User login

Complex trauma in the perinatal period

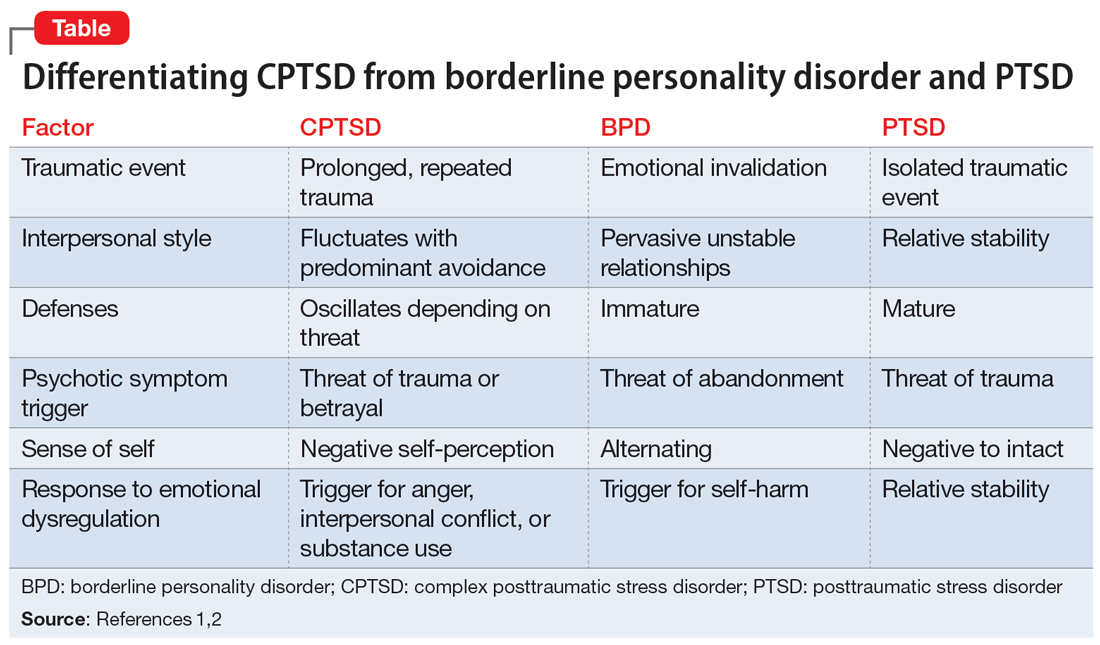

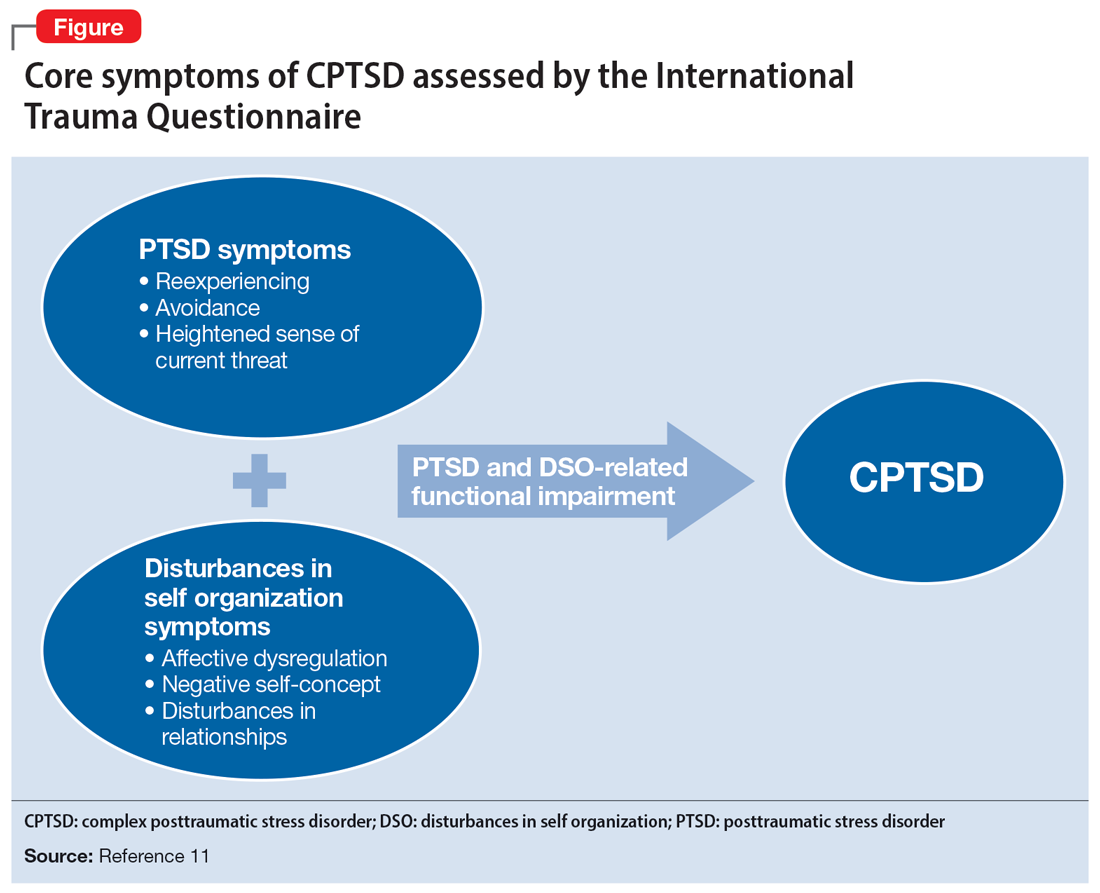

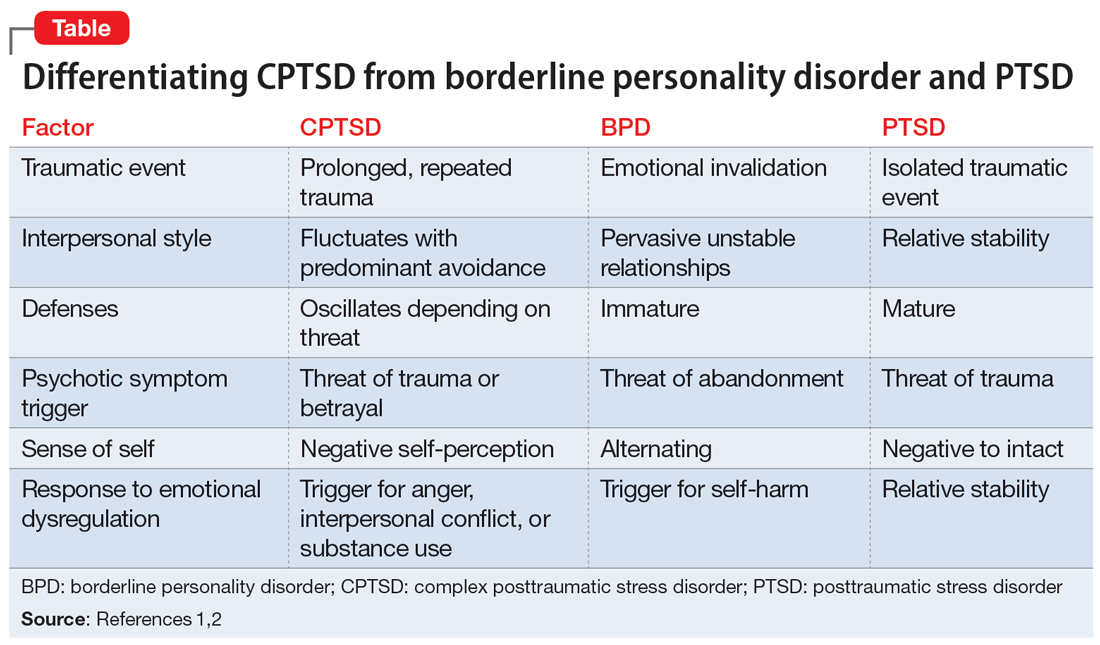

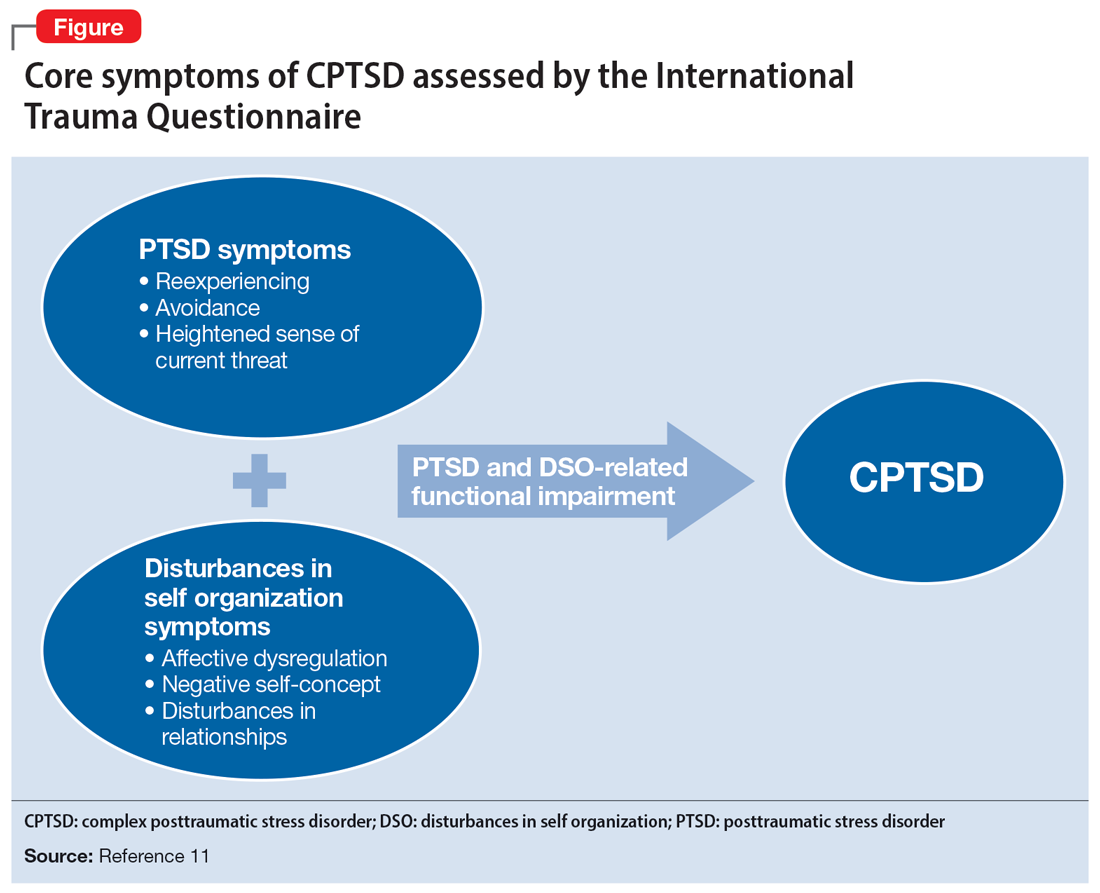

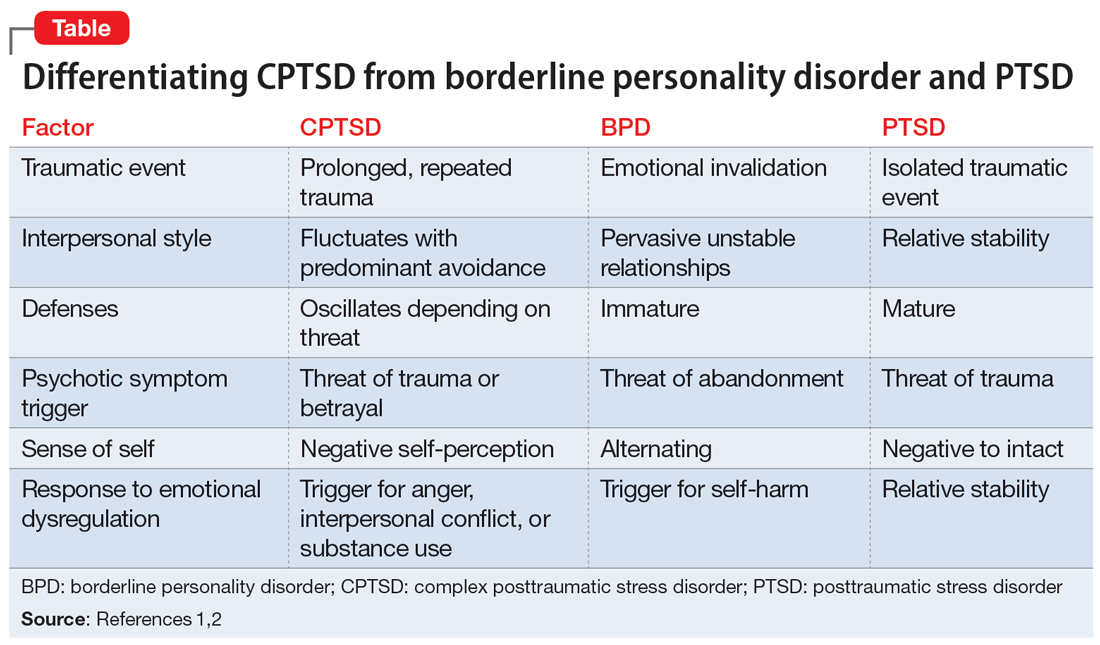

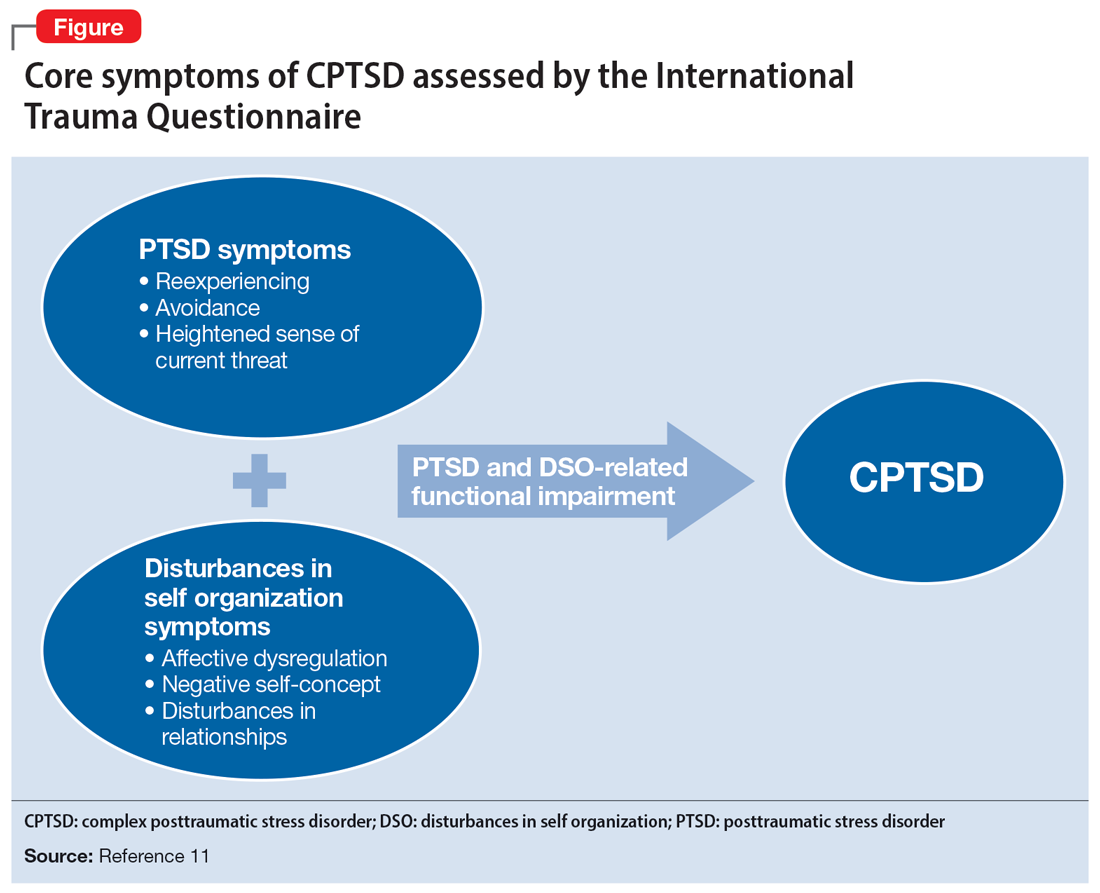

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is a condition characterized by classic trauma-related symptoms in addition to disturbances in self organization (DSO).1-3 DSO symptoms include negative self-concept, emotional dysregulation, and interpersonal problems. CPTSD differs from PTSD in that it includes symptoms of DSO, and differs from borderline personality disorder (BPD) in that it does not include extreme self-injurious behavior, a complete lack of sense of self, and avoidance of rejection or abandonment (Table1,2). The maladaptive traits of CPTSD are often the result of a chronic lack of safety in early childhood, particularly childhood sexual abuse (CSA). CSA may affect up to 20% of women and is defined by the CDC as “any completed or attempted sexual act, sexual contact with, or exploitation of a child by a caregiver.”4,5

Maternal lifetime trauma is more common among women who are in low-income minority groups and can lead to adverse birth outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.6 Recent research has found that trauma can increase cortisol levels during pregnancy, leading to increased placental permeability, inflammatory response, and longstanding alterations in the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis.6 A CPTSD diagnosis is of particular interest during the perinatal period because CPTSD is often a response to interpersonal trauma and attachment adversity, which can be reactivated during the perinatal period.7 CPTSD in survivors of CSA can be exacerbated due to feelings of disempowerment secondary to loss of bodily control throughout pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding, and obstetrical exams.5,8 Little is known about perinatal CPTSD, but we can extrapolate from trauma research that it is likely associated with the worsening of other maternal mental health conditions, suicidality, physical complaints, quality of life, maternal-child bonding outcomes, and low birth weight in offspring.5,9,10

