User login

States judged on smoking cessation services

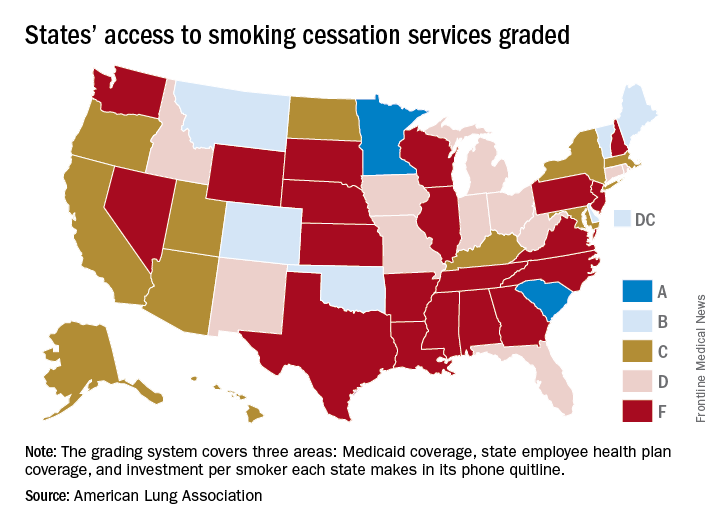

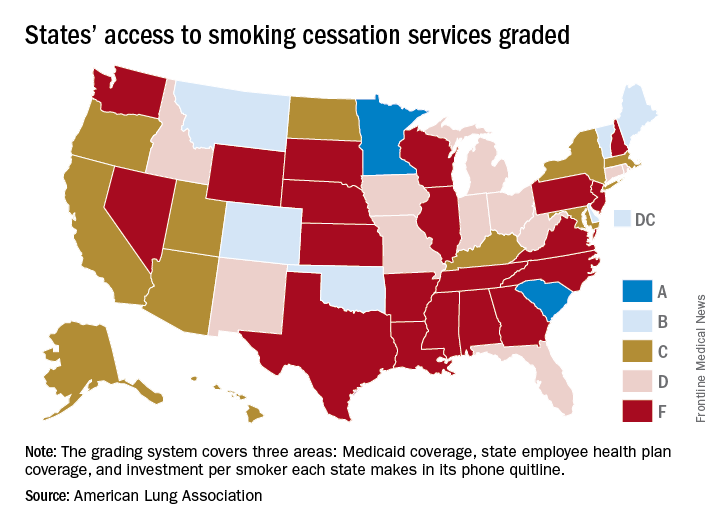

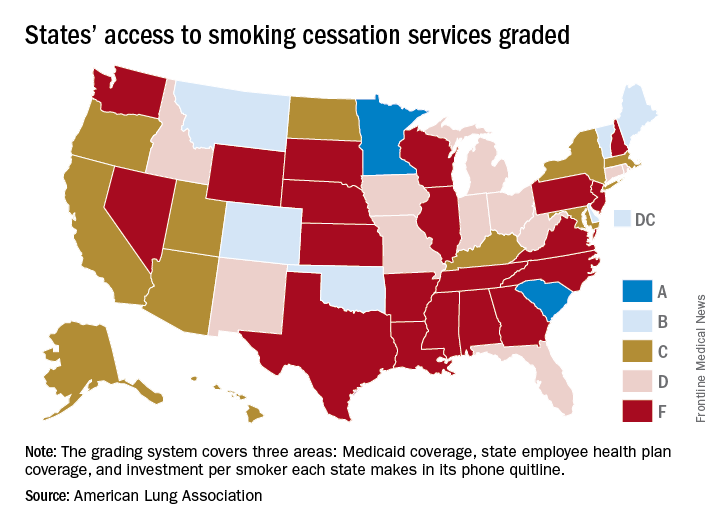

Minnesota and South Carolina are at the top of the class for access to shows that the treatment coverage in most states earned barely passable or failing grades.

In fact, 31 states received either a D (11 states) or an F (20 states) on the grading system. There were also 11 C’s and 7 B’s to go along with the two A’s, the ALA said in “State of Tobacco Control 2018.”

Minnesota received 66 points and South Carolina earned 63 after a 5-point deduction for not expanding Medicaid up to Affordable Care Act standards. The highest-finishing states with B’s were Vermont with 62 points and Maine with 61, and the lowest total score was the 23 points earned by Virginia and Washington, although Washington’s grade did not include the state employee category since the state did not provide data on its plan, the ALA noted.

The Department of Health & Human Services recommends that tobacco cessation coverage include the use of five nicotine-replacement therapies (gum, patch, lozenge, nasal spray, inhaler), bupropion and varenicline (nonnicotine medications), and three types of counseling (individual, group, and phone), the report said.

“It’s imperative that all state Medicaid programs cover a comprehensive tobacco cessation benefit, with no barriers, to help smokers quit, including all seven [Food and Drug Administration]–approved medications and three forms of counseling for Medicaid enrollees. In 2017, only Kentucky, Missouri, and South Carolina provided this coverage,” wrote Harold P. Wimmer, national president and CEO of the ALA.

Minnesota and South Carolina are at the top of the class for access to shows that the treatment coverage in most states earned barely passable or failing grades.

In fact, 31 states received either a D (11 states) or an F (20 states) on the grading system. There were also 11 C’s and 7 B’s to go along with the two A’s, the ALA said in “State of Tobacco Control 2018.”

Minnesota received 66 points and South Carolina earned 63 after a 5-point deduction for not expanding Medicaid up to Affordable Care Act standards. The highest-finishing states with B’s were Vermont with 62 points and Maine with 61, and the lowest total score was the 23 points earned by Virginia and Washington, although Washington’s grade did not include the state employee category since the state did not provide data on its plan, the ALA noted.

The Department of Health & Human Services recommends that tobacco cessation coverage include the use of five nicotine-replacement therapies (gum, patch, lozenge, nasal spray, inhaler), bupropion and varenicline (nonnicotine medications), and three types of counseling (individual, group, and phone), the report said.

“It’s imperative that all state Medicaid programs cover a comprehensive tobacco cessation benefit, with no barriers, to help smokers quit, including all seven [Food and Drug Administration]–approved medications and three forms of counseling for Medicaid enrollees. In 2017, only Kentucky, Missouri, and South Carolina provided this coverage,” wrote Harold P. Wimmer, national president and CEO of the ALA.

Minnesota and South Carolina are at the top of the class for access to shows that the treatment coverage in most states earned barely passable or failing grades.

In fact, 31 states received either a D (11 states) or an F (20 states) on the grading system. There were also 11 C’s and 7 B’s to go along with the two A’s, the ALA said in “State of Tobacco Control 2018.”

Minnesota received 66 points and South Carolina earned 63 after a 5-point deduction for not expanding Medicaid up to Affordable Care Act standards. The highest-finishing states with B’s were Vermont with 62 points and Maine with 61, and the lowest total score was the 23 points earned by Virginia and Washington, although Washington’s grade did not include the state employee category since the state did not provide data on its plan, the ALA noted.

The Department of Health & Human Services recommends that tobacco cessation coverage include the use of five nicotine-replacement therapies (gum, patch, lozenge, nasal spray, inhaler), bupropion and varenicline (nonnicotine medications), and three types of counseling (individual, group, and phone), the report said.

“It’s imperative that all state Medicaid programs cover a comprehensive tobacco cessation benefit, with no barriers, to help smokers quit, including all seven [Food and Drug Administration]–approved medications and three forms of counseling for Medicaid enrollees. In 2017, only Kentucky, Missouri, and South Carolina provided this coverage,” wrote Harold P. Wimmer, national president and CEO of the ALA.

Pembrolizumab plus SBRT shows promise for advanced solid tumors

SAN FRANCISCO – Pembrolizumab immunotherapy with multi-site stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) appears to be a safe and effective treatment in patients with advanced solid tumors, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

Of 79 patients with metastatic solid tumors who progressed on standard treatment and who were enrolled in the study, 68 underwent multi-site SBRT, received at least one cycle of pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and had imaging follow-up. The overall objective response rate in those 68 patients was 13.2%, Jeffrey Lemons, MD, reported at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

When responses in the non-irradiated lesions (out-of-field responses) were measured based on a 30% reduction in any single lesion, the rate was 26.9%. But when defined by a 30% reduction in aggregate diameter of the non-irradiated measurable lesions, the rate was 13.5%, he said. While both approaches for measuring response are acceptable, Dr. Lemons noted, it’s important to be sure which one is being used in a given study.

Overall, 73 patients received both SBRT and pembrolizumab (5 had no imaging follow-up). They had a mean age of 62 years and a median of five prior therapies. Cancer types included ovarian/fallopian tube cancer (12.3%), non–small cell lung cancer (9.6%), breast cancer (8.2%), cholangiocarcinoma (8.2%), endometrial cancer (8.2%), colorectal cancer (6.8%), head and neck cancer (5.5%), and other tumors, each with less than 5% accrual (41.2%).

