User login

No increase in primary ovarian insufficiency with HPV vaccine

The human papillomavirus vaccine does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of ovarian insufficiency, according to researchers.

Allison L. Naleway, PhD, of the Center for Health Research at Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Ore., and her coauthors wrote that a previous case series had raised concerns about a possible link between the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) in six young women who developed the condition within 12 months of vaccination.

Using EHR data, researchers identified 46 women aged 11-34 years with idiopathic POI – 33 probable cases and 13 possible cases – after excluding cases with known causes. Eighteen of these cases also were excluded because they were diagnosed before the HPV vaccine was available.

They found that only 1 of the remaining 28 patients had been vaccinated against HPV before the symptom onset: a 16-year-old girl who was vaccinated about 23 months before the first clinical evaluation for delayed menarche. Their report was published in Pediatrics.

The adjusted hazard ratio for POI was therefore 0.30 after HPV vaccine, compared with 0.88 after Tdap, 1.42 after inactivated influenza vaccine, and 0.94 after meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

More than one-half of the 46 confirmed POI cases were diagnosed at age 27 years or older, and only one patient was diagnosed under 15 years of age.

“If POI is triggered by HPV or other adolescent vaccine exposure, we would have expected to see elevated incidence in the younger women who were most likely to be vaccinated, but instead we observed higher incidence in older women (greater than 26 years of age), which is consistent with 1 other population-based study of POI prevalence,” the authors wrote.

They acknowledged that studying POI as a vaccine-related adverse event was challenging because the time from symptom onset to diagnosis was variable. However, they said that 81% of their cohort was followed up for more than 2 years, and a mean of 5.14 years, so the potential for misclassification was “minimal.”

Dr. Naleway and her associates also noted that diagnoses of POI can be difficult to accurately identify, and symptoms may be masked by oral contraceptive use.

“Despite the challenges and limitations discussed above, we believe this study should lessen concern surrounding potential impact on fertility from HPV or other adolescent vaccination,” they wrote.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention supported the study. Three authors declared funding from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated studies. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Naleway A et al. Pediatrics 2018;42(3):e20180943.

The human papillomavirus vaccine does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of ovarian insufficiency, according to researchers.

Allison L. Naleway, PhD, of the Center for Health Research at Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Ore., and her coauthors wrote that a previous case series had raised concerns about a possible link between the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) in six young women who developed the condition within 12 months of vaccination.

Using EHR data, researchers identified 46 women aged 11-34 years with idiopathic POI – 33 probable cases and 13 possible cases – after excluding cases with known causes. Eighteen of these cases also were excluded because they were diagnosed before the HPV vaccine was available.

They found that only 1 of the remaining 28 patients had been vaccinated against HPV before the symptom onset: a 16-year-old girl who was vaccinated about 23 months before the first clinical evaluation for delayed menarche. Their report was published in Pediatrics.

The adjusted hazard ratio for POI was therefore 0.30 after HPV vaccine, compared with 0.88 after Tdap, 1.42 after inactivated influenza vaccine, and 0.94 after meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

More than one-half of the 46 confirmed POI cases were diagnosed at age 27 years or older, and only one patient was diagnosed under 15 years of age.

“If POI is triggered by HPV or other adolescent vaccine exposure, we would have expected to see elevated incidence in the younger women who were most likely to be vaccinated, but instead we observed higher incidence in older women (greater than 26 years of age), which is consistent with 1 other population-based study of POI prevalence,” the authors wrote.

They acknowledged that studying POI as a vaccine-related adverse event was challenging because the time from symptom onset to diagnosis was variable. However, they said that 81% of their cohort was followed up for more than 2 years, and a mean of 5.14 years, so the potential for misclassification was “minimal.”

Dr. Naleway and her associates also noted that diagnoses of POI can be difficult to accurately identify, and symptoms may be masked by oral contraceptive use.

“Despite the challenges and limitations discussed above, we believe this study should lessen concern surrounding potential impact on fertility from HPV or other adolescent vaccination,” they wrote.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention supported the study. Three authors declared funding from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated studies. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Naleway A et al. Pediatrics 2018;42(3):e20180943.

The human papillomavirus vaccine does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of ovarian insufficiency, according to researchers.

Allison L. Naleway, PhD, of the Center for Health Research at Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Ore., and her coauthors wrote that a previous case series had raised concerns about a possible link between the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) in six young women who developed the condition within 12 months of vaccination.

Using EHR data, researchers identified 46 women aged 11-34 years with idiopathic POI – 33 probable cases and 13 possible cases – after excluding cases with known causes. Eighteen of these cases also were excluded because they were diagnosed before the HPV vaccine was available.

They found that only 1 of the remaining 28 patients had been vaccinated against HPV before the symptom onset: a 16-year-old girl who was vaccinated about 23 months before the first clinical evaluation for delayed menarche. Their report was published in Pediatrics.

The adjusted hazard ratio for POI was therefore 0.30 after HPV vaccine, compared with 0.88 after Tdap, 1.42 after inactivated influenza vaccine, and 0.94 after meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

More than one-half of the 46 confirmed POI cases were diagnosed at age 27 years or older, and only one patient was diagnosed under 15 years of age.

“If POI is triggered by HPV or other adolescent vaccine exposure, we would have expected to see elevated incidence in the younger women who were most likely to be vaccinated, but instead we observed higher incidence in older women (greater than 26 years of age), which is consistent with 1 other population-based study of POI prevalence,” the authors wrote.

They acknowledged that studying POI as a vaccine-related adverse event was challenging because the time from symptom onset to diagnosis was variable. However, they said that 81% of their cohort was followed up for more than 2 years, and a mean of 5.14 years, so the potential for misclassification was “minimal.”

Dr. Naleway and her associates also noted that diagnoses of POI can be difficult to accurately identify, and symptoms may be masked by oral contraceptive use.

“Despite the challenges and limitations discussed above, we believe this study should lessen concern surrounding potential impact on fertility from HPV or other adolescent vaccination,” they wrote.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention supported the study. Three authors declared funding from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated studies. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Naleway A et al. Pediatrics 2018;42(3):e20180943.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The adjusted hazard ratio for POI was 0.30 after HPV vaccine, compared with 0.88 after Tdap, 1.42 after inactivated influenza vaccine, and 0.94 after meningococcal conjugate vaccine.

Study details: Analysis of medical records data for 46 women with confirmed iatrogenic primary ovarian failure.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Three authors declared funding from pharmaceutical companies for unrelated studies. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Naleway A et al. Pediatrics 2018;142(3):e20180943.

Sexual minorities seeking abortion report high levels of male violence

Pregnant lesbian and bisexual women who seek abortions are more likely than are their heterosexual counterparts to be the victims of violence by the men who impregnated them, a new study finds.

Rachel K. Jones, PhD, of the Guttmacher Institute, New York, and her associates also found that these sexual minority women, plus a group of individuals who described their sexual orientation as “something else,” were much more likely to report exposure to sexual and physical violence.

“No patient should be presumed to be heterosexual for any reason, including a pregnancy history. All pregnancies – like all patients – should be treated as unique and operating within the dynamic and interconnected circumstances of peoples’ lives, which may encompass differences in sexual orientation and exposure to violence,” the researchers wrote. Their report is in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Previous research has suggested that nonheterosexual women are more likely than are straight women to become pregnant unintentionally. There also are signs suggesting that they have more abortions, too, although the findings are iffy, the study authors wrote.

For this study, Dr. Jones and her associates examined questionnaire answers of 8,380 women who responded to the Guttmacher Institute’s 2014 Abortion Patient Survey. All were undergoing abortions at 87 U.S. nonhospital facilities that performed 30 or more abortions each per year.

Of the sample, about 9% declined to describe their sexual orientation. Of the rest, 94% described themselves as heterosexual; of those, 41% were white, 28% were black, and 22% were Hispanic. Most were in their 20s, 47% were never married, and 48% had incomes below the federal poverty level.

