User login

To Vaccinate, or Not, in Patients With MS

Q) Are vaccines safe for patients with multiple sclerosis?

Vaccines are an important component of general disease prevention and are especially useful for patients with chronic illnesses, such as MS, who may be at elevated risk due to disability or medications that alter the immune system. Currently, there are many disease-modifying therapies that attempt to reduce relapses and impact the immune system, MRI activity, and disability. But is it safe for patients with MS to receive vaccines, given the multitude of studies suggesting that infections may increase relapse rate?

In 2002, the American Academy of Neurology published a summary of evidence and recommendations to provide guidance for practitioners.1 The data showed an increased risk for MS relapse during the weeks following infection.2,3 Therefore, preventing infections is beneficial for patients with MS. An analysis of studies in patients with MS who were vaccinated with inactivated vaccines (influenza, hepatitis B, tetanus) found sufficient evidence to support this practice. Studies of patients with MS who were given attenuated vaccines did not find enough evidence to support or reject these vaccines, except in the case of varicella. A study with sufficient follow-up concluded that varicella vaccination was safe for patients with MS who were not immunosuppressed. As a result of this effort, the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines recommends that patients and health care providers follow the CDC’s indications for immunizations (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html).1

On the other hand, administration of the live-virus yellow fever vaccine in patients with clinically relapsing MS was correlated with an increased risk for disease progression in one study.4 The researchers followed disease progression, measured by relapses and MRI activity, in patients taking glatiramer acetate and interferon ß. Relapse rates reached 8.57 within three months after vaccination, compared to a rate of 0.67 the year prior to vaccine administration. Additionally, significant changes were seen on MRI; new or enlarging T2-weighted lesions and gadolinium-enhancing lesions were observed at three months, compared to 12 months prior and nine months after.4 Therefore, the researchers concluded that patients with MS traveling to endemic yellow fever areas should be cautioned regarding the risk for disease progression with vaccination, versus the risk for exposure to yellow fever.

Over the past decade, as newer therapies with different mechanisms of action have become available, concern has risen that patients may not respond to immunizations or may have a higher risk for infection after vaccination. For that reason, several studies have evaluated the ability of patients with MS to mount a normal antibody and cellular immune response after vaccine administration. In 2016, a study by Lin et al determined that patients who received daclizumab were able to mount a normal response after influenza vaccination.5

By contrast, Kappos et al, in a 2015 study, found that patients receiving fingolimod had lower response rates to influenza and tetanus booster vaccines than patients who took a placebo.6 Similarly, in a 2014 study, Olberg et al examined patients receiving interferon ß, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, and mitoxantrone after receiving influenza and H1N1 vaccinations. The researchers found that those treated with any therapy other than interferon ß had a reduced rate of response and should therefore be considered for vaccine response analysis.7 Bar-Or et al also published data on response rates of patients treated with teriflunomide (7 mg or 14 mg) or interferon ß; rates were reduced with 14-mg teriflunomide compared to the other treatments—but most patients exhibited seroprotection regardless.8 Studying vaccine efficacy in 2013, McCarthy et al evaluated serum antibodies against common viruses before and after treatment with alemtuzumab and found that antibodies remained detectable six months post-alemtuzumab.9

In summary, most specialists agree that vaccines are helpful for patients with MS. However, due to the varied response rates among disease-modifying therapies and the correlation between infection and increased relapse rates, special care should be taken when treating this population. Generally, inactivated vaccines are safe, but seroprotection should be established to determine if a booster is necessary. Attenuated vaccines are generally safe for patients who are not immunosuppressed and can reduce the risk for infection if given prior to immunosuppression. After immunosuppression, attenuated vaccines should not be given until immune recovery has been established. —PP

Patricia Pagnotta, ARNP, MSN, CNRN, MSCN

Neurology Associates, PA

MS Center of Greater Orlando

1. Rutschmann OT, McCrory DC, Matchar DB. Immunization and MS: a summary of published evidence and recommendations. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1837-1843.

2. Anderson O, Lygner PE, Bergstrom T, et al. Viral infections trigger multiple sclerosis relapses: a prospective seroepidemiological study. J Neurol. 1993;240(7):417-422.

3. Panitch HS, Bever CT, Katz E, Johnson KP. Upper respiratory tract infections trigger attacks of multiple sclerosis in patients treated with interferon. J Neuroimmunol. 1991; 36:125.

4. Farez MF, Correale J. Yellow fever vaccination and increased relapse rate in travelers with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(10):1267-1271.

5. Lin YC, Winokur P, Blake A, et al. Patients with MS under daclizumab therapy mount normal immune responses to influenza vaccine. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016;3(1):1-10.

6. Kappos L, Mehling M, Arroyo R, et al. Randomized trial of vaccination in fingolimod-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84(9):872-879.

