User login

FDA allows marketing of morcellation containment system

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared for marketing a novel tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators.

The PneumoLiner system is intended to be used to contain morcellated uterine tissue in a limited population of patients, including women without uterine fibroids undergoing hysterectomy and some premenopausal women with fibroids who want to maintain their fertility, according to the FDA. The agency is requiring the manufacturer to warn patients and physicians that the device has not been proven to reduce the risk of spreading cancer during surgery.

This approval – through the FDA’s de novo classification process for novel, low- and moderate-risk medical devices – comes about 2 years after the FDA first warned physicians and patients about the risk of spreading unsuspected uterine sarcomas during laparoscopic power morcellation in hysterectomy or myomectomy.

“This new device does not change our position on the risks associated with power morcellation,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science and chief scientist at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in an April 7 statement. “We are continuing to warn against the use of power morcellators for the vast majority of women undergoing removal of the uterus or uterine fibroids.”

The device, which is manufactured by Advanced Surgical Concepts of Bray, Ireland, consists of a containment bag and a tube-like plunger to deliver the device into the abdominal cavity. The tissue being removed is placed in the bag and the bag is sealed and inflated. The inflation is intended to create working space around the tissue and better visualization during morcellation to prevent the morcellator tip or other surgical instruments from puncturing the bag. During laboratory testing, the containment bag was found to be impermeable to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids, according to the FDA.

Risks associated with the device include dissemination of morcellated tissue, injury to surrounding tissues or organs, infections, and a potentially longer surgical time. The FDA is requiring that the device’s label state that use of the PneumoLiner system is limited to physicians who have successfully completed the manufacturer’s validated training program.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared for marketing a novel tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators.

The PneumoLiner system is intended to be used to contain morcellated uterine tissue in a limited population of patients, including women without uterine fibroids undergoing hysterectomy and some premenopausal women with fibroids who want to maintain their fertility, according to the FDA. The agency is requiring the manufacturer to warn patients and physicians that the device has not been proven to reduce the risk of spreading cancer during surgery.

This approval – through the FDA’s de novo classification process for novel, low- and moderate-risk medical devices – comes about 2 years after the FDA first warned physicians and patients about the risk of spreading unsuspected uterine sarcomas during laparoscopic power morcellation in hysterectomy or myomectomy.

“This new device does not change our position on the risks associated with power morcellation,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science and chief scientist at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in an April 7 statement. “We are continuing to warn against the use of power morcellators for the vast majority of women undergoing removal of the uterus or uterine fibroids.”

The device, which is manufactured by Advanced Surgical Concepts of Bray, Ireland, consists of a containment bag and a tube-like plunger to deliver the device into the abdominal cavity. The tissue being removed is placed in the bag and the bag is sealed and inflated. The inflation is intended to create working space around the tissue and better visualization during morcellation to prevent the morcellator tip or other surgical instruments from puncturing the bag. During laboratory testing, the containment bag was found to be impermeable to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids, according to the FDA.

Risks associated with the device include dissemination of morcellated tissue, injury to surrounding tissues or organs, infections, and a potentially longer surgical time. The FDA is requiring that the device’s label state that use of the PneumoLiner system is limited to physicians who have successfully completed the manufacturer’s validated training program.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

The Food and Drug Administration has cleared for marketing a novel tissue containment system for use with certain laparoscopic power morcellators.

The PneumoLiner system is intended to be used to contain morcellated uterine tissue in a limited population of patients, including women without uterine fibroids undergoing hysterectomy and some premenopausal women with fibroids who want to maintain their fertility, according to the FDA. The agency is requiring the manufacturer to warn patients and physicians that the device has not been proven to reduce the risk of spreading cancer during surgery.

This approval – through the FDA’s de novo classification process for novel, low- and moderate-risk medical devices – comes about 2 years after the FDA first warned physicians and patients about the risk of spreading unsuspected uterine sarcomas during laparoscopic power morcellation in hysterectomy or myomectomy.

“This new device does not change our position on the risks associated with power morcellation,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science and chief scientist at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in an April 7 statement. “We are continuing to warn against the use of power morcellators for the vast majority of women undergoing removal of the uterus or uterine fibroids.”

The device, which is manufactured by Advanced Surgical Concepts of Bray, Ireland, consists of a containment bag and a tube-like plunger to deliver the device into the abdominal cavity. The tissue being removed is placed in the bag and the bag is sealed and inflated. The inflation is intended to create working space around the tissue and better visualization during morcellation to prevent the morcellator tip or other surgical instruments from puncturing the bag. During laboratory testing, the containment bag was found to be impermeable to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids, according to the FDA.

Risks associated with the device include dissemination of morcellated tissue, injury to surrounding tissues or organs, infections, and a potentially longer surgical time. The FDA is requiring that the device’s label state that use of the PneumoLiner system is limited to physicians who have successfully completed the manufacturer’s validated training program.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

Robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy

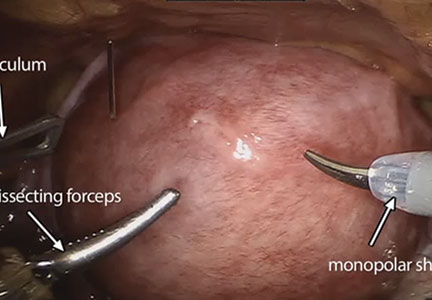

The management of symptomatic uterine fibroids in the patient desiring conservative surgical therapy can be challenging at times. The advent of robot-assisted laparoscopy has provided surgeons with an enabling tool and patients with the option for a minimally invasive approach to myomectomy.

This month’s video was produced in order to demonstrate a systematic approach to the robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy in patients who are candidates. The example case is removal of a 5-cm, intrauterine posterior myoma in a 39-year-old woman (G3P1021) with heavy menstrual bleeding who desires future fertility.

Key objectives of the video include:

- understanding the role of radiologic imaging as part of preoperative surgical planning

- recognizing the key robotic instruments and suture selected to perform the procedure

- discussing robot-specific techniques that facilitate fibroid enucleation and hysterotomy repair.

Also integrated into this video is the application of the ExCITE technique—a manual cold knife tissue extraction technique utilizing an extracorporeal semi-circle “C-incision” approach—for tissue extraction. This technique was featured in an earlier installment of the video channel.1

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Truong M, Advincula A. Minimally invasive tissue extraction made simple: the Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction (ExCITE) technique. OBG Manag. 2014;26(11):56.

The management of symptomatic uterine fibroids in the patient desiring conservative surgical therapy can be challenging at times. The advent of robot-assisted laparoscopy has provided surgeons with an enabling tool and patients with the option for a minimally invasive approach to myomectomy.

This month’s video was produced in order to demonstrate a systematic approach to the robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy in patients who are candidates. The example case is removal of a 5-cm, intrauterine posterior myoma in a 39-year-old woman (G3P1021) with heavy menstrual bleeding who desires future fertility.

Key objectives of the video include:

- understanding the role of radiologic imaging as part of preoperative surgical planning

- recognizing the key robotic instruments and suture selected to perform the procedure

- discussing robot-specific techniques that facilitate fibroid enucleation and hysterotomy repair.

Also integrated into this video is the application of the ExCITE technique—a manual cold knife tissue extraction technique utilizing an extracorporeal semi-circle “C-incision” approach—for tissue extraction. This technique was featured in an earlier installment of the video channel.1

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The management of symptomatic uterine fibroids in the patient desiring conservative surgical therapy can be challenging at times. The advent of robot-assisted laparoscopy has provided surgeons with an enabling tool and patients with the option for a minimally invasive approach to myomectomy.

This month’s video was produced in order to demonstrate a systematic approach to the robot-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy in patients who are candidates. The example case is removal of a 5-cm, intrauterine posterior myoma in a 39-year-old woman (G3P1021) with heavy menstrual bleeding who desires future fertility.

Key objectives of the video include:

- understanding the role of radiologic imaging as part of preoperative surgical planning

- recognizing the key robotic instruments and suture selected to perform the procedure

- discussing robot-specific techniques that facilitate fibroid enucleation and hysterotomy repair.

Also integrated into this video is the application of the ExCITE technique—a manual cold knife tissue extraction technique utilizing an extracorporeal semi-circle “C-incision” approach—for tissue extraction. This technique was featured in an earlier installment of the video channel.1

I hope that you find this month’s video helpful to your surgical practice.

Share your thoughts on this video! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Truong M, Advincula A. Minimally invasive tissue extraction made simple: the Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction (ExCITE) technique. OBG Manag. 2014;26(11):56.

- Truong M, Advincula A. Minimally invasive tissue extraction made simple: the Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction (ExCITE) technique. OBG Manag. 2014;26(11):56.

New Findings Show: Factors Contributing to the Prevalence in readmission for Bariatric Surgery Patients

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - About one in 20 bariatric surgery patients are readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of having the procedure, according to new findings.

Readmissions are increasingly being used as a quality metric for surgical procedures, Dr. John Morton of Stanford University in California and colleagues note in their report, published online March 19 in the American Journal of Surgery.

"While (the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) has not addressed bariatric surgery readmissions to date, other payors have made readmissions a priority," they add. "Data regarding bariatric surgery readmissions are critical to help better understand and drive quality improvement in this area.

"To investigate the prevalence, causes and risk factors for readmission following bariatric surgery, the researchers looked at data from the 2012 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Public Use File dataset on nearly 18,300 bariatric patients, of whom 55% had laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), 10% had laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), and 35% had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG).

