User login

No-shows

Of all the headaches inherent in a private medical practice, few are more frustrating than patients who make appointments and then fail to keep them.

– almost double the average for all medical offices.

The problem has become so pervasive that many physicians are now charging a fee for missed appointments. I have never been a fan of such fees for a variety of reasons, starting with the anger and bad will that they engender; but also, in my experience, they seldom accomplish their intended goal of changing the behavior.

That’s because fees imply some sort of conscious decision made by a patient to miss an appointment, but studies show that this is rarely the case. Some patients cite transportation issues or childcare obligations. One Canadian study found that nearly a quarter of patients who missed an appointment felt too sick to keep it. Another reason is lack of insurance coverage. Studies have shown that the no-show rate is far higher when the patient is paying out-of-pocket for the visit.

Patients who don’t show up for appointments tend to be younger and poorer, and live farther away from the office than those who attend consistently. Some patients may be unaware that they need to cancel, while others report that they don’t feel obliged to keep appointments because they feel disrespected by the system. One person posted on a medical forum, “Everyone’s time is valuable. When the doctor makes me wait, there are consequences too. Why are there two standards in the situation?”

The most common reason for missed appointments, however, according to multiple studies, is that patients simply forget that they have one. One reason for that is a lag between appointment and visit. Many dermatologists are booked well in advance; by the time the appointment arrives, some patients’ complaints will have resolved spontaneously, while other patients will have found another office willing to see them sooner.

Another big reason is the absence of a strong physician-patient relationship. Perhaps the patient sees a different doctor or physician assistant at each visit and doesn’t feel a particular bond with any of them. Some patients may perceive a lack of concern on the part of the physician. And others may suffer from poor communication; for example, patients frequently become frustrated that a chronic condition has not resolved, when it has not been clearly explained to them that such problems cannot be expected to resolve rapidly or completely.

Whatever the reasons, no-shows are an economic and medicolegal liability. It is worth the considerable effort it often takes to minimize them.

Research suggests that no-show rates can be reduced by providing more same-day or next-day appointments. One large-scale analysis of national data found that same-day appointments accounted for just 2% of no-shows, while appointments booked 15 days or more in advance accounted for nearly a third of them. Canadian studies have likewise found the risk of no-shows increases the further in advance clinics book patients.

Deal with simple forgetfulness by calling your patients the day before to remind them of their appointments. Reasonably priced phone software is available from a variety of vendors to automate this process. Or hire a teenager to do it after school each day.

Whenever possible, use cellphone numbers for reminder calls. Patients often aren’t home during the day, and many don’t listen to their messages when they come in. And patients who have moved will often have a new home phone number, but their cellphone number will be the same.

Decrease the wait for new appointments. Keep some slots open each week for new patients, who will often “shop around” for a faster appointment while they’re waiting for an appointment they already have elsewhere.

But above all, seek to maximize the strength of your physician-patient relationships. Try not to shuttle patients between different physicians or PAs, and make it clear that you are genuinely concerned about their health. Impress upon them the crucial role they play in their own care, which includes keeping all their appointments.

In our office, significant no-shows (for example, a patient with a melanoma who misses a follow-up visit) receive a phone call and a certified letter, and their records go into a special file for close follow-up by the nursing staff.

If you choose to go the missed-appointment-fee route, be sure to post notices in your office and on your website clearly delineating your policy. Emphasize that it is not a service fee, and cannot be billed to insurance.

All missed appointments should be documented in the patient’s record; it’s important clinical and medicolegal information. And habitual no-shows should be dismissed from your practice. You cannot afford them.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Of all the headaches inherent in a private medical practice, few are more frustrating than patients who make appointments and then fail to keep them.

– almost double the average for all medical offices.

The problem has become so pervasive that many physicians are now charging a fee for missed appointments. I have never been a fan of such fees for a variety of reasons, starting with the anger and bad will that they engender; but also, in my experience, they seldom accomplish their intended goal of changing the behavior.

That’s because fees imply some sort of conscious decision made by a patient to miss an appointment, but studies show that this is rarely the case. Some patients cite transportation issues or childcare obligations. One Canadian study found that nearly a quarter of patients who missed an appointment felt too sick to keep it. Another reason is lack of insurance coverage. Studies have shown that the no-show rate is far higher when the patient is paying out-of-pocket for the visit.

Patients who don’t show up for appointments tend to be younger and poorer, and live farther away from the office than those who attend consistently. Some patients may be unaware that they need to cancel, while others report that they don’t feel obliged to keep appointments because they feel disrespected by the system. One person posted on a medical forum, “Everyone’s time is valuable. When the doctor makes me wait, there are consequences too. Why are there two standards in the situation?”

The most common reason for missed appointments, however, according to multiple studies, is that patients simply forget that they have one. One reason for that is a lag between appointment and visit. Many dermatologists are booked well in advance; by the time the appointment arrives, some patients’ complaints will have resolved spontaneously, while other patients will have found another office willing to see them sooner.

Another big reason is the absence of a strong physician-patient relationship. Perhaps the patient sees a different doctor or physician assistant at each visit and doesn’t feel a particular bond with any of them. Some patients may perceive a lack of concern on the part of the physician. And others may suffer from poor communication; for example, patients frequently become frustrated that a chronic condition has not resolved, when it has not been clearly explained to them that such problems cannot be expected to resolve rapidly or completely.

Whatever the reasons, no-shows are an economic and medicolegal liability. It is worth the considerable effort it often takes to minimize them.

Research suggests that no-show rates can be reduced by providing more same-day or next-day appointments. One large-scale analysis of national data found that same-day appointments accounted for just 2% of no-shows, while appointments booked 15 days or more in advance accounted for nearly a third of them. Canadian studies have likewise found the risk of no-shows increases the further in advance clinics book patients.