7. Olberg HK, Cox RJ, Nostbakken JK, et al. Immunotherapies influence the influenza vaccination response in multiple sclerosis patients: an explorative study. Mult Scler. 2014;20(8):1074-1080.

8. Bar-Or A, Freedman MS, Kremenchutzky M, et al. Teriflunomide effect on immune response to influenza vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(6):552-558.

9. McCarthy CL, Tuohy O, Compston DA, et al. Immune competence after alemtuzumab treatment of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(10):872-876.

Q) Are vaccines safe for patients with multiple sclerosis?

Vaccines are an important component of general disease prevention and are especially useful for patients with chronic illnesses, such as MS, who may be at elevated risk due to disability or medications that alter the immune system. Currently, there are many disease-modifying therapies that attempt to reduce relapses and impact the immune system, MRI activity, and disability. But is it safe for patients with MS to receive vaccines, given the multitude of studies suggesting that infections may increase relapse rate?

In 2002, the American Academy of Neurology published a summary of evidence and recommendations to provide guidance for practitioners.1 The data showed an increased risk for MS relapse during the weeks following infection.2,3 Therefore, preventing infections is beneficial for patients with MS. An analysis of studies in patients with MS who were vaccinated with inactivated vaccines (influenza, hepatitis B, tetanus) found sufficient evidence to support this practice. Studies of patients with MS who were given attenuated vaccines did not find enough evidence to support or reject these vaccines, except in the case of varicella. A study with sufficient follow-up concluded that varicella vaccination was safe for patients with MS who were not immunosuppressed. As a result of this effort, the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines recommends that patients and health care providers follow the CDC’s indications for immunizations (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html).1

On the other hand, administration of the live-virus yellow fever vaccine in patients with clinically relapsing MS was correlated with an increased risk for disease progression in one study.4 The researchers followed disease progression, measured by relapses and MRI activity, in patients taking glatiramer acetate and interferon ß. Relapse rates reached 8.57 within three months after vaccination, compared to a rate of 0.67 the year prior to vaccine administration. Additionally, significant changes were seen on MRI; new or enlarging T2-weighted lesions and gadolinium-enhancing lesions were observed at three months, compared to 12 months prior and nine months after.4 Therefore, the researchers concluded that patients with MS traveling to endemic yellow fever areas should be cautioned regarding the risk for disease progression with vaccination, versus the risk for exposure to yellow fever.

Over the past decade, as newer therapies with different mechanisms of action have become available, concern has risen that patients may not respond to immunizations or may have a higher risk for infection after vaccination. For that reason, several studies have evaluated the ability of patients with MS to mount a normal antibody and cellular immune response after vaccine administration. In 2016, a study by Lin et al determined that patients who received daclizumab were able to mount a normal response after influenza vaccination.5

By contrast, Kappos et al, in a 2015 study, found that patients receiving fingolimod had lower response rates to influenza and tetanus booster vaccines than patients who took a placebo.6 Similarly, in a 2014 study, Olberg et al examined patients receiving interferon ß, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, and mitoxantrone after receiving influenza and H1N1 vaccinations. The researchers found that those treated with any therapy other than interferon ß had a reduced rate of response and should therefore be considered for vaccine response analysis.7 Bar-Or et al also published data on response rates of patients treated with teriflunomide (7 mg or 14 mg) or interferon ß; rates were reduced with 14-mg teriflunomide compared to the other treatments—but most patients exhibited seroprotection regardless.8 Studying vaccine efficacy in 2013, McCarthy et al evaluated serum antibodies against common viruses before and after treatment with alemtuzumab and found that antibodies remained detectable six months post-alemtuzumab.9

In summary, most specialists agree that vaccines are helpful for patients with MS. However, due to the varied response rates among disease-modifying therapies and the correlation between infection and increased relapse rates, special care should be taken when treating this population. Generally, inactivated vaccines are safe, but seroprotection should be established to determine if a booster is necessary. Attenuated vaccines are generally safe for patients who are not immunosuppressed and can reduce the risk for infection if given prior to immunosuppression. After immunosuppression, attenuated vaccines should not be given until immune recovery has been established. —PP

Patricia Pagnotta, ARNP, MSN, CNRN, MSCN

Neurology Associates, PA

MS Center of Greater Orlando

Q) Are vaccines safe for patients with multiple sclerosis?

Vaccines are an important component of general disease prevention and are especially useful for patients with chronic illnesses, such as MS, who may be at elevated risk due to disability or medications that alter the immune system. Currently, there are many disease-modifying therapies that attempt to reduce relapses and impact the immune system, MRI activity, and disability. But is it safe for patients with MS to receive vaccines, given the multitude of studies suggesting that infections may increase relapse rate?

