User login

Laparoscopic nerve-sparing approach is effective in deep infiltrating endometriosis

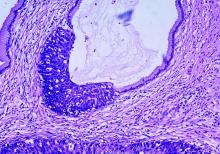

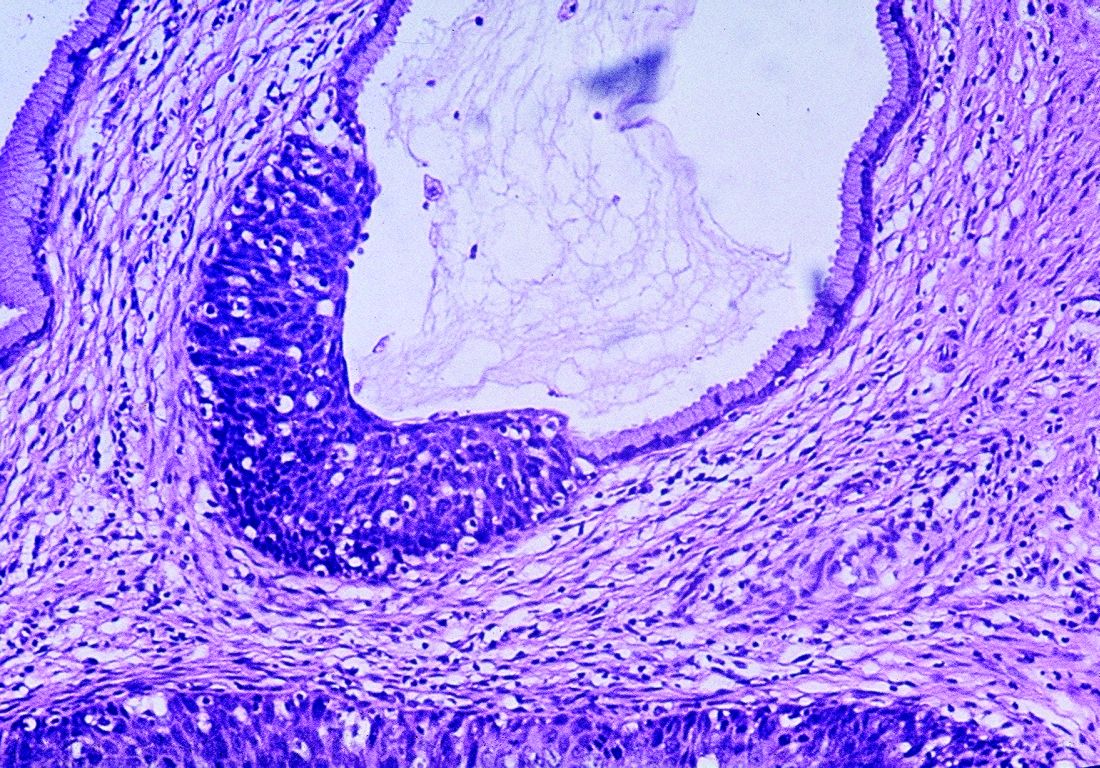

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopic retroperitoneal nerve-sparing surgery is a safe approach that relieves pain in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis, according to findings presented by Giovanni Roviglione, MD, at the AAGL Global Congress.

The prospective case series study with a single gynecologic surgeon in Verona, Italy, involved 382 women who had deep infiltrating endometriosis with sciatica and anogenital pain. All of the women had some level of nervous compression of somatic structures and infiltration of their fascial envelope.

The surgery involved whole decompression and partial neurolysis of nervous structures for most patients, while nearly 20% of women required complete neurolysis based on their level of infiltration. Most women (64%) had severe enough infiltration that a concomitant bowel resection was also necessary.

The surgeon performed a medial approach for deep pelvic endometriosis with rectal and/or parametrial involvement extending to the pelvic wall and somatic nerve, or a lateral approach for isolated endometriosis of the pelvic wall and somatic nerves.

At 6 months after surgery, all patients reported complete relief from pain. However, 77 women (20%) experienced postoperative neuritis, which was successfully treated with corticosteroids, antiepileptics, and opioids.

Endometriosis that extends into somatic nerves and the sacral roots is a common cause of pelvic pain, Dr. Roviglione said.

“This kind of endometriosis is resistant to opioids and drugs,” he said. The difficulty in treating deep infiltrating endometriosis is compounded by the often long delay in diagnosis, he added.

Using laparoscopy for neurolysis and decompression of somatic nerves affected by endometriosis is a “more accurate and effective treatment” for providing pain relief, Dr. Roviglione said. But laparoscopic retroperitoneal nerve-sparing surgery should be performed only by skilled neuroanatomy surgeons at referral centers because of the complex nature of the procedure, he noted.

Dr. Roviglione reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ceccaroni M et al. AAGL 2017 Abstract 166.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopic retroperitoneal nerve-sparing surgery is a safe approach that relieves pain in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis, according to findings presented by Giovanni Roviglione, MD, at the AAGL Global Congress.

The prospective case series study with a single gynecologic surgeon in Verona, Italy, involved 382 women who had deep infiltrating endometriosis with sciatica and anogenital pain. All of the women had some level of nervous compression of somatic structures and infiltration of their fascial envelope.

The surgery involved whole decompression and partial neurolysis of nervous structures for most patients, while nearly 20% of women required complete neurolysis based on their level of infiltration. Most women (64%) had severe enough infiltration that a concomitant bowel resection was also necessary.

The surgeon performed a medial approach for deep pelvic endometriosis with rectal and/or parametrial involvement extending to the pelvic wall and somatic nerve, or a lateral approach for isolated endometriosis of the pelvic wall and somatic nerves.

At 6 months after surgery, all patients reported complete relief from pain. However, 77 women (20%) experienced postoperative neuritis, which was successfully treated with corticosteroids, antiepileptics, and opioids.

Endometriosis that extends into somatic nerves and the sacral roots is a common cause of pelvic pain, Dr. Roviglione said.

“This kind of endometriosis is resistant to opioids and drugs,” he said. The difficulty in treating deep infiltrating endometriosis is compounded by the often long delay in diagnosis, he added.

Using laparoscopy for neurolysis and decompression of somatic nerves affected by endometriosis is a “more accurate and effective treatment” for providing pain relief, Dr. Roviglione said. But laparoscopic retroperitoneal nerve-sparing surgery should be performed only by skilled neuroanatomy surgeons at referral centers because of the complex nature of the procedure, he noted.

Dr. Roviglione reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ceccaroni M et al. AAGL 2017 Abstract 166.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopic retroperitoneal nerve-sparing surgery is a safe approach that relieves pain in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis, according to findings presented by Giovanni Roviglione, MD, at the AAGL Global Congress.

The prospective case series study with a single gynecologic surgeon in Verona, Italy, involved 382 women who had deep infiltrating endometriosis with sciatica and anogenital pain. All of the women had some level of nervous compression of somatic structures and infiltration of their fascial envelope.

The surgery involved whole decompression and partial neurolysis of nervous structures for most patients, while nearly 20% of women required complete neurolysis based on their level of infiltration. Most women (64%) had severe enough infiltration that a concomitant bowel resection was also necessary.

The surgeon performed a medial approach for deep pelvic endometriosis with rectal and/or parametrial involvement extending to the pelvic wall and somatic nerve, or a lateral approach for isolated endometriosis of the pelvic wall and somatic nerves.

At 6 months after surgery, all patients reported complete relief from pain. However, 77 women (20%) experienced postoperative neuritis, which was successfully treated with corticosteroids, antiepileptics, and opioids.

Endometriosis that extends into somatic nerves and the sacral roots is a common cause of pelvic pain, Dr. Roviglione said.

“This kind of endometriosis is resistant to opioids and drugs,” he said. The difficulty in treating deep infiltrating endometriosis is compounded by the often long delay in diagnosis, he added.

Using laparoscopy for neurolysis and decompression of somatic nerves affected by endometriosis is a “more accurate and effective treatment” for providing pain relief, Dr. Roviglione said. But laparoscopic retroperitoneal nerve-sparing surgery should be performed only by skilled neuroanatomy surgeons at referral centers because of the complex nature of the procedure, he noted.

Dr. Roviglione reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ceccaroni M et al. AAGL 2017 Abstract 166.

