User login

Medicare adds HPV test for cervical cancer screening

Medicare officials have added the human papillomavirus test to its list of covered services for cervical cancer screening.

In a national coverage decision issued on July 9, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that the “evidence is sufficient” to add HPV testing once every 5 years as a preventive service benefit under the Medicare program for asymptomatic women aged 30-65 years in conjunction with the Pap smear test.

Previously Medicare only covered a screening pelvic examination and Pap smear test at 12- and 24-month intervals based on specific risk factors.

The decision has the potential to affect about 5 million women aged 30-65 who are enrolled in the Medicare program, according to a CMS estimate.

In 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening with a combination of Pap smear and HPV testing every 5 years for women aged 30-65 years. The task force recommends against using HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in women younger than age 30.

The American Academy of Family Physicians, which had urged Medicare officials to add the HPV test as a covered option for cervical screening, praised the decision.

“This decision is consistent with the best medical evidence and provides women and their physicians more options for cervical cancer screening,” Dr. Robert L. Wergin, AAFP president, said in a statement.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

Medicare officials have added the human papillomavirus test to its list of covered services for cervical cancer screening.

In a national coverage decision issued on July 9, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that the “evidence is sufficient” to add HPV testing once every 5 years as a preventive service benefit under the Medicare program for asymptomatic women aged 30-65 years in conjunction with the Pap smear test.

Previously Medicare only covered a screening pelvic examination and Pap smear test at 12- and 24-month intervals based on specific risk factors.

The decision has the potential to affect about 5 million women aged 30-65 who are enrolled in the Medicare program, according to a CMS estimate.

In 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening with a combination of Pap smear and HPV testing every 5 years for women aged 30-65 years. The task force recommends against using HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in women younger than age 30.

The American Academy of Family Physicians, which had urged Medicare officials to add the HPV test as a covered option for cervical screening, praised the decision.

“This decision is consistent with the best medical evidence and provides women and their physicians more options for cervical cancer screening,” Dr. Robert L. Wergin, AAFP president, said in a statement.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

Medicare officials have added the human papillomavirus test to its list of covered services for cervical cancer screening.

In a national coverage decision issued on July 9, officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that the “evidence is sufficient” to add HPV testing once every 5 years as a preventive service benefit under the Medicare program for asymptomatic women aged 30-65 years in conjunction with the Pap smear test.

Previously Medicare only covered a screening pelvic examination and Pap smear test at 12- and 24-month intervals based on specific risk factors.

The decision has the potential to affect about 5 million women aged 30-65 who are enrolled in the Medicare program, according to a CMS estimate.

In 2012, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening with a combination of Pap smear and HPV testing every 5 years for women aged 30-65 years. The task force recommends against using HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in women younger than age 30.

The American Academy of Family Physicians, which had urged Medicare officials to add the HPV test as a covered option for cervical screening, praised the decision.

“This decision is consistent with the best medical evidence and provides women and their physicians more options for cervical cancer screening,” Dr. Robert L. Wergin, AAFP president, said in a statement.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

Does a high-dose influenza vaccine protect older adults to a greater extent than the standard-dose vaccine?

The objective of this investigation was to compare a standard-dose trivalent influenza vaccine with a high-dose vaccine in adults older than 65 years. The standard dose of the vaccine contained 15 µg of hemagglutinin per strain, and the high dose contained 60 µg hemagglutinin per strain. The study was conducted during the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 flu seasons. Key outcome measures were efficacy, as assessed by the occurrence of laboratory-confirmed influenza at least 14 days after vaccination; immunogenicity of the vaccines; and frequency of adverse events.

Details of the study

The study involved 15,991 patients in the high-dose group and 15,998 patients in the standard-dose group. Two hundred twenty-eight participants (1.4%) in the high-dose group developed influenza, compared with 301 participants (1.9%) in the standard-dose group.

The overall efficacy of the high-dose vaccine was 24.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 9.7–36.5), meaning that approximately 24% of influenza cases could have been prevented if the high-dose vaccine had been administered to all patients.

In the high-dose group, 8.3% of patients had at least 1 adverse event, compared with 9% in the standard-dose group (relative risk, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.85–0.99).

After vaccination, the hemagglutination inhibition titers were significantly higher in the high-dose group.

Fewer adverse events with the higher dose, but some events were graver

Influenza is a serious viral illness, and it can be associated with mortality in certain populations, such as very young children, pregnant women, and people older than 65 years.

As a general rule, older patients do not respond as well to the vaccine as younger patients do. The standard dose of vaccine provides about 50% protection against influenza in older patients, compared with approximately 60% to 65% in younger individuals. With the added protection of the high-dose vaccine (overall efficacy, 24.2%), approximately 62% of adults older than age 65 would be protected—a figure similar to that reported for younger patients.

The increase in effectiveness was achieved with no increase in the overall frequency of adverse effects. In fact, the frequency of adverse effects was actually slightly lower in the recipients of the higher dose. However, in 3 recipients of the high-dose vaccine the adverse effects were notable. One had a transient sixth cranial nerve palsy that started 1 day after vaccination. One had hypovolemic shock due to diarrhea that started 1 day after vaccination. One had acute disseminated encephalomyelitis that started 117 days after vaccination. All 3 patients recovered fully. No such serious events occurred in the standard-dose group.

Several barriers prevent widespread vaccination

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices strongly recommends influenza vaccination for everyone over the age of 6 months. Barriers to widespread vaccination include reluctance on the part of the patient, failure on the part of the physician to advocate for vaccination, and cost of the vaccine for patients who have suboptimal insurance or no insurance.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

We should strongly advise older women in our practice to receive the high-dose influenza vaccine. We should caution them that the overall risk of adverse effects is actually lower than with the standard-dose vaccine but that serious effects can occur in rare instances.

—Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The objective of this investigation was to compare a standard-dose trivalent influenza vaccine with a high-dose vaccine in adults older than 65 years. The standard dose of the vaccine contained 15 µg of hemagglutinin per strain, and the high dose contained 60 µg hemagglutinin per strain. The study was conducted during the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 flu seasons. Key outcome measures were efficacy, as assessed by the occurrence of laboratory-confirmed influenza at least 14 days after vaccination; immunogenicity of the vaccines; and frequency of adverse events.

Details of the study

The study involved 15,991 patients in the high-dose group and 15,998 patients in the standard-dose group. Two hundred twenty-eight participants (1.4%) in the high-dose group developed influenza, compared with 301 participants (1.9%) in the standard-dose group.

The overall efficacy of the high-dose vaccine was 24.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 9.7–36.5), meaning that approximately 24% of influenza cases could have been prevented if the high-dose vaccine had been administered to all patients.

In the high-dose group, 8.3% of patients had at least 1 adverse event, compared with 9% in the standard-dose group (relative risk, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.85–0.99).

After vaccination, the hemagglutination inhibition titers were significantly higher in the high-dose group.

Fewer adverse events with the higher dose, but some events were graver

Influenza is a serious viral illness, and it can be associated with mortality in certain populations, such as very young children, pregnant women, and people older than 65 years.

As a general rule, older patients do not respond as well to the vaccine as younger patients do. The standard dose of vaccine provides about 50% protection against influenza in older patients, compared with approximately 60% to 65% in younger individuals. With the added protection of the high-dose vaccine (overall efficacy, 24.2%), approximately 62% of adults older than age 65 would be protected—a figure similar to that reported for younger patients.

