User login

Folic acid tied to a reduction in suicide attempts

new research suggests.

After adjusting for multiple factors, results from a large pharmaco-epidemiological study showed taking folic acid was associated with a 44% reduction in suicide events.

“These results are really putting folic acid squarely on the map as a potential for large-scale, population-level prevention,” lead author Robert D. Gibbons, PhD, professor of biostatistics, Center for Health Statistics, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“Folic acid is safe, inexpensive, and generally available, and if future randomized controlled trials show this association is beyond a shadow of a doubt causal, we have a new tool in the arsenal,” Dr. Gibbons said.

Having such a tool would be extremely important given that suicide is such a significant public health crisis worldwide, he added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Previous research ‘fairly thin’

Folate, the naturally occurring form of B9, is essential for neurogenesis, nucleotide synthesis, and methylation of homocysteine. Past research has suggested that taking folate can prevent neural tube and heart defects in the fetus during pregnancy – and may prevent strokes and reduce age-related hearing loss in adults.

In psychiatry, the role of folate has been recognized for more than a decade. It may enhance the effects of antidepressants; and folate deficiency can predict poorer response to SSRIs.

This has led to recommendations for folate augmentation in patients with low or normal levels at the start of depression treatment.

Although previous research has shown a link between folic acid and suicidality, the findings have been “fairly thin,” with studies being “generally small, and many are case series,” Dr. Gibbons said.

The current study follows an earlier analysis that used a novel statistical methodology for generating drug safety signals that was developed by Dr. Gibbons and colleagues. That study compared rates of suicide attempts before and after initiation of 922 drugs with at least 3,000 prescriptions.

Its results showed 10 drugs were associated with increased risk after exposure, with the strongest associations for alprazolam, butalbital, hydrocodone, and combination codeine/promethazine. In addition, 44 drugs were associated with decreased risk, many of which were antidepressants and antipsychotics.

“One of the most interesting findings in terms of the decreased risk was for folic acid,” said Dr. Gibbons.

He and his colleagues initially thought this was because of women taking folic acid during pregnancy. But when restricting the analysis to men, they found the same effect.

Their next step was to carry out the current large-scale pharmaco-epidemiological study.

Prescriptions for pain

The researchers used a health claims database that included 164 million enrollees. The study cohort was comprised of 866,586 adults with private health insurance (81.3% women; 10.4% aged 60 years and older) who filled a folic acid prescription between 2012 and 2017.

More than half of the folic acid prescriptions were associated with pain disorders. About 48% were for a single agent at a dosage of 1 mg/d, which is the upper tolerable limit for adults – including in pregnancy and lactation.

Other single-agent daily dosages ranging from 0.4 mg to 5 mg accounted for 0.11% of prescriptions. The remainder were multivitamins.

The participants were followed for 24 months. The within-person analysis compared suicide attempts or self-harm events resulting in an outpatient visit or inpatient admission during periods of folic acid treatment versus during periods without treatment.

During the study period, the overall suicidal event rate was 133 per 100,000 population, which is one-fourth the national rate reported by the National Institutes of Health of 600 per 100,000.

After adjusting for age, sex, diagnoses related to suicidal behavior and folic acid deficiency, history of folate-reducing medications, and history of suicidal events, the estimated hazard ratio for suicide events when taking folic acid was 0.56 (95% confidence interal, 0.48-0.65) – which indicates a 44% reduction in suicide events.

“This is a very large decrease and is extremely significant and exciting,” Dr. Gibbons said.

He noted the decrease in suicidal events may have been even greater considering the study captured only prescription folic acid, and participants may also have also taken over-the-counter products.

“The 44% reduction in suicide attempts may actually be an underestimate,” said Dr. Gibbons.

Age and sex did not moderate the association between folic acid and suicide attempts, and a similar association was found in women of childbearing age.

Provocative results?

The investigators also assessed a negative control group of 236,610 individuals using cyanocobalamin during the study period. Cyanocobalamin is a form of vitamin B12 that is essential for metabolism, blood cell synthesis, and the nervous system. It does not contain folic acid and is commonly used to treat anemia.

Results showed no association between cyanocobalamin and suicidal events in the adjusted analysis (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.27) or unadjusted analysis (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28).

Dr. Gibbons noted this result boosts the argument that the association between folic acid and reduced suicidal attempts “isn’t just about health-seeking behavior like taking vitamin supplements.”

Another sensitivity analysis showed every additional month of treatment was associated with a 5% reduction in the suicidal event rate.

“This means the longer you take folic acid, the greater the benefit, which is what you would expect to see if there was a real association between a treatment and an outcome,” said Dr. Gibbons.

The new results “are so provocative that they really mandate the need for a well-controlled randomized controlled trial of folic acid and suicide events,” possibly in a high-risk population such as veterans, he noted.

Such a study could use longitudinal assessments of suicidal events, such as the validated Computerized Adaptive Test Suicide Scale, he added. This continuous scale of suicidality ranges from subclinical, signifying helplessness, hopelessness, and loss of pleasure, to suicide attempts and completion.

As for study limitations, the investigators noted that this study was observational, so there could be selection effects. And using claims data likely underrepresented the number of suicidal events because of incomplete reporting. As the researchers pointed out, the rate of suicidal events in this study was much lower than the national rate.

Other limitations cited were that the association between folic acid and suicidal events may be explained by healthy user bias; and although the investigators conducted a sensitivity analysis in women of childbearing age, they did not have data on women actively planning for a pregnancy.

‘Impressive, encouraging’

In a comment, Shirley Yen, PhD, associate professor of psychology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, described the new findings as “quite impressive” and “extremely encouraging.”

However, she noted “it’s too premature” to suggest widespread use of folic acid in patients with depressive symptoms.

Dr. Yen, who has researched suicide risks previously, was not involved with the current study.

She did agree with the investigators that the results call for “more robustly controlled studies. These could include double-blind, randomized, controlled trials that could “more formally assess” all folic acid usage as opposed to prescriptions only, Dr. Yen said.

The study was funded by the NIH, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention. Dr. Gibbons reported serving as an expert witness in cases for the Department of Justice; receiving expert witness fees from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth; and having founded Adaptive Testing Technologies, which distributes the Computerized Adaptive Test Suicide Scale. Dr. Yen reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

After adjusting for multiple factors, results from a large pharmaco-epidemiological study showed taking folic acid was associated with a 44% reduction in suicide events.

“These results are really putting folic acid squarely on the map as a potential for large-scale, population-level prevention,” lead author Robert D. Gibbons, PhD, professor of biostatistics, Center for Health Statistics, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“Folic acid is safe, inexpensive, and generally available, and if future randomized controlled trials show this association is beyond a shadow of a doubt causal, we have a new tool in the arsenal,” Dr. Gibbons said.

Having such a tool would be extremely important given that suicide is such a significant public health crisis worldwide, he added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Previous research ‘fairly thin’

Folate, the naturally occurring form of B9, is essential for neurogenesis, nucleotide synthesis, and methylation of homocysteine. Past research has suggested that taking folate can prevent neural tube and heart defects in the fetus during pregnancy – and may prevent strokes and reduce age-related hearing loss in adults.

In psychiatry, the role of folate has been recognized for more than a decade. It may enhance the effects of antidepressants; and folate deficiency can predict poorer response to SSRIs.

This has led to recommendations for folate augmentation in patients with low or normal levels at the start of depression treatment.

Although previous research has shown a link between folic acid and suicidality, the findings have been “fairly thin,” with studies being “generally small, and many are case series,” Dr. Gibbons said.

The current study follows an earlier analysis that used a novel statistical methodology for generating drug safety signals that was developed by Dr. Gibbons and colleagues. That study compared rates of suicide attempts before and after initiation of 922 drugs with at least 3,000 prescriptions.

Its results showed 10 drugs were associated with increased risk after exposure, with the strongest associations for alprazolam, butalbital, hydrocodone, and combination codeine/promethazine. In addition, 44 drugs were associated with decreased risk, many of which were antidepressants and antipsychotics.

“One of the most interesting findings in terms of the decreased risk was for folic acid,” said Dr. Gibbons.

He and his colleagues initially thought this was because of women taking folic acid during pregnancy. But when restricting the analysis to men, they found the same effect.

Their next step was to carry out the current large-scale pharmaco-epidemiological study.

Prescriptions for pain

The researchers used a health claims database that included 164 million enrollees. The study cohort was comprised of 866,586 adults with private health insurance (81.3% women; 10.4% aged 60 years and older) who filled a folic acid prescription between 2012 and 2017.

