User login

Prospective algorithm favors vaginal hysterectomy

based on data from a prospective study of 365 patients.

“Total vaginal hysterectomy is the most cost-effective route, with a low complication rate, and, therefore, should be performed when feasible,” wrote Jennifer J. Schmitt, DO, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues.

However, algorithms to support the decision to choose vaginal hysterectomy are not widely used, they said.

To assess the optimal surgical route for hysterectomy, the researchers devised a prospective algorithm and decision tree based on history of laparotomy, uterine size, and vaginal access. The results of their study were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study population included 365 women aged 18 years and older who underwent hysterectomies between Nov. 24, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2017, at a single center. A total of 202 patients (55%) met criteria for a total vaginal hysterectomy using the algorithm, and 57 (15.6%) were assigned to have an examination under anesthesia followed by total vaginal hysterectomy, for a total of 259 expected vaginal hysterectomies. Ultimately, 211 (81.5%) of the patients identified as being the best candidates for having a vaginal hysterectomy underwent the procedure. Almost all of the procedures – 99.1% – were completed successfully.

The algorithm predicted that 52 patients were expected to have an examination under anesthesia followed by a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy and 54 were expected to have an abdominal, robotic, or laparoscopic hysterectomy. A total of 46 procedures (44 robotic, when vaginal was expected and 2 abdominal, when vaginal was expected) deviated to a more invasive route than prescribed by the algorithm, and 7 procedures deviated from the algorithm-predicted robotic or abdominal procedure to total vaginal hysterectomy.

Approximately 95% of the patients were discharged within 24 hours of surgery. These patients included 7 who had vaginal surgery when a more invasive method was predicted and did not experience intraoperative complications or Accordion grade 3 complications.

“Prospective algorithm use predicts that 55.3% of all hysterectomies were expected to have an a priori total vaginal hysterectomy, which is higher than the actual total vaginal hysterectomy rate of 11.5% reported previously,” the researchers noted, and they added that vaginal hysterectomy would be associated with cost savings of $657,524 if the total hysterectomy rate was 55% instead of 11%.

The study findings were limited by several factors including an expertise bias at the center where the study was conducted, as well as the small number of patients with algorithm deviations or poor outcomes, and the lack of a control group, the researchers noted. However, the results support the use of the algorithm “in combination with educating gynecologic surgeons about the feasibility of vaginal surgery,” they said.

“Prospective use of this algorithm nationally may increase the rate of total vaginal hysterectomy and decrease health care delivery costs,” they concluded.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continues to recommend vaginal hysterectomy as the approach of choice whenever feasible, and although clinical evidence and societal endorsements support vaginal hysterectomy as a superior high-value modality, the rate of vaginal hysterectomy in the United States has continued to decline,” Arnold P. Advincula, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Many variables beyond clinical will determine the optimal hysterectomy route, Dr. Advincula said.

“Although historical evidence demonstrates that vaginal hysterectomy is associated with better outcomes when compared with other approaches, a multitude of studies now exist that challenge this notion. Given the financial implications and overall costs of care with surgical complications and 30-day readmissions, experienced high-volume surgeons using all available routes have shown robotics to be the best surgical approach in terms of fewer postoperative complications and lowest 30-day readmission rates,” he noted. However, “one should not split hairs and subtly pit one minimally invasive option against another, but instead should work toward the goal of minimizing laparotomy, which is still performed at a high rate,” Dr. Advincula emphasized.

The study was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. Dr. Schmitt had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Advincula disclosed serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Baxter, ConMed, Eximis Surgical, Intuitive Surgical, and Titan Medical, and performing consultancy work and receiving royalties from Cooper Surgical.

SOURCES: Schmitt JJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:761-9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003725; Advincula A. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:759-60. doi: doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003814.

based on data from a prospective study of 365 patients.

“Total vaginal hysterectomy is the most cost-effective route, with a low complication rate, and, therefore, should be performed when feasible,” wrote Jennifer J. Schmitt, DO, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues.

However, algorithms to support the decision to choose vaginal hysterectomy are not widely used, they said.

To assess the optimal surgical route for hysterectomy, the researchers devised a prospective algorithm and decision tree based on history of laparotomy, uterine size, and vaginal access. The results of their study were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study population included 365 women aged 18 years and older who underwent hysterectomies between Nov. 24, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2017, at a single center. A total of 202 patients (55%) met criteria for a total vaginal hysterectomy using the algorithm, and 57 (15.6%) were assigned to have an examination under anesthesia followed by total vaginal hysterectomy, for a total of 259 expected vaginal hysterectomies. Ultimately, 211 (81.5%) of the patients identified as being the best candidates for having a vaginal hysterectomy underwent the procedure. Almost all of the procedures – 99.1% – were completed successfully.

The algorithm predicted that 52 patients were expected to have an examination under anesthesia followed by a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy and 54 were expected to have an abdominal, robotic, or laparoscopic hysterectomy. A total of 46 procedures (44 robotic, when vaginal was expected and 2 abdominal, when vaginal was expected) deviated to a more invasive route than prescribed by the algorithm, and 7 procedures deviated from the algorithm-predicted robotic or abdominal procedure to total vaginal hysterectomy.

Approximately 95% of the patients were discharged within 24 hours of surgery. These patients included 7 who had vaginal surgery when a more invasive method was predicted and did not experience intraoperative complications or Accordion grade 3 complications.

“Prospective algorithm use predicts that 55.3% of all hysterectomies were expected to have an a priori total vaginal hysterectomy, which is higher than the actual total vaginal hysterectomy rate of 11.5% reported previously,” the researchers noted, and they added that vaginal hysterectomy would be associated with cost savings of $657,524 if the total hysterectomy rate was 55% instead of 11%.

The study findings were limited by several factors including an expertise bias at the center where the study was conducted, as well as the small number of patients with algorithm deviations or poor outcomes, and the lack of a control group, the researchers noted. However, the results support the use of the algorithm “in combination with educating gynecologic surgeons about the feasibility of vaginal surgery,” they said.

“Prospective use of this algorithm nationally may increase the rate of total vaginal hysterectomy and decrease health care delivery costs,” they concluded.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continues to recommend vaginal hysterectomy as the approach of choice whenever feasible, and although clinical evidence and societal endorsements support vaginal hysterectomy as a superior high-value modality, the rate of vaginal hysterectomy in the United States has continued to decline,” Arnold P. Advincula, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Many variables beyond clinical will determine the optimal hysterectomy route, Dr. Advincula said.

“Although historical evidence demonstrates that vaginal hysterectomy is associated with better outcomes when compared with other approaches, a multitude of studies now exist that challenge this notion. Given the financial implications and overall costs of care with surgical complications and 30-day readmissions, experienced high-volume surgeons using all available routes have shown robotics to be the best surgical approach in terms of fewer postoperative complications and lowest 30-day readmission rates,” he noted. However, “one should not split hairs and subtly pit one minimally invasive option against another, but instead should work toward the goal of minimizing laparotomy, which is still performed at a high rate,” Dr. Advincula emphasized.

The study was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. Dr. Schmitt had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Advincula disclosed serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Baxter, ConMed, Eximis Surgical, Intuitive Surgical, and Titan Medical, and performing consultancy work and receiving royalties from Cooper Surgical.

SOURCES: Schmitt JJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:761-9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003725; Advincula A. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:759-60. doi: doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003814.

based on data from a prospective study of 365 patients.

“Total vaginal hysterectomy is the most cost-effective route, with a low complication rate, and, therefore, should be performed when feasible,” wrote Jennifer J. Schmitt, DO, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues.

However, algorithms to support the decision to choose vaginal hysterectomy are not widely used, they said.

