User login

Herbal medicine can reduce pain, fatigue in SCD patients

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were most likely dose-related from an excipient of SCD-101, Dr Gillette said.

He and his colleagues found no significant side effects after 28 days of dosing, and there were no dose reductions or interruptions due to drug-related AEs.

There were also no laboratory or electrocardiogram abnormalities.

“Almost all pain AEs stopped by day 13 in 22 of 23 patients,” Dr Gillette said.

“And unexpectedly, patients began to report that they slept better and had improved energy and cognition,” he noted.

Six patients in the 2200 and 4400 mg BID cohorts reported reduced fatigue as measured by the PROMIS fatigue questionnaire.

And 2 patients with ankle ulcers in the 2 highest dose cohorts reported improved healing.

Two weeks after treatment stopped, patients were almost back to baseline in terms of their chronic pain and fatigue levels, Dr Gillette said.

A parallel design, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the 2750 mg TID dose is ongoing.

Future studies include a crossover-design, exploratory study of the 2750 mg TID dose and a phase 2 parallel design study of the 2200 mg BID and 2750 mg TID doses.

While the researchers are uncertain about the mechanism of action of SCD-101, they hypothesize that its effects could be due to increased vascular flow, increased oxygen delivery, or a reduction in inflammation.

“This is a promising drug potentially for low-income countries or middle-income countries elsewhere in the world where gene therapy and transplant are really not that feasible,” Dr Gillette said.

Research for this study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were most likely dose-related from an excipient of SCD-101, Dr Gillette said.

He and his colleagues found no significant side effects after 28 days of dosing, and there were no dose reductions or interruptions due to drug-related AEs.

There were also no laboratory or electrocardiogram abnormalities.

“Almost all pain AEs stopped by day 13 in 22 of 23 patients,” Dr Gillette said.

“And unexpectedly, patients began to report that they slept better and had improved energy and cognition,” he noted.

Six patients in the 2200 and 4400 mg BID cohorts reported reduced fatigue as measured by the PROMIS fatigue questionnaire.

And 2 patients with ankle ulcers in the 2 highest dose cohorts reported improved healing.

Two weeks after treatment stopped, patients were almost back to baseline in terms of their chronic pain and fatigue levels, Dr Gillette said.

A parallel design, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the 2750 mg TID dose is ongoing.

Future studies include a crossover-design, exploratory study of the 2750 mg TID dose and a phase 2 parallel design study of the 2200 mg BID and 2750 mg TID doses.

While the researchers are uncertain about the mechanism of action of SCD-101, they hypothesize that its effects could be due to increased vascular flow, increased oxygen delivery, or a reduction in inflammation.

“This is a promising drug potentially for low-income countries or middle-income countries elsewhere in the world where gene therapy and transplant are really not that feasible,” Dr Gillette said.

Research for this study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were most likely dose-related from an excipient of SCD-101, Dr Gillette said.

He and his colleagues found no significant side effects after 28 days of dosing, and there were no dose reductions or interruptions due to drug-related AEs.

There were also no laboratory or electrocardiogram abnormalities.

“Almost all pain AEs stopped by day 13 in 22 of 23 patients,” Dr Gillette said.

“And unexpectedly, patients began to report that they slept better and had improved energy and cognition,” he noted.

Six patients in the 2200 and 4400 mg BID cohorts reported reduced fatigue as measured by the PROMIS fatigue questionnaire.

And 2 patients with ankle ulcers in the 2 highest dose cohorts reported improved healing.

Two weeks after treatment stopped, patients were almost back to baseline in terms of their chronic pain and fatigue levels, Dr Gillette said.

A parallel design, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the 2750 mg TID dose is ongoing.

Future studies include a crossover-design, exploratory study of the 2750 mg TID dose and a phase 2 parallel design study of the 2200 mg BID and 2750 mg TID doses.

While the researchers are uncertain about the mechanism of action of SCD-101, they hypothesize that its effects could be due to increased vascular flow, increased oxygen delivery, or a reduction in inflammation.

“This is a promising drug potentially for low-income countries or middle-income countries elsewhere in the world where gene therapy and transplant are really not that feasible,” Dr Gillette said.

Research for this study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Phase II trial: Drug reduces sickle cell ‘pain crises’

An industry-funded phase II trial has shown that high doses of the experimental drug crizanlizumab significantly reduced the number of dangerous “pain crises” in subjects with sickle cell disease.

The median per-year rate of pain crises was 45.3% lower among those who took the high dose of crizanlizumab, compared with the placebo group (P = .01) More than a third of the subjects who took the high dose reported no pain crises during the treatment phase, more than double the rate among the placebo group.

The trial findings were released at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611770).

The American Society of Hematology estimates that 70,000-100,000 people in the United States have sickle cell anemia and some patients are treated with hydroxyurea (Hydrea) are available. According to background material provided in the trial report, however, hydroxyurea has limited value, and some patients still face the prospect of pain crises which can lead to end-organ damage, and early death.

The SUSTAIN trial focuses on pain crises, also known as vaso-occlusive and sickle cell crises, which can occur without warning when sickle cells block blood flow and decrease oxygen delivery.

Researchers led by Kenneth I. Ataga, MB, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, recruited 198 subjects who had sickle cell disease and who had experienced 2-10 pain crises related to their condition over the past year. They randomly assigned 67 subjects to receive a low 2.5-mg/kg dose of crizanlizumab (also known as SelG1), 66 to a high 5.0-mg/kg dose, and 65 to a placebo. Crizanlizumab is an antibody against the molecule P-selectin, whose up-regulation in certain cells and platelets is thought to contribute to vaso-occlusion and sickle cell pain crises.

All the doses were administered intravenously 14 times over a year at sites in Brazil, the United States, and Jamaica. Risk groups for sickle cell include people of African and South American descent, among groups.

The first two doses were loading doses given at 2-week intervals, and the rest were given at 4-week intervals.

Subjects were aged 16-63 years; the median age was 29 for the two crizanlizumab groups and 26 for the placebo group. The percentage of black subjects ranged from 90% to 94% in each group, and the percentage of female subjects ranged from 52% to 58%.

Some subjects, but not all, were taking hydroxyurea. If they were taking the drug, they needed to have been on it for at least 6 months prior to the trial, and at least the last 3 months at a steady dose. Those who didn’t take hydroxyurea weren’t allowed to start taking it.

The researchers found that the median number of pain crises per year was 1.63 in the high-dose group, 2.01 in the low-dose group, and 2.98 in the placebo group. That translates to a 45.3% lower rate for the high-dose group than placebo (P = .01) and a 32.6% lower rate for low-dose than placebo (P = .18).

A total of 36% of the subjects in the high-dose group had no pain crises during the treatment phase, compared with 18% and 17% in the low-dose and placebo groups, respectively.

In a per-protocol analysis of 125 subjects, the researchers found similar numbers for median pain crises and no pain crises with one exception: The rate of annual pain crises was only 8.3% lower for the low-dose group than the placebo (P = .13).