The number of sites treated with SBRT was two in 94.5% of patients, three in 4.1%, and four in 1.3%; 151 lesions in total were treated.

The premise for combining pembrolizumab and SBRT is that response to anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD1) therapy seems to correspond with interferon-gamma signaling, and that SBRT can stimulate innate and adaptive immunity to potentially augment immunotherapy, Dr. Lemons explained. In addition, anti-PD1 treatment outcomes are improved with lower disease burden.

Multi-site radiation is an emerging paradigm for eradicating metastatic disease, he said.

Patients included in the study had metastatic solid tumors and had progressed on standard treatment. They had measurable disease by RECIST, and metastases amenable to SBRT with 0.25 cc to 65 cc of viable tumor.

Tumors larger than 65 cc were partially targeted with radiotherapy. Radiation doses were adapted from recently completed and ongoing National Cancer Institute trials and ranged from 30-50 Gy (3-5 fractions) based on anatomic location.

Pembrolizumab was initiated within 7 days of the final SBRT treatment.

Dose-limiting toxicities, all grade 3, occurred in six patients during a median follow-up of 5.5 months, and included pneumonitis in three patients, hepatic failure in one patient, and colitis in two patients, but there were no radiation dose reductions, Dr. Lemons said.

“This is the first and largest prospective trial to determine the safety of this combination,” he explained. “There was some intriguing clinical activity ... and we feel that this justifies further randomized studies

The University of Chicago sponsored the study. Dr. Lemons reported having no disclosures.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Lemons J et al., ASCO-SITC abstract #20.

SAN FRANCISCO – Pembrolizumab immunotherapy with multi-site stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) appears to be a safe and effective treatment in patients with advanced solid tumors, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

Of 79 patients with metastatic solid tumors who progressed on standard treatment and who were enrolled in the study, 68 underwent multi-site SBRT, received at least one cycle of pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and had imaging follow-up. The overall objective response rate in those 68 patients was 13.2%, Jeffrey Lemons, MD, reported at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

When responses in the non-irradiated lesions (out-of-field responses) were measured based on a 30% reduction in any single lesion, the rate was 26.9%. But when defined by a 30% reduction in aggregate diameter of the non-irradiated measurable lesions, the rate was 13.5%, he said. While both approaches for measuring response are acceptable, Dr. Lemons noted, it’s important to be sure which one is being used in a given study.

Overall, 73 patients received both SBRT and pembrolizumab (5 had no imaging follow-up). They had a mean age of 62 years and a median of five prior therapies. Cancer types included ovarian/fallopian tube cancer (12.3%), non–small cell lung cancer (9.6%), breast cancer (8.2%), cholangiocarcinoma (8.2%), endometrial cancer (8.2%), colorectal cancer (6.8%), head and neck cancer (5.5%), and other tumors, each with less than 5% accrual (41.2%).

The number of sites treated with SBRT was two in 94.5% of patients, three in 4.1%, and four in 1.3%; 151 lesions in total were treated.

The premise for combining pembrolizumab and SBRT is that response to anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD1) therapy seems to correspond with interferon-gamma signaling, and that SBRT can stimulate innate and adaptive immunity to potentially augment immunotherapy, Dr. Lemons explained. In addition, anti-PD1 treatment outcomes are improved with lower disease burden.

Multi-site radiation is an emerging paradigm for eradicating metastatic disease, he said.

Patients included in the study had metastatic solid tumors and had progressed on standard treatment. They had measurable disease by RECIST, and metastases amenable to SBRT with 0.25 cc to 65 cc of viable tumor.

Tumors larger than 65 cc were partially targeted with radiotherapy. Radiation doses were adapted from recently completed and ongoing National Cancer Institute trials and ranged from 30-50 Gy (3-5 fractions) based on anatomic location.

Pembrolizumab was initiated within 7 days of the final SBRT treatment.

Dose-limiting toxicities, all grade 3, occurred in six patients during a median follow-up of 5.5 months, and included pneumonitis in three patients, hepatic failure in one patient, and colitis in two patients, but there were no radiation dose reductions, Dr. Lemons said.

“This is the first and largest prospective trial to determine the safety of this combination,” he explained. “There was some intriguing clinical activity ... and we feel that this justifies further randomized studies

The University of Chicago sponsored the study. Dr. Lemons reported having no disclosures.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Lemons J et al., ASCO-SITC abstract #20.

SAN FRANCISCO – Pembrolizumab immunotherapy with multi-site stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) appears to be a safe and effective treatment in patients with advanced solid tumors, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

Of 79 patients with metastatic solid tumors who progressed on standard treatment and who were enrolled in the study, 68 underwent multi-site SBRT, received at least one cycle of pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and had imaging follow-up. The overall objective response rate in those 68 patients was 13.2%, Jeffrey Lemons, MD, reported at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

When responses in the non-irradiated lesions (out-of-field responses) were measured based on a 30% reduction in any single lesion, the rate was 26.9%. But when defined by a 30% reduction in aggregate diameter of the non-irradiated measurable lesions, the rate was 13.5%, he said. While both approaches for measuring response are acceptable, Dr. Lemons noted, it’s important to be sure which one is being used in a given study.

Overall, 73 patients received both SBRT and pembrolizumab (5 had no imaging follow-up). They had a mean age of 62 years and a median of five prior therapies. Cancer types included ovarian/fallopian tube cancer (12.3%), non–small cell lung cancer (9.6%), breast cancer (8.2%), cholangiocarcinoma (8.2%), endometrial cancer (8.2%), colorectal cancer (6.8%), head and neck cancer (5.5%), and other tumors, each with less than 5% accrual (41.2%).

The number of sites treated with SBRT was two in 94.5% of patients, three in 4.1%, and four in 1.3%; 151 lesions in total were treated.

The premise for combining pembrolizumab and SBRT is that response to anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD1) therapy seems to correspond with interferon-gamma signaling, and that SBRT can stimulate innate and adaptive immunity to potentially augment immunotherapy, Dr. Lemons explained. In addition, anti-PD1 treatment outcomes are improved with lower disease burden.

Multi-site radiation is an emerging paradigm for eradicating metastatic disease, he said.

Patients included in the study had metastatic solid tumors and had progressed on standard treatment. They had measurable disease by RECIST, and metastases amenable to SBRT with 0.25 cc to 65 cc of viable tumor.

Tumors larger than 65 cc were partially targeted with radiotherapy. Radiation doses were adapted from recently completed and ongoing National Cancer Institute trials and ranged from 30-50 Gy (3-5 fractions) based on anatomic location.

Pembrolizumab was initiated within 7 days of the final SBRT treatment.

Dose-limiting toxicities, all grade 3, occurred in six patients during a median follow-up of 5.5 months, and included pneumonitis in three patients, hepatic failure in one patient, and colitis in two patients, but there were no radiation dose reductions, Dr. Lemons said.

“This is the first and largest prospective trial to determine the safety of this combination,” he explained. “There was some intriguing clinical activity ... and we feel that this justifies further randomized studies

The University of Chicago sponsored the study. Dr. Lemons reported having no disclosures.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Lemons J et al., ASCO-SITC abstract #20.

REPORTING FROM THE CLINICAL IMMUNO-ONCOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Pembrolizumab plus multi-site SBRT appears safe and effective for advanced solid tumors.

Major finding: The overall objective response rate was 13.2%.

Study details: A phase 1 study of 79 patients.

Disclosures: The University of Chicago sponsored the study. Dr. Lemons reported having no disclosures

Source: Lemons J et al. ASCO-SITC abstract #20.

Analysis of Twitter lung cancer content reveals opportunity for clinicians

Social media communication around lung cancer is focused primarily on cancer treatment and use of pharmaceutical and research interventions, followed closely by awareness, prevention, and risk topics, according to an analysis of Twitter conversation over a 10-day period.

Although awareness and risk prevention tweets were likely to contain cues toward action, “messages focused on treatment, end of life ... were significantly less likely to integrate cues for personal activity,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in Journal of the American College of Radiology.

The investigators collected 1.3 million unique Twitter messages between Sept. 30 and Oct. 9, 2016, that contained at least one of six keywords commonly used to describe cancer: cancer, chemo, tumor, malignant, biopsy, and metastasis. They then drew a random, proportional stratified sample of 3,000 messages (12.5%) for manual coding from the 23,926 messages posted that included keywords related to lung cancer. Tweets were examined by user type (individuals, media, and organizations) to identify content and structural message features.

Message content was most frequently related to treatment (32.1%), followed by awareness (22.9%), end of life (15.5%), prevention and risk information (13.3%), active cancer-unknown phase (7.6%), diagnosis (6.1%), early detection (2.7%), and survivorship (1%), Dr. Sutton and her colleagues reported.

