User login

Prescriber adherence to antiemetic guidelines with the new agent trifluridine-tipiracil

Cancer drugs are becoming available at an unprecedented rate. In 2015 alone, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 18 new agents.1 Although many of those agents have adverse event profiles that are more favorable than those seen with conventional chemotherapy, nausea and vomiting still occur. In fact, nausea and vomiting continue to be ranked as among the most common and distressing of cancer symptoms.2,3 In a 2004 study, Grunberg and colleagues reported that as many as 75% of health care providers misjudge the risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), even when prescribing cancer drugs that have been available for years,4 thus amplifying concerns that such risk assessment might be even worse when new cancer agents are prescribed for the first time.

In this study, we hypothesized that patients prescribed a new cancer drug, trifluridine-tipiracil, would be at risk for CINV because of poor guideline adherence on the part of health care providers. The correct matching of antiemetics to chemotherapy is important. Inadequate antiemetic prophylaxis predisposes to nausea and vomiting with dehydration and metabolic and electrolyte derangements – complications that can occur in up to one-third of patients who receive moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy and who have been reported to achieve poor symptom control.4 Over-prophylaxis also has drawbacks. For example, antiemetics are expensive and, at times, they can induce their own adverse events, such as lethargy, dyskinesia, constipation, headaches, hiccups, fatigue, and even cardiac arrhythmias.5 The best approach is to appropriately match the antiemetic to the chemotherapy. Indeed, adherence to evidence-based guidelines has yielded success in symptom control, but the guidelines work on the assumption that the emetogenic potential of new chemotherapy agents has been accurately determined and then disseminated to and acted upon by health care providers.6,7 To our knowledge, no previous studies have tested that assumption, as we do in the present study.

Trifluridine-tipiracil was selected as the focus of this project and as illustrative of other newly approved chemotherapy agents for two reasons. First, it became available for routine prescribing in pretreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in the United States in September 2015.1 That timing allowed us to analyze much of the early prescribing period, both during the 9 months before approval, when the drug was available on a compassionate-use basis at our institution, and the 3 months after approval. Second, trifluridine-tipiracil has classifiably low emetogenic potential, and mismatching of antiemetics tends to occur more often with low emetogenic chemotherapy.9 Trifluridine-tipiracil and placebo patients manifest rates of nausea at 48% and 24%, respectively, and rates of vomiting at 28% and 14%, respectively.8

Hence, the goal of this study was to explore whether a guideline-based prophylactic antiemetic regimen was appropriately matched to the new chemotherapy agent, trifluridine-tipiracil, to report whether such symptoms of nausea and vomiting are kept at bay, and to identify a potentially vulnerable interval – immediately after drug approval – when cancer patients may be at risk for CINV because of poor adherence to antiemetic guideline prescribing practices by health care providers.

Methods

Overview

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study. We obtained the identifying information of all patients treated with trifluridine-tipiracil at our institution from the Mayo Clinic Specialty Pharmacy, which uses an electronic prescribing system that contributed to the comprehensiveness of the data set. Patients included those who had participated in a colorectal cancer compassionate-use program before the September 2015 approval of the drug and those who received the drug shortly after its approval. In essence, this retrospective, single-institution study included every patient who received trifluridine-tipiracil for metastatic colorectal cancer in 2015 (January through December); this approach enabled us to systematically report on early first-cycle prescribing practices 9 months before and 3 months after the drug’s approval in September of 2015.

Determination of guideline adherence

This project relied on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines (v1.2015, behind paywall) because they had been updated in 2015 (and hence coincided with this project’s study dates) to incorporate recommendations specific to oral chemotherapy and because they seemed concordant with other guidelines.10,11

Antiemetic prophylaxis for a specific patient was deemed guideline adherent if a version of the recommended NCCN antiemetic regimen had been prescribed during the first cycle of chemotherapy. This regimen consisted of metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, haloperidol, or a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor antagonist. In contrast, if a patient had been prescribed a more aggressive or less aggressive regimen, such prescribing practices were deemed non–guideline adherent/aggressive (received more prophylaxis than called for) or non–guideline adherent/less aggressive (including no antiemetics), respectively. Again, medical record prescribing determined adherence.

Data reporting

The primary goal of this study was to report the percentage of patients who had been prescribed a first-cycle antiemetic prophylaxis regimen concordant with NCCN guidelines. Secondary goals included reporting the incidence of nausea and vomiting, the use of rescue antiemetics other than those prescribed up front, the need for an unplanned medical encounter to address nausea and vomiting, and change in antiemetic prescribing before the second chemotherapy cycle. Confidence intervals were calculated with JMP Pro 10.0.0. This study was too limited in sample size to assess sex-based differences in outcomes.

Results

Demographics

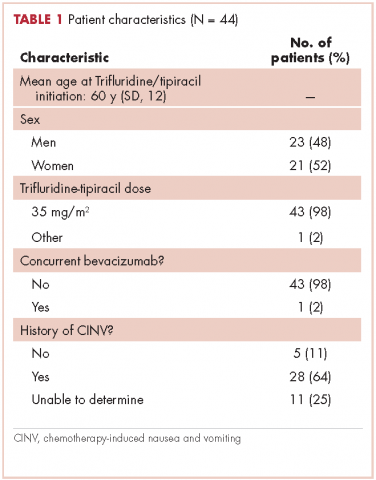

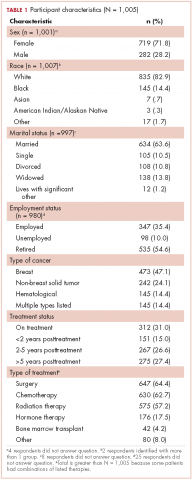

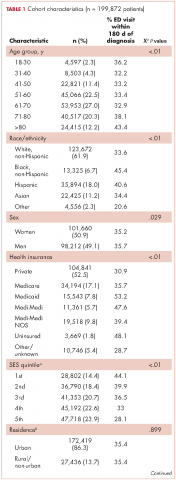

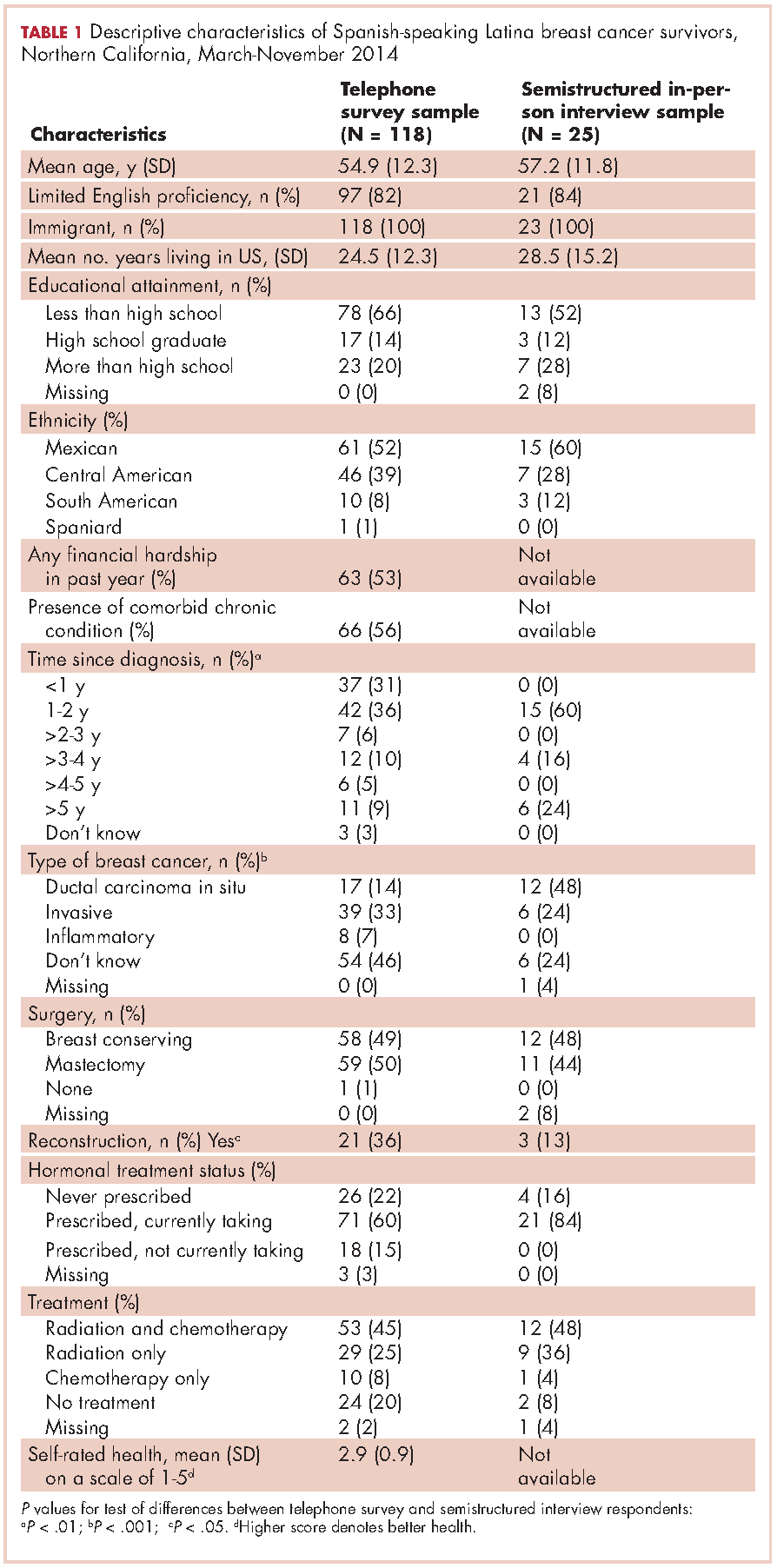

This report focuses on 44 patients who received first-cycle trifluridine-tipiracil during the first calendar year of the drug’s FDA approval. All patients had metastatic colorectal cancer and had previous exposures to other chemotherapy agents (Table 1). Of note, 28 patients (64%) had experienced CINV before starting trifluridine-tipiracil and all these patients had been heavily pretreated with multiple lines of chemotherapy.

