User login

Advancements help guide achalasia management, experts say

at a pace that has left the line-tracing technology considered to have debatable merit just 15 years ago “now as obsolete as a typewriter,” experts said recently in a review in Gastro Hep Advances.

“We have come to conceptualize esophageal motility disorders by specific aspects of physiological dysfunction,” wrote a trio of experts – Peter Kahrilas, MD, professor of medicine; Dustin Carlson, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine, and John Pandolfino, MD, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, all at Northwestern University, Chicago. “A major implication of this approach is a shift in management strategy toward rendering treatment in a phenotype-specific manner.”

High-resolution manometry (HRM) was trail-blazing, they said, as it replaced line-tracing manometry in evaluating the motility of the esophagus. HRM led to the subtyping of achalasia based on the three patterns of pressurization in the esophagus that are associated with obstruction at the esophagogastric junction. But the field has continued to advance.

“It has since become clear that obstructive physiology also occurs in syndromes besides achalasia involving the esophagogastric junction and/or distal esophagus,” Dr. Kahrilas, Dr. Carlson, and Dr. Pandolfino said. “In fact, obstructive physiology is increasingly recognized as the fundamental abnormality leading to the perception of dysphagia with esophageal motility disorders. This concept of obstructive physiology as the fundamental abnormality has substantially morphed the clinical management of esophageal motility disorders.”

HRM, has many limitations, but in cases of an uncertain achalasia diagnosis, functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) technology can help, they said. FLIP can also help surgeons tailor myotomy procedures.

In FLIP, a probe is carefully filled with fluid, causing distension of the esophagus. In the test, the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction is measured. The procedure allows a more refined assessment of the movement of the esophagus, and the subtypes of achalasia.

Identifying the achalasia subtype is crucial to choosing the right treatment, data suggests. There have been no randomized controlled trials on achalasia management that prospectively consider achalasia subtype, but retrospective analysis of RCT data “suggests that achalasia subtypes are of great relevance in forecasting treatment effectiveness,” they said.

In one trial, pneumatic dilation was effective in 100% of type II achalasia, which involves panesophageal pressurization, significantly better than laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM). But it was much less effective than LHM in type III achalasia, the spastic form, although a significance couldn’t be established because of the number of cases. Data from a meta-analysis showed that peroral endoscopic myotomy, which allows for a longer myotomy if needed, was better than LHM for classic achalasia and spastic achalasia and was most efficacious overall.

The writers said that the diagnostic classifications for achalasia are likely to continue to evolve, pointing to the dynamic nature of the Chicago Classification for the disorder.

“The fact that it has now gone through four iterations since 2008 emphasizes that this is a work in progress and that no classification scheme of esophageal motility disorders based on a single test will ever be perfect,” they said. “After all, there are no biomarkers of esophageal motility disorders and, in the absence of a biomarker, there can be no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis.”

Dr. Pandolfino, Dr. Kahrilas, and Northwestern University hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP Panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic. Dr. Kahrilas reported consulting with Ironwood, Reckitt, and Phathom. Dr. Carlson reported conflicts of interest with Medtronic and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pandolfino reported conflicts of interest with Sandhill Scientific/Diversatek, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Torax, and Ironwood.

16% of the U.S. population experience dysphagia, only half of whom seek medical care and the others manage their symptoms by modifying diet.

X-ray barium swallow and endoscopy with biopsy to exclude eosinophilic esophagitis are the initial tests for dysphagia diagnosis. If the above are normal, a high-resolution esophageal manometry impedance (HRMZ) is recommended to diagnose primary and secondary esophageal motility disorder.

However, only in a minority of patients is it likely to cause dysphagia because uncontrolled studies show that therapeutic strategies to address EGJOO (botox, dilation, and myotomy) relieve dysphagia symptoms in a minority of patients. Hence, in significant number of patients the cause of dysphagia symptoms remains obscure. It might be that our testing is inadequate, or possibly, patients have functional dysphagia (sensory dysfunction of the esophagus). My opinion is that it is the former.

The esophagus has only one simple function, that is, to transfer the pharyngeal pump driven, that is, swallowed contents to the stomach, for which its luminal cross-sectional area must be larger than that of the swallowed bolus and contraction (measured by manometry) behind the bolus must be of adequate strength. The latter is likely less relevant because humans eat in the upright position and gravity provides propulsion for the bolus. Stated simply, as long as esophagus can distend well and there is no resistance to the outflow at the EGJ, esophagus can achieve its goal. However, until recently, there was no single test to determine the distension and contraction, the two essential elements of primary esophageal peristalsis.

Endoscopy and x-ray barium swallow are tests to determine the luminal diameter but have limitations. Endoflip measures the opening function of the EGJ and is useful when the HRM is normal. However, pressures that are currently being used to measure the EGJ distensibility by Endoflip are not physiological. Furthermore, esophageal body motor function assessed by a bag that distends a long segment of the esophagus under high pressure is unphysiological. The distension-contraction plots, which determines the luminal CSA and contraction simultaneously during primary peristalsis is ideally suited to study the pathophysiology of esophageal motility disorders. Several studies from my laboratory show that in patients with nutcracker esophagus, EGJOO and normal HRM, the esophagus distends significantly less than that of normal subjects during primary peristalsis. I suspect that an esophageal contraction pushing bolus through a narrow lumen esophagus is the cause of dysphagia sensation in many patients that have been labeled as functional dysphagia.

The last 2 decades have seen significant progress in the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders using HRM, Endoflip, and distension-contraction plots of peristalsis. Furthermore, endoscopic treatment of achalasia and “achalasia-like syndromes” is revolutionary. What is desperately needed is an understanding of the pathogenesis of esophageal motor disorders, pharmacotherapy of esophageal symptoms, such as chest pain, proton pump inhibitor–resistant heartburn, and others because dysfunctional esophagus is a huge burden on health care expenditures worldwide.

Ravinder K. Mittal, MD, is a professor of medicine and gastroenterologist with UC San Diego Health. He has patent application pending on the computer software Dplots.

16% of the U.S. population experience dysphagia, only half of whom seek medical care and the others manage their symptoms by modifying diet.

X-ray barium swallow and endoscopy with biopsy to exclude eosinophilic esophagitis are the initial tests for dysphagia diagnosis. If the above are normal, a high-resolution esophageal manometry impedance (HRMZ) is recommended to diagnose primary and secondary esophageal motility disorder.

However, only in a minority of patients is it likely to cause dysphagia because uncontrolled studies show that therapeutic strategies to address EGJOO (botox, dilation, and myotomy) relieve dysphagia symptoms in a minority of patients. Hence, in significant number of patients the cause of dysphagia symptoms remains obscure. It might be that our testing is inadequate, or possibly, patients have functional dysphagia (sensory dysfunction of the esophagus). My opinion is that it is the former.

The esophagus has only one simple function, that is, to transfer the pharyngeal pump driven, that is, swallowed contents to the stomach, for which its luminal cross-sectional area must be larger than that of the swallowed bolus and contraction (measured by manometry) behind the bolus must be of adequate strength. The latter is likely less relevant because humans eat in the upright position and gravity provides propulsion for the bolus. Stated simply, as long as esophagus can distend well and there is no resistance to the outflow at the EGJ, esophagus can achieve its goal. However, until recently, there was no single test to determine the distension and contraction, the two essential elements of primary esophageal peristalsis.

Endoscopy and x-ray barium swallow are tests to determine the luminal diameter but have limitations. Endoflip measures the opening function of the EGJ and is useful when the HRM is normal. However, pressures that are currently being used to measure the EGJ distensibility by Endoflip are not physiological. Furthermore, esophageal body motor function assessed by a bag that distends a long segment of the esophagus under high pressure is unphysiological. The distension-contraction plots, which determines the luminal CSA and contraction simultaneously during primary peristalsis is ideally suited to study the pathophysiology of esophageal motility disorders. Several studies from my laboratory show that in patients with nutcracker esophagus, EGJOO and normal HRM, the esophagus distends significantly less than that of normal subjects during primary peristalsis. I suspect that an esophageal contraction pushing bolus through a narrow lumen esophagus is the cause of dysphagia sensation in many patients that have been labeled as functional dysphagia.

