User login

ACC, AHA release first cardiovascular disease primary prevention guideline

that takes into account each person’s social determinants of health. The guideline substantially dialed down prior recommendations on aspirin for primary prevention by calling for no use in people older than 70 years and infrequent use in those 40-70 years old.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association released their 2019 guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease on March 17, during the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology (J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March 17;doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010.). The guideline is a “one-stop shop” that pulls together existing recommendations from the two organizations and combines it with some new recommendations that address issues such as aspirin prophylaxis, and the social setting of each person, said Donna K. Arnett, Ph.D., professor of epidemiology at the University of Kentucky, dean of the university’s College of Public Health, and co-chair of the guideline writing panel.

“We made the social determinants of health front and center. With many people, clinicians don’t ask whether they have access to healthy foods or a way to get to the pharmacy. Asking about these issues is step one,” toward helping people address their social situation, Dr. Arnett said while introducing the new guideline in a press briefing. The guideline recommends that clinicians assess the social determinants for each person treated for cardiovascular disease prevention using a screening tool developed by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and made available by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM Perspectives. 2017; doi:10.31478/201705b).

“No other guideline has highlighted the social determinants of health,” noted Erin D. Michos, MD, associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, and a member of the guideline-writing panel. Other overarching themes of the guideline are its emphasis on the need for a team of clinicians to deliver all the disparate and time-consuming facets of care needed for comprehensive primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and its call for a healthy lifestyle throughout life as foundations for prevention, Dr. Michos said in an interview.

With 48 recommendations, the guideline also deals with prevention issues such as a healthy diet and body mass, appropriate control of diabetes, smoking cessation, and control of blood pressure and cholesterol (see chart). The writing committee took the cholesterol and blood pressure recommendations directly from recent guidelines from the ACC and AHA in 2017 (blood pressure:J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e177-e248) and 2018 (cholesterol:Circulation. 2018 Nov 10;doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625).

The other major, new recommendations in the guideline deal with aspirin use for primary prevention, which recently underwent a shake up with publication of results from several studies that showed less cardiovascular benefit and more potential bleeding harm from routine aspirin prophylaxis than previously appreciated. Among the most notable of these reports, which led to a class III recommendation – do not use – for aspirin in people more than 70 years old came from the ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) study (New Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18;379[16]:1519-28). For those 40-70 years old, the recommendation is class IIb, worded as “might be considered for select adults.”

“Generally no, occasionally yes,” is aspirin appropriate for people in this age group, notably those at high risk for cardiovascular disease and also at low risk for bleeding, explained Amit Khera, MD, a guideline-panel member, and professor of medicine and director of preventive cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

As a guideline for primary prevention, a prime target audience is primary care physicians, who would need to be instrumental in applying the guideline. But the guideline recommendations released by the ACC and AHA for blood pressure management in 2017 were not accepted by U.S. groups that represent primary care physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

John J. Warner, MD, an interventional cardiologist, executive vice president for health system affairs at UT Southwestern, and president of the AHA when the blood pressure guideline came out said that the ACC and AHA “learned some lessons” from the blood pressure experience. The societies responded this time around by “trying to view the document through as many lenses as possible” during the peer review process, Dr. Warner said during the press conference.

“I don’t think the new guideline will be seen as anything except positive,” commented Martha Gulati, MD, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at the University of Arizona in Phoenix. Collecting all the cardiovascular disease recommendations for primary prevention in one document “helps clinicians access the information easily and helps patients see the big picture,” said Dr. Gulati, who was not involved in the guideline’s writing or review.

She especially applauded the recommendations to assess each person’s social determinants of health, the team-care approach, and the recommendations dealing with diet and other aspects of a healthy lifestyle. “This was a perfect time” to bring together the existing blood pressure and cholesterol guidelines, the new guidance on aspirin use, and the other recommendation in a single document, she said in an interview.

Dr. Arnett, Dr. Michos, Dr. Khera, Dr. Warner, and Dr. Gulati had no disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Arnett DK et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March 17;doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010.

that takes into account each person’s social determinants of health. The guideline substantially dialed down prior recommendations on aspirin for primary prevention by calling for no use in people older than 70 years and infrequent use in those 40-70 years old.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association released their 2019 guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease on March 17, during the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology (J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March 17;doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010.). The guideline is a “one-stop shop” that pulls together existing recommendations from the two organizations and combines it with some new recommendations that address issues such as aspirin prophylaxis, and the social setting of each person, said Donna K. Arnett, Ph.D., professor of epidemiology at the University of Kentucky, dean of the university’s College of Public Health, and co-chair of the guideline writing panel.

“We made the social determinants of health front and center. With many people, clinicians don’t ask whether they have access to healthy foods or a way to get to the pharmacy. Asking about these issues is step one,” toward helping people address their social situation, Dr. Arnett said while introducing the new guideline in a press briefing. The guideline recommends that clinicians assess the social determinants for each person treated for cardiovascular disease prevention using a screening tool developed by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and made available by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM Perspectives. 2017; doi:10.31478/201705b).

“No other guideline has highlighted the social determinants of health,” noted Erin D. Michos, MD, associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, and a member of the guideline-writing panel. Other overarching themes of the guideline are its emphasis on the need for a team of clinicians to deliver all the disparate and time-consuming facets of care needed for comprehensive primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and its call for a healthy lifestyle throughout life as foundations for prevention, Dr. Michos said in an interview.

With 48 recommendations, the guideline also deals with prevention issues such as a healthy diet and body mass, appropriate control of diabetes, smoking cessation, and control of blood pressure and cholesterol (see chart). The writing committee took the cholesterol and blood pressure recommendations directly from recent guidelines from the ACC and AHA in 2017 (blood pressure:J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e177-e248) and 2018 (cholesterol:Circulation. 2018 Nov 10;doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625).

The other major, new recommendations in the guideline deal with aspirin use for primary prevention, which recently underwent a shake up with publication of results from several studies that showed less cardiovascular benefit and more potential bleeding harm from routine aspirin prophylaxis than previously appreciated. Among the most notable of these reports, which led to a class III recommendation – do not use – for aspirin in people more than 70 years old came from the ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) study (New Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18;379[16]:1519-28). For those 40-70 years old, the recommendation is class IIb, worded as “might be considered for select adults.”

“Generally no, occasionally yes,” is aspirin appropriate for people in this age group, notably those at high risk for cardiovascular disease and also at low risk for bleeding, explained Amit Khera, MD, a guideline-panel member, and professor of medicine and director of preventive cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

As a guideline for primary prevention, a prime target audience is primary care physicians, who would need to be instrumental in applying the guideline. But the guideline recommendations released by the ACC and AHA for blood pressure management in 2017 were not accepted by U.S. groups that represent primary care physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

John J. Warner, MD, an interventional cardiologist, executive vice president for health system affairs at UT Southwestern, and president of the AHA when the blood pressure guideline came out said that the ACC and AHA “learned some lessons” from the blood pressure experience. The societies responded this time around by “trying to view the document through as many lenses as possible” during the peer review process, Dr. Warner said during the press conference.

“I don’t think the new guideline will be seen as anything except positive,” commented Martha Gulati, MD, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at the University of Arizona in Phoenix. Collecting all the cardiovascular disease recommendations for primary prevention in one document “helps clinicians access the information easily and helps patients see the big picture,” said Dr. Gulati, who was not involved in the guideline’s writing or review.

She especially applauded the recommendations to assess each person’s social determinants of health, the team-care approach, and the recommendations dealing with diet and other aspects of a healthy lifestyle. “This was a perfect time” to bring together the existing blood pressure and cholesterol guidelines, the new guidance on aspirin use, and the other recommendation in a single document, she said in an interview.

