User login

CDC: Contact lens wearers must be careful to avoid risk, burden of keratitis

Nearly 1 million visits to physicians’ offices, outpatient clinics, and emergency departments occur every year that are directly related to keratitis or other contact lens–related disorders, at a cost of millions of dollars in direct health care expenditures, according to a new study released Nov. 14 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Here at CDC, we’ve long suspected that keratitis poses a significant burden on Americans’ health and on our health care system, both in individual cases and in periodic, multistate outbreaks associated with contact lens wearers,” Dr. Jennifer Cope, a CDC medical epidemiologist, said in a telebriefing. “But until now, we didn’t have any estimates as to how large that burden might be.”

According to an analysis of 2010 data from three national ambulatory care and emergency department databases, the CDC estimated that keratitis and other contact lens–related disorders cost Americans $175 million in direct healthcare costs each year, including $58 million for Medicare patients and $12 million for Medicaid patients. Of the nearly 1 million healthcare visits related to keratitis and other contact lens–related disorders, roughly 930,000 were to physicians’ offices and outpatient clinics, while around 58,000 were to emergency departments, ultimately accounting for 250,000 clinician hours yearly (MMWR 2014:63:1027-30).

The CDC study indicated that 76.5% of keratitis-related health care visits every year result in prescriptions for antimicrobial agents. Separately, another roughly 230,000 visits to clinicians’ offices or outpatient clinics for corneal disorders every year are related to use of contact lenses, and 70% of those require antimicrobial prescriptions. In an effort to increase public awareness of contact lens disorders ahead of its “Contact Lens Health Week,” which runs from Nov. 17 to 21, the CDC is warning the nearly 38 million American contact lens wearers to practice good lens hygiene to ensure that they do not develop keratitis, which is known to lead to partial or complete loss of vision in many cases.

“Wearing contacts and not taking care of them properly is the single largest risk factor for [developing] keratitis,” said Dr. Cope. “Some bad habits, like sleeping in your contact lenses, failing to clean and replace your storage case frequently, and letting contact lenses get in water – whether you’re swimming, showering, or rinsing the lenses in water instead of in contact lens solution – greatly increase a person’s risk for developing keratitis.”

The CDC recommends washing your hands with soap and water before putting contact lenses into your eyes in order to mitigate the chances of introducing bacteria into your eyes while touching them, putting fresh contact lens solution into your storage case daily, replacing contact lens cases every 3 months, and never sleeping in your contact lenses unless explicitly advised to by your doctor.

“People who wear their contact lenses overnight are more than 20 times more likely to get keratitis,” Dr. Cope noted, adding that “Contact lenses can provide many benefits, but they are not risk-free.”

More information on the CDC’s contact lens “Wear and Care” guidelines can be found at the CDC website.

Nearly 1 million visits to physicians’ offices, outpatient clinics, and emergency departments occur every year that are directly related to keratitis or other contact lens–related disorders, at a cost of millions of dollars in direct health care expenditures, according to a new study released Nov. 14 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Here at CDC, we’ve long suspected that keratitis poses a significant burden on Americans’ health and on our health care system, both in individual cases and in periodic, multistate outbreaks associated with contact lens wearers,” Dr. Jennifer Cope, a CDC medical epidemiologist, said in a telebriefing. “But until now, we didn’t have any estimates as to how large that burden might be.”

According to an analysis of 2010 data from three national ambulatory care and emergency department databases, the CDC estimated that keratitis and other contact lens–related disorders cost Americans $175 million in direct healthcare costs each year, including $58 million for Medicare patients and $12 million for Medicaid patients. Of the nearly 1 million healthcare visits related to keratitis and other contact lens–related disorders, roughly 930,000 were to physicians’ offices and outpatient clinics, while around 58,000 were to emergency departments, ultimately accounting for 250,000 clinician hours yearly (MMWR 2014:63:1027-30).

The CDC study indicated that 76.5% of keratitis-related health care visits every year result in prescriptions for antimicrobial agents. Separately, another roughly 230,000 visits to clinicians’ offices or outpatient clinics for corneal disorders every year are related to use of contact lenses, and 70% of those require antimicrobial prescriptions. In an effort to increase public awareness of contact lens disorders ahead of its “Contact Lens Health Week,” which runs from Nov. 17 to 21, the CDC is warning the nearly 38 million American contact lens wearers to practice good lens hygiene to ensure that they do not develop keratitis, which is known to lead to partial or complete loss of vision in many cases.

“Wearing contacts and not taking care of them properly is the single largest risk factor for [developing] keratitis,” said Dr. Cope. “Some bad habits, like sleeping in your contact lenses, failing to clean and replace your storage case frequently, and letting contact lenses get in water – whether you’re swimming, showering, or rinsing the lenses in water instead of in contact lens solution – greatly increase a person’s risk for developing keratitis.”

The CDC recommends washing your hands with soap and water before putting contact lenses into your eyes in order to mitigate the chances of introducing bacteria into your eyes while touching them, putting fresh contact lens solution into your storage case daily, replacing contact lens cases every 3 months, and never sleeping in your contact lenses unless explicitly advised to by your doctor.

“People who wear their contact lenses overnight are more than 20 times more likely to get keratitis,” Dr. Cope noted, adding that “Contact lenses can provide many benefits, but they are not risk-free.”

More information on the CDC’s contact lens “Wear and Care” guidelines can be found at the CDC website.

Nearly 1 million visits to physicians’ offices, outpatient clinics, and emergency departments occur every year that are directly related to keratitis or other contact lens–related disorders, at a cost of millions of dollars in direct health care expenditures, according to a new study released Nov. 14 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Here at CDC, we’ve long suspected that keratitis poses a significant burden on Americans’ health and on our health care system, both in individual cases and in periodic, multistate outbreaks associated with contact lens wearers,” Dr. Jennifer Cope, a CDC medical epidemiologist, said in a telebriefing. “But until now, we didn’t have any estimates as to how large that burden might be.”

According to an analysis of 2010 data from three national ambulatory care and emergency department databases, the CDC estimated that keratitis and other contact lens–related disorders cost Americans $175 million in direct healthcare costs each year, including $58 million for Medicare patients and $12 million for Medicaid patients. Of the nearly 1 million healthcare visits related to keratitis and other contact lens–related disorders, roughly 930,000 were to physicians’ offices and outpatient clinics, while around 58,000 were to emergency departments, ultimately accounting for 250,000 clinician hours yearly (MMWR 2014:63:1027-30).

The CDC study indicated that 76.5% of keratitis-related health care visits every year result in prescriptions for antimicrobial agents. Separately, another roughly 230,000 visits to clinicians’ offices or outpatient clinics for corneal disorders every year are related to use of contact lenses, and 70% of those require antimicrobial prescriptions. In an effort to increase public awareness of contact lens disorders ahead of its “Contact Lens Health Week,” which runs from Nov. 17 to 21, the CDC is warning the nearly 38 million American contact lens wearers to practice good lens hygiene to ensure that they do not develop keratitis, which is known to lead to partial or complete loss of vision in many cases.

“Wearing contacts and not taking care of them properly is the single largest risk factor for [developing] keratitis,” said Dr. Cope. “Some bad habits, like sleeping in your contact lenses, failing to clean and replace your storage case frequently, and letting contact lenses get in water – whether you’re swimming, showering, or rinsing the lenses in water instead of in contact lens solution – greatly increase a person’s risk for developing keratitis.”