“The large volume of messages containing content about pharmaceuticals suggests that Twitter is also a forum for sharing information and discussing emerging treatments. Importantly, treatment messages were shared primarily by individuals, suggesting that this online user community jointly includes members of the public as well as medical practitioners and companies who have an awareness of emerging treatment approaches, suggesting an opportunity for online engagement between these various groups (e.g., Lung Cancer Social Media #LCSM community and related chats),” the investigators wrote.

The National Science Foundation supported parts of this research. None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sutton J. et al., J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.043

Social media communication around lung cancer is focused primarily on cancer treatment and use of pharmaceutical and research interventions, followed closely by awareness, prevention, and risk topics, according to an analysis of Twitter conversation over a 10-day period.

Although awareness and risk prevention tweets were likely to contain cues toward action, “messages focused on treatment, end of life ... were significantly less likely to integrate cues for personal activity,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in Journal of the American College of Radiology.

The investigators collected 1.3 million unique Twitter messages between Sept. 30 and Oct. 9, 2016, that contained at least one of six keywords commonly used to describe cancer: cancer, chemo, tumor, malignant, biopsy, and metastasis. They then drew a random, proportional stratified sample of 3,000 messages (12.5%) for manual coding from the 23,926 messages posted that included keywords related to lung cancer. Tweets were examined by user type (individuals, media, and organizations) to identify content and structural message features.

Message content was most frequently related to treatment (32.1%), followed by awareness (22.9%), end of life (15.5%), prevention and risk information (13.3%), active cancer-unknown phase (7.6%), diagnosis (6.1%), early detection (2.7%), and survivorship (1%), Dr. Sutton and her colleagues reported.

“The large volume of messages containing content about pharmaceuticals suggests that Twitter is also a forum for sharing information and discussing emerging treatments. Importantly, treatment messages were shared primarily by individuals, suggesting that this online user community jointly includes members of the public as well as medical practitioners and companies who have an awareness of emerging treatment approaches, suggesting an opportunity for online engagement between these various groups (e.g., Lung Cancer Social Media #LCSM community and related chats),” the investigators wrote.

The National Science Foundation supported parts of this research. None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sutton J. et al., J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.043

Social media communication around lung cancer is focused primarily on cancer treatment and use of pharmaceutical and research interventions, followed closely by awareness, prevention, and risk topics, according to an analysis of Twitter conversation over a 10-day period.

Although awareness and risk prevention tweets were likely to contain cues toward action, “messages focused on treatment, end of life ... were significantly less likely to integrate cues for personal activity,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in Journal of the American College of Radiology.

The investigators collected 1.3 million unique Twitter messages between Sept. 30 and Oct. 9, 2016, that contained at least one of six keywords commonly used to describe cancer: cancer, chemo, tumor, malignant, biopsy, and metastasis. They then drew a random, proportional stratified sample of 3,000 messages (12.5%) for manual coding from the 23,926 messages posted that included keywords related to lung cancer. Tweets were examined by user type (individuals, media, and organizations) to identify content and structural message features.

Message content was most frequently related to treatment (32.1%), followed by awareness (22.9%), end of life (15.5%), prevention and risk information (13.3%), active cancer-unknown phase (7.6%), diagnosis (6.1%), early detection (2.7%), and survivorship (1%), Dr. Sutton and her colleagues reported.

“The large volume of messages containing content about pharmaceuticals suggests that Twitter is also a forum for sharing information and discussing emerging treatments. Importantly, treatment messages were shared primarily by individuals, suggesting that this online user community jointly includes members of the public as well as medical practitioners and companies who have an awareness of emerging treatment approaches, suggesting an opportunity for online engagement between these various groups (e.g., Lung Cancer Social Media #LCSM community and related chats),” the investigators wrote.

The National Science Foundation supported parts of this research. None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sutton J. et al., J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.043

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RADIOLOGY

Key clinical point: In a random sample of Twitter conversation related to lung cancer, message content was most frequently related to treatment.

Major finding: Majority of tweets evaluated focused on lung cancer treatment and the use of pharmaceutical and research interventions, followed by awareness, prevention, and risk topics.

Study details: Random sample of 3,000 tweets posted in a 10-day period between Sept. 30 and Oct. 9, 2016. Lung cancer–specific tweets by user type (individuals, media, and organizations) were examined to identify content and structural message features.

Disclosures: The National Science Foundation supported parts of this research. None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

Source: Sutton J. et al., J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.043.

New multi-analyte blood test shows promise in screening for several common solid tumors

Imagine a single blood test that would cost less than $500 and could screen for at least eight cancer types.

It’s early days for the technology, called CancerSEEK, but the test had a sensitivity of 69%-98%, depending on the cancer type, and a specificity of 99% in a cohort of 1,005 patients with stage I-III cancers and 850 healthy controls, wrote Joshua D. Cohen of the Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics and Therapeutics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues. The report was published in Science.

CancerSEEK tests for mutations in 2,001 genomic positions and eight proteins. The researchers examined a 61-amplicon panel with each amplicon analyzing an average of 33 base pairs within a gene. They theorized the test could detect between 41% and 95% of the cancers in the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer dataset. They next used multiplex-PCR techniques to minimize errors associated with large sequencing and identified protein biomarkers for early stage cancers that may not release detectable ctDNA.

The researchers used the technology to examine blood samples from 1,005 patients with stage I (20%), stage II (49%), or stage III (31%) cancers of the ovary, liver, stomach, pancreas, esophagus, colorectum, lung, or breast prior to undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Participants had a median age of 64 years (range of 22-93 years). The healthy controls did not have a history of cancer, chronic kidney disease, autoimmune disease, or high-grade dysplasia.

The sensitivity of the test ranged from 98% in ovarian cancer to 33% in breast cancer, but the specificity was greater than 99% with only 7 of 812 control participants having a positive result. “We could not be certain that the few ‘false positive’ individuals identified among the healthy cohort did not actually have an as-yet undetected cancer, but classifying them as false positives provided the most conservative approach to classification and interpretation of the data,” the authors wrote.

Based on cancer stage, sensitivity for stage I cancers was 43%, for stage II 73%, and for stage III 78%. Again, sensitivity varied depending on cancer type, with 100% sensitivity for stage I liver cancer and 20% sensitivity for stage I esophageal cancer.

When tumor tissue samples from 153 patients with statistically significant ctDNA levels were analyzed, identical mutations were found in the plasma and tumor in 90% (138) of all cases.

The protein markers in the CancerSEEK test might also be able to anatomically locate malignancies. Using machine learning to analyze patients testing positive with CancerSEEK, the results narrowed the source of the cancer to two possible anatomical sites in approximately 83% of patients and to one anatomical site in approximately 63% of patients. Accuracy was highest for colorectal cancer and lowest for lung cancer.

As the study included otherwise healthy patients with known malignancies, the results need to be confirmed with prospective studies of incidence cancer types in a large population. Patients in the screening setting may have less advanced disease and other comorbidities that could impact the sensitivity and specificity of the CancerSEEK test, the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by multiple sources including grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported various disclosures involving diagnostics and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Cohen JD et al., Science 2018 Jan 18. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3247.

Molecular panels are here to stay – and the GI community will in some shape or form be impacted, be it in performing diagnostic procedures on test-positive patients, or risk-stratifying patients prior to testing.

The conceptual challenge is that it is not about what any given test measures – various panels use separate combination of markers from epigenetics to DNA mutations as well as whole or truncated proteins – but how well a specific test with its somewhat arbitrarily chosen components and cutoffs performs. And, more importantly, what the clinical implications of positive or negative test results are. And no one knows that. At least for now.

A recent report in Science from a group from the Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics at Johns Hopkins proposes a new cancer blood test based on a very systematic and thoughtful approach to include select mutations in cell-free DNA and circulating proteins associated with various solid organ tumors. For validation, they used healthy and advanced but nonmetastatic cancer cohorts. Through stringent controls and a series of validations, the authors present a range of sensitivities for the various cancer types with an impressive specificity. This is a technically very strong approach with many nifty and thoughtful additions to give this test a very promising first foray – did anybody watch CNN?

While not ready for prime time, which is a tall order for a first report, the authors dutifully point out the need for a prospective real life cohort validation. In the meantime, regardless of the outcome of this particular test, it is a repeated reminder that we need to stay abreast of the advances and the details of each molecular test, especially with a likely very diverse and distinct group of tests to choose from.

Many of us will be part of interpreting results and determining further management. Just as with hereditary cancer genetic panel testing, our technical ability may have stretched beyond our ability to fully understand the implications. Many questions will arise: What about true false positives? False negatives? Intervals? Can such tests replace other screening? How to choose any given test over the other? Should tests be combined or alternated? The tests will be technically refined and are here to stay – we need to get to work on finding answers to the clinically relevant questions.

Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, is the Thomas J. Layden Endowed Professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago.

Molecular panels are here to stay – and the GI community will in some shape or form be impacted, be it in performing diagnostic procedures on test-positive patients, or risk-stratifying patients prior to testing.

The conceptual challenge is that it is not about what any given test measures – various panels use separate combination of markers from epigenetics to DNA mutations as well as whole or truncated proteins – but how well a specific test with its somewhat arbitrarily chosen components and cutoffs performs. And, more importantly, what the clinical implications of positive or negative test results are. And no one knows that. At least for now.

A recent report in Science from a group from the Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics at Johns Hopkins proposes a new cancer blood test based on a very systematic and thoughtful approach to include select mutations in cell-free DNA and circulating proteins associated with various solid organ tumors. For validation, they used healthy and advanced but nonmetastatic cancer cohorts. Through stringent controls and a series of validations, the authors present a range of sensitivities for the various cancer types with an impressive specificity. This is a technically very strong approach with many nifty and thoughtful additions to give this test a very promising first foray – did anybody watch CNN?

While not ready for prime time, which is a tall order for a first report, the authors dutifully point out the need for a prospective real life cohort validation. In the meantime, regardless of the outcome of this particular test, it is a repeated reminder that we need to stay abreast of the advances and the details of each molecular test, especially with a likely very diverse and distinct group of tests to choose from.

Many of us will be part of interpreting results and determining further management. Just as with hereditary cancer genetic panel testing, our technical ability may have stretched beyond our ability to fully understand the implications. Many questions will arise: What about true false positives? False negatives? Intervals? Can such tests replace other screening? How to choose any given test over the other? Should tests be combined or alternated? The tests will be technically refined and are here to stay – we need to get to work on finding answers to the clinically relevant questions.

Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, is the Thomas J. Layden Endowed Professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago.

Molecular panels are here to stay – and the GI community will in some shape or form be impacted, be it in performing diagnostic procedures on test-positive patients, or risk-stratifying patients prior to testing.

The conceptual challenge is that it is not about what any given test measures – various panels use separate combination of markers from epigenetics to DNA mutations as well as whole or truncated proteins – but how well a specific test with its somewhat arbitrarily chosen components and cutoffs performs. And, more importantly, what the clinical implications of positive or negative test results are. And no one knows that. At least for now.

A recent report in Science from a group from the Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics at Johns Hopkins proposes a new cancer blood test based on a very systematic and thoughtful approach to include select mutations in cell-free DNA and circulating proteins associated with various solid organ tumors. For validation, they used healthy and advanced but nonmetastatic cancer cohorts. Through stringent controls and a series of validations, the authors present a range of sensitivities for the various cancer types with an impressive specificity. This is a technically very strong approach with many nifty and thoughtful additions to give this test a very promising first foray – did anybody watch CNN?

While not ready for prime time, which is a tall order for a first report, the authors dutifully point out the need for a prospective real life cohort validation. In the meantime, regardless of the outcome of this particular test, it is a repeated reminder that we need to stay abreast of the advances and the details of each molecular test, especially with a likely very diverse and distinct group of tests to choose from.

Many of us will be part of interpreting results and determining further management. Just as with hereditary cancer genetic panel testing, our technical ability may have stretched beyond our ability to fully understand the implications. Many questions will arise: What about true false positives? False negatives? Intervals? Can such tests replace other screening? How to choose any given test over the other? Should tests be combined or alternated? The tests will be technically refined and are here to stay – we need to get to work on finding answers to the clinically relevant questions.

Barbara Jung, MD, AGAF, is the Thomas J. Layden Endowed Professor and chief of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago.

Imagine a single blood test that would cost less than $500 and could screen for at least eight cancer types.

It’s early days for the technology, called CancerSEEK, but the test had a sensitivity of 69%-98%, depending on the cancer type, and a specificity of 99% in a cohort of 1,005 patients with stage I-III cancers and 850 healthy controls, wrote Joshua D. Cohen of the Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics and Therapeutics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues. The report was published in Science.

CancerSEEK tests for mutations in 2,001 genomic positions and eight proteins. The researchers examined a 61-amplicon panel with each amplicon analyzing an average of 33 base pairs within a gene. They theorized the test could detect between 41% and 95% of the cancers in the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer dataset. They next used multiplex-PCR techniques to minimize errors associated with large sequencing and identified protein biomarkers for early stage cancers that may not release detectable ctDNA.

The researchers used the technology to examine blood samples from 1,005 patients with stage I (20%), stage II (49%), or stage III (31%) cancers of the ovary, liver, stomach, pancreas, esophagus, colorectum, lung, or breast prior to undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Participants had a median age of 64 years (range of 22-93 years). The healthy controls did not have a history of cancer, chronic kidney disease, autoimmune disease, or high-grade dysplasia.

The sensitivity of the test ranged from 98% in ovarian cancer to 33% in breast cancer, but the specificity was greater than 99% with only 7 of 812 control participants having a positive result. “We could not be certain that the few ‘false positive’ individuals identified among the healthy cohort did not actually have an as-yet undetected cancer, but classifying them as false positives provided the most conservative approach to classification and interpretation of the data,” the authors wrote.

Based on cancer stage, sensitivity for stage I cancers was 43%, for stage II 73%, and for stage III 78%. Again, sensitivity varied depending on cancer type, with 100% sensitivity for stage I liver cancer and 20% sensitivity for stage I esophageal cancer.

When tumor tissue samples from 153 patients with statistically significant ctDNA levels were analyzed, identical mutations were found in the plasma and tumor in 90% (138) of all cases.

The protein markers in the CancerSEEK test might also be able to anatomically locate malignancies. Using machine learning to analyze patients testing positive with CancerSEEK, the results narrowed the source of the cancer to two possible anatomical sites in approximately 83% of patients and to one anatomical site in approximately 63% of patients. Accuracy was highest for colorectal cancer and lowest for lung cancer.

As the study included otherwise healthy patients with known malignancies, the results need to be confirmed with prospective studies of incidence cancer types in a large population. Patients in the screening setting may have less advanced disease and other comorbidities that could impact the sensitivity and specificity of the CancerSEEK test, the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by multiple sources including grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported various disclosures involving diagnostics and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Cohen JD et al., Science 2018 Jan 18. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3247.

Imagine a single blood test that would cost less than $500 and could screen for at least eight cancer types.

It’s early days for the technology, called CancerSEEK, but the test had a sensitivity of 69%-98%, depending on the cancer type, and a specificity of 99% in a cohort of 1,005 patients with stage I-III cancers and 850 healthy controls, wrote Joshua D. Cohen of the Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics and Therapeutics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues. The report was published in Science.

CancerSEEK tests for mutations in 2,001 genomic positions and eight proteins. The researchers examined a 61-amplicon panel with each amplicon analyzing an average of 33 base pairs within a gene. They theorized the test could detect between 41% and 95% of the cancers in the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer dataset. They next used multiplex-PCR techniques to minimize errors associated with large sequencing and identified protein biomarkers for early stage cancers that may not release detectable ctDNA.

The researchers used the technology to examine blood samples from 1,005 patients with stage I (20%), stage II (49%), or stage III (31%) cancers of the ovary, liver, stomach, pancreas, esophagus, colorectum, lung, or breast prior to undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Participants had a median age of 64 years (range of 22-93 years). The healthy controls did not have a history of cancer, chronic kidney disease, autoimmune disease, or high-grade dysplasia.

The sensitivity of the test ranged from 98% in ovarian cancer to 33% in breast cancer, but the specificity was greater than 99% with only 7 of 812 control participants having a positive result. “We could not be certain that the few ‘false positive’ individuals identified among the healthy cohort did not actually have an as-yet undetected cancer, but classifying them as false positives provided the most conservative approach to classification and interpretation of the data,” the authors wrote.

Based on cancer stage, sensitivity for stage I cancers was 43%, for stage II 73%, and for stage III 78%. Again, sensitivity varied depending on cancer type, with 100% sensitivity for stage I liver cancer and 20% sensitivity for stage I esophageal cancer.

When tumor tissue samples from 153 patients with statistically significant ctDNA levels were analyzed, identical mutations were found in the plasma and tumor in 90% (138) of all cases.

The protein markers in the CancerSEEK test might also be able to anatomically locate malignancies. Using machine learning to analyze patients testing positive with CancerSEEK, the results narrowed the source of the cancer to two possible anatomical sites in approximately 83% of patients and to one anatomical site in approximately 63% of patients. Accuracy was highest for colorectal cancer and lowest for lung cancer.

As the study included otherwise healthy patients with known malignancies, the results need to be confirmed with prospective studies of incidence cancer types in a large population. Patients in the screening setting may have less advanced disease and other comorbidities that could impact the sensitivity and specificity of the CancerSEEK test, the researchers wrote.