Dr. Arnett, Dr. Michos, Dr. Khera, Dr. Warner, and Dr. Gulati had no disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Arnett DK et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March 17;doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010.

that takes into account each person’s social determinants of health. The guideline substantially dialed down prior recommendations on aspirin for primary prevention by calling for no use in people older than 70 years and infrequent use in those 40-70 years old.

The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association released their 2019 guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease on March 17, during the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology (J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March 17;doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010.). The guideline is a “one-stop shop” that pulls together existing recommendations from the two organizations and combines it with some new recommendations that address issues such as aspirin prophylaxis, and the social setting of each person, said Donna K. Arnett, Ph.D., professor of epidemiology at the University of Kentucky, dean of the university’s College of Public Health, and co-chair of the guideline writing panel.

“We made the social determinants of health front and center. With many people, clinicians don’t ask whether they have access to healthy foods or a way to get to the pharmacy. Asking about these issues is step one,” toward helping people address their social situation, Dr. Arnett said while introducing the new guideline in a press briefing. The guideline recommends that clinicians assess the social determinants for each person treated for cardiovascular disease prevention using a screening tool developed by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and made available by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM Perspectives. 2017; doi:10.31478/201705b).

“No other guideline has highlighted the social determinants of health,” noted Erin D. Michos, MD, associate director of preventive cardiology at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, and a member of the guideline-writing panel. Other overarching themes of the guideline are its emphasis on the need for a team of clinicians to deliver all the disparate and time-consuming facets of care needed for comprehensive primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, and its call for a healthy lifestyle throughout life as foundations for prevention, Dr. Michos said in an interview.

With 48 recommendations, the guideline also deals with prevention issues such as a healthy diet and body mass, appropriate control of diabetes, smoking cessation, and control of blood pressure and cholesterol (see chart). The writing committee took the cholesterol and blood pressure recommendations directly from recent guidelines from the ACC and AHA in 2017 (blood pressure:J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2018 May;71[19]:e177-e248) and 2018 (cholesterol:Circulation. 2018 Nov 10;doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625).

The other major, new recommendations in the guideline deal with aspirin use for primary prevention, which recently underwent a shake up with publication of results from several studies that showed less cardiovascular benefit and more potential bleeding harm from routine aspirin prophylaxis than previously appreciated. Among the most notable of these reports, which led to a class III recommendation – do not use – for aspirin in people more than 70 years old came from the ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) study (New Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18;379[16]:1519-28). For those 40-70 years old, the recommendation is class IIb, worded as “might be considered for select adults.”

“Generally no, occasionally yes,” is aspirin appropriate for people in this age group, notably those at high risk for cardiovascular disease and also at low risk for bleeding, explained Amit Khera, MD, a guideline-panel member, and professor of medicine and director of preventive cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

As a guideline for primary prevention, a prime target audience is primary care physicians, who would need to be instrumental in applying the guideline. But the guideline recommendations released by the ACC and AHA for blood pressure management in 2017 were not accepted by U.S. groups that represent primary care physicians, the American College of Physicians, and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

John J. Warner, MD, an interventional cardiologist, executive vice president for health system affairs at UT Southwestern, and president of the AHA when the blood pressure guideline came out said that the ACC and AHA “learned some lessons” from the blood pressure experience. The societies responded this time around by “trying to view the document through as many lenses as possible” during the peer review process, Dr. Warner said during the press conference.

“I don’t think the new guideline will be seen as anything except positive,” commented Martha Gulati, MD, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at the University of Arizona in Phoenix. Collecting all the cardiovascular disease recommendations for primary prevention in one document “helps clinicians access the information easily and helps patients see the big picture,” said Dr. Gulati, who was not involved in the guideline’s writing or review.

She especially applauded the recommendations to assess each person’s social determinants of health, the team-care approach, and the recommendations dealing with diet and other aspects of a healthy lifestyle. “This was a perfect time” to bring together the existing blood pressure and cholesterol guidelines, the new guidance on aspirin use, and the other recommendation in a single document, she said in an interview.

Dr. Arnett, Dr. Michos, Dr. Khera, Dr. Warner, and Dr. Gulati had no disclosures.

mzoler@mdedge.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Arnett DK et al. J Amer Coll Cardiol. 2019 March 17;doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010.

REPORTING FROM ACC 2019

Hypoglycemia in the elderly: Watch for atypical symptoms

We read with interest the review article by Keber and Fiebert, “Diabetes in the elderly: Matching meds to needs” (J Fam Pract. 2018;67:408-410,412-415). The authors have provided a timely overview of antidiabetes medications for elderly people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and their relative risks for hypoglycemia.

We’d like to add to this important conversation.

Aging, per se, modifies the glycemic thresholds for autonomic symptoms and cognitive impairment; in older nondiabetic men (mean + SD: age 65 ± 3 years), autonomic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction commence at identical glycemic thresholds (3 ± 0.2 mmol/L [54 ± 4 mg/dL]). By contrast, in younger men (age 23 ± 2 years), a significant gap is observed between the glycemic threshold for symptom generation (3.6 mmol/L [65 mg/dL]) and the onset of cognitive dysfunction (2.6 mmol/L [47 mg/dL]).1,2 The simultaneous occurrence of symptoms and cognitive impairment in older people may adversely affect their ability to recognize and treat hypoglycemia promptly.

In addition, hypoglycemia in older T2DM patients often presents with atypical neurologic symptoms, including incoordination and ataxia, slurring of speech, and visual disturbances, which either are not identified as hypoglycemia or are misdiagnosed as other medical disorders (eg, transient ischemic attack).3 Knowledge about hypoglycemia symptoms is poor, in both elderly people with diabetes and their relatives and caregivers, which compromises the ability to identify hypoglycemia and provide effective treatment.4 Education about the possible presentations of hypoglycemia and its effective treatment is essential for older patients and their relatives.

Jan Brož, MD

Prague, Czech Republic

1. Meneilly GS, Elahi D. Physiological importance of first-phase insulin release in elderly patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1326-1329.

2. Matyka K, Evans M, Lomas J, et al. Altered hierarchy of protective responses against severe hypoglycemia in normal aging in healthy men. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:135-141.

3. Jaap AJ, Jones GC, McCrimmon RJ, et al. Perceived symptoms of hypoglycaemia in elderly type 2 diabetic patients treated with insulin. Diabet Med. 1998;15:398-401.

4. Thomson FJ, Masson EA, Leeming JT, et al. Lack of knowledge of symptoms of hypoglycaemia by elderly diabetic patients. Age Ageing. 1991;20:404-406.

We read with interest the review article by Keber and Fiebert, “Diabetes in the elderly: Matching meds to needs” (J Fam Pract. 2018;67:408-410,412-415). The authors have provided a timely overview of antidiabetes medications for elderly people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and their relative risks for hypoglycemia.

We’d like to add to this important conversation.

Aging, per se, modifies the glycemic thresholds for autonomic symptoms and cognitive impairment; in older nondiabetic men (mean + SD: age 65 ± 3 years), autonomic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction commence at identical glycemic thresholds (3 ± 0.2 mmol/L [54 ± 4 mg/dL]). By contrast, in younger men (age 23 ± 2 years), a significant gap is observed between the glycemic threshold for symptom generation (3.6 mmol/L [65 mg/dL]) and the onset of cognitive dysfunction (2.6 mmol/L [47 mg/dL]).1,2 The simultaneous occurrence of symptoms and cognitive impairment in older people may adversely affect their ability to recognize and treat hypoglycemia promptly.

