User login

Geographic Clusters Show Uneven Cancer Screening in the US

Geographic Clusters Show Uneven Cancer Screening in the US

TOPLINE:

An analysis of 3142 US counties revealed that county-level screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer increased overall between 1997 and 2019; however, despite the reduced geographic variation, persistently high-screening clusters remained in the Northeast, whereas persistently low-screening clusters remained in the Southwest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cancer screening reduces mortality. Despite guideline recommendation, the uptake of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening in the US falls short of national goals and varies across sociodemographic groups. To date, only a few studies have examined geographic and temporal patterns of screening.

- To address this gap, researchers conducted a cross-sectional study using an ecological panel design to analyze county-level screening prevalence across 3142 US mainland counties from 1997 to 2019, deriving prevalence estimates from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data over 3- to 5-year periods.

- Spatial autocorrelation analyses, including Global Moran I and the bivariate local indicator of spatial autocorrelation, were performed to assess geographic clusters of cancer screening within each period. Four types of local geographic clusters of county-level cancer screening were identified: counties with persistently high screening rates, counties with persistently low screening rates, counties in which screening rates decreased from high to low, and counties in which screening rates increased from low to high.

- Screening prevalence was compared across multiple time windows for different modalities (mammography, a Papanicolaou test, colonoscopy, colorectal cancer test, endoscopy, and a fecal occult blood test [FOBT]). Overall, 3101 counties were analyzed for mammography and the Papanicolaou test, 3107 counties for colonoscopy, 3100 counties for colorectal cancer test, 3089 counties for endoscopy, and 3090 counties for the FOBT.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall screening prevalence increased from 1997 to 2019, and global spatial autocorrelation declined over time. For instance, the distribution of mammography screening became 83% more uniform in more recent years (Moran I, 0.57 in 1997-1999 vs 0.10 in 2017-2019). Similarly, Papanicolaou test screening became more uniform in more recent years (Moran I, 0.44 vs. 0.07). These changes indicate reduced geographic heterogeneity.

- Colonoscopy and endoscopy use increased, surpassing a 50% prevalence in many counties for 2010; however, FOBT use declined. Spatial clustering also attenuated, with a 23.4% declined in Moran I for colonoscopy from 2011-2016 to 2017-2019, a 12.3% decline in the colorectal cancer test from 2004-2007 to 2008-2010, and a 14.0% decline for endoscopy from 2004-2007 to 2008-2010.

- Persistently high-/high-screening clusters were concentrated in the Northeast for mammography and colorectal cancer screening and in the East for Papanicolaou test screening, whereas persistently low-/low-screening clusters were concentrated in the Southwest for the same modalities.

- Clusters of low- and high-screening counties were more disadvantaged -- with lower socioeconomic status and a higher proportion of non-White residents -- than other cluster types, suggesting some improvement in screening uptake in more disadvantaged areas. Counties with persistently low screening exhibited greater socioeconomic disadvantages -- lower media household income, higher poverty, lower home values, and lower educational attainment -- than those with persistently high screening.

IN PRACTICE:

"This cross-sectional study found that despite secular increases that reduced geographic variation in screening, local clusters of high and low screening persisted in the Northeast and Southwest US, respectively. Future studies could incorporate health care access characteristics to explain why areas of low screening did not catch up to optimize cancer screening practice," the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Pranoti Pradhan, PhD, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The county-level estimates were modeled using BRFSS, NHIS, and US Census data, which might be susceptible to sampling biases despite corrections for nonresponse and noncoverage. Researchers lacked data on specific health systems characteristics that may have directly driven changes in prevalence and were restricted to using screening time intervals available from the Small Area Estimates for Cancer-Relates Measures from the National Cancer Institute, rather than those according to US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines. Additionally, the spatial cluster method was sensitive to county size and arrangement, which may have influenced local cluster detection.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported by the T32 Cancer Prevention and Control Funding Fellowship and T32 Cancer Epidemiology Fellowship at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The authors declared having no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An analysis of 3142 US counties revealed that county-level screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer increased overall between 1997 and 2019; however, despite the reduced geographic variation, persistently high-screening clusters remained in the Northeast, whereas persistently low-screening clusters remained in the Southwest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cancer screening reduces mortality. Despite guideline recommendation, the uptake of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening in the US falls short of national goals and varies across sociodemographic groups. To date, only a few studies have examined geographic and temporal patterns of screening.

- To address this gap, researchers conducted a cross-sectional study using an ecological panel design to analyze county-level screening prevalence across 3142 US mainland counties from 1997 to 2019, deriving prevalence estimates from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data over 3- to 5-year periods.

- Spatial autocorrelation analyses, including Global Moran I and the bivariate local indicator of spatial autocorrelation, were performed to assess geographic clusters of cancer screening within each period. Four types of local geographic clusters of county-level cancer screening were identified: counties with persistently high screening rates, counties with persistently low screening rates, counties in which screening rates decreased from high to low, and counties in which screening rates increased from low to high.

- Screening prevalence was compared across multiple time windows for different modalities (mammography, a Papanicolaou test, colonoscopy, colorectal cancer test, endoscopy, and a fecal occult blood test [FOBT]). Overall, 3101 counties were analyzed for mammography and the Papanicolaou test, 3107 counties for colonoscopy, 3100 counties for colorectal cancer test, 3089 counties for endoscopy, and 3090 counties for the FOBT.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall screening prevalence increased from 1997 to 2019, and global spatial autocorrelation declined over time. For instance, the distribution of mammography screening became 83% more uniform in more recent years (Moran I, 0.57 in 1997-1999 vs 0.10 in 2017-2019). Similarly, Papanicolaou test screening became more uniform in more recent years (Moran I, 0.44 vs. 0.07). These changes indicate reduced geographic heterogeneity.

- Colonoscopy and endoscopy use increased, surpassing a 50% prevalence in many counties for 2010; however, FOBT use declined. Spatial clustering also attenuated, with a 23.4% declined in Moran I for colonoscopy from 2011-2016 to 2017-2019, a 12.3% decline in the colorectal cancer test from 2004-2007 to 2008-2010, and a 14.0% decline for endoscopy from 2004-2007 to 2008-2010.

- Persistently high-/high-screening clusters were concentrated in the Northeast for mammography and colorectal cancer screening and in the East for Papanicolaou test screening, whereas persistently low-/low-screening clusters were concentrated in the Southwest for the same modalities.

- Clusters of low- and high-screening counties were more disadvantaged -- with lower socioeconomic status and a higher proportion of non-White residents -- than other cluster types, suggesting some improvement in screening uptake in more disadvantaged areas. Counties with persistently low screening exhibited greater socioeconomic disadvantages -- lower media household income, higher poverty, lower home values, and lower educational attainment -- than those with persistently high screening.

IN PRACTICE:

"This cross-sectional study found that despite secular increases that reduced geographic variation in screening, local clusters of high and low screening persisted in the Northeast and Southwest US, respectively. Future studies could incorporate health care access characteristics to explain why areas of low screening did not catch up to optimize cancer screening practice," the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Pranoti Pradhan, PhD, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The county-level estimates were modeled using BRFSS, NHIS, and US Census data, which might be susceptible to sampling biases despite corrections for nonresponse and noncoverage. Researchers lacked data on specific health systems characteristics that may have directly driven changes in prevalence and were restricted to using screening time intervals available from the Small Area Estimates for Cancer-Relates Measures from the National Cancer Institute, rather than those according to US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines. Additionally, the spatial cluster method was sensitive to county size and arrangement, which may have influenced local cluster detection.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported by the T32 Cancer Prevention and Control Funding Fellowship and T32 Cancer Epidemiology Fellowship at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The authors declared having no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An analysis of 3142 US counties revealed that county-level screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer increased overall between 1997 and 2019; however, despite the reduced geographic variation, persistently high-screening clusters remained in the Northeast, whereas persistently low-screening clusters remained in the Southwest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cancer screening reduces mortality. Despite guideline recommendation, the uptake of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening in the US falls short of national goals and varies across sociodemographic groups. To date, only a few studies have examined geographic and temporal patterns of screening.