Overall, the researchers wrote, the rates of adverse and serious adverse events were “similar” among all the subjects regardless of their randomized group.

Five patients died during the trial: two from the high dose group, one in the low dose group, and two in the placebo group. Among serious adverse events, pyrexia and pneumonia occurred more frequently in at least one of the crizanlizumab groups than in the placebo group, but their levels were low at zero to three cases of each event in the three groups.

The researchers noted that they didn’t detect any antibody response against crizanlizumab. However, “longer follow-up and monitoring are necessary to ensure that late neutralizing antibodies do not emerge that might limit the ability to administer crizanlizumab on a long-term basis.”

The study was funded by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, which received grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Food and Drug Administration’s Orphan Products Grant Program. Dr. Ataga reports personal fees from Selexys Pharmaceuticals. The other authors report various disclosures or none. The complete list of disclosures is available at NEJM.org.

An industry-funded phase II trial has shown that high doses of the experimental drug crizanlizumab significantly reduced the number of dangerous “pain crises” in subjects with sickle cell disease.

The median per-year rate of pain crises was 45.3% lower among those who took the high dose of crizanlizumab, compared with the placebo group (P = .01) More than a third of the subjects who took the high dose reported no pain crises during the treatment phase, more than double the rate among the placebo group.

The trial findings were released at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611770).

The American Society of Hematology estimates that 70,000-100,000 people in the United States have sickle cell anemia and some patients are treated with hydroxyurea (Hydrea) are available. According to background material provided in the trial report, however, hydroxyurea has limited value, and some patients still face the prospect of pain crises which can lead to end-organ damage, and early death.

The SUSTAIN trial focuses on pain crises, also known as vaso-occlusive and sickle cell crises, which can occur without warning when sickle cells block blood flow and decrease oxygen delivery.

Researchers led by Kenneth I. Ataga, MB, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, recruited 198 subjects who had sickle cell disease and who had experienced 2-10 pain crises related to their condition over the past year. They randomly assigned 67 subjects to receive a low 2.5-mg/kg dose of crizanlizumab (also known as SelG1), 66 to a high 5.0-mg/kg dose, and 65 to a placebo. Crizanlizumab is an antibody against the molecule P-selectin, whose up-regulation in certain cells and platelets is thought to contribute to vaso-occlusion and sickle cell pain crises.

All the doses were administered intravenously 14 times over a year at sites in Brazil, the United States, and Jamaica. Risk groups for sickle cell include people of African and South American descent, among groups.

The first two doses were loading doses given at 2-week intervals, and the rest were given at 4-week intervals.

Subjects were aged 16-63 years; the median age was 29 for the two crizanlizumab groups and 26 for the placebo group. The percentage of black subjects ranged from 90% to 94% in each group, and the percentage of female subjects ranged from 52% to 58%.

Some subjects, but not all, were taking hydroxyurea. If they were taking the drug, they needed to have been on it for at least 6 months prior to the trial, and at least the last 3 months at a steady dose. Those who didn’t take hydroxyurea weren’t allowed to start taking it.

The researchers found that the median number of pain crises per year was 1.63 in the high-dose group, 2.01 in the low-dose group, and 2.98 in the placebo group. That translates to a 45.3% lower rate for the high-dose group than placebo (P = .01) and a 32.6% lower rate for low-dose than placebo (P = .18).

A total of 36% of the subjects in the high-dose group had no pain crises during the treatment phase, compared with 18% and 17% in the low-dose and placebo groups, respectively.

In a per-protocol analysis of 125 subjects, the researchers found similar numbers for median pain crises and no pain crises with one exception: The rate of annual pain crises was only 8.3% lower for the low-dose group than the placebo (P = .13).

Overall, the researchers wrote, the rates of adverse and serious adverse events were “similar” among all the subjects regardless of their randomized group.

Five patients died during the trial: two from the high dose group, one in the low dose group, and two in the placebo group. Among serious adverse events, pyrexia and pneumonia occurred more frequently in at least one of the crizanlizumab groups than in the placebo group, but their levels were low at zero to three cases of each event in the three groups.

The researchers noted that they didn’t detect any antibody response against crizanlizumab. However, “longer follow-up and monitoring are necessary to ensure that late neutralizing antibodies do not emerge that might limit the ability to administer crizanlizumab on a long-term basis.”

The study was funded by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, which received grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Food and Drug Administration’s Orphan Products Grant Program. Dr. Ataga reports personal fees from Selexys Pharmaceuticals. The other authors report various disclosures or none. The complete list of disclosures is available at NEJM.org.

An industry-funded phase II trial has shown that high doses of the experimental drug crizanlizumab significantly reduced the number of dangerous “pain crises” in subjects with sickle cell disease.

The median per-year rate of pain crises was 45.3% lower among those who took the high dose of crizanlizumab, compared with the placebo group (P = .01) More than a third of the subjects who took the high dose reported no pain crises during the treatment phase, more than double the rate among the placebo group.

The trial findings were released at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611770).

The American Society of Hematology estimates that 70,000-100,000 people in the United States have sickle cell anemia and some patients are treated with hydroxyurea (Hydrea) are available. According to background material provided in the trial report, however, hydroxyurea has limited value, and some patients still face the prospect of pain crises which can lead to end-organ damage, and early death.

The SUSTAIN trial focuses on pain crises, also known as vaso-occlusive and sickle cell crises, which can occur without warning when sickle cells block blood flow and decrease oxygen delivery.

Researchers led by Kenneth I. Ataga, MB, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, recruited 198 subjects who had sickle cell disease and who had experienced 2-10 pain crises related to their condition over the past year. They randomly assigned 67 subjects to receive a low 2.5-mg/kg dose of crizanlizumab (also known as SelG1), 66 to a high 5.0-mg/kg dose, and 65 to a placebo. Crizanlizumab is an antibody against the molecule P-selectin, whose up-regulation in certain cells and platelets is thought to contribute to vaso-occlusion and sickle cell pain crises.

All the doses were administered intravenously 14 times over a year at sites in Brazil, the United States, and Jamaica. Risk groups for sickle cell include people of African and South American descent, among groups.

The first two doses were loading doses given at 2-week intervals, and the rest were given at 4-week intervals.

Subjects were aged 16-63 years; the median age was 29 for the two crizanlizumab groups and 26 for the placebo group. The percentage of black subjects ranged from 90% to 94% in each group, and the percentage of female subjects ranged from 52% to 58%.

Some subjects, but not all, were taking hydroxyurea. If they were taking the drug, they needed to have been on it for at least 6 months prior to the trial, and at least the last 3 months at a steady dose. Those who didn’t take hydroxyurea weren’t allowed to start taking it.

The researchers found that the median number of pain crises per year was 1.63 in the high-dose group, 2.01 in the low-dose group, and 2.98 in the placebo group. That translates to a 45.3% lower rate for the high-dose group than placebo (P = .01) and a 32.6% lower rate for low-dose than placebo (P = .18).

