User login

Lateral Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction: An Analysis of Ulnar Tunnel Locations

Posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) of the elbow is well recognized1 and is the most common type of chronic elbow instability. PLRI is often an end result of traumatic elbow dislocation.2 The “essential lesion” in patients with PLRI of the elbow is injury to the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL).1 However, more recent research has emphasized the importance of other ligaments in the lateral ligament complex (radial collateral and annular ligaments) in preventing PLRI.3-5 Nevertheless, when conservative treatment fails, the most commonly used surgical treatment involves LUCL reconstruction.1,6-11

Numerous techniques for LUCL reconstruction have been described.1,7-9,11-13 The chosen technique ideally restores normal anatomy. Therefore, the isometric point of origin at the lateral epicondyle and insertion at the supinator tubercle are important landmarks for creating tunnels that reproduce isometry, function, and normal anatomy. Most often, 2 tunnels are created in the ulna to secure the graft. It has been our experience that ulnar tunnel creation can affect the length of the bony bridge and the orientation of the graft.

We conducted a study to identify the precise proximal ulna tunnel location—anterior to posterior, with the distal tunnel at the supinator tubercle on the crest—that allows for the largest bony bridge and most geometrically favorable construct. We hypothesized that a most posteriorly placed proximal tunnel would increase bony bridge size and allow for a more isosceles graft configuration. An isosceles configuration with the humerus tunnel at the isometric location would allow for anterior and posterior bands of the same length with theoretically equal force distribution.

Methods

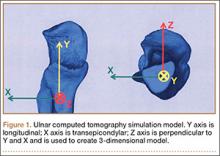

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of 17 adults with elbow computed tomography (CT) scans for inclusion in this study. The scans were previously performed for diagnostic workup of several pathologies, including valgus instability, olecranon stress fracture, and valgus extension overload. The scan protocol involved 0.5-mm axial cuts with inclusion of the distal humerus through the proximal radius and ulna in the DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format. Exclusion criteria included poor CT quality, inadequate visualization of the entire supinator crest, and age under 18 years. Fifteen patients with adequate CT scans met the inclusion criteria. MIMICS (Materialise’s Interactive Medical Image Control System) software was used to convert scans into patient-specific 3-dimensional (3-D) computer models. (Use of this software to produce anatomically accurate models has been verified in shoulder14 and elbow15 models.) These models were uploaded into Magics rapid prototyping software (Materialise) and manipulated for simulated tunnel drilling by precise bone subtraction methods. This software was used to define an ulnar Cartesian coordinate system with anatomical landmarks as reference points in order to standardize the position of each model (Figure 1).16 The y-axis was defined by the longitudinal axis of the ulna, and the x-axis was the transepicondylar axis, defined as the perpendicular line connecting the y-axis with the supinator crest. The z-axis was then established as the line perpendicular to the x- and y-axes—yielding a 3-D coordinate system that allowed us to manipulate the models in standardized fashion, maintaining the exact positions of the ulna while making measurements.

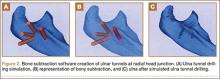

Surgical simulations were performed in the rapid prototyping software by creating a cylinder and placing it at the desired location of each tunnel. Cylinder diameter was 4 mm, matching the diameter of the drill we use to create each tunnel in our practice. The cylinder was inserted into the bone, perpendicular to the surface of the ulna at the point of insertion, so the cylinder’s deepest point entered the medullary canal of the ulna. Using a Boolean operation in the rapid prototyping software, we subtracted cylinder from bone to create a tunnel (Figure 2).15

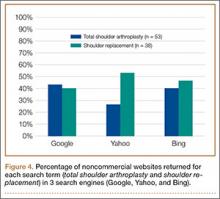

In a previous study,17 we determined that the radial head junction is reproducibly about 15 mm proximal to the distinct supinator tubercle, which may be absent or not readily appreciated in up to 50% of cases. Therefore, proximal ulnar tunnels were placed 0, 5, and 10 mm posterior to the supinator crest at the radial head junction. Distal tunnels were placed 15 mm anterior to the radial head junction on the supinator crest (Figure 2). The bony bridges created by these tunnels were measured, as was the distance between the distal tunnel and the supinator tubercle.

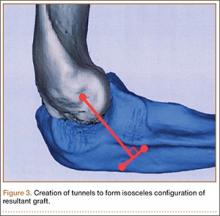

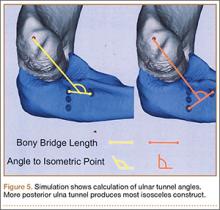

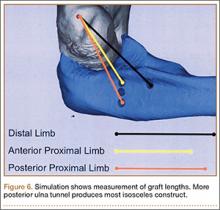

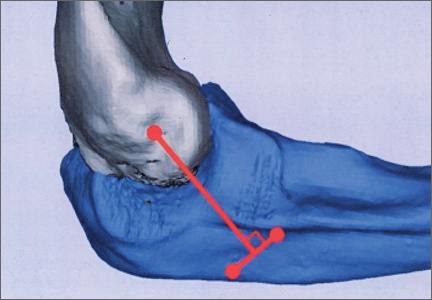

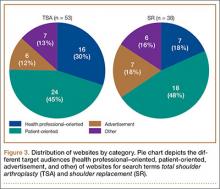

Ideal graft configuration was described as an isosceles triangle with ulna tunnels perpendicular to the humeral tunnel (Figure 3).11 Location of the humeral origin in the sagittal plane was determined by finding the isometric point of the lateral humerus using only bony landmarks. Similar techniques have been used to find the isometric point on the medial epicondyle for medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.15,18 With a circle fit into the trochlear notch of the ulna, the isometric point can be determined by the center of the circle. This point was then superimposed on the humerus to identify the starting point (Figure 4). In our simulation, we measured the isosceles configuration by drawing a line between the proximal and distal tunnels, and then another line connecting the bisecting point of the first line with the isometric point on the humerus from which the graft would originate. The angle between the 2 lines was measured; if isosceles, the angle was 90° (Figure 5). Length of the more proximal limb of the graft and the more distal limb of the graft was determined by measuring the distance from the isometric point to the proximal and distal tunnels, respectively (Figure 6).

One-way analysis of variance was used to compare all the tunnels’ bony bridge sizes, graft lengths, and angles to the isometric point. For all comparisons, statistical significance was set at P < .05. As no other studies have compared bony bridges by varying tunnel creation parameters, and as the present study is observational and not comparative, no power analysis was performed.

Results

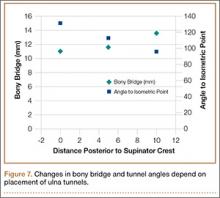

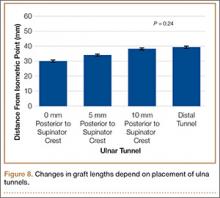

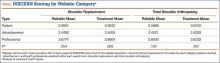

Bony bridges were significantly longer, and angles more perpendicular, with increasing distance from the proximal tunnel to the supinator crest (Table 1, Figure 5, Figure 7). The bony bridge 0 mm posterior to the supinator crest yielded a mean (SE) bony bridge length of 11.0 (0.2) mm. This proximal tunnel also yielded the smallest mean (SE) perpendicular angle to the isometric point, 131.2° (1.9°). The tunnel most posterior to the supinator crest yielded the longest mean (SE) bony bridge, 13.7 (0.2) mm, and the largest mean (SE) degree of perpendicularity, 95.8° (1.4°). The differences between all tunnels’ bony bridges and isometric angles were statistically significant (P < .00001). The difference between the more distal limb and the more proximal limb of the graft was smallest in the more posteriorly placed proximal tunnel (Table 2, Figure 8). In fact, there was no statistical difference between the proximal and distal limbs of the graft when the proximal tunnel was placed 10 mm posterior to the supinator crest: Mean (SE) was 9.4 (0.5) mm at 0 mm (P < .00001) and 1.1 (0.6) mm at 10 mm (P = .24).

Discussion

PLRI of the elbow is best initially managed nonoperatively. However, when nonoperative management fails, the LUCL is often surgically reconstructed. Reconstruction methods vary by fixation method, graft choice, and bone tunnels.1,7-9,11-13 In 1991, O’Driscoll and colleagues1 described a “yoke” technique for LUCL reconstruction. Since then, the docking technique7 and other techniques have been developed. All these techniques emphasize maximizing anatomical precision and isometry with careful placement of tunnels or fixation devices. The humeral fixation site, at the anterior inferior aspect of the lateral epicondyle at the point of isometry, can be accessed relatively reproducibly. By contrast, the ulnar points of fixation are more variable, because of increased bone stock and overlying soft-tissue and bony anatomy.

Among the challenges in determining the points of ulnar fixation is the bony anatomy that is often used for landmarks. In the literature, the supinator crest or the supintor tubercle is the landmark for placing the distal tunnel.1,7-9,11-13 This is a problem for 2 reasons. First, the supintor crest, a longitudinal structure on the lateral aspect of the ulna, originates from the radial head junction and extends tens of millimeters distally; further specification is needed to guide these ulnar tunnels. The second reason is that use of the supinator tubercle, a prominence on the supinator crest, adds specificity to the location of the ulnar tunnels. During surgery, however, the supinator tubercle may not be a reliable, independently prominent structure; instead, it may be indistinguishable from the supinator crest, on which it rests. One study determined that only about 50% of computer models of patient ulnas had a distinct prominence that could be classified as the supinator tubercle.17 The percentage presumably is lower during surgery, with limited exposure and overlying soft tissues.

In a study of patients with a prominent tubercle, mean (SE) distance from radial head junction to tubercle was 15 (2) mm.17 This finding led us to use the radial head junction as the primary bony landmark in determining the location of the proximal tunnel and placing the distal tunnel 15 mm distally—achieving the same fixation described in the literature but using more distinct landmarks. Our study thus provided a reliable, verified approach to locating the ulnar tunnels in the proximal-distal axis.

We also explored the anterior-posterior orientation of the proximal ulnar tunnel. The 2 primary considerations surrounding the varied proximal tunnel placements were the bony bridge formed between the proximal and distal tunnels and the perpendicularity of the triangle formed by the fixation points. Maximizing the bony bridge is obviously ideal in securing and preventing fixation blowout. Achieving an isoceles reconstruction has been reported in the literature on the various fixation techniques for LUCL reconstruction.11 Although the biomechanical advantage of this fixation type is not fully clear, we assume the construct produces graft stands of equal length, tension, and stability. In addition, the larger footprint created by an isoceles reconstructed ligament increases the stability of the radial head.

