User login

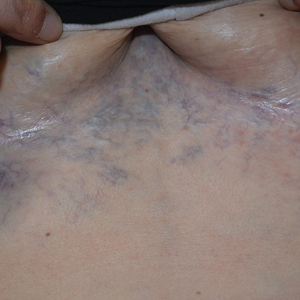

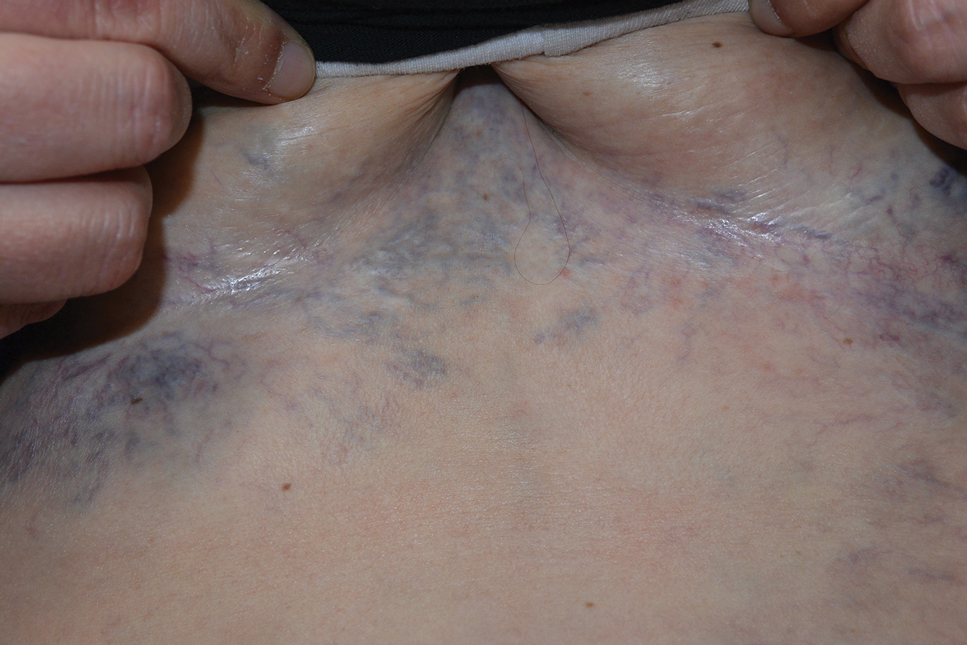

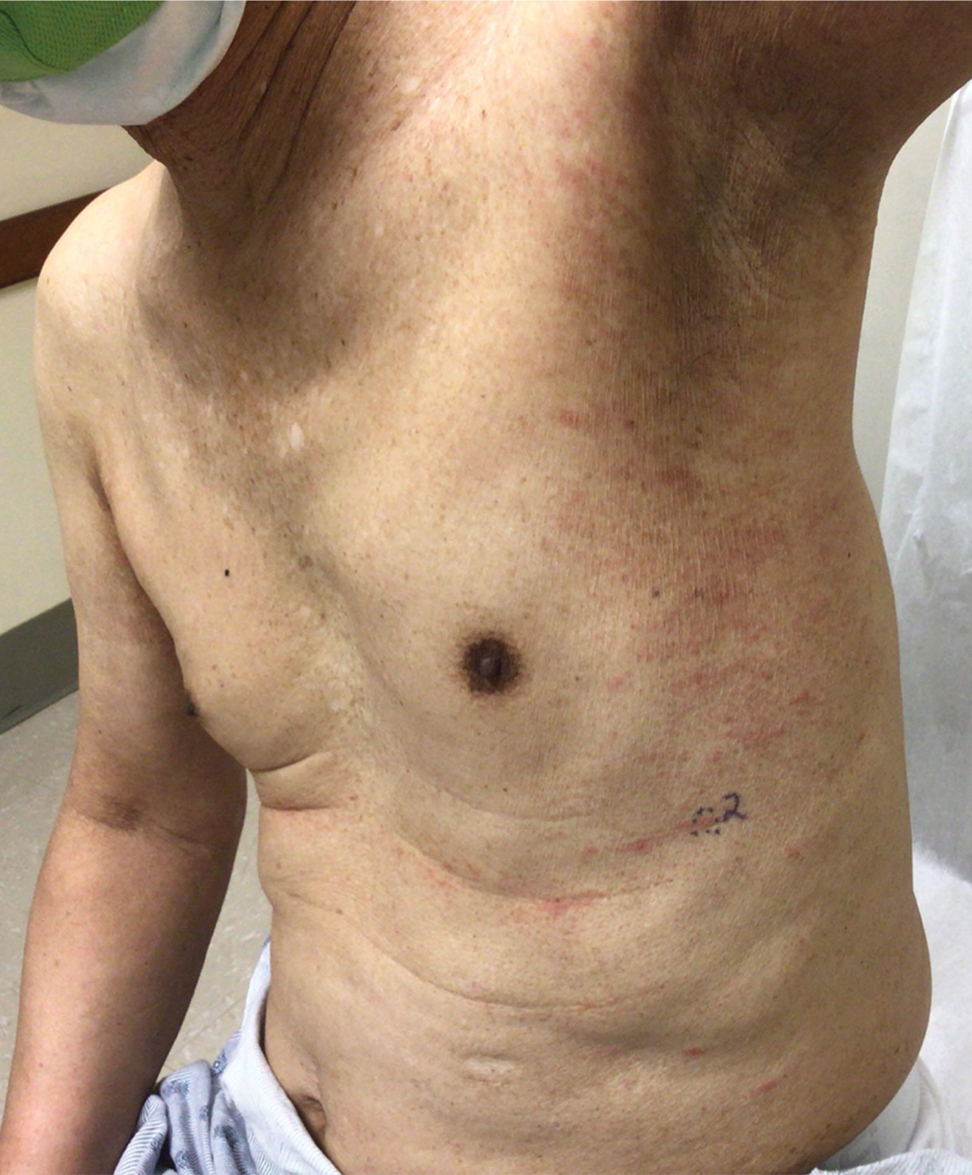

Ectatic Vessels on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

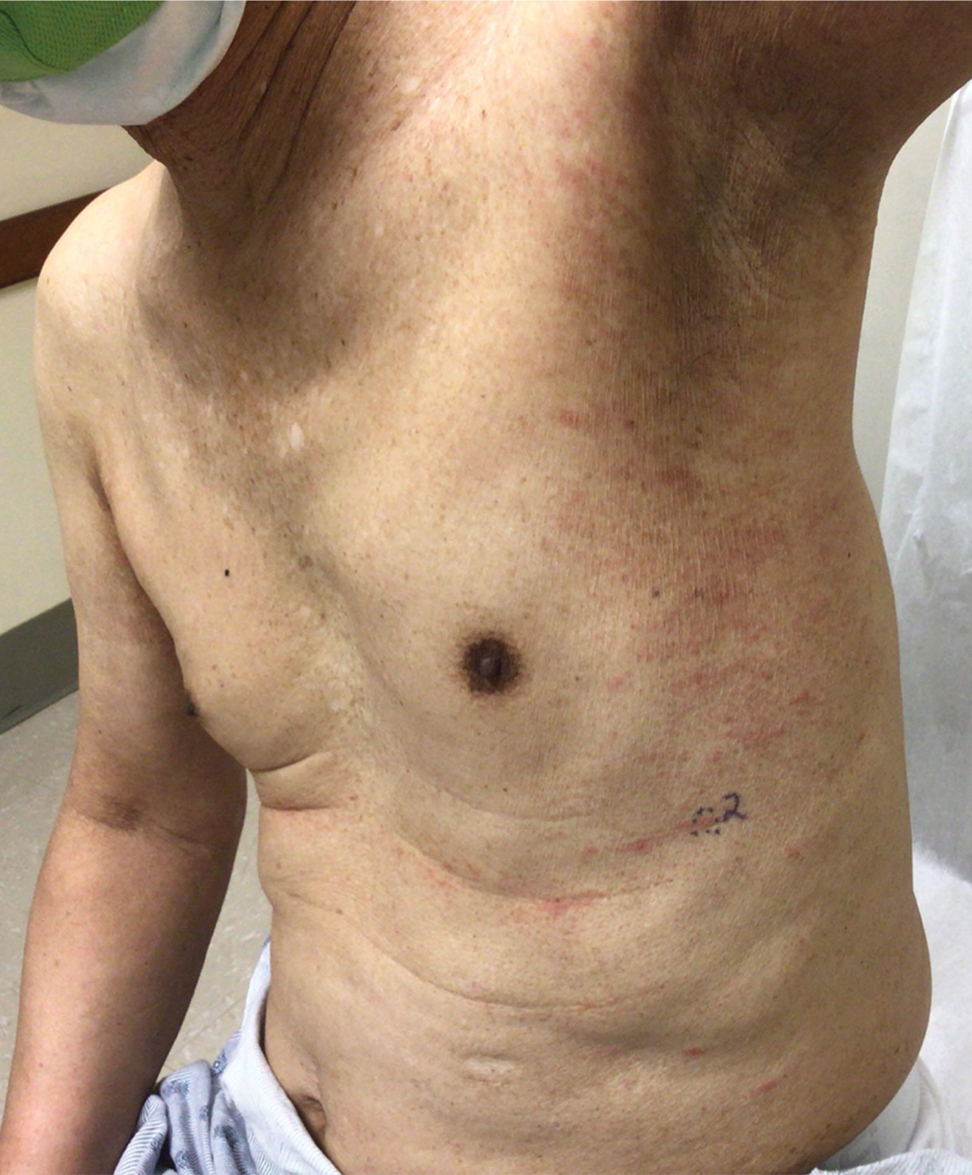

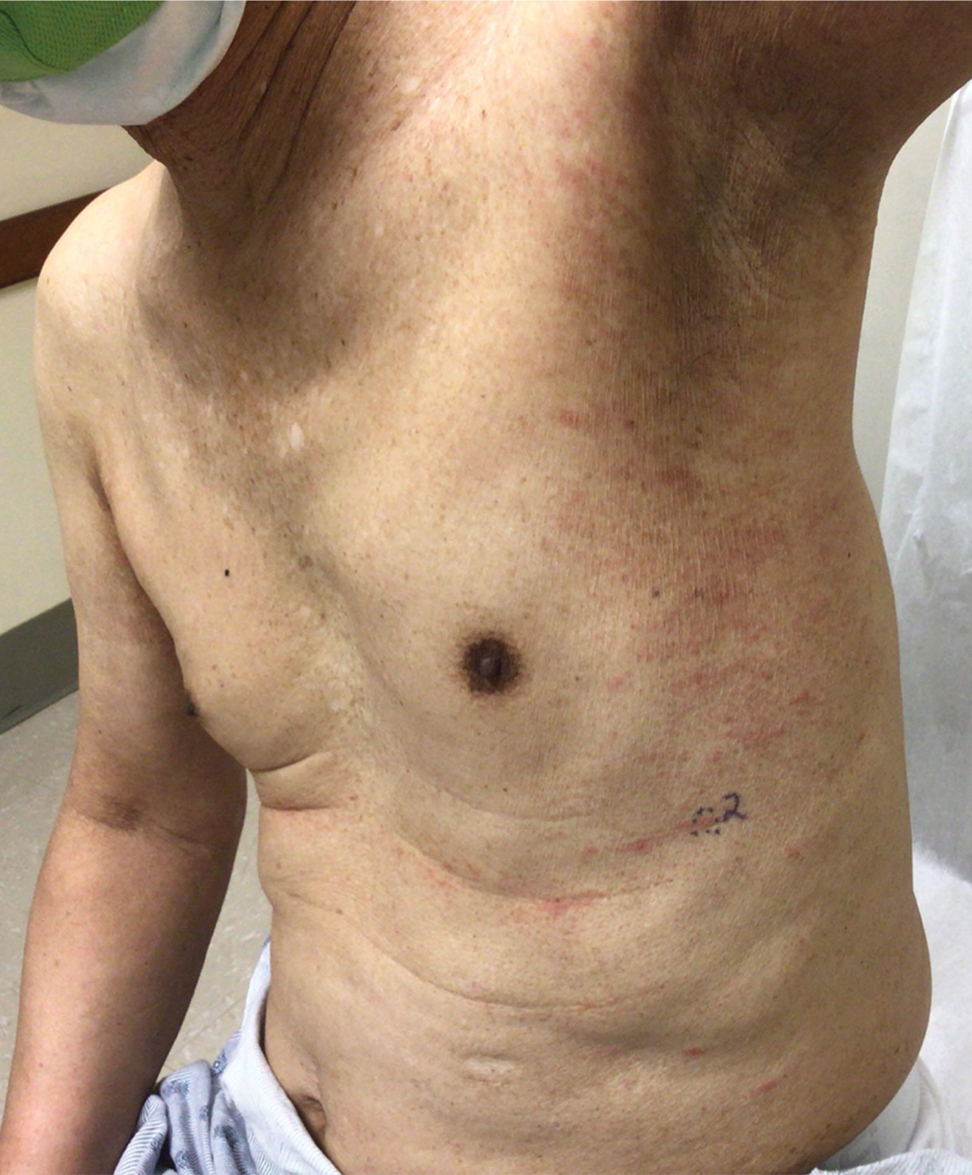

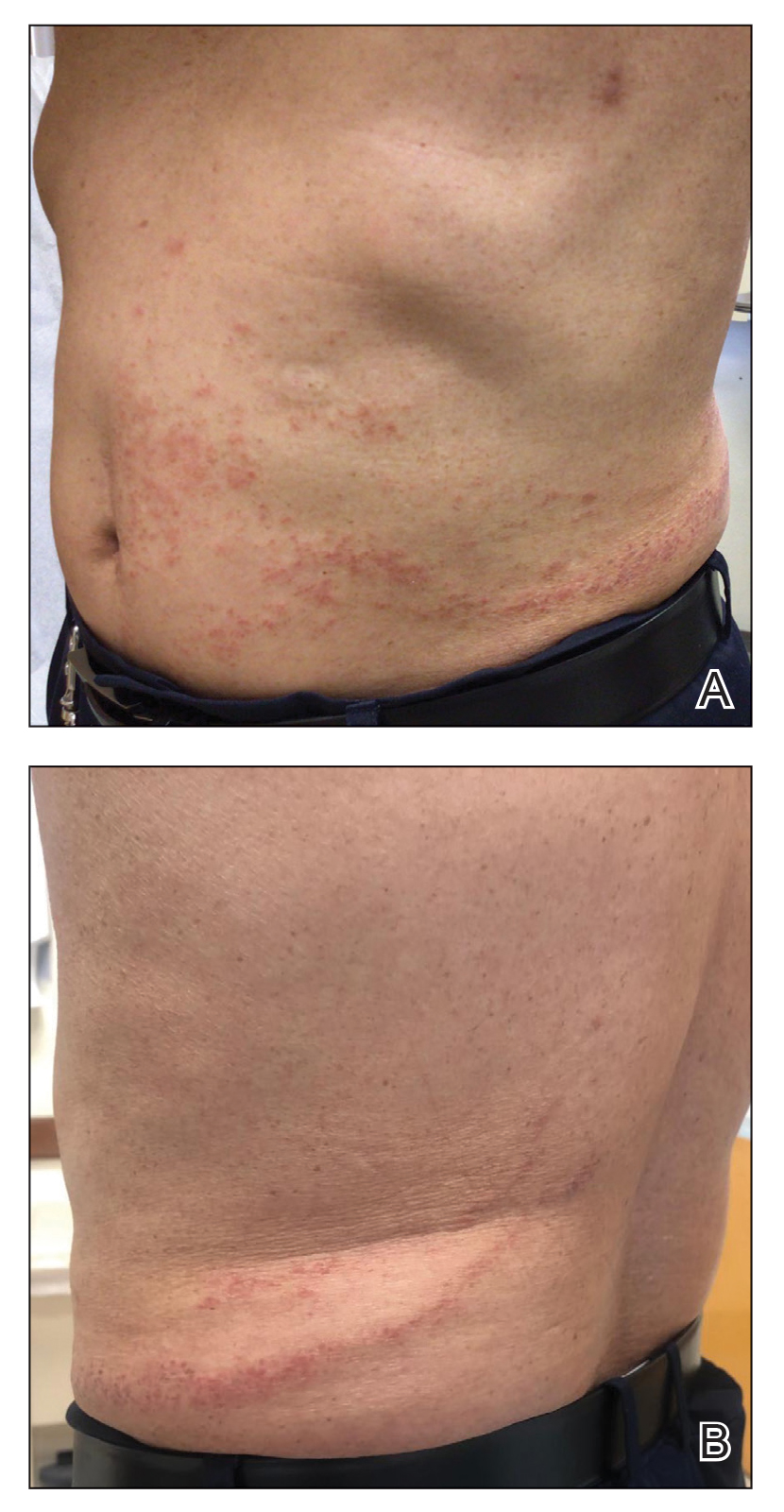

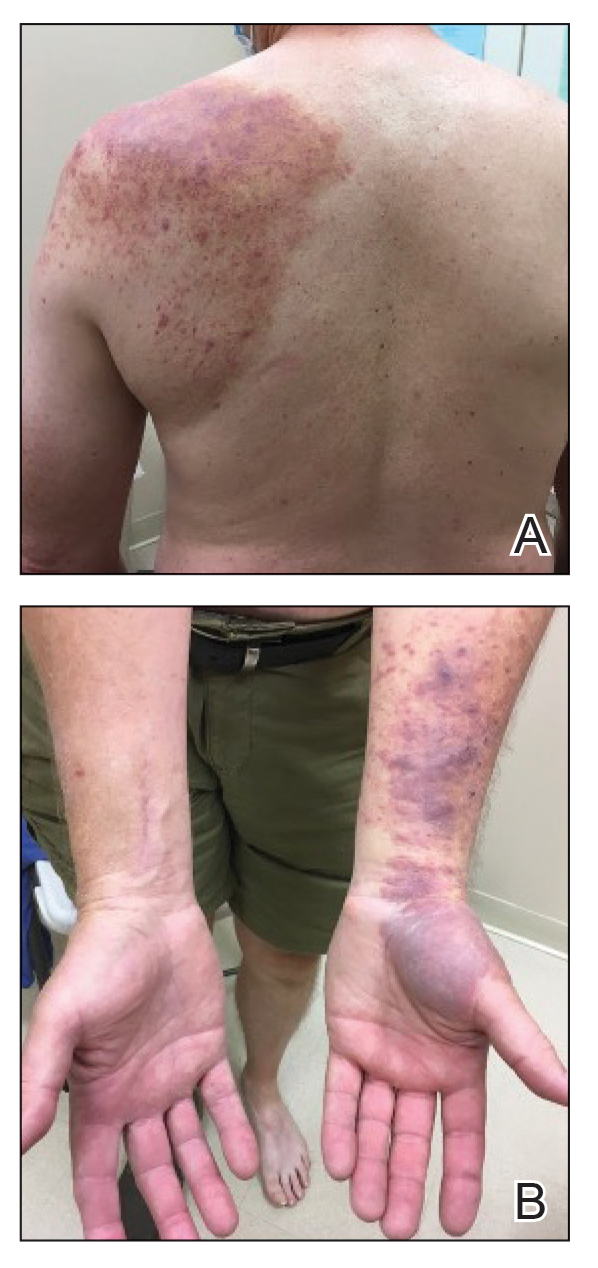

Computed tomography angiography of the chest confirmed a diagnosis of superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome due to external pressure of the indwelling catheter. Upon diagnosis, the left indwelling catheter was removed. Further testing to assess for a potential pulmonary embolism was negative. Resolution of the ectatic spider veins and patientreported intermittent facial swelling was achieved after catheter removal.

Superior vena cava syndrome occurs when the SVC is occluded due to extrinsic pressure or thrombosis. Although classically thought to be due to underlying bronchogenic carcinomas, all pathologies that cause compression of the SVC also can lead to vessel occlusion.1 Superior vena cava syndrome initially can be detected on physical examination. The most prominent skin finding includes diffusely dilated blood vessels on the central chest wall, which indicate the presence of collateral blood vessels.1 Imaging studies such as abdominal computed tomography can provide information on the etiology of the condition but are not required for diagnosis. Given the high correlation of SVC syndrome with underlying lung and mediastinal carcinomas, imaging was warranted in our patient. Imaging also can distinguish if the condition is due to external pressure or thrombosis.2 For SVC syndrome due to thrombosis, endovascular therapy is first-line management; however, mechanical thrombectomy may be preferred in patients with absolute contraindication to thrombolytic agents.3 In the setting of increased external pressure on the SVC, treatment includes the removal of the source of pressure.4

In a case series including 78 patients, ports and indwelling catheters accounted for 71% of benign SVC cases.5 Our patient’s SVC syndrome most likely was due to the indwelling catheter pressing on the SVC. The goal of treatment is to address the underlying cause—whether it be pressure or thrombosis. In the setting of increased external pressure, treatment includes removal of the source of pressure from the SVC.4

Other differential diagnoses to consider for newonset ectatic vessels on the chest wall include generalized essential telangiectasia, scleroderma, poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, and caput medusae. Generalized essential telangiectasia is characterized by red or pink dilated capillary blood vessels in a branch or lacelike pattern predominantly on the lower limbs. The eruption primarily is asymptomatic, though tingling or numbness may be reported.6 The diagnosis can be made with a punch biopsy, with histopathology showing dilated vessels in the dermis.7

Scleroderma is a connective tissue fibrosis disorder with variable clinical presentations. The systemic sclerosis subset can be divided into localized systemic sclerosis and diffuse systemic sclerosis. Physical examination reveals cutaneous sclerosis in various areas of the body. Localized systemic sclerosis includes sclerosis of the fingers and face, while diffuse systemic sclerosis is notable for progression to the arms, legs, and trunk.8 In addition to sclerosis, diffuse telangiectases also can be observed. Systemic sclerosis is a clinical diagnosis based on physical examination and laboratory studies to identify antibodies such as antinuclear antibodies.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is a variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The initial presentation is characterized by plaques of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation with atrophy and telangiectases. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and classically involve the trunk and flexural areas.9 The diagnosis is made with skin biopsy and immunohistochemical studies, with findings reflective of mycosis fungoides.

Caput medusae (palm tree sign) is a cardinal feature of portal hypertension characterized by grossly dilated and engorged periumbilical veins. To shunt blood from the portal venous system, cutaneous collateral veins between the umbilical veins and abdominal wall veins are used, resulting in the appearance of engorged veins in the anterior abdominal wall.10 The diagnosis can be made with abdominal ultrasonography showing the direction of blood flow through abdominal vessels.

- Drouin L, Pistorius MA, Lafforgue A, et al. Upper-extremity venous thrombosis: a retrospective study about 160 cases [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2019;40:9-15.

- Richie E. Clinical pearl: diagnosing superior vena cava syndrome. Emergency Medicine News. 2017;39:22. doi:10.1097/01 .EEM.0000522220.37441.d2

- Azizi A, Shafi I, Shah N, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2896-2910. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.038

- Dumantepe M, Tarhan A, Ozler A. Successful treatment of central venous catheter induced superior vena cava syndrome with ultrasound accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E269-E273.

- Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:37-42. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0

- Long D, Marshman G. Generalized essential telangiectasia. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:67-69. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00033.x

- Braverman IM. Ultrastructure and organization of the cutaneous microvasculature in normal and pathologic states. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93(2 suppl):2S-9S.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336. doi:10.1007 /s12016-017-8625-4

- Bloom B, Marchbein S, Fischer M, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Sharma B, Raina S. Caput medusae. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:494. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.159322

The Diagnosis: Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Computed tomography angiography of the chest confirmed a diagnosis of superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome due to external pressure of the indwelling catheter. Upon diagnosis, the left indwelling catheter was removed. Further testing to assess for a potential pulmonary embolism was negative. Resolution of the ectatic spider veins and patientreported intermittent facial swelling was achieved after catheter removal.

Superior vena cava syndrome occurs when the SVC is occluded due to extrinsic pressure or thrombosis. Although classically thought to be due to underlying bronchogenic carcinomas, all pathologies that cause compression of the SVC also can lead to vessel occlusion.1 Superior vena cava syndrome initially can be detected on physical examination. The most prominent skin finding includes diffusely dilated blood vessels on the central chest wall, which indicate the presence of collateral blood vessels.1 Imaging studies such as abdominal computed tomography can provide information on the etiology of the condition but are not required for diagnosis. Given the high correlation of SVC syndrome with underlying lung and mediastinal carcinomas, imaging was warranted in our patient. Imaging also can distinguish if the condition is due to external pressure or thrombosis.2 For SVC syndrome due to thrombosis, endovascular therapy is first-line management; however, mechanical thrombectomy may be preferred in patients with absolute contraindication to thrombolytic agents.3 In the setting of increased external pressure on the SVC, treatment includes the removal of the source of pressure.4

In a case series including 78 patients, ports and indwelling catheters accounted for 71% of benign SVC cases.5 Our patient’s SVC syndrome most likely was due to the indwelling catheter pressing on the SVC. The goal of treatment is to address the underlying cause—whether it be pressure or thrombosis. In the setting of increased external pressure, treatment includes removal of the source of pressure from the SVC.4

Other differential diagnoses to consider for newonset ectatic vessels on the chest wall include generalized essential telangiectasia, scleroderma, poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, and caput medusae. Generalized essential telangiectasia is characterized by red or pink dilated capillary blood vessels in a branch or lacelike pattern predominantly on the lower limbs. The eruption primarily is asymptomatic, though tingling or numbness may be reported.6 The diagnosis can be made with a punch biopsy, with histopathology showing dilated vessels in the dermis.7

Scleroderma is a connective tissue fibrosis disorder with variable clinical presentations. The systemic sclerosis subset can be divided into localized systemic sclerosis and diffuse systemic sclerosis. Physical examination reveals cutaneous sclerosis in various areas of the body. Localized systemic sclerosis includes sclerosis of the fingers and face, while diffuse systemic sclerosis is notable for progression to the arms, legs, and trunk.8 In addition to sclerosis, diffuse telangiectases also can be observed. Systemic sclerosis is a clinical diagnosis based on physical examination and laboratory studies to identify antibodies such as antinuclear antibodies.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is a variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The initial presentation is characterized by plaques of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation with atrophy and telangiectases. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and classically involve the trunk and flexural areas.9 The diagnosis is made with skin biopsy and immunohistochemical studies, with findings reflective of mycosis fungoides.

Caput medusae (palm tree sign) is a cardinal feature of portal hypertension characterized by grossly dilated and engorged periumbilical veins. To shunt blood from the portal venous system, cutaneous collateral veins between the umbilical veins and abdominal wall veins are used, resulting in the appearance of engorged veins in the anterior abdominal wall.10 The diagnosis can be made with abdominal ultrasonography showing the direction of blood flow through abdominal vessels.

The Diagnosis: Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

Computed tomography angiography of the chest confirmed a diagnosis of superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome due to external pressure of the indwelling catheter. Upon diagnosis, the left indwelling catheter was removed. Further testing to assess for a potential pulmonary embolism was negative. Resolution of the ectatic spider veins and patientreported intermittent facial swelling was achieved after catheter removal.