The study was funded by multiple sources including grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported various disclosures involving diagnostics and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Cohen JD et al., Science 2018 Jan 18. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3247.

FROM SCIENCE

Key clinical point: New blood test demonstrates ability to identify presence of eight common cancers.

Major finding: CancerSEEK demonstrated a mean sensitivity of 70% for the eight cancer types and a specificity of greater than 99%.

Data source: Retrospective study of 1,005 patients with known malignancy and 812 healthy controls.

Disclosures: The study was funded by multiple sources including grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported several disclosures involving diagnostics and pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Cohen JD et al. Science 2018 Jan 18. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3247.

Immune-modified RECIST can help identify survival benefit from cancer immunotherapy

Cancer immunotherapy-specific response criteria not only provide improved estimates of treatment response versus standard criteria, but may also better identify patients who achieve an overall survival benefit from therapy.

Compared to standard Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1, the immune-modified RECIST provided a 1%-2% greater overall response and an 8%-13% greater rate of disease control, and added 0.5-1.5 months to median progression-free survival among patients treated with the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab, according to analyses of different phase 1 and 2 trials.

In addition, overall survival (OS) benefit in some of the trials could be better delineated using the immune-modified criteria, which account for unique patterns of progression sometimes experienced by patients on cancer immunotherapy, noted the study authors. The report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Using immune-specific criteria to evaluate response to cancer immunotherapy is not a new concept. However, there are only limited data on how those criteria might apply to predictions of OS, according to lead author F. Stephen Hodi, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his coauthors.

“These analyses reveal aspects of immune-modified RECIST that seem to predict OS better than RECIST v1.1, and aspects needing refinement to improve the ability to predict clinical benefit,” wrote Dr. Hodi and his colleagues.

Typical response criteria may not adequately predict the potential OS benefit of cancer immunotherapy, since patients receiving cancer immunotherapy may exhibit response patterns outside of the “classic response patterns” seen with other anticancer treatments, they noted.

In particular, some patients may experience an initial transient increase in tumor burden before responding, while in other cases, patients with responding baseline lesions might develop new lesions.

Immune-modified criteria have been developed to account for those “other patterns” that can manifest with cancer immunotherapy, the authors said.

Dr. Hodi and his colleagues sought to evaluate outcomes by RECIST vs. immune-related RECIST criteria among patients treated with atezolizumab in studies of non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

In the phase 2 BIRCH study of first-line atezolizumab for NSCLC, they found that immune-related RECIST criteria appeared to predict OS better than RECIST. Median overall survival was 4.0 months longer among patients who had progressive disease (PD) by RECIST criteria within 90 days of study enrollment, versus patients who had PD by both RECIST and immune-modified RECIST at that time point, Dr. Hodi and his colleagues reported.

In the POPLAR trial of atezolizumab in NSCLC, median overall survival was 1.4 months longer for patients with PD by RECIST vs. patients with PD by both RECIST and immune-modified RECIST at 90 days, they reported.

For patients with metastatic urothelial bladder cancer treated with atezolizumab in the IMvigor210 study, median overall survival was 4.4 months longer for patients with PD by RECIST only vs. PD by both RECIST and immune-related RECIST within 180 days of enrollment, the researchers noted.

An international effort is underway to compare data sets from larger trial sets and multiple cancer immunotherapy agents, they wrote.

SOURCE: Hodi FS et al., J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jan 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.1644

Cancer immunotherapy-specific response criteria not only provide improved estimates of treatment response versus standard criteria, but may also better identify patients who achieve an overall survival benefit from therapy.

Compared to standard Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1, the immune-modified RECIST provided a 1%-2% greater overall response and an 8%-13% greater rate of disease control, and added 0.5-1.5 months to median progression-free survival among patients treated with the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab, according to analyses of different phase 1 and 2 trials.

In addition, overall survival (OS) benefit in some of the trials could be better delineated using the immune-modified criteria, which account for unique patterns of progression sometimes experienced by patients on cancer immunotherapy, noted the study authors. The report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Using immune-specific criteria to evaluate response to cancer immunotherapy is not a new concept. However, there are only limited data on how those criteria might apply to predictions of OS, according to lead author F. Stephen Hodi, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his coauthors.

“These analyses reveal aspects of immune-modified RECIST that seem to predict OS better than RECIST v1.1, and aspects needing refinement to improve the ability to predict clinical benefit,” wrote Dr. Hodi and his colleagues.

Typical response criteria may not adequately predict the potential OS benefit of cancer immunotherapy, since patients receiving cancer immunotherapy may exhibit response patterns outside of the “classic response patterns” seen with other anticancer treatments, they noted.

In particular, some patients may experience an initial transient increase in tumor burden before responding, while in other cases, patients with responding baseline lesions might develop new lesions.

Immune-modified criteria have been developed to account for those “other patterns” that can manifest with cancer immunotherapy, the authors said.

Dr. Hodi and his colleagues sought to evaluate outcomes by RECIST vs. immune-related RECIST criteria among patients treated with atezolizumab in studies of non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

In the phase 2 BIRCH study of first-line atezolizumab for NSCLC, they found that immune-related RECIST criteria appeared to predict OS better than RECIST. Median overall survival was 4.0 months longer among patients who had progressive disease (PD) by RECIST criteria within 90 days of study enrollment, versus patients who had PD by both RECIST and immune-modified RECIST at that time point, Dr. Hodi and his colleagues reported.

In the POPLAR trial of atezolizumab in NSCLC, median overall survival was 1.4 months longer for patients with PD by RECIST vs. patients with PD by both RECIST and immune-modified RECIST at 90 days, they reported.

For patients with metastatic urothelial bladder cancer treated with atezolizumab in the IMvigor210 study, median overall survival was 4.4 months longer for patients with PD by RECIST only vs. PD by both RECIST and immune-related RECIST within 180 days of enrollment, the researchers noted.

An international effort is underway to compare data sets from larger trial sets and multiple cancer immunotherapy agents, they wrote.

SOURCE: Hodi FS et al., J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jan 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.1644

Cancer immunotherapy-specific response criteria not only provide improved estimates of treatment response versus standard criteria, but may also better identify patients who achieve an overall survival benefit from therapy.

Compared to standard Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1, the immune-modified RECIST provided a 1%-2% greater overall response and an 8%-13% greater rate of disease control, and added 0.5-1.5 months to median progression-free survival among patients treated with the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab, according to analyses of different phase 1 and 2 trials.

In addition, overall survival (OS) benefit in some of the trials could be better delineated using the immune-modified criteria, which account for unique patterns of progression sometimes experienced by patients on cancer immunotherapy, noted the study authors. The report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Using immune-specific criteria to evaluate response to cancer immunotherapy is not a new concept. However, there are only limited data on how those criteria might apply to predictions of OS, according to lead author F. Stephen Hodi, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, and his coauthors.

“These analyses reveal aspects of immune-modified RECIST that seem to predict OS better than RECIST v1.1, and aspects needing refinement to improve the ability to predict clinical benefit,” wrote Dr. Hodi and his colleagues.

Typical response criteria may not adequately predict the potential OS benefit of cancer immunotherapy, since patients receiving cancer immunotherapy may exhibit response patterns outside of the “classic response patterns” seen with other anticancer treatments, they noted.

In particular, some patients may experience an initial transient increase in tumor burden before responding, while in other cases, patients with responding baseline lesions might develop new lesions.

Immune-modified criteria have been developed to account for those “other patterns” that can manifest with cancer immunotherapy, the authors said.

Dr. Hodi and his colleagues sought to evaluate outcomes by RECIST vs. immune-related RECIST criteria among patients treated with atezolizumab in studies of non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

In the phase 2 BIRCH study of first-line atezolizumab for NSCLC, they found that immune-related RECIST criteria appeared to predict OS better than RECIST. Median overall survival was 4.0 months longer among patients who had progressive disease (PD) by RECIST criteria within 90 days of study enrollment, versus patients who had PD by both RECIST and immune-modified RECIST at that time point, Dr. Hodi and his colleagues reported.

In the POPLAR trial of atezolizumab in NSCLC, median overall survival was 1.4 months longer for patients with PD by RECIST vs. patients with PD by both RECIST and immune-modified RECIST at 90 days, they reported.

For patients with metastatic urothelial bladder cancer treated with atezolizumab in the IMvigor210 study, median overall survival was 4.4 months longer for patients with PD by RECIST only vs. PD by both RECIST and immune-related RECIST within 180 days of enrollment, the researchers noted.

An international effort is underway to compare data sets from larger trial sets and multiple cancer immunotherapy agents, they wrote.

SOURCE: Hodi FS et al., J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jan 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.1644

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Compared to standard criteria for response evaluation, criteria developed specifically to evaluate response to cancer immunotherapy better identified patients with an overall survival (OS) benefit.