To assess the optimal surgical route for hysterectomy, the researchers devised a prospective algorithm and decision tree based on history of laparotomy, uterine size, and vaginal access. The results of their study were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study population included 365 women aged 18 years and older who underwent hysterectomies between Nov. 24, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2017, at a single center. A total of 202 patients (55%) met criteria for a total vaginal hysterectomy using the algorithm, and 57 (15.6%) were assigned to have an examination under anesthesia followed by total vaginal hysterectomy, for a total of 259 expected vaginal hysterectomies. Ultimately, 211 (81.5%) of the patients identified as being the best candidates for having a vaginal hysterectomy underwent the procedure. Almost all of the procedures – 99.1% – were completed successfully.

The algorithm predicted that 52 patients were expected to have an examination under anesthesia followed by a robot-assisted total laparoscopic hysterectomy and 54 were expected to have an abdominal, robotic, or laparoscopic hysterectomy. A total of 46 procedures (44 robotic, when vaginal was expected and 2 abdominal, when vaginal was expected) deviated to a more invasive route than prescribed by the algorithm, and 7 procedures deviated from the algorithm-predicted robotic or abdominal procedure to total vaginal hysterectomy.

Approximately 95% of the patients were discharged within 24 hours of surgery. These patients included 7 who had vaginal surgery when a more invasive method was predicted and did not experience intraoperative complications or Accordion grade 3 complications.

“Prospective algorithm use predicts that 55.3% of all hysterectomies were expected to have an a priori total vaginal hysterectomy, which is higher than the actual total vaginal hysterectomy rate of 11.5% reported previously,” the researchers noted, and they added that vaginal hysterectomy would be associated with cost savings of $657,524 if the total hysterectomy rate was 55% instead of 11%.

The study findings were limited by several factors including an expertise bias at the center where the study was conducted, as well as the small number of patients with algorithm deviations or poor outcomes, and the lack of a control group, the researchers noted. However, the results support the use of the algorithm “in combination with educating gynecologic surgeons about the feasibility of vaginal surgery,” they said.

“Prospective use of this algorithm nationally may increase the rate of total vaginal hysterectomy and decrease health care delivery costs,” they concluded.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists continues to recommend vaginal hysterectomy as the approach of choice whenever feasible, and although clinical evidence and societal endorsements support vaginal hysterectomy as a superior high-value modality, the rate of vaginal hysterectomy in the United States has continued to decline,” Arnold P. Advincula, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Many variables beyond clinical will determine the optimal hysterectomy route, Dr. Advincula said.

“Although historical evidence demonstrates that vaginal hysterectomy is associated with better outcomes when compared with other approaches, a multitude of studies now exist that challenge this notion. Given the financial implications and overall costs of care with surgical complications and 30-day readmissions, experienced high-volume surgeons using all available routes have shown robotics to be the best surgical approach in terms of fewer postoperative complications and lowest 30-day readmission rates,” he noted. However, “one should not split hairs and subtly pit one minimally invasive option against another, but instead should work toward the goal of minimizing laparotomy, which is still performed at a high rate,” Dr. Advincula emphasized.

The study was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science. Dr. Schmitt had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Advincula disclosed serving as a consultant for AbbVie, Baxter, ConMed, Eximis Surgical, Intuitive Surgical, and Titan Medical, and performing consultancy work and receiving royalties from Cooper Surgical.

SOURCES: Schmitt JJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:761-9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003725; Advincula A. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:759-60. doi: doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003814.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Resident experience with hysterectomy is on the decline

The total number of hysterectomies performed during residency training has declined significantly since 2008, despite an increase in laparoscopic hysterectomies performed, according to a new analysis of data from graduating ob.gyn. residents that has implications for the structure of resident education.

The investigators abstracted case log data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) database to assess trends in residents’ operative experience and found decreases in abdominal and vaginal cases but an increase in experience with laparoscopic hysterectomy.

(from 85 cases to 37), and the median number of vaginal hysterectomies decreased by 36% (from 31 to 20 cases).

Laparoscopic hysterectomy increased by 115% from a median of 20 procedures in 2008-2009 to 43 in 2017-2018. Even so, the median total number of hysterectomies per resident decreased by 6%, from 112 to 105 procedures during those two time periods. (Data on total hysterectomy and laparoscopic hysterectomy were not collected by ACGME until 2008.)

While the absolute decrease in the total number of hysterectomies is “relatively small,” the trend “raises questions about what the appropriate number of hysterectomies per graduating resident should be,” Gregory M. Gressel, MD, MSc, of the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“These data point,” they wrote, “to the necessity of maximizing surgical exposure in the face of a declining availability of procedures and the importance of reflecting on which (and how many) procedures an obstetrics and gynecology resident needs to complete before entering clinical practice.”

The training numbers parallel an increased use of laparoscopic hysterectomy in the United States and other countries, as well as a well-documented decline in the total number of hysterectomies performed in the United States, the latter of which is driven largely by the availability and increasing use of alternatives to the procedure (such as hormone therapy, endometrial ablation, and uterine artery embolization).

Hysterectomy still is a “core procedure of gynecologic surgery,” however, and is “at the heart of surgical training in obstetrics and gynecology,” as surgical techniques developed from learning hysterectomy “are applied broadly in the pelvis,” Saketh R. Guntupalli, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Guntupalli, of the University of Colorado at Aurora, Denver, was involved in a survey of fellowship program directors, published in 2015, that found only 20% of first-year fellows were able to independently perform a vaginal hysterectomy and 46% to independently perform an abdominal hysterectomy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:559-68).

This and other research suggest that fellowship training is “used to address deficiencies in residency training rather than to develop new, specialized surgical skills,” he wrote. Given a dearth of fellowship positions in ob.gyn., “it is impossible to adequately use those avenues to train the number of competent surgeons necessary to address the surgical needs of women’s health in the United States.”

To address such concerns, some residency programs have instituted resident tracking to direct more hysterectomy cases toward those residents who plan to pursue surgical subspecialties. The Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Guntupalli noted, has tried the latter approach “with success.”

An increase in the number of accredited training programs and a decrease in the number of residents per program also might help to improve surgical exposure for residents, Dr. Gressel and associates wrote. Over the 16-year study period, the number of graduating residents increased significantly (by 12 per year) and the number of residency programs decreased significantly (0.52 fewer programs per year).

Additionally, Dr. Guntupalli wrote, regulatory bodies may need to reevaluate how competencies are assessed, and whether minimal numbers of cases “continue to carry the same weight as they did in previous generations.”

In the study, one coauthor is a full-time employee of ACGME, and another receives funds as a director for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The remaining authors had no relevant financial disclosures. There was no outside funding for the study. Dr. Guntupalli said he had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Gressel GM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):268-73; Guntupalli SR. Obstet Gynecol 2020 Feb;135(2):266-7.

This excellent paper by Dr. Gressel and coauthors shows decreasing numbers of hysterectomies – especially open and vaginal approaches – being performed by ob.gyn. residents. Considering also the 2015 publication by Guntupalli et al. showing the low numbers of incoming fellows able to perform hysterectomy, as well as Dr. Guntupalli’s editorial on this new research, we all must question how our patients will be able to undergo safe and effective surgery in the future.

Furthermore, it would truly be disheartening and disconcerting for a young physician to choose a residency with the desire of a specific track, only to lose that choice to a coresident.

In his presidential address to the AAGL some years ago, Javier Magrina, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, discussed separating the “O from the G” (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21[4]:501-3). Among his points: From 1979 to 2006, there was a 46% decrease in the number of gynecologic operations (2,852,000 vs. 1,309,000), a 54% increase in the number of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ fellows (21,364 vs. 51,123), and an 81% decrease in the number of gynecologic operations performed per ACOG fellow (132 vs. 25).

