User login

Skip lymphadenectomy if SLN mapping finds low-grade endometrial cancer

SAN DIEGO – Lymphadenectomy is unnecessary if sentinel lymph node mapping successfully stages low-grade endometrial cancer, according to researchers from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Lymphadenectomy guided by frozen section remains common in the United States. But the Johns Hopkins research team found that using sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping and biopsy instead cuts the rate of lymphadenectomy by 76%, without reducing the detection of lymphatic metastases.

It’s an important finding for cancer patients likely to survive their diagnosis. “We see low-grade patients in the clinic” who’ve had unnecessary lymphadenectomies, “and they are in terrible shape,” said investigator Dr. Abdulrahman Sinno, a gynecologic oncology fellow at Johns Hopkins. Up to half “have horrible side effects,” including crippling lymphedema and pain.

SLN mapping is “an alternative that gives us the information we need for nodal assessment without putting patients at risk. You’ll know if patients have metastases or not. If they fail to map, you do a frozen section, and if you have high-risk features, a lymphadenectomy only on [the side] that didn’t map,” Dr. Sinno said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

For the past several years, physicians at Johns Hopkins has been doing both SLN mapping for low-grade endometrial cancer as well as frozen sections to decide the need for lymphadenectomy. Using both approaches allowed the investigators to review how patients would have fared if they had gotten only one.

“[We could] safely study the utility of SLN mapping while maintaining the historical standard of using frozen sections to direct the need for lymphadenectomy,” Dr. Sinno said.

SLN mapping outperformed frozen section. Among 114 women, most with grade 1 disease but some with grade 2 or complex atypical hyperplasia, 8 had lymph node metastases. Mapping identified every one, five by standard hematoxylin-eosin staining, and three by ultrastaging. Frozen-section guided lymphadenectomy missed three.

Eighty four (37%) of the 224 hemi-pelvises in the study had lymphadenectomies based on worrisome frozen-section findings. If SLN mapping had been relied on to make the call, lymphadenectomies would have been performed in 20 (9%), a statistically significant difference (P = 0.004).

“Strategies that rely exclusively on uterine frozen section result in significant overtreatment. In the absence of a therapeutic benefit to lymphadenectomy, we believe” this is “unjustifiable when an alternative exists.” At Johns Hopkins these days, “if you map, you’re done,” Dr. Sinno said.

Almost two-thirds of the women had grade 1 endometrial cancer on preoperative histopathology, and about the same number on final pathology. Bilateral SLN mapping was successful in 71 cases (62%) and unilateral mapping in 27 cases (24%). At least one SLN was detected in 98 women (86%).

There were six recurrences after a median follow-up of 15 months. Four were in women who had full pelvic and periaortic lymphadenectomies that were negative. There was also a port site recurrence and a recurrence in an outlying patient with advanced disease. Overall, “recurrence was independent of whether sentinel nodes were applied,” Dr. Sinno said.

Women in the study were a median of 60 years old, with a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2.

Dr. Sinno reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Lymphadenectomy is unnecessary if sentinel lymph node mapping successfully stages low-grade endometrial cancer, according to researchers from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Lymphadenectomy guided by frozen section remains common in the United States. But the Johns Hopkins research team found that using sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping and biopsy instead cuts the rate of lymphadenectomy by 76%, without reducing the detection of lymphatic metastases.

It’s an important finding for cancer patients likely to survive their diagnosis. “We see low-grade patients in the clinic” who’ve had unnecessary lymphadenectomies, “and they are in terrible shape,” said investigator Dr. Abdulrahman Sinno, a gynecologic oncology fellow at Johns Hopkins. Up to half “have horrible side effects,” including crippling lymphedema and pain.

SLN mapping is “an alternative that gives us the information we need for nodal assessment without putting patients at risk. You’ll know if patients have metastases or not. If they fail to map, you do a frozen section, and if you have high-risk features, a lymphadenectomy only on [the side] that didn’t map,” Dr. Sinno said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

For the past several years, physicians at Johns Hopkins has been doing both SLN mapping for low-grade endometrial cancer as well as frozen sections to decide the need for lymphadenectomy. Using both approaches allowed the investigators to review how patients would have fared if they had gotten only one.

“[We could] safely study the utility of SLN mapping while maintaining the historical standard of using frozen sections to direct the need for lymphadenectomy,” Dr. Sinno said.

SLN mapping outperformed frozen section. Among 114 women, most with grade 1 disease but some with grade 2 or complex atypical hyperplasia, 8 had lymph node metastases. Mapping identified every one, five by standard hematoxylin-eosin staining, and three by ultrastaging. Frozen-section guided lymphadenectomy missed three.

Eighty four (37%) of the 224 hemi-pelvises in the study had lymphadenectomies based on worrisome frozen-section findings. If SLN mapping had been relied on to make the call, lymphadenectomies would have been performed in 20 (9%), a statistically significant difference (P = 0.004).

“Strategies that rely exclusively on uterine frozen section result in significant overtreatment. In the absence of a therapeutic benefit to lymphadenectomy, we believe” this is “unjustifiable when an alternative exists.” At Johns Hopkins these days, “if you map, you’re done,” Dr. Sinno said.

Almost two-thirds of the women had grade 1 endometrial cancer on preoperative histopathology, and about the same number on final pathology. Bilateral SLN mapping was successful in 71 cases (62%) and unilateral mapping in 27 cases (24%). At least one SLN was detected in 98 women (86%).

There were six recurrences after a median follow-up of 15 months. Four were in women who had full pelvic and periaortic lymphadenectomies that were negative. There was also a port site recurrence and a recurrence in an outlying patient with advanced disease. Overall, “recurrence was independent of whether sentinel nodes were applied,” Dr. Sinno said.

Women in the study were a median of 60 years old, with a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2.

Dr. Sinno reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Lymphadenectomy is unnecessary if sentinel lymph node mapping successfully stages low-grade endometrial cancer, according to researchers from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Lymphadenectomy guided by frozen section remains common in the United States. But the Johns Hopkins research team found that using sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping and biopsy instead cuts the rate of lymphadenectomy by 76%, without reducing the detection of lymphatic metastases.

It’s an important finding for cancer patients likely to survive their diagnosis. “We see low-grade patients in the clinic” who’ve had unnecessary lymphadenectomies, “and they are in terrible shape,” said investigator Dr. Abdulrahman Sinno, a gynecologic oncology fellow at Johns Hopkins. Up to half “have horrible side effects,” including crippling lymphedema and pain.

SLN mapping is “an alternative that gives us the information we need for nodal assessment without putting patients at risk. You’ll know if patients have metastases or not. If they fail to map, you do a frozen section, and if you have high-risk features, a lymphadenectomy only on [the side] that didn’t map,” Dr. Sinno said at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

For the past several years, physicians at Johns Hopkins has been doing both SLN mapping for low-grade endometrial cancer as well as frozen sections to decide the need for lymphadenectomy. Using both approaches allowed the investigators to review how patients would have fared if they had gotten only one.

“[We could] safely study the utility of SLN mapping while maintaining the historical standard of using frozen sections to direct the need for lymphadenectomy,” Dr. Sinno said.

SLN mapping outperformed frozen section. Among 114 women, most with grade 1 disease but some with grade 2 or complex atypical hyperplasia, 8 had lymph node metastases. Mapping identified every one, five by standard hematoxylin-eosin staining, and three by ultrastaging. Frozen-section guided lymphadenectomy missed three.

Eighty four (37%) of the 224 hemi-pelvises in the study had lymphadenectomies based on worrisome frozen-section findings. If SLN mapping had been relied on to make the call, lymphadenectomies would have been performed in 20 (9%), a statistically significant difference (P = 0.004).

