User login

Most Americans incorrectly identify homicide as more common than suicide

Most adults do not realize that suicide is a more frequent cause of death than homicide, according to the first nationally representative study of public perceptions of firearm and non-firearm-related violent death in the United States.

“These findings are consistent with the well-established relationship between risk perception and the ease with which a pertinent categorical example can be summoned from memory, which in most persons is probably affected by the salience of homicides in media coverage,” lead author Erin R. Morgan, MS, and her coauthors wrote in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The coauthors reviewed 3,811 responses to a question in the National Firearms Survey on the intent and means of violent death; participants were given 4 options – homicide with a gun, homicide with a weapon other than a gun, suicide with a gun, and suicide by a method other than a gun – and asked to rank them by frequency. A study of those responses found that only 13.5% of U.S. adults could correctly identify their state’s most frequent cause of violent death. Of the 1,880 respondents who shared their occupations, only 20% of health care professionals answered the question correctly.

The survey was conducted in April 2015; between 2014 and 2015, suicide was more common than homicide in all 50 states. Suicide by firearm was also more common than homicide by firearm in every state but Illinois, Maryland, and New Jersey. When reviewing firearm options only, the percentage of respondents who identified suicide as most frequent increased to 25.9%, according to Ms. Morgan of the School of Public Health and of Harborview Injury Prevention & Research Center at the University of Washington in Seattle, and her colleagues.

The coauthors noted that accurate identification was not impacted by the respondents’ firearm ownership status, but also that future research should evaluate if promoting awareness of suicide frequency and risk might “motivate behavioral change regarding firearm storage.”

“Our findings suggest that correcting misperceptions about the relative frequency of firearm-related violent deaths may make persons more cognizant of the actuarial risks to themselves and their family, thus creating new opportunities for prevention,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Fund for a Safer Future and the Joyce Foundation. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Morgan E et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 30. doi:10.7326/M18-1533.

Most adults do not realize that suicide is a more frequent cause of death than homicide, according to the first nationally representative study of public perceptions of firearm and non-firearm-related violent death in the United States.

“These findings are consistent with the well-established relationship between risk perception and the ease with which a pertinent categorical example can be summoned from memory, which in most persons is probably affected by the salience of homicides in media coverage,” lead author Erin R. Morgan, MS, and her coauthors wrote in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The coauthors reviewed 3,811 responses to a question in the National Firearms Survey on the intent and means of violent death; participants were given 4 options – homicide with a gun, homicide with a weapon other than a gun, suicide with a gun, and suicide by a method other than a gun – and asked to rank them by frequency. A study of those responses found that only 13.5% of U.S. adults could correctly identify their state’s most frequent cause of violent death. Of the 1,880 respondents who shared their occupations, only 20% of health care professionals answered the question correctly.

The survey was conducted in April 2015; between 2014 and 2015, suicide was more common than homicide in all 50 states. Suicide by firearm was also more common than homicide by firearm in every state but Illinois, Maryland, and New Jersey. When reviewing firearm options only, the percentage of respondents who identified suicide as most frequent increased to 25.9%, according to Ms. Morgan of the School of Public Health and of Harborview Injury Prevention & Research Center at the University of Washington in Seattle, and her colleagues.

The coauthors noted that accurate identification was not impacted by the respondents’ firearm ownership status, but also that future research should evaluate if promoting awareness of suicide frequency and risk might “motivate behavioral change regarding firearm storage.”

“Our findings suggest that correcting misperceptions about the relative frequency of firearm-related violent deaths may make persons more cognizant of the actuarial risks to themselves and their family, thus creating new opportunities for prevention,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Fund for a Safer Future and the Joyce Foundation. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Morgan E et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 30. doi:10.7326/M18-1533.

Most adults do not realize that suicide is a more frequent cause of death than homicide, according to the first nationally representative study of public perceptions of firearm and non-firearm-related violent death in the United States.

“These findings are consistent with the well-established relationship between risk perception and the ease with which a pertinent categorical example can be summoned from memory, which in most persons is probably affected by the salience of homicides in media coverage,” lead author Erin R. Morgan, MS, and her coauthors wrote in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The coauthors reviewed 3,811 responses to a question in the National Firearms Survey on the intent and means of violent death; participants were given 4 options – homicide with a gun, homicide with a weapon other than a gun, suicide with a gun, and suicide by a method other than a gun – and asked to rank them by frequency. A study of those responses found that only 13.5% of U.S. adults could correctly identify their state’s most frequent cause of violent death. Of the 1,880 respondents who shared their occupations, only 20% of health care professionals answered the question correctly.

The survey was conducted in April 2015; between 2014 and 2015, suicide was more common than homicide in all 50 states. Suicide by firearm was also more common than homicide by firearm in every state but Illinois, Maryland, and New Jersey. When reviewing firearm options only, the percentage of respondents who identified suicide as most frequent increased to 25.9%, according to Ms. Morgan of the School of Public Health and of Harborview Injury Prevention & Research Center at the University of Washington in Seattle, and her colleagues.

The coauthors noted that accurate identification was not impacted by the respondents’ firearm ownership status, but also that future research should evaluate if promoting awareness of suicide frequency and risk might “motivate behavioral change regarding firearm storage.”

“Our findings suggest that correcting misperceptions about the relative frequency of firearm-related violent deaths may make persons more cognizant of the actuarial risks to themselves and their family, thus creating new opportunities for prevention,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Fund for a Safer Future and the Joyce Foundation. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Morgan E et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 30. doi:10.7326/M18-1533.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Only 13.5% of U.S. adults – and 20% of health care professionals – could identify the most frequent cause of violent death in their state.

Major finding:

Study details: A study of 3,811 responses to the National Firearms Survey.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Fund for a Safer Future and the Joyce Foundation. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Morgan E et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Oct 30. doi:10.7326/M18-1533.

Collaborative approach for suicidal youth helps providers, too

SEATTLE – When it comes to treating children and adolescents who have experienced trauma and present suicidality, it is not just the patients who need support. Clinicians also experience grave anxiety when dealing with a traumatized child exhibiting suicidal behavior. The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS) framework can help clinicians or health care workers manage the care of these challenging patients.

CAMS is well established in adults with suicidal behavior, but it is unproven in youth and adolescents. The key is to its success in younger patients will be whether the program is developmentally appropriate, according to Molly C. Adrian, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Adrian discussed CAMS and its potential applications at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The CAMS approach emphasizes cooperation between the therapist and patient. “Adolescents are seeking autonomy and independence, and so it’s a good fit philosophically that you would partner alongside the teen as opposed to starting in a more adversarial sort of way – not that we as therapists ever do that. But it can be more tense when suicide is on the table and you feel unprepared,” Dr. Adrian said.

Seattle Children’s Hospital is persuaded enough to make CAMS part of its standard of care, Dr. Adrian said.

CAMS is a framework for patient management that has no prerequisites for the therapeutic approach. “It’s principle driven, not protocol driven. Clinicians can use whatever specific interventions they feel are appropriate for the drivers (of the suicidality). What we’re trying to change is the approach to the suicidal patient, so that it is not an anxiety-provoking, terrifying experience for the clinician – because we know that a suicidal patient is the most anxiety-provoking task for clinicians,” Dr. Adrian said. “We want clinicians to feel prepared and protected in providing the elements of care,” Dr. Adrian said in an interview.

The framework incorporates a suicide-status form (SSF), which assesses theory-driven and epidemiologically guided risk factors and helps to identify the drivers or the reasons why suicide is compelling to the patient. Those drivers then help inform crisis prevention efforts and the selection of interventions.

Three randomized, controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of CAMS over standard of care in adult patients, showing that the SSF is an effective assessment tool and that CAMS reduces suicidal ideation and leads to decreases in distress, depression, and hopelessness. There are no randomized, controlled trials showing its efficacy in children, but Seattle Children’s Hospital is conducting a pilot study in 12 youth and have found a 40% response rate at 8 weeks.

The SSF gauges the patient’s status and trajectory, while the CAMS therapeutic worksheet helps to distinguish direct and indirect drivers of suicidal behavior. In cases in which trauma symptoms or experiences are tied to suicidal behavior, they receive priority for treatment. The framework provides for discussion of options and treatment choice through collaboration between the clinician and the patient.

The patient and clinician fill out an SSF in the first session and use it to create a crisis convention plan, which includes gaining a commitment to treatment, removing or restricting access to lethal means, and incorporating parental monitoring.

