User login

Pembrolizumab-Induced Lobular Panniculitis in the Setting of Metastatic Melanoma

To the Editor:

Pembrolizumab is an anti–programmed death receptor 1 humanized monoclonal antibody used for treating advanced or metastatic melanoma.1 It is associated with several immune-related adverse events because it blocks a T-cell receptor checkpoint.2 The most common dermatologic immune-related adverse event seen with anti–programmed death receptor 1 medications is a nonspecific morbilliform rash, usually seen after the second treatment cycle; however, pruritus, vitiligo, bullous disorders, and lichenoid reactions also have been reported.3 We report a case of pembrolizumab-induced, self-limited lobular panniculitis in a patient with metastatic melanoma.

A 37-year-old woman with malignant melanoma presented with tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules on the hips and legs of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Twelve years prior to the current presentation, she was diagnosed with metastases to the cecum, lung, and brain. A review of systems was otherwise negative. She had been receiving pembrolizumab infusions (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks) for the last 2.7 years as second-line therapy after previously undergoing chemotherapy, radiation, and resection. She was not taking oral contraceptives or other hormone-based medications and did not report any new medications.

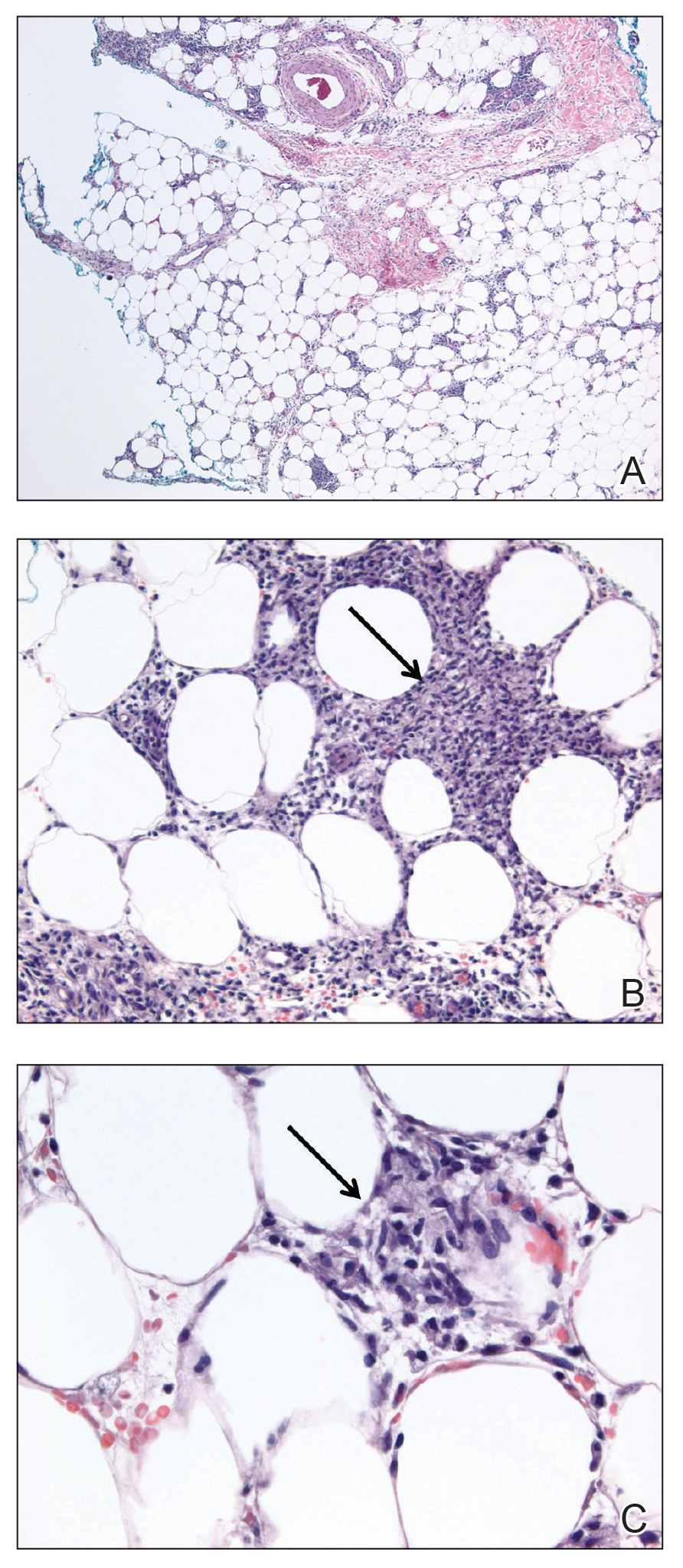

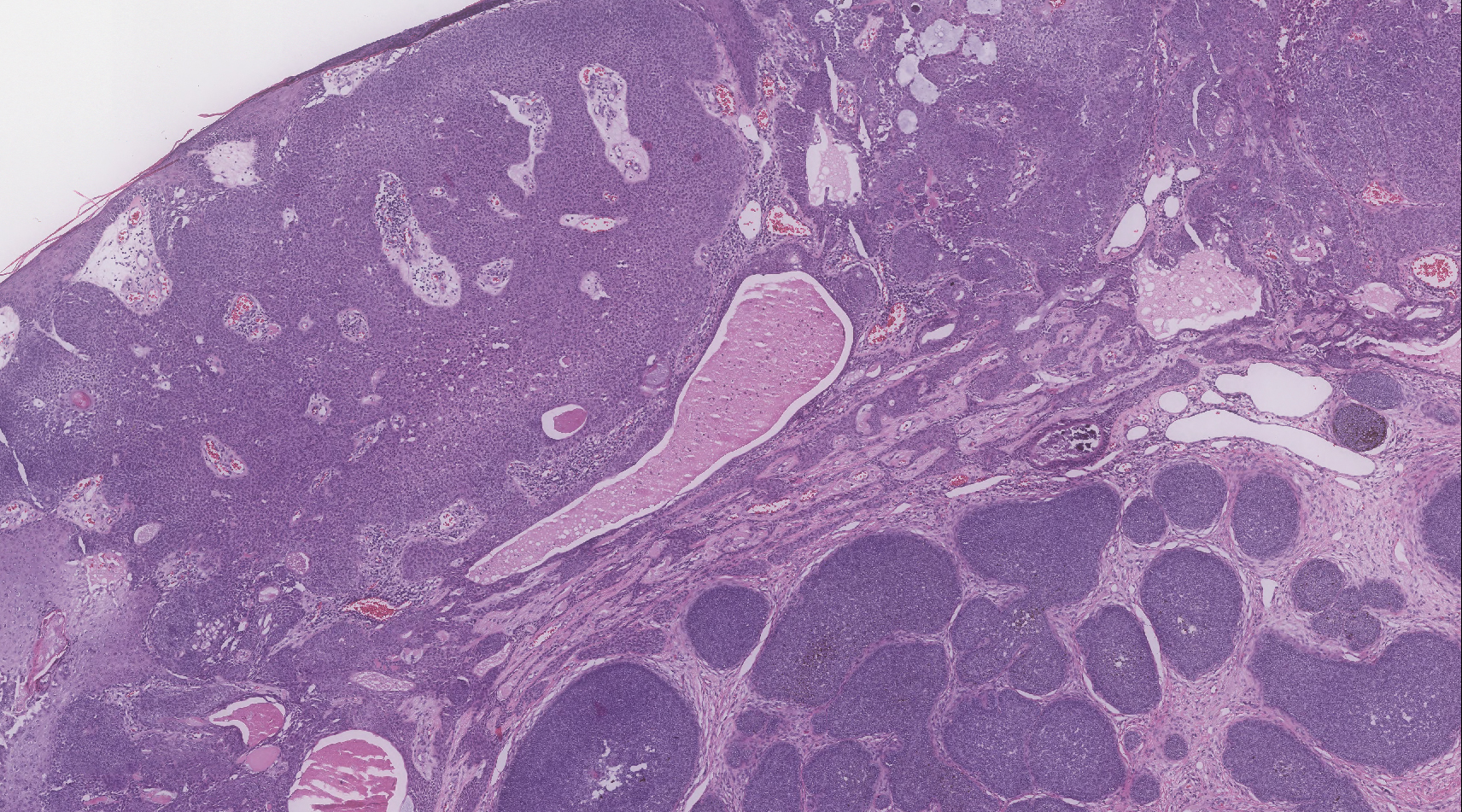

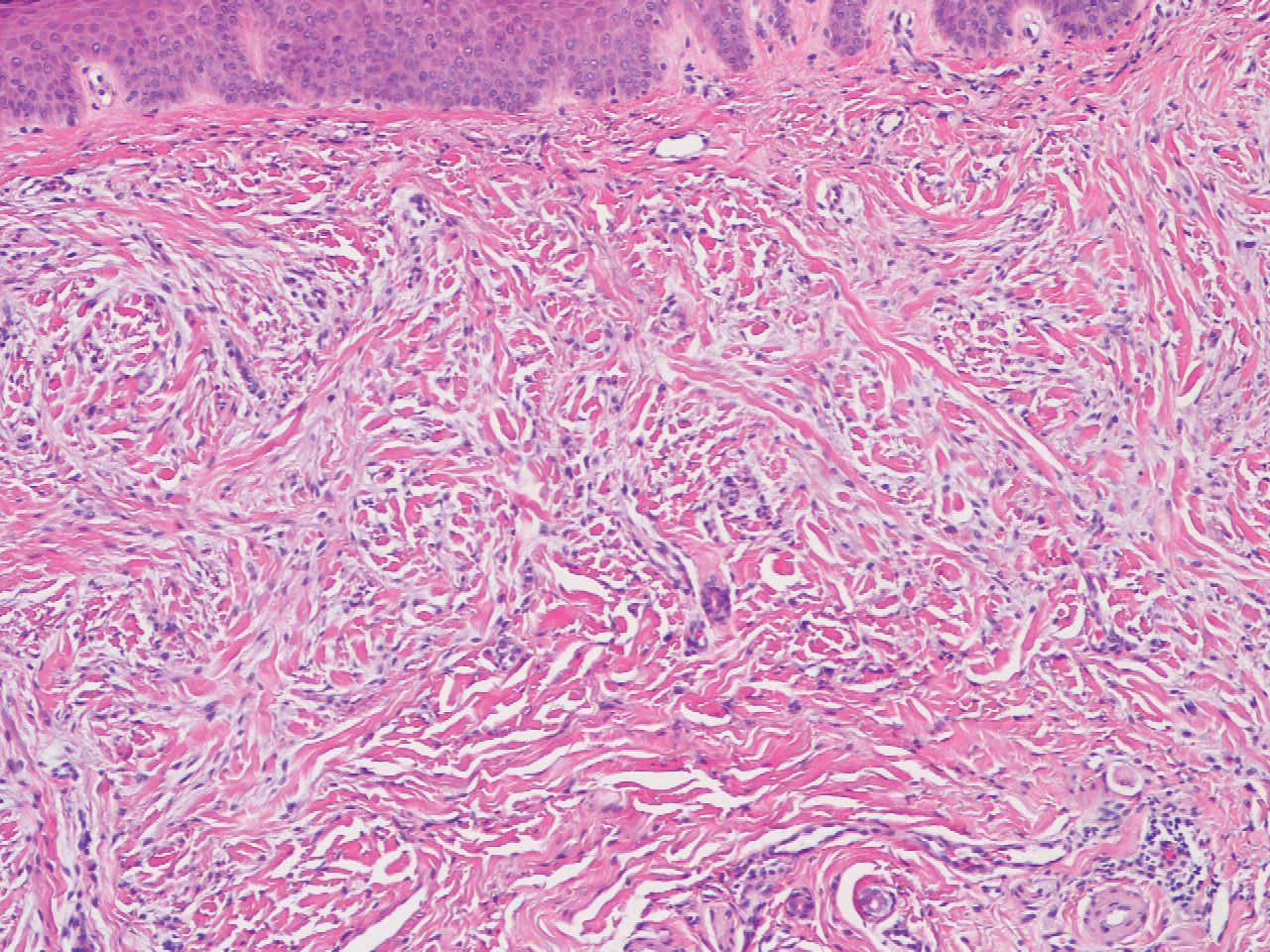

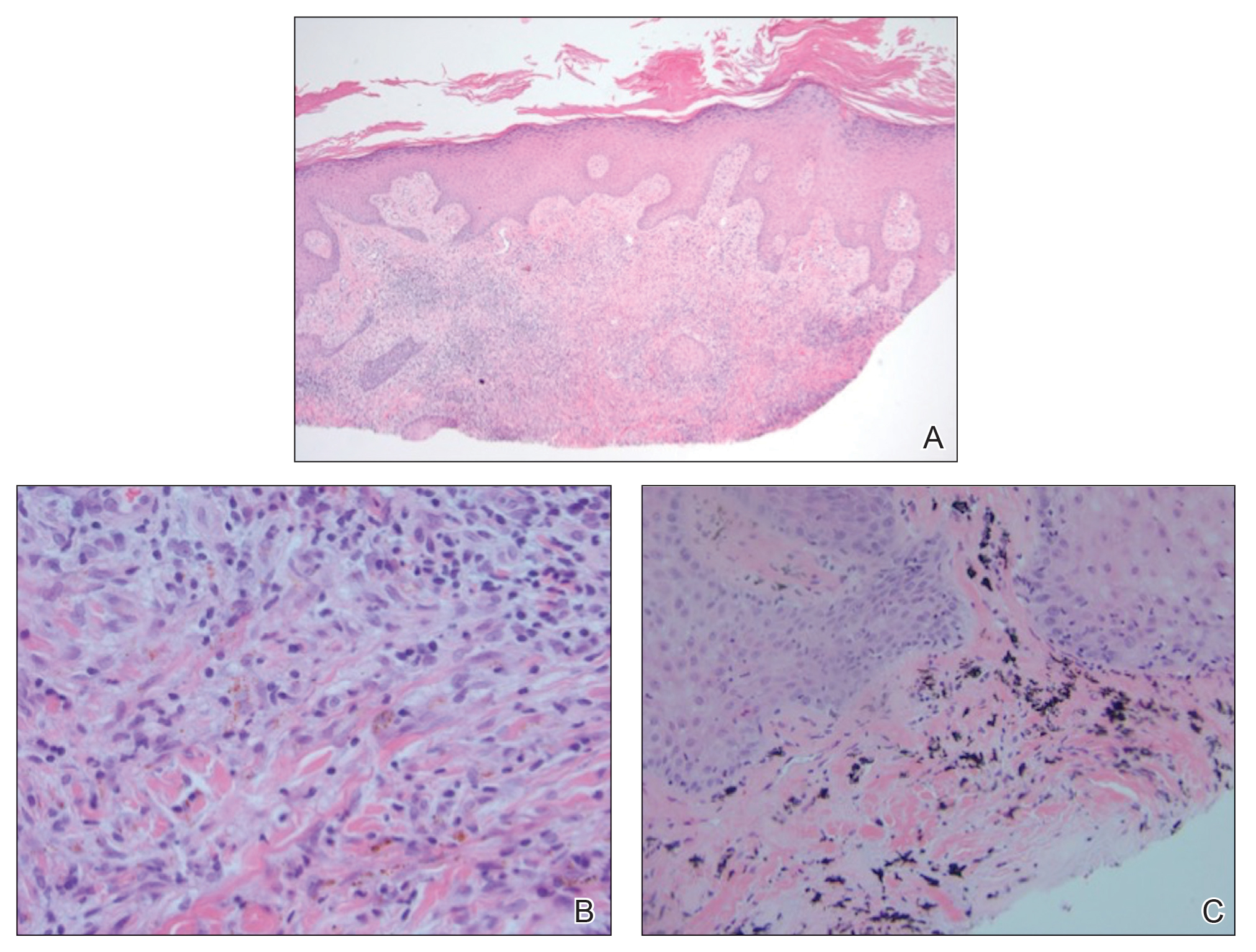

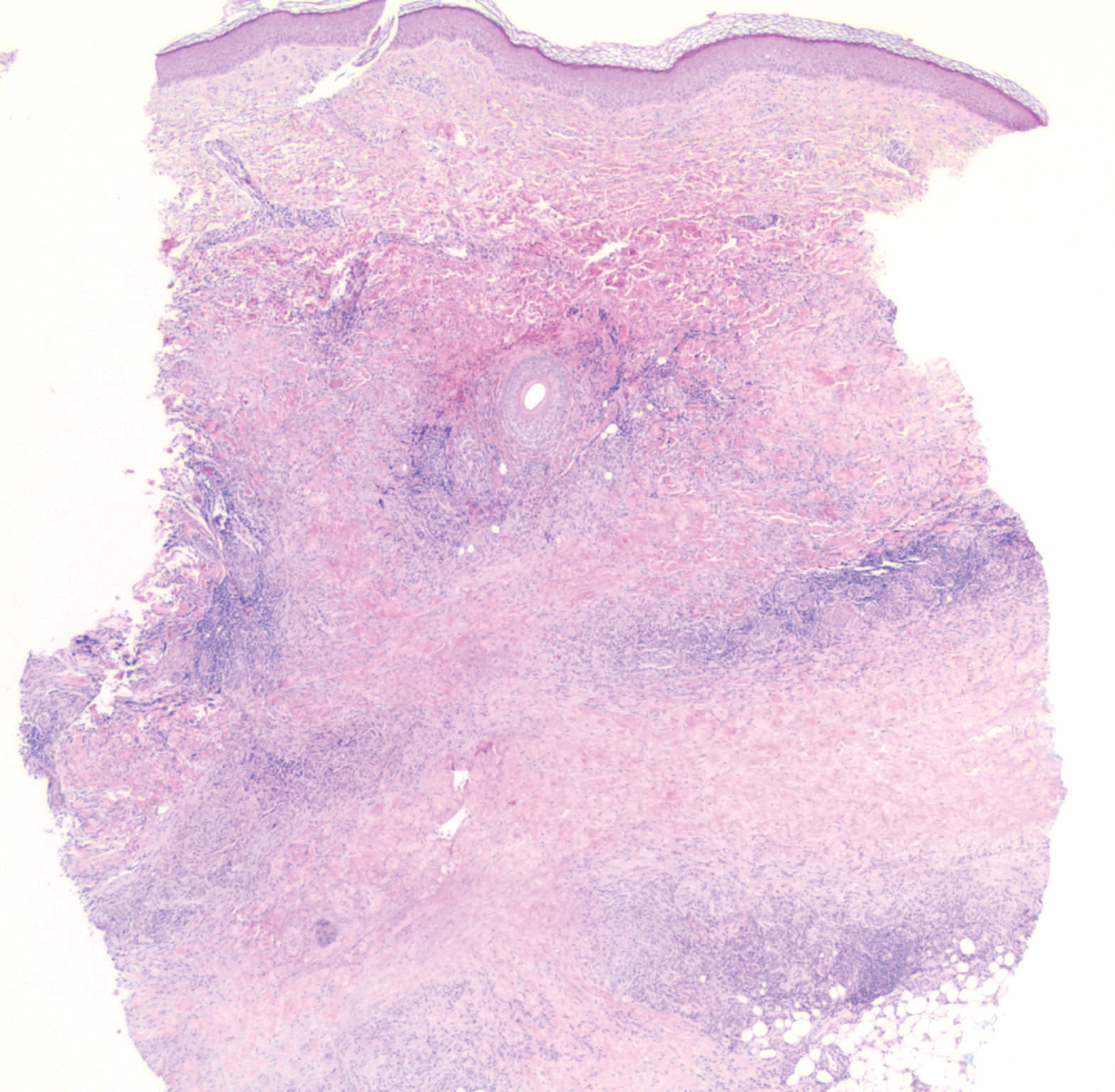

Laboratory testing was negative for infectious processes including Lyme disease, tuberculosis, and Streptococcus due to recent upper respiratory infection. Punch biopsy of a left shin lesion revealed a lobular panniculitis with lymphohistiocytic inflammation, a focal lymphocytic vasculitis, and small granulomas (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. After ruling out alternative causes, the etiology of the panniculitis was deemed to be a pembrolizumab side effect. The patient was treated conservatively with ibuprofen; pembrolizumab was not discontinued. Two weeks later, the panniculitis had resolved without additional treatment. She remains on pembrolizumab and is doing well.

Panniculitis is known to be associated with certain BRAF inhibitors used for the treatment of melanoma positive for the BRAF V600E mutation, including vemurafenib and dabrafenib.4,5 Reports of panniculitis in the setting of pembrolizumab are limited and are seen within the larger context of sarcoidosis. One patient on pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma developed granulomatous lobular panniculitis with oligoarthritis, high fever, and hilar/mediastinal adenopathy, consistent with pembrolizumab-induced sarcoidosis. It developed after her second pembrolizumab infusion and resolved with prednisone and temporary pembrolizumab cessation.6 In another case, pembrolizumab triggered a flare of sarcoidosis with similar granulomatous subcutaneous nodules in a patient with stage IV lymphoma who was previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis but lacked cutaneous manifestations. The lesions resolved with prednisone therapy.7

Chest computed tomography was normal in our patient, and she reported no systemic symptoms. Additional laboratory studies to evaluate for sarcoidosis were not obtained. Furthermore, the lesions quickly resolved despite continued use of pembrolizumab. We report this case to highlight that pembrolizumab may induce an isolated, self-limited lobular panniculitis years after medication initiation.

- Poole RM. Pembrolizumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:1973-1981.

- Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139-148.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Ramani NS, Curry JL, Kapil J, et al. Panniculitis with necrotizing granulomata in a patient on BRAF inhibitor (dabrafenib) therapy for metastatic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:E96-E99.

- Burillo-Martinez S, Morales-Raya C, Prieto-Barrios M, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced extensive panniculitis and nevus regression: two novel cutaneous manifestations of the post-immunotherapy granulomatous reactions spectrum. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:721-722.

- Cotliar J, Querfeld C, Boswell WJ, et al. Pembrolizumab-associated sarcoidosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:290-293.

To the Editor:

Pembrolizumab is an anti–programmed death receptor 1 humanized monoclonal antibody used for treating advanced or metastatic melanoma.1 It is associated with several immune-related adverse events because it blocks a T-cell receptor checkpoint.2 The most common dermatologic immune-related adverse event seen with anti–programmed death receptor 1 medications is a nonspecific morbilliform rash, usually seen after the second treatment cycle; however, pruritus, vitiligo, bullous disorders, and lichenoid reactions also have been reported.3 We report a case of pembrolizumab-induced, self-limited lobular panniculitis in a patient with metastatic melanoma.

A 37-year-old woman with malignant melanoma presented with tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules on the hips and legs of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Twelve years prior to the current presentation, she was diagnosed with metastases to the cecum, lung, and brain. A review of systems was otherwise negative. She had been receiving pembrolizumab infusions (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks) for the last 2.7 years as second-line therapy after previously undergoing chemotherapy, radiation, and resection. She was not taking oral contraceptives or other hormone-based medications and did not report any new medications.

Laboratory testing was negative for infectious processes including Lyme disease, tuberculosis, and Streptococcus due to recent upper respiratory infection. Punch biopsy of a left shin lesion revealed a lobular panniculitis with lymphohistiocytic inflammation, a focal lymphocytic vasculitis, and small granulomas (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. After ruling out alternative causes, the etiology of the panniculitis was deemed to be a pembrolizumab side effect. The patient was treated conservatively with ibuprofen; pembrolizumab was not discontinued. Two weeks later, the panniculitis had resolved without additional treatment. She remains on pembrolizumab and is doing well.

