User login

Atopic dermatitis associated with increased suicidality

Patients with atopic dermatitis might face up to a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation and are 36% more likely to attempt suicide than those without the disorder, a large meta-analysis has determined.

The analysis, which included data from studies published as far back as 1945, also found some correlation of increased suicide risk and increasing disease severity, although the numbers were small, Jeena K. Sandhu and her colleagues reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Both physical and psychological factors could be involved in the link, wrote Ms. Sandhu, a medical student at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and her coauthors.

“Atopic dermatitis is associated with multiple physical comorbidities, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, metabolic syndrome, and sleep disturbances, which all contribute to the overall physical burden of the disease. Many patients also have a profound psychosocial burden. Because of the visibility of the disease, patients may experience shame, embarrassment, and stigmatization,” they wrote.

But the disease also is associated with high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, and those proteins have been isolated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients who have attempted suicide, the investigators noted. “Treatments targeting cytokines, such as interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, have been shown to decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with atopic dermatitis.”

The investigators plumbed several databases of medical literature, searching for studies that mentioned both atopic dermatitis (AD) and suicide, suicidal ideation, or suicidal behavior. They found 15 studies, published from 1945 to May 2018. Most (13) were cross sectional; the remainder were cohort studies. Together, they comprised a total of 4.7 million subjects, 310,681 of whom had AD. The analysis looked at risks in three areas: suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

Of the studies, 11 investigated suicidal ideation. Pooled data determined that patients with AD were a significant 44% more likely to experience suicidal ideation than those without the disease.

Three studies mentioned suicide attempts and had complete data for pooling. Taken together, they showed a significant 36% increased risk of attempted suicide among patients with AD, compared with those without the disorder.

Two studies investigated the prevalence of completed suicides among patients. One did report a significantly increased risk of 40%, compared with the control group, but it failed to report the number of suicides in the control group. The other study found no increased risk of completed suicides in patients with either mild or moderate to severe disease, compared with controls.

Two studies involved only pediatric patients. One, conducted in Korea, found a significant 23% increased risk of suicidal ideation and a 31% increased risk of attempted suicide. The other failed to find any increased risks in the overall analysis, but did find small increases in the risks of ideation and attempt in girls with AD, compared with healthy controls.

the team concluded. “Dermatology providers may use several tools to screen patients for suicidality. Asking patients about suicidal ideation with a question may be integrated into a patient visit. If a patient screens positive for suicidality, the dermatology provider should send a referral to the patient’s primary care or mental health provider for follow-up care. If the patient reports an orchestrated plan to commit suicide, this patient should be urgently referred to the emergency department for further assessment.”

Ms. Sandhu reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sandhu JK et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566.

Patients with atopic dermatitis might face up to a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation and are 36% more likely to attempt suicide than those without the disorder, a large meta-analysis has determined.

The analysis, which included data from studies published as far back as 1945, also found some correlation of increased suicide risk and increasing disease severity, although the numbers were small, Jeena K. Sandhu and her colleagues reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Both physical and psychological factors could be involved in the link, wrote Ms. Sandhu, a medical student at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and her coauthors.

“Atopic dermatitis is associated with multiple physical comorbidities, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, metabolic syndrome, and sleep disturbances, which all contribute to the overall physical burden of the disease. Many patients also have a profound psychosocial burden. Because of the visibility of the disease, patients may experience shame, embarrassment, and stigmatization,” they wrote.

But the disease also is associated with high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, and those proteins have been isolated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients who have attempted suicide, the investigators noted. “Treatments targeting cytokines, such as interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, have been shown to decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with atopic dermatitis.”

The investigators plumbed several databases of medical literature, searching for studies that mentioned both atopic dermatitis (AD) and suicide, suicidal ideation, or suicidal behavior. They found 15 studies, published from 1945 to May 2018. Most (13) were cross sectional; the remainder were cohort studies. Together, they comprised a total of 4.7 million subjects, 310,681 of whom had AD. The analysis looked at risks in three areas: suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

Of the studies, 11 investigated suicidal ideation. Pooled data determined that patients with AD were a significant 44% more likely to experience suicidal ideation than those without the disease.

Three studies mentioned suicide attempts and had complete data for pooling. Taken together, they showed a significant 36% increased risk of attempted suicide among patients with AD, compared with those without the disorder.

Two studies investigated the prevalence of completed suicides among patients. One did report a significantly increased risk of 40%, compared with the control group, but it failed to report the number of suicides in the control group. The other study found no increased risk of completed suicides in patients with either mild or moderate to severe disease, compared with controls.

Two studies involved only pediatric patients. One, conducted in Korea, found a significant 23% increased risk of suicidal ideation and a 31% increased risk of attempted suicide. The other failed to find any increased risks in the overall analysis, but did find small increases in the risks of ideation and attempt in girls with AD, compared with healthy controls.

the team concluded. “Dermatology providers may use several tools to screen patients for suicidality. Asking patients about suicidal ideation with a question may be integrated into a patient visit. If a patient screens positive for suicidality, the dermatology provider should send a referral to the patient’s primary care or mental health provider for follow-up care. If the patient reports an orchestrated plan to commit suicide, this patient should be urgently referred to the emergency department for further assessment.”

Ms. Sandhu reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sandhu JK et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566.

Patients with atopic dermatitis might face up to a 44% increased risk of suicidal ideation and are 36% more likely to attempt suicide than those without the disorder, a large meta-analysis has determined.

The analysis, which included data from studies published as far back as 1945, also found some correlation of increased suicide risk and increasing disease severity, although the numbers were small, Jeena K. Sandhu and her colleagues reported in JAMA Dermatology.

Both physical and psychological factors could be involved in the link, wrote Ms. Sandhu, a medical student at the University of Missouri–Kansas City, and her coauthors.

“Atopic dermatitis is associated with multiple physical comorbidities, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, metabolic syndrome, and sleep disturbances, which all contribute to the overall physical burden of the disease. Many patients also have a profound psychosocial burden. Because of the visibility of the disease, patients may experience shame, embarrassment, and stigmatization,” they wrote.

But the disease also is associated with high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, and those proteins have been isolated in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients who have attempted suicide, the investigators noted. “Treatments targeting cytokines, such as interleukin-4 and interleukin-13, have been shown to decrease symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with atopic dermatitis.”

The investigators plumbed several databases of medical literature, searching for studies that mentioned both atopic dermatitis (AD) and suicide, suicidal ideation, or suicidal behavior. They found 15 studies, published from 1945 to May 2018. Most (13) were cross sectional; the remainder were cohort studies. Together, they comprised a total of 4.7 million subjects, 310,681 of whom had AD. The analysis looked at risks in three areas: suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

Of the studies, 11 investigated suicidal ideation. Pooled data determined that patients with AD were a significant 44% more likely to experience suicidal ideation than those without the disease.

Three studies mentioned suicide attempts and had complete data for pooling. Taken together, they showed a significant 36% increased risk of attempted suicide among patients with AD, compared with those without the disorder.

Two studies investigated the prevalence of completed suicides among patients. One did report a significantly increased risk of 40%, compared with the control group, but it failed to report the number of suicides in the control group. The other study found no increased risk of completed suicides in patients with either mild or moderate to severe disease, compared with controls.

Two studies involved only pediatric patients. One, conducted in Korea, found a significant 23% increased risk of suicidal ideation and a 31% increased risk of attempted suicide. The other failed to find any increased risks in the overall analysis, but did find small increases in the risks of ideation and attempt in girls with AD, compared with healthy controls.

the team concluded. “Dermatology providers may use several tools to screen patients for suicidality. Asking patients about suicidal ideation with a question may be integrated into a patient visit. If a patient screens positive for suicidality, the dermatology provider should send a referral to the patient’s primary care or mental health provider for follow-up care. If the patient reports an orchestrated plan to commit suicide, this patient should be urgently referred to the emergency department for further assessment.”

Ms. Sandhu reported no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sandhu JK et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts seem to be more common among people with atopic dermatitis than those without the disease.

Major finding: Patients were 44% more likely to have suicidal ideation and 36% more likely to attempt suicide.

Study details: The meta-analysis comprised 15 studies with a total of 4.7 million participants, 310,681 of whom had the disease.

Disclosures: Ms. Sandhu reported no financial disclosures.

Source: Sandhu JK et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Dec 12. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4566.

New worldwide atopic dermatitis survey brings big surprises

PARIS – A major worldwide survey of the 12-month prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) across the course of life provides new insights into global disease trends, Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Among the most important takeaways from this Internet-based survey of more than 273,645 infants, children, and adults in 18 countries across five continents conducted in 2017 was that “global atopic dermatitis prevalence appears to be higher in adults, at 10%, than in younger cohorts, where it’s 4%-8%, which I think is quite provocative and requires further study and confirmation,” said Dr. Silverberg, a dermatologist at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“Let’s keep in mind that there’s this accepted dogma in the literature than atopic dermatitis is somehow only a childhood disorder – it doesn’t affect adults. Well, these data tell a very different story because we’re actually seeing overall highest prevalences throughout the world occurring in adulthood,” based on the U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis (Br J Dermatol. 1994 Sep;131[3]:383-96).

