User login

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: An often unrecognized cause of acute coronary syndrome

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (Figure 1) showed ST-segment elevation of more than 2 mm in leads V2, V3, V4, and V5, with no reciprocal changes.

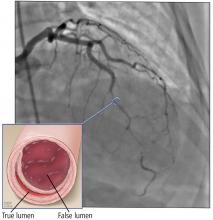

Based on the classic angiographic appearance and the absence of atherosclerotic disease in other coronary arteries, type 2 spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) was diagnosed.

CORONARY ARTERY WALL SEPARATION

SCAD is defined as a nontraumatic, noniatrogenic intramural hemorrhage leading to separation of the coronary arterial wall and the formation of a false lumen. The separation can occur between any of the coronary artery wall layers and may or may not involve an intimal tear. The bleeding may result in an intramural hematoma and possible narrowing of the arterial lumen. Depending on the severity of narrowing, blood supply to the myocardium could be compromised, resulting in symptoms of ischemia.1

SCAD usually involves a single coronary artery, although multiple coronary artery involvement has been reported.2

CASE CONTINUED: MANAGEMENT

The patient recovered completely and was discharged home with plans to return for outpatient imaging for fibromuscular dysplasia.

SCAD: RARE OR JUST RARELY RECOGNIZED?

SCAD appears to be a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome, but it is likely underdiagnosed and is becoming increasingly recognized worldwide. Typically, it affects women younger than 50, with women in general outnumbering men 9 to 1.3 Overall, SCAD causes up to 4% of acute myocardial infarctions, but in women age 50 or younger, it is responsible for 24% to 35% of acute myocardial infarctions, and the proportion is even higher in pregnant women.4

Not just pregnancy-associated

SCAD was previously thought to be mainly idiopathic and mostly affecting women peripartum. Current understanding paints a different picture: pregnancy-associated SCAD does not account for the majority of cases. That said, SCAD is the most common cause of myocardial infarction peripartum, with the third trimester and early postpartum period being the times of highest risk.5 SCAD development at those times is believed to be related to hormonal changes causing weakening of coronary artery walls.6

Weakening of the coronary artery wall also may occur in the setting of fibromuscular dysplasia, connective tissue disease, recurrent pregnancies, systemic inflammatory disease, hormonal therapy, and other disease states that cause arteriopathy. Exposure to a stressor in a patient with underlying risk factors can lead to either an intimal tear or rupture of the vasa vasorum, with subsequent formation of intramural hemorrhage and eventually SCAD.7 Stressors can be emotional or physical and can include labor and delivery, intense physical exercise, the Valsalva maneuver, and drug abuse.8

Presentation is variable

SCAD presentation depends on the degree of flow limitation and extent of the dissection. Presentation can range from asymptomatic to sudden cardiac death and can include signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome caused by ST-segment elevation or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

DIAGNOSIS BY ANGIOGRAPHY

SCAD can be diagnosed by coronary angiography. There are 3 angiographic types:

Type 1 (about 25% of SCAD cases) has typical contrast dye staining of the arterial wall and multiple radiolucent luminal abnormalities, with or without dye hang-up.

Type 2 (about 70%) has diffuse, smooth narrowing of the coronary artery, with the left anterior descending artery the most frequently affected.8

Type 3 (about 5%) mimics atherosclerosis, with focal or tubular stenosis.9

Types 1 and 2 are usually easy to recognize. To diagnose type 2, intravenous nitroglycerin should first be administered to rule out coronary spasm.

Type 3 SCAD is more challenging to diagnose because its appearance on angiography is similar to that of atherosclerosis. For equivocal findings in any type, but especially in type 3, intravascular ultrasonography or optical coherence tomography can help.10 Optical coherence tomography is preferred because of superior image resolution, although ultrasonography offers better tissue penetration.11

MANAGE MOST CASES CONSERVATIVELY

Management algorithms for SCAD are available.8,12

The initial and most critical step is to make the correct diagnosis. Although the presentation of acute coronary syndrome caused by SCAD is often identical to that of atherosclerosis, the conditions have different pathophysiologies and thus require different management. Theoretically, systemic anticoagulation may worsen an intramural hemorrhage.

First-line therapy for most patients with SCAD is conservative management and close inpatient monitoring for 3 to 5 days.13 More aggressive management is indicated for any of the following:

- Left main or severe proximal 2-vessel dissection

- Hemodynamic instability

- Ongoing ischemic symptoms.

In a prospective cohort of 168 patients, 134 (80%) were initially treated conservatively; of those, in-hospital myocardial infarction recurred in 4.5%, a major cardiac event occurred within 2 years in 17%, and SCAD recurred in 13%.8

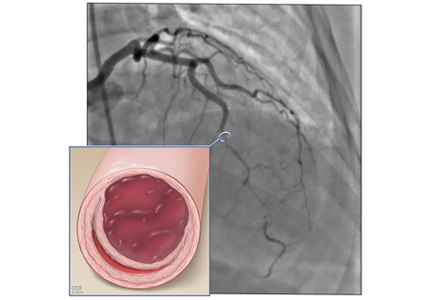

Observational data on patients with SCAD who had repeat angiography weeks to months after the initial event has shown that lesions heal in 70% to 97% of patients.12

WHEN TO CONSIDER AGGRESSIVE MANAGEMENT

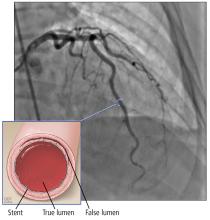

Under the circumstances listed above, revascularization with PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) should be considered, with choice of procedure determined by feasibility, technical considerations, and local expertise.

The American Heart Association recommendations are as follows12:

- For left main or severe proximal 2-vessel dissection in clinically stable patients, consider CABG

- For active ischemia or hemodynamic instability, consider PCI if feasible or perform urgent CABG.

