User login

Perianal North American Blastomycosis

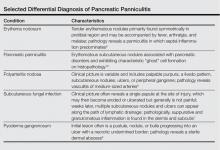

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report

A 57-year-old man presented with a palpable perianal mass that produced small amounts of blood in his underwear and on toilet paper. The patient reported no history of hemorrhoids, anoreceptive intercourse, or sexually transmitted disease. Four months prior to presentation, he had a prolonged upper respiratory tract illness with a subjective fever and productive cough of 2 months’ duration. The patient described himself as an avid outdoorsman who worked at a summer resort and spent a great deal of time in the forests of central Wisconsin last autumn. Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, firm, moist plaque with a verrucous surface that measured 3.5×2.7 cm and extended from the anal verge to the perianal skin (Figure 1).

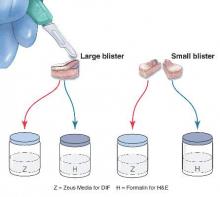

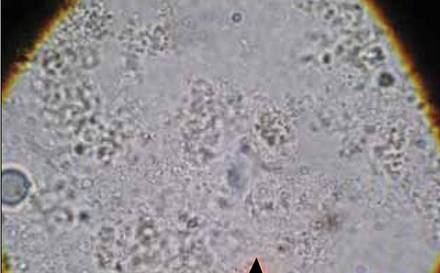

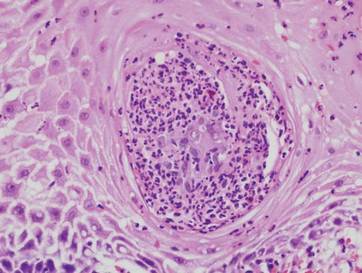

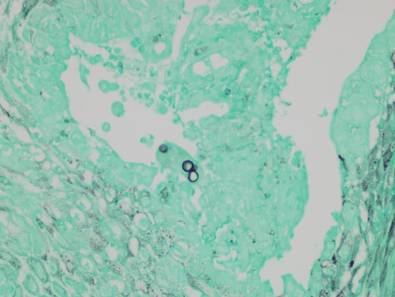

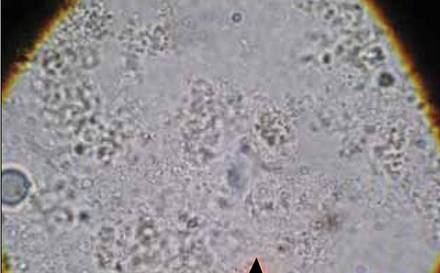

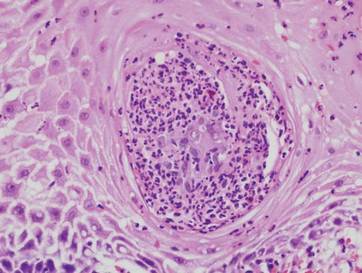

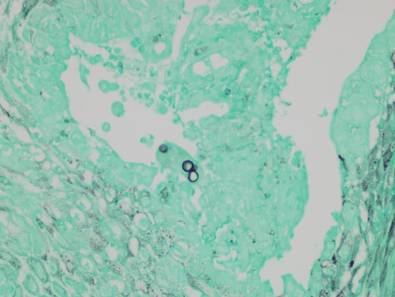

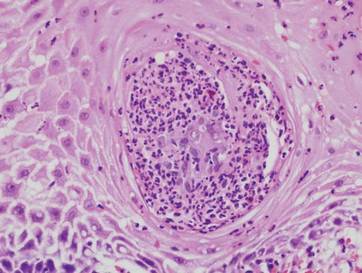

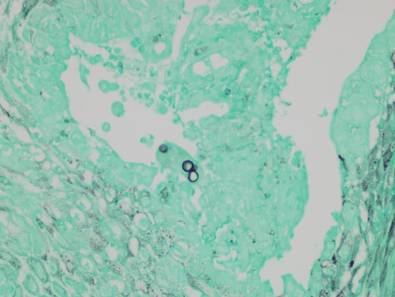

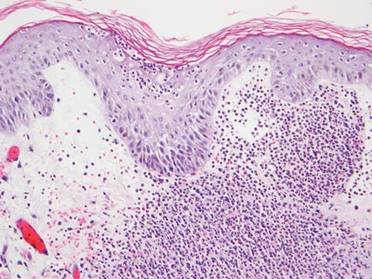

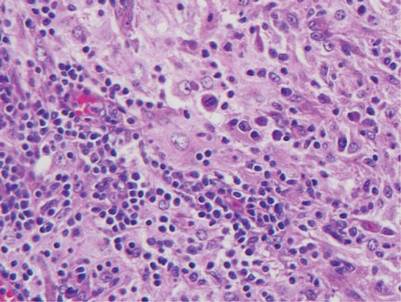

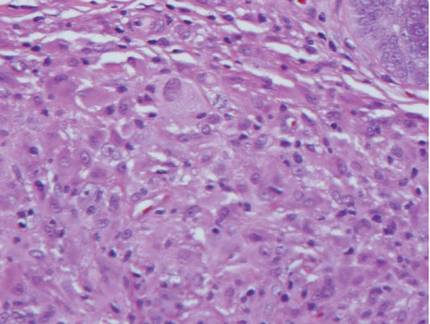

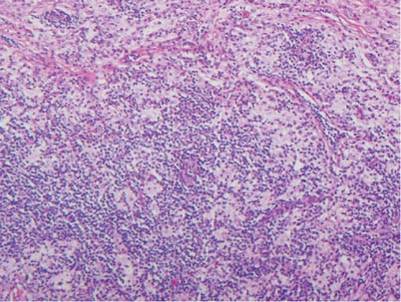

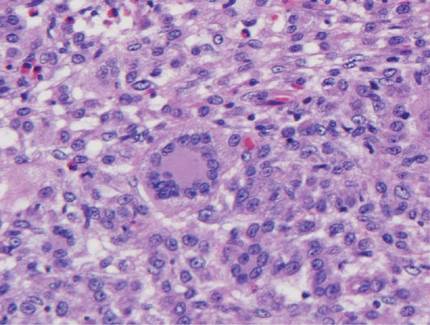

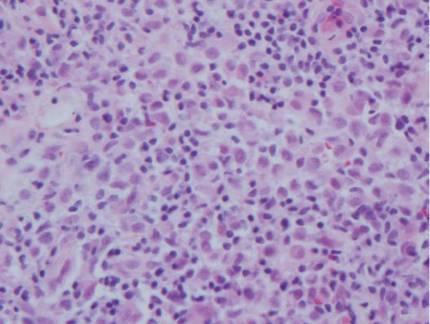

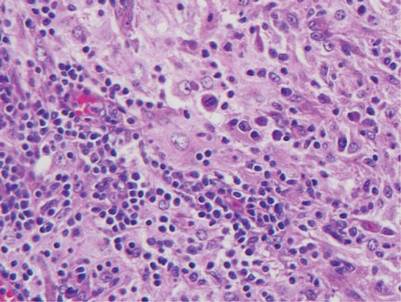

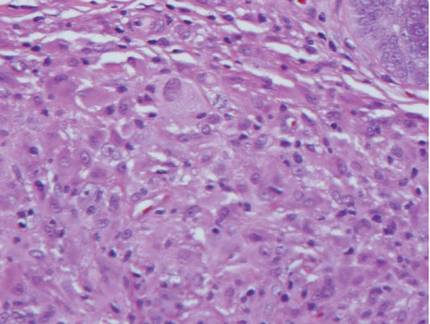

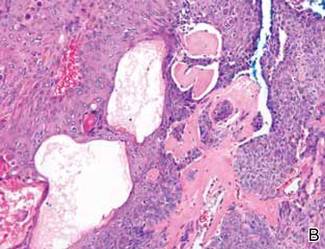

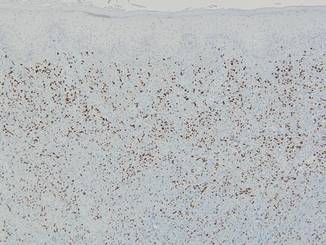

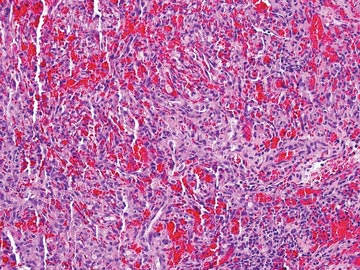

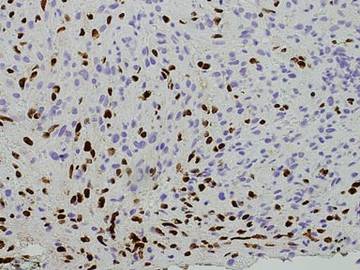

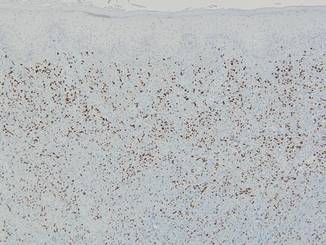

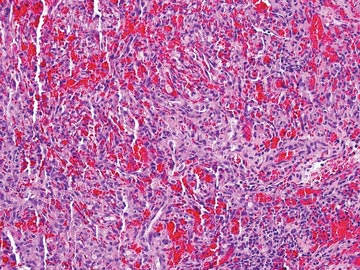

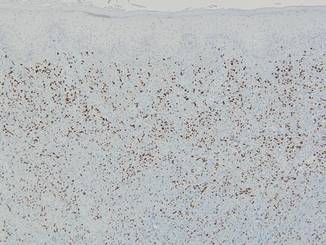

Potassium hydroxide preparation of a biopsy specimen (Figure 2), a punch biopsy of the lesion (Figure 3), and Gomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 4) revealed scattered yeast spores, some demonstrating broad-based budding, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal neutrophils, and intraepithelial microabscesses. The patient’s urine was positive for Blastomyces antigen (1.04 ng/mL). Chest radiography demonstrated a localized infiltrate in the right hilum with possible mass effect. Computed tomography showed a consolidative opacity measuring 4.0×3.4 cm in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 5).

