User login

Squamoid Eccrine Ductal Carcinoma

Eccrine carcinomas are uncommon cutaneous neoplasms demonstrating nonuniform histologic features, behavior, and nomenclature. Given the rarity of these tumors, no known criteria by which to diagnose the tumor or guidelines for treatment have been proposed. We report a rare case of an immunocompromised patient with a primary squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) who was subsequently treated with radical resection and axillary dissection. It was later determined that the patient had distant metastasis of SEDC. A review of the literature on the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of SEDC also is provided.

Case Report

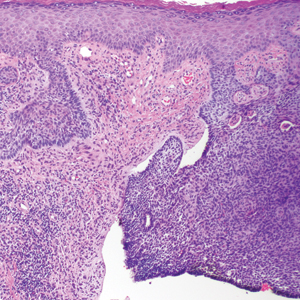

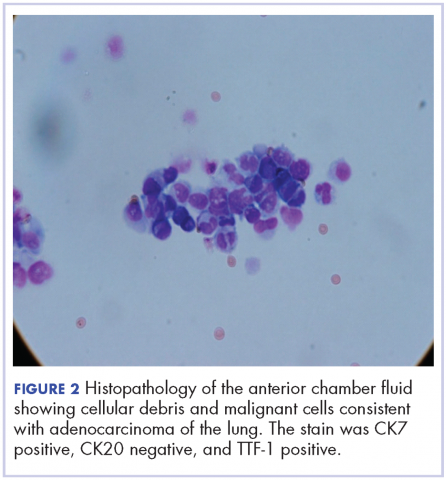

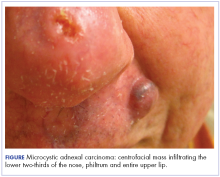

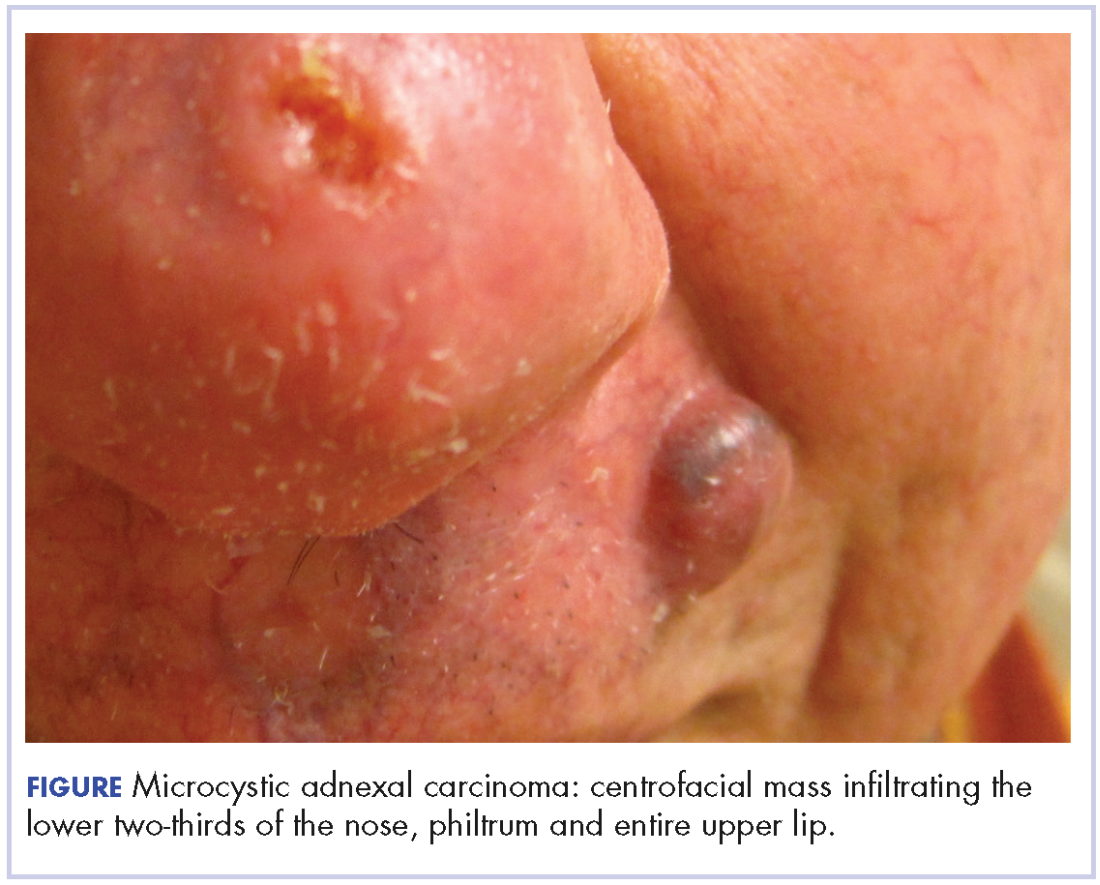

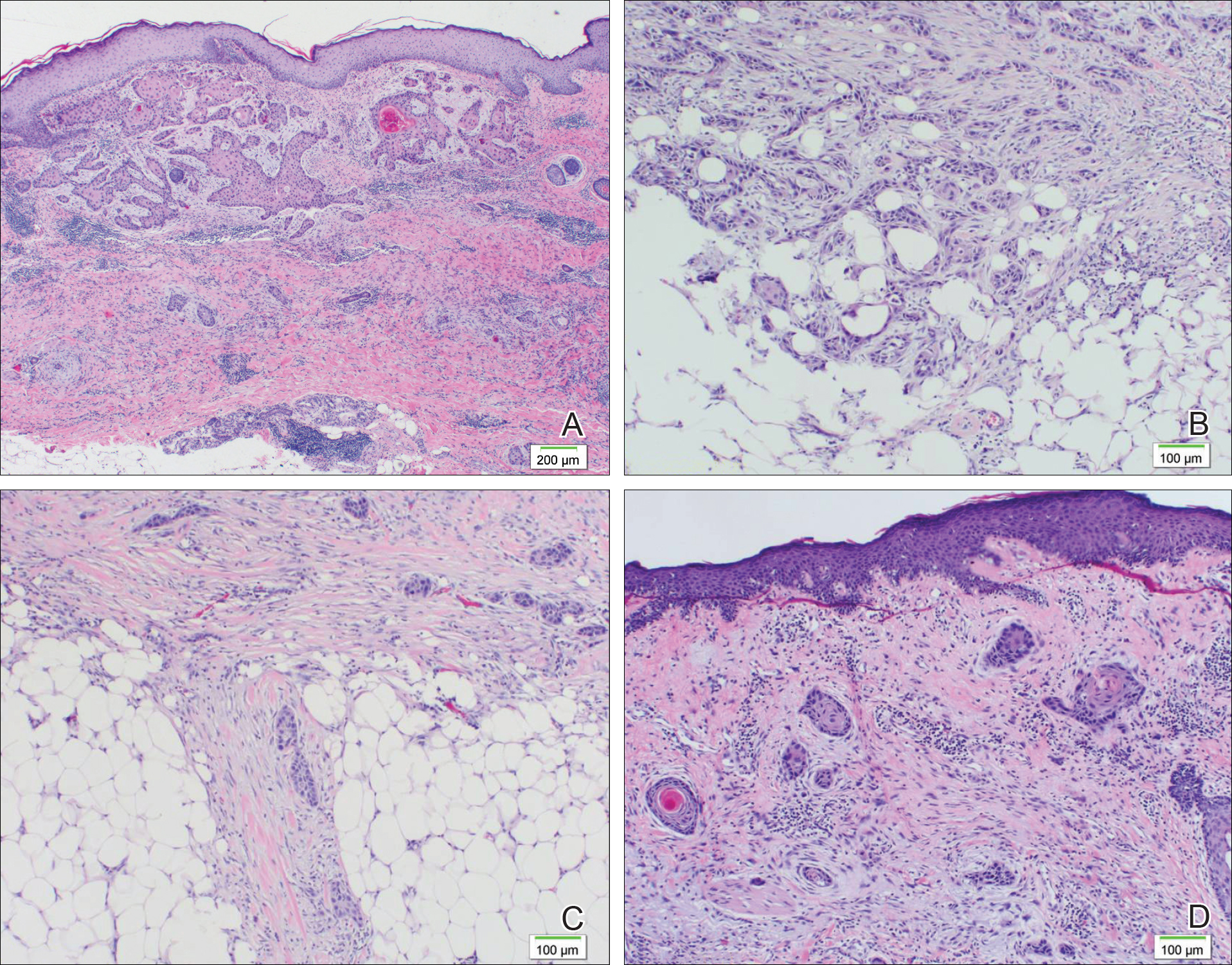

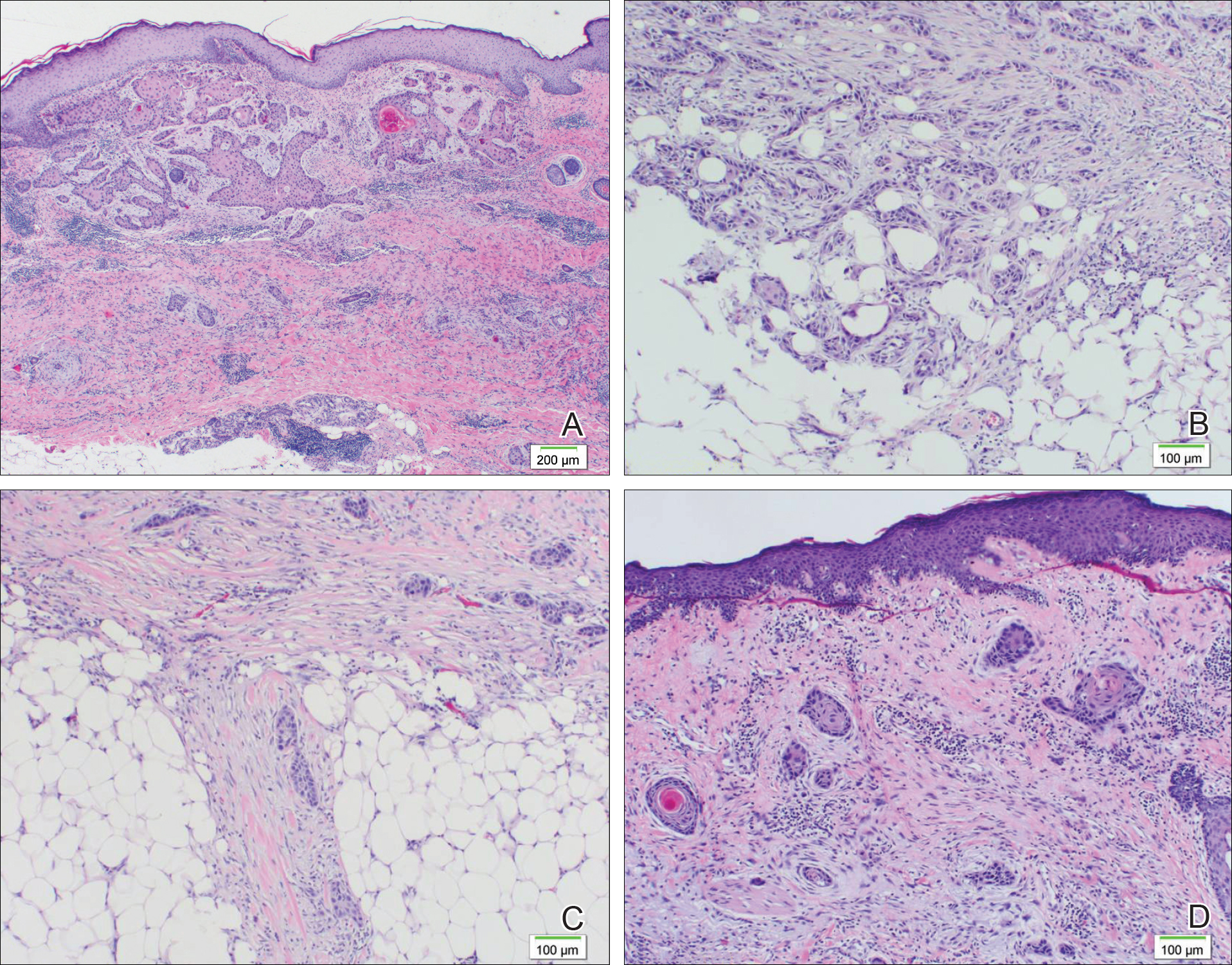

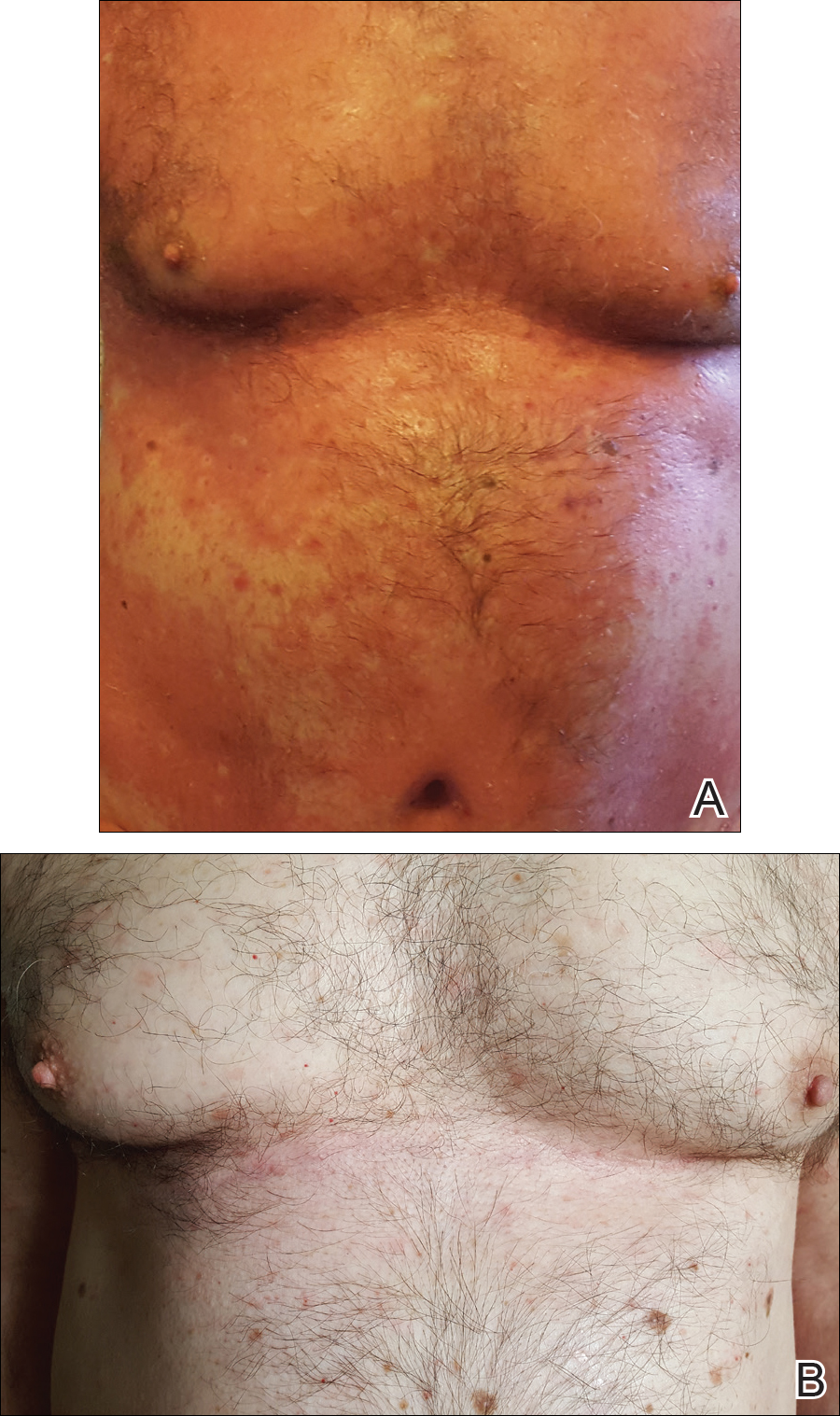

A 77-year-old man whose medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and numerous previous basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) presented with a 5-cm, stellate, sclerotic plaque on the left chest of approximately 2 years’ duration (Figure 1) and a 3-mm pink papule on the right nasal sidewall of 2 months’ duration. Initial histology of both lesions revealed carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation extending from the undersurface of the epidermis, favoring a diagnosis of SEDC (Figure 2). At the time of initial presentation, the patient also had a 6-mm pink papule on the right chest of several months duration that was consistent with a well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma on histology.

Further analysis of the lesion on the left chest revealed positive staining for cytokeratin (CK) 5/14 and p63, suggestive of a cutaneous malignancy. Staining for S100 protein highlighted rare cells in the basal layer of tumor aggregates. The immunohistochemical profile showed negative staining for CK7, CK5D3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor 2.