The increase in effectiveness was achieved with no increase in the overall frequency of adverse effects. In fact, the frequency of adverse effects was actually slightly lower in the recipients of the higher dose. However, in 3 recipients of the high-dose vaccine the adverse effects were notable. One had a transient sixth cranial nerve palsy that started 1 day after vaccination. One had hypovolemic shock due to diarrhea that started 1 day after vaccination. One had acute disseminated encephalomyelitis that started 117 days after vaccination. All 3 patients recovered fully. No such serious events occurred in the standard-dose group.

Several barriers prevent widespread vaccination

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices strongly recommends influenza vaccination for everyone over the age of 6 months. Barriers to widespread vaccination include reluctance on the part of the patient, failure on the part of the physician to advocate for vaccination, and cost of the vaccine for patients who have suboptimal insurance or no insurance.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

We should strongly advise older women in our practice to receive the high-dose influenza vaccine. We should caution them that the overall risk of adverse effects is actually lower than with the standard-dose vaccine but that serious effects can occur in rare instances.

—Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The objective of this investigation was to compare a standard-dose trivalent influenza vaccine with a high-dose vaccine in adults older than 65 years. The standard dose of the vaccine contained 15 µg of hemagglutinin per strain, and the high dose contained 60 µg hemagglutinin per strain. The study was conducted during the 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 flu seasons. Key outcome measures were efficacy, as assessed by the occurrence of laboratory-confirmed influenza at least 14 days after vaccination; immunogenicity of the vaccines; and frequency of adverse events.

Details of the study

The study involved 15,991 patients in the high-dose group and 15,998 patients in the standard-dose group. Two hundred twenty-eight participants (1.4%) in the high-dose group developed influenza, compared with 301 participants (1.9%) in the standard-dose group.

The overall efficacy of the high-dose vaccine was 24.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 9.7–36.5), meaning that approximately 24% of influenza cases could have been prevented if the high-dose vaccine had been administered to all patients.

In the high-dose group, 8.3% of patients had at least 1 adverse event, compared with 9% in the standard-dose group (relative risk, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.85–0.99).

After vaccination, the hemagglutination inhibition titers were significantly higher in the high-dose group.

Fewer adverse events with the higher dose, but some events were graver

Influenza is a serious viral illness, and it can be associated with mortality in certain populations, such as very young children, pregnant women, and people older than 65 years.

As a general rule, older patients do not respond as well to the vaccine as younger patients do. The standard dose of vaccine provides about 50% protection against influenza in older patients, compared with approximately 60% to 65% in younger individuals. With the added protection of the high-dose vaccine (overall efficacy, 24.2%), approximately 62% of adults older than age 65 would be protected—a figure similar to that reported for younger patients.

The increase in effectiveness was achieved with no increase in the overall frequency of adverse effects. In fact, the frequency of adverse effects was actually slightly lower in the recipients of the higher dose. However, in 3 recipients of the high-dose vaccine the adverse effects were notable. One had a transient sixth cranial nerve palsy that started 1 day after vaccination. One had hypovolemic shock due to diarrhea that started 1 day after vaccination. One had acute disseminated encephalomyelitis that started 117 days after vaccination. All 3 patients recovered fully. No such serious events occurred in the standard-dose group.

Several barriers prevent widespread vaccination

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices strongly recommends influenza vaccination for everyone over the age of 6 months. Barriers to widespread vaccination include reluctance on the part of the patient, failure on the part of the physician to advocate for vaccination, and cost of the vaccine for patients who have suboptimal insurance or no insurance.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

We should strongly advise older women in our practice to receive the high-dose influenza vaccine. We should caution them that the overall risk of adverse effects is actually lower than with the standard-dose vaccine but that serious effects can occur in rare instances.

—Patrick Duff, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Gaining immediate postpartum IUD coverage one state at a time

As more physicians and women consider immediate postpartum insertion of an intrauterine device as a way to prevent rapid repeat pregnancy, the next step is getting the procedure covered by Medicaid.

Already, 12 state Medicaid agencies offer coverage for this procedure immediately postpartum, with California being the latest to join Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Montana, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.

The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) has been working with state Medicaid agencies and physicians to expand that roster. So far, states have been receptive to the idea, said Dr. Lisa F. Waddell, ASTHO’s chief program officer for community health and prevention, adding that as more states make the necessary policy change to cover the device and insertion procedure, it becomes easier for other states to follow suit.

“Medicaid was a partner at the table and continues to be,” she said. “I really believe they’re wanting to get better outcomes for their dollars they are investing and therefore are opening up to listening to partners and the providers in the state.”

The key challenge is defining the economics of this policy change. Normally, birth services are paid under a flat fee, which does not include coverage of immediate postpartum IUD insertion.

“Any time you make any type of change where there is going to be a cost incurred, people want to know that there will be a return on investment,” Dr. Waddell said.

They are making the case from an outcomes perspective, arguing that the Medicaid program will save money by preventing unplanned rapid repeat pregnancies. And by paying physicians to insert immediate postpartum IUDs, it promotes planned pregnancies in the future, which in turn promotes healthy babies and mothers, another way to help rein in overall costs and improve overall outcomes, she said.

The other challenge is training physicians on the policies and codes in their state, as well the actual IUD insertion protocols.

“There is a lot of emphasis on provider training,” Dr. Waddell said.

Education has been a key emphasis in New Mexico, said Dr. Eve Espey, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, who noted that her university hospital is the only location in the state that “very routinely” does this procedure.

“What I’d like to do is through our perinatal collaborative is take the show on the road and talk to other hospitals about how to deal with the reimbursement mechanism and then train providers to be able to offer it to women with Medicaid,” Dr. Espey said. “Then I think an important next step is to talk to private insurers. We have a lot of work to do and I think starting with Medicaid does make a lot of sense.”

ASTHO is also focusing on gaining coverage in the Medicaid setting first. If they can help get the majority of state Medicaid agencies to cover the procedure, it will be easier to convince private insurers to follow suit, as coverage is also not common in the private sector, Dr. Waddell said.

In New Mexico, the state Medicaid program had covered IUD devices and insertion but didn’t pay for immediate postpartum insertion. But with “substantial” no-show rates for follow-up postpartum appointments to insert the devices, it became important to gain that coverage so that patients could have the procedure when they were the most motivated, Dr. Espey said.

In Georgia, the experience has been similar. Dr. Melissa Kottke, director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health at Emory University in Atlanta said there was a lot of hospital-level coordination needed once the state-approved coverage.

“The changes that have to get instituted are really at a particular institution or organizational level,” Dr. Kottke said. “There are a lot of stakeholders that need to be involved,” from clinicians to coding staff to electronic health record vendors and other key personnel.

“There is a lot of education and a lot of cooperation that is necessary, but it’s certainly something that’s definitely doable,” she said.

Dr. Kottke said there have not been any issues with the adequacy of payment for this procedure and the state Medicaid agency has been “really supportive of this approach,” particularly since there had already been a number of states that had instituted coverage and have seen improved outcomes, both clinical and financial.

“It’s a huge opportunity for taking really good care of women,” Dr. Kottke said. “We know that the immediate postpartum period is a time of unmet contraceptive need and to remove the financial barrier is really exciting to see.”

As more physicians and women consider immediate postpartum insertion of an intrauterine device as a way to prevent rapid repeat pregnancy, the next step is getting the procedure covered by Medicaid.

Already, 12 state Medicaid agencies offer coverage for this procedure immediately postpartum, with California being the latest to join Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Montana, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.

The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) has been working with state Medicaid agencies and physicians to expand that roster. So far, states have been receptive to the idea, said Dr. Lisa F. Waddell, ASTHO’s chief program officer for community health and prevention, adding that as more states make the necessary policy change to cover the device and insertion procedure, it becomes easier for other states to follow suit.