Results of the present study showed that the more posterior the proximal ulnar tunnel, the longer the bony bridge and the more isoceles the reconstruction. The difference in bony bridge distance from the most anterior to the most posterior tunnel was about 2 mm, or 18%. For every 1 mm of posteriorization, the bony bridge was 0.2 mm longer. The line from the isometric point of humeral fixation bisecting the proximal and distal tunnels was also more perpendicular with the most posterior tunnel, by about 40°. The resulting proximal and distal limbs of the reconstruction were equal in length, as demonstrated by the smaller difference between the limbs. We assume this isoceles reconstruction more likely applies uniform restraint on the radial head. Thus, an effort should be made to posteriorize the proximal ulnar tunnel during reconstruction.

The study was limited by the number of patient-specific elbow models used. However, given the statistical consistency of measurements, sample size was sufficient. Another limitation, inherent to the model, was that only bony anatomy was incorporated. However, the overlying muscles, tendons, and ligaments can significantly alter tunnel placement, and this study provided other means and cues using more reliable landmarks to adequately place the tunnels. As this was a simulation study, we cannot confirm whether these results would make a difference clinically. The strengths of this study include development and verification of reliable landmarks that can be used to guide ulnar tunnel locations during LUCL reconstruction; these landmarks have been used for medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.15 Other strengths include precise and accurate placement of tunnels and measurement of resulting bony bridges—accomplished independently and without compromising specimen quality.

Conclusion

We recommend drilling the proximal ulnar tunnel posterior to the supinator crest at the level of the radial head junction. A reasonable goal is 10 mm posterior to the crest, though the overlying soft tissue must be considered, and care should be taken to aim the drill anteriorly, toward the ulna’s intramedullary canal, to avoid posterior cortical breach. The distal ulnar tunnel should be drilled just posterior to the supinator crest, 15 mm distal to the radial head junction.

1. O’Driscoll SW, Bell DF, Morrey BF. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(3):440-446.

2. O’Driscoll SW. Classification and evaluation of recurrent instability of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;370:34-43.

3. Takigawa N, Ryu J, Kish VL, Kinoshita M, Abe M. Functional anatomy of the lateral collateral ligament complex of the elbow: morphology and strain. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30(2):143-147.

4. McAdams TR, Masters GW, Srivastava S. The effect of arthroscopic sectioning of the lateral ligament complex of the elbow on posterolateral rotatory stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(3):298-301.

5. Dunning CE, Zarzour ZD, Patterson SD, Johnson JA, King GJ. Ligamentous stabilizers against posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(12):1823-1828.

6. Eygendaal D. Ligamentous reconstruction around the elbow using triceps tendon. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(5):516-523.

7. Jones KJ, Dodson CC, Osbahr DC, et al. The docking technique for lateral ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: surgical technique and clinical outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(3):389-395.

8. Lee BP, Teo LH. Surgical reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):476-479.

9. Lin KY, Shen PH, Lee CH, Pan RY, Lin LC, Shen HC. Functional outcomes of surgical reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Injury. 2012;43(10):1657-1661.

10. Olsen BS, Søjbjerg JO. The treatment of recurrent posterolateral instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(3):342-346.

11. Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Ligamentous repair and reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(1):54-61.

12. Savoie FH 3rd, Field LD, Gurley DJ. Arthroscopic and open radial ulnohumeral ligament reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Hand Clin. 2009;25(3):323-329.

13. Savoie FH 3rd, O’Brien MJ, Field LD, Gurley DJ. Arthroscopic and open radial ulnohumeral ligament reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29(4):611-618.

14. Bryce CD, Pennypacker JL, Kulkarni N, et al. Validation of three-dimensional models of in situ scapulae. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):825-832.

15. Byram IR, Khanna K, Gardner TR, Ahmad CS. Characterizing bone tunnel placement in medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction using patient-specific 3-dimensional computed tomography modeling. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):894-902.

16. Shiba R, Sorbie C, Siu DW, Bryant JT, Cooke TD, Wevers HW. Geometry of the humeroulnar joint. J Orthop Res. 1988;6(6):897-906.

17. Anakwenze OA, Khanna K, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Characterization of the supinator tubercle for lateral ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(4):2325967114530969. doi:10.1177/2325967114530969.

18. Sasashige Y, Ochi M, Ikuta Y. Optimal attachment site for reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. A cadaver study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1994;113(5):265-270.

Posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) of the elbow is well recognized1 and is the most common type of chronic elbow instability. PLRI is often an end result of traumatic elbow dislocation.2 The “essential lesion” in patients with PLRI of the elbow is injury to the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL).1 However, more recent research has emphasized the importance of other ligaments in the lateral ligament complex (radial collateral and annular ligaments) in preventing PLRI.3-5 Nevertheless, when conservative treatment fails, the most commonly used surgical treatment involves LUCL reconstruction.1,6-11

Numerous techniques for LUCL reconstruction have been described.1,7-9,11-13 The chosen technique ideally restores normal anatomy. Therefore, the isometric point of origin at the lateral epicondyle and insertion at the supinator tubercle are important landmarks for creating tunnels that reproduce isometry, function, and normal anatomy. Most often, 2 tunnels are created in the ulna to secure the graft. It has been our experience that ulnar tunnel creation can affect the length of the bony bridge and the orientation of the graft.

We conducted a study to identify the precise proximal ulna tunnel location—anterior to posterior, with the distal tunnel at the supinator tubercle on the crest—that allows for the largest bony bridge and most geometrically favorable construct. We hypothesized that a most posteriorly placed proximal tunnel would increase bony bridge size and allow for a more isosceles graft configuration. An isosceles configuration with the humerus tunnel at the isometric location would allow for anterior and posterior bands of the same length with theoretically equal force distribution.

Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of 17 adults with elbow computed tomography (CT) scans for inclusion in this study. The scans were previously performed for diagnostic workup of several pathologies, including valgus instability, olecranon stress fracture, and valgus extension overload. The scan protocol involved 0.5-mm axial cuts with inclusion of the distal humerus through the proximal radius and ulna in the DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format. Exclusion criteria included poor CT quality, inadequate visualization of the entire supinator crest, and age under 18 years. Fifteen patients with adequate CT scans met the inclusion criteria. MIMICS (Materialise’s Interactive Medical Image Control System) software was used to convert scans into patient-specific 3-dimensional (3-D) computer models. (Use of this software to produce anatomically accurate models has been verified in shoulder14 and elbow15 models.) These models were uploaded into Magics rapid prototyping software (Materialise) and manipulated for simulated tunnel drilling by precise bone subtraction methods. This software was used to define an ulnar Cartesian coordinate system with anatomical landmarks as reference points in order to standardize the position of each model (Figure 1).16 The y-axis was defined by the longitudinal axis of the ulna, and the x-axis was the transepicondylar axis, defined as the perpendicular line connecting the y-axis with the supinator crest. The z-axis was then established as the line perpendicular to the x- and y-axes—yielding a 3-D coordinate system that allowed us to manipulate the models in standardized fashion, maintaining the exact positions of the ulna while making measurements.

Surgical simulations were performed in the rapid prototyping software by creating a cylinder and placing it at the desired location of each tunnel. Cylinder diameter was 4 mm, matching the diameter of the drill we use to create each tunnel in our practice. The cylinder was inserted into the bone, perpendicular to the surface of the ulna at the point of insertion, so the cylinder’s deepest point entered the medullary canal of the ulna. Using a Boolean operation in the rapid prototyping software, we subtracted cylinder from bone to create a tunnel (Figure 2).15

In a previous study,17 we determined that the radial head junction is reproducibly about 15 mm proximal to the distinct supinator tubercle, which may be absent or not readily appreciated in up to 50% of cases. Therefore, proximal ulnar tunnels were placed 0, 5, and 10 mm posterior to the supinator crest at the radial head junction. Distal tunnels were placed 15 mm anterior to the radial head junction on the supinator crest (Figure 2). The bony bridges created by these tunnels were measured, as was the distance between the distal tunnel and the supinator tubercle.

Ideal graft configuration was described as an isosceles triangle with ulna tunnels perpendicular to the humeral tunnel (Figure 3).11 Location of the humeral origin in the sagittal plane was determined by finding the isometric point of the lateral humerus using only bony landmarks. Similar techniques have been used to find the isometric point on the medial epicondyle for medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.15,18 With a circle fit into the trochlear notch of the ulna, the isometric point can be determined by the center of the circle. This point was then superimposed on the humerus to identify the starting point (Figure 4). In our simulation, we measured the isosceles configuration by drawing a line between the proximal and distal tunnels, and then another line connecting the bisecting point of the first line with the isometric point on the humerus from which the graft would originate. The angle between the 2 lines was measured; if isosceles, the angle was 90° (Figure 5). Length of the more proximal limb of the graft and the more distal limb of the graft was determined by measuring the distance from the isometric point to the proximal and distal tunnels, respectively (Figure 6).

One-way analysis of variance was used to compare all the tunnels’ bony bridge sizes, graft lengths, and angles to the isometric point. For all comparisons, statistical significance was set at P < .05. As no other studies have compared bony bridges by varying tunnel creation parameters, and as the present study is observational and not comparative, no power analysis was performed.

Results

Bony bridges were significantly longer, and angles more perpendicular, with increasing distance from the proximal tunnel to the supinator crest (Table 1, Figure 5, Figure 7). The bony bridge 0 mm posterior to the supinator crest yielded a mean (SE) bony bridge length of 11.0 (0.2) mm. This proximal tunnel also yielded the smallest mean (SE) perpendicular angle to the isometric point, 131.2° (1.9°). The tunnel most posterior to the supinator crest yielded the longest mean (SE) bony bridge, 13.7 (0.2) mm, and the largest mean (SE) degree of perpendicularity, 95.8° (1.4°). The differences between all tunnels’ bony bridges and isometric angles were statistically significant (P < .00001). The difference between the more distal limb and the more proximal limb of the graft was smallest in the more posteriorly placed proximal tunnel (Table 2, Figure 8). In fact, there was no statistical difference between the proximal and distal limbs of the graft when the proximal tunnel was placed 10 mm posterior to the supinator crest: Mean (SE) was 9.4 (0.5) mm at 0 mm (P < .00001) and 1.1 (0.6) mm at 10 mm (P = .24).

