User login

Septic Arthritis and Osteomyelitis Caused by Pasteurella multocida

A few days after an incidental cat bite, a patient presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure. He was discharged with oral methylprednisolone for the dermatitis and returned 1 week later with symptoms, examination findings, and laboratory results consistent with sepsis and bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infections. After administering multiple irrigation and débridement procedures, hyperbaric oxygen treatments, and an antibiotic regimen, the patient’s status greatly improved. However, the patient returned 1 month later with a new sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. Additionally, he noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful. Imaging studies showed a lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint bilaterally, consistent with osteomyelitis. The patient was treated with ertapenem for 6 weeks, and his polyarthropathy resolved. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old, right-hand–dominant man with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure, incidentally, a few days after being bitten by a cat on the bilateral distal upper extremities. He was prescribed a course of oral methylprednisolone for dermatitis. A week later, the patient returned to the emergency department with altered mental status, fevers, diaphoresis, lethargy, and polyarthralgia. At the time of presentation, the patient’s vital signs were labile, and he was found to have extensive bilateral upper extremity erythema, blistering, petechiae, purpuric lesions, and exquisite pain with passive range of motion of his fingers and wrists. His leukocyte count was 25.1 × 109/L, and he had elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 150 mg/L and 120 mm/h, respectively. He was admitted for management of sepsis and presumed bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infection.

Broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin, tazobactam) were initiated after blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating theatre for irrigation and débridement of his hands and wrists bilaterally. Arthrotomy of the wrist and débridement of the distal extensor compartment and its tenosynovium were performed on the right forearm, in addition to a decompressive fasciotomy of the left forearm. Postoperatively, the patient’s mental status improved and his vital signs gradually normalized. He received multiple hyperbaric oxygen treatments and underwent several additional operative débridement procedures with eventual closure of his wounds. At initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for the severe soft-tissue infection included necrotizing fasciitis or myositis caused by any of a variety of bacterial pathogens. Most notably, it was important to elicit the history of a cat bite to include and consider Pasteurella multocida as a potential pathogen. Initial cultures supported the diagnosis of acute P multocida necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infection, in addition to septic arthritis. The patient’s blood and intraoperative wound cultures grew P multocida. The antibiotic treatment was tailored initially to ampicillin and sulbactam and then to a final regimen of orally administered ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice a day), once susceptibility testing was performed on the cultures. On hospital day 10, the patient was discharged home, receiving a 6-week course of ciprofloxacin to complete the 8-week course of treatment.

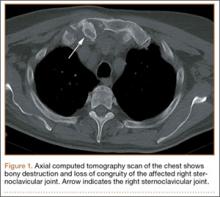

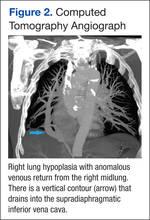

At follow-up, approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient noted that he had developed a new right sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. He also noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful bilaterally. Computed tomography scans of the chest were obtained to evaluate the sternoclavicular joint (Figure 1). Repeat radiographs of the wrists were also obtained (Figure 2). Imaging showed lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint, consistent with osteomyelitis. The C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at this time were 34 mg/L and 124 mm/h, respectively.

The patient returned to the operating room for débridement and biopsy of the right sternoclavicular joint and left wrist. This patient’s delayed presentation was characterized by a subacute worsening of isolated musculoskeletal complaints. The differential diagnosis then included infection with the same bacterial pathogen versus reactive or inflammatory arthritis. Several intraoperative cultures failed to grow any bacteria, including P multocida, although P multocida was the presumptive cause of the erosive polyarthropathy, considering that symptoms eventually resolved with a repeated course of IV-administered ertapenem for 6 weeks. The patient experienced complete resolution of his joint pain and swelling. He was able to resume his activities of daily living and had no further recurrence of symptoms at follow-up 3 months later.

Discussion

Cat bites often are the source of Pasteurella species infections because the bacteria are carried by more than 90% of cats.1 These types of infections can cause septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and deep subcutaneous and myofascial infections because of the sharp and narrow morphology of cat teeth. The infections can progress to necrotizing fasciitis and myositis if not recognized early, as was the case with our patient. Prophylactic antibiotic administration for animal bites is controversial and is not a universal practice.1,2Pasteurella bacteremia is an atypical progression that occurs more often in patients with pneumonia, septic arthritis, or meningitis. Cases of Pasteurella sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and septic arthritis have been reported.3-7 However, associated progressive septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, despite initial clinical improvement, have not been reported. Severe infection (ie, sepsis and septic shock) can occur in infants, pregnant women, and other immunocompromised patients.7 Immune suppression of our patient with steroid medication for poison sumac dermatitis likely contributed to the progression and systemic spread of an initially benign cat bite. Before prescribing steroids, it is imperative to ask about exposures and encourage patients to seek prompt medical attention with worsening or new symptoms. Healthy individuals rarely develop bacteremia; however, in these cases, mortality remains high at approximately 25%.4,6

The clinical course of this case emphasizes the need for vigilance and thoroughness in obtaining histories from patients presenting with seemingly benign complaints, especially in vulnerable populations, such as infants, pregnant women, and immunocompromised adults. In this case, the progression of symptoms might have been avoided if the patient’s dermatitis had been treated conservatively or with topical rather than systemic steroids.

1. Esposito S, Picciolli I, Semino M, Principi N. Dog and cat bite-associated infections in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(8):971-976.

2. Medeiros I, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD001738.

3. Haybaeck J, Schindler C, Braza P, Willinger B, Drlicek M. Rapidly progressive and lethal septicemia due to infection with Pasteurella multocida in an infant. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2009;121(5-6):216-219.

4. Migliore E, Serraino C, Brignone C, et al. Pasteurella multocida infection in a cirrhotic patient: case report, microbiological aspects and a review of the literature. Adv Med Sci. 2009;54(1):109-112.

5. Mugambi SM, Ullian ME. Bacteremia, sepsis, and peritonitis with Pasteurella multocida in a peritoneal dialysis patient. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(3):381-383.

6. Weber DJ, Wolfson JS, Swartz MN, Hooper DC. Pasteurella multocida infections. Report of 34 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63(3):133-154.

7. Oehler RL, Velez AP, Mizrachi M, Lamarche J, Gompf S. Bite-related and septic syndromes caused by cats and dogs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(7):439-447.

A few days after an incidental cat bite, a patient presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure. He was discharged with oral methylprednisolone for the dermatitis and returned 1 week later with symptoms, examination findings, and laboratory results consistent with sepsis and bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infections. After administering multiple irrigation and débridement procedures, hyperbaric oxygen treatments, and an antibiotic regimen, the patient’s status greatly improved. However, the patient returned 1 month later with a new sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. Additionally, he noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful. Imaging studies showed a lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint bilaterally, consistent with osteomyelitis. The patient was treated with ertapenem for 6 weeks, and his polyarthropathy resolved. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old, right-hand–dominant man with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure, incidentally, a few days after being bitten by a cat on the bilateral distal upper extremities. He was prescribed a course of oral methylprednisolone for dermatitis. A week later, the patient returned to the emergency department with altered mental status, fevers, diaphoresis, lethargy, and polyarthralgia. At the time of presentation, the patient’s vital signs were labile, and he was found to have extensive bilateral upper extremity erythema, blistering, petechiae, purpuric lesions, and exquisite pain with passive range of motion of his fingers and wrists. His leukocyte count was 25.1 × 109/L, and he had elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 150 mg/L and 120 mm/h, respectively. He was admitted for management of sepsis and presumed bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infection.

Broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin, tazobactam) were initiated after blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating theatre for irrigation and débridement of his hands and wrists bilaterally. Arthrotomy of the wrist and débridement of the distal extensor compartment and its tenosynovium were performed on the right forearm, in addition to a decompressive fasciotomy of the left forearm. Postoperatively, the patient’s mental status improved and his vital signs gradually normalized. He received multiple hyperbaric oxygen treatments and underwent several additional operative débridement procedures with eventual closure of his wounds. At initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for the severe soft-tissue infection included necrotizing fasciitis or myositis caused by any of a variety of bacterial pathogens. Most notably, it was important to elicit the history of a cat bite to include and consider Pasteurella multocida as a potential pathogen. Initial cultures supported the diagnosis of acute P multocida necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infection, in addition to septic arthritis. The patient’s blood and intraoperative wound cultures grew P multocida. The antibiotic treatment was tailored initially to ampicillin and sulbactam and then to a final regimen of orally administered ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice a day), once susceptibility testing was performed on the cultures. On hospital day 10, the patient was discharged home, receiving a 6-week course of ciprofloxacin to complete the 8-week course of treatment.

At follow-up, approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient noted that he had developed a new right sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. He also noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful bilaterally. Computed tomography scans of the chest were obtained to evaluate the sternoclavicular joint (Figure 1). Repeat radiographs of the wrists were also obtained (Figure 2). Imaging showed lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint, consistent with osteomyelitis. The C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at this time were 34 mg/L and 124 mm/h, respectively.

