User login

Confusion and hypercalcemia in an 80-year-old man

A retired 80-year-old man presented to the emergency department after 10 days of increasing polydipsia, polyuria, dry mouth, confusion, and slurred speech. He also reported that he had gradually and unintentionally lost 20 pounds and had loss of appetite, constipation, and chronic itching. He denied fevers, chills, night sweats, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Medical history. He had type 2 diabetes mellitus that was well controlled by oral hypoglycemics, hypothyroidism treated with levothyroxine in stable doses, and chronic hepatitis C complicated by liver cirrhosis without focal hepatic lesions. He also had hypertension, well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide and losartan. For his long-standing pruritus he had tried prescription drugs including gabapentin and pregabalin without improvement. He had also seen a naturopathic practitioner, who had prescribed supplements that relieved the symptoms.

Examination. The patient was in no acute distress. He appeared thin, with a weight of 140 lb and a body mass index of 21 kg/m2. His temperature was 36.8°C (98.2°F), blood pressure 198/82 mm Hg, heart rate 72 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 97%. His skin was without jaundice or rashes. The mucous membranes in the oropharynx were dry.

Neurologic examination revealed mild confusion, dysarthria, and ataxic gait. Sensation to light touch, pinprick, and vibration was intact. Generalized weakness was noted. Cranial nerves II through XII were intact. Deep tendon reflexes were symmetrically globally suppressed. Asterixis was absent. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory values in the emergency department. We initially suspected he had symptomatic hyperglycemia, but a bedside blood glucose value of 113 mg/dL ruled this out. Other initial laboratory values:

- Blood urea nitrogen 31 mg/dL (reference range 9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.7 mg/dL (0.73–1.22; an earlier value had been 1.0 mg/dL)

- Total serum calcium 14.4 mg/dL (8.6–10.0)

Complete blood cell counts were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the head was negative for acute pathology.

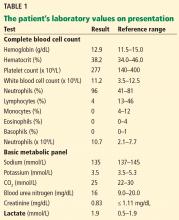

In view of the patient’s hypercalcemia, he was given aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation (2 L of normal saline over 2 hours) and was admitted to the hospital. His laboratory values on admission are shown in Table 1. Fluid resuscitation was continued while the laboratory results were pending.

CAUSES OF HYPERCALCEMIA

1. Based on this information, which is the most likely cause of this patient’s hypercalcemia?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypervitaminosis D

- Sarcoidosis

Traditionally, the workup for hypercalcemia in an outpatient starts with measuring the serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) level. Based on the results, a further evaluation of PTH-mediated vs PTH-independent causes of hypercalcemia would be initiated.

Primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy account for 90% of all cases of hypercalcemia. The serum PTH concentration is usually high in primary hyperparathyroidism but low in malignancy, which helps distinguish the conditions from each other.1

Primary hyperparathyroidism

In primary hyperparathyroidism, there is overproduction of PTH, most commonly from a parathyroid adenoma, though parathyroid hyperplasia or, more rarely, parathyroid carcinoma can also overproduce the hormone.

PTH increases serum calcium levels through 3 primary mechanisms: increasing bone resorption, increasing intestinal absorption of calcium, and decreasing renal excretion of calcium. It also induces renal phosphorus excretion.

Typically, in primary hyperparathyroidism, the increases in serum calcium are small (with serum levels of total calcium rising to no higher than 11 mg/dL) and often intermittent.2 Our patient had extremely high serum calcium, low PTH, and high phosphorus levels—all of which are inconsistent with primary hyperparathyroidism.

Malignancy

In some solid tumors, the major mechanism of hypercalcemia is secretion of PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) through promotion of osteoclast function and also increased renal absorption of calcium.3 Hematologic malignancies (eg, multiple myeloma) produce osteoclast-activating factors such as RANK ligand, lymphotoxin, and interleukin 6. Direct tumor invasion of bone can cause osteolysis and subsequent hypercalcemia.4 These mechanisms are usually associated with a fall in PTH.

Less commonly, tumors can also increase levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D or produce PTH independently of the parathyroid gland.5 There have also been reports of severe hypercalcemia from hepatocellular carcinoma due to PTHrP production.6

Our patient is certainly at risk for malignancy, given his long-standing history of hepatitis C and cirrhosis. He also had a mildly elevated alpha fetoprotein level and suppressed PTH. However, his PTHrP level was normal, and ultrasonography done recently to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma (recommended every 6 months by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases in high-risk patients) was negative.7

Multiple myeloma screening involves testing with serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation in combination with either a serum free light chain assay or 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation. This provides a 97% sensitivity.8 In this patient, these tests for multiple myeloma were negative.

Hyperthyroidism

As many as half of all patients with hyperthyroidism have elevated levels of ionized serum calcium.9 Increased osteoclastic activity is the likely mechanism. Hyperthyroid patients have increased levels of serum interleukin 6 and increased sensitivity of bone to this factor. This cytokine induces differentiation of monocytic cells into osteoclast precursors.10 These patients also have normal or low PTH levels.9

Our patient was receiving levothyroxine for hypothyroidism, but there was no evidence that the dosage was too high, as his thyroid-stimulating hormone level was within an acceptable range.