There were 955 readmissions (5.22%), most commonly for gastrointestinal causes (45%), dietary reasons (34%) and bleeding (7%). Readmission rates were nearly 7% for LRYGB; just under 2% for LAGB; and 4% for LSG.

The patients who were readmitted had a significantly longer average operating time (132 vs. 115 minutes) and length of stay (2.76 days vs. 2.23). Forty percent had a complication, versus 4% of patients who were not readmitted. Patients who were readmitted were also more likely to have a body mass index above 50, preoperative diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension.

Factors independently associated with readmission included African-American race (odds ratio, 1.53), complication (OR, 11.3) and resident involvement (OR, 0.53).

"Other studies have also demonstrated similar predictors of readmission and have also demonstrated that length of stay may also play a role in readmission rates," Dr. Morton and his team state. "This study helps demonstrate that bariatric surgery readmissions are prevalent and potentially preventable."

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - About one in 20 bariatric surgery patients are readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of having the procedure, according to new findings.

Readmissions are increasingly being used as a quality metric for surgical procedures, Dr. John Morton of Stanford University in California and colleagues note in their report, published online March 19 in the American Journal of Surgery.

"While (the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) has not addressed bariatric surgery readmissions to date, other payors have made readmissions a priority," they add. "Data regarding bariatric surgery readmissions are critical to help better understand and drive quality improvement in this area.

"To investigate the prevalence, causes and risk factors for readmission following bariatric surgery, the researchers looked at data from the 2012 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Public Use File dataset on nearly 18,300 bariatric patients, of whom 55% had laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), 10% had laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), and 35% had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG).

There were 955 readmissions (5.22%), most commonly for gastrointestinal causes (45%), dietary reasons (34%) and bleeding (7%). Readmission rates were nearly 7% for LRYGB; just under 2% for LAGB; and 4% for LSG.

The patients who were readmitted had a significantly longer average operating time (132 vs. 115 minutes) and length of stay (2.76 days vs. 2.23). Forty percent had a complication, versus 4% of patients who were not readmitted. Patients who were readmitted were also more likely to have a body mass index above 50, preoperative diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension.

Factors independently associated with readmission included African-American race (odds ratio, 1.53), complication (OR, 11.3) and resident involvement (OR, 0.53).

"Other studies have also demonstrated similar predictors of readmission and have also demonstrated that length of stay may also play a role in readmission rates," Dr. Morton and his team state. "This study helps demonstrate that bariatric surgery readmissions are prevalent and potentially preventable."

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - About one in 20 bariatric surgery patients are readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of having the procedure, according to new findings.

Readmissions are increasingly being used as a quality metric for surgical procedures, Dr. John Morton of Stanford University in California and colleagues note in their report, published online March 19 in the American Journal of Surgery.

"While (the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) has not addressed bariatric surgery readmissions to date, other payors have made readmissions a priority," they add. "Data regarding bariatric surgery readmissions are critical to help better understand and drive quality improvement in this area.

"To investigate the prevalence, causes and risk factors for readmission following bariatric surgery, the researchers looked at data from the 2012 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Public Use File dataset on nearly 18,300 bariatric patients, of whom 55% had laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), 10% had laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), and 35% had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG).

There were 955 readmissions (5.22%), most commonly for gastrointestinal causes (45%), dietary reasons (34%) and bleeding (7%). Readmission rates were nearly 7% for LRYGB; just under 2% for LAGB; and 4% for LSG.

The patients who were readmitted had a significantly longer average operating time (132 vs. 115 minutes) and length of stay (2.76 days vs. 2.23). Forty percent had a complication, versus 4% of patients who were not readmitted. Patients who were readmitted were also more likely to have a body mass index above 50, preoperative diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension.

Factors independently associated with readmission included African-American race (odds ratio, 1.53), complication (OR, 11.3) and resident involvement (OR, 0.53).

"Other studies have also demonstrated similar predictors of readmission and have also demonstrated that length of stay may also play a role in readmission rates," Dr. Morton and his team state. "This study helps demonstrate that bariatric surgery readmissions are prevalent and potentially preventable."

2016 Update on minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

Rightly so, the topics of mechanical tissue extraction and hysterectomy approach have dominated the field of obstetrics and gynecology over the past 12 months and more. A profusion of literature has been published on these subjects. However, there are 2 important topics within the field of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that deserve our attention as well, and I have chosen to focus on these for this Update.

First, laparoscopic treatment of ovarian endometriomas is one of the most commonly performed gynecologic procedures worldwide. Many women undergoing such surgery are of childbearing age and have the desire for future pregnancy. What are best practices for preserving ovarian function in these women? Two studies recently published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology addressed this question.

Second, until recently, the rate of bowel injury at laparoscopic gynecologic surgery has not been well established.1 Moreover, mechanical bowel preparation is commonly employed in case intestinal injury does occur, despite the lack of evidence that outcomes of these possible injuries can be improved.2 Understanding the rate of bowel injury can shed light on the overall value of the perceived benefits of bowel preparation. Therefore, I examine 2 recent systematic reviews that analyze the incidence of bowel injury and the value of bowel prep in gynecologic laparoscopic surgery.

bipolar coagulation inferior to suturing or hemostatic sealant for preserving ovarian function

Song T, Kim WY, Lee KW, Kim KH. Effect on ovarian reserve of hemostasis by bipolar coagulation versus suture during laparoendoscopic single-site cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(3):415−420.

Ata B, Turkgeldi E, Seyhan A, Urman B. Effect of hemostatic method on ovarian reserve following laparoscopic endometrioma excision; comparison of suture, hemostatic sealant, and bipolar dessication. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(3):363−372.

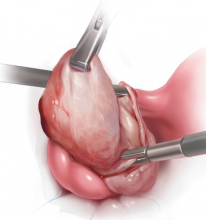

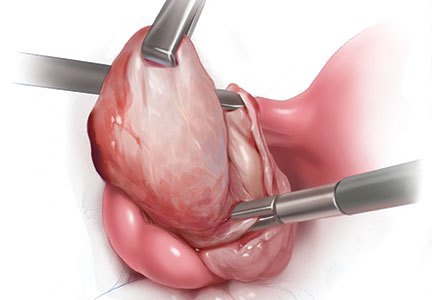

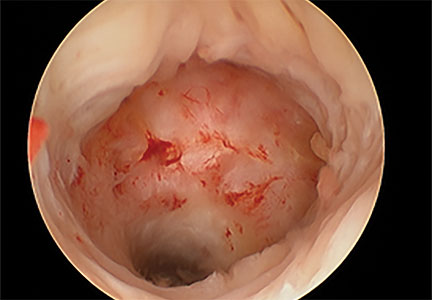

The customary surgical approach for laparoscopic cystectomy is by mechanical stripping of the cyst wall (FIGURE) and the use of bipolar desiccation for hemostasis. Stripping inevitably leads to removal of healthy ovarian cortex,3 especially in inexperienced hands,4 and ovarian follicles inevitably are destroyed during electrosurgical desiccation. When compared with the use of suturing or a hemostatic agent to control bleeding in the ovarian defect, the use of bipolar electrosurgery may harm more of the ovarian cortex, resulting in a comparatively diminished follicular cohort.

Possible deleterious effects on the ovarian reserve can be determined with a blood test to measure anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels postoperatively. Produced by the granulosa cells of the ovary, this hormone directly reflects the remaining ovarian egg supply. Lower levels of AMH have been shown to significantly decrease the success rate of in vitro fertilization (IVF), especially in women older than age 35.5 Moreover, AMH levels in the late reproductive years can be used as a predictive marker of menopause, with lower levels predicting significantly earlier onset.6

Data from 2 recent studies, a quasi-randomized trial by Song and colleagues and a systematic review and meta-analysis by Ata and colleagues emphasize that bipolar desiccation for hemostasis may not be best practice for protecting ovarian reserve during laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for an endometrioma.

AMH levels decline more significantly for women undergoing bipolar desiccation

Song and colleagues conducted a prospective quasi-randomized study of 125 women whose endometriomas were laparoscopically removed via a single-site approach and managed for hemostasis with either bipolar desiccation or suturing of the ovarian defect with a 2-0 barbed suture. All surgeries were conducted by a single surgeon.

At 3 months postsurgery, mean AMH levels had declined from baseline by 42.2% (interquartile range [IR], 16.5−53.0 ng/mL) in the desiccation group and by 24.6% (IR, 11.6−37.0 ng/mL) in the suture group (P = .001). Multivariate analysis showed that the method used for hemostasis was the only determinant for reduced ovarian reserve.

In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Ata and colleagues included 10 studies--6 qualitative and 4 quantitative. All studies examined the rate of change of serum AMH levels 3 months after laparoscopic removal of an endometrioma.

In their qualitative analysis, 5 of the 6 studies reported a significantly greater decrease in ovarian reserve after bipolar desiccation (varying from 13% to 44%) or a strong trend in the same direction. In the sixth study, the desiccation group had a lower decline in absolute AMH level than in the other 5 studies. The authors note that this 2.7% decline was much lower than the values reported for the bipolar desiccation group of any other study. (Those declines ranged between 19% and 58%.)

Although not significant, in all 3 of the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the desiccation groups had a greater loss in AMH level than the hemostatic sealant groups, and in 2 of these RCTs, bipolar desiccation groups had a greater loss than the suturing groups.

Among the 213 study participants in the 3 RCTs and the prospective cohort study included in the quantitative meta-analysis, alternative methods to bipolar desiccation were associated with a 6.95% lower decrease in AMH-level decline (95% confidence interval [CI], −13.0% to −0.9%; P = .02).

