User login

Win Whitcomb: Introducing Neuroquality and Neurosafety

The prefix “neuro” has become quite popular the last couple of years. We have neuroeconomics, neuroplasticity, neuroergonomics, and, of course, neurohospitalist. The explosion of interest in the brain can be seen in the popular press, television, blogs, and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

I predict that recent breakthroughs in brain science and related fields (cognitive psychology, neurobiology, molecular biology, linguistics, and artificial intelligence, among others) will have a profound impact on the fields of quality improvement (QI) and patient safety, and, consequently on HM. To date, the patient safety movement has focused on systems issues in an effort to reduce harm induced by the healthcare system. I submit that for healthcare to be reliable and error-free in the future, we must leverage the innate strengths of the brain. Here I mention four areas where brain science breakthroughs can enable us to improve patient safety practices.

Diagnostic Error

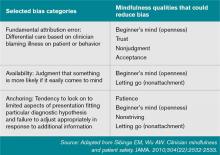

Patrick Croskerry, an emergency physician and researcher, has described errors in diagnosis as stemming in part from cognitive bias. He offers “de-biasing strategies” as an approach to decreasing diagnostic error.

One of the most powerful de-biasing strategies is metacognition, or awareness of one’s own thinking processes. Closely related to metacognition is mindfulness, defined as the “nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment.” A growing body of literature makes the case that enhancing mindfulness might reduce the impact bias has on diagnostic error.1 Table 1 (right) mentions a subset of bias types and how mindfulness might mitigate them. I’m sure you can think of cases you’ve encountered where bias has affected the diagnostic outcome.

Empathy and Patient Experience

As the focus on patient experience grows, approaches to improving performance on patient satisfaction surveys are proliferating. Whatever technical components you choose to employ, a capacity for caregiver empathy is a crucial underlying factor to a better patient experience. Harvard psychiatrist Helen Riess, MD, points out that we are now beginning to understand the neurobiological basis of empathy. She and others present evidence that we may be able to “up-regulate” empathy through education or cognitive practices.2 Several studies suggest we might be able to realize improved therapeutic relationships between physicians and patients, and they have led to programs, such as the ones at Stanford and Emory universities, that train caregivers to enhance empathy and compassion.

Interruptions and Cognitive Error

It has been customary in high-risk industries to ensure that certain procedures are free of interruptions. There is recognition that disturbances during high-stakes tasks, such as airline takeoff, carry disastrous consequences. We now know that multitasking is a myth and that the brain instead switches between tasks sequentially. But task-switching comes at the high cost of a marked increase in the rate of cognitive error.3 As we learn more, decreasing interruptions or delineating “interruption-free” zones in healthcare could be a way to mitigate an inherent vulnerability in our cognitive abilities.

Fatigue and Medical Error

It is well documented that sleep deprivation correlates with a decline in cognitive

performance in a number of classes of healthcare workers. Fatigue has also increased diagnostic error among residents. A 2011 Sentinel Alert from The Joint Commission creates a standard that healthcare organizations implement a fatigue-management plan to mitigate the potential harm caused by tired professionals.

Most of the approaches to improving outcomes in the hospital have focused on process improvement and systems thinking. But errors also occur due to the thinking process of clinicians. In the book “Brain Rules,” author John Medina argues that schools and businesses create an environment that is less than friendly to the brain, citing current classroom design and cubicles for office workers. As a result, he states, we often have poor educational and business performance. I have little doubt that if Medina spent a few hours in a hospital, he would come to a similar conclusion: We don’t do the brain any favors when it comes to creating a healthy environment for providing safe and reliable care to our patients.

References

- Sibinga EM, Wu AW. Clinician mindfulness and patient safety. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2532-2533.

- Riess H. Empathy in medicine─a neurobiological perspective. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1604-1605.

- Rogers RD, Monsell S. The costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. J Exper Psychol. 1995;124(2):207–231.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The prefix “neuro” has become quite popular the last couple of years. We have neuroeconomics, neuroplasticity, neuroergonomics, and, of course, neurohospitalist. The explosion of interest in the brain can be seen in the popular press, television, blogs, and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

I predict that recent breakthroughs in brain science and related fields (cognitive psychology, neurobiology, molecular biology, linguistics, and artificial intelligence, among others) will have a profound impact on the fields of quality improvement (QI) and patient safety, and, consequently on HM. To date, the patient safety movement has focused on systems issues in an effort to reduce harm induced by the healthcare system. I submit that for healthcare to be reliable and error-free in the future, we must leverage the innate strengths of the brain. Here I mention four areas where brain science breakthroughs can enable us to improve patient safety practices.