This is the biggest epidemiologic survey ever to examine the 12-month prevalence and severity of AD around the world for both adults and children. Survey respondents included 172,627 adults aged 18 years and older, 34,212 adolescents aged 12-17 years, 54,806 children aged 2-11 years, and more than 12,000 infants.

Key findings from the study include the following:

- AD prevalence rates varied widely from country to country around the world, as well as by age groups (see graphic).

- The highest rate in adults was observed in China. South Korea had the highest rates in both children and adolescents. The top AD rates in infancy occurred in France and the United Kingdom.

- Rates across the age spectrum were consistently lowest in Israel and Switzerland.

“These kinds of patterns raise fascinating questions about the potential risk factors or protective factors that happen in different countries. There are some startling differences in terms of the different regions,” Dr. Silverberg observed. “Certain regions of the world really stand out as having much higher prevalences, particularly China and South Korea, and then as you get into the adult years, Brazil and Mexico, which I think are areas that, at least in the global atopic dermatitis epidemiology community, are not quite as well recognized as being hot spots for atopic dermatitis.”

Indeed, the 12-month prevalence rate of AD among adults was 14% in Mexico and 12% in Brazil, as compared with 13% in Saudi Arabia, 11% in Australia and Spain, 10% in Canada and the United Kingdom, and 9% in the United States.

The prevalence was generally lowest in infants, then jumped substantially within countries during the childhood years, declined slightly in adolescents, and then peaked in adulthood.

AD severity was assessed using PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Oriented Scoring AD measure. Most affected individuals had moderate AD as defined by a PO-SCORAD score of 25-50. Across the age spectrum, the highest proportion of infants with AD who had moderate disease was in China, with 72%. In Taiwan, 63% of children with AD had moderate disease, as did 68% of adolescents and an equal proportion of adults.

In the United Kingdom, 49% percent of infants with AD had severe disease, making that country the world leader in the youngest age group. Severe AD was most common among Turkish children, where 30% of kids with the skin disease had a PO-SCORAD score greater than 50. In Brazil, 31% of adolescents with AD had severe disease, the world’s highest rate in that age group. Among adults with AD, the world’s highest rate of severe disease was 25%, which was seen in the United States, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia.

Across the age spectrum, Japan had a consistently lower-end, overall, 12-month AD prevalence rate of 5%. Germany, Italy, and France had overall rates of 6%, 7%, and 8%, respectively. The rate was 9% in the United States and Canada, and it was 10% in Australia.

Dr. Silverberg performed validation analyses using the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and diagnostic criteria similar to the earlier landmark International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, or ISAAC (Lancet. 1998 Apr 25;351[9111]:1225-32). This was a huge study that excluded the United States, leaving a hole in the epidemiologic picture of the disease that the new survey fills. The validation analyses were supportive of the main findings based on the U.K. Working Party criteria.

Dr. Silverberg reported serving as a consultant to Pfizer, which sponsored the global epidemiologic survey, as well as to roughly a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

bjancin@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Silverberg JI. EADV Congress, Abstract FC01.01.

PARIS – A major worldwide survey of the 12-month prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) across the course of life provides new insights into global disease trends, Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Among the most important takeaways from this Internet-based survey of more than 273,645 infants, children, and adults in 18 countries across five continents conducted in 2017 was that “global atopic dermatitis prevalence appears to be higher in adults, at 10%, than in younger cohorts, where it’s 4%-8%, which I think is quite provocative and requires further study and confirmation,” said Dr. Silverberg, a dermatologist at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“Let’s keep in mind that there’s this accepted dogma in the literature than atopic dermatitis is somehow only a childhood disorder – it doesn’t affect adults. Well, these data tell a very different story because we’re actually seeing overall highest prevalences throughout the world occurring in adulthood,” based on the U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis (Br J Dermatol. 1994 Sep;131[3]:383-96).

This is the biggest epidemiologic survey ever to examine the 12-month prevalence and severity of AD around the world for both adults and children. Survey respondents included 172,627 adults aged 18 years and older, 34,212 adolescents aged 12-17 years, 54,806 children aged 2-11 years, and more than 12,000 infants.

Key findings from the study include the following:

- AD prevalence rates varied widely from country to country around the world, as well as by age groups (see graphic).

- The highest rate in adults was observed in China. South Korea had the highest rates in both children and adolescents. The top AD rates in infancy occurred in France and the United Kingdom.

- Rates across the age spectrum were consistently lowest in Israel and Switzerland.

“These kinds of patterns raise fascinating questions about the potential risk factors or protective factors that happen in different countries. There are some startling differences in terms of the different regions,” Dr. Silverberg observed. “Certain regions of the world really stand out as having much higher prevalences, particularly China and South Korea, and then as you get into the adult years, Brazil and Mexico, which I think are areas that, at least in the global atopic dermatitis epidemiology community, are not quite as well recognized as being hot spots for atopic dermatitis.”

Indeed, the 12-month prevalence rate of AD among adults was 14% in Mexico and 12% in Brazil, as compared with 13% in Saudi Arabia, 11% in Australia and Spain, 10% in Canada and the United Kingdom, and 9% in the United States.

The prevalence was generally lowest in infants, then jumped substantially within countries during the childhood years, declined slightly in adolescents, and then peaked in adulthood.

AD severity was assessed using PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Oriented Scoring AD measure. Most affected individuals had moderate AD as defined by a PO-SCORAD score of 25-50. Across the age spectrum, the highest proportion of infants with AD who had moderate disease was in China, with 72%. In Taiwan, 63% of children with AD had moderate disease, as did 68% of adolescents and an equal proportion of adults.

In the United Kingdom, 49% percent of infants with AD had severe disease, making that country the world leader in the youngest age group. Severe AD was most common among Turkish children, where 30% of kids with the skin disease had a PO-SCORAD score greater than 50. In Brazil, 31% of adolescents with AD had severe disease, the world’s highest rate in that age group. Among adults with AD, the world’s highest rate of severe disease was 25%, which was seen in the United States, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia.

Across the age spectrum, Japan had a consistently lower-end, overall, 12-month AD prevalence rate of 5%. Germany, Italy, and France had overall rates of 6%, 7%, and 8%, respectively. The rate was 9% in the United States and Canada, and it was 10% in Australia.

Dr. Silverberg performed validation analyses using the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and diagnostic criteria similar to the earlier landmark International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, or ISAAC (Lancet. 1998 Apr 25;351[9111]:1225-32). This was a huge study that excluded the United States, leaving a hole in the epidemiologic picture of the disease that the new survey fills. The validation analyses were supportive of the main findings based on the U.K. Working Party criteria.

Dr. Silverberg reported serving as a consultant to Pfizer, which sponsored the global epidemiologic survey, as well as to roughly a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

bjancin@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Silverberg JI. EADV Congress, Abstract FC01.01.

PARIS – A major worldwide survey of the 12-month prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) across the course of life provides new insights into global disease trends, Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Among the most important takeaways from this Internet-based survey of more than 273,645 infants, children, and adults in 18 countries across five continents conducted in 2017 was that “global atopic dermatitis prevalence appears to be higher in adults, at 10%, than in younger cohorts, where it’s 4%-8%, which I think is quite provocative and requires further study and confirmation,” said Dr. Silverberg, a dermatologist at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“Let’s keep in mind that there’s this accepted dogma in the literature than atopic dermatitis is somehow only a childhood disorder – it doesn’t affect adults. Well, these data tell a very different story because we’re actually seeing overall highest prevalences throughout the world occurring in adulthood,” based on the U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis (Br J Dermatol. 1994 Sep;131[3]:383-96).

This is the biggest epidemiologic survey ever to examine the 12-month prevalence and severity of AD around the world for both adults and children. Survey respondents included 172,627 adults aged 18 years and older, 34,212 adolescents aged 12-17 years, 54,806 children aged 2-11 years, and more than 12,000 infants.

Key findings from the study include the following:

- AD prevalence rates varied widely from country to country around the world, as well as by age groups (see graphic).

- The highest rate in adults was observed in China. South Korea had the highest rates in both children and adolescents. The top AD rates in infancy occurred in France and the United Kingdom.

- Rates across the age spectrum were consistently lowest in Israel and Switzerland.

“These kinds of patterns raise fascinating questions about the potential risk factors or protective factors that happen in different countries. There are some startling differences in terms of the different regions,” Dr. Silverberg observed. “Certain regions of the world really stand out as having much higher prevalences, particularly China and South Korea, and then as you get into the adult years, Brazil and Mexico, which I think are areas that, at least in the global atopic dermatitis epidemiology community, are not quite as well recognized as being hot spots for atopic dermatitis.”

Indeed, the 12-month prevalence rate of AD among adults was 14% in Mexico and 12% in Brazil, as compared with 13% in Saudi Arabia, 11% in Australia and Spain, 10% in Canada and the United Kingdom, and 9% in the United States.