A total of 36% of the subjects in the high-dose group had no pain crises during the treatment phase, compared with 18% and 17% in the low-dose and placebo groups, respectively.

In a per-protocol analysis of 125 subjects, the researchers found similar numbers for median pain crises and no pain crises with one exception: The rate of annual pain crises was only 8.3% lower for the low-dose group than the placebo (P = .13).

Overall, the researchers wrote, the rates of adverse and serious adverse events were “similar” among all the subjects regardless of their randomized group.

Five patients died during the trial: two from the high dose group, one in the low dose group, and two in the placebo group. Among serious adverse events, pyrexia and pneumonia occurred more frequently in at least one of the crizanlizumab groups than in the placebo group, but their levels were low at zero to three cases of each event in the three groups.

The researchers noted that they didn’t detect any antibody response against crizanlizumab. However, “longer follow-up and monitoring are necessary to ensure that late neutralizing antibodies do not emerge that might limit the ability to administer crizanlizumab on a long-term basis.”

The study was funded by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, which received grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Food and Drug Administration’s Orphan Products Grant Program. Dr. Ataga reports personal fees from Selexys Pharmaceuticals. The other authors report various disclosures or none. The complete list of disclosures is available at NEJM.org.

FROM ASH 2016

Key clinical point: High-dose crizanlizumab significantly lowers, but does not eliminate, dangerous ‘pain crises’ that strike sickle cell patients.

Major finding: Patients who took high-dose crizanlizumab had a median of 1.63 pain crises a year versus 2.98 for the placebo group. (P = .01)

Data source: A phase II, 12-month, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of 198 patients with sickle cell disease; 129 subjects completed the trial.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, which received grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the FDA’s Orphan Products Grant Program. Dr. Ataga reports personal fees from Selexys Pharmaceuticals. The other authors report various disclosures or none. The complete list of disclosures is available at NEJM.org.

Ferric citrate effective for anemia in non–dialysis-dependent CKD

CHICAGO – Ferric citrate was safe and effective for treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in patients who had non–dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (NDD-CKD), based on data from a phase III, randomized, double-blind study.

The responses were durable, and none of the patients received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), presenter Pablo Pergola, MD, PhD, of Renal Associates, San Antonio, said in an interview at a meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The trial involved 234 anemic adults who had NDD-CKD and had not responded to oral iron supplements. The subjects were randomized to receive oral ferric citrate (n = 117) or placebo (n = 115) with meals (one patient did not receive placebo and laboratory data were lacking for one patient). The mean dose in the treatment arm was 5 pills per day.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with hemoglobin (Hgb) greater than or equal to 1.0 g/dL anytime from baseline through week 16. Secondary endpoints included mean changes from baseline in Hgb, transferrin saturation, ferritin, and serum phosphate and evidence of sustained treatment effect based on target changes in Hgb with time.

Both arms were comparable at baseline for demographic and clinical characteristics, including phosphorus and hemoglobin levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The primary endpoint was met by 51.2% of patients receiving ferric citrate and 19.1% of patients receiving placebo (P less than .001). All secondary efficacy endpoints were met, with statistically significant differences between the treatment and placebo arms, Dr. Pergola reported.

Serum phosphate level was significantly reduced from baseline at week 16 (–0.21 mg/dL; 95% confidence interval, –0.39 to –0.03 mg/dL; P equal to .02) in the active treatment group, and the levels remained in the normal range, he said.

During the 16-week treatment period and subsequent 8-week, open-label safety extension period, ferric citrate was well tolerated. Treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), most commonly diarrhea, occurred in 93 (79.5%) and 75 (64.7%) patients in the treatment and placebo arms, respectively. Serious AEs developed in 14 (12.0%) and 13 (11.2%) of patients in the same respective order. Two deaths occurred, both in the treatment group. The deaths and serious AEs were not considered drug related.

Ferric citrate binds with dietary phosphate in the gastrointestinal tract. The resulting ferric phosphate is insoluble and is excreted. The remaining unbound ferric citrate increases serum iron parameters, including ferritin and transferrin saturation.

The findings potentially extend the therapeutic reach of the drug beyond its Food and Drug Administration–approved use for control of phosphorus levels in CKD patients on dialysis, Dr. Pergola said. The trial data will be used to seek approval for the oral iron medication as a treatment for iron-deficiency anemia in adults with NDD-CKD.

The study was sponsored by Keryx Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Pergola is supported by honoraria and lecture fees from Akebia Therapeutics, Keryx, Relypsa, Vifor/Fresenius Pharma, and ZS Pharma.

CHICAGO – Ferric citrate was safe and effective for treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in patients who had non–dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (NDD-CKD), based on data from a phase III, randomized, double-blind study.

The responses were durable, and none of the patients received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), presenter Pablo Pergola, MD, PhD, of Renal Associates, San Antonio, said in an interview at a meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The trial involved 234 anemic adults who had NDD-CKD and had not responded to oral iron supplements. The subjects were randomized to receive oral ferric citrate (n = 117) or placebo (n = 115) with meals (one patient did not receive placebo and laboratory data were lacking for one patient). The mean dose in the treatment arm was 5 pills per day.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with hemoglobin (Hgb) greater than or equal to 1.0 g/dL anytime from baseline through week 16. Secondary endpoints included mean changes from baseline in Hgb, transferrin saturation, ferritin, and serum phosphate and evidence of sustained treatment effect based on target changes in Hgb with time.

Both arms were comparable at baseline for demographic and clinical characteristics, including phosphorus and hemoglobin levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The primary endpoint was met by 51.2% of patients receiving ferric citrate and 19.1% of patients receiving placebo (P less than .001). All secondary efficacy endpoints were met, with statistically significant differences between the treatment and placebo arms, Dr. Pergola reported.

Serum phosphate level was significantly reduced from baseline at week 16 (–0.21 mg/dL; 95% confidence interval, –0.39 to –0.03 mg/dL; P equal to .02) in the active treatment group, and the levels remained in the normal range, he said.

During the 16-week treatment period and subsequent 8-week, open-label safety extension period, ferric citrate was well tolerated. Treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), most commonly diarrhea, occurred in 93 (79.5%) and 75 (64.7%) patients in the treatment and placebo arms, respectively. Serious AEs developed in 14 (12.0%) and 13 (11.2%) of patients in the same respective order. Two deaths occurred, both in the treatment group. The deaths and serious AEs were not considered drug related.

Ferric citrate binds with dietary phosphate in the gastrointestinal tract. The resulting ferric phosphate is insoluble and is excreted. The remaining unbound ferric citrate increases serum iron parameters, including ferritin and transferrin saturation.

The findings potentially extend the therapeutic reach of the drug beyond its Food and Drug Administration–approved use for control of phosphorus levels in CKD patients on dialysis, Dr. Pergola said. The trial data will be used to seek approval for the oral iron medication as a treatment for iron-deficiency anemia in adults with NDD-CKD.

The study was sponsored by Keryx Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Pergola is supported by honoraria and lecture fees from Akebia Therapeutics, Keryx, Relypsa, Vifor/Fresenius Pharma, and ZS Pharma.