In addition, hypoglycemia in older T2DM patients often presents with atypical neurologic symptoms, including incoordination and ataxia, slurring of speech, and visual disturbances, which either are not identified as hypoglycemia or are misdiagnosed as other medical disorders (eg, transient ischemic attack).3 Knowledge about hypoglycemia symptoms is poor, in both elderly people with diabetes and their relatives and caregivers, which compromises the ability to identify hypoglycemia and provide effective treatment.4 Education about the possible presentations of hypoglycemia and its effective treatment is essential for older patients and their relatives.

Jan Brož, MD

Prague, Czech Republic

We read with interest the review article by Keber and Fiebert, “Diabetes in the elderly: Matching meds to needs” (J Fam Pract. 2018;67:408-410,412-415). The authors have provided a timely overview of antidiabetes medications for elderly people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and their relative risks for hypoglycemia.

We’d like to add to this important conversation.

Aging, per se, modifies the glycemic thresholds for autonomic symptoms and cognitive impairment; in older nondiabetic men (mean + SD: age 65 ± 3 years), autonomic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction commence at identical glycemic thresholds (3 ± 0.2 mmol/L [54 ± 4 mg/dL]). By contrast, in younger men (age 23 ± 2 years), a significant gap is observed between the glycemic threshold for symptom generation (3.6 mmol/L [65 mg/dL]) and the onset of cognitive dysfunction (2.6 mmol/L [47 mg/dL]).1,2 The simultaneous occurrence of symptoms and cognitive impairment in older people may adversely affect their ability to recognize and treat hypoglycemia promptly.

In addition, hypoglycemia in older T2DM patients often presents with atypical neurologic symptoms, including incoordination and ataxia, slurring of speech, and visual disturbances, which either are not identified as hypoglycemia or are misdiagnosed as other medical disorders (eg, transient ischemic attack).3 Knowledge about hypoglycemia symptoms is poor, in both elderly people with diabetes and their relatives and caregivers, which compromises the ability to identify hypoglycemia and provide effective treatment.4 Education about the possible presentations of hypoglycemia and its effective treatment is essential for older patients and their relatives.

Jan Brož, MD

Prague, Czech Republic

1. Meneilly GS, Elahi D. Physiological importance of first-phase insulin release in elderly patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1326-1329.

2. Matyka K, Evans M, Lomas J, et al. Altered hierarchy of protective responses against severe hypoglycemia in normal aging in healthy men. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:135-141.

3. Jaap AJ, Jones GC, McCrimmon RJ, et al. Perceived symptoms of hypoglycaemia in elderly type 2 diabetic patients treated with insulin. Diabet Med. 1998;15:398-401.

4. Thomson FJ, Masson EA, Leeming JT, et al. Lack of knowledge of symptoms of hypoglycaemia by elderly diabetic patients. Age Ageing. 1991;20:404-406.

1. Meneilly GS, Elahi D. Physiological importance of first-phase insulin release in elderly patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1326-1329.

2. Matyka K, Evans M, Lomas J, et al. Altered hierarchy of protective responses against severe hypoglycemia in normal aging in healthy men. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:135-141.

3. Jaap AJ, Jones GC, McCrimmon RJ, et al. Perceived symptoms of hypoglycaemia in elderly type 2 diabetic patients treated with insulin. Diabet Med. 1998;15:398-401.

4. Thomson FJ, Masson EA, Leeming JT, et al. Lack of knowledge of symptoms of hypoglycaemia by elderly diabetic patients. Age Ageing. 1991;20:404-406.

Newer antihyperglycemic drugs have distinctive CV, kidney benefits

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

The two newer classes of antihyperglycemic drugs that lower cardiovascular risk have different effects on specific cardiovascular and kidney disease outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes, results of a meta-analysis suggest. Sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors significantly reduced hospitalization from heart failure, whereas glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) did not, according to the reported results.

The GLP-1–RA class reduced risk of kidney disease progression, largely driven by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, according to the authors, whereas only the SGLT2 inhibitors reduced adverse kidney disease outcomes in a composite excluding that biomarker.

“The prevention of heart failure and progression of kidney disease by SGLT2 [inhibitors] should be considered in the decision-making process when treating patients with type 2 diabetes,” study senior author Marc S. Sabatine, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and his coauthors wrote in a report on the study appearing in Circulation.

Both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and, as shown in other recent findings, their benefits were confined to patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, Dr. Sabatine and his colleagues wrote.

The systematic review and meta-analysis of eight cardiovascular outcomes trials included 77,242 patients, of whom about 56% participated in GLP-1–RA studies and 44% in SGLT2-inhibitor trials. Just under three-quarters of the patients had established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while the remainder had multiple risk factors for it.

Relative risk of hospitalization for heart failure was reduced by 31% with SGLT2 inhibitors, but it was not significantly reduced by GLP-1 RAs, the authors noted.

Risk of kidney disease progression was reduced by 38% with SGLT2 inhibitors and by 18% with GLP-1 RAs when the researchers used a broad composite endpoint including macroalbuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), end-stage kidney disease, and death due to renal causes.

By contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors reduced by 45% the relative risk of a narrower kidney outcome that excluded macroalbuminuria, whereas GLP-1 RAs had only a nonsignificant effect on the risk of doubling serum creatinine. That suggests the relative risk reduction of the kidney composite with GLP-1 RAs was driven mainly by a reduction in macroalbuminuria, the authors wrote.

Although albuminuria is an established biomarker for kidney and cardiovascular disease, it is a surrogate marker and can even be absent in patients with reduced eGFR, they said.

“Reduction in eGFR has emerged as a more meaningful endpoint of greater importance and is used in ongoing diabetes trials for kidney outcomes,” the authors said in a discussion of their results.

Relative risk of the composite MACE endpoint, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, was reduced by 12% for GLP-1 RAs and by 11% for SGLT2 [inhibitors], according to results of the analysis. However, the benefit was confined to patients with established cardiovascular disease, who had a 14% reduction of risk, compared with no treatment effect in patients who had multiple risk factors only.

Looking at individual MACE components, investigators found that both drug classes significantly reduced relative risk of myocardial infarction and of cardiovascular death, whereas only GLP-1 RAs significantly reduced relative risk of stroke.

Study authors provided disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Intarcia, Janssen Research and Development, and Medimmune, among others.

SOURCE: Zelniker TA et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038868.

FROM CIRCULATION

Semaglutide plus SGLT2 inhibitors improves glycemic control in type 2 diabetes

Adding once-weekly treatment with the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) semaglutide helped most patients with type 2 diabetes already being treated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors meet their glycemic targets and lose weight, researchers reported.

“Combining the distinct modes of action of these two drug classes has beneficial effects on glucose and weight outcomes,” wrote Bernard Zinman, MD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, and his coauthors. Their report is in Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology.

In the international, double-blind, phase 3 SUSTAIN 9 trial, 302 patients with type 2 diabetes whose hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were 7.0% to 10.0% (53 to 86 mmol/mol) despite at least 90 days of SGLT2-inhibitor therapy (alone or with metformin or sulfonylurea) were randomly assigned to add either once-weekly semaglutide (1-mg injection) or placebo to their regimen.

A total of 294 patients completed the trial. After 30 weeks, those who had received adjunctive semaglutide had significantly greater reductions in their HbA1c levels (estimated treatment difference, –1.42%; P less than .0001). They also lost about 3.81 kg more bodyweight than did patients in the placebo group and they had significantly greater reductions in mean body mass index, waist circumference, fasting and self-measured blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, pulse rate, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels.

The most commonly reported adverse effects of semaglutide were nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and constipation, which were usually mild in severity. Severe or blood-glucose–confirmed hypoglycemia occurred in 2.7% patients on semaglutide and none on placebo. However, most patients who received semaglutide achieved an HbA1c of 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) or less without weight gain or severe or blood-glucose–confirmed hypoglycemia (P less than .0001 vs. placebo).