The prevalence was generally lowest in infants, then jumped substantially within countries during the childhood years, declined slightly in adolescents, and then peaked in adulthood.

AD severity was assessed using PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Oriented Scoring AD measure. Most affected individuals had moderate AD as defined by a PO-SCORAD score of 25-50. Across the age spectrum, the highest proportion of infants with AD who had moderate disease was in China, with 72%. In Taiwan, 63% of children with AD had moderate disease, as did 68% of adolescents and an equal proportion of adults.

In the United Kingdom, 49% percent of infants with AD had severe disease, making that country the world leader in the youngest age group. Severe AD was most common among Turkish children, where 30% of kids with the skin disease had a PO-SCORAD score greater than 50. In Brazil, 31% of adolescents with AD had severe disease, the world’s highest rate in that age group. Among adults with AD, the world’s highest rate of severe disease was 25%, which was seen in the United States, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia.

Across the age spectrum, Japan had a consistently lower-end, overall, 12-month AD prevalence rate of 5%. Germany, Italy, and France had overall rates of 6%, 7%, and 8%, respectively. The rate was 9% in the United States and Canada, and it was 10% in Australia.

Dr. Silverberg performed validation analyses using the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) and diagnostic criteria similar to the earlier landmark International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, or ISAAC (Lancet. 1998 Apr 25;351[9111]:1225-32). This was a huge study that excluded the United States, leaving a hole in the epidemiologic picture of the disease that the new survey fills. The validation analyses were supportive of the main findings based on the U.K. Working Party criteria.

Dr. Silverberg reported serving as a consultant to Pfizer, which sponsored the global epidemiologic survey, as well as to roughly a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

bjancin@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Silverberg JI. EADV Congress, Abstract FC01.01.

REPORTING FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Worldwide, the 12-month prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) varies substantially but is unexpectedly highest in adults.

Major finding: The global 12-month prevalence of AD in adults is 10%, substantially higher than in infants, children, or adolescents.

Study details: This was an Internet survey of 273,654 subjects conducted in 2017 in 18 countries on five continents.

Disclosures: The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Pfizer, the study sponsor, as well as to roughly a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Silverberg JI. EADV Congress, Abstract FC01.01.

Gestational, umbilical cord vitamin D levels don’t predict atopic disease in offspring

according to study results published in the journal Allergy.

Áine Hennessy, PhD, from the School of Food and Nutritional Sciences at the University College Cork (Ireland), and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort study of 1,537 women in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study who underwent measurement of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) from maternal sera followed by measurement of 25(OH)D in umbilical cord blood (1,050 cases). They then measured the prevalence of eczema, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in infants at aged 2 and 5 years.

The researchers found at 2 years old, 5% of infants had persistent eczema, 4% of infants had a food allergy and 8% of infants had aeroallergen sensitization. At age 5 years, 15% of infants had asthma, while 5% had allergic rhinitis. Mothers whose children went on to have atopy did not differ in their 25(OH)D levels at 15 weeks’ gestation (mean 58.4 nmol/L vs. 58.5 nmol/L) or in the levels in umbilical cord blood (mean 35.2 nmol/L and 35.4 nmol/L).

Of the women in the cohort, 74% ranged in age from 25 to 34 years; 49% reported a personal history of allergy and 37% reported a paternal allergy. The mean birth weight of the infants was 3,458 g; infants were breastfed for mean 11.9 weeks, 73% of infants were breastfeeding by the time they left the hospital and 45% of infants were breastfeeding by age 2 months.

Limitations of the study included that parental atopy status was self-reported and that the researchers noted they did not examine genetic variants of immunoglobulin E synthesis or vitamin D receptor polymorphisms.

“To fully characterize relationships between intrauterine vitamin D exposure and allergic disease, analysis of well‐constructed, large‐scale prospective cohorts of maternal‐infant dyads, which take due consideration of an individual’s inherited risk, early‐life exposures and environmental confounders, is still needed,” Dr. Hennessy and her colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the European Commission, Ireland Health Research Board, National Children’s Research Centre, Food Standards Agency and Science Foundation Ireland. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hennessy A et al. Allergy. 2018 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/all.13590.

according to study results published in the journal Allergy.

Áine Hennessy, PhD, from the School of Food and Nutritional Sciences at the University College Cork (Ireland), and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort study of 1,537 women in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study who underwent measurement of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) from maternal sera followed by measurement of 25(OH)D in umbilical cord blood (1,050 cases). They then measured the prevalence of eczema, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in infants at aged 2 and 5 years.

The researchers found at 2 years old, 5% of infants had persistent eczema, 4% of infants had a food allergy and 8% of infants had aeroallergen sensitization. At age 5 years, 15% of infants had asthma, while 5% had allergic rhinitis. Mothers whose children went on to have atopy did not differ in their 25(OH)D levels at 15 weeks’ gestation (mean 58.4 nmol/L vs. 58.5 nmol/L) or in the levels in umbilical cord blood (mean 35.2 nmol/L and 35.4 nmol/L).

Of the women in the cohort, 74% ranged in age from 25 to 34 years; 49% reported a personal history of allergy and 37% reported a paternal allergy. The mean birth weight of the infants was 3,458 g; infants were breastfed for mean 11.9 weeks, 73% of infants were breastfeeding by the time they left the hospital and 45% of infants were breastfeeding by age 2 months.

Limitations of the study included that parental atopy status was self-reported and that the researchers noted they did not examine genetic variants of immunoglobulin E synthesis or vitamin D receptor polymorphisms.

“To fully characterize relationships between intrauterine vitamin D exposure and allergic disease, analysis of well‐constructed, large‐scale prospective cohorts of maternal‐infant dyads, which take due consideration of an individual’s inherited risk, early‐life exposures and environmental confounders, is still needed,” Dr. Hennessy and her colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the European Commission, Ireland Health Research Board, National Children’s Research Centre, Food Standards Agency and Science Foundation Ireland. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hennessy A et al. Allergy. 2018 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/all.13590.

according to study results published in the journal Allergy.

Áine Hennessy, PhD, from the School of Food and Nutritional Sciences at the University College Cork (Ireland), and her colleagues performed a prospective cohort study of 1,537 women in the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study who underwent measurement of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) from maternal sera followed by measurement of 25(OH)D in umbilical cord blood (1,050 cases). They then measured the prevalence of eczema, food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma in infants at aged 2 and 5 years.

The researchers found at 2 years old, 5% of infants had persistent eczema, 4% of infants had a food allergy and 8% of infants had aeroallergen sensitization. At age 5 years, 15% of infants had asthma, while 5% had allergic rhinitis. Mothers whose children went on to have atopy did not differ in their 25(OH)D levels at 15 weeks’ gestation (mean 58.4 nmol/L vs. 58.5 nmol/L) or in the levels in umbilical cord blood (mean 35.2 nmol/L and 35.4 nmol/L).

Of the women in the cohort, 74% ranged in age from 25 to 34 years; 49% reported a personal history of allergy and 37% reported a paternal allergy. The mean birth weight of the infants was 3,458 g; infants were breastfed for mean 11.9 weeks, 73% of infants were breastfeeding by the time they left the hospital and 45% of infants were breastfeeding by age 2 months.

Limitations of the study included that parental atopy status was self-reported and that the researchers noted they did not examine genetic variants of immunoglobulin E synthesis or vitamin D receptor polymorphisms.

“To fully characterize relationships between intrauterine vitamin D exposure and allergic disease, analysis of well‐constructed, large‐scale prospective cohorts of maternal‐infant dyads, which take due consideration of an individual’s inherited risk, early‐life exposures and environmental confounders, is still needed,” Dr. Hennessy and her colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by grants from the European Commission, Ireland Health Research Board, National Children’s Research Centre, Food Standards Agency and Science Foundation Ireland. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hennessy A et al. Allergy. 2018 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/all.13590.

FROM ALLERGY

Key clinical point: There was no association between prevalence of atopic disease and vitamin D levels measured in maternal sera during pregnancy or in umbilical cord blood.

Major finding: Maternal vitamin D levels at 15 weeks of gestation (mean 58.4 nmol/L vs. 58.5 nmol/L) and concentrations in umbilical cord blood (mean 35.2 nmol/L and 35.4 nmol/L) were not associated with such atopic diseases as eczema, food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinitis in children.

Study details: A prospective group of 1,537 women and infant pairs from the Cork BASELINE Birth Cohort Study.

Disclosures: This study was funded by grants from the European Commission, Ireland Health Research Board, National Children’s Research Centre, Food Standards Agency and Science Foundation Ireland. The authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Hennessy A et al. Allergy 2018 Aug 7. doi:10.1111/all.13590.

Allergy Testing in Dermatology and Beyond

Allergy testing typically refers to evaluation of a patient for suspected type I or type IV hypersensitivity.1,2 The possibility of type I hypersensitivity is raised in patients presenting with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and immediate adverse reactions to medications, whereas type IV hypersensitivity is suspected in patients with eczematous eruptions, delayed adverse cutaneous reactions to medications, and failure of metallic implants (eg, metal joint replacements, cardiac stents) in conjunction with overlying skin rashes (Table 1).1-5 Type II (eg, pemphigus vulgaris) and type III (eg, IgA vasculitis) hypersensitivities are not evaluated with screening allergy tests.

