User login

Case Report: An Unusual Case of Morel-Lavallée Lesion of the Upper Extremity

Case

A 32-year-old previously healthy woman presented to the ED with right upper arm pain and swelling of 6 days duration. According to the patient, the swelling began 2 days after she sustained a work-related injury at a coin-manufacturing factory. She stated that her right arm had gotten caught inside of a rolling press while she was cleaning it. The roller had stopped over her upper arm, trapping it between the roller and the platform for several minutes before it was extricated. She was brought to the ED by emergency medical services for evaluation immediately following this incident. At this first visit to the ED, the patient complained of mild pain in her right arm. Physical examination at that time revealed mild diffuse swelling extending from her hand to her distal humerus, with mild pain on passive flexion, and extension without associated numbness or tingling. Plain films of her right upper extremity were ordered, the results of which were relatively unremarkable. She was evaluated by an orthopedist, who ruled out compartment syndrome based on her benign physical examination and soft compartments. She was ultimately discharged and told to follow up with her primary care provider.

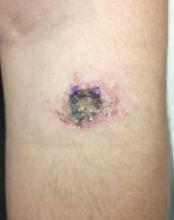

Over the course of 48 hours from the first ED visit, the patient developed large bullae on the dorsal and volar aspect of her forearm, elbow, and upper arm with associated pain. In addition to dark discolorations of the skin over her affected arm, she noticed that the bullae had become numerous and discolored. These symptoms continued to grow progressively worse, prompting her second presentation to the ED.

The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent debridement and resection of the circumferential necrotic skin and subcutaneous tissue in her right arm, and the placement of a skin graft with overlying wound vacuum-assisted closure. During the procedure, a large amount of serosanguinous fluid was drained and cultured, and was found to be sterile. Due to the size of her injury, she underwent two additional episodes of debridement and graft placement over the course of the next 2 weeks.

Discussion

First described in the 1850s by the French physician Maurice Morel-Lavallée, Morel-Lavallée lesion is a rare, traumatic, soft-tissue injury.1 It is an internal degloving injury wherein the skin and subcutaneous tissue have been forcibly separated from the underlying fascia as a result of shear stress. The lymphatic and blood vessels between the layers are also disrupted in this process, resulting in the accumulation of blood and lymphatic fluid as well as subcutaneous debris in the potential space that forms. Excess accumulation over time can compromise blood supply to the overlying skin and cause necrosis.2 Morel-Lavallée lesion is missed on initial evaluation in up to one-third of the cases and may have a delay in presentation ranging from hours to months after the inciting injury.3

Morel-Lavallée lesions typically involve the flank, hips, thigh, and prepatellar regions as a result of shear injuries sustained from bicycle falls and motor vehicle accidents.4 These lesions are often associated with concomitant acetabular and pelvic fractures.5 Involvement of the upper extremities is unusual. Typically, presentation consists of a fluctuant and painful mass underneath the skin which increases over time. The overlying skin may show the mechanism of the original injury, for example, as abrasions after a crush injury. The excessive skin necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae seen in this particular case is a very rare presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes compartment syndrome, coma blisters, a missed fracture, bullous pemphigoid, bullous drug reactions, and linear immunoglobulin A disease. Most of these conditions were easily ruled out in this case as the patient was previously healthy and not on any medications. The lesions in this case could have been confused with coma blisters, which are similar in appearance, self-limiting, and can develop on the extremities. However, coma blisters are classically associated with toxicity from various central nervous system depressants, as well as reduced consciousness from other causes—all of which were readily ruled-out based on the patient’s history. Moreover, the Morel-Lavallée lesion is a degloving injury of the subcutaneous tissue from the fascia underneath, whereas the pathology of coma blisters includes subepidermal bullae formation as well as immunoglobulin and complement deposition.6

Diagnostic Imaging

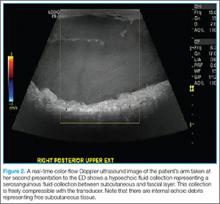

Morel-Lavallée lesion can often be confirmed via several imaging modalities, including ultrasound, CT, 3D CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).3,7 Ultrasound will usually show a well-circumscribed hypoechoic fluid collection with hyperechoic fat globules from the subcutaneous tissue, whereas CT tends to show an encapsulated mass with fluid collection underneath. In MRI, Morel-Lavallée lesion often appears as a hypointense T1-sequence and hyperintense T2-sequence similar to most other fluid collections. There may be variable T1- and T2-intensities with subcutaneous tissues in the fluid collection.2

Management

Despite recognition of this disease entity, controversies still exist regarding management. Case reports have demonstrated a relatively high rate of infected fluid collections depending on the chronicity of the injury.8 A recent algorithm to management described by Nickerson et al4 proposes that for patients with viable skin, percutaneous aspiration of more than 50 cc of fluid from these lesions should be treated with more extensive operative intervention based on the increased likelihood of recurrence. Patients without viable skin require formal debridement with possible skin grafting.

Other treatment options include conservative management, surgical drainage, sclerodesis, and extensive open surgery.8-10 Management is always case-based and dependent upon the size of the lesion and associated injuries.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of Morel-Lavallée lesions in their most severe and atypical form. It also serves as a reminder that vigilance and knowledge of this disease process is important in helping to diagnose this rare but potentially devastating condition. The key to recognizing this injury lies in keeping this disease process in the differential diagnosis of traumatic injuries with suspicious mechanism involving significant shear forces. Significant physical examination findings may not be present initially and evolve over a time period of hours to days. Once this injury is identified, management hinges on the size of the lesion and affected body part. Despite timely interventions, Morel-Lavallée lesions may result in significant morbidity and functional disability.

Dr Ye is an emergency medicine resident at the Brown Alpert Medical School in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr Rosenberg is a clinical assistant professor at Brown Alpert Medical School, and an emergency medicine attending physican at Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island.

- Morel-Lavallée M. Epanchements traumatique de serosite. Arc Générales Méd. 1853;691-731.

- Chokshi F, Jose J, Clifford P. Morel Lavallée Lesion. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2010;39(5): 252-253.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21(1):35-43.

- Nickerson T, Zielinski M, Jenkins D, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014:76(2);493-497.

- Powers ML, Hatem SF, Sundaram M. Morel-Lavallee lesion. Orthopedics. 2007;30(4):322-323.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online Journal. 2012:18(3);10.

- Reddix RN, Carrol E, Webb LX. Early diagnosis of a Morel-Lavallee lesion using three-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions: a case report. J Trauma. 2009;67(2):e57-e59.

- Lin HL, Lee WC, Kuo LC, Chen CW. Closed internal degloving injury with conservative treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2008:26(2);254.e5-e6.

- Luria S, Applbaum Y,Weil Y, Liebergall M, Peyser A. Talc sclerodhesis of persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions (posttraumatic pseudocysts): case report of 4 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):435-438.

- Penaud A, Quignon R, Danin A, Bahé L, Zakine G. Alcohol sclerodhesis: an innovative treatment for chronic Morel-Lavallée lesions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(10): e262-264.

Case

A 32-year-old previously healthy woman presented to the ED with right upper arm pain and swelling of 6 days duration. According to the patient, the swelling began 2 days after she sustained a work-related injury at a coin-manufacturing factory. She stated that her right arm had gotten caught inside of a rolling press while she was cleaning it. The roller had stopped over her upper arm, trapping it between the roller and the platform for several minutes before it was extricated. She was brought to the ED by emergency medical services for evaluation immediately following this incident. At this first visit to the ED, the patient complained of mild pain in her right arm. Physical examination at that time revealed mild diffuse swelling extending from her hand to her distal humerus, with mild pain on passive flexion, and extension without associated numbness or tingling. Plain films of her right upper extremity were ordered, the results of which were relatively unremarkable. She was evaluated by an orthopedist, who ruled out compartment syndrome based on her benign physical examination and soft compartments. She was ultimately discharged and told to follow up with her primary care provider.

Over the course of 48 hours from the first ED visit, the patient developed large bullae on the dorsal and volar aspect of her forearm, elbow, and upper arm with associated pain. In addition to dark discolorations of the skin over her affected arm, she noticed that the bullae had become numerous and discolored. These symptoms continued to grow progressively worse, prompting her second presentation to the ED.