A few series have shown that the prognosis with conservative management or CABG is better than with PCI.8,13,14 The success rate for revascularization with PCI is only about 60% because of challenges including risk of inducing iatrogenic dissection, passing the wire into the false lumen and worsening a dissection, and propagating an intramural hematoma with stenting and further compromising coronary blood flow. In addition, dissection tends to extend into distal arteries that are difficult to stent. There is also the risk of stent malapposition after resorption of the intramural hematoma, causing late stent thrombosis.7

SCREEN FOR OTHER VASCULAR PROBLEMS

Imaging of the renal, iliac, and cerebral vasculature is recommended for all patients with SCAD.12 Screening for fibromuscular dysplasia can be done with angiography, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).12

Multifocal fibromuscular dysplasia in extracoronary arteries occurs with SCAD in 25% to 86% of cases. In a single-center series of 115 patients with confirmed SCAD who underwent CTA from 2010 to 2014, extracoronary vascular abnormalities were found in 66%, with fibromuscular dysplasia being the most common type (45%).15 In another single-center study, 327 patients with SCAD were prospectively followed from 2012 to 2016 with screening for cerebrovascular, renal, and iliac fibromuscular dysplasia using CTA or catheter angiography. Fibromuscular dysplasia was found in 63%, and intracranial aneurysm was found in 14% of patients with fibromuscular dysplasia.9

SCAD can also be associated with connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV and Marfan syndrome.16,17

LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT

Patients with SCAD should start long-term aspirin and 1 year of clopidogrel. Statins are indicated for patients with hyperlipidemia8,18 but otherwise offer no clear benefit for SCAD alone. If there are no contraindications, a beta-adrenergic blocker should be considered, especially if left ventricular dysfunction or arrhythmias are present. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers should also be considered with concomitant left ventricular dysfunction. Antianginal therapy can be used for post-SCAD chest pain syndromes.12

Repeat angiography is recommended only to evaluate recurrent symptoms, to confirm an unclear initial diagnosis, to assess for atherosclerosis-related stenosis, or to evaluate high-risk anatomy, eg, involvement of the left main coronary artery.12

Genetic testing is reserved for patients with a high clinical suspicion of connective tissue disease or systemic arteriopathy.19

- Garcia NA, Khan AN, Boppana RC, Smith HL. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a case series and literature review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2014; 4(4). doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25261

- Lempereur M, Gin K, Saw J. Multivessel spontaneous coronary artery dissection mimicking atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(7):e87–e88. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2013.12.207

- Mahmoud AN, Taduru SS, Mentias A, et al. Trends of incidence, clinical presentation, and in-hospital mortality among women with acute myocardial infarction with or without spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a population-based analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018; 11(1):80–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.016

- Saw J. Pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection represents an exceptionally high-risk spontaneous coronary artery dissection cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017; 10(3)pii:e005119. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005119

- Elkayam U, Jalnapurkar S, Barakkat MN, et al. Pregnancy-associated acute myocardial infarction: a review of contemporary experience in 150 cases between 2006 and 2011. Circulation 2014; 129(16):1695–1702. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002054

- Vijayaraghavan R, Verma S, Gupta N, Saw J. Pregnancy-related spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation 2014; 130(21):1915–1920. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011422

- Saw J, Mancini GBJ, Humphries KH. Contemporary review on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68(3):297–312. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.034

- Saw J, Aymong E, Sedlak T, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: association with predisposing arteriopathies and precipitating stressors and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(5):645–655. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001760

- Saw J, Humphries K ,Aymong E, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: clinical outcomes and risk of recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(9):1148–1158. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.053

- Alfonso F, Bastante T, Cuesta J, Rodríguez D, Benedicto A, Rivero F. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: novel insights on diagnosis and management. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2015; 5(2):133–140. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.03.05

- Kern MJ, Meier B. Evaluation of the culprit plaque and the physiological significance of coronary atherosclerotic narrowings. Circulation 2001; 103(25):3142–3149. pmid:11425782

- Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; and Stroke Council. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: current state of the science: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137(19):e523–e557. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000564

- Tweet MS, Eleid MF, Best PJ, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: revascularization versus conservative therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(6):777–786. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001659

- Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation 2012; 126(5):579–588. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105718

- Prasad M, Tweet MS, Hayes SN, et al. Prevalence of extracoronary vascular abnormalities and fibromuscular dysplasia in patients with spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol 2015; 115(12):1672–1677. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.011

- Adès LC, Waltham RD, Chiodo AA, Bateman JF. Myocardial infarction resulting from coronary artery dissection in an adolescent with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV due to a type III collagen mutation. Br Heart J 1995; 74(2):112–116. pmid:7546986

- Judge DP, Dietz HC. Marfan’s syndrome. Lancet 2005; 366(9501):1965–1976. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67789-6

- Saw J. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Can J Cardiol 2013; 29(9):1027–1033. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2012.12.018

- Poloskey SL, Kim ES, Sanghani R, et al. Low yield of genetic testing for known vascular connective tissue disorders in patients with fibromuscular dysplasia. Vasc Med 2012; 17(6):371–378. doi:10.1177/1358863X12459650

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (Figure 1) showed ST-segment elevation of more than 2 mm in leads V2, V3, V4, and V5, with no reciprocal changes.

Based on the classic angiographic appearance and the absence of atherosclerotic disease in other coronary arteries, type 2 spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) was diagnosed.

CORONARY ARTERY WALL SEPARATION

SCAD is defined as a nontraumatic, noniatrogenic intramural hemorrhage leading to separation of the coronary arterial wall and the formation of a false lumen. The separation can occur between any of the coronary artery wall layers and may or may not involve an intimal tear. The bleeding may result in an intramural hematoma and possible narrowing of the arterial lumen. Depending on the severity of narrowing, blood supply to the myocardium could be compromised, resulting in symptoms of ischemia.1

SCAD usually involves a single coronary artery, although multiple coronary artery involvement has been reported.2

CASE CONTINUED: MANAGEMENT

The patient recovered completely and was discharged home with plans to return for outpatient imaging for fibromuscular dysplasia.

SCAD: RARE OR JUST RARELY RECOGNIZED?

SCAD appears to be a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome, but it is likely underdiagnosed and is becoming increasingly recognized worldwide. Typically, it affects women younger than 50, with women in general outnumbering men 9 to 1.3 Overall, SCAD causes up to 4% of acute myocardial infarctions, but in women age 50 or younger, it is responsible for 24% to 35% of acute myocardial infarctions, and the proportion is even higher in pregnant women.4

Not just pregnancy-associated

SCAD was previously thought to be mainly idiopathic and mostly affecting women peripartum. Current understanding paints a different picture: pregnancy-associated SCAD does not account for the majority of cases. That said, SCAD is the most common cause of myocardial infarction peripartum, with the third trimester and early postpartum period being the times of highest risk.5 SCAD development at those times is believed to be related to hormonal changes causing weakening of coronary artery walls.6

Weakening of the coronary artery wall also may occur in the setting of fibromuscular dysplasia, connective tissue disease, recurrent pregnancies, systemic inflammatory disease, hormonal therapy, and other disease states that cause arteriopathy. Exposure to a stressor in a patient with underlying risk factors can lead to either an intimal tear or rupture of the vasa vasorum, with subsequent formation of intramural hemorrhage and eventually SCAD.7 Stressors can be emotional or physical and can include labor and delivery, intense physical exercise, the Valsalva maneuver, and drug abuse.8

Presentation is variable

SCAD presentation depends on the degree of flow limitation and extent of the dissection. Presentation can range from asymptomatic to sudden cardiac death and can include signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome caused by ST-segment elevation or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

DIAGNOSIS BY ANGIOGRAPHY

SCAD can be diagnosed by coronary angiography. There are 3 angiographic types:

Type 1 (about 25% of SCAD cases) has typical contrast dye staining of the arterial wall and multiple radiolucent luminal abnormalities, with or without dye hang-up.