Dr. Adrian is hopeful that the CAMS framework will help health care workers address suicidality in traumatized youth and adolescents. Currently, they may feel intimidated by a stricken child’s issues. “You don’t want to be responsible for a child dying, so you may overrespond with an intervention like an emergency department evaluation or an inpatient hospitalization that may be iatrogenic – there are data coming out from adults that hospitalization contributes to suicide risk above and beyond other risk factors,” Dr. Adrian said.

CAMS is simple and flexible, according to Dr. Adrian, and can be used by psychiatrists, social workers, substance use counselors, and others. At Seattle Children’s Hospital, clinicians have embraced it. “They feel it changes their practice. It gets to the heart of the matter quickly, and they feel more confident having that framework,” Dr. Adrian said.

Dr. Adrian has no conflicts of interest or disclosures.

SEATTLE – When it comes to treating children and adolescents who have experienced trauma and present suicidality, it is not just the patients who need support. Clinicians also experience grave anxiety when dealing with a traumatized child exhibiting suicidal behavior. The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS) framework can help clinicians or health care workers manage the care of these challenging patients.

CAMS is well established in adults with suicidal behavior, but it is unproven in youth and adolescents. The key is to its success in younger patients will be whether the program is developmentally appropriate, according to Molly C. Adrian, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Adrian discussed CAMS and its potential applications at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The CAMS approach emphasizes cooperation between the therapist and patient. “Adolescents are seeking autonomy and independence, and so it’s a good fit philosophically that you would partner alongside the teen as opposed to starting in a more adversarial sort of way – not that we as therapists ever do that. But it can be more tense when suicide is on the table and you feel unprepared,” Dr. Adrian said.

Seattle Children’s Hospital is persuaded enough to make CAMS part of its standard of care, Dr. Adrian said.

CAMS is a framework for patient management that has no prerequisites for the therapeutic approach. “It’s principle driven, not protocol driven. Clinicians can use whatever specific interventions they feel are appropriate for the drivers (of the suicidality). What we’re trying to change is the approach to the suicidal patient, so that it is not an anxiety-provoking, terrifying experience for the clinician – because we know that a suicidal patient is the most anxiety-provoking task for clinicians,” Dr. Adrian said. “We want clinicians to feel prepared and protected in providing the elements of care,” Dr. Adrian said in an interview.

The framework incorporates a suicide-status form (SSF), which assesses theory-driven and epidemiologically guided risk factors and helps to identify the drivers or the reasons why suicide is compelling to the patient. Those drivers then help inform crisis prevention efforts and the selection of interventions.

Three randomized, controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of CAMS over standard of care in adult patients, showing that the SSF is an effective assessment tool and that CAMS reduces suicidal ideation and leads to decreases in distress, depression, and hopelessness. There are no randomized, controlled trials showing its efficacy in children, but Seattle Children’s Hospital is conducting a pilot study in 12 youth and have found a 40% response rate at 8 weeks.

The SSF gauges the patient’s status and trajectory, while the CAMS therapeutic worksheet helps to distinguish direct and indirect drivers of suicidal behavior. In cases in which trauma symptoms or experiences are tied to suicidal behavior, they receive priority for treatment. The framework provides for discussion of options and treatment choice through collaboration between the clinician and the patient.

The patient and clinician fill out an SSF in the first session and use it to create a crisis convention plan, which includes gaining a commitment to treatment, removing or restricting access to lethal means, and incorporating parental monitoring.

Dr. Adrian is hopeful that the CAMS framework will help health care workers address suicidality in traumatized youth and adolescents. Currently, they may feel intimidated by a stricken child’s issues. “You don’t want to be responsible for a child dying, so you may overrespond with an intervention like an emergency department evaluation or an inpatient hospitalization that may be iatrogenic – there are data coming out from adults that hospitalization contributes to suicide risk above and beyond other risk factors,” Dr. Adrian said.

CAMS is simple and flexible, according to Dr. Adrian, and can be used by psychiatrists, social workers, substance use counselors, and others. At Seattle Children’s Hospital, clinicians have embraced it. “They feel it changes their practice. It gets to the heart of the matter quickly, and they feel more confident having that framework,” Dr. Adrian said.

Dr. Adrian has no conflicts of interest or disclosures.

SEATTLE – When it comes to treating children and adolescents who have experienced trauma and present suicidality, it is not just the patients who need support. Clinicians also experience grave anxiety when dealing with a traumatized child exhibiting suicidal behavior. The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS) framework can help clinicians or health care workers manage the care of these challenging patients.

CAMS is well established in adults with suicidal behavior, but it is unproven in youth and adolescents. The key is to its success in younger patients will be whether the program is developmentally appropriate, according to Molly C. Adrian, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Adrian discussed CAMS and its potential applications at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

The CAMS approach emphasizes cooperation between the therapist and patient. “Adolescents are seeking autonomy and independence, and so it’s a good fit philosophically that you would partner alongside the teen as opposed to starting in a more adversarial sort of way – not that we as therapists ever do that. But it can be more tense when suicide is on the table and you feel unprepared,” Dr. Adrian said.

Seattle Children’s Hospital is persuaded enough to make CAMS part of its standard of care, Dr. Adrian said.

CAMS is a framework for patient management that has no prerequisites for the therapeutic approach. “It’s principle driven, not protocol driven. Clinicians can use whatever specific interventions they feel are appropriate for the drivers (of the suicidality). What we’re trying to change is the approach to the suicidal patient, so that it is not an anxiety-provoking, terrifying experience for the clinician – because we know that a suicidal patient is the most anxiety-provoking task for clinicians,” Dr. Adrian said. “We want clinicians to feel prepared and protected in providing the elements of care,” Dr. Adrian said in an interview.

The framework incorporates a suicide-status form (SSF), which assesses theory-driven and epidemiologically guided risk factors and helps to identify the drivers or the reasons why suicide is compelling to the patient. Those drivers then help inform crisis prevention efforts and the selection of interventions.

Three randomized, controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of CAMS over standard of care in adult patients, showing that the SSF is an effective assessment tool and that CAMS reduces suicidal ideation and leads to decreases in distress, depression, and hopelessness. There are no randomized, controlled trials showing its efficacy in children, but Seattle Children’s Hospital is conducting a pilot study in 12 youth and have found a 40% response rate at 8 weeks.

The SSF gauges the patient’s status and trajectory, while the CAMS therapeutic worksheet helps to distinguish direct and indirect drivers of suicidal behavior. In cases in which trauma symptoms or experiences are tied to suicidal behavior, they receive priority for treatment. The framework provides for discussion of options and treatment choice through collaboration between the clinician and the patient.

The patient and clinician fill out an SSF in the first session and use it to create a crisis convention plan, which includes gaining a commitment to treatment, removing or restricting access to lethal means, and incorporating parental monitoring.

Dr. Adrian is hopeful that the CAMS framework will help health care workers address suicidality in traumatized youth and adolescents. Currently, they may feel intimidated by a stricken child’s issues. “You don’t want to be responsible for a child dying, so you may overrespond with an intervention like an emergency department evaluation or an inpatient hospitalization that may be iatrogenic – there are data coming out from adults that hospitalization contributes to suicide risk above and beyond other risk factors,” Dr. Adrian said.

CAMS is simple and flexible, according to Dr. Adrian, and can be used by psychiatrists, social workers, substance use counselors, and others. At Seattle Children’s Hospital, clinicians have embraced it. “They feel it changes their practice. It gets to the heart of the matter quickly, and they feel more confident having that framework,” Dr. Adrian said.

Dr. Adrian has no conflicts of interest or disclosures.

FROM AACAP 2018

Low and high BMI tied to higher postpartum depression risk

Women with high and low body mass index in the first trimester of their first pregnancies are at an increased risk of developing postpartum depression, a population-based study of more than 600,000 new mothers shows.

“Our findings show a U-shaped association between BMI extremes and clinically significant depression after childbirth,” Michael E. Silverman, PhD, and his associates reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders. “Specifically, women in the lowest and highest groups were at a significantly increased risk for developing [postpartum depression].”

Dr. Silverman and his associates used the Swedish Medical Birth Register to identify women who delivered first live singleton infants from 1997 to 2008. They then calculated the risk of postpartum depression in relation to each woman’s BMI and history of depression. Postpartum depression was defined as a clinical depression diagnosis within 1 year after delivery, Dr. Silverman and his associates wrote.

