User login

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: What to do when dysplasia persists after hysterectomy

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is a condition that frequently poses therapeutic dilemmas for gynecologists. VAIN represents dysplastic changes to the epithelium of the vaginal mucosa, and like cervical neoplasia, the extent of disease is characterized as levels I, II, or III dependent upon the depth of involvement in the epithelial layer by dysplastic cells. While VAIN itself typically is asymptomatic and not a harmful condition, it carries a 12% risk of progression to invasive vaginal carcinoma, so accurate identification, thorough treatment, and ongoing surveillance are essential.1

VAIN is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco use, and prior cervical dysplasia. Of women with VAIN, 65% have undergone a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia, which emphasizes the nondefinitive nature of such an intervention.2 These women should be very closely followed for at least 20 years with vaginal cytologic and/or HPV surveillance. High-risk HPV infection is present in 85% of women with VAIN, and the presence of high-risk HPV is a predictor for recurrent VAIN. Recurrent and persistent VAIN also is more common in postmenopausal women and those with multifocal disease.

The most common location for VAIN is at the upper third of the vagina (including the vaginal cuff). It commonly arises within the vaginal fornices, which may be difficult to fully visualize because of their puckered appearance, redundant vaginal tissues, and extensive vaginal rogation.

A diagnosis of VAIN is typically obtained from vaginal cytology which reveals atypical or dysplastic cells. Such a result should prompt the physician to perform vaginal colposcopy and directed biopsies. Comprehensive visualization of the vaginal cuff can be limited in cases where the vaginal fornices are tethered, deeply puckered, or when there is significant mucosal rogation.

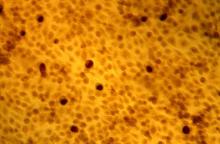

The application of 4% acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine are techniques that can enhance the detection of dysplastic vaginal mucosa. Lugol’s iodine selectively stains normal, glycogenated cells, and spares dysplastic glycogen-free cells. The sharp contrast between the brown iodine-stained tissues and the white dysplastic tissues aids in detection of dysplastic areas.

If colposcopic biopsy reveals low grade dysplasia (VAIN I) it does not require intervention, and has a very low rate of conversion to invasive vaginal carcinoma. However moderate- and high-grade vaginal dysplastic lesions should be treated because of the potential for malignant transformation.

Options for treatment of VAIN include topical, ablative, and excisional procedures. Observation also is an option but should be reserved for patients who are closely monitored with repeated colposcopic examinations, and probably should best be reserved for patients with VAIN I or II lesions.

Excisional procedures

The most common excisional procedure employed for VAIN is upper vaginectomy. In this procedure, the surgeon grasps and tents up the vaginal mucosa, incises the mucosa without penetrating the subepithelial tissue layers such as bladder and rectum. The vaginal mucosa then is carefully separated from the underlying endopelvic fascial plane. The specimen should be oriented, ideally on a cork board, with pins or sutures to ascribe margins and borders. Excision is best utilized for women with unifocal disease, or those who fail or do not tolerate ablative or topical interventions.

The most significant risks of excision include the potential for damage to underlying pelvic visceral structures, which is particularly concerning in postmenopausal women with thin vaginal epithelium. Vaginectomy is commonly associated with vaginal shortening or narrowing, which can be deleterious for quality of life. Retrospective series have described a 30% incidence of recurrence after vaginectomy, likely secondary to incomplete excision of all affected tissue.3

Ablation

Ablation of dysplastic foci with a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is a common method for treatment of VAIN. CO2 laser should ablate tissue to a 1.5 mm minimum depth.3 The benefit of using CO2 laser is its ability to treat multifocal disease in situ without an extensive excisional procedure.

It is technically more straightforward than upper vaginectomy with less blood loss and shorter surgical times, and it can be easily accomplished in an outpatient surgical or office setting. However, one of its greatest limitations is the difficulty in visualizing all lesions and therefore adequately treating all sites. The vaginal rogations also make adequate laser ablation challenging because laser only is able to effectively ablate tissue that is oriented perpendicular to the laser beam.

In addition, there is no pathologic confirmation of adequacy of excision or margin status. These features may contribute to the modestly higher rates of recurrence of dysplasia following laser ablation, compared with vaginectomy.3 It also has been associated with more vaginal scarring than vaginectomy, which can have a negative effect on sexual health.

Topical agents

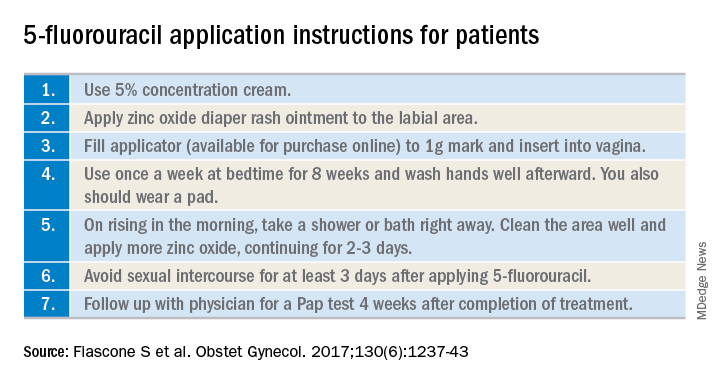

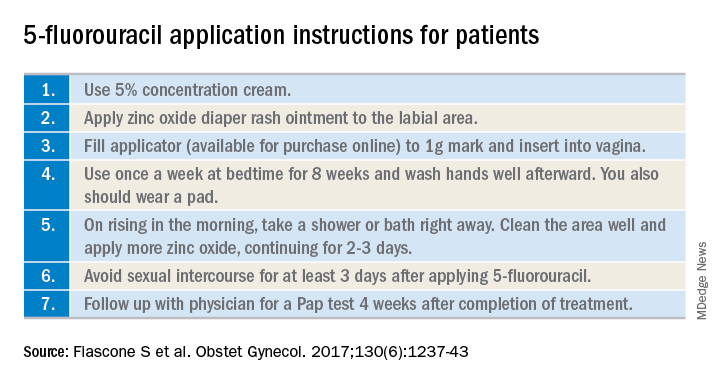

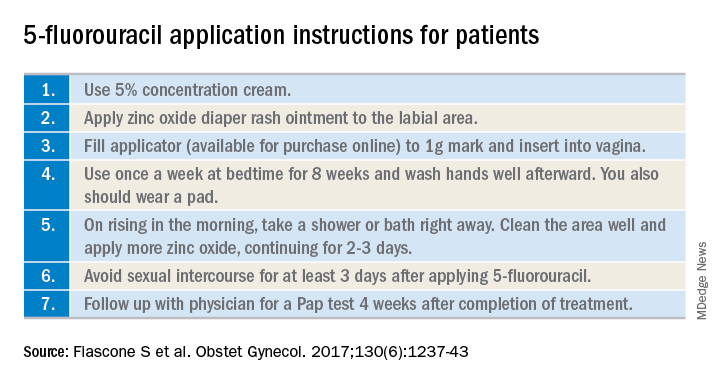

The most commonly utilized topical therapy for VAIN is the antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil (5FU). A typical schedule for 5FU treatment is to apply vaginally, at night, once a week for 8 weeks.4 Because it can cause extensive irritation to the vulvar and urethral epithelium, patients are recommended to apply barrier creams or ointments before and following the use of 5FU for several days, wash hands thoroughly after application, and to rinse and shower in the morning after rising. Severe irritation occurs in up to 16% of patients, but in general it is very well tolerated.

Its virtue is that it is able to conform and travel to all parts of the vaginal mucosa, including those that are poorly visualized within the fornices or vaginal folds. 5FU does not require a hospitalization or surgical procedure, can be applied by the patient at home, and preserves vaginal length and function. In recent reports, 5FU is associated with the lowest rates of recurrence (10%-30%), compared with excision or ablation, and therefore is a very attractive option for primary therapy.3 However, it requires patients to have a degree of comfort with vaginal application of drug and adherence with perineal care strategies to minimize the likelihood of toxicity.