The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent debridement and resection of the circumferential necrotic skin and subcutaneous tissue in her right arm, and the placement of a skin graft with overlying wound vacuum-assisted closure. During the procedure, a large amount of serosanguinous fluid was drained and cultured, and was found to be sterile. Due to the size of her injury, she underwent two additional episodes of debridement and graft placement over the course of the next 2 weeks.

Discussion

First described in the 1850s by the French physician Maurice Morel-Lavallée, Morel-Lavallée lesion is a rare, traumatic, soft-tissue injury.1 It is an internal degloving injury wherein the skin and subcutaneous tissue have been forcibly separated from the underlying fascia as a result of shear stress. The lymphatic and blood vessels between the layers are also disrupted in this process, resulting in the accumulation of blood and lymphatic fluid as well as subcutaneous debris in the potential space that forms. Excess accumulation over time can compromise blood supply to the overlying skin and cause necrosis.2 Morel-Lavallée lesion is missed on initial evaluation in up to one-third of the cases and may have a delay in presentation ranging from hours to months after the inciting injury.3

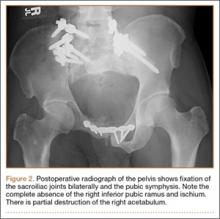

Morel-Lavallée lesions typically involve the flank, hips, thigh, and prepatellar regions as a result of shear injuries sustained from bicycle falls and motor vehicle accidents.4 These lesions are often associated with concomitant acetabular and pelvic fractures.5 Involvement of the upper extremities is unusual. Typically, presentation consists of a fluctuant and painful mass underneath the skin which increases over time. The overlying skin may show the mechanism of the original injury, for example, as abrasions after a crush injury. The excessive skin necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae seen in this particular case is a very rare presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes compartment syndrome, coma blisters, a missed fracture, bullous pemphigoid, bullous drug reactions, and linear immunoglobulin A disease. Most of these conditions were easily ruled out in this case as the patient was previously healthy and not on any medications. The lesions in this case could have been confused with coma blisters, which are similar in appearance, self-limiting, and can develop on the extremities. However, coma blisters are classically associated with toxicity from various central nervous system depressants, as well as reduced consciousness from other causes—all of which were readily ruled-out based on the patient’s history. Moreover, the Morel-Lavallée lesion is a degloving injury of the subcutaneous tissue from the fascia underneath, whereas the pathology of coma blisters includes subepidermal bullae formation as well as immunoglobulin and complement deposition.6

Diagnostic Imaging

Morel-Lavallée lesion can often be confirmed via several imaging modalities, including ultrasound, CT, 3D CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).3,7 Ultrasound will usually show a well-circumscribed hypoechoic fluid collection with hyperechoic fat globules from the subcutaneous tissue, whereas CT tends to show an encapsulated mass with fluid collection underneath. In MRI, Morel-Lavallée lesion often appears as a hypointense T1-sequence and hyperintense T2-sequence similar to most other fluid collections. There may be variable T1- and T2-intensities with subcutaneous tissues in the fluid collection.2

Management

Despite recognition of this disease entity, controversies still exist regarding management. Case reports have demonstrated a relatively high rate of infected fluid collections depending on the chronicity of the injury.8 A recent algorithm to management described by Nickerson et al4 proposes that for patients with viable skin, percutaneous aspiration of more than 50 cc of fluid from these lesions should be treated with more extensive operative intervention based on the increased likelihood of recurrence. Patients without viable skin require formal debridement with possible skin grafting.

Other treatment options include conservative management, surgical drainage, sclerodesis, and extensive open surgery.8-10 Management is always case-based and dependent upon the size of the lesion and associated injuries.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of Morel-Lavallée lesions in their most severe and atypical form. It also serves as a reminder that vigilance and knowledge of this disease process is important in helping to diagnose this rare but potentially devastating condition. The key to recognizing this injury lies in keeping this disease process in the differential diagnosis of traumatic injuries with suspicious mechanism involving significant shear forces. Significant physical examination findings may not be present initially and evolve over a time period of hours to days. Once this injury is identified, management hinges on the size of the lesion and affected body part. Despite timely interventions, Morel-Lavallée lesions may result in significant morbidity and functional disability.

Dr Ye is an emergency medicine resident at the Brown Alpert Medical School in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr Rosenberg is a clinical assistant professor at Brown Alpert Medical School, and an emergency medicine attending physican at Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island.

Case

A 32-year-old previously healthy woman presented to the ED with right upper arm pain and swelling of 6 days duration. According to the patient, the swelling began 2 days after she sustained a work-related injury at a coin-manufacturing factory. She stated that her right arm had gotten caught inside of a rolling press while she was cleaning it. The roller had stopped over her upper arm, trapping it between the roller and the platform for several minutes before it was extricated. She was brought to the ED by emergency medical services for evaluation immediately following this incident. At this first visit to the ED, the patient complained of mild pain in her right arm. Physical examination at that time revealed mild diffuse swelling extending from her hand to her distal humerus, with mild pain on passive flexion, and extension without associated numbness or tingling. Plain films of her right upper extremity were ordered, the results of which were relatively unremarkable. She was evaluated by an orthopedist, who ruled out compartment syndrome based on her benign physical examination and soft compartments. She was ultimately discharged and told to follow up with her primary care provider.

Over the course of 48 hours from the first ED visit, the patient developed large bullae on the dorsal and volar aspect of her forearm, elbow, and upper arm with associated pain. In addition to dark discolorations of the skin over her affected arm, she noticed that the bullae had become numerous and discolored. These symptoms continued to grow progressively worse, prompting her second presentation to the ED.

The patient was taken to the operating room and underwent debridement and resection of the circumferential necrotic skin and subcutaneous tissue in her right arm, and the placement of a skin graft with overlying wound vacuum-assisted closure. During the procedure, a large amount of serosanguinous fluid was drained and cultured, and was found to be sterile. Due to the size of her injury, she underwent two additional episodes of debridement and graft placement over the course of the next 2 weeks.

Discussion

First described in the 1850s by the French physician Maurice Morel-Lavallée, Morel-Lavallée lesion is a rare, traumatic, soft-tissue injury.1 It is an internal degloving injury wherein the skin and subcutaneous tissue have been forcibly separated from the underlying fascia as a result of shear stress. The lymphatic and blood vessels between the layers are also disrupted in this process, resulting in the accumulation of blood and lymphatic fluid as well as subcutaneous debris in the potential space that forms. Excess accumulation over time can compromise blood supply to the overlying skin and cause necrosis.2 Morel-Lavallée lesion is missed on initial evaluation in up to one-third of the cases and may have a delay in presentation ranging from hours to months after the inciting injury.3

Morel-Lavallée lesions typically involve the flank, hips, thigh, and prepatellar regions as a result of shear injuries sustained from bicycle falls and motor vehicle accidents.4 These lesions are often associated with concomitant acetabular and pelvic fractures.5 Involvement of the upper extremities is unusual. Typically, presentation consists of a fluctuant and painful mass underneath the skin which increases over time. The overlying skin may show the mechanism of the original injury, for example, as abrasions after a crush injury. The excessive skin necrosis and hemorrhagic bullae seen in this particular case is a very rare presentation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes compartment syndrome, coma blisters, a missed fracture, bullous pemphigoid, bullous drug reactions, and linear immunoglobulin A disease. Most of these conditions were easily ruled out in this case as the patient was previously healthy and not on any medications. The lesions in this case could have been confused with coma blisters, which are similar in appearance, self-limiting, and can develop on the extremities. However, coma blisters are classically associated with toxicity from various central nervous system depressants, as well as reduced consciousness from other causes—all of which were readily ruled-out based on the patient’s history. Moreover, the Morel-Lavallée lesion is a degloving injury of the subcutaneous tissue from the fascia underneath, whereas the pathology of coma blisters includes subepidermal bullae formation as well as immunoglobulin and complement deposition.6

Diagnostic Imaging

Morel-Lavallée lesion can often be confirmed via several imaging modalities, including ultrasound, CT, 3D CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).3,7 Ultrasound will usually show a well-circumscribed hypoechoic fluid collection with hyperechoic fat globules from the subcutaneous tissue, whereas CT tends to show an encapsulated mass with fluid collection underneath. In MRI, Morel-Lavallée lesion often appears as a hypointense T1-sequence and hyperintense T2-sequence similar to most other fluid collections. There may be variable T1- and T2-intensities with subcutaneous tissues in the fluid collection.2

Management

Despite recognition of this disease entity, controversies still exist regarding management. Case reports have demonstrated a relatively high rate of infected fluid collections depending on the chronicity of the injury.8 A recent algorithm to management described by Nickerson et al4 proposes that for patients with viable skin, percutaneous aspiration of more than 50 cc of fluid from these lesions should be treated with more extensive operative intervention based on the increased likelihood of recurrence. Patients without viable skin require formal debridement with possible skin grafting.