“Strategies that rely exclusively on uterine frozen section result in significant overtreatment. In the absence of a therapeutic benefit to lymphadenectomy, we believe” this is “unjustifiable when an alternative exists.” At Johns Hopkins these days, “if you map, you’re done,” Dr. Sinno said.

Almost two-thirds of the women had grade 1 endometrial cancer on preoperative histopathology, and about the same number on final pathology. Bilateral SLN mapping was successful in 71 cases (62%) and unilateral mapping in 27 cases (24%). At least one SLN was detected in 98 women (86%).

There were six recurrences after a median follow-up of 15 months. Four were in women who had full pelvic and periaortic lymphadenectomies that were negative. There was also a port site recurrence and a recurrence in an outlying patient with advanced disease. Overall, “recurrence was independent of whether sentinel nodes were applied,” Dr. Sinno said.

Women in the study were a median of 60 years old, with a median body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2.

Dr. Sinno reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN’S CANCER

Key clinical point: Successful sentinel lymph node mapping gives all the information needed for nodal assessment.

Major finding: Sentinel lymph node mapping identified all eight nodal metastases; frozen-section guided lymphadenectomy missed three.

Data source: A review of 114 cases at Johns Hopkins University.

Disclosures: Dr. Sinno reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Endometriosis linked to higher CHD risk

Endometriosis is associated with a significantly increased risk of coronary heart disease, at least in part because of one of its principal treatments – hysterectomy/oophorectomy, according to a new analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study II.

In what the researchers described as the first large prospective study to examine this possible association, the link between endometriosis and coronary heart disease (CHD) was mediated by patient age.

Women with endometriosis had a higher incidence of CHD than those without the gynecologic disorder until they reached their late 50s; after that, the two populations had similar CHD rates, wrote Fan Mu, Sc.D., of the department of epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, and her associates (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.115.002224).

“This association may have important clinical and public health implications among women in their early 40s to early 50s,” the researchers wrote. “It is possible that the observed increased risk associated with surgical menopause from hysterectomy/oophorectomy among women with endometriosis started to diminish with age partially because nearly every woman had reached menopause by the age of 55 years.”

The researchers chose to study this topic because endometriosis has been linked to chronic systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and adverse lipid profiles, factors that also play key roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic CHD. They assessed the incidence of myocardial infarction, angina, and the combined outcome of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)/angioplasty/stenting using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study involving 116,430 women, aged 25-42 years at baseline in 1989, who were followed for approximately 20 years.

A total of 5,296 of the study participants had laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis at baseline, and another 6,607 developed the disorder during follow-up. There were 1,438 incident cases of CHD during follow-up.

Compared with women who didn’t have endometriosis, those who did showed increased relative risks for myocardial infarction (1.63), angiographically confirmed angina (2.07), CABG/angioplasty/stent (1.49), and combined CHD (1.73). The results remained statistically significant after the researchers adjusted for potential confounders.

About 42% of this association was statistically accounted for by the greater frequency of hysterectomy/oophorectomy among women who had endometriosis and the earlier age of these surgeries among women with endometriosis. Women who underwent the surgery had an absolute incidence of CHD of 139 per 100,000 person-years, compared with an incidence of 60 per 100,000 person-years among the women who didn’t have hysterectomy/oophorectomy.

“Physicians need to consider the potential long-term impact that the surgeries may cause and weigh the risks and benefits of the treatment in dialogue with patients, particularly with respect to endometriosis where pain recurrence risk remains,” the researchers wrote. “Although oophorectomy confers obvious prevention for ovarian cancer, with which endometriosis has been associated, CHD is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in women in the United States and United Kingdom.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Endometriosis is associated with a significantly increased risk of coronary heart disease, at least in part because of one of its principal treatments – hysterectomy/oophorectomy, according to a new analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study II.

In what the researchers described as the first large prospective study to examine this possible association, the link between endometriosis and coronary heart disease (CHD) was mediated by patient age.

Women with endometriosis had a higher incidence of CHD than those without the gynecologic disorder until they reached their late 50s; after that, the two populations had similar CHD rates, wrote Fan Mu, Sc.D., of the department of epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, and her associates (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.115.002224).

“This association may have important clinical and public health implications among women in their early 40s to early 50s,” the researchers wrote. “It is possible that the observed increased risk associated with surgical menopause from hysterectomy/oophorectomy among women with endometriosis started to diminish with age partially because nearly every woman had reached menopause by the age of 55 years.”

The researchers chose to study this topic because endometriosis has been linked to chronic systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and adverse lipid profiles, factors that also play key roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic CHD. They assessed the incidence of myocardial infarction, angina, and the combined outcome of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)/angioplasty/stenting using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study involving 116,430 women, aged 25-42 years at baseline in 1989, who were followed for approximately 20 years.

A total of 5,296 of the study participants had laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis at baseline, and another 6,607 developed the disorder during follow-up. There were 1,438 incident cases of CHD during follow-up.

Compared with women who didn’t have endometriosis, those who did showed increased relative risks for myocardial infarction (1.63), angiographically confirmed angina (2.07), CABG/angioplasty/stent (1.49), and combined CHD (1.73). The results remained statistically significant after the researchers adjusted for potential confounders.

About 42% of this association was statistically accounted for by the greater frequency of hysterectomy/oophorectomy among women who had endometriosis and the earlier age of these surgeries among women with endometriosis. Women who underwent the surgery had an absolute incidence of CHD of 139 per 100,000 person-years, compared with an incidence of 60 per 100,000 person-years among the women who didn’t have hysterectomy/oophorectomy.

“Physicians need to consider the potential long-term impact that the surgeries may cause and weigh the risks and benefits of the treatment in dialogue with patients, particularly with respect to endometriosis where pain recurrence risk remains,” the researchers wrote. “Although oophorectomy confers obvious prevention for ovarian cancer, with which endometriosis has been associated, CHD is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in women in the United States and United Kingdom.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Endometriosis is associated with a significantly increased risk of coronary heart disease, at least in part because of one of its principal treatments – hysterectomy/oophorectomy, according to a new analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study II.

In what the researchers described as the first large prospective study to examine this possible association, the link between endometriosis and coronary heart disease (CHD) was mediated by patient age.

Women with endometriosis had a higher incidence of CHD than those without the gynecologic disorder until they reached their late 50s; after that, the two populations had similar CHD rates, wrote Fan Mu, Sc.D., of the department of epidemiology, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, and her associates (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016 Mar 29. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.115.002224).

“This association may have important clinical and public health implications among women in their early 40s to early 50s,” the researchers wrote. “It is possible that the observed increased risk associated with surgical menopause from hysterectomy/oophorectomy among women with endometriosis started to diminish with age partially because nearly every woman had reached menopause by the age of 55 years.”

The researchers chose to study this topic because endometriosis has been linked to chronic systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and adverse lipid profiles, factors that also play key roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic CHD. They assessed the incidence of myocardial infarction, angina, and the combined outcome of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)/angioplasty/stenting using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study involving 116,430 women, aged 25-42 years at baseline in 1989, who were followed for approximately 20 years.

A total of 5,296 of the study participants had laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis at baseline, and another 6,607 developed the disorder during follow-up. There were 1,438 incident cases of CHD during follow-up.

Compared with women who didn’t have endometriosis, those who did showed increased relative risks for myocardial infarction (1.63), angiographically confirmed angina (2.07), CABG/angioplasty/stent (1.49), and combined CHD (1.73). The results remained statistically significant after the researchers adjusted for potential confounders.

