User login

Bilateral Superior Labrum Anterior to Posterior (SLAP) Tears With Abnormal Anatomy of Biceps Tendon

The biceps brachii derives its name from the 2 heads of the muscle. The short head originates from the coracoid apex, with the coracobrachialis muscle. The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) starts within the capsule of the shoulder joint, running from the supraglenoid tubercle or labrum.1 The tendon typically runs free along its intra-articular course, but it is also extrasynovial and ensheathed by a continuation of the synovial lining of the articular capsule that extends to the inferior-most extent of the bicipital groove.2 Congenital anomalies of the LHBT are uncommon, although several atypical forms have been described. A literature search for anomalous LHBT identified several variations in anatomic descriptions, including Y-shaped variant, complete absence of tendon, extra-articular attachment, and a variety of intracapsular attachments. In all, 8 case reports of aberrant intracapsular attachment of LHBT3-12 were identified. These cases presented with a variety of clinical manifestations and pathologic changes. Often, these anatomic variations are considered innocuous, yet some present with pathologic findings.

We present the clinical, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and arthroscopic findings of a relatively young athletic patient who was experiencing symptoms of bilateral superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears that were unresponsive to conservative management. A unique anatomic variant of the LHBT that involved confluence of the LHBT with the undersurface of the anterosuperior capsule at the rotator interval, as well as a Buford complex anteriorly, was identified and treated. We believe that the tethering of the biceps tendon to the capsule combined with the Buford complex created increased stress on the superior labrum and biceps anchor variant, leading to the development of bilateral symptomatic type II SLAP tears. Knowledge of this variant, though perhaps rare, may be relevant for diagnostic recognition of young athletic patients who present with recalcitrant shoulder symptoms. The patient and the patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 15-year-old healthy and active athletic boy presented with pain in the right shoulder without history of trauma. He was active in both swimming and baseball. He complained of pain that was present with activities, such as lifting weights, swimming, and throwing. His treatment prior to the office visit consisted of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, rest, and a therapy program initiated by his high school athletic trainer.

Physical examination demonstrated tenderness to palpation over the posterior capsule and biceps. Motion was full, cuff strength was normal, and SLAP signs (O’Brien, Speed, and Jobe relocation) were positive. A radiograph showed no sign of fracture or dislocation, and no evidence of bony abnormality.

The patient was sent for an MRI arthrogram, which showed a SLAP tear extending from 1 o’clock anteriorly to 10 o’clock posteriorly without intra-articular displacement. No rotator cuff tear was noted. The biceps tendon was noted to be unremarkable and located within the bicipital groove, although retrospective review of the MRI showed that the intra-articular biceps tendon was somewhat confluent with the adjacent tissues.

The patient underwent right shoulder arthroscopy. The shoulder was stable to ligamentous examination under anesthesia. Arthroscopic evaluation revealed that there was a type II SLAP tear extending from the 11-o’clock to the 2-o’clock positions. The superior glenohumeral ligament was identified as it arose from the upper pole of the glenoid labrum and then ran parallel and inferior to the tendon of the biceps towards the lesser tubercle. Surprisingly, there was a very unusual attachment of the intracapsular LHBT to the undersurface of the rotator interval, which restricted biceps excursion in relation to the rotator cuff. Additionally, there was a thick cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament anteriorly that lacked the normal glenoid attachments, thus representing a Buford complex. Interestingly, the labral tear could not only be displaced with a probe, but placing the shoulder through a range of motion also led to increased displacement of the labrum from the glenoid, likely because the biceps tendon was tethered to the undersurface of the capsule.

At the time of arthroscopy, the LHBT was released from its attachment to the capsule at the rotator interval with a radiofrequency wand and shaver. A labral repair was performed using three 2.9-mm bioabsorbable suture anchors, placing 2 posterior and 1 anterior to the biceps tendon. The integrity of the labral repair was observed while placing the shoulder through range of motion.

Postoperatively, the patient was kept in a sling for 5 weeks. Home exercises were initiated at 2 weeks, and outpatient physical therapy was implemented at 4 weeks. The patient resumed swimming, throwing, and other activities—with minimal discomfort—at 6 months postoperatively.

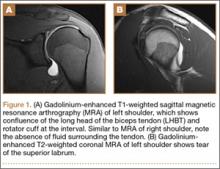

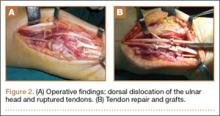

Three years after his initial visit, the patient returned to the office with a similar complaint of pain and limitation of function in his left shoulder after returning to full athletic competition. Once again, there was no history of injury, and history, physical examination, and MRI arthrogram (Figures 1A, 1B) evaluation proved to be very similar to this young athlete’s right shoulder work-up.

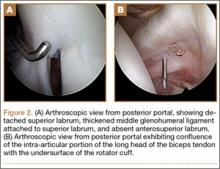

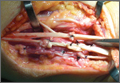

The patient once again underwent shoulder arthroscopy and treatment. Although this was now the left shoulder, the findings were essentially identical to the right shoulder. Once again, the labrum was detached from the 11-o’clock to 2-o’clock positions, and a Buford complex was present anteriorly (Figure 2A). The labral tear was easily displaceable from the glenoid with a probe, and placing the shoulder through a range of motion led to increased displacement of the labrum from the glenoid. There was also confluence of the intra-articular LHBT with the undersurface of the capsule within the rotator interval (Figure 2B). A radiofrequency wand, shaver, and elevator were used to define the biceps tendon and separate it from the undersurface of the capsule. The SLAP repair was performed using three 2.9-mm absorbable suture anchors with 2 posterior and 1 anterior to the biceps tendon insertion. The labral repair was observed while placing the shoulder through range of motion and the shoulder was seen to be free of any undue tension on the labrum.

Postoperatively, the patient’s sling and rehabilitation protocol was identical to that of the right shoulder. The patient progressed well, was released to full activity at 6 months, and has not returned with any further complaints of left or right shoulder pain. Approximately 3 years after treatment the patient was contacted via phone and asked about symptoms, pain, and activity. He denies current symptoms of clicking or instability and has no pain that he can identify as being related to previous pathology or treatment. Since the surgery, he has ceased competitive sports and weight lifting, which he attributes to deconditioning associated with postsurgical immobilization and lack of motivation.

Discussion

Of the 8 case reports in the literature that identified variable intra-articular biceps insertional anatomy, only 2 reports represented confluence of the biceps within the rotator interval.7 Interestingly, of the cases identified, the single case that presented a patient with similar pathology of a type II SLAP lesion had an almost identical anatomical variant presentation consisting of both the anomalous insertion of the LHBT into the undersurface of the rotator interval and a Buford variant of the anterosuperior glenohumeral ligament complex. To our knowledge, our bilateral case of an altered intra-articular biceps insertion and a concomitant SLAP tear supports the theory that this pattern of anomalous insertion may very well have altered the biomechanics of the tendon, resulting in acquired pathology to the superior labrum.

The literature reviewed showed the prevalence of anatomic variations of the LHBT ranged from 1.9% to 7.4%.13,14 These variations are generally considered benign; however, in some cases—as in the cases of the young athletes presented by Wahl and MacGillivray7 and in this report—anatomic variation may play an important role in pathogenesis of different injury patterns. The primary function of the LHBT is the stabilization of the glenohumeral joint during abduction and external rotation.15 When the insertion diverges from normal (eg, when the tendon is tethered to the undersurface of the rotator cuff), the biomechanical stresses on the tendon likely change. As a result of the anomalous position of the LHBT origin, there may be a change in the shoulder joint’s biomechanics, with increased strain on the glenohumeral ligament and its attachment onto the glenoid.16

This case report differs from publications on variable superior glenohumeral ligament attachments because a discrete superior glenohumeral ligament structure was isolated from the biceps tendon. Although a larger case series or patient cohort, as well as more involved biomechanical analysis, would certainly be necessary to prove our hypothesis, we believe that this case suggests certain anatomic LHBT and labral variations can contribute to the develop of SLAP tears in younger individuals.

1. Vangsness CT Jr, Jorgenson SS, Watson T, Johnson DL. The origin of the long head of the biceps from the scapula and glenoid labrum. An anatomical study of 100 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(6):951-954.

2. Burkhead WZ Jr. The biceps tendon. In: Rockwood CA Jr, Matsen FA III, eds. The Shoulder. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:791-836.

3. Parikh SN, Bonnaig N, Zbojniewicz A. Intracapsular origin of the long head biceps tendon with glenoid avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments. Orthopedics. 2011;34(11):781-784.

4. Gaskin CM, Golish SR, Blount KJ, Diduch DR. Anomalies of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon: clinical significance, MR arthrographic findings, and arthroscopic correlation in two patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36(8):785-789.