The last 2 decades have seen significant progress in the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders using HRM, Endoflip, and distension-contraction plots of peristalsis. Furthermore, endoscopic treatment of achalasia and “achalasia-like syndromes” is revolutionary. What is desperately needed is an understanding of the pathogenesis of esophageal motor disorders, pharmacotherapy of esophageal symptoms, such as chest pain, proton pump inhibitor–resistant heartburn, and others because dysfunctional esophagus is a huge burden on health care expenditures worldwide.

Ravinder K. Mittal, MD, is a professor of medicine and gastroenterologist with UC San Diego Health. He has patent application pending on the computer software Dplots.

16% of the U.S. population experience dysphagia, only half of whom seek medical care and the others manage their symptoms by modifying diet.

X-ray barium swallow and endoscopy with biopsy to exclude eosinophilic esophagitis are the initial tests for dysphagia diagnosis. If the above are normal, a high-resolution esophageal manometry impedance (HRMZ) is recommended to diagnose primary and secondary esophageal motility disorder.

However, only in a minority of patients is it likely to cause dysphagia because uncontrolled studies show that therapeutic strategies to address EGJOO (botox, dilation, and myotomy) relieve dysphagia symptoms in a minority of patients. Hence, in significant number of patients the cause of dysphagia symptoms remains obscure. It might be that our testing is inadequate, or possibly, patients have functional dysphagia (sensory dysfunction of the esophagus). My opinion is that it is the former.

The esophagus has only one simple function, that is, to transfer the pharyngeal pump driven, that is, swallowed contents to the stomach, for which its luminal cross-sectional area must be larger than that of the swallowed bolus and contraction (measured by manometry) behind the bolus must be of adequate strength. The latter is likely less relevant because humans eat in the upright position and gravity provides propulsion for the bolus. Stated simply, as long as esophagus can distend well and there is no resistance to the outflow at the EGJ, esophagus can achieve its goal. However, until recently, there was no single test to determine the distension and contraction, the two essential elements of primary esophageal peristalsis.

Endoscopy and x-ray barium swallow are tests to determine the luminal diameter but have limitations. Endoflip measures the opening function of the EGJ and is useful when the HRM is normal. However, pressures that are currently being used to measure the EGJ distensibility by Endoflip are not physiological. Furthermore, esophageal body motor function assessed by a bag that distends a long segment of the esophagus under high pressure is unphysiological. The distension-contraction plots, which determines the luminal CSA and contraction simultaneously during primary peristalsis is ideally suited to study the pathophysiology of esophageal motility disorders. Several studies from my laboratory show that in patients with nutcracker esophagus, EGJOO and normal HRM, the esophagus distends significantly less than that of normal subjects during primary peristalsis. I suspect that an esophageal contraction pushing bolus through a narrow lumen esophagus is the cause of dysphagia sensation in many patients that have been labeled as functional dysphagia.

The last 2 decades have seen significant progress in the diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders using HRM, Endoflip, and distension-contraction plots of peristalsis. Furthermore, endoscopic treatment of achalasia and “achalasia-like syndromes” is revolutionary. What is desperately needed is an understanding of the pathogenesis of esophageal motor disorders, pharmacotherapy of esophageal symptoms, such as chest pain, proton pump inhibitor–resistant heartburn, and others because dysfunctional esophagus is a huge burden on health care expenditures worldwide.

Ravinder K. Mittal, MD, is a professor of medicine and gastroenterologist with UC San Diego Health. He has patent application pending on the computer software Dplots.

at a pace that has left the line-tracing technology considered to have debatable merit just 15 years ago “now as obsolete as a typewriter,” experts said recently in a review in Gastro Hep Advances.

“We have come to conceptualize esophageal motility disorders by specific aspects of physiological dysfunction,” wrote a trio of experts – Peter Kahrilas, MD, professor of medicine; Dustin Carlson, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine, and John Pandolfino, MD, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, all at Northwestern University, Chicago. “A major implication of this approach is a shift in management strategy toward rendering treatment in a phenotype-specific manner.”

High-resolution manometry (HRM) was trail-blazing, they said, as it replaced line-tracing manometry in evaluating the motility of the esophagus. HRM led to the subtyping of achalasia based on the three patterns of pressurization in the esophagus that are associated with obstruction at the esophagogastric junction. But the field has continued to advance.

“It has since become clear that obstructive physiology also occurs in syndromes besides achalasia involving the esophagogastric junction and/or distal esophagus,” Dr. Kahrilas, Dr. Carlson, and Dr. Pandolfino said. “In fact, obstructive physiology is increasingly recognized as the fundamental abnormality leading to the perception of dysphagia with esophageal motility disorders. This concept of obstructive physiology as the fundamental abnormality has substantially morphed the clinical management of esophageal motility disorders.”

HRM, has many limitations, but in cases of an uncertain achalasia diagnosis, functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) technology can help, they said. FLIP can also help surgeons tailor myotomy procedures.

In FLIP, a probe is carefully filled with fluid, causing distension of the esophagus. In the test, the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction is measured. The procedure allows a more refined assessment of the movement of the esophagus, and the subtypes of achalasia.

Identifying the achalasia subtype is crucial to choosing the right treatment, data suggests. There have been no randomized controlled trials on achalasia management that prospectively consider achalasia subtype, but retrospective analysis of RCT data “suggests that achalasia subtypes are of great relevance in forecasting treatment effectiveness,” they said.

In one trial, pneumatic dilation was effective in 100% of type II achalasia, which involves panesophageal pressurization, significantly better than laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM). But it was much less effective than LHM in type III achalasia, the spastic form, although a significance couldn’t be established because of the number of cases. Data from a meta-analysis showed that peroral endoscopic myotomy, which allows for a longer myotomy if needed, was better than LHM for classic achalasia and spastic achalasia and was most efficacious overall.

The writers said that the diagnostic classifications for achalasia are likely to continue to evolve, pointing to the dynamic nature of the Chicago Classification for the disorder.

“The fact that it has now gone through four iterations since 2008 emphasizes that this is a work in progress and that no classification scheme of esophageal motility disorders based on a single test will ever be perfect,” they said. “After all, there are no biomarkers of esophageal motility disorders and, in the absence of a biomarker, there can be no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis.”

Dr. Pandolfino, Dr. Kahrilas, and Northwestern University hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP Panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic. Dr. Kahrilas reported consulting with Ironwood, Reckitt, and Phathom. Dr. Carlson reported conflicts of interest with Medtronic and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pandolfino reported conflicts of interest with Sandhill Scientific/Diversatek, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Torax, and Ironwood.

at a pace that has left the line-tracing technology considered to have debatable merit just 15 years ago “now as obsolete as a typewriter,” experts said recently in a review in Gastro Hep Advances.

“We have come to conceptualize esophageal motility disorders by specific aspects of physiological dysfunction,” wrote a trio of experts – Peter Kahrilas, MD, professor of medicine; Dustin Carlson, MD, MS, assistant professor of medicine, and John Pandolfino, MD, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology, all at Northwestern University, Chicago. “A major implication of this approach is a shift in management strategy toward rendering treatment in a phenotype-specific manner.”

High-resolution manometry (HRM) was trail-blazing, they said, as it replaced line-tracing manometry in evaluating the motility of the esophagus. HRM led to the subtyping of achalasia based on the three patterns of pressurization in the esophagus that are associated with obstruction at the esophagogastric junction. But the field has continued to advance.

“It has since become clear that obstructive physiology also occurs in syndromes besides achalasia involving the esophagogastric junction and/or distal esophagus,” Dr. Kahrilas, Dr. Carlson, and Dr. Pandolfino said. “In fact, obstructive physiology is increasingly recognized as the fundamental abnormality leading to the perception of dysphagia with esophageal motility disorders. This concept of obstructive physiology as the fundamental abnormality has substantially morphed the clinical management of esophageal motility disorders.”

HRM, has many limitations, but in cases of an uncertain achalasia diagnosis, functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) technology can help, they said. FLIP can also help surgeons tailor myotomy procedures.