The investigators found that women with low BMI (less than 18.5 kg/m2) were at an increased postpartum depression risk (relative risk [RR], 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.78), as were those with high BMI (greater than 35 kg/m2) (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.04-1.45).

In addition, an important difference was found between women with low and high BMI.

“Women in the highest BMI group were only at an increased risk for [postpartum depression] if they had no history of depression, showing for the first time how [postpartum depression] risk factors associated with BMI are modified by maternal depression history,” said Dr. Silverman of the department of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and his associates.

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, only first births were analyzed, which suggests that the incidence of postpartum depression might have been underestimated. Another limitation is that the registry might not have captured women with mild depression. Nevertheless, they said, the study has important implications.

“ Because pregnant women represent a medically captured population,” they wrote, the findings support implementing preventive strategies for postpartum depression and health literacy for high-risk women.

Dr. Silverman and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Silverman ME et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Nov;240:193-8.

Women with high and low body mass index in the first trimester of their first pregnancies are at an increased risk of developing postpartum depression, a population-based study of more than 600,000 new mothers shows.

“Our findings show a U-shaped association between BMI extremes and clinically significant depression after childbirth,” Michael E. Silverman, PhD, and his associates reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders. “Specifically, women in the lowest and highest groups were at a significantly increased risk for developing [postpartum depression].”

Dr. Silverman and his associates used the Swedish Medical Birth Register to identify women who delivered first live singleton infants from 1997 to 2008. They then calculated the risk of postpartum depression in relation to each woman’s BMI and history of depression. Postpartum depression was defined as a clinical depression diagnosis within 1 year after delivery, Dr. Silverman and his associates wrote.

The investigators found that women with low BMI (less than 18.5 kg/m2) were at an increased postpartum depression risk (relative risk [RR], 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.78), as were those with high BMI (greater than 35 kg/m2) (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.04-1.45).

In addition, an important difference was found between women with low and high BMI.

“Women in the highest BMI group were only at an increased risk for [postpartum depression] if they had no history of depression, showing for the first time how [postpartum depression] risk factors associated with BMI are modified by maternal depression history,” said Dr. Silverman of the department of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and his associates.

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, only first births were analyzed, which suggests that the incidence of postpartum depression might have been underestimated. Another limitation is that the registry might not have captured women with mild depression. Nevertheless, they said, the study has important implications.

“ Because pregnant women represent a medically captured population,” they wrote, the findings support implementing preventive strategies for postpartum depression and health literacy for high-risk women.

Dr. Silverman and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Silverman ME et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Nov;240:193-8.

Women with high and low body mass index in the first trimester of their first pregnancies are at an increased risk of developing postpartum depression, a population-based study of more than 600,000 new mothers shows.

“Our findings show a U-shaped association between BMI extremes and clinically significant depression after childbirth,” Michael E. Silverman, PhD, and his associates reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders. “Specifically, women in the lowest and highest groups were at a significantly increased risk for developing [postpartum depression].”

Dr. Silverman and his associates used the Swedish Medical Birth Register to identify women who delivered first live singleton infants from 1997 to 2008. They then calculated the risk of postpartum depression in relation to each woman’s BMI and history of depression. Postpartum depression was defined as a clinical depression diagnosis within 1 year after delivery, Dr. Silverman and his associates wrote.

The investigators found that women with low BMI (less than 18.5 kg/m2) were at an increased postpartum depression risk (relative risk [RR], 1.52; 95% confidence interval, 1.30-1.78), as were those with high BMI (greater than 35 kg/m2) (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.04-1.45).

In addition, an important difference was found between women with low and high BMI.

“Women in the highest BMI group were only at an increased risk for [postpartum depression] if they had no history of depression, showing for the first time how [postpartum depression] risk factors associated with BMI are modified by maternal depression history,” said Dr. Silverman of the department of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and his associates.

The investigators cited several limitations. For example, only first births were analyzed, which suggests that the incidence of postpartum depression might have been underestimated. Another limitation is that the registry might not have captured women with mild depression. Nevertheless, they said, the study has important implications.

“ Because pregnant women represent a medically captured population,” they wrote, the findings support implementing preventive strategies for postpartum depression and health literacy for high-risk women.

Dr. Silverman and his associates reported having no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Silverman ME et al. J Affect Disord. 2018 Nov;240:193-8.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

This year’s top papers on mood disorders

BARCELONA – Among the handful of top publications on mood disorders during the first three-quarters of 2018 was a landmark comparison of the efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressants for acute treatment of major depressive disorder, Íria Grande, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Dr. Grande, a psychiatrist at the bipolar disorders clinic of the University of Barcelona, shared her personal top picks.

‘Antidepressants work’

This epic systematic review and network meta-analysis (Lancet. 2018 Apr 7;391[10128]:1357-66) encompassed 522 randomized double-blind trials with 116,477 participants with major depressive disorder assigned to 21 antidepressants or placebo, in some instances with an additional active comparator antidepressant arm. The report is a major extension of previous work by the same multinational group of investigators (Lancet. 2009 Feb 28;373[9665]:746-58), who initially scrutinized 12 older antidepressants in a total population only one-quarter the size of the updated analysis.

Based upon this vast randomized trial evidence, some of which came from unpublished studies tracked down by the investigators, the 21 antidepressants were rank-ordered in terms of effectiveness and acceptability. But in Dr. Grande’s view, the most important study finding wasn’t which antidepressant donned the crown of most effective or patient acceptable, it was the fact that all 21 drugs proved significantly more effective than placebo, with odds ratios ranging from 2.13 at the top end to 1.37 for reboxetine.

“The results showed antidepressants work. All of the antipsychiatry system is trying to show us that antidepressants do not work in major depression. Well, in this study, it has been proven that all antidepressants are more effective than placebo in major depressive disorder. I think social media should be made aware of that. (Lead investigator) Dr. Andrea Cipriani talked on the BBC about this article, and it had a high impact,” according to Dr. Grande.

All but three of the 21 antidepressants were deemed to be as acceptable as placebo, based upon study dropout rates. The exceptions were agomelatine and fluoxetine, which were 12%-14% more acceptable than placebo. “That’s strange, I think, but that’s what the clinical trial results showed,” she noted. The findings on clomipramine, which was 30% less acceptable than placebo, make sense, Dr. Grande said, “due to its muscarinic effects.”

She took issue with some of the specific study findings. For example, the two top-rated antidepressants in terms of efficacy were amitriptyline and mirtazapine, with odds ratios of 2.13 and 1.89, respectively.

“As a clinician, I don’t consider mirtazapine to be one of the best antidepressants, especially in major depression,” she said. “But these are the results, and as always, we have to adapt the evidence-based medicine and consider it from our clinical point of view.”

The investigators conducted a subanalysis restricted to placebo-controlled head-to-head studies with a comparator antidepressant which Dr. Grande found more interesting and informative than the overall analysis. In the head-to-head analysis, vortioxetine emerged as the top-rated antidepressant, both in efficacy, with an odds ratio of 2.0, as well as in acceptability.

Lithium vs. quetiapine

Finnish investigators used prospective national databases to examine the rates of psychiatric and all-cause hospitalization during a mean 7.2 years of follow-up in all 18,018 Finns hospitalized for bipolar disorder. The purpose was to assess the impact of various mood stabilizers on overall health outcomes in a real-world setting.

The big winner was lithium. In an analysis adjusted for concomitant psychotropic medications, duration of bipolar illness, and intervals of drug exposure and nonexposure, lithium was associated with the lowest risks of psychiatric rehospitalization and all-cause hospitalization, with relative risk reductions of 33% and 29%, respectively. In contrast, quetiapine, the most widely used antipsychotic agent, paled by comparison, achieving only an 8% reduction in the risk of psychiatric rehospitalization and a 7% decrease in all-cause hospitalization (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 1;75[4]:347-55).

In addition, long-acting injectable antipsychotics were significantly more effective for prevention of hospitalization than oral antipsychotics.

“That is kind of shocking, because in some countries, long-acting injectables are not authorized and cannot be used. But I think after this article some regulatory changes are going to take place as a result,” Dr. Grande predicted.

“Another issue I thought was interesting, although it was not the main aim of the study, involved benzodiazepines. They increased the risk of hospitalizations, both for psychiatric illness and all other causes. So apart from giving lithium and long-acting injectable antipsychotics to our bipolar patients, we should also be really careful about the use of benzodiazepines,” she commented.

Intranasal esketamine for suicidality?

