User login

Poor sleep quality as a teen may up MS risk in adulthood

Too little sleep or poor sleep quality during the teen years can significantly increase the risk for multiple sclerosis (MS) during adulthood, new research suggests.

In a large case-control study, individuals who slept less than 7 hours a night on average during adolescence were 40% more likely to develop MS later on. The risk was even higher for those who rated their sleep quality as bad.

On the other hand, MS was significantly less common among individuals who slept longer as teens – indicating a possible protective benefit.

While sleep duration has been associated with mortality or disease risk for other conditions, sleep quality usually has little to no effect on risk, lead investigator Torbjörn Åkerstedt, PhD, sleep researcher and professor of psychology, department of neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I hadn’t really expected that, but those results were quite strong, even stronger than sleep duration,” Dr. Åkerstedt said.

“We don’t really know why this is happening in young age, but the most suitable explanation is that the brain in still developing quite a bit, and you’re interfering with it,” he added.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Strong association

Other studies have tied sleep deprivation to increased risk for serious illness, but the link between sleep and MS risk isn’t as well studied.

Previous research by Dr. Åkerstedt showed that the risk for MS was higher among individuals who took part in shift work before the age of 20. However, the impact of sleep duration or quality among teens was unknown.

The current Swedish population-based case-control study included 2,075 patients with MS and 3,164 without the disorder. All participants were asked to recall how many hours on average they slept per night between the ages of 15 and 19 years and to rate their sleep quality during that time.

Results showed that individuals who slept fewer than 7 hours a night during their teen years were 40% more likely to have MS as adults (odds ratio [OR], 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-1.7).

Poor sleep quality increased MS risk even more (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3-1.9).

The association remained strong even after adjustment for additional sleep on weekends and breaks and excluding shift workers.

Long sleep ‘apparently good’

The researchers also conducted several sensitivity studies to rule out confounders that might bias the association, such as excluding participants who reported currently experiencing less sleep or poor sleep.

“You would expect that people who are suffering from sleep problems today would be the people who reported sleep problems during their youth,” but that didn’t happen, Dr. Åkerstedt noted.

The investigators also entered data on sleep duration and sleep quality at the same time, thinking the data would cancel each other out. However, the association remained the same.

“Quite often you see that sleep duration would eliminate the effect of sleep complaints in the prediction of disease, but here both remain significant when they are entered at the same time,” Dr. Åkerstedt said. “You get the feeling that this might mean they act together to produce results,” he added.

“One other thing that surprised me is that long sleep was apparently good,” said Dr. Åkerstedt.

The investigators have conducted several studies on sleep duration and mortality. In recent research, they found that both short sleep and long sleep predicted mortality – “and often, long sleep is a stronger predictor than short sleep,” he said.

Underestimated problem?

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen Zackowski, PhD, associate vice president of research for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in Baltimore, noted that participants were asked to rate their own sleep quality during adolescence, a subjective report that may mean sleep quality has an even larger association with MS risk.

“That they found a result with sleep quality says to me that there probably is a bigger problem, because I don’t know if people over- or underestimate their sleep quality,” said Dr. Zackowski, who was not involved with the research.

“If we could get to that sleep quality question a little more objectively, I bet that we’d find there’s a lot more to the story,” she said.

That’s a story the researchers would like to explore, Dr. Åkerstedt reported. Designing a prospective study that more closely tracks sleeping habits during adolescence and follows individuals through adulthood could provide valuable information about how sleep quality and duration affect immune system development and MS risk, he said.

Dr. Zackowski said clinicians know that MS is not caused just by a genetic abnormality and that other environmental lifestyle factors seem to play a part.

“If we find out that sleep is one of those lifestyle factors, this is very changeable,” she added.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Swedish Brain Foundation, AFA Insurance, the European Aviation Safety Authority, the Tercentenary Fund of the Bank of Sweden, the Margaretha af Ugglas Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for MS Research, and NEURO Sweden. Dr. Åkerstadt has been supported by Tercentenary Fund of Bank of Sweden, AFA Insurance, and the European Aviation Safety Authority. Dr. Zackowski reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Too little sleep or poor sleep quality during the teen years can significantly increase the risk for multiple sclerosis (MS) during adulthood, new research suggests.

In a large case-control study, individuals who slept less than 7 hours a night on average during adolescence were 40% more likely to develop MS later on. The risk was even higher for those who rated their sleep quality as bad.

On the other hand, MS was significantly less common among individuals who slept longer as teens – indicating a possible protective benefit.

While sleep duration has been associated with mortality or disease risk for other conditions, sleep quality usually has little to no effect on risk, lead investigator Torbjörn Åkerstedt, PhD, sleep researcher and professor of psychology, department of neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I hadn’t really expected that, but those results were quite strong, even stronger than sleep duration,” Dr. Åkerstedt said.

“We don’t really know why this is happening in young age, but the most suitable explanation is that the brain in still developing quite a bit, and you’re interfering with it,” he added.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Strong association

Other studies have tied sleep deprivation to increased risk for serious illness, but the link between sleep and MS risk isn’t as well studied.

Previous research by Dr. Åkerstedt showed that the risk for MS was higher among individuals who took part in shift work before the age of 20. However, the impact of sleep duration or quality among teens was unknown.

The current Swedish population-based case-control study included 2,075 patients with MS and 3,164 without the disorder. All participants were asked to recall how many hours on average they slept per night between the ages of 15 and 19 years and to rate their sleep quality during that time.

Results showed that individuals who slept fewer than 7 hours a night during their teen years were 40% more likely to have MS as adults (odds ratio [OR], 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-1.7).

Poor sleep quality increased MS risk even more (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3-1.9).

The association remained strong even after adjustment for additional sleep on weekends and breaks and excluding shift workers.

Long sleep ‘apparently good’

The researchers also conducted several sensitivity studies to rule out confounders that might bias the association, such as excluding participants who reported currently experiencing less sleep or poor sleep.

“You would expect that people who are suffering from sleep problems today would be the people who reported sleep problems during their youth,” but that didn’t happen, Dr. Åkerstedt noted.

The investigators also entered data on sleep duration and sleep quality at the same time, thinking the data would cancel each other out. However, the association remained the same.

“Quite often you see that sleep duration would eliminate the effect of sleep complaints in the prediction of disease, but here both remain significant when they are entered at the same time,” Dr. Åkerstedt said. “You get the feeling that this might mean they act together to produce results,” he added.

“One other thing that surprised me is that long sleep was apparently good,” said Dr. Åkerstedt.

The investigators have conducted several studies on sleep duration and mortality. In recent research, they found that both short sleep and long sleep predicted mortality – “and often, long sleep is a stronger predictor than short sleep,” he said.

Underestimated problem?

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen Zackowski, PhD, associate vice president of research for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in Baltimore, noted that participants were asked to rate their own sleep quality during adolescence, a subjective report that may mean sleep quality has an even larger association with MS risk.

“That they found a result with sleep quality says to me that there probably is a bigger problem, because I don’t know if people over- or underestimate their sleep quality,” said Dr. Zackowski, who was not involved with the research.

“If we could get to that sleep quality question a little more objectively, I bet that we’d find there’s a lot more to the story,” she said.

That’s a story the researchers would like to explore, Dr. Åkerstedt reported. Designing a prospective study that more closely tracks sleeping habits during adolescence and follows individuals through adulthood could provide valuable information about how sleep quality and duration affect immune system development and MS risk, he said.

Dr. Zackowski said clinicians know that MS is not caused just by a genetic abnormality and that other environmental lifestyle factors seem to play a part.

“If we find out that sleep is one of those lifestyle factors, this is very changeable,” she added.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Swedish Brain Foundation, AFA Insurance, the European Aviation Safety Authority, the Tercentenary Fund of the Bank of Sweden, the Margaretha af Ugglas Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for MS Research, and NEURO Sweden. Dr. Åkerstadt has been supported by Tercentenary Fund of Bank of Sweden, AFA Insurance, and the European Aviation Safety Authority. Dr. Zackowski reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Too little sleep or poor sleep quality during the teen years can significantly increase the risk for multiple sclerosis (MS) during adulthood, new research suggests.