The immune response modifier, imiquimod, that is commonly used in the treatment of vulvar dysplasia also has been described in the treatment of VAIN. It appears to have high rates of clearance (greater than 75%) and be most effective in the treatment of VAIN I.5 It requires application under colposcopic guidance three times a week for 8 weeks, which is a laborious undertaking for both patient and physician. Like 5FU, imiquimod is associated with vulvar and perineal irritation.

Vaginal estrogens are an alternative topical therapy for moderate- and high-grade VAIN and particularly useful for postmenopausal patients. They have been associated with a high rate (up to 90%) of resolution on follow-up vaginal cytology testing and are not associated with toxicities of the above stated therapies.6 Vaginal estrogen can be used alone or in addition to other therapeutic strategies. For example, it can be added to the nontreatment days of 5FU or postoperatively prescribed following laser or excisional procedures.

Radiation

Intracavitary brachytherapy is a technique in which a radiation source is placed within a cylinder or ovoids and placed within the vagina.7 Typically 45 Gy is delivered to a depth 0.5mm below the vaginal mucosal surface (“point z”). Recurrence occurs is approximately 10%-15% of patients, and toxicities can be severe, including vaginal stenosis and ulceration. This aggressive therapy typically is best reserved for cases that are refractory to other therapies. Following radiation, subsequent treatments are more difficult because of radiation-induced changes to the vaginal mucosa that can affect healing.

Vaginal dysplasia is a relatively common sequelae of high-risk HPV, particularly among women who have had a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia. Because of anatomic changes following hysterectomy, adequate visualization and comprehensive vaginal treatment is difficult. Therefore, surgeons should avoid utilization of hysterectomy as a routine strategy to “cure” dysplasia as it may fail to achieve this cure and make subsequent evaluations and treatments of persistent dysplasia more difficult. Women who have had a hysterectomy for dysplasia should be closely followed for several decades, and they should be counseled that they have a persistent risk for vaginal disease. When VAIN develops, clinicians should consider topical therapies as primary treatment options because they may minimize toxicity and have high rates of enduring response.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Jun;141(3):507-10.

2. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Feb;293(2):415-9.

3. Anticancer Res. 2013 Jan;33(1):29-38.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Dec;130(6):1237-43.

5. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 Nov;218:129-36.

6. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014 Apr;18(2):115-21.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jul;106(1):105-11.

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is a condition that frequently poses therapeutic dilemmas for gynecologists. VAIN represents dysplastic changes to the epithelium of the vaginal mucosa, and like cervical neoplasia, the extent of disease is characterized as levels I, II, or III dependent upon the depth of involvement in the epithelial layer by dysplastic cells. While VAIN itself typically is asymptomatic and not a harmful condition, it carries a 12% risk of progression to invasive vaginal carcinoma, so accurate identification, thorough treatment, and ongoing surveillance are essential.1

VAIN is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco use, and prior cervical dysplasia. Of women with VAIN, 65% have undergone a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia, which emphasizes the nondefinitive nature of such an intervention.2 These women should be very closely followed for at least 20 years with vaginal cytologic and/or HPV surveillance. High-risk HPV infection is present in 85% of women with VAIN, and the presence of high-risk HPV is a predictor for recurrent VAIN. Recurrent and persistent VAIN also is more common in postmenopausal women and those with multifocal disease.

The most common location for VAIN is at the upper third of the vagina (including the vaginal cuff). It commonly arises within the vaginal fornices, which may be difficult to fully visualize because of their puckered appearance, redundant vaginal tissues, and extensive vaginal rogation.

A diagnosis of VAIN is typically obtained from vaginal cytology which reveals atypical or dysplastic cells. Such a result should prompt the physician to perform vaginal colposcopy and directed biopsies. Comprehensive visualization of the vaginal cuff can be limited in cases where the vaginal fornices are tethered, deeply puckered, or when there is significant mucosal rogation.

The application of 4% acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine are techniques that can enhance the detection of dysplastic vaginal mucosa. Lugol’s iodine selectively stains normal, glycogenated cells, and spares dysplastic glycogen-free cells. The sharp contrast between the brown iodine-stained tissues and the white dysplastic tissues aids in detection of dysplastic areas.

If colposcopic biopsy reveals low grade dysplasia (VAIN I) it does not require intervention, and has a very low rate of conversion to invasive vaginal carcinoma. However moderate- and high-grade vaginal dysplastic lesions should be treated because of the potential for malignant transformation.

Options for treatment of VAIN include topical, ablative, and excisional procedures. Observation also is an option but should be reserved for patients who are closely monitored with repeated colposcopic examinations, and probably should best be reserved for patients with VAIN I or II lesions.

Excisional procedures

The most common excisional procedure employed for VAIN is upper vaginectomy. In this procedure, the surgeon grasps and tents up the vaginal mucosa, incises the mucosa without penetrating the subepithelial tissue layers such as bladder and rectum. The vaginal mucosa then is carefully separated from the underlying endopelvic fascial plane. The specimen should be oriented, ideally on a cork board, with pins or sutures to ascribe margins and borders. Excision is best utilized for women with unifocal disease, or those who fail or do not tolerate ablative or topical interventions.

The most significant risks of excision include the potential for damage to underlying pelvic visceral structures, which is particularly concerning in postmenopausal women with thin vaginal epithelium. Vaginectomy is commonly associated with vaginal shortening or narrowing, which can be deleterious for quality of life. Retrospective series have described a 30% incidence of recurrence after vaginectomy, likely secondary to incomplete excision of all affected tissue.3

Ablation

Ablation of dysplastic foci with a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is a common method for treatment of VAIN. CO2 laser should ablate tissue to a 1.5 mm minimum depth.3 The benefit of using CO2 laser is its ability to treat multifocal disease in situ without an extensive excisional procedure.

It is technically more straightforward than upper vaginectomy with less blood loss and shorter surgical times, and it can be easily accomplished in an outpatient surgical or office setting. However, one of its greatest limitations is the difficulty in visualizing all lesions and therefore adequately treating all sites. The vaginal rogations also make adequate laser ablation challenging because laser only is able to effectively ablate tissue that is oriented perpendicular to the laser beam.

In addition, there is no pathologic confirmation of adequacy of excision or margin status. These features may contribute to the modestly higher rates of recurrence of dysplasia following laser ablation, compared with vaginectomy.3 It also has been associated with more vaginal scarring than vaginectomy, which can have a negative effect on sexual health.

Topical agents

The most commonly utilized topical therapy for VAIN is the antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil (5FU). A typical schedule for 5FU treatment is to apply vaginally, at night, once a week for 8 weeks.4 Because it can cause extensive irritation to the vulvar and urethral epithelium, patients are recommended to apply barrier creams or ointments before and following the use of 5FU for several days, wash hands thoroughly after application, and to rinse and shower in the morning after rising. Severe irritation occurs in up to 16% of patients, but in general it is very well tolerated.

Its virtue is that it is able to conform and travel to all parts of the vaginal mucosa, including those that are poorly visualized within the fornices or vaginal folds. 5FU does not require a hospitalization or surgical procedure, can be applied by the patient at home, and preserves vaginal length and function. In recent reports, 5FU is associated with the lowest rates of recurrence (10%-30%), compared with excision or ablation, and therefore is a very attractive option for primary therapy.3 However, it requires patients to have a degree of comfort with vaginal application of drug and adherence with perineal care strategies to minimize the likelihood of toxicity.

The immune response modifier, imiquimod, that is commonly used in the treatment of vulvar dysplasia also has been described in the treatment of VAIN. It appears to have high rates of clearance (greater than 75%) and be most effective in the treatment of VAIN I.5 It requires application under colposcopic guidance three times a week for 8 weeks, which is a laborious undertaking for both patient and physician. Like 5FU, imiquimod is associated with vulvar and perineal irritation.

Vaginal estrogens are an alternative topical therapy for moderate- and high-grade VAIN and particularly useful for postmenopausal patients. They have been associated with a high rate (up to 90%) of resolution on follow-up vaginal cytology testing and are not associated with toxicities of the above stated therapies.6 Vaginal estrogen can be used alone or in addition to other therapeutic strategies. For example, it can be added to the nontreatment days of 5FU or postoperatively prescribed following laser or excisional procedures.