Women also described themselves as bisexual (4%), “something else” (1%), and lesbian (0.4%). All these groups were more likely than were heterosexuals to be below the federal poverty level; more than half of the lesbian and bisexual respondents said they had previously given birth.

Fifteen percent of lesbians said their current pregnancy was caused by forced sex, compared with 1% of heterosexuals and 3% of bisexuals. (P less than .001).

Bisexuals (9%) and lesbians (33%) were more likely than were heterosexuals (4%) to say the men who impregnated them had physically abused them. The same was true for sexual abuse, which was reported by 7% of bisexuals, 35% of lesbians, and 2% of heterosexuals. After the researchers controlled for various factors including age and race, lesbians remained much more likely to report physical abuse, sexual abuse, and forced sex at the hands of the men who impregnated them (odds ratios = 15, 25, and 10, respectively, P less than .001).

“Exposure to physical and sexual violence was substantially higher among each of the sexual minority groups compared with their heterosexual counterparts, sometimes by a factor of 15 or more,” the study authors wrote. “We found that lesbian respondents had the highest levels of exposure to violence, perhaps because this population was more likely to have had sex with a man only in the context of forced sex.”

The researchers noted that their study has various limitations, such as low numbers of sexual minority women and the 4-year gap since the data were collected.

Still, Dr. Jones and her associates wrote, the study has strengths. “Health care providers, including those working in abortion settings, need to be aware that a proportion of their patient population identifies as something other than heterosexual,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation with support from the National Institutes of Health via a grant to the Guttmacher Center for Population Research Innovation and Dissemination. The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Jones R et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Sep;132(3):605-11.

Pregnant lesbian and bisexual women who seek abortions are more likely than are their heterosexual counterparts to be the victims of violence by the men who impregnated them, a new study finds.

Rachel K. Jones, PhD, of the Guttmacher Institute, New York, and her associates also found that these sexual minority women, plus a group of individuals who described their sexual orientation as “something else,” were much more likely to report exposure to sexual and physical violence.

“No patient should be presumed to be heterosexual for any reason, including a pregnancy history. All pregnancies – like all patients – should be treated as unique and operating within the dynamic and interconnected circumstances of peoples’ lives, which may encompass differences in sexual orientation and exposure to violence,” the researchers wrote. Their report is in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Previous research has suggested that nonheterosexual women are more likely than are straight women to become pregnant unintentionally. There also are signs suggesting that they have more abortions, too, although the findings are iffy, the study authors wrote.

For this study, Dr. Jones and her associates examined questionnaire answers of 8,380 women who responded to the Guttmacher Institute’s 2014 Abortion Patient Survey. All were undergoing abortions at 87 U.S. nonhospital facilities that performed 30 or more abortions each per year.

Of the sample, about 9% declined to describe their sexual orientation. Of the rest, 94% described themselves as heterosexual; of those, 41% were white, 28% were black, and 22% were Hispanic. Most were in their 20s, 47% were never married, and 48% had incomes below the federal poverty level.

Women also described themselves as bisexual (4%), “something else” (1%), and lesbian (0.4%). All these groups were more likely than were heterosexuals to be below the federal poverty level; more than half of the lesbian and bisexual respondents said they had previously given birth.

Fifteen percent of lesbians said their current pregnancy was caused by forced sex, compared with 1% of heterosexuals and 3% of bisexuals. (P less than .001).

Bisexuals (9%) and lesbians (33%) were more likely than were heterosexuals (4%) to say the men who impregnated them had physically abused them. The same was true for sexual abuse, which was reported by 7% of bisexuals, 35% of lesbians, and 2% of heterosexuals. After the researchers controlled for various factors including age and race, lesbians remained much more likely to report physical abuse, sexual abuse, and forced sex at the hands of the men who impregnated them (odds ratios = 15, 25, and 10, respectively, P less than .001).

“Exposure to physical and sexual violence was substantially higher among each of the sexual minority groups compared with their heterosexual counterparts, sometimes by a factor of 15 or more,” the study authors wrote. “We found that lesbian respondents had the highest levels of exposure to violence, perhaps because this population was more likely to have had sex with a man only in the context of forced sex.”

The researchers noted that their study has various limitations, such as low numbers of sexual minority women and the 4-year gap since the data were collected.

Still, Dr. Jones and her associates wrote, the study has strengths. “Health care providers, including those working in abortion settings, need to be aware that a proportion of their patient population identifies as something other than heterosexual,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation with support from the National Institutes of Health via a grant to the Guttmacher Center for Population Research Innovation and Dissemination. The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Jones R et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Sep;132(3):605-11.

Pregnant lesbian and bisexual women who seek abortions are more likely than are their heterosexual counterparts to be the victims of violence by the men who impregnated them, a new study finds.

Rachel K. Jones, PhD, of the Guttmacher Institute, New York, and her associates also found that these sexual minority women, plus a group of individuals who described their sexual orientation as “something else,” were much more likely to report exposure to sexual and physical violence.

“No patient should be presumed to be heterosexual for any reason, including a pregnancy history. All pregnancies – like all patients – should be treated as unique and operating within the dynamic and interconnected circumstances of peoples’ lives, which may encompass differences in sexual orientation and exposure to violence,” the researchers wrote. Their report is in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Previous research has suggested that nonheterosexual women are more likely than are straight women to become pregnant unintentionally. There also are signs suggesting that they have more abortions, too, although the findings are iffy, the study authors wrote.

For this study, Dr. Jones and her associates examined questionnaire answers of 8,380 women who responded to the Guttmacher Institute’s 2014 Abortion Patient Survey. All were undergoing abortions at 87 U.S. nonhospital facilities that performed 30 or more abortions each per year.

Of the sample, about 9% declined to describe their sexual orientation. Of the rest, 94% described themselves as heterosexual; of those, 41% were white, 28% were black, and 22% were Hispanic. Most were in their 20s, 47% were never married, and 48% had incomes below the federal poverty level.

Women also described themselves as bisexual (4%), “something else” (1%), and lesbian (0.4%). All these groups were more likely than were heterosexuals to be below the federal poverty level; more than half of the lesbian and bisexual respondents said they had previously given birth.

Fifteen percent of lesbians said their current pregnancy was caused by forced sex, compared with 1% of heterosexuals and 3% of bisexuals. (P less than .001).

Bisexuals (9%) and lesbians (33%) were more likely than were heterosexuals (4%) to say the men who impregnated them had physically abused them. The same was true for sexual abuse, which was reported by 7% of bisexuals, 35% of lesbians, and 2% of heterosexuals. After the researchers controlled for various factors including age and race, lesbians remained much more likely to report physical abuse, sexual abuse, and forced sex at the hands of the men who impregnated them (odds ratios = 15, 25, and 10, respectively, P less than .001).

“Exposure to physical and sexual violence was substantially higher among each of the sexual minority groups compared with their heterosexual counterparts, sometimes by a factor of 15 or more,” the study authors wrote. “We found that lesbian respondents had the highest levels of exposure to violence, perhaps because this population was more likely to have had sex with a man only in the context of forced sex.”

The researchers noted that their study has various limitations, such as low numbers of sexual minority women and the 4-year gap since the data were collected.

Still, Dr. Jones and her associates wrote, the study has strengths. “Health care providers, including those working in abortion settings, need to be aware that a proportion of their patient population identifies as something other than heterosexual,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation with support from the National Institutes of Health via a grant to the Guttmacher Center for Population Research Innovation and Dissemination. The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Jones R et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Sep;132(3):605-11.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Fifteen percent of lesbians said their current pregnancy was caused by forced sex, compared with 1% of heterosexuals (P less than .001), and 3% of bisexuals. Lesbians (33%) were more likely than were heterosexuals (4%) to say the man who impregnated them had physically and/or sexually abused them.

Study details: A 2014 survey of 8,380 women seeking abortions at 87 U.S. nonhospital facilities.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation with support from the National Institutes of Health via a grant to the Guttmacher Center for Population Research Innovation and Dissemination. The study authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Jones R et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Sep;132(3):605-11.