More than half of the folic acid prescriptions were associated with pain disorders. About 48% were for a single agent at a dosage of 1 mg/d, which is the upper tolerable limit for adults – including in pregnancy and lactation.

Other single-agent daily dosages ranging from 0.4 mg to 5 mg accounted for 0.11% of prescriptions. The remainder were multivitamins.

The participants were followed for 24 months. The within-person analysis compared suicide attempts or self-harm events resulting in an outpatient visit or inpatient admission during periods of folic acid treatment versus during periods without treatment.

During the study period, the overall suicidal event rate was 133 per 100,000 population, which is one-fourth the national rate reported by the National Institutes of Health of 600 per 100,000.

After adjusting for age, sex, diagnoses related to suicidal behavior and folic acid deficiency, history of folate-reducing medications, and history of suicidal events, the estimated hazard ratio for suicide events when taking folic acid was 0.56 (95% confidence interal, 0.48-0.65) – which indicates a 44% reduction in suicide events.

“This is a very large decrease and is extremely significant and exciting,” Dr. Gibbons said.

He noted the decrease in suicidal events may have been even greater considering the study captured only prescription folic acid, and participants may also have also taken over-the-counter products.

“The 44% reduction in suicide attempts may actually be an underestimate,” said Dr. Gibbons.

Age and sex did not moderate the association between folic acid and suicide attempts, and a similar association was found in women of childbearing age.

Provocative results?

The investigators also assessed a negative control group of 236,610 individuals using cyanocobalamin during the study period. Cyanocobalamin is a form of vitamin B12 that is essential for metabolism, blood cell synthesis, and the nervous system. It does not contain folic acid and is commonly used to treat anemia.

Results showed no association between cyanocobalamin and suicidal events in the adjusted analysis (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.27) or unadjusted analysis (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28).

Dr. Gibbons noted this result boosts the argument that the association between folic acid and reduced suicidal attempts “isn’t just about health-seeking behavior like taking vitamin supplements.”

Another sensitivity analysis showed every additional month of treatment was associated with a 5% reduction in the suicidal event rate.

“This means the longer you take folic acid, the greater the benefit, which is what you would expect to see if there was a real association between a treatment and an outcome,” said Dr. Gibbons.

The new results “are so provocative that they really mandate the need for a well-controlled randomized controlled trial of folic acid and suicide events,” possibly in a high-risk population such as veterans, he noted.

Such a study could use longitudinal assessments of suicidal events, such as the validated Computerized Adaptive Test Suicide Scale, he added. This continuous scale of suicidality ranges from subclinical, signifying helplessness, hopelessness, and loss of pleasure, to suicide attempts and completion.

As for study limitations, the investigators noted that this study was observational, so there could be selection effects. And using claims data likely underrepresented the number of suicidal events because of incomplete reporting. As the researchers pointed out, the rate of suicidal events in this study was much lower than the national rate.

Other limitations cited were that the association between folic acid and suicidal events may be explained by healthy user bias; and although the investigators conducted a sensitivity analysis in women of childbearing age, they did not have data on women actively planning for a pregnancy.

‘Impressive, encouraging’

In a comment, Shirley Yen, PhD, associate professor of psychology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, described the new findings as “quite impressive” and “extremely encouraging.”

However, she noted “it’s too premature” to suggest widespread use of folic acid in patients with depressive symptoms.

Dr. Yen, who has researched suicide risks previously, was not involved with the current study.

She did agree with the investigators that the results call for “more robustly controlled studies. These could include double-blind, randomized, controlled trials that could “more formally assess” all folic acid usage as opposed to prescriptions only, Dr. Yen said.

The study was funded by the NIH, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention. Dr. Gibbons reported serving as an expert witness in cases for the Department of Justice; receiving expert witness fees from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth; and having founded Adaptive Testing Technologies, which distributes the Computerized Adaptive Test Suicide Scale. Dr. Yen reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

After adjusting for multiple factors, results from a large pharmaco-epidemiological study showed taking folic acid was associated with a 44% reduction in suicide events.

“These results are really putting folic acid squarely on the map as a potential for large-scale, population-level prevention,” lead author Robert D. Gibbons, PhD, professor of biostatistics, Center for Health Statistics, University of Chicago, said in an interview.

“Folic acid is safe, inexpensive, and generally available, and if future randomized controlled trials show this association is beyond a shadow of a doubt causal, we have a new tool in the arsenal,” Dr. Gibbons said.

Having such a tool would be extremely important given that suicide is such a significant public health crisis worldwide, he added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Previous research ‘fairly thin’

Folate, the naturally occurring form of B9, is essential for neurogenesis, nucleotide synthesis, and methylation of homocysteine. Past research has suggested that taking folate can prevent neural tube and heart defects in the fetus during pregnancy – and may prevent strokes and reduce age-related hearing loss in adults.

In psychiatry, the role of folate has been recognized for more than a decade. It may enhance the effects of antidepressants; and folate deficiency can predict poorer response to SSRIs.

This has led to recommendations for folate augmentation in patients with low or normal levels at the start of depression treatment.

Although previous research has shown a link between folic acid and suicidality, the findings have been “fairly thin,” with studies being “generally small, and many are case series,” Dr. Gibbons said.

The current study follows an earlier analysis that used a novel statistical methodology for generating drug safety signals that was developed by Dr. Gibbons and colleagues. That study compared rates of suicide attempts before and after initiation of 922 drugs with at least 3,000 prescriptions.

Its results showed 10 drugs were associated with increased risk after exposure, with the strongest associations for alprazolam, butalbital, hydrocodone, and combination codeine/promethazine. In addition, 44 drugs were associated with decreased risk, many of which were antidepressants and antipsychotics.

“One of the most interesting findings in terms of the decreased risk was for folic acid,” said Dr. Gibbons.

He and his colleagues initially thought this was because of women taking folic acid during pregnancy. But when restricting the analysis to men, they found the same effect.

Their next step was to carry out the current large-scale pharmaco-epidemiological study.

Prescriptions for pain

The researchers used a health claims database that included 164 million enrollees. The study cohort was comprised of 866,586 adults with private health insurance (81.3% women; 10.4% aged 60 years and older) who filled a folic acid prescription between 2012 and 2017.

More than half of the folic acid prescriptions were associated with pain disorders. About 48% were for a single agent at a dosage of 1 mg/d, which is the upper tolerable limit for adults – including in pregnancy and lactation.

Other single-agent daily dosages ranging from 0.4 mg to 5 mg accounted for 0.11% of prescriptions. The remainder were multivitamins.

The participants were followed for 24 months. The within-person analysis compared suicide attempts or self-harm events resulting in an outpatient visit or inpatient admission during periods of folic acid treatment versus during periods without treatment.

During the study period, the overall suicidal event rate was 133 per 100,000 population, which is one-fourth the national rate reported by the National Institutes of Health of 600 per 100,000.

After adjusting for age, sex, diagnoses related to suicidal behavior and folic acid deficiency, history of folate-reducing medications, and history of suicidal events, the estimated hazard ratio for suicide events when taking folic acid was 0.56 (95% confidence interal, 0.48-0.65) – which indicates a 44% reduction in suicide events.

“This is a very large decrease and is extremely significant and exciting,” Dr. Gibbons said.

He noted the decrease in suicidal events may have been even greater considering the study captured only prescription folic acid, and participants may also have also taken over-the-counter products.

“The 44% reduction in suicide attempts may actually be an underestimate,” said Dr. Gibbons.

Age and sex did not moderate the association between folic acid and suicide attempts, and a similar association was found in women of childbearing age.

Provocative results?

The investigators also assessed a negative control group of 236,610 individuals using cyanocobalamin during the study period. Cyanocobalamin is a form of vitamin B12 that is essential for metabolism, blood cell synthesis, and the nervous system. It does not contain folic acid and is commonly used to treat anemia.

Results showed no association between cyanocobalamin and suicidal events in the adjusted analysis (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.27) or unadjusted analysis (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28).

Dr. Gibbons noted this result boosts the argument that the association between folic acid and reduced suicidal attempts “isn’t just about health-seeking behavior like taking vitamin supplements.”

Another sensitivity analysis showed every additional month of treatment was associated with a 5% reduction in the suicidal event rate.

“This means the longer you take folic acid, the greater the benefit, which is what you would expect to see if there was a real association between a treatment and an outcome,” said Dr. Gibbons.

The new results “are so provocative that they really mandate the need for a well-controlled randomized controlled trial of folic acid and suicide events,” possibly in a high-risk population such as veterans, he noted.

