User login

Aspirin interacts with epigenetics to influence breast cancer mortality

The impact of prediagnosis aspirin use on mortality in women with breast cancer is significantly tied to epigenetic changes in certain breast cancer-related genes, investigators reported.

While studies have shown aspirin reduces the risk of breast cancer development, there is limited and inconsistent data on the effect of aspirin on prognosis and mortality after a diagnosis of breast cancer, Tengteng Wang, PhD, from the department of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and coauthors wrote in Cancer.

To address this, they analyzed data from 1,508 women who had a first diagnosis of primary breast cancer and were involved in the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project; they then looked at the women’s methylation status, which is a mechanism of epigenetic change.

Around one in five participants reported ever using aspirin, and the analysis showed that ever use of aspirin was associated with an overall 13% decrease in breast cancer–specific mortality.

However researchers saw significant interactions between aspirin use and LINE-1 methylation status – which is a marker of methylation of genetic elements that play key roles in maintaining genomic stability – and breast cancer–specific genes.

They found that aspirin use in women with LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with a risk of breast cancer–specific mortality that was 45% higher than that of nonusers (P = .05).

Compared with nonusers, aspirin users with methylated tumor BRCA1 promoter had significant 16% higher breast cancer mortality (P = .04) and 67% higher all-cause mortality (P = .02). However the study showed aspirin did not affect mortality in women with unmethylated BRCA1 promoter.

Among women with the PR breast cancer gene, aspirin use by those with methylation of the PR promoter was associated with a 63% higher breast cancer–specific mortality, but methylation showed no statistically significant effect on all-cause mortality, compared with nonusers.

The study found no significant change when they restricted the analysis to receptor-positive or invasive breast cancer, and the associations remained consistent even after adjusting for global methylation.

“Our findings suggest that the association between aspirin use and mortality after breast cancer may depend on methylation profiles and warrant further investigation,” the authors wrote. “These findings, if confirmed, may provide new biological insights into the association between aspirin use and breast cancer prognosis, may affect clinical decision making by identifying a subgroup of patients with breast cancer using epigenetic markers for whom prediagnosis aspirin use affects subsequent mortality, and may help refine risk-reduction strategies to improve survival among women with breast cancer.”

The study was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health. One author declared personal fees from the private sector outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Wang T et al. Cancer. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32364.

This study offers new insights into the intersection of epigenetics, prediagnosis aspirin use, and breast cancer survival at a time when there is an urgent need to understand why some women respond differently to treatment and to find cost-effective therapies for the disease.

Epigenetics is a promising avenue of investigation because epigenetic shifts, such as DNA methylation, that impact the genes responsible for cell behavior and DNA damage and repair are known to contribute to and exacerbate cancer. These epigenetic signatures could act as biomarkers for risk in cancer and also aid with more effective treatment approaches. For example, aspirin is known to affect DNA methylation at certain sites in colon cancer, hence this study’s hypothesis that pre–cancer diagnosis aspirin use would interact with epigenetic signatures and influence breast cancer outcomes.

Kristen M. C. Malecki, PhD, is from the department of population health sciences in the School of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Cancer. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32365). Dr. Malecki declared support from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences Breast Cancer, and the Environment Research Program.

This study offers new insights into the intersection of epigenetics, prediagnosis aspirin use, and breast cancer survival at a time when there is an urgent need to understand why some women respond differently to treatment and to find cost-effective therapies for the disease.

Epigenetics is a promising avenue of investigation because epigenetic shifts, such as DNA methylation, that impact the genes responsible for cell behavior and DNA damage and repair are known to contribute to and exacerbate cancer. These epigenetic signatures could act as biomarkers for risk in cancer and also aid with more effective treatment approaches. For example, aspirin is known to affect DNA methylation at certain sites in colon cancer, hence this study’s hypothesis that pre–cancer diagnosis aspirin use would interact with epigenetic signatures and influence breast cancer outcomes.

Kristen M. C. Malecki, PhD, is from the department of population health sciences in the School of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Cancer. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32365). Dr. Malecki declared support from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences Breast Cancer, and the Environment Research Program.

This study offers new insights into the intersection of epigenetics, prediagnosis aspirin use, and breast cancer survival at a time when there is an urgent need to understand why some women respond differently to treatment and to find cost-effective therapies for the disease.

Epigenetics is a promising avenue of investigation because epigenetic shifts, such as DNA methylation, that impact the genes responsible for cell behavior and DNA damage and repair are known to contribute to and exacerbate cancer. These epigenetic signatures could act as biomarkers for risk in cancer and also aid with more effective treatment approaches. For example, aspirin is known to affect DNA methylation at certain sites in colon cancer, hence this study’s hypothesis that pre–cancer diagnosis aspirin use would interact with epigenetic signatures and influence breast cancer outcomes.

Kristen M. C. Malecki, PhD, is from the department of population health sciences in the School of Medicine and Public Health at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Cancer. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32365). Dr. Malecki declared support from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences Breast Cancer, and the Environment Research Program.

The impact of prediagnosis aspirin use on mortality in women with breast cancer is significantly tied to epigenetic changes in certain breast cancer-related genes, investigators reported.

While studies have shown aspirin reduces the risk of breast cancer development, there is limited and inconsistent data on the effect of aspirin on prognosis and mortality after a diagnosis of breast cancer, Tengteng Wang, PhD, from the department of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and coauthors wrote in Cancer.

To address this, they analyzed data from 1,508 women who had a first diagnosis of primary breast cancer and were involved in the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project; they then looked at the women’s methylation status, which is a mechanism of epigenetic change.

Around one in five participants reported ever using aspirin, and the analysis showed that ever use of aspirin was associated with an overall 13% decrease in breast cancer–specific mortality.

However researchers saw significant interactions between aspirin use and LINE-1 methylation status – which is a marker of methylation of genetic elements that play key roles in maintaining genomic stability – and breast cancer–specific genes.

They found that aspirin use in women with LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with a risk of breast cancer–specific mortality that was 45% higher than that of nonusers (P = .05).

Compared with nonusers, aspirin users with methylated tumor BRCA1 promoter had significant 16% higher breast cancer mortality (P = .04) and 67% higher all-cause mortality (P = .02). However the study showed aspirin did not affect mortality in women with unmethylated BRCA1 promoter.

Among women with the PR breast cancer gene, aspirin use by those with methylation of the PR promoter was associated with a 63% higher breast cancer–specific mortality, but methylation showed no statistically significant effect on all-cause mortality, compared with nonusers.

The study found no significant change when they restricted the analysis to receptor-positive or invasive breast cancer, and the associations remained consistent even after adjusting for global methylation.

“Our findings suggest that the association between aspirin use and mortality after breast cancer may depend on methylation profiles and warrant further investigation,” the authors wrote. “These findings, if confirmed, may provide new biological insights into the association between aspirin use and breast cancer prognosis, may affect clinical decision making by identifying a subgroup of patients with breast cancer using epigenetic markers for whom prediagnosis aspirin use affects subsequent mortality, and may help refine risk-reduction strategies to improve survival among women with breast cancer.”

The study was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health. One author declared personal fees from the private sector outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Wang T et al. Cancer. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32364.

The impact of prediagnosis aspirin use on mortality in women with breast cancer is significantly tied to epigenetic changes in certain breast cancer-related genes, investigators reported.