FDA approves first mobile app for contraceptive use

The Food and Drug Administration has approved marketing of the first medical mobile application that can be used as a contraceptive, the agency announced in a written statement.

The app, called Natural Cycles, contains an algorithm that calculates the days of the month women are likely to be fertile, based on daily body temperature readings and menstrual cycle information, and is intended for premenopausal women aged 18 years and older. App users are instructed to take their daily body temperatures with a basal body thermometer and enter the information into the app. The more-sensitive basal body thermometer can detect temperature elevations during ovulation, and the app will display a warning on days when users are most fertile. During these days, women should either abstain from sex or use protection.

In clinical studies comprising more than 15,000 women, Natural Cycles had a “perfect use” failure rate of 1.8% and a “normal use” failure rate of 6.5%. This compares favorably with other forms of contraception and birth control: Male condoms have a perfect use failure rate of 2.0% and a normal use failure rate of 18.0%, and combined oral contraceptives have a perfect use failure rate of 0.3% and a normal use failure rate of 9.0%, according to the Association of Reproductive Care Professionals.

“Consumers are increasingly using digital health technologies to inform their everyday health decisions, and this new app can provide an effective method of contraception if it’s used carefully and correctly,” Terri Cornelison, MD, PhD, assistant director for the health of women in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The app should not be used by women with a condition in which a pregnancy would present risk to the mother or fetus or by women who are using a birth control or hormonal treatment that inhibits ovulation. Natural Cycles does not protect against sexually transmitted infections.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved marketing of the first medical mobile application that can be used as a contraceptive, the agency announced in a written statement.

The app, called Natural Cycles, contains an algorithm that calculates the days of the month women are likely to be fertile, based on daily body temperature readings and menstrual cycle information, and is intended for premenopausal women aged 18 years and older. App users are instructed to take their daily body temperatures with a basal body thermometer and enter the information into the app. The more-sensitive basal body thermometer can detect temperature elevations during ovulation, and the app will display a warning on days when users are most fertile. During these days, women should either abstain from sex or use protection.

In clinical studies comprising more than 15,000 women, Natural Cycles had a “perfect use” failure rate of 1.8% and a “normal use” failure rate of 6.5%. This compares favorably with other forms of contraception and birth control: Male condoms have a perfect use failure rate of 2.0% and a normal use failure rate of 18.0%, and combined oral contraceptives have a perfect use failure rate of 0.3% and a normal use failure rate of 9.0%, according to the Association of Reproductive Care Professionals.

“Consumers are increasingly using digital health technologies to inform their everyday health decisions, and this new app can provide an effective method of contraception if it’s used carefully and correctly,” Terri Cornelison, MD, PhD, assistant director for the health of women in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The app should not be used by women with a condition in which a pregnancy would present risk to the mother or fetus or by women who are using a birth control or hormonal treatment that inhibits ovulation. Natural Cycles does not protect against sexually transmitted infections.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved marketing of the first medical mobile application that can be used as a contraceptive, the agency announced in a written statement.

The app, called Natural Cycles, contains an algorithm that calculates the days of the month women are likely to be fertile, based on daily body temperature readings and menstrual cycle information, and is intended for premenopausal women aged 18 years and older. App users are instructed to take their daily body temperatures with a basal body thermometer and enter the information into the app. The more-sensitive basal body thermometer can detect temperature elevations during ovulation, and the app will display a warning on days when users are most fertile. During these days, women should either abstain from sex or use protection.

In clinical studies comprising more than 15,000 women, Natural Cycles had a “perfect use” failure rate of 1.8% and a “normal use” failure rate of 6.5%. This compares favorably with other forms of contraception and birth control: Male condoms have a perfect use failure rate of 2.0% and a normal use failure rate of 18.0%, and combined oral contraceptives have a perfect use failure rate of 0.3% and a normal use failure rate of 9.0%, according to the Association of Reproductive Care Professionals.

“Consumers are increasingly using digital health technologies to inform their everyday health decisions, and this new app can provide an effective method of contraception if it’s used carefully and correctly,” Terri Cornelison, MD, PhD, assistant director for the health of women in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

The app should not be used by women with a condition in which a pregnancy would present risk to the mother or fetus or by women who are using a birth control or hormonal treatment that inhibits ovulation. Natural Cycles does not protect against sexually transmitted infections.

FDA warning shines light on vaginal rejuvenation

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a stern warning to several manufacturers and a statement of caution to the public concerning “vaginal rejuvenation,” an umbrella term for a host of procedures to alter vaginal tissue for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes.

Lasers and other energy-based devices have been approved to treat abnormal or precancerous cervical or vaginal tissue and general warts, but the FDA has not approved any to treat vaginal atrophy, urinary incontinence, or reduced sexual function.

Device manufacturers claim lasers can address these conditions despite limited scientific evidence for their safety or efficacy. Insurers do not reimburse the procedures, considering them to be cosmetic.

In a July 30 statement, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, slammed “deceptive” marketing practices on the part of manufacturers.

The FDA has reviewed 12 complaints since December 2015 of adverse effects related to vaginal procedures using the devices. Two were from manufacturers reporting pain and bleeding in patients following treatment, FDA spokeswoman Deborah Kotz said in an interview. “The FDA has also received voluntary MedWatch reports from individual patients who experienced significant pain and discomfort from procedures performed with these devices.”

The agency has targeted seven firms: Alma Lasers, BTL Aesthetics, BTL Industries, Cynosure, InMode, Sciton, and ThermiGen, with letters demanding evidence of FDA approval, clearance, or intent to seek clearance for use of their products on female genitalia. They also asked for evidence backing specific claims.

In a July 26 letter to BTL Industries, for example, the FDA demanded to know why the firm was marketing its Exilis laser device, approved for the treatment of facial wrinkles, as “Ultra Femme 360,” which it called “a whole new approach to women’s intimate health.” The device, according to the manufacturer, “provides the shortest noninvasive radio-frequency treatment available for female intimate parts” and “is proven to increase elastin and collagen in the treatment area.”

The FDA asked Cynosure, the maker of the Mona Lisa Touch, a system marketed as an FDA-approved treatment for vaginal atrophy, for evidence to support its claims that Mona Lisa Touch “is the only technology for vaginal and vulvar health with over 18+ published clinical studies” and is clinically proven to treat “painful symptoms of menopause, including intimacy.” They also asked for information about a modification to the originally approved device that was not brought to the FDA’s attention.

In a letter to Alma Lasers, whose Pixel CO2 Laser System was approved for use in a broad use of surgical applications including gynecologic surgery, the FDA noted that the device was being marketed as “FEMILIFT,” a laser procedure designed to “improve vaginal irregularities” and to assist “in vaginal mucosa revitalization.” The FDA demanded evidence for those claims.

The manufacturers have 30 days to respond to the FDA, which has not ruled out seeking enforcement action against firms with unsatisfactory responses.

For more than a decade, researchers have shown that healthy vaginal morphology is exceptionally wide ranging, including a recent study in more than 650 women, the largest to date (BJOG. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15387). Nonetheless, interest in elective vaginal procedures has only increased, with an industry report from the International Society of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery describing a 45% increase in the use of one surgery, vaginal labiaplasty, between 2014 and 2016. Most procedures were performed in Brazil and the United States.

While plastic surgery societies support vaginal rejuvenation procedures, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has long frowned on them, with its first critique issued in a 2007 committee opinion. “No adequate studies have been published assessing the long-term satisfaction, safety, and complication rates for these procedures,” the association said last year in its most recent update on the subject.

Gynecologist David M. Jaspan, DO, of the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, echoed ACOG’s views and said he welcomed FDA interest in vaginal rejuvenation.

The practice has “never been endorsed by the College or a board. It’s been considered a cosmetic procedure and it’s been under scrutiny for at least a decade,” Dr. Jaspan said. “I have reservations about the clinical outcomes and the training surrounds these procedures and I anxiously await randomized controlled trials to further evaluate them.”