In 2002, the American Academy of Neurology published a summary of evidence and recommendations to provide guidance for practitioners.1 The data showed an increased risk for MS relapse during the weeks following infection.2,3 Therefore, preventing infections is beneficial for patients with MS. An analysis of studies in patients with MS who were vaccinated with inactivated vaccines (influenza, hepatitis B, tetanus) found sufficient evidence to support this practice. Studies of patients with MS who were given attenuated vaccines did not find enough evidence to support or reject these vaccines, except in the case of varicella. A study with sufficient follow-up concluded that varicella vaccination was safe for patients with MS who were not immunosuppressed. As a result of this effort, the MS Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines recommends that patients and health care providers follow the CDC’s indications for immunizations (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/adult.html).1

On the other hand, administration of the live-virus yellow fever vaccine in patients with clinically relapsing MS was correlated with an increased risk for disease progression in one study.4 The researchers followed disease progression, measured by relapses and MRI activity, in patients taking glatiramer acetate and interferon ß. Relapse rates reached 8.57 within three months after vaccination, compared to a rate of 0.67 the year prior to vaccine administration. Additionally, significant changes were seen on MRI; new or enlarging T2-weighted lesions and gadolinium-enhancing lesions were observed at three months, compared to 12 months prior and nine months after.4 Therefore, the researchers concluded that patients with MS traveling to endemic yellow fever areas should be cautioned regarding the risk for disease progression with vaccination, versus the risk for exposure to yellow fever.

Over the past decade, as newer therapies with different mechanisms of action have become available, concern has risen that patients may not respond to immunizations or may have a higher risk for infection after vaccination. For that reason, several studies have evaluated the ability of patients with MS to mount a normal antibody and cellular immune response after vaccine administration. In 2016, a study by Lin et al determined that patients who received daclizumab were able to mount a normal response after influenza vaccination.5

By contrast, Kappos et al, in a 2015 study, found that patients receiving fingolimod had lower response rates to influenza and tetanus booster vaccines than patients who took a placebo.6 Similarly, in a 2014 study, Olberg et al examined patients receiving interferon ß, glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, and mitoxantrone after receiving influenza and H1N1 vaccinations. The researchers found that those treated with any therapy other than interferon ß had a reduced rate of response and should therefore be considered for vaccine response analysis.7 Bar-Or et al also published data on response rates of patients treated with teriflunomide (7 mg or 14 mg) or interferon ß; rates were reduced with 14-mg teriflunomide compared to the other treatments—but most patients exhibited seroprotection regardless.8 Studying vaccine efficacy in 2013, McCarthy et al evaluated serum antibodies against common viruses before and after treatment with alemtuzumab and found that antibodies remained detectable six months post-alemtuzumab.9

In summary, most specialists agree that vaccines are helpful for patients with MS. However, due to the varied response rates among disease-modifying therapies and the correlation between infection and increased relapse rates, special care should be taken when treating this population. Generally, inactivated vaccines are safe, but seroprotection should be established to determine if a booster is necessary. Attenuated vaccines are generally safe for patients who are not immunosuppressed and can reduce the risk for infection if given prior to immunosuppression. After immunosuppression, attenuated vaccines should not be given until immune recovery has been established. —PP

Patricia Pagnotta, ARNP, MSN, CNRN, MSCN

Neurology Associates, PA

MS Center of Greater Orlando

1. Rutschmann OT, McCrory DC, Matchar DB. Immunization and MS: a summary of published evidence and recommendations. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1837-1843.

2. Anderson O, Lygner PE, Bergstrom T, et al. Viral infections trigger multiple sclerosis relapses: a prospective seroepidemiological study. J Neurol. 1993;240(7):417-422.

3. Panitch HS, Bever CT, Katz E, Johnson KP. Upper respiratory tract infections trigger attacks of multiple sclerosis in patients treated with interferon. J Neuroimmunol. 1991; 36:125.

4. Farez MF, Correale J. Yellow fever vaccination and increased relapse rate in travelers with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(10):1267-1271.

5. Lin YC, Winokur P, Blake A, et al. Patients with MS under daclizumab therapy mount normal immune responses to influenza vaccine. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016;3(1):1-10.

6. Kappos L, Mehling M, Arroyo R, et al. Randomized trial of vaccination in fingolimod-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84(9):872-879.

7. Olberg HK, Cox RJ, Nostbakken JK, et al. Immunotherapies influence the influenza vaccination response in multiple sclerosis patients: an explorative study. Mult Scler. 2014;20(8):1074-1080.

8. Bar-Or A, Freedman MS, Kremenchutzky M, et al. Teriflunomide effect on immune response to influenza vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(6):552-558.

9. McCarthy CL, Tuohy O, Compston DA, et al. Immune competence after alemtuzumab treatment of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(10):872-876.

1. Rutschmann OT, McCrory DC, Matchar DB. Immunization and MS: a summary of published evidence and recommendations. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1837-1843.