Type I Sensitization

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate hypersensitivity mediated predominantly by IgE activation of mast cells in the skin as well as the respiratory and gastric mucosa.1 Sensitization of an individual patient occurs when antigen-presenting cells induce a helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response leading to B-cell class switching and allergen-specific IgE production. Upon repeat exposure to the allergen, circulating antibodies then bind to high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils and initiate an allergic inflammatory response, leading to a clinical presentation of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or immediate drug reactions. Confirming type I sensitization may be performed via serologic (in vitro) or skin testing (in vivo).5,6

Serologic Testing (In Vitro)

Serologic testing is a blood test that detects circulating IgE levels against specific allergens.5 The first such test, the radioallergosorbent test, was introduced in the 1970s but is not quantitative and is no longer used. Although common, it is inaccurate to describe current serum IgE (s-IgE) testing as radioallergosorbent testing. There are several US Food and Drug Administration-approved s-IgE assays in common use, and these tests may be helpful in elucidating relevant allergens and for tailoring therapy appropriately, which may consist of avoidance of certain foods or environmental agents and/or allergen immunotherapy.

Skin Testing (In Vivo)

Skin testing can be performed percutaneously (eg, percutaneous skin testing) or intradermally (eg, intradermal testing).6 Percutaneous skin testing is performed by placing a drop of allergen extract on the skin, after which a lancet is used to lightly scratch the skin; intradermal testing is performed by injecting a small amount of allergen extract into the dermis. In both cases, the skin is evaluated after 15 to 20 minutes for the presence and size of a cutaneous wheal. Medications with antihistaminergic activity must be discontinued prior to testing. Both s-IgE and skin testing assess for type I hypersensitivity, and factors such as extensive rash, concern for anaphylaxis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines may favor s-IgE testing versus skin testing. False-positive results can occur with both tests, and for this reason, test results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical examination and patient history to determine relevant allergies.

Type IV Sensitization

Type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed hypersensitivity mediated primarily by lymphocytes.2 Sensitization occurs when haptens bind to host proteins and are presented by epidermal and dermal dendritic cells to T lymphocytes in the skin. These lymphocytes then migrate to regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are produced and home back to the skin. Upon reexposure to the allergen, these memory T lymphocytes become activated and incite a delayed allergic response. Confirming type IV hypersensitivity primarily is accomplished via patch testing, though other testing modalities exist.

Skin Biopsy

Biopsy is sometimes performed in the workup of an individual presenting with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and typically will show spongiosis with normal stratum corneum and epidermal thickness in the setting of acute ACD and mild to marked acanthosis and parakeratosis in chronic ACD.7 The findings, however, are nonspecific and the differential of these histopathologic findings encompasses nummular dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. The presence of eosinophils and Langerhans cell microabscesses may provide supportive evidence for ACD over the other spongiotic dermatitides.7,8

Patch Testing

Patch testing is the gold standard in diagnosing type IV hypersensitivities resulting in a clinical presentation of ACD. Hundreds of allergens are commercially available for patch testing, and more commonly tested allergens fall into one of several categories, such as cosmetic preservatives, rubbers, metals, textiles, fragrances, adhesives, antibiotics, plants, and even corticosteroids. Of note, a common misconception is that ACD must result from new exposures; however, patients may develop ACD secondary to an exposure or product they have been using for many years without a problem.

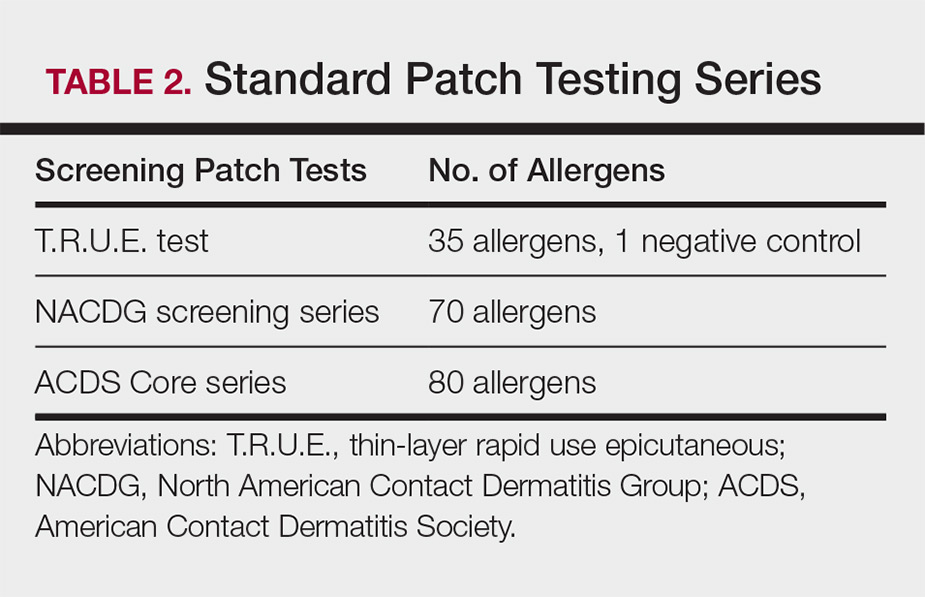

Three commonly used screening series are the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series, and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 80 allergen series, which have some variation in the type and number of allergens included (Table 2). The T.R.U.E. test will miss a notable number of clinically relevant allergens in comparison to the North American Contact Dermatitis Group and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core series, and it may be of particularly low utility in identifying fragrance or preservative ACD.9