Guideline adherence

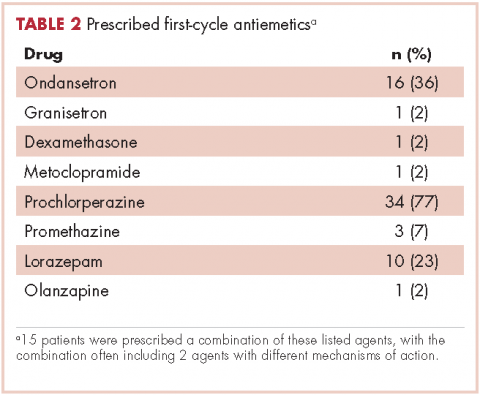

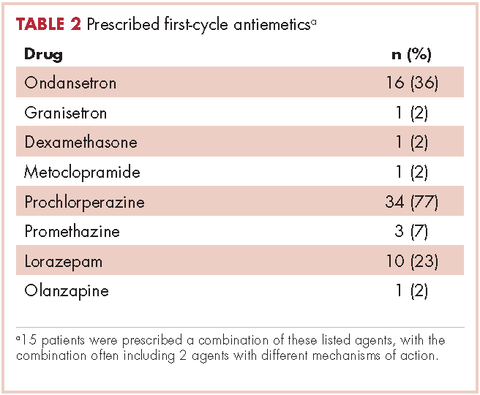

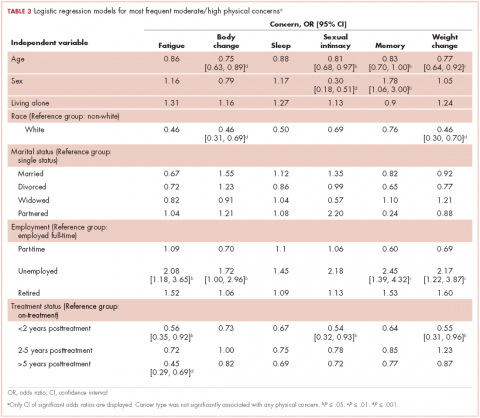

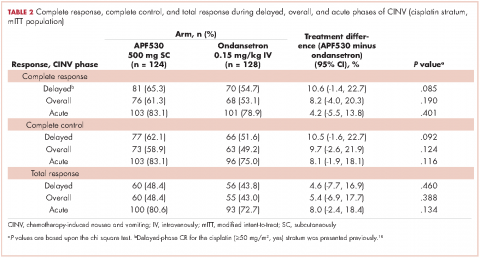

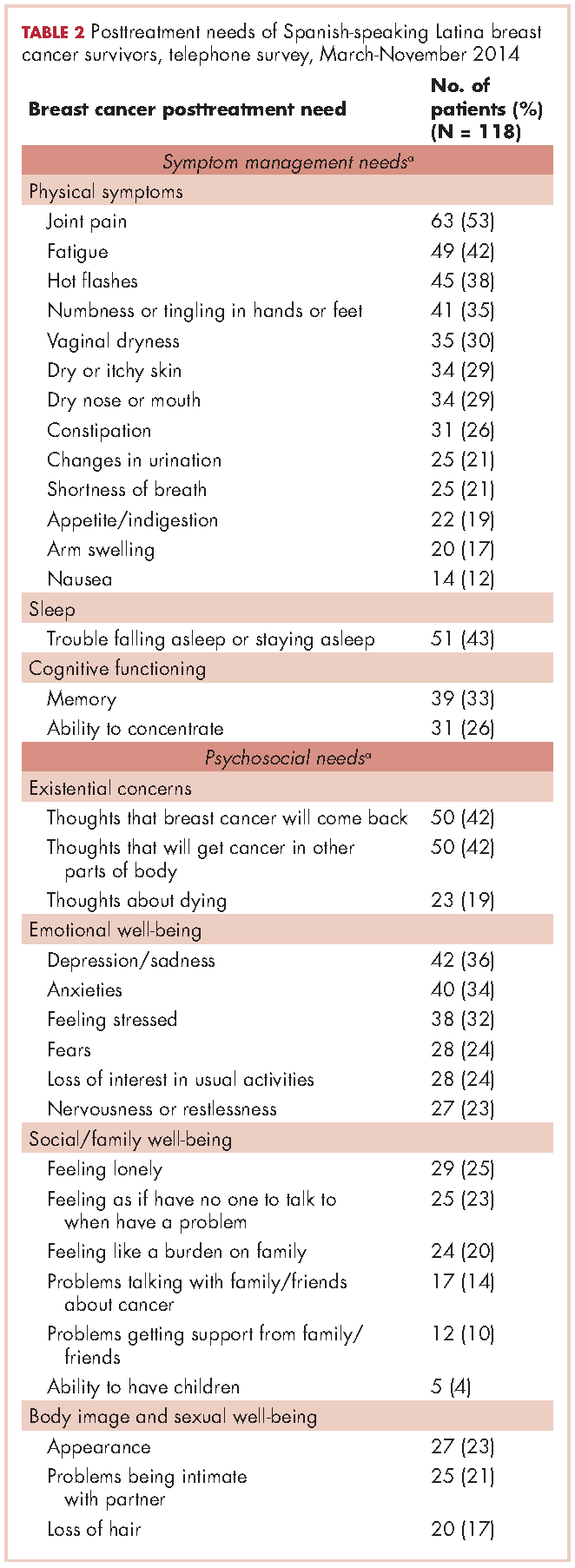

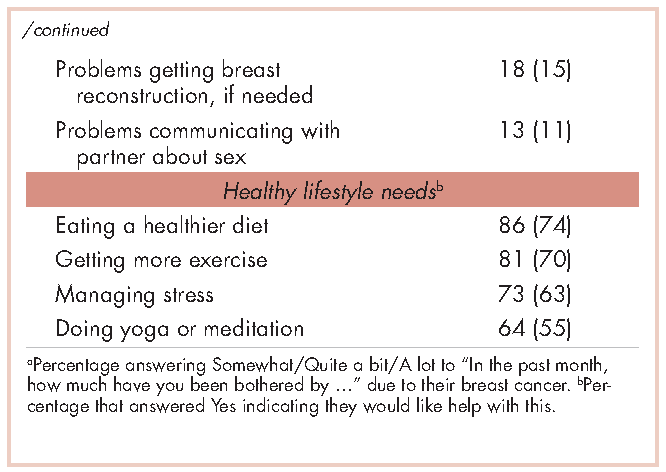

Patients were most commonly prescribed prochlorperazine and ondansetron prophylaxis for CINV before the first chemotherapy cycle of trifluridine-tipiracil (Table 2): 15 patients were prescribed combination antiemetic therapy, typically two of the most commonly prescribed single agents with different mechanisms of action. Twenty-five patients (57%; 95% confidence interval (CI): 42%, 70%) were prescribed antiemetics in a manner consistent with guidelines; 15 (34%; 95% CI: 22%, 49%) were prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/more aggressive manner (received more prophylaxis than called for); and 4 (9%; 95% CI: 4%, 21%) were prescribed them in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner.

Clinical outcomes based on guideline adherence

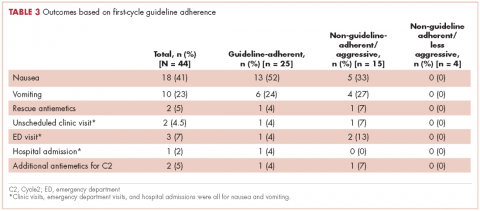

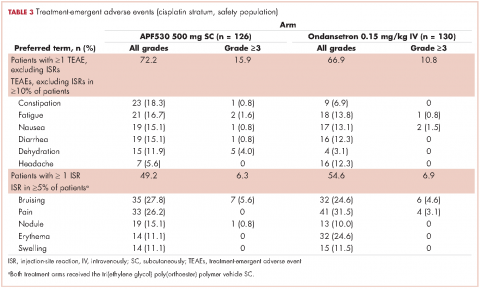

In guideline-adherent patients, first-cycle nausea and vomiting occurred in 13 patients (52%) and 6 patients (24%), respectively, with 1 patient requiring an unscheduled clinic visit and another an emergency department visit and hospital admission – all for nausea and vomiting (Table 3). In non–guideline-adherent/more aggressive patients, those symptoms occurred in 5 patients (33%, nausea) and 4 patients (27%, vomiting), with 1 patient requiring a clinic visit and emergency department visit and another an emergency department visit – again, all for nausea and vomiting. In non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive patients, no nausea or vomiting was reported.