Novo Nordisk funded the study. Three of the authors were employees of Novo Nordisk at the time of the study, and the remaining authors reported that they and/or their institutions had received funding from the company.

SOURCE: Zinman B et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30066-X.

Adding once-weekly treatment with the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) semaglutide helped most patients with type 2 diabetes already being treated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors meet their glycemic targets and lose weight, researchers reported.

“Combining the distinct modes of action of these two drug classes has beneficial effects on glucose and weight outcomes,” wrote Bernard Zinman, MD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, and his coauthors. Their report is in Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology.

In the international, double-blind, phase 3 SUSTAIN 9 trial, 302 patients with type 2 diabetes whose hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were 7.0% to 10.0% (53 to 86 mmol/mol) despite at least 90 days of SGLT2-inhibitor therapy (alone or with metformin or sulfonylurea) were randomly assigned to add either once-weekly semaglutide (1-mg injection) or placebo to their regimen.

A total of 294 patients completed the trial. After 30 weeks, those who had received adjunctive semaglutide had significantly greater reductions in their HbA1c levels (estimated treatment difference, –1.42%; P less than .0001). They also lost about 3.81 kg more bodyweight than did patients in the placebo group and they had significantly greater reductions in mean body mass index, waist circumference, fasting and self-measured blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, pulse rate, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels.

The most commonly reported adverse effects of semaglutide were nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and constipation, which were usually mild in severity. Severe or blood-glucose–confirmed hypoglycemia occurred in 2.7% patients on semaglutide and none on placebo. However, most patients who received semaglutide achieved an HbA1c of 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) or less without weight gain or severe or blood-glucose–confirmed hypoglycemia (P less than .0001 vs. placebo).

Novo Nordisk funded the study. Three of the authors were employees of Novo Nordisk at the time of the study, and the remaining authors reported that they and/or their institutions had received funding from the company.

SOURCE: Zinman B et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30066-X.

Adding once-weekly treatment with the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) semaglutide helped most patients with type 2 diabetes already being treated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors meet their glycemic targets and lose weight, researchers reported.

“Combining the distinct modes of action of these two drug classes has beneficial effects on glucose and weight outcomes,” wrote Bernard Zinman, MD, of Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, and his coauthors. Their report is in Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology.

In the international, double-blind, phase 3 SUSTAIN 9 trial, 302 patients with type 2 diabetes whose hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were 7.0% to 10.0% (53 to 86 mmol/mol) despite at least 90 days of SGLT2-inhibitor therapy (alone or with metformin or sulfonylurea) were randomly assigned to add either once-weekly semaglutide (1-mg injection) or placebo to their regimen.

A total of 294 patients completed the trial. After 30 weeks, those who had received adjunctive semaglutide had significantly greater reductions in their HbA1c levels (estimated treatment difference, –1.42%; P less than .0001). They also lost about 3.81 kg more bodyweight than did patients in the placebo group and they had significantly greater reductions in mean body mass index, waist circumference, fasting and self-measured blood glucose, systolic blood pressure, pulse rate, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein and triglyceride levels.

The most commonly reported adverse effects of semaglutide were nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and constipation, which were usually mild in severity. Severe or blood-glucose–confirmed hypoglycemia occurred in 2.7% patients on semaglutide and none on placebo. However, most patients who received semaglutide achieved an HbA1c of 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) or less without weight gain or severe or blood-glucose–confirmed hypoglycemia (P less than .0001 vs. placebo).

Novo Nordisk funded the study. Three of the authors were employees of Novo Nordisk at the time of the study, and the remaining authors reported that they and/or their institutions had received funding from the company.

SOURCE: Zinman B et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30066-X.

FROM LANCET DIABETES AND ENDOCRINOLOGY

Key clinical point: Adding once-weekly treatment with the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) semaglutide helped most patients with type 2 diabetes on sodium-glucose contransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors meet glycemic targets and lose weight.

Major finding: After 30 weeks, the estimated treatment difference for hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) favored semaglutide over placebo (–1.42; P less than .0001). Patients also lost about 3.81 kg more bodyweight with adjunctive semaglutide, compared with placebo (P less than .0001)

Study details: International, double-blind, phase 3 trial of 302 patients with type 2 diabetes with HbA1c levels of 7.0% to 10.0% despite having received at least 90 days of SGLT2-inhibitor therapy (SUSTAIN 9).

Disclosures: Novo Nordisk funded the study. Three of the authors were employees of Novo Nordisk at the time of the study, and the remaining authors reported that they and/or their institutions had received funding from the company.

Source: Zinman B et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019 Mar 1. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30066-X.

How much difference will Eli Lilly’s half-price insulin make?

When Erin Gilmer filled her insulin prescription at a Denver-area Walgreens in January, she paid $8.50. U.S. taxpayers paid another $280.51.

“It eats at me to know that taxpayer money is being wasted,” said Gilmer, who has Medicare and was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes while a sophomore at the University of Colorado in 2002.

The diagnosis meant that for the rest of her life she’d require daily insulin shots to stay alive. But the price of that insulin is skyrocketing.

Between 2009 and 2017 the wholesale price of a single vial of Humalog, the Eli Lilly and Co.–manufactured insulin Gilmer uses, nearly tripled – rising from $92.70 to $274.70, according to data from IBM Watson Health.

Six years ago, Gilmer qualified for Social Security Disability Insurance – and thus, Medicare – because of a range of health issues. At the time, the insulin she needed cost $167.70 per vial, according to IBM Watson Health.

“When it’s taxpayer money paying for medication for someone like me, it makes it a national issue, not just a diabetic issue,” Gilmer said.

Stories about people with type 1 diabetes dying when they couldn’t afford insulin have made headlines. Patient activists like Gilmer have protested high prices outside Lilly’s headquarters in Indianapolis.

Last October in Minnesota, State Attorney General Lori Swanson sued insulin manufacturers, alleging price gouging. Pharmaceutical executives were grilled about high drug prices by the Senate Finance Committee on Feb. 26.

This is the backdrop for Lilly’s announcement March 4 that it is rolling out a half-priced, generic version of Humalog called “insulin lispro.” The list price: $137.35 per vial.

“Patients, doctors and policymakers are demanding lower list prices for medicines and lower patient costs at the pharmacy counter,” Eli Lilly CEO David Ricks wrote in a blog post about the move. “You might be surprised to hear that we agree – it’s time for change in our system and for consumer prices to come down.”

No panacea

When Lilly’s Humalog, the first short-acting insulin, came to market in 1996, the list price was about $21 per vial. The price didn’t reach $275 overnight, but yearly price increases added up.

In February 2009, for example, the wholesale price was $92.70, according to IBM Watson Health. It rose to $99.65 in December 2009, then to $107.60 in September 2010, $115.70 in May 2011, and so on.

“There’s no justification for why prices should keep increasing at an average rate of 10% every year,” said Inmaculada Hernandez of the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy, who was lead author of a January report in Health Affairs attributing the skyrocketing cost of prescription drugs to accumulated yearly price hikes.

“The public perception that we have in general is that drugs are so expensive because we need to pay for research and development, and that’s true,” Hernandez said. “However, usually research and development is paid for in the first years of life of a drug.”

At $137.35 per vial, Lilly’s generic insulin is priced at about the same level as Humalog was in 2012, 16 years after it came to market.

“We want to recognize that this is not a panacea,” said company spokesman Greg Kueterman. “This is an option that we hope can help people in the current system that we work with.”