In FLIP, a probe is carefully filled with fluid, causing distension of the esophagus. In the test, the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction is measured. The procedure allows a more refined assessment of the movement of the esophagus, and the subtypes of achalasia.

Identifying the achalasia subtype is crucial to choosing the right treatment, data suggests. There have been no randomized controlled trials on achalasia management that prospectively consider achalasia subtype, but retrospective analysis of RCT data “suggests that achalasia subtypes are of great relevance in forecasting treatment effectiveness,” they said.

In one trial, pneumatic dilation was effective in 100% of type II achalasia, which involves panesophageal pressurization, significantly better than laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM). But it was much less effective than LHM in type III achalasia, the spastic form, although a significance couldn’t be established because of the number of cases. Data from a meta-analysis showed that peroral endoscopic myotomy, which allows for a longer myotomy if needed, was better than LHM for classic achalasia and spastic achalasia and was most efficacious overall.

The writers said that the diagnostic classifications for achalasia are likely to continue to evolve, pointing to the dynamic nature of the Chicago Classification for the disorder.

“The fact that it has now gone through four iterations since 2008 emphasizes that this is a work in progress and that no classification scheme of esophageal motility disorders based on a single test will ever be perfect,” they said. “After all, there are no biomarkers of esophageal motility disorders and, in the absence of a biomarker, there can be no ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis.”

Dr. Pandolfino, Dr. Kahrilas, and Northwestern University hold shared intellectual property rights and ownership surrounding FLIP Panometry systems, methods, and apparatus with Medtronic. Dr. Kahrilas reported consulting with Ironwood, Reckitt, and Phathom. Dr. Carlson reported conflicts of interest with Medtronic and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Pandolfino reported conflicts of interest with Sandhill Scientific/Diversatek, Takeda, AstraZeneca, Medtronic, Torax, and Ironwood.

FROM GASTRO HEP ADVANCES

Can ChatGPT help clinicians manage GERD?

managing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), investigators have found.

The researchers say the tool’s conversational format could improve clinical efficiency and reduce the volume of patient messages and calls, potentially diminishing clinician burnout.

However, inconsistencies and content errors observed require a certain level of clinical oversight, caution the researchers, led by Jacqueline Henson, MD, with the division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Putting ChatGPT to the GERD test

Affecting nearly 30% of U.S. adults, GERD is a common and increasingly complex condition to manage. AI technologies like ChatGPT (Open AI/Microsoft) have demonstrated an increasing role in medicine, although the ability of ChatGPT to provide guidance for GERD management is uncertain.

Dr. Henson and colleagues assessed ChatGPT’s ability to provide accurate and specific responses to questions regarding GERD care.

They generated 23 GERD management prompts based on published clinical guidelines and expert consensus recommendations. Five questions were about diagnosis, eleven on treatment, and seven on both diagnosis and treatment.

Each prompt was submitted to ChatGPT 3.5 (version 3/14/2023) three times on separate occasions without feedback to assess the consistency of the answer. Responses were rated by three board-certified gastroenterologists for appropriateness and specificity.

ChatGPT returned appropriate responses to 63 of 69 (91.3%) queries, with 29% considered completely appropriate and 62.3% mostly appropriate.

However, responses to the same prompt were often inconsistent, with 16 of 23 (70%) prompts yielding varying appropriateness, including three (13%) with both inappropriate and appropriate responses.

Prompts regarding treatment received the highest proportion of completely appropriate responses (39.4%), while prompts for diagnosis and management had the highest proportion of mostly inappropriate responses (14.3%).

For example, the chatbot failed to recommend consideration of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for ongoing GERD symptoms with pathologic acid exposure in the setting of obesity, and some potential risks associated with proton pump inhibitor therapy were stated as fact.

However, the majority (78.3%) of responses contained at least some specific guidance, especially for prompts assessing diagnosis (93.3%). In all responses, ChatGPT suggested contacting a health care professional for further advice.

Eight patients from a range of educational backgrounds who provided feedback on the responses generally felt that the ChatGPT responses were both understandable and useful.

Overall, ChatGPT “provided largely appropriate and at least some specific guidance for GERD management, highlighting the potential for this technology to serve as a source of information for patients, as well as an aid for clinicians,” Dr. Henson and colleagues write.

However, “the presence of inappropriate responses with inconsistencies to the same prompt largely preclude its application within health care in its present state, at least for GERD,” they add.

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Henson has served as a consultant for Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

managing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), investigators have found.

The researchers say the tool’s conversational format could improve clinical efficiency and reduce the volume of patient messages and calls, potentially diminishing clinician burnout.

However, inconsistencies and content errors observed require a certain level of clinical oversight, caution the researchers, led by Jacqueline Henson, MD, with the division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Putting ChatGPT to the GERD test

Affecting nearly 30% of U.S. adults, GERD is a common and increasingly complex condition to manage. AI technologies like ChatGPT (Open AI/Microsoft) have demonstrated an increasing role in medicine, although the ability of ChatGPT to provide guidance for GERD management is uncertain.

Dr. Henson and colleagues assessed ChatGPT’s ability to provide accurate and specific responses to questions regarding GERD care.

They generated 23 GERD management prompts based on published clinical guidelines and expert consensus recommendations. Five questions were about diagnosis, eleven on treatment, and seven on both diagnosis and treatment.

Each prompt was submitted to ChatGPT 3.5 (version 3/14/2023) three times on separate occasions without feedback to assess the consistency of the answer. Responses were rated by three board-certified gastroenterologists for appropriateness and specificity.

ChatGPT returned appropriate responses to 63 of 69 (91.3%) queries, with 29% considered completely appropriate and 62.3% mostly appropriate.

However, responses to the same prompt were often inconsistent, with 16 of 23 (70%) prompts yielding varying appropriateness, including three (13%) with both inappropriate and appropriate responses.

Prompts regarding treatment received the highest proportion of completely appropriate responses (39.4%), while prompts for diagnosis and management had the highest proportion of mostly inappropriate responses (14.3%).

For example, the chatbot failed to recommend consideration of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for ongoing GERD symptoms with pathologic acid exposure in the setting of obesity, and some potential risks associated with proton pump inhibitor therapy were stated as fact.

However, the majority (78.3%) of responses contained at least some specific guidance, especially for prompts assessing diagnosis (93.3%). In all responses, ChatGPT suggested contacting a health care professional for further advice.

Eight patients from a range of educational backgrounds who provided feedback on the responses generally felt that the ChatGPT responses were both understandable and useful.

Overall, ChatGPT “provided largely appropriate and at least some specific guidance for GERD management, highlighting the potential for this technology to serve as a source of information for patients, as well as an aid for clinicians,” Dr. Henson and colleagues write.

However, “the presence of inappropriate responses with inconsistencies to the same prompt largely preclude its application within health care in its present state, at least for GERD,” they add.

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Henson has served as a consultant for Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

managing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), investigators have found.

The researchers say the tool’s conversational format could improve clinical efficiency and reduce the volume of patient messages and calls, potentially diminishing clinician burnout.

However, inconsistencies and content errors observed require a certain level of clinical oversight, caution the researchers, led by Jacqueline Henson, MD, with the division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The study was published online in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Putting ChatGPT to the GERD test

Affecting nearly 30% of U.S. adults, GERD is a common and increasingly complex condition to manage. AI technologies like ChatGPT (Open AI/Microsoft) have demonstrated an increasing role in medicine, although the ability of ChatGPT to provide guidance for GERD management is uncertain.

Dr. Henson and colleagues assessed ChatGPT’s ability to provide accurate and specific responses to questions regarding GERD care.

They generated 23 GERD management prompts based on published clinical guidelines and expert consensus recommendations. Five questions were about diagnosis, eleven on treatment, and seven on both diagnosis and treatment.

Each prompt was submitted to ChatGPT 3.5 (version 3/14/2023) three times on separate occasions without feedback to assess the consistency of the answer. Responses were rated by three board-certified gastroenterologists for appropriateness and specificity.

ChatGPT returned appropriate responses to 63 of 69 (91.3%) queries, with 29% considered completely appropriate and 62.3% mostly appropriate.