In a large case-control study, individuals who slept less than 7 hours a night on average during adolescence were 40% more likely to develop MS later on. The risk was even higher for those who rated their sleep quality as bad.

On the other hand, MS was significantly less common among individuals who slept longer as teens – indicating a possible protective benefit.

While sleep duration has been associated with mortality or disease risk for other conditions, sleep quality usually has little to no effect on risk, lead investigator Torbjörn Åkerstedt, PhD, sleep researcher and professor of psychology, department of neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“I hadn’t really expected that, but those results were quite strong, even stronger than sleep duration,” Dr. Åkerstedt said.

“We don’t really know why this is happening in young age, but the most suitable explanation is that the brain in still developing quite a bit, and you’re interfering with it,” he added.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry.

Strong association

Other studies have tied sleep deprivation to increased risk for serious illness, but the link between sleep and MS risk isn’t as well studied.

Previous research by Dr. Åkerstedt showed that the risk for MS was higher among individuals who took part in shift work before the age of 20. However, the impact of sleep duration or quality among teens was unknown.

The current Swedish population-based case-control study included 2,075 patients with MS and 3,164 without the disorder. All participants were asked to recall how many hours on average they slept per night between the ages of 15 and 19 years and to rate their sleep quality during that time.

Results showed that individuals who slept fewer than 7 hours a night during their teen years were 40% more likely to have MS as adults (odds ratio [OR], 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-1.7).

Poor sleep quality increased MS risk even more (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.3-1.9).

The association remained strong even after adjustment for additional sleep on weekends and breaks and excluding shift workers.

Long sleep ‘apparently good’

The researchers also conducted several sensitivity studies to rule out confounders that might bias the association, such as excluding participants who reported currently experiencing less sleep or poor sleep.

“You would expect that people who are suffering from sleep problems today would be the people who reported sleep problems during their youth,” but that didn’t happen, Dr. Åkerstedt noted.

The investigators also entered data on sleep duration and sleep quality at the same time, thinking the data would cancel each other out. However, the association remained the same.

“Quite often you see that sleep duration would eliminate the effect of sleep complaints in the prediction of disease, but here both remain significant when they are entered at the same time,” Dr. Åkerstedt said. “You get the feeling that this might mean they act together to produce results,” he added.

“One other thing that surprised me is that long sleep was apparently good,” said Dr. Åkerstedt.

The investigators have conducted several studies on sleep duration and mortality. In recent research, they found that both short sleep and long sleep predicted mortality – “and often, long sleep is a stronger predictor than short sleep,” he said.

Underestimated problem?

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen Zackowski, PhD, associate vice president of research for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in Baltimore, noted that participants were asked to rate their own sleep quality during adolescence, a subjective report that may mean sleep quality has an even larger association with MS risk.

“That they found a result with sleep quality says to me that there probably is a bigger problem, because I don’t know if people over- or underestimate their sleep quality,” said Dr. Zackowski, who was not involved with the research.

“If we could get to that sleep quality question a little more objectively, I bet that we’d find there’s a lot more to the story,” she said.

That’s a story the researchers would like to explore, Dr. Åkerstedt reported. Designing a prospective study that more closely tracks sleeping habits during adolescence and follows individuals through adulthood could provide valuable information about how sleep quality and duration affect immune system development and MS risk, he said.

Dr. Zackowski said clinicians know that MS is not caused just by a genetic abnormality and that other environmental lifestyle factors seem to play a part.

“If we find out that sleep is one of those lifestyle factors, this is very changeable,” she added.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, the Swedish Brain Foundation, AFA Insurance, the European Aviation Safety Authority, the Tercentenary Fund of the Bank of Sweden, the Margaretha af Ugglas Foundation, the Swedish Foundation for MS Research, and NEURO Sweden. Dr. Åkerstadt has been supported by Tercentenary Fund of Bank of Sweden, AFA Insurance, and the European Aviation Safety Authority. Dr. Zackowski reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite ongoing challenges, experts are optimistic about the future of MS therapy

Prior to 1993, a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis could often mean an abbreviated lifespan marked by progressive disability and loss of function. That changed when the Food and Drug Administration approved interferon beta-1b (Betaseron) in 1993, which revolutionized MS therapy and gave hope to the entire MS community.

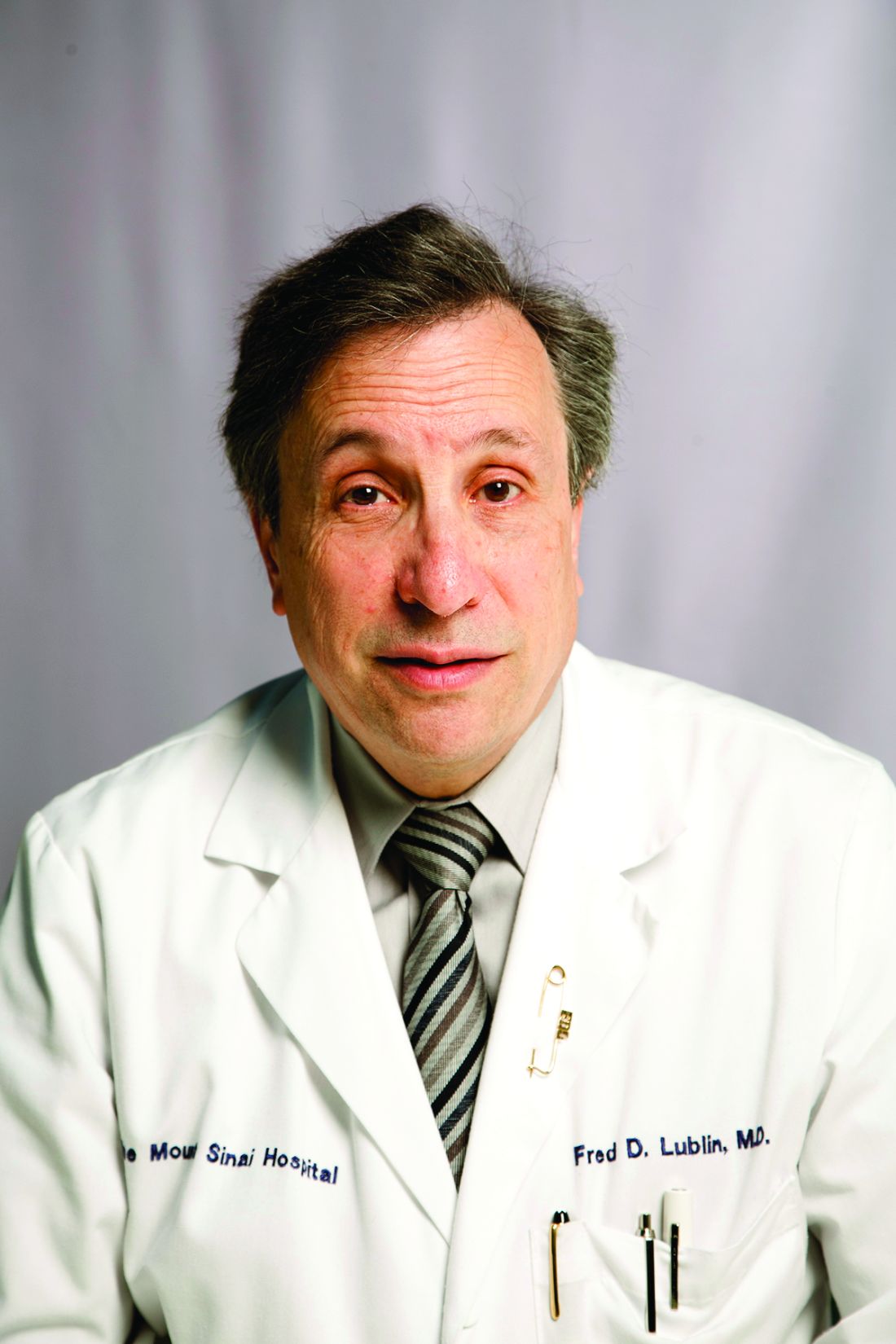

"The most surprising thing about MS management over the last 30 years is that we’ve been able to treat MS – especially relapsing MS,” said Fred D. Lublin, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis in Mount Sinai in New York. “The approval of interferon was a major therapeutic advancement because it was the first treatment for what was an untreatable disease.”