It’s worth noting that Humalog is a rapid-acting insulin, but that’s only one of the two types of insulin most people with type 1 diabetes use every day. The second kind is long-lasting. Lilly makes one called Basaglar. The most popular long-lasting insulin is Lantus, produced by Sanofi. Neither has a lower-cost alternative.

Still, Lilly’s move on Humalog could put pressure on the other two big makers of insulin to act.

Novo Nordisk called Lilly’s lower-priced generic insulin “an important development,” in an emailed statement.

“Bringing affordable insulin to the market requires ideas from all stakeholders,” Novo Nordisk’s Ken Inchausti said in an email, which also listed steps the company has taken, such as a patient assistance program. The statement didn’t say whether Novo Nordisk is considering offering a lower-priced version of its popular insulin Novolog, a rival of Humalog.

A statement from Sanofi, the third major insulin maker, also didn’t say whether the company would offer lower-priced versions of its insulins.

“Sanofi supports any actions that increase access to insulins for patients living with diabetes at an affordable price,” spokeswoman Ashleigh Koss said in the email, which also touted the company’s patient assistance program.

A different kind of generic

One twist in this story is that Lilly’s new insulin is just a repackaged version of Humalog, minus the brand name. It’s called an “authorized generic.”

“Whoever came up with the term ‘authorized generic’?” Dr. Vincent Rajkumar said, laughing. Rajkumar is a hematologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“It’s the same exact drug” as the brand name, he continued.

Typically, Rajkumar said, authorized generics are introduced by brand-name drugmakers to compete with generic versions of their drugs made by rival companies.

But in the case of Humalog and other insulins, there are no generics made by competitors, as there are for, say, the cholesterol medicine Lipitor or even other diabetes drugs, such as metformin.

So when Lilly’s authorized generic comes to market, the company will have both Humalog insulin and the authorized generic version of that medicine on the market.

Rajkumar said it’s a public relations move.

“There’s outrage over the price of insulin that is being discussed in Congress and elsewhere. And so the company basically says, ‘Hey, we will make the identical product available at half price.’ On the surface that sounds great,” Rajkumar said.

“But you look at the problems and you think, ‘OK, how crazy is this that someone is actually going to be buying the brand-name drug?’ ”

In fact, it’s possible that Lilly could break even or profit off its authorized generic compared to the name-brand Humalog, according to University of Pittsburgh’s Hernandez.

The profit margin would depend on the rebates paid by the company to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers. Rebates are getting a lot of attention these days as one factor that pushes drug prices higher. They’re usually not disclosed and increase as a drug’s price increases, providing an incentive to some companies to raise prices.

“Doing an authorized generic is nothing else than giving insurers two options,” Hernandez said: Pay the full list price for a brand-name drug and receive a higher rebate, or pay the lower price for the authorized generic and receive a presumably smaller rebate.

“What we really need to get insulin prices down is to get generics into the market, and we need more than one,” Hernandez said, adding that previous research has shown that prices begin to go down when two or three generics are competing in the marketplace.

Even so, Lillly’s Kueterman said the authorized generic insulin “is going to help hopefully move the system toward a more sustainable model.”

“I can guarantee you the reason that we’re doing this is to help people,” Kueterman said, noting the company’s Diabetes Solution Center has also helped “10,000 people each month pay significantly less for their insulin” since it opened in August.

For Erin Gilmer, the news about an authorized generic insulin from Lilly has left her mildly encouraged.

“It sounds really good, and it will help some people, which is great,” Gilmer said. “It’s Eli Lilly and pharma starting to understand that grassroots activism has to be taken seriously, and we are at a tipping point.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes NPR and Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

When Erin Gilmer filled her insulin prescription at a Denver-area Walgreens in January, she paid $8.50. U.S. taxpayers paid another $280.51.

“It eats at me to know that taxpayer money is being wasted,” said Gilmer, who has Medicare and was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes while a sophomore at the University of Colorado in 2002.

The diagnosis meant that for the rest of her life she’d require daily insulin shots to stay alive. But the price of that insulin is skyrocketing.

Between 2009 and 2017 the wholesale price of a single vial of Humalog, the Eli Lilly and Co.–manufactured insulin Gilmer uses, nearly tripled – rising from $92.70 to $274.70, according to data from IBM Watson Health.

Six years ago, Gilmer qualified for Social Security Disability Insurance – and thus, Medicare – because of a range of health issues. At the time, the insulin she needed cost $167.70 per vial, according to IBM Watson Health.

“When it’s taxpayer money paying for medication for someone like me, it makes it a national issue, not just a diabetic issue,” Gilmer said.

Stories about people with type 1 diabetes dying when they couldn’t afford insulin have made headlines. Patient activists like Gilmer have protested high prices outside Lilly’s headquarters in Indianapolis.

Last October in Minnesota, State Attorney General Lori Swanson sued insulin manufacturers, alleging price gouging. Pharmaceutical executives were grilled about high drug prices by the Senate Finance Committee on Feb. 26.

This is the backdrop for Lilly’s announcement March 4 that it is rolling out a half-priced, generic version of Humalog called “insulin lispro.” The list price: $137.35 per vial.

“Patients, doctors and policymakers are demanding lower list prices for medicines and lower patient costs at the pharmacy counter,” Eli Lilly CEO David Ricks wrote in a blog post about the move. “You might be surprised to hear that we agree – it’s time for change in our system and for consumer prices to come down.”

No panacea

When Lilly’s Humalog, the first short-acting insulin, came to market in 1996, the list price was about $21 per vial. The price didn’t reach $275 overnight, but yearly price increases added up.

In February 2009, for example, the wholesale price was $92.70, according to IBM Watson Health. It rose to $99.65 in December 2009, then to $107.60 in September 2010, $115.70 in May 2011, and so on.

“There’s no justification for why prices should keep increasing at an average rate of 10% every year,” said Inmaculada Hernandez of the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy, who was lead author of a January report in Health Affairs attributing the skyrocketing cost of prescription drugs to accumulated yearly price hikes.

“The public perception that we have in general is that drugs are so expensive because we need to pay for research and development, and that’s true,” Hernandez said. “However, usually research and development is paid for in the first years of life of a drug.”

At $137.35 per vial, Lilly’s generic insulin is priced at about the same level as Humalog was in 2012, 16 years after it came to market.

“We want to recognize that this is not a panacea,” said company spokesman Greg Kueterman. “This is an option that we hope can help people in the current system that we work with.”

It’s worth noting that Humalog is a rapid-acting insulin, but that’s only one of the two types of insulin most people with type 1 diabetes use every day. The second kind is long-lasting. Lilly makes one called Basaglar. The most popular long-lasting insulin is Lantus, produced by Sanofi. Neither has a lower-cost alternative.

Still, Lilly’s move on Humalog could put pressure on the other two big makers of insulin to act.

Novo Nordisk called Lilly’s lower-priced generic insulin “an important development,” in an emailed statement.

“Bringing affordable insulin to the market requires ideas from all stakeholders,” Novo Nordisk’s Ken Inchausti said in an email, which also listed steps the company has taken, such as a patient assistance program. The statement didn’t say whether Novo Nordisk is considering offering a lower-priced version of its popular insulin Novolog, a rival of Humalog.

A statement from Sanofi, the third major insulin maker, also didn’t say whether the company would offer lower-priced versions of its insulins.

“Sanofi supports any actions that increase access to insulins for patients living with diabetes at an affordable price,” spokeswoman Ashleigh Koss said in the email, which also touted the company’s patient assistance program.

A different kind of generic

One twist in this story is that Lilly’s new insulin is just a repackaged version of Humalog, minus the brand name. It’s called an “authorized generic.”