However, responses to the same prompt were often inconsistent, with 16 of 23 (70%) prompts yielding varying appropriateness, including three (13%) with both inappropriate and appropriate responses.

Prompts regarding treatment received the highest proportion of completely appropriate responses (39.4%), while prompts for diagnosis and management had the highest proportion of mostly inappropriate responses (14.3%).

For example, the chatbot failed to recommend consideration of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for ongoing GERD symptoms with pathologic acid exposure in the setting of obesity, and some potential risks associated with proton pump inhibitor therapy were stated as fact.

However, the majority (78.3%) of responses contained at least some specific guidance, especially for prompts assessing diagnosis (93.3%). In all responses, ChatGPT suggested contacting a health care professional for further advice.

Eight patients from a range of educational backgrounds who provided feedback on the responses generally felt that the ChatGPT responses were both understandable and useful.

Overall, ChatGPT “provided largely appropriate and at least some specific guidance for GERD management, highlighting the potential for this technology to serve as a source of information for patients, as well as an aid for clinicians,” Dr. Henson and colleagues write.

However, “the presence of inappropriate responses with inconsistencies to the same prompt largely preclude its application within health care in its present state, at least for GERD,” they add.

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Henson has served as a consultant for Medtronic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Eosinophilic esophagitis: A year in review

At the AGA postgraduate course in May, we highlighted recent noteworthy randomized controlled trials (RCT) using eosinophil-targeting biologic therapy, esophageal-optimized corticosteroid preparations, and dietary elimination in EoE.

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-4 and IL-13 signaling, was tested in a phase 3 trial for adults and adolescents with EoE.1 In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the efficacy of subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every other week was compared against placebo. Stringent histologic remission (≤ 6 eosinophils/high power field) occurred in approximately 60% who received dupilumab (either dose) versus 5% in placebo. However, significant symptom improvement was seen only with 300 g weekly dupilumab.

On the topical corticosteroid front, the results of two RCTs using fluticasone orally disintegrating tablet (APT-1011) and budesonide oral suspension (BOS) were published. In the APT-1011 phase 2b trial, patients were randomized to receive 1.5 mg or 3 mg daily or b.i.d. versus placebo for 12 weeks.2 High histologic response rates and improvement in dysphagia frequency were seen with all ≥ 3-mg daily-dose APT-1011, compared with placebo. However, adverse events (that is, candidiasis) were highest among those on 3 mg b.i.d. Thus, 3 mg daily APT-1011 was thought to offer the most favorable risk-benefit profile. In the BOS phase 3 trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to received BOS 2 mg b.i.d. or placebo for 12 weeks.3 BOS was superior to placebo in histologic, symptomatic, and endoscopic outcomes.

Diet remains the only therapy targeting the cause of EoE and offers a potential drug-free remission. In the randomized, open label trial of 1- versus 6-food elimination diet, adult patients were allocated 1:1 to 1FED (animal milk) or 6FED (animal milk, wheat, egg, soy, fish/shellfish, and peanuts/tree nuts) for 6 weeks.4 No significant difference in partial or stringent remission was found between the two groups. Step-up therapy resulted in an additional 43% histologic response in those who underwent 6FED after failing 1FED and 82% histologic response in those who received swallowed fluticasone 880 mcg b.i.d after failing 6FED. Hence, eliminating animal milk alone in a step-up treatment approach is reasonable.

We have witnessed major progress to expand EoE treatment options in the last year. Long-term efficacy and side-effect data, as well as studies comparing between therapies are needed to improve shared decision-making and strategies to implement tailored care in EoE.

Dr. Chen is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She disclosed consultancy work with Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2317-30.

2. Dellon ES et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2485-94e15.

3. Hirano I et al. Budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-34e10.

4. Kliewer KL et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(5):408-21.

At the AGA postgraduate course in May, we highlighted recent noteworthy randomized controlled trials (RCT) using eosinophil-targeting biologic therapy, esophageal-optimized corticosteroid preparations, and dietary elimination in EoE.

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-4 and IL-13 signaling, was tested in a phase 3 trial for adults and adolescents with EoE.1 In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the efficacy of subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every other week was compared against placebo. Stringent histologic remission (≤ 6 eosinophils/high power field) occurred in approximately 60% who received dupilumab (either dose) versus 5% in placebo. However, significant symptom improvement was seen only with 300 g weekly dupilumab.

On the topical corticosteroid front, the results of two RCTs using fluticasone orally disintegrating tablet (APT-1011) and budesonide oral suspension (BOS) were published. In the APT-1011 phase 2b trial, patients were randomized to receive 1.5 mg or 3 mg daily or b.i.d. versus placebo for 12 weeks.2 High histologic response rates and improvement in dysphagia frequency were seen with all ≥ 3-mg daily-dose APT-1011, compared with placebo. However, adverse events (that is, candidiasis) were highest among those on 3 mg b.i.d. Thus, 3 mg daily APT-1011 was thought to offer the most favorable risk-benefit profile. In the BOS phase 3 trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to received BOS 2 mg b.i.d. or placebo for 12 weeks.3 BOS was superior to placebo in histologic, symptomatic, and endoscopic outcomes.

Diet remains the only therapy targeting the cause of EoE and offers a potential drug-free remission. In the randomized, open label trial of 1- versus 6-food elimination diet, adult patients were allocated 1:1 to 1FED (animal milk) or 6FED (animal milk, wheat, egg, soy, fish/shellfish, and peanuts/tree nuts) for 6 weeks.4 No significant difference in partial or stringent remission was found between the two groups. Step-up therapy resulted in an additional 43% histologic response in those who underwent 6FED after failing 1FED and 82% histologic response in those who received swallowed fluticasone 880 mcg b.i.d after failing 6FED. Hence, eliminating animal milk alone in a step-up treatment approach is reasonable.

We have witnessed major progress to expand EoE treatment options in the last year. Long-term efficacy and side-effect data, as well as studies comparing between therapies are needed to improve shared decision-making and strategies to implement tailored care in EoE.

Dr. Chen is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She disclosed consultancy work with Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2317-30.

2. Dellon ES et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2485-94e15.

3. Hirano I et al. Budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-34e10.

4. Kliewer KL et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(5):408-21.

At the AGA postgraduate course in May, we highlighted recent noteworthy randomized controlled trials (RCT) using eosinophil-targeting biologic therapy, esophageal-optimized corticosteroid preparations, and dietary elimination in EoE.

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-4 and IL-13 signaling, was tested in a phase 3 trial for adults and adolescents with EoE.1 In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the efficacy of subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg weekly or every other week was compared against placebo. Stringent histologic remission (≤ 6 eosinophils/high power field) occurred in approximately 60% who received dupilumab (either dose) versus 5% in placebo. However, significant symptom improvement was seen only with 300 g weekly dupilumab.

On the topical corticosteroid front, the results of two RCTs using fluticasone orally disintegrating tablet (APT-1011) and budesonide oral suspension (BOS) were published. In the APT-1011 phase 2b trial, patients were randomized to receive 1.5 mg or 3 mg daily or b.i.d. versus placebo for 12 weeks.2 High histologic response rates and improvement in dysphagia frequency were seen with all ≥ 3-mg daily-dose APT-1011, compared with placebo. However, adverse events (that is, candidiasis) were highest among those on 3 mg b.i.d. Thus, 3 mg daily APT-1011 was thought to offer the most favorable risk-benefit profile. In the BOS phase 3 trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to received BOS 2 mg b.i.d. or placebo for 12 weeks.3 BOS was superior to placebo in histologic, symptomatic, and endoscopic outcomes.

Diet remains the only therapy targeting the cause of EoE and offers a potential drug-free remission. In the randomized, open label trial of 1- versus 6-food elimination diet, adult patients were allocated 1:1 to 1FED (animal milk) or 6FED (animal milk, wheat, egg, soy, fish/shellfish, and peanuts/tree nuts) for 6 weeks.4 No significant difference in partial or stringent remission was found between the two groups. Step-up therapy resulted in an additional 43% histologic response in those who underwent 6FED after failing 1FED and 82% histologic response in those who received swallowed fluticasone 880 mcg b.i.d after failing 6FED. Hence, eliminating animal milk alone in a step-up treatment approach is reasonable.