Diagnosis of SEDC of the chest and nasal lesions was based on the morphologic architecture, which included ductal formation noted within the tumor. The chest lesion also had prominent squamoid differentiation. Another histologic feature consistent with SEDC was poorly demarcated, infiltrative neoplastic cells extending into the dermis and subcutis. Although there was some positive focal staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), variegation within the tumor and the prominent squamoid component might have contributed to this unexpected staining pattern.

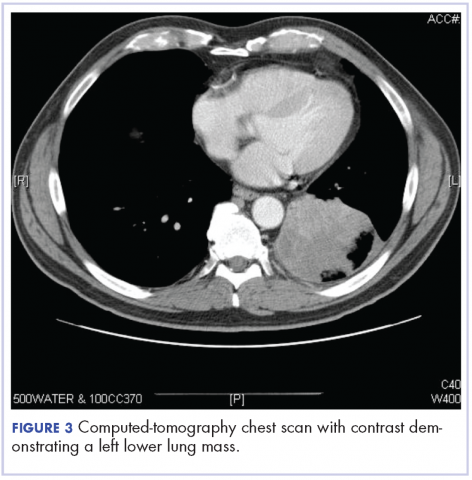

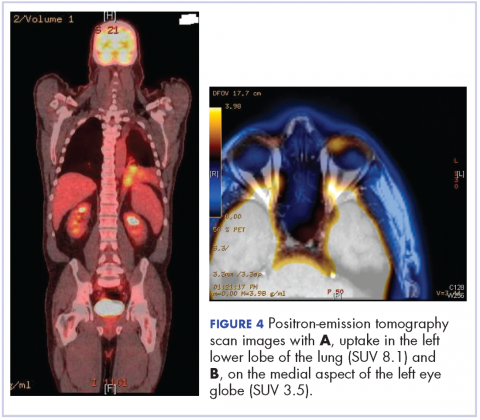

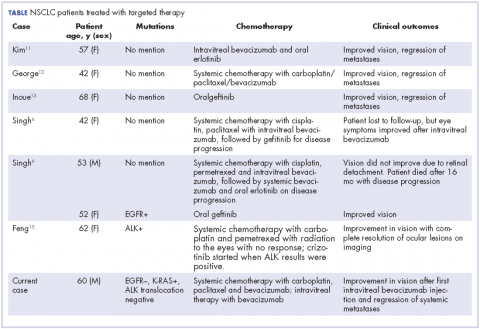

The patient was admitted to the hospital for excision of the lesion on the chest wall. Initial workup revealed macrocytic anemia, which required transfusion, and an incidental finding of non–small-cell lung cancer. The chest lesion was unrelated to the non–small-cell lung cancer based on the staining profile. Material from the lung stained positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and exhibited rare staining for p63; however, the chest lesion did not stain positive for TTF-1 and had strong staining affinity for p63, indicative of a cutaneous malignancy.

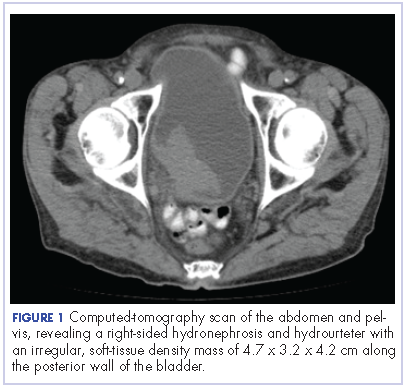

The lesion on the chest wall was definitively excised. Pathologic analysis revealed a dermal-based infiltrative tumor of irregular nests and cords of squamoid cells with focal ductal formation in a fibromyxoid background stroma, suggestive of an adnexal carcinoma with a considerable degree of squamous differentiation and favoring a diagnosis of SEDC. Focal perineural invasion was noted, but no lymphovascular spread was identified; however, metastasis was identified in 1 of 26 axillary lymph nodes. The patient underwent 9 sessions of radiation therapy for the lung cancer and also was given cetuximab.

Three months later, the nasal tumor was subsequently excised in an outpatient procedure, and the final biopsy report indicated a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. One-and-a-half years later, in follow-up with surgery after removal of the chest lesion, a 2×3-cm mass was excised from the left neck that demonstrated lymph nodes consistent with metastatic SEDC. Careful evaluation of this patient, including family history and genetic screening, was considered. Our patient continues to follow-up with the dermatology department every 3 months. He has been doing well and has had multiple additional primary SCCs in the subsequent 5 years of follow-up.