Diagnostic Error

Patrick Croskerry, an emergency physician and researcher, has described errors in diagnosis as stemming in part from cognitive bias. He offers “de-biasing strategies” as an approach to decreasing diagnostic error.

One of the most powerful de-biasing strategies is metacognition, or awareness of one’s own thinking processes. Closely related to metacognition is mindfulness, defined as the “nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment.” A growing body of literature makes the case that enhancing mindfulness might reduce the impact bias has on diagnostic error.1 Table 1 (right) mentions a subset of bias types and how mindfulness might mitigate them. I’m sure you can think of cases you’ve encountered where bias has affected the diagnostic outcome.

Empathy and Patient Experience

As the focus on patient experience grows, approaches to improving performance on patient satisfaction surveys are proliferating. Whatever technical components you choose to employ, a capacity for caregiver empathy is a crucial underlying factor to a better patient experience. Harvard psychiatrist Helen Riess, MD, points out that we are now beginning to understand the neurobiological basis of empathy. She and others present evidence that we may be able to “up-regulate” empathy through education or cognitive practices.2 Several studies suggest we might be able to realize improved therapeutic relationships between physicians and patients, and they have led to programs, such as the ones at Stanford and Emory universities, that train caregivers to enhance empathy and compassion.

Interruptions and Cognitive Error

It has been customary in high-risk industries to ensure that certain procedures are free of interruptions. There is recognition that disturbances during high-stakes tasks, such as airline takeoff, carry disastrous consequences. We now know that multitasking is a myth and that the brain instead switches between tasks sequentially. But task-switching comes at the high cost of a marked increase in the rate of cognitive error.3 As we learn more, decreasing interruptions or delineating “interruption-free” zones in healthcare could be a way to mitigate an inherent vulnerability in our cognitive abilities.

Fatigue and Medical Error

It is well documented that sleep deprivation correlates with a decline in cognitive

performance in a number of classes of healthcare workers. Fatigue has also increased diagnostic error among residents. A 2011 Sentinel Alert from The Joint Commission creates a standard that healthcare organizations implement a fatigue-management plan to mitigate the potential harm caused by tired professionals.

Most of the approaches to improving outcomes in the hospital have focused on process improvement and systems thinking. But errors also occur due to the thinking process of clinicians. In the book “Brain Rules,” author John Medina argues that schools and businesses create an environment that is less than friendly to the brain, citing current classroom design and cubicles for office workers. As a result, he states, we often have poor educational and business performance. I have little doubt that if Medina spent a few hours in a hospital, he would come to a similar conclusion: We don’t do the brain any favors when it comes to creating a healthy environment for providing safe and reliable care to our patients.

References

- Sibinga EM, Wu AW. Clinician mindfulness and patient safety. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2532-2533.

- Riess H. Empathy in medicine─a neurobiological perspective. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1604-1605.

- Rogers RD, Monsell S. The costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. J Exper Psychol. 1995;124(2):207–231.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The prefix “neuro” has become quite popular the last couple of years. We have neuroeconomics, neuroplasticity, neuroergonomics, and, of course, neurohospitalist. The explosion of interest in the brain can be seen in the popular press, television, blogs, and the Journal of the American Medical Association.

I predict that recent breakthroughs in brain science and related fields (cognitive psychology, neurobiology, molecular biology, linguistics, and artificial intelligence, among others) will have a profound impact on the fields of quality improvement (QI) and patient safety, and, consequently on HM. To date, the patient safety movement has focused on systems issues in an effort to reduce harm induced by the healthcare system. I submit that for healthcare to be reliable and error-free in the future, we must leverage the innate strengths of the brain. Here I mention four areas where brain science breakthroughs can enable us to improve patient safety practices.

Diagnostic Error

Patrick Croskerry, an emergency physician and researcher, has described errors in diagnosis as stemming in part from cognitive bias. He offers “de-biasing strategies” as an approach to decreasing diagnostic error.

One of the most powerful de-biasing strategies is metacognition, or awareness of one’s own thinking processes. Closely related to metacognition is mindfulness, defined as the “nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment.” A growing body of literature makes the case that enhancing mindfulness might reduce the impact bias has on diagnostic error.1 Table 1 (right) mentions a subset of bias types and how mindfulness might mitigate them. I’m sure you can think of cases you’ve encountered where bias has affected the diagnostic outcome.