- To address this gap, researchers conducted a cross-sectional study using an ecological panel design to analyze county-level screening prevalence across 3142 US mainland counties from 1997 to 2019, deriving prevalence estimates from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data over 3- to 5-year periods.

- Spatial autocorrelation analyses, including Global Moran I and the bivariate local indicator of spatial autocorrelation, were performed to assess geographic clusters of cancer screening within each period. Four types of local geographic clusters of county-level cancer screening were identified: counties with persistently high screening rates, counties with persistently low screening rates, counties in which screening rates decreased from high to low, and counties in which screening rates increased from low to high.

- Screening prevalence was compared across multiple time windows for different modalities (mammography, a Papanicolaou test, colonoscopy, colorectal cancer test, endoscopy, and a fecal occult blood test [FOBT]). Overall, 3101 counties were analyzed for mammography and the Papanicolaou test, 3107 counties for colonoscopy, 3100 counties for colorectal cancer test, 3089 counties for endoscopy, and 3090 counties for the FOBT.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall screening prevalence increased from 1997 to 2019, and global spatial autocorrelation declined over time. For instance, the distribution of mammography screening became 83% more uniform in more recent years (Moran I, 0.57 in 1997-1999 vs 0.10 in 2017-2019). Similarly, Papanicolaou test screening became more uniform in more recent years (Moran I, 0.44 vs. 0.07). These changes indicate reduced geographic heterogeneity.

- Colonoscopy and endoscopy use increased, surpassing a 50% prevalence in many counties for 2010; however, FOBT use declined. Spatial clustering also attenuated, with a 23.4% declined in Moran I for colonoscopy from 2011-2016 to 2017-2019, a 12.3% decline in the colorectal cancer test from 2004-2007 to 2008-2010, and a 14.0% decline for endoscopy from 2004-2007 to 2008-2010.

- Persistently high-/high-screening clusters were concentrated in the Northeast for mammography and colorectal cancer screening and in the East for Papanicolaou test screening, whereas persistently low-/low-screening clusters were concentrated in the Southwest for the same modalities.

- Clusters of low- and high-screening counties were more disadvantaged -- with lower socioeconomic status and a higher proportion of non-White residents -- than other cluster types, suggesting some improvement in screening uptake in more disadvantaged areas. Counties with persistently low screening exhibited greater socioeconomic disadvantages -- lower media household income, higher poverty, lower home values, and lower educational attainment -- than those with persistently high screening.

IN PRACTICE:

"This cross-sectional study found that despite secular increases that reduced geographic variation in screening, local clusters of high and low screening persisted in the Northeast and Southwest US, respectively. Future studies could incorporate health care access characteristics to explain why areas of low screening did not catch up to optimize cancer screening practice," the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Pranoti Pradhan, PhD, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The county-level estimates were modeled using BRFSS, NHIS, and US Census data, which might be susceptible to sampling biases despite corrections for nonresponse and noncoverage. Researchers lacked data on specific health systems characteristics that may have directly driven changes in prevalence and were restricted to using screening time intervals available from the Small Area Estimates for Cancer-Relates Measures from the National Cancer Institute, rather than those according to US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines. Additionally, the spatial cluster method was sensitive to county size and arrangement, which may have influenced local cluster detection.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was supported by the T32 Cancer Prevention and Control Funding Fellowship and T32 Cancer Epidemiology Fellowship at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The authors declared having no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Geographic Clusters Show Uneven Cancer Screening in the US

Geographic Clusters Show Uneven Cancer Screening in the US

Artificial Intelligence Shows Promise in Detecting Missed Interval Breast Cancer on Screening Mammograms

TOPLINE:

An artificial intelligence (AI) system flagged high-risk areas on mammograms for potentially missed interval breast cancers (IBCs), which radiologists had also retrospectively identified as abnormal. Moreover, the AI detected a substantial number of IBCs that manual review had overlooked.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of 119 IBC screening mammograms of women (mean age, 57.3 years) with a high breast density (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System [BI-RADS] c/d, 63.0%) using data retrieved from Cancer Registries of Eastern Switzerland and Grisons-Glarus databases.

- A recorded tumour was classified as IBC when an invasive or in situ BC was diagnosed within 24 months after a normal screening mammogram.

- Three radiologists retrospectively assessed the mammograms for visible signs of BC, which were then classified as either potentially missed IBCs or IBCs without retrospective abnormalities on the basis of consensus conference recommendations of radiologists.

- An AI system generated two scores (a scale of 0 to 100): a case score reflecting the likelihood that the mammogram currently harbours cancer and a risk score estimating the probability of a BC diagnosis within 2 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Radiologists classified 68.9% of IBCs as those having no retrospective abnormalities and assigned significantly higher BI-RADS scores to the remaining 31.1% of potentially missed IBCs (P < .05).

- Potentially missed IBCs received significantly higher AI case scores (mean, 54.1 vs 23.1; P < .05) and were assigned to a higher risk category (48.7% vs 14.6%; P < .05) than IBCs without retrospective abnormalities.

- Of all IBC cases, 46.2% received an AI case score > 25, 25.2% scored > 50, and 13.4% scored > 75.

- Potentially missed IBCs scored widely between low and high risk and case scores, whereas IBCs without retrospective abnormalities scored low case and risk scores. Specifically, 73.0% of potentially missed IBCs vs 34.1% of IBCs without retrospective abnormalities had case scores > 25, 51.4% vs 13.4% had case scores > 50, and 29.7% vs 6.1% had case scores > 75.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our research highlights that an AI system can identify BC signs in relevant portions of IBC screening mammograms and thus potentially reduce the number of IBCs in an MSP [mammography screening program] that currently does not utilize an AI system,” the authors of the study concluded, adding that “it can identify some IBCs that are not visible to humans (IBCs without retrospective abnormalities).”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Jonas Subelack, Chair of Health Economics, Policy and Management, School of Medicine, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. It was published online in European Radiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective study design inherently limited causal conclusions. Without access to diagnostic mammograms or the detailed position of BC, researchers could not evaluate whether AI-marked lesions corresponded to later detected BCs.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was funded by the Cancer League of Eastern Switzerland. One author reported receiving consulting and speaker fees from iCAD.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An artificial intelligence (AI) system flagged high-risk areas on mammograms for potentially missed interval breast cancers (IBCs), which radiologists had also retrospectively identified as abnormal. Moreover, the AI detected a substantial number of IBCs that manual review had overlooked.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of 119 IBC screening mammograms of women (mean age, 57.3 years) with a high breast density (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System [BI-RADS] c/d, 63.0%) using data retrieved from Cancer Registries of Eastern Switzerland and Grisons-Glarus databases.

- A recorded tumour was classified as IBC when an invasive or in situ BC was diagnosed within 24 months after a normal screening mammogram.

- Three radiologists retrospectively assessed the mammograms for visible signs of BC, which were then classified as either potentially missed IBCs or IBCs without retrospective abnormalities on the basis of consensus conference recommendations of radiologists.