Hypervitaminosis D

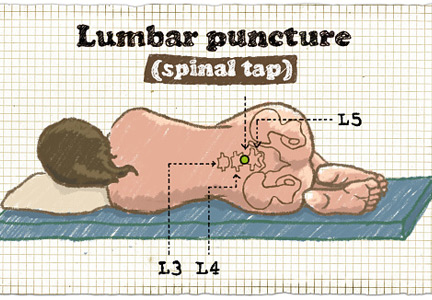

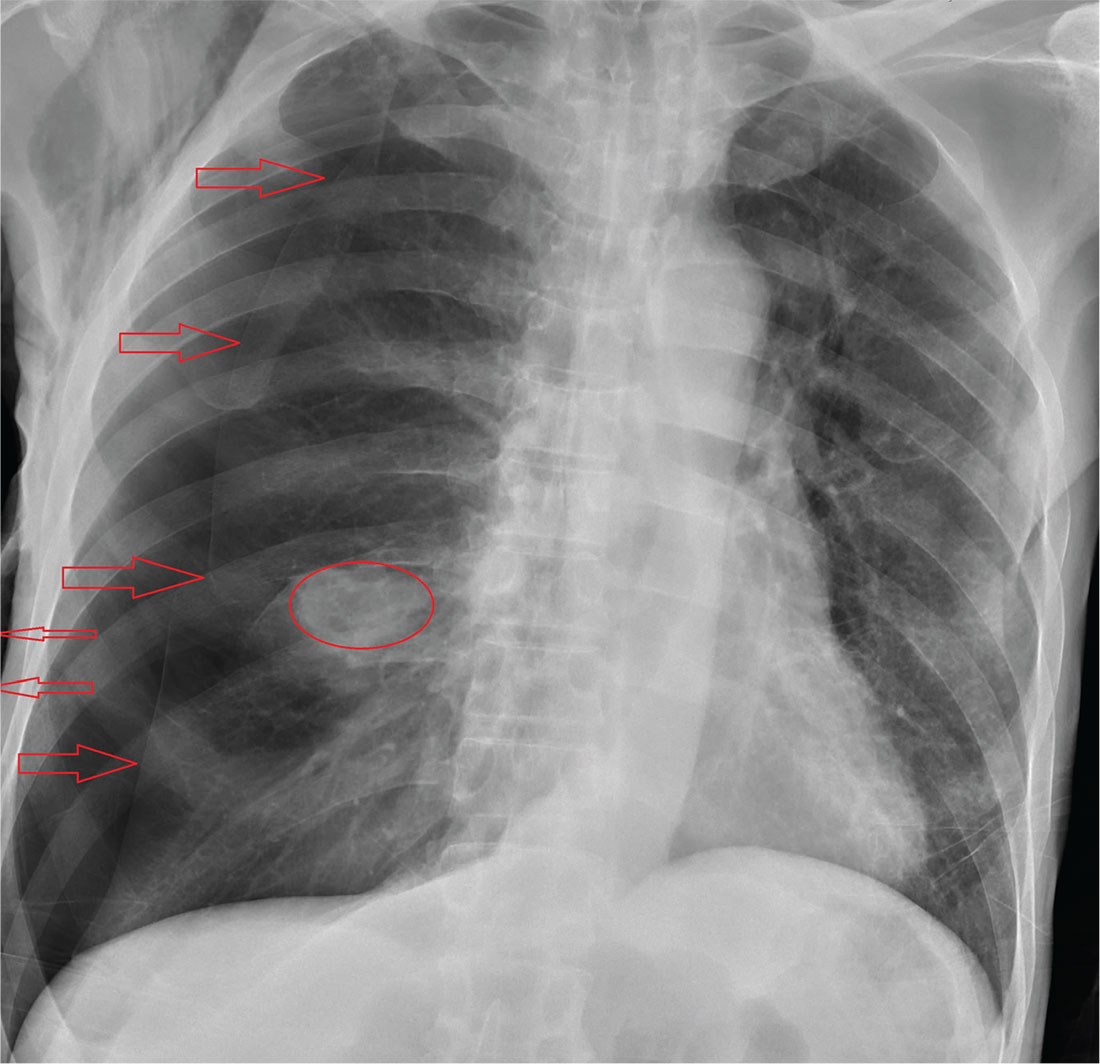

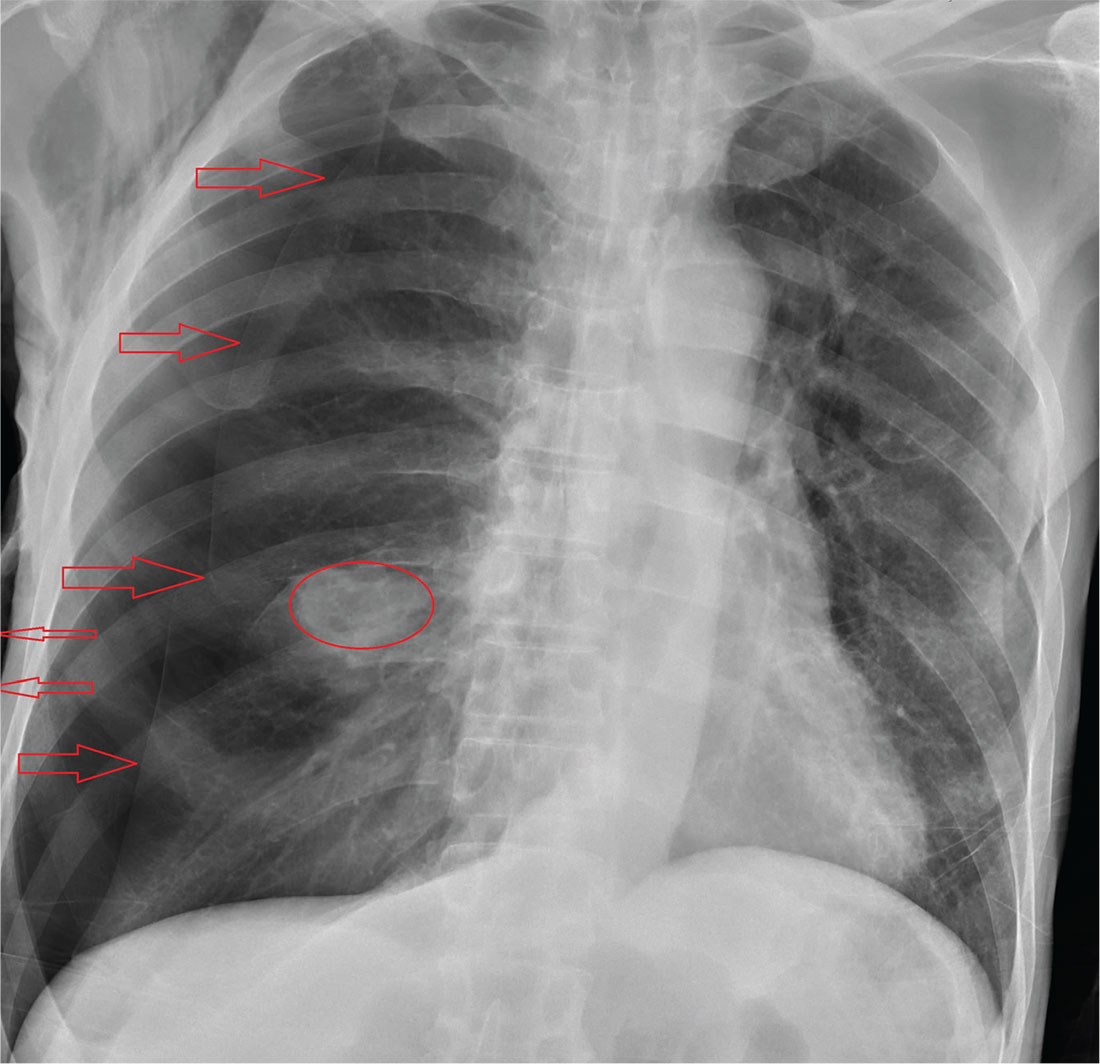

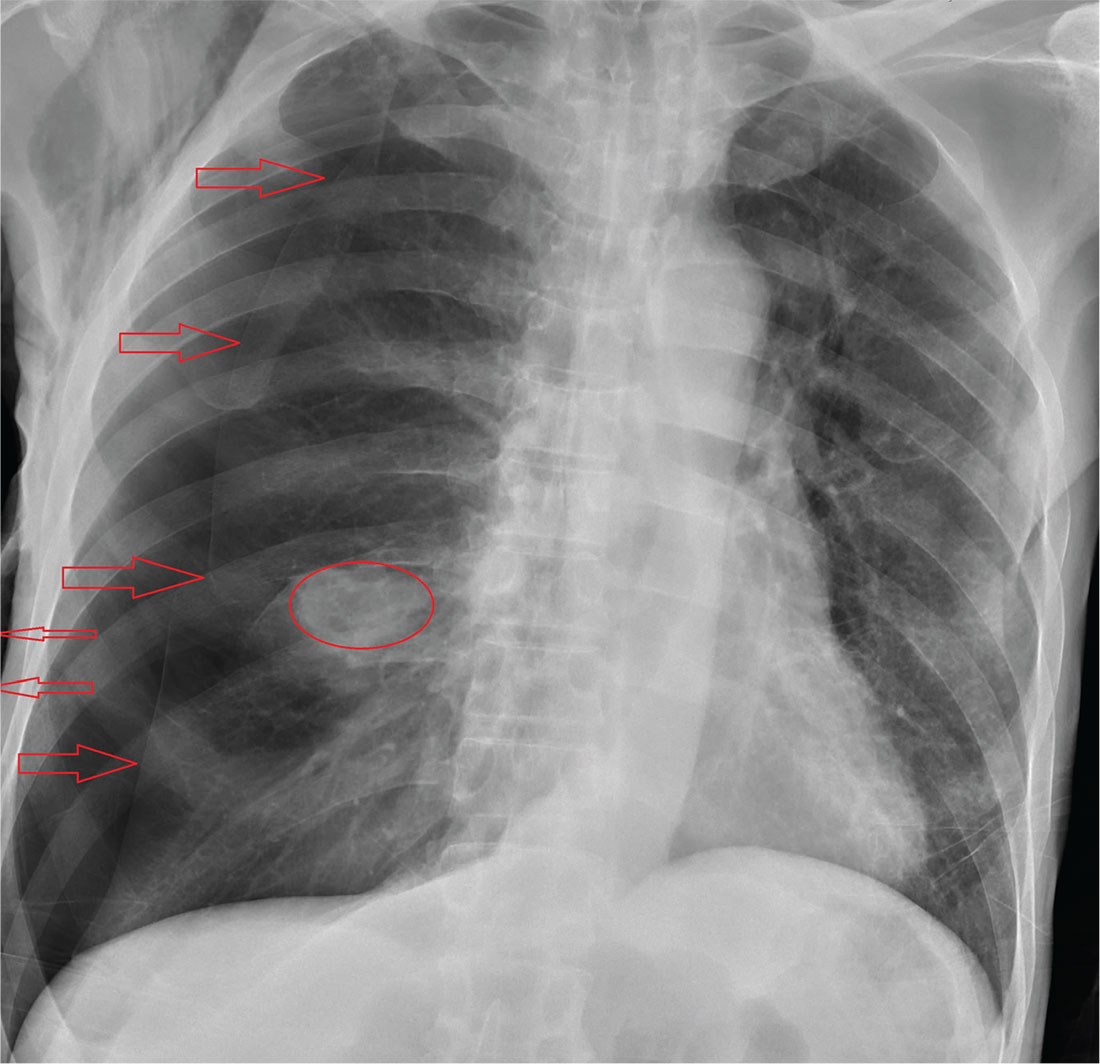

Vitamin D precursors arise from the skin and from the diet. These precursors are hydroxylated in the liver and then the kidneys to biologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (Figure 1).11 Vitamin D’s primary actions are in the intestines to increase absorption of calcium and in bone to induce osteoclast action. These actions raise the serum calcium level, which in turn lowers the PTH level through negative feedback on the parathyroid gland.

Most vitamin D supplements consist of the inactive precursor cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). To assess the degree of supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, which indicate the size of the body’s vitamin D reservoir, are measured.11,12

Our patient’s 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is extremely elevated, well beyond the 250-ng/mL upper limit that is considered safe.13 His low PTH level, lack of other likely causes, and history of supplement use point toward the diagnosis of hypervitaminosis D.

Sarcoidosis

Up to 10% of patients with sarcoidosis have hypercalcemia that is not mediated by PTH. Hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis has several potential mechanisms, including increased activity of the enzyme 1-alpha hydroxylase with a subsequent increase in physiologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production.14

Our patient had elevated levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, but his biologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level remained within the laboratory’s reference range.

LESS LIKELY CAUSES OF HYPERCALCEMIA

2. Which of the following would be least likely to cause hypercalcemia?

- Thiazide diuretics

- Over-the-counter antacid tablets

- Lithium

- Vitamin A supplementation

- Proton pump inhibitors

Thiazide diuretics

This class of drugs is well known to cause hypercalcemia. The most familiar of the mechanisms is a reduction in urinary calcium excretion. There is also an increase in intestinal absorption of dietary calcium. Evidence is increasing that most patients (as many as two-thirds) who develop hypercalcemia while using a thiazide diuretic have subclinical primary hyperparathyroidism that is uncovered with use of the diuretic.

Of importance, the hypercalcemia that thiazide diuretics cause is mild. In a series of 72 patients with thiazide-induced hypercalcemia, the average serum calcium level was 10.7 mg/dL.15

Our patient was receiving a thiazide diuretic but presented with severe hypercalcemia, which is inconsistent with thiazide-induced hypercalcemia.

Over-the-counter antacid tablets

Calcium carbonate, a popular over-the-counter antacid, can cause a milk-alkali syndrome that is defined by ingestion of excessive calcium and alkalotic substances, leading to metabolic alkalosis, hypercalcemia, and renal insufficiency. To induce this syndrome generally requires up to 4 g of calcium intake daily, but even lower levels (1.0 to 1.5 g) are known to cause it.16

Lithium

Lithium is known to cause hypercalcemia. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed, including direct action on renal tubules and the intestines leading to calcium reabsorption and stimulation of PTH release. Interestingly, parathyroid gland hyperplasia has been noted in long-term users of lithium. An often-proposed mechanism is that lithium increases the threshold at which the parathyroid glands slow their production of PTH, making them less sensitive to serum calcium levels.17

Vitamin A supplementation

Multiple case reports have linked hypercalcemia to ingestion of large doses of vitamin A. The mechanism is thought to be increased bone resorption.18.19

Although our patient reported supplement use, he denied taking vitamin A in any form.