Panniculitis is known to be associated with certain BRAF inhibitors used for the treatment of melanoma positive for the BRAF V600E mutation, including vemurafenib and dabrafenib.4,5 Reports of panniculitis in the setting of pembrolizumab are limited and are seen within the larger context of sarcoidosis. One patient on pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma developed granulomatous lobular panniculitis with oligoarthritis, high fever, and hilar/mediastinal adenopathy, consistent with pembrolizumab-induced sarcoidosis. It developed after her second pembrolizumab infusion and resolved with prednisone and temporary pembrolizumab cessation.6 In another case, pembrolizumab triggered a flare of sarcoidosis with similar granulomatous subcutaneous nodules in a patient with stage IV lymphoma who was previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis but lacked cutaneous manifestations. The lesions resolved with prednisone therapy.7

Chest computed tomography was normal in our patient, and she reported no systemic symptoms. Additional laboratory studies to evaluate for sarcoidosis were not obtained. Furthermore, the lesions quickly resolved despite continued use of pembrolizumab. We report this case to highlight that pembrolizumab may induce an isolated, self-limited lobular panniculitis years after medication initiation.

To the Editor:

Pembrolizumab is an anti–programmed death receptor 1 humanized monoclonal antibody used for treating advanced or metastatic melanoma.1 It is associated with several immune-related adverse events because it blocks a T-cell receptor checkpoint.2 The most common dermatologic immune-related adverse event seen with anti–programmed death receptor 1 medications is a nonspecific morbilliform rash, usually seen after the second treatment cycle; however, pruritus, vitiligo, bullous disorders, and lichenoid reactions also have been reported.3 We report a case of pembrolizumab-induced, self-limited lobular panniculitis in a patient with metastatic melanoma.

A 37-year-old woman with malignant melanoma presented with tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules on the hips and legs of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Twelve years prior to the current presentation, she was diagnosed with metastases to the cecum, lung, and brain. A review of systems was otherwise negative. She had been receiving pembrolizumab infusions (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks) for the last 2.7 years as second-line therapy after previously undergoing chemotherapy, radiation, and resection. She was not taking oral contraceptives or other hormone-based medications and did not report any new medications.

Laboratory testing was negative for infectious processes including Lyme disease, tuberculosis, and Streptococcus due to recent upper respiratory infection. Punch biopsy of a left shin lesion revealed a lobular panniculitis with lymphohistiocytic inflammation, a focal lymphocytic vasculitis, and small granulomas (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. After ruling out alternative causes, the etiology of the panniculitis was deemed to be a pembrolizumab side effect. The patient was treated conservatively with ibuprofen; pembrolizumab was not discontinued. Two weeks later, the panniculitis had resolved without additional treatment. She remains on pembrolizumab and is doing well.

Panniculitis is known to be associated with certain BRAF inhibitors used for the treatment of melanoma positive for the BRAF V600E mutation, including vemurafenib and dabrafenib.4,5 Reports of panniculitis in the setting of pembrolizumab are limited and are seen within the larger context of sarcoidosis. One patient on pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma developed granulomatous lobular panniculitis with oligoarthritis, high fever, and hilar/mediastinal adenopathy, consistent with pembrolizumab-induced sarcoidosis. It developed after her second pembrolizumab infusion and resolved with prednisone and temporary pembrolizumab cessation.6 In another case, pembrolizumab triggered a flare of sarcoidosis with similar granulomatous subcutaneous nodules in a patient with stage IV lymphoma who was previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis but lacked cutaneous manifestations. The lesions resolved with prednisone therapy.7

Chest computed tomography was normal in our patient, and she reported no systemic symptoms. Additional laboratory studies to evaluate for sarcoidosis were not obtained. Furthermore, the lesions quickly resolved despite continued use of pembrolizumab. We report this case to highlight that pembrolizumab may induce an isolated, self-limited lobular panniculitis years after medication initiation.

- Poole RM. Pembrolizumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:1973-1981.

- Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139-148.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Ramani NS, Curry JL, Kapil J, et al. Panniculitis with necrotizing granulomata in a patient on BRAF inhibitor (dabrafenib) therapy for metastatic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:E96-E99.

- Burillo-Martinez S, Morales-Raya C, Prieto-Barrios M, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced extensive panniculitis and nevus regression: two novel cutaneous manifestations of the post-immunotherapy granulomatous reactions spectrum. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:721-722.

- Cotliar J, Querfeld C, Boswell WJ, et al. Pembrolizumab-associated sarcoidosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:290-293.

- Poole RM. Pembrolizumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:1973-1981.

- Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139-148.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Ramani NS, Curry JL, Kapil J, et al. Panniculitis with necrotizing granulomata in a patient on BRAF inhibitor (dabrafenib) therapy for metastatic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:E96-E99.

- Burillo-Martinez S, Morales-Raya C, Prieto-Barrios M, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced extensive panniculitis and nevus regression: two novel cutaneous manifestations of the post-immunotherapy granulomatous reactions spectrum. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:721-722.

- Cotliar J, Querfeld C, Boswell WJ, et al. Pembrolizumab-associated sarcoidosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:290-293.

Practice Points

- Pembrolizumab may cause lobular panniculitis years after treatment initiation.

- Pembrolizumab-induced lobular panniculitis may self-resolve without discontinuing the medication.