- An AI system generated two scores (a scale of 0 to 100): a case score reflecting the likelihood that the mammogram currently harbours cancer and a risk score estimating the probability of a BC diagnosis within 2 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Radiologists classified 68.9% of IBCs as those having no retrospective abnormalities and assigned significantly higher BI-RADS scores to the remaining 31.1% of potentially missed IBCs (P < .05).

- Potentially missed IBCs received significantly higher AI case scores (mean, 54.1 vs 23.1; P < .05) and were assigned to a higher risk category (48.7% vs 14.6%; P < .05) than IBCs without retrospective abnormalities.

- Of all IBC cases, 46.2% received an AI case score > 25, 25.2% scored > 50, and 13.4% scored > 75.

- Potentially missed IBCs scored widely between low and high risk and case scores, whereas IBCs without retrospective abnormalities scored low case and risk scores. Specifically, 73.0% of potentially missed IBCs vs 34.1% of IBCs without retrospective abnormalities had case scores > 25, 51.4% vs 13.4% had case scores > 50, and 29.7% vs 6.1% had case scores > 75.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our research highlights that an AI system can identify BC signs in relevant portions of IBC screening mammograms and thus potentially reduce the number of IBCs in an MSP [mammography screening program] that currently does not utilize an AI system,” the authors of the study concluded, adding that “it can identify some IBCs that are not visible to humans (IBCs without retrospective abnormalities).”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Jonas Subelack, Chair of Health Economics, Policy and Management, School of Medicine, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. It was published online in European Radiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective study design inherently limited causal conclusions. Without access to diagnostic mammograms or the detailed position of BC, researchers could not evaluate whether AI-marked lesions corresponded to later detected BCs.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was funded by the Cancer League of Eastern Switzerland. One author reported receiving consulting and speaker fees from iCAD.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

An artificial intelligence (AI) system flagged high-risk areas on mammograms for potentially missed interval breast cancers (IBCs), which radiologists had also retrospectively identified as abnormal. Moreover, the AI detected a substantial number of IBCs that manual review had overlooked.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of 119 IBC screening mammograms of women (mean age, 57.3 years) with a high breast density (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System [BI-RADS] c/d, 63.0%) using data retrieved from Cancer Registries of Eastern Switzerland and Grisons-Glarus databases.

- A recorded tumour was classified as IBC when an invasive or in situ BC was diagnosed within 24 months after a normal screening mammogram.

- Three radiologists retrospectively assessed the mammograms for visible signs of BC, which were then classified as either potentially missed IBCs or IBCs without retrospective abnormalities on the basis of consensus conference recommendations of radiologists.

- An AI system generated two scores (a scale of 0 to 100): a case score reflecting the likelihood that the mammogram currently harbours cancer and a risk score estimating the probability of a BC diagnosis within 2 years.

TAKEAWAY:

- Radiologists classified 68.9% of IBCs as those having no retrospective abnormalities and assigned significantly higher BI-RADS scores to the remaining 31.1% of potentially missed IBCs (P < .05).

- Potentially missed IBCs received significantly higher AI case scores (mean, 54.1 vs 23.1; P < .05) and were assigned to a higher risk category (48.7% vs 14.6%; P < .05) than IBCs without retrospective abnormalities.

- Of all IBC cases, 46.2% received an AI case score > 25, 25.2% scored > 50, and 13.4% scored > 75.

- Potentially missed IBCs scored widely between low and high risk and case scores, whereas IBCs without retrospective abnormalities scored low case and risk scores. Specifically, 73.0% of potentially missed IBCs vs 34.1% of IBCs without retrospective abnormalities had case scores > 25, 51.4% vs 13.4% had case scores > 50, and 29.7% vs 6.1% had case scores > 75.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our research highlights that an AI system can identify BC signs in relevant portions of IBC screening mammograms and thus potentially reduce the number of IBCs in an MSP [mammography screening program] that currently does not utilize an AI system,” the authors of the study concluded, adding that “it can identify some IBCs that are not visible to humans (IBCs without retrospective abnormalities).”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Jonas Subelack, Chair of Health Economics, Policy and Management, School of Medicine, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. It was published online in European Radiology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective study design inherently limited causal conclusions. Without access to diagnostic mammograms or the detailed position of BC, researchers could not evaluate whether AI-marked lesions corresponded to later detected BCs.

DISCLOSURES:

This research was funded by the Cancer League of Eastern Switzerland. One author reported receiving consulting and speaker fees from iCAD.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

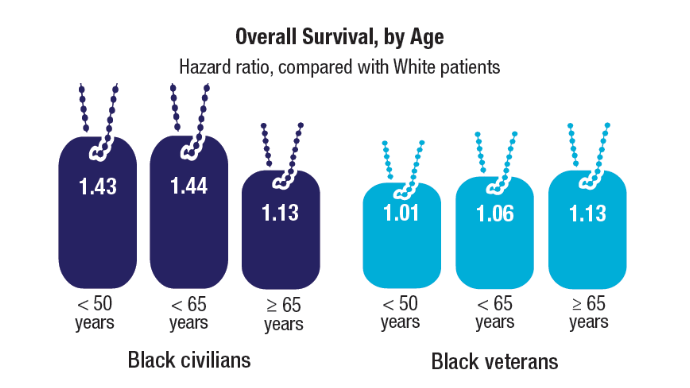

Cancer Data Trends 2025

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

In this issue:

- Access, Race, and "Colon Age": Improving CRC Screening

- Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

- Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

- Breast and Uterine Cancer: Screening Guidelines, Genetic Testing, and Mortality Trends

- HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

- Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

- Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

- AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

- Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

In this issue:

- Access, Race, and "Colon Age": Improving CRC Screening

- Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

- Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

- Breast and Uterine Cancer: Screening Guidelines, Genetic Testing, and Mortality Trends

- HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

- Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

- Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

- AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

- Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

In this issue:

- Access, Race, and "Colon Age": Improving CRC Screening

- Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

- Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

- Breast and Uterine Cancer: Screening Guidelines, Genetic Testing, and Mortality Trends

- HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

- Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

- Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

- AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

- Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

VA Revises Policy For Male Breast Cancer

Male veterans with breast cancer may have a more difficult time receiving appropriate health care due to a recently revised US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) policy that requires each individual to prove the disease’s connection to their service to qualify for coverage.

According to a VA memo obtained by ProPublica, the change is based on a Jan. 1 presidential order titled “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government.” VA Press Secretary Pete Kasperowicz told ProPublica that the policy was changed because the previous policy “falsely classified male breasts as reproductive organs.”

In 2024, the VA added male breast cancer (along with urethral cancer and cancer of the paraurethral glands) to its list of presumed service-connected disabilities due to military environmental exposure, such as toxic burn pits. Male breast cancer was added to the category of “reproductive cancer of any type” after experts pointed to the similarity of male and female breast cancers.

Establishing a connection between a variety of cancers and military service has been a years-long fight only resolved recently in the form of the 2022 PACT Act. The VA lists > 20 medical conditions as “presumptive” for service connection, with some caveats, such as area of service. The act reduced the burden of proof needed: The terms “presumptive conditions” and “presumptive-exposure locations” mean veterans only have to provide their military records to show they were in an exposure location to have their care for certain conditions covered.

Supporters of the PACT Act say the policy change could make it harder for veterans to receive timely care, a serious issue for men with breast cancer who have been “severely underrepresented” in clinical studies and many studies specifically exclude males. The American Cancer Society estimates about 2800 men have been or will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in 2025. Less than 1% of breast cancers in the US occur in men, but breast cancer is notably higher among veterans: 11% of 3304 veterans, according to a 2023 study.

Breast cancer is more aggressive in men—they’re more often diagnosed at Stage IV and tend to be older—and survival rates have been lower than in women. In a 2019 study of 16,025 male and 1,800,708 female patients with breast cancer, men had 19% higher overall mortality.