|  |

The patient was diagnosed with cutaneous North American blastomycosis and prescribed a 6-month course of oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily. At his 3-month follow-up visit, the perianal plaque hadalmost completely resolved (Figure 6). However, because the patient had increasing lower extremity edema, subjective hearing loss, and abnormal liver function tests, itraconazole treatment was discontinued and replaced with oral fluconazole 400 mg daily for the next 3 months. The right hilar mass had visibly improved on follow-up chest radiography 2 months after the patient started antifungal therapy with itraconazole and had resolved within another 3 months of treatment.

|

|

Comment

Cutaneous blastomycosis results most often from the hematogenous spread of B dermatitidis from the lungs and rarely from direct inoculation.5,10 Skin lesions tend to occur on exposed areas, such as the face, scalp, hands, wrists, feet, and ankles.7,11-13 Dissemination to the perianal skin is rare, though it has been reported in 2 other patients; both patients, similar to our patient, had evidence of pulmonary involvement at some point in their clinical course.9,14

Diagnosis is based on identification of B dermatitidis by microscopy or culture. Potassium hydroxide preparation of biopsy specimens typically shows broad-based budding yeast.13 Characteristic findings of histopathologic studies include pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal abscesses, and a dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.15 On fungal culture, B dermatitidis is slow growing and may require a 2- to 4-week incubation period. Serologic tests are available, but sensitivity is low, at 9%, 28%, and 77% for complement fixation, immunodiffusion, and enzyme immunoassay, respectively.16

Conclusion

North American blastomycosis should be considered in patients who have verrucous or ulcerative perianal lesions and have lived in or traveled to endemic regions, especially if they have recent or ongoing pulmonary symptoms. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal staining of biopsy specimens can aid in diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication (Marshfield, Wisconsin) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29-39.

2. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529-534.

3. Reingold AL, Lu XD, Plikaytis BD, et al. Systemic mycoses in the United States, 1980-1982. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:433-436.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Blastomycosis—Wisconsin, 1986-1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:601-603.

5. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:173-180.

6. Goldman M, Johnson PC, Sarosi GA. Fungal pneumonias. the endemic mycoses. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:507-519.

7. Mercurio MG, Elewski BE. Cutaneous blastomycosis. Cutis. 1992;50:422-424.

8. Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

9. Ricciardi R, Alavi K, Filice GA, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis of the perianal skin: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:118-121.

10. Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis [published online ahead of print April 17, 2002]. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:e44-e49.

11. Kisso B, Mahmoud F, Thakkar JR. Blastomycosis presenting as recurrent tender cutaneous nodules. S D Med. 2006;59:255-259.

12. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

13. Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

14. Linn JE. Pseudo-epitheliomatous lesions of the perirectal tissue: report of a case of squamous epithelioma due to blastomycosis. South Med J. 1958;51:1101-1104.

15. Woofter MJ, Cripps DJ, Warner TF. Verrucous plaques on the face. North American blastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547, 550.

16. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, et al. Serological tests for blastomycosis: assessments during a large point-source outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:262-268.

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report

A 57-year-old man presented with a palpable perianal mass that produced small amounts of blood in his underwear and on toilet paper. The patient reported no history of hemorrhoids, anoreceptive intercourse, or sexually transmitted disease. Four months prior to presentation, he had a prolonged upper respiratory tract illness with a subjective fever and productive cough of 2 months’ duration. The patient described himself as an avid outdoorsman who worked at a summer resort and spent a great deal of time in the forests of central Wisconsin last autumn. Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, firm, moist plaque with a verrucous surface that measured 3.5×2.7 cm and extended from the anal verge to the perianal skin (Figure 1).

Potassium hydroxide preparation of a biopsy specimen (Figure 2), a punch biopsy of the lesion (Figure 3), and Gomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 4) revealed scattered yeast spores, some demonstrating broad-based budding, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal neutrophils, and intraepithelial microabscesses. The patient’s urine was positive for Blastomyces antigen (1.04 ng/mL). Chest radiography demonstrated a localized infiltrate in the right hilum with possible mass effect. Computed tomography showed a consolidative opacity measuring 4.0×3.4 cm in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 5).

|  |

The patient was diagnosed with cutaneous North American blastomycosis and prescribed a 6-month course of oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily. At his 3-month follow-up visit, the perianal plaque hadalmost completely resolved (Figure 6). However, because the patient had increasing lower extremity edema, subjective hearing loss, and abnormal liver function tests, itraconazole treatment was discontinued and replaced with oral fluconazole 400 mg daily for the next 3 months. The right hilar mass had visibly improved on follow-up chest radiography 2 months after the patient started antifungal therapy with itraconazole and had resolved within another 3 months of treatment.

|

|

Comment

Cutaneous blastomycosis results most often from the hematogenous spread of B dermatitidis from the lungs and rarely from direct inoculation.5,10 Skin lesions tend to occur on exposed areas, such as the face, scalp, hands, wrists, feet, and ankles.7,11-13 Dissemination to the perianal skin is rare, though it has been reported in 2 other patients; both patients, similar to our patient, had evidence of pulmonary involvement at some point in their clinical course.9,14

Diagnosis is based on identification of B dermatitidis by microscopy or culture. Potassium hydroxide preparation of biopsy specimens typically shows broad-based budding yeast.13 Characteristic findings of histopathologic studies include pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal abscesses, and a dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.15 On fungal culture, B dermatitidis is slow growing and may require a 2- to 4-week incubation period. Serologic tests are available, but sensitivity is low, at 9%, 28%, and 77% for complement fixation, immunodiffusion, and enzyme immunoassay, respectively.16

Conclusion

North American blastomycosis should be considered in patients who have verrucous or ulcerative perianal lesions and have lived in or traveled to endemic regions, especially if they have recent or ongoing pulmonary symptoms. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal staining of biopsy specimens can aid in diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication (Marshfield, Wisconsin) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Cutaneous North American blastomycosis is a deep fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus that is endemic to the Great Lakes region as well as the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys where it thrives in moist acidic soil enriched with organic material.1,2 In humans, the annual incidence rate is estimated to be 0.6 cases per million,3 though it may be as high as 42 cases per 100,000 in endemic areas.4 Infection typically results from the inhalation of conidia and manifests as either acute or chronic pneumonia.5 Most patients with acute disease present with nonspecific flulike symptoms and a nonproductive cough.

Dissemination occurs in approximately 25% of cases,6 most commonly affecting the skin. Other potential sites of dissemination include bone, the genitourinary tract, and the central nervous system. Cutaneous lesions, which may be either verrucous or ulcerative plaques, often occur on or around orifices contiguous to the respiratory tract.7 Verrucous lesions tend to have an irregular shape with well-defined borders and surface crusting. Ulcerative lesions have heaped-up borders and often have an exudative base.8 The differential diagnosis of cutaneous North American blastomycosis lesions includes squamous cell carcinoma, giant keratoacanthoma, verrucae, basal cell carcinoma, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, nocardiosis, syphilis, bromoderma, iododerma, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, mycetoma, and actinomycosis.7,8

Although periorificial cutaneous manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis are common, perianal lesions are rare. The differential diagnosis of perianal verrucous plaques includes condyloma acuminatum, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, Buschke-Löwenstein tumor, actinomycosis, and localized fungal infections such as blastomycosis.9

Case Report

A 57-year-old man presented with a palpable perianal mass that produced small amounts of blood in his underwear and on toilet paper. The patient reported no history of hemorrhoids, anoreceptive intercourse, or sexually transmitted disease. Four months prior to presentation, he had a prolonged upper respiratory tract illness with a subjective fever and productive cough of 2 months’ duration. The patient described himself as an avid outdoorsman who worked at a summer resort and spent a great deal of time in the forests of central Wisconsin last autumn. Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, firm, moist plaque with a verrucous surface that measured 3.5×2.7 cm and extended from the anal verge to the perianal skin (Figure 1).

Potassium hydroxide preparation of a biopsy specimen (Figure 2), a punch biopsy of the lesion (Figure 3), and Gomori methenamine-silver staining (Figure 4) revealed scattered yeast spores, some demonstrating broad-based budding, with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal neutrophils, and intraepithelial microabscesses. The patient’s urine was positive for Blastomyces antigen (1.04 ng/mL). Chest radiography demonstrated a localized infiltrate in the right hilum with possible mass effect. Computed tomography showed a consolidative opacity measuring 4.0×3.4 cm in the upper lobe of the right lung (Figure 5).

|  |

The patient was diagnosed with cutaneous North American blastomycosis and prescribed a 6-month course of oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily. At his 3-month follow-up visit, the perianal plaque hadalmost completely resolved (Figure 6). However, because the patient had increasing lower extremity edema, subjective hearing loss, and abnormal liver function tests, itraconazole treatment was discontinued and replaced with oral fluconazole 400 mg daily for the next 3 months. The right hilar mass had visibly improved on follow-up chest radiography 2 months after the patient started antifungal therapy with itraconazole and had resolved within another 3 months of treatment.

|

|

Comment

Cutaneous blastomycosis results most often from the hematogenous spread of B dermatitidis from the lungs and rarely from direct inoculation.5,10 Skin lesions tend to occur on exposed areas, such as the face, scalp, hands, wrists, feet, and ankles.7,11-13 Dissemination to the perianal skin is rare, though it has been reported in 2 other patients; both patients, similar to our patient, had evidence of pulmonary involvement at some point in their clinical course.9,14

Diagnosis is based on identification of B dermatitidis by microscopy or culture. Potassium hydroxide preparation of biopsy specimens typically shows broad-based budding yeast.13 Characteristic findings of histopathologic studies include pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal abscesses, and a dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes.15 On fungal culture, B dermatitidis is slow growing and may require a 2- to 4-week incubation period. Serologic tests are available, but sensitivity is low, at 9%, 28%, and 77% for complement fixation, immunodiffusion, and enzyme immunoassay, respectively.16

Conclusion

North American blastomycosis should be considered in patients who have verrucous or ulcerative perianal lesions and have lived in or traveled to endemic regions, especially if they have recent or ongoing pulmonary symptoms. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal staining of biopsy specimens can aid in diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication (Marshfield, Wisconsin) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

1. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29-39.

2. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529-534.

3. Reingold AL, Lu XD, Plikaytis BD, et al. Systemic mycoses in the United States, 1980-1982. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:433-436.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Blastomycosis—Wisconsin, 1986-1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:601-603.

5. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:173-180.

6. Goldman M, Johnson PC, Sarosi GA. Fungal pneumonias. the endemic mycoses. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:507-519.

7. Mercurio MG, Elewski BE. Cutaneous blastomycosis. Cutis. 1992;50:422-424.

8. Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

9. Ricciardi R, Alavi K, Filice GA, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis of the perianal skin: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:118-121.

10. Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis [published online ahead of print April 17, 2002]. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:e44-e49.

11. Kisso B, Mahmoud F, Thakkar JR. Blastomycosis presenting as recurrent tender cutaneous nodules. S D Med. 2006;59:255-259.

12. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

13. Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

14. Linn JE. Pseudo-epitheliomatous lesions of the perirectal tissue: report of a case of squamous epithelioma due to blastomycosis. South Med J. 1958;51:1101-1104.

15. Woofter MJ, Cripps DJ, Warner TF. Verrucous plaques on the face. North American blastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547, 550.

16. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, et al. Serological tests for blastomycosis: assessments during a large point-source outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:262-268.

1. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29-39.

2. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529-534.

3. Reingold AL, Lu XD, Plikaytis BD, et al. Systemic mycoses in the United States, 1980-1982. J Med Vet Mycol. 1986;24:433-436.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Blastomycosis—Wisconsin, 1986-1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996;45:601-603.

5. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7:173-180.

6. Goldman M, Johnson PC, Sarosi GA. Fungal pneumonias. the endemic mycoses. Clin Chest Med. 1999;20:507-519.

7. Mercurio MG, Elewski BE. Cutaneous blastomycosis. Cutis. 1992;50:422-424.

8. Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

9. Ricciardi R, Alavi K, Filice GA, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis of the perianal skin: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:118-121.

10. Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis [published online ahead of print April 17, 2002]. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:e44-e49.

11. Kisso B, Mahmoud F, Thakkar JR. Blastomycosis presenting as recurrent tender cutaneous nodules. S D Med. 2006;59:255-259.

12. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

13. Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

14. Linn JE. Pseudo-epitheliomatous lesions of the perirectal tissue: report of a case of squamous epithelioma due to blastomycosis. South Med J. 1958;51:1101-1104.

15. Woofter MJ, Cripps DJ, Warner TF. Verrucous plaques on the face. North American blastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:547, 550.

16. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, et al. Serological tests for blastomycosis: assessments during a large point-source outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:262-268.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous North American blastomycosis usually occurs in a periorificial distribution.

- The perianal region should be included in the periorificial regions considered in North American blastomycosis infections.

Nodular Scleroderma in a Patient With Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Coexistent or Causal Infection?

Case Report

A 63-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of multiple papules and nodules on the neck and trunk that had been present for 2 years. Three years prior to presentation she had been diagnosed with systemic sclerosis (SSc) after developing progressive diffuse cutaneous sclerosis, Raynaud phenomenon with digital pitted scarring, esophageal dysmotility, myositis, pericardial effusion, and interstitial lung disease. Serologic test results were positive for anti-Scl-70 antibodies. Antinuclear antibody test results were negative for anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-nRNP, anti-Ro/La, anti-Sm, and anti-Jo-1 antibodies. The patient was treated with prednisolone 7.5 mg daily, nifedipine 15 mg daily, valsartan 80 mg daily, manidipine 20 mg daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily, and beraprost 80 mg daily. One year later, numerous asymptomatic flesh-colored papules and nodules developed on the neck, chest, abdomen, and back. There was no history of trauma or surgery at any of the affected sites.

On further investigation, anti–hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies were identified and confirmed by HCV ribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction at the same time that the diagnosis of SSc was established. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3a was noted, and the patient’s viral load was 378,000 IU/mL. Therefore, a diagnosis of chronic HCV infection was established. The patient was initially unable to receive medical treatment due to lack of finances. A year and a half following the diagnosis of HCV infection, with worsening liver function tests and increasing viral load (1,369,113 IU/mL), the patient began therapy with peginterferon alfa-2b 80 mg weekly and ribavirin 800 mg daily. However, the medications were discontinued after 2 months when she developed severe hemolytic anemia related to ribavirin.

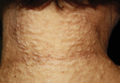

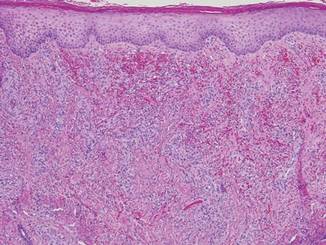

On physical examination, the patient was noted to have a masklike facies with a pinched nose and constricted opening of the mouth. Her skin was tightened and stiff extending from the fingers to the proximal extremities. Numerous well-circumscribed, flesh-colored, firm papules and nodules ranging from 2 to 20 mm in diameter were present on the neck (Figure 1), chest, abdomen (Figure 2), and back.

|  |

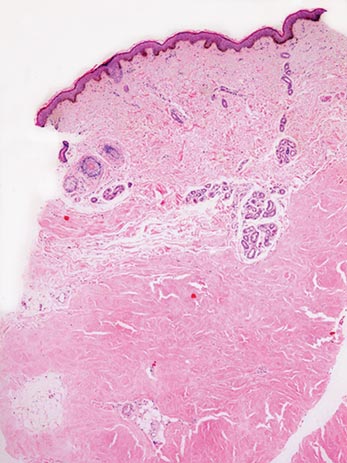

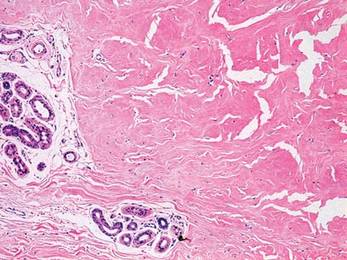

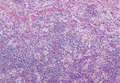

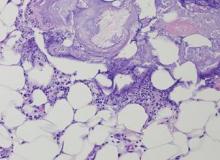

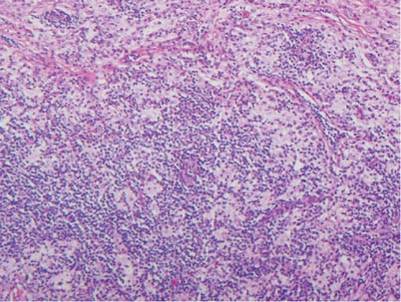

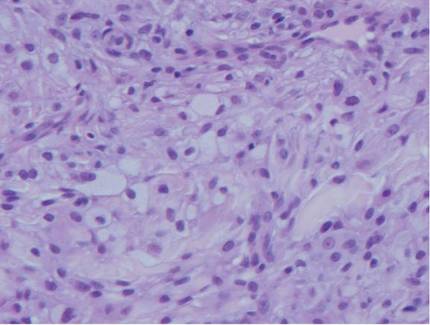

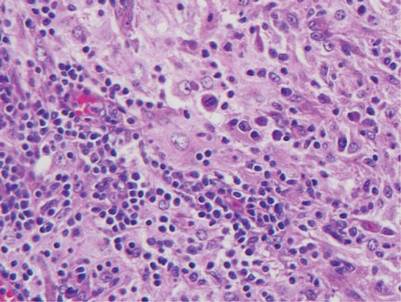

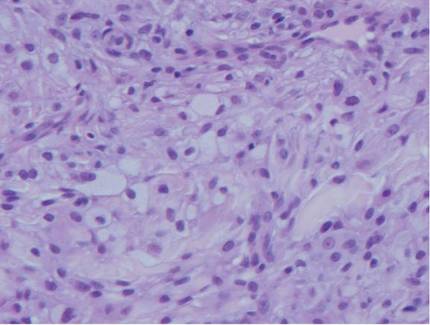

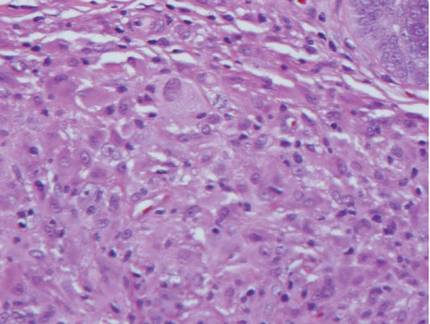

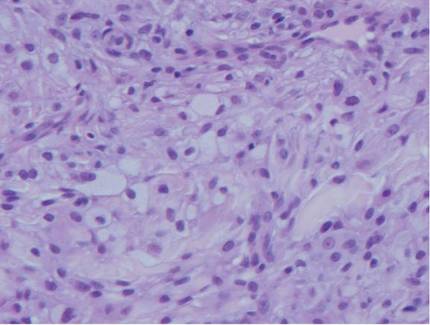

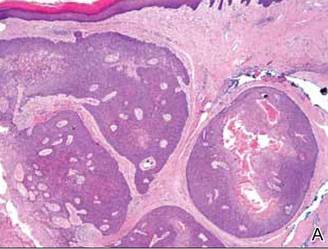

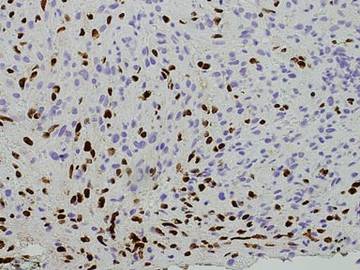

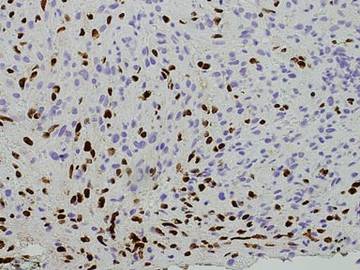

Two 4-mm punch biopsy samples obtained from a papule on the neck and a nodule on the abdomen revealed homogenized collagen bundles with scattered plump fibroblasts in the lower reticular dermis. Clinicopathologic correlation of the biopsy findings with the cutaneous examination resulted in a diagnosis of nodular scleroderma (Figures 3 and 4).

|

The patient began treatment with intralesional injections of triamcinolone 5 to 10 mg/mL for nodules as well as an ultrapotent corticosteroid cream, clobetasol propionate 0.05%, for small papules. Injections were performed at 4- to 8-week intervals and resulted in modest clinical improvement.