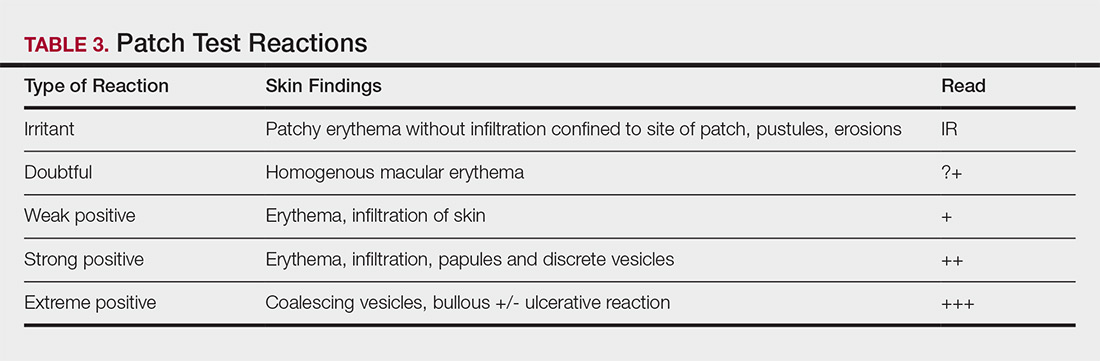

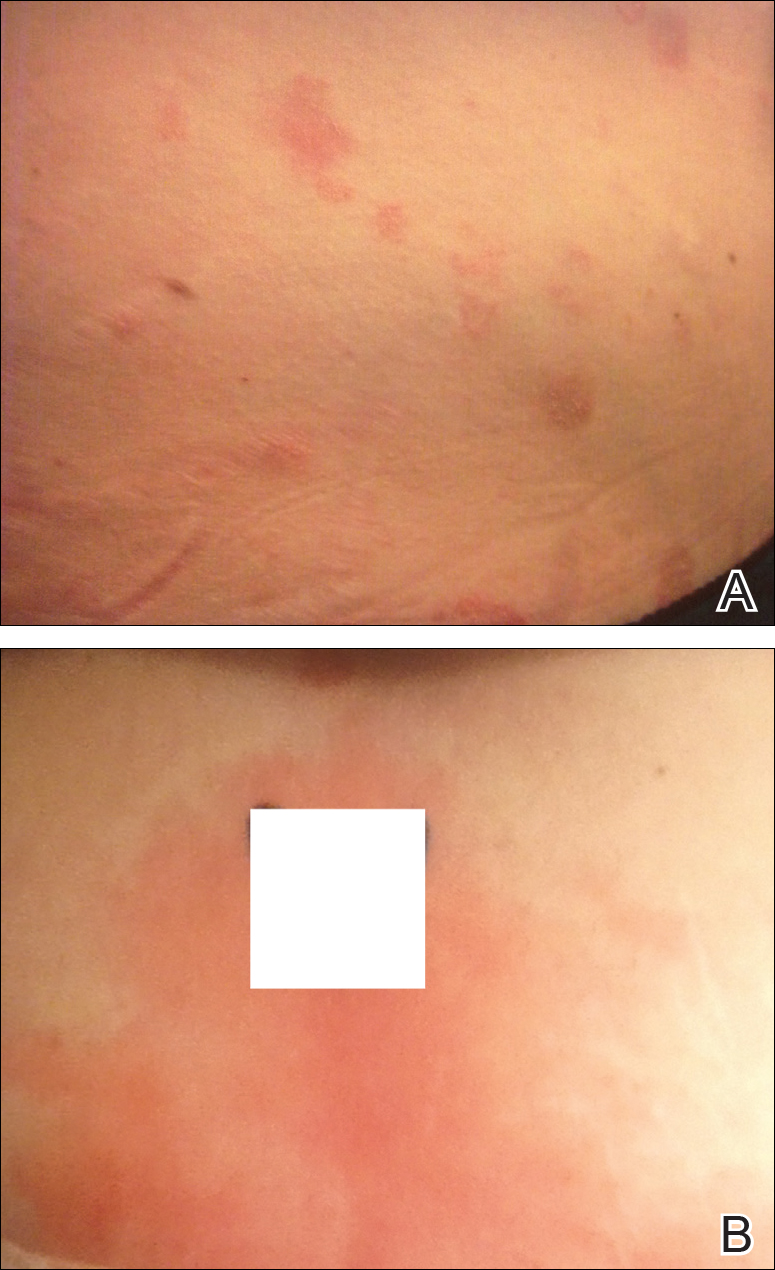

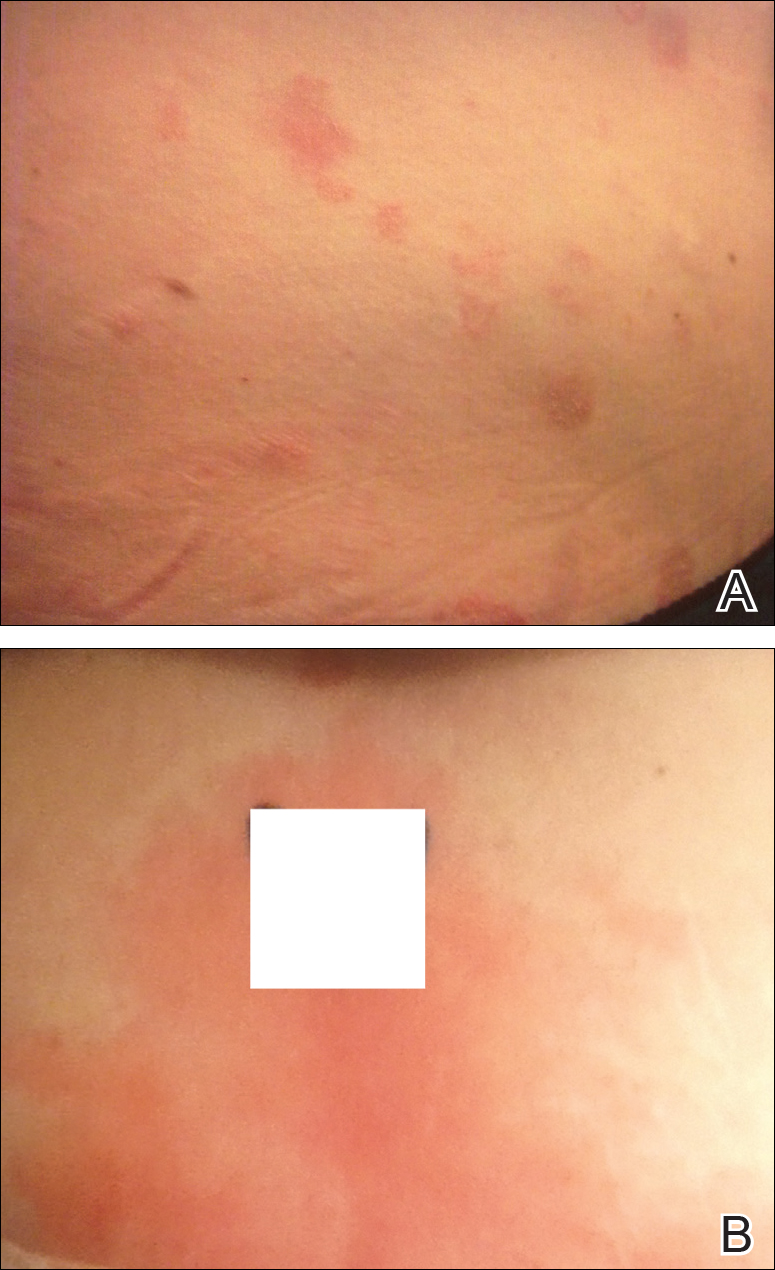

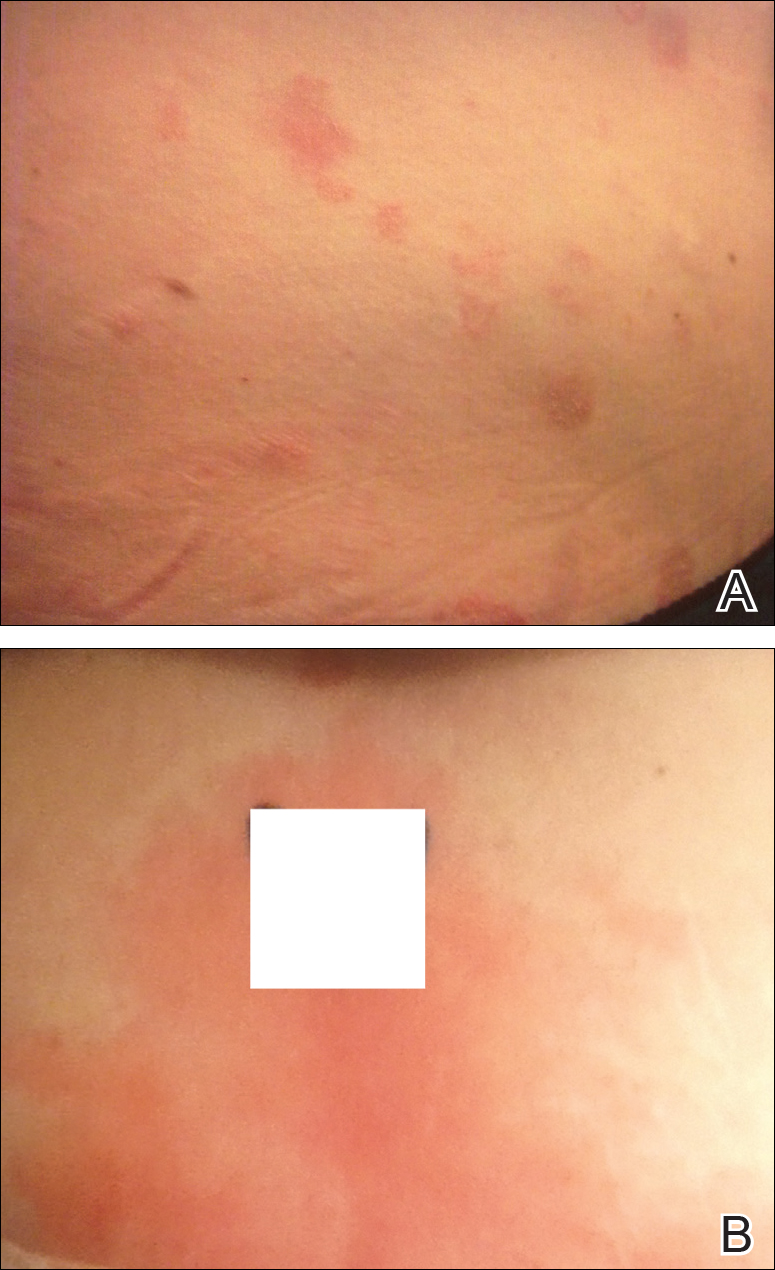

Allergens are placed on the back in chambers in a petrolatum or aqueous medium. The patches remain affixed for 48 hours, during which time the patient is asked to refrain from showering or exercising to prevent loss of patches. The patient's skin is then evaluated for reactions to allergens on 2 separate occasions: at the time of patch removal 48 hours after initial placement, then the areas of patches are marked for delayed readings at day 4 to day 7 after initial patch placement. Results are scored based on the degree of the inflammatory reaction (Table 3). Delayed readings beyond day 7 may be necessary for metals, specific preservatives (eg, dodecyl gallate, propolis), and neomycin.10

There is a wide spectrum of cutaneous disease that should prompt consideration of patch testing, including well-circumscribed eczematous dermatitis (eg, recurrent lip, hand, and foot dermatitis); patchy or diffuse eczema, especially if recently worsened and/or unresponsive to topical steroids; lichenoid eruptions, particularly of mucosal surfaces; mucous membrane eruptions (eg, stomatitis, vulvitis); and eczematous presentations that raise concern for airborne (photodistributed) or systemic contact dermatitis.11-13 Although further studies of efficacy and safety are ongoing, patch testing also may be useful in the diagnosis of nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions, especially fixed drug eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, systemic contact dermatitis from medications, and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.3 Lastly, patients with type IV hypersensitivity to metals, adhesives, or antibiotics used in metallic orthopedic or cardiac implants may experience implant failure, regional contact dermatitis, or both, and benefit from patch testing prior to implant replacement to assess for potential allergens. Of the joints that fail, it is estimated that up to 5% are due to metal hypersensitivity.4

