User login

What’s the true role of Demodex mites in the development of papulopustular rosacea?

, a narrative review proposes.

According to the author, Fabienne Forton, MD, PhD, a dermatologist based in Brussels, recent studies suggest that Demodex induces two opposite actions on host immunity: A defensive immune response aimed at eliminating the mite and an immunosuppressive action aimed at favoring its own proliferation. “Moreover, the initial defensive immune response is likely diverted towards benefit for the mite, via T-cell exhaustion induced by the immunosuppressive properties of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which may also explain the favorable influence that the altered vascular background of rosacea seems to exert on Demodex proliferation,” she wrote in the review, which was published in JEADV, the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She presented several arguments for and against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea. Three on the “for” side are:

High Demodex densities (Dds) are observed in almost all cases of rosacea with papulopustules (PPR). Dr. Forton pointed out that Demodex proliferation presents in as many as 98.6% of cases of PPR when two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies (SSSBs) are performed (Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:242-8). “Dds in patients with PPR are as high as those in patients with demodicosis, much higher than in healthy skin and other facial dermatoses (except when these are associated with demodicosis [as is often the case with seborrheic dermatitis and acne vulgaris]),” she wrote.

The Demodex mite has the elements necessary to stimulate the host’s innate and adaptative immune system. Dr. Forton characterized Demodex as “the only microorganism found in abundance in almost all subjects with PPR, which can, in addition, alter the skin barrier. To feed and move around, Demodex mites attack the epidermal wall of the pilosebaceous follicles mechanically (via their stylets, mouth palps and motor palps) and chemically (through enzymes secreted from salivary glands for pre-oral digestion).”

