User login

SHM Allies with Leading Health Care Groups to Advance Hospital Patient Nutrition

SHM announced in May the launch of a new interdisciplinary partnership, the Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition, in conjunction with four other organizations. The alliance’s mission is to improve patient outcomes through nutrition intervention in the hospital.

Representing more than 100,000 dietitians, nurses, hospitalists, and other physicians and clinicians from across the nation, the following organizations have come together with SHM to champion for early nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in hospitals:

- Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN);

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND);

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN); and

- Abbott Nutrition.

Malnutrition increases costs, length of stay, and unfavorable outcomes. Properly addressing hospital malnutrition creates an opportunity to improve quality of care while also reducing healthcare costs. Additional clinical research finds that malnourished patients are two times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer, while patients with malnutrition have three times the rate of infection.

Yet when hospitalized patients are provided intervention via oral nutrition supplements, health economic research finds associated benefits:

Nutrition intervention can reduce hospital length of stay by an average of two days, and nutrition intervention has been shown to reduce patient hospitalization costs by 21.6%, or $4,734 per episode.

Additionally, there was a 6.7% reduction in the probability of 30-day readmission with patients who had at least one known subsequent readmission and were offered oral nutrition supplements during hospitalization.

“There is a growing body of evidence supporting the positive impact nutrition has on improving patient outcomes,” says hospitalist Melissa Parkhurst, MD, FHM, who serves as medical director for the University of Kansas Hospital’s hospitalist section and its nutrition support service. “We are seeing that early intervention can make a significant difference. As physicians, we need to work with the entire clinician team to ensure that nutrition is an integral part of our patients’ treatment plans.”

The alliance launched a website at www.malnutrition.org to provide hospital-based clinicians with the following resources:

- Research and fact sheets about malnutrition and the positive impact nutrition intervention has on patient care and outcomes;

- The Alliance Nutrition Toolkit, which facilitates clinician collaboration and nutrition integration; and

- Information about educational events, such as quick learning modules, continuing medical education (CME) programs.

The Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition is made possible with support from Abbott’s nutrition business.

SHM announced in May the launch of a new interdisciplinary partnership, the Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition, in conjunction with four other organizations. The alliance’s mission is to improve patient outcomes through nutrition intervention in the hospital.

Representing more than 100,000 dietitians, nurses, hospitalists, and other physicians and clinicians from across the nation, the following organizations have come together with SHM to champion for early nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in hospitals:

- Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN);

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND);

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN); and

- Abbott Nutrition.

Malnutrition increases costs, length of stay, and unfavorable outcomes. Properly addressing hospital malnutrition creates an opportunity to improve quality of care while also reducing healthcare costs. Additional clinical research finds that malnourished patients are two times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer, while patients with malnutrition have three times the rate of infection.

Yet when hospitalized patients are provided intervention via oral nutrition supplements, health economic research finds associated benefits:

Nutrition intervention can reduce hospital length of stay by an average of two days, and nutrition intervention has been shown to reduce patient hospitalization costs by 21.6%, or $4,734 per episode.

Additionally, there was a 6.7% reduction in the probability of 30-day readmission with patients who had at least one known subsequent readmission and were offered oral nutrition supplements during hospitalization.

“There is a growing body of evidence supporting the positive impact nutrition has on improving patient outcomes,” says hospitalist Melissa Parkhurst, MD, FHM, who serves as medical director for the University of Kansas Hospital’s hospitalist section and its nutrition support service. “We are seeing that early intervention can make a significant difference. As physicians, we need to work with the entire clinician team to ensure that nutrition is an integral part of our patients’ treatment plans.”

The alliance launched a website at www.malnutrition.org to provide hospital-based clinicians with the following resources:

- Research and fact sheets about malnutrition and the positive impact nutrition intervention has on patient care and outcomes;

- The Alliance Nutrition Toolkit, which facilitates clinician collaboration and nutrition integration; and

- Information about educational events, such as quick learning modules, continuing medical education (CME) programs.

The Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition is made possible with support from Abbott’s nutrition business.

SHM announced in May the launch of a new interdisciplinary partnership, the Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition, in conjunction with four other organizations. The alliance’s mission is to improve patient outcomes through nutrition intervention in the hospital.

Representing more than 100,000 dietitians, nurses, hospitalists, and other physicians and clinicians from across the nation, the following organizations have come together with SHM to champion for early nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in hospitals:

- Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN);

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND);

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN); and

- Abbott Nutrition.

Malnutrition increases costs, length of stay, and unfavorable outcomes. Properly addressing hospital malnutrition creates an opportunity to improve quality of care while also reducing healthcare costs. Additional clinical research finds that malnourished patients are two times more likely to develop a pressure ulcer, while patients with malnutrition have three times the rate of infection.

Yet when hospitalized patients are provided intervention via oral nutrition supplements, health economic research finds associated benefits:

Nutrition intervention can reduce hospital length of stay by an average of two days, and nutrition intervention has been shown to reduce patient hospitalization costs by 21.6%, or $4,734 per episode.

Additionally, there was a 6.7% reduction in the probability of 30-day readmission with patients who had at least one known subsequent readmission and were offered oral nutrition supplements during hospitalization.

“There is a growing body of evidence supporting the positive impact nutrition has on improving patient outcomes,” says hospitalist Melissa Parkhurst, MD, FHM, who serves as medical director for the University of Kansas Hospital’s hospitalist section and its nutrition support service. “We are seeing that early intervention can make a significant difference. As physicians, we need to work with the entire clinician team to ensure that nutrition is an integral part of our patients’ treatment plans.”

The alliance launched a website at www.malnutrition.org to provide hospital-based clinicians with the following resources:

- Research and fact sheets about malnutrition and the positive impact nutrition intervention has on patient care and outcomes;

- The Alliance Nutrition Toolkit, which facilitates clinician collaboration and nutrition integration; and

- Information about educational events, such as quick learning modules, continuing medical education (CME) programs.

The Alliance to Advance Patient Nutrition is made possible with support from Abbott’s nutrition business.

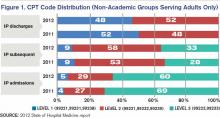

Hospitalist-Specific Data Shows Rise in Use of Some CPT Codes

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Before 2011, hospitalists had only Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) specialty-specific CPT distribution data, and no hospitalist-specific data, available when looking for benchmarks against which to compare their billing practices. Thanks to recent State of Hospital Medicine surveys, however, we now have hospitalist-specific data for the distribution of commonly used CPT codes. It’s interesting to analyze how 2011 data compares to 2012, and how the use of high-level codes varies by geographic region, employment model, compensation structure, and practice size.

In 2012, the use of the higher-level inpatient (IP) discharge code (99239) increased to 52% from 48% in 2011 among HM groups serving adults only, and the use of the highest-level IP subsequent code (99233) increased to 33% from 28% in the same comparison. This increase is in keeping with national trends. According to a May 2012 report by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General, from 2001 to 2010, physicians’ billing shifted from lower-level to higher-level codes. For example, the billing of the lowest-level code (99231) decreased 16%, while the billing of the two higher-level codes (99232 and 99233) increased 6% and 9%, respectively.

Possible drivers of this change include:

- Expanded use of electronic health records (EHRs);

- Increased physician education about documentation requirements; and

- A sicker hospitalized patient population due to expanded outpatient care capabilities.

Although the proportion of high-level subsequent and discharge codes reported by SHM increased in 2012, the percent of highest-level IP admission codes (99223) actually decreased to 66% from 69%. There are many possible reasons for this. First, the elimination of consult codes by CMS in 2010 increased the overall use of admission codes but might have decreased the proportion of highest-level admission codes. Additionally, there may be an increased use of higher RVU-generating critical-care codes preferentially over billing of the highest-level admission codes. Third, there is the possibility that the extra documentation required for high-level admissions is a billing deterrent. Similarly, higher-level codes may be downcoded if documentation is lacking or incomplete.