Other treatment options include conservative management, surgical drainage, sclerodesis, and extensive open surgery.8-10 Management is always case-based and dependent upon the size of the lesion and associated injuries.

Conclusion

This case represents an example of Morel-Lavallée lesions in their most severe and atypical form. It also serves as a reminder that vigilance and knowledge of this disease process is important in helping to diagnose this rare but potentially devastating condition. The key to recognizing this injury lies in keeping this disease process in the differential diagnosis of traumatic injuries with suspicious mechanism involving significant shear forces. Significant physical examination findings may not be present initially and evolve over a time period of hours to days. Once this injury is identified, management hinges on the size of the lesion and affected body part. Despite timely interventions, Morel-Lavallée lesions may result in significant morbidity and functional disability.

Dr Ye is an emergency medicine resident at the Brown Alpert Medical School in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr Rosenberg is a clinical assistant professor at Brown Alpert Medical School, and an emergency medicine attending physican at Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital, Providence, Rhode Island.

- Morel-Lavallée M. Epanchements traumatique de serosite. Arc Générales Méd. 1853;691-731.

- Chokshi F, Jose J, Clifford P. Morel Lavallée Lesion. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2010;39(5): 252-253.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21(1):35-43.

- Nickerson T, Zielinski M, Jenkins D, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014:76(2);493-497.

- Powers ML, Hatem SF, Sundaram M. Morel-Lavallee lesion. Orthopedics. 2007;30(4):322-323.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online Journal. 2012:18(3);10.

- Reddix RN, Carrol E, Webb LX. Early diagnosis of a Morel-Lavallee lesion using three-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions: a case report. J Trauma. 2009;67(2):e57-e59.

- Lin HL, Lee WC, Kuo LC, Chen CW. Closed internal degloving injury with conservative treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2008:26(2);254.e5-e6.

- Luria S, Applbaum Y,Weil Y, Liebergall M, Peyser A. Talc sclerodhesis of persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions (posttraumatic pseudocysts): case report of 4 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):435-438.

- Penaud A, Quignon R, Danin A, Bahé L, Zakine G. Alcohol sclerodhesis: an innovative treatment for chronic Morel-Lavallée lesions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(10): e262-264.

- Morel-Lavallée M. Epanchements traumatique de serosite. Arc Générales Méd. 1853;691-731.

- Chokshi F, Jose J, Clifford P. Morel Lavallée Lesion. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2010;39(5): 252-253.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21(1):35-43.

- Nickerson T, Zielinski M, Jenkins D, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014:76(2);493-497.

- Powers ML, Hatem SF, Sundaram M. Morel-Lavallee lesion. Orthopedics. 2007;30(4):322-323.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online Journal. 2012:18(3);10.

- Reddix RN, Carrol E, Webb LX. Early diagnosis of a Morel-Lavallee lesion using three-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions: a case report. J Trauma. 2009;67(2):e57-e59.

- Lin HL, Lee WC, Kuo LC, Chen CW. Closed internal degloving injury with conservative treatment. Am J Emerg Med. 2008:26(2);254.e5-e6.

- Luria S, Applbaum Y,Weil Y, Liebergall M, Peyser A. Talc sclerodhesis of persistent Morel-Lavallée lesions (posttraumatic pseudocysts): case report of 4 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):435-438.

- Penaud A, Quignon R, Danin A, Bahé L, Zakine G. Alcohol sclerodhesis: an innovative treatment for chronic Morel-Lavallée lesions. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(10): e262-264.

When it's beneficial to defer dialysis

THE CASE

A 94-year-old Hispanic man with hypertension, congestive heart failure (CHF), anemia of chronic disease, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) presented to our facility with weakness and shortness of breath. We diagnosed a CHF exacerbation. Initially, he exhibited some respiratory distress that required observation in the coronary care unit and bi-level positive airway pressure therapy to maintain oxygen saturation. Our patient was then moved to a step-down unit where his primary caregiver, his granddaughter, told the medical team that he was limited at home in some of his instrumental activities of daily living. Specifically, he was unable to prepare meals or manage his finances on his own.

Nephrology was consulted for consideration of hemodialysis (HD) because our patient’s creatinine on admission was 7.2 mg/dL (normal for men is 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and his estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 7 mL/min (normal is 90-120 mL/min). The patient’s family was conflicted over whether or not to start HD. Palliative Care was consulted to help establish goals of care.

A decision is made. In light of the patient’s limited functional status and his expressed desire to stay at home with his family and receive limited medical care there, the Nephrology and Palliative Care teams recommended delaying HD despite the patient’s worsening renal function. The patient was discharged home with home care services, and he and the family were instructed to follow up with Nephrology for supportive renal management.

DISCUSSION

The decision to delay HD in patients with ESRD is a difficult one that requires shared decision-making between patients and medical providers. Palliative Care consultation services are often involved in this process.

Recent literature supports an “intent-to-defer” based on an evaluation of the patient’s functionality. This represents a paradigm shift from the previous “intent-to-start-early” treatment strategy. In fact, rather than starting early, the Canadian Society of Nephrology recommends delaying initiation of HD in patients with a GFR <15 mL/min.1 Close monitoring of these patients by both a primary care physician and nephrologist is essential.

When considering initiation of HD, it’s important to look at the overall benefit of this intervention in light of the patient’s mortality risk and quality of life. Many patients who receive HD—especially the elderly—report that it takes more than 6 hours to recover following a dialysis treatment.2

Not surprisingly, depression is common in elderly HD patients. Compared to their younger cohorts, older HD patients have a 62% increased risk of developing depression.3 Also, patients who are considered frail and are receiving HD have more than 3 times the mortality risk within one year than those who are not (hazard ratio=3.42; 95% confidence interval, 2.45-4.76).4 (The researchers’ definition of frailty included poor self-reported physical function, exhaustion/fatigue, low physical activity, and undernutrition.4)

Functional status. Although a patient’s age should not be a limiting factor for HD referral, functional status should be considered. Patients with limited functionality and significant dependence have an increased risk of death during the first year of HD.5

Palliative approach gains acceptance. It is becoming more accepted within the nephrology community to consider a palliative approach to patients with ESRD. Organizations such as the Renal Physicians Association recommend effective prognostication, early advanced care planning, forgoing HD in patients with a poor prognosis, and involving Palliative Care early in the decision-making process.6 Aligning the patient’s goals of care with the appropriate treatment method—particularly in patients with comorbid conditions—is an important practice when caring for those with limited life expectancy and functionality.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Intent-to-defer HD may be a preferred strategy when caring for many patients with ESRD. Taking into consideration a patient’s comorbidities and functional status, while considering mortality risk and quality of life are essential. Involving palliative care and nephrology specialists can help patients and families understand HD and make an educated decision regarding when to start it.

1. Nesrallah GE, Mustafa RA, Clark WF, et al; Canadian Society of Nephrology. Canadian Society of Nephrology 2014 clinical practice guideline for timing the initiation of chronic dialysis. CMAJ. 2014;186:112-117.

2. Rayner HC, Zepel L, Fuller DS, et al. Recovery time, quality of life, and mortality in hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:86-94.

3. Canaud B, Tong L, Tentori F, et al. Clinical practices and outcomes in elderly hemodialysis patients: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1651-1662.

4. Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, et al. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2960-2967.

5. Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, et al. Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1012-1021.

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis: clinical practice guideline. 2nd ed. Rockville, MD: Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. Grubbs V, Moss AH, Cohen LM, et al; Dialysis Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology. A palliative approach to dialysis care: a patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:2203-2209.

THE CASE

A 94-year-old Hispanic man with hypertension, congestive heart failure (CHF), anemia of chronic disease, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) presented to our facility with weakness and shortness of breath. We diagnosed a CHF exacerbation. Initially, he exhibited some respiratory distress that required observation in the coronary care unit and bi-level positive airway pressure therapy to maintain oxygen saturation. Our patient was then moved to a step-down unit where his primary caregiver, his granddaughter, told the medical team that he was limited at home in some of his instrumental activities of daily living. Specifically, he was unable to prepare meals or manage his finances on his own.

