User login

Mood disorders worsen multiple sclerosis disability

BERLIN – Depression and bipolar disorder are major risk factors for worsening disability in people with multiple sclerosis, according to the results of a large Swedish registry-based study.

The presence of depression increased the risk of having a sustained Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 3.0 by 54% and 4.0 by 87%, and it doubled the risk of an EDSS of 6.0.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment also upped the risk of greater disability, with patients exposed to SSRIs having a 40% increased risk of a sustained EDSS of 3.0, a 97% chance of having a sustained EDSS of 4.0, and 2.2-fold increased risk of a sustained EDSS of 6.0.

“We know that mood disorders are highly prevalent in people with multiple sclerosis,” Stefanie Binzer, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. She gave her presentation at the meeting on Oct. 10, which was World Mental Health Day.

The presence of mood disorders is associated with reduced quality of life, said Dr. Binzer of the department of clinical neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Furthermore, depression is the major risk factor for suicidality in patients with MS. However, before this study the effect of having a comorbid mood disorder on MS patients’ disability levels had not been established.

The investigators analyzed data from 5,875 patients in the Swedish MS registry between 2001 and 2014. By matching these patients to records in the Swedish National Patient Registry and the Swedish National Prescribed Drug Registry, they found that 8.5% (n = 502) had an International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), code for depression. Of these, 261 had received a diagnosis of depression before their diagnosis of MS.

Of 3,817 patients with MS onset between 2005 and 2014, 27.4% (n = 1,048) had collected at least one prescription for an SSRI.

“What we found was that MS patients with either an ICD code for depression or having been exposed to SSRIs had a significantly increased risk of reaching EDSS 3.0,” Dr. Binzer reported. The age at which patients reached these milestones were younger in both groups when compared with MS patients without depression, she observed.

“The difference between the groups [MS with and MS without depression] seemed to increased with EDSS,” Dr. Binzer said.

Although not statistically significant, there was a trend for patients with depression to be more likely to convert to secondary progressive MS, with a hazard ratio of 1.38 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-2.1).

“For a sensitivity analysis, we found that those who had depression prior to their first MS symptom, the median age when they reached EDSS 3.0 and 4.0 was reduced by 3 and 7 years, respectively,” Dr. Binzer said, adding that, unfortunately, there wasn’t enough power to look at the other endpoints.

In regard to bipolar disorder, 1.5% (n = 200) of 13,125 MS patients diagnosed between 1973 and 2014 were identified with this mood disorder. Its presence significantly increased the risk of MS patients reaching an EDSS score of 4.0 by 58% (95% CI, 1.1-2.28), but not EDSS 3.0 (HR = 1.34; 95% CI, 0.94-1.92) or 6.0 (HR = 1.16; 95% CI, 0.79-1.69). The latter could be due to smaller sample size, Dr. Binzer suggested.

The investigators’ analysis of the results stratified by sex, conducted because men tend to fare worse than women with MS and progress faster, showed that for both depression and bipolar disorder, men were at significantly higher risk of reaching sustained disability milestones. Indeed, compared with women, men with depression had a 61% increased risk and those with bipolar disorder a 31% increased risk of reaching an EDSS score of 6.0. They also had 51% and 32% increased risks of conversion to secondary progressive MS.

“We don’t know the mechanisms that underlie these associations,” Dr. Binzer noted. “Irrespective of the underlying mechanisms, [the study] clearly shows that it’s imperative that we recognize, early, mood disorders in MS patients, and manage them effectively in order to provide better care and hopefully reduce MS disability worsening.”

The research was funded by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Brain Foundation. Dr. Binzer has received speaker fees and travel grants from Biogen.

SOURCE: Binzer S et al. Mult Scler. 2018;24(Suppl 2):41. Abstract 99.

BERLIN – Depression and bipolar disorder are major risk factors for worsening disability in people with multiple sclerosis, according to the results of a large Swedish registry-based study.

The presence of depression increased the risk of having a sustained Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 3.0 by 54% and 4.0 by 87%, and it doubled the risk of an EDSS of 6.0.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment also upped the risk of greater disability, with patients exposed to SSRIs having a 40% increased risk of a sustained EDSS of 3.0, a 97% chance of having a sustained EDSS of 4.0, and 2.2-fold increased risk of a sustained EDSS of 6.0.

“We know that mood disorders are highly prevalent in people with multiple sclerosis,” Stefanie Binzer, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. She gave her presentation at the meeting on Oct. 10, which was World Mental Health Day.

The presence of mood disorders is associated with reduced quality of life, said Dr. Binzer of the department of clinical neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Furthermore, depression is the major risk factor for suicidality in patients with MS. However, before this study the effect of having a comorbid mood disorder on MS patients’ disability levels had not been established.

The investigators analyzed data from 5,875 patients in the Swedish MS registry between 2001 and 2014. By matching these patients to records in the Swedish National Patient Registry and the Swedish National Prescribed Drug Registry, they found that 8.5% (n = 502) had an International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), code for depression. Of these, 261 had received a diagnosis of depression before their diagnosis of MS.

Of 3,817 patients with MS onset between 2005 and 2014, 27.4% (n = 1,048) had collected at least one prescription for an SSRI.

“What we found was that MS patients with either an ICD code for depression or having been exposed to SSRIs had a significantly increased risk of reaching EDSS 3.0,” Dr. Binzer reported. The age at which patients reached these milestones were younger in both groups when compared with MS patients without depression, she observed.

“The difference between the groups [MS with and MS without depression] seemed to increased with EDSS,” Dr. Binzer said.

Although not statistically significant, there was a trend for patients with depression to be more likely to convert to secondary progressive MS, with a hazard ratio of 1.38 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-2.1).

“For a sensitivity analysis, we found that those who had depression prior to their first MS symptom, the median age when they reached EDSS 3.0 and 4.0 was reduced by 3 and 7 years, respectively,” Dr. Binzer said, adding that, unfortunately, there wasn’t enough power to look at the other endpoints.

In regard to bipolar disorder, 1.5% (n = 200) of 13,125 MS patients diagnosed between 1973 and 2014 were identified with this mood disorder. Its presence significantly increased the risk of MS patients reaching an EDSS score of 4.0 by 58% (95% CI, 1.1-2.28), but not EDSS 3.0 (HR = 1.34; 95% CI, 0.94-1.92) or 6.0 (HR = 1.16; 95% CI, 0.79-1.69). The latter could be due to smaller sample size, Dr. Binzer suggested.

The investigators’ analysis of the results stratified by sex, conducted because men tend to fare worse than women with MS and progress faster, showed that for both depression and bipolar disorder, men were at significantly higher risk of reaching sustained disability milestones. Indeed, compared with women, men with depression had a 61% increased risk and those with bipolar disorder a 31% increased risk of reaching an EDSS score of 6.0. They also had 51% and 32% increased risks of conversion to secondary progressive MS.

“We don’t know the mechanisms that underlie these associations,” Dr. Binzer noted. “Irrespective of the underlying mechanisms, [the study] clearly shows that it’s imperative that we recognize, early, mood disorders in MS patients, and manage them effectively in order to provide better care and hopefully reduce MS disability worsening.”

The research was funded by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Brain Foundation. Dr. Binzer has received speaker fees and travel grants from Biogen.

SOURCE: Binzer S et al. Mult Scler. 2018;24(Suppl 2):41. Abstract 99.

BERLIN – Depression and bipolar disorder are major risk factors for worsening disability in people with multiple sclerosis, according to the results of a large Swedish registry-based study.

The presence of depression increased the risk of having a sustained Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 3.0 by 54% and 4.0 by 87%, and it doubled the risk of an EDSS of 6.0.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment also upped the risk of greater disability, with patients exposed to SSRIs having a 40% increased risk of a sustained EDSS of 3.0, a 97% chance of having a sustained EDSS of 4.0, and 2.2-fold increased risk of a sustained EDSS of 6.0.