Comment

Eccrine carcinoma is the most common subtype of adnexal carcinoma, representing 0.01% of all cutaneous tumors.1 S

Eccrine carcinoma is observed clinically as a slow-growing, nodular plaque on the scalp, arms, legs, or trunk in middle-aged and elderly individuals.1 Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma also has been reported in a young woman.5 Another immunocompromised patient was identified in the literature with a great toe lesion that showed follicular differentiation along with the usual SEDC features of squamoid and ductal differentiation.6 The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be an SCC arising from eccrine glands, a subtype of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation, or a biphenotypic carcinoma.1,7

Histologically, SEDC is poorly circumscribed with an infiltrative growth pattern and deep extension into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The lesion is characterized by prominent squamous epithelial proliferation superficially with cellular atypia, keratinous cyst formation, squamous eddies, and eccrine ductal differentiation.1

The differential diagnosis of SEDC includes SCC; metastatic carcinoma with squamoid features; and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

Immunohistochemistry has a role in the diagnosis of SEDC. Findings include positive staining for S100 protein, EMA, CKs, and CEA. Glandular tissue stains positive for EMA and CEA, supporting an adnexal origin.1 Positivity for p63 and CK5/6 supports the conclusion that this is a primary cutaneous malignancy, not a metastatic disease.1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma has an indeterminate malignant potential. There is a disparity of clinical behavior between SCC and eccrine cancers; however, because squamous differentiation sometimes dominates the histological picture, eccrine carcinomas can be misdiagnosed as SCC.1,8 Eccrine adnexal tumors are characterized by multiple local recurrences (70%–80% of cases); perineural invasion; and metastasis (50% of cases) to regional lymph nodes and viscera, including the lungs, liver, bones, and brain.1 Squamous cell carcinoma, however, has a markedly lower recurrence rate (3.1%–18.7% of cases) and rate of metastasis (5.2%–37.8%).1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is classified as one of the less aggressive eccrine tumors, although the low number of cases makes it a controversial conclusion.1 To our knowledge, no cases of SEDC metastasis have been reported with SEDC. Recurrence of SEDC has been reported locally, and perineural or perivascular invasion (or both) has been demonstrated in 3 cases.1

Since SEDC has invasive and metastatic potential, as demonstrated in our case, along with elevated local recurrence rates, physicians must be able to properly diagnose this rare entity and recommend an appropriate surgical modality. Due to the low incidence of SEDC, there are no known randomized studies comparing treatment modalities.1 O

Surgical extirpation with complete margin examination is recommended, as SEDC tends to be underestimated in size, is aggressive in its infiltration, and is predisposed to perineural and perivascular invasion. T

Along with the rarity of SEDC in our patient, the simultaneous occurrence of 3 primary malignancies also is unusual. Patients with CLL have progressive defects of cell- and humoral-mediated immunity, causing immunosuppression. In a retrospective study, Tsimberidou et al9 reviewed the records of 2028 untreated CLL patients and determined that 27% had another primary malignancy, including skin (30%) and lung cancers (6%), which were two of the malignancies seen in our patient. The investigators concluded that patients with CLL have more than twice the risk of developing a second primary malignancy and an increased frequency of certain cancer types.9 Furthermore, treatment regimens for CLL have been considered to increase cell- and humoral-mediated immune defects at specific cancer sites,10 although the exact mechanism of this action is unknown. Development of a second primary malignancy (or even a third) in patients with SEDC is increasingly being reported in CLL patients.9,10

A high index of suspicion with SEDC in the differential diagnosis should be maintained in elderly men with slow-growing, solitary, nodular lesions of the scalp, nose, arms, legs, or trunk.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;916:799-802.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma)[published online April 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, McLaughlin P, et al. Other malignancies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:904-910.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT. Risk for second nonlymphoid neoplasms in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med Gen Med. 2007;9:35.

Eccrine carcinomas are uncommon cutaneous neoplasms demonstrating nonuniform histologic features, behavior, and nomenclature. Given the rarity of these tumors, no known criteria by which to diagnose the tumor or guidelines for treatment have been proposed. We report a rare case of an immunocompromised patient with a primary squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) who was subsequently treated with radical resection and axillary dissection. It was later determined that the patient had distant metastasis of SEDC. A review of the literature on the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of SEDC also is provided.

Case Report

A 77-year-old man whose medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and numerous previous basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) presented with a 5-cm, stellate, sclerotic plaque on the left chest of approximately 2 years’ duration (Figure 1) and a 3-mm pink papule on the right nasal sidewall of 2 months’ duration. Initial histology of both lesions revealed carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation extending from the undersurface of the epidermis, favoring a diagnosis of SEDC (Figure 2). At the time of initial presentation, the patient also had a 6-mm pink papule on the right chest of several months duration that was consistent with a well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma on histology.

Further analysis of the lesion on the left chest revealed positive staining for cytokeratin (CK) 5/14 and p63, suggestive of a cutaneous malignancy. Staining for S100 protein highlighted rare cells in the basal layer of tumor aggregates. The immunohistochemical profile showed negative staining for CK7, CK5D3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor 2.

Diagnosis of SEDC of the chest and nasal lesions was based on the morphologic architecture, which included ductal formation noted within the tumor. The chest lesion also had prominent squamoid differentiation. Another histologic feature consistent with SEDC was poorly demarcated, infiltrative neoplastic cells extending into the dermis and subcutis. Although there was some positive focal staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), variegation within the tumor and the prominent squamoid component might have contributed to this unexpected staining pattern.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for excision of the lesion on the chest wall. Initial workup revealed macrocytic anemia, which required transfusion, and an incidental finding of non–small-cell lung cancer. The chest lesion was unrelated to the non–small-cell lung cancer based on the staining profile. Material from the lung stained positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and exhibited rare staining for p63; however, the chest lesion did not stain positive for TTF-1 and had strong staining affinity for p63, indicative of a cutaneous malignancy.

The lesion on the chest wall was definitively excised. Pathologic analysis revealed a dermal-based infiltrative tumor of irregular nests and cords of squamoid cells with focal ductal formation in a fibromyxoid background stroma, suggestive of an adnexal carcinoma with a considerable degree of squamous differentiation and favoring a diagnosis of SEDC. Focal perineural invasion was noted, but no lymphovascular spread was identified; however, metastasis was identified in 1 of 26 axillary lymph nodes. The patient underwent 9 sessions of radiation therapy for the lung cancer and also was given cetuximab.

Three months later, the nasal tumor was subsequently excised in an outpatient procedure, and the final biopsy report indicated a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. One-and-a-half years later, in follow-up with surgery after removal of the chest lesion, a 2×3-cm mass was excised from the left neck that demonstrated lymph nodes consistent with metastatic SEDC. Careful evaluation of this patient, including family history and genetic screening, was considered. Our patient continues to follow-up with the dermatology department every 3 months. He has been doing well and has had multiple additional primary SCCs in the subsequent 5 years of follow-up.

Comment

Eccrine carcinoma is the most common subtype of adnexal carcinoma, representing 0.01% of all cutaneous tumors.1 S

Eccrine carcinoma is observed clinically as a slow-growing, nodular plaque on the scalp, arms, legs, or trunk in middle-aged and elderly individuals.1 Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma also has been reported in a young woman.5 Another immunocompromised patient was identified in the literature with a great toe lesion that showed follicular differentiation along with the usual SEDC features of squamoid and ductal differentiation.6 The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be an SCC arising from eccrine glands, a subtype of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation, or a biphenotypic carcinoma.1,7

Histologically, SEDC is poorly circumscribed with an infiltrative growth pattern and deep extension into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The lesion is characterized by prominent squamous epithelial proliferation superficially with cellular atypia, keratinous cyst formation, squamous eddies, and eccrine ductal differentiation.1

The differential diagnosis of SEDC includes SCC; metastatic carcinoma with squamoid features; and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

Immunohistochemistry has a role in the diagnosis of SEDC. Findings include positive staining for S100 protein, EMA, CKs, and CEA. Glandular tissue stains positive for EMA and CEA, supporting an adnexal origin.1 Positivity for p63 and CK5/6 supports the conclusion that this is a primary cutaneous malignancy, not a metastatic disease.1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma has an indeterminate malignant potential. There is a disparity of clinical behavior between SCC and eccrine cancers; however, because squamous differentiation sometimes dominates the histological picture, eccrine carcinomas can be misdiagnosed as SCC.1,8 Eccrine adnexal tumors are characterized by multiple local recurrences (70%–80% of cases); perineural invasion; and metastasis (50% of cases) to regional lymph nodes and viscera, including the lungs, liver, bones, and brain.1 Squamous cell carcinoma, however, has a markedly lower recurrence rate (3.1%–18.7% of cases) and rate of metastasis (5.2%–37.8%).1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is classified as one of the less aggressive eccrine tumors, although the low number of cases makes it a controversial conclusion.1 To our knowledge, no cases of SEDC metastasis have been reported with SEDC. Recurrence of SEDC has been reported locally, and perineural or perivascular invasion (or both) has been demonstrated in 3 cases.1

Since SEDC has invasive and metastatic potential, as demonstrated in our case, along with elevated local recurrence rates, physicians must be able to properly diagnose this rare entity and recommend an appropriate surgical modality. Due to the low incidence of SEDC, there are no known randomized studies comparing treatment modalities.1 O

Surgical extirpation with complete margin examination is recommended, as SEDC tends to be underestimated in size, is aggressive in its infiltration, and is predisposed to perineural and perivascular invasion. T

Along with the rarity of SEDC in our patient, the simultaneous occurrence of 3 primary malignancies also is unusual. Patients with CLL have progressive defects of cell- and humoral-mediated immunity, causing immunosuppression. In a retrospective study, Tsimberidou et al9 reviewed the records of 2028 untreated CLL patients and determined that 27% had another primary malignancy, including skin (30%) and lung cancers (6%), which were two of the malignancies seen in our patient. The investigators concluded that patients with CLL have more than twice the risk of developing a second primary malignancy and an increased frequency of certain cancer types.9 Furthermore, treatment regimens for CLL have been considered to increase cell- and humoral-mediated immune defects at specific cancer sites,10 although the exact mechanism of this action is unknown. Development of a second primary malignancy (or even a third) in patients with SEDC is increasingly being reported in CLL patients.9,10

A high index of suspicion with SEDC in the differential diagnosis should be maintained in elderly men with slow-growing, solitary, nodular lesions of the scalp, nose, arms, legs, or trunk.

Eccrine carcinomas are uncommon cutaneous neoplasms demonstrating nonuniform histologic features, behavior, and nomenclature. Given the rarity of these tumors, no known criteria by which to diagnose the tumor or guidelines for treatment have been proposed. We report a rare case of an immunocompromised patient with a primary squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) who was subsequently treated with radical resection and axillary dissection. It was later determined that the patient had distant metastasis of SEDC. A review of the literature on the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of SEDC also is provided.

Case Report

A 77-year-old man whose medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and numerous previous basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) presented with a 5-cm, stellate, sclerotic plaque on the left chest of approximately 2 years’ duration (Figure 1) and a 3-mm pink papule on the right nasal sidewall of 2 months’ duration. Initial histology of both lesions revealed carcinoma with squamous and ductal differentiation extending from the undersurface of the epidermis, favoring a diagnosis of SEDC (Figure 2). At the time of initial presentation, the patient also had a 6-mm pink papule on the right chest of several months duration that was consistent with a well-differentiated sebaceous carcinoma on histology.

Further analysis of the lesion on the left chest revealed positive staining for cytokeratin (CK) 5/14 and p63, suggestive of a cutaneous malignancy. Staining for S100 protein highlighted rare cells in the basal layer of tumor aggregates. The immunohistochemical profile showed negative staining for CK7, CK5D3, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor 2.

Diagnosis of SEDC of the chest and nasal lesions was based on the morphologic architecture, which included ductal formation noted within the tumor. The chest lesion also had prominent squamoid differentiation. Another histologic feature consistent with SEDC was poorly demarcated, infiltrative neoplastic cells extending into the dermis and subcutis. Although there was some positive focal staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), variegation within the tumor and the prominent squamoid component might have contributed to this unexpected staining pattern.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for excision of the lesion on the chest wall. Initial workup revealed macrocytic anemia, which required transfusion, and an incidental finding of non–small-cell lung cancer. The chest lesion was unrelated to the non–small-cell lung cancer based on the staining profile. Material from the lung stained positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and exhibited rare staining for p63; however, the chest lesion did not stain positive for TTF-1 and had strong staining affinity for p63, indicative of a cutaneous malignancy.