Such a study could use longitudinal assessments of suicidal events, such as the validated Computerized Adaptive Test Suicide Scale, he added. This continuous scale of suicidality ranges from subclinical, signifying helplessness, hopelessness, and loss of pleasure, to suicide attempts and completion.

As for study limitations, the investigators noted that this study was observational, so there could be selection effects. And using claims data likely underrepresented the number of suicidal events because of incomplete reporting. As the researchers pointed out, the rate of suicidal events in this study was much lower than the national rate.

Other limitations cited were that the association between folic acid and suicidal events may be explained by healthy user bias; and although the investigators conducted a sensitivity analysis in women of childbearing age, they did not have data on women actively planning for a pregnancy.

‘Impressive, encouraging’

In a comment, Shirley Yen, PhD, associate professor of psychology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, described the new findings as “quite impressive” and “extremely encouraging.”

However, she noted “it’s too premature” to suggest widespread use of folic acid in patients with depressive symptoms.

Dr. Yen, who has researched suicide risks previously, was not involved with the current study.

She did agree with the investigators that the results call for “more robustly controlled studies. These could include double-blind, randomized, controlled trials that could “more formally assess” all folic acid usage as opposed to prescriptions only, Dr. Yen said.

The study was funded by the NIH, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Center of Excellence for Suicide Prevention. Dr. Gibbons reported serving as an expert witness in cases for the Department of Justice; receiving expert witness fees from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Wyeth; and having founded Adaptive Testing Technologies, which distributes the Computerized Adaptive Test Suicide Scale. Dr. Yen reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

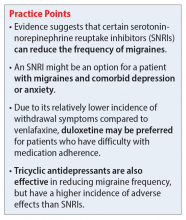

Using SNRIs to prevent migraines in patients with depression

Ms. D, age 45, has major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), migraines, and hypertension. At a follow-up visit, she says she has been under a lot of stress at work in the past several months and feels her antidepressant is not working well for her depression or anxiety. Ms. D notes that lately she has had more frequent migraines, occurring approximately 4 times per month during the past 3 months. She describes a severe throbbing frontal pain that occurs primarily on the left side of her head, but sometimes on the right side. Ms. D says she experiences nausea, vomiting, and photophobia during these migraine episodes. The migraines last up to 12 hours, but often resolve with sumatriptan 50 mg as needed.

Ms. D takes fluoxetine 60 mg/d for depression and anxiety, lisinopril 20 mg/d for hypertension, as well as a women’s multivitamin and vitamin D3 daily. She has not tried other antidepressants and misses doses of her medications about once every other week. Her blood pressure is 125/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 80 beats per minute; and temperature is 37° C. Ms. D’s treatment team is considering switching her to a medication that can act as preventative therapy for migraines while also treating her depression and anxiety.

Migraine is a chronic, disabling neurovascular disorder that affects approximately 15% of the United States population.1 It is the second-leading disabling condition worldwide and may negatively affect social, family, personal, academic, and occupational domains.2 Migraine is often characterized by throbbing pain, is frequently unilateral, and may last 24 to 72 hours.3 It may occur with or without aura and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, or sensitivity to light.3 Episodic migraines occur <15 days a month, while chronic migraines occur ≥15 days a month.4

Many psychiatric, neurologic, vascular, and cardiac comorbidities are more prevalent in individuals who experience migraine headaches compared to the general population. Common psychiatric comorbidities found in patients with migraines are depression, bipolar disorder, GAD, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder5; MDD is the most common.4 A person who experiences migraine headaches is 2 to 4 times more likely to develop MDD than one who does not experience migraine headaches.4

First-line treatments for preventing migraine including divalproex, topiramate, metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol.6 However, for some patients with migraines and comorbid depression or anxiety, an antidepressant may be an option. This article briefly reviews the evidence for using antidepressants that have been studied for their ability to decrease migraine frequency.

Antidepressants that can prevent migraine

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are second- or third-line options for migraine prevention.6 While TCAs have proven to be effective for preventing migraines, many patients are unable to tolerate their adverse effects (ie, anticholinergic effects, sedation).7 TCAs may be more appealing for younger patients, who may be less bothered by anticholinergic burden, or those who have difficulty sleeping.

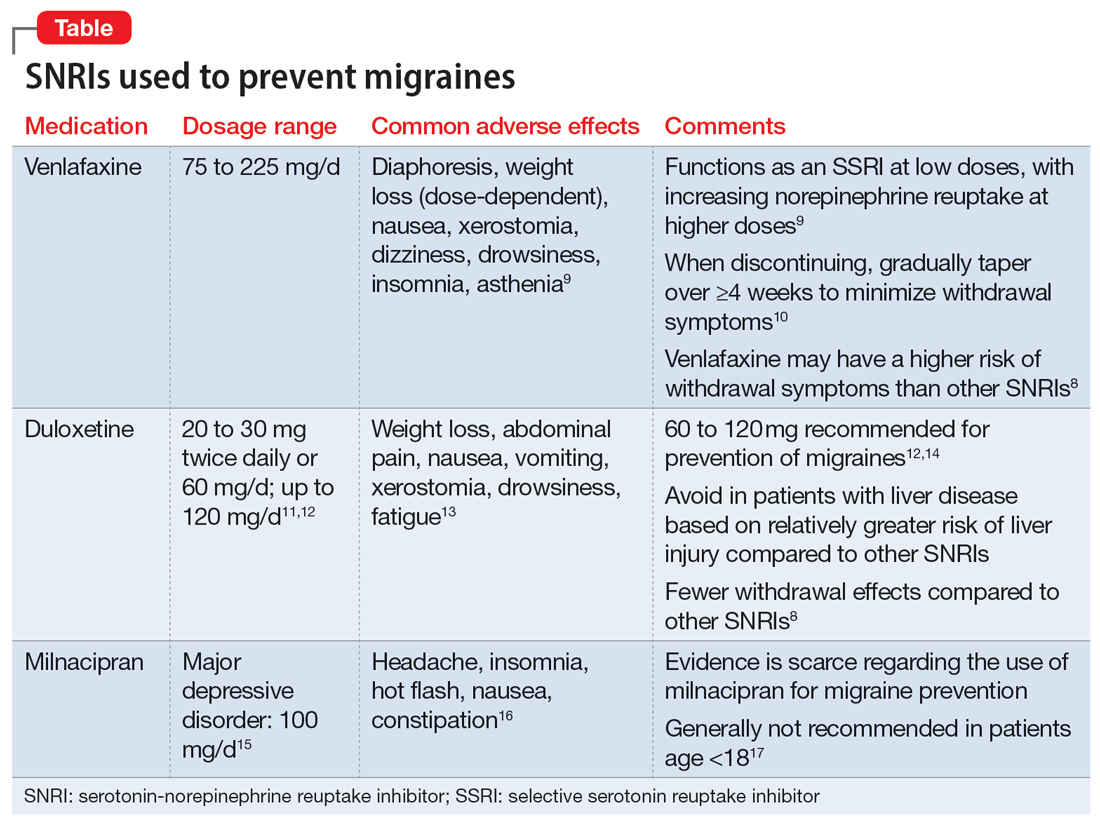

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). There has been growing interest in understanding the potential utility of SNRIs as a preventative treatment for migraines. Research has found that SNRIs are as effective as TCAs for preventing migraines and also more tolerable in terms of adverse effects.7 SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine are currently prescribed off-label to prevent migraines despite a lack of FDA approval for this indication.8

Continue to: Understanding the safety and efficacy...