Throughout patch testing, patients may continue to manage their skin condition with oral antihistamines and topical steroids, though application to the site at which the patches are applied should be avoided throughout patch testing and during the week prior. According to expert consensus, immunosuppressive medications that are less likely to impact patch testing and therefore may be continued include low-dose methotrexate, oral prednisone less than 10 mg daily, biologic therapy, and low-dose cyclosporine (<2 mg/kg daily). Therapeutic interventions that are more likely to impact patch testing and should be avoided include phototherapy or extensive sun exposure within a week prior to testing, oral prednisone more than 10 mg daily, intramuscular triamcinolone within the preceding month, and high-dose cyclosporine (>2 mg/kg daily).14

An important component to successful patch testing is posttest patient counseling. Providers can create a safe list of products for patients by logging onto the American Contact Dermatitis Society website and accessing the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP).15 All relevant allergens found on patch testing may be selected and patient-specific identification codes generated. Once these codes are entered into the CAMP app on the patient's cellular device, a personalized, regularly updated list of safe products appears for many categories of products, including shampoos, sunscreens, moisturizers, cosmetic products, and laundry or dish detergents, among others. Of note, this app is not helpful for avoidance in patients with textile allergies. Patients should be counseled that improvement occurs with avoidance, which usually occurs within weeks but may slowly occur over time in some cases.

Lymphocyte Transformation Test (In Vitro)

The lymphocyte transformation test is an experimental in vitro test for type IV hypersensitivity. This serologic test utilizes allergens to stimulate memory T lymphocytes in vitro and measures the degree of response to the allergen. Although this test has generated excitement, particularly for the potential to safely evaluate for severe adverse cutaneous drug reactions, it currently is not the standard of care and is not utilized in the United States.16

Conclusion

Dermatologists play a vital role in the workup of suspected type IV hypersensitivities. Patch testing is an important but underutilized tool in the arsenal of allergy testing and may be indicated in a wide variety of cutaneous presentations, adverse reactions to medications, and implanted device failures. Identification and avoidance of a culprit allergen has the potential to lead to complete resolution of disease and notable improvement in quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nina Botto, MD (San Francisco, California), for her mentorship in the arena of ACD as well as the Women's Dermatologic Society for the support they provided through the mentorship program.

- Oettgen H, Broide DH. Introduction to the mechanisms of allergic disease. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1-32.

- Werfel T, Kapp A. Atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:263-286.

- Zinn A, Gayam S, Chelliah MP, et al. Patch testing for nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:421-423.

- Thyssen JP, Menne T, Schalock PC, et al. Pragmatic approach to the clinical work-up of patients with putative allergic disease to metallic orthopaedic implants before and after surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:473-478.

- Cox L. Overview of serological-specific IgE antibody testing in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:447-453.

- Dolen WK. Skin testing and immunoassays for allergen-specific IgE. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001;21:229-239.

- Keeling BH, Gavino AC, Gavino AC. Skin biopsy, the allergists' tool: how to interpret a report. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:62.

- Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Belsito DV. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2013-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:33-46.

- Davis MD, Bhate K, Rohlinger AL, et al. Delayed patch test reading after 5 days: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:225-233.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson RT. The profile of a patient with contact dermatitis and a suspicion of contact allergy (history, physical characteristics, and dermatology-specific quality of life). Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:26-31.

- Huygens S, Goossens A. An update on airborne contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:1-6.

- Salam TN, Fowler JF. Balsam-related systemic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:377-381.

- Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Zirwas M, et al. Effects of immunomodulatory agents on patch testing: expert opinion 2012. Dermatitis. 2012;23:301-303.

- ACDS CAMP. American Contact Dermatitis Society website. https://www.contactderm.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3489. Accessed November 14, 2018.

- Popple A, Williams J, Maxwell G, et al. The lymphocyte transformation test in allergic contact dermatitis: new opportunities. J Immunotoxicol. 2016;13:84-91.

Allergy testing typically refers to evaluation of a patient for suspected type I or type IV hypersensitivity.1,2 The possibility of type I hypersensitivity is raised in patients presenting with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and immediate adverse reactions to medications, whereas type IV hypersensitivity is suspected in patients with eczematous eruptions, delayed adverse cutaneous reactions to medications, and failure of metallic implants (eg, metal joint replacements, cardiac stents) in conjunction with overlying skin rashes (Table 1).1-5 Type II (eg, pemphigus vulgaris) and type III (eg, IgA vasculitis) hypersensitivities are not evaluated with screening allergy tests.

Type I Sensitization

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate hypersensitivity mediated predominantly by IgE activation of mast cells in the skin as well as the respiratory and gastric mucosa.1 Sensitization of an individual patient occurs when antigen-presenting cells induce a helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response leading to B-cell class switching and allergen-specific IgE production. Upon repeat exposure to the allergen, circulating antibodies then bind to high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils and initiate an allergic inflammatory response, leading to a clinical presentation of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or immediate drug reactions. Confirming type I sensitization may be performed via serologic (in vitro) or skin testing (in vivo).5,6

Serologic Testing (In Vitro)

Serologic testing is a blood test that detects circulating IgE levels against specific allergens.5 The first such test, the radioallergosorbent test, was introduced in the 1970s but is not quantitative and is no longer used. Although common, it is inaccurate to describe current serum IgE (s-IgE) testing as radioallergosorbent testing. There are several US Food and Drug Administration-approved s-IgE assays in common use, and these tests may be helpful in elucidating relevant allergens and for tailoring therapy appropriately, which may consist of avoidance of certain foods or environmental agents and/or allergen immunotherapy.

Skin Testing (In Vivo)

Skin testing can be performed percutaneously (eg, percutaneous skin testing) or intradermally (eg, intradermal testing).6 Percutaneous skin testing is performed by placing a drop of allergen extract on the skin, after which a lancet is used to lightly scratch the skin; intradermal testing is performed by injecting a small amount of allergen extract into the dermis. In both cases, the skin is evaluated after 15 to 20 minutes for the presence and size of a cutaneous wheal. Medications with antihistaminergic activity must be discontinued prior to testing. Both s-IgE and skin testing assess for type I hypersensitivity, and factors such as extensive rash, concern for anaphylaxis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines may favor s-IgE testing versus skin testing. False-positive results can occur with both tests, and for this reason, test results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical examination and patient history to determine relevant allergies.

Type IV Sensitization

Type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed hypersensitivity mediated primarily by lymphocytes.2 Sensitization occurs when haptens bind to host proteins and are presented by epidermal and dermal dendritic cells to T lymphocytes in the skin. These lymphocytes then migrate to regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are produced and home back to the skin. Upon reexposure to the allergen, these memory T lymphocytes become activated and incite a delayed allergic response. Confirming type IV hypersensitivity primarily is accomplished via patch testing, though other testing modalities exist.

Skin Biopsy

Biopsy is sometimes performed in the workup of an individual presenting with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and typically will show spongiosis with normal stratum corneum and epidermal thickness in the setting of acute ACD and mild to marked acanthosis and parakeratosis in chronic ACD.7 The findings, however, are nonspecific and the differential of these histopathologic findings encompasses nummular dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. The presence of eosinophils and Langerhans cell microabscesses may provide supportive evidence for ACD over the other spongiotic dermatitides.7,8

Patch Testing

Patch testing is the gold standard in diagnosing type IV hypersensitivities resulting in a clinical presentation of ACD. Hundreds of allergens are commercially available for patch testing, and more commonly tested allergens fall into one of several categories, such as cosmetic preservatives, rubbers, metals, textiles, fragrances, adhesives, antibiotics, plants, and even corticosteroids. Of note, a common misconception is that ACD must result from new exposures; however, patients may develop ACD secondary to an exposure or product they have been using for many years without a problem.