Mark Gudesblatt, MD, medical director of the Comprehensive MS Care Center of South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, N.Y., agrees.

“For people with MS, it’s an extraordinarily lucky and amazingly optimistic time,” he said. “Before interferon beta-1b, MS was called ‘the crippler of young adults’ because more than 50% of these people would require a walker 10 years after diagnosis, and a large number of young and middle-age patients with MS were residing in nursing homes.”

According to Dr. Lublin, the emergence of the immunomodulating therapies placed MS at the leading edge of neurotherapeutics. Interferon beta-1b laid the foundation for new therapies such as another interferon (interferon beta-1a; Avonex), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), and many other effective therapies with different mechanisms of action. Since the emergence of the first therapy, more than 20 oral and infusion agents with moderate to high efficacy have come to market for relapsing MS.

Treatment options, treatment challenges

Dr. Gudesblatt points out that having numerous therapies from which to choose is both a blessing and a problem.

“The good news is that there are so many options for treating relapsing MS today,” he said. “The bad news is there are so many options. Like doctors who are treating high blood pressure, doctors managing patients with MS often struggle to determine which medication is best for individual patients.”

Despite the promise of vastly better outcomes and prolonged lifespan, MS therapy still faces its share of challenges, including effective therapies for progressive MS and reparative-restorative therapies.

“Choice in route of administration and timing of administration allow for larger and broader discussions to try to meet patients’ needs,” Dr. Lublin said. “We’ve been extremely successful at treating relapses, but not as successful in treating progressive disease.”

The unclear mechanism of pathogenesis amplifies the challenges clinicians face in successful management of patients with MS. For example, experts agree that the therapies for progressive MS have only proven moderately effective at best. The paucity of therapies available for progressive MS and the limitations of the current therapies further limit the outcomes.

Looking ahead

Experts expressed optimistic views about the future of MS therapy as a whole. From Dr. Lublin’s perspective, the MS community stands to gain valuable insights from emerging research focused on treating progressive disease along with new testing to understand the underlying mechanism of progressive disease. Enhanced understanding of the underlying pathogenesis of progressive MS coupled with the ability to diagnose MS – such as improved MRI techniques – have facilitated this process.

Among the therapies with novel mechanisms of action in the pipeline include agents that generate myelin sheath repair. Another potential therapeutic class on the horizon, known as TPK inhibitors, addresses the smoldering of the disease. With these and other therapeutic advances, Dr. Lublin hopes to see better control of progressive disease.

An agenda for the future

In addition, barriers such as access to care, cost, insurance coverage, and tolerance remain ongoing stressors that will likely continue weighing on the MS community and its stakeholders into the future.

Dr. Gudesblatt concluded that advancing MS outcomes in the future hinges on several additional factors.

“We need medicines that are better for relapse and progression; medicines that are better tolerated and safer; and better medicine to address the underlying disease as well as its symptoms. But we also need to appreciate, recognize, and address cognitive impairment along the MS continuum and develop effective reparative options,” he said.

Regardless, he emphasized that these “amazing advancements” in MS therapy have renewed hope that research may identify and expand effective treatments for multiple other neurologic conditions such as muscular dystrophies, neurodegenerative and genetic disorders, movement disorders, and dysautonomia-related diseases. Like MS, all of these conditions have limited therapies, some of which have minimal efficacy. But none of these other disorders has disease-modifying therapies currently available.

‘A beacon of hope’

“MS is the beacon of hope for multiple disease states because it’s cracked the door wide open,” Dr. Gudesblatt said. Relapse no longer gauges the prognosis of today’s MS patient – a prognosis both experts think will only continue to improve with forthcoming innovations.

While the challenges for MS still exist, the bright future that lies ahead may eventually eclipse them.

Prior to 1993, a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis could often mean an abbreviated lifespan marked by progressive disability and loss of function. That changed when the Food and Drug Administration approved interferon beta-1b (Betaseron) in 1993, which revolutionized MS therapy and gave hope to the entire MS community.

"The most surprising thing about MS management over the last 30 years is that we’ve been able to treat MS – especially relapsing MS,” said Fred D. Lublin, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis in Mount Sinai in New York. “The approval of interferon was a major therapeutic advancement because it was the first treatment for what was an untreatable disease.”

Mark Gudesblatt, MD, medical director of the Comprehensive MS Care Center of South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, N.Y., agrees.

“For people with MS, it’s an extraordinarily lucky and amazingly optimistic time,” he said. “Before interferon beta-1b, MS was called ‘the crippler of young adults’ because more than 50% of these people would require a walker 10 years after diagnosis, and a large number of young and middle-age patients with MS were residing in nursing homes.”

According to Dr. Lublin, the emergence of the immunomodulating therapies placed MS at the leading edge of neurotherapeutics. Interferon beta-1b laid the foundation for new therapies such as another interferon (interferon beta-1a; Avonex), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), and many other effective therapies with different mechanisms of action. Since the emergence of the first therapy, more than 20 oral and infusion agents with moderate to high efficacy have come to market for relapsing MS.

Treatment options, treatment challenges

Dr. Gudesblatt points out that having numerous therapies from which to choose is both a blessing and a problem.

“The good news is that there are so many options for treating relapsing MS today,” he said. “The bad news is there are so many options. Like doctors who are treating high blood pressure, doctors managing patients with MS often struggle to determine which medication is best for individual patients.”

Despite the promise of vastly better outcomes and prolonged lifespan, MS therapy still faces its share of challenges, including effective therapies for progressive MS and reparative-restorative therapies.

“Choice in route of administration and timing of administration allow for larger and broader discussions to try to meet patients’ needs,” Dr. Lublin said. “We’ve been extremely successful at treating relapses, but not as successful in treating progressive disease.”

The unclear mechanism of pathogenesis amplifies the challenges clinicians face in successful management of patients with MS. For example, experts agree that the therapies for progressive MS have only proven moderately effective at best. The paucity of therapies available for progressive MS and the limitations of the current therapies further limit the outcomes.

Looking ahead

Experts expressed optimistic views about the future of MS therapy as a whole. From Dr. Lublin’s perspective, the MS community stands to gain valuable insights from emerging research focused on treating progressive disease along with new testing to understand the underlying mechanism of progressive disease. Enhanced understanding of the underlying pathogenesis of progressive MS coupled with the ability to diagnose MS – such as improved MRI techniques – have facilitated this process.

Among the therapies with novel mechanisms of action in the pipeline include agents that generate myelin sheath repair. Another potential therapeutic class on the horizon, known as TPK inhibitors, addresses the smoldering of the disease. With these and other therapeutic advances, Dr. Lublin hopes to see better control of progressive disease.

An agenda for the future

In addition, barriers such as access to care, cost, insurance coverage, and tolerance remain ongoing stressors that will likely continue weighing on the MS community and its stakeholders into the future.

Dr. Gudesblatt concluded that advancing MS outcomes in the future hinges on several additional factors.

“We need medicines that are better for relapse and progression; medicines that are better tolerated and safer; and better medicine to address the underlying disease as well as its symptoms. But we also need to appreciate, recognize, and address cognitive impairment along the MS continuum and develop effective reparative options,” he said.

Regardless, he emphasized that these “amazing advancements” in MS therapy have renewed hope that research may identify and expand effective treatments for multiple other neurologic conditions such as muscular dystrophies, neurodegenerative and genetic disorders, movement disorders, and dysautonomia-related diseases. Like MS, all of these conditions have limited therapies, some of which have minimal efficacy. But none of these other disorders has disease-modifying therapies currently available.

‘A beacon of hope’

“MS is the beacon of hope for multiple disease states because it’s cracked the door wide open,” Dr. Gudesblatt said. Relapse no longer gauges the prognosis of today’s MS patient – a prognosis both experts think will only continue to improve with forthcoming innovations.

While the challenges for MS still exist, the bright future that lies ahead may eventually eclipse them.

Prior to 1993, a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis could often mean an abbreviated lifespan marked by progressive disability and loss of function. That changed when the Food and Drug Administration approved interferon beta-1b (Betaseron) in 1993, which revolutionized MS therapy and gave hope to the entire MS community.