Superior vena cava syndrome occurs when the SVC is occluded due to extrinsic pressure or thrombosis. Although classically thought to be due to underlying bronchogenic carcinomas, all pathologies that cause compression of the SVC also can lead to vessel occlusion.1 Superior vena cava syndrome initially can be detected on physical examination. The most prominent skin finding includes diffusely dilated blood vessels on the central chest wall, which indicate the presence of collateral blood vessels.1 Imaging studies such as abdominal computed tomography can provide information on the etiology of the condition but are not required for diagnosis. Given the high correlation of SVC syndrome with underlying lung and mediastinal carcinomas, imaging was warranted in our patient. Imaging also can distinguish if the condition is due to external pressure or thrombosis.2 For SVC syndrome due to thrombosis, endovascular therapy is first-line management; however, mechanical thrombectomy may be preferred in patients with absolute contraindication to thrombolytic agents.3 In the setting of increased external pressure on the SVC, treatment includes the removal of the source of pressure.4

In a case series including 78 patients, ports and indwelling catheters accounted for 71% of benign SVC cases.5 Our patient’s SVC syndrome most likely was due to the indwelling catheter pressing on the SVC. The goal of treatment is to address the underlying cause—whether it be pressure or thrombosis. In the setting of increased external pressure, treatment includes removal of the source of pressure from the SVC.4

Other differential diagnoses to consider for newonset ectatic vessels on the chest wall include generalized essential telangiectasia, scleroderma, poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans, and caput medusae. Generalized essential telangiectasia is characterized by red or pink dilated capillary blood vessels in a branch or lacelike pattern predominantly on the lower limbs. The eruption primarily is asymptomatic, though tingling or numbness may be reported.6 The diagnosis can be made with a punch biopsy, with histopathology showing dilated vessels in the dermis.7

Scleroderma is a connective tissue fibrosis disorder with variable clinical presentations. The systemic sclerosis subset can be divided into localized systemic sclerosis and diffuse systemic sclerosis. Physical examination reveals cutaneous sclerosis in various areas of the body. Localized systemic sclerosis includes sclerosis of the fingers and face, while diffuse systemic sclerosis is notable for progression to the arms, legs, and trunk.8 In addition to sclerosis, diffuse telangiectases also can be observed. Systemic sclerosis is a clinical diagnosis based on physical examination and laboratory studies to identify antibodies such as antinuclear antibodies.

Poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans is a variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The initial presentation is characterized by plaques of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation with atrophy and telangiectases. The lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic and classically involve the trunk and flexural areas.9 The diagnosis is made with skin biopsy and immunohistochemical studies, with findings reflective of mycosis fungoides.

Caput medusae (palm tree sign) is a cardinal feature of portal hypertension characterized by grossly dilated and engorged periumbilical veins. To shunt blood from the portal venous system, cutaneous collateral veins between the umbilical veins and abdominal wall veins are used, resulting in the appearance of engorged veins in the anterior abdominal wall.10 The diagnosis can be made with abdominal ultrasonography showing the direction of blood flow through abdominal vessels.

- Drouin L, Pistorius MA, Lafforgue A, et al. Upper-extremity venous thrombosis: a retrospective study about 160 cases [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2019;40:9-15.

- Richie E. Clinical pearl: diagnosing superior vena cava syndrome. Emergency Medicine News. 2017;39:22. doi:10.1097/01 .EEM.0000522220.37441.d2

- Azizi A, Shafi I, Shah N, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2896-2910. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.038

- Dumantepe M, Tarhan A, Ozler A. Successful treatment of central venous catheter induced superior vena cava syndrome with ultrasound accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E269-E273.

- Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:37-42. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0

- Long D, Marshman G. Generalized essential telangiectasia. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:67-69. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00033.x

- Braverman IM. Ultrastructure and organization of the cutaneous microvasculature in normal and pathologic states. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93(2 suppl):2S-9S.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336. doi:10.1007 /s12016-017-8625-4

- Bloom B, Marchbein S, Fischer M, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Sharma B, Raina S. Caput medusae. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:494. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.159322

- Drouin L, Pistorius MA, Lafforgue A, et al. Upper-extremity venous thrombosis: a retrospective study about 160 cases [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2019;40:9-15.

- Richie E. Clinical pearl: diagnosing superior vena cava syndrome. Emergency Medicine News. 2017;39:22. doi:10.1097/01 .EEM.0000522220.37441.d2

- Azizi A, Shafi I, Shah N, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2896-2910. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2020.08.038

- Dumantepe M, Tarhan A, Ozler A. Successful treatment of central venous catheter induced superior vena cava syndrome with ultrasound accelerated catheter-directed thrombolysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E269-E273.

- Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:37-42. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0

- Long D, Marshman G. Generalized essential telangiectasia. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45:67-69. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2004.00033.x

- Braverman IM. Ultrastructure and organization of the cutaneous microvasculature in normal and pathologic states. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93(2 suppl):2S-9S.

- Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:306-336. doi:10.1007 /s12016-017-8625-4

- Bloom B, Marchbein S, Fischer M, et al. Poikilodermatous mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Sharma B, Raina S. Caput medusae. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:494. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.159322

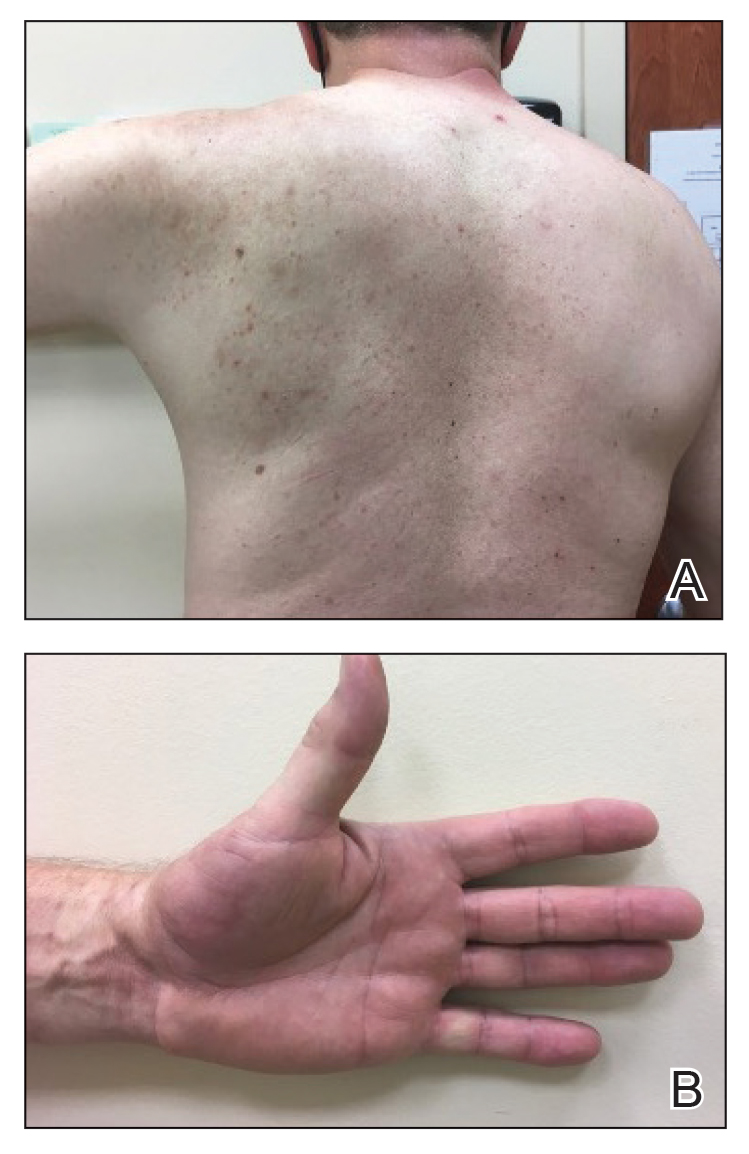

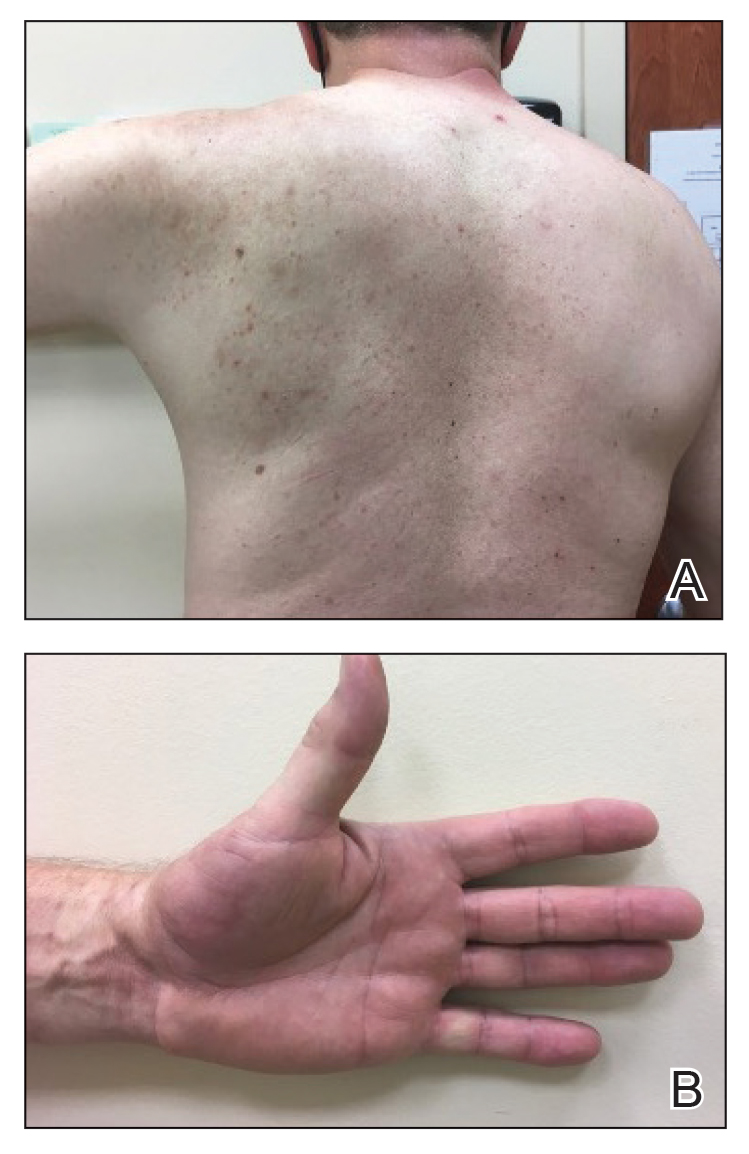

A 32-year-old woman presented to vascular surgery for evaluation of spider veins of 2 years’ duration that originated on the breasts but later spread to include the central chest, inframammary folds, and back. She reported associated pain and discomfort as well as intermittent facial swelling and tachycardia but denied pruritus and bleeding. The patient had a history of a kidney transplant 6 months prior, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and Sjögren syndrome with a left indwelling catheter. Her current medications included systemic immunosuppressive agents. Physical examination revealed blue-purple ectatic vessels on the inframammary folds and central chest extending to the back. Erythema on the face, neck, and arms was not appreciated. No palpable cervical, supraclavicular, or axillary lymph nodes were noted.