Source: 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report

Comparatively, my health system, Allina Health, showed an increase in the use of highest-level codes for all three CPT codes analyzed.

With the increasing sophistication of EHRs and coding technology tools, it will be interesting to see the future impact on coding distribution as providers adapt to new documentation processes that support health information exchange across systems.

Comparing geographic regions, the West uses the highest proportion of high-level codes for admission, follow-up, and discharge, followed by the Midwest.

Interestingly, variation in billing by group size is only correlated directly to admission codes, but not to follow-up or discharge codes—with larger services tending to bill more of the highest-level admission codes.

Admission code use correlates directly with compensation structure; groups providing 100% of total compensation in the form of salary bill the lowest percentage of high-level admission codes. As compensation trends away from straight salaries, the percentage of high-level admission codes increases. The picture is less clear for high-level follow-up and discharge codes.

Comparing academic and nonacademic HM groups shows greater use of the highest- level admission, follow-up, and discharge codes for nonacademic HM groups. This is likely because academic hospitalists can only bill for their own time and not for time spent by medical residents.

Employment model (e.g. hospital system, private hospitalist-only groups, management companies, etc.) showed no categorical effect on CPT distribution.

Dr. Stephan is regional hospitalist medical director for Allina Health in Minneapolis and the incoming chair of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Peer Benchmarking Network May Reduce Overutilization in Pediatric Bronchiolitis

Clinical question: What is the impact of a peer benchmarking network on resource utilization in acute bronchiolitis?

Background: Acute bronchiolitis is the most common illness requiring hospitalization in children. Despite the publication of national evidence-based guidelines, variation and overuse of common therapies remains. Despite one report of successful implementation of evidence-based guidelines in a collaborative of freestanding children’s hospitals, most children are hospitalized outside of such institutions, and large-scale, lower-resource efforts have not been described.

Study design: Voluntary, quality-improvement (QI), and benchmarking collaborative.

Setting: Seventeen hospitals, including both community and freestanding children’s facilities.

Synopsis: Over a four-year period, data on 11,568 bronchiolitis hospitalizations were collected. The collaborative facilitated sharing of resources (e.g. scoring tools, guidelines), celebrated high performers on an annual basis, and encouraged regular data collection, primarily via conference calls and email. Notably, a common bundle of interventions were not used; groups worked on local improvement cycles, with only a few groups forming a small subcollaborative utilizing a shared pathway. A significant decrease in bronchodilator utilization and chest physiotherapy was seen over the course of the collaborative, although no change in chest radiography, steroid utilization, and RSV testing was noted.

This voluntary and low-resource effort by similarly motivated peers across a variety of inpatient settings demonstrated improvement over time. It is particularly notable as inpatient collaboratives with face-to-face meeting requirements, and annual fees, become more commonplace.

Study limitations include the lack of a conceptual model for studying contextual factors that might have led to improvement in the varied settings and secular changes over this time period. Additionally, EDs were not included in this initiative, which likely accounted for the lack of improvement in chest radiography and RSV testing. Nonetheless, scalable innovations such as this will become increasingly important as hospitalists search for value in health care.

Bottom line: Creating a national community of practice may reduce overutilization in bronchiolitis.

Citation: Ralston S, Garber M, Narang S, et al. Decreasing unnecessary utilization in acute bronchiolitis care: results from the Value in Inpatient Pediatrics Network. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):25-30.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the impact of a peer benchmarking network on resource utilization in acute bronchiolitis?

Background: Acute bronchiolitis is the most common illness requiring hospitalization in children. Despite the publication of national evidence-based guidelines, variation and overuse of common therapies remains. Despite one report of successful implementation of evidence-based guidelines in a collaborative of freestanding children’s hospitals, most children are hospitalized outside of such institutions, and large-scale, lower-resource efforts have not been described.