About 42% of this association was statistically accounted for by the greater frequency of hysterectomy/oophorectomy among women who had endometriosis and the earlier age of these surgeries among women with endometriosis. Women who underwent the surgery had an absolute incidence of CHD of 139 per 100,000 person-years, compared with an incidence of 60 per 100,000 person-years among the women who didn’t have hysterectomy/oophorectomy.

“Physicians need to consider the potential long-term impact that the surgeries may cause and weigh the risks and benefits of the treatment in dialogue with patients, particularly with respect to endometriosis where pain recurrence risk remains,” the researchers wrote. “Although oophorectomy confers obvious prevention for ovarian cancer, with which endometriosis has been associated, CHD is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in women in the United States and United Kingdom.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM CIRCULATION: CARDIOVASCULAR QUALITY AND OUTCOMES

Key clinical point: Endometriosis is associated with a significantly increased risk of coronary heart disease.

Major finding: Women with endometriosis showed increased relative risks for MI (1.63), angiographically confirmed angina (2.07), CABG/angioplasty/stent (1.49), and combined CHD (1.73).

Data source: A secondary analysis of data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, a prospective cohort study involving 116,430 women followed for 20 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Malpractice claims for small bowel obstruction costly, frequent for general surgeons

MONTREAL – When surgeons are sued and lose or settle in cases relating to management of small bowel obstruction, the payout is often costly, according a study involving a close examination of 158 such cases.

The odds of a positive outcome aren’t great. “When looking at award payouts, close to half of cases resulted in a verdict with monetary compensation for the patient,” said Dr. Asad Choudhry, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of trauma, critical care, and surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Choudhry, presenting his findings at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association, said that general surgeons are the third most likely specialty to be sued, coming only after neurosurgeons and cardiothoracic surgeons. In a given year, about 15% of all general surgeons will be sued, with almost a third of those suits resulting in a payment to the plaintiff. By age 65 years, said Dr. Choudhry, 99% of physicians in higher-risk specialties will face a malpractice claim, compared with 75% of those in lower-risk specialties.

Overall, one-third of malpractice payments come from suits that allege diagnostic error; 24% of suits allege malpractice in surgery. “Small bowel obstruction accounts for 12% to 16% of surgical admissions, with 300,000 operations performed each year,” he said.

Dr. Choudhry and his colleagues searched the Westlaw database using key search terms to identify U.S. malpractice cases that involved small bowel obstruction (SBO), focusing only on cases in which management of SBO was the primary reason for the suit. Cases from 1982 to 2015 were included.

Looking more closely at the 158 cases that resulted from the search, Dr. Choudhry examined variables that included patient demographics, the alleged reason for the malpractice, the settlement or verdict, and the amount paid out, adjusted to 2015 dollars.

In this sample of SBO cases, 139 patients were adults and 19 were children. The median age was 45 years. Over half of the patients in the group died (94/158, 60%), although neither age nor patient death were factors significantly associated with verdict outcome or award amount, he said.

The decade-over-decade growth in the number of suits was striking, increasing 188% during the 1994-2004 period from the previous decade and another 87% from 2005 to 2015.

In a lawsuit involving a SBO, the defendant is more likely to be a general surgeon than to belong to any other specialty. General surgeons were the defendant in 37% of cases, followed by internists in 24% and emergency physicians in 11%.

Dr. Choudhry and his associates conceptually grouped the reasons for the suits into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care. Among the reasons for litigation, by far the most common was untimely intervention in managing of the SBO, a preoperative care component. This was the primary allegation in over 100 of the 158 cases; the next most common reason for bringing suit was incomplete or incorrect surgical procedure, deemed an intraoperative problem and seen in fewer than 20 of the suits.

Almost half of the cases resulted either in a verdict in favor of the plaintiff (n = 37, 23%) or a settlement (n = 36, 23%). When verdicts were returned against the defendant physician, payout amounts varied widely. The smallest amount paid was $29,575 and the largest was over $12 million. Payment amounts were larger with a verdict in favor of the plaintiff, at a median $1,438,800, compared with the median of $1,043,100 received by the plaintiff in a settlement.

Dr. Choudhry noted that early intervention may improve mortality from SBO in some patient groups. “Small bowel obstruction protocols which identify patients at high risk for adverse outcomes and ensure timely management may lessen the chance of litigation,” he said.

Dr. Choudhry acknowledged that the Westlaw database included just a limited amount of medical information. Various tort reform initiatives may have had a confounding effect on award size. It’s possible that using malpractice insurance data could provide more detailed medical information, he said.

Dr. Choudhry reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – When surgeons are sued and lose or settle in cases relating to management of small bowel obstruction, the payout is often costly, according a study involving a close examination of 158 such cases.

The odds of a positive outcome aren’t great. “When looking at award payouts, close to half of cases resulted in a verdict with monetary compensation for the patient,” said Dr. Asad Choudhry, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of trauma, critical care, and surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Choudhry, presenting his findings at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association, said that general surgeons are the third most likely specialty to be sued, coming only after neurosurgeons and cardiothoracic surgeons. In a given year, about 15% of all general surgeons will be sued, with almost a third of those suits resulting in a payment to the plaintiff. By age 65 years, said Dr. Choudhry, 99% of physicians in higher-risk specialties will face a malpractice claim, compared with 75% of those in lower-risk specialties.

Overall, one-third of malpractice payments come from suits that allege diagnostic error; 24% of suits allege malpractice in surgery. “Small bowel obstruction accounts for 12% to 16% of surgical admissions, with 300,000 operations performed each year,” he said.

Dr. Choudhry and his colleagues searched the Westlaw database using key search terms to identify U.S. malpractice cases that involved small bowel obstruction (SBO), focusing only on cases in which management of SBO was the primary reason for the suit. Cases from 1982 to 2015 were included.

Looking more closely at the 158 cases that resulted from the search, Dr. Choudhry examined variables that included patient demographics, the alleged reason for the malpractice, the settlement or verdict, and the amount paid out, adjusted to 2015 dollars.

In this sample of SBO cases, 139 patients were adults and 19 were children. The median age was 45 years. Over half of the patients in the group died (94/158, 60%), although neither age nor patient death were factors significantly associated with verdict outcome or award amount, he said.

The decade-over-decade growth in the number of suits was striking, increasing 188% during the 1994-2004 period from the previous decade and another 87% from 2005 to 2015.

In a lawsuit involving a SBO, the defendant is more likely to be a general surgeon than to belong to any other specialty. General surgeons were the defendant in 37% of cases, followed by internists in 24% and emergency physicians in 11%.

Dr. Choudhry and his associates conceptually grouped the reasons for the suits into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care. Among the reasons for litigation, by far the most common was untimely intervention in managing of the SBO, a preoperative care component. This was the primary allegation in over 100 of the 158 cases; the next most common reason for bringing suit was incomplete or incorrect surgical procedure, deemed an intraoperative problem and seen in fewer than 20 of the suits.

Almost half of the cases resulted either in a verdict in favor of the plaintiff (n = 37, 23%) or a settlement (n = 36, 23%). When verdicts were returned against the defendant physician, payout amounts varied widely. The smallest amount paid was $29,575 and the largest was over $12 million. Payment amounts were larger with a verdict in favor of the plaintiff, at a median $1,438,800, compared with the median of $1,043,100 received by the plaintiff in a settlement.

Dr. Choudhry noted that early intervention may improve mortality from SBO in some patient groups. “Small bowel obstruction protocols which identify patients at high risk for adverse outcomes and ensure timely management may lessen the chance of litigation,” he said.