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Compared with the use of bipolar electrosurgery to attain hemostasis, the use of a topical biosurgical agent or suturing could be significantly better for protection of the ovarian follicles during laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for endometrioma. These alternative methods especially could benefit those women desiring future pregnancy who are demonstrated preoperatively to have a low ovarian reserve. As needed, electrosurgery should be sparingly employed for ovarian hemostasis.

Large Study identifies incidence of bowel injury during gynecologic laproscopy

Llarena NC, Shah AB, Milad MP. Bowel injury in gynecologic laparoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1407−1417.

In no aspect of laparoscopic surgery are preventive strategies more cautiously employed than during peritoneal access. Regardless of the applied technique, there is an irreducible risk of injury to the underlying viscera by either adhesions between the underlying bowel and abdominal wall or during the course of pilot error. Moreover, in the best of hands, bowel injury can occur whenever normal anatomic relationships need to be restored using intra-abdominal adhesiolysis. Given the ubiquity, these risks are never out of the surgeon's mind. Gynecologists are obliged to discuss these risks during the informed consent process.

Until recently, the rate of bowel injury has not been well established. Llarena and colleagues recently have conducted the largest systematic review of the medical literature to date for incidence, presentation, mortality, cause, and location of bowel injury associated with laparoscopic surgery while not necessarily distinguishing for the type of bowel injury. Sixty retrospective and 27 prospective studies met inclusion criteria.

The risk of bowel injury overall and defined

Among 474,063 laparoscopic surgeries conducted between 1972 and 2014, 604 bowel injuries were found, for an incidence of 1 in 769, or 0.13% (95% CI, 0.12−0.14%).

The rate of bowel injury varied by procedure, year, study type, and definition of bowel injury. The incidence of injury according to:

- definition, was 1 in 416 (0.24%) for studies that clearly included serosal injuries and enterotomies versus 1 in 833 (0.12%) for studies not clearly defining the type of bowel injury (relative risk [RR], 0.47; 95% CI, 0.38−0.59; P<.001)

- study type, was 1 in 666 (0.15%) for prospective studies versus 1 in 909 (0.11%) for retrospective studies (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63−0.96; P = .02)

- procedure, was 1 in 3,333 (0.03%; 95% CI, 0.01−0.03%) for sterilization and 1 in 256 (0.39%; 95% CI, 0.35−0.45%) for hysterectomy

- year, for laparoscopic hysterectomy only, was 1 in 222 (0.45%) before the year 2000 and 1 in 294 (0.34%) after 2000 (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57−0.98; P = .03).

How were injuries caused, found, and managed?

Thirty studies described the laparoscopic instrument used during 366 reported bowel injuries. The majority of injuries (55%) occurred during initial peritoneal access, with the Veress needle or trocar causing the damage. This was followed by electrosurgery (29%), dissection (11%), and forceps or scissors (4.1%).

According to 40 studies describing 307 injuries, bowel injuries most often were managed by converting to laparotomy (80%); only 8% of injuries were managed with laparoscopy and 2% expectantly.

Surgery to repair the bowel injury was delayed in 154 (41%) of 375 cases. The median time to injury discovery was 3 days (range, 1−13 days).

In only 19 cases were the presenting signs and symptoms of bowel injury recorded. Those reported from most to least often were: peritonitis, abdominal pain, fever, abdominal distention, leukocytosis, leukopenia, and septic shock.

Mortality

Mortality as an outcome was only reported in 29 of the total 90 studies; therefore, mortality may be underreported. Overall, however, death occurred in 1 (0.8%) of 125 bowel injuries.

The overall mortality rate from bowel injury--calculated from the only 42 studies that explicitly mentioned mortality as an outcome--was 1 in 125, or 0.8% (95% CI, 0.36%-1.9%). All 5 reported deaths occurred as a result of delayed recognition of bowel injury, which made the mortality rate for unrecognized bowel injury 1 in 31, or 3.2% (95% CI, 1%-7%). No deaths occurred when the bowel injury was noted intraoperatively.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In this review of 474,063 laparoscopic procedures, bowel injury occurred in 1 in 769, or 0.13% of procedures. Bowel injury is more apt to occur during more complicated laparoscopic procedures (compared with laparoscopic sterilization procedures, the risk during hysterectomy was greater than 10-fold).

Most of the injuries were managed by laparotomic surgery despite the potential to repair bowel injury by laparoscopy. Validating that peritoneal access is a high risk part of laparoscopic surgery, the majority of the injuries occurred during insufflation with a Veress needle or during abdominal access by trocar insertion. Nearly one-third of the injuries were from the use of electrosurgery, which are typically associated with a delay in presentation.

In this study, 41% of the injuries were unrecognized at the time of surgery. All 5 of the reported deaths were associated with a delay in diagnosis, with an overall mortality rate of 1 of 125, or 0.8%. Since all of these deaths were associated with a delay in diagnosis, the rate of mortality in unrecognized bowel injury was 5 of 154, or 3.2%. Among women who experienced delayed diagnosis, only 19 of 154 experienced signs or symptoms diagnostic for an underlying bowel injury, particularly when the small bowel was injured.

Can mechanical bowel prep positively affect outcomes in gynecologic laparoscopy, or should it be discarded?

Arnold A, Aitchison LP, Abbott J. Preoperative mechanical bowel preparation for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal surgery: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(5):737−752.

Popularized for more than 4 decades, the practice of presurgical bowel preparation is predicated on the notion that the presence of less, versus more, feces can minimize bacterial count and thereby reduce peritoneal contamination. Logically then, surgical site infections (SSIs) should be reduced with bowel preparation. Moreover, the surgical view and bowel handling during laparoscopic surgery should be improved, with surgical times consequently reduced.

Surgeons must weigh the putative benefits of mechanical bowel preparation against the unpleasant experience it causes for patients, as well as the risks of dehydration or electrolyte disturbance it may cause. To this day, a considerable percentage of gynecologists and colorectal surgeons routinely prep the bowel after weighing all of these factors, despite the paucity of evidence for the practice's efficacy to reduce SSI and improve surgical outcomes.7

The results of this recent systematic review critically question the usefulness of preoperative bowel preparation for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal surgery.

Details of the analysis

The authors evaluated high-quality studies on mechanical bowel preparation to assess evidence for:

- surgeon outcomes, including the surgical field and bowel handling

- operative outcomes, including intraoperative complications and operative times

- patient outcomes, including postoperative complications, overall morbidity, and length of stay.

The authors identified RCTs and prospective or retrospective cohort studies in various surgical specialties comparing preoperative bowel preparation to no such prep. Forty-three studies met inclusion criteria: 38 compared prep to no prep, and 5 compared prep to a single rectal enema. Five high-grade studies in gynecology were included (n = 795), with 4 of them RCTs of gynecologic laparoscopy (n = 645).

Operative field and duration

Of the studies comparing bowel prep with no prep, only the 5 gynecologic ones assessed operative field. Surgical view was perceived as improved in only 1 study. In another, surgeons only could guess allocation half the time.

Sixteen studies evaluated impact of mechanical bowel preparation on duration of surgery: 1 high-quality study found a significant reduction in OR time with bowel prep, and 1 moderate-quality study found longer operative time with bowel prep.

Patient outcomes

Of all studies assessing patient outcomes, 3 high-quality studies of colorectal patients (n = 490) found increased complications from prep versus no prep, including anastomotic dehiscence (P = .05), abdominal complications (P = .028), and infectious complications (P = .05).

Length of stay was assessed in 26 studies, with 4 reporting longer hospital stay with bowel prep and the remaining finding no difference between prep and no prep.

Across all specialties, only 2 studies reported improved outcomes with mechanical bowel preparation. One was a high-quality study reporting reduced 30-day morbidity (P = .018) and infectious complication rates (P = .018), and the other was a moderate-quality study that found reduced SSI (P = .0001) and organ space infection (P = .024) in patients undergoing bowel prep.

Mechanical bowel preparation vs enema

Bowel prep was compared with a single rectal enema in 5 studies. In 2 of these, patient outcomes were worse with enema. One high-quality study of 294 patients reported increased intra-abdominal fecal soiling (P = .008) in the enema group. (The surgeons believed that bowel preparation was more likely to be inadequate in this group, 25% compared with 6%, P<.05.) Whereas there was no statistical difference in the incidence of anastomotic leak between these groups, there was higher reoperation rate in the enema-only group where leakage was diagnosed (6 [4.1%] vs 0, respectively; P = .013).

Bowel prep and preoperative and postoperative symptoms

Six high-quality studies reported on the impact of mechanical bowel preparation on patient symptoms, such as nausea, weakness, abdominal distention, and satisfaction before and after surgery. In all but 1 study patients had significantly greater discomfort with bowel preparation. In 2 of the 6 studies, patients had more diarrhea (P = .0003), a delay in the first bowel movement (P = .001), and a slower return to normal diet (P = .004).

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The theory behind mechanical bowel preparation is not supported by the evidence. Despite the fact that the bowel is not customarily entered, up to 50% of gynecologic surgeons employ bowel preparation, with the hope of improving visualization and decreasing risk of an anastomotic leak. The colorectal studies in this review demonstrate no evidence for decreased anastomotic leak or infectious complications. By extrapolation, there is no evidence that using preoperative bowel prep bestows any benefit if bowel injury occurs inadvertently and if resection or reanastomosis is then required.