“Whoever came up with the term ‘authorized generic’?” Dr. Vincent Rajkumar said, laughing. Rajkumar is a hematologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“It’s the same exact drug” as the brand name, he continued.

Typically, Rajkumar said, authorized generics are introduced by brand-name drugmakers to compete with generic versions of their drugs made by rival companies.

But in the case of Humalog and other insulins, there are no generics made by competitors, as there are for, say, the cholesterol medicine Lipitor or even other diabetes drugs, such as metformin.

So when Lilly’s authorized generic comes to market, the company will have both Humalog insulin and the authorized generic version of that medicine on the market.

Rajkumar said it’s a public relations move.

“There’s outrage over the price of insulin that is being discussed in Congress and elsewhere. And so the company basically says, ‘Hey, we will make the identical product available at half price.’ On the surface that sounds great,” Rajkumar said.

“But you look at the problems and you think, ‘OK, how crazy is this that someone is actually going to be buying the brand-name drug?’ ”

In fact, it’s possible that Lilly could break even or profit off its authorized generic compared to the name-brand Humalog, according to University of Pittsburgh’s Hernandez.

The profit margin would depend on the rebates paid by the company to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers. Rebates are getting a lot of attention these days as one factor that pushes drug prices higher. They’re usually not disclosed and increase as a drug’s price increases, providing an incentive to some companies to raise prices.

“Doing an authorized generic is nothing else than giving insurers two options,” Hernandez said: Pay the full list price for a brand-name drug and receive a higher rebate, or pay the lower price for the authorized generic and receive a presumably smaller rebate.

“What we really need to get insulin prices down is to get generics into the market, and we need more than one,” Hernandez said, adding that previous research has shown that prices begin to go down when two or three generics are competing in the marketplace.

Even so, Lillly’s Kueterman said the authorized generic insulin “is going to help hopefully move the system toward a more sustainable model.”

“I can guarantee you the reason that we’re doing this is to help people,” Kueterman said, noting the company’s Diabetes Solution Center has also helped “10,000 people each month pay significantly less for their insulin” since it opened in August.

For Erin Gilmer, the news about an authorized generic insulin from Lilly has left her mildly encouraged.

“It sounds really good, and it will help some people, which is great,” Gilmer said. “It’s Eli Lilly and pharma starting to understand that grassroots activism has to be taken seriously, and we are at a tipping point.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes NPR and Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

When Erin Gilmer filled her insulin prescription at a Denver-area Walgreens in January, she paid $8.50. U.S. taxpayers paid another $280.51.

“It eats at me to know that taxpayer money is being wasted,” said Gilmer, who has Medicare and was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes while a sophomore at the University of Colorado in 2002.

The diagnosis meant that for the rest of her life she’d require daily insulin shots to stay alive. But the price of that insulin is skyrocketing.

Between 2009 and 2017 the wholesale price of a single vial of Humalog, the Eli Lilly and Co.–manufactured insulin Gilmer uses, nearly tripled – rising from $92.70 to $274.70, according to data from IBM Watson Health.

Six years ago, Gilmer qualified for Social Security Disability Insurance – and thus, Medicare – because of a range of health issues. At the time, the insulin she needed cost $167.70 per vial, according to IBM Watson Health.

“When it’s taxpayer money paying for medication for someone like me, it makes it a national issue, not just a diabetic issue,” Gilmer said.

Stories about people with type 1 diabetes dying when they couldn’t afford insulin have made headlines. Patient activists like Gilmer have protested high prices outside Lilly’s headquarters in Indianapolis.

Last October in Minnesota, State Attorney General Lori Swanson sued insulin manufacturers, alleging price gouging. Pharmaceutical executives were grilled about high drug prices by the Senate Finance Committee on Feb. 26.

This is the backdrop for Lilly’s announcement March 4 that it is rolling out a half-priced, generic version of Humalog called “insulin lispro.” The list price: $137.35 per vial.

“Patients, doctors and policymakers are demanding lower list prices for medicines and lower patient costs at the pharmacy counter,” Eli Lilly CEO David Ricks wrote in a blog post about the move. “You might be surprised to hear that we agree – it’s time for change in our system and for consumer prices to come down.”

No panacea

When Lilly’s Humalog, the first short-acting insulin, came to market in 1996, the list price was about $21 per vial. The price didn’t reach $275 overnight, but yearly price increases added up.

In February 2009, for example, the wholesale price was $92.70, according to IBM Watson Health. It rose to $99.65 in December 2009, then to $107.60 in September 2010, $115.70 in May 2011, and so on.

“There’s no justification for why prices should keep increasing at an average rate of 10% every year,” said Inmaculada Hernandez of the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy, who was lead author of a January report in Health Affairs attributing the skyrocketing cost of prescription drugs to accumulated yearly price hikes.

“The public perception that we have in general is that drugs are so expensive because we need to pay for research and development, and that’s true,” Hernandez said. “However, usually research and development is paid for in the first years of life of a drug.”

At $137.35 per vial, Lilly’s generic insulin is priced at about the same level as Humalog was in 2012, 16 years after it came to market.

“We want to recognize that this is not a panacea,” said company spokesman Greg Kueterman. “This is an option that we hope can help people in the current system that we work with.”

It’s worth noting that Humalog is a rapid-acting insulin, but that’s only one of the two types of insulin most people with type 1 diabetes use every day. The second kind is long-lasting. Lilly makes one called Basaglar. The most popular long-lasting insulin is Lantus, produced by Sanofi. Neither has a lower-cost alternative.

Still, Lilly’s move on Humalog could put pressure on the other two big makers of insulin to act.

Novo Nordisk called Lilly’s lower-priced generic insulin “an important development,” in an emailed statement.

“Bringing affordable insulin to the market requires ideas from all stakeholders,” Novo Nordisk’s Ken Inchausti said in an email, which also listed steps the company has taken, such as a patient assistance program. The statement didn’t say whether Novo Nordisk is considering offering a lower-priced version of its popular insulin Novolog, a rival of Humalog.

A statement from Sanofi, the third major insulin maker, also didn’t say whether the company would offer lower-priced versions of its insulins.

“Sanofi supports any actions that increase access to insulins for patients living with diabetes at an affordable price,” spokeswoman Ashleigh Koss said in the email, which also touted the company’s patient assistance program.

A different kind of generic

One twist in this story is that Lilly’s new insulin is just a repackaged version of Humalog, minus the brand name. It’s called an “authorized generic.”

“Whoever came up with the term ‘authorized generic’?” Dr. Vincent Rajkumar said, laughing. Rajkumar is a hematologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“It’s the same exact drug” as the brand name, he continued.

Typically, Rajkumar said, authorized generics are introduced by brand-name drugmakers to compete with generic versions of their drugs made by rival companies.

But in the case of Humalog and other insulins, there are no generics made by competitors, as there are for, say, the cholesterol medicine Lipitor or even other diabetes drugs, such as metformin.

So when Lilly’s authorized generic comes to market, the company will have both Humalog insulin and the authorized generic version of that medicine on the market.

Rajkumar said it’s a public relations move.

“There’s outrage over the price of insulin that is being discussed in Congress and elsewhere. And so the company basically says, ‘Hey, we will make the identical product available at half price.’ On the surface that sounds great,” Rajkumar said.

“But you look at the problems and you think, ‘OK, how crazy is this that someone is actually going to be buying the brand-name drug?’ ”

In fact, it’s possible that Lilly could break even or profit off its authorized generic compared to the name-brand Humalog, according to University of Pittsburgh’s Hernandez.

The profit margin would depend on the rebates paid by the company to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers. Rebates are getting a lot of attention these days as one factor that pushes drug prices higher. They’re usually not disclosed and increase as a drug’s price increases, providing an incentive to some companies to raise prices.