We have witnessed major progress to expand EoE treatment options in the last year. Long-term efficacy and side-effect data, as well as studies comparing between therapies are needed to improve shared decision-making and strategies to implement tailored care in EoE.

Dr. Chen is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She disclosed consultancy work with Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2317-30.

2. Dellon ES et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2485-94e15.

3. Hirano I et al. Budesonide. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-34e10.

4. Kliewer KL et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(5):408-21.

Esophageal diseases: Key new concepts

CHICAGO – These include novel care approaches for esophageal diseases that were published in recent AGA best practice updates on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), extraesophageal reflux, and Barrett’s esophagus, as well as randomized clinical trial data examining therapeutic approaches for erosive esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Here are a few highlights: Complications of chronic gastroesophageal reflux include erosive esophagitis for which healing and maintenance of healing is crucial to reduce further erosive sequelae. Healing is typically achieved with pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Potassium competitive acid blockers are active prodrugs that bind to the H+/K+ ATPase and have been demonstrated to have a more potent and faster onset in suppressing gastric acid secretion, compared with PPIs.

In a recent phase 3 randomized trial of more than 1,000 adults with erosive esophagitis, the potassium competitive acid blocker vonoprazan was found to be noninferior to lansoprazole in inducing and maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Overall, the proportions of subjects that achieved healing by week 8 and maintained healing up to 24 weeks were higher with vonoprazan, when compared with lansoprazole, with a greater treatment effect seen in subjects with severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) (Laine L et al. Gastroenterology. Jan 2023;164[1]:61-71).

Screening patients at risk of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), another erosive sequelae of chronic GERD, is critical for early detection and prevention of esophageal cancer. Upper GI endoscopy is standard for Barrett’s screening; however, screening rates of at-risk populations are suboptimal.

In a recent retrospective analysis of a multipractice health care network, only 39% of a screen-eligible population were noted to have undergone upper GI endoscopy. These findings highlight the critical need to improve screening for Barrett’s, including potential of the newer nonendoscopic screening modalities such as swallowable capsule devices combined with a biomarker or cell-collection devices, as well as the need for risk stratification/prediction tools and collaboration with primary care physicians (Eluri S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Nov 2022;117[11]:1764-71).

Therapeutic options for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) have expanded over the past year. Randomized trials demonstrate the efficacy of varied therapeutic approaches including the monoclonal antibody dupilumab as well as topical corticosteroids such as fluticasone propionate orally disintegrated tablet and budesonide oral suspension.

In terms of food elimination diets, a recent multicenter randomized open-label trial identified comparable rates of partial histologic remission with both a traditional six-food elimination diet and a one-food animal milk elimination diet in patients with EoE, though those treated with a six-food elimination were more likely to achieve complete remission (< 1 eosinophil/high power field). Results suggest elimination of animal milk alone is an acceptable initial dietary therapy for EoE, with potential to convert to six-food elimination or alternative therapy when histologic response is not achieved (Kliewer K. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. [published online Feb 2023]).

Dr. Yadlapati is an associate professor in gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego. She disclosed relationships with Medtronic (Institutional), Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (Institutional), Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She serves on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix.

These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2023.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

CHICAGO – These include novel care approaches for esophageal diseases that were published in recent AGA best practice updates on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), extraesophageal reflux, and Barrett’s esophagus, as well as randomized clinical trial data examining therapeutic approaches for erosive esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Here are a few highlights: Complications of chronic gastroesophageal reflux include erosive esophagitis for which healing and maintenance of healing is crucial to reduce further erosive sequelae. Healing is typically achieved with pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Potassium competitive acid blockers are active prodrugs that bind to the H+/K+ ATPase and have been demonstrated to have a more potent and faster onset in suppressing gastric acid secretion, compared with PPIs.

In a recent phase 3 randomized trial of more than 1,000 adults with erosive esophagitis, the potassium competitive acid blocker vonoprazan was found to be noninferior to lansoprazole in inducing and maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Overall, the proportions of subjects that achieved healing by week 8 and maintained healing up to 24 weeks were higher with vonoprazan, when compared with lansoprazole, with a greater treatment effect seen in subjects with severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) (Laine L et al. Gastroenterology. Jan 2023;164[1]:61-71).

Screening patients at risk of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), another erosive sequelae of chronic GERD, is critical for early detection and prevention of esophageal cancer. Upper GI endoscopy is standard for Barrett’s screening; however, screening rates of at-risk populations are suboptimal.

In a recent retrospective analysis of a multipractice health care network, only 39% of a screen-eligible population were noted to have undergone upper GI endoscopy. These findings highlight the critical need to improve screening for Barrett’s, including potential of the newer nonendoscopic screening modalities such as swallowable capsule devices combined with a biomarker or cell-collection devices, as well as the need for risk stratification/prediction tools and collaboration with primary care physicians (Eluri S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Nov 2022;117[11]:1764-71).

Therapeutic options for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) have expanded over the past year. Randomized trials demonstrate the efficacy of varied therapeutic approaches including the monoclonal antibody dupilumab as well as topical corticosteroids such as fluticasone propionate orally disintegrated tablet and budesonide oral suspension.

In terms of food elimination diets, a recent multicenter randomized open-label trial identified comparable rates of partial histologic remission with both a traditional six-food elimination diet and a one-food animal milk elimination diet in patients with EoE, though those treated with a six-food elimination were more likely to achieve complete remission (< 1 eosinophil/high power field). Results suggest elimination of animal milk alone is an acceptable initial dietary therapy for EoE, with potential to convert to six-food elimination or alternative therapy when histologic response is not achieved (Kliewer K. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. [published online Feb 2023]).

Dr. Yadlapati is an associate professor in gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego. She disclosed relationships with Medtronic (Institutional), Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (Institutional), Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She serves on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix.

These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2023.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

CHICAGO – These include novel care approaches for esophageal diseases that were published in recent AGA best practice updates on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), extraesophageal reflux, and Barrett’s esophagus, as well as randomized clinical trial data examining therapeutic approaches for erosive esophagitis and eosinophilic esophagitis.

Here are a few highlights: Complications of chronic gastroesophageal reflux include erosive esophagitis for which healing and maintenance of healing is crucial to reduce further erosive sequelae. Healing is typically achieved with pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Potassium competitive acid blockers are active prodrugs that bind to the H+/K+ ATPase and have been demonstrated to have a more potent and faster onset in suppressing gastric acid secretion, compared with PPIs.

In a recent phase 3 randomized trial of more than 1,000 adults with erosive esophagitis, the potassium competitive acid blocker vonoprazan was found to be noninferior to lansoprazole in inducing and maintaining healing of erosive esophagitis. Overall, the proportions of subjects that achieved healing by week 8 and maintained healing up to 24 weeks were higher with vonoprazan, when compared with lansoprazole, with a greater treatment effect seen in subjects with severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C or D) (Laine L et al. Gastroenterology. Jan 2023;164[1]:61-71).

Screening patients at risk of Barrett’s esophagus (BE), another erosive sequelae of chronic GERD, is critical for early detection and prevention of esophageal cancer. Upper GI endoscopy is standard for Barrett’s screening; however, screening rates of at-risk populations are suboptimal.

In a recent retrospective analysis of a multipractice health care network, only 39% of a screen-eligible population were noted to have undergone upper GI endoscopy. These findings highlight the critical need to improve screening for Barrett’s, including potential of the newer nonendoscopic screening modalities such as swallowable capsule devices combined with a biomarker or cell-collection devices, as well as the need for risk stratification/prediction tools and collaboration with primary care physicians (Eluri S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. Nov 2022;117[11]:1764-71).

Therapeutic options for eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) have expanded over the past year. Randomized trials demonstrate the efficacy of varied therapeutic approaches including the monoclonal antibody dupilumab as well as topical corticosteroids such as fluticasone propionate orally disintegrated tablet and budesonide oral suspension.