5. Yeh L, Pedowitz R, Kwak S, et al. Intracapsular origin of the long head of the biceps tendon. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28(3):178-181.

6. Richards DP, Schwartz M. Anomalous intraarticular origin of the long head of the biceps brachii. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(2):122-124.

7. Wahl CJ, MacGillivray JD. Three congenital variations in the long head of the biceps tendon: a review of the pathoanatomic considerations and case reports. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):e25-e30.I

8. Egea JM, Melguizo C, Prados J, Aránega A. Capsular origin of the long head of the biceps tendon: a clinical case. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2010;51(2):375-377.

9. Hyman JL, Warren RF. Extra-articular origin of biceps brachii. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(7): E29.

10. Enad JG. Bifurcate origin of the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(10):1081-1083.

11. Mariani PP, Bellelli A, Botticella C. Arthroscopic absence of the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(4):499-501.

12. Koplas MC, Winalski CS, Ulmer WH Jr, Recht M. Bilateral congenital absence of the long head of the biceps tendon. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(7):715-719.

13. Kanatli U, Ozturk BY, Eisen E, Bolukbasi S. Intra-articular variations of the long head of the biceps tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1576-1581.

14. Dierickx C, Ceccarelli E, Conti M, Vanlommel J, Castagna A. Variations of the intra-articular portion of the long head of the biceps tendon: a classification of embryologically explained variations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):556-565.

15. Rodosky MW, Harner CD, Fu FH. The role of the long head of the biceps muscle and superior glenoid labrum in anterior stability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):121-130.

16. Bigliani LU, Kelkar R, Flatow EL, Pollock RG, Mow VC. Glenohumeral stability. Biomechanical properties of passive and active stabilizers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):13-30.

The biceps brachii derives its name from the 2 heads of the muscle. The short head originates from the coracoid apex, with the coracobrachialis muscle. The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) starts within the capsule of the shoulder joint, running from the supraglenoid tubercle or labrum.1 The tendon typically runs free along its intra-articular course, but it is also extrasynovial and ensheathed by a continuation of the synovial lining of the articular capsule that extends to the inferior-most extent of the bicipital groove.2 Congenital anomalies of the LHBT are uncommon, although several atypical forms have been described. A literature search for anomalous LHBT identified several variations in anatomic descriptions, including Y-shaped variant, complete absence of tendon, extra-articular attachment, and a variety of intracapsular attachments. In all, 8 case reports of aberrant intracapsular attachment of LHBT3-12 were identified. These cases presented with a variety of clinical manifestations and pathologic changes. Often, these anatomic variations are considered innocuous, yet some present with pathologic findings.

We present the clinical, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and arthroscopic findings of a relatively young athletic patient who was experiencing symptoms of bilateral superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears that were unresponsive to conservative management. A unique anatomic variant of the LHBT that involved confluence of the LHBT with the undersurface of the anterosuperior capsule at the rotator interval, as well as a Buford complex anteriorly, was identified and treated. We believe that the tethering of the biceps tendon to the capsule combined with the Buford complex created increased stress on the superior labrum and biceps anchor variant, leading to the development of bilateral symptomatic type II SLAP tears. Knowledge of this variant, though perhaps rare, may be relevant for diagnostic recognition of young athletic patients who present with recalcitrant shoulder symptoms. The patient and the patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 15-year-old healthy and active athletic boy presented with pain in the right shoulder without history of trauma. He was active in both swimming and baseball. He complained of pain that was present with activities, such as lifting weights, swimming, and throwing. His treatment prior to the office visit consisted of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, rest, and a therapy program initiated by his high school athletic trainer.

Physical examination demonstrated tenderness to palpation over the posterior capsule and biceps. Motion was full, cuff strength was normal, and SLAP signs (O’Brien, Speed, and Jobe relocation) were positive. A radiograph showed no sign of fracture or dislocation, and no evidence of bony abnormality.

The patient was sent for an MRI arthrogram, which showed a SLAP tear extending from 1 o’clock anteriorly to 10 o’clock posteriorly without intra-articular displacement. No rotator cuff tear was noted. The biceps tendon was noted to be unremarkable and located within the bicipital groove, although retrospective review of the MRI showed that the intra-articular biceps tendon was somewhat confluent with the adjacent tissues.

The patient underwent right shoulder arthroscopy. The shoulder was stable to ligamentous examination under anesthesia. Arthroscopic evaluation revealed that there was a type II SLAP tear extending from the 11-o’clock to the 2-o’clock positions. The superior glenohumeral ligament was identified as it arose from the upper pole of the glenoid labrum and then ran parallel and inferior to the tendon of the biceps towards the lesser tubercle. Surprisingly, there was a very unusual attachment of the intracapsular LHBT to the undersurface of the rotator interval, which restricted biceps excursion in relation to the rotator cuff. Additionally, there was a thick cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament anteriorly that lacked the normal glenoid attachments, thus representing a Buford complex. Interestingly, the labral tear could not only be displaced with a probe, but placing the shoulder through a range of motion also led to increased displacement of the labrum from the glenoid, likely because the biceps tendon was tethered to the undersurface of the capsule.

At the time of arthroscopy, the LHBT was released from its attachment to the capsule at the rotator interval with a radiofrequency wand and shaver. A labral repair was performed using three 2.9-mm bioabsorbable suture anchors, placing 2 posterior and 1 anterior to the biceps tendon. The integrity of the labral repair was observed while placing the shoulder through range of motion.

Postoperatively, the patient was kept in a sling for 5 weeks. Home exercises were initiated at 2 weeks, and outpatient physical therapy was implemented at 4 weeks. The patient resumed swimming, throwing, and other activities—with minimal discomfort—at 6 months postoperatively.

Three years after his initial visit, the patient returned to the office with a similar complaint of pain and limitation of function in his left shoulder after returning to full athletic competition. Once again, there was no history of injury, and history, physical examination, and MRI arthrogram (Figures 1A, 1B) evaluation proved to be very similar to this young athlete’s right shoulder work-up.

The patient once again underwent shoulder arthroscopy and treatment. Although this was now the left shoulder, the findings were essentially identical to the right shoulder. Once again, the labrum was detached from the 11-o’clock to 2-o’clock positions, and a Buford complex was present anteriorly (Figure 2A). The labral tear was easily displaceable from the glenoid with a probe, and placing the shoulder through a range of motion led to increased displacement of the labrum from the glenoid. There was also confluence of the intra-articular LHBT with the undersurface of the capsule within the rotator interval (Figure 2B). A radiofrequency wand, shaver, and elevator were used to define the biceps tendon and separate it from the undersurface of the capsule. The SLAP repair was performed using three 2.9-mm absorbable suture anchors with 2 posterior and 1 anterior to the biceps tendon insertion. The labral repair was observed while placing the shoulder through range of motion and the shoulder was seen to be free of any undue tension on the labrum.

Postoperatively, the patient’s sling and rehabilitation protocol was identical to that of the right shoulder. The patient progressed well, was released to full activity at 6 months, and has not returned with any further complaints of left or right shoulder pain. Approximately 3 years after treatment the patient was contacted via phone and asked about symptoms, pain, and activity. He denies current symptoms of clicking or instability and has no pain that he can identify as being related to previous pathology or treatment. Since the surgery, he has ceased competitive sports and weight lifting, which he attributes to deconditioning associated with postsurgical immobilization and lack of motivation.

Discussion

Of the 8 case reports in the literature that identified variable intra-articular biceps insertional anatomy, only 2 reports represented confluence of the biceps within the rotator interval.7 Interestingly, of the cases identified, the single case that presented a patient with similar pathology of a type II SLAP lesion had an almost identical anatomical variant presentation consisting of both the anomalous insertion of the LHBT into the undersurface of the rotator interval and a Buford variant of the anterosuperior glenohumeral ligament complex. To our knowledge, our bilateral case of an altered intra-articular biceps insertion and a concomitant SLAP tear supports the theory that this pattern of anomalous insertion may very well have altered the biomechanics of the tendon, resulting in acquired pathology to the superior labrum.

The literature reviewed showed the prevalence of anatomic variations of the LHBT ranged from 1.9% to 7.4%.13,14 These variations are generally considered benign; however, in some cases—as in the cases of the young athletes presented by Wahl and MacGillivray7 and in this report—anatomic variation may play an important role in pathogenesis of different injury patterns. The primary function of the LHBT is the stabilization of the glenohumeral joint during abduction and external rotation.15 When the insertion diverges from normal (eg, when the tendon is tethered to the undersurface of the rotator cuff), the biomechanical stresses on the tendon likely change. As a result of the anomalous position of the LHBT origin, there may be a change in the shoulder joint’s biomechanics, with increased strain on the glenohumeral ligament and its attachment onto the glenoid.16

This case report differs from publications on variable superior glenohumeral ligament attachments because a discrete superior glenohumeral ligament structure was isolated from the biceps tendon. Although a larger case series or patient cohort, as well as more involved biomechanical analysis, would certainly be necessary to prove our hypothesis, we believe that this case suggests certain anatomic LHBT and labral variations can contribute to the develop of SLAP tears in younger individuals.