Comment

Scleroderma may be present only in the skin (morphea) or as a systemic disease (systemic scleroderma). Rarely, cutaneous involvement can exhibit a nodular or hypertrophic morphology, which has been described in the literature as nodular or keloidal scleroderma in a patient with known SSc1-10 and as nodular or keloidal morphea in localized cutaneous scleroderma.3,11-13

Histopathology

The distinction between the terms nodular scleroderma and keloidal scleroderma is not clear, and they are not necessarily interchangeable. To provide clarity, we find it useful to delineate specific histologic findings associated with the diagnoses of keloid, scleroderma, and the uncommon keloid/scleroderma overlap. The histopathologic findings of keloids include a fibrotic dermis and broad dispersed bundles of eosinophilic hyalinized collagen. The histopathologic findings of scleroderma include broad sclerotic bands of collagen throughout the dermis with loss of perieccrine fat. In the overlapping keloid/scleroderma condition, which is a variant of scleroderma, hyalinized collagen fibers and keloidal collagen appear in the same specimen.3,4

To distinguish these conditions, Barzilai et al5 proposed that only cases showing both clinical and histologic characteristics of a keloid should be referred to as keloidal morphea/scleroderma. They further stated that the terms nodular morphea or nodular scleroderma ought to be used only for cases that are indistinguishable histologically from scleroderma. The term morphea is appropriate when only a limited amount of skin disease is present, while scleroderma implies association with systemic disease.5 Likely, there is a histologic continuum in this variant of scleroderma, in which nodular morphea/scleroderma exists at one end and keloidal morphea/scleroderma exists at the other end.5,13

In the case of our patient, papulonodular lesions developed 1 year after the diagnosis of SSc was made, and the histopathologic examination revealed classic findings of scleroderma. As a result, our patient is most appropriately classified as having nodular scleroderma.

Clinical Features

Nodular scleroderma mostly affects young and middle-aged women and is clinically characterized by solitary or multiple firm, long-lasting papules or nodules on the upper trunk and chest, neck, and proximal extremities.1-4,6

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The triggers and cellular mechanisms of nodular scleroderma are unclear. Some authors have implicated matricellular protein and growth factors such as tenascin, connective tissue growth factor, and epidermal growth factor in nodule formation.7,8,11 Yamamoto et al9 cited chemical exposure to a silica-containing abrasive as the cause of nodular scleroderma in a worker.

Possible HCV Association

Some reports have indicated an association between nodular scleroderma and pathogens such as acid-fast bacteria10 and HCV.6 Of note, many extrahepatic conditions have been associated with HCV infection, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, cutaneous vasculitis, lichen planus, and porphyria cutanea tarda.14

The association of HCV infection with systemic autoimmune disease (SAD) has been described in a number of instances; cryoglobulinemia has most commonly been linked to HCV.15 Although the association between HCV and other SADs is less clear, there is growing interest in a possible relationship between them. To that end, physicians of the HISPAMEC (Hispanoamerican Study Group of Autoimmune Manifestations Associated With Hepatitis C Virus) study group described the clinical and immunologic characteristics of 1020 patients with SAD and associated chronic HCV infection. The 3 most frequent SADs (>90% of cases) were Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.16 However, the strength of association differs for each SAD based on existing descriptions.16,17 Less commonly, there may be a causal relationship between HCV infection and SSc. It should be noted that most of these data are based on small series and case reports.6,16-19

The role of HCV in the pathogenesis of systemic scleroderma and other autoimmune diseases is unknown. It is also possible that the replication of HCV outside the liver, particularly in mononuclear cells, may suppress immune tolerance in genetically predisposed individuals.20

Conclusion

Nodular scleroderma associated with HCV infection is a rare entity. At present, it cannot be determined whether there is an etiopathologic association between HCV infection and SSc or whether the simultaneous diagnosis may be coincidental. Routine determination of HCV serology in scleroderma patients may help to clarify this issue.

1. Krell JM, Solomon AR, Glavey CM, et al. Nodular scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:343-345.

2. Cannick L 3rd, Douglas G, Crater S, et al. Nodular scleroderma: case report and literature review. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2500-2502.

3. Rencic A, Brinster NK, Nousari CH. Keloid morphea and nodular scleroderma: two distinct clinical variants of scleroderma? J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:20-24.

4. Wriston CC, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Nodular scleroderma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:385-388.

5. Barzilai A, Lyakhovitsky A, Horowitz A, et al. Keloid-like scleroderma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:327-330.

6. Melani L, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al. A case of nodular scleroderma. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1028-1031.

7. Mizutani H, Taniguchi H, Sakakura T, et al. Nodular scleroderma: focally increased tenascin expression differing from that in the surrounding scleroderma skin. J Dermatol. 1995;22:267-271.

8. Yamamoto T, Sawada Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma: increased expression of connective tissue growth factor. Dermatology. 2005;211:218-223.

9. Yamamoto T, Furuse Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma in a worker using a silica-containing abrasive. J Dermatol. 1994;21:751-754.

10. Cantwell AR Jr, Rowe L, Kelso DW. Nodular scleroderma and pleomorphic acid-fast bacteria. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1283-1290.

11. Yamamoto T, Sakashita S, Sawada Y, et al. Possible role of epidermal growth factor in the lesional skin of nodular morphea. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:312-313.

12. Jain K, Dayal S, Jain VK, et al. Blaschko linear nodular morphea with dermal mucinosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:953-955.

13. Kauer F, Simon JC, Sticherling M. Nodular morphea. Dermatology. 2009;218:63-66.

14. Gumber SC, Chopra S. Hepatitis C: a multifaceted disease. review of extrahepatic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:615-620.

15. Ferri C, Greco F, Longombardo G, et al. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1606-1610.

16. Ramos-Casals M, Munoz S, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: characterization of 1020 cases (The HISPAMEC Registry). J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1442-1448.

17. Ramos-Casals M, Jara LJ, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases co-existing with chronic hepatitis C virus infection (the HISPAMEC Registry): patterns of clinical and immunological expression in 180 cases. J Intern Med. 2005;257:549-557.

18. Abu-Shakra M, Sukenik S, Buskila D. Systemic sclerosis: another rheumatic disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:378-380.

19. Yamamoto M, Yamamoto T, Tsuboi R. Discoid lupus erythematosus in a patient with scleroderma and hepatitis C virus infection. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:969-971.

20. Abu-Shakra M, Shoenfeld Y. Chronic infections and autoimmunity. Immunol Ser. 1992;55:285-313.

Case Report

A 63-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of multiple papules and nodules on the neck and trunk that had been present for 2 years. Three years prior to presentation she had been diagnosed with systemic sclerosis (SSc) after developing progressive diffuse cutaneous sclerosis, Raynaud phenomenon with digital pitted scarring, esophageal dysmotility, myositis, pericardial effusion, and interstitial lung disease. Serologic test results were positive for anti-Scl-70 antibodies. Antinuclear antibody test results were negative for anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-nRNP, anti-Ro/La, anti-Sm, and anti-Jo-1 antibodies. The patient was treated with prednisolone 7.5 mg daily, nifedipine 15 mg daily, valsartan 80 mg daily, manidipine 20 mg daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily, and beraprost 80 mg daily. One year later, numerous asymptomatic flesh-colored papules and nodules developed on the neck, chest, abdomen, and back. There was no history of trauma or surgery at any of the affected sites.

On further investigation, anti–hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies were identified and confirmed by HCV ribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction at the same time that the diagnosis of SSc was established. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3a was noted, and the patient’s viral load was 378,000 IU/mL. Therefore, a diagnosis of chronic HCV infection was established. The patient was initially unable to receive medical treatment due to lack of finances. A year and a half following the diagnosis of HCV infection, with worsening liver function tests and increasing viral load (1,369,113 IU/mL), the patient began therapy with peginterferon alfa-2b 80 mg weekly and ribavirin 800 mg daily. However, the medications were discontinued after 2 months when she developed severe hemolytic anemia related to ribavirin.

On physical examination, the patient was noted to have a masklike facies with a pinched nose and constricted opening of the mouth. Her skin was tightened and stiff extending from the fingers to the proximal extremities. Numerous well-circumscribed, flesh-colored, firm papules and nodules ranging from 2 to 20 mm in diameter were present on the neck (Figure 1), chest, abdomen (Figure 2), and back.

|  |

Two 4-mm punch biopsy samples obtained from a papule on the neck and a nodule on the abdomen revealed homogenized collagen bundles with scattered plump fibroblasts in the lower reticular dermis. Clinicopathologic correlation of the biopsy findings with the cutaneous examination resulted in a diagnosis of nodular scleroderma (Figures 3 and 4).

|

The patient began treatment with intralesional injections of triamcinolone 5 to 10 mg/mL for nodules as well as an ultrapotent corticosteroid cream, clobetasol propionate 0.05%, for small papules. Injections were performed at 4- to 8-week intervals and resulted in modest clinical improvement.