In terms of food elimination diets, a recent multicenter randomized open-label trial identified comparable rates of partial histologic remission with both a traditional six-food elimination diet and a one-food animal milk elimination diet in patients with EoE, though those treated with a six-food elimination were more likely to achieve complete remission (< 1 eosinophil/high power field). Results suggest elimination of animal milk alone is an acceptable initial dietary therapy for EoE, with potential to convert to six-food elimination or alternative therapy when histologic response is not achieved (Kliewer K. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. [published online Feb 2023]).

Dr. Yadlapati is an associate professor in gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego. She disclosed relationships with Medtronic (Institutional), Ironwood Pharmaceuticals (Institutional), Phathom Pharmaceuticals, and Ironwood Pharmaceuticals. She serves on the advisory board with stock options for RJS Mediagnostix.

These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2023.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

AT DDW 2023

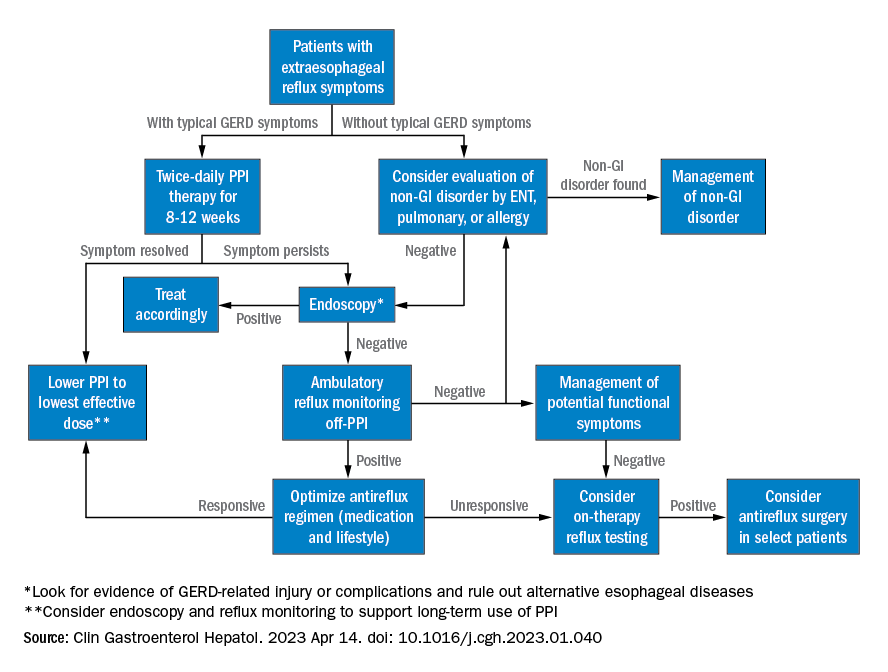

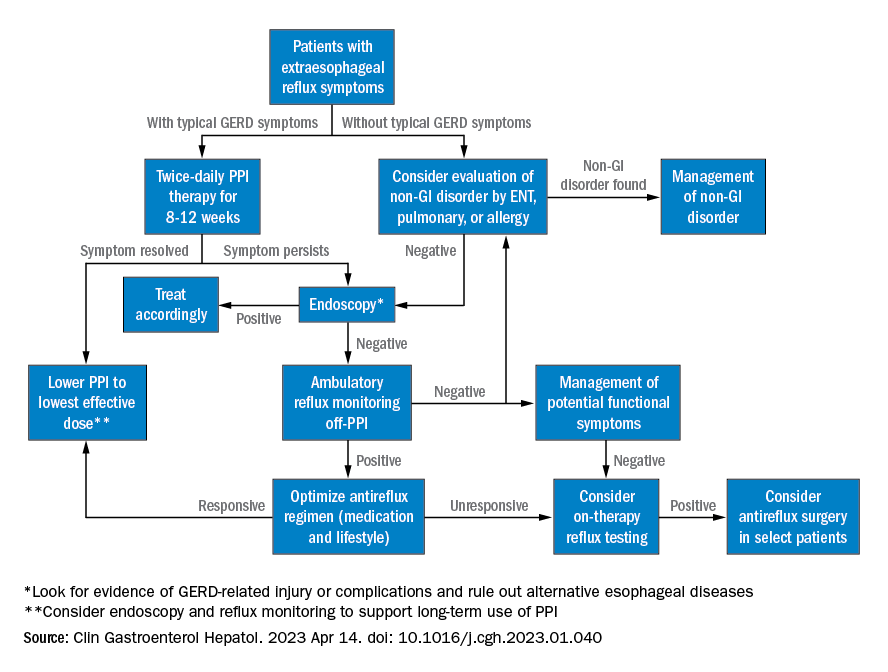

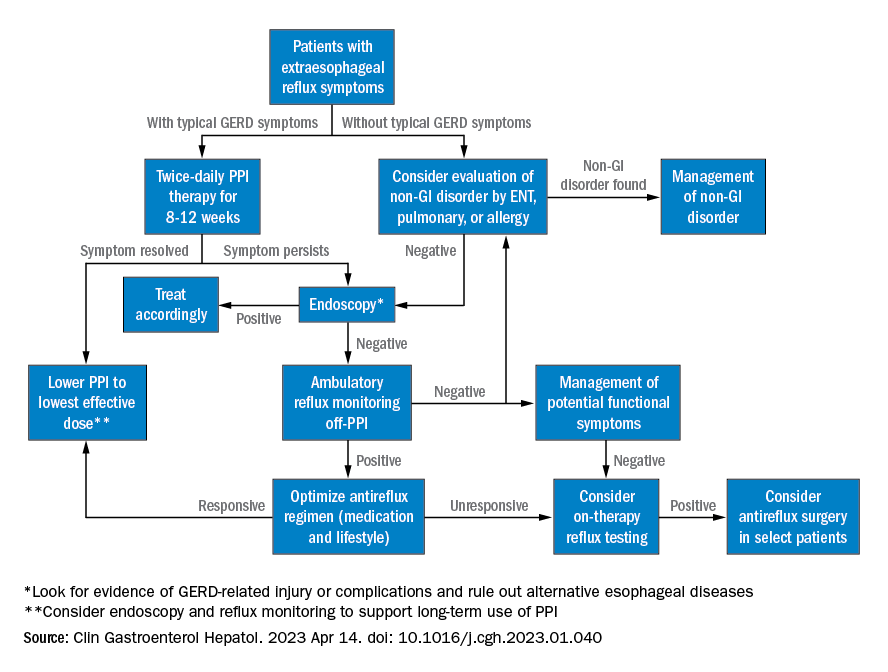

AGA clinical practice update: Extraesophageal gastroesophageal reflux disease

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

Extraesophageal reflux (EER) symptoms are a subset of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that can be difficult to diagnose because of its heterogeneous nature and symptoms that overlap with other conditions.

That puts the onus on physicians to take all symptoms into account and work across disciplines to diagnose, manage, and treat the condition, according to a new clinical practice update from the American Gastroenterological Association, which was published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

GERD is becoming increasingly common, which in turn has led to greater awareness and consideration of EER symptoms. EER symptoms can present a challenge because they may vary considerably and are not unique to GERD. The symptoms often do not respond well to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy.

EER symptoms can include cough, laryngeal hoarseness, dysphonia, pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, dental erosions/caries, sinus disease, ear disease, postnasal drip, and throat clearing. Some patients with EER symptoms do not report heartburn or regurgitation, which leaves it up to the physician to determine if acid reflux is present and contributing to symptoms.

“The concept of extraesophageal symptoms secondary to GERD is complex and often controversial, leading to diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Several extraesophageal symptoms have been associated with GERD, although the strength of evidence to support a causal relation varies,” wrote the authors, who were led by Joan W. Chen, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist with the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

There is also debate over whether fluid refluxate is the source of damage that causes EER symptoms, and if so, whether it is sufficient that the fluid be acidic or that pepsin be present, or if the cause is related to neurogenic signaling and resulting inflammation. Because of these questions, a PPI trial will not necessarily provide insight into the role of acid reflux in EER symptoms.

Best practice advice 1: The authors emphasized that gastroenterologists need to be aware of the potential extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. They should inquire with GERD patients to determine if laryngitis, chronic cough, asthma, and dental erosions are present.