Deal with simple forgetfulness by calling your patients the day before to remind them of their appointments. Reasonably priced phone software is available from a variety of vendors to automate this process. Or hire a teenager to do it after school each day.

Whenever possible, use cellphone numbers for reminder calls. Patients often aren’t home during the day, and many don’t listen to their messages when they come in. And patients who have moved will often have a new home phone number, but their cellphone number will be the same.

Decrease the wait for new appointments. Keep some slots open each week for new patients, who will often “shop around” for a faster appointment while they’re waiting for an appointment they already have elsewhere.

But above all, seek to maximize the strength of your physician-patient relationships. Try not to shuttle patients between different physicians or PAs, and make it clear that you are genuinely concerned about their health. Impress upon them the crucial role they play in their own care, which includes keeping all their appointments.

In our office, significant no-shows (for example, a patient with a melanoma who misses a follow-up visit) receive a phone call and a certified letter, and their records go into a special file for close follow-up by the nursing staff.

If you choose to go the missed-appointment-fee route, be sure to post notices in your office and on your website clearly delineating your policy. Emphasize that it is not a service fee, and cannot be billed to insurance.

All missed appointments should be documented in the patient’s record; it’s important clinical and medicolegal information. And habitual no-shows should be dismissed from your practice. You cannot afford them.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Of all the headaches inherent in a private medical practice, few are more frustrating than patients who make appointments and then fail to keep them.

– almost double the average for all medical offices.

The problem has become so pervasive that many physicians are now charging a fee for missed appointments. I have never been a fan of such fees for a variety of reasons, starting with the anger and bad will that they engender; but also, in my experience, they seldom accomplish their intended goal of changing the behavior.

That’s because fees imply some sort of conscious decision made by a patient to miss an appointment, but studies show that this is rarely the case. Some patients cite transportation issues or childcare obligations. One Canadian study found that nearly a quarter of patients who missed an appointment felt too sick to keep it. Another reason is lack of insurance coverage. Studies have shown that the no-show rate is far higher when the patient is paying out-of-pocket for the visit.

Patients who don’t show up for appointments tend to be younger and poorer, and live farther away from the office than those who attend consistently. Some patients may be unaware that they need to cancel, while others report that they don’t feel obliged to keep appointments because they feel disrespected by the system. One person posted on a medical forum, “Everyone’s time is valuable. When the doctor makes me wait, there are consequences too. Why are there two standards in the situation?”

The most common reason for missed appointments, however, according to multiple studies, is that patients simply forget that they have one. One reason for that is a lag between appointment and visit. Many dermatologists are booked well in advance; by the time the appointment arrives, some patients’ complaints will have resolved spontaneously, while other patients will have found another office willing to see them sooner.

Another big reason is the absence of a strong physician-patient relationship. Perhaps the patient sees a different doctor or physician assistant at each visit and doesn’t feel a particular bond with any of them. Some patients may perceive a lack of concern on the part of the physician. And others may suffer from poor communication; for example, patients frequently become frustrated that a chronic condition has not resolved, when it has not been clearly explained to them that such problems cannot be expected to resolve rapidly or completely.

Whatever the reasons, no-shows are an economic and medicolegal liability. It is worth the considerable effort it often takes to minimize them.

Research suggests that no-show rates can be reduced by providing more same-day or next-day appointments. One large-scale analysis of national data found that same-day appointments accounted for just 2% of no-shows, while appointments booked 15 days or more in advance accounted for nearly a third of them. Canadian studies have likewise found the risk of no-shows increases the further in advance clinics book patients.

Deal with simple forgetfulness by calling your patients the day before to remind them of their appointments. Reasonably priced phone software is available from a variety of vendors to automate this process. Or hire a teenager to do it after school each day.

Whenever possible, use cellphone numbers for reminder calls. Patients often aren’t home during the day, and many don’t listen to their messages when they come in. And patients who have moved will often have a new home phone number, but their cellphone number will be the same.

Decrease the wait for new appointments. Keep some slots open each week for new patients, who will often “shop around” for a faster appointment while they’re waiting for an appointment they already have elsewhere.

But above all, seek to maximize the strength of your physician-patient relationships. Try not to shuttle patients between different physicians or PAs, and make it clear that you are genuinely concerned about their health. Impress upon them the crucial role they play in their own care, which includes keeping all their appointments.

In our office, significant no-shows (for example, a patient with a melanoma who misses a follow-up visit) receive a phone call and a certified letter, and their records go into a special file for close follow-up by the nursing staff.

If you choose to go the missed-appointment-fee route, be sure to post notices in your office and on your website clearly delineating your policy. Emphasize that it is not a service fee, and cannot be billed to insurance.

All missed appointments should be documented in the patient’s record; it’s important clinical and medicolegal information. And habitual no-shows should be dismissed from your practice. You cannot afford them.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Medical assistants identify strategies and barriers to clinic efficiency

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Efficiency and competing priorities