“We know that mood disorders are highly prevalent in people with multiple sclerosis,” Stefanie Binzer, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis. She gave her presentation at the meeting on Oct. 10, which was World Mental Health Day.

The presence of mood disorders is associated with reduced quality of life, said Dr. Binzer of the department of clinical neuroscience at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Furthermore, depression is the major risk factor for suicidality in patients with MS. However, before this study the effect of having a comorbid mood disorder on MS patients’ disability levels had not been established.

The investigators analyzed data from 5,875 patients in the Swedish MS registry between 2001 and 2014. By matching these patients to records in the Swedish National Patient Registry and the Swedish National Prescribed Drug Registry, they found that 8.5% (n = 502) had an International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), code for depression. Of these, 261 had received a diagnosis of depression before their diagnosis of MS.

Of 3,817 patients with MS onset between 2005 and 2014, 27.4% (n = 1,048) had collected at least one prescription for an SSRI.

“What we found was that MS patients with either an ICD code for depression or having been exposed to SSRIs had a significantly increased risk of reaching EDSS 3.0,” Dr. Binzer reported. The age at which patients reached these milestones were younger in both groups when compared with MS patients without depression, she observed.

“The difference between the groups [MS with and MS without depression] seemed to increased with EDSS,” Dr. Binzer said.

Although not statistically significant, there was a trend for patients with depression to be more likely to convert to secondary progressive MS, with a hazard ratio of 1.38 (95% confidence interval, 0.91-2.1).

“For a sensitivity analysis, we found that those who had depression prior to their first MS symptom, the median age when they reached EDSS 3.0 and 4.0 was reduced by 3 and 7 years, respectively,” Dr. Binzer said, adding that, unfortunately, there wasn’t enough power to look at the other endpoints.

In regard to bipolar disorder, 1.5% (n = 200) of 13,125 MS patients diagnosed between 1973 and 2014 were identified with this mood disorder. Its presence significantly increased the risk of MS patients reaching an EDSS score of 4.0 by 58% (95% CI, 1.1-2.28), but not EDSS 3.0 (HR = 1.34; 95% CI, 0.94-1.92) or 6.0 (HR = 1.16; 95% CI, 0.79-1.69). The latter could be due to smaller sample size, Dr. Binzer suggested.

The investigators’ analysis of the results stratified by sex, conducted because men tend to fare worse than women with MS and progress faster, showed that for both depression and bipolar disorder, men were at significantly higher risk of reaching sustained disability milestones. Indeed, compared with women, men with depression had a 61% increased risk and those with bipolar disorder a 31% increased risk of reaching an EDSS score of 6.0. They also had 51% and 32% increased risks of conversion to secondary progressive MS.

“We don’t know the mechanisms that underlie these associations,” Dr. Binzer noted. “Irrespective of the underlying mechanisms, [the study] clearly shows that it’s imperative that we recognize, early, mood disorders in MS patients, and manage them effectively in order to provide better care and hopefully reduce MS disability worsening.”

The research was funded by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Brain Foundation. Dr. Binzer has received speaker fees and travel grants from Biogen.

SOURCE: Binzer S et al. Mult Scler. 2018;24(Suppl 2):41. Abstract 99.

REPORTING FROM ECTRIMS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Depression and bipolar disorder increased the risk of reaching Expanded Disability Status Scale scores of 3.0, 4.0, and 6.0, particularly in men with MS.

Study details: Swedish registry study of nearly 6,000 individuals with confirmed MS, 8.5% of whom had depression and 1.5% of whom had bipolar disorder.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Brain Foundation. Dr. Binzer has received speaker fees and travel grants from Biogen.

Source: Binzer S et al. Mult Scler. 2018;24(Suppl 2):41. Abstract 99.

Anxiety and depression widespread among arthritis patients

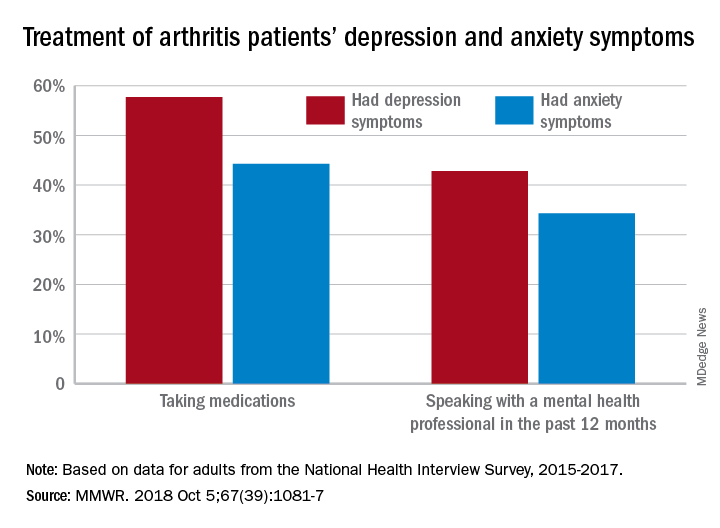

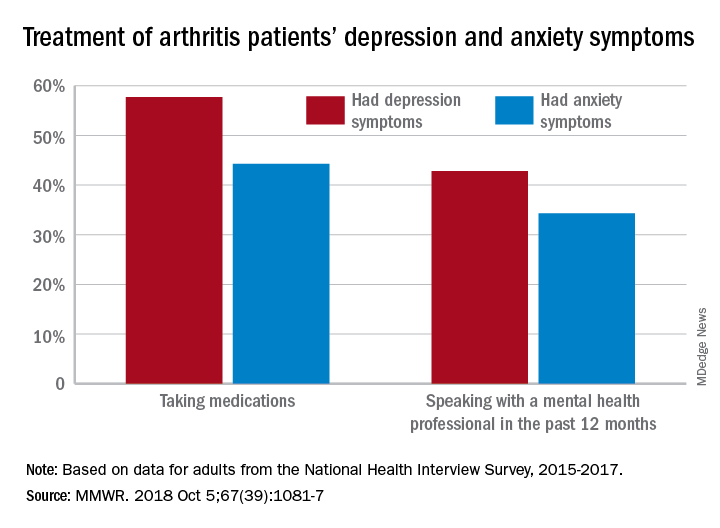

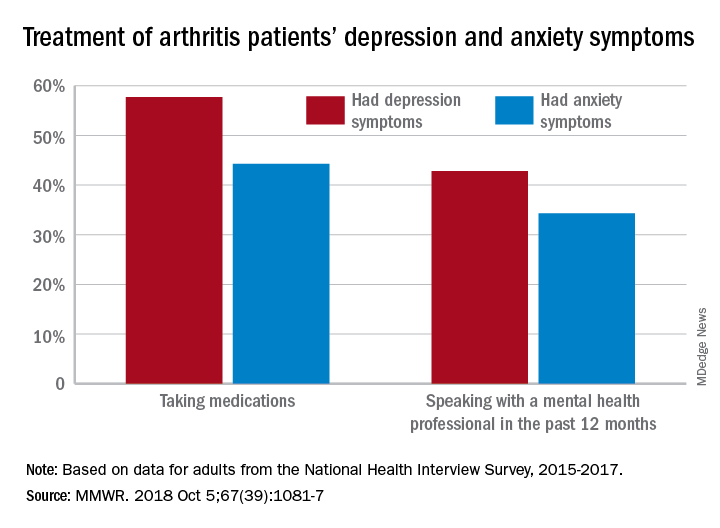

Adults with arthritis are almost twice as likely to have symptoms of anxiety than depression, but the depressed patients are more likely to receive treatment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During 2015-2017, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms was 22.5% in adults with arthritis, compared with 12.1% for depression symptoms. Treatment of those symptoms, however, was another story: 57.7% of arthritis patients with depression symptoms were taking medications, versus 44.3% of those with anxiety symptoms, and 42.8% of those with symptoms of depression reported seeing a mental health professional the past 12 months, compared with 34.3% of adults with anxiety, Dana Guglielmo, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and her associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Prevalences of anxiety and depression symptoms varied considerably by sociodemographic characteristic during 2015-2017. Anxiety and depression were both more common in those aged 18-44 years (28.3% and 13.7%, respectively) than in those aged over 65 (9.7% and 6.2%), and women with arthritis were more likely than were men to experience symptoms of anxiety (26.9% vs. 16%) and depression (14% vs. 9.2%), the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Among racial/ethnic groups, the prevalence of anxiety was highest for whites (23.9%) and lowest for Asians (10.6%), who also had lowest depression symptom prevalence at 3.3%, with American Indians/Alaska Natives highest at 15.4%. Adults categorized as other/multiple race, however, were highest in both cases at 32.3% for anxiety and 17.4% for depression, Ms. Guglielmo and her associates said.