REPORTING FROM AAGL 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: All patients reported complete relief of neurologic symptoms at 6 months after surgery.

Study details: Single center, prospective case series of 382 women who underwent laparoscopic retroperitoneal nerve-sparing surgery to treat pain associated with deep infiltrating endometriosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Roviglione reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Ceccaroni M et al. AAGL 2017 Abstract 166.

Clinical trial: Study underway of robot-assisted surgery for pelvic prolapse

Robotic Assisted Sacral Colpopexy: A Prospective Study Assessing Outcomes With Learning Curves is an open-label study that is being conducted on a new pelvic floor program for women with pelvic organ prolapse.

A prospective cohort of 100 patients will be recruited and the study will assess surgical time (total and specific essential portions), simulator training, and observed surgeon skills. Secondary endpoints include subjective outcomes for issues of sexual function and incontinence and adverse events such as genitourinary injury, blood loss, wound infection, and mesh erosion.

Kaiser Permanente is the trial sponsor, and patients aged 18-80 years who are undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with or without other procedures for pelvic organ prolapse are being recruited. For more details about the trial, visit https://goo.gl/pWq7qe.

SOURCE: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01535833.

Robotic Assisted Sacral Colpopexy: A Prospective Study Assessing Outcomes With Learning Curves is an open-label study that is being conducted on a new pelvic floor program for women with pelvic organ prolapse.

A prospective cohort of 100 patients will be recruited and the study will assess surgical time (total and specific essential portions), simulator training, and observed surgeon skills. Secondary endpoints include subjective outcomes for issues of sexual function and incontinence and adverse events such as genitourinary injury, blood loss, wound infection, and mesh erosion.

Kaiser Permanente is the trial sponsor, and patients aged 18-80 years who are undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with or without other procedures for pelvic organ prolapse are being recruited. For more details about the trial, visit https://goo.gl/pWq7qe.

SOURCE: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01535833.

Robotic Assisted Sacral Colpopexy: A Prospective Study Assessing Outcomes With Learning Curves is an open-label study that is being conducted on a new pelvic floor program for women with pelvic organ prolapse.

A prospective cohort of 100 patients will be recruited and the study will assess surgical time (total and specific essential portions), simulator training, and observed surgeon skills. Secondary endpoints include subjective outcomes for issues of sexual function and incontinence and adverse events such as genitourinary injury, blood loss, wound infection, and mesh erosion.

Kaiser Permanente is the trial sponsor, and patients aged 18-80 years who are undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with or without other procedures for pelvic organ prolapse are being recruited. For more details about the trial, visit https://goo.gl/pWq7qe.

SOURCE: ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01535833.

SUMMARY FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

E-visits less likely to generate antibiotic prescriptions for common ailments

MONTREAL – When the same patient was assessed in person and via an electronic visit (e-visit) for several common complaints, a prescription for antibiotics was more likely to be generated from the face-to-face encounter.

In a recent study, if antibiotics were prescribed in one setting, but not the other, the office visit rather than the e-visit was where the antibiotic prescription was written in 73% of cases. Visits for sinus problems and vaginal symptoms made up over 80% of these cases of nonconcordant prescribing.

The study compared the diagnosis and treatment of five common acute conditions in an outpatient and e-visit setting, examining the concordance of both diagnosis and treatment between the two settings for complaints of vaginal irritation or discharge, urinary symptoms, sinus problems, rash, and diarrhea.

Outcomes tracked included concordance between the office visits and mock e-visits for the diagnosis, whether antibiotics were prescribed, and the general choice of antibiotics. Determinations about concordance were made by a third provider who was not involved with either the in-person visit or the mock e-visit, said Dr. Player, of the department of family medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

Nonconcordance in treatment could occur either because an antibiotic was prescribed in one setting, but not the other, or because the broad choice of antibiotic class differed between the two settings.

Adult patients who came to the outpatient clinic and agreed to be enrolled in the study also completed the e-visit questionnaires appropriate to their condition before they saw the provider in an office visit. Thus, mock e-visits were created that mirrored the office visit with the e-visit format used in practice.

At a later point in time, the blinded e-visit questionnaires were given to e-visit providers who treated the patients as they would if the questionnaires had been generated in an actual e-visit.

The study generated a total of 142 office visits with accompanying mock e-visits, but 29 were excluded for lack of completeness or inappropriateness for e-visit care. In all, 113 paired visits were evaluated. All but seven patients (94%) were female; slightly more than half (53%) of patients were aged 45 years or older.

About one-third of visits (34%; n = 38) were for vaginal discharge or irritation. Sinus problems were reported by 36 patients (32%). Twenty-five patients (22%) reported urinary problems, while eight patients (7%) reported diarrhea. Six patients (5%) complained of a rash.

In total, 78 visit pairs (69%) were assessed as being concordant. Of the 35 nonconcordant visits, over half (54%) were for sinus problems, 40% were for vaginal discharge or irritation, and 6% were for rash. None of the visits involving urinary problems or diarrhea were assessed as nonconcordant.

Examining the data another way, Dr. Player and his coinvestigators also looked at how many visits involved antibiotic prescribing, and how many of those visits were assessed as nonconcordant. Of the 96 patients (85%) who were prescribed antibiotics, 37 had office and mock e-visits that were assessed as discordant in antibiotic prescribing.

Of these visit pairs, about half (51%) were for sinus problems, and a third (32%) were for vaginal complaints. Urinary complaints made up 11% of the nonconcordant visit pairs where antibiotics were prescribed, and rashes made up the remaining 5%.

Diagnostic concordance was seen in about two-thirds of rash (67%) and vaginal discharge (63%) visit pairs. Concordance of diagnosis for sinus problems occurred in fewer than half (47%) of visit pairs.

Dr. Player said that the investigators excluded visits involving urinary or vaginal complaints that did not have an accompanying urinalysis or vaginal wet mount. This decision was made because the standard of care for both office visits and e-visits requires these laboratory tests for diagnosis, he said.

The study design came with some limitations, said Dr. Player. “Patients self-select for e-visits, and the patients in this study might be different from those in true e-visit encounters,” he said. Also, the diagnosis and treatment of sinus problems, rash, and diarrhea relied on clinical judgment alone in each visit setting. Still, he said, the study supports what many clinicians report anecdotally: Patients want to leave the office knowing that the clinician has “done something” for them, and often, that means walking out with a prescription in hand.

Dr. Player reported no conflicts of interest.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – When the same patient was assessed in person and via an electronic visit (e-visit) for several common complaints, a prescription for antibiotics was more likely to be generated from the face-to-face encounter.

In a recent study, if antibiotics were prescribed in one setting, but not the other, the office visit rather than the e-visit was where the antibiotic prescription was written in 73% of cases. Visits for sinus problems and vaginal symptoms made up over 80% of these cases of nonconcordant prescribing.

The study compared the diagnosis and treatment of five common acute conditions in an outpatient and e-visit setting, examining the concordance of both diagnosis and treatment between the two settings for complaints of vaginal irritation or discharge, urinary symptoms, sinus problems, rash, and diarrhea.

Outcomes tracked included concordance between the office visits and mock e-visits for the diagnosis, whether antibiotics were prescribed, and the general choice of antibiotics. Determinations about concordance were made by a third provider who was not involved with either the in-person visit or the mock e-visit, said Dr. Player, of the department of family medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

Nonconcordance in treatment could occur either because an antibiotic was prescribed in one setting, but not the other, or because the broad choice of antibiotic class differed between the two settings.

Adult patients who came to the outpatient clinic and agreed to be enrolled in the study also completed the e-visit questionnaires appropriate to their condition before they saw the provider in an office visit. Thus, mock e-visits were created that mirrored the office visit with the e-visit format used in practice.

At a later point in time, the blinded e-visit questionnaires were given to e-visit providers who treated the patients as they would if the questionnaires had been generated in an actual e-visit.

The study generated a total of 142 office visits with accompanying mock e-visits, but 29 were excluded for lack of completeness or inappropriateness for e-visit care. In all, 113 paired visits were evaluated. All but seven patients (94%) were female; slightly more than half (53%) of patients were aged 45 years or older.