Among the 7 studies examining bowel prep in laparoscopy (4 gynecology, 3 urology, and 1 colorectal), only data from 1 demonstrated an improved surgical field (and in this case only by 1 out of 10 on a Likert scale). The impact of mechanical bowel preparation on the visual field is the same for diagnostic or complex laparoscopic surgeries. One high-quality study with deep endometriosis resection demonstrated no change in the operative field as reflected by no practical differences in OR time or complications.

Preparing the bowel for surgery is an intrusive process that reduces patient satisfaction by inducing weakness, abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, hunger, and thirst. Whereas this systematic analysis failed to confirm any benefit of the process, it provides evidence for the potential for harm. Mechanical bowel preparation should be discarded as a routine preoperative treatment for patients undergoing minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Rightly so, the topics of mechanical tissue extraction and hysterectomy approach have dominated the field of obstetrics and gynecology over the past 12 months and more. A profusion of literature has been published on these subjects. However, there are 2 important topics within the field of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that deserve our attention as well, and I have chosen to focus on these for this Update.

First, laparoscopic treatment of ovarian endometriomas is one of the most commonly performed gynecologic procedures worldwide. Many women undergoing such surgery are of childbearing age and have the desire for future pregnancy. What are best practices for preserving ovarian function in these women? Two studies recently published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology addressed this question.

Second, until recently, the rate of bowel injury at laparoscopic gynecologic surgery has not been well established.1 Moreover, mechanical bowel preparation is commonly employed in case intestinal injury does occur, despite the lack of evidence that outcomes of these possible injuries can be improved.2 Understanding the rate of bowel injury can shed light on the overall value of the perceived benefits of bowel preparation. Therefore, I examine 2 recent systematic reviews that analyze the incidence of bowel injury and the value of bowel prep in gynecologic laparoscopic surgery.

bipolar coagulation inferior to suturing or hemostatic sealant for preserving ovarian function

Song T, Kim WY, Lee KW, Kim KH. Effect on ovarian reserve of hemostasis by bipolar coagulation versus suture during laparoendoscopic single-site cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(3):415−420.

Ata B, Turkgeldi E, Seyhan A, Urman B. Effect of hemostatic method on ovarian reserve following laparoscopic endometrioma excision; comparison of suture, hemostatic sealant, and bipolar dessication. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(3):363−372.

The customary surgical approach for laparoscopic cystectomy is by mechanical stripping of the cyst wall (FIGURE) and the use of bipolar desiccation for hemostasis. Stripping inevitably leads to removal of healthy ovarian cortex,3 especially in inexperienced hands,4 and ovarian follicles inevitably are destroyed during electrosurgical desiccation. When compared with the use of suturing or a hemostatic agent to control bleeding in the ovarian defect, the use of bipolar electrosurgery may harm more of the ovarian cortex, resulting in a comparatively diminished follicular cohort.

Possible deleterious effects on the ovarian reserve can be determined with a blood test to measure anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels postoperatively. Produced by the granulosa cells of the ovary, this hormone directly reflects the remaining ovarian egg supply. Lower levels of AMH have been shown to significantly decrease the success rate of in vitro fertilization (IVF), especially in women older than age 35.5 Moreover, AMH levels in the late reproductive years can be used as a predictive marker of menopause, with lower levels predicting significantly earlier onset.6

Data from 2 recent studies, a quasi-randomized trial by Song and colleagues and a systematic review and meta-analysis by Ata and colleagues emphasize that bipolar desiccation for hemostasis may not be best practice for protecting ovarian reserve during laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for an endometrioma.

AMH levels decline more significantly for women undergoing bipolar desiccation

Song and colleagues conducted a prospective quasi-randomized study of 125 women whose endometriomas were laparoscopically removed via a single-site approach and managed for hemostasis with either bipolar desiccation or suturing of the ovarian defect with a 2-0 barbed suture. All surgeries were conducted by a single surgeon.

At 3 months postsurgery, mean AMH levels had declined from baseline by 42.2% (interquartile range [IR], 16.5−53.0 ng/mL) in the desiccation group and by 24.6% (IR, 11.6−37.0 ng/mL) in the suture group (P = .001). Multivariate analysis showed that the method used for hemostasis was the only determinant for reduced ovarian reserve.

In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Ata and colleagues included 10 studies--6 qualitative and 4 quantitative. All studies examined the rate of change of serum AMH levels 3 months after laparoscopic removal of an endometrioma.

In their qualitative analysis, 5 of the 6 studies reported a significantly greater decrease in ovarian reserve after bipolar desiccation (varying from 13% to 44%) or a strong trend in the same direction. In the sixth study, the desiccation group had a lower decline in absolute AMH level than in the other 5 studies. The authors note that this 2.7% decline was much lower than the values reported for the bipolar desiccation group of any other study. (Those declines ranged between 19% and 58%.)

Although not significant, in all 3 of the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the desiccation groups had a greater loss in AMH level than the hemostatic sealant groups, and in 2 of these RCTs, bipolar desiccation groups had a greater loss than the suturing groups.

Among the 213 study participants in the 3 RCTs and the prospective cohort study included in the quantitative meta-analysis, alternative methods to bipolar desiccation were associated with a 6.95% lower decrease in AMH-level decline (95% confidence interval [CI], −13.0% to −0.9%; P = .02).

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Compared with the use of bipolar electrosurgery to attain hemostasis, the use of a topical biosurgical agent or suturing could be significantly better for protection of the ovarian follicles during laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for endometrioma. These alternative methods especially could benefit those women desiring future pregnancy who are demonstrated preoperatively to have a low ovarian reserve. As needed, electrosurgery should be sparingly employed for ovarian hemostasis.

Large Study identifies incidence of bowel injury during gynecologic laproscopy

Llarena NC, Shah AB, Milad MP. Bowel injury in gynecologic laparoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1407−1417.

In no aspect of laparoscopic surgery are preventive strategies more cautiously employed than during peritoneal access. Regardless of the applied technique, there is an irreducible risk of injury to the underlying viscera by either adhesions between the underlying bowel and abdominal wall or during the course of pilot error. Moreover, in the best of hands, bowel injury can occur whenever normal anatomic relationships need to be restored using intra-abdominal adhesiolysis. Given the ubiquity, these risks are never out of the surgeon's mind. Gynecologists are obliged to discuss these risks during the informed consent process.

Until recently, the rate of bowel injury has not been well established. Llarena and colleagues recently have conducted the largest systematic review of the medical literature to date for incidence, presentation, mortality, cause, and location of bowel injury associated with laparoscopic surgery while not necessarily distinguishing for the type of bowel injury. Sixty retrospective and 27 prospective studies met inclusion criteria.

The risk of bowel injury overall and defined

Among 474,063 laparoscopic surgeries conducted between 1972 and 2014, 604 bowel injuries were found, for an incidence of 1 in 769, or 0.13% (95% CI, 0.12−0.14%).

The rate of bowel injury varied by procedure, year, study type, and definition of bowel injury. The incidence of injury according to:

- definition, was 1 in 416 (0.24%) for studies that clearly included serosal injuries and enterotomies versus 1 in 833 (0.12%) for studies not clearly defining the type of bowel injury (relative risk [RR], 0.47; 95% CI, 0.38−0.59; P<.001)

- study type, was 1 in 666 (0.15%) for prospective studies versus 1 in 909 (0.11%) for retrospective studies (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63−0.96; P = .02)

- procedure, was 1 in 3,333 (0.03%; 95% CI, 0.01−0.03%) for sterilization and 1 in 256 (0.39%; 95% CI, 0.35−0.45%) for hysterectomy

- year, for laparoscopic hysterectomy only, was 1 in 222 (0.45%) before the year 2000 and 1 in 294 (0.34%) after 2000 (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57−0.98; P = .03).

How were injuries caused, found, and managed?

Thirty studies described the laparoscopic instrument used during 366 reported bowel injuries. The majority of injuries (55%) occurred during initial peritoneal access, with the Veress needle or trocar causing the damage. This was followed by electrosurgery (29%), dissection (11%), and forceps or scissors (4.1%).

According to 40 studies describing 307 injuries, bowel injuries most often were managed by converting to laparotomy (80%); only 8% of injuries were managed with laparoscopy and 2% expectantly.

Surgery to repair the bowel injury was delayed in 154 (41%) of 375 cases. The median time to injury discovery was 3 days (range, 1−13 days).

In only 19 cases were the presenting signs and symptoms of bowel injury recorded. Those reported from most to least often were: peritonitis, abdominal pain, fever, abdominal distention, leukocytosis, leukopenia, and septic shock.

Mortality

Mortality as an outcome was only reported in 29 of the total 90 studies; therefore, mortality may be underreported. Overall, however, death occurred in 1 (0.8%) of 125 bowel injuries.

The overall mortality rate from bowel injury--calculated from the only 42 studies that explicitly mentioned mortality as an outcome--was 1 in 125, or 0.8% (95% CI, 0.36%-1.9%). All 5 reported deaths occurred as a result of delayed recognition of bowel injury, which made the mortality rate for unrecognized bowel injury 1 in 31, or 3.2% (95% CI, 1%-7%). No deaths occurred when the bowel injury was noted intraoperatively.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In this review of 474,063 laparoscopic procedures, bowel injury occurred in 1 in 769, or 0.13% of procedures. Bowel injury is more apt to occur during more complicated laparoscopic procedures (compared with laparoscopic sterilization procedures, the risk during hysterectomy was greater than 10-fold).

Most of the injuries were managed by laparotomic surgery despite the potential to repair bowel injury by laparoscopy. Validating that peritoneal access is a high risk part of laparoscopic surgery, the majority of the injuries occurred during insufflation with a Veress needle or during abdominal access by trocar insertion. Nearly one-third of the injuries were from the use of electrosurgery, which are typically associated with a delay in presentation.