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors are not known to cause hypercalcemia. On the contrary, case reports suggest that prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors is associated with hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia, although the mechanism is still not fully understood. A low magnesium level is known to reduce PTH secretion and also skeletal responsiveness to PTH, which can lead to profound hypocalcemia.20

CASE CONTINUED

On further questioning, the patient revealed that the supplement prescribed by his naturopathic practitioner contained vitamin D. Although he had been instructed to take 1 tablet weekly, he had begun taking it daily with his other routine medications, resulting in a daily dose in excess of 60,000 IU of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). The recommended dose is no more than 4,000 IU/day.

The supplement was immediately discontinued. His hydrochlorothiazide was also held due to its known effect of reducing urinary calcium excretion.

INITIAL TREATMENT OF HYPERCALCEMIA

3. Which of the following treatments is not recommended as part of this patient’s initial treatment?

- Bisphosphonates

- Calcitonin

- Intravenous fluids

- Furosemide

Our patient met the criteria for the diagnosis of hypercalcemic crisis, usually defined as an albumin-corrected serum calcium level higher than 14 mg/dL associated with multiorgan dysfunction resulting from the hypercalcemia.21 The mnemonic “stones, bones, abdominal moans, and psychic groans” captures the renal, skeletal, gastrointestinal, and neurologic manifestations.1

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are analogues of pyrophosphonates, which are normally incorporated into bone. Unlike pyrophosphonates, bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast function. They are often used to treat hypercalcemia of any cause, although they are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating hypercalcemia of malignancy only. As intravenous monotherapy, they are superior to other forms of treatment and are among the first-line agents in management.

Two bisphosphonates shown to be effective in hypercalcemia are zoledronate and pamidronate. Pamidronate begins to lower serum calcium levels within 2 days, with a peak effect at around 6 days.22 However, in studies comparing the 2 drugs, zoledronate has been shown to be more effective in normalizing serum calcium, with the additional benefit of having a much more rapid infusion time.23 Zoledronate is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min; however, pamidronate may continue to be used.24

Calcitonin

This hormone inhibits bone resorption and increases excretion of calcium in the kidneys. It is not recommended for use alone because of its short duration of action and tachyphylaxis, but it can be used in combination with other agents, particularly in hypercalcemic crisis.22 It has the most rapid onset (within 2 hours) of the available medications, and when used in combination with bisphosphonates it produces a more substantial and rapid reduction in serum calcium.25,26

In a patient such as ours, with severe hypercalcemia and evidence of neurologic consequences, calcitonin should be used for its rapid and effective action in lowering serum calcium as other interventions take effect.

Intravenous fluids

Like our patient, many patients with significant hypercalcemia have volume depletion as a result of calciuresis-induced polyuria. Many also have nephrogenic diabetes insipidus from the cytotoxic effect of calcium on renal cells, leading to further volume depletion.27

All management approaches call for fluid repletion as an initial step in hypercalcemia. However, for severe hypercalcemia, volume resuscitation alone is unlikely to completely correct the imbalance. In addition to correcting dehydration, giving fluids increases glomerular filtration, allowing for increased secretion of calcium at the distal tubule.28 The recommendation is 2.5 to 4 L of normal saline over the first 24 hours, with continued aggressive hydration until good urine output is established.21

Our patient, in addition to having acute kidney injury thought to be due to prerenal azotemia, appeared to be volume-depleted and was given aggressive intravenous hydration.

Furosemide

Furosemide inhibits calcium reabsorption at the thick ascending loop of Henle, but this effect depends on the glomerular filtration rate. While our patient would likely eventually benefit from furosemide, it should not be considered the first-line therapy, as diuretic use in the setting of volume depletion can cause circulatory collapse.29 A relative contraindication was his presentation with acute kidney injury.

LONG-TERM TREATMENT

4. In the continued management of a patient with vitamin D toxicity with severe hypercalcemia, which of the following provides prolonged benefit?

- Intravenous hydrocortisone

- Fluid repletion

- Pamidronate

- Calcium-restricted diet

Much has been postulated concerning the mechanism of vitamin D intoxication and subsequent hypercalcemia. Studies have shown it is not an increase in dietary calcium absorption that drives the hypercalcemia but rather an increase in bone resorption. As such, bisphosphonates such as pamidronate have been shown to have a dramatic and rapid effect on severe hypercalcemia from vitamin D toxicity. The duration of action varies but is typically between 1 and 2 weeks.22,30

Corticosteroids such as hydrocortisone are also indicated in situations of severe toxicity. They block the action of 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which converts inactive 25-hydroxyvitamin D to the active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Corticosteroids have also been shown to more directly reduce calcium resorption from bone and intestine in addition to increasing calciuresis.31 A small study in the United Kingdom noted that while bisphosphonates and steroids were equally effective in reducing serum calcium levels, bisphosphonates accomplished this reduction more rapidly, with a time to therapeutic effect of 9 days as opposed to 22 days.

Fluid hydration, though necessary, is unlikely to produce complete correction on its own, as previously discussed.

THE PATIENT RECOVERS

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids over 3 days and received 1 dose of pamidronate. Calcitonin was provided over the first 48 hours after presentation to more rapidly reduce his calcium levels. He was advised to avoid taking the supplements prescribed by his naturopathic practitioner.

On follow-up with an endocrinologist 1 week later, his symptoms had entirely resolved, and his calcium level was 10.5 mg/dL.

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- A good medication history includes over-the-counter products such as vitamin D supplements, as more and more people are taking them.

- The level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D should be monitored within 3 to 4 months after initiating treatment for vitamin D deficiency.11

- Vitamin D toxicity can have profound consequences, which are usually seen when levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D rise above 250 ng/mL.13

- The Institute of Medicine recommends that the dosage of vitamin D supplements be no more than 4,000 IU/day and that doses may need to be lowered to account for concurrent use of hypercalcemia-inducing drugs and other vitamin D-containing supplements.32

- Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician 2003; 67:1959–1966.

- al Zahrani A, Levine MA. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Lancet 1997; 349:1233–1238.

- Mundy GR, Edwards JR. PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) in hypercalcemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19:672–675.

- Ratcliffe WA, Hutchesson AC, Bundred NJ, Ratcliffe JG. Role of assays for parathyroid-hormone-related protein in investigation of hypercalcaemia. Lancet 1992; 339:164–167.

- Hewison M, Kantorovich V, Liker HR, et al. Vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia in lymphoma: evidence for hormone production by tumor-adjacent macrophages. J Bone Miner Res 2003; 18:579–582.

- Ghobrial MW, George J, Mannam S, Henien SR. Severe hypercalcemia as an initial presenting manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol 2002; 16:607–609.

- Zhao C, Nguyen MH. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening and surveillance: practice guidelines and real-life practice. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 50:120–133.

- Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91:101–119.

- Burman KD, Monchik JM, Earll JM, Wartofsky L. Ionized and total serum calcium and parathyroid hormone in hyperthyroidism. Ann Intern Med 1976; 84:668–671.

- Iqbal AA, Burgess EH, Gallina DL, Nanes MS, Cook CB. Hypercalcemia in hyperthyroidism: patterns of serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels during management of thyrotoxicosis. Endocr Pract 2003; 9:517–521.

- Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:266–281.

- Wolpowitz D, Gilchrest BA. The vitamin D questions: how much do you need and how should you get it? J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:301–317.

- Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 88:582S–586S.

- Inui N, Murayama A, Sasaki S, et al. Correlation between 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1 alpha-hydroxylase gene expression in alveolar macrophages and the activity of sarcoidosis. Am J Med 2001; 110:687–693.

- Wermers RA, Kearns AE, Jenkins GD, Melton LJ 3rd. Incidence and clinical spectrum of thiazide-associated hypercalcemia. Am J Med 2007; 120:911.e9–e15.

- Patel AM, Goldfarb S. Got calcium? Welcome to the calcium-alkali syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21:1440–1443.

- Shapiro HI, Davis KA. Hypercalcemia and “primary” hyperparathyroidism during lithium therapy. Am J Psychiatry 2015; 172:12–15.

- Farrington K, Miller P, Varghese Z, Baillod RA, Moorhead JF. Vitamin A toxicity and hypercalcaemia in chronic renal failure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981; 282:1999–2002.

- Frame B, Jackson CE, Reynolds WA, Umphrey JE. Hypercalcemia and skeletal effects in chronic hypervitaminosis A. Ann Intern Med 1974; 80:44–48.

- Florentin M, Elisaf MS. Proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: a new challenge. World J Nephrol 2012; 1:151–154.

- Ahmad S, Kuraganti G, Steenkamp D. Hypercalcemic crisis: a clinical review. Am J Med 2015; 128:239–245.

- Nussbaum SR, Younger J, Vandepol CJ, et al. Single-dose intravenous therapy with pamidronate for the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: comparison of 30-, 60-, and 90-mg dosages. Am J Med 1993; 95:297–304.

- Major P, Lortholary A, Hon J, et al. Zoledronic acid is superior to pamidronate in the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: a pooled analysis of two randomized, controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:558–567.

- Perazella MA, Markowitz GS. Bisphosphonate nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int 2008; 74:1385–1393.

- Bilezikian JP. Management of acute hypercalcemia. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:1196–1203.

- Ralston SH. Medical management of hypercalcaemia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 34:11–20.