About one-third of visits (34%; n = 38) were for vaginal discharge or irritation. Sinus problems were reported by 36 patients (32%). Twenty-five patients (22%) reported urinary problems, while eight patients (7%) reported diarrhea. Six patients (5%) complained of a rash.

In total, 78 visit pairs (69%) were assessed as being concordant. Of the 35 nonconcordant visits, over half (54%) were for sinus problems, 40% were for vaginal discharge or irritation, and 6% were for rash. None of the visits involving urinary problems or diarrhea were assessed as nonconcordant.

Examining the data another way, Dr. Player and his coinvestigators also looked at how many visits involved antibiotic prescribing, and how many of those visits were assessed as nonconcordant. Of the 96 patients (85%) who were prescribed antibiotics, 37 had office and mock e-visits that were assessed as discordant in antibiotic prescribing.

Of these visit pairs, about half (51%) were for sinus problems, and a third (32%) were for vaginal complaints. Urinary complaints made up 11% of the nonconcordant visit pairs where antibiotics were prescribed, and rashes made up the remaining 5%.

Diagnostic concordance was seen in about two-thirds of rash (67%) and vaginal discharge (63%) visit pairs. Concordance of diagnosis for sinus problems occurred in fewer than half (47%) of visit pairs.

Dr. Player said that the investigators excluded visits involving urinary or vaginal complaints that did not have an accompanying urinalysis or vaginal wet mount. This decision was made because the standard of care for both office visits and e-visits requires these laboratory tests for diagnosis, he said.

The study design came with some limitations, said Dr. Player. “Patients self-select for e-visits, and the patients in this study might be different from those in true e-visit encounters,” he said. Also, the diagnosis and treatment of sinus problems, rash, and diarrhea relied on clinical judgment alone in each visit setting. Still, he said, the study supports what many clinicians report anecdotally: Patients want to leave the office knowing that the clinician has “done something” for them, and often, that means walking out with a prescription in hand.

Dr. Player reported no conflicts of interest.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – When the same patient was assessed in person and via an electronic visit (e-visit) for several common complaints, a prescription for antibiotics was more likely to be generated from the face-to-face encounter.

In a recent study, if antibiotics were prescribed in one setting, but not the other, the office visit rather than the e-visit was where the antibiotic prescription was written in 73% of cases. Visits for sinus problems and vaginal symptoms made up over 80% of these cases of nonconcordant prescribing.

The study compared the diagnosis and treatment of five common acute conditions in an outpatient and e-visit setting, examining the concordance of both diagnosis and treatment between the two settings for complaints of vaginal irritation or discharge, urinary symptoms, sinus problems, rash, and diarrhea.

Outcomes tracked included concordance between the office visits and mock e-visits for the diagnosis, whether antibiotics were prescribed, and the general choice of antibiotics. Determinations about concordance were made by a third provider who was not involved with either the in-person visit or the mock e-visit, said Dr. Player, of the department of family medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

Nonconcordance in treatment could occur either because an antibiotic was prescribed in one setting, but not the other, or because the broad choice of antibiotic class differed between the two settings.

Adult patients who came to the outpatient clinic and agreed to be enrolled in the study also completed the e-visit questionnaires appropriate to their condition before they saw the provider in an office visit. Thus, mock e-visits were created that mirrored the office visit with the e-visit format used in practice.

At a later point in time, the blinded e-visit questionnaires were given to e-visit providers who treated the patients as they would if the questionnaires had been generated in an actual e-visit.

The study generated a total of 142 office visits with accompanying mock e-visits, but 29 were excluded for lack of completeness or inappropriateness for e-visit care. In all, 113 paired visits were evaluated. All but seven patients (94%) were female; slightly more than half (53%) of patients were aged 45 years or older.

About one-third of visits (34%; n = 38) were for vaginal discharge or irritation. Sinus problems were reported by 36 patients (32%). Twenty-five patients (22%) reported urinary problems, while eight patients (7%) reported diarrhea. Six patients (5%) complained of a rash.

In total, 78 visit pairs (69%) were assessed as being concordant. Of the 35 nonconcordant visits, over half (54%) were for sinus problems, 40% were for vaginal discharge or irritation, and 6% were for rash. None of the visits involving urinary problems or diarrhea were assessed as nonconcordant.

Examining the data another way, Dr. Player and his coinvestigators also looked at how many visits involved antibiotic prescribing, and how many of those visits were assessed as nonconcordant. Of the 96 patients (85%) who were prescribed antibiotics, 37 had office and mock e-visits that were assessed as discordant in antibiotic prescribing.

Of these visit pairs, about half (51%) were for sinus problems, and a third (32%) were for vaginal complaints. Urinary complaints made up 11% of the nonconcordant visit pairs where antibiotics were prescribed, and rashes made up the remaining 5%.

Diagnostic concordance was seen in about two-thirds of rash (67%) and vaginal discharge (63%) visit pairs. Concordance of diagnosis for sinus problems occurred in fewer than half (47%) of visit pairs.

Dr. Player said that the investigators excluded visits involving urinary or vaginal complaints that did not have an accompanying urinalysis or vaginal wet mount. This decision was made because the standard of care for both office visits and e-visits requires these laboratory tests for diagnosis, he said.

The study design came with some limitations, said Dr. Player. “Patients self-select for e-visits, and the patients in this study might be different from those in true e-visit encounters,” he said. Also, the diagnosis and treatment of sinus problems, rash, and diarrhea relied on clinical judgment alone in each visit setting. Still, he said, the study supports what many clinicians report anecdotally: Patients want to leave the office knowing that the clinician has “done something” for them, and often, that means walking out with a prescription in hand.

Dr. Player reported no conflicts of interest.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT NAPCRG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Antibiotics were given in the office but not the e-visit in 73% of cases.

Data source: Prospective study of 113 office visits that were paired with independently assessed e-visits for the same patient and complaint.

Disclosures: Dr. Player reported no conflicts of interest.

How to assess a patient for a bisphosphonate drug holiday

Recorded at the 2017 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

Recorded at the 2017 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

Recorded at the 2017 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

What is the optimal opioid prescription length after women’s health surgical procedures?

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PRACTICE?

- 7-day opioid prescriptions should be sufficient after common gyn procedures

- Monitor patients closely

- Transfer patients as soon as possible to non-opioid pain medication

Real-world data support extended cervical cancer screening interval

A cervical cancer screening interval of 5 years or longer may be safe for women with one or more negative cotests using the high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) test and cervical cytology, according to the results of a large observational study.

The findings also suggest that one or two negative HPV tests, regardless of cytology, may be enough to extend the screening interval, the researchers noted.

The 5-year risk decreased with each successive HPV-negative and cytology-negative result, falling from 0.098% in the first cotesting round, to 0.052% in the second round, and 0.035% in the third round. The 5-year risks were similar with an HPV-negative cotest result, regardless of the outcome of cytology: 0.114%, 0.061%, and 0.041%.

The results are based on data from more than 990,000 women in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California health care system who had one or more cotests from 2003 to 2014.

These findings come as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has issued draft recommendations that would call for either HPV testing alone every 5 years starting at age 30 years or cytology every 3 years, but no cotesting. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The study was partially funded by the National Cancer Institute. Some of the researchers are employees of the National Cancer Institute. The researchers reported receiving cervical screening tests and diagnostics at reduced or no cost from Roche, BD Biosciences, Cepheid, Arbor Vita, and Hologic.

The study by Castle et al provides important insight into the effects of repeated testing of HPV, cervical cytology, and testing both together. The authors are to be commended for performing their analysis, which involved almost 1 million women.

There are several important observations that can be made. One is that the risk of detecting cancer is decreased after cotesting HPV and cervical cytology both show a negative result, and that this risk is further reduced after the second and third negative HPV/cytology test. This could mean less frequent screening could be safely adopted in women who are HPV and cytology negative, which would lead to fewer women referred for unnecessary colposcopy and treatment, reducing their stress and discomfort.

These data could alter how women are triaged on the basis of the HPV test. In HPV-positive women, for example, current practices are appropriate for the first and perhaps second round of HPV testing, but perhaps subsequent rounds could become less stringent. Conversely, when there is an HPV-negative result, even in the presence of a positive or equivocal cytology, screening intervals may still be safe to lengthen as there is only a small increase in risk versus being both HPV and cytology negative.