The CDC recommends washing your hands with soap and water before putting contact lenses into your eyes in order to mitigate the chances of introducing bacteria into your eyes while touching them, putting fresh contact lens solution into your storage case daily, replacing contact lens cases every 3 months, and never sleeping in your contact lenses unless explicitly advised to by your doctor.

“People who wear their contact lenses overnight are more than 20 times more likely to get keratitis,” Dr. Cope noted, adding that “Contact lenses can provide many benefits, but they are not risk-free.”

More information on the CDC’s contact lens “Wear and Care” guidelines can be found at the CDC website.

FROM MMWR

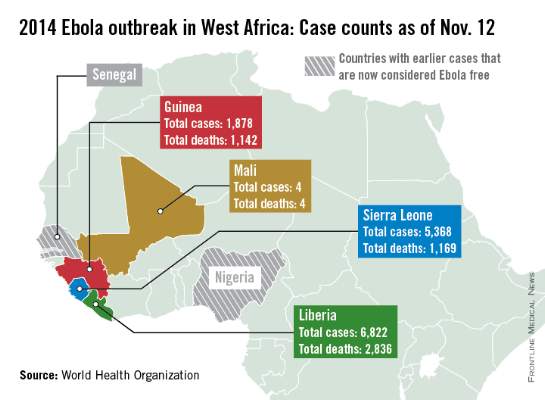

Ebola outbreak in Mali expands to capital

New cases in Mali, unrelated to the initial Ebola case in the country, have been reported in the capital city of Bamako, according to a report from the World Health Organization.

Four Ebola patients were reported in Mali as of Nov. 11; all have died. The new outbreak started on Nov. 10 with a nurse who treated an imam who traveled to Mali from Guinea and died of undiagnosed kidney failure, a common symptom of Ebola. The nurse was isolated and Ebola was confirmed, but the nurse died the next day. A friend of the imam who visited him in Bamako also died suddenly, and is suspected to have had Ebola, the WHO said.

There were over 14,000 reported cases of Ebola in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia as of Nov. 9, with nearly half in Liberia, which has reported more than 6,800 cases and over 2,800 deaths. The reported decline in cases in Liberia has stabilized, and a reversal is possible, according to the WHO report. Guinea has reported nearly 1,900 cases and more than 1,110 deaths; and Sierra Leone has reported over 5,350 cases and more than 1,150 deaths.

In the United States and Spain, all potential Ebola contacts have completed a 21 day follow-up; both countries should be declared Ebola-free by the end of November. While contacts in the United States have completed the follow-up, health care workers who contracted Ebola in West Africa and were moved to the U.S. continue to be treated, according to the WHO.

New cases in Mali, unrelated to the initial Ebola case in the country, have been reported in the capital city of Bamako, according to a report from the World Health Organization.

Four Ebola patients were reported in Mali as of Nov. 11; all have died. The new outbreak started on Nov. 10 with a nurse who treated an imam who traveled to Mali from Guinea and died of undiagnosed kidney failure, a common symptom of Ebola. The nurse was isolated and Ebola was confirmed, but the nurse died the next day. A friend of the imam who visited him in Bamako also died suddenly, and is suspected to have had Ebola, the WHO said.

There were over 14,000 reported cases of Ebola in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia as of Nov. 9, with nearly half in Liberia, which has reported more than 6,800 cases and over 2,800 deaths. The reported decline in cases in Liberia has stabilized, and a reversal is possible, according to the WHO report. Guinea has reported nearly 1,900 cases and more than 1,110 deaths; and Sierra Leone has reported over 5,350 cases and more than 1,150 deaths.

In the United States and Spain, all potential Ebola contacts have completed a 21 day follow-up; both countries should be declared Ebola-free by the end of November. While contacts in the United States have completed the follow-up, health care workers who contracted Ebola in West Africa and were moved to the U.S. continue to be treated, according to the WHO.

New cases in Mali, unrelated to the initial Ebola case in the country, have been reported in the capital city of Bamako, according to a report from the World Health Organization.

Four Ebola patients were reported in Mali as of Nov. 11; all have died. The new outbreak started on Nov. 10 with a nurse who treated an imam who traveled to Mali from Guinea and died of undiagnosed kidney failure, a common symptom of Ebola. The nurse was isolated and Ebola was confirmed, but the nurse died the next day. A friend of the imam who visited him in Bamako also died suddenly, and is suspected to have had Ebola, the WHO said.

There were over 14,000 reported cases of Ebola in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia as of Nov. 9, with nearly half in Liberia, which has reported more than 6,800 cases and over 2,800 deaths. The reported decline in cases in Liberia has stabilized, and a reversal is possible, according to the WHO report. Guinea has reported nearly 1,900 cases and more than 1,110 deaths; and Sierra Leone has reported over 5,350 cases and more than 1,150 deaths.

In the United States and Spain, all potential Ebola contacts have completed a 21 day follow-up; both countries should be declared Ebola-free by the end of November. While contacts in the United States have completed the follow-up, health care workers who contracted Ebola in West Africa and were moved to the U.S. continue to be treated, according to the WHO.

Number of Homeless Veterans Still Dropping

Homelessness has dropped 33% since 2010, according to a 2014 survey by the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), VA, and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). The annual Point-in-Time Count conducted in January 2014 showed there were 24,837 fewer homeless veterans, down from 49,933 in 2010.

The data also revealed a nearly 40% drop in the number of veterans sleeping on the streets. HUD, VA, USICH, and local partners have been working to get veterans off the streets and into stable housing, using evidence-based practices, such as Housing First, and federal resources, such as the HUD-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) voucher program. Since 2008, the HUD-VASH program has served nearly 75,000 veterans, “but we have more work to do,” said HUD Secretary Julián Castro in an August 26, 2014, HUD press release. “We have an obligation to ensure that every veteran has a place to call home.”

In spring 2014, First Lady Michelle Obama launched the Administration’s Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness. So far, more than 250 mayors and county and state officials have committed to the program, which helps communities pursue strategies to end veteran homelessness.

Homelessness has dropped 33% since 2010, according to a 2014 survey by the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), VA, and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). The annual Point-in-Time Count conducted in January 2014 showed there were 24,837 fewer homeless veterans, down from 49,933 in 2010.

The data also revealed a nearly 40% drop in the number of veterans sleeping on the streets. HUD, VA, USICH, and local partners have been working to get veterans off the streets and into stable housing, using evidence-based practices, such as Housing First, and federal resources, such as the HUD-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) voucher program. Since 2008, the HUD-VASH program has served nearly 75,000 veterans, “but we have more work to do,” said HUD Secretary Julián Castro in an August 26, 2014, HUD press release. “We have an obligation to ensure that every veteran has a place to call home.”

In spring 2014, First Lady Michelle Obama launched the Administration’s Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness. So far, more than 250 mayors and county and state officials have committed to the program, which helps communities pursue strategies to end veteran homelessness.

Homelessness has dropped 33% since 2010, according to a 2014 survey by the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), VA, and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH). The annual Point-in-Time Count conducted in January 2014 showed there were 24,837 fewer homeless veterans, down from 49,933 in 2010.