The lesion on the chest wall was definitively excised. Pathologic analysis revealed a dermal-based infiltrative tumor of irregular nests and cords of squamoid cells with focal ductal formation in a fibromyxoid background stroma, suggestive of an adnexal carcinoma with a considerable degree of squamous differentiation and favoring a diagnosis of SEDC. Focal perineural invasion was noted, but no lymphovascular spread was identified; however, metastasis was identified in 1 of 26 axillary lymph nodes. The patient underwent 9 sessions of radiation therapy for the lung cancer and also was given cetuximab.

Three months later, the nasal tumor was subsequently excised in an outpatient procedure, and the final biopsy report indicated a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. One-and-a-half years later, in follow-up with surgery after removal of the chest lesion, a 2×3-cm mass was excised from the left neck that demonstrated lymph nodes consistent with metastatic SEDC. Careful evaluation of this patient, including family history and genetic screening, was considered. Our patient continues to follow-up with the dermatology department every 3 months. He has been doing well and has had multiple additional primary SCCs in the subsequent 5 years of follow-up.

Comment

Eccrine carcinoma is the most common subtype of adnexal carcinoma, representing 0.01% of all cutaneous tumors.1 S

Eccrine carcinoma is observed clinically as a slow-growing, nodular plaque on the scalp, arms, legs, or trunk in middle-aged and elderly individuals.1 Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma also has been reported in a young woman.5 Another immunocompromised patient was identified in the literature with a great toe lesion that showed follicular differentiation along with the usual SEDC features of squamoid and ductal differentiation.6 The etiology of SEDC is controversial but is thought to be an SCC arising from eccrine glands, a subtype of eccrine carcinoma with extensive squamoid differentiation, or a biphenotypic carcinoma.1,7

Histologically, SEDC is poorly circumscribed with an infiltrative growth pattern and deep extension into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The lesion is characterized by prominent squamous epithelial proliferation superficially with cellular atypia, keratinous cyst formation, squamous eddies, and eccrine ductal differentiation.1

The differential diagnosis of SEDC includes SCC; metastatic carcinoma with squamoid features; and eccrine tumors, including eccrine poroma, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and porocarcinoma with squamous differentiation.1

Immunohistochemistry has a role in the diagnosis of SEDC. Findings include positive staining for S100 protein, EMA, CKs, and CEA. Glandular tissue stains positive for EMA and CEA, supporting an adnexal origin.1 Positivity for p63 and CK5/6 supports the conclusion that this is a primary cutaneous malignancy, not a metastatic disease.1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma has an indeterminate malignant potential. There is a disparity of clinical behavior between SCC and eccrine cancers; however, because squamous differentiation sometimes dominates the histological picture, eccrine carcinomas can be misdiagnosed as SCC.1,8 Eccrine adnexal tumors are characterized by multiple local recurrences (70%–80% of cases); perineural invasion; and metastasis (50% of cases) to regional lymph nodes and viscera, including the lungs, liver, bones, and brain.1 Squamous cell carcinoma, however, has a markedly lower recurrence rate (3.1%–18.7% of cases) and rate of metastasis (5.2%–37.8%).1

Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma is classified as one of the less aggressive eccrine tumors, although the low number of cases makes it a controversial conclusion.1 To our knowledge, no cases of SEDC metastasis have been reported with SEDC. Recurrence of SEDC has been reported locally, and perineural or perivascular invasion (or both) has been demonstrated in 3 cases.1

Since SEDC has invasive and metastatic potential, as demonstrated in our case, along with elevated local recurrence rates, physicians must be able to properly diagnose this rare entity and recommend an appropriate surgical modality. Due to the low incidence of SEDC, there are no known randomized studies comparing treatment modalities.1 O

Surgical extirpation with complete margin examination is recommended, as SEDC tends to be underestimated in size, is aggressive in its infiltration, and is predisposed to perineural and perivascular invasion. T

Along with the rarity of SEDC in our patient, the simultaneous occurrence of 3 primary malignancies also is unusual. Patients with CLL have progressive defects of cell- and humoral-mediated immunity, causing immunosuppression. In a retrospective study, Tsimberidou et al9 reviewed the records of 2028 untreated CLL patients and determined that 27% had another primary malignancy, including skin (30%) and lung cancers (6%), which were two of the malignancies seen in our patient. The investigators concluded that patients with CLL have more than twice the risk of developing a second primary malignancy and an increased frequency of certain cancer types.9 Furthermore, treatment regimens for CLL have been considered to increase cell- and humoral-mediated immune defects at specific cancer sites,10 although the exact mechanism of this action is unknown. Development of a second primary malignancy (or even a third) in patients with SEDC is increasingly being reported in CLL patients.9,10

A high index of suspicion with SEDC in the differential diagnosis should be maintained in elderly men with slow-growing, solitary, nodular lesions of the scalp, nose, arms, legs, or trunk.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;916:799-802.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma)[published online April 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, McLaughlin P, et al. Other malignancies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:904-910.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT. Risk for second nonlymphoid neoplasms in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med Gen Med. 2007;9:35.

- Clark S, Young A, Piatigorsky E, et al. Mohs micrographic surgery in the setting of squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: addressing a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:33-36.

- Saraiva MI, Vieira MA, Portocarrero LK, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;916:799-802.

- van der Horst MP, Garcia-Herrera A, Markiewicz D, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:755-760.

- Frouin E, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Balme B, et al. Anatomoclinical study of 30 cases of sclerosing sweat duct carcinomas (microcystic adnexal carcinoma, syringomatous carcinoma and squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma)[published online April 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1978-1994.

- Kim YJ, Kim AR, Yu DS. Mohs micrographic surgery for squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1462-1464.

- Kavand S, Cassarino DS. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: an unusual low-grade case with follicular differentiation. are these tumors squamoid variants of microcystic adnexal carcinoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:849-852.

- Terushkin E, Leffell DJ, Futoryan T, et al. Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:287-292.

- Chhibber V, Lyle S, Mahalingam M. Ductal eccrine carcinoma with squamous differentiation: apropos a case. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:503-507.

- Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, McLaughlin P, et al. Other malignancies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:904-910.

- Dasanu CA, Alexandrescu DT. Risk for second nonlymphoid neoplasms in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Med Gen Med. 2007;9:35.

Practice Points

- Squamoid eccrine ductal carcinoma (SEDC) is an extremely rare cutaneous tumor of unknown etiology.

- A high index of suspicion with SEDC in the differential diagnosis should be maintained in elderly men with slow-growing, solitary, nodular lesions of the scalp, nose, arms, legs, or trunk.

- Development of a second or even a third primary malignancy in patients with SEDC is increasingly being reported in CLL patients.

Pigmented Squamous Cell Carcinoma Presenting as Longitudinal Melanonychia in a Transplant Recipient

Case Report

A 62-year-old black man presented for examination of a dark longitudinal streak located adjacent to the lateral nail fold on the third finger of the left hand. The lesion had been present for several months, during which time it had slowly expanded in size. The fingertip had recently become tender, which interfered with the patient’s ability to work. His past medical history was remarkable for end-stage renal disease secondary to glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome of unclear etiology. He initially was treated by an outside physician using peritoneal dialysis for 3 years until he underwent renal transplantation in 2004 with a cadaveric organ. Other remarkable medical conditions included posttransplantation diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and gout. His multidrug regimen included 2 immunosuppressive medications: oral cyclosporine 125 mg twice daily and oral mycophenolate mofetil 250 mg twice daily.