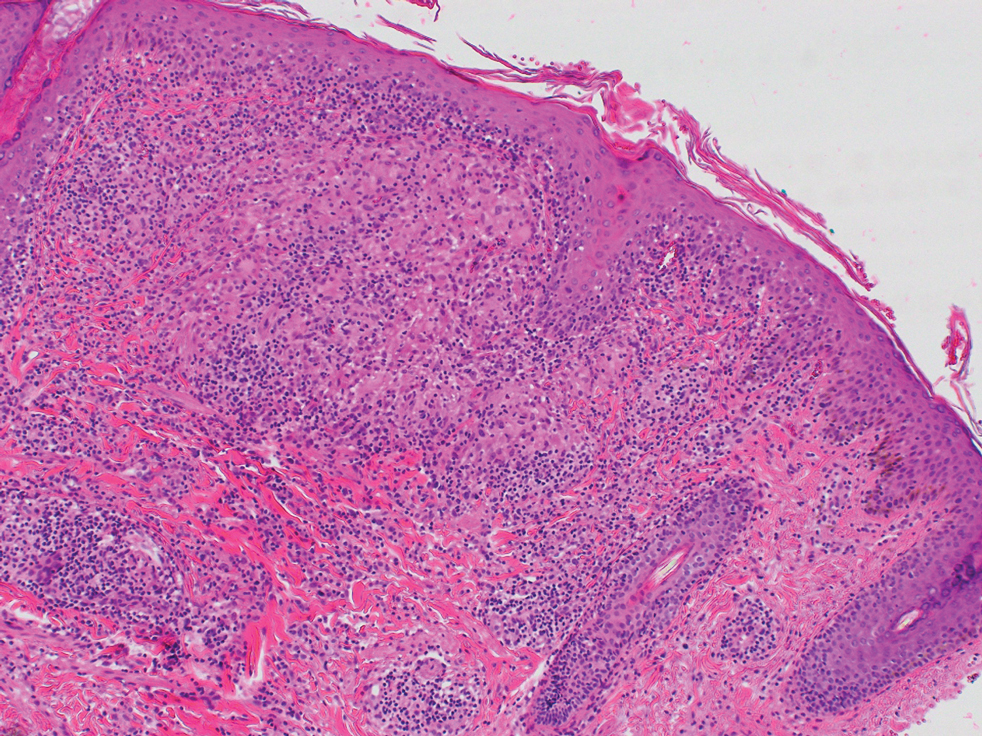

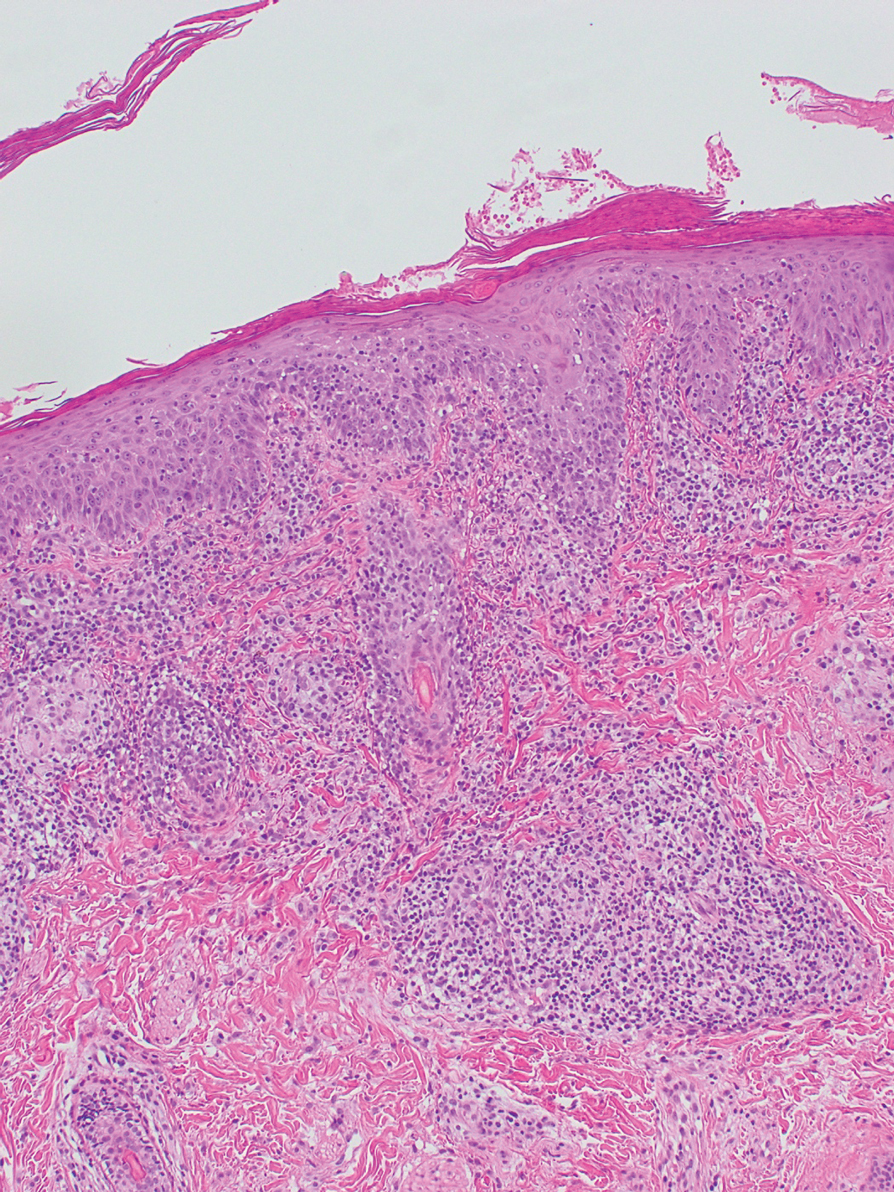

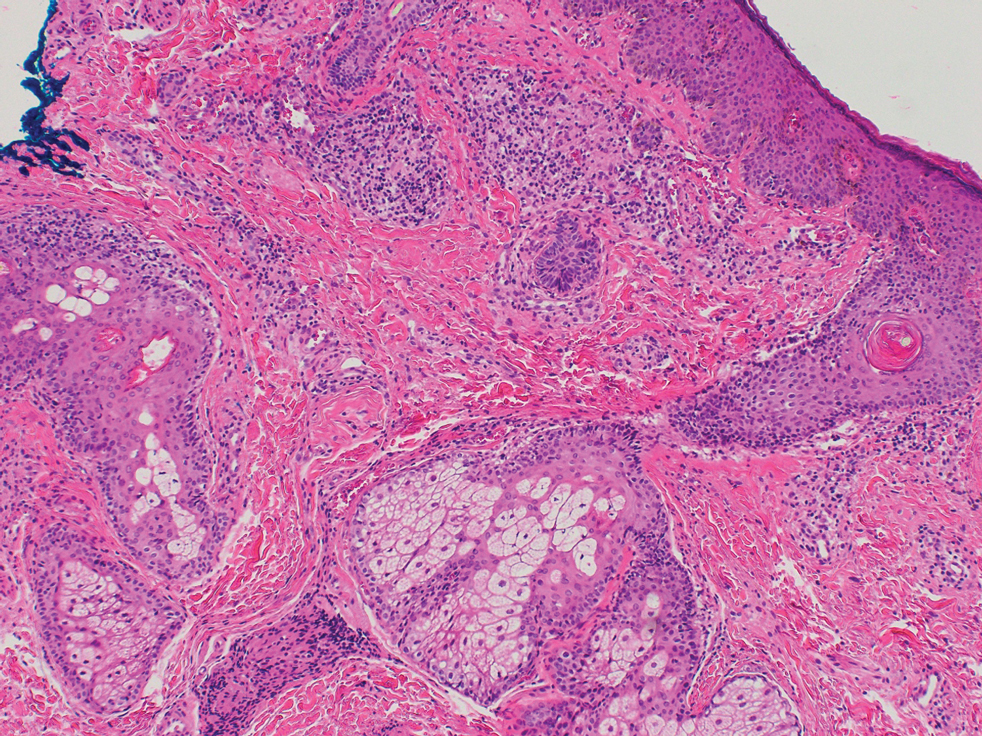

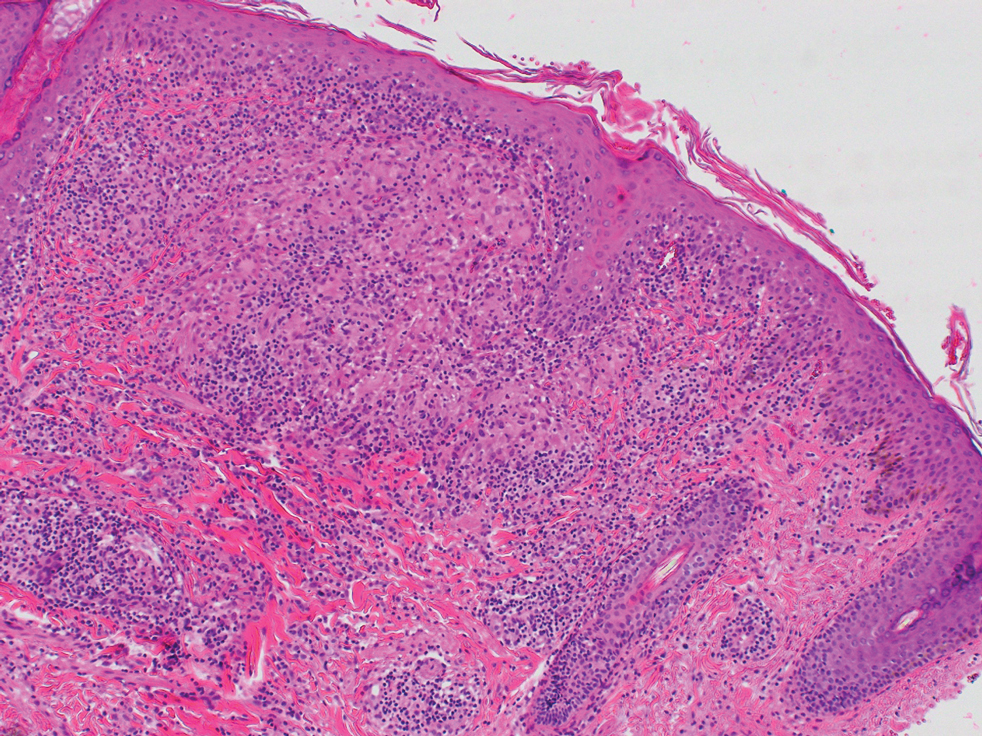

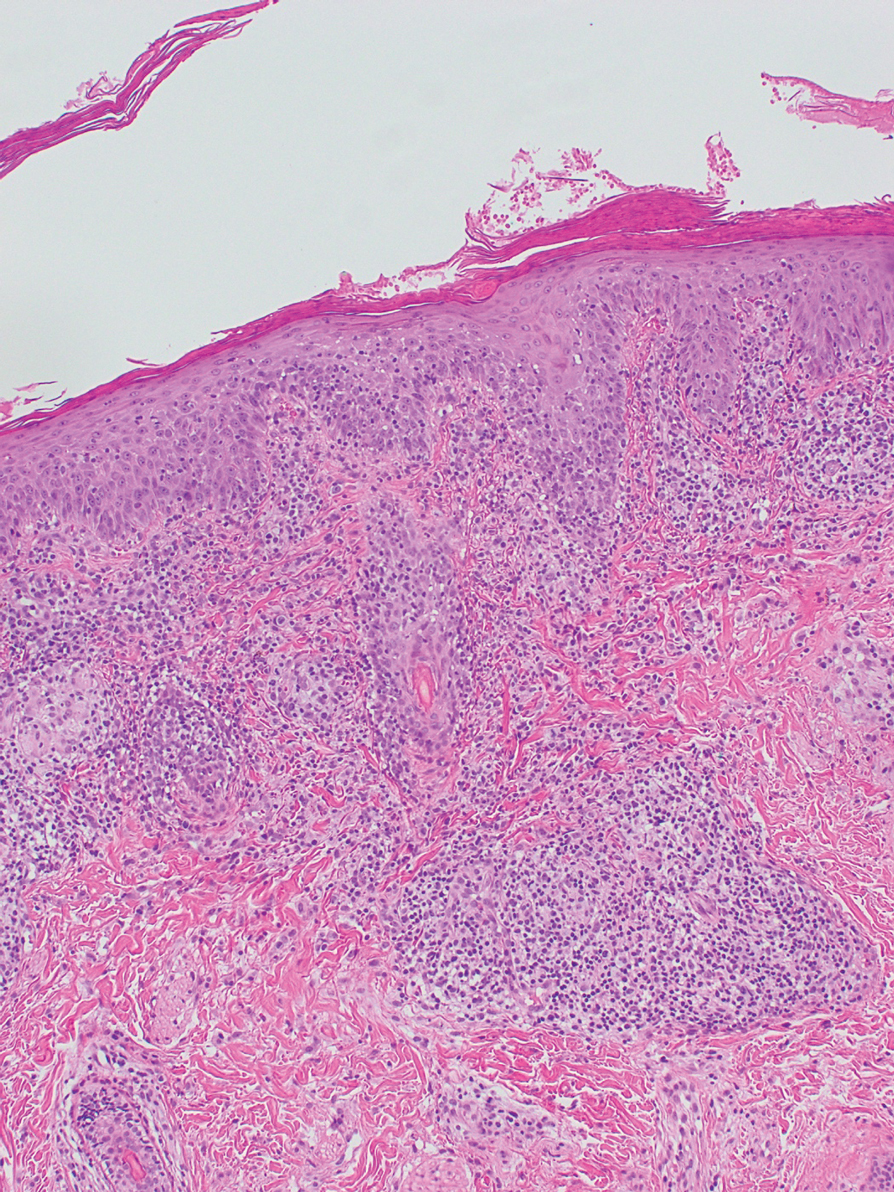

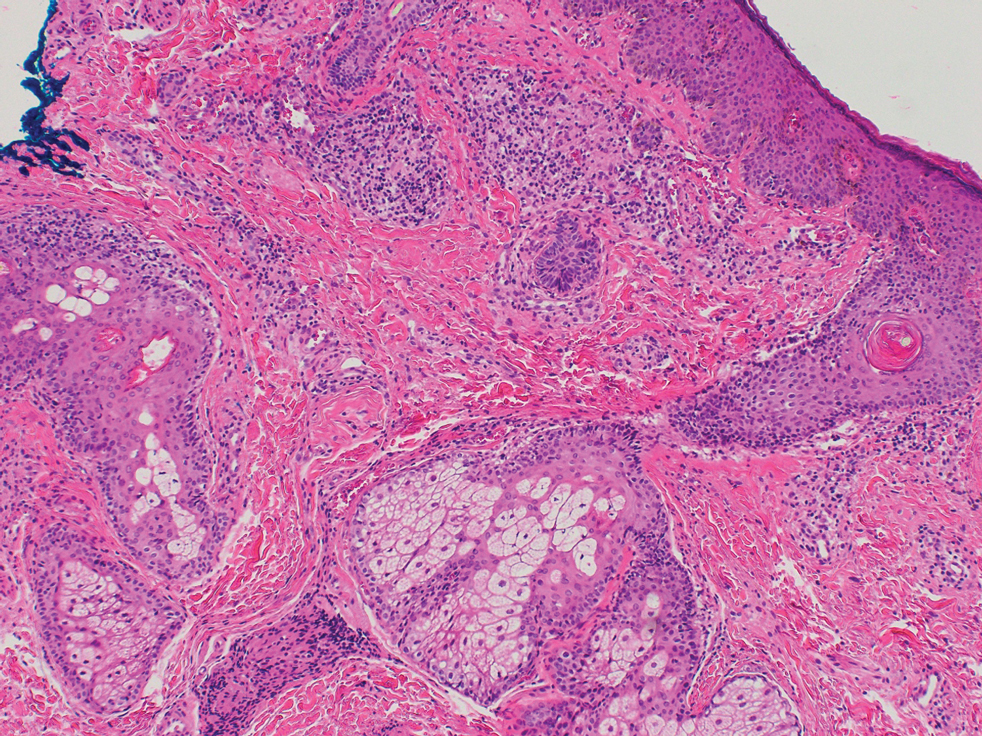

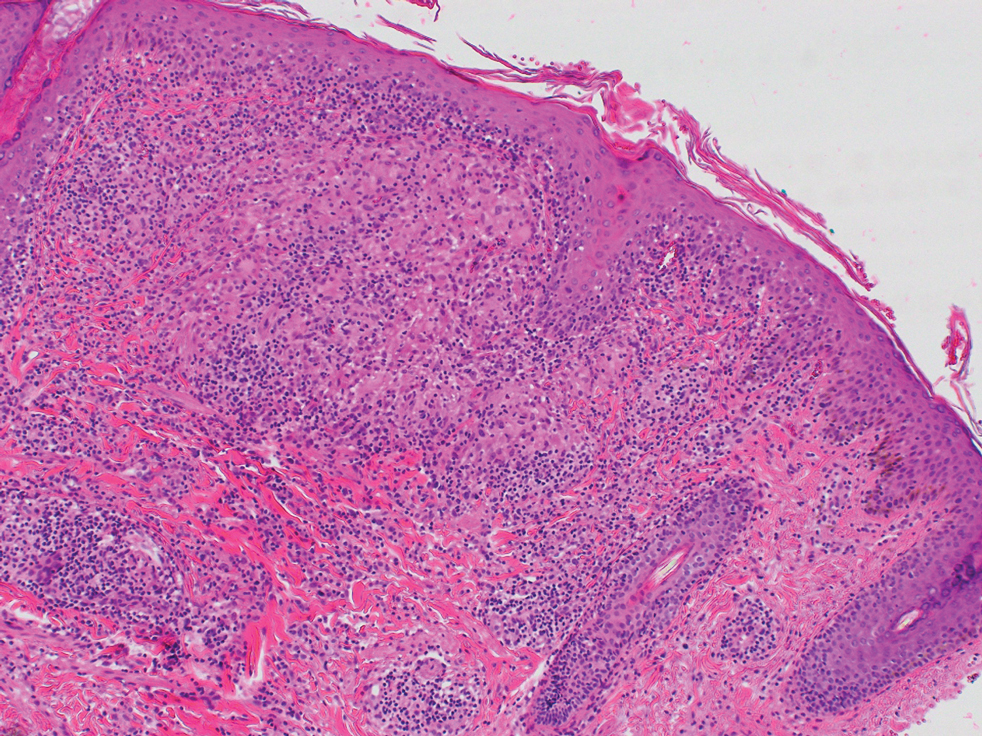

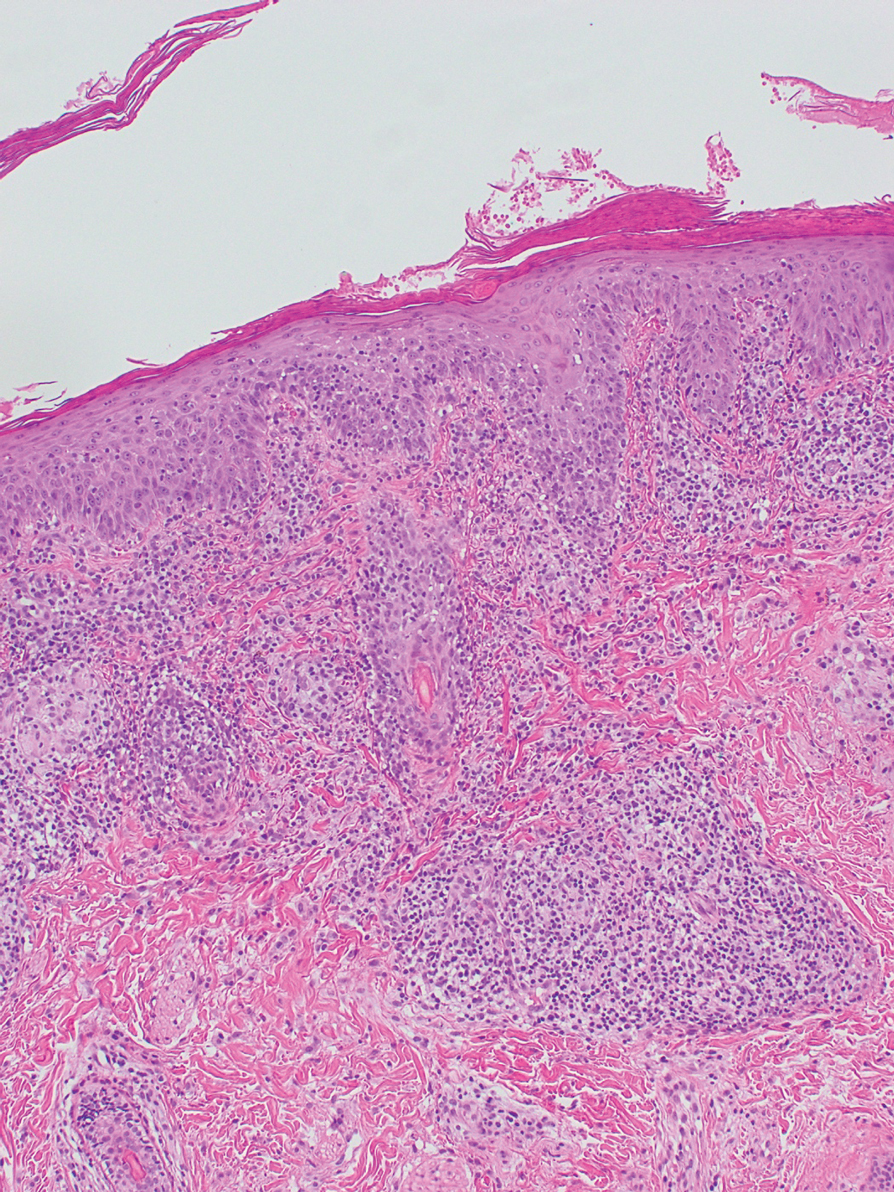

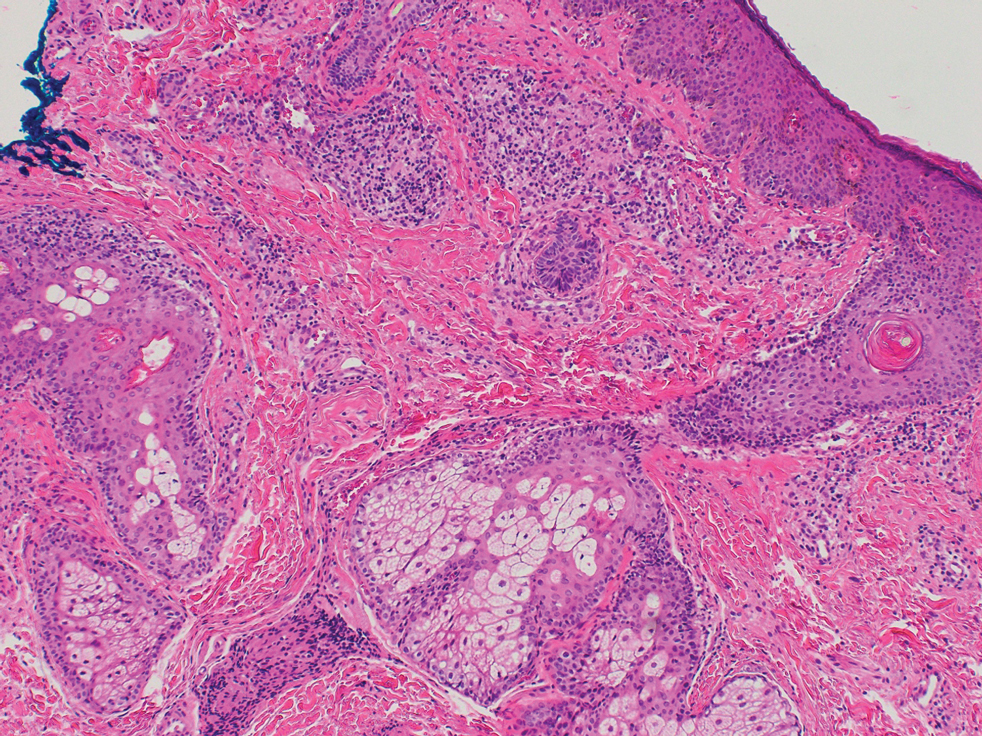

The Demodex mite stimulates the immune system (which ultimately results in phymatous changes). A healthy immune system, including T helper 17 cells, seems necessary to adequately control mite proliferation. Dr. Forton noted that researchers have observed a perivascular and perifollicular infiltrate in people with rosacea, “which invades the epidermis and is often associated with the presence of Demodex. The lympho-histiocytic perifollicular infiltrate is correlated with the presence and the numbers of mites inside the follicles, and giant cell granulomas can be seen around intradermal Demodex mites, which attempt to phagocytize the mites.”