While studies have shown aspirin reduces the risk of breast cancer development, there is limited and inconsistent data on the effect of aspirin on prognosis and mortality after a diagnosis of breast cancer, Tengteng Wang, PhD, from the department of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and coauthors wrote in Cancer.

To address this, they analyzed data from 1,508 women who had a first diagnosis of primary breast cancer and were involved in the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project; they then looked at the women’s methylation status, which is a mechanism of epigenetic change.

Around one in five participants reported ever using aspirin, and the analysis showed that ever use of aspirin was associated with an overall 13% decrease in breast cancer–specific mortality.

However researchers saw significant interactions between aspirin use and LINE-1 methylation status – which is a marker of methylation of genetic elements that play key roles in maintaining genomic stability – and breast cancer–specific genes.

They found that aspirin use in women with LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with a risk of breast cancer–specific mortality that was 45% higher than that of nonusers (P = .05).

Compared with nonusers, aspirin users with methylated tumor BRCA1 promoter had significant 16% higher breast cancer mortality (P = .04) and 67% higher all-cause mortality (P = .02). However the study showed aspirin did not affect mortality in women with unmethylated BRCA1 promoter.

Among women with the PR breast cancer gene, aspirin use by those with methylation of the PR promoter was associated with a 63% higher breast cancer–specific mortality, but methylation showed no statistically significant effect on all-cause mortality, compared with nonusers.

The study found no significant change when they restricted the analysis to receptor-positive or invasive breast cancer, and the associations remained consistent even after adjusting for global methylation.

“Our findings suggest that the association between aspirin use and mortality after breast cancer may depend on methylation profiles and warrant further investigation,” the authors wrote. “These findings, if confirmed, may provide new biological insights into the association between aspirin use and breast cancer prognosis, may affect clinical decision making by identifying a subgroup of patients with breast cancer using epigenetic markers for whom prediagnosis aspirin use affects subsequent mortality, and may help refine risk-reduction strategies to improve survival among women with breast cancer.”

The study was partly supported by the National Institutes of Health. One author declared personal fees from the private sector outside the submitted work.

SOURCE: Wang T et al. Cancer. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32364.

FROM CANCER

Genomic Medicine and Genetic Counseling in the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (FULL)

Vickie Venne, MS. What is the Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)?

Renee Rider, JD, MS, LCGC. GMS is a telehealth service. We are part of central office and field stationed at the George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Salt Lake City, Utah. We provide care to about 90 VAMCs and their associated clinics. Veterans are referred to us by entering an interfacility consult in the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). We review the consult to determine whether the patient needs to be seen, whether we can answer with an e-consult, or whether we need more information. For the patients who need an appointment, the telehealth department at the veteran’s VA facility will contact the patient to arrange a visit with us. At the time of the appointment, the facility has a staff member available to seat the patient and connect them to us using video equipment.

We provide genetic care for all specialties, including cancer, women’s health, cardiology and neurology. In today’s discussion, we are focusing on cancer care.

Vickie Venne. What do patients do at facilities that don’t get care through GMS?

Renee Rider. There are a handful of facilities that provide their own genetic care in-house. For example, VA Boston Healthcare System in Massachusetts and the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC in Houston, Texas each have their own programs. For veterans who are not at a VA facility that has an agreement with GMS and do not have a different genetics program, their providers need to make referrals to community care.

Vickie Venne. How do patients get referred and what happens at their facility when the patients return to the specialty and primary care providers (PCP)? Ishta, who do you refer to GMS and how do you define them initially?

Ishta Thakar, MD, FACP. Referrals can come at a couple of points during a veteran’s journey at the VA. The VA covers obstetrics care for women veterans. Whenever a PCP or a women’s health provider is doing the initial history and physical on a new patient, if the female veteran has an extensive family history of breast, ovarian, colon, or endometrial cancer, then we take more history and we send a consult to GMS. The second instance would be if she tells us that she has had a personal history of breast, ovarian, or endometrial cancer and she has never had genetic testing. The third instance would be whenever we have a female veteran who is diagnosed with breast, ovarian, endometrial, or colon cancer. We would definitely talk to her about genetic counseling and send a referral to GMS. We would ask for a GMS consult for a patient with advanced maternal age, with exposure to some kind of teratogens, with an abnormal ultrasound, a family history of chromosomal disorders, or if she’s seeing an obstetrician who wants her to be tested. And finally, if a patient has a constellation of multiple cancers in the family and we don’t know what’s going on, we would also refer the patient to GMS.

Vickie Venne. That would be why GMS fields over 150 referrals every week. It is a large list. We also see veterans with personal or family histories of neurologic or cardiologic concerns as well.

Renee, as somebody who fields many of these referrals from unaffected individuals, what is the family history process?

Renee Rider. We don’t expect the referring provider to be a genetic expert. When a provider is seeing a constellation of several different cancers and he or she doesn’t know if there’s anything going on genetically or even if it’s possible, absolutely they should put in a referral to GMS. We have a triage counselor who reviews every consult that comes into our service within 24 hours.

Many cancers are due to exposures that are not concerning for a genetic etiology. We can let you know that it is not concerning, and the PCP can counsel the patient that it is very unlikely to be genetic in nature. We still give feedback even if it’s not someone who is appropriate for genetic counseling and testing. It is important to reach out to GMS even if you don’t know whether a cancer is genetic in nature.

It also is important to take your time when gathering family histories. We get a lot of patients who say, “There’s a lot of cancer in my family. I have no idea who had cancer, but I know a lot of people had cancer.” That’s not the day to put in a referral to GMS. At that point, providers should tell the patient to get as much information as they can about the family history and then reassess. It’s important for us to have accurate information. We’ve had several times where we receive a referral because the veteran says that their sister had ovarian cancer. And then when our staff calls, they later find out it was cervical cancer. That’s not a good use of the veteran’s time, and it’s not a good use of VA resources.

The other important thing about family histories is keeping the questions open-ended. Often a PCP or specialist will ask about a certain type of cancer: “Does anyone in your family have breast cancer, ovarian cancer?” Or if the veteran

is getting a colonoscopy, they ask, “Does anybody have colon cancer?” Where really, we need to be a little bit more open-ended. We prefer questions like, “Has anyone in your family

had cancer?” because that’s the question that prompts a response of, “Yes, 3 people in my family have had thyroid cancer.” That’s very important for us to know, too.

If you do get a positive response, probe a little bit more: what kind of cancer did someone have, how old were they when they had their cancer? And how are they related? Is this an aunt on your mom’s side or on your dad’s side? Those are the types of information that we need to figure out if that person needs a referral.

Vickie Venne. It’s a different story when people already have a cancer diagnosis. Which hematology or oncology patients are good referrals and why?

Lisa Arfons, MD. When patients come in with newly diagnosed cancer, breast for example, it is an emotional diagnosis and psychologicallydistressing. Oftentimes, they want to know why this happened to them. The issues surrounding

genetic testing also becomes very emotional. They want to know whether their children are at risk as well.

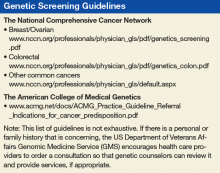

Genetic discussions take a long time. I rarely do that on the first visit. I always record for myself in my clinic note if something strikes me regarding the patient’s diagnosis. I quickly run through the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines to remind myself of what I need to go over with the patient at our next meeting. Most patients don’t need to be referred to GMS, and most patients don’t need to be tested once they’re seen.