“Medicaid was a partner at the table and continues to be,” she said. “I really believe they’re wanting to get better outcomes for their dollars they are investing and therefore are opening up to listening to partners and the providers in the state.”

The key challenge is defining the economics of this policy change. Normally, birth services are paid under a flat fee, which does not include coverage of immediate postpartum IUD insertion.

“Any time you make any type of change where there is going to be a cost incurred, people want to know that there will be a return on investment,” Dr. Waddell said.

They are making the case from an outcomes perspective, arguing that the Medicaid program will save money by preventing unplanned rapid repeat pregnancies. And by paying physicians to insert immediate postpartum IUDs, it promotes planned pregnancies in the future, which in turn promotes healthy babies and mothers, another way to help rein in overall costs and improve overall outcomes, she said.

The other challenge is training physicians on the policies and codes in their state, as well the actual IUD insertion protocols.

“There is a lot of emphasis on provider training,” Dr. Waddell said.

Education has been a key emphasis in New Mexico, said Dr. Eve Espey, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, who noted that her university hospital is the only location in the state that “very routinely” does this procedure.

“What I’d like to do is through our perinatal collaborative is take the show on the road and talk to other hospitals about how to deal with the reimbursement mechanism and then train providers to be able to offer it to women with Medicaid,” Dr. Espey said. “Then I think an important next step is to talk to private insurers. We have a lot of work to do and I think starting with Medicaid does make a lot of sense.”

ASTHO is also focusing on gaining coverage in the Medicaid setting first. If they can help get the majority of state Medicaid agencies to cover the procedure, it will be easier to convince private insurers to follow suit, as coverage is also not common in the private sector, Dr. Waddell said.

In New Mexico, the state Medicaid program had covered IUD devices and insertion but didn’t pay for immediate postpartum insertion. But with “substantial” no-show rates for follow-up postpartum appointments to insert the devices, it became important to gain that coverage so that patients could have the procedure when they were the most motivated, Dr. Espey said.

In Georgia, the experience has been similar. Dr. Melissa Kottke, director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health at Emory University in Atlanta said there was a lot of hospital-level coordination needed once the state-approved coverage.

“The changes that have to get instituted are really at a particular institution or organizational level,” Dr. Kottke said. “There are a lot of stakeholders that need to be involved,” from clinicians to coding staff to electronic health record vendors and other key personnel.

“There is a lot of education and a lot of cooperation that is necessary, but it’s certainly something that’s definitely doable,” she said.

Dr. Kottke said there have not been any issues with the adequacy of payment for this procedure and the state Medicaid agency has been “really supportive of this approach,” particularly since there had already been a number of states that had instituted coverage and have seen improved outcomes, both clinical and financial.

“It’s a huge opportunity for taking really good care of women,” Dr. Kottke said. “We know that the immediate postpartum period is a time of unmet contraceptive need and to remove the financial barrier is really exciting to see.”

As more physicians and women consider immediate postpartum insertion of an intrauterine device as a way to prevent rapid repeat pregnancy, the next step is getting the procedure covered by Medicaid.

Already, 12 state Medicaid agencies offer coverage for this procedure immediately postpartum, with California being the latest to join Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Montana, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, and South Carolina.

The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) has been working with state Medicaid agencies and physicians to expand that roster. So far, states have been receptive to the idea, said Dr. Lisa F. Waddell, ASTHO’s chief program officer for community health and prevention, adding that as more states make the necessary policy change to cover the device and insertion procedure, it becomes easier for other states to follow suit.

“Medicaid was a partner at the table and continues to be,” she said. “I really believe they’re wanting to get better outcomes for their dollars they are investing and therefore are opening up to listening to partners and the providers in the state.”

The key challenge is defining the economics of this policy change. Normally, birth services are paid under a flat fee, which does not include coverage of immediate postpartum IUD insertion.

“Any time you make any type of change where there is going to be a cost incurred, people want to know that there will be a return on investment,” Dr. Waddell said.

They are making the case from an outcomes perspective, arguing that the Medicaid program will save money by preventing unplanned rapid repeat pregnancies. And by paying physicians to insert immediate postpartum IUDs, it promotes planned pregnancies in the future, which in turn promotes healthy babies and mothers, another way to help rein in overall costs and improve overall outcomes, she said.

The other challenge is training physicians on the policies and codes in their state, as well the actual IUD insertion protocols.

“There is a lot of emphasis on provider training,” Dr. Waddell said.

Education has been a key emphasis in New Mexico, said Dr. Eve Espey, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, who noted that her university hospital is the only location in the state that “very routinely” does this procedure.

“What I’d like to do is through our perinatal collaborative is take the show on the road and talk to other hospitals about how to deal with the reimbursement mechanism and then train providers to be able to offer it to women with Medicaid,” Dr. Espey said. “Then I think an important next step is to talk to private insurers. We have a lot of work to do and I think starting with Medicaid does make a lot of sense.”

ASTHO is also focusing on gaining coverage in the Medicaid setting first. If they can help get the majority of state Medicaid agencies to cover the procedure, it will be easier to convince private insurers to follow suit, as coverage is also not common in the private sector, Dr. Waddell said.

In New Mexico, the state Medicaid program had covered IUD devices and insertion but didn’t pay for immediate postpartum insertion. But with “substantial” no-show rates for follow-up postpartum appointments to insert the devices, it became important to gain that coverage so that patients could have the procedure when they were the most motivated, Dr. Espey said.

In Georgia, the experience has been similar. Dr. Melissa Kottke, director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health at Emory University in Atlanta said there was a lot of hospital-level coordination needed once the state-approved coverage.

“The changes that have to get instituted are really at a particular institution or organizational level,” Dr. Kottke said. “There are a lot of stakeholders that need to be involved,” from clinicians to coding staff to electronic health record vendors and other key personnel.

“There is a lot of education and a lot of cooperation that is necessary, but it’s certainly something that’s definitely doable,” she said.

Dr. Kottke said there have not been any issues with the adequacy of payment for this procedure and the state Medicaid agency has been “really supportive of this approach,” particularly since there had already been a number of states that had instituted coverage and have seen improved outcomes, both clinical and financial.

“It’s a huge opportunity for taking really good care of women,” Dr. Kottke said. “We know that the immediate postpartum period is a time of unmet contraceptive need and to remove the financial barrier is really exciting to see.”

BMI-based dosing suboptimal for ovarian cancer

Body mass index should not be a major determinant of whether women with ovarian cancer receive reduced-dose chemotherapy, investigators say.

Because body surface area calculations are used to determine the dose of paclitaxel in the standard paclitaxel and carboplatin regimen for ovarian cancer, some centers treat obese women with reduced doses, in the belief that dose reduction can provide clinical benefit while minimizing toxicity. Normal-weight women may also have dose reductions when they experience serious adverse events following early cycles of chemotherapy.

But those dose reductions may be compromising survival, caution Dr. Elisa V. Bandera from the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J., and her colleagues. They found that in a cohort of 806 obese and normal-weight women with epithelial ovarian cancer receiving first-line paclitaxel and carboplatin with curative intent, women with class 3 obesity (body mass index >40 kg/mg2) received 38% lower doses of paclitaxel, and 45% lower doses of carboplatin than did normal-weight women, and also received lower relative dose intensity (RDI) than did normal-weight women for each agent separately and for the combination regimen.