Study design: Voluntary, quality-improvement (QI), and benchmarking collaborative.

Setting: Seventeen hospitals, including both community and freestanding children’s facilities.

Synopsis: Over a four-year period, data on 11,568 bronchiolitis hospitalizations were collected. The collaborative facilitated sharing of resources (e.g. scoring tools, guidelines), celebrated high performers on an annual basis, and encouraged regular data collection, primarily via conference calls and email. Notably, a common bundle of interventions were not used; groups worked on local improvement cycles, with only a few groups forming a small subcollaborative utilizing a shared pathway. A significant decrease in bronchodilator utilization and chest physiotherapy was seen over the course of the collaborative, although no change in chest radiography, steroid utilization, and RSV testing was noted.

This voluntary and low-resource effort by similarly motivated peers across a variety of inpatient settings demonstrated improvement over time. It is particularly notable as inpatient collaboratives with face-to-face meeting requirements, and annual fees, become more commonplace.

Study limitations include the lack of a conceptual model for studying contextual factors that might have led to improvement in the varied settings and secular changes over this time period. Additionally, EDs were not included in this initiative, which likely accounted for the lack of improvement in chest radiography and RSV testing. Nonetheless, scalable innovations such as this will become increasingly important as hospitalists search for value in health care.

Bottom line: Creating a national community of practice may reduce overutilization in bronchiolitis.

Citation: Ralston S, Garber M, Narang S, et al. Decreasing unnecessary utilization in acute bronchiolitis care: results from the Value in Inpatient Pediatrics Network. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):25-30.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the impact of a peer benchmarking network on resource utilization in acute bronchiolitis?

Background: Acute bronchiolitis is the most common illness requiring hospitalization in children. Despite the publication of national evidence-based guidelines, variation and overuse of common therapies remains. Despite one report of successful implementation of evidence-based guidelines in a collaborative of freestanding children’s hospitals, most children are hospitalized outside of such institutions, and large-scale, lower-resource efforts have not been described.

Study design: Voluntary, quality-improvement (QI), and benchmarking collaborative.

Setting: Seventeen hospitals, including both community and freestanding children’s facilities.

Synopsis: Over a four-year period, data on 11,568 bronchiolitis hospitalizations were collected. The collaborative facilitated sharing of resources (e.g. scoring tools, guidelines), celebrated high performers on an annual basis, and encouraged regular data collection, primarily via conference calls and email. Notably, a common bundle of interventions were not used; groups worked on local improvement cycles, with only a few groups forming a small subcollaborative utilizing a shared pathway. A significant decrease in bronchodilator utilization and chest physiotherapy was seen over the course of the collaborative, although no change in chest radiography, steroid utilization, and RSV testing was noted.

This voluntary and low-resource effort by similarly motivated peers across a variety of inpatient settings demonstrated improvement over time. It is particularly notable as inpatient collaboratives with face-to-face meeting requirements, and annual fees, become more commonplace.

Study limitations include the lack of a conceptual model for studying contextual factors that might have led to improvement in the varied settings and secular changes over this time period. Additionally, EDs were not included in this initiative, which likely accounted for the lack of improvement in chest radiography and RSV testing. Nonetheless, scalable innovations such as this will become increasingly important as hospitalists search for value in health care.

Bottom line: Creating a national community of practice may reduce overutilization in bronchiolitis.

Citation: Ralston S, Garber M, Narang S, et al. Decreasing unnecessary utilization in acute bronchiolitis care: results from the Value in Inpatient Pediatrics Network. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):25-30.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Commemorating Round-the-Clock Hospital Medicine Programs

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

IPC-UCSF Fellowship for Hospitalist Group Leaders Demands a Stretch

The yearlong IPC-UCSF Fellowship for Hospitalist Leaders brings about 40 IPC: The Hospitalist Company group leaders together for a series of three-day training sessions and ongoing distance learning, executive coaching, and project mentoring.