The biceps brachii derives its name from the 2 heads of the muscle. The short head originates from the coracoid apex, with the coracobrachialis muscle. The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) starts within the capsule of the shoulder joint, running from the supraglenoid tubercle or labrum.1 The tendon typically runs free along its intra-articular course, but it is also extrasynovial and ensheathed by a continuation of the synovial lining of the articular capsule that extends to the inferior-most extent of the bicipital groove.2 Congenital anomalies of the LHBT are uncommon, although several atypical forms have been described. A literature search for anomalous LHBT identified several variations in anatomic descriptions, including Y-shaped variant, complete absence of tendon, extra-articular attachment, and a variety of intracapsular attachments. In all, 8 case reports of aberrant intracapsular attachment of LHBT3-12 were identified. These cases presented with a variety of clinical manifestations and pathologic changes. Often, these anatomic variations are considered innocuous, yet some present with pathologic findings.

We present the clinical, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and arthroscopic findings of a relatively young athletic patient who was experiencing symptoms of bilateral superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears that were unresponsive to conservative management. A unique anatomic variant of the LHBT that involved confluence of the LHBT with the undersurface of the anterosuperior capsule at the rotator interval, as well as a Buford complex anteriorly, was identified and treated. We believe that the tethering of the biceps tendon to the capsule combined with the Buford complex created increased stress on the superior labrum and biceps anchor variant, leading to the development of bilateral symptomatic type II SLAP tears. Knowledge of this variant, though perhaps rare, may be relevant for diagnostic recognition of young athletic patients who present with recalcitrant shoulder symptoms. The patient and the patient’s parents provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 15-year-old healthy and active athletic boy presented with pain in the right shoulder without history of trauma. He was active in both swimming and baseball. He complained of pain that was present with activities, such as lifting weights, swimming, and throwing. His treatment prior to the office visit consisted of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, rest, and a therapy program initiated by his high school athletic trainer.

Physical examination demonstrated tenderness to palpation over the posterior capsule and biceps. Motion was full, cuff strength was normal, and SLAP signs (O’Brien, Speed, and Jobe relocation) were positive. A radiograph showed no sign of fracture or dislocation, and no evidence of bony abnormality.

The patient was sent for an MRI arthrogram, which showed a SLAP tear extending from 1 o’clock anteriorly to 10 o’clock posteriorly without intra-articular displacement. No rotator cuff tear was noted. The biceps tendon was noted to be unremarkable and located within the bicipital groove, although retrospective review of the MRI showed that the intra-articular biceps tendon was somewhat confluent with the adjacent tissues.

The patient underwent right shoulder arthroscopy. The shoulder was stable to ligamentous examination under anesthesia. Arthroscopic evaluation revealed that there was a type II SLAP tear extending from the 11-o’clock to the 2-o’clock positions. The superior glenohumeral ligament was identified as it arose from the upper pole of the glenoid labrum and then ran parallel and inferior to the tendon of the biceps towards the lesser tubercle. Surprisingly, there was a very unusual attachment of the intracapsular LHBT to the undersurface of the rotator interval, which restricted biceps excursion in relation to the rotator cuff. Additionally, there was a thick cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament anteriorly that lacked the normal glenoid attachments, thus representing a Buford complex. Interestingly, the labral tear could not only be displaced with a probe, but placing the shoulder through a range of motion also led to increased displacement of the labrum from the glenoid, likely because the biceps tendon was tethered to the undersurface of the capsule.

At the time of arthroscopy, the LHBT was released from its attachment to the capsule at the rotator interval with a radiofrequency wand and shaver. A labral repair was performed using three 2.9-mm bioabsorbable suture anchors, placing 2 posterior and 1 anterior to the biceps tendon. The integrity of the labral repair was observed while placing the shoulder through range of motion.

Postoperatively, the patient was kept in a sling for 5 weeks. Home exercises were initiated at 2 weeks, and outpatient physical therapy was implemented at 4 weeks. The patient resumed swimming, throwing, and other activities—with minimal discomfort—at 6 months postoperatively.

Three years after his initial visit, the patient returned to the office with a similar complaint of pain and limitation of function in his left shoulder after returning to full athletic competition. Once again, there was no history of injury, and history, physical examination, and MRI arthrogram (Figures 1A, 1B) evaluation proved to be very similar to this young athlete’s right shoulder work-up.

The patient once again underwent shoulder arthroscopy and treatment. Although this was now the left shoulder, the findings were essentially identical to the right shoulder. Once again, the labrum was detached from the 11-o’clock to 2-o’clock positions, and a Buford complex was present anteriorly (Figure 2A). The labral tear was easily displaceable from the glenoid with a probe, and placing the shoulder through a range of motion led to increased displacement of the labrum from the glenoid. There was also confluence of the intra-articular LHBT with the undersurface of the capsule within the rotator interval (Figure 2B). A radiofrequency wand, shaver, and elevator were used to define the biceps tendon and separate it from the undersurface of the capsule. The SLAP repair was performed using three 2.9-mm absorbable suture anchors with 2 posterior and 1 anterior to the biceps tendon insertion. The labral repair was observed while placing the shoulder through range of motion and the shoulder was seen to be free of any undue tension on the labrum.

Postoperatively, the patient’s sling and rehabilitation protocol was identical to that of the right shoulder. The patient progressed well, was released to full activity at 6 months, and has not returned with any further complaints of left or right shoulder pain. Approximately 3 years after treatment the patient was contacted via phone and asked about symptoms, pain, and activity. He denies current symptoms of clicking or instability and has no pain that he can identify as being related to previous pathology or treatment. Since the surgery, he has ceased competitive sports and weight lifting, which he attributes to deconditioning associated with postsurgical immobilization and lack of motivation.

Discussion

Of the 8 case reports in the literature that identified variable intra-articular biceps insertional anatomy, only 2 reports represented confluence of the biceps within the rotator interval.7 Interestingly, of the cases identified, the single case that presented a patient with similar pathology of a type II SLAP lesion had an almost identical anatomical variant presentation consisting of both the anomalous insertion of the LHBT into the undersurface of the rotator interval and a Buford variant of the anterosuperior glenohumeral ligament complex. To our knowledge, our bilateral case of an altered intra-articular biceps insertion and a concomitant SLAP tear supports the theory that this pattern of anomalous insertion may very well have altered the biomechanics of the tendon, resulting in acquired pathology to the superior labrum.

The literature reviewed showed the prevalence of anatomic variations of the LHBT ranged from 1.9% to 7.4%.13,14 These variations are generally considered benign; however, in some cases—as in the cases of the young athletes presented by Wahl and MacGillivray7 and in this report—anatomic variation may play an important role in pathogenesis of different injury patterns. The primary function of the LHBT is the stabilization of the glenohumeral joint during abduction and external rotation.15 When the insertion diverges from normal (eg, when the tendon is tethered to the undersurface of the rotator cuff), the biomechanical stresses on the tendon likely change. As a result of the anomalous position of the LHBT origin, there may be a change in the shoulder joint’s biomechanics, with increased strain on the glenohumeral ligament and its attachment onto the glenoid.16

This case report differs from publications on variable superior glenohumeral ligament attachments because a discrete superior glenohumeral ligament structure was isolated from the biceps tendon. Although a larger case series or patient cohort, as well as more involved biomechanical analysis, would certainly be necessary to prove our hypothesis, we believe that this case suggests certain anatomic LHBT and labral variations can contribute to the develop of SLAP tears in younger individuals.

1. Vangsness CT Jr, Jorgenson SS, Watson T, Johnson DL. The origin of the long head of the biceps from the scapula and glenoid labrum. An anatomical study of 100 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(6):951-954.

2. Burkhead WZ Jr. The biceps tendon. In: Rockwood CA Jr, Matsen FA III, eds. The Shoulder. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:791-836.

3. Parikh SN, Bonnaig N, Zbojniewicz A. Intracapsular origin of the long head biceps tendon with glenoid avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments. Orthopedics. 2011;34(11):781-784.

4. Gaskin CM, Golish SR, Blount KJ, Diduch DR. Anomalies of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon: clinical significance, MR arthrographic findings, and arthroscopic correlation in two patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36(8):785-789.