The mean average RDI was 73.7% for women in obese class 3, compared with 88.2% for normal-weight women (P < .001). Average RDI lower than 70% was associated with both worse overall survival (OS; hazard ratio, 1.62; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-2.37) and worse ovarian cancer-specific survival (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.12-2.55), the investigators report (JAMA Oncology 2015 July 2 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1796]).

Although women who were obese at diagnosis appeared to have better survival than normal-weight women did in an analysis adjusted for prognostic factors, that survival advantage disappeared with dose reduction.

In a multivariable analysis looking at the joint effects of BMI and average RDI, the authors found that normal-weight women who received less than 85% of the standard dose had a 1.5-fold higher risk for mortality than did similar women who did not have dose reduction. For each category of BMI, patients who had average RDI less than 85% of normal had worse survival than did similar-sized patients with no dose-reductions.

“In this study we found that obese patients with ovarian cancer received considerably less paclitaxel and carboplatin/kg of body weight and lower RDI for each chemotherapy agent and for the combined regimen. We also found that the strongest predictor of dose reduction, defined as an RDI below 85%, was a high BMI. Dose reduction was associated with reduced survival time, particularly for normal-weight women. This association was apparent even after accounting for diagnostic and prognostic factors such as stage of disease, comorbid conditions, or posttreatment CA125 levels, a marker of residual disease,” they write.

The conclusion that “body size should not be a major factor influencing dose-reduction decisions in women with ovarian cancer” deserves further thought. Does “body size” cover both BSA [body surface area] and BMI [body mass index]? If not a “major” factor, could body size still play a “minor” role in such decisions? Do the authors suggest applying this principle to more chemotherapeutics than merely carboplatin and paclitaxel, the subject of the present study?

The reader is left to struggle with the conundrum of dosing based on BSA, whether to use lean body mass or actual weight in the C-G [Cockcroft-Gault] formula, and whether dose capping still has a place. How to resolve these issues in an evidence-based fashion is challenging. Clearly, treatment outcome is closely related to RDI [relative dose intensity] for a number of drugs, but not all drugs are created equal. Decisions on dosing considering size remain both an art and a science until definitive data are generated.

Dr. S. Percy Ivy is with the Investigational Drug Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md., and Dr. Jan H. Beumer is with the Cancer Therapeutics Program, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute. These comments are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Bandera et al.

The conclusion that “body size should not be a major factor influencing dose-reduction decisions in women with ovarian cancer” deserves further thought. Does “body size” cover both BSA [body surface area] and BMI [body mass index]? If not a “major” factor, could body size still play a “minor” role in such decisions? Do the authors suggest applying this principle to more chemotherapeutics than merely carboplatin and paclitaxel, the subject of the present study?

The reader is left to struggle with the conundrum of dosing based on BSA, whether to use lean body mass or actual weight in the C-G [Cockcroft-Gault] formula, and whether dose capping still has a place. How to resolve these issues in an evidence-based fashion is challenging. Clearly, treatment outcome is closely related to RDI [relative dose intensity] for a number of drugs, but not all drugs are created equal. Decisions on dosing considering size remain both an art and a science until definitive data are generated.

Dr. S. Percy Ivy is with the Investigational Drug Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md., and Dr. Jan H. Beumer is with the Cancer Therapeutics Program, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute. These comments are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Bandera et al.

The conclusion that “body size should not be a major factor influencing dose-reduction decisions in women with ovarian cancer” deserves further thought. Does “body size” cover both BSA [body surface area] and BMI [body mass index]? If not a “major” factor, could body size still play a “minor” role in such decisions? Do the authors suggest applying this principle to more chemotherapeutics than merely carboplatin and paclitaxel, the subject of the present study?

The reader is left to struggle with the conundrum of dosing based on BSA, whether to use lean body mass or actual weight in the C-G [Cockcroft-Gault] formula, and whether dose capping still has a place. How to resolve these issues in an evidence-based fashion is challenging. Clearly, treatment outcome is closely related to RDI [relative dose intensity] for a number of drugs, but not all drugs are created equal. Decisions on dosing considering size remain both an art and a science until definitive data are generated.

Dr. S. Percy Ivy is with the Investigational Drug Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md., and Dr. Jan H. Beumer is with the Cancer Therapeutics Program, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute. These comments are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Bandera et al.

Body mass index should not be a major determinant of whether women with ovarian cancer receive reduced-dose chemotherapy, investigators say.

Because body surface area calculations are used to determine the dose of paclitaxel in the standard paclitaxel and carboplatin regimen for ovarian cancer, some centers treat obese women with reduced doses, in the belief that dose reduction can provide clinical benefit while minimizing toxicity. Normal-weight women may also have dose reductions when they experience serious adverse events following early cycles of chemotherapy.

But those dose reductions may be compromising survival, caution Dr. Elisa V. Bandera from the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J., and her colleagues. They found that in a cohort of 806 obese and normal-weight women with epithelial ovarian cancer receiving first-line paclitaxel and carboplatin with curative intent, women with class 3 obesity (body mass index >40 kg/mg2) received 38% lower doses of paclitaxel, and 45% lower doses of carboplatin than did normal-weight women, and also received lower relative dose intensity (RDI) than did normal-weight women for each agent separately and for the combination regimen.

The mean average RDI was 73.7% for women in obese class 3, compared with 88.2% for normal-weight women (P < .001). Average RDI lower than 70% was associated with both worse overall survival (OS; hazard ratio, 1.62; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-2.37) and worse ovarian cancer-specific survival (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.12-2.55), the investigators report (JAMA Oncology 2015 July 2 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1796]).

Although women who were obese at diagnosis appeared to have better survival than normal-weight women did in an analysis adjusted for prognostic factors, that survival advantage disappeared with dose reduction.

In a multivariable analysis looking at the joint effects of BMI and average RDI, the authors found that normal-weight women who received less than 85% of the standard dose had a 1.5-fold higher risk for mortality than did similar women who did not have dose reduction. For each category of BMI, patients who had average RDI less than 85% of normal had worse survival than did similar-sized patients with no dose-reductions.

“In this study we found that obese patients with ovarian cancer received considerably less paclitaxel and carboplatin/kg of body weight and lower RDI for each chemotherapy agent and for the combined regimen. We also found that the strongest predictor of dose reduction, defined as an RDI below 85%, was a high BMI. Dose reduction was associated with reduced survival time, particularly for normal-weight women. This association was apparent even after accounting for diagnostic and prognostic factors such as stage of disease, comorbid conditions, or posttreatment CA125 levels, a marker of residual disease,” they write.

Body mass index should not be a major determinant of whether women with ovarian cancer receive reduced-dose chemotherapy, investigators say.

Because body surface area calculations are used to determine the dose of paclitaxel in the standard paclitaxel and carboplatin regimen for ovarian cancer, some centers treat obese women with reduced doses, in the belief that dose reduction can provide clinical benefit while minimizing toxicity. Normal-weight women may also have dose reductions when they experience serious adverse events following early cycles of chemotherapy.

But those dose reductions may be compromising survival, caution Dr. Elisa V. Bandera from the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J., and her colleagues. They found that in a cohort of 806 obese and normal-weight women with epithelial ovarian cancer receiving first-line paclitaxel and carboplatin with curative intent, women with class 3 obesity (body mass index >40 kg/mg2) received 38% lower doses of paclitaxel, and 45% lower doses of carboplatin than did normal-weight women, and also received lower relative dose intensity (RDI) than did normal-weight women for each agent separately and for the combination regimen.