Radiation

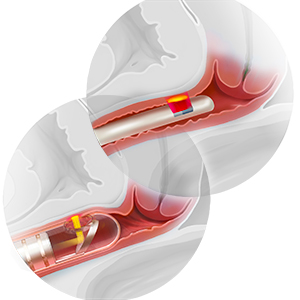

Intracavitary brachytherapy is a technique in which a radiation source is placed within a cylinder or ovoids and placed within the vagina.7 Typically 45 Gy is delivered to a depth 0.5mm below the vaginal mucosal surface (“point z”). Recurrence occurs is approximately 10%-15% of patients, and toxicities can be severe, including vaginal stenosis and ulceration. This aggressive therapy typically is best reserved for cases that are refractory to other therapies. Following radiation, subsequent treatments are more difficult because of radiation-induced changes to the vaginal mucosa that can affect healing.

Vaginal dysplasia is a relatively common sequelae of high-risk HPV, particularly among women who have had a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia. Because of anatomic changes following hysterectomy, adequate visualization and comprehensive vaginal treatment is difficult. Therefore, surgeons should avoid utilization of hysterectomy as a routine strategy to “cure” dysplasia as it may fail to achieve this cure and make subsequent evaluations and treatments of persistent dysplasia more difficult. Women who have had a hysterectomy for dysplasia should be closely followed for several decades, and they should be counseled that they have a persistent risk for vaginal disease. When VAIN develops, clinicians should consider topical therapies as primary treatment options because they may minimize toxicity and have high rates of enduring response.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Jun;141(3):507-10.

2. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Feb;293(2):415-9.

3. Anticancer Res. 2013 Jan;33(1):29-38.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Dec;130(6):1237-43.

5. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 Nov;218:129-36.

6. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014 Apr;18(2):115-21.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jul;106(1):105-11.

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) is a condition that frequently poses therapeutic dilemmas for gynecologists. VAIN represents dysplastic changes to the epithelium of the vaginal mucosa, and like cervical neoplasia, the extent of disease is characterized as levels I, II, or III dependent upon the depth of involvement in the epithelial layer by dysplastic cells. While VAIN itself typically is asymptomatic and not a harmful condition, it carries a 12% risk of progression to invasive vaginal carcinoma, so accurate identification, thorough treatment, and ongoing surveillance are essential.1

VAIN is associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco use, and prior cervical dysplasia. Of women with VAIN, 65% have undergone a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia, which emphasizes the nondefinitive nature of such an intervention.2 These women should be very closely followed for at least 20 years with vaginal cytologic and/or HPV surveillance. High-risk HPV infection is present in 85% of women with VAIN, and the presence of high-risk HPV is a predictor for recurrent VAIN. Recurrent and persistent VAIN also is more common in postmenopausal women and those with multifocal disease.

The most common location for VAIN is at the upper third of the vagina (including the vaginal cuff). It commonly arises within the vaginal fornices, which may be difficult to fully visualize because of their puckered appearance, redundant vaginal tissues, and extensive vaginal rogation.

A diagnosis of VAIN is typically obtained from vaginal cytology which reveals atypical or dysplastic cells. Such a result should prompt the physician to perform vaginal colposcopy and directed biopsies. Comprehensive visualization of the vaginal cuff can be limited in cases where the vaginal fornices are tethered, deeply puckered, or when there is significant mucosal rogation.

The application of 4% acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine are techniques that can enhance the detection of dysplastic vaginal mucosa. Lugol’s iodine selectively stains normal, glycogenated cells, and spares dysplastic glycogen-free cells. The sharp contrast between the brown iodine-stained tissues and the white dysplastic tissues aids in detection of dysplastic areas.

If colposcopic biopsy reveals low grade dysplasia (VAIN I) it does not require intervention, and has a very low rate of conversion to invasive vaginal carcinoma. However moderate- and high-grade vaginal dysplastic lesions should be treated because of the potential for malignant transformation.

Options for treatment of VAIN include topical, ablative, and excisional procedures. Observation also is an option but should be reserved for patients who are closely monitored with repeated colposcopic examinations, and probably should best be reserved for patients with VAIN I or II lesions.

Excisional procedures

The most common excisional procedure employed for VAIN is upper vaginectomy. In this procedure, the surgeon grasps and tents up the vaginal mucosa, incises the mucosa without penetrating the subepithelial tissue layers such as bladder and rectum. The vaginal mucosa then is carefully separated from the underlying endopelvic fascial plane. The specimen should be oriented, ideally on a cork board, with pins or sutures to ascribe margins and borders. Excision is best utilized for women with unifocal disease, or those who fail or do not tolerate ablative or topical interventions.

The most significant risks of excision include the potential for damage to underlying pelvic visceral structures, which is particularly concerning in postmenopausal women with thin vaginal epithelium. Vaginectomy is commonly associated with vaginal shortening or narrowing, which can be deleterious for quality of life. Retrospective series have described a 30% incidence of recurrence after vaginectomy, likely secondary to incomplete excision of all affected tissue.3

Ablation

Ablation of dysplastic foci with a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is a common method for treatment of VAIN. CO2 laser should ablate tissue to a 1.5 mm minimum depth.3 The benefit of using CO2 laser is its ability to treat multifocal disease in situ without an extensive excisional procedure.

It is technically more straightforward than upper vaginectomy with less blood loss and shorter surgical times, and it can be easily accomplished in an outpatient surgical or office setting. However, one of its greatest limitations is the difficulty in visualizing all lesions and therefore adequately treating all sites. The vaginal rogations also make adequate laser ablation challenging because laser only is able to effectively ablate tissue that is oriented perpendicular to the laser beam.

In addition, there is no pathologic confirmation of adequacy of excision or margin status. These features may contribute to the modestly higher rates of recurrence of dysplasia following laser ablation, compared with vaginectomy.3 It also has been associated with more vaginal scarring than vaginectomy, which can have a negative effect on sexual health.

Topical agents

The most commonly utilized topical therapy for VAIN is the antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil (5FU). A typical schedule for 5FU treatment is to apply vaginally, at night, once a week for 8 weeks.4 Because it can cause extensive irritation to the vulvar and urethral epithelium, patients are recommended to apply barrier creams or ointments before and following the use of 5FU for several days, wash hands thoroughly after application, and to rinse and shower in the morning after rising. Severe irritation occurs in up to 16% of patients, but in general it is very well tolerated.

Its virtue is that it is able to conform and travel to all parts of the vaginal mucosa, including those that are poorly visualized within the fornices or vaginal folds. 5FU does not require a hospitalization or surgical procedure, can be applied by the patient at home, and preserves vaginal length and function. In recent reports, 5FU is associated with the lowest rates of recurrence (10%-30%), compared with excision or ablation, and therefore is a very attractive option for primary therapy.3 However, it requires patients to have a degree of comfort with vaginal application of drug and adherence with perineal care strategies to minimize the likelihood of toxicity.

The immune response modifier, imiquimod, that is commonly used in the treatment of vulvar dysplasia also has been described in the treatment of VAIN. It appears to have high rates of clearance (greater than 75%) and be most effective in the treatment of VAIN I.5 It requires application under colposcopic guidance three times a week for 8 weeks, which is a laborious undertaking for both patient and physician. Like 5FU, imiquimod is associated with vulvar and perineal irritation.

Vaginal estrogens are an alternative topical therapy for moderate- and high-grade VAIN and particularly useful for postmenopausal patients. They have been associated with a high rate (up to 90%) of resolution on follow-up vaginal cytology testing and are not associated with toxicities of the above stated therapies.6 Vaginal estrogen can be used alone or in addition to other therapeutic strategies. For example, it can be added to the nontreatment days of 5FU or postoperatively prescribed following laser or excisional procedures.

Radiation

Intracavitary brachytherapy is a technique in which a radiation source is placed within a cylinder or ovoids and placed within the vagina.7 Typically 45 Gy is delivered to a depth 0.5mm below the vaginal mucosal surface (“point z”). Recurrence occurs is approximately 10%-15% of patients, and toxicities can be severe, including vaginal stenosis and ulceration. This aggressive therapy typically is best reserved for cases that are refractory to other therapies. Following radiation, subsequent treatments are more difficult because of radiation-induced changes to the vaginal mucosa that can affect healing.