CHICAGO – Ferric citrate was safe and effective for treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in patients who had non–dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (NDD-CKD), based on data from a phase III, randomized, double-blind study.

The responses were durable, and none of the patients received erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), presenter Pablo Pergola, MD, PhD, of Renal Associates, San Antonio, said in an interview at a meeting sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

The trial involved 234 anemic adults who had NDD-CKD and had not responded to oral iron supplements. The subjects were randomized to receive oral ferric citrate (n = 117) or placebo (n = 115) with meals (one patient did not receive placebo and laboratory data were lacking for one patient). The mean dose in the treatment arm was 5 pills per day.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients with hemoglobin (Hgb) greater than or equal to 1.0 g/dL anytime from baseline through week 16. Secondary endpoints included mean changes from baseline in Hgb, transferrin saturation, ferritin, and serum phosphate and evidence of sustained treatment effect based on target changes in Hgb with time.

Both arms were comparable at baseline for demographic and clinical characteristics, including phosphorus and hemoglobin levels and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The primary endpoint was met by 51.2% of patients receiving ferric citrate and 19.1% of patients receiving placebo (P less than .001). All secondary efficacy endpoints were met, with statistically significant differences between the treatment and placebo arms, Dr. Pergola reported.

Serum phosphate level was significantly reduced from baseline at week 16 (–0.21 mg/dL; 95% confidence interval, –0.39 to –0.03 mg/dL; P equal to .02) in the active treatment group, and the levels remained in the normal range, he said.

During the 16-week treatment period and subsequent 8-week, open-label safety extension period, ferric citrate was well tolerated. Treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), most commonly diarrhea, occurred in 93 (79.5%) and 75 (64.7%) patients in the treatment and placebo arms, respectively. Serious AEs developed in 14 (12.0%) and 13 (11.2%) of patients in the same respective order. Two deaths occurred, both in the treatment group. The deaths and serious AEs were not considered drug related.

Ferric citrate binds with dietary phosphate in the gastrointestinal tract. The resulting ferric phosphate is insoluble and is excreted. The remaining unbound ferric citrate increases serum iron parameters, including ferritin and transferrin saturation.

The findings potentially extend the therapeutic reach of the drug beyond its Food and Drug Administration–approved use for control of phosphorus levels in CKD patients on dialysis, Dr. Pergola said. The trial data will be used to seek approval for the oral iron medication as a treatment for iron-deficiency anemia in adults with NDD-CKD.

The study was sponsored by Keryx Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Pergola is supported by honoraria and lecture fees from Akebia Therapeutics, Keryx, Relypsa, Vifor/Fresenius Pharma, and ZS Pharma.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2016

Key clinical point: Ferric citrate appears to be safe and effective for treating anemia in non–dialysis-dependent CKD patients.

Major finding: Prevalence of increased hemoglobin was 52.1% in patients receiving the active drug and 19.1% in those given placebo.

Data source: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial with 234 patients.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Keryx Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Pergola is supported by honoraria and lecture fees from Akebia Therapeutics, Keryx, Relypsa, Vifor/Fresenius Pharma, and ZS Pharma.

EC grants drug orphan designation for SCD

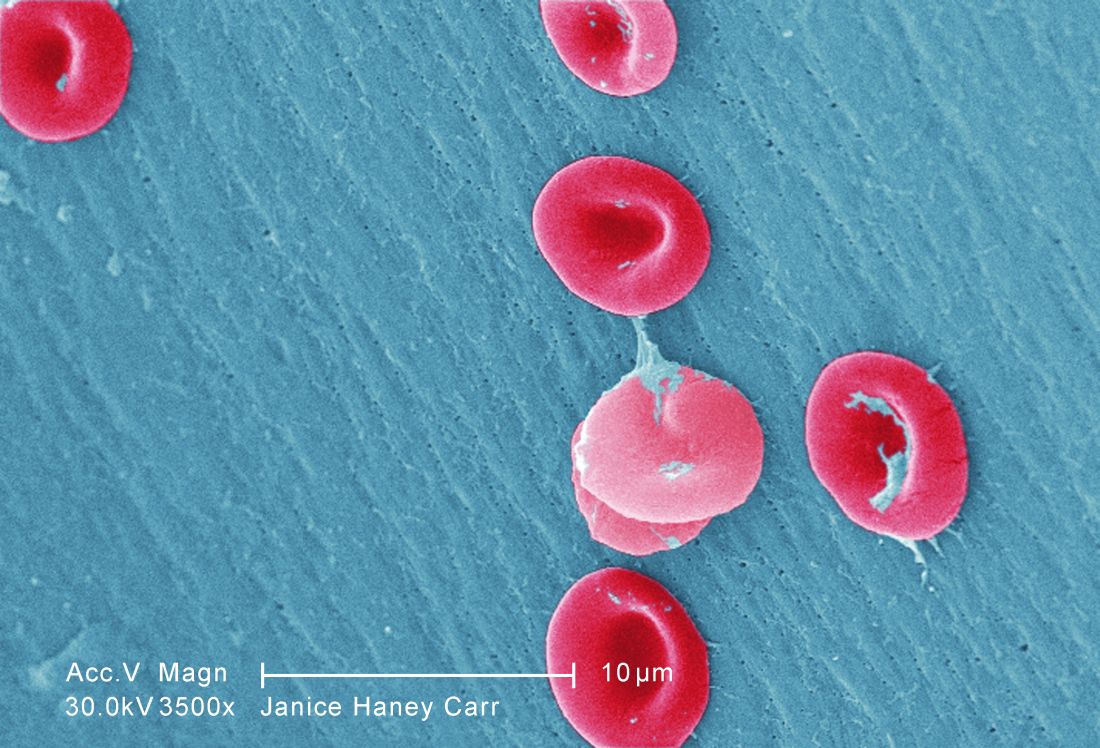

beside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

The European Commission (EC) has designated GBT440 as an orphan medicinal product for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD).

GBT440 is being developed as a potentially disease-modifying therapy for SCD. The drug works by increasing hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen.

Since oxygenated sickle hemoglobin does not polymerize, it is believed that GBT440 blocks polymerization and the resultant sickling of red blood cells.

If GBT440 can restore normal hemoglobin function and improve oxygen delivery, the drug may be capable of modifying the progression of SCD.

Preclinical research published in the British Journal of Haematology earlier this year suggests that GBT440 is disease-modifying.

Early results from an ongoing phase 1/2 study of GBT440, which were presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, appeared promising as well.

Results from that study suggest that GBT440 can increase hemoglobin levels while decreasing reticulocyte counts, erythropoietin levels, and sickle cell counts.

Researchers also found the drug to be well tolerated, with no serious adverse events attributed to GBT440.

“Receiving orphan designation from the EC marks a significant milestone both for the SCD community and for GBT [Global Blood Therapeutics Inc.],” said Ted W. Love, MD, president and chief executive officer of Global Blood Therapeutics Inc., the company developing GBT440.