Pink Papules on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

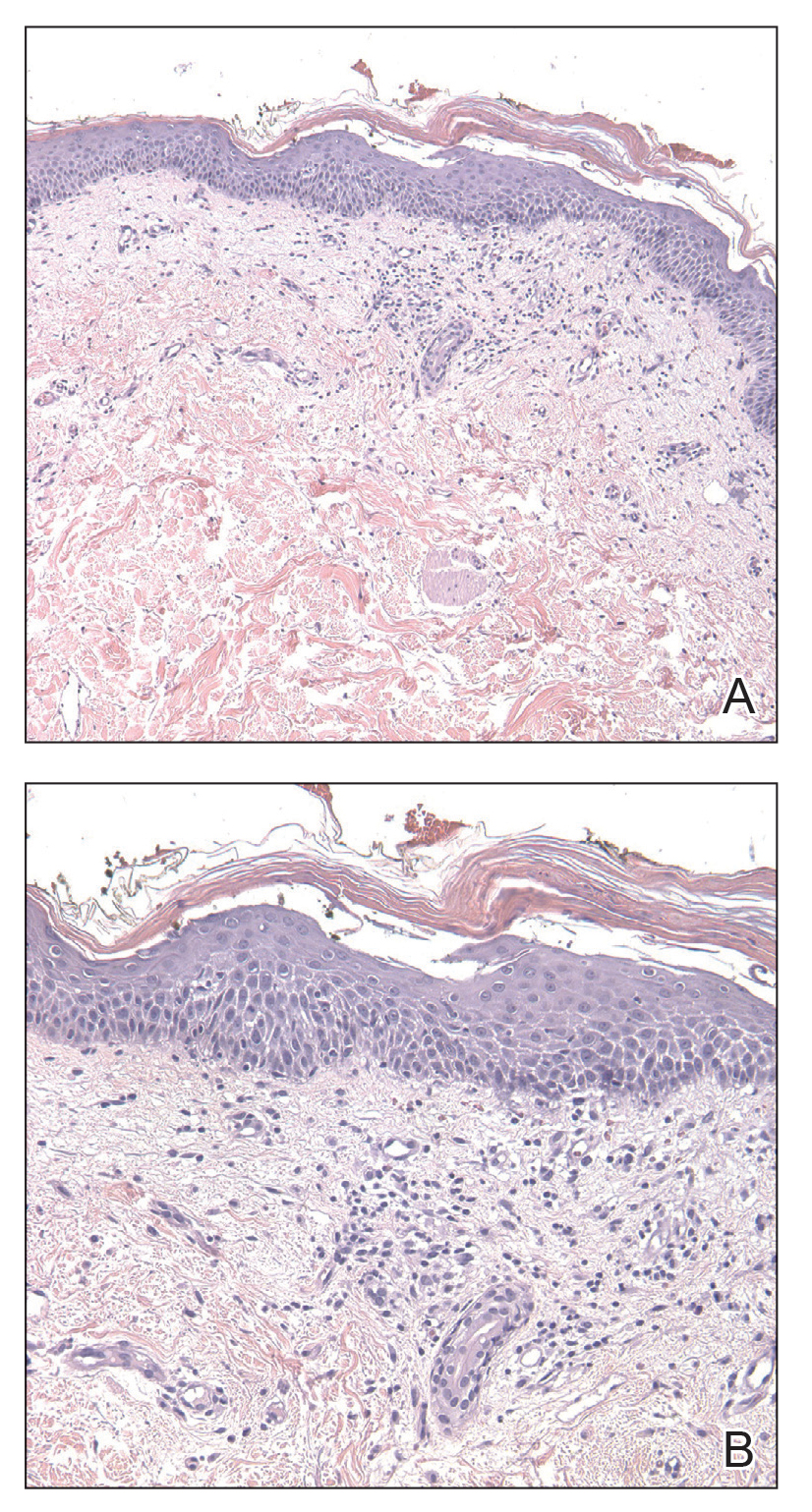

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

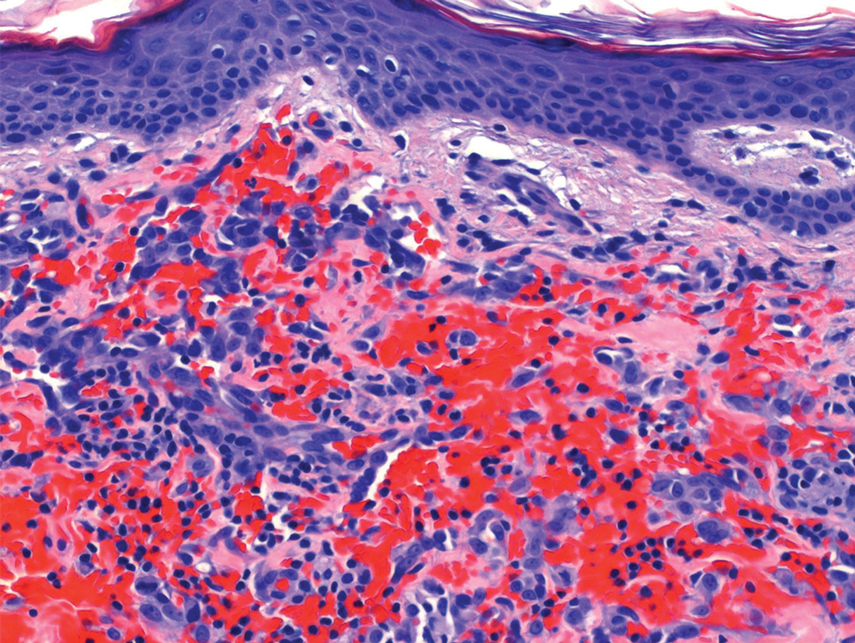

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

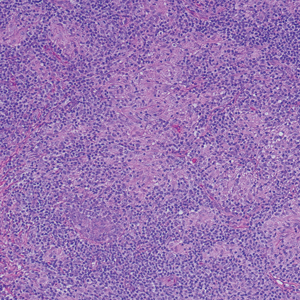

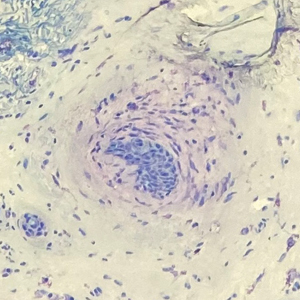

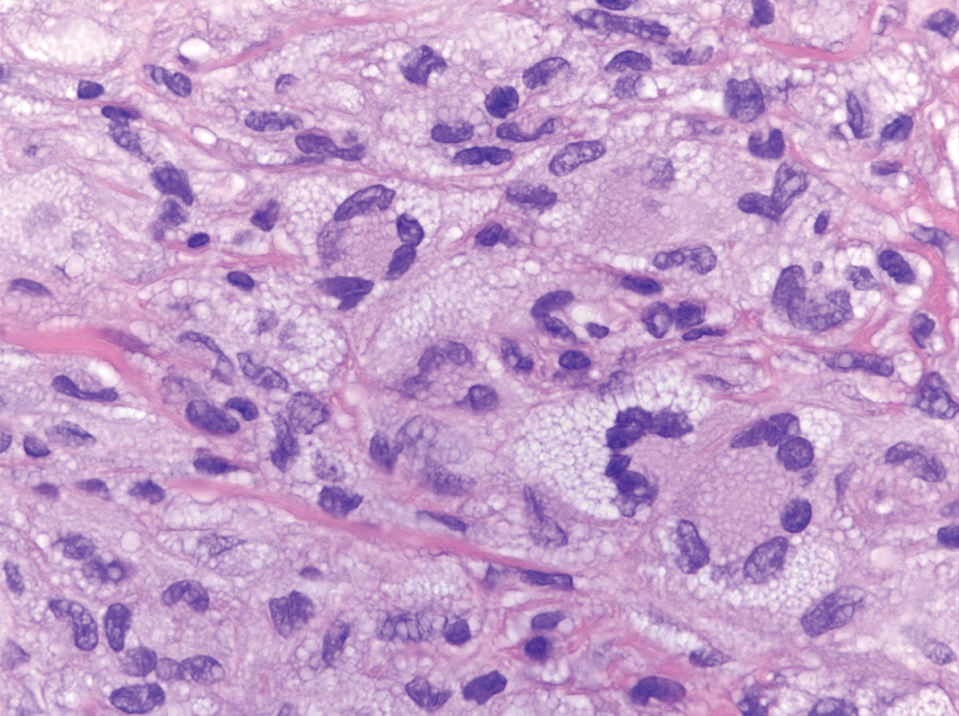

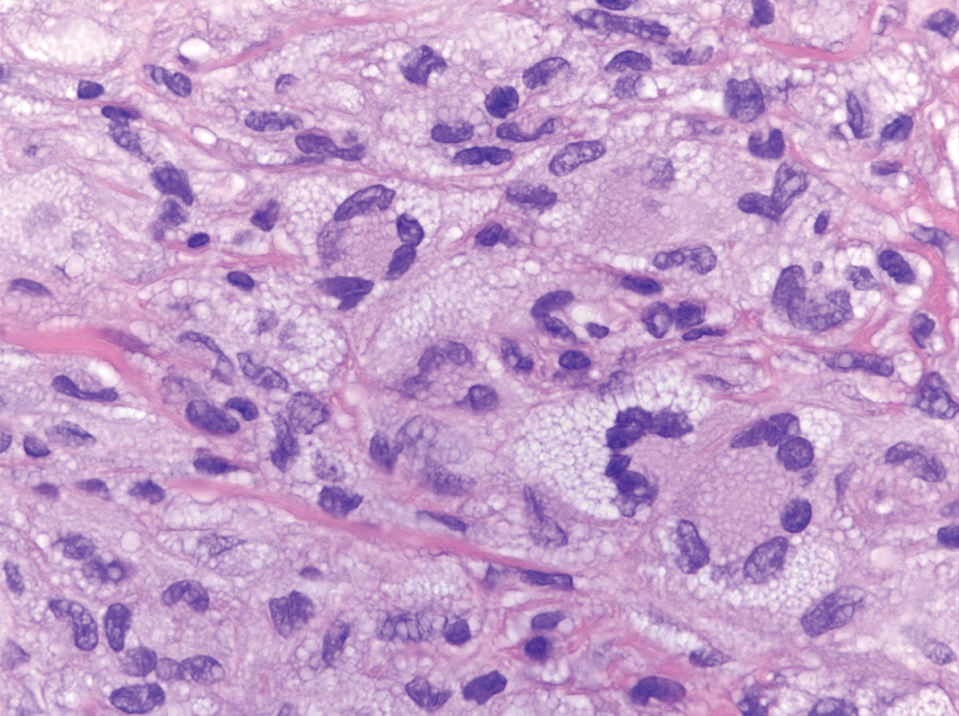

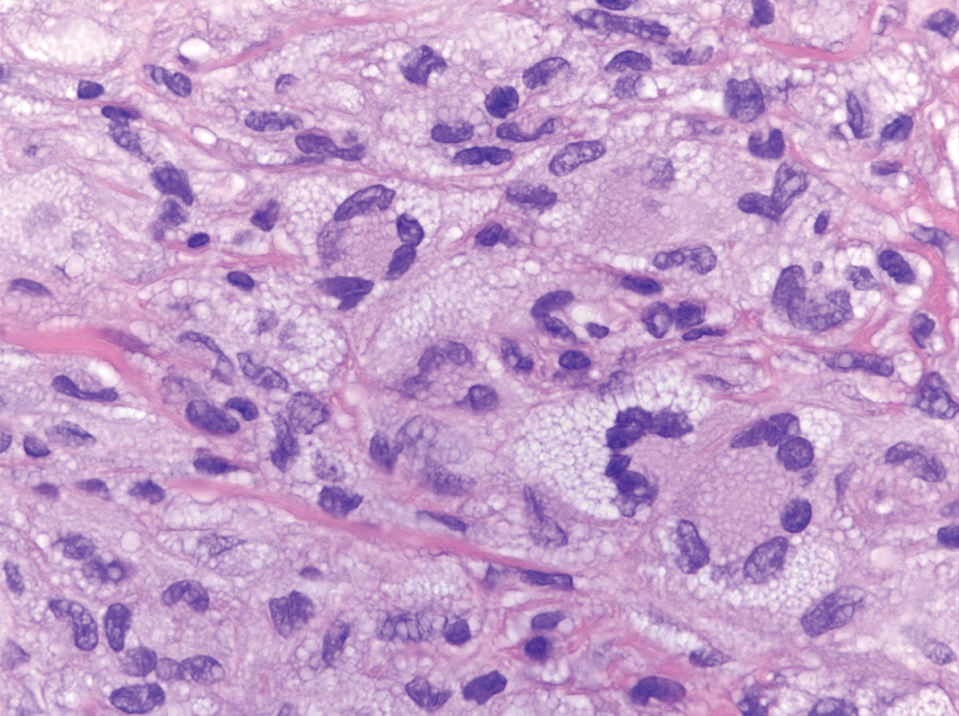

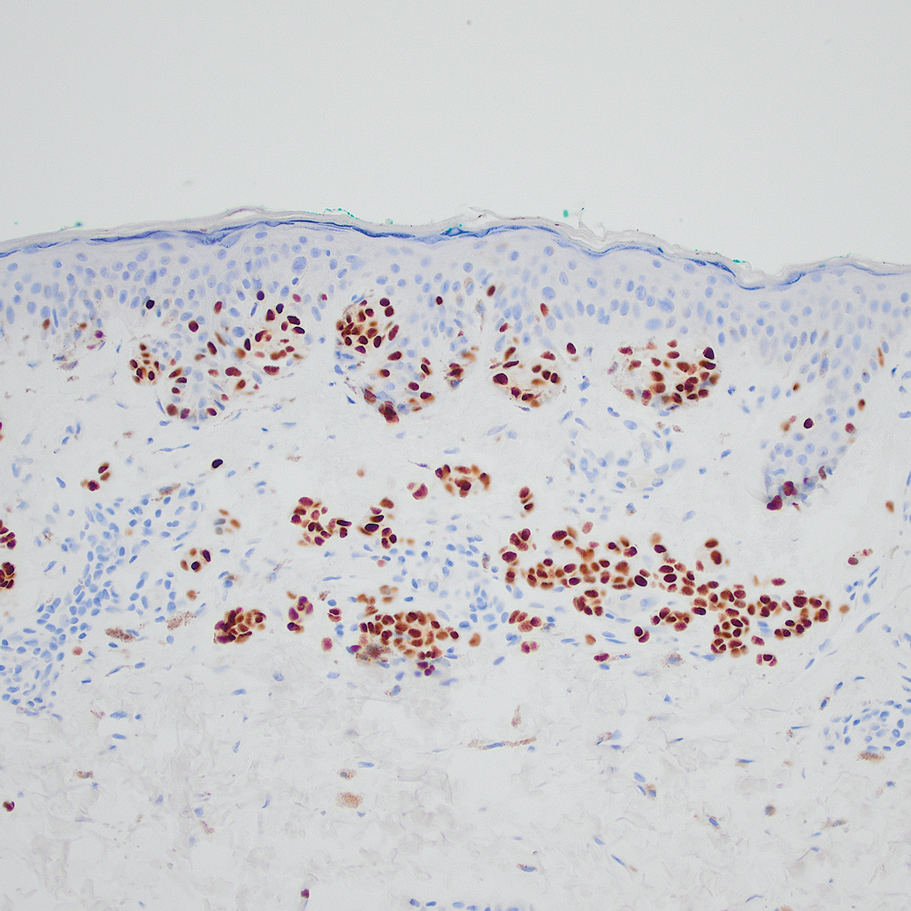

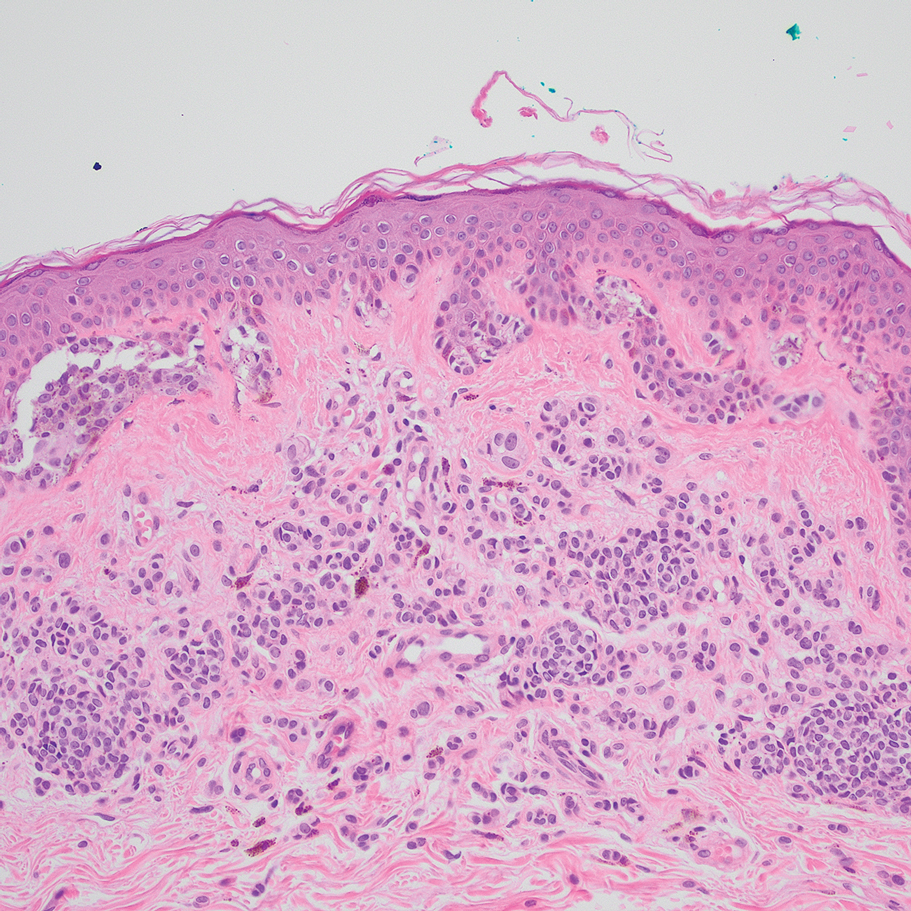

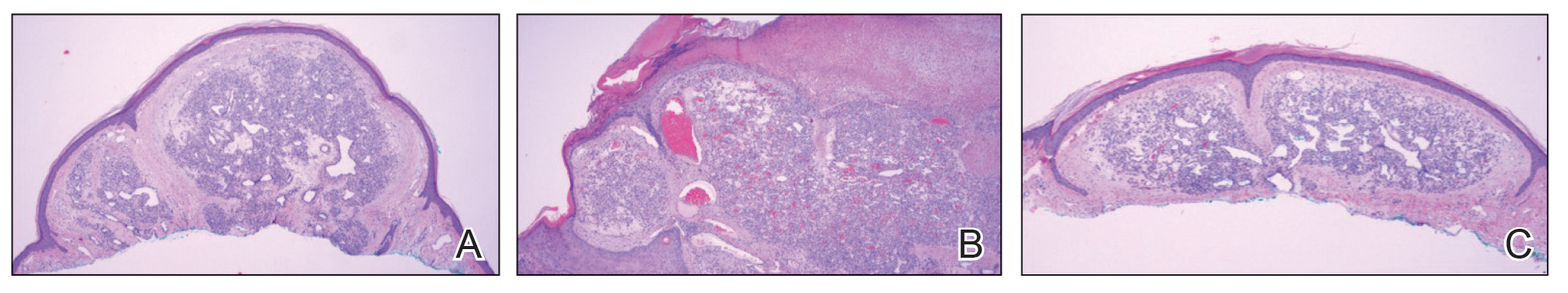

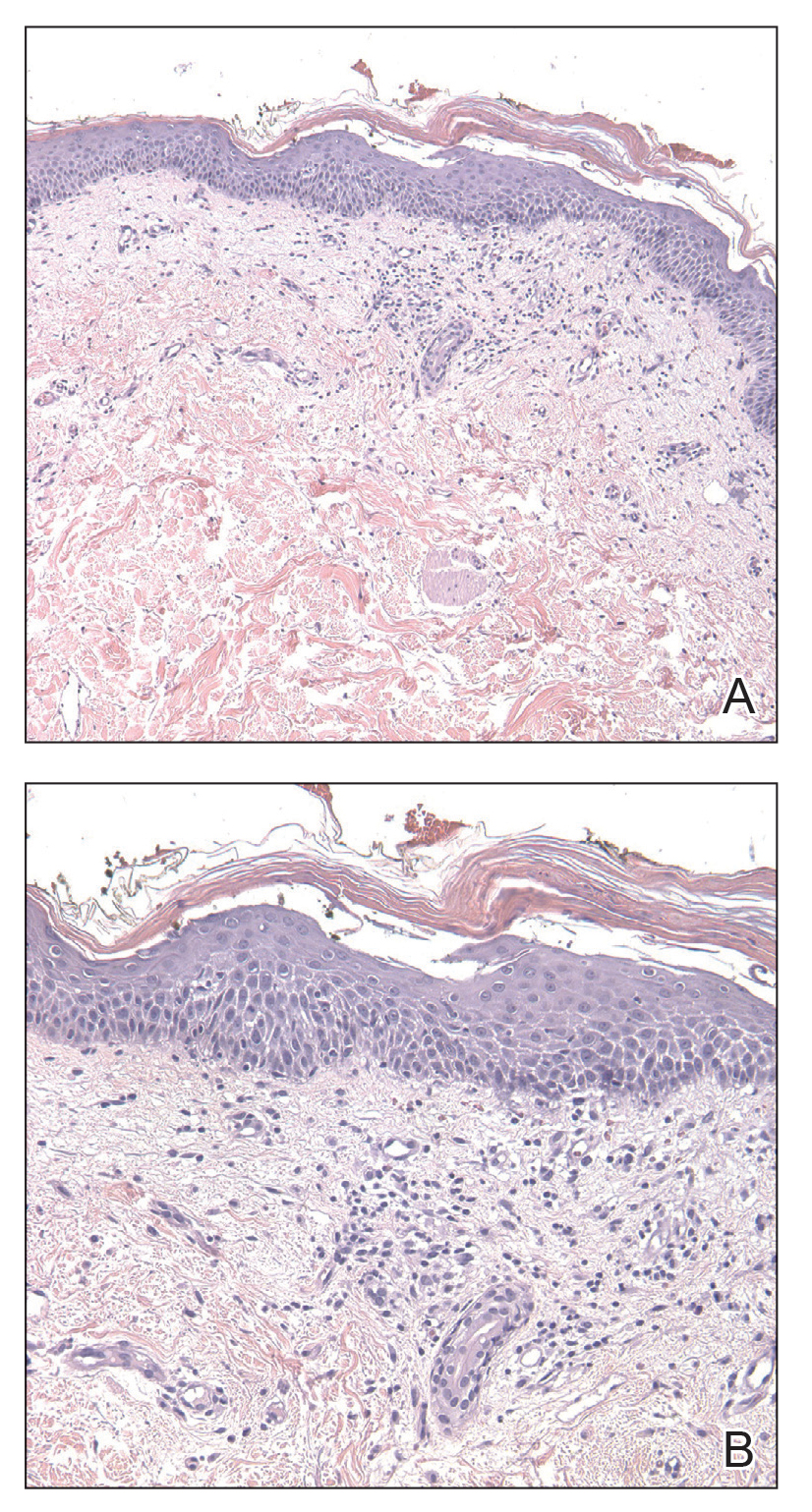

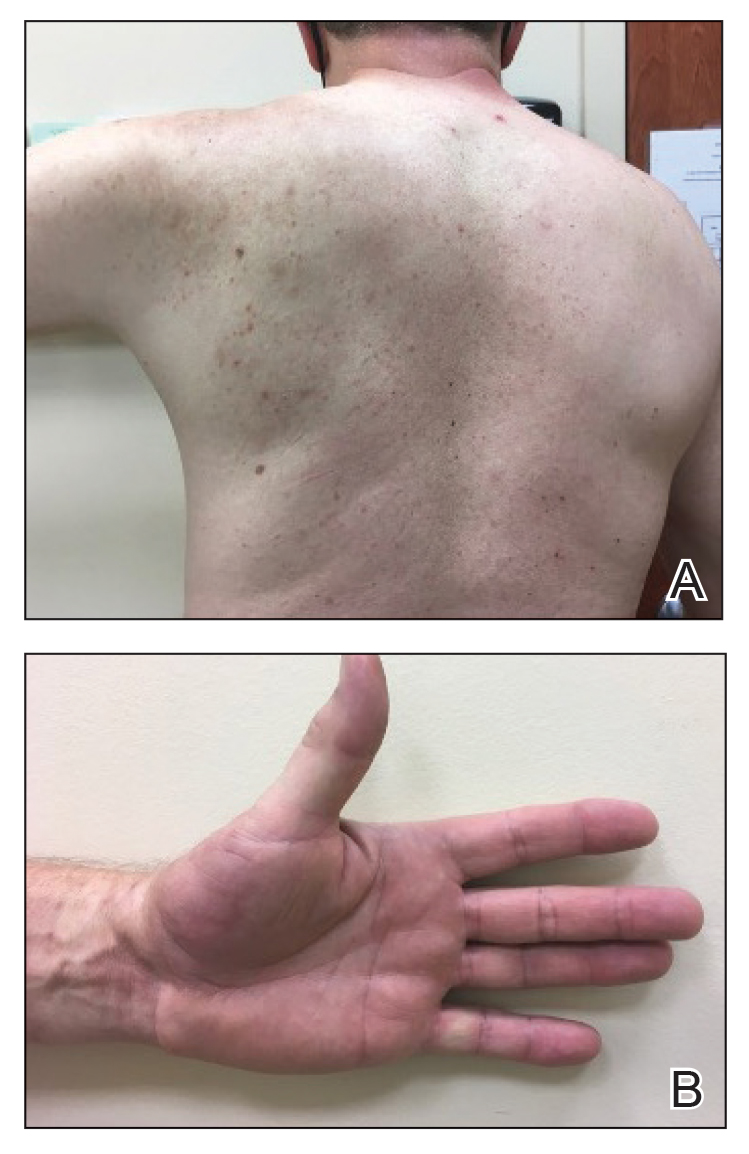

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

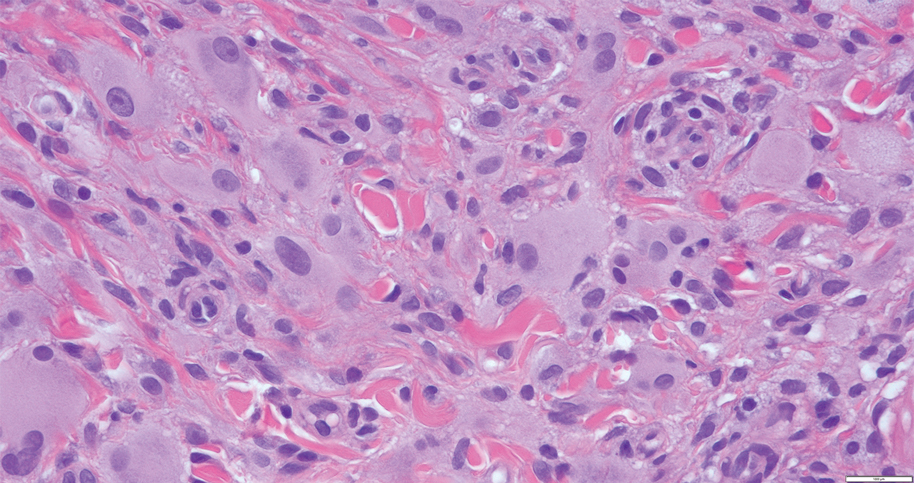

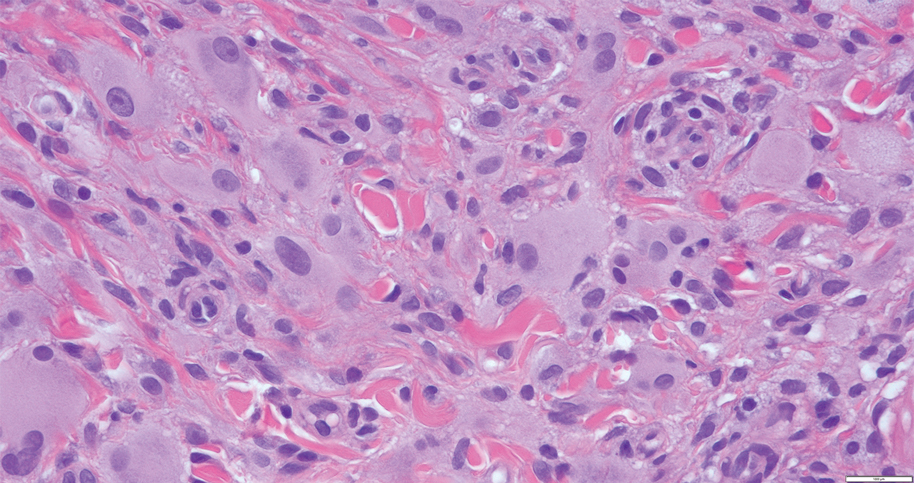

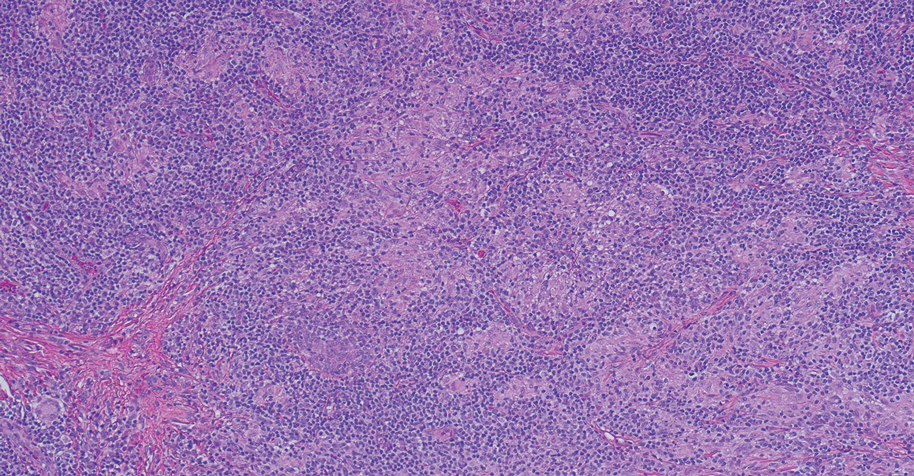

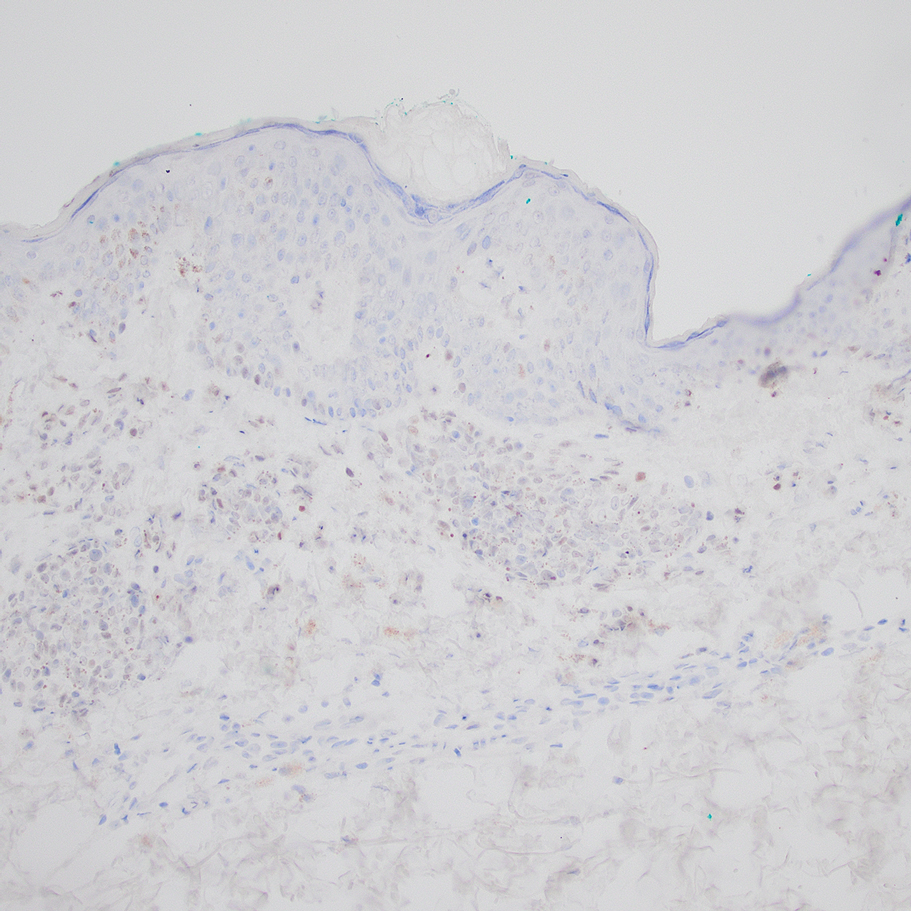

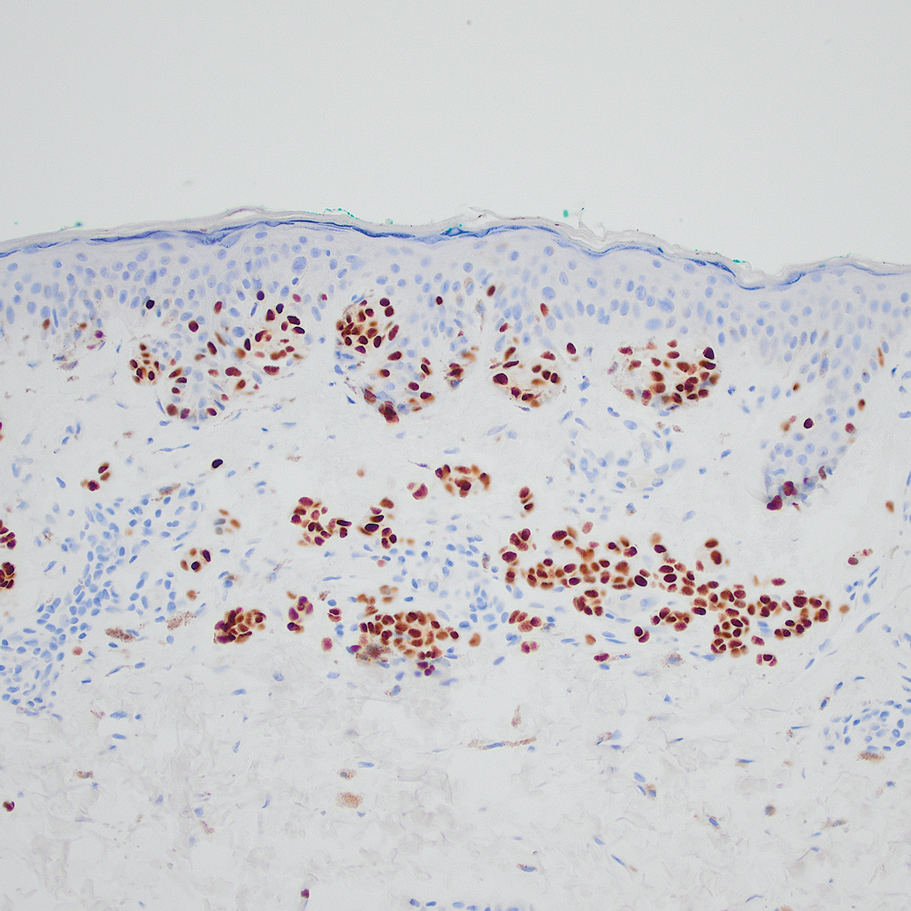

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

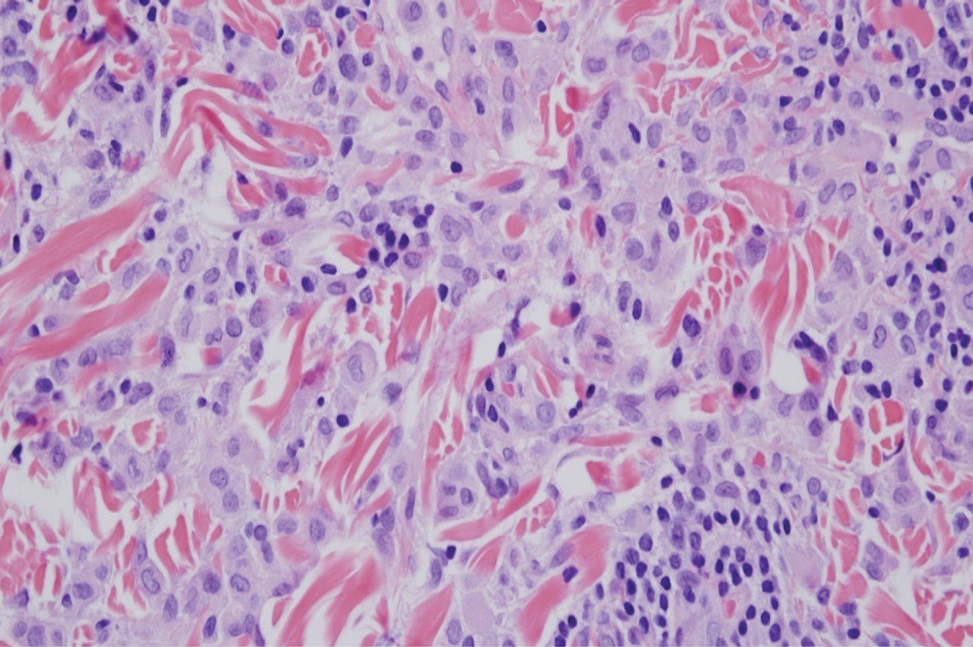

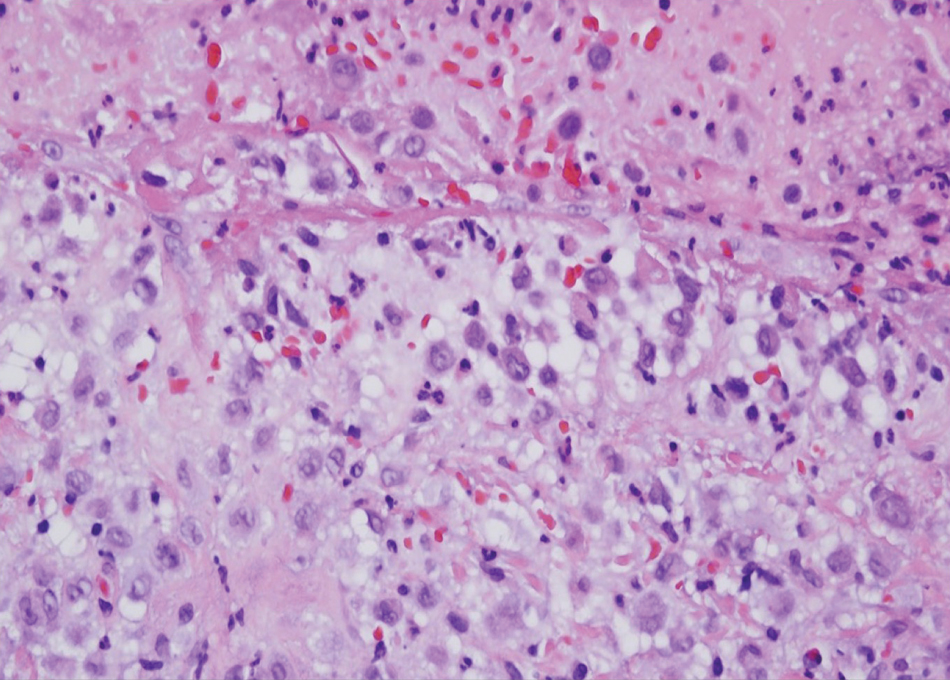

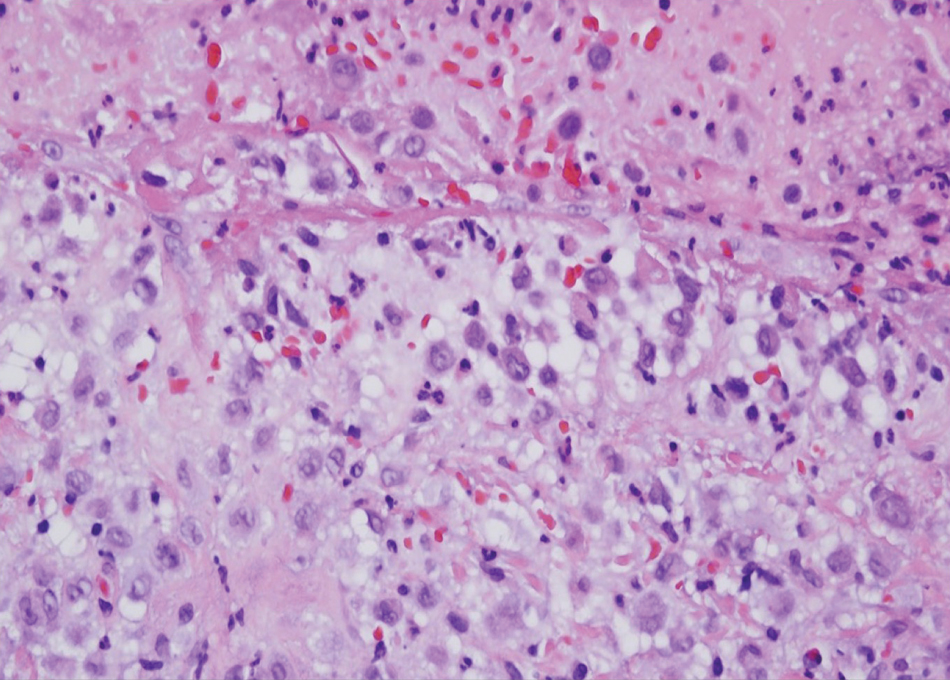

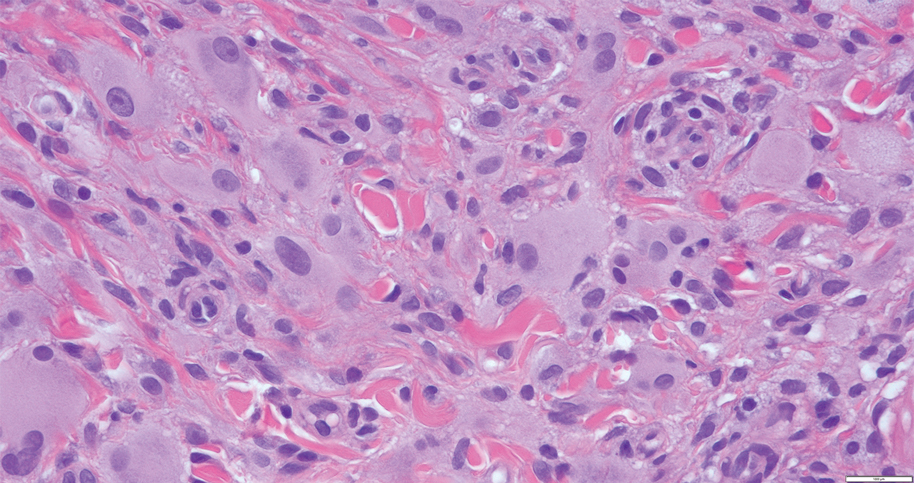

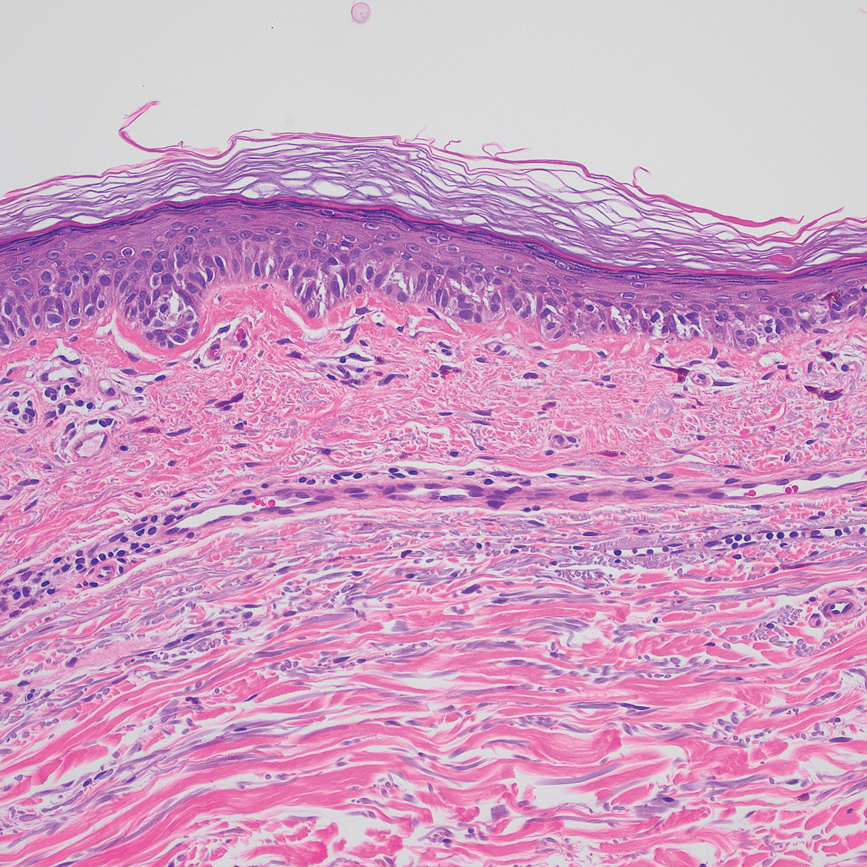

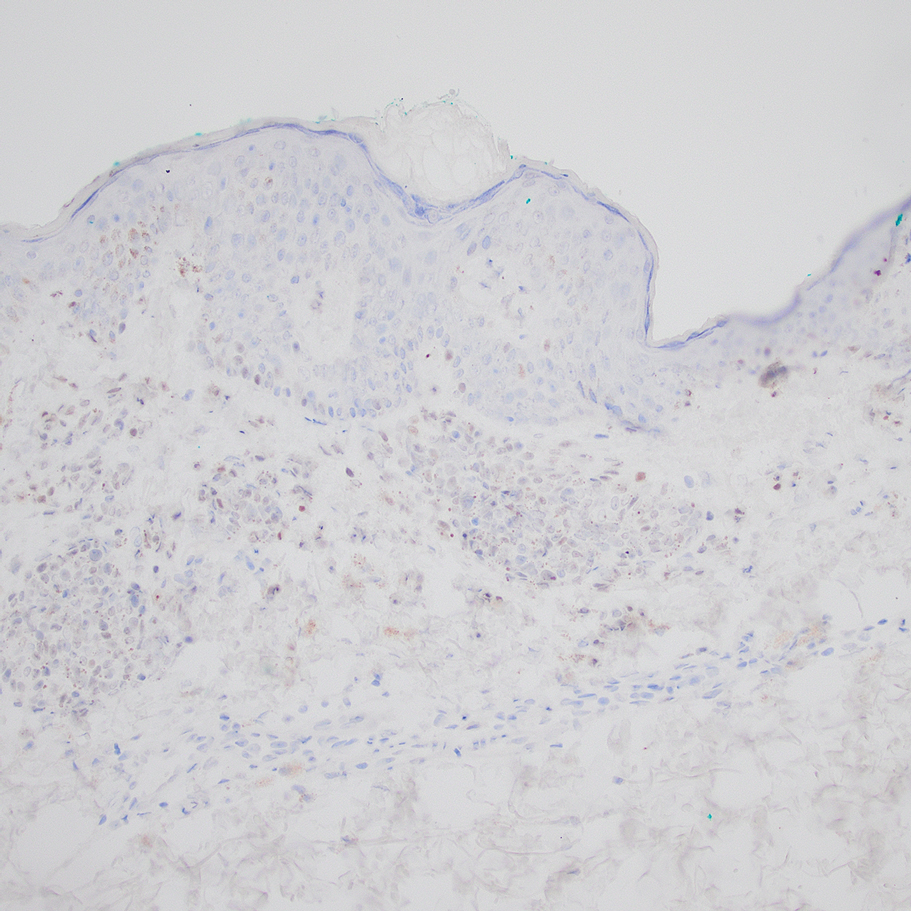

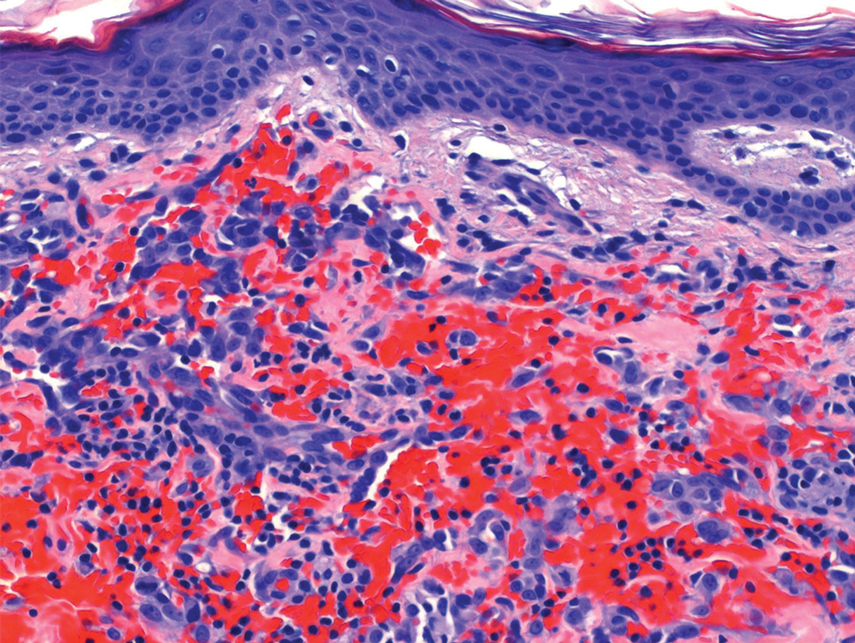

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

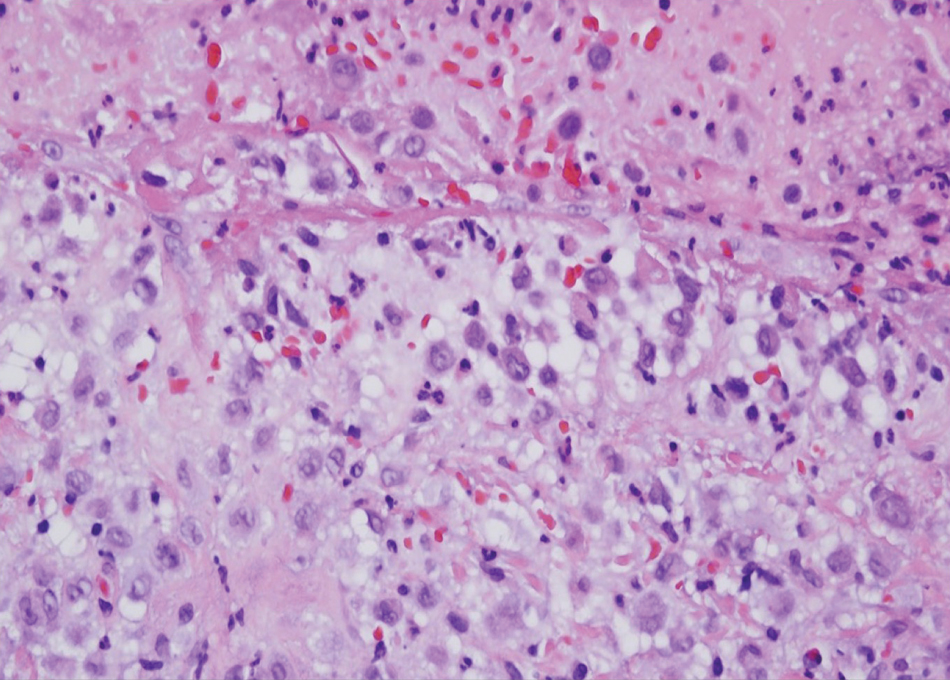

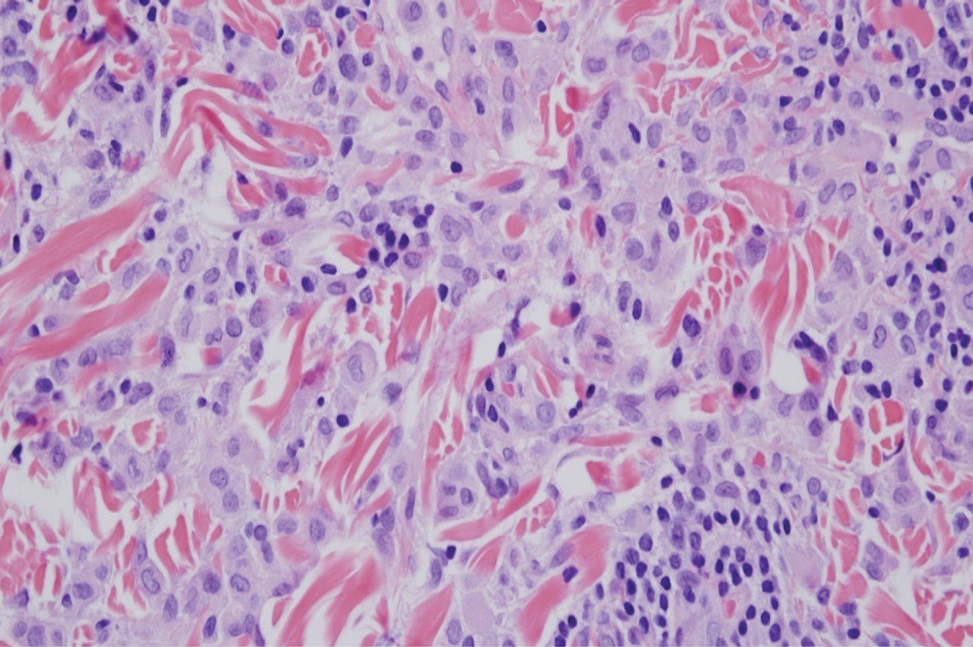

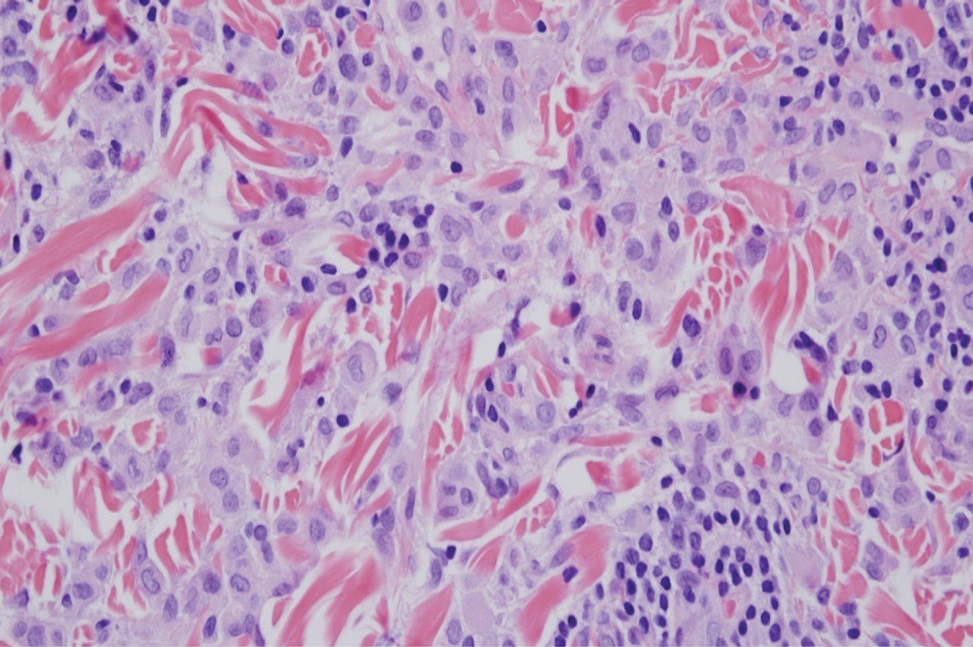

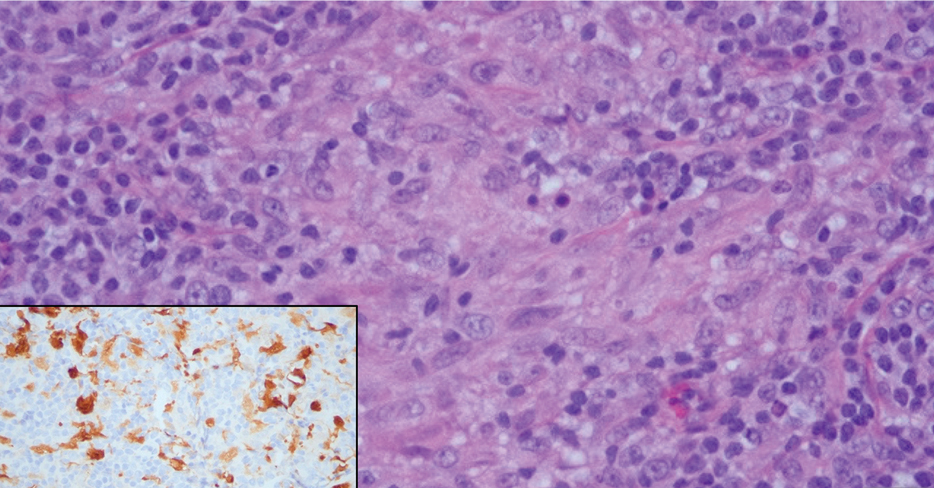

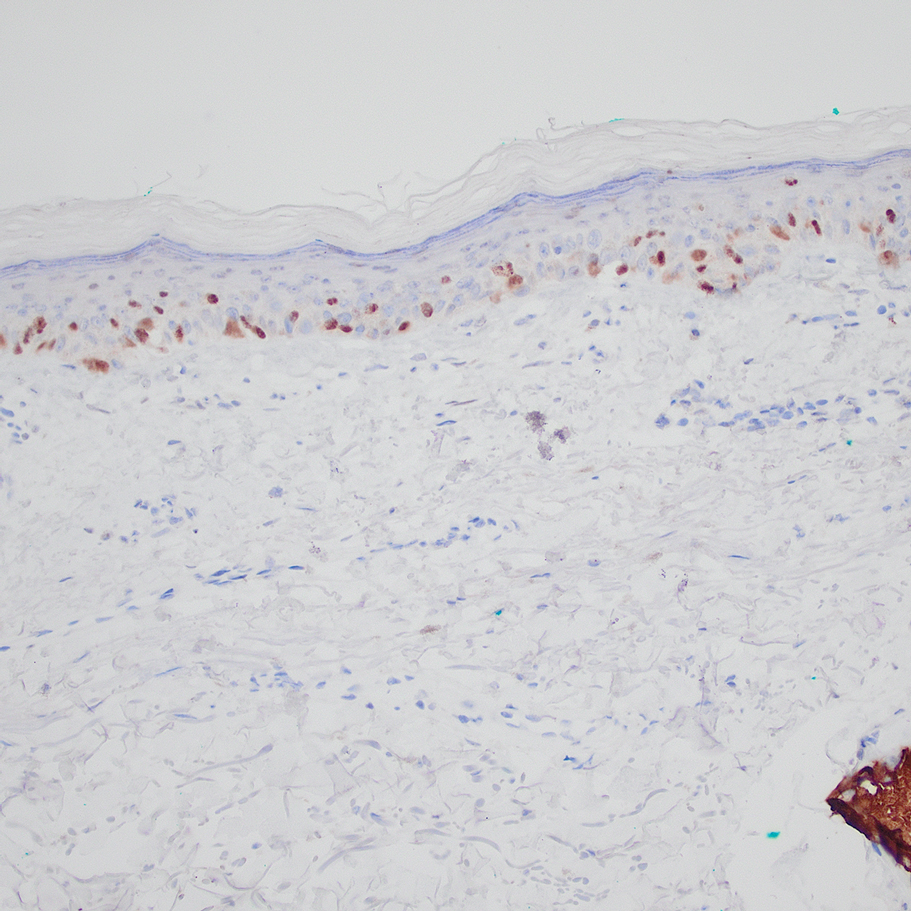

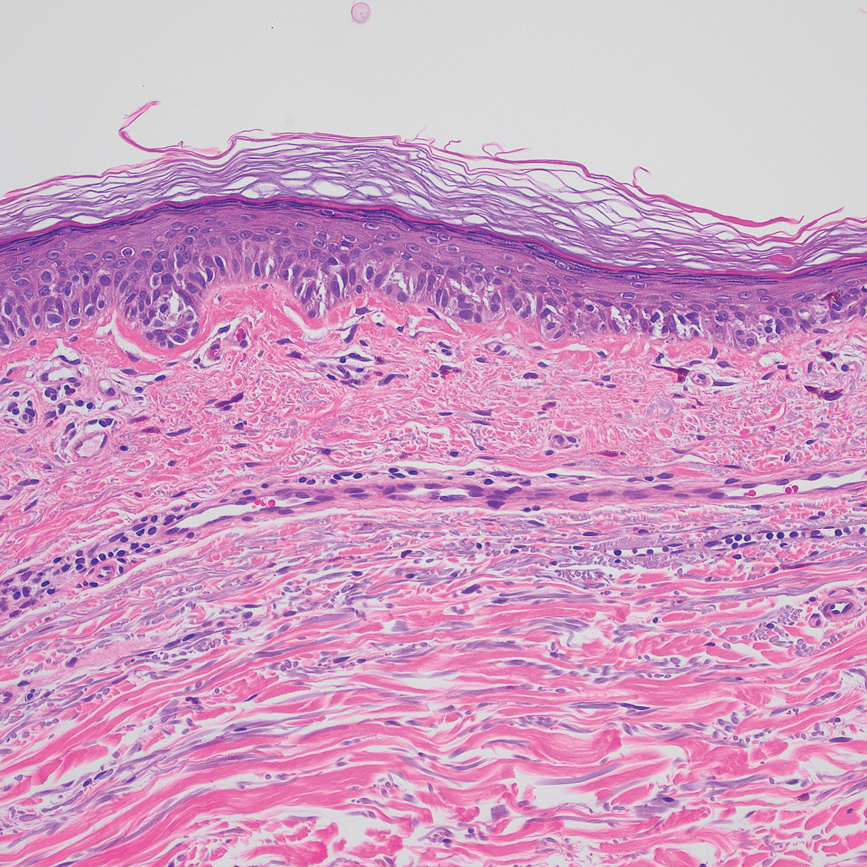

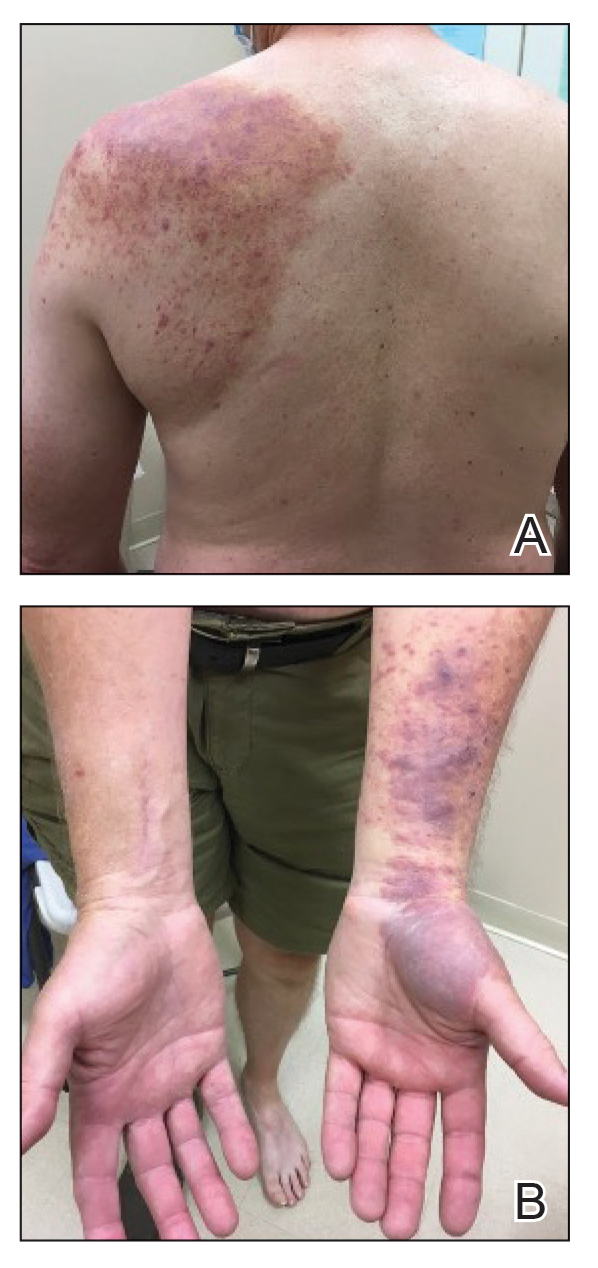

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

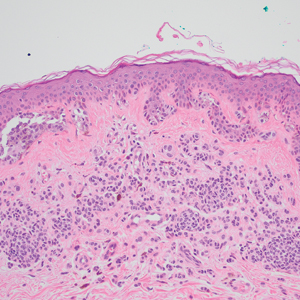

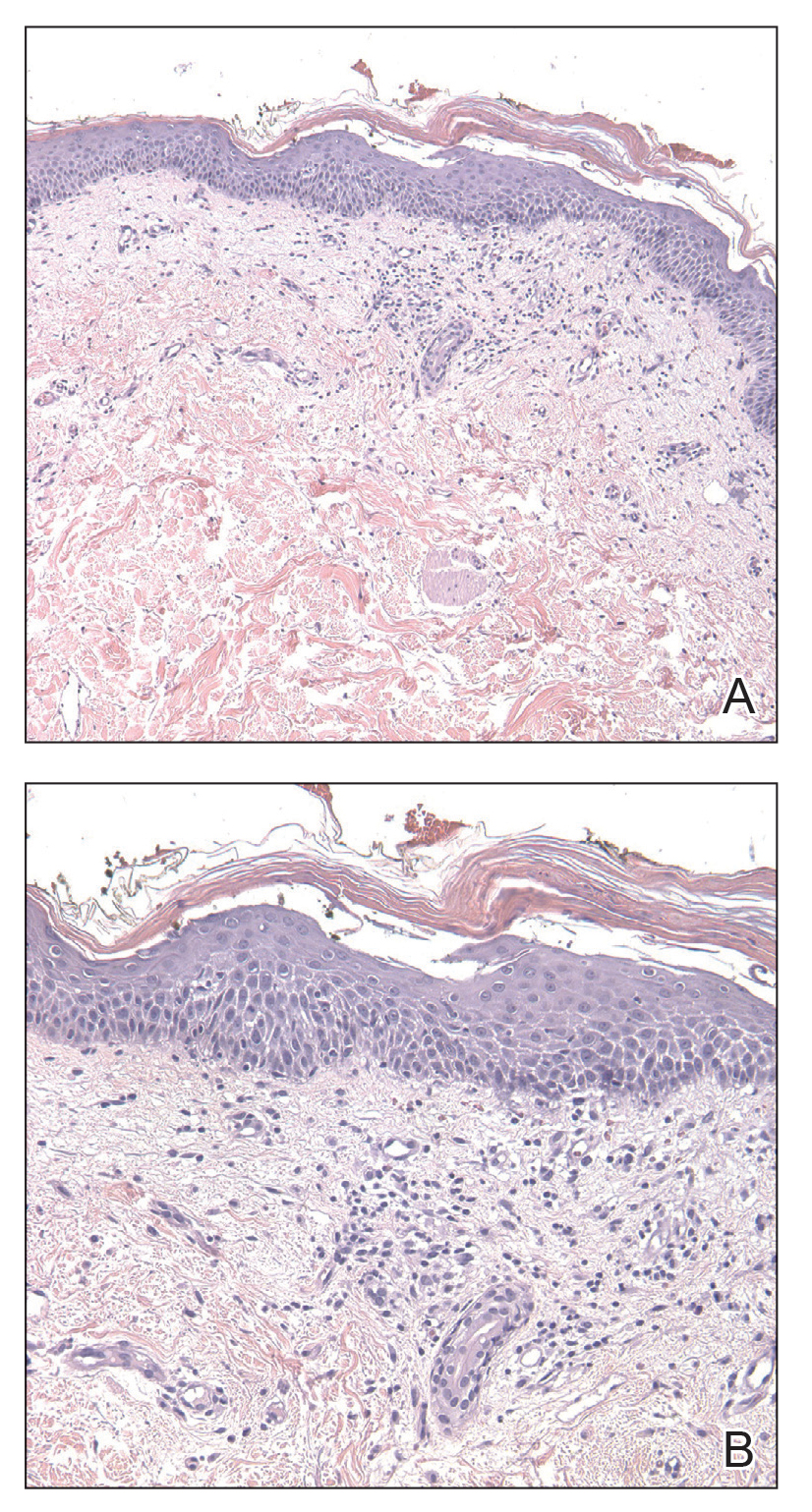

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

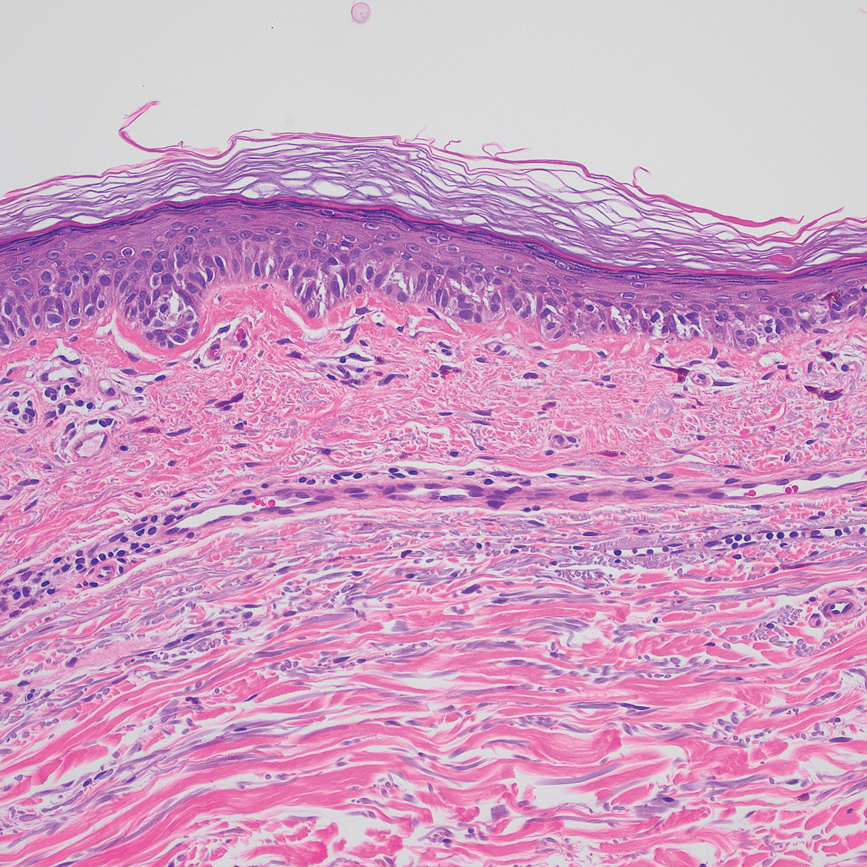

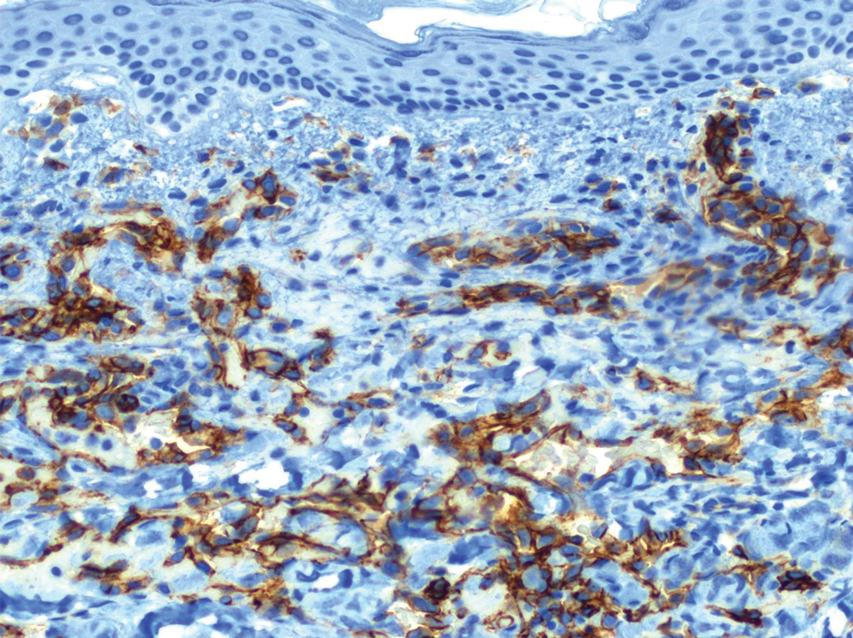

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

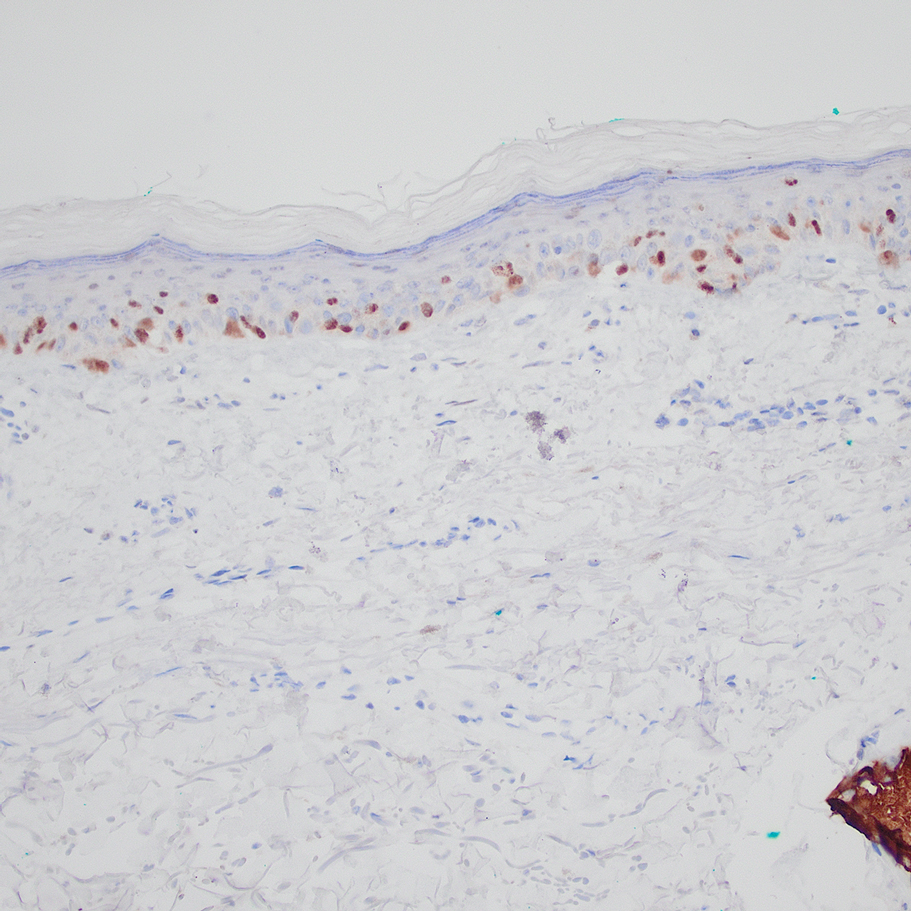

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

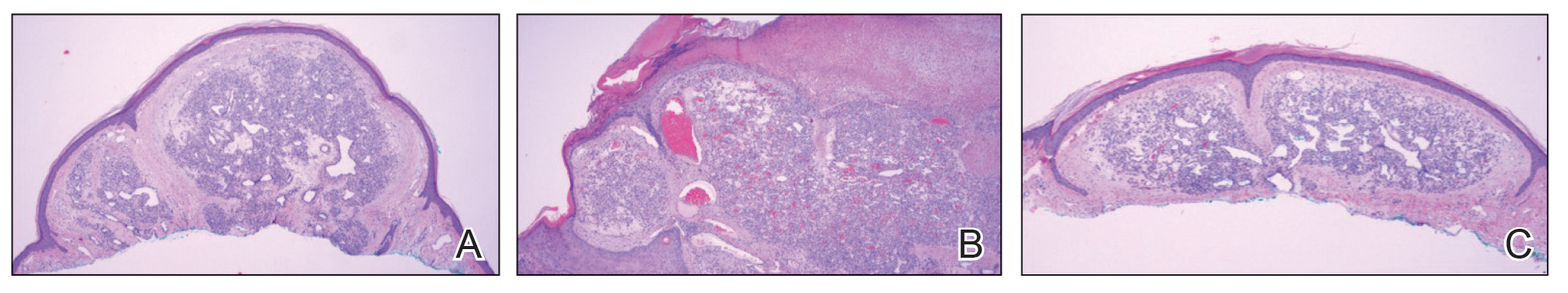

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

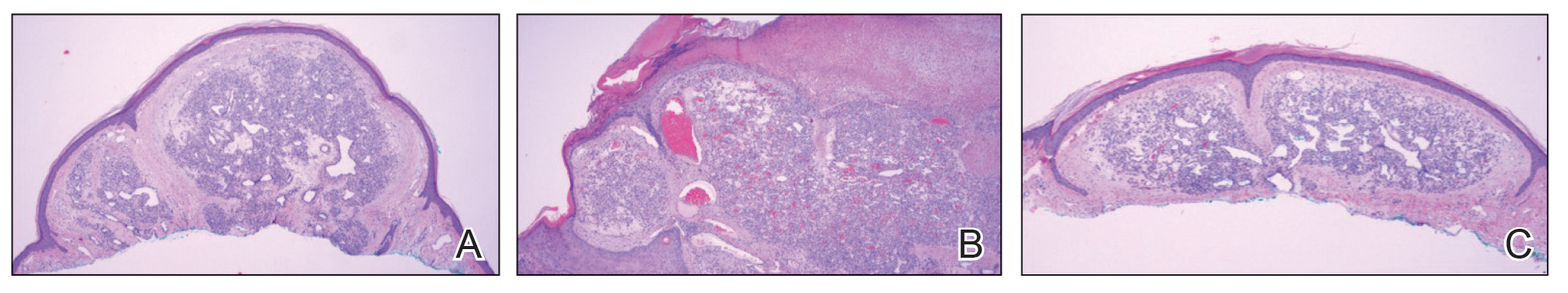

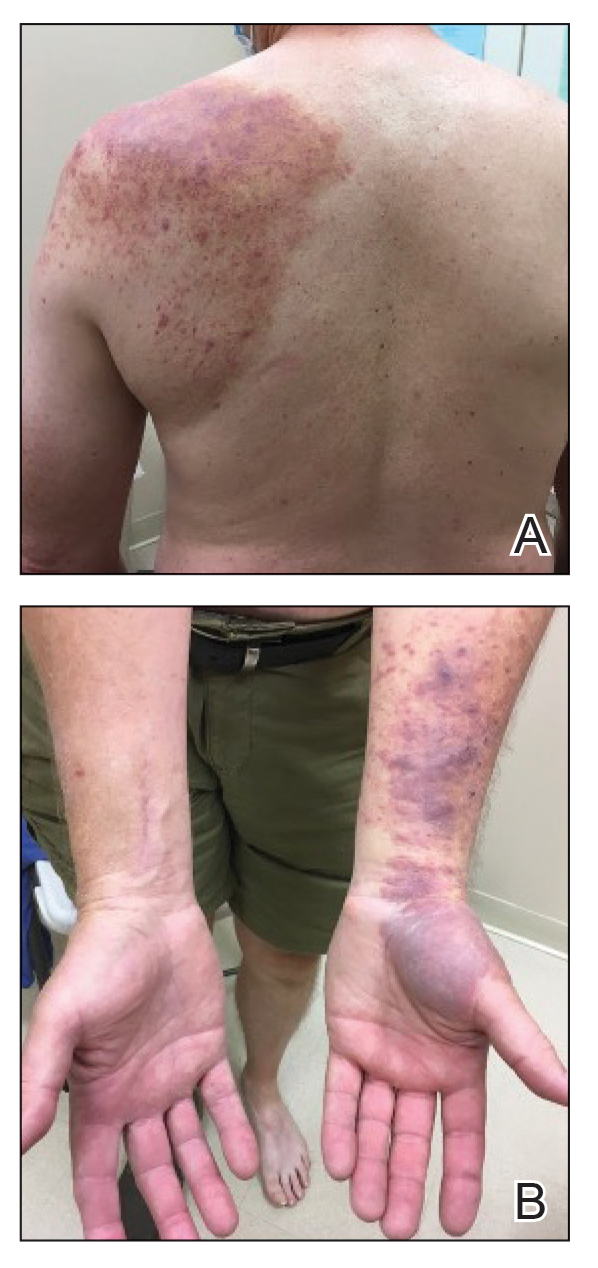

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare benign non- Langerhans cell histiocytopathy that can manifest initially with lymph node involvement—classically, massive painless cervical lymphadenopathy.1 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD) is a variant that can be associated with lymph node and internal involvement, but more than 80% of cases lack extracutaneous involvement.2,3 In cases with extracutaneous involvement, lymph node disease is most frequent.3 Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease unassociated with extracutaneous disease is a benign self-limiting histiocytopathy that manifests as painless red-brown, yellow, or fleshcolored nodules, plaques, or papules that may become tender or ulcerated.4

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease represents a benign histiocytopathy of resident dendritic cell derivation.3 A characteristic immunohistochemical finding is S-100 positivity, which might suggest a Langerhans cell transdifferentiation phenotype, but other markers corroborative of a Langerhans cell phenotype—namely CD1a and langerin—will be negative. Biopsies typically show a mid to deep dermal histiocytic infiltration in a variably dense polymorphous inflammatory cell background comprised of a mixture of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils.3 At times the extent of lymphocytic infiltration can be to a magnitude that resembles a lymphoma on histopathology. In our patient, lymphoma was excluded based on clinical presentation, as this patient lacked the typical symptoms of lymphadenopathy or B symptoms that come with B-cell lymphoma.5

The histiocytes in CRDD are characteristically large mononuclear cells exhibiting a low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio reflective of the voluminous, nonvacuolated, watery cytoplasm. They have ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes resulting in a seemingly syncytial growth pattern. A hallmark of the histiocytes is emperipolesis characterized by intracytoplasmic localization of intact inflammatory cells including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.3

The differential diagnosis of CRDD includes Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. All of these conditions can be differentiated by their unique histopathologic and phenotypic characteristics.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a distinct clonal histiocytopathy that has a varied presentation ranging from cutaneous confined cases manifesting as a solitary lesion to one of disseminated cutaneous disease with the potential for multiorgan involvement. Regardless of the variant of LCH, the hallmark cell is one showing an eccentrically disposed, reniform nucleus with an open chromatin and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1).6 Both LCH and CRDD stain positive for S-100. However, unlike the histiocytes in CRDD, those seen in LCH stain positive for CD1a and langerin and would not express factor XIIIA. Additionally, the neoplastic cells would not exhibit the same extent of CD68 positivity seen in CRDD.6 Treatment of LCH depends on the extent of disease, especially for the presence or absence of extracutaneous disease.7

A variant of LCH is indeterminate cell histiocytosis, which can be seen in neonates or adults. It represents a neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells that are devoid of Birbeck granules, reflective of an immature early phase of differentiation in the skin prior to the cells acquiring the Birbeck granule (as would be seen in neonates) or a later phase of differentiation after the mature Langerhans cell has encountered antigen and is en route to the lymph node (typically seen in adults).8 The phenotypic profile is identical to conventional LCH except the cells do not express langerin. Microscopically, the infiltrates are composed of Langerhans cells that are morphologically indistinguishable from classic LCH but without epidermotropism and exhibit a dominant localization in the dermis typically unassociated with other inflammatory cell elements (Figure 2).9