- Garofeanu CG, Weir M, Rosas-Arellano MP, Henson G, Garg AX, Clark WF. Causes of reversible nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45:626–637.

- Hosking DJ, Cowley A, Bucknall CA. Rehydration in the treatment of severe hypercalcaemia. Q J Med 1981; 50:473–481.

- Suki WN, Yium JJ, Von Minden M, Saller-Hebert C, Eknoyan G, Martinez-Maldonado M. Acute treatment of hypercalcemia with furosemide. N Engl J Med 1970; 283:836–840.

- Selby PL, Davies M, Marks JS, Mawer EB. Vitamin D intoxication causes hypercalcaemia by increased bone resorption which responds to pamidronate. Clin Endocrinol 1995; 43:531–536.

- Davies M, Mawer EB, Freemont AJ. The osteodystrophy of hypervitaminosis D: a metabolic study. Q J Med 1986; 61:911–919.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium; Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al, eds. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011.

A retired 80-year-old man presented to the emergency department after 10 days of increasing polydipsia, polyuria, dry mouth, confusion, and slurred speech. He also reported that he had gradually and unintentionally lost 20 pounds and had loss of appetite, constipation, and chronic itching. He denied fevers, chills, night sweats, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Medical history. He had type 2 diabetes mellitus that was well controlled by oral hypoglycemics, hypothyroidism treated with levothyroxine in stable doses, and chronic hepatitis C complicated by liver cirrhosis without focal hepatic lesions. He also had hypertension, well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide and losartan. For his long-standing pruritus he had tried prescription drugs including gabapentin and pregabalin without improvement. He had also seen a naturopathic practitioner, who had prescribed supplements that relieved the symptoms.

Examination. The patient was in no acute distress. He appeared thin, with a weight of 140 lb and a body mass index of 21 kg/m2. His temperature was 36.8°C (98.2°F), blood pressure 198/82 mm Hg, heart rate 72 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 97%. His skin was without jaundice or rashes. The mucous membranes in the oropharynx were dry.

Neurologic examination revealed mild confusion, dysarthria, and ataxic gait. Sensation to light touch, pinprick, and vibration was intact. Generalized weakness was noted. Cranial nerves II through XII were intact. Deep tendon reflexes were symmetrically globally suppressed. Asterixis was absent. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory values in the emergency department. We initially suspected he had symptomatic hyperglycemia, but a bedside blood glucose value of 113 mg/dL ruled this out. Other initial laboratory values:

- Blood urea nitrogen 31 mg/dL (reference range 9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.7 mg/dL (0.73–1.22; an earlier value had been 1.0 mg/dL)

- Total serum calcium 14.4 mg/dL (8.6–10.0)

Complete blood cell counts were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the head was negative for acute pathology.

In view of the patient’s hypercalcemia, he was given aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation (2 L of normal saline over 2 hours) and was admitted to the hospital. His laboratory values on admission are shown in Table 1. Fluid resuscitation was continued while the laboratory results were pending.

CAUSES OF HYPERCALCEMIA

1. Based on this information, which is the most likely cause of this patient’s hypercalcemia?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypervitaminosis D

- Sarcoidosis

Traditionally, the workup for hypercalcemia in an outpatient starts with measuring the serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) level. Based on the results, a further evaluation of PTH-mediated vs PTH-independent causes of hypercalcemia would be initiated.

Primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy account for 90% of all cases of hypercalcemia. The serum PTH concentration is usually high in primary hyperparathyroidism but low in malignancy, which helps distinguish the conditions from each other.1

Primary hyperparathyroidism

In primary hyperparathyroidism, there is overproduction of PTH, most commonly from a parathyroid adenoma, though parathyroid hyperplasia or, more rarely, parathyroid carcinoma can also overproduce the hormone.

PTH increases serum calcium levels through 3 primary mechanisms: increasing bone resorption, increasing intestinal absorption of calcium, and decreasing renal excretion of calcium. It also induces renal phosphorus excretion.

Typically, in primary hyperparathyroidism, the increases in serum calcium are small (with serum levels of total calcium rising to no higher than 11 mg/dL) and often intermittent.2 Our patient had extremely high serum calcium, low PTH, and high phosphorus levels—all of which are inconsistent with primary hyperparathyroidism.

Malignancy

In some solid tumors, the major mechanism of hypercalcemia is secretion of PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) through promotion of osteoclast function and also increased renal absorption of calcium.3 Hematologic malignancies (eg, multiple myeloma) produce osteoclast-activating factors such as RANK ligand, lymphotoxin, and interleukin 6. Direct tumor invasion of bone can cause osteolysis and subsequent hypercalcemia.4 These mechanisms are usually associated with a fall in PTH.

Less commonly, tumors can also increase levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D or produce PTH independently of the parathyroid gland.5 There have also been reports of severe hypercalcemia from hepatocellular carcinoma due to PTHrP production.6

Our patient is certainly at risk for malignancy, given his long-standing history of hepatitis C and cirrhosis. He also had a mildly elevated alpha fetoprotein level and suppressed PTH. However, his PTHrP level was normal, and ultrasonography done recently to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma (recommended every 6 months by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases in high-risk patients) was negative.7

Multiple myeloma screening involves testing with serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation in combination with either a serum free light chain assay or 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation. This provides a 97% sensitivity.8 In this patient, these tests for multiple myeloma were negative.

Hyperthyroidism

As many as half of all patients with hyperthyroidism have elevated levels of ionized serum calcium.9 Increased osteoclastic activity is the likely mechanism. Hyperthyroid patients have increased levels of serum interleukin 6 and increased sensitivity of bone to this factor. This cytokine induces differentiation of monocytic cells into osteoclast precursors.10 These patients also have normal or low PTH levels.9

Our patient was receiving levothyroxine for hypothyroidism, but there was no evidence that the dosage was too high, as his thyroid-stimulating hormone level was within an acceptable range.

Hypervitaminosis D

Vitamin D precursors arise from the skin and from the diet. These precursors are hydroxylated in the liver and then the kidneys to biologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (Figure 1).11 Vitamin D’s primary actions are in the intestines to increase absorption of calcium and in bone to induce osteoclast action. These actions raise the serum calcium level, which in turn lowers the PTH level through negative feedback on the parathyroid gland.

Most vitamin D supplements consist of the inactive precursor cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). To assess the degree of supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, which indicate the size of the body’s vitamin D reservoir, are measured.11,12

Our patient’s 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is extremely elevated, well beyond the 250-ng/mL upper limit that is considered safe.13 His low PTH level, lack of other likely causes, and history of supplement use point toward the diagnosis of hypervitaminosis D.

Sarcoidosis

Up to 10% of patients with sarcoidosis have hypercalcemia that is not mediated by PTH. Hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis has several potential mechanisms, including increased activity of the enzyme 1-alpha hydroxylase with a subsequent increase in physiologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production.14

Our patient had elevated levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, but his biologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level remained within the laboratory’s reference range.

LESS LIKELY CAUSES OF HYPERCALCEMIA

2. Which of the following would be least likely to cause hypercalcemia?

- Thiazide diuretics

- Over-the-counter antacid tablets

- Lithium

- Vitamin A supplementation

- Proton pump inhibitors

Thiazide diuretics

This class of drugs is well known to cause hypercalcemia. The most familiar of the mechanisms is a reduction in urinary calcium excretion. There is also an increase in intestinal absorption of dietary calcium. Evidence is increasing that most patients (as many as two-thirds) who develop hypercalcemia while using a thiazide diuretic have subclinical primary hyperparathyroidism that is uncovered with use of the diuretic.

Of importance, the hypercalcemia that thiazide diuretics cause is mild. In a series of 72 patients with thiazide-induced hypercalcemia, the average serum calcium level was 10.7 mg/dL.15

Our patient was receiving a thiazide diuretic but presented with severe hypercalcemia, which is inconsistent with thiazide-induced hypercalcemia.

Over-the-counter antacid tablets

Calcium carbonate, a popular over-the-counter antacid, can cause a milk-alkali syndrome that is defined by ingestion of excessive calcium and alkalotic substances, leading to metabolic alkalosis, hypercalcemia, and renal insufficiency. To induce this syndrome generally requires up to 4 g of calcium intake daily, but even lower levels (1.0 to 1.5 g) are known to cause it.16

Lithium

Lithium is known to cause hypercalcemia. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed, including direct action on renal tubules and the intestines leading to calcium reabsorption and stimulation of PTH release. Interestingly, parathyroid gland hyperplasia has been noted in long-term users of lithium. An often-proposed mechanism is that lithium increases the threshold at which the parathyroid glands slow their production of PTH, making them less sensitive to serum calcium levels.17

Vitamin A supplementation

Multiple case reports have linked hypercalcemia to ingestion of large doses of vitamin A. The mechanism is thought to be increased bone resorption.18.19

Although our patient reported supplement use, he denied taking vitamin A in any form.

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors are not known to cause hypercalcemia. On the contrary, case reports suggest that prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors is associated with hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia, although the mechanism is still not fully understood. A low magnesium level is known to reduce PTH secretion and also skeletal responsiveness to PTH, which can lead to profound hypocalcemia.20

CASE CONTINUED

On further questioning, the patient revealed that the supplement prescribed by his naturopathic practitioner contained vitamin D. Although he had been instructed to take 1 tablet weekly, he had begun taking it daily with his other routine medications, resulting in a daily dose in excess of 60,000 IU of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). The recommended dose is no more than 4,000 IU/day.

The supplement was immediately discontinued. His hydrochlorothiazide was also held due to its known effect of reducing urinary calcium excretion.