5. Yeh L, Pedowitz R, Kwak S, et al. Intracapsular origin of the long head of the biceps tendon. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28(3):178-181.

6. Richards DP, Schwartz M. Anomalous intraarticular origin of the long head of the biceps brachii. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(2):122-124.

7. Wahl CJ, MacGillivray JD. Three congenital variations in the long head of the biceps tendon: a review of the pathoanatomic considerations and case reports. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):e25-e30.I

8. Egea JM, Melguizo C, Prados J, Aránega A. Capsular origin of the long head of the biceps tendon: a clinical case. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2010;51(2):375-377.

9. Hyman JL, Warren RF. Extra-articular origin of biceps brachii. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(7): E29.

10. Enad JG. Bifurcate origin of the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(10):1081-1083.

11. Mariani PP, Bellelli A, Botticella C. Arthroscopic absence of the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(4):499-501.

12. Koplas MC, Winalski CS, Ulmer WH Jr, Recht M. Bilateral congenital absence of the long head of the biceps tendon. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(7):715-719.

13. Kanatli U, Ozturk BY, Eisen E, Bolukbasi S. Intra-articular variations of the long head of the biceps tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1576-1581.

14. Dierickx C, Ceccarelli E, Conti M, Vanlommel J, Castagna A. Variations of the intra-articular portion of the long head of the biceps tendon: a classification of embryologically explained variations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):556-565.

15. Rodosky MW, Harner CD, Fu FH. The role of the long head of the biceps muscle and superior glenoid labrum in anterior stability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):121-130.

16. Bigliani LU, Kelkar R, Flatow EL, Pollock RG, Mow VC. Glenohumeral stability. Biomechanical properties of passive and active stabilizers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):13-30.

1. Vangsness CT Jr, Jorgenson SS, Watson T, Johnson DL. The origin of the long head of the biceps from the scapula and glenoid labrum. An anatomical study of 100 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(6):951-954.

2. Burkhead WZ Jr. The biceps tendon. In: Rockwood CA Jr, Matsen FA III, eds. The Shoulder. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:791-836.

3. Parikh SN, Bonnaig N, Zbojniewicz A. Intracapsular origin of the long head biceps tendon with glenoid avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments. Orthopedics. 2011;34(11):781-784.

4. Gaskin CM, Golish SR, Blount KJ, Diduch DR. Anomalies of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon: clinical significance, MR arthrographic findings, and arthroscopic correlation in two patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36(8):785-789.

5. Yeh L, Pedowitz R, Kwak S, et al. Intracapsular origin of the long head of the biceps tendon. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28(3):178-181.

6. Richards DP, Schwartz M. Anomalous intraarticular origin of the long head of the biceps brachii. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(2):122-124.

7. Wahl CJ, MacGillivray JD. Three congenital variations in the long head of the biceps tendon: a review of the pathoanatomic considerations and case reports. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):e25-e30.I

8. Egea JM, Melguizo C, Prados J, Aránega A. Capsular origin of the long head of the biceps tendon: a clinical case. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2010;51(2):375-377.

9. Hyman JL, Warren RF. Extra-articular origin of biceps brachii. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(7): E29.

10. Enad JG. Bifurcate origin of the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(10):1081-1083.

11. Mariani PP, Bellelli A, Botticella C. Arthroscopic absence of the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(4):499-501.

12. Koplas MC, Winalski CS, Ulmer WH Jr, Recht M. Bilateral congenital absence of the long head of the biceps tendon. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38(7):715-719.

13. Kanatli U, Ozturk BY, Eisen E, Bolukbasi S. Intra-articular variations of the long head of the biceps tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1576-1581.

14. Dierickx C, Ceccarelli E, Conti M, Vanlommel J, Castagna A. Variations of the intra-articular portion of the long head of the biceps tendon: a classification of embryologically explained variations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(4):556-565.

15. Rodosky MW, Harner CD, Fu FH. The role of the long head of the biceps muscle and superior glenoid labrum in anterior stability of the shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):121-130.

16. Bigliani LU, Kelkar R, Flatow EL, Pollock RG, Mow VC. Glenohumeral stability. Biomechanical properties of passive and active stabilizers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):13-30.

Xanthogranulomatous Osteomyelitis of Proximal Femur Masquerading as Benign Bone Tumor

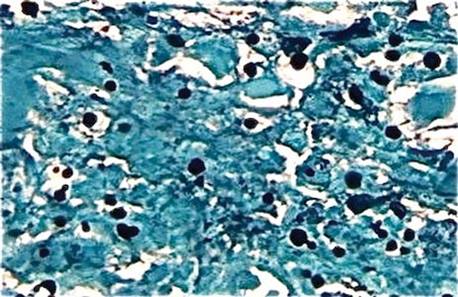

Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis (XO) is a type of chronic inflammatory process that is characterized by the collection of foamy macrophages along with mononuclear cells in the tissue.1 Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis is characterized by the presence of granular, eosinophilic, periodic acid–Schiff–positive histiocytes in the initial stages, followed by the mixture of foamy macrophages and activated plasma cells and, last, by the presence of suppurative foci and hemorrhage. This is an uncommon process best known to occur in the gallbladder, kidney, urinary bladder, fallopian tube, ovary, vagina, prostate, testis, epididymis, colon, and appendix.2-4 Very rarely, it can affect lungs, brain, or bone. Only 5 cases of XO have been reported in the literature.5-8

We report XO of the proximal femur in a 65-year-old woman who initially had a clinical and radiologic diagnosis of aneurysmal bone cyst; however, histopathologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of XO. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis mimics a neoplastic pathology in gallbladder, kidney, and prostrate on gross clinical and radiologic examination.9 The pathogenesis of XO is best characterized by a delayed type of hypersensitivity reaction.10 The differential diagnosis includes chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, xanthoma, infiltrative storage disorder, malakoplakia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, fibrohistiocytic tumor, Erdheim-Chester disease, and metastatic renal cell carcinoma.11-14 The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 65-year-old hypertensive woman presented with complaints of pain in the right hip for a duration of 6 months. Pain was radiating from the right hip region to the anteromedial aspect of the knee and progressively increasing, with a history of pain at rest suggestive of a nonmechanical pathology in the hip. There was no history of fever, weight loss, loss of appetite, pain in any other joint, or morning stiffness. The patient was mobile without support and was able to squat and sit cross-legged; however, the stance phase on the right side was less than on the left side, suggestive of an antalgic component in the gait.

On examining the patient, there was anterior hip joint tenderness with no local sign of any infective or inflammatory pathology. Trochanteric tenderness was present, but there was no irregularity, broadening, or thickening of the trochanter. There was no restriction in the range of motion, and no coronal or sagittal plane deformity in the right hip. There was no limb-length discrepancy. However, the patient was not able to raise her leg actively, probably because of pain in the right hip.

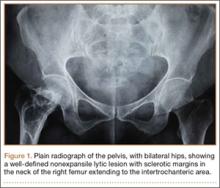

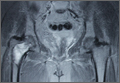

On plain radiographs of the pelvis with bilateral hips, a well-defined nonexpansile uniloculated lytic lesion with sclerotic margins was present in the neck of the right femur, extending to the intertrochanteric area (Figure 1). Ground-glass appearance was also noted. Considering the benign nature of the lesion radiologically and clinically, a differential diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism, renal osteodystrophy, multiple myeloma, and fibrous dysplasia was considered. Hematologic investigations, skeletal survey, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the bilateral hips were performed to rule out the differential diagnosis.

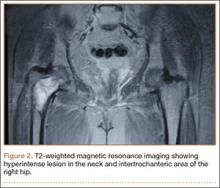

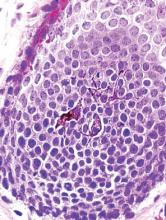

The patient’s hemoglobin level was 11.8 g/dL with total white blood cell count of 10,300/µL. Renal and hepatic functions were within normal limit. Serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 12 mm/h and C-reactive protein level was normal. Serum parathyroid level was 32 pg/mL, which was within normal limits, with an alkaline phosphatase level of 101 U/L. The skeletal survey showed no other bony lesion in the body. T1-weighted MRI of both hips showed a well-defined hypointense lesion in the neck and intertrochanteric area of the right hip, which was hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI, suggestive of aneurysmal bone cyst (Figure 2).

Normal ESR, hemoglobin, alkaline phosphatase, and serum parathyroid levels and normal skeletal survey almost ruled out multiple myeloma and hyperparathyroidism. Normal renal profile ruled out renal osteodystrophy and the osteitis fibrosa cystica lesion associated with it. We planned for prophylactic internal fixation of the lesion to prevent a pathologic fracture. According to Mirels,15 if there is a lytic lesion covering more than two-thirds of the circumference of the bone in the peritrochanteric area, the chances of a pathologic fracture are high and such fractures should be fixed.

