User login

Type 2 diabetes may promote Parkinson development

Type 2 diabetes mellitus may be associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, according to a large retrospective cohort study published online June 13 in Neurology.

Researchers accessed the linked English national Hospital Episode Statistics and mortality data from 1999-2011 to compare data from 2,017,115 individuals admitted to hospital who had a diagnostic code for type 2 diabetes with data from a reference cohort of 6,173,208 individuals admitted for a range of other minor procedures.

They found a significant 32% higher incidence of Parkinson’s disease among individuals with type 2 diabetes, compared with the reference cohort (95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.35; P less than .001).

The incidence was particularly high among younger individuals with type 2 diabetes; those aged 25-44 years at the time of admission had a 3.8-fold higher rate of Parkinson’s disease, compared with the reference group (P less than .001). Individuals aged 45-64 years with type 2 diabetes had 71% greater rate of Parkinson, those aged 65-74 years had a 40% higher incidence, and those aged 75 years or over had an 18% higher rate.

Individuals with complicated type 2 diabetes, defined as the presence of diabetic neuropathy, nephropathy, or retinopathy, had a 49% higher incidence of Parkinson disease than did the reference cohort.

Eduardo De Pablo-Fernandez, MD, from the University College London Institute of Neurology, and his coauthors suggested that the interaction between the two, apparently unconnected, diseases may be a function of both genetics and shared pathogenic pathways.

“The magnitude of risk in our study was greater in younger individuals, whereby genetic factors may relatively exert more of an effect, and more than 400 genes, previously identified through genome-wide association studies, have been closely linked to both conditions using integrative network analysis,” the authors wrote.

“However, the association in elderly patients may be the consequence of disrupted insulin signaling secondary to additional lifestyle and environmental factors causing cumulative pathogenic brain changes.”

They proposed that disrupted brain insulin signaling could lead to neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased oxidative stress that could contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease.

The findings were similar to those seen in a previous meta-analysis of five studies, although the authors commented that there was significant heterogeneity among the studies included in that analysis.

The authors of this study also noted that their study did not adjust for potential confounders such as smoking or antidiabetic medication use.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University of Oxford, England, and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London. Two authors declared funding and payments from private industry outside the submitted work, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: De Pablo Fernandez E et al. Neurology. 2018 June 13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005771.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus may be associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, according to a large retrospective cohort study published online June 13 in Neurology.

Researchers accessed the linked English national Hospital Episode Statistics and mortality data from 1999-2011 to compare data from 2,017,115 individuals admitted to hospital who had a diagnostic code for type 2 diabetes with data from a reference cohort of 6,173,208 individuals admitted for a range of other minor procedures.

They found a significant 32% higher incidence of Parkinson’s disease among individuals with type 2 diabetes, compared with the reference cohort (95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.35; P less than .001).

The incidence was particularly high among younger individuals with type 2 diabetes; those aged 25-44 years at the time of admission had a 3.8-fold higher rate of Parkinson’s disease, compared with the reference group (P less than .001). Individuals aged 45-64 years with type 2 diabetes had 71% greater rate of Parkinson, those aged 65-74 years had a 40% higher incidence, and those aged 75 years or over had an 18% higher rate.

Individuals with complicated type 2 diabetes, defined as the presence of diabetic neuropathy, nephropathy, or retinopathy, had a 49% higher incidence of Parkinson disease than did the reference cohort.

Eduardo De Pablo-Fernandez, MD, from the University College London Institute of Neurology, and his coauthors suggested that the interaction between the two, apparently unconnected, diseases may be a function of both genetics and shared pathogenic pathways.

“The magnitude of risk in our study was greater in younger individuals, whereby genetic factors may relatively exert more of an effect, and more than 400 genes, previously identified through genome-wide association studies, have been closely linked to both conditions using integrative network analysis,” the authors wrote.

“However, the association in elderly patients may be the consequence of disrupted insulin signaling secondary to additional lifestyle and environmental factors causing cumulative pathogenic brain changes.”

They proposed that disrupted brain insulin signaling could lead to neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased oxidative stress that could contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease.

The findings were similar to those seen in a previous meta-analysis of five studies, although the authors commented that there was significant heterogeneity among the studies included in that analysis.

The authors of this study also noted that their study did not adjust for potential confounders such as smoking or antidiabetic medication use.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University of Oxford, England, and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London. Two authors declared funding and payments from private industry outside the submitted work, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: De Pablo Fernandez E et al. Neurology. 2018 June 13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005771.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus may be associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, according to a large retrospective cohort study published online June 13 in Neurology.

Researchers accessed the linked English national Hospital Episode Statistics and mortality data from 1999-2011 to compare data from 2,017,115 individuals admitted to hospital who had a diagnostic code for type 2 diabetes with data from a reference cohort of 6,173,208 individuals admitted for a range of other minor procedures.

They found a significant 32% higher incidence of Parkinson’s disease among individuals with type 2 diabetes, compared with the reference cohort (95% confidence interval, 1.29-1.35; P less than .001).

The incidence was particularly high among younger individuals with type 2 diabetes; those aged 25-44 years at the time of admission had a 3.8-fold higher rate of Parkinson’s disease, compared with the reference group (P less than .001). Individuals aged 45-64 years with type 2 diabetes had 71% greater rate of Parkinson, those aged 65-74 years had a 40% higher incidence, and those aged 75 years or over had an 18% higher rate.

Individuals with complicated type 2 diabetes, defined as the presence of diabetic neuropathy, nephropathy, or retinopathy, had a 49% higher incidence of Parkinson disease than did the reference cohort.

Eduardo De Pablo-Fernandez, MD, from the University College London Institute of Neurology, and his coauthors suggested that the interaction between the two, apparently unconnected, diseases may be a function of both genetics and shared pathogenic pathways.

“The magnitude of risk in our study was greater in younger individuals, whereby genetic factors may relatively exert more of an effect, and more than 400 genes, previously identified through genome-wide association studies, have been closely linked to both conditions using integrative network analysis,” the authors wrote.

“However, the association in elderly patients may be the consequence of disrupted insulin signaling secondary to additional lifestyle and environmental factors causing cumulative pathogenic brain changes.”

They proposed that disrupted brain insulin signaling could lead to neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased oxidative stress that could contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease.

The findings were similar to those seen in a previous meta-analysis of five studies, although the authors commented that there was significant heterogeneity among the studies included in that analysis.

The authors of this study also noted that their study did not adjust for potential confounders such as smoking or antidiabetic medication use.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University of Oxford, England, and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London. Two authors declared funding and payments from private industry outside the submitted work, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: De Pablo Fernandez E et al. Neurology. 2018 June 13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005771.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Type 2 diabetes may be associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Major finding: The incidence of Parkinson’s disease is 32% higher in people with type 2 diabetes.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study including 2,017,115 individuals with type 2 diabetes and 6,173,208 controls.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University of Oxford, England, and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University College London. Two authors declared funding and payments from private industry outside the submitted work, but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: De Pablo-Fernandez E et al. Neurology. 2018 June 13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005771.

Serum uromodulin independently predicts mortality in CAD

ORLANDO – Low serum uromodulin proved to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in a prospective study of 529 patients with stable coronary artery disease followed for up to 8 years, according to Christoph Saely, MD, vice president of the Vorarlberg Institute for Vascular Investigation and Treatment in Feldkirch, Austria.

“Baseline serum uromodulin is a valuable biomarker to predict overall mortality in coronary patients independent from kidney disease and the presence of type 2 diabetes. The lower the serum uromodulin, the higher the mortality,” he noted in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In addition to presenting new evidence at ACC 2018 of serum uromodulin’s merits as a predictor of increased mortality risk in patients with CAD, Dr. Saely and his coinvestigators also showed that low serum uromodulin is associated with chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, and prediabetes. Moreover, those with normal glucose metabolism and kidney function but a low serum uromodulin at baseline were at increased risk of developing abnormal glucose metabolism and impaired renal function during 4 years of follow-up.