Major finding: Median OS was 4.0 and 1.4 months longer, respectively, in the BIRCH and POPLAR non–small-cell lung cancer trial among patients who had progressive disease (PD) by standard criteria only, as opposed to patients who also had PD according to the immunotherapy-specific response criteria.

Data source: Analysis of patients treated with single-agent atezolizumab in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials.

Disclosures: The study was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Authors reported disclosures related to Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Genentech/Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and others.

Source: Hodi FS et al., J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jan 17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.1644.

Young e-cigarette users graduating to the real thing

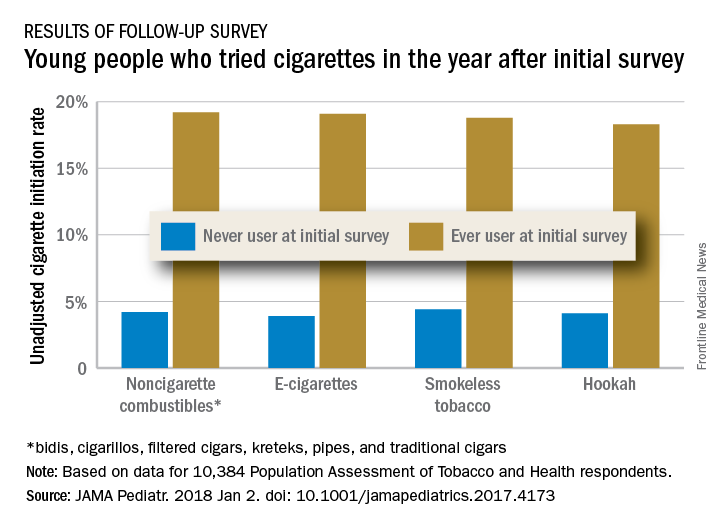

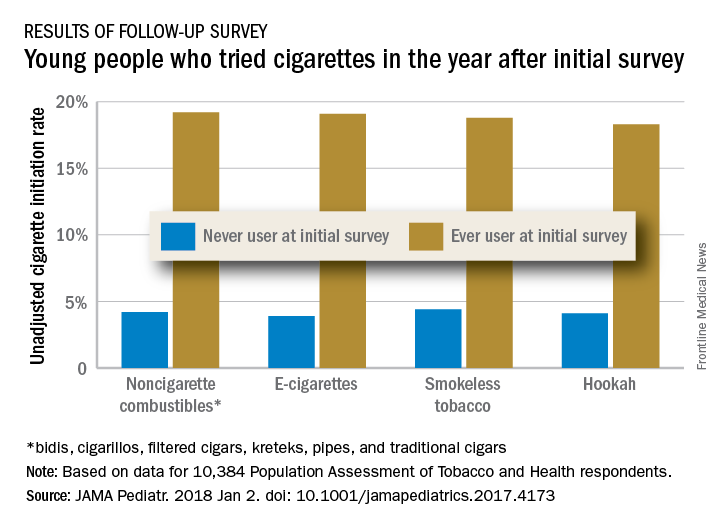

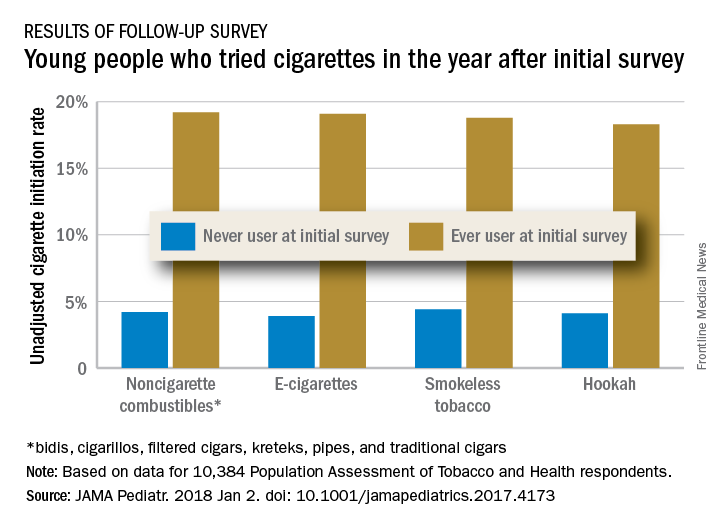

Children who use noncigarette forms of tobacco are significantly more likely to try cigarettes in the future, according to survey data from over 10,000 young people aged 12-17 years.

An initial survey (wave 1) was conducted as part of the nationally representative Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study, with a follow-up (wave 2) administered to participants a year later. The analysis by Shannon L. Watkins, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates was based on data for 10,384 respondents who reported never smoking a cigarette in wave 1 and whose later cigarette use, which occurred in less than 5% overall, was reported in wave 2.

Those who used multiple noncigarette products were more likely than users of a single product to initiate cigarette use by wave 2. With never use of any tobacco as the reference, one model used by the investigators put the odds ratios of cigarette ever use at 4.98 for e-cigarettes only, 3.57 for combustibles only, and 8.57 for use of multiple products.

This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Watkins S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4173.

Children who use noncigarette forms of tobacco are significantly more likely to try cigarettes in the future, according to survey data from over 10,000 young people aged 12-17 years.

An initial survey (wave 1) was conducted as part of the nationally representative Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study, with a follow-up (wave 2) administered to participants a year later. The analysis by Shannon L. Watkins, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates was based on data for 10,384 respondents who reported never smoking a cigarette in wave 1 and whose later cigarette use, which occurred in less than 5% overall, was reported in wave 2.

Those who used multiple noncigarette products were more likely than users of a single product to initiate cigarette use by wave 2. With never use of any tobacco as the reference, one model used by the investigators put the odds ratios of cigarette ever use at 4.98 for e-cigarettes only, 3.57 for combustibles only, and 8.57 for use of multiple products.

This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Watkins S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4173.

Children who use noncigarette forms of tobacco are significantly more likely to try cigarettes in the future, according to survey data from over 10,000 young people aged 12-17 years.

An initial survey (wave 1) was conducted as part of the nationally representative Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) study, with a follow-up (wave 2) administered to participants a year later. The analysis by Shannon L. Watkins, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates was based on data for 10,384 respondents who reported never smoking a cigarette in wave 1 and whose later cigarette use, which occurred in less than 5% overall, was reported in wave 2.

Those who used multiple noncigarette products were more likely than users of a single product to initiate cigarette use by wave 2. With never use of any tobacco as the reference, one model used by the investigators put the odds ratios of cigarette ever use at 4.98 for e-cigarettes only, 3.57 for combustibles only, and 8.57 for use of multiple products.

This study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute, Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Watkins S et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Jan 2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4173.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Phase 1 study: Human IL-10 plus checkpoint blockade looks promising in RCC, NSCLC

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pegylated human interleukin-10 in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy is well tolerated and shows promise for the treatment of both renal cell carcinoma and non–small cell lung cancer, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

The IL-10 product, AM0010 (pegilodecakin), was shown to be well tolerated as monotherapy, and was evaluated in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy in the two expansion cohorts included in the current analysis, Martin Oft, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Of 34 evaluable renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients included in one expansion cohort, 15 (44%) had an objective response at a median follow-up of 27 months, and two of those had a complete response (CR), Dr. Oft of ARMO BioSciences, Redwood City, Calif. reported.

In contrast, only 4 of 16 evaluable patients who received AM0010 monotherapy (25%) had an objective response, he said.

In eight patients who received AM0010 + pembrolizumab (Keytruda), the objective response rate was 50%, and both patients who had a complete response were in that group. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 16.7 months. In 26 who received AM0010 + nivolumab (Opdivo), 11 had an objective response, but neither the complete response nor PFS rates had been reached in patients in that group, he noted.

The responses were durable.

“In fact, we had one patient who stopped treatment after a year in [complete remission] and is now 1 year in total remission without any further treatment,” he said.

Patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) also experienced some benefit from the combination therapy. Objective responses were observed in 11 of 27 evaluable NSCLC patients (41%) who were treated with AM0010 and an anti–PD-1(9 of 22 [41%] who received AM0010 and nivolumab, and 2 of 5 [40%] who received AM0010 and pembrolizumab).

Progression-free survival was not reached in this cohort.

An analysis by PD-L1 status showed that 33% of NSCLC patients with PD-L1 levels less than 1% achieved a response, 67% of those with PD-L1 levels of 1%-49% achieved a response, and 80% of those with PD-L1 levels of 50% or greater achieved a response, he said, adding that the responses were very durable in all three groups.

Of note, NSCLC patients with liver metastasis have been shown in prior trials to have a lower overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibition, but in this trial, 7 of 9 patients with NSCLC metastasis to the liver had a partial response (PR), Dr. Oft said.

The RCC and NSCLC patients had a median of 1 and 2 prior therapies, respectively.