"The most surprising thing about MS management over the last 30 years is that we’ve been able to treat MS – especially relapsing MS,” said Fred D. Lublin, MD, professor of neurology and director of the Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis in Mount Sinai in New York. “The approval of interferon was a major therapeutic advancement because it was the first treatment for what was an untreatable disease.”

Mark Gudesblatt, MD, medical director of the Comprehensive MS Care Center of South Shore Neurologic Associates in Patchogue, N.Y., agrees.

“For people with MS, it’s an extraordinarily lucky and amazingly optimistic time,” he said. “Before interferon beta-1b, MS was called ‘the crippler of young adults’ because more than 50% of these people would require a walker 10 years after diagnosis, and a large number of young and middle-age patients with MS were residing in nursing homes.”

According to Dr. Lublin, the emergence of the immunomodulating therapies placed MS at the leading edge of neurotherapeutics. Interferon beta-1b laid the foundation for new therapies such as another interferon (interferon beta-1a; Avonex), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone), and many other effective therapies with different mechanisms of action. Since the emergence of the first therapy, more than 20 oral and infusion agents with moderate to high efficacy have come to market for relapsing MS.

Treatment options, treatment challenges

Dr. Gudesblatt points out that having numerous therapies from which to choose is both a blessing and a problem.

“The good news is that there are so many options for treating relapsing MS today,” he said. “The bad news is there are so many options. Like doctors who are treating high blood pressure, doctors managing patients with MS often struggle to determine which medication is best for individual patients.”

Despite the promise of vastly better outcomes and prolonged lifespan, MS therapy still faces its share of challenges, including effective therapies for progressive MS and reparative-restorative therapies.

“Choice in route of administration and timing of administration allow for larger and broader discussions to try to meet patients’ needs,” Dr. Lublin said. “We’ve been extremely successful at treating relapses, but not as successful in treating progressive disease.”

The unclear mechanism of pathogenesis amplifies the challenges clinicians face in successful management of patients with MS. For example, experts agree that the therapies for progressive MS have only proven moderately effective at best. The paucity of therapies available for progressive MS and the limitations of the current therapies further limit the outcomes.

Looking ahead

Experts expressed optimistic views about the future of MS therapy as a whole. From Dr. Lublin’s perspective, the MS community stands to gain valuable insights from emerging research focused on treating progressive disease along with new testing to understand the underlying mechanism of progressive disease. Enhanced understanding of the underlying pathogenesis of progressive MS coupled with the ability to diagnose MS – such as improved MRI techniques – have facilitated this process.

Among the therapies with novel mechanisms of action in the pipeline include agents that generate myelin sheath repair. Another potential therapeutic class on the horizon, known as TPK inhibitors, addresses the smoldering of the disease. With these and other therapeutic advances, Dr. Lublin hopes to see better control of progressive disease.

An agenda for the future

In addition, barriers such as access to care, cost, insurance coverage, and tolerance remain ongoing stressors that will likely continue weighing on the MS community and its stakeholders into the future.

Dr. Gudesblatt concluded that advancing MS outcomes in the future hinges on several additional factors.

“We need medicines that are better for relapse and progression; medicines that are better tolerated and safer; and better medicine to address the underlying disease as well as its symptoms. But we also need to appreciate, recognize, and address cognitive impairment along the MS continuum and develop effective reparative options,” he said.

Regardless, he emphasized that these “amazing advancements” in MS therapy have renewed hope that research may identify and expand effective treatments for multiple other neurologic conditions such as muscular dystrophies, neurodegenerative and genetic disorders, movement disorders, and dysautonomia-related diseases. Like MS, all of these conditions have limited therapies, some of which have minimal efficacy. But none of these other disorders has disease-modifying therapies currently available.

‘A beacon of hope’

“MS is the beacon of hope for multiple disease states because it’s cracked the door wide open,” Dr. Gudesblatt said. Relapse no longer gauges the prognosis of today’s MS patient – a prognosis both experts think will only continue to improve with forthcoming innovations.

While the challenges for MS still exist, the bright future that lies ahead may eventually eclipse them.

Stem cell transplant superior to DMTs for secondary progressive MS

new research suggests.

Results from a retrospective study show that more than 60% of patients with SPMS who received AHSCT were free from disability progression at 5 years. Also for these patients, improvement was more likely to be maintained for years after treatment.

The investigators noted that patients with secondary progressive disease often show little benefit from other DMTs, so interest in other treatments is high. While AHSCT is known to offer good results for patients with relapsing remitting MS, studies of its efficacy for SPMS have yielded conflicting results.

The new findings suggest it may be time to take another look at this therapy for patients with active, more severe disease, the researchers wrote.

“AHSCT may become a treatment option in secondary progressive MS patients with inflammatory activity who have failed available treatments,” said coinvestigator Matilde Inglese, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at the University of Genoa (Italy).

“Patients selection is very important to ensure the best treatment response and minimize safety issues, including transplant-related mortality,” Dr. Inglese added.

The findings were published online in Neurology.

Class III evidence

In the retrospective, propensity-matching study, researchers used two Italian registries to identify 79 patients who were treated off label with AHSCT and 1,975 patients who received another therapy.

Other DMTs included in the control-group analysis were beta-interferons, azathioprine, glatiramer acetate, mitoxantrone, fingolimod, natalizumab, methotrexate, teriflunomide, cyclophosphamide, dimethyl fumarate, or alemtuzumab.

Results showed that time to first disability progression was significantly longer for patients who had received transplants (hazard ratio, 0.5; P = .005); 61.7% of the AHSCT group were free of disability progression at 5 years versus 46.3% of the control group.

Among patients who received AHSCT, relapse rates were lower in comparison with those who received other DMTs (P < .001), and disability scores were lower over 10 years (P < .001).

The transplant group was also significantly more likely than the other-DMTs group to achieve sustained improvement in disability 3 years after treatment (34.7% vs. 4.6%; P < .001).

“This study provides Class III evidence that autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants prolonged the time to confirmed disability progression compared to other disease-modifying therapies,” the investigators wrote.

Extends the treatment population

Commenting on the study, Jeff Cohen, MD, director of experimental therapeutics at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research at the Cleveland Clinic, said the research “extends the population for which hematopoietic stem cell transplant should be considered.”

Although previous studies did not show a benefit for patients with severe progressive MS, participants in the current study had secondary progressive MS and superimposed relapse activity, said Dr. Cohen, who was not involved with the research.

“We think that indicates a greater likelihood of benefit” from AHSCT, he noted. “The fact that someone has overt progression or somewhat more severe disability doesn’t preclude the use of stem cell transplant.”

Dr. Cohen pointed out, however, that the study is not without limitations. The exclusion of patients taking B-cell therapies from the SPMS control group raises the question of whether similar results would come from a comparison with AHSCT.

In addition, Dr. Cohen noted there are safety concerns about the therapy, which has yielded higher transplant-related mortality among patients with SPMS – although only one patient in the current study died following the transplant.

Still, the findings are promising, Dr. Cohen added.

“I think as more data accumulate that supports its benefit and reasonable safety in a variety of populations, we’ll see it used more,” he said.

The study was funded by the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. Dr. Inglese has received fees for consultation from Roche, Genzyme, Merck, Biogen, and Novartis. Dr. Cohen reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Results from a retrospective study show that more than 60% of patients with SPMS who received AHSCT were free from disability progression at 5 years. Also for these patients, improvement was more likely to be maintained for years after treatment.

The investigators noted that patients with secondary progressive disease often show little benefit from other DMTs, so interest in other treatments is high. While AHSCT is known to offer good results for patients with relapsing remitting MS, studies of its efficacy for SPMS have yielded conflicting results.

The new findings suggest it may be time to take another look at this therapy for patients with active, more severe disease, the researchers wrote.

“AHSCT may become a treatment option in secondary progressive MS patients with inflammatory activity who have failed available treatments,” said coinvestigator Matilde Inglese, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at the University of Genoa (Italy).

“Patients selection is very important to ensure the best treatment response and minimize safety issues, including transplant-related mortality,” Dr. Inglese added.

The findings were published online in Neurology.

Class III evidence

In the retrospective, propensity-matching study, researchers used two Italian registries to identify 79 patients who were treated off label with AHSCT and 1,975 patients who received another therapy.