Gynecologists who offer the procedures caution that they may have a role, and that randomized trials are underway to determine which groups of women might be best helped.

Marie Paraiso, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic, said she uses the Mona Lisa Touch, a CO2 fractionated laser, to treat patients with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). These patients, Dr. Paraiso said, “complain of vaginal dryness and are unable to have intercourse or experience significant pain during or after intercourse. Some of them also may have irritative voiding, urinary frequency and urgency, or mild stress incontinence.”

Dr. Paraiso’s group has performed some 300 treatments with the laser and “we have fortunately not had patients complaining of persistent vaginal pain or scarring.” About 80%-90% of patients respond, she said, with some 20%-25% seeking retreatment within a year. “I believe for women who have contraindications to hormonal therapy or do not tolerate or cannot afford prolonged hormonal therapy, the CO2 fractional vaginal laser has been effective.”

Dr. Paraiso is also leading a multisite clinical trial randomizing about 200 patients with GSM to the laser treatment or estrogen-based vaginal creams, and following them for 6 months; thus far, she said, 6 of 89 patients, half in the laser arm, have reported mild to moderate adverse events.

Dr. Paraiso said she does not have a financial relationship with the manufacturer of Mona Lisa Touch, and that the trial was funded by the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which receives unrestricted research grants from some device makers. “Our institute owns the laser and I have never been paid to train anyone to perform these procedures,” Dr. Paraiso added. “Our onus was to study the laser in order to improve the lives of our patients.”

Other trials comparing vaginal lasers with sham treatment are currently underway or in planning.

The North American Menopause Society struck a cautious note in response to the FDA criticism. In a statement issued August 1, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, the society’s executive director, said the field needed prospective, randomized, sham-controlled trials of the laser and energy therapies. The therapies “may turn out to be an appropriate choice for many women, particularly for those concerned about breast cancer risk” associated with hormonal treatments. But until more robust data are available, doctors should “discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, and FDA-approved vaginal therapies such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone and oral therapies such as hormone therapy and ospemifene to determine the best treatment for women with GSM.”

Any discussion of vaginal energy-based therapies, should include the disclosure that these have not been approved for the specific indication, Dr. Pinkerton cautioned.

The term “vaginal rejuvenation,” coined by cosmetic gynecologists, incorporates surgeries designed to modify the appearance of the vulva, reduce the redundancy of vaginal tissue, and improve vaginal tone.

Endorsed by some well-known academic gynecologists, these devices have been promoted as “safe and effective” without any prospective, randomized studies and without accountability for conflicts of interest including “educational stipends” from device manufacturers and clinicians’ need to recoup the high cost of the devices themselves.

Studies have generally been limited to fewer than 100 patients followed for 12 weeks or less. Companies are not informing doctors that the devices may not be FDA approved for the purposes advertised, nor are they providing adverse effects reports. Laser and radio-frequency procedures at best demonstrate temporary, marginal improvement in vaginal tone and dyspareunia, and at worst are associated with increased pelvic pain and dyspareunia, as well as vaginal, rectal, and bladder thermal burns. For those of us who specialize in cosmetic surgery, they have very limited benefit with a significant risk of injury to the patient even when properly used.

Julio Cesar Novoa, MD, is a private practice ob.gyn from El Paso, Tex. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The term “vaginal rejuvenation,” coined by cosmetic gynecologists, incorporates surgeries designed to modify the appearance of the vulva, reduce the redundancy of vaginal tissue, and improve vaginal tone.

Endorsed by some well-known academic gynecologists, these devices have been promoted as “safe and effective” without any prospective, randomized studies and without accountability for conflicts of interest including “educational stipends” from device manufacturers and clinicians’ need to recoup the high cost of the devices themselves.

Studies have generally been limited to fewer than 100 patients followed for 12 weeks or less. Companies are not informing doctors that the devices may not be FDA approved for the purposes advertised, nor are they providing adverse effects reports. Laser and radio-frequency procedures at best demonstrate temporary, marginal improvement in vaginal tone and dyspareunia, and at worst are associated with increased pelvic pain and dyspareunia, as well as vaginal, rectal, and bladder thermal burns. For those of us who specialize in cosmetic surgery, they have very limited benefit with a significant risk of injury to the patient even when properly used.

Julio Cesar Novoa, MD, is a private practice ob.gyn from El Paso, Tex. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The term “vaginal rejuvenation,” coined by cosmetic gynecologists, incorporates surgeries designed to modify the appearance of the vulva, reduce the redundancy of vaginal tissue, and improve vaginal tone.

Endorsed by some well-known academic gynecologists, these devices have been promoted as “safe and effective” without any prospective, randomized studies and without accountability for conflicts of interest including “educational stipends” from device manufacturers and clinicians’ need to recoup the high cost of the devices themselves.

Studies have generally been limited to fewer than 100 patients followed for 12 weeks or less. Companies are not informing doctors that the devices may not be FDA approved for the purposes advertised, nor are they providing adverse effects reports. Laser and radio-frequency procedures at best demonstrate temporary, marginal improvement in vaginal tone and dyspareunia, and at worst are associated with increased pelvic pain and dyspareunia, as well as vaginal, rectal, and bladder thermal burns. For those of us who specialize in cosmetic surgery, they have very limited benefit with a significant risk of injury to the patient even when properly used.

Julio Cesar Novoa, MD, is a private practice ob.gyn from El Paso, Tex. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a stern warning to several manufacturers and a statement of caution to the public concerning “vaginal rejuvenation,” an umbrella term for a host of procedures to alter vaginal tissue for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes.

Lasers and other energy-based devices have been approved to treat abnormal or precancerous cervical or vaginal tissue and general warts, but the FDA has not approved any to treat vaginal atrophy, urinary incontinence, or reduced sexual function.

Device manufacturers claim lasers can address these conditions despite limited scientific evidence for their safety or efficacy. Insurers do not reimburse the procedures, considering them to be cosmetic.

In a July 30 statement, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, slammed “deceptive” marketing practices on the part of manufacturers.

The FDA has reviewed 12 complaints since December 2015 of adverse effects related to vaginal procedures using the devices. Two were from manufacturers reporting pain and bleeding in patients following treatment, FDA spokeswoman Deborah Kotz said in an interview. “The FDA has also received voluntary MedWatch reports from individual patients who experienced significant pain and discomfort from procedures performed with these devices.”

The agency has targeted seven firms: Alma Lasers, BTL Aesthetics, BTL Industries, Cynosure, InMode, Sciton, and ThermiGen, with letters demanding evidence of FDA approval, clearance, or intent to seek clearance for use of their products on female genitalia. They also asked for evidence backing specific claims.

In a July 26 letter to BTL Industries, for example, the FDA demanded to know why the firm was marketing its Exilis laser device, approved for the treatment of facial wrinkles, as “Ultra Femme 360,” which it called “a whole new approach to women’s intimate health.” The device, according to the manufacturer, “provides the shortest noninvasive radio-frequency treatment available for female intimate parts” and “is proven to increase elastin and collagen in the treatment area.”

The FDA asked Cynosure, the maker of the Mona Lisa Touch, a system marketed as an FDA-approved treatment for vaginal atrophy, for evidence to support its claims that Mona Lisa Touch “is the only technology for vaginal and vulvar health with over 18+ published clinical studies” and is clinically proven to treat “painful symptoms of menopause, including intimacy.” They also asked for information about a modification to the originally approved device that was not brought to the FDA’s attention.

In a letter to Alma Lasers, whose Pixel CO2 Laser System was approved for use in a broad use of surgical applications including gynecologic surgery, the FDA noted that the device was being marketed as “FEMILIFT,” a laser procedure designed to “improve vaginal irregularities” and to assist “in vaginal mucosa revitalization.” The FDA demanded evidence for those claims.