I often save the referral discussion for after I have established a rapport with a patient, we have a treatment plan, or they already have had their first surgery. Therefore, we are not making decisions about their first surgery based on the genetic medicine results.

If I’m considering a referral, I do a deeper dive with the patient. Is the patient older or younger than 45 years? I pull up NCCN guidelines and we go through the entire checklist.

We have male breast cancer patients at the VA—probably more than the community—so we refer those patients. At the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC in Ohio, we have had some in-depth discussions about referring male breast cancer patients for genetic testing and whether it was beneficial to older patients with male breast cancer. Ultimately, we decided that it was important for our male veterans to be tested because it empowered them to have better understanding of their medical conditions that may not just have effect on them but on their offspring, and that that can be a source of psychological and emotional support.

I don’t refer most people to GMS once I go through the checklist. I appreciate the action for an e-consult within the CPRS telemedicine consult itself, as Renee noted. If it is not necessary, GMS makes it an e-consult. I try to communicate that I don’t know whether it is necessary or not so that GMS understands where I’m coming from.

Vickie Venne. In the US Department of Defense (DoD) the process is quite different. Mauricio, can you explain the clinical referral process, who is referred, and how that works from a laboratory perspective?

Maj De Castro, MD, FACMG, USAF. The VA has led the way in demonstrating how to best provide for the medical genetic needs of a large, decentralized population distributed all over the country. Over the last 5 to 10 years, the DoD has made strides in recognizing the role genetics plays in the practice of everyday medicine and redoubling efforts to meet the needs of servicemembers.

The way that it traditionally has worked in the DoD is that military treatment facilities (MTFs) that have dedicated geneticists and genetic counselors: Kessler Medical Center in Mississippi, Walter Reed National Military Medical

Center in Maryland, Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii, Madigan Army Medical Center in Washington, Brooke Army Medical Center in Texas, Naval Medical Center San Diego in California, and Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in Virginia. A patient seeking genetic evaluation, counseling, or testing in those larger facilities would be referred to the genetics service by their primary care manager. Wait times vary, but it would usually be weeks, maybe months. However, the great majority of MTFs do not have dedicated genetics support. Most of the time, those patients would have to be referred to the local civilian community—there was no process for them to be seen in in the military healthcare system—with wait times that exceed 6 to 8 months in some cases. This is due to just not a military but a national shortage of genetics professionals (counselors and physicians).

Last year we started the telegenetics initiative, which is small compared to the VA—it is comprised of 2 geneticists and 1 genetic counselor—but with the full intent of growing it over time. Its purpose is to extend the resources we

had to other MTFs. Genetics professionals stationed state-side can provide care to remote facilities with limited access to local genetics support such as Cannon Air Force Base (AFB) or overseas facilities such as Spangdahlem AFB in Germany.

We recognize there are military-specific needs for the DoD regarding the genetic counseling process that have to take into account readiness, genetic discrimination, continued ability to serve and fitness for duty. For this important reason, we are seeking to expand our telegenetics initiative. The goal is to be able to provide 100% of all genetic counseling in-house, so to speak.

Currently, providers at the 4 pilot sites (Cannon AFB, Fort Bragg, Spangdahlem AFB, and Guantanamo Bay) send us referrals. We triage them and assign the patient to see a geneticist or a counselor depending on the indication.

On the laboratory side, it has been a very interesting experience. Because we provide comprehensive germline cancer testing at very little cost to the provider at any MTF, we have had high numbers of test requests over the years.

In addition to saving the DoD millions of dollars in testing, we have learned some interesting lessons in the process. For instance, we have worked closely with several different groups to better understand how to educate providers on the genetic counseling and testing process. This has allowed us to craft a thorough and inclusive consent form that addresses the needs of the DoD. We have also learned valuable lessons about population-based screening vs evidence-based testing, and lessons surrounding narrow-based testing (BRCA1 and BRCA2 only testing) vs ordering a more comprehensive panel that includes other genes supported by strong evidence (such as PALB2, CHEK2, or TP53).

For example, we have found that in a significant proportion of individuals with and without family history, there are clinically relevant variants in genes other than BRCA1 or BRCA2. And so, we have made part of our consent process,

a statement on secondary findings. If the patient consents, we will report pathogenic variants in other genes known to be associated with cancer (with strong evidence) even if the provider ordered a narrow panel such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing only. In about 1% to 4% of patients that would otherwise not meet NCCN guidelines, we’ve reported variants that were clinically actionable and changed the medical management of that patient.

We feel strongly that this is a conversation that we need to have in our field, and we realize it’s a complex issue, maybe we need to expand who gets testing. Guideline based testing is missing some patients out there that could benefit from it.

Vickie Venne. There certainly are many sides to the conversation of population-based vs evidence-based genetic testing. Genetic testing policies are changing rapidly. There are teams exploring comprehensive gene sequencing for

newborns and how that potential 1-time test can provide information will be reinterpreted as a person goes from cradle to grave. However, unlike the current DoD process, in the VA there are patients who we don’t see.

Renee Rider. I want to talk about money. When we order a genetic test, that test is paid for by the pathology department at the patient’s VAMC. Most of the pathology departments we work with are clear that they only can provide

genetic testing that is considered medically necessary. Thus, we review each test to make sure it meets established guidelines for testing. We don’t do population genetic screening as there isn’t evidence or guidelines to support offering it. We are strict about who does and does not get genetic testing, partly because we have a responsibility to pathology departments and to the taxpayers.

GMS focuses on conditions that are inherited, that is to say, we deal with germline genetics. Therefore, we discontinue referrals for somatic requests, such as when an OncotypeDX test is requested. It is my understanding that pharmacogenetic referrals may be sent to the new PHASeR initiative, which is a joint collaboration between the VA and Sanford Health and is headed by Deepak Voora, MD.

We generally don’t see patients who still are having diagnostic procedures done. For example, if a veteran has a suspicious breast mass, we recommend that the provider workup the mass before referring to GMS. Regardless of a genetic test result, a suspicious mass needs to be worked up. And, knowing if the mass is cancerous could change how we would proceed with the genetic workup. For example, if the mass were not cancerous, we may recommend that an affected relative have the first genetic evaluation. Furthermore, knowing if the patient has cancer changes how we interpret negative test results.

Another group of patients we don’t see are those who already had genetic testing done by the referring provider. It’s a VA directive that if you order a test, you’re the person who is responsible for giving the results. We agree with

this directive. If you don’t feel comfortable giving back test results, don’t order the test. Often, when a provider sends a patient to us after the test was done, we discover that the patient didn’t have appropriate pretest counseling. A test result, such as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS), should never be a surprise to either the provider or the patient.

Ishta Thakar. For newly diagnosed cancers, the first call is to the patient to inform them that they have cancer. We usually bring up genetic counseling or testing, if applicable, when they are ready to accept the diagnosis and have a conversation about it. All our consults are via telehealth, so none of our patients physically come to GMS in Salt Lake City. All the consults are done virtually.

For newly diagnosed patients, we would send a consult in within a couple of weeks. For patients who had a family history, the referral would not be urgent: They can be seen within about 3 months. The turnaround times for GMS are so much better than what we have available in the community where it’s often at least 6 months, as previously noted.

Vickie Venne. Thank you. We continue to work on that. One of the interesting things that we’ve done, which is the brainchild of Renee, is shared medical appointments.