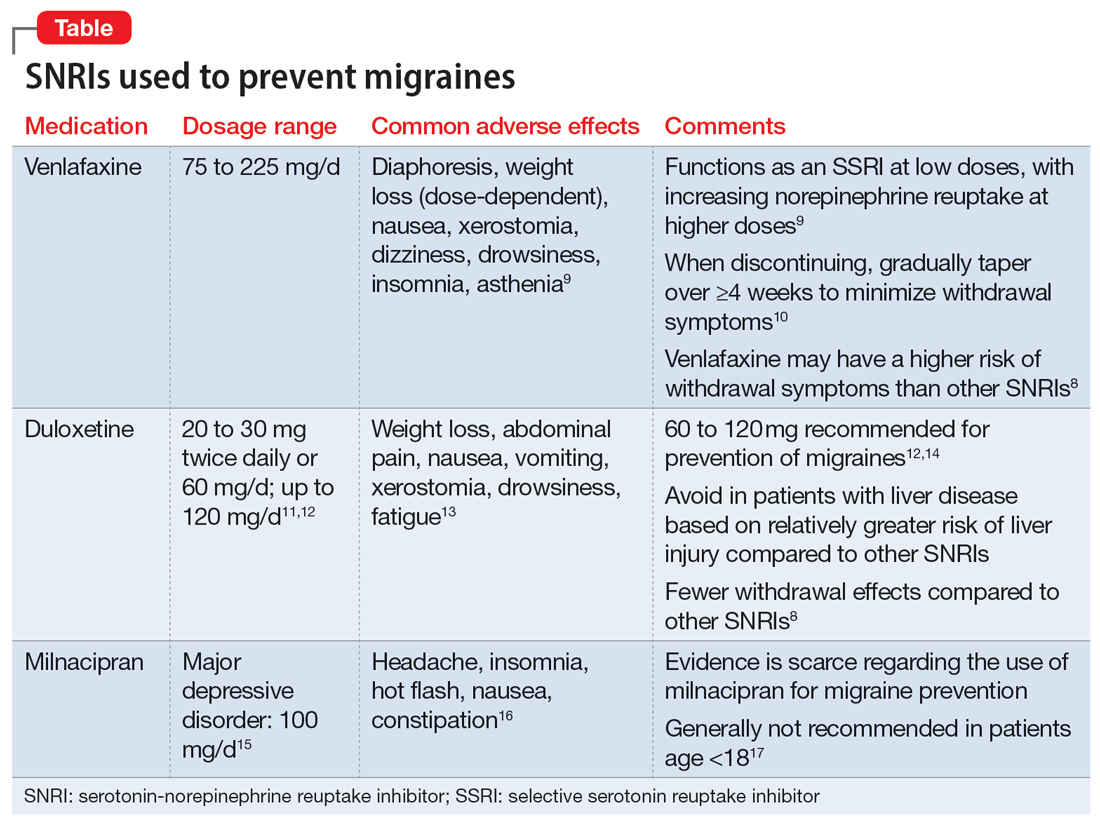

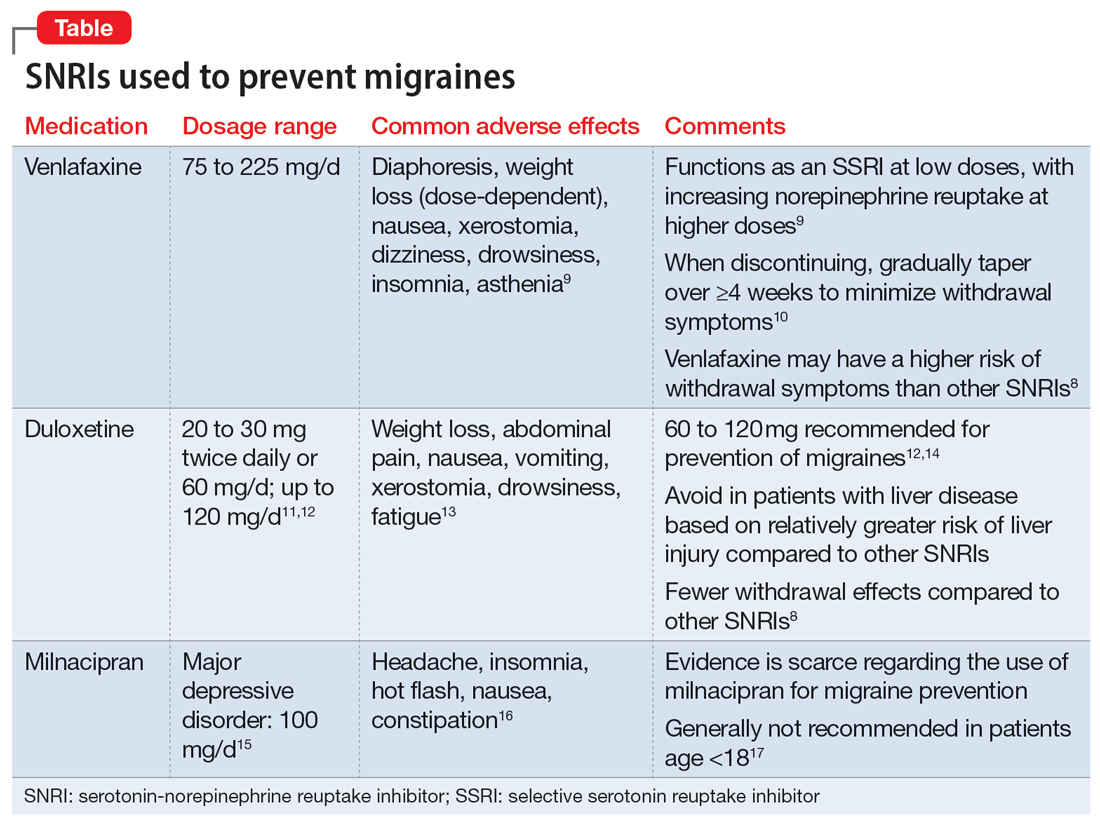

Understanding the safety and efficacy of SNRIs as preventative treatment for episodic migraines is useful, particularly for patients with comorbid depression. The Table8-17 details clinical information related to SNRI use.

Duloxetine has demonstrated efficacy in preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 In a 2019 study, Kisler et al14 found that duloxetine 60 mg/d for 7 weeks was more effective for migraine prophylaxis than placebo as measured by the percentage of self-estimated migraine improvement by each patient compared to pretreatment levels (duloxetine: 52.3% ± 30.4%; placebo: 26.0% ± 27.3%; P = .001).

Venlafaxine has also demonstrated efficacy for preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 One study demonstrated a significant decrease in headaches per month with the use of venlafaxine 150 mg/d compared to placebo.18 Adelman et al19 found a reduction in migraine headaches per month (16.1 to 11.1, P < .0001) in patients who took venlafaxine for an average of 6 months with a mean dose of 150 mg/d. In a study of patients who did not have a mood disorder, Tarlaci20 found that venlafaxine reduced migraine headache independent of its antidepressant action.

Though milnacipran has not been studied as extensively as other SNRIs, evidence suggests it reduces the incidence of headaches and migraines, especially among episodic migraine patients. Although it has an equipotent effect on both serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake, milnacipran has a greater NE effect compared to other SNRIs approved for treating mood disorders. A prospective, single-arm study by Engel et al21 found a significant (P < .005) reduction from baseline in all headache and migraine days per month with the use of milnacipran 100 mg/d over the course of 3 months. The number of headache days per month was reduced by 4.2 compared to baseline. This same study reported improved functionality and reduced use of acute and symptomatic medications overall due to the decrease in headaches and migraines.21

In addition to demonstrating that certain SNRIs can effectively prevent migraine, some evidence suggests certain patients may benefit from the opportunity to decrease pill burden by using a single medication to treat both depression and migraine.22 Duloxetine may be preferred for patients who struggle with adherence (such as Ms. D) due to its relatively lower incidence of withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine.8

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. D’s psychiatrist concludes she would be an appropriate candidate for treatment with an SNRI due to her history of MDD and chronic migraines. Because Ms. D expresses some difficulty remembering to take her medications, the psychiatrist recommends duloxetine because it is less likely to produce withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine. To decrease pill burden, fluoxetine 60 mg is stopped with no taper due to its long half-life, and duloxetine is started at 30 mg/d, with a planned increase to 60 mg/d after 1 to 2 weeks as tolerated to target both mood and migraine prophylaxis. Duloxetine will not interact with Ms. D’s current medication regimen, including lisinopril, women’s multivitamin, or vitamin D3. The psychiatrist discusses the importance of medication adherence to improve her conditions effectively and safely. Ms. D’s heart rate and blood pressure will continue to be monitored.

Related Resources

- Leo RJ, Khalid K. Antidepressants for chronic pain. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):8-16,21-22.

- Williams AM, Knox ED. When to prescribe antidepressants to treat comorbid depression and pain disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):55-58.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex • Depakote

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Milnacipran • Savella

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Topiramate • Topamax

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Burch R, Rizzoli P, Loder E. The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States: figures and trends from government health studies. Headache. 2018;58(4):496-505. doi:10.1111/head.13281

2. GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954-976. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3

3. Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine--current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):257-270. doi:10.1056/NEJMra010917

4. Amoozegar F. Depression comorbidity in migraine. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):504-515. doi:10.1080/09540261.2017.1326882

5. Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):631-649. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001

6. Ha H, Gonzalez A. Migraine headache prophylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(1):17-24.

7. Xu XM, Liu Y, Dong MX, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for preventing migraine in adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(22):e6989. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006989

8. Burch R. Antidepressants for preventive treatment of migraine. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21(4):18. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0557-2

9. Venlafaxine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

10. Ogle NR, Akkerman SR. Guidance for the discontinuation or switching of antidepressant therapies in adults. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(4):389-396. doi:10.1177/0897190012467210

11. Duloxetine [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2004.

12. Young WB, Bradley KC, Anjum MW, et al. Duloxetine prophylaxis for episodic migraine in persons without depression: a prospective study. Headache. 2013;53(9):1430-1437.

