User login

Indurated Plaque on the Eyebrow

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma

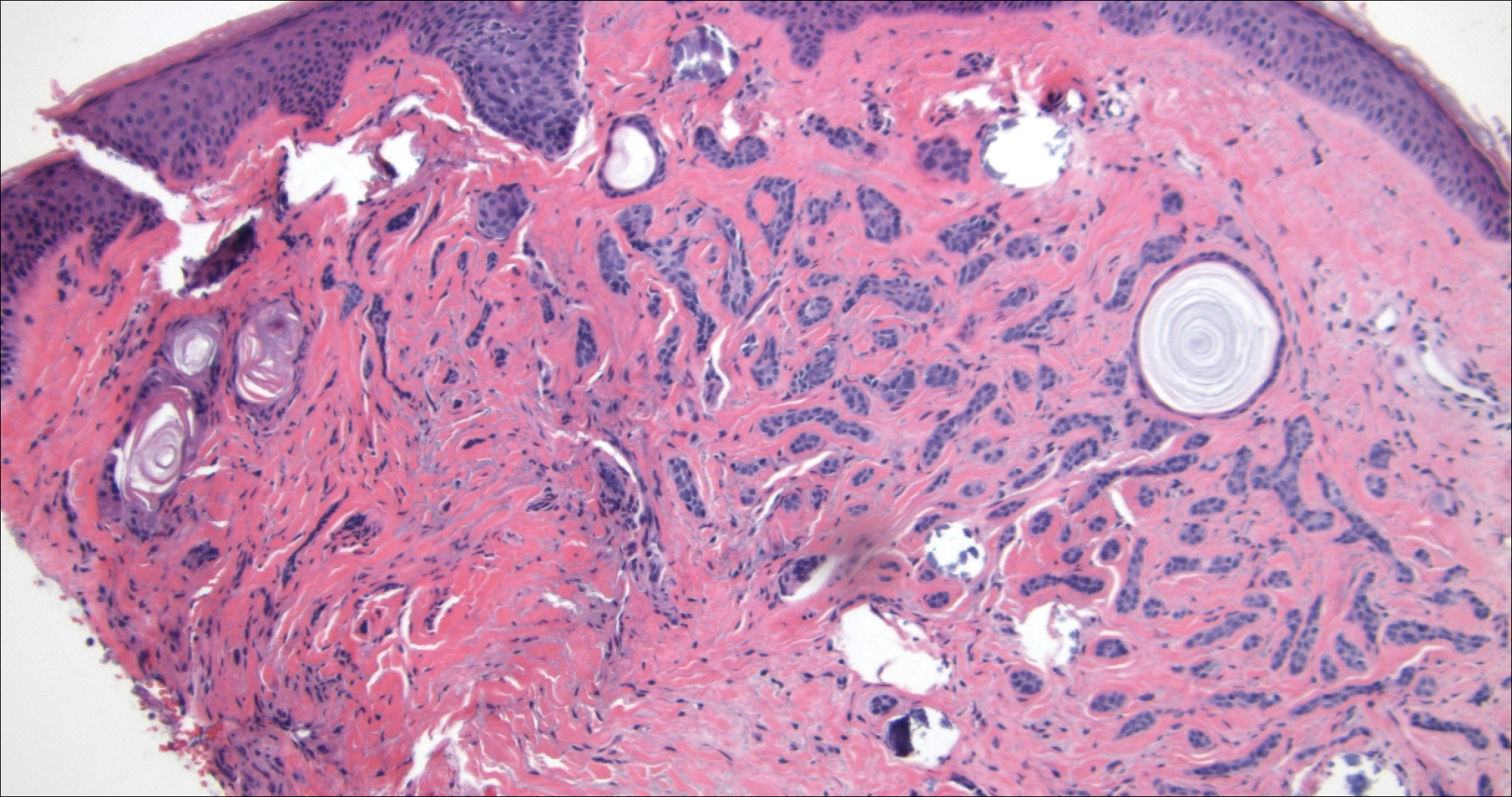

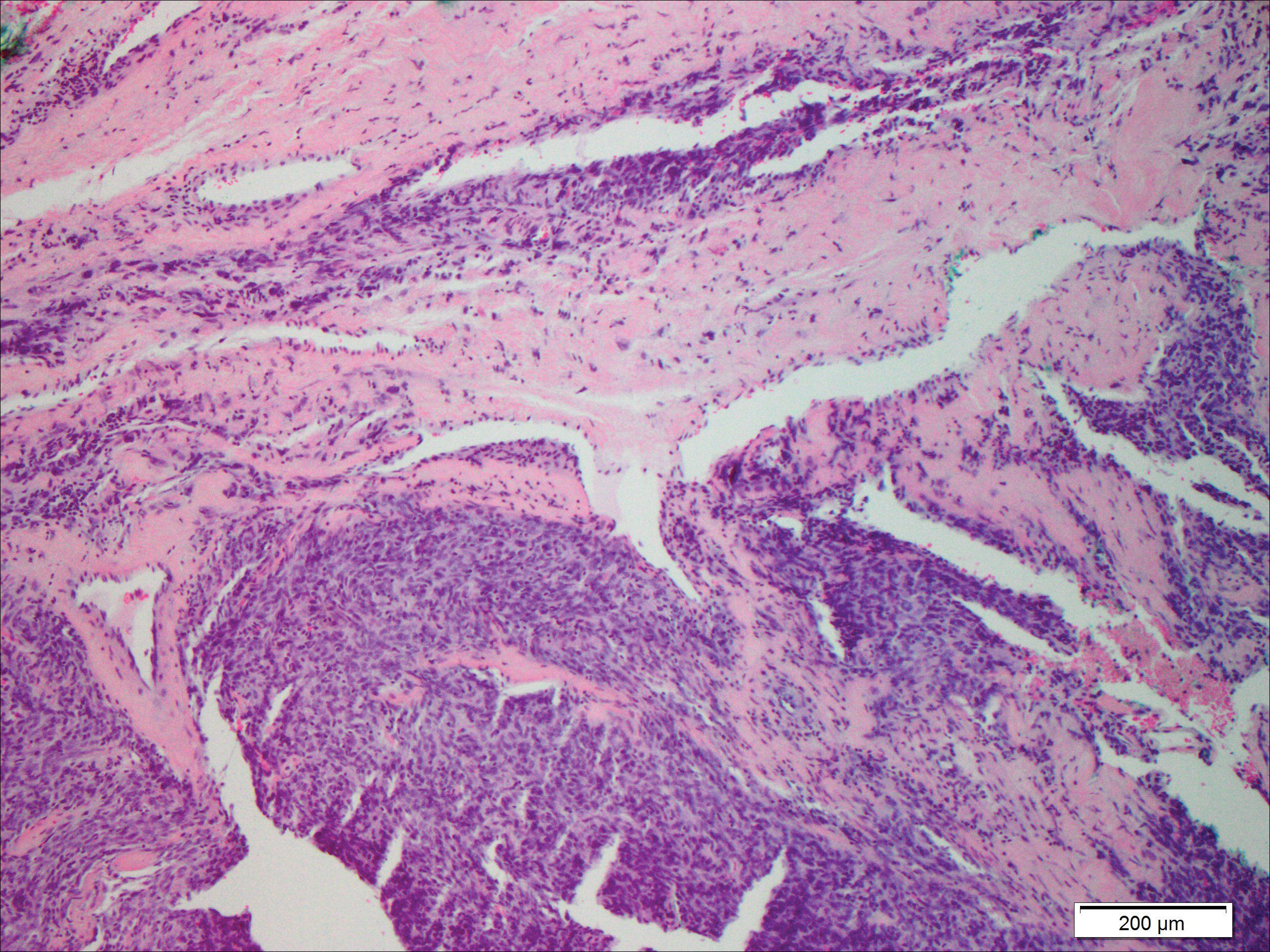

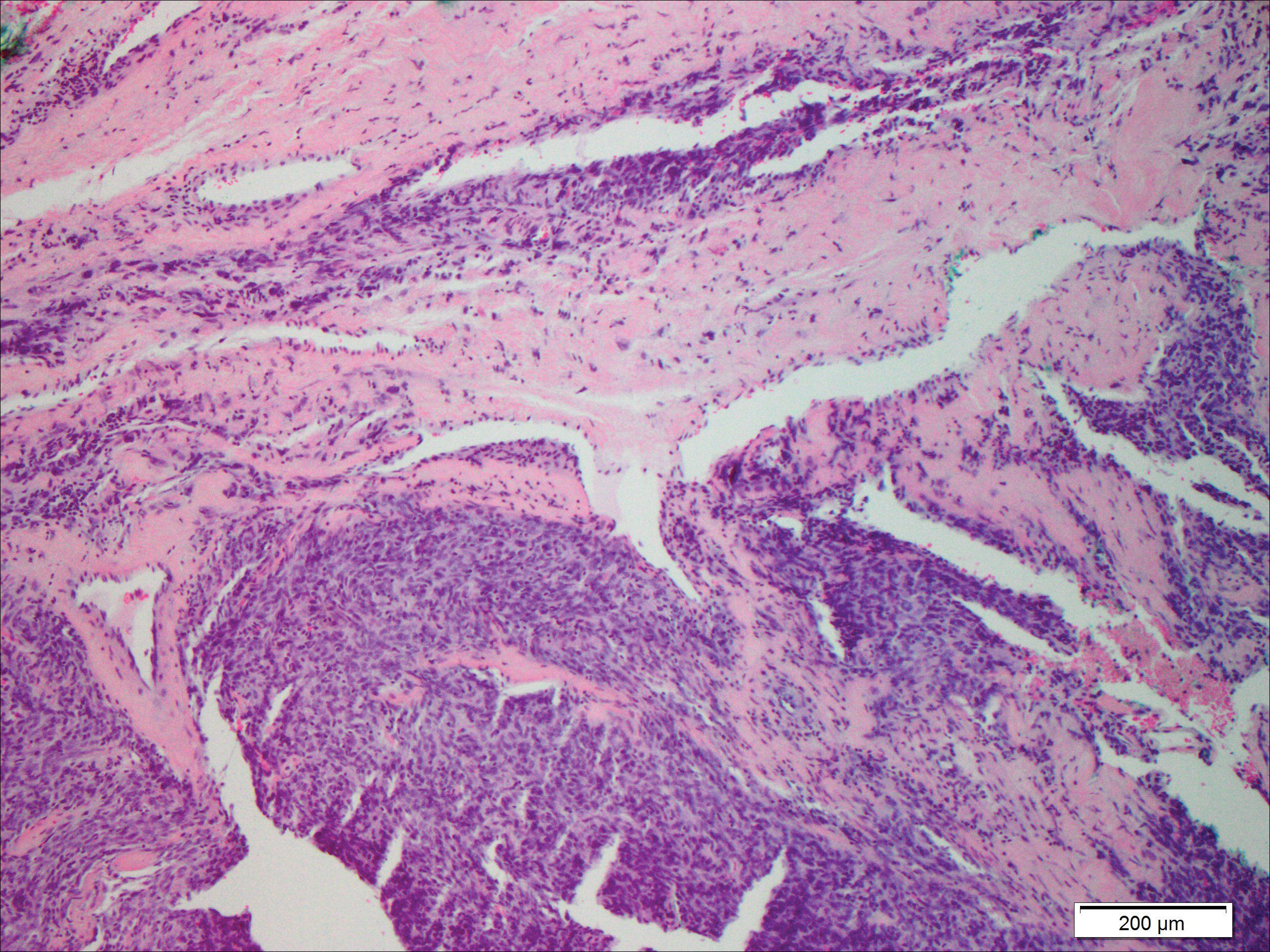

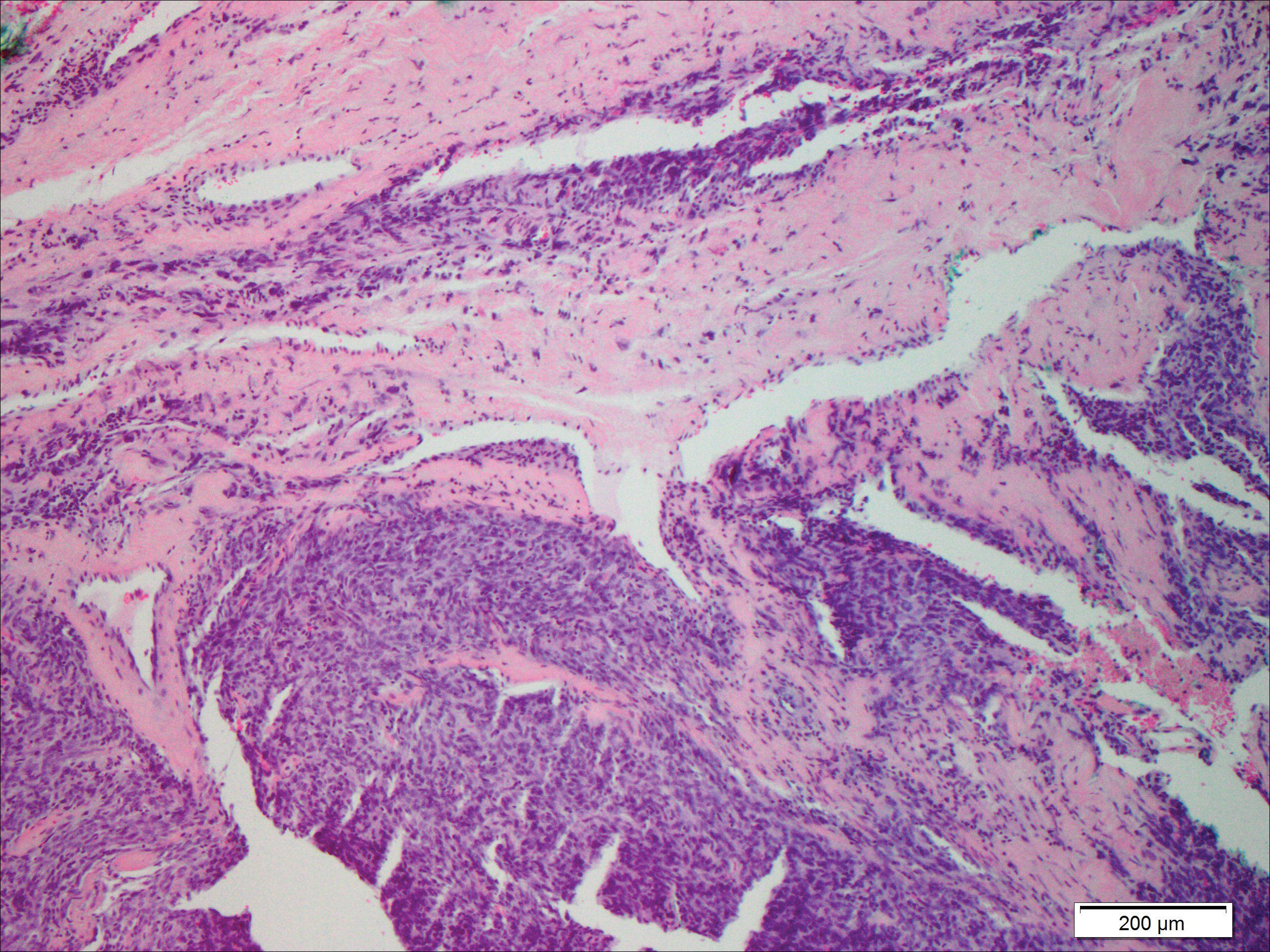

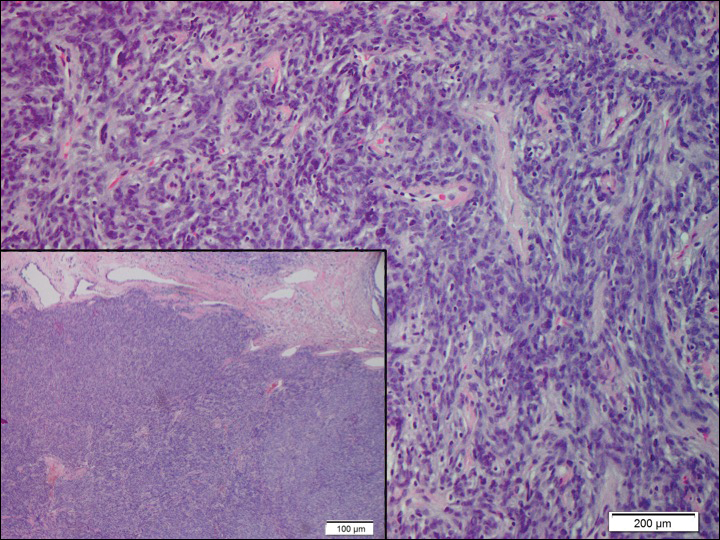

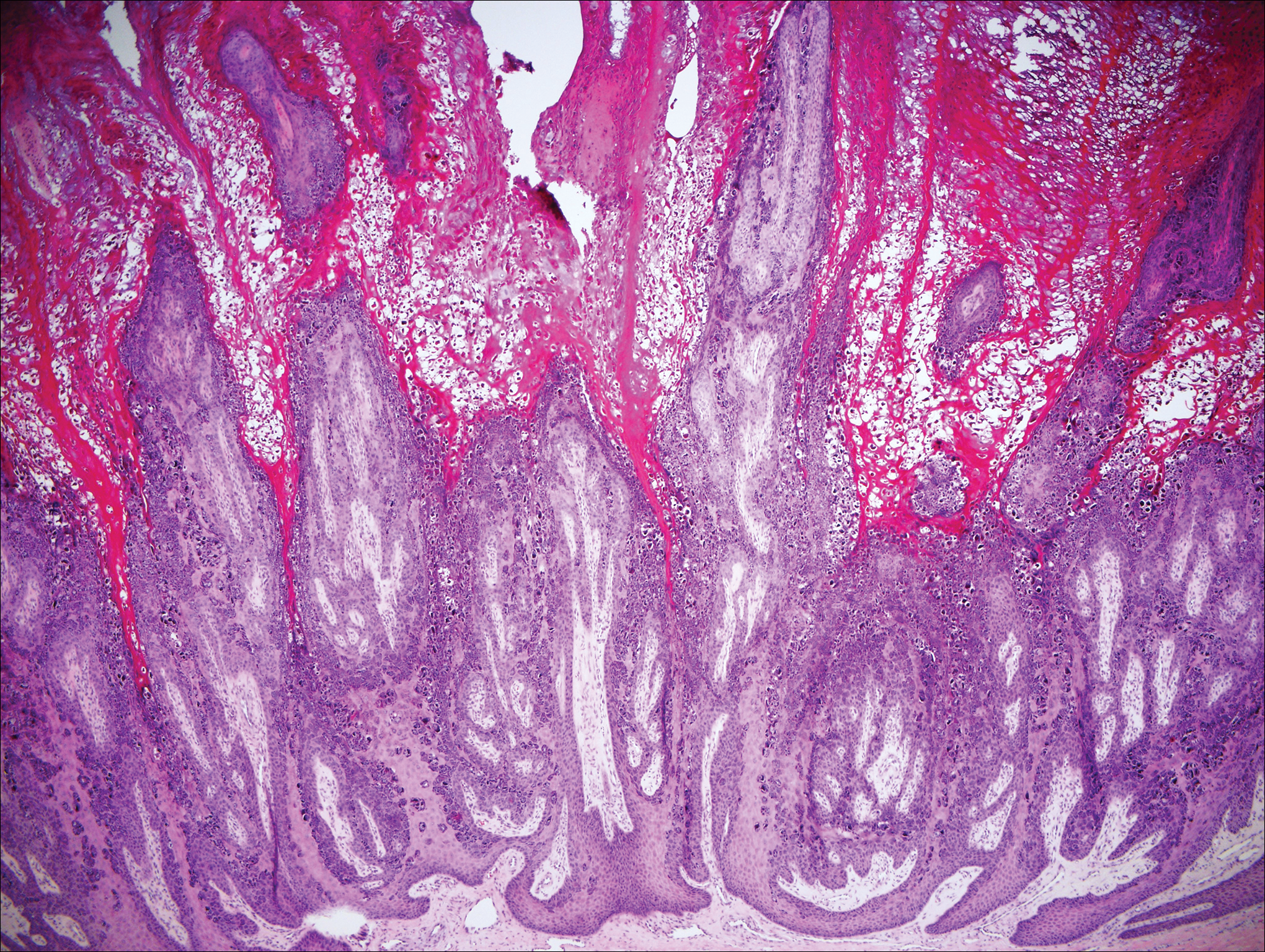

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) is a rare, low-grade adnexal carcinoma consisting of both ductal and pilar differentiation.1 It typically presents in young to middle-aged adults as a flesh-colored or yellow indurated plaque on the upper lip, medial cheek, or chin. Histologically, MACs exhibit a biphasic pattern consisting of epithelial islands of cords and lumina creating tadpolelike ducts intermixed with basaloid nests (quiz image). Keratin horn cysts are common superficially. A dense red sclerotic stroma is seen interspersed between the ducts and epithelial islands creating a "paisley tie" appearance. The lesion displays an infiltrative pattern and can be deeply invasive, extending down to the fat and muscle (quiz image, inset). Perineural invasion is common. Atypia, when present, is minimal or mild and