Although there are no consensus guidelines on how to diagnose and treat CPTSD during the perinatal period, or how to promote family functioning thereafter, there are many opportunities for intervention. Mental health clinicians are in a particularly important position to care for women in the perinatal period, as collaborative work with obstetricians, pediatricians, and social services can have long-lasting effects.

In this article, we present cases of 3 CSA survivors who experienced worsening of CPTSD symptoms during the perinatal period and received psychiatric care via telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also identify best practice approaches and highlight areas for future research.

Case descriptions

Case 1

Ms. A, age 33, is married, has 3 children, has asthma, and is vaccinated against COVID-19. Her psychiatric history includes self-reported dissociative identity disorder and bulimia nervosa. At 2 months postpartum following an unplanned yet desired pregnancy, Ms. A presents to the outpatient clinic after a violent episode toward her husband during sexual intercourse. Since the first trimester of her pregnancy, she has expressed increased anxiety and difficulty sleeping, hypervigilance, intimacy avoidance, and negative views of herself and the world, yet she denies persistent depressive, manic, or psychotic symptoms, other maladaptive personality traits, or substance use. She recalls experiencing similar symptoms during her 2 previous peripartum periods, and attributes it to worsening memories of sexual abuse during childhood. Ms. A has a history of psychiatric hospitalizations during adolescence and young adulthood for suicidal ideation. She had been treated with various medications, including chlorpromazine, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and clonazepam, but self-discontinued these medications in 2016 because she felt they were ineffective. Since becoming a mother, she has consistently denied depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation, and intermittently engaged in interpersonal psychotherapy targeting her conflictual relationship with her husband and parenting struggles.