Distinct Violaceous Plaques in Conjunction With Blisters

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

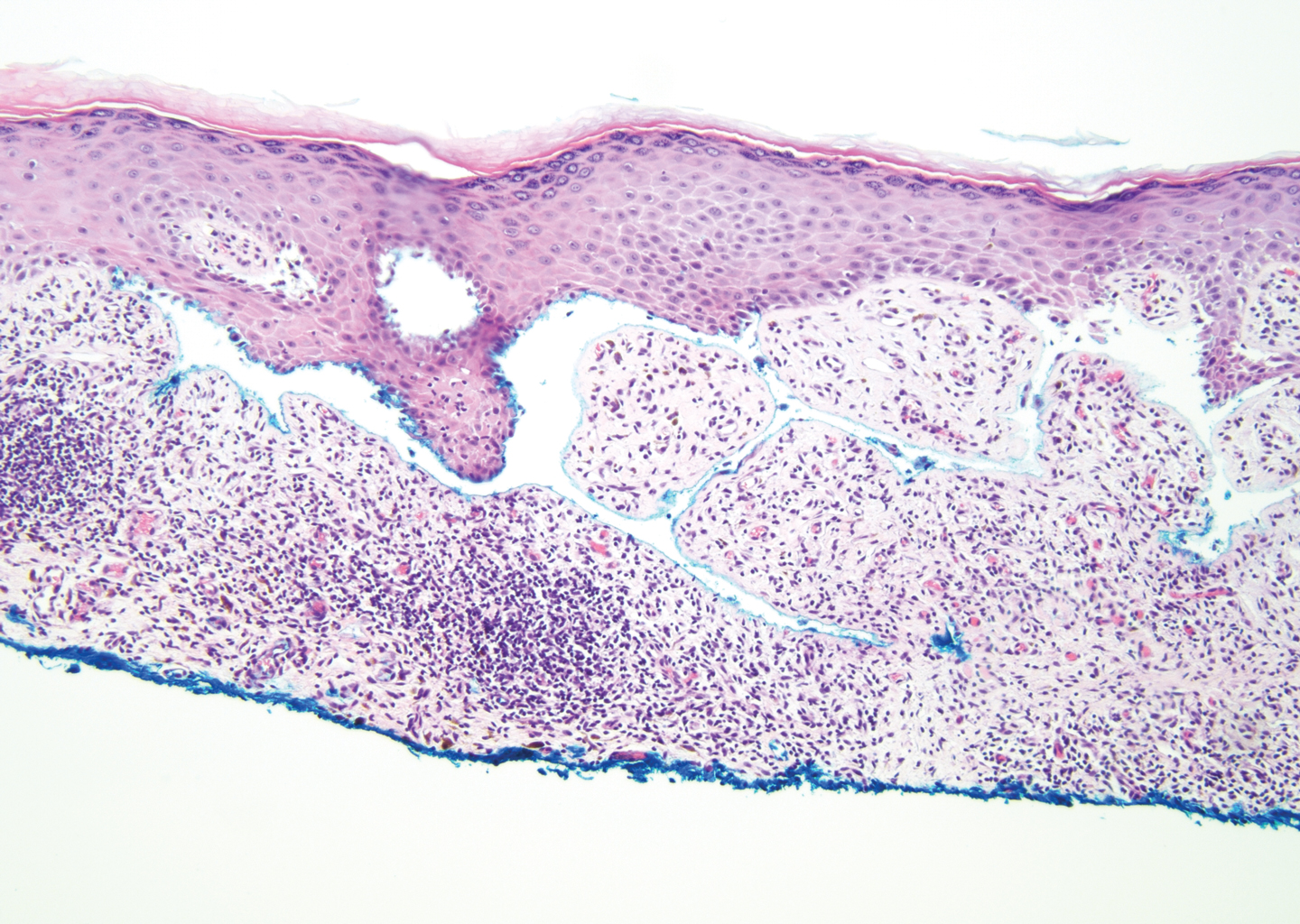

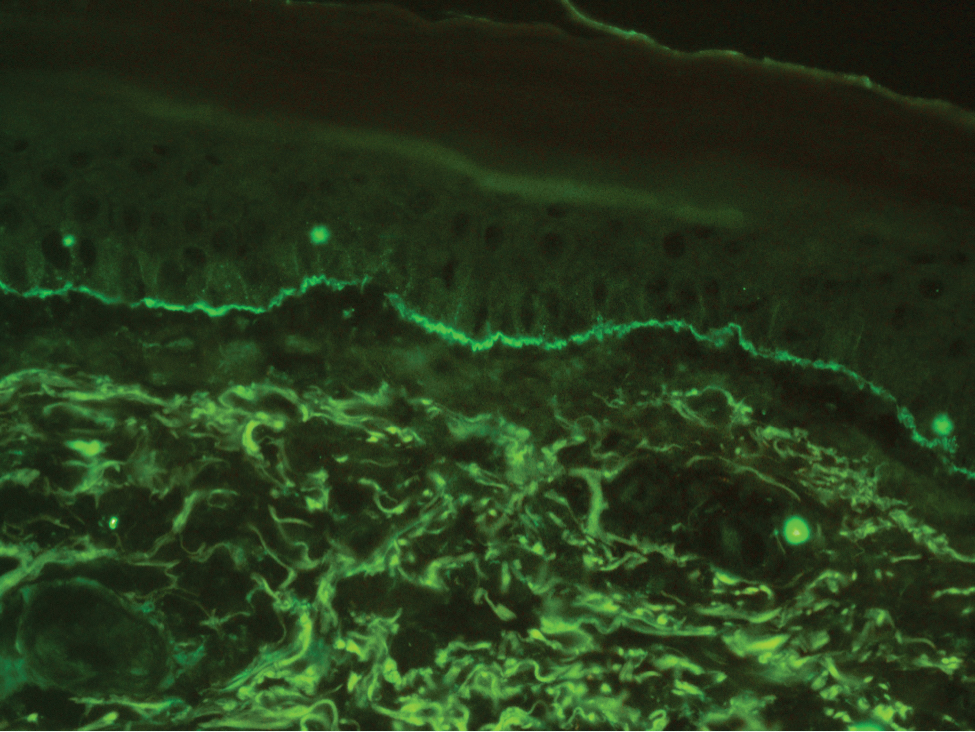

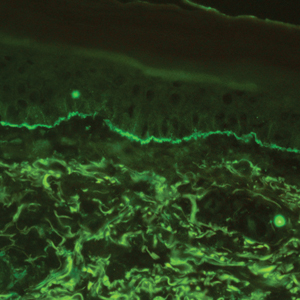

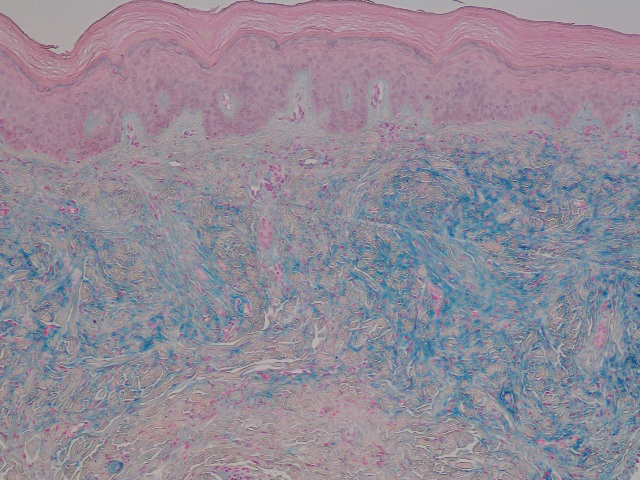

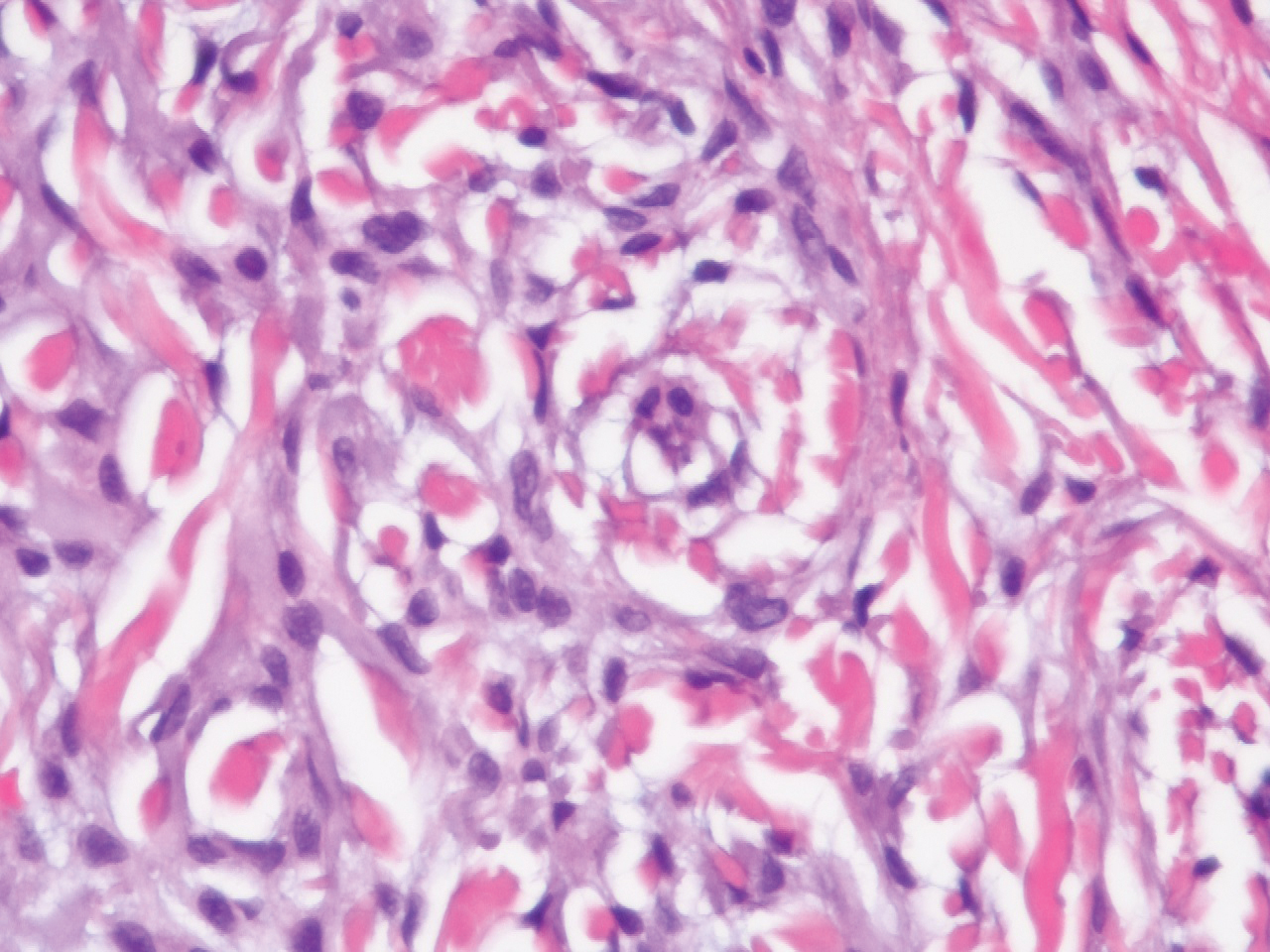

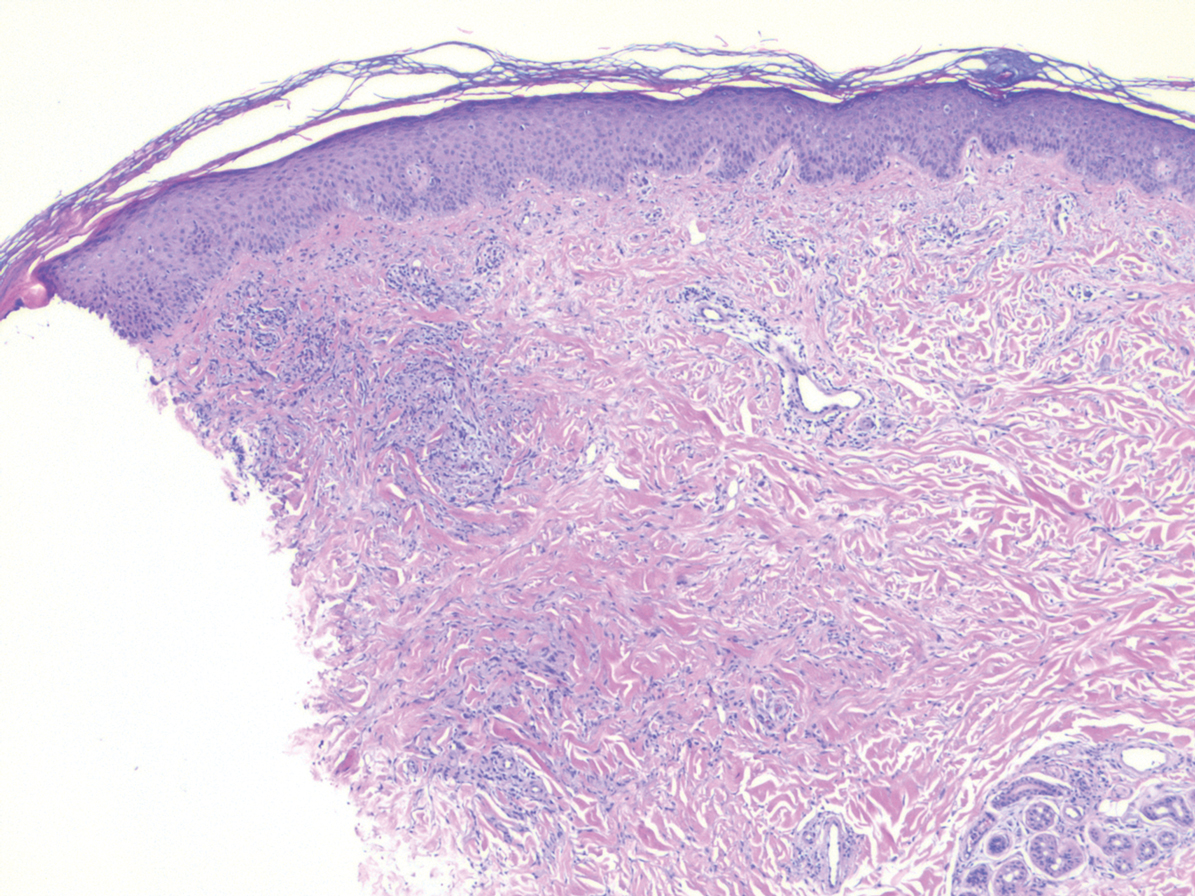

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

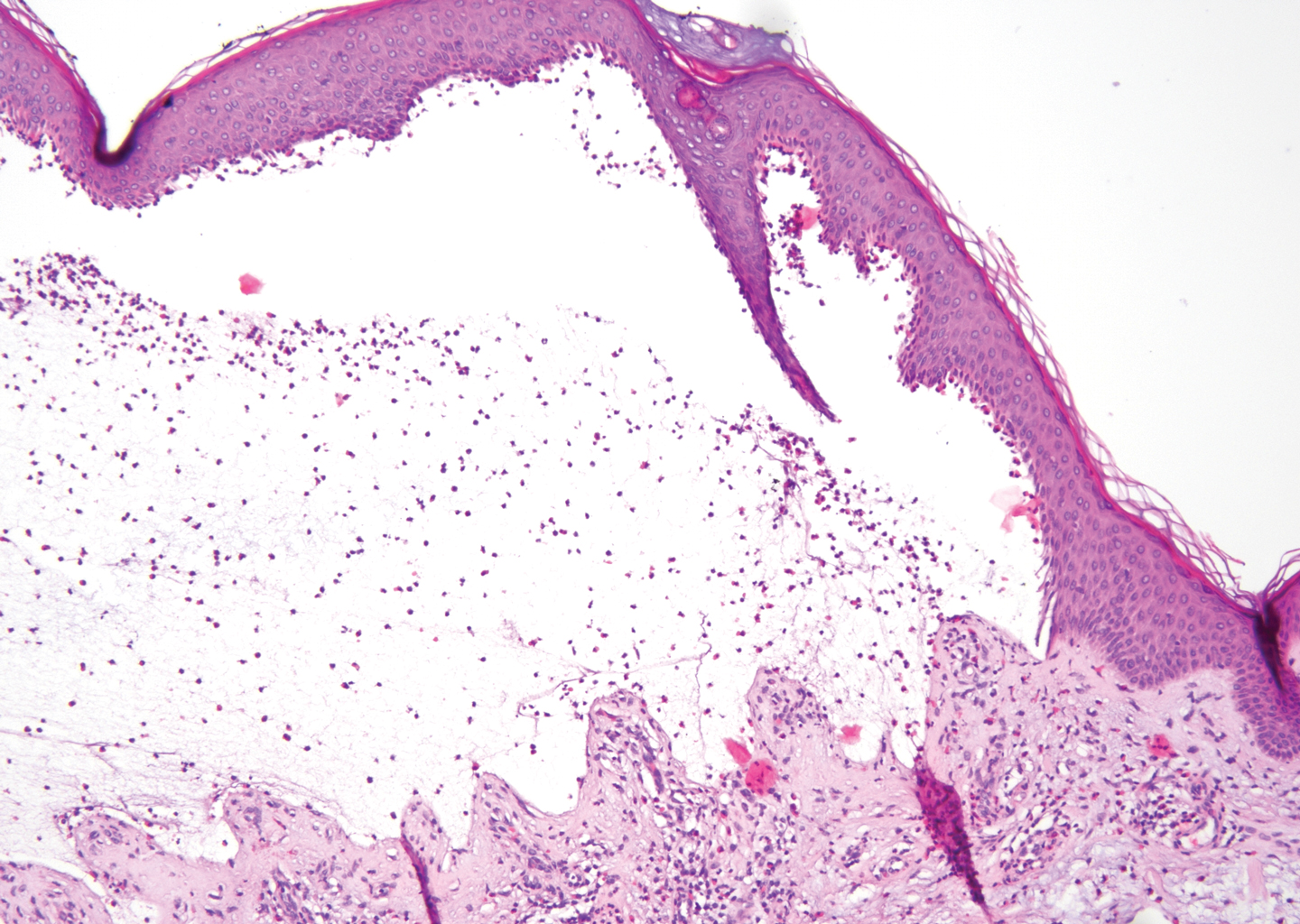

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

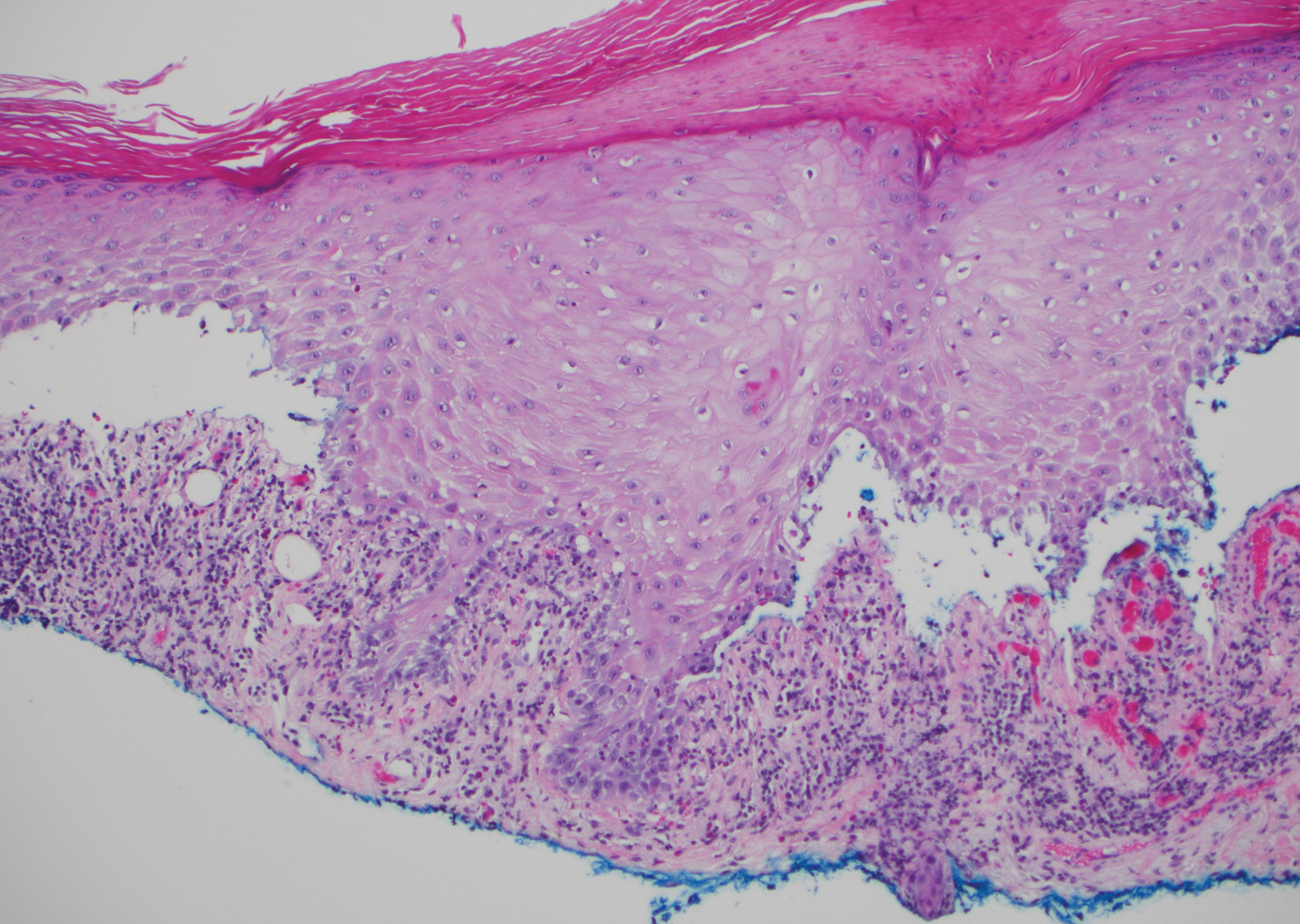

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Mohanarao TS, Kumar GA, Chennamsetty K, et al. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S98-S100.

- Onprasert W, Chanprapaph K. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by enalapril: a case report and a review of literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:217-224.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Shimada H, Shono T, Sakai T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides concomitant with rectal adenocarcinoma: fortuitous or a true association? Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:501-503.

- Matos-Pires E, Campos S, Lencastre A, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335-337.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Wagner G, Rose C, Sachse MM. Clinical variants of lichen planus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:309-319.

- Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Miller DD, Bhawan J. Bullous tinea pedis with direct immunofluorescence positivity: when is a positive result not autoimmune bullous disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:587-594.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