Of the 529 patients with stable CAD, 95 died during follow-up. Among those with a low baseline serum uromodulin, defined bimodally as a level below 123.3 ng/mL, the mortality rate was 27.6%, roughly twice the 13.7% figure in patients with a baseline uromodulin above that threshold.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted extensively for age, sex, smoking, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, C-reactive protein, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide level, a high baseline serum uromodulin was independently associated with a 43% reduction in the risk of mortality, according to Dr. Saely, who is both a cardiologist and an endocrinologist.

The overall mortality rate was 41% in patients with diabetes and a low baseline uromodulin, 20% in those with low uromodulin but not diabetes, 18% in diabetic patients with high uromodulin, and less than 13% with high uromodulin and no diabetes.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests for uromodulin are marketed in Europe but remain investigational for now in the United States.

Dr. Saely reported having no financial conflicts of interest; the study was conducted without commercial support.

SOURCE: Saely C. ACC 2018, Abstract 1212-418/418.

ORLANDO – Low serum uromodulin proved to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in a prospective study of 529 patients with stable coronary artery disease followed for up to 8 years, according to Christoph Saely, MD, vice president of the Vorarlberg Institute for Vascular Investigation and Treatment in Feldkirch, Austria.

“Baseline serum uromodulin is a valuable biomarker to predict overall mortality in coronary patients independent from kidney disease and the presence of type 2 diabetes. The lower the serum uromodulin, the higher the mortality,” he noted in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In addition to presenting new evidence at ACC 2018 of serum uromodulin’s merits as a predictor of increased mortality risk in patients with CAD, Dr. Saely and his coinvestigators also showed that low serum uromodulin is associated with chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, and prediabetes. Moreover, those with normal glucose metabolism and kidney function but a low serum uromodulin at baseline were at increased risk of developing abnormal glucose metabolism and impaired renal function during 4 years of follow-up.

Of the 529 patients with stable CAD, 95 died during follow-up. Among those with a low baseline serum uromodulin, defined bimodally as a level below 123.3 ng/mL, the mortality rate was 27.6%, roughly twice the 13.7% figure in patients with a baseline uromodulin above that threshold.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted extensively for age, sex, smoking, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, C-reactive protein, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide level, a high baseline serum uromodulin was independently associated with a 43% reduction in the risk of mortality, according to Dr. Saely, who is both a cardiologist and an endocrinologist.

The overall mortality rate was 41% in patients with diabetes and a low baseline uromodulin, 20% in those with low uromodulin but not diabetes, 18% in diabetic patients with high uromodulin, and less than 13% with high uromodulin and no diabetes.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests for uromodulin are marketed in Europe but remain investigational for now in the United States.

Dr. Saely reported having no financial conflicts of interest; the study was conducted without commercial support.

SOURCE: Saely C. ACC 2018, Abstract 1212-418/418.

ORLANDO – Low serum uromodulin proved to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in a prospective study of 529 patients with stable coronary artery disease followed for up to 8 years, according to Christoph Saely, MD, vice president of the Vorarlberg Institute for Vascular Investigation and Treatment in Feldkirch, Austria.

“Baseline serum uromodulin is a valuable biomarker to predict overall mortality in coronary patients independent from kidney disease and the presence of type 2 diabetes. The lower the serum uromodulin, the higher the mortality,” he noted in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

In addition to presenting new evidence at ACC 2018 of serum uromodulin’s merits as a predictor of increased mortality risk in patients with CAD, Dr. Saely and his coinvestigators also showed that low serum uromodulin is associated with chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, and prediabetes. Moreover, those with normal glucose metabolism and kidney function but a low serum uromodulin at baseline were at increased risk of developing abnormal glucose metabolism and impaired renal function during 4 years of follow-up.

Of the 529 patients with stable CAD, 95 died during follow-up. Among those with a low baseline serum uromodulin, defined bimodally as a level below 123.3 ng/mL, the mortality rate was 27.6%, roughly twice the 13.7% figure in patients with a baseline uromodulin above that threshold.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted extensively for age, sex, smoking, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, C-reactive protein, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide level, a high baseline serum uromodulin was independently associated with a 43% reduction in the risk of mortality, according to Dr. Saely, who is both a cardiologist and an endocrinologist.

The overall mortality rate was 41% in patients with diabetes and a low baseline uromodulin, 20% in those with low uromodulin but not diabetes, 18% in diabetic patients with high uromodulin, and less than 13% with high uromodulin and no diabetes.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests for uromodulin are marketed in Europe but remain investigational for now in the United States.

Dr. Saely reported having no financial conflicts of interest; the study was conducted without commercial support.

SOURCE: Saely C. ACC 2018, Abstract 1212-418/418.

REPORTING FROM ACC 2018

Key clinical point: The lower the baseline serum uromodulin in patients with CAD, the higher the subsequent mortality.

Major finding: A high baseline serum uromodulin was independently associated with a 43% reduction in all-cause mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease.

Study details: This was a prospective study of 529 patients with stable CAD followed for up to 8 years.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted without commercial support.

Source: Saely C. ACC 2018, Abstract 1212-418/418.

Thyroid markers linked to risk of gestational diabetes

Thyroid dysfunction early in pregnancy may increase risk of gestational diabetes, results of a longitudinal study suggest.

Increased levels of free triiodothyronine (fT3) and the ratio of fT3 to free thyroxine (fT4) were associated with increased risk of this common metabolic complication of pregnancy, study authors reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify fT3 and the fT3:fT4 ratio measured early in pregnancy as independent risk factors of gestational diabetes,” wrote Shristi Rawal, PhD, of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) , and her colleagues.

Although routine thyroid function screening during pregnancy remains controversial, Dr. Rawal and colleagues said their results support the “potential benefits” of the practice, particularly in light of other recent evidence suggesting thyroid-related adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The current case control study by Dr. Rawal and her coinvestigators included 107 women with gestational diabetes and 214 nongestational diabetes controls selected from a 12-center pregnancy cohort, which included 2,802 women aged between 18 and 40 years. The thyroid markers fT3, fT4, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) were measured at four pregnancy visits, including first trimester (weeks 10-14) and second trimester (weeks 15-26).

The fT3:fT4 ratio had the strongest association with gestational diabetes. In the second trimester measurement, women in the highest quartile had an almost 14-fold increase in risk when compared to the lowest quartile, after adjusting for potential confounders including prepregnancy body mass index and diabetes family history (adjusted odds ratio, 13.60; 95% confidence interval, 3.97-46.30), Dr. Rawal and her colleagues reported. The ratio of fT3:fT4 at the first trimester was also associated with increased risk (aOR, 8.63; 95% CI, 2.87-26.00).

Similarly, fT3 was positively associated with gestational diabetes at the first trimester (aOR, 4.25; 95% CI, 1.67-10.80) and second trimester (aOR, 3.89; 95% CI, 1.50-10.10), investigators reported.

By contrast, there was no association between fT4 or TSH and gestational diabetes, they found.

“These findings, in combination with previous evidence of thyroid-related adverse pregnancy outcomes, support the benefits of thyroid screening among pregnant women in early to mid pregnancy,” senior author Cuilin Zhang, MD, MPH, PhD, of the NICHD, said in a press statement.

Thyroid function abnormalities are relatively common in pregnant women and have been associated with obstetric complications such as pregnancy loss and premature delivery, investigators noted.

Previous evidence is sparse regarding a potential link between thyroid dysfunction and gestational diabetes. There are some prospective studies that show women with hypothyroidism have an increased incidence of gestational diabetes, Dr. Rawal and her colleagues wrote. Isolated hypothyroxinema, or normal TSH and low fT4, has also been linked to increased risk in some studies, but not in others, they added.