Treatment for male breast cancer has lagged. A 2021 study found men were less likely than women to receive radiation therapy. However, that’s changing. Since that study, however, the American Cancer Society claims treatments and survival rates have improved. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, 5-year survival rates are 97% for localized, 86% for regional, and 31% for distant; 84% for all stages combined.

Screening and treatment have focused on women. But the VA Breast and Gynecologic Oncology System of Excellence (BGSoE) provides cancer care for all veterans diagnosed with breast malignancies. Male veterans with breast cancer do face additional challenges in addressing a cancer that is most often associated with females. “I must admit, it was awkward every time I went [to the Women’s Health Center for postmastectomy follow-ups]” William K. Lewis, described in his patient perspective on male breast cancer treatment in the VA.

Though the policy has changed, Kasperowicz told ProPublica that veterans who previously qualified for coverage can keep it: “The department grants disability benefits compensation claims for male Veterans with breast cancer on an individual basis and will continue to do so. VA encourages any male Veterans with breast cancer who feel their health may have been impacted by their military service to submit a disability compensation claim.”

Male veterans with breast cancer may have a more difficult time receiving appropriate health care due to a recently revised US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) policy that requires each individual to prove the disease’s connection to their service to qualify for coverage.

According to a VA memo obtained by ProPublica, the change is based on a Jan. 1 presidential order titled “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government.” VA Press Secretary Pete Kasperowicz told ProPublica that the policy was changed because the previous policy “falsely classified male breasts as reproductive organs.”

In 2024, the VA added male breast cancer (along with urethral cancer and cancer of the paraurethral glands) to its list of presumed service-connected disabilities due to military environmental exposure, such as toxic burn pits. Male breast cancer was added to the category of “reproductive cancer of any type” after experts pointed to the similarity of male and female breast cancers.

Establishing a connection between a variety of cancers and military service has been a years-long fight only resolved recently in the form of the 2022 PACT Act. The VA lists > 20 medical conditions as “presumptive” for service connection, with some caveats, such as area of service. The act reduced the burden of proof needed: The terms “presumptive conditions” and “presumptive-exposure locations” mean veterans only have to provide their military records to show they were in an exposure location to have their care for certain conditions covered.

Supporters of the PACT Act say the policy change could make it harder for veterans to receive timely care, a serious issue for men with breast cancer who have been “severely underrepresented” in clinical studies and many studies specifically exclude males. The American Cancer Society estimates about 2800 men have been or will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in 2025. Less than 1% of breast cancers in the US occur in men, but breast cancer is notably higher among veterans: 11% of 3304 veterans, according to a 2023 study.

Breast cancer is more aggressive in men—they’re more often diagnosed at Stage IV and tend to be older—and survival rates have been lower than in women. In a 2019 study of 16,025 male and 1,800,708 female patients with breast cancer, men had 19% higher overall mortality.

Treatment for male breast cancer has lagged. A 2021 study found men were less likely than women to receive radiation therapy. However, that’s changing. Since that study, however, the American Cancer Society claims treatments and survival rates have improved. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, 5-year survival rates are 97% for localized, 86% for regional, and 31% for distant; 84% for all stages combined.

Screening and treatment have focused on women. But the VA Breast and Gynecologic Oncology System of Excellence (BGSoE) provides cancer care for all veterans diagnosed with breast malignancies. Male veterans with breast cancer do face additional challenges in addressing a cancer that is most often associated with females. “I must admit, it was awkward every time I went [to the Women’s Health Center for postmastectomy follow-ups]” William K. Lewis, described in his patient perspective on male breast cancer treatment in the VA.

Though the policy has changed, Kasperowicz told ProPublica that veterans who previously qualified for coverage can keep it: “The department grants disability benefits compensation claims for male Veterans with breast cancer on an individual basis and will continue to do so. VA encourages any male Veterans with breast cancer who feel their health may have been impacted by their military service to submit a disability compensation claim.”

Male veterans with breast cancer may have a more difficult time receiving appropriate health care due to a recently revised US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) policy that requires each individual to prove the disease’s connection to their service to qualify for coverage.

According to a VA memo obtained by ProPublica, the change is based on a Jan. 1 presidential order titled “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government.” VA Press Secretary Pete Kasperowicz told ProPublica that the policy was changed because the previous policy “falsely classified male breasts as reproductive organs.”

In 2024, the VA added male breast cancer (along with urethral cancer and cancer of the paraurethral glands) to its list of presumed service-connected disabilities due to military environmental exposure, such as toxic burn pits. Male breast cancer was added to the category of “reproductive cancer of any type” after experts pointed to the similarity of male and female breast cancers.

Establishing a connection between a variety of cancers and military service has been a years-long fight only resolved recently in the form of the 2022 PACT Act. The VA lists > 20 medical conditions as “presumptive” for service connection, with some caveats, such as area of service. The act reduced the burden of proof needed: The terms “presumptive conditions” and “presumptive-exposure locations” mean veterans only have to provide their military records to show they were in an exposure location to have their care for certain conditions covered.

Supporters of the PACT Act say the policy change could make it harder for veterans to receive timely care, a serious issue for men with breast cancer who have been “severely underrepresented” in clinical studies and many studies specifically exclude males. The American Cancer Society estimates about 2800 men have been or will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in 2025. Less than 1% of breast cancers in the US occur in men, but breast cancer is notably higher among veterans: 11% of 3304 veterans, according to a 2023 study.

Breast cancer is more aggressive in men—they’re more often diagnosed at Stage IV and tend to be older—and survival rates have been lower than in women. In a 2019 study of 16,025 male and 1,800,708 female patients with breast cancer, men had 19% higher overall mortality.

Treatment for male breast cancer has lagged. A 2021 study found men were less likely than women to receive radiation therapy. However, that’s changing. Since that study, however, the American Cancer Society claims treatments and survival rates have improved. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, 5-year survival rates are 97% for localized, 86% for regional, and 31% for distant; 84% for all stages combined.

Screening and treatment have focused on women. But the VA Breast and Gynecologic Oncology System of Excellence (BGSoE) provides cancer care for all veterans diagnosed with breast malignancies. Male veterans with breast cancer do face additional challenges in addressing a cancer that is most often associated with females. “I must admit, it was awkward every time I went [to the Women’s Health Center for postmastectomy follow-ups]” William K. Lewis, described in his patient perspective on male breast cancer treatment in the VA.

Though the policy has changed, Kasperowicz told ProPublica that veterans who previously qualified for coverage can keep it: “The department grants disability benefits compensation claims for male Veterans with breast cancer on an individual basis and will continue to do so. VA encourages any male Veterans with breast cancer who feel their health may have been impacted by their military service to submit a disability compensation claim.”

Two ADCs Offer More Hope for Patients With Advanced TNBC

BERLIN — Patients with previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) who are not candidates for immunotherapy may experience improved survival outcomes with TROP2-directed antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), suggested two trials presented at European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Annual Meeting 2025 on October 19.

ASCENT-03 compared sacituzumab govitecan with standard of care chemotherapy, finding that the drug was associated with a 38% improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in this patient population that has, traditionally, a poor prognosis. Overall survival data remain immature.

TROPION-Breast02 studied datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) against investigator’s choice of chemotherapy. The PFS improvement with the ADC was 43%, while patients also experienced a 21% improvement in overall survival. In both cases, the safety profile of the experimental drugs was deemed to be manageable.

Discussant Ana C. Garrido-Castro, MD, director, Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, who was not involved in either study, said that both sacituzumab govitecan and Dato-DXd showed a PFS benefit. The choice between them, leaving aside overall survival until the data are mature, will be largely based on factors such as the safety profile and the patient preference, she continued.