The manufacturers have 30 days to respond to the FDA, which has not ruled out seeking enforcement action against firms with unsatisfactory responses.

For more than a decade, researchers have shown that healthy vaginal morphology is exceptionally wide ranging, including a recent study in more than 650 women, the largest to date (BJOG. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15387). Nonetheless, interest in elective vaginal procedures has only increased, with an industry report from the International Society of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery describing a 45% increase in the use of one surgery, vaginal labiaplasty, between 2014 and 2016. Most procedures were performed in Brazil and the United States.

While plastic surgery societies support vaginal rejuvenation procedures, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has long frowned on them, with its first critique issued in a 2007 committee opinion. “No adequate studies have been published assessing the long-term satisfaction, safety, and complication rates for these procedures,” the association said last year in its most recent update on the subject.

Gynecologist David M. Jaspan, DO, of the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, echoed ACOG’s views and said he welcomed FDA interest in vaginal rejuvenation.

The practice has “never been endorsed by the College or a board. It’s been considered a cosmetic procedure and it’s been under scrutiny for at least a decade,” Dr. Jaspan said. “I have reservations about the clinical outcomes and the training surrounds these procedures and I anxiously await randomized controlled trials to further evaluate them.”

Gynecologists who offer the procedures caution that they may have a role, and that randomized trials are underway to determine which groups of women might be best helped.

Marie Paraiso, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic, said she uses the Mona Lisa Touch, a CO2 fractionated laser, to treat patients with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). These patients, Dr. Paraiso said, “complain of vaginal dryness and are unable to have intercourse or experience significant pain during or after intercourse. Some of them also may have irritative voiding, urinary frequency and urgency, or mild stress incontinence.”

Dr. Paraiso’s group has performed some 300 treatments with the laser and “we have fortunately not had patients complaining of persistent vaginal pain or scarring.” About 80%-90% of patients respond, she said, with some 20%-25% seeking retreatment within a year. “I believe for women who have contraindications to hormonal therapy or do not tolerate or cannot afford prolonged hormonal therapy, the CO2 fractional vaginal laser has been effective.”

Dr. Paraiso is also leading a multisite clinical trial randomizing about 200 patients with GSM to the laser treatment or estrogen-based vaginal creams, and following them for 6 months; thus far, she said, 6 of 89 patients, half in the laser arm, have reported mild to moderate adverse events.

Dr. Paraiso said she does not have a financial relationship with the manufacturer of Mona Lisa Touch, and that the trial was funded by the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which receives unrestricted research grants from some device makers. “Our institute owns the laser and I have never been paid to train anyone to perform these procedures,” Dr. Paraiso added. “Our onus was to study the laser in order to improve the lives of our patients.”

Other trials comparing vaginal lasers with sham treatment are currently underway or in planning.

The North American Menopause Society struck a cautious note in response to the FDA criticism. In a statement issued August 1, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, the society’s executive director, said the field needed prospective, randomized, sham-controlled trials of the laser and energy therapies. The therapies “may turn out to be an appropriate choice for many women, particularly for those concerned about breast cancer risk” associated with hormonal treatments. But until more robust data are available, doctors should “discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, and FDA-approved vaginal therapies such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone and oral therapies such as hormone therapy and ospemifene to determine the best treatment for women with GSM.”

Any discussion of vaginal energy-based therapies, should include the disclosure that these have not been approved for the specific indication, Dr. Pinkerton cautioned.

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a stern warning to several manufacturers and a statement of caution to the public concerning “vaginal rejuvenation,” an umbrella term for a host of procedures to alter vaginal tissue for therapeutic or cosmetic purposes.

Lasers and other energy-based devices have been approved to treat abnormal or precancerous cervical or vaginal tissue and general warts, but the FDA has not approved any to treat vaginal atrophy, urinary incontinence, or reduced sexual function.

Device manufacturers claim lasers can address these conditions despite limited scientific evidence for their safety or efficacy. Insurers do not reimburse the procedures, considering them to be cosmetic.

In a July 30 statement, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, slammed “deceptive” marketing practices on the part of manufacturers.

The FDA has reviewed 12 complaints since December 2015 of adverse effects related to vaginal procedures using the devices. Two were from manufacturers reporting pain and bleeding in patients following treatment, FDA spokeswoman Deborah Kotz said in an interview. “The FDA has also received voluntary MedWatch reports from individual patients who experienced significant pain and discomfort from procedures performed with these devices.”

The agency has targeted seven firms: Alma Lasers, BTL Aesthetics, BTL Industries, Cynosure, InMode, Sciton, and ThermiGen, with letters demanding evidence of FDA approval, clearance, or intent to seek clearance for use of their products on female genitalia. They also asked for evidence backing specific claims.

In a July 26 letter to BTL Industries, for example, the FDA demanded to know why the firm was marketing its Exilis laser device, approved for the treatment of facial wrinkles, as “Ultra Femme 360,” which it called “a whole new approach to women’s intimate health.” The device, according to the manufacturer, “provides the shortest noninvasive radio-frequency treatment available for female intimate parts” and “is proven to increase elastin and collagen in the treatment area.”

The FDA asked Cynosure, the maker of the Mona Lisa Touch, a system marketed as an FDA-approved treatment for vaginal atrophy, for evidence to support its claims that Mona Lisa Touch “is the only technology for vaginal and vulvar health with over 18+ published clinical studies” and is clinically proven to treat “painful symptoms of menopause, including intimacy.” They also asked for information about a modification to the originally approved device that was not brought to the FDA’s attention.

In a letter to Alma Lasers, whose Pixel CO2 Laser System was approved for use in a broad use of surgical applications including gynecologic surgery, the FDA noted that the device was being marketed as “FEMILIFT,” a laser procedure designed to “improve vaginal irregularities” and to assist “in vaginal mucosa revitalization.” The FDA demanded evidence for those claims.

The manufacturers have 30 days to respond to the FDA, which has not ruled out seeking enforcement action against firms with unsatisfactory responses.

For more than a decade, researchers have shown that healthy vaginal morphology is exceptionally wide ranging, including a recent study in more than 650 women, the largest to date (BJOG. 2018 Jun 25. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15387). Nonetheless, interest in elective vaginal procedures has only increased, with an industry report from the International Society of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery describing a 45% increase in the use of one surgery, vaginal labiaplasty, between 2014 and 2016. Most procedures were performed in Brazil and the United States.

While plastic surgery societies support vaginal rejuvenation procedures, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has long frowned on them, with its first critique issued in a 2007 committee opinion. “No adequate studies have been published assessing the long-term satisfaction, safety, and complication rates for these procedures,” the association said last year in its most recent update on the subject.

Gynecologist David M. Jaspan, DO, of the Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, echoed ACOG’s views and said he welcomed FDA interest in vaginal rejuvenation.

The practice has “never been endorsed by the College or a board. It’s been considered a cosmetic procedure and it’s been under scrutiny for at least a decade,” Dr. Jaspan said. “I have reservations about the clinical outcomes and the training surrounds these procedures and I anxiously await randomized controlled trials to further evaluate them.”

Gynecologists who offer the procedures caution that they may have a role, and that randomized trials are underway to determine which groups of women might be best helped.

Marie Paraiso, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Cleveland Clinic, said she uses the Mona Lisa Touch, a CO2 fractionated laser, to treat patients with genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). These patients, Dr. Paraiso said, “complain of vaginal dryness and are unable to have intercourse or experience significant pain during or after intercourse. Some of them also may have irritative voiding, urinary frequency and urgency, or mild stress incontinence.”

Dr. Paraiso’s group has performed some 300 treatments with the laser and “we have fortunately not had patients complaining of persistent vaginal pain or scarring.” About 80%-90% of patients respond, she said, with some 20%-25% seeking retreatment within a year. “I believe for women who have contraindications to hormonal therapy or do not tolerate or cannot afford prolonged hormonal therapy, the CO2 fractional vaginal laser has been effective.”