Discussion

This study examined adherence to antiemetic guidelines in the setting of a soon-to-be-approved or newly approved antineoplastic agent. As hypothesized, a substantial proportion of patients (43% in this study) were prescribed antiemetics in a nonadherent manner with respect to guidelines, thus identifying the period shortly before and after FDA approval as a particularly vulnerable interval with respect to antiemetic guideline adherence. It is possible that our institution’s practice of testing novel chemotherapy agents for the treatment of colorectal cancer prompted a heightened awareness of potential adverse events, leading to greater guideline adherence than might have occurred in other settings and resulting in judicious straying from guideline adherence only when appropriate.12-14 Thus, these high rates of poor adherence may in fact represent an underestimate of what one might see in other clinical practices; and, similarly, these rates of symptom control might also be more favorable than those one might see in other clinical practices. To our knowledge, antiemetic prescribing practices with newer chemotherapy agents have not been explored before now, and our data underscore a clear need to do so – particularly during this limited interval when health care providers begin to prescribe new chemotherapy agents for the first time.

It is worth noting that despite the high rates of guideline nonadherence, rates of nausea and vomiting seemed to be comparable in patients prescribed antiemetics in a guideline-adherent manner and those prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/aggressive manner.A small number of patients in both the guideline-adherent and non–guideline-adherent/aggressive groups required rescue medications, unscheduled medical visits for nausea and vomiting, and additional antiemetics during the second cycle of chemotherapy. Of note,none of those interventions occurred in patients who were prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner. These findings might reflect the fact that the patients had proven themselves to be at risk for nausea and vomiting with previous chemotherapy. Before they became candidates for trifluridine-tipiracil, patients had been heavily pretreated with other chemotherapy agents, most had experienced CINV, and many were therefore highly predisposed to nausea and vomiting. These observations underscore the fact that guidelines – even those that are well accepted and widely used – should be implemented in concert with good clinical judgment.10,11 This study has shortcomings, most notably its small sample size. However, had we extended our study beyond 3 months of the FDA approval to include more patients, our findings would have reflected more experienced prescribing practices and we thereby would have deviated from our primary goal of assessing antiemetic prescribing practices with only recently-approved and available chemotherapy agents. In this context, this limited sample size aptly serves a primary role of capturing outcomes within a fleeting but critical interval of new drug availability.In summary, this study found a notable rate of poor guideline adherence when prescribing antiemetics for trifluridine-tipiracil, a new chemotherapy agent of low emetogenic potential. Although the resultant rates of nausea and vomiting suggest that good clinical judgment might have influenced whether or not guidelines were adhered to, these findings nonetheless underscore the need to assess adherence to antiemetic guidelines when new chemotherapy drugs become available and potentially to put in place institutional infrastructure rapidly to promote improved adherence. Such an assessment should be deliberate, formalized, and prompt within individual oncology clinics and cancer centers after a new cancer drug becomes available. In conjunction with clinical judgment, such measures might lead to improved symptom control.

Acknowledgment

This paper is based on a poster that was presented at the 2016 Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium, on September 10, 2016: Adherence to antiemetic guidelines with a newly approved chemotherapy agent, trifluridine-tipiracil (TAS-102): a single-institution study. Daniel Childs and Aminah Jatoi, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/136444/abstract. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 26S):abstract 221.

1. CenterWatch. FDA website. FDA approved drugs for oncology: drugs approved for 2015. https://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/therapeutic-area/12/oncology. Last updated April 2017. Accessed June 4, 2016.

2. Navari RM, Aapro M. Antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1356-1367.

3. Kottschade L, Novotny P, Lyss A, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: incidence and characteristics of persistent symptoms and future directions NCCTG N08C3. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2661-2667.

4. Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100:2261-2268.

5. Navari RM. The safety of antiemetic medications for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016; 15:343-356.

6. Gilmore JW, Peacock NW, Gu A, et al. Antiemetic guideline consistency and incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in US community oncology practice: INSPIRE study. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:68-74.

7. Mertens WC, Higby DJ, Brown D, et al. Improving the care of patients with regard to chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis: the effect of feedback to clinicians on adherence to antiemetic prescribing guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1373-1378.

8. Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1909-1919.

9. Schwartzberg L, Morrow G, Balu S, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and antiemetic prophylaxis with palonosetron versus other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in patients with cancer treated with low emetogenic chemotherapy in a hospital outpatient setting in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1613-1622.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines on Antiemesis, Version1,2015 [behind paywall]. https://www.nccn.org. Last update not known. Accessed June 4, 2016.

11. Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:v232-v243.

12. Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2013;381:303-312.

13. Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Nair S, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1383-1393.

14. Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, et al. Randomized controlled trial of reduced-dose bolus fluorouracil plus leucovorin and irinotecan or infused fluorouracil plus leucovorin and oxaliplatin in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: a North American Intergroup Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3347-3353.

Cancer drugs are becoming available at an unprecedented rate. In 2015 alone, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 18 new agents.1 Although many of those agents have adverse event profiles that are more favorable than those seen with conventional chemotherapy, nausea and vomiting still occur. In fact, nausea and vomiting continue to be ranked as among the most common and distressing of cancer symptoms.2,3 In a 2004 study, Grunberg and colleagues reported that as many as 75% of health care providers misjudge the risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), even when prescribing cancer drugs that have been available for years,4 thus amplifying concerns that such risk assessment might be even worse when new cancer agents are prescribed for the first time.

In this study, we hypothesized that patients prescribed a new cancer drug, trifluridine-tipiracil, would be at risk for CINV because of poor guideline adherence on the part of health care providers. The correct matching of antiemetics to chemotherapy is important. Inadequate antiemetic prophylaxis predisposes to nausea and vomiting with dehydration and metabolic and electrolyte derangements – complications that can occur in up to one-third of patients who receive moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy and who have been reported to achieve poor symptom control.4 Over-prophylaxis also has drawbacks. For example, antiemetics are expensive and, at times, they can induce their own adverse events, such as lethargy, dyskinesia, constipation, headaches, hiccups, fatigue, and even cardiac arrhythmias.5 The best approach is to appropriately match the antiemetic to the chemotherapy. Indeed, adherence to evidence-based guidelines has yielded success in symptom control, but the guidelines work on the assumption that the emetogenic potential of new chemotherapy agents has been accurately determined and then disseminated to and acted upon by health care providers.6,7 To our knowledge, no previous studies have tested that assumption, as we do in the present study.

Trifluridine-tipiracil was selected as the focus of this project and as illustrative of other newly approved chemotherapy agents for two reasons. First, it became available for routine prescribing in pretreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in the United States in September 2015.1 That timing allowed us to analyze much of the early prescribing period, both during the 9 months before approval, when the drug was available on a compassionate-use basis at our institution, and the 3 months after approval. Second, trifluridine-tipiracil has classifiably low emetogenic potential, and mismatching of antiemetics tends to occur more often with low emetogenic chemotherapy.9 Trifluridine-tipiracil and placebo patients manifest rates of nausea at 48% and 24%, respectively, and rates of vomiting at 28% and 14%, respectively.8

Hence, the goal of this study was to explore whether a guideline-based prophylactic antiemetic regimen was appropriately matched to the new chemotherapy agent, trifluridine-tipiracil, to report whether such symptoms of nausea and vomiting are kept at bay, and to identify a potentially vulnerable interval – immediately after drug approval – when cancer patients may be at risk for CINV because of poor adherence to antiemetic guideline prescribing practices by health care providers.

Methods

Overview

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study. We obtained the identifying information of all patients treated with trifluridine-tipiracil at our institution from the Mayo Clinic Specialty Pharmacy, which uses an electronic prescribing system that contributed to the comprehensiveness of the data set. Patients included those who had participated in a colorectal cancer compassionate-use program before the September 2015 approval of the drug and those who received the drug shortly after its approval. In essence, this retrospective, single-institution study included every patient who received trifluridine-tipiracil for metastatic colorectal cancer in 2015 (January through December); this approach enabled us to systematically report on early first-cycle prescribing practices 9 months before and 3 months after the drug’s approval in September of 2015.

Determination of guideline adherence

This project relied on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines (v1.2015, behind paywall) because they had been updated in 2015 (and hence coincided with this project’s study dates) to incorporate recommendations specific to oral chemotherapy and because they seemed concordant with other guidelines.10,11

Antiemetic prophylaxis for a specific patient was deemed guideline adherent if a version of the recommended NCCN antiemetic regimen had been prescribed during the first cycle of chemotherapy. This regimen consisted of metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, haloperidol, or a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor antagonist. In contrast, if a patient had been prescribed a more aggressive or less aggressive regimen, such prescribing practices were deemed non–guideline adherent/aggressive (received more prophylaxis than called for) or non–guideline adherent/less aggressive (including no antiemetics), respectively. Again, medical record prescribing determined adherence.

Data reporting

The primary goal of this study was to report the percentage of patients who had been prescribed a first-cycle antiemetic prophylaxis regimen concordant with NCCN guidelines. Secondary goals included reporting the incidence of nausea and vomiting, the use of rescue antiemetics other than those prescribed up front, the need for an unplanned medical encounter to address nausea and vomiting, and change in antiemetic prescribing before the second chemotherapy cycle. Confidence intervals were calculated with JMP Pro 10.0.0. This study was too limited in sample size to assess sex-based differences in outcomes.