The overall prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with arthritis was much higher than in those without arthritis – 10.7% for anxiety and 4.7% for depression – which “suggests that all adults with arthritis would benefit from mental health screening,” they noted.

, and encouraging physical activity, which is an effective nonpharmacologic strategy that can help reduce the symptoms of anxiety and depression, improve arthritis symptoms, and promote better quality of life,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Guglielmo D et al. MMWR. 2018 Oct 5;67(39):1081-7.

Adults with arthritis are almost twice as likely to have symptoms of anxiety than depression, but the depressed patients are more likely to receive treatment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During 2015-2017, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms was 22.5% in adults with arthritis, compared with 12.1% for depression symptoms. Treatment of those symptoms, however, was another story: 57.7% of arthritis patients with depression symptoms were taking medications, versus 44.3% of those with anxiety symptoms, and 42.8% of those with symptoms of depression reported seeing a mental health professional the past 12 months, compared with 34.3% of adults with anxiety, Dana Guglielmo, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and her associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Prevalences of anxiety and depression symptoms varied considerably by sociodemographic characteristic during 2015-2017. Anxiety and depression were both more common in those aged 18-44 years (28.3% and 13.7%, respectively) than in those aged over 65 (9.7% and 6.2%), and women with arthritis were more likely than were men to experience symptoms of anxiety (26.9% vs. 16%) and depression (14% vs. 9.2%), the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Among racial/ethnic groups, the prevalence of anxiety was highest for whites (23.9%) and lowest for Asians (10.6%), who also had lowest depression symptom prevalence at 3.3%, with American Indians/Alaska Natives highest at 15.4%. Adults categorized as other/multiple race, however, were highest in both cases at 32.3% for anxiety and 17.4% for depression, Ms. Guglielmo and her associates said.

The overall prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with arthritis was much higher than in those without arthritis – 10.7% for anxiety and 4.7% for depression – which “suggests that all adults with arthritis would benefit from mental health screening,” they noted.

, and encouraging physical activity, which is an effective nonpharmacologic strategy that can help reduce the symptoms of anxiety and depression, improve arthritis symptoms, and promote better quality of life,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Guglielmo D et al. MMWR. 2018 Oct 5;67(39):1081-7.

Adults with arthritis are almost twice as likely to have symptoms of anxiety than depression, but the depressed patients are more likely to receive treatment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

During 2015-2017, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms was 22.5% in adults with arthritis, compared with 12.1% for depression symptoms. Treatment of those symptoms, however, was another story: 57.7% of arthritis patients with depression symptoms were taking medications, versus 44.3% of those with anxiety symptoms, and 42.8% of those with symptoms of depression reported seeing a mental health professional the past 12 months, compared with 34.3% of adults with anxiety, Dana Guglielmo, MPH, of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and her associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Prevalences of anxiety and depression symptoms varied considerably by sociodemographic characteristic during 2015-2017. Anxiety and depression were both more common in those aged 18-44 years (28.3% and 13.7%, respectively) than in those aged over 65 (9.7% and 6.2%), and women with arthritis were more likely than were men to experience symptoms of anxiety (26.9% vs. 16%) and depression (14% vs. 9.2%), the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Among racial/ethnic groups, the prevalence of anxiety was highest for whites (23.9%) and lowest for Asians (10.6%), who also had lowest depression symptom prevalence at 3.3%, with American Indians/Alaska Natives highest at 15.4%. Adults categorized as other/multiple race, however, were highest in both cases at 32.3% for anxiety and 17.4% for depression, Ms. Guglielmo and her associates said.

The overall prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with arthritis was much higher than in those without arthritis – 10.7% for anxiety and 4.7% for depression – which “suggests that all adults with arthritis would benefit from mental health screening,” they noted.

, and encouraging physical activity, which is an effective nonpharmacologic strategy that can help reduce the symptoms of anxiety and depression, improve arthritis symptoms, and promote better quality of life,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Guglielmo D et al. MMWR. 2018 Oct 5;67(39):1081-7.

FROM MMWR

Promising novel antidepressant cruising in pipeline

BARCELONA – An investigational antidepressant known for now simply as MIN-117 shows the potential – at least, in phase 2 development – of offering significant advantages over currently available antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder, Michael Davidson, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“This is a compound with a very, very rich pharmacology – so rich that we don’t know exactly which of the pharmacologic effects are really making the difference. This rich pharmacology is related to pathways that may confer to MIN-117 a unique positioning in the field of antidepressants and address unmet medical needs not well covered by existing therapies. For example, faster onset of action, complete restoration of euthymia, and beneficial effects on cognition and sexual functioning,” according to Michael Davidson, MD, chief medical officer at Minerva Neurosciences, which is developing the drug..

In the completed phase 2 study, the drug also displayed a strong anxiolytic effect and no prolongation of REM sleep latency in polysomnographic testing.

“So it may be that this is the first antidepressant which does not affect sleep architecture,” observed Dr. Davidson, professor of psychiatry at the Sackler School of Medicine in Tel Aviv.

Preclinical studies established that MIN-117 has high affinity for the 5HT serotonin transporter, serotonin 1A and 2A receptors, the dopamine transporter, and the alpha-1A and -1B adrenergic receptors. In animal models of depression, the drug results in sustained release of dopamine and serotonin. In human studies, the drug has a long half-life of roughly 60 hours.

“One possibility is that MIN-117 will be administered not once a day, but once or twice a week. It may be that here we have an antidepressant that doesn’t have to be administered every day,” the psychiatrist said.

In the completed phase 2 study, however, the drug was given once daily in what he described as a “classic design” for an antidepressant clinical trial: a 4-week washout period, then 6 weeks of double-blind treatment with MIN-117 at 2.5 or 0.5 mg/day, paroxetine at 20 mg/day, or placebo, then a 2-week posttreatment follow-up phase.

In describing the results of the study of 84 patients with major depressive disorder, Dr. Davidson painted a picture of MIN-117’s safety and efficacy with broad strokes because the trial wasn’t powered to demonstrate statistically significant differences. But the treatment effect sizes for the novel drug were impressive. A much more complete picture of the safety and efficacy of MIN-117 will be provided by an ongoing 324-patient phase 2b multicenter U.S. and European trial of the drug given at 2.5 or 5 mg/day or placebo.

The primary endpoint in the completed trial was change from baseline to 6 weeks in mean Montgomery-Åsberg Rating Depression Scale (MADRS) score. From a baseline score of about 33, MADRS scores improved by 9 points with placebo, 11 with MIN-117 at 0.5 mg, and by 12 points with 2.5 mg of the drug. MIN-117 was superior to placebo in this regard from the time of the earliest assessment, at 2 weeks.

One-quarter of patients on MIN-117 at 2.5 mg/day achieved remission, prospectively defined as a MADRS score below 12. Remission was 2.1-fold more likely in this group than with placebo at week 4 and 3.1-fold more likely at 6 weeks. The remission rate with MIN-117 also was better than with paroxetine.

“So , and that we’ll be able to produce full remission of the depressive symptoms,” Dr. Davidson said.

MIN-117 also showed a solid anxiolytic effect, with mean scores on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale – a secondary endpoint – improving by 10 points in both the 0.5- and 2.5-mg groups from a baseline of 26 points. As a result of this impressive showing, the large ongoing phase 2b study is recruiting patients with an ongoing episode of major depressive disorder and prominent secondary anxiety.