Vaginal dysplasia is a relatively common sequelae of high-risk HPV, particularly among women who have had a prior hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia. Because of anatomic changes following hysterectomy, adequate visualization and comprehensive vaginal treatment is difficult. Therefore, surgeons should avoid utilization of hysterectomy as a routine strategy to “cure” dysplasia as it may fail to achieve this cure and make subsequent evaluations and treatments of persistent dysplasia more difficult. Women who have had a hysterectomy for dysplasia should be closely followed for several decades, and they should be counseled that they have a persistent risk for vaginal disease. When VAIN develops, clinicians should consider topical therapies as primary treatment options because they may minimize toxicity and have high rates of enduring response.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She had no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2016 Jun;141(3):507-10.

2. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016 Feb;293(2):415-9.

3. Anticancer Res. 2013 Jan;33(1):29-38.

4. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Dec;130(6):1237-43.

5. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 Nov;218:129-36.

6. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014 Apr;18(2):115-21.

7. Gynecol Oncol. 2007 Jul;106(1):105-11.

The opioid crisis: Treating pregnant women with addiction

Age cutoff suggested for STI screening in HIV patients

WASHINGTON – Current guidelines recommend a minimum of annual screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in all sexually active individuals with HIV infection. However, this goal, which is frequently not attained in HIV clinics, may be excessive in certain populations with HIV infection.

In particular, women as well as men who have sex exclusively with women (MSW) may best be served by targeted, age-based screening rather than universal screening, according to a presentation by Susan A. Tuddenham, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“Detection and treatment of gonorrhea and chlamydia in HIV-positive patients in the United States is a priority both because of patient morbidity and because of the potential for these infections to enhance transmission of HIV,” said Dr. Tuddenham.

She and her colleagues assessed data from 16,864 gonorrhea and chlamydia tests of all adults in care at three HIV Research Network sites during 2011-2014. She presented the data at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They assessed the number needed to screen (NNS) in order to identify a single infection across three risk populations of individuals with HIV infection: 1,123 women, 1,236 men who have sex only with women (MSW), and 3,501 men who have sex with men (MSM). NNS was defined as the number of persons tested divided by the number who tested positive and was calculated for the three risk groups for urogenital and extragenital (rectal and pharyngeal) sampling and by age.

Dr. Tuddenham and her colleagues found that NNS based on urogenital screening was similar in all three groups for those individuals aged younger than or equal to 25 years: 15 for women (95% confidence interval, 9-71); 21 for MSW (95% CI, 6-171); and 20 for MSM (95% CI, 12-36). However at ages greater than 25 years, the picture changed, with urogenital NNS increasing to 363 for women (95% CI, 167-1000); 160 for MSW (95% CI, 100-333). For MSM over the age of 25 years, however, the NNS only increased to 46 (95% CI, 38-56).

There were insufficient numbers of extragenital screenings of women and MSW for analysis. But for MSM, rectal NNS was 5 and 10 for those men aged 25 years and younger and those aged over age 25 years, respectively, and pharyngeal NNS was 8 and 20 for the two groups, respectively.

“Our results provide some support for age-based screening cutoffs for women and MSW, with universal screening appropriate for those less than or equal to 25 years of age, and targeted screening for those over 25,” said Dr. Tuddenham. She emphasized the importance of continued universal screening of MSM of all ages for gonorrhea/chlamydia, in particular using extragenital screening as well in order to capture those missed by urogenital screening alone.

Dr. Tuddenham reported that she had no disclosures.

mlesney@mdedge.com

WASHINGTON – Current guidelines recommend a minimum of annual screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in all sexually active individuals with HIV infection. However, this goal, which is frequently not attained in HIV clinics, may be excessive in certain populations with HIV infection.

In particular, women as well as men who have sex exclusively with women (MSW) may best be served by targeted, age-based screening rather than universal screening, according to a presentation by Susan A. Tuddenham, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“Detection and treatment of gonorrhea and chlamydia in HIV-positive patients in the United States is a priority both because of patient morbidity and because of the potential for these infections to enhance transmission of HIV,” said Dr. Tuddenham.

She and her colleagues assessed data from 16,864 gonorrhea and chlamydia tests of all adults in care at three HIV Research Network sites during 2011-2014. She presented the data at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They assessed the number needed to screen (NNS) in order to identify a single infection across three risk populations of individuals with HIV infection: 1,123 women, 1,236 men who have sex only with women (MSW), and 3,501 men who have sex with men (MSM). NNS was defined as the number of persons tested divided by the number who tested positive and was calculated for the three risk groups for urogenital and extragenital (rectal and pharyngeal) sampling and by age.

Dr. Tuddenham and her colleagues found that NNS based on urogenital screening was similar in all three groups for those individuals aged younger than or equal to 25 years: 15 for women (95% confidence interval, 9-71); 21 for MSW (95% CI, 6-171); and 20 for MSM (95% CI, 12-36). However at ages greater than 25 years, the picture changed, with urogenital NNS increasing to 363 for women (95% CI, 167-1000); 160 for MSW (95% CI, 100-333). For MSM over the age of 25 years, however, the NNS only increased to 46 (95% CI, 38-56).

There were insufficient numbers of extragenital screenings of women and MSW for analysis. But for MSM, rectal NNS was 5 and 10 for those men aged 25 years and younger and those aged over age 25 years, respectively, and pharyngeal NNS was 8 and 20 for the two groups, respectively.

“Our results provide some support for age-based screening cutoffs for women and MSW, with universal screening appropriate for those less than or equal to 25 years of age, and targeted screening for those over 25,” said Dr. Tuddenham. She emphasized the importance of continued universal screening of MSM of all ages for gonorrhea/chlamydia, in particular using extragenital screening as well in order to capture those missed by urogenital screening alone.

Dr. Tuddenham reported that she had no disclosures.

mlesney@mdedge.com

WASHINGTON – Current guidelines recommend a minimum of annual screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in all sexually active individuals with HIV infection. However, this goal, which is frequently not attained in HIV clinics, may be excessive in certain populations with HIV infection.

In particular, women as well as men who have sex exclusively with women (MSW) may best be served by targeted, age-based screening rather than universal screening, according to a presentation by Susan A. Tuddenham, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

“Detection and treatment of gonorrhea and chlamydia in HIV-positive patients in the United States is a priority both because of patient morbidity and because of the potential for these infections to enhance transmission of HIV,” said Dr. Tuddenham.

She and her colleagues assessed data from 16,864 gonorrhea and chlamydia tests of all adults in care at three HIV Research Network sites during 2011-2014. She presented the data at a conference on STD prevention sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They assessed the number needed to screen (NNS) in order to identify a single infection across three risk populations of individuals with HIV infection: 1,123 women, 1,236 men who have sex only with women (MSW), and 3,501 men who have sex with men (MSM). NNS was defined as the number of persons tested divided by the number who tested positive and was calculated for the three risk groups for urogenital and extragenital (rectal and pharyngeal) sampling and by age.

Dr. Tuddenham and her colleagues found that NNS based on urogenital screening was similar in all three groups for those individuals aged younger than or equal to 25 years: 15 for women (95% confidence interval, 9-71); 21 for MSW (95% CI, 6-171); and 20 for MSM (95% CI, 12-36). However at ages greater than 25 years, the picture changed, with urogenital NNS increasing to 363 for women (95% CI, 167-1000); 160 for MSW (95% CI, 100-333). For MSM over the age of 25 years, however, the NNS only increased to 46 (95% CI, 38-56).

There were insufficient numbers of extragenital screenings of women and MSW for analysis. But for MSM, rectal NNS was 5 and 10 for those men aged 25 years and younger and those aged over age 25 years, respectively, and pharyngeal NNS was 8 and 20 for the two groups, respectively.

“Our results provide some support for age-based screening cutoffs for women and MSW, with universal screening appropriate for those less than or equal to 25 years of age, and targeted screening for those over 25,” said Dr. Tuddenham. She emphasized the importance of continued universal screening of MSM of all ages for gonorrhea/chlamydia, in particular using extragenital screening as well in order to capture those missed by urogenital screening alone.

Dr. Tuddenham reported that she had no disclosures.

mlesney@mdedge.com

REPORTING FROM THE 2018 STD PREVENTION CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Men who have sex with men with HIV should be regularly screened for STIs regardless of age.