Results

Demographics

This report focuses on 44 patients who received first-cycle trifluridine-tipiracil during the first calendar year of the drug’s FDA approval. All patients had metastatic colorectal cancer and had previous exposures to other chemotherapy agents (Table 1). Of note, 28 patients (64%) had experienced CINV before starting trifluridine-tipiracil and all these patients had been heavily pretreated with multiple lines of chemotherapy.

Guideline adherence

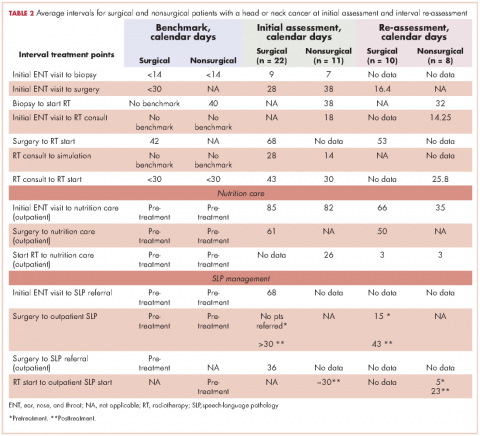

Patients were most commonly prescribed prochlorperazine and ondansetron prophylaxis for CINV before the first chemotherapy cycle of trifluridine-tipiracil (Table 2): 15 patients were prescribed combination antiemetic therapy, typically two of the most commonly prescribed single agents with different mechanisms of action. Twenty-five patients (57%; 95% confidence interval (CI): 42%, 70%) were prescribed antiemetics in a manner consistent with guidelines; 15 (34%; 95% CI: 22%, 49%) were prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/more aggressive manner (received more prophylaxis than called for); and 4 (9%; 95% CI: 4%, 21%) were prescribed them in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner.

Clinical outcomes based on guideline adherence

In guideline-adherent patients, first-cycle nausea and vomiting occurred in 13 patients (52%) and 6 patients (24%), respectively, with 1 patient requiring an unscheduled clinic visit and another an emergency department visit and hospital admission – all for nausea and vomiting (Table 3). In non–guideline-adherent/more aggressive patients, those symptoms occurred in 5 patients (33%, nausea) and 4 patients (27%, vomiting), with 1 patient requiring a clinic visit and emergency department visit and another an emergency department visit – again, all for nausea and vomiting. In non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive patients, no nausea or vomiting was reported.

Discussion

This study examined adherence to antiemetic guidelines in the setting of a soon-to-be-approved or newly approved antineoplastic agent. As hypothesized, a substantial proportion of patients (43% in this study) were prescribed antiemetics in a nonadherent manner with respect to guidelines, thus identifying the period shortly before and after FDA approval as a particularly vulnerable interval with respect to antiemetic guideline adherence. It is possible that our institution’s practice of testing novel chemotherapy agents for the treatment of colorectal cancer prompted a heightened awareness of potential adverse events, leading to greater guideline adherence than might have occurred in other settings and resulting in judicious straying from guideline adherence only when appropriate.12-14 Thus, these high rates of poor adherence may in fact represent an underestimate of what one might see in other clinical practices; and, similarly, these rates of symptom control might also be more favorable than those one might see in other clinical practices. To our knowledge, antiemetic prescribing practices with newer chemotherapy agents have not been explored before now, and our data underscore a clear need to do so – particularly during this limited interval when health care providers begin to prescribe new chemotherapy agents for the first time.

It is worth noting that despite the high rates of guideline nonadherence, rates of nausea and vomiting seemed to be comparable in patients prescribed antiemetics in a guideline-adherent manner and those prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/aggressive manner.A small number of patients in both the guideline-adherent and non–guideline-adherent/aggressive groups required rescue medications, unscheduled medical visits for nausea and vomiting, and additional antiemetics during the second cycle of chemotherapy. Of note,none of those interventions occurred in patients who were prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner. These findings might reflect the fact that the patients had proven themselves to be at risk for nausea and vomiting with previous chemotherapy. Before they became candidates for trifluridine-tipiracil, patients had been heavily pretreated with other chemotherapy agents, most had experienced CINV, and many were therefore highly predisposed to nausea and vomiting. These observations underscore the fact that guidelines – even those that are well accepted and widely used – should be implemented in concert with good clinical judgment.10,11 This study has shortcomings, most notably its small sample size. However, had we extended our study beyond 3 months of the FDA approval to include more patients, our findings would have reflected more experienced prescribing practices and we thereby would have deviated from our primary goal of assessing antiemetic prescribing practices with only recently-approved and available chemotherapy agents. In this context, this limited sample size aptly serves a primary role of capturing outcomes within a fleeting but critical interval of new drug availability.In summary, this study found a notable rate of poor guideline adherence when prescribing antiemetics for trifluridine-tipiracil, a new chemotherapy agent of low emetogenic potential. Although the resultant rates of nausea and vomiting suggest that good clinical judgment might have influenced whether or not guidelines were adhered to, these findings nonetheless underscore the need to assess adherence to antiemetic guidelines when new chemotherapy drugs become available and potentially to put in place institutional infrastructure rapidly to promote improved adherence. Such an assessment should be deliberate, formalized, and prompt within individual oncology clinics and cancer centers after a new cancer drug becomes available. In conjunction with clinical judgment, such measures might lead to improved symptom control.

Acknowledgment

This paper is based on a poster that was presented at the 2016 Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium, on September 10, 2016: Adherence to antiemetic guidelines with a newly approved chemotherapy agent, trifluridine-tipiracil (TAS-102): a single-institution study. Daniel Childs and Aminah Jatoi, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/136444/abstract. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 26S):abstract 221.

Cancer drugs are becoming available at an unprecedented rate. In 2015 alone, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 18 new agents.1 Although many of those agents have adverse event profiles that are more favorable than those seen with conventional chemotherapy, nausea and vomiting still occur. In fact, nausea and vomiting continue to be ranked as among the most common and distressing of cancer symptoms.2,3 In a 2004 study, Grunberg and colleagues reported that as many as 75% of health care providers misjudge the risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), even when prescribing cancer drugs that have been available for years,4 thus amplifying concerns that such risk assessment might be even worse when new cancer agents are prescribed for the first time.

In this study, we hypothesized that patients prescribed a new cancer drug, trifluridine-tipiracil, would be at risk for CINV because of poor guideline adherence on the part of health care providers. The correct matching of antiemetics to chemotherapy is important. Inadequate antiemetic prophylaxis predisposes to nausea and vomiting with dehydration and metabolic and electrolyte derangements – complications that can occur in up to one-third of patients who receive moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy and who have been reported to achieve poor symptom control.4 Over-prophylaxis also has drawbacks. For example, antiemetics are expensive and, at times, they can induce their own adverse events, such as lethargy, dyskinesia, constipation, headaches, hiccups, fatigue, and even cardiac arrhythmias.5 The best approach is to appropriately match the antiemetic to the chemotherapy. Indeed, adherence to evidence-based guidelines has yielded success in symptom control, but the guidelines work on the assumption that the emetogenic potential of new chemotherapy agents has been accurately determined and then disseminated to and acted upon by health care providers.6,7 To our knowledge, no previous studies have tested that assumption, as we do in the present study.

Trifluridine-tipiracil was selected as the focus of this project and as illustrative of other newly approved chemotherapy agents for two reasons. First, it became available for routine prescribing in pretreated patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in the United States in September 2015.1 That timing allowed us to analyze much of the early prescribing period, both during the 9 months before approval, when the drug was available on a compassionate-use basis at our institution, and the 3 months after approval. Second, trifluridine-tipiracil has classifiably low emetogenic potential, and mismatching of antiemetics tends to occur more often with low emetogenic chemotherapy.9 Trifluridine-tipiracil and placebo patients manifest rates of nausea at 48% and 24%, respectively, and rates of vomiting at 28% and 14%, respectively.8

Hence, the goal of this study was to explore whether a guideline-based prophylactic antiemetic regimen was appropriately matched to the new chemotherapy agent, trifluridine-tipiracil, to report whether such symptoms of nausea and vomiting are kept at bay, and to identify a potentially vulnerable interval – immediately after drug approval – when cancer patients may be at risk for CINV because of poor adherence to antiemetic guideline prescribing practices by health care providers.

Methods

Overview

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study. We obtained the identifying information of all patients treated with trifluridine-tipiracil at our institution from the Mayo Clinic Specialty Pharmacy, which uses an electronic prescribing system that contributed to the comprehensiveness of the data set. Patients included those who had participated in a colorectal cancer compassionate-use program before the September 2015 approval of the drug and those who received the drug shortly after its approval. In essence, this retrospective, single-institution study included every patient who received trifluridine-tipiracil for metastatic colorectal cancer in 2015 (January through December); this approach enabled us to systematically report on early first-cycle prescribing practices 9 months before and 3 months after the drug’s approval in September of 2015.

Determination of guideline adherence

This project relied on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines (v1.2015, behind paywall) because they had been updated in 2015 (and hence coincided with this project’s study dates) to incorporate recommendations specific to oral chemotherapy and because they seemed concordant with other guidelines.10,11

Antiemetic prophylaxis for a specific patient was deemed guideline adherent if a version of the recommended NCCN antiemetic regimen had been prescribed during the first cycle of chemotherapy. This regimen consisted of metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, haloperidol, or a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor antagonist. In contrast, if a patient had been prescribed a more aggressive or less aggressive regimen, such prescribing practices were deemed non–guideline adherent/aggressive (received more prophylaxis than called for) or non–guideline adherent/less aggressive (including no antiemetics), respectively. Again, medical record prescribing determined adherence.