In 1980, he pointed out, the total number of hysterectomy procedures performed in the United States was 647,000. In 2007, this total was 517,000. The total number of ACOG fellows in 1980 was 22,516, compared with 52,385 in 2007. And the total number of hysterectomies performed per ACOG fellow was 28, compared with 9.8 hysterectomies per fellow in 2007.

Dr. Magrina’s data goes hand in hand with Dr. Gressel’s new study. The surgical experience of the gynecologic surgeon certainly is on the wane. The result of this lack of experience is noted by Dr. Guntupalli in his 2015 publication. To us, it is readily apparent that Dr. Magrina is right: The only true solution is to finally realize that we must separate the O from the G.

Charles E. Miller, MD, is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, and director of the AAGL fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is associate director of the AAGL fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran. They have no other conflicts of interest.

This excellent paper by Dr. Gressel and coauthors shows decreasing numbers of hysterectomies – especially open and vaginal approaches – being performed by ob.gyn. residents. Considering also the 2015 publication by Guntupalli et al. showing the low numbers of incoming fellows able to perform hysterectomy, as well as Dr. Guntupalli’s editorial on this new research, we all must question how our patients will be able to undergo safe and effective surgery in the future.

Furthermore, it would truly be disheartening and disconcerting for a young physician to choose a residency with the desire of a specific track, only to lose that choice to a coresident.

In his presidential address to the AAGL some years ago, Javier Magrina, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, discussed separating the “O from the G” (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21[4]:501-3). Among his points: From 1979 to 2006, there was a 46% decrease in the number of gynecologic operations (2,852,000 vs. 1,309,000), a 54% increase in the number of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ fellows (21,364 vs. 51,123), and an 81% decrease in the number of gynecologic operations performed per ACOG fellow (132 vs. 25).

In 1980, he pointed out, the total number of hysterectomy procedures performed in the United States was 647,000. In 2007, this total was 517,000. The total number of ACOG fellows in 1980 was 22,516, compared with 52,385 in 2007. And the total number of hysterectomies performed per ACOG fellow was 28, compared with 9.8 hysterectomies per fellow in 2007.

Dr. Magrina’s data goes hand in hand with Dr. Gressel’s new study. The surgical experience of the gynecologic surgeon certainly is on the wane. The result of this lack of experience is noted by Dr. Guntupalli in his 2015 publication. To us, it is readily apparent that Dr. Magrina is right: The only true solution is to finally realize that we must separate the O from the G.

Charles E. Miller, MD, is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, and director of the AAGL fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is associate director of the AAGL fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran. They have no other conflicts of interest.

This excellent paper by Dr. Gressel and coauthors shows decreasing numbers of hysterectomies – especially open and vaginal approaches – being performed by ob.gyn. residents. Considering also the 2015 publication by Guntupalli et al. showing the low numbers of incoming fellows able to perform hysterectomy, as well as Dr. Guntupalli’s editorial on this new research, we all must question how our patients will be able to undergo safe and effective surgery in the future.

Furthermore, it would truly be disheartening and disconcerting for a young physician to choose a residency with the desire of a specific track, only to lose that choice to a coresident.

In his presidential address to the AAGL some years ago, Javier Magrina, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, discussed separating the “O from the G” (J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21[4]:501-3). Among his points: From 1979 to 2006, there was a 46% decrease in the number of gynecologic operations (2,852,000 vs. 1,309,000), a 54% increase in the number of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ fellows (21,364 vs. 51,123), and an 81% decrease in the number of gynecologic operations performed per ACOG fellow (132 vs. 25).

In 1980, he pointed out, the total number of hysterectomy procedures performed in the United States was 647,000. In 2007, this total was 517,000. The total number of ACOG fellows in 1980 was 22,516, compared with 52,385 in 2007. And the total number of hysterectomies performed per ACOG fellow was 28, compared with 9.8 hysterectomies per fellow in 2007.

Dr. Magrina’s data goes hand in hand with Dr. Gressel’s new study. The surgical experience of the gynecologic surgeon certainly is on the wane. The result of this lack of experience is noted by Dr. Guntupalli in his 2015 publication. To us, it is readily apparent that Dr. Magrina is right: The only true solution is to finally realize that we must separate the O from the G.

Charles E. Miller, MD, is director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, and director of the AAGL fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. Kirsten Sasaki, MD, is associate director of the AAGL fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran. They have no other conflicts of interest.

The total number of hysterectomies performed during residency training has declined significantly since 2008, despite an increase in laparoscopic hysterectomies performed, according to a new analysis of data from graduating ob.gyn. residents that has implications for the structure of resident education.

The investigators abstracted case log data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) database to assess trends in residents’ operative experience and found decreases in abdominal and vaginal cases but an increase in experience with laparoscopic hysterectomy.

(from 85 cases to 37), and the median number of vaginal hysterectomies decreased by 36% (from 31 to 20 cases).

Laparoscopic hysterectomy increased by 115% from a median of 20 procedures in 2008-2009 to 43 in 2017-2018. Even so, the median total number of hysterectomies per resident decreased by 6%, from 112 to 105 procedures during those two time periods. (Data on total hysterectomy and laparoscopic hysterectomy were not collected by ACGME until 2008.)

While the absolute decrease in the total number of hysterectomies is “relatively small,” the trend “raises questions about what the appropriate number of hysterectomies per graduating resident should be,” Gregory M. Gressel, MD, MSc, of the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“These data point,” they wrote, “to the necessity of maximizing surgical exposure in the face of a declining availability of procedures and the importance of reflecting on which (and how many) procedures an obstetrics and gynecology resident needs to complete before entering clinical practice.”

The training numbers parallel an increased use of laparoscopic hysterectomy in the United States and other countries, as well as a well-documented decline in the total number of hysterectomies performed in the United States, the latter of which is driven largely by the availability and increasing use of alternatives to the procedure (such as hormone therapy, endometrial ablation, and uterine artery embolization).

Hysterectomy still is a “core procedure of gynecologic surgery,” however, and is “at the heart of surgical training in obstetrics and gynecology,” as surgical techniques developed from learning hysterectomy “are applied broadly in the pelvis,” Saketh R. Guntupalli, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Guntupalli, of the University of Colorado at Aurora, Denver, was involved in a survey of fellowship program directors, published in 2015, that found only 20% of first-year fellows were able to independently perform a vaginal hysterectomy and 46% to independently perform an abdominal hysterectomy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:559-68).

This and other research suggest that fellowship training is “used to address deficiencies in residency training rather than to develop new, specialized surgical skills,” he wrote. Given a dearth of fellowship positions in ob.gyn., “it is impossible to adequately use those avenues to train the number of competent surgeons necessary to address the surgical needs of women’s health in the United States.”

To address such concerns, some residency programs have instituted resident tracking to direct more hysterectomy cases toward those residents who plan to pursue surgical subspecialties. The Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Guntupalli noted, has tried the latter approach “with success.”

An increase in the number of accredited training programs and a decrease in the number of residents per program also might help to improve surgical exposure for residents, Dr. Gressel and associates wrote. Over the 16-year study period, the number of graduating residents increased significantly (by 12 per year) and the number of residency programs decreased significantly (0.52 fewer programs per year).

Additionally, Dr. Guntupalli wrote, regulatory bodies may need to reevaluate how competencies are assessed, and whether minimal numbers of cases “continue to carry the same weight as they did in previous generations.”

In the study, one coauthor is a full-time employee of ACGME, and another receives funds as a director for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The remaining authors had no relevant financial disclosures. There was no outside funding for the study. Dr. Guntupalli said he had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Gressel GM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):268-73; Guntupalli SR. Obstet Gynecol 2020 Feb;135(2):266-7.