mitoses are rare. Although this tumor's histologic pattern appears aggressive in nature, it lacks immunohistochemical staining such as p53, Ki-67, bcl-2, and c-erbB-2 that correlate with malignant behavior.2 A common diagnostic pitfall is examination of a superficial biopsy in which an MAC may be mistakenly identified as another entity.

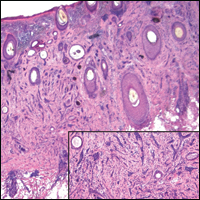

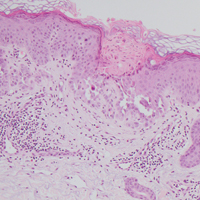

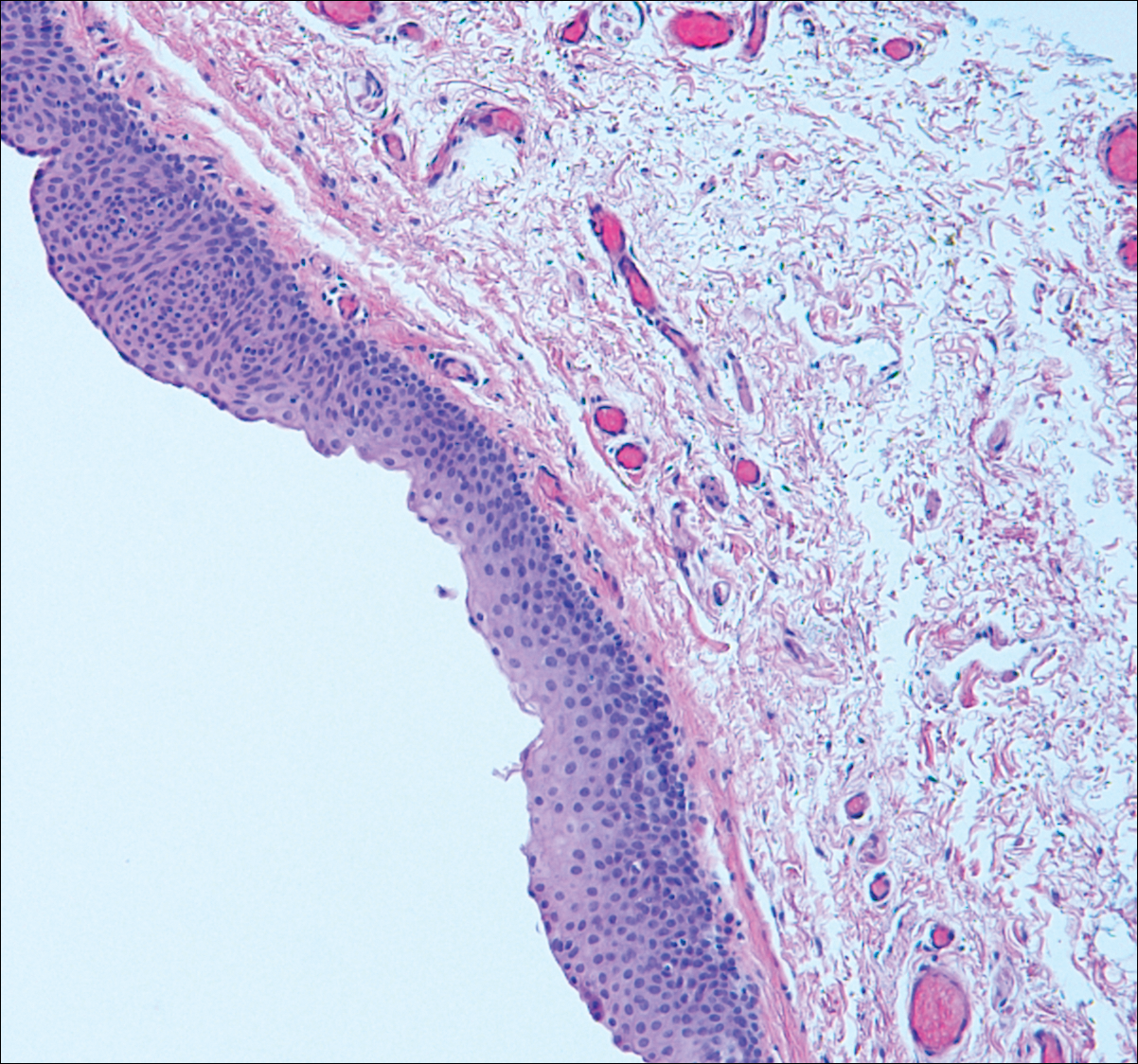

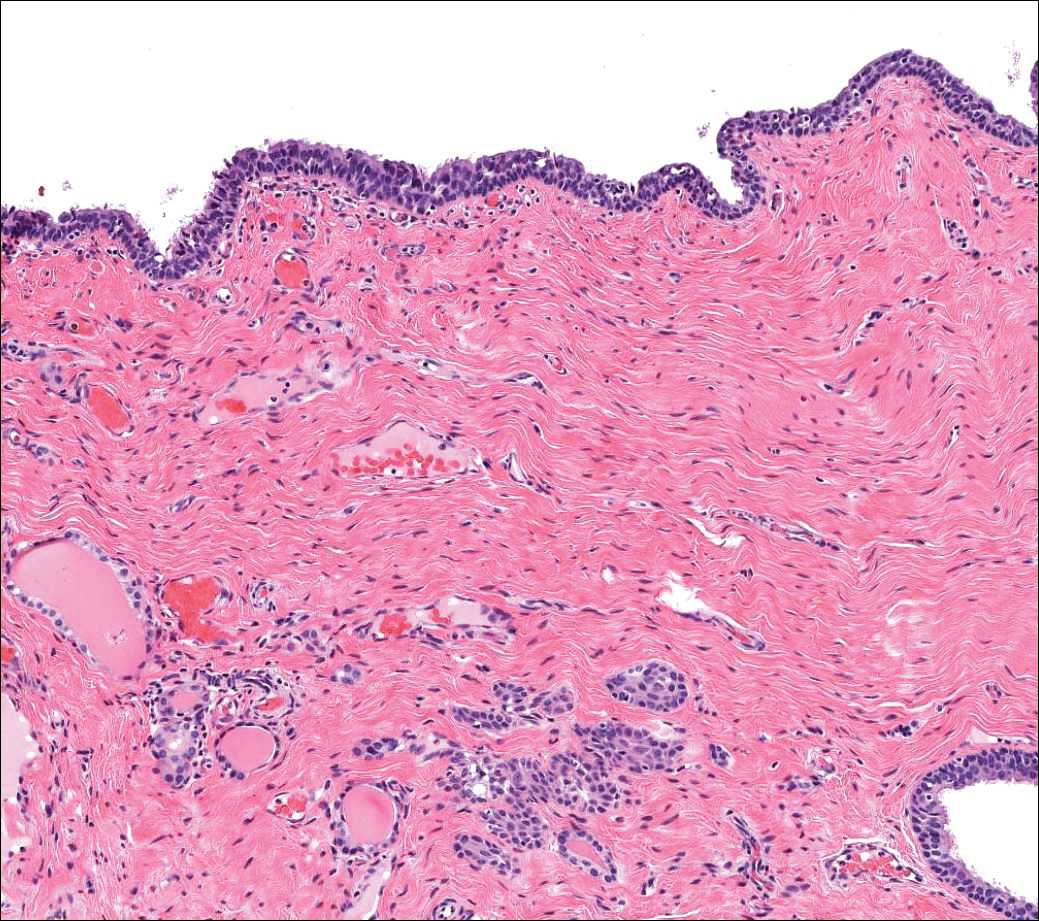

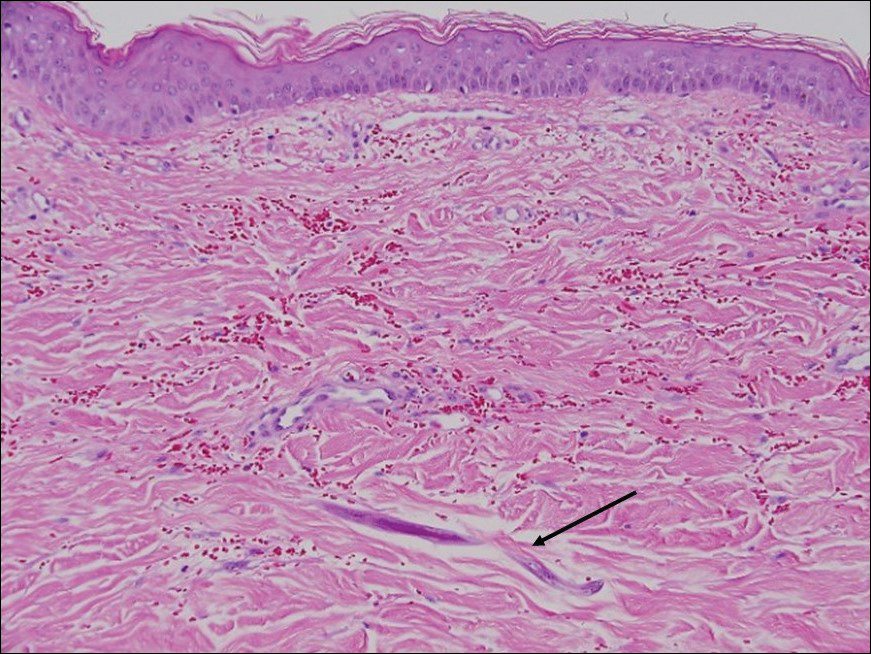

Syringomas are benign adnexal neoplasms with ductal differentiation.3 They are more common in women, especially those of Asian descent, and in patients with Down syndrome. They typically present as multiple small, firm, flesh-colored papules in the periorbital area or upper trunk. Histologically, syringomas also display comma-shaped tubules and ducts with a tadpolelike appearance and a dense red stroma creating a paisley tie-like pattern. Ductal cells have an abundant pink cytoplasm. Syringomas are well-circumscribed and more superficial than MACs without an infiltrative pattern. They lack mitotic activity or perineural invasion (Figure 1).