Type 2 (about 70%) has diffuse, smooth narrowing of the coronary artery, with the left anterior descending artery the most frequently affected.8

Type 3 (about 5%) mimics atherosclerosis, with focal or tubular stenosis.9

Types 1 and 2 are usually easy to recognize. To diagnose type 2, intravenous nitroglycerin should first be administered to rule out coronary spasm.

Type 3 SCAD is more challenging to diagnose because its appearance on angiography is similar to that of atherosclerosis. For equivocal findings in any type, but especially in type 3, intravascular ultrasonography or optical coherence tomography can help.10 Optical coherence tomography is preferred because of superior image resolution, although ultrasonography offers better tissue penetration.11

MANAGE MOST CASES CONSERVATIVELY

Management algorithms for SCAD are available.8,12

The initial and most critical step is to make the correct diagnosis. Although the presentation of acute coronary syndrome caused by SCAD is often identical to that of atherosclerosis, the conditions have different pathophysiologies and thus require different management. Theoretically, systemic anticoagulation may worsen an intramural hemorrhage.

First-line therapy for most patients with SCAD is conservative management and close inpatient monitoring for 3 to 5 days.13 More aggressive management is indicated for any of the following:

- Left main or severe proximal 2-vessel dissection

- Hemodynamic instability

- Ongoing ischemic symptoms.

In a prospective cohort of 168 patients, 134 (80%) were initially treated conservatively; of those, in-hospital myocardial infarction recurred in 4.5%, a major cardiac event occurred within 2 years in 17%, and SCAD recurred in 13%.8

Observational data on patients with SCAD who had repeat angiography weeks to months after the initial event has shown that lesions heal in 70% to 97% of patients.12

WHEN TO CONSIDER AGGRESSIVE MANAGEMENT

Under the circumstances listed above, revascularization with PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) should be considered, with choice of procedure determined by feasibility, technical considerations, and local expertise.

The American Heart Association recommendations are as follows12:

- For left main or severe proximal 2-vessel dissection in clinically stable patients, consider CABG

- For active ischemia or hemodynamic instability, consider PCI if feasible or perform urgent CABG.

A few series have shown that the prognosis with conservative management or CABG is better than with PCI.8,13,14 The success rate for revascularization with PCI is only about 60% because of challenges including risk of inducing iatrogenic dissection, passing the wire into the false lumen and worsening a dissection, and propagating an intramural hematoma with stenting and further compromising coronary blood flow. In addition, dissection tends to extend into distal arteries that are difficult to stent. There is also the risk of stent malapposition after resorption of the intramural hematoma, causing late stent thrombosis.7

SCREEN FOR OTHER VASCULAR PROBLEMS

Imaging of the renal, iliac, and cerebral vasculature is recommended for all patients with SCAD.12 Screening for fibromuscular dysplasia can be done with angiography, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).12

Multifocal fibromuscular dysplasia in extracoronary arteries occurs with SCAD in 25% to 86% of cases. In a single-center series of 115 patients with confirmed SCAD who underwent CTA from 2010 to 2014, extracoronary vascular abnormalities were found in 66%, with fibromuscular dysplasia being the most common type (45%).15 In another single-center study, 327 patients with SCAD were prospectively followed from 2012 to 2016 with screening for cerebrovascular, renal, and iliac fibromuscular dysplasia using CTA or catheter angiography. Fibromuscular dysplasia was found in 63%, and intracranial aneurysm was found in 14% of patients with fibromuscular dysplasia.9

SCAD can also be associated with connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV and Marfan syndrome.16,17

LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT

Patients with SCAD should start long-term aspirin and 1 year of clopidogrel. Statins are indicated for patients with hyperlipidemia8,18 but otherwise offer no clear benefit for SCAD alone. If there are no contraindications, a beta-adrenergic blocker should be considered, especially if left ventricular dysfunction or arrhythmias are present. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers should also be considered with concomitant left ventricular dysfunction. Antianginal therapy can be used for post-SCAD chest pain syndromes.12

Repeat angiography is recommended only to evaluate recurrent symptoms, to confirm an unclear initial diagnosis, to assess for atherosclerosis-related stenosis, or to evaluate high-risk anatomy, eg, involvement of the left main coronary artery.12

Genetic testing is reserved for patients with a high clinical suspicion of connective tissue disease or systemic arteriopathy.19

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (Figure 1) showed ST-segment elevation of more than 2 mm in leads V2, V3, V4, and V5, with no reciprocal changes.

Based on the classic angiographic appearance and the absence of atherosclerotic disease in other coronary arteries, type 2 spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) was diagnosed.

CORONARY ARTERY WALL SEPARATION

SCAD is defined as a nontraumatic, noniatrogenic intramural hemorrhage leading to separation of the coronary arterial wall and the formation of a false lumen. The separation can occur between any of the coronary artery wall layers and may or may not involve an intimal tear. The bleeding may result in an intramural hematoma and possible narrowing of the arterial lumen. Depending on the severity of narrowing, blood supply to the myocardium could be compromised, resulting in symptoms of ischemia.1

SCAD usually involves a single coronary artery, although multiple coronary artery involvement has been reported.2

CASE CONTINUED: MANAGEMENT

The patient recovered completely and was discharged home with plans to return for outpatient imaging for fibromuscular dysplasia.

SCAD: RARE OR JUST RARELY RECOGNIZED?