Dr. Choudhry acknowledged that the Westlaw database included just a limited amount of medical information. Various tort reform initiatives may have had a confounding effect on award size. It’s possible that using malpractice insurance data could provide more detailed medical information, he said.

Dr. Choudhry reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

MONTREAL – When surgeons are sued and lose or settle in cases relating to management of small bowel obstruction, the payout is often costly, according a study involving a close examination of 158 such cases.

The odds of a positive outcome aren’t great. “When looking at award payouts, close to half of cases resulted in a verdict with monetary compensation for the patient,” said Dr. Asad Choudhry, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of trauma, critical care, and surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Dr. Choudhry, presenting his findings at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association, said that general surgeons are the third most likely specialty to be sued, coming only after neurosurgeons and cardiothoracic surgeons. In a given year, about 15% of all general surgeons will be sued, with almost a third of those suits resulting in a payment to the plaintiff. By age 65 years, said Dr. Choudhry, 99% of physicians in higher-risk specialties will face a malpractice claim, compared with 75% of those in lower-risk specialties.

Overall, one-third of malpractice payments come from suits that allege diagnostic error; 24% of suits allege malpractice in surgery. “Small bowel obstruction accounts for 12% to 16% of surgical admissions, with 300,000 operations performed each year,” he said.

Dr. Choudhry and his colleagues searched the Westlaw database using key search terms to identify U.S. malpractice cases that involved small bowel obstruction (SBO), focusing only on cases in which management of SBO was the primary reason for the suit. Cases from 1982 to 2015 were included.

Looking more closely at the 158 cases that resulted from the search, Dr. Choudhry examined variables that included patient demographics, the alleged reason for the malpractice, the settlement or verdict, and the amount paid out, adjusted to 2015 dollars.

In this sample of SBO cases, 139 patients were adults and 19 were children. The median age was 45 years. Over half of the patients in the group died (94/158, 60%), although neither age nor patient death were factors significantly associated with verdict outcome or award amount, he said.

The decade-over-decade growth in the number of suits was striking, increasing 188% during the 1994-2004 period from the previous decade and another 87% from 2005 to 2015.

In a lawsuit involving a SBO, the defendant is more likely to be a general surgeon than to belong to any other specialty. General surgeons were the defendant in 37% of cases, followed by internists in 24% and emergency physicians in 11%.

Dr. Choudhry and his associates conceptually grouped the reasons for the suits into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care. Among the reasons for litigation, by far the most common was untimely intervention in managing of the SBO, a preoperative care component. This was the primary allegation in over 100 of the 158 cases; the next most common reason for bringing suit was incomplete or incorrect surgical procedure, deemed an intraoperative problem and seen in fewer than 20 of the suits.

Almost half of the cases resulted either in a verdict in favor of the plaintiff (n = 37, 23%) or a settlement (n = 36, 23%). When verdicts were returned against the defendant physician, payout amounts varied widely. The smallest amount paid was $29,575 and the largest was over $12 million. Payment amounts were larger with a verdict in favor of the plaintiff, at a median $1,438,800, compared with the median of $1,043,100 received by the plaintiff in a settlement.

Dr. Choudhry noted that early intervention may improve mortality from SBO in some patient groups. “Small bowel obstruction protocols which identify patients at high risk for adverse outcomes and ensure timely management may lessen the chance of litigation,” he said.

Dr. Choudhry acknowledged that the Westlaw database included just a limited amount of medical information. Various tort reform initiatives may have had a confounding effect on award size. It’s possible that using malpractice insurance data could provide more detailed medical information, he said.

Dr. Choudhry reported no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Almost half of surgical small bowel obstruction lawsuits involved a payout of a median $1.1 million.

Major finding: About 15% of general surgeons are sued annually, and SBO is a common diagnosis in these suits.

Data source: Review of the Westlaw database that identified 158 lawsuits involving general surgeons and small bowel obstruction from 1982 to 2015.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Small bowel surgery for the benign gynecologist

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

This video is brought to you by ![]()

ACOG releases new Choosing Wisely list

Prenatal ultrasounds for nonmedical purposes and routine use of robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery for benign gynecologic disease are among the interventions physicians and patients should question, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The organization produced the list of five interventions to be questioned as part of the ABIM (American Board of Internal Medicine) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative, which “aims to promote conversations between clinicians and patients by helping patients choose care that is supported by evidence, not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received, free from harm, and truly necessary,” according to the Choosing Wisely website.

ACOG released its first Choosing Wisely list in 2003, advising clinicians to avoid elective labor inductions before 39 weeks as well as annual pap tests in women aged 30-65.

“These are good topics to bring up in discussion with patients,” said Dr. Gerardo Bustillo, an ob.gyn. at Orange Coast Memorial Medical Center in Fountain Valley, Calif. “Patients may ask for inappropriate interventions such as early induction of labor, and these recommendations will equip physicians and other healthcare providers in explaining the dangers of certain interventions.”

The five new items include:

1. Avoid using robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery for benign gynecologic disease when it is feasible to use a conventional laparoscopic or vaginal approach.

ACOG states that comparable perioperative outcomes, intraoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and rate of conversion to open surgery result from both robotic-assisted and conventional laparoscopic surgeries but that robotic-assisted techniques cost more and can take longer. But Dr. Bustillo questioned this item’s addition to the list in light of new evidence that “robotic-assisted hysterectomies resulted in fewer postoperative complications than conventional laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies, when performed by high-volume robotic gynecologic surgeons,” he said.

The patients undergoing robotic-assisted hysterectomy, he added, experienced the same or decreased intraoperative and postoperative complications compared with those undergoing conventional techniques despite being more complex patients. They were older with higher rates of adhesive disease, large uteri, and morbid obesity.

2. Don’t perform prenatal ultrasounds for nonmedical purposes, for example, solely to create keepsake videos or photographs.

Keepsake imaging is not an approved use of a medical device by the Food and Drug Administration and is also discouraged by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. These “comfort ultrasounds” are often performed by the request of the patient and are done without true medical indications,” said Dr. Sherry Ross, an ob.gyn. at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, Calif.

“Not only are these types of ultrasounds excessive, but they are costly as well,” she said. “Counseling the pregnant woman is the best way to reduce unnecessary ultrasounds, especially those performed at the local mall.”

3. Don’t routinely transfuse stable, asymptomatic hospitalized patients with a hemoglobin level greater than 7-8 grams.

“Arbitrary hemoglobin or hematocrit thresholds should not be used as the only criterion for transfusions of packed red blood cells,” ACOG advises. The potential risks of transfusion make this item the most important of the additions, according to Dr. Bustillo. “These risks include infection with certain pathogens, allergic and immune transfusion reactions, volume overload, hyperkalemia, and iron overload,” he said.

4. Don’t perform pelvic ultrasound in average risk women to screen for ovarian cancer.

With an age-adjusted incidence of just 13 ovarian cancer cases per 100,000 women annually, the positive predictive value is low for screening for ovarian cancer, leading to a high rate of false positives, ACOG notes.

“The tools that are currently available for screening women who are high risk include transvaginal pelvic ultrasound and CA 125 blood tests done every 6 months to 1 year along with pelvic examinations,” Dr. Ross said. “Those at high risk include those with a family history or who test positive for BRCA1 and 2 mutations and Ashkenazi women with a single family member with breast cancer before age 50 or with ovarian cancer.” Without a family history or other risk factors, a CA 125 or pelvic ultrasound in asymptomatic women does not reduce deaths, she added.