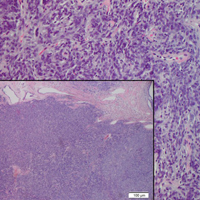

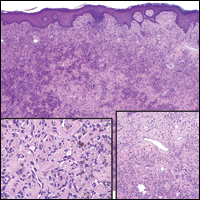

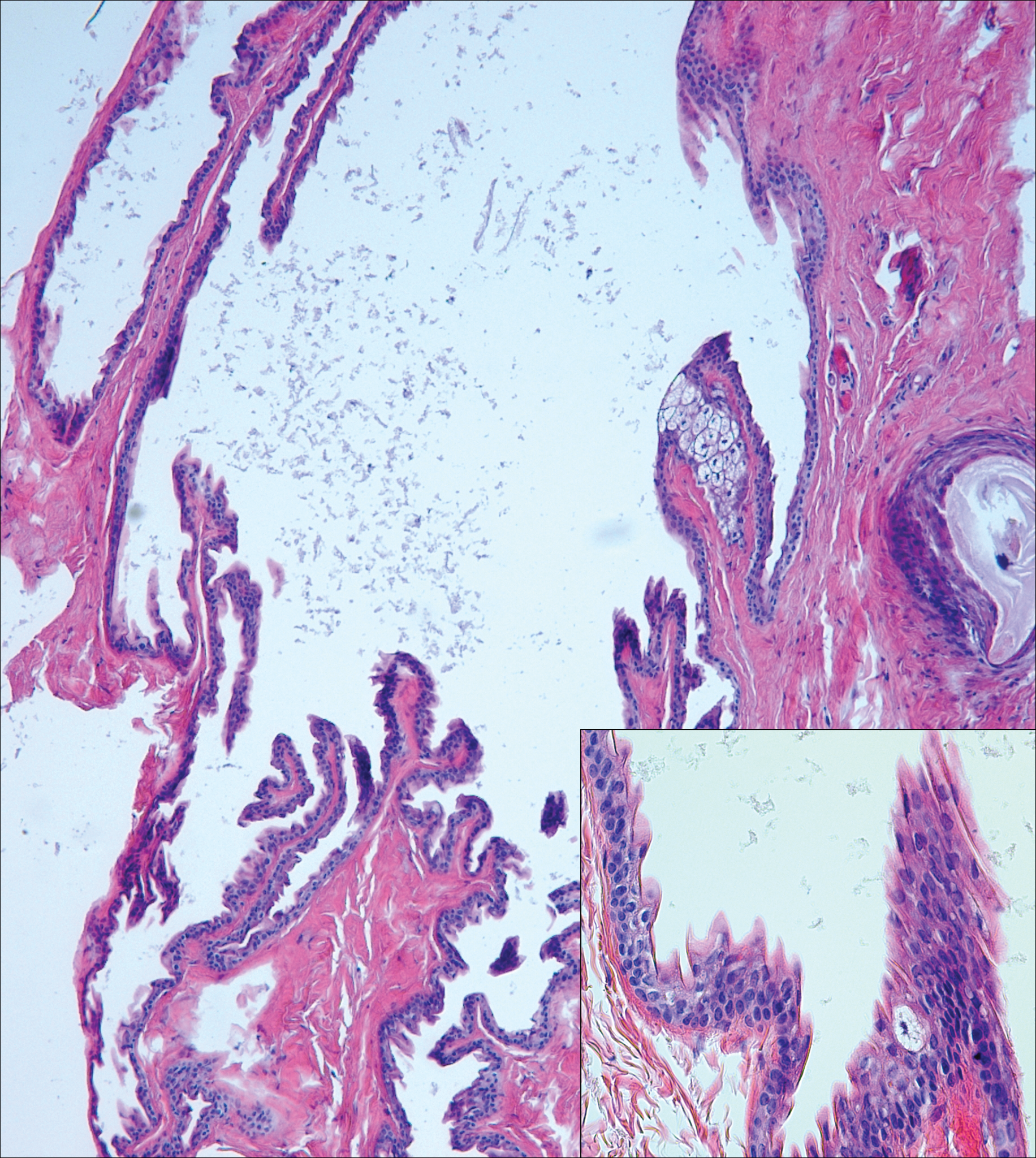

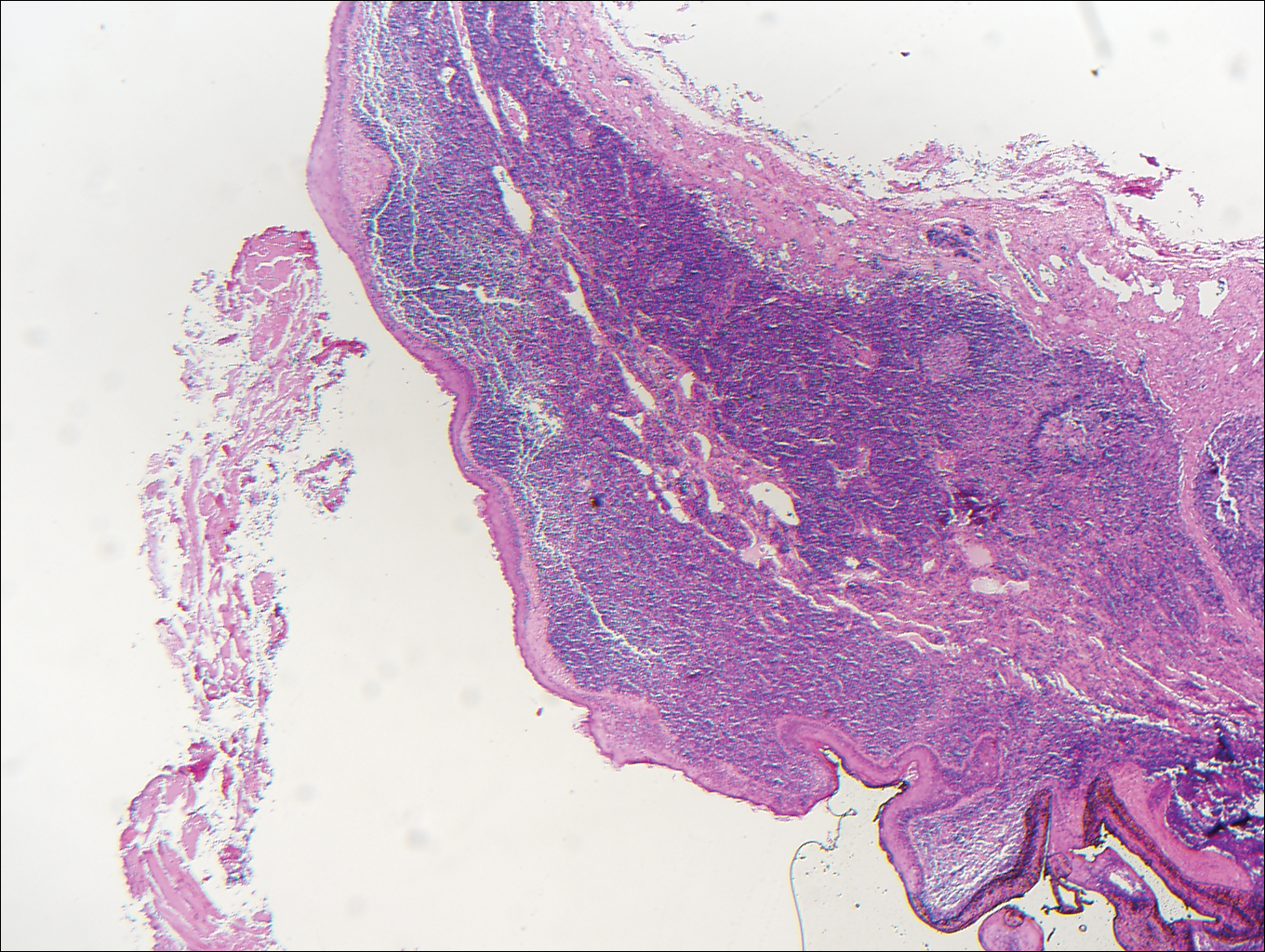

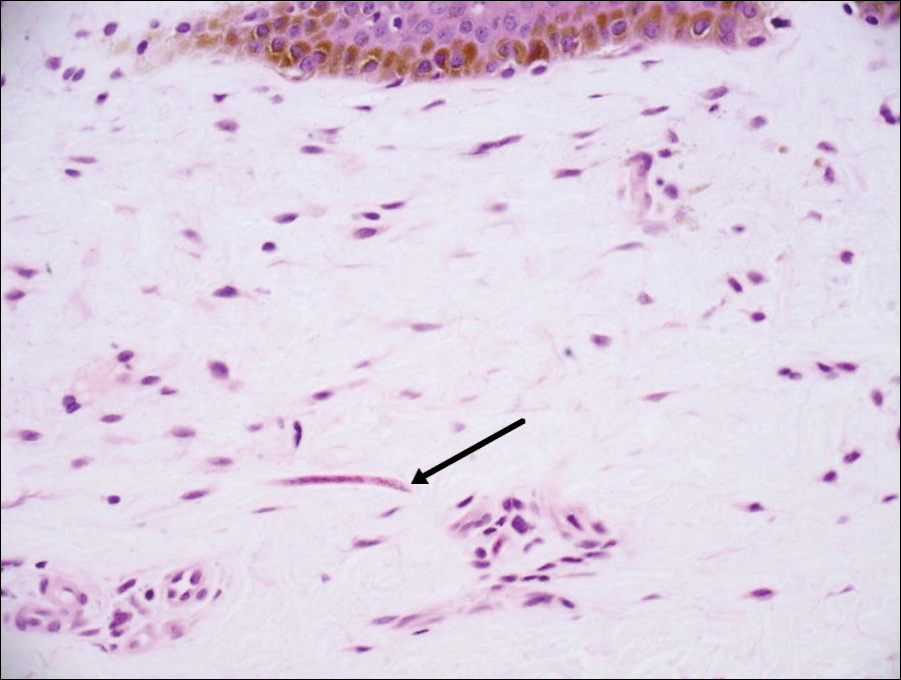

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE) is a benign follicular neoplasm.4 It presents in adulthood with a female predominance. Clinically, it appears as a solitary flesh-colored to yellow annular plaque with raised borders and a depressed central area, often on the medial cheek. Histologically, DTEs are well-circumscribed with narrow branching cords lined with polygonal cells. A dense red stroma in combination with the epithelioid aggregates also creates the paisley tie-like pattern in this lesion. Retraction between collagen bundles within the stroma can be seen, helping distinguish this lesion from a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which has retraction between the epithelium and stroma. Immunohistochemistry also can be a useful tool to help differentiate DTEs from morpheaform BCCs in that sparse cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells can be seen within the basaloid islands of DTE but not BCC.5 Also seen with DTEs are numerous keratin horn cysts that commonly are filled with dystrophic calcifications. Cellular atypia and mitoses are not seen (Figure 2). Compared to MACs, DTEs lack abundant ductal structures and also contain papillary mesenchymal bodies and a more fibroblast-rich stroma.

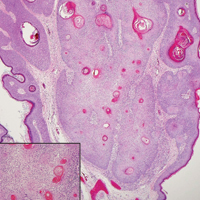

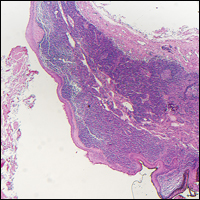

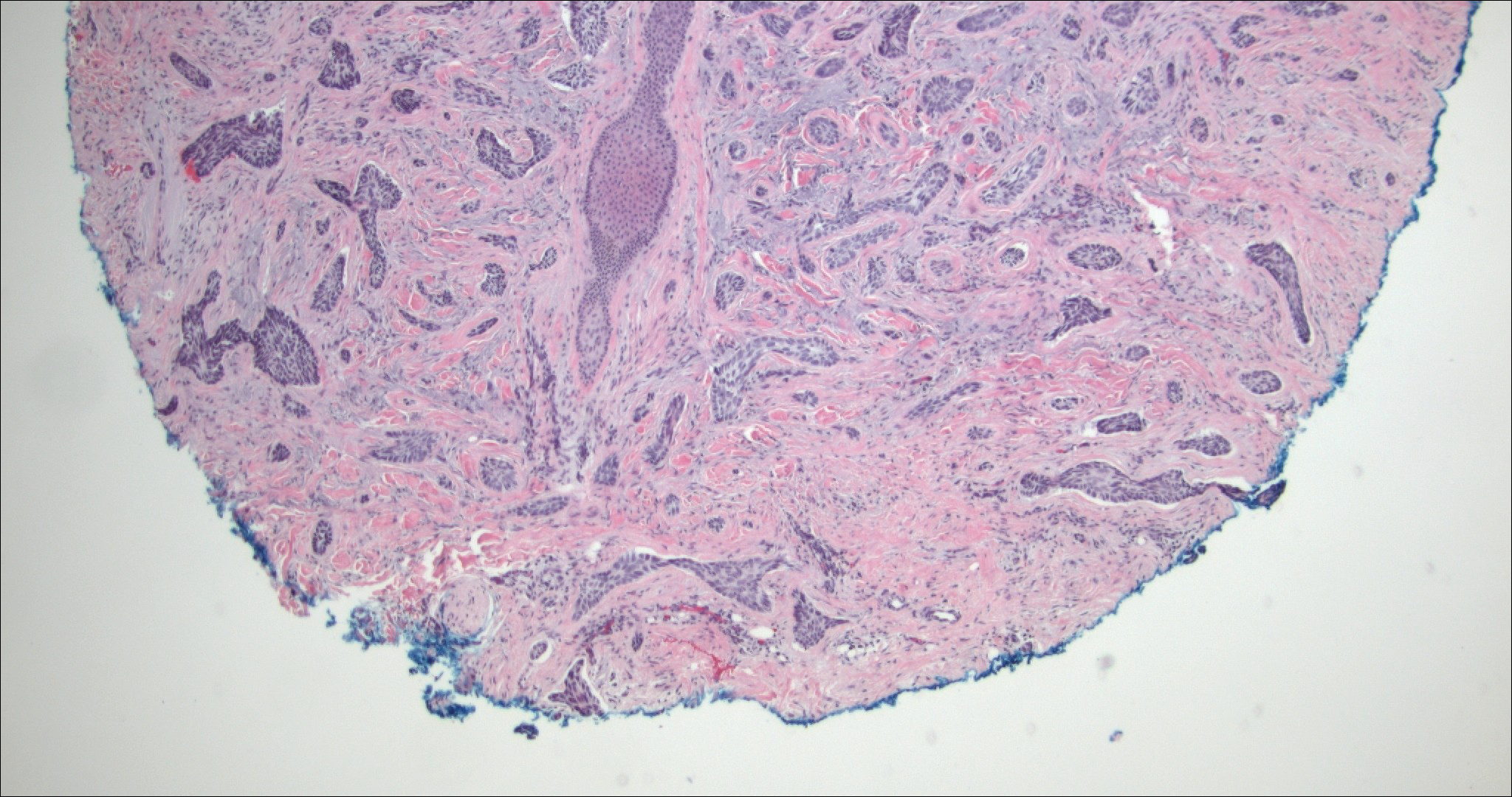

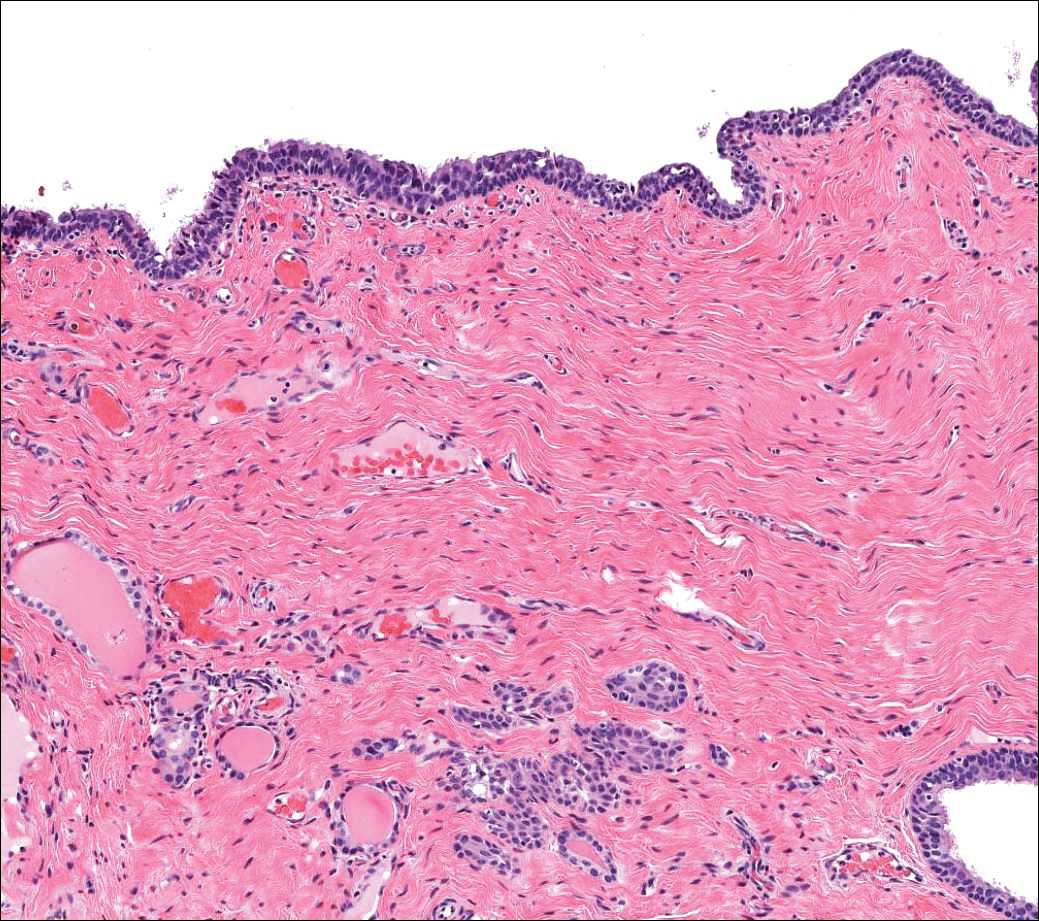

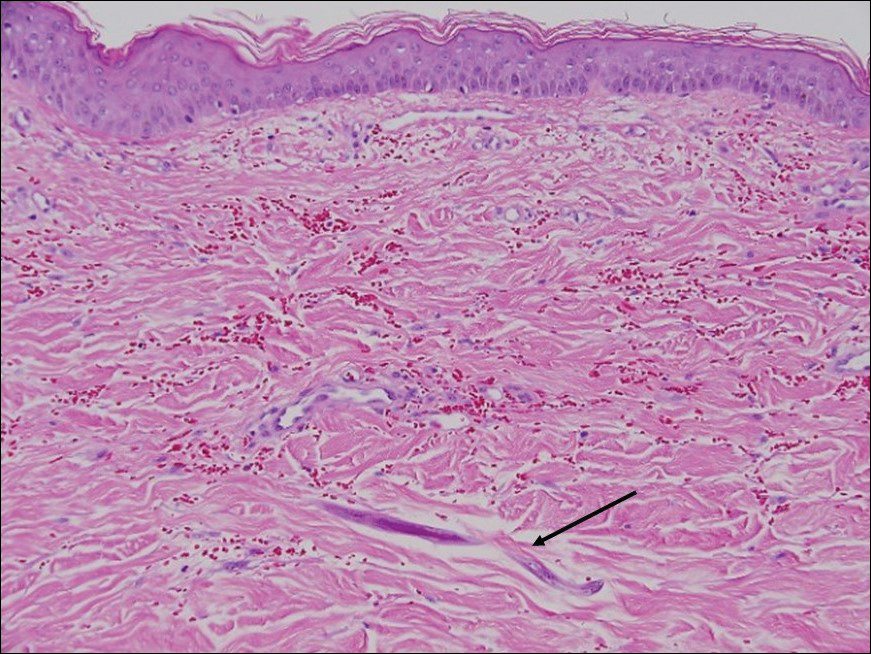

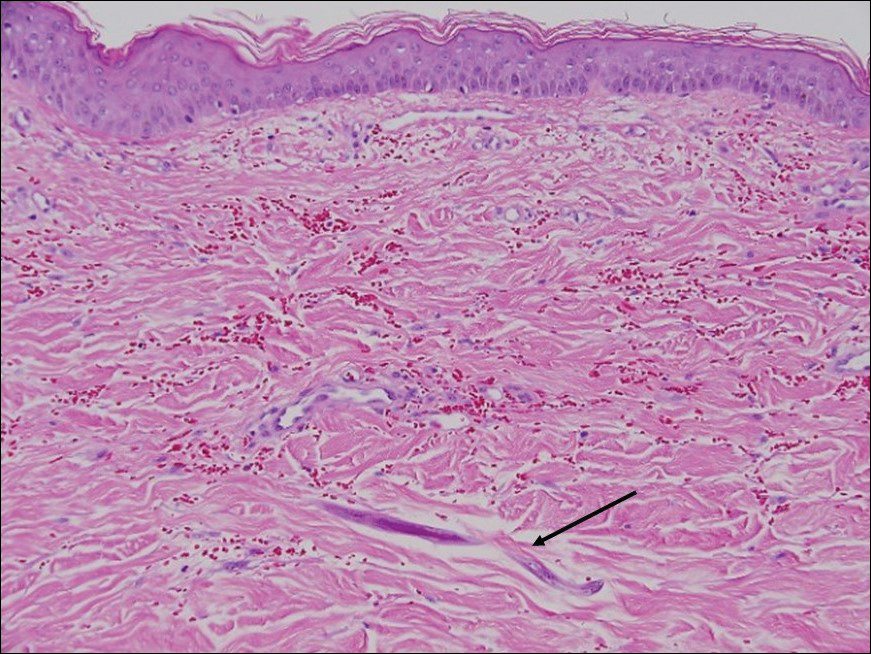

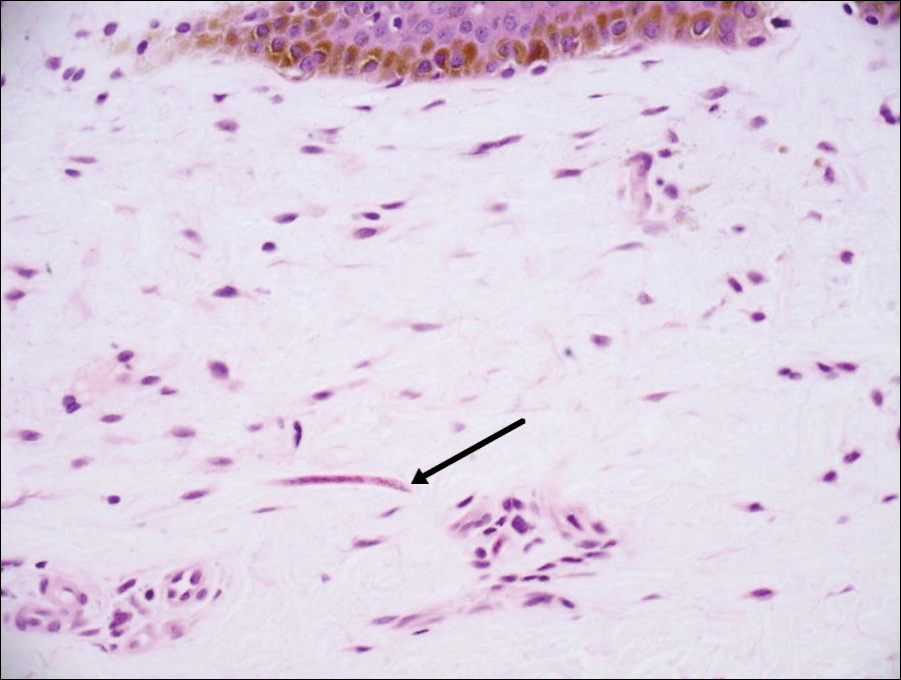

Morpheaform BCC is an aggressive subtype of BCC. It presents as a scarlike plaque that gradually expands. Thin infiltrating strands of basaloid cells are seen haphazardly throughout a pink sclerotic stroma. Tadpolelike basaloid islands and rarely horn cysts can be seen scattered superficially, creating the paisley tie-like pattern. This lesion is more infiltrating than a syringoma or a DTE, and perineural invasion is common. Retraction is uncommon, but when present, it is seen between the epithelial cords and adjacent stroma (Figure 3).