The program emphasizes role plays and simulations, and even involves an acting coach to help participants learn to make more effective presentations, such as harnessing the power of storytelling, says Niraj L. Sehgal, MD, MPH, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) who directs the fellowship through UCSF’s Center for Health Professions.

The first class graduated in November 2011, and the third is in session. Participants implement a mentored project in their home facility, with measurable results, as a vehicle for leadership development in such areas as quality improvement (QI), patient safety, or readmissions prevention. But the specific project is not as important as whether or not that project is well-designed to stretch the individual in areas where they weren’t comfortable before, Dr. Sehgal says.

Through her QI project, Jasmin Baleva, MD, of Memorial Hermann Memorial City Medical Center in Houston, a 2012 participant, found an alternate to the costly nocturnist model while maintaining the time it takes for the first hospitalist encounter with newly admitted patients. “I think the IPC-UCSF project gave my proposal a little more legitimacy,” she tells TH. “They also taught me how to present it in an effective package and to approach the C-suite feeling less intimidated.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

The yearlong IPC-UCSF Fellowship for Hospitalist Leaders brings about 40 IPC: The Hospitalist Company group leaders together for a series of three-day training sessions and ongoing distance learning, executive coaching, and project mentoring.

The program emphasizes role plays and simulations, and even involves an acting coach to help participants learn to make more effective presentations, such as harnessing the power of storytelling, says Niraj L. Sehgal, MD, MPH, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) who directs the fellowship through UCSF’s Center for Health Professions.

The first class graduated in November 2011, and the third is in session. Participants implement a mentored project in their home facility, with measurable results, as a vehicle for leadership development in such areas as quality improvement (QI), patient safety, or readmissions prevention. But the specific project is not as important as whether or not that project is well-designed to stretch the individual in areas where they weren’t comfortable before, Dr. Sehgal says.

Through her QI project, Jasmin Baleva, MD, of Memorial Hermann Memorial City Medical Center in Houston, a 2012 participant, found an alternate to the costly nocturnist model while maintaining the time it takes for the first hospitalist encounter with newly admitted patients. “I think the IPC-UCSF project gave my proposal a little more legitimacy,” she tells TH. “They also taught me how to present it in an effective package and to approach the C-suite feeling less intimidated.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

The yearlong IPC-UCSF Fellowship for Hospitalist Leaders brings about 40 IPC: The Hospitalist Company group leaders together for a series of three-day training sessions and ongoing distance learning, executive coaching, and project mentoring.

The program emphasizes role plays and simulations, and even involves an acting coach to help participants learn to make more effective presentations, such as harnessing the power of storytelling, says Niraj L. Sehgal, MD, MPH, a hospitalist at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) who directs the fellowship through UCSF’s Center for Health Professions.

The first class graduated in November 2011, and the third is in session. Participants implement a mentored project in their home facility, with measurable results, as a vehicle for leadership development in such areas as quality improvement (QI), patient safety, or readmissions prevention. But the specific project is not as important as whether or not that project is well-designed to stretch the individual in areas where they weren’t comfortable before, Dr. Sehgal says.

Through her QI project, Jasmin Baleva, MD, of Memorial Hermann Memorial City Medical Center in Houston, a 2012 participant, found an alternate to the costly nocturnist model while maintaining the time it takes for the first hospitalist encounter with newly admitted patients. “I think the IPC-UCSF project gave my proposal a little more legitimacy,” she tells TH. “They also taught me how to present it in an effective package and to approach the C-suite feeling less intimidated.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

Hospital ICUs Chart Progress in Preventing Central-Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections

New CDC research published in the June issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology estimates that as many as 200,000 central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) in ICUs nationally have been prevented since 1990.3 The report indicates much of the success is due to U.S. hospitals adopting successful prevention strategies, namely the dissemination of guideline-supported central-line insertion and maintenance best practices, infection-control treatment bundles, and widespread availability of alcohol-based hand rubs.