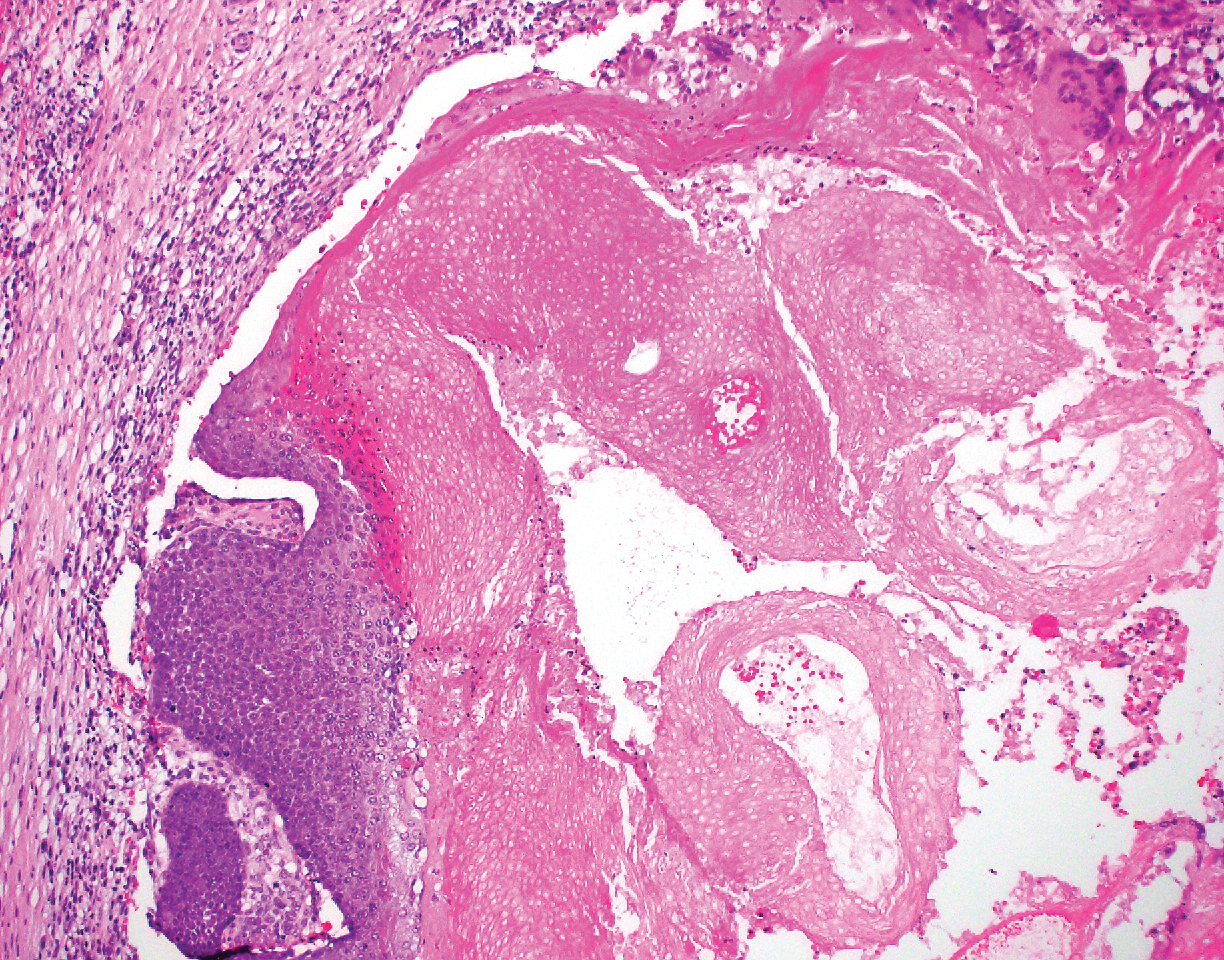

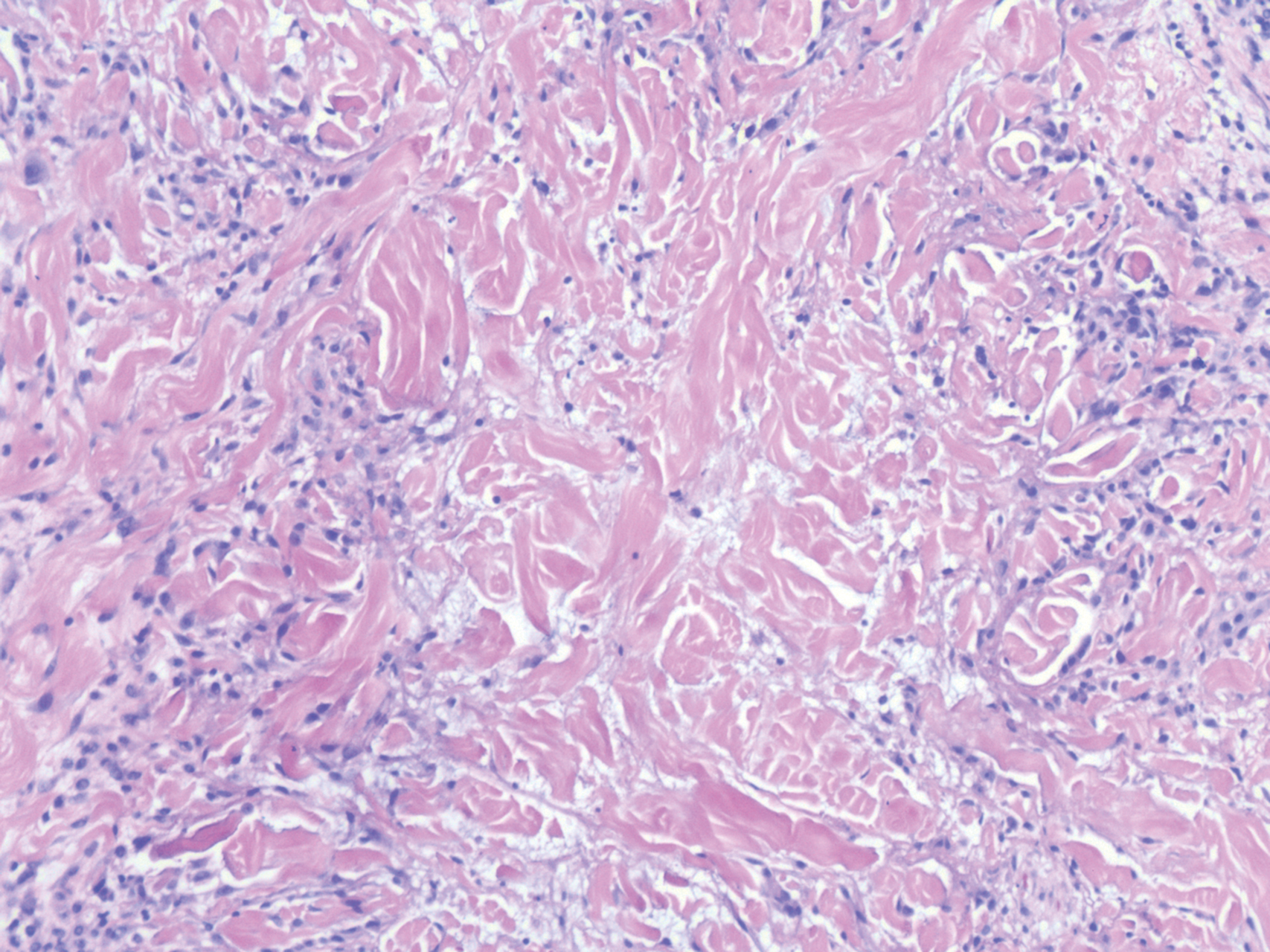

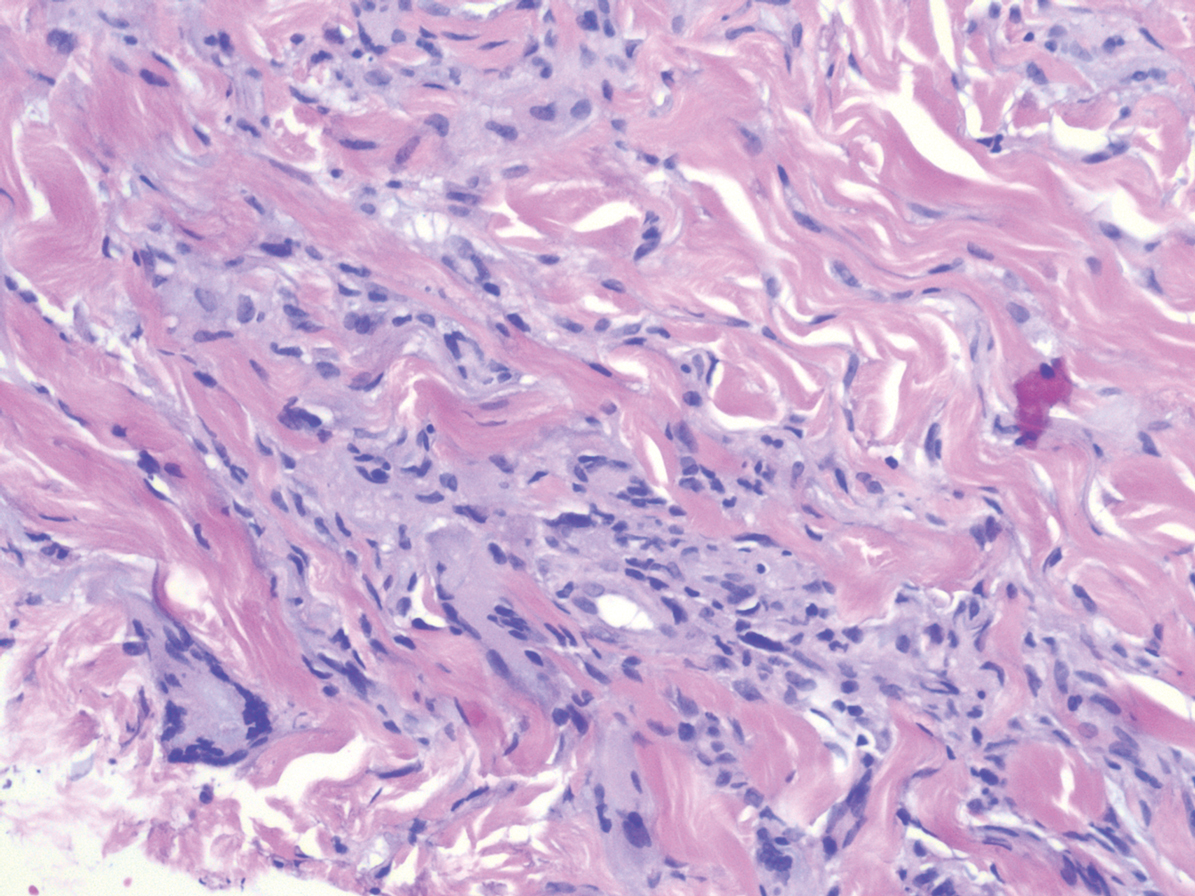

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Mohanarao TS, Kumar GA, Chennamsetty K, et al. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S98-S100.

- Onprasert W, Chanprapaph K. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by enalapril: a case report and a review of literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:217-224.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Shimada H, Shono T, Sakai T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides concomitant with rectal adenocarcinoma: fortuitous or a true association? Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:501-503.

- Matos-Pires E, Campos S, Lencastre A, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335-337.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Wagner G, Rose C, Sachse MM. Clinical variants of lichen planus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:309-319.

- Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Miller DD, Bhawan J. Bullous tinea pedis with direct immunofluorescence positivity: when is a positive result not autoimmune bullous disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:587-594.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Mohanarao TS, Kumar GA, Chennamsetty K, et al. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S98-S100.

- Onprasert W, Chanprapaph K. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by enalapril: a case report and a review of literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:217-224.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Shimada H, Shono T, Sakai T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides concomitant with rectal adenocarcinoma: fortuitous or a true association? Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:501-503.

- Matos-Pires E, Campos S, Lencastre A, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335-337.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Wagner G, Rose C, Sachse MM. Clinical variants of lichen planus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:309-319.

- Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Miller DD, Bhawan J. Bullous tinea pedis with direct immunofluorescence positivity: when is a positive result not autoimmune bullous disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:587-594.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a rash of several months' duration that began as itchy bumps on the wrists and spread to involve the legs. Approximately 2 months prior to presentation, she noted blisters on the feet and legs. She initially went to her primary care physician, who prescribed levofloxacin, cephalexin, and a 5-day course of prednisone. The prednisone initially helped; however the rash worsened on discontinuation. In our clinic, the patient had scattered tense bullae and numerous erosions with crust on the dorsum of the feet and legs, some of which were in conjunction with violaceous papules and plaques. There also was hypertrophic scale on the soles of the feet. A potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings from the feet was negative for fungal elements. Two shave biopsies of a violaceous plaque and bulla as well as a perilesional punch biopsy from the leg were obtained.

Friable Scalp Nodule

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

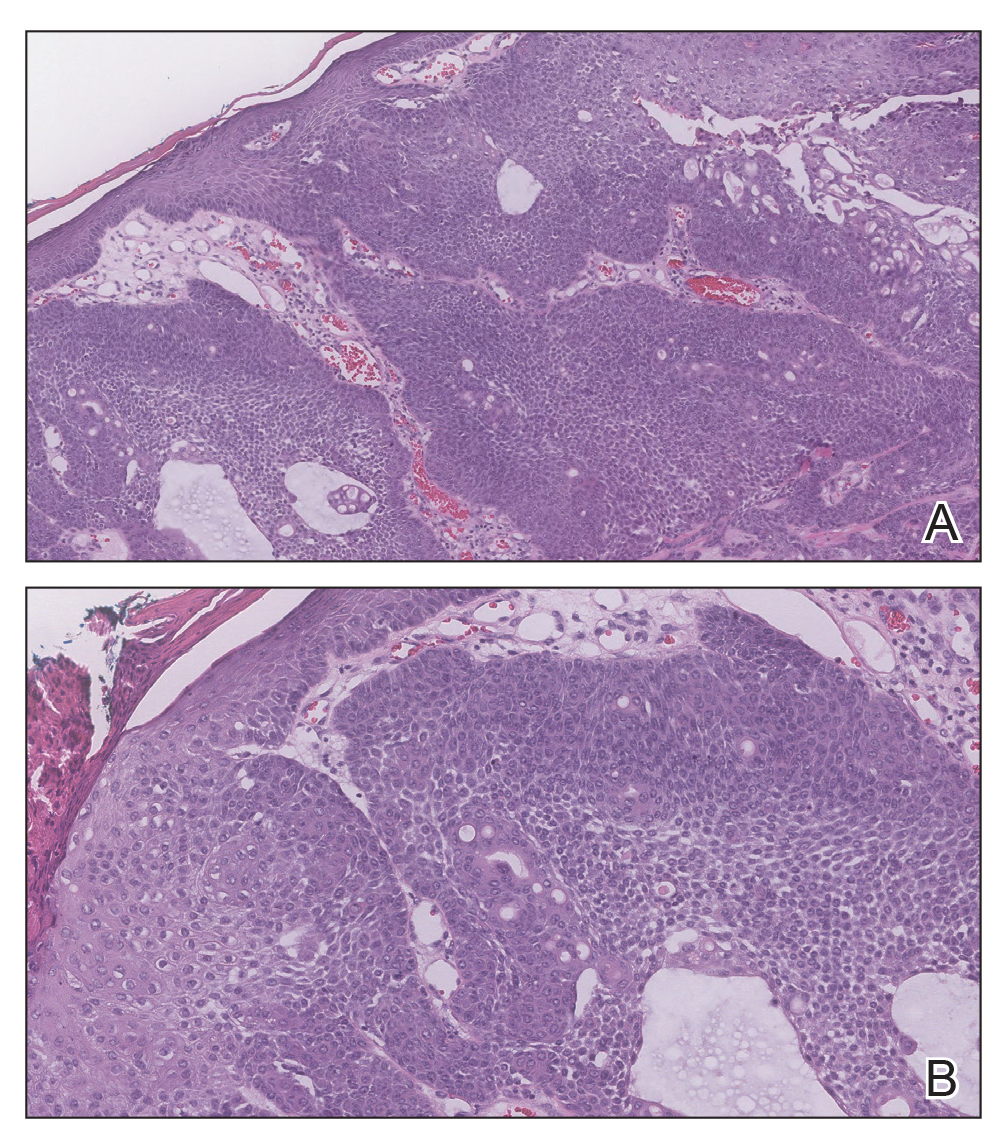

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

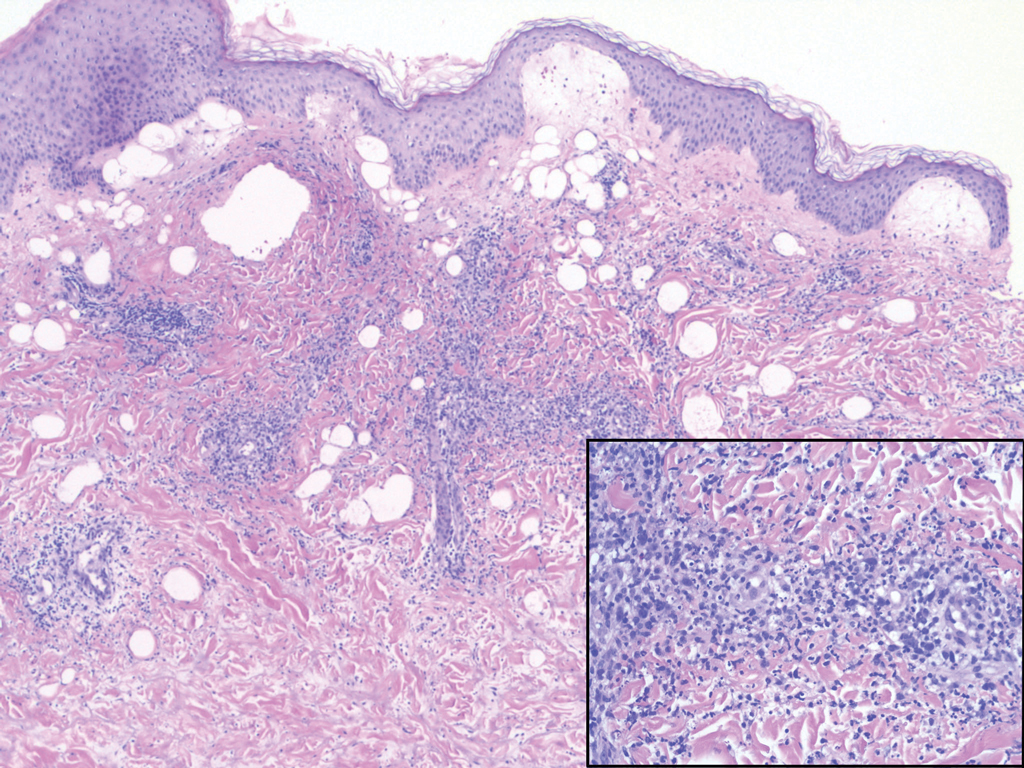

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

The Diagnosis: Adnexal Neoplasm Arising in a Nevus Sebaceus

Biopsy of the lesion showed a proliferation of basaloid-appearing cells with focal ductal differentiation and ulceration consistent with poroma (Figure 1). Due to the superficial nature of the biopsy, the pathologist recommended excision to ensure complete removal and to rule out a well-differentiated porocarcinoma. Excision of the lesion showed large basaloid aggregates with a hypercellular stroma and a surrounding papillomatous epidermis with well-developed sebaceous lobules consistent with a trichoblastoma and a nevus sebaceus, respectively (Figure 2). There also was evidence of poroma; however, there were no findings concerning for porocarcinoma, which could lead to metastasis (Figure 3).

Nevus sebaceus is a benign, hamartomatous, congenital growth that occurs in approximately 1% of patients presenting to dermatology offices. It usually presents as a single asymptomatic plaque on the scalp (62.5%) or face (24.5%) that changes in morphology over its lifetime.1,2 In children, a nevus manifests as a yellowish, smooth, waxy skin lesion. As the sebaceous glands become more developed during adolescence, the lesion takes on more of a verrucous appearance and also can darken.