Ms. A underwent an induced vaginal delivery at 36 weeks gestation due to preeclampsia and had success with breastfeeding. While engaging in sexual activity for the first time postpartum, she dissociated and later learned she had forcefully grabbed her husband’s neck for several seconds but did not cause any longstanding physical damage. Upon learning of this episode, Ms. A’s psychiatrist asks her to complete the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ), a brief self-report measure developed for the assessment of the ICD-11 diagnosis of CPTSD (Figure11). Ms. A also completes the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), the Dissociative Experiences Scale, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assist with assessing her symptoms.12-15 The psychiatrist uses ICD-11 criteria to diagnose Ms. A with CPTSD, given her functional impairment associated with both PTSD and DSO symptoms, which have acutely worsened during the perinatal period.

Ms. A initially engages in extensive trauma psychoeducation and supportive psychotherapy for 3 months. She later pursues prolonged exposure psychotherapy targeting intimacy, and after 6 months of treatment, improves her avoidance behaviors and marriage.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2

Ms. R, age 35, is a partnered mother expecting her third child. She has no relevant medical history and is not vaccinated against COVID-19. Her psychiatric history includes self-reported panic attacks and bipolar affective disorder (BPAD). During the second trimester of a desired, unplanned pregnancy, Ms. R presents to an outpatient psychiatry clinic with symptoms of worsening dysphoria and insomnia. She endorses frequent nightmares and flashbacks of CSA as well as remote intimate partner violence. These symptoms, along with hypervigilance, insomnia, anxiety, dysphoria, negative views of herself and her surroundings, and hallucinations of a shadow that whispers “come” when she is alone, worsened during the first trimester of her pregnancy. She recalls experiencing similar trauma-related symptoms during a previous pregnancy but denies a history of pervasive depressive, manic, or psychotic symptoms. She has no other maladaptive personality traits, denies prior substance use or suicidal behavior, and has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or taken psychotropic medications.

Ms. R completes the PCL-5, ITQ, EPDS, and Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). The results are notable for significant functional impairment related to PTSD and DSO symptoms with minimal concern for BPAD symptoms. The psychiatrist uses ICD-11 criteria to diagnose Ms. R with CPTSD and discusses treatment options with her and her obstetrician. Ms. R is reluctant to take medication until she delivers her baby. She intermittently attends supportive therapy while pregnant. Her pregnancy is complicated by gestational diabetes, and she often misses appointments with her obstetrician and nutritionist.

Ms. R has an uncomplicated vaginal delivery at 38 weeks gestation and success with breastfeeding, but continues to have CPTSD symptoms. She is prescribed quetiapine 25 mg/d for anxiety, insomnia, mood, and psychotic symptoms, but stops taking the medication after 3 days due to excessive sedation. Ms. R is then prescribed sertraline 50 mg/d, which she finds helpful, but has intermittent adherence. She misses multiple virtual appointments with the psychiatrist and does not want to attend in-person sessions due to fear of contracting COVID-19. The psychiatrist encourages Ms. R to get vaccinated, focuses on organizational skills during sessions to promote attendance, and recommends in-person appointments to increase her motivation for treatment and alliance building. Despite numerous outreach attempts, Ms. R is lost to follow-up at 10 months postpartum.

Case 3

Ms. S, age 29, is a partnered mother expecting her fourth child. Her medical history includes chronic back pain. She is not vaccinated against COVID-19, and her psychiatric history includes BPAD. During the first trimester of an undesired, unplanned pregnancy, Ms. S presents to an outpatient psychiatric clinic following an episode where she held a knife over her gravid abdomen during a fight with her partner. She recounts that she became dysregulated and held a knife to her body to communicate her distress, but she did not cut herself, and adamantly denies wanting to hurt herself or the fetus. Ms. S struggles with affective instability, poor frustration tolerance, and irritability. After 1 month of treatment, she discloses surviving prolonged CSA that led to her current nightmares and flashbacks. She also endorses impaired sleep, intimacy avoidance, hypervigilance, impulsive reckless behaviors (including excessive gambling), and negative views about herself and the world that worsened since she learned she was pregnant. Ms. S reports that these same symptoms were aggravated during prior perinatal periods and recalls 2 episodes of severe dysregulation that led to an interrupted suicide attempt and a violent episode toward a loved one. She denies other self-harm behaviors, substance use, or psychotic symptoms, and denies having a history of psychiatric hospitalizations. Ms. S recalls receiving a brief trial of topiramate for BPAD and migraine when she was last in outpatient psychiatric care 8 years ago.

Her psychiatrist administers the PCL-5, ITQ, MDQ, EPDS, and Borderline Symptoms List 23 (BLS-23). The results are notable for significant PTSD and DSO symptoms.16 The psychiatrist diagnoses Ms. S with CPTSD and bipolar II disorder, exacerbated during the peripartum period. Throughout the remainder of her pregnancy, she endorses mood instability with significant irritability but declines pharmacotherapy. Ms. S intermittently engages in psychotherapy using dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) focusing on distress tolerance because she is unable to tolerate trauma-focused psychotherapy.

Continue to: Ms. S maintains the pregnancy...

Ms. S maintains the pregnancy without any additional complications and has a vaginal delivery at 39 weeks gestation. She initiates breastfeeding but chooses not to continue after 1 month due to fatigue, insomnia, and worsening mood. Her psychiatrist wants to contact Ms. S’s partner to discuss childcare support at night to promote better sleep conditions for Ms. S, but Ms. S declines. Ms. S intermittently attends virtual appointments, adamantly refuses the COVID-19 vaccine, and is fearful of starting a mood stabilizer despite extensive psychoeducation. At 5 months postpartum, Ms. S reports that she is in a worse mood and does not want to continue the appointment or further treatment, and abruptly ends the telepsychiatry session. Her psychiatrist reaches out the following week to schedule an in-person session if Ms. S agrees to wear personal protective equipment, which she is amenable to. During that appointment, the psychiatrist discusses the risks of bipolar depression and CPTSD on both her and her childrens’ development, against the risk of lamotrigine. Ms. S begins taking lamotrigine, which she tolerates without adverse effects, and quickly notices improvement in her mood as the medication is titrated up slowly to 200 mg/d. Ms. S then engages more consistently in psychotherapy and her CPTSD and bipolar II disorder symptoms much improve at 9 months postpartum.

Ensuring an accurate CPTSD diagnosis

These 3 cases illustrate the diversity and complexity of presentations for perinatal CPTSD following CSA. A CPTSD diagnosis is complicated because the differential is broad for those reporting PTSD and DSO symptoms, and CPTSD is commonly comorbid with other disorders such as anxiety and depression.17 While various scales can facilitate PTSD screening, the ITQ is helpful because it catalogs the symptoms of disturbances in self organization and functional impairment inherent in CPTSD. The ITQ can help clinicians and patients conceptualize symptoms and track progress (Figure11).

Once a patient screens positive, a CPTSD diagnosis is best made by the clinician after a full psychiatric interview, similar to other diagnoses. Psychiatrists must use ICD-11 criteria,1 as currently there are no formal DSM-5 criteria for CPTSD.2 Additional scales facilitate CPTSD symptom inventory, such as the PCL-5 to screen and monitor for PTSD symptoms and the BLS-23 to delineate between BPD or DSO symptoms.18 Furthermore, clinicians should screen for other comorbid conditions using additional scales such as the MDQ for BPAD and the EPDS for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Sharing a CPTSD diagnosis with a patient is an essential step when initiating treatment. Sensitive psychoeducation on the condition and its application to the perinatal period is key to establishing safety and trust, while also empowering survivors to make their own choices regarding treatment, all essential elements to trauma-informed care.19

A range of treatment options

Once CPTSD is appropriately diagnosed, clinicians must determine whether to use pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or both. A meta-analysis by Coventry et al20 sought to determine the best treatment strategies for complex traumatic events such as CSA, Multicomponent interventions were most promising, and psychological interventions were associated with larger effect sizes than pharmacologic interventions for managing PTSD, mood, and sleep. Therapeutic targets include trauma memory processing, self-perception, and dissociation, along with emotion, interpersonal, and somatic regulation.21

Psychotherapy. While there are no standardized guidelines for treating CPTSD, PTSD guidelines suggest using trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) as a first-line therapy, though a longer course may be needed to resolve CPTSD symptoms compared to PTSD symptoms.3 DBT for PTSD can be particularly helpful in targeting DSO symptoms.22 Narrative therapy focused on identity, embodiment, and parenting has also shown to be effective for survivors of CSA in the perinatal period, specifically with the goal of meaning-making.5 Therapy can also be effective in a group setting (ie, a “Victim to Survivor” TF-CBT group).23 Sex and couples therapy may be indicated to reestablish trust, especially when it is evident there is sexual inhibition from trauma that influences the relationship, as seen in Case 1.24

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy. Case 2 and Case 3 both demonstrate that while the peripartum period presents an increased risk for exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms, patients and clinicians may be reluctant to start medications due to concerns for safety during pregnancy or lactation.25 Clinicians must weigh the risks of medication exposure against the risks of exposing the fetus or newborn to untreated psychiatric disease and consult an expert in reproductive psychiatry if questions or concerns arise.26

Adverse effects of psychotropic medications must be considered, especially sedation. Medications that lead to sedation may not be safe or feasible for a mother following delivery, especially if she is breastfeeding. This was exemplified in Case 2, when Ms. R was having troubling hallucinations for which the clinician prescribed quetiapine. The medication resulted in excessive sedation and Ms. R did not feel comfortable performing childcare duties while taking the medication, which greatly influenced future therapy decisions.