Other DMTs included in the control-group analysis were beta-interferons, azathioprine, glatiramer acetate, mitoxantrone, fingolimod, natalizumab, methotrexate, teriflunomide, cyclophosphamide, dimethyl fumarate, or alemtuzumab.

Results showed that time to first disability progression was significantly longer for patients who had received transplants (hazard ratio, 0.5; P = .005); 61.7% of the AHSCT group were free of disability progression at 5 years versus 46.3% of the control group.

Among patients who received AHSCT, relapse rates were lower in comparison with those who received other DMTs (P < .001), and disability scores were lower over 10 years (P < .001).

The transplant group was also significantly more likely than the other-DMTs group to achieve sustained improvement in disability 3 years after treatment (34.7% vs. 4.6%; P < .001).

“This study provides Class III evidence that autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants prolonged the time to confirmed disability progression compared to other disease-modifying therapies,” the investigators wrote.

Extends the treatment population

Commenting on the study, Jeff Cohen, MD, director of experimental therapeutics at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research at the Cleveland Clinic, said the research “extends the population for which hematopoietic stem cell transplant should be considered.”

Although previous studies did not show a benefit for patients with severe progressive MS, participants in the current study had secondary progressive MS and superimposed relapse activity, said Dr. Cohen, who was not involved with the research.

“We think that indicates a greater likelihood of benefit” from AHSCT, he noted. “The fact that someone has overt progression or somewhat more severe disability doesn’t preclude the use of stem cell transplant.”

Dr. Cohen pointed out, however, that the study is not without limitations. The exclusion of patients taking B-cell therapies from the SPMS control group raises the question of whether similar results would come from a comparison with AHSCT.

In addition, Dr. Cohen noted there are safety concerns about the therapy, which has yielded higher transplant-related mortality among patients with SPMS – although only one patient in the current study died following the transplant.

Still, the findings are promising, Dr. Cohen added.

“I think as more data accumulate that supports its benefit and reasonable safety in a variety of populations, we’ll see it used more,” he said.

The study was funded by the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. Dr. Inglese has received fees for consultation from Roche, Genzyme, Merck, Biogen, and Novartis. Dr. Cohen reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Results from a retrospective study show that more than 60% of patients with SPMS who received AHSCT were free from disability progression at 5 years. Also for these patients, improvement was more likely to be maintained for years after treatment.

The investigators noted that patients with secondary progressive disease often show little benefit from other DMTs, so interest in other treatments is high. While AHSCT is known to offer good results for patients with relapsing remitting MS, studies of its efficacy for SPMS have yielded conflicting results.

The new findings suggest it may be time to take another look at this therapy for patients with active, more severe disease, the researchers wrote.

“AHSCT may become a treatment option in secondary progressive MS patients with inflammatory activity who have failed available treatments,” said coinvestigator Matilde Inglese, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at the University of Genoa (Italy).

“Patients selection is very important to ensure the best treatment response and minimize safety issues, including transplant-related mortality,” Dr. Inglese added.

The findings were published online in Neurology.

Class III evidence

In the retrospective, propensity-matching study, researchers used two Italian registries to identify 79 patients who were treated off label with AHSCT and 1,975 patients who received another therapy.

Other DMTs included in the control-group analysis were beta-interferons, azathioprine, glatiramer acetate, mitoxantrone, fingolimod, natalizumab, methotrexate, teriflunomide, cyclophosphamide, dimethyl fumarate, or alemtuzumab.

Results showed that time to first disability progression was significantly longer for patients who had received transplants (hazard ratio, 0.5; P = .005); 61.7% of the AHSCT group were free of disability progression at 5 years versus 46.3% of the control group.

Among patients who received AHSCT, relapse rates were lower in comparison with those who received other DMTs (P < .001), and disability scores were lower over 10 years (P < .001).

The transplant group was also significantly more likely than the other-DMTs group to achieve sustained improvement in disability 3 years after treatment (34.7% vs. 4.6%; P < .001).

“This study provides Class III evidence that autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants prolonged the time to confirmed disability progression compared to other disease-modifying therapies,” the investigators wrote.

Extends the treatment population

Commenting on the study, Jeff Cohen, MD, director of experimental therapeutics at the Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research at the Cleveland Clinic, said the research “extends the population for which hematopoietic stem cell transplant should be considered.”

Although previous studies did not show a benefit for patients with severe progressive MS, participants in the current study had secondary progressive MS and superimposed relapse activity, said Dr. Cohen, who was not involved with the research.

“We think that indicates a greater likelihood of benefit” from AHSCT, he noted. “The fact that someone has overt progression or somewhat more severe disability doesn’t preclude the use of stem cell transplant.”

Dr. Cohen pointed out, however, that the study is not without limitations. The exclusion of patients taking B-cell therapies from the SPMS control group raises the question of whether similar results would come from a comparison with AHSCT.

In addition, Dr. Cohen noted there are safety concerns about the therapy, which has yielded higher transplant-related mortality among patients with SPMS – although only one patient in the current study died following the transplant.

Still, the findings are promising, Dr. Cohen added.

“I think as more data accumulate that supports its benefit and reasonable safety in a variety of populations, we’ll see it used more,” he said.

The study was funded by the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Foundation. Dr. Inglese has received fees for consultation from Roche, Genzyme, Merck, Biogen, and Novartis. Dr. Cohen reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Four-gene signature linked to increased PML risk

a team of European and U.S. investigators reported.

The four-gene signature could be used to screen patients who are currently taking or are candidates for drugs know to increase risk for PML, a rare but frequently lethal demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system, according to Eli Hatchwell, MD, PhD, from Population BIO UK in Oxfordshire, England, and colleagues.

“Due to the seriousness of a PML diagnosis – particularly because it often leads to life-threatening outcomes and the lack of treatment options once it develops – it would seem unethical not to test individuals considering immunosuppressive therapies with PML risk for our top four variants, and advising those with a positive result to consider an alternative therapy or treatment strategy,” they wrote in a study published in Frontiers in Neurology.

Benign virus, bad disease

PML is caused by reactivation of the otherwise benign JC virus (JCV), also known as human polyomavirus 2. (The “J” and “C” in the virus’ common name stand for John Cunningham, a man with Hodgkin lymphoma from whose brain the virus was first isolated, in 1971.)

The estimated prevalence of JCV infection ranges from 40% to 70% of the population worldwide, although PML itself is rare, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 200,000.

PML is a complication of treatment with targeted monoclonal antibodies, such as natalizumab (Tysabri), rituximab (Rituxan), alemtuzumab (Campath; Lemtrada), and other agents with immunosuppressive properties, such as dimethyl fumarate and mycophenolate mofetil.

In addition, PML can occur among patients with diseases that disrupt or inhibit natural immunity, such as HIV/AIDS, hematologic cancers, and autoimmune diseases.

Predisposing variants suspected

Dr. Hatchwell and colleagues hypothesized that some patients may have rare genetic variants in immune-system genes that predispose them to increased risk for PML. The researchers had previously shown an association between PML and 19 genetic risk variants among 184 patients with PML.

In the current study, they looked at variants in an additional 152 patients with PML who served as a validation sample. Of the 19 risk variants they had previously identified, the investigators narrowed the field down to 4 variants in both population controls and in a matched control set consisting of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who were positive for JCV and who were on therapy with a PML-linked drug for at least 2 years.

The four variants they identified, all linked to immune viral defense, were C8B, 1-57409459-C-A, rs139498867; LY9 (a checkpoint regulator also known as SLAMF3), 1-160769595-AG-A, rs763811636; FCN2, 9-137779251-G-A, rs76267164; and STXBP2, 19-7712287-G-C, rs35490401.

In all, 10.9% of patients with PML carried at least one of the variants.

The investigators reported that carriers of any one of the variants has a nearly ninefold risk for developing PML after exposure to a PML-linked drug compared with non-carriers with similar drug exposures (odds ratio, 8.7; P < .001).

“Measures of clinical validity and utility compare favorably to other genetic risk tests, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 screening for breast cancer risk and HLA-B_15:02 pharmacogenetic screening for pharmacovigilance of carbamazepine to prevent Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis,” the authors noted.