Although nevus sebaceus is benign, it may give rise to both benign and malignant neoplasms. In a 2014 study of 707 cases of nevus sebaceus, 21.4% developed secondary neoplasms, 88% of which were benign.2 The origins of these neoplasms can be epithelial, sebaceous, apocrine, and/or follicular. The 3 most common secondary neoplasms found in nevus sebaceus are trichoblastoma (34.7%), syringocystadenoma papilliferum (24.7%), and apocrine/eccrine adenoma (10%), all of which are benign.2 Trichoblastomas represent a type of hair follicle tumor. Malignant lesions manifest in approximately 2.5% of cases, with basal cell carcinoma (BCC) being the most common (5.3% of all neoplasms), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (2.7% of all neoplasms).2 Differentiating BCC from trichoblastoma can be difficult, but histologically BCCs usually have tumor stromal clefting while trichoblastomas do not.3 The incidence of secondary tumors in nevus sebaceus displays a strong correlation with age; thus, the highest proportion of neoplasms occur in adults.

Treatment of nevus sebaceus depends on the patient's age. In children, because of the low probability of secondary neoplasms, observation in lieu of surgical excision is a common approach. In adults, the approach typically is surgical excision or close follow-up, as there is a concern for secondary neoplasm and the potential for malignant degeneration.

A nevus sebaceus leading to 2 or more tumors within the same lesion is rare (seen in only 4.2% of lesions). The most common combination is trichoblastoma with syringocystadenoma papilliferum (0.6% of all cases).2 Poromas represent sweat gland tumors that usually appear on the soles (65%) or palms (10%).4 It is uncommon for these neoplasms to manifest on the scalp or within a nevus sebaceus. Three independent studies (N=596; N=707; N=450) did not report any occurrences of eccrine poroma.1,2,5 Eccrine poroma in conjunction with nodular trichoblastoma arising in a nevus sebaceus is unusual, and definitive excision should be strongly considered because of the possibility to develop a porocarcinoma.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma presents on sun-exposed areas as an exophytic nodule or plaque that frequently ulcerates. Pathology of this tumor shows a spindled cell proliferation that can stain positively for CD10 and procollagen 1. Basal cell carcinoma presents as a pearly papule or nodule displaying basaloid-appearing aggregates with tumor stromal clefting and can stain with Ber-EP4. Cylindromas typically present on the scalp as large rubbery-appearing plaques and nodules. Cylindromas usually present as a solitary tumor, but in the familial form there can be clusters of multiple nodules. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma frequently appears as a bleeding nodule on the scalp in patients with known renal cell cancer or as the initial presentation.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(pt 1):263-268.

- Idriss MH, Elston DM. Secondary neoplasms associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn: a study of 707 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:332-337.

- Wang E, Lee JS, Kazakov DV. A rare combination of sebaceoma with carcinomatous change (sebaceous carcinoma), trichoblastoma, and poroma arising from a nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:676-682.

- Bae MI, Cho TH, Shin MK, et al. An unusual clinical presentation of eccrine poroma occurring on the auricle. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:523.

- Hsu MC, Liau JY, Hong JL, et al. Secondary neoplasms arising from nevus sebaceus: a retrospective study of 450 cases in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2016;43:175-180.

- Takhan II, Domingo J. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma developing in a sebaceous nevus of Jadassohn. report of a case. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:413-415.

A 75-year-old woman presented with an enlarging plaque on the scalp of 5 years' duration. Physical examination revealed a 5.6.2 ×2.9-cm, tan-colored, verrucous plaque with an overlying pink friable nodule on the left occipital scalp. The lesion was not painful or pruritic, and the patient did not have any constitutional symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or weight loss. The patient denied prior tanning bed use and reported intermittent sun exposure over her lifetime. She denied any prior surgical intervention. There was no family history of similar lesions.