Major finding: The number needed to screen to detect an STI in individuals infected with HIV aged over 25 years were 363 (women); 160 (men who have sex exclusively with women); and 46 (men who have sex with men).

Study details: Gonorrhea/chlamydia tests were assessed from 16,864 individuals infected with HIV and number needed to screen calculated.

Disclosures: Dr. Tuddenham reported that she had no disclosures.

Product Update: PICO NPWT; Encision; TimerCap; AMA

SURGICAL SITE WOUND THERAPY

PICO NPWT is a negative-pressure wound therapy device to treat surgical site infection (SSI). According to Smith & Nephew, a new meta-analysis demonstrates that the prophylactic application of PICO with AIRLOCK™ Technology significantly reduces surgical site complications by 58%, the rate of dehiscence by 26%, and length of stay by one-half day when compared with standard care.

The PICO System is canister-free and disposable. Patients can be discharged safely with PICO in place. Seven days of therapy are provided in each kit, with 1 pump, 2 dressings, and fixation strips to allow for a dressing change.

PICO uses a 4-layer multifunction dressing design in which the layers work together to ensure that negative pressure is delivered to the wound bed and exudate is removed through absorption and evaporation. Approximately 20% of fluid still remains in the dressing. The top film layer has a high-moisture vapor transmission rate to transpire as much as 80% of the exudate, says Smith & Nephew.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.smith-nephew.com/

SHIELDED LAPAROSCOPIC INSTRUMENTS PREVENT BURNS

Encision’s patented Active Electrode Monitoring (AEM®) Shielded Laparoscopic Instruments eliminate patient burns and the associated complications.

Every 90 minutes in the United States, a patient is severely injured from a stray energy burn during laparoscopic surgery, according to Encision. The AEM® Shielded Instruments are designed to eliminate burns caused by monopolar energy insulation failure and capacitive coupling, reducing complications and re-admissions.

In addition to helping health care professionals improve patient safety in line with a recent FDA safety communication, Active Electrode Monitoring is a recommended practice of AORN and AAGL.

Encision offers a complete line of premium laparoscopic monopolar surgical instruments with integrated AEM® technology as well as complimentary products to improve clinical effectiveness and patient safety, including bipolar and cold instrumentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.encision.com/

iSORT: 7-DAY BLUETOOTH PILLBOX

TimerCap has a new Bluetooth-enabled 7-day pill box called the iSort that sends reminders to take medication to a patient’s phone using a free TimerCap App found at the AppStore and Android Market.

The iSort automatically records and stores the times when each door/slot is opened and closed. It knows which door has been used and seamlessly updates the TimerCap App. The app will notify the patient and, if designated, a caregiver, whenever a dose is due or missed using pictures to show what and how many meds are scheduled. More than one iSort box can be used with the app.

iSort provides reminders that help improve adherence to medication dosing instructions and eliminates annoying false alarms, double entries, and unnecessary reminders when pills already have been taken. The portable iSort uses 2 AA batteries that need to be changed about once per year.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.timercap.com/isort

PLATFORM TO COORDINATE HEALTH AND TECHNOLOGY

The American Medical Association (AMA) recently has established a new initiative that introduces a solution to improve, organize, and share health care information. The Integrated Health Model Initiative (IHMI) is a platform that coordinates the health and technology sectors around a common data model. IHMI fills the national imperative to pioneer a shared framework for organizing health data, emphasizing patient-centric information, and refining data elements to those most predictive of better outcomes. The AMA says that evolving available health data to depict a complete picture of a patient’s journey from wellness to illness to treatment and beyond allows health care delivery to fully focus on patient outcomes, goals, and wellness. Participation in IHMI is open to all health care and technology stakeholders.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.ama-assn.org/ihmi

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

SURGICAL SITE WOUND THERAPY

PICO NPWT is a negative-pressure wound therapy device to treat surgical site infection (SSI). According to Smith & Nephew, a new meta-analysis demonstrates that the prophylactic application of PICO with AIRLOCK™ Technology significantly reduces surgical site complications by 58%, the rate of dehiscence by 26%, and length of stay by one-half day when compared with standard care.

The PICO System is canister-free and disposable. Patients can be discharged safely with PICO in place. Seven days of therapy are provided in each kit, with 1 pump, 2 dressings, and fixation strips to allow for a dressing change.

PICO uses a 4-layer multifunction dressing design in which the layers work together to ensure that negative pressure is delivered to the wound bed and exudate is removed through absorption and evaporation. Approximately 20% of fluid still remains in the dressing. The top film layer has a high-moisture vapor transmission rate to transpire as much as 80% of the exudate, says Smith & Nephew.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.smith-nephew.com/

SHIELDED LAPAROSCOPIC INSTRUMENTS PREVENT BURNS

Encision’s patented Active Electrode Monitoring (AEM®) Shielded Laparoscopic Instruments eliminate patient burns and the associated complications.

Every 90 minutes in the United States, a patient is severely injured from a stray energy burn during laparoscopic surgery, according to Encision. The AEM® Shielded Instruments are designed to eliminate burns caused by monopolar energy insulation failure and capacitive coupling, reducing complications and re-admissions.

In addition to helping health care professionals improve patient safety in line with a recent FDA safety communication, Active Electrode Monitoring is a recommended practice of AORN and AAGL.

Encision offers a complete line of premium laparoscopic monopolar surgical instruments with integrated AEM® technology as well as complimentary products to improve clinical effectiveness and patient safety, including bipolar and cold instrumentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.encision.com/

iSORT: 7-DAY BLUETOOTH PILLBOX

TimerCap has a new Bluetooth-enabled 7-day pill box called the iSort that sends reminders to take medication to a patient’s phone using a free TimerCap App found at the AppStore and Android Market.

The iSort automatically records and stores the times when each door/slot is opened and closed. It knows which door has been used and seamlessly updates the TimerCap App. The app will notify the patient and, if designated, a caregiver, whenever a dose is due or missed using pictures to show what and how many meds are scheduled. More than one iSort box can be used with the app.

iSort provides reminders that help improve adherence to medication dosing instructions and eliminates annoying false alarms, double entries, and unnecessary reminders when pills already have been taken. The portable iSort uses 2 AA batteries that need to be changed about once per year.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.timercap.com/isort

PLATFORM TO COORDINATE HEALTH AND TECHNOLOGY

The American Medical Association (AMA) recently has established a new initiative that introduces a solution to improve, organize, and share health care information. The Integrated Health Model Initiative (IHMI) is a platform that coordinates the health and technology sectors around a common data model. IHMI fills the national imperative to pioneer a shared framework for organizing health data, emphasizing patient-centric information, and refining data elements to those most predictive of better outcomes. The AMA says that evolving available health data to depict a complete picture of a patient’s journey from wellness to illness to treatment and beyond allows health care delivery to fully focus on patient outcomes, goals, and wellness. Participation in IHMI is open to all health care and technology stakeholders.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.ama-assn.org/ihmi

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

SURGICAL SITE WOUND THERAPY

PICO NPWT is a negative-pressure wound therapy device to treat surgical site infection (SSI). According to Smith & Nephew, a new meta-analysis demonstrates that the prophylactic application of PICO with AIRLOCK™ Technology significantly reduces surgical site complications by 58%, the rate of dehiscence by 26%, and length of stay by one-half day when compared with standard care.

The PICO System is canister-free and disposable. Patients can be discharged safely with PICO in place. Seven days of therapy are provided in each kit, with 1 pump, 2 dressings, and fixation strips to allow for a dressing change.

PICO uses a 4-layer multifunction dressing design in which the layers work together to ensure that negative pressure is delivered to the wound bed and exudate is removed through absorption and evaporation. Approximately 20% of fluid still remains in the dressing. The top film layer has a high-moisture vapor transmission rate to transpire as much as 80% of the exudate, says Smith & Nephew.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.smith-nephew.com/

SHIELDED LAPAROSCOPIC INSTRUMENTS PREVENT BURNS

Encision’s patented Active Electrode Monitoring (AEM®) Shielded Laparoscopic Instruments eliminate patient burns and the associated complications.