Data reporting

The primary goal of this study was to report the percentage of patients who had been prescribed a first-cycle antiemetic prophylaxis regimen concordant with NCCN guidelines. Secondary goals included reporting the incidence of nausea and vomiting, the use of rescue antiemetics other than those prescribed up front, the need for an unplanned medical encounter to address nausea and vomiting, and change in antiemetic prescribing before the second chemotherapy cycle. Confidence intervals were calculated with JMP Pro 10.0.0. This study was too limited in sample size to assess sex-based differences in outcomes.

Results

Demographics

This report focuses on 44 patients who received first-cycle trifluridine-tipiracil during the first calendar year of the drug’s FDA approval. All patients had metastatic colorectal cancer and had previous exposures to other chemotherapy agents (Table 1). Of note, 28 patients (64%) had experienced CINV before starting trifluridine-tipiracil and all these patients had been heavily pretreated with multiple lines of chemotherapy.

Guideline adherence

Patients were most commonly prescribed prochlorperazine and ondansetron prophylaxis for CINV before the first chemotherapy cycle of trifluridine-tipiracil (Table 2): 15 patients were prescribed combination antiemetic therapy, typically two of the most commonly prescribed single agents with different mechanisms of action. Twenty-five patients (57%; 95% confidence interval (CI): 42%, 70%) were prescribed antiemetics in a manner consistent with guidelines; 15 (34%; 95% CI: 22%, 49%) were prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/more aggressive manner (received more prophylaxis than called for); and 4 (9%; 95% CI: 4%, 21%) were prescribed them in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner.

Clinical outcomes based on guideline adherence

In guideline-adherent patients, first-cycle nausea and vomiting occurred in 13 patients (52%) and 6 patients (24%), respectively, with 1 patient requiring an unscheduled clinic visit and another an emergency department visit and hospital admission – all for nausea and vomiting (Table 3). In non–guideline-adherent/more aggressive patients, those symptoms occurred in 5 patients (33%, nausea) and 4 patients (27%, vomiting), with 1 patient requiring a clinic visit and emergency department visit and another an emergency department visit – again, all for nausea and vomiting. In non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive patients, no nausea or vomiting was reported.

Discussion

This study examined adherence to antiemetic guidelines in the setting of a soon-to-be-approved or newly approved antineoplastic agent. As hypothesized, a substantial proportion of patients (43% in this study) were prescribed antiemetics in a nonadherent manner with respect to guidelines, thus identifying the period shortly before and after FDA approval as a particularly vulnerable interval with respect to antiemetic guideline adherence. It is possible that our institution’s practice of testing novel chemotherapy agents for the treatment of colorectal cancer prompted a heightened awareness of potential adverse events, leading to greater guideline adherence than might have occurred in other settings and resulting in judicious straying from guideline adherence only when appropriate.12-14 Thus, these high rates of poor adherence may in fact represent an underestimate of what one might see in other clinical practices; and, similarly, these rates of symptom control might also be more favorable than those one might see in other clinical practices. To our knowledge, antiemetic prescribing practices with newer chemotherapy agents have not been explored before now, and our data underscore a clear need to do so – particularly during this limited interval when health care providers begin to prescribe new chemotherapy agents for the first time.

It is worth noting that despite the high rates of guideline nonadherence, rates of nausea and vomiting seemed to be comparable in patients prescribed antiemetics in a guideline-adherent manner and those prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/aggressive manner.A small number of patients in both the guideline-adherent and non–guideline-adherent/aggressive groups required rescue medications, unscheduled medical visits for nausea and vomiting, and additional antiemetics during the second cycle of chemotherapy. Of note,none of those interventions occurred in patients who were prescribed antiemetics in a non–guideline-adherent/less aggressive manner. These findings might reflect the fact that the patients had proven themselves to be at risk for nausea and vomiting with previous chemotherapy. Before they became candidates for trifluridine-tipiracil, patients had been heavily pretreated with other chemotherapy agents, most had experienced CINV, and many were therefore highly predisposed to nausea and vomiting. These observations underscore the fact that guidelines – even those that are well accepted and widely used – should be implemented in concert with good clinical judgment.10,11 This study has shortcomings, most notably its small sample size. However, had we extended our study beyond 3 months of the FDA approval to include more patients, our findings would have reflected more experienced prescribing practices and we thereby would have deviated from our primary goal of assessing antiemetic prescribing practices with only recently-approved and available chemotherapy agents. In this context, this limited sample size aptly serves a primary role of capturing outcomes within a fleeting but critical interval of new drug availability.In summary, this study found a notable rate of poor guideline adherence when prescribing antiemetics for trifluridine-tipiracil, a new chemotherapy agent of low emetogenic potential. Although the resultant rates of nausea and vomiting suggest that good clinical judgment might have influenced whether or not guidelines were adhered to, these findings nonetheless underscore the need to assess adherence to antiemetic guidelines when new chemotherapy drugs become available and potentially to put in place institutional infrastructure rapidly to promote improved adherence. Such an assessment should be deliberate, formalized, and prompt within individual oncology clinics and cancer centers after a new cancer drug becomes available. In conjunction with clinical judgment, such measures might lead to improved symptom control.

Acknowledgment

This paper is based on a poster that was presented at the 2016 Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium, on September 10, 2016: Adherence to antiemetic guidelines with a newly approved chemotherapy agent, trifluridine-tipiracil (TAS-102): a single-institution study. Daniel Childs and Aminah Jatoi, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/record/136444/abstract. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 26S):abstract 221.

1. CenterWatch. FDA website. FDA approved drugs for oncology: drugs approved for 2015. https://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/therapeutic-area/12/oncology. Last updated April 2017. Accessed June 4, 2016.

2. Navari RM, Aapro M. Antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1356-1367.

3. Kottschade L, Novotny P, Lyss A, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: incidence and characteristics of persistent symptoms and future directions NCCTG N08C3. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2661-2667.

4. Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100:2261-2268.

5. Navari RM. The safety of antiemetic medications for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016; 15:343-356.

6. Gilmore JW, Peacock NW, Gu A, et al. Antiemetic guideline consistency and incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in US community oncology practice: INSPIRE study. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:68-74.

7. Mertens WC, Higby DJ, Brown D, et al. Improving the care of patients with regard to chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis: the effect of feedback to clinicians on adherence to antiemetic prescribing guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1373-1378.

8. Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1909-1919.

9. Schwartzberg L, Morrow G, Balu S, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and antiemetic prophylaxis with palonosetron versus other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in patients with cancer treated with low emetogenic chemotherapy in a hospital outpatient setting in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1613-1622.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines on Antiemesis, Version1,2015 [behind paywall]. https://www.nccn.org. Last update not known. Accessed June 4, 2016.

11. Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:v232-v243.

12. Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2013;381:303-312.

13. Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Nair S, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1383-1393.

14. Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, et al. Randomized controlled trial of reduced-dose bolus fluorouracil plus leucovorin and irinotecan or infused fluorouracil plus leucovorin and oxaliplatin in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: a North American Intergroup Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3347-3353.

1. CenterWatch. FDA website. FDA approved drugs for oncology: drugs approved for 2015. https://www.centerwatch.com/drug-information/fda-approved-drugs/therapeutic-area/12/oncology. Last updated April 2017. Accessed June 4, 2016.

2. Navari RM, Aapro M. Antiemetic prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1356-1367.

3. Kottschade L, Novotny P, Lyss A, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: incidence and characteristics of persistent symptoms and future directions NCCTG N08C3. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:2661-2667.

4. Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004;100:2261-2268.

5. Navari RM. The safety of antiemetic medications for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016; 15:343-356.

6. Gilmore JW, Peacock NW, Gu A, et al. Antiemetic guideline consistency and incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in US community oncology practice: INSPIRE study. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:68-74.

7. Mertens WC, Higby DJ, Brown D, et al. Improving the care of patients with regard to chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis: the effect of feedback to clinicians on adherence to antiemetic prescribing guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1373-1378.

8. Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1909-1919.

9. Schwartzberg L, Morrow G, Balu S, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and antiemetic prophylaxis with palonosetron versus other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in patients with cancer treated with low emetogenic chemotherapy in a hospital outpatient setting in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:1613-1622.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines on Antiemesis, Version1,2015 [behind paywall]. https://www.nccn.org. Last update not known. Accessed June 4, 2016.

11. Roila F, Herrstedt J, Aapro M, et al. Guideline update for MASCC and ESMO in the prevention of chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: results of the Perugia consensus conference. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:v232-v243.

12. Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2013;381:303-312.

13. Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Nair S, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1383-1393.

14. Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Morton RF, et al. Randomized controlled trial of reduced-dose bolus fluorouracil plus leucovorin and irinotecan or infused fluorouracil plus leucovorin and oxaliplatin in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: a North American Intergroup Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3347-3353.