SCAD appears to be a rare cause of acute coronary syndrome, but it is likely underdiagnosed and is becoming increasingly recognized worldwide. Typically, it affects women younger than 50, with women in general outnumbering men 9 to 1.3 Overall, SCAD causes up to 4% of acute myocardial infarctions, but in women age 50 or younger, it is responsible for 24% to 35% of acute myocardial infarctions, and the proportion is even higher in pregnant women.4

Not just pregnancy-associated

SCAD was previously thought to be mainly idiopathic and mostly affecting women peripartum. Current understanding paints a different picture: pregnancy-associated SCAD does not account for the majority of cases. That said, SCAD is the most common cause of myocardial infarction peripartum, with the third trimester and early postpartum period being the times of highest risk.5 SCAD development at those times is believed to be related to hormonal changes causing weakening of coronary artery walls.6

Weakening of the coronary artery wall also may occur in the setting of fibromuscular dysplasia, connective tissue disease, recurrent pregnancies, systemic inflammatory disease, hormonal therapy, and other disease states that cause arteriopathy. Exposure to a stressor in a patient with underlying risk factors can lead to either an intimal tear or rupture of the vasa vasorum, with subsequent formation of intramural hemorrhage and eventually SCAD.7 Stressors can be emotional or physical and can include labor and delivery, intense physical exercise, the Valsalva maneuver, and drug abuse.8

Presentation is variable

SCAD presentation depends on the degree of flow limitation and extent of the dissection. Presentation can range from asymptomatic to sudden cardiac death and can include signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome caused by ST-segment elevation or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

DIAGNOSIS BY ANGIOGRAPHY

SCAD can be diagnosed by coronary angiography. There are 3 angiographic types:

Type 1 (about 25% of SCAD cases) has typical contrast dye staining of the arterial wall and multiple radiolucent luminal abnormalities, with or without dye hang-up.

Type 2 (about 70%) has diffuse, smooth narrowing of the coronary artery, with the left anterior descending artery the most frequently affected.8

Type 3 (about 5%) mimics atherosclerosis, with focal or tubular stenosis.9

Types 1 and 2 are usually easy to recognize. To diagnose type 2, intravenous nitroglycerin should first be administered to rule out coronary spasm.

Type 3 SCAD is more challenging to diagnose because its appearance on angiography is similar to that of atherosclerosis. For equivocal findings in any type, but especially in type 3, intravascular ultrasonography or optical coherence tomography can help.10 Optical coherence tomography is preferred because of superior image resolution, although ultrasonography offers better tissue penetration.11

MANAGE MOST CASES CONSERVATIVELY

Management algorithms for SCAD are available.8,12

The initial and most critical step is to make the correct diagnosis. Although the presentation of acute coronary syndrome caused by SCAD is often identical to that of atherosclerosis, the conditions have different pathophysiologies and thus require different management. Theoretically, systemic anticoagulation may worsen an intramural hemorrhage.

First-line therapy for most patients with SCAD is conservative management and close inpatient monitoring for 3 to 5 days.13 More aggressive management is indicated for any of the following:

- Left main or severe proximal 2-vessel dissection

- Hemodynamic instability

- Ongoing ischemic symptoms.

In a prospective cohort of 168 patients, 134 (80%) were initially treated conservatively; of those, in-hospital myocardial infarction recurred in 4.5%, a major cardiac event occurred within 2 years in 17%, and SCAD recurred in 13%.8

Observational data on patients with SCAD who had repeat angiography weeks to months after the initial event has shown that lesions heal in 70% to 97% of patients.12

WHEN TO CONSIDER AGGRESSIVE MANAGEMENT

Under the circumstances listed above, revascularization with PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) should be considered, with choice of procedure determined by feasibility, technical considerations, and local expertise.

The American Heart Association recommendations are as follows12:

- For left main or severe proximal 2-vessel dissection in clinically stable patients, consider CABG

- For active ischemia or hemodynamic instability, consider PCI if feasible or perform urgent CABG.

A few series have shown that the prognosis with conservative management or CABG is better than with PCI.8,13,14 The success rate for revascularization with PCI is only about 60% because of challenges including risk of inducing iatrogenic dissection, passing the wire into the false lumen and worsening a dissection, and propagating an intramural hematoma with stenting and further compromising coronary blood flow. In addition, dissection tends to extend into distal arteries that are difficult to stent. There is also the risk of stent malapposition after resorption of the intramural hematoma, causing late stent thrombosis.7

SCREEN FOR OTHER VASCULAR PROBLEMS

Imaging of the renal, iliac, and cerebral vasculature is recommended for all patients with SCAD.12 Screening for fibromuscular dysplasia can be done with angiography, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).12

Multifocal fibromuscular dysplasia in extracoronary arteries occurs with SCAD in 25% to 86% of cases. In a single-center series of 115 patients with confirmed SCAD who underwent CTA from 2010 to 2014, extracoronary vascular abnormalities were found in 66%, with fibromuscular dysplasia being the most common type (45%).15 In another single-center study, 327 patients with SCAD were prospectively followed from 2012 to 2016 with screening for cerebrovascular, renal, and iliac fibromuscular dysplasia using CTA or catheter angiography. Fibromuscular dysplasia was found in 63%, and intracranial aneurysm was found in 14% of patients with fibromuscular dysplasia.9

SCAD can also be associated with connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV and Marfan syndrome.16,17

LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT

Patients with SCAD should start long-term aspirin and 1 year of clopidogrel. Statins are indicated for patients with hyperlipidemia8,18 but otherwise offer no clear benefit for SCAD alone. If there are no contraindications, a beta-adrenergic blocker should be considered, especially if left ventricular dysfunction or arrhythmias are present. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers should also be considered with concomitant left ventricular dysfunction. Antianginal therapy can be used for post-SCAD chest pain syndromes.12

Repeat angiography is recommended only to evaluate recurrent symptoms, to confirm an unclear initial diagnosis, to assess for atherosclerosis-related stenosis, or to evaluate high-risk anatomy, eg, involvement of the left main coronary artery.12

Genetic testing is reserved for patients with a high clinical suspicion of connective tissue disease or systemic arteriopathy.19

- Garcia NA, Khan AN, Boppana RC, Smith HL. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a case series and literature review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2014; 4(4). doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25261

- Lempereur M, Gin K, Saw J. Multivessel spontaneous coronary artery dissection mimicking atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(7):e87–e88. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2013.12.207

- Mahmoud AN, Taduru SS, Mentias A, et al. Trends of incidence, clinical presentation, and in-hospital mortality among women with acute myocardial infarction with or without spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a population-based analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018; 11(1):80–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.016

- Saw J. Pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection represents an exceptionally high-risk spontaneous coronary artery dissection cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017; 10(3)pii:e005119. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005119

- Elkayam U, Jalnapurkar S, Barakkat MN, et al. Pregnancy-associated acute myocardial infarction: a review of contemporary experience in 150 cases between 2006 and 2011. Circulation 2014; 129(16):1695–1702. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002054

- Vijayaraghavan R, Verma S, Gupta N, Saw J. Pregnancy-related spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation 2014; 130(21):1915–1920. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011422