13. Duloxetine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

14. Kisler LB, Weissman-Fogel I, Coghill RC, et al. Individualization of migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial of psychophysical-based prediction of duloxetine efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(9):753-765.

15. Mansuy L. Antidepressant therapy with milnacipran and venlafaxine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6 (Suppl I):17-22.

16. Milnacipran. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

17. Milnacipran. MedlinePlus. Updated January 22, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a609016.html

18. Ozyalcin SN, Talu GK, Kiziltan E, et al. The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine. Headache. 2005;45(2):144-152. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05029.x

19. Adelman LC, Adelman JU, Von Seggern R, et al. Venlafaxine extended release (XR) for the prophylaxis of migraine and tension-type headache: a retrospective study in a clinical setting. Headache. 2000;40(7):572-580. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00089.x

20. Tarlaci S. Escitalopram and venlafaxine for the prophylaxis of migraine headache without mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):254-258. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181a8c84f

21. Engel ER, Kudrow D, Rapoport AM. A prospective, open-label study of milnacipran in the prevention of headache in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(3):429-435. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1536-0

22. Baumgartner A, Drame K, Geutjens S, et al. Does the polypill improve patient adherence compared to its individual formulations? A systematic review. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(2):190.

Ms. D, age 45, has major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), migraines, and hypertension. At a follow-up visit, she says she has been under a lot of stress at work in the past several months and feels her antidepressant is not working well for her depression or anxiety. Ms. D notes that lately she has had more frequent migraines, occurring approximately 4 times per month during the past 3 months. She describes a severe throbbing frontal pain that occurs primarily on the left side of her head, but sometimes on the right side. Ms. D says she experiences nausea, vomiting, and photophobia during these migraine episodes. The migraines last up to 12 hours, but often resolve with sumatriptan 50 mg as needed.

Ms. D takes fluoxetine 60 mg/d for depression and anxiety, lisinopril 20 mg/d for hypertension, as well as a women’s multivitamin and vitamin D3 daily. She has not tried other antidepressants and misses doses of her medications about once every other week. Her blood pressure is 125/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 80 beats per minute; and temperature is 37° C. Ms. D’s treatment team is considering switching her to a medication that can act as preventative therapy for migraines while also treating her depression and anxiety.

Migraine is a chronic, disabling neurovascular disorder that affects approximately 15% of the United States population.1 It is the second-leading disabling condition worldwide and may negatively affect social, family, personal, academic, and occupational domains.2 Migraine is often characterized by throbbing pain, is frequently unilateral, and may last 24 to 72 hours.3 It may occur with or without aura and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, or sensitivity to light.3 Episodic migraines occur <15 days a month, while chronic migraines occur ≥15 days a month.4

Many psychiatric, neurologic, vascular, and cardiac comorbidities are more prevalent in individuals who experience migraine headaches compared to the general population. Common psychiatric comorbidities found in patients with migraines are depression, bipolar disorder, GAD, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder5; MDD is the most common.4 A person who experiences migraine headaches is 2 to 4 times more likely to develop MDD than one who does not experience migraine headaches.4

First-line treatments for preventing migraine including divalproex, topiramate, metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol.6 However, for some patients with migraines and comorbid depression or anxiety, an antidepressant may be an option. This article briefly reviews the evidence for using antidepressants that have been studied for their ability to decrease migraine frequency.

Antidepressants that can prevent migraine

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are second- or third-line options for migraine prevention.6 While TCAs have proven to be effective for preventing migraines, many patients are unable to tolerate their adverse effects (ie, anticholinergic effects, sedation).7 TCAs may be more appealing for younger patients, who may be less bothered by anticholinergic burden, or those who have difficulty sleeping.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). There has been growing interest in understanding the potential utility of SNRIs as a preventative treatment for migraines. Research has found that SNRIs are as effective as TCAs for preventing migraines and also more tolerable in terms of adverse effects.7 SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine are currently prescribed off-label to prevent migraines despite a lack of FDA approval for this indication.8

Continue to: Understanding the safety and efficacy...

Understanding the safety and efficacy of SNRIs as preventative treatment for episodic migraines is useful, particularly for patients with comorbid depression. The Table8-17 details clinical information related to SNRI use.

Duloxetine has demonstrated efficacy in preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 In a 2019 study, Kisler et al14 found that duloxetine 60 mg/d for 7 weeks was more effective for migraine prophylaxis than placebo as measured by the percentage of self-estimated migraine improvement by each patient compared to pretreatment levels (duloxetine: 52.3% ± 30.4%; placebo: 26.0% ± 27.3%; P = .001).

Venlafaxine has also demonstrated efficacy for preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 One study demonstrated a significant decrease in headaches per month with the use of venlafaxine 150 mg/d compared to placebo.18 Adelman et al19 found a reduction in migraine headaches per month (16.1 to 11.1, P < .0001) in patients who took venlafaxine for an average of 6 months with a mean dose of 150 mg/d. In a study of patients who did not have a mood disorder, Tarlaci20 found that venlafaxine reduced migraine headache independent of its antidepressant action.

Though milnacipran has not been studied as extensively as other SNRIs, evidence suggests it reduces the incidence of headaches and migraines, especially among episodic migraine patients. Although it has an equipotent effect on both serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake, milnacipran has a greater NE effect compared to other SNRIs approved for treating mood disorders. A prospective, single-arm study by Engel et al21 found a significant (P < .005) reduction from baseline in all headache and migraine days per month with the use of milnacipran 100 mg/d over the course of 3 months. The number of headache days per month was reduced by 4.2 compared to baseline. This same study reported improved functionality and reduced use of acute and symptomatic medications overall due to the decrease in headaches and migraines.21

In addition to demonstrating that certain SNRIs can effectively prevent migraine, some evidence suggests certain patients may benefit from the opportunity to decrease pill burden by using a single medication to treat both depression and migraine.22 Duloxetine may be preferred for patients who struggle with adherence (such as Ms. D) due to its relatively lower incidence of withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine.8

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. D’s psychiatrist concludes she would be an appropriate candidate for treatment with an SNRI due to her history of MDD and chronic migraines. Because Ms. D expresses some difficulty remembering to take her medications, the psychiatrist recommends duloxetine because it is less likely to produce withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine. To decrease pill burden, fluoxetine 60 mg is stopped with no taper due to its long half-life, and duloxetine is started at 30 mg/d, with a planned increase to 60 mg/d after 1 to 2 weeks as tolerated to target both mood and migraine prophylaxis. Duloxetine will not interact with Ms. D’s current medication regimen, including lisinopril, women’s multivitamin, or vitamin D3. The psychiatrist discusses the importance of medication adherence to improve her conditions effectively and safely. Ms. D’s heart rate and blood pressure will continue to be monitored.

Related Resources

- Leo RJ, Khalid K. Antidepressants for chronic pain. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):8-16,21-22.

- Williams AM, Knox ED. When to prescribe antidepressants to treat comorbid depression and pain disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):55-58.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex • Depakote

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Milnacipran • Savella

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Topiramate • Topamax

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ms. D, age 45, has major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), migraines, and hypertension. At a follow-up visit, she says she has been under a lot of stress at work in the past several months and feels her antidepressant is not working well for her depression or anxiety. Ms. D notes that lately she has had more frequent migraines, occurring approximately 4 times per month during the past 3 months. She describes a severe throbbing frontal pain that occurs primarily on the left side of her head, but sometimes on the right side. Ms. D says she experiences nausea, vomiting, and photophobia during these migraine episodes. The migraines last up to 12 hours, but often resolve with sumatriptan 50 mg as needed.

Ms. D takes fluoxetine 60 mg/d for depression and anxiety, lisinopril 20 mg/d for hypertension, as well as a women’s multivitamin and vitamin D3 daily. She has not tried other antidepressants and misses doses of her medications about once every other week. Her blood pressure is 125/80 mm Hg; heart rate is 80 beats per minute; and temperature is 37° C. Ms. D’s treatment team is considering switching her to a medication that can act as preventative therapy for migraines while also treating her depression and anxiety.