The patient returned to the operating room for débridement and biopsy of the right sternoclavicular joint and left wrist. This patient’s delayed presentation was characterized by a subacute worsening of isolated musculoskeletal complaints. The differential diagnosis then included infection with the same bacterial pathogen versus reactive or inflammatory arthritis. Several intraoperative cultures failed to grow any bacteria, including P multocida, although P multocida was the presumptive cause of the erosive polyarthropathy, considering that symptoms eventually resolved with a repeated course of IV-administered ertapenem for 6 weeks. The patient experienced complete resolution of his joint pain and swelling. He was able to resume his activities of daily living and had no further recurrence of symptoms at follow-up 3 months later.

Discussion

Cat bites often are the source of Pasteurella species infections because the bacteria are carried by more than 90% of cats.1 These types of infections can cause septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and deep subcutaneous and myofascial infections because of the sharp and narrow morphology of cat teeth. The infections can progress to necrotizing fasciitis and myositis if not recognized early, as was the case with our patient. Prophylactic antibiotic administration for animal bites is controversial and is not a universal practice.1,2Pasteurella bacteremia is an atypical progression that occurs more often in patients with pneumonia, septic arthritis, or meningitis. Cases of Pasteurella sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and septic arthritis have been reported.3-7 However, associated progressive septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, despite initial clinical improvement, have not been reported. Severe infection (ie, sepsis and septic shock) can occur in infants, pregnant women, and other immunocompromised patients.7 Immune suppression of our patient with steroid medication for poison sumac dermatitis likely contributed to the progression and systemic spread of an initially benign cat bite. Before prescribing steroids, it is imperative to ask about exposures and encourage patients to seek prompt medical attention with worsening or new symptoms. Healthy individuals rarely develop bacteremia; however, in these cases, mortality remains high at approximately 25%.4,6

The clinical course of this case emphasizes the need for vigilance and thoroughness in obtaining histories from patients presenting with seemingly benign complaints, especially in vulnerable populations, such as infants, pregnant women, and immunocompromised adults. In this case, the progression of symptoms might have been avoided if the patient’s dermatitis had been treated conservatively or with topical rather than systemic steroids.

A few days after an incidental cat bite, a patient presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure. He was discharged with oral methylprednisolone for the dermatitis and returned 1 week later with symptoms, examination findings, and laboratory results consistent with sepsis and bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infections. After administering multiple irrigation and débridement procedures, hyperbaric oxygen treatments, and an antibiotic regimen, the patient’s status greatly improved. However, the patient returned 1 month later with a new sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. Additionally, he noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful. Imaging studies showed a lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint bilaterally, consistent with osteomyelitis. The patient was treated with ertapenem for 6 weeks, and his polyarthropathy resolved. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old, right-hand–dominant man with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department for treatment of poison sumac exposure, incidentally, a few days after being bitten by a cat on the bilateral distal upper extremities. He was prescribed a course of oral methylprednisolone for dermatitis. A week later, the patient returned to the emergency department with altered mental status, fevers, diaphoresis, lethargy, and polyarthralgia. At the time of presentation, the patient’s vital signs were labile, and he was found to have extensive bilateral upper extremity erythema, blistering, petechiae, purpuric lesions, and exquisite pain with passive range of motion of his fingers and wrists. His leukocyte count was 25.1 × 109/L, and he had elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 150 mg/L and 120 mm/h, respectively. He was admitted for management of sepsis and presumed bilateral upper extremity necrotizing soft-tissue infection.

Broad-spectrum intravenous (IV) antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin, tazobactam) were initiated after blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating theatre for irrigation and débridement of his hands and wrists bilaterally. Arthrotomy of the wrist and débridement of the distal extensor compartment and its tenosynovium were performed on the right forearm, in addition to a decompressive fasciotomy of the left forearm. Postoperatively, the patient’s mental status improved and his vital signs gradually normalized. He received multiple hyperbaric oxygen treatments and underwent several additional operative débridement procedures with eventual closure of his wounds. At initial presentation, the differential diagnosis for the severe soft-tissue infection included necrotizing fasciitis or myositis caused by any of a variety of bacterial pathogens. Most notably, it was important to elicit the history of a cat bite to include and consider Pasteurella multocida as a potential pathogen. Initial cultures supported the diagnosis of acute P multocida necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infection, in addition to septic arthritis. The patient’s blood and intraoperative wound cultures grew P multocida. The antibiotic treatment was tailored initially to ampicillin and sulbactam and then to a final regimen of orally administered ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice a day), once susceptibility testing was performed on the cultures. On hospital day 10, the patient was discharged home, receiving a 6-week course of ciprofloxacin to complete the 8-week course of treatment.

At follow-up, approximately 1 month after discharge, the patient noted that he had developed a new right sternoclavicular joint prominence that was associated with painful crepitus. He also noted that his wrists were gradually becoming more swollen and painful bilaterally. Computed tomography scans of the chest were obtained to evaluate the sternoclavicular joint (Figure 1). Repeat radiographs of the wrists were also obtained (Figure 2). Imaging showed lytic destruction of the sternoclavicular joint and erosive changes throughout the carpus and radiocarpal joint, consistent with osteomyelitis. The C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at this time were 34 mg/L and 124 mm/h, respectively.

The patient returned to the operating room for débridement and biopsy of the right sternoclavicular joint and left wrist. This patient’s delayed presentation was characterized by a subacute worsening of isolated musculoskeletal complaints. The differential diagnosis then included infection with the same bacterial pathogen versus reactive or inflammatory arthritis. Several intraoperative cultures failed to grow any bacteria, including P multocida, although P multocida was the presumptive cause of the erosive polyarthropathy, considering that symptoms eventually resolved with a repeated course of IV-administered ertapenem for 6 weeks. The patient experienced complete resolution of his joint pain and swelling. He was able to resume his activities of daily living and had no further recurrence of symptoms at follow-up 3 months later.

Discussion

Cat bites often are the source of Pasteurella species infections because the bacteria are carried by more than 90% of cats.1 These types of infections can cause septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and deep subcutaneous and myofascial infections because of the sharp and narrow morphology of cat teeth. The infections can progress to necrotizing fasciitis and myositis if not recognized early, as was the case with our patient. Prophylactic antibiotic administration for animal bites is controversial and is not a universal practice.1,2Pasteurella bacteremia is an atypical progression that occurs more often in patients with pneumonia, septic arthritis, or meningitis. Cases of Pasteurella sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and septic arthritis have been reported.3-7 However, associated progressive septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, despite initial clinical improvement, have not been reported. Severe infection (ie, sepsis and septic shock) can occur in infants, pregnant women, and other immunocompromised patients.7 Immune suppression of our patient with steroid medication for poison sumac dermatitis likely contributed to the progression and systemic spread of an initially benign cat bite. Before prescribing steroids, it is imperative to ask about exposures and encourage patients to seek prompt medical attention with worsening or new symptoms. Healthy individuals rarely develop bacteremia; however, in these cases, mortality remains high at approximately 25%.4,6

The clinical course of this case emphasizes the need for vigilance and thoroughness in obtaining histories from patients presenting with seemingly benign complaints, especially in vulnerable populations, such as infants, pregnant women, and immunocompromised adults. In this case, the progression of symptoms might have been avoided if the patient’s dermatitis had been treated conservatively or with topical rather than systemic steroids.

1. Esposito S, Picciolli I, Semino M, Principi N. Dog and cat bite-associated infections in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(8):971-976.

2. Medeiros I, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD001738.

3. Haybaeck J, Schindler C, Braza P, Willinger B, Drlicek M. Rapidly progressive and lethal septicemia due to infection with Pasteurella multocida in an infant. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2009;121(5-6):216-219.

4. Migliore E, Serraino C, Brignone C, et al. Pasteurella multocida infection in a cirrhotic patient: case report, microbiological aspects and a review of the literature. Adv Med Sci. 2009;54(1):109-112.

5. Mugambi SM, Ullian ME. Bacteremia, sepsis, and peritonitis with Pasteurella multocida in a peritoneal dialysis patient. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(3):381-383.

6. Weber DJ, Wolfson JS, Swartz MN, Hooper DC. Pasteurella multocida infections. Report of 34 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63(3):133-154.

7. Oehler RL, Velez AP, Mizrachi M, Lamarche J, Gompf S. Bite-related and septic syndromes caused by cats and dogs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(7):439-447.

1. Esposito S, Picciolli I, Semino M, Principi N. Dog and cat bite-associated infections in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(8):971-976.

2. Medeiros I, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD001738.

3. Haybaeck J, Schindler C, Braza P, Willinger B, Drlicek M. Rapidly progressive and lethal septicemia due to infection with Pasteurella multocida in an infant. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2009;121(5-6):216-219.