Renee Rider. We have now created 4 group appointments for people who have concerns surrounding cancer. One group is for people who don’t have cancer but have family members who have cancer who may be the best testing candidate. For example, that might be a 30-year old who tells you that her mother had breast cancer at age 45 years. Her mother is still living, but she’s never had genetic testing. We would put her in a group where we discuss the importance of talking to the family members and encouraging them to go get that first genetic evaluation in the family.

Our second group is for people who don’t have cancer themselves, but have a family history of cancer and those affected relatives have passed away. The family needs a genetic evaluation, and the veteran is the best living testing candidate.

That group is geared towards education about the test and informed consent.

The third group is for people with cancer who qualify for genetic testing. We provide all of the information that they need to make an informed decision on having (or not having) genetic testing.

The final group is for people who have family histories of known genetic mutations in cancer genes. Again, we provide them with all of the information that they need to make an informed decision regarding genetic testing.

With the shared medical appointments, we have been able to greatly increase the number of patients that we can see. Our first 3 groups all meet once a week and can have 10 or 12 veterans. Our last group meets every other week and has a maximum of 6 veterans. Wait times for our groups are generally ≤ 2 weeks. All veterans can choose to have an individual appointment if they prefer. We regularly get unsolicited feedback from veterans that they learn a lot during our groups and appreciate it.

Our group appointments have lowered the wait time for the people in the groups. And, they’ve lowered the wait time for the people who are seen individually. They’ve allowed us to address the backlog of patients waiting to see us in a more timely manner. Our wait time for individual appointment had been approaching 6 months, and it is now about 1.5 months.

We also think that being in a group normalizes the experience. Most people don’t know anyone who has had genetic testing. Now, they are in a group with others going through the same experience. In one of my groups, a male veteran talked about his breast cancer being really rare. Another male in the group volunteer that he had breast cancer, too. They both seemed to appreciate not feeling alone.

Vickie Venne. I want to move to our final piece. What do the referring providers tell the patients about a genetics referral and what should they expect?

Lisa Arfons. First and foremost, I tell the patient that it is a discussion with a genetic counselor. I make it clear that they understand that it is a discussion. They then can agree or not agree to accept genetic testing if it’s recommended.

I talk in general terms about why I think it can be important for them to have the discussion, but that we don’t have great data for decisionmaking. We understand that there are more options for preventive measures but then it ultimately will be a discussion between the PCP, the patient, and their family members about how they proceed about the preventive measures. I want them to start thinking about how the genetic test results, regardless of if they are positive, negative, or a variant that is not yet understood, can impact their offspring.

Probably I am biased, as my mom had breast cancer and she underwent genetic testing. So, I have a bit of an offspring focus as well. I already mentioned that you must discuss about whether or not it’s worth screening or doing any preventive measures on contralateral breast, or screening for things like prostate cancer at age 75 years. And so I focus more on the family members.

I try to stay in my lane. I am extremely uncomfortable when I hear about someone in our facility sending off a blood test and then asking someone else to interpret the results and discuss it with the patient. Just because it’s a blood test and it’s easy to order doesn’t mean that it is easy to know what to do with it, and it needs to be respected as such.

Ishta Thakar. Our PCPs let the patients know that GMS will contact the patient to schedule a video appointment and that if they want to bring any family members along with them, they’re welcome to. We also explain that certain cancers are genetically based and that if they have a genetic mutation, it can be passed on to their offspring. I also explain that if they have certain mutations, then we would be more vigilant in screening them for other kinds of cancers. That’s the reason that we refer that they get counseled. After counseling if they’re ready for the testing, then the counselor orders the test and does the posttest discussion with the patient.

Vickie Venne. In the VA, people are invited to attend a genetic counseling session but can certainly decline. Does the the DoD have a different approach?

Maj De Castro. I would say that the great majority of active duty patients have limited knowledge of what to expect out of a genetics appointment. One of the main things we do is educate them on their rights and protections and the potential risks associated with performing genetic testing, in particular when it comes to their continued ability to serve. Genetic testing for clinical purposes is not mandatory in the DoD, patients can certainly decline testing. Because genetic testing has the potential to alter someone’s career, it is critical we have a very thorough and comprehensive pre- and posttest counseling sessions that includes everything from career implications to the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) and genetic discrimination in the military, in addition to the standard of care medical information.

Scenarios in which a servicemember is negatively impacted by pursuing a genetic diagnosis are very rare. More than 90% of the time, genetic counseling and/or testing has no adverse career effect. When they do, it is out of concern for the safety and wellbeing of a servicemember. For instance, if we diagnosis a patient with a genetic form of some arrhythmogenic disorder, part of the treatment plan can be to limit that person’s level of exertion, because it could potentially lead to death. We don’t want to put someone in a situation that may trigger that.

Vickie Venne. We also have a certain number of veterans who ask us about their service disability pay and the impact of genetic testing on it. One example is veterans with prostate cancer who were exposed to Agent Orange, which has been associated with increased risk for developing prostate cancer. I have had men who have been referred for genetic evaluation ask, “Well, if I have an identifiable mutation, how will that impact my service disability?” So we discuss the carcinogenic process that may include an inherited component as well as the environmental risk factors. I think that’s a unique issue for a population we’re honored to be able to serve.

Renee Rider. When we are talking about how the population of veterans is unique, I think it is also important to acknowledge mental health. I’ve had several patients tell me that they have posttraumatic stress disorder or anxiety and the idea of getting an indeterminant test result, such as VUS, would really weigh on them.

In the community, a lot of providers order the biggest panel they can, but for these patients who are worried about getting those indeterminant test results, I’ve been able to work with them to limit the size of the panel. I order a small panel that only has genes that have implications for that veteran’s clinical management. For example, in a patient with ductal breast cancer, I remove the genes that cause lobular breast cancer. This takes a bit of knowledge and critical thinking that our VA genetic counselors have because they have experience with veterans and their needs.

As our time draws to a close, I have one final thought. This has been a heartwarming conversation today. It is really nice to hear that GMS services are appreciated. We in GMS want to partner with our referring providers. Help us help you! When you enter a referral, please let us know how we can help you. The more we understand why you are sending your veteran to GMS, the more we can help meet your needs. If there are any questions or problems, feel free to send us an email or pick up the phone and call us.

Vickie Venne, MS. What is the Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)?

Renee Rider, JD, MS, LCGC. GMS is a telehealth service. We are part of central office and field stationed at the George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Salt Lake City, Utah. We provide care to about 90 VAMCs and their associated clinics. Veterans are referred to us by entering an interfacility consult in the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). We review the consult to determine whether the patient needs to be seen, whether we can answer with an e-consult, or whether we need more information. For the patients who need an appointment, the telehealth department at the veteran’s VA facility will contact the patient to arrange a visit with us. At the time of the appointment, the facility has a staff member available to seat the patient and connect them to us using video equipment.

We provide genetic care for all specialties, including cancer, women’s health, cardiology and neurology. In today’s discussion, we are focusing on cancer care.

Vickie Venne. What do patients do at facilities that don’t get care through GMS?

Renee Rider. There are a handful of facilities that provide their own genetic care in-house. For example, VA Boston Healthcare System in Massachusetts and the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC in Houston, Texas each have their own programs. For veterans who are not at a VA facility that has an agreement with GMS and do not have a different genetics program, their providers need to make referrals to community care.

Vickie Venne. How do patients get referred and what happens at their facility when the patients return to the specialty and primary care providers (PCP)? Ishta, who do you refer to GMS and how do you define them initially?