Ulcerated Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Tumor

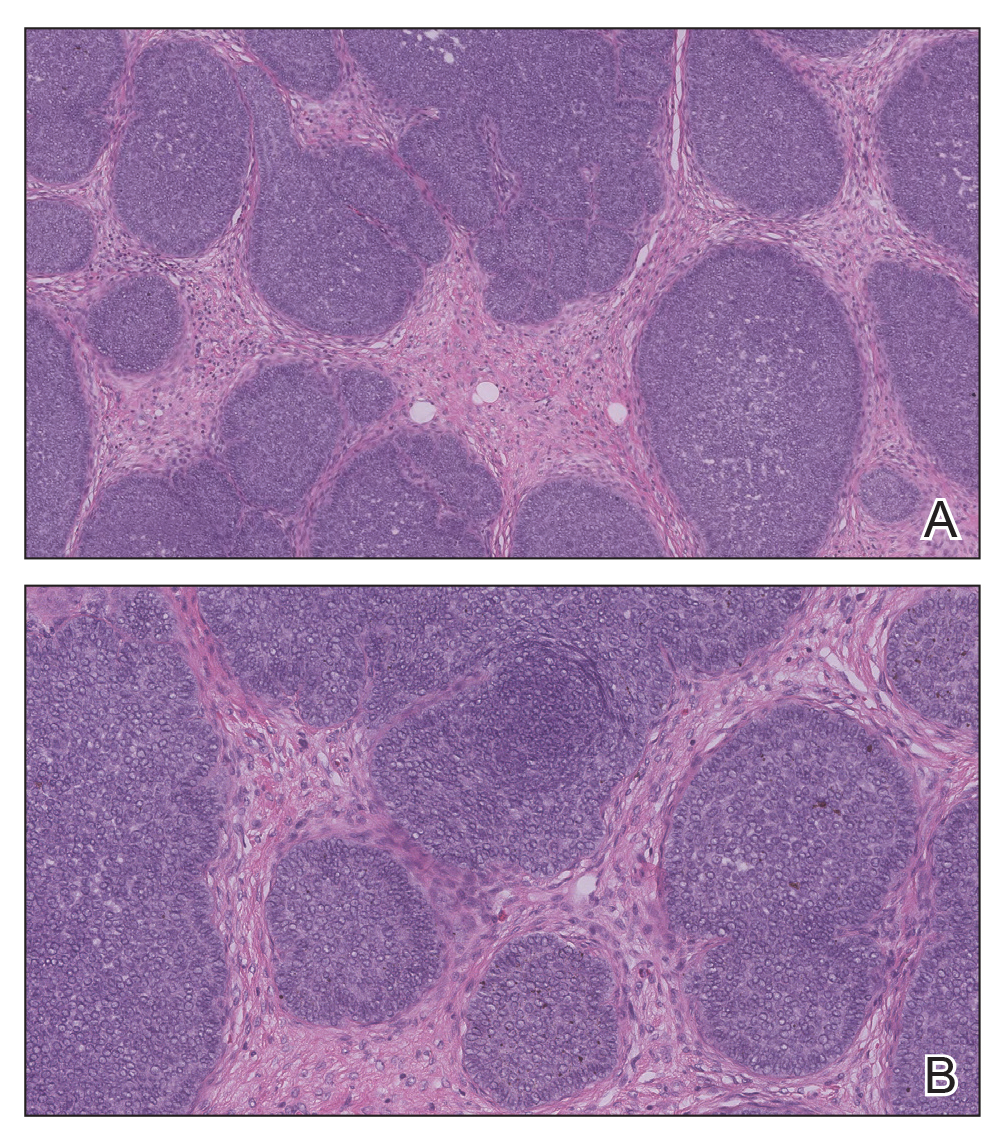

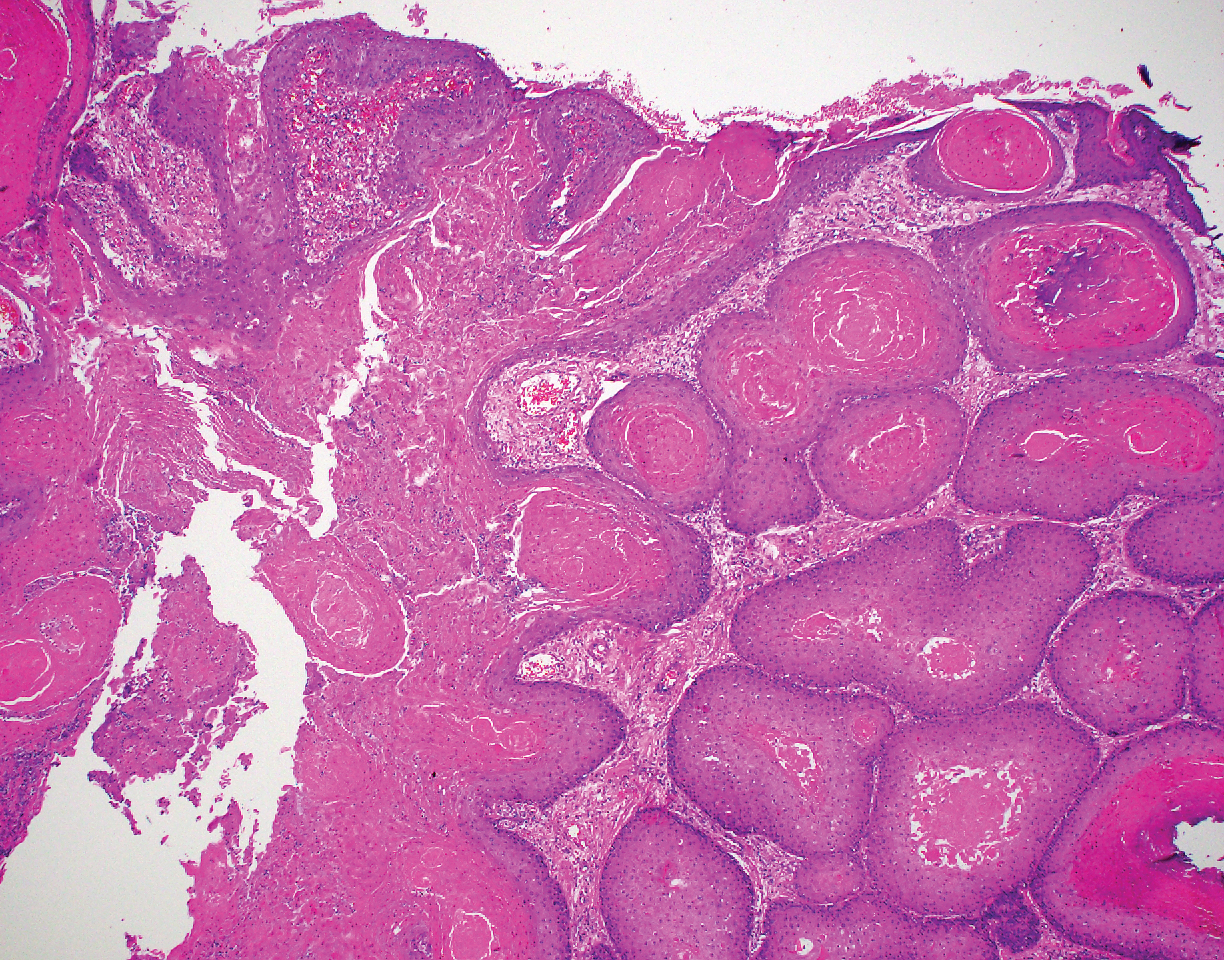

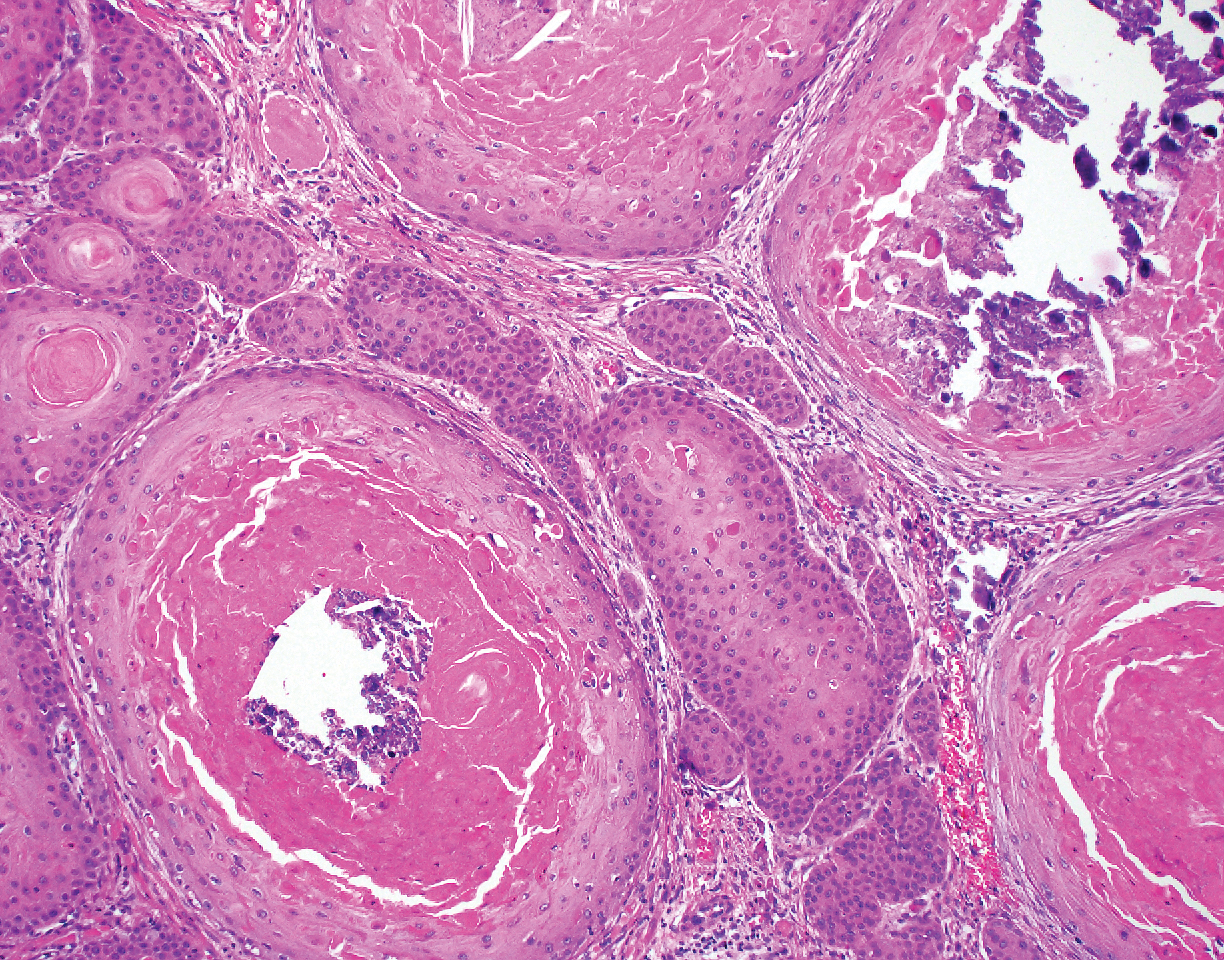

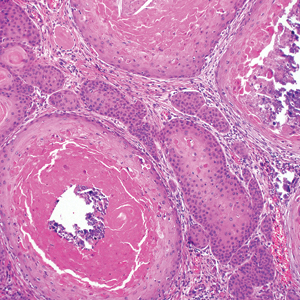

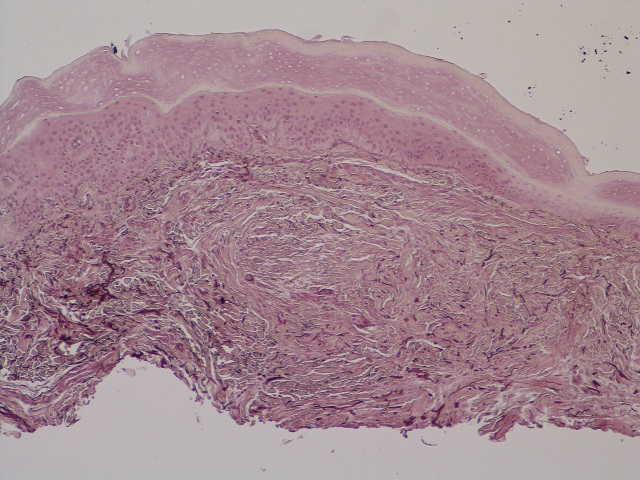

Proliferating pilar tumor (PPT), or cyst, is a neoplasm of trichilemmal keratinization first described by Wilson-Jones1 in 1966. Proliferating pilar tumors lie on a spectrum with malignant PPT, which is a rare adnexal neoplasm first described by Saida et al2 in 1983. The incidence of PPT is unknown given the paucity of cases and the possible misdiagnosis as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Proliferating pilar tumors tend to present on the head and neck of older females as a multilobular and sometimes ulcerating nodule.3 Although PPT can occur de novo, the majority of cases are thought to develop progressively from a benign pilar cyst. Histopathologically, PPT is characterized by cords and nests of squamous cells that display trichilemmal keratinization (quiz images).