Empathy and Patient Experience

As the focus on patient experience grows, approaches to improving performance on patient satisfaction surveys are proliferating. Whatever technical components you choose to employ, a capacity for caregiver empathy is a crucial underlying factor to a better patient experience. Harvard psychiatrist Helen Riess, MD, points out that we are now beginning to understand the neurobiological basis of empathy. She and others present evidence that we may be able to “up-regulate” empathy through education or cognitive practices.2 Several studies suggest we might be able to realize improved therapeutic relationships between physicians and patients, and they have led to programs, such as the ones at Stanford and Emory universities, that train caregivers to enhance empathy and compassion.

Interruptions and Cognitive Error

It has been customary in high-risk industries to ensure that certain procedures are free of interruptions. There is recognition that disturbances during high-stakes tasks, such as airline takeoff, carry disastrous consequences. We now know that multitasking is a myth and that the brain instead switches between tasks sequentially. But task-switching comes at the high cost of a marked increase in the rate of cognitive error.3 As we learn more, decreasing interruptions or delineating “interruption-free” zones in healthcare could be a way to mitigate an inherent vulnerability in our cognitive abilities.

Fatigue and Medical Error

It is well documented that sleep deprivation correlates with a decline in cognitive

performance in a number of classes of healthcare workers. Fatigue has also increased diagnostic error among residents. A 2011 Sentinel Alert from The Joint Commission creates a standard that healthcare organizations implement a fatigue-management plan to mitigate the potential harm caused by tired professionals.

Most of the approaches to improving outcomes in the hospital have focused on process improvement and systems thinking. But errors also occur due to the thinking process of clinicians. In the book “Brain Rules,” author John Medina argues that schools and businesses create an environment that is less than friendly to the brain, citing current classroom design and cubicles for office workers. As a result, he states, we often have poor educational and business performance. I have little doubt that if Medina spent a few hours in a hospital, he would come to a similar conclusion: We don’t do the brain any favors when it comes to creating a healthy environment for providing safe and reliable care to our patients.

References

- Sibinga EM, Wu AW. Clinician mindfulness and patient safety. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2532-2533.

- Riess H. Empathy in medicine─a neurobiological perspective. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1604-1605.

- Rogers RD, Monsell S. The costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. J Exper Psychol. 1995;124(2):207–231.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Hospital Home Team: Physicians Increase Focus on Inpatient Care

For most of my medical career, the hospital functioned more as a swap meet, where every physician had his or her own booth, than as an integrated, community health resource with a focused mission. Although the innovation of HM might be counted as the beginning of a new, more aligned approach between physicians and the hospital as an institution, the rapidly evolving employment of physicians by hospitals and the focusing of physician practice primarily on inpatient care has taken this to another level.

The New Paradigm

A number of recent surveys by physician recruitment firms and physician management companies have found that less than 25% of physicians are self-employed. Planned changes to insurance and Medicare reimbursement for healthcare have driven cardiologists, orthopedists, surgeons, and many other physicians, who want to protect their flow of patients and dollars, to readily become hospital or large-group-practice employees. The entrance of accountable-care organizations (ACOs) to the landscape and the greater need for physician and hospital alignment have only accelerated this trend.

At the same time, the growth of all sorts of hospitalist specialties has further changed the medical staff of the hospital. Internal-medicine and family-practice hospitalists now number more than 35,000. There are probably more than 2,000 pediatric hospitalists. The newly formed Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists (SOGH) estimates there are more than 1,500 so-called laborists in the U.S., and there are several hundred neurohospitalists, orthopedic hospitalists, and acute-care surgeons.

It is clear to me that a “home team” for the hospital of the future is developing, and it includes hospitalists, ED physicians, critical-care physicians, and the growing panoply of hospital-employed cardiologists and surgeons. There is an opportunity for alignment and integration in what has been a fragmented delivery of healthcare.

On the commercial side of the equation, this new opportunity for physician-hospital alignment might allow for a new distribution of compensation. It already is common for hospitals to be transferring some of “their” Medicare Part A dollars to hospitalists. With penalties or additional payments in the ACO model (e.g. shared savings) or in value-based purchasing, there certainly are mechanisms to redistribute funding to new physician compensation models, based more on performance than on volume of services (i.e. the old productivity model).