5. Don’t routinely recommend activity restriction or bed rest during pregnancy for any indication.

Historically, physicians have recommended bed rest for a range of pregnancy conditions, including multiple gestation, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, vaginal bleeding, and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, ACOG notes. “The negative financial and psychosocial implications of putting women on activity restriction, specifically bed rest, are well documented,” said Dr. Anthony C. Sciscione, director of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at Christiana Care Health System and program director for Christiana Care’s ob.gyn. residency program in Wilmington, Del. “However, no study has demonstrated a benefit to activity restriction during pregnancy for any diagnosis.”

The only clinical benefit resulting from bed rest has been a modest decrease in blood pressure that does not translate to improved outcomes, Dr. Sciscione said. Additional risks of activity restriction include an increase in maternal anxiety and depression, significant financial impact on the family, physical deconditioning, bone loss, and a potential increase in blood clots. Being active in pregnancy, however, is linked to a decrease in preterm birth, he added.

The 2013 list

Among the previous five items included in the 2013 list are not scheduling elective, nonmedically indicated inductions of labor or cesarean deliveries before 39 weeks 0 days of gestational age and not scheduling elective, non-medically indicated labor inductions between 39 weeks 0 days and 41 weeks 0 days unless the cervix is favorable.

ACOG also recommended that asymptomatic women of average risk do not receive screenings for ovarian cancer, that patients with mild dysplasia for less than 2 years do not receive treatment, and that women aged 30-65 years do not receive routine annual cervical cytology screenings.

Prenatal ultrasounds for nonmedical purposes and routine use of robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery for benign gynecologic disease are among the interventions physicians and patients should question, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The organization produced the list of five interventions to be questioned as part of the ABIM (American Board of Internal Medicine) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative, which “aims to promote conversations between clinicians and patients by helping patients choose care that is supported by evidence, not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received, free from harm, and truly necessary,” according to the Choosing Wisely website.

ACOG released its first Choosing Wisely list in 2003, advising clinicians to avoid elective labor inductions before 39 weeks as well as annual pap tests in women aged 30-65.

“These are good topics to bring up in discussion with patients,” said Dr. Gerardo Bustillo, an ob.gyn. at Orange Coast Memorial Medical Center in Fountain Valley, Calif. “Patients may ask for inappropriate interventions such as early induction of labor, and these recommendations will equip physicians and other healthcare providers in explaining the dangers of certain interventions.”

The five new items include:

1. Avoid using robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery for benign gynecologic disease when it is feasible to use a conventional laparoscopic or vaginal approach.

ACOG states that comparable perioperative outcomes, intraoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and rate of conversion to open surgery result from both robotic-assisted and conventional laparoscopic surgeries but that robotic-assisted techniques cost more and can take longer. But Dr. Bustillo questioned this item’s addition to the list in light of new evidence that “robotic-assisted hysterectomies resulted in fewer postoperative complications than conventional laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies, when performed by high-volume robotic gynecologic surgeons,” he said.

The patients undergoing robotic-assisted hysterectomy, he added, experienced the same or decreased intraoperative and postoperative complications compared with those undergoing conventional techniques despite being more complex patients. They were older with higher rates of adhesive disease, large uteri, and morbid obesity.

2. Don’t perform prenatal ultrasounds for nonmedical purposes, for example, solely to create keepsake videos or photographs.

Keepsake imaging is not an approved use of a medical device by the Food and Drug Administration and is also discouraged by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. These “comfort ultrasounds” are often performed by the request of the patient and are done without true medical indications,” said Dr. Sherry Ross, an ob.gyn. at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, Calif.

“Not only are these types of ultrasounds excessive, but they are costly as well,” she said. “Counseling the pregnant woman is the best way to reduce unnecessary ultrasounds, especially those performed at the local mall.”

3. Don’t routinely transfuse stable, asymptomatic hospitalized patients with a hemoglobin level greater than 7-8 grams.

“Arbitrary hemoglobin or hematocrit thresholds should not be used as the only criterion for transfusions of packed red blood cells,” ACOG advises. The potential risks of transfusion make this item the most important of the additions, according to Dr. Bustillo. “These risks include infection with certain pathogens, allergic and immune transfusion reactions, volume overload, hyperkalemia, and iron overload,” he said.

4. Don’t perform pelvic ultrasound in average risk women to screen for ovarian cancer.

With an age-adjusted incidence of just 13 ovarian cancer cases per 100,000 women annually, the positive predictive value is low for screening for ovarian cancer, leading to a high rate of false positives, ACOG notes.

“The tools that are currently available for screening women who are high risk include transvaginal pelvic ultrasound and CA 125 blood tests done every 6 months to 1 year along with pelvic examinations,” Dr. Ross said. “Those at high risk include those with a family history or who test positive for BRCA1 and 2 mutations and Ashkenazi women with a single family member with breast cancer before age 50 or with ovarian cancer.” Without a family history or other risk factors, a CA 125 or pelvic ultrasound in asymptomatic women does not reduce deaths, she added.

5. Don’t routinely recommend activity restriction or bed rest during pregnancy for any indication.

Historically, physicians have recommended bed rest for a range of pregnancy conditions, including multiple gestation, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, vaginal bleeding, and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, ACOG notes. “The negative financial and psychosocial implications of putting women on activity restriction, specifically bed rest, are well documented,” said Dr. Anthony C. Sciscione, director of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at Christiana Care Health System and program director for Christiana Care’s ob.gyn. residency program in Wilmington, Del. “However, no study has demonstrated a benefit to activity restriction during pregnancy for any diagnosis.”

The only clinical benefit resulting from bed rest has been a modest decrease in blood pressure that does not translate to improved outcomes, Dr. Sciscione said. Additional risks of activity restriction include an increase in maternal anxiety and depression, significant financial impact on the family, physical deconditioning, bone loss, and a potential increase in blood clots. Being active in pregnancy, however, is linked to a decrease in preterm birth, he added.

The 2013 list

Among the previous five items included in the 2013 list are not scheduling elective, nonmedically indicated inductions of labor or cesarean deliveries before 39 weeks 0 days of gestational age and not scheduling elective, non-medically indicated labor inductions between 39 weeks 0 days and 41 weeks 0 days unless the cervix is favorable.

ACOG also recommended that asymptomatic women of average risk do not receive screenings for ovarian cancer, that patients with mild dysplasia for less than 2 years do not receive treatment, and that women aged 30-65 years do not receive routine annual cervical cytology screenings.

Prenatal ultrasounds for nonmedical purposes and routine use of robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery for benign gynecologic disease are among the interventions physicians and patients should question, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The organization produced the list of five interventions to be questioned as part of the ABIM (American Board of Internal Medicine) Foundation’s Choosing Wisely initiative, which “aims to promote conversations between clinicians and patients by helping patients choose care that is supported by evidence, not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received, free from harm, and truly necessary,” according to the Choosing Wisely website.

ACOG released its first Choosing Wisely list in 2003, advising clinicians to avoid elective labor inductions before 39 weeks as well as annual pap tests in women aged 30-65.

“These are good topics to bring up in discussion with patients,” said Dr. Gerardo Bustillo, an ob.gyn. at Orange Coast Memorial Medical Center in Fountain Valley, Calif. “Patients may ask for inappropriate interventions such as early induction of labor, and these recommendations will equip physicians and other healthcare providers in explaining the dangers of certain interventions.”

The five new items include:

1. Avoid using robotic assisted laparoscopic surgery for benign gynecologic disease when it is feasible to use a conventional laparoscopic or vaginal approach.