The data also revealed a nearly 40% drop in the number of veterans sleeping on the streets. HUD, VA, USICH, and local partners have been working to get veterans off the streets and into stable housing, using evidence-based practices, such as Housing First, and federal resources, such as the HUD-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) voucher program. Since 2008, the HUD-VASH program has served nearly 75,000 veterans, “but we have more work to do,” said HUD Secretary Julián Castro in an August 26, 2014, HUD press release. “We have an obligation to ensure that every veteran has a place to call home.”

In spring 2014, First Lady Michelle Obama launched the Administration’s Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness. So far, more than 250 mayors and county and state officials have committed to the program, which helps communities pursue strategies to end veteran homelessness.

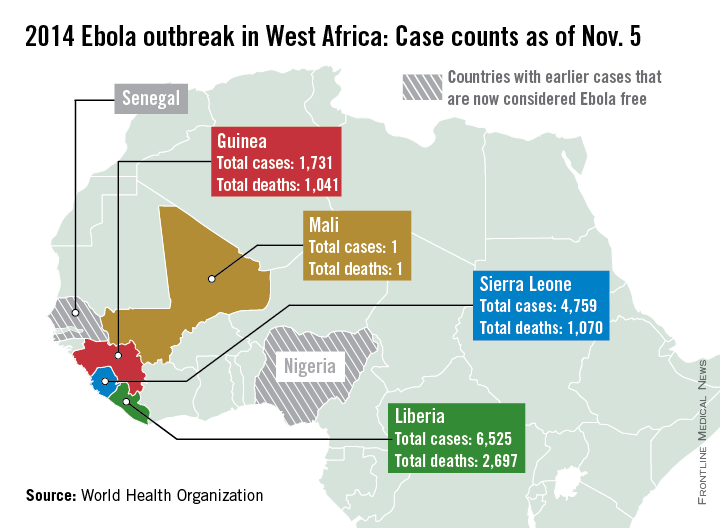

Liberia reporting fewer new Ebola cases in recent weeks

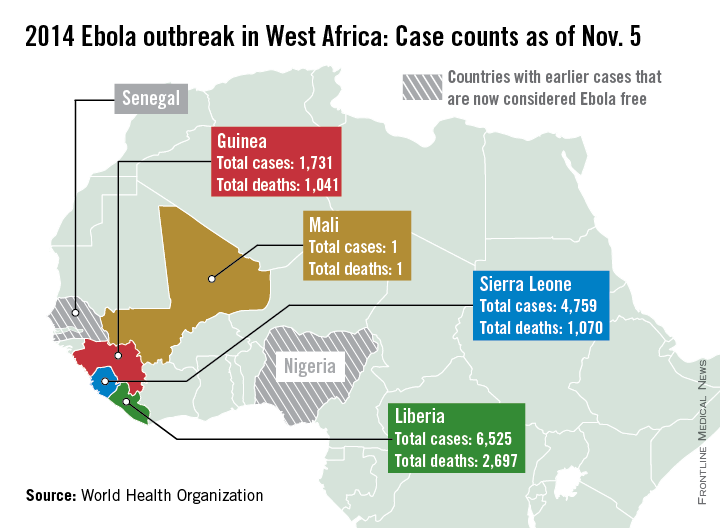

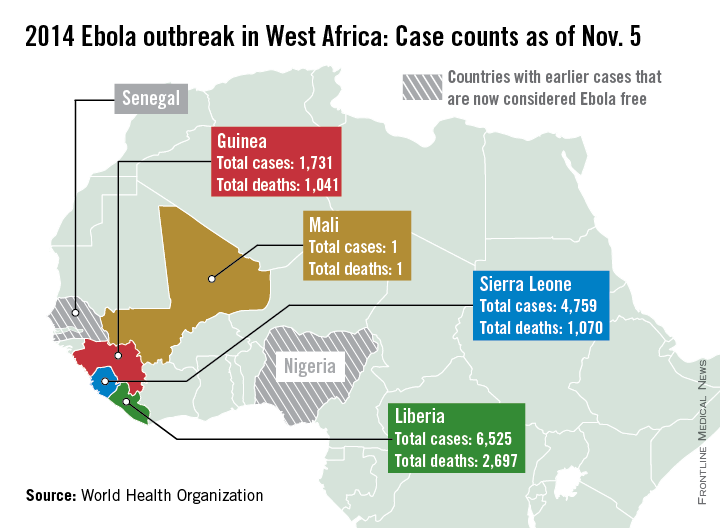

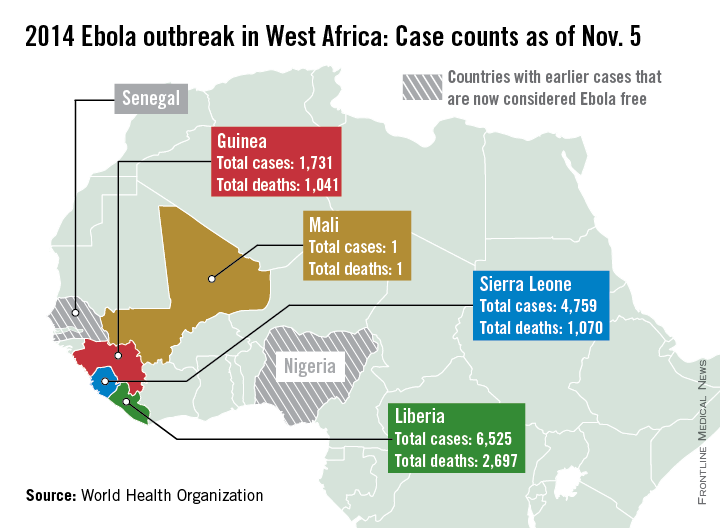

New Ebola case numbers appear to be declining in Liberia and stabilizing in Guinea, according to a report from the World Health Organization.

Only 89 new cases were reported in Liberia in the past week, considerably lower than in August and September when upward of 400 new cases were being reported weekly, the WHO reported, although data for Liberia are missing for Nov. 1 and 2. Guinea reported 93 new cases last week, slightly down from a peak in September and October; with the region of Gueckedou, the starting point of the epidemic, reporting no new cases.

Because of a change in the use of data sources, the number of cases and deaths is less than last week, the WHO explained, with just over 13,000 reported cases and about 4,800 deaths. Liberia has reported more than 6,500 cases and just under 2,700 deaths. Guinea has reported more than 1,700 cases and more than 1,000 deaths. Sierra Leone has more than 4,750 reported cases, but less than 1,100 deaths, only about 30 more than in Guinea. The reason for this is unclear, the report noted.

There have been no new reported cases of Ebola outside the outbreak area of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Mali and the United States continue to monitor potential contacts, while all contacts in Spain have completed a 21-day follow-up. Spain will be declared Ebola free 42 days from Oct. 21, the WHO reported. The unrelated Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo also appears to be over, and the country should be declared Ebola free by the end of November.

New Ebola case numbers appear to be declining in Liberia and stabilizing in Guinea, according to a report from the World Health Organization.