Nephrology was consulted for consideration of hemodialysis (HD) because our patient’s creatinine on admission was 7.2 mg/dL (normal for men is 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and his estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 7 mL/min (normal is 90-120 mL/min). The patient’s family was conflicted over whether or not to start HD. Palliative Care was consulted to help establish goals of care.

A decision is made. In light of the patient’s limited functional status and his expressed desire to stay at home with his family and receive limited medical care there, the Nephrology and Palliative Care teams recommended delaying HD despite the patient’s worsening renal function. The patient was discharged home with home care services, and he and the family were instructed to follow up with Nephrology for supportive renal management.

DISCUSSION

The decision to delay HD in patients with ESRD is a difficult one that requires shared decision-making between patients and medical providers. Palliative Care consultation services are often involved in this process.

Recent literature supports an “intent-to-defer” based on an evaluation of the patient’s functionality. This represents a paradigm shift from the previous “intent-to-start-early” treatment strategy. In fact, rather than starting early, the Canadian Society of Nephrology recommends delaying initiation of HD in patients with a GFR <15 mL/min.1 Close monitoring of these patients by both a primary care physician and nephrologist is essential.

When considering initiation of HD, it’s important to look at the overall benefit of this intervention in light of the patient’s mortality risk and quality of life. Many patients who receive HD—especially the elderly—report that it takes more than 6 hours to recover following a dialysis treatment.2

Not surprisingly, depression is common in elderly HD patients. Compared to their younger cohorts, older HD patients have a 62% increased risk of developing depression.3 Also, patients who are considered frail and are receiving HD have more than 3 times the mortality risk within one year than those who are not (hazard ratio=3.42; 95% confidence interval, 2.45-4.76).4 (The researchers’ definition of frailty included poor self-reported physical function, exhaustion/fatigue, low physical activity, and undernutrition.4)

Functional status. Although a patient’s age should not be a limiting factor for HD referral, functional status should be considered. Patients with limited functionality and significant dependence have an increased risk of death during the first year of HD.5

Palliative approach gains acceptance. It is becoming more accepted within the nephrology community to consider a palliative approach to patients with ESRD. Organizations such as the Renal Physicians Association recommend effective prognostication, early advanced care planning, forgoing HD in patients with a poor prognosis, and involving Palliative Care early in the decision-making process.6 Aligning the patient’s goals of care with the appropriate treatment method—particularly in patients with comorbid conditions—is an important practice when caring for those with limited life expectancy and functionality.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Intent-to-defer HD may be a preferred strategy when caring for many patients with ESRD. Taking into consideration a patient’s comorbidities and functional status, while considering mortality risk and quality of life are essential. Involving palliative care and nephrology specialists can help patients and families understand HD and make an educated decision regarding when to start it.

THE CASE

A 94-year-old Hispanic man with hypertension, congestive heart failure (CHF), anemia of chronic disease, and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) presented to our facility with weakness and shortness of breath. We diagnosed a CHF exacerbation. Initially, he exhibited some respiratory distress that required observation in the coronary care unit and bi-level positive airway pressure therapy to maintain oxygen saturation. Our patient was then moved to a step-down unit where his primary caregiver, his granddaughter, told the medical team that he was limited at home in some of his instrumental activities of daily living. Specifically, he was unable to prepare meals or manage his finances on his own.

Nephrology was consulted for consideration of hemodialysis (HD) because our patient’s creatinine on admission was 7.2 mg/dL (normal for men is 0.7-1.3 mg/dL) and his estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 7 mL/min (normal is 90-120 mL/min). The patient’s family was conflicted over whether or not to start HD. Palliative Care was consulted to help establish goals of care.

A decision is made. In light of the patient’s limited functional status and his expressed desire to stay at home with his family and receive limited medical care there, the Nephrology and Palliative Care teams recommended delaying HD despite the patient’s worsening renal function. The patient was discharged home with home care services, and he and the family were instructed to follow up with Nephrology for supportive renal management.

DISCUSSION

The decision to delay HD in patients with ESRD is a difficult one that requires shared decision-making between patients and medical providers. Palliative Care consultation services are often involved in this process.

Recent literature supports an “intent-to-defer” based on an evaluation of the patient’s functionality. This represents a paradigm shift from the previous “intent-to-start-early” treatment strategy. In fact, rather than starting early, the Canadian Society of Nephrology recommends delaying initiation of HD in patients with a GFR <15 mL/min.1 Close monitoring of these patients by both a primary care physician and nephrologist is essential.

When considering initiation of HD, it’s important to look at the overall benefit of this intervention in light of the patient’s mortality risk and quality of life. Many patients who receive HD—especially the elderly—report that it takes more than 6 hours to recover following a dialysis treatment.2

Not surprisingly, depression is common in elderly HD patients. Compared to their younger cohorts, older HD patients have a 62% increased risk of developing depression.3 Also, patients who are considered frail and are receiving HD have more than 3 times the mortality risk within one year than those who are not (hazard ratio=3.42; 95% confidence interval, 2.45-4.76).4 (The researchers’ definition of frailty included poor self-reported physical function, exhaustion/fatigue, low physical activity, and undernutrition.4)

Functional status. Although a patient’s age should not be a limiting factor for HD referral, functional status should be considered. Patients with limited functionality and significant dependence have an increased risk of death during the first year of HD.5

Palliative approach gains acceptance. It is becoming more accepted within the nephrology community to consider a palliative approach to patients with ESRD. Organizations such as the Renal Physicians Association recommend effective prognostication, early advanced care planning, forgoing HD in patients with a poor prognosis, and involving Palliative Care early in the decision-making process.6 Aligning the patient’s goals of care with the appropriate treatment method—particularly in patients with comorbid conditions—is an important practice when caring for those with limited life expectancy and functionality.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Intent-to-defer HD may be a preferred strategy when caring for many patients with ESRD. Taking into consideration a patient’s comorbidities and functional status, while considering mortality risk and quality of life are essential. Involving palliative care and nephrology specialists can help patients and families understand HD and make an educated decision regarding when to start it.

1. Nesrallah GE, Mustafa RA, Clark WF, et al; Canadian Society of Nephrology. Canadian Society of Nephrology 2014 clinical practice guideline for timing the initiation of chronic dialysis. CMAJ. 2014;186:112-117.

2. Rayner HC, Zepel L, Fuller DS, et al. Recovery time, quality of life, and mortality in hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:86-94.

3. Canaud B, Tong L, Tentori F, et al. Clinical practices and outcomes in elderly hemodialysis patients: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1651-1662.

4. Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, et al. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2960-2967.

5. Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, et al. Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1012-1021.

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis: clinical practice guideline. 2nd ed. Rockville, MD: Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. Grubbs V, Moss AH, Cohen LM, et al; Dialysis Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology. A palliative approach to dialysis care: a patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:2203-2209.

1. Nesrallah GE, Mustafa RA, Clark WF, et al; Canadian Society of Nephrology. Canadian Society of Nephrology 2014 clinical practice guideline for timing the initiation of chronic dialysis. CMAJ. 2014;186:112-117.

2. Rayner HC, Zepel L, Fuller DS, et al. Recovery time, quality of life, and mortality in hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:86-94.

3. Canaud B, Tong L, Tentori F, et al. Clinical practices and outcomes in elderly hemodialysis patients: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1651-1662.

4. Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, et al. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2960-2967.

5. Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, et al. Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1012-1021.

6. Renal Physicians Association. Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis: clinical practice guideline. 2nd ed. Rockville, MD: Renal Physicians Association; 2010.

7. Grubbs V, Moss AH, Cohen LM, et al; Dialysis Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology. A palliative approach to dialysis care: a patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:2203-2209.

Weight loss • fatigue • joint pain • Dx?

THE CASE

A 49-year-old Mexican immigrant woman was admitted to the hospital with a 5-month history of fatigue and a 30-pound unintentional weight loss. She was also experiencing arthralgia, swelling, and stiffness in her hands and feet that was worse in the morning. The patient, who was obese and suffered from type 2 diabetes and hypertension, said that at the onset of her illness 5 months earlier, she’d experienced approximately 2 weeks of night sweats and a few days of fever.