Making the decision to prescribe a certain medication for CPTSD is highly influenced by the patient’s most troubling symptoms and their comorbid diagnoses. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) generally are considered safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and should be considered as a first-line intervention for PTSD, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders during the perinatal period.27 While prazosin is effective for PTSD symptoms outside of pregnancy, there is limited data regarding its safety during pregnancy and lactation, and it may lead to maternal hypotension and subsequent fetal adverse effects.28

Many patients with a history of CSA experience hallucinations and dissociative symptoms, as demonstrated by Case 1 and Case 2.29 In Case 3, Ms. S displayed features of BPAD with significant hypomanic symptoms and worsening suicidality during prior postpartum periods. The clinician felt comfortable prescribing lamotrigine, a relatively safe medication during the perinatal period compared to other mood stabilizers. Ms. S was amenable to taking lamotrigine, and her clinician avoided the use of an SSRI due to a concern of worsening a bipolar diathesis in this high-risk case.30 Case 2 and Case 3 both highlight the need to closely screen for comorbid conditions such as BPAD and using caution when considering an SSRI in light of the risk of precipitating mania, especially as the patient population is younger and at higher risk for antidepressant-associated mania.31,32

Help patients tap into their sources for strength

Other therapeutic strategies when treating patients with perinatal CPTSD include encouraging survivors to mobilize their support network and sources for strength. Chamberlain et al8 suggest incorporating socioecological and cultural contexts when considering outlets for social support systems and encourage collaborating with families, especially partners, along with community and spiritual networks. As seen in Case 3, clinicians should attempt to speak to family members on behalf of their patients to promote better sleeping conditions, which can greatly alleviate CPTSD and comorbid mood symptoms, and thus reduce suicide risk.33 Sources for strength should be accentuated and clinicians may need to advocate with child protective services to support parenting rights. As demonstrated in Case 1, motherhood can greatly reduce suicide risk, and should be promoted if a child’s safety is not in danger.34

Continue to: Clinicians must recognize...

Clinicians must recognize that patients in the perinatal period face barriers to obtaining health care, especially those with CPTSD, as these patients can be difficult to engage and retain. Each case described in this article challenged the psychiatrist with engagement and alliance-building, stemming from the patient’s CPTSD symptoms of interpersonal difficulties and negative views of surroundings. Case 2 demonstrates how the diagnosis can prevent patients from receiving appropriate prenatal care, while Case 3 shows how clinicians may need more flexible attendance policies and assertive outreach attempts to deliver the mental health care these patients deserve.

These vignettes highlight the psychosocial barriers women face during the perinatal period, such as caring for their child, financial stressors, and COVID-19 pandemic–related factors that can hinder treatment, which can be compounded by trauma. The uncertainty, unpredictability, loss of control, and loss of support structures collectively experienced during the pandemic can be triggering and precipitate worsening CPTSD symptoms.35 Women who experience trauma are less likely to obtain the COVID-19 vaccine for themselves or their children, and this hesitancy is often driven by institutional distrust.36 Policy leaders and clinicians should consider these factors to promote trauma-informed COVID-19 vaccine initiatives and expand mental health access using less orthodox treatment settings, such as telepsychiatry. Telepsychiatry can serve as a bridge to in-person care as patients may feel a higher sense of control when in a familiar home environment. Case 2 and Case 3 exemplify the difficulties of delivering mental health care to perinatal women with CPTSD during the pandemic, especially those who are vaccine-hesitant, and illustrate the importance of adapting a patient’s treatment plan in a personalized and trauma-informed way.

Psychiatrists can help obstetricians and pediatricians by explaining that avoidance patterns and distrust in the clinical setting may be related to trauma and are not grounds for conscious or subconscious punishment or abandonment. Educating other clinicians about trauma-informed care, precautions to use for perinatal patients, and ways to effectively support survivors of CSA can greatly improve health outcomes for perinatal women and their offspring.37

Bottom Line

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is characterized by classic PTSD symptoms as well as disturbances in self organization, which can include mood symptoms, psychotic symptoms, and maladaptive personality traits. CPTSD resulting from childhood sexual abuse is of particular concern for women, especially during the perinatal period. Clinicians must know how to recognize the signs and symptoms of CPTSD so they can tailor a trauma-informed treatment plan and promote treatment access in this highly vulnerable patient population.

Related Resources

- Tillman B, Sloan N, Westmoreland P. How COVID-19 affects peripartum women’s mental health. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):18-22. doi:10.12788/cp.0129

- Keswani M, Nemcek S, Rashid N. Is it bipolar disorder, or a complex form of PTSD? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(12):42-49. doi:10.12788/cp.0188

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Prazosin • Minipress

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topamax

1. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). Complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Accessed November 6, 2021. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/585833559

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Cloitre M, Garvert DW, Brewin CR, et al. Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complexPTSD: a latent profile analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013;4:10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706

4. Leeb RT, Paulozzi LJ, Melanson C, et al. Child Maltreatment Surveillance: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health & Human Services; 2008. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cm_surveillance-a.pdf

5. Byrne J, Smart C, Watson G. “I felt like I was being abused all over again”: how survivors of child sexual abuse make sense of the perinatal period through their narratives. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26(4):465-486. doi:10.1080/10538712.2017.1297880

6. Flom JD, Chiu YM, Hsu HL, et al. Maternal lifetime trauma and birthweight: effect modification by in utero cortisol and child sex. J Pediatr. 2018;203:301-308. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.069

7. Spinazzola J, van der Kolk B, Ford JD. When nowhere is safe: interpersonal trauma and attachment adversity as antecedents of posttraumatic stress disorder and developmental trauma disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(5):631-642. doi:10.1002/jts.22320

8. Chamberlain C, Gee G, Harfield S, et al. Parenting after a history of childhood maltreatment: a scoping review and map of evidence in the perinatal period. PloS One. 2019;14(3):e0213460. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213460

9. Cook N, Ayers S, Horsch A. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder during the perinatal period and child outcomes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:18-31. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.045

10. Gavin AR, Morris J. The association between maternal early life forced sexual intercourse and offspring birth weight: the role of socioeconomic status. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(5):442-449. doi:10.1089/jwh.2016.5789

11. Cloitre M, Shevlin M, Brewin CR, et al. The international trauma questionnaire: development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(6):536-546.

12. Cloitre M, Hyland P, Prins A, et al. The international trauma questionnaire (ITQ) measures reliable and clinically significant treatment-related change in PTSD and complex PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12(1):1930961. doi:10.1080/20008198.2021.1930961

13. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, et al. PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). US Department of Veterans Affairs. April 11, 2018. Accessed November 25, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_Standard_form.PDF

14. Dissociative Experiences Scale – II. TraumaDissociation.com. Accessed November 25, 2021. http://traumadissociation.com/des

15. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782-786. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

16. Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). Oregon Health & Science University. Accessed November 7, 2021. https://www.ohsu.edu/sites/default/files/2019-06/cms-quality-bipolar_disorder_mdq_screener.pdf

17. Karatzias T, Hyland P, Bradley A, et al. Risk factors and comorbidity of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: findings from a trauma-exposed population based sample of adults in the United Kingdom. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(9):887-894. doi:10.1002/da.22934

18. Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, et al. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32-39.

19. Fallot RD, Harris M. A trauma-informed approach to screening and assessment. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 2001;(89):23-31. doi:10.1002/yd.23320018904

20. Coventry PA, Meader N, Melton H, et al. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(8):e1003262. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003262

21. Ford JD. Progress and limitations in the treatment of complex PTSD and developmental trauma disorder. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2021;8:1-17. doi:10.1007/s40501-020-00236-6

22. Becker-Sadzio J, Gundel F, Kroczek A, et al. Trauma exposure therapy in a pregnant woman suffering from complex posttraumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse: risk or benefit? Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1697581. doi:10.1080/20008198.2019.1697581

23. Mendelsohn M, Zachary RS, Harney PA. Group therapy as an ecological bridge to new community for trauma survivors. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2007;14(1-2):227-243. doi:10.1300/J146v14n01_12

24. Macintosh HB, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Bergeron S. Sex and couple therapy with survivors of childhood trauma. In: Hall KS, Binik YM, eds. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. 6th ed. Guilford Press; 2020.

25. Dresner N, Byatt N, Gopalan P, et al. Psychiatric care of peripartum women. Psychiatric Times. 2015;32(12).

26. Zagorski N. How to manage meds before, during, and after pregnancy. Psychiatric News. 2019;54(14):13. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.PN.2019.6B36

27. Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2397-2407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828

28. Davidson AD, Bhat A, Chu F, et al. A systematic review of the use of prazosin in pregnancy and lactation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;71:134-136. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.03.012

29. Shinn AK, Wolff JD, Hwang M, et al. Assessing voice hearing in trauma spectrum disorders: a comparison of two measures and a review of the literature. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:1011. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01011

30. Raffi ER, Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Safety of psychotropic medications during pregnancy. Clin Perinatol. 2019;46(2):215-234. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2019.02.004

31. Martin A, Young C, Leckman JF, et al. Age effects on antidepressant-induced manic conversion. Arch Pediatr Adoles Med. 2004;158(8):773-780. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.8.773

32. Gill N, Bayes A, Parker G. A review of antidepressant-associated hypomania in those diagnosed with unipolar depression-risk factors, conceptual models, and management. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(4):20. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-01143-6

33. Harris LM, Huang X, Linthicum KP, et al. Sleep disturbances as risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviours: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13888. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70866-6

34. Dehara M, Wells MB, Sjöqvist H, et al. Parenthood is associated with lower suicide risk: a register-based cohort study of 1.5 million Swedes. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;143(3):206-215. doi:10.1111/acps.13240

35. Iyengar U, Jaiprakash B, Haitsuka H, et al. One year into the pandemic: a systematic review of perinatal mental health outcomes during COVID-19. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:674194. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.674194

36. Milan S, Dáu ALBT. The role of trauma in mothers’ COVID-19 vaccine beliefs and intentions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2021;46(5):526-535. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsab043

37. Coles J, Jones K. “Universal precautions”: perinatal touch and examination after childhood sexual abuse. Birth. 2009;36(3):230-236. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00327