- Saw J, Mancini GBJ, Humphries KH. Contemporary review on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68(3):297–312. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.034

- Saw J, Aymong E, Sedlak T, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: association with predisposing arteriopathies and precipitating stressors and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(5):645–655. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001760

- Saw J, Humphries K ,Aymong E, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: clinical outcomes and risk of recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(9):1148–1158. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.053

- Alfonso F, Bastante T, Cuesta J, Rodríguez D, Benedicto A, Rivero F. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: novel insights on diagnosis and management. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2015; 5(2):133–140. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.03.05

- Kern MJ, Meier B. Evaluation of the culprit plaque and the physiological significance of coronary atherosclerotic narrowings. Circulation 2001; 103(25):3142–3149. pmid:11425782

- Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; and Stroke Council. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: current state of the science: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137(19):e523–e557. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000564

- Tweet MS, Eleid MF, Best PJ, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: revascularization versus conservative therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(6):777–786. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001659

- Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation 2012; 126(5):579–588. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105718

- Prasad M, Tweet MS, Hayes SN, et al. Prevalence of extracoronary vascular abnormalities and fibromuscular dysplasia in patients with spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol 2015; 115(12):1672–1677. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.011

- Adès LC, Waltham RD, Chiodo AA, Bateman JF. Myocardial infarction resulting from coronary artery dissection in an adolescent with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV due to a type III collagen mutation. Br Heart J 1995; 74(2):112–116. pmid:7546986

- Judge DP, Dietz HC. Marfan’s syndrome. Lancet 2005; 366(9501):1965–1976. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67789-6

- Saw J. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Can J Cardiol 2013; 29(9):1027–1033. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2012.12.018

- Poloskey SL, Kim ES, Sanghani R, et al. Low yield of genetic testing for known vascular connective tissue disorders in patients with fibromuscular dysplasia. Vasc Med 2012; 17(6):371–378. doi:10.1177/1358863X12459650

- Garcia NA, Khan AN, Boppana RC, Smith HL. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a case series and literature review. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2014; 4(4). doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.25261

- Lempereur M, Gin K, Saw J. Multivessel spontaneous coronary artery dissection mimicking atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(7):e87–e88. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2013.12.207

- Mahmoud AN, Taduru SS, Mentias A, et al. Trends of incidence, clinical presentation, and in-hospital mortality among women with acute myocardial infarction with or without spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a population-based analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018; 11(1):80–90. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.016

- Saw J. Pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection represents an exceptionally high-risk spontaneous coronary artery dissection cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2017; 10(3)pii:e005119. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.117.005119

- Elkayam U, Jalnapurkar S, Barakkat MN, et al. Pregnancy-associated acute myocardial infarction: a review of contemporary experience in 150 cases between 2006 and 2011. Circulation 2014; 129(16):1695–1702. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002054

- Vijayaraghavan R, Verma S, Gupta N, Saw J. Pregnancy-related spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation 2014; 130(21):1915–1920. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011422

- Saw J, Mancini GBJ, Humphries KH. Contemporary review on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68(3):297–312. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.034

- Saw J, Aymong E, Sedlak T, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: association with predisposing arteriopathies and precipitating stressors and cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(5):645–655. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001760

- Saw J, Humphries K ,Aymong E, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: clinical outcomes and risk of recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(9):1148–1158. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.06.053

- Alfonso F, Bastante T, Cuesta J, Rodríguez D, Benedicto A, Rivero F. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: novel insights on diagnosis and management. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2015; 5(2):133–140. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2015.03.05

- Kern MJ, Meier B. Evaluation of the culprit plaque and the physiological significance of coronary atherosclerotic narrowings. Circulation 2001; 103(25):3142–3149. pmid:11425782

- Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine; and Stroke Council. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: current state of the science: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018; 137(19):e523–e557. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000564

- Tweet MS, Eleid MF, Best PJ, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: revascularization versus conservative therapy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 7(6):777–786. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001659

- Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation 2012; 126(5):579–588. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105718

- Prasad M, Tweet MS, Hayes SN, et al. Prevalence of extracoronary vascular abnormalities and fibromuscular dysplasia in patients with spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol 2015; 115(12):1672–1677. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.011

- Adès LC, Waltham RD, Chiodo AA, Bateman JF. Myocardial infarction resulting from coronary artery dissection in an adolescent with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV due to a type III collagen mutation. Br Heart J 1995; 74(2):112–116. pmid:7546986

- Judge DP, Dietz HC. Marfan’s syndrome. Lancet 2005; 366(9501):1965–1976. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67789-6

- Saw J. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Can J Cardiol 2013; 29(9):1027–1033. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2012.12.018

- Poloskey SL, Kim ES, Sanghani R, et al. Low yield of genetic testing for known vascular connective tissue disorders in patients with fibromuscular dysplasia. Vasc Med 2012; 17(6):371–378. doi:10.1177/1358863X12459650

KEY POINTS

- SCAD often presents with symptoms of acute coronary syndrome but can be asymptomatic or cause sudden death.

- Management is generally conservative, but a left main or severe proximal 2-vessel dissection, hemodynamic instability, or ongoing ischemic symptoms may warrant revascularization.

- All patients with SCAD should be screened for other vascular problems, especially fibromuscular dysplasia.

- Long-term aspirin therapy and 1 year of clopidogrel are recommended after an episode of SCAD.

Gastroparesis in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

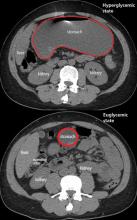

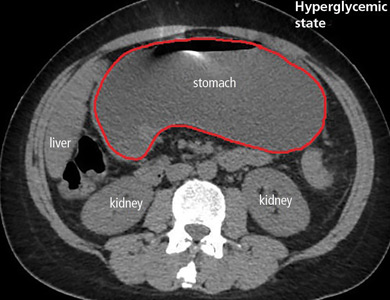

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

A 40-year-old man with type 1 diabetes mellitus and recurrent renal calculi presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain for the past day. He had been checking his blood glucose level regularly, and it had usually been within the normal range until 2 or 3 days previously, when he stopped taking his insulin because he ran out and could not afford to buy more.

He said he initially vomited clear mucus but then had 2 episodes of black vomit. His abdominal pain was diffuse but more intense in his flanks. He said he had never had nausea or vomiting before this episode.

In the emergency department, his heart rate was 136 beats per minute and respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. He appeared to be in mild distress, and physical examination revealed a distended abdomen, decreased bowel sounds on auscultation, tympanic sound elicited by percussion, and diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation without rebound tenderness or rigidity. His blood glucose level was 993 mg/dL, and his anion gap was 36 mmol/L.