Dr. Paraiso is also leading a multisite clinical trial randomizing about 200 patients with GSM to the laser treatment or estrogen-based vaginal creams, and following them for 6 months; thus far, she said, 6 of 89 patients, half in the laser arm, have reported mild to moderate adverse events.

Dr. Paraiso said she does not have a financial relationship with the manufacturer of Mona Lisa Touch, and that the trial was funded by the Foundation for Female Health Awareness, which receives unrestricted research grants from some device makers. “Our institute owns the laser and I have never been paid to train anyone to perform these procedures,” Dr. Paraiso added. “Our onus was to study the laser in order to improve the lives of our patients.”

Other trials comparing vaginal lasers with sham treatment are currently underway or in planning.

The North American Menopause Society struck a cautious note in response to the FDA criticism. In a statement issued August 1, JoAnn Pinkerton, MD, the society’s executive director, said the field needed prospective, randomized, sham-controlled trials of the laser and energy therapies. The therapies “may turn out to be an appropriate choice for many women, particularly for those concerned about breast cancer risk” associated with hormonal treatments. But until more robust data are available, doctors should “discuss the benefits and risks of all available treatment options for vaginal symptoms, including over-the-counter lubricants, vaginal moisturizers, and FDA-approved vaginal therapies such as vaginal estrogen and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone and oral therapies such as hormone therapy and ospemifene to determine the best treatment for women with GSM.”

Any discussion of vaginal energy-based therapies, should include the disclosure that these have not been approved for the specific indication, Dr. Pinkerton cautioned.

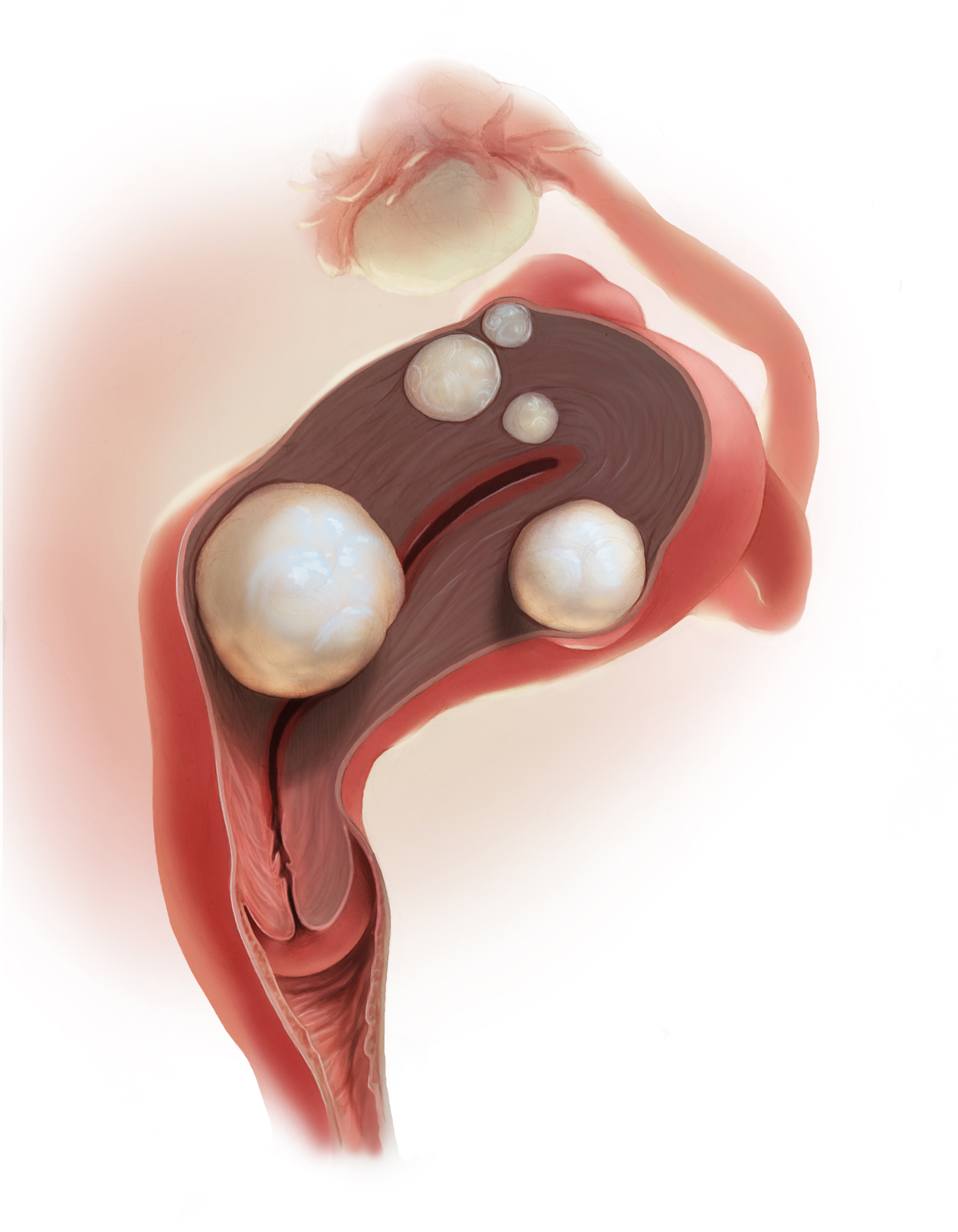

2018 Update on abnormal uterine bleeding

Over the past year, a few gems have been published to help us manage and treat abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). One study suggests an order of performing hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy, another emphasizes the continued cost-effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), while a third provides more evidence that ulipristal acetate is effective in the management of leiomyomas.

Optimal order of office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy?

Sarkar P, Mikhail E, Schickler R, Plosker S, Imudia AN. Optimal order of successive office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):565-572.

Office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy are frequently used in the evaluation of women presenting with AUB. Sarkar and colleagues conducted a study aimed at estimating the optimal order of office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy when performed successively among premenopausal women.

Pain perception, procedure duration, and other outcomes

This prospective single-blind randomized trial included 78 consecutive patients. The primary outcome was detection of any difference in patients' global pain perception based on the order of the procedures. Secondary outcome measures included determining whether the procedure order affected the duration of the procedures, the adequacy of the endometrial biopsy sample, the number of attempts to obtain an adequate tissue sample, and optimal visualization of the endometrial cavity during office hysteroscopy.

Order not important, but other factors may be

Not surprisingly, the results showed that the order in which the procedures were performed had no effect on patients' pain perception or on the overall procedure duration. Assessed using a visual analog scale scored from 1 to 10, global pain perception in the hysteroscopy-first patients (group A, n = 40) compared with the biopsy-first patients (group B, n = 38) was similar (7 vs 7, P = .57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 5.8-7.1). Procedure duration also was similar in group A and group B (3 vs 3, P = .32; 95% CI, 3.3-4.1).

However, when hysteroscopy was performed first, the quality of endometrial cavity images was superior compared with images from patients in whom biopsy was performed first. The number of endometrial biopsy curette passes required to obtain an adequate tissue sample was lower in the biopsy-first patients. The endometrial biopsy specimen was adequate for histologic evaluation regardless of whether hysteroscopy or biopsy was performed first.

Sarkar and colleagues suggested that their study findings emphasize the importance of individualizing the order of successive procedures to achieve the most clinically relevant result with maximum ease and comfort. They proposed that patients who have a high index of suspicion for occult malignancy or endometrial hyperplasia should have a biopsy procedure first so that adequate tissue samples can be obtained with fewer attempts. In patients with underlying uterine anatomic defects, performing hysteroscopy first would be clinically relevant to obtain the best images for optimal surgical planning.

Read next: Which treatment for AUB is most cost-effective?

Which treatment for AUB is most cost-effective?

Spencer JC, Louie M, Moulder JK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):574.e1-574e.9.