Migraine is a chronic, disabling neurovascular disorder that affects approximately 15% of the United States population.1 It is the second-leading disabling condition worldwide and may negatively affect social, family, personal, academic, and occupational domains.2 Migraine is often characterized by throbbing pain, is frequently unilateral, and may last 24 to 72 hours.3 It may occur with or without aura and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, or sensitivity to light.3 Episodic migraines occur <15 days a month, while chronic migraines occur ≥15 days a month.4

Many psychiatric, neurologic, vascular, and cardiac comorbidities are more prevalent in individuals who experience migraine headaches compared to the general population. Common psychiatric comorbidities found in patients with migraines are depression, bipolar disorder, GAD, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder5; MDD is the most common.4 A person who experiences migraine headaches is 2 to 4 times more likely to develop MDD than one who does not experience migraine headaches.4

First-line treatments for preventing migraine including divalproex, topiramate, metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol.6 However, for some patients with migraines and comorbid depression or anxiety, an antidepressant may be an option. This article briefly reviews the evidence for using antidepressants that have been studied for their ability to decrease migraine frequency.

Antidepressants that can prevent migraine

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are second- or third-line options for migraine prevention.6 While TCAs have proven to be effective for preventing migraines, many patients are unable to tolerate their adverse effects (ie, anticholinergic effects, sedation).7 TCAs may be more appealing for younger patients, who may be less bothered by anticholinergic burden, or those who have difficulty sleeping.

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). There has been growing interest in understanding the potential utility of SNRIs as a preventative treatment for migraines. Research has found that SNRIs are as effective as TCAs for preventing migraines and also more tolerable in terms of adverse effects.7 SNRIs such as venlafaxine and duloxetine are currently prescribed off-label to prevent migraines despite a lack of FDA approval for this indication.8

Continue to: Understanding the safety and efficacy...

Understanding the safety and efficacy of SNRIs as preventative treatment for episodic migraines is useful, particularly for patients with comorbid depression. The Table8-17 details clinical information related to SNRI use.

Duloxetine has demonstrated efficacy in preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 In a 2019 study, Kisler et al14 found that duloxetine 60 mg/d for 7 weeks was more effective for migraine prophylaxis than placebo as measured by the percentage of self-estimated migraine improvement by each patient compared to pretreatment levels (duloxetine: 52.3% ± 30.4%; placebo: 26.0% ± 27.3%; P = .001).

Venlafaxine has also demonstrated efficacy for preventing migraines in patients with comorbid depression.8 One study demonstrated a significant decrease in headaches per month with the use of venlafaxine 150 mg/d compared to placebo.18 Adelman et al19 found a reduction in migraine headaches per month (16.1 to 11.1, P < .0001) in patients who took venlafaxine for an average of 6 months with a mean dose of 150 mg/d. In a study of patients who did not have a mood disorder, Tarlaci20 found that venlafaxine reduced migraine headache independent of its antidepressant action.

Though milnacipran has not been studied as extensively as other SNRIs, evidence suggests it reduces the incidence of headaches and migraines, especially among episodic migraine patients. Although it has an equipotent effect on both serotonin and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake, milnacipran has a greater NE effect compared to other SNRIs approved for treating mood disorders. A prospective, single-arm study by Engel et al21 found a significant (P < .005) reduction from baseline in all headache and migraine days per month with the use of milnacipran 100 mg/d over the course of 3 months. The number of headache days per month was reduced by 4.2 compared to baseline. This same study reported improved functionality and reduced use of acute and symptomatic medications overall due to the decrease in headaches and migraines.21

In addition to demonstrating that certain SNRIs can effectively prevent migraine, some evidence suggests certain patients may benefit from the opportunity to decrease pill burden by using a single medication to treat both depression and migraine.22 Duloxetine may be preferred for patients who struggle with adherence (such as Ms. D) due to its relatively lower incidence of withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine.8

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. D’s psychiatrist concludes she would be an appropriate candidate for treatment with an SNRI due to her history of MDD and chronic migraines. Because Ms. D expresses some difficulty remembering to take her medications, the psychiatrist recommends duloxetine because it is less likely to produce withdrawal symptoms compared to venlafaxine. To decrease pill burden, fluoxetine 60 mg is stopped with no taper due to its long half-life, and duloxetine is started at 30 mg/d, with a planned increase to 60 mg/d after 1 to 2 weeks as tolerated to target both mood and migraine prophylaxis. Duloxetine will not interact with Ms. D’s current medication regimen, including lisinopril, women’s multivitamin, or vitamin D3. The psychiatrist discusses the importance of medication adherence to improve her conditions effectively and safely. Ms. D’s heart rate and blood pressure will continue to be monitored.

Related Resources

- Leo RJ, Khalid K. Antidepressants for chronic pain. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):8-16,21-22.

- Williams AM, Knox ED. When to prescribe antidepressants to treat comorbid depression and pain disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):55-58.

Drug Brand Names

Divalproex • Depakote

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lisinopril • Zestril, Prinivil

Milnacipran • Savella

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Topiramate • Topamax

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Burch R, Rizzoli P, Loder E. The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States: figures and trends from government health studies. Headache. 2018;58(4):496-505. doi:10.1111/head.13281

2. GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954-976. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3

3. Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine--current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):257-270. doi:10.1056/NEJMra010917

4. Amoozegar F. Depression comorbidity in migraine. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):504-515. doi:10.1080/09540261.2017.1326882

5. Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):631-649. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001

6. Ha H, Gonzalez A. Migraine headache prophylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(1):17-24.

7. Xu XM, Liu Y, Dong MX, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for preventing migraine in adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(22):e6989. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006989

8. Burch R. Antidepressants for preventive treatment of migraine. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21(4):18. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0557-2

9. Venlafaxine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

10. Ogle NR, Akkerman SR. Guidance for the discontinuation or switching of antidepressant therapies in adults. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(4):389-396. doi:10.1177/0897190012467210

11. Duloxetine [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2004.

12. Young WB, Bradley KC, Anjum MW, et al. Duloxetine prophylaxis for episodic migraine in persons without depression: a prospective study. Headache. 2013;53(9):1430-1437.

13. Duloxetine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

14. Kisler LB, Weissman-Fogel I, Coghill RC, et al. Individualization of migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial of psychophysical-based prediction of duloxetine efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(9):753-765.

15. Mansuy L. Antidepressant therapy with milnacipran and venlafaxine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6 (Suppl I):17-22.

16. Milnacipran. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

17. Milnacipran. MedlinePlus. Updated January 22, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a609016.html

18. Ozyalcin SN, Talu GK, Kiziltan E, et al. The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine. Headache. 2005;45(2):144-152. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05029.x

19. Adelman LC, Adelman JU, Von Seggern R, et al. Venlafaxine extended release (XR) for the prophylaxis of migraine and tension-type headache: a retrospective study in a clinical setting. Headache. 2000;40(7):572-580. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00089.x

20. Tarlaci S. Escitalopram and venlafaxine for the prophylaxis of migraine headache without mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):254-258. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181a8c84f

21. Engel ER, Kudrow D, Rapoport AM. A prospective, open-label study of milnacipran in the prevention of headache in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(3):429-435. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1536-0

22. Baumgartner A, Drame K, Geutjens S, et al. Does the polypill improve patient adherence compared to its individual formulations? A systematic review. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(2):190.

1. Burch R, Rizzoli P, Loder E. The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States: figures and trends from government health studies. Headache. 2018;58(4):496-505. doi:10.1111/head.13281

2. GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954-976. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3

3. Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine--current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):257-270. doi:10.1056/NEJMra010917

4. Amoozegar F. Depression comorbidity in migraine. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2017;29(5):504-515. doi:10.1080/09540261.2017.1326882

5. Burch RC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine: epidemiology, burden, and comorbidity. Neurol Clin. 2019;37(4):631-649. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2019.06.001

6. Ha H, Gonzalez A. Migraine headache prophylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(1):17-24.

7. Xu XM, Liu Y, Dong MX, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants for preventing migraine in adults. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(22):e6989. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006989

8. Burch R. Antidepressants for preventive treatment of migraine. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2019;21(4):18. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0557-2

9. Venlafaxine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

10. Ogle NR, Akkerman SR. Guidance for the discontinuation or switching of antidepressant therapies in adults. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(4):389-396. doi:10.1177/0897190012467210

11. Duloxetine [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2004.

12. Young WB, Bradley KC, Anjum MW, et al. Duloxetine prophylaxis for episodic migraine in persons without depression: a prospective study. Headache. 2013;53(9):1430-1437.

13. Duloxetine. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

14. Kisler LB, Weissman-Fogel I, Coghill RC, et al. Individualization of migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial of psychophysical-based prediction of duloxetine efficacy. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(9):753-765.