Esketamine nasal spray, a fast-acting N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist whose application for marketing approval in combination with a standard oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression is now under Food and Drug Administration review, also is being developed for another indication: reduction of suicidality in patients at imminent suicide risk. In a proof-of-concept study, intranasal esketamine resulted in a significant reduction in suicidal thoughts 4 hours after administration, compared with usual care – but not at 24 hours (Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Jul 1;175[7]:620-30).

New and effective medications for this indication are sorely needed. The only drug approved for the indication of suicide prevention is clozapine.

‘Latest thinking’ on bipolar disorders

Dr. Grande coauthored a comprehensive review article on bipolar disorders that she recommended as worthwhile reading (Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 Mar 8;4:18008. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.8).

“It covers all the latest thinking. It focuses on the early stages of the disorder, how epigenetic factors are essential, and many other topics, including the bipolarity index being developed at the University of Barcelona to classify drugs in terms of their capacity to prevent episodes of mania or depression in terms of number needed to treat and number needed to harm. It emphasizes the importance of intervening early and focusing on cognitive dysfunction,” Dr Grande said.

Psychedelics making a comeback

German and Swiss investigators used a facial expression discrimination task to demonstrate that psilocybin, a 5-hydroxytryptamine2A–receptor agonist, decreases connectivity between the amygdala and regions of the brain important in emotion processing, including the striatum and frontal pole. The investigators theorized that this might be the mechanism for the psychedelic’s apparent antidepressant effects (Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018 Jun;28[6]:691-700).

Dr. Grande included this study in her top publications list because it reflects the rapidly growing rebirth of interest in psychedelics research among European psychiatrists.

Indeed, elsewhere at the ECNP congress David J. Nutt, DM, declared, “We now have the beginnings of some swinging of the pendulum back in a modern direction. Over the last 10 years there have been a small number of open studies, all done with psilocybin, which is somewhat easier to use than LSD. There are studies in OCD [obsessive-compulsive disorder], tobacco dependence, alcoholism, resistant depression, end-of-life mood changes with cancer and other terminal diseases, and at least two ongoing randomized trials in resistant depression.”

Dr. Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, was senior author of the first proof-of-concept study of psilocybin accompanied by psychologic support as a novel therapy for moderate to severe treatment-resistant major depression (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Jul;3[7]:619-27).

Methylphenidate ineffective for treatment of acute mania

The MEMAP study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial testing what has been called the vigilance regulation model of mania. This model hypothesized that unstable regulation of wakefulness figures prominently in the pathogenesis of both mania and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. If true, investigators reasoned, then 2.5 days of methylphenidate at 20-40 mg/day should have a rapid antimanic effect similar to the drug’s benefits in ADHD. Dr. Grande had been a skeptic, and indeed, the trial was halted early for futility (Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018 Jan;28[1]:185-94).

She reported serving as a paid speaker for Lunbeck, Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Janssen. Her own research is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

BARCELONA – Among the handful of top publications on mood disorders during the first three-quarters of 2018 was a landmark comparison of the efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressants for acute treatment of major depressive disorder, Íria Grande, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Dr. Grande, a psychiatrist at the bipolar disorders clinic of the University of Barcelona, shared her personal top picks.

‘Antidepressants work’

This epic systematic review and network meta-analysis (Lancet. 2018 Apr 7;391[10128]:1357-66) encompassed 522 randomized double-blind trials with 116,477 participants with major depressive disorder assigned to 21 antidepressants or placebo, in some instances with an additional active comparator antidepressant arm. The report is a major extension of previous work by the same multinational group of investigators (Lancet. 2009 Feb 28;373[9665]:746-58), who initially scrutinized 12 older antidepressants in a total population only one-quarter the size of the updated analysis.

Based upon this vast randomized trial evidence, some of which came from unpublished studies tracked down by the investigators, the 21 antidepressants were rank-ordered in terms of effectiveness and acceptability. But in Dr. Grande’s view, the most important study finding wasn’t which antidepressant donned the crown of most effective or patient acceptable, it was the fact that all 21 drugs proved significantly more effective than placebo, with odds ratios ranging from 2.13 at the top end to 1.37 for reboxetine.

“The results showed antidepressants work. All of the antipsychiatry system is trying to show us that antidepressants do not work in major depression. Well, in this study, it has been proven that all antidepressants are more effective than placebo in major depressive disorder. I think social media should be made aware of that. (Lead investigator) Dr. Andrea Cipriani talked on the BBC about this article, and it had a high impact,” according to Dr. Grande.

All but three of the 21 antidepressants were deemed to be as acceptable as placebo, based upon study dropout rates. The exceptions were agomelatine and fluoxetine, which were 12%-14% more acceptable than placebo. “That’s strange, I think, but that’s what the clinical trial results showed,” she noted. The findings on clomipramine, which was 30% less acceptable than placebo, make sense, Dr. Grande said, “due to its muscarinic effects.”

She took issue with some of the specific study findings. For example, the two top-rated antidepressants in terms of efficacy were amitriptyline and mirtazapine, with odds ratios of 2.13 and 1.89, respectively.

“As a clinician, I don’t consider mirtazapine to be one of the best antidepressants, especially in major depression,” she said. “But these are the results, and as always, we have to adapt the evidence-based medicine and consider it from our clinical point of view.”

The investigators conducted a subanalysis restricted to placebo-controlled head-to-head studies with a comparator antidepressant which Dr. Grande found more interesting and informative than the overall analysis. In the head-to-head analysis, vortioxetine emerged as the top-rated antidepressant, both in efficacy, with an odds ratio of 2.0, as well as in acceptability.

Lithium vs. quetiapine

Finnish investigators used prospective national databases to examine the rates of psychiatric and all-cause hospitalization during a mean 7.2 years of follow-up in all 18,018 Finns hospitalized for bipolar disorder. The purpose was to assess the impact of various mood stabilizers on overall health outcomes in a real-world setting.

The big winner was lithium. In an analysis adjusted for concomitant psychotropic medications, duration of bipolar illness, and intervals of drug exposure and nonexposure, lithium was associated with the lowest risks of psychiatric rehospitalization and all-cause hospitalization, with relative risk reductions of 33% and 29%, respectively. In contrast, quetiapine, the most widely used antipsychotic agent, paled by comparison, achieving only an 8% reduction in the risk of psychiatric rehospitalization and a 7% decrease in all-cause hospitalization (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 1;75[4]:347-55).

In addition, long-acting injectable antipsychotics were significantly more effective for prevention of hospitalization than oral antipsychotics.

“That is kind of shocking, because in some countries, long-acting injectables are not authorized and cannot be used. But I think after this article some regulatory changes are going to take place as a result,” Dr. Grande predicted.

“Another issue I thought was interesting, although it was not the main aim of the study, involved benzodiazepines. They increased the risk of hospitalizations, both for psychiatric illness and all other causes. So apart from giving lithium and long-acting injectable antipsychotics to our bipolar patients, we should also be really careful about the use of benzodiazepines,” she commented.

Intranasal esketamine for suicidality?

Esketamine nasal spray, a fast-acting N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist whose application for marketing approval in combination with a standard oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression is now under Food and Drug Administration review, also is being developed for another indication: reduction of suicidality in patients at imminent suicide risk. In a proof-of-concept study, intranasal esketamine resulted in a significant reduction in suicidal thoughts 4 hours after administration, compared with usual care – but not at 24 hours (Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Jul 1;175[7]:620-30).

New and effective medications for this indication are sorely needed. The only drug approved for the indication of suicide prevention is clozapine.

‘Latest thinking’ on bipolar disorders

Dr. Grande coauthored a comprehensive review article on bipolar disorders that she recommended as worthwhile reading (Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 Mar 8;4:18008. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.8).

“It covers all the latest thinking. It focuses on the early stages of the disorder, how epigenetic factors are essential, and many other topics, including the bipolarity index being developed at the University of Barcelona to classify drugs in terms of their capacity to prevent episodes of mania or depression in terms of number needed to treat and number needed to harm. It emphasizes the importance of intervening early and focusing on cognitive dysfunction,” Dr Grande said.

Psychedelics making a comeback

German and Swiss investigators used a facial expression discrimination task to demonstrate that psilocybin, a 5-hydroxytryptamine2A–receptor agonist, decreases connectivity between the amygdala and regions of the brain important in emotion processing, including the striatum and frontal pole. The investigators theorized that this might be the mechanism for the psychedelic’s apparent antidepressant effects (Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018 Jun;28[6]:691-700).