Support for the study came from NICHD and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act research grants. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rawal S et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jun 7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-024421.

Thyroid dysfunction early in pregnancy may increase risk of gestational diabetes, results of a longitudinal study suggest.

Increased levels of free triiodothyronine (fT3) and the ratio of fT3 to free thyroxine (fT4) were associated with increased risk of this common metabolic complication of pregnancy, study authors reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify fT3 and the fT3:fT4 ratio measured early in pregnancy as independent risk factors of gestational diabetes,” wrote Shristi Rawal, PhD, of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) , and her colleagues.

Although routine thyroid function screening during pregnancy remains controversial, Dr. Rawal and colleagues said their results support the “potential benefits” of the practice, particularly in light of other recent evidence suggesting thyroid-related adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The current case control study by Dr. Rawal and her coinvestigators included 107 women with gestational diabetes and 214 nongestational diabetes controls selected from a 12-center pregnancy cohort, which included 2,802 women aged between 18 and 40 years. The thyroid markers fT3, fT4, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) were measured at four pregnancy visits, including first trimester (weeks 10-14) and second trimester (weeks 15-26).

The fT3:fT4 ratio had the strongest association with gestational diabetes. In the second trimester measurement, women in the highest quartile had an almost 14-fold increase in risk when compared to the lowest quartile, after adjusting for potential confounders including prepregnancy body mass index and diabetes family history (adjusted odds ratio, 13.60; 95% confidence interval, 3.97-46.30), Dr. Rawal and her colleagues reported. The ratio of fT3:fT4 at the first trimester was also associated with increased risk (aOR, 8.63; 95% CI, 2.87-26.00).

Similarly, fT3 was positively associated with gestational diabetes at the first trimester (aOR, 4.25; 95% CI, 1.67-10.80) and second trimester (aOR, 3.89; 95% CI, 1.50-10.10), investigators reported.

By contrast, there was no association between fT4 or TSH and gestational diabetes, they found.

“These findings, in combination with previous evidence of thyroid-related adverse pregnancy outcomes, support the benefits of thyroid screening among pregnant women in early to mid pregnancy,” senior author Cuilin Zhang, MD, MPH, PhD, of the NICHD, said in a press statement.

Thyroid function abnormalities are relatively common in pregnant women and have been associated with obstetric complications such as pregnancy loss and premature delivery, investigators noted.

Previous evidence is sparse regarding a potential link between thyroid dysfunction and gestational diabetes. There are some prospective studies that show women with hypothyroidism have an increased incidence of gestational diabetes, Dr. Rawal and her colleagues wrote. Isolated hypothyroxinema, or normal TSH and low fT4, has also been linked to increased risk in some studies, but not in others, they added.

Support for the study came from NICHD and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act research grants. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rawal S et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jun 7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-024421.

Thyroid dysfunction early in pregnancy may increase risk of gestational diabetes, results of a longitudinal study suggest.

Increased levels of free triiodothyronine (fT3) and the ratio of fT3 to free thyroxine (fT4) were associated with increased risk of this common metabolic complication of pregnancy, study authors reported in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify fT3 and the fT3:fT4 ratio measured early in pregnancy as independent risk factors of gestational diabetes,” wrote Shristi Rawal, PhD, of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) , and her colleagues.

Although routine thyroid function screening during pregnancy remains controversial, Dr. Rawal and colleagues said their results support the “potential benefits” of the practice, particularly in light of other recent evidence suggesting thyroid-related adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The current case control study by Dr. Rawal and her coinvestigators included 107 women with gestational diabetes and 214 nongestational diabetes controls selected from a 12-center pregnancy cohort, which included 2,802 women aged between 18 and 40 years. The thyroid markers fT3, fT4, and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) were measured at four pregnancy visits, including first trimester (weeks 10-14) and second trimester (weeks 15-26).

The fT3:fT4 ratio had the strongest association with gestational diabetes. In the second trimester measurement, women in the highest quartile had an almost 14-fold increase in risk when compared to the lowest quartile, after adjusting for potential confounders including prepregnancy body mass index and diabetes family history (adjusted odds ratio, 13.60; 95% confidence interval, 3.97-46.30), Dr. Rawal and her colleagues reported. The ratio of fT3:fT4 at the first trimester was also associated with increased risk (aOR, 8.63; 95% CI, 2.87-26.00).

Similarly, fT3 was positively associated with gestational diabetes at the first trimester (aOR, 4.25; 95% CI, 1.67-10.80) and second trimester (aOR, 3.89; 95% CI, 1.50-10.10), investigators reported.

By contrast, there was no association between fT4 or TSH and gestational diabetes, they found.

“These findings, in combination with previous evidence of thyroid-related adverse pregnancy outcomes, support the benefits of thyroid screening among pregnant women in early to mid pregnancy,” senior author Cuilin Zhang, MD, MPH, PhD, of the NICHD, said in a press statement.

Thyroid function abnormalities are relatively common in pregnant women and have been associated with obstetric complications such as pregnancy loss and premature delivery, investigators noted.

Previous evidence is sparse regarding a potential link between thyroid dysfunction and gestational diabetes. There are some prospective studies that show women with hypothyroidism have an increased incidence of gestational diabetes, Dr. Rawal and her colleagues wrote. Isolated hypothyroxinema, or normal TSH and low fT4, has also been linked to increased risk in some studies, but not in others, they added.

Support for the study came from NICHD and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act research grants. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rawal S et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jun 7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-024421.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM.

Key clinical point: Thyroid dysfunction early in pregnancy may increase risk of gestational diabetes.

Major finding: The triiodothyronine to thyroxine ratio in the second trimester had the strongest association with gestational diabetes (adjusted odds ratio, 13.60; 95% confidence interval, 3.97-46.30).

Study details: A case control study including 107 gestational diabetes cases and 214 nongestational diabetes controls.

Disclosures: The authors had no disclosures. Support for the study came from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act research grants.

Source: Rawal S et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jun 7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-024421.

Headline can be up to 255 characters

- The article body can contain (4 total):

- Images

- Videos

- Poll Daddy surveys

- Hyerplinks

- And text formatting (ital, bold, underline, etc.).

- 2,500 character limit with spaces

Image

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. "Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum."

"Quote or highlighted text."

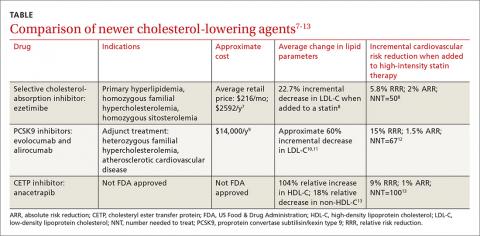

Table

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Video

Poll

[polldaddy:10018427]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Table

| Column Header | Column Header | Column Header |

|---|---|---|

| Column Text | Column Text | Column Text |

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

- The article body can contain (4 total):

- Images

- Videos

- Poll Daddy surveys

- Hyerplinks

- And text formatting (ital, bold, underline, etc.).

- 2,500 character limit with spaces

Image

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. "Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum."

"Quote or highlighted text."

Table

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Video

Poll

[polldaddy:10018427]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Table

| Column Header | Column Header | Column Header |

|---|---|---|

| Column Text | Column Text | Column Text |

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

- The article body can contain (4 total):

- Images

- Videos

- Poll Daddy surveys

- Hyerplinks

- And text formatting (ital, bold, underline, etc.).

- 2,500 character limit with spaces

Image

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. "Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum."

"Quote or highlighted text."

Table

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Video

Poll

[polldaddy:10018427]

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Table

| Column Header | Column Header | Column Header |

|---|---|---|

| Column Text | Column Text | Column Text |

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

The case for bariatric surgery to manage CV risk in diabetes

BOSTON – For patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes ( health over the lifespan.