The total number of hysterectomies performed during residency training has declined significantly since 2008, despite an increase in laparoscopic hysterectomies performed, according to a new analysis of data from graduating ob.gyn. residents that has implications for the structure of resident education.

The investigators abstracted case log data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) database to assess trends in residents’ operative experience and found decreases in abdominal and vaginal cases but an increase in experience with laparoscopic hysterectomy.

(from 85 cases to 37), and the median number of vaginal hysterectomies decreased by 36% (from 31 to 20 cases).

Laparoscopic hysterectomy increased by 115% from a median of 20 procedures in 2008-2009 to 43 in 2017-2018. Even so, the median total number of hysterectomies per resident decreased by 6%, from 112 to 105 procedures during those two time periods. (Data on total hysterectomy and laparoscopic hysterectomy were not collected by ACGME until 2008.)

While the absolute decrease in the total number of hysterectomies is “relatively small,” the trend “raises questions about what the appropriate number of hysterectomies per graduating resident should be,” Gregory M. Gressel, MD, MSc, of the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, and coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“These data point,” they wrote, “to the necessity of maximizing surgical exposure in the face of a declining availability of procedures and the importance of reflecting on which (and how many) procedures an obstetrics and gynecology resident needs to complete before entering clinical practice.”

The training numbers parallel an increased use of laparoscopic hysterectomy in the United States and other countries, as well as a well-documented decline in the total number of hysterectomies performed in the United States, the latter of which is driven largely by the availability and increasing use of alternatives to the procedure (such as hormone therapy, endometrial ablation, and uterine artery embolization).

Hysterectomy still is a “core procedure of gynecologic surgery,” however, and is “at the heart of surgical training in obstetrics and gynecology,” as surgical techniques developed from learning hysterectomy “are applied broadly in the pelvis,” Saketh R. Guntupalli, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Guntupalli, of the University of Colorado at Aurora, Denver, was involved in a survey of fellowship program directors, published in 2015, that found only 20% of first-year fellows were able to independently perform a vaginal hysterectomy and 46% to independently perform an abdominal hysterectomy (Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:559-68).

This and other research suggest that fellowship training is “used to address deficiencies in residency training rather than to develop new, specialized surgical skills,” he wrote. Given a dearth of fellowship positions in ob.gyn., “it is impossible to adequately use those avenues to train the number of competent surgeons necessary to address the surgical needs of women’s health in the United States.”

To address such concerns, some residency programs have instituted resident tracking to direct more hysterectomy cases toward those residents who plan to pursue surgical subspecialties. The Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Guntupalli noted, has tried the latter approach “with success.”

An increase in the number of accredited training programs and a decrease in the number of residents per program also might help to improve surgical exposure for residents, Dr. Gressel and associates wrote. Over the 16-year study period, the number of graduating residents increased significantly (by 12 per year) and the number of residency programs decreased significantly (0.52 fewer programs per year).

Additionally, Dr. Guntupalli wrote, regulatory bodies may need to reevaluate how competencies are assessed, and whether minimal numbers of cases “continue to carry the same weight as they did in previous generations.”

In the study, one coauthor is a full-time employee of ACGME, and another receives funds as a director for the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The remaining authors had no relevant financial disclosures. There was no outside funding for the study. Dr. Guntupalli said he had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Gressel GM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Feb;135(2):268-73; Guntupalli SR. Obstet Gynecol 2020 Feb;135(2):266-7.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

In hysterectomy, consider wider risks of ovary removal

LAS VEGAS – While it’s fading in popularity, ovary removal in hysterectomy is still far from uncommon. A gynecologic surgeon urged colleagues to give deeper consideration to whether the ovaries can stay in place.

“Gynecologists should truly familiarize themselves with the data on cardiovascular, endocrine, bone, and sexual health implications of removing the ovaries when there isn’t a medical indication to do so,” Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, director of the Kelly gynecologic oncology service and the director of the center for rare gynecologic cancers at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, said in an interview following her presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

“Until I started giving this talk, I thought I knew this data. However, once I took a deeper dive into the studies of how hormonally active the postmenopausal ovaries are, as well as the population-based studies demonstrating worse all-cause mortality outcomes in low-risk women who have their ovaries surgically removed prior to their 60s, I was stunned at how compelling this data is,” she said.

The conventional wisdom about ovary removal in hysterectomy has changed dramatically over the decades. As Dr. Nickles Fader explained in the interview, “in the ’80s and early ’90s, the mantra was ‘just take everything out’ at hysterectomy surgery – tubes and ovaries should be removed – without understanding the implications. Then in the late ’90s and early 2000s, it was a more selective strategy of ‘wait until menopause to remove the ovaries.’ ”

Now, “more contemporary data suggests that the ovaries appear to be hormonally active to some degree well into the seventh decade of life, and even women in their early 60s who have their ovaries removed without a medical indication may be harmed.”

Still, ovary removal occurs in about 50%-60% of the 450,000-500,000 hysterectomies performed each year in the United States, Dr. Nickles Fader said at the meeting, which was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

These findings seem to suggest that messages about the potential benefits of ovary preservation are not getting through to surgeons and patients.

Indeed, a 2017 study of 57,776 benign premenopausal hysterectomies with ovary removal in California from 2005 to 2011 found that 38% had no documented sign of an appropriate diagnosis signaling a need for oophorectomy. These included “ovarian cyst, breast cancer susceptibility gene carrier status, and other diagnoses,” the study authors wrote (Menopause. 2017 Aug;24[8]:947-53).

Dr. Nickles Fader emphasized that ovary removal is appropriate in cases of gynecologic malignancy, while patients at high genetic risk of ovarian cancer may consider salpingo-oophorectomy or salpingectomy.

What about other situations? She offered these pearls in the presentation:

- Don’t remove ovaries before age 60 “without a good reason” because the procedure may lower lifespan and increase cardiovascular risk.

- Ovary removal is linked to cognitive decline, Parkinson’s disease, depression and anxiety, glaucoma, sexual dysfunction, and bone fractures.

- Ovary preservation, in contrast, is linked to improvement of menopausal symptoms, sleep quality, urogenital atrophy, skin conditions, and metabolism.

- Fallopian tubes may be the true trouble area. “The prevailing theory amongst scientists and clinicians is that ‘ovarian cancer’ is in most cases a misnomer, and most of these malignancies start in the fallopian tube,” Dr. Nickles Fader said in the interview.

“It’s a better time than ever to be thoughtful about removing a woman’s ovaries in someone who is at low risk for ovarian cancer. The new, universal guideline is that to best optimize cancer risk reduction and general health outcomes.”

Dr. Nickles Fader disclosed consulting work for Ethicon and Merck.

LAS VEGAS – While it’s fading in popularity, ovary removal in hysterectomy is still far from uncommon. A gynecologic surgeon urged colleagues to give deeper consideration to whether the ovaries can stay in place.

“Gynecologists should truly familiarize themselves with the data on cardiovascular, endocrine, bone, and sexual health implications of removing the ovaries when there isn’t a medical indication to do so,” Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, director of the Kelly gynecologic oncology service and the director of the center for rare gynecologic cancers at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, said in an interview following her presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

“Until I started giving this talk, I thought I knew this data. However, once I took a deeper dive into the studies of how hormonally active the postmenopausal ovaries are, as well as the population-based studies demonstrating worse all-cause mortality outcomes in low-risk women who have their ovaries surgically removed prior to their 60s, I was stunned at how compelling this data is,” she said.