Physician attitudes and prevalence of molecular testing in lung cancer

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States. It is estimated that there will be 222,500 new cases of lung cancer and 155,870 deaths from lung cancer in 2017. Non–small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) accounts for 80%-85% of lung cancers, with adenocarcinoma being the most common histologic subtype. Other less common subtypes include squamous-cell carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma, and NSCLC that cannot be further classified.1 Nearly 70% of patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and are not candidates for surgical resection.2 For that group of patients, the mainstay of treatment is platinum-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. Patients who are chemotherapy naive often experience a modest response, however; durable remission is short lived, and the 5-year survival rate remains staggeringly low.3 Improved understanding of the molecular pathways that drive malignancy in NSCLC has led to the development of drugs that target specific molecular pathways.4 By definition, these driver mutations facilitate oncogenesis by conferring a selective advantage during clonal evolution.5 Moreover, agents targeting these pathways are extremely active and induce durable responses in many patients.6,7,8

Predictive biomarkers in NSCLC include anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion oncogene and sensitizing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. Mutations in the EGFR tyrosine kinase are observed in about 15%-20% of NSCLC adenocarcinomas in the United States and upward of 60% in Asian populations. They are also found more frequently in nonsmokers and women.6 The two most prevalent mutations in the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain are in-frame deletions of exon 19 and L858R substitution in exon 21, representing about 45% and 40% of mutations, respectively.9 Both mutations result in activation of the tyrosine kinase domain, and both are associated with sensitivity to the small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as erlotinib, gefitinib, and afatinib.10 Other drug-sensitive mutations include point mutations at exon 21 (L861Q) and exon 18 (G719X).11 Targeted therapy produces durable responses in the majority of patients.12,13,14 Unfortunately, most patients develop acquired resistance to these therapies, which leads to disease progression.4,15-17

ALK gene rearrangements, although less prevalent, are another important molecular target in NSCLC and are seen in 2%-7% of cases in the United States.7 As with EGFR mutations, these mutations are more prevalent in nonsmokers, and they are found more commonly in younger patients and in men.8

Identification of driver mutations early in the course of disease and acquired resistance mutations later are crucial for the optimal management of advanced NSCLC. DNA analysis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing is the preferred method for testing for EGFR mutations, and ALK rearrangements are generally tested either by flourescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or immunohistochemistry.18,19 Newer blood-based assays have shown great promise, and clinicians may soon have the ability to monitor subtle genetic changes, identify resistance patterns, and change therapy when acquired resistance occurs.20

The American College of Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology have proposed guidelines for molecular testing in lung cancer. It is recommended that all advanced squamous and nonsquamous cell lung cancers with an adenocarcinoma component should be tested for EGFR and ALK mutations independent of age, sex, ethnicity, or smoking history. In the setting of smaller lung cancer specimens (eg, from biopsies, cytology) where an adenocarcinoma component cannot be completely excluded, EGFR and ALK testing may be performed in cases showing squamous or small cell histology but clinical criteria (eg, young age, lack of smoking history) may be useful in selecting a subset of these samples for testing. Samples obtained through surgical resection, open biopsy, endoscopy, transthoracic needle biopsy, fine-needle aspiration, and thoracentesis are all considered suitable for testing, but large biopsy samples are generally preferred over small biopsy samples, cell-blocks, and cytology samples.21 Despite this recommendation, not all patients who are eligible for mutation analysis are tested. At our institution, preliminary observations suggested that the percentage of patients being tested and the prevalence of driver mutations were significantly lower compared with published data. The purpose of this study was to evaluate physician attitudes about molecular testing, and to determine the rate of testing, the effect of biopsy sample size on rate of testing, and the prevalence of driver mutations at our institution.

Methods

In this retrospective clinical study, we identified 206 cases of advanced nsNSCLC from the tumor registry (February 2011-February 2013). Registry data was obtained from three hospitals within our health network – two academic tertiary care centers, and one community-based hospital. The other hospitals in the network were excluded because their EHR systems were not integrated with the rest of the hospitals and/or there was a lack of registry data. The testing rates for driver mutations, prevalence of driver mutations, and the tissue procurement techniques were obtained from individual chart review. Surgical specimens, core biopsy samples, and large volume thoracentesis specimens were categorized as large biopsy samples, and samples obtained by fine-needle aspiration, bronchial washing, and bronchial brushing were considered small biopsy samples. We used a chi-square analysis to compare mutation testing rates between the large and small biopsy sample groups. The prevalence of driver mutations was determined, excluding unknown or inadequate samples.

EGFR analysis had been conducted at Integrated Oncology, using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Genomic DNA was isolated, and EGFR mutation analysis was performed using SNaPShot multiplex PCR, primer extension assay for exons 18-21; samples with >4mm2 and ≥50% tumor content were preferred. Macrodissection was used to enrich for tumor cells when samples had lower tumor cellularity and content. ALK rearrangements were tested in the hospital using the Vysis ALK Break Apart FISH probe kit (Abott Molecular Inc, Des Plaines, IL).

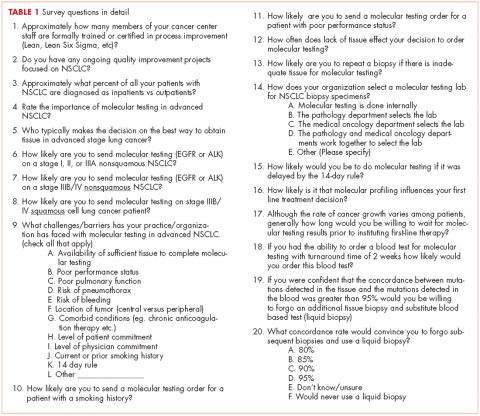

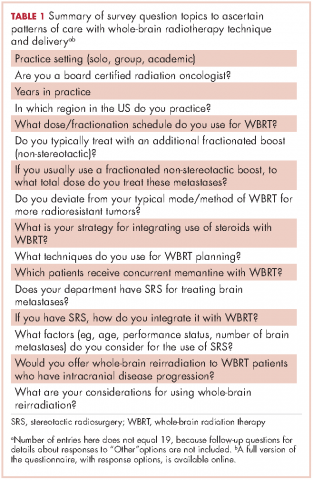

We conducted a web-based, 20-question survey about molecular profiling among 110 practitioners to gauge their knowledge and opinions about molecular testing. The practitioners included medical oncologists, thoracic surgeons, pulmonologists, and interventional radiologists. Each received an initial e-mail informing them of the study, inviting them to complete survey, and providing a link to it, and two reminder e-mails at biweekly intervals to maximize survey participation and responses. The questions were aimed at understanding the challenges surrounding molecular testing within our network. Apart from the questions gathering demographic information about the respondents, the questions were intended to highlight the disparities between guideline recommendations and physician practices; to gauge the perceived importance of molecular evaluation; to identify individual, subspecialty, and hospital-based challenges; and to assess physician attitudes toward alternatives to traditional tissue-based testing (Table 1, p. e150). Nineteen of the questions were structured as single or best answer, whereas Question 9, which was aimed at identifying system-based challenges, allowed for multiple answer selections.

Results

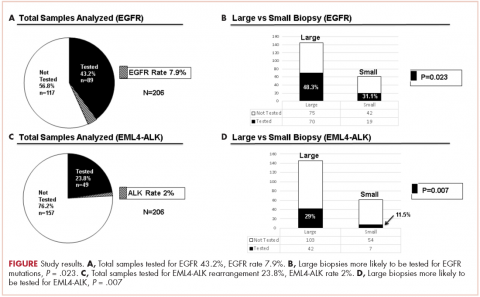

There were a total of 206 cases of advanced stage IIIb or IV nsNSCLC identified at three hospitals during 2011-2013. Of those 206 cases, 161 (78.2%) were recorded at the two large academic medical centers, and 45 (21.9%) were recorded at the smaller community-based hospital. Of the total, there were 145 (70.4%) large biopsy specimens and 61 (29.6%) small biopsy specimens. We found that 89 of the 206 cases (43.2 %) had been tested for EGFR mutations, and 49 (23.8%) had been tested for ALK rearrangements (Figure, A and C). In all, 70 (48.3%) large-sample biopsies and 19 (31.1%) small-sample biopsies were submitted for EGFR analysis (Figure, B), and 42 (29%) large-sample biopsies and 7 (11.5%) small-sample biopsies were tested for ALK rearrangements (Figure, D). Large-sample biopsies were more likely to be analyzed for EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements, with the results reaching statistical significance (P = .023 and P = .007, respectively). Across all samples, a total of 7 EGFR mutations and 1 ALK rearrangement were identified, yielding a prevalence of 7.9% and 2% respectively (Figure, A and C).

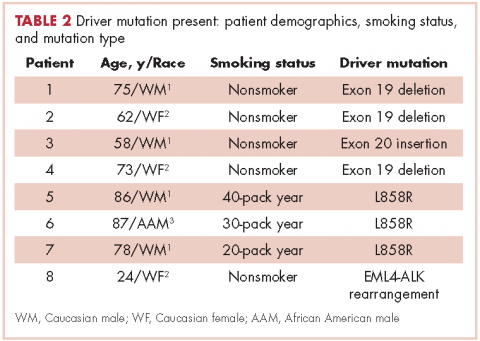

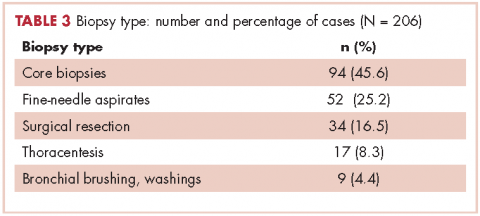

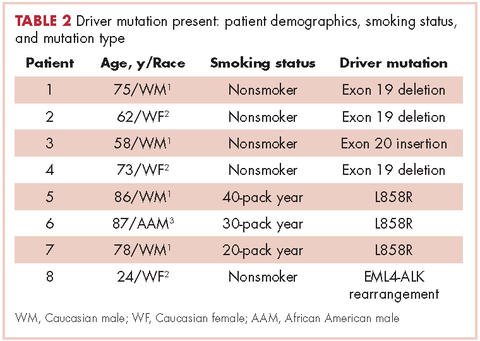

Table 2 shows the demographics, smoking status and type of driver mutation identified. Core biopsies were obtained in 45.6% of the cases and fine-needle aspiration biopsies were obtained in 25.2% of the cases with surgical resections, with thoracentesis and bronchial washings comprising the rest of the biopsies (Table 3).