Screening? Maybe

In a press release, Lawrence Steinman, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, who was not involved in the study, stated that “preventative screening for these variants should become part of the standard of care. I wish we had more powerful tools like this for other therapies.”

But another neurologist who was not involved in the study commented that the finding, while “exciting” as a confirmation study, is not as yet practice changing.

“It does give us very good confidence that these four genes are indeed risk factors that increase the risk of this brain infection by quite a bit, so that makes it very exciting,” said Robert Fox, MD, from the Neurological Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Indeed, we are trying to risk-stratify patients to try to reduce the risk of PML in the patients treated with our MS drugs. So for natalizumab we risk stratify by testing them for JC virus serology. Half of people don’t have it and we say ‘OK, you’re good to go.’ With other drugs like Tecfidera – dimethyl fumarate – we follow their lymphocyte counts, so when their lymphocyte counts drop too low we say ‘OK, you need to come off the drug because of the risk of PML,’ ” he said in an interview.

The four-gene signature, however, only identifies about 11% of patients with PML, which is not a sufficiently large enough effect to be clinically useful. For example, the risk for PML in patients treated with natalizumab is about 1%, and if the test can only detect enhanced risk in about 11% of those patients, the risk would drop from 1% to 0.9%, which “doesn’t really the move needle much,” he pointed out.

Dr. Fox also noted that neurologists now have a large formulary of drugs to offer their patients, including agents (such as interferon-beta and corticosteroids that are not associated with increased risk for PML).

The study was funded by Emerald Lake Safety and Population Bio. Dr. Hatchwell and several coauthors are employees of the respective companies, and several are inventors of genetic screening methods for PML. Dr. Steiman has disclosed consulting for TG Therapeutics. Dr. Fox reported consulting for manufacturers of MS therapies.

a team of European and U.S. investigators reported.

The four-gene signature could be used to screen patients who are currently taking or are candidates for drugs know to increase risk for PML, a rare but frequently lethal demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system, according to Eli Hatchwell, MD, PhD, from Population BIO UK in Oxfordshire, England, and colleagues.

“Due to the seriousness of a PML diagnosis – particularly because it often leads to life-threatening outcomes and the lack of treatment options once it develops – it would seem unethical not to test individuals considering immunosuppressive therapies with PML risk for our top four variants, and advising those with a positive result to consider an alternative therapy or treatment strategy,” they wrote in a study published in Frontiers in Neurology.

Benign virus, bad disease

PML is caused by reactivation of the otherwise benign JC virus (JCV), also known as human polyomavirus 2. (The “J” and “C” in the virus’ common name stand for John Cunningham, a man with Hodgkin lymphoma from whose brain the virus was first isolated, in 1971.)

The estimated prevalence of JCV infection ranges from 40% to 70% of the population worldwide, although PML itself is rare, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 200,000.

PML is a complication of treatment with targeted monoclonal antibodies, such as natalizumab (Tysabri), rituximab (Rituxan), alemtuzumab (Campath; Lemtrada), and other agents with immunosuppressive properties, such as dimethyl fumarate and mycophenolate mofetil.

In addition, PML can occur among patients with diseases that disrupt or inhibit natural immunity, such as HIV/AIDS, hematologic cancers, and autoimmune diseases.

Predisposing variants suspected

Dr. Hatchwell and colleagues hypothesized that some patients may have rare genetic variants in immune-system genes that predispose them to increased risk for PML. The researchers had previously shown an association between PML and 19 genetic risk variants among 184 patients with PML.

In the current study, they looked at variants in an additional 152 patients with PML who served as a validation sample. Of the 19 risk variants they had previously identified, the investigators narrowed the field down to 4 variants in both population controls and in a matched control set consisting of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who were positive for JCV and who were on therapy with a PML-linked drug for at least 2 years.

The four variants they identified, all linked to immune viral defense, were C8B, 1-57409459-C-A, rs139498867; LY9 (a checkpoint regulator also known as SLAMF3), 1-160769595-AG-A, rs763811636; FCN2, 9-137779251-G-A, rs76267164; and STXBP2, 19-7712287-G-C, rs35490401.

In all, 10.9% of patients with PML carried at least one of the variants.

The investigators reported that carriers of any one of the variants has a nearly ninefold risk for developing PML after exposure to a PML-linked drug compared with non-carriers with similar drug exposures (odds ratio, 8.7; P < .001).

“Measures of clinical validity and utility compare favorably to other genetic risk tests, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 screening for breast cancer risk and HLA-B_15:02 pharmacogenetic screening for pharmacovigilance of carbamazepine to prevent Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis,” the authors noted.

Screening? Maybe

In a press release, Lawrence Steinman, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, who was not involved in the study, stated that “preventative screening for these variants should become part of the standard of care. I wish we had more powerful tools like this for other therapies.”

But another neurologist who was not involved in the study commented that the finding, while “exciting” as a confirmation study, is not as yet practice changing.

“It does give us very good confidence that these four genes are indeed risk factors that increase the risk of this brain infection by quite a bit, so that makes it very exciting,” said Robert Fox, MD, from the Neurological Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Indeed, we are trying to risk-stratify patients to try to reduce the risk of PML in the patients treated with our MS drugs. So for natalizumab we risk stratify by testing them for JC virus serology. Half of people don’t have it and we say ‘OK, you’re good to go.’ With other drugs like Tecfidera – dimethyl fumarate – we follow their lymphocyte counts, so when their lymphocyte counts drop too low we say ‘OK, you need to come off the drug because of the risk of PML,’ ” he said in an interview.

The four-gene signature, however, only identifies about 11% of patients with PML, which is not a sufficiently large enough effect to be clinically useful. For example, the risk for PML in patients treated with natalizumab is about 1%, and if the test can only detect enhanced risk in about 11% of those patients, the risk would drop from 1% to 0.9%, which “doesn’t really the move needle much,” he pointed out.

Dr. Fox also noted that neurologists now have a large formulary of drugs to offer their patients, including agents (such as interferon-beta and corticosteroids that are not associated with increased risk for PML).

The study was funded by Emerald Lake Safety and Population Bio. Dr. Hatchwell and several coauthors are employees of the respective companies, and several are inventors of genetic screening methods for PML. Dr. Steiman has disclosed consulting for TG Therapeutics. Dr. Fox reported consulting for manufacturers of MS therapies.

a team of European and U.S. investigators reported.

The four-gene signature could be used to screen patients who are currently taking or are candidates for drugs know to increase risk for PML, a rare but frequently lethal demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system, according to Eli Hatchwell, MD, PhD, from Population BIO UK in Oxfordshire, England, and colleagues.

“Due to the seriousness of a PML diagnosis – particularly because it often leads to life-threatening outcomes and the lack of treatment options once it develops – it would seem unethical not to test individuals considering immunosuppressive therapies with PML risk for our top four variants, and advising those with a positive result to consider an alternative therapy or treatment strategy,” they wrote in a study published in Frontiers in Neurology.

Benign virus, bad disease

PML is caused by reactivation of the otherwise benign JC virus (JCV), also known as human polyomavirus 2. (The “J” and “C” in the virus’ common name stand for John Cunningham, a man with Hodgkin lymphoma from whose brain the virus was first isolated, in 1971.)

The estimated prevalence of JCV infection ranges from 40% to 70% of the population worldwide, although PML itself is rare, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 200,000.

PML is a complication of treatment with targeted monoclonal antibodies, such as natalizumab (Tysabri), rituximab (Rituxan), alemtuzumab (Campath; Lemtrada), and other agents with immunosuppressive properties, such as dimethyl fumarate and mycophenolate mofetil.

In addition, PML can occur among patients with diseases that disrupt or inhibit natural immunity, such as HIV/AIDS, hematologic cancers, and autoimmune diseases.

Predisposing variants suspected

Dr. Hatchwell and colleagues hypothesized that some patients may have rare genetic variants in immune-system genes that predispose them to increased risk for PML. The researchers had previously shown an association between PML and 19 genetic risk variants among 184 patients with PML.

In the current study, they looked at variants in an additional 152 patients with PML who served as a validation sample. Of the 19 risk variants they had previously identified, the investigators narrowed the field down to 4 variants in both population controls and in a matched control set consisting of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who were positive for JCV and who were on therapy with a PML-linked drug for at least 2 years.