Sacituzumab govitecan is associated with an increase in neutropenia, nausea, and diarrhea, she pointed out, while Dato-DXd has increased rates of ocular surface toxicity, oral mucositis/stomatitis, and requires monitoring for interstitial lung disease.

Dato-DXd has a higher objective response rate than chemotherapy, unlike sacituzumab govitecan, but, crucially, requires one infusion vs 2 for sacituzumab govitecan per 21-day cycle, and has a shorter total infusion time.

There are nevertheless a number of unanswered questions about the drugs, including how the ADCs affect quality of life, and how common patient adherence to the recommended prophylaxis is. Patients with early relapse of < 12 months remain an “urgent unmet need,” Garrido-Castro said, and the role of immunotherapy rechallenge remains to be explored.

ADCs are also being tested in the neo-adjuvant TNBC setting, and the potential impact of that on the use of the drugs in the metastatic setting is currently unclear. In addition, there are questions around access to therapy.

“Ultimately, it will be very important to have a better understanding of the biomarkers of response and resistance and toxicity to these agents, and whether we should be sequencing antibody drug conjugates,” Garrido-Castro said. “All of this will help shape the next wave of treatment strategies for this patient population.”

She concluded: “Today, marks a paradigm shift of metastatic TNBC, in my opinion. ASCENT-03 and TROPION-Breast02 support TROP2 ADC therapy as the new preferred first-line regimen for this patient population.”

Method and Results of ASCENT-03

ASCENT-03 study presenter Javier C. Cortés, MD, PhD, International Breast Cancer Center, Pangaea Oncology, Quiron Group, Barcelona, Spain, said there is currently an unmet clinical need in the approximately 60% of patients with previously untreated metastatic TNBC who are not candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Median PFS in previous first-line studies was < 6 months with chemotherapy — the current standard of care — and Cortés said that around half of the patients who receive that in the first-line do not receive second-line therapy because of clinical deterioration or death.

“The sobering truth is that across studies in the US and Europe, approximately 25% to 30% of patients diagnosed with metastatic TNBC are no longer alive at 6 months from their metastatic diagnosis,” said Garrido-Castro. “So if there is a new drug that is able to significantly improve PFS with an acceptable toxicity profile, this should be sufficient to change the current standard of care in the first-line setting.”

As sacituzumab govitecan is already approved for second-line metastatic TNBC and for pretreated hormone receptor positive/HER2- metastatic breast cancer, the ASCENT-03 researchers studied the drug in patients with previously untreated locally advanced inoperable, or metastatic TNBC.

The patients were deemed not to be candidates for PD-L1 inhibitors through having PD-L1-negative tumors, by having PD-L1-positive tumors that had previously been treated with PD-L1 inhibitors in the curative setting, or by having a comorbidity that precluded PD-L1 inhibitor use.

The patients were required to have finished any prior treatment in the curative setting at least 6 months previously. Previously treated, stable central nervous system metastases were allowed.

They were randomized to sacituzumab govitecan or chemotherapy, comprising paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel, or gemcitabine plus carboplatin, until progression, as verified by blinded independent central review (BICR), or unacceptable toxicity. Patients who progressed on chemotherapy were offered crossover to second-line sacituzumab govitecan.

In all, 558 patients were randomized. The median age was 56 years in the sacituzumab govitecan group vs 54 years in the chemotherapy group. The majority (64% in both groups) of patients were White individuals. The most common metastatic site was the lung (59% vs 61%), and 58% of patients in both groups had previously received a taxane.

Cortés reported that sacituzumab govitecan was associated with a “statistically significant and clinically meaningful” improvement in PFS by BICR, at a median of 9.7 months vs 6.9 months, or a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.62 (P < .0001). This benefit was seen across prespecified subgroups.

The objective response rate was almost identical between the two treatment groups, at 48% with sacituzumab govitecan vs 46% with chemotherapy, although the median duration of response was longer with the ADC, at 12.2 months vs 7.2 months.

Cortés showed the latest results on overall survival. This showed no significant difference between the two treatments, although he underlined that the data are not yet mature.

He also reported that the rates of grade ≥ 3 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were similar in the two groups, at 66% with sacituzumab govitecan vs 62% with chemotherapy. However, the rates of TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation (4% vs 12%) or dose reduction (37% vs 45%) were lower with the ADC.

Cortés concluded that the results suggest that sacituzumab govitecan “is a good option for patients with triple negative breast cancer when they develop metastasis and are unable to receive immune checkpoint inhibitors.”

TROPION-Breast02 Methods and Results

Presenting TROPION-Breast02, Rebecca A. Dent, MD, MSc, National Cancer Center Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, explained that the trial looked at a patient population similar to that of ASCENT-03, here focusing instead on Dato-DXd.

Patients were included if they had histologically or cytologically documented locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC, no prior chemotherapy or targeted systemic therapy in this setting, and in whom immunotherapy was not an option.

They were randomized to Dato-DXd or the investigator’s choice of chemotherapy, with treatment continued until investigator-assessed progressive disease on RECIST v1.1, unacceptable toxicity, or another criterion for discontinuation was met.

In total, 642 patients were enrolled. The median age was 56 years for those in the Dato-DXd group and 57 years for those in chemotherapy group, and less than half (41% in the Dato-DXd group and 48% in the chemotherapy group) were White individuals. The number of metastatic sites was less than three in 64% and 67% of patients, respectively.

Dent showed that Dato-DXd was associated with a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in BICR-assessed PFS, at a median of 10.8 months vs 5.6 months with chemotherapy, at a HR of 0.57 (P < .0001). The findings were replicated across the prespecified subgroups.

There was a marked overall survival benefit with Dato-DXd, at a median of 23.7 months vs 18.7 months, at a HR of 0.79 (P = .0291). Dent reported that, at 18 months, 61.2% of patients in the Dato-DXd group were still alive vs 51.3% in the chemotherapy group. Again, the benefit was seen across subgroups.

The confirmed objective response rate with Dato-DXd was far higher than that with chemotherapy, at 62.5% vs 29.3%, or an odds ratio of 4.24. The duration of response was also longer, at 12.3 months vs 7.1 months.

Rates of grade ≥ 3 adverse events were comparable, at 33% with Dato-DXd vs 29% with chemotherapy, although there were more events associated with dose reduction (27% vs 18%) and dose interruption (24% vs 19%) with the ADC.

“These results support Dato-DXd as the first new first-line standard of care for patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC for whom immunotherapy is not an option,” Dent said.

“What’s important is the patients enrolled into this trial are clearly representative of real world patients that we are treating in our clinics every day. These patients are often excluded from our current clinical trials,” she said.

ASCENT-03 was funded by Gilead Sciences.

TROPION-Breast02 was funded by AstraZeneca.Cortés declared relationships with Roche, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Leuko, Bioasis, Clovis oncology, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ellipses, HiberCell, BioInvent, GEMoaB, Gilead, Menarini, Zymeworks, Reveal Genomics, Expres2ion Biotechnologies, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Scorpion Therapeutics, Bridgebio, Biocon, Biontech, Circle Pharma, Delcath Systems, Hexagon Bio, Novartis, Eisai, Pfizer, Stemline Therapeutics, MAJ3 Capital, Leuko, Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Baxalta GmbH/Servier Affaires, Bayer healthcare, Guardant Health, and PIQUR Therapeutics.

Dent declared relationships with AstraZeneca, MSD, Pfizer, Eisai, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca, Roche, and Gilead Sciences.