On another level, where compensation and performance merge, the new medical staff has the ability to deliver a safer hospital experience to our patients and to improve performance. This could take the form of reduction in hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) or reducing unnecessary DVTs and PEs. It could take the form of a better discharge process that leads to fewer unnecessary readmissions or fewer preventable ED visits. On the OB side, 24-hour on-site availability of OB hospitalists has been shown to reduce adverse birth events and, therefore, reduce liability risk and malpractice premiums. On-site availability for patients with fractures and trauma cases by orthopedic hospitalists or hospital-employed orthopedists also can reduce expenses and adverse events for these acutely ill patients.

HM’s Role

With all these changes occurring so rapidly and with all these new players being thrown into the stew at the hospital, it may be worth a few minutes for the “traditional” hospitalist on the medical service to step back and see how our role may evolve. We already have an increasing role in comanagement of surgical and subspecialty patients, as well as a more integrated role at the ED-hospitalist interface. As hospitals look for hospital-focused physicians, there is a potential for scope creep that must be thoughtfully managed.

This may require “rules of engagement” with other key services. While it may be appropriate for a patient with an acute abdomen to be admitted to the hospitalist service, if the hospitalist determines that this patient needs surgery sooner rather than later, there needs to be a straightforward way to get the surgeon in house and on the case and the patient to the operating room. To this point, medical hospitalists can help manage the medical aspects of a neurosurgical case, but we don’t do burr holes. And if there is to be pushback from the surgeon, this can’t happen at 2 a.m. over the telephone; it must be handled by the service leaders at their weekly meeting.

On another level, hospitalists need to be careful that the hospital doesn’t just hand us the administrative functions of other physicians’ care. Hospitalists are not the default to do H&Ps on surgical cases or handle their discharges, even if this falls into the hospital strategy to be able to employ fewer high-priced surgeons and subspecialists by handing off some of their work to their hospitalists.

On the other hand, it is totally appropriate for many of the hospital-focused physicians to come together, possibly under the leadership of the hospital CMO, to look at the workflow and to set up a new way to deliver healthcare that not only redefines the workload, but also involves the rest of the team, including nursing, pharmacy, case management, and social services. Medical hospitalists will need to consider whether we should be the hub of the new physician enterprise and what that would mean for workload, FTEs, and scope of practice.

Such organizations as SHM and the American Hospital Association (AHA) are thinking how best to support and convene the hospital-based physician. AHA has developed a Physician Forum with more than 6,000 members who now have their practices aligned with their hospital. SHM has held meetings of the leaders of hospital-focused practice and is developing virtual forums on Hospital Medicine Exchange to keep the discussion going. Through the Hospital Care Collaborative (HCC), SHM is engaging the leadership of pharmacy, nursing, case management, social services, and respiratory therapy.

Although we are still early in creating the direction for the new medical staff, the water is rising and the current is moving rapidly. The strong forces that are driving new payment paradigms are leading to changes in compensation and an emphasis on definable, measureable outcomes of performance and safety. Hospitalists, who have been thinking in this way and who have some experience in the new ways, should be well positioned to lead and participate actively in the formation of the new hospital home team.

When opportunity knocks, you still have to get up and answer the door. It’s time to get ready to step up.

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

For most of my medical career, the hospital functioned more as a swap meet, where every physician had his or her own booth, than as an integrated, community health resource with a focused mission. Although the innovation of HM might be counted as the beginning of a new, more aligned approach between physicians and the hospital as an institution, the rapidly evolving employment of physicians by hospitals and the focusing of physician practice primarily on inpatient care has taken this to another level.

The New Paradigm

A number of recent surveys by physician recruitment firms and physician management companies have found that less than 25% of physicians are self-employed. Planned changes to insurance and Medicare reimbursement for healthcare have driven cardiologists, orthopedists, surgeons, and many other physicians, who want to protect their flow of patients and dollars, to readily become hospital or large-group-practice employees. The entrance of accountable-care organizations (ACOs) to the landscape and the greater need for physician and hospital alignment have only accelerated this trend.

At the same time, the growth of all sorts of hospitalist specialties has further changed the medical staff of the hospital. Internal-medicine and family-practice hospitalists now number more than 35,000. There are probably more than 2,000 pediatric hospitalists. The newly formed Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists (SOGH) estimates there are more than 1,500 so-called laborists in the U.S., and there are several hundred neurohospitalists, orthopedic hospitalists, and acute-care surgeons.

It is clear to me that a “home team” for the hospital of the future is developing, and it includes hospitalists, ED physicians, critical-care physicians, and the growing panoply of hospital-employed cardiologists and surgeons. There is an opportunity for alignment and integration in what has been a fragmented delivery of healthcare.