“SCD is a devastatingly severe disease with limited treatment options, and this designation, together with our fast track and orphan drug designations by the United States Food and Drug Administration, reflect the recognition of the broader regulatory community of this urgent unmet medical need.”

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and reductions in, or exemptions from, fees. ![]()

beside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

The European Commission (EC) has designated GBT440 as an orphan medicinal product for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD).

GBT440 is being developed as a potentially disease-modifying therapy for SCD. The drug works by increasing hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen.

Since oxygenated sickle hemoglobin does not polymerize, it is believed that GBT440 blocks polymerization and the resultant sickling of red blood cells.

If GBT440 can restore normal hemoglobin function and improve oxygen delivery, the drug may be capable of modifying the progression of SCD.

Preclinical research published in the British Journal of Haematology earlier this year suggests that GBT440 is disease-modifying.

Early results from an ongoing phase 1/2 study of GBT440, which were presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, appeared promising as well.

Results from that study suggest that GBT440 can increase hemoglobin levels while decreasing reticulocyte counts, erythropoietin levels, and sickle cell counts.

Researchers also found the drug to be well tolerated, with no serious adverse events attributed to GBT440.

“Receiving orphan designation from the EC marks a significant milestone both for the SCD community and for GBT [Global Blood Therapeutics Inc.],” said Ted W. Love, MD, president and chief executive officer of Global Blood Therapeutics Inc., the company developing GBT440.

“SCD is a devastatingly severe disease with limited treatment options, and this designation, together with our fast track and orphan drug designations by the United States Food and Drug Administration, reflect the recognition of the broader regulatory community of this urgent unmet medical need.”

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and reductions in, or exemptions from, fees. ![]()

beside a normal one

Image by Betty Pace

The European Commission (EC) has designated GBT440 as an orphan medicinal product for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD).

GBT440 is being developed as a potentially disease-modifying therapy for SCD. The drug works by increasing hemoglobin’s affinity for oxygen.

Since oxygenated sickle hemoglobin does not polymerize, it is believed that GBT440 blocks polymerization and the resultant sickling of red blood cells.

If GBT440 can restore normal hemoglobin function and improve oxygen delivery, the drug may be capable of modifying the progression of SCD.

Preclinical research published in the British Journal of Haematology earlier this year suggests that GBT440 is disease-modifying.

Early results from an ongoing phase 1/2 study of GBT440, which were presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, appeared promising as well.

Results from that study suggest that GBT440 can increase hemoglobin levels while decreasing reticulocyte counts, erythropoietin levels, and sickle cell counts.

Researchers also found the drug to be well tolerated, with no serious adverse events attributed to GBT440.

“Receiving orphan designation from the EC marks a significant milestone both for the SCD community and for GBT [Global Blood Therapeutics Inc.],” said Ted W. Love, MD, president and chief executive officer of Global Blood Therapeutics Inc., the company developing GBT440.

“SCD is a devastatingly severe disease with limited treatment options, and this designation, together with our fast track and orphan drug designations by the United States Food and Drug Administration, reflect the recognition of the broader regulatory community of this urgent unmet medical need.”

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and reductions in, or exemptions from, fees. ![]()

Decitabine produces responses in high-risk MDS, AML

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Patients with TP53-mutated myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may benefit from treatment with decitabine, according to a study published in NEJM.

All patients in this study who had TP53 mutations responded to decitabine.

Although these responses were not durable, the patients’ median overall survival was similar to that of patients with lower-risk disease who received decitabine.

“The findings need to be validated in a larger trial, but they do suggest that TP53 mutations can reliably predict responses to decitabine, potentially prolonging survival in this ultra-high-risk group of patients and providing a bridge to transplantation in some patients who might not otherwise be candidates,” said study author Timothy J. Ley, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

For this study, Dr Ley and his colleagues analyzed 116 patients—54 with AML, 36 with relapsed AML, and 26 with MDS.

Eighty-four of the patients were enrolled in a prospective trial and received decitabine at a dose of 20 mg/m2/day for 10 consecutive days in monthly cycles. Thirty-two additional patients received decitabine on different protocols.

To determine whether genetic mutations could be used to predict responses to decitabine, the researchers performed enhanced exome or gene-panel sequencing in 67 of the patients. The team also performed sequencing at multiple time points to evaluate patterns of mutation clearance in 54 patients.

Response

Thirteen percent of patients (n=15) achieved a complete response (CR), 21% (n=24) had a CR with incomplete count recovery, 5% (n=6) had a morphologic CR with hematologic improvement, and 7% (n=8) had a morphologic CR without hematologic improvement.

Eight percent of patients (n=9) had a partial response, 20% (n=23) had stable disease, and 16% (n=19) had progressive disease.

There were 21 patients with TP53 mutations, and all of them achieved bone marrow blast clearance with less than 5% blasts.

Nineteen percent (n=4) had a CR, 43% (n=9) had a CR with incomplete count recovery, 24% (n=5) had morphologic CR with hematologic improvement, and 14% (n=3) had morphologic CR without hematologic improvement.

“What’s really unique here is that all the patients in the study with TP53 mutations had a response to decitabine and achieved an initial remission,” Dr Ley said.

“With standard aggressive chemotherapy, we only see about 20% to 30% of these patients achieving remission, which is the critical first step to have a chance to cure patients with additional therapies.”

Dr Ley and his colleagues also found that patients in this study were likely to respond to decitabine if they were considered “unfavorable risk” based on extensive chromosomal rearrangements. (Many of these patients also had TP53 mutations.)

Indeed, 67% (29/43) of patients with an unfavorable risk had less than 5% blasts after treatment with decitabine, compared with 34% (24/71) of patients with intermediate or favorable risk.

“The challenge with using decitabine has been knowing which patients are most likely to respond,” said study author Amanda Cashen, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“The value of this study is the comprehensive mutational analysis that helps us figure out which patients are likely to benefit. This information opens the door to using decitabine in a more targeted fashion to treat not just older patients, but also younger patients who carry TP53 mutations.”

Survival and next steps

The researchers found that responses to decitabine were usually short-lived. The drug did not provide complete mutation clearance, which led to relapse.

“Remissions with decitabine typically don’t last long, and no one was cured with this drug,” Dr Ley noted. “But patients who responded to decitabine live longer than what you would expect with aggressive chemotherapy, and that can mean something. Some people live a year or 2 and with a good quality of life because the chemotherapy is not too toxic.”

The median overall survival was 11.6 months among patients with unfavorable risk and 10 months among patients with favorable or intermediate risk (P=0.29).

The median overall survival was 12.7 months among patients with TP53 mutations and 15.4 months among patients with wild-type TP53 (P=0.79).