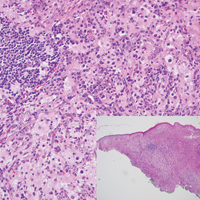

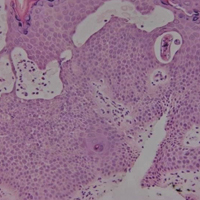

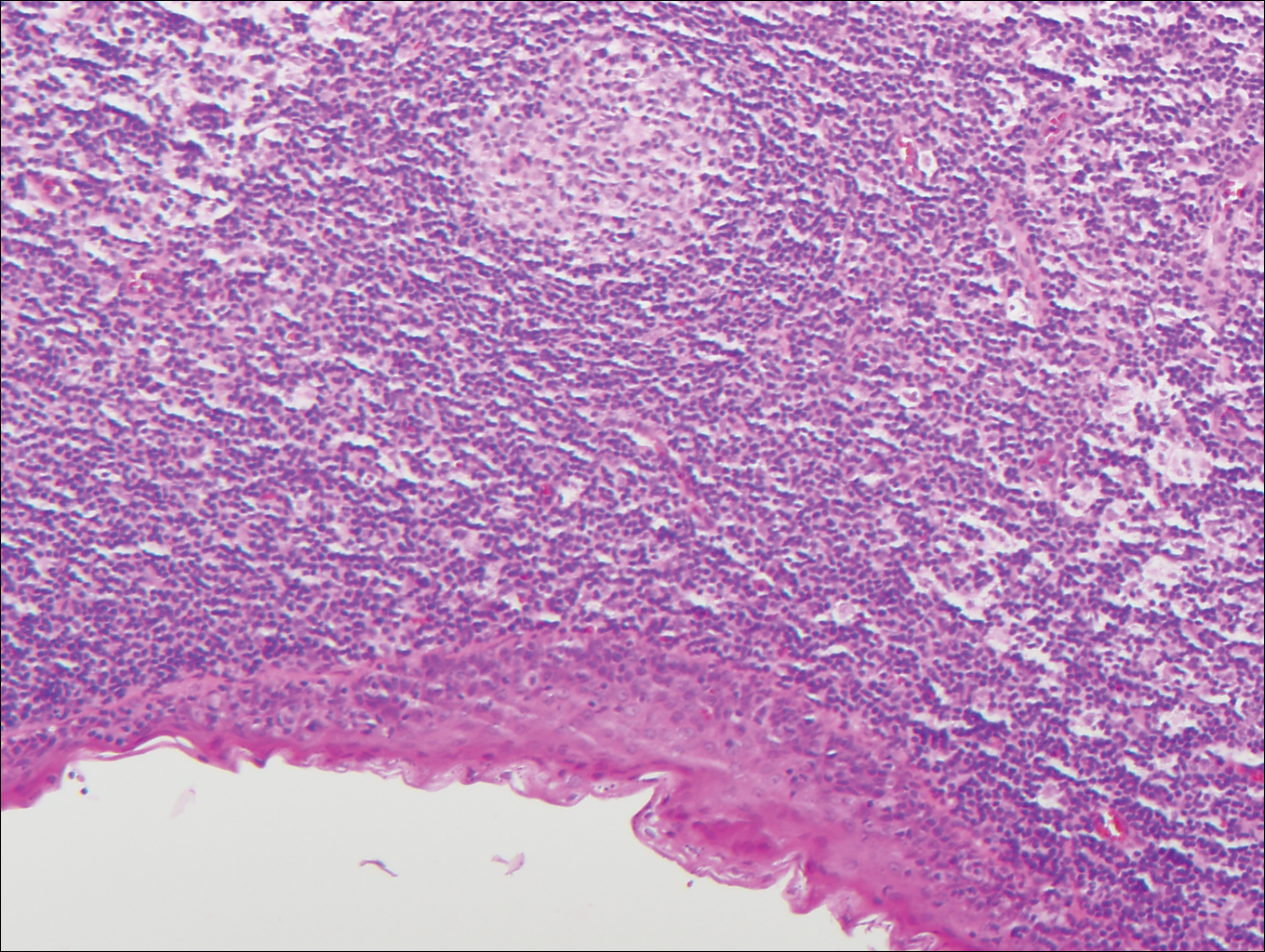

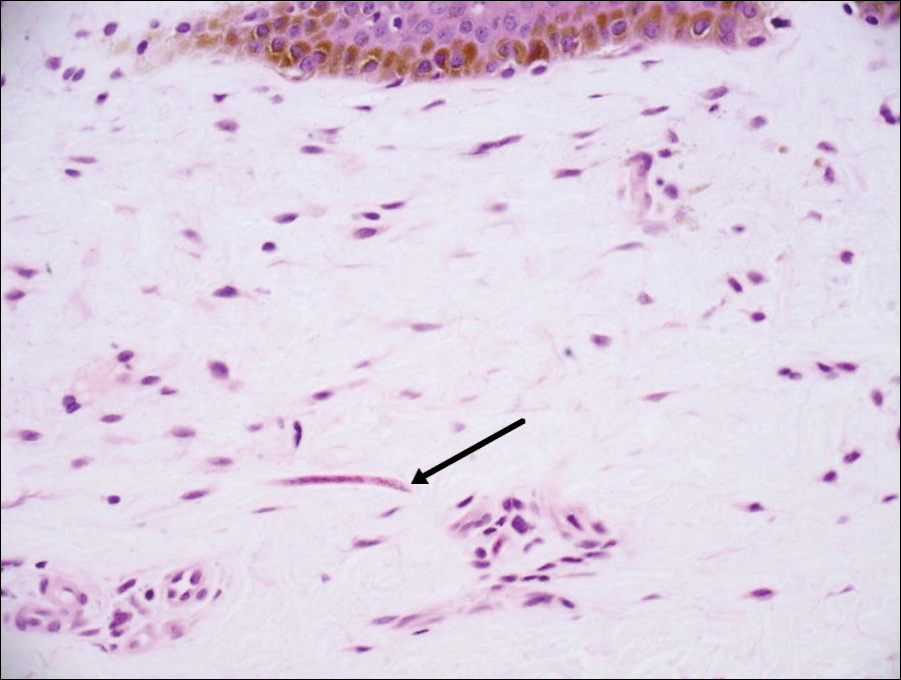

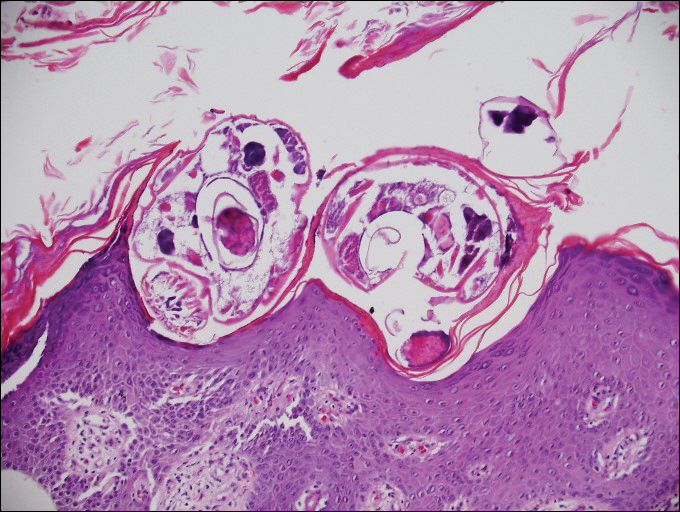

Trichoadenoma is another benign neoplasm of follicular differentiation.6 It typically presents as a dome-shaped papule or plaque on the head or neck. Histologically it displays numerous dilated cystic spaces that reflect its origin from isthmic and infundibular differentiation. There is no attachment to the overlying epidermis. It can be distinguished from MAC, DTE, and syringoma due to a lack of basaloid aggregates and only a small number of non-cyst-forming epithelial cells (Figure 4).

- Nickoloff BJ, Fleischmann HE, Carmel J. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: immunohistologic observations suggesting dual (pilar and eccrine) differentiation. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:290-294.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

- Hashimoto K, Lever WF. Histogenesis of skin appendage tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:356-369.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cancer. 1977;40:2979-2986.

- Hartschuh W, Schulz T. Merkel cells are integral constituents of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:413-421.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan A, Pinkus A. Trichoadenoma of Nikolowski. J Cutan Pathol. 1977;4:90-98.

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) is a rare, low-grade adnexal carcinoma consisting of both ductal and pilar differentiation.1 It typically presents in young to middle-aged adults as a flesh-colored or yellow indurated plaque on the upper lip, medial cheek, or chin. Histologically, MACs exhibit a biphasic pattern consisting of epithelial islands of cords and lumina creating tadpolelike ducts intermixed with basaloid nests (quiz image). Keratin horn cysts are common superficially. A dense red sclerotic stroma is seen interspersed between the ducts and epithelial islands creating a "paisley tie" appearance. The lesion displays an infiltrative pattern and can be deeply invasive, extending down to the fat and muscle (quiz image, inset). Perineural invasion is common. Atypia, when present, is minimal or mild and mitoses are rare. Although this tumor's histologic pattern appears aggressive in nature, it lacks immunohistochemical staining such as p53, Ki-67, bcl-2, and c-erbB-2 that correlate with malignant behavior.2 A common diagnostic pitfall is examination of a superficial biopsy in which an MAC may be mistakenly identified as another entity.

Syringomas are benign adnexal neoplasms with ductal differentiation.3 They are more common in women, especially those of Asian descent, and in patients with Down syndrome. They typically present as multiple small, firm, flesh-colored papules in the periorbital area or upper trunk. Histologically, syringomas also display comma-shaped tubules and ducts with a tadpolelike appearance and a dense red stroma creating a paisley tie-like pattern. Ductal cells have an abundant pink cytoplasm. Syringomas are well-circumscribed and more superficial than MACs without an infiltrative pattern. They lack mitotic activity or perineural invasion (Figure 1).

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE) is a benign follicular neoplasm.4 It presents in adulthood with a female predominance. Clinically, it appears as a solitary flesh-colored to yellow annular plaque with raised borders and a depressed central area, often on the medial cheek. Histologically, DTEs are well-circumscribed with narrow branching cords lined with polygonal cells. A dense red stroma in combination with the epithelioid aggregates also creates the paisley tie-like pattern in this lesion. Retraction between collagen bundles within the stroma can be seen, helping distinguish this lesion from a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which has retraction between the epithelium and stroma. Immunohistochemistry also can be a useful tool to help differentiate DTEs from morpheaform BCCs in that sparse cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells can be seen within the basaloid islands of DTE but not BCC.5 Also seen with DTEs are numerous keratin horn cysts that commonly are filled with dystrophic calcifications. Cellular atypia and mitoses are not seen (Figure 2). Compared to MACs, DTEs lack abundant ductal structures and also contain papillary mesenchymal bodies and a more fibroblast-rich stroma.

Morpheaform BCC is an aggressive subtype of BCC. It presents as a scarlike plaque that gradually expands. Thin infiltrating strands of basaloid cells are seen haphazardly throughout a pink sclerotic stroma. Tadpolelike basaloid islands and rarely horn cysts can be seen scattered superficially, creating the paisley tie-like pattern. This lesion is more infiltrating than a syringoma or a DTE, and perineural invasion is common. Retraction is uncommon, but when present, it is seen between the epithelial cords and adjacent stroma (Figure 3).

Trichoadenoma is another benign neoplasm of follicular differentiation.6 It typically presents as a dome-shaped papule or plaque on the head or neck. Histologically it displays numerous dilated cystic spaces that reflect its origin from isthmic and infundibular differentiation. There is no attachment to the overlying epidermis. It can be distinguished from MAC, DTE, and syringoma due to a lack of basaloid aggregates and only a small number of non-cyst-forming epithelial cells (Figure 4).

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Adnexal Carcinoma

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) is a rare, low-grade adnexal carcinoma consisting of both ductal and pilar differentiation.1 It typically presents in young to middle-aged adults as a flesh-colored or yellow indurated plaque on the upper lip, medial cheek, or chin. Histologically, MACs exhibit a biphasic pattern consisting of epithelial islands of cords and lumina creating tadpolelike ducts intermixed with basaloid nests (quiz image). Keratin horn cysts are common superficially. A dense red sclerotic stroma is seen interspersed between the ducts and epithelial islands creating a "paisley tie" appearance. The lesion displays an infiltrative pattern and can be deeply invasive, extending down to the fat and muscle (quiz image, inset). Perineural invasion is common. Atypia, when present, is minimal or mild and mitoses are rare. Although this tumor's histologic pattern appears aggressive in nature, it lacks immunohistochemical staining such as p53, Ki-67, bcl-2, and c-erbB-2 that correlate with malignant behavior.2 A common diagnostic pitfall is examination of a superficial biopsy in which an MAC may be mistakenly identified as another entity.

Syringomas are benign adnexal neoplasms with ductal differentiation.3 They are more common in women, especially those of Asian descent, and in patients with Down syndrome. They typically present as multiple small, firm, flesh-colored papules in the periorbital area or upper trunk. Histologically, syringomas also display comma-shaped tubules and ducts with a tadpolelike appearance and a dense red stroma creating a paisley tie-like pattern. Ductal cells have an abundant pink cytoplasm. Syringomas are well-circumscribed and more superficial than MACs without an infiltrative pattern. They lack mitotic activity or perineural invasion (Figure 1).

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma (DTE) is a benign follicular neoplasm.4 It presents in adulthood with a female predominance. Clinically, it appears as a solitary flesh-colored to yellow annular plaque with raised borders and a depressed central area, often on the medial cheek. Histologically, DTEs are well-circumscribed with narrow branching cords lined with polygonal cells. A dense red stroma in combination with the epithelioid aggregates also creates the paisley tie-like pattern in this lesion. Retraction between collagen bundles within the stroma can be seen, helping distinguish this lesion from a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), which has retraction between the epithelium and stroma. Immunohistochemistry also can be a useful tool to help differentiate DTEs from morpheaform BCCs in that sparse cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells can be seen within the basaloid islands of DTE but not BCC.5 Also seen with DTEs are numerous keratin horn cysts that commonly are filled with dystrophic calcifications. Cellular atypia and mitoses are not seen (Figure 2). Compared to MACs, DTEs lack abundant ductal structures and also contain papillary mesenchymal bodies and a more fibroblast-rich stroma.

Morpheaform BCC is an aggressive subtype of BCC. It presents as a scarlike plaque that gradually expands. Thin infiltrating strands of basaloid cells are seen haphazardly throughout a pink sclerotic stroma. Tadpolelike basaloid islands and rarely horn cysts can be seen scattered superficially, creating the paisley tie-like pattern. This lesion is more infiltrating than a syringoma or a DTE, and perineural invasion is common. Retraction is uncommon, but when present, it is seen between the epithelial cords and adjacent stroma (Figure 3).

Trichoadenoma is another benign neoplasm of follicular differentiation.6 It typically presents as a dome-shaped papule or plaque on the head or neck. Histologically it displays numerous dilated cystic spaces that reflect its origin from isthmic and infundibular differentiation. There is no attachment to the overlying epidermis. It can be distinguished from MAC, DTE, and syringoma due to a lack of basaloid aggregates and only a small number of non-cyst-forming epithelial cells (Figure 4).

- Nickoloff BJ, Fleischmann HE, Carmel J. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: immunohistologic observations suggesting dual (pilar and eccrine) differentiation. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:290-294.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

- Hashimoto K, Lever WF. Histogenesis of skin appendage tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:356-369.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cancer. 1977;40:2979-2986.

- Hartschuh W, Schulz T. Merkel cells are integral constituents of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:413-421.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan A, Pinkus A. Trichoadenoma of Nikolowski. J Cutan Pathol. 1977;4:90-98.

- Nickoloff BJ, Fleischmann HE, Carmel J. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: immunohistologic observations suggesting dual (pilar and eccrine) differentiation. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:290-294.

- Smith KJ, Williams J, Corbett D, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study including markers of proliferation and apoptosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:464-471.

- Hashimoto K, Lever WF. Histogenesis of skin appendage tumors. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:356-369.

- Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cancer. 1977;40:2979-2986.

- Hartschuh W, Schulz T. Merkel cells are integral constituents of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:413-421.

- Rahbari H, Mehregan A, Pinkus A. Trichoadenoma of Nikolowski. J Cutan Pathol. 1977;4:90-98.

A 52-year-old woman presented with an indurated plaque on the right lateral eyebrow that had been slowly enlarging over the last 4 months.