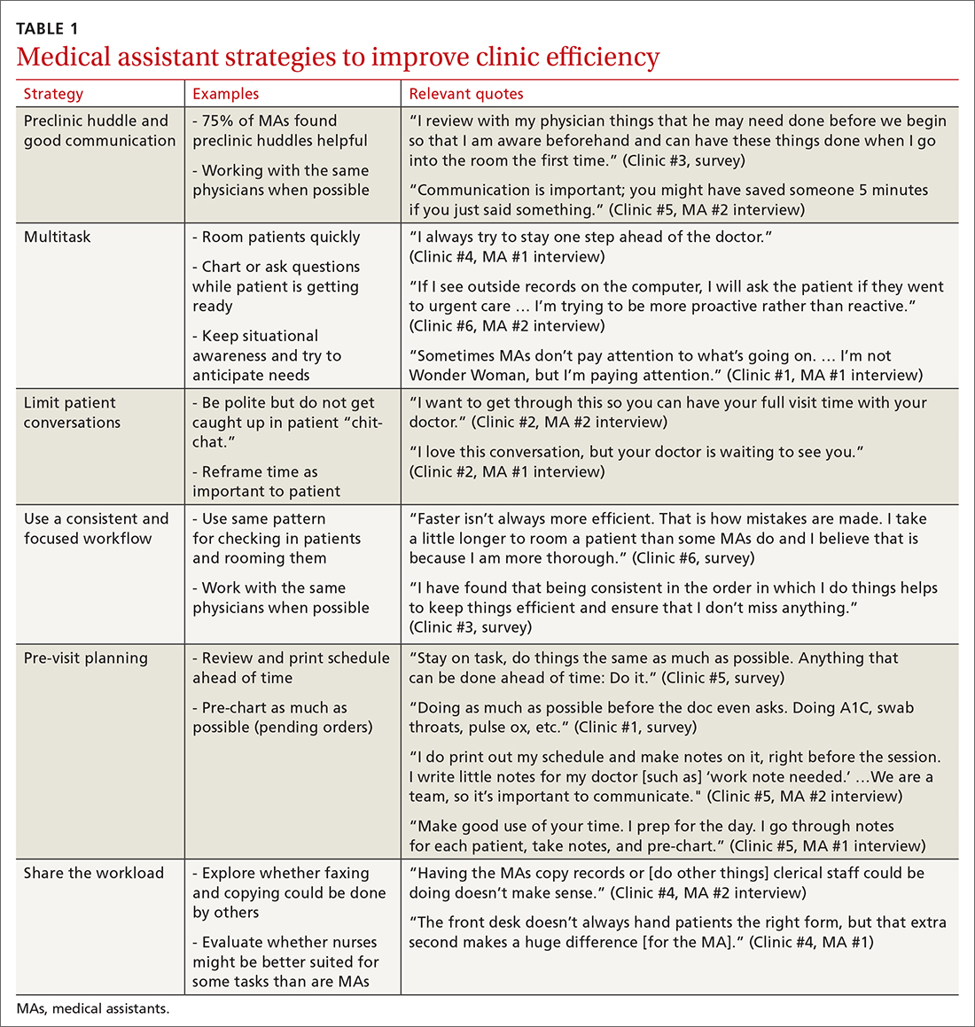

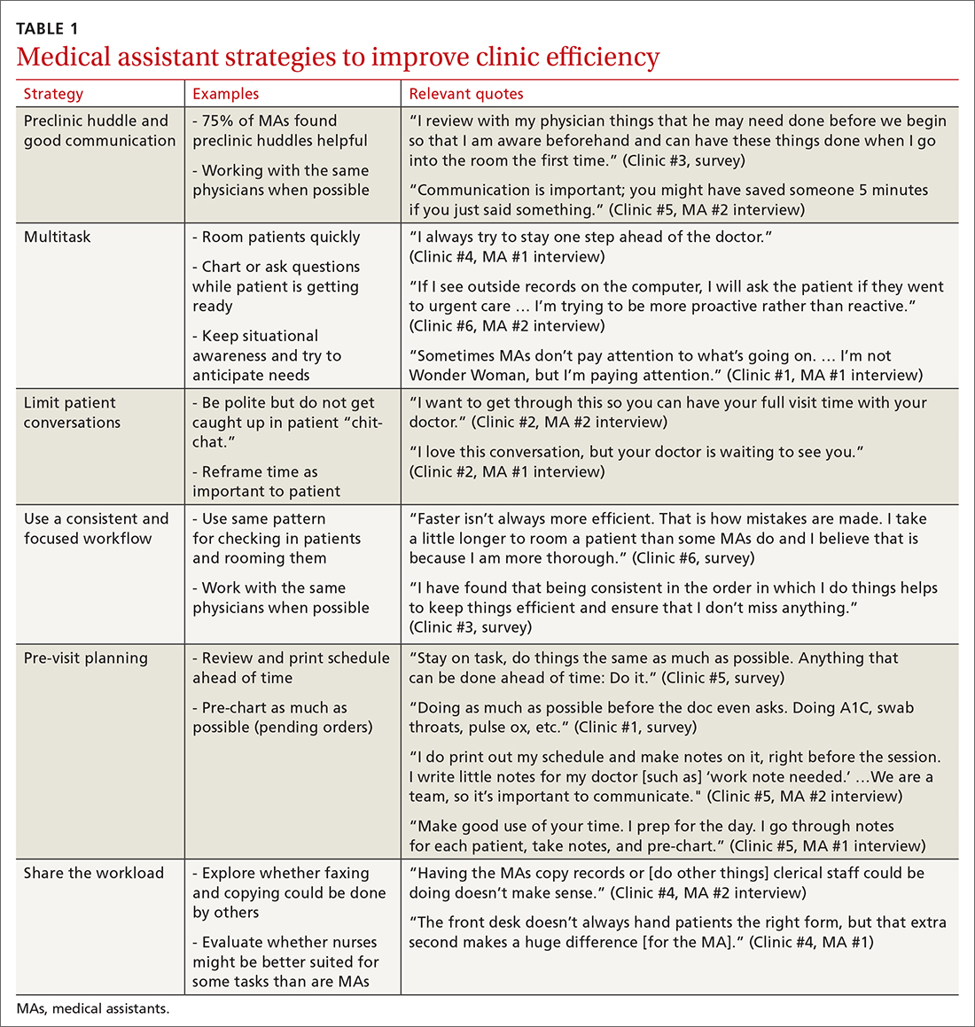

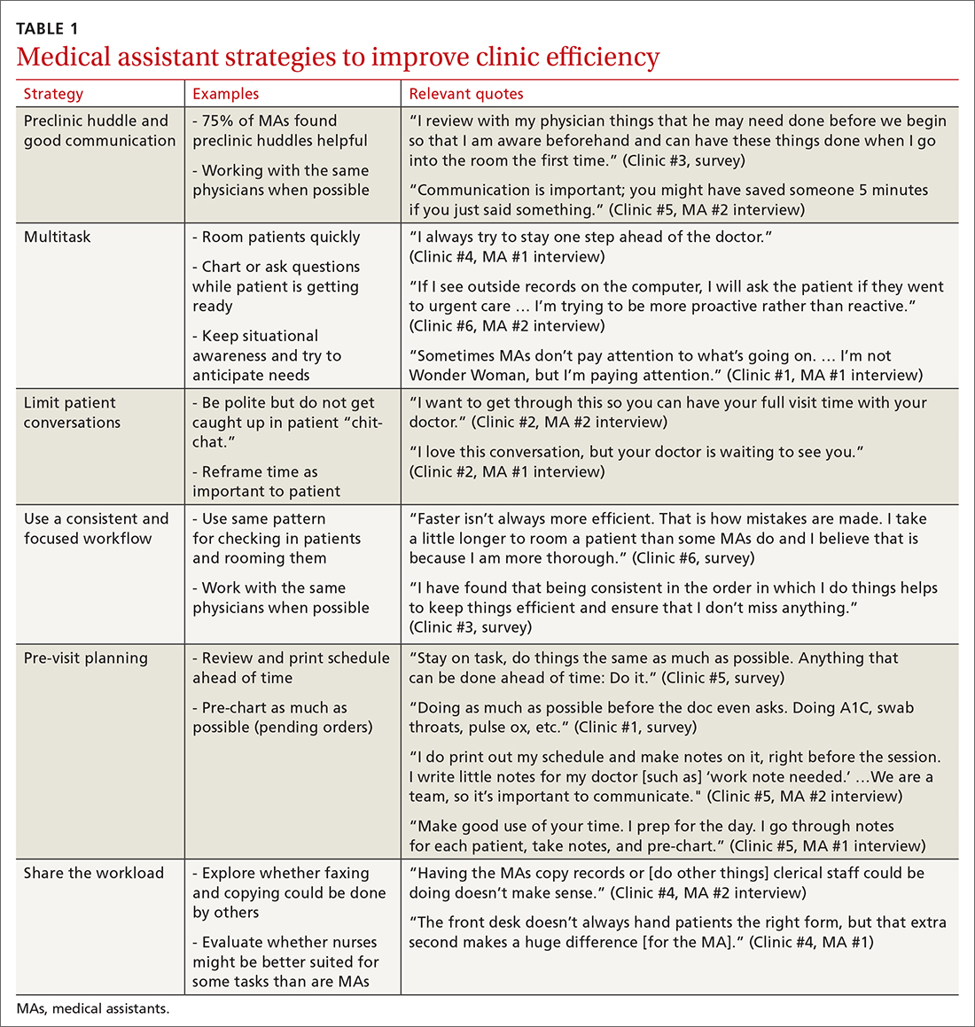

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

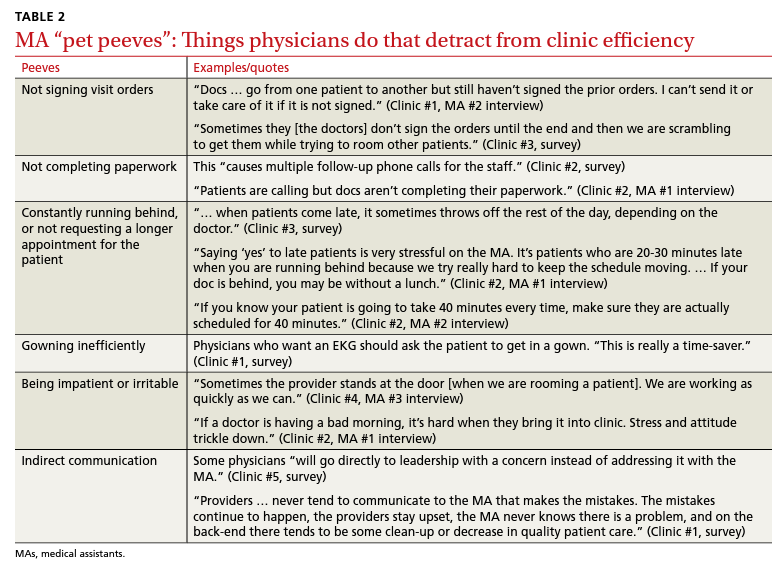

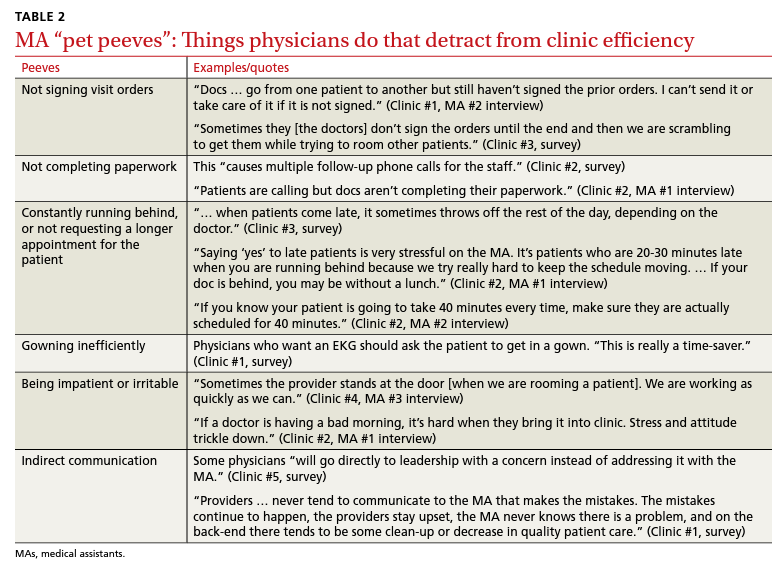

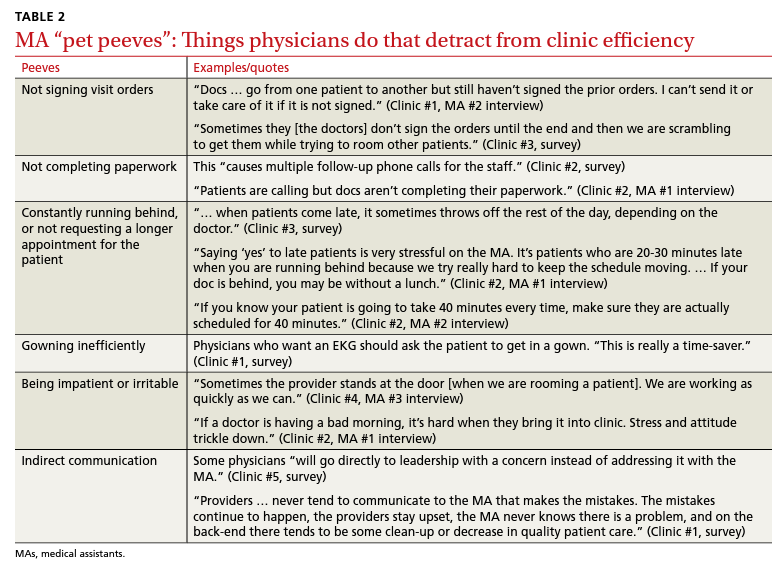

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Continue to: Clinic environment...

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“[Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male- dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries. 19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs. 8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; ktgold@umich.edu

- Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):383-406.

- Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:226-235.

- Atkins B. The outlook for medical assisting in 2016 and beyond. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.medicalassistantdegrees.net/ articles/medical-assisting-trends/

- Unqualified medical “assistants.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1897;23:163-164.

- Ameritech College of Healthcare. The origins of the AAMA. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.ameritech.edu/blog/medicalassisting-history/

- Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:368-377.

- Harper PG, Van Riper K, Ramer T, et al. Team-based care: an expanded medical assistant role—enhanced rooming and visit assistance. J Interprof Care. 2018:1-7.

- Sheridan B, Chien AT, Peters AS, et al. Team-based primary care: the medical assistant perspective. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43:115-125.

- Tache S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manag. 2010;24:288-305.

- STROBE checklist for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.strobe-statement.org/ fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_ combined.pdf

- Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:181-191.

- Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Bolon SK, et al. Patterns of relating between physicians and medical assistants in small family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:150-157.

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92:415-422.

- Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:167-173.