Three commonly used screening series are the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series, and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 80 allergen series, which have some variation in the type and number of allergens included (Table 2). The T.R.U.E. test will miss a notable number of clinically relevant allergens in comparison to the North American Contact Dermatitis Group and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core series, and it may be of particularly low utility in identifying fragrance or preservative ACD.9

Allergens are placed on the back in chambers in a petrolatum or aqueous medium. The patches remain affixed for 48 hours, during which time the patient is asked to refrain from showering or exercising to prevent loss of patches. The patient's skin is then evaluated for reactions to allergens on 2 separate occasions: at the time of patch removal 48 hours after initial placement, then the areas of patches are marked for delayed readings at day 4 to day 7 after initial patch placement. Results are scored based on the degree of the inflammatory reaction (Table 3). Delayed readings beyond day 7 may be necessary for metals, specific preservatives (eg, dodecyl gallate, propolis), and neomycin.10

There is a wide spectrum of cutaneous disease that should prompt consideration of patch testing, including well-circumscribed eczematous dermatitis (eg, recurrent lip, hand, and foot dermatitis); patchy or diffuse eczema, especially if recently worsened and/or unresponsive to topical steroids; lichenoid eruptions, particularly of mucosal surfaces; mucous membrane eruptions (eg, stomatitis, vulvitis); and eczematous presentations that raise concern for airborne (photodistributed) or systemic contact dermatitis.11-13 Although further studies of efficacy and safety are ongoing, patch testing also may be useful in the diagnosis of nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions, especially fixed drug eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, systemic contact dermatitis from medications, and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.3 Lastly, patients with type IV hypersensitivity to metals, adhesives, or antibiotics used in metallic orthopedic or cardiac implants may experience implant failure, regional contact dermatitis, or both, and benefit from patch testing prior to implant replacement to assess for potential allergens. Of the joints that fail, it is estimated that up to 5% are due to metal hypersensitivity.4

Throughout patch testing, patients may continue to manage their skin condition with oral antihistamines and topical steroids, though application to the site at which the patches are applied should be avoided throughout patch testing and during the week prior. According to expert consensus, immunosuppressive medications that are less likely to impact patch testing and therefore may be continued include low-dose methotrexate, oral prednisone less than 10 mg daily, biologic therapy, and low-dose cyclosporine (<2 mg/kg daily). Therapeutic interventions that are more likely to impact patch testing and should be avoided include phototherapy or extensive sun exposure within a week prior to testing, oral prednisone more than 10 mg daily, intramuscular triamcinolone within the preceding month, and high-dose cyclosporine (>2 mg/kg daily).14

An important component to successful patch testing is posttest patient counseling. Providers can create a safe list of products for patients by logging onto the American Contact Dermatitis Society website and accessing the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP).15 All relevant allergens found on patch testing may be selected and patient-specific identification codes generated. Once these codes are entered into the CAMP app on the patient's cellular device, a personalized, regularly updated list of safe products appears for many categories of products, including shampoos, sunscreens, moisturizers, cosmetic products, and laundry or dish detergents, among others. Of note, this app is not helpful for avoidance in patients with textile allergies. Patients should be counseled that improvement occurs with avoidance, which usually occurs within weeks but may slowly occur over time in some cases.

Lymphocyte Transformation Test (In Vitro)

The lymphocyte transformation test is an experimental in vitro test for type IV hypersensitivity. This serologic test utilizes allergens to stimulate memory T lymphocytes in vitro and measures the degree of response to the allergen. Although this test has generated excitement, particularly for the potential to safely evaluate for severe adverse cutaneous drug reactions, it currently is not the standard of care and is not utilized in the United States.16

Conclusion

Dermatologists play a vital role in the workup of suspected type IV hypersensitivities. Patch testing is an important but underutilized tool in the arsenal of allergy testing and may be indicated in a wide variety of cutaneous presentations, adverse reactions to medications, and implanted device failures. Identification and avoidance of a culprit allergen has the potential to lead to complete resolution of disease and notable improvement in quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nina Botto, MD (San Francisco, California), for her mentorship in the arena of ACD as well as the Women's Dermatologic Society for the support they provided through the mentorship program.

Allergy testing typically refers to evaluation of a patient for suspected type I or type IV hypersensitivity.1,2 The possibility of type I hypersensitivity is raised in patients presenting with food allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and immediate adverse reactions to medications, whereas type IV hypersensitivity is suspected in patients with eczematous eruptions, delayed adverse cutaneous reactions to medications, and failure of metallic implants (eg, metal joint replacements, cardiac stents) in conjunction with overlying skin rashes (Table 1).1-5 Type II (eg, pemphigus vulgaris) and type III (eg, IgA vasculitis) hypersensitivities are not evaluated with screening allergy tests.

Type I Sensitization

Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate hypersensitivity mediated predominantly by IgE activation of mast cells in the skin as well as the respiratory and gastric mucosa.1 Sensitization of an individual patient occurs when antigen-presenting cells induce a helper T cell (TH2) cytokine response leading to B-cell class switching and allergen-specific IgE production. Upon repeat exposure to the allergen, circulating antibodies then bind to high-affinity receptors on mast cells and basophils and initiate an allergic inflammatory response, leading to a clinical presentation of allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or immediate drug reactions. Confirming type I sensitization may be performed via serologic (in vitro) or skin testing (in vivo).5,6

Serologic Testing (In Vitro)

Serologic testing is a blood test that detects circulating IgE levels against specific allergens.5 The first such test, the radioallergosorbent test, was introduced in the 1970s but is not quantitative and is no longer used. Although common, it is inaccurate to describe current serum IgE (s-IgE) testing as radioallergosorbent testing. There are several US Food and Drug Administration-approved s-IgE assays in common use, and these tests may be helpful in elucidating relevant allergens and for tailoring therapy appropriately, which may consist of avoidance of certain foods or environmental agents and/or allergen immunotherapy.

Skin Testing (In Vivo)

Skin testing can be performed percutaneously (eg, percutaneous skin testing) or intradermally (eg, intradermal testing).6 Percutaneous skin testing is performed by placing a drop of allergen extract on the skin, after which a lancet is used to lightly scratch the skin; intradermal testing is performed by injecting a small amount of allergen extract into the dermis. In both cases, the skin is evaluated after 15 to 20 minutes for the presence and size of a cutaneous wheal. Medications with antihistaminergic activity must be discontinued prior to testing. Both s-IgE and skin testing assess for type I hypersensitivity, and factors such as extensive rash, concern for anaphylaxis, or inability to discontinue antihistamines may favor s-IgE testing versus skin testing. False-positive results can occur with both tests, and for this reason, test results should always be interpreted in conjunction with clinical examination and patient history to determine relevant allergies.

Type IV Sensitization

Type IV hypersensitivity is a delayed hypersensitivity mediated primarily by lymphocytes.2 Sensitization occurs when haptens bind to host proteins and are presented by epidermal and dermal dendritic cells to T lymphocytes in the skin. These lymphocytes then migrate to regional lymph nodes where antigen-specific T lymphocytes are produced and home back to the skin. Upon reexposure to the allergen, these memory T lymphocytes become activated and incite a delayed allergic response. Confirming type IV hypersensitivity primarily is accomplished via patch testing, though other testing modalities exist.

Skin Biopsy

Biopsy is sometimes performed in the workup of an individual presenting with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) and typically will show spongiosis with normal stratum corneum and epidermal thickness in the setting of acute ACD and mild to marked acanthosis and parakeratosis in chronic ACD.7 The findings, however, are nonspecific and the differential of these histopathologic findings encompasses nummular dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, irritant contact dermatitis, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. The presence of eosinophils and Langerhans cell microabscesses may provide supportive evidence for ACD over the other spongiotic dermatitides.7,8

Patch Testing

Patch testing is the gold standard in diagnosing type IV hypersensitivities resulting in a clinical presentation of ACD. Hundreds of allergens are commercially available for patch testing, and more commonly tested allergens fall into one of several categories, such as cosmetic preservatives, rubbers, metals, textiles, fragrances, adhesives, antibiotics, plants, and even corticosteroids. Of note, a common misconception is that ACD must result from new exposures; however, patients may develop ACD secondary to an exposure or product they have been using for many years without a problem.

Three commonly used screening series are the thin-layer rapid use epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (SmartPractice), North American Contact Dermatitis Group screening series, and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 80 allergen series, which have some variation in the type and number of allergens included (Table 2). The T.R.U.E. test will miss a notable number of clinically relevant allergens in comparison to the North American Contact Dermatitis Group and American Contact Dermatitis Society Core series, and it may be of particularly low utility in identifying fragrance or preservative ACD.9

Allergens are placed on the back in chambers in a petrolatum or aqueous medium. The patches remain affixed for 48 hours, during which time the patient is asked to refrain from showering or exercising to prevent loss of patches. The patient's skin is then evaluated for reactions to allergens on 2 separate occasions: at the time of patch removal 48 hours after initial placement, then the areas of patches are marked for delayed readings at day 4 to day 7 after initial patch placement. Results are scored based on the degree of the inflammatory reaction (Table 3). Delayed readings beyond day 7 may be necessary for metals, specific preservatives (eg, dodecyl gallate, propolis), and neomycin.10

There is a wide spectrum of cutaneous disease that should prompt consideration of patch testing, including well-circumscribed eczematous dermatitis (eg, recurrent lip, hand, and foot dermatitis); patchy or diffuse eczema, especially if recently worsened and/or unresponsive to topical steroids; lichenoid eruptions, particularly of mucosal surfaces; mucous membrane eruptions (eg, stomatitis, vulvitis); and eczematous presentations that raise concern for airborne (photodistributed) or systemic contact dermatitis.11-13 Although further studies of efficacy and safety are ongoing, patch testing also may be useful in the diagnosis of nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions, especially fixed drug eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, systemic contact dermatitis from medications, and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.3 Lastly, patients with type IV hypersensitivity to metals, adhesives, or antibiotics used in metallic orthopedic or cardiac implants may experience implant failure, regional contact dermatitis, or both, and benefit from patch testing prior to implant replacement to assess for potential allergens. Of the joints that fail, it is estimated that up to 5% are due to metal hypersensitivity.4