The mean average RDI was 73.7% for women in obese class 3, compared with 88.2% for normal-weight women (P < .001). Average RDI lower than 70% was associated with both worse overall survival (OS; hazard ratio, 1.62; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-2.37) and worse ovarian cancer-specific survival (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.12-2.55), the investigators report (JAMA Oncology 2015 July 2 [doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1796]).

Although women who were obese at diagnosis appeared to have better survival than normal-weight women did in an analysis adjusted for prognostic factors, that survival advantage disappeared with dose reduction.

In a multivariable analysis looking at the joint effects of BMI and average RDI, the authors found that normal-weight women who received less than 85% of the standard dose had a 1.5-fold higher risk for mortality than did similar women who did not have dose reduction. For each category of BMI, patients who had average RDI less than 85% of normal had worse survival than did similar-sized patients with no dose-reductions.

“In this study we found that obese patients with ovarian cancer received considerably less paclitaxel and carboplatin/kg of body weight and lower RDI for each chemotherapy agent and for the combined regimen. We also found that the strongest predictor of dose reduction, defined as an RDI below 85%, was a high BMI. Dose reduction was associated with reduced survival time, particularly for normal-weight women. This association was apparent even after accounting for diagnostic and prognostic factors such as stage of disease, comorbid conditions, or posttreatment CA125 levels, a marker of residual disease,” they write.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Reduced chemotherapy doses based on BMI may compromise survival.

Major finding: Average relative dose intensity lower than 70% was associated with both worse overall survival and worse ovarian cancer–specific survival.

Data source: Cohort study of 806 women with epithelial ovarian cancer.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the Kaiser Permanente Center for Effectiveness and Safety Research. The authors and the editorialists reported no conflicts of interest.

Cochrane review finds midurethral slings safe, effective

Midurethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) are safe, and – regardless of the routes traversed – are highly effective in the short and mid term, according to a new Cochrane systematic review.

Evidence showing long-term effectiveness is also accruing, but too few of the existing trials have reported outcomes beyond 5 years, Dr. Abigail A. Ford of Bradford (England) Royal Infirmary and her colleagues from the Cochrane Incontinence Group reported.

The findings, based on a review of 81 trials involving a total of 12,113 women, were published July 1 (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006375.pub3]).

Moderate-quality evidence indicates that the transobturator route and retropubic route provide similar rates of subjective and objective cure at up to 1 year (relative risk, 0.98 for both). Low-quality evidence suggests the subjective cure rates are similar with these two approaches at between 1 and 5 years (RR, 0.97), and moderate-quality evidence suggests the subjective cure rates are similar beyond 5 years with the two approaches (RR, 0.95), the investigators said.

Overall, about 80% of women undergoing surgery using either approach experience significant improvement in symptoms at up to 5 years after the surgery; that drops to about 70% after 5 years, based on the few studies that followed patients that long.

Although the overall adverse event rate was low, morbidity rates were higher with the retropubic route. For example, the rate of bladder perforation was 0.6% with the transobturator route vs. 4.5% with the retropubic route. Major vascular/visceral injury, mean operating time, operative blood loss, and hospital length of stay were all lower with the transobturator route. Further, voiding dysfunction was less common with the transobturator route (RR, 0.53).

Groin pain was more common in women in the transobturator vs. retropubic groups (6.4% vs. 1.3%), but suprapubic pain was less common (0.8% vs. 2.9%); both types of pain were of short duration.

The Cochrane investigators also found moderate-quality evidence for the following.

The overall rate of vaginal tape erosion, exposure, or extrusion was low (24 per 1,000 and 21 per 1,000 procedures for the transobturator and retropubic routes, respectively (RR, 1.13).

A retropubic bottom-to-top route was more effective than a top-to-bottom route for subjective cure (RR, 1.10).

Subjective cure rates in the short and mid term were similar when transobturator tape was passed using a medial-to-lateral or lateral-to-medial approach (RR, 1.00 and 1.06, respectively).

Voiding dysfunction was more common with the medial-to-lateral approach (RR, 1.74), but vaginal perforation was less frequent in the medial-to-lateral route (RR, 0.25).

It was unclear, due to very low-quality evidence, whether the lower rates of vaginal epithelial perforation affected vaginal tape erosion, the investigators noted.

The investigators reviewed the literature from 1947 up to June 2014, including only randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials involving women with stress urinary incontinence, urodynamic stress incontinence, or mixed urinary incontinence, which contribute to up to 80% of cases of urinary incontinence.

They noted that concerns regarding mesh erosion are ongoing, but that the latest white paper and safety communications on meshes released by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011 “relates to ongoing concern with mesh used to treat pelvic organ prolapse and not the small strip of mesh/tape/sling used to treat SUI. In fact, the FDA states that the safety and effectiveness of midurethral slings is well established in clinical trials with 1-year follow-up.”

Overall, the current review highlights the positive impact that midurethral sling operations have on quality of life in women with stress urinary incontinence, but additional reporting of long-term outcomes is needed, the investigators wrote.

“We need to know more about what happens to women in the long term,” Dr. Joseph Ogah, one of the Cochrane investigators and a consultant gynecologist at the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust in Cumbria, England, said in a statement. “This review found 35 trials carried out more than 5 years ago: If all the women in these trials were followed up, we would know much more about how long the operations last and, crucially, whether they had developed late but important side effects. Rather than starting any new trials in this area we need to obtain long-term follow-up from the existing trials.”

The review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. Some of the review authors reported industry sponsorship to attend scientific conferences.

Midurethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) are safe, and – regardless of the routes traversed – are highly effective in the short and mid term, according to a new Cochrane systematic review.

Evidence showing long-term effectiveness is also accruing, but too few of the existing trials have reported outcomes beyond 5 years, Dr. Abigail A. Ford of Bradford (England) Royal Infirmary and her colleagues from the Cochrane Incontinence Group reported.

The findings, based on a review of 81 trials involving a total of 12,113 women, were published July 1 (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006375.pub3]).

Moderate-quality evidence indicates that the transobturator route and retropubic route provide similar rates of subjective and objective cure at up to 1 year (relative risk, 0.98 for both). Low-quality evidence suggests the subjective cure rates are similar with these two approaches at between 1 and 5 years (RR, 0.97), and moderate-quality evidence suggests the subjective cure rates are similar beyond 5 years with the two approaches (RR, 0.95), the investigators said.

Overall, about 80% of women undergoing surgery using either approach experience significant improvement in symptoms at up to 5 years after the surgery; that drops to about 70% after 5 years, based on the few studies that followed patients that long.

Although the overall adverse event rate was low, morbidity rates were higher with the retropubic route. For example, the rate of bladder perforation was 0.6% with the transobturator route vs. 4.5% with the retropubic route. Major vascular/visceral injury, mean operating time, operative blood loss, and hospital length of stay were all lower with the transobturator route. Further, voiding dysfunction was less common with the transobturator route (RR, 0.53).

Groin pain was more common in women in the transobturator vs. retropubic groups (6.4% vs. 1.3%), but suprapubic pain was less common (0.8% vs. 2.9%); both types of pain were of short duration.

The Cochrane investigators also found moderate-quality evidence for the following.

The overall rate of vaginal tape erosion, exposure, or extrusion was low (24 per 1,000 and 21 per 1,000 procedures for the transobturator and retropubic routes, respectively (RR, 1.13).

A retropubic bottom-to-top route was more effective than a top-to-bottom route for subjective cure (RR, 1.10).

Subjective cure rates in the short and mid term were similar when transobturator tape was passed using a medial-to-lateral or lateral-to-medial approach (RR, 1.00 and 1.06, respectively).