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is a condition characterized by classic trauma-related symptoms in addition to disturbances in self organization (DSO).1-3 DSO symptoms include negative self-concept, emotional dysregulation, and interpersonal problems. CPTSD differs from PTSD in that it includes symptoms of DSO, and differs from borderline personality disorder (BPD) in that it does not include extreme self-injurious behavior, a complete lack of sense of self, and avoidance of rejection or abandonment (Table1,2). The maladaptive traits of CPTSD are often the result of a chronic lack of safety in early childhood, particularly childhood sexual abuse (CSA). CSA may affect up to 20% of women and is defined by the CDC as “any completed or attempted sexual act, sexual contact with, or exploitation of a child by a caregiver.”4,5

Maternal lifetime trauma is more common among women who are in low-income minority groups and can lead to adverse birth outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.6 Recent research has found that trauma can increase cortisol levels during pregnancy, leading to increased placental permeability, inflammatory response, and longstanding alterations in the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis.6 A CPTSD diagnosis is of particular interest during the perinatal period because CPTSD is often a response to interpersonal trauma and attachment adversity, which can be reactivated during the perinatal period.7 CPTSD in survivors of CSA can be exacerbated due to feelings of disempowerment secondary to loss of bodily control throughout pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding, and obstetrical exams.5,8 Little is known about perinatal CPTSD, but we can extrapolate from trauma research that it is likely associated with the worsening of other maternal mental health conditions, suicidality, physical complaints, quality of life, maternal-child bonding outcomes, and low birth weight in offspring.5,9,10

Although there are no consensus guidelines on how to diagnose and treat CPTSD during the perinatal period, or how to promote family functioning thereafter, there are many opportunities for intervention. Mental health clinicians are in a particularly important position to care for women in the perinatal period, as collaborative work with obstetricians, pediatricians, and social services can have long-lasting effects.

In this article, we present cases of 3 CSA survivors who experienced worsening of CPTSD symptoms during the perinatal period and received psychiatric care via telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also identify best practice approaches and highlight areas for future research.

Case descriptions

Case 1

Ms. A, age 33, is married, has 3 children, has asthma, and is vaccinated against COVID-19. Her psychiatric history includes self-reported dissociative identity disorder and bulimia nervosa. At 2 months postpartum following an unplanned yet desired pregnancy, Ms. A presents to the outpatient clinic after a violent episode toward her husband during sexual intercourse. Since the first trimester of her pregnancy, she has expressed increased anxiety and difficulty sleeping, hypervigilance, intimacy avoidance, and negative views of herself and the world, yet she denies persistent depressive, manic, or psychotic symptoms, other maladaptive personality traits, or substance use. She recalls experiencing similar symptoms during her 2 previous peripartum periods, and attributes it to worsening memories of sexual abuse during childhood. Ms. A has a history of psychiatric hospitalizations during adolescence and young adulthood for suicidal ideation. She had been treated with various medications, including chlorpromazine, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and clonazepam, but self-discontinued these medications in 2016 because she felt they were ineffective. Since becoming a mother, she has consistently denied depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation, and intermittently engaged in interpersonal psychotherapy targeting her conflictual relationship with her husband and parenting struggles.

Ms. A underwent an induced vaginal delivery at 36 weeks gestation due to preeclampsia and had success with breastfeeding. While engaging in sexual activity for the first time postpartum, she dissociated and later learned she had forcefully grabbed her husband’s neck for several seconds but did not cause any longstanding physical damage. Upon learning of this episode, Ms. A’s psychiatrist asks her to complete the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ), a brief self-report measure developed for the assessment of the ICD-11 diagnosis of CPTSD (Figure11). Ms. A also completes the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), the Dissociative Experiences Scale, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assist with assessing her symptoms.12-15 The psychiatrist uses ICD-11 criteria to diagnose Ms. A with CPTSD, given her functional impairment associated with both PTSD and DSO symptoms, which have acutely worsened during the perinatal period.

Ms. A initially engages in extensive trauma psychoeducation and supportive psychotherapy for 3 months. She later pursues prolonged exposure psychotherapy targeting intimacy, and after 6 months of treatment, improves her avoidance behaviors and marriage.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2

Ms. R, age 35, is a partnered mother expecting her third child. She has no relevant medical history and is not vaccinated against COVID-19. Her psychiatric history includes self-reported panic attacks and bipolar affective disorder (BPAD). During the second trimester of a desired, unplanned pregnancy, Ms. R presents to an outpatient psychiatry clinic with symptoms of worsening dysphoria and insomnia. She endorses frequent nightmares and flashbacks of CSA as well as remote intimate partner violence. These symptoms, along with hypervigilance, insomnia, anxiety, dysphoria, negative views of herself and her surroundings, and hallucinations of a shadow that whispers “come” when she is alone, worsened during the first trimester of her pregnancy. She recalls experiencing similar trauma-related symptoms during a previous pregnancy but denies a history of pervasive depressive, manic, or psychotic symptoms. She has no other maladaptive personality traits, denies prior substance use or suicidal behavior, and has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or taken psychotropic medications.

Ms. R completes the PCL-5, ITQ, EPDS, and Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). The results are notable for significant functional impairment related to PTSD and DSO symptoms with minimal concern for BPAD symptoms. The psychiatrist uses ICD-11 criteria to diagnose Ms. R with CPTSD and discusses treatment options with her and her obstetrician. Ms. R is reluctant to take medication until she delivers her baby. She intermittently attends supportive therapy while pregnant. Her pregnancy is complicated by gestational diabetes, and she often misses appointments with her obstetrician and nutritionist.

Ms. R has an uncomplicated vaginal delivery at 38 weeks gestation and success with breastfeeding, but continues to have CPTSD symptoms. She is prescribed quetiapine 25 mg/d for anxiety, insomnia, mood, and psychotic symptoms, but stops taking the medication after 3 days due to excessive sedation. Ms. R is then prescribed sertraline 50 mg/d, which she finds helpful, but has intermittent adherence. She misses multiple virtual appointments with the psychiatrist and does not want to attend in-person sessions due to fear of contracting COVID-19. The psychiatrist encourages Ms. R to get vaccinated, focuses on organizational skills during sessions to promote attendance, and recommends in-person appointments to increase her motivation for treatment and alliance building. Despite numerous outreach attempts, Ms. R is lost to follow-up at 10 months postpartum.

Case 3

Ms. S, age 29, is a partnered mother expecting her fourth child. Her medical history includes chronic back pain. She is not vaccinated against COVID-19, and her psychiatric history includes BPAD. During the first trimester of an undesired, unplanned pregnancy, Ms. S presents to an outpatient psychiatric clinic following an episode where she held a knife over her gravid abdomen during a fight with her partner. She recounts that she became dysregulated and held a knife to her body to communicate her distress, but she did not cut herself, and adamantly denies wanting to hurt herself or the fetus. Ms. S struggles with affective instability, poor frustration tolerance, and irritability. After 1 month of treatment, she discloses surviving prolonged CSA that led to her current nightmares and flashbacks. She also endorses impaired sleep, intimacy avoidance, hypervigilance, impulsive reckless behaviors (including excessive gambling), and negative views about herself and the world that worsened since she learned she was pregnant. Ms. S reports that these same symptoms were aggravated during prior perinatal periods and recalls 2 episodes of severe dysregulation that led to an interrupted suicide attempt and a violent episode toward a loved one. She denies other self-harm behaviors, substance use, or psychotic symptoms, and denies having a history of psychiatric hospitalizations. Ms. S recalls receiving a brief trial of topiramate for BPAD and migraine when she was last in outpatient psychiatric care 8 years ago.

Her psychiatrist administers the PCL-5, ITQ, MDQ, EPDS, and Borderline Symptoms List 23 (BLS-23). The results are notable for significant PTSD and DSO symptoms.16 The psychiatrist diagnoses Ms. S with CPTSD and bipolar II disorder, exacerbated during the peripartum period. Throughout the remainder of her pregnancy, she endorses mood instability with significant irritability but declines pharmacotherapy. Ms. S intermittently engages in psychotherapy using dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) focusing on distress tolerance because she is unable to tolerate trauma-focused psychotherapy.

Continue to: Ms. S maintains the pregnancy...

Ms. S maintains the pregnancy without any additional complications and has a vaginal delivery at 39 weeks gestation. She initiates breastfeeding but chooses not to continue after 1 month due to fatigue, insomnia, and worsening mood. Her psychiatrist wants to contact Ms. S’s partner to discuss childcare support at night to promote better sleep conditions for Ms. S, but Ms. S declines. Ms. S intermittently attends virtual appointments, adamantly refuses the COVID-19 vaccine, and is fearful of starting a mood stabilizer despite extensive psychoeducation. At 5 months postpartum, Ms. S reports that she is in a worse mood and does not want to continue the appointment or further treatment, and abruptly ends the telepsychiatry session. Her psychiatrist reaches out the following week to schedule an in-person session if Ms. S agrees to wear personal protective equipment, which she is amenable to. During that appointment, the psychiatrist discusses the risks of bipolar depression and CPTSD on both her and her childrens’ development, against the risk of lamotrigine. Ms. S begins taking lamotrigine, which she tolerates without adverse effects, and quickly notices improvement in her mood as the medication is titrated up slowly to 200 mg/d. Ms. S then engages more consistently in psychotherapy and her CPTSD and bipolar II disorder symptoms much improve at 9 months postpartum.

Ensuring an accurate CPTSD diagnosis

These 3 cases illustrate the diversity and complexity of presentations for perinatal CPTSD following CSA. A CPTSD diagnosis is complicated because the differential is broad for those reporting PTSD and DSO symptoms, and CPTSD is commonly comorbid with other disorders such as anxiety and depression.17 While various scales can facilitate PTSD screening, the ITQ is helpful because it catalogs the symptoms of disturbances in self organization and functional impairment inherent in CPTSD. The ITQ can help clinicians and patients conceptualize symptoms and track progress (Figure11).