Only 89 new cases were reported in Liberia in the past week, considerably lower than in August and September when upward of 400 new cases were being reported weekly, the WHO reported, although data for Liberia are missing for Nov. 1 and 2. Guinea reported 93 new cases last week, slightly down from a peak in September and October; with the region of Gueckedou, the starting point of the epidemic, reporting no new cases.

Because of a change in the use of data sources, the number of cases and deaths is less than last week, the WHO explained, with just over 13,000 reported cases and about 4,800 deaths. Liberia has reported more than 6,500 cases and just under 2,700 deaths. Guinea has reported more than 1,700 cases and more than 1,000 deaths. Sierra Leone has more than 4,750 reported cases, but less than 1,100 deaths, only about 30 more than in Guinea. The reason for this is unclear, the report noted.

There have been no new reported cases of Ebola outside the outbreak area of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Mali and the United States continue to monitor potential contacts, while all contacts in Spain have completed a 21-day follow-up. Spain will be declared Ebola free 42 days from Oct. 21, the WHO reported. The unrelated Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo also appears to be over, and the country should be declared Ebola free by the end of November.

New Ebola case numbers appear to be declining in Liberia and stabilizing in Guinea, according to a report from the World Health Organization.

Only 89 new cases were reported in Liberia in the past week, considerably lower than in August and September when upward of 400 new cases were being reported weekly, the WHO reported, although data for Liberia are missing for Nov. 1 and 2. Guinea reported 93 new cases last week, slightly down from a peak in September and October; with the region of Gueckedou, the starting point of the epidemic, reporting no new cases.

Because of a change in the use of data sources, the number of cases and deaths is less than last week, the WHO explained, with just over 13,000 reported cases and about 4,800 deaths. Liberia has reported more than 6,500 cases and just under 2,700 deaths. Guinea has reported more than 1,700 cases and more than 1,000 deaths. Sierra Leone has more than 4,750 reported cases, but less than 1,100 deaths, only about 30 more than in Guinea. The reason for this is unclear, the report noted.

There have been no new reported cases of Ebola outside the outbreak area of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Mali and the United States continue to monitor potential contacts, while all contacts in Spain have completed a 21-day follow-up. Spain will be declared Ebola free 42 days from Oct. 21, the WHO reported. The unrelated Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo also appears to be over, and the country should be declared Ebola free by the end of November.

Taking a New Approach to Tribal Child Welfare

Two years ago, the Children’s Bureau launched the Roadmap for Co-Creating Collaborative & Effective Evaluation to Improve Tribal Child Welfare Programs. It’s a long title for a concise aim: to change the way child welfare is handled for tribal families.

To that end, the Children’s Bureau convened the Tribal Evaluation Workgroup in 2012. Most of the 21 members in the workgroup were tribal members, representing regions and cultural communities across the country. Focusing on the need for “fundamental change in the way evaluation is practiced within tribal contexts,” as noted in the Roadmap, they created this strategic plan to direct and manage that change.

The workgroup had found that some research and evaluation approaches were “not well aligned” with tribes’ experiences, worldviews, values, and resources. “Many Tribes,” the workgroup members noted, “can recount past experiences of having been unwilling subjects of outsiders’ research, refused access to the data collected about them, or harmed by conclusions drawn from data that were deemed more valid than their own.”

Part of the problem, the workgroup concluded, was that evaluation questions and methods failed previously to acknowledge and respect familial and community social structures, caretaking norms and traditions, cultural values, political and economic contexts, and worldviews about life, the human condition, family, permanency, well-being, and knowledge.

The Roadmap’s visual representation of overlapping and interwoven circles in its overall strategic plan is both functional and symbolic. One circle, for instance, represents the continuous cycle of program improvement through evaluation, and a larger outer circle shows how history has shaped current practice and how lessons learned can improve practice. Values such as respect for tribal sovereignty head the map. The center of it all—“Building a New Narrative”—includes locally guided questions, data, and insight.

Value 1, Indigenous Ways of Knowing, advocates using the best and most rigorous scientific methods but with an emphasis on respecting cultural protocols, such as identifying who can speak for the tribe in approving evaluation and research projects. It also acknowledges the importance of the oral tradition in gathering and disseminating information. Evaluations, the workgroup advises, should be grounded in the Native community’s ways of understanding, including the community’s unique perspective on what it means “to come to know” and how to establish research outcomes and data collection methods.

Workgroup members intend the Roadmap as a tool to facilitate discussions, partnerships, planning, policy making, and developing new ways of conducting evaluations in and with tribal communities. They suggest federal and state funders could use the Roadmap to establish more consistent and responsive evaluation requirements that promote the inclusion of tribally identified evaluation questions. Another possible use could be for tribal governments, research review boards, or Institutional Review Boards to incorporate components of the Roadmap into their guidelines for researchers and evaluators working within tribal communities.

Ultimately, the workgroup says, the goal of evaluation is to learn how to support the population’s well-being, not to test a model to export to other tribal communities. “Evaluations should tell stories that teach lessons,” they say. “Evaluation, like storytelling, is about learning.”

Two years ago, the Children’s Bureau launched the Roadmap for Co-Creating Collaborative & Effective Evaluation to Improve Tribal Child Welfare Programs. It’s a long title for a concise aim: to change the way child welfare is handled for tribal families.

To that end, the Children’s Bureau convened the Tribal Evaluation Workgroup in 2012. Most of the 21 members in the workgroup were tribal members, representing regions and cultural communities across the country. Focusing on the need for “fundamental change in the way evaluation is practiced within tribal contexts,” as noted in the Roadmap, they created this strategic plan to direct and manage that change.

The workgroup had found that some research and evaluation approaches were “not well aligned” with tribes’ experiences, worldviews, values, and resources. “Many Tribes,” the workgroup members noted, “can recount past experiences of having been unwilling subjects of outsiders’ research, refused access to the data collected about them, or harmed by conclusions drawn from data that were deemed more valid than their own.”

Part of the problem, the workgroup concluded, was that evaluation questions and methods failed previously to acknowledge and respect familial and community social structures, caretaking norms and traditions, cultural values, political and economic contexts, and worldviews about life, the human condition, family, permanency, well-being, and knowledge.

The Roadmap’s visual representation of overlapping and interwoven circles in its overall strategic plan is both functional and symbolic. One circle, for instance, represents the continuous cycle of program improvement through evaluation, and a larger outer circle shows how history has shaped current practice and how lessons learned can improve practice. Values such as respect for tribal sovereignty head the map. The center of it all—“Building a New Narrative”—includes locally guided questions, data, and insight.

Value 1, Indigenous Ways of Knowing, advocates using the best and most rigorous scientific methods but with an emphasis on respecting cultural protocols, such as identifying who can speak for the tribe in approving evaluation and research projects. It also acknowledges the importance of the oral tradition in gathering and disseminating information. Evaluations, the workgroup advises, should be grounded in the Native community’s ways of understanding, including the community’s unique perspective on what it means “to come to know” and how to establish research outcomes and data collection methods.

Workgroup members intend the Roadmap as a tool to facilitate discussions, partnerships, planning, policy making, and developing new ways of conducting evaluations in and with tribal communities. They suggest federal and state funders could use the Roadmap to establish more consistent and responsive evaluation requirements that promote the inclusion of tribally identified evaluation questions. Another possible use could be for tribal governments, research review boards, or Institutional Review Boards to incorporate components of the Roadmap into their guidelines for researchers and evaluators working within tribal communities.