4. Migliore E, Serraino C, Brignone C, et al. Pasteurella multocida infection in a cirrhotic patient: case report, microbiological aspects and a review of the literature. Adv Med Sci. 2009;54(1):109-112.

5. Mugambi SM, Ullian ME. Bacteremia, sepsis, and peritonitis with Pasteurella multocida in a peritoneal dialysis patient. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(3):381-383.

6. Weber DJ, Wolfson JS, Swartz MN, Hooper DC. Pasteurella multocida infections. Report of 34 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63(3):133-154.

7. Oehler RL, Velez AP, Mizrachi M, Lamarche J, Gompf S. Bite-related and septic syndromes caused by cats and dogs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(7):439-447.

Supinator Cyst in a Young Female Softball Player Successfully Treated With Aspiration

Ganglion cysts around the elbow joint are unusual, with fewer than 25 citations (most of which are case reports) in the English-language literature. Among the many causes of elbow pain, cysts are chiefly diagnosed by advanced imaging. When an elbow ganglion or perineural cyst is symptomatic, treatment has ranged from nonoperative to surgical intervention. Our case report is the first documented ultrasound-guided aspiration and cortisone injection to successfully alleviate a patient’s symptoms. The procedures and outcomes of minimally invasive ultrasound-guided aspiration and steroid injections have not been described for cysts around the elbow. The patient and patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 14-year-old female freshman varsity softball pitcher on multiple teams presented with 6 months of vague right elbow pain. She was unable to pitch and had intermittent sharp pain localized to the lateral proximal forearm. She was, however, able to bat without pain and denied any radiating paresthesias. Despite a reduction in sports activities, the symptoms did not improve.

On physical examination, there was preserved strength that was symmetric with the contralateral side of all major muscles innervated by the radial nerve in the right arm, including full wrist, thumb, and finger extension. Sensation was intact to light touch in all major nervous distributions of the right and left upper extremities. She was tender to palpation at the radiocapitellar joint anteriorly, as well as just distally. The patient was also tender with motion through the proximal radial head. She had pain with resisted finger extension; however, resisted supination elicited no discomfort or pain.

The initial diagnostic workup included radiographs of the right elbow, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and an ultrasound. Elbow radiographs revealed no abnormalities. The MRI scan showed a well-circumscribed ovoid T2-hyperintense structure within the supinator muscle measuring 0.6×0.6×0.4 cm (longitudinal × anteroposterior × transverse), just deep to the split of the superficial and deep radial nerves (Figures 1A-1C). A musculoskeletal ultrasound was performed to further characterize and determine the relationship to neurovascular structures. Longitudinal (Figure 2A) and transverse (Figure 2B) images showed a hypoechoic cystic structure, separate from any local nerve, and without Doppler flow, consistent with what was seen on MRI. Additionally, there was an apparent stalk communicating with the anterior margin of the radiocapitellar articulation, seen on longitudinal images, suggesting an extension of the joint capsule (Figure 3A).

We diagnosed the patient with a radiocapitellar ganglion cyst. Her symptoms continued despite several sessions of physical therapy and cessation from all throwing. Given the ultrasound and MRI findings, and continuation of the symptoms despite conservative treatment, alternative treatment plans were discussed with the patient. These included continued activity modification and nonoperative treatment, open excision of the cyst, or aspiration of the cyst under ultrasound guidance. All appropriate risks and benefits were discussed, including possibility of nerve damage given the proximity of the cyst to the radial nerve branches. After a thorough discussion with both patient and family, a plan was made to undergo aspiration under ultrasound guidance. This was carried out using a lateral-to-medial in-plane approach, transverse to the radius. Using a 19-g, 1.5-inch needle (Figure 3B), 1 mL of serosanguinous fluid was aspirated from the cyst, followed by injection of 40 mg methylprednisolone sodium succinate.

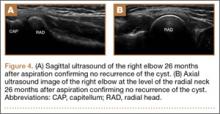

The patient made a dramatic recovery within 8 days after aspiration. On examination, she had full strength to resisted flexion, extension, pronation, and supination; had no tenderness to palpation over the supinator; and no pain with resisted finger extension. She began dedicated physical therapy and a gradual return to throwing. She was able to return to her original level of softball activities 2 months after the aspiration. The patient continued to be symptom-free 26 months after the aspiration/injection. There was no evidence of recurrence of the ganglion on repeat ultrasound at her most recent follow-up (Figures 4A, 4B).

Discussion

Our review of the English-language literature identified 23 reports of cysts in and around the supinator muscle. Ganglion cysts are benign lesions that are uncommonly seen about the elbow. This highlights the rarity of this diagnosis, as well as the need for recognition of its existence. Cysts located in the substance of the nerve1-5 and extraneural ganglia causing symptomatic nerve compression have been described. These extraneural ganglia have been reported to cause compression of the ulnar nerve,1-4,6 posterior interosseous nerve (PIN),5,7-12 and radial nerve,13 and isolated compression of the radial sensory branch.14-17 Ganglion cyst compression in the elbow can result in pain, decreased motor function, and decreased sensation. The PIN syndrome is primarily a motor deficiency, whereas isolated compression of the sensory branches of the radial nerve presents as pain along the radial tunnel and extensor muscle mass.17

Most ganglion cysts are formed when joint fluid extrudes through a defect in the joint capsule; they have also been described originating from a nonunion site.18 When conservative treatment fails, surgical excision has been recommended.5,6,8-10,12-16 We present the first known case of successful ultrasound-guided aspiration and injection of a ganglion cyst from the proximal radiocapitellar joint.

In the earliest described case in 1955, Broomhead19 noted exploration was essential to establish the diagnosis of nerve palsy. In 1966, Bowen and Stone7 were the first to report PIN compression by a ganglion and that compression was likely where nerves pass through confined spaces. In keeping with the known potential for compression of the common peroneal nerve around the fibular head, Bowen and Stone7 posited that the same could be true of the PIN coursing through the supinator and around the radial neck.

Many authors have noted that nerve palsy either improves with rest or worsens with heavy manual work.3,20,21 These observations suggest that dynamic factors in addition to compression of the nerve by the ganglion may influence the occurrence of the nerve palsy.14 This is in line with our patient whose symptoms worsened after pitching.

Ogino and colleagues20 reported on the first use of ultrasonography as a screening examination for a ganglion, particularly when palpation was difficult. Ultrasound allows a detailed assessment of peripheral nerve continuity with a mass, differentiating an intraneural lesion from an adjacent extrinsic ganglion.13 Tonkin10 published the first description of MRI used for the diagnosis of an elbow cyst, and its use has been supported by others.5,8,20 The typical appearance of ganglion cysts on MRI include low signal on T1-weighted images and very high signal on T2-weighted images. Only the periphery of the mass is enhanced by gadolinium, if used.

As recently as 2009, Jou and associates13 suggested that surgical excision should be performed promptly to ensure optimal recovery from a nerve palsy. Many authors agree that early diagnosis and careful surgical excision is associated with a satisfactory outcome without recurrence of the cyst.5,6,8-10,12-15 There are only 4 published case reports14-17 of ganglions causing isolated compression of the superficial radial sensory nerve, as in our case. Their patients had pain with exertional trauma14 as did our patient, a positive Tinel sign,15 and resolution of symptoms after surgical excision without recurrence.14-16 Mileti and colleagues16 state that standard management for resistant radial tunnel syndrome is open decompression of the radial nerve.

In the last decade, a few reports of arthroscopic excision being a viable and safe alternative to open excision have been published.16,22,23 In 2000, Feldman22 described the benefits of an arthroscopic approach as decreased soft-tissue dissection, increased ability to identify intra-articular pathology, and similar recurrence rates to open procedures. He reported 1 transient neurapraxia of the superficial radial nerve from the arthroscopy, highlighting a risk of arthroscopic treatment.

An alternative to open or arthroscopic cyst decompression is aspiration. The only mention of aspiration in the literature comes from Broomhead19 in 1955 when he described 2 patients in whom treatment by aspiration was unsuccessful in relieving their symptoms. Yamazaki and colleagues12 noted that 1 of their 14 patients with PIN palsies caused by ganglions at the elbow underwent puncture of the ganglion with recovery of the paralysis. With the aid of ultrasound guidance, we were able to accurately locate the ganglion cyst, aspirate its contents, and inject methylprednisolone sodium succinate. Our patient continued to be symptom-free and was an active pitcher on a varsity softball team 26 months after aspiration.

Conclusion

This case report describes a rare location for a ganglion cyst in a high-level softball player. To our knowledge, successful treatment with ultrasound-guided aspiration and injection of a supinator cyst has not been reported in the literature. This case report highlights the importance of a careful diagnosis of this condition and an alternative treatment algorithm.