Every 90 minutes in the United States, a patient is severely injured from a stray energy burn during laparoscopic surgery, according to Encision. The AEM® Shielded Instruments are designed to eliminate burns caused by monopolar energy insulation failure and capacitive coupling, reducing complications and re-admissions.

In addition to helping health care professionals improve patient safety in line with a recent FDA safety communication, Active Electrode Monitoring is a recommended practice of AORN and AAGL.

Encision offers a complete line of premium laparoscopic monopolar surgical instruments with integrated AEM® technology as well as complimentary products to improve clinical effectiveness and patient safety, including bipolar and cold instrumentation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.encision.com/

iSORT: 7-DAY BLUETOOTH PILLBOX

TimerCap has a new Bluetooth-enabled 7-day pill box called the iSort that sends reminders to take medication to a patient’s phone using a free TimerCap App found at the AppStore and Android Market.

The iSort automatically records and stores the times when each door/slot is opened and closed. It knows which door has been used and seamlessly updates the TimerCap App. The app will notify the patient and, if designated, a caregiver, whenever a dose is due or missed using pictures to show what and how many meds are scheduled. More than one iSort box can be used with the app.

iSort provides reminders that help improve adherence to medication dosing instructions and eliminates annoying false alarms, double entries, and unnecessary reminders when pills already have been taken. The portable iSort uses 2 AA batteries that need to be changed about once per year.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.timercap.com/isort

PLATFORM TO COORDINATE HEALTH AND TECHNOLOGY

The American Medical Association (AMA) recently has established a new initiative that introduces a solution to improve, organize, and share health care information. The Integrated Health Model Initiative (IHMI) is a platform that coordinates the health and technology sectors around a common data model. IHMI fills the national imperative to pioneer a shared framework for organizing health data, emphasizing patient-centric information, and refining data elements to those most predictive of better outcomes. The AMA says that evolving available health data to depict a complete picture of a patient’s journey from wellness to illness to treatment and beyond allows health care delivery to fully focus on patient outcomes, goals, and wellness. Participation in IHMI is open to all health care and technology stakeholders.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: www.ama-assn.org/ihmi

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The techno vagina: The laser and radiofrequency device boom in gynecology

In recent years, an increasing number of laser and radiofrequency device outpatient treatments have been heralded as safe and effective interventions for various gynecologic conditions. Laser devices and radiofrequency technology rapidly have been incorporated into certain clinical settings, including medical practices specializing in dermatology, plastic surgery, and gynecology. While this developing technology has excellent promise, many clinical and research questions remain unanswered.

Concerns about energy-based vaginal treatments

Although marketing material often suggests otherwise, most laser and radiofrequency devices are cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only for nonspecific gynecologic and hematologic interventions. However, both laser and radiofrequency device treatments, performed as outpatient procedures, have been touted as appropriate interventions for many conditions, including female sexual dysfunction, arousal and orgasmic concerns, vaginal laxity, vaginismus, lichen sclerosus, urinary incontinence, and vulvar vestibulitis.

Well-designed studies are needed. Prospective, randomized sham-controlled trials of energy-based devices are rare, and most data in the public domain are derived from case series. Many studies are of short duration with limited follow-up. Randomized controlled trials therefore are warranted and should have stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria. Body dysmorphic syndrome, for example, should be a trial exclusion. Study design for research should include the use of standardized, validated scales and long-term follow-up of participants.

Which specialists have the expertise to offer treatment? Important ethical and medical concerns regarding the technology need to be addressed. A prime concern is determining which health care professional specialist is best qualified to assess and treat underlying gynecologic conditions. It is not uncommon to see internists, emergency medicine providers, family physicians, plastic surgeons, psychiatrists, and dermatologists self-proclaiming their gynecologic “vaginal rejuvenation” expertise.

In my experience, some ObGyns have voiced concern about the diverse medical specialties involved in performing these procedures. Currently, no standard level of training is required to perform them. In addition, those providers lack the training needed to adequately and accurately assess the potential for confounding, underlying gynecologic pathology, and they are inadequately trained to offer patients the full gamut of therapeutic interventions. Many may be unfamiliar with female pelvic anatomy and sexual function and a multidisciplinary treatment paradigm.

We need established standards. A common vernacular, nosology, classification, and decision-tree assessment paradigm for genitopelvic laxity (related to the condition of the pelvic floor and not simply a loose feeling in the vagina) is lacking, which may make research and peer-to-peer discussions difficult.

Which patients are appropriate candidates? Proper patient selection criteria for energy-based vaginal treatment have not been standardized, yet this remains a paramount need. A comprehensive patient evaluation should be performed and include a discussion on the difference between an aesthetic complaint and a functional medical problem. Assessment should include the patient’s level of concern or distress and the impact of her symptoms on her overall quality of life. Patients should be evaluated for body dysmorphic syndrome and relationship discord. A complete physical examination, including a detailed pelvic assessment, often is indicated. A treatment algorithm that incorporates conservative therapies coupled with medical, technologic, and psychologic interventions also should be developed.

Various energy-based devices are available for outpatient procedures

Although the number of procedures performed (such as vaginal rejuvenation, labiaplasty, vulvar liposculpturing, hymenoplasty, G-spot amplification, and O-Shot treatment) for both cosmetic and functional problems has increased, the published scientific data on the procedures’ short- and long-term efficacy and safety are limited. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a committee opinion stating that many of these procedures, including “vaginal rejuvenation,” may not be considered medically indicated and may lack scientific merit or ample supportive data to confirm their efficacy and safety.1 ObGyns should proceed with caution before incorporating these technologic treatments into their medical practice.

Much diversity exists within the device-technology space. The underpinnings of each device vary regarding their proposed mechanism of action and theoretical therapeutic and tissue effect. In device marketing materials, many devices have been claimed to have effects on multiple tissue types (for example, both vaginal mucosa and vulvar tissue), whereas others are said to have more focal and localized effects (that is, targeted behind the hymenal ring). Some are marketed as a one-time treatment, while others require multiple repeated treatments over an extended period. When it comes to published data, adverse effect reporting remains limited and follow-up data often are short term.

Radiofrequency and laser devices are separate and very distinct technologies with similar and differing proposed utilizations. Combining radiofrequency and laser treatments in tandem or sequentially may have clinical utility, but long-term safety may be a concern for lasers.

Radiofrequency-based devices

Typically, radiofrequency device treatments:

- are used for outpatient procedures

- do not require topical anesthesia

- are constructed to emit focused electromagnetic waves

- are applied to vaginal, vulvar, or vaginal introital or vestibular tissue

- deliver energy to the deeper connective tissue of the vaginal wall architecture.

Radiofrequency device energy can be monopolar, unipolar, bipolar, or multipolar depending on design. Design also dictates current and the number of electrodes that pass from the device to the grounding pad. Monopolar is the only type of radiofrequency that has a grounding pad; bipolar and multipolar energy returns to the treatment tip.

Radiofrequency devices typically are FDA 510(k)-cleared devices for nonspecific electrocoagulation and hemostasis for surgical procedures. None are currently FDA cleared in the United States for the treatment of vaginal or vulvar laxity or genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). These energy-based devices aim to induce collagen contraction, neocollagenesis, vascularization, and growth factor infiltration to restore the elasticity and moisture of the underlying vaginal mucosa. Heat shock protein activation and inflammation activation are thought to be the underlying mechanisms of action.2–5

Treatment outcomes with 2 radiofrequency devices

Multiple prospective small case series studies have reported outcomes of women treated with the ThermiVa (ThermiAesthetics LLC) radiofrequency system.3,4 Typically, 3 treatments (with a between-treatment interval of 4 to 6 weeks) were applied. The clinical end point temperature had a range of 40°C to 45°C, which was maintained for 3 to 5 minutes per treated zone during 30 minutes’ total treatment time.