ACOG states that comparable perioperative outcomes, intraoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and rate of conversion to open surgery result from both robotic-assisted and conventional laparoscopic surgeries but that robotic-assisted techniques cost more and can take longer. But Dr. Bustillo questioned this item’s addition to the list in light of new evidence that “robotic-assisted hysterectomies resulted in fewer postoperative complications than conventional laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies, when performed by high-volume robotic gynecologic surgeons,” he said.

The patients undergoing robotic-assisted hysterectomy, he added, experienced the same or decreased intraoperative and postoperative complications compared with those undergoing conventional techniques despite being more complex patients. They were older with higher rates of adhesive disease, large uteri, and morbid obesity.

2. Don’t perform prenatal ultrasounds for nonmedical purposes, for example, solely to create keepsake videos or photographs.

Keepsake imaging is not an approved use of a medical device by the Food and Drug Administration and is also discouraged by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. These “comfort ultrasounds” are often performed by the request of the patient and are done without true medical indications,” said Dr. Sherry Ross, an ob.gyn. at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, Calif.

“Not only are these types of ultrasounds excessive, but they are costly as well,” she said. “Counseling the pregnant woman is the best way to reduce unnecessary ultrasounds, especially those performed at the local mall.”

3. Don’t routinely transfuse stable, asymptomatic hospitalized patients with a hemoglobin level greater than 7-8 grams.

“Arbitrary hemoglobin or hematocrit thresholds should not be used as the only criterion for transfusions of packed red blood cells,” ACOG advises. The potential risks of transfusion make this item the most important of the additions, according to Dr. Bustillo. “These risks include infection with certain pathogens, allergic and immune transfusion reactions, volume overload, hyperkalemia, and iron overload,” he said.

4. Don’t perform pelvic ultrasound in average risk women to screen for ovarian cancer.

With an age-adjusted incidence of just 13 ovarian cancer cases per 100,000 women annually, the positive predictive value is low for screening for ovarian cancer, leading to a high rate of false positives, ACOG notes.

“The tools that are currently available for screening women who are high risk include transvaginal pelvic ultrasound and CA 125 blood tests done every 6 months to 1 year along with pelvic examinations,” Dr. Ross said. “Those at high risk include those with a family history or who test positive for BRCA1 and 2 mutations and Ashkenazi women with a single family member with breast cancer before age 50 or with ovarian cancer.” Without a family history or other risk factors, a CA 125 or pelvic ultrasound in asymptomatic women does not reduce deaths, she added.

5. Don’t routinely recommend activity restriction or bed rest during pregnancy for any indication.

Historically, physicians have recommended bed rest for a range of pregnancy conditions, including multiple gestation, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, vaginal bleeding, and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, ACOG notes. “The negative financial and psychosocial implications of putting women on activity restriction, specifically bed rest, are well documented,” said Dr. Anthony C. Sciscione, director of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at Christiana Care Health System and program director for Christiana Care’s ob.gyn. residency program in Wilmington, Del. “However, no study has demonstrated a benefit to activity restriction during pregnancy for any diagnosis.”

The only clinical benefit resulting from bed rest has been a modest decrease in blood pressure that does not translate to improved outcomes, Dr. Sciscione said. Additional risks of activity restriction include an increase in maternal anxiety and depression, significant financial impact on the family, physical deconditioning, bone loss, and a potential increase in blood clots. Being active in pregnancy, however, is linked to a decrease in preterm birth, he added.

The 2013 list

Among the previous five items included in the 2013 list are not scheduling elective, nonmedically indicated inductions of labor or cesarean deliveries before 39 weeks 0 days of gestational age and not scheduling elective, non-medically indicated labor inductions between 39 weeks 0 days and 41 weeks 0 days unless the cervix is favorable.

ACOG also recommended that asymptomatic women of average risk do not receive screenings for ovarian cancer, that patients with mild dysplasia for less than 2 years do not receive treatment, and that women aged 30-65 years do not receive routine annual cervical cytology screenings.

Flu vaccination found safe in surgical patients

Immunizing surgical patients against seasonal influenza before they are discharged from the hospital appears safe and is a sound strategy for expanding vaccine coverage, especially among people at high risk, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

All health care contacts, including hospitalizations, are considered excellent opportunities for influenza vaccination, and current recommendations advise that eligible inpatients receive the immunization before discharge. However, surgical patients don’t often get the flu vaccine before they leave the hospital, likely because of concerns that potential adverse effects like fever and myalgia could be falsely attributed to surgical complications. This would lead to unnecessary patient evaluations and could interfere with postsurgical care, said Sara Y. Tartof, Ph.D., and her associates in the department of research and evaluation, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena.

“Although this concern is understandable, few clinical data support it,” they noted.

“To provide clinical evidence that would either substantiate or refute” these concerns about perioperative flu vaccination, the investigators analyzed data in the electronic health records for 81,647 surgeries. All the study participants were deemed eligible for flu vaccination. They were socioeconomically and ethnically diverse, ranged in age from 6 months to 106 years, and underwent surgery at 14 hospitals during three consecutive flu seasons. Operations included general, cardiac, eye, dermatologic, ENT, neurologic, ob.gyn., oral/maxillofacial, orthopedic, plastic, podiatric, urologic, and vascular procedures.

Patients received a flu vaccine in 6,420 hospital stays for surgery – only 15% of 42,777 eligible hospitalizations – usually on the day of discharge. (The remaining 38,870 patients either had been vaccinated before hospital admission or were vaccinated more than a week after discharge and were not included in further analyses.)

Compared with eligible patients who didn’t receive a flu vaccine during hospitalization for surgery, those who did showed no increased risk for subsequent inpatient visits, ED visits, or clinical work-ups for infection. Patients who received the flu vaccine before discharge showed a minimally increased risk for outpatient visits during the week following hospitalization, but this was considered unlikely “to translate into substantial clinical impact,” especially when balanced against the benefit of immunization, Dr. Tartof and her associates said (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M15-1667).

Giving the flu vaccine during a surgical hospitalization “is an opportunity to protect a high-risk population,” because surgery patients tend to be of an age, and to have comorbid conditions, that raise their risk for flu complications. In addition, previous research has reported that 39%-46% of adults hospitalized for influenza-related disease in a given year had been hospitalized during the preceding autumn, indicating that recent hospitalization also raises the risk for flu complications, the investigators said.

“Our data support the rationale for increasing vaccination rates among surgical inpatients,” they said.

This study was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Vaccine Safety Datalink program. Dr. Tartof reported receiving grants from Merck outside of this work; two of her associates reported receiving grants from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline outside of this work.

Immunizing surgical patients against seasonal influenza before they are discharged from the hospital appears safe and is a sound strategy for expanding vaccine coverage, especially among people at high risk, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

All health care contacts, including hospitalizations, are considered excellent opportunities for influenza vaccination, and current recommendations advise that eligible inpatients receive the immunization before discharge. However, surgical patients don’t often get the flu vaccine before they leave the hospital, likely because of concerns that potential adverse effects like fever and myalgia could be falsely attributed to surgical complications. This would lead to unnecessary patient evaluations and could interfere with postsurgical care, said Sara Y. Tartof, Ph.D., and her associates in the department of research and evaluation, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena.

“Although this concern is understandable, few clinical data support it,” they noted.

“To provide clinical evidence that would either substantiate or refute” these concerns about perioperative flu vaccination, the investigators analyzed data in the electronic health records for 81,647 surgeries. All the study participants were deemed eligible for flu vaccination. They were socioeconomically and ethnically diverse, ranged in age from 6 months to 106 years, and underwent surgery at 14 hospitals during three consecutive flu seasons. Operations included general, cardiac, eye, dermatologic, ENT, neurologic, ob.gyn., oral/maxillofacial, orthopedic, plastic, podiatric, urologic, and vascular procedures.