2. Anderson O, Lygner PE, Bergstrom T, et al. Viral infections trigger multiple sclerosis relapses: a prospective seroepidemiological study. J Neurol. 1993;240(7):417-422.

3. Panitch HS, Bever CT, Katz E, Johnson KP. Upper respiratory tract infections trigger attacks of multiple sclerosis in patients treated with interferon. J Neuroimmunol. 1991; 36:125.

4. Farez MF, Correale J. Yellow fever vaccination and increased relapse rate in travelers with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(10):1267-1271.

5. Lin YC, Winokur P, Blake A, et al. Patients with MS under daclizumab therapy mount normal immune responses to influenza vaccine. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016;3(1):1-10.

6. Kappos L, Mehling M, Arroyo R, et al. Randomized trial of vaccination in fingolimod-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2015;84(9):872-879.

7. Olberg HK, Cox RJ, Nostbakken JK, et al. Immunotherapies influence the influenza vaccination response in multiple sclerosis patients: an explorative study. Mult Scler. 2014;20(8):1074-1080.

8. Bar-Or A, Freedman MS, Kremenchutzky M, et al. Teriflunomide effect on immune response to influenza vaccine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(6):552-558.

9. McCarthy CL, Tuohy O, Compston DA, et al. Immune competence after alemtuzumab treatment of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(10):872-876.

Fighting Fatigue in MS

Q) Why do my patients with multiple sclerosis experience so much fatigue, and what can I do to help them?

Fatigue is an extremely common symptom of multiple sclerosis (MS) and one of the most disabling complications of the disease.1 More than 75% of patients with MS experience fatigue, which can worsen motor function, sleep quality, mood, and overall quality of life.1,2 Fatigue can also adversely affect employment; among patients with MS who reduce their work hours from full- to part-time, 90% do so because of fatigue.3

The

Patients with MS may have primary or secondary causes of fatigue. Primary fatigue is believed to result from the disease itself. Although it is not well understood, one hypothesis suggests that it is caused by an immune-related process involving inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration.7 Another theory relates it to impaired nerve conduction.8

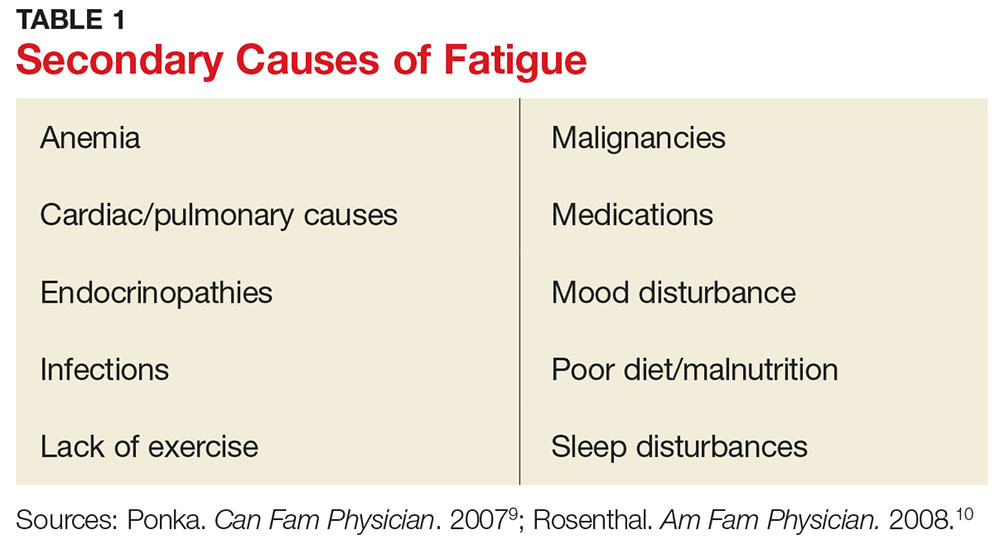

Secondary fatigue is unrelated to MS itself, and it is often treatable. Common causes include anemia, infection, or insomnia (see Table 1).9,10 These possibilities should be considered and ruled out in all patients with MS who complain of fatigue. A comprehensive history, exam, and evaluation performed by the clinician may help identify alternative reasons for fatigue.