“Behavioral changes in diet and activity may be effective over the short term, but they are often ineffective over the long term,” said Daniel L. Hurley, MD. By contrast, “Bariatric surgery is very effective long-term,” he said.

At the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Dr. Hurley made the case for bariatric surgery in effective and durable management of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk, weighing risks and benefits for those with higher and lower levels of obesity.

Speaking during a morning session focused on bariatric surgery, Dr. Hurley, an endocrionologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that bariatric surgery reduces not just weight, but also visceral adiposity. This, he said, is important when thinking about type 2 diabetes (T2D), because diabetes prevalence has climbed in the United States as obesity has also increased, according to examination of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Additionally, increased abdominal adiposity is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular-related deaths, myocardial infarctions, and all-cause deaths. Some of this relationship is mediated by T2D, which itself “is a major cause of cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Hurley.

From a population health perspective, the increased prevalence of T2D – expected to reach 10% in the United States by 2030 – will also boost cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, said Dr. Hurley. Those with T2D die 5 to 10 years earlier, and have double the risk for heart attack and stroke of their peers without diabetes. The risk of lower limb amputation can be as much as 40 times greater for an individual with T2D across the lifespan, he said.

The National Institutes of Health recognizes bariatric surgery as an appropriate weight loss therapy for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 35 kg/m2 and comorbidity. Whether bariatric surgery might be appropriate for individuals with T2D and BMIs of less than 35 kg/m2 is less settled, though at least some RCTs support the surgical approach, said Dr. Hurley.

The body of data that support long-term metabolic and cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery as obesity therapy is growing, said Dr. Hurley. A large prospective observational study by the American College of Surgeons’ Bariatric Surgery Center Network followed 28,616 patients, finding that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was most effective in improving or resolving CVD comorbidities. At 1 year post surgery, 83% of RYGB patients saw improvement or resolution of T2D; the figure was 79% for hypertension and 66% for dyslipidemia (Ann Surg. 2011;254[3]:410-20).

Weight loss for patients receiving bariatric procedures has generally been durable: for laparoscopic RYGB patients tracked to 7 years after surgery, 75% had maintained at least a 20% weight loss (JAMA Surg. 2018;153[5]427-34).

Longer-term clinical follow-up points toward favorable metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes, said Dr. Hurley, citing data from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial. This study followed over 4,000 patients with high BMIs (at least 34 kg/m2 for men and 38 kg/m2 for women) over 10 years. At that point, 36% of gastric bypass patients, compared with 13% of non-surgical high BMI patients, saw resolution of T2D, a significant difference. Triglyceride levels also fell significantly more for the bypass recipients. Hypertension was resolved in just 19% of patients at 10 years, a non-significant difference from the 11% of control patients. Data from the same patient set also showed a significant reduction in total cardiovascular events in the surgical versus non-surgical patients (n = 49 vs. 28, hazard ratio 0.83, log-rank P = .05). Fatal cardiovascular events were significantly lower for patients who had received bariatric surgery, with a 24% decline in mortality for bariatric surgery patients at about 11 years post surgery.

Canadian data showed even greater reductions in mortality, with an 89% decrease in mortality after RYGB, compared with non-surgical patients at the 5-year mark (Ann Surg 2004;240:416-24).

In trials that afforded a direct comparison of medical therapy and bariatric surgery obesity and diabetes, Dr. Hurley said that randomized trials generally show no change to modest change in HbA1c levels with medical management. By contrast, patients in the surgical arms showed a range of improvement ranging from a reduction of just under 1% to reductions of over 5%, with an average reduction of more than 2% across the trials.

Separating out data from the randomized controlled trials with patient BMIs averaging 35 kg/m2 or less, odds ratios still favored bariatric surgery over medication therapy for diabetes-related outcomes in this lower-BMI population, said Dr. Hurley (Diabetes Care 2016;39:924-33).

More data come from a recently reported randomized trial that assigned patients with T2D and a mean BMI of 37 kg/m2 (range, 27-43) to intensive medical therapy, or either sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or RYGB. The study, which had a 90% completion rate at the 5-year mark, found that both surgical procedures were significantly more effective at reducing HbA1c to 6% or less 12 months into the study (P less than .001).

At the 60-month mark, 45% of the RYGB and 25% of the SG patients were on no diabetes medications, while just 2% of the medical therapy arm had stopped all medications, and 40% of this group remained on insulin 5 years into the study, said Dr. Hurley (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651).

“For treatment of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular co-morbidities, long-term goals often are met following bariatric surgery versus behavior change,” said Dr. Hurley.

Dr. Hurley reported that he had no financial disclosures.

koakes@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Hurley, D. AACE 2018, Session SGS-4.

BOSTON – For patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes ( health over the lifespan.

“Behavioral changes in diet and activity may be effective over the short term, but they are often ineffective over the long term,” said Daniel L. Hurley, MD. By contrast, “Bariatric surgery is very effective long-term,” he said.

At the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Dr. Hurley made the case for bariatric surgery in effective and durable management of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk, weighing risks and benefits for those with higher and lower levels of obesity.

Speaking during a morning session focused on bariatric surgery, Dr. Hurley, an endocrionologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that bariatric surgery reduces not just weight, but also visceral adiposity. This, he said, is important when thinking about type 2 diabetes (T2D), because diabetes prevalence has climbed in the United States as obesity has also increased, according to examination of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Additionally, increased abdominal adiposity is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular-related deaths, myocardial infarctions, and all-cause deaths. Some of this relationship is mediated by T2D, which itself “is a major cause of cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Hurley.

From a population health perspective, the increased prevalence of T2D – expected to reach 10% in the United States by 2030 – will also boost cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, said Dr. Hurley. Those with T2D die 5 to 10 years earlier, and have double the risk for heart attack and stroke of their peers without diabetes. The risk of lower limb amputation can be as much as 40 times greater for an individual with T2D across the lifespan, he said.

The National Institutes of Health recognizes bariatric surgery as an appropriate weight loss therapy for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 35 kg/m2 and comorbidity. Whether bariatric surgery might be appropriate for individuals with T2D and BMIs of less than 35 kg/m2 is less settled, though at least some RCTs support the surgical approach, said Dr. Hurley.

The body of data that support long-term metabolic and cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery as obesity therapy is growing, said Dr. Hurley. A large prospective observational study by the American College of Surgeons’ Bariatric Surgery Center Network followed 28,616 patients, finding that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was most effective in improving or resolving CVD comorbidities. At 1 year post surgery, 83% of RYGB patients saw improvement or resolution of T2D; the figure was 79% for hypertension and 66% for dyslipidemia (Ann Surg. 2011;254[3]:410-20).

Weight loss for patients receiving bariatric procedures has generally been durable: for laparoscopic RYGB patients tracked to 7 years after surgery, 75% had maintained at least a 20% weight loss (JAMA Surg. 2018;153[5]427-34).

Longer-term clinical follow-up points toward favorable metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes, said Dr. Hurley, citing data from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial. This study followed over 4,000 patients with high BMIs (at least 34 kg/m2 for men and 38 kg/m2 for women) over 10 years. At that point, 36% of gastric bypass patients, compared with 13% of non-surgical high BMI patients, saw resolution of T2D, a significant difference. Triglyceride levels also fell significantly more for the bypass recipients. Hypertension was resolved in just 19% of patients at 10 years, a non-significant difference from the 11% of control patients. Data from the same patient set also showed a significant reduction in total cardiovascular events in the surgical versus non-surgical patients (n = 49 vs. 28, hazard ratio 0.83, log-rank P = .05). Fatal cardiovascular events were significantly lower for patients who had received bariatric surgery, with a 24% decline in mortality for bariatric surgery patients at about 11 years post surgery.

Canadian data showed even greater reductions in mortality, with an 89% decrease in mortality after RYGB, compared with non-surgical patients at the 5-year mark (Ann Surg 2004;240:416-24).