The four variants they identified, all linked to immune viral defense, were C8B, 1-57409459-C-A, rs139498867; LY9 (a checkpoint regulator also known as SLAMF3), 1-160769595-AG-A, rs763811636; FCN2, 9-137779251-G-A, rs76267164; and STXBP2, 19-7712287-G-C, rs35490401.

In all, 10.9% of patients with PML carried at least one of the variants.

The investigators reported that carriers of any one of the variants has a nearly ninefold risk for developing PML after exposure to a PML-linked drug compared with non-carriers with similar drug exposures (odds ratio, 8.7; P < .001).

“Measures of clinical validity and utility compare favorably to other genetic risk tests, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 screening for breast cancer risk and HLA-B_15:02 pharmacogenetic screening for pharmacovigilance of carbamazepine to prevent Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis,” the authors noted.

Screening? Maybe

In a press release, Lawrence Steinman, MD, from Stanford (Calif.) University, who was not involved in the study, stated that “preventative screening for these variants should become part of the standard of care. I wish we had more powerful tools like this for other therapies.”

But another neurologist who was not involved in the study commented that the finding, while “exciting” as a confirmation study, is not as yet practice changing.

“It does give us very good confidence that these four genes are indeed risk factors that increase the risk of this brain infection by quite a bit, so that makes it very exciting,” said Robert Fox, MD, from the Neurological Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

“Indeed, we are trying to risk-stratify patients to try to reduce the risk of PML in the patients treated with our MS drugs. So for natalizumab we risk stratify by testing them for JC virus serology. Half of people don’t have it and we say ‘OK, you’re good to go.’ With other drugs like Tecfidera – dimethyl fumarate – we follow their lymphocyte counts, so when their lymphocyte counts drop too low we say ‘OK, you need to come off the drug because of the risk of PML,’ ” he said in an interview.

The four-gene signature, however, only identifies about 11% of patients with PML, which is not a sufficiently large enough effect to be clinically useful. For example, the risk for PML in patients treated with natalizumab is about 1%, and if the test can only detect enhanced risk in about 11% of those patients, the risk would drop from 1% to 0.9%, which “doesn’t really the move needle much,” he pointed out.

Dr. Fox also noted that neurologists now have a large formulary of drugs to offer their patients, including agents (such as interferon-beta and corticosteroids that are not associated with increased risk for PML).

The study was funded by Emerald Lake Safety and Population Bio. Dr. Hatchwell and several coauthors are employees of the respective companies, and several are inventors of genetic screening methods for PML. Dr. Steiman has disclosed consulting for TG Therapeutics. Dr. Fox reported consulting for manufacturers of MS therapies.

FROM FRONTIERS IN NEUROLOGY

MS and Emotional Stress: Is There a Relation?

Sir Augustus d’Este (1794-1848) described the circumstances preceding his development of neurological symptoms as follows:1 “I travelled from Ramsgate to the Highlands of Scotland for the purpose of passing some days with a Relation for whom I had the affection of a Son. On my arrival I found him dead. Shortly after the funeral I was obliged to have my letters read to me, and their answers written for me, as my eyes were so attacked that when fixed upon minute objects indistinctness of vision was the consequence: Soon after I went to Ireland, and without any thing having been done to my eyes, they completely recovered their strength and distinctness of vision…" He then described a clinical course of relapsing-remitting neurologic symptoms merging into a progressive stage of unrelenting illness, most fitting with what we know today as multiple sclerosis (MS).1 Why did Sir Augustus d'Este connect the event of the unexpected death to the onset of a lifelong neurologic disease?

Jean-Martin Charcot first described MS in a way close to what we know it as today. Charcot considered stress a factor in MS. He linked grief, vexation, and adverse changes in social circumstances to the onset of MS at that time.2 I, as a practicing MS specialist, am surprised neither by Sir Augustus d'Este's diary nor by Charcot's earlier assessments of MS triggers.3 As I write this narrative, I think of the many times I heard from people diagnosed with MS. "It happened to me because of stress" is a statement not estranged from my daily clinical practice

MS as a multifactorial disease

It is tempting to make a case for emotional stress as a cause of MS, but one must remember that MS is a very complex disease with unclear etiologies. MS, a treatable but not yet curable disease, is the interplay between the genetics of the host and numerous environmental factors that exploit a susceptible immune system leading to unrelenting immune dysregulation.4 Recent studies have brought some pieces of this intricate puzzle together. The role of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in the pathogenesis of MS is being dissected.5 The possible synergy between vitamin D deficiency, EBV, and certain genetic variations is being studied.6 The roles of smoking, environmental toxins, obesity, diet, Western lifestyle, and the gut microbiome are some of the top areas of clinical, translational, and basic research.7-11 But what about emotional stress? Where does it fit, if anywhere, in the current research paradigm?

Emotional stress and MS—Causality or not?

In the scientific method, several criteria must be proven for an element to be suspected in the etiology of a disease.12 First, the suspect element must be present before the disease starts—i.e., a temporal association. Second, there must be a plausible biological explanation of how the suspect element acts in the disease's causation. Third, other variables that could confound the picture must be controlled for or dismissed. It is clear that no single factor is the cause of MS. By now, MS is agreed upon as a disease caused by multiple factors, some of which remain to be unraveled.9 The term "cause" has been utilized more recently by many authors when referring to EBV in relation to MS development, reasoning that in one study, in a small number of individuals with MS, EBV infection preceded the MS clinical diagnosis.13 Thus, the temporal association was provided. But does MS start at the onset of clinical symptoms?

For Sir Augustus d'Este, the disease may have started years before he visited the Highlands of Scotland, but only at that visit did MS become clinically apparent. So, the emotional trauma may have acted as a "trigger" for an MS flare-up rather than being a "cause" of MS. This might be a more plausible explanation of the association between emotional trauma and MS development. However, MS pathogenesis is complex, and one could argue that the disease starts many years before the first clinical symptoms that lead to diagnosis.

The MS prodrome has been demonstrated by several studies that suggest that MS may start many years before the clinical diagnosis.14 Radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS) further argues that MS may be clinically dormant for years, and clinical symptoms may not appear until later in the disease process.15 One may think that immune attacks on the optic nerves, spinal cord, or areas of the brainstem might be readily symptomatic compared to attacks on other structures of the central nervous system (e.g., periventricular or juxtacortical brain areas) that may be clinically silent. So, while for Sir Augustus d'Este it seemed that the disease started at the time of his visit to the Highlands of Scotland, it is equally plausible that it started years before the first clinical attack. Nevertheless, how could emotional stress play a role in the pathophysiology of MS?

Stress and the Immune System

At times of chronic stress, one may become more susceptible to infections. Reactivation of certain viruses can lead to oral ulcers, increased common cold symptoms, or other illnesses. For example, stress can reactivate herpes simplex type 1 and interestingly, EBV.16,17 In MS, the immune system is dysregulated and has an autoimmune component. The effect of acute emotional stress differs from that of chronic stress.18 Several studies have examined the immune responses to both forms of stress.19-21

Interestingly, acute stress activates cell-mediated immunity, increases immune cell trafficking to areas of injury, and, importantly, increases blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability by activating resident mast cells in the brain and other areas, including the optic nerves.22,23 Mast cell activation leads to BBB disruption, which is a key early step in the pathogenesis of MS. Thus, it is plausible that the proinflammatory changes associated with acute stress could be implicated in the pathogenesis of MS. This contrasts with chronic stress, which attenuates various immune responses, including suppressing cell-mediated immunity, but also dysregulate the immune system.

One could establish a biological plausibility for stress playing a role in the proinflammatory responses in MS. Whether it is causal or not, scientists can further explore the potential biologic explanations. While studying the association between acute stress and MS development or disease activity is difficult, several groups have examined the potential association. Many studies, however, have limitations due to the difficult nature of studying such an association, especially in quantifying or defining acute stress in general.

A limited number of studies on MS and stress: What do we know? And what are the challenges?