Ultimately, the workgroup says, the goal of evaluation is to learn how to support the population’s well-being, not to test a model to export to other tribal communities. “Evaluations should tell stories that teach lessons,” they say. “Evaluation, like storytelling, is about learning.”

Two years ago, the Children’s Bureau launched the Roadmap for Co-Creating Collaborative & Effective Evaluation to Improve Tribal Child Welfare Programs. It’s a long title for a concise aim: to change the way child welfare is handled for tribal families.

To that end, the Children’s Bureau convened the Tribal Evaluation Workgroup in 2012. Most of the 21 members in the workgroup were tribal members, representing regions and cultural communities across the country. Focusing on the need for “fundamental change in the way evaluation is practiced within tribal contexts,” as noted in the Roadmap, they created this strategic plan to direct and manage that change.

The workgroup had found that some research and evaluation approaches were “not well aligned” with tribes’ experiences, worldviews, values, and resources. “Many Tribes,” the workgroup members noted, “can recount past experiences of having been unwilling subjects of outsiders’ research, refused access to the data collected about them, or harmed by conclusions drawn from data that were deemed more valid than their own.”

Part of the problem, the workgroup concluded, was that evaluation questions and methods failed previously to acknowledge and respect familial and community social structures, caretaking norms and traditions, cultural values, political and economic contexts, and worldviews about life, the human condition, family, permanency, well-being, and knowledge.

The Roadmap’s visual representation of overlapping and interwoven circles in its overall strategic plan is both functional and symbolic. One circle, for instance, represents the continuous cycle of program improvement through evaluation, and a larger outer circle shows how history has shaped current practice and how lessons learned can improve practice. Values such as respect for tribal sovereignty head the map. The center of it all—“Building a New Narrative”—includes locally guided questions, data, and insight.

Value 1, Indigenous Ways of Knowing, advocates using the best and most rigorous scientific methods but with an emphasis on respecting cultural protocols, such as identifying who can speak for the tribe in approving evaluation and research projects. It also acknowledges the importance of the oral tradition in gathering and disseminating information. Evaluations, the workgroup advises, should be grounded in the Native community’s ways of understanding, including the community’s unique perspective on what it means “to come to know” and how to establish research outcomes and data collection methods.

Workgroup members intend the Roadmap as a tool to facilitate discussions, partnerships, planning, policy making, and developing new ways of conducting evaluations in and with tribal communities. They suggest federal and state funders could use the Roadmap to establish more consistent and responsive evaluation requirements that promote the inclusion of tribally identified evaluation questions. Another possible use could be for tribal governments, research review boards, or Institutional Review Boards to incorporate components of the Roadmap into their guidelines for researchers and evaluators working within tribal communities.

Ultimately, the workgroup says, the goal of evaluation is to learn how to support the population’s well-being, not to test a model to export to other tribal communities. “Evaluations should tell stories that teach lessons,” they say. “Evaluation, like storytelling, is about learning.”

Bob Wachter Says Cost Equation Is Shifting in Ever-Changing Healthcare Paradigm

HM pioneer says hospitalists who have flown under radar soon will be counted on to produce cost, waste reduction.

HM pioneer says hospitalists who have flown under radar soon will be counted on to produce cost, waste reduction.

HM pioneer says hospitalists who have flown under radar soon will be counted on to produce cost, waste reduction.

Emergency Departments Monitored, Investigated by Hospital Committees, Governmental Agencies

Why is it that there are no focused looks into the ED? We all know, as hospitalists, that the ED locks us into many admissions. Yet I see no initiatives through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) going after the ED for wanting patients admitted rather than trying to get these patients sent home for outpatient therapy.

–Ray Nowaczyk, DO

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Au contraire, my fellow hospitalist! The ED is monitored and investigated by many hospital committees and governmental agencies. Although we physicians, and I’m sure most hospitals, have always acknowledged our responsibilities to take care of patients during an emergency, this responsibility was enshrined in legalese in 1986 with the passage of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), also known as the “antidumping law.” Since its passage, any hospital that receives Medicare or Medicaid funding, which includes almost all of them, is at risk of being fined or losing this vital source of funding if this law is violated.

EMTALA essentially states that any patient who presents to the ED must be provided a screening exam and treatment for any “emergent medical condition” (including labor), regardless of the individual’s ability to pay. The hospital is then required to provide “stabilizing” treatment for these patients or transfer them to another facility where this treatment can be provided. Furthermore, hospitals that refuse to accept these patients in transfer without valid reasons (e.g. no open beds) can be charged with an EMTALA violation.

As you well know, what is considered stabilized or at baseline by one clinician can be seen as unstable or requiring urgent care by another. The real day-to-day practice of medicine often defies evidence-based logic and forces us to make decisions based on many clinical and nonclinical variables.

These situations are further compounded by recent CMS attempts to hold hospitals publicly accountable for ED throughput by posting these measures on its website. Along with other metrics, the citizenry can now see how long it takes an ED patient to be seen by a health professional, receive pain medication if they have a broken bone, receive appropriate treatment and be sent home, or, if admitted, how long it takes to get into a bed.

This information makes it clearer that in situations of clinical uncertainty, it may be easier for many ED physicians to admit than to discharge. The “treat-‘em or street-‘em” mentality of triaging patients, of course, varies from doc to doc and can definitely create antipathy towards physicians in the ED. As much as I may disagree with some of our ED doc’s admissions, I always—OK, maybe not always—try to assume they have the patient’s best interest at heart.

Once admitted, the onus is placed on us, as hospitalists, to determine whether the patient requires ongoing inpatient care, can be cared for in an “observation” capacity, or should be discharged. We all have received calls from a nurse informing us that the patient “does not meet inpatient criteria”—even if the patient is hypotensive with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and lactic acidosis. Oh, if we could only send them back to the ED!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to drhospit@wiley.com.

Why is it that there are no focused looks into the ED? We all know, as hospitalists, that the ED locks us into many admissions. Yet I see no initiatives through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) going after the ED for wanting patients admitted rather than trying to get these patients sent home for outpatient therapy.

–Ray Nowaczyk, DO

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Au contraire, my fellow hospitalist! The ED is monitored and investigated by many hospital committees and governmental agencies. Although we physicians, and I’m sure most hospitals, have always acknowledged our responsibilities to take care of patients during an emergency, this responsibility was enshrined in legalese in 1986 with the passage of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), also known as the “antidumping law.” Since its passage, any hospital that receives Medicare or Medicaid funding, which includes almost all of them, is at risk of being fined or losing this vital source of funding if this law is violated.

EMTALA essentially states that any patient who presents to the ED must be provided a screening exam and treatment for any “emergent medical condition” (including labor), regardless of the individual’s ability to pay. The hospital is then required to provide “stabilizing” treatment for these patients or transfer them to another facility where this treatment can be provided. Furthermore, hospitals that refuse to accept these patients in transfer without valid reasons (e.g. no open beds) can be charged with an EMTALA violation.

As you well know, what is considered stabilized or at baseline by one clinician can be seen as unstable or requiring urgent care by another. The real day-to-day practice of medicine often defies evidence-based logic and forces us to make decisions based on many clinical and nonclinical variables.