Once a patient screens positive, a CPTSD diagnosis is best made by the clinician after a full psychiatric interview, similar to other diagnoses. Psychiatrists must use ICD-11 criteria,1 as currently there are no formal DSM-5 criteria for CPTSD.2 Additional scales facilitate CPTSD symptom inventory, such as the PCL-5 to screen and monitor for PTSD symptoms and the BLS-23 to delineate between BPD or DSO symptoms.18 Furthermore, clinicians should screen for other comorbid conditions using additional scales such as the MDQ for BPAD and the EPDS for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Sharing a CPTSD diagnosis with a patient is an essential step when initiating treatment. Sensitive psychoeducation on the condition and its application to the perinatal period is key to establishing safety and trust, while also empowering survivors to make their own choices regarding treatment, all essential elements to trauma-informed care.19

A range of treatment options

Once CPTSD is appropriately diagnosed, clinicians must determine whether to use pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or both. A meta-analysis by Coventry et al20 sought to determine the best treatment strategies for complex traumatic events such as CSA, Multicomponent interventions were most promising, and psychological interventions were associated with larger effect sizes than pharmacologic interventions for managing PTSD, mood, and sleep. Therapeutic targets include trauma memory processing, self-perception, and dissociation, along with emotion, interpersonal, and somatic regulation.21

Psychotherapy. While there are no standardized guidelines for treating CPTSD, PTSD guidelines suggest using trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) as a first-line therapy, though a longer course may be needed to resolve CPTSD symptoms compared to PTSD symptoms.3 DBT for PTSD can be particularly helpful in targeting DSO symptoms.22 Narrative therapy focused on identity, embodiment, and parenting has also shown to be effective for survivors of CSA in the perinatal period, specifically with the goal of meaning-making.5 Therapy can also be effective in a group setting (ie, a “Victim to Survivor” TF-CBT group).23 Sex and couples therapy may be indicated to reestablish trust, especially when it is evident there is sexual inhibition from trauma that influences the relationship, as seen in Case 1.24

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy. Case 2 and Case 3 both demonstrate that while the peripartum period presents an increased risk for exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms, patients and clinicians may be reluctant to start medications due to concerns for safety during pregnancy or lactation.25 Clinicians must weigh the risks of medication exposure against the risks of exposing the fetus or newborn to untreated psychiatric disease and consult an expert in reproductive psychiatry if questions or concerns arise.26

Adverse effects of psychotropic medications must be considered, especially sedation. Medications that lead to sedation may not be safe or feasible for a mother following delivery, especially if she is breastfeeding. This was exemplified in Case 2, when Ms. R was having troubling hallucinations for which the clinician prescribed quetiapine. The medication resulted in excessive sedation and Ms. R did not feel comfortable performing childcare duties while taking the medication, which greatly influenced future therapy decisions.

Making the decision to prescribe a certain medication for CPTSD is highly influenced by the patient’s most troubling symptoms and their comorbid diagnoses. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) generally are considered safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and should be considered as a first-line intervention for PTSD, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders during the perinatal period.27 While prazosin is effective for PTSD symptoms outside of pregnancy, there is limited data regarding its safety during pregnancy and lactation, and it may lead to maternal hypotension and subsequent fetal adverse effects.28

Many patients with a history of CSA experience hallucinations and dissociative symptoms, as demonstrated by Case 1 and Case 2.29 In Case 3, Ms. S displayed features of BPAD with significant hypomanic symptoms and worsening suicidality during prior postpartum periods. The clinician felt comfortable prescribing lamotrigine, a relatively safe medication during the perinatal period compared to other mood stabilizers. Ms. S was amenable to taking lamotrigine, and her clinician avoided the use of an SSRI due to a concern of worsening a bipolar diathesis in this high-risk case.30 Case 2 and Case 3 both highlight the need to closely screen for comorbid conditions such as BPAD and using caution when considering an SSRI in light of the risk of precipitating mania, especially as the patient population is younger and at higher risk for antidepressant-associated mania.31,32

Help patients tap into their sources for strength

Other therapeutic strategies when treating patients with perinatal CPTSD include encouraging survivors to mobilize their support network and sources for strength. Chamberlain et al8 suggest incorporating socioecological and cultural contexts when considering outlets for social support systems and encourage collaborating with families, especially partners, along with community and spiritual networks. As seen in Case 3, clinicians should attempt to speak to family members on behalf of their patients to promote better sleeping conditions, which can greatly alleviate CPTSD and comorbid mood symptoms, and thus reduce suicide risk.33 Sources for strength should be accentuated and clinicians may need to advocate with child protective services to support parenting rights. As demonstrated in Case 1, motherhood can greatly reduce suicide risk, and should be promoted if a child’s safety is not in danger.34

Continue to: Clinicians must recognize...

Clinicians must recognize that patients in the perinatal period face barriers to obtaining health care, especially those with CPTSD, as these patients can be difficult to engage and retain. Each case described in this article challenged the psychiatrist with engagement and alliance-building, stemming from the patient’s CPTSD symptoms of interpersonal difficulties and negative views of surroundings. Case 2 demonstrates how the diagnosis can prevent patients from receiving appropriate prenatal care, while Case 3 shows how clinicians may need more flexible attendance policies and assertive outreach attempts to deliver the mental health care these patients deserve.

These vignettes highlight the psychosocial barriers women face during the perinatal period, such as caring for their child, financial stressors, and COVID-19 pandemic–related factors that can hinder treatment, which can be compounded by trauma. The uncertainty, unpredictability, loss of control, and loss of support structures collectively experienced during the pandemic can be triggering and precipitate worsening CPTSD symptoms.35 Women who experience trauma are less likely to obtain the COVID-19 vaccine for themselves or their children, and this hesitancy is often driven by institutional distrust.36 Policy leaders and clinicians should consider these factors to promote trauma-informed COVID-19 vaccine initiatives and expand mental health access using less orthodox treatment settings, such as telepsychiatry. Telepsychiatry can serve as a bridge to in-person care as patients may feel a higher sense of control when in a familiar home environment. Case 2 and Case 3 exemplify the difficulties of delivering mental health care to perinatal women with CPTSD during the pandemic, especially those who are vaccine-hesitant, and illustrate the importance of adapting a patient’s treatment plan in a personalized and trauma-informed way.

Psychiatrists can help obstetricians and pediatricians by explaining that avoidance patterns and distrust in the clinical setting may be related to trauma and are not grounds for conscious or subconscious punishment or abandonment. Educating other clinicians about trauma-informed care, precautions to use for perinatal patients, and ways to effectively support survivors of CSA can greatly improve health outcomes for perinatal women and their offspring.37

Bottom Line

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is characterized by classic PTSD symptoms as well as disturbances in self organization, which can include mood symptoms, psychotic symptoms, and maladaptive personality traits. CPTSD resulting from childhood sexual abuse is of particular concern for women, especially during the perinatal period. Clinicians must know how to recognize the signs and symptoms of CPTSD so they can tailor a trauma-informed treatment plan and promote treatment access in this highly vulnerable patient population.

Related Resources

- Tillman B, Sloan N, Westmoreland P. How COVID-19 affects peripartum women’s mental health. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):18-22. doi:10.12788/cp.0129

- Keswani M, Nemcek S, Rashid N. Is it bipolar disorder, or a complex form of PTSD? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(12):42-49. doi:10.12788/cp.0188

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Prazosin • Minipress

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topamax

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is a condition characterized by classic trauma-related symptoms in addition to disturbances in self organization (DSO).1-3 DSO symptoms include negative self-concept, emotional dysregulation, and interpersonal problems. CPTSD differs from PTSD in that it includes symptoms of DSO, and differs from borderline personality disorder (BPD) in that it does not include extreme self-injurious behavior, a complete lack of sense of self, and avoidance of rejection or abandonment (Table1,2). The maladaptive traits of CPTSD are often the result of a chronic lack of safety in early childhood, particularly childhood sexual abuse (CSA). CSA may affect up to 20% of women and is defined by the CDC as “any completed or attempted sexual act, sexual contact with, or exploitation of a child by a caregiver.”4,5

Maternal lifetime trauma is more common among women who are in low-income minority groups and can lead to adverse birth outcomes in this vulnerable patient population.6 Recent research has found that trauma can increase cortisol levels during pregnancy, leading to increased placental permeability, inflammatory response, and longstanding alterations in the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis.6 A CPTSD diagnosis is of particular interest during the perinatal period because CPTSD is often a response to interpersonal trauma and attachment adversity, which can be reactivated during the perinatal period.7 CPTSD in survivors of CSA can be exacerbated due to feelings of disempowerment secondary to loss of bodily control throughout pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding, and obstetrical exams.5,8 Little is known about perinatal CPTSD, but we can extrapolate from trauma research that it is likely associated with the worsening of other maternal mental health conditions, suicidality, physical complaints, quality of life, maternal-child bonding outcomes, and low birth weight in offspring.5,9,10

Although there are no consensus guidelines on how to diagnose and treat CPTSD during the perinatal period, or how to promote family functioning thereafter, there are many opportunities for intervention. Mental health clinicians are in a particularly important position to care for women in the perinatal period, as collaborative work with obstetricians, pediatricians, and social services can have long-lasting effects.

In this article, we present cases of 3 CSA survivors who experienced worsening of CPTSD symptoms during the perinatal period and received psychiatric care via telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also identify best practice approaches and highlight areas for future research.

Case descriptions

Case 1

Ms. A, age 33, is married, has 3 children, has asthma, and is vaccinated against COVID-19. Her psychiatric history includes self-reported dissociative identity disorder and bulimia nervosa. At 2 months postpartum following an unplanned yet desired pregnancy, Ms. A presents to the outpatient clinic after a violent episode toward her husband during sexual intercourse. Since the first trimester of her pregnancy, she has expressed increased anxiety and difficulty sleeping, hypervigilance, intimacy avoidance, and negative views of herself and the world, yet she denies persistent depressive, manic, or psychotic symptoms, other maladaptive personality traits, or substance use. She recalls experiencing similar symptoms during her 2 previous peripartum periods, and attributes it to worsening memories of sexual abuse during childhood. Ms. A has a history of psychiatric hospitalizations during adolescence and young adulthood for suicidal ideation. She had been treated with various medications, including chlorpromazine, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and clonazepam, but self-discontinued these medications in 2016 because she felt they were ineffective. Since becoming a mother, she has consistently denied depressive symptoms or suicidal ideation, and intermittently engaged in interpersonal psychotherapy targeting her conflictual relationship with her husband and parenting struggles.