- Mohr DC, Young GJ, Meterko M, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care team members and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:18-25.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ oes/current/oes319092.htm

- Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning medical assistants for a greater role in the era of health reform. Acad Med. 2015;90:1347-1352.

- Mandel H. The role of occupational attributes in gender earnings inequality, 1970-2010. Soc Sci Res. 2016;55:122-138.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: medical assistants. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.bls.gov/ooh/ healthcare/medical-assistants.htm

- Skillman SM, Dahal A, Frogner BK, et al. Frontline workers’ career pathways: a detailed look at Washington state’s medical assistant workforce. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718812950.

- Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39:341-352.

- Dubois CA, Bentein K, Ben Mansour JB, et al. Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2014;11: 187-201.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264.

- O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, et al. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:183-192.

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Efficiency and competing priorities

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Continue to: Clinic environment...

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“[Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male- dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries. 19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs. 8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; ktgold@umich.edu

ABSTRACT

Background: Medical assistant (MA) roles have expanded rapidly as primary care has evolved and MAs take on new patient care duties. Research that looks at the MA experience and factors that enhance or reduce efficiency among MAs is limited.

Methods: We surveyed all MAs working in 6 clinics run by a large academic family medicine department in Ann Arbor, Michigan. MAs deemed by peers as “most efficient” were selected for follow-up interviews. We evaluated personal strategies for efficiency, barriers to efficient care, impact of physician actions on efficiency, and satisfaction.