Between 462,000 and 636,000 CLABSIs occurred in non-neonatal ICU patients from 1990-2010, CDC estimates, about 104,000 to 198,000 less CLABSIs than would have occurred if rates had remained the same as they were in 1990.

“These findings suggest that technical innovations and dissemination of evidence-based CLABSI prevention practices have likely been effective on a national scale,” Matthew Wise, PhD, lead author of the study, said in a statement.

At the same time, a CLABSI-reduction intervention in a hospital in Hawaii found that while the costs of care were much higher for patients who developed a CLABSI, reimbursement and the hospital’s margin also were higher (margin of $54,906 vs. $6,506).4 The authors conclude that current reimbursement practices offer a perverse incentive for hospitals to have more line infections, “while an optimal reimbursement system would reward them for prevention rather than treating illness.”

Lead author Eugene Hsu, MD, MBA, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine said in an email that the study demonstrates how a quality initiative led by providers and funded by a major commercial insurer can save both lives and money. “Hospitalists, like all healthcare providers, must be aware of the distorted financial incentives that may affect how they provide care to patients,” Dr. Hsu said.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

New CDC research published in the June issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology estimates that as many as 200,000 central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) in ICUs nationally have been prevented since 1990.3 The report indicates much of the success is due to U.S. hospitals adopting successful prevention strategies, namely the dissemination of guideline-supported central-line insertion and maintenance best practices, infection-control treatment bundles, and widespread availability of alcohol-based hand rubs.

Between 462,000 and 636,000 CLABSIs occurred in non-neonatal ICU patients from 1990-2010, CDC estimates, about 104,000 to 198,000 less CLABSIs than would have occurred if rates had remained the same as they were in 1990.

“These findings suggest that technical innovations and dissemination of evidence-based CLABSI prevention practices have likely been effective on a national scale,” Matthew Wise, PhD, lead author of the study, said in a statement.

At the same time, a CLABSI-reduction intervention in a hospital in Hawaii found that while the costs of care were much higher for patients who developed a CLABSI, reimbursement and the hospital’s margin also were higher (margin of $54,906 vs. $6,506).4 The authors conclude that current reimbursement practices offer a perverse incentive for hospitals to have more line infections, “while an optimal reimbursement system would reward them for prevention rather than treating illness.”

Lead author Eugene Hsu, MD, MBA, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine said in an email that the study demonstrates how a quality initiative led by providers and funded by a major commercial insurer can save both lives and money. “Hospitalists, like all healthcare providers, must be aware of the distorted financial incentives that may affect how they provide care to patients,” Dr. Hsu said.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

New CDC research published in the June issue of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology estimates that as many as 200,000 central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) in ICUs nationally have been prevented since 1990.3 The report indicates much of the success is due to U.S. hospitals adopting successful prevention strategies, namely the dissemination of guideline-supported central-line insertion and maintenance best practices, infection-control treatment bundles, and widespread availability of alcohol-based hand rubs.

Between 462,000 and 636,000 CLABSIs occurred in non-neonatal ICU patients from 1990-2010, CDC estimates, about 104,000 to 198,000 less CLABSIs than would have occurred if rates had remained the same as they were in 1990.

“These findings suggest that technical innovations and dissemination of evidence-based CLABSI prevention practices have likely been effective on a national scale,” Matthew Wise, PhD, lead author of the study, said in a statement.

At the same time, a CLABSI-reduction intervention in a hospital in Hawaii found that while the costs of care were much higher for patients who developed a CLABSI, reimbursement and the hospital’s margin also were higher (margin of $54,906 vs. $6,506).4 The authors conclude that current reimbursement practices offer a perverse incentive for hospitals to have more line infections, “while an optimal reimbursement system would reward them for prevention rather than treating illness.”