Comment

Scleroderma may be present only in the skin (morphea) or as a systemic disease (systemic scleroderma). Rarely, cutaneous involvement can exhibit a nodular or hypertrophic morphology, which has been described in the literature as nodular or keloidal scleroderma in a patient with known SSc1-10 and as nodular or keloidal morphea in localized cutaneous scleroderma.3,11-13

Histopathology

The distinction between the terms nodular scleroderma and keloidal scleroderma is not clear, and they are not necessarily interchangeable. To provide clarity, we find it useful to delineate specific histologic findings associated with the diagnoses of keloid, scleroderma, and the uncommon keloid/scleroderma overlap. The histopathologic findings of keloids include a fibrotic dermis and broad dispersed bundles of eosinophilic hyalinized collagen. The histopathologic findings of scleroderma include broad sclerotic bands of collagen throughout the dermis with loss of perieccrine fat. In the overlapping keloid/scleroderma condition, which is a variant of scleroderma, hyalinized collagen fibers and keloidal collagen appear in the same specimen.3,4

To distinguish these conditions, Barzilai et al5 proposed that only cases showing both clinical and histologic characteristics of a keloid should be referred to as keloidal morphea/scleroderma. They further stated that the terms nodular morphea or nodular scleroderma ought to be used only for cases that are indistinguishable histologically from scleroderma. The term morphea is appropriate when only a limited amount of skin disease is present, while scleroderma implies association with systemic disease.5 Likely, there is a histologic continuum in this variant of scleroderma, in which nodular morphea/scleroderma exists at one end and keloidal morphea/scleroderma exists at the other end.5,13

In the case of our patient, papulonodular lesions developed 1 year after the diagnosis of SSc was made, and the histopathologic examination revealed classic findings of scleroderma. As a result, our patient is most appropriately classified as having nodular scleroderma.

Clinical Features

Nodular scleroderma mostly affects young and middle-aged women and is clinically characterized by solitary or multiple firm, long-lasting papules or nodules on the upper trunk and chest, neck, and proximal extremities.1-4,6

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The triggers and cellular mechanisms of nodular scleroderma are unclear. Some authors have implicated matricellular protein and growth factors such as tenascin, connective tissue growth factor, and epidermal growth factor in nodule formation.7,8,11 Yamamoto et al9 cited chemical exposure to a silica-containing abrasive as the cause of nodular scleroderma in a worker.

Possible HCV Association

Some reports have indicated an association between nodular scleroderma and pathogens such as acid-fast bacteria10 and HCV.6 Of note, many extrahepatic conditions have been associated with HCV infection, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, cutaneous vasculitis, lichen planus, and porphyria cutanea tarda.14

The association of HCV infection with systemic autoimmune disease (SAD) has been described in a number of instances; cryoglobulinemia has most commonly been linked to HCV.15 Although the association between HCV and other SADs is less clear, there is growing interest in a possible relationship between them. To that end, physicians of the HISPAMEC (Hispanoamerican Study Group of Autoimmune Manifestations Associated With Hepatitis C Virus) study group described the clinical and immunologic characteristics of 1020 patients with SAD and associated chronic HCV infection. The 3 most frequent SADs (>90% of cases) were Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.16 However, the strength of association differs for each SAD based on existing descriptions.16,17 Less commonly, there may be a causal relationship between HCV infection and SSc. It should be noted that most of these data are based on small series and case reports.6,16-19

The role of HCV in the pathogenesis of systemic scleroderma and other autoimmune diseases is unknown. It is also possible that the replication of HCV outside the liver, particularly in mononuclear cells, may suppress immune tolerance in genetically predisposed individuals.20

Conclusion

Nodular scleroderma associated with HCV infection is a rare entity. At present, it cannot be determined whether there is an etiopathologic association between HCV infection and SSc or whether the simultaneous diagnosis may be coincidental. Routine determination of HCV serology in scleroderma patients may help to clarify this issue.

Case Report

A 63-year-old woman was referred to our clinic for evaluation of multiple papules and nodules on the neck and trunk that had been present for 2 years. Three years prior to presentation she had been diagnosed with systemic sclerosis (SSc) after developing progressive diffuse cutaneous sclerosis, Raynaud phenomenon with digital pitted scarring, esophageal dysmotility, myositis, pericardial effusion, and interstitial lung disease. Serologic test results were positive for anti-Scl-70 antibodies. Antinuclear antibody test results were negative for anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-nRNP, anti-Ro/La, anti-Sm, and anti-Jo-1 antibodies. The patient was treated with prednisolone 7.5 mg daily, nifedipine 15 mg daily, valsartan 80 mg daily, manidipine 20 mg daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily, and beraprost 80 mg daily. One year later, numerous asymptomatic flesh-colored papules and nodules developed on the neck, chest, abdomen, and back. There was no history of trauma or surgery at any of the affected sites.

On further investigation, anti–hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies were identified and confirmed by HCV ribonucleic acid polymerase chain reaction at the same time that the diagnosis of SSc was established. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3a was noted, and the patient’s viral load was 378,000 IU/mL. Therefore, a diagnosis of chronic HCV infection was established. The patient was initially unable to receive medical treatment due to lack of finances. A year and a half following the diagnosis of HCV infection, with worsening liver function tests and increasing viral load (1,369,113 IU/mL), the patient began therapy with peginterferon alfa-2b 80 mg weekly and ribavirin 800 mg daily. However, the medications were discontinued after 2 months when she developed severe hemolytic anemia related to ribavirin.

On physical examination, the patient was noted to have a masklike facies with a pinched nose and constricted opening of the mouth. Her skin was tightened and stiff extending from the fingers to the proximal extremities. Numerous well-circumscribed, flesh-colored, firm papules and nodules ranging from 2 to 20 mm in diameter were present on the neck (Figure 1), chest, abdomen (Figure 2), and back.

|  |

Two 4-mm punch biopsy samples obtained from a papule on the neck and a nodule on the abdomen revealed homogenized collagen bundles with scattered plump fibroblasts in the lower reticular dermis. Clinicopathologic correlation of the biopsy findings with the cutaneous examination resulted in a diagnosis of nodular scleroderma (Figures 3 and 4).

|

The patient began treatment with intralesional injections of triamcinolone 5 to 10 mg/mL for nodules as well as an ultrapotent corticosteroid cream, clobetasol propionate 0.05%, for small papules. Injections were performed at 4- to 8-week intervals and resulted in modest clinical improvement.

Comment

Scleroderma may be present only in the skin (morphea) or as a systemic disease (systemic scleroderma). Rarely, cutaneous involvement can exhibit a nodular or hypertrophic morphology, which has been described in the literature as nodular or keloidal scleroderma in a patient with known SSc1-10 and as nodular or keloidal morphea in localized cutaneous scleroderma.3,11-13

Histopathology

The distinction between the terms nodular scleroderma and keloidal scleroderma is not clear, and they are not necessarily interchangeable. To provide clarity, we find it useful to delineate specific histologic findings associated with the diagnoses of keloid, scleroderma, and the uncommon keloid/scleroderma overlap. The histopathologic findings of keloids include a fibrotic dermis and broad dispersed bundles of eosinophilic hyalinized collagen. The histopathologic findings of scleroderma include broad sclerotic bands of collagen throughout the dermis with loss of perieccrine fat. In the overlapping keloid/scleroderma condition, which is a variant of scleroderma, hyalinized collagen fibers and keloidal collagen appear in the same specimen.3,4

To distinguish these conditions, Barzilai et al5 proposed that only cases showing both clinical and histologic characteristics of a keloid should be referred to as keloidal morphea/scleroderma. They further stated that the terms nodular morphea or nodular scleroderma ought to be used only for cases that are indistinguishable histologically from scleroderma. The term morphea is appropriate when only a limited amount of skin disease is present, while scleroderma implies association with systemic disease.5 Likely, there is a histologic continuum in this variant of scleroderma, in which nodular morphea/scleroderma exists at one end and keloidal morphea/scleroderma exists at the other end.5,13

In the case of our patient, papulonodular lesions developed 1 year after the diagnosis of SSc was made, and the histopathologic examination revealed classic findings of scleroderma. As a result, our patient is most appropriately classified as having nodular scleroderma.

Clinical Features

Nodular scleroderma mostly affects young and middle-aged women and is clinically characterized by solitary or multiple firm, long-lasting papules or nodules on the upper trunk and chest, neck, and proximal extremities.1-4,6

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The triggers and cellular mechanisms of nodular scleroderma are unclear. Some authors have implicated matricellular protein and growth factors such as tenascin, connective tissue growth factor, and epidermal growth factor in nodule formation.7,8,11 Yamamoto et al9 cited chemical exposure to a silica-containing abrasive as the cause of nodular scleroderma in a worker.

Possible HCV Association

Some reports have indicated an association between nodular scleroderma and pathogens such as acid-fast bacteria10 and HCV.6 Of note, many extrahepatic conditions have been associated with HCV infection, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, cutaneous vasculitis, lichen planus, and porphyria cutanea tarda.14

The association of HCV infection with systemic autoimmune disease (SAD) has been described in a number of instances; cryoglobulinemia has most commonly been linked to HCV.15 Although the association between HCV and other SADs is less clear, there is growing interest in a possible relationship between them. To that end, physicians of the HISPAMEC (Hispanoamerican Study Group of Autoimmune Manifestations Associated With Hepatitis C Virus) study group described the clinical and immunologic characteristics of 1020 patients with SAD and associated chronic HCV infection. The 3 most frequent SADs (>90% of cases) were Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus.16 However, the strength of association differs for each SAD based on existing descriptions.16,17 Less commonly, there may be a causal relationship between HCV infection and SSc. It should be noted that most of these data are based on small series and case reports.6,16-19

The role of HCV in the pathogenesis of systemic scleroderma and other autoimmune diseases is unknown. It is also possible that the replication of HCV outside the liver, particularly in mononuclear cells, may suppress immune tolerance in genetically predisposed individuals.20

Conclusion

Nodular scleroderma associated with HCV infection is a rare entity. At present, it cannot be determined whether there is an etiopathologic association between HCV infection and SSc or whether the simultaneous diagnosis may be coincidental. Routine determination of HCV serology in scleroderma patients may help to clarify this issue.

1. Krell JM, Solomon AR, Glavey CM, et al. Nodular scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:343-345.

2. Cannick L 3rd, Douglas G, Crater S, et al. Nodular scleroderma: case report and literature review. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2500-2502.

3. Rencic A, Brinster NK, Nousari CH. Keloid morphea and nodular scleroderma: two distinct clinical variants of scleroderma? J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:20-24.