Xanthogranuloma is seen in young children (juvenile xanthogranuloma) as a solitary lesion, though a multifocal cutaneous variant and extracutaneous presentations have been described. Similar lesions can be seen in adults.10 These lesions are evolutionary in their morphology. In the inception of a juvenile xanthogranuloma, the lesions are highly cellular, and the histiocytes typically are poorly lipidized; there may be a dearth of other inflammatory cell elements. As the lesions mature, the histiocytes become lipidized, and characteristic Touton giant cells that exhibit a wreath of nuclei with peripheral lipidization may develop (Figure 3). In the later stages, there is considerable hyalinizing fibrosis, and the cells can acquire a spindled appearance. The absence of emperipolesis and the presence of notable lipidization are useful light microscopy features differentiating xanthogranuloma from CRDD.11 Treatment of xanthogranuloma can range from a conservative monitoring approach to an aggressive approach combining various antineoplastic therapies with immunosuppressive agents.12

Solitary and multicentric reticulohistiocytoma is another form of resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can resemble Rosai-Dorfman disease. It is a dermal histiocytic infiltrate accompanied by a polymorphous inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 4) and can show variable fibrosis.13 One of the hallmarks is the distinct amphophilic cytoplasms, possibly attributable to nuclear DNA released into the cytoplasm from effete nuclei.13 The solitary form is unassociated with systemic disease, whereas the multicentric variant can be a paraneoplastic syndrome in the setting of solid and hematologic malignancies.14 In addition, in the multicentric variant, similar lesions can affect any organ but there can be a proclivity to involve the hand and knee joints, leading to a crippling arthritis.15 We presented a case of CRDD, a benign resident dendritic cell histiocytopathy that can manifest as a cutaneous confined process in the skin where the clinical course is characteristically benign. It potentially can be confused with LCH, indeterminate cell histiocytosis, xanthogranuloma, and reticulohistiocytoma. For a solitary lesion, intralesional triamcinolone injection and excision are options. Multifocal cutaneous disease or CRDD with notable extracutaneous disease may require systemic treatment.16 In our patient, one intralesional triamcinolone injection was performed with notable resolution.

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

- Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87:63-70.

- Brenn T, Calonje E, Granter SR, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease is a distinct clinical entity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:385.

- Ahmed A, Crowson N, Magro CM. A comprehensive assessment of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019;40:166-173.

- Frater JL, Maddox JS, Obadiah JM, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: comprehensive review of cases reported in the medical literature since 1990 and presentation of an illustrative case. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:281-290.

- Friedberg JW, Fisher RI. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:941-952. Doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.07.002

- Allen CE, Merad M, McClain KL. Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:856-868.

- Board PPTE. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment (PDQ®). In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2009.

- Chu A, Eisinger M, Lee JS, et al. Immunoelectron microscopic identification of Langerhans cells using a new antigenic marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982;78:177-180. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506352

- Berti E, Gianotti R, Alessi E. Unusual cutaneous histiocytosis expressing an intermediate immunophenotype between Langerhans’ cells and dermal macrophages. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1250-1253. doi:10.1001/archderm.1988.01670080062020

- Cypel TKS, Zuker RM. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2008;16:175-177.

- Rodriguez J, Ackerman AB. Xanthogranuloma in adults. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:43-44.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492. doi:10.1016/j. clindermatol.2006.07.010

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521.

- Gold RH, Metzger AL, Mirra JM, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (lipoid dermato-arthritis). An erosive polyarthritis with distinctive clinical, roentgenographic and pathologic features. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:610-624. doi:10.2214/ajr.124.4.610

- Dalia S, Sagatys E, Sokol L, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: tumor biology, clinical features, pathology, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:322-327. doi:10.1177/107327481402100408

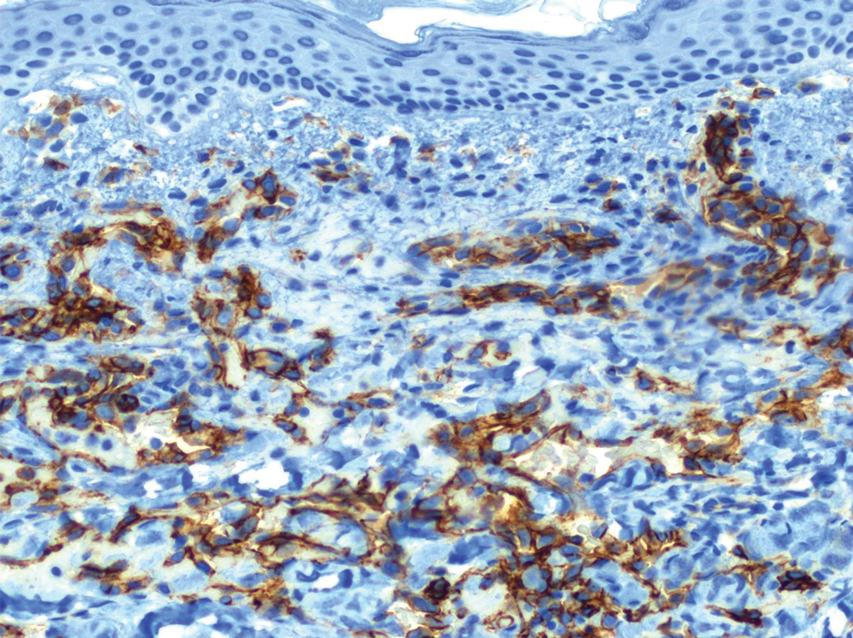

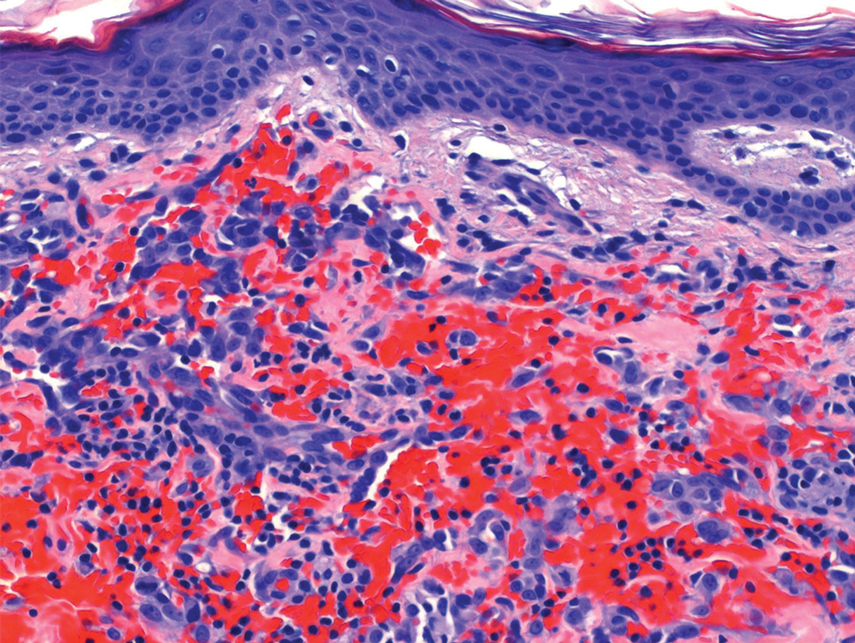

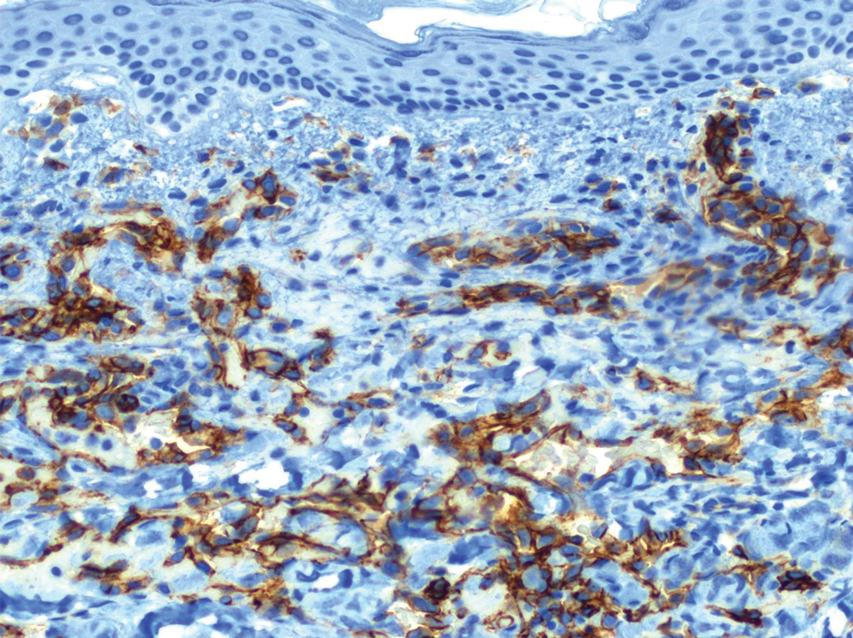

