User login

A (former) skeptic’s view of bariatric surgery

Because of the high prevalence of obesity and diabetes, bariatric surgery has become very popular. In the United States alone, there were an estimated 228,000 weight loss surgical procedures performed in 2017.1

But I must confess that for many years, I was skeptical about the value of surgery to treat obesity. Yes, everyone who had a bariatric procedure lost weight, but did the long-term benefits really outweigh the harms? I wondered if most people gradually gained back the weight they lost. And the harms can be significant, including dumping syndrome, hypoglycemia, and malabsorption—in addition to the potential for surgical complications and repeat surgery. And, I must confess that my views were likely affected by the death of a friend from complications of gastric bypass 25 years ago.

My skepticism, however, has changed to cautious optimism for carefully selected patients. I say this because we now have long-term follow-up studies demonstrating the value of bariatric procedures—especially for people with type 2 diabetes.

Most studies have been cohort studies that compare results to similar patients with obesity who did not have surgery, and the outcomes have been consistently better in patients who underwent surgery. Two recent meta-analyses summarized these results; one for all patients with obesity and the other for patients with type 2 diabetes.

Continue to: The first meta-analysis

The first meta-analysis included 11 randomized trials, 4 nonrandomized controlled trials, and 17 cohort studies and showed probable reductions in all-cause mortality and possible reductions in cancer and cardiovascular events.2 The second demonstrated significant improvements in microvascular and macrovascular disease and reduced mortality.3 The data were limited, however, because of the lack of large randomized trials with long-term follow-up.

The Stampede trial is one of a few bariatric surgery randomized trials focusing on patients with diabetes.4 The 5-year follow-up results are impressive. Nearly 30% of patients who had gastric bypass and 23% who had sleeve gastrectomy had an A1C ≤6 at 5 years compared to only 5% of those treated medically. Some patients discontinued all medications for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

There is now adequate research to show that bariatric surgery provides significant benefits to properly selected patients who understand the risks. I no longer hesitate to refer patients for bariatric surgery who have been unsuccessful with weight loss—despite their best efforts.

Where do you stand?

1. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed September 18, 2018.

2. Zhou X, Yu J, Li L, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality, cardiovascular events, and cancer outcomes in obese patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2590-2601.

3. Sheng B, Truong K, Spitler H, et al. The long-term effects of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes remission, microvascular and macrovascular complications, and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2724-2732.

4. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

Because of the high prevalence of obesity and diabetes, bariatric surgery has become very popular. In the United States alone, there were an estimated 228,000 weight loss surgical procedures performed in 2017.1

But I must confess that for many years, I was skeptical about the value of surgery to treat obesity. Yes, everyone who had a bariatric procedure lost weight, but did the long-term benefits really outweigh the harms? I wondered if most people gradually gained back the weight they lost. And the harms can be significant, including dumping syndrome, hypoglycemia, and malabsorption—in addition to the potential for surgical complications and repeat surgery. And, I must confess that my views were likely affected by the death of a friend from complications of gastric bypass 25 years ago.

My skepticism, however, has changed to cautious optimism for carefully selected patients. I say this because we now have long-term follow-up studies demonstrating the value of bariatric procedures—especially for people with type 2 diabetes.

Most studies have been cohort studies that compare results to similar patients with obesity who did not have surgery, and the outcomes have been consistently better in patients who underwent surgery. Two recent meta-analyses summarized these results; one for all patients with obesity and the other for patients with type 2 diabetes.

Continue to: The first meta-analysis

The first meta-analysis included 11 randomized trials, 4 nonrandomized controlled trials, and 17 cohort studies and showed probable reductions in all-cause mortality and possible reductions in cancer and cardiovascular events.2 The second demonstrated significant improvements in microvascular and macrovascular disease and reduced mortality.3 The data were limited, however, because of the lack of large randomized trials with long-term follow-up.

The Stampede trial is one of a few bariatric surgery randomized trials focusing on patients with diabetes.4 The 5-year follow-up results are impressive. Nearly 30% of patients who had gastric bypass and 23% who had sleeve gastrectomy had an A1C ≤6 at 5 years compared to only 5% of those treated medically. Some patients discontinued all medications for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

There is now adequate research to show that bariatric surgery provides significant benefits to properly selected patients who understand the risks. I no longer hesitate to refer patients for bariatric surgery who have been unsuccessful with weight loss—despite their best efforts.

Where do you stand?

Because of the high prevalence of obesity and diabetes, bariatric surgery has become very popular. In the United States alone, there were an estimated 228,000 weight loss surgical procedures performed in 2017.1

But I must confess that for many years, I was skeptical about the value of surgery to treat obesity. Yes, everyone who had a bariatric procedure lost weight, but did the long-term benefits really outweigh the harms? I wondered if most people gradually gained back the weight they lost. And the harms can be significant, including dumping syndrome, hypoglycemia, and malabsorption—in addition to the potential for surgical complications and repeat surgery. And, I must confess that my views were likely affected by the death of a friend from complications of gastric bypass 25 years ago.

My skepticism, however, has changed to cautious optimism for carefully selected patients. I say this because we now have long-term follow-up studies demonstrating the value of bariatric procedures—especially for people with type 2 diabetes.

Most studies have been cohort studies that compare results to similar patients with obesity who did not have surgery, and the outcomes have been consistently better in patients who underwent surgery. Two recent meta-analyses summarized these results; one for all patients with obesity and the other for patients with type 2 diabetes.

Continue to: The first meta-analysis

The first meta-analysis included 11 randomized trials, 4 nonrandomized controlled trials, and 17 cohort studies and showed probable reductions in all-cause mortality and possible reductions in cancer and cardiovascular events.2 The second demonstrated significant improvements in microvascular and macrovascular disease and reduced mortality.3 The data were limited, however, because of the lack of large randomized trials with long-term follow-up.

The Stampede trial is one of a few bariatric surgery randomized trials focusing on patients with diabetes.4 The 5-year follow-up results are impressive. Nearly 30% of patients who had gastric bypass and 23% who had sleeve gastrectomy had an A1C ≤6 at 5 years compared to only 5% of those treated medically. Some patients discontinued all medications for diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

There is now adequate research to show that bariatric surgery provides significant benefits to properly selected patients who understand the risks. I no longer hesitate to refer patients for bariatric surgery who have been unsuccessful with weight loss—despite their best efforts.

Where do you stand?

1. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed September 18, 2018.

2. Zhou X, Yu J, Li L, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality, cardiovascular events, and cancer outcomes in obese patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2590-2601.

3. Sheng B, Truong K, Spitler H, et al. The long-term effects of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes remission, microvascular and macrovascular complications, and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2724-2732.

4. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

1. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed September 18, 2018.

2. Zhou X, Yu J, Li L, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality, cardiovascular events, and cancer outcomes in obese patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2590-2601.

3. Sheng B, Truong K, Spitler H, et al. The long-term effects of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes remission, microvascular and macrovascular complications, and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2724-2732.

4. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

Obesity: When to consider surgery

Patients with overweight and obesity are at increased risk of multiple morbidities, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes (T2D), osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and all-cause mortality.1 Even modest weight loss—5% to 10%—can lead to a clinically relevant reduction in this risk of disease.2,3 The American Academy of Family Physicians recognizes obesity as a disease, and recommends screening of all adults for obesity and referral for those with body mass index (BMI)* ≥30 to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions.4,5

For some patients, diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications are sufficient; for the great majority, however, weight loss achieved by lifestyle modification is counteracted by metabolic adaptations that promote weight regain.6 For patients with obesity who are unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with lifestyle modification alone, options include pharmacotherapy, devices, endoscopic bariatric therapies, and bariatric surgery.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective of these treatments, due to its association with significant and sustained weight loss, reduction in obesity-related comorbidities, and improved quality of life.1,7 Furthermore, compared with usual care, bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced number of cardiovascular deaths, a lower incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with obesity, and a long-term reduction in overall mortality.8-10

What are the options? Who is a candidate?

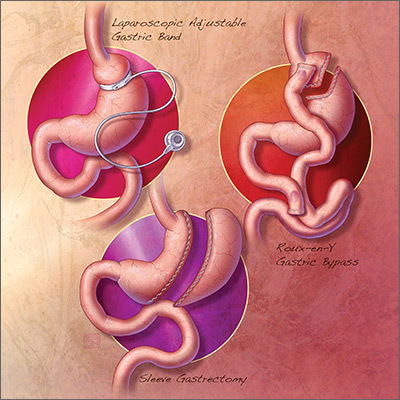

The 3 most common bariatric procedures in the United States are sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB).11 SG and RYGB are performed more often than the LAGB, consequent to greater efficacy and fewer complications.12 Weight loss is maximal at 1 to 2 years, and is estimated to be 15% of total body weight for LAGB; 25% for SG; and 35% for RYGB.13,14

Not all patients are candidates for bariatric surgery. Contraindications include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or respiratory dysfunction, poor cardiac reserve, nonadherence to medical treatment, and severe psychological disorders.15 Because some patients have difficulty maintaining weight loss following bariatric surgery and, on average, patients regain at least some weight, patients must understand that long-term lifestyle changes and follow-up are critical to the success of bariatric surgery.16

When should bariatric surgery be considered?

American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society guidelines16 conceptualize 2 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 who have obesity-related comorbid conditions and are motivated to lose weight but have not responded to behavioral treatment, with or without pharmacotherapy, to achieve sufficient weight loss for target health goals.

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines17 conceptualize 3 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 with 1 or more severe obesity-related complications

- adults with BMI 30-34.9 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome (evidence for this recommendation is limited).

Continue to: The 3 illustrative vignettes presented...

The 3 illustrative vignettes presented in this article offer examples of patients with obesity who could benefit from bariatric surgery. Each has been unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with nonsurgical interventions alone.

CASE 1

Sleep apnea persists despite weight loss

Robin W, a 50-year-old woman with class-II obesity (5’8”; 250 lb; BMI, 38 ), OSA requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and iron-deficiency anemia secondary to menorrhagia, and taking an iron supplement, presents for weight management. She has lost 50 lb, reducing her BMI from 45.6 with behavioral modifications and pharmacotherapy, but she has been unsuccessful at achieving further weight loss despite a reduced-calorie diet and at least 30 minutes of physical activity most days.

Ms. W is frustrated that she has reached a weight plateau; she is motivated to lose more weight. Her goal is to improve her weight-related comorbid conditions and reduce her medication requirement. Despite the initial weight loss, she continues to require CPAP therapy for OSA and remains on 3 medications for hypertension. She does not have cardiac or respiratory disease, psychiatric diagnoses, or a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Is bariatric surgery a reasonable option for Ms. W? If so, which procedure would you recommend?

Good option for Ms. W: Sleeve gastrectomy

It is reasonable to consider bariatric surgery—in particular, SG—for this patient with class-II obesity and multiple weight-related comorbid conditions because she has been unable to achieve further weight loss with more conservative measures.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? SG removes a large portion of the stomach along the greater curvature, reducing the organ to approximately 15% to 25% of its original size.18 The procedure leaves the pyloric valve intact and does not involve removal or bypass of the intestines.

How appealing and successful is it? The majority of patients who undergo SG experience significant weight loss; studies report approximately 25% total body weight loss after 1 to 2 years.14 Furthermore, most patients with T2D experience resolution of, or improvement in, disease markers.19 Because SG leaves the pylorus intact, there are fewer restrictions on what a patient can eat after surgery, compared with RYGB. With further weight loss, Ms. W may experience improvement in, or resolution of, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and OSA.

The SG procedure itself is simpler than some other bariatric procedures and presents less risk of malabsorption because the intestines are left intact. Patients who undergo SG report feeling less hungry because the fundus of the stomach, which secretes ghrelin (the so-called hunger hormone), is removed.18,20

What are special considerations, including candidacy? Patients with GERD are not ideal candidates for this procedure because exacerbation of the disease is a potential associated adverse event. SG is a reasonable surgical option for Ms. W because the procedure is less likely to exacerbate her nutritional deficiency (iron-deficiency anemia), compared to RYGB, and she does not have a history of GERD.

What are the complications? Complications of SG occur at a lower rate than they do with RYGB, which is associated with a greater risk of nutritional deficiency.18 Common early complications of SG include leaking, bleeding, stenosis, GERD, and vomiting due to excessive eating. Late complications include stomach expansion by 12 months, leading to decreased restriction.15 Unlike RYGB and LAGB, SG is not reversible.

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Severe obesity, polypharmacy for type 2 diabetes

Anne P, a 42-year-old woman with class-III obesity (5’6”; 290 lb; BMI, 46.8 kg/m2), presents to discuss bariatric surgery. Comorbidities include T2D, for which she takes metformin, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor; GERD; hypertension, for which she takes an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a calcium-channel blocker; hyperlipidemia, for which she takes a statin; and osteoarthritis.

Ms. P lost 30 pounds—reducing her BMI from 51.6—when the sulfonylurea and thiazolidinedione she was taking were switched to the GLP-1 receptor agonist and the SGLT2 inhibitor. She also made behavioral modifications, including 30 minutes a day of physical activity and a reduced-calorie meal plan under the guidance of a dietitian.

However, Ms. P has been unable to lose more weight or reduce her hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level below 8%. Her goal is to avoid the need to take insulin (which several members of her family take), lower her HbA1c level, and decrease her medication requirement.

Ms. P does not have cardiac or respiratory disease or psychiatric diagnoses. Which surgical intervention would you recommend for her?

Good option for Ms. P: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

RYGB is a reasonable option for a patient with class-III obesity and multiple comorbidities, including poorly controlled T2D and GERD, who has failed conservative measures but wants to lose more weight, reduce her HbA1c, reduce her medication requirement, and avoid the need for insulin.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? RYGB constructs a small pouch from the proximal portion of the stomach and attaches it directly to the jejunum, thus bypassing part of the stomach and duodenum. The procedure is effective for weight loss because it is both restrictive and malabsorptive: patients not only eat smaller portions, but cannot absorb all they eat. Other mechanisms attributed to RYGB that are hypothesized to promote weight loss include21:

- alteration of endogenous gut hormones, which promotes postprandial satiety

- increased levels of bile acids, which promotes alteration of the gut microbiome

- intestinal hypertrophy.

How successful is it? RYGB is associated with significant total body weight loss of approximately 35% at 2 years.9 The procedure has been shown to produce superior outcomes in reducing comorbid disease compared to other bariatric procedures or medical therapy alone. Of the procedures discussed in this article, RYGB is associated with the greatest reduction in triglycerides, HbA1c, and use of diabetes medications, including insulin.22

What are special considerations, including candidacy? For patients with mild or moderate T2D (calculated using the Individualized Metabolic Surgery Score [http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/], which categorizes patients by number of diabetes medications, insulin use, duration of diabetes before surgery, and HbA1c), RYGB is recommended over SG because it leads to greater long-term remission of T2D.