Guglielmo Ronco, MD, PhD, is formerly of the City of Health and Science University Hospital of Turin (Italy). Silvia Franceschi, MD, PhD, is with the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Their comments were adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2017. doi: 10.7326/M17-2872).

The study by Castle et al provides important insight into the effects of repeated testing of HPV, cervical cytology, and testing both together. The authors are to be commended for performing their analysis, which involved almost 1 million women.

There are several important observations that can be made. One is that the risk of detecting cancer is decreased after cotesting HPV and cervical cytology both show a negative result, and that this risk is further reduced after the second and third negative HPV/cytology test. This could mean less frequent screening could be safely adopted in women who are HPV and cytology negative, which would lead to fewer women referred for unnecessary colposcopy and treatment, reducing their stress and discomfort.

These data could alter how women are triaged on the basis of the HPV test. In HPV-positive women, for example, current practices are appropriate for the first and perhaps second round of HPV testing, but perhaps subsequent rounds could become less stringent. Conversely, when there is an HPV-negative result, even in the presence of a positive or equivocal cytology, screening intervals may still be safe to lengthen as there is only a small increase in risk versus being both HPV and cytology negative.

Guglielmo Ronco, MD, PhD, is formerly of the City of Health and Science University Hospital of Turin (Italy). Silvia Franceschi, MD, PhD, is with the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Their comments were adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2017. doi: 10.7326/M17-2872).

The study by Castle et al provides important insight into the effects of repeated testing of HPV, cervical cytology, and testing both together. The authors are to be commended for performing their analysis, which involved almost 1 million women.

There are several important observations that can be made. One is that the risk of detecting cancer is decreased after cotesting HPV and cervical cytology both show a negative result, and that this risk is further reduced after the second and third negative HPV/cytology test. This could mean less frequent screening could be safely adopted in women who are HPV and cytology negative, which would lead to fewer women referred for unnecessary colposcopy and treatment, reducing their stress and discomfort.

These data could alter how women are triaged on the basis of the HPV test. In HPV-positive women, for example, current practices are appropriate for the first and perhaps second round of HPV testing, but perhaps subsequent rounds could become less stringent. Conversely, when there is an HPV-negative result, even in the presence of a positive or equivocal cytology, screening intervals may still be safe to lengthen as there is only a small increase in risk versus being both HPV and cytology negative.

Guglielmo Ronco, MD, PhD, is formerly of the City of Health and Science University Hospital of Turin (Italy). Silvia Franceschi, MD, PhD, is with the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Their comments were adapted from an accompanying editorial (Ann Intern Med. 2017. doi: 10.7326/M17-2872).

A cervical cancer screening interval of 5 years or longer may be safe for women with one or more negative cotests using the high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) test and cervical cytology, according to the results of a large observational study.

The findings also suggest that one or two negative HPV tests, regardless of cytology, may be enough to extend the screening interval, the researchers noted.

The 5-year risk decreased with each successive HPV-negative and cytology-negative result, falling from 0.098% in the first cotesting round, to 0.052% in the second round, and 0.035% in the third round. The 5-year risks were similar with an HPV-negative cotest result, regardless of the outcome of cytology: 0.114%, 0.061%, and 0.041%.

The results are based on data from more than 990,000 women in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California health care system who had one or more cotests from 2003 to 2014.

These findings come as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has issued draft recommendations that would call for either HPV testing alone every 5 years starting at age 30 years or cytology every 3 years, but no cotesting. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The study was partially funded by the National Cancer Institute. Some of the researchers are employees of the National Cancer Institute. The researchers reported receiving cervical screening tests and diagnostics at reduced or no cost from Roche, BD Biosciences, Cepheid, Arbor Vita, and Hologic.

A cervical cancer screening interval of 5 years or longer may be safe for women with one or more negative cotests using the high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) test and cervical cytology, according to the results of a large observational study.

The findings also suggest that one or two negative HPV tests, regardless of cytology, may be enough to extend the screening interval, the researchers noted.

The 5-year risk decreased with each successive HPV-negative and cytology-negative result, falling from 0.098% in the first cotesting round, to 0.052% in the second round, and 0.035% in the third round. The 5-year risks were similar with an HPV-negative cotest result, regardless of the outcome of cytology: 0.114%, 0.061%, and 0.041%.

The results are based on data from more than 990,000 women in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California health care system who had one or more cotests from 2003 to 2014.

These findings come as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has issued draft recommendations that would call for either HPV testing alone every 5 years starting at age 30 years or cytology every 3 years, but no cotesting. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommends cotesting with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years in women aged 30-65 years (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128[4]:e111-30).

The study was partially funded by the National Cancer Institute. Some of the researchers are employees of the National Cancer Institute. The researchers reported receiving cervical screening tests and diagnostics at reduced or no cost from Roche, BD Biosciences, Cepheid, Arbor Vita, and Hologic.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 5-year cumulative detection of invasive cervical cancer, CIN3, and adenocarcinoma in situ decreased with each successive HPV-negative and cytology-negative result (0.098%, 0.052%, and 0.035%).

Data source: Data on more than 990,000 women who received cotesting between 2003 and 2014.

Disclosures: The research was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute. Some of the researchers are employees of the National Cancer Institute. The researchers reported receiving cervical screening tests and diagnostics at reduced or no cost from Roche, BD Biosciences, Cepheid, Arbor Vita, and Hologic.