Ishta Thakar, MD, FACP. Referrals can come at a couple of points during a veteran’s journey at the VA. The VA covers obstetrics care for women veterans. Whenever a PCP or a women’s health provider is doing the initial history and physical on a new patient, if the female veteran has an extensive family history of breast, ovarian, colon, or endometrial cancer, then we take more history and we send a consult to GMS. The second instance would be if she tells us that she has had a personal history of breast, ovarian, or endometrial cancer and she has never had genetic testing. The third instance would be whenever we have a female veteran who is diagnosed with breast, ovarian, endometrial, or colon cancer. We would definitely talk to her about genetic counseling and send a referral to GMS. We would ask for a GMS consult for a patient with advanced maternal age, with exposure to some kind of teratogens, with an abnormal ultrasound, a family history of chromosomal disorders, or if she’s seeing an obstetrician who wants her to be tested. And finally, if a patient has a constellation of multiple cancers in the family and we don’t know what’s going on, we would also refer the patient to GMS.

Vickie Venne. That would be why GMS fields over 150 referrals every week. It is a large list. We also see veterans with personal or family histories of neurologic or cardiologic concerns as well.

Renee, as somebody who fields many of these referrals from unaffected individuals, what is the family history process?

Renee Rider. We don’t expect the referring provider to be a genetic expert. When a provider is seeing a constellation of several different cancers and he or she doesn’t know if there’s anything going on genetically or even if it’s possible, absolutely they should put in a referral to GMS. We have a triage counselor who reviews every consult that comes into our service within 24 hours.

Many cancers are due to exposures that are not concerning for a genetic etiology. We can let you know that it is not concerning, and the PCP can counsel the patient that it is very unlikely to be genetic in nature. We still give feedback even if it’s not someone who is appropriate for genetic counseling and testing. It is important to reach out to GMS even if you don’t know whether a cancer is genetic in nature.

It also is important to take your time when gathering family histories. We get a lot of patients who say, “There’s a lot of cancer in my family. I have no idea who had cancer, but I know a lot of people had cancer.” That’s not the day to put in a referral to GMS. At that point, providers should tell the patient to get as much information as they can about the family history and then reassess. It’s important for us to have accurate information. We’ve had several times where we receive a referral because the veteran says that their sister had ovarian cancer. And then when our staff calls, they later find out it was cervical cancer. That’s not a good use of the veteran’s time, and it’s not a good use of VA resources.

The other important thing about family histories is keeping the questions open-ended. Often a PCP or specialist will ask about a certain type of cancer: “Does anyone in your family have breast cancer, ovarian cancer?” Or if the veteran

is getting a colonoscopy, they ask, “Does anybody have colon cancer?” Where really, we need to be a little bit more open-ended. We prefer questions like, “Has anyone in your family

had cancer?” because that’s the question that prompts a response of, “Yes, 3 people in my family have had thyroid cancer.” That’s very important for us to know, too.

If you do get a positive response, probe a little bit more: what kind of cancer did someone have, how old were they when they had their cancer? And how are they related? Is this an aunt on your mom’s side or on your dad’s side? Those are the types of information that we need to figure out if that person needs a referral.

Vickie Venne. It’s a different story when people already have a cancer diagnosis. Which hematology or oncology patients are good referrals and why?

Lisa Arfons, MD. When patients come in with newly diagnosed cancer, breast for example, it is an emotional diagnosis and psychologicallydistressing. Oftentimes, they want to know why this happened to them. The issues surrounding

genetic testing also becomes very emotional. They want to know whether their children are at risk as well.

Genetic discussions take a long time. I rarely do that on the first visit. I always record for myself in my clinic note if something strikes me regarding the patient’s diagnosis. I quickly run through the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines to remind myself of what I need to go over with the patient at our next meeting. Most patients don’t need to be referred to GMS, and most patients don’t need to be tested once they’re seen.

I often save the referral discussion for after I have established a rapport with a patient, we have a treatment plan, or they already have had their first surgery. Therefore, we are not making decisions about their first surgery based on the genetic medicine results.

If I’m considering a referral, I do a deeper dive with the patient. Is the patient older or younger than 45 years? I pull up NCCN guidelines and we go through the entire checklist.

We have male breast cancer patients at the VA—probably more than the community—so we refer those patients. At the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC in Ohio, we have had some in-depth discussions about referring male breast cancer patients for genetic testing and whether it was beneficial to older patients with male breast cancer. Ultimately, we decided that it was important for our male veterans to be tested because it empowered them to have better understanding of their medical conditions that may not just have effect on them but on their offspring, and that that can be a source of psychological and emotional support.

I don’t refer most people to GMS once I go through the checklist. I appreciate the action for an e-consult within the CPRS telemedicine consult itself, as Renee noted. If it is not necessary, GMS makes it an e-consult. I try to communicate that I don’t know whether it is necessary or not so that GMS understands where I’m coming from.

Vickie Venne. In the US Department of Defense (DoD) the process is quite different. Mauricio, can you explain the clinical referral process, who is referred, and how that works from a laboratory perspective?

Maj De Castro, MD, FACMG, USAF. The VA has led the way in demonstrating how to best provide for the medical genetic needs of a large, decentralized population distributed all over the country. Over the last 5 to 10 years, the DoD has made strides in recognizing the role genetics plays in the practice of everyday medicine and redoubling efforts to meet the needs of servicemembers.

The way that it traditionally has worked in the DoD is that military treatment facilities (MTFs) that have dedicated geneticists and genetic counselors: Kessler Medical Center in Mississippi, Walter Reed National Military Medical

Center in Maryland, Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii, Madigan Army Medical Center in Washington, Brooke Army Medical Center in Texas, Naval Medical Center San Diego in California, and Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in Virginia. A patient seeking genetic evaluation, counseling, or testing in those larger facilities would be referred to the genetics service by their primary care manager. Wait times vary, but it would usually be weeks, maybe months. However, the great majority of MTFs do not have dedicated genetics support. Most of the time, those patients would have to be referred to the local civilian community—there was no process for them to be seen in in the military healthcare system—with wait times that exceed 6 to 8 months in some cases. This is due to just not a military but a national shortage of genetics professionals (counselors and physicians).

Last year we started the telegenetics initiative, which is small compared to the VA—it is comprised of 2 geneticists and 1 genetic counselor—but with the full intent of growing it over time. Its purpose is to extend the resources we

had to other MTFs. Genetics professionals stationed state-side can provide care to remote facilities with limited access to local genetics support such as Cannon Air Force Base (AFB) or overseas facilities such as Spangdahlem AFB in Germany.

We recognize there are military-specific needs for the DoD regarding the genetic counseling process that have to take into account readiness, genetic discrimination, continued ability to serve and fitness for duty. For this important reason, we are seeking to expand our telegenetics initiative. The goal is to be able to provide 100% of all genetic counseling in-house, so to speak.

Currently, providers at the 4 pilot sites (Cannon AFB, Fort Bragg, Spangdahlem AFB, and Guantanamo Bay) send us referrals. We triage them and assign the patient to see a geneticist or a counselor depending on the indication.

On the laboratory side, it has been a very interesting experience. Because we provide comprehensive germline cancer testing at very little cost to the provider at any MTF, we have had high numbers of test requests over the years.