Classification of PPT as benign or malignant is challenging, though criteria have been proposed.3-7 Lesions with minimal infiltration into the surrounding dermis and scant mitosis typically behave in a benign manner, while lesions showing nuclear atypia, atypical mitosis, and irregular infiltration into the surrounding dermis can have up to a 50% locoregional recurrence rate.3 In addition, distinguishing a PPT from an SCC or trichilemmal carcinoma also can be difficult; however, SCC is favored when there is a lack of trichilemmal keratinization or when squamous atypia is present in the adjacent epidermis.8 Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare tumor that has been questioned as a distinct entity.9-12

Pilomatricoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign pilar tumor that presents as a slowly growing nodule on the head or neck area or arms.13,14 Most pilomatricomas develop by the second decade of life. Multiple lesions may be present in association with myotonic dystrophy or Gardner syndrome among other syndromes.15-17 Similar to PPT, pilomatricomas present as large dermal nodules; however, they tend to be circumscribed and have a trabecular network that consists of basophilic cells and eosinophilic keratinized shadow cells (Figure 1).18 Calcification may be seen and bone formation subsequently may occur.19

Most sources now consider keratoacanthoma (KA) as a well-differentiated SCC.20 The typical presentation consists of a rapidly growing erythematous to flesh-colored nodule with a central keratinous plug that develops over a period of weeks. If untreated, KAs may resolve over a period of months and leave a depressed scar. Local destruction can result from KAs, and they have the potential to transform into a more aggressive SCC. Accordingly, most clinicians use tissue destructive methods, excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment based on location. Histologically, a well-circumscribed proliferation of glassy cytoplasm is noted. A depressed keratin-filled center is surrounded by a lip of epithelium extending over the lesion (Figure 2).20,21 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia accompanied by hypergranulosis is seen in the center of KAs rather than at the periphery, which is typical of non-KA SCCs. Typical KAs lack acantholysis, a feature suggesting a non-KA type of SCC. Neutrophilic microabscesses and eosinophils commonly are seen in KAs.20,21

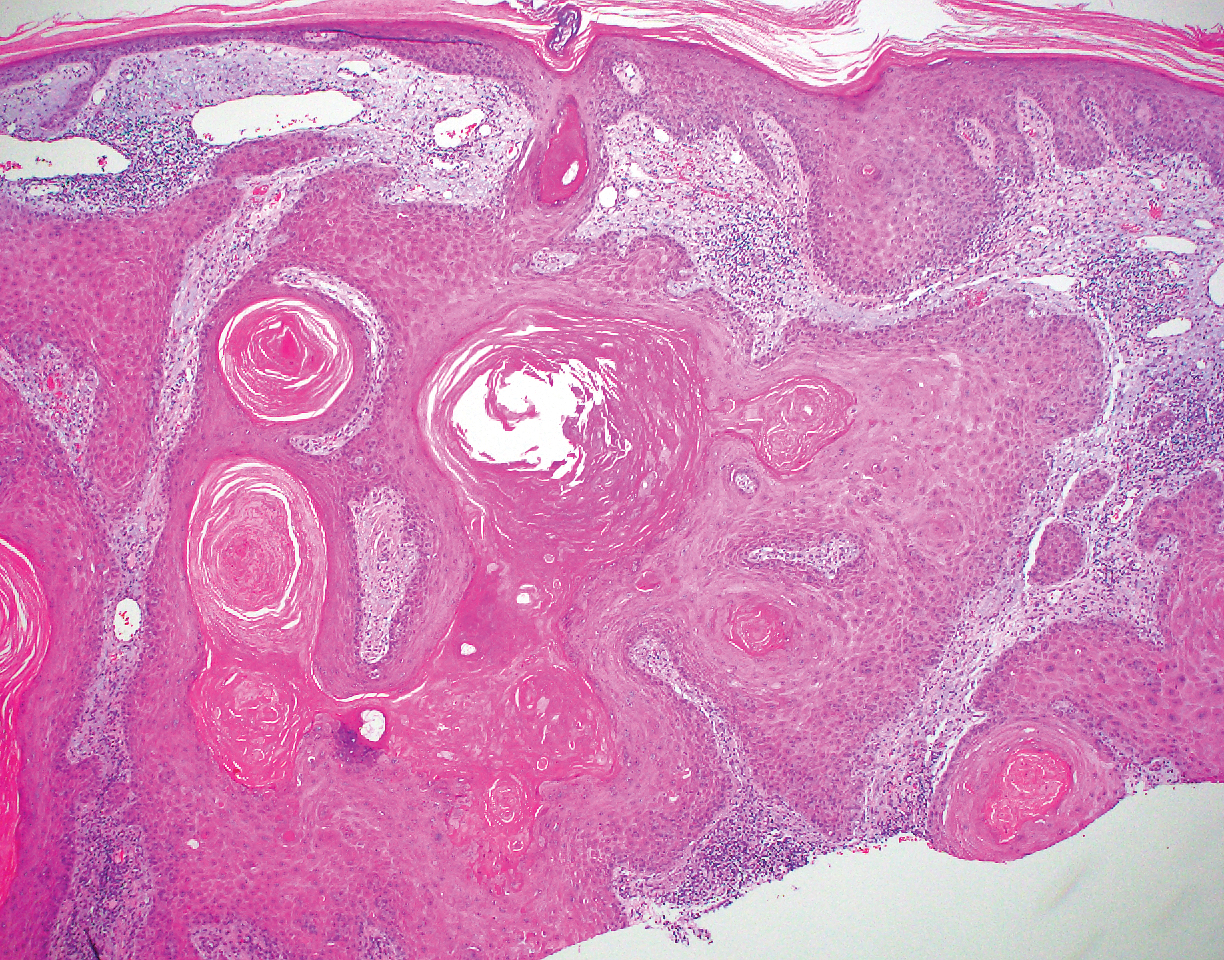

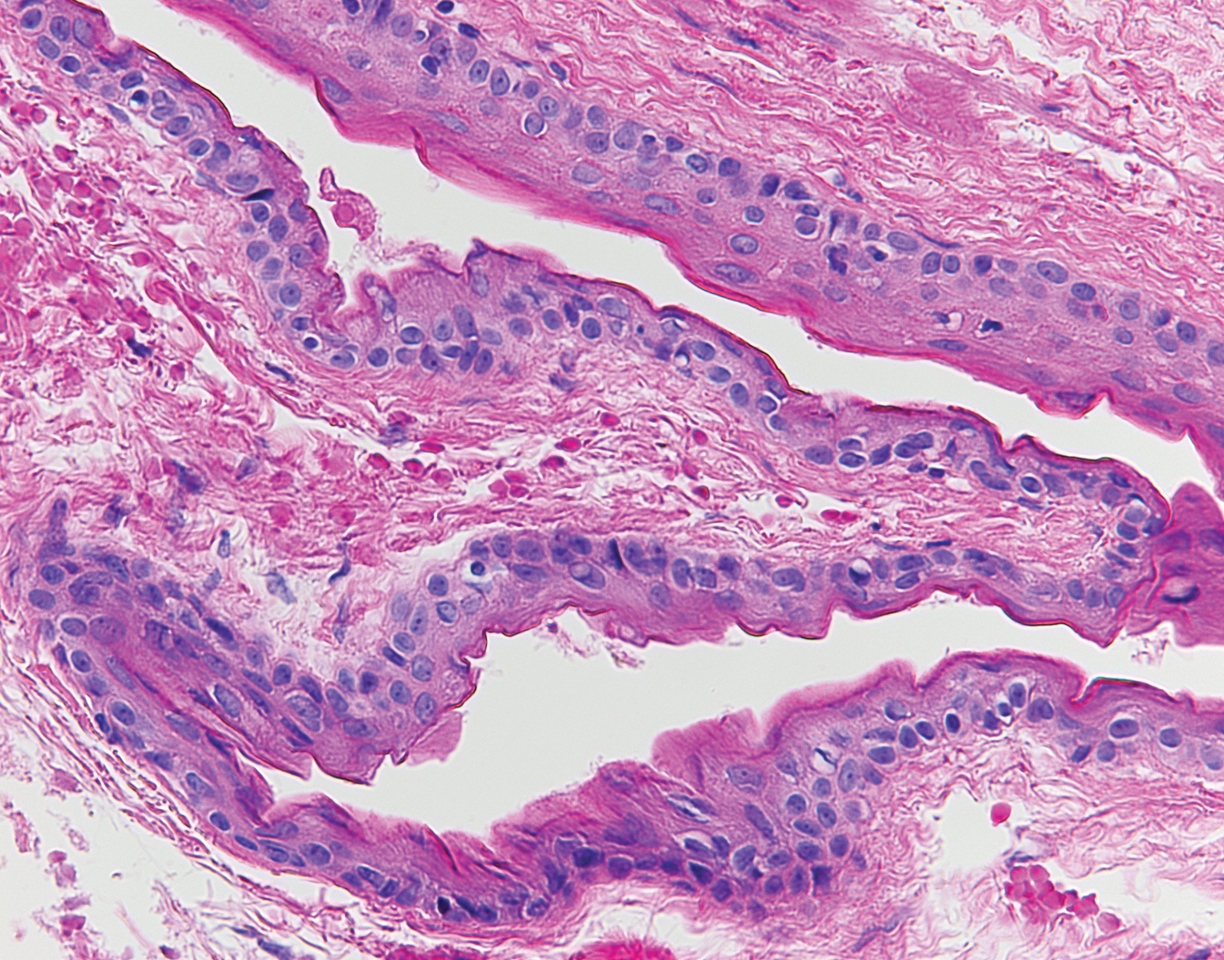

Inverted follicular keratosis is a benign tumor that gained traction as its own entity in the 1960s.22 These lesions typically develop from the follicular infundibulum, but some consider them a version of a wart or seborrheic keratosis.23 They generally are flesh-colored nodules on the upper cutaneous lip or face. Treatment usually consists of complete excision. There are many different growth patterns described, but they typically are endophytic tumors with eosinophilic squamous cells in the center and more basophilic cells at the periphery (Figure 3).24 Characteristically, there are squamous eddies throughout the tumor (Figure 3 [inset]). There also may be a scant lymphohistiocytic infiltrate within the dermis surrounding the lesion.

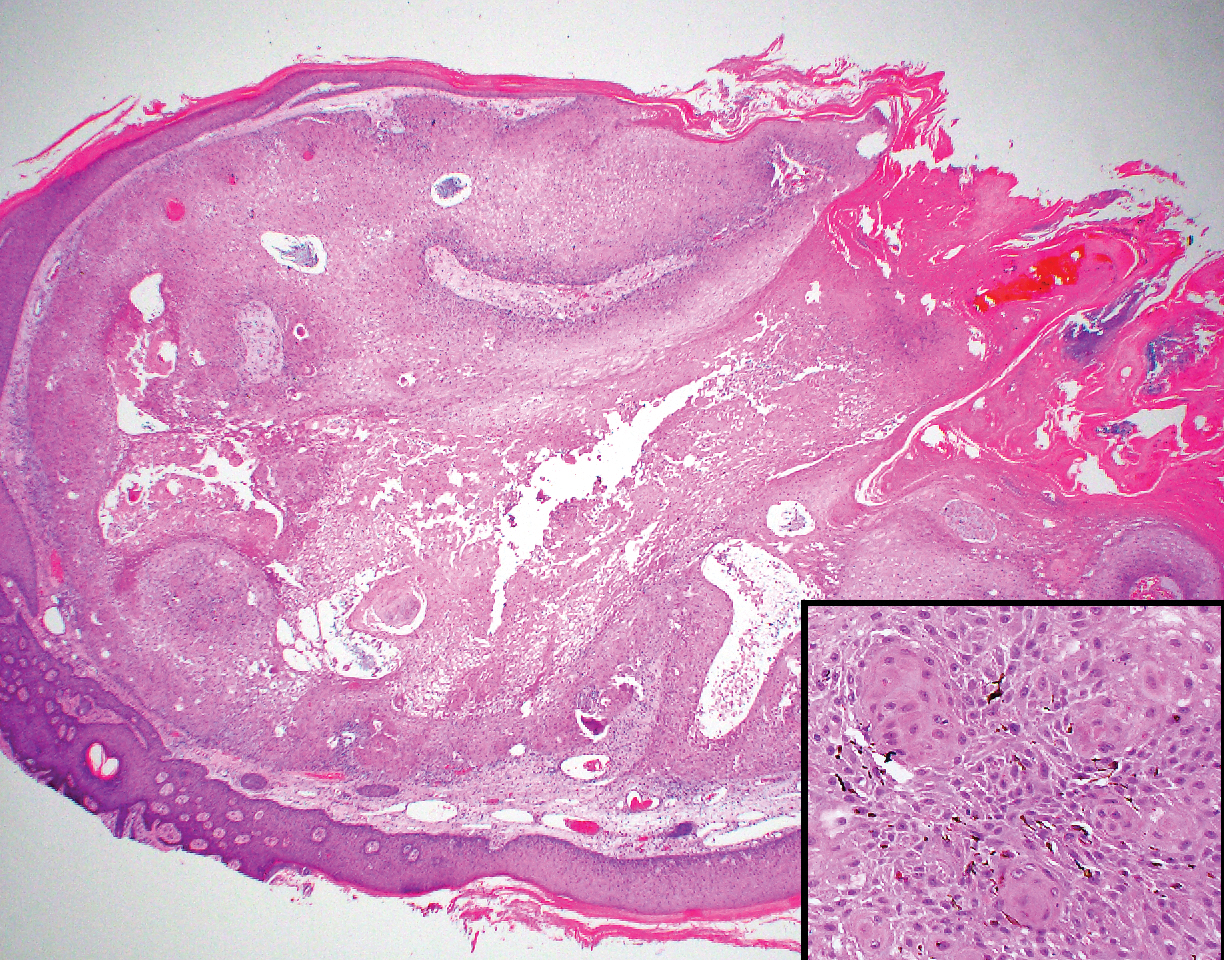

Trichilemmomas are flesh-colored adnexal neoplasms that may present as a solitary lesion or in clusters on the face. They have been reported to occur on all nonglabrous skin sites.25 Multiple lesions may occur in association with Cowden syndrome or with nevus sebaceous.26 A desmoplastic variant of trichilemmomas has been reported.27 Desmoplastic trichilemmomas appear as well-circumscribed tumors of outer root sheath differentiation with lobules extending down into the dermis.28 Vacuolated glycogen-filled keratinocytes are scattered throughout the lesion but are most prominent at the base. At the periphery of the lobules, peripheral palisading of basaloid cells is accompanied by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane that is periodic acid-Schiff positive. Typical trichilemmomas also can display these features; however, the main differentiating feature of a desmoplastic trichilemmoma is the pink hyalinized stroma separating small islets of basophilic cells (Figure 4). Differentiation from an invasive malignant carcinoma sometimes can be challenging without a focus of typical trichilemmoma or if the biopsy specimen is too superficial.29

Pilar cysts are common tumors that typically arise on the scalp and sometimes are proliferating. Proliferating pilar tumor should be kept on the differential when secondary changes such as ulceration occur in the primary lesion of the scalp. Microscopically, and sometimes clinically, PPT can be difficult to differentiate from other mimickers.

- Wilson-Jones E. Proliferating epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:11-19.

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208.

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumours: a clinicopathological study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574.

- Garg PK, Dangi A, Khurana N, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a case report with review of literature. Malaysian J Pathol. 2009;31:71-76.

- Herrero J, Monteagudo C, Ruiz A, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study of three cases with DNA ploidy and morphometric evaluation. Histopathology. 1998;33:542-546.

- Haas N, Audring H, Sterry W. Carcinoma arising in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst expresses fetal and trichilemmal hair phenotype. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:340-344.

- Rutty GN, Richman PI, Laing JH. Malignant change in trichilemmal cysts: a study of cell proliferation and DNA content. Histopathology. 1992;21:465-468.

- Brownstein MH, Arluk DJ. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a simulant of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:1207-1214.

- Misago N, Ackerman AB. Tricholemmal carcinoma? Dermatopathol Pract Concept. 1999;5:205-206.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y. Tricholemmal carcinoma in continuity with trichoblastoma within nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:149-155.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze TA, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

- Swanson PE, Marrogi AJ, Williams DJ, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:100-109.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:191-195.

- Marrogi AJ, Wick MR, Dehner LP. Pilomatrical neoplasms in children and young adults. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:87-94.

- Berberian BJ, Colonna TM, Battaglia M, et al. Multiple pilomatricomas in association with myotonic dystrophy and a family history of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:268-269.

- Cooper PH, Fechner RE. Pilomatricoma-like changes in the epidermal cysts of Gardner's syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:639-644.

- Kaddu S, Soyer HP, Cerroni L, et al. Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of pilomatricomas in adults. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:705-708.

- Sano Y, Mihara M, Miyamoto T, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of calcification and amyloid deposit in pilomatricoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70:256-259.

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:117-123.