Discussion

PLRI of the elbow is best initially managed nonoperatively. However, when nonoperative management fails, the LUCL is often surgically reconstructed. Reconstruction methods vary by fixation method, graft choice, and bone tunnels.1,7-9,11-13 In 1991, O’Driscoll and colleagues1 described a “yoke” technique for LUCL reconstruction. Since then, the docking technique7 and other techniques have been developed. All these techniques emphasize maximizing anatomical precision and isometry with careful placement of tunnels or fixation devices. The humeral fixation site, at the anterior inferior aspect of the lateral epicondyle at the point of isometry, can be accessed relatively reproducibly. By contrast, the ulnar points of fixation are more variable, because of increased bone stock and overlying soft-tissue and bony anatomy.

Among the challenges in determining the points of ulnar fixation is the bony anatomy that is often used for landmarks. In the literature, the supinator crest or the supintor tubercle is the landmark for placing the distal tunnel.1,7-9,11-13 This is a problem for 2 reasons. First, the supintor crest, a longitudinal structure on the lateral aspect of the ulna, originates from the radial head junction and extends tens of millimeters distally; further specification is needed to guide these ulnar tunnels. The second reason is that use of the supinator tubercle, a prominence on the supinator crest, adds specificity to the location of the ulnar tunnels. During surgery, however, the supinator tubercle may not be a reliable, independently prominent structure; instead, it may be indistinguishable from the supinator crest, on which it rests. One study determined that only about 50% of computer models of patient ulnas had a distinct prominence that could be classified as the supinator tubercle.17 The percentage presumably is lower during surgery, with limited exposure and overlying soft tissues.

In a study of patients with a prominent tubercle, mean (SE) distance from radial head junction to tubercle was 15 (2) mm.17 This finding led us to use the radial head junction as the primary bony landmark in determining the location of the proximal tunnel and placing the distal tunnel 15 mm distally—achieving the same fixation described in the literature but using more distinct landmarks. Our study thus provided a reliable, verified approach to locating the ulnar tunnels in the proximal-distal axis.

We also explored the anterior-posterior orientation of the proximal ulnar tunnel. The 2 primary considerations surrounding the varied proximal tunnel placements were the bony bridge formed between the proximal and distal tunnels and the perpendicularity of the triangle formed by the fixation points. Maximizing the bony bridge is obviously ideal in securing and preventing fixation blowout. Achieving an isoceles reconstruction has been reported in the literature on the various fixation techniques for LUCL reconstruction.11 Although the biomechanical advantage of this fixation type is not fully clear, we assume the construct produces graft stands of equal length, tension, and stability. In addition, the larger footprint created by an isoceles reconstructed ligament increases the stability of the radial head.

Results of the present study showed that the more posterior the proximal ulnar tunnel, the longer the bony bridge and the more isoceles the reconstruction. The difference in bony bridge distance from the most anterior to the most posterior tunnel was about 2 mm, or 18%. For every 1 mm of posteriorization, the bony bridge was 0.2 mm longer. The line from the isometric point of humeral fixation bisecting the proximal and distal tunnels was also more perpendicular with the most posterior tunnel, by about 40°. The resulting proximal and distal limbs of the reconstruction were equal in length, as demonstrated by the smaller difference between the limbs. We assume this isoceles reconstruction more likely applies uniform restraint on the radial head. Thus, an effort should be made to posteriorize the proximal ulnar tunnel during reconstruction.

The study was limited by the number of patient-specific elbow models used. However, given the statistical consistency of measurements, sample size was sufficient. Another limitation, inherent to the model, was that only bony anatomy was incorporated. However, the overlying muscles, tendons, and ligaments can significantly alter tunnel placement, and this study provided other means and cues using more reliable landmarks to adequately place the tunnels. As this was a simulation study, we cannot confirm whether these results would make a difference clinically. The strengths of this study include development and verification of reliable landmarks that can be used to guide ulnar tunnel locations during LUCL reconstruction; these landmarks have been used for medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.15 Other strengths include precise and accurate placement of tunnels and measurement of resulting bony bridges—accomplished independently and without compromising specimen quality.

Conclusion

We recommend drilling the proximal ulnar tunnel posterior to the supinator crest at the level of the radial head junction. A reasonable goal is 10 mm posterior to the crest, though the overlying soft tissue must be considered, and care should be taken to aim the drill anteriorly, toward the ulna’s intramedullary canal, to avoid posterior cortical breach. The distal ulnar tunnel should be drilled just posterior to the supinator crest, 15 mm distal to the radial head junction.

Posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) of the elbow is well recognized1 and is the most common type of chronic elbow instability. PLRI is often an end result of traumatic elbow dislocation.2 The “essential lesion” in patients with PLRI of the elbow is injury to the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL).1 However, more recent research has emphasized the importance of other ligaments in the lateral ligament complex (radial collateral and annular ligaments) in preventing PLRI.3-5 Nevertheless, when conservative treatment fails, the most commonly used surgical treatment involves LUCL reconstruction.1,6-11

Numerous techniques for LUCL reconstruction have been described.1,7-9,11-13 The chosen technique ideally restores normal anatomy. Therefore, the isometric point of origin at the lateral epicondyle and insertion at the supinator tubercle are important landmarks for creating tunnels that reproduce isometry, function, and normal anatomy. Most often, 2 tunnels are created in the ulna to secure the graft. It has been our experience that ulnar tunnel creation can affect the length of the bony bridge and the orientation of the graft.

We conducted a study to identify the precise proximal ulna tunnel location—anterior to posterior, with the distal tunnel at the supinator tubercle on the crest—that allows for the largest bony bridge and most geometrically favorable construct. We hypothesized that a most posteriorly placed proximal tunnel would increase bony bridge size and allow for a more isosceles graft configuration. An isosceles configuration with the humerus tunnel at the isometric location would allow for anterior and posterior bands of the same length with theoretically equal force distribution.

Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of 17 adults with elbow computed tomography (CT) scans for inclusion in this study. The scans were previously performed for diagnostic workup of several pathologies, including valgus instability, olecranon stress fracture, and valgus extension overload. The scan protocol involved 0.5-mm axial cuts with inclusion of the distal humerus through the proximal radius and ulna in the DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format. Exclusion criteria included poor CT quality, inadequate visualization of the entire supinator crest, and age under 18 years. Fifteen patients with adequate CT scans met the inclusion criteria. MIMICS (Materialise’s Interactive Medical Image Control System) software was used to convert scans into patient-specific 3-dimensional (3-D) computer models. (Use of this software to produce anatomically accurate models has been verified in shoulder14 and elbow15 models.) These models were uploaded into Magics rapid prototyping software (Materialise) and manipulated for simulated tunnel drilling by precise bone subtraction methods. This software was used to define an ulnar Cartesian coordinate system with anatomical landmarks as reference points in order to standardize the position of each model (Figure 1).16 The y-axis was defined by the longitudinal axis of the ulna, and the x-axis was the transepicondylar axis, defined as the perpendicular line connecting the y-axis with the supinator crest. The z-axis was then established as the line perpendicular to the x- and y-axes—yielding a 3-D coordinate system that allowed us to manipulate the models in standardized fashion, maintaining the exact positions of the ulna while making measurements.

Surgical simulations were performed in the rapid prototyping software by creating a cylinder and placing it at the desired location of each tunnel. Cylinder diameter was 4 mm, matching the diameter of the drill we use to create each tunnel in our practice. The cylinder was inserted into the bone, perpendicular to the surface of the ulna at the point of insertion, so the cylinder’s deepest point entered the medullary canal of the ulna. Using a Boolean operation in the rapid prototyping software, we subtracted cylinder from bone to create a tunnel (Figure 2).15

In a previous study,17 we determined that the radial head junction is reproducibly about 15 mm proximal to the distinct supinator tubercle, which may be absent or not readily appreciated in up to 50% of cases. Therefore, proximal ulnar tunnels were placed 0, 5, and 10 mm posterior to the supinator crest at the radial head junction. Distal tunnels were placed 15 mm anterior to the radial head junction on the supinator crest (Figure 2). The bony bridges created by these tunnels were measured, as was the distance between the distal tunnel and the supinator tubercle.

Ideal graft configuration was described as an isosceles triangle with ulna tunnels perpendicular to the humeral tunnel (Figure 3).11 Location of the humeral origin in the sagittal plane was determined by finding the isometric point of the lateral humerus using only bony landmarks. Similar techniques have been used to find the isometric point on the medial epicondyle for medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.15,18 With a circle fit into the trochlear notch of the ulna, the isometric point can be determined by the center of the circle. This point was then superimposed on the humerus to identify the starting point (Figure 4). In our simulation, we measured the isosceles configuration by drawing a line between the proximal and distal tunnels, and then another line connecting the bisecting point of the first line with the isometric point on the humerus from which the graft would originate. The angle between the 2 lines was measured; if isosceles, the angle was 90° (Figure 5). Length of the more proximal limb of the graft and the more distal limb of the graft was determined by measuring the distance from the isometric point to the proximal and distal tunnels, respectively (Figure 6).

One-way analysis of variance was used to compare all the tunnels’ bony bridge sizes, graft lengths, and angles to the isometric point. For all comparisons, statistical significance was set at P < .05. As no other studies have compared bony bridges by varying tunnel creation parameters, and as the present study is observational and not comparative, no power analysis was performed.

Results

Bony bridges were significantly longer, and angles more perpendicular, with increasing distance from the proximal tunnel to the supinator crest (Table 1, Figure 5, Figure 7). The bony bridge 0 mm posterior to the supinator crest yielded a mean (SE) bony bridge length of 11.0 (0.2) mm. This proximal tunnel also yielded the smallest mean (SE) perpendicular angle to the isometric point, 131.2° (1.9°). The tunnel most posterior to the supinator crest yielded the longest mean (SE) bony bridge, 13.7 (0.2) mm, and the largest mean (SE) degree of perpendicularity, 95.8° (1.4°). The differences between all tunnels’ bony bridges and isometric angles were statistically significant (P < .00001). The difference between the more distal limb and the more proximal limb of the graft was smallest in the more posteriorly placed proximal tunnel (Table 2, Figure 8). In fact, there was no statistical difference between the proximal and distal limbs of the graft when the proximal tunnel was placed 10 mm posterior to the supinator crest: Mean (SE) was 9.4 (0.5) mm at 0 mm (P < .00001) and 1.1 (0.6) mm at 10 mm (P = .24).

Discussion

PLRI of the elbow is best initially managed nonoperatively. However, when nonoperative management fails, the LUCL is often surgically reconstructed. Reconstruction methods vary by fixation method, graft choice, and bone tunnels.1,7-9,11-13 In 1991, O’Driscoll and colleagues1 described a “yoke” technique for LUCL reconstruction. Since then, the docking technique7 and other techniques have been developed. All these techniques emphasize maximizing anatomical precision and isometry with careful placement of tunnels or fixation devices. The humeral fixation site, at the anterior inferior aspect of the lateral epicondyle at the point of isometry, can be accessed relatively reproducibly. By contrast, the ulnar points of fixation are more variable, because of increased bone stock and overlying soft-tissue and bony anatomy.