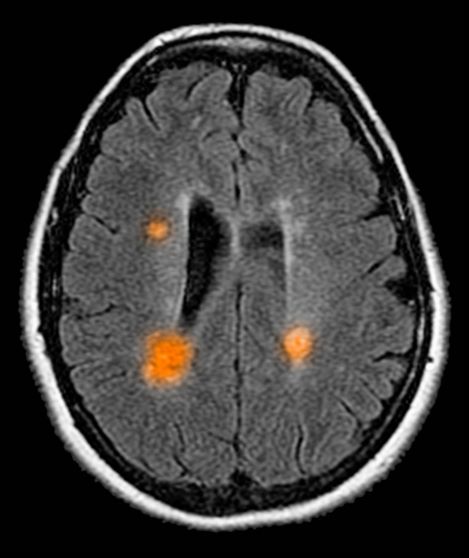

Rare studies have reported a potential association between MS development and stressful life events, while others reported no association.24-26 Also, some studies observed an increase in MS relapses or the development of new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesions following stressful life events or wartime, while others failed to show such an association.26-30 There are few studies directly addressing the potential association between acute emotional stress and MS. The results of published studies are variable, and limitations are numerous. Limitations include the difficulty in measuring acute emotional stress, difficulty in its prediction, and ethical challenges of experimental design and recruiting participants. So, studies have focused on observational aspects, retrospective reviews, and surveys of memories prone to various biases. Rarely was the design of these clinical studies prospective. A few prospective studies reported an association between stressful life events and increased MS relapses and increased number of brain lesions.27,31,32 Rare clinical trials have attempted to test stress reduction strategies and reported on the modest improvement of patient-reported outcomes and, in one study, a modest improvement in new MRI lesions.33-35

Overall, several lines of evidence support a potential association between acute emotional stress and MS. Yet, the association is challenging to study, and future research might focus on stress-mitigation strategies and improving coping mechanisms in persons living with MS. It is important to note that it will be very difficult to design prospective studies to examine the potential association between acute emotional trauma and the development of de novo MS. Such studies will require a large number of participants (e.g., hundreds of thousands), long durations of follow-up (e.g., decades), and ways to classify repeated stressful events. An alternative approach is to ask persons newly diagnosed with MS at the time of initial diagnosis about any temporal association between their first symptom and stressful life events. However, this approach would provide some information on any association between the two, but not on causality of the disease itself.

Conclusion

The potential association between acute emotional stress and MS dates to the times of early descriptions of MS. Yet, research has been very limited and challenging. To date, the potential association remains elusive. Lines of evidence, while with limitations, have provided possible biologic explanations for the relationship between MS symptom onset and acute emotional stress. Although avoiding acute emotional stress is nearly impossible, incorporating global stress-coping strategies in early childhood education and secondary education might theoretically have potential beneficial effects on the subsequent risk of MS development or symptom flare-up, depending on a variety of factors.

But for now, when patients and colleagues ask me, “Can acute emotional stress be a ‘trigger’ for MS symptomology?,” my answer will remain, “Potentially, until proven otherwise.”

- Firth D. The case of Augustus d'Este (1794-1848): the first account of disseminated sclerosis: (section of the History of Medicine). Proc R Soc Med. 1941;34(7):381-384.

- Lectures on the diseases of the nervous system. Br Foreign Med Chir Rev. 1877;60(119):180-181.

- Obeidat, A, Cope T. Stressful life events and multiple sclerosis: a call for re-evaluation. Paper presented at: Fifth Cooperative Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; May 13, 2013; Orlando, FL.

- Waubant E, Lucas R, Mowry E, et al. Environmental and genetic risk factors for MS: an integrated review. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(9):1905-1922. doi:10.1002/acn3.50862

- Soldan SS, Lieberman PM. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;1-14. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00770-5

- Marcucci SB, Obeidat AZ. EBNA1, EBNA2, and EBNA3 link Epstein-Barr virus and hypovitaminosis D in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. J Neuroimmunol. 2020;339:57711 doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2019.577116

- Alfredsson L, Olsson T. Lifestyle and environmental factors in multiple sclerosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2019;9(4):a028944. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a028944

- Thompson AJ, Baranzini SE, Geurts J, Hemmer B, Ciccarelli O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2018;391(10130):1622-1636. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30481-1

- Dobson R, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis – a review. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(1):27-40. doi:10.1111/ene.13819

- Arneth B. Multiple sclerosis and smoking. Am J Med. 2020;133(7):783-788. doi:1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.008

- Correale J, Hohlfeld R, Baranzini SE. The role of the gut microbiota in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022;18(9):544-558. doi:10.1038/s41582-022-00697-8

- Gianicolo EAL, Eichler M, Muensterer O, Strauch K, Blettner M. Methods for evaluating causality in observational studies. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;116(7):101-107. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2020.0101

- Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296-301. doi:10.1126/science.abj8222

- Makhani N, Tremlett H. The multiple sclerosis prodrome. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(8):515-521. doi:10.1038/s41582-021-00519-3

- Hosseiny M, Newsome SD, Yousem DM. Radiologically isolated syndrome: a review for neuroradiologists. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41(9):1542-1549. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A6649

- Padgett DA, Sheridan JF, Dorne J, Berntson GG, Candelora J, Glaser R. Social stress and the reactivation of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 [published correction appears in Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(20):12070]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(12):7231-7235. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.12.7231

- Glaser R, Pearson GR, Jones JF, et al. Stress-related activation of Epstein-Barr virus. Brain Behav Immun. 1991;5(2):219-232. doi:10.1016/0889-1591(91)90018-6

- Dhabhar FS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress on immune function: implications for immunoprotection and immunopathology. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2009;16(5):300-317. doi:10.1159/000216188

- Musazzi L, Tornese P, Sala N, Popoli M. Acute or chronic? A stressful question. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40(9):525-535. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2017.07.002

- Dhabhar FS, McEwen BS. Acute stress enhances while chronic stress suppresses cell-mediated immunity in vivo: a potential role for leukocyte trafficking. Brain Behav Immun. 1997;11(4):286-306. doi:10.1006/brbi.1997.0508

- Maydych V, Claus M, Dychus N, et al. Impact of chronic and acute academic stress on lymphocyte subsets and monocyte function. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0188108. Published 2017 Nov 16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0188108

- Esposito P, Gheorghe D, Kandere K, et al. Acute stress increases permeability of the blood-brain-barrier through activation of brain mast cells. Brain Res. 2001;888(1):117-127. doi:10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03026-2

- Kempuraj D, Mentor S, Thangavel R, et al. Mast cells in stress, pain, blood-brain barrier, neuroinflammation and Alzheimer's disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:54. doi:10.3389/fncel.2019.00054

- Karagkouni A, Alevizos M, Theoharides TC. Effect of stress on brain inflammation and multiple sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2013;12(10):947-953. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.006

- Briones-Buixassa L, Milà R, Mª Aragonès J, Bufill E, Olaya B, Arrufat FX. Stress and multiple sclerosis: a systematic review considering potential moderating and mediating factors and methods of assessing stress. Health Psychol Open. 2015;2(2):2055102915612271. doi:10.1177/2055102915612271

- Riise T, Mohr DC, Munger KL, Rich-Edwards JW, Kawachi I, Ascherio A. Stress and the risk of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011;76(22):1866-1871. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821d74c5

- Burns MN, Nawacki E, Kwasny MJ, Pelletier D, Mohr DC. Do positive or negative stressful events predict the development of new brain lesions in people with multiple sclerosis? Psychol Med. 2014;44(2):349-359. doi:10.1017/S0033291713000755

- Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Bacchetti P, et al. Psychological stress and the subsequent appearance of new brain MRI lesions in MS. Neurology. 2000;55(1):55-61. doi:10.1212/wnl.55.1.55

- Yamout B, Itani S, Hourany R, Sibaii AM, Yaghi S. The effect of war stress on multiple sclerosis exacerbations and radiological disease activity. J Neurol Sci. 2010;288(1-2):42-44. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2009.10.012

- Artemiadis AK, Anagnostouli MC, Alexopoulos EC. Stress as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis onset or relapse: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36(2):109-120. doi:10.1159/000323953

- Brown RF, Tennant CC, Sharrock M, Hodgkinson S, Dunn SM, Pollard JD. Relationship between stress and relapse in multiple sclerosis: Part I. Important features. Mult Scler. 2006;12(4):453-464. doi:10.1191/1352458506ms1295oa