RYGB is associated with a lower rate of GERD than SG and can even alleviate GERD in patients who have the disease. Furthermore, for patients with limited pancreatic beta cell reserve, RYBG and SG have similarly low efficacy for T2D remission; SG is therefore recommended over RYGB in this specific circumstance, given its slightly lower risk profile.23

What are the complications? Patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure require long-term follow-up and vitamin supplementation, but those who undergo RYGB require stricter dietary adherence after the procedure; lifelong vitamin (D, B12, folic acid, and thiamine), iron, and calcium supplementation; and long-term follow-up to reduce the risk and severity of complications and to monitor for nutritional deficiencies.7 As such, patients who have shown poor adherence to medical treatment are not good candidates for the procedure.

Continue to: Early complications include...

Early complications include leak, stricture, obstruction, and failure of the staple partition of the upper stomach. Late complications include nutritional deficiencies, as noted, and ulceration of the anastomosis. Dumping syndrome (overly rapid transit of food from the stomach into the small intestine) can develop early or late; early dumping leads to osmotic diarrhea and abdominal cramping, and late dumping leads to reactive hypoglycemia.15

Technically, RYGB is a reversible procedure, although generally it is reversed only in extreme circumstances.

CASE 3

Fatty liver disease, hesitation to undergo surgery

Walt Z, a 35 year-old-man with class-II obesity (5’10”; 265 lb; BMI, 38 kg/m2), T2D, and hepatic steatosis, presents for weight management. He has been able to lose modest weight over the years with behavioral modifications, but has been unsuccessful in maintaining that loss. He requests referral to a bariatric surgeon but is concerned about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures.

Which surgical intervention would you recommend for this patient?

Good option for Mr. Z: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

Given that Mr. Z is a candidate for a surgical intervention but does not want a permanent or invasive procedure, LAGB is a reasonable option.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? LAGB is a reversible procedure in which an inflatable band is placed around the fundus of the stomach to create a small pouch. The band can be adjusted to regulate food intake by adding or removing saline through a subcutaneous access port.

How appealing and successful is it? LAGB results in approximately 15% total body weight loss at 2 years.13 Because the procedure is purely restrictive, it carries a reduced risk of nutritional deficiency associated more commonly with malabsorptive procedures.

What are special considerations, including candidacy? As noted, Mr. Z expressed concern about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures, and therefore wants to undergo a reversible procedure; LAGB can be a reasonable option for such a patient. Patients who want a reversible or minimally invasive procedure should also be made aware that endoscopic bariatric therapies and other devices are being developed to fill the treatment gap in the management of obesity.

What are the complications? Although LAGB is the least invasive procedure discussed here, it is associated with the highest rate of complications—most commonly, complications associated with the band itself (eg, nausea, vomiting, obstruction, band erosion or migration, esophageal dysmotility leading to acid reflux) and failure to lose weight.7 LAGB also requires more postoperative visits than other procedures, to optimize band tightness. A high number of bands are removed eventually because of complications or inadequate weight loss, or both.13,24

Shared decision-making and dialogue are essential to overcome obstacles

Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, including greater reduction in the risk and severity of obesity-related comorbid conditions than seen with other interventions and a long-term reduction in overall mortality when compared with usual care, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo a weight-loss procedure.25 Likely, this is due to:

- limited patient knowledge of the health benefits of surgery

- limited provider comfort recommending surgery

- inadequate insurance coverage, which might, in part, be due to a lack of prospective studies comparing various bariatric procedures.18

Continue to: Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure...

Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure, and which one(s) to consider, should be the product of a thorough conversation between patient and provider.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarah R. Barenbaum, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, 530 East 70th Street, M-507, New York, NY 10021; srb9023@nyp.org

1. Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, et al. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523-1529.

2. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481-1486.

3. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23:591-601.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation: Obesity. www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/obesity.html. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. American Academy of Family Physicians: USPSTF draft recommendation: Intensive behavioral interventions recommended for obesity. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180221uspstfobesity.html. Published February 21, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

6. Saunders KH, Shukla AP, Igel LI, Aronne LJ. Obesity: When to consider medication. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:608-616.

7. Roux CW, Heneghan HM. Bariatric surgery for obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:165-182.

8. Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307:56-65.

9. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219-234.

10. Reges O, Greenland P, Dicker D, et al. Association of bariatric surgery using laparoscopic banding, Roux-en-Y, gastric bypass, or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs usual care obesity management with all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2018;319:279-290.

11. Lee JH, Nguyen QN, Le QA. Comparative effectiveness of 3 bariatric surgery procedures: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:997-1002.

12. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Published June 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

13. Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:427-434.

14. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:254-266.

15. Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8):CD003641.

16. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

17. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for comprehensive medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 3:1-203.

18. Carlin Am, Zeni Tm, English WJ, et al; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:791-797.

19. Gill RS, Birch DW, Shi X, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:707-713.

20. Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401-407.

21. Abdeen G, le Roux CW. Mechanism underlying the weight loss and complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26:410-421.

22. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

23. Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Andalib A, et al. Individualized metabolic surgery score: procedure selection based on diabetes severity. Ann Surg. 2017;266:4:650-657.

24. Smetana GW, Jones DB, Wee CC. Beyond the guidelines: Should this patient have weight loss surgery? Grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:808-817.

25. Wolfe BM, Morton JM. Weighing in on bariatric surgery: procedure use, readmission rates, and mortality [editorial]. JAMA. 2005;294:1960-1963.

Patients with overweight and obesity are at increased risk of multiple morbidities, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes (T2D), osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and all-cause mortality.1 Even modest weight loss—5% to 10%—can lead to a clinically relevant reduction in this risk of disease.2,3 The American Academy of Family Physicians recognizes obesity as a disease, and recommends screening of all adults for obesity and referral for those with body mass index (BMI)* ≥30 to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions.4,5

For some patients, diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications are sufficient; for the great majority, however, weight loss achieved by lifestyle modification is counteracted by metabolic adaptations that promote weight regain.6 For patients with obesity who are unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with lifestyle modification alone, options include pharmacotherapy, devices, endoscopic bariatric therapies, and bariatric surgery.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective of these treatments, due to its association with significant and sustained weight loss, reduction in obesity-related comorbidities, and improved quality of life.1,7 Furthermore, compared with usual care, bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced number of cardiovascular deaths, a lower incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with obesity, and a long-term reduction in overall mortality.8-10

What are the options? Who is a candidate?

The 3 most common bariatric procedures in the United States are sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB).11 SG and RYGB are performed more often than the LAGB, consequent to greater efficacy and fewer complications.12 Weight loss is maximal at 1 to 2 years, and is estimated to be 15% of total body weight for LAGB; 25% for SG; and 35% for RYGB.13,14

Not all patients are candidates for bariatric surgery. Contraindications include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or respiratory dysfunction, poor cardiac reserve, nonadherence to medical treatment, and severe psychological disorders.15 Because some patients have difficulty maintaining weight loss following bariatric surgery and, on average, patients regain at least some weight, patients must understand that long-term lifestyle changes and follow-up are critical to the success of bariatric surgery.16

When should bariatric surgery be considered?