Among the challenges in determining the points of ulnar fixation is the bony anatomy that is often used for landmarks. In the literature, the supinator crest or the supintor tubercle is the landmark for placing the distal tunnel.1,7-9,11-13 This is a problem for 2 reasons. First, the supintor crest, a longitudinal structure on the lateral aspect of the ulna, originates from the radial head junction and extends tens of millimeters distally; further specification is needed to guide these ulnar tunnels. The second reason is that use of the supinator tubercle, a prominence on the supinator crest, adds specificity to the location of the ulnar tunnels. During surgery, however, the supinator tubercle may not be a reliable, independently prominent structure; instead, it may be indistinguishable from the supinator crest, on which it rests. One study determined that only about 50% of computer models of patient ulnas had a distinct prominence that could be classified as the supinator tubercle.17 The percentage presumably is lower during surgery, with limited exposure and overlying soft tissues.

In a study of patients with a prominent tubercle, mean (SE) distance from radial head junction to tubercle was 15 (2) mm.17 This finding led us to use the radial head junction as the primary bony landmark in determining the location of the proximal tunnel and placing the distal tunnel 15 mm distally—achieving the same fixation described in the literature but using more distinct landmarks. Our study thus provided a reliable, verified approach to locating the ulnar tunnels in the proximal-distal axis.

We also explored the anterior-posterior orientation of the proximal ulnar tunnel. The 2 primary considerations surrounding the varied proximal tunnel placements were the bony bridge formed between the proximal and distal tunnels and the perpendicularity of the triangle formed by the fixation points. Maximizing the bony bridge is obviously ideal in securing and preventing fixation blowout. Achieving an isoceles reconstruction has been reported in the literature on the various fixation techniques for LUCL reconstruction.11 Although the biomechanical advantage of this fixation type is not fully clear, we assume the construct produces graft stands of equal length, tension, and stability. In addition, the larger footprint created by an isoceles reconstructed ligament increases the stability of the radial head.

Results of the present study showed that the more posterior the proximal ulnar tunnel, the longer the bony bridge and the more isoceles the reconstruction. The difference in bony bridge distance from the most anterior to the most posterior tunnel was about 2 mm, or 18%. For every 1 mm of posteriorization, the bony bridge was 0.2 mm longer. The line from the isometric point of humeral fixation bisecting the proximal and distal tunnels was also more perpendicular with the most posterior tunnel, by about 40°. The resulting proximal and distal limbs of the reconstruction were equal in length, as demonstrated by the smaller difference between the limbs. We assume this isoceles reconstruction more likely applies uniform restraint on the radial head. Thus, an effort should be made to posteriorize the proximal ulnar tunnel during reconstruction.

The study was limited by the number of patient-specific elbow models used. However, given the statistical consistency of measurements, sample size was sufficient. Another limitation, inherent to the model, was that only bony anatomy was incorporated. However, the overlying muscles, tendons, and ligaments can significantly alter tunnel placement, and this study provided other means and cues using more reliable landmarks to adequately place the tunnels. As this was a simulation study, we cannot confirm whether these results would make a difference clinically. The strengths of this study include development and verification of reliable landmarks that can be used to guide ulnar tunnel locations during LUCL reconstruction; these landmarks have been used for medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.15 Other strengths include precise and accurate placement of tunnels and measurement of resulting bony bridges—accomplished independently and without compromising specimen quality.

Conclusion

We recommend drilling the proximal ulnar tunnel posterior to the supinator crest at the level of the radial head junction. A reasonable goal is 10 mm posterior to the crest, though the overlying soft tissue must be considered, and care should be taken to aim the drill anteriorly, toward the ulna’s intramedullary canal, to avoid posterior cortical breach. The distal ulnar tunnel should be drilled just posterior to the supinator crest, 15 mm distal to the radial head junction.

1. O’Driscoll SW, Bell DF, Morrey BF. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(3):440-446.

2. O’Driscoll SW. Classification and evaluation of recurrent instability of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;370:34-43.

3. Takigawa N, Ryu J, Kish VL, Kinoshita M, Abe M. Functional anatomy of the lateral collateral ligament complex of the elbow: morphology and strain. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30(2):143-147.

4. McAdams TR, Masters GW, Srivastava S. The effect of arthroscopic sectioning of the lateral ligament complex of the elbow on posterolateral rotatory stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(3):298-301.

5. Dunning CE, Zarzour ZD, Patterson SD, Johnson JA, King GJ. Ligamentous stabilizers against posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(12):1823-1828.

6. Eygendaal D. Ligamentous reconstruction around the elbow using triceps tendon. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(5):516-523.

7. Jones KJ, Dodson CC, Osbahr DC, et al. The docking technique for lateral ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: surgical technique and clinical outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(3):389-395.

8. Lee BP, Teo LH. Surgical reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):476-479.

9. Lin KY, Shen PH, Lee CH, Pan RY, Lin LC, Shen HC. Functional outcomes of surgical reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Injury. 2012;43(10):1657-1661.

10. Olsen BS, Søjbjerg JO. The treatment of recurrent posterolateral instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(3):342-346.

11. Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Ligamentous repair and reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(1):54-61.

12. Savoie FH 3rd, Field LD, Gurley DJ. Arthroscopic and open radial ulnohumeral ligament reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Hand Clin. 2009;25(3):323-329.

13. Savoie FH 3rd, O’Brien MJ, Field LD, Gurley DJ. Arthroscopic and open radial ulnohumeral ligament reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29(4):611-618.

14. Bryce CD, Pennypacker JL, Kulkarni N, et al. Validation of three-dimensional models of in situ scapulae. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):825-832.

15. Byram IR, Khanna K, Gardner TR, Ahmad CS. Characterizing bone tunnel placement in medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction using patient-specific 3-dimensional computed tomography modeling. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):894-902.

16. Shiba R, Sorbie C, Siu DW, Bryant JT, Cooke TD, Wevers HW. Geometry of the humeroulnar joint. J Orthop Res. 1988;6(6):897-906.

17. Anakwenze OA, Khanna K, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Characterization of the supinator tubercle for lateral ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(4):2325967114530969. doi:10.1177/2325967114530969.

18. Sasashige Y, Ochi M, Ikuta Y. Optimal attachment site for reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. A cadaver study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1994;113(5):265-270.

1. O’Driscoll SW, Bell DF, Morrey BF. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(3):440-446.

2. O’Driscoll SW. Classification and evaluation of recurrent instability of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;370:34-43.

3. Takigawa N, Ryu J, Kish VL, Kinoshita M, Abe M. Functional anatomy of the lateral collateral ligament complex of the elbow: morphology and strain. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30(2):143-147.

4. McAdams TR, Masters GW, Srivastava S. The effect of arthroscopic sectioning of the lateral ligament complex of the elbow on posterolateral rotatory stability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(3):298-301.

5. Dunning CE, Zarzour ZD, Patterson SD, Johnson JA, King GJ. Ligamentous stabilizers against posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(12):1823-1828.

6. Eygendaal D. Ligamentous reconstruction around the elbow using triceps tendon. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(5):516-523.

7. Jones KJ, Dodson CC, Osbahr DC, et al. The docking technique for lateral ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: surgical technique and clinical outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(3):389-395.

8. Lee BP, Teo LH. Surgical reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):476-479.

9. Lin KY, Shen PH, Lee CH, Pan RY, Lin LC, Shen HC. Functional outcomes of surgical reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Injury. 2012;43(10):1657-1661.

10. Olsen BS, Søjbjerg JO. The treatment of recurrent posterolateral instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(3):342-346.

11. Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey BF, O’Driscoll SW. Ligamentous repair and reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(1):54-61.

12. Savoie FH 3rd, Field LD, Gurley DJ. Arthroscopic and open radial ulnohumeral ligament reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Hand Clin. 2009;25(3):323-329.

13. Savoie FH 3rd, O’Brien MJ, Field LD, Gurley DJ. Arthroscopic and open radial ulnohumeral ligament reconstruction for posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29(4):611-618.

14. Bryce CD, Pennypacker JL, Kulkarni N, et al. Validation of three-dimensional models of in situ scapulae. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):825-832.

15. Byram IR, Khanna K, Gardner TR, Ahmad CS. Characterizing bone tunnel placement in medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction using patient-specific 3-dimensional computed tomography modeling. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(4):894-902.

16. Shiba R, Sorbie C, Siu DW, Bryant JT, Cooke TD, Wevers HW. Geometry of the humeroulnar joint. J Orthop Res. 1988;6(6):897-906.

17. Anakwenze OA, Khanna K, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Characterization of the supinator tubercle for lateral ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(4):2325967114530969. doi:10.1177/2325967114530969.

18. Sasashige Y, Ochi M, Ikuta Y. Optimal attachment site for reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. A cadaver study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1994;113(5):265-270.

Real‐Time Patient Experience Surveys

In 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services implemented value‐based purchasing, a payment model that incentivizes hospitals for reaching certain quality and patient experience thresholds and penalizes those that do not, in part on the basis of patient satisfaction scores.[1] Although low patient satisfaction scores will adversely affect institutions financially, they also reflect patients' perceptions of their care. Some studies suggest that hospitals with higher patient satisfaction scores score higher overall on clinical care processes such as core measures compliance, readmission rates, lower mortality rates, and other quality‐of‐care metrics.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey assesses patients' experience following their hospital stay.[1] The percent of top box scores (ie, response of always on a four point scale, or scores of 9 or 10 on a 10‐point scale) are utilized to compare hospitals and determine the reimbursement or penalty a hospital will receive. Although these scores are available to the public on the Hospital Compare website,[12] physicians may not know how their hospital is ranked or how they are individually perceived by their patients. Additionally, these surveys are typically conducted 48 hours to 6 weeks after patients are discharged, and the results are distributed back to the hospitals well after the time that care was provided, thereby offering providers no chance of improving patient satisfaction during a given hospital stay.

Institutions across the country are trying to improve their HCAHPS scores, but there is limited research identifying specific measures providers can implement. Some studies have suggested that utilizing etiquette‐based communication and sitting at the bedside[13, 14] may help improve patient experience with their providers, and more recently, it has been suggested that providing real‐time deidentified patient experience survey results with education and a rewards/emncentive system to residents may help as well.[15]

Surveys conducted during a patient's hospitalization can offer real‐time actionable feedback to providers. We performed a quality‐improvement project that was designed to determine if real‐time feedback to hospitalist physicians, followed by coaching, and revisits to the patients' bedside could improve the results recorded on provider‐specific patient surveys and/or patients' HCAHPS scores or percentile rankings.