The patient was treated with hydration, insulin, and a nasogastric tube to relieve the pressure. The following day, his symptoms had significantly improved, his abdomen was less distended, his bowel sounds had returned, and his plasma glucose levels were in the normal range. The nasogastric tube was removed after he started to have bowel movements; he was given liquids by mouth and eventually solid food. Since his condition had significantly improved and he had started to have bowel movements, no follow-up imaging was done. The next day, he was symptom-free, his laboratory values were normal, and he was discharged home.

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is defined by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of a mechanical obstruction, with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. Most commonly it is idiopathic or caused by long-standing uncontrolled diabetes.

Diabetic gastroparesis is thought to result from impaired neural control of gastric function. Damage to the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal and underlying smooth muscle may be contributing factors.1 It is usually chronic, with a mean duration of symptoms of 26.5 months.2 However, acute gastroparesis can occur after an acute elevation in the plasma glucose concentration, which can affect gastric sensory and motor function3 via relaxation of the proximal stomach, decrease in antral pressure waves, and increase in pyloric pressure waves.4

Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis often present with symptoms similar to those of gastroparesis, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.5 But acute gastroparesis can coexist with diabetic ketoacidosis, as in our patient, and the gastroparesis can go undiagnosed, since imaging studies are not routinely done for diabetic ketoacidosis unless there is another reason—as in our patient.

More study is needed to answer questions on long-term outcomes for patients presenting with acute gastroparesis: Do they develop chronic gastroparesis? And is there is a correlation with progression of neuropathy?

The diagnosis usually requires a high level of suspicion in patients with nausea, vomiting, fullness, abdominal pain, and bloating; exclusion of gastric outlet obstruction by a mass or antral stenosis; and evidence of delayed gastric emptying. Gastric outlet obstruction can be ruled out by endoscopy, abdominal CT, or magnetic resonance enterography. Delayed gastric emptying can be quantified with scintigraphy and endoscopy. In our patient, gastroparesis was diagnosed on the basis of the clinical symptoms and CT findings.

Treatment is usually directed at symptoms, with better glycemic control and dietary modification for moderate cases, and prokinetics and a gastrostomy tube for severe cases.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Gastroparesis is usually chronic but can present acutely with acute severe hyperglycemia.

- Gastrointestinal tract motor function is affected by plasma glucose levels and can change over brief intervals.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis symptoms can mask acute gastroparesis, as imaging studies are not routinely done.

- Acute gastroparesis can be diagnosed clinically along with abdominal CT or endoscopy to rule out gastric outlet obstruction.

- Acute gastroparesis caused by diabetic ketoacidosis can resolve promptly with tight control of plasma glucose levels, anion gap closing, and nasogastric tube placement.

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

- Parkman HP, Hasler WL, Fisher RS; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(5):1592–1622. pmid:15521026

- Dudekula A, O’Connell M, Bielefeldt K. Hospitalizations and testing in gastroparesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26(8):1275–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06735.x

- Fraser RJ, Horowitz M, Maddox AF, Harding PE, Chatterton BE, Dent J. Hyperglycaemia slows gastric emptying in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33(11):675–680. pmid:2076799

- Mearin F, Malagelada JR. Gastroparesis and dyspepsia in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1995; 7(8):717–723. pmid:7496857

- Malone ML, Gennis V, Goodwin JS. Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(11):1100–1104. pmid:1401693

How should I treat acute agitation in pregnancy?

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4

For the agitated pregnant woman who is not belligerent at presentation, triage should start with a basic assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation, as well as vital signs and glucose level.5 A thorough medical history and a description of events leading to the presentation, obtained from the patient or the patient’s family or friends, are vital for narrowing the diagnosis and deciding treatment.

The initial evaluation should include consideration of delirium, trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, amniotic and venous thromboembolism, hypoxia and hypercapnia, and signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, cocaine, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, and substituted cathinones (“bath salts”). From 20 weeks of gestation to 6 weeks postpartum, eclampsia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.1 Ruling out these conditions is important since the management of each differs vastly from the protocol for agitation secondary to psychosis, mania, or delirium.

NEW SYSTEM TO DETERMINE RISK DURING PREGNANCY, LACTATION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discontinued its pregnancy category labeling system that used the letters A, B, C, D, and X to convey reproductive and lactation safety. The new system, established under the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule,6 provides descriptive, up-to-date explanations of risk, as well as previously absent context regarding baseline risk for major malformations in the general population to help with informed decision-making.7 This allows the healthcare provider to interpret the risk for an individual patient.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS SAFE, EFFECTIVE IN PREGNANCY

Reproductive safety of first-generation (ie, typical) neuroleptics such as haloperidol is supported by extensive data accumulated over the past 50 years.2,3,8 No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with this drug class,7 although a 1996 meta-analysis found a small increase in the relative risk of congenital malformations in offspring exposed to low-potency antipsychotics compared with those exposed to high-potency antipsychotics.2

In general, mid- and high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine) are often recommended because they are less likely to have associated sedative or hypotensive effects than low-potency antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, perphenazine), which may be a significant consideration for a pregnant patient.2,8

There is a theoretical risk of neonatal extrapyramidal symptoms with exposure to first-generation antipsychotics in the third trimester, but the data to support this are from sparse case reports and small observational cohorts.9

NEWER ANTIPSYCHOTICS ALSO SAFE IN PREGNANCY

Newer antipsychotics such as the second-generation antipsychotics, available since the mid-1990s, are increasingly used as primary or adjunctive therapy across a wide range of psychiatric disorders.10 Recent data from large, prospective cohort studies investigating reproductive safety of these agents are reassuring, with no specific patterns of organ malformation.11,12

DIPHENHYDRAMINE

Recent studies of antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have not reported any risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure to antihistamines.13,14 Dose-dependent anticholinergic adverse effects of antihistamines can induce or exacerbate delirium and agitation, although these effects are classically seen in elderly, nonpregnant patients.15 Thus, given the paucity of adverse effects and the low risk, diphenhydramine is considered safe to use in pregnancy.13

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not contraindicated for the treatment of acute agitation in pregnancy.16 Reproductive safety data from meta-analyses and large population-based cohort studies have found no evidence of increased risk of major malformations in neonates born to mothers on prescription benzodiazepines in the first trimester.17,18 While third-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines has been associated with “floppy-baby” syndrome and neonatal withdrawal syndrome,16 these are more likely to occur in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy. No study has yet assessed the risk of these outcomes with a 1-time acute exposure in the emergency department; however, the risk is likely minimal given the aforementioned data observed in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy.