Ms. A underwent an induced vaginal delivery at 36 weeks gestation due to preeclampsia and had success with breastfeeding. While engaging in sexual activity for the first time postpartum, she dissociated and later learned she had forcefully grabbed her husband’s neck for several seconds but did not cause any longstanding physical damage. Upon learning of this episode, Ms. A’s psychiatrist asks her to complete the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ), a brief self-report measure developed for the assessment of the ICD-11 diagnosis of CPTSD (Figure11). Ms. A also completes the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), the Dissociative Experiences Scale, and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assist with assessing her symptoms.12-15 The psychiatrist uses ICD-11 criteria to diagnose Ms. A with CPTSD, given her functional impairment associated with both PTSD and DSO symptoms, which have acutely worsened during the perinatal period.

Ms. A initially engages in extensive trauma psychoeducation and supportive psychotherapy for 3 months. She later pursues prolonged exposure psychotherapy targeting intimacy, and after 6 months of treatment, improves her avoidance behaviors and marriage.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2

Ms. R, age 35, is a partnered mother expecting her third child. She has no relevant medical history and is not vaccinated against COVID-19. Her psychiatric history includes self-reported panic attacks and bipolar affective disorder (BPAD). During the second trimester of a desired, unplanned pregnancy, Ms. R presents to an outpatient psychiatry clinic with symptoms of worsening dysphoria and insomnia. She endorses frequent nightmares and flashbacks of CSA as well as remote intimate partner violence. These symptoms, along with hypervigilance, insomnia, anxiety, dysphoria, negative views of herself and her surroundings, and hallucinations of a shadow that whispers “come” when she is alone, worsened during the first trimester of her pregnancy. She recalls experiencing similar trauma-related symptoms during a previous pregnancy but denies a history of pervasive depressive, manic, or psychotic symptoms. She has no other maladaptive personality traits, denies prior substance use or suicidal behavior, and has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or taken psychotropic medications.

Ms. R completes the PCL-5, ITQ, EPDS, and Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). The results are notable for significant functional impairment related to PTSD and DSO symptoms with minimal concern for BPAD symptoms. The psychiatrist uses ICD-11 criteria to diagnose Ms. R with CPTSD and discusses treatment options with her and her obstetrician. Ms. R is reluctant to take medication until she delivers her baby. She intermittently attends supportive therapy while pregnant. Her pregnancy is complicated by gestational diabetes, and she often misses appointments with her obstetrician and nutritionist.

Ms. R has an uncomplicated vaginal delivery at 38 weeks gestation and success with breastfeeding, but continues to have CPTSD symptoms. She is prescribed quetiapine 25 mg/d for anxiety, insomnia, mood, and psychotic symptoms, but stops taking the medication after 3 days due to excessive sedation. Ms. R is then prescribed sertraline 50 mg/d, which she finds helpful, but has intermittent adherence. She misses multiple virtual appointments with the psychiatrist and does not want to attend in-person sessions due to fear of contracting COVID-19. The psychiatrist encourages Ms. R to get vaccinated, focuses on organizational skills during sessions to promote attendance, and recommends in-person appointments to increase her motivation for treatment and alliance building. Despite numerous outreach attempts, Ms. R is lost to follow-up at 10 months postpartum.

Case 3

Ms. S, age 29, is a partnered mother expecting her fourth child. Her medical history includes chronic back pain. She is not vaccinated against COVID-19, and her psychiatric history includes BPAD. During the first trimester of an undesired, unplanned pregnancy, Ms. S presents to an outpatient psychiatric clinic following an episode where she held a knife over her gravid abdomen during a fight with her partner. She recounts that she became dysregulated and held a knife to her body to communicate her distress, but she did not cut herself, and adamantly denies wanting to hurt herself or the fetus. Ms. S struggles with affective instability, poor frustration tolerance, and irritability. After 1 month of treatment, she discloses surviving prolonged CSA that led to her current nightmares and flashbacks. She also endorses impaired sleep, intimacy avoidance, hypervigilance, impulsive reckless behaviors (including excessive gambling), and negative views about herself and the world that worsened since she learned she was pregnant. Ms. S reports that these same symptoms were aggravated during prior perinatal periods and recalls 2 episodes of severe dysregulation that led to an interrupted suicide attempt and a violent episode toward a loved one. She denies other self-harm behaviors, substance use, or psychotic symptoms, and denies having a history of psychiatric hospitalizations. Ms. S recalls receiving a brief trial of topiramate for BPAD and migraine when she was last in outpatient psychiatric care 8 years ago.

Her psychiatrist administers the PCL-5, ITQ, MDQ, EPDS, and Borderline Symptoms List 23 (BLS-23). The results are notable for significant PTSD and DSO symptoms.16 The psychiatrist diagnoses Ms. S with CPTSD and bipolar II disorder, exacerbated during the peripartum period. Throughout the remainder of her pregnancy, she endorses mood instability with significant irritability but declines pharmacotherapy. Ms. S intermittently engages in psychotherapy using dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) focusing on distress tolerance because she is unable to tolerate trauma-focused psychotherapy.

Continue to: Ms. S maintains the pregnancy...

Ms. S maintains the pregnancy without any additional complications and has a vaginal delivery at 39 weeks gestation. She initiates breastfeeding but chooses not to continue after 1 month due to fatigue, insomnia, and worsening mood. Her psychiatrist wants to contact Ms. S’s partner to discuss childcare support at night to promote better sleep conditions for Ms. S, but Ms. S declines. Ms. S intermittently attends virtual appointments, adamantly refuses the COVID-19 vaccine, and is fearful of starting a mood stabilizer despite extensive psychoeducation. At 5 months postpartum, Ms. S reports that she is in a worse mood and does not want to continue the appointment or further treatment, and abruptly ends the telepsychiatry session. Her psychiatrist reaches out the following week to schedule an in-person session if Ms. S agrees to wear personal protective equipment, which she is amenable to. During that appointment, the psychiatrist discusses the risks of bipolar depression and CPTSD on both her and her childrens’ development, against the risk of lamotrigine. Ms. S begins taking lamotrigine, which she tolerates without adverse effects, and quickly notices improvement in her mood as the medication is titrated up slowly to 200 mg/d. Ms. S then engages more consistently in psychotherapy and her CPTSD and bipolar II disorder symptoms much improve at 9 months postpartum.

Ensuring an accurate CPTSD diagnosis

These 3 cases illustrate the diversity and complexity of presentations for perinatal CPTSD following CSA. A CPTSD diagnosis is complicated because the differential is broad for those reporting PTSD and DSO symptoms, and CPTSD is commonly comorbid with other disorders such as anxiety and depression.17 While various scales can facilitate PTSD screening, the ITQ is helpful because it catalogs the symptoms of disturbances in self organization and functional impairment inherent in CPTSD. The ITQ can help clinicians and patients conceptualize symptoms and track progress (Figure11).

Once a patient screens positive, a CPTSD diagnosis is best made by the clinician after a full psychiatric interview, similar to other diagnoses. Psychiatrists must use ICD-11 criteria,1 as currently there are no formal DSM-5 criteria for CPTSD.2 Additional scales facilitate CPTSD symptom inventory, such as the PCL-5 to screen and monitor for PTSD symptoms and the BLS-23 to delineate between BPD or DSO symptoms.18 Furthermore, clinicians should screen for other comorbid conditions using additional scales such as the MDQ for BPAD and the EPDS for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. Sharing a CPTSD diagnosis with a patient is an essential step when initiating treatment. Sensitive psychoeducation on the condition and its application to the perinatal period is key to establishing safety and trust, while also empowering survivors to make their own choices regarding treatment, all essential elements to trauma-informed care.19

A range of treatment options

Once CPTSD is appropriately diagnosed, clinicians must determine whether to use pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or both. A meta-analysis by Coventry et al20 sought to determine the best treatment strategies for complex traumatic events such as CSA, Multicomponent interventions were most promising, and psychological interventions were associated with larger effect sizes than pharmacologic interventions for managing PTSD, mood, and sleep. Therapeutic targets include trauma memory processing, self-perception, and dissociation, along with emotion, interpersonal, and somatic regulation.21

Psychotherapy. While there are no standardized guidelines for treating CPTSD, PTSD guidelines suggest using trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) as a first-line therapy, though a longer course may be needed to resolve CPTSD symptoms compared to PTSD symptoms.3 DBT for PTSD can be particularly helpful in targeting DSO symptoms.22 Narrative therapy focused on identity, embodiment, and parenting has also shown to be effective for survivors of CSA in the perinatal period, specifically with the goal of meaning-making.5 Therapy can also be effective in a group setting (ie, a “Victim to Survivor” TF-CBT group).23 Sex and couples therapy may be indicated to reestablish trust, especially when it is evident there is sexual inhibition from trauma that influences the relationship, as seen in Case 1.24

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy. Case 2 and Case 3 both demonstrate that while the peripartum period presents an increased risk for exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms, patients and clinicians may be reluctant to start medications due to concerns for safety during pregnancy or lactation.25 Clinicians must weigh the risks of medication exposure against the risks of exposing the fetus or newborn to untreated psychiatric disease and consult an expert in reproductive psychiatry if questions or concerns arise.26

Adverse effects of psychotropic medications must be considered, especially sedation. Medications that lead to sedation may not be safe or feasible for a mother following delivery, especially if she is breastfeeding. This was exemplified in Case 2, when Ms. R was having troubling hallucinations for which the clinician prescribed quetiapine. The medication resulted in excessive sedation and Ms. R did not feel comfortable performing childcare duties while taking the medication, which greatly influenced future therapy decisions.