Voiding dysfunction was more common with the medial-to-lateral approach (RR, 1.74), but vaginal perforation was less frequent in the medial-to-lateral route (RR, 0.25).

It was unclear, due to very low-quality evidence, whether the lower rates of vaginal epithelial perforation affected vaginal tape erosion, the investigators noted.

The investigators reviewed the literature from 1947 up to June 2014, including only randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials involving women with stress urinary incontinence, urodynamic stress incontinence, or mixed urinary incontinence, which contribute to up to 80% of cases of urinary incontinence.

They noted that concerns regarding mesh erosion are ongoing, but that the latest white paper and safety communications on meshes released by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011 “relates to ongoing concern with mesh used to treat pelvic organ prolapse and not the small strip of mesh/tape/sling used to treat SUI. In fact, the FDA states that the safety and effectiveness of midurethral slings is well established in clinical trials with 1-year follow-up.”

Overall, the current review highlights the positive impact that midurethral sling operations have on quality of life in women with stress urinary incontinence, but additional reporting of long-term outcomes is needed, the investigators wrote.

“We need to know more about what happens to women in the long term,” Dr. Joseph Ogah, one of the Cochrane investigators and a consultant gynecologist at the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust in Cumbria, England, said in a statement. “This review found 35 trials carried out more than 5 years ago: If all the women in these trials were followed up, we would know much more about how long the operations last and, crucially, whether they had developed late but important side effects. Rather than starting any new trials in this area we need to obtain long-term follow-up from the existing trials.”

The review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. Some of the review authors reported industry sponsorship to attend scientific conferences.

Midurethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) are safe, and – regardless of the routes traversed – are highly effective in the short and mid term, according to a new Cochrane systematic review.

Evidence showing long-term effectiveness is also accruing, but too few of the existing trials have reported outcomes beyond 5 years, Dr. Abigail A. Ford of Bradford (England) Royal Infirmary and her colleagues from the Cochrane Incontinence Group reported.

The findings, based on a review of 81 trials involving a total of 12,113 women, were published July 1 (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 [doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006375.pub3]).

Moderate-quality evidence indicates that the transobturator route and retropubic route provide similar rates of subjective and objective cure at up to 1 year (relative risk, 0.98 for both). Low-quality evidence suggests the subjective cure rates are similar with these two approaches at between 1 and 5 years (RR, 0.97), and moderate-quality evidence suggests the subjective cure rates are similar beyond 5 years with the two approaches (RR, 0.95), the investigators said.

Overall, about 80% of women undergoing surgery using either approach experience significant improvement in symptoms at up to 5 years after the surgery; that drops to about 70% after 5 years, based on the few studies that followed patients that long.

Although the overall adverse event rate was low, morbidity rates were higher with the retropubic route. For example, the rate of bladder perforation was 0.6% with the transobturator route vs. 4.5% with the retropubic route. Major vascular/visceral injury, mean operating time, operative blood loss, and hospital length of stay were all lower with the transobturator route. Further, voiding dysfunction was less common with the transobturator route (RR, 0.53).

Groin pain was more common in women in the transobturator vs. retropubic groups (6.4% vs. 1.3%), but suprapubic pain was less common (0.8% vs. 2.9%); both types of pain were of short duration.

The Cochrane investigators also found moderate-quality evidence for the following.

The overall rate of vaginal tape erosion, exposure, or extrusion was low (24 per 1,000 and 21 per 1,000 procedures for the transobturator and retropubic routes, respectively (RR, 1.13).

A retropubic bottom-to-top route was more effective than a top-to-bottom route for subjective cure (RR, 1.10).

Subjective cure rates in the short and mid term were similar when transobturator tape was passed using a medial-to-lateral or lateral-to-medial approach (RR, 1.00 and 1.06, respectively).

Voiding dysfunction was more common with the medial-to-lateral approach (RR, 1.74), but vaginal perforation was less frequent in the medial-to-lateral route (RR, 0.25).

It was unclear, due to very low-quality evidence, whether the lower rates of vaginal epithelial perforation affected vaginal tape erosion, the investigators noted.

The investigators reviewed the literature from 1947 up to June 2014, including only randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials involving women with stress urinary incontinence, urodynamic stress incontinence, or mixed urinary incontinence, which contribute to up to 80% of cases of urinary incontinence.

They noted that concerns regarding mesh erosion are ongoing, but that the latest white paper and safety communications on meshes released by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011 “relates to ongoing concern with mesh used to treat pelvic organ prolapse and not the small strip of mesh/tape/sling used to treat SUI. In fact, the FDA states that the safety and effectiveness of midurethral slings is well established in clinical trials with 1-year follow-up.”

Overall, the current review highlights the positive impact that midurethral sling operations have on quality of life in women with stress urinary incontinence, but additional reporting of long-term outcomes is needed, the investigators wrote.

“We need to know more about what happens to women in the long term,” Dr. Joseph Ogah, one of the Cochrane investigators and a consultant gynecologist at the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust in Cumbria, England, said in a statement. “This review found 35 trials carried out more than 5 years ago: If all the women in these trials were followed up, we would know much more about how long the operations last and, crucially, whether they had developed late but important side effects. Rather than starting any new trials in this area we need to obtain long-term follow-up from the existing trials.”

The review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. Some of the review authors reported industry sponsorship to attend scientific conferences.

FROM THE COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

Key clinical point: Midurethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence are safe and effective in the short and mid term.

Major finding: About 80% of women continue to experience significant improvement at up to 5 years.

Data source: A systematic review of the literature, including 81 studies involving 12,113 women.

Disclosures: The review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. Some of the review authors reported industry sponsorship to attend scientific conferences.

ACOG adds HPV-9 to vaccination advice

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continues to urge routine vaccination against human papillomavirus for girls and boys and has now added the recently licensed 9-valent HPV vaccine to its recommendation.

The updated policy statement from ACOG’s Committee on Adolescent Health Care and the Immunization Expert Work Group suggest starting vaccination as part of the adolescent immunization platform, but patients who were not vaccinated in the target age can receive the vaccine through age 26 years. The new policy statement adds the 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9), which is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2014 for girls and boys aged 11-12 years.

“Although obstetrician-gynecologists are not likely to care for many patients in the initial HPV vaccination target group, they have the opportunity to educate mothers about the importance of vaccinating their children at the recommended age,” the committee members wrote in the updated policy statement. “Furthermore, obstetrician-gynecologists and play a critical role in vaccinating adolescent girls and young women during the catch-up period.”

They noted in the policy statement that vaccination is not associated with an earlier onset of sexual activity or increased incidence of sexually transmitted infections.

Vaccination is recommended even if the results of HPV DNA testing are positive. Revaccination is not routinely recommended for individuals who completed the three-dose series with the quadrivalent HPV vaccine or the bivalent HPV vaccine, the committee noted.

HPV vaccination is not recommended during pregnancy, but routine pregnancy testing is not recommended before vaccination. Safety data on inadvertent vaccine administration during pregnancy are “reassuring,” according to ACOG.

For the complete recommendation, visit here.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continues to urge routine vaccination against human papillomavirus for girls and boys and has now added the recently licensed 9-valent HPV vaccine to its recommendation.

The updated policy statement from ACOG’s Committee on Adolescent Health Care and the Immunization Expert Work Group suggest starting vaccination as part of the adolescent immunization platform, but patients who were not vaccinated in the target age can receive the vaccine through age 26 years. The new policy statement adds the 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9), which is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2014 for girls and boys aged 11-12 years.