In addition to saving the DoD millions of dollars in testing, we have learned some interesting lessons in the process. For instance, we have worked closely with several different groups to better understand how to educate providers on the genetic counseling and testing process. This has allowed us to craft a thorough and inclusive consent form that addresses the needs of the DoD. We have also learned valuable lessons about population-based screening vs evidence-based testing, and lessons surrounding narrow-based testing (BRCA1 and BRCA2 only testing) vs ordering a more comprehensive panel that includes other genes supported by strong evidence (such as PALB2, CHEK2, or TP53).

For example, we have found that in a significant proportion of individuals with and without family history, there are clinically relevant variants in genes other than BRCA1 or BRCA2. And so, we have made part of our consent process,

a statement on secondary findings. If the patient consents, we will report pathogenic variants in other genes known to be associated with cancer (with strong evidence) even if the provider ordered a narrow panel such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing only. In about 1% to 4% of patients that would otherwise not meet NCCN guidelines, we’ve reported variants that were clinically actionable and changed the medical management of that patient.

We feel strongly that this is a conversation that we need to have in our field, and we realize it’s a complex issue, maybe we need to expand who gets testing. Guideline based testing is missing some patients out there that could benefit from it.

Vickie Venne. There certainly are many sides to the conversation of population-based vs evidence-based genetic testing. Genetic testing policies are changing rapidly. There are teams exploring comprehensive gene sequencing for

newborns and how that potential 1-time test can provide information will be reinterpreted as a person goes from cradle to grave. However, unlike the current DoD process, in the VA there are patients who we don’t see.

Renee Rider. I want to talk about money. When we order a genetic test, that test is paid for by the pathology department at the patient’s VAMC. Most of the pathology departments we work with are clear that they only can provide

genetic testing that is considered medically necessary. Thus, we review each test to make sure it meets established guidelines for testing. We don’t do population genetic screening as there isn’t evidence or guidelines to support offering it. We are strict about who does and does not get genetic testing, partly because we have a responsibility to pathology departments and to the taxpayers.

GMS focuses on conditions that are inherited, that is to say, we deal with germline genetics. Therefore, we discontinue referrals for somatic requests, such as when an OncotypeDX test is requested. It is my understanding that pharmacogenetic referrals may be sent to the new PHASeR initiative, which is a joint collaboration between the VA and Sanford Health and is headed by Deepak Voora, MD.

We generally don’t see patients who still are having diagnostic procedures done. For example, if a veteran has a suspicious breast mass, we recommend that the provider workup the mass before referring to GMS. Regardless of a genetic test result, a suspicious mass needs to be worked up. And, knowing if the mass is cancerous could change how we would proceed with the genetic workup. For example, if the mass were not cancerous, we may recommend that an affected relative have the first genetic evaluation. Furthermore, knowing if the patient has cancer changes how we interpret negative test results.

Another group of patients we don’t see are those who already had genetic testing done by the referring provider. It’s a VA directive that if you order a test, you’re the person who is responsible for giving the results. We agree with

this directive. If you don’t feel comfortable giving back test results, don’t order the test. Often, when a provider sends a patient to us after the test was done, we discover that the patient didn’t have appropriate pretest counseling. A test result, such as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS), should never be a surprise to either the provider or the patient.

Ishta Thakar. For newly diagnosed cancers, the first call is to the patient to inform them that they have cancer. We usually bring up genetic counseling or testing, if applicable, when they are ready to accept the diagnosis and have a conversation about it. All our consults are via telehealth, so none of our patients physically come to GMS in Salt Lake City. All the consults are done virtually.

For newly diagnosed patients, we would send a consult in within a couple of weeks. For patients who had a family history, the referral would not be urgent: They can be seen within about 3 months. The turnaround times for GMS are so much better than what we have available in the community where it’s often at least 6 months, as previously noted.

Vickie Venne. Thank you. We continue to work on that. One of the interesting things that we’ve done, which is the brainchild of Renee, is shared medical appointments.

Renee Rider. We have now created 4 group appointments for people who have concerns surrounding cancer. One group is for people who don’t have cancer but have family members who have cancer who may be the best testing candidate. For example, that might be a 30-year old who tells you that her mother had breast cancer at age 45 years. Her mother is still living, but she’s never had genetic testing. We would put her in a group where we discuss the importance of talking to the family members and encouraging them to go get that first genetic evaluation in the family.

Our second group is for people who don’t have cancer themselves, but have a family history of cancer and those affected relatives have passed away. The family needs a genetic evaluation, and the veteran is the best living testing candidate.

That group is geared towards education about the test and informed consent.

The third group is for people with cancer who qualify for genetic testing. We provide all of the information that they need to make an informed decision on having (or not having) genetic testing.

The final group is for people who have family histories of known genetic mutations in cancer genes. Again, we provide them with all of the information that they need to make an informed decision regarding genetic testing.

With the shared medical appointments, we have been able to greatly increase the number of patients that we can see. Our first 3 groups all meet once a week and can have 10 or 12 veterans. Our last group meets every other week and has a maximum of 6 veterans. Wait times for our groups are generally ≤ 2 weeks. All veterans can choose to have an individual appointment if they prefer. We regularly get unsolicited feedback from veterans that they learn a lot during our groups and appreciate it.

Our group appointments have lowered the wait time for the people in the groups. And, they’ve lowered the wait time for the people who are seen individually. They’ve allowed us to address the backlog of patients waiting to see us in a more timely manner. Our wait time for individual appointment had been approaching 6 months, and it is now about 1.5 months.

We also think that being in a group normalizes the experience. Most people don’t know anyone who has had genetic testing. Now, they are in a group with others going through the same experience. In one of my groups, a male veteran talked about his breast cancer being really rare. Another male in the group volunteer that he had breast cancer, too. They both seemed to appreciate not feeling alone.

Vickie Venne. I want to move to our final piece. What do the referring providers tell the patients about a genetics referral and what should they expect?

Lisa Arfons. First and foremost, I tell the patient that it is a discussion with a genetic counselor. I make it clear that they understand that it is a discussion. They then can agree or not agree to accept genetic testing if it’s recommended.

I talk in general terms about why I think it can be important for them to have the discussion, but that we don’t have great data for decisionmaking. We understand that there are more options for preventive measures but then it ultimately will be a discussion between the PCP, the patient, and their family members about how they proceed about the preventive measures. I want them to start thinking about how the genetic test results, regardless of if they are positive, negative, or a variant that is not yet understood, can impact their offspring.

Probably I am biased, as my mom had breast cancer and she underwent genetic testing. So, I have a bit of an offspring focus as well. I already mentioned that you must discuss about whether or not it’s worth screening or doing any preventive measures on contralateral breast, or screening for things like prostate cancer at age 75 years. And so I focus more on the family members.

I try to stay in my lane. I am extremely uncomfortable when I hear about someone in our facility sending off a blood test and then asking someone else to interpret the results and discuss it with the patient. Just because it’s a blood test and it’s easy to order doesn’t mean that it is easy to know what to do with it, and it needs to be respected as such.

Ishta Thakar. Our PCPs let the patients know that GMS will contact the patient to schedule a video appointment and that if they want to bring any family members along with them, they’re welcome to. We also explain that certain cancers are genetically based and that if they have a genetic mutation, it can be passed on to their offspring. I also explain that if they have certain mutations, then we would be more vigilant in screening them for other kinds of cancers. That’s the reason that we refer that they get counseled. After counseling if they’re ready for the testing, then the counselor orders the test and does the posttest discussion with the patient.