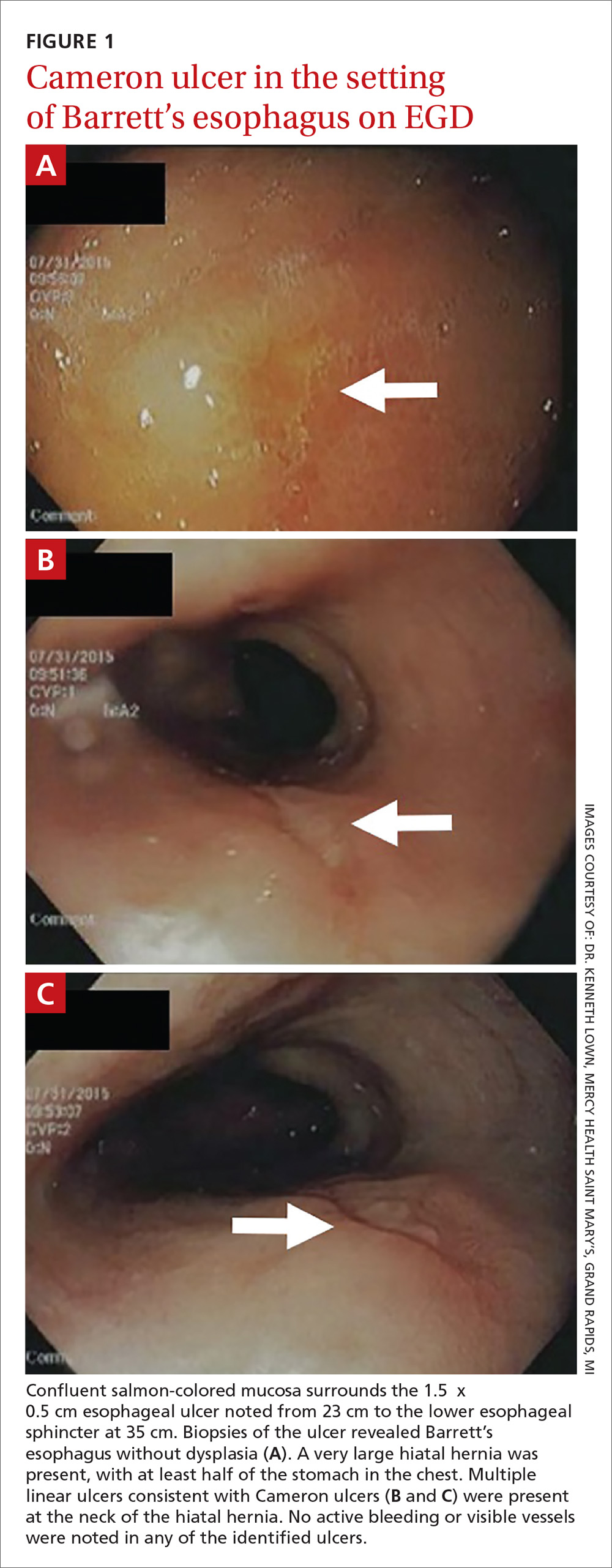

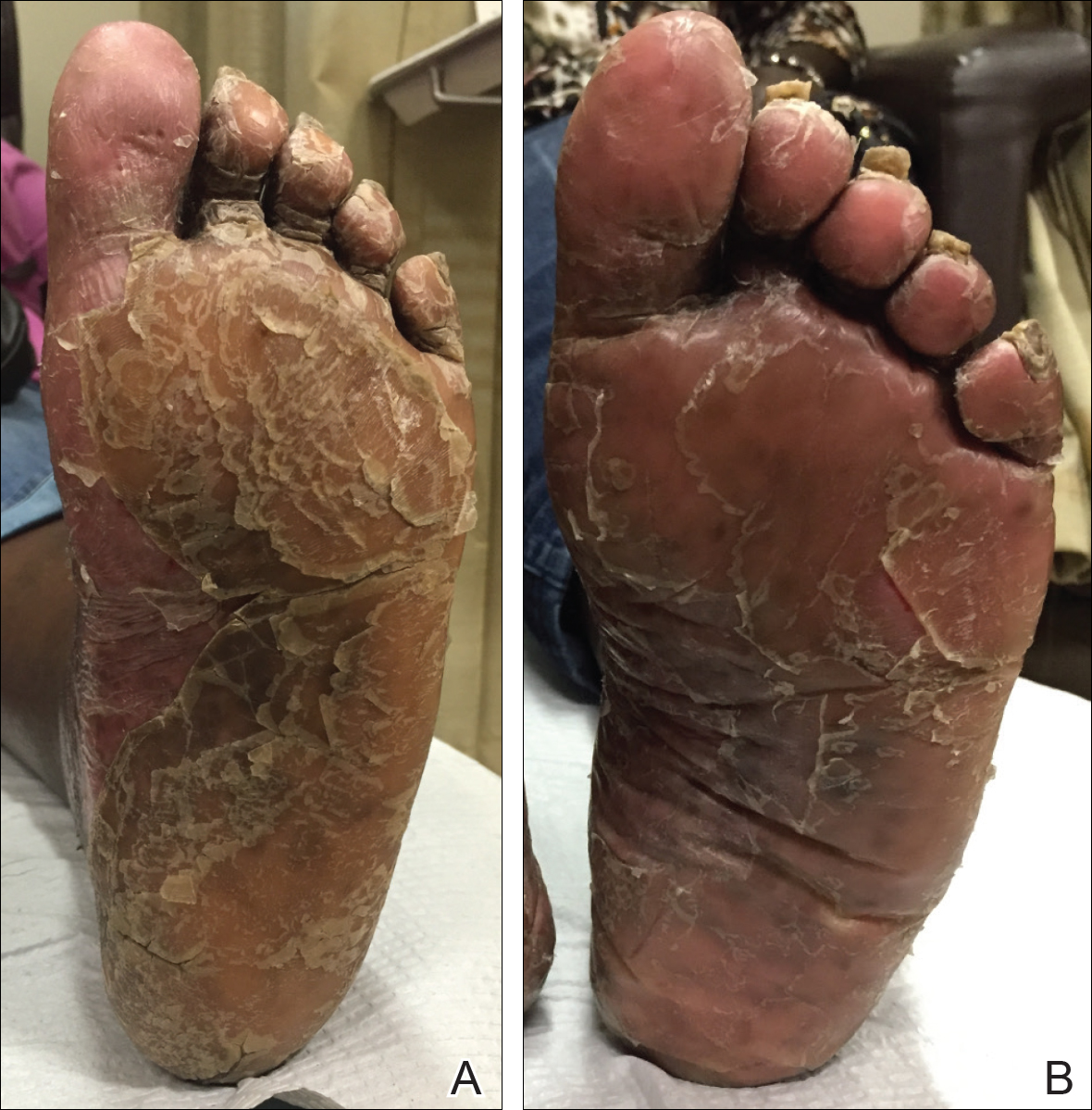

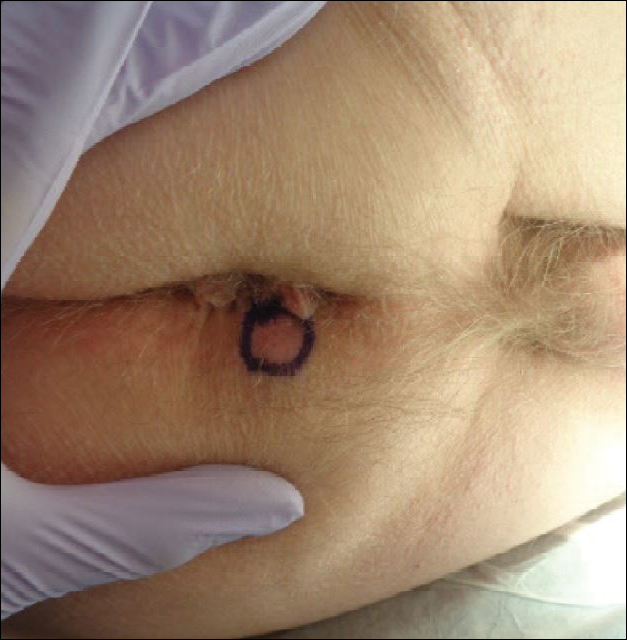

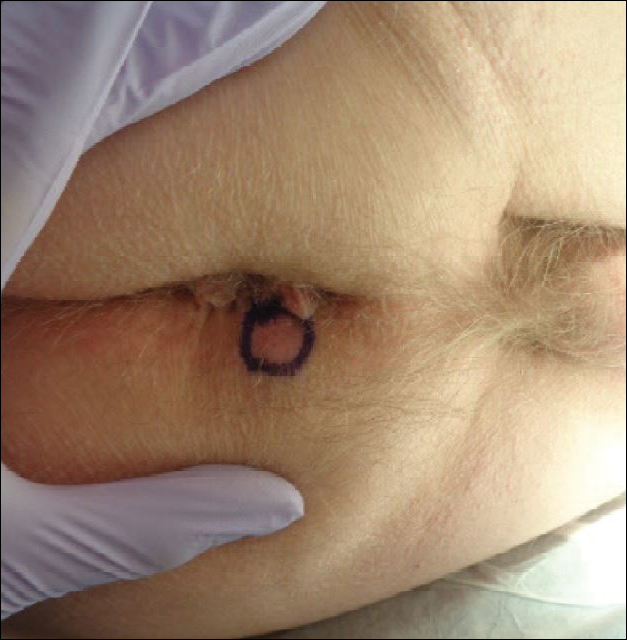

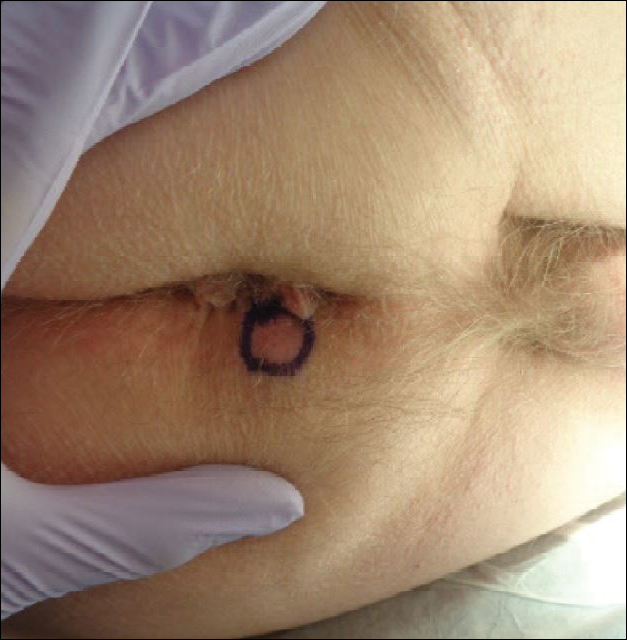

A broad, irregular, black, pigmented, subungual band was noted on the left third finger. The lesion appeared to emanate from below the nail cuticle and traveled along the nail longitudinally toward the distal tip. The band appeared darker at the edge adjacent to the lateral nail fold and grew lighter near the middle of the nail where its free edge was noted to be irregular. A slightly thickened lateral nail fold with an irregular, small, sawtoothlike hyperkeratosis and hyperpigmentation also was noted (Figure 1).

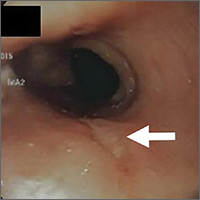

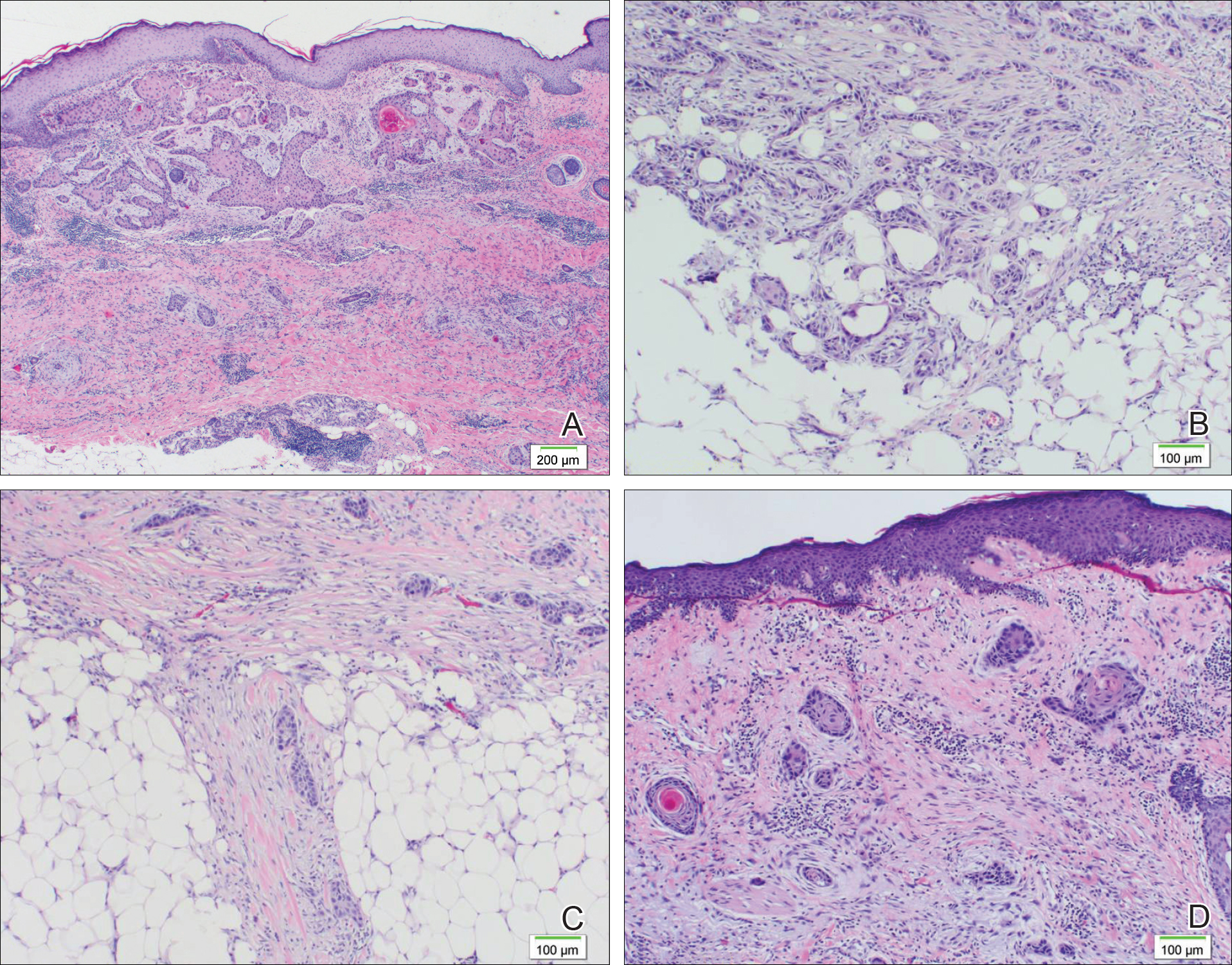

Subungual melanoma, onychomycosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and a verruca copresenting with onychomycosis were considered in the differential diagnosis. The patient underwent nail avulsion and biopsy of the nail bed as well as the nail matrix. Histopathology was notable for malignant dyskeratosis with a lack of nuclear maturation, occasional mitoses, multinucleation, and individual cell keratinization (Figure 2). Immunostaining for S100 was negative, while staining for cytokeratins AE1/AE3 was positive. Deposition of melanin pigment in the malignant dyskeratotic cells was noted. Periodic acid–Schiff staining identified pseudohyphae without invasion of the nail plate. A diagnosis of pigmented SCC (pSCC) was made. The patient’s nail also was sent for fungal cultures that later grew Candida glabrata and Candida parapsilosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for removal of the pSCC, which was found to be more extensive than originally suspected and required en bloc excision of the nail repaired with a full-thickness skin graft from the left forearm. The area healed well with some hyperpigmentation (Figure 3).