STEPWISE MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

If untreated, agitation in pregnancy is independently associated with outcomes that include premature delivery, low birth weight, growth retardation, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1 The risk of these outcomes greatly outweighs any potential risk from psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, intervention should progress in a stepwise manner, starting with the least restrictive and progressing toward more restrictive interventions, including pharmacotherapy, use of a seclusion room, and physical restraints (Figure 1).4,19

Before medications are considered, attempts should be made to engage with and “de-escalate” the patient in a safe, nonstimulating environment.19 If this approach is not effective, the patient should be offered oral medications to help with her agitation. However, if the patient’s behavior continues to escalate, presenting a danger to herself or staff, the use of emergency medications is clearly indicated. Providers should succinctly inform the patient of the need for immediate intervention.

If the patient has had a good response in the past to one of these medications or is currently taking one as needed, the same medication should be offered. If the patient has never been treated for agitation, it is important to consider the presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, and the route and rapidity of administration of medication. If the patient has experienced a fall or other trauma, confirming a viable fetal heart rate between 10 to 22 weeks of gestation with Doppler ultrasonography and obstetric consultation should be considered.

DRUG THERAPY RECOMMENDATIONS

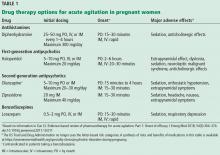

Mild to moderate agitation in pregnancy should be managed conservatively with diphenhydramine. Other options include a benzodiazepine, particularly lorazepam, if alcohol withdrawal is suspected. A second-generation antipsychotic such as olanzapine in a rapidly dissolving form or ziprasidone is another option if a rapid response is required.20Table 1 provides a summary of pharmacotherapy recommendations.

Severe agitation may require a combination of agents. A commonly used, safe regimen—colloquially called the “B52 bomb”—is haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg for prophylaxis of dystonia.20

The patient’s response should be monitored closely, as dosing may require modification as a result of pregnancy-related changes in drug distribution, metabolism, and clearance.21

Although no study to our knowledge has assessed risk associated with 1-time exposure to any of these classes of medications in pregnant women, the aforementioned data on long-term exposure provide reassurance that single exposure in emergency departments likely has little or no effect for the developing fetus.

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS FOR AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

Physical restraints along with emergency medications (ie, chemical restraint) may be indicated when the patient poses a danger to herself or others. In some cases, both types of restraint may be required, whether in the emergency room or an inpatient setting.

However, during the second and third trimesters, physical restraints such as 4-point restraints may predispose the patient to inferior vena cava compression syndrome and compromise placental blood flow.4 Therefore, pregnant patients after 20 weeks of gestation should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, with the right hip positioned 10 to 12 cm off the bed with pillows or blankets. And when restraints are used in pregnant patients, frequent checking of vital signs and physical assessment is needed to mitigate risks.4

- Aftab A, Shah AA. Behavioral emergencies: special considerations in the pregnant patient. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017; 40(3):435–448. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2017.05.017

- Altshuler LL, Cohen L, Szuba MP, Burt VK, Gitlin M, Mintz J. Pharmacologic management of psychiatric illness during pregnancy: dilemmas and guidelines. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153(5):592–606. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.5.592

- Einarson A. Safety of psychotropic drug use during pregnancy: a review. MedGenMed 2005; 7(4):3. pmid:16614625

- Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Shah AA, Vilke GM. Psychiatric emergencies in pregnant women. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2015; 33(4):841–851. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.07.010

- Brown HE, Stoklosa J, Freundenreich O. How to stabilize an acutely psychotic patient. Curr Psychiatry 2012; 11(12):10–16.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed January 8, 2019.

- Brucker MC, King TL. The 2015 US Food and Drug Administration pregnancy and lactation labeling rule. J Midwifery Womens Health 2017; 62(3):308–316. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12611

- Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Ornoy S, et al. Safety of haloperidol and penfluridol in pregnancy: a multicenter, prospective, controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66(3):317–322. pmid:15766297

- Galbally M, Snellen M, Power J. Antipsychotic drugs in pregnancy: a review of their maternal and fetal effects. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014; 5(2):100–109. doi:10.1177/2042098614522682

- Kulkarni J, Storch A, Baraniuk A, Gilbert H, Gavrilidis E, Worsley R. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015; 16(9):1335–1345. doi:10.1517/14656566.2015.1041501

- Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(9):938–946. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1520

- Cohen LS, Viguera AC, McInerney KA, et al. Reproductive safety of second-generation antipsychotics: current data from the Massachusetts General Hospital national pregnancy registry for atypical antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(3):263–270. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15040506

- Li Q, Mitchell AA, Werler MM, Yau WP, Hernández-Díaz S. Assessment of antihistamine use in early pregnancy and birth defects. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1(6):666–674.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.008

- Gilboa SM, Strickland MJ, Olshan AF, Werler MM, Correa A; National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Use of antihistamine medications during early pregnancy and isolated major malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009; 85(2):137–150. doi:10.1002/bdra.20513

- Meuleman JR. Association of diphenhydramine use with adverse effects in hospitalized older patients: possible confounders. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(6):720–721. pmid:11911733

- Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2011; 33(1):46–48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7

- Dolovich LR, Addis A, Vaillancourt JM, Power JD, Koren G, Einarson TR. Benzodiazepine use in pregnancy and major malformations or oral cleft: meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. BMJ 1998; 317(7162):839–843. pmid:9748174

- Bellantuono C, Tofani S, Di Sciascio G, Santone G. Benzodiazepine exposure in pregnancy and risk of major malformations: a critical overview. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013; 35(1):3–8. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.09.003

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012; 13(1):17–25. doi:10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864

- Prager LM, Ivkovic A. Emergency psychiatry. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. The Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2016:937–949.

- Feghali M, Venkataramanan R, Caritis S. Pharmacokinetics of drugs in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2015; 39(7):512–519. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2015.08.003

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4

For the agitated pregnant woman who is not belligerent at presentation, triage should start with a basic assessment of airways, breathing, and circulation, as well as vital signs and glucose level.5 A thorough medical history and a description of events leading to the presentation, obtained from the patient or the patient’s family or friends, are vital for narrowing the diagnosis and deciding treatment.

The initial evaluation should include consideration of delirium, trauma, intracranial hemorrhage, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, amniotic and venous thromboembolism, hypoxia and hypercapnia, and signs and symptoms of intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, cocaine, phencyclidine, methamphetamine, and substituted cathinones (“bath salts”). From 20 weeks of gestation to 6 weeks postpartum, eclampsia should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.1 Ruling out these conditions is important since the management of each differs vastly from the protocol for agitation secondary to psychosis, mania, or delirium.