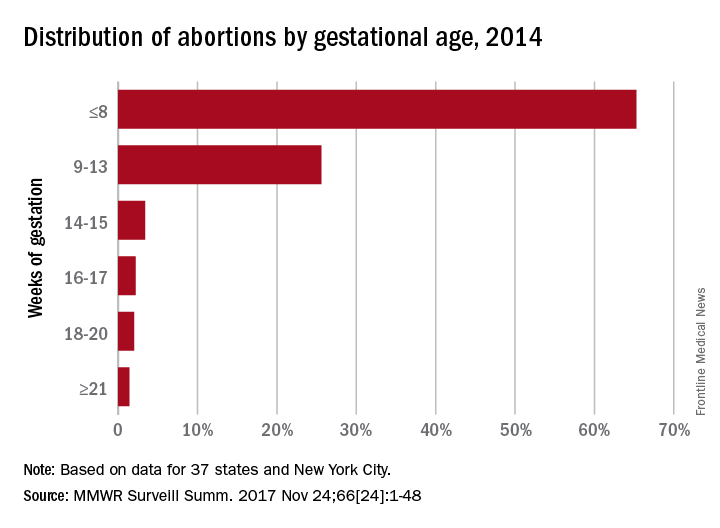

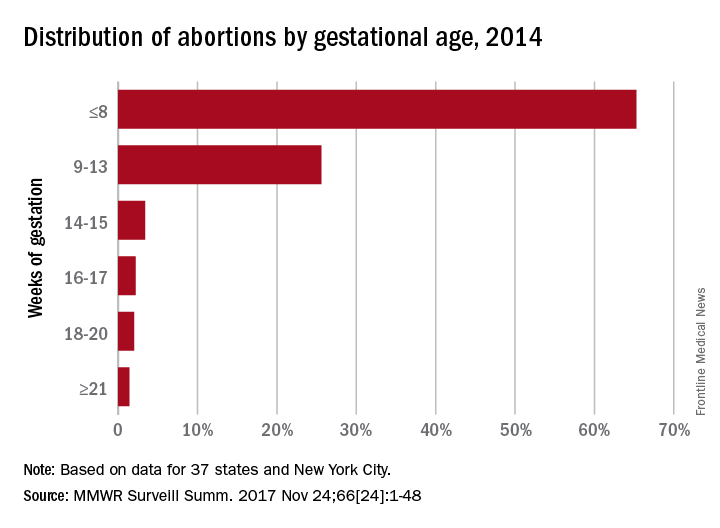

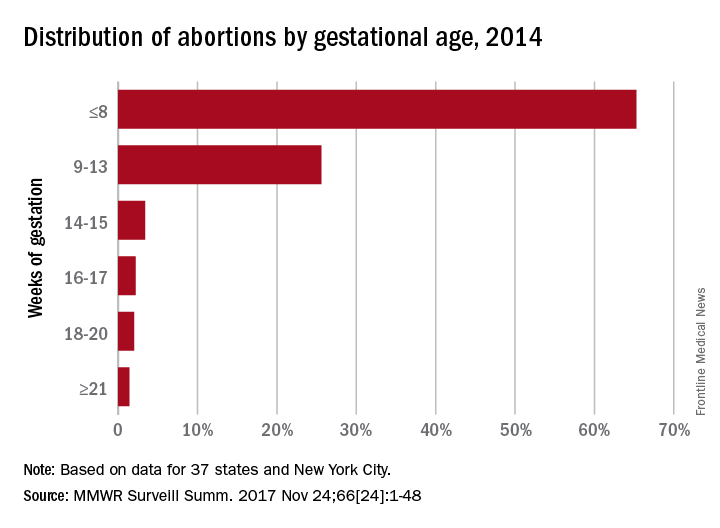

Two-thirds of abortions occur by 8 weeks’ gestation

, although there was variation by maternal age and race/ethnicity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That year, 65.3% of abortions were performed at a gestational age of 8 weeks or earlier, with 25.6% occurring at 9-13 weeks. Gestational distribution of the remaining abortions was fairly even: 3.4% at 14-15 weeks, 2.2% at 16-17 weeks, 2.0% at 18-20 weeks, and 1.4% at 21 weeks or later, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017 Nov 25;66[24]:1-48).

The percentage of abortions occurring at 8 weeks or earlier was lowest for the youngest age group and increased along with maternal age: 43% for those under 15 years of age and progressing up to 72.5% for women over age 40. That scenario was basically reversed for all of the other gestational periods, as the under-15 group had the highest percentage for 9-13 weeks (34.4%), 14-15 (6.7%), 16-17 (3.6%), 18-20 (5.0%), and 21 weeks and later (7.3%). Those over age 40 had the lowest or almost the lowest percentage in each period, reported Tara C. Jatlaoui, MD, and her associates.

The data for gestational period analysis came from 37 states and New York City. New York State, along with 12 other states, did not report, did not report by gestational age, or did not meet reporting standards.

, although there was variation by maternal age and race/ethnicity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That year, 65.3% of abortions were performed at a gestational age of 8 weeks or earlier, with 25.6% occurring at 9-13 weeks. Gestational distribution of the remaining abortions was fairly even: 3.4% at 14-15 weeks, 2.2% at 16-17 weeks, 2.0% at 18-20 weeks, and 1.4% at 21 weeks or later, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017 Nov 25;66[24]:1-48).

The percentage of abortions occurring at 8 weeks or earlier was lowest for the youngest age group and increased along with maternal age: 43% for those under 15 years of age and progressing up to 72.5% for women over age 40. That scenario was basically reversed for all of the other gestational periods, as the under-15 group had the highest percentage for 9-13 weeks (34.4%), 14-15 (6.7%), 16-17 (3.6%), 18-20 (5.0%), and 21 weeks and later (7.3%). Those over age 40 had the lowest or almost the lowest percentage in each period, reported Tara C. Jatlaoui, MD, and her associates.

The data for gestational period analysis came from 37 states and New York City. New York State, along with 12 other states, did not report, did not report by gestational age, or did not meet reporting standards.

, although there was variation by maternal age and race/ethnicity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That year, 65.3% of abortions were performed at a gestational age of 8 weeks or earlier, with 25.6% occurring at 9-13 weeks. Gestational distribution of the remaining abortions was fairly even: 3.4% at 14-15 weeks, 2.2% at 16-17 weeks, 2.0% at 18-20 weeks, and 1.4% at 21 weeks or later, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017 Nov 25;66[24]:1-48).

The percentage of abortions occurring at 8 weeks or earlier was lowest for the youngest age group and increased along with maternal age: 43% for those under 15 years of age and progressing up to 72.5% for women over age 40. That scenario was basically reversed for all of the other gestational periods, as the under-15 group had the highest percentage for 9-13 weeks (34.4%), 14-15 (6.7%), 16-17 (3.6%), 18-20 (5.0%), and 21 weeks and later (7.3%). Those over age 40 had the lowest or almost the lowest percentage in each period, reported Tara C. Jatlaoui, MD, and her associates.

The data for gestational period analysis came from 37 states and New York City. New York State, along with 12 other states, did not report, did not report by gestational age, or did not meet reporting standards.

FROM MMWR SURVEILLANCE SUMMARIES

2017 Update on bone health

Bone health remains one of the most important health care concerns in the United States today. In 2004, the Surgeon General released a report on bone health and osteoporosis. According to the report’s introduction:

This first-ever Surgeon General’s Report on bone health and osteoporosis illustrates the large burden that bone disease places on our Nation and its citizens. Like other chronic diseases that disproportionately affect the elderly, the prevalence of bone disease and fractures is projected to increase markedly as the population ages. If these predictions come true, bone disease and fractures will have a tremendous negative impact on the future well-being of Americans. But as this report makes clear, they need not come true: by working together we can change the picture of aging in America. Osteoporosis and fractures…no longer should be thought of as an inevitable part of growing old. By focusing on prevention and lifestyle changes, including physical activity and nutrition, as well as early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, Americans can avoid much of the damaging impact of bone disease.1

Related article:

2016 Update on bone health

Although men also experience osteoporosis as they age, in women the rapid loss of bone at menopause makes their disease burden much greater. As women’s health care providers, we stand at the front line for preventing, diagnosing, and treating osteoporosis to reduce the impact of this disease. In this Update I focus on important information that has emerged in the past year.

Read about new ACP guidelines to assess fracture risk

Guidelines for therapy: How to assess fracture risk and when to treat

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 129: Osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):718-734.

Qaseem A, Forciea MA, McLean RM, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures in men and women: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(11):818-839.

A crucial component for good bone health maintenance and osteoporotic fracture prevention is understanding the current guidelines for therapy. The most recent practice bulletin of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on osteoporosis was published in 2012. ACOG states that treatment be recommended for women who have a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of -2.5 or lower.

For women in the low bone mass category (T-score between -1 and -2.5), use of the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) calculator can assist in making an informed treatment decision.2 Based on the FRAX calculator, women who have a 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture of 20% or greater, or a risk of hip fracture of 3% or greater, are candidates for pharmacologic therapy.

Women who have experienced a low-trauma fracture (especially of the vertebra or hip) also are candidates for treatment, even in the absence of osteoporosis on a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) report.

Related article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Updated recommendations from the ACP

The 2017 guideline published by the American College of Physicians (ACP), whose target audience is "all clinicians," recommends that, for women who have known osteoporosis, clinicians offer pharmacologic treatment with alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, or denosumab to reduce the risk for hip and vertebral fractures.

In addition, the ACP recommends that clinicians make the decision whether or not to treat osteopenic women 65 years of age or older who are at a high risk for fracture based on a discussion of patient preferences, fracture risk profile, and benefits, harms, and costs of medications. This may seem somewhat contradictory to ACOG's guidance vis-a-vis women younger than 65 years of age.

The ACP further states that given the limited evidence supporting the benefit of treatment, the balance of benefits and harms in treating osteopenic women is most favorable when the risk for fracture is high. Women younger than 65 years with osteopenia and women older than 65 years with mild osteopenia (T-score between -1.0 and -1.5) will benefit less than women who are 65 years of age or older with severe osteopenia (T-score <-2.0).

Risk factors and risk assessment tools

Clinicians can use their own judgment based on risk factors for fracture (lower body weight, smoking, weight loss, family history of fractures, decreased physical activity, alcohol or caffeine use, low calcium and vitamin D intake, corticosteroid use), or they can use a risk assessment tool. Several risk assessment tools, such as the FRAX calculator mentioned earlier, are available to predict fracture risk among untreated people with low bone density. Although the FRAX calculator is widely used, there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrating a benefit of fracture reduction when FRAX scores are used in treatment decision making.

Duration of therapy. The ACP recommends that clinicians treat osteoporotic women with pharmacologic therapy for 5 years. Bone density monitoring is not recommended during the 5-year treatment period for osteoporosis in women; current evidence does not show any benefit for bone density monitoring during treatment.

Moderate-quality evidence demonstrated that women treated with antiresorptive therapies (including bisphosphonates, raloxifene, and teriparatide) benefited from reduced fractures, even if no increase in BMD occurred or if BMD decreased.