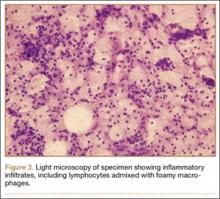

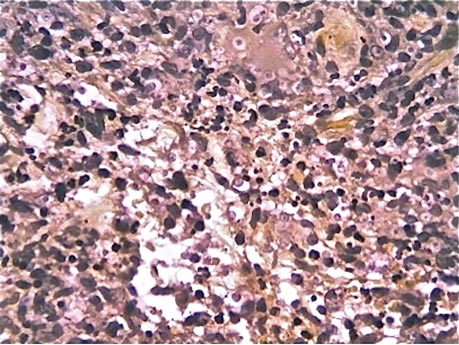

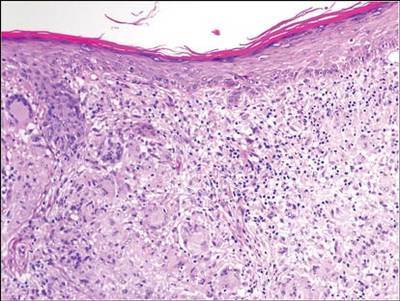

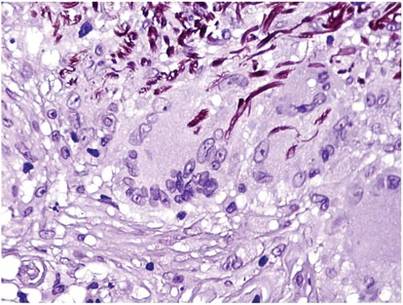

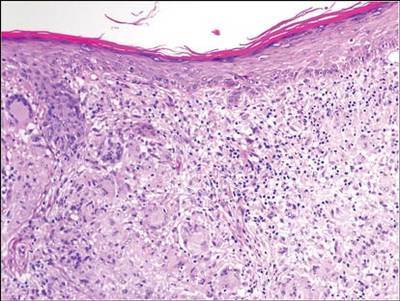

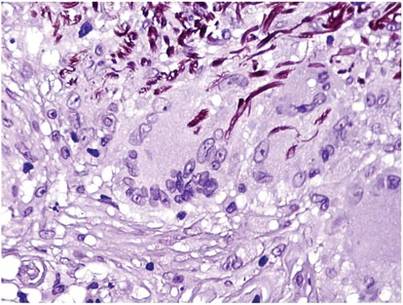

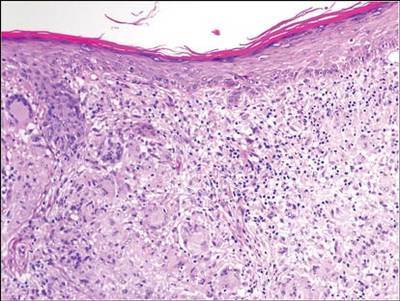

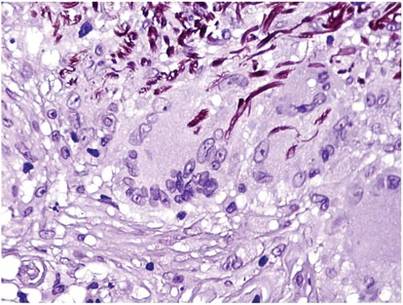

We planned for curettage of the lesion with bone grafting and in situ intramedullary fixation of the lesion. Curettage was done according to the plan and the sample was sent for histopathologic examination. In situ internal fixation and bone grafting were performed by using a proximal femoral intramedullary nail. To our surprise, the biopsy sample was reported as xanthogranuloma, with multiple foamy macrophages mixed with inflammatory cells and aggregates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Mycobacterial and routine bacterial cultures were reported as negative. The patient was kept on oral antibiotics (cefixime and moxifloxacin) for 6 weeks, and she made an uneventful recovery. At 6-month follow-up, a radiograph of the right hip showed a healed lesion with proximal femoral nail in situ (Figure 4).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, a total of 5 cases of XO have been reported in the literature. The earliest of these reports were by Cozzutto and Carbone,1 who reported 2 cases of XO of the first rib and of the epiphysis of the tibia, respectively. The importance of these lesions to diagnosis is their confusion with a neoplastic disease, as XO is itself a benign disorder. These lesions can mimic a neoplastic lesion in clinical and radiologic presentation and the only way to differentiate the lesion from a neoplastic disease is by histopathologic examination of the tissue. Hypothetically, xanthogranulomatous disorders can be related to trauma or infection.

In 2007, Vankalakunti and colleagues6 reported XO of the ulna in a 50-year-old postmenopausal woman. In that case, progressive swelling was present on the extensor aspect of her right forearm for a period of 2 years, for which curettage and bone grafting were performed, using autograft from the ipsilateral iliac crest. The tissue culture was sterile, and XO was diagnosed as a result of the histopathologic examination. In 2009, Cennimo and colleagues7 reported XO of the index finger and wrist of a man complaining of pain and swelling for 1 year, which was unresponsive to antibiotics. The diagnosis of XO was confirmed histopathologically, when the culture of the same tissue grew Mycobacterium marinum. Radical synovectomy of the lesion was performed, after which minocycline, clarithromycin, and ethambutol were administered. In 2012, Borjian and colleagues8 reported a case of XO of the proximal humerus and proximal fibula in a 14-year-old child. The child, who presented with fever, pain, and restriction of shoulder movements, was started on oral antibiotics as the tissue culture grew Staphylococcus aureus; the patient did not complete the course of treatment in the hospital. No surgical intervention was done in this case. The diagnosis of XO was confirmed by microscopic examination of the tissue.

An association between bacterial infection and xanthogranulomatous inflammation has existed in several organs, such as the kidneys, and in the gastrointestinal system, but such an association of the 2 is yet to be determined for bone.5,10,16-19 Because of the paucity of literature on the disease, a management protocol for XO of bone has not been defined, and decisions have to be made considering the natural history of the disease in other organs. We present this case primarily because of its rarity, curability, and its close resemblance to bone tumors. While XO is benign, it can mimic a neoplastic bone lesion in its imaging and clinical manifestations, and appropriate differentiation is crucial. Currently, histopathologic examination of lesions is the most specific and is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Conclusion

Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis is a very rare entity, and only a few cases have been reported in the English-language literature. Though rare, XO warrants greater emphasis than it receives in the literature. It is a chronic inflammatory disease having a close resemblance to bone tumors. A high index of suspicion must be practiced to differentiate XO from tumors. Histopathologic examination is mandatory to establish definitive diagnosis and correct treatment.

1. Cozzutto C, Carbone A. The xanthogranulomatous process. Xanthogranulomatous inflammation. Pathol Res Pract. 1988;183(4):395-402.

2. Ladefoged C, Lorentzen M. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. A clinicopathological study of 20 cases and review of the literature. APMIS. 1993;101(11):869-875.

3. Nistal M, Gonzalez-Peramato P, Serrano A, Regadera J. Xanthogranulomatous funiculitis and orchiepididymitis: report of 2 cases with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128(8):911-914.

4. Oh YH, Seong SS, Jang KS, et al. Xanthogranulomatous inflammation presenting as a submucosal mass of the sigmoid colon. Pathol Int. 2005;55(7):440-444.

5. Cozzutto C. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108(12):973-6.

6. Vankalakunti M, Saikia UN, Mathew M, Kang M. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis of ulna mimicking neoplasm. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;30(5):46.

7. Cennimo DJ, Agag R, Fleegler E, et al. Mycobacterium marinum hand infection in a “sushi chef.” Eplasty. 2009;14(9):e43.

8. Borjian A, Rezaei F, Eshaghi MA, Shemshaki H. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis. J Orthop Traumatol. 2012;13(4):217-220.

9. Rafique M, Yaqoob N. Xanthogranulomatous prostatitis: a mimic of carcinoma of prostate. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:30.

10. Nakashiro H, Haraoka S, Fujiwara K, Harada S, Hisatsugu T, Watanabe T. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystis. Cell composition and a possible pathogenetic role of cell-mediated immunity. Pathol Res Pract. 1995;191(11):1078-1086.

11. Hamada T, Ito H, Araki Y, Fujii K, Inoue M, Ishida O. Benign fibrous histiocytoma of the femur: review of three cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25(1):25-29.

12. Kossard S, Chow E, Wilkinson B, Killingsworth M. Lipid and giant cell poor necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27(7):374-378.

13. Girschick HJ, Huppertz HI, Harmsen D, Krauspe R, Müller-Hermelink HK, Papadopoulos T. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children: diagnostic value of histopathology and microbial testing. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(1):59-65.