In trials that afforded a direct comparison of medical therapy and bariatric surgery obesity and diabetes, Dr. Hurley said that randomized trials generally show no change to modest change in HbA1c levels with medical management. By contrast, patients in the surgical arms showed a range of improvement ranging from a reduction of just under 1% to reductions of over 5%, with an average reduction of more than 2% across the trials.

Separating out data from the randomized controlled trials with patient BMIs averaging 35 kg/m2 or less, odds ratios still favored bariatric surgery over medication therapy for diabetes-related outcomes in this lower-BMI population, said Dr. Hurley (Diabetes Care 2016;39:924-33).

More data come from a recently reported randomized trial that assigned patients with T2D and a mean BMI of 37 kg/m2 (range, 27-43) to intensive medical therapy, or either sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or RYGB. The study, which had a 90% completion rate at the 5-year mark, found that both surgical procedures were significantly more effective at reducing HbA1c to 6% or less 12 months into the study (P less than .001).

At the 60-month mark, 45% of the RYGB and 25% of the SG patients were on no diabetes medications, while just 2% of the medical therapy arm had stopped all medications, and 40% of this group remained on insulin 5 years into the study, said Dr. Hurley (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651).

“For treatment of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular co-morbidities, long-term goals often are met following bariatric surgery versus behavior change,” said Dr. Hurley.

Dr. Hurley reported that he had no financial disclosures.

koakes@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Hurley, D. AACE 2018, Session SGS-4.

BOSTON – For patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes ( health over the lifespan.

“Behavioral changes in diet and activity may be effective over the short term, but they are often ineffective over the long term,” said Daniel L. Hurley, MD. By contrast, “Bariatric surgery is very effective long-term,” he said.

At the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Dr. Hurley made the case for bariatric surgery in effective and durable management of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk, weighing risks and benefits for those with higher and lower levels of obesity.

Speaking during a morning session focused on bariatric surgery, Dr. Hurley, an endocrionologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., noted that bariatric surgery reduces not just weight, but also visceral adiposity. This, he said, is important when thinking about type 2 diabetes (T2D), because diabetes prevalence has climbed in the United States as obesity has also increased, according to examination of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Additionally, increased abdominal adiposity is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular-related deaths, myocardial infarctions, and all-cause deaths. Some of this relationship is mediated by T2D, which itself “is a major cause of cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Hurley.

From a population health perspective, the increased prevalence of T2D – expected to reach 10% in the United States by 2030 – will also boost cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, said Dr. Hurley. Those with T2D die 5 to 10 years earlier, and have double the risk for heart attack and stroke of their peers without diabetes. The risk of lower limb amputation can be as much as 40 times greater for an individual with T2D across the lifespan, he said.

The National Institutes of Health recognizes bariatric surgery as an appropriate weight loss therapy for individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 35 kg/m2 and comorbidity. Whether bariatric surgery might be appropriate for individuals with T2D and BMIs of less than 35 kg/m2 is less settled, though at least some RCTs support the surgical approach, said Dr. Hurley.

The body of data that support long-term metabolic and cardiovascular benefits of bariatric surgery as obesity therapy is growing, said Dr. Hurley. A large prospective observational study by the American College of Surgeons’ Bariatric Surgery Center Network followed 28,616 patients, finding that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) was most effective in improving or resolving CVD comorbidities. At 1 year post surgery, 83% of RYGB patients saw improvement or resolution of T2D; the figure was 79% for hypertension and 66% for dyslipidemia (Ann Surg. 2011;254[3]:410-20).

Weight loss for patients receiving bariatric procedures has generally been durable: for laparoscopic RYGB patients tracked to 7 years after surgery, 75% had maintained at least a 20% weight loss (JAMA Surg. 2018;153[5]427-34).

Longer-term clinical follow-up points toward favorable metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes, said Dr. Hurley, citing data from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial. This study followed over 4,000 patients with high BMIs (at least 34 kg/m2 for men and 38 kg/m2 for women) over 10 years. At that point, 36% of gastric bypass patients, compared with 13% of non-surgical high BMI patients, saw resolution of T2D, a significant difference. Triglyceride levels also fell significantly more for the bypass recipients. Hypertension was resolved in just 19% of patients at 10 years, a non-significant difference from the 11% of control patients. Data from the same patient set also showed a significant reduction in total cardiovascular events in the surgical versus non-surgical patients (n = 49 vs. 28, hazard ratio 0.83, log-rank P = .05). Fatal cardiovascular events were significantly lower for patients who had received bariatric surgery, with a 24% decline in mortality for bariatric surgery patients at about 11 years post surgery.

Canadian data showed even greater reductions in mortality, with an 89% decrease in mortality after RYGB, compared with non-surgical patients at the 5-year mark (Ann Surg 2004;240:416-24).

In trials that afforded a direct comparison of medical therapy and bariatric surgery obesity and diabetes, Dr. Hurley said that randomized trials generally show no change to modest change in HbA1c levels with medical management. By contrast, patients in the surgical arms showed a range of improvement ranging from a reduction of just under 1% to reductions of over 5%, with an average reduction of more than 2% across the trials.

Separating out data from the randomized controlled trials with patient BMIs averaging 35 kg/m2 or less, odds ratios still favored bariatric surgery over medication therapy for diabetes-related outcomes in this lower-BMI population, said Dr. Hurley (Diabetes Care 2016;39:924-33).

More data come from a recently reported randomized trial that assigned patients with T2D and a mean BMI of 37 kg/m2 (range, 27-43) to intensive medical therapy, or either sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or RYGB. The study, which had a 90% completion rate at the 5-year mark, found that both surgical procedures were significantly more effective at reducing HbA1c to 6% or less 12 months into the study (P less than .001).

At the 60-month mark, 45% of the RYGB and 25% of the SG patients were on no diabetes medications, while just 2% of the medical therapy arm had stopped all medications, and 40% of this group remained on insulin 5 years into the study, said Dr. Hurley (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651).

“For treatment of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular co-morbidities, long-term goals often are met following bariatric surgery versus behavior change,” said Dr. Hurley.

Dr. Hurley reported that he had no financial disclosures.

koakes@mdedge.com

SOURCE: Hurley, D. AACE 2018, Session SGS-4.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AACE 2018

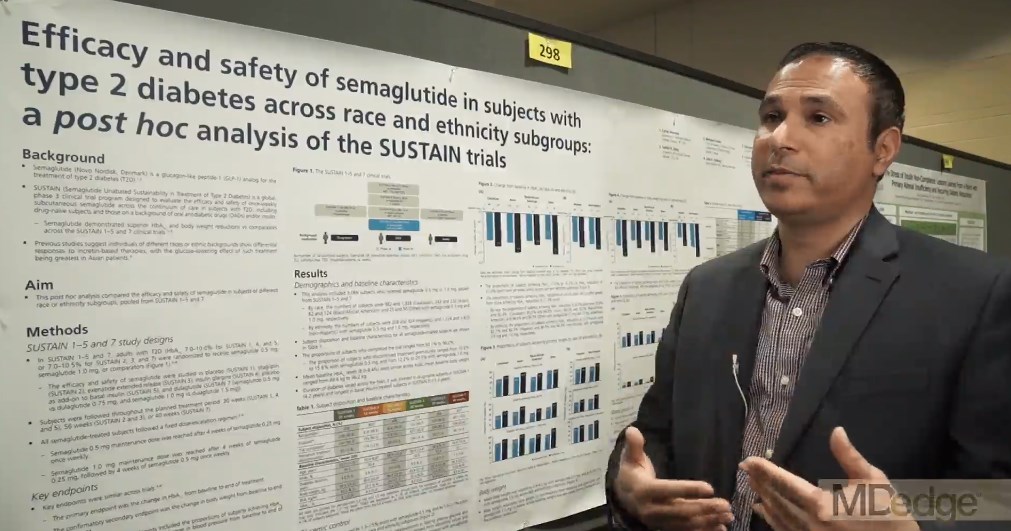

Semaglutide drops HbA1c, weight, across ethnicities

BOSTON – studied in a series of clinical trials; the efficacy did not come at the cost of frequent hypoglycemia or other serious adverse events, according to a pooled subgroup analysis of the SUSTAIN trials.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The trials investigated the safety and efficacy of semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, in the treatment of T2DM. Cyrus V. Desouza, MBBS, presented results of a post hoc analysis of racial and ethnic subgroups, drawing on SUSTAIN trials 1-5 and 7 (SUSTAIN 6 had a different design, focusing on cardiovascular outcomes).