INITIAL TREATMENT OF HYPERCALCEMIA

3. Which of the following treatments is not recommended as part of this patient’s initial treatment?

- Bisphosphonates

- Calcitonin

- Intravenous fluids

- Furosemide

Our patient met the criteria for the diagnosis of hypercalcemic crisis, usually defined as an albumin-corrected serum calcium level higher than 14 mg/dL associated with multiorgan dysfunction resulting from the hypercalcemia.21 The mnemonic “stones, bones, abdominal moans, and psychic groans” captures the renal, skeletal, gastrointestinal, and neurologic manifestations.1

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are analogues of pyrophosphonates, which are normally incorporated into bone. Unlike pyrophosphonates, bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast function. They are often used to treat hypercalcemia of any cause, although they are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating hypercalcemia of malignancy only. As intravenous monotherapy, they are superior to other forms of treatment and are among the first-line agents in management.

Two bisphosphonates shown to be effective in hypercalcemia are zoledronate and pamidronate. Pamidronate begins to lower serum calcium levels within 2 days, with a peak effect at around 6 days.22 However, in studies comparing the 2 drugs, zoledronate has been shown to be more effective in normalizing serum calcium, with the additional benefit of having a much more rapid infusion time.23 Zoledronate is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min; however, pamidronate may continue to be used.24

Calcitonin

This hormone inhibits bone resorption and increases excretion of calcium in the kidneys. It is not recommended for use alone because of its short duration of action and tachyphylaxis, but it can be used in combination with other agents, particularly in hypercalcemic crisis.22 It has the most rapid onset (within 2 hours) of the available medications, and when used in combination with bisphosphonates it produces a more substantial and rapid reduction in serum calcium.25,26

In a patient such as ours, with severe hypercalcemia and evidence of neurologic consequences, calcitonin should be used for its rapid and effective action in lowering serum calcium as other interventions take effect.

Intravenous fluids

Like our patient, many patients with significant hypercalcemia have volume depletion as a result of calciuresis-induced polyuria. Many also have nephrogenic diabetes insipidus from the cytotoxic effect of calcium on renal cells, leading to further volume depletion.27

All management approaches call for fluid repletion as an initial step in hypercalcemia. However, for severe hypercalcemia, volume resuscitation alone is unlikely to completely correct the imbalance. In addition to correcting dehydration, giving fluids increases glomerular filtration, allowing for increased secretion of calcium at the distal tubule.28 The recommendation is 2.5 to 4 L of normal saline over the first 24 hours, with continued aggressive hydration until good urine output is established.21

Our patient, in addition to having acute kidney injury thought to be due to prerenal azotemia, appeared to be volume-depleted and was given aggressive intravenous hydration.

Furosemide

Furosemide inhibits calcium reabsorption at the thick ascending loop of Henle, but this effect depends on the glomerular filtration rate. While our patient would likely eventually benefit from furosemide, it should not be considered the first-line therapy, as diuretic use in the setting of volume depletion can cause circulatory collapse.29 A relative contraindication was his presentation with acute kidney injury.

LONG-TERM TREATMENT

4. In the continued management of a patient with vitamin D toxicity with severe hypercalcemia, which of the following provides prolonged benefit?

- Intravenous hydrocortisone

- Fluid repletion

- Pamidronate

- Calcium-restricted diet

Much has been postulated concerning the mechanism of vitamin D intoxication and subsequent hypercalcemia. Studies have shown it is not an increase in dietary calcium absorption that drives the hypercalcemia but rather an increase in bone resorption. As such, bisphosphonates such as pamidronate have been shown to have a dramatic and rapid effect on severe hypercalcemia from vitamin D toxicity. The duration of action varies but is typically between 1 and 2 weeks.22,30

Corticosteroids such as hydrocortisone are also indicated in situations of severe toxicity. They block the action of 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which converts inactive 25-hydroxyvitamin D to the active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Corticosteroids have also been shown to more directly reduce calcium resorption from bone and intestine in addition to increasing calciuresis.31 A small study in the United Kingdom noted that while bisphosphonates and steroids were equally effective in reducing serum calcium levels, bisphosphonates accomplished this reduction more rapidly, with a time to therapeutic effect of 9 days as opposed to 22 days.

Fluid hydration, though necessary, is unlikely to produce complete correction on its own, as previously discussed.

THE PATIENT RECOVERS

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids over 3 days and received 1 dose of pamidronate. Calcitonin was provided over the first 48 hours after presentation to more rapidly reduce his calcium levels. He was advised to avoid taking the supplements prescribed by his naturopathic practitioner.

On follow-up with an endocrinologist 1 week later, his symptoms had entirely resolved, and his calcium level was 10.5 mg/dL.

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- A good medication history includes over-the-counter products such as vitamin D supplements, as more and more people are taking them.

- The level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D should be monitored within 3 to 4 months after initiating treatment for vitamin D deficiency.11

- Vitamin D toxicity can have profound consequences, which are usually seen when levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D rise above 250 ng/mL.13

- The Institute of Medicine recommends that the dosage of vitamin D supplements be no more than 4,000 IU/day and that doses may need to be lowered to account for concurrent use of hypercalcemia-inducing drugs and other vitamin D-containing supplements.32

A retired 80-year-old man presented to the emergency department after 10 days of increasing polydipsia, polyuria, dry mouth, confusion, and slurred speech. He also reported that he had gradually and unintentionally lost 20 pounds and had loss of appetite, constipation, and chronic itching. He denied fevers, chills, night sweats, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Medical history. He had type 2 diabetes mellitus that was well controlled by oral hypoglycemics, hypothyroidism treated with levothyroxine in stable doses, and chronic hepatitis C complicated by liver cirrhosis without focal hepatic lesions. He also had hypertension, well controlled with hydrochlorothiazide and losartan. For his long-standing pruritus he had tried prescription drugs including gabapentin and pregabalin without improvement. He had also seen a naturopathic practitioner, who had prescribed supplements that relieved the symptoms.

Examination. The patient was in no acute distress. He appeared thin, with a weight of 140 lb and a body mass index of 21 kg/m2. His temperature was 36.8°C (98.2°F), blood pressure 198/82 mm Hg, heart rate 72 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 97%. His skin was without jaundice or rashes. The mucous membranes in the oropharynx were dry.

Neurologic examination revealed mild confusion, dysarthria, and ataxic gait. Sensation to light touch, pinprick, and vibration was intact. Generalized weakness was noted. Cranial nerves II through XII were intact. Deep tendon reflexes were symmetrically globally suppressed. Asterixis was absent. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory values in the emergency department. We initially suspected he had symptomatic hyperglycemia, but a bedside blood glucose value of 113 mg/dL ruled this out. Other initial laboratory values:

- Blood urea nitrogen 31 mg/dL (reference range 9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.7 mg/dL (0.73–1.22; an earlier value had been 1.0 mg/dL)

- Total serum calcium 14.4 mg/dL (8.6–10.0)

Complete blood cell counts were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the head was negative for acute pathology.

In view of the patient’s hypercalcemia, he was given aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation (2 L of normal saline over 2 hours) and was admitted to the hospital. His laboratory values on admission are shown in Table 1. Fluid resuscitation was continued while the laboratory results were pending.

CAUSES OF HYPERCALCEMIA

1. Based on this information, which is the most likely cause of this patient’s hypercalcemia?

- Primary hyperparathyroidism

- Malignancy

- Hyperthyroidism

- Hypervitaminosis D

- Sarcoidosis

Traditionally, the workup for hypercalcemia in an outpatient starts with measuring the serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) level. Based on the results, a further evaluation of PTH-mediated vs PTH-independent causes of hypercalcemia would be initiated.

Primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy account for 90% of all cases of hypercalcemia. The serum PTH concentration is usually high in primary hyperparathyroidism but low in malignancy, which helps distinguish the conditions from each other.1

Primary hyperparathyroidism

In primary hyperparathyroidism, there is overproduction of PTH, most commonly from a parathyroid adenoma, though parathyroid hyperplasia or, more rarely, parathyroid carcinoma can also overproduce the hormone.

PTH increases serum calcium levels through 3 primary mechanisms: increasing bone resorption, increasing intestinal absorption of calcium, and decreasing renal excretion of calcium. It also induces renal phosphorus excretion.

Typically, in primary hyperparathyroidism, the increases in serum calcium are small (with serum levels of total calcium rising to no higher than 11 mg/dL) and often intermittent.2 Our patient had extremely high serum calcium, low PTH, and high phosphorus levels—all of which are inconsistent with primary hyperparathyroidism.

Malignancy

In some solid tumors, the major mechanism of hypercalcemia is secretion of PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) through promotion of osteoclast function and also increased renal absorption of calcium.3 Hematologic malignancies (eg, multiple myeloma) produce osteoclast-activating factors such as RANK ligand, lymphotoxin, and interleukin 6. Direct tumor invasion of bone can cause osteolysis and subsequent hypercalcemia.4 These mechanisms are usually associated with a fall in PTH.

Less commonly, tumors can also increase levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D or produce PTH independently of the parathyroid gland.5 There have also been reports of severe hypercalcemia from hepatocellular carcinoma due to PTHrP production.6

Our patient is certainly at risk for malignancy, given his long-standing history of hepatitis C and cirrhosis. He also had a mildly elevated alpha fetoprotein level and suppressed PTH. However, his PTHrP level was normal, and ultrasonography done recently to screen for hepatocellular carcinoma (recommended every 6 months by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases in high-risk patients) was negative.7

Multiple myeloma screening involves testing with serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation in combination with either a serum free light chain assay or 24-hour urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation. This provides a 97% sensitivity.8 In this patient, these tests for multiple myeloma were negative.