Both doses of MIN-117 were well tolerated. Scores on the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale showed that the drug did not result in any impairment of sexual function. Nor was MIN-117 associated with evidence of cognitive impairment; in fact, scores on the Digit-Symbol Substitution Test and Digit Span Backwards tool were better than in the placebo arm.

The study was sponsored by Minerva Neurosciences and presented by the company’s chief medical officer.

BARCELONA – An investigational antidepressant known for now simply as MIN-117 shows the potential – at least, in phase 2 development – of offering significant advantages over currently available antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder, Michael Davidson, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“This is a compound with a very, very rich pharmacology – so rich that we don’t know exactly which of the pharmacologic effects are really making the difference. This rich pharmacology is related to pathways that may confer to MIN-117 a unique positioning in the field of antidepressants and address unmet medical needs not well covered by existing therapies. For example, faster onset of action, complete restoration of euthymia, and beneficial effects on cognition and sexual functioning,” according to Michael Davidson, MD, chief medical officer at Minerva Neurosciences, which is developing the drug..

In the completed phase 2 study, the drug also displayed a strong anxiolytic effect and no prolongation of REM sleep latency in polysomnographic testing.

“So it may be that this is the first antidepressant which does not affect sleep architecture,” observed Dr. Davidson, professor of psychiatry at the Sackler School of Medicine in Tel Aviv.

Preclinical studies established that MIN-117 has high affinity for the 5HT serotonin transporter, serotonin 1A and 2A receptors, the dopamine transporter, and the alpha-1A and -1B adrenergic receptors. In animal models of depression, the drug results in sustained release of dopamine and serotonin. In human studies, the drug has a long half-life of roughly 60 hours.

“One possibility is that MIN-117 will be administered not once a day, but once or twice a week. It may be that here we have an antidepressant that doesn’t have to be administered every day,” the psychiatrist said.

In the completed phase 2 study, however, the drug was given once daily in what he described as a “classic design” for an antidepressant clinical trial: a 4-week washout period, then 6 weeks of double-blind treatment with MIN-117 at 2.5 or 0.5 mg/day, paroxetine at 20 mg/day, or placebo, then a 2-week posttreatment follow-up phase.

In describing the results of the study of 84 patients with major depressive disorder, Dr. Davidson painted a picture of MIN-117’s safety and efficacy with broad strokes because the trial wasn’t powered to demonstrate statistically significant differences. But the treatment effect sizes for the novel drug were impressive. A much more complete picture of the safety and efficacy of MIN-117 will be provided by an ongoing 324-patient phase 2b multicenter U.S. and European trial of the drug given at 2.5 or 5 mg/day or placebo.

The primary endpoint in the completed trial was change from baseline to 6 weeks in mean Montgomery-Åsberg Rating Depression Scale (MADRS) score. From a baseline score of about 33, MADRS scores improved by 9 points with placebo, 11 with MIN-117 at 0.5 mg, and by 12 points with 2.5 mg of the drug. MIN-117 was superior to placebo in this regard from the time of the earliest assessment, at 2 weeks.

One-quarter of patients on MIN-117 at 2.5 mg/day achieved remission, prospectively defined as a MADRS score below 12. Remission was 2.1-fold more likely in this group than with placebo at week 4 and 3.1-fold more likely at 6 weeks. The remission rate with MIN-117 also was better than with paroxetine.

“So , and that we’ll be able to produce full remission of the depressive symptoms,” Dr. Davidson said.

MIN-117 also showed a solid anxiolytic effect, with mean scores on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale – a secondary endpoint – improving by 10 points in both the 0.5- and 2.5-mg groups from a baseline of 26 points. As a result of this impressive showing, the large ongoing phase 2b study is recruiting patients with an ongoing episode of major depressive disorder and prominent secondary anxiety.

Both doses of MIN-117 were well tolerated. Scores on the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale showed that the drug did not result in any impairment of sexual function. Nor was MIN-117 associated with evidence of cognitive impairment; in fact, scores on the Digit-Symbol Substitution Test and Digit Span Backwards tool were better than in the placebo arm.

The study was sponsored by Minerva Neurosciences and presented by the company’s chief medical officer.

BARCELONA – An investigational antidepressant known for now simply as MIN-117 shows the potential – at least, in phase 2 development – of offering significant advantages over currently available antidepressants in patients with major depressive disorder, Michael Davidson, MD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

“This is a compound with a very, very rich pharmacology – so rich that we don’t know exactly which of the pharmacologic effects are really making the difference. This rich pharmacology is related to pathways that may confer to MIN-117 a unique positioning in the field of antidepressants and address unmet medical needs not well covered by existing therapies. For example, faster onset of action, complete restoration of euthymia, and beneficial effects on cognition and sexual functioning,” according to Michael Davidson, MD, chief medical officer at Minerva Neurosciences, which is developing the drug..

In the completed phase 2 study, the drug also displayed a strong anxiolytic effect and no prolongation of REM sleep latency in polysomnographic testing.

“So it may be that this is the first antidepressant which does not affect sleep architecture,” observed Dr. Davidson, professor of psychiatry at the Sackler School of Medicine in Tel Aviv.

Preclinical studies established that MIN-117 has high affinity for the 5HT serotonin transporter, serotonin 1A and 2A receptors, the dopamine transporter, and the alpha-1A and -1B adrenergic receptors. In animal models of depression, the drug results in sustained release of dopamine and serotonin. In human studies, the drug has a long half-life of roughly 60 hours.

“One possibility is that MIN-117 will be administered not once a day, but once or twice a week. It may be that here we have an antidepressant that doesn’t have to be administered every day,” the psychiatrist said.

In the completed phase 2 study, however, the drug was given once daily in what he described as a “classic design” for an antidepressant clinical trial: a 4-week washout period, then 6 weeks of double-blind treatment with MIN-117 at 2.5 or 0.5 mg/day, paroxetine at 20 mg/day, or placebo, then a 2-week posttreatment follow-up phase.

In describing the results of the study of 84 patients with major depressive disorder, Dr. Davidson painted a picture of MIN-117’s safety and efficacy with broad strokes because the trial wasn’t powered to demonstrate statistically significant differences. But the treatment effect sizes for the novel drug were impressive. A much more complete picture of the safety and efficacy of MIN-117 will be provided by an ongoing 324-patient phase 2b multicenter U.S. and European trial of the drug given at 2.5 or 5 mg/day or placebo.

The primary endpoint in the completed trial was change from baseline to 6 weeks in mean Montgomery-Åsberg Rating Depression Scale (MADRS) score. From a baseline score of about 33, MADRS scores improved by 9 points with placebo, 11 with MIN-117 at 0.5 mg, and by 12 points with 2.5 mg of the drug. MIN-117 was superior to placebo in this regard from the time of the earliest assessment, at 2 weeks.

One-quarter of patients on MIN-117 at 2.5 mg/day achieved remission, prospectively defined as a MADRS score below 12. Remission was 2.1-fold more likely in this group than with placebo at week 4 and 3.1-fold more likely at 6 weeks. The remission rate with MIN-117 also was better than with paroxetine.

“So , and that we’ll be able to produce full remission of the depressive symptoms,” Dr. Davidson said.

MIN-117 also showed a solid anxiolytic effect, with mean scores on the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale – a secondary endpoint – improving by 10 points in both the 0.5- and 2.5-mg groups from a baseline of 26 points. As a result of this impressive showing, the large ongoing phase 2b study is recruiting patients with an ongoing episode of major depressive disorder and prominent secondary anxiety.

Both doses of MIN-117 were well tolerated. Scores on the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale showed that the drug did not result in any impairment of sexual function. Nor was MIN-117 associated with evidence of cognitive impairment; in fact, scores on the Digit-Symbol Substitution Test and Digit Span Backwards tool were better than in the placebo arm.