Results: A total of 75/86 MAs (87%) responded to at least some survey questions and 61/86 (71%) completed the full survey. We interviewed 18 MAs face to face. Most saw their role as essential to clinic functioning and viewed health care as a personal calling. MAs identified common strategies to improve efficiency and described the MA role to orchestrate the flow of the clinic day. Staff recognized differing priorities of patients, staff, and physicians and articulated frustrations with hierarchy and competing priorities as well as behaviors that impeded clinic efficiency. Respondents emphasized the importance of feeling valued by others on their team.

Conclusions: With the evolving demands made on MAs’ time, it is critical to understand how the most effective staff members manage their role and highlight the strategies they employ to provide efficient clinical care. Understanding factors that increase or decrease MA job satisfaction can help identify high-efficiency practices and promote a clinic culture that values and supports all staff.

As primary care continues to evolve into more team-based practice, the role of the medical assistant (MA) has rapidly transformed.1 Staff may assist with patient management, documentation in the electronic medical record, order entry, pre-visit planning, and fulfillment of quality metrics, particularly in a Primary Care Medical Home (PCMH).2 From 2012 through 2014, MA job postings per graduate increased from 1.3 to 2.3, suggesting twice as many job postings as graduates.3 As the demand for experienced MAs increases, the ability to recruit and retain high-performing staff members will be critical.

MAs are referenced in medical literature as early as the 1800s.4 The American Association of Medical Assistants was founded in 1956, which led to educational standardization and certifications.5 Despite the important role that MAs have long played in the proper functioning of a medical clinic—and the knowledge that team configurations impact a clinic’s efficiency and quality6,7—few investigations have sought out the MA’s perspective.8,9 Given the increasing clinical demands placed on all members of the primary care team (and the burnout that often results), it seems that MA insights into clinic efficiency could be valuable.