15. Mansuy L. Antidepressant therapy with milnacipran and venlafaxine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6 (Suppl I):17-22.

16. Milnacipran. Lexicomp. 2021. http://online.lexi.com/

17. Milnacipran. MedlinePlus. Updated January 22, 2022. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a609016.html

18. Ozyalcin SN, Talu GK, Kiziltan E, et al. The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine. Headache. 2005;45(2):144-152. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05029.x

19. Adelman LC, Adelman JU, Von Seggern R, et al. Venlafaxine extended release (XR) for the prophylaxis of migraine and tension-type headache: a retrospective study in a clinical setting. Headache. 2000;40(7):572-580. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00089.x

20. Tarlaci S. Escitalopram and venlafaxine for the prophylaxis of migraine headache without mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32(5):254-258. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181a8c84f

21. Engel ER, Kudrow D, Rapoport AM. A prospective, open-label study of milnacipran in the prevention of headache in patients with episodic or chronic migraine. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(3):429-435. doi:10.1007/s10072-013-1536-0

22. Baumgartner A, Drame K, Geutjens S, et al. Does the polypill improve patient adherence compared to its individual formulations? A systematic review. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(2):190.

Timing of food intake a novel strategy for treating mood disorders?

new research suggests.

Investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, created a simulated nightwork schedule for 19 individuals in a laboratory setting. Participants then engaged in two different meal timing models – daytime-only meals (DMI), and meals taken during both daytime and nighttime (DNMC).

Depression- and anxiety-like mood levels increased by 26% and 16%, respectively, among the daytime and nighttime eaters, but there was no such increase in daytime-only eaters.

“Our findings provide evidence for the timing of food intake as a novel strategy to potentially minimize mood vulnerability in individuals experiencing circadian misalignment, such as people engaged in shift work, experiencing jet lag, or suffering from circadian rhythm disorders,” co–corresponding author Frank A.J.L. Scheer, PhD, director of the medical chronobiology program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in a news release.

The study was published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Misaligned circadian clock

“Shift workers often experience a misalignment between their central circadian clock in the brain and daily behaviors, such as sleep/wake and fasting/eating cycles,” senior author Sarah Chellappa, MD, PhD, currently the Alexander Von Humboldt Experienced Fellow in the department of nuclear medicine, University of Cologne (Germany). Dr. Chellappa was a postdoctoral fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital when the study was conducted.

“They also have a 25%-40% higher risk of depression and anxiety,” she continued. “Since meal timing is important for physical health and diet is important for mood, we sought to find out whether meal timing can benefit mental health as well.”

Given that impaired glycemic control is a “risk factor for mood disruption,” the researchers tested the prediction that daytime eating “would prevent mood vulnerability, despite simulated night work.”

To investigate the question, they conducted a parallel-design, randomized clinical trial that included a 14-day circadian laboratory protocol with 19 healthy adults (12 men, 7 women; mean age, 26.5 ± 4.1 years) who underwent a forced desynchrony (FD) in dim light for 4 “days,” each of which consisted of 28 hours. Each 28-hour “day” resulted in an additional 4-hour misalignment between the central circadian clock and external behavioral/environmental cycles.

By the fourth day, the participants were misaligned by 12 hours, compared to baseline (that is, the first day). They were then randomly assigned to two groups.

The DNMC group – the control group – had a “typical 28-hour FD protocol,” with behavioral and environmental cycles (sleep/wake, rest/activity, supine/upright posture, dark during scheduled sleep/dim light during wakefulness) scheduled on a 28-hour cycle. Thus, they took their meals during both “daytime” and “nighttime,” which is the typical way that night workers eat.

The DMI group underwent a modified 28-hour FD protocol, with all cycles scheduled on a 28-hour basis, except for the fasting/eating cycle, which was scheduled on a 24-hour basis, resulting in meals consumed only during the “daytime.”

Depression- and anxiety-like mood (which “correspond to an amalgam of mood states typically observed in depression and anxiety) were assessed every hour during the 4 FD days, using computerized visual analogue scales.

Nutritional psychiatry

Participants in the DNMC group experienced an increase from baseline in depression- and anxiety-like mood levels of 26.2% (95% confidence interval, 21-31.5; P = .001; P value using false discovery rate, .01; effect-size r, 0.78) and 16.1% (95% CI, 8.5-23.6; P = .005; PFDR, .001; effect-size r, 0.47), respectively.

By contrast, a similar increase did not take place in the DMI group for either depression- or anxiety-like mood levels (95% CI, –5.7% to 7.4%, P not significant and 95% CI, –3.1% to 9.9%, P not significant, respectively).

The researchers tested “whether increase mood vulnerability during simulated night work was associated with the degree of internal circadian misalignment” — defined as “change in the phase difference between the acrophase of circadian glucose rhythms and the bathyphase of circadian body temperature rhythms.”

They found that a larger degree of internal circadian misalignment was “robustly associated” with more depression-like (r, 0.77; P = .001) and anxiety-like (r, 0.67; P = .002) mood levels during simulated night work.

The findings imply that meal timing had “moderate to large effects in depression-like and anxiety-like mood levels during night work, and that such effects were associated with the degree of internal circadian misalignment,” the authors wrote.

The laboratory protocol of both groups was identical except for the timing of meals. The authors noted that the “relevance of diet on sleep, circadian rhythms, and mental health is receiving growing awareness with the emergence of a new field, nutritional psychiatry.”

People who experience depression “often report poor-quality diets with high carbohydrate intake,” and there is evidence that adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated “with lower odds of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress.”

They cautioned that although these emerging studies suggest an association between dietary factors and mental health, “experimental studies in individuals with depression and/or anxiety/anxiety-related disorders are required to determine causality and direction of effects.”

They described meal timing as “an emerging aspect of nutrition, with increasing research interest because of its influence on physical health.” However, they noted, “the causal role of the timing of food intake on mental health remains to be tested.”

Novel findings

Commenting for this article, Kathleen Merikangas, PhD, distinguished investigator and chief, genetic epidemiology research branch, intramural research program, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Md., described the research as important with novel findings.

The research “employs the elegant, carefully controlled laboratory procedures that have unraveled the influence of light and other environmental cues on sleep and circadian rhythms over the past 2 decades,” said Dr. Merikangas, who was not involved with the study.

“One of the most significant contributions of this work is its demonstration of the importance of investigating circadian rhythms of multiple systems rather than solely focusing on sleep, eating, or emotional states that have often been studied in isolation,” she pointed out.

“Growing evidence from basic research highlights the interdependence of multiple human systems that should be built into interventions that tend to focus on one or two domains.”

She recommended that this work be replicated “in more diverse samples ... in both controlled and naturalistic settings...to test both the generalizability and mechanism of these intriguing findings.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Individual investigators were funded by the Alexander Von Humboldt Foundation and the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Chellappa disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Merikangas disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, created a simulated nightwork schedule for 19 individuals in a laboratory setting. Participants then engaged in two different meal timing models – daytime-only meals (DMI), and meals taken during both daytime and nighttime (DNMC).

Depression- and anxiety-like mood levels increased by 26% and 16%, respectively, among the daytime and nighttime eaters, but there was no such increase in daytime-only eaters.

“Our findings provide evidence for the timing of food intake as a novel strategy to potentially minimize mood vulnerability in individuals experiencing circadian misalignment, such as people engaged in shift work, experiencing jet lag, or suffering from circadian rhythm disorders,” co–corresponding author Frank A.J.L. Scheer, PhD, director of the medical chronobiology program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in a news release.

The study was published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Misaligned circadian clock

“Shift workers often experience a misalignment between their central circadian clock in the brain and daily behaviors, such as sleep/wake and fasting/eating cycles,” senior author Sarah Chellappa, MD, PhD, currently the Alexander Von Humboldt Experienced Fellow in the department of nuclear medicine, University of Cologne (Germany). Dr. Chellappa was a postdoctoral fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital when the study was conducted.

“They also have a 25%-40% higher risk of depression and anxiety,” she continued. “Since meal timing is important for physical health and diet is important for mood, we sought to find out whether meal timing can benefit mental health as well.”

Given that impaired glycemic control is a “risk factor for mood disruption,” the researchers tested the prediction that daytime eating “would prevent mood vulnerability, despite simulated night work.”

To investigate the question, they conducted a parallel-design, randomized clinical trial that included a 14-day circadian laboratory protocol with 19 healthy adults (12 men, 7 women; mean age, 26.5 ± 4.1 years) who underwent a forced desynchrony (FD) in dim light for 4 “days,” each of which consisted of 28 hours. Each 28-hour “day” resulted in an additional 4-hour misalignment between the central circadian clock and external behavioral/environmental cycles.