These situations are further compounded by recent CMS attempts to hold hospitals publicly accountable for ED throughput by posting these measures on its website. Along with other metrics, the citizenry can now see how long it takes an ED patient to be seen by a health professional, receive pain medication if they have a broken bone, receive appropriate treatment and be sent home, or, if admitted, how long it takes to get into a bed.

This information makes it clearer that in situations of clinical uncertainty, it may be easier for many ED physicians to admit than to discharge. The “treat-‘em or street-‘em” mentality of triaging patients, of course, varies from doc to doc and can definitely create antipathy towards physicians in the ED. As much as I may disagree with some of our ED doc’s admissions, I always—OK, maybe not always—try to assume they have the patient’s best interest at heart.

Once admitted, the onus is placed on us, as hospitalists, to determine whether the patient requires ongoing inpatient care, can be cared for in an “observation” capacity, or should be discharged. We all have received calls from a nurse informing us that the patient “does not meet inpatient criteria”—even if the patient is hypotensive with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and lactic acidosis. Oh, if we could only send them back to the ED!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to drhospit@wiley.com.

Why is it that there are no focused looks into the ED? We all know, as hospitalists, that the ED locks us into many admissions. Yet I see no initiatives through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) going after the ED for wanting patients admitted rather than trying to get these patients sent home for outpatient therapy.

–Ray Nowaczyk, DO

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Au contraire, my fellow hospitalist! The ED is monitored and investigated by many hospital committees and governmental agencies. Although we physicians, and I’m sure most hospitals, have always acknowledged our responsibilities to take care of patients during an emergency, this responsibility was enshrined in legalese in 1986 with the passage of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA), also known as the “antidumping law.” Since its passage, any hospital that receives Medicare or Medicaid funding, which includes almost all of them, is at risk of being fined or losing this vital source of funding if this law is violated.

EMTALA essentially states that any patient who presents to the ED must be provided a screening exam and treatment for any “emergent medical condition” (including labor), regardless of the individual’s ability to pay. The hospital is then required to provide “stabilizing” treatment for these patients or transfer them to another facility where this treatment can be provided. Furthermore, hospitals that refuse to accept these patients in transfer without valid reasons (e.g. no open beds) can be charged with an EMTALA violation.

As you well know, what is considered stabilized or at baseline by one clinician can be seen as unstable or requiring urgent care by another. The real day-to-day practice of medicine often defies evidence-based logic and forces us to make decisions based on many clinical and nonclinical variables.

These situations are further compounded by recent CMS attempts to hold hospitals publicly accountable for ED throughput by posting these measures on its website. Along with other metrics, the citizenry can now see how long it takes an ED patient to be seen by a health professional, receive pain medication if they have a broken bone, receive appropriate treatment and be sent home, or, if admitted, how long it takes to get into a bed.

This information makes it clearer that in situations of clinical uncertainty, it may be easier for many ED physicians to admit than to discharge. The “treat-‘em or street-‘em” mentality of triaging patients, of course, varies from doc to doc and can definitely create antipathy towards physicians in the ED. As much as I may disagree with some of our ED doc’s admissions, I always—OK, maybe not always—try to assume they have the patient’s best interest at heart.

Once admitted, the onus is placed on us, as hospitalists, to determine whether the patient requires ongoing inpatient care, can be cared for in an “observation” capacity, or should be discharged. We all have received calls from a nurse informing us that the patient “does not meet inpatient criteria”—even if the patient is hypotensive with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and lactic acidosis. Oh, if we could only send them back to the ED!

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to drhospit@wiley.com.

VIDEO: Getting over the mystery of Ebola

PHILADELPHIA– The swath cut by the Ebola virus in West Africa needs to be understood by Westerners in the context of the health care infrastructure available in West Africa, according to Dr. Robert Fowler, who worked as a consulting physician with the World Health Organization and health ministries in West Africa.

The health care infrastructure in West Africa is inadequate to support implementation of infection prevention and control and triage, including even the most basic standard precautions, such as access to soap and water, alcohol-based hand rubs, and sharps disposal boxes, safe needle handling, and rational use of personal protective equipment.

During a special session on the Ebola virus at the recent Infectious Diseases Week 2014, Dr. Fowler described infected patients lying outdoors because of a lack of beds, soiled personal protective equipment piled up where dogs and chickens could run through them, and a room where an Ebola patient hemorrhaged to death after being left untended for days.

Couple this with a limited ability to monitor patients or provide lifesaving rehydration therapy, and one begins to see how health systems in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe are far better prepared to handle the crisis than were their West African counterparts, according to Dr. Fowler of the department of critical care medicine, University of Toronto.

In a video interview, Dr. Fowler discussed the fears surrounding Ebola in the United States and Canada, and highlighted the realities of those countries’ capabilities to combat the outbreak.

Dr. Fowler reported no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHILADELPHIA– The swath cut by the Ebola virus in West Africa needs to be understood by Westerners in the context of the health care infrastructure available in West Africa, according to Dr. Robert Fowler, who worked as a consulting physician with the World Health Organization and health ministries in West Africa.

The health care infrastructure in West Africa is inadequate to support implementation of infection prevention and control and triage, including even the most basic standard precautions, such as access to soap and water, alcohol-based hand rubs, and sharps disposal boxes, safe needle handling, and rational use of personal protective equipment.

During a special session on the Ebola virus at the recent Infectious Diseases Week 2014, Dr. Fowler described infected patients lying outdoors because of a lack of beds, soiled personal protective equipment piled up where dogs and chickens could run through them, and a room where an Ebola patient hemorrhaged to death after being left untended for days.

Couple this with a limited ability to monitor patients or provide lifesaving rehydration therapy, and one begins to see how health systems in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe are far better prepared to handle the crisis than were their West African counterparts, according to Dr. Fowler of the department of critical care medicine, University of Toronto.

In a video interview, Dr. Fowler discussed the fears surrounding Ebola in the United States and Canada, and highlighted the realities of those countries’ capabilities to combat the outbreak.

Dr. Fowler reported no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

PHILADELPHIA– The swath cut by the Ebola virus in West Africa needs to be understood by Westerners in the context of the health care infrastructure available in West Africa, according to Dr. Robert Fowler, who worked as a consulting physician with the World Health Organization and health ministries in West Africa.

The health care infrastructure in West Africa is inadequate to support implementation of infection prevention and control and triage, including even the most basic standard precautions, such as access to soap and water, alcohol-based hand rubs, and sharps disposal boxes, safe needle handling, and rational use of personal protective equipment.

During a special session on the Ebola virus at the recent Infectious Diseases Week 2014, Dr. Fowler described infected patients lying outdoors because of a lack of beds, soiled personal protective equipment piled up where dogs and chickens could run through them, and a room where an Ebola patient hemorrhaged to death after being left untended for days.

Couple this with a limited ability to monitor patients or provide lifesaving rehydration therapy, and one begins to see how health systems in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe are far better prepared to handle the crisis than were their West African counterparts, according to Dr. Fowler of the department of critical care medicine, University of Toronto.

In a video interview, Dr. Fowler discussed the fears surrounding Ebola in the United States and Canada, and highlighted the realities of those countries’ capabilities to combat the outbreak.