American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society guidelines16 conceptualize 2 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 who have obesity-related comorbid conditions and are motivated to lose weight but have not responded to behavioral treatment, with or without pharmacotherapy, to achieve sufficient weight loss for target health goals.

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines17 conceptualize 3 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 with 1 or more severe obesity-related complications

- adults with BMI 30-34.9 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome (evidence for this recommendation is limited).

Continue to: The 3 illustrative vignettes presented...

The 3 illustrative vignettes presented in this article offer examples of patients with obesity who could benefit from bariatric surgery. Each has been unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with nonsurgical interventions alone.

CASE 1

Sleep apnea persists despite weight loss

Robin W, a 50-year-old woman with class-II obesity (5’8”; 250 lb; BMI, 38 ), OSA requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and iron-deficiency anemia secondary to menorrhagia, and taking an iron supplement, presents for weight management. She has lost 50 lb, reducing her BMI from 45.6 with behavioral modifications and pharmacotherapy, but she has been unsuccessful at achieving further weight loss despite a reduced-calorie diet and at least 30 minutes of physical activity most days.

Ms. W is frustrated that she has reached a weight plateau; she is motivated to lose more weight. Her goal is to improve her weight-related comorbid conditions and reduce her medication requirement. Despite the initial weight loss, she continues to require CPAP therapy for OSA and remains on 3 medications for hypertension. She does not have cardiac or respiratory disease, psychiatric diagnoses, or a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Is bariatric surgery a reasonable option for Ms. W? If so, which procedure would you recommend?

Good option for Ms. W: Sleeve gastrectomy

It is reasonable to consider bariatric surgery—in particular, SG—for this patient with class-II obesity and multiple weight-related comorbid conditions because she has been unable to achieve further weight loss with more conservative measures.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? SG removes a large portion of the stomach along the greater curvature, reducing the organ to approximately 15% to 25% of its original size.18 The procedure leaves the pyloric valve intact and does not involve removal or bypass of the intestines.

How appealing and successful is it? The majority of patients who undergo SG experience significant weight loss; studies report approximately 25% total body weight loss after 1 to 2 years.14 Furthermore, most patients with T2D experience resolution of, or improvement in, disease markers.19 Because SG leaves the pylorus intact, there are fewer restrictions on what a patient can eat after surgery, compared with RYGB. With further weight loss, Ms. W may experience improvement in, or resolution of, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and OSA.

The SG procedure itself is simpler than some other bariatric procedures and presents less risk of malabsorption because the intestines are left intact. Patients who undergo SG report feeling less hungry because the fundus of the stomach, which secretes ghrelin (the so-called hunger hormone), is removed.18,20

What are special considerations, including candidacy? Patients with GERD are not ideal candidates for this procedure because exacerbation of the disease is a potential associated adverse event. SG is a reasonable surgical option for Ms. W because the procedure is less likely to exacerbate her nutritional deficiency (iron-deficiency anemia), compared to RYGB, and she does not have a history of GERD.

What are the complications? Complications of SG occur at a lower rate than they do with RYGB, which is associated with a greater risk of nutritional deficiency.18 Common early complications of SG include leaking, bleeding, stenosis, GERD, and vomiting due to excessive eating. Late complications include stomach expansion by 12 months, leading to decreased restriction.15 Unlike RYGB and LAGB, SG is not reversible.

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Severe obesity, polypharmacy for type 2 diabetes

Anne P, a 42-year-old woman with class-III obesity (5’6”; 290 lb; BMI, 46.8 kg/m2), presents to discuss bariatric surgery. Comorbidities include T2D, for which she takes metformin, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor; GERD; hypertension, for which she takes an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a calcium-channel blocker; hyperlipidemia, for which she takes a statin; and osteoarthritis.

Ms. P lost 30 pounds—reducing her BMI from 51.6—when the sulfonylurea and thiazolidinedione she was taking were switched to the GLP-1 receptor agonist and the SGLT2 inhibitor. She also made behavioral modifications, including 30 minutes a day of physical activity and a reduced-calorie meal plan under the guidance of a dietitian.

However, Ms. P has been unable to lose more weight or reduce her hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level below 8%. Her goal is to avoid the need to take insulin (which several members of her family take), lower her HbA1c level, and decrease her medication requirement.

Ms. P does not have cardiac or respiratory disease or psychiatric diagnoses. Which surgical intervention would you recommend for her?

Good option for Ms. P: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

RYGB is a reasonable option for a patient with class-III obesity and multiple comorbidities, including poorly controlled T2D and GERD, who has failed conservative measures but wants to lose more weight, reduce her HbA1c, reduce her medication requirement, and avoid the need for insulin.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? RYGB constructs a small pouch from the proximal portion of the stomach and attaches it directly to the jejunum, thus bypassing part of the stomach and duodenum. The procedure is effective for weight loss because it is both restrictive and malabsorptive: patients not only eat smaller portions, but cannot absorb all they eat. Other mechanisms attributed to RYGB that are hypothesized to promote weight loss include21:

- alteration of endogenous gut hormones, which promotes postprandial satiety

- increased levels of bile acids, which promotes alteration of the gut microbiome

- intestinal hypertrophy.

How successful is it? RYGB is associated with significant total body weight loss of approximately 35% at 2 years.9 The procedure has been shown to produce superior outcomes in reducing comorbid disease compared to other bariatric procedures or medical therapy alone. Of the procedures discussed in this article, RYGB is associated with the greatest reduction in triglycerides, HbA1c, and use of diabetes medications, including insulin.22

What are special considerations, including candidacy? For patients with mild or moderate T2D (calculated using the Individualized Metabolic Surgery Score [http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/], which categorizes patients by number of diabetes medications, insulin use, duration of diabetes before surgery, and HbA1c), RYGB is recommended over SG because it leads to greater long-term remission of T2D.

RYGB is associated with a lower rate of GERD than SG and can even alleviate GERD in patients who have the disease. Furthermore, for patients with limited pancreatic beta cell reserve, RYBG and SG have similarly low efficacy for T2D remission; SG is therefore recommended over RYGB in this specific circumstance, given its slightly lower risk profile.23

What are the complications? Patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure require long-term follow-up and vitamin supplementation, but those who undergo RYGB require stricter dietary adherence after the procedure; lifelong vitamin (D, B12, folic acid, and thiamine), iron, and calcium supplementation; and long-term follow-up to reduce the risk and severity of complications and to monitor for nutritional deficiencies.7 As such, patients who have shown poor adherence to medical treatment are not good candidates for the procedure.

Continue to: Early complications include...

Early complications include leak, stricture, obstruction, and failure of the staple partition of the upper stomach. Late complications include nutritional deficiencies, as noted, and ulceration of the anastomosis. Dumping syndrome (overly rapid transit of food from the stomach into the small intestine) can develop early or late; early dumping leads to osmotic diarrhea and abdominal cramping, and late dumping leads to reactive hypoglycemia.15

Technically, RYGB is a reversible procedure, although generally it is reversed only in extreme circumstances.

CASE 3

Fatty liver disease, hesitation to undergo surgery

Walt Z, a 35 year-old-man with class-II obesity (5’10”; 265 lb; BMI, 38 kg/m2), T2D, and hepatic steatosis, presents for weight management. He has been able to lose modest weight over the years with behavioral modifications, but has been unsuccessful in maintaining that loss. He requests referral to a bariatric surgeon but is concerned about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures.