METHODS

Design

This was a prospective, randomized quality‐improvement initiative that was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and conducted at Denver Health, a 525‐bed university‐affiliated public safety net hospital. The initiative was conducted on both teaching and nonteaching general internal medicine services, which typically have a daily census of between 10 and 15 patients. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included all English‐ or Spanish‐speaking patients who were hospitalized on a general internal medicine service, had been admitted within the 2 days prior to enrollment, and had a hospitalist as their attending physician. Patients were excluded if they were enrolled in the study during a previous hospitalization, refused to participate, lacked capacity to participate, had hearing or speech impediments precluding regular conversation, were prisoners, if their clinical condition precluded participation, or their attending was an investigator in the project.

Intervention

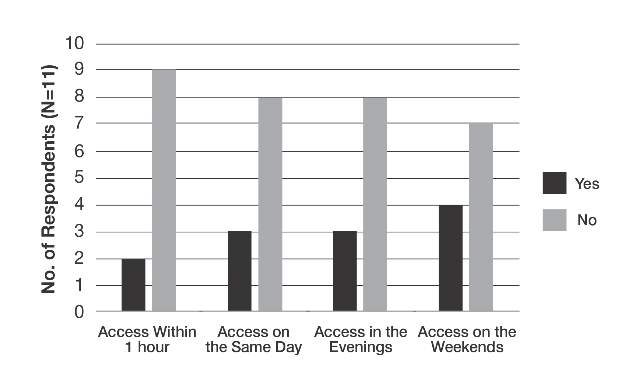

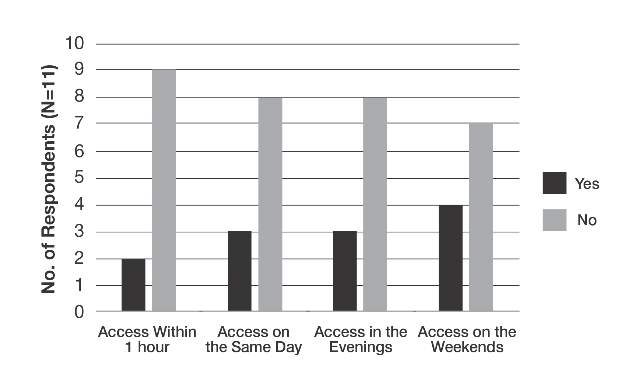

Participants were prescreened by investigators by reviewing team sign‐outs to determine if patients had any exclusion criteria. Investigators attempted to survey each patient who met inclusion criteria on a daily basis between 9:00 am and 11:00 am. An investigator administered the survey to each patient verbally using scripted language. Patients were asked to rate how well their doctors were listening to them, explaining what they wanted to know, and whether the doctors were being friendly and helpful, all questions taken from a survey that was available on the US Department of Health and Human Services website (to be referred to as here forward daily survey).[16] We converted the original 5‐point Likert scale used in this survey to a 4‐point scale by removing the option of ok, leaving participants the options of poor, fair, good, or great. Patients were also asked to provide any personalized feedback they had, and these comments were recorded in writing by the investigator.

After being surveyed on day 1, patients were randomized to an intervention or control group using an automated randomization module in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).[17] Patients in both groups who did not provide answers to all 3 questions that qualified as being top box (ie, great) were resurveyed on a daily basis until their responses were all top box or they were discharged, met exclusion criteria, or had been surveyed for a total of 4 consecutive days. In the pilot phase of this study, we found that if patients reported all top box scores on the initial survey their responses typically did not change over time, and the patients became frustrated if asked the same questions again when the patient felt there was not room for improvement. Accordingly, we elected to stop surveying patients when all top box responses were reported.

The attending hospitalist caring for each patient in the intervention group was given feedback about their patients' survey results (both their scores and any specific comments) on a daily basis. Feedback was provided in person by 1 of the investigators. The hospitalist also received an automatically generated electronic mail message with the survey results at 11:00 am on each study day. After informing the hospitalists of the patients' scores, the investigator provided a brief education session that included discussing Denver Health's most recent HCAHPS scores, value‐based purchasing, and the financial consequences of poor patient satisfaction scores. The investigator then coached the hospitalist on etiquette‐based communication,[18, 19] suggested that they sit down when communicating with their patients,[19, 20] and then asked the hospitalist to revisit each patient to discuss how the team could improve in any of the 3 areas where the patient did not give a top box score. These educational sessions were conducted in person and lasted a maximum of 5 minutes. An investigator followed up with each hospitalist the following day to determine whether the revisit occurred. Hospitalists caring for patients who were randomized to the control group were not given real‐time feedback or coaching and were not asked to revisit patients.

A random sample of patients surveyed for this initiative also received HCAHPS surveys 48 hours to 6 weeks following their hospital discharge, according to the standard methodology used to acquire HCAHPS data,[21] by an outside vendor contracted by Denver Health. Our vendor conducted these surveys via telephone in English or Spanish.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients in each group who reported top box scores on the daily surveys. Secondary outcomes included the percent change for the scores recorded for 3 provider‐specific questions from the daily survey, the median top box HCAHPS scores for the 3 provider related questions and overall hospital rating, and the HCAHPS percentiles of top box scores for these questions.

Sample Size

The sample size for this intervention assumed that the proportion of patients whose treating physicians did not receive real‐time feedback who rated their providers as top box would be 75%, and that the effect of providing real‐time feedback would increase this proportion to 85% on the daily surveys. To have 80% power with a type 1 error of 0.05, we estimated a need to enroll 430 patients, 215 in each group.

Statistics

Data were collected and managed using a secure, Web‐based electronic data capture tool hosted at Denver Health (REDCap), which is designed to support data collection for research studies providing: (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry, (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures, (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages, and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources.[17]

A 2 test was used to compare the proportion of patients in the 2 groups who reported great scores for each question on the study survey on the first and last day. With the intent of providing a framework for understanding the effect real‐time feedback could have on patient experience, a secondary analysis of HCAHPS results was conducted using several different methods.

First, the proportion of patients in the 2 groups who reported scores of 9 or 10 for the overall hospital rating question or reported always for each doctor communication question on the HCHAPS survey was compared using a 2. Second, to allow for detection of differences in a sample with a smaller N, the median overall hospital rating scores from the HCAHPS survey reported by patients in the 2 groups who completed a survey following discharge were compared using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Lastly, to place changes in proportion into a larger context (ie, how these changes would relate to value‐based purchasing), HCAHPS scores were converted to percentiles of national performance using the 2014 percentile rankings obtained from the external vendor that conducts the HCAHPS surveys for our hospital and compared between the intervention and control groups using a Wilcoxon rank sum test.

All comments collected from patients during their daily surveys were reviewed, and key words were abstracted from each comment. These key words were sorted and reviewed to categorize recurring key words into themes. Exemplars were then selected for each theme derived from patient comments.