Patients received a flu vaccine in 6,420 hospital stays for surgery – only 15% of 42,777 eligible hospitalizations – usually on the day of discharge. (The remaining 38,870 patients either had been vaccinated before hospital admission or were vaccinated more than a week after discharge and were not included in further analyses.)

Compared with eligible patients who didn’t receive a flu vaccine during hospitalization for surgery, those who did showed no increased risk for subsequent inpatient visits, ED visits, or clinical work-ups for infection. Patients who received the flu vaccine before discharge showed a minimally increased risk for outpatient visits during the week following hospitalization, but this was considered unlikely “to translate into substantial clinical impact,” especially when balanced against the benefit of immunization, Dr. Tartof and her associates said (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M15-1667).

Giving the flu vaccine during a surgical hospitalization “is an opportunity to protect a high-risk population,” because surgery patients tend to be of an age, and to have comorbid conditions, that raise their risk for flu complications. In addition, previous research has reported that 39%-46% of adults hospitalized for influenza-related disease in a given year had been hospitalized during the preceding autumn, indicating that recent hospitalization also raises the risk for flu complications, the investigators said.

“Our data support the rationale for increasing vaccination rates among surgical inpatients,” they said.

This study was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Vaccine Safety Datalink program. Dr. Tartof reported receiving grants from Merck outside of this work; two of her associates reported receiving grants from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline outside of this work.

Immunizing surgical patients against seasonal influenza before they are discharged from the hospital appears safe and is a sound strategy for expanding vaccine coverage, especially among people at high risk, according to a report published online March 14 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

All health care contacts, including hospitalizations, are considered excellent opportunities for influenza vaccination, and current recommendations advise that eligible inpatients receive the immunization before discharge. However, surgical patients don’t often get the flu vaccine before they leave the hospital, likely because of concerns that potential adverse effects like fever and myalgia could be falsely attributed to surgical complications. This would lead to unnecessary patient evaluations and could interfere with postsurgical care, said Sara Y. Tartof, Ph.D., and her associates in the department of research and evaluation, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena.

“Although this concern is understandable, few clinical data support it,” they noted.

“To provide clinical evidence that would either substantiate or refute” these concerns about perioperative flu vaccination, the investigators analyzed data in the electronic health records for 81,647 surgeries. All the study participants were deemed eligible for flu vaccination. They were socioeconomically and ethnically diverse, ranged in age from 6 months to 106 years, and underwent surgery at 14 hospitals during three consecutive flu seasons. Operations included general, cardiac, eye, dermatologic, ENT, neurologic, ob.gyn., oral/maxillofacial, orthopedic, plastic, podiatric, urologic, and vascular procedures.

Patients received a flu vaccine in 6,420 hospital stays for surgery – only 15% of 42,777 eligible hospitalizations – usually on the day of discharge. (The remaining 38,870 patients either had been vaccinated before hospital admission or were vaccinated more than a week after discharge and were not included in further analyses.)

Compared with eligible patients who didn’t receive a flu vaccine during hospitalization for surgery, those who did showed no increased risk for subsequent inpatient visits, ED visits, or clinical work-ups for infection. Patients who received the flu vaccine before discharge showed a minimally increased risk for outpatient visits during the week following hospitalization, but this was considered unlikely “to translate into substantial clinical impact,” especially when balanced against the benefit of immunization, Dr. Tartof and her associates said (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Mar 14. doi: 10.7326/M15-1667).

Giving the flu vaccine during a surgical hospitalization “is an opportunity to protect a high-risk population,” because surgery patients tend to be of an age, and to have comorbid conditions, that raise their risk for flu complications. In addition, previous research has reported that 39%-46% of adults hospitalized for influenza-related disease in a given year had been hospitalized during the preceding autumn, indicating that recent hospitalization also raises the risk for flu complications, the investigators said.

“Our data support the rationale for increasing vaccination rates among surgical inpatients,” they said.

This study was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Vaccine Safety Datalink program. Dr. Tartof reported receiving grants from Merck outside of this work; two of her associates reported receiving grants from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline outside of this work.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Immunizing surgical patients against seasonal influenza before they leave the hospital appears safe.

Major finding: Patients received a flu vaccine in only 6,420 hospital stays for surgery, comprising only 15% of the patient hospitalizations that were eligible.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study involving 81,647 surgeries at 14 California hospitals during three consecutive flu seasons.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Vaccine Safety Datalink program. Dr. Tartof reported receiving grants from Merck outside of this work; two of her associates reported receiving grants from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline outside of this work.

Enlarged uterus helps predict morcellation in vaginal hysterectomy

Women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy are more likely to receive cold-knife morcellation if they have an enlarged uterus, leiomyoma, or no prolapse, according to new research.

Electromechanical morcellation, a technique used during laparoscopic hysterectomy to cut the uterus into small pieces for removal, has come under heavy scrutiny in recent years due to risk of disseminating undiagnosed uterine cancers. However, morcellation can also be performed manually during a vaginal hysterectomy. While current recommendations stress caution for all types of morcellation, the risks and prognostic factors for cold-knife morcellation are poorly understood.

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Megan Wasson, of the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Phoenix, and her colleagues examined a cohort of 743 women who underwent hysterectomy with either intact uterine removal (383 women) or with cold-knife morcellation (360 women).

Dr. Wasson and her colleagues found that women were significantly more likely to undergo morcellation, compared with intact uterine removal if they had larger uterine weight (adjusted odds ratio, 7.25; P less than .001), lack of prolapse (aOR, 3.87; P less than .001), or the presence of leiomyoma (aOR, 2.77, P = .035).

Women with prior vaginal delivery were significantly less likely to receive morcellation (aOR, 0.79, P = .005).

Younger age, lower parity, and nonwhite race were also associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing morcellation (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:752–7).

“This study identified prognostic factors associated with an increased likelihood of morcellation required at the time of vaginal hysterectomy,” Dr. Wasson and her colleagues wrote, stressing that higher uterine weight was the strongest predictor. “The ability to preoperatively predict uterine weight and size is essential for surgical planning given that a large uterus is most predictive of needing morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.”

The findings, they wrote, may help clinicians identify those patients who need additional counseling about the potential risks of morcellation, as well as patients who may need to avoid vaginal hysterectomy to negate the risks of morcellation.

The investigators identified limitations to their study, including that the majority of the women (88%) were white, and that candidates for vaginal hysterectomy were carefully chosen by expert surgeons, leading to likely selection bias.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy are more likely to receive cold-knife morcellation if they have an enlarged uterus, leiomyoma, or no prolapse, according to new research.

Electromechanical morcellation, a technique used during laparoscopic hysterectomy to cut the uterus into small pieces for removal, has come under heavy scrutiny in recent years due to risk of disseminating undiagnosed uterine cancers. However, morcellation can also be performed manually during a vaginal hysterectomy. While current recommendations stress caution for all types of morcellation, the risks and prognostic factors for cold-knife morcellation are poorly understood.

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Megan Wasson, of the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Phoenix, and her colleagues examined a cohort of 743 women who underwent hysterectomy with either intact uterine removal (383 women) or with cold-knife morcellation (360 women).

Dr. Wasson and her colleagues found that women were significantly more likely to undergo morcellation, compared with intact uterine removal if they had larger uterine weight (adjusted odds ratio, 7.25; P less than .001), lack of prolapse (aOR, 3.87; P less than .001), or the presence of leiomyoma (aOR, 2.77, P = .035).

Women with prior vaginal delivery were significantly less likely to receive morcellation (aOR, 0.79, P = .005).