4. Wriston CC, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Nodular scleroderma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:385-388.

5. Barzilai A, Lyakhovitsky A, Horowitz A, et al. Keloid-like scleroderma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:327-330.

6. Melani L, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al. A case of nodular scleroderma. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1028-1031.

7. Mizutani H, Taniguchi H, Sakakura T, et al. Nodular scleroderma: focally increased tenascin expression differing from that in the surrounding scleroderma skin. J Dermatol. 1995;22:267-271.

8. Yamamoto T, Sawada Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma: increased expression of connective tissue growth factor. Dermatology. 2005;211:218-223.

9. Yamamoto T, Furuse Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma in a worker using a silica-containing abrasive. J Dermatol. 1994;21:751-754.

10. Cantwell AR Jr, Rowe L, Kelso DW. Nodular scleroderma and pleomorphic acid-fast bacteria. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1283-1290.

11. Yamamoto T, Sakashita S, Sawada Y, et al. Possible role of epidermal growth factor in the lesional skin of nodular morphea. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:312-313.

12. Jain K, Dayal S, Jain VK, et al. Blaschko linear nodular morphea with dermal mucinosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:953-955.

13. Kauer F, Simon JC, Sticherling M. Nodular morphea. Dermatology. 2009;218:63-66.

14. Gumber SC, Chopra S. Hepatitis C: a multifaceted disease. review of extrahepatic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:615-620.

15. Ferri C, Greco F, Longombardo G, et al. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1606-1610.

16. Ramos-Casals M, Munoz S, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: characterization of 1020 cases (The HISPAMEC Registry). J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1442-1448.

17. Ramos-Casals M, Jara LJ, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases co-existing with chronic hepatitis C virus infection (the HISPAMEC Registry): patterns of clinical and immunological expression in 180 cases. J Intern Med. 2005;257:549-557.

18. Abu-Shakra M, Sukenik S, Buskila D. Systemic sclerosis: another rheumatic disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:378-380.

19. Yamamoto M, Yamamoto T, Tsuboi R. Discoid lupus erythematosus in a patient with scleroderma and hepatitis C virus infection. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:969-971.

20. Abu-Shakra M, Shoenfeld Y. Chronic infections and autoimmunity. Immunol Ser. 1992;55:285-313.

1. Krell JM, Solomon AR, Glavey CM, et al. Nodular scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:343-345.

2. Cannick L 3rd, Douglas G, Crater S, et al. Nodular scleroderma: case report and literature review. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2500-2502.

3. Rencic A, Brinster NK, Nousari CH. Keloid morphea and nodular scleroderma: two distinct clinical variants of scleroderma? J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:20-24.

4. Wriston CC, Rubin AI, Elenitsas R, et al. Nodular scleroderma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:385-388.

5. Barzilai A, Lyakhovitsky A, Horowitz A, et al. Keloid-like scleroderma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:327-330.

6. Melani L, Caproni M, Cardinali C, et al. A case of nodular scleroderma. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1028-1031.

7. Mizutani H, Taniguchi H, Sakakura T, et al. Nodular scleroderma: focally increased tenascin expression differing from that in the surrounding scleroderma skin. J Dermatol. 1995;22:267-271.

8. Yamamoto T, Sawada Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma: increased expression of connective tissue growth factor. Dermatology. 2005;211:218-223.

9. Yamamoto T, Furuse Y, Katayama I, et al. Nodular scleroderma in a worker using a silica-containing abrasive. J Dermatol. 1994;21:751-754.

10. Cantwell AR Jr, Rowe L, Kelso DW. Nodular scleroderma and pleomorphic acid-fast bacteria. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1283-1290.

11. Yamamoto T, Sakashita S, Sawada Y, et al. Possible role of epidermal growth factor in the lesional skin of nodular morphea. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:312-313.

12. Jain K, Dayal S, Jain VK, et al. Blaschko linear nodular morphea with dermal mucinosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:953-955.

13. Kauer F, Simon JC, Sticherling M. Nodular morphea. Dermatology. 2009;218:63-66.

14. Gumber SC, Chopra S. Hepatitis C: a multifaceted disease. review of extrahepatic manifestations. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:615-620.

15. Ferri C, Greco F, Longombardo G, et al. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1606-1610.

16. Ramos-Casals M, Munoz S, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: characterization of 1020 cases (The HISPAMEC Registry). J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1442-1448.

17. Ramos-Casals M, Jara LJ, Medina F, et al. Systemic autoimmune diseases co-existing with chronic hepatitis C virus infection (the HISPAMEC Registry): patterns of clinical and immunological expression in 180 cases. J Intern Med. 2005;257:549-557.

18. Abu-Shakra M, Sukenik S, Buskila D. Systemic sclerosis: another rheumatic disease associated with hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19:378-380.

19. Yamamoto M, Yamamoto T, Tsuboi R. Discoid lupus erythematosus in a patient with scleroderma and hepatitis C virus infection. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:969-971.

20. Abu-Shakra M, Shoenfeld Y. Chronic infections and autoimmunity. Immunol Ser. 1992;55:285-313.

Practice Points

- Nodular scleroderma is a rare form of cutaneous scleroderma that can occur in association with systemic scleroderma or localized morphea.

- The clinical features are characterized by solitary or multiple, firm, long-lasting papules or nodules on the neck, upper trunk, and proximal extremities.

- The pathogenesis is still unclear. Some reports have suggested that matricellular protein and growth factor, acid-fast bacteria, organic solvents, or the hepatitis C virus may be involved.

Sweet Syndrome Presenting With an Unusual Morphology

To the Editor:

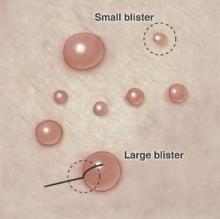

Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that typically presents as an acute onset of multiple, painful, sharply demarcated, small (measuring a few centimeters), raised, red plaques that occasionally present with superimposed pustules, vesicles, or bullae on the face, neck, upper chest, back, and extremities. Patients are often febrile and may have mucosal and systemic involvement.1 Although 71% of cases are idiopathic, others are associated with malignancy; autoimmune disorders; infections; pregnancy; and rarely medications, especially all-trans-retinoic acid, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, vaccines, and antibiotics.1,2 We present a case of Sweet syndrome induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) with an unusual clinical presentation.

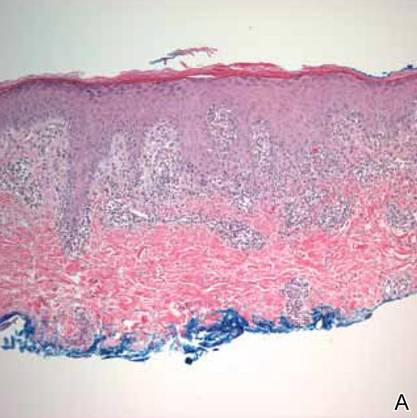

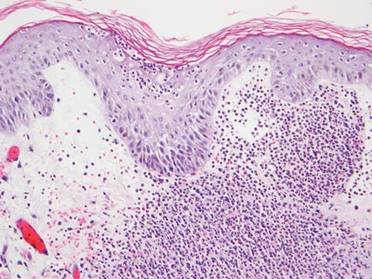

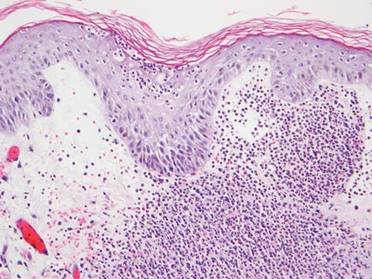

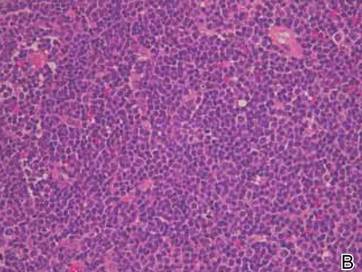

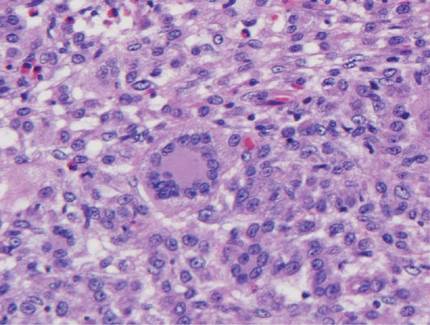

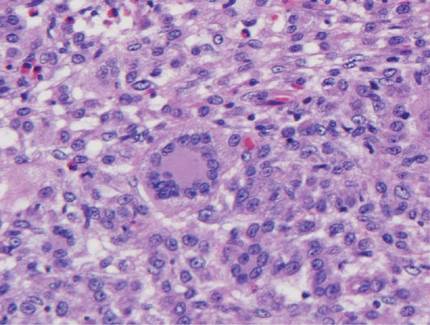

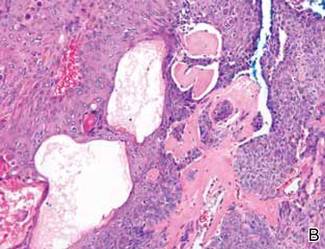

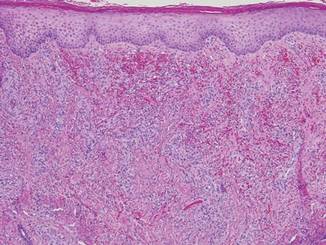

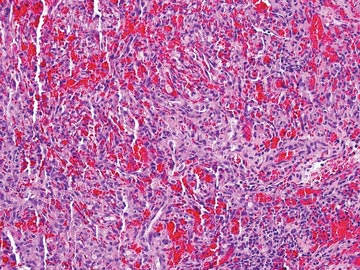

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of nonmelanoma skin cancer initiated a course of TMP-SMX for a wound infection of the lower leg following Mohs micrographic surgery. Eight days later, he developed a painful eruption preceded by 1 day of fever, malaise, blurry vision, and myalgia. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was discontinued. Physical examination revealed ill-defined, discrete and coalescing, 1- to 6-mm edematous erythematous papules studded with pustules involving the scalp, face, neck, back (Figure 1), and extremities. The patient also had conjunctival erythema and an elevated temperature (38.3°C). Laboratory workup revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,300/mL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), blood urea nitrogen level (33 mg/µL [reference range, 7–20 mg/dL]), and creatinine level (2.00 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Liver function tests were normal. A biopsy demonstrated marked papillary dermal edema with a dense, bandlike, superficial dermal neutrophilic infiltrate (Figure 2). A few neutrophils were present in the epidermis with formation of minute intraepidermal pustules. The patient was diagnosed with Sweet syndrome and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 60 mg 3 times daily (1.5 mg/kg body weight) tapered over 17 days and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily. His fever and leukocytosis resolved within 1 day and the eruption improved within 2 days with residual desquamation that cleared by 3 weeks.