In this study, 41% of the injuries were unrecognized at the time of surgery. All 5 of the reported deaths were associated with a delay in diagnosis, with an overall mortality rate of 1 of 125, or 0.8%. Since all of these deaths were associated with a delay in diagnosis, the rate of mortality in unrecognized bowel injury was 5 of 154, or 3.2%. Among women who experienced delayed diagnosis, only 19 of 154 experienced signs or symptoms diagnostic for an underlying bowel injury, particularly when the small bowel was injured.

Can mechanical bowel prep positively affect outcomes in gynecologic laparoscopy, or should it be discarded?

Arnold A, Aitchison LP, Abbott J. Preoperative mechanical bowel preparation for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal surgery: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(5):737−752.

Popularized for more than 4 decades, the practice of presurgical bowel preparation is predicated on the notion that the presence of less, versus more, feces can minimize bacterial count and thereby reduce peritoneal contamination. Logically then, surgical site infections (SSIs) should be reduced with bowel preparation. Moreover, the surgical view and bowel handling during laparoscopic surgery should be improved, with surgical times consequently reduced.

Surgeons must weigh the putative benefits of mechanical bowel preparation against the unpleasant experience it causes for patients, as well as the risks of dehydration or electrolyte disturbance it may cause. To this day, a considerable percentage of gynecologists and colorectal surgeons routinely prep the bowel after weighing all of these factors, despite the paucity of evidence for the practice's efficacy to reduce SSI and improve surgical outcomes.7

The results of this recent systematic review critically question the usefulness of preoperative bowel preparation for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal surgery.

Details of the analysis

The authors evaluated high-quality studies on mechanical bowel preparation to assess evidence for:

- surgeon outcomes, including the surgical field and bowel handling

- operative outcomes, including intraoperative complications and operative times

- patient outcomes, including postoperative complications, overall morbidity, and length of stay.

The authors identified RCTs and prospective or retrospective cohort studies in various surgical specialties comparing preoperative bowel preparation to no such prep. Forty-three studies met inclusion criteria: 38 compared prep to no prep, and 5 compared prep to a single rectal enema. Five high-grade studies in gynecology were included (n = 795), with 4 of them RCTs of gynecologic laparoscopy (n = 645).

Operative field and duration

Of the studies comparing bowel prep with no prep, only the 5 gynecologic ones assessed operative field. Surgical view was perceived as improved in only 1 study. In another, surgeons only could guess allocation half the time.

Sixteen studies evaluated impact of mechanical bowel preparation on duration of surgery: 1 high-quality study found a significant reduction in OR time with bowel prep, and 1 moderate-quality study found longer operative time with bowel prep.

Patient outcomes

Of all studies assessing patient outcomes, 3 high-quality studies of colorectal patients (n = 490) found increased complications from prep versus no prep, including anastomotic dehiscence (P = .05), abdominal complications (P = .028), and infectious complications (P = .05).

Length of stay was assessed in 26 studies, with 4 reporting longer hospital stay with bowel prep and the remaining finding no difference between prep and no prep.

Across all specialties, only 2 studies reported improved outcomes with mechanical bowel preparation. One was a high-quality study reporting reduced 30-day morbidity (P = .018) and infectious complication rates (P = .018), and the other was a moderate-quality study that found reduced SSI (P = .0001) and organ space infection (P = .024) in patients undergoing bowel prep.

Mechanical bowel preparation vs enema

Bowel prep was compared with a single rectal enema in 5 studies. In 2 of these, patient outcomes were worse with enema. One high-quality study of 294 patients reported increased intra-abdominal fecal soiling (P = .008) in the enema group. (The surgeons believed that bowel preparation was more likely to be inadequate in this group, 25% compared with 6%, P<.05.) Whereas there was no statistical difference in the incidence of anastomotic leak between these groups, there was higher reoperation rate in the enema-only group where leakage was diagnosed (6 [4.1%] vs 0, respectively; P = .013).

Bowel prep and preoperative and postoperative symptoms

Six high-quality studies reported on the impact of mechanical bowel preparation on patient symptoms, such as nausea, weakness, abdominal distention, and satisfaction before and after surgery. In all but 1 study patients had significantly greater discomfort with bowel preparation. In 2 of the 6 studies, patients had more diarrhea (P = .0003), a delay in the first bowel movement (P = .001), and a slower return to normal diet (P = .004).

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The theory behind mechanical bowel preparation is not supported by the evidence. Despite the fact that the bowel is not customarily entered, up to 50% of gynecologic surgeons employ bowel preparation, with the hope of improving visualization and decreasing risk of an anastomotic leak. The colorectal studies in this review demonstrate no evidence for decreased anastomotic leak or infectious complications. By extrapolation, there is no evidence that using preoperative bowel prep bestows any benefit if bowel injury occurs inadvertently and if resection or reanastomosis is then required.

Among the 7 studies examining bowel prep in laparoscopy (4 gynecology, 3 urology, and 1 colorectal), only data from 1 demonstrated an improved surgical field (and in this case only by 1 out of 10 on a Likert scale). The impact of mechanical bowel preparation on the visual field is the same for diagnostic or complex laparoscopic surgeries. One high-quality study with deep endometriosis resection demonstrated no change in the operative field as reflected by no practical differences in OR time or complications.

Preparing the bowel for surgery is an intrusive process that reduces patient satisfaction by inducing weakness, abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, hunger, and thirst. Whereas this systematic analysis failed to confirm any benefit of the process, it provides evidence for the potential for harm. Mechanical bowel preparation should be discarded as a routine preoperative treatment for patients undergoing minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Rightly so, the topics of mechanical tissue extraction and hysterectomy approach have dominated the field of obstetrics and gynecology over the past 12 months and more. A profusion of literature has been published on these subjects. However, there are 2 important topics within the field of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that deserve our attention as well, and I have chosen to focus on these for this Update.

First, laparoscopic treatment of ovarian endometriomas is one of the most commonly performed gynecologic procedures worldwide. Many women undergoing such surgery are of childbearing age and have the desire for future pregnancy. What are best practices for preserving ovarian function in these women? Two studies recently published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology addressed this question.

Second, until recently, the rate of bowel injury at laparoscopic gynecologic surgery has not been well established.1 Moreover, mechanical bowel preparation is commonly employed in case intestinal injury does occur, despite the lack of evidence that outcomes of these possible injuries can be improved.2 Understanding the rate of bowel injury can shed light on the overall value of the perceived benefits of bowel preparation. Therefore, I examine 2 recent systematic reviews that analyze the incidence of bowel injury and the value of bowel prep in gynecologic laparoscopic surgery.

bipolar coagulation inferior to suturing or hemostatic sealant for preserving ovarian function

Song T, Kim WY, Lee KW, Kim KH. Effect on ovarian reserve of hemostasis by bipolar coagulation versus suture during laparoendoscopic single-site cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(3):415−420.

Ata B, Turkgeldi E, Seyhan A, Urman B. Effect of hemostatic method on ovarian reserve following laparoscopic endometrioma excision; comparison of suture, hemostatic sealant, and bipolar dessication. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(3):363−372.

The customary surgical approach for laparoscopic cystectomy is by mechanical stripping of the cyst wall (FIGURE) and the use of bipolar desiccation for hemostasis. Stripping inevitably leads to removal of healthy ovarian cortex,3 especially in inexperienced hands,4 and ovarian follicles inevitably are destroyed during electrosurgical desiccation. When compared with the use of suturing or a hemostatic agent to control bleeding in the ovarian defect, the use of bipolar electrosurgery may harm more of the ovarian cortex, resulting in a comparatively diminished follicular cohort.

Possible deleterious effects on the ovarian reserve can be determined with a blood test to measure anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels postoperatively. Produced by the granulosa cells of the ovary, this hormone directly reflects the remaining ovarian egg supply. Lower levels of AMH have been shown to significantly decrease the success rate of in vitro fertilization (IVF), especially in women older than age 35.5 Moreover, AMH levels in the late reproductive years can be used as a predictive marker of menopause, with lower levels predicting significantly earlier onset.6

Data from 2 recent studies, a quasi-randomized trial by Song and colleagues and a systematic review and meta-analysis by Ata and colleagues emphasize that bipolar desiccation for hemostasis may not be best practice for protecting ovarian reserve during laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for an endometrioma.

AMH levels decline more significantly for women undergoing bipolar desiccation

Song and colleagues conducted a prospective quasi-randomized study of 125 women whose endometriomas were laparoscopically removed via a single-site approach and managed for hemostasis with either bipolar desiccation or suturing of the ovarian defect with a 2-0 barbed suture. All surgeries were conducted by a single surgeon.

At 3 months postsurgery, mean AMH levels had declined from baseline by 42.2% (interquartile range [IR], 16.5−53.0 ng/mL) in the desiccation group and by 24.6% (IR, 11.6−37.0 ng/mL) in the suture group (P = .001). Multivariate analysis showed that the method used for hemostasis was the only determinant for reduced ovarian reserve.

In their systematic review and meta-analysis, Ata and colleagues included 10 studies--6 qualitative and 4 quantitative. All studies examined the rate of change of serum AMH levels 3 months after laparoscopic removal of an endometrioma.

In their qualitative analysis, 5 of the 6 studies reported a significantly greater decrease in ovarian reserve after bipolar desiccation (varying from 13% to 44%) or a strong trend in the same direction. In the sixth study, the desiccation group had a lower decline in absolute AMH level than in the other 5 studies. The authors note that this 2.7% decline was much lower than the values reported for the bipolar desiccation group of any other study. (Those declines ranged between 19% and 58%.)