“It’s important to note that patients with an extremely poor prognosis in this relatively small study had the same survival outcomes as patients facing a better prognosis, which is encouraging,” said study author John Welch, MD, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“We don’t yet understand why patients with TP53 mutations consistently respond to decitabine, and more work is needed to understand that phenomenon. We’re now planning a larger trial to evaluate decitabine in AML patients of all ages who carry TP53 mutations. It’s exciting to think we may have a therapy that has the potential to improve response rates in this group of high-risk patients.” ![]()

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Patients with TP53-mutated myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may benefit from treatment with decitabine, according to a study published in NEJM.

All patients in this study who had TP53 mutations responded to decitabine.

Although these responses were not durable, the patients’ median overall survival was similar to that of patients with lower-risk disease who received decitabine.

“The findings need to be validated in a larger trial, but they do suggest that TP53 mutations can reliably predict responses to decitabine, potentially prolonging survival in this ultra-high-risk group of patients and providing a bridge to transplantation in some patients who might not otherwise be candidates,” said study author Timothy J. Ley, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

For this study, Dr Ley and his colleagues analyzed 116 patients—54 with AML, 36 with relapsed AML, and 26 with MDS.

Eighty-four of the patients were enrolled in a prospective trial and received decitabine at a dose of 20 mg/m2/day for 10 consecutive days in monthly cycles. Thirty-two additional patients received decitabine on different protocols.

To determine whether genetic mutations could be used to predict responses to decitabine, the researchers performed enhanced exome or gene-panel sequencing in 67 of the patients. The team also performed sequencing at multiple time points to evaluate patterns of mutation clearance in 54 patients.

Response

Thirteen percent of patients (n=15) achieved a complete response (CR), 21% (n=24) had a CR with incomplete count recovery, 5% (n=6) had a morphologic CR with hematologic improvement, and 7% (n=8) had a morphologic CR without hematologic improvement.

Eight percent of patients (n=9) had a partial response, 20% (n=23) had stable disease, and 16% (n=19) had progressive disease.

There were 21 patients with TP53 mutations, and all of them achieved bone marrow blast clearance with less than 5% blasts.

Nineteen percent (n=4) had a CR, 43% (n=9) had a CR with incomplete count recovery, 24% (n=5) had morphologic CR with hematologic improvement, and 14% (n=3) had morphologic CR without hematologic improvement.

“What’s really unique here is that all the patients in the study with TP53 mutations had a response to decitabine and achieved an initial remission,” Dr Ley said.

“With standard aggressive chemotherapy, we only see about 20% to 30% of these patients achieving remission, which is the critical first step to have a chance to cure patients with additional therapies.”

Dr Ley and his colleagues also found that patients in this study were likely to respond to decitabine if they were considered “unfavorable risk” based on extensive chromosomal rearrangements. (Many of these patients also had TP53 mutations.)

Indeed, 67% (29/43) of patients with an unfavorable risk had less than 5% blasts after treatment with decitabine, compared with 34% (24/71) of patients with intermediate or favorable risk.

“The challenge with using decitabine has been knowing which patients are most likely to respond,” said study author Amanda Cashen, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“The value of this study is the comprehensive mutational analysis that helps us figure out which patients are likely to benefit. This information opens the door to using decitabine in a more targeted fashion to treat not just older patients, but also younger patients who carry TP53 mutations.”

Survival and next steps

The researchers found that responses to decitabine were usually short-lived. The drug did not provide complete mutation clearance, which led to relapse.

“Remissions with decitabine typically don’t last long, and no one was cured with this drug,” Dr Ley noted. “But patients who responded to decitabine live longer than what you would expect with aggressive chemotherapy, and that can mean something. Some people live a year or 2 and with a good quality of life because the chemotherapy is not too toxic.”

The median overall survival was 11.6 months among patients with unfavorable risk and 10 months among patients with favorable or intermediate risk (P=0.29).

The median overall survival was 12.7 months among patients with TP53 mutations and 15.4 months among patients with wild-type TP53 (P=0.79).

“It’s important to note that patients with an extremely poor prognosis in this relatively small study had the same survival outcomes as patients facing a better prognosis, which is encouraging,” said study author John Welch, MD, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“We don’t yet understand why patients with TP53 mutations consistently respond to decitabine, and more work is needed to understand that phenomenon. We’re now planning a larger trial to evaluate decitabine in AML patients of all ages who carry TP53 mutations. It’s exciting to think we may have a therapy that has the potential to improve response rates in this group of high-risk patients.” ![]()

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Patients with TP53-mutated myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) may benefit from treatment with decitabine, according to a study published in NEJM.

All patients in this study who had TP53 mutations responded to decitabine.

Although these responses were not durable, the patients’ median overall survival was similar to that of patients with lower-risk disease who received decitabine.

“The findings need to be validated in a larger trial, but they do suggest that TP53 mutations can reliably predict responses to decitabine, potentially prolonging survival in this ultra-high-risk group of patients and providing a bridge to transplantation in some patients who might not otherwise be candidates,” said study author Timothy J. Ley, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

For this study, Dr Ley and his colleagues analyzed 116 patients—54 with AML, 36 with relapsed AML, and 26 with MDS.

Eighty-four of the patients were enrolled in a prospective trial and received decitabine at a dose of 20 mg/m2/day for 10 consecutive days in monthly cycles. Thirty-two additional patients received decitabine on different protocols.

To determine whether genetic mutations could be used to predict responses to decitabine, the researchers performed enhanced exome or gene-panel sequencing in 67 of the patients. The team also performed sequencing at multiple time points to evaluate patterns of mutation clearance in 54 patients.

Response

Thirteen percent of patients (n=15) achieved a complete response (CR), 21% (n=24) had a CR with incomplete count recovery, 5% (n=6) had a morphologic CR with hematologic improvement, and 7% (n=8) had a morphologic CR without hematologic improvement.

Eight percent of patients (n=9) had a partial response, 20% (n=23) had stable disease, and 16% (n=19) had progressive disease.

There were 21 patients with TP53 mutations, and all of them achieved bone marrow blast clearance with less than 5% blasts.

Nineteen percent (n=4) had a CR, 43% (n=9) had a CR with incomplete count recovery, 24% (n=5) had morphologic CR with hematologic improvement, and 14% (n=3) had morphologic CR without hematologic improvement.

“What’s really unique here is that all the patients in the study with TP53 mutations had a response to decitabine and achieved an initial remission,” Dr Ley said.

“With standard aggressive chemotherapy, we only see about 20% to 30% of these patients achieving remission, which is the critical first step to have a chance to cure patients with additional therapies.”

Dr Ley and his colleagues also found that patients in this study were likely to respond to decitabine if they were considered “unfavorable risk” based on extensive chromosomal rearrangements. (Many of these patients also had TP53 mutations.)

Indeed, 67% (29/43) of patients with an unfavorable risk had less than 5% blasts after treatment with decitabine, compared with 34% (24/71) of patients with intermediate or favorable risk.

“The challenge with using decitabine has been knowing which patients are most likely to respond,” said study author Amanda Cashen, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“The value of this study is the comprehensive mutational analysis that helps us figure out which patients are likely to benefit. This information opens the door to using decitabine in a more targeted fashion to treat not just older patients, but also younger patients who carry TP53 mutations.”