|  |

Morphologically, our case resembled acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which presents with edematous erythema studded with pustules.3 Although fever and leukocytosis are often present in both AGEP and Sweet syndrome, our patient’s pain, malaise, and myalgia favored Sweet syndrome, as did his conjunctivitis, which is unusual in AGEP.1,3 Histologically, our case was characteristic for Sweet syndrome, which presents with marked papillary dermal edema and a dense neutrophilic dermal infiltrate with neutrophil exocytosis and spongiform pustules in 21% of cases.1 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, characterized by spongiform pustules and a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, does not exhibit the dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate of Sweet syndrome.3 Mecca et al4 also reported a case displaying overlapping features of Sweet syndrome and AGEP. The patient presented with photodistributed papules and pinpoint pustules on an erythematous base favoring a diagnosis of AGEP with histologic findings compatible with Sweet syndrome. The authors suggested a clinicopathologic continuum may exist among drug-related neutrophilic dermatoses.4

In conclusion, we present a case of TMP-SMX–induced Sweet syndrome that morphologically resembled AGEP. It is important to recognize that Sweet syndrome may present in this unusual manner, as it may have notable internal involvement, and responds rapidly to systemic steroids, whereas AGEP has minimal systemic involvement and clears spontaneously.

1. von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Kluger N, Marque M, Stoebner PE, et al. Possible drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:637-638.

3. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

4. Mecca P, Tobin E, Andrew Carlson J. Photo-distributed neutrophilic drug eruption and adult respiratory distress syndrome associated with antidepressant therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:189-194.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that typically presents as an acute onset of multiple, painful, sharply demarcated, small (measuring a few centimeters), raised, red plaques that occasionally present with superimposed pustules, vesicles, or bullae on the face, neck, upper chest, back, and extremities. Patients are often febrile and may have mucosal and systemic involvement.1 Although 71% of cases are idiopathic, others are associated with malignancy; autoimmune disorders; infections; pregnancy; and rarely medications, especially all-trans-retinoic acid, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, vaccines, and antibiotics.1,2 We present a case of Sweet syndrome induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) with an unusual clinical presentation.

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of nonmelanoma skin cancer initiated a course of TMP-SMX for a wound infection of the lower leg following Mohs micrographic surgery. Eight days later, he developed a painful eruption preceded by 1 day of fever, malaise, blurry vision, and myalgia. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was discontinued. Physical examination revealed ill-defined, discrete and coalescing, 1- to 6-mm edematous erythematous papules studded with pustules involving the scalp, face, neck, back (Figure 1), and extremities. The patient also had conjunctival erythema and an elevated temperature (38.3°C). Laboratory workup revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,300/mL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), blood urea nitrogen level (33 mg/µL [reference range, 7–20 mg/dL]), and creatinine level (2.00 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Liver function tests were normal. A biopsy demonstrated marked papillary dermal edema with a dense, bandlike, superficial dermal neutrophilic infiltrate (Figure 2). A few neutrophils were present in the epidermis with formation of minute intraepidermal pustules. The patient was diagnosed with Sweet syndrome and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 60 mg 3 times daily (1.5 mg/kg body weight) tapered over 17 days and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily. His fever and leukocytosis resolved within 1 day and the eruption improved within 2 days with residual desquamation that cleared by 3 weeks.

|  |

Morphologically, our case resembled acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which presents with edematous erythema studded with pustules.3 Although fever and leukocytosis are often present in both AGEP and Sweet syndrome, our patient’s pain, malaise, and myalgia favored Sweet syndrome, as did his conjunctivitis, which is unusual in AGEP.1,3 Histologically, our case was characteristic for Sweet syndrome, which presents with marked papillary dermal edema and a dense neutrophilic dermal infiltrate with neutrophil exocytosis and spongiform pustules in 21% of cases.1 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, characterized by spongiform pustules and a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, does not exhibit the dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate of Sweet syndrome.3 Mecca et al4 also reported a case displaying overlapping features of Sweet syndrome and AGEP. The patient presented with photodistributed papules and pinpoint pustules on an erythematous base favoring a diagnosis of AGEP with histologic findings compatible with Sweet syndrome. The authors suggested a clinicopathologic continuum may exist among drug-related neutrophilic dermatoses.4

In conclusion, we present a case of TMP-SMX–induced Sweet syndrome that morphologically resembled AGEP. It is important to recognize that Sweet syndrome may present in this unusual manner, as it may have notable internal involvement, and responds rapidly to systemic steroids, whereas AGEP has minimal systemic involvement and clears spontaneously.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that typically presents as an acute onset of multiple, painful, sharply demarcated, small (measuring a few centimeters), raised, red plaques that occasionally present with superimposed pustules, vesicles, or bullae on the face, neck, upper chest, back, and extremities. Patients are often febrile and may have mucosal and systemic involvement.1 Although 71% of cases are idiopathic, others are associated with malignancy; autoimmune disorders; infections; pregnancy; and rarely medications, especially all-trans-retinoic acid, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, vaccines, and antibiotics.1,2 We present a case of Sweet syndrome induced by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) with an unusual clinical presentation.

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of nonmelanoma skin cancer initiated a course of TMP-SMX for a wound infection of the lower leg following Mohs micrographic surgery. Eight days later, he developed a painful eruption preceded by 1 day of fever, malaise, blurry vision, and myalgia. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was discontinued. Physical examination revealed ill-defined, discrete and coalescing, 1- to 6-mm edematous erythematous papules studded with pustules involving the scalp, face, neck, back (Figure 1), and extremities. The patient also had conjunctival erythema and an elevated temperature (38.3°C). Laboratory workup revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11,300/mL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), blood urea nitrogen level (33 mg/µL [reference range, 7–20 mg/dL]), and creatinine level (2.00 mg/dL [reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL]). Liver function tests were normal. A biopsy demonstrated marked papillary dermal edema with a dense, bandlike, superficial dermal neutrophilic infiltrate (Figure 2). A few neutrophils were present in the epidermis with formation of minute intraepidermal pustules. The patient was diagnosed with Sweet syndrome and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 60 mg 3 times daily (1.5 mg/kg body weight) tapered over 17 days and triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily. His fever and leukocytosis resolved within 1 day and the eruption improved within 2 days with residual desquamation that cleared by 3 weeks.

|  |

Morphologically, our case resembled acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), which presents with edematous erythema studded with pustules.3 Although fever and leukocytosis are often present in both AGEP and Sweet syndrome, our patient’s pain, malaise, and myalgia favored Sweet syndrome, as did his conjunctivitis, which is unusual in AGEP.1,3 Histologically, our case was characteristic for Sweet syndrome, which presents with marked papillary dermal edema and a dense neutrophilic dermal infiltrate with neutrophil exocytosis and spongiform pustules in 21% of cases.1 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, characterized by spongiform pustules and a perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, does not exhibit the dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate of Sweet syndrome.3 Mecca et al4 also reported a case displaying overlapping features of Sweet syndrome and AGEP. The patient presented with photodistributed papules and pinpoint pustules on an erythematous base favoring a diagnosis of AGEP with histologic findings compatible with Sweet syndrome. The authors suggested a clinicopathologic continuum may exist among drug-related neutrophilic dermatoses.4

In conclusion, we present a case of TMP-SMX–induced Sweet syndrome that morphologically resembled AGEP. It is important to recognize that Sweet syndrome may present in this unusual manner, as it may have notable internal involvement, and responds rapidly to systemic steroids, whereas AGEP has minimal systemic involvement and clears spontaneously.

1. von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Kluger N, Marque M, Stoebner PE, et al. Possible drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:637-638.

3. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

4. Mecca P, Tobin E, Andrew Carlson J. Photo-distributed neutrophilic drug eruption and adult respiratory distress syndrome associated with antidepressant therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:189-194.

1. von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Kluger N, Marque M, Stoebner PE, et al. Possible drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome due to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:637-638.

3. Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:113-119.

4. Mecca P, Tobin E, Andrew Carlson J. Photo-distributed neutrophilic drug eruption and adult respiratory distress syndrome associated with antidepressant therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:189-194.