As before, all women with osteoporosis or a previous low-trauma fracture should be treated. Use of the FRAX calculator should involve clinician judgment, and other risk factors should be taken into account. For most women, treatment should be continued for 5 years. There is no benefit in continued bone mass assessment (DXA testing) while a patient is on pharmacologic therapy.

Read about fracture risk after stopping HT

Another WHI update: No increase in fractures after stopping HT

Watts NB, Cauley JA, Jackson RD, et al; Women's Health Initiative Investigators. No increase in fractures after stopping hormone therapy: results from the Women's Health Initiative. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(1):302-308.

The analysis and reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial data seems never-ending, yet the article by Watts and colleagues is important. Although the WHI hormone therapy (HT) trials showed that treatment protects against hip and total fractures, a later observational report suggested loss of benefit and rebound increased risk after HT was discontinued.3 The purpose of the Watts' study was to examine fractures after stopping HT.

Related article:

Did long-term follow-up of WHI participants reveal any mortality increase among women who received HT?

Details of the study

Two placebo-controlled randomized trials served as the study setting. The study included WHI participants (n = 15,187) who continued to take active HT or placebo through the intervention period and who did not take HT in the postintervention period. The trial interventions included conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for women with natural menopause and CEE alone for women with prior hysterectomy. The investigators recorded total fractures and hip fractures through 5 years after HT discontinuation.

Findings on fractures. Hip fractures occurred infrequently, with approximately 2.5 per 1,000 person-years. This finding was similar between trials and in former HT users and placebo groups.

No difference was found in total fractures in the CEE plus MPA trial for former HT users compared with former placebo users (28.9 per 1,000 person-years and 29.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively; hazard ratio [HR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-1.09; P = .63). In the CEE-alone trial, however, total fractures were higher in former placebo users (36.9 per 1,000 person-years) compared with the former active-treatment group (31.1 per 1,000 person-years). This finding suggests a residual benefit of CEE in reducing total fractures (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.98; P = .03).

Investigators' takeaway. The authors concluded that, after discontinuing HT, there was no evidence of increased fracture risk (sustained or transient) in former HT users compared with former placebo users. In the CEE-alone trial, there was a residual benefit for total fracture reduction in former HT users compared with placebo users.

Gynecologists have long believed that on stopping HT, the loss of bone mass will follow at the same rate as it would at natural menopause. These WHI trials demonstrate, however, that through 5 years, women who stopped HT had no increase in hip or total fractures, and hysterectomized women who stopped estrogen therapy actually had fewer fractures than the placebo group. Keep in mind that this large cohort was not chosen based on risk of osteoporotic fractures. In fact, baseline bone mass was not even measured in these women, making the results even more "real world."

Read about reassessing FRAX scores

A new look at fracture risk assessment scores

Gourlay ML, Overman RA, Fine JP, et al; Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Time to clinically relevant fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e15-e23.

Jiang X, Gruner M, Trémollieres F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of FRAX in predicting the 10-year risk of osteoporotic fractures using the USA treatment thresholds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone. 2017;99:20-25.

The FRAX score has become a popular form of triage for women who do not yet meet the bone mass criteria of osteoporosis. Current practice guidelines recommend use of fracture risk scores for screening and pharmacologic therapeutic decision making. Some newer data, however, may give rise to questions about its utility, especially in younger women.

Fracture risk analysis in a large postmenopausal population

Gourlay and colleagues conducted a retrospective competing risk analysis of new occurrence of treatment-level and screening-level fracture risk scores. Study participants were postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older who had not previously received pharmacologic treatment and had not had a first hip or clinical vertebral facture.

Details of the study

In 54,280 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 64 years who did not have a bone mineral density test, the time for 10% to develop a treatment-level FRAX score could not be estimated accurately because the incidence of treatment-level scores was rare.

A total of 6,096 women had FRAX scores calculated with bone mineral density testing. In this group, the estimated unadjusted time to treatment-level FRAX scores was 7.6 years (95% CI, 6.6-8.7) for those aged 65 to 69, and 5.1 years (95% CI, 3.5-7.5) for women aged 75 to 79 at baseline.

Of 17,967 women aged 50 to 64 who had a screening-level FRAX at baseline, 100 (0.6%) experienced a hip or clinical vertebral fracture by age 65 years.

Age is key factor. Gourlay and colleagues concluded that postmenopausal women who had subthreshold fracture risk scores at baseline would be unlikely to develop a treatment-level FRAX score between ages 50 and 64. The increased incidence of treatment-level fracture risk scores, osteoporosis, and major osteoporotic fracture after age 65, however, supports more frequent consideration of FRAX assessment and bone mineral density testing.

Related article:

2015 Update on osteoporosis

Meta-analysis of FRAX tool accuracy

In another study, Jiang and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine how the FRAX score performed in predicting the 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures. The investigators used the US treatment thresholds.

Details of the study

Seven studies (n = 57,027) were analyzed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of FRAX in predicting major osteoporotic fractures; 20% was used as the 10-year fracture risk threshold for intervention. The mean sensitivity and specificity, along with their 95% CIs, were 10.25% (3.76%-25.06%) and 97.02% (91.17%-99.03%), respectively.

For hip fracture prediction, 6 studies (n = 50,944) were analyzed, and 3% was used as the 10-year fracture risk threshold. The mean sensitivity and specificity, along with their 95% CIs, were 45.70% (24.88%-68.13%) and 84.70% (76.41%-90.44%), respectively.

Predictive value of FRAX. The authors concluded that, using the 10-year intervention thresholds of 20% for major osteoporotic fracture and 3% for hip fracture, FRAX performed better in identifying individuals who will not have a major osteoporotic fracture or hip fracture within 10 years than in identifying those who will experience a fracture. A substantial number of those who developed fractures, especially major osteoporotic fracture within 10 years of follow up, were missed by the baseline FRAX assessment.

Increasing age is still arguably among the most important factors for decreasing bone health. Older women are more likely to develop treatment-level FRAX scores more quickly than younger women. In addition, the FRAX tool is better in predicting which women will not develop a fracture in the next 10 years than in predicting those who will experience a fracture.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- United States Office of the Surgeon General. Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Maryland: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45513/. Accessed November 6, 2017.

- Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, United Kingdom. FRAX Fracture Risk Assessment Tool website. www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX. Accessed November 6, 2017.

- Yates J, Barrett-Connor E, Barlas S, Chen YT, Miller PD, Siris ES. Rapid loss of hip fracture protection after estrogen cessation: evidence from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(3):440–446.

Bone health remains one of the most important health care concerns in the United States today. In 2004, the Surgeon General released a report on bone health and osteoporosis. According to the report’s introduction:

This first-ever Surgeon General’s Report on bone health and osteoporosis illustrates the large burden that bone disease places on our Nation and its citizens. Like other chronic diseases that disproportionately affect the elderly, the prevalence of bone disease and fractures is projected to increase markedly as the population ages. If these predictions come true, bone disease and fractures will have a tremendous negative impact on the future well-being of Americans. But as this report makes clear, they need not come true: by working together we can change the picture of aging in America. Osteoporosis and fractures…no longer should be thought of as an inevitable part of growing old. By focusing on prevention and lifestyle changes, including physical activity and nutrition, as well as early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, Americans can avoid much of the damaging impact of bone disease.1

Related article:

2016 Update on bone health

Although men also experience osteoporosis as they age, in women the rapid loss of bone at menopause makes their disease burden much greater. As women’s health care providers, we stand at the front line for preventing, diagnosing, and treating osteoporosis to reduce the impact of this disease. In this Update I focus on important information that has emerged in the past year.

Read about new ACP guidelines to assess fracture risk

Guidelines for therapy: How to assess fracture risk and when to treat

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 129: Osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):718-734.

Qaseem A, Forciea MA, McLean RM, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures in men and women: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(11):818-839.

A crucial component for good bone health maintenance and osteoporotic fracture prevention is understanding the current guidelines for therapy. The most recent practice bulletin of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on osteoporosis was published in 2012. ACOG states that treatment be recommended for women who have a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of -2.5 or lower.

For women in the low bone mass category (T-score between -1 and -2.5), use of the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) calculator can assist in making an informed treatment decision.2 Based on the FRAX calculator, women who have a 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture of 20% or greater, or a risk of hip fracture of 3% or greater, are candidates for pharmacologic therapy.