The conventional wisdom about ovary removal in hysterectomy has changed dramatically over the decades. As Dr. Nickles Fader explained in the interview, “in the ’80s and early ’90s, the mantra was ‘just take everything out’ at hysterectomy surgery – tubes and ovaries should be removed – without understanding the implications. Then in the late ’90s and early 2000s, it was a more selective strategy of ‘wait until menopause to remove the ovaries.’ ”

Now, “more contemporary data suggests that the ovaries appear to be hormonally active to some degree well into the seventh decade of life, and even women in their early 60s who have their ovaries removed without a medical indication may be harmed.”

Still, ovary removal occurs in about 50%-60% of the 450,000-500,000 hysterectomies performed each year in the United States, Dr. Nickles Fader said at the meeting, which was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

These findings seem to suggest that messages about the potential benefits of ovary preservation are not getting through to surgeons and patients.

Indeed, a 2017 study of 57,776 benign premenopausal hysterectomies with ovary removal in California from 2005 to 2011 found that 38% had no documented sign of an appropriate diagnosis signaling a need for oophorectomy. These included “ovarian cyst, breast cancer susceptibility gene carrier status, and other diagnoses,” the study authors wrote (Menopause. 2017 Aug;24[8]:947-53).

Dr. Nickles Fader emphasized that ovary removal is appropriate in cases of gynecologic malignancy, while patients at high genetic risk of ovarian cancer may consider salpingo-oophorectomy or salpingectomy.

What about other situations? She offered these pearls in the presentation:

- Don’t remove ovaries before age 60 “without a good reason” because the procedure may lower lifespan and increase cardiovascular risk.

- Ovary removal is linked to cognitive decline, Parkinson’s disease, depression and anxiety, glaucoma, sexual dysfunction, and bone fractures.

- Ovary preservation, in contrast, is linked to improvement of menopausal symptoms, sleep quality, urogenital atrophy, skin conditions, and metabolism.

- Fallopian tubes may be the true trouble area. “The prevailing theory amongst scientists and clinicians is that ‘ovarian cancer’ is in most cases a misnomer, and most of these malignancies start in the fallopian tube,” Dr. Nickles Fader said in the interview.

“It’s a better time than ever to be thoughtful about removing a woman’s ovaries in someone who is at low risk for ovarian cancer. The new, universal guideline is that to best optimize cancer risk reduction and general health outcomes.”

Dr. Nickles Fader disclosed consulting work for Ethicon and Merck.

LAS VEGAS – While it’s fading in popularity, ovary removal in hysterectomy is still far from uncommon. A gynecologic surgeon urged colleagues to give deeper consideration to whether the ovaries can stay in place.

“Gynecologists should truly familiarize themselves with the data on cardiovascular, endocrine, bone, and sexual health implications of removing the ovaries when there isn’t a medical indication to do so,” Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, director of the Kelly gynecologic oncology service and the director of the center for rare gynecologic cancers at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, said in an interview following her presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

“Until I started giving this talk, I thought I knew this data. However, once I took a deeper dive into the studies of how hormonally active the postmenopausal ovaries are, as well as the population-based studies demonstrating worse all-cause mortality outcomes in low-risk women who have their ovaries surgically removed prior to their 60s, I was stunned at how compelling this data is,” she said.

The conventional wisdom about ovary removal in hysterectomy has changed dramatically over the decades. As Dr. Nickles Fader explained in the interview, “in the ’80s and early ’90s, the mantra was ‘just take everything out’ at hysterectomy surgery – tubes and ovaries should be removed – without understanding the implications. Then in the late ’90s and early 2000s, it was a more selective strategy of ‘wait until menopause to remove the ovaries.’ ”

Now, “more contemporary data suggests that the ovaries appear to be hormonally active to some degree well into the seventh decade of life, and even women in their early 60s who have their ovaries removed without a medical indication may be harmed.”

Still, ovary removal occurs in about 50%-60% of the 450,000-500,000 hysterectomies performed each year in the United States, Dr. Nickles Fader said at the meeting, which was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

These findings seem to suggest that messages about the potential benefits of ovary preservation are not getting through to surgeons and patients.

Indeed, a 2017 study of 57,776 benign premenopausal hysterectomies with ovary removal in California from 2005 to 2011 found that 38% had no documented sign of an appropriate diagnosis signaling a need for oophorectomy. These included “ovarian cyst, breast cancer susceptibility gene carrier status, and other diagnoses,” the study authors wrote (Menopause. 2017 Aug;24[8]:947-53).

Dr. Nickles Fader emphasized that ovary removal is appropriate in cases of gynecologic malignancy, while patients at high genetic risk of ovarian cancer may consider salpingo-oophorectomy or salpingectomy.

What about other situations? She offered these pearls in the presentation:

- Don’t remove ovaries before age 60 “without a good reason” because the procedure may lower lifespan and increase cardiovascular risk.

- Ovary removal is linked to cognitive decline, Parkinson’s disease, depression and anxiety, glaucoma, sexual dysfunction, and bone fractures.

- Ovary preservation, in contrast, is linked to improvement of menopausal symptoms, sleep quality, urogenital atrophy, skin conditions, and metabolism.

- Fallopian tubes may be the true trouble area. “The prevailing theory amongst scientists and clinicians is that ‘ovarian cancer’ is in most cases a misnomer, and most of these malignancies start in the fallopian tube,” Dr. Nickles Fader said in the interview.

“It’s a better time than ever to be thoughtful about removing a woman’s ovaries in someone who is at low risk for ovarian cancer. The new, universal guideline is that to best optimize cancer risk reduction and general health outcomes.”

Dr. Nickles Fader disclosed consulting work for Ethicon and Merck.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAGS 2019

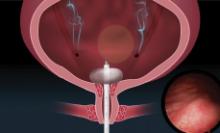

The removal of the multiple-kilogram uterus using MIGSs

It has now been 30 years since the first total laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed. The benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS) – and of minimally invasive hysterectomy specifically – are now well documented. Since this milestone procedure, both instrumentation and technique have improved significantly.

This includes traditional laparoscopy, as well as the robotically assisted laparoscopic approach. However, certain patient characteristics also may influence the choice. A uterus that is undescended, combined with a narrow introitus, for instance, can be a contributory factor in choosing to perform laparoscopic hysterectomy. Additionally, so can an extremely large uterus and an extremely high body mass index (BMI).

These latter two factors – a very large uterus (which we define as more than 15-16 weeks’ gestational size) and a BMI over 60 kg/m2 – historically were considered to be contraindications to laparoscopic hysterectomy. But as the proficiency, comfort, and skill of a new generation of laparoscopic surgeons increases, the tide is shifting with respect to both morbid obesity and the very large uterus.

With growing experience and improved instrumentation, the majority of gynecologists who are fellowship-trained in MIGS are able to routinely and safely perform laparoscopic hysterectomy for uteri weighing 1-2 kg and in patients who have extreme morbid obesity. The literature, moreover, increasingly features case reports of laparoscopic removal of very large uteri and reviews/discussions of total laparoscopic hysterectomy being feasible.

In our own experience, total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus can be safely and advantageously performed using key instruments and refinements in technique, as well as thorough patient counseling regarding the risk of unexpected sarcomas. Recently, we safely performed total laparoscopic hysterectomy for a patient with a uterus that – somewhat unexpectedly – weighed 7.4 kg.

Surgical pearls

Performing safe and effective total laparoscopic hysterectomy for large uteri – and for morbidly obese patients – hinges largely on modifications in entry and port placement, patient positioning, and choice of instrumentation. With these modifications, we can achieve adequate visualization of critical anatomy and can minimize bleeding. Otherwise, the surgery itself is largely the same. Here are the principles we find most helpful.

Entry and port placement

Traditionally, for TLHs, a camera port is placed at the umbilicus to provide a full view of the pelvis. For the larger uterus – and in women who are extremely obese – we aim to introduce the laparoscope higher. A reliable landmark is the Palmer’s point in the left upper quadrant. From here, we can identify areas for the placement of additional trocars.