Solitary Tender Nodule on the Back

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

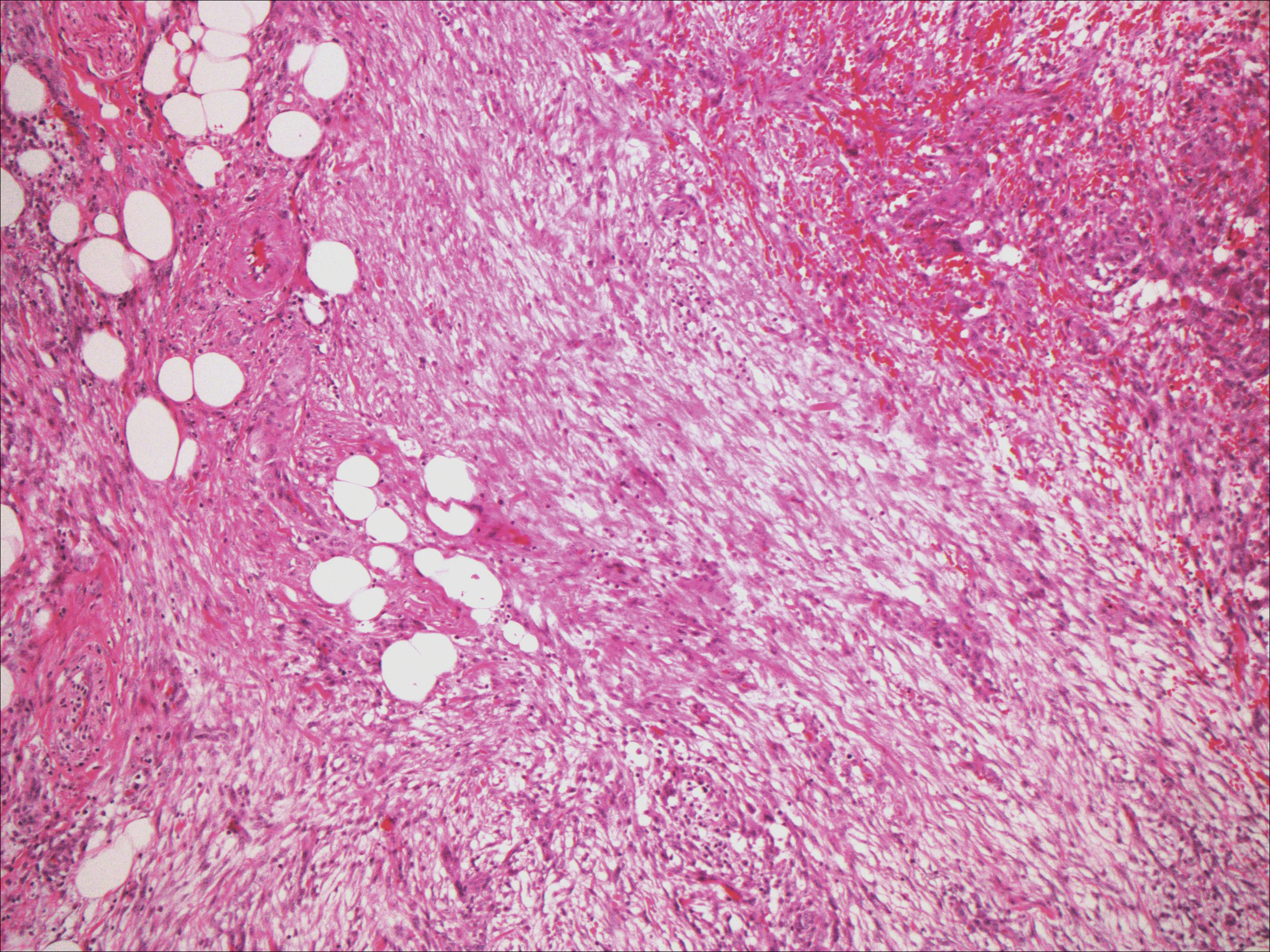

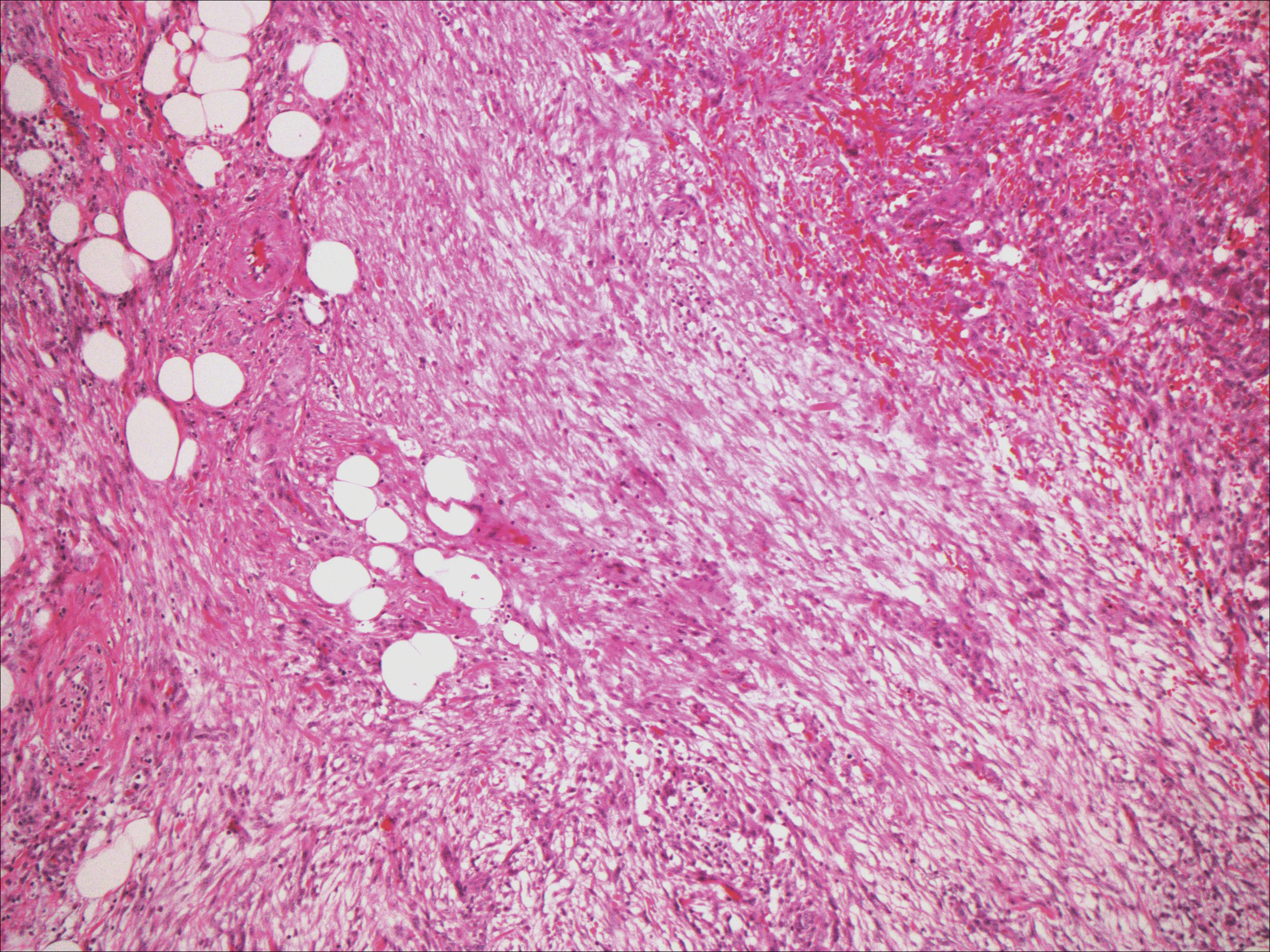

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

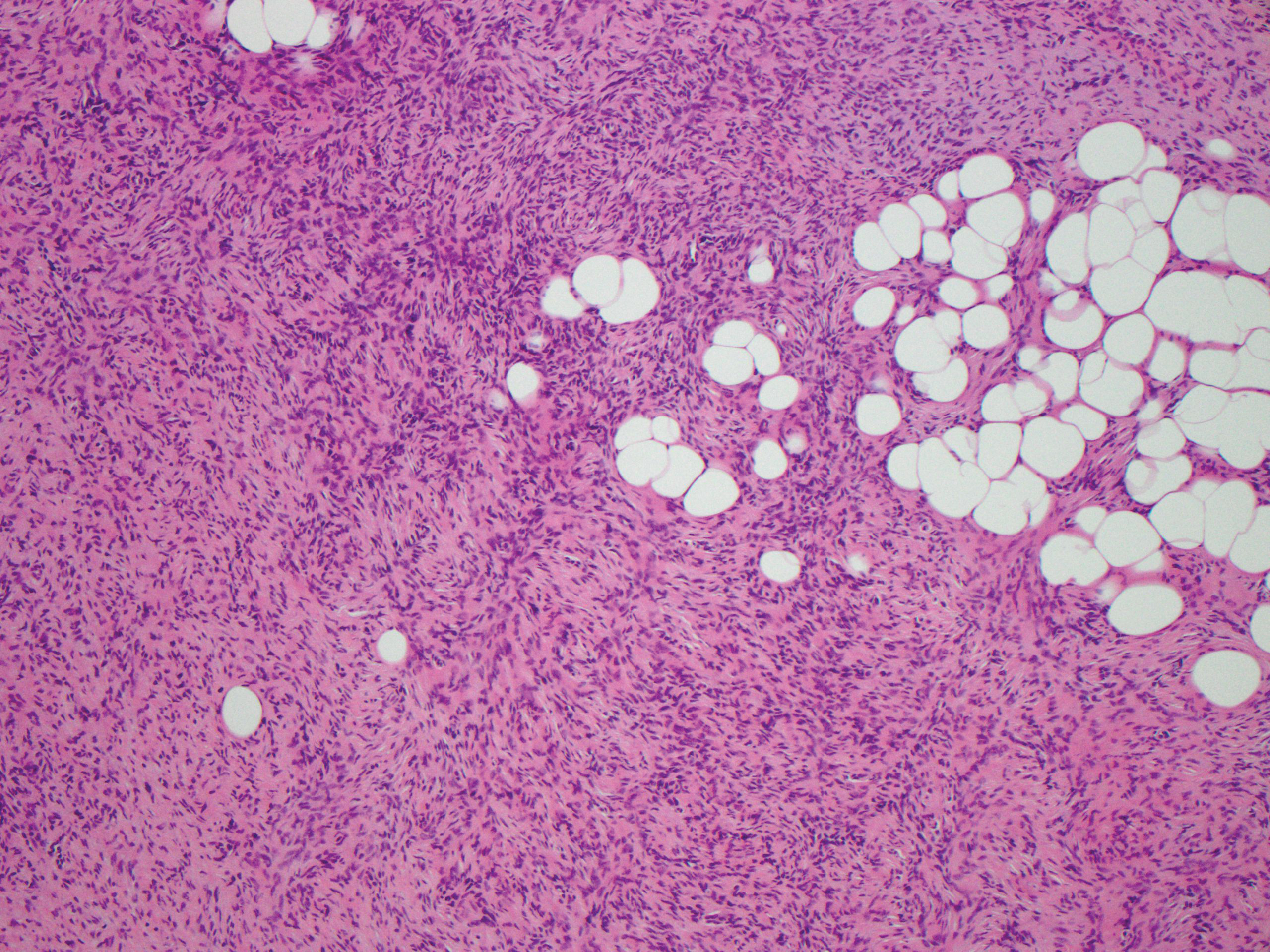

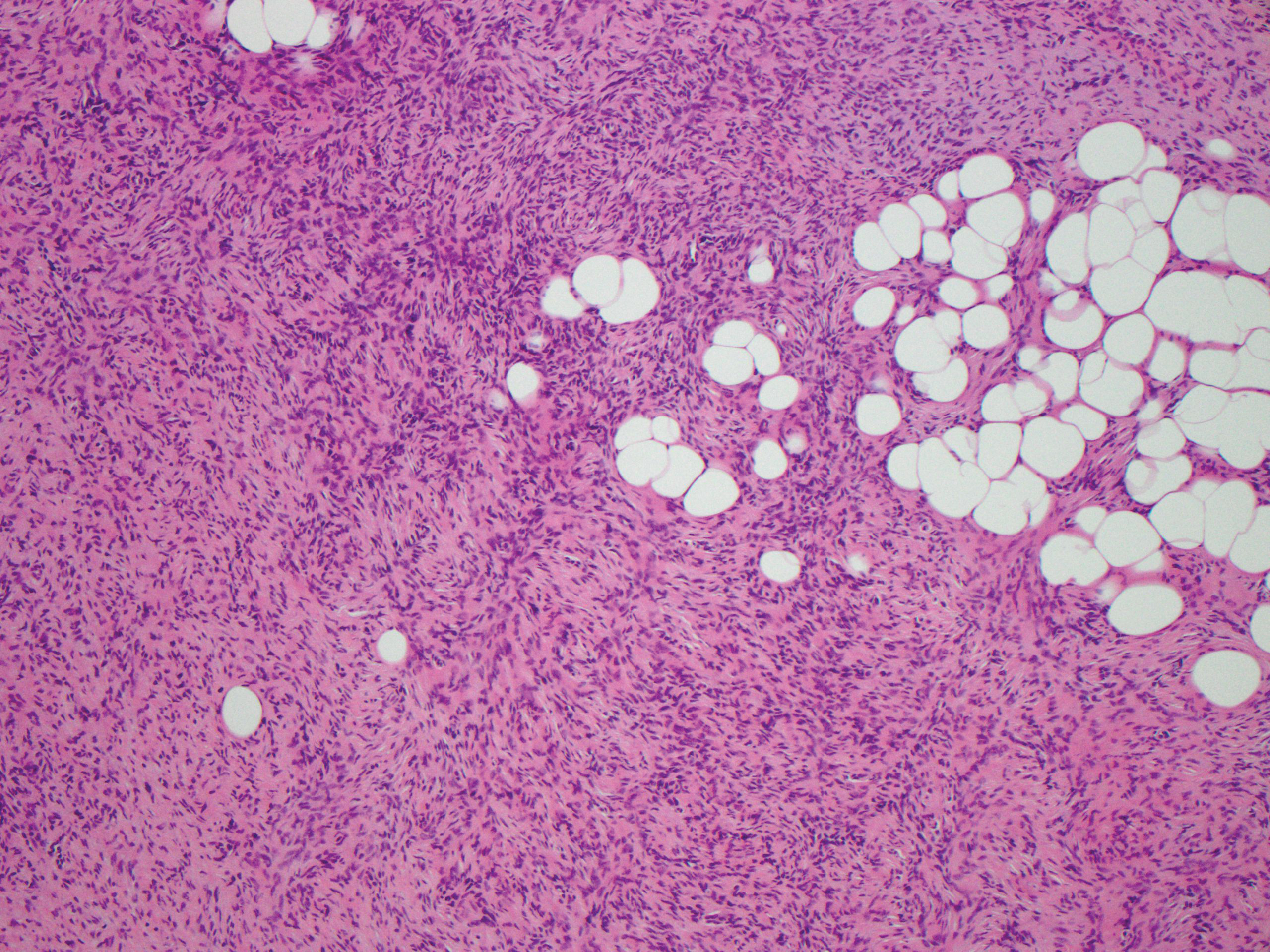

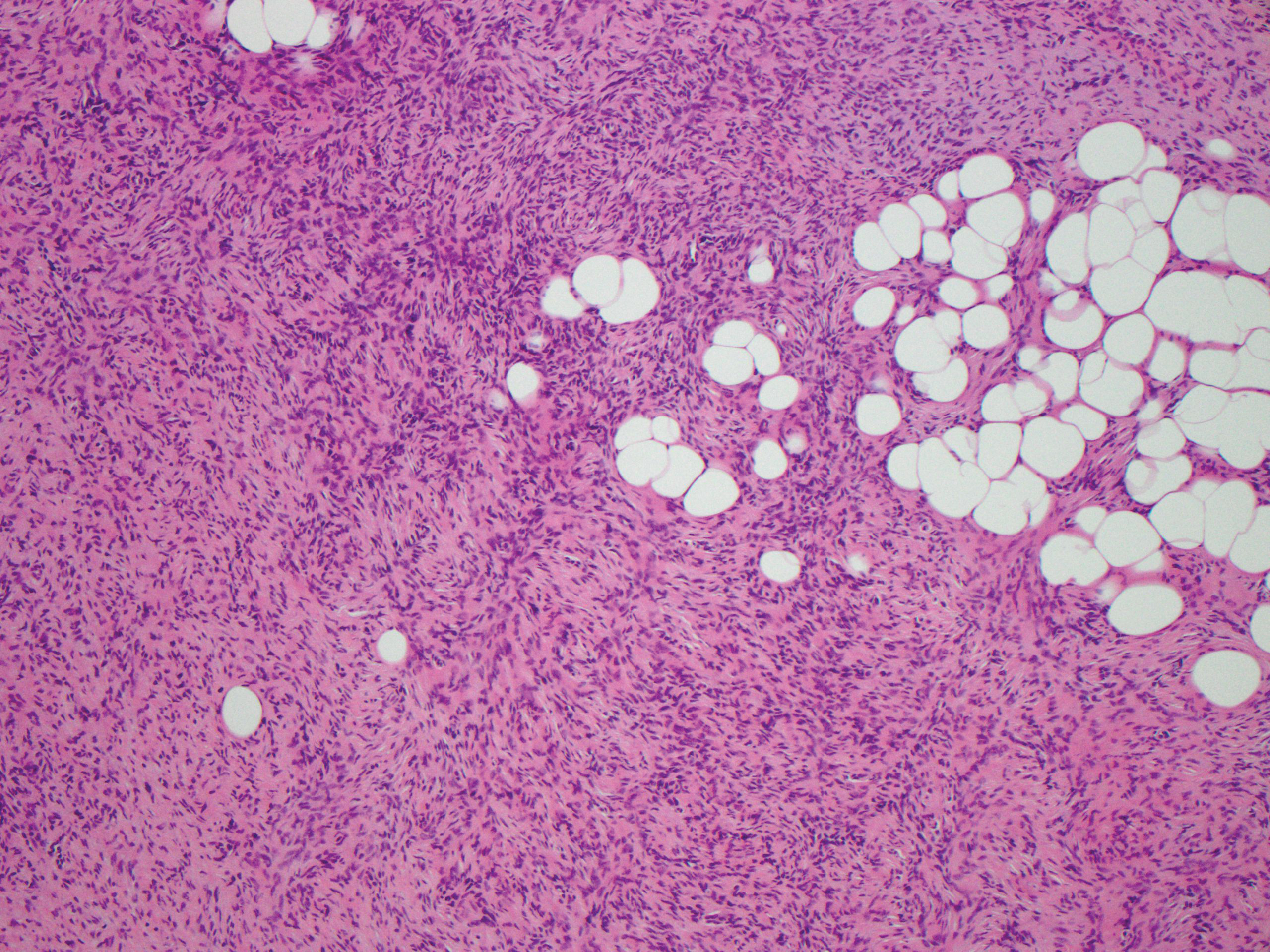

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

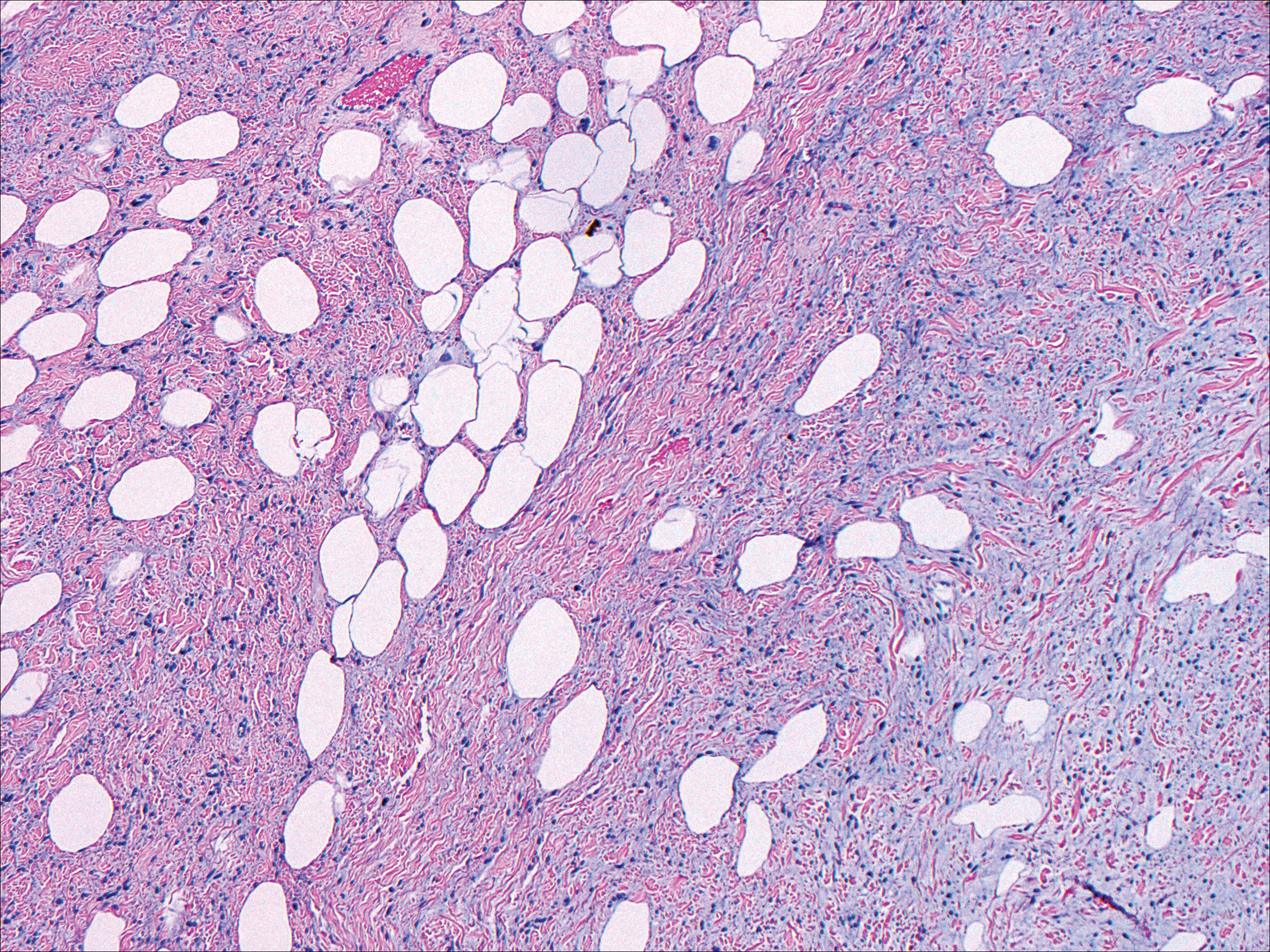

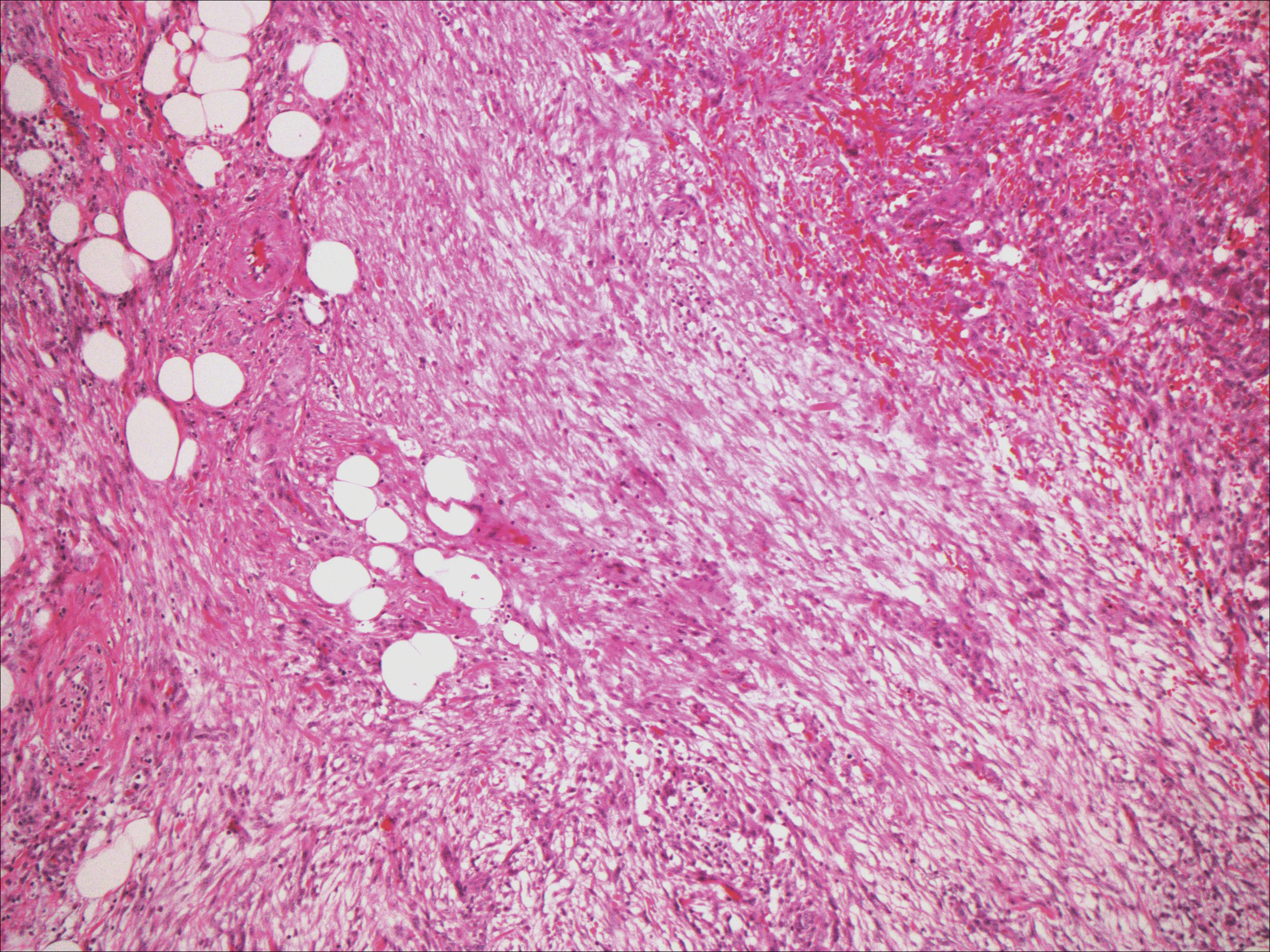

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

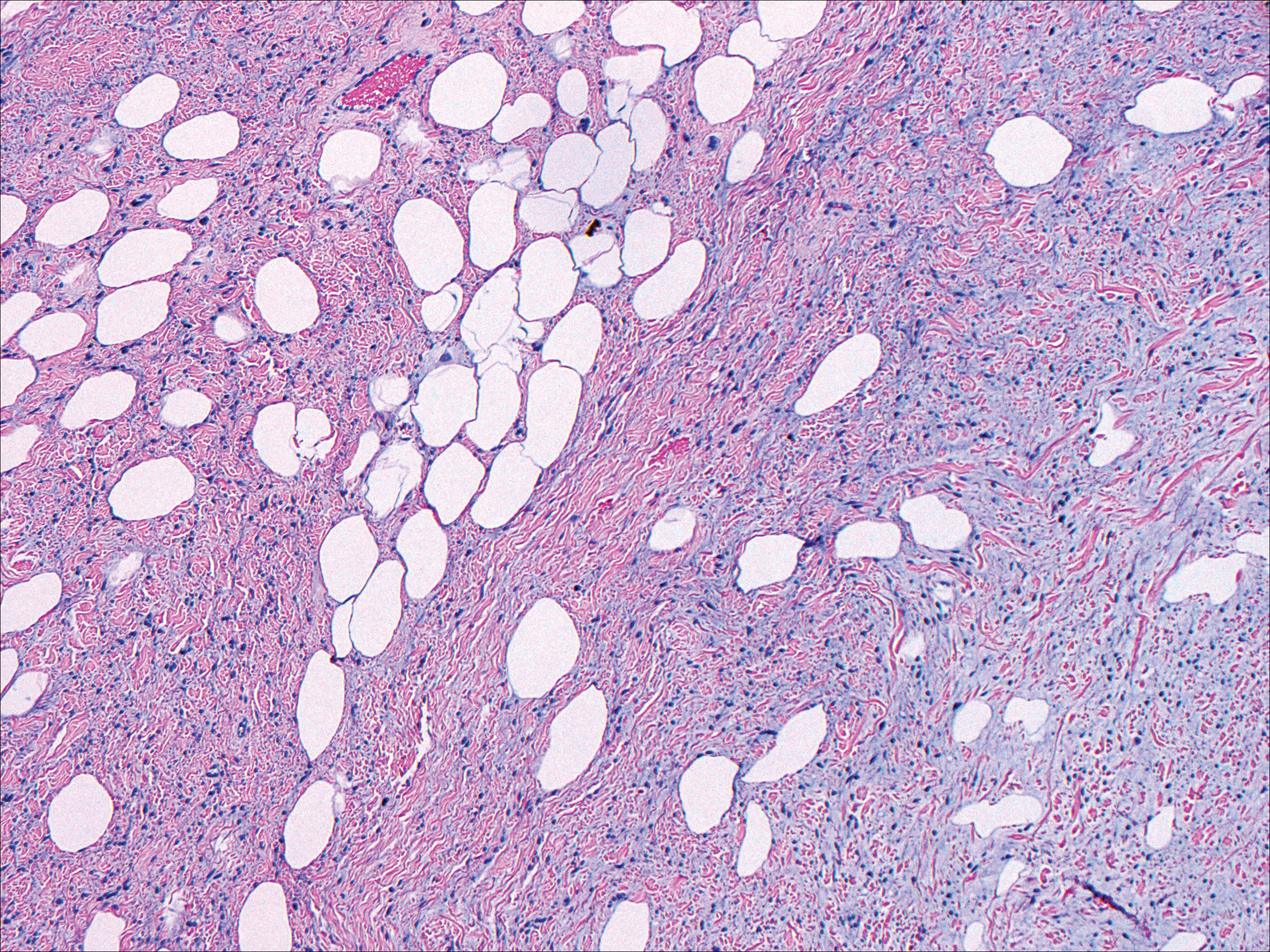

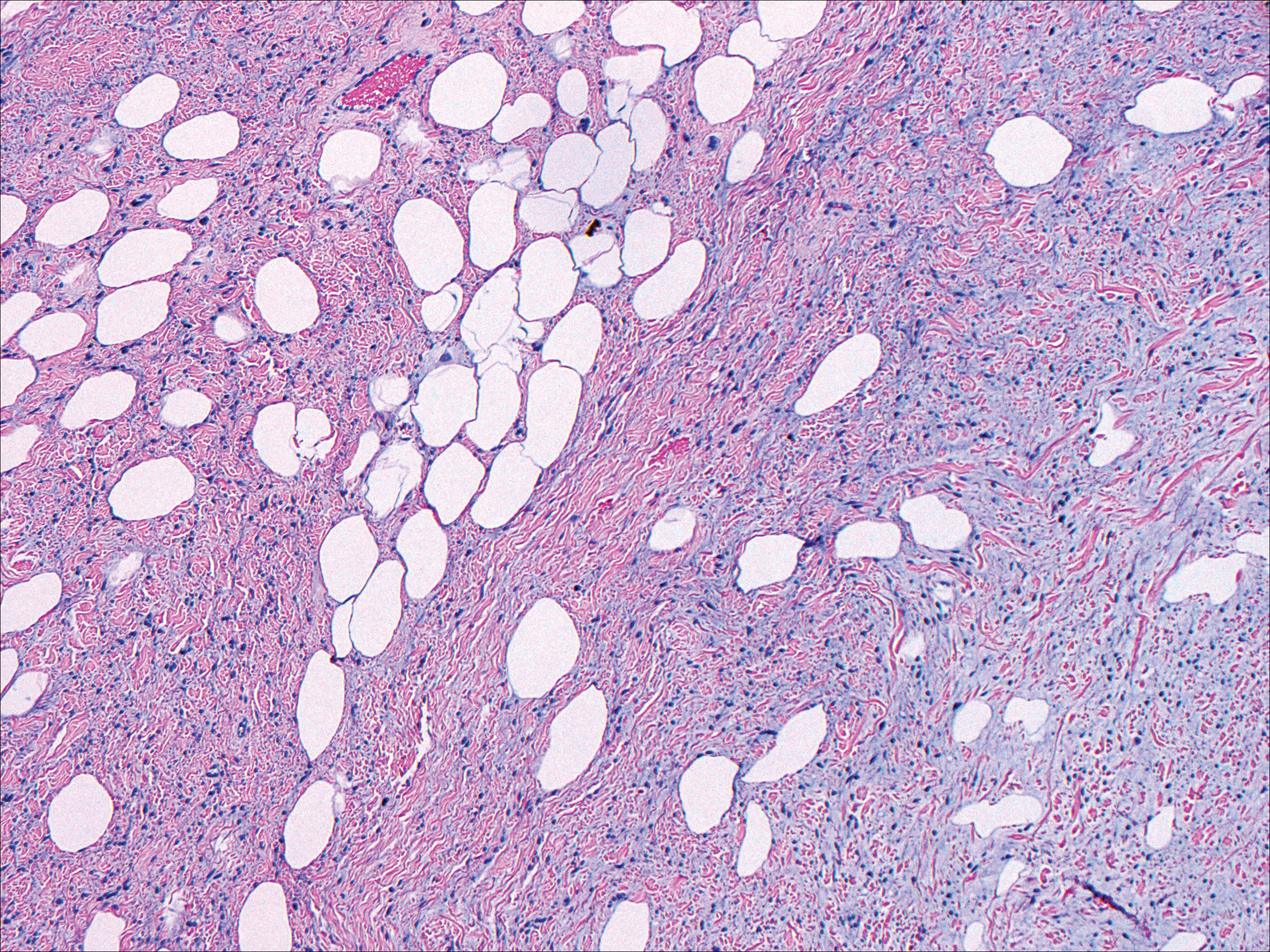

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs), as first described by Klemperer and Rabin1 in 1931, are relatively uncommon mesenchymal neoplasms that occur primarily in the pleura. This lesion is now known to affect many other extrathoracic sites, such as the liver, kidney, adrenal glands, thyroid, central nervous system, and soft tissue, with rare examples originating from the skin.2 Okamura et al3 reported the first known case of cutaneous SFT in 1997, with most of the literature limited to case reports. Erdag et al2 described one of the largest case series of primary cutaneous SFTs. These lesions can occur across a wide age range but tend to primarily affect middle-aged adults. Solitary fibrous tumors have been known to have no sex predilection; however, Erdag et al2 found a male predominance with a male to female ratio of 4 to 1.

Histopathologically, a cutaneous SFT is known to appear as a well-circumscribed nodular spindle cell proliferation arranged in interlacing fascicles with an abundant hyalinized collagen stroma (quiz image). Alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas can be seen. Supporting vasculature often is relatively prominent, represented by angulated and branching staghorn blood vessels (Figure 1).2 A common histopathologic finding of SFTs is a patternless pattern, which suggests that the tumor can have a variety of morphologic appearances (eg, storiform, fascicular, neural, herringbone growth patterns), making histologic diagnosis difficult (quiz image).4 Therefore, immunohistochemistry plays a large role in the diagnosis of this tumor. The most important positive markers include CD34, CD99, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6).5 Nuclear STAT6 staining is an immunomarker for NGFI-A binding protein 2 (NAB2)-STAT6 gene fusion, which is specific for SFT.5,6 Vivero et al7 also reported glutamate receptor, inotropic, AMPA 2 (GRIA2) as a useful immunostain in SFT, though it is also expressed in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP). In this case, the clinical and histopathologic findings best supported a diagnosis of SFT. Some consider hemangiopericytomas to be examples of SFTs; however, true hemangiopericytomas lack the thick hyalinized collagen and hypercellular areas seen in SFT.

A cellular dermatofibroma generally presents as a single round, reddish brown papule or nodule approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter that is firm to palpation with a central depression or dimple created over the lesion from the lateral pressure. Cellular dermatofibromas mostly occur in middle-aged adults, with the most common locations on the legs and on the sides of the trunk. They are thought to arise after injuries to the skin. On histopathologic examination, cellular dermatofibromas typically exhibit a proliferation of fibrohistiocytic cells with collagen trapping, often at the periphery of the tumor (Figure 2). Although cellular dermatofibromas appear clinically different than SFTs, they often mimic SFTs histopathologically. Immunostaining also can be helpful in differentiating cellular dermatofibromas in which cells stain positive for factor XIIIa. CD34 staining is negative.