- Spielvogel RL, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Inverted follicular keratosis is not a specific keratosis but a verruca vulgaris (or seborrheic keratosis) with squamous eddies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:427-445.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

- Brownstein MH. Trichilemmoma. benign follicular tumor or viral wart? Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:229-231.

- Brownstein MH. Multiple trichilemmomas in Cowden's syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:111.

- Roson E, Gomez Centeno P, Sanchez Aguilar D, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma arising within a nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:495-497.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.

- Sharma R, Sirohi D, Sengupta P, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma of the facial region mimicking invasive carcinoma. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;10:71-73.

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Tumor

Proliferating pilar tumor (PPT), or cyst, is a neoplasm of trichilemmal keratinization first described by Wilson-Jones1 in 1966. Proliferating pilar tumors lie on a spectrum with malignant PPT, which is a rare adnexal neoplasm first described by Saida et al2 in 1983. The incidence of PPT is unknown given the paucity of cases and the possible misdiagnosis as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Proliferating pilar tumors tend to present on the head and neck of older females as a multilobular and sometimes ulcerating nodule.3 Although PPT can occur de novo, the majority of cases are thought to develop progressively from a benign pilar cyst. Histopathologically, PPT is characterized by cords and nests of squamous cells that display trichilemmal keratinization (quiz images).

Classification of PPT as benign or malignant is challenging, though criteria have been proposed.3-7 Lesions with minimal infiltration into the surrounding dermis and scant mitosis typically behave in a benign manner, while lesions showing nuclear atypia, atypical mitosis, and irregular infiltration into the surrounding dermis can have up to a 50% locoregional recurrence rate.3 In addition, distinguishing a PPT from an SCC or trichilemmal carcinoma also can be difficult; however, SCC is favored when there is a lack of trichilemmal keratinization or when squamous atypia is present in the adjacent epidermis.8 Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare tumor that has been questioned as a distinct entity.9-12

Pilomatricoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign pilar tumor that presents as a slowly growing nodule on the head or neck area or arms.13,14 Most pilomatricomas develop by the second decade of life. Multiple lesions may be present in association with myotonic dystrophy or Gardner syndrome among other syndromes.15-17 Similar to PPT, pilomatricomas present as large dermal nodules; however, they tend to be circumscribed and have a trabecular network that consists of basophilic cells and eosinophilic keratinized shadow cells (Figure 1).18 Calcification may be seen and bone formation subsequently may occur.19

Most sources now consider keratoacanthoma (KA) as a well-differentiated SCC.20 The typical presentation consists of a rapidly growing erythematous to flesh-colored nodule with a central keratinous plug that develops over a period of weeks. If untreated, KAs may resolve over a period of months and leave a depressed scar. Local destruction can result from KAs, and they have the potential to transform into a more aggressive SCC. Accordingly, most clinicians use tissue destructive methods, excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment based on location. Histologically, a well-circumscribed proliferation of glassy cytoplasm is noted. A depressed keratin-filled center is surrounded by a lip of epithelium extending over the lesion (Figure 2).20,21 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia accompanied by hypergranulosis is seen in the center of KAs rather than at the periphery, which is typical of non-KA SCCs. Typical KAs lack acantholysis, a feature suggesting a non-KA type of SCC. Neutrophilic microabscesses and eosinophils commonly are seen in KAs.20,21

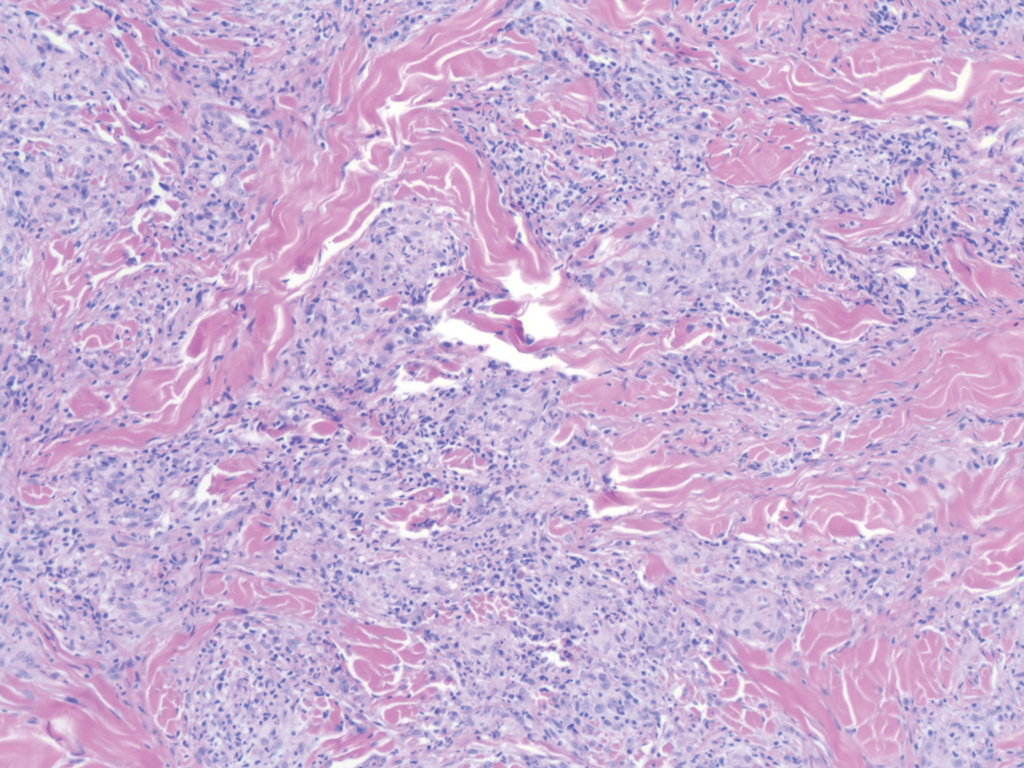

Inverted follicular keratosis is a benign tumor that gained traction as its own entity in the 1960s.22 These lesions typically develop from the follicular infundibulum, but some consider them a version of a wart or seborrheic keratosis.23 They generally are flesh-colored nodules on the upper cutaneous lip or face. Treatment usually consists of complete excision. There are many different growth patterns described, but they typically are endophytic tumors with eosinophilic squamous cells in the center and more basophilic cells at the periphery (Figure 3).24 Characteristically, there are squamous eddies throughout the tumor (Figure 3 [inset]). There also may be a scant lymphohistiocytic infiltrate within the dermis surrounding the lesion.

Trichilemmomas are flesh-colored adnexal neoplasms that may present as a solitary lesion or in clusters on the face. They have been reported to occur on all nonglabrous skin sites.25 Multiple lesions may occur in association with Cowden syndrome or with nevus sebaceous.26 A desmoplastic variant of trichilemmomas has been reported.27 Desmoplastic trichilemmomas appear as well-circumscribed tumors of outer root sheath differentiation with lobules extending down into the dermis.28 Vacuolated glycogen-filled keratinocytes are scattered throughout the lesion but are most prominent at the base. At the periphery of the lobules, peripheral palisading of basaloid cells is accompanied by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane that is periodic acid-Schiff positive. Typical trichilemmomas also can display these features; however, the main differentiating feature of a desmoplastic trichilemmoma is the pink hyalinized stroma separating small islets of basophilic cells (Figure 4). Differentiation from an invasive malignant carcinoma sometimes can be challenging without a focus of typical trichilemmoma or if the biopsy specimen is too superficial.29

Pilar cysts are common tumors that typically arise on the scalp and sometimes are proliferating. Proliferating pilar tumor should be kept on the differential when secondary changes such as ulceration occur in the primary lesion of the scalp. Microscopically, and sometimes clinically, PPT can be difficult to differentiate from other mimickers.

The Diagnosis: Proliferating Pilar Tumor

Proliferating pilar tumor (PPT), or cyst, is a neoplasm of trichilemmal keratinization first described by Wilson-Jones1 in 1966. Proliferating pilar tumors lie on a spectrum with malignant PPT, which is a rare adnexal neoplasm first described by Saida et al2 in 1983. The incidence of PPT is unknown given the paucity of cases and the possible misdiagnosis as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Proliferating pilar tumors tend to present on the head and neck of older females as a multilobular and sometimes ulcerating nodule.3 Although PPT can occur de novo, the majority of cases are thought to develop progressively from a benign pilar cyst. Histopathologically, PPT is characterized by cords and nests of squamous cells that display trichilemmal keratinization (quiz images).

Classification of PPT as benign or malignant is challenging, though criteria have been proposed.3-7 Lesions with minimal infiltration into the surrounding dermis and scant mitosis typically behave in a benign manner, while lesions showing nuclear atypia, atypical mitosis, and irregular infiltration into the surrounding dermis can have up to a 50% locoregional recurrence rate.3 In addition, distinguishing a PPT from an SCC or trichilemmal carcinoma also can be difficult; however, SCC is favored when there is a lack of trichilemmal keratinization or when squamous atypia is present in the adjacent epidermis.8 Trichilemmal carcinoma is a rare tumor that has been questioned as a distinct entity.9-12

Pilomatricoma, also known as calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, is a benign pilar tumor that presents as a slowly growing nodule on the head or neck area or arms.13,14 Most pilomatricomas develop by the second decade of life. Multiple lesions may be present in association with myotonic dystrophy or Gardner syndrome among other syndromes.15-17 Similar to PPT, pilomatricomas present as large dermal nodules; however, they tend to be circumscribed and have a trabecular network that consists of basophilic cells and eosinophilic keratinized shadow cells (Figure 1).18 Calcification may be seen and bone formation subsequently may occur.19

Most sources now consider keratoacanthoma (KA) as a well-differentiated SCC.20 The typical presentation consists of a rapidly growing erythematous to flesh-colored nodule with a central keratinous plug that develops over a period of weeks. If untreated, KAs may resolve over a period of months and leave a depressed scar. Local destruction can result from KAs, and they have the potential to transform into a more aggressive SCC. Accordingly, most clinicians use tissue destructive methods, excision, or Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment based on location. Histologically, a well-circumscribed proliferation of glassy cytoplasm is noted. A depressed keratin-filled center is surrounded by a lip of epithelium extending over the lesion (Figure 2).20,21 Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia accompanied by hypergranulosis is seen in the center of KAs rather than at the periphery, which is typical of non-KA SCCs. Typical KAs lack acantholysis, a feature suggesting a non-KA type of SCC. Neutrophilic microabscesses and eosinophils commonly are seen in KAs.20,21

Inverted follicular keratosis is a benign tumor that gained traction as its own entity in the 1960s.22 These lesions typically develop from the follicular infundibulum, but some consider them a version of a wart or seborrheic keratosis.23 They generally are flesh-colored nodules on the upper cutaneous lip or face. Treatment usually consists of complete excision. There are many different growth patterns described, but they typically are endophytic tumors with eosinophilic squamous cells in the center and more basophilic cells at the periphery (Figure 3).24 Characteristically, there are squamous eddies throughout the tumor (Figure 3 [inset]). There also may be a scant lymphohistiocytic infiltrate within the dermis surrounding the lesion.

Trichilemmomas are flesh-colored adnexal neoplasms that may present as a solitary lesion or in clusters on the face. They have been reported to occur on all nonglabrous skin sites.25 Multiple lesions may occur in association with Cowden syndrome or with nevus sebaceous.26 A desmoplastic variant of trichilemmomas has been reported.27 Desmoplastic trichilemmomas appear as well-circumscribed tumors of outer root sheath differentiation with lobules extending down into the dermis.28 Vacuolated glycogen-filled keratinocytes are scattered throughout the lesion but are most prominent at the base. At the periphery of the lobules, peripheral palisading of basaloid cells is accompanied by a thickened eosinophilic basement membrane that is periodic acid-Schiff positive. Typical trichilemmomas also can display these features; however, the main differentiating feature of a desmoplastic trichilemmoma is the pink hyalinized stroma separating small islets of basophilic cells (Figure 4). Differentiation from an invasive malignant carcinoma sometimes can be challenging without a focus of typical trichilemmoma or if the biopsy specimen is too superficial.29

Pilar cysts are common tumors that typically arise on the scalp and sometimes are proliferating. Proliferating pilar tumor should be kept on the differential when secondary changes such as ulceration occur in the primary lesion of the scalp. Microscopically, and sometimes clinically, PPT can be difficult to differentiate from other mimickers.

- Wilson-Jones E. Proliferating epidermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:11-19.

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208.

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumours: a clinicopathological study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574.

- Garg PK, Dangi A, Khurana N, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a case report with review of literature. Malaysian J Pathol. 2009;31:71-76.

- Herrero J, Monteagudo C, Ruiz A, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study of three cases with DNA ploidy and morphometric evaluation. Histopathology. 1998;33:542-546.

- Haas N, Audring H, Sterry W. Carcinoma arising in a proliferating trichilemmal cyst expresses fetal and trichilemmal hair phenotype. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:340-344.

- Rutty GN, Richman PI, Laing JH. Malignant change in trichilemmal cysts: a study of cell proliferation and DNA content. Histopathology. 1992;21:465-468.

- Brownstein MH, Arluk DJ. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: a simulant of squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:1207-1214.

- Misago N, Ackerman AB. Tricholemmal carcinoma? Dermatopathol Pract Concept. 1999;5:205-206.

- Misago N, Narisawa Y. Tricholemmal carcinoma in continuity with trichoblastoma within nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:149-155.

- Liang H, Wu H, Giorgadze TA, et al. Podoplanin is a highly sensitive and specific marker to distinguish primary skin adnexal carcinomas from adenocarcinomas metastatic to skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:304-310.

- Swanson PE, Marrogi AJ, Williams DJ, et al. Trichilemmal carcinoma: clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:100-109.

- Mehregan AH. Hair follicle tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1985;12:189-195.

- Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:191-195.

- Marrogi AJ, Wick MR, Dehner LP. Pilomatrical neoplasms in children and young adults. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:87-94.

- Berberian BJ, Colonna TM, Battaglia M, et al. Multiple pilomatricomas in association with myotonic dystrophy and a family history of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:268-269.

- Cooper PH, Fechner RE. Pilomatricoma-like changes in the epidermal cysts of Gardner's syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:639-644.

- Kaddu S, Soyer HP, Cerroni L, et al. Clinical and histopathologic spectrum of pilomatricomas in adults. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:705-708.

- Sano Y, Mihara M, Miyamoto T, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of calcification and amyloid deposit in pilomatricoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70:256-259.

- Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:1-19.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:117-123.

- Spielvogel RL, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Inverted follicular keratosis is not a specific keratosis but a verruca vulgaris (or seborrheic keratosis) with squamous eddies. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:427-445.

- Mehregan AH. Inverted follicular keratosis is a distinct follicular tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:467-470.

- Brownstein MH. Trichilemmoma. benign follicular tumor or viral wart? Am J Dermatopathol. 1980;2:229-231.

- Brownstein MH. Multiple trichilemmomas in Cowden's syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:111.

- Roson E, Gomez Centeno P, Sanchez Aguilar D, et al. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma arising within a nevus sebaceous. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:495-497.

- Tellechea O, Reis JP, Baptista AP. Desmoplastic trichilemmoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:107-114.