Dr. Grande included this study in her top publications list because it reflects the rapidly growing rebirth of interest in psychedelics research among European psychiatrists.

Indeed, elsewhere at the ECNP congress David J. Nutt, DM, declared, “We now have the beginnings of some swinging of the pendulum back in a modern direction. Over the last 10 years there have been a small number of open studies, all done with psilocybin, which is somewhat easier to use than LSD. There are studies in OCD [obsessive-compulsive disorder], tobacco dependence, alcoholism, resistant depression, end-of-life mood changes with cancer and other terminal diseases, and at least two ongoing randomized trials in resistant depression.”

Dr. Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, was senior author of the first proof-of-concept study of psilocybin accompanied by psychologic support as a novel therapy for moderate to severe treatment-resistant major depression (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Jul;3[7]:619-27).

Methylphenidate ineffective for treatment of acute mania

The MEMAP study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial testing what has been called the vigilance regulation model of mania. This model hypothesized that unstable regulation of wakefulness figures prominently in the pathogenesis of both mania and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. If true, investigators reasoned, then 2.5 days of methylphenidate at 20-40 mg/day should have a rapid antimanic effect similar to the drug’s benefits in ADHD. Dr. Grande had been a skeptic, and indeed, the trial was halted early for futility (Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018 Jan;28[1]:185-94).

She reported serving as a paid speaker for Lunbeck, Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Janssen. Her own research is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

BARCELONA – Among the handful of top publications on mood disorders during the first three-quarters of 2018 was a landmark comparison of the efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressants for acute treatment of major depressive disorder, Íria Grande, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Dr. Grande, a psychiatrist at the bipolar disorders clinic of the University of Barcelona, shared her personal top picks.

‘Antidepressants work’

This epic systematic review and network meta-analysis (Lancet. 2018 Apr 7;391[10128]:1357-66) encompassed 522 randomized double-blind trials with 116,477 participants with major depressive disorder assigned to 21 antidepressants or placebo, in some instances with an additional active comparator antidepressant arm. The report is a major extension of previous work by the same multinational group of investigators (Lancet. 2009 Feb 28;373[9665]:746-58), who initially scrutinized 12 older antidepressants in a total population only one-quarter the size of the updated analysis.

Based upon this vast randomized trial evidence, some of which came from unpublished studies tracked down by the investigators, the 21 antidepressants were rank-ordered in terms of effectiveness and acceptability. But in Dr. Grande’s view, the most important study finding wasn’t which antidepressant donned the crown of most effective or patient acceptable, it was the fact that all 21 drugs proved significantly more effective than placebo, with odds ratios ranging from 2.13 at the top end to 1.37 for reboxetine.

“The results showed antidepressants work. All of the antipsychiatry system is trying to show us that antidepressants do not work in major depression. Well, in this study, it has been proven that all antidepressants are more effective than placebo in major depressive disorder. I think social media should be made aware of that. (Lead investigator) Dr. Andrea Cipriani talked on the BBC about this article, and it had a high impact,” according to Dr. Grande.

All but three of the 21 antidepressants were deemed to be as acceptable as placebo, based upon study dropout rates. The exceptions were agomelatine and fluoxetine, which were 12%-14% more acceptable than placebo. “That’s strange, I think, but that’s what the clinical trial results showed,” she noted. The findings on clomipramine, which was 30% less acceptable than placebo, make sense, Dr. Grande said, “due to its muscarinic effects.”

She took issue with some of the specific study findings. For example, the two top-rated antidepressants in terms of efficacy were amitriptyline and mirtazapine, with odds ratios of 2.13 and 1.89, respectively.

“As a clinician, I don’t consider mirtazapine to be one of the best antidepressants, especially in major depression,” she said. “But these are the results, and as always, we have to adapt the evidence-based medicine and consider it from our clinical point of view.”

The investigators conducted a subanalysis restricted to placebo-controlled head-to-head studies with a comparator antidepressant which Dr. Grande found more interesting and informative than the overall analysis. In the head-to-head analysis, vortioxetine emerged as the top-rated antidepressant, both in efficacy, with an odds ratio of 2.0, as well as in acceptability.

Lithium vs. quetiapine

Finnish investigators used prospective national databases to examine the rates of psychiatric and all-cause hospitalization during a mean 7.2 years of follow-up in all 18,018 Finns hospitalized for bipolar disorder. The purpose was to assess the impact of various mood stabilizers on overall health outcomes in a real-world setting.

The big winner was lithium. In an analysis adjusted for concomitant psychotropic medications, duration of bipolar illness, and intervals of drug exposure and nonexposure, lithium was associated with the lowest risks of psychiatric rehospitalization and all-cause hospitalization, with relative risk reductions of 33% and 29%, respectively. In contrast, quetiapine, the most widely used antipsychotic agent, paled by comparison, achieving only an 8% reduction in the risk of psychiatric rehospitalization and a 7% decrease in all-cause hospitalization (JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 1;75[4]:347-55).

In addition, long-acting injectable antipsychotics were significantly more effective for prevention of hospitalization than oral antipsychotics.

“That is kind of shocking, because in some countries, long-acting injectables are not authorized and cannot be used. But I think after this article some regulatory changes are going to take place as a result,” Dr. Grande predicted.

“Another issue I thought was interesting, although it was not the main aim of the study, involved benzodiazepines. They increased the risk of hospitalizations, both for psychiatric illness and all other causes. So apart from giving lithium and long-acting injectable antipsychotics to our bipolar patients, we should also be really careful about the use of benzodiazepines,” she commented.

Intranasal esketamine for suicidality?

Esketamine nasal spray, a fast-acting N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist whose application for marketing approval in combination with a standard oral antidepressant in treatment-resistant depression is now under Food and Drug Administration review, also is being developed for another indication: reduction of suicidality in patients at imminent suicide risk. In a proof-of-concept study, intranasal esketamine resulted in a significant reduction in suicidal thoughts 4 hours after administration, compared with usual care – but not at 24 hours (Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Jul 1;175[7]:620-30).

New and effective medications for this indication are sorely needed. The only drug approved for the indication of suicide prevention is clozapine.

‘Latest thinking’ on bipolar disorders

Dr. Grande coauthored a comprehensive review article on bipolar disorders that she recommended as worthwhile reading (Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 Mar 8;4:18008. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.8).

“It covers all the latest thinking. It focuses on the early stages of the disorder, how epigenetic factors are essential, and many other topics, including the bipolarity index being developed at the University of Barcelona to classify drugs in terms of their capacity to prevent episodes of mania or depression in terms of number needed to treat and number needed to harm. It emphasizes the importance of intervening early and focusing on cognitive dysfunction,” Dr Grande said.

Psychedelics making a comeback

German and Swiss investigators used a facial expression discrimination task to demonstrate that psilocybin, a 5-hydroxytryptamine2A–receptor agonist, decreases connectivity between the amygdala and regions of the brain important in emotion processing, including the striatum and frontal pole. The investigators theorized that this might be the mechanism for the psychedelic’s apparent antidepressant effects (Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018 Jun;28[6]:691-700).

Dr. Grande included this study in her top publications list because it reflects the rapidly growing rebirth of interest in psychedelics research among European psychiatrists.

Indeed, elsewhere at the ECNP congress David J. Nutt, DM, declared, “We now have the beginnings of some swinging of the pendulum back in a modern direction. Over the last 10 years there have been a small number of open studies, all done with psilocybin, which is somewhat easier to use than LSD. There are studies in OCD [obsessive-compulsive disorder], tobacco dependence, alcoholism, resistant depression, end-of-life mood changes with cancer and other terminal diseases, and at least two ongoing randomized trials in resistant depression.”

Dr. Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, was senior author of the first proof-of-concept study of psilocybin accompanied by psychologic support as a novel therapy for moderate to severe treatment-resistant major depression (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016 Jul;3[7]:619-27).

Methylphenidate ineffective for treatment of acute mania

The MEMAP study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter clinical trial testing what has been called the vigilance regulation model of mania. This model hypothesized that unstable regulation of wakefulness figures prominently in the pathogenesis of both mania and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. If true, investigators reasoned, then 2.5 days of methylphenidate at 20-40 mg/day should have a rapid antimanic effect similar to the drug’s benefits in ADHD. Dr. Grande had been a skeptic, and indeed, the trial was halted early for futility (Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018 Jan;28[1]:185-94).