The study was sponsored by Minerva Neurosciences and presented by the company’s chief medical officer.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point: An investigational antidepressant might address important unmet needs in the treatment of major depression.

Major finding: Patients with major depressive disorder were 3.1-fold more likely to be in remission after 6 weeks on MIN-117 at 2.5 mg/day than with placebo.

Study details: This prospective, double-blind, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled study included 84 patients with major depressive disorder.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Minerva Neurosciences and presented by the company’s chief medical officer.

Sexual assault and harassment linked to hypertension, depression, and anxiety

Sexual harassment and assault may have significant health impacts on women in midlife, including greater risk of hypertension, poor sleep, depression, and anxiety, research suggests.

In the Oct. 3 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, a study of 304 women aged 40-60 years showed that 19% reported a history of workplace sexual harassment, 22% reported a history of sexual assault, and 10% reported both. The report was presented simultaneously at the North American Menopause Society annual meeting in San Diego.

The researchers found that those with a history of sexual assault had an almost threefold higher odds of clinically elevated depressive symptoms (OR, 2.86, P = .003), and more than twofold greater odds of anxiety and poor sleep (OR, 2.26, P = .006 and OR, 2.15, P = .007 respectively).

Women who reported experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace – and who were not taking antihypertensive medication – were more than twice as likely to have stage 1 or 2 hypertension, compared with women who had not experienced sexual harassment (OR, 2.36, P = .03). They also had 89% higher odds of poor sleep consistent with clinical insomnia (P = .03).

These associations all persisted even after adjustment for demographic and biomedical factors such as age, ethnicity, body mass index, snoring, and the use of antihypertensive, antidepressant, and anti-anxiety medications.

“Given the high prevalence of sexual harassment and assault, addressing these prevalent and potent social exposures may be critical to promoting health and preventing disease in women,” wrote Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and her coauthors.

They noted that the 1-in-5 rate of sexual harassment or assault seen in the study was actually lower than that seen in national samples, which may be have been because of the exclusion of women who smoked, had undergone hysterectomies, or were using common antidepressants or cardiovascular medications.

“Few characteristics distinguished between women who had been sexually harassed and those who had been sexually assaulted, with the exception that women who were sexually harassed were more highly educated yet more financially strained,” they wrote. “Notably, women who are younger or are in more precarious employment situations are more likely to be harassed, and financially stressed women can lack the financial security to leave abusive work situations.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr. Thurston declared consultancies for MAS Innovations, Procter & Gamble, and Pfizer, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Thurston R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018, Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4886.

Sexual harassment and assault may have significant health impacts on women in midlife, including greater risk of hypertension, poor sleep, depression, and anxiety, research suggests.

In the Oct. 3 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, a study of 304 women aged 40-60 years showed that 19% reported a history of workplace sexual harassment, 22% reported a history of sexual assault, and 10% reported both. The report was presented simultaneously at the North American Menopause Society annual meeting in San Diego.

The researchers found that those with a history of sexual assault had an almost threefold higher odds of clinically elevated depressive symptoms (OR, 2.86, P = .003), and more than twofold greater odds of anxiety and poor sleep (OR, 2.26, P = .006 and OR, 2.15, P = .007 respectively).

Women who reported experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace – and who were not taking antihypertensive medication – were more than twice as likely to have stage 1 or 2 hypertension, compared with women who had not experienced sexual harassment (OR, 2.36, P = .03). They also had 89% higher odds of poor sleep consistent with clinical insomnia (P = .03).

These associations all persisted even after adjustment for demographic and biomedical factors such as age, ethnicity, body mass index, snoring, and the use of antihypertensive, antidepressant, and anti-anxiety medications.

“Given the high prevalence of sexual harassment and assault, addressing these prevalent and potent social exposures may be critical to promoting health and preventing disease in women,” wrote Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and her coauthors.

They noted that the 1-in-5 rate of sexual harassment or assault seen in the study was actually lower than that seen in national samples, which may be have been because of the exclusion of women who smoked, had undergone hysterectomies, or were using common antidepressants or cardiovascular medications.

“Few characteristics distinguished between women who had been sexually harassed and those who had been sexually assaulted, with the exception that women who were sexually harassed were more highly educated yet more financially strained,” they wrote. “Notably, women who are younger or are in more precarious employment situations are more likely to be harassed, and financially stressed women can lack the financial security to leave abusive work situations.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr. Thurston declared consultancies for MAS Innovations, Procter & Gamble, and Pfizer, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Thurston R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018, Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4886.

Sexual harassment and assault may have significant health impacts on women in midlife, including greater risk of hypertension, poor sleep, depression, and anxiety, research suggests.

In the Oct. 3 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, a study of 304 women aged 40-60 years showed that 19% reported a history of workplace sexual harassment, 22% reported a history of sexual assault, and 10% reported both. The report was presented simultaneously at the North American Menopause Society annual meeting in San Diego.

The researchers found that those with a history of sexual assault had an almost threefold higher odds of clinically elevated depressive symptoms (OR, 2.86, P = .003), and more than twofold greater odds of anxiety and poor sleep (OR, 2.26, P = .006 and OR, 2.15, P = .007 respectively).

Women who reported experiencing sexual harassment in the workplace – and who were not taking antihypertensive medication – were more than twice as likely to have stage 1 or 2 hypertension, compared with women who had not experienced sexual harassment (OR, 2.36, P = .03). They also had 89% higher odds of poor sleep consistent with clinical insomnia (P = .03).

These associations all persisted even after adjustment for demographic and biomedical factors such as age, ethnicity, body mass index, snoring, and the use of antihypertensive, antidepressant, and anti-anxiety medications.

“Given the high prevalence of sexual harassment and assault, addressing these prevalent and potent social exposures may be critical to promoting health and preventing disease in women,” wrote Rebecca C. Thurston, PhD, of the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, and her coauthors.

They noted that the 1-in-5 rate of sexual harassment or assault seen in the study was actually lower than that seen in national samples, which may be have been because of the exclusion of women who smoked, had undergone hysterectomies, or were using common antidepressants or cardiovascular medications.

“Few characteristics distinguished between women who had been sexually harassed and those who had been sexually assaulted, with the exception that women who were sexually harassed were more highly educated yet more financially strained,” they wrote. “Notably, women who are younger or are in more precarious employment situations are more likely to be harassed, and financially stressed women can lack the financial security to leave abusive work situations.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr. Thurston declared consultancies for MAS Innovations, Procter & Gamble, and Pfizer, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Thurston R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018, Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4886.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Women who have experienced sexual assault showed nearly threefold higher odds of depressive symptoms.

Study details: Study of 304 women aged 40-60 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, and the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Dr. Thurston declared consultancies for MAS Innovations, Procter & Gamble, and Pfizer, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Thurston R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4886.

Could group CBT help survivors of Florence?

Rising waters forced hundreds of people, mainly in the Carolinas, to call for emergency rescues, and some people were forced to abandon their cars because of flooding. One man reportedly died by electrocution while trying to hook up a generator. Another man died after going out to check the status of hunting dogs, according to media reports. And in one of the most heart-wrenching tragedies, a mother and her infant were killed when a tree fell on their home.

Watching the TV reports and listening to the news of Hurricane Florence’s devastating impact on so many millions of people has been shocking. The death toll from this catastrophic weather event as of this writing stands at 39. Besides the current and future physical problems and illnesses left in Florence’s wake, the extent of property damage and loss must be overwhelming for the survivors.

I worry about the extent of the emotional toll left behind by Florence, just as Hurricane Maria did last year in Puerto Rico. The storm and its subsequent damage to the individual psyche – including the loss of identity and the fracturing of social structures and networks – almost certainly will lead to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and utter despair for many survivors.

While monitoring Florence’s impact, I thought about Hurricane Sandy, which upended me personally when it hit New York in 2012. As I’ve written previously, Sandy’s impact left me without power, running water, or toilet facilities. Almost 3 days of this uncertainty shook me from my comfort zone and truly affected my emotions. Before day 3, I left my home and drove (yes, I could still use my car; the roads were clear and my garage was not flooded) to my older son’s home – where I had a great support system and was able to continue to live a relatively normal life while watching the storm’s developments on TV. To this day, many areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut that were hit by Sandy have not fully recovered.