The three arguments that she presented against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea are the following:

No relationship with the mite was observed in two early histological studies. Rosacea biopsies conducted in these two analyses, published in 1969 and 1988, showed only mild infiltrate, with few parasites and no inflammation around the infested follicles.

However, she countered, “these data are now obsolete, because it has since been clearly demonstrated that the perifollicular infiltrate is a characteristic of rosacea, that this infiltrate is statistically related to the presence and the number of Demodex mites, and that high Dds are observed in almost all subjects with PPR.”

Demodex is not always associated with inflammatory symptoms. This argument holds that Demodex is present in all individuals and can be observed in very high densities without causing significant symptoms. Studies that support this viewpoint include the following: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:441–4 and J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:998-1007.

However, Dr. Forton pointed out that the normal, low-density presence of Demodex in the skin “does not contradict a pathogenic effect when it proliferates excessively or penetrates into the dermis. The absence of intense inflammatory symptoms when the Dd is very high does not negate its potential pathogenicity.”

Demodex proliferation could be a consequence rather than a cause. Dr. Forton cited a study, suggesting that inflammation could be responsible for alteration of the skin barrier, “which, secondarily, would favor proliferation of the parasites, as with skin affected by atopic dermatitis that becomes superinfected by Staphylococcus aureus”. On the other hand, she argued, “unlike S. aureus, Demodex does not require alteration of the skin barrier to implant or proliferate. It also does not require an inflammatory background.” She added that if mite proliferation was a consequence of clinical lesions, “the Demodex mite should logically proliferate in other inflammatory facial skin conditions, which is not the case.”

A Sept. 14 National Rosacea Society (NRS) press release featured the paper by Dr. Forton, titled, “Which Comes First, The Rosacea Blemish or The Mite?” In the release, Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, who chaired the NRS Expert Committee that updated the standard classification of rosacea in 2018, said that “growing knowledge of rosacea’s pathophysiology has established that a consistent multivariate disease process underlies its potential manifestations, and the clinical significance of each of these elements is increasing as more is understood.”

While the potential role of Demodex in rosacea has been controversial in the past, “these new insights suggest where it may play a role as a meaningful cofactor in the development of the disorder,” added Dr. Gallo, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Forton reported having no financial disclosures.

, a narrative review proposes.

According to the author, Fabienne Forton, MD, PhD, a dermatologist based in Brussels, recent studies suggest that Demodex induces two opposite actions on host immunity: A defensive immune response aimed at eliminating the mite and an immunosuppressive action aimed at favoring its own proliferation. “Moreover, the initial defensive immune response is likely diverted towards benefit for the mite, via T-cell exhaustion induced by the immunosuppressive properties of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which may also explain the favorable influence that the altered vascular background of rosacea seems to exert on Demodex proliferation,” she wrote in the review, which was published in JEADV, the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She presented several arguments for and against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea. Three on the “for” side are:

High Demodex densities (Dds) are observed in almost all cases of rosacea with papulopustules (PPR). Dr. Forton pointed out that Demodex proliferation presents in as many as 98.6% of cases of PPR when two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies (SSSBs) are performed (Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:242-8). “Dds in patients with PPR are as high as those in patients with demodicosis, much higher than in healthy skin and other facial dermatoses (except when these are associated with demodicosis [as is often the case with seborrheic dermatitis and acne vulgaris]),” she wrote.

The Demodex mite has the elements necessary to stimulate the host’s innate and adaptative immune system. Dr. Forton characterized Demodex as “the only microorganism found in abundance in almost all subjects with PPR, which can, in addition, alter the skin barrier. To feed and move around, Demodex mites attack the epidermal wall of the pilosebaceous follicles mechanically (via their stylets, mouth palps and motor palps) and chemically (through enzymes secreted from salivary glands for pre-oral digestion).”

The Demodex mite stimulates the immune system (which ultimately results in phymatous changes). A healthy immune system, including T helper 17 cells, seems necessary to adequately control mite proliferation. Dr. Forton noted that researchers have observed a perivascular and perifollicular infiltrate in people with rosacea, “which invades the epidermis and is often associated with the presence of Demodex. The lympho-histiocytic perifollicular infiltrate is correlated with the presence and the numbers of mites inside the follicles, and giant cell granulomas can be seen around intradermal Demodex mites, which attempt to phagocytize the mites.”

The three arguments that she presented against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea are the following:

No relationship with the mite was observed in two early histological studies. Rosacea biopsies conducted in these two analyses, published in 1969 and 1988, showed only mild infiltrate, with few parasites and no inflammation around the infested follicles.

However, she countered, “these data are now obsolete, because it has since been clearly demonstrated that the perifollicular infiltrate is a characteristic of rosacea, that this infiltrate is statistically related to the presence and the number of Demodex mites, and that high Dds are observed in almost all subjects with PPR.”

Demodex is not always associated with inflammatory symptoms. This argument holds that Demodex is present in all individuals and can be observed in very high densities without causing significant symptoms. Studies that support this viewpoint include the following: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:441–4 and J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:998-1007.

However, Dr. Forton pointed out that the normal, low-density presence of Demodex in the skin “does not contradict a pathogenic effect when it proliferates excessively or penetrates into the dermis. The absence of intense inflammatory symptoms when the Dd is very high does not negate its potential pathogenicity.”

Demodex proliferation could be a consequence rather than a cause. Dr. Forton cited a study, suggesting that inflammation could be responsible for alteration of the skin barrier, “which, secondarily, would favor proliferation of the parasites, as with skin affected by atopic dermatitis that becomes superinfected by Staphylococcus aureus”. On the other hand, she argued, “unlike S. aureus, Demodex does not require alteration of the skin barrier to implant or proliferate. It also does not require an inflammatory background.” She added that if mite proliferation was a consequence of clinical lesions, “the Demodex mite should logically proliferate in other inflammatory facial skin conditions, which is not the case.”

A Sept. 14 National Rosacea Society (NRS) press release featured the paper by Dr. Forton, titled, “Which Comes First, The Rosacea Blemish or The Mite?” In the release, Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, who chaired the NRS Expert Committee that updated the standard classification of rosacea in 2018, said that “growing knowledge of rosacea’s pathophysiology has established that a consistent multivariate disease process underlies its potential manifestations, and the clinical significance of each of these elements is increasing as more is understood.”

While the potential role of Demodex in rosacea has been controversial in the past, “these new insights suggest where it may play a role as a meaningful cofactor in the development of the disorder,” added Dr. Gallo, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Forton reported having no financial disclosures.

, a narrative review proposes.

According to the author, Fabienne Forton, MD, PhD, a dermatologist based in Brussels, recent studies suggest that Demodex induces two opposite actions on host immunity: A defensive immune response aimed at eliminating the mite and an immunosuppressive action aimed at favoring its own proliferation. “Moreover, the initial defensive immune response is likely diverted towards benefit for the mite, via T-cell exhaustion induced by the immunosuppressive properties of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which may also explain the favorable influence that the altered vascular background of rosacea seems to exert on Demodex proliferation,” she wrote in the review, which was published in JEADV, the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She presented several arguments for and against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea. Three on the “for” side are:

High Demodex densities (Dds) are observed in almost all cases of rosacea with papulopustules (PPR). Dr. Forton pointed out that Demodex proliferation presents in as many as 98.6% of cases of PPR when two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies (SSSBs) are performed (Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:242-8). “Dds in patients with PPR are as high as those in patients with demodicosis, much higher than in healthy skin and other facial dermatoses (except when these are associated with demodicosis [as is often the case with seborrheic dermatitis and acne vulgaris]),” she wrote.

The Demodex mite has the elements necessary to stimulate the host’s innate and adaptative immune system. Dr. Forton characterized Demodex as “the only microorganism found in abundance in almost all subjects with PPR, which can, in addition, alter the skin barrier. To feed and move around, Demodex mites attack the epidermal wall of the pilosebaceous follicles mechanically (via their stylets, mouth palps and motor palps) and chemically (through enzymes secreted from salivary glands for pre-oral digestion).”

The Demodex mite stimulates the immune system (which ultimately results in phymatous changes). A healthy immune system, including T helper 17 cells, seems necessary to adequately control mite proliferation. Dr. Forton noted that researchers have observed a perivascular and perifollicular infiltrate in people with rosacea, “which invades the epidermis and is often associated with the presence of Demodex. The lympho-histiocytic perifollicular infiltrate is correlated with the presence and the numbers of mites inside the follicles, and giant cell granulomas can be seen around intradermal Demodex mites, which attempt to phagocytize the mites.”