Garrido-Castro declared relationships with AstraZeneca, MSD, Pfizer, Eisai, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca, Roche, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, TD Cowen, and Roche/Genentech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BERLIN — Patients with previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) who are not candidates for immunotherapy may experience improved survival outcomes with TROP2-directed antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), suggested two trials presented at European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Annual Meeting 2025 on October 19.

ASCENT-03 compared sacituzumab govitecan with standard of care chemotherapy, finding that the drug was associated with a 38% improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in this patient population that has, traditionally, a poor prognosis. Overall survival data remain immature.

TROPION-Breast02 studied datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) against investigator’s choice of chemotherapy. The PFS improvement with the ADC was 43%, while patients also experienced a 21% improvement in overall survival. In both cases, the safety profile of the experimental drugs was deemed to be manageable.

Discussant Ana C. Garrido-Castro, MD, director, Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, who was not involved in either study, said that both sacituzumab govitecan and Dato-DXd showed a PFS benefit. The choice between them, leaving aside overall survival until the data are mature, will be largely based on factors such as the safety profile and the patient preference, she continued.

Sacituzumab govitecan is associated with an increase in neutropenia, nausea, and diarrhea, she pointed out, while Dato-DXd has increased rates of ocular surface toxicity, oral mucositis/stomatitis, and requires monitoring for interstitial lung disease.

Dato-DXd has a higher objective response rate than chemotherapy, unlike sacituzumab govitecan, but, crucially, requires one infusion vs 2 for sacituzumab govitecan per 21-day cycle, and has a shorter total infusion time.

There are nevertheless a number of unanswered questions about the drugs, including how the ADCs affect quality of life, and how common patient adherence to the recommended prophylaxis is. Patients with early relapse of < 12 months remain an “urgent unmet need,” Garrido-Castro said, and the role of immunotherapy rechallenge remains to be explored.

ADCs are also being tested in the neo-adjuvant TNBC setting, and the potential impact of that on the use of the drugs in the metastatic setting is currently unclear. In addition, there are questions around access to therapy.

“Ultimately, it will be very important to have a better understanding of the biomarkers of response and resistance and toxicity to these agents, and whether we should be sequencing antibody drug conjugates,” Garrido-Castro said. “All of this will help shape the next wave of treatment strategies for this patient population.”

She concluded: “Today, marks a paradigm shift of metastatic TNBC, in my opinion. ASCENT-03 and TROPION-Breast02 support TROP2 ADC therapy as the new preferred first-line regimen for this patient population.”

Method and Results of ASCENT-03

ASCENT-03 study presenter Javier C. Cortés, MD, PhD, International Breast Cancer Center, Pangaea Oncology, Quiron Group, Barcelona, Spain, said there is currently an unmet clinical need in the approximately 60% of patients with previously untreated metastatic TNBC who are not candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Median PFS in previous first-line studies was < 6 months with chemotherapy — the current standard of care — and Cortés said that around half of the patients who receive that in the first-line do not receive second-line therapy because of clinical deterioration or death.

“The sobering truth is that across studies in the US and Europe, approximately 25% to 30% of patients diagnosed with metastatic TNBC are no longer alive at 6 months from their metastatic diagnosis,” said Garrido-Castro. “So if there is a new drug that is able to significantly improve PFS with an acceptable toxicity profile, this should be sufficient to change the current standard of care in the first-line setting.”

As sacituzumab govitecan is already approved for second-line metastatic TNBC and for pretreated hormone receptor positive/HER2- metastatic breast cancer, the ASCENT-03 researchers studied the drug in patients with previously untreated locally advanced inoperable, or metastatic TNBC.

The patients were deemed not to be candidates for PD-L1 inhibitors through having PD-L1-negative tumors, by having PD-L1-positive tumors that had previously been treated with PD-L1 inhibitors in the curative setting, or by having a comorbidity that precluded PD-L1 inhibitor use.

The patients were required to have finished any prior treatment in the curative setting at least 6 months previously. Previously treated, stable central nervous system metastases were allowed.

They were randomized to sacituzumab govitecan or chemotherapy, comprising paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel, or gemcitabine plus carboplatin, until progression, as verified by blinded independent central review (BICR), or unacceptable toxicity. Patients who progressed on chemotherapy were offered crossover to second-line sacituzumab govitecan.

In all, 558 patients were randomized. The median age was 56 years in the sacituzumab govitecan group vs 54 years in the chemotherapy group. The majority (64% in both groups) of patients were White individuals. The most common metastatic site was the lung (59% vs 61%), and 58% of patients in both groups had previously received a taxane.

Cortés reported that sacituzumab govitecan was associated with a “statistically significant and clinically meaningful” improvement in PFS by BICR, at a median of 9.7 months vs 6.9 months, or a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.62 (P < .0001). This benefit was seen across prespecified subgroups.

The objective response rate was almost identical between the two treatment groups, at 48% with sacituzumab govitecan vs 46% with chemotherapy, although the median duration of response was longer with the ADC, at 12.2 months vs 7.2 months.

Cortés showed the latest results on overall survival. This showed no significant difference between the two treatments, although he underlined that the data are not yet mature.

He also reported that the rates of grade ≥ 3 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were similar in the two groups, at 66% with sacituzumab govitecan vs 62% with chemotherapy. However, the rates of TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation (4% vs 12%) or dose reduction (37% vs 45%) were lower with the ADC.

Cortés concluded that the results suggest that sacituzumab govitecan “is a good option for patients with triple negative breast cancer when they develop metastasis and are unable to receive immune checkpoint inhibitors.”

TROPION-Breast02 Methods and Results

Presenting TROPION-Breast02, Rebecca A. Dent, MD, MSc, National Cancer Center Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, explained that the trial looked at a patient population similar to that of ASCENT-03, here focusing instead on Dato-DXd.

Patients were included if they had histologically or cytologically documented locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC, no prior chemotherapy or targeted systemic therapy in this setting, and in whom immunotherapy was not an option.

They were randomized to Dato-DXd or the investigator’s choice of chemotherapy, with treatment continued until investigator-assessed progressive disease on RECIST v1.1, unacceptable toxicity, or another criterion for discontinuation was met.

In total, 642 patients were enrolled. The median age was 56 years for those in the Dato-DXd group and 57 years for those in chemotherapy group, and less than half (41% in the Dato-DXd group and 48% in the chemotherapy group) were White individuals. The number of metastatic sites was less than three in 64% and 67% of patients, respectively.

Dent showed that Dato-DXd was associated with a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in BICR-assessed PFS, at a median of 10.8 months vs 5.6 months with chemotherapy, at a HR of 0.57 (P < .0001). The findings were replicated across the prespecified subgroups.

There was a marked overall survival benefit with Dato-DXd, at a median of 23.7 months vs 18.7 months, at a HR of 0.79 (P = .0291). Dent reported that, at 18 months, 61.2% of patients in the Dato-DXd group were still alive vs 51.3% in the chemotherapy group. Again, the benefit was seen across subgroups.

The confirmed objective response rate with Dato-DXd was far higher than that with chemotherapy, at 62.5% vs 29.3%, or an odds ratio of 4.24. The duration of response was also longer, at 12.3 months vs 7.1 months.

Rates of grade ≥ 3 adverse events were comparable, at 33% with Dato-DXd vs 29% with chemotherapy, although there were more events associated with dose reduction (27% vs 18%) and dose interruption (24% vs 19%) with the ADC.

“These results support Dato-DXd as the first new first-line standard of care for patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC for whom immunotherapy is not an option,” Dent said.

“What’s important is the patients enrolled into this trial are clearly representative of real world patients that we are treating in our clinics every day. These patients are often excluded from our current clinical trials,” she said.