Once any secondary causes have been addressed, primary fatigue should be evaluated and managed. One method for assessing the severity of fatigue and its impact on functional disability is to discuss it with the patient. The Fatigue Severity Scale can also be used as a measure; this self-assessment is quick, easy, and can be downloaded for free at www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf.11Identifying potential triggers of fatigue can help clinicians develop appropriate interventions. Heat intolerance is common and can precipitate or contribute to fatigue; cooling equipment can be a helpful solution (see Figure). Urinary tract infections frequently cause fatigue and can exacerbate many symptoms of MS. Bladder dysfunction and subsequent nocturnal wakening may contribute to the problem. Psychological stress is another common trigger; managing it can reduce fatigue.1,12 Screening for depression in patients with MS who complain of fatigue is imperative; if diagnosed, it must be addressed as the first line of treatment.1

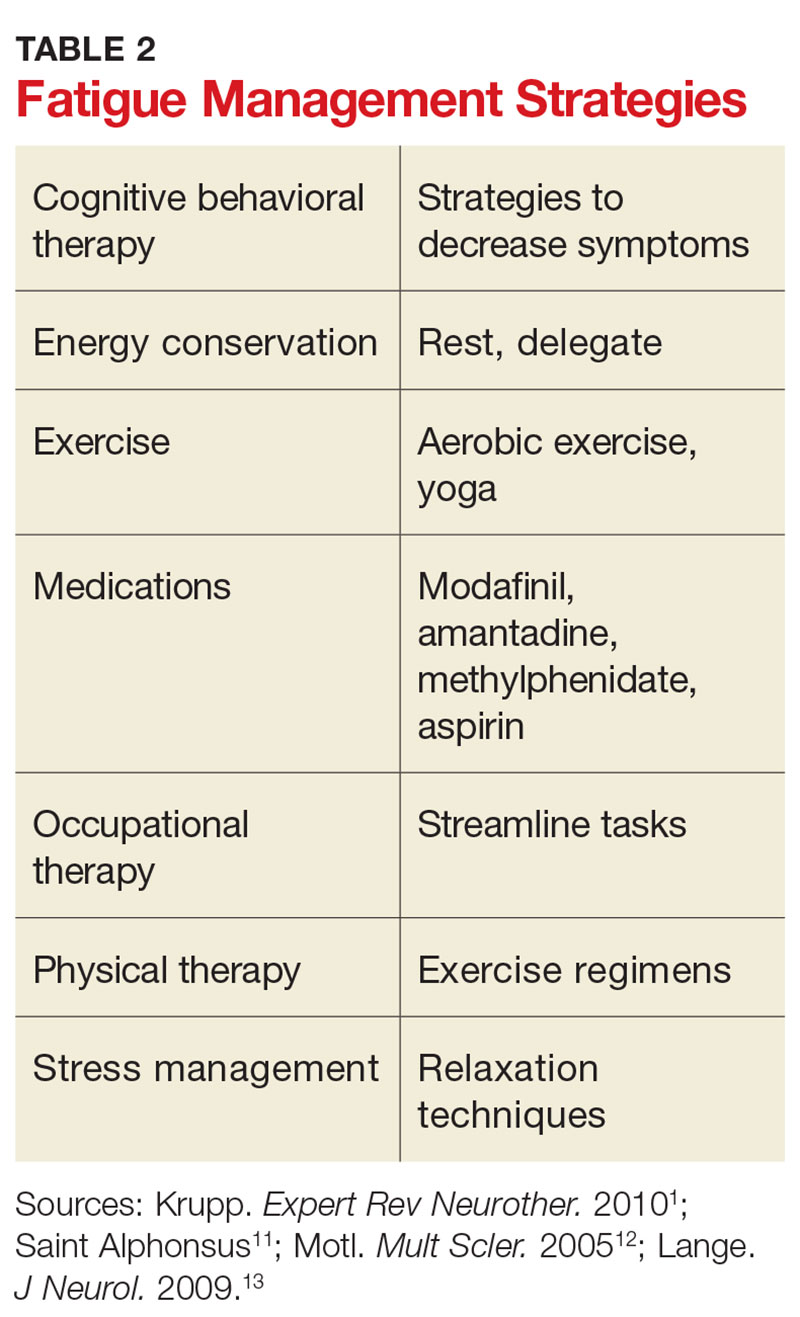

Other clinician-initiated intervention strategies include exercise, therapy, and medication. Modafinil is frequently prescribed for MS fatigue; small trials have demonstrated dramatic improvements with its use.13 Interestingly, aspirin has been shown to reduce fatigue in randomized controlled trials.14 This may be due to its indirect effects on neuroendocrine and autonomic responses, both of which are involved in the perception of fatigue.14 Additional interventions are listed in Table 2. As always, before prescribing any new medication, ensure that it is appropriate and that the patient’s other medical providers agree to the plan.

Counsel patients by emphasizing the importance of good sleep hygiene, a healthy diet, and avoidance of unhealthy habits. Taking an interdisciplinary approach can help patients with MS receive the best possible health care. While you may not be treating your patient’s disease, you will be managing much of his or her health care; treating the underlying causes of fatigue can significantly improve quality of life. —SA

Stephanie Agrella, MSN, RN, APRN, ANP-BC, MSCN

Director of Clinical Services, Multiple Scerlosis Clinic of Central Texas, Round Rock

1. Krupp B, Serafin D, Christodoulou C. Multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(9):1437-1447.

2. Krupp L. Fatigue is intrinsic to multiple sclerosis (MS) and is the most commonly reported symptom of the disease. Mult Scler. 2006;12(4):367-368.