Which surgical intervention would you recommend for this patient?

Good option for Mr. Z: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

Given that Mr. Z is a candidate for a surgical intervention but does not want a permanent or invasive procedure, LAGB is a reasonable option.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? LAGB is a reversible procedure in which an inflatable band is placed around the fundus of the stomach to create a small pouch. The band can be adjusted to regulate food intake by adding or removing saline through a subcutaneous access port.

How appealing and successful is it? LAGB results in approximately 15% total body weight loss at 2 years.13 Because the procedure is purely restrictive, it carries a reduced risk of nutritional deficiency associated more commonly with malabsorptive procedures.

What are special considerations, including candidacy? As noted, Mr. Z expressed concern about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures, and therefore wants to undergo a reversible procedure; LAGB can be a reasonable option for such a patient. Patients who want a reversible or minimally invasive procedure should also be made aware that endoscopic bariatric therapies and other devices are being developed to fill the treatment gap in the management of obesity.

What are the complications? Although LAGB is the least invasive procedure discussed here, it is associated with the highest rate of complications—most commonly, complications associated with the band itself (eg, nausea, vomiting, obstruction, band erosion or migration, esophageal dysmotility leading to acid reflux) and failure to lose weight.7 LAGB also requires more postoperative visits than other procedures, to optimize band tightness. A high number of bands are removed eventually because of complications or inadequate weight loss, or both.13,24

Shared decision-making and dialogue are essential to overcome obstacles

Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, including greater reduction in the risk and severity of obesity-related comorbid conditions than seen with other interventions and a long-term reduction in overall mortality when compared with usual care, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo a weight-loss procedure.25 Likely, this is due to:

- limited patient knowledge of the health benefits of surgery

- limited provider comfort recommending surgery

- inadequate insurance coverage, which might, in part, be due to a lack of prospective studies comparing various bariatric procedures.18

Continue to: Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure...

Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure, and which one(s) to consider, should be the product of a thorough conversation between patient and provider.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarah R. Barenbaum, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, 530 East 70th Street, M-507, New York, NY 10021; srb9023@nyp.org

Patients with overweight and obesity are at increased risk of multiple morbidities, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes (T2D), osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and all-cause mortality.1 Even modest weight loss—5% to 10%—can lead to a clinically relevant reduction in this risk of disease.2,3 The American Academy of Family Physicians recognizes obesity as a disease, and recommends screening of all adults for obesity and referral for those with body mass index (BMI)* ≥30 to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions.4,5

For some patients, diet, exercise, and behavioral modifications are sufficient; for the great majority, however, weight loss achieved by lifestyle modification is counteracted by metabolic adaptations that promote weight regain.6 For patients with obesity who are unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with lifestyle modification alone, options include pharmacotherapy, devices, endoscopic bariatric therapies, and bariatric surgery.

Bariatric surgery is the most effective of these treatments, due to its association with significant and sustained weight loss, reduction in obesity-related comorbidities, and improved quality of life.1,7 Furthermore, compared with usual care, bariatric surgery is associated with a reduced number of cardiovascular deaths, a lower incidence of cardiovascular events in adults with obesity, and a long-term reduction in overall mortality.8-10

What are the options? Who is a candidate?

The 3 most common bariatric procedures in the United States are sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB).11 SG and RYGB are performed more often than the LAGB, consequent to greater efficacy and fewer complications.12 Weight loss is maximal at 1 to 2 years, and is estimated to be 15% of total body weight for LAGB; 25% for SG; and 35% for RYGB.13,14

Not all patients are candidates for bariatric surgery. Contraindications include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or respiratory dysfunction, poor cardiac reserve, nonadherence to medical treatment, and severe psychological disorders.15 Because some patients have difficulty maintaining weight loss following bariatric surgery and, on average, patients regain at least some weight, patients must understand that long-term lifestyle changes and follow-up are critical to the success of bariatric surgery.16

When should bariatric surgery be considered?

American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society guidelines16 conceptualize 2 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 who have obesity-related comorbid conditions and are motivated to lose weight but have not responded to behavioral treatment, with or without pharmacotherapy, to achieve sufficient weight loss for target health goals.

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines17 conceptualize 3 indications for bariatric surgery:

- adults with BMI ≥40

- adults with BMI ≥35 with 1 or more severe obesity-related complications

- adults with BMI 30-34.9 with diabetes or metabolic syndrome (evidence for this recommendation is limited).

Continue to: The 3 illustrative vignettes presented...

The 3 illustrative vignettes presented in this article offer examples of patients with obesity who could benefit from bariatric surgery. Each has been unable to achieve or maintain sufficient weight loss to improve health outcomes with nonsurgical interventions alone.

CASE 1

Sleep apnea persists despite weight loss

Robin W, a 50-year-old woman with class-II obesity (5’8”; 250 lb; BMI, 38 ), OSA requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and iron-deficiency anemia secondary to menorrhagia, and taking an iron supplement, presents for weight management. She has lost 50 lb, reducing her BMI from 45.6 with behavioral modifications and pharmacotherapy, but she has been unsuccessful at achieving further weight loss despite a reduced-calorie diet and at least 30 minutes of physical activity most days.

Ms. W is frustrated that she has reached a weight plateau; she is motivated to lose more weight. Her goal is to improve her weight-related comorbid conditions and reduce her medication requirement. Despite the initial weight loss, she continues to require CPAP therapy for OSA and remains on 3 medications for hypertension. She does not have cardiac or respiratory disease, psychiatric diagnoses, or a history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Is bariatric surgery a reasonable option for Ms. W? If so, which procedure would you recommend?

Good option for Ms. W: Sleeve gastrectomy

It is reasonable to consider bariatric surgery—in particular, SG—for this patient with class-II obesity and multiple weight-related comorbid conditions because she has been unable to achieve further weight loss with more conservative measures.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? SG removes a large portion of the stomach along the greater curvature, reducing the organ to approximately 15% to 25% of its original size.18 The procedure leaves the pyloric valve intact and does not involve removal or bypass of the intestines.

How appealing and successful is it? The majority of patients who undergo SG experience significant weight loss; studies report approximately 25% total body weight loss after 1 to 2 years.14 Furthermore, most patients with T2D experience resolution of, or improvement in, disease markers.19 Because SG leaves the pylorus intact, there are fewer restrictions on what a patient can eat after surgery, compared with RYGB. With further weight loss, Ms. W may experience improvement in, or resolution of, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and OSA.

The SG procedure itself is simpler than some other bariatric procedures and presents less risk of malabsorption because the intestines are left intact. Patients who undergo SG report feeling less hungry because the fundus of the stomach, which secretes ghrelin (the so-called hunger hormone), is removed.18,20

What are special considerations, including candidacy? Patients with GERD are not ideal candidates for this procedure because exacerbation of the disease is a potential associated adverse event. SG is a reasonable surgical option for Ms. W because the procedure is less likely to exacerbate her nutritional deficiency (iron-deficiency anemia), compared to RYGB, and she does not have a history of GERD.

What are the complications? Complications of SG occur at a lower rate than they do with RYGB, which is associated with a greater risk of nutritional deficiency.18 Common early complications of SG include leaking, bleeding, stenosis, GERD, and vomiting due to excessive eating. Late complications include stomach expansion by 12 months, leading to decreased restriction.15 Unlike RYGB and LAGB, SG is not reversible.