ASCENT-03 was funded by Gilead Sciences.

TROPION-Breast02 was funded by AstraZeneca.Cortés declared relationships with Roche, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Leuko, Bioasis, Clovis oncology, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ellipses, HiberCell, BioInvent, GEMoaB, Gilead, Menarini, Zymeworks, Reveal Genomics, Expres2ion Biotechnologies, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Scorpion Therapeutics, Bridgebio, Biocon, Biontech, Circle Pharma, Delcath Systems, Hexagon Bio, Novartis, Eisai, Pfizer, Stemline Therapeutics, MAJ3 Capital, Leuko, Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Baxalta GmbH/Servier Affaires, Bayer healthcare, Guardant Health, and PIQUR Therapeutics.

Dent declared relationships with AstraZeneca, MSD, Pfizer, Eisai, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca, Roche, and Gilead Sciences.

Garrido-Castro declared relationships with AstraZeneca, MSD, Pfizer, Eisai, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca, Roche, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, TD Cowen, and Roche/Genentech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BERLIN — Patients with previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) who are not candidates for immunotherapy may experience improved survival outcomes with TROP2-directed antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), suggested two trials presented at European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Annual Meeting 2025 on October 19.

ASCENT-03 compared sacituzumab govitecan with standard of care chemotherapy, finding that the drug was associated with a 38% improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) in this patient population that has, traditionally, a poor prognosis. Overall survival data remain immature.

TROPION-Breast02 studied datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd) against investigator’s choice of chemotherapy. The PFS improvement with the ADC was 43%, while patients also experienced a 21% improvement in overall survival. In both cases, the safety profile of the experimental drugs was deemed to be manageable.

Discussant Ana C. Garrido-Castro, MD, director, Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, who was not involved in either study, said that both sacituzumab govitecan and Dato-DXd showed a PFS benefit. The choice between them, leaving aside overall survival until the data are mature, will be largely based on factors such as the safety profile and the patient preference, she continued.

Sacituzumab govitecan is associated with an increase in neutropenia, nausea, and diarrhea, she pointed out, while Dato-DXd has increased rates of ocular surface toxicity, oral mucositis/stomatitis, and requires monitoring for interstitial lung disease.

Dato-DXd has a higher objective response rate than chemotherapy, unlike sacituzumab govitecan, but, crucially, requires one infusion vs 2 for sacituzumab govitecan per 21-day cycle, and has a shorter total infusion time.

There are nevertheless a number of unanswered questions about the drugs, including how the ADCs affect quality of life, and how common patient adherence to the recommended prophylaxis is. Patients with early relapse of < 12 months remain an “urgent unmet need,” Garrido-Castro said, and the role of immunotherapy rechallenge remains to be explored.

ADCs are also being tested in the neo-adjuvant TNBC setting, and the potential impact of that on the use of the drugs in the metastatic setting is currently unclear. In addition, there are questions around access to therapy.

“Ultimately, it will be very important to have a better understanding of the biomarkers of response and resistance and toxicity to these agents, and whether we should be sequencing antibody drug conjugates,” Garrido-Castro said. “All of this will help shape the next wave of treatment strategies for this patient population.”

She concluded: “Today, marks a paradigm shift of metastatic TNBC, in my opinion. ASCENT-03 and TROPION-Breast02 support TROP2 ADC therapy as the new preferred first-line regimen for this patient population.”

Method and Results of ASCENT-03

ASCENT-03 study presenter Javier C. Cortés, MD, PhD, International Breast Cancer Center, Pangaea Oncology, Quiron Group, Barcelona, Spain, said there is currently an unmet clinical need in the approximately 60% of patients with previously untreated metastatic TNBC who are not candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Median PFS in previous first-line studies was < 6 months with chemotherapy — the current standard of care — and Cortés said that around half of the patients who receive that in the first-line do not receive second-line therapy because of clinical deterioration or death.

“The sobering truth is that across studies in the US and Europe, approximately 25% to 30% of patients diagnosed with metastatic TNBC are no longer alive at 6 months from their metastatic diagnosis,” said Garrido-Castro. “So if there is a new drug that is able to significantly improve PFS with an acceptable toxicity profile, this should be sufficient to change the current standard of care in the first-line setting.”

As sacituzumab govitecan is already approved for second-line metastatic TNBC and for pretreated hormone receptor positive/HER2- metastatic breast cancer, the ASCENT-03 researchers studied the drug in patients with previously untreated locally advanced inoperable, or metastatic TNBC.

The patients were deemed not to be candidates for PD-L1 inhibitors through having PD-L1-negative tumors, by having PD-L1-positive tumors that had previously been treated with PD-L1 inhibitors in the curative setting, or by having a comorbidity that precluded PD-L1 inhibitor use.

The patients were required to have finished any prior treatment in the curative setting at least 6 months previously. Previously treated, stable central nervous system metastases were allowed.

They were randomized to sacituzumab govitecan or chemotherapy, comprising paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel, or gemcitabine plus carboplatin, until progression, as verified by blinded independent central review (BICR), or unacceptable toxicity. Patients who progressed on chemotherapy were offered crossover to second-line sacituzumab govitecan.

In all, 558 patients were randomized. The median age was 56 years in the sacituzumab govitecan group vs 54 years in the chemotherapy group. The majority (64% in both groups) of patients were White individuals. The most common metastatic site was the lung (59% vs 61%), and 58% of patients in both groups had previously received a taxane.

Cortés reported that sacituzumab govitecan was associated with a “statistically significant and clinically meaningful” improvement in PFS by BICR, at a median of 9.7 months vs 6.9 months, or a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.62 (P < .0001). This benefit was seen across prespecified subgroups.

The objective response rate was almost identical between the two treatment groups, at 48% with sacituzumab govitecan vs 46% with chemotherapy, although the median duration of response was longer with the ADC, at 12.2 months vs 7.2 months.

Cortés showed the latest results on overall survival. This showed no significant difference between the two treatments, although he underlined that the data are not yet mature.

He also reported that the rates of grade ≥ 3 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were similar in the two groups, at 66% with sacituzumab govitecan vs 62% with chemotherapy. However, the rates of TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation (4% vs 12%) or dose reduction (37% vs 45%) were lower with the ADC.

Cortés concluded that the results suggest that sacituzumab govitecan “is a good option for patients with triple negative breast cancer when they develop metastasis and are unable to receive immune checkpoint inhibitors.”

TROPION-Breast02 Methods and Results

Presenting TROPION-Breast02, Rebecca A. Dent, MD, MSc, National Cancer Center Singapore and Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, explained that the trial looked at a patient population similar to that of ASCENT-03, here focusing instead on Dato-DXd.

Patients were included if they had histologically or cytologically documented locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC, no prior chemotherapy or targeted systemic therapy in this setting, and in whom immunotherapy was not an option.

They were randomized to Dato-DXd or the investigator’s choice of chemotherapy, with treatment continued until investigator-assessed progressive disease on RECIST v1.1, unacceptable toxicity, or another criterion for discontinuation was met.

In total, 642 patients were enrolled. The median age was 56 years for those in the Dato-DXd group and 57 years for those in chemotherapy group, and less than half (41% in the Dato-DXd group and 48% in the chemotherapy group) were White individuals. The number of metastatic sites was less than three in 64% and 67% of patients, respectively.

Dent showed that Dato-DXd was associated with a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in BICR-assessed PFS, at a median of 10.8 months vs 5.6 months with chemotherapy, at a HR of 0.57 (P < .0001). The findings were replicated across the prespecified subgroups.