Back to the human tragedy still unfolding for the survivors of Florence: I believe – and the data suggest – that early intervention and treatment of PTSD leads to better outcomes and should be addressed sooner than later. There is no specific medicinal “magic bullet” for PTSD, although some medications may help as well as treat a depressive component of the disorder and other medications may assist in improving sleep and disruptive sleep patterns. It’s been shown, time and again, that cognitive-behavioral therapy, various types of prolonged exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization therapies work best. The most updated federal guidelines from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, coauthored by Lori L. Davis, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reinforce those treatments.

I also believe that, in situations in which masses of people are affected or potentially affected by PTSD, another first line of care that should be added is supportive, educational, interactive group therapy. In other words, it is possible that a cognitive-behavioral group therapy (CBGT) approach would reach many more people, make psychiatric intervention acceptable, and help the survivors of Florence. A recent study by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston that examined the role of “decentering” as part of CBGT for patients with specific anxiety disorders, for example, social anxiety disorder, might provide some hints. Decentering involves learning to observe thoughts and feelings as objective events in the mind rather than identifying with them personally. Aaron T. Beck, MD, and others hypothesized decentering as a mechanism of change in CBT.

In the UMass study, researchers recruited 81 people with a principal diagnosis of social anxiety disorder based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Scheduled for DSM-IV. Other inclusion criteria for the study included stability on medications for 3 months or 1 month on benzodiazepines (Behav Ther. 2018 Sep;49[5]:809-12). Sixty-three of participants had 12 sessions of CBGT. The researchers found that people who received the CBGT experienced an increase in decentering. An increase in decentering, in turn, predicted improvement on most outcome measures.

Just as primary care physicians and surgeons know how to address serious physical health issues related natural and man-made disasters, psychiatrists must quickly know how to address the mental health aspects of care. Group therapy has the greatest potential to help more people and perhaps treat – and even prevent not only PTSD but many anxiety disorders as well.

Dr. London, a psychiatrist who practices in New York, developed and ran a short-term psychotherapy program for 20 years at NYU Langone Medical Center and has been writing columns for 35 years. His new book about helping people feel better fast is expected to be published in fall 2018. He has no disclosures.

Rising waters forced hundreds of people, mainly in the Carolinas, to call for emergency rescues, and some people were forced to abandon their cars because of flooding. One man reportedly died by electrocution while trying to hook up a generator. Another man died after going out to check the status of hunting dogs, according to media reports. And in one of the most heart-wrenching tragedies, a mother and her infant were killed when a tree fell on their home.

Watching the TV reports and listening to the news of Hurricane Florence’s devastating impact on so many millions of people has been shocking. The death toll from this catastrophic weather event as of this writing stands at 39. Besides the current and future physical problems and illnesses left in Florence’s wake, the extent of property damage and loss must be overwhelming for the survivors.

I worry about the extent of the emotional toll left behind by Florence, just as Hurricane Maria did last year in Puerto Rico. The storm and its subsequent damage to the individual psyche – including the loss of identity and the fracturing of social structures and networks – almost certainly will lead to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and utter despair for many survivors.

While monitoring Florence’s impact, I thought about Hurricane Sandy, which upended me personally when it hit New York in 2012. As I’ve written previously, Sandy’s impact left me without power, running water, or toilet facilities. Almost 3 days of this uncertainty shook me from my comfort zone and truly affected my emotions. Before day 3, I left my home and drove (yes, I could still use my car; the roads were clear and my garage was not flooded) to my older son’s home – where I had a great support system and was able to continue to live a relatively normal life while watching the storm’s developments on TV. To this day, many areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut that were hit by Sandy have not fully recovered.

Back to the human tragedy still unfolding for the survivors of Florence: I believe – and the data suggest – that early intervention and treatment of PTSD leads to better outcomes and should be addressed sooner than later. There is no specific medicinal “magic bullet” for PTSD, although some medications may help as well as treat a depressive component of the disorder and other medications may assist in improving sleep and disruptive sleep patterns. It’s been shown, time and again, that cognitive-behavioral therapy, various types of prolonged exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization therapies work best. The most updated federal guidelines from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, coauthored by Lori L. Davis, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reinforce those treatments.

I also believe that, in situations in which masses of people are affected or potentially affected by PTSD, another first line of care that should be added is supportive, educational, interactive group therapy. In other words, it is possible that a cognitive-behavioral group therapy (CBGT) approach would reach many more people, make psychiatric intervention acceptable, and help the survivors of Florence. A recent study by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston that examined the role of “decentering” as part of CBGT for patients with specific anxiety disorders, for example, social anxiety disorder, might provide some hints. Decentering involves learning to observe thoughts and feelings as objective events in the mind rather than identifying with them personally. Aaron T. Beck, MD, and others hypothesized decentering as a mechanism of change in CBT.

In the UMass study, researchers recruited 81 people with a principal diagnosis of social anxiety disorder based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Scheduled for DSM-IV. Other inclusion criteria for the study included stability on medications for 3 months or 1 month on benzodiazepines (Behav Ther. 2018 Sep;49[5]:809-12). Sixty-three of participants had 12 sessions of CBGT. The researchers found that people who received the CBGT experienced an increase in decentering. An increase in decentering, in turn, predicted improvement on most outcome measures.

Just as primary care physicians and surgeons know how to address serious physical health issues related natural and man-made disasters, psychiatrists must quickly know how to address the mental health aspects of care. Group therapy has the greatest potential to help more people and perhaps treat – and even prevent not only PTSD but many anxiety disorders as well.

Dr. London, a psychiatrist who practices in New York, developed and ran a short-term psychotherapy program for 20 years at NYU Langone Medical Center and has been writing columns for 35 years. His new book about helping people feel better fast is expected to be published in fall 2018. He has no disclosures.

Rising waters forced hundreds of people, mainly in the Carolinas, to call for emergency rescues, and some people were forced to abandon their cars because of flooding. One man reportedly died by electrocution while trying to hook up a generator. Another man died after going out to check the status of hunting dogs, according to media reports. And in one of the most heart-wrenching tragedies, a mother and her infant were killed when a tree fell on their home.

Watching the TV reports and listening to the news of Hurricane Florence’s devastating impact on so many millions of people has been shocking. The death toll from this catastrophic weather event as of this writing stands at 39. Besides the current and future physical problems and illnesses left in Florence’s wake, the extent of property damage and loss must be overwhelming for the survivors.

I worry about the extent of the emotional toll left behind by Florence, just as Hurricane Maria did last year in Puerto Rico. The storm and its subsequent damage to the individual psyche – including the loss of identity and the fracturing of social structures and networks – almost certainly will lead to posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and utter despair for many survivors.

While monitoring Florence’s impact, I thought about Hurricane Sandy, which upended me personally when it hit New York in 2012. As I’ve written previously, Sandy’s impact left me without power, running water, or toilet facilities. Almost 3 days of this uncertainty shook me from my comfort zone and truly affected my emotions. Before day 3, I left my home and drove (yes, I could still use my car; the roads were clear and my garage was not flooded) to my older son’s home – where I had a great support system and was able to continue to live a relatively normal life while watching the storm’s developments on TV. To this day, many areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut that were hit by Sandy have not fully recovered.

Back to the human tragedy still unfolding for the survivors of Florence: I believe – and the data suggest – that early intervention and treatment of PTSD leads to better outcomes and should be addressed sooner than later. There is no specific medicinal “magic bullet” for PTSD, although some medications may help as well as treat a depressive component of the disorder and other medications may assist in improving sleep and disruptive sleep patterns. It’s been shown, time and again, that cognitive-behavioral therapy, various types of prolonged exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization therapies work best. The most updated federal guidelines from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, coauthored by Lori L. Davis, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, reinforce those treatments.