Although not significant, in all 3 of the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the desiccation groups had a greater loss in AMH level than the hemostatic sealant groups, and in 2 of these RCTs, bipolar desiccation groups had a greater loss than the suturing groups.

Among the 213 study participants in the 3 RCTs and the prospective cohort study included in the quantitative meta-analysis, alternative methods to bipolar desiccation were associated with a 6.95% lower decrease in AMH-level decline (95% confidence interval [CI], −13.0% to −0.9%; P = .02).

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

Compared with the use of bipolar electrosurgery to attain hemostasis, the use of a topical biosurgical agent or suturing could be significantly better for protection of the ovarian follicles during laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy for endometrioma. These alternative methods especially could benefit those women desiring future pregnancy who are demonstrated preoperatively to have a low ovarian reserve. As needed, electrosurgery should be sparingly employed for ovarian hemostasis.

Large Study identifies incidence of bowel injury during gynecologic laproscopy

Llarena NC, Shah AB, Milad MP. Bowel injury in gynecologic laparoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1407−1417.

In no aspect of laparoscopic surgery are preventive strategies more cautiously employed than during peritoneal access. Regardless of the applied technique, there is an irreducible risk of injury to the underlying viscera by either adhesions between the underlying bowel and abdominal wall or during the course of pilot error. Moreover, in the best of hands, bowel injury can occur whenever normal anatomic relationships need to be restored using intra-abdominal adhesiolysis. Given the ubiquity, these risks are never out of the surgeon's mind. Gynecologists are obliged to discuss these risks during the informed consent process.

Until recently, the rate of bowel injury has not been well established. Llarena and colleagues recently have conducted the largest systematic review of the medical literature to date for incidence, presentation, mortality, cause, and location of bowel injury associated with laparoscopic surgery while not necessarily distinguishing for the type of bowel injury. Sixty retrospective and 27 prospective studies met inclusion criteria.

The risk of bowel injury overall and defined

Among 474,063 laparoscopic surgeries conducted between 1972 and 2014, 604 bowel injuries were found, for an incidence of 1 in 769, or 0.13% (95% CI, 0.12−0.14%).

The rate of bowel injury varied by procedure, year, study type, and definition of bowel injury. The incidence of injury according to:

- definition, was 1 in 416 (0.24%) for studies that clearly included serosal injuries and enterotomies versus 1 in 833 (0.12%) for studies not clearly defining the type of bowel injury (relative risk [RR], 0.47; 95% CI, 0.38−0.59; P<.001)

- study type, was 1 in 666 (0.15%) for prospective studies versus 1 in 909 (0.11%) for retrospective studies (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63−0.96; P = .02)

- procedure, was 1 in 3,333 (0.03%; 95% CI, 0.01−0.03%) for sterilization and 1 in 256 (0.39%; 95% CI, 0.35−0.45%) for hysterectomy

- year, for laparoscopic hysterectomy only, was 1 in 222 (0.45%) before the year 2000 and 1 in 294 (0.34%) after 2000 (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57−0.98; P = .03).

How were injuries caused, found, and managed?

Thirty studies described the laparoscopic instrument used during 366 reported bowel injuries. The majority of injuries (55%) occurred during initial peritoneal access, with the Veress needle or trocar causing the damage. This was followed by electrosurgery (29%), dissection (11%), and forceps or scissors (4.1%).

According to 40 studies describing 307 injuries, bowel injuries most often were managed by converting to laparotomy (80%); only 8% of injuries were managed with laparoscopy and 2% expectantly.

Surgery to repair the bowel injury was delayed in 154 (41%) of 375 cases. The median time to injury discovery was 3 days (range, 1−13 days).

In only 19 cases were the presenting signs and symptoms of bowel injury recorded. Those reported from most to least often were: peritonitis, abdominal pain, fever, abdominal distention, leukocytosis, leukopenia, and septic shock.

Mortality

Mortality as an outcome was only reported in 29 of the total 90 studies; therefore, mortality may be underreported. Overall, however, death occurred in 1 (0.8%) of 125 bowel injuries.

The overall mortality rate from bowel injury--calculated from the only 42 studies that explicitly mentioned mortality as an outcome--was 1 in 125, or 0.8% (95% CI, 0.36%-1.9%). All 5 reported deaths occurred as a result of delayed recognition of bowel injury, which made the mortality rate for unrecognized bowel injury 1 in 31, or 3.2% (95% CI, 1%-7%). No deaths occurred when the bowel injury was noted intraoperatively.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In this review of 474,063 laparoscopic procedures, bowel injury occurred in 1 in 769, or 0.13% of procedures. Bowel injury is more apt to occur during more complicated laparoscopic procedures (compared with laparoscopic sterilization procedures, the risk during hysterectomy was greater than 10-fold).

Most of the injuries were managed by laparotomic surgery despite the potential to repair bowel injury by laparoscopy. Validating that peritoneal access is a high risk part of laparoscopic surgery, the majority of the injuries occurred during insufflation with a Veress needle or during abdominal access by trocar insertion. Nearly one-third of the injuries were from the use of electrosurgery, which are typically associated with a delay in presentation.

In this study, 41% of the injuries were unrecognized at the time of surgery. All 5 of the reported deaths were associated with a delay in diagnosis, with an overall mortality rate of 1 of 125, or 0.8%. Since all of these deaths were associated with a delay in diagnosis, the rate of mortality in unrecognized bowel injury was 5 of 154, or 3.2%. Among women who experienced delayed diagnosis, only 19 of 154 experienced signs or symptoms diagnostic for an underlying bowel injury, particularly when the small bowel was injured.

Can mechanical bowel prep positively affect outcomes in gynecologic laparoscopy, or should it be discarded?

Arnold A, Aitchison LP, Abbott J. Preoperative mechanical bowel preparation for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal surgery: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(5):737−752.

Popularized for more than 4 decades, the practice of presurgical bowel preparation is predicated on the notion that the presence of less, versus more, feces can minimize bacterial count and thereby reduce peritoneal contamination. Logically then, surgical site infections (SSIs) should be reduced with bowel preparation. Moreover, the surgical view and bowel handling during laparoscopic surgery should be improved, with surgical times consequently reduced.

Surgeons must weigh the putative benefits of mechanical bowel preparation against the unpleasant experience it causes for patients, as well as the risks of dehydration or electrolyte disturbance it may cause. To this day, a considerable percentage of gynecologists and colorectal surgeons routinely prep the bowel after weighing all of these factors, despite the paucity of evidence for the practice's efficacy to reduce SSI and improve surgical outcomes.7

The results of this recent systematic review critically question the usefulness of preoperative bowel preparation for abdominal, laparoscopic, and vaginal surgery.

Details of the analysis

The authors evaluated high-quality studies on mechanical bowel preparation to assess evidence for:

- surgeon outcomes, including the surgical field and bowel handling

- operative outcomes, including intraoperative complications and operative times

- patient outcomes, including postoperative complications, overall morbidity, and length of stay.

The authors identified RCTs and prospective or retrospective cohort studies in various surgical specialties comparing preoperative bowel preparation to no such prep. Forty-three studies met inclusion criteria: 38 compared prep to no prep, and 5 compared prep to a single rectal enema. Five high-grade studies in gynecology were included (n = 795), with 4 of them RCTs of gynecologic laparoscopy (n = 645).

Operative field and duration

Of the studies comparing bowel prep with no prep, only the 5 gynecologic ones assessed operative field. Surgical view was perceived as improved in only 1 study. In another, surgeons only could guess allocation half the time.

Sixteen studies evaluated impact of mechanical bowel preparation on duration of surgery: 1 high-quality study found a significant reduction in OR time with bowel prep, and 1 moderate-quality study found longer operative time with bowel prep.

Patient outcomes

Of all studies assessing patient outcomes, 3 high-quality studies of colorectal patients (n = 490) found increased complications from prep versus no prep, including anastomotic dehiscence (P = .05), abdominal complications (P = .028), and infectious complications (P = .05).

Length of stay was assessed in 26 studies, with 4 reporting longer hospital stay with bowel prep and the remaining finding no difference between prep and no prep.

Across all specialties, only 2 studies reported improved outcomes with mechanical bowel preparation. One was a high-quality study reporting reduced 30-day morbidity (P = .018) and infectious complication rates (P = .018), and the other was a moderate-quality study that found reduced SSI (P = .0001) and organ space infection (P = .024) in patients undergoing bowel prep.

Mechanical bowel preparation vs enema

Bowel prep was compared with a single rectal enema in 5 studies. In 2 of these, patient outcomes were worse with enema. One high-quality study of 294 patients reported increased intra-abdominal fecal soiling (P = .008) in the enema group. (The surgeons believed that bowel preparation was more likely to be inadequate in this group, 25% compared with 6%, P<.05.) Whereas there was no statistical difference in the incidence of anastomotic leak between these groups, there was higher reoperation rate in the enema-only group where leakage was diagnosed (6 [4.1%] vs 0, respectively; P = .013).

Bowel prep and preoperative and postoperative symptoms

Six high-quality studies reported on the impact of mechanical bowel preparation on patient symptoms, such as nausea, weakness, abdominal distention, and satisfaction before and after surgery. In all but 1 study patients had significantly greater discomfort with bowel preparation. In 2 of the 6 studies, patients had more diarrhea (P = .0003), a delay in the first bowel movement (P = .001), and a slower return to normal diet (P = .004).