Continue to: Methods...

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to April 2019 at a large academic institution with 6 regional ambulatory care family medicine clinics, each one with 11,000 to 18,000 patient visits annually. Faculty work at all 6 clinics and residents at 2 of them. All MAs are hired, paid, and managed by a central administrative department rather than by the family medicine department. The family medicine clinics are currently PCMH certified, with a mix of fee-for-service and capitated reimbursement.

We developed and piloted a voluntary, anonymous 39-question (29 closed-ended and 10 brief open-ended) online Qualtrics survey, which we distributed via an email link to all the MAs in the department. The survey included clinic site, years as an MA, perceptions of the clinic environment, perception of teamwork at their site, identification of efficient practices, and feedback for physicians to improve efficiency and flow. Most questions were Likert-style with 5 choices ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” or short answer. Age and gender were omitted to protect confidentiality, as most MAs in the department are female. Participants could opt to enter in a drawing for three $25 gift cards. The survey was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and deemed exempt.

We asked MAs to nominate peers in their clinic who were “especially efficient and do their jobs well—people that others can learn from.” The staff members who were nominated most frequently by their peers were invited to share additional perspectives via a 10- to 30-minute semi-structured interview with the first author. Interviews covered highly efficient practices, barriers and facilitators to efficient care, and physician behaviors that impaired efficiency. We interviewed a minimum of 2 MAs per clinic and increased the number of interviews through snowball sampling, as needed, to reach data saturation (eg, the point at which we were no longer hearing new content). MAs were assured that all comments would be anonymized. There was no monetary incentive for the interviews. The interviewer had previously met only 3 of the 18 MAs interviewed.

Analysis. Summary statistics were calculated for quantitative data. To compare subgroups (such as individual clinics), a chi-square test was used. In cases when there were small cell sizes (< 5 subjects), we used the Fisher’s Exact test. Qualitative data was collected with real-time typewritten notes during the interviews to capture ideas and verbatim quotes when possible. We also included open-ended comments shared on the Qualtrics survey. Data were organized by theme using a deductive coding approach. Both authors reviewed and discussed observations, and coding was conducted by the first author. Reporting followed the STROBE Statement checklist for cross-sectional studies.10 Results were shared with MAs, supervisory staff, and physicians, which allowed for feedback and comments and served as “member-checking.” MAs reported that the data reflected their lived experiences.

Continue to: RESULTS...

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to all 86 MAs working in family medicine clinics. A total of 75 (87%) responded to at least some questions (typically just demographics). We used those who completed the full survey (n = 61; 71%) for data analysis. Eighteen MAs participated in face-to-face interviews. Among respondents, 35 (47%) had worked at least 10 years as an MA and 21 (28%) had worked at least a decade in the family medicine department.

Perception of role

All respondents (n = 61; 100%) somewhat or strongly agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and 58 (95%) reported that working in health care was “a calling” for them. Only 7 (11%) agreed that family medicine was an easier environment for MAs compared to a specialty clinic; 30 (49%) disagreed with this. Among respondents, 32 (53%) strongly or somewhat agreed that their work was very stressful and just half (n = 28; 46%) agreed there were adequate MA staff at their clinic.

Efficiency and competing priorities

MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included clinic culture (good communication and strong teamwork), as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and doing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy. (See TABLE 1.) They identified ways physicians bolster or hurt efficiency and ways in which the relationship between the physician and the MA shapes the MA’s perception of their value in clinic.

Communication was emphasized as critical for efficient care, and MAs encouraged the use of preclinic huddles and communication as priorities. Seventy-five percent of MAs reported preclinic huddles to plan for patient care were helpful, but only half said huddles took place “always” or “most of the time.” Many described reviewing the schedule and completing tasks ahead of patient arrival as critical to efficiency.

Participants described the tension between their identified role of orchestrating clinic flow and responding to directives by others that disrupted the flow. Several MAs found it challenging when physicians agreed to see very late patients and felt frustrated when decisions that changed the flow were made by the physician or front desk staff without including the MA. MAs were also able to articulate how they managed competing priorities within the clinic, such as when a patient- or physician-driven need to extend appointments was at odds with maintaining a timely schedule. They were eager to share personal tips for time management and prided themselves on careful and accurate performance and skills they had learned on the job. MAs also described how efficiency could be adversely affected by the behaviors or attitudes of physicians. (See TABLE 2.)

Continue to: Clinic environment...

Clinic environment

Thirty-six MAs (59%) reported that other MAs on their team were willing to help them out in clinic “a great deal” or “a lot” of the time, by helping to room a patient, acting as a chaperone for an exam, or doing a point-of-care lab. This sense of support varied across clinics (38% to 91% reported good support), suggesting that cultures vary by site. Some MAs expressed frustration at peers they saw as resistant to helping, exemplified by this verbatim quote from an interview:

“Some don’t want to help out. They may sigh. It’s how they react—you just know.” (Clinic #1, MA #2 interview)

Efficient MAs stressed the need for situational awareness to recognize when co-workers need help:

“[Peers often] are not aware that another MA is drowning. There’s 5 people who could have done that, and here I am running around and nobody budged.” (Clinic #5, MA #2 interview)

A minority of staff used the open-ended survey sections to describe clinic hierarchy. When asked about “pet peeves,” a few advised that physicians should not “talk down” to staff and should try to teach rather than criticize. Another asked that physicians not “bark orders” or have “low gratitude” for staff work. MAs found micromanaging stressful—particularly when the physician prompted the MA about patient arrivals:

“[I don’t like] when providers will make a comment about a patient arriving when you already know this information. You then rush to put [the] patient in [a] room, then [the] provider ends up making [the] patient wait an extensive amount of time. I’m perfectly capable of knowing when a patient arrives.” (Clinic #6, survey)

MAs did not like physicians “talking bad about us” or blaming the MA if the clinic is running behind.