3. Dennett SL, Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MK. The impact of multiple sclerosis on patient employment: a review of the medical literature. J Health Productivity. 2007;2(2):12-18.

4. Fatigue Guidelines Development Panel of the Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence-based Management Strategies for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

5. Kalb R. Multiple Sclerosis: The Questions You Have—The Answers You Need. New York, NY: Demos; 2012.

6. Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(4):435-437.

7. Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, Zettl UK. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: a review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(3):210-220.

8. Davis S, Wilson T, White A, Frohman E. Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis. J Appl Physiol. 2016;109(5):1531-1537.

9. Ponka D, Kirlew M. Top 10 differential diagnoses in family medicine: fatigue. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(5):892.

10. Rosenthal TC, Majeroni BA, Pretorius R, Malik K. Fatigue: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(10):1173-1179.

11. Saint Alphonsus. Fatigue severity scale. www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2017.

12. Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):459-463.

13. Lange R, Volkmer M, Heesen C, Liepert J. Modafinil effects in multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. J Neurol. 2009; 256(4):645-650.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.

Q) Why do my patients with multiple sclerosis experience so much fatigue, and what can I do to help them?

Fatigue is an extremely common symptom of multiple sclerosis (MS) and one of the most disabling complications of the disease.1 More than 75% of patients with MS experience fatigue, which can worsen motor function, sleep quality, mood, and overall quality of life.1,2 Fatigue can also adversely affect employment; among patients with MS who reduce their work hours from full- to part-time, 90% do so because of fatigue.3

The

Patients with MS may have primary or secondary causes of fatigue. Primary fatigue is believed to result from the disease itself. Although it is not well understood, one hypothesis suggests that it is caused by an immune-related process involving inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration.7 Another theory relates it to impaired nerve conduction.8

Secondary fatigue is unrelated to MS itself, and it is often treatable. Common causes include anemia, infection, or insomnia (see Table 1).9,10 These possibilities should be considered and ruled out in all patients with MS who complain of fatigue. A comprehensive history, exam, and evaluation performed by the clinician may help identify alternative reasons for fatigue.

Once any secondary causes have been addressed, primary fatigue should be evaluated and managed. One method for assessing the severity of fatigue and its impact on functional disability is to discuss it with the patient. The Fatigue Severity Scale can also be used as a measure; this self-assessment is quick, easy, and can be downloaded for free at www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf.11Identifying potential triggers of fatigue can help clinicians develop appropriate interventions. Heat intolerance is common and can precipitate or contribute to fatigue; cooling equipment can be a helpful solution (see Figure). Urinary tract infections frequently cause fatigue and can exacerbate many symptoms of MS. Bladder dysfunction and subsequent nocturnal wakening may contribute to the problem. Psychological stress is another common trigger; managing it can reduce fatigue.1,12 Screening for depression in patients with MS who complain of fatigue is imperative; if diagnosed, it must be addressed as the first line of treatment.1

Other clinician-initiated intervention strategies include exercise, therapy, and medication. Modafinil is frequently prescribed for MS fatigue; small trials have demonstrated dramatic improvements with its use.13 Interestingly, aspirin has been shown to reduce fatigue in randomized controlled trials.14 This may be due to its indirect effects on neuroendocrine and autonomic responses, both of which are involved in the perception of fatigue.14 Additional interventions are listed in Table 2. As always, before prescribing any new medication, ensure that it is appropriate and that the patient’s other medical providers agree to the plan.

Counsel patients by emphasizing the importance of good sleep hygiene, a healthy diet, and avoidance of unhealthy habits. Taking an interdisciplinary approach can help patients with MS receive the best possible health care. While you may not be treating your patient’s disease, you will be managing much of his or her health care; treating the underlying causes of fatigue can significantly improve quality of life. —SA

Stephanie Agrella, MSN, RN, APRN, ANP-BC, MSCN

Director of Clinical Services, Multiple Scerlosis Clinic of Central Texas, Round Rock

Q) Why do my patients with multiple sclerosis experience so much fatigue, and what can I do to help them?