There was a marked overall survival benefit with Dato-DXd, at a median of 23.7 months vs 18.7 months, at a HR of 0.79 (P = .0291). Dent reported that, at 18 months, 61.2% of patients in the Dato-DXd group were still alive vs 51.3% in the chemotherapy group. Again, the benefit was seen across subgroups.

The confirmed objective response rate with Dato-DXd was far higher than that with chemotherapy, at 62.5% vs 29.3%, or an odds ratio of 4.24. The duration of response was also longer, at 12.3 months vs 7.1 months.

Rates of grade ≥ 3 adverse events were comparable, at 33% with Dato-DXd vs 29% with chemotherapy, although there were more events associated with dose reduction (27% vs 18%) and dose interruption (24% vs 19%) with the ADC.

“These results support Dato-DXd as the first new first-line standard of care for patients with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC for whom immunotherapy is not an option,” Dent said.

“What’s important is the patients enrolled into this trial are clearly representative of real world patients that we are treating in our clinics every day. These patients are often excluded from our current clinical trials,” she said.

ASCENT-03 was funded by Gilead Sciences.

TROPION-Breast02 was funded by AstraZeneca.Cortés declared relationships with Roche, AstraZeneca, Seattle Genetics, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Leuko, Bioasis, Clovis oncology, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ellipses, HiberCell, BioInvent, GEMoaB, Gilead, Menarini, Zymeworks, Reveal Genomics, Expres2ion Biotechnologies, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Scorpion Therapeutics, Bridgebio, Biocon, Biontech, Circle Pharma, Delcath Systems, Hexagon Bio, Novartis, Eisai, Pfizer, Stemline Therapeutics, MAJ3 Capital, Leuko, Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Baxalta GmbH/Servier Affaires, Bayer healthcare, Guardant Health, and PIQUR Therapeutics.

Dent declared relationships with AstraZeneca, MSD, Pfizer, Eisai, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca, Roche, and Gilead Sciences.

Garrido-Castro declared relationships with AstraZeneca, MSD, Pfizer, Eisai, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo/AstraZeneca, Roche, Gilead Sciences, Pfizer, TD Cowen, and Roche/Genentech.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESMO 2025

AI in Mammography: Inside the Tangible Benefits Ready Now

In this Practical AI column, we’ve explored everything from large language models to the nuances of trial matching, but one of the most immediate and impactful applications of AI is unfolding right now in breast imaging. For oncologists, this isn’t an abstract future — with new screening guidelines, dense-breast mandates, and a shrinking radiology workforce, it’s the imaging reports and patient questions landing in your clinic today.

Here is what oncologists need to know, and how to put it to work for their patients.

Why AI in Mammography Matters

More than 200 million women undergo breast cancer screening each year. In the US alone, 10% of the 40 million women screened annually require additional diagnostic imaging, and 4%–5% of these women are eventually diagnosed with breast cancer.

Two major shifts are redefining breast cancer screening in the US: The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) now recommends biennial screening from age 40 to 74 years, and notifying patients of breast density is a federal requirement as of September 10, 2024. That means more mammograms, more patient questions, and more downstream oncology decisions. Patients will increasingly ask about “dense” breast results and what to do next. Add a national radiologist shortage into the mix, and the pressure on timely callbacks, biopsies, and treatment planning will only grow.

Can AI Help Without Compromising Care?

The short answer is yes. With AI, we may be able to transform these rate-limiting steps into opportunities for earlier detection, decentralized screening, and smarter triage and save hundreds of thousands of women from an unnecessary diagnostic procedure, if implemented deliberately.

Don’t Confuse Today’s AI With Yesterday’s CAD

Think of older computer-aided detection (CAD) like a 1990s chemotherapy drug: It sometimes helped, but it came with significant toxicity and rarely delivered consistent survival benefits. Today’s deep-learning AI is closer to targeted therapy — trained on millions of “trial participants” (mammograms), more precise, and applied in specific contexts where it adds value. If you once dismissed CAD as noise, it’s time to revisit what AI can now offer.

The role of AI is broader than drawing boxes. It provides second readings, worklist triage, risk prediction, density assessment, and decision support. FDA has cleared several AI tools for both 2D and digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), which include iCAD ProFound (DBT), ScreenPoint Transpara (2D/DBT), and Lunit INSIGHT DBT.

Some of the strongest evidence for AI in mammography is as a second reader during screening. Large trials show that AI plus one radiologist can match reading from two radiologists, cutting workload by about 40%. For example, the MASAI randomized trial showed that AI-supported screening achieved similar cancer detection but cut human screen-reading workload about 44% vs standard double reading (39,996 vs 40,024 participants). The primary interval cancer outcomes are maturing, but the safety analysis is reassuring.

Reducing second reads and arbitration time are important for clinicians because it frees capacity for callbacks and diagnostic workups. This will be especially key given that screening now starts at age 40. That will mean about 21 to 22 million more women are newly eligible, translating to about 10 to 11 million additional mammograms each year under biennial screening.

Another important area where AI can make its mark in mammography is triage and time to diagnosis. The results from a randomized implementation study showed that AI-prioritized worklists accelerated time to additional imaging and biopsy diagnosis without harming efficiency for others — exactly the kind of outcome patients feel.

Multiple studies have demonstrated improved diagnostic performance and shorter reading times when AI supports DBT interpretation, which is important because DBT can otherwise be time intensive.

We are also seeing rapid advancement in risk-based screening, moving beyond a single dense vs not dense approach. Deep-learning risk models, such as Mirai, predict 1- to 5-year breast cancer risk directly from the mammogram, and these tools are now being assessed prospectively to guide supplemental MRI. Cost-effectiveness modeling supports risk-stratified intervals vs one-size-fits-all schedules.

Finally, automated density tools, such as Transpara Density and Volpara, offer objective, reproducible volumetric measures that map to the Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System, which is useful for Mammography Quality Standards Act-required reporting and as inputs to risk calculators.

While early evidence suggests AI may help surface future or interval cancers earlier, including more invasive tumors, the definitive impacts on interval cancer rates and mortality require longitudinal follow-up, which is now in progress.

Pitfalls to Watch For

Bias is real. Studies show false-positive differences by race, age, and density. AI can even infer racial identity from images, potentially amplifying disparities. Performance can also shift by vendor, demographics, and prevalence.

A Radiology study of 4855 DBT exams showed that an algorithm produced more false-positive case scores in Black patients and older patients (aged 71-80 years) patients and in women with extremely dense breasts. This can happen because AI can infer proxies for race directly from images, even when humans cannot, and this can propagate disparities if not addressed. External validations and reviews emphasize that performance can shift with device manufacturer, demographics, and prevalence, which is why all tools need to undergo local validation and calibration.

Here’s a pragmatic adoption checklist before going live with an AI tool.

- Confirm FDA clearance: Verify the name and version of the algorithm, imaging modes (2D vs DBT), and operating points. Confirm 510(k) numbers.

- Local validation: Test on your patient mix and vendor stack (Hologic, GE, Siemens, Fuji). Compare this to your baseline recall rate, positive predictive value of recall (PPV1), cancer detection rate, and reading time. Commit to recalibration if drift occurs.

- Equity plan: Monitor false-positive and negative false-rates by age, race/ethnicity, and density; document corrective actions if disparities emerge. (This isn’t optional.)

- Workflow clarity: Is AI a second reader, an additional reader, or a triage tool? Who arbitrates discordance? What’s the escalation path for high-risk or interval cancer-like patterns?

- Regulatory strategy: Confirm whether the vendor has (or will file) a Predetermined Change Control Plan so models can be updated safely without repeated submissions. Also confirm how you’ll be notified about performance-relevant changes.