A month before being admitted to the hospital, she’d been seen in our southern New Mexico family medicine office. Her recent history of fever, joint symptoms, and weight loss raised concerns of an insidious infection, a new-onset rheumatologic condition, or an occult malignancy.

Initial lab tests revealed leukopenia (white blood cell count, 3200/mcL), microcytic anemia (hemoglobin, 9.4 g/dL), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 30 mm/hr (normal range, 0-20 mm/hr). A rheumatoid factor test was negative, and her thyroid, kidney, and liver function tests were all normal.

More testing… The patient frequently traveled between New Mexico and her hometown of Chihuahua, Mexico, but there had been no recent changes in her diet or environmental exposures. She denied drinking any unpasteurized milk in Chihuahua. But based on her travel history, we ordered enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody titers for Brucella, immunoglobulin G, and immunoglobulin M, which all came back negative. Additionally, we ordered an abdominal and pelvic ultrasound and a chest x-ray that were nondiagnostic. Given the patient’s weight loss and anemia, we referred her to a gastroenterologist for upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluations. Unfortunately, the patient was uninsured and did not go to see the gastroenterologist.

A month after seeing us, our patient’s fatigue, lack of appetite, and joint pain became debilitating and she was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation, including a consultation with an oncologist.

THE DIAGNOSIS

During our patient’s 6-day hospital stay, a bone scintigraphy showed a focus of uptake in her left parietal bone and computed tomography scans of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a left thyroid nodule, as well as multiple noncalcified pulmonary nodules. Blood cultures were also obtained.

Despite the initial negative antibody tests, the blood cultures drawn in the hospital revealed the presence of Brucella melitensis, and we diagnosed brucellosis in this patient.

DISCUSSION

Brucella melitensis is one of the 4 recognized, land-based species of the Brucella genus that can cause disease in humans. Goats, sheep, and camels are natural hosts of B melitensis and consumption of their unpasteurized, infected milk and milk products (especially soft cheeses, ice cream, milk, and butter) leads to human disease. (Once hospitalized, our patient admitted to frequently eating unpasteurized goat cheese from Chihuahua. The only other person in her household that ate the cheese was her 26-year-old daughter, who was also experiencing similar symptoms.)

Brucellosis can also result from inhaling infected, aerosolized material; therefore, individuals whose occupations involve close work with host animals or work in laboratories with the bacteria have an increased risk of infection.1 Due to the risk of acquiring the infection via inhalation, brucellosis is considered a bioterrorism threat.2 Additionally, there have been reports of human-to-human transmission via sexual intercourse, transplacental infection, blood and bone marrow transfusion, and breastfeeding.3

B melitensis is the cause of the majority of Brucella-related illnesses in the world, though symptoms of infection are similar among the different Brucella species. The pathogen can affect almost all organ systems after the initial 2- to 4-week incubation period. Symptoms of brucellosis can be highly variable, although fever is consistently present.1 Other red flags include arthritis (usually affecting the peripheral joints, the sacroiliac joints, and the lower spine), epididymo-orchitis, and hepatitis resulting in transaminase elevation. Abscess formation can be seen in the liver, spleen, and other organs.

Less common but more ominous complications include central nervous system infections and abscesses, endocarditis, and pulmonary infections. Endocarditis and the resulting aortic valve involvement is the major cause of mortality.1Brucella-related uveitis, thyroiditis, nephritis, vasculitis, and acalculous cholecystitis have also been reported.4-9

Rare in the United States. Pasteurization of dairy products and mass vaccination of livestock make Brucella infection rare in the United States. While there have only been 80 to 139 cases of brucellosis reported per year in the United States since 1993, it remains a persistent threat. International travel is common from the United States to the Middle East and other parts of the world where brucellosis is endemic.

Additionally, infection of livestock with Brucella remains widespread in Mexico and the consumption of unpasteurized Mexican dairy products from goats and sheep remains a high-risk activity for acquiring the disease.10 Consequently, Texas and California account for more than half of the brucellosis diagnoses in the United States. However, in 2010, cases were reported in 25 other states and the District of Columbia.11

Repeat serology tests are preferred for confirming the Dx

It is interesting that our patient’s initial Brucella serology by ELISA was negative, because it was ordered months after her initial symptoms. Antibodies should be seen within a month of symptom onset. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends taking 2 serum samples to establish a serologic diagnosis of brucellosis. The first should be drawn within 7 days of symptom onset and the second should be taken 2 to 4 weeks later. A greater than 4-fold rise in the antibody titer confirms the diagnosis. While ELISA is an acceptable serologic test, the CDC recommends using a serum tube agglutination test called the Brucella microagglutination test (BMAT).12 Repeat serology was not performed on our patient because the diagnosis had been confirmed by blood culture.

A combination of antibiotics is the recommended treatment

Treatment of brucellosis should include a tetracycline for at least 6 weeks in combination with an aminoglycoside or rifampin 600 mg/d for an all-oral regimen.13 Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day is preferred due to fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects than tetracycline. Relapse is not uncommon (10%) and usually occurs within one year of completing the antibiotics.8 However, there is a case report of a patient having reactivated brucellosis manifested as acalculous cholecystitis 28 years after completing antibiotics.8

Our patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day and oral rifampin 600 mg/d for 6 weeks. Within days of starting the antibiotics, her joint symptoms and fatigue rapidly abated and her appetite returned. Follow-up radiological testing was not performed after her initial hospital studies due to her lack of financial resources.

The patient’s daughter had also been experiencing night sweats, chills, malaise, anorexia, joint pains, weight loss, and alopecia over the previous 2 months. Her blood cultures were positive for B melitensis as well, and she was started on the same antibiotic regimen as her mother. The daughter was also seen in our clinic by another physician and improved quickly within a week of starting treatment.

Both our patient and her daughter remained symptom-free 6 years after treatment.

THE TAKEAWAY

Brucellosis is rare in the United States, but international travel to endemic areas is commonplace and consumption of unpasteurized Mexican dairy products from goats and sheep is widespread. Brucellosis has a wide range of symptoms, but a prompt diagnosis by an ELISA or BMAT serologic test and appropriate treatment can avoid morbidity and mortality. Treatment includes a tetracycline for at least 6 weeks in combination with an aminoglycoside or rifampin.

1. Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, et al. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2325-2336.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suspected brucellosis case prompts investigation of possible bioterrorismrelated activity—New Hampshire and Massachusetts, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:509-512.

3. Chen S, Zhang H, Liu X, et al. Increasing threat of brucellosis to low-risk persons in urban settings, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:126-130.

4. Rolando I, Vilchez G, Olarte L, et al. Brucellar uveitis: intraocular fluids and biopsy studies. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e206-e211.

5. Azizi F, Katchoui A. Brucella infection of the thyroid gland. Thyroid. 1996;6:461-463.

6. Siegelmann N, Abraham AS, Rudensky B, et al. Brucellosis with nephrotic syndrome, nephritis and IgA nephropathy. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:834-836.

7. Tanyel E, Tasdelen Fisgin N, Yildiz L, et al. Panniculitis as the initial manifestation of brucellosis: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:169-171.

8. Ögredici Ö, Erb S, Langer I, et al. Brucellosis reactivation after 28 years. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:2021-2022.

9. Dhand A, Ross JJ. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infection due to Brucella melitensis: case report and review of brucellosis of cardiac devices. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e37-e39.

10. Solorio-Rivera JL, Segura-Correa JC, Sánchez-Gil LG. Seroprevalence of and risk factors for brucellosis of goats in herds of Michoacan, Mexico. Prev Vet Med. 2007;82:282-290.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Brucellosis surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/resources/surveillance.html. Accessed October 30, 2015.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Serology. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/clinicians/serology.html. Accessed October 30, 2015.

13. Corbel MJ. Brucellosis in humans and animals. World Health Organization (WHO);2006:36-41. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/Brucellosis.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2015.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old Mexican immigrant woman was admitted to the hospital with a 5-month history of fatigue and a 30-pound unintentional weight loss. She was also experiencing arthralgia, swelling, and stiffness in her hands and feet that was worse in the morning. The patient, who was obese and suffered from type 2 diabetes and hypertension, said that at the onset of her illness 5 months earlier, she’d experienced approximately 2 weeks of night sweats and a few days of fever.