She reported serving as a paid speaker for Lunbeck, Ferrer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Janssen. Her own research is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Improve cognitive symptoms of depression to boost work productivity

BARCELONA – (Assessment in Work Productivity and the Relationship with Cognitive Symptoms).

“We found that as patients rated themselves as improved in terms of cognition – ‘I can think better,’ ‘I can focus,’ ‘I’m concentrating better’ – there was a strong correlation at 12 weeks and later extended to 1 year with improved work productivity by as much as 75%. It’s pretty dramatic,” lead investigator Pratap Chokka, MD, said in an interview at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

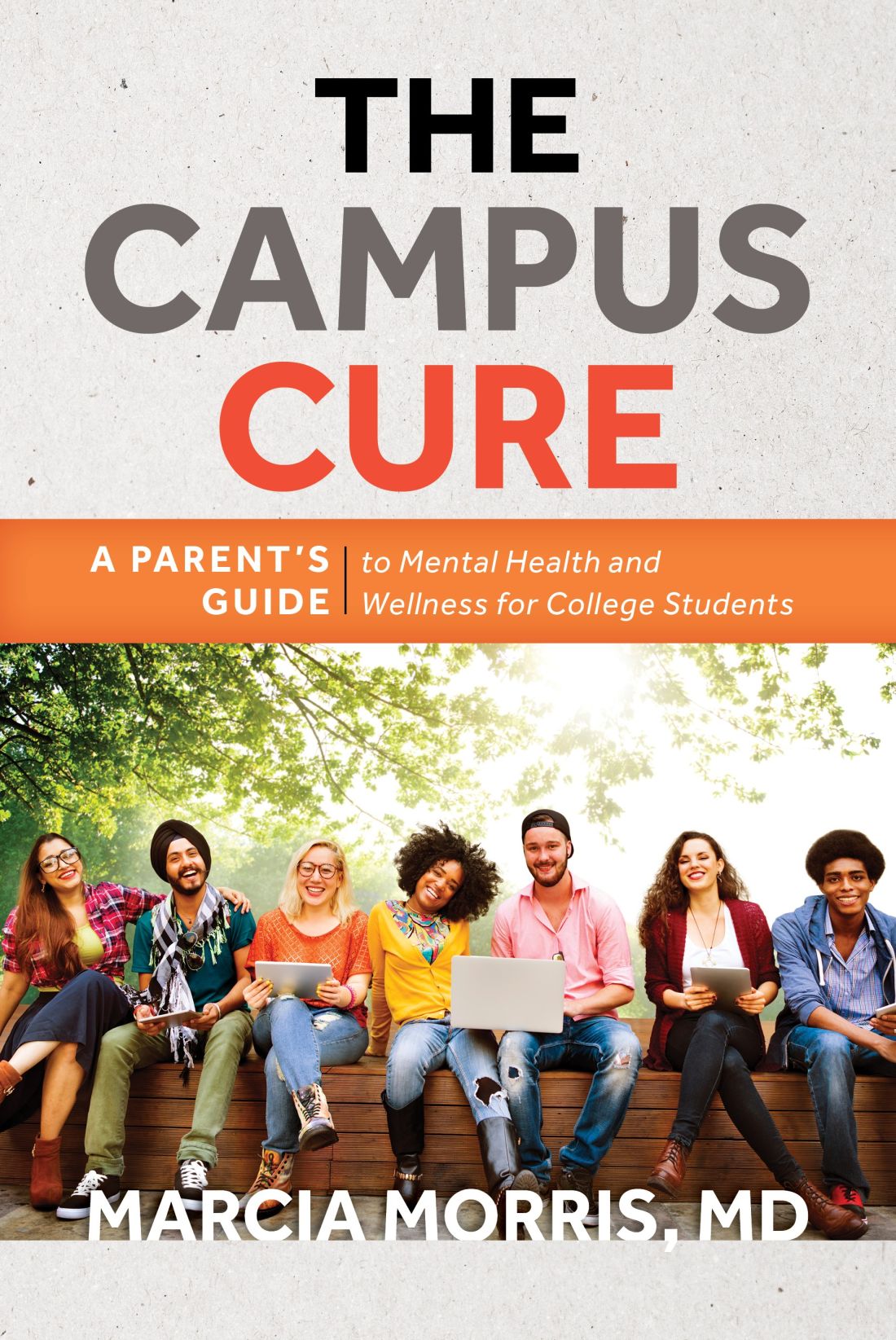

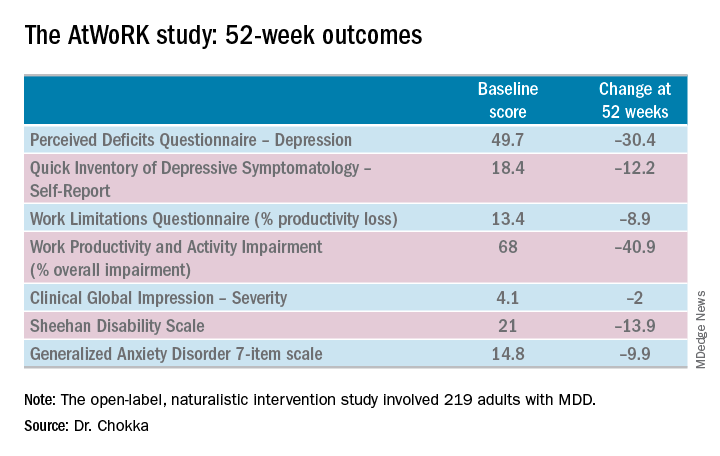

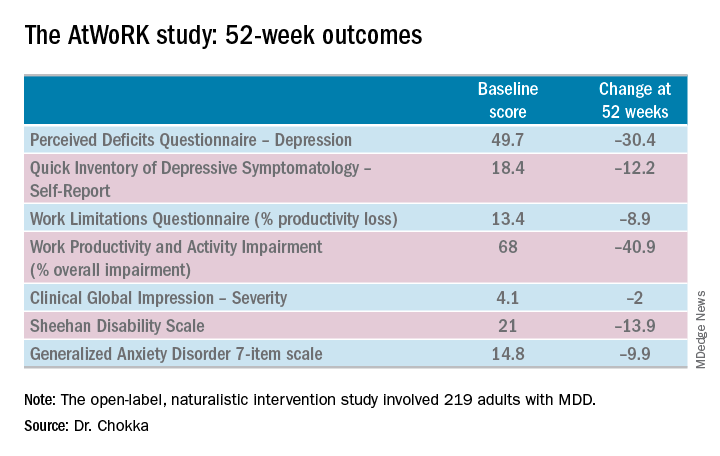

AtWoRK was a multicenter, open-label, naturalistic intervention study in which 219 gainfully employed Canadian adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) who had presented to primary care physicians or psychiatrists were placed on vortioxetine (Trintellex) flexibly dosed at 10-20 mg/day and scheduled for routine follow-up visits every 4 weeks for 52 weeks.

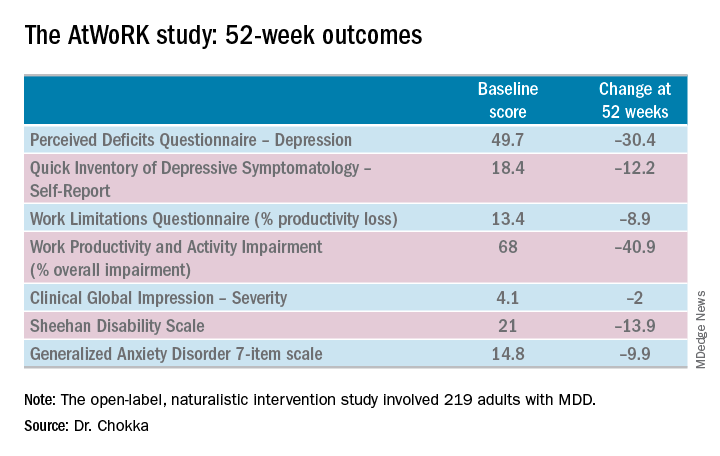

This was a patient population with severe depression, severe cognitive dysfunction, severe anxiety, and substantial functional impairment as reflected in their baseline scores on a variety of validated measures (see graphic). The study was designed to emulate real-world clinical practice.