Comment

Among the various types of skin cancer, an estimated 700,000 patients are diagnosed with SCC annually, making it the second most common form of skin cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer among whites in the United States, while in contrast SCC is the most common skin cancer in patients with skin of color.2 Only an estimated 2% to 5% of all SCCs are pigmented, and this variant is more commonly seen in patients with skin of color.3-5 One analysis of 52 cases of pSCC showed that common features included a flat or slightly raised appearance and hyperpigmentation with varying levels of scaling.6 Studies have shown an altered presentation of pSCC in black skin with increased melanin production and thickness of the stratum corneum in contrast with cases seen in white patients.7 Other potential features include scaling, erosive changes, and sharply demarcated borders. Squamous cell carcinoma typically occurs in sun-exposed areas, reflecting its association with UV light damage; however, SCC in skin of color patients has been noted to occur in sun-protected areas and in areas of chronic scarring.8 Pigmented SCC also appears to follow this distribution, as affected areas are not necessarily in direct exposure to the sun. Pigmented SCCs have been associated with pruritus and/or burning pain, which also was seen in our case when our patient complained of tenderness at the site.

We describe the case of a subungual pSCC clinically presenting as longitudinal melanonychia. Pigmented SCC presenting as longitudinal melanonychia was first described by Baran and Simon in 1988.9 Since that time, it has been reported that approximately 10% of subungual pSCCs clinically present as longitudinal melanonychia.10,11 A retrospective study reviewing 35 cases of SCC of the nail apparatus found that 5 (14.3%) cases presented as longitudinal melanonychia.10 Another retrospective study found that 6 of 51 (11.8%) cases of SCCs affecting the nail unit presented as the warty type of SCC in association with longitudinal melanonychia.12 Cases of pSCC in situ appearing as longitudinal melanonychia also have been reported.13,14

Risk factors for the development of pSCC include advanced age, male sex, presence of human papilloma virus, and use of immunosuppressants.15 Male predominance and advanced age at the time of diagnosis (mean age, 67 years) have been observed in pSCC cases.16 It is now well established that renal transplant recipients have an increased risk of SCC, with a reported incidence rate of 5% to 6%.16 When these patients develop an SCC, they typically follow a more aggressive course. Renal transplantation has a higher ratio than cardiac transplantation for SCC development (2.37:1), whereas cardiac transplantation is associated with a higher risk of BCC development.17 A study of 384 transplant recipients found that 96 (25.0%) had a postsurgical nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), with a ratio of SCC to BCC of 1.2:1.16 The calculated incidence of NMSC at 10 and 20 years posttransplantation was 24.2% and 54.4%, respectively. Another study also determined that SCC rates (50.0%) in postrenal transplant recipients were approximately twice that of BCC (27.0%).18

A daily regimen of immunosuppressive medications such as cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil showed an increased risk for development of NMSC.15 Immunosuppressive medications play an important role in the pathogenesis of SCC due to a direct oncogenic effect as well as impairment of the immune system’s ability to fight precancerous developments.15 A 4-year study of 100 renal transplant recipients using mycophenolate mofetil as part of an immunosuppressive regimen reported 22% NMSC findings among 9 patients.19 On average, patients developed an NMSC approximately 61 months posttransplantation, with a wide range from 2 to 120 months.

Advanced age was another important risk factor, with each decade of life producing a 60% increase in instantaneous risk of SCC development for transplant recipients.15 A steady increase in risk was related to the length of time adhering to an immunosuppressive regimen, especially from 2 to 6 years, and then remaining constant in subsequent years. For older patients on immunosuppressant regimens for more than 8 years, the calculated relative risk was noted to be over 200 times greater than the normal population’s development of skin cancers.18

Conclusion

Although cases of pSCC presenting as longitudinal melanonychia have previously been reported,9-14,20 our case is unique in that it describes pSCC in a renal transplant recipient. Our patient had many of the known risk factors for the development of pSCC including male sex, advanced age, skin of color, history of renal transplantation, and immunosuppressive therapy. Although regular full-body skin examinations are an accepted part of renal transplantation follow-up due to SCC risk, our case emphasizes the need to remain vigilant due to possible atypical presentations among the immunosuppressed. The nail unit should not be overlooked during the clinical examination of renal transplant recipients as demonstrated by our patient’s rare presentation of pSCC in the nail.

- Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012 [published online February 1, 2013]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:957-966.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- McCall CO, Chen SC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the legs in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:524-529.

- Krishna R, Lewis A, Orengo IF, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ): a mimic of malignant melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:673-674.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Goncalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-818.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Singh B, Bhaya M, Shaha A, et al. Presentation, course, and outcome of head and neck cancers in African Americans: a case-control study. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(8 pt 1):1159-1163.

- Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006.

- Baran R, Simon C. Longitudinal melanonychia: a symptom of Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:1359-1360.

- Dalle S, Depape L, Phan A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail apparatus: clinicopathological study of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:871-874.

- Ishida M, Iwai M, Yoshida K, et al. Subungual pigmented squamous cell carcinoma presenting as longitudinal melanonychia: a case report with review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:844-847.

- Lecerf P, Richert B, Theunis A, et al. A retrospective study of squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit diagnosed in a Belgian general hospital over a 15-year period. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:253-261.

- Saito T, Uchi H, Moroi Y, et al. Subungual Bowen disease revealed by longitudinal melanonychia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E240-E241.

- Saxena A, Kasper DA, Campanelli CD, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease clinically mimicking melanoma on the nail. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1522-1525.

- Mackenzie KA, Wells JE, Lynn KL, et al. First and subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancers: incidence and predictors in a population of New Zealand renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:300-306.

- Gutiérrez-Mendoza D, Narro-Llorente R, Karam-Orantes M, et al. Dermoscopy clues in pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online ahead of print September 16, 2010]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010.

- Euvards S, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Comparative epidemiologic study of premalignant and malignant epithelial cutaneous lesions developing after kidney and heart transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):222-229.

- Moloney FJ, Comber H, O’Lorcain P, et al. A population-based study of skin cancer incidence and prevalence in renal transplant patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:498-504.

- Formicone F, Fargnoli MC, Pisani F, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in Italian kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2527-2528.

- Fernandes Massa A, Debarbieux S, Depaepe L, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed presenting as a melanonychia striata: diagnosis by perioperative reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:198-199.

Case Report

A 62-year-old black man presented for examination of a dark longitudinal streak located adjacent to the lateral nail fold on the third finger of the left hand. The lesion had been present for several months, during which time it had slowly expanded in size. The fingertip had recently become tender, which interfered with the patient’s ability to work. His past medical history was remarkable for end-stage renal disease secondary to glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome of unclear etiology. He initially was treated by an outside physician using peritoneal dialysis for 3 years until he underwent renal transplantation in 2004 with a cadaveric organ. Other remarkable medical conditions included posttransplantation diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and gout. His multidrug regimen included 2 immunosuppressive medications: oral cyclosporine 125 mg twice daily and oral mycophenolate mofetil 250 mg twice daily.

A broad, irregular, black, pigmented, subungual band was noted on the left third finger. The lesion appeared to emanate from below the nail cuticle and traveled along the nail longitudinally toward the distal tip. The band appeared darker at the edge adjacent to the lateral nail fold and grew lighter near the middle of the nail where its free edge was noted to be irregular. A slightly thickened lateral nail fold with an irregular, small, sawtoothlike hyperkeratosis and hyperpigmentation also was noted (Figure 1).

Subungual melanoma, onychomycosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and a verruca copresenting with onychomycosis were considered in the differential diagnosis. The patient underwent nail avulsion and biopsy of the nail bed as well as the nail matrix. Histopathology was notable for malignant dyskeratosis with a lack of nuclear maturation, occasional mitoses, multinucleation, and individual cell keratinization (Figure 2). Immunostaining for S100 was negative, while staining for cytokeratins AE1/AE3 was positive. Deposition of melanin pigment in the malignant dyskeratotic cells was noted. Periodic acid–Schiff staining identified pseudohyphae without invasion of the nail plate. A diagnosis of pigmented SCC (pSCC) was made. The patient’s nail also was sent for fungal cultures that later grew Candida glabrata and Candida parapsilosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for removal of the pSCC, which was found to be more extensive than originally suspected and required en bloc excision of the nail repaired with a full-thickness skin graft from the left forearm. The area healed well with some hyperpigmentation (Figure 3).

Comment

Among the various types of skin cancer, an estimated 700,000 patients are diagnosed with SCC annually, making it the second most common form of skin cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer among whites in the United States, while in contrast SCC is the most common skin cancer in patients with skin of color.2 Only an estimated 2% to 5% of all SCCs are pigmented, and this variant is more commonly seen in patients with skin of color.3-5 One analysis of 52 cases of pSCC showed that common features included a flat or slightly raised appearance and hyperpigmentation with varying levels of scaling.6 Studies have shown an altered presentation of pSCC in black skin with increased melanin production and thickness of the stratum corneum in contrast with cases seen in white patients.7 Other potential features include scaling, erosive changes, and sharply demarcated borders. Squamous cell carcinoma typically occurs in sun-exposed areas, reflecting its association with UV light damage; however, SCC in skin of color patients has been noted to occur in sun-protected areas and in areas of chronic scarring.8 Pigmented SCC also appears to follow this distribution, as affected areas are not necessarily in direct exposure to the sun. Pigmented SCCs have been associated with pruritus and/or burning pain, which also was seen in our case when our patient complained of tenderness at the site.