The costs associated with heavy menstrual bleeding are significant. Spencer and colleagues sought to evaluate the relative cost-effectiveness of 4 treatment options for heavy menstrual bleeding: hysterectomy, resectoscopic endometrial ablation, nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation, and the LNG-IUS in a hypothetical cohort of 100,000 premenopausal women. No previous studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of these options in the context of the US health care setting.

Decision tree used for analysis

The authors formulated a decision tree to evaluate private payer costs and quality-adjusted life-years over a 5-year time horizon for premenopausal women with heavy menstrual bleeding and no suspected malignancy. For each treatment option, the authors used probabilities to estimate frequencies of complications and treatment failure leading to additional therapies. They compared the treatments in terms of total average costs, quality-adjusted life years, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios.

Comparing costs, quality of life, and complications

Quality of life was fairly high for all treatment options; however, the estimated costs and the complications of each treatment were markedly different between treatment options. The LNG-IUS was superior to all alternatives in terms of both cost and quality, making it the dominant strategy. The 5-year cost for the LNG-IUS was $4,500, about half the cost of endometrial ablation ($9,500) and about one-third the cost of hysterectomy ($13,500). When examined over a range of possible values, the LNG-IUS was cost-effective compared with hysterectomy in the large majority of scenarios (90%).

If the LNG-IUS is removed from consideration because of either patient preference or clinical judgment, the decision between hysterectomy and ablation is more complex. Hysterectomy results in better quality of life in the majority of simulations, but it is cost-effective in just more than half of the simulations compared with either resectoscopic or nonresectoscopic ablation. Therefore, consideration of cost, procedure-specific complications, and patient preferences may guide the therapeutic decision between hysterectomy and endometrial ablation.

The 52-mg LNG-IUS was superior to all treatment alternatives in both cost and quality, making it the dominant strategy for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Ulipristal may be useful for managing AUB associated with uterine leiomyomas

Simon JA, Catherino W, Segars JH, et al. Ulipristal acetate for treatment of symptomatic uterine leiomyomas: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):431-439.

Managing uterine leiomyomas is a common issue for gynecologists, as up to 70% of white women and more than 80% of black women of reproductive age in the United States have leiomyomas.

Ulipristal acetate is an orally administered selective progesterone-receptor modulator that decreases bleeding and reduces leiomyoma size. Although trials conducted in Europe found ulipristal to be superior to placebo and noninferior to leuprolide acetate in controlling bleeding and reducing leiomyoma size, those initial trials were conducted in a predominantly white population.

Study assessed efficacy and safety

Simon and colleagues recently conducted a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial designed to assess the safety and efficacy of ulipristal in a more diverse population, such as patients in the United States. The 148 participants included in the study were randomly assigned on a 1:1:1 basis to once-daily oral ulipristal 5 mg, ulipristal 10 mg, or placebo for 12 weeks, with a 12-week drug-free follow-up.

Amenorrhea achieved and quality of life improved

The investigators found that ulipristal in 5-mg and 10-mg doses was well tolerated and superior to placebo in both the rate of and the time to amenorrhea (the coprimary end points) in women with symptomatic leiomyomas. In women treated with ulipristal 5 mg, amenorrhea was achieved in 25 of 53 (47.2%; 97.5% CI, 31.6-63.2), and of those treated with the 10-mg dose, 28 of 48 (58.3%; 97.5% CI, 41.2-74.1) achieved amenorrhea (P<.001 for both groups), compared with 1 of 56 (1.8%; 97.5% CI, 0.0-10.9) in the placebo group.

AUB continues to be a significant issue for many women. As women's health care providers, it is important that we deliver care with high value (Quality ÷ Cost). Therefore, consider these takeaway points:

- The LNG-IUS consistently delivers high value by affecting both sides of this equation. We should use it more.

- Although we do not yet know what ulipristal acetate will cost in the United States, effective medical treatments usually affect both sides of the Quality ÷ Cost equation, and new medications on the horizon are worth knowing about.

- Last, efficiency with office-based hysteroscopy is also an opportunity to increase value by improving biopsy and visualization quality.

Ulipristal treatment also was shown to improve health-related quality of life, including physical and social activities. No patient discontinued ulipristal because of lack of efficacy, and 1 patient in the placebo group stopped taking the drug because of an adverse event. Estradiol levels were maintained at midfollicular levels during ulipristal treatment, and endometrial biopsies did not show any atypical or malignant changes. These results are consistent with those of the studies conducted in Europe in a predominantly white, nonobese population.

Results of this study help to define a niche for ulipristal when hysterectomy is not an option for women who wish to preserve fertility. Further, although leuprolide is used for preoperative hematologic improvement of anemia, its use results in hypoestrogenic adverse effects.

The findings from this and other studies suggest that ulipristal may be useful for the medical management of AUB associated with uterine leiomyomas, especially for patients desiring uterine- and fertility-sparing treatment. Hopefully, this treatment will be available soon in the United States.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Over the past year, a few gems have been published to help us manage and treat abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). One study suggests an order of performing hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy, another emphasizes the continued cost-effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), while a third provides more evidence that ulipristal acetate is effective in the management of leiomyomas.

Optimal order of office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy?

Sarkar P, Mikhail E, Schickler R, Plosker S, Imudia AN. Optimal order of successive office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):565-572.

Office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy are frequently used in the evaluation of women presenting with AUB. Sarkar and colleagues conducted a study aimed at estimating the optimal order of office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy when performed successively among premenopausal women.

Pain perception, procedure duration, and other outcomes

This prospective single-blind randomized trial included 78 consecutive patients. The primary outcome was detection of any difference in patients' global pain perception based on the order of the procedures. Secondary outcome measures included determining whether the procedure order affected the duration of the procedures, the adequacy of the endometrial biopsy sample, the number of attempts to obtain an adequate tissue sample, and optimal visualization of the endometrial cavity during office hysteroscopy.

Order not important, but other factors may be

Not surprisingly, the results showed that the order in which the procedures were performed had no effect on patients' pain perception or on the overall procedure duration. Assessed using a visual analog scale scored from 1 to 10, global pain perception in the hysteroscopy-first patients (group A, n = 40) compared with the biopsy-first patients (group B, n = 38) was similar (7 vs 7, P = .57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 5.8-7.1). Procedure duration also was similar in group A and group B (3 vs 3, P = .32; 95% CI, 3.3-4.1).

However, when hysteroscopy was performed first, the quality of endometrial cavity images was superior compared with images from patients in whom biopsy was performed first. The number of endometrial biopsy curette passes required to obtain an adequate tissue sample was lower in the biopsy-first patients. The endometrial biopsy specimen was adequate for histologic evaluation regardless of whether hysteroscopy or biopsy was performed first.

Sarkar and colleagues suggested that their study findings emphasize the importance of individualizing the order of successive procedures to achieve the most clinically relevant result with maximum ease and comfort. They proposed that patients who have a high index of suspicion for occult malignancy or endometrial hyperplasia should have a biopsy procedure first so that adequate tissue samples can be obtained with fewer attempts. In patients with underlying uterine anatomic defects, performing hysteroscopy first would be clinically relevant to obtain the best images for optimal surgical planning.

Read next: Which treatment for AUB is most cost-effective?

Which treatment for AUB is most cost-effective?

Spencer JC, Louie M, Moulder JK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):574.e1-574e.9.

The costs associated with heavy menstrual bleeding are significant. Spencer and colleagues sought to evaluate the relative cost-effectiveness of 4 treatment options for heavy menstrual bleeding: hysterectomy, resectoscopic endometrial ablation, nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation, and the LNG-IUS in a hypothetical cohort of 100,000 premenopausal women. No previous studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of these options in the context of the US health care setting.

Decision tree used for analysis

The authors formulated a decision tree to evaluate private payer costs and quality-adjusted life-years over a 5-year time horizon for premenopausal women with heavy menstrual bleeding and no suspected malignancy. For each treatment option, the authors used probabilities to estimate frequencies of complications and treatment failure leading to additional therapies. They compared the treatments in terms of total average costs, quality-adjusted life years, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios.