Lead author Eugene Hsu, MD, MBA, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine said in an email that the study demonstrates how a quality initiative led by providers and funded by a major commercial insurer can save both lives and money. “Hospitalists, like all healthcare providers, must be aware of the distorted financial incentives that may affect how they provide care to patients,” Dr. Hsu said.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

Hospitals' Battle Against Superbugs Goes Robotic

One in 20 hospitalized patients picks up an infection in the hospital, and a recent article by the Associated Press describes the emergence of new technologies to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs: “They sweep. They swab. They sterilize. And still the germs persist.”1

Hospitals across the country are testing new approaches to stop the spread of superbugs, which are tied to an estimated 100,000 deaths per year, according to the CDC. New approaches include robotlike machines that emit ultraviolet light or hydrogen-peroxide vapors, germ-resistant copper bed rails and call buttons, antimicrobial linens and wall paint, and hydrogel post-surgical dressings infused with silver ions that have antimicrobial properties.

Research firm Frost & Sullivan estimates that the market for bug-killing products and technologies will grow to $80 million from $30 million in the next three years. And yet evidence of positive outcomes from them continues to be debated.

“In short, escalating antimicrobial-resistance issues have us facing the prospect of untreatable bacterial pathogens, particularly involving gram-negative organisms,” James Pile, MD, FACP, SFHM, a hospital medicine and infectious diseases physician at Cleveland Clinic, wrote in an email. “In fact, many of our hospitals already deal with a limited number of infections caused by bacteria we have no clearly effective antibiotics against; the issue is only going to get worse.”

As an example, the CDC recently issued a warning about carbapenum-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), which has a 40% mortality rate and last year was reported in 4.6% of U.S. hospitals.2 CDC recommends that hospitals use more of the existing prevention measures against CRE, including active-case detection and segregation of patients and the staff who care for them. Dr. Pile says health facilities need to do a better job of preventing infections involving multi-drug-resistant pathogens, but in the meantime, “proven technologies such as proper hand hygiene and antimicrobial stewardship are more important than ever.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

One in 20 hospitalized patients picks up an infection in the hospital, and a recent article by the Associated Press describes the emergence of new technologies to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs: “They sweep. They swab. They sterilize. And still the germs persist.”1

Hospitals across the country are testing new approaches to stop the spread of superbugs, which are tied to an estimated 100,000 deaths per year, according to the CDC. New approaches include robotlike machines that emit ultraviolet light or hydrogen-peroxide vapors, germ-resistant copper bed rails and call buttons, antimicrobial linens and wall paint, and hydrogel post-surgical dressings infused with silver ions that have antimicrobial properties.

Research firm Frost & Sullivan estimates that the market for bug-killing products and technologies will grow to $80 million from $30 million in the next three years. And yet evidence of positive outcomes from them continues to be debated.

“In short, escalating antimicrobial-resistance issues have us facing the prospect of untreatable bacterial pathogens, particularly involving gram-negative organisms,” James Pile, MD, FACP, SFHM, a hospital medicine and infectious diseases physician at Cleveland Clinic, wrote in an email. “In fact, many of our hospitals already deal with a limited number of infections caused by bacteria we have no clearly effective antibiotics against; the issue is only going to get worse.”

As an example, the CDC recently issued a warning about carbapenum-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), which has a 40% mortality rate and last year was reported in 4.6% of U.S. hospitals.2 CDC recommends that hospitals use more of the existing prevention measures against CRE, including active-case detection and segregation of patients and the staff who care for them. Dr. Pile says health facilities need to do a better job of preventing infections involving multi-drug-resistant pathogens, but in the meantime, “proven technologies such as proper hand hygiene and antimicrobial stewardship are more important than ever.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

One in 20 hospitalized patients picks up an infection in the hospital, and a recent article by the Associated Press describes the emergence of new technologies to fight antibiotic-resistant superbugs: “They sweep. They swab. They sterilize. And still the germs persist.”1

Hospitals across the country are testing new approaches to stop the spread of superbugs, which are tied to an estimated 100,000 deaths per year, according to the CDC. New approaches include robotlike machines that emit ultraviolet light or hydrogen-peroxide vapors, germ-resistant copper bed rails and call buttons, antimicrobial linens and wall paint, and hydrogel post-surgical dressings infused with silver ions that have antimicrobial properties.