14. Kayser R, Mahlfeld K, Grasshoff H. Vertebral Langerhans-cell histiocytosis in childhood – a differential diagnosis of spinal osteomyelitis. Klin Padiatr. 1999;211(5):399-402.

15. Mirels H. Metastatic disease in long bones. A proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathologic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;249:256-264.

16. Machiz S, Gordon J, Block N, Politano VA. Salmonella typhosa urinary tract infection and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Case report and review of literature. J Fla Med Assoc. 1974;61(9):703-705.

17. Gauperaa T, Stalsberg H. Renal endometriosis. A case report. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1977;11(2):189-191.

18. Goodman M, Curry T, Russell T. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP): a local disease with systemic manifestations. Report of 23 patients and review of the literature. Medicine. 1979;58(2):171-181.

19. Guarino M, Reale D, Micoli G, Tricomi P, Cristofori E. Xanthogranulomatous gastritis: association with xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46(1):88-90.

Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis (XO) is a type of chronic inflammatory process that is characterized by the collection of foamy macrophages along with mononuclear cells in the tissue.1 Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis is characterized by the presence of granular, eosinophilic, periodic acid–Schiff–positive histiocytes in the initial stages, followed by the mixture of foamy macrophages and activated plasma cells and, last, by the presence of suppurative foci and hemorrhage. This is an uncommon process best known to occur in the gallbladder, kidney, urinary bladder, fallopian tube, ovary, vagina, prostate, testis, epididymis, colon, and appendix.2-4 Very rarely, it can affect lungs, brain, or bone. Only 5 cases of XO have been reported in the literature.5-8

We report XO of the proximal femur in a 65-year-old woman who initially had a clinical and radiologic diagnosis of aneurysmal bone cyst; however, histopathologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of XO. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis mimics a neoplastic pathology in gallbladder, kidney, and prostrate on gross clinical and radiologic examination.9 The pathogenesis of XO is best characterized by a delayed type of hypersensitivity reaction.10 The differential diagnosis includes chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, xanthoma, infiltrative storage disorder, malakoplakia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, fibrohistiocytic tumor, Erdheim-Chester disease, and metastatic renal cell carcinoma.11-14 The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 65-year-old hypertensive woman presented with complaints of pain in the right hip for a duration of 6 months. Pain was radiating from the right hip region to the anteromedial aspect of the knee and progressively increasing, with a history of pain at rest suggestive of a nonmechanical pathology in the hip. There was no history of fever, weight loss, loss of appetite, pain in any other joint, or morning stiffness. The patient was mobile without support and was able to squat and sit cross-legged; however, the stance phase on the right side was less than on the left side, suggestive of an antalgic component in the gait.

On examining the patient, there was anterior hip joint tenderness with no local sign of any infective or inflammatory pathology. Trochanteric tenderness was present, but there was no irregularity, broadening, or thickening of the trochanter. There was no restriction in the range of motion, and no coronal or sagittal plane deformity in the right hip. There was no limb-length discrepancy. However, the patient was not able to raise her leg actively, probably because of pain in the right hip.

On plain radiographs of the pelvis with bilateral hips, a well-defined nonexpansile uniloculated lytic lesion with sclerotic margins was present in the neck of the right femur, extending to the intertrochanteric area (Figure 1). Ground-glass appearance was also noted. Considering the benign nature of the lesion radiologically and clinically, a differential diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism, renal osteodystrophy, multiple myeloma, and fibrous dysplasia was considered. Hematologic investigations, skeletal survey, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the bilateral hips were performed to rule out the differential diagnosis.

The patient’s hemoglobin level was 11.8 g/dL with total white blood cell count of 10,300/µL. Renal and hepatic functions were within normal limit. Serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 12 mm/h and C-reactive protein level was normal. Serum parathyroid level was 32 pg/mL, which was within normal limits, with an alkaline phosphatase level of 101 U/L. The skeletal survey showed no other bony lesion in the body. T1-weighted MRI of both hips showed a well-defined hypointense lesion in the neck and intertrochanteric area of the right hip, which was hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI, suggestive of aneurysmal bone cyst (Figure 2).

Normal ESR, hemoglobin, alkaline phosphatase, and serum parathyroid levels and normal skeletal survey almost ruled out multiple myeloma and hyperparathyroidism. Normal renal profile ruled out renal osteodystrophy and the osteitis fibrosa cystica lesion associated with it. We planned for prophylactic internal fixation of the lesion to prevent a pathologic fracture. According to Mirels,15 if there is a lytic lesion covering more than two-thirds of the circumference of the bone in the peritrochanteric area, the chances of a pathologic fracture are high and such fractures should be fixed.

We planned for curettage of the lesion with bone grafting and in situ intramedullary fixation of the lesion. Curettage was done according to the plan and the sample was sent for histopathologic examination. In situ internal fixation and bone grafting were performed by using a proximal femoral intramedullary nail. To our surprise, the biopsy sample was reported as xanthogranuloma, with multiple foamy macrophages mixed with inflammatory cells and aggregates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Mycobacterial and routine bacterial cultures were reported as negative. The patient was kept on oral antibiotics (cefixime and moxifloxacin) for 6 weeks, and she made an uneventful recovery. At 6-month follow-up, a radiograph of the right hip showed a healed lesion with proximal femoral nail in situ (Figure 4).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, a total of 5 cases of XO have been reported in the literature. The earliest of these reports were by Cozzutto and Carbone,1 who reported 2 cases of XO of the first rib and of the epiphysis of the tibia, respectively. The importance of these lesions to diagnosis is their confusion with a neoplastic disease, as XO is itself a benign disorder. These lesions can mimic a neoplastic lesion in clinical and radiologic presentation and the only way to differentiate the lesion from a neoplastic disease is by histopathologic examination of the tissue. Hypothetically, xanthogranulomatous disorders can be related to trauma or infection.

In 2007, Vankalakunti and colleagues6 reported XO of the ulna in a 50-year-old postmenopausal woman. In that case, progressive swelling was present on the extensor aspect of her right forearm for a period of 2 years, for which curettage and bone grafting were performed, using autograft from the ipsilateral iliac crest. The tissue culture was sterile, and XO was diagnosed as a result of the histopathologic examination. In 2009, Cennimo and colleagues7 reported XO of the index finger and wrist of a man complaining of pain and swelling for 1 year, which was unresponsive to antibiotics. The diagnosis of XO was confirmed histopathologically, when the culture of the same tissue grew Mycobacterium marinum. Radical synovectomy of the lesion was performed, after which minocycline, clarithromycin, and ethambutol were administered. In 2012, Borjian and colleagues8 reported a case of XO of the proximal humerus and proximal fibula in a 14-year-old child. The child, who presented with fever, pain, and restriction of shoulder movements, was started on oral antibiotics as the tissue culture grew Staphylococcus aureus; the patient did not complete the course of treatment in the hospital. No surgical intervention was done in this case. The diagnosis of XO was confirmed by microscopic examination of the tissue.

An association between bacterial infection and xanthogranulomatous inflammation has existed in several organs, such as the kidneys, and in the gastrointestinal system, but such an association of the 2 is yet to be determined for bone.5,10,16-19 Because of the paucity of literature on the disease, a management protocol for XO of bone has not been defined, and decisions have to be made considering the natural history of the disease in other organs. We present this case primarily because of its rarity, curability, and its close resemblance to bone tumors. While XO is benign, it can mimic a neoplastic bone lesion in its imaging and clinical manifestations, and appropriate differentiation is crucial. Currently, histopathologic examination of lesions is the most specific and is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Conclusion

Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis is a very rare entity, and only a few cases have been reported in the English-language literature. Though rare, XO warrants greater emphasis than it receives in the literature. It is a chronic inflammatory disease having a close resemblance to bone tumors. A high index of suspicion must be practiced to differentiate XO from tumors. Histopathologic examination is mandatory to establish definitive diagnosis and correct treatment.

Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis (XO) is a type of chronic inflammatory process that is characterized by the collection of foamy macrophages along with mononuclear cells in the tissue.1 Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis is characterized by the presence of granular, eosinophilic, periodic acid–Schiff–positive histiocytes in the initial stages, followed by the mixture of foamy macrophages and activated plasma cells and, last, by the presence of suppurative foci and hemorrhage. This is an uncommon process best known to occur in the gallbladder, kidney, urinary bladder, fallopian tube, ovary, vagina, prostate, testis, epididymis, colon, and appendix.2-4 Very rarely, it can affect lungs, brain, or bone. Only 5 cases of XO have been reported in the literature.5-8

We report XO of the proximal femur in a 65-year-old woman who initially had a clinical and radiologic diagnosis of aneurysmal bone cyst; however, histopathologic examination confirmed the diagnosis of XO. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis mimics a neoplastic pathology in gallbladder, kidney, and prostrate on gross clinical and radiologic examination.9 The pathogenesis of XO is best characterized by a delayed type of hypersensitivity reaction.10 The differential diagnosis includes chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, xanthoma, infiltrative storage disorder, malakoplakia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, fibrohistiocytic tumor, Erdheim-Chester disease, and metastatic renal cell carcinoma.11-14 The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 65-year-old hypertensive woman presented with complaints of pain in the right hip for a duration of 6 months. Pain was radiating from the right hip region to the anteromedial aspect of the knee and progressively increasing, with a history of pain at rest suggestive of a nonmechanical pathology in the hip. There was no history of fever, weight loss, loss of appetite, pain in any other joint, or morning stiffness. The patient was mobile without support and was able to squat and sit cross-legged; however, the stance phase on the right side was less than on the left side, suggestive of an antalgic component in the gait.

On examining the patient, there was anterior hip joint tenderness with no local sign of any infective or inflammatory pathology. Trochanteric tenderness was present, but there was no irregularity, broadening, or thickening of the trochanter. There was no restriction in the range of motion, and no coronal or sagittal plane deformity in the right hip. There was no limb-length discrepancy. However, the patient was not able to raise her leg actively, probably because of pain in the right hip.

On plain radiographs of the pelvis with bilateral hips, a well-defined nonexpansile uniloculated lytic lesion with sclerotic margins was present in the neck of the right femur, extending to the intertrochanteric area (Figure 1). Ground-glass appearance was also noted. Considering the benign nature of the lesion radiologically and clinically, a differential diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism, renal osteodystrophy, multiple myeloma, and fibrous dysplasia was considered. Hematologic investigations, skeletal survey, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the bilateral hips were performed to rule out the differential diagnosis.

The patient’s hemoglobin level was 11.8 g/dL with total white blood cell count of 10,300/µL. Renal and hepatic functions were within normal limit. Serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 12 mm/h and C-reactive protein level was normal. Serum parathyroid level was 32 pg/mL, which was within normal limits, with an alkaline phosphatase level of 101 U/L. The skeletal survey showed no other bony lesion in the body. T1-weighted MRI of both hips showed a well-defined hypointense lesion in the neck and intertrochanteric area of the right hip, which was hyperintense on T2-weighted MRI, suggestive of aneurysmal bone cyst (Figure 2).

Normal ESR, hemoglobin, alkaline phosphatase, and serum parathyroid levels and normal skeletal survey almost ruled out multiple myeloma and hyperparathyroidism. Normal renal profile ruled out renal osteodystrophy and the osteitis fibrosa cystica lesion associated with it. We planned for prophylactic internal fixation of the lesion to prevent a pathologic fracture. According to Mirels,15 if there is a lytic lesion covering more than two-thirds of the circumference of the bone in the peritrochanteric area, the chances of a pathologic fracture are high and such fractures should be fixed.

We planned for curettage of the lesion with bone grafting and in situ intramedullary fixation of the lesion. Curettage was done according to the plan and the sample was sent for histopathologic examination. In situ internal fixation and bone grafting were performed by using a proximal femoral intramedullary nail. To our surprise, the biopsy sample was reported as xanthogranuloma, with multiple foamy macrophages mixed with inflammatory cells and aggregates of lymphocytes (Figure 3). Mycobacterial and routine bacterial cultures were reported as negative. The patient was kept on oral antibiotics (cefixime and moxifloxacin) for 6 weeks, and she made an uneventful recovery. At 6-month follow-up, a radiograph of the right hip showed a healed lesion with proximal femoral nail in situ (Figure 4).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, a total of 5 cases of XO have been reported in the literature. The earliest of these reports were by Cozzutto and Carbone,1 who reported 2 cases of XO of the first rib and of the epiphysis of the tibia, respectively. The importance of these lesions to diagnosis is their confusion with a neoplastic disease, as XO is itself a benign disorder. These lesions can mimic a neoplastic lesion in clinical and radiologic presentation and the only way to differentiate the lesion from a neoplastic disease is by histopathologic examination of the tissue. Hypothetically, xanthogranulomatous disorders can be related to trauma or infection.

In 2007, Vankalakunti and colleagues6 reported XO of the ulna in a 50-year-old postmenopausal woman. In that case, progressive swelling was present on the extensor aspect of her right forearm for a period of 2 years, for which curettage and bone grafting were performed, using autograft from the ipsilateral iliac crest. The tissue culture was sterile, and XO was diagnosed as a result of the histopathologic examination. In 2009, Cennimo and colleagues7 reported XO of the index finger and wrist of a man complaining of pain and swelling for 1 year, which was unresponsive to antibiotics. The diagnosis of XO was confirmed histopathologically, when the culture of the same tissue grew Mycobacterium marinum. Radical synovectomy of the lesion was performed, after which minocycline, clarithromycin, and ethambutol were administered. In 2012, Borjian and colleagues8 reported a case of XO of the proximal humerus and proximal fibula in a 14-year-old child. The child, who presented with fever, pain, and restriction of shoulder movements, was started on oral antibiotics as the tissue culture grew Staphylococcus aureus; the patient did not complete the course of treatment in the hospital. No surgical intervention was done in this case. The diagnosis of XO was confirmed by microscopic examination of the tissue.

An association between bacterial infection and xanthogranulomatous inflammation has existed in several organs, such as the kidneys, and in the gastrointestinal system, but such an association of the 2 is yet to be determined for bone.5,10,16-19 Because of the paucity of literature on the disease, a management protocol for XO of bone has not been defined, and decisions have to be made considering the natural history of the disease in other organs. We present this case primarily because of its rarity, curability, and its close resemblance to bone tumors. While XO is benign, it can mimic a neoplastic bone lesion in its imaging and clinical manifestations, and appropriate differentiation is crucial. Currently, histopathologic examination of lesions is the most specific and is the gold standard for diagnosis.

Conclusion

Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis is a very rare entity, and only a few cases have been reported in the English-language literature. Though rare, XO warrants greater emphasis than it receives in the literature. It is a chronic inflammatory disease having a close resemblance to bone tumors. A high index of suspicion must be practiced to differentiate XO from tumors. Histopathologic examination is mandatory to establish definitive diagnosis and correct treatment.

1. Cozzutto C, Carbone A. The xanthogranulomatous process. Xanthogranulomatous inflammation. Pathol Res Pract. 1988;183(4):395-402.

2. Ladefoged C, Lorentzen M. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. A clinicopathological study of 20 cases and review of the literature. APMIS. 1993;101(11):869-875.

3. Nistal M, Gonzalez-Peramato P, Serrano A, Regadera J. Xanthogranulomatous funiculitis and orchiepididymitis: report of 2 cases with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128(8):911-914.

4. Oh YH, Seong SS, Jang KS, et al. Xanthogranulomatous inflammation presenting as a submucosal mass of the sigmoid colon. Pathol Int. 2005;55(7):440-444.

5. Cozzutto C. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108(12):973-6.

6. Vankalakunti M, Saikia UN, Mathew M, Kang M. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis of ulna mimicking neoplasm. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;30(5):46.

7. Cennimo DJ, Agag R, Fleegler E, et al. Mycobacterium marinum hand infection in a “sushi chef.” Eplasty. 2009;14(9):e43.

8. Borjian A, Rezaei F, Eshaghi MA, Shemshaki H. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis. J Orthop Traumatol. 2012;13(4):217-220.

9. Rafique M, Yaqoob N. Xanthogranulomatous prostatitis: a mimic of carcinoma of prostate. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:30.

10. Nakashiro H, Haraoka S, Fujiwara K, Harada S, Hisatsugu T, Watanabe T. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystis. Cell composition and a possible pathogenetic role of cell-mediated immunity. Pathol Res Pract. 1995;191(11):1078-1086.

11. Hamada T, Ito H, Araki Y, Fujii K, Inoue M, Ishida O. Benign fibrous histiocytoma of the femur: review of three cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25(1):25-29.

12. Kossard S, Chow E, Wilkinson B, Killingsworth M. Lipid and giant cell poor necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27(7):374-378.

13. Girschick HJ, Huppertz HI, Harmsen D, Krauspe R, Müller-Hermelink HK, Papadopoulos T. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children: diagnostic value of histopathology and microbial testing. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(1):59-65.

14. Kayser R, Mahlfeld K, Grasshoff H. Vertebral Langerhans-cell histiocytosis in childhood – a differential diagnosis of spinal osteomyelitis. Klin Padiatr. 1999;211(5):399-402.

15. Mirels H. Metastatic disease in long bones. A proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathologic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;249:256-264.