Comparing costs, quality of life, and complications

Quality of life was fairly high for all treatment options; however, the estimated costs and the complications of each treatment were markedly different between treatment options. The LNG-IUS was superior to all alternatives in terms of both cost and quality, making it the dominant strategy. The 5-year cost for the LNG-IUS was $4,500, about half the cost of endometrial ablation ($9,500) and about one-third the cost of hysterectomy ($13,500). When examined over a range of possible values, the LNG-IUS was cost-effective compared with hysterectomy in the large majority of scenarios (90%).

If the LNG-IUS is removed from consideration because of either patient preference or clinical judgment, the decision between hysterectomy and ablation is more complex. Hysterectomy results in better quality of life in the majority of simulations, but it is cost-effective in just more than half of the simulations compared with either resectoscopic or nonresectoscopic ablation. Therefore, consideration of cost, procedure-specific complications, and patient preferences may guide the therapeutic decision between hysterectomy and endometrial ablation.

The 52-mg LNG-IUS was superior to all treatment alternatives in both cost and quality, making it the dominant strategy for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Ulipristal may be useful for managing AUB associated with uterine leiomyomas

Simon JA, Catherino W, Segars JH, et al. Ulipristal acetate for treatment of symptomatic uterine leiomyomas: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):431-439.

Managing uterine leiomyomas is a common issue for gynecologists, as up to 70% of white women and more than 80% of black women of reproductive age in the United States have leiomyomas.

Ulipristal acetate is an orally administered selective progesterone-receptor modulator that decreases bleeding and reduces leiomyoma size. Although trials conducted in Europe found ulipristal to be superior to placebo and noninferior to leuprolide acetate in controlling bleeding and reducing leiomyoma size, those initial trials were conducted in a predominantly white population.

Study assessed efficacy and safety

Simon and colleagues recently conducted a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial designed to assess the safety and efficacy of ulipristal in a more diverse population, such as patients in the United States. The 148 participants included in the study were randomly assigned on a 1:1:1 basis to once-daily oral ulipristal 5 mg, ulipristal 10 mg, or placebo for 12 weeks, with a 12-week drug-free follow-up.

Amenorrhea achieved and quality of life improved

The investigators found that ulipristal in 5-mg and 10-mg doses was well tolerated and superior to placebo in both the rate of and the time to amenorrhea (the coprimary end points) in women with symptomatic leiomyomas. In women treated with ulipristal 5 mg, amenorrhea was achieved in 25 of 53 (47.2%; 97.5% CI, 31.6-63.2), and of those treated with the 10-mg dose, 28 of 48 (58.3%; 97.5% CI, 41.2-74.1) achieved amenorrhea (P<.001 for both groups), compared with 1 of 56 (1.8%; 97.5% CI, 0.0-10.9) in the placebo group.

AUB continues to be a significant issue for many women. As women's health care providers, it is important that we deliver care with high value (Quality ÷ Cost). Therefore, consider these takeaway points:

- The LNG-IUS consistently delivers high value by affecting both sides of this equation. We should use it more.

- Although we do not yet know what ulipristal acetate will cost in the United States, effective medical treatments usually affect both sides of the Quality ÷ Cost equation, and new medications on the horizon are worth knowing about.

- Last, efficiency with office-based hysteroscopy is also an opportunity to increase value by improving biopsy and visualization quality.

Ulipristal treatment also was shown to improve health-related quality of life, including physical and social activities. No patient discontinued ulipristal because of lack of efficacy, and 1 patient in the placebo group stopped taking the drug because of an adverse event. Estradiol levels were maintained at midfollicular levels during ulipristal treatment, and endometrial biopsies did not show any atypical or malignant changes. These results are consistent with those of the studies conducted in Europe in a predominantly white, nonobese population.

Results of this study help to define a niche for ulipristal when hysterectomy is not an option for women who wish to preserve fertility. Further, although leuprolide is used for preoperative hematologic improvement of anemia, its use results in hypoestrogenic adverse effects.

The findings from this and other studies suggest that ulipristal may be useful for the medical management of AUB associated with uterine leiomyomas, especially for patients desiring uterine- and fertility-sparing treatment. Hopefully, this treatment will be available soon in the United States.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Over the past year, a few gems have been published to help us manage and treat abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). One study suggests an order of performing hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy, another emphasizes the continued cost-effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), while a third provides more evidence that ulipristal acetate is effective in the management of leiomyomas.

Optimal order of office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy?

Sarkar P, Mikhail E, Schickler R, Plosker S, Imudia AN. Optimal order of successive office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):565-572.

Office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy are frequently used in the evaluation of women presenting with AUB. Sarkar and colleagues conducted a study aimed at estimating the optimal order of office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy when performed successively among premenopausal women.

Pain perception, procedure duration, and other outcomes

This prospective single-blind randomized trial included 78 consecutive patients. The primary outcome was detection of any difference in patients' global pain perception based on the order of the procedures. Secondary outcome measures included determining whether the procedure order affected the duration of the procedures, the adequacy of the endometrial biopsy sample, the number of attempts to obtain an adequate tissue sample, and optimal visualization of the endometrial cavity during office hysteroscopy.

Order not important, but other factors may be

Not surprisingly, the results showed that the order in which the procedures were performed had no effect on patients' pain perception or on the overall procedure duration. Assessed using a visual analog scale scored from 1 to 10, global pain perception in the hysteroscopy-first patients (group A, n = 40) compared with the biopsy-first patients (group B, n = 38) was similar (7 vs 7, P = .57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 5.8-7.1). Procedure duration also was similar in group A and group B (3 vs 3, P = .32; 95% CI, 3.3-4.1).

However, when hysteroscopy was performed first, the quality of endometrial cavity images was superior compared with images from patients in whom biopsy was performed first. The number of endometrial biopsy curette passes required to obtain an adequate tissue sample was lower in the biopsy-first patients. The endometrial biopsy specimen was adequate for histologic evaluation regardless of whether hysteroscopy or biopsy was performed first.

Sarkar and colleagues suggested that their study findings emphasize the importance of individualizing the order of successive procedures to achieve the most clinically relevant result with maximum ease and comfort. They proposed that patients who have a high index of suspicion for occult malignancy or endometrial hyperplasia should have a biopsy procedure first so that adequate tissue samples can be obtained with fewer attempts. In patients with underlying uterine anatomic defects, performing hysteroscopy first would be clinically relevant to obtain the best images for optimal surgical planning.

Read next: Which treatment for AUB is most cost-effective?

Which treatment for AUB is most cost-effective?

Spencer JC, Louie M, Moulder JK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):574.e1-574e.9.

The costs associated with heavy menstrual bleeding are significant. Spencer and colleagues sought to evaluate the relative cost-effectiveness of 4 treatment options for heavy menstrual bleeding: hysterectomy, resectoscopic endometrial ablation, nonresectoscopic endometrial ablation, and the LNG-IUS in a hypothetical cohort of 100,000 premenopausal women. No previous studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of these options in the context of the US health care setting.

Decision tree used for analysis

The authors formulated a decision tree to evaluate private payer costs and quality-adjusted life-years over a 5-year time horizon for premenopausal women with heavy menstrual bleeding and no suspected malignancy. For each treatment option, the authors used probabilities to estimate frequencies of complications and treatment failure leading to additional therapies. They compared the treatments in terms of total average costs, quality-adjusted life years, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios.

Comparing costs, quality of life, and complications

Quality of life was fairly high for all treatment options; however, the estimated costs and the complications of each treatment were markedly different between treatment options. The LNG-IUS was superior to all alternatives in terms of both cost and quality, making it the dominant strategy. The 5-year cost for the LNG-IUS was $4,500, about half the cost of endometrial ablation ($9,500) and about one-third the cost of hysterectomy ($13,500). When examined over a range of possible values, the LNG-IUS was cost-effective compared with hysterectomy in the large majority of scenarios (90%).