RESULTS

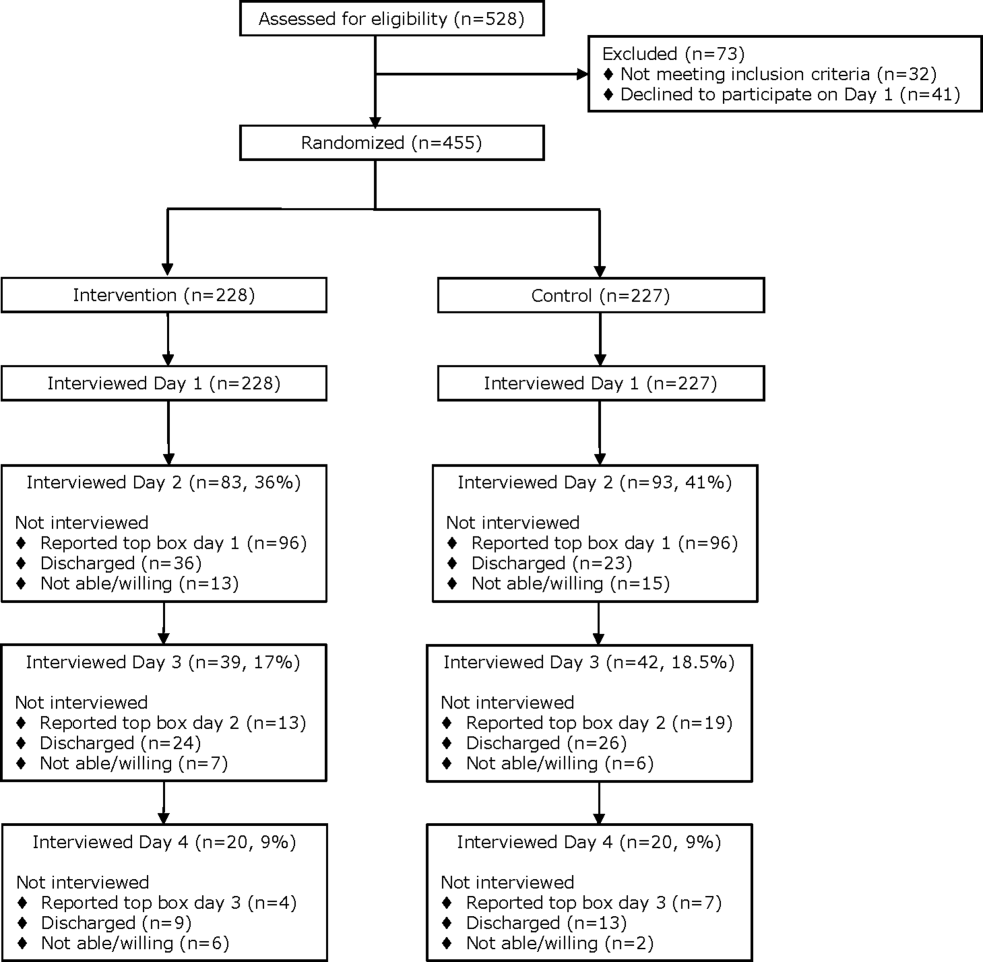

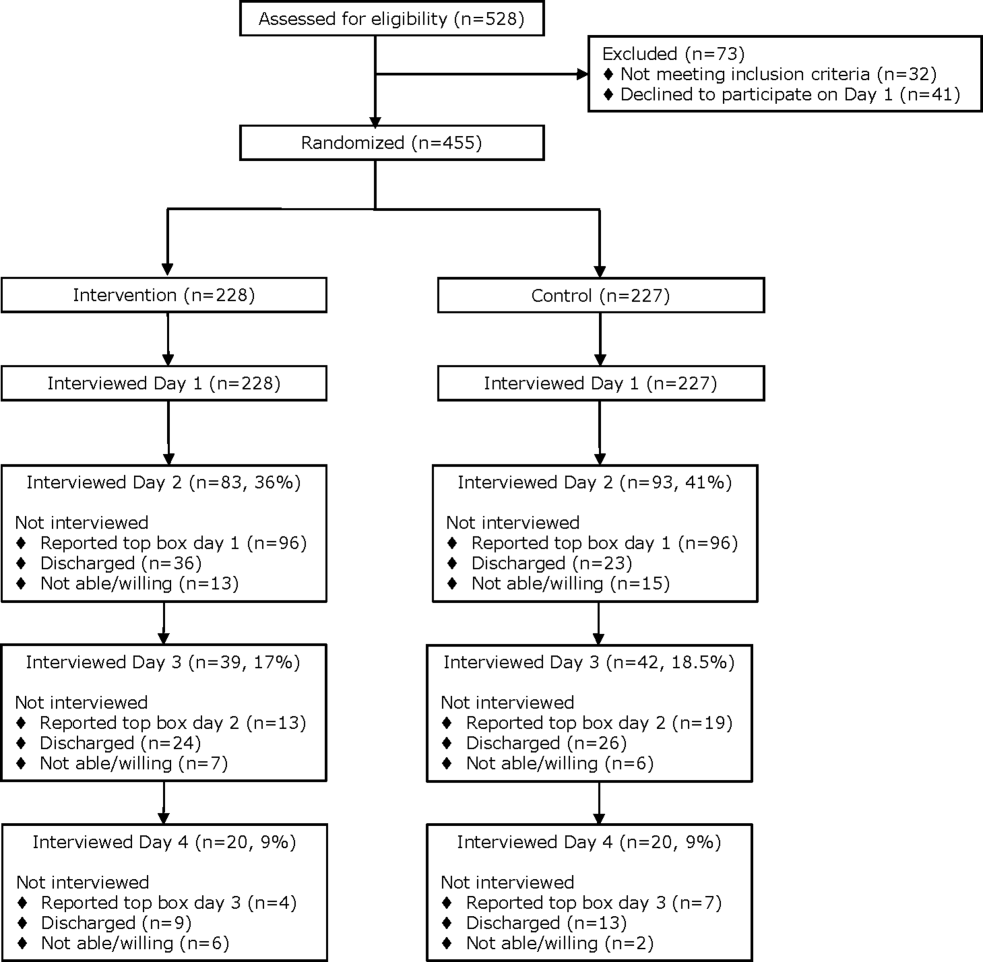

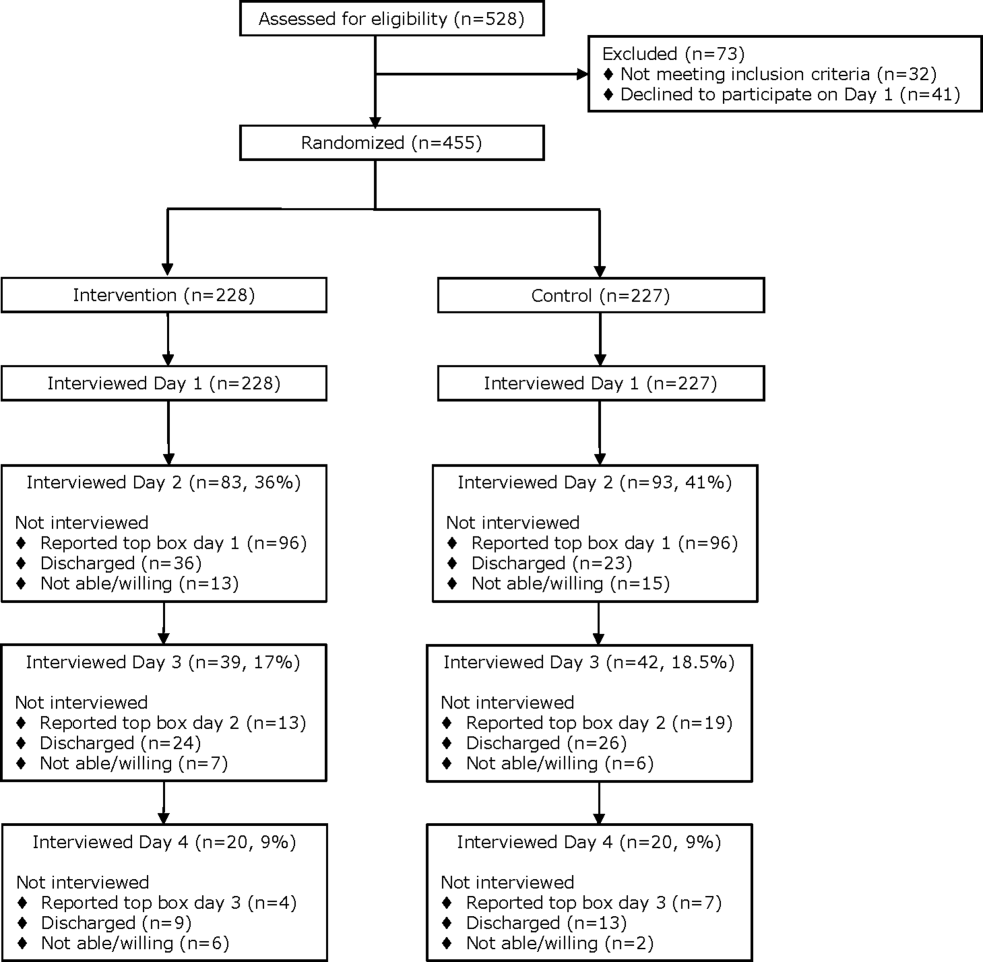

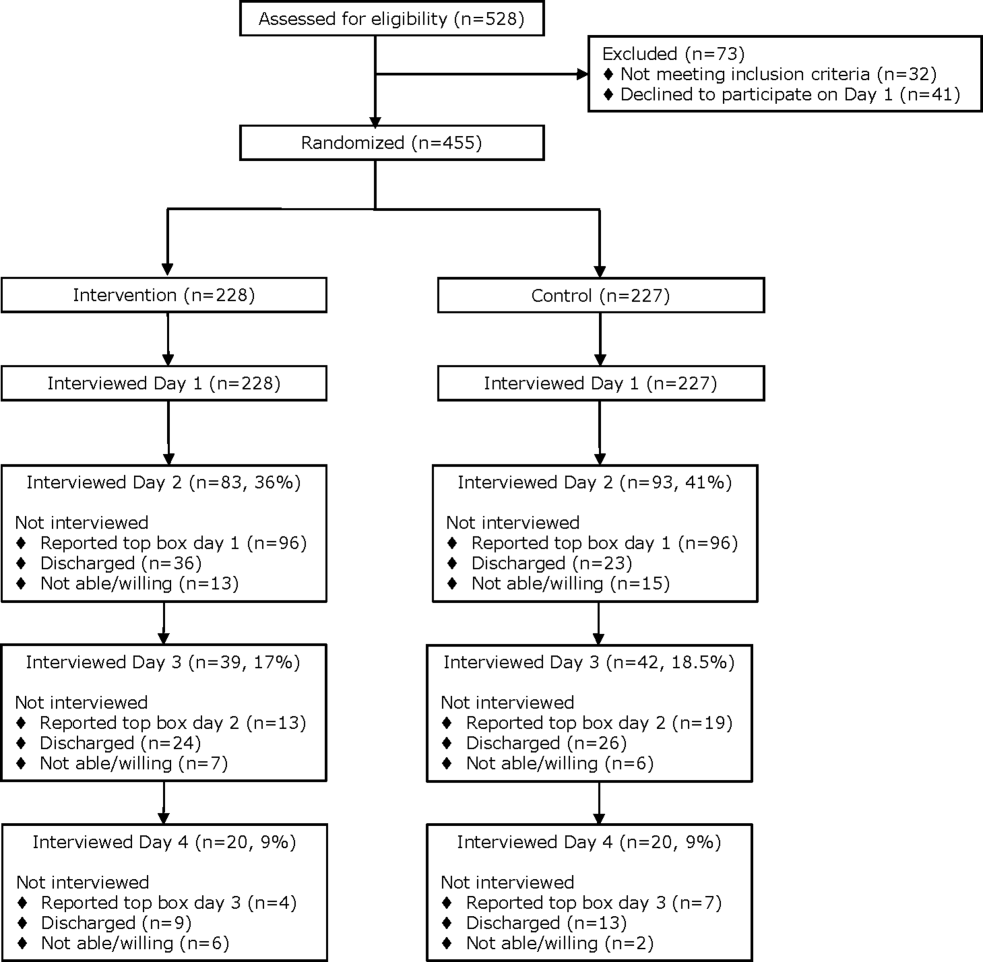

From April 14, 2014 to September 19, 2014, we enrolled 227 patients in the control group and 228 in the intervention group (Figure 1). Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. Of the 132 patients in the intervention group who reported anything less than top box scores for any of the 3 questions (thus prompting a revisit by their provider), 106 (80%) were revisited by their provider at least once during their hospitalization.

| All Patients | HCAHPS Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control, N = 227 | Intervention, N = 228 | Control, N = 35 | Intervention, N = 30 | |

| ||||

| Age, mean SD | 55 14 | 55 15 | 55 15 | 57 16 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 126 (60) | 121 (55) | 20 (57) | 12 (40) |

| Female | 85 (40) | 98 (45) | 15(43) | 18 (60) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 84 (40) | 90 (41) | 17 (49) | 12 (40) |

| Black | 38 (18) | 28 (13) | 6 (17) | 7 (23) |

| White | 87 (41) | 97 (44) | 12 (34) | 10 (33) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Payer | ||||

| Medicare | 65 (29) | 82 (36) | 15 (43) | 12 (40) |

| Medicaid | 122 (54) | 108 (47) | 17 (49) | 14 (47) |

| Commercial | 12 (5) | 15 (7) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Medically indigent | 4 (2) | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) |

| Self‐pay | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Other/unknown | 19 (8) | 12 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Team | ||||

| Teaching | 187 (82) | 196 (86) | 27 (77) | 24 (80) |

| Nonteaching | 40 (18) | 32 (14) | 8 (23) | 6 (20) |

| Top 5 primary discharge diagnoses* | ||||

| Septicemia | 26 (11) | 34 (15) | 3 (9) | 5 (17) |

| Heart failure | 14 (6) | 13 (6) | 2 (6) | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 12 (5) | 9 (4) | 3 (9) | 2 (7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (5) | 8 (4) | 2 (6) | |

| Alcohol withdrawal | 9 (4) | |||

| Cellulitis | 7 (3) | 2 (7) | ||

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 (7) | |||

| Chest pain | 2 (7) | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (6) | |||