“Although obstetrician-gynecologists are not likely to care for many patients in the initial HPV vaccination target group, they have the opportunity to educate mothers about the importance of vaccinating their children at the recommended age,” the committee members wrote in the updated policy statement. “Furthermore, obstetrician-gynecologists and play a critical role in vaccinating adolescent girls and young women during the catch-up period.”

They noted in the policy statement that vaccination is not associated with an earlier onset of sexual activity or increased incidence of sexually transmitted infections.

Vaccination is recommended even if the results of HPV DNA testing are positive. Revaccination is not routinely recommended for individuals who completed the three-dose series with the quadrivalent HPV vaccine or the bivalent HPV vaccine, the committee noted.

HPV vaccination is not recommended during pregnancy, but routine pregnancy testing is not recommended before vaccination. Safety data on inadvertent vaccine administration during pregnancy are “reassuring,” according to ACOG.

For the complete recommendation, visit here.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continues to urge routine vaccination against human papillomavirus for girls and boys and has now added the recently licensed 9-valent HPV vaccine to its recommendation.

The updated policy statement from ACOG’s Committee on Adolescent Health Care and the Immunization Expert Work Group suggest starting vaccination as part of the adolescent immunization platform, but patients who were not vaccinated in the target age can receive the vaccine through age 26 years. The new policy statement adds the 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9), which is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2014 for girls and boys aged 11-12 years.

“Although obstetrician-gynecologists are not likely to care for many patients in the initial HPV vaccination target group, they have the opportunity to educate mothers about the importance of vaccinating their children at the recommended age,” the committee members wrote in the updated policy statement. “Furthermore, obstetrician-gynecologists and play a critical role in vaccinating adolescent girls and young women during the catch-up period.”

They noted in the policy statement that vaccination is not associated with an earlier onset of sexual activity or increased incidence of sexually transmitted infections.

Vaccination is recommended even if the results of HPV DNA testing are positive. Revaccination is not routinely recommended for individuals who completed the three-dose series with the quadrivalent HPV vaccine or the bivalent HPV vaccine, the committee noted.

HPV vaccination is not recommended during pregnancy, but routine pregnancy testing is not recommended before vaccination. Safety data on inadvertent vaccine administration during pregnancy are “reassuring,” according to ACOG.

For the complete recommendation, visit here.

You have identified a pelvic mass in your teenage patient. What now?

Pelvic masses frequently are the reason for the medical evaluation of young women and girls. Regardless of what prompted the work-up that led to the mass’ discovery, the patient inevitably will be sent to a gynecologist for further evaluation, and such a practitioner should be involved whenever there is suspicion for a mass involving the reproductive tract.

While it does not happen often, it is possible that a mass diagnosed as ovarian, based on imaging, is then determined to be of another organ system at the time of surgery. Most frequently, this occurs with ruptured appendicitis, as the presence of an appendiceal abscess can mimic a complex ovarian mass or tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA).1

The full differential diagnosis of non-gynecologic pelvic masses is extensive and includes mesenteric duplication cysts, presacral masses, pelvic kidney, peritoneal inclusion cysts, and urachal cysts (TABLE). It can be difficult to distinguish pathology as gynecologic or nongynecologic even if a thorough work-up is performed.

Differential diagnosis for a pelvic mass

|

In this review, we offer several cases involving varying presentations of pelvic masses related to the reproductive tract.

Case 1: Severe pelvic pain in an 18-year-old

An 18-year-old adolescent presents to your office reporting worsening pelvic pain over the past 3 days. The pain is severe in the left lower quadrant. She reports a foul discharge and thinks she has a fever but hasn’t checked her temperature. She says she has been sexually active in the past few months with 2 different male partners. She has not been using condoms consistently and hasn’t been tested for sexually transmitted infections. Physical examination reveals a mucopurulent discharge at the cervix and copious white blood cells noted on wet mount. Bimanual examination reveals cervical motion tenderness and tenderness over the left adnexa. Ultrasound reveals a mass in the left adnexa with debris and internal echoes.

Diagnosis: Tubo-ovarian abscess.

Treatment: Admission to the hospital for intravenous antibiotic therapy.

It is important to note that TOAs can be seen in patients who have not been sexually active, as well as in cases related not to an ascending infection but rather to a history of pelvic surgery or complex structural anomaly.2 The majority of the time a TOA is a result of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Often, patients with uncomplicated PID can be treated on an outpatient basis if they meet strict criteria, but patients with a TOA need to be treated as an inpatient due to the severity of this infection.

Clinical pearl. If a patient has an IUD in place, close clinical follow up is critical to determine response to therapy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s sexually transmitted infection treatment guidelines state that removal of the IUD is not mandatory, but if the patient is not responding to treatment removal ultimately may be necessary. The IUD should be removed if there is no improvement in the patient’s symptoms with antibiotic therapy, there is no decrease in size of the TOA with antibiotic therapy, or if there is no positive test of cure after treatment for the TOA is completed.

If a patient has progressive abdominal pain and other findings consistent with infectious etiology, consider that a ruptured appendix could have a very similar appearance to a TOA. Computed tomography can be a useful tool to aid in firm diagnosis in cases in which gastroenterologic entities must be ruled out, but ultimately the gold standard of diagnosis for both of these procedures is diagnostic laparoscopy. Diagnostic surgery can be performed if the patient does not respond to medical therapy. In an effort to avoid surgical intervention, interventional radiology may be an option to drain the TOA. If this is performed, it is useful to repeat the ultrasound to confirm resolution prior to removal of the drain.

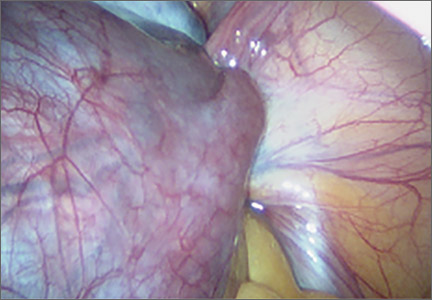

Case 2: Acute-onset severe pelvic pain in a young adolescent

A 12-year-old girl presents to the emergency department with acute-onset right lower quadrant pain. She states that about 2 hours ago she was playing in the yard and suddenly doubled over with pain. She also has had nausea and vomiting since that time.

She is in obvious distress and is resting in the fetal position. Examination reveals normal vital signs and tenderness to palpation over the right lower pelvic quadrant. There is no palpable abdominal mass. Genital examination reveals Tanner stage 4 external genitalia with normal introitus and patent, intact, annular hymen.

An abdominal ultrasound reveals a normal appendix, and pelvic ultrasonography reveals that the right ovary is enlarged (volume = 25 mL). The left ovary shows no obvious mass and a volume of 8 mL.

She is taken to the operating room, where you perform diagnostic laparoscopy.

Diagnosis: Adnexal torsion (FIGURE 1).

Treatment: Surgical detorsion with or without cystectomy.

Ultrasonography certainly can be useful in determining the size of an adnexal mass. An adnexal volume of less than 20 mL is strong evidence against adnexal torsion in an adolescent. This information, in addition to the remainder of the clinical picture, can be used to determine if surgery is immediately necessary or can be delayed.3

Several studies have attempted to draw a link between size of an ovarian mass and risk of malignancy. Unfortunately, such attempts have been unsuccessful, especially for large and small masses.4 In addition, many studies have explored the use of Doppler technology to confirm a diagnosis of torsion found on sonography. Studies have shown, however, that diminished or absent Doppler flow is not a reliable finding and that ovarian blood flow can be preserved in cases of surgically confirmed adnexal torsion.5

Torsion ultimately is a clinical diagnosis, and medical history and physical examination are critical in the decision-making process. The decision to go to the operating room for further evaluation never should be made based on ultrasound findings alone, as not all ovarian torsions result in a mass greater than 20 mL.