Despite these concerns, most MAs reported feeling appreciated for the job they do. Only 10 (16%) reported that the people they work with rarely say “thank you,” and 2 (3%) stated they were not well supported by the physicians in clinic. Most (n = 38; 62%) strongly agreed or agreed that they felt part of the team and that their opinions matter. In the interviews, many expanded on this idea:

“I really feel like I’m valued, so I want to do everything I can to make [my doctor’s] day go better. If you want a good clinic, the best thing a doc can do is make the MA feel valued.” (Clinic #1, MA #1 interview)

Continue to: DISCUSSION...

DISCUSSION

Participants described their role much as an orchestra director, with MAs as the key to clinic flow and timeliness.9 Respondents articulated multiple common strategies used to increase their own efficiency and clinic flow; these may be considered best practices and incorporated as part of the basic training. Most MAs reported their day-to-day jobs were stressful and believed this was underrecognized, so efficiency strategies are critical. With staff completing multiple time-sensitive tasks during clinic, consistent co-worker support is crucial and may impact efficiency.8 Proper training of managers to provide that support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial.

Several comments reflected the power differential within medical offices. One study reported that MAs and physicians “occupy roles at opposite ends of social and occupational hierarchies.”11 It’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.9 Prior research has found that MAs have higher perceptions of their own competence than do the physicians working with them.12 If there is a fundamental lack of trust between the 2 groups, this will undoubtedly hinder team-building. Attention to this issue is key to a more favorable work environment.

Almost all respondents reported health care was a “calling,” which mirrors physician research that suggests seeing work as a “calling” is protective against burnout.13,14 Open-ended comments indicated great pride in contributions, and most staff members felt appreciated by their teams. Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier. Staff job satisfaction is linked to improved quality of care, so treating staff well contributes to high-value care for patients.15 We also uncovered some MA “pet peeves” that hinder efficiency and could be shared with physicians to emphasize the importance of patience and civility.

One barrier to expansion of MA roles within PCMH practices is the limited pay and career ladder for MAs who adopt new job responsibilities that require advanced skills or training.1,2 The mean MA salary at our institution ($37,372) is higher than in our state overall ($33,760), which may impact satisfaction.16 In addition, 93% of MAs are women; thus, they may continue to struggle more with lower pay than do workers in male- dominated professions.17,18 Expected job growth from 2018-2028 is predicted at 23%, which may help to boost salaries. 19 Prior studies describe the lack of a job ladder or promotion opportunities as a challenge1,20; this was not formally assessed in our study.

MAs see work in family medicine as much harder than it is in other specialty clinics. Being trusted with more responsibility, greater autonomy,21-23 and expanded patient care roles can boost MA self-efficacy, which can reduce burnout for both physicians and MAs. 8,24 However, new responsibilities should include appropriate training, support, and compensation, and match staff interests.7

Study limitations. The study was limited to 6 clinics in 1 department at a large academic medical center. Interviewed participants were selected by convenience and snowball sampling and thus, the results cannot be generalized to the population of MAs as a whole. As the initial interview goal was simply to gather efficiency tips, the project was not designed to be formal qualitative research. However, the discussions built on open-ended comments from the written survey helped contextualize our quantitative findings about efficiency. Notes were documented in real time by a single interviewer with rapid typing skills, which allowed capture of quotes verbatim. Subsequent studies would benefit from more formal qualitative research methods (recording and transcribing interviews, multiple coders to reduce risk of bias, and more complex thematic analysis).

Our research demonstrated how MAs perceive their roles in primary care and the facilitators and barriers to high efficiency in the workplace, which begins to fill an important knowledge gap in primary care. Disseminating practices that staff members themselves have identified as effective, and being attentive to how staff members are treated, may increase individual efficiency while improving staff retention and satisfaction.

CORRESPONDENCE Katherine J. Gold, MD, MSW, MS, Department of Family Medicine and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Michigan, 1018 Fuller Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1213; ktgold@umich.edu

- Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):383-406.

- Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:226-235.

- Atkins B. The outlook for medical assisting in 2016 and beyond. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.medicalassistantdegrees.net/ articles/medical-assisting-trends/

- Unqualified medical “assistants.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1897;23:163-164.

- Ameritech College of Healthcare. The origins of the AAMA. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.ameritech.edu/blog/medicalassisting-history/

- Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:368-377.

- Harper PG, Van Riper K, Ramer T, et al. Team-based care: an expanded medical assistant role—enhanced rooming and visit assistance. J Interprof Care. 2018:1-7.

- Sheridan B, Chien AT, Peters AS, et al. Team-based primary care: the medical assistant perspective. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43:115-125.

- Tache S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manag. 2010;24:288-305.

- STROBE checklist for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.strobe-statement.org/ fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_ combined.pdf

- Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:181-191.

- Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Bolon SK, et al. Patterns of relating between physicians and medical assistants in small family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:150-157.

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92:415-422.

- Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:167-173.

- Mohr DC, Young GJ, Meterko M, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care team members and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:18-25.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ oes/current/oes319092.htm

- Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning medical assistants for a greater role in the era of health reform. Acad Med. 2015;90:1347-1352.

- Mandel H. The role of occupational attributes in gender earnings inequality, 1970-2010. Soc Sci Res. 2016;55:122-138.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: medical assistants. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.bls.gov/ooh/ healthcare/medical-assistants.htm

- Skillman SM, Dahal A, Frogner BK, et al. Frontline workers’ career pathways: a detailed look at Washington state’s medical assistant workforce. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718812950.

- Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39:341-352.

- Dubois CA, Bentein K, Ben Mansour JB, et al. Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2014;11: 187-201.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264.

- O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, et al. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:183-192.

- Chapman SA, Blash LK. New roles for medical assistants in innovative primary care practices. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(suppl 1):383-406.

- Ferrante JM, Shaw EK, Bayly JE, et al. Barriers and facilitators to expanding roles of medical assistants in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:226-235.

- Atkins B. The outlook for medical assisting in 2016 and beyond. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.medicalassistantdegrees.net/ articles/medical-assisting-trends/

- Unqualified medical “assistants.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1897;23:163-164.

- Ameritech College of Healthcare. The origins of the AAMA. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.ameritech.edu/blog/medicalassisting-history/

- Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:368-377.

- Harper PG, Van Riper K, Ramer T, et al. Team-based care: an expanded medical assistant role—enhanced rooming and visit assistance. J Interprof Care. 2018:1-7.

- Sheridan B, Chien AT, Peters AS, et al. Team-based primary care: the medical assistant perspective. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;43:115-125.

- Tache S, Hill-Sakurai L. Medical assistants: the invisible “glue” of primary health care practices in the United States? J Health Organ Manag. 2010;24:288-305.

- STROBE checklist for cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.strobe-statement.org/ fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_ combined.pdf

- Gray CP, Harrison MI, Hung D. Medical assistants as flow managers in primary care: challenges and recommendations. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61:181-191.

- Elder NC, Jacobson CJ, Bolon SK, et al. Patterns of relating between physicians and medical assistants in small family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:150-157.

- Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2017;92:415-422.

- Yoon JD, Daley BM, Curlin FA. The association between a sense of calling and physician well-being: a national study of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:167-173.

- Mohr DC, Young GJ, Meterko M, et al. Job satisfaction of primary care team members and quality of care. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26:18-25.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wage statistics. Accessed January 27, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ oes/current/oes319092.htm

- Chapman SA, Marks A, Dower C. Positioning medical assistants for a greater role in the era of health reform. Acad Med. 2015;90:1347-1352.

- Mandel H. The role of occupational attributes in gender earnings inequality, 1970-2010. Soc Sci Res. 2016;55:122-138.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: medical assistants. Accessed January 27, 2022. www.bls.gov/ooh/ healthcare/medical-assistants.htm

- Skillman SM, Dahal A, Frogner BK, et al. Frontline workers’ career pathways: a detailed look at Washington state’s medical assistant workforce. Med Care Res Rev. 2018:1077558718812950.

- Morse G, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, et al. Burnout in mental health services: a review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2012;39:341-352.

- Dubois CA, Bentein K, Ben Mansour JB, et al. Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2014;11: 187-201.

- Aronsson G, Theorell T, Grape T, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:264.

- O’Malley AS, Gourevitch R, Draper K, et al. Overcoming challenges to teamwork in patient-centered medical homes: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:183-192.

Medical assistants

When I began in private practice several eons ago, I employed only registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) in my office – as did, I think, most other physicians.

That is still the preferred way to go from an efficiency perspective, as well as the ability to delegate such tasks as blood collection and administering intramuscular injections. Unfortunately,

Given this reality, it makes sense to understand how the use of medical assistants has changed private medical practice, and how the most effective MAs manage their roles and maximize their efficiency in the office.

A recent article by two physicians at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, is one of the few published papers to address this issue. It presents the results of a cross-sectional study examining the MA’s experience and key factors that enhance or reduce efficiencies.

The authors sent an email survey to 86 MAs working in six clinics within the department of family medicine at the University of Michigan Medical Center, and received responses from 75 of them, including 61 who completed the entire survey. They then singled out 18 individuals deemed “most efficient” by their peers and conducted face-to-face interviews with them.

The surveys and interviews looked at how MAs identified personal strategies for efficiency, dealt with barriers to implementing those strategies, and navigated interoffice relationships, as well as how all of this affected overall job satisfaction.

All 61 respondents who completed the full survey agreed that the MA role was “very important to keep the clinic functioning” and nearly all said that working in health care was “a calling” for them. About half agreed that their work was very stressful, and about the same percentage reported that there was inadequate MA staffing at their clinic. Others complained of limited pay and promotion opportunities.

The surveyed MAs described important work values that increased their efficiency. These included good communication, strong teamwork, and workload sharing, as well as individual strategies such as multitasking, limiting patient conversations, and completing tasks in a consistent way to improve accuracy.

Other strategies identified as contributing to an efficient operation included preclinic huddles, reviews of patient records before the patient’s arrival, and completing routine office duties before the start of office hours.

Respondents were then asked to identify barriers to clinic efficiency, and most of them involved physicians who barked orders at them, did not complete paperwork or sign orders in a timely manner, and agreed to see late-arriving patients. Some MAs suggested that physicians refrain from “talking down” to them, and teach rather than criticize. They also faulted decisions affecting patient flow made by other staffers without soliciting the MAs’ input.

Despite these barriers, the authors found that most of the surveyed MAs agreed that their work was valued by doctors. “Proper training of managers to provide ... support and ensure equitable workloads may be one strategy to ensure that staff members feel the workplace is fair and collegial,” they said.

“Many described the working relationships with physicians as critical to their satisfaction at work and indicated that strong partnerships motivated them to do their best to make the physician’s day easier,” they added.

At the same time, the authors noted that most survey subjects reported that their jobs were “stressful,” and believed that their stress went underrecognized by physicians. They argued that “it’s important for physicians to be cognizant of these patterns and clinic culture, as reducing a hierarchy-based environment will be appreciated by MAs.”

Since this study involved only MAs in a family practice setting, further studies will be needed to determine whether these results translate to specialty offices – and whether the unique issues inherent in various specialty environments elicit different efficiency contributors and barriers.