In general, we place ancillary 5-mm ports more cephalad and lateral to the uterus than we otherwise would. Such placement facilitates effective visualization while accommodating manipulation of the uterus and allows us to avoid bleeding around the vascular upper pedicles. Overall, we have much better control through all parts of the surgery when we operate lateral to the uterus.

Patient positioning

In addition to the Trendelenburg position, we have adopted an “airplaning” technique for patients with a very large uterus in which the bed is tilted from side to side so that the left and right sides of the body are rotated upward as needed. This allows for gravitational-assisted retraction when it otherwise is not possible.

Instrumentation

For morbidly obese patients, we use Kii Fios advanced fixation trocars. These come in 5- and 10-mm sizes and are equipped with an intraperitoneal balloon that can be inflated to prevent sliding of the trocar out of the abdominal wall.

By far the most valuable instrument for the morbidly obese and the very large uterus is a 30-degree laparoscope. With our higher port placement as described, the 30-degree scope provides visualization of critical structures that wouldn’t be possible with a 0-degree scope.

The Rumi uterine manipulator comes with cups that come in different sizes and can fit around the cervix and help delineate the cervicouterine junction. We use this manipulator for all laparoscopic hysterectomies, but it is a must for the very large uterus.

Extensive desiccation of the utero-ovarian pedicles and uterine arteries is critical, and for this we advise using the rotating bipolar RoBi instrument. Use of the conventional bipolar instrument allows us to use targeted and anatomically guided application of energy. This ensures certainty that vessels whose limits exceed the diameter for advanced bipolar devices (typically 7 mm) are completely sealed. In-depth knowledge of pelvic anatomy and advanced laparoscopic dissection is paramount during these steps to ensure that vital structures are not damaged by the wider thermal spread of the traditional bipolar device. For cutting, the use of ultrasonic energy is important to prevent energy from spreading laterally.

Lastly, we recommend a good suction irrigator because, if bleeding occurs, it tends to be heavy because of the enlarged nature of feeding vasculature. When placed through an umbilical or suprapubic port, the suction irrigator also may be used to help with the rotational vectors and traction for further uterine manipulation.

Technique

We usually operate from top to bottom, transecting the upper pedicles such as the infundibulopelvic (IP) ligaments or utero-ovarian ligaments first, rather than the round ligaments. This helps us achieve additional mobility of the uterus. Some surgeons believe that retroperitoneal dissection and ligation of the uterine arteries at their origin is essential, but we find that, with good uterine manipulation and the use of a 30-degree scope, we achieve adequate visualization for identifying the ureter and uterine artery on the sidewall and consequently do not need to dissect retroperitoneally.

When using the uterine manipulator with the colpotomy cup, the uterus is pushed upward, increasing the distance between the vaginal fornix and the ureters. Uterine arteries can easily be identified and desiccated using conventional bipolar energy. When the colpotomy cup is pushed cephalad, the application of the bipolar energy within the limits of the cup is safe. The thermal spread does not pose a threat to the ureters, which are displaced 1.5-2 cm laterally. Large fibroids often contribute to distorted anatomical planes, and a colpotomy cup provides a firm palpable surface between the cervix and vagina during dissection.

When dealing with large uteri, one must sometimes think outside the box and deviate from standard technique. For instance, in patients with distorted anatomy because of large fibroids, it helps to first control the pedicles that are most easily accessible. Sometimes it is acceptable to perform oophorectomy if the IP ligament is more accessible and the utero-ovarian pedicle is distorted by dilated veins and adherent to the uterus. After transection of each pedicle, we gain more mobility of the uterus and better visualization for the next step.

Inserting the camera through ancillary ports – a technique known as “port hopping” – helps to visualize and take down adhesions much better and more safely than using the camera from the umbilical port only. Port hopping with a 30-degree laparoscope helps to obtain a 360-degree view of adhesions and anatomy, which is exceedingly helpful in cases in which crucial anatomical structures are within close proximity of one another.

In general it is more challenging to perform TLH on a patient with a broad uterus or a patient with low posterior fibroids that are occupying the pelvis than on a patient with fibroids in the upper abdomen. The main challenge for the surgeon is to safely secure the uterine arteries and control the blood supply to the uterus.

Access to the pelvic sidewall is obtained with the combination of 30-degree scope, uterine manipulator, and the suction irrigator introduced through the midline port; the cervix and uterus are deviated upward. Instead of the suction irrigator or blunt dissector used for internal uterine manipulation, some surgeons use myoma screws or a 5-mm single-tooth tenaculum to manipulate a large uterus. Both of those instruments are valuable and work well, but often a large uterus requires extensive manipulation. Repositioning of any sharp instruments that pierce the serosa can often lead to additional blood loss. It is preferable to avoid this blood loss on a large uterus at all costs because it can be brisk and stains the surgical pedicles, making the remainder of the procedure unnecessarily difficult.

Once the uterine arteries are desiccated, if fibroids are obscuring the view, the corpus of the uterus can be detached from the cervix as in supracervical hysterectomy fashion. From there, the uterus can be placed in the upper abdomen while colpotomy can be performed.

In patients with multiple fibroids, we do not recommend performing myomectomy first, unless the fibroid is pedunculated and on a very small stalk. Improved uterine manipulation and retroperitoneal dissection are preferred over myomectomy to safely complete hysterectomy for the broad uterus. In our opinion, any attempt at myomectomy would lead to unnecessary blood loss and additional operative time with minimal benefit.

In patients with fibroids that grow into the broad ligament and pelvic sidewall, the natural course of the ureter becomes displaced laterally. This is contrary to the popular misconception that the ureter is more medially located in the setting of broad-ligament fibroids. To ensure safe access to the uterine arteries, the vesicouterine peritoneum can be incised and extended cephalad along the broad ligament and, then, using the above-mentioned technique, by pushing the uterus and the fibroid to the contralateral side via the suction irrigator, the uterine arteries can be easily accessed.

Another useful technique is to use diluted vasopressin injected into the lower pole of the uterus to cause vasoconstriction and minimize the bleeding. The concentration is 1 cc of 20 units of vasopressin in 100-400 cc of saline. This technique is very useful for myomectomies, and some surgeons find it also helpful for hysterectomy. The plasma half-life of vasopressin is 10-20 minutes, and a large quantity is needed to help with vasoconstriction in a big uterus. The safe upper limits of vasopressin dosing are not firmly established. A fibroid uterus with aberrant vasculature may require a greater-than-acceptable dose to control bleeding.

It is important to ensure that patients have an optimized hemoglobin level preoperatively. We use a hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL as a lowest cutoff value for performing TLH without preoperative transfusion. Regarding bowel preparation, neither the literature nor our own experience support its value, so we typically do not use it.

Morcellation and patient counseling

Uteri up to 12 weeks’ gestational size usually can be extracted transvaginally, and most uteri regardless of size can be morcellated and extracted through the vagina, providing that the vaginal fornix is accessible from below. In some cases, such as when the apex is too high, a minilaparotomic incision is needed to extract the uterus, or when available, power morcellation can be performed.

A major challenge, given our growing ability to laparoscopically remove very larger uteri, is that uteri heavier than about 2.5 kg in weight cannot be morcellated inside a morcellation bag. The risk of upstaging a known or suspected uterine malignancy, or of spreading an unknown malignant sarcoma (presumed benign myoma), should be incorporated in each patient’s decision making.

Thorough counseling about surgical options and on the risks of morcellating a very large uterus without containment in a bag is essential. Each patient must understand the risks and decide whether the benefits of minimally invasive surgery outweigh these risks. While MRI can sometimes provide increased suspicion of a leiomyosarcoma, malignancy can never be completed excluded preoperatively.