“We know that patients with depression are very impaired in terms of work productivity. Depressed patients really suffer from absenteeism and presenteeism [reduced productivity at work caused by depression]. And very few naturalistic studies have been done in working patients with depression,” according to Dr. Chokka. “The randomized trials are really important. They show us that a drug is working. But in terms of the real world that I work in, I need to have effectiveness: Does the drug work in patients with comorbid conditions, problems in their home lives, who are maybe drinking alcohol? Those are cases we’d rule out from participation in the RCTs.”

“The patients in our study walked into our clinics saying, ‘You know what, doctor, my mind isn’t working very good. I’m depressed, I can’t think, I can’t focus, I’m missing work, my boss is on my case, I’m making errors. I need help.’ These are the kinds of practicalities we wanted to address,” explained Dr. Chokka, a psychiatrist at Grey Nuns Community Hospital in Edmonton, Can.

The primary endpoint in AtWoRK was the correlation between changes in patients’ self-reported cognitive symptoms on the 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire–Depression (PDQ-D-20) and changes in work productivity loss measured on the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) at week 12. Those 12-week results were recently published (CNS Spectr. 2018 May 24:1-10). At the ECNP congress, Dr. Chokka presented the expanded 52-week outcomes.

The correlation between change from baseline to week 12 in PDQ-D-20 and change in WLQ was strong (r = 0.606), and it remained strong at week 52 (r = 0.731; P less than .001).

At 52 weeks on vortioxetine, 77% of patients fulfilled criteria for MDD response, which required at least a 50% reduction in Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self-Report (QIDS-SR) score from baseline, and 56% for disease remission, which meant the QIDS-SR score was 5 or less. The response and remission rates were 71% and 45%, respectively, in the 107 subjects for whom the drug was the first treatment for their current MDD episode and 83% and 67% for the 112 switched to vortioxetine at study outset because the antidepressant they’d been on was ineffective.

Subjects also displayed significant improvement at 12 and 52 weeks in mood as assessed using QIDS-SR and global functioning as measured using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Of note, however, improvement in cognitive symptoms was independent of and not predictive of improvement in overall depressive symptoms on the QIDS-SR. Nor did improvement in depressive symptoms predict functional outcomes as assessed by the WLQ or SDS.

In Dr. Chokka’s view, these findings have clear implications for clinical practice: “In the past we thought that, if we can get the mood better, things will all get better. We now we know that treating depression is about more than just getting the mood better.”

Vortioxetine is an antidepressant with multiple agonist and antagonist effects on various 5-HT serotonin receptors.

The AtWoRK study was supported by Lundbeck Canada. Dr. Chokka reported receiving research grants from and serving on advisory boards and as a speaker for that company and others.

SOURCE: Chokka P. ECNP, P.022.

BARCELONA – (Assessment in Work Productivity and the Relationship with Cognitive Symptoms).

“We found that as patients rated themselves as improved in terms of cognition – ‘I can think better,’ ‘I can focus,’ ‘I’m concentrating better’ – there was a strong correlation at 12 weeks and later extended to 1 year with improved work productivity by as much as 75%. It’s pretty dramatic,” lead investigator Pratap Chokka, MD, said in an interview at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

AtWoRK was a multicenter, open-label, naturalistic intervention study in which 219 gainfully employed Canadian adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) who had presented to primary care physicians or psychiatrists were placed on vortioxetine (Trintellex) flexibly dosed at 10-20 mg/day and scheduled for routine follow-up visits every 4 weeks for 52 weeks.

This was a patient population with severe depression, severe cognitive dysfunction, severe anxiety, and substantial functional impairment as reflected in their baseline scores on a variety of validated measures (see graphic). The study was designed to emulate real-world clinical practice.

“We know that patients with depression are very impaired in terms of work productivity. Depressed patients really suffer from absenteeism and presenteeism [reduced productivity at work caused by depression]. And very few naturalistic studies have been done in working patients with depression,” according to Dr. Chokka. “The randomized trials are really important. They show us that a drug is working. But in terms of the real world that I work in, I need to have effectiveness: Does the drug work in patients with comorbid conditions, problems in their home lives, who are maybe drinking alcohol? Those are cases we’d rule out from participation in the RCTs.”

“The patients in our study walked into our clinics saying, ‘You know what, doctor, my mind isn’t working very good. I’m depressed, I can’t think, I can’t focus, I’m missing work, my boss is on my case, I’m making errors. I need help.’ These are the kinds of practicalities we wanted to address,” explained Dr. Chokka, a psychiatrist at Grey Nuns Community Hospital in Edmonton, Can.

The primary endpoint in AtWoRK was the correlation between changes in patients’ self-reported cognitive symptoms on the 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire–Depression (PDQ-D-20) and changes in work productivity loss measured on the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) at week 12. Those 12-week results were recently published (CNS Spectr. 2018 May 24:1-10). At the ECNP congress, Dr. Chokka presented the expanded 52-week outcomes.

The correlation between change from baseline to week 12 in PDQ-D-20 and change in WLQ was strong (r = 0.606), and it remained strong at week 52 (r = 0.731; P less than .001).

At 52 weeks on vortioxetine, 77% of patients fulfilled criteria for MDD response, which required at least a 50% reduction in Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self-Report (QIDS-SR) score from baseline, and 56% for disease remission, which meant the QIDS-SR score was 5 or less. The response and remission rates were 71% and 45%, respectively, in the 107 subjects for whom the drug was the first treatment for their current MDD episode and 83% and 67% for the 112 switched to vortioxetine at study outset because the antidepressant they’d been on was ineffective.

Subjects also displayed significant improvement at 12 and 52 weeks in mood as assessed using QIDS-SR and global functioning as measured using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Of note, however, improvement in cognitive symptoms was independent of and not predictive of improvement in overall depressive symptoms on the QIDS-SR. Nor did improvement in depressive symptoms predict functional outcomes as assessed by the WLQ or SDS.

In Dr. Chokka’s view, these findings have clear implications for clinical practice: “In the past we thought that, if we can get the mood better, things will all get better. We now we know that treating depression is about more than just getting the mood better.”

Vortioxetine is an antidepressant with multiple agonist and antagonist effects on various 5-HT serotonin receptors.

The AtWoRK study was supported by Lundbeck Canada. Dr. Chokka reported receiving research grants from and serving on advisory boards and as a speaker for that company and others.

SOURCE: Chokka P. ECNP, P.022.

BARCELONA – (Assessment in Work Productivity and the Relationship with Cognitive Symptoms).

“We found that as patients rated themselves as improved in terms of cognition – ‘I can think better,’ ‘I can focus,’ ‘I’m concentrating better’ – there was a strong correlation at 12 weeks and later extended to 1 year with improved work productivity by as much as 75%. It’s pretty dramatic,” lead investigator Pratap Chokka, MD, said in an interview at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

AtWoRK was a multicenter, open-label, naturalistic intervention study in which 219 gainfully employed Canadian adults with major depressive disorder (MDD) who had presented to primary care physicians or psychiatrists were placed on vortioxetine (Trintellex) flexibly dosed at 10-20 mg/day and scheduled for routine follow-up visits every 4 weeks for 52 weeks.

This was a patient population with severe depression, severe cognitive dysfunction, severe anxiety, and substantial functional impairment as reflected in their baseline scores on a variety of validated measures (see graphic). The study was designed to emulate real-world clinical practice.

“We know that patients with depression are very impaired in terms of work productivity. Depressed patients really suffer from absenteeism and presenteeism [reduced productivity at work caused by depression]. And very few naturalistic studies have been done in working patients with depression,” according to Dr. Chokka. “The randomized trials are really important. They show us that a drug is working. But in terms of the real world that I work in, I need to have effectiveness: Does the drug work in patients with comorbid conditions, problems in their home lives, who are maybe drinking alcohol? Those are cases we’d rule out from participation in the RCTs.”

“The patients in our study walked into our clinics saying, ‘You know what, doctor, my mind isn’t working very good. I’m depressed, I can’t think, I can’t focus, I’m missing work, my boss is on my case, I’m making errors. I need help.’ These are the kinds of practicalities we wanted to address,” explained Dr. Chokka, a psychiatrist at Grey Nuns Community Hospital in Edmonton, Can.

The primary endpoint in AtWoRK was the correlation between changes in patients’ self-reported cognitive symptoms on the 20-item Perceived Deficits Questionnaire–Depression (PDQ-D-20) and changes in work productivity loss measured on the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) at week 12. Those 12-week results were recently published (CNS Spectr. 2018 May 24:1-10). At the ECNP congress, Dr. Chokka presented the expanded 52-week outcomes.