NEW SYSTEM TO DETERMINE RISK DURING PREGNANCY, LACTATION

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has discontinued its pregnancy category labeling system that used the letters A, B, C, D, and X to convey reproductive and lactation safety. The new system, established under the FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule,6 provides descriptive, up-to-date explanations of risk, as well as previously absent context regarding baseline risk for major malformations in the general population to help with informed decision-making.7 This allows the healthcare provider to interpret the risk for an individual patient.

FIRST-GENERATION ANTIPSYCHOTICS SAFE, EFFECTIVE IN PREGNANCY

Reproductive safety of first-generation (ie, typical) neuroleptics such as haloperidol is supported by extensive data accumulated over the past 50 years.2,3,8 No significant teratogenic effect has been documented with this drug class,7 although a 1996 meta-analysis found a small increase in the relative risk of congenital malformations in offspring exposed to low-potency antipsychotics compared with those exposed to high-potency antipsychotics.2

In general, mid- and high-potency antipsychotics (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine) are often recommended because they are less likely to have associated sedative or hypotensive effects than low-potency antipsychotics (eg, chlorpromazine, perphenazine), which may be a significant consideration for a pregnant patient.2,8

There is a theoretical risk of neonatal extrapyramidal symptoms with exposure to first-generation antipsychotics in the third trimester, but the data to support this are from sparse case reports and small observational cohorts.9

NEWER ANTIPSYCHOTICS ALSO SAFE IN PREGNANCY

Newer antipsychotics such as the second-generation antipsychotics, available since the mid-1990s, are increasingly used as primary or adjunctive therapy across a wide range of psychiatric disorders.10 Recent data from large, prospective cohort studies investigating reproductive safety of these agents are reassuring, with no specific patterns of organ malformation.11,12

DIPHENHYDRAMINE

Recent studies of antihistamines such as diphenhydramine have not reported any risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure to antihistamines.13,14 Dose-dependent anticholinergic adverse effects of antihistamines can induce or exacerbate delirium and agitation, although these effects are classically seen in elderly, nonpregnant patients.15 Thus, given the paucity of adverse effects and the low risk, diphenhydramine is considered safe to use in pregnancy.13

BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are not contraindicated for the treatment of acute agitation in pregnancy.16 Reproductive safety data from meta-analyses and large population-based cohort studies have found no evidence of increased risk of major malformations in neonates born to mothers on prescription benzodiazepines in the first trimester.17,18 While third-trimester exposure to benzodiazepines has been associated with “floppy-baby” syndrome and neonatal withdrawal syndrome,16 these are more likely to occur in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy. No study has yet assessed the risk of these outcomes with a 1-time acute exposure in the emergency department; however, the risk is likely minimal given the aforementioned data observed in women on long-term prescription benzodiazepine therapy.

STEPWISE MANAGEMENT OF AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

If untreated, agitation in pregnancy is independently associated with outcomes that include premature delivery, low birth weight, growth retardation, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1 The risk of these outcomes greatly outweighs any potential risk from psychotropic medications during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, intervention should progress in a stepwise manner, starting with the least restrictive and progressing toward more restrictive interventions, including pharmacotherapy, use of a seclusion room, and physical restraints (Figure 1).4,19

Before medications are considered, attempts should be made to engage with and “de-escalate” the patient in a safe, nonstimulating environment.19 If this approach is not effective, the patient should be offered oral medications to help with her agitation. However, if the patient’s behavior continues to escalate, presenting a danger to herself or staff, the use of emergency medications is clearly indicated. Providers should succinctly inform the patient of the need for immediate intervention.

If the patient has had a good response in the past to one of these medications or is currently taking one as needed, the same medication should be offered. If the patient has never been treated for agitation, it is important to consider the presenting symptoms, differential diagnosis, and the route and rapidity of administration of medication. If the patient has experienced a fall or other trauma, confirming a viable fetal heart rate between 10 to 22 weeks of gestation with Doppler ultrasonography and obstetric consultation should be considered.

DRUG THERAPY RECOMMENDATIONS

Mild to moderate agitation in pregnancy should be managed conservatively with diphenhydramine. Other options include a benzodiazepine, particularly lorazepam, if alcohol withdrawal is suspected. A second-generation antipsychotic such as olanzapine in a rapidly dissolving form or ziprasidone is another option if a rapid response is required.20Table 1 provides a summary of pharmacotherapy recommendations.

Severe agitation may require a combination of agents. A commonly used, safe regimen—colloquially called the “B52 bomb”—is haloperidol 5 mg, lorazepam 2 mg, and diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg for prophylaxis of dystonia.20

The patient’s response should be monitored closely, as dosing may require modification as a result of pregnancy-related changes in drug distribution, metabolism, and clearance.21

Although no study to our knowledge has assessed risk associated with 1-time exposure to any of these classes of medications in pregnant women, the aforementioned data on long-term exposure provide reassurance that single exposure in emergency departments likely has little or no effect for the developing fetus.

PHYSICAL RESTRAINTS FOR AGITATION IN PREGNANCY

Physical restraints along with emergency medications (ie, chemical restraint) may be indicated when the patient poses a danger to herself or others. In some cases, both types of restraint may be required, whether in the emergency room or an inpatient setting.

However, during the second and third trimesters, physical restraints such as 4-point restraints may predispose the patient to inferior vena cava compression syndrome and compromise placental blood flow.4 Therefore, pregnant patients after 20 weeks of gestation should be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, with the right hip positioned 10 to 12 cm off the bed with pillows or blankets. And when restraints are used in pregnant patients, frequent checking of vital signs and physical assessment is needed to mitigate risks.4

Acute agitation in the pregnant patient should be treated as an obstetric emergency, as it jeopardizes the safety of the patient and fetus, as well as others in the emergency room. Uncontrolled agitation is associated with obstetric complications such as preterm delivery, placental abnormalities, postnatal death, and spontaneous abortion.1

Current data on the reproductive safety of drugs commonly used to treat acute agitation—benzodiazepines, typical (first-generation) antipsychotics, atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, and diphenhydramine—suggest no increase in risk beyond the 2% to 3% risk of congenital malformations in the general population when used in the first trimester.2,3

FOCUS OF THE EMERGENCY EVALUATION

Agitation is defined as the physical manifestation of internal distress, due to an underlying medical condition such as delirium or to a psychiatric condition such as acute intoxication or withdrawal, psychosis, mania, or personality disorder.4