Continue to: CASE 2

CASE 2

Severe obesity, polypharmacy for type 2 diabetes

Anne P, a 42-year-old woman with class-III obesity (5’6”; 290 lb; BMI, 46.8 kg/m2), presents to discuss bariatric surgery. Comorbidities include T2D, for which she takes metformin, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, and a sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor; GERD; hypertension, for which she takes an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a calcium-channel blocker; hyperlipidemia, for which she takes a statin; and osteoarthritis.

Ms. P lost 30 pounds—reducing her BMI from 51.6—when the sulfonylurea and thiazolidinedione she was taking were switched to the GLP-1 receptor agonist and the SGLT2 inhibitor. She also made behavioral modifications, including 30 minutes a day of physical activity and a reduced-calorie meal plan under the guidance of a dietitian.

However, Ms. P has been unable to lose more weight or reduce her hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level below 8%. Her goal is to avoid the need to take insulin (which several members of her family take), lower her HbA1c level, and decrease her medication requirement.

Ms. P does not have cardiac or respiratory disease or psychiatric diagnoses. Which surgical intervention would you recommend for her?

Good option for Ms. P: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

RYGB is a reasonable option for a patient with class-III obesity and multiple comorbidities, including poorly controlled T2D and GERD, who has failed conservative measures but wants to lose more weight, reduce her HbA1c, reduce her medication requirement, and avoid the need for insulin.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? RYGB constructs a small pouch from the proximal portion of the stomach and attaches it directly to the jejunum, thus bypassing part of the stomach and duodenum. The procedure is effective for weight loss because it is both restrictive and malabsorptive: patients not only eat smaller portions, but cannot absorb all they eat. Other mechanisms attributed to RYGB that are hypothesized to promote weight loss include21:

- alteration of endogenous gut hormones, which promotes postprandial satiety

- increased levels of bile acids, which promotes alteration of the gut microbiome

- intestinal hypertrophy.

How successful is it? RYGB is associated with significant total body weight loss of approximately 35% at 2 years.9 The procedure has been shown to produce superior outcomes in reducing comorbid disease compared to other bariatric procedures or medical therapy alone. Of the procedures discussed in this article, RYGB is associated with the greatest reduction in triglycerides, HbA1c, and use of diabetes medications, including insulin.22

What are special considerations, including candidacy? For patients with mild or moderate T2D (calculated using the Individualized Metabolic Surgery Score [http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/], which categorizes patients by number of diabetes medications, insulin use, duration of diabetes before surgery, and HbA1c), RYGB is recommended over SG because it leads to greater long-term remission of T2D.

RYGB is associated with a lower rate of GERD than SG and can even alleviate GERD in patients who have the disease. Furthermore, for patients with limited pancreatic beta cell reserve, RYBG and SG have similarly low efficacy for T2D remission; SG is therefore recommended over RYGB in this specific circumstance, given its slightly lower risk profile.23

What are the complications? Patients who undergo any bariatric surgical procedure require long-term follow-up and vitamin supplementation, but those who undergo RYGB require stricter dietary adherence after the procedure; lifelong vitamin (D, B12, folic acid, and thiamine), iron, and calcium supplementation; and long-term follow-up to reduce the risk and severity of complications and to monitor for nutritional deficiencies.7 As such, patients who have shown poor adherence to medical treatment are not good candidates for the procedure.

Continue to: Early complications include...

Early complications include leak, stricture, obstruction, and failure of the staple partition of the upper stomach. Late complications include nutritional deficiencies, as noted, and ulceration of the anastomosis. Dumping syndrome (overly rapid transit of food from the stomach into the small intestine) can develop early or late; early dumping leads to osmotic diarrhea and abdominal cramping, and late dumping leads to reactive hypoglycemia.15

Technically, RYGB is a reversible procedure, although generally it is reversed only in extreme circumstances.

CASE 3

Fatty liver disease, hesitation to undergo surgery

Walt Z, a 35 year-old-man with class-II obesity (5’10”; 265 lb; BMI, 38 kg/m2), T2D, and hepatic steatosis, presents for weight management. He has been able to lose modest weight over the years with behavioral modifications, but has been unsuccessful in maintaining that loss. He requests referral to a bariatric surgeon but is concerned about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures.

Which surgical intervention would you recommend for this patient?

Good option for Mr. Z: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band

Given that Mr. Z is a candidate for a surgical intervention but does not want a permanent or invasive procedure, LAGB is a reasonable option.

Continue to: How does the procedure work?

How does the procedure work? LAGB is a reversible procedure in which an inflatable band is placed around the fundus of the stomach to create a small pouch. The band can be adjusted to regulate food intake by adding or removing saline through a subcutaneous access port.

How appealing and successful is it? LAGB results in approximately 15% total body weight loss at 2 years.13 Because the procedure is purely restrictive, it carries a reduced risk of nutritional deficiency associated more commonly with malabsorptive procedures.

What are special considerations, including candidacy? As noted, Mr. Z expressed concern about the permanence and invasiveness of most bariatric procedures, and therefore wants to undergo a reversible procedure; LAGB can be a reasonable option for such a patient. Patients who want a reversible or minimally invasive procedure should also be made aware that endoscopic bariatric therapies and other devices are being developed to fill the treatment gap in the management of obesity.

What are the complications? Although LAGB is the least invasive procedure discussed here, it is associated with the highest rate of complications—most commonly, complications associated with the band itself (eg, nausea, vomiting, obstruction, band erosion or migration, esophageal dysmotility leading to acid reflux) and failure to lose weight.7 LAGB also requires more postoperative visits than other procedures, to optimize band tightness. A high number of bands are removed eventually because of complications or inadequate weight loss, or both.13,24

Shared decision-making and dialogue are essential to overcome obstacles

Despite the known benefits of bariatric surgery, including greater reduction in the risk and severity of obesity-related comorbid conditions than seen with other interventions and a long-term reduction in overall mortality when compared with usual care, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo a weight-loss procedure.25 Likely, this is due to:

- limited patient knowledge of the health benefits of surgery

- limited provider comfort recommending surgery

- inadequate insurance coverage, which might, in part, be due to a lack of prospective studies comparing various bariatric procedures.18

Continue to: Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure...

Ultimately, the decision whether to undergo a bariatric procedure, and which one(s) to consider, should be the product of a thorough conversation between patient and provider.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sarah R. Barenbaum, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical College, 530 East 70th Street, M-507, New York, NY 10021; srb9023@nyp.org

1. Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, et al. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523-1529.

2. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481-1486.

3. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23:591-601.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation: Obesity. www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/obesity.html. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. American Academy of Family Physicians: USPSTF draft recommendation: Intensive behavioral interventions recommended for obesity. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180221uspstfobesity.html. Published February 21, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

6. Saunders KH, Shukla AP, Igel LI, Aronne LJ. Obesity: When to consider medication. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:608-616.

7. Roux CW, Heneghan HM. Bariatric surgery for obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:165-182.

8. Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307:56-65.

9. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219-234.

10. Reges O, Greenland P, Dicker D, et al. Association of bariatric surgery using laparoscopic banding, Roux-en-Y, gastric bypass, or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs usual care obesity management with all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2018;319:279-290.

11. Lee JH, Nguyen QN, Le QA. Comparative effectiveness of 3 bariatric surgery procedures: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:997-1002.

12. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Published June 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

13. Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:427-434.

14. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:254-266.

15. Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8):CD003641.

16. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

17. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for comprehensive medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 3:1-203.

18. Carlin Am, Zeni Tm, English WJ, et al; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:791-797.

19. Gill RS, Birch DW, Shi X, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:707-713.

20. Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401-407.

21. Abdeen G, le Roux CW. Mechanism underlying the weight loss and complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26:410-421.

22. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

23. Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Andalib A, et al. Individualized metabolic surgery score: procedure selection based on diabetes severity. Ann Surg. 2017;266:4:650-657.

24. Smetana GW, Jones DB, Wee CC. Beyond the guidelines: Should this patient have weight loss surgery? Grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:808-817.

25. Wolfe BM, Morton JM. Weighing in on bariatric surgery: procedure use, readmission rates, and mortality [editorial]. JAMA. 2005;294:1960-1963.

1. Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, et al. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA. 1999;282:1523-1529.

2. Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481-1486.

3. Magkos F, Fraterrigo G, Yoshino J, et al. Effects of moderate and subsequent progressive weight loss on metabolic function and adipose tissue biology in humans with obesity. Cell Metab. 2016;23:591-601.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical preventive service recommendation: Obesity. www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/obesity.html. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. American Academy of Family Physicians: USPSTF draft recommendation: Intensive behavioral interventions recommended for obesity. www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20180221uspstfobesity.html. Published February 21, 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

6. Saunders KH, Shukla AP, Igel LI, Aronne LJ. Obesity: When to consider medication. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:608-616.

7. Roux CW, Heneghan HM. Bariatric surgery for obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:165-182.

8. Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307:56-65.

9. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219-234.

10. Reges O, Greenland P, Dicker D, et al. Association of bariatric surgery using laparoscopic banding, Roux-en-Y, gastric bypass, or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs usual care obesity management with all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2018;319:279-290.

11. Lee JH, Nguyen QN, Le QA. Comparative effectiveness of 3 bariatric surgery procedures: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, and sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:997-1002.

12. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Published June 2018. Accessed August 22, 2018.

13. Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:427-434.

14. Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:254-266.

15. Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8):CD003641.

16. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

17. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology clinical practice guidelines for comprehensive medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract. 2016;22 Suppl 3:1-203.

18. Carlin Am, Zeni Tm, English WJ, et al; Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:791-797.

19. Gill RS, Birch DW, Shi X, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:707-713.

20. Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401-407.

21. Abdeen G, le Roux CW. Mechanism underlying the weight loss and complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26:410-421.

22. Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP et al; STAMPEDE Investigators. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641-651.

23. Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Andalib A, et al. Individualized metabolic surgery score: procedure selection based on diabetes severity. Ann Surg. 2017;266:4:650-657.

24. Smetana GW, Jones DB, Wee CC. Beyond the guidelines: Should this patient have weight loss surgery? Grand rounds discussion from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:808-817.

25. Wolfe BM, Morton JM. Weighing in on bariatric surgery: procedure use, readmission rates, and mortality [editorial]. JAMA. 2005;294:1960-1963.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

Among adult patients with body mass index* ≥40, or ≥35 with obesity-related comorbid conditions:

› Consider bariatric surgery in those who are motivated to lose weight but who have not responded to lifestyle modification with or without pharmacotherapy in order to achieve sufficient and sustained weight loss. A

› Consider bariatric surgery to help patients achieve target health goals and reduce/improve obesity-related comorbidities. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

*Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

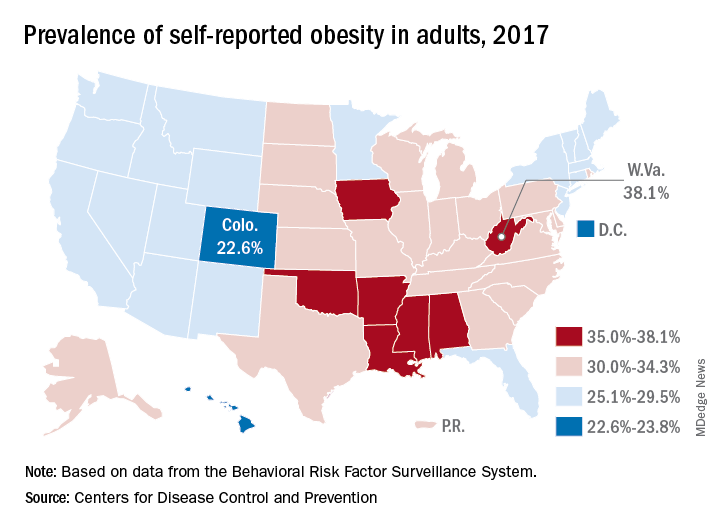

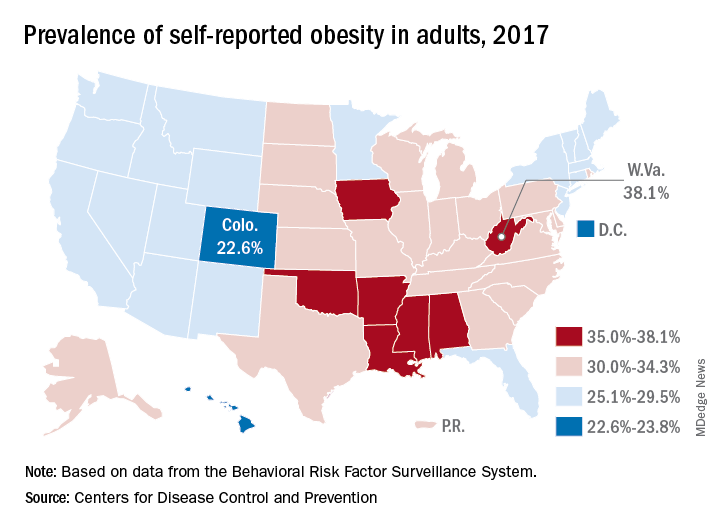

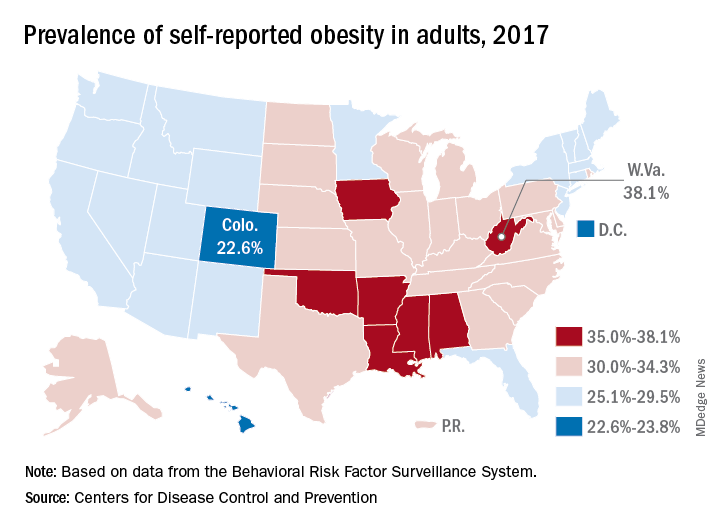

U.S. obesity continues to advance

The prevalence of adult obesity was at or above 35% for seven states in 2017, which is up from five states in 2016 and no states in 2012, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Iowa and Oklahoma, the two newest states with prevalences at or exceeding 35%, joined Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, which has the country’s highest rate of adult obesity at 38.1%. Colorado’s 22.6% rate is the lowest prevalence among all states. The District of Columbia and Hawaii also have prevalences under 25%; previously, Massachusetts also was in this group, but its prevalence went up to 25.9% last year, the CDC reported.