The average age at diagnosis of the patients in the cases that were analyzed was 69.3 years. Most of the patients (83.9%) identified as white, 3.8% were African American, and 12.6% were in the Unknown category. Of the total number of patients, 11 were identified as never-smokers (5.3%), 50 (24.3%) had a 1-15 pack-year smoking history, 104 (50.5%) had a 16-45 pack-year smoking history, and 41 (19.9%) had a >45 pack-year smoking history.

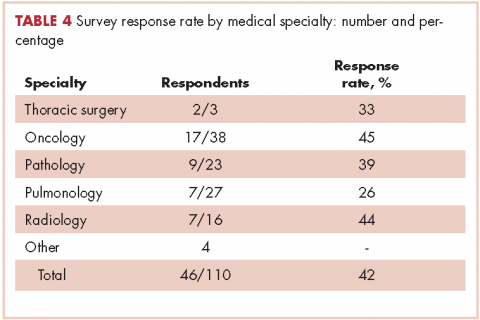

In regard to the survey, 46 of the 110 physicians asked to participate in the survey responded, representing a response rate of 41.8% (range across medical specialties, 26%-45%, Table 4). Of those respondents, 38 (82.6%) indicated they believed molecular evaluation was a very important aspect of NSCLC care, with the remainder indicating it was somewhat important. 91.4% of the respondents who routinely ordered molecular testing agreed that stage IIIb or IV nsNSCLC should undergo molecular evaluation.

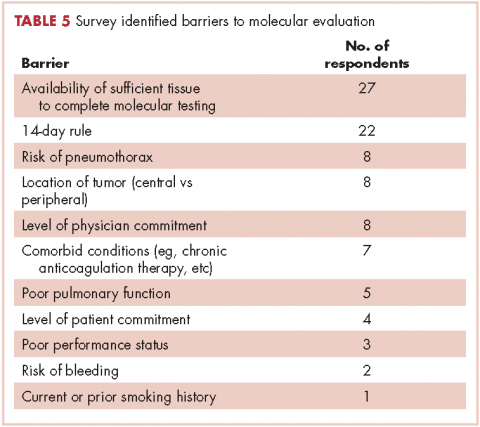

The top barriers to molecular evaluation identified through this survey were the availability of sufficient tissue to complete molecular testing and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’s (CMS’s) 14-day rule that requires hospitals to wait 14 days after the patient is discharged for the lab to receive reimbursement for molecular testing (Table 5).

Discussion

The treatment of advanced nsNSCLC has evolved significantly over the past decade. Molecular profiling is now an essential part of initial evaluation, and larger-sample biopsies are needed to ensure accurate evaluation and appropriate treatment. The detection of EGFR and EML4-ALK driver mutations are associated with increased response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors and are associated with improvement in progression-free survival, patient quality of life, and even overall survival in some studies.12,22,23,24 Early identification of these driver mutations is crucial, however, preliminary observation in our network suggested that a large percentage of patients with advanced nsNSCLC in were not being appropriately evaluated for those mutations. To evaluate our molecular profiling rates, we conducted a retrospective study and reviewed 3 years of registry data at 3 hospitals within our health system. Two of the hospitals included in our analysis were large tertiary academic centers, and one was a community hospital. Our findings confirmed that a large percentage of our patients who are eligible for molecular evaluation are not tested: 56.7% of cases were not tested for EGFR mutations, and 76.2% of cases were not tested for ALK rearrangements.

In a similar study, the Association for Community Cancer Centers conducted a project aimed at understanding the landscape and current challenges for molecular profiling in NSCLC. Eight institutions participated in the study, and baseline testing rates were analyzed. The findings demonstrated that high-volume institutions (treating >100 lung cancer patients a year tested 62% and 60% of advanced lung cancer patients for EGFR and EML4-ALK, respectively, and low-volume institutions (treating <100 lung cancer patients a year tested 52% and 47% for EGFR and EML4-ALK, respectively.25,26 In a recent international physician self-reported survey, Spicer and colleagues found that EGFR testing was requested before first-line therapy in patients with stage IIIB or IV disease in 81% of cases, and mutation results were available before start of therapy in 77% of the cases.27 Those percentages are relatively low, given that current guidelines recommend that molecular testing should be done for all patients with stage IIIB or IV nsNSCLC. This highlights the need for objective performance feedback so oncologists can make the necessary practice changes so that molecular testing is done before the start of therapy to ensure high-quality cancer care that will translate into better, cost-effective outcomes and improved patient quality of life.

Our study findings showed that the prevalence of EGFR and ALK mutations is substantially lower among the patients we treat in our network compared with other published data on prevalence. The reason for those low rates is not clear, but it is likely multifactorial. First, Western Pennsylvania, the region our network serves, has a large proportion of older adults – 17.3% of the population is older than 65 years (national average, 14.5%) and advanced age might have contributed to the lower EGFR and ALK rates measured in our study.28 Second, the smoking rate in Pennsylvania is higher than the national average, 20%-24% compared with 18%, respectively.29 Third, the air quality in Western Pennsylvania has historically been very poor as a result of the large steel and coal mining industries. Even though the air quality has improved in recent decades, the American Lung Association’s 2017 State of the Air report ranked Pittsburgh and surrounding areas in Western Pennsylvania among the top 25 most air polluted areas in the United States.30 It is not certain whether air pollution and air quality have any impact on driver mutation rates, but the correlation with smoking, ethnicity, and geographic distribution highlight the need for further epidemiologic studies.

Biopsy sufficiency – getting an adequate amount of sample tissue during biopsy – is a known challenge to molecular profiling, and we found that biopsy sample size had an impact on the testing rates in a large percentage of our cases. To fully understand the impact of biopsy sufficiency, we conducted a subset analysis and compared the testing rates between our large and small biopsy samples. Our analysis showed that larger-sample biopsies were more likely to be tested for mutations than were smaller-sample biopsies (EGFR: P = .023; ALK: P = .007).

Those results suggest that larger-sample biopsies should be encouraged, but procedural risks, tumor location, and patient age and wishes need to be considered before tissue acquisition.21 Furthermore, clinicians who are responsible for tissue procurement need to be properly educated on the tissue sample requirements and the impact these results have on treatment decisions.31 Our institution, like many others, has adopted rapid onsite evaluation (ROSE) of biopsy samples, whereby a trained cytopathologist reviews sample adequacy at the time of tissue procurement. Although there is scant data directly comparing molecular testing success rates with and without the ROSE protocol, a meta-analysis conducted by Schmidt and colleagues concluded that ROSE improved the adequacy rate of fine-needle aspiration cytology by 12%.32,33 Given that molecular profiling depends on both the absolute and relative amount of tumor cells present in the sample, the ROSE protocol likely enhances the procedural success rate and reduces the need for repeat and subsequent biopsies.

It is interesting to note that our data also demonstrated that we are obtaining large-sample biopsies in most of our patients (about 70%). However, we are still failing to test more than half of our cases for driver mutations (Figure, A and C). This strongly suggests there are additional factors beyond tissue adequacy that are contributing to our high failure rate. It is essential to understand the dynamics and system practices that influence testing rates if we are to improve the care and outcomes of our cancer patients. To better understand those barriers, we surveyed 110 practitioners (including medical oncologists, pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, and interventional radiologists) about the molecular profiling process and their responses highlighted several important areas that deserve special attention (Tables 1, 4, 5).

In our institution, testing initiation is primarily the responsibility of the treating medical oncologist. This presents a challenge because there is often a significant delay between tissue acquisition, histologic confirmation, and oncologic review. Many institutions have adopted pathology-driven reflex testing to help overcome such delays. Automatic testing after pathologic confirmation streamlines the process, increases testing rates, and eliminates unnecessary delay between the time of diagnosis and the time of test ordering.34 It also allows for the molecular and histologic diagnosis to be integrated into a single pathology report before therapy is initiated.

Another barrier to timely testing according to the respondents, was the CMS’s 14-day rule. The 14-day rule requires hospitals to wait 14 days after the patient is discharged for the lab to receive reimbursement for molecular testing and was frequently identified as a cause for significant delay in testing and having an impact on first-line treatment decisions.35,36

Often clinicians will choose to defer testing until this time has elapsed to reduce the financial burden placed on the hospital but by that time, they might well have initiated treatment without knowing if the patient has a mutation. This is a significant challenge identified by many of our oncologists, and is a limitation to our analysis above as it is unclear what percentage of patients received follow up testing once care was established at an outside facility and once the 14-day time period had elapsed.

The data from our institution suggests there is discordance between physician attitudes and molecular testing practices. However, there are several limitations in our study. First, most of the survey respondents agreed that molecular testing is an important aspect of treating advanced lung cancer patients, but the retrospective nature of the study made it difficult to identify why testing was deferred or never conducted. Second, the absence of a centralized reporting system for molecular testing results at our institution, may have resulted in an overestimation of our testing failure rate in cases where results were not integrated our electronic medical record.