Hyperthyroidism

As many as half of all patients with hyperthyroidism have elevated levels of ionized serum calcium.9 Increased osteoclastic activity is the likely mechanism. Hyperthyroid patients have increased levels of serum interleukin 6 and increased sensitivity of bone to this factor. This cytokine induces differentiation of monocytic cells into osteoclast precursors.10 These patients also have normal or low PTH levels.9

Our patient was receiving levothyroxine for hypothyroidism, but there was no evidence that the dosage was too high, as his thyroid-stimulating hormone level was within an acceptable range.

Hypervitaminosis D

Vitamin D precursors arise from the skin and from the diet. These precursors are hydroxylated in the liver and then the kidneys to biologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (Figure 1).11 Vitamin D’s primary actions are in the intestines to increase absorption of calcium and in bone to induce osteoclast action. These actions raise the serum calcium level, which in turn lowers the PTH level through negative feedback on the parathyroid gland.

Most vitamin D supplements consist of the inactive precursor cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). To assess the degree of supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, which indicate the size of the body’s vitamin D reservoir, are measured.11,12

Our patient’s 25-hydroxyvitamin D level is extremely elevated, well beyond the 250-ng/mL upper limit that is considered safe.13 His low PTH level, lack of other likely causes, and history of supplement use point toward the diagnosis of hypervitaminosis D.

Sarcoidosis

Up to 10% of patients with sarcoidosis have hypercalcemia that is not mediated by PTH. Hypercalcemia in sarcoidosis has several potential mechanisms, including increased activity of the enzyme 1-alpha hydroxylase with a subsequent increase in physiologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production.14

Our patient had elevated levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, but his biologically active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D level remained within the laboratory’s reference range.

LESS LIKELY CAUSES OF HYPERCALCEMIA

2. Which of the following would be least likely to cause hypercalcemia?

- Thiazide diuretics

- Over-the-counter antacid tablets

- Lithium

- Vitamin A supplementation

- Proton pump inhibitors

Thiazide diuretics

This class of drugs is well known to cause hypercalcemia. The most familiar of the mechanisms is a reduction in urinary calcium excretion. There is also an increase in intestinal absorption of dietary calcium. Evidence is increasing that most patients (as many as two-thirds) who develop hypercalcemia while using a thiazide diuretic have subclinical primary hyperparathyroidism that is uncovered with use of the diuretic.

Of importance, the hypercalcemia that thiazide diuretics cause is mild. In a series of 72 patients with thiazide-induced hypercalcemia, the average serum calcium level was 10.7 mg/dL.15

Our patient was receiving a thiazide diuretic but presented with severe hypercalcemia, which is inconsistent with thiazide-induced hypercalcemia.

Over-the-counter antacid tablets

Calcium carbonate, a popular over-the-counter antacid, can cause a milk-alkali syndrome that is defined by ingestion of excessive calcium and alkalotic substances, leading to metabolic alkalosis, hypercalcemia, and renal insufficiency. To induce this syndrome generally requires up to 4 g of calcium intake daily, but even lower levels (1.0 to 1.5 g) are known to cause it.16

Lithium

Lithium is known to cause hypercalcemia. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed, including direct action on renal tubules and the intestines leading to calcium reabsorption and stimulation of PTH release. Interestingly, parathyroid gland hyperplasia has been noted in long-term users of lithium. An often-proposed mechanism is that lithium increases the threshold at which the parathyroid glands slow their production of PTH, making them less sensitive to serum calcium levels.17

Vitamin A supplementation

Multiple case reports have linked hypercalcemia to ingestion of large doses of vitamin A. The mechanism is thought to be increased bone resorption.18.19

Although our patient reported supplement use, he denied taking vitamin A in any form.

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors are not known to cause hypercalcemia. On the contrary, case reports suggest that prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors is associated with hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia, although the mechanism is still not fully understood. A low magnesium level is known to reduce PTH secretion and also skeletal responsiveness to PTH, which can lead to profound hypocalcemia.20

CASE CONTINUED

On further questioning, the patient revealed that the supplement prescribed by his naturopathic practitioner contained vitamin D. Although he had been instructed to take 1 tablet weekly, he had begun taking it daily with his other routine medications, resulting in a daily dose in excess of 60,000 IU of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). The recommended dose is no more than 4,000 IU/day.

The supplement was immediately discontinued. His hydrochlorothiazide was also held due to its known effect of reducing urinary calcium excretion.

INITIAL TREATMENT OF HYPERCALCEMIA

3. Which of the following treatments is not recommended as part of this patient’s initial treatment?

- Bisphosphonates

- Calcitonin

- Intravenous fluids

- Furosemide

Our patient met the criteria for the diagnosis of hypercalcemic crisis, usually defined as an albumin-corrected serum calcium level higher than 14 mg/dL associated with multiorgan dysfunction resulting from the hypercalcemia.21 The mnemonic “stones, bones, abdominal moans, and psychic groans” captures the renal, skeletal, gastrointestinal, and neurologic manifestations.1

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are analogues of pyrophosphonates, which are normally incorporated into bone. Unlike pyrophosphonates, bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast function. They are often used to treat hypercalcemia of any cause, although they are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating hypercalcemia of malignancy only. As intravenous monotherapy, they are superior to other forms of treatment and are among the first-line agents in management.

Two bisphosphonates shown to be effective in hypercalcemia are zoledronate and pamidronate. Pamidronate begins to lower serum calcium levels within 2 days, with a peak effect at around 6 days.22 However, in studies comparing the 2 drugs, zoledronate has been shown to be more effective in normalizing serum calcium, with the additional benefit of having a much more rapid infusion time.23 Zoledronate is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min; however, pamidronate may continue to be used.24

Calcitonin

This hormone inhibits bone resorption and increases excretion of calcium in the kidneys. It is not recommended for use alone because of its short duration of action and tachyphylaxis, but it can be used in combination with other agents, particularly in hypercalcemic crisis.22 It has the most rapid onset (within 2 hours) of the available medications, and when used in combination with bisphosphonates it produces a more substantial and rapid reduction in serum calcium.25,26

In a patient such as ours, with severe hypercalcemia and evidence of neurologic consequences, calcitonin should be used for its rapid and effective action in lowering serum calcium as other interventions take effect.

Intravenous fluids

Like our patient, many patients with significant hypercalcemia have volume depletion as a result of calciuresis-induced polyuria. Many also have nephrogenic diabetes insipidus from the cytotoxic effect of calcium on renal cells, leading to further volume depletion.27

All management approaches call for fluid repletion as an initial step in hypercalcemia. However, for severe hypercalcemia, volume resuscitation alone is unlikely to completely correct the imbalance. In addition to correcting dehydration, giving fluids increases glomerular filtration, allowing for increased secretion of calcium at the distal tubule.28 The recommendation is 2.5 to 4 L of normal saline over the first 24 hours, with continued aggressive hydration until good urine output is established.21

Our patient, in addition to having acute kidney injury thought to be due to prerenal azotemia, appeared to be volume-depleted and was given aggressive intravenous hydration.

Furosemide

Furosemide inhibits calcium reabsorption at the thick ascending loop of Henle, but this effect depends on the glomerular filtration rate. While our patient would likely eventually benefit from furosemide, it should not be considered the first-line therapy, as diuretic use in the setting of volume depletion can cause circulatory collapse.29 A relative contraindication was his presentation with acute kidney injury.

LONG-TERM TREATMENT

4. In the continued management of a patient with vitamin D toxicity with severe hypercalcemia, which of the following provides prolonged benefit?

- Intravenous hydrocortisone

- Fluid repletion

- Pamidronate

- Calcium-restricted diet

Much has been postulated concerning the mechanism of vitamin D intoxication and subsequent hypercalcemia. Studies have shown it is not an increase in dietary calcium absorption that drives the hypercalcemia but rather an increase in bone resorption. As such, bisphosphonates such as pamidronate have been shown to have a dramatic and rapid effect on severe hypercalcemia from vitamin D toxicity. The duration of action varies but is typically between 1 and 2 weeks.22,30

Corticosteroids such as hydrocortisone are also indicated in situations of severe toxicity. They block the action of 1-alpha-hydroxylase, which converts inactive 25-hydroxyvitamin D to the active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Corticosteroids have also been shown to more directly reduce calcium resorption from bone and intestine in addition to increasing calciuresis.31 A small study in the United Kingdom noted that while bisphosphonates and steroids were equally effective in reducing serum calcium levels, bisphosphonates accomplished this reduction more rapidly, with a time to therapeutic effect of 9 days as opposed to 22 days.

Fluid hydration, though necessary, is unlikely to produce complete correction on its own, as previously discussed.

THE PATIENT RECOVERS

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids over 3 days and received 1 dose of pamidronate. Calcitonin was provided over the first 48 hours after presentation to more rapidly reduce his calcium levels. He was advised to avoid taking the supplements prescribed by his naturopathic practitioner.

On follow-up with an endocrinologist 1 week later, his symptoms had entirely resolved, and his calcium level was 10.5 mg/dL.

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- A good medication history includes over-the-counter products such as vitamin D supplements, as more and more people are taking them.

- The level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D should be monitored within 3 to 4 months after initiating treatment for vitamin D deficiency.11

- Vitamin D toxicity can have profound consequences, which are usually seen when levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D rise above 250 ng/mL.13

- The Institute of Medicine recommends that the dosage of vitamin D supplements be no more than 4,000 IU/day and that doses may need to be lowered to account for concurrent use of hypercalcemia-inducing drugs and other vitamin D-containing supplements.32

- Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician 2003; 67:1959–1966.

- al Zahrani A, Levine MA. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Lancet 1997; 349:1233–1238.

- Mundy GR, Edwards JR. PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) in hypercalcemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19:672–675.

- Ratcliffe WA, Hutchesson AC, Bundred NJ, Ratcliffe JG. Role of assays for parathyroid-hormone-related protein in investigation of hypercalcaemia. Lancet 1992; 339:164–167.