Some participants self-reported improvement in vaginal laxity symptoms with the 3 treatments. In addition, women reported subjective improvements in both vaginal atrophy symptoms and sexual function, including positive effect in multiple domains. No serious adverse events were reported in these case series. However, there was no placebo-controlled arm, and validated questionnaires were not used in much of this research.3,4

In another trial, the ThermiVa system was studied in a cohort of 25 sexually active women with self-reported anorgasmia or increased latency to orgasmic response.6 Participants received 3 treatments 4 weeks apart. Approximately three-quarters of the participants reported improved orgasmic responsivity, vaginal lubrication, and clitoral sensitivity. Notably, this research did not use validated questionnaires or a placebo or sham-controlled design. The authors suggested sustained treatment benefits at 9 to 12 months. While repeat treatment was advocated, data were lacking to support the optimal time for repeat treatment efficacy.6

A cryogen-cooled monopolar radiofrequency device, the Viveve system (Viveve Medical, Inc) differs from other radiofrequency procedures because it systematically cryogen cools and protects the surface of the vaginal mucosal tissue while heating the underlying structures.

The Viveve system was evaluated in 2 small pilot studies (24 and 30 participants) and in a large, randomized, sham-controlled, prospective trial that included 108 participants (VIVEVE I trial).5,7,8 Results from both preliminary small studies indicated that participants experienced significant improvement in overall sexual function at 6 months. In one of the small studies (in Japanese women), sustained efficacy at 12 months posttreatment was reported.7 Neither small study included a placebo-control arm, but they did include the use of validated questionnaires.

In the VIVEVE I trial (a multicenter international study), treatment in the active group consisted of a single, 30-minute outpatient procedure that delivered 90 J/cm2 of radiofrequency energy at the level just behind the hymenal ring behind the vaginal introitus. The sham-treated group received ≤1 J/cm2 of energy with a similar machine tip.8

Statistically significant improvements were reported in the arousal and orgasm domains of the validated Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) for the active-treatment group compared with the sham-treated group. In addition, there were statistically significant differences in the FSFI and the Female Sexual Distress Scale–Revised total scores in favor of active treatment. Participants in the active-treatment arm reported statistically significant improvement in overall sexual satisfaction coupled with lowered overall sexual distress.8

These data are provocative, since the Viveve treatment demonstrated superior efficacy compared with the sham treatment, and prior evidence demonstrated that medical device trials employing a sham arm often demonstrate particularly large placebo/sham effects.9 A confirmatory randomized, sham-controlled multicenter US-based trial is currently underway. At present, the VIVEVE I trial remains the only published, large-scale, randomized, sham-controlled, blinded study of a radiofrequency-based treatment.

New emerging data support the efficacy and safety of this specific radiofrequency treatment in patients with mild to moderate urinary stress incontinence; further studies confirming these outcomes are anticipated. The Viveve system is approved in many countries for various conditions, including urinary incontinence (1 country), sexual function (17 countries), vaginal laxity (41 countries), and electrocoagulation and hemostasis (4 countries, including the United States).

Laser technology devices

Laser (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) therapy, which uses a carbon dioxide (CO2), argon, YAG, or erbium energy source, also is currently marketed as a method to improve various gynecologic conditions, including genital pelvic relaxation syndrome, vaginal laxity, GSM, lichen sclerosus, and sexual problems such as dyspareunia and arousal or orgasmic disorders.

The CO2 laser therapy device, such as the MonaLisa Touch (DEKA Laser), appears to be very popular and widely available. It delivers fractional CO2 laser energy to the vaginal wall, creating sequential micro traumas that subsequently undergo a healing reaction; the newly healed area has an improved underlying tissue architecture (but at a superficial level). The laser’s proposed mechanism of action is that it ablates only a minute fraction of the superficial lamina propria; it acts primarily to stimulate rapid healing of the tissue, creating new collagen and elastic fibers. There is no evidence of scarring.10

Treatment outcomes with laser device therapy

Authors of a 2017 study series of CO2 laser treatments in women with moderate to severe GSM found that 84% of participants experienced significant improvement in sexual function, dyspareunia, and otherwise unspecified sexual issues from pretreatment to 12 to 24 months posttreatment.11 These findings are consistent with several other case series and provide supportive evidence for the efficacy and safety of CO2 laser therapy. This technology may be appropriate for the treatment of GSM.

Laser technology shows excellent promise for the treatment of GSM symptoms by virtue of its superficial mechanism of action. In addition, several trials have demonstrated efficacy and safety in breast cancer patient populations.12 This is particularly interesting since breast cancer treatments, such as aromatase inhibitors (considered a mainstay of cancer treatment), can cause severe atrophic vaginitis. Breast cancer survivors often avoid minimally absorbed local vaginal hormonal products, and over-the-counter products (moisturizers and lubricants) are not widely accepted. Hence, a nonhormonal treatment for distressing GSM symptoms is welcomed in this population.

Pagano and colleagues recently studied 82 breast cancer survivors in whom treatment with vaginal moisturizers and lubricants failed.12 Participants underwent 3 laser treatment cycles approximately 30 to 40 days apart; they demonstrated improvements in vaginal dryness, vaginal itchiness, stinging, dyspareunia, and reduced sensitivity.

Microablative fractional CO2 laser may help reestablish a normative vaginal microbiome by altering the prevalence of lactobacillus species and reestablishing a normative postmenopausal vaginal flora.13

The tracking and reporting of adverse events associated with laser procedures has been less than optimal. In my personal clinical experience, consequences from both short- and long-term laser treatments have included vaginal canal agglutination, worsening dyspareunia, and constricture causing vaginal hemorrhage.

Cruz and colleagues recently conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial designed to evaluate the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol and laser plus estriol for the treatment of vaginal atrophy in 45 postmenopausal women.14 They found statistically significant differences in dyspareunia, dryness, and burning compared with baseline levels in all 3 treatment groups. Results with the fractional CO2 laser treatment were deemed to be similar to those of the topical estriol and the combined therapy.14

By contrast, an erbium (Er):YAG laser, such as the IntimaLase (Fotona, LLC) laser, functions by heating the pelvic tissue and collagen within the introitus and vaginal canal.15,16 When the underlying collagen is heated, the fibers are thought to thicken and shorten, which may result in immediate contracture of the treated tissue. Additionally, this process stimulates the existing collagen to undergo remodeling and it also may cause neocollagen deposition.15 In a general review of gynecologic procedures, after 1 to 4 treatment sessions (depending on the study), most patients reported improved sexual satisfaction or vaginal tightness.15

Although trials have included small numbers of patients, early evidence suggests some lasers with reportedly deeper penetration may be useful for treatment of vaginal laxity, but further studies are needed. In smaller studies, the Er:YAG laser has shown efficacy and safety in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence and improved lower urinary tract symptoms, quality of life, and sexual function.16,17

Insurance does not cover energy-based treatment costs

Currently, both laser and radiofrequency device treatments are considered fee-for-service interventions. Radiofrequency and laser treatments for gynecologic conditions are not covered by health insurance, and treatment costs can be prohibitive for many patients. In addition, the long-term safety of these treatments remains to be studied further, and the optimal time for a repeat procedure has yet to be elucidated.

The FDA cautions against energy-based procedures

In July 2018, the FDA released a statement of concern reiterating the need for research and randomized clinical trials before energy-based device treatments can be widely accepted, and that they are currently cleared only for general gynecologic indications and not for disorders and symptoms related to menopause, urinary incontinence, or sexual function.18

The FDA stated that “we have not cleared or approved for marketing any energy-based devices to treat these symptoms or conditions [vaginal laxity; vaginal atrophy, dryness, or itching; pain during sexual intercourse; pain during urination; decreased sexual sensation], or any symptoms related to menopause, urinary incontinence, or sexual function.” The FDA noted that serious complications have been reported, including vaginal burns, scarring, pain during sexual intercourse, and recurring, chronic pain. The FDA issued letters to 7 companies regarding concerns about the marketing of their devices for off-label use and promotion.

Several societies have responded. ACOG reaffirmed its 2016 position statement on fractional laser treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy.19 JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, Executive Director of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS), and Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD, President of NAMS, alerted their members that both health care professionals and consumers should tread cautiously, and they encouraged scrutiny of existing evidence as all energy-based treatments are not created equal.20 They noted that some research does exist and cited 2 randomized, sham-controlled clinical trials that have been published.

Looking forward

Various novel technologic therapies are entering the gynecologic market. ObGyns must critically evaluate these emerging technologies with a keen understanding of their underlying mechanism of action, the level of scientific evidence, and the treatment’s proposed therapeutic value.