A 31-year-old woman presented with a slow-growing, tender, pruritic lesion on the right cheek of 4 to 5 months’ duration. She had been applying petroleum jelly and hydrocortisone cream 2.5% without any improvement. Physical examination revealed a 1×5-mm, pearly pink, erythematous, crusted papule with arborizing vessels surrounded by scattered pink papules with white dots within. No cervical lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination, and the patient denied any other systemic symptoms. Shave and punch biopsies of the lesion were performed; stains for microorganisms were negative. The biopsy showed a dense reticular mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate comprised of a mixture of histiocytes (top), lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells that assumed a diffuse growth pattern within the dermis. The histiocytes exhibited abundant watery cytoplasms with ill-defined cytoplasmic membranes; intact leukocytes were found within the cytoplasms. The histiocytes demonstrated a unique phenotype characterized by S-100 (bottom) and CD68 positivity.

The Many Uses of the Humble Alcohol Swab

Practice Gap

In light of inflation, rising costs of procedures, and decreased reimbursements,1 there is an increased need to identify and utilize inexpensive multitasking tools that can serve the dermatologic surgeon from preoperative to postoperative care. The 70% isopropyl alcohol swab may be the dermatologist’s most cost-effective and versatile surgical tool.

The Technique

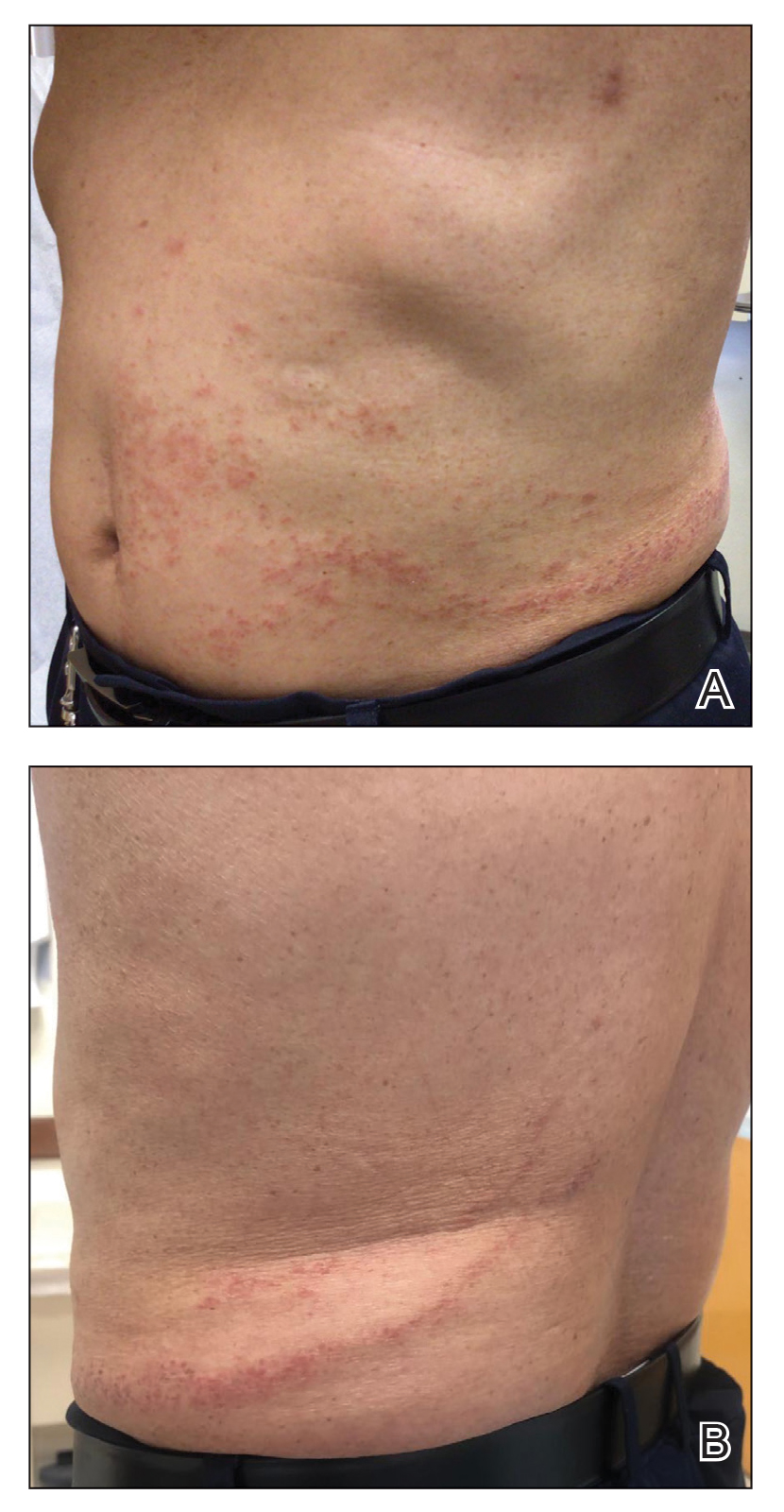

When assessing a lesion, alcohol swabs can remove scale, crust, or residue from personal care products to help reveal primary morphology. They aid in the diagnosis of porokeratosis by highlighting the cornoid lamella when used following application of gentian violet.2 The alcohol swab also can lay down a liquid interface to facilitate contact dermoscopy and improve visualization while also reducing the transmission of pathogens by the dermatoscope.3 Rubbing an area with an alcohol swab can induce vasodilation of scar tissue, which also may help localize a prior biopsy or surgical site (Figure).

Before a surgical site is marked, an initial cleanse with an alcohol swab serves to both remove debris and provide antisepsis ahead of the procedure. Additionally, the swab may improve adherence of skin markers by clearing excess lipid from the skin surface. Assessing the amount of debris and oil removed in the process can help determine a patient’s baseline level of hygiene, which can aid postoperative wound care planning. In extreme cases, use of an alcohol swab may help diagnose dermatitis neglecta or terra firma-forme dermatosis by completely removing any pigmentation.4

After surgery, the alcohol swab can remove skin marker(s) and blood and prepare the site for the surgical dressing. There also is some evidence to suggest that cleansing the surgical site with an alcohol swab as part of routine postoperative wound care may decrease incidence of surgical-site infection.5 At follow-up, the swab can remove crust and clean the skin before suture removal. If infection is suspected, the swab can cleanse skin before a wound culture is obtained to remove skin commensals and flora on the outer surface of the wound.

Practice Implications

The 70% isopropyl alcohol swab can assist the dermatologist in numerous tasks related to everyday procedures. It is readily available in every clinic and costs only a few cents.

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Thomas CJ, Elston DM. Medical pearl: Gentian violet to highlight the cornoid lamella in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3 pt 1):513-514.

- Kelly SC, Purcell SM. Prevention of nosocomial infection during dermoscopy? Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:552-555.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Snider K, et al. Clinical pearl: increasing utility of isopropyl alcohol for cutaneous dyschromia. Cutis. 2016;97:287;301.

- Vogt KN, Chadi S, Parry N, et al. Daily incision cleansing with alcohol reduces the rate of surgical site infections: a pilot study. Am Surg. 2015;81:1182-1186.

Practice Gap

In light of inflation, rising costs of procedures, and decreased reimbursements,1 there is an increased need to identify and utilize inexpensive multitasking tools that can serve the dermatologic surgeon from preoperative to postoperative care. The 70% isopropyl alcohol swab may be the dermatologist’s most cost-effective and versatile surgical tool.

The Technique

When assessing a lesion, alcohol swabs can remove scale, crust, or residue from personal care products to help reveal primary morphology. They aid in the diagnosis of porokeratosis by highlighting the cornoid lamella when used following application of gentian violet.2 The alcohol swab also can lay down a liquid interface to facilitate contact dermoscopy and improve visualization while also reducing the transmission of pathogens by the dermatoscope.3 Rubbing an area with an alcohol swab can induce vasodilation of scar tissue, which also may help localize a prior biopsy or surgical site (Figure).

Before a surgical site is marked, an initial cleanse with an alcohol swab serves to both remove debris and provide antisepsis ahead of the procedure. Additionally, the swab may improve adherence of skin markers by clearing excess lipid from the skin surface. Assessing the amount of debris and oil removed in the process can help determine a patient’s baseline level of hygiene, which can aid postoperative wound care planning. In extreme cases, use of an alcohol swab may help diagnose dermatitis neglecta or terra firma-forme dermatosis by completely removing any pigmentation.4

After surgery, the alcohol swab can remove skin marker(s) and blood and prepare the site for the surgical dressing. There also is some evidence to suggest that cleansing the surgical site with an alcohol swab as part of routine postoperative wound care may decrease incidence of surgical-site infection.5 At follow-up, the swab can remove crust and clean the skin before suture removal. If infection is suspected, the swab can cleanse skin before a wound culture is obtained to remove skin commensals and flora on the outer surface of the wound.

Practice Implications

The 70% isopropyl alcohol swab can assist the dermatologist in numerous tasks related to everyday procedures. It is readily available in every clinic and costs only a few cents.