Bilateral Auricular Swelling: Marginal Zone Lymphoma With Cutaneous Involvement

To the Editor:

A 66-year-old man with hypertension presented with asymptomatic, edematous, swelling plaques without local heat on the bilateral auricles of 2 months’ duration (Figure 1). Topical corticosteroids and multiple oral antihistamines were prescribed without any improvement. He reported no history of trauma or use of any topical agents except topical corticosteroids. There was no sensory defect or numbness.

|

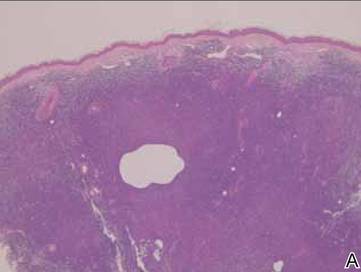

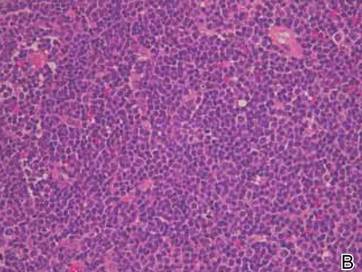

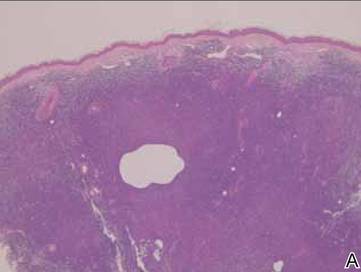

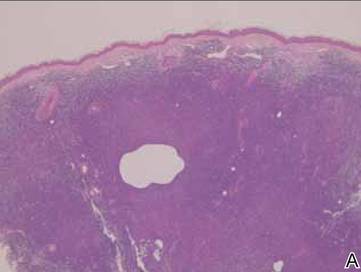

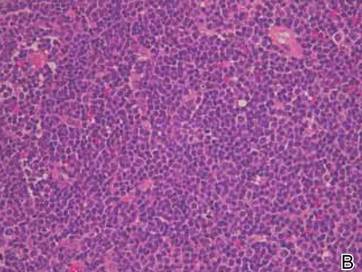

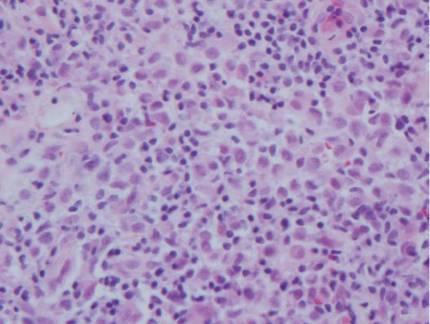

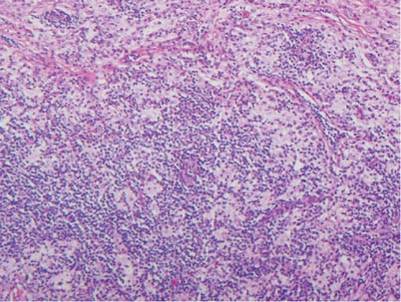

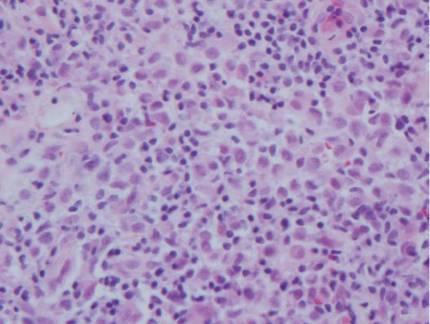

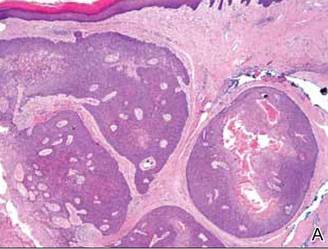

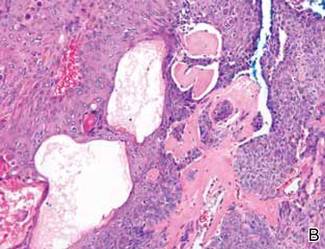

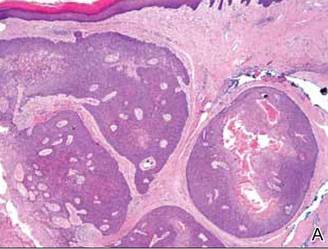

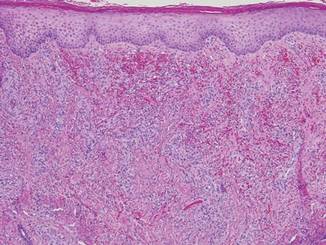

Laboratory results revealed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 13,900/mL (reference range, 3500–9900/μL) and 55.8% lymphocytes (reference range, 20%–40%). Biochemistry and tumor markers data were normal. No palpable neck lymphadenopathy was found. A skin biopsy was performed on the left earlobe showing a grenz zone between the tumor infiltrate and epidermis and a dense neoplastic lymphoid proliferation with a bottom-heavy configuration in the reticular dermis (Figure 2A). These lymphoid cells were small to medium sized with indented and irregular nuclei and abundant pale cytoplasm (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for CD20 and BCL2; stains for CD5, CD10, CD23, and BCL6 were negative. Positron emission tomography scan showed bilateral auricular infiltration and bilateral neck lymph node involvement. A bone marrow biopsy was performed during hospitalization and was positive for lymphoma involvement. On the basis of histologic and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of malignant nodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) with cutaneous involvement was made. The patient underwent chemotherapy with R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone).

Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed basket weave hyperkeratosis, a grenz zone between the tumor infiltrate and epidermis, and dense lymphoid proliferation with a bottom-heavy configuration in the reticular dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells with indented and irregular nuclei and abundant pale cytoplasm were seen (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Cutaneous MZL may be a primary cutaneous condition or the result of secondary involvement from noncutaneous MZL. The histologic and immunophenotypic changes in skin lesions from secondary cutaneous MZL may be indistinguishable from those in primary cutaneous MZL. Primary cutaneous MZL may be seen in younger patients and favors the trunk and extremities, whereas MZL secondarily involves the skin, favors the head and neck regions, and is limited to older patients.1 Histologic aspects include a dense, nodular, deep-seated infiltrate containing various proportions of small cells displaying a centrocytelike, plasmacytoid, or monocytoid appearance.2 Chronic antigen stimulation is a key player in the pathogenesis and involves deregulation of the nuclear factor κb pathway. While Helicobacter pylori and Epstein-Barr virus do not seem to be implicated in primary cutaneous MZL, the role of Borrelia burgdorferi is still a matter of debate with discordant results.3,4

Treatment may include excision, curative or adjunctive radiotherapy, topical or intralesional corticosteroids, interferon or intralesional rituximab, or systemic therapies such as chemotherapy and/or intravenous rituximab depending on disease stage and tumor burden.5

Cutaneous presentation of MZL as bilateral auricular swelling is unique. Because there may be considerable overlap in the clinical presentations for patients with primary and secondary cutaneous MZL, it is imperative to perform a systemic evaluation. Clinicians should be aware of possible hematologic malignancy in patients with unexplained and refractory bilateral auricular swelling.

1. Gerami P, Wickless SC, Querfeld C, et al. Cutaneous involvement with marginal zone lymphoma [published online ahead of print May 11, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:142-145.

2. de la Fouchardière A, Balme B, Chouvet B, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: a report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):181-188.

3. Dalle S, Thomas L, Balme B, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma [published online ahead of print October 12, 2009]. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;74:156-162.

4. Li C, Inagaki H, Kuo TT, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: a molecular and clinicopathologic study of 24 Asian cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1061-1069.

5. Grange F, D’Incan M, Ortonne N, et al. Management of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: recommendations of the French cutaneous lymphoma study group [published online ahead of print June 18, 2010]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:523-531.

To the Editor:

A 66-year-old man with hypertension presented with asymptomatic, edematous, swelling plaques without local heat on the bilateral auricles of 2 months’ duration (Figure 1). Topical corticosteroids and multiple oral antihistamines were prescribed without any improvement. He reported no history of trauma or use of any topical agents except topical corticosteroids. There was no sensory defect or numbness.

|

Laboratory results revealed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 13,900/mL (reference range, 3500–9900/μL) and 55.8% lymphocytes (reference range, 20%–40%). Biochemistry and tumor markers data were normal. No palpable neck lymphadenopathy was found. A skin biopsy was performed on the left earlobe showing a grenz zone between the tumor infiltrate and epidermis and a dense neoplastic lymphoid proliferation with a bottom-heavy configuration in the reticular dermis (Figure 2A). These lymphoid cells were small to medium sized with indented and irregular nuclei and abundant pale cytoplasm (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for CD20 and BCL2; stains for CD5, CD10, CD23, and BCL6 were negative. Positron emission tomography scan showed bilateral auricular infiltration and bilateral neck lymph node involvement. A bone marrow biopsy was performed during hospitalization and was positive for lymphoma involvement. On the basis of histologic and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of malignant nodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) with cutaneous involvement was made. The patient underwent chemotherapy with R-CHOP (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone).

Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed basket weave hyperkeratosis, a grenz zone between the tumor infiltrate and epidermis, and dense lymphoid proliferation with a bottom-heavy configuration in the reticular dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells with indented and irregular nuclei and abundant pale cytoplasm were seen (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

Cutaneous MZL may be a primary cutaneous condition or the result of secondary involvement from noncutaneous MZL. The histologic and immunophenotypic changes in skin lesions from secondary cutaneous MZL may be indistinguishable from those in primary cutaneous MZL. Primary cutaneous MZL may be seen in younger patients and favors the trunk and extremities, whereas MZL secondarily involves the skin, favors the head and neck regions, and is limited to older patients.1 Histologic aspects include a dense, nodular, deep-seated infiltrate containing various proportions of small cells displaying a centrocytelike, plasmacytoid, or monocytoid appearance.2 Chronic antigen stimulation is a key player in the pathogenesis and involves deregulation of the nuclear factor κb pathway. While Helicobacter pylori and Epstein-Barr virus do not seem to be implicated in primary cutaneous MZL, the role of Borrelia burgdorferi is still a matter of debate with discordant results.3,4

Treatment may include excision, curative or adjunctive radiotherapy, topical or intralesional corticosteroids, interferon or intralesional rituximab, or systemic therapies such as chemotherapy and/or intravenous rituximab depending on disease stage and tumor burden.5

Cutaneous presentation of MZL as bilateral auricular swelling is unique. Because there may be considerable overlap in the clinical presentations for patients with primary and secondary cutaneous MZL, it is imperative to perform a systemic evaluation. Clinicians should be aware of possible hematologic malignancy in patients with unexplained and refractory bilateral auricular swelling.

To the Editor:

A 66-year-old man with hypertension presented with asymptomatic, edematous, swelling plaques without local heat on the bilateral auricles of 2 months’ duration (Figure 1). Topical corticosteroids and multiple oral antihistamines were prescribed without any improvement. He reported no history of trauma or use of any topical agents except topical corticosteroids. There was no sensory defect or numbness.

|