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The theory behind mechanical bowel preparation is not supported by the evidence. Despite the fact that the bowel is not customarily entered, up to 50% of gynecologic surgeons employ bowel preparation, with the hope of improving visualization and decreasing risk of an anastomotic leak. The colorectal studies in this review demonstrate no evidence for decreased anastomotic leak or infectious complications. By extrapolation, there is no evidence that using preoperative bowel prep bestows any benefit if bowel injury occurs inadvertently and if resection or reanastomosis is then required.

Among the 7 studies examining bowel prep in laparoscopy (4 gynecology, 3 urology, and 1 colorectal), only data from 1 demonstrated an improved surgical field (and in this case only by 1 out of 10 on a Likert scale). The impact of mechanical bowel preparation on the visual field is the same for diagnostic or complex laparoscopic surgeries. One high-quality study with deep endometriosis resection demonstrated no change in the operative field as reflected by no practical differences in OR time or complications.

Preparing the bowel for surgery is an intrusive process that reduces patient satisfaction by inducing weakness, abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, hunger, and thirst. Whereas this systematic analysis failed to confirm any benefit of the process, it provides evidence for the potential for harm. Mechanical bowel preparation should be discarded as a routine preoperative treatment for patients undergoing minimally invasive gynecologic surgery.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this article

- Preserving ovarian function at laparoscopic cystectomy

- Incidence of bowel injury during gyn surgery

- Usefulness and safety of mechanical bowel preparation

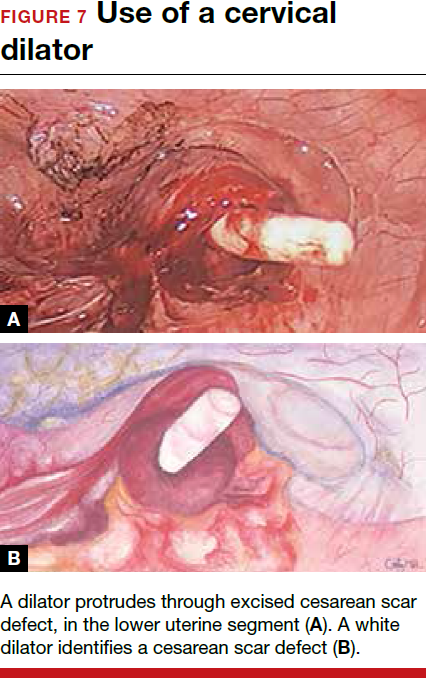

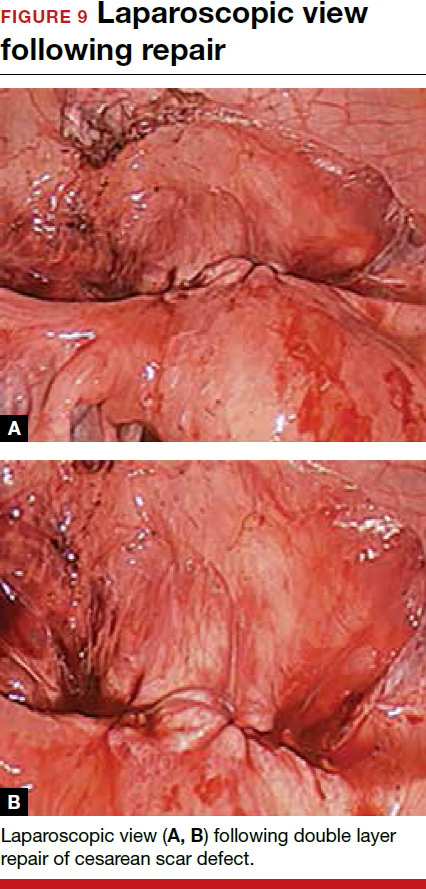

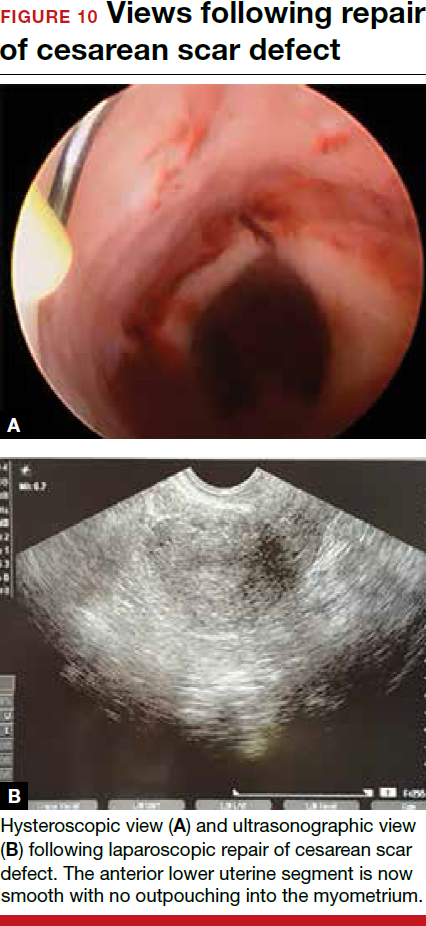

Cesarean scar defect: What is it and how should it be treated?

Cesarean delivery is one of the most common surgical procedures in women, with rates of 30% or more in the United States.1 As a result, the rate is rising for cesarean scar defect—the presence of a “niche” at the site of cesarean delivery scar—with the reported prevalence between 24% and 70% in a random population of women with at least one cesarean delivery.2 Other terms for cesarean scar defect include a niche, isthmocele, uteroperitoneal fistula, and diverticulum.1–9

Formation of cesarean scar defect

Cesarean scar defect forms after cesarean delivery, at the site of hysterotomy, on the anterior wall of the uterine isthmus (FIGURE 1). While this is the typical location, the defect has also been found at the endocervical canal and mid-uterine body. Improper healing of the cesarean incision leads to thinning of the anterior uterine wall, which creates an indentation and fluid-filled pouch at the cesarean scar site. The exact reason why a niche develops has not yet been determined; however, there are several hypotheses, broken down by pregnancy-related and patient-related factors. Surgical techniques that may increase the chance of niche development include low (cervical) hysterotomy, single-layer uterine wall closure, use of locking sutures, closure of hysterotomy with endometrial-sparing technique, and multiple cesarean deliveries.3,4 Patients with medical conditions that may impact wound healing (such as diabetes and smoking) may be at increased risk for niche formation.

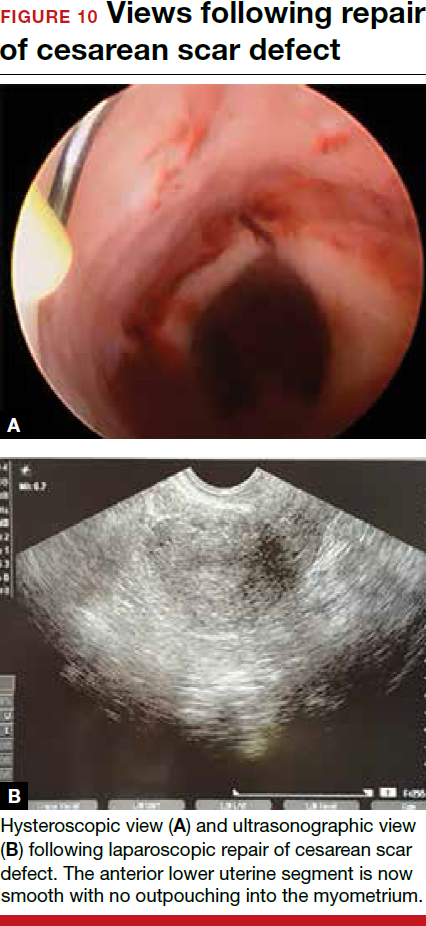

Viewed hysteroscopically, the defect appears as a concave shape in the anterior uterine wall; to the inexperienced eye, it may resemble a second cavity (FIGURE 2).

Pelvic pain and other serious consequences

The presence of fibrotic tissue in the niche acts like a valve, leading to the accumulation of blood in this reservoir-like area. A niche thus can cause delayed menstruation through the cervix, resulting in abnormal bleeding, pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility. Accumulated blood in this area can ultimately degrade cervical mucus and sperm quality, as well as inhibit sperm transport, a proposed mechanism of infertility.5,6 Women with a niche who conceive are at potential risk for cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy, with the embryo implanting in the pouch and subsequently growing and developing improperly.

Read about evaluation and treatment.