Removal of a 7.4-kg uterus

Our patient was a 44-year-old with a markedly enlarged fibroid uterus. Having been told by other providers that she was not a candidate for minimally invasive hysterectomy, she had delayed surgical management for a number of years, allowing for such a generous uterine size to develop.

The patient was knowledgeable about her condition and, given her comorbid obesity, she requested a minimally invasive approach. Preoperative imaging included an ultrasound, which had to be completed abdominally because of the size of her uterus, and an additional MRI was needed to further characterize the extent and nature of her uterus. A very detailed discussion regarding risk of leiomyosarcoma, operative complications, and conversion to laparotomy ensued.

Intraoperatively, we placed the first 5 mm port in the left upper quadrant initially to survey the anatomy for feasibility of laparoscopic hysterectomy. The left utero-ovarian pedicle was easily viewed by airplaning the bed alone. While the right utero-ovarian pedicle was much more skewed and enlarged, the right IP was easily accessible and the ureter well visualized.

The decision was made to place additional ports and proceed with laparoscopic hysterectomy. The 5-mm assistant ports were placed lateral and directly above the upper vascular pedicles. Operative time was 4 hours and 12 minutes, and blood loss was only 700 cc. Her preoperative hemoglobin was optimized at 13.3 g/dL and dropped to 11.3 g/dL postoperatively. The patient was discharged home the next morning and had a normal recovery with no complications.

Dr. Pasic is professor of obstetrics, gynecology & women’s health; director of the section of advanced gynecologic endoscopy; and codirector of the AAGL fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of Louisville (Ky.). Dr. Pasic is the current president of the International Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is also a past president of the AAGL (2009). Dr. Cesta is Dr. Pasic’s current fellow in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery as well as an instructor in obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Louisville. Dr. Pasic disclosed he is a consultant for Ethicon Endo, Medtronic, and Olympus and is a speaker for Cooper Surgical, which manufactures some of the instruments mentioned in this article. Dr. Cesta had no relevant financial disclosures.

It has now been 30 years since the first total laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed. The benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS) – and of minimally invasive hysterectomy specifically – are now well documented. Since this milestone procedure, both instrumentation and technique have improved significantly.

This includes traditional laparoscopy, as well as the robotically assisted laparoscopic approach. However, certain patient characteristics also may influence the choice. A uterus that is undescended, combined with a narrow introitus, for instance, can be a contributory factor in choosing to perform laparoscopic hysterectomy. Additionally, so can an extremely large uterus and an extremely high body mass index (BMI).

These latter two factors – a very large uterus (which we define as more than 15-16 weeks’ gestational size) and a BMI over 60 kg/m2 – historically were considered to be contraindications to laparoscopic hysterectomy. But as the proficiency, comfort, and skill of a new generation of laparoscopic surgeons increases, the tide is shifting with respect to both morbid obesity and the very large uterus.

With growing experience and improved instrumentation, the majority of gynecologists who are fellowship-trained in MIGS are able to routinely and safely perform laparoscopic hysterectomy for uteri weighing 1-2 kg and in patients who have extreme morbid obesity. The literature, moreover, increasingly features case reports of laparoscopic removal of very large uteri and reviews/discussions of total laparoscopic hysterectomy being feasible.

In our own experience, total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus can be safely and advantageously performed using key instruments and refinements in technique, as well as thorough patient counseling regarding the risk of unexpected sarcomas. Recently, we safely performed total laparoscopic hysterectomy for a patient with a uterus that – somewhat unexpectedly – weighed 7.4 kg.

Surgical pearls

Performing safe and effective total laparoscopic hysterectomy for large uteri – and for morbidly obese patients – hinges largely on modifications in entry and port placement, patient positioning, and choice of instrumentation. With these modifications, we can achieve adequate visualization of critical anatomy and can minimize bleeding. Otherwise, the surgery itself is largely the same. Here are the principles we find most helpful.

Entry and port placement

Traditionally, for TLHs, a camera port is placed at the umbilicus to provide a full view of the pelvis. For the larger uterus – and in women who are extremely obese – we aim to introduce the laparoscope higher. A reliable landmark is the Palmer’s point in the left upper quadrant. From here, we can identify areas for the placement of additional trocars.

In general, we place ancillary 5-mm ports more cephalad and lateral to the uterus than we otherwise would. Such placement facilitates effective visualization while accommodating manipulation of the uterus and allows us to avoid bleeding around the vascular upper pedicles. Overall, we have much better control through all parts of the surgery when we operate lateral to the uterus.

Patient positioning

In addition to the Trendelenburg position, we have adopted an “airplaning” technique for patients with a very large uterus in which the bed is tilted from side to side so that the left and right sides of the body are rotated upward as needed. This allows for gravitational-assisted retraction when it otherwise is not possible.

Instrumentation

For morbidly obese patients, we use Kii Fios advanced fixation trocars. These come in 5- and 10-mm sizes and are equipped with an intraperitoneal balloon that can be inflated to prevent sliding of the trocar out of the abdominal wall.

By far the most valuable instrument for the morbidly obese and the very large uterus is a 30-degree laparoscope. With our higher port placement as described, the 30-degree scope provides visualization of critical structures that wouldn’t be possible with a 0-degree scope.

The Rumi uterine manipulator comes with cups that come in different sizes and can fit around the cervix and help delineate the cervicouterine junction. We use this manipulator for all laparoscopic hysterectomies, but it is a must for the very large uterus.

Extensive desiccation of the utero-ovarian pedicles and uterine arteries is critical, and for this we advise using the rotating bipolar RoBi instrument. Use of the conventional bipolar instrument allows us to use targeted and anatomically guided application of energy. This ensures certainty that vessels whose limits exceed the diameter for advanced bipolar devices (typically 7 mm) are completely sealed. In-depth knowledge of pelvic anatomy and advanced laparoscopic dissection is paramount during these steps to ensure that vital structures are not damaged by the wider thermal spread of the traditional bipolar device. For cutting, the use of ultrasonic energy is important to prevent energy from spreading laterally.

Lastly, we recommend a good suction irrigator because, if bleeding occurs, it tends to be heavy because of the enlarged nature of feeding vasculature. When placed through an umbilical or suprapubic port, the suction irrigator also may be used to help with the rotational vectors and traction for further uterine manipulation.

Technique

We usually operate from top to bottom, transecting the upper pedicles such as the infundibulopelvic (IP) ligaments or utero-ovarian ligaments first, rather than the round ligaments. This helps us achieve additional mobility of the uterus. Some surgeons believe that retroperitoneal dissection and ligation of the uterine arteries at their origin is essential, but we find that, with good uterine manipulation and the use of a 30-degree scope, we achieve adequate visualization for identifying the ureter and uterine artery on the sidewall and consequently do not need to dissect retroperitoneally.

When using the uterine manipulator with the colpotomy cup, the uterus is pushed upward, increasing the distance between the vaginal fornix and the ureters. Uterine arteries can easily be identified and desiccated using conventional bipolar energy. When the colpotomy cup is pushed cephalad, the application of the bipolar energy within the limits of the cup is safe. The thermal spread does not pose a threat to the ureters, which are displaced 1.5-2 cm laterally. Large fibroids often contribute to distorted anatomical planes, and a colpotomy cup provides a firm palpable surface between the cervix and vagina during dissection.

When dealing with large uteri, one must sometimes think outside the box and deviate from standard technique. For instance, in patients with distorted anatomy because of large fibroids, it helps to first control the pedicles that are most easily accessible. Sometimes it is acceptable to perform oophorectomy if the IP ligament is more accessible and the utero-ovarian pedicle is distorted by dilated veins and adherent to the uterus. After transection of each pedicle, we gain more mobility of the uterus and better visualization for the next step.