- Hewison M, Kantorovich V, Liker HR, et al. Vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia in lymphoma: evidence for hormone production by tumor-adjacent macrophages. J Bone Miner Res 2003; 18:579–582.

- Ghobrial MW, George J, Mannam S, Henien SR. Severe hypercalcemia as an initial presenting manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol 2002; 16:607–609.

- Zhao C, Nguyen MH. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening and surveillance: practice guidelines and real-life practice. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 50:120–133.

- Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91:101–119.

- Burman KD, Monchik JM, Earll JM, Wartofsky L. Ionized and total serum calcium and parathyroid hormone in hyperthyroidism. Ann Intern Med 1976; 84:668–671.

- Iqbal AA, Burgess EH, Gallina DL, Nanes MS, Cook CB. Hypercalcemia in hyperthyroidism: patterns of serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels during management of thyrotoxicosis. Endocr Pract 2003; 9:517–521.

- Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:266–281.

- Wolpowitz D, Gilchrest BA. The vitamin D questions: how much do you need and how should you get it? J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:301–317.

- Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 88:582S–586S.

- Inui N, Murayama A, Sasaki S, et al. Correlation between 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1 alpha-hydroxylase gene expression in alveolar macrophages and the activity of sarcoidosis. Am J Med 2001; 110:687–693.

- Wermers RA, Kearns AE, Jenkins GD, Melton LJ 3rd. Incidence and clinical spectrum of thiazide-associated hypercalcemia. Am J Med 2007; 120:911.e9–e15.

- Patel AM, Goldfarb S. Got calcium? Welcome to the calcium-alkali syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21:1440–1443.

- Shapiro HI, Davis KA. Hypercalcemia and “primary” hyperparathyroidism during lithium therapy. Am J Psychiatry 2015; 172:12–15.

- Farrington K, Miller P, Varghese Z, Baillod RA, Moorhead JF. Vitamin A toxicity and hypercalcaemia in chronic renal failure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981; 282:1999–2002.

- Frame B, Jackson CE, Reynolds WA, Umphrey JE. Hypercalcemia and skeletal effects in chronic hypervitaminosis A. Ann Intern Med 1974; 80:44–48.

- Florentin M, Elisaf MS. Proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: a new challenge. World J Nephrol 2012; 1:151–154.

- Ahmad S, Kuraganti G, Steenkamp D. Hypercalcemic crisis: a clinical review. Am J Med 2015; 128:239–245.

- Nussbaum SR, Younger J, Vandepol CJ, et al. Single-dose intravenous therapy with pamidronate for the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: comparison of 30-, 60-, and 90-mg dosages. Am J Med 1993; 95:297–304.

- Major P, Lortholary A, Hon J, et al. Zoledronic acid is superior to pamidronate in the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: a pooled analysis of two randomized, controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:558–567.

- Perazella MA, Markowitz GS. Bisphosphonate nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int 2008; 74:1385–1393.

- Bilezikian JP. Management of acute hypercalcemia. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:1196–1203.

- Ralston SH. Medical management of hypercalcaemia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 34:11–20.

- Garofeanu CG, Weir M, Rosas-Arellano MP, Henson G, Garg AX, Clark WF. Causes of reversible nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45:626–637.

- Hosking DJ, Cowley A, Bucknall CA. Rehydration in the treatment of severe hypercalcaemia. Q J Med 1981; 50:473–481.

- Suki WN, Yium JJ, Von Minden M, Saller-Hebert C, Eknoyan G, Martinez-Maldonado M. Acute treatment of hypercalcemia with furosemide. N Engl J Med 1970; 283:836–840.

- Selby PL, Davies M, Marks JS, Mawer EB. Vitamin D intoxication causes hypercalcaemia by increased bone resorption which responds to pamidronate. Clin Endocrinol 1995; 43:531–536.

- Davies M, Mawer EB, Freemont AJ. The osteodystrophy of hypervitaminosis D: a metabolic study. Q J Med 1986; 61:911–919.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium; Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al, eds. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011.

- Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician 2003; 67:1959–1966.

- al Zahrani A, Levine MA. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Lancet 1997; 349:1233–1238.

- Mundy GR, Edwards JR. PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) in hypercalcemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008; 19:672–675.

- Ratcliffe WA, Hutchesson AC, Bundred NJ, Ratcliffe JG. Role of assays for parathyroid-hormone-related protein in investigation of hypercalcaemia. Lancet 1992; 339:164–167.

- Hewison M, Kantorovich V, Liker HR, et al. Vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia in lymphoma: evidence for hormone production by tumor-adjacent macrophages. J Bone Miner Res 2003; 18:579–582.

- Ghobrial MW, George J, Mannam S, Henien SR. Severe hypercalcemia as an initial presenting manifestation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol 2002; 16:607–609.

- Zhao C, Nguyen MH. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening and surveillance: practice guidelines and real-life practice. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 50:120–133.

- Rajkumar SV, Kumar S. Multiple myeloma: diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2016; 91:101–119.

- Burman KD, Monchik JM, Earll JM, Wartofsky L. Ionized and total serum calcium and parathyroid hormone in hyperthyroidism. Ann Intern Med 1976; 84:668–671.

- Iqbal AA, Burgess EH, Gallina DL, Nanes MS, Cook CB. Hypercalcemia in hyperthyroidism: patterns of serum calcium, parathyroid hormone, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 levels during management of thyrotoxicosis. Endocr Pract 2003; 9:517–521.

- Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:266–281.

- Wolpowitz D, Gilchrest BA. The vitamin D questions: how much do you need and how should you get it? J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:301–317.

- Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 88:582S–586S.

- Inui N, Murayama A, Sasaki S, et al. Correlation between 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1 alpha-hydroxylase gene expression in alveolar macrophages and the activity of sarcoidosis. Am J Med 2001; 110:687–693.

- Wermers RA, Kearns AE, Jenkins GD, Melton LJ 3rd. Incidence and clinical spectrum of thiazide-associated hypercalcemia. Am J Med 2007; 120:911.e9–e15.

- Patel AM, Goldfarb S. Got calcium? Welcome to the calcium-alkali syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21:1440–1443.

- Shapiro HI, Davis KA. Hypercalcemia and “primary” hyperparathyroidism during lithium therapy. Am J Psychiatry 2015; 172:12–15.

- Farrington K, Miller P, Varghese Z, Baillod RA, Moorhead JF. Vitamin A toxicity and hypercalcaemia in chronic renal failure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981; 282:1999–2002.

- Frame B, Jackson CE, Reynolds WA, Umphrey JE. Hypercalcemia and skeletal effects in chronic hypervitaminosis A. Ann Intern Med 1974; 80:44–48.

- Florentin M, Elisaf MS. Proton pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: a new challenge. World J Nephrol 2012; 1:151–154.

- Ahmad S, Kuraganti G, Steenkamp D. Hypercalcemic crisis: a clinical review. Am J Med 2015; 128:239–245.

- Nussbaum SR, Younger J, Vandepol CJ, et al. Single-dose intravenous therapy with pamidronate for the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: comparison of 30-, 60-, and 90-mg dosages. Am J Med 1993; 95:297–304.

- Major P, Lortholary A, Hon J, et al. Zoledronic acid is superior to pamidronate in the treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy: a pooled analysis of two randomized, controlled clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19:558–567.

- Perazella MA, Markowitz GS. Bisphosphonate nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int 2008; 74:1385–1393.

- Bilezikian JP. Management of acute hypercalcemia. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:1196–1203.

- Ralston SH. Medical management of hypercalcaemia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1992; 34:11–20.

- Garofeanu CG, Weir M, Rosas-Arellano MP, Henson G, Garg AX, Clark WF. Causes of reversible nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45:626–637.

- Hosking DJ, Cowley A, Bucknall CA. Rehydration in the treatment of severe hypercalcaemia. Q J Med 1981; 50:473–481.

- Suki WN, Yium JJ, Von Minden M, Saller-Hebert C, Eknoyan G, Martinez-Maldonado M. Acute treatment of hypercalcemia with furosemide. N Engl J Med 1970; 283:836–840.

- Selby PL, Davies M, Marks JS, Mawer EB. Vitamin D intoxication causes hypercalcaemia by increased bone resorption which responds to pamidronate. Clin Endocrinol 1995; 43:531–536.

- Davies M, Mawer EB, Freemont AJ. The osteodystrophy of hypervitaminosis D: a metabolic study. Q J Med 1986; 61:911–919.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium; Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al, eds. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011.

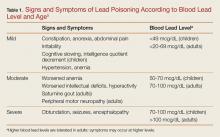

Case Studies in Toxicology: Drink the Water, but Don’t Eat the Paint

Case

A 2-year-old boy and his mother were referred to the ED by the child’s pediatrician after a routine venous blood lead level (BLL) taken at the boy’s recent well visit revealed an elevated lead level of 52 mcg/dL (normal range, <5 mcg/dL). The child’s mother reported that although her son had always been a picky eater, he had recently been complaining of abdominal pain.

The patient’s well-child visits had been normal until his recent 2-year checkup, at which time his pediatrician noticed some speech delay. On further history taking, the emergency physician (EP) learned the patient and his mother resided in an older home (built in the 1950s) that was in disrepair. The mother asked the EP if the elevation in the child’s BLL could be due to the drinking water in their town.

What are the most likely sources of environmental lead exposure?

In 2016, the topic of lead poisoning grabbed national attention when a pediatrician in Flint, Michigan detected an abrupt doubling of the number of children with elevated lead levels in her practice.1 Upon further investigation, it was discovered that these kids had one thing in common: the source of their drinking water. The City of Flint had recently switched the source of its potable water from Lake Huron to the Flint River. The lower quality water, which was not properly treated with an anticorrosive agent such as orthophosphate, led to widespread pipe corrosion and lead contamination. This finding resulted in a cascade of water testing by other municipalities and school systems, many of which identified lead concentrations above the currently accepted drinking water standard of 15 parts per billion (ppb).