Survival and next steps

The researchers found that responses to decitabine were usually short-lived. The drug did not provide complete mutation clearance, which led to relapse.

“Remissions with decitabine typically don’t last long, and no one was cured with this drug,” Dr Ley noted. “But patients who responded to decitabine live longer than what you would expect with aggressive chemotherapy, and that can mean something. Some people live a year or 2 and with a good quality of life because the chemotherapy is not too toxic.”

The median overall survival was 11.6 months among patients with unfavorable risk and 10 months among patients with favorable or intermediate risk (P=0.29).

The median overall survival was 12.7 months among patients with TP53 mutations and 15.4 months among patients with wild-type TP53 (P=0.79).

“It’s important to note that patients with an extremely poor prognosis in this relatively small study had the same survival outcomes as patients facing a better prognosis, which is encouraging,” said study author John Welch, MD, PhD, of Washington University School of Medicine.

“We don’t yet understand why patients with TP53 mutations consistently respond to decitabine, and more work is needed to understand that phenomenon. We’re now planning a larger trial to evaluate decitabine in AML patients of all ages who carry TP53 mutations. It’s exciting to think we may have a therapy that has the potential to improve response rates in this group of high-risk patients.” ![]()

EC grants drug orphan designation for PNH

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation to RA101495 for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

RA101495 is a synthetic macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of complement component C5.

Ra Pharmaceuticals is developing RA101495 as a self-administered, subcutaneous injection for the treatment of PNH, refractory generalized myasthenia gravis, and lupus nephritis.

RA101495 binds complement C5 with subnanomolar affinity and allosterically inhibits its cleavage into C5a and C5b upon activation of the classical, alternative, or lectin pathways.

RA101495 also directly binds to C5b, disrupting the interaction between C5b and C6 and preventing assembly of the membrane attack complex.

According to Ra Pharmaceuticals, repeat dosing of RA101495 in vivo has demonstrated “sustained and predictable” inhibition of complement activity with an “excellent” safety profile.

The company also said phase 1 data have suggested that RA101495 is potent inhibitor of C5-mediated hemolysis with a favorable safety profile.

Preclinical research involving RA101495 was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, and phase 1 data were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association earlier this year.

RA101495’s orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

In situations where there is already an approved standard of care—such as with PNH, where the monoclonal antibody eculizumab (Soliris) is currently available—the EC requires companies developing a potential orphan drug to provide evidence that the drug is expected to provide significant benefits over the standard of care.

In the case of RA101495, the decision to grant orphan designation was based on the potential for improved patient convenience with subcutaneous self-administration, as well as the potential to treat patients who do not respond to eculizumab.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and, in some cases, reductions in fees. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation to RA101495 for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

RA101495 is a synthetic macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of complement component C5.

Ra Pharmaceuticals is developing RA101495 as a self-administered, subcutaneous injection for the treatment of PNH, refractory generalized myasthenia gravis, and lupus nephritis.

RA101495 binds complement C5 with subnanomolar affinity and allosterically inhibits its cleavage into C5a and C5b upon activation of the classical, alternative, or lectin pathways.

RA101495 also directly binds to C5b, disrupting the interaction between C5b and C6 and preventing assembly of the membrane attack complex.

According to Ra Pharmaceuticals, repeat dosing of RA101495 in vivo has demonstrated “sustained and predictable” inhibition of complement activity with an “excellent” safety profile.

The company also said phase 1 data have suggested that RA101495 is potent inhibitor of C5-mediated hemolysis with a favorable safety profile.

Preclinical research involving RA101495 was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, and phase 1 data were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association earlier this year.

RA101495’s orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

In situations where there is already an approved standard of care—such as with PNH, where the monoclonal antibody eculizumab (Soliris) is currently available—the EC requires companies developing a potential orphan drug to provide evidence that the drug is expected to provide significant benefits over the standard of care.

In the case of RA101495, the decision to grant orphan designation was based on the potential for improved patient convenience with subcutaneous self-administration, as well as the potential to treat patients who do not respond to eculizumab.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and, in some cases, reductions in fees. ![]()

The European Commission (EC) has granted orphan drug designation to RA101495 for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

RA101495 is a synthetic macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of complement component C5.

Ra Pharmaceuticals is developing RA101495 as a self-administered, subcutaneous injection for the treatment of PNH, refractory generalized myasthenia gravis, and lupus nephritis.

RA101495 binds complement C5 with subnanomolar affinity and allosterically inhibits its cleavage into C5a and C5b upon activation of the classical, alternative, or lectin pathways.

RA101495 also directly binds to C5b, disrupting the interaction between C5b and C6 and preventing assembly of the membrane attack complex.

According to Ra Pharmaceuticals, repeat dosing of RA101495 in vivo has demonstrated “sustained and predictable” inhibition of complement activity with an “excellent” safety profile.

The company also said phase 1 data have suggested that RA101495 is potent inhibitor of C5-mediated hemolysis with a favorable safety profile.

Preclinical research involving RA101495 was presented at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting, and phase 1 data were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association earlier this year.

RA101495’s orphan designation

The EC grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat life-threatening or chronically debilitating conditions affecting no more than 5 in 10,000 people in the European Union, and where no satisfactory treatment is available.

In situations where there is already an approved standard of care—such as with PNH, where the monoclonal antibody eculizumab (Soliris) is currently available—the EC requires companies developing a potential orphan drug to provide evidence that the drug is expected to provide significant benefits over the standard of care.

In the case of RA101495, the decision to grant orphan designation was based on the potential for improved patient convenience with subcutaneous self-administration, as well as the potential to treat patients who do not respond to eculizumab.

Orphan designation provides the company developing a drug with regulatory and financial incentives, including protocol assistance, 10 years of market exclusivity once the drug is approved, and, in some cases, reductions in fees. ![]()

SelG1 cut pain crises in sickle cell disease

The humanized antibody SelG1 decreased the frequency of acute pain episodes in people with sickle cell disease, based on results from the multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled SUSTAIN study that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego.

In other sickle cell disease research to be presented at the meeting, researchers will be presenting new findings from two studies conducted in Africa. One study examines a team approach to reduce mortality in pregnant women with sickle cell disease in Ghana. The other study, called SPIN, is a safety and feasibility study conducted in advance of a randomized trial in Nigerian children at risk for stroke.

After 1 year, the annual rate of sickle cell–related pain crises resulting in a visit to a medical facility was 1.6 in the group receiving the 5 mg/kg dose, compared with 3 in the placebo group. The 47% difference was statistically significant (P = .01).

Also, time to first pain crisis was a median of 4 months in those who received the 5 mg/kg dose and 1.4 months for those in the placebo group (P = .001).