The correlation between change from baseline to week 12 in PDQ-D-20 and change in WLQ was strong (r = 0.606), and it remained strong at week 52 (r = 0.731; P less than .001).

At 52 weeks on vortioxetine, 77% of patients fulfilled criteria for MDD response, which required at least a 50% reduction in Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self-Report (QIDS-SR) score from baseline, and 56% for disease remission, which meant the QIDS-SR score was 5 or less. The response and remission rates were 71% and 45%, respectively, in the 107 subjects for whom the drug was the first treatment for their current MDD episode and 83% and 67% for the 112 switched to vortioxetine at study outset because the antidepressant they’d been on was ineffective.

Subjects also displayed significant improvement at 12 and 52 weeks in mood as assessed using QIDS-SR and global functioning as measured using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). Of note, however, improvement in cognitive symptoms was independent of and not predictive of improvement in overall depressive symptoms on the QIDS-SR. Nor did improvement in depressive symptoms predict functional outcomes as assessed by the WLQ or SDS.

In Dr. Chokka’s view, these findings have clear implications for clinical practice: “In the past we thought that, if we can get the mood better, things will all get better. We now we know that treating depression is about more than just getting the mood better.”

Vortioxetine is an antidepressant with multiple agonist and antagonist effects on various 5-HT serotonin receptors.

The AtWoRK study was supported by Lundbeck Canada. Dr. Chokka reported receiving research grants from and serving on advisory boards and as a speaker for that company and others.

SOURCE: Chokka P. ECNP, P.022.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Treat cognitive symptoms of depression to improve impaired work productivity.

Major finding: Impaired work productivity in depressed patients improved greatly in response to reduction in cognitive symptoms, but not with enhanced mood.

Study details: A 52-week, multicenter, open-label study in which 219 employed adults with major depression were placed on vortioxetine and serially assessed for changes in cognitive dysfunction, mood, and work productivity.

Disclosures: The AtWoRK study was supported by Lundbeck Canada. The presenter reported receiving research grants from and serving on advisory boards and as a speaker for that company and others.

Source: Chokka P. ECNP, P.022.

For most veterans with PTSD, helping others is a lifeline

I am a former military psychiatrist who has published extensively about posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological effects of war. Thus, I got sent the news clips many times about a potential candidate for mayor of Kansas City leaving the race to care for himself, his depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Like many of our readers who are physicians, I have a very mixed response to the former candidate’s news.

On the one hand, kudos to him that he has decided to 1) get the help he says he needs, and 2) go public. On the other hand, I really wish that he did not have to drop out of the race to do so.

There are some parallels with leaving for severe physical illness, such as getting chemotherapy for cancer. However, for example, when Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland received treatment for his cancer, he stayed in office.

Why can you stay in a race or office with cancer or heart disease but not with the very common psychiatric and treatable condition of PTSD?

I certainly do not know all the reasons the candidate for Kansas City mayor made this decision. He said he is encouraging other veterans to follow his example and get treatment for PTSD. He also alluded to suicidal ideation.

This got me thinking about the concept of needing to leave work to take care of yourself – a decision that is often lauded as both noble and wise. I will not opine much on nobility, other than saying it is always noble to help fellow veterans. Maybe his decision to go public will help other veterans. Hard to say. But I can on opine on wisdom, based on many years of working with veterans with PTSD. I almost always advise them to keep their jobs, if at all possible.

Taking time off from a job you care for actually might increase suicidal thoughts. That is due to less structure in the day, less socialization, and fewer feelings of self-worth. A consequent lack of funds might not help. I have long called holding a good job one of the best mental health interventions, superior to medicine and therapy alone (OK – I am being doctrinaire; there are no placebo-controlled, double blind trials on the topic. But I am also serious.)

In general, Why is it work or saving oneself? In my opinion, work helps to save oneself. Helping others, for most veterans, is a lifeline.

I wonder why he should have to drop out of work to receive treatment. Perhaps he was placed in a residential Veterans Affairs program, which often are 30-60 days long. It is notoriously hard to maintain a job during such treatment.

I believe that we should structure our PTSD therapy so that one can both work and receive appropriate treatment. We need war veterans, with or without PTSD, to run for office. And win.

Dr. Ritchie is chief of psychiatry at MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

I am a former military psychiatrist who has published extensively about posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological effects of war. Thus, I got sent the news clips many times about a potential candidate for mayor of Kansas City leaving the race to care for himself, his depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Like many of our readers who are physicians, I have a very mixed response to the former candidate’s news.

On the one hand, kudos to him that he has decided to 1) get the help he says he needs, and 2) go public. On the other hand, I really wish that he did not have to drop out of the race to do so.

There are some parallels with leaving for severe physical illness, such as getting chemotherapy for cancer. However, for example, when Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland received treatment for his cancer, he stayed in office.

Why can you stay in a race or office with cancer or heart disease but not with the very common psychiatric and treatable condition of PTSD?

I certainly do not know all the reasons the candidate for Kansas City mayor made this decision. He said he is encouraging other veterans to follow his example and get treatment for PTSD. He also alluded to suicidal ideation.

This got me thinking about the concept of needing to leave work to take care of yourself – a decision that is often lauded as both noble and wise. I will not opine much on nobility, other than saying it is always noble to help fellow veterans. Maybe his decision to go public will help other veterans. Hard to say. But I can on opine on wisdom, based on many years of working with veterans with PTSD. I almost always advise them to keep their jobs, if at all possible.

Taking time off from a job you care for actually might increase suicidal thoughts. That is due to less structure in the day, less socialization, and fewer feelings of self-worth. A consequent lack of funds might not help. I have long called holding a good job one of the best mental health interventions, superior to medicine and therapy alone (OK – I am being doctrinaire; there are no placebo-controlled, double blind trials on the topic. But I am also serious.)

In general, Why is it work or saving oneself? In my opinion, work helps to save oneself. Helping others, for most veterans, is a lifeline.

I wonder why he should have to drop out of work to receive treatment. Perhaps he was placed in a residential Veterans Affairs program, which often are 30-60 days long. It is notoriously hard to maintain a job during such treatment.

I believe that we should structure our PTSD therapy so that one can both work and receive appropriate treatment. We need war veterans, with or without PTSD, to run for office. And win.

Dr. Ritchie is chief of psychiatry at MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

I am a former military psychiatrist who has published extensively about posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological effects of war. Thus, I got sent the news clips many times about a potential candidate for mayor of Kansas City leaving the race to care for himself, his depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Like many of our readers who are physicians, I have a very mixed response to the former candidate’s news.

On the one hand, kudos to him that he has decided to 1) get the help he says he needs, and 2) go public. On the other hand, I really wish that he did not have to drop out of the race to do so.

There are some parallels with leaving for severe physical illness, such as getting chemotherapy for cancer. However, for example, when Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland received treatment for his cancer, he stayed in office.

Why can you stay in a race or office with cancer or heart disease but not with the very common psychiatric and treatable condition of PTSD?

I certainly do not know all the reasons the candidate for Kansas City mayor made this decision. He said he is encouraging other veterans to follow his example and get treatment for PTSD. He also alluded to suicidal ideation.

This got me thinking about the concept of needing to leave work to take care of yourself – a decision that is often lauded as both noble and wise. I will not opine much on nobility, other than saying it is always noble to help fellow veterans. Maybe his decision to go public will help other veterans. Hard to say. But I can on opine on wisdom, based on many years of working with veterans with PTSD. I almost always advise them to keep their jobs, if at all possible.

Taking time off from a job you care for actually might increase suicidal thoughts. That is due to less structure in the day, less socialization, and fewer feelings of self-worth. A consequent lack of funds might not help. I have long called holding a good job one of the best mental health interventions, superior to medicine and therapy alone (OK – I am being doctrinaire; there are no placebo-controlled, double blind trials on the topic. But I am also serious.)

In general, Why is it work or saving oneself? In my opinion, work helps to save oneself. Helping others, for most veterans, is a lifeline.

I wonder why he should have to drop out of work to receive treatment. Perhaps he was placed in a residential Veterans Affairs program, which often are 30-60 days long. It is notoriously hard to maintain a job during such treatment.

I believe that we should structure our PTSD therapy so that one can both work and receive appropriate treatment. We need war veterans, with or without PTSD, to run for office. And win.

Dr. Ritchie is chief of psychiatry at MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

Older adults who self-harm face increased suicide risk