The three arguments that she presented against a causal role of Demodex in rosacea are the following:

No relationship with the mite was observed in two early histological studies. Rosacea biopsies conducted in these two analyses, published in 1969 and 1988, showed only mild infiltrate, with few parasites and no inflammation around the infested follicles.

However, she countered, “these data are now obsolete, because it has since been clearly demonstrated that the perifollicular infiltrate is a characteristic of rosacea, that this infiltrate is statistically related to the presence and the number of Demodex mites, and that high Dds are observed in almost all subjects with PPR.”

Demodex is not always associated with inflammatory symptoms. This argument holds that Demodex is present in all individuals and can be observed in very high densities without causing significant symptoms. Studies that support this viewpoint include the following: J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:441–4 and J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:998-1007.

However, Dr. Forton pointed out that the normal, low-density presence of Demodex in the skin “does not contradict a pathogenic effect when it proliferates excessively or penetrates into the dermis. The absence of intense inflammatory symptoms when the Dd is very high does not negate its potential pathogenicity.”

Demodex proliferation could be a consequence rather than a cause. Dr. Forton cited a study, suggesting that inflammation could be responsible for alteration of the skin barrier, “which, secondarily, would favor proliferation of the parasites, as with skin affected by atopic dermatitis that becomes superinfected by Staphylococcus aureus”. On the other hand, she argued, “unlike S. aureus, Demodex does not require alteration of the skin barrier to implant or proliferate. It also does not require an inflammatory background.” She added that if mite proliferation was a consequence of clinical lesions, “the Demodex mite should logically proliferate in other inflammatory facial skin conditions, which is not the case.”

A Sept. 14 National Rosacea Society (NRS) press release featured the paper by Dr. Forton, titled, “Which Comes First, The Rosacea Blemish or The Mite?” In the release, Richard Gallo, MD, PhD, who chaired the NRS Expert Committee that updated the standard classification of rosacea in 2018, said that “growing knowledge of rosacea’s pathophysiology has established that a consistent multivariate disease process underlies its potential manifestations, and the clinical significance of each of these elements is increasing as more is understood.”

While the potential role of Demodex in rosacea has been controversial in the past, “these new insights suggest where it may play a role as a meaningful cofactor in the development of the disorder,” added Dr. Gallo, chair of the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego.

Dr. Forton reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JEADV

Can dietary tweaks improve some skin diseases?

Since 1950, the terms “diet and skin” in the medical literature have markedly increased, said Vivian Shi, MD associate professor of dermatology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who talked about nutritional approaches for select skin diseases at MedscapeLive’s Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

Myths abound, but some associations of diet with skin diseases hold water, and she said.

Acne

What’s known, Dr. Shi said, is that the prevalence of acne is substantially lower in non-Westernized countries, and that diets in those countries generally have a low glycemic load, which decreases IGF-1 insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) concentrations, an accepted risk factor for acne. The Western diet also includes the hormonal effects of cow’s milk products.

Whey protein, which is popular as a supplement, isn’t good for acne, Dr. Shi said. It takes a couple of hours to digest, while casein protein digests more slowly, over 5-7 hours. If casein protein isn’t acceptable, good alternatives to whey protein are hemp seed, plant protein blends (peas, seeds, berries), egg white, brown rice isolate, and soy isolate protein.

Dairy products increase IGF-1 levels, hormonal mediators that can make acne worse. In addition, industrial cow’s milk can contain anabolic steroids and growth factor, leading to sebogenesis, Dr. Shi said. As for the type of milk, skim milk tends to be the most acnegenic and associated with the highest blood levels of IGF-1.

Supplementing with omega-3 fatty acids and gamma-linolenic acid improved mild to moderate acne in a double-blind, controlled study. Researchers randomized 45 patients with mild to moderate acne to an omega-3 fatty acid group (2,000 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid), a gamma-linolenic acid group (borage oil with 400 mg gamma-linolenic acid) or a control group. After 10 weeks in both treatment groups, there was a significant reduction in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions.

Those with acne are more likely to be deficient in Vitamin D, research suggests. Researchers also found that among those who had vitamin D deficiency, supplementing with 1,000 IU daily for 2 months reduced inflammatory lesions by 35% after 8 weeks, compared with a 6% reduction in the control group.

Other research has found that those with a low serum zinc level had more severe acne and that 30-200 mg of zinc orally for 2-4 months reduced inflammatory acne. However, Dr. Shi cautioned that those taking zinc for more than 2 months also need a copper supplement, as zinc reduces the amount of copper absorbed by the body.

Dr. Shi’s “do’s” diet list for acne patients is a follows: Paleolithic and Mediterranean diets, omega-3 fatty acids, gamma-linolenic acids, Vitamin D, zinc, tubers, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and fish.

Unknowns, she said, include chocolate, caffeine, green tea, and high salt.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Patents with HS who follow a Mediterranean diet most closely have less severe disease, research has found. In this study, those patients with HS with the lowest adherence had a Sartorius HS score of 59.38, while those who followed it the most closely had a score of 39 (of 80).

In another study, patients with HS reported the following foods as exacerbating HS: sweets, bread/pasta/rice, dairy, and high-fat foods. Alleviating foods included vegetables, fruit, chicken, and fish.

Dr. Shi’s dietary recommendations for patients with HS: Follow a Mediterranean diet, avoid high fat foods and highly processed foods, and focus on eating more vegetables, fresh fruit, corn-based cereal, white meat, and fish.

A retrospective study of patients with Hurley stage 1 and 2 found that oral zinc gluconate, 90 mg a day, combined with 2% topical triclosan twice a day, resulted in significantly decreased HS scores and nodules and improved quality of life after 3 months. Expect vitamin D deficiency, she added.

Lastly, Dr. Shi recommended, if necessary, “weight loss to reduce the inflammatory burden.”

Rosacea

Dietary triggers for rosacea are thought to include high-fat foods, dairy foods, spicy foods, hot drinks, cinnamon, and vanilla.

A population-based case-control study in China, which evaluated 1,347 rosacea patients and 1,290 healthy controls, found that a high intake of fatty foods positively correlated with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (ETR) and phymatous rosacea. High-frequency dairy intake negatively correlated with ETR and papulopustular rosacea, which was a surprise, she said. And in this study, no significant correlations were found between sweets, coffee, and spicy foods. That goes against the traditional thinking, she said, but this was a Chinese cohort and their diet is probably vastly different than those in the United States.

Other rosacea triggers, Dr. Shi said, are niacin-containing foods such as turkey, chicken breast, crustaceans, dried Shiitake mushrooms, peanuts, tuna, and liver, as well as cold drinks, and formalin-containing foods (fish, squid, tofu, wet noodles).

As the field of nutrigenics – how genes affect how the body responds to food – evolves, more answers about the impact of diet on these diseases will be forthcoming, Dr. Shi said.

In an interactive panel discussion, she was asked if she talks about diet with all her patients with acne, rosacea, and HS, or just those not responding to traditional therapy.

“I think it’s an important conversation to have,” Dr. Shi responded. “When I’m done with the medication [instructions], I say: ‘There is something else you can do to augment what I just told you.’ ” That’s when she explains the dietary information. She also has a handout on diet and routinely refers patients for dietary counseling.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Shi disclosed consulting, investigative and research funding from several sources, but not directly related to the content of her talk.

Since 1950, the terms “diet and skin” in the medical literature have markedly increased, said Vivian Shi, MD associate professor of dermatology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who talked about nutritional approaches for select skin diseases at MedscapeLive’s Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

Myths abound, but some associations of diet with skin diseases hold water, and she said.

Acne

What’s known, Dr. Shi said, is that the prevalence of acne is substantially lower in non-Westernized countries, and that diets in those countries generally have a low glycemic load, which decreases IGF-1 insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) concentrations, an accepted risk factor for acne. The Western diet also includes the hormonal effects of cow’s milk products.

Whey protein, which is popular as a supplement, isn’t good for acne, Dr. Shi said. It takes a couple of hours to digest, while casein protein digests more slowly, over 5-7 hours. If casein protein isn’t acceptable, good alternatives to whey protein are hemp seed, plant protein blends (peas, seeds, berries), egg white, brown rice isolate, and soy isolate protein.

Dairy products increase IGF-1 levels, hormonal mediators that can make acne worse. In addition, industrial cow’s milk can contain anabolic steroids and growth factor, leading to sebogenesis, Dr. Shi said. As for the type of milk, skim milk tends to be the most acnegenic and associated with the highest blood levels of IGF-1.

Supplementing with omega-3 fatty acids and gamma-linolenic acid improved mild to moderate acne in a double-blind, controlled study. Researchers randomized 45 patients with mild to moderate acne to an omega-3 fatty acid group (2,000 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid), a gamma-linolenic acid group (borage oil with 400 mg gamma-linolenic acid) or a control group. After 10 weeks in both treatment groups, there was a significant reduction in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions.