Infections were not seen increased in either of the groups randomized to SelG1, and no treatment-related deaths occurred during the course of the study. The first-in-class agent “appears to be safe and well tolerated,” as well as effective in reducing pain episodes, Dr. Ataga and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the Nigerian trial, led by Najibah Aliyu Galadanci, MD, MPH, of Bayero University in Kano, Nigeria, the goal was to determine whether families of children with sickle cell disease and transcranial Doppler measurements indicative of increased risk for stroke could be recruited and retained in a large clinical trial, and whether they could adhere to the medication regimen. The trial also obtained preliminary evidence for hydroxyurea’s safety in this clinical setting, where transfusion therapy is not an option for most children.

Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues approached 375 families for transcranial Doppler screening, and 90% accepted. Among families of children found to have elevated measures of risk on transcranial Doppler, 92% participated in the study and received a moderate dose of hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg) for 2 years. A comparison group included 210 children without elevated measures on transcranial Doppler. These children underwent regular monitoring but were not offered medication unless transcranial Doppler measures were found to be elevated.

Study adherence was exceptionally high: the families missed no monthly research visits, and no participants in the active treatment group dropped out voluntarily.

Also, at 2 years, the children treated with hydroxyurea did not have evidence of excessive toxicity, compared with the children who did not receive the drug. “Our results provide strong preliminary evidence supporting the current multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg per day vs. 10 mg/kg per day) for preventing primary strokes in children with sickle cell anemia living in Nigeria,” Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the third study, a multidisciplinary team decreased mortality in pregnant women who had sickle cell disease and lived in low and middle income settings, according to Eugenia Vicky Naa Kwarley Asare, MD, of the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics and the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra.

In a prospective trial in Ghana, where maternal mortality among women with sickle cell disease is estimated to be 8,300 per 100,000 live births, compared with 690 for women without sickle cell disease, Dr. Asare and her colleagues’ multidisciplinary team included obstetricians, hematologists, pulmonologists, and nurses, and the planned intervention protocols included a number of changes to make management more consistent and intensive. A total of 154 pregnancies were evaluated before the intervention, and 91 after. Median gestational age was 24 weeks at enrollment, and median maternal age was 29 years for both pre- and post-intervention cohorts.

Maternal mortality before the intervention was 9.7% (15 of 154) and after the intervention was 1.1% (1 of 91) of total deliveries.

Dr. Ataga’s study was sponsored by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, the drug’s manufacturer, and included coinvestigators who are employees of Selexys Pharmaceuticals or who disclosed relationships with other drug manufacturers. Dr. Galadanci’s and Dr. Asare’s groups disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The humanized antibody SelG1 decreased the frequency of acute pain episodes in people with sickle cell disease, based on results from the multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled SUSTAIN study that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego.

In other sickle cell disease research to be presented at the meeting, researchers will be presenting new findings from two studies conducted in Africa. One study examines a team approach to reduce mortality in pregnant women with sickle cell disease in Ghana. The other study, called SPIN, is a safety and feasibility study conducted in advance of a randomized trial in Nigerian children at risk for stroke.

After 1 year, the annual rate of sickle cell–related pain crises resulting in a visit to a medical facility was 1.6 in the group receiving the 5 mg/kg dose, compared with 3 in the placebo group. The 47% difference was statistically significant (P = .01).

Also, time to first pain crisis was a median of 4 months in those who received the 5 mg/kg dose and 1.4 months for those in the placebo group (P = .001).

Infections were not seen increased in either of the groups randomized to SelG1, and no treatment-related deaths occurred during the course of the study. The first-in-class agent “appears to be safe and well tolerated,” as well as effective in reducing pain episodes, Dr. Ataga and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the Nigerian trial, led by Najibah Aliyu Galadanci, MD, MPH, of Bayero University in Kano, Nigeria, the goal was to determine whether families of children with sickle cell disease and transcranial Doppler measurements indicative of increased risk for stroke could be recruited and retained in a large clinical trial, and whether they could adhere to the medication regimen. The trial also obtained preliminary evidence for hydroxyurea’s safety in this clinical setting, where transfusion therapy is not an option for most children.

Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues approached 375 families for transcranial Doppler screening, and 90% accepted. Among families of children found to have elevated measures of risk on transcranial Doppler, 92% participated in the study and received a moderate dose of hydroxyurea (20 mg/kg) for 2 years. A comparison group included 210 children without elevated measures on transcranial Doppler. These children underwent regular monitoring but were not offered medication unless transcranial Doppler measures were found to be elevated.

Study adherence was exceptionally high: the families missed no monthly research visits, and no participants in the active treatment group dropped out voluntarily.

Also, at 2 years, the children treated with hydroxyurea did not have evidence of excessive toxicity, compared with the children who did not receive the drug. “Our results provide strong preliminary evidence supporting the current multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing hydroxyurea therapy (20 mg/kg per day vs. 10 mg/kg per day) for preventing primary strokes in children with sickle cell anemia living in Nigeria,” Dr. Galadanci and her colleagues wrote in their abstract.

In the third study, a multidisciplinary team decreased mortality in pregnant women who had sickle cell disease and lived in low and middle income settings, according to Eugenia Vicky Naa Kwarley Asare, MD, of the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics and the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra.

In a prospective trial in Ghana, where maternal mortality among women with sickle cell disease is estimated to be 8,300 per 100,000 live births, compared with 690 for women without sickle cell disease, Dr. Asare and her colleagues’ multidisciplinary team included obstetricians, hematologists, pulmonologists, and nurses, and the planned intervention protocols included a number of changes to make management more consistent and intensive. A total of 154 pregnancies were evaluated before the intervention, and 91 after. Median gestational age was 24 weeks at enrollment, and median maternal age was 29 years for both pre- and post-intervention cohorts.

Maternal mortality before the intervention was 9.7% (15 of 154) and after the intervention was 1.1% (1 of 91) of total deliveries.

Dr. Ataga’s study was sponsored by Selexys Pharmaceuticals, the drug’s manufacturer, and included coinvestigators who are employees of Selexys Pharmaceuticals or who disclosed relationships with other drug manufacturers. Dr. Galadanci’s and Dr. Asare’s groups disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The humanized antibody SelG1 decreased the frequency of acute pain episodes in people with sickle cell disease, based on results from the multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled SUSTAIN study that will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego.

In other sickle cell disease research to be presented at the meeting, researchers will be presenting new findings from two studies conducted in Africa. One study examines a team approach to reduce mortality in pregnant women with sickle cell disease in Ghana. The other study, called SPIN, is a safety and feasibility study conducted in advance of a randomized trial in Nigerian children at risk for stroke.

After 1 year, the annual rate of sickle cell–related pain crises resulting in a visit to a medical facility was 1.6 in the group receiving the 5 mg/kg dose, compared with 3 in the placebo group. The 47% difference was statistically significant (P = .01).

Also, time to first pain crisis was a median of 4 months in those who received the 5 mg/kg dose and 1.4 months for those in the placebo group (P = .001).

Infections were not seen increased in either of the groups randomized to SelG1, and no treatment-related deaths occurred during the course of the study. The first-in-class agent “appears to be safe and well tolerated,” as well as effective in reducing pain episodes, Dr. Ataga and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.