On the commercial side of the equation, this new opportunity for physician-hospital alignment might allow for a new distribution of compensation. It already is common for hospitals to be transferring some of “their” Medicare Part A dollars to hospitalists. With penalties or additional payments in the ACO model (e.g. shared savings) or in value-based purchasing, there certainly are mechanisms to redistribute funding to new physician compensation models, based more on performance than on volume of services (i.e. the old productivity model).

On another level, where compensation and performance merge, the new medical staff has the ability to deliver a safer hospital experience to our patients and to improve performance. This could take the form of reduction in hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) or reducing unnecessary DVTs and PEs. It could take the form of a better discharge process that leads to fewer unnecessary readmissions or fewer preventable ED visits. On the OB side, 24-hour on-site availability of OB hospitalists has been shown to reduce adverse birth events and, therefore, reduce liability risk and malpractice premiums. On-site availability for patients with fractures and trauma cases by orthopedic hospitalists or hospital-employed orthopedists also can reduce expenses and adverse events for these acutely ill patients.

HM’s Role

With all these changes occurring so rapidly and with all these new players being thrown into the stew at the hospital, it may be worth a few minutes for the “traditional” hospitalist on the medical service to step back and see how our role may evolve. We already have an increasing role in comanagement of surgical and subspecialty patients, as well as a more integrated role at the ED-hospitalist interface. As hospitals look for hospital-focused physicians, there is a potential for scope creep that must be thoughtfully managed.

This may require “rules of engagement” with other key services. While it may be appropriate for a patient with an acute abdomen to be admitted to the hospitalist service, if the hospitalist determines that this patient needs surgery sooner rather than later, there needs to be a straightforward way to get the surgeon in house and on the case and the patient to the operating room. To this point, medical hospitalists can help manage the medical aspects of a neurosurgical case, but we don’t do burr holes. And if there is to be pushback from the surgeon, this can’t happen at 2 a.m. over the telephone; it must be handled by the service leaders at their weekly meeting.

On another level, hospitalists need to be careful that the hospital doesn’t just hand us the administrative functions of other physicians’ care. Hospitalists are not the default to do H&Ps on surgical cases or handle their discharges, even if this falls into the hospital strategy to be able to employ fewer high-priced surgeons and subspecialists by handing off some of their work to their hospitalists.

On the other hand, it is totally appropriate for many of the hospital-focused physicians to come together, possibly under the leadership of the hospital CMO, to look at the workflow and to set up a new way to deliver healthcare that not only redefines the workload, but also involves the rest of the team, including nursing, pharmacy, case management, and social services. Medical hospitalists will need to consider whether we should be the hub of the new physician enterprise and what that would mean for workload, FTEs, and scope of practice.

Such organizations as SHM and the American Hospital Association (AHA) are thinking how best to support and convene the hospital-based physician. AHA has developed a Physician Forum with more than 6,000 members who now have their practices aligned with their hospital. SHM has held meetings of the leaders of hospital-focused practice and is developing virtual forums on Hospital Medicine Exchange to keep the discussion going. Through the Hospital Care Collaborative (HCC), SHM is engaging the leadership of pharmacy, nursing, case management, social services, and respiratory therapy.

Although we are still early in creating the direction for the new medical staff, the water is rising and the current is moving rapidly. The strong forces that are driving new payment paradigms are leading to changes in compensation and an emphasis on definable, measureable outcomes of performance and safety. Hospitalists, who have been thinking in this way and who have some experience in the new ways, should be well positioned to lead and participate actively in the formation of the new hospital home team.

When opportunity knocks, you still have to get up and answer the door. It’s time to get ready to step up.

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

For most of my medical career, the hospital functioned more as a swap meet, where every physician had his or her own booth, than as an integrated, community health resource with a focused mission. Although the innovation of HM might be counted as the beginning of a new, more aligned approach between physicians and the hospital as an institution, the rapidly evolving employment of physicians by hospitals and the focusing of physician practice primarily on inpatient care has taken this to another level.

The New Paradigm

A number of recent surveys by physician recruitment firms and physician management companies have found that less than 25% of physicians are self-employed. Planned changes to insurance and Medicare reimbursement for healthcare have driven cardiologists, orthopedists, surgeons, and many other physicians, who want to protect their flow of patients and dollars, to readily become hospital or large-group-practice employees. The entrance of accountable-care organizations (ACOs) to the landscape and the greater need for physician and hospital alignment have only accelerated this trend.