Those with acne are more likely to be deficient in Vitamin D, research suggests. Researchers also found that among those who had vitamin D deficiency, supplementing with 1,000 IU daily for 2 months reduced inflammatory lesions by 35% after 8 weeks, compared with a 6% reduction in the control group.

Other research has found that those with a low serum zinc level had more severe acne and that 30-200 mg of zinc orally for 2-4 months reduced inflammatory acne. However, Dr. Shi cautioned that those taking zinc for more than 2 months also need a copper supplement, as zinc reduces the amount of copper absorbed by the body.

Dr. Shi’s “do’s” diet list for acne patients is a follows: Paleolithic and Mediterranean diets, omega-3 fatty acids, gamma-linolenic acids, Vitamin D, zinc, tubers, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and fish.

Unknowns, she said, include chocolate, caffeine, green tea, and high salt.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Patents with HS who follow a Mediterranean diet most closely have less severe disease, research has found. In this study, those patients with HS with the lowest adherence had a Sartorius HS score of 59.38, while those who followed it the most closely had a score of 39 (of 80).

In another study, patients with HS reported the following foods as exacerbating HS: sweets, bread/pasta/rice, dairy, and high-fat foods. Alleviating foods included vegetables, fruit, chicken, and fish.

Dr. Shi’s dietary recommendations for patients with HS: Follow a Mediterranean diet, avoid high fat foods and highly processed foods, and focus on eating more vegetables, fresh fruit, corn-based cereal, white meat, and fish.

A retrospective study of patients with Hurley stage 1 and 2 found that oral zinc gluconate, 90 mg a day, combined with 2% topical triclosan twice a day, resulted in significantly decreased HS scores and nodules and improved quality of life after 3 months. Expect vitamin D deficiency, she added.

Lastly, Dr. Shi recommended, if necessary, “weight loss to reduce the inflammatory burden.”

Rosacea

Dietary triggers for rosacea are thought to include high-fat foods, dairy foods, spicy foods, hot drinks, cinnamon, and vanilla.

A population-based case-control study in China, which evaluated 1,347 rosacea patients and 1,290 healthy controls, found that a high intake of fatty foods positively correlated with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (ETR) and phymatous rosacea. High-frequency dairy intake negatively correlated with ETR and papulopustular rosacea, which was a surprise, she said. And in this study, no significant correlations were found between sweets, coffee, and spicy foods. That goes against the traditional thinking, she said, but this was a Chinese cohort and their diet is probably vastly different than those in the United States.

Other rosacea triggers, Dr. Shi said, are niacin-containing foods such as turkey, chicken breast, crustaceans, dried Shiitake mushrooms, peanuts, tuna, and liver, as well as cold drinks, and formalin-containing foods (fish, squid, tofu, wet noodles).

As the field of nutrigenics – how genes affect how the body responds to food – evolves, more answers about the impact of diet on these diseases will be forthcoming, Dr. Shi said.

In an interactive panel discussion, she was asked if she talks about diet with all her patients with acne, rosacea, and HS, or just those not responding to traditional therapy.

“I think it’s an important conversation to have,” Dr. Shi responded. “When I’m done with the medication [instructions], I say: ‘There is something else you can do to augment what I just told you.’ ” That’s when she explains the dietary information. She also has a handout on diet and routinely refers patients for dietary counseling.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Shi disclosed consulting, investigative and research funding from several sources, but not directly related to the content of her talk.

Since 1950, the terms “diet and skin” in the medical literature have markedly increased, said Vivian Shi, MD associate professor of dermatology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who talked about nutritional approaches for select skin diseases at MedscapeLive’s Women’s and Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

Myths abound, but some associations of diet with skin diseases hold water, and she said.

Acne

What’s known, Dr. Shi said, is that the prevalence of acne is substantially lower in non-Westernized countries, and that diets in those countries generally have a low glycemic load, which decreases IGF-1 insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) concentrations, an accepted risk factor for acne. The Western diet also includes the hormonal effects of cow’s milk products.

Whey protein, which is popular as a supplement, isn’t good for acne, Dr. Shi said. It takes a couple of hours to digest, while casein protein digests more slowly, over 5-7 hours. If casein protein isn’t acceptable, good alternatives to whey protein are hemp seed, plant protein blends (peas, seeds, berries), egg white, brown rice isolate, and soy isolate protein.

Dairy products increase IGF-1 levels, hormonal mediators that can make acne worse. In addition, industrial cow’s milk can contain anabolic steroids and growth factor, leading to sebogenesis, Dr. Shi said. As for the type of milk, skim milk tends to be the most acnegenic and associated with the highest blood levels of IGF-1.

Supplementing with omega-3 fatty acids and gamma-linolenic acid improved mild to moderate acne in a double-blind, controlled study. Researchers randomized 45 patients with mild to moderate acne to an omega-3 fatty acid group (2,000 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid), a gamma-linolenic acid group (borage oil with 400 mg gamma-linolenic acid) or a control group. After 10 weeks in both treatment groups, there was a significant reduction in inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions.

Those with acne are more likely to be deficient in Vitamin D, research suggests. Researchers also found that among those who had vitamin D deficiency, supplementing with 1,000 IU daily for 2 months reduced inflammatory lesions by 35% after 8 weeks, compared with a 6% reduction in the control group.

Other research has found that those with a low serum zinc level had more severe acne and that 30-200 mg of zinc orally for 2-4 months reduced inflammatory acne. However, Dr. Shi cautioned that those taking zinc for more than 2 months also need a copper supplement, as zinc reduces the amount of copper absorbed by the body.

Dr. Shi’s “do’s” diet list for acne patients is a follows: Paleolithic and Mediterranean diets, omega-3 fatty acids, gamma-linolenic acids, Vitamin D, zinc, tubers, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and fish.

Unknowns, she said, include chocolate, caffeine, green tea, and high salt.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Patents with HS who follow a Mediterranean diet most closely have less severe disease, research has found. In this study, those patients with HS with the lowest adherence had a Sartorius HS score of 59.38, while those who followed it the most closely had a score of 39 (of 80).

In another study, patients with HS reported the following foods as exacerbating HS: sweets, bread/pasta/rice, dairy, and high-fat foods. Alleviating foods included vegetables, fruit, chicken, and fish.

Dr. Shi’s dietary recommendations for patients with HS: Follow a Mediterranean diet, avoid high fat foods and highly processed foods, and focus on eating more vegetables, fresh fruit, corn-based cereal, white meat, and fish.

A retrospective study of patients with Hurley stage 1 and 2 found that oral zinc gluconate, 90 mg a day, combined with 2% topical triclosan twice a day, resulted in significantly decreased HS scores and nodules and improved quality of life after 3 months. Expect vitamin D deficiency, she added.

Lastly, Dr. Shi recommended, if necessary, “weight loss to reduce the inflammatory burden.”

Rosacea

Dietary triggers for rosacea are thought to include high-fat foods, dairy foods, spicy foods, hot drinks, cinnamon, and vanilla.

A population-based case-control study in China, which evaluated 1,347 rosacea patients and 1,290 healthy controls, found that a high intake of fatty foods positively correlated with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (ETR) and phymatous rosacea. High-frequency dairy intake negatively correlated with ETR and papulopustular rosacea, which was a surprise, she said. And in this study, no significant correlations were found between sweets, coffee, and spicy foods. That goes against the traditional thinking, she said, but this was a Chinese cohort and their diet is probably vastly different than those in the United States.

Other rosacea triggers, Dr. Shi said, are niacin-containing foods such as turkey, chicken breast, crustaceans, dried Shiitake mushrooms, peanuts, tuna, and liver, as well as cold drinks, and formalin-containing foods (fish, squid, tofu, wet noodles).

As the field of nutrigenics – how genes affect how the body responds to food – evolves, more answers about the impact of diet on these diseases will be forthcoming, Dr. Shi said.

In an interactive panel discussion, she was asked if she talks about diet with all her patients with acne, rosacea, and HS, or just those not responding to traditional therapy.