Clinical pearl. In the setting of a known adnexal cyst, it is important to impress upon patients and their parents the warning signs of torsion and the need to proceed directly to the emergency center if acute pelvic pain occurs.

Historically, adnexal torsion is correlated with oophorectomy, but recent studies indicate that ovarian function can be preserved in the majority of cases with detorsion and cystectomy alone.6,7 In cases in which no cyst is present, detorsion is therapeutic.

In addition, studies have shown that the appearance of the ovary is not indicative of damage to the ovary. Regardless of “necrotic” appearance, the adnexa should be preserved.8,9 Ovarian function after detorsion also has been assessed in a case series that showed normal follicular development on ultrasonography in more than 90% of patients after detorsion. In this group, 6 of 102 patients with torsion eventually underwent in vitro fertilization and, in all 6 patients, oocytes retrieved from the ischemic ovary were fertilized.10

Case 3: 15-year-old girl with nontender, palpable abdominal mass

A 15-year-old adolescent comes to your office for a well woman exam and to establish gynecologic care. Abdominal examination reveals a mass below the umbilicus that is nontender to palpation. The remainder of the examination is normal, and the patient is sent for ultrasonography. Results reveal a complex-appearing mass in the left ovary that measures 8 cm x 7 cm x 8 cm. The report states that the mass shows areas of fat and calcifications. There are no other abnormalities noted in the abdomen or pelvis.

Diagnosis: Dermoid cyst.

Treatment: Surgical intervention versus expectant management.

Germ cell ovarian tumors are a diverse category of tumors that include both benign and malignant disease. The ovarian teratoma (“dermoid”) is the most common and perhaps best-known example of a benign ovarian germ cell tumor (FIGURE 2). While the incidence in the general population is unknown, dermoids account for approximately 65% of adnexal masses in pediatric patients presenting for treatment.11 Most of the time, patients with ovarian dermoids will be asymptomatic; however, pain is the most common presenting symptom.

The spectrum of sonographic features includes:

- mixed echogenicity with posterior sound attenuation owing to sebaceous material and hair within the cyst

- echogenic interface at the edge of the mass that obscures deep structures (the tip-of-the-iceberg sign)

- mural hyperechoic Rokitansky nodule (dermoid plug)

- shadowing due to calcific or dental (tooth) components

- presence of layered-fluid levels

- multiple thin, echogenic bands caused by hair in the cyst cavity (the dot-dash pattern)

- absence of internal vascularity noted with color Doppler evaluation.

The notation of internal vascularity is concerning for malignancy.12

Fortunately, malignant ovarian germ cell tumors are much less common than benign lesions. Of these, the most common pediatric ovarian germ cell tumor is dysgerminoma (FIGURE 3).13

Clinical pearl. A unique consideration in patients with dysgerminoma or choriocarcinoma is the possible diagnosis of XY gonadal dysgenesis, or Swyer syndrome.14,15 This may be seen in young girls with female external genitalia and primary amenorrhea. Depending on the level of concern, obtaining a karyotype also may be beneficial.13

Sex cord−stromal tumors also are relatively common in the pediatric population.16 Of these, granulosa cell tumors are the most common and account for 2% to 5% of ovarian malignancies regardless of age at diagnosis. Juvenile-type granulosa ovarian cancers occur mainly in premenarchal girls and comprise roughly 5% of all granulosa cell tumors.17 The presenting problem usually is precocious puberty. Therefore, in any situation in which a prepubertal girl is developing too early and peripheral precocious puberty is suspected, sonography should be obtained to rule out a hormone-producing ovarian mass. Tumor markers most helpful in this situation include estradiol, testosterone, and inhibin B.17

When an adolescent is diagnosed with ovarian cancer, it is ideal to perform a fertility-sparing procedure whenever it is reasonable.18 While dermoid cysts can look concerning on sonography because of their heterogeneous appearance, the vast majority can be safely and effectively resected without oophorectomy in order to preserve fertility, as in most cases they are benign. Nonetheless, cystectomy does have a small, theoretic risk of cyst rupture, with the potential for pelvic peritonitis from dermoid content spillage.19 In the vast majority of cases in which a benign adnexal mass is identified, ovarian cystectomy is appropriate and oophorectomy is not indicated.20

Another very rare presentation of mature cystic teratoma can include acute neurologic decline in cases of paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Frequently, these teratomas will be small in size and discovered only incidentally during the work-up of a patient with altered mental status. Resection is indicated as soon as possible to stop the neurologic decline.21

Case 4: Cyclic pelvic pain and a pelvic mass in a 16-year-old

A 16-year-old adolescent presents to your office for evaluation of cyclic pelvic pain. She states that menarche occurred at age 12 years and menses have been irregular ever since, occurring every few months and associated with significant pain with the onset of bleeding.

Physical examination reveals Tanner stage 4 breasts and Tanner stage 4 external genitalia. The introitus is normal with a visible intact, annular hymen. A mildly tender palpable mass at the level of the umbilicus is noted. The patient consents to having a Q-tip placed in the vagina, which reveals a bulge in the left vaginal wall that is nontender and fluctuant. Pelvic ultrasonography reveals uterine didelphys and an obstructed left hemivagina. A renal ultrasound reveals an absent left kidney.

Diagnosis: OHVIRA (obstructed hemivagina and ipsilateral renal anomaly) syndrome.

Treatment: Surgical resection of the vaginal septum.

Masses that appear complex on imaging can be deceiving, as they also can be related to obstructive reproductive tract anomalies. “Pelvic mass” is often the working diagnosis in cases of imperforate hymen, vaginal atresia, cervical agenesis, and uterine didelphys with obstructed hemivagina. This underscores the importance of taking an accurate menstrual history as well as performing a thorough physical examination. Usually this does not require an internal vaginal examination if the patient is unable to tolerate one, but a rectal examination can provide similar information in a patient presenting with a “pelvic mass” who will consent to this portion of the exam.

Clinical pearl. If a patient is not comfortable consenting to a rectal exam, a lubricated Q-tip can be used to palpate the vagina to minimize patient discomfort.

Before performing surgery…

Vaginal surgery can be corrective in the majority of these cases; however, magnetic resonance imaging is the gold standard for diagnosis and should be performed prior to surgical planning to further characterize the anomaly.22 Because Müllerian anomalies are associated with renal malformation such as absent kidney, pelvic kidney, collecting system duplication, or ectopic ureteral insertion around 40% of the time, imaging studies to assess for these structures is important prior to surgical intervention.23 If the patient is symptomatic and surgery cannot be performed immediately in a safe manner, she may require admission for pain control and placement of a Foley catheter (if the mass is obstructing urinary flow) until surgery can be performed safely.

A comprehensive review of Müllerian anomalies is beyond the scope of this article; it is important to note that these clinical scenarios are always unique and treatment should be individualized.

Conclusion

There are many sources of pelvic masses in children, adolescents, and young women; not all sources will be gynecologic. To avoid unnecessary surgical intervention, it is important to obtain as much information as possible from the patient’s history, physical examination, and laboratory and imaging studies.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Petroianu A, Alberti LR. Accuracy of the new radiographic sign of fecal loading in the cecum for differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis in comparison with other inflammatory diseases of right abdomen: a prospective study. J Med Life. 2012;5(1):85–91.

2. Emans SJ, Laufer MR, eds. Goldstein’s Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.