“Doing an authorized generic is nothing else than giving insurers two options,” Hernandez said: Pay the full list price for a brand-name drug and receive a higher rebate, or pay the lower price for the authorized generic and receive a presumably smaller rebate.

“What we really need to get insulin prices down is to get generics into the market, and we need more than one,” Hernandez said, adding that previous research has shown that prices begin to go down when two or three generics are competing in the marketplace.

Even so, Lillly’s Kueterman said the authorized generic insulin “is going to help hopefully move the system toward a more sustainable model.”

“I can guarantee you the reason that we’re doing this is to help people,” Kueterman said, noting the company’s Diabetes Solution Center has also helped “10,000 people each month pay significantly less for their insulin” since it opened in August.

For Erin Gilmer, the news about an authorized generic insulin from Lilly has left her mildly encouraged.

“It sounds really good, and it will help some people, which is great,” Gilmer said. “It’s Eli Lilly and pharma starting to understand that grassroots activism has to be taken seriously, and we are at a tipping point.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes NPR and Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Nonadherent Diabetes Patients: An Unexpected Group

“Time-specific” dosing of insulin can be an obstacle to adherence for patients with complicated, busy lives. More than half of patients with type 2 diabetes do not achieve their target HbA1c of 7% after insulin is added to their treatment regimen. Researchers from CAPHRI School for Public Health and Primary Care, and CARIM Institute in The Netherlands, who surveyed 1,483 adults with diabetes suggest that it may be time to rethink both prescribing and patient education, in part because of who fell into the nonadherent group.

The researchers conducted a web-based self-report survey. Of the respondents, 58% used bolus insulin before meals, 24% after meals, and 18% before, during, or after meals. The researchers excluded the “mixed” cohort, including 1,218 in the analysis.

Half the respondents in the postmeal cohort reported experiencing minor hypoglycemic events at least once a week compared with 35% of the premeal cohort. Similarly, more in the postmeal group had had major hypoglycemic events (38% vs 26%). The postmeal respondents also were more likely to have HbA1c ≥ 9% (40% vs 29%). And they were less likely to report always testing their blood glucose before injecting insulin (36% vs 54%).

Perhaps contrary to some expectations, the respondents who injected insulin postmeal were younger, had shorter duration of diabetes, had the highest level of college or university education, were more likely to be employed, and more frequently participated in diabetes education programs (including one-on-one programs).

The researchers say those data suggest that factors other than lack of diabetes education, education, or low socioeconomic status should be considered in explaining the nonadherence. They add that some research has shown that education programs have an “inconsistent relationship with patient adherence.” They suggest that such programs might be improved by placing greater emphasis on the importance of dosing insulin before meals.

Of the nearly 20% of patients who use insulin treatment, > 90% receive bolus insulin. The researchers note that respondents preferred a form of bolus insulin they can administer before, after, or during meals as they see fit. The respondents who injected postmeal were more likely than the premeal respondents to prefer this formulation.

“Time-specific” dosing of insulin can be an obstacle to adherence for patients with complicated, busy lives. More than half of patients with type 2 diabetes do not achieve their target HbA1c of 7% after insulin is added to their treatment regimen. Researchers from CAPHRI School for Public Health and Primary Care, and CARIM Institute in The Netherlands, who surveyed 1,483 adults with diabetes suggest that it may be time to rethink both prescribing and patient education, in part because of who fell into the nonadherent group.

The researchers conducted a web-based self-report survey. Of the respondents, 58% used bolus insulin before meals, 24% after meals, and 18% before, during, or after meals. The researchers excluded the “mixed” cohort, including 1,218 in the analysis.

Half the respondents in the postmeal cohort reported experiencing minor hypoglycemic events at least once a week compared with 35% of the premeal cohort. Similarly, more in the postmeal group had had major hypoglycemic events (38% vs 26%). The postmeal respondents also were more likely to have HbA1c ≥ 9% (40% vs 29%). And they were less likely to report always testing their blood glucose before injecting insulin (36% vs 54%).

Perhaps contrary to some expectations, the respondents who injected insulin postmeal were younger, had shorter duration of diabetes, had the highest level of college or university education, were more likely to be employed, and more frequently participated in diabetes education programs (including one-on-one programs).

The researchers say those data suggest that factors other than lack of diabetes education, education, or low socioeconomic status should be considered in explaining the nonadherence. They add that some research has shown that education programs have an “inconsistent relationship with patient adherence.” They suggest that such programs might be improved by placing greater emphasis on the importance of dosing insulin before meals.

Of the nearly 20% of patients who use insulin treatment, > 90% receive bolus insulin. The researchers note that respondents preferred a form of bolus insulin they can administer before, after, or during meals as they see fit. The respondents who injected postmeal were more likely than the premeal respondents to prefer this formulation.

“Time-specific” dosing of insulin can be an obstacle to adherence for patients with complicated, busy lives. More than half of patients with type 2 diabetes do not achieve their target HbA1c of 7% after insulin is added to their treatment regimen. Researchers from CAPHRI School for Public Health and Primary Care, and CARIM Institute in The Netherlands, who surveyed 1,483 adults with diabetes suggest that it may be time to rethink both prescribing and patient education, in part because of who fell into the nonadherent group.

The researchers conducted a web-based self-report survey. Of the respondents, 58% used bolus insulin before meals, 24% after meals, and 18% before, during, or after meals. The researchers excluded the “mixed” cohort, including 1,218 in the analysis.

Half the respondents in the postmeal cohort reported experiencing minor hypoglycemic events at least once a week compared with 35% of the premeal cohort. Similarly, more in the postmeal group had had major hypoglycemic events (38% vs 26%). The postmeal respondents also were more likely to have HbA1c ≥ 9% (40% vs 29%). And they were less likely to report always testing their blood glucose before injecting insulin (36% vs 54%).

Perhaps contrary to some expectations, the respondents who injected insulin postmeal were younger, had shorter duration of diabetes, had the highest level of college or university education, were more likely to be employed, and more frequently participated in diabetes education programs (including one-on-one programs).

The researchers say those data suggest that factors other than lack of diabetes education, education, or low socioeconomic status should be considered in explaining the nonadherence. They add that some research has shown that education programs have an “inconsistent relationship with patient adherence.” They suggest that such programs might be improved by placing greater emphasis on the importance of dosing insulin before meals.

Of the nearly 20% of patients who use insulin treatment, > 90% receive bolus insulin. The researchers note that respondents preferred a form of bolus insulin they can administer before, after, or during meals as they see fit. The respondents who injected postmeal were more likely than the premeal respondents to prefer this formulation.

Sudden-onset rash on the trunk and limbs • morbid obesity • family history of diabetes mellitus • Dx?

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man presented with a sudden-onset, nonpruritic, nonpainful, papular rash of 1 month’s duration on his trunk and both arms and legs. Two weeks prior to the current presentation, he consulted a general practitioner, who treated the rash with a course of unknown oral antibiotics; the patient showed no improvement. He recalled that on a few occasions, he used his fingers to express a creamy discharge from some of the lesions. This temporarily reduced the size of those papules.

His medical history was unremarkable except for morbid obesity. He did not drink alcohol regularly and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the rash. He had no family history of hyperlipidemia, but his mother had a history of diabetes mellitus.