Dr. Fowler reported no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ID WEEK 2014

CDC releases interim guidance on Ebola risk and monitoring

New interim guidance that categorizes the risk of people who may have been exposed to Ebola, with recommendations on monitoring and movement restrictions, was announced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Oct. 27.

The document, released the week after enhanced screening of travelers from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea began at selected U.S. airports, provides guidance to state and local health officials on “managing the movement of individuals being monitored, including travelers from the countries with widespread transmission and others who may have been exposed in the United States,” the statement said.

People traveling from those three countries who have no fever or Ebola symptoms on arrival at airports in six states -- New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Georgia -– are subject to active monitoring, where they will be contacted daily for 21 days from the time they left the affected country. Other states will start active monitoring in the following days, according to the statement. If returned travelers develop symptoms, “they can rapidly be assessed and, if they’re found to have Ebola, effectively isolated and treated,” CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden said during a telebriefing announcing the guidance.

The interim guidance outlines four levels of exposure and delineates different public health actions that may be taken for each level. Dr. Frieden acknowledged that it is within the authority of state and local governments to adopt different strategies than those outlined in the guidance.

High-risk: This category includes someone with known exposure to Ebola, such as a needle stick or mucous membrane exposure from the blood or body fluids of a symptomatic patient. For exposed individuals who are asymptomatic, recommendations include direct active monitoring by public health officials, and ensuring, through orders if necessary, no travel on public transportation and no public gatherings. If travel is allowed, it should be by non-commercial conveyances only, coordinated with public health authorities to ensure active monitoring is not interrupted.

“Some risk”: This category would include a person who may have been in the home of someone who was ill with Ebola but who had no direct contact with that person. It also includes health care workers returning from a country where they cared for Ebola patients. Additional precautions, such as daily direct active monitoring, are recommended for this group. The guidance recommends that public health officials “determine on an individualized case-by-case basis whether additional restrictions, such as controlled movement, workplace exclusions, or restrictions on other activities, are appropriate” for this category, the CDC statement said.

“Low but not zero risk”: This group includes people who have traveled in a country affected by the Ebola epidemic but have no known exposure to the virus. It includes health care workers caring for patients with Ebola in the United States. There are “very important differences” from providing care in Africa compared with U.S. hospitals, where the setting is more controlled, Dr. Frieden said. No restrictions on travel, work, or public gathering are recommended for asymptomatic individuals in this group. Direct active monitoring is recommended for U.S.-based health care workers who have cared for symptomatic patients with Ebola, while wearing appropriate protective gear, as well as travelers on an aircraft sitting within 3 feet of a person with Ebola.

“No risk”: This group includes people who have not traveled to an affected country or who have traveled to an affected country more than 21 days previously. Dr. Frieden said that the CDC has received more than 500 inquires from physicians, health departments, and hospitals about patients who were thought to be at risk for Ebola, and in 90% of those cases, the pattern of symptoms or travel history has not been consistent with Ebola.

An average of about 100 people a day enter the United States after having traveled to one of the West African countries affected by Ebola, of which about 5%-6% are returning health care workers, Dr. Frieden said. He emphasized that Ebola is spread only when people are symptomatic and via direct contact with the infected individual or their body fluids. Those caring for Ebola patients are at the greatest risk.

New interim guidance that categorizes the risk of people who may have been exposed to Ebola, with recommendations on monitoring and movement restrictions, was announced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Oct. 27.

The document, released the week after enhanced screening of travelers from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea began at selected U.S. airports, provides guidance to state and local health officials on “managing the movement of individuals being monitored, including travelers from the countries with widespread transmission and others who may have been exposed in the United States,” the statement said.

People traveling from those three countries who have no fever or Ebola symptoms on arrival at airports in six states -- New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Georgia -– are subject to active monitoring, where they will be contacted daily for 21 days from the time they left the affected country. Other states will start active monitoring in the following days, according to the statement. If returned travelers develop symptoms, “they can rapidly be assessed and, if they’re found to have Ebola, effectively isolated and treated,” CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden said during a telebriefing announcing the guidance.

The interim guidance outlines four levels of exposure and delineates different public health actions that may be taken for each level. Dr. Frieden acknowledged that it is within the authority of state and local governments to adopt different strategies than those outlined in the guidance.

High-risk: This category includes someone with known exposure to Ebola, such as a needle stick or mucous membrane exposure from the blood or body fluids of a symptomatic patient. For exposed individuals who are asymptomatic, recommendations include direct active monitoring by public health officials, and ensuring, through orders if necessary, no travel on public transportation and no public gatherings. If travel is allowed, it should be by non-commercial conveyances only, coordinated with public health authorities to ensure active monitoring is not interrupted.

“Some risk”: This category would include a person who may have been in the home of someone who was ill with Ebola but who had no direct contact with that person. It also includes health care workers returning from a country where they cared for Ebola patients. Additional precautions, such as daily direct active monitoring, are recommended for this group. The guidance recommends that public health officials “determine on an individualized case-by-case basis whether additional restrictions, such as controlled movement, workplace exclusions, or restrictions on other activities, are appropriate” for this category, the CDC statement said.

“Low but not zero risk”: This group includes people who have traveled in a country affected by the Ebola epidemic but have no known exposure to the virus. It includes health care workers caring for patients with Ebola in the United States. There are “very important differences” from providing care in Africa compared with U.S. hospitals, where the setting is more controlled, Dr. Frieden said. No restrictions on travel, work, or public gathering are recommended for asymptomatic individuals in this group. Direct active monitoring is recommended for U.S.-based health care workers who have cared for symptomatic patients with Ebola, while wearing appropriate protective gear, as well as travelers on an aircraft sitting within 3 feet of a person with Ebola.

“No risk”: This group includes people who have not traveled to an affected country or who have traveled to an affected country more than 21 days previously. Dr. Frieden said that the CDC has received more than 500 inquires from physicians, health departments, and hospitals about patients who were thought to be at risk for Ebola, and in 90% of those cases, the pattern of symptoms or travel history has not been consistent with Ebola.

An average of about 100 people a day enter the United States after having traveled to one of the West African countries affected by Ebola, of which about 5%-6% are returning health care workers, Dr. Frieden said. He emphasized that Ebola is spread only when people are symptomatic and via direct contact with the infected individual or their body fluids. Those caring for Ebola patients are at the greatest risk.

New interim guidance that categorizes the risk of people who may have been exposed to Ebola, with recommendations on monitoring and movement restrictions, was announced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Oct. 27.

The document, released the week after enhanced screening of travelers from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea began at selected U.S. airports, provides guidance to state and local health officials on “managing the movement of individuals being monitored, including travelers from the countries with widespread transmission and others who may have been exposed in the United States,” the statement said.

People traveling from those three countries who have no fever or Ebola symptoms on arrival at airports in six states -- New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Georgia -– are subject to active monitoring, where they will be contacted daily for 21 days from the time they left the affected country. Other states will start active monitoring in the following days, according to the statement. If returned travelers develop symptoms, “they can rapidly be assessed and, if they’re found to have Ebola, effectively isolated and treated,” CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden said during a telebriefing announcing the guidance.

The interim guidance outlines four levels of exposure and delineates different public health actions that may be taken for each level. Dr. Frieden acknowledged that it is within the authority of state and local governments to adopt different strategies than those outlined in the guidance.