We describe the case of a subungual pSCC clinically presenting as longitudinal melanonychia. Pigmented SCC presenting as longitudinal melanonychia was first described by Baran and Simon in 1988.9 Since that time, it has been reported that approximately 10% of subungual pSCCs clinically present as longitudinal melanonychia.10,11 A retrospective study reviewing 35 cases of SCC of the nail apparatus found that 5 (14.3%) cases presented as longitudinal melanonychia.10 Another retrospective study found that 6 of 51 (11.8%) cases of SCCs affecting the nail unit presented as the warty type of SCC in association with longitudinal melanonychia.12 Cases of pSCC in situ appearing as longitudinal melanonychia also have been reported.13,14

Risk factors for the development of pSCC include advanced age, male sex, presence of human papilloma virus, and use of immunosuppressants.15 Male predominance and advanced age at the time of diagnosis (mean age, 67 years) have been observed in pSCC cases.16 It is now well established that renal transplant recipients have an increased risk of SCC, with a reported incidence rate of 5% to 6%.16 When these patients develop an SCC, they typically follow a more aggressive course. Renal transplantation has a higher ratio than cardiac transplantation for SCC development (2.37:1), whereas cardiac transplantation is associated with a higher risk of BCC development.17 A study of 384 transplant recipients found that 96 (25.0%) had a postsurgical nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), with a ratio of SCC to BCC of 1.2:1.16 The calculated incidence of NMSC at 10 and 20 years posttransplantation was 24.2% and 54.4%, respectively. Another study also determined that SCC rates (50.0%) in postrenal transplant recipients were approximately twice that of BCC (27.0%).18

A daily regimen of immunosuppressive medications such as cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil showed an increased risk for development of NMSC.15 Immunosuppressive medications play an important role in the pathogenesis of SCC due to a direct oncogenic effect as well as impairment of the immune system’s ability to fight precancerous developments.15 A 4-year study of 100 renal transplant recipients using mycophenolate mofetil as part of an immunosuppressive regimen reported 22% NMSC findings among 9 patients.19 On average, patients developed an NMSC approximately 61 months posttransplantation, with a wide range from 2 to 120 months.

Advanced age was another important risk factor, with each decade of life producing a 60% increase in instantaneous risk of SCC development for transplant recipients.15 A steady increase in risk was related to the length of time adhering to an immunosuppressive regimen, especially from 2 to 6 years, and then remaining constant in subsequent years. For older patients on immunosuppressant regimens for more than 8 years, the calculated relative risk was noted to be over 200 times greater than the normal population’s development of skin cancers.18

Conclusion

Although cases of pSCC presenting as longitudinal melanonychia have previously been reported,9-14,20 our case is unique in that it describes pSCC in a renal transplant recipient. Our patient had many of the known risk factors for the development of pSCC including male sex, advanced age, skin of color, history of renal transplantation, and immunosuppressive therapy. Although regular full-body skin examinations are an accepted part of renal transplantation follow-up due to SCC risk, our case emphasizes the need to remain vigilant due to possible atypical presentations among the immunosuppressed. The nail unit should not be overlooked during the clinical examination of renal transplant recipients as demonstrated by our patient’s rare presentation of pSCC in the nail.

Case Report

A 62-year-old black man presented for examination of a dark longitudinal streak located adjacent to the lateral nail fold on the third finger of the left hand. The lesion had been present for several months, during which time it had slowly expanded in size. The fingertip had recently become tender, which interfered with the patient’s ability to work. His past medical history was remarkable for end-stage renal disease secondary to glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome of unclear etiology. He initially was treated by an outside physician using peritoneal dialysis for 3 years until he underwent renal transplantation in 2004 with a cadaveric organ. Other remarkable medical conditions included posttransplantation diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and gout. His multidrug regimen included 2 immunosuppressive medications: oral cyclosporine 125 mg twice daily and oral mycophenolate mofetil 250 mg twice daily.

A broad, irregular, black, pigmented, subungual band was noted on the left third finger. The lesion appeared to emanate from below the nail cuticle and traveled along the nail longitudinally toward the distal tip. The band appeared darker at the edge adjacent to the lateral nail fold and grew lighter near the middle of the nail where its free edge was noted to be irregular. A slightly thickened lateral nail fold with an irregular, small, sawtoothlike hyperkeratosis and hyperpigmentation also was noted (Figure 1).

Subungual melanoma, onychomycosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and a verruca copresenting with onychomycosis were considered in the differential diagnosis. The patient underwent nail avulsion and biopsy of the nail bed as well as the nail matrix. Histopathology was notable for malignant dyskeratosis with a lack of nuclear maturation, occasional mitoses, multinucleation, and individual cell keratinization (Figure 2). Immunostaining for S100 was negative, while staining for cytokeratins AE1/AE3 was positive. Deposition of melanin pigment in the malignant dyskeratotic cells was noted. Periodic acid–Schiff staining identified pseudohyphae without invasion of the nail plate. A diagnosis of pigmented SCC (pSCC) was made. The patient’s nail also was sent for fungal cultures that later grew Candida glabrata and Candida parapsilosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for removal of the pSCC, which was found to be more extensive than originally suspected and required en bloc excision of the nail repaired with a full-thickness skin graft from the left forearm. The area healed well with some hyperpigmentation (Figure 3).

Comment

Among the various types of skin cancer, an estimated 700,000 patients are diagnosed with SCC annually, making it the second most common form of skin cancer in the United States.1 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer among whites in the United States, while in contrast SCC is the most common skin cancer in patients with skin of color.2 Only an estimated 2% to 5% of all SCCs are pigmented, and this variant is more commonly seen in patients with skin of color.3-5 One analysis of 52 cases of pSCC showed that common features included a flat or slightly raised appearance and hyperpigmentation with varying levels of scaling.6 Studies have shown an altered presentation of pSCC in black skin with increased melanin production and thickness of the stratum corneum in contrast with cases seen in white patients.7 Other potential features include scaling, erosive changes, and sharply demarcated borders. Squamous cell carcinoma typically occurs in sun-exposed areas, reflecting its association with UV light damage; however, SCC in skin of color patients has been noted to occur in sun-protected areas and in areas of chronic scarring.8 Pigmented SCC also appears to follow this distribution, as affected areas are not necessarily in direct exposure to the sun. Pigmented SCCs have been associated with pruritus and/or burning pain, which also was seen in our case when our patient complained of tenderness at the site.

We describe the case of a subungual pSCC clinically presenting as longitudinal melanonychia. Pigmented SCC presenting as longitudinal melanonychia was first described by Baran and Simon in 1988.9 Since that time, it has been reported that approximately 10% of subungual pSCCs clinically present as longitudinal melanonychia.10,11 A retrospective study reviewing 35 cases of SCC of the nail apparatus found that 5 (14.3%) cases presented as longitudinal melanonychia.10 Another retrospective study found that 6 of 51 (11.8%) cases of SCCs affecting the nail unit presented as the warty type of SCC in association with longitudinal melanonychia.12 Cases of pSCC in situ appearing as longitudinal melanonychia also have been reported.13,14

Risk factors for the development of pSCC include advanced age, male sex, presence of human papilloma virus, and use of immunosuppressants.15 Male predominance and advanced age at the time of diagnosis (mean age, 67 years) have been observed in pSCC cases.16 It is now well established that renal transplant recipients have an increased risk of SCC, with a reported incidence rate of 5% to 6%.16 When these patients develop an SCC, they typically follow a more aggressive course. Renal transplantation has a higher ratio than cardiac transplantation for SCC development (2.37:1), whereas cardiac transplantation is associated with a higher risk of BCC development.17 A study of 384 transplant recipients found that 96 (25.0%) had a postsurgical nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), with a ratio of SCC to BCC of 1.2:1.16 The calculated incidence of NMSC at 10 and 20 years posttransplantation was 24.2% and 54.4%, respectively. Another study also determined that SCC rates (50.0%) in postrenal transplant recipients were approximately twice that of BCC (27.0%).18

A daily regimen of immunosuppressive medications such as cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil showed an increased risk for development of NMSC.15 Immunosuppressive medications play an important role in the pathogenesis of SCC due to a direct oncogenic effect as well as impairment of the immune system’s ability to fight precancerous developments.15 A 4-year study of 100 renal transplant recipients using mycophenolate mofetil as part of an immunosuppressive regimen reported 22% NMSC findings among 9 patients.19 On average, patients developed an NMSC approximately 61 months posttransplantation, with a wide range from 2 to 120 months.

Advanced age was another important risk factor, with each decade of life producing a 60% increase in instantaneous risk of SCC development for transplant recipients.15 A steady increase in risk was related to the length of time adhering to an immunosuppressive regimen, especially from 2 to 6 years, and then remaining constant in subsequent years. For older patients on immunosuppressant regimens for more than 8 years, the calculated relative risk was noted to be over 200 times greater than the normal population’s development of skin cancers.18

Conclusion

Although cases of pSCC presenting as longitudinal melanonychia have previously been reported,9-14,20 our case is unique in that it describes pSCC in a renal transplant recipient. Our patient had many of the known risk factors for the development of pSCC including male sex, advanced age, skin of color, history of renal transplantation, and immunosuppressive therapy. Although regular full-body skin examinations are an accepted part of renal transplantation follow-up due to SCC risk, our case emphasizes the need to remain vigilant due to possible atypical presentations among the immunosuppressed. The nail unit should not be overlooked during the clinical examination of renal transplant recipients as demonstrated by our patient’s rare presentation of pSCC in the nail.

- Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012 [published online February 1, 2013]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:957-966.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- McCall CO, Chen SC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the legs in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:524-529.

- Krishna R, Lewis A, Orengo IF, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ): a mimic of malignant melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:673-674.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Goncalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-818.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Singh B, Bhaya M, Shaha A, et al. Presentation, course, and outcome of head and neck cancers in African Americans: a case-control study. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(8 pt 1):1159-1163.

- Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006.

- Baran R, Simon C. Longitudinal melanonychia: a symptom of Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:1359-1360.

- Dalle S, Depape L, Phan A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail apparatus: clinicopathological study of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:871-874.

- Ishida M, Iwai M, Yoshida K, et al. Subungual pigmented squamous cell carcinoma presenting as longitudinal melanonychia: a case report with review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:844-847.

- Lecerf P, Richert B, Theunis A, et al. A retrospective study of squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit diagnosed in a Belgian general hospital over a 15-year period. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:253-261.

- Saito T, Uchi H, Moroi Y, et al. Subungual Bowen disease revealed by longitudinal melanonychia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E240-E241.

- Saxena A, Kasper DA, Campanelli CD, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease clinically mimicking melanoma on the nail. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1522-1525.

- Mackenzie KA, Wells JE, Lynn KL, et al. First and subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancers: incidence and predictors in a population of New Zealand renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:300-306.

- Gutiérrez-Mendoza D, Narro-Llorente R, Karam-Orantes M, et al. Dermoscopy clues in pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online ahead of print September 16, 2010]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010.

- Euvards S, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Comparative epidemiologic study of premalignant and malignant epithelial cutaneous lesions developing after kidney and heart transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):222-229.

- Moloney FJ, Comber H, O’Lorcain P, et al. A population-based study of skin cancer incidence and prevalence in renal transplant patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:498-504.

- Formicone F, Fargnoli MC, Pisani F, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in Italian kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2527-2528.

- Fernandes Massa A, Debarbieux S, Depaepe L, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed presenting as a melanonychia striata: diagnosis by perioperative reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:198-199.

- Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012 [published online February 1, 2013]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:957-966.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- McCall CO, Chen SC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the legs in African Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:524-529.

- Krishna R, Lewis A, Orengo IF, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ): a mimic of malignant melanoma. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:673-674.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Goncalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-818.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Singh B, Bhaya M, Shaha A, et al. Presentation, course, and outcome of head and neck cancers in African Americans: a case-control study. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(8 pt 1):1159-1163.

- Cancer Facts and Figures 2006. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2006.

- Baran R, Simon C. Longitudinal melanonychia: a symptom of Bowen’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:1359-1360.