Evaluation and treatment

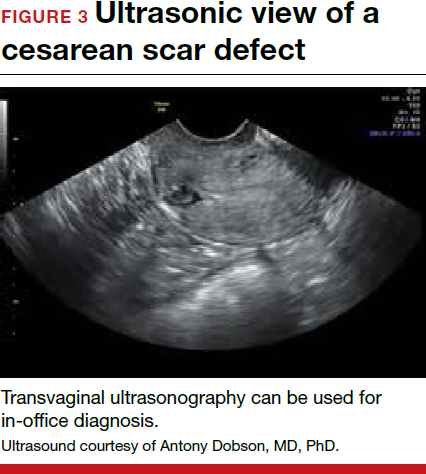

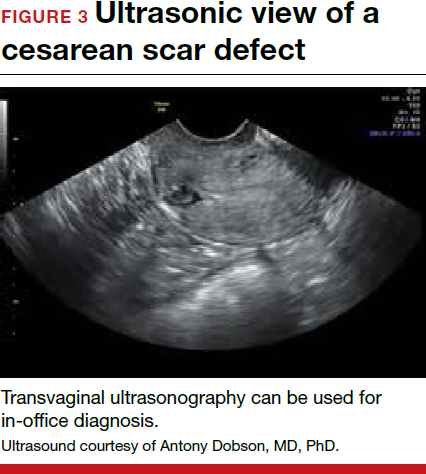

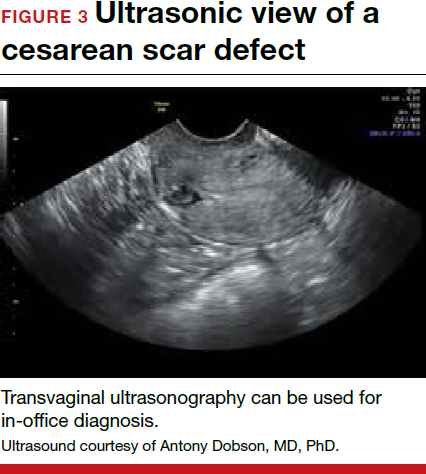

Patients presenting with the symptoms de-scribed above who have had a prior cesarean delivery should be evaluated for a cesarean scar defect.9 The best time to assess for the abnormality is after the patient’s menstrual cycle, when the endometrial lining is at its thinnest and recently menstruated blood has collected in the defect (this can highlight the niche on imaging). Transvaginal ultrasonography (FIGURE 3) or saline-infusion sonohysterogram serve as a first-line test for in-office diagnosis.7 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 3-D ultrasonography, and hysteroscopy are additional useful imaging modalities that can aid in the diagnosis.

Treatments for cesarean scar defect vary dramatically and include hormonal therapy, hysteroscopic resection, vaginal or laparoscopic repair, and hysterectomy. Nonsurgical treatment should be reserved for women who desire a noninvasive approach, as the evidence for symptom resolution is limited.8

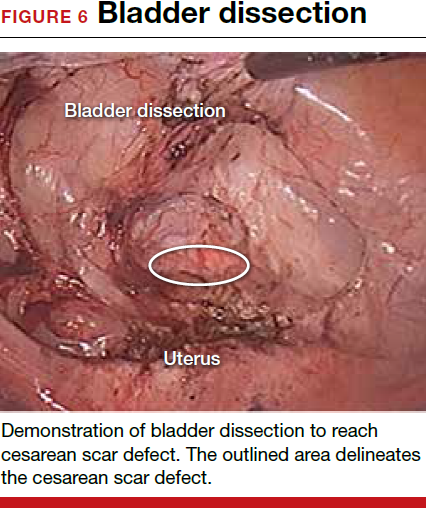

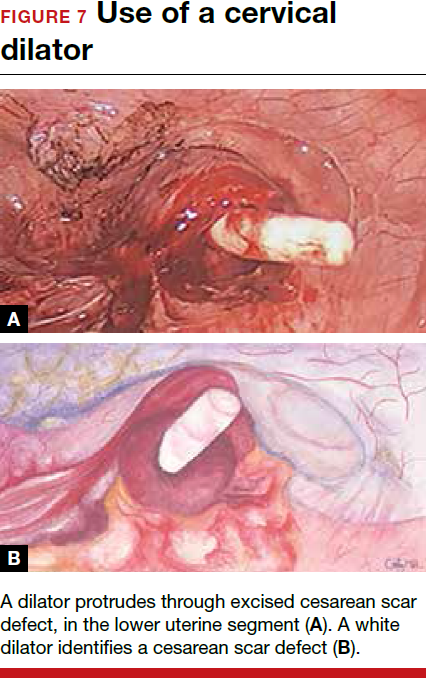

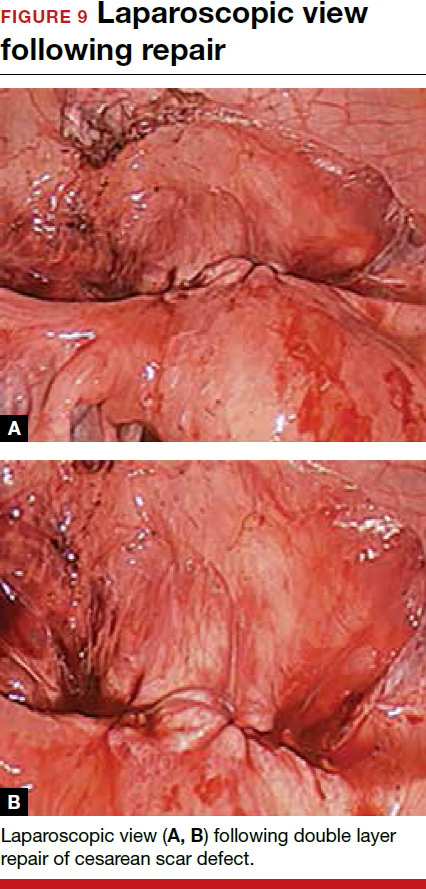

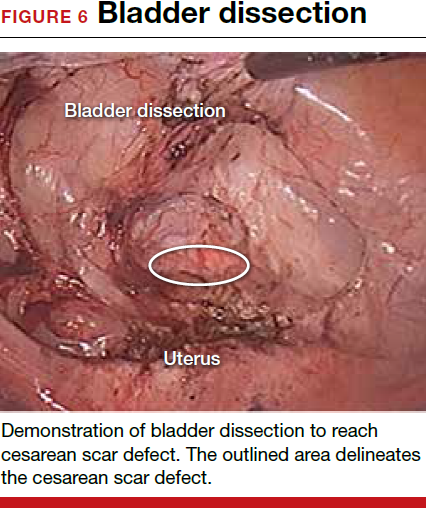

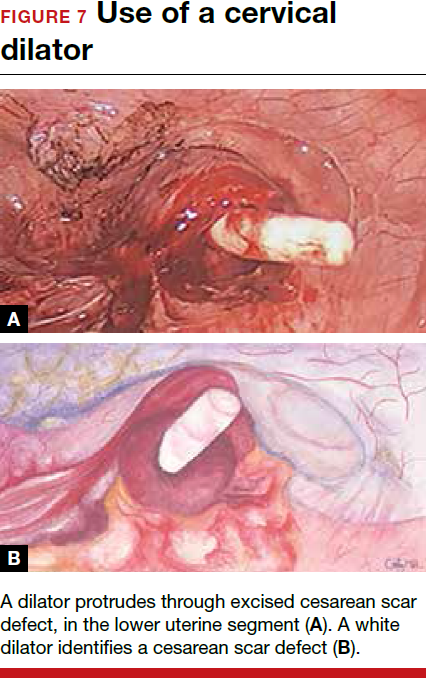

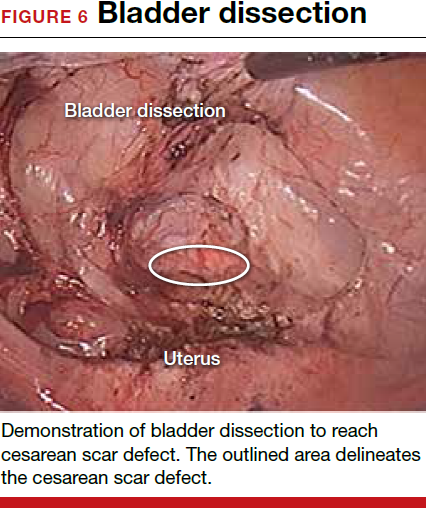

To promote fertility and decrease symptoms, the abnormal, fibrotic tissue must be removed. In our experience, since 2003, we have found that use of a laparoscopic approach is best for women desiring future fertility and that hysteroscopic resection is best for women whose childbearing is completed.9 Our management is dictated by the patient’s fertility plans, since there is concern that cesarean scar defect in a gravid uterus presents a risk for uterine rupture. The laparoscopic approach allows the defect to be repaired and the integrity of the myometrium restored.9

What are the coding options for cesarean scar defect repair?

Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

As the accompanying article discusses, the primary treatment for a cesarean scar defect depends on whether the patient wishes to preserve fertility, but assigning a procedure code for either surgical option will entail reporting an unlisted procedure code.

Under Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) guidelines (which are developed and copyrighted by the American Medical Association), procedure code selected must accurately describe the service/procedure performed rather than just approximate the service. This means that when a procedure-specific code does not exist, an unlisted procedure code that represents the type of surgery, the approach, and the anatomic site needs to be selected.

When an unlisted CPT code is reported, payment is based on the complexity of the surgery, and one way to communicate this to a payer is to provide additional documentation that not only includes the operative report but also suggests one or more existing CPT codes that have a published relative value unit (RVU) that approximates the work involved for the unlisted procedure.

The coding options for hysteroscopic and laparoscopic treatment options are listed below. The comparison codes offered will give the surgeon a range to look at, but the ultimate decision to use one of those suggested, or to choose an entirely different comparison code, is entirely within the control of the physician.

ICD-10-CM diagnostic coding

While the cesarean scar defect is a sequela of cesarean delivery, which is always reported as a secondary code, the choice of a primary diagnosis code can be either a gynecologic and/or an obstetric complication code. The choice may be determined by payer policy, as the use of an obstetric complication may not be accepted with a gynecologic procedure code. From a coding perspective, however, use of all 3 of these codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) paints the most accurate description of the defect and its cause:

- N85.8 Other specified noninflammatory disorders of uterus versus

- O34.21 Maternal care for scar from previous cesarean delivery plus

- O94 Sequelae of complication of pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium.

Hysteroscopic resection codes:

- 58579 Unlisted hysteroscopy procedure, uterus