I also believe that, in situations in which masses of people are affected or potentially affected by PTSD, another first line of care that should be added is supportive, educational, interactive group therapy. In other words, it is possible that a cognitive-behavioral group therapy (CBGT) approach would reach many more people, make psychiatric intervention acceptable, and help the survivors of Florence. A recent study by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Boston that examined the role of “decentering” as part of CBGT for patients with specific anxiety disorders, for example, social anxiety disorder, might provide some hints. Decentering involves learning to observe thoughts and feelings as objective events in the mind rather than identifying with them personally. Aaron T. Beck, MD, and others hypothesized decentering as a mechanism of change in CBT.

In the UMass study, researchers recruited 81 people with a principal diagnosis of social anxiety disorder based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Scheduled for DSM-IV. Other inclusion criteria for the study included stability on medications for 3 months or 1 month on benzodiazepines (Behav Ther. 2018 Sep;49[5]:809-12). Sixty-three of participants had 12 sessions of CBGT. The researchers found that people who received the CBGT experienced an increase in decentering. An increase in decentering, in turn, predicted improvement on most outcome measures.

Just as primary care physicians and surgeons know how to address serious physical health issues related natural and man-made disasters, psychiatrists must quickly know how to address the mental health aspects of care. Group therapy has the greatest potential to help more people and perhaps treat – and even prevent not only PTSD but many anxiety disorders as well.

Dr. London, a psychiatrist who practices in New York, developed and ran a short-term psychotherapy program for 20 years at NYU Langone Medical Center and has been writing columns for 35 years. His new book about helping people feel better fast is expected to be published in fall 2018. He has no disclosures.

Previous psychiatric admissions predict suicide attempts

SAN DIEGO – Among patients presenting to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, the number of previous psychiatric admissions is the most important predictor of a subsequent suicide attempt, results from a 2-year-long study showed.

Momentary measures – significant current difficulties with sleep, energy, or appetite, and anhedonia – “are important considerations during suicide risk assessment, regardless of whether the patient meets the threshold for major depressive disorder, lead study author Anne C. Knorr said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

“Many traditionally studied psychiatric risk factors do not significantly differ between individuals who think about suicide and those who act on their suicidal thoughts, an important distinction as only one-third of those who think about suicide carry out a suicide attempt. While there is support for some psychiatric factors – for example, anxiety, substance use disorders, sleep disturbance – being useful in differentiating these groups, the current study is unique in its use of a longitudinal design to identify influential risk factors that predict future suicide attempt among those with suicidal ideation,” she said.

Ms. Knorr, a research project manager at Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pa., and her colleagues collected electronic medical record data from 908 patients who had received a psychiatric evaluation at an index emergency department visit for suicidal ideation over a 2-year period. The mean age of patients was 39 years. The target sample was 30 patients who had returned to the ED following a suicide attempt within 6 months of their index ED visit.

The researchers analyzed 32 predictor variables from patient charts, including demographics, psychiatric history, and current psychiatric presentation. The evaluation was done with “a machine learning statistical approach which is more capable than traditional statistical approaches in handling a large number of predictor variables,” Ms. Knorr said.

The number of previous psychiatric admissions was the most important predictor of a subsequent suicide attempt. The next nine most important variables were sleep disturbance, history of family suicide, low energy, patient age, psychiatrist determination of severe suicide risk, psychiatrist determination of moderate suicide risk, appetite issues, presence of a support system, and loss of interest/pleasure.

These symptoms may not typically be weighed heavily in risk assessments, Ms. Knorr said. “Additionally, given that research suggests that the clinical determination of suicide risk is historically poor, it was interesting that psychiatrist determination of moderate or high risk was influential in predicting a return visit for suicide attempt. Finally, we were surprised that a past history of suicide attempt, often viewed as the strongest predictor of a future suicide attempt, did not emerge as one of the top 10 influential predictors.

“Limitations of this study include the use of a return visit to a Geisinger emergency department as the only measure of a future suicide attempt and the utilization of data from only one health system,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Geisinger Clinic Research Fund. One of the coauthors, Andrei Nemoianu, MD, reported receipt of a research grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals for a separate study.

SOURCE: Knorr A et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct;72;4:S23. doi. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.055.

SAN DIEGO – Among patients presenting to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, the number of previous psychiatric admissions is the most important predictor of a subsequent suicide attempt, results from a 2-year-long study showed.

Momentary measures – significant current difficulties with sleep, energy, or appetite, and anhedonia – “are important considerations during suicide risk assessment, regardless of whether the patient meets the threshold for major depressive disorder, lead study author Anne C. Knorr said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

“Many traditionally studied psychiatric risk factors do not significantly differ between individuals who think about suicide and those who act on their suicidal thoughts, an important distinction as only one-third of those who think about suicide carry out a suicide attempt. While there is support for some psychiatric factors – for example, anxiety, substance use disorders, sleep disturbance – being useful in differentiating these groups, the current study is unique in its use of a longitudinal design to identify influential risk factors that predict future suicide attempt among those with suicidal ideation,” she said.

Ms. Knorr, a research project manager at Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pa., and her colleagues collected electronic medical record data from 908 patients who had received a psychiatric evaluation at an index emergency department visit for suicidal ideation over a 2-year period. The mean age of patients was 39 years. The target sample was 30 patients who had returned to the ED following a suicide attempt within 6 months of their index ED visit.

The researchers analyzed 32 predictor variables from patient charts, including demographics, psychiatric history, and current psychiatric presentation. The evaluation was done with “a machine learning statistical approach which is more capable than traditional statistical approaches in handling a large number of predictor variables,” Ms. Knorr said.

The number of previous psychiatric admissions was the most important predictor of a subsequent suicide attempt. The next nine most important variables were sleep disturbance, history of family suicide, low energy, patient age, psychiatrist determination of severe suicide risk, psychiatrist determination of moderate suicide risk, appetite issues, presence of a support system, and loss of interest/pleasure.

These symptoms may not typically be weighed heavily in risk assessments, Ms. Knorr said. “Additionally, given that research suggests that the clinical determination of suicide risk is historically poor, it was interesting that psychiatrist determination of moderate or high risk was influential in predicting a return visit for suicide attempt. Finally, we were surprised that a past history of suicide attempt, often viewed as the strongest predictor of a future suicide attempt, did not emerge as one of the top 10 influential predictors.

“Limitations of this study include the use of a return visit to a Geisinger emergency department as the only measure of a future suicide attempt and the utilization of data from only one health system,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Geisinger Clinic Research Fund. One of the coauthors, Andrei Nemoianu, MD, reported receipt of a research grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals for a separate study.

SOURCE: Knorr A et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct;72;4:S23. doi. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.055.

SAN DIEGO – Among patients presenting to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, the number of previous psychiatric admissions is the most important predictor of a subsequent suicide attempt, results from a 2-year-long study showed.

Momentary measures – significant current difficulties with sleep, energy, or appetite, and anhedonia – “are important considerations during suicide risk assessment, regardless of whether the patient meets the threshold for major depressive disorder, lead study author Anne C. Knorr said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

“Many traditionally studied psychiatric risk factors do not significantly differ between individuals who think about suicide and those who act on their suicidal thoughts, an important distinction as only one-third of those who think about suicide carry out a suicide attempt. While there is support for some psychiatric factors – for example, anxiety, substance use disorders, sleep disturbance – being useful in differentiating these groups, the current study is unique in its use of a longitudinal design to identify influential risk factors that predict future suicide attempt among those with suicidal ideation,” she said.

Ms. Knorr, a research project manager at Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pa., and her colleagues collected electronic medical record data from 908 patients who had received a psychiatric evaluation at an index emergency department visit for suicidal ideation over a 2-year period. The mean age of patients was 39 years. The target sample was 30 patients who had returned to the ED following a suicide attempt within 6 months of their index ED visit.