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans usually appears as one or multiple firm, red to violaceous nodules or plaques. They most often occur on the trunk in middle-aged adults. Histopathologically, DFSP presents with a dense, hypercellular, spindle cell proliferation that demonstrates a typical storiform pattern. The tumor generally infiltrates into the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose layer with characteristic adipocyte entrapment (Figure 3). Positive CD34 and negative factor XIIIa staining helps to differentiate DFSP from a cellular dermatofibroma. Immunohistochemically, it is more difficult to distinguish DFSP from SFT, as both are CD34+ spindle cell neoplasms that also stain positive for CD99 and BCL-2.2 GRIA2 positivity also is seen in both SFT and DFSP.7 However, differentiation can be made on morphologic grounds alone, as DFSP has ill-defined tumor borders with adnexal and fat entrapment and SFT tends to be more circumscribed with prominent arborizing hyalinized vessels.8

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is an asymptomatic subcutaneous tumor commonly located on the back, neck, and shoulders in older patients, typically men. It often presents as a solitary lesion, though multiple lesions may occur. It is a well-circumscribed tumor of mature adipose tissue with areas of spindle cell proliferation and ropey collagen bundles (Figure 4). In early lesions, the spindle cell areas are myxoid with the presence of many mast cells.9 The spindle cells stain positive for CD34. Although spindle cell lipoma would be included in both the clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis for SFT, its histopathologic features often are enough to differentiate SCL, which is highlighted by the aforementioned features as well as a relatively low cellularity and lack of ectatic vessels.8 However, discerning tumor variants, such as low-fat pseudoangiomatous SCL and lipomatous or myxoid SFT, might prove more challenging.

Nodular fasciitis typically presents as a rapidly growing subcutaneous nodule that may be tender. It is a benign reactive process usually affecting the arms and trunk of young to middle-aged adults, though it commonly involves the head and neck region in children.10 The tumor histopathologically appears as a well-circumscribed subcutaneous or fascial nodule with an angulated appearance. Spindle-shaped and stellate fibroblasts are loosely arranged in an edematous myxomatous stroma with a feathered appearance (Figure 5). Extravasated erythrocytes often are present. With time, collagen bundles become thicker and hyalinized. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for vimentin, calponin, muscle-specific actin, and smooth muscle actin. Desmin, CD34, cytokeratin, and S-100 typically are negative.10-12 Therefore, CD34 staining is one of the main differentiating factors between nodular fasciitis and SFTs.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385-412.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Okamura JM, Barr RJ, Battifora H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:515-518.

- Lee JY, Park SE, Shin SJ, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor with myxoid stromal change. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:570-573.

- Geramizadeh B, Marzban M, Churg A. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumor, a review. Iran J Pathol. 2016;11:195-293.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Dorpe JV. Histopathologically malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the skin: a report of an unusual case. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:629-631.