“The trials incorporated patients on the whole spectrum of diabetes, starting from people who are newly diagnosed ... all the way to patients who were on a combination of oral antidiabetic drugs plus insulin,” Dr. Desouza explained in an interview at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The mean time since diagnosis in the SUSTAIN trials varied from 4.2 years in SUSTAIN 1 to 13.3 years in SUSTAIN 5. Dr. Desouza and his colleagues pooled data from the six trials to conduct the subgroup analyses.

Patients in the intervention arms of all trials received once weekly subcutaneous semaglutide, at a dose of either 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg, according to Dr. Desouza, professor of diabetes, endocrinology, and metabolism and Schultz Professor of Diabetes Research, Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolism at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

In all, data from 3,066 patients were available. In the racial analysis, 982 low- and 1,328 high-dose semaglutide recipients were white, 243 and 232 were Asian, 82 and 124 were African American, and 25 and 50 identified as “other,” respectively.

An analysis by ethnicity found that 208 low- and 324 high-dose recipients were Hispanic.

At baseline in all trials, mean hemoglobin A1c levels were similar, ranging from 8% to 8.4%; weights at baseline were a mean 89.6 kg to 96.2 kg across the trials.

The range of reductions in HbA1c was similar across racial and ethnic groups. “If you look at the proportion of patients who actually achieved an A1c below 7[%], it’s pretty impressive – it’s between 70% to 80%.” Between 50% and 60% of patients reached an HbA1c less than 6.5%, said Dr. Desouza.

Looking at the data another way, 62.2%-72.4% of patients saw an HbA1c reduction of at least 1% on low-dose semaglutide; the range across ethnicities was 74.2%-87.1% on high-dose semaglutide. Dr. Desouza said that the sample sizes weren’t large enough to calculate statistical significance for these subgroup differences.

“But I think what is impressive is that over 50% of patients in all the races and ethnicities were able to achieve a 5% body weight loss, which is metabolically significant in terms of improving outcomes,” he said. “I think that’s a really important fact.” A smaller proportion – around 20% – lost at least 10% of body weight, mostly on high-dose semaglutide.

Severe hypoglycemia, as defined by American Diabetes Association classification, was very rare across trials, except that 4.7% of African Americans saw this adverse event on high-dose semaglutide. Incidence in other subgroups, at either dose, ranged from 0% to 2.4%.

Otherwise, the medication was generally well tolerated, though gastrointestinal side effects were seen. “Asian people have a little higher GI side effects – up to 50% of Asians did develop GI side effects, and between 10% and 13% of Asians had to stop medication due to side effects,” said Dr. Desouza. “So I think that would be the one caveat in terms of tolerance that we did learn.”

The SUSTAIN trials were sponsored by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Desouza has received consulting fees for Novo Nordisk and has received grant support from several other pharmaceutical companies. Two coauthors are Novo Nordisk employees.

SOURCE: Desouza C et al. AACE 2018, Abstract 298

BOSTON – studied in a series of clinical trials; the efficacy did not come at the cost of frequent hypoglycemia or other serious adverse events, according to a pooled subgroup analysis of the SUSTAIN trials.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The trials investigated the safety and efficacy of semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, in the treatment of T2DM. Cyrus V. Desouza, MBBS, presented results of a post hoc analysis of racial and ethnic subgroups, drawing on SUSTAIN trials 1-5 and 7 (SUSTAIN 6 had a different design, focusing on cardiovascular outcomes).

“The trials incorporated patients on the whole spectrum of diabetes, starting from people who are newly diagnosed ... all the way to patients who were on a combination of oral antidiabetic drugs plus insulin,” Dr. Desouza explained in an interview at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The mean time since diagnosis in the SUSTAIN trials varied from 4.2 years in SUSTAIN 1 to 13.3 years in SUSTAIN 5. Dr. Desouza and his colleagues pooled data from the six trials to conduct the subgroup analyses.

Patients in the intervention arms of all trials received once weekly subcutaneous semaglutide, at a dose of either 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg, according to Dr. Desouza, professor of diabetes, endocrinology, and metabolism and Schultz Professor of Diabetes Research, Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolism at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

In all, data from 3,066 patients were available. In the racial analysis, 982 low- and 1,328 high-dose semaglutide recipients were white, 243 and 232 were Asian, 82 and 124 were African American, and 25 and 50 identified as “other,” respectively.

An analysis by ethnicity found that 208 low- and 324 high-dose recipients were Hispanic.

At baseline in all trials, mean hemoglobin A1c levels were similar, ranging from 8% to 8.4%; weights at baseline were a mean 89.6 kg to 96.2 kg across the trials.

The range of reductions in HbA1c was similar across racial and ethnic groups. “If you look at the proportion of patients who actually achieved an A1c below 7[%], it’s pretty impressive – it’s between 70% to 80%.” Between 50% and 60% of patients reached an HbA1c less than 6.5%, said Dr. Desouza.

Looking at the data another way, 62.2%-72.4% of patients saw an HbA1c reduction of at least 1% on low-dose semaglutide; the range across ethnicities was 74.2%-87.1% on high-dose semaglutide. Dr. Desouza said that the sample sizes weren’t large enough to calculate statistical significance for these subgroup differences.

“But I think what is impressive is that over 50% of patients in all the races and ethnicities were able to achieve a 5% body weight loss, which is metabolically significant in terms of improving outcomes,” he said. “I think that’s a really important fact.” A smaller proportion – around 20% – lost at least 10% of body weight, mostly on high-dose semaglutide.

Severe hypoglycemia, as defined by American Diabetes Association classification, was very rare across trials, except that 4.7% of African Americans saw this adverse event on high-dose semaglutide. Incidence in other subgroups, at either dose, ranged from 0% to 2.4%.

Otherwise, the medication was generally well tolerated, though gastrointestinal side effects were seen. “Asian people have a little higher GI side effects – up to 50% of Asians did develop GI side effects, and between 10% and 13% of Asians had to stop medication due to side effects,” said Dr. Desouza. “So I think that would be the one caveat in terms of tolerance that we did learn.”

The SUSTAIN trials were sponsored by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Desouza has received consulting fees for Novo Nordisk and has received grant support from several other pharmaceutical companies. Two coauthors are Novo Nordisk employees.

SOURCE: Desouza C et al. AACE 2018, Abstract 298

BOSTON – studied in a series of clinical trials; the efficacy did not come at the cost of frequent hypoglycemia or other serious adverse events, according to a pooled subgroup analysis of the SUSTAIN trials.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The trials investigated the safety and efficacy of semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, in the treatment of T2DM. Cyrus V. Desouza, MBBS, presented results of a post hoc analysis of racial and ethnic subgroups, drawing on SUSTAIN trials 1-5 and 7 (SUSTAIN 6 had a different design, focusing on cardiovascular outcomes).

“The trials incorporated patients on the whole spectrum of diabetes, starting from people who are newly diagnosed ... all the way to patients who were on a combination of oral antidiabetic drugs plus insulin,” Dr. Desouza explained in an interview at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

The mean time since diagnosis in the SUSTAIN trials varied from 4.2 years in SUSTAIN 1 to 13.3 years in SUSTAIN 5. Dr. Desouza and his colleagues pooled data from the six trials to conduct the subgroup analyses.