Making the decision to prescribe a certain medication for CPTSD is highly influenced by the patient’s most troubling symptoms and their comorbid diagnoses. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) generally are considered safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding, and should be considered as a first-line intervention for PTSD, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders during the perinatal period.27 While prazosin is effective for PTSD symptoms outside of pregnancy, there is limited data regarding its safety during pregnancy and lactation, and it may lead to maternal hypotension and subsequent fetal adverse effects.28

Many patients with a history of CSA experience hallucinations and dissociative symptoms, as demonstrated by Case 1 and Case 2.29 In Case 3, Ms. S displayed features of BPAD with significant hypomanic symptoms and worsening suicidality during prior postpartum periods. The clinician felt comfortable prescribing lamotrigine, a relatively safe medication during the perinatal period compared to other mood stabilizers. Ms. S was amenable to taking lamotrigine, and her clinician avoided the use of an SSRI due to a concern of worsening a bipolar diathesis in this high-risk case.30 Case 2 and Case 3 both highlight the need to closely screen for comorbid conditions such as BPAD and using caution when considering an SSRI in light of the risk of precipitating mania, especially as the patient population is younger and at higher risk for antidepressant-associated mania.31,32

Help patients tap into their sources for strength

Other therapeutic strategies when treating patients with perinatal CPTSD include encouraging survivors to mobilize their support network and sources for strength. Chamberlain et al8 suggest incorporating socioecological and cultural contexts when considering outlets for social support systems and encourage collaborating with families, especially partners, along with community and spiritual networks. As seen in Case 3, clinicians should attempt to speak to family members on behalf of their patients to promote better sleeping conditions, which can greatly alleviate CPTSD and comorbid mood symptoms, and thus reduce suicide risk.33 Sources for strength should be accentuated and clinicians may need to advocate with child protective services to support parenting rights. As demonstrated in Case 1, motherhood can greatly reduce suicide risk, and should be promoted if a child’s safety is not in danger.34

Continue to: Clinicians must recognize...

Clinicians must recognize that patients in the perinatal period face barriers to obtaining health care, especially those with CPTSD, as these patients can be difficult to engage and retain. Each case described in this article challenged the psychiatrist with engagement and alliance-building, stemming from the patient’s CPTSD symptoms of interpersonal difficulties and negative views of surroundings. Case 2 demonstrates how the diagnosis can prevent patients from receiving appropriate prenatal care, while Case 3 shows how clinicians may need more flexible attendance policies and assertive outreach attempts to deliver the mental health care these patients deserve.

These vignettes highlight the psychosocial barriers women face during the perinatal period, such as caring for their child, financial stressors, and COVID-19 pandemic–related factors that can hinder treatment, which can be compounded by trauma. The uncertainty, unpredictability, loss of control, and loss of support structures collectively experienced during the pandemic can be triggering and precipitate worsening CPTSD symptoms.35 Women who experience trauma are less likely to obtain the COVID-19 vaccine for themselves or their children, and this hesitancy is often driven by institutional distrust.36 Policy leaders and clinicians should consider these factors to promote trauma-informed COVID-19 vaccine initiatives and expand mental health access using less orthodox treatment settings, such as telepsychiatry. Telepsychiatry can serve as a bridge to in-person care as patients may feel a higher sense of control when in a familiar home environment. Case 2 and Case 3 exemplify the difficulties of delivering mental health care to perinatal women with CPTSD during the pandemic, especially those who are vaccine-hesitant, and illustrate the importance of adapting a patient’s treatment plan in a personalized and trauma-informed way.

Psychiatrists can help obstetricians and pediatricians by explaining that avoidance patterns and distrust in the clinical setting may be related to trauma and are not grounds for conscious or subconscious punishment or abandonment. Educating other clinicians about trauma-informed care, precautions to use for perinatal patients, and ways to effectively support survivors of CSA can greatly improve health outcomes for perinatal women and their offspring.37

Bottom Line

Complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is characterized by classic PTSD symptoms as well as disturbances in self organization, which can include mood symptoms, psychotic symptoms, and maladaptive personality traits. CPTSD resulting from childhood sexual abuse is of particular concern for women, especially during the perinatal period. Clinicians must know how to recognize the signs and symptoms of CPTSD so they can tailor a trauma-informed treatment plan and promote treatment access in this highly vulnerable patient population.

Related Resources

- Tillman B, Sloan N, Westmoreland P. How COVID-19 affects peripartum women’s mental health. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):18-22. doi:10.12788/cp.0129

- Keswani M, Nemcek S, Rashid N. Is it bipolar disorder, or a complex form of PTSD? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(12):42-49. doi:10.12788/cp.0188

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Prazosin • Minipress

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topamax

1. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). Complex posttraumatic stress disorder. Accessed November 6, 2021. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/585833559

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Cloitre M, Garvert DW, Brewin CR, et al. Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complexPTSD: a latent profile analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013;4:10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706

4. Leeb RT, Paulozzi LJ, Melanson C, et al. Child Maltreatment Surveillance: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health & Human Services; 2008. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/cm_surveillance-a.pdf

5. Byrne J, Smart C, Watson G. “I felt like I was being abused all over again”: how survivors of child sexual abuse make sense of the perinatal period through their narratives. J Child Sex Abus. 2017;26(4):465-486. doi:10.1080/10538712.2017.1297880

6. Flom JD, Chiu YM, Hsu HL, et al. Maternal lifetime trauma and birthweight: effect modification by in utero cortisol and child sex. J Pediatr. 2018;203:301-308. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.069

7. Spinazzola J, van der Kolk B, Ford JD. When nowhere is safe: interpersonal trauma and attachment adversity as antecedents of posttraumatic stress disorder and developmental trauma disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(5):631-642. doi:10.1002/jts.22320

8. Chamberlain C, Gee G, Harfield S, et al. Parenting after a history of childhood maltreatment: a scoping review and map of evidence in the perinatal period. PloS One. 2019;14(3):e0213460. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213460

9. Cook N, Ayers S, Horsch A. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder during the perinatal period and child outcomes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:18-31. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.045

10. Gavin AR, Morris J. The association between maternal early life forced sexual intercourse and offspring birth weight: the role of socioeconomic status. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(5):442-449. doi:10.1089/jwh.2016.5789

11. Cloitre M, Shevlin M, Brewin CR, et al. The international trauma questionnaire: development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(6):536-546.

12. Cloitre M, Hyland P, Prins A, et al. The international trauma questionnaire (ITQ) measures reliable and clinically significant treatment-related change in PTSD and complex PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12(1):1930961. doi:10.1080/20008198.2021.1930961

13. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, et al. PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). US Department of Veterans Affairs. April 11, 2018. Accessed November 25, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/PCL5_Standard_form.PDF

14. Dissociative Experiences Scale – II. TraumaDissociation.com. Accessed November 25, 2021. http://traumadissociation.com/des

15. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782-786. doi:10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

16. Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). Oregon Health & Science University. Accessed November 7, 2021. https://www.ohsu.edu/sites/default/files/2019-06/cms-quality-bipolar_disorder_mdq_screener.pdf

17. Karatzias T, Hyland P, Bradley A, et al. Risk factors and comorbidity of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: findings from a trauma-exposed population based sample of adults in the United Kingdom. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(9):887-894. doi:10.1002/da.22934

18. Bohus M, Kleindienst N, Limberger MF, et al. The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology. 2009;42(1):32-39.

19. Fallot RD, Harris M. A trauma-informed approach to screening and assessment. New Dir Ment Health Serv. 2001;(89):23-31. doi:10.1002/yd.23320018904

20. Coventry PA, Meader N, Melton H, et al. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(8):e1003262. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003262

21. Ford JD. Progress and limitations in the treatment of complex PTSD and developmental trauma disorder. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2021;8:1-17. doi:10.1007/s40501-020-00236-6

22. Becker-Sadzio J, Gundel F, Kroczek A, et al. Trauma exposure therapy in a pregnant woman suffering from complex posttraumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse: risk or benefit? Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1697581. doi:10.1080/20008198.2019.1697581

23. Mendelsohn M, Zachary RS, Harney PA. Group therapy as an ecological bridge to new community for trauma survivors. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2007;14(1-2):227-243. doi:10.1300/J146v14n01_12

24. Macintosh HB, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Bergeron S. Sex and couple therapy with survivors of childhood trauma. In: Hall KS, Binik YM, eds. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. 6th ed. Guilford Press; 2020.

25. Dresner N, Byatt N, Gopalan P, et al. Psychiatric care of peripartum women. Psychiatric Times. 2015;32(12).

26. Zagorski N. How to manage meds before, during, and after pregnancy. Psychiatric News. 2019;54(14):13. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.PN.2019.6B36

27. Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2397-2407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828

28. Davidson AD, Bhat A, Chu F, et al. A systematic review of the use of prazosin in pregnancy and lactation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;71:134-136. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.03.012

29. Shinn AK, Wolff JD, Hwang M, et al. Assessing voice hearing in trauma spectrum disorders: a comparison of two measures and a review of the literature. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:1011. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01011

30. Raffi ER, Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Safety of psychotropic medications during pregnancy. Clin Perinatol. 2019;46(2):215-234. doi:10.1016/j.clp.2019.02.004

31. Martin A, Young C, Leckman JF, et al. Age effects on antidepressant-induced manic conversion. Arch Pediatr Adoles Med. 2004;158(8):773-780. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.8.773

32. Gill N, Bayes A, Parker G. A review of antidepressant-associated hypomania in those diagnosed with unipolar depression-risk factors, conceptual models, and management. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(4):20. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-01143-6

33. Harris LM, Huang X, Linthicum KP, et al. Sleep disturbances as risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviours: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13888. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70866-6