Younger age, lower parity, and nonwhite race were also associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing morcellation (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:752–7).

“This study identified prognostic factors associated with an increased likelihood of morcellation required at the time of vaginal hysterectomy,” Dr. Wasson and her colleagues wrote, stressing that higher uterine weight was the strongest predictor. “The ability to preoperatively predict uterine weight and size is essential for surgical planning given that a large uterus is most predictive of needing morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.”

The findings, they wrote, may help clinicians identify those patients who need additional counseling about the potential risks of morcellation, as well as patients who may need to avoid vaginal hysterectomy to negate the risks of morcellation.

The investigators identified limitations to their study, including that the majority of the women (88%) were white, and that candidates for vaginal hysterectomy were carefully chosen by expert surgeons, leading to likely selection bias.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy are more likely to receive cold-knife morcellation if they have an enlarged uterus, leiomyoma, or no prolapse, according to new research.

Electromechanical morcellation, a technique used during laparoscopic hysterectomy to cut the uterus into small pieces for removal, has come under heavy scrutiny in recent years due to risk of disseminating undiagnosed uterine cancers. However, morcellation can also be performed manually during a vaginal hysterectomy. While current recommendations stress caution for all types of morcellation, the risks and prognostic factors for cold-knife morcellation are poorly understood.

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Megan Wasson, of the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Phoenix, and her colleagues examined a cohort of 743 women who underwent hysterectomy with either intact uterine removal (383 women) or with cold-knife morcellation (360 women).

Dr. Wasson and her colleagues found that women were significantly more likely to undergo morcellation, compared with intact uterine removal if they had larger uterine weight (adjusted odds ratio, 7.25; P less than .001), lack of prolapse (aOR, 3.87; P less than .001), or the presence of leiomyoma (aOR, 2.77, P = .035).

Women with prior vaginal delivery were significantly less likely to receive morcellation (aOR, 0.79, P = .005).

Younger age, lower parity, and nonwhite race were also associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing morcellation (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:752–7).

“This study identified prognostic factors associated with an increased likelihood of morcellation required at the time of vaginal hysterectomy,” Dr. Wasson and her colleagues wrote, stressing that higher uterine weight was the strongest predictor. “The ability to preoperatively predict uterine weight and size is essential for surgical planning given that a large uterus is most predictive of needing morcellation at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.”

The findings, they wrote, may help clinicians identify those patients who need additional counseling about the potential risks of morcellation, as well as patients who may need to avoid vaginal hysterectomy to negate the risks of morcellation.

The investigators identified limitations to their study, including that the majority of the women (88%) were white, and that candidates for vaginal hysterectomy were carefully chosen by expert surgeons, leading to likely selection bias.

The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Women with a larger-than-normal uterus are likelier to undergo cold-knife morcellation versus intact uterine removal during a vaginal hysterectomy.

Major finding: Larger-than-normal uterine weight was associated with increased odds of morcellation (aOR, 7.25; P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 743 women selected for vaginal hysterectomy.

Disclosures: The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

14-Year-Old Boy With Mild Antecedent Neck Pain in Setting of Acute Trauma: A Rare Case of Benign Fibrous Histiocytoma of the Spine

Benign fibrous histiocytoma (BFH) is a rare, well-recognized, primary skeletal tumor accounting for approximately 1% of all benign bone tumors. Spinal involvement is exceedingly rare with only 11 cases reported in the literature.1,2 We present a case of BFH located in the cervical spine of a pediatric patient that was successfully treated with curretage through an anterior surgical approach, along with a review of the literature and appropriate management concerning BFH of the spine.

Case Report

A 14-year-old boy was tackled while playing football and noticed immediate neck pain and subjective paresthesia in the upper extremities. Examination revealed a nontender spine (cervical, thoracic, lumbar) and normal strength and range of motion in all extremities. Sensation was diffusely intact, long tract signs were absent, and gait was normal. On questioning, the patient endorsed mild antecedent neck pain but denied prior history of any trauma. Neck pain did not radiate and was slightly worsened by activity but was mostly intermittent and random. As the neck pain was very mild and was not interfering with daily activities, the patient had not sought care before presenting to the emergency department. He had no pertinent past medical or surgical history.

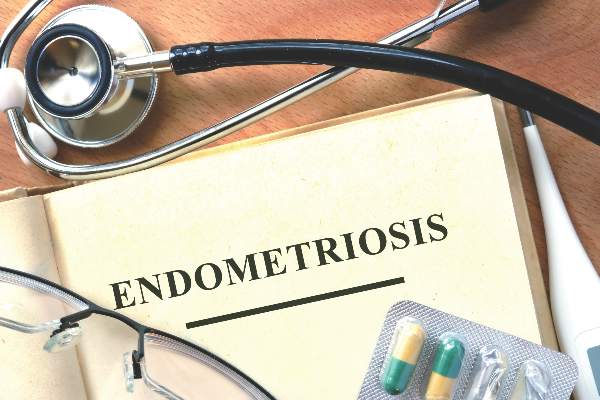

The patient presented with a computed tomography (CT) scan of his head and cervical spine and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the cervical spine. A magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) scan of the neck was ordered after his arrival.

Axial and sagittal CT (Figures 1A, 1B) showed a 1×1.2-cm discrete, expansile, lytic, radiolucent mass extending anterior from the left C2 vertebral body. The mass appeared to abut the left vertebral artery foramen. The cortical bone surrounding the lesion was thin but uniform. Sagittal and axial T1-weighted MRI (Figures 2A, 2B) showed the discrete, expansile, homogenous lesion with the same intensity as normal bone marrow. Sagittal and axial T2-weighted MRI (Figures 2C, 2D) showed a discrete, expansile, homogenous lesion with primarily high signal intensity. Sagittal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) MRI (Figure 2E) again showed the lesion with primarily low intensity. Given the close proximity of the lesion to the vertebral foramen, MRA was ordered; it showed the lesion was not interfering with the vertebral artery (Figure 2F).

The tumor’s location, in the left anterior aspect of the C2 vertebral body, was not conducive to percutaneous biopsy for establishing tissue diagnosis, so the decision was made to surgically excise the lesion. A left-sided anterior incision was made 2 fingerbreadths inferior to the jaw line in a neck crease. A head and neck surgeon assisted with dissection. Dissection was carried down through the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and platysma on to the anterior part of the spine medial to the carotid sheath. Superior thyroid nerve and vessels and superior laryngeal nerve were identified and preserved. Fluoroscopy confirmed correct location at C2. The tumor was easily visualized, and the outer shell broke easily with palpation. Gentle curettage was necessary when removing the tumor off the vertebral artery. A portion of the specimen was sent during surgery for frozen section, which showed infrequent mitotic figures and no other findings concerning for malignancy. No instability was created after curettage and excision of the tumor, so no grafting or instrumentation was necessary.

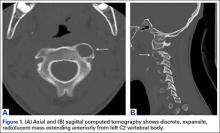

Grossly, the tumor was pale tan and firm. Histologic examination with hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed a bland spindle-cell neoplasm that focally involved bone. A storiform pattern was present. The cells had scant cytoplasm and oval to elongate nuclei with tapered ends. Significant nuclear pleomorphism was not seen. The stroma was loose, with focal myxoid change. Benign multinucleated giant cells were present. Mitotic activity was infrequent (Figures 3A–3D). Two attending pathologists reviewed the case material and the frozen and formalin-fixed specimens independently and concurred with the diagnosis of BFH. In addition, the case was reviewed at the surgical pathology consensus conference; the reviewers agreed on BFH, and additional studies were deemed unnecessary.