“I think it’s an important conversation to have,” Dr. Shi responded. “When I’m done with the medication [instructions], I say: ‘There is something else you can do to augment what I just told you.’ ” That’s when she explains the dietary information. She also has a handout on diet and routinely refers patients for dietary counseling.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Shi disclosed consulting, investigative and research funding from several sources, but not directly related to the content of her talk.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE WOMEN’S & PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Cutaneous Body Image: How the Mental Health Benefits of Treating Dermatologic Disease Support Military Readiness in Service Members

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

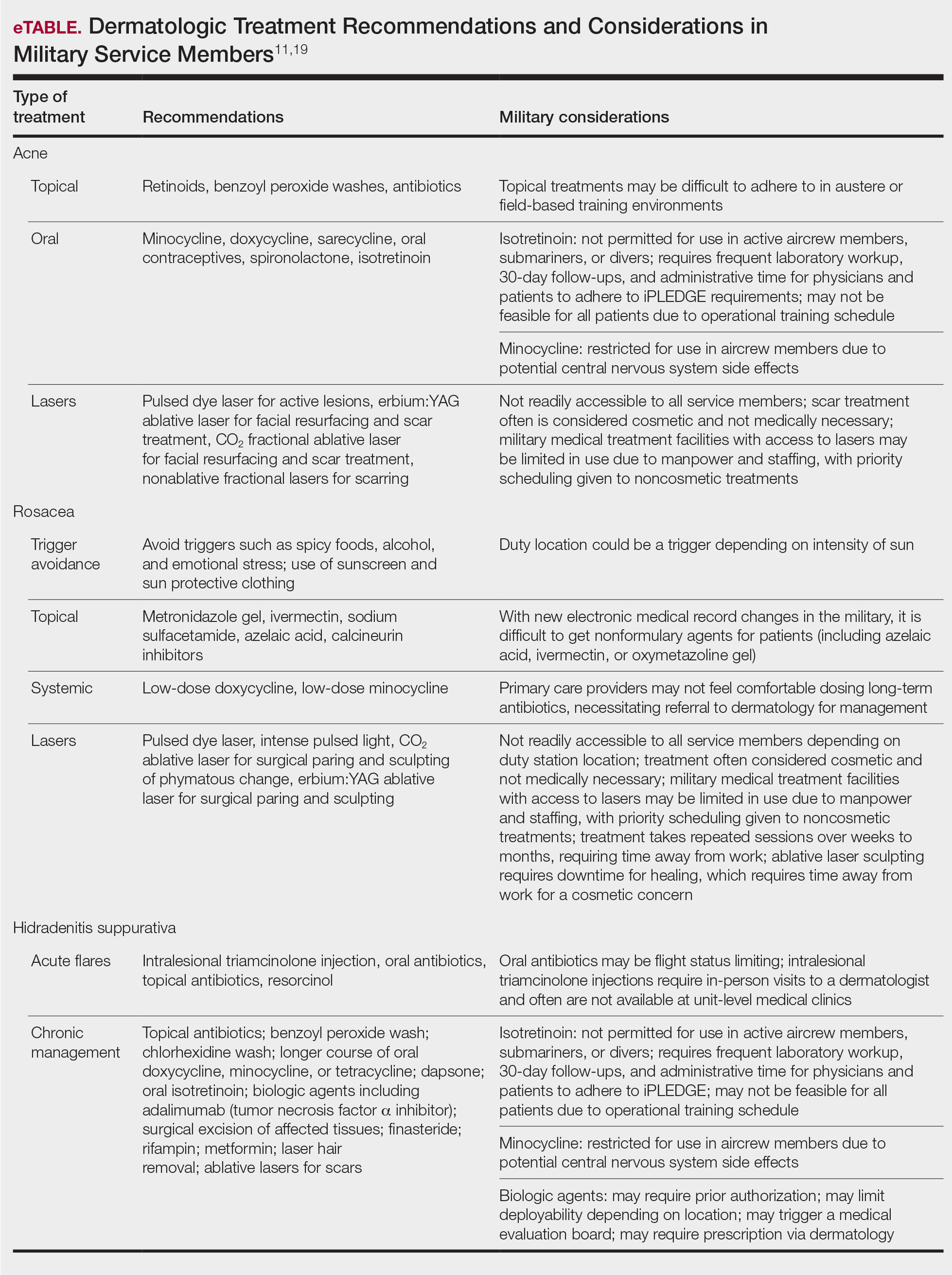

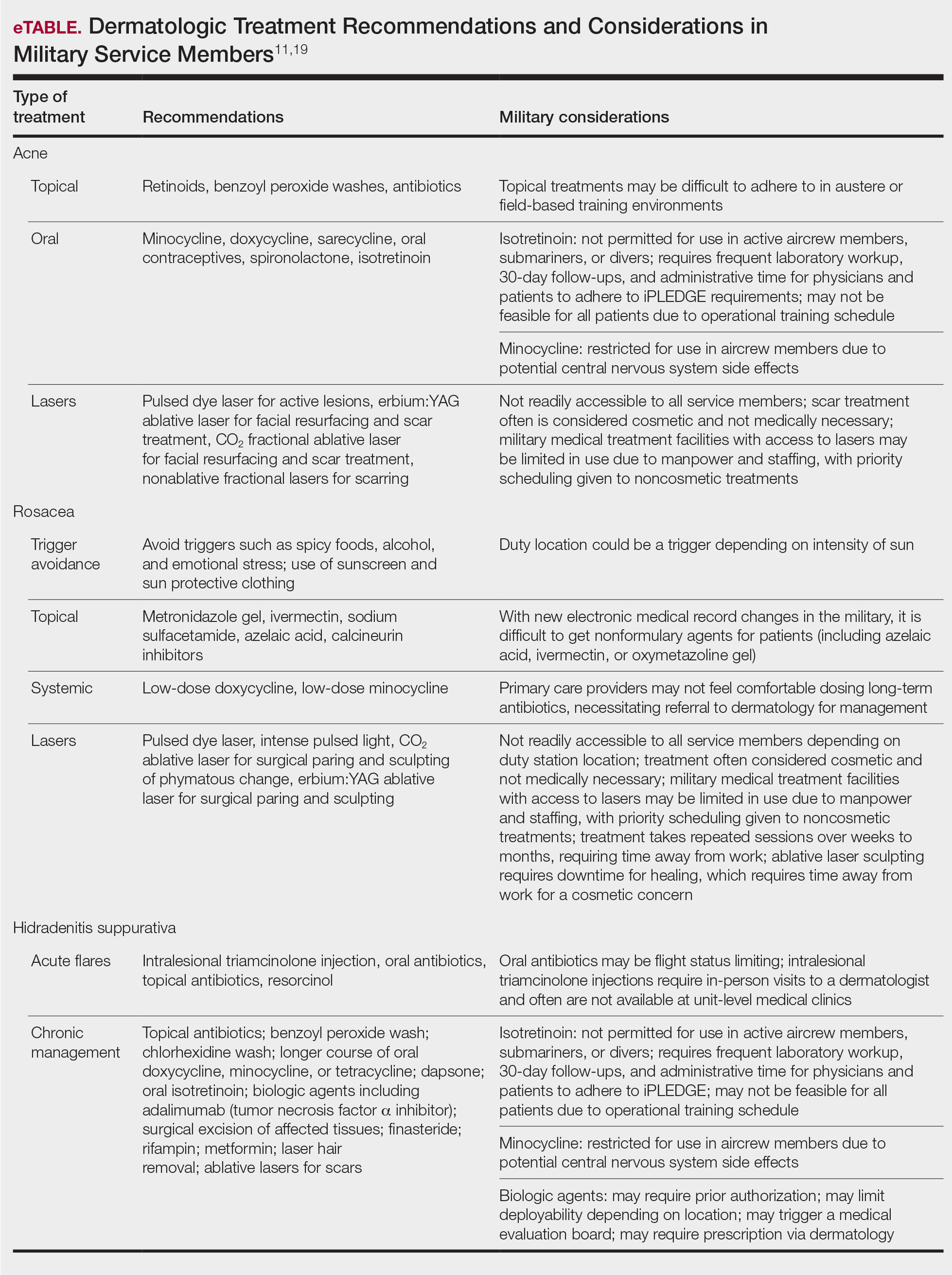

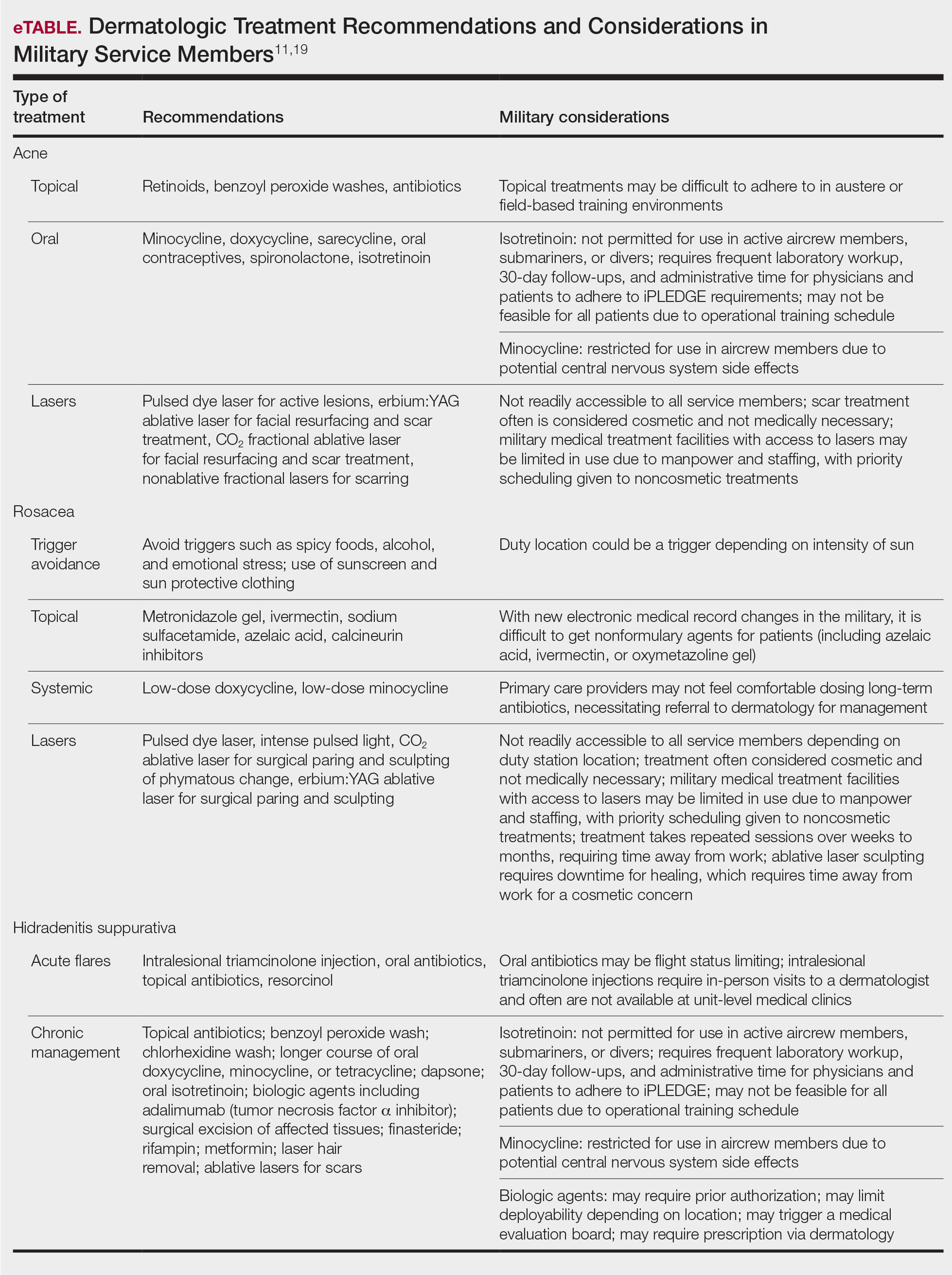

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts

Maintaining readiness in the military is essential to the ability to not only “fight tonight” but also to win tonight in whatever operational or combat mission a service member may be. Although many factors impact readiness, the rates of suicide within the armed forces cannot be ignored. Suicide not only eliminates the readiness of the deceased service member but has lasting ripple effects on the overall readiness of their unit and command at large. Most suicides in the military occur in personnel with no prior documented mental health diagnoses or treatment. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all service members to recognize and mitigate stressors and risk factors that may lead to mental health distress and suicidality. In the medical corps, this translates to a responsibility of all medical specialists to recognize and understand unique risk factors for suicidality and to do as much as they can to reduce these risks. For military dermatologists and for civilian physicians treating military service members, it is imperative to predict and understand the relationship between common dermatoses; reduced satisfaction with CBI; and increased risk for mental health illness, self-harm, and suicide. Military dermatologists, as well as other specialists, may be limited in the care they are able to provide due to manpower, staffing, demand, and institutional guidelines; however, to better serve those who serve in a holistic manner, consideration must be given to rethink what is “medically essential” and “cosmetic” and leverage the available skills, techniques, and equipment to increase the readiness of the force.

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, LaCroix JM, Koss K, et al. Outpatient mental health treatment utilization and military career impact in the United States Marine Corps. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:828. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040828

- Ottignon DA. Marine Corps Suicide Prevention System (MCSPS). Marine Corps Order 1720.2A. 2021. Headquarters United States Marine Corps. Published August 2, 2021. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%201720.2A.pdf?ver=QPxZ_qMS-X-d037B65N9Tg%3d%3d

- Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Carter SP. Suicide prevention in the US Army: a mission for more than mental health clinicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:991-992. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2042

- Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, et al. Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2015 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology (T2); 2016. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Psychological-Health-Center-of-Excellence/Department-of-Defense-Suicide-Event-Report

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, et al. Risk factors associated with attempted suicide among US Army soldiers without a history of mental health diagnosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:1022-1032. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2069

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Cutaneous body image dissatisfaction and suicidal ideation: mediation by interpersonal sensitivity. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:55-59. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.015

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Evaluation of cutaneous body image dissatisfaction in the dermatology patient. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.010

- Hinkley SB, Holub SC, Menter A. The validity of cutaneous body image as a construct and as a mediator of the relationship between cutaneous disease and mental health. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:203-211. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00351-5

- Stamu-O’Brien C, Jafferany M, Carniciu S, et al. Psychodermatology of acne: psychological aspects and effects of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1080-1083. doi:10.1111/jocd.13765

- Sood S, Jafferany M, Vinaya Kumar S. Depression, psychiatric comorbidities, and psychosocial implications associated with acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:3177-3182. doi:10.1111/jocd.13753

- Brahe C, Peters K. Fighting acne for the fighting forces. Cutis. 2020;106:18-20, 22. doi:10.12788/cutis.0057

- Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:246-250.

- Xu S, Zhu Y, Hu H, et al. The analysis of acne increasing suicide risk. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:E26035. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026035