By the fourth day, the participants were misaligned by 12 hours, compared to baseline (that is, the first day). They were then randomly assigned to two groups.

The DNMC group – the control group – had a “typical 28-hour FD protocol,” with behavioral and environmental cycles (sleep/wake, rest/activity, supine/upright posture, dark during scheduled sleep/dim light during wakefulness) scheduled on a 28-hour cycle. Thus, they took their meals during both “daytime” and “nighttime,” which is the typical way that night workers eat.

The DMI group underwent a modified 28-hour FD protocol, with all cycles scheduled on a 28-hour basis, except for the fasting/eating cycle, which was scheduled on a 24-hour basis, resulting in meals consumed only during the “daytime.”

Depression- and anxiety-like mood (which “correspond to an amalgam of mood states typically observed in depression and anxiety) were assessed every hour during the 4 FD days, using computerized visual analogue scales.

Nutritional psychiatry

Participants in the DNMC group experienced an increase from baseline in depression- and anxiety-like mood levels of 26.2% (95% confidence interval, 21-31.5; P = .001; P value using false discovery rate, .01; effect-size r, 0.78) and 16.1% (95% CI, 8.5-23.6; P = .005; PFDR, .001; effect-size r, 0.47), respectively.

By contrast, a similar increase did not take place in the DMI group for either depression- or anxiety-like mood levels (95% CI, –5.7% to 7.4%, P not significant and 95% CI, –3.1% to 9.9%, P not significant, respectively).

The researchers tested “whether increase mood vulnerability during simulated night work was associated with the degree of internal circadian misalignment” — defined as “change in the phase difference between the acrophase of circadian glucose rhythms and the bathyphase of circadian body temperature rhythms.”

They found that a larger degree of internal circadian misalignment was “robustly associated” with more depression-like (r, 0.77; P = .001) and anxiety-like (r, 0.67; P = .002) mood levels during simulated night work.

The findings imply that meal timing had “moderate to large effects in depression-like and anxiety-like mood levels during night work, and that such effects were associated with the degree of internal circadian misalignment,” the authors wrote.

The laboratory protocol of both groups was identical except for the timing of meals. The authors noted that the “relevance of diet on sleep, circadian rhythms, and mental health is receiving growing awareness with the emergence of a new field, nutritional psychiatry.”

People who experience depression “often report poor-quality diets with high carbohydrate intake,” and there is evidence that adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated “with lower odds of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress.”

They cautioned that although these emerging studies suggest an association between dietary factors and mental health, “experimental studies in individuals with depression and/or anxiety/anxiety-related disorders are required to determine causality and direction of effects.”

They described meal timing as “an emerging aspect of nutrition, with increasing research interest because of its influence on physical health.” However, they noted, “the causal role of the timing of food intake on mental health remains to be tested.”

Novel findings

Commenting for this article, Kathleen Merikangas, PhD, distinguished investigator and chief, genetic epidemiology research branch, intramural research program, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Md., described the research as important with novel findings.

The research “employs the elegant, carefully controlled laboratory procedures that have unraveled the influence of light and other environmental cues on sleep and circadian rhythms over the past 2 decades,” said Dr. Merikangas, who was not involved with the study.

“One of the most significant contributions of this work is its demonstration of the importance of investigating circadian rhythms of multiple systems rather than solely focusing on sleep, eating, or emotional states that have often been studied in isolation,” she pointed out.

“Growing evidence from basic research highlights the interdependence of multiple human systems that should be built into interventions that tend to focus on one or two domains.”

She recommended that this work be replicated “in more diverse samples ... in both controlled and naturalistic settings...to test both the generalizability and mechanism of these intriguing findings.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Individual investigators were funded by the Alexander Von Humboldt Foundation and the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Chellappa disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Merikangas disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, created a simulated nightwork schedule for 19 individuals in a laboratory setting. Participants then engaged in two different meal timing models – daytime-only meals (DMI), and meals taken during both daytime and nighttime (DNMC).

Depression- and anxiety-like mood levels increased by 26% and 16%, respectively, among the daytime and nighttime eaters, but there was no such increase in daytime-only eaters.

“Our findings provide evidence for the timing of food intake as a novel strategy to potentially minimize mood vulnerability in individuals experiencing circadian misalignment, such as people engaged in shift work, experiencing jet lag, or suffering from circadian rhythm disorders,” co–corresponding author Frank A.J.L. Scheer, PhD, director of the medical chronobiology program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said in a news release.

The study was published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Misaligned circadian clock

“Shift workers often experience a misalignment between their central circadian clock in the brain and daily behaviors, such as sleep/wake and fasting/eating cycles,” senior author Sarah Chellappa, MD, PhD, currently the Alexander Von Humboldt Experienced Fellow in the department of nuclear medicine, University of Cologne (Germany). Dr. Chellappa was a postdoctoral fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital when the study was conducted.

“They also have a 25%-40% higher risk of depression and anxiety,” she continued. “Since meal timing is important for physical health and diet is important for mood, we sought to find out whether meal timing can benefit mental health as well.”

Given that impaired glycemic control is a “risk factor for mood disruption,” the researchers tested the prediction that daytime eating “would prevent mood vulnerability, despite simulated night work.”

To investigate the question, they conducted a parallel-design, randomized clinical trial that included a 14-day circadian laboratory protocol with 19 healthy adults (12 men, 7 women; mean age, 26.5 ± 4.1 years) who underwent a forced desynchrony (FD) in dim light for 4 “days,” each of which consisted of 28 hours. Each 28-hour “day” resulted in an additional 4-hour misalignment between the central circadian clock and external behavioral/environmental cycles.

By the fourth day, the participants were misaligned by 12 hours, compared to baseline (that is, the first day). They were then randomly assigned to two groups.

The DNMC group – the control group – had a “typical 28-hour FD protocol,” with behavioral and environmental cycles (sleep/wake, rest/activity, supine/upright posture, dark during scheduled sleep/dim light during wakefulness) scheduled on a 28-hour cycle. Thus, they took their meals during both “daytime” and “nighttime,” which is the typical way that night workers eat.

The DMI group underwent a modified 28-hour FD protocol, with all cycles scheduled on a 28-hour basis, except for the fasting/eating cycle, which was scheduled on a 24-hour basis, resulting in meals consumed only during the “daytime.”

Depression- and anxiety-like mood (which “correspond to an amalgam of mood states typically observed in depression and anxiety) were assessed every hour during the 4 FD days, using computerized visual analogue scales.

Nutritional psychiatry

Participants in the DNMC group experienced an increase from baseline in depression- and anxiety-like mood levels of 26.2% (95% confidence interval, 21-31.5; P = .001; P value using false discovery rate, .01; effect-size r, 0.78) and 16.1% (95% CI, 8.5-23.6; P = .005; PFDR, .001; effect-size r, 0.47), respectively.

By contrast, a similar increase did not take place in the DMI group for either depression- or anxiety-like mood levels (95% CI, –5.7% to 7.4%, P not significant and 95% CI, –3.1% to 9.9%, P not significant, respectively).

The researchers tested “whether increase mood vulnerability during simulated night work was associated with the degree of internal circadian misalignment” — defined as “change in the phase difference between the acrophase of circadian glucose rhythms and the bathyphase of circadian body temperature rhythms.”

They found that a larger degree of internal circadian misalignment was “robustly associated” with more depression-like (r, 0.77; P = .001) and anxiety-like (r, 0.67; P = .002) mood levels during simulated night work.

The findings imply that meal timing had “moderate to large effects in depression-like and anxiety-like mood levels during night work, and that such effects were associated with the degree of internal circadian misalignment,” the authors wrote.

The laboratory protocol of both groups was identical except for the timing of meals. The authors noted that the “relevance of diet on sleep, circadian rhythms, and mental health is receiving growing awareness with the emergence of a new field, nutritional psychiatry.”

People who experience depression “often report poor-quality diets with high carbohydrate intake,” and there is evidence that adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated “with lower odds of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress.”

They cautioned that although these emerging studies suggest an association between dietary factors and mental health, “experimental studies in individuals with depression and/or anxiety/anxiety-related disorders are required to determine causality and direction of effects.”

They described meal timing as “an emerging aspect of nutrition, with increasing research interest because of its influence on physical health.” However, they noted, “the causal role of the timing of food intake on mental health remains to be tested.”

Novel findings

Commenting for this article, Kathleen Merikangas, PhD, distinguished investigator and chief, genetic epidemiology research branch, intramural research program, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Md., described the research as important with novel findings.