Vickie Venne. In the VA, people are invited to attend a genetic counseling session but can certainly decline. Does the the DoD have a different approach?

Maj De Castro. I would say that the great majority of active duty patients have limited knowledge of what to expect out of a genetics appointment. One of the main things we do is educate them on their rights and protections and the potential risks associated with performing genetic testing, in particular when it comes to their continued ability to serve. Genetic testing for clinical purposes is not mandatory in the DoD, patients can certainly decline testing. Because genetic testing has the potential to alter someone’s career, it is critical we have a very thorough and comprehensive pre- and posttest counseling sessions that includes everything from career implications to the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) and genetic discrimination in the military, in addition to the standard of care medical information.

Scenarios in which a servicemember is negatively impacted by pursuing a genetic diagnosis are very rare. More than 90% of the time, genetic counseling and/or testing has no adverse career effect. When they do, it is out of concern for the safety and wellbeing of a servicemember. For instance, if we diagnosis a patient with a genetic form of some arrhythmogenic disorder, part of the treatment plan can be to limit that person’s level of exertion, because it could potentially lead to death. We don’t want to put someone in a situation that may trigger that.

Vickie Venne. We also have a certain number of veterans who ask us about their service disability pay and the impact of genetic testing on it. One example is veterans with prostate cancer who were exposed to Agent Orange, which has been associated with increased risk for developing prostate cancer. I have had men who have been referred for genetic evaluation ask, “Well, if I have an identifiable mutation, how will that impact my service disability?” So we discuss the carcinogenic process that may include an inherited component as well as the environmental risk factors. I think that’s a unique issue for a population we’re honored to be able to serve.

Renee Rider. When we are talking about how the population of veterans is unique, I think it is also important to acknowledge mental health. I’ve had several patients tell me that they have posttraumatic stress disorder or anxiety and the idea of getting an indeterminant test result, such as VUS, would really weigh on them.

In the community, a lot of providers order the biggest panel they can, but for these patients who are worried about getting those indeterminant test results, I’ve been able to work with them to limit the size of the panel. I order a small panel that only has genes that have implications for that veteran’s clinical management. For example, in a patient with ductal breast cancer, I remove the genes that cause lobular breast cancer. This takes a bit of knowledge and critical thinking that our VA genetic counselors have because they have experience with veterans and their needs.

As our time draws to a close, I have one final thought. This has been a heartwarming conversation today. It is really nice to hear that GMS services are appreciated. We in GMS want to partner with our referring providers. Help us help you! When you enter a referral, please let us know how we can help you. The more we understand why you are sending your veteran to GMS, the more we can help meet your needs. If there are any questions or problems, feel free to send us an email or pick up the phone and call us.

Vickie Venne, MS. What is the Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)?

Renee Rider, JD, MS, LCGC. GMS is a telehealth service. We are part of central office and field stationed at the George E. Wahlen VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Salt Lake City, Utah. We provide care to about 90 VAMCs and their associated clinics. Veterans are referred to us by entering an interfacility consult in the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS). We review the consult to determine whether the patient needs to be seen, whether we can answer with an e-consult, or whether we need more information. For the patients who need an appointment, the telehealth department at the veteran’s VA facility will contact the patient to arrange a visit with us. At the time of the appointment, the facility has a staff member available to seat the patient and connect them to us using video equipment.

We provide genetic care for all specialties, including cancer, women’s health, cardiology and neurology. In today’s discussion, we are focusing on cancer care.

Vickie Venne. What do patients do at facilities that don’t get care through GMS?

Renee Rider. There are a handful of facilities that provide their own genetic care in-house. For example, VA Boston Healthcare System in Massachusetts and the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC in Houston, Texas each have their own programs. For veterans who are not at a VA facility that has an agreement with GMS and do not have a different genetics program, their providers need to make referrals to community care.

Vickie Venne. How do patients get referred and what happens at their facility when the patients return to the specialty and primary care providers (PCP)? Ishta, who do you refer to GMS and how do you define them initially?

Ishta Thakar, MD, FACP. Referrals can come at a couple of points during a veteran’s journey at the VA. The VA covers obstetrics care for women veterans. Whenever a PCP or a women’s health provider is doing the initial history and physical on a new patient, if the female veteran has an extensive family history of breast, ovarian, colon, or endometrial cancer, then we take more history and we send a consult to GMS. The second instance would be if she tells us that she has had a personal history of breast, ovarian, or endometrial cancer and she has never had genetic testing. The third instance would be whenever we have a female veteran who is diagnosed with breast, ovarian, endometrial, or colon cancer. We would definitely talk to her about genetic counseling and send a referral to GMS. We would ask for a GMS consult for a patient with advanced maternal age, with exposure to some kind of teratogens, with an abnormal ultrasound, a family history of chromosomal disorders, or if she’s seeing an obstetrician who wants her to be tested. And finally, if a patient has a constellation of multiple cancers in the family and we don’t know what’s going on, we would also refer the patient to GMS.

Vickie Venne. That would be why GMS fields over 150 referrals every week. It is a large list. We also see veterans with personal or family histories of neurologic or cardiologic concerns as well.

Renee, as somebody who fields many of these referrals from unaffected individuals, what is the family history process?

Renee Rider. We don’t expect the referring provider to be a genetic expert. When a provider is seeing a constellation of several different cancers and he or she doesn’t know if there’s anything going on genetically or even if it’s possible, absolutely they should put in a referral to GMS. We have a triage counselor who reviews every consult that comes into our service within 24 hours.

Many cancers are due to exposures that are not concerning for a genetic etiology. We can let you know that it is not concerning, and the PCP can counsel the patient that it is very unlikely to be genetic in nature. We still give feedback even if it’s not someone who is appropriate for genetic counseling and testing. It is important to reach out to GMS even if you don’t know whether a cancer is genetic in nature.

It also is important to take your time when gathering family histories. We get a lot of patients who say, “There’s a lot of cancer in my family. I have no idea who had cancer, but I know a lot of people had cancer.” That’s not the day to put in a referral to GMS. At that point, providers should tell the patient to get as much information as they can about the family history and then reassess. It’s important for us to have accurate information. We’ve had several times where we receive a referral because the veteran says that their sister had ovarian cancer. And then when our staff calls, they later find out it was cervical cancer. That’s not a good use of the veteran’s time, and it’s not a good use of VA resources.

The other important thing about family histories is keeping the questions open-ended. Often a PCP or specialist will ask about a certain type of cancer: “Does anyone in your family have breast cancer, ovarian cancer?” Or if the veteran

is getting a colonoscopy, they ask, “Does anybody have colon cancer?” Where really, we need to be a little bit more open-ended. We prefer questions like, “Has anyone in your family

had cancer?” because that’s the question that prompts a response of, “Yes, 3 people in my family have had thyroid cancer.” That’s very important for us to know, too.

If you do get a positive response, probe a little bit more: what kind of cancer did someone have, how old were they when they had their cancer? And how are they related? Is this an aunt on your mom’s side or on your dad’s side? Those are the types of information that we need to figure out if that person needs a referral.

Vickie Venne. It’s a different story when people already have a cancer diagnosis. Which hematology or oncology patients are good referrals and why?

Lisa Arfons, MD. When patients come in with newly diagnosed cancer, breast for example, it is an emotional diagnosis and psychologicallydistressing. Oftentimes, they want to know why this happened to them. The issues surrounding

genetic testing also becomes very emotional. They want to know whether their children are at risk as well.