Patients in the intervention arms of all trials received once weekly subcutaneous semaglutide, at a dose of either 0.5 mg or 1.0 mg, according to Dr. Desouza, professor of diabetes, endocrinology, and metabolism and Schultz Professor of Diabetes Research, Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolism at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

In all, data from 3,066 patients were available. In the racial analysis, 982 low- and 1,328 high-dose semaglutide recipients were white, 243 and 232 were Asian, 82 and 124 were African American, and 25 and 50 identified as “other,” respectively.

An analysis by ethnicity found that 208 low- and 324 high-dose recipients were Hispanic.

At baseline in all trials, mean hemoglobin A1c levels were similar, ranging from 8% to 8.4%; weights at baseline were a mean 89.6 kg to 96.2 kg across the trials.

The range of reductions in HbA1c was similar across racial and ethnic groups. “If you look at the proportion of patients who actually achieved an A1c below 7[%], it’s pretty impressive – it’s between 70% to 80%.” Between 50% and 60% of patients reached an HbA1c less than 6.5%, said Dr. Desouza.

Looking at the data another way, 62.2%-72.4% of patients saw an HbA1c reduction of at least 1% on low-dose semaglutide; the range across ethnicities was 74.2%-87.1% on high-dose semaglutide. Dr. Desouza said that the sample sizes weren’t large enough to calculate statistical significance for these subgroup differences.

“But I think what is impressive is that over 50% of patients in all the races and ethnicities were able to achieve a 5% body weight loss, which is metabolically significant in terms of improving outcomes,” he said. “I think that’s a really important fact.” A smaller proportion – around 20% – lost at least 10% of body weight, mostly on high-dose semaglutide.

Severe hypoglycemia, as defined by American Diabetes Association classification, was very rare across trials, except that 4.7% of African Americans saw this adverse event on high-dose semaglutide. Incidence in other subgroups, at either dose, ranged from 0% to 2.4%.

Otherwise, the medication was generally well tolerated, though gastrointestinal side effects were seen. “Asian people have a little higher GI side effects – up to 50% of Asians did develop GI side effects, and between 10% and 13% of Asians had to stop medication due to side effects,” said Dr. Desouza. “So I think that would be the one caveat in terms of tolerance that we did learn.”

The SUSTAIN trials were sponsored by Novo Nordisk. Dr. Desouza has received consulting fees for Novo Nordisk and has received grant support from several other pharmaceutical companies. Two coauthors are Novo Nordisk employees.

SOURCE: Desouza C et al. AACE 2018, Abstract 298

REPORTING FROM AACE 2018

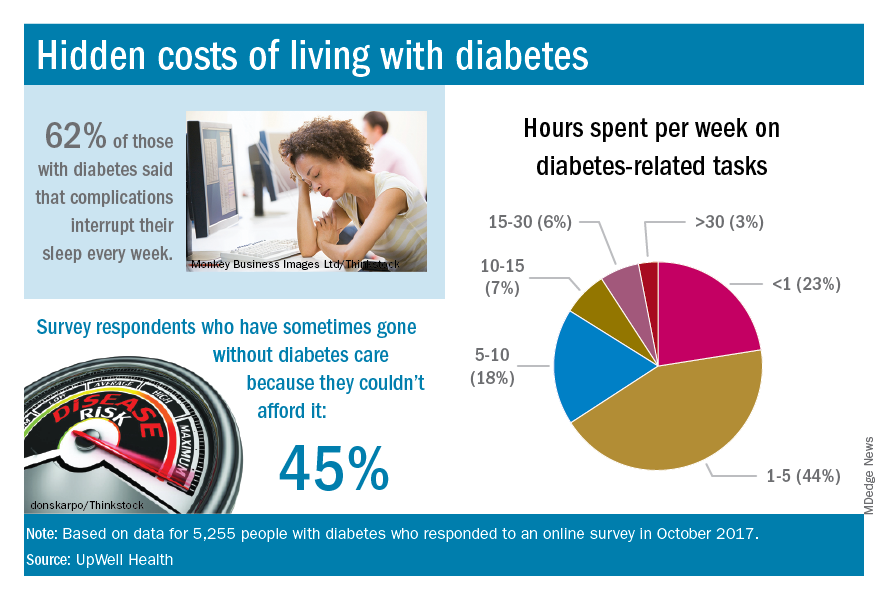

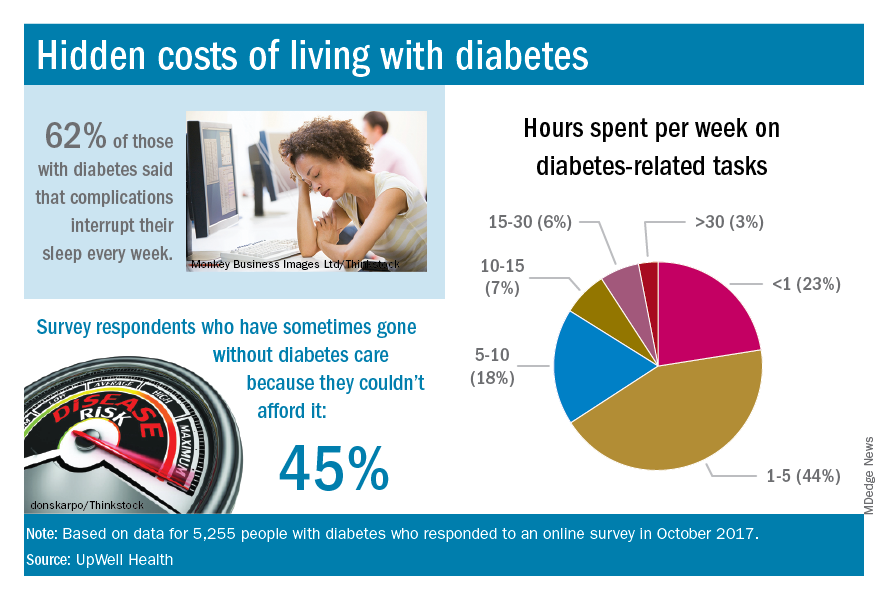

Diabetes places burden on patients

according to a new survey by prescription manager UpWell Health.

The time spent on activities that come with diabetes management – blood glucose monitoring, diet planning, medical appointments – can add up to several hours a week. Among the 5,255 respondents to the online survey, 18% said that such tasks took up 5-10 hours each week, 7% said it was 10-15 hours, and 9% said they spent 15 or more hours a week on diabetes-related tasks, UpWell reported.

Since medical expenses aren’t always fully covered by insurance, 43% of respondents paid up to $1,000 a year out of pocket to treat diabetes complications, 16% paid $1,000 to $2,000 a year, and 4% paid more than $5,000. Five percent also paid over $5,000 a year out of pocket for diabetes care from a physician and 45% said that they had sometimes gone without diabetes care because they couldn’t afford it, the survey data showed.

“Most people with diabetes are able to manage it successfully and live active, satisfying lives. But doing so requires constant planning, vigilance, and care. They eagerly seek trustworthy resources to help them reduce the burden of living with diabetes,” UpWell said.

according to a new survey by prescription manager UpWell Health.

The time spent on activities that come with diabetes management – blood glucose monitoring, diet planning, medical appointments – can add up to several hours a week. Among the 5,255 respondents to the online survey, 18% said that such tasks took up 5-10 hours each week, 7% said it was 10-15 hours, and 9% said they spent 15 or more hours a week on diabetes-related tasks, UpWell reported.

Since medical expenses aren’t always fully covered by insurance, 43% of respondents paid up to $1,000 a year out of pocket to treat diabetes complications, 16% paid $1,000 to $2,000 a year, and 4% paid more than $5,000. Five percent also paid over $5,000 a year out of pocket for diabetes care from a physician and 45% said that they had sometimes gone without diabetes care because they couldn’t afford it, the survey data showed.