1. Boursinos LA, Dimitriou CG. Ulnar nerve compression in the cubital tunnel by an epineural ganglion: a case report. Hand (N Y). 2007;2(1):12-15.

2. Ferlic DC, Ries MD. Epineural ganglion of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15(6):996-998.

3. Ming Chan K, Thompson S, Amirjani N, Satkunam L, Strohschlein FJ, Lobay GL. Compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow by an intraneural ganglion. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10(2):245-248.

4. Sharma RR, Pawar SJ, Delmendo A, Mahapatra AK. Symptomatic epineural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel: a case report and brief review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7(6):542-543.

5. Hashizume H, Nishida K, Nanba Y, Inoue H, Konishiike T. Intraneural ganglion of the posterior interosseous nerve with lateral elbow pain. J Hand Surg Br. 1995;20(5):649-651.

6. Kato H, Hirayama T, Minami A, Iwasaki N, Hirachi K. Cubital tunnel syndrome associated with medial elbow Ganglia and osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(8):1413-1419.

7. Bowen TL, Stone KH. Posterior interosseous nerve paralysis caused by a ganglion at the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1966;48(4):774-776.

8. Ly JQ, Barrett TJ, Beall DP, Bertagnolli R. MRI diagnosis of occult ganglion compression of the posterior interosseous nerve and associated supinator muscle pathology. Clin Imaging. 2005;29(5):362-363.

9. McCollam SM, Corley FG, Green DP. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy caused by ganglions of the proximal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13(5):725-728.

10. Tonkin MA. Posterior interosseous nerve axonotmesis from compression by a ganglion. J Hand Surg Br. 1990;15(4):491-493.

11. Tuygun H, Kose O, Gorgec M. Partial paralysis of the posterior interosseous nerve caused by a ganglion. J Hand Surg Eur. 2008;33(4):540-541.

12. Yamazaki H, Kato H, Hata Y, Murakami N, Saitoh S. The two locations of ganglions causing radial nerve palsy. J Hand Surg Eur. 2007;32(3):341-345.

13. Jou IM, Wang HN, Wang PH, Yong IS, Su WR. Compression of the radial nerve at the elbow by a ganglion: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7258.

14. Hermansdorfer JD, Greider JL, Dell PC. A case report of a compressive neuropathy of the radial sensory nerve caused by a ganglion cyst at the elbow. Orthopedics. 1986;9(7):1005-1006.

15. McFarlane J, Trehan R, Olivera M, Jones C, Blease S, Davey P. A ganglion cyst at the elbow causing superficial radial nerve compression: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:122.

16. Mileti J, Largacha M, O’Driscoll SW. Radial tunnel syndrome caused by ganglion cyst: treatment by arthroscopic cyst decompression. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):e39-e44.

17. Plancher KD, Peterson RK, Steichen JB. Compressive neuropathies and tendinopathies in the athletic elbow and wrist. Clin Sports Med. 1996;15(2):331-371.

18. Chim H, Yam AK, Teoh LC. Elbow ganglion arising from medial epicondyle pseudarthrosis. Hand Surg. 2007;12(3):155-158.

19. Broomhead IW. Ganglia associated with elbow and knee joints. Lancet. 1955;269(6885):317-319.

20. Ogino T, Minami A, Kato H. Diagnosis of radial nerve palsy caused by ganglion with use of different imaging techniques. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16(2):230-235.

21. Spinner M, Spencer PS. Nerve compression lesions of the upper extremity. A clinical and experimental review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;(104):46-67.

22. Feldman MD. Arthroscopic excision of a ganglion cyst from the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(6):661-664.

23. Kirpalani PA, Lee HK, Lee YS, Han CW. Transarticular arthroscopic excision of an elbow cyst. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71(4):477-480.

Ganglion cysts around the elbow joint are unusual, with fewer than 25 citations (most of which are case reports) in the English-language literature. Among the many causes of elbow pain, cysts are chiefly diagnosed by advanced imaging. When an elbow ganglion or perineural cyst is symptomatic, treatment has ranged from nonoperative to surgical intervention. Our case report is the first documented ultrasound-guided aspiration and cortisone injection to successfully alleviate a patient’s symptoms. The procedures and outcomes of minimally invasive ultrasound-guided aspiration and steroid injections have not been described for cysts around the elbow. The patient and patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 14-year-old female freshman varsity softball pitcher on multiple teams presented with 6 months of vague right elbow pain. She was unable to pitch and had intermittent sharp pain localized to the lateral proximal forearm. She was, however, able to bat without pain and denied any radiating paresthesias. Despite a reduction in sports activities, the symptoms did not improve.

On physical examination, there was preserved strength that was symmetric with the contralateral side of all major muscles innervated by the radial nerve in the right arm, including full wrist, thumb, and finger extension. Sensation was intact to light touch in all major nervous distributions of the right and left upper extremities. She was tender to palpation at the radiocapitellar joint anteriorly, as well as just distally. The patient was also tender with motion through the proximal radial head. She had pain with resisted finger extension; however, resisted supination elicited no discomfort or pain.

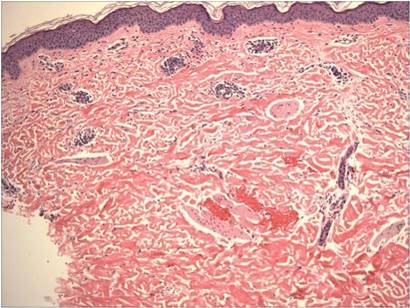

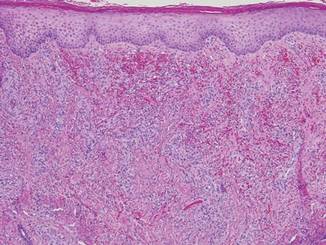

The initial diagnostic workup included radiographs of the right elbow, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and an ultrasound. Elbow radiographs revealed no abnormalities. The MRI scan showed a well-circumscribed ovoid T2-hyperintense structure within the supinator muscle measuring 0.6×0.6×0.4 cm (longitudinal × anteroposterior × transverse), just deep to the split of the superficial and deep radial nerves (Figures 1A-1C). A musculoskeletal ultrasound was performed to further characterize and determine the relationship to neurovascular structures. Longitudinal (Figure 2A) and transverse (Figure 2B) images showed a hypoechoic cystic structure, separate from any local nerve, and without Doppler flow, consistent with what was seen on MRI. Additionally, there was an apparent stalk communicating with the anterior margin of the radiocapitellar articulation, seen on longitudinal images, suggesting an extension of the joint capsule (Figure 3A).

We diagnosed the patient with a radiocapitellar ganglion cyst. Her symptoms continued despite several sessions of physical therapy and cessation from all throwing. Given the ultrasound and MRI findings, and continuation of the symptoms despite conservative treatment, alternative treatment plans were discussed with the patient. These included continued activity modification and nonoperative treatment, open excision of the cyst, or aspiration of the cyst under ultrasound guidance. All appropriate risks and benefits were discussed, including possibility of nerve damage given the proximity of the cyst to the radial nerve branches. After a thorough discussion with both patient and family, a plan was made to undergo aspiration under ultrasound guidance. This was carried out using a lateral-to-medial in-plane approach, transverse to the radius. Using a 19-g, 1.5-inch needle (Figure 3B), 1 mL of serosanguinous fluid was aspirated from the cyst, followed by injection of 40 mg methylprednisolone sodium succinate.

The patient made a dramatic recovery within 8 days after aspiration. On examination, she had full strength to resisted flexion, extension, pronation, and supination; had no tenderness to palpation over the supinator; and no pain with resisted finger extension. She began dedicated physical therapy and a gradual return to throwing. She was able to return to her original level of softball activities 2 months after the aspiration. The patient continued to be symptom-free 26 months after the aspiration/injection. There was no evidence of recurrence of the ganglion on repeat ultrasound at her most recent follow-up (Figures 4A, 4B).

Discussion

Our review of the English-language literature identified 23 reports of cysts in and around the supinator muscle. Ganglion cysts are benign lesions that are uncommonly seen about the elbow. This highlights the rarity of this diagnosis, as well as the need for recognition of its existence. Cysts located in the substance of the nerve1-5 and extraneural ganglia causing symptomatic nerve compression have been described. These extraneural ganglia have been reported to cause compression of the ulnar nerve,1-4,6 posterior interosseous nerve (PIN),5,7-12 and radial nerve,13 and isolated compression of the radial sensory branch.14-17 Ganglion cyst compression in the elbow can result in pain, decreased motor function, and decreased sensation. The PIN syndrome is primarily a motor deficiency, whereas isolated compression of the sensory branches of the radial nerve presents as pain along the radial tunnel and extensor muscle mass.17

Most ganglion cysts are formed when joint fluid extrudes through a defect in the joint capsule; they have also been described originating from a nonunion site.18 When conservative treatment fails, surgical excision has been recommended.5,6,8-10,12-16 We present the first known case of successful ultrasound-guided aspiration and injection of a ganglion cyst from the proximal radiocapitellar joint.