Practice Gap

In light of inflation, rising costs of procedures, and decreased reimbursements,1 there is an increased need to identify and utilize inexpensive multitasking tools that can serve the dermatologic surgeon from preoperative to postoperative care. The 70% isopropyl alcohol swab may be the dermatologist’s most cost-effective and versatile surgical tool.

The Technique

When assessing a lesion, alcohol swabs can remove scale, crust, or residue from personal care products to help reveal primary morphology. They aid in the diagnosis of porokeratosis by highlighting the cornoid lamella when used following application of gentian violet.2 The alcohol swab also can lay down a liquid interface to facilitate contact dermoscopy and improve visualization while also reducing the transmission of pathogens by the dermatoscope.3 Rubbing an area with an alcohol swab can induce vasodilation of scar tissue, which also may help localize a prior biopsy or surgical site (Figure).

Before a surgical site is marked, an initial cleanse with an alcohol swab serves to both remove debris and provide antisepsis ahead of the procedure. Additionally, the swab may improve adherence of skin markers by clearing excess lipid from the skin surface. Assessing the amount of debris and oil removed in the process can help determine a patient’s baseline level of hygiene, which can aid postoperative wound care planning. In extreme cases, use of an alcohol swab may help diagnose dermatitis neglecta or terra firma-forme dermatosis by completely removing any pigmentation.4

After surgery, the alcohol swab can remove skin marker(s) and blood and prepare the site for the surgical dressing. There also is some evidence to suggest that cleansing the surgical site with an alcohol swab as part of routine postoperative wound care may decrease incidence of surgical-site infection.5 At follow-up, the swab can remove crust and clean the skin before suture removal. If infection is suspected, the swab can cleanse skin before a wound culture is obtained to remove skin commensals and flora on the outer surface of the wound.

Practice Implications

The 70% isopropyl alcohol swab can assist the dermatologist in numerous tasks related to everyday procedures. It is readily available in every clinic and costs only a few cents.

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Thomas CJ, Elston DM. Medical pearl: Gentian violet to highlight the cornoid lamella in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3 pt 1):513-514.

- Kelly SC, Purcell SM. Prevention of nosocomial infection during dermoscopy? Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:552-555.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Snider K, et al. Clinical pearl: increasing utility of isopropyl alcohol for cutaneous dyschromia. Cutis. 2016;97:287;301.

- Vogt KN, Chadi S, Parry N, et al. Daily incision cleansing with alcohol reduces the rate of surgical site infections: a pilot study. Am Surg. 2015;81:1182-1186.

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Thomas CJ, Elston DM. Medical pearl: Gentian violet to highlight the cornoid lamella in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3 pt 1):513-514.

- Kelly SC, Purcell SM. Prevention of nosocomial infection during dermoscopy? Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:552-555.

- Blattner CM, Perry B, Snider K, et al. Clinical pearl: increasing utility of isopropyl alcohol for cutaneous dyschromia. Cutis. 2016;97:287;301.

- Vogt KN, Chadi S, Parry N, et al. Daily incision cleansing with alcohol reduces the rate of surgical site infections: a pilot study. Am Surg. 2015;81:1182-1186.

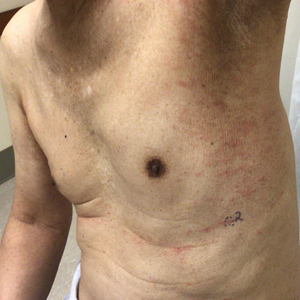

PRAME Expression in Melanocytic Proliferations in Special Sites

The assessment and diagnosis of melanocytic lesions can present a formidable challenge to even a seasoned pathologist, which is especially true when dealing with the subset of nevi occurring at special sites—where baseline variations inherent to particular locations on the body can preclude the use of features routinely used to diagnose malignancy elsewhere. These so-called special-site nevi previously have been described in the literature along with suggested criteria for differentiating malignant lesions from their benign counterparts.1 Locations generally considered to be special sites include the acral skin, anogenital region, breast, ear, and flexural regions.1,2

When evaluating non–special-site melanocytic lesions, general characteristics associated with a malignant diagnosis include confluence or pagetoid spread of melanocytes, nuclear pleomorphism, cytologic atypia, and irregular architecture3; however, these features can be compatible with a benign diagnosis in special-site nevi depending on their extent and the site in question. Although they can be atypical, special-site nevi tend to have the bulk of their architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in the center of the lesion as opposed to the edges.1 If a given lesion is from a special site but lacks this reassuring feature, special care should be taken to rule out malignancy.

Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) is an antigen first identified in tumor-reactive T-cell populations in patients with malignant melanoma. It is the product of an oncogene that frequently is overexpressed in melanomas, lung squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas, and acute leukemias.4 It functions as an antagonist of the retinoic acid signaling pathway, which normally serves to induce further cell differentiation, senescence, or apoptosis.5 PRAME inhibits retinoid signaling by forming a complex with both the ligand-bound retinoic acid holoreceptor and the polycomb protein EZH2, which blocks retinoid-dependent gene expression by encouraging chromatin condensation at the RARβ promoter site5; therefore, expressing PRAME allows lesional cells a substantial growth advantage.

PRAME expression has been extensively characterized in non–special-site nevi and has filled the need for a rather specific marker of melanoma.6-10 Although PRAME has been studied in acral nevi,11 the expression pattern in nevi of special sites has yet to be elucidated. Herein, we present a dataset characterizing PRAME expression in these challenging lesions.

Methods

We performed a retrospective case review at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia) and collected a panel of 36 special-site nevi that previously were diagnosed as benign by a trained dermatopathologist from January 2020 through December 2022. Special-site nevi were identified using a natural language filter for the following terms: acral, palm, sole, ear, auricular, lip, axilla, armpit, breast, groin, labia, vulva, umbilicus, and penis. This study was approved by the University of Virginia institutional review board.

The original hematoxylin and eosin slides used for primary diagnosis were re-examined to verify the prior diagnosis of benign nevus at a special site. We performed a detailed microscopic examination of all benign nevi in our cohort to determine the frequency of various characteristics at each special site. Sections were prepared from the formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and stained with a commercial PRAME antibody (#219650 [Abcam] at a 1:50 dilution) and counterstain. A trained dermatopathologist (S.S.R.) examined the stained sections and recorded the percentage of tumor cells with nuclear PRAME staining. We reported our results using previously established criteria for scoring PRAME immunohistochemistry7: 0 for no expression, 1+ for 1% to 25% expression, 2+ for 26% to 50% expression, 3+ for 51% to 75% expression, and 4+ for diffuse or 76% to 100% expression. Only strong clonal expression within a population of cells was graded.

Data handling and statistical testing were performed using the R Project for Statistical Computing (https://www.r-project.org/). Significance testing was performed using the Fisher exact test. Plot construction was performed using ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/).