A month before being admitted to the hospital, she’d been seen in our southern New Mexico family medicine office. Her recent history of fever, joint symptoms, and weight loss raised concerns of an insidious infection, a new-onset rheumatologic condition, or an occult malignancy.

Initial lab tests revealed leukopenia (white blood cell count, 3200/mcL), microcytic anemia (hemoglobin, 9.4 g/dL), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 30 mm/hr (normal range, 0-20 mm/hr). A rheumatoid factor test was negative, and her thyroid, kidney, and liver function tests were all normal.

More testing… The patient frequently traveled between New Mexico and her hometown of Chihuahua, Mexico, but there had been no recent changes in her diet or environmental exposures. She denied drinking any unpasteurized milk in Chihuahua. But based on her travel history, we ordered enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody titers for Brucella, immunoglobulin G, and immunoglobulin M, which all came back negative. Additionally, we ordered an abdominal and pelvic ultrasound and a chest x-ray that were nondiagnostic. Given the patient’s weight loss and anemia, we referred her to a gastroenterologist for upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluations. Unfortunately, the patient was uninsured and did not go to see the gastroenterologist.

A month after seeing us, our patient’s fatigue, lack of appetite, and joint pain became debilitating and she was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation, including a consultation with an oncologist.

THE DIAGNOSIS

During our patient’s 6-day hospital stay, a bone scintigraphy showed a focus of uptake in her left parietal bone and computed tomography scans of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a left thyroid nodule, as well as multiple noncalcified pulmonary nodules. Blood cultures were also obtained.

Despite the initial negative antibody tests, the blood cultures drawn in the hospital revealed the presence of Brucella melitensis, and we diagnosed brucellosis in this patient.

DISCUSSION

Brucella melitensis is one of the 4 recognized, land-based species of the Brucella genus that can cause disease in humans. Goats, sheep, and camels are natural hosts of B melitensis and consumption of their unpasteurized, infected milk and milk products (especially soft cheeses, ice cream, milk, and butter) leads to human disease. (Once hospitalized, our patient admitted to frequently eating unpasteurized goat cheese from Chihuahua. The only other person in her household that ate the cheese was her 26-year-old daughter, who was also experiencing similar symptoms.)

Brucellosis can also result from inhaling infected, aerosolized material; therefore, individuals whose occupations involve close work with host animals or work in laboratories with the bacteria have an increased risk of infection.1 Due to the risk of acquiring the infection via inhalation, brucellosis is considered a bioterrorism threat.2 Additionally, there have been reports of human-to-human transmission via sexual intercourse, transplacental infection, blood and bone marrow transfusion, and breastfeeding.3

B melitensis is the cause of the majority of Brucella-related illnesses in the world, though symptoms of infection are similar among the different Brucella species. The pathogen can affect almost all organ systems after the initial 2- to 4-week incubation period. Symptoms of brucellosis can be highly variable, although fever is consistently present.1 Other red flags include arthritis (usually affecting the peripheral joints, the sacroiliac joints, and the lower spine), epididymo-orchitis, and hepatitis resulting in transaminase elevation. Abscess formation can be seen in the liver, spleen, and other organs.

Less common but more ominous complications include central nervous system infections and abscesses, endocarditis, and pulmonary infections. Endocarditis and the resulting aortic valve involvement is the major cause of mortality.1Brucella-related uveitis, thyroiditis, nephritis, vasculitis, and acalculous cholecystitis have also been reported.4-9

Rare in the United States. Pasteurization of dairy products and mass vaccination of livestock make Brucella infection rare in the United States. While there have only been 80 to 139 cases of brucellosis reported per year in the United States since 1993, it remains a persistent threat. International travel is common from the United States to the Middle East and other parts of the world where brucellosis is endemic.

Additionally, infection of livestock with Brucella remains widespread in Mexico and the consumption of unpasteurized Mexican dairy products from goats and sheep remains a high-risk activity for acquiring the disease.10 Consequently, Texas and California account for more than half of the brucellosis diagnoses in the United States. However, in 2010, cases were reported in 25 other states and the District of Columbia.11

Repeat serology tests are preferred for confirming the Dx

It is interesting that our patient’s initial Brucella serology by ELISA was negative, because it was ordered months after her initial symptoms. Antibodies should be seen within a month of symptom onset. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends taking 2 serum samples to establish a serologic diagnosis of brucellosis. The first should be drawn within 7 days of symptom onset and the second should be taken 2 to 4 weeks later. A greater than 4-fold rise in the antibody titer confirms the diagnosis. While ELISA is an acceptable serologic test, the CDC recommends using a serum tube agglutination test called the Brucella microagglutination test (BMAT).12 Repeat serology was not performed on our patient because the diagnosis had been confirmed by blood culture.

A combination of antibiotics is the recommended treatment

Treatment of brucellosis should include a tetracycline for at least 6 weeks in combination with an aminoglycoside or rifampin 600 mg/d for an all-oral regimen.13 Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day is preferred due to fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects than tetracycline. Relapse is not uncommon (10%) and usually occurs within one year of completing the antibiotics.8 However, there is a case report of a patient having reactivated brucellosis manifested as acalculous cholecystitis 28 years after completing antibiotics.8

Our patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day and oral rifampin 600 mg/d for 6 weeks. Within days of starting the antibiotics, her joint symptoms and fatigue rapidly abated and her appetite returned. Follow-up radiological testing was not performed after her initial hospital studies due to her lack of financial resources.

The patient’s daughter had also been experiencing night sweats, chills, malaise, anorexia, joint pains, weight loss, and alopecia over the previous 2 months. Her blood cultures were positive for B melitensis as well, and she was started on the same antibiotic regimen as her mother. The daughter was also seen in our clinic by another physician and improved quickly within a week of starting treatment.

Both our patient and her daughter remained symptom-free 6 years after treatment.

THE TAKEAWAY

Brucellosis is rare in the United States, but international travel to endemic areas is commonplace and consumption of unpasteurized Mexican dairy products from goats and sheep is widespread. Brucellosis has a wide range of symptoms, but a prompt diagnosis by an ELISA or BMAT serologic test and appropriate treatment can avoid morbidity and mortality. Treatment includes a tetracycline for at least 6 weeks in combination with an aminoglycoside or rifampin.

THE CASE

A 49-year-old Mexican immigrant woman was admitted to the hospital with a 5-month history of fatigue and a 30-pound unintentional weight loss. She was also experiencing arthralgia, swelling, and stiffness in her hands and feet that was worse in the morning. The patient, who was obese and suffered from type 2 diabetes and hypertension, said that at the onset of her illness 5 months earlier, she’d experienced approximately 2 weeks of night sweats and a few days of fever.

A month before being admitted to the hospital, she’d been seen in our southern New Mexico family medicine office. Her recent history of fever, joint symptoms, and weight loss raised concerns of an insidious infection, a new-onset rheumatologic condition, or an occult malignancy.

Initial lab tests revealed leukopenia (white blood cell count, 3200/mcL), microcytic anemia (hemoglobin, 9.4 g/dL), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 30 mm/hr (normal range, 0-20 mm/hr). A rheumatoid factor test was negative, and her thyroid, kidney, and liver function tests were all normal.

More testing… The patient frequently traveled between New Mexico and her hometown of Chihuahua, Mexico, but there had been no recent changes in her diet or environmental exposures. She denied drinking any unpasteurized milk in Chihuahua. But based on her travel history, we ordered enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody titers for Brucella, immunoglobulin G, and immunoglobulin M, which all came back negative. Additionally, we ordered an abdominal and pelvic ultrasound and a chest x-ray that were nondiagnostic. Given the patient’s weight loss and anemia, we referred her to a gastroenterologist for upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluations. Unfortunately, the patient was uninsured and did not go to see the gastroenterologist.

A month after seeing us, our patient’s fatigue, lack of appetite, and joint pain became debilitating and she was admitted to the hospital for further evaluation, including a consultation with an oncologist.

THE DIAGNOSIS

During our patient’s 6-day hospital stay, a bone scintigraphy showed a focus of uptake in her left parietal bone and computed tomography scans of her chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a left thyroid nodule, as well as multiple noncalcified pulmonary nodules. Blood cultures were also obtained.

Despite the initial negative antibody tests, the blood cultures drawn in the hospital revealed the presence of Brucella melitensis, and we diagnosed brucellosis in this patient.