Genetic discussions take a long time. I rarely do that on the first visit. I always record for myself in my clinic note if something strikes me regarding the patient’s diagnosis. I quickly run through the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines to remind myself of what I need to go over with the patient at our next meeting. Most patients don’t need to be referred to GMS, and most patients don’t need to be tested once they’re seen.

I often save the referral discussion for after I have established a rapport with a patient, we have a treatment plan, or they already have had their first surgery. Therefore, we are not making decisions about their first surgery based on the genetic medicine results.

If I’m considering a referral, I do a deeper dive with the patient. Is the patient older or younger than 45 years? I pull up NCCN guidelines and we go through the entire checklist.

We have male breast cancer patients at the VA—probably more than the community—so we refer those patients. At the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC in Ohio, we have had some in-depth discussions about referring male breast cancer patients for genetic testing and whether it was beneficial to older patients with male breast cancer. Ultimately, we decided that it was important for our male veterans to be tested because it empowered them to have better understanding of their medical conditions that may not just have effect on them but on their offspring, and that that can be a source of psychological and emotional support.

I don’t refer most people to GMS once I go through the checklist. I appreciate the action for an e-consult within the CPRS telemedicine consult itself, as Renee noted. If it is not necessary, GMS makes it an e-consult. I try to communicate that I don’t know whether it is necessary or not so that GMS understands where I’m coming from.

Vickie Venne. In the US Department of Defense (DoD) the process is quite different. Mauricio, can you explain the clinical referral process, who is referred, and how that works from a laboratory perspective?

Maj De Castro, MD, FACMG, USAF. The VA has led the way in demonstrating how to best provide for the medical genetic needs of a large, decentralized population distributed all over the country. Over the last 5 to 10 years, the DoD has made strides in recognizing the role genetics plays in the practice of everyday medicine and redoubling efforts to meet the needs of servicemembers.

The way that it traditionally has worked in the DoD is that military treatment facilities (MTFs) that have dedicated geneticists and genetic counselors: Kessler Medical Center in Mississippi, Walter Reed National Military Medical

Center in Maryland, Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii, Madigan Army Medical Center in Washington, Brooke Army Medical Center in Texas, Naval Medical Center San Diego in California, and Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in Virginia. A patient seeking genetic evaluation, counseling, or testing in those larger facilities would be referred to the genetics service by their primary care manager. Wait times vary, but it would usually be weeks, maybe months. However, the great majority of MTFs do not have dedicated genetics support. Most of the time, those patients would have to be referred to the local civilian community—there was no process for them to be seen in in the military healthcare system—with wait times that exceed 6 to 8 months in some cases. This is due to just not a military but a national shortage of genetics professionals (counselors and physicians).

Last year we started the telegenetics initiative, which is small compared to the VA—it is comprised of 2 geneticists and 1 genetic counselor—but with the full intent of growing it over time. Its purpose is to extend the resources we

had to other MTFs. Genetics professionals stationed state-side can provide care to remote facilities with limited access to local genetics support such as Cannon Air Force Base (AFB) or overseas facilities such as Spangdahlem AFB in Germany.

We recognize there are military-specific needs for the DoD regarding the genetic counseling process that have to take into account readiness, genetic discrimination, continued ability to serve and fitness for duty. For this important reason, we are seeking to expand our telegenetics initiative. The goal is to be able to provide 100% of all genetic counseling in-house, so to speak.

Currently, providers at the 4 pilot sites (Cannon AFB, Fort Bragg, Spangdahlem AFB, and Guantanamo Bay) send us referrals. We triage them and assign the patient to see a geneticist or a counselor depending on the indication.

On the laboratory side, it has been a very interesting experience. Because we provide comprehensive germline cancer testing at very little cost to the provider at any MTF, we have had high numbers of test requests over the years.

In addition to saving the DoD millions of dollars in testing, we have learned some interesting lessons in the process. For instance, we have worked closely with several different groups to better understand how to educate providers on the genetic counseling and testing process. This has allowed us to craft a thorough and inclusive consent form that addresses the needs of the DoD. We have also learned valuable lessons about population-based screening vs evidence-based testing, and lessons surrounding narrow-based testing (BRCA1 and BRCA2 only testing) vs ordering a more comprehensive panel that includes other genes supported by strong evidence (such as PALB2, CHEK2, or TP53).

For example, we have found that in a significant proportion of individuals with and without family history, there are clinically relevant variants in genes other than BRCA1 or BRCA2. And so, we have made part of our consent process,

a statement on secondary findings. If the patient consents, we will report pathogenic variants in other genes known to be associated with cancer (with strong evidence) even if the provider ordered a narrow panel such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing only. In about 1% to 4% of patients that would otherwise not meet NCCN guidelines, we’ve reported variants that were clinically actionable and changed the medical management of that patient.

We feel strongly that this is a conversation that we need to have in our field, and we realize it’s a complex issue, maybe we need to expand who gets testing. Guideline based testing is missing some patients out there that could benefit from it.

Vickie Venne. There certainly are many sides to the conversation of population-based vs evidence-based genetic testing. Genetic testing policies are changing rapidly. There are teams exploring comprehensive gene sequencing for

newborns and how that potential 1-time test can provide information will be reinterpreted as a person goes from cradle to grave. However, unlike the current DoD process, in the VA there are patients who we don’t see.

Renee Rider. I want to talk about money. When we order a genetic test, that test is paid for by the pathology department at the patient’s VAMC. Most of the pathology departments we work with are clear that they only can provide

genetic testing that is considered medically necessary. Thus, we review each test to make sure it meets established guidelines for testing. We don’t do population genetic screening as there isn’t evidence or guidelines to support offering it. We are strict about who does and does not get genetic testing, partly because we have a responsibility to pathology departments and to the taxpayers.

GMS focuses on conditions that are inherited, that is to say, we deal with germline genetics. Therefore, we discontinue referrals for somatic requests, such as when an OncotypeDX test is requested. It is my understanding that pharmacogenetic referrals may be sent to the new PHASeR initiative, which is a joint collaboration between the VA and Sanford Health and is headed by Deepak Voora, MD.

We generally don’t see patients who still are having diagnostic procedures done. For example, if a veteran has a suspicious breast mass, we recommend that the provider workup the mass before referring to GMS. Regardless of a genetic test result, a suspicious mass needs to be worked up. And, knowing if the mass is cancerous could change how we would proceed with the genetic workup. For example, if the mass were not cancerous, we may recommend that an affected relative have the first genetic evaluation. Furthermore, knowing if the patient has cancer changes how we interpret negative test results.

Another group of patients we don’t see are those who already had genetic testing done by the referring provider. It’s a VA directive that if you order a test, you’re the person who is responsible for giving the results. We agree with

this directive. If you don’t feel comfortable giving back test results, don’t order the test. Often, when a provider sends a patient to us after the test was done, we discover that the patient didn’t have appropriate pretest counseling. A test result, such as a variant of uncertain significance (VUS), should never be a surprise to either the provider or the patient.

Ishta Thakar. For newly diagnosed cancers, the first call is to the patient to inform them that they have cancer. We usually bring up genetic counseling or testing, if applicable, when they are ready to accept the diagnosis and have a conversation about it. All our consults are via telehealth, so none of our patients physically come to GMS in Salt Lake City. All the consults are done virtually.