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 4) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 1 (0, 3) | 2 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 3) | 1.5 (1, 3) |

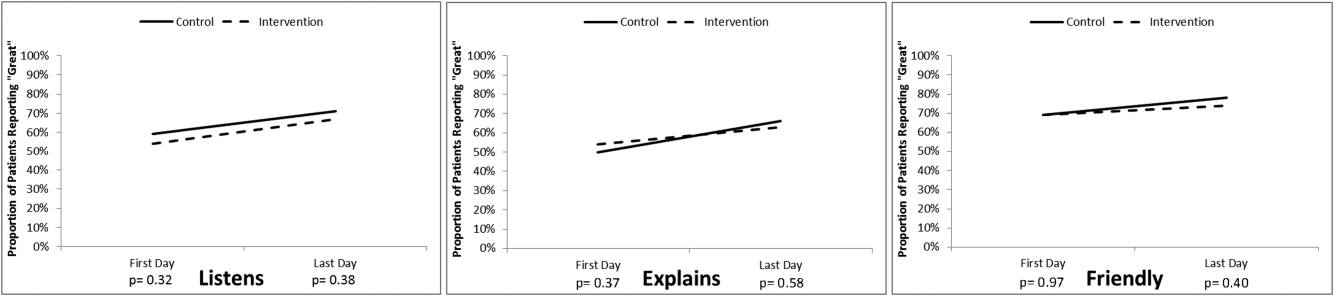

Daily Surveys

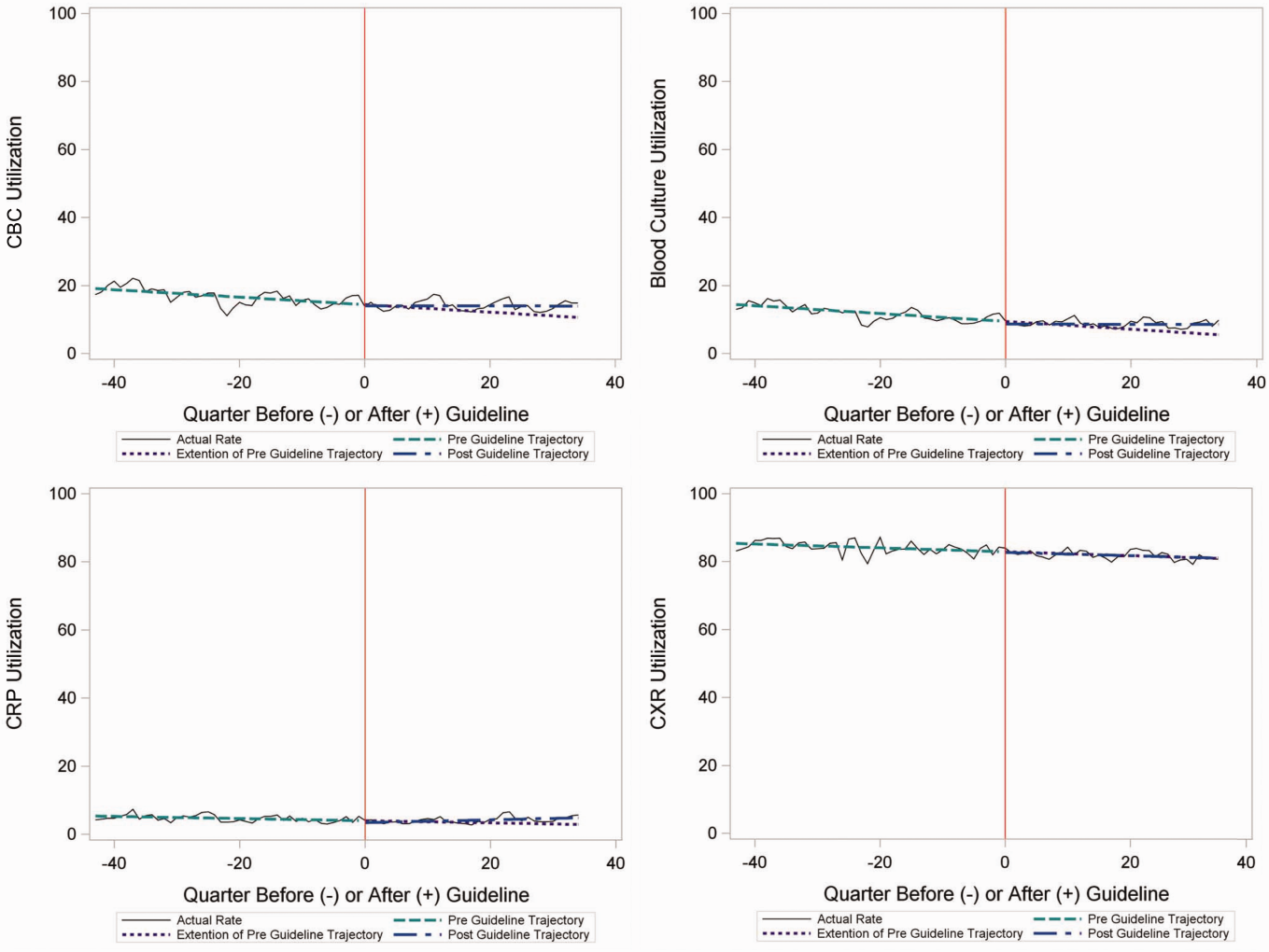

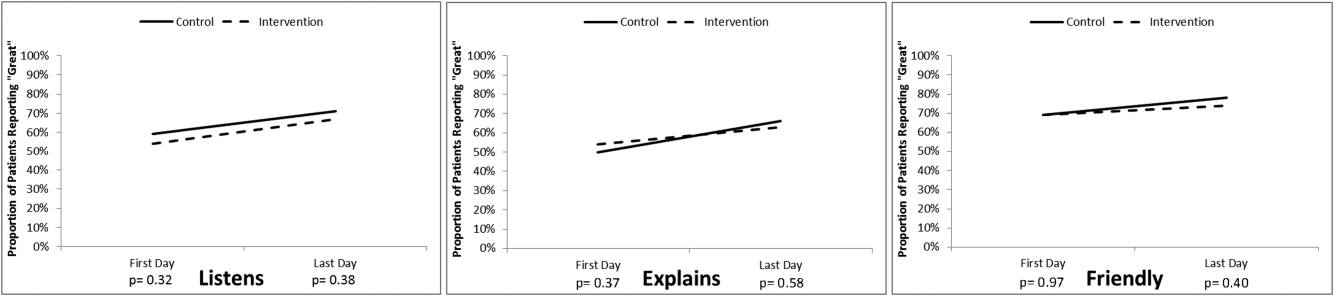

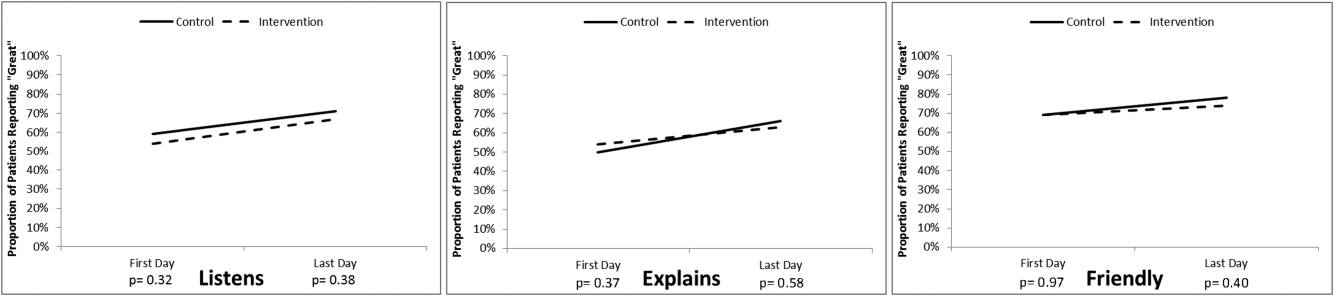

The proportion of patients in both study groups reporting top box scores tended to increase from the first day to the last day of the survey (Figure 2); however, we found no statistically significant differences between the proportion of patients who reported top box scores on first day or last day in the intervention group compared to the control group. The comments made by the patients are summarized in Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article.

HCAHPS Scores

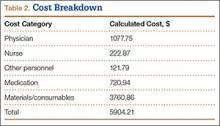

The proportion of top box scores from the HCAHPS surveys were higher, though not statistically significant, for all 3 provider‐specific questions and for the overall hospital rating for patients whose hospitalists received real‐time feedback (Table 2). The median [interquartile range] score for the overall hospital rating was higher for patients in the intervention group compared with those in the control group, (10 [9, 10] vs 9 [8, 10], P = 0.04]. After converting the HCAHPS scores to percentiles, we found considerably higher rankings for all 3 provider‐related questions and for the overall hospital rating in the intervention group compared to the control group (P = 0.02 for overall differences in percentiles [Table 2]).

| HCAHPS Questions | Proportion Top Box* | Percentile Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control, N = 35 | Intervention, N = 30 | Control, N = 35 | Intervention, N = 30 | |

| ||||

| Overall hospital rating | 61% | 80% | 6 | 87 |

| Courtesy/respect | 86% | 93% | 23 | 88 |

| Clear communication | 77% | 80% | 39 | 60 |

| Listening | 83% | 90% | 57 | 95 |

No adverse events occurred during the course of the study in either group.

DISCUSSION

The important findings of this study were that (1) daily patient satisfaction scores improved from first day to last day regardless of study group, (2) patients whose providers received real‐time feedback had a trend toward higher HCAHPS proportions for the 3 provider‐related questions as well as the overall rating of the hospital but were not statistically significant, (3) the percentile differences in these 3 questions as well as the overall rating of the hospital were significantly higher in the intervention group as was the median score for the overall hospital rating.