Research firm Frost & Sullivan estimates that the market for bug-killing products and technologies will grow to $80 million from $30 million in the next three years. And yet evidence of positive outcomes from them continues to be debated.

“In short, escalating antimicrobial-resistance issues have us facing the prospect of untreatable bacterial pathogens, particularly involving gram-negative organisms,” James Pile, MD, FACP, SFHM, a hospital medicine and infectious diseases physician at Cleveland Clinic, wrote in an email. “In fact, many of our hospitals already deal with a limited number of infections caused by bacteria we have no clearly effective antibiotics against; the issue is only going to get worse.”

As an example, the CDC recently issued a warning about carbapenum-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), which has a 40% mortality rate and last year was reported in 4.6% of U.S. hospitals.2 CDC recommends that hospitals use more of the existing prevention measures against CRE, including active-case detection and segregation of patients and the staff who care for them. Dr. Pile says health facilities need to do a better job of preventing infections involving multi-drug-resistant pathogens, but in the meantime, “proven technologies such as proper hand hygiene and antimicrobial stewardship are more important than ever.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Stobbe, M. Germ-zapping “robots”: Hospitals combat superbugs. Associated Press website. Available at: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hospitals-see-surge-superbug-fighting-products. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6209a3.htm?s_cid=mm6209a3_w. Accessed June 7, 2013.

- Wise ME, Scott RD, Baggs JM, et al. National estimates of central line-associated bloodstream infections in critical care patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2013;34(6):547-554.

- Hsu E, Lin D, Evans SJ, et al. Doing well by doing good: assessing the cost savings of an intervention to reduce central line-associated bloodstream infections in a Hawaii hospital. Am J Med Qual, 2013 May 7 [Epub ahead of print].

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school enrollment on pace to reach 30 percent increase by 2017. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/newsroom/newsreleases/ 335244/050213.html. Accessed June 7, 2013.

Nutritional Intervention Can Improve Hospital Patients' Outcome, Reduce Costs

Health-care reform is on everyone’s mind these days, and SHM, along with numerous other groups, believes some reform goals can be achieved through the stomach.

Data show an effective program of nutritional intervention during a patient’s hospital stay can go a long way toward improving patient outcomes and reducing costs.1 Hospitalists, however, often have little formal nutrition training. A multidisciplinary approach to patient nutrition that brings together multiple stakeholders—hospitalists, nurses, and dietitians—might effectively address this need with a team tactic, according to Melissa Parkhurst, MD, medical director of the hospital medicine section at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City.1

Between 20% and 50% of inpatients suffer from malnutrition.2 Many patients, especially the elderly, are malnourished on admission. Many more become malnourished within a few days of their hospital stay due to NPO orders and the effects of disease on metabolism.2 Malnutrition has been associated with worsened discharge status, longer length of stay, higher costs, and greater mortality, as well as increased risk of:2

- Nosocomial infections;

- Falls;

- Pressure ulcers; and

- 30-day readmissions.

To address malnutrition prevalence and its detrimental effects, SHM and the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses (AMSN), the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN), and Abbott Nutrition have formed the Alliance for Patient Nutrition. Kelly Tappenden, MD, PhD, professor of food science and human nutrition at the University of Illinois at Urbana, says the alliance aims to raise awareness of the impact nutrition can have on patient outcomes (see “Three Steps to Better Nutrition,” below).