Regional disparities in self-reported adult obesity put the South (32.4%) and the Midwest (32.3%) well ahead of the Northeast (27.7%) and the West (26.1%) in 2017. Racial and ethnic disparities also were seen, with large gaps between blacks, who had a prevalence of 39%, and Hispanics (32.4%) and whites (29.3%). Obesity prevalence was 35% or higher among black adults in 31 states and D.C., while this was true among Hispanics in eight states and among whites in one (West Virginia), although the prevalence was at or above 35% for multiple racial groups in some of these states, the CDC reported based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Obesity costs the United States health care system over $147 billion a year [and] research has shown that obesity affects work productivity and military readiness,” the CDC said in a written statement. “To protect the health of the next generation, support for healthy behaviors such as healthy eating, better sleep, stress management, and physical activity should start early and expand to reach Americans across the lifespan in the communities where they live, learn, work, and play.”

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/p1Fh30lOXYD

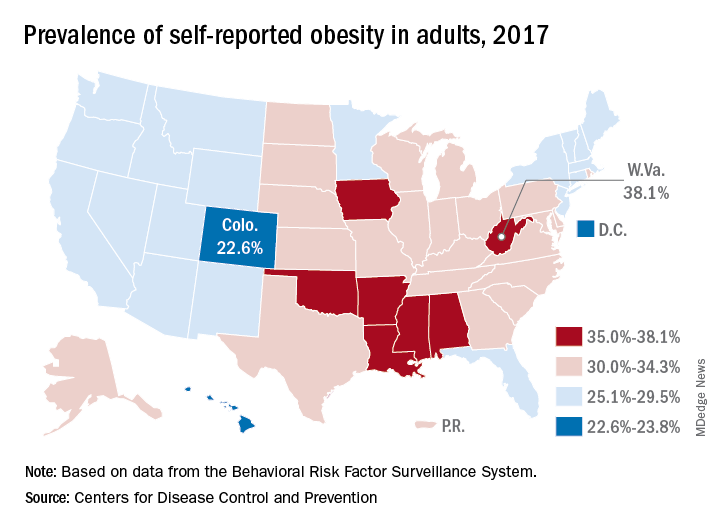

The prevalence of adult obesity was at or above 35% for seven states in 2017, which is up from five states in 2016 and no states in 2012, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Iowa and Oklahoma, the two newest states with prevalences at or exceeding 35%, joined Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, which has the country’s highest rate of adult obesity at 38.1%. Colorado’s 22.6% rate is the lowest prevalence among all states. The District of Columbia and Hawaii also have prevalences under 25%; previously, Massachusetts also was in this group, but its prevalence went up to 25.9% last year, the CDC reported.

Regional disparities in self-reported adult obesity put the South (32.4%) and the Midwest (32.3%) well ahead of the Northeast (27.7%) and the West (26.1%) in 2017. Racial and ethnic disparities also were seen, with large gaps between blacks, who had a prevalence of 39%, and Hispanics (32.4%) and whites (29.3%). Obesity prevalence was 35% or higher among black adults in 31 states and D.C., while this was true among Hispanics in eight states and among whites in one (West Virginia), although the prevalence was at or above 35% for multiple racial groups in some of these states, the CDC reported based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Obesity costs the United States health care system over $147 billion a year [and] research has shown that obesity affects work productivity and military readiness,” the CDC said in a written statement. “To protect the health of the next generation, support for healthy behaviors such as healthy eating, better sleep, stress management, and physical activity should start early and expand to reach Americans across the lifespan in the communities where they live, learn, work, and play.”

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/p1Fh30lOXYD

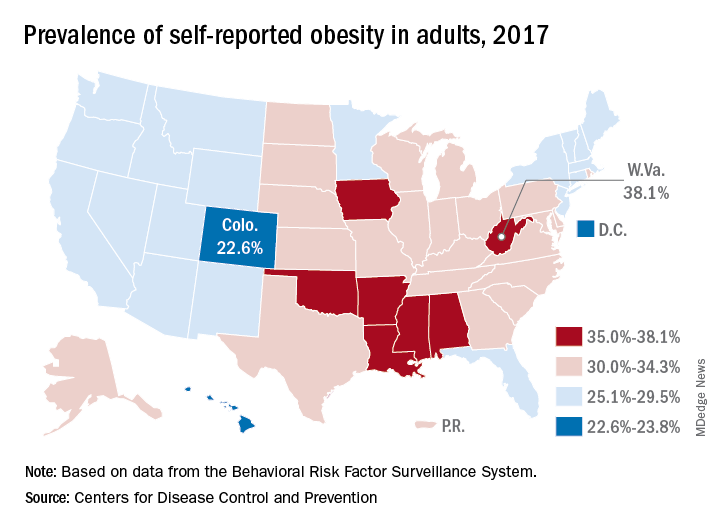

The prevalence of adult obesity was at or above 35% for seven states in 2017, which is up from five states in 2016 and no states in 2012, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Iowa and Oklahoma, the two newest states with prevalences at or exceeding 35%, joined Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, which has the country’s highest rate of adult obesity at 38.1%. Colorado’s 22.6% rate is the lowest prevalence among all states. The District of Columbia and Hawaii also have prevalences under 25%; previously, Massachusetts also was in this group, but its prevalence went up to 25.9% last year, the CDC reported.

Regional disparities in self-reported adult obesity put the South (32.4%) and the Midwest (32.3%) well ahead of the Northeast (27.7%) and the West (26.1%) in 2017. Racial and ethnic disparities also were seen, with large gaps between blacks, who had a prevalence of 39%, and Hispanics (32.4%) and whites (29.3%). Obesity prevalence was 35% or higher among black adults in 31 states and D.C., while this was true among Hispanics in eight states and among whites in one (West Virginia), although the prevalence was at or above 35% for multiple racial groups in some of these states, the CDC reported based on data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

“Obesity costs the United States health care system over $147 billion a year [and] research has shown that obesity affects work productivity and military readiness,” the CDC said in a written statement. “To protect the health of the next generation, support for healthy behaviors such as healthy eating, better sleep, stress management, and physical activity should start early and expand to reach Americans across the lifespan in the communities where they live, learn, work, and play.”

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides physicians with a comprehensive, multi-disciplinary process to guide and personalize innovative obesity care for safe and effective weight management. Learn more at http://ow.ly/p1Fh30lOXYD

Online diabetes prevention programs as good as face-to-face programs

, researchers report.

Writing in background information to their paper, Tannaz Moin, MD, an endocrinologist at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the Veterans Affairs’ Health Services Research and Development Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation, and Policy, and her associates, said intensive lifestyle interventions such as diabetes prevention programs (DPP) could lower the risk of incident diabetes by 58%, but a lack of reach significantly attenuated their population impact in real-world settings.

“Building evidence for online DPP is important because of its potential for increasing reach because most U.S. adults (87%) use the Internet,” they wrote in their paper, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

They therefore set out to compare weight loss results from 114 veterans taking part in the Veterans Administration’s face-to-face standard-of-care weight management program MOVE! with an online program involving 268 obese or overweight veterans with prediabetes and 273 people taking part in an in-person program.