Inserting the camera through ancillary ports – a technique known as “port hopping” – helps to visualize and take down adhesions much better and more safely than using the camera from the umbilical port only. Port hopping with a 30-degree laparoscope helps to obtain a 360-degree view of adhesions and anatomy, which is exceedingly helpful in cases in which crucial anatomical structures are within close proximity of one another.

In general it is more challenging to perform TLH on a patient with a broad uterus or a patient with low posterior fibroids that are occupying the pelvis than on a patient with fibroids in the upper abdomen. The main challenge for the surgeon is to safely secure the uterine arteries and control the blood supply to the uterus.

Access to the pelvic sidewall is obtained with the combination of 30-degree scope, uterine manipulator, and the suction irrigator introduced through the midline port; the cervix and uterus are deviated upward. Instead of the suction irrigator or blunt dissector used for internal uterine manipulation, some surgeons use myoma screws or a 5-mm single-tooth tenaculum to manipulate a large uterus. Both of those instruments are valuable and work well, but often a large uterus requires extensive manipulation. Repositioning of any sharp instruments that pierce the serosa can often lead to additional blood loss. It is preferable to avoid this blood loss on a large uterus at all costs because it can be brisk and stains the surgical pedicles, making the remainder of the procedure unnecessarily difficult.

Once the uterine arteries are desiccated, if fibroids are obscuring the view, the corpus of the uterus can be detached from the cervix as in supracervical hysterectomy fashion. From there, the uterus can be placed in the upper abdomen while colpotomy can be performed.

In patients with multiple fibroids, we do not recommend performing myomectomy first, unless the fibroid is pedunculated and on a very small stalk. Improved uterine manipulation and retroperitoneal dissection are preferred over myomectomy to safely complete hysterectomy for the broad uterus. In our opinion, any attempt at myomectomy would lead to unnecessary blood loss and additional operative time with minimal benefit.

In patients with fibroids that grow into the broad ligament and pelvic sidewall, the natural course of the ureter becomes displaced laterally. This is contrary to the popular misconception that the ureter is more medially located in the setting of broad-ligament fibroids. To ensure safe access to the uterine arteries, the vesicouterine peritoneum can be incised and extended cephalad along the broad ligament and, then, using the above-mentioned technique, by pushing the uterus and the fibroid to the contralateral side via the suction irrigator, the uterine arteries can be easily accessed.

Another useful technique is to use diluted vasopressin injected into the lower pole of the uterus to cause vasoconstriction and minimize the bleeding. The concentration is 1 cc of 20 units of vasopressin in 100-400 cc of saline. This technique is very useful for myomectomies, and some surgeons find it also helpful for hysterectomy. The plasma half-life of vasopressin is 10-20 minutes, and a large quantity is needed to help with vasoconstriction in a big uterus. The safe upper limits of vasopressin dosing are not firmly established. A fibroid uterus with aberrant vasculature may require a greater-than-acceptable dose to control bleeding.

It is important to ensure that patients have an optimized hemoglobin level preoperatively. We use a hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL as a lowest cutoff value for performing TLH without preoperative transfusion. Regarding bowel preparation, neither the literature nor our own experience support its value, so we typically do not use it.

Morcellation and patient counseling

Uteri up to 12 weeks’ gestational size usually can be extracted transvaginally, and most uteri regardless of size can be morcellated and extracted through the vagina, providing that the vaginal fornix is accessible from below. In some cases, such as when the apex is too high, a minilaparotomic incision is needed to extract the uterus, or when available, power morcellation can be performed.

A major challenge, given our growing ability to laparoscopically remove very larger uteri, is that uteri heavier than about 2.5 kg in weight cannot be morcellated inside a morcellation bag. The risk of upstaging a known or suspected uterine malignancy, or of spreading an unknown malignant sarcoma (presumed benign myoma), should be incorporated in each patient’s decision making.

Thorough counseling about surgical options and on the risks of morcellating a very large uterus without containment in a bag is essential. Each patient must understand the risks and decide whether the benefits of minimally invasive surgery outweigh these risks. While MRI can sometimes provide increased suspicion of a leiomyosarcoma, malignancy can never be completed excluded preoperatively.

Removal of a 7.4-kg uterus

Our patient was a 44-year-old with a markedly enlarged fibroid uterus. Having been told by other providers that she was not a candidate for minimally invasive hysterectomy, she had delayed surgical management for a number of years, allowing for such a generous uterine size to develop.

The patient was knowledgeable about her condition and, given her comorbid obesity, she requested a minimally invasive approach. Preoperative imaging included an ultrasound, which had to be completed abdominally because of the size of her uterus, and an additional MRI was needed to further characterize the extent and nature of her uterus. A very detailed discussion regarding risk of leiomyosarcoma, operative complications, and conversion to laparotomy ensued.

Intraoperatively, we placed the first 5 mm port in the left upper quadrant initially to survey the anatomy for feasibility of laparoscopic hysterectomy. The left utero-ovarian pedicle was easily viewed by airplaning the bed alone. While the right utero-ovarian pedicle was much more skewed and enlarged, the right IP was easily accessible and the ureter well visualized.

The decision was made to place additional ports and proceed with laparoscopic hysterectomy. The 5-mm assistant ports were placed lateral and directly above the upper vascular pedicles. Operative time was 4 hours and 12 minutes, and blood loss was only 700 cc. Her preoperative hemoglobin was optimized at 13.3 g/dL and dropped to 11.3 g/dL postoperatively. The patient was discharged home the next morning and had a normal recovery with no complications.

Dr. Pasic is professor of obstetrics, gynecology & women’s health; director of the section of advanced gynecologic endoscopy; and codirector of the AAGL fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of Louisville (Ky.). Dr. Pasic is the current president of the International Society of Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is also a past president of the AAGL (2009). Dr. Cesta is Dr. Pasic’s current fellow in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery as well as an instructor in obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Louisville. Dr. Pasic disclosed he is a consultant for Ethicon Endo, Medtronic, and Olympus and is a speaker for Cooper Surgical, which manufactures some of the instruments mentioned in this article. Dr. Cesta had no relevant financial disclosures.

It has now been 30 years since the first total laparoscopic hysterectomy was performed. The benefits of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS) – and of minimally invasive hysterectomy specifically – are now well documented. Since this milestone procedure, both instrumentation and technique have improved significantly.

This includes traditional laparoscopy, as well as the robotically assisted laparoscopic approach. However, certain patient characteristics also may influence the choice. A uterus that is undescended, combined with a narrow introitus, for instance, can be a contributory factor in choosing to perform laparoscopic hysterectomy. Additionally, so can an extremely large uterus and an extremely high body mass index (BMI).

These latter two factors – a very large uterus (which we define as more than 15-16 weeks’ gestational size) and a BMI over 60 kg/m2 – historically were considered to be contraindications to laparoscopic hysterectomy. But as the proficiency, comfort, and skill of a new generation of laparoscopic surgeons increases, the tide is shifting with respect to both morbid obesity and the very large uterus.

With growing experience and improved instrumentation, the majority of gynecologists who are fellowship-trained in MIGS are able to routinely and safely perform laparoscopic hysterectomy for uteri weighing 1-2 kg and in patients who have extreme morbid obesity. The literature, moreover, increasingly features case reports of laparoscopic removal of very large uteri and reviews/discussions of total laparoscopic hysterectomy being feasible.

In our own experience, total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) of the very large uterus can be safely and advantageously performed using key instruments and refinements in technique, as well as thorough patient counseling regarding the risk of unexpected sarcomas. Recently, we safely performed total laparoscopic hysterectomy for a patient with a uterus that – somewhat unexpectedly – weighed 7.4 kg.

Surgical pearls