Fatigue is an extremely common symptom of multiple sclerosis (MS) and one of the most disabling complications of the disease.1 More than 75% of patients with MS experience fatigue, which can worsen motor function, sleep quality, mood, and overall quality of life.1,2 Fatigue can also adversely affect employment; among patients with MS who reduce their work hours from full- to part-time, 90% do so because of fatigue.3

The

Patients with MS may have primary or secondary causes of fatigue. Primary fatigue is believed to result from the disease itself. Although it is not well understood, one hypothesis suggests that it is caused by an immune-related process involving inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration.7 Another theory relates it to impaired nerve conduction.8

Secondary fatigue is unrelated to MS itself, and it is often treatable. Common causes include anemia, infection, or insomnia (see Table 1).9,10 These possibilities should be considered and ruled out in all patients with MS who complain of fatigue. A comprehensive history, exam, and evaluation performed by the clinician may help identify alternative reasons for fatigue.

Once any secondary causes have been addressed, primary fatigue should be evaluated and managed. One method for assessing the severity of fatigue and its impact on functional disability is to discuss it with the patient. The Fatigue Severity Scale can also be used as a measure; this self-assessment is quick, easy, and can be downloaded for free at www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf.11Identifying potential triggers of fatigue can help clinicians develop appropriate interventions. Heat intolerance is common and can precipitate or contribute to fatigue; cooling equipment can be a helpful solution (see Figure). Urinary tract infections frequently cause fatigue and can exacerbate many symptoms of MS. Bladder dysfunction and subsequent nocturnal wakening may contribute to the problem. Psychological stress is another common trigger; managing it can reduce fatigue.1,12 Screening for depression in patients with MS who complain of fatigue is imperative; if diagnosed, it must be addressed as the first line of treatment.1

Other clinician-initiated intervention strategies include exercise, therapy, and medication. Modafinil is frequently prescribed for MS fatigue; small trials have demonstrated dramatic improvements with its use.13 Interestingly, aspirin has been shown to reduce fatigue in randomized controlled trials.14 This may be due to its indirect effects on neuroendocrine and autonomic responses, both of which are involved in the perception of fatigue.14 Additional interventions are listed in Table 2. As always, before prescribing any new medication, ensure that it is appropriate and that the patient’s other medical providers agree to the plan.

Counsel patients by emphasizing the importance of good sleep hygiene, a healthy diet, and avoidance of unhealthy habits. Taking an interdisciplinary approach can help patients with MS receive the best possible health care. While you may not be treating your patient’s disease, you will be managing much of his or her health care; treating the underlying causes of fatigue can significantly improve quality of life. —SA

Stephanie Agrella, MSN, RN, APRN, ANP-BC, MSCN

Director of Clinical Services, Multiple Scerlosis Clinic of Central Texas, Round Rock

1. Krupp B, Serafin D, Christodoulou C. Multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(9):1437-1447.

2. Krupp L. Fatigue is intrinsic to multiple sclerosis (MS) and is the most commonly reported symptom of the disease. Mult Scler. 2006;12(4):367-368.

3. Dennett SL, Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MK. The impact of multiple sclerosis on patient employment: a review of the medical literature. J Health Productivity. 2007;2(2):12-18.

4. Fatigue Guidelines Development Panel of the Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence-based Management Strategies for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

5. Kalb R. Multiple Sclerosis: The Questions You Have—The Answers You Need. New York, NY: Demos; 2012.

6. Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(4):435-437.

7. Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, Zettl UK. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: a review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(3):210-220.

8. Davis S, Wilson T, White A, Frohman E. Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis. J Appl Physiol. 2016;109(5):1531-1537.

9. Ponka D, Kirlew M. Top 10 differential diagnoses in family medicine: fatigue. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(5):892.

10. Rosenthal TC, Majeroni BA, Pretorius R, Malik K. Fatigue: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(10):1173-1179.

11. Saint Alphonsus. Fatigue severity scale. www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2017.

12. Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):459-463.

13. Lange R, Volkmer M, Heesen C, Liepert J. Modafinil effects in multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. J Neurol. 2009; 256(4):645-650.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.

1. Krupp B, Serafin D, Christodoulou C. Multiple sclerosis-associated fatigue. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(9):1437-1447.

2. Krupp L. Fatigue is intrinsic to multiple sclerosis (MS) and is the most commonly reported symptom of the disease. Mult Scler. 2006;12(4):367-368.

3. Dennett SL, Castelli-Haley J, Oleen-Burkey MK. The impact of multiple sclerosis on patient employment: a review of the medical literature. J Health Productivity. 2007;2(2):12-18.

4. Fatigue Guidelines Development Panel of the Multiple Sclerosis Council for Clinical Practice Guidelines. Fatigue and Multiple Sclerosis: Evidence-based Management Strategies for Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

5. Kalb R. Multiple Sclerosis: The Questions You Have—The Answers You Need. New York, NY: Demos; 2012.

6. Krupp LB, Alvarez LA, LaRocca NG, Scheinberg LC. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(4):435-437.

7. Patejdl R, Penner IK, Noack TK, Zettl UK. Multiple sclerosis and fatigue: a review on the contribution of inflammation and immune-mediated neurodegeneration. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(3):210-220.