- Chen M, Deng Z, Huang Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression in rosacea patients: a cross-sectional study in China [published online June 16, 2021]. Front Psychiatry. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659171

- Incel Uysal P, Akdogan N, Hayran Y, et al. Rosacea associated with increased risk of generalized anxiety disorder: a case-control study of prevalence and risk of anxiety in patients with rosacea. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:704-709. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.03.002

- Alinia H, Cardwell LA, Tuchayi SM, et al. Screening for depression in rosacea patients. Cutis. 2018;102:36-38.

- Wright S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online June 16, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.843

- Misitzis A, Goldust M, Jafferany M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13541. doi:10.1111/dth.13541

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts

Maintaining readiness in the military is essential to the ability to not only “fight tonight” but also to win tonight in whatever operational or combat mission a service member may be. Although many factors impact readiness, the rates of suicide within the armed forces cannot be ignored. Suicide not only eliminates the readiness of the deceased service member but has lasting ripple effects on the overall readiness of their unit and command at large. Most suicides in the military occur in personnel with no prior documented mental health diagnoses or treatment. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all service members to recognize and mitigate stressors and risk factors that may lead to mental health distress and suicidality. In the medical corps, this translates to a responsibility of all medical specialists to recognize and understand unique risk factors for suicidality and to do as much as they can to reduce these risks. For military dermatologists and for civilian physicians treating military service members, it is imperative to predict and understand the relationship between common dermatoses; reduced satisfaction with CBI; and increased risk for mental health illness, self-harm, and suicide. Military dermatologists, as well as other specialists, may be limited in the care they are able to provide due to manpower, staffing, demand, and institutional guidelines; however, to better serve those who serve in a holistic manner, consideration must be given to rethink what is “medically essential” and “cosmetic” and leverage the available skills, techniques, and equipment to increase the readiness of the force.

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts

Maintaining readiness in the military is essential to the ability to not only “fight tonight” but also to win tonight in whatever operational or combat mission a service member may be. Although many factors impact readiness, the rates of suicide within the armed forces cannot be ignored. Suicide not only eliminates the readiness of the deceased service member but has lasting ripple effects on the overall readiness of their unit and command at large. Most suicides in the military occur in personnel with no prior documented mental health diagnoses or treatment. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all service members to recognize and mitigate stressors and risk factors that may lead to mental health distress and suicidality. In the medical corps, this translates to a responsibility of all medical specialists to recognize and understand unique risk factors for suicidality and to do as much as they can to reduce these risks. For military dermatologists and for civilian physicians treating military service members, it is imperative to predict and understand the relationship between common dermatoses; reduced satisfaction with CBI; and increased risk for mental health illness, self-harm, and suicide. Military dermatologists, as well as other specialists, may be limited in the care they are able to provide due to manpower, staffing, demand, and institutional guidelines; however, to better serve those who serve in a holistic manner, consideration must be given to rethink what is “medically essential” and “cosmetic” and leverage the available skills, techniques, and equipment to increase the readiness of the force.

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, LaCroix JM, Koss K, et al. Outpatient mental health treatment utilization and military career impact in the United States Marine Corps. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:828. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040828

- Ottignon DA. Marine Corps Suicide Prevention System (MCSPS). Marine Corps Order 1720.2A. 2021. Headquarters United States Marine Corps. Published August 2, 2021. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%201720.2A.pdf?ver=QPxZ_qMS-X-d037B65N9Tg%3d%3d

- Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Carter SP. Suicide prevention in the US Army: a mission for more than mental health clinicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:991-992. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2042

- Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, et al. Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2015 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology (T2); 2016. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Psychological-Health-Center-of-Excellence/Department-of-Defense-Suicide-Event-Report