AM0010 was given subcutaneously at a dose of 10 or 20 mcg/kg daily, pembrolizumab was given intravenously at 2mg/kg every 3 weeks, and nivolumab was given intravenously at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events included anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue, and all were reversible and transient, Dr. Oft said, noting that grade 3 or 4 adverse events were mostly absent in patients receiving the lower dose; thus the recommended phase 2 dose is 10 mcg/kg.

“It’s important to note that three of those six patients [receiving the lower dose] in fact had a PR or CR so this lower dose did not come at the expense of efficacy,” he added.

The mechanistic rationale for combining AM0010 and anti-PD1 for the treatment of cancer patients lies in the fact that IL‐10 has anti‐inflammatory functions and stimulates the cytotoxicity and proliferation of antigen-activated CD8+ T cells. T cell receptor–mediated activation of CD8+ T cells elevates IL‐10 receptors and PD‐1, Dr. Oft explained.

The robust efficacy data and the observed CD8+ T cell activation seen in these expansion cohorts is promising and encourages the continued study of AM0010 in combination with PD-1 inhibition, he concluded, noting that larger studies are planned for the coming year.

Dr. Oft is a founder and employee of ARMO BioSciences, which sponsored this study.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Naing A et al. SITC Abstract 012.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pegylated human interleukin-10 in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy is well tolerated and shows promise for the treatment of both renal cell carcinoma and non–small cell lung cancer, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

The IL-10 product, AM0010 (pegilodecakin), was shown to be well tolerated as monotherapy, and was evaluated in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy in the two expansion cohorts included in the current analysis, Martin Oft, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Of 34 evaluable renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients included in one expansion cohort, 15 (44%) had an objective response at a median follow-up of 27 months, and two of those had a complete response (CR), Dr. Oft of ARMO BioSciences, Redwood City, Calif. reported.

In contrast, only 4 of 16 evaluable patients who received AM0010 monotherapy (25%) had an objective response, he said.

In eight patients who received AM0010 + pembrolizumab (Keytruda), the objective response rate was 50%, and both patients who had a complete response were in that group. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 16.7 months. In 26 who received AM0010 + nivolumab (Opdivo), 11 had an objective response, but neither the complete response nor PFS rates had been reached in patients in that group, he noted.

The responses were durable.

“In fact, we had one patient who stopped treatment after a year in [complete remission] and is now 1 year in total remission without any further treatment,” he said.

Patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) also experienced some benefit from the combination therapy. Objective responses were observed in 11 of 27 evaluable NSCLC patients (41%) who were treated with AM0010 and an anti–PD-1(9 of 22 [41%] who received AM0010 and nivolumab, and 2 of 5 [40%] who received AM0010 and pembrolizumab).

Progression-free survival was not reached in this cohort.

An analysis by PD-L1 status showed that 33% of NSCLC patients with PD-L1 levels less than 1% achieved a response, 67% of those with PD-L1 levels of 1%-49% achieved a response, and 80% of those with PD-L1 levels of 50% or greater achieved a response, he said, adding that the responses were very durable in all three groups.

Of note, NSCLC patients with liver metastasis have been shown in prior trials to have a lower overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibition, but in this trial, 7 of 9 patients with NSCLC metastasis to the liver had a partial response (PR), Dr. Oft said.

The RCC and NSCLC patients had a median of 1 and 2 prior therapies, respectively.

AM0010 was given subcutaneously at a dose of 10 or 20 mcg/kg daily, pembrolizumab was given intravenously at 2mg/kg every 3 weeks, and nivolumab was given intravenously at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events included anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue, and all were reversible and transient, Dr. Oft said, noting that grade 3 or 4 adverse events were mostly absent in patients receiving the lower dose; thus the recommended phase 2 dose is 10 mcg/kg.

“It’s important to note that three of those six patients [receiving the lower dose] in fact had a PR or CR so this lower dose did not come at the expense of efficacy,” he added.

The mechanistic rationale for combining AM0010 and anti-PD1 for the treatment of cancer patients lies in the fact that IL‐10 has anti‐inflammatory functions and stimulates the cytotoxicity and proliferation of antigen-activated CD8+ T cells. T cell receptor–mediated activation of CD8+ T cells elevates IL‐10 receptors and PD‐1, Dr. Oft explained.

The robust efficacy data and the observed CD8+ T cell activation seen in these expansion cohorts is promising and encourages the continued study of AM0010 in combination with PD-1 inhibition, he concluded, noting that larger studies are planned for the coming year.

Dr. Oft is a founder and employee of ARMO BioSciences, which sponsored this study.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Naing A et al. SITC Abstract 012.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Pegylated human interleukin-10 in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy is well tolerated and shows promise for the treatment of both renal cell carcinoma and non–small cell lung cancer, according to findings from a phase 1 study.

The IL-10 product, AM0010 (pegilodecakin), was shown to be well tolerated as monotherapy, and was evaluated in combination with anti–PD-1 therapy in the two expansion cohorts included in the current analysis, Martin Oft, MD, said at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

Of 34 evaluable renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients included in one expansion cohort, 15 (44%) had an objective response at a median follow-up of 27 months, and two of those had a complete response (CR), Dr. Oft of ARMO BioSciences, Redwood City, Calif. reported.

In contrast, only 4 of 16 evaluable patients who received AM0010 monotherapy (25%) had an objective response, he said.

In eight patients who received AM0010 + pembrolizumab (Keytruda), the objective response rate was 50%, and both patients who had a complete response were in that group. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 16.7 months. In 26 who received AM0010 + nivolumab (Opdivo), 11 had an objective response, but neither the complete response nor PFS rates had been reached in patients in that group, he noted.

The responses were durable.

“In fact, we had one patient who stopped treatment after a year in [complete remission] and is now 1 year in total remission without any further treatment,” he said.

Patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) also experienced some benefit from the combination therapy. Objective responses were observed in 11 of 27 evaluable NSCLC patients (41%) who were treated with AM0010 and an anti–PD-1(9 of 22 [41%] who received AM0010 and nivolumab, and 2 of 5 [40%] who received AM0010 and pembrolizumab).

Progression-free survival was not reached in this cohort.

An analysis by PD-L1 status showed that 33% of NSCLC patients with PD-L1 levels less than 1% achieved a response, 67% of those with PD-L1 levels of 1%-49% achieved a response, and 80% of those with PD-L1 levels of 50% or greater achieved a response, he said, adding that the responses were very durable in all three groups.

Of note, NSCLC patients with liver metastasis have been shown in prior trials to have a lower overall response rate to immune checkpoint inhibition, but in this trial, 7 of 9 patients with NSCLC metastasis to the liver had a partial response (PR), Dr. Oft said.

The RCC and NSCLC patients had a median of 1 and 2 prior therapies, respectively.

AM0010 was given subcutaneously at a dose of 10 or 20 mcg/kg daily, pembrolizumab was given intravenously at 2mg/kg every 3 weeks, and nivolumab was given intravenously at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks.

Treatment-related adverse events included anemia, thrombocytopenia, and fatigue, and all were reversible and transient, Dr. Oft said, noting that grade 3 or 4 adverse events were mostly absent in patients receiving the lower dose; thus the recommended phase 2 dose is 10 mcg/kg.

“It’s important to note that three of those six patients [receiving the lower dose] in fact had a PR or CR so this lower dose did not come at the expense of efficacy,” he added.

The mechanistic rationale for combining AM0010 and anti-PD1 for the treatment of cancer patients lies in the fact that IL‐10 has anti‐inflammatory functions and stimulates the cytotoxicity and proliferation of antigen-activated CD8+ T cells. T cell receptor–mediated activation of CD8+ T cells elevates IL‐10 receptors and PD‐1, Dr. Oft explained.

The robust efficacy data and the observed CD8+ T cell activation seen in these expansion cohorts is promising and encourages the continued study of AM0010 in combination with PD-1 inhibition, he concluded, noting that larger studies are planned for the coming year.

Dr. Oft is a founder and employee of ARMO BioSciences, which sponsored this study.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Naing A et al. SITC Abstract 012.

REPORTING FROM SITC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 15 of 34 RCC patients had an objective response and two of those had a complete response.

Study details: Expansion cohorts including 64 patients from a phase 1 study.

Disclosures: Dr. Oft is a founder and employee of ARMO BioSciences, which sponsored this study.

Source: A. Naing et al. SITC 2017 Abstract 012.

Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of typical and atypical bronchopulmonary carcinoid

Carcinoid lung tumors represent the most indolent form of a spectrum of bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) that includes small-cell carcinoma as its most malignant member, as well as several other forms of intermediately aggressive tumors, such as atypical carcinoid.1 Carcinoids represent 1.2% of all primary lung malignancies. Their incidence in the United States has increased rapidly over the last 30 years and is currently about 6% a year. Lung carcinoids are more prevalent in whites compared with blacks, and in Asians compared with non-Asians. They are less common in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics.1 Typical carcinoids represent 80%-90% of all lung carcinoids and occur more frequently in the fifth and sixth decades of life. They can, however, occur at any age, and are the most common lung tumor in childhood.1

Etiology and risk factors

Unlike carcinoma of the lung, no external environmental toxin or other stimulus has been identified as a causative agent for the development of pulmonary carcinoid tumors. It is not clear if there is an association between bronchial NETs and smoking.1 Nearly all bronchial NETs are sporadic; however, they can rarely occur in the setting of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.1

Presentation

About 60% of the patients with bronchial carcinoids are symptomatic at presentation. The most common clinical findings are those associated with bronchial obstruction, such as persistent cough, hemoptysis, and recurrent or obstructive pneumonitis. Wheezing, chest pain, and dyspnea also may be noted.2 Various endocrine or neuroendocrine syndromes can be initial clinical manifestations of either typical or atypical pulmonary carcinoid tumors, but that is not common Cushing syndrome (ectopic production and secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]) may occur in about 2% of lung carcinoid.3 In cases of malignancy, the presence of metastatic disease can produce weight loss, weakness, and a general feeling of ill health.

Diagnostic work-up

Biochemical test

There is no biochemical study that can be used as a screening test to determine the presence of a carcinoid tumor or to diagnose a known pulmonary mass as a carcinoid tumor. Neuroendocrine cells produce biologically active amines and peptides that can be detected in serum and urine. Although the syndromes associated with lung carcinoids are seen in about 1%-2% of the patients, assays of specific hormones or other circulating neuroendocrine substances, such as ACTH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, or growth hormone may establish the existence of a clinically suspected syndrome.

Chest radiography

An abnormal finding on chest radiography is present in about 75% of patients with a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.1 Findings include either the presence of the tumor mass itself or indirect evidence of its presence observed as parenchymal changes associated with bronchial obstruction from the mass.

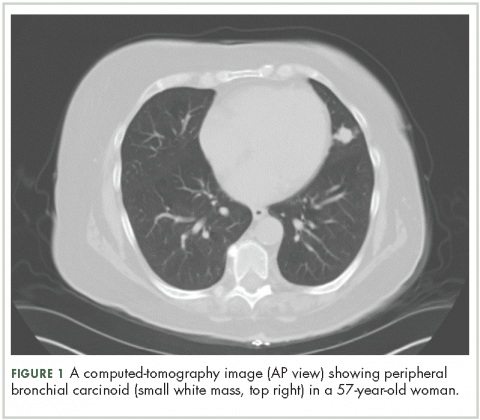

Computed-tomography imaging

High-resolution computed-tomography (CT) imaging is the one of the best types of CT examination for evaluation of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.4 A CT scan provides excellent resolution of tumor extent, location, and the presence or absence of mediastinal adenopathy. It also aids in morphologic characterization of peripheral (Figure 1) and especially centrally located carcinoids, which may be purely intraluminal (polypoid configuration), exclusively extra luminal, or more frequently, a mixture of intraluminal and extraluminal components.

CT scans may also be helpful for differentiating tumor from postobstructive atelectasis or bronchial obstruction-related mucoid impaction. Intravenous contrast in CT imaging can be useful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Because carcinoid tumors are highly vascular, they show greater enhancement on contrast CT than do benign lesions. The sensitivity of CT for detecting metastatic hilar or mediastinal nodes is high, but specificity is as low as 45%.4

Typical carcinoid is rarely metastatic so most patients do not need CT or MRI imaging to evaluate for liver involvement. Liver imaging is appropriate in patients with evidence of mediastinal involvement, relatively high mitotic rate, or clinical evidence of the carcinoid syndrome.8 To evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver, multiphase contrast-enhanced liver CT scans should be performed with arterial and portal-venous phases because carcinoid liver metastases are often hypervascular and appear isodense relative to the liver parenchyma after contrast administration.4 An MRI is often preferred the modality to evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver because of its higher sensitivity.5

Positron-emission tomography

Although carcinoid tumors of the lung are highly vascular, they do not show increased metabolic activity on positron-emission tomography (PET) and would be incorrectly designated as benign lesions on the basis of findings from a PET scan. Fludeoxyglucose F-18 PET has shown utility as a radiologic marker for atypical carcinoids, particularly for those with a higher proliferation index with Ki-67 index of 10%-20%.6

Radionucleotide studies

Somatostatin receptors (SSRs) are present in many tumors of neuroendocrine origin, including carcinoid tumors. These receptors interact with each other and undergo dimerization and internalization. SSTR subtypes (SSTRs) overexpressed in NETs are related to the type, origin, and grade of differentiation of tumor. The overexpression of an SSTR is a characteristic feature of bronchial NETs, which can be used to localize the primary tumor and its metastases by imaging with the radiolabeled SST analogues. Radionucleotide imaging modalities commonly used include single-photon–emission tomography and positron-emission tomography.

With regard to SSR scintigraphy testing, PET using Ga–DOTATATE/TOC is preferable to Octreoscan if it is available, because offers better spatial resolution and has a shorter scanning time. It has sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 92% and hence is preferable over Octreoscan in highly aggressive, atypical bronchial NETs. It also provides an estimate of receptor density and evidence of the functionality of receptors, which helps with selection of suitable treatments that act on these receptors.7

Tumor markers

Serum levels of chromogranin A in bronchial NETs are expressed at a lower rate than are other sites of carcinoid tumors, so its measurement is of limited utility in following disease activity in bronchial NETs.4,8

Bronchoscopy

About 75% of pulmonary carcinoids are visible on bronchoscopy. The bronchoscopic appearance may be characteristic but it is preferable that brushings or biopsy be performed to confirm the diagnosis. For central tumors endobronchial; and for peripheral tumors, CT-guided percutaneous biopsy is the accepted diagnostic approach. Cytologic study of bronchial brushings is more sensitive than sputum cytology, but the diagnostic yield of brushing is low overall (about 40%) and hence fine-needle biopsy is preferred. 8

A negative finding on biopsy should not produce a false sense of confidence. If a suspicion of malignancy exists despite a negative finding on transthoracic biopsy, surgical excision of the nodule and pathologic analysis should be undertaken.

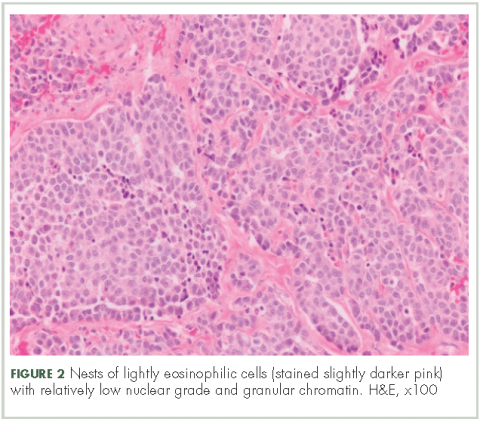

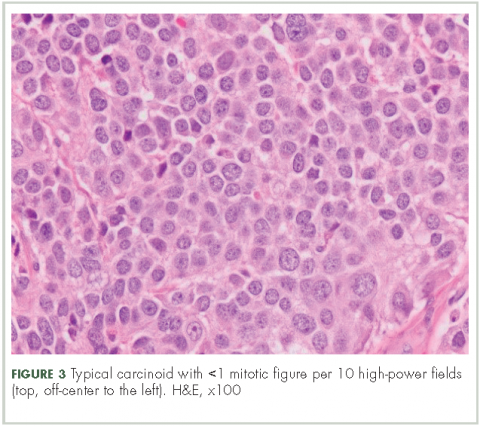

Histological findings

In typical carcinoid tumors, cells tend to group in nests, cords, or broad sheets. Arrangement is orderly, with groups of cells separated by highly vascular septa of connective tissue.9Individual cell features include small and polygonal cells with finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2). Nuclei are small and round. Mitoses are infrequent (Figure 3).

On electron microscopy, well-formed desmosomes and abundant neurosecretory granules are seen. Many pulmonary carcinoid tumors stain positive for a variety of neuroendocrine markers. Electron microscopy is of historical interest but is not used for tissue diagnosis for bronchial carcinoid patients.

Typical vs atypical tumors

In all, 10% of the carcinoid tumors are atypical in nature. They are generally larger than typical carcinoids and are located in the periphery of the lung in about 50% of cases. They have more aggressive behavior and tend to metastasize more commonly.2 Neither location nor size are distinguishing features. The distinction is based on histology and includes one or all of the following features:8,9

n Increased mitotic activity in a tumor with an identifiable carcinoid cellular arrangement with 2-10 mitotic figures per high-power field.9

n Pleomorphism and irregular nuclei with hyperchromatism and prominent nucleoli.

n Areas of increased cellularity with loss of the regular, organized architecture observed in typical carcinoid.