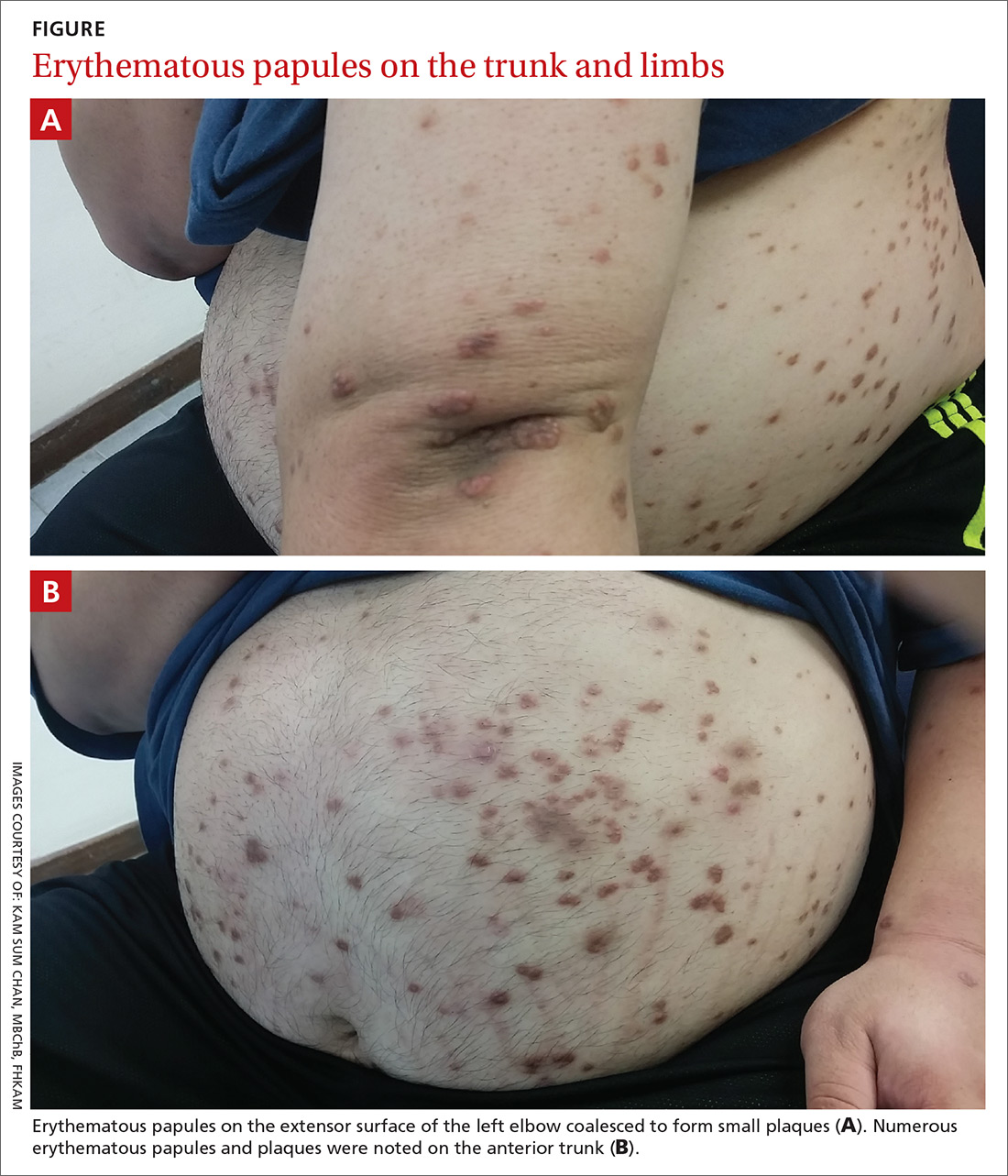

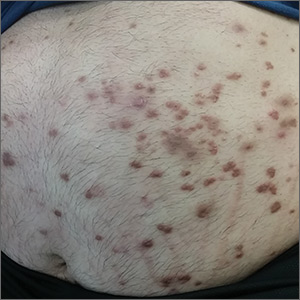

Physical examination showed numerous discrete erythematous papules with a creamy center on his trunk and his arms and legs. The lesions were more numerous on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs. Some of the papules coalesced to form small plaques (FIGURE). There was no scaling, and the lesions were firm in texture. The patient’s face was spared, and there was no mucosal involvement. The patient was otherwise systemically well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the morphology, distribution, and abrupt onset of the diffuse nonpruritic papules in this morbidly obese (but otherwise systemically well) middle-aged man, a clinical diagnosis of eruptive xanthoma was suspected. Subsequent blood testing revealed an elevated serum triglyceride level of 47.8 mmol/L (reference range, <1.7 mmol/L), elevated serum total cholesterol of 7.1 mmol/L (reference range, <6.2 mmol/L), and low serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol of 0.7 mmol/L (reference range, >1 mmol/L in men). He also had an elevated fasting serum glucose level of 12.9 mmol/L (reference range, 3.9–5.6 mmol/L) and an elevated hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin) level of 10.9%.

Subsequent thyroid, liver, and renal function tests were normal, but the patient had heavy proteinuria, with an elevated urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio of 355.6 mg/mmol (reference range, ≤2.5 mg/mmol). The patient was referred to a dermatologist, who confirmed the clinical diagnosis without the need for a skin biopsy.

DISCUSSION

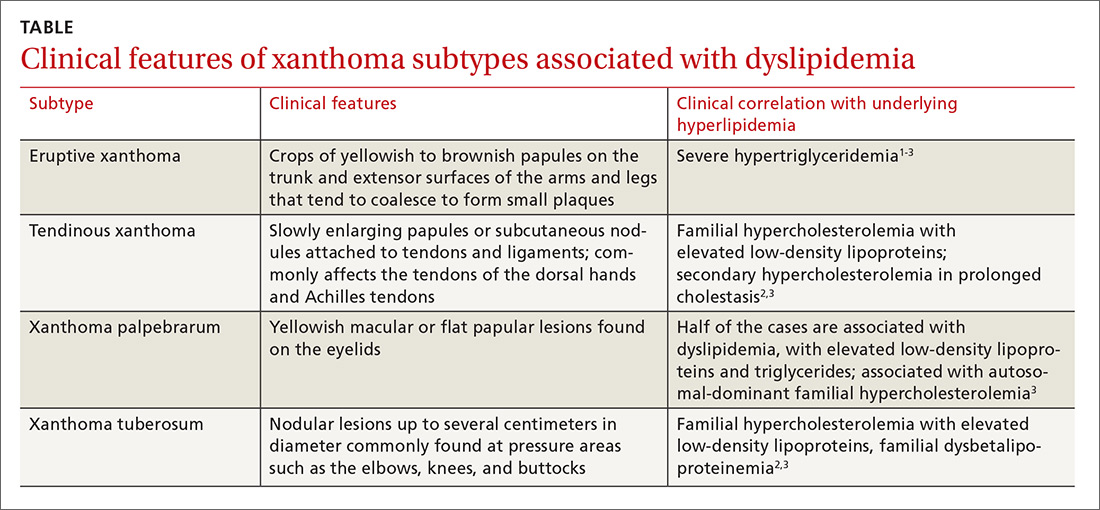

Eruptive xanthoma is characterized by an abrupt onset of crops of multiple yellowish to brownish papules that can coalesce into small plaques. The lesions can be generalized, but tend to be more densely distributed on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, buttocks, and thighs.5 Eruptive xanthoma often is associated with hypertriglyceridemia, which can be primary—as a result of a genetic defect caused by familial hypertriglyceridemia—or secondary, associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, nephrotic syndrome, hypothyroidism, primary biliary cholangitis, and drugs like estrogen replacement therapies, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin.6 Pruritus and tenderness may or may not be present, and the Köbner phenomenon may occur.7

Continue to: The differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for eruptive xanthoma includes xanthoma disseminatum, non–Langerhans cell histiocytoses (eg, generalized eruptive histiocytosis), and cutaneous mastocytosis.1