Women who have experienced a low-trauma fracture (especially of the vertebra or hip) also are candidates for treatment, even in the absence of osteoporosis on a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) report.

Related article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Updated recommendations from the ACP

The 2017 guideline published by the American College of Physicians (ACP), whose target audience is "all clinicians," recommends that, for women who have known osteoporosis, clinicians offer pharmacologic treatment with alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, or denosumab to reduce the risk for hip and vertebral fractures.

In addition, the ACP recommends that clinicians make the decision whether or not to treat osteopenic women 65 years of age or older who are at a high risk for fracture based on a discussion of patient preferences, fracture risk profile, and benefits, harms, and costs of medications. This may seem somewhat contradictory to ACOG's guidance vis-a-vis women younger than 65 years of age.

The ACP further states that given the limited evidence supporting the benefit of treatment, the balance of benefits and harms in treating osteopenic women is most favorable when the risk for fracture is high. Women younger than 65 years with osteopenia and women older than 65 years with mild osteopenia (T-score between -1.0 and -1.5) will benefit less than women who are 65 years of age or older with severe osteopenia (T-score <-2.0).

Risk factors and risk assessment tools

Clinicians can use their own judgment based on risk factors for fracture (lower body weight, smoking, weight loss, family history of fractures, decreased physical activity, alcohol or caffeine use, low calcium and vitamin D intake, corticosteroid use), or they can use a risk assessment tool. Several risk assessment tools, such as the FRAX calculator mentioned earlier, are available to predict fracture risk among untreated people with low bone density. Although the FRAX calculator is widely used, there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrating a benefit of fracture reduction when FRAX scores are used in treatment decision making.

Duration of therapy. The ACP recommends that clinicians treat osteoporotic women with pharmacologic therapy for 5 years. Bone density monitoring is not recommended during the 5-year treatment period for osteoporosis in women; current evidence does not show any benefit for bone density monitoring during treatment.

Moderate-quality evidence demonstrated that women treated with antiresorptive therapies (including bisphosphonates, raloxifene, and teriparatide) benefited from reduced fractures, even if no increase in BMD occurred or if BMD decreased.

As before, all women with osteoporosis or a previous low-trauma fracture should be treated. Use of the FRAX calculator should involve clinician judgment, and other risk factors should be taken into account. For most women, treatment should be continued for 5 years. There is no benefit in continued bone mass assessment (DXA testing) while a patient is on pharmacologic therapy.

Read about fracture risk after stopping HT

Another WHI update: No increase in fractures after stopping HT

Watts NB, Cauley JA, Jackson RD, et al; Women's Health Initiative Investigators. No increase in fractures after stopping hormone therapy: results from the Women's Health Initiative. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(1):302-308.

The analysis and reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial data seems never-ending, yet the article by Watts and colleagues is important. Although the WHI hormone therapy (HT) trials showed that treatment protects against hip and total fractures, a later observational report suggested loss of benefit and rebound increased risk after HT was discontinued.3 The purpose of the Watts' study was to examine fractures after stopping HT.

Related article:

Did long-term follow-up of WHI participants reveal any mortality increase among women who received HT?

Details of the study

Two placebo-controlled randomized trials served as the study setting. The study included WHI participants (n = 15,187) who continued to take active HT or placebo through the intervention period and who did not take HT in the postintervention period. The trial interventions included conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for women with natural menopause and CEE alone for women with prior hysterectomy. The investigators recorded total fractures and hip fractures through 5 years after HT discontinuation.

Findings on fractures. Hip fractures occurred infrequently, with approximately 2.5 per 1,000 person-years. This finding was similar between trials and in former HT users and placebo groups.

No difference was found in total fractures in the CEE plus MPA trial for former HT users compared with former placebo users (28.9 per 1,000 person-years and 29.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively; hazard ratio [HR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-1.09; P = .63). In the CEE-alone trial, however, total fractures were higher in former placebo users (36.9 per 1,000 person-years) compared with the former active-treatment group (31.1 per 1,000 person-years). This finding suggests a residual benefit of CEE in reducing total fractures (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.98; P = .03).

Investigators' takeaway. The authors concluded that, after discontinuing HT, there was no evidence of increased fracture risk (sustained or transient) in former HT users compared with former placebo users. In the CEE-alone trial, there was a residual benefit for total fracture reduction in former HT users compared with placebo users.

Gynecologists have long believed that on stopping HT, the loss of bone mass will follow at the same rate as it would at natural menopause. These WHI trials demonstrate, however, that through 5 years, women who stopped HT had no increase in hip or total fractures, and hysterectomized women who stopped estrogen therapy actually had fewer fractures than the placebo group. Keep in mind that this large cohort was not chosen based on risk of osteoporotic fractures. In fact, baseline bone mass was not even measured in these women, making the results even more "real world."

Read about reassessing FRAX scores

A new look at fracture risk assessment scores

Gourlay ML, Overman RA, Fine JP, et al; Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Time to clinically relevant fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e15-e23.

Jiang X, Gruner M, Trémollieres F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of FRAX in predicting the 10-year risk of osteoporotic fractures using the USA treatment thresholds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone. 2017;99:20-25.

The FRAX score has become a popular form of triage for women who do not yet meet the bone mass criteria of osteoporosis. Current practice guidelines recommend use of fracture risk scores for screening and pharmacologic therapeutic decision making. Some newer data, however, may give rise to questions about its utility, especially in younger women.

Fracture risk analysis in a large postmenopausal population

Gourlay and colleagues conducted a retrospective competing risk analysis of new occurrence of treatment-level and screening-level fracture risk scores. Study participants were postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older who had not previously received pharmacologic treatment and had not had a first hip or clinical vertebral facture.

Details of the study

In 54,280 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 64 years who did not have a bone mineral density test, the time for 10% to develop a treatment-level FRAX score could not be estimated accurately because the incidence of treatment-level scores was rare.

A total of 6,096 women had FRAX scores calculated with bone mineral density testing. In this group, the estimated unadjusted time to treatment-level FRAX scores was 7.6 years (95% CI, 6.6-8.7) for those aged 65 to 69, and 5.1 years (95% CI, 3.5-7.5) for women aged 75 to 79 at baseline.

Of 17,967 women aged 50 to 64 who had a screening-level FRAX at baseline, 100 (0.6%) experienced a hip or clinical vertebral fracture by age 65 years.

Age is key factor. Gourlay and colleagues concluded that postmenopausal women who had subthreshold fracture risk scores at baseline would be unlikely to develop a treatment-level FRAX score between ages 50 and 64. The increased incidence of treatment-level fracture risk scores, osteoporosis, and major osteoporotic fracture after age 65, however, supports more frequent consideration of FRAX assessment and bone mineral density testing.

Related article:

2015 Update on osteoporosis

Meta-analysis of FRAX tool accuracy

In another study, Jiang and colleagues conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine how the FRAX score performed in predicting the 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures. The investigators used the US treatment thresholds.

Details of the study

Seven studies (n = 57,027) were analyzed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of FRAX in predicting major osteoporotic fractures; 20% was used as the 10-year fracture risk threshold for intervention. The mean sensitivity and specificity, along with their 95% CIs, were 10.25% (3.76%-25.06%) and 97.02% (91.17%-99.03%), respectively.

For hip fracture prediction, 6 studies (n = 50,944) were analyzed, and 3% was used as the 10-year fracture risk threshold. The mean sensitivity and specificity, along with their 95% CIs, were 45.70% (24.88%-68.13%) and 84.70% (76.41%-90.44%), respectively.

Predictive value of FRAX. The authors concluded that, using the 10-year intervention thresholds of 20% for major osteoporotic fracture and 3% for hip fracture, FRAX performed better in identifying individuals who will not have a major osteoporotic fracture or hip fracture within 10 years than in identifying those who will experience a fracture. A substantial number of those who developed fractures, especially major osteoporotic fracture within 10 years of follow up, were missed by the baseline FRAX assessment.