Best practice advice 2: Consider a multidisciplinary approach to EER manifestations. Cases may require input from non-GI specialties. Tests performed by other specialists, such as bronchoscopy, thoracic imaging, or laryngoscopy, should be taken into account, since patients will also seek out multiple specialists to address their symptoms.

Best practice advice 3: There is no specific diagnostic test available to determine if GER is the cause of EER symptoms. Instead, physicians should interpret patient symptoms, response to GER therapy, and input from endoscopy and reflux tests.

Best practice advice 4: Rather than subject the patient to the cost and potential for even rare adverse events of a PPI trial, physicians should first consider conducting reflux testing. A PPI trial has clinical value but is insufficient on its own to help diagnose or manage EER. Initial single-dose PPI trial, titrating up to twice daily in those with typical GERD symptoms, is reasonable.

Best practice advice 5: The inconsistent therapeutic response to PPI therapy means that positive effects of PPI therapy on EER symptoms can’t confirm a GERD diagnosis because a placebo effect may be involved, and because symptom improvement can occur through mechanisms other than acid suppression. A meta-analysis found that a PPI trial has a sensitivity of 71%-78% and a specificity of 41%-54% with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. “Considering the greater variation expected with PPI response for extraesophageal symptoms, the diagnostic performance of empiric PPI trial for a diagnosis of EER would be anticipated to be substantially lower,” the authors wrote.

Best practice advice 6: When EER symptoms related to GERD are suspected and a PPI trial of up to 12 weeks does not lead to adequate improvement, the physician should consider testing for pathologic GER. Additional trials employing other PPIs are unlikely to succeed.

Best practice advice 7: Initial testing to evaluate for reflux should be tailored to patients’ clinical presentation. Potential methods to evaluate reflux include upper endoscopy and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies of acid suppressive therapy, which can assist with a GERD diagnosis, particularly when nonerosive reflux is present.

Best practice advice 8: About 50%-60% of patients with EER symptoms will not have GERD. Testing can be considered for those with an established objective diagnosis of GERD who do not respond well to high doses of acid suppression. Cost-effectiveness studies have confirmed the value of starting with ambulatory reflux monitoring, which can include a catheter-based pH sensor, pH impedance, or wireless pH capsule.

Ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring can also assist in making a GERD diagnosis, but it does not indicate whether GERD may be contributing to EER symptoms.

“Whichever the reflux testing modality, the strongest confidence for EER is achieved after ambulatory reflux testing showing pathologic acid exposure and a positive symptom-reflux association for EER symptoms,” the authors wrote. They also pointed out that ambulatory reflux monitoring in EER patients should be done in the absence of acid suppression unless there is already objective evidence for the presence of GERD.

Best practice advice 9: Aside from acid suppression, EER symptoms can also be managed through other means, including lifestyle modifications, such as eating avoidance prior to lying down, elevation of the head of the bed, sleeping on the left side, and weight loss. Or, alginate containing antacids, external upper esophageal sphincter compression device, cognitive behavioral therapy, and neuromodulators.

Best practice advice 10: In cases where the EER patient has objectively defined evidence of GERD, physicians should employ shared decision-making before considering anti-reflux surgery. If the patient did not respond to PPI therapy, this predicts a lack of response to antireflux surgery.

All four authors reported financial ties to multiple pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

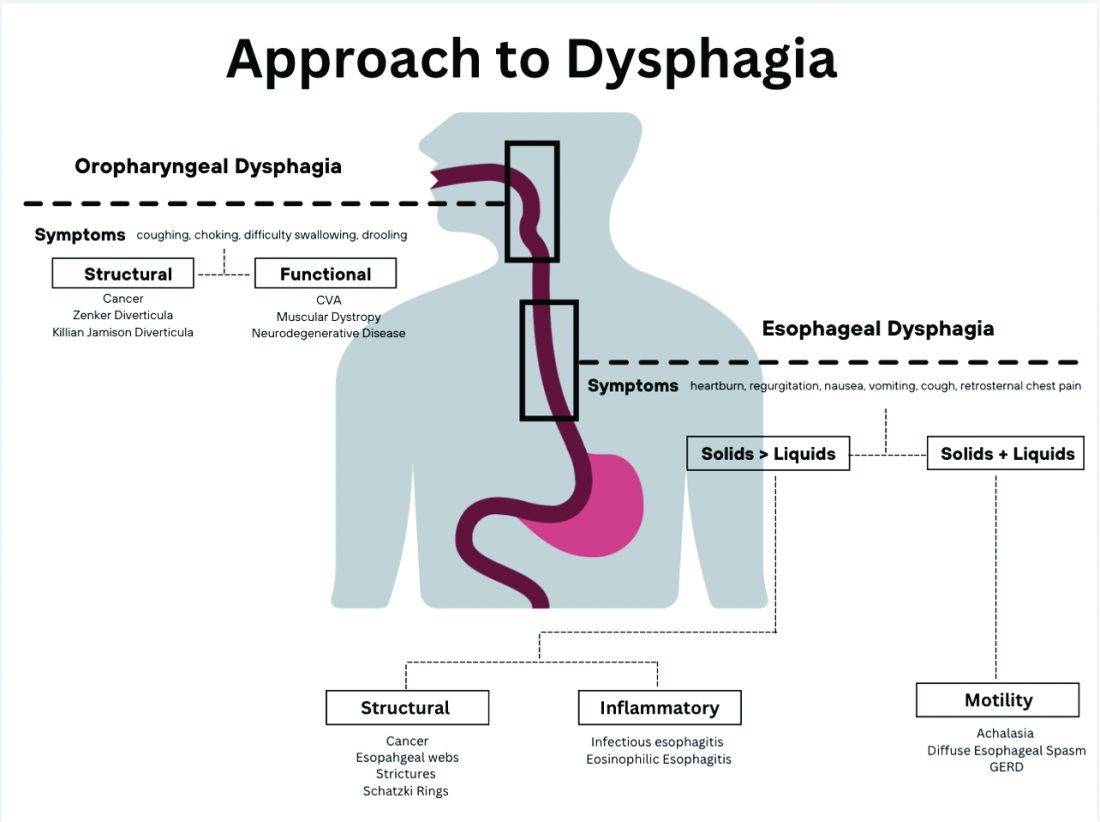

Approach to dysphagia

Introduction

Dysphagia is the sensation of difficulty swallowing food or liquid in the acute or chronic setting. The prevalence of dysphagia ranges based on the type and etiology but may impact up to one in six adults.1,2 Dysphagia can cause a significant impact on a patient’s health and overall quality of life. A recent study found that only 50% of symptomatic adults seek medical care despite modifying their eating habits by either eating slowly or changing to softer foods or liquids.1 The most common, serious complications of dysphagia include aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration.3 According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, dysphagia may be responsible for up to 60,000 deaths annually.3