In the earliest described case in 1955, Broomhead19 noted exploration was essential to establish the diagnosis of nerve palsy. In 1966, Bowen and Stone7 were the first to report PIN compression by a ganglion and that compression was likely where nerves pass through confined spaces. In keeping with the known potential for compression of the common peroneal nerve around the fibular head, Bowen and Stone7 posited that the same could be true of the PIN coursing through the supinator and around the radial neck.

Many authors have noted that nerve palsy either improves with rest or worsens with heavy manual work.3,20,21 These observations suggest that dynamic factors in addition to compression of the nerve by the ganglion may influence the occurrence of the nerve palsy.14 This is in line with our patient whose symptoms worsened after pitching.

Ogino and colleagues20 reported on the first use of ultrasonography as a screening examination for a ganglion, particularly when palpation was difficult. Ultrasound allows a detailed assessment of peripheral nerve continuity with a mass, differentiating an intraneural lesion from an adjacent extrinsic ganglion.13 Tonkin10 published the first description of MRI used for the diagnosis of an elbow cyst, and its use has been supported by others.5,8,20 The typical appearance of ganglion cysts on MRI include low signal on T1-weighted images and very high signal on T2-weighted images. Only the periphery of the mass is enhanced by gadolinium, if used.

As recently as 2009, Jou and associates13 suggested that surgical excision should be performed promptly to ensure optimal recovery from a nerve palsy. Many authors agree that early diagnosis and careful surgical excision is associated with a satisfactory outcome without recurrence of the cyst.5,6,8-10,12-15 There are only 4 published case reports14-17 of ganglions causing isolated compression of the superficial radial sensory nerve, as in our case. Their patients had pain with exertional trauma14 as did our patient, a positive Tinel sign,15 and resolution of symptoms after surgical excision without recurrence.14-16 Mileti and colleagues16 state that standard management for resistant radial tunnel syndrome is open decompression of the radial nerve.

In the last decade, a few reports of arthroscopic excision being a viable and safe alternative to open excision have been published.16,22,23 In 2000, Feldman22 described the benefits of an arthroscopic approach as decreased soft-tissue dissection, increased ability to identify intra-articular pathology, and similar recurrence rates to open procedures. He reported 1 transient neurapraxia of the superficial radial nerve from the arthroscopy, highlighting a risk of arthroscopic treatment.

An alternative to open or arthroscopic cyst decompression is aspiration. The only mention of aspiration in the literature comes from Broomhead19 in 1955 when he described 2 patients in whom treatment by aspiration was unsuccessful in relieving their symptoms. Yamazaki and colleagues12 noted that 1 of their 14 patients with PIN palsies caused by ganglions at the elbow underwent puncture of the ganglion with recovery of the paralysis. With the aid of ultrasound guidance, we were able to accurately locate the ganglion cyst, aspirate its contents, and inject methylprednisolone sodium succinate. Our patient continued to be symptom-free and was an active pitcher on a varsity softball team 26 months after aspiration.

Conclusion

This case report describes a rare location for a ganglion cyst in a high-level softball player. To our knowledge, successful treatment with ultrasound-guided aspiration and injection of a supinator cyst has not been reported in the literature. This case report highlights the importance of a careful diagnosis of this condition and an alternative treatment algorithm.

Ganglion cysts around the elbow joint are unusual, with fewer than 25 citations (most of which are case reports) in the English-language literature. Among the many causes of elbow pain, cysts are chiefly diagnosed by advanced imaging. When an elbow ganglion or perineural cyst is symptomatic, treatment has ranged from nonoperative to surgical intervention. Our case report is the first documented ultrasound-guided aspiration and cortisone injection to successfully alleviate a patient’s symptoms. The procedures and outcomes of minimally invasive ultrasound-guided aspiration and steroid injections have not been described for cysts around the elbow. The patient and patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 14-year-old female freshman varsity softball pitcher on multiple teams presented with 6 months of vague right elbow pain. She was unable to pitch and had intermittent sharp pain localized to the lateral proximal forearm. She was, however, able to bat without pain and denied any radiating paresthesias. Despite a reduction in sports activities, the symptoms did not improve.

On physical examination, there was preserved strength that was symmetric with the contralateral side of all major muscles innervated by the radial nerve in the right arm, including full wrist, thumb, and finger extension. Sensation was intact to light touch in all major nervous distributions of the right and left upper extremities. She was tender to palpation at the radiocapitellar joint anteriorly, as well as just distally. The patient was also tender with motion through the proximal radial head. She had pain with resisted finger extension; however, resisted supination elicited no discomfort or pain.

The initial diagnostic workup included radiographs of the right elbow, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, and an ultrasound. Elbow radiographs revealed no abnormalities. The MRI scan showed a well-circumscribed ovoid T2-hyperintense structure within the supinator muscle measuring 0.6×0.6×0.4 cm (longitudinal × anteroposterior × transverse), just deep to the split of the superficial and deep radial nerves (Figures 1A-1C). A musculoskeletal ultrasound was performed to further characterize and determine the relationship to neurovascular structures. Longitudinal (Figure 2A) and transverse (Figure 2B) images showed a hypoechoic cystic structure, separate from any local nerve, and without Doppler flow, consistent with what was seen on MRI. Additionally, there was an apparent stalk communicating with the anterior margin of the radiocapitellar articulation, seen on longitudinal images, suggesting an extension of the joint capsule (Figure 3A).

We diagnosed the patient with a radiocapitellar ganglion cyst. Her symptoms continued despite several sessions of physical therapy and cessation from all throwing. Given the ultrasound and MRI findings, and continuation of the symptoms despite conservative treatment, alternative treatment plans were discussed with the patient. These included continued activity modification and nonoperative treatment, open excision of the cyst, or aspiration of the cyst under ultrasound guidance. All appropriate risks and benefits were discussed, including possibility of nerve damage given the proximity of the cyst to the radial nerve branches. After a thorough discussion with both patient and family, a plan was made to undergo aspiration under ultrasound guidance. This was carried out using a lateral-to-medial in-plane approach, transverse to the radius. Using a 19-g, 1.5-inch needle (Figure 3B), 1 mL of serosanguinous fluid was aspirated from the cyst, followed by injection of 40 mg methylprednisolone sodium succinate.

The patient made a dramatic recovery within 8 days after aspiration. On examination, she had full strength to resisted flexion, extension, pronation, and supination; had no tenderness to palpation over the supinator; and no pain with resisted finger extension. She began dedicated physical therapy and a gradual return to throwing. She was able to return to her original level of softball activities 2 months after the aspiration. The patient continued to be symptom-free 26 months after the aspiration/injection. There was no evidence of recurrence of the ganglion on repeat ultrasound at her most recent follow-up (Figures 4A, 4B).

Discussion

Our review of the English-language literature identified 23 reports of cysts in and around the supinator muscle. Ganglion cysts are benign lesions that are uncommonly seen about the elbow. This highlights the rarity of this diagnosis, as well as the need for recognition of its existence. Cysts located in the substance of the nerve1-5 and extraneural ganglia causing symptomatic nerve compression have been described. These extraneural ganglia have been reported to cause compression of the ulnar nerve,1-4,6 posterior interosseous nerve (PIN),5,7-12 and radial nerve,13 and isolated compression of the radial sensory branch.14-17 Ganglion cyst compression in the elbow can result in pain, decreased motor function, and decreased sensation. The PIN syndrome is primarily a motor deficiency, whereas isolated compression of the sensory branches of the radial nerve presents as pain along the radial tunnel and extensor muscle mass.17

Most ganglion cysts are formed when joint fluid extrudes through a defect in the joint capsule; they have also been described originating from a nonunion site.18 When conservative treatment fails, surgical excision has been recommended.5,6,8-10,12-16 We present the first known case of successful ultrasound-guided aspiration and injection of a ganglion cyst from the proximal radiocapitellar joint.

In the earliest described case in 1955, Broomhead19 noted exploration was essential to establish the diagnosis of nerve palsy. In 1966, Bowen and Stone7 were the first to report PIN compression by a ganglion and that compression was likely where nerves pass through confined spaces. In keeping with the known potential for compression of the common peroneal nerve around the fibular head, Bowen and Stone7 posited that the same could be true of the PIN coursing through the supinator and around the radial neck.

Many authors have noted that nerve palsy either improves with rest or worsens with heavy manual work.3,20,21 These observations suggest that dynamic factors in addition to compression of the nerve by the ganglion may influence the occurrence of the nerve palsy.14 This is in line with our patient whose symptoms worsened after pitching.