“Most people with diabetes are able to manage it successfully and live active, satisfying lives. But doing so requires constant planning, vigilance, and care. They eagerly seek trustworthy resources to help them reduce the burden of living with diabetes,” UpWell said.

according to a new survey by prescription manager UpWell Health.

The time spent on activities that come with diabetes management – blood glucose monitoring, diet planning, medical appointments – can add up to several hours a week. Among the 5,255 respondents to the online survey, 18% said that such tasks took up 5-10 hours each week, 7% said it was 10-15 hours, and 9% said they spent 15 or more hours a week on diabetes-related tasks, UpWell reported.

Since medical expenses aren’t always fully covered by insurance, 43% of respondents paid up to $1,000 a year out of pocket to treat diabetes complications, 16% paid $1,000 to $2,000 a year, and 4% paid more than $5,000. Five percent also paid over $5,000 a year out of pocket for diabetes care from a physician and 45% said that they had sometimes gone without diabetes care because they couldn’t afford it, the survey data showed.

“Most people with diabetes are able to manage it successfully and live active, satisfying lives. But doing so requires constant planning, vigilance, and care. They eagerly seek trustworthy resources to help them reduce the burden of living with diabetes,” UpWell said.

Patient adjustments needed for closed-loop insulin delivery

TORONTO – Closed-loop insulin delivery is expected to become the standard of care in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), but there are multiple barriers that patients need to overcome.

“Many people who are potentially going to be using closed-loop systems are enthusiastic but have unrealistic expectations of how the systems are going to perform, and there are many barriers to uptake and optimal use that we still haven’t quite figured out,” said Korey K. Hood, PhD, a professor in the departments of pediatrics and psychiatry & behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University.

In a session dedicated to all aspects of closed-loop automated insulin delivery at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, Dr. Hood offered comments on patient and family factors important to the uptake and use of closed-loop technologies. His research at Stanford is focused on understanding the psychosocial aspects of diabetes management and how these factors contribute to disease outcomes.

Closed-loop insulin delivery refers to technologies that combine automated glucose monitoring (AGM) with an algorithm to determine insulin needs and an insulin delivery device. Sometimes called an “artificial pancreas” or “bionic pancreas,” closed-loop insulin delivery is considered a significant advance in the management of T1DM, relegating daily finger sticks and nighttime hypoglycemia to things of the past.

In a recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, use of any automated device added nearly 2.5 hours of time in near normoglycemia over 24 hours in patients with TIDM, compared with any other type of insulin-based treatment (BMJ. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1310). The benefit was primarily based on better glucose control in the overnight period.

In September 2016, the Food and Drug Administration approved the MiniMed 670G Insulin Pump System (Medtronic), the first hybrid automated insulin delivery device for T1DM and the only one approved in the United States. The system is intended for subcutaneous continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and continuous delivery of basal insulin and administration of insulin for the management of T1DM in persons 14 years of age and older.

Barriers from different perspectives

Barriers to uptake and use are common for the devices that are components of closed-loop systems. In a survey of 1,503 adults with TIDM, Dr. Hood’s group found a wide range of barriers to adoption of CGM or insulin pumps that could potentially also impact use of closed-loop systems (Diabetes Care. 2017;40:181-7). Some were nonmodifiable, like costs, but most were modifiable.

“Many people talk about the hassle of wearing devices. They don’t like having multiple devices on their bodies. They don’t always like the way that they look, and so these are things that we can have some kind of impact on and need to be paying attention to,” he said.

“The younger participants indicated a lot more barriers to using devices, and as they got older, they indicated fewer barriers. But what was also interesting is that the younger participants also indicated a lot more diabetes distress. As time went on, that was less of a factor in whether or not people were using diabetes devices,” reported Dr. Hood.

Not surprisingly, he added, was that younger participants had more favorable views of technology in general. “But they had less favorable views of diabetes technology [than older participants], so they’re really not crazy about using these devices.”

Dr. Hood’s group has also studied whether patient-reported barriers to CGM use align with what clinicians perceive to be patient-related barriers (Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11[3]484-92). Similar to the patients, clinicians most frequently endorsed the perception that patients dislike having the device on their body. However, other things they felt their patients worried about were the alarms on the device and the difficulty in understanding its features, neither of which patients considered a primary barrier to CGM or insulin pump adoption.

“So, we need to be cautious and mindful as we move forward that there are mismatches between the patient-reported and clinician-reported barriers,” said Dr. Hood. “Our response, often, is to teach and to provide some kind of education, when that’s not necessarily what the patient is asking for.”

Would you use it?

In 2017, a group of investigators conducted a qualitative study of 284 participants, ranging in age from 8 to 86 years, with T1DM. The researchers used structured interviews or focus groups to explore expectations, desired features, potential benefits, and perceived burdens of automated insulin delivery systems (Diabetes Care. 2017;40[11]:1453-61).

“We were interested in children, adolescents, and adults with type 1, and then also the partners of the adults and the parents of the youth,” he explained.

“The findings revealed three themes identified as pressing for the uptake of automated insulin delivery: considerations of trust and control, system features, and concerns and barriers to adoption.

“For children, the areas of most concern revolved around specific social situations. Adolescents, on the other hand, were more concerned about the physical features of the device, the wearability, the discreetness of using it, and the comfort,” said Dr. Hood.

Adults and parents were much more interested in device accuracy, safety, adaptability, and algorithm quality. “For the kids and teens, not surprisingly, this wasn’t high on their list,” he added.

A clear indication of the unrealistic expectations surrounding this technology came from a 2018 study of almost 200 family members, which found that “reducing the constant concerns about diabetes, relieving family stress, and improving overall family relationships” were the three major areas the participants hoped would be helped with automated insulin delivery (Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20[3]:222-8).

“If we come up with a device that does this, then I think we will have fixed everything!” Dr. Hood said, adding that it really highlights the “very high hopes and expectations” of what closed-loop systems should deliver.

Device readiness is another area researchers have studied in the run-up to closed-loop systems. “The idea that everybody’s going to be ready to start in the same way, I think, is going to set us up for some failures,” he noted, adding that, in general, parents are much more enthusiastic about this than pediatric patients.

“Individuals who had been using diabetes devices – and some had already been in closed-loop studies – They had more realistic expectations of what these systems are going to be, because they knew that it wasn’t going to be a complete fix. Whereas others with more limited experience with component devices and these systems had much higher expectations and reported a fair amount of dissatisfaction at the end of the study because it didn’t do everything that they wanted it to do.”

Waves of uptake

“Ultimately, a closed-loop system is going to be judged by whether it can increase time on target and reduce cognitive burden,” said Dr. Hood. He finished his talk with some projections about the future of closed-loop systems. “I think we’re going to probably to have different waves, or types, of closed-loop users.”

The first wave will be the group that’s already “sold” on the idea, which might encompass about 15% of patients. The second wave, which might represent about 30% of the relevant patient population, will be those who are sold on the idea and will likely use it but will have high expectations of the system’s ease of use and effectiveness and thus are highly likely to discontinue its use if those expectations are not met.

“The third wave will be those who might use a closed-loop system but might be unaware of them currently and will need a fair amount of education.” And, finally, the fourth group are unlikely to ever use closed-loop insulin delivery. “They are a group that feels burned by previous generations of systems, and I think that they may not perceive benefit,” Dr. Hood suggested.

“But all of this is to say that I do think that a tailored experience, and one that is focused on different profiles, can optimize both the uptake and the use of these systems.”

Dr. Hood reported receiving grant/research support from Dexcom and being a consultant for Lilly Innovation Center, J&J Diabetes Institute, and Bigfoot Biomedical.

TORONTO – Closed-loop insulin delivery is expected to become the standard of care in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), but there are multiple barriers that patients need to overcome.