The researchers analyzed 32 predictor variables from patient charts, including demographics, psychiatric history, and current psychiatric presentation. The evaluation was done with “a machine learning statistical approach which is more capable than traditional statistical approaches in handling a large number of predictor variables,” Ms. Knorr said.

The number of previous psychiatric admissions was the most important predictor of a subsequent suicide attempt. The next nine most important variables were sleep disturbance, history of family suicide, low energy, patient age, psychiatrist determination of severe suicide risk, psychiatrist determination of moderate suicide risk, appetite issues, presence of a support system, and loss of interest/pleasure.

These symptoms may not typically be weighed heavily in risk assessments, Ms. Knorr said. “Additionally, given that research suggests that the clinical determination of suicide risk is historically poor, it was interesting that psychiatrist determination of moderate or high risk was influential in predicting a return visit for suicide attempt. Finally, we were surprised that a past history of suicide attempt, often viewed as the strongest predictor of a future suicide attempt, did not emerge as one of the top 10 influential predictors.

“Limitations of this study include the use of a return visit to a Geisinger emergency department as the only measure of a future suicide attempt and the utilization of data from only one health system,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Geisinger Clinic Research Fund. One of the coauthors, Andrei Nemoianu, MD, reported receipt of a research grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals for a separate study.

SOURCE: Knorr A et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct;72;4:S23. doi. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.08.055.

AT ACEP18

Key clinical point: A number of factors representing momentary experiences such as low energy emerged as predictors of suicide attempts among suicidal ideators following an ED visit.

Major finding: The number of past psychiatric admissions was the most influential predictor of a subsequent suicide attempt.

Study details: A study of 30 patients who had returned to the ED following a suicide attempt within 6 months of their index ED visit.

Disclosures: The Geisinger Clinic Research Fund supported the study. A coauthor, Andrei Nemoianu, MD, reported receipt of a research grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals for a separate study.

Source: Knorr A et al. Ann Emerg Med. 2018 Oct;72;4:S23.

Family therapy and cultural conflicts

I recently had the privilege of treating a family who spoke my first language, Hindi. My patient, Ms. M, was 16 years old and struggling to adjust to her new life in the United States, having recently come from India. America’s schooling, culture, and “open society” was a contrast to her life in a semi-rural town, especially her close-knit family structure in which her parents and siblings are everything. Due to their cultural beliefs and religious faith in Islam, both Ms. M and her father were initially resistant to begin treatment for her depression and anxiety. “Let’s give it a trial” was the attitude I finally got from the father. But to me, there was a clear discordance in the communication among the family members in addition to the primary mental illness that led them to come for treatment. I was attracted to work with this family because I had a reasonable understanding of their faith, their culture, and their family system, and I have an inclination toward spirituality. Even though I recognized this family’s social isolation, I wondered why they were still in a state of unrest, given their deep commitment to their faith.

Ms. M was isolating herself at home, in an environment that wasn’t supportive of talking about her concerns. These included being bullied for being “different,” for how she dressed, and for having home-cooked traditional meals for lunch, and being unable to socialize with most of her male peers, except for those from her same community. This led her to dream of returning to India.

The family did not have a social life. Ms. M told me, “I wanted to socialize, but I cannot because of my faith and religion.” So she chose to wear attire to identify with her mother and her culture of origin. She also did this to hide her emotional pain from enduring trauma related to bullying at her school. It was a challenge to understand how faith, resilience, and trauma were intermingled in Ms. M and her family.

I saw Ms. M and her family for 12 one-hour family psychotherapy sessions. The initial session unfolded uneasily. It was a challenge to build rapport and help them understand how family therapy works. Circular inquiries to each family member, specifically to get the mother’s point of view, brought mourning, shame, and guilt to this family. The importance of marriage, education, and immigration were processed in reference to their culture and their incomplete acculturation to life in the United States.

I wondered if there were other families with different cultural backgrounds who struggled with similar conflicts. I also wondered if those families understood the value of family therapy or had ever experienced this therapeutic process.

The 3 key signs that made me believe that this family was making progress through our work together included:

- They complied with treatment; the family never missed a session.

- The parents acknowledged that their daughter was doing better.

- The mother brought me a dinner as a gesture of gratitude in our last session. This is a particularly meaningful gesture on the part of people with their cultural background.

I clearly remember our first meeting, when Ms. M asked

I recently had the privilege of treating a family who spoke my first language, Hindi. My patient, Ms. M, was 16 years old and struggling to adjust to her new life in the United States, having recently come from India. America’s schooling, culture, and “open society” was a contrast to her life in a semi-rural town, especially her close-knit family structure in which her parents and siblings are everything. Due to their cultural beliefs and religious faith in Islam, both Ms. M and her father were initially resistant to begin treatment for her depression and anxiety. “Let’s give it a trial” was the attitude I finally got from the father. But to me, there was a clear discordance in the communication among the family members in addition to the primary mental illness that led them to come for treatment. I was attracted to work with this family because I had a reasonable understanding of their faith, their culture, and their family system, and I have an inclination toward spirituality. Even though I recognized this family’s social isolation, I wondered why they were still in a state of unrest, given their deep commitment to their faith.

Ms. M was isolating herself at home, in an environment that wasn’t supportive of talking about her concerns. These included being bullied for being “different,” for how she dressed, and for having home-cooked traditional meals for lunch, and being unable to socialize with most of her male peers, except for those from her same community. This led her to dream of returning to India.

The family did not have a social life. Ms. M told me, “I wanted to socialize, but I cannot because of my faith and religion.” So she chose to wear attire to identify with her mother and her culture of origin. She also did this to hide her emotional pain from enduring trauma related to bullying at her school. It was a challenge to understand how faith, resilience, and trauma were intermingled in Ms. M and her family.

I saw Ms. M and her family for 12 one-hour family psychotherapy sessions. The initial session unfolded uneasily. It was a challenge to build rapport and help them understand how family therapy works. Circular inquiries to each family member, specifically to get the mother’s point of view, brought mourning, shame, and guilt to this family. The importance of marriage, education, and immigration were processed in reference to their culture and their incomplete acculturation to life in the United States.

I wondered if there were other families with different cultural backgrounds who struggled with similar conflicts. I also wondered if those families understood the value of family therapy or had ever experienced this therapeutic process.

The 3 key signs that made me believe that this family was making progress through our work together included:

- They complied with treatment; the family never missed a session.

- The parents acknowledged that their daughter was doing better.

- The mother brought me a dinner as a gesture of gratitude in our last session. This is a particularly meaningful gesture on the part of people with their cultural background.

I clearly remember our first meeting, when Ms. M asked

I recently had the privilege of treating a family who spoke my first language, Hindi. My patient, Ms. M, was 16 years old and struggling to adjust to her new life in the United States, having recently come from India. America’s schooling, culture, and “open society” was a contrast to her life in a semi-rural town, especially her close-knit family structure in which her parents and siblings are everything. Due to their cultural beliefs and religious faith in Islam, both Ms. M and her father were initially resistant to begin treatment for her depression and anxiety. “Let’s give it a trial” was the attitude I finally got from the father. But to me, there was a clear discordance in the communication among the family members in addition to the primary mental illness that led them to come for treatment. I was attracted to work with this family because I had a reasonable understanding of their faith, their culture, and their family system, and I have an inclination toward spirituality. Even though I recognized this family’s social isolation, I wondered why they were still in a state of unrest, given their deep commitment to their faith.

Ms. M was isolating herself at home, in an environment that wasn’t supportive of talking about her concerns. These included being bullied for being “different,” for how she dressed, and for having home-cooked traditional meals for lunch, and being unable to socialize with most of her male peers, except for those from her same community. This led her to dream of returning to India.

The family did not have a social life. Ms. M told me, “I wanted to socialize, but I cannot because of my faith and religion.” So she chose to wear attire to identify with her mother and her culture of origin. She also did this to hide her emotional pain from enduring trauma related to bullying at her school. It was a challenge to understand how faith, resilience, and trauma were intermingled in Ms. M and her family.