Ogino and colleagues20 reported on the first use of ultrasonography as a screening examination for a ganglion, particularly when palpation was difficult. Ultrasound allows a detailed assessment of peripheral nerve continuity with a mass, differentiating an intraneural lesion from an adjacent extrinsic ganglion.13 Tonkin10 published the first description of MRI used for the diagnosis of an elbow cyst, and its use has been supported by others.5,8,20 The typical appearance of ganglion cysts on MRI include low signal on T1-weighted images and very high signal on T2-weighted images. Only the periphery of the mass is enhanced by gadolinium, if used.

As recently as 2009, Jou and associates13 suggested that surgical excision should be performed promptly to ensure optimal recovery from a nerve palsy. Many authors agree that early diagnosis and careful surgical excision is associated with a satisfactory outcome without recurrence of the cyst.5,6,8-10,12-15 There are only 4 published case reports14-17 of ganglions causing isolated compression of the superficial radial sensory nerve, as in our case. Their patients had pain with exertional trauma14 as did our patient, a positive Tinel sign,15 and resolution of symptoms after surgical excision without recurrence.14-16 Mileti and colleagues16 state that standard management for resistant radial tunnel syndrome is open decompression of the radial nerve.

In the last decade, a few reports of arthroscopic excision being a viable and safe alternative to open excision have been published.16,22,23 In 2000, Feldman22 described the benefits of an arthroscopic approach as decreased soft-tissue dissection, increased ability to identify intra-articular pathology, and similar recurrence rates to open procedures. He reported 1 transient neurapraxia of the superficial radial nerve from the arthroscopy, highlighting a risk of arthroscopic treatment.

An alternative to open or arthroscopic cyst decompression is aspiration. The only mention of aspiration in the literature comes from Broomhead19 in 1955 when he described 2 patients in whom treatment by aspiration was unsuccessful in relieving their symptoms. Yamazaki and colleagues12 noted that 1 of their 14 patients with PIN palsies caused by ganglions at the elbow underwent puncture of the ganglion with recovery of the paralysis. With the aid of ultrasound guidance, we were able to accurately locate the ganglion cyst, aspirate its contents, and inject methylprednisolone sodium succinate. Our patient continued to be symptom-free and was an active pitcher on a varsity softball team 26 months after aspiration.

Conclusion

This case report describes a rare location for a ganglion cyst in a high-level softball player. To our knowledge, successful treatment with ultrasound-guided aspiration and injection of a supinator cyst has not been reported in the literature. This case report highlights the importance of a careful diagnosis of this condition and an alternative treatment algorithm.

1. Boursinos LA, Dimitriou CG. Ulnar nerve compression in the cubital tunnel by an epineural ganglion: a case report. Hand (N Y). 2007;2(1):12-15.

2. Ferlic DC, Ries MD. Epineural ganglion of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15(6):996-998.

3. Ming Chan K, Thompson S, Amirjani N, Satkunam L, Strohschlein FJ, Lobay GL. Compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow by an intraneural ganglion. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10(2):245-248.

4. Sharma RR, Pawar SJ, Delmendo A, Mahapatra AK. Symptomatic epineural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel: a case report and brief review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7(6):542-543.

5. Hashizume H, Nishida K, Nanba Y, Inoue H, Konishiike T. Intraneural ganglion of the posterior interosseous nerve with lateral elbow pain. J Hand Surg Br. 1995;20(5):649-651.

6. Kato H, Hirayama T, Minami A, Iwasaki N, Hirachi K. Cubital tunnel syndrome associated with medial elbow Ganglia and osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(8):1413-1419.

7. Bowen TL, Stone KH. Posterior interosseous nerve paralysis caused by a ganglion at the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1966;48(4):774-776.

8. Ly JQ, Barrett TJ, Beall DP, Bertagnolli R. MRI diagnosis of occult ganglion compression of the posterior interosseous nerve and associated supinator muscle pathology. Clin Imaging. 2005;29(5):362-363.

9. McCollam SM, Corley FG, Green DP. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy caused by ganglions of the proximal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13(5):725-728.

10. Tonkin MA. Posterior interosseous nerve axonotmesis from compression by a ganglion. J Hand Surg Br. 1990;15(4):491-493.

11. Tuygun H, Kose O, Gorgec M. Partial paralysis of the posterior interosseous nerve caused by a ganglion. J Hand Surg Eur. 2008;33(4):540-541.

12. Yamazaki H, Kato H, Hata Y, Murakami N, Saitoh S. The two locations of ganglions causing radial nerve palsy. J Hand Surg Eur. 2007;32(3):341-345.

13. Jou IM, Wang HN, Wang PH, Yong IS, Su WR. Compression of the radial nerve at the elbow by a ganglion: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7258.

14. Hermansdorfer JD, Greider JL, Dell PC. A case report of a compressive neuropathy of the radial sensory nerve caused by a ganglion cyst at the elbow. Orthopedics. 1986;9(7):1005-1006.

15. McFarlane J, Trehan R, Olivera M, Jones C, Blease S, Davey P. A ganglion cyst at the elbow causing superficial radial nerve compression: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:122.

16. Mileti J, Largacha M, O’Driscoll SW. Radial tunnel syndrome caused by ganglion cyst: treatment by arthroscopic cyst decompression. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):e39-e44.

17. Plancher KD, Peterson RK, Steichen JB. Compressive neuropathies and tendinopathies in the athletic elbow and wrist. Clin Sports Med. 1996;15(2):331-371.

18. Chim H, Yam AK, Teoh LC. Elbow ganglion arising from medial epicondyle pseudarthrosis. Hand Surg. 2007;12(3):155-158.

19. Broomhead IW. Ganglia associated with elbow and knee joints. Lancet. 1955;269(6885):317-319.

20. Ogino T, Minami A, Kato H. Diagnosis of radial nerve palsy caused by ganglion with use of different imaging techniques. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16(2):230-235.

21. Spinner M, Spencer PS. Nerve compression lesions of the upper extremity. A clinical and experimental review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;(104):46-67.

22. Feldman MD. Arthroscopic excision of a ganglion cyst from the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(6):661-664.

23. Kirpalani PA, Lee HK, Lee YS, Han CW. Transarticular arthroscopic excision of an elbow cyst. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71(4):477-480.

1. Boursinos LA, Dimitriou CG. Ulnar nerve compression in the cubital tunnel by an epineural ganglion: a case report. Hand (N Y). 2007;2(1):12-15.

2. Ferlic DC, Ries MD. Epineural ganglion of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15(6):996-998.

3. Ming Chan K, Thompson S, Amirjani N, Satkunam L, Strohschlein FJ, Lobay GL. Compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow by an intraneural ganglion. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10(2):245-248.

4. Sharma RR, Pawar SJ, Delmendo A, Mahapatra AK. Symptomatic epineural ganglion cyst of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel: a case report and brief review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7(6):542-543.

5. Hashizume H, Nishida K, Nanba Y, Inoue H, Konishiike T. Intraneural ganglion of the posterior interosseous nerve with lateral elbow pain. J Hand Surg Br. 1995;20(5):649-651.

6. Kato H, Hirayama T, Minami A, Iwasaki N, Hirachi K. Cubital tunnel syndrome associated with medial elbow Ganglia and osteoarthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(8):1413-1419.

7. Bowen TL, Stone KH. Posterior interosseous nerve paralysis caused by a ganglion at the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1966;48(4):774-776.

8. Ly JQ, Barrett TJ, Beall DP, Bertagnolli R. MRI diagnosis of occult ganglion compression of the posterior interosseous nerve and associated supinator muscle pathology. Clin Imaging. 2005;29(5):362-363.

9. McCollam SM, Corley FG, Green DP. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy caused by ganglions of the proximal radioulnar joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1988;13(5):725-728.

10. Tonkin MA. Posterior interosseous nerve axonotmesis from compression by a ganglion. J Hand Surg Br. 1990;15(4):491-493.

11. Tuygun H, Kose O, Gorgec M. Partial paralysis of the posterior interosseous nerve caused by a ganglion. J Hand Surg Eur. 2008;33(4):540-541.

12. Yamazaki H, Kato H, Hata Y, Murakami N, Saitoh S. The two locations of ganglions causing radial nerve palsy. J Hand Surg Eur. 2007;32(3):341-345.

13. Jou IM, Wang HN, Wang PH, Yong IS, Su WR. Compression of the radial nerve at the elbow by a ganglion: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7258.

14. Hermansdorfer JD, Greider JL, Dell PC. A case report of a compressive neuropathy of the radial sensory nerve caused by a ganglion cyst at the elbow. Orthopedics. 1986;9(7):1005-1006.

15. McFarlane J, Trehan R, Olivera M, Jones C, Blease S, Davey P. A ganglion cyst at the elbow causing superficial radial nerve compression: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:122.

16. Mileti J, Largacha M, O’Driscoll SW. Radial tunnel syndrome caused by ganglion cyst: treatment by arthroscopic cyst decompression. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):e39-e44.

17. Plancher KD, Peterson RK, Steichen JB. Compressive neuropathies and tendinopathies in the athletic elbow and wrist. Clin Sports Med. 1996;15(2):331-371.