- Vivero M, Doyle LA, Fletcher CD, et al. GRIA2 is a novel diagnostic marker for solitary fibrous tumour identified through gene expression profiling. Histopathology. 2014;65:71-80.

- Wood L, Fountaine TJ, Rosamilia L, et al. Cutaneous CD34 spindle cell neoplasms: histopathologic features distinguish spindle cell lipoma, solitary fibrous tumor, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:764-768.

- Khatib Y, Khade AL, Shah VB, et al. Cytohistological features of spindle cell lipoma--a case report with differential diagnosis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:10-11.

- Kumar E, Patel NR, Demicco EG, et al. Cutaneous nodular fasciitis with genetic analysis: a case series. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1143-1149.

- Bracey TS, Wharton S, Smith ME. Nodular 'fasciitis' presenting as a cutaneous polyp. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:980-982.

- Perez-Montiel MD, Plaza JA, Dominguez-Malagon H, et al. Differential expression of smooth muscle myosin, smooth muscle actin, h-caldesmon, and calponin in the diagnosis of myofibroblastic and smooth muscle lesions of skin and soft tissue. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:105-111.

A 73-year-old man presented with a tender nodule on the back that had recently increased in size. On physical examination, a solitary 4-cm nodule was noted in the right trapezius region. The patient denied any personal or family history of similar lesions or a penchant for cysts. Due to the symptomatic nature of the lesion, surgical excision was performed.

Verrucoid Lesion on the Eyelid

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

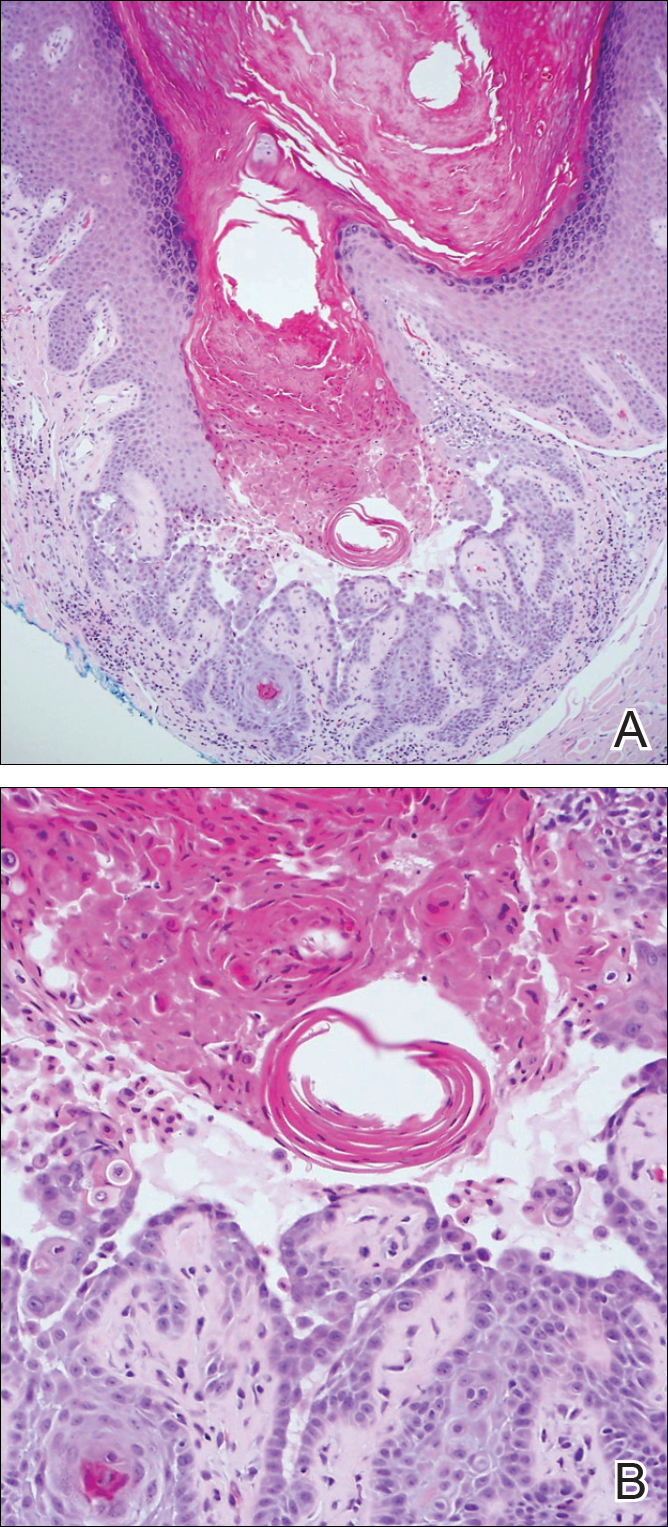

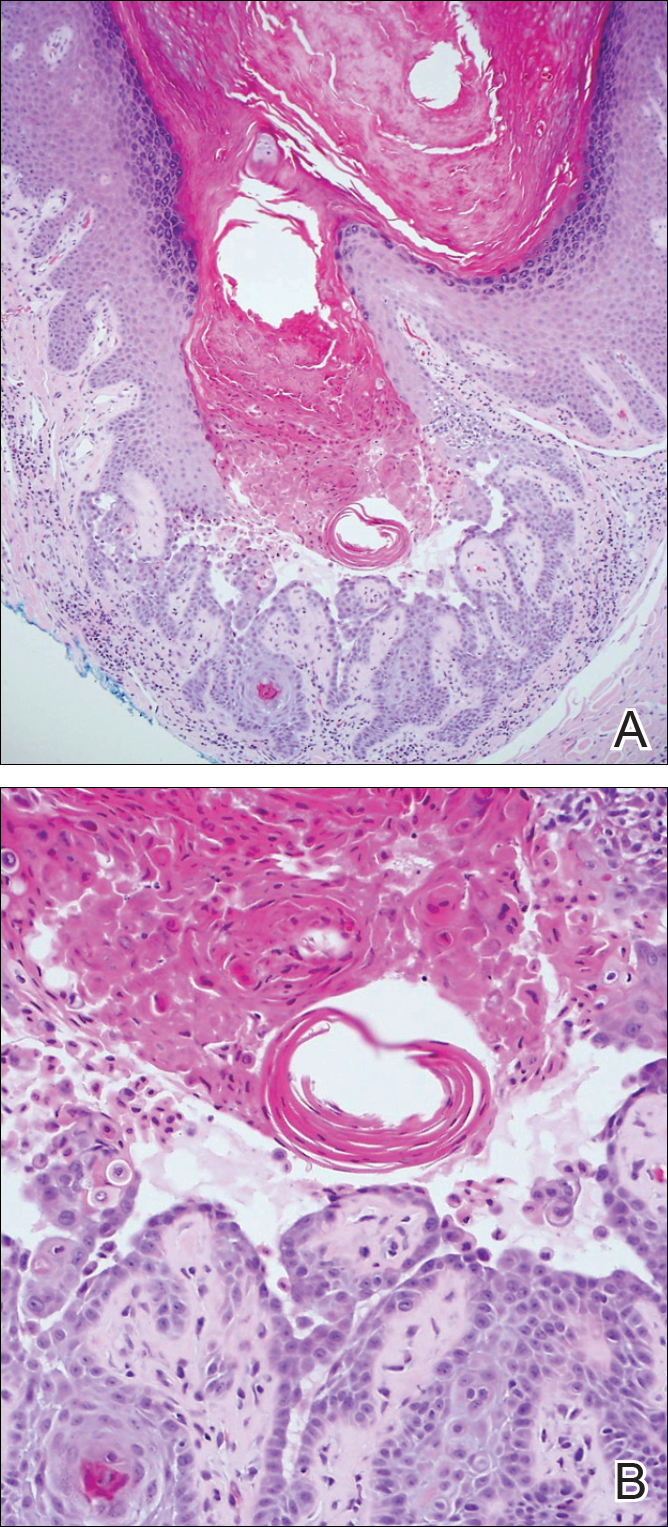

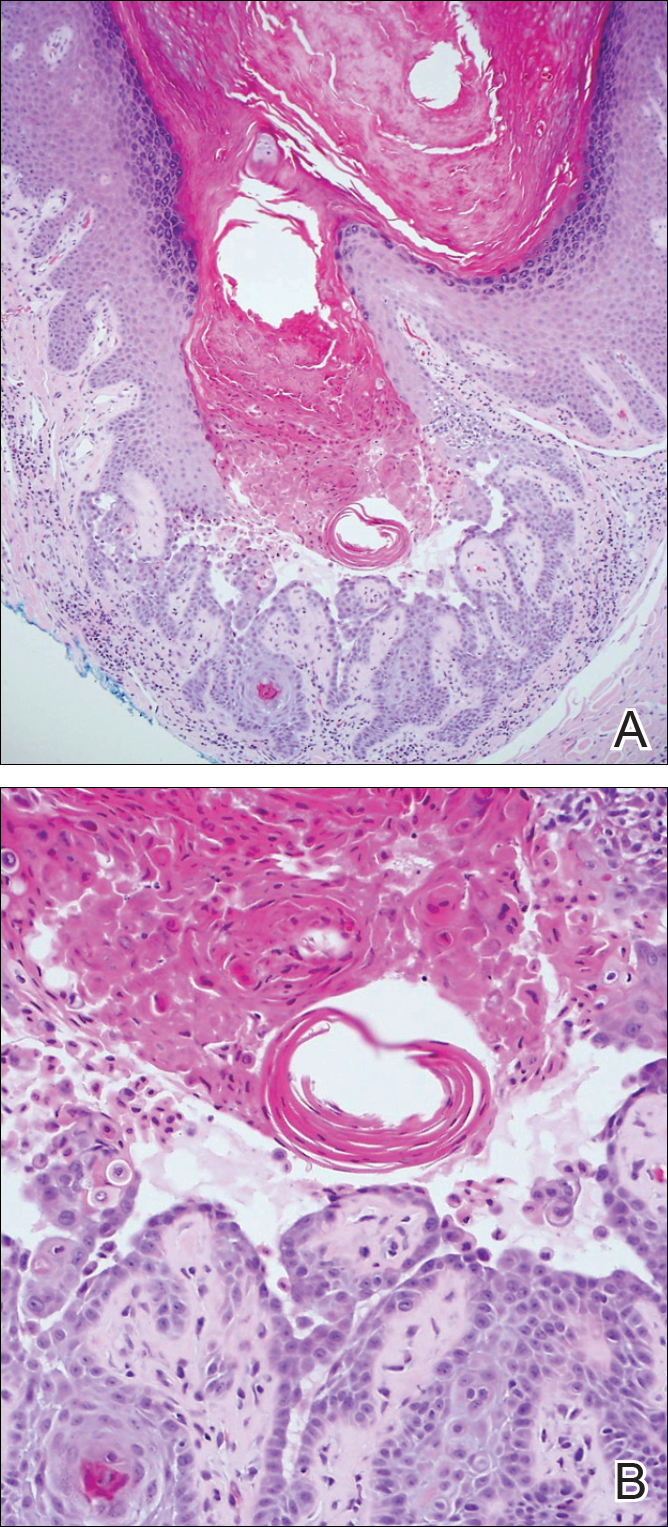

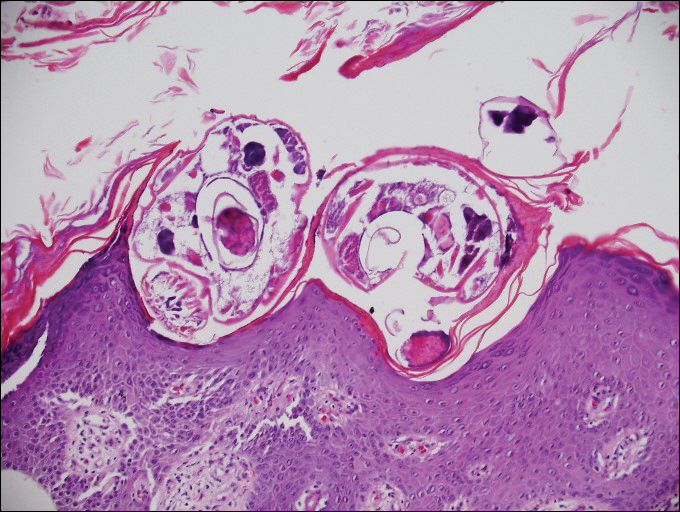

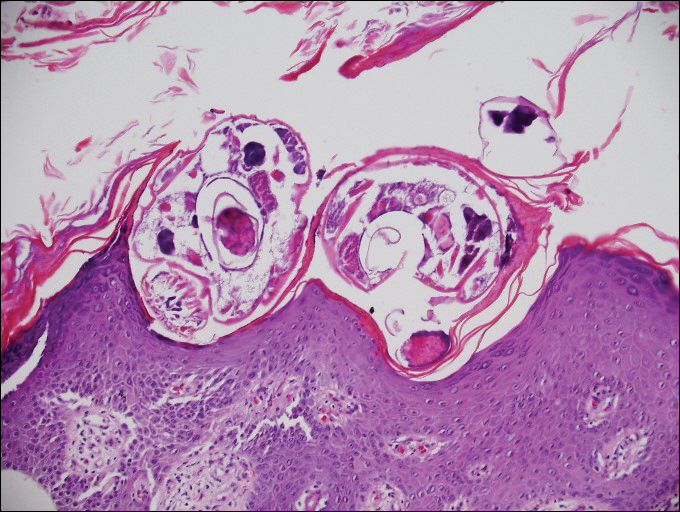

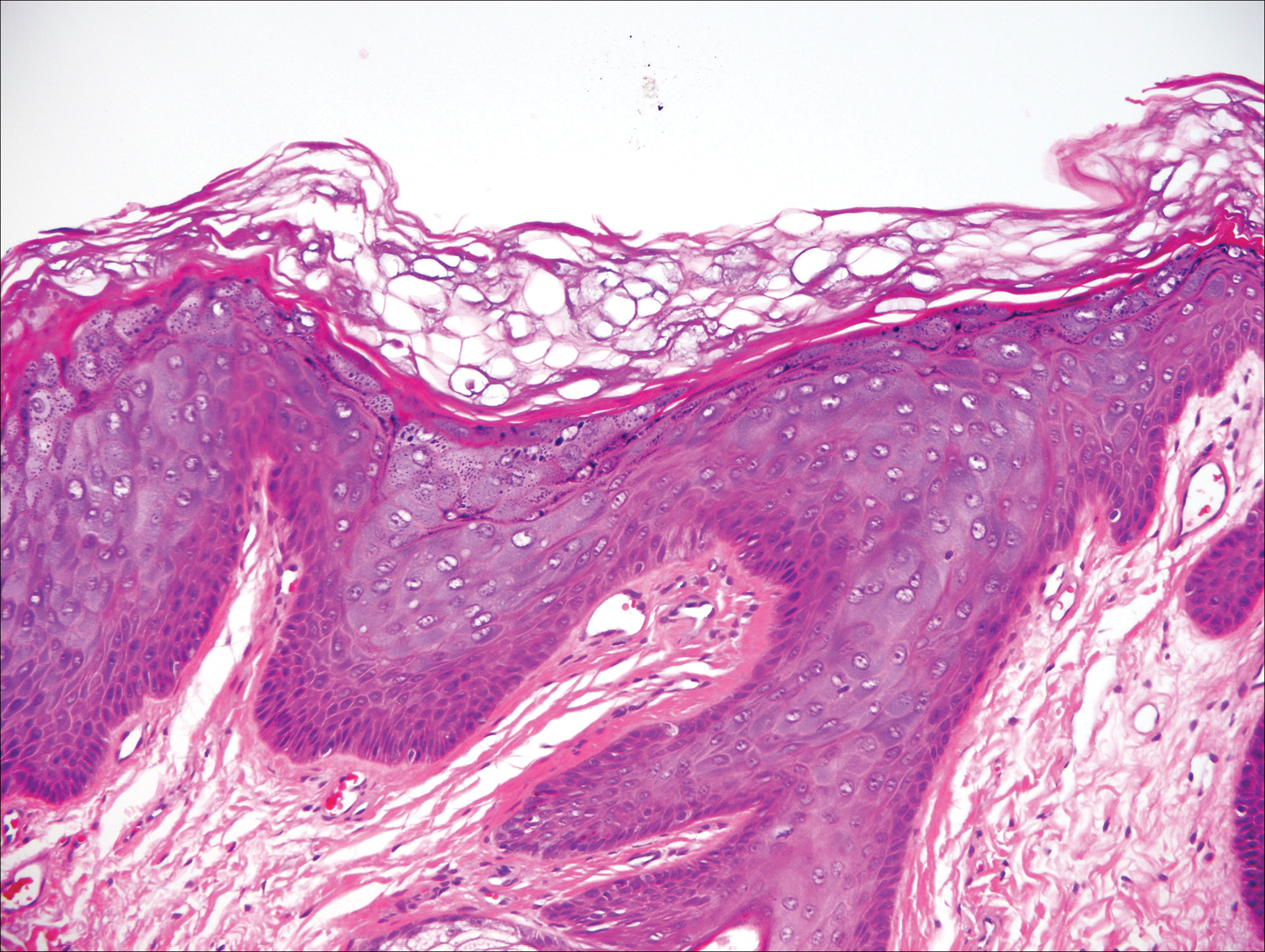

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.

Trichilemmoma is an endophytic benign neoplasm derived from the outer sheath of the pilosebaceous follicle characterized by lobules of clear cells hanging from the epidermis.7 A study investigating the relationship between HPV and trichilemmomas failed to definitively detect HPV in trichilemmomas and this relationship remains unclear.8 Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is a subtype histologically characterized by jagged islands of epithelial cells separated by dense pink stroma and encased in a glassy basement membrane (Figure 2). The presence of desmoplasia and a jagged growth pattern can mimic invasive SCC, but the absence of cytologic atypia and the surrounding basement membrane differs from SCC.4,7 Trichilemmomas typically are solitary, but multiple lesions are associated with Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the presence of benign hamartomas and a predisposition to the development of malignancies including breast, endometrial, and thyroid cancers.9,10 There is no such association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.11

Pilar sheath acanthoma is a benign neoplasm that clinically presents as a solitary flesh-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratin.12 Histologically, pilar sheath acanthoma is similar to a dilated pore of Winer with the addition of acanthotic epidermal projections (Figure 3).