Increasing age is still arguably among the most important factors for decreasing bone health. Older women are more likely to develop treatment-level FRAX scores more quickly than younger women. In addition, the FRAX tool is better in predicting which women will not develop a fracture in the next 10 years than in predicting those who will experience a fracture.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Bone health remains one of the most important health care concerns in the United States today. In 2004, the Surgeon General released a report on bone health and osteoporosis. According to the report’s introduction:

This first-ever Surgeon General’s Report on bone health and osteoporosis illustrates the large burden that bone disease places on our Nation and its citizens. Like other chronic diseases that disproportionately affect the elderly, the prevalence of bone disease and fractures is projected to increase markedly as the population ages. If these predictions come true, bone disease and fractures will have a tremendous negative impact on the future well-being of Americans. But as this report makes clear, they need not come true: by working together we can change the picture of aging in America. Osteoporosis and fractures…no longer should be thought of as an inevitable part of growing old. By focusing on prevention and lifestyle changes, including physical activity and nutrition, as well as early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, Americans can avoid much of the damaging impact of bone disease.1

Related article:

2016 Update on bone health

Although men also experience osteoporosis as they age, in women the rapid loss of bone at menopause makes their disease burden much greater. As women’s health care providers, we stand at the front line for preventing, diagnosing, and treating osteoporosis to reduce the impact of this disease. In this Update I focus on important information that has emerged in the past year.

Read about new ACP guidelines to assess fracture risk

Guidelines for therapy: How to assess fracture risk and when to treat

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 129: Osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(3):718-734.

Qaseem A, Forciea MA, McLean RM, Denberg TD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures in men and women: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(11):818-839.

A crucial component for good bone health maintenance and osteoporotic fracture prevention is understanding the current guidelines for therapy. The most recent practice bulletin of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on osteoporosis was published in 2012. ACOG states that treatment be recommended for women who have a bone mineral density (BMD) T-score of -2.5 or lower.

For women in the low bone mass category (T-score between -1 and -2.5), use of the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) calculator can assist in making an informed treatment decision.2 Based on the FRAX calculator, women who have a 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture of 20% or greater, or a risk of hip fracture of 3% or greater, are candidates for pharmacologic therapy.

Women who have experienced a low-trauma fracture (especially of the vertebra or hip) also are candidates for treatment, even in the absence of osteoporosis on a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) report.

Related article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Updated recommendations from the ACP

The 2017 guideline published by the American College of Physicians (ACP), whose target audience is "all clinicians," recommends that, for women who have known osteoporosis, clinicians offer pharmacologic treatment with alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, or denosumab to reduce the risk for hip and vertebral fractures.

In addition, the ACP recommends that clinicians make the decision whether or not to treat osteopenic women 65 years of age or older who are at a high risk for fracture based on a discussion of patient preferences, fracture risk profile, and benefits, harms, and costs of medications. This may seem somewhat contradictory to ACOG's guidance vis-a-vis women younger than 65 years of age.

The ACP further states that given the limited evidence supporting the benefit of treatment, the balance of benefits and harms in treating osteopenic women is most favorable when the risk for fracture is high. Women younger than 65 years with osteopenia and women older than 65 years with mild osteopenia (T-score between -1.0 and -1.5) will benefit less than women who are 65 years of age or older with severe osteopenia (T-score <-2.0).

Risk factors and risk assessment tools

Clinicians can use their own judgment based on risk factors for fracture (lower body weight, smoking, weight loss, family history of fractures, decreased physical activity, alcohol or caffeine use, low calcium and vitamin D intake, corticosteroid use), or they can use a risk assessment tool. Several risk assessment tools, such as the FRAX calculator mentioned earlier, are available to predict fracture risk among untreated people with low bone density. Although the FRAX calculator is widely used, there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrating a benefit of fracture reduction when FRAX scores are used in treatment decision making.

Duration of therapy. The ACP recommends that clinicians treat osteoporotic women with pharmacologic therapy for 5 years. Bone density monitoring is not recommended during the 5-year treatment period for osteoporosis in women; current evidence does not show any benefit for bone density monitoring during treatment.

Moderate-quality evidence demonstrated that women treated with antiresorptive therapies (including bisphosphonates, raloxifene, and teriparatide) benefited from reduced fractures, even if no increase in BMD occurred or if BMD decreased.

As before, all women with osteoporosis or a previous low-trauma fracture should be treated. Use of the FRAX calculator should involve clinician judgment, and other risk factors should be taken into account. For most women, treatment should be continued for 5 years. There is no benefit in continued bone mass assessment (DXA testing) while a patient is on pharmacologic therapy.

Read about fracture risk after stopping HT

Another WHI update: No increase in fractures after stopping HT

Watts NB, Cauley JA, Jackson RD, et al; Women's Health Initiative Investigators. No increase in fractures after stopping hormone therapy: results from the Women's Health Initiative. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(1):302-308.

The analysis and reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial data seems never-ending, yet the article by Watts and colleagues is important. Although the WHI hormone therapy (HT) trials showed that treatment protects against hip and total fractures, a later observational report suggested loss of benefit and rebound increased risk after HT was discontinued.3 The purpose of the Watts' study was to examine fractures after stopping HT.

Related article:

Did long-term follow-up of WHI participants reveal any mortality increase among women who received HT?

Details of the study

Two placebo-controlled randomized trials served as the study setting. The study included WHI participants (n = 15,187) who continued to take active HT or placebo through the intervention period and who did not take HT in the postintervention period. The trial interventions included conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for women with natural menopause and CEE alone for women with prior hysterectomy. The investigators recorded total fractures and hip fractures through 5 years after HT discontinuation.

Findings on fractures. Hip fractures occurred infrequently, with approximately 2.5 per 1,000 person-years. This finding was similar between trials and in former HT users and placebo groups.

No difference was found in total fractures in the CEE plus MPA trial for former HT users compared with former placebo users (28.9 per 1,000 person-years and 29.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively; hazard ratio [HR], 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-1.09; P = .63). In the CEE-alone trial, however, total fractures were higher in former placebo users (36.9 per 1,000 person-years) compared with the former active-treatment group (31.1 per 1,000 person-years). This finding suggests a residual benefit of CEE in reducing total fractures (HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73-0.98; P = .03).

Investigators' takeaway. The authors concluded that, after discontinuing HT, there was no evidence of increased fracture risk (sustained or transient) in former HT users compared with former placebo users. In the CEE-alone trial, there was a residual benefit for total fracture reduction in former HT users compared with placebo users.

Gynecologists have long believed that on stopping HT, the loss of bone mass will follow at the same rate as it would at natural menopause. These WHI trials demonstrate, however, that through 5 years, women who stopped HT had no increase in hip or total fractures, and hysterectomized women who stopped estrogen therapy actually had fewer fractures than the placebo group. Keep in mind that this large cohort was not chosen based on risk of osteoporotic fractures. In fact, baseline bone mass was not even measured in these women, making the results even more "real world."

Read about reassessing FRAX scores

A new look at fracture risk assessment scores

Gourlay ML, Overman RA, Fine JP, et al; Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Time to clinically relevant fracture risk scores in postmenopausal women. Am J Med. 2017;130:862.e15-e23.

Jiang X, Gruner M, Trémollieres F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of FRAX in predicting the 10-year risk of osteoporotic fractures using the USA treatment thresholds: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone. 2017;99:20-25.

The FRAX score has become a popular form of triage for women who do not yet meet the bone mass criteria of osteoporosis. Current practice guidelines recommend use of fracture risk scores for screening and pharmacologic therapeutic decision making. Some newer data, however, may give rise to questions about its utility, especially in younger women.

Fracture risk analysis in a large postmenopausal population

Gourlay and colleagues conducted a retrospective competing risk analysis of new occurrence of treatment-level and screening-level fracture risk scores. Study participants were postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older who had not previously received pharmacologic treatment and had not had a first hip or clinical vertebral facture.

Details of the study

In 54,280 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 64 years who did not have a bone mineral density test, the time for 10% to develop a treatment-level FRAX score could not be estimated accurately because the incidence of treatment-level scores was rare.

A total of 6,096 women had FRAX scores calculated with bone mineral density testing. In this group, the estimated unadjusted time to treatment-level FRAX scores was 7.6 years (95% CI, 6.6-8.7) for those aged 65 to 69, and 5.1 years (95% CI, 3.5-7.5) for women aged 75 to 79 at baseline.