High-risk: This category includes someone with known exposure to Ebola, such as a needle stick or mucous membrane exposure from the blood or body fluids of a symptomatic patient. For exposed individuals who are asymptomatic, recommendations include direct active monitoring by public health officials, and ensuring, through orders if necessary, no travel on public transportation and no public gatherings. If travel is allowed, it should be by non-commercial conveyances only, coordinated with public health authorities to ensure active monitoring is not interrupted.

“Some risk”: This category would include a person who may have been in the home of someone who was ill with Ebola but who had no direct contact with that person. It also includes health care workers returning from a country where they cared for Ebola patients. Additional precautions, such as daily direct active monitoring, are recommended for this group. The guidance recommends that public health officials “determine on an individualized case-by-case basis whether additional restrictions, such as controlled movement, workplace exclusions, or restrictions on other activities, are appropriate” for this category, the CDC statement said.

“Low but not zero risk”: This group includes people who have traveled in a country affected by the Ebola epidemic but have no known exposure to the virus. It includes health care workers caring for patients with Ebola in the United States. There are “very important differences” from providing care in Africa compared with U.S. hospitals, where the setting is more controlled, Dr. Frieden said. No restrictions on travel, work, or public gathering are recommended for asymptomatic individuals in this group. Direct active monitoring is recommended for U.S.-based health care workers who have cared for symptomatic patients with Ebola, while wearing appropriate protective gear, as well as travelers on an aircraft sitting within 3 feet of a person with Ebola.

“No risk”: This group includes people who have not traveled to an affected country or who have traveled to an affected country more than 21 days previously. Dr. Frieden said that the CDC has received more than 500 inquires from physicians, health departments, and hospitals about patients who were thought to be at risk for Ebola, and in 90% of those cases, the pattern of symptoms or travel history has not been consistent with Ebola.

An average of about 100 people a day enter the United States after having traveled to one of the West African countries affected by Ebola, of which about 5%-6% are returning health care workers, Dr. Frieden said. He emphasized that Ebola is spread only when people are symptomatic and via direct contact with the infected individual or their body fluids. Those caring for Ebola patients are at the greatest risk.

FROM A CDC TELECONFERENCE

Patient Dumping Lawsuit Raises Awareness of Needs of Homeless

As reported in the Los Angeles Times, Glendale Adventist Medical Center in Glendale, Calif., has agreed to pay $700,000 in civil penalties to settle a lawsuit brought against it by the Los Angeles City Attorney. A hospital spokesperson said the medical center denies the charges but has agreed to pay the fine to avoid the cost of fighting the allegations.

"We have to be able to recognize that just writing a discharge order is not meeting any of our patients' needs," says Gregory Misky, MD, hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado (UC) Hospital in Denver. "It's hard to expect we can fix their COPD or manage their diabetes when there are all these layers of social and behavioral health needs."

Dr. Misky says he gradually became interested in issues affecting indigent patients while researching ways to help patients transition from hospital to home.

"Some patients are dealing with financial issues," he says. "Some have acute family crises they're dealing with. Some have homelessness issues or housing issues. All those things interfere with their health and ability to prioritize health needs over these other things."

One of Dr. Misky's current research projects involves performing qualitative interviews with patients who are readmitted within 30 days to learn what challenges they dealt with after being discharged.

As for "patient dumping," Dr. Misky says that, in his experience, hospitals typically do the opposite: hospitalize patients for indefinite periods of time when they seem to have no family to turn to, for example, or are dealing with cognitive issues.

Here are Dr. Misky's tips for providing better discharges:

- Be aware: Not all patients are equal. It's important to realize patients may not recuperate from pneumonia if they are living on the street;

- Rely on case managers: Hospitalists at the UC Hospital perform discharge rounds with a team that includes a case manager, who is usually a registered nurse or social worker. Let the case manager know about your patients’ needs; and

- Form partnerships: Learn about how you can match up your patients with resources for homeless people available in your community.

As reported in the Los Angeles Times, Glendale Adventist Medical Center in Glendale, Calif., has agreed to pay $700,000 in civil penalties to settle a lawsuit brought against it by the Los Angeles City Attorney. A hospital spokesperson said the medical center denies the charges but has agreed to pay the fine to avoid the cost of fighting the allegations.

"We have to be able to recognize that just writing a discharge order is not meeting any of our patients' needs," says Gregory Misky, MD, hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado (UC) Hospital in Denver. "It's hard to expect we can fix their COPD or manage their diabetes when there are all these layers of social and behavioral health needs."

Dr. Misky says he gradually became interested in issues affecting indigent patients while researching ways to help patients transition from hospital to home.

"Some patients are dealing with financial issues," he says. "Some have acute family crises they're dealing with. Some have homelessness issues or housing issues. All those things interfere with their health and ability to prioritize health needs over these other things."

One of Dr. Misky's current research projects involves performing qualitative interviews with patients who are readmitted within 30 days to learn what challenges they dealt with after being discharged.

As for "patient dumping," Dr. Misky says that, in his experience, hospitals typically do the opposite: hospitalize patients for indefinite periods of time when they seem to have no family to turn to, for example, or are dealing with cognitive issues.

Here are Dr. Misky's tips for providing better discharges:

- Be aware: Not all patients are equal. It's important to realize patients may not recuperate from pneumonia if they are living on the street;

- Rely on case managers: Hospitalists at the UC Hospital perform discharge rounds with a team that includes a case manager, who is usually a registered nurse or social worker. Let the case manager know about your patients’ needs; and

- Form partnerships: Learn about how you can match up your patients with resources for homeless people available in your community.

As reported in the Los Angeles Times, Glendale Adventist Medical Center in Glendale, Calif., has agreed to pay $700,000 in civil penalties to settle a lawsuit brought against it by the Los Angeles City Attorney. A hospital spokesperson said the medical center denies the charges but has agreed to pay the fine to avoid the cost of fighting the allegations.

"We have to be able to recognize that just writing a discharge order is not meeting any of our patients' needs," says Gregory Misky, MD, hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado (UC) Hospital in Denver. "It's hard to expect we can fix their COPD or manage their diabetes when there are all these layers of social and behavioral health needs."

Dr. Misky says he gradually became interested in issues affecting indigent patients while researching ways to help patients transition from hospital to home.

"Some patients are dealing with financial issues," he says. "Some have acute family crises they're dealing with. Some have homelessness issues or housing issues. All those things interfere with their health and ability to prioritize health needs over these other things."

One of Dr. Misky's current research projects involves performing qualitative interviews with patients who are readmitted within 30 days to learn what challenges they dealt with after being discharged.

As for "patient dumping," Dr. Misky says that, in his experience, hospitals typically do the opposite: hospitalize patients for indefinite periods of time when they seem to have no family to turn to, for example, or are dealing with cognitive issues.

Here are Dr. Misky's tips for providing better discharges:

- Be aware: Not all patients are equal. It's important to realize patients may not recuperate from pneumonia if they are living on the street;

- Rely on case managers: Hospitalists at the UC Hospital perform discharge rounds with a team that includes a case manager, who is usually a registered nurse or social worker. Let the case manager know about your patients’ needs; and

- Form partnerships: Learn about how you can match up your patients with resources for homeless people available in your community.