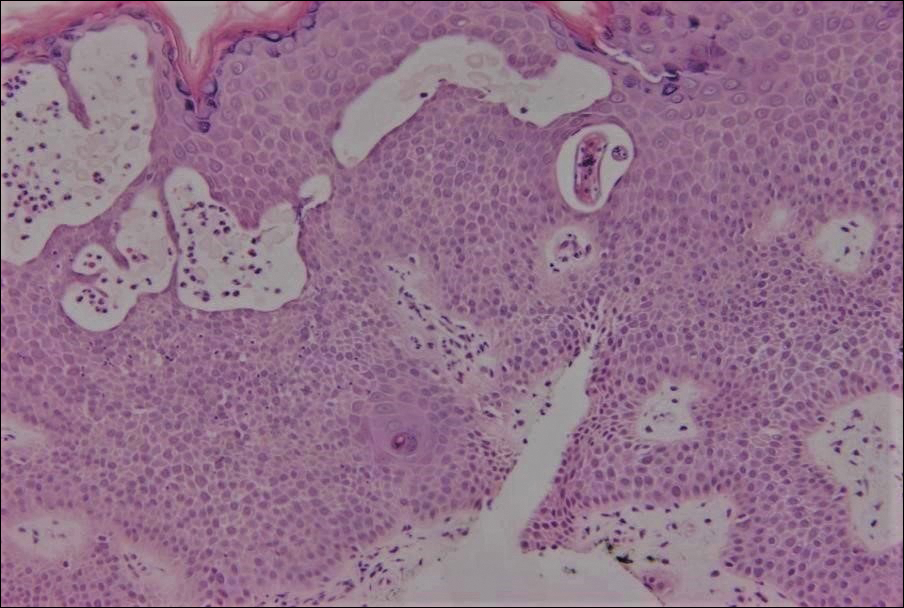

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign endophytic neoplasm traditionally seen as a solitary lesion histologically similar to Darier disease. Warty dyskeratomas are known to occur both on the skin and oral mucosa.13 Histologically, WD is characterized as a cup-shaped lesion with numerous villi at the base of the lesion along with acantholysis and dyskeratosis (Figure 4). The dyskeratotic cells in WD consist of corps ronds, which are cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, and small nuclei along with grains, which are flattened basophilic cells. These dyskeratotic cells help differentiate WD from IFK. Although they are endophytic neoplasms, WDs are well circumscribed and should not be confused with SCC. Despite this entity's name and histologic similarity to verrucae, no relationship with HPV has been established.14

- Ruhoy SM, Thomas D, Nuovo GJ. Multiple inverted follicular keratoses as a presenting sign of Cowden's syndrome: case report with human papillomavirus studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:411-415.

- Lever WF. Inverted follicular keratosis is an irritated seborrheic keratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:474.

- Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, et al. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid may not be detected in non-genital benign papillomatous skin lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:334-338.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- Ogawa T, Kiuru M, Konia TH, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma is usually associated with hair follicles, not acantholytic actinic keratosis, and is not "high risk": diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes in a series of 115 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:327-333.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Sano DT, Yang JJ, Tebcherani AJ, et al. A rare clinical presentation of desmoplastic trichilemmoma mimicking invasive carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:796-798.

- Stierman S, Chen S, Nuovo G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus infection in trichilemmomas and verrucae using in situ hybridization. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:75-80.

- Ngeow J, Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: clinical risk assessment and management protocol [published online October 22, 2014]. Methods. 2015;77-78:11-19.

- Molvi M, Sharma YK, Dash K. Cowden syndrome: case report, update and proposed diagnostic and surveillance routines. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:255-259.

- Jin M, Hampel H, Pilarski R, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog immunohistochemical staining and clinical criteria for Cowden syndrome in patients with trichilemmoma or associated lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:637-640.

- Mehregan AH, Brownstein MH. Pilar sheath acanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1495-1497.

- Newland JR, Leventon GS. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. correlated light and electron microscopic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:176-183.

- Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma--"follicular dyskeratoma": analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.

Trichilemmoma is an endophytic benign neoplasm derived from the outer sheath of the pilosebaceous follicle characterized by lobules of clear cells hanging from the epidermis.7 A study investigating the relationship between HPV and trichilemmomas failed to definitively detect HPV in trichilemmomas and this relationship remains unclear.8 Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is a subtype histologically characterized by jagged islands of epithelial cells separated by dense pink stroma and encased in a glassy basement membrane (Figure 2). The presence of desmoplasia and a jagged growth pattern can mimic invasive SCC, but the absence of cytologic atypia and the surrounding basement membrane differs from SCC.4,7 Trichilemmomas typically are solitary, but multiple lesions are associated with Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the presence of benign hamartomas and a predisposition to the development of malignancies including breast, endometrial, and thyroid cancers.9,10 There is no such association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.11

Pilar sheath acanthoma is a benign neoplasm that clinically presents as a solitary flesh-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratin.12 Histologically, pilar sheath acanthoma is similar to a dilated pore of Winer with the addition of acanthotic epidermal projections (Figure 3).

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign endophytic neoplasm traditionally seen as a solitary lesion histologically similar to Darier disease. Warty dyskeratomas are known to occur both on the skin and oral mucosa.13 Histologically, WD is characterized as a cup-shaped lesion with numerous villi at the base of the lesion along with acantholysis and dyskeratosis (Figure 4). The dyskeratotic cells in WD consist of corps ronds, which are cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, and small nuclei along with grains, which are flattened basophilic cells. These dyskeratotic cells help differentiate WD from IFK. Although they are endophytic neoplasms, WDs are well circumscribed and should not be confused with SCC. Despite this entity's name and histologic similarity to verrucae, no relationship with HPV has been established.14

The Diagnosis: Inverted Follicular Keratosis

The differential diagnosis for endophytic squamous neoplasms encompasses benign and malignant entities. The histologic findings of our patient's lesion were compatible with the diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis (IFK), a benign neoplasm that usually presents as a keratotic papule on the head or neck. Histologically, IFK is characterized by an endophytic growth pattern with squamous eddies (quiz images). Inverted follicular keratosis may represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis or a distinct neoplasm derived from the infundibular portion of the hair follicle; the exact etiology is uncertain.1,2 No relationship between IFK and human papillomavirus (HPV) has been established.3 Inverted follicular keratosis can mimic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Important clues to the diagnosis of IFK are the presence of squamous eddies and the lack of squamous pearls or cytologic atypia.4 Squamous eddies consist of whorled keratinocytes without keratinization or atypia. Superficial shave biopsies may fail to demonstrate the characteristic well-circumscribed architecture and may lead to an erroneous diagnosis.

Acantholytic SCC is characterized by atypical keratinocytes that have lost cohesive properties, resulting in acantholysis (Figure 1).5 This histologic variant was once categorized as an aggressive variant of SCC, but studies have failed to support this assertion.5,6 Acantholytic SCC has a discohesive nature producing a pseudoglandular appearance sometimes mistaken for adenosquamous carcinoma or metastatic carcinoma. Recent literature has suggested that acantholytic SCCs, similar to IFKs, are derived from the follicular infundibulum.5,6 Also similar to IFKs, acantholytic SCCs often are located on the face. The invasive architecture and atypical cytology of acantholytic SCCs can differentiate them from IFKs. Acantholytic SCCs can contain keratin pearls with concentric keratinocytes showing incomplete keratinization centrally, often with retained nuclei, but rare to no squamous eddies unless irritated.

Trichilemmoma is an endophytic benign neoplasm derived from the outer sheath of the pilosebaceous follicle characterized by lobules of clear cells hanging from the epidermis.7 A study investigating the relationship between HPV and trichilemmomas failed to definitively detect HPV in trichilemmomas and this relationship remains unclear.8 Desmoplastic trichilemmoma is a subtype histologically characterized by jagged islands of epithelial cells separated by dense pink stroma and encased in a glassy basement membrane (Figure 2). The presence of desmoplasia and a jagged growth pattern can mimic invasive SCC, but the absence of cytologic atypia and the surrounding basement membrane differs from SCC.4,7 Trichilemmomas typically are solitary, but multiple lesions are associated with Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the presence of benign hamartomas and a predisposition to the development of malignancies including breast, endometrial, and thyroid cancers.9,10 There is no such association with desmoplastic trichilemmomas.11

Pilar sheath acanthoma is a benign neoplasm that clinically presents as a solitary flesh-colored nodule with a central pore containing keratin.12 Histologically, pilar sheath acanthoma is similar to a dilated pore of Winer with the addition of acanthotic epidermal projections (Figure 3).

Warty dyskeratoma (WD) is a benign endophytic neoplasm traditionally seen as a solitary lesion histologically similar to Darier disease. Warty dyskeratomas are known to occur both on the skin and oral mucosa.13 Histologically, WD is characterized as a cup-shaped lesion with numerous villi at the base of the lesion along with acantholysis and dyskeratosis (Figure 4). The dyskeratotic cells in WD consist of corps ronds, which are cells with abundant pink cytoplasm, and small nuclei along with grains, which are flattened basophilic cells. These dyskeratotic cells help differentiate WD from IFK. Although they are endophytic neoplasms, WDs are well circumscribed and should not be confused with SCC. Despite this entity's name and histologic similarity to verrucae, no relationship with HPV has been established.14

- Ruhoy SM, Thomas D, Nuovo GJ. Multiple inverted follicular keratoses as a presenting sign of Cowden's syndrome: case report with human papillomavirus studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:411-415.

- Lever WF. Inverted follicular keratosis is an irritated seborrheic keratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:474.

- Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, et al. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid may not be detected in non-genital benign papillomatous skin lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:334-338.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- Ogawa T, Kiuru M, Konia TH, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma is usually associated with hair follicles, not acantholytic actinic keratosis, and is not "high risk": diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes in a series of 115 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:327-333.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Sano DT, Yang JJ, Tebcherani AJ, et al. A rare clinical presentation of desmoplastic trichilemmoma mimicking invasive carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:796-798.

- Stierman S, Chen S, Nuovo G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus infection in trichilemmomas and verrucae using in situ hybridization. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:75-80.

- Ngeow J, Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: clinical risk assessment and management protocol [published online October 22, 2014]. Methods. 2015;77-78:11-19.

- Molvi M, Sharma YK, Dash K. Cowden syndrome: case report, update and proposed diagnostic and surveillance routines. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:255-259.

- Jin M, Hampel H, Pilarski R, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog immunohistochemical staining and clinical criteria for Cowden syndrome in patients with trichilemmoma or associated lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:637-640.

- Mehregan AH, Brownstein MH. Pilar sheath acanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1495-1497.

- Newland JR, Leventon GS. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. correlated light and electron microscopic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:176-183.

- Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma--"follicular dyskeratoma": analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

- Ruhoy SM, Thomas D, Nuovo GJ. Multiple inverted follicular keratoses as a presenting sign of Cowden's syndrome: case report with human papillomavirus studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:411-415.

- Lever WF. Inverted follicular keratosis is an irritated seborrheic keratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:474.

- Kambiz KH, Kaveh D, Maede D, et al. Human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid may not be detected in non-genital benign papillomatous skin lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:334-338.

- Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DC, et al. Simulators of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation [published online June 25, 2013]. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

- Ogawa T, Kiuru M, Konia TH, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma is usually associated with hair follicles, not acantholytic actinic keratosis, and is not "high risk": diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes in a series of 115 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:327-333.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Sano DT, Yang JJ, Tebcherani AJ, et al. A rare clinical presentation of desmoplastic trichilemmoma mimicking invasive carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:796-798.

- Stierman S, Chen S, Nuovo G, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus infection in trichilemmomas and verrucae using in situ hybridization. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:75-80.

- Ngeow J, Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: clinical risk assessment and management protocol [published online October 22, 2014]. Methods. 2015;77-78:11-19.

- Molvi M, Sharma YK, Dash K. Cowden syndrome: case report, update and proposed diagnostic and surveillance routines. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:255-259.

- Jin M, Hampel H, Pilarski R, et al. Phosphatase and tensin homolog immunohistochemical staining and clinical criteria for Cowden syndrome in patients with trichilemmoma or associated lesions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:637-640.

- Mehregan AH, Brownstein MH. Pilar sheath acanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1495-1497.

- Newland JR, Leventon GS. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. correlated light and electron microscopic study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58:176-183.

- Kaddu S, Dong H, Mayer G, et al. Warty dyskeratoma--"follicular dyskeratoma": analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:423-428.

A 60-year-old man presented with a 3-mm verrucous papule on the right upper eyelid of 2 years' duration.

Orange Nodules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare histiocytic proliferative disorder of unknown etiology. It has 2 forms: limited cutaneous and systemic. The systemic form, also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, affects the lymph nodes and other organs at times. The disease is characterized by a proliferation of histiocytes in the lymph nodes, most commonly in the cervical basin1; however, the inguinal, axillary, mediastinal, or para-aortic nodes also may be affected.1,2 The skin is the most common site of extranodal disease, seen in approximately 10% of cases.1 Cutaneous involvement often is in the facial area but also can be found on the trunk, ears, neck, arms, legs, and genitals. Clinically, skin lesions appear as papules, plaques, and/or nodules.2

Histopathologic examination of Rosai-Dorfman disease generally shows a dense sheetlike dermal infiltrate of large polygonal histiocytes (Figure 1). Histiocytes may display pale pink or clear cytoplasm. The pathognomonic finding is emperipolesis, which consists of histiocytes with engulfed lymphocytes, erythrocytes, plasma cells, and/or granulocytes surrounded by a clear halo. Immunohistochemical staining also is characteristic, with lesional histiocytes showing expression of S-100 protein (Figure 1, inset) and CD68. The associated inflammatory infiltrate is mixed, containing primarily plasma cells but also lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.

Blastomycosis (Figure 2) is a systemic infection due to inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia. Primary infection occurs in the lungs, and with dissemination the skin is the most common subsequently involved organ.3 Cutaneous blastomycosis shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with neutrophilic microabscesses and a dense dermal infiltrate containing suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The nonpigmented yeast phase typically is 8 to 15 µm in length with a refractile cell wall and characteristic single, broad-based budding.3

Granuloma faciale (Figure 3) is a rare disease with unknown etiology characterized by reddish brown plaques or nodules most commonly occurring on the face.4,5 Histology shows a dense nodular dermal infiltrate with a grenz zone. The infiltrate is mixed, containing mostly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis and eosinophils. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present with associated extravasated erythrocytes. In chronic fibrosing granuloma faciale, lesions can demonstrate fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition, similar to erythema elevatum diutinum.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma (Figure 4) is a common histiocytic disease of early childhood, though adult cases have been reported.6 Tumors are found on the head and trunk and are typically firm, reddish yellow papules or nodules.6,7 Histologic examination shows a nodular infiltrate of foamy histiocytes in the superficial dermis. Touton-type multinucleated giant cells with a peripheral rim of xanthomatized foamy cytoplasm and a wreathlike arrangement of nuclei are characteristic. Associated eosinophils are seen. No emperipolesis is present.

Reticulohistiocytoma (Figure 5) is a benign dermal lesion that presents as solitary or less commonly multiple red-brown papules or nodules.8 Lesions consist of well-delineated nodular aggregates of histiocytes containing a finely granular eosinophilic ground glass cytoplasm. Few, if any, eosinophils are found. The lack of Touton multinucleated giant cells or emperipolesis and lack of expression of S-100 protein helps to distinguish reticulohistiocytoma from other entities in the differential diagnosis.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

- Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman R. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease): review of the entity. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:19-73.

- Kutlubay Z, Bairamov O, Sevim A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report with nodal and cutaneous involvement and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:353-357.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra AP. Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyrí J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Tanz WS, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. Cutis. 1994;54:241-245.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatology Online J. 2014;20. pii:doj_21725.

A 59-year-old man presented with itchy and mildly painful nodules on the head and neck of 7 months' duration. The patient denied fever, chills, unintentional weight loss, night sweats, and other systemic symptoms. Physical examination revealed multiple firm pink-orange nodules of varying sizes distributed on the scalp, face, and neck. Right-sided, painless, bulky cervical lymphadenopathy also was noted. An incisional biopsy was performed.

Pruritic Eruption on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Grover Disease

Grover disease (also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis) was first described by Ralph W. Grover in 1970 as an idiopathic, acquired, monomorphous, papulovesicular eruption. Although originally characterized by solely transient acantholytic dermatosis, over time the term Grover disease has been expanded to include persistent acantholytic dermatoses. Grover disease chiefly affects white adults older than 40 years and is more prevalent in males than females. Cases generally are self-limited but correlate with age, as older adults are more likely to have prolonged eruptions.1

Grover disease typically erupts with discrete, erythematous, edematous, acneform, red-brown or flesh-colored papules, papulovesicles, or keratotic papules that primarily are seen on the trunk and anterior portion of the chest. As the rash spreads, it can erupt on the neck and thighs. The etiology of Grover disease is unknown, but many factors have been associated with the condition in a limited number of patients, including exposure to UV radiation, excessive heat or sweating, use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and recombinant human IL-4, and infection with Malassezia furfur and Demodex folliculorum.1 Grover disease also has been associated with other conditions such as asteatotic eczema, allergic contact dermatitis, and atopic dermatitis.2

Histologically, Grover disease (Figure 1) is an acantholytic process that can exhibit dyskeratosis (corps ronds and grains). Foci often are small and multiple foci are seen on shave biopsy. There also may be spongiotic changes when associated with an eczematous element. A perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with eosinophils usually is seen.3 Basket weave keratin may be seen; however, as the lesions cause pruritus, erosions and ulcerations often are present.4

Grover disease has multiple histologic variants that may resemble Darier disease, Hailey-Hailey disease, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, and spongiotic dermatitis and can present in combination.5

The variant of Grover disease that has a Darier-like pattern is difficult to distinguish from Darier disease, an autosomal-dominant-inherited disorder classified by small papules that emerge in seborrheic areas during childhood and adolescence. Histologically, Darier disease (Figure 2) shows broad areas of dyskeratosis and acantholysis that lead to suprabasal cleavage. Follicular extension may be present. In addition, there often is prominent vertical parakeratosis in Darier disease.6 Histologic features that favor Darier disease over the Darier-like variant of Grover disease include a broad focus of acanthotic dyskeratosis with follicular extension; the presence of a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum; and a lack of spongiosis and eosinophils, which are notably absent in Darier disease but may be present in Grover disease.4

Another variant of Grover disease has a Hailey-Hailey-like pattern, which is characterized by Hailey-Hailey disease's dilapidated brick wall appearance or the diffuse suprabasal acantholysis of all epidermal layers without notable dyskeratosis.4 Hailey-Hailey disease, also known as familial benign pemphigus, is an autosomal-dominant disorder that presents with erythematous vesicular plaques in flexural areas. The plaques progress to flaccid bullae with rupture and crusting and spread peripherally.7 Pathology shows suprabasilar clefts and numerous acantholytic cells (Figure 3). Dyskeratotic keratinocytes are rare with infrequent corps ronds and rare grains. The epidermis also is less hyperplastic in Grover disease than in Hailey-Hailey disease.1