Results

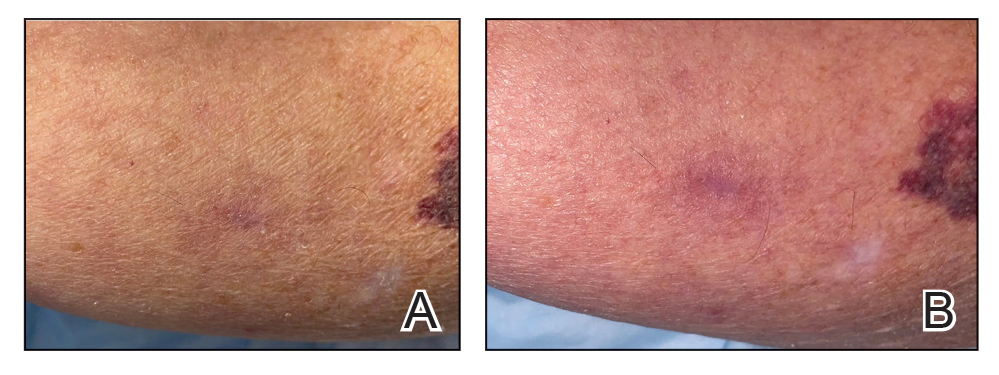

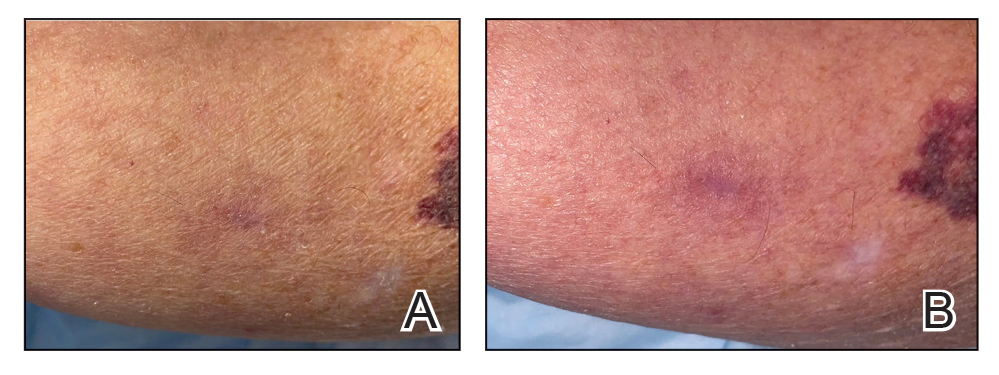

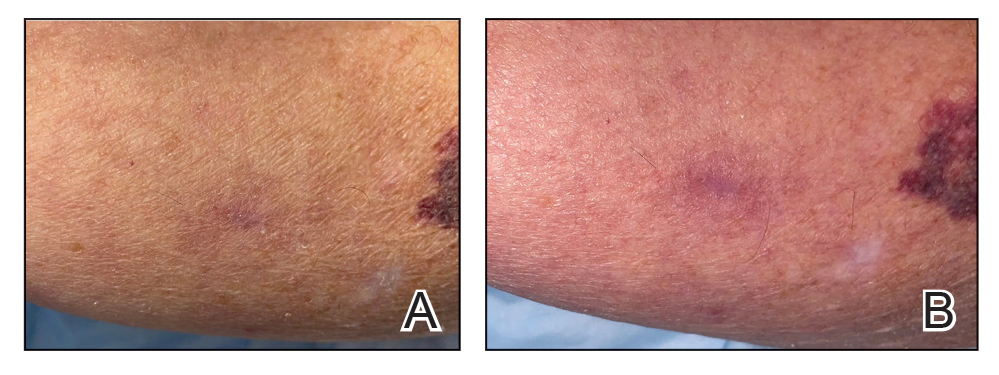

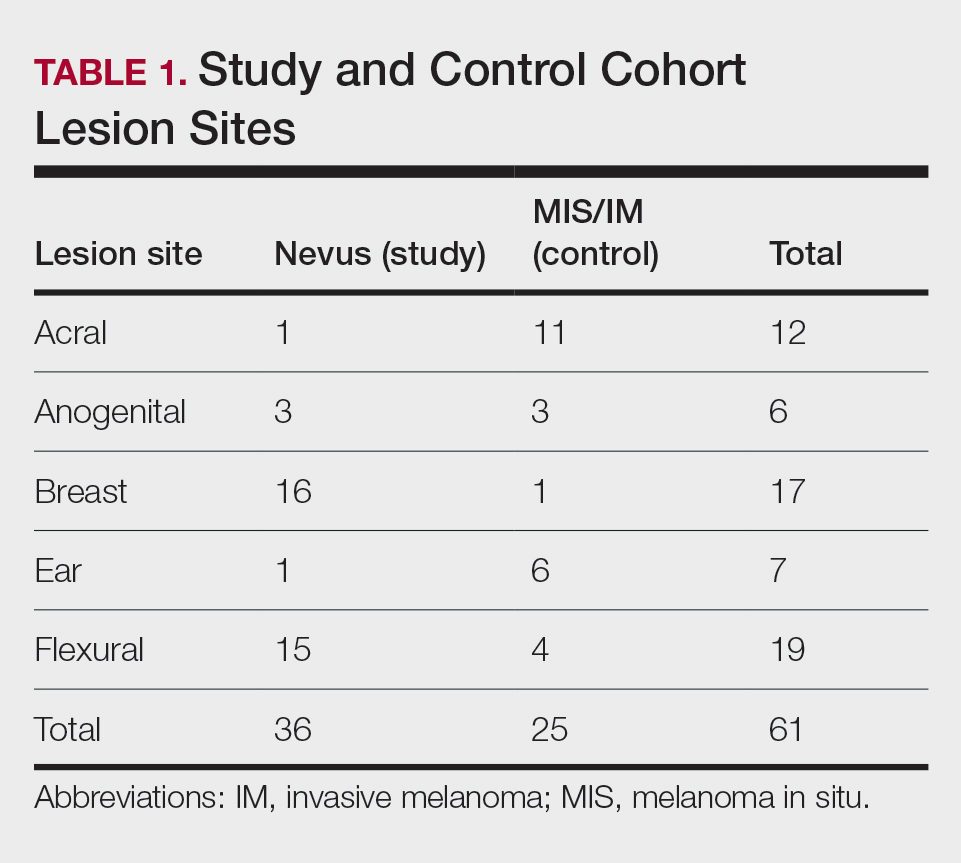

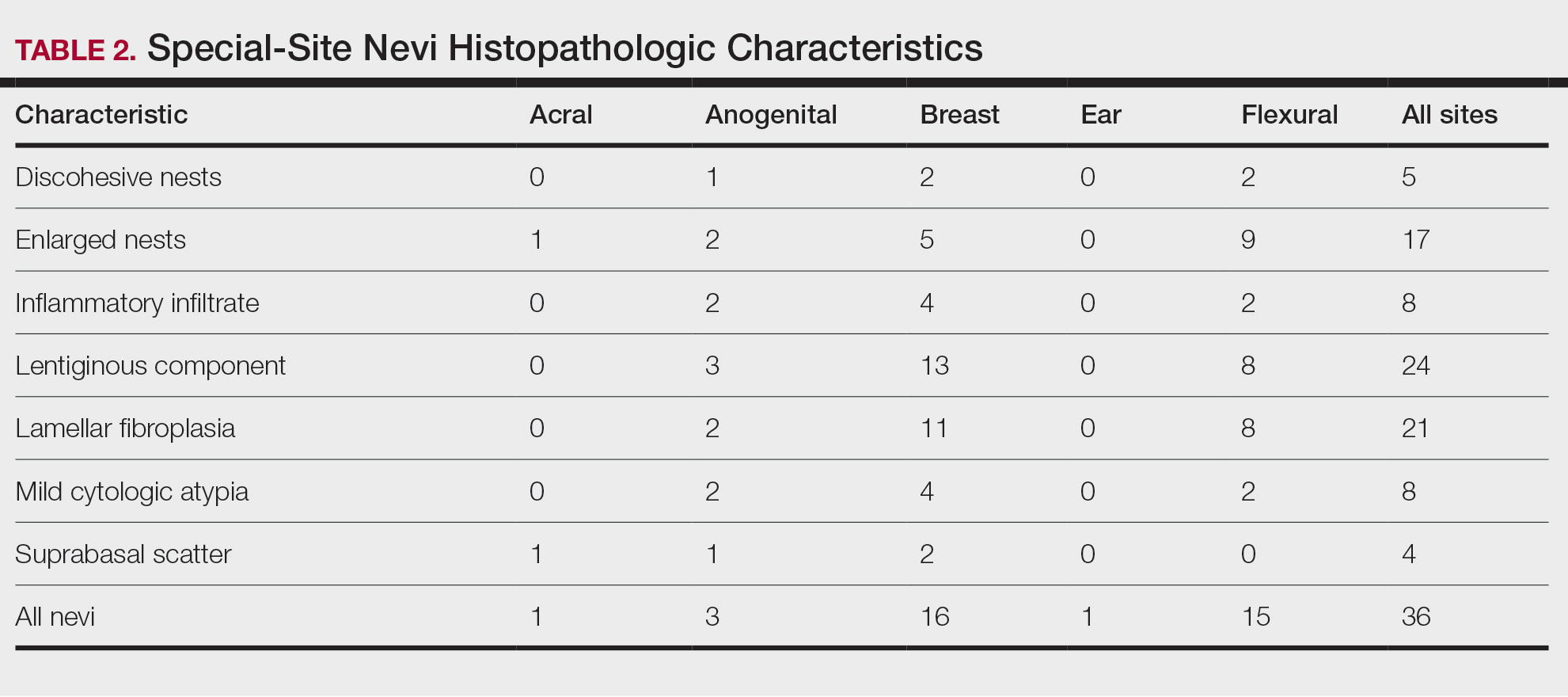

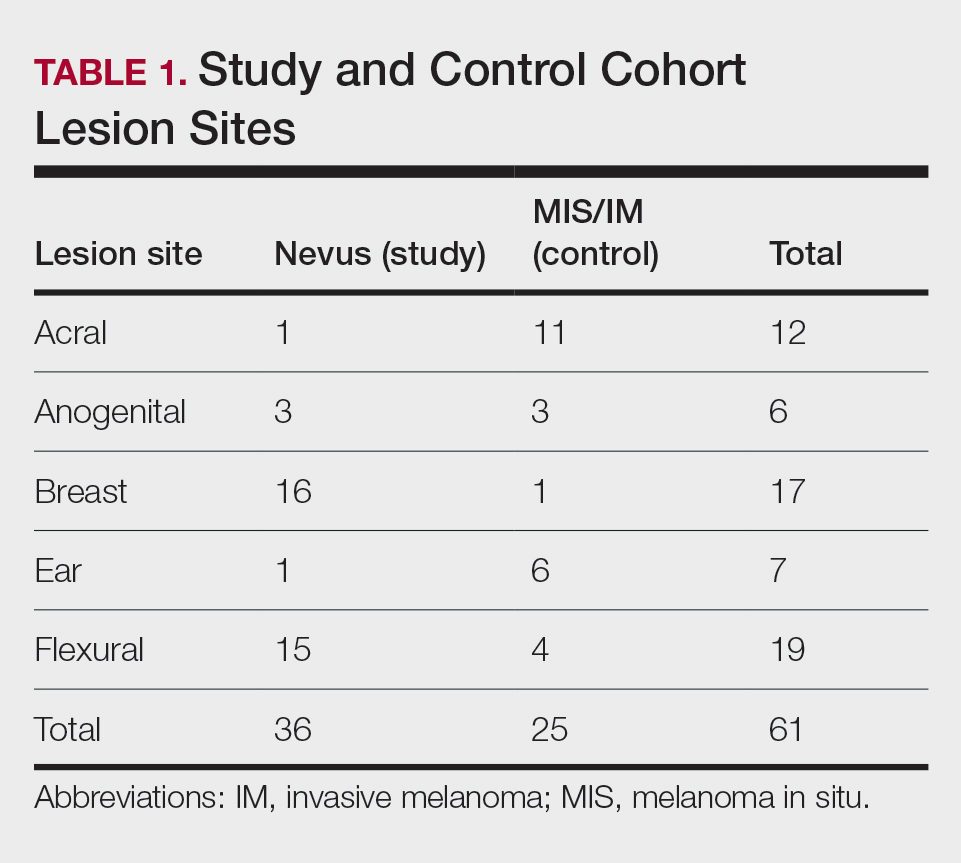

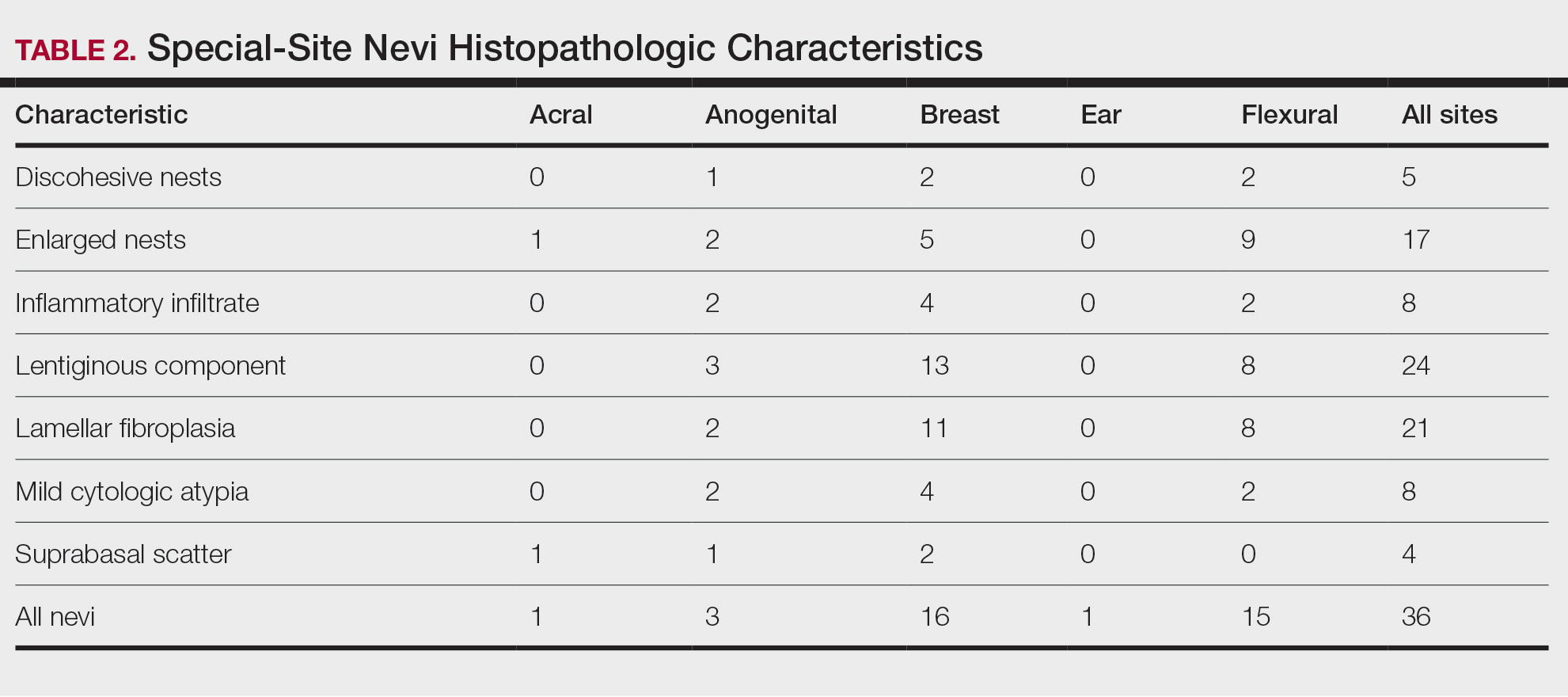

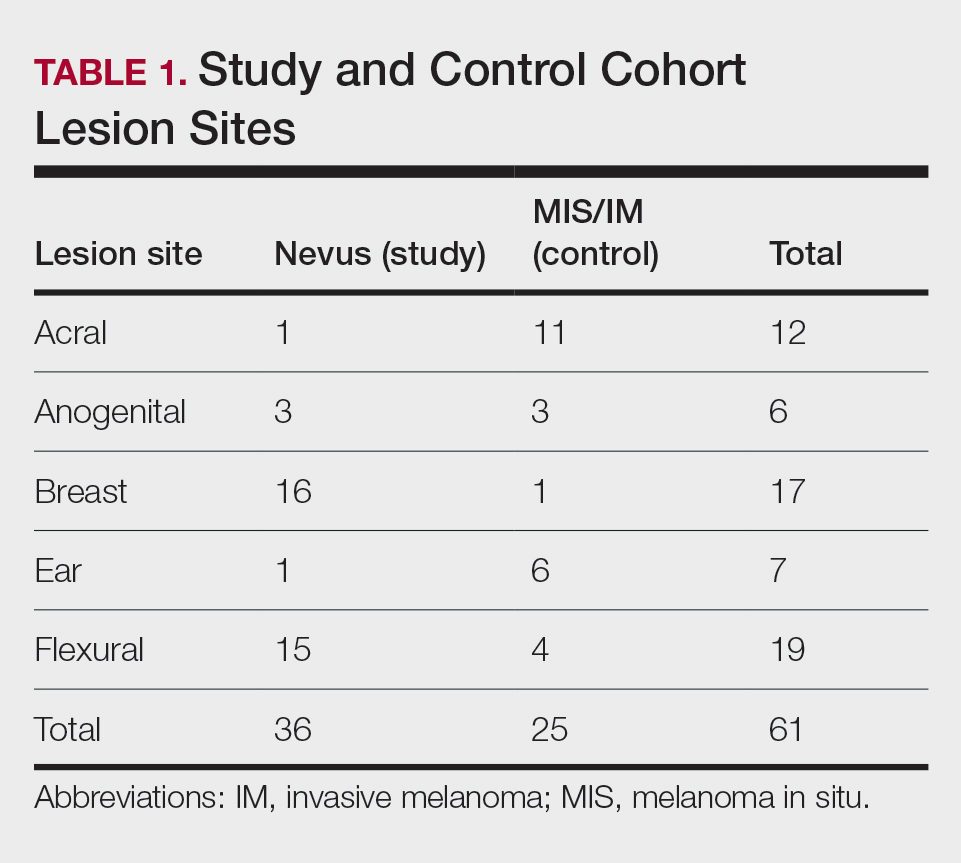

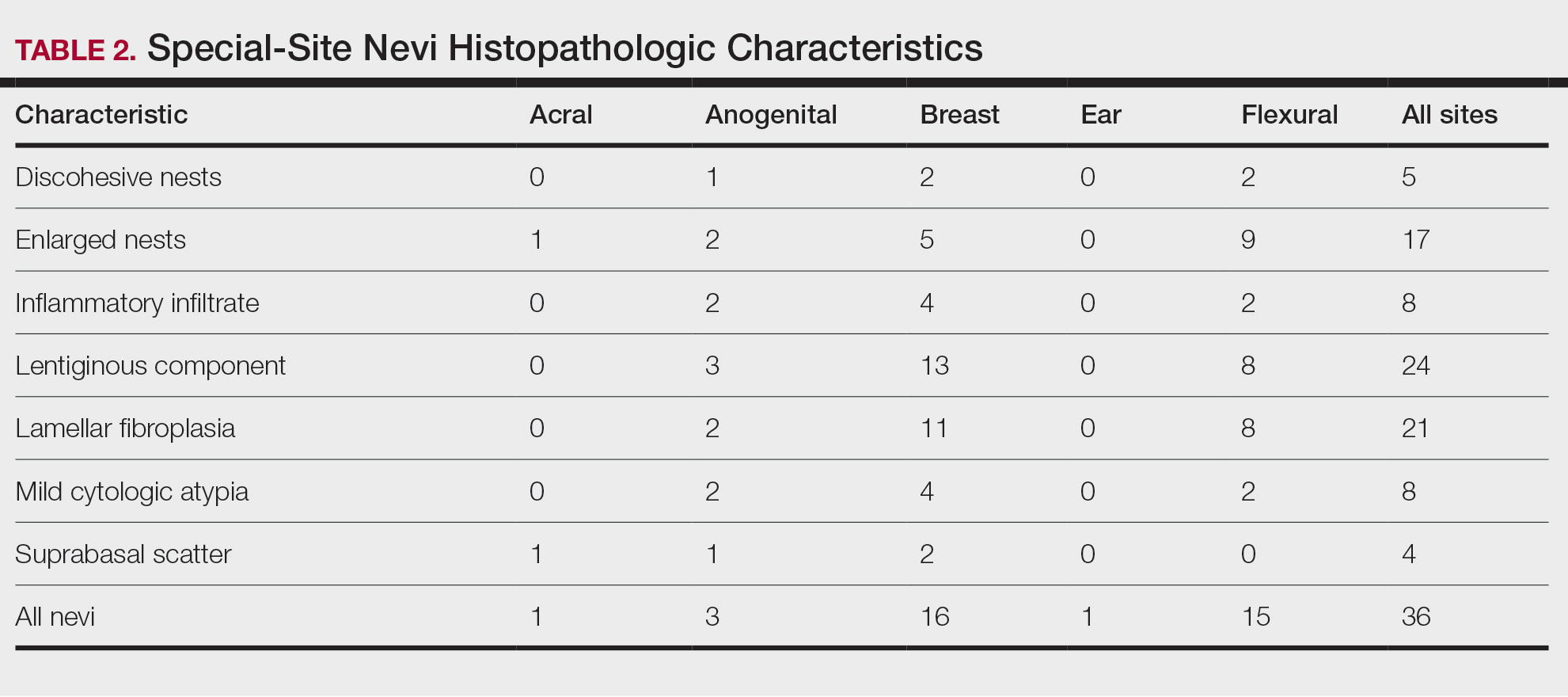

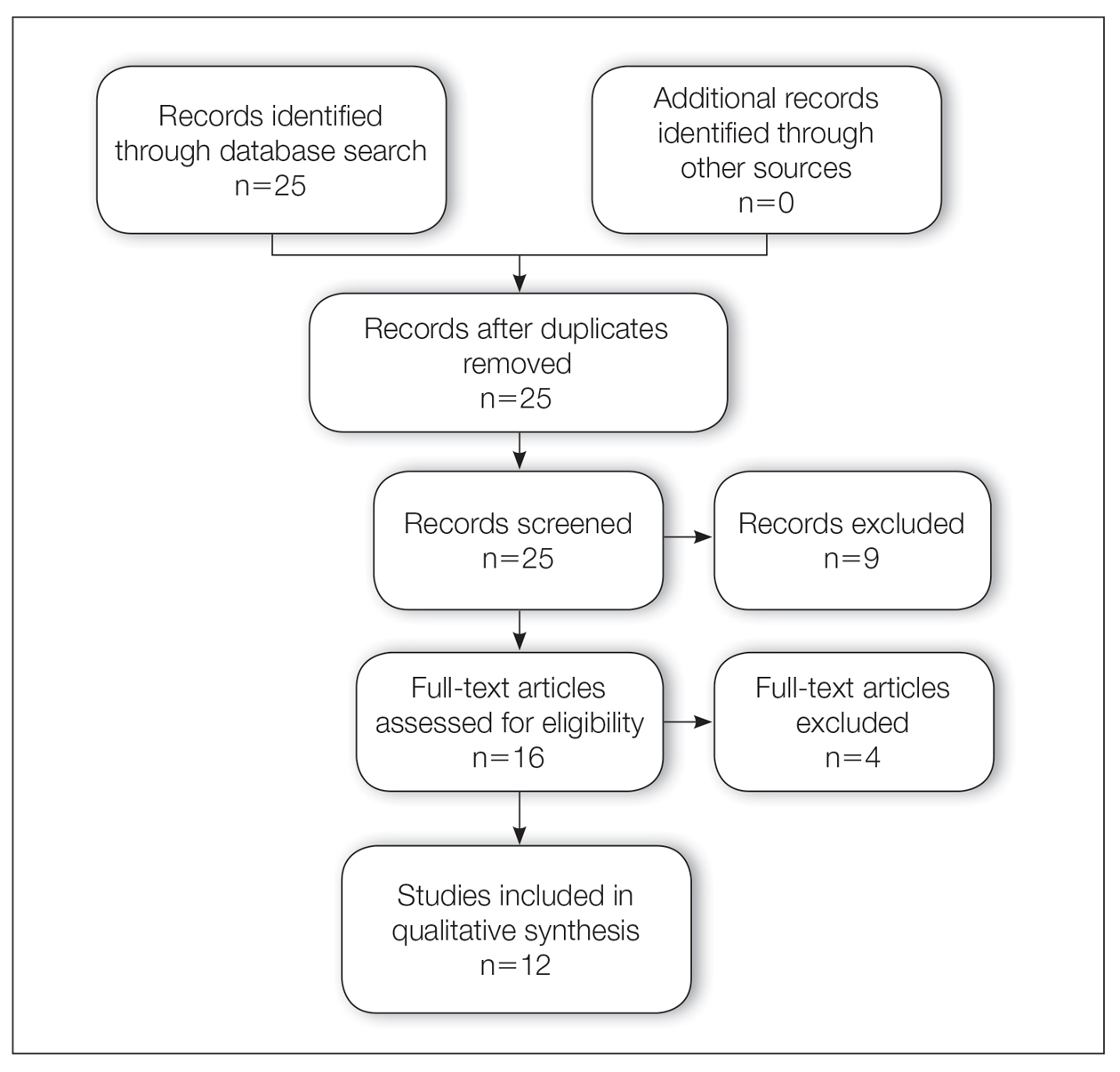

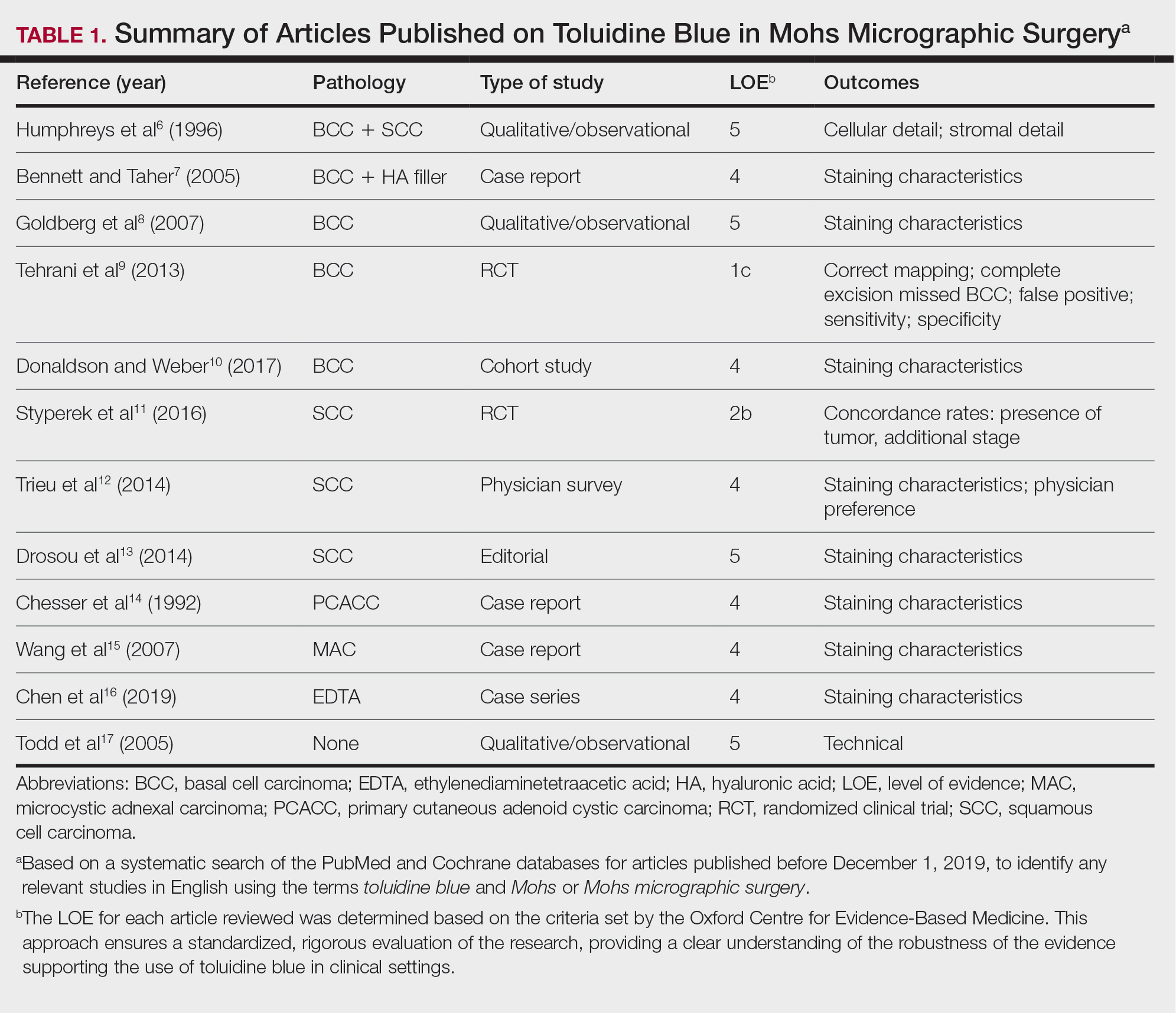

Our study cohort included 36 special-site nevi, and the control cohort comprised 25 melanoma in situ (MIS) or invasive melanoma (IM) lesions occurring at special sites. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the study and control cohorts by lesion site. Table 2 details the results of our microscopic examination, describing frequency of various characteristics of special-site nevi stratified by site.

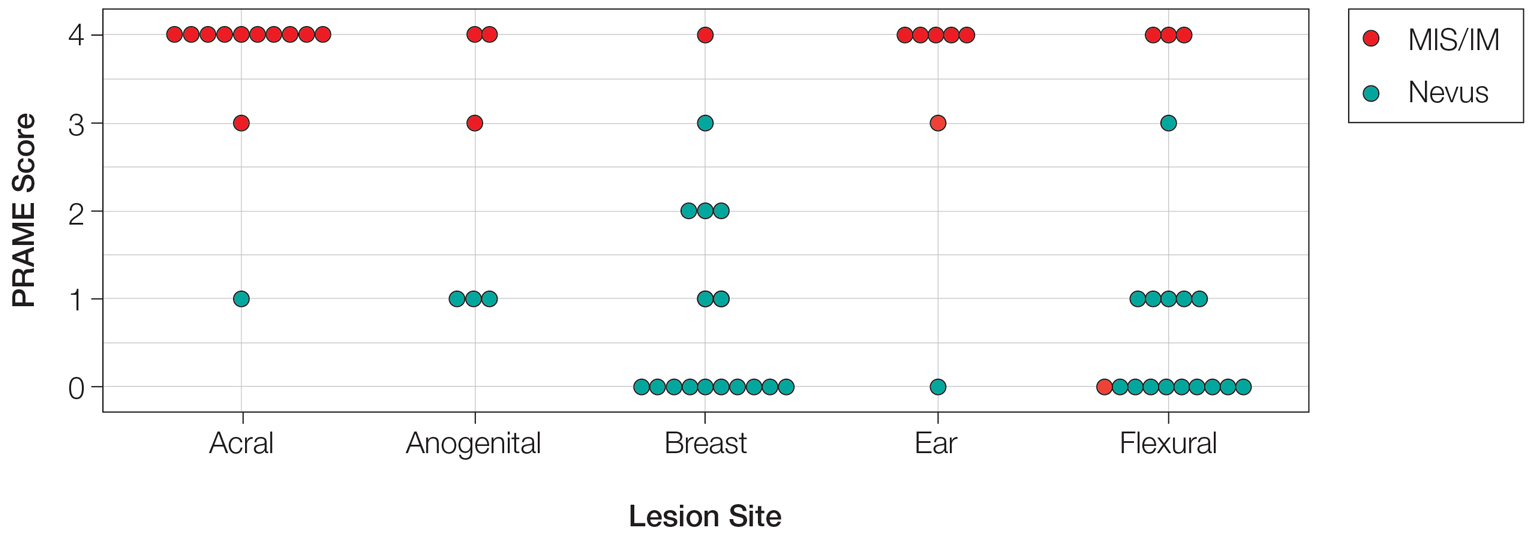

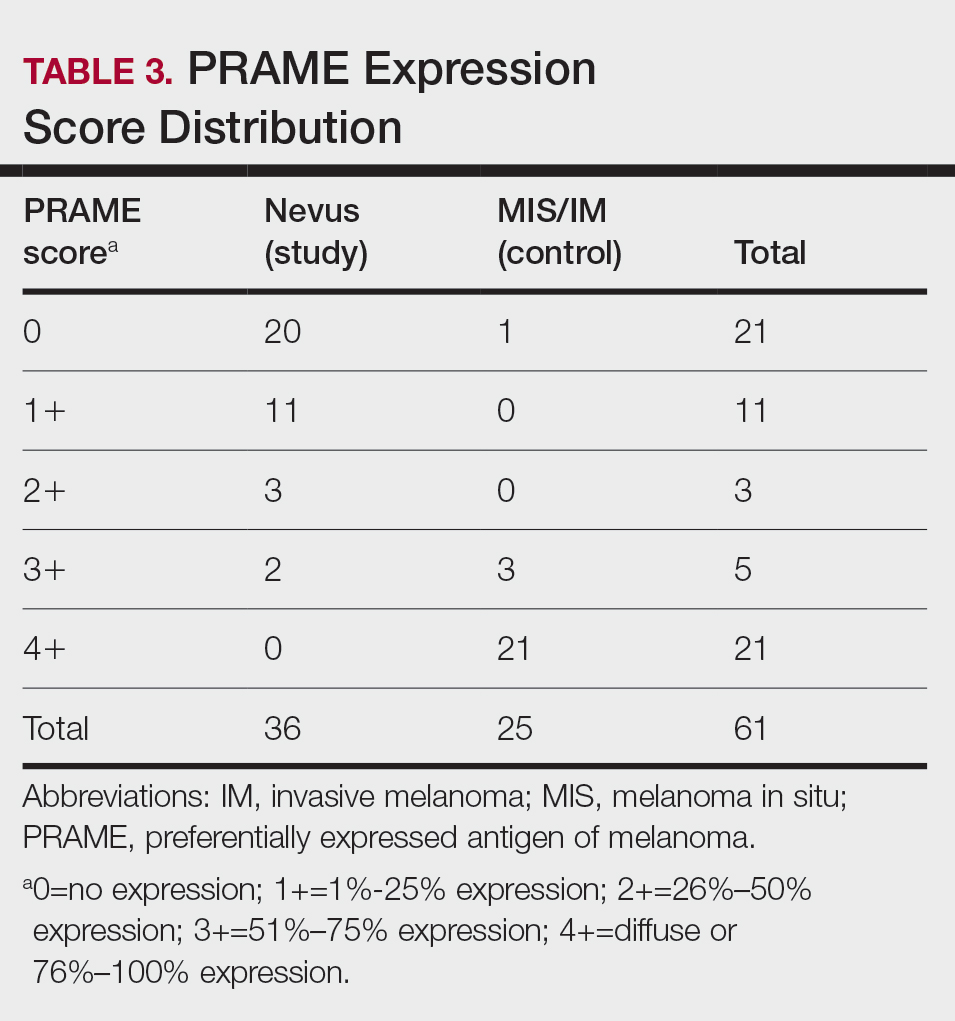

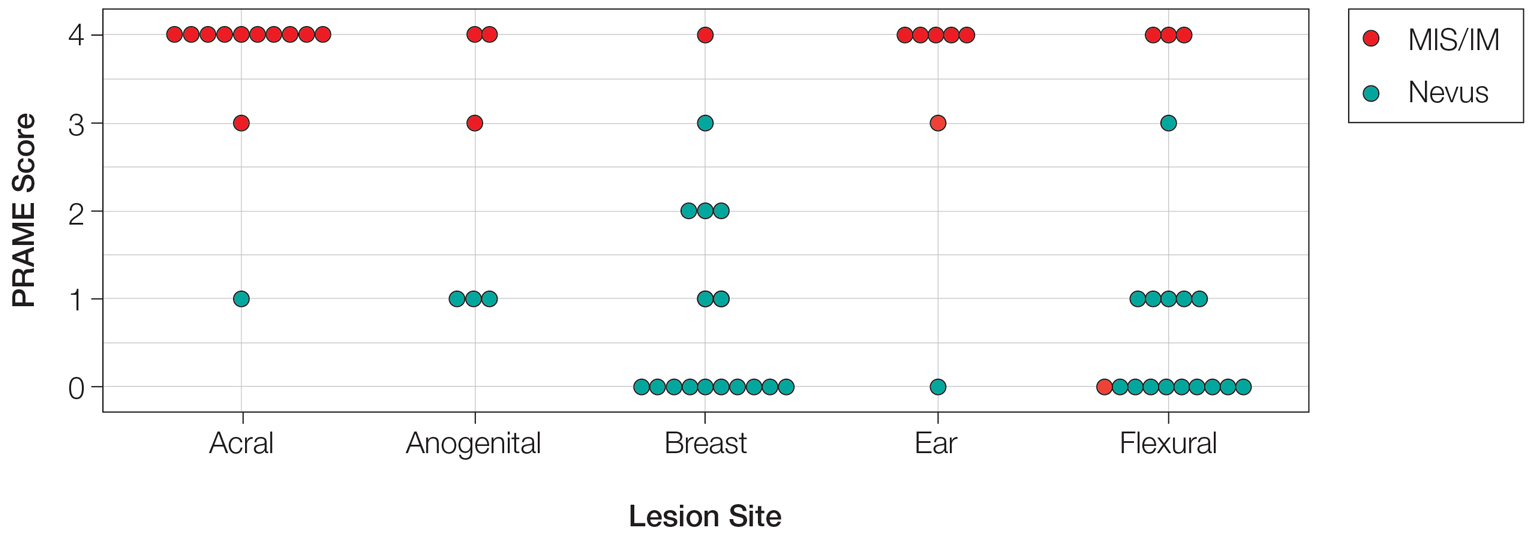

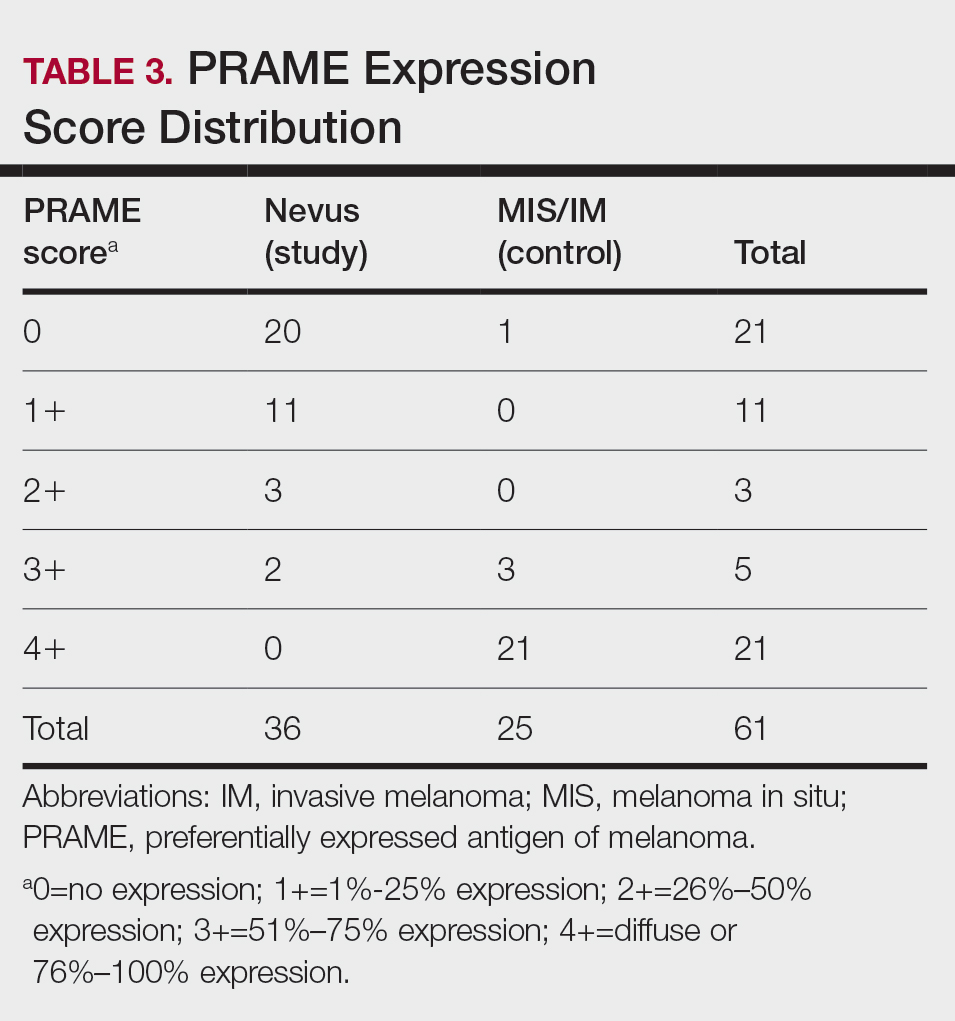

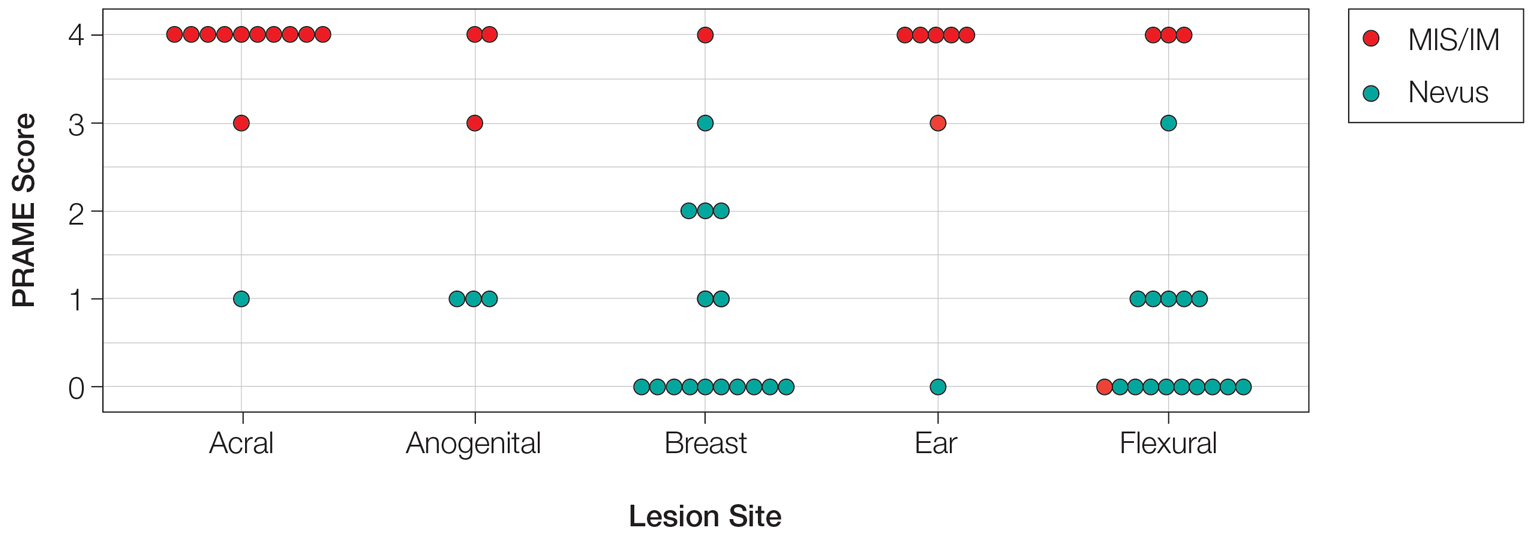

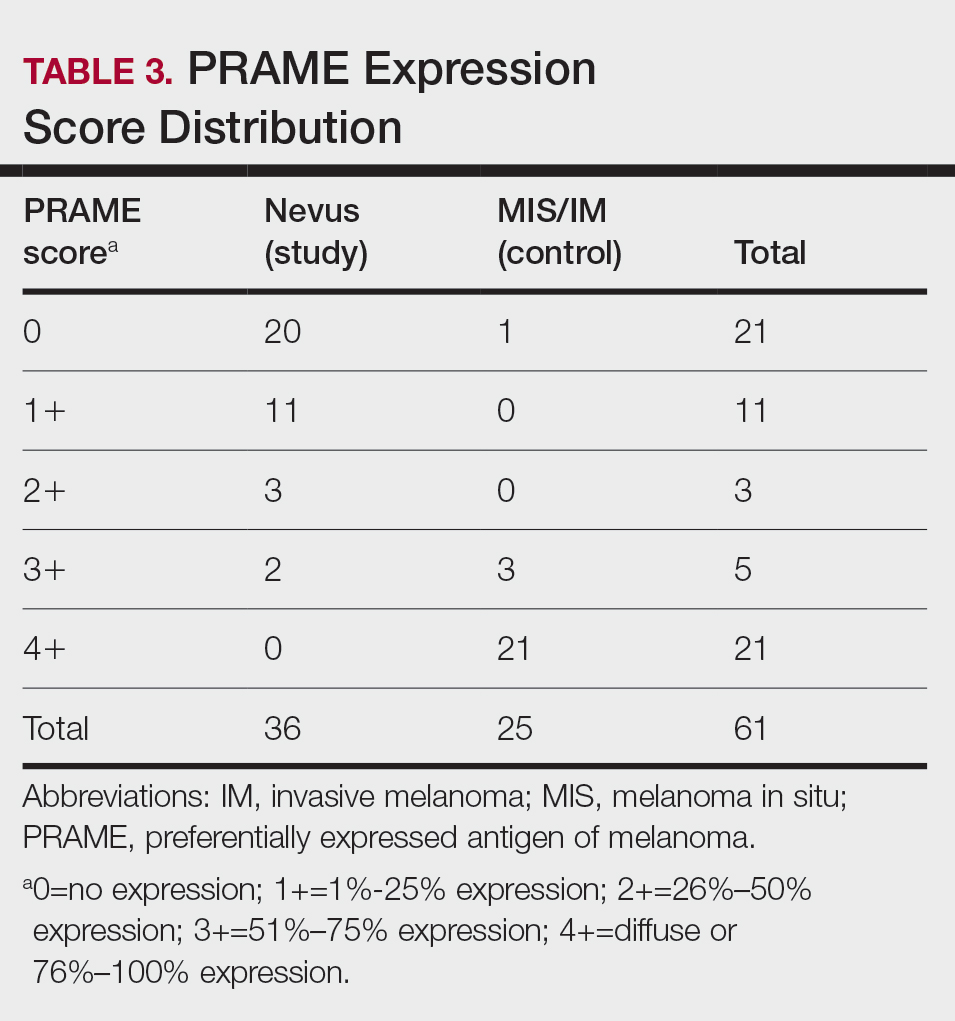

Of the 36 special-site nevi in our cohort, 20 (56%) had no staining (0) for PRAME, 11 (31%) demonstrated 1+ PRAME expression, 3 (8%) demonstrated 2+ PRAME expression, and 2 (6%) demonstrated 3+ PRAME expression. No nevi showed 4+ expression. In the control cohort, 24 of 25 (96%) MIS and IM showed 3+ or 4+ expression, with 21 (84%) demonstrating diffuse/4+ expression. One control case (4%) demonstrated 0 PRAME expression. These data are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 1. There is a significant difference in diffuse (4+) PRAME expression between special-site nevi and MIS/IM occurring at special sites (P=1.039×10-12).