DISCUSSION

Brucella melitensis is one of the 4 recognized, land-based species of the Brucella genus that can cause disease in humans. Goats, sheep, and camels are natural hosts of B melitensis and consumption of their unpasteurized, infected milk and milk products (especially soft cheeses, ice cream, milk, and butter) leads to human disease. (Once hospitalized, our patient admitted to frequently eating unpasteurized goat cheese from Chihuahua. The only other person in her household that ate the cheese was her 26-year-old daughter, who was also experiencing similar symptoms.)

Brucellosis can also result from inhaling infected, aerosolized material; therefore, individuals whose occupations involve close work with host animals or work in laboratories with the bacteria have an increased risk of infection.1 Due to the risk of acquiring the infection via inhalation, brucellosis is considered a bioterrorism threat.2 Additionally, there have been reports of human-to-human transmission via sexual intercourse, transplacental infection, blood and bone marrow transfusion, and breastfeeding.3

B melitensis is the cause of the majority of Brucella-related illnesses in the world, though symptoms of infection are similar among the different Brucella species. The pathogen can affect almost all organ systems after the initial 2- to 4-week incubation period. Symptoms of brucellosis can be highly variable, although fever is consistently present.1 Other red flags include arthritis (usually affecting the peripheral joints, the sacroiliac joints, and the lower spine), epididymo-orchitis, and hepatitis resulting in transaminase elevation. Abscess formation can be seen in the liver, spleen, and other organs.

Less common but more ominous complications include central nervous system infections and abscesses, endocarditis, and pulmonary infections. Endocarditis and the resulting aortic valve involvement is the major cause of mortality.1Brucella-related uveitis, thyroiditis, nephritis, vasculitis, and acalculous cholecystitis have also been reported.4-9

Rare in the United States. Pasteurization of dairy products and mass vaccination of livestock make Brucella infection rare in the United States. While there have only been 80 to 139 cases of brucellosis reported per year in the United States since 1993, it remains a persistent threat. International travel is common from the United States to the Middle East and other parts of the world where brucellosis is endemic.

Additionally, infection of livestock with Brucella remains widespread in Mexico and the consumption of unpasteurized Mexican dairy products from goats and sheep remains a high-risk activity for acquiring the disease.10 Consequently, Texas and California account for more than half of the brucellosis diagnoses in the United States. However, in 2010, cases were reported in 25 other states and the District of Columbia.11

Repeat serology tests are preferred for confirming the Dx

It is interesting that our patient’s initial Brucella serology by ELISA was negative, because it was ordered months after her initial symptoms. Antibodies should be seen within a month of symptom onset. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends taking 2 serum samples to establish a serologic diagnosis of brucellosis. The first should be drawn within 7 days of symptom onset and the second should be taken 2 to 4 weeks later. A greater than 4-fold rise in the antibody titer confirms the diagnosis. While ELISA is an acceptable serologic test, the CDC recommends using a serum tube agglutination test called the Brucella microagglutination test (BMAT).12 Repeat serology was not performed on our patient because the diagnosis had been confirmed by blood culture.

A combination of antibiotics is the recommended treatment

Treatment of brucellosis should include a tetracycline for at least 6 weeks in combination with an aminoglycoside or rifampin 600 mg/d for an all-oral regimen.13 Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day is preferred due to fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects than tetracycline. Relapse is not uncommon (10%) and usually occurs within one year of completing the antibiotics.8 However, there is a case report of a patient having reactivated brucellosis manifested as acalculous cholecystitis 28 years after completing antibiotics.8

Our patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day and oral rifampin 600 mg/d for 6 weeks. Within days of starting the antibiotics, her joint symptoms and fatigue rapidly abated and her appetite returned. Follow-up radiological testing was not performed after her initial hospital studies due to her lack of financial resources.

The patient’s daughter had also been experiencing night sweats, chills, malaise, anorexia, joint pains, weight loss, and alopecia over the previous 2 months. Her blood cultures were positive for B melitensis as well, and she was started on the same antibiotic regimen as her mother. The daughter was also seen in our clinic by another physician and improved quickly within a week of starting treatment.

Both our patient and her daughter remained symptom-free 6 years after treatment.

THE TAKEAWAY

Brucellosis is rare in the United States, but international travel to endemic areas is commonplace and consumption of unpasteurized Mexican dairy products from goats and sheep is widespread. Brucellosis has a wide range of symptoms, but a prompt diagnosis by an ELISA or BMAT serologic test and appropriate treatment can avoid morbidity and mortality. Treatment includes a tetracycline for at least 6 weeks in combination with an aminoglycoside or rifampin.

1. Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, et al. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2325-2336.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suspected brucellosis case prompts investigation of possible bioterrorismrelated activity—New Hampshire and Massachusetts, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:509-512.

3. Chen S, Zhang H, Liu X, et al. Increasing threat of brucellosis to low-risk persons in urban settings, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:126-130.

4. Rolando I, Vilchez G, Olarte L, et al. Brucellar uveitis: intraocular fluids and biopsy studies. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e206-e211.

5. Azizi F, Katchoui A. Brucella infection of the thyroid gland. Thyroid. 1996;6:461-463.

6. Siegelmann N, Abraham AS, Rudensky B, et al. Brucellosis with nephrotic syndrome, nephritis and IgA nephropathy. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:834-836.

7. Tanyel E, Tasdelen Fisgin N, Yildiz L, et al. Panniculitis as the initial manifestation of brucellosis: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:169-171.

8. Ögredici Ö, Erb S, Langer I, et al. Brucellosis reactivation after 28 years. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:2021-2022.

9. Dhand A, Ross JJ. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infection due to Brucella melitensis: case report and review of brucellosis of cardiac devices. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e37-e39.

10. Solorio-Rivera JL, Segura-Correa JC, Sánchez-Gil LG. Seroprevalence of and risk factors for brucellosis of goats in herds of Michoacan, Mexico. Prev Vet Med. 2007;82:282-290.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Brucellosis surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/resources/surveillance.html. Accessed October 30, 2015.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Serology. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/clinicians/serology.html. Accessed October 30, 2015.

13. Corbel MJ. Brucellosis in humans and animals. World Health Organization (WHO);2006:36-41. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/Brucellosis.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2015.

1. Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, et al. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2325-2336.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Suspected brucellosis case prompts investigation of possible bioterrorismrelated activity—New Hampshire and Massachusetts, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:509-512.

3. Chen S, Zhang H, Liu X, et al. Increasing threat of brucellosis to low-risk persons in urban settings, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:126-130.

4. Rolando I, Vilchez G, Olarte L, et al. Brucellar uveitis: intraocular fluids and biopsy studies. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e206-e211.

5. Azizi F, Katchoui A. Brucella infection of the thyroid gland. Thyroid. 1996;6:461-463.

6. Siegelmann N, Abraham AS, Rudensky B, et al. Brucellosis with nephrotic syndrome, nephritis and IgA nephropathy. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:834-836.

7. Tanyel E, Tasdelen Fisgin N, Yildiz L, et al. Panniculitis as the initial manifestation of brucellosis: a case report. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:169-171.

8. Ögredici Ö, Erb S, Langer I, et al. Brucellosis reactivation after 28 years. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:2021-2022.

9. Dhand A, Ross JJ. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infection due to Brucella melitensis: case report and review of brucellosis of cardiac devices. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e37-e39.

10. Solorio-Rivera JL, Segura-Correa JC, Sánchez-Gil LG. Seroprevalence of and risk factors for brucellosis of goats in herds of Michoacan, Mexico. Prev Vet Med. 2007;82:282-290.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Brucellosis surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/resources/surveillance.html. Accessed October 30, 2015.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Serology. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brucellosis/clinicians/serology.html. Accessed October 30, 2015.

13. Corbel MJ. Brucellosis in humans and animals. World Health Organization (WHO);2006:36-41. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/Brucellosis.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2015.