Thousands of children each year are identified to have elevated BLLs, based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of a “level of concern” as more than 5 mcg/dL.2 The majority of these exposures stem from environmental exposure to lead paint dust in the home, but drinking water normally contributes as a low-level, constant, “basal” exposure. While lead-contaminated drinking water is not acceptable, it is unlikely to generate many ED visits. However, there are a variety of other lead sources that may prompt children to present to the ED with acute or subacute lead poisoning.

Lead is a heavy metal whose physical properties indicate its common uses. It provides durability and opacity to pigments, which is why it is found in oil paint, house paint used before 1976, and on paint for large outdoor structures, where it is still used. Lead is also found in the pigments used in cosmetics, stained glass, and painted pottery, and as an adulterant in highly colored foodstuffs such as imported turmeric.3

The physicochemical characteristics of lead make it an ideal component of solder. Many plumbing pipes in use today are not lead, but join one another using lead solder at the joints, sites that are vulnerable to corrosion. The heavy molecular weight of lead makes it a useful component of bullets and munitions.

Tetraethyl lead was used as an “anti-knock” agent to smooth out the combustion of heterogenous compounds in automotive fuel before it was removed in the mid-1970s.4 Prior to its removal, leaded gasoline was the largest source of air, soil, and groundwater contamination leading to environmental exposures.4 At present, the most common source of environmental lead exposure among young children is through peeling paint in deteriorating residential buildings. Hazardous occupational lead exposures arise from work involving munitions, reclamation and salvage, painting, welding, and numerous other settings—particularly sites where industrial hygiene is suboptimal. Lead from these sites can be inadvertently transported home on clothing or shoes, raising the exposure risk for children in the household.4

What are the health effects of lead exposure?

Like most heavy metals, lead is toxic to many organ systems in the body. The signs and symptoms of lead poisoning vary depending on the patient’s BLL and age (Table 1).5 The most common clinical effect of lead in the adult population is hypertension.6 Additional renal effects include a Fanconi-type syndrome with glycosuria and proteinuria. Lead can cause a peripheral neuropathy that is predominantly motor, classically causing foot or wrist drop. Abdominal pain from lead exposure is sometimes termed “lead colic” due to its intermittent and often severe nature. Abnormalities in urate metabolism cause a gouty arthritis referred to as “saturnine gout.” 6

The young pediatric central nervous system (CNS) is much more vulnerable to the effects of lead than the adult CNS. Even low-level lead exposure to the developing brain causes deficits in intelligence quotient, attention, impulse control, and other neurocognitive functions that are largely irreversible.7

Children with an elevated BLL may also develop constipation, anorexia, pallor, and pica.8 The development of geophagia (subtype of pica in which one craves and ingests nonfood clay or soil-like materials), represents a “chicken-or-egg” phenomena as it both causes and results from lead poisoning.

Lead impairs multiple steps of the heme synthesis pathway, causing microcytic anemia with basophilic stippling. Lead-induced anemia exacerbates pica as anemic patients are more likely to eat leaded paint chips and other lead-containing materials such as pottery.8 Of note, leaded white paint is reported to have a pleasant taste due to the sweet-tasting lead acetate used as a pigment.

The most dramatic and consequential manifestation of lead poisoning is lead encephalopathy. This can occur at any age, but manifests in children at much lower BLLs than in adults. Patients can be altered or obtunded, have convulsive activity, and may develop cerebral edema. Encephalopathy is a life-threatening emergency and must be recognized and treated immediately. Lead encephalopathy should be suspected in any young child with hand-to-mouth behavior who has any of the above environmental risk factors.4 The findings of anemia or the other diagnostic signs described below are too unreliable and take too long to be truly helpful in making the diagnosis.

How is the diagnosis of lead poisoning made?

The gold standard for the diagnosis of lead poisoning is the measurement of BLL. However, the turnaround time for this test is usually at least 24 hours, but may take up to several days. As such, adjunctive testing can accelerate obtaining a diagnosis. A complete blood count (CBC) to evaluate for microcytic anemia may demonstrate a characteristic pattern of basophilic stippling.9 A protoporphyrin level—either a free erythrocyte protoporphyrin (FEP) or a zinc protoporphyrin level—will be elevated, a result of heme synthesis disruption.9 Urinalysis may demonstrate glycosuria or proteinuria.6 Hypertension is often present, even in pediatric patients.

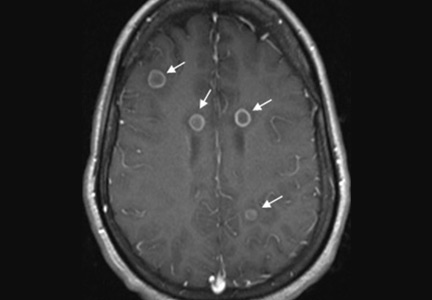

An abdominal radiograph is essential in children to determine whether a lead foreign body, such as a paint chip, is present in the intestinal lumen. Long bone films may demonstrate “lead lines” at the metaphysis, which in fact do not reflect lead itself but abnormal calcium deposition in growing bone due to lead’s interference with bone remodeling. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain in patients with encephalopathy will often demonstrate cerebral edema.6

Of note, capillary BLLs taken via finger-stick can be falsely elevated due contamination during collection (eg, the presence of lead dust on the skin). However, this screening method is often used by clinicians in the pediatric primary care setting because of its feasibility. Elevated BLLs from capillary testing should always be followed by a BLL obtained by venipuncture.2

Case Continuation

The patient’s mother was counseled on sources of lead contamination. She was informed that although drinking water may contribute some amount to an elevated BLL, the most likely source of contamination is still lead paint found in older homes such as the one in which she and her son resided.

Diagnostic studies to support the diagnosis of lead poisoning were performed. A CBC revealed a hemoglobin of 9.8 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 68 fL. A microscopic smear of blood demonstrated basophilic stippling of red blood cells. An FEP level was 386 mcg/dL. An abdominal radiograph demonstrated small radiopacities throughout the large intestine, without obstruction, which was suggestive of ingested lead paint chips.

What is the best management approach to patients with suspected lead poisoning?

The first-line treatment for patients with lead poisoning is removal from the exposure source, which first and foremost requires identification of the hazard through careful history taking and scene investigation by the local health department. This will avoid recurrent visits following successful chelation for repeat exposure to an unidentified source. Relocation to another dwelling will often be required for patients with presumed exposure until the hazard can be identified and abated.

Patients who have ingested or have embedded leaded foreign bodies will require removal via whole bowel irrigation or surgical means.

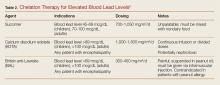

Following decontamination, chelation is required for children with a BLL more than 45 mcg/dL, and adults with CNS symptomatology and a BLL more than 70 mcg/dL. Table 2 provides guidelines for chelation therapy based on BLL.5

There are three chelating agents commonly used to reduce the body lead burden (Table 2).5 The most common, owing largely to it being the only agent used orally, is succimer (or dimercaptosuccinic acid, DMSA). The second agent is calcium disodium edetate (CaNa2EDTA), which is given intravenously. In patients with encephalopathy, EDTA should be given after the first dose of the third agent, British anti-Lewisite (BAL; 2,3-dimercaptopropanol), in order to prevent redistribution of lead from the peripheral compartment into the CNS.10 However, BAL is the most difficult of the three agents to administer as it is suspended in peanut oil and is given via intramuscular injection every 4 hours.

Unfortunately, while chelation therapy is highly beneficial for patients with severe lead poisoning, it has not been demonstrated to positively impact children who already have developed neurocognitive sequelae associated with lower level lead exposure.11 This highlights the importance of prevention.

Work-up and Management in the ED

The patient with lead poisoning, while an unusual presentation in the ED, requires specialized management to minimize sequelae of exposure. Careful attention to history is vital. When in doubt, the EP should consult with her or his regional poison control center (800-222-1222) or with a medical toxicologist or other expert.

There are several scenarios in which a patient may present to the ED with lead toxicity. The following scenarios, along with their respective clinical approach strategies, represent three of the most common presentations.

Scenario 1: The Pediatric Patient With Elevated Venous Blood Lead Levels

The EP should employ the following clinical approach when evaluating and managing the pediatric patient with normal mental status whose routine screening reveals a BLL sufficiently elevated to warrant evaluation or admission—perhaps to discontinue exposure or initiate chelation therapy.

- Obtain a history, including possible lead sources; perform a complete physical examination; and obtain a repeat BLL, CBC with microscopic examination, and renal function test.

- Obtain an abdominal film to look for radiopacities, including paint chips or larger ingested foreign bodies.

- If radiopaque foreign bodies are present on abdominal radiograph, whole bowel irrigation with polyethylene glycol solution given via a nasogastric tube at 250 to 500 cc/h for a pediatric patient (1 to 2 L/h for adult patients) should be given until no residual foreign bodies remain.

- Obtain a radiograph of the long bone, which may demonstrate metaphyseal enhancement in the pediatric patient, suggesting long-term exposure.

- Ensure local or state health departments are contacted to arrange for environmental inspection of the home. This is essential prior to discharge to the home environment.

- Begin chelation therapy according to the BLL (Table 2).

Scenario 2: Adult Patients Presenting With Signs and Symptoms of Lead Toxicity

The adult patient who presents to the ED with complaints suggestive of lead poisoning and whose history is indicative of lead exposure should be evaluated and managed as follows:

- Obtain a thorough history, including the occupation and hobbies of the patient and all family members.

- Obtain vital signs to evaluate for hypertension; repeat BLL, CBC with smear, and serum creatinine test. Perform a physical examination to evaluate for lead lines.