zygomycosis infection is suspected, rapid histologic diagnosis should be attempted. However, as histologic diagnosis can take time, empiric therapy with amphotericin should always be administered.

-

Amphotericin remains the primary medical therapy for this disease; however, there is limited emerging evidence to suggest that echinocandins can be used in combination with amphotericin for improved treatment of severe rhinocerebral zygomyocosis. Posaconazole has a role as salvage therapy in zygomycosis, but should not be used as the sole primary treatment.

The approach to clinical conundrums by an expert clinician is revealed through the presentation of an actual patient's case in an approach typical of a morning report. Similarly to patient care, sequential pieces of information are provided to the clinician, who is unfamiliar with the case. The focus is on the thought processes of both the clinical team caring for the patient and the discussant.

This icon represents the patient's case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant's thoughts.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Dr Glenn Roberson at the Department of Radiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, for providing the radiographic images; to Dr Aleodor Andea at the Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, for providing the pathology images; and to Dr. Crysten Brinkley at the Department of Neurology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for her assistance with this case presentation.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- ,,,.Mucormycosis: emerging prominence of cutaneous infections.Clin Infect Dis.1994;19:67–76.

- ,,,.Zygomycosis in the 1990s in a tertiary‐care cancer center.Clin Infect Dis.2000;30:851–856.

- ,,, et al.Mucormycosis during deferoxamine therapy is a siderophore‐mediated infection. In vitro and in vivo animal studies.J Clin Invest.1993;91:1979–1986.

- ,,, et al.Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases.Clin Infect Dis.2005;41:634–653.

- ,,,,,.Cutaneous mucormycosis of the head and neck with parotid gland involvement: first report of a case.Ear Nose Throat J.2004;83:282–286.

- ,,,,,.A successful combined endovascular and surgical treatment of a cranial base mucormycosis with an associated internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm.Neurosurgery.2009;65:733–740.

- ,.Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases.Science.1974;185:1124–1131.

- ,,,,.Clinical problem‐solving. Anchors away.N Engl J Med.2007;356:504–509.

- ,,,.Clinical problem‐solving. Empirically incorrect.N Engl J Med.2006;354:509–514.

- ,,.Dealing with uncertainty, risks, and tradeoffs in clinical decisions. A cognitive science approach.Ann Intern Med.1988;108:435–449.

- ,,.Fatal strokes in patients with rhino‐orbito‐cerebral mucormycosis and associated vasculopathy.Scand J Infect Dis.2004;36:643–648.

- ,,, et al.Combination polyene‐caspofungin treatment of rhino‐orbital‐cerebral mucormycosis.Clin Infect Dis.2008;47:364–371.

- ,,,,.Posaconazole is effective as salvage therapy in zygomycosis: a retrospective summary of 91 cases.Clin Infect Dis.2006;42:e61–e65.