Our original sample size calculation was based upon our own preliminary data, indicating that our baseline top box scores for the daily survey was around 75%. The daily survey top box score on the first day was, however, much lower (Figure 2). Accordingly, although we did not find a significant difference in these daily scores, we were underpowered to find such a difference. Additionally, because only a small percentage of patients are selected for the HCAHPS survey, our ability to detect a difference in this secondary outcome was also limited. We felt that it was important to analyze the percentile comparisons in addition to the proportion of top box scores on the HCAHPS, because the metrics for value‐based purchasing are based upon, in part, how a hospital system compares to other systems. Finally, to improve our power to detect a difference given a small sample size, we converted the scoring system for overall hospital ranking to a continuous variable, which again was noted to be significant.

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized investigation designed to assess the effect of real‐time, patient‐specific feedback to physicians. Real‐time feedback is increasingly being incorporated into medical practice, but there is only limited information available describing how this type of feedback affects outcomes.[22, 23, 24] Banka et al.[15] found that HCAHPS scores improved as a result of real‐time feedback given to residents, but the study was not randomized, utilized a pre‐post design that resulted in there being differences between the patients studied before and after the intervention, and did not provide patient‐specific data to the residents. Tabib et al.[25] found that operating costs decreased 17% after instituting real‐time feedback to providers about these costs. Reeves et al.[26] conducted a cluster randomized trial of a patient feedback survey that was designed to improve nursing care, but the results were reviewed by the nurses several months after patients had been discharged.

The differences in median top box scores and percentile rank that we observed could have resulted from the real‐time feedback, the educational coaching, the fact that the providers revisited the majority of the patients, or a combination of all of the above. Gross et al.[27] found that longer visits lead to higher satisfaction, though others have not found this to necessarily be the case.[28, 29] Lin et al.[30] found that patient satisfaction was affected by the perceived duration of the visit as well as whether expectations on visit length were met and/or exceeded. Brown et al.[31] found that training providers in communication skills improved the providers perception of their communication skills, although patient experience scores did not improve. We feel that the results seen are more likely a combination thereof as opposed to any 1 component of the intervention.

The most commonly reported complaints or concerns in patients' undirected comments often related to communication issues. Comments on subsequent surveys suggested that patient satisfaction improved over time in the intervention group, indicating that perhaps physicians did try to improve in areas that were highlighted by the real‐time feedback, and that patients perceived the physician efforts to do so (eg, They're doing better than the last time you asked. They sat down and talked to me and listened better. They came back and explained to me about my care. They listened better. They should do this survey at the clinic. See Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article).

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not randomize providers, and many of our providers (approximately 65%) participated in both the control group and also in the intervention group, and thus received real‐time feedback at some point during the study, which could have affected their overall practice and limited our ability to find a difference between the 2 groups. In an attempt to control for this possibility, the study was conducted on an intermittent basis during the study time frame. Furthermore, the proportion of patients who reported top box scores at the beginning of the study did not have a clear trend of change by the end of the study, suggesting that overall clinician practices with respect to patient satisfaction did not change during this short time period.

Second, only a small number of our patients were randomly selected for the HCAHPS survey, which limited our ability to detect significant differences in HCAHPS proportions. Third, the HCAHPS percentiles at our institution at that time were low. Accordingly, the improvements that we observed in patient satisfaction scores might not be reproducible at institutions with higher satisfactions scores. Fourth, time and resources were needed to obtain patient feedback to provide to providers during this study. There are, however, other ways to obtain feedback that are less resource intensive (eg, electronic feedback, the utilization of volunteers, or partnering this with manager rounding). Finally, the study was conducted at a single, university‐affiliated public teaching hospital and was a quality‐improvement initiative, and thus our results are not generalizable to other institutions.

In conclusion, real‐time feedback of patient experience to their providers, coupled with provider education, coaching, and revisits, seems to improve satisfaction of patients hospitalized on general internal medicine units who were cared for by hospitalists.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kate Fagan, MPH, for her excellent technical assistance.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- HCAHPS Fact Sheet. 2015. Available at: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/Files/HCAHPS_Fact_Sheet_June_2015.pdf. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- , , , . The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:194–202.

- , , , . Patients' perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1921–1931.

- , , , . The relationship between patients' perception of care and measures of hospital quality and safety. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1024–1040.

- , , , et al. Relationship between quality of diabetes care and patient satisfaction. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:64–70.

- , , , , . Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:41–48.

- , , . A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1).

- , . The association between satisfaction with services provided in primary care and outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2003;20:486–490.

- , , , et al. Associations between Web‐based patient ratings and objective measures of hospital quality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:435–436.

- , , , et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:188–195.

- , , , , . Patients' perceptions of care are associated with quality of hospital care: a survey of 4605 hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(4):382–388.

- Centers for Medicare 28:908–913.

- , , , , , . Effect of sitting vs. standing on perception of provider time at bedside: a pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:166–171.

- , , , et al. Improving patient satisfaction through physician education, feedback, and incentives. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:497–502.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Patient satisfaction survey. Available at: http://bphc.hrsa.gov/policiesregulations/performancemeasures/patientsurvey/surveyform.html. Accessed November 15, 2013.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381.

- . The HCAHPS Handbook. Gulf Breeze, FL: Fire Starter; 2010.

- . Etiquette‐based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1988–1989.

- . 5 years after the Kahn's etiquette‐based medicine: a brief checklist proposal for a functional second meeting with the patient. Front Psychol. 2013;4:723.

- Frequently Asked Questions. Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing Program. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/hospital‐value‐based‐purchasing/Downloads/FY‐2013‐Program‐Frequently‐Asked‐Questions‐about‐Hospital‐VBP‐3‐9‐12.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2014.

- , , , . Real‐time patient survey data during routine clinical activities for rapid‐cycle quality improvement. JMIR Med Inform. 2015;3:e13.

- . Mount Sinai launches real‐time patient‐feedback survey tool. Healthcare Informatics website. Available at: http://www.healthcare‐informatics.com/news‐item/mount‐sinai‐launches‐real‐time‐patient‐feedback‐survey‐tool. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- , . Hospitals are finally starting to put real‐time data to use. Harvard Business Review website. Available at: https://hbr.org/2014/11/hospitals‐are‐finally‐starting‐to‐put‐real‐time‐data‐to‐use. Published November 12, 2014. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- , , , , . Reducing operating room costs through real‐time cost information feedback: a pilot study. J Endourol. 2015;29:963–968.

- , , . Facilitated patient experience feedback can improve nursing care: a pilot study for a phase III cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:259.

- , , , , . Patient satisfaction with time spent with their physician. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:133–137.

- , , , , , . The relationship between time spent communicating and communication outcomes on a hospital medicine service. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:185–189.

- , . Cognitive interview techniques reveal specific behaviors and issues that could affect patient satisfaction relative to hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:E1–E6.

- , , , et al. Is patients' perception of time spent with the physician a determinant of ambulatory patient satisfaction? Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1437–1442.

- , , , . Effect of clinician communication skills training on patient satisfaction. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:822–829.

In 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services implemented value‐based purchasing, a payment model that incentivizes hospitals for reaching certain quality and patient experience thresholds and penalizes those that do not, in part on the basis of patient satisfaction scores.[1] Although low patient satisfaction scores will adversely affect institutions financially, they also reflect patients' perceptions of their care. Some studies suggest that hospitals with higher patient satisfaction scores score higher overall on clinical care processes such as core measures compliance, readmission rates, lower mortality rates, and other quality‐of‐care metrics.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey assesses patients' experience following their hospital stay.[1] The percent of top box scores (ie, response of always on a four point scale, or scores of 9 or 10 on a 10‐point scale) are utilized to compare hospitals and determine the reimbursement or penalty a hospital will receive. Although these scores are available to the public on the Hospital Compare website,[12] physicians may not know how their hospital is ranked or how they are individually perceived by their patients. Additionally, these surveys are typically conducted 48 hours to 6 weeks after patients are discharged, and the results are distributed back to the hospitals well after the time that care was provided, thereby offering providers no chance of improving patient satisfaction during a given hospital stay.

Institutions across the country are trying to improve their HCAHPS scores, but there is limited research identifying specific measures providers can implement. Some studies have suggested that utilizing etiquette‐based communication and sitting at the bedside[13, 14] may help improve patient experience with their providers, and more recently, it has been suggested that providing real‐time deidentified patient experience survey results with education and a rewards/emncentive system to residents may help as well.[15]

Surveys conducted during a patient's hospitalization can offer real‐time actionable feedback to providers. We performed a quality‐improvement project that was designed to determine if real‐time feedback to hospitalist physicians, followed by coaching, and revisits to the patients' bedside could improve the results recorded on provider‐specific patient surveys and/or patients' HCAHPS scores or percentile rankings.

METHODS

Design

This was a prospective, randomized quality‐improvement initiative that was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and conducted at Denver Health, a 525‐bed university‐affiliated public safety net hospital. The initiative was conducted on both teaching and nonteaching general internal medicine services, which typically have a daily census of between 10 and 15 patients. No protocol changes occurred during the study.

Participants

Participants included all English‐ or Spanish‐speaking patients who were hospitalized on a general internal medicine service, had been admitted within the 2 days prior to enrollment, and had a hospitalist as their attending physician. Patients were excluded if they were enrolled in the study during a previous hospitalization, refused to participate, lacked capacity to participate, had hearing or speech impediments precluding regular conversation, were prisoners, if their clinical condition precluded participation, or their attending was an investigator in the project.

Intervention

Participants were prescreened by investigators by reviewing team sign‐outs to determine if patients had any exclusion criteria. Investigators attempted to survey each patient who met inclusion criteria on a daily basis between 9:00 am and 11:00 am. An investigator administered the survey to each patient verbally using scripted language. Patients were asked to rate how well their doctors were listening to them, explaining what they wanted to know, and whether the doctors were being friendly and helpful, all questions taken from a survey that was available on the US Department of Health and Human Services website (to be referred to as here forward daily survey).[16] We converted the original 5‐point Likert scale used in this survey to a 4‐point scale by removing the option of ok, leaving participants the options of poor, fair, good, or great. Patients were also asked to provide any personalized feedback they had, and these comments were recorded in writing by the investigator.

After being surveyed on day 1, patients were randomized to an intervention or control group using an automated randomization module in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).[17] Patients in both groups who did not provide answers to all 3 questions that qualified as being top box (ie, great) were resurveyed on a daily basis until their responses were all top box or they were discharged, met exclusion criteria, or had been surveyed for a total of 4 consecutive days. In the pilot phase of this study, we found that if patients reported all top box scores on the initial survey their responses typically did not change over time, and the patients became frustrated if asked the same questions again when the patient felt there was not room for improvement. Accordingly, we elected to stop surveying patients when all top box responses were reported.