16. Machiz S, Gordon J, Block N, Politano VA. Salmonella typhosa urinary tract infection and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Case report and review of literature. J Fla Med Assoc. 1974;61(9):703-705.

17. Gauperaa T, Stalsberg H. Renal endometriosis. A case report. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1977;11(2):189-191.

18. Goodman M, Curry T, Russell T. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP): a local disease with systemic manifestations. Report of 23 patients and review of the literature. Medicine. 1979;58(2):171-181.

19. Guarino M, Reale D, Micoli G, Tricomi P, Cristofori E. Xanthogranulomatous gastritis: association with xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46(1):88-90.

1. Cozzutto C, Carbone A. The xanthogranulomatous process. Xanthogranulomatous inflammation. Pathol Res Pract. 1988;183(4):395-402.

2. Ladefoged C, Lorentzen M. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. A clinicopathological study of 20 cases and review of the literature. APMIS. 1993;101(11):869-875.

3. Nistal M, Gonzalez-Peramato P, Serrano A, Regadera J. Xanthogranulomatous funiculitis and orchiepididymitis: report of 2 cases with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128(8):911-914.

4. Oh YH, Seong SS, Jang KS, et al. Xanthogranulomatous inflammation presenting as a submucosal mass of the sigmoid colon. Pathol Int. 2005;55(7):440-444.

5. Cozzutto C. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108(12):973-6.

6. Vankalakunti M, Saikia UN, Mathew M, Kang M. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis of ulna mimicking neoplasm. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;30(5):46.

7. Cennimo DJ, Agag R, Fleegler E, et al. Mycobacterium marinum hand infection in a “sushi chef.” Eplasty. 2009;14(9):e43.

8. Borjian A, Rezaei F, Eshaghi MA, Shemshaki H. Xanthogranulomatous osteomyelitis. J Orthop Traumatol. 2012;13(4):217-220.

9. Rafique M, Yaqoob N. Xanthogranulomatous prostatitis: a mimic of carcinoma of prostate. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:30.

10. Nakashiro H, Haraoka S, Fujiwara K, Harada S, Hisatsugu T, Watanabe T. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystis. Cell composition and a possible pathogenetic role of cell-mediated immunity. Pathol Res Pract. 1995;191(11):1078-1086.

11. Hamada T, Ito H, Araki Y, Fujii K, Inoue M, Ishida O. Benign fibrous histiocytoma of the femur: review of three cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25(1):25-29.

12. Kossard S, Chow E, Wilkinson B, Killingsworth M. Lipid and giant cell poor necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. J Cutan Pathol. 2000;27(7):374-378.

13. Girschick HJ, Huppertz HI, Harmsen D, Krauspe R, Müller-Hermelink HK, Papadopoulos T. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in children: diagnostic value of histopathology and microbial testing. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(1):59-65.

14. Kayser R, Mahlfeld K, Grasshoff H. Vertebral Langerhans-cell histiocytosis in childhood – a differential diagnosis of spinal osteomyelitis. Klin Padiatr. 1999;211(5):399-402.

15. Mirels H. Metastatic disease in long bones. A proposed scoring system for diagnosing impending pathologic fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;249:256-264.

16. Machiz S, Gordon J, Block N, Politano VA. Salmonella typhosa urinary tract infection and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Case report and review of literature. J Fla Med Assoc. 1974;61(9):703-705.

17. Gauperaa T, Stalsberg H. Renal endometriosis. A case report. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1977;11(2):189-191.

18. Goodman M, Curry T, Russell T. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis (XGP): a local disease with systemic manifestations. Report of 23 patients and review of the literature. Medicine. 1979;58(2):171-181.

19. Guarino M, Reale D, Micoli G, Tricomi P, Cristofori E. Xanthogranulomatous gastritis: association with xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46(1):88-90.

Case Studies in Toxicology: Managing Missed Methadone

A 53-year-old woman presented to the ED after experiencing a fall. Her medical history was significant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis, and a remote history of intravenous drug use, for which she had been maintained on methadone for the past 20 years. She reported that she had suffered several “fainting episodes” over the past month, and the morning prior to arrival, had sustained what she thought was a mechanical fall outside of the methadone program she attended. She complained of tenderness on her head but denied any other injuries.

The methadone program had referred the patient to the ED for evaluation, noting to the ED staff that her daily methadone dose of 185 mg had not been dispensed prior to transfer. During evaluation, the patient requested that the emergency physician (EP) provide the methadone dose since the clinic would close prior to her discharge from the ED.

How can requests for methadone be managed in the ED?

Methadone is a long-acting oral opioid that is used for both opioid replacement therapy and pain management. When used to reduce craving in opioid-dependent patients, methadone is administered daily through federally sanctioned methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs. Patients who consistently adhere to the required guidelines are given “take home” doses. When used for pain management, methadone is typically administered several times daily and may be prescribed by any provider with an appropriate DEA registration.

When given for MMT, methadone saturates the µ-opioid receptors and hinders their binding and agonism by other opioids such as heroin or oxycodone. Patients in MMT programs are started on a low initial dose and slowly titrated upward as tolerance to the adverse effects (eg, sedation) develop.

How are symptomatic patients with methadone withdrawal treated?

Most methadone programs have limited hours and require that patients who miss a dose wait until the following day to return to the program. This is typically without medical consequence because the high dose dispensed by these programs maintains a therapeutic blood concentration for far longer than the expected delay. Although the half-life of methadone exhibits wide interindividual variability, it generally ranges from 12 hours to more than 40 hours.1 Regardless, patients may feel anxious about potential opioid withdrawal, and this often leads them to access the ED for a missed dose.

The neuropsychiatric symptoms attending withdrawal may precede the objective signs of opioid withdrawal. Patients with objective signs of opioid withdrawal (eg, piloerection, vomiting, diarrhea, dilated pupils) may be sufficiently treated with supportive care alone, using antiemetics, hydration, and sometimes clonidine.

Administration of substitute opioids is problematic due to the patient’s underlying tolerance necessitating careful dose titration. Therefore, direct replacement of methadone in the ED remains controversial, and some EDs have strict policies prohibiting the administration of methadone to patients who have missed an MMT dose. Such policies, which are intended to discourage patients from using the ED as a convenience, may be appropriate given the generally benign—though uncomfortable—course of opioid withdrawal due to abstinence.

Other EDs provide replacement methadone for asymptomatic, treat-and-release patients confirmed to be enrolled in an MMT program when the time to the next dose is likely to be 24 hours or greater from the missed dose. Typically, a dose of no more than 10 mg orally or 10 mg intramuscularly (IM) is recommended, and patients should be advised that they will be receiving only a low dose to sufficient to prevent withdrawal—one that may not have the equivalent effects of the outpatient dose.

Whenever possible, a patient’s MMT program should be contacted and informed of the ED visit. For patients who display objective signs of withdrawal and who cannot be confirmed or who do not participate in an MMT program, 10 mg of methadone IM will prevent uncertainty of drug absorption in the setting of nausea or vomiting. All patients receiving oral methadone should be observed for 1 hour, and those receiving IM methadone should be observed for at least 90 minutes to assess for unexpected sedation.2

Patients encountering circumstances that prevent opioid access (eg, incarceration) and who are not in withdrawal but have gone without opioids for more than 5 days may have a loss of tolerance to their usual doses—whether the medication was obtained through an MMT program or illicitly. Harm-reduction strategies aimed at educating patients on the potential vulnerability to their familiar dosing regimens are warranted to avert inadvertent overdoses in chronic opioid users who are likely to resume illicit opoiod use.

Does this patient need syncope evaluation?

Further complicating the decision regarding ED dispensing of methadone are the effects of the drug on myocardial repolarization. Methadone affects conduction across the hERG potassium rectifier current and can prolong the QTc interval on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG), predisposing a patient to torsade de pointes (TdP). Although there is controversy regarding the role of ECG screening during the enrollment of patients in methadone maintenance clinics, doses above 60 mg, underlying myocardial disease, female sex, and electrolyte disturbances may increase the risk of QT prolongation and TdP.3

Whether there is value in obtaining a screening ECG in a patient receiving an initial dose of methadone in the ED is unclear, and this practice is controversial even among methadone clinics. However, some of the excess death in patients taking methadone may be explained by the dysrhythmogenic potential of methadone.4 An ECG therefore may elucidate a correctable cause in methadone patients presenting with syncope.

Administering methadone to patients with documented QT prolongation must weigh the risk of methadone’s conduction effects against the substantial risks of illicit opioid self-administration. For some patients at-risk for TdP, it may be preferable to use buprenorphine if possible, since it does not carry the same cardiac effects as methadone.1,5 Such therapy requires referral to a physician licensed to prescribe this medication.

How should admitted patients be managed?