Third, the low survey response rate only allowed us to make generalizations regarding the conclusions, although it does provide a framework for future process improvements.

We believe the poor testing rates observed in our study are not isolated to our institution and reflect a significant challenge within the broader oncology community.27 A system of best practices is essential for capturing this subset of patients who are never tested. There is agreement among oncologists that improving our current testing rates will require a multidisciplinary approach, a refined process for molecular evaluation, a push toward reflex testing, and standardization of biopsy techniques and tissue handling procedures. In our institution, we have initiated a Lean Six Sigma and PDSA (plan, do, study, act) initiative to improve our current molecular testing process. In addition, because obtaining larger-sample biopsies or additional biopsies is often not feasible for many of our advanced cancer patients, we have started using whole blood circulating tumor cells (CTC) and plasma ctDNA (cell-free circulating DNA) for molecular testing. Recent studies have shown high concordance (89%) between tissue biopsies and blood-based mutation testing, which will likely have a positive impact on the cancer care of our patients and help to capture a subset of patients who are not candidates for traditional biopsies.37

Conclusions

Despite current guidelines for testing driver mutations in advanced nsNSCLC, a large segment of our patients are not being tested for those genetic aberrations. There are several barriers that continue to thwart the recommendation, including failure to integrate driver mutation testing into routine pathology practice (ie, reflex testing), insufficient tissue obtained from biopsy, and difficulty in obtaining tissue because of tumor location or risk of complications from the biopsy procedure. More important, these trends are not isolated to our institution and reflect a significant challenge within the oncology community. Our data show that for the purpose of driver mutation testing, larger-sample biopsies, such as surgical/core biopsies, are better than small-sample biopsies, such as needle aspiration. We have also demonstrated that the prevalence of driver mutations is lower in Western Pennsylvania, which is served by our network, than elsewhere in the United States.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30.

2. Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(5):584-594.

3. Kim TE, Murren JR. Therapy for stage IIIB and stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23(1):209-224.

4. Black RC, Khurshid H. NSCLC: An update of driver mutations, their role in pathogenesis and clinical significance. R I Med J (2013). 2015;98(10):25-28.

5. Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481(7381):306-313.

6. Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3327-3334.

7. Fukuoka M, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS). J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(21):2866-2874.

8. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239-246.

9. Gazdar AF. Activating and resistance mutations of EGFR in non-small-cell lung cancer: role in clinical response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Oncogene. 2009;28(suppl 1):S24-31.

10. Langer CJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition in mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: is afatinib better or simply newer? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(27):3303-3306.

11. Riely GJ, Politi KA, Miller VA, et al. Update on epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(24):7232-7241.

12. Shi Y, Siu-Kie JA, Thongprasert S, et al. A prospective, molecular epidemiology study of EGFR mutations in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology (PIONEER). J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(2):154-162.

13. Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947-957.

14. Khozin S, Blumenthal GM, Jiang X, et al. US Food and Drug Administration approval summary: Erlotinib for the first-line treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 deletions or exon 21 (L858R) substitution mutations. Oncologist. 2014;19(7):774-779.

15. Arcila ME, Nafa K, Chaft JE, et al. EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: prevalence, molecular heterogeneity, and clinicopathologic characteristics. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12(2):220-229.

16. Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2(3):e73.

17. Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(8):2240-2247.

18. Ellison G, Zhu G, Moulis A, Dearden S, et al. EGFR mutation testing in lung cancer: a review of available methods and their use for analysis of tumour tissue and cytology samples. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66(2):79-89.

19. Alì G, Proietti A, Pelliccioni S, et al. ALK rearrangement in a large series of consecutive non-small cell lung cancers: comparison between a new immunohistochemical approach and fluorescence in situ hybridization for the screening of patients eligible for crizotinib treatment. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(11):1449-1158.

20. Crowley E, Di Nicolantonio F, Loupakis F, et al. Liquid biopsy: monitoring cancer-genetics in the blood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(8):472-484.

21. Lindeman NI, Cagle PT, Beasley MB, et al. Molecular testing guideline for selection of lung cancer patients for EGFR and ALK tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(7):823-859.

22. Kwak EL, Bany YJ, Cambridge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(18):1693-1703.

23. Shaw A, Yeap BY, Kenudson MM, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4247-4253.

24. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2380-2388.

25. Association of Community Cancer Centers. Molecular Testing in the Community Setting. In: Molecular testing: resources and tools for the multidisciplinary team. http://accc-cancer.org/resources/molecularTesting-Overview.asp. Accessed November 15, 2015.

26. Association of Community Cancer Centers. Molecular testing: ACCC peer-to-peer webinars. The tissue issue: sampling and testing with Gail Probst, RN, MS, AOCN. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lapmni938Mc&feature=youtu.be. Published September 14, 2015. Accessed November 2015.

27. Spicer J S, Tischer B, Peters M. EGFR mutation testing and oncologist treatment choice in advanced NSCLC: global trends and differences. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(suppl 1):i60.

28. West L, Cole S, Goodkind D. US Census Bureau, 65+ in the United States: 2010, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2014

29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State tobacco activities tracking and evaluation system. Current cigarette use among adults (Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System) 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/statesystem/cigaretteuseadult.html. Last updated September 16, 2016. Accessed May 26, 2017.

30. The American Lung Association. State of the Air 2017. http://www.lung.org/assets/documents/healthy-air/state-of-the-air/state-of-the-air-2017.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed May 26, 2017.

31. Gaga M, Powell CA, Schraufnagel DE, Schönfeld N, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: the role of the pulmonologist in the diagnosis and management of lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(4):503-507.

32. Ferguson PE, Sales CM, Hodges DC, et al. Effects of a multidisciplinary approach to improve volume of diagnostic material in CT-guided lung biopsies. PLoS One. 2015 Oct 19;10(10).

33. Schmidt RL, Witt BL, Lopez-Calderon LE, et al. The influence of rapid onsite evaluation on the adequacy rate of fine-needle aspiration cytology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139(3):300-309.

34. Cengiz Inal, Yilmaz E, Chenget H, et al. Effect of reflex testing by pathologists on molecular testing rates in lung cancer patients: Experience from a community-based academic center. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl):5s. [abstract 8098].

35. Grzegorz K, Leighl, M. Challenges in NSCLC molecular testing barriers to implementation. Oncology Exchange. 2012;11(4):8-10.

36. Lynch JA, Khoury MJ, Ann Borzecket A, et al. Utilization of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) testing in the United States: a case study of T3 translational research. Genet Med. 2013;15(8):630-638.

37. Reck M. Investigating the utility of circulating-free tumour-derived DNA (ctDNA) in plasma for the detection of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation status in European and Japanese patients (pts) with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ASSESS study. Presented at the European Lung Cancer Conference (ELCC) Annual Meeting, Geneva; 15-18 April 2015.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States. It is estimated that there will be 222,500 new cases of lung cancer and 155,870 deaths from lung cancer in 2017. Non–small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) accounts for 80%-85% of lung cancers, with adenocarcinoma being the most common histologic subtype. Other less common subtypes include squamous-cell carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma, and NSCLC that cannot be further classified.1 Nearly 70% of patients present with locally advanced or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and are not candidates for surgical resection.2 For that group of patients, the mainstay of treatment is platinum-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. Patients who are chemotherapy naive often experience a modest response, however; durable remission is short lived, and the 5-year survival rate remains staggeringly low.3 Improved understanding of the molecular pathways that drive malignancy in NSCLC has led to the development of drugs that target specific molecular pathways.4 By definition, these driver mutations facilitate oncogenesis by conferring a selective advantage during clonal evolution.5 Moreover, agents targeting these pathways are extremely active and induce durable responses in many patients.6,7,8

Predictive biomarkers in NSCLC include anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) fusion oncogene and sensitizing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. Mutations in the EGFR tyrosine kinase are observed in about 15%-20% of NSCLC adenocarcinomas in the United States and upward of 60% in Asian populations. They are also found more frequently in nonsmokers and women.6 The two most prevalent mutations in the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain are in-frame deletions of exon 19 and L858R substitution in exon 21, representing about 45% and 40% of mutations, respectively.9 Both mutations result in activation of the tyrosine kinase domain, and both are associated with sensitivity to the small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as erlotinib, gefitinib, and afatinib.10 Other drug-sensitive mutations include point mutations at exon 21 (L861Q) and exon 18 (G719X).11 Targeted therapy produces durable responses in the majority of patients.12,13,14 Unfortunately, most patients develop acquired resistance to these therapies, which leads to disease progression.4,15-17

ALK gene rearrangements, although less prevalent, are another important molecular target in NSCLC and are seen in 2%-7% of cases in the United States.7 As with EGFR mutations, these mutations are more prevalent in nonsmokers, and they are found more commonly in younger patients and in men.8

Identification of driver mutations early in the course of disease and acquired resistance mutations later are crucial for the optimal management of advanced NSCLC. DNA analysis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing is the preferred method for testing for EGFR mutations, and ALK rearrangements are generally tested either by flourescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or immunohistochemistry.18,19 Newer blood-based assays have shown great promise, and clinicians may soon have the ability to monitor subtle genetic changes, identify resistance patterns, and change therapy when acquired resistance occurs.20