Throughout patch testing, patients may continue to manage their skin condition with oral antihistamines and topical steroids, though application to the site at which the patches are applied should be avoided throughout patch testing and during the week prior. According to expert consensus, immunosuppressive medications that are less likely to impact patch testing and therefore may be continued include low-dose methotrexate, oral prednisone less than 10 mg daily, biologic therapy, and low-dose cyclosporine (<2 mg/kg daily). Therapeutic interventions that are more likely to impact patch testing and should be avoided include phototherapy or extensive sun exposure within a week prior to testing, oral prednisone more than 10 mg daily, intramuscular triamcinolone within the preceding month, and high-dose cyclosporine (>2 mg/kg daily).14

An important component to successful patch testing is posttest patient counseling. Providers can create a safe list of products for patients by logging onto the American Contact Dermatitis Society website and accessing the Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP).15 All relevant allergens found on patch testing may be selected and patient-specific identification codes generated. Once these codes are entered into the CAMP app on the patient's cellular device, a personalized, regularly updated list of safe products appears for many categories of products, including shampoos, sunscreens, moisturizers, cosmetic products, and laundry or dish detergents, among others. Of note, this app is not helpful for avoidance in patients with textile allergies. Patients should be counseled that improvement occurs with avoidance, which usually occurs within weeks but may slowly occur over time in some cases.

Lymphocyte Transformation Test (In Vitro)

The lymphocyte transformation test is an experimental in vitro test for type IV hypersensitivity. This serologic test utilizes allergens to stimulate memory T lymphocytes in vitro and measures the degree of response to the allergen. Although this test has generated excitement, particularly for the potential to safely evaluate for severe adverse cutaneous drug reactions, it currently is not the standard of care and is not utilized in the United States.16

Conclusion

Dermatologists play a vital role in the workup of suspected type IV hypersensitivities. Patch testing is an important but underutilized tool in the arsenal of allergy testing and may be indicated in a wide variety of cutaneous presentations, adverse reactions to medications, and implanted device failures. Identification and avoidance of a culprit allergen has the potential to lead to complete resolution of disease and notable improvement in quality of life for patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Nina Botto, MD (San Francisco, California), for her mentorship in the arena of ACD as well as the Women's Dermatologic Society for the support they provided through the mentorship program.

- Oettgen H, Broide DH. Introduction to the mechanisms of allergic disease. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1-32.

- Werfel T, Kapp A. Atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:263-286.

- Zinn A, Gayam S, Chelliah MP, et al. Patch testing for nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:421-423.

- Thyssen JP, Menne T, Schalock PC, et al. Pragmatic approach to the clinical work-up of patients with putative allergic disease to metallic orthopaedic implants before and after surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:473-478.

- Cox L. Overview of serological-specific IgE antibody testing in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:447-453.

- Dolen WK. Skin testing and immunoassays for allergen-specific IgE. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001;21:229-239.

- Keeling BH, Gavino AC, Gavino AC. Skin biopsy, the allergists' tool: how to interpret a report. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:62.

- Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Belsito DV. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2013-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:33-46.

- Davis MD, Bhate K, Rohlinger AL, et al. Delayed patch test reading after 5 days: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:225-233.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson RT. The profile of a patient with contact dermatitis and a suspicion of contact allergy (history, physical characteristics, and dermatology-specific quality of life). Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:26-31.

- Huygens S, Goossens A. An update on airborne contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:1-6.

- Salam TN, Fowler JF. Balsam-related systemic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:377-381.

- Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Zirwas M, et al. Effects of immunomodulatory agents on patch testing: expert opinion 2012. Dermatitis. 2012;23:301-303.

- ACDS CAMP. American Contact Dermatitis Society website. https://www.contactderm.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3489. Accessed November 14, 2018.

- Popple A, Williams J, Maxwell G, et al. The lymphocyte transformation test in allergic contact dermatitis: new opportunities. J Immunotoxicol. 2016;13:84-91.

- Oettgen H, Broide DH. Introduction to the mechanisms of allergic disease. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1-32.

- Werfel T, Kapp A. Atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis. In: Holgate ST, Church MK, Broide DH, et al, eds. Allergy. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:263-286.

- Zinn A, Gayam S, Chelliah MP, et al. Patch testing for nonimmediate cutaneous adverse drug reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:421-423.

- Thyssen JP, Menne T, Schalock PC, et al. Pragmatic approach to the clinical work-up of patients with putative allergic disease to metallic orthopaedic implants before and after surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:473-478.

- Cox L. Overview of serological-specific IgE antibody testing in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11:447-453.

- Dolen WK. Skin testing and immunoassays for allergen-specific IgE. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2001;21:229-239.

- Keeling BH, Gavino AC, Gavino AC. Skin biopsy, the allergists' tool: how to interpret a report. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:62.

- Rosa G, Fernandez AP, Vij A, et al. Langerhans cell collections, but not eosinophils, are clues to a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis in appropriate skin biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:498-504.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Belsito DV. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results 2013-2014. Dermatitis. 2017;28:33-46.

- Davis MD, Bhate K, Rohlinger AL, et al. Delayed patch test reading after 5 days: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:225-233.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson RT. The profile of a patient with contact dermatitis and a suspicion of contact allergy (history, physical characteristics, and dermatology-specific quality of life). Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:26-31.

- Huygens S, Goossens A. An update on airborne contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:1-6.

- Salam TN, Fowler JF. Balsam-related systemic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:377-381.

- Fowler JF, Maibach HI, Zirwas M, et al. Effects of immunomodulatory agents on patch testing: expert opinion 2012. Dermatitis. 2012;23:301-303.

- ACDS CAMP. American Contact Dermatitis Society website. https://www.contactderm.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3489. Accessed November 14, 2018.

- Popple A, Williams J, Maxwell G, et al. The lymphocyte transformation test in allergic contact dermatitis: new opportunities. J Immunotoxicol. 2016;13:84-91.

Review of pediatric data indicates link between vitamin D levels and atopic dermatitis severity

in the majority of studies, but evidence on whether supplementation can improve symptoms of the condition was inconsistent.

The data on the effect of vitamin D supplementation on AD severity “suggested potential benefit but were conflicting,” concluded Christina M. Huang, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, and her coinvestigators from the department of dermatology, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. They reported the results of their systematic review of 21 studies published between 2008 and 2017, which included quantitative data on serum vitamin D levels or vitamin D supplementation and AD severity in patients aged 18 years or younger, in Pediatrics.

In the review, 16 studies explored the relationship between serum vitamin D status and disease severity (one was a randomized controlled trial; the rest were cohort, cross-sectional, or case control studies) in 1,847 children (average age, 5.6 years). Disease severity was measured with the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) system. In 10 of the 16 studies, there was a significant inverse association between vitamin D levels and AD severity.

The studies that supported this association generally had larger sample sizes, which, the authors pointed out, suggested they were of higher quality and more reliable. However, the randomized controlled study of 89 children did not find a correlation, although in the study, vitamin D level and AD severity was a secondary outcome.

The randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation used lower SCORAD cut-offs for the different severities of AD, which complicated interpretation the results, “as it may indicate that the severities reported in these articles were exaggerated as compared to other studies,” they wrote.

Six studies – four randomized controlled trials (including the study that was among the 16 studies on vitamin D and severity) and two cohort studies – with 354 participants (average age, 6.8 years) looked at the effects of oral vitamin D supplementation on the severity of AD, although dosage and duration of use varied across the studies. In four of the six studies, there were significant improvement in AD in patients given supplements, but the data were “conflicting,” partly because the largest study showing benefit used a different measure of disease severity, the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), not SCORAD. “The inconsistency of tools used to measure outcomes makes it difficult to compare and understand results,” so the effects of vitamin D supplementation “are controversial and should be interpreted with caution, as certain patient populations may benefit more than others,” the authors wrote.

They also drew attention to previous research suggesting that vitamin D supplementation in the first year of life might actually increase the risk of AD in children. “Therefore, although there is a growing body of evidence supporting the beneficial effects of VD [vitamin D] supplementation, the age at which supplementation is given should be considered carefully.” The authors added that the inconclusive findings “may have been due to confounding factors that were not accounted for, such as age, season, latitude, dose, and duration. It is also possible that the lack of a true effect of VD may be contributing to the inconsistent results. Future large‐scale RCTs with consideration of these factors are needed.”

Funding and conflict of interest disclosures were not included in the study.

SOURCE: Huang C et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35: 754-60. doi: 10.1111/pde.13639.

in the majority of studies, but evidence on whether supplementation can improve symptoms of the condition was inconsistent.

The data on the effect of vitamin D supplementation on AD severity “suggested potential benefit but were conflicting,” concluded Christina M. Huang, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, and her coinvestigators from the department of dermatology, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. They reported the results of their systematic review of 21 studies published between 2008 and 2017, which included quantitative data on serum vitamin D levels or vitamin D supplementation and AD severity in patients aged 18 years or younger, in Pediatrics.