18. Chim H, Yam AK, Teoh LC. Elbow ganglion arising from medial epicondyle pseudarthrosis. Hand Surg. 2007;12(3):155-158.

19. Broomhead IW. Ganglia associated with elbow and knee joints. Lancet. 1955;269(6885):317-319.

20. Ogino T, Minami A, Kato H. Diagnosis of radial nerve palsy caused by ganglion with use of different imaging techniques. J Hand Surg Am. 1991;16(2):230-235.

21. Spinner M, Spencer PS. Nerve compression lesions of the upper extremity. A clinical and experimental review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;(104):46-67.

22. Feldman MD. Arthroscopic excision of a ganglion cyst from the elbow. Arthroscopy. 2000;16(6):661-664.

23. Kirpalani PA, Lee HK, Lee YS, Han CW. Transarticular arthroscopic excision of an elbow cyst. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71(4):477-480.

Abdominal distention • loss of appetite • elevated creatinine • Dx?

THE CASE

A 21-year-old male college student sought care at our urology clinic for a 2-year history of progressive abdominal distention and loss of appetite due to abdominal pressure. On physical examination, his abdomen was distended and tense, but without any tenderness on palpation or any costovertebral angle tenderness. He had no abdominal or flank pain, and wasn’t in acute distress. His blood pressure was normal.

Initial lab test results were significant for elevated creatinine at 2.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at 31.1 mg/dL (normal: 6-20 mg/dL). Results of a complete blood count (CBC) were within normal ranges, including a white blood cell (WBC) count of 7900, hemoglobin level of 15.1 g/dL, and platelet count of 217,000/mcL. A urinalysis showed only a mild increase in the WBC count.

THE DIAGNOSIS

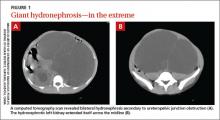

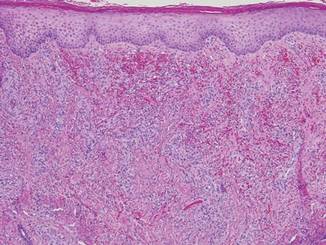

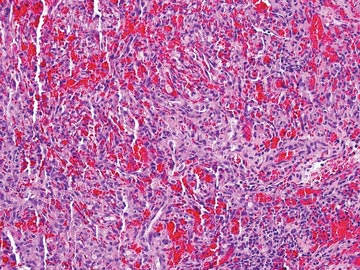

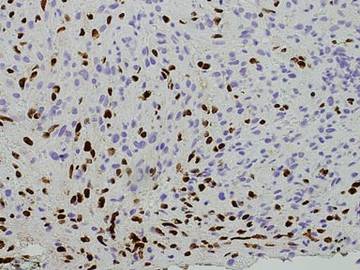

We performed a computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s abdomen, which revealed bilateral hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). The patient’s right kidney was mildly to moderately enlarged, but the left kidney was massive (FIGURE 1A). The hydronephrotic left kidney had extended itself across the midline (FIGURE 1B), pushed the ipsilateral diaphragm upward, and displaced the bladder downward.

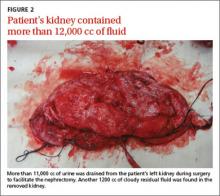

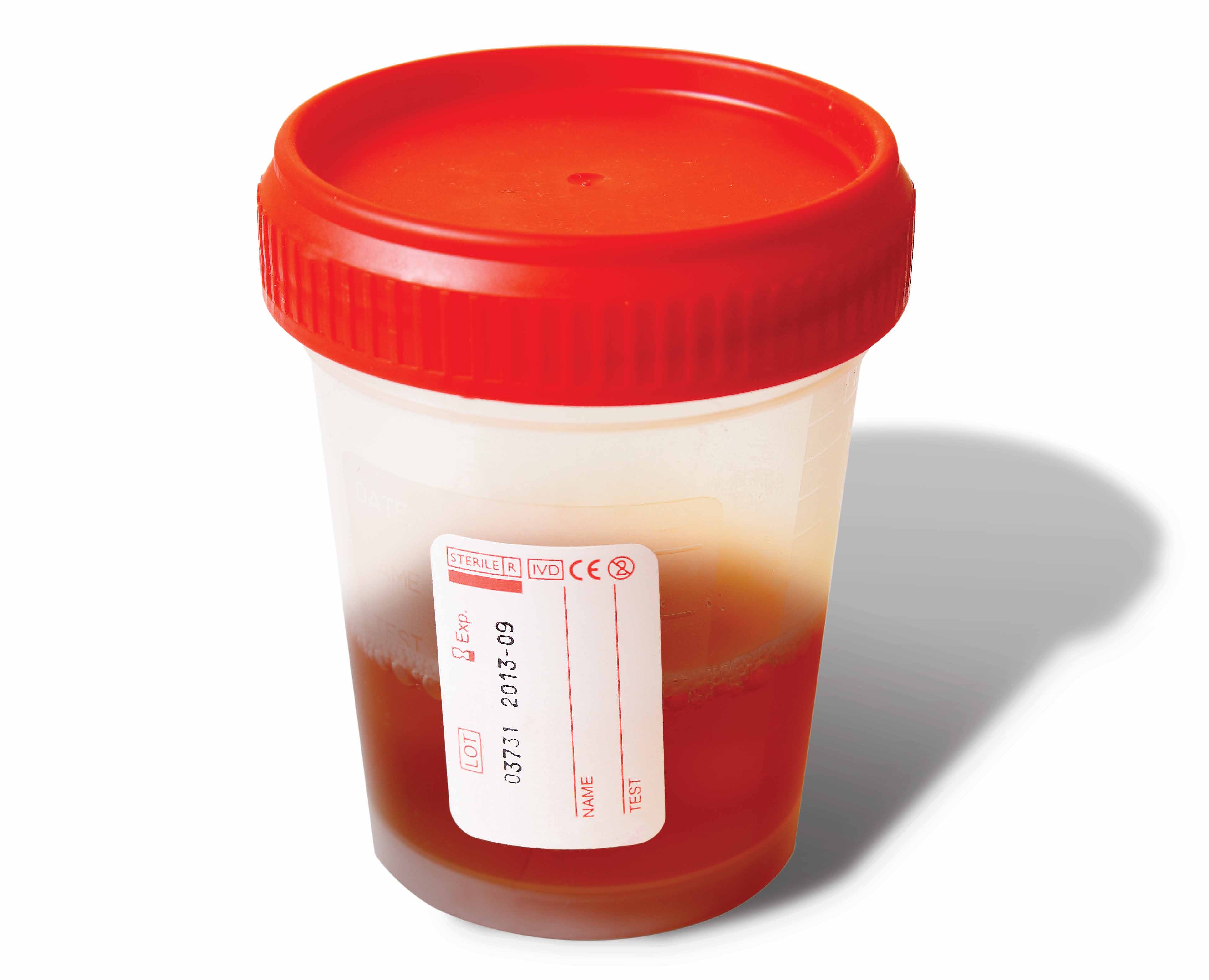

The patient underwent right-sided ureteral stent placement for temporary drainage and a complete left-sided nephrectomy. During the surgery, the left kidney was first aspirated, and more than 11,000 cc of clear urine was drained. (Aspiration reduced the kidney size, allowing the surgeon to make a smaller incision.) The removed kidney contained an additional 1200 cc of cloudy residual fluid (FIGURE 2). UPJO was confirmed by the pathological examination of the excised organ.

DISCUSSION

UPJO is the most common etiology for congenital hydronephrosis.1 Because it can cause little to no pain, hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Frequently, an abdominal mass is the initial clinical presentation.

When the hydronephrotic fluid exceeds 1000 cc, the condition is referred to as giant hydronephrosis.2 Although several cases of giant hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO have been reported in the medical literature,3-5 the volume of the hydronephrotic fluid in these cases rarely exceeded 10,000 cc. We believe our patient may be the most severe case of hydronephrosis secondary to bilateral UPJO, with 12,200 cc of fluid. His condition reached this late stage only because his right kidney retained adequate function.

Diagnosis of hydronephrosis is straightforward with an abdominal ultrasound and/or CT scan. Widespread use of abdominal ultrasound as a screening tool has significantly increased the diagnosis of asymptomatic hydronephrosis, and many cases are secondary to UPJO.6 The true incidence of UPJO is unknown, but it is more prevalent in males than in females, and in 10% to 40% of cases, the condition is bilateral.7 Congenital UPJO typically results from intrinsic pathology of the ureter. The diseased segment is often fibrotic, strictured, and aperistaltic.8

Treatment choice depends on whether renal function can be preserved

Treatment of hydronephrosis is straightforward; when there is little or no salvageable renal function (<10%), a simple nephrectomy is indicated, as was the case for our patient. Nephrectomy can be accomplished by either an open or laparoscopic approach.