8. Davis S, Wilson T, White A, Frohman E. Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis. J Appl Physiol. 2016;109(5):1531-1537.

9. Ponka D, Kirlew M. Top 10 differential diagnoses in family medicine: fatigue. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(5):892.

10. Rosenthal TC, Majeroni BA, Pretorius R, Malik K. Fatigue: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(10):1173-1179.

11. Saint Alphonsus. Fatigue severity scale. www.saintalphonsus.org/documents/boise/sleep-Fatigue-Severity-Scale.pdf. Accessed May 16, 2017.

12. Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM. Physical activity and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(4):459-463.

13. Lange R, Volkmer M, Heesen C, Liepert J. Modafinil effects in multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. J Neurol. 2009; 256(4):645-650.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Benarroch EE, O’Brien PC, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of aspirin for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1267-1269.

Factors tied to parents’ intent to vaccinate teens for HPV

in a large study, said Kahee A. Mohammed, MD, of Saint Louis (Missouri) University Center for Outcomes Research, and associates.

Messages to boost HPV vaccination rates may need to be targeted based on maternal education, non-Hispanic white ethnicity, and provider recommendations, the researchers said.

Among unvaccinated girls, independent variables predicting parents’ intent to vaccinate teens for HPV were Hispanic race/ethnicity (AOR, 1.57), compared with non-Hispanic whites; mothers with less than a high school diploma (AOR, 1.86), compared with mothers with a college education; and a provider recommendation for HPV vaccine (AOR, 1.38).

Also, mothers with some college education were more likely to intend to vaccinate their sons (AOR, 1.21), but less likely to intend to vaccinate their daughters (AOR, .69) than mothers with a college education.

About 7% of the survey respondents said “not sure/don’t know” regarding their intent to vaccinate their teens. The largest percentage had boys (66%), were non-Hispanic whites (47%), lived in the South (38%), lived above the poverty line (62%), the mother was a college graduate (31%), and had never received a recommendation for HPV vaccination from a health care provider (75%).

“Health care providers should actively engage in discussions with parents about HPV and strongly recommend the vaccine to all eligible patients concurrently with other routinely administered vaccinations to dispel any potential negative assumptions or opinions regarding HPV vaccination, especially among girls,” Dr. Mohammed and his associates said.

Read more at (Prev Chronic Dis. 2017. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160314).

in a large study, said Kahee A. Mohammed, MD, of Saint Louis (Missouri) University Center for Outcomes Research, and associates.

Messages to boost HPV vaccination rates may need to be targeted based on maternal education, non-Hispanic white ethnicity, and provider recommendations, the researchers said.

Among unvaccinated girls, independent variables predicting parents’ intent to vaccinate teens for HPV were Hispanic race/ethnicity (AOR, 1.57), compared with non-Hispanic whites; mothers with less than a high school diploma (AOR, 1.86), compared with mothers with a college education; and a provider recommendation for HPV vaccine (AOR, 1.38).

Also, mothers with some college education were more likely to intend to vaccinate their sons (AOR, 1.21), but less likely to intend to vaccinate their daughters (AOR, .69) than mothers with a college education.

About 7% of the survey respondents said “not sure/don’t know” regarding their intent to vaccinate their teens. The largest percentage had boys (66%), were non-Hispanic whites (47%), lived in the South (38%), lived above the poverty line (62%), the mother was a college graduate (31%), and had never received a recommendation for HPV vaccination from a health care provider (75%).

“Health care providers should actively engage in discussions with parents about HPV and strongly recommend the vaccine to all eligible patients concurrently with other routinely administered vaccinations to dispel any potential negative assumptions or opinions regarding HPV vaccination, especially among girls,” Dr. Mohammed and his associates said.

Read more at (Prev Chronic Dis. 2017. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160314).

in a large study, said Kahee A. Mohammed, MD, of Saint Louis (Missouri) University Center for Outcomes Research, and associates.

Messages to boost HPV vaccination rates may need to be targeted based on maternal education, non-Hispanic white ethnicity, and provider recommendations, the researchers said.

Among unvaccinated girls, independent variables predicting parents’ intent to vaccinate teens for HPV were Hispanic race/ethnicity (AOR, 1.57), compared with non-Hispanic whites; mothers with less than a high school diploma (AOR, 1.86), compared with mothers with a college education; and a provider recommendation for HPV vaccine (AOR, 1.38).

Also, mothers with some college education were more likely to intend to vaccinate their sons (AOR, 1.21), but less likely to intend to vaccinate their daughters (AOR, .69) than mothers with a college education.

About 7% of the survey respondents said “not sure/don’t know” regarding their intent to vaccinate their teens. The largest percentage had boys (66%), were non-Hispanic whites (47%), lived in the South (38%), lived above the poverty line (62%), the mother was a