At the same time, the growth of all sorts of hospitalist specialties has further changed the medical staff of the hospital. Internal-medicine and family-practice hospitalists now number more than 35,000. There are probably more than 2,000 pediatric hospitalists. The newly formed Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists (SOGH) estimates there are more than 1,500 so-called laborists in the U.S., and there are several hundred neurohospitalists, orthopedic hospitalists, and acute-care surgeons.

It is clear to me that a “home team” for the hospital of the future is developing, and it includes hospitalists, ED physicians, critical-care physicians, and the growing panoply of hospital-employed cardiologists and surgeons. There is an opportunity for alignment and integration in what has been a fragmented delivery of healthcare.

On the commercial side of the equation, this new opportunity for physician-hospital alignment might allow for a new distribution of compensation. It already is common for hospitals to be transferring some of “their” Medicare Part A dollars to hospitalists. With penalties or additional payments in the ACO model (e.g. shared savings) or in value-based purchasing, there certainly are mechanisms to redistribute funding to new physician compensation models, based more on performance than on volume of services (i.e. the old productivity model).

On another level, where compensation and performance merge, the new medical staff has the ability to deliver a safer hospital experience to our patients and to improve performance. This could take the form of reduction in hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) or reducing unnecessary DVTs and PEs. It could take the form of a better discharge process that leads to fewer unnecessary readmissions or fewer preventable ED visits. On the OB side, 24-hour on-site availability of OB hospitalists has been shown to reduce adverse birth events and, therefore, reduce liability risk and malpractice premiums. On-site availability for patients with fractures and trauma cases by orthopedic hospitalists or hospital-employed orthopedists also can reduce expenses and adverse events for these acutely ill patients.

HM’s Role

With all these changes occurring so rapidly and with all these new players being thrown into the stew at the hospital, it may be worth a few minutes for the “traditional” hospitalist on the medical service to step back and see how our role may evolve. We already have an increasing role in comanagement of surgical and subspecialty patients, as well as a more integrated role at the ED-hospitalist interface. As hospitals look for hospital-focused physicians, there is a potential for scope creep that must be thoughtfully managed.

This may require “rules of engagement” with other key services. While it may be appropriate for a patient with an acute abdomen to be admitted to the hospitalist service, if the hospitalist determines that this patient needs surgery sooner rather than later, there needs to be a straightforward way to get the surgeon in house and on the case and the patient to the operating room. To this point, medical hospitalists can help manage the medical aspects of a neurosurgical case, but we don’t do burr holes. And if there is to be pushback from the surgeon, this can’t happen at 2 a.m. over the telephone; it must be handled by the service leaders at their weekly meeting.

On another level, hospitalists need to be careful that the hospital doesn’t just hand us the administrative functions of other physicians’ care. Hospitalists are not the default to do H&Ps on surgical cases or handle their discharges, even if this falls into the hospital strategy to be able to employ fewer high-priced surgeons and subspecialists by handing off some of their work to their hospitalists.

On the other hand, it is totally appropriate for many of the hospital-focused physicians to come together, possibly under the leadership of the hospital CMO, to look at the workflow and to set up a new way to deliver healthcare that not only redefines the workload, but also involves the rest of the team, including nursing, pharmacy, case management, and social services. Medical hospitalists will need to consider whether we should be the hub of the new physician enterprise and what that would mean for workload, FTEs, and scope of practice.

Such organizations as SHM and the American Hospital Association (AHA) are thinking how best to support and convene the hospital-based physician. AHA has developed a Physician Forum with more than 6,000 members who now have their practices aligned with their hospital. SHM has held meetings of the leaders of hospital-focused practice and is developing virtual forums on Hospital Medicine Exchange to keep the discussion going. Through the Hospital Care Collaborative (HCC), SHM is engaging the leadership of pharmacy, nursing, case management, social services, and respiratory therapy.

Although we are still early in creating the direction for the new medical staff, the water is rising and the current is moving rapidly. The strong forces that are driving new payment paradigms are leading to changes in compensation and an emphasis on definable, measureable outcomes of performance and safety. Hospitalists, who have been thinking in this way and who have some experience in the new ways, should be well positioned to lead and participate actively in the formation of the new hospital home team.

When opportunity knocks, you still have to get up and answer the door. It’s time to get ready to step up.

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

The Numerators: Treating Noncompliant, Medically Complicated Hospital Patients

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

Reference

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

Reference

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

Reference

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing Off-Label Drugs

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Win Whitcomb: Hospitalists Must Grin and Bear the Hospital-Acquired Conditions Program

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

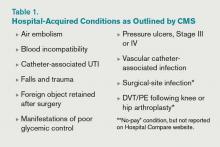

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.