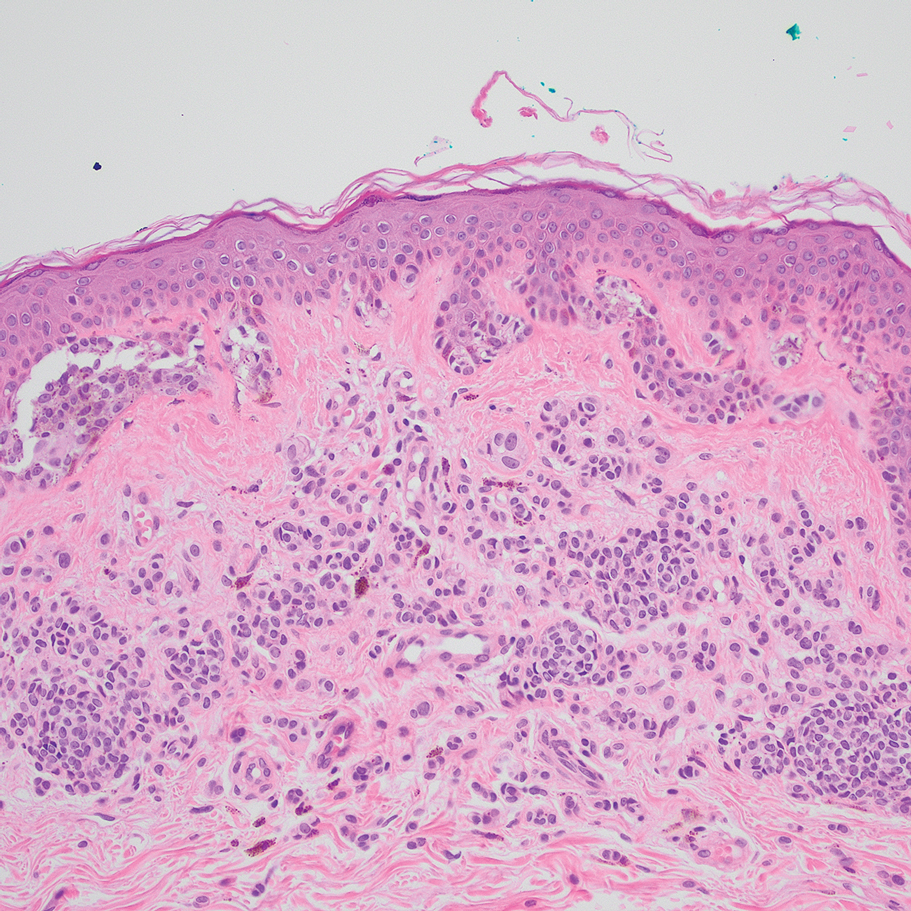

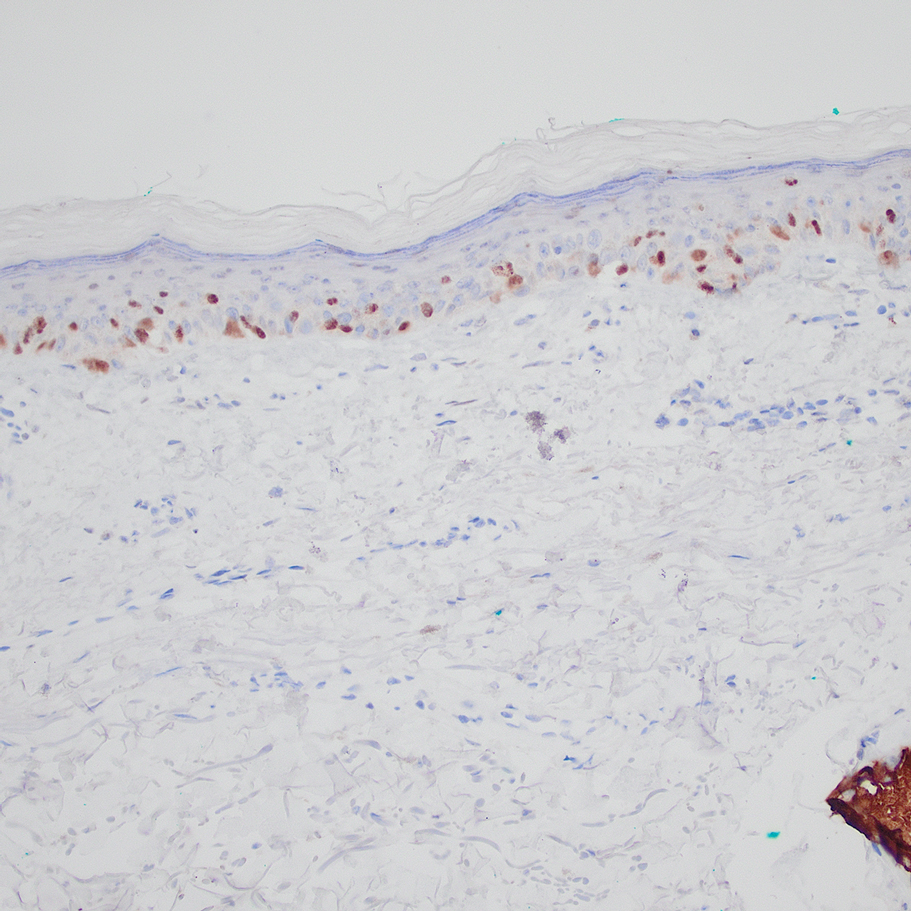

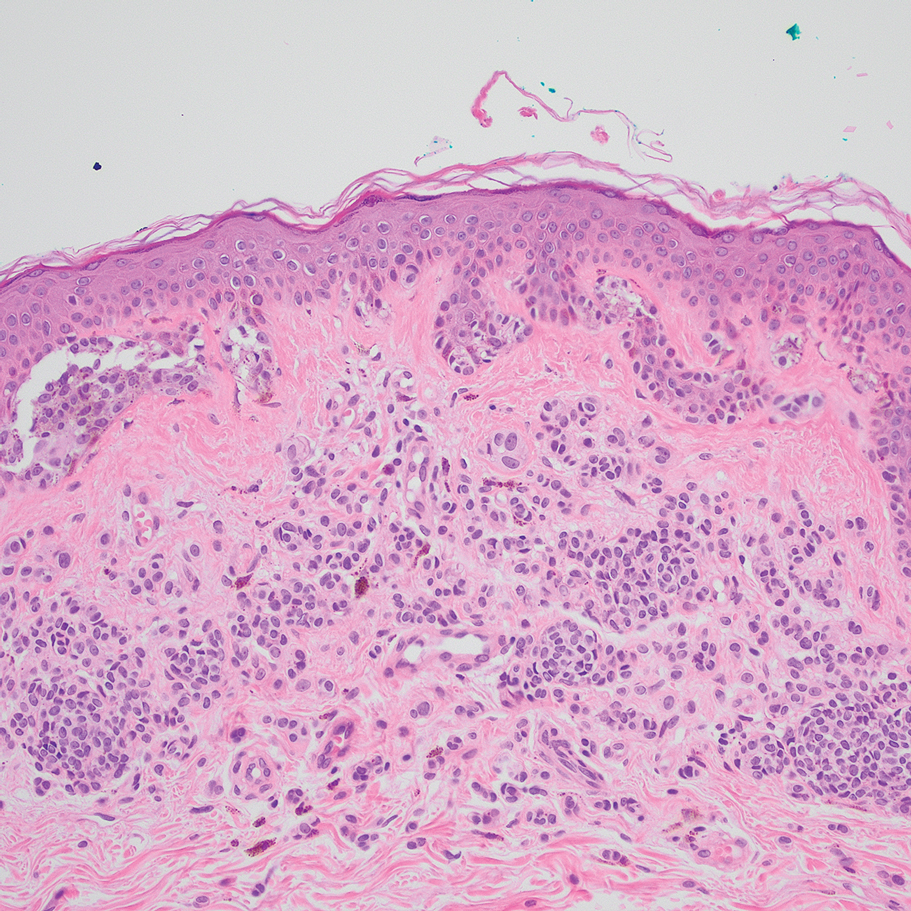

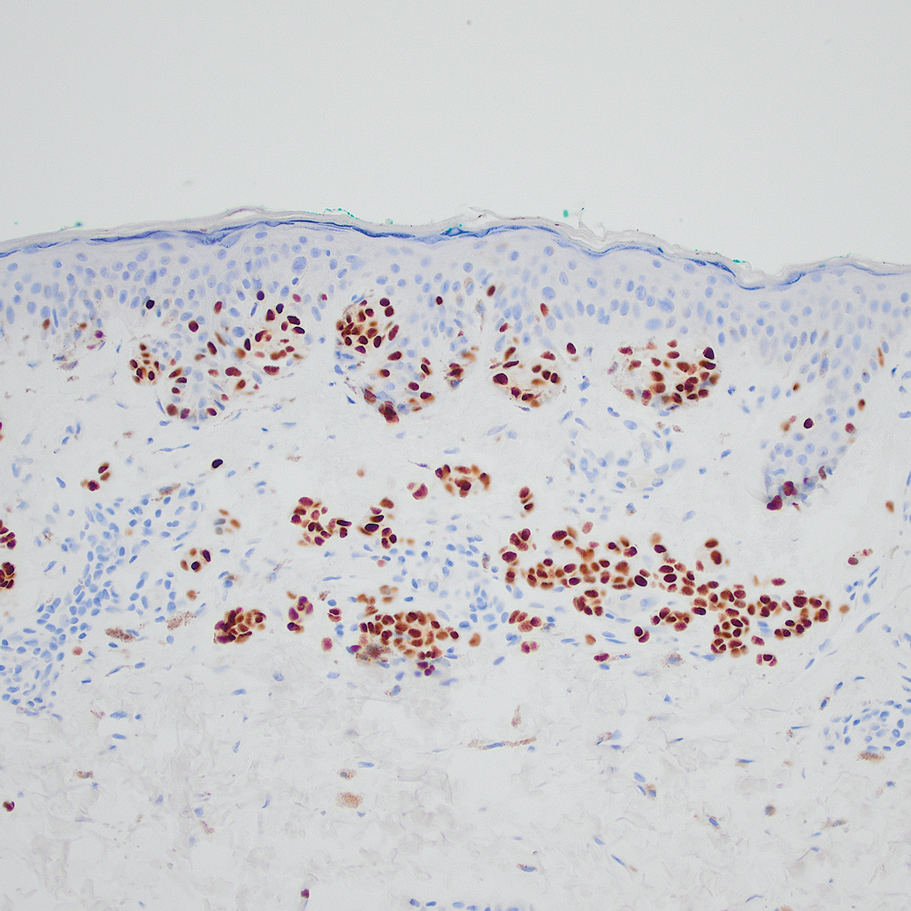

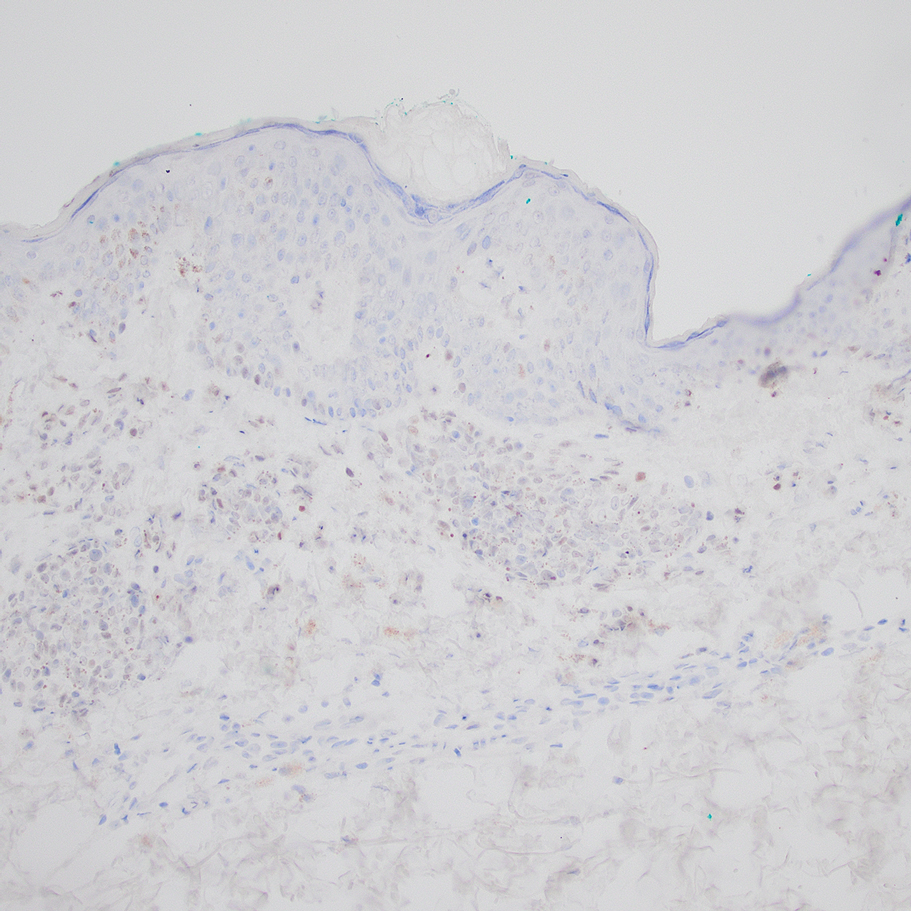

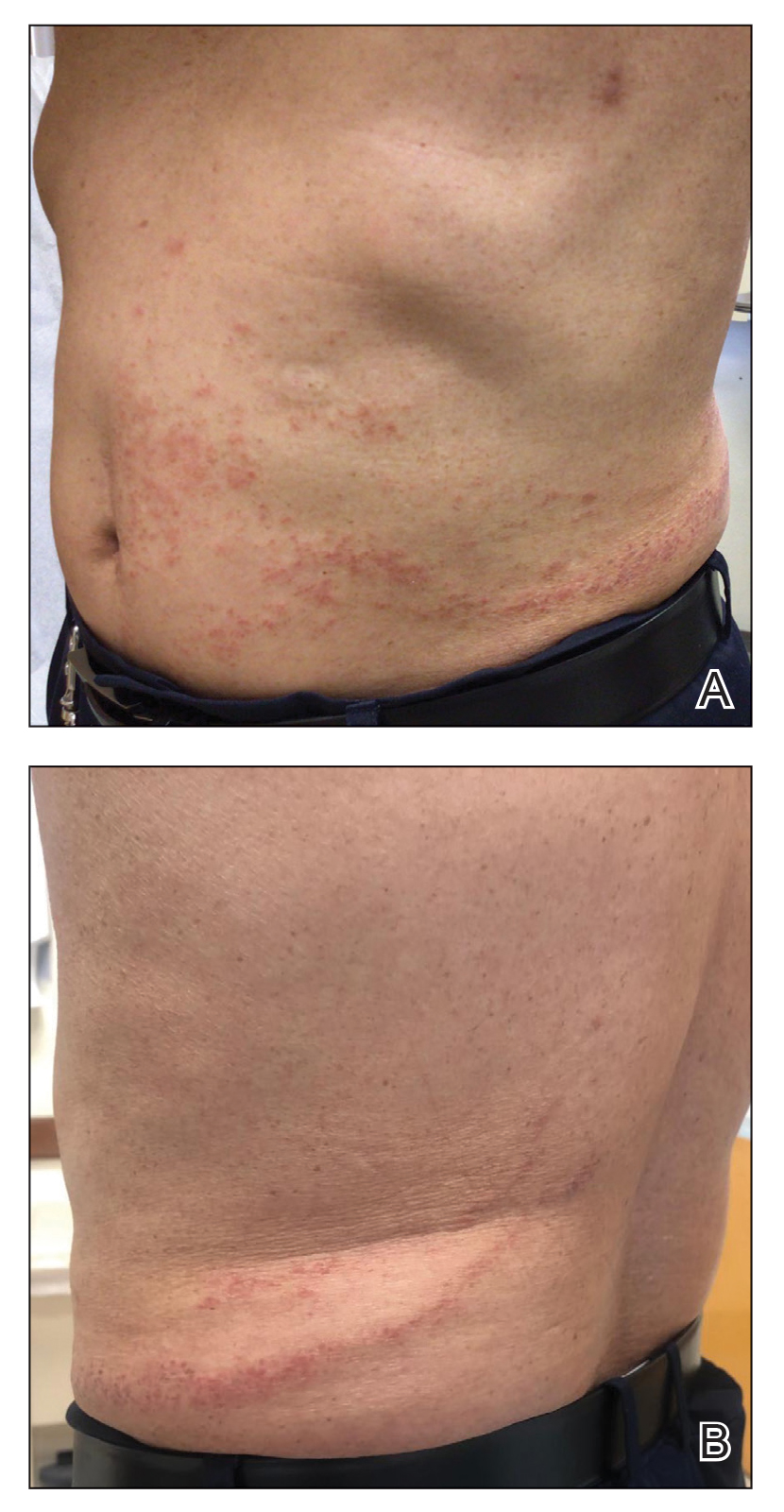

Based on our cohort, a positivity threshold of 3+ for PRAME expression for the diagnosis of melanoma in a special-site lesion would have a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 94%, while a positivity threshold of 4+ for PRAME expression would have a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 100%. Figures 2 through 4 show photomicrographs of a special-site nevus of the breast, which appropriately does not stain for PRAME; Figures 5 and 6 show an MIS at a special site that appropriately stains for PRAME.

Comment

The distinction between benign and malignant pigmented lesions at special sites presents a fair challenge for pathologists due to the larger degree of leniency for architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in benign lesions at these sites. The presence of architectural distortion or cytologic atypia at the lesion’s edge makes rendering a benign diagnosis especially difficult, and the need for a validated immunohistochemical stain is apparent. In our cohort, strong clonal PRAME expression provided a reliable immunohistochemical marker, allowing for the distinction of malignant lesions from benign nevi at special sites. Diffuse faint PRAME expression was present in several benign nevi within our cohort, and these lesions were considered negative (0) in our analysis.

Given the described test characteristics, we support the implementation of PRAME immunohistochemistry with a positivity threshold of 4+ expression as an ancillary test supporting the diagnosis of IM or MIS in special sites, which would allow clinicians to leverage the high specificity of 4+ PRAME expression to distinguish an IM or MIS from a benign nevus occurring at a special site. We do not recommend the use of 4+ PRAME expression as a screening test for melanoma or MIS among special-site nevi due to its comparatively low sensitivity; however, no one marker is always reliable, and we recommend continued clinicopathologic correlation for all cases.

Although our case series included nevi and MIS/IM from all special sites, we were limited in the number of acrogenital and ear nevi included due to a relative paucity of biopsied benign nevi from these locations at the University of Virginia. Additionally, although the magnitude of the difference in PRAME expression between the study and control groups is sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance, the overall strength of our argument would be increased with a larger study group. We were limited by the number of cases available at our institution, which did not utilize PRAME during the initial diagnosis of the case; including these cases in the study group would have undermined the integrity of our argument because the differentiation of benign vs malignant initially was made using PRAME immunohistochemistry.

Conclusion

Due to their atypical features, special-site nevi can be challenging to assess. In this study, we showed that PRAME expression can be a reliable marker to distinguish benign from malignant lesions. Our results showed that 100% of benign special-site nevi demonstrated 3+ expression or less, with 56% (20/36) demonstrating no expression at all. The presence of diffuse PRAME expression (4+ PRAME staining) appears to be a specific indicator of a malignant lesion, but results should always be interpreted with respect to the patient’s clinical history and the lesion’s histomorphologic features. Further study of a larger sample size would allow refinement of the sensitivity and specificity of diffuse PRAME expression in the determination of malignancy for special-site lesions.

Acknowledgment—The authors thank the pathologistsat the University of Virginia Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (Charlottesville, Virginia) for their skill and expertise in performing immunohistochemical staining for this study.

- VandenBoom T, Gerami P. Melanocytic nevi of special sites. In: Pathology of Melanocytic Tumors. Elsevier; 2019:90-100. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-37457-6.00007-9

- Hosler GA, Moresi JM, Barrett TL. Nevi with site-related atypia: a review of melanocytic nevi with atypical histologic features based on anatomic site. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:889-898. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01041.x.

- Brenn T. Melanocytic lesions—staying out of trouble. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;37:91-102. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.09.010

- Ikeda H, Lethé B, Lehmann F, et al. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1997;6:199-208. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80426-4

- Epping MT, Wang L, Edel MJ, et al. The human tumor antigen PRAME is a dominant repressor of retinoic acid receptor signaling. Cell. 2005;122:835-847. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.003

- Alomari AK, Tharp AW, Umphress B, et al. The utility of PRAME immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of challenging melanocytic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:1115-1123. doi:10.1111/cup.14000

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001134

- Gill P, Prieto VG, Austin MT, et al. Diagnostic utility of PRAME in distinguishing proliferative nodules from melanoma in giant congenital melanocytic nevi. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:1410-1415. doi:10.1111/cup.14091

- Googe PB, Flanigan KL, Miedema JR. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma immunostaining in a series of melanocytic neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43):794-800. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001885

- Raghavan SS, Wang JY, Kwok S, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic proliferations with intermediate histopathologic or spitzoid features. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:1123-1131. doi:10.1111/cup.13818

- McBride JD, McAfee JL, Piliang M, et al. Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma and p16 expression in acral melanocytic neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:220-230. doi:10.1111/cup.14130

The assessment and diagnosis of melanocytic lesions can present a formidable challenge to even a seasoned pathologist, which is especially true when dealing with the subset of nevi occurring at special sites—where baseline variations inherent to particular locations on the body can preclude the use of features routinely used to diagnose malignancy elsewhere. These so-called special-site nevi previously have been described in the literature along with suggested criteria for differentiating malignant lesions from their benign counterparts.1 Locations generally considered to be special sites include the acral skin, anogenital region, breast, ear, and flexural regions.1,2

When evaluating non–special-site melanocytic lesions, general characteristics associated with a malignant diagnosis include confluence or pagetoid spread of melanocytes, nuclear pleomorphism, cytologic atypia, and irregular architecture3; however, these features can be compatible with a benign diagnosis in special-site nevi depending on their extent and the site in question. Although they can be atypical, special-site nevi tend to have the bulk of their architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in the center of the lesion as opposed to the edges.1 If a given lesion is from a special site but lacks this reassuring feature, special care should be taken to rule out malignancy.

Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) is an antigen first identified in tumor-reactive T-cell populations in patients with malignant melanoma. It is the product of an oncogene that frequently is overexpressed in melanomas, lung squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas, and acute leukemias.4 It functions as an antagonist of the retinoic acid signaling pathway, which normally serves to induce further cell differentiation, senescence, or apoptosis.5 PRAME inhibits retinoid signaling by forming a complex with both the ligand-bound retinoic acid holoreceptor and the polycomb protein EZH2, which blocks retinoid-dependent gene expression by encouraging chromatin condensation at the RARβ promoter site5; therefore, expressing PRAME allows lesional cells a substantial growth advantage.

PRAME expression has been extensively characterized in non–special-site nevi and has filled the need for a rather specific marker of melanoma.6-10 Although PRAME has been studied in acral nevi,11 the expression pattern in nevi of special sites has yet to be elucidated. Herein, we present a dataset characterizing PRAME expression in these challenging lesions.

Methods

We performed a retrospective case review at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia) and collected a panel of 36 special-site nevi that previously were diagnosed as benign by a trained dermatopathologist from January 2020 through December 2022. Special-site nevi were identified using a natural language filter for the following terms: acral, palm, sole, ear, auricular, lip, axilla, armpit, breast, groin, labia, vulva, umbilicus, and penis. This study was approved by the University of Virginia institutional review board.

The original hematoxylin and eosin slides used for primary diagnosis were re-examined to verify the prior diagnosis of benign nevus at a special site. We performed a detailed microscopic examination of all benign nevi in our cohort to determine the frequency of various characteristics at each special site. Sections were prepared from the formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and stained with a commercial PRAME antibody (#219650 [Abcam] at a 1:50 dilution) and counterstain. A trained dermatopathologist (S.S.R.) examined the stained sections and recorded the percentage of tumor cells with nuclear PRAME staining. We reported our results using previously established criteria for scoring PRAME immunohistochemistry7: 0 for no expression, 1+ for 1% to 25% expression, 2+ for 26% to 50% expression, 3+ for 51% to 75% expression, and 4+ for diffuse or 76% to 100% expression. Only strong clonal expression within a population of cells was graded.

Data handling and statistical testing were performed using the R Project for Statistical Computing (https://www.r-project.org/). Significance testing was performed using the Fisher exact test. Plot construction was performed using ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/).

Results

Our study cohort included 36 special-site nevi, and the control cohort comprised 25 melanoma in situ (MIS) or invasive melanoma (IM) lesions occurring at special sites. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the study and control cohorts by lesion site. Table 2 details the results of our microscopic examination, describing frequency of various characteristics of special-site nevi stratified by site.

Of the 36 special-site nevi in our cohort, 20 (56%) had no staining (0) for PRAME, 11 (31%) demonstrated 1+ PRAME expression, 3 (8%) demonstrated 2+ PRAME expression, and 2 (6%) demonstrated 3+ PRAME expression. No nevi showed 4+ expression. In the control cohort, 24 of 25 (96%) MIS and IM showed 3+ or 4+ expression, with 21 (84%) demonstrating diffuse/4+ expression. One control case (4%) demonstrated 0 PRAME expression. These data are summarized in Table 3 and Figure 1. There is a significant difference in diffuse (4+) PRAME expression between special-site nevi and MIS/IM occurring at special sites (P=1.039×10-12).

Based on our cohort, a positivity threshold of 3+ for PRAME expression for the diagnosis of melanoma in a special-site lesion would have a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 94%, while a positivity threshold of 4+ for PRAME expression would have a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 100%. Figures 2 through 4 show photomicrographs of a special-site nevus of the breast, which appropriately does not stain for PRAME; Figures 5 and 6 show an MIS at a special site that appropriately stains for PRAME.

Comment

The distinction between benign and malignant pigmented lesions at special sites presents a fair challenge for pathologists due to the larger degree of leniency for architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in benign lesions at these sites. The presence of architectural distortion or cytologic atypia at the lesion’s edge makes rendering a benign diagnosis especially difficult, and the need for a validated immunohistochemical stain is apparent. In our cohort, strong clonal PRAME expression provided a reliable immunohistochemical marker, allowing for the distinction of malignant lesions from benign nevi at special sites. Diffuse faint PRAME expression was present in several benign nevi within our cohort, and these lesions were considered negative (0) in our analysis.

Given the described test characteristics, we support the implementation of PRAME immunohistochemistry with a positivity threshold of 4+ expression as an ancillary test supporting the diagnosis of IM or MIS in special sites, which would allow clinicians to leverage the high specificity of 4+ PRAME expression to distinguish an IM or MIS from a benign nevus occurring at a special site. We do not recommend the use of 4+ PRAME expression as a screening test for melanoma or MIS among special-site nevi due to its comparatively low sensitivity; however, no one marker is always reliable, and we recommend continued clinicopathologic correlation for all cases.

Although our case series included nevi and MIS/IM from all special sites, we were limited in the number of acrogenital and ear nevi included due to a relative paucity of biopsied benign nevi from these locations at the University of Virginia. Additionally, although the magnitude of the difference in PRAME expression between the study and control groups is sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance, the overall strength of our argument would be increased with a larger study group. We were limited by the number of cases available at our institution, which did not utilize PRAME during the initial diagnosis of the case; including these cases in the study group would have undermined the integrity of our argument because the differentiation of benign vs malignant initially was made using PRAME immunohistochemistry.

Conclusion

Due to their atypical features, special-site nevi can be challenging to assess. In this study, we showed that PRAME expression can be a reliable marker to distinguish benign from malignant lesions. Our results showed that 100% of benign special-site nevi demonstrated 3+ expression or less, with 56% (20/36) demonstrating no expression at all. The presence of diffuse PRAME expression (4+ PRAME staining) appears to be a specific indicator of a malignant lesion, but results should always be interpreted with respect to the patient’s clinical history and the lesion’s histomorphologic features. Further study of a larger sample size would allow refinement of the sensitivity and specificity of diffuse PRAME expression in the determination of malignancy for special-site lesions.

Acknowledgment—The authors thank the pathologistsat the University of Virginia Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (Charlottesville, Virginia) for their skill and expertise in performing immunohistochemical staining for this study.

The assessment and diagnosis of melanocytic lesions can present a formidable challenge to even a seasoned pathologist, which is especially true when dealing with the subset of nevi occurring at special sites—where baseline variations inherent to particular locations on the body can preclude the use of features routinely used to diagnose malignancy elsewhere. These so-called special-site nevi previously have been described in the literature along with suggested criteria for differentiating malignant lesions from their benign counterparts.1 Locations generally considered to be special sites include the acral skin, anogenital region, breast, ear, and flexural regions.1,2

When evaluating non–special-site melanocytic lesions, general characteristics associated with a malignant diagnosis include confluence or pagetoid spread of melanocytes, nuclear pleomorphism, cytologic atypia, and irregular architecture3; however, these features can be compatible with a benign diagnosis in special-site nevi depending on their extent and the site in question. Although they can be atypical, special-site nevi tend to have the bulk of their architectural distortion and cytologic atypia in the center of the lesion as opposed to the edges.1 If a given lesion is from a special site but lacks this reassuring feature, special care should be taken to rule out malignancy.

Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) is an antigen first identified in tumor-reactive T-cell populations in patients with malignant melanoma. It is the product of an oncogene that frequently is overexpressed in melanomas, lung squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas, and acute leukemias.4 It functions as an antagonist of the retinoic acid signaling pathway, which normally serves to induce further cell differentiation, senescence, or apoptosis.5 PRAME inhibits retinoid signaling by forming a complex with both the ligand-bound retinoic acid holoreceptor and the polycomb protein EZH2, which blocks retinoid-dependent gene expression by encouraging chromatin condensation at the RARβ promoter site5; therefore, expressing PRAME allows lesional cells a substantial growth advantage.