- Dalle S, Depape L, Phan A, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the nail apparatus: clinicopathological study of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:871-874.

- Ishida M, Iwai M, Yoshida K, et al. Subungual pigmented squamous cell carcinoma presenting as longitudinal melanonychia: a case report with review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:844-847.

- Lecerf P, Richert B, Theunis A, et al. A retrospective study of squamous cell carcinoma of the nail unit diagnosed in a Belgian general hospital over a 15-year period. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:253-261.

- Saito T, Uchi H, Moroi Y, et al. Subungual Bowen disease revealed by longitudinal melanonychia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E240-E241.

- Saxena A, Kasper DA, Campanelli CD, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease clinically mimicking melanoma on the nail. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1522-1525.

- Mackenzie KA, Wells JE, Lynn KL, et al. First and subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancers: incidence and predictors in a population of New Zealand renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:300-306.

- Gutiérrez-Mendoza D, Narro-Llorente R, Karam-Orantes M, et al. Dermoscopy clues in pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online ahead of print September 16, 2010]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010.

- Euvards S, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Comparative epidemiologic study of premalignant and malignant epithelial cutaneous lesions developing after kidney and heart transplantation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):222-229.

- Moloney FJ, Comber H, O’Lorcain P, et al. A population-based study of skin cancer incidence and prevalence in renal transplant patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:498-504.

- Formicone F, Fargnoli MC, Pisani F, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in Italian kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2527-2528.

- Fernandes Massa A, Debarbieux S, Depaepe L, et al. Pigmented squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed presenting as a melanonychia striata: diagnosis by perioperative reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:198-199.

Practice Points

- Risk factors for the development of pigmented squamous cell carcinoma (pSCC) include older age, male sex, and use of immunosuppressant medications.

- Subungual pSCC can present as longitudinal melanonychia and should be considered in the differential diagnosis for melanonychia in patients with skin of color or those who are immunosuppressed.

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus Following Herpes Zoster

Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be classified as lupus-specific or lupus-nonspecific skin lesions. Lupus-specific lesions commonly are photodistributed, with involvement of the malar region, arms, and trunk. The development of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) in areas of trauma, including sun-exposed skin, is not uncommon and may be associated with an isomorphic response. We present a rare case of an isomorphic response following herpes zoster (HZ) in a young woman undergoing treatment with immunosuppressive agents for SLE and DLE. Potential prophylactic therapy also is discussed.

Case Report

A 19-year-old woman initially presented to an outside dermatologist for evaluation of new-onset scarring alopecia, crusted erythematous plaques on the face and arms, and arthralgia. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered necrotic keratinocytes, perifollicular inflammation, and focally thickened basement membrane at the dermoepidermal junction consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). A laboratory workup for SLE revealed 1:1280 antinuclear antibodies (reference range, negative <1:80) with elevated titers of double-stranded DNA, Smith, ribonucleoprotein, Sjögren syndrome A, and Sjögren syndrome B autoantibodies with low complement levels. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of SLE and DLE was made.

At that time, the patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily for SLE. Four days later she developed swelling in both hands and feet, and hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to a presumed adverse reaction; however, her symptoms subsequently were determined to be polyarthritis secondary to a lupus flare. Prednisone 10 mg once daily was then initiated. The patient was encouraged to restart hydroxychloroquine, but she declined.

Over the next 13 months, the patient developed severe photosensitivity, oral ulcers, Raynaud phenomenon, anemia, and nephrotic-range proteinuria. She ultimately was diagnosed by the nephrology department at our institution with mixed diffuse proliferative and membranous glomerulonephritis. Induction therapy with oral mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily and prednisone 60 mg once daily was started, followed by the addition of tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily. Despite immunosuppressive therapy, she continued to develop new discoid lesions on the face, chest, and arms. Th

After 4 weeks of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, prednisone, and tacrolimus, the patient developed a painful vesicular rash on the left breast with extension over the left axilla and scapula in a T3 to T4 dermatomal distribution. A clinical diagnosis of HZ was made, and she was started on intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg in dextrose 5% every 8 hours for 4 days followed by oral valacyclovir 1000 mg every 8 hours for 14 days, which led to resolution of the eruption.

Over the next 4 months, the patient continued to experience pain confined to the same dermatomal area as the HZ, which was consistent with postherpetic neuralgia. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued after she developed acute liver toxicity attributed to the drug. Upon discontinuation, the patient developed a new pruritic rash on both arms and the back. Physical examination by the dermatology department at our institution revealed diffuse, scaly, hyperpigmented papules and annular plaques with central pink hypopigmentation on the face, ears, anterior chest, arms, hands, and back. On the left anterior chest and back, the distribution was strikingly unilateral and multidermatomal (Figure 1). Upon further questioning, the patient confirmed that the areas of the new rash coincided with areas previously affected by HZ. Histologic examination of a representative lesion from the left lateral breast revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, a patchy lichenoid and perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate, and pigment incontinence (Figure 2A). These histologic features were subtle and were not diagnostic for lupus; however, direct immunofluorescence demonstrated a continuous granular band of IgG and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction, confirming the diagnosis of DLE (Figure 2B). The histologic findings and clinical presentation were consistent with the development of DLE in areas of previous trauma from HZ. The patient continues to follow-up with the rheumatology and nephrology departments but was lost to dermatology follow-up.

Comment

The pathogenesis of DLE is poorly understood but is thought to be multifactorial, involving genetics, sun exposure, and immune dysregulation.1 Development of DLE lesions in skin traumatized by tattoos, scratches, scars, and prolonged heat exposure has been reported.2 Clarification of the mechanism(s) underlying these traumatized areas may provide insight into the pathophysiology of DLE.

The isomorphic response, also known as the Köbner phenomenon, is the development of a preexisting skin condition at a site of trauma. This phenomenon has been observed in several dermatologic conditions including psoriasis, lichen planus, systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis, sarcoidosis, vitiligo, and DLE.3 Koebnerization may result from trauma to the skin caused by scratches, sun exposure, radiography, prolonged heat and cold exposure, pressure, tattoos, scars, and inflammatory dermatoses.2,4 Ueki4 suggested that localized trauma to the skin stimulates an immune response that makes the traumatized site a target for a preexisting skin condition. Inflammatory mediators such as IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, IL-6, and interferon γ have been implicated in the pathophysiology of the isomorphic response.4

Wolf isotopic response is a similar entity that refers to the development of a novel skin condition at the site of a distinct, previously resolved skin disorder. This phenomenon was described by Wolf et al5 in 1995, and since then over 170 cases have been reported.5-7 In most cases the initial skin condition is HZ, although herpes simplex virus has also been implicated. The common resulting skin conditions include granulomatous reactions, malignant tumors, lichen planus, morphea, and infections. The notion that the antecedent skin disease alters the affected site and causes it to be more susceptible to autoimmunity has been proposed as a mechanism for the isotopic response.7,8 While one might consider our presentation of DLE following HZ to be an isotopic response, we believe this case is best classified as an isomorphic response, as the patient already had an established diagnosis of DLE.

The development of DLE at the site of a previous HZ eruption has been described in 2 other cases of young women with SLE.9,10 Unique to our case is the development of a multidermatomal eruption, which may be an indication of her degree of immunosuppression, as immunosuppressed patients are more likely to present with multidermatomal reactivation of varicella zoster virus and postherpetic neuralgia.11 The similarities between our case and the 2 prior reports—including the patients’ age, sex, history of SLE, and degree of immunosuppression—are noteworthy in that they may represent a subset of SLE patients who are predisposed to developing koebnerization following HZ. Physicians should be aware of this phenomenon and consider being proactive in preventing long-term damage.

When feasible, physicians should consider administering the HZ vaccine to reduce the course and severity of HZ before prescribing immunosuppressive agents. When HZ presents in young, immunosuppressed women with a history of SLE, we suggest monitoring the affected sites closely for any evidence of DLE. Topical corticosteroids should be applied to involved areas of the face or body at the earliest appearance of such lesions, which may prevent the isomorphic response and its potentially scarring DLE lesions. This will be our therapeutic approach if we encounter a similar clinical situation in the future. Fur

Acknowledgment

We thank Carolyn E. Grotkowski, MD, from the Department of Pathology, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey, for her assistance in photographing the pathology slides.

- Lin JH, Dutz JP, Sontheimer RD, et al. Pathophysiology of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2007;33:85-106.

- Ueki H. Köbner phenomenon in lupus erythematosus [in German]. Hautarzt. 1994;45:154-160.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. The isomorphic response of Koebner. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:401-410.

- Ueki H. Koebner phenomenon in lupus erythematosus with special consideration of clinical findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:219-223.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV, et al. The immunocompromised district: a unifying concept for lymphoedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1364-1373.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-vs-host disease to sites of skin injury. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both [published online May 29, 2012]? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e110-e113.

- Longhi BS, Centeville M, Marini R, et al. Koebner’s phenomenon in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1403-1405.

- Failla V, Jacques J, Castronovo C, et al. Herpes zoster in patients treated with biologicals. Dermatology. 2012;224:251-256.

Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be classified as lupus-specific or lupus-nonspecific skin lesions. Lupus-specific lesions commonly are photodistributed, with involvement of the malar region, arms, and trunk. The development of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) in areas of trauma, including sun-exposed skin, is not uncommon and may be associated with an isomorphic response. We present a rare case of an isomorphic response following herpes zoster (HZ) in a young woman undergoing treatment with immunosuppressive agents for SLE and DLE. Potential prophylactic therapy also is discussed.

Case Report

A 19-year-old woman initially presented to an outside dermatologist for evaluation of new-onset scarring alopecia, crusted erythematous plaques on the face and arms, and arthralgia. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered necrotic keratinocytes, perifollicular inflammation, and focally thickened basement membrane at the dermoepidermal junction consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). A laboratory workup for SLE revealed 1:1280 antinuclear antibodies (reference range, negative <1:80) with elevated titers of double-stranded DNA, Smith, ribonucleoprotein, Sjögren syndrome A, and Sjögren syndrome B autoantibodies with low complement levels. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of SLE and DLE was made.

At that time, the patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily for SLE. Four days later she developed swelling in both hands and feet, and hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to a presumed adverse reaction; however, her symptoms subsequently were determined to be polyarthritis secondary to a lupus flare. Prednisone 10 mg once daily was then initiated. The patient was encouraged to restart hydroxychloroquine, but she declined.

Over the next 13 months, the patient developed severe photosensitivity, oral ulcers, Raynaud phenomenon, anemia, and nephrotic-range proteinuria. She ultimately was diagnosed by the nephrology department at our institution with mixed diffuse proliferative and membranous glomerulonephritis. Induction therapy with oral mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily and prednisone 60 mg once daily was started, followed by the addition of tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily. Despite immunosuppressive therapy, she continued to develop new discoid lesions on the face, chest, and arms. Th

After 4 weeks of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, prednisone, and tacrolimus, the patient developed a painful vesicular rash on the left breast with extension over the left axilla and scapula in a T3 to T4 dermatomal distribution. A clinical diagnosis of HZ was made, and she was started on intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg in dextrose 5% every 8 hours for 4 days followed by oral valacyclovir 1000 mg every 8 hours for 14 days, which led to resolution of the eruption.