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: An Emerging Infectious Disease in Travelers

Leishmaniasis describes any disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania1 and can manifest in 3 different forms: cutaneous (the most common); mucosal, a destructive metastatic sequela of the cutaneous form; and visceral, which is potentially fatal.2 According to the World Health Organization, the leishmaniases are endemic in 88 countries.3 It is estimated that 95% of cutaneous cases occur in the Americas (most notably Central and South America), the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, and Central Asia.2 Most cutaneous cases diagnosed among nonmilitary personnel in the United States are acquired in Mexico and Central America.4 In Central and South America, the causative human pathogens include species of the Leishmania (Viannia) complex (eg, Leishmania panamensis, Leishmania braziliensis, Leishmania guyanensis, Leishmania peruviana) and the Leishmania mexicana complex (eg, Leishmania mexicana, Leishmania amazonensis, Leishmania venezuelensis). All of these species can cause localized cutaneous lesions, but only L panamensis, L braziliensis, and L guyanensis are associated with metastatic mucosal lesions. In Central and South Americas, only Leishmaniasis chagasi (also known as Leishmaniasis infantum) is known to cause visceral leishmaniasis.5

Case Report

A 26-year-old man was referred to the dermatology clinic by his primary care provider for evaluation of a nonhealing sore on the left volar forearm of 6 weeks’ duration. The patient described the initial lesion as a red bump resembling a mosquito bite. Over 6 weeks the papule evolved into an indurated plaque with painless ulceration. The patient’s primary care provider had prescribed antibiotics for a presumed Staphylococcus aureus infection of the skin 5 weeks prior to presentation; however, the lesion continued to enlarge in size, resulting in referral to our dermatology clinic.

Skin examination revealed a solitary, 4-cm, painless, ulcerated plaque on the left volar forearm (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was noted. The patient reported that he had returned from a mission trip to rural Costa Rica 2 weeks prior to the appearance of the lesion. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable and his vital signs were within normal limits. Our initial differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet syndrome, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and an insect bite.

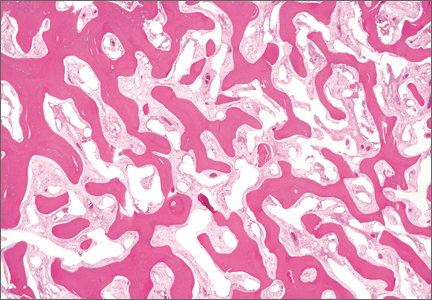

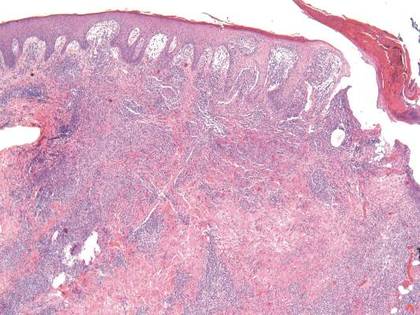

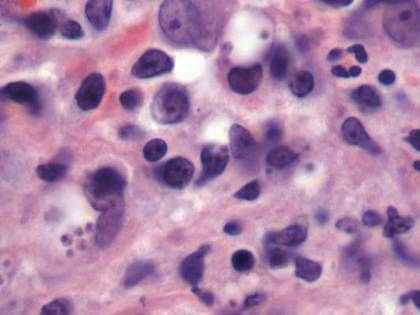

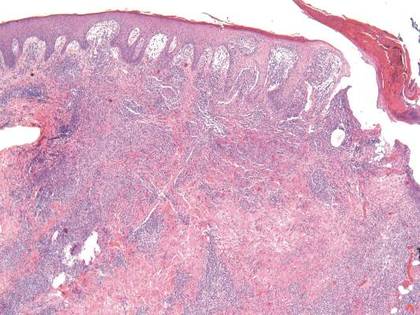

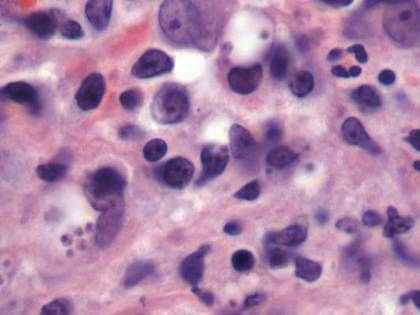

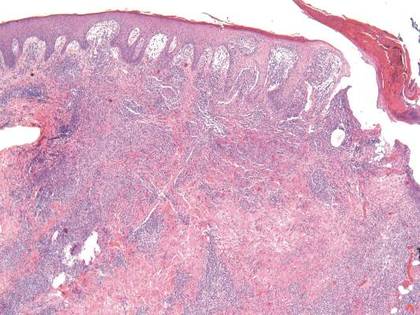

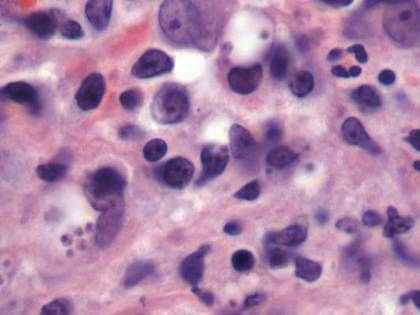

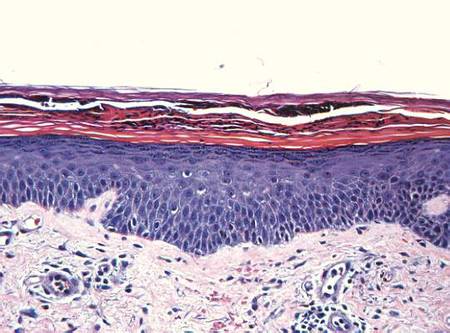

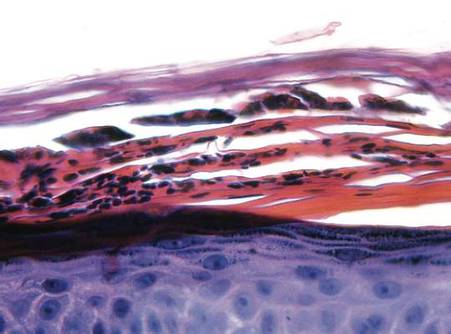

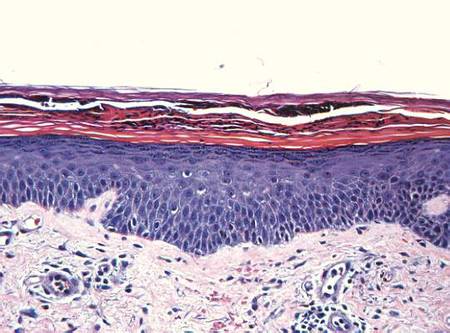

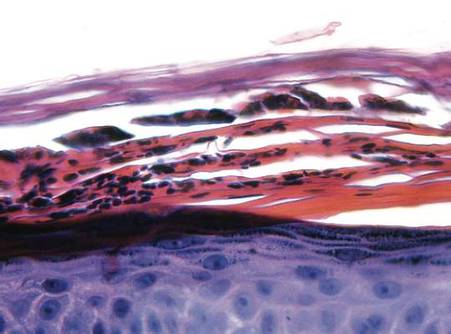

Histopathologic study of a 5-mm punch biopsy specimen from the lesion showed a dense nodular and diffuse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing foci of suppuration. Within these suppurative foci were histiocytes parasitized by intracellular organisms that appeared to be of uniform size and shape on Giemsa staining, all of which are considered to be pathognomonic features of cutaneous leishmaniasis6 (Figures 2 and 3). The dermatopathologist’s diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis was confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The species was identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as L panamensis.

The patient was treated with intravenous sodium stibogluconate 20 mg/kg for 20 consecutive days as recommended by expert consensus. The decision to treat a frequently self-limited cutaneous lesion with a highly toxic systemic drug was based on the small but real risk of metastatic mucosal lesions, which is caused by the Viannia subgenus, including L panamensis. Of note, sodium stibogluconate and other antimony drugs are not sold in the United States. Sodium stibogluconate is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to be distributed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under a protocol requiring baseline and weekly electrocardiograms and monitoring of patients’ creatinine, transaminase, lipase, amylase, and complete blood count levels.7 Our patient tolerated treatment but experienced mild to moderate flulike symptoms. The patient experienced no remarkable sequelae other than scarring in the affected area. He was warned to notify his health care providers of any persistent nasal symptoms, including nasal stuffiness, mucosal bleeding, and increased secretions, heralding the possibility of mucosal metastasis.

|  | |

Figure 2. Dense nodular and diffuse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate containing foci of suppuration (H&E, original magnification ×10). | Figure 3. Histiocytes parasitized by intracellular organisms of uniform shape and size on Giemsa staining (original magnification ×1000). |

Comment