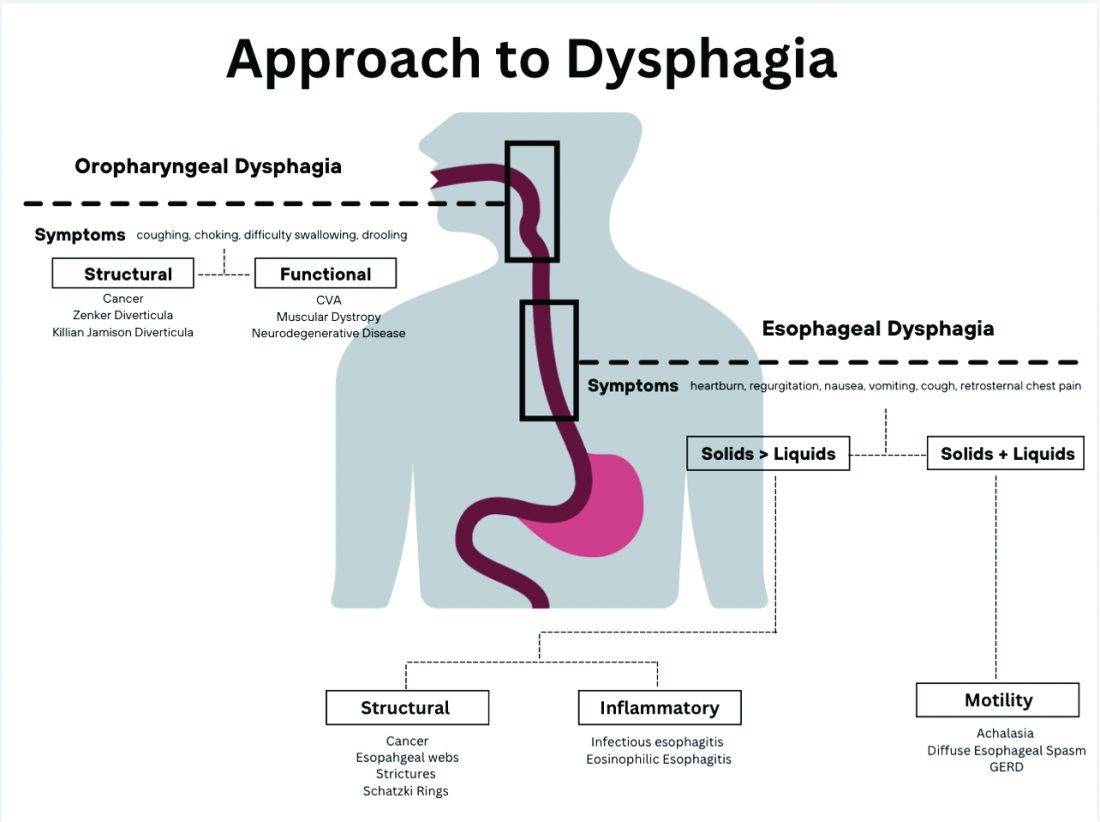

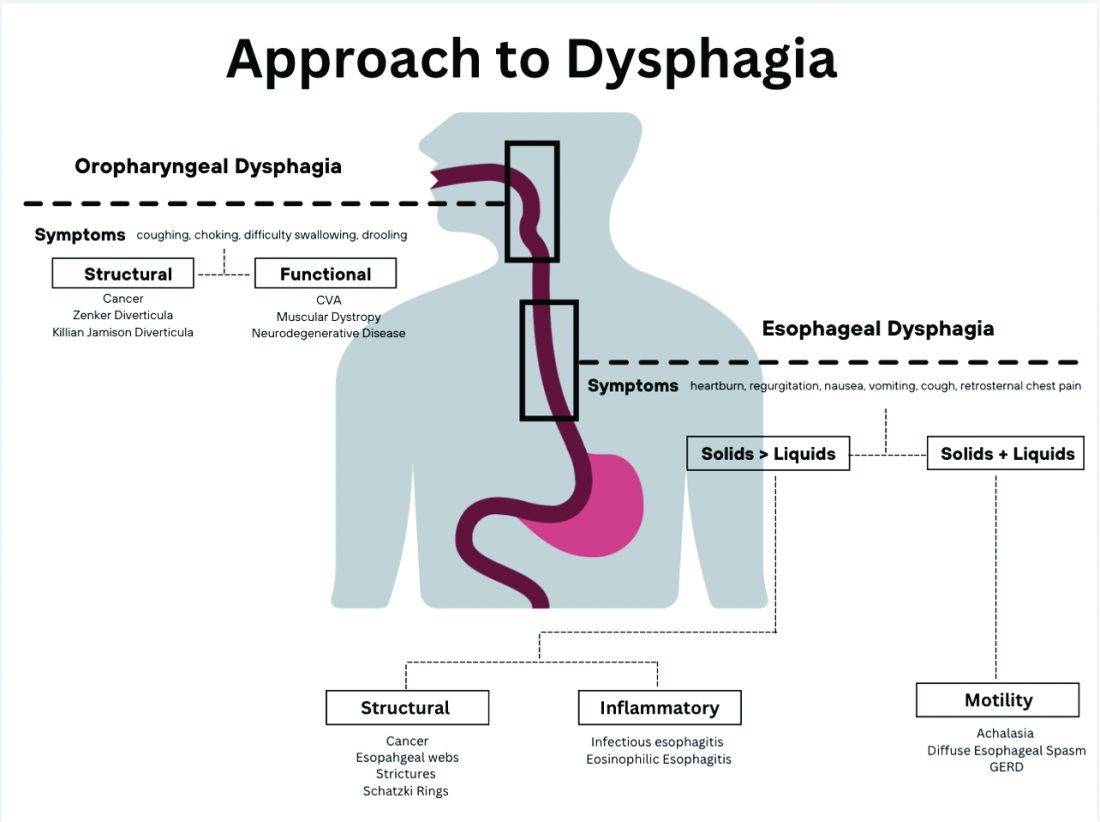

The diagnosis of esophageal dysphagia can be challenging. An initial, thorough history is essential to delineate between oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia and guide subsequent diagnostic testing. In recent years, there have been a number of advances in the approach to diagnosing dysphagia, including novel diagnostic modalities. The goal of this review article is to discuss the current approach to esophageal dysphagia and future direction to allow for timely diagnosis and management.

History

The diagnosis of dysphagia begins with a thorough history. Questions about the timing, onset, progression, localization of symptoms, and types of food that are difficult to swallow are essential in differentiating oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia.3,4 Further history taking must include medication and allergy review, smoking history, and review of prior radiation or surgical therapies to the head and neck.

Briefly, oropharyngeal dysphagia is difficulty initiating a swallow or passing food from the mouth or throat and can be caused by structural or functional etiologies.5 Clinical presentations include a sensation of food stuck in the back of the throat, coughing or choking while eating, or drooling. Structural causes include head and neck cancer, Zenker diverticulum, Killian Jamieson diverticula, prolonged intubation, or changes secondary to prior surgery or radiation.3 Functional causes may include neurologic, rheumatologic, or muscular disorders.6

Esophageal dysphagia refers to difficulty transporting food or liquid down the esophagus and can be caused by structural, inflammatory, or functional disorders.5 Patients typically localize symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, cough, or chest pain along the sternum or epigastric region. Alarm signs concerning for malignancy include unintentional weight loss, fevers, or night sweats.3,7 Aside from symptoms, medication review is essential, as dysphagia is a common side effect of antipsychotics, anticholinergics, antimuscarinics, narcotics, and immunosuppressant drugs.8 Larger pills such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, bisphosphonates, potassium supplements, and methylxanthines can cause drug-induced esophagitis, which can initially present as dysphagia.8 Inflammatory causes can be elucidated by obtaining a history about allergies, tobacco use, and recent infections such as thrush or pneumonia. Patients with a history of recurrent pneumonias may be silently aspirating, a complication of dysphagia.3 Once esophageal dysphagia is clinically suspected based on history, workup can begin.

Differentiating etiologies of esophageal dysphagia

The next step in diagnosing esophageal dysphagia is differentiating between structural, inflammatory, or dysmotility etiology (Figure 1).

Patients with a structural cause typically have difficulty swallowing solids but are able to swallow liquids unless the disease progresses. Symptoms can rapidly worsen and lead to odynophagia, weight loss, and vomiting. In comparison, patients with motility disorders typically have difficulty swallowing both solids and liquids initially, and symptoms can be constant or intermittent.5

Prior to diagnostic studies, a 4-week trial of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is appropriate for patients with reflux symptoms who are younger than 50 with no alarm features concerning for malignancy.7,9 If symptoms persist after a PPI trial, then an upper endoscopy (EGD) is indicated. An EGD allows for visualization of structural etiologies, obtaining biopsies to rule out inflammatory etiologies, and the option to therapeutically treat reduced luminal diameter with dilatation.10 The most common structural and inflammatory etiologies noted on EGD include strictures, webs, carcinomas, Schatzki rings, and gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis.4

If upper endoscopy is normal and clinical suspicion for an obstructive cause remains high, barium esophagram can be utilized as an adjunctive study. Previously, barium esophagram was the initial test to distinguish between structural and motility disorders. The benefits of endoscopy over barium esophagram as the first diagnostic study include higher diagnostic yield, higher sensitivity and specificity, and lower costs.7 However, barium studies may be more sensitive for lower esophageal rings or extrinsic esophageal compression.3

Evaluation of esophageal motility disorder