Radiofrequency energy devices appear to be better positioned to treat urinary incontinence and vaginal relaxation syndrome because of their capability for deep tissue penetration. Current data show that laser technology has excellent promise for the treatment and management of GSM. Both technologies warrant further investigation in long-term randomized, sham-controlled trials that assess efficacy and safety with validated instruments over an extended period. In addition, should these technologies prove useful in the overall treatment armamentarium for gynecologic conditions, the question of affordability and insurance coverage needs to be addressed.

ObGyns must advocate for female sexual wellness and encourage a comprehensive multidisciplinary team approach for offering various therapies. Ultimately, responsible use of evidence-based innovative technology should be incorporated into the treatment paradigm.

Despite recent technologic advancements and applications in gynecologic care, minimally absorbed local vaginal hormonal products (creams, rings, intravaginal tablets) and estrogen agonists/antagonists remain the mainstay and frontline treatment for moderate to severe dyspareunia, a symptom of vulvovaginal atrophy due to menopause. Newer medications, such as intravaginal steroids1 and the recently approved bioidentical estradiol nonapplicator vaginal inserts,2 also offer excellent efficacy and safety in the treatment of this condition. These medications now are included under expanded insurance coverage, and they offer safe, simple, and cost-effective treatments for this underdiagnosed condition.

References

- Intrarosa [package insert]. Waltham, MA: AMAG Pharmaceuticals Inc; February 2018.

- Imvexxy [package insert]. Boca Raton, FL: TherapeuticsMD; 2018.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: Vaginal "rejuvenation" and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):737-738.

- Dunbar SW, Goldberg DJ. Radiofrequency in cosmetic dermatology: an update. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(11):1229-1238.

- Leibaschoff G, Izasa PG, Cardona JL, Miklos JR, Moore RD. Transcutaneous temperature-controlled radiofrequency (TTCRF) for the treatment of menopausal vaginal/genitourinary symptoms. Surg Technol Int. 2016;29:149-159.

- Alinsod RM. Temperature controlled radiofrequency for vulvovaginal laxity. Prime J. July 23, 2015. https://www.prime-journal.com/temperature-controlled-radiofrequency-for-vulvovaginal-laxity/. Accessed August 15, 2018.

- Millheiser LS, Pauls RN, Herbst SJ, Chen BH. Radiofrequency treatment of vaginal laxity after vaginal delivery: nonsurgical vaginal tightening. J Sex Med. 2010;7(9):3088-3095.

- Alinsod RM. Transcutaneous temperature controlled radiofrequency for orgasmic dysfunction. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48(7):641-645.

- Sekiguchi Y, Utsugisawa Y, Azekosi Y, et al. Laxity of the vaginal introitus after childbirth: nonsurgical outpatient procedure for vaginal tissue restoration and improved sexual satisfaction using low-energy radiofrequency thermal therapy. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22 (9):775-781 .

- Krychman M, Rowan CG, Allan BB, et al. Effect of single-treatment, surface-cooled radiofrequency therapy on vaginal laxity and female sexual function: the VIVEVE I randomized controlled trial. J Sex Med. 2017;14(2):215-225.

- Kaptchuk TJ, Goldman P, Stone DA, Statson WB. Do medical devices have enhanced placebo effects? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(8): 786-792.

- Gotkin RH, Sarnoff SD, Cannarozzo G, Sadick NS, Alexiades-Armenakas M. Ablative skin resurfacing with a novel microablative CO2 laser. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8(2):138-144.

- Behnia-Willison F, Sarraf S, Miller J, et al. Safety and long-term efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in women suffering from genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;213:39-44.

- Pagano T, De Rosa P, Vallone R, et al. Fractional microablative CO2 laser in breast cancer survivors affected by iatrogenic vulvovaginal atrophy after failure of nonestrogenic local treatments, a retrospective study. Menopause. 2018;25(6):657-662.

- Anthanasiou S, Pitsouni E, Antonopoulou S, et al. The effect of microablative fractional CO2 laser on vaginal flora of postmenopausal women. Climateric. 2016;19(5):512-518.

- Cruz VL, Steiner ML, Pompei LM, et al. Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial for evaluating the efficacy of fractional CO2 laser compared with topical estriol in the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018;25(1): 21-28.

- Vizintin Z, Rivera M, Fistonic I, et al. Novel minimally invasive VSP Er:YAG laser treatments in gynecology. J Laser Health Acad. 2012;2012(1):46-58.

- Tien YM, Hsio SM, Lee CN, Lin HH. Effects of laser procedure for female urodynamic stress incontinence on pad weight, urodynamics, and sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(3):469-476.

- Oginc UB, Sencar S, Lenasi H. Novel minimally invasive laser treatment of urinary incontinence in women. Laser Surg Med. 2015;47(9):689-697.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns against use of energy based devices to perform vaginal 'rejuvenation' or vaginal cosmetic procedures: FDA safety communication. July 30, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm615013.htm. Accessed August 16, 2018.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Fractional laser treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and US Food and Drug Administration clearance: position statement. May 2016. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Position-Statements/Fractional-Laser-Treatment-of-Vulvovaginal-Atrophy-and-US-Food-and-Drug-Administration-Clearance. Accessed August 16, 2018.

- The North American Menopause Society. FDA mandating vaginal laser manufacturers present valid data before marketing. August 1, 2018. https://www.menopause.org/docs/default-source/default-document-library/nams-responds-to-fda-mandate-on-vaginal-laser-manufacturers-08-01-2018.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2018.

In recent years, an increasing number of laser and radiofrequency device outpatient treatments have been heralded as safe and effective interventions for various gynecologic conditions. Laser devices and radiofrequency technology rapidly have been incorporated into certain clinical settings, including medical practices specializing in dermatology, plastic surgery, and gynecology. While this developing technology has excellent promise, many clinical and research questions remain unanswered.

Concerns about energy-based vaginal treatments

Although marketing material often suggests otherwise, most laser and radiofrequency devices are cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only for nonspecific gynecologic and hematologic interventions. However, both laser and radiofrequency device treatments, performed as outpatient procedures, have been touted as appropriate interventions for many conditions, including female sexual dysfunction, arousal and orgasmic concerns, vaginal laxity, vaginismus, lichen sclerosus, urinary incontinence, and vulvar vestibulitis.

Well-designed studies are needed. Prospective, randomized sham-controlled trials of energy-based devices are rare, and most data in the public domain are derived from case series. Many studies are of short duration with limited follow-up. Randomized controlled trials therefore are warranted and should have stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria. Body dysmorphic syndrome, for example, should be a trial exclusion. Study design for research should include the use of standardized, validated scales and long-term follow-up of participants.

Which specialists have the expertise to offer treatment? Important ethical and medical concerns regarding the technology need to be addressed. A prime concern is determining which health care professional specialist is best qualified to assess and treat underlying gynecologic conditions. It is not uncommon to see internists, emergency medicine providers, family physicians, plastic surgeons, psychiatrists, and dermatologists self-proclaiming their gynecologic “vaginal rejuvenation” expertise.

In my experience, some ObGyns have voiced concern about the diverse medical specialties involved in performing these procedures. Currently, no standard level of training is required to perform them. In addition, those providers lack the training needed to adequately and accurately assess the potential for confounding, underlying gynecologic pathology, and they are inadequately trained to offer patients the full gamut of therapeutic interventions. Many may be unfamiliar with female pelvic anatomy and sexual function and a multidisciplinary treatment paradigm.

We need established standards. A common vernacular, nosology, classification, and decision-tree assessment paradigm for genitopelvic laxity (related to the condition of the pelvic floor and not simply a loose feeling in the vagina) is lacking, which may make research and peer-to-peer discussions difficult.

Which patients are appropriate candidates? Proper patient selection criteria for energy-based vaginal treatment have not been standardized, yet this remains a paramount need. A comprehensive patient evaluation should be performed and include a discussion on the difference between an aesthetic complaint and a functional medical problem. Assessment should include the patient’s level of concern or distress and the impact of her symptoms on her overall quality of life. Patients should be evaluated for body dysmorphic syndrome and relationship discord. A complete physical examination, including a detailed pelvic assessment, often is indicated. A treatment algorithm that incorporates conservative therapies coupled with medical, technologic, and psychologic interventions also should be developed.

Various energy-based devices are available for outpatient procedures