When there is salvageable renal function, treatment options include pyeloplasty and pyelotomy. Traditionally, open dismembered pyeloplasty has been the gold standard. However, with advances in endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques, there has been a shift toward minimally invasive procedures. Laparoscopic pyeloplasty—with or without robotic assistance—and endoscopic pyelotomy—with either a percutaneous or retrograde approach—are now typically performed. Ureteral stenting should only be used as a temporary measure.

Our patient. Four weeks after the nephrectomy, our patient underwent a right side pyeloplasty, which was successful. He had an uneventful recovery from both procedures. His renal function stabilized and other than routine follow-up, he required no additional treatment.

THE TAKEAWAY

Most cases of hydronephrosis in young people are due to congenital abnormalities, and UPJO is the leading cause. However, the condition can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Whenever a patient presents with an asymptomatic abdominal mass, hydronephrosis should be part of the differential diagnosis. Treatment options include nephrectomy when there is no salvageable kidney function or pyeloplasty and pyelotomy when some kidney function can be preserved.

1. Brown T, Mandell J, Lebowitz RL. Neonatal hydronephrosis in the era ultrasonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:959-963.

2. Stirling WC. Massive hydronephrosis complicated by hydroureter: Report of 3 cases. J Urol. 1939;42:520.

3. Chiang PH, Chen MT, Chou YH, et al. Giant hydronephrosis: report of 4 cases with review of the literature. J Formos Med Assoc. 1990;89:811-817.

4. Aguiar MFM, Oliveira APS, Silva SC, et al. Giant hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Gazzetta Medica Italiana-Archivio per le Scienze Mediche. 2009;168:207.

5. Sepulveda L, Rodriguesa F. Giant hydronephrosis - a late diagnosis of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. World J Nephrol Urol. 2013;2:33.

6. Bernstein GT, Mandell J, Lebowitz RL, et al. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction in neonate. J Urol. 1988;140:1216-1221.

7. Johnston JH, Evans JP, Glassberg KI, et al. Pelvic hydronephrosis in children: a review of 219 personal cases. J Urol. 1977;117:97-101.

8. Gosling JA, Dixon JS. Functional obstruction of the ureter and renal pelvis. A histological and electron microscopic study. Br J Urol. 1978;50:145-152.

THE CASE

A 21-year-old male college student sought care at our urology clinic for a 2-year history of progressive abdominal distention and loss of appetite due to abdominal pressure. On physical examination, his abdomen was distended and tense, but without any tenderness on palpation or any costovertebral angle tenderness. He had no abdominal or flank pain, and wasn’t in acute distress. His blood pressure was normal.

Initial lab test results were significant for elevated creatinine at 2.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at 31.1 mg/dL (normal: 6-20 mg/dL). Results of a complete blood count (CBC) were within normal ranges, including a white blood cell (WBC) count of 7900, hemoglobin level of 15.1 g/dL, and platelet count of 217,000/mcL. A urinalysis showed only a mild increase in the WBC count.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We performed a computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s abdomen, which revealed bilateral hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). The patient’s right kidney was mildly to moderately enlarged, but the left kidney was massive (FIGURE 1A). The hydronephrotic left kidney had extended itself across the midline (FIGURE 1B), pushed the ipsilateral diaphragm upward, and displaced the bladder downward.

The patient underwent right-sided ureteral stent placement for temporary drainage and a complete left-sided nephrectomy. During the surgery, the left kidney was first aspirated, and more than 11,000 cc of clear urine was drained. (Aspiration reduced the kidney size, allowing the surgeon to make a smaller incision.) The removed kidney contained an additional 1200 cc of cloudy residual fluid (FIGURE 2). UPJO was confirmed by the pathological examination of the excised organ.

DISCUSSION

UPJO is the most common etiology for congenital hydronephrosis.1 Because it can cause little to no pain, hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Frequently, an abdominal mass is the initial clinical presentation.

When the hydronephrotic fluid exceeds 1000 cc, the condition is referred to as giant hydronephrosis.2 Although several cases of giant hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO have been reported in the medical literature,3-5 the volume of the hydronephrotic fluid in these cases rarely exceeded 10,000 cc. We believe our patient may be the most severe case of hydronephrosis secondary to bilateral UPJO, with 12,200 cc of fluid. His condition reached this late stage only because his right kidney retained adequate function.

Diagnosis of hydronephrosis is straightforward with an abdominal ultrasound and/or CT scan. Widespread use of abdominal ultrasound as a screening tool has significantly increased the diagnosis of asymptomatic hydronephrosis, and many cases are secondary to UPJO.6 The true incidence of UPJO is unknown, but it is more prevalent in males than in females, and in 10% to 40% of cases, the condition is bilateral.7 Congenital UPJO typically results from intrinsic pathology of the ureter. The diseased segment is often fibrotic, strictured, and aperistaltic.8

Treatment choice depends on whether renal function can be preserved

Treatment of hydronephrosis is straightforward; when there is little or no salvageable renal function (<10%), a simple nephrectomy is indicated, as was the case for our patient. Nephrectomy can be accomplished by either an open or laparoscopic approach.

When there is salvageable renal function, treatment options include pyeloplasty and pyelotomy. Traditionally, open dismembered pyeloplasty has been the gold standard. However, with advances in endoscopic and laparoscopic techniques, there has been a shift toward minimally invasive procedures. Laparoscopic pyeloplasty—with or without robotic assistance—and endoscopic pyelotomy—with either a percutaneous or retrograde approach—are now typically performed. Ureteral stenting should only be used as a temporary measure.

Our patient. Four weeks after the nephrectomy, our patient underwent a right side pyeloplasty, which was successful. He had an uneventful recovery from both procedures. His renal function stabilized and other than routine follow-up, he required no additional treatment.

THE TAKEAWAY

Most cases of hydronephrosis in young people are due to congenital abnormalities, and UPJO is the leading cause. However, the condition can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Whenever a patient presents with an asymptomatic abdominal mass, hydronephrosis should be part of the differential diagnosis. Treatment options include nephrectomy when there is no salvageable kidney function or pyeloplasty and pyelotomy when some kidney function can be preserved.

THE CASE

A 21-year-old male college student sought care at our urology clinic for a 2-year history of progressive abdominal distention and loss of appetite due to abdominal pressure. On physical examination, his abdomen was distended and tense, but without any tenderness on palpation or any costovertebral angle tenderness. He had no abdominal or flank pain, and wasn’t in acute distress. His blood pressure was normal.

Initial lab test results were significant for elevated creatinine at 2.7 mg/dL (normal: 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at 31.1 mg/dL (normal: 6-20 mg/dL). Results of a complete blood count (CBC) were within normal ranges, including a white blood cell (WBC) count of 7900, hemoglobin level of 15.1 g/dL, and platelet count of 217,000/mcL. A urinalysis showed only a mild increase in the WBC count.

THE DIAGNOSIS

We performed a computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s abdomen, which revealed bilateral hydronephrosis secondary to ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). The patient’s right kidney was mildly to moderately enlarged, but the left kidney was massive (FIGURE 1A). The hydronephrotic left kidney had extended itself across the midline (FIGURE 1B), pushed the ipsilateral diaphragm upward, and displaced the bladder downward.

The patient underwent right-sided ureteral stent placement for temporary drainage and a complete left-sided nephrectomy. During the surgery, the left kidney was first aspirated, and more than 11,000 cc of clear urine was drained. (Aspiration reduced the kidney size, allowing the surgeon to make a smaller incision.) The removed kidney contained an additional 1200 cc of cloudy residual fluid (FIGURE 2). UPJO was confirmed by the pathological examination of the excised organ.

DISCUSSION

UPJO is the most common etiology for congenital hydronephrosis.1 Because it can cause little to no pain, hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO can be asymptomatic and may not present until later in life. Frequently, an abdominal mass is the initial clinical presentation.

When the hydronephrotic fluid exceeds 1000 cc, the condition is referred to as giant hydronephrosis.2 Although several cases of giant hydronephrosis secondary to UPJO have been reported in the medical literature,3-5 the volume of the hydronephrotic fluid in these cases rarely exceeded 10,000 cc. We believe our patient may be the most severe case of hydronephrosis secondary to bilateral UPJO, with 12,200 cc of fluid. His condition reached this late stage only because his right kidney retained adequate function.

Diagnosis of hydronephrosis is straightforward with an abdominal ultrasound and/or CT scan. Widespread use of abdominal ultrasound as a screening tool has significantly increased the diagnosis of asymptomatic hydronephrosis, and many cases are secondary to UPJO.6 The true incidence of UPJO is unknown, but it is more prevalent in males than in females, and in 10% to 40% of cases, the condition is bilateral.7 Congenital UPJO typically results from intrinsic pathology of the ureter. The diseased segment is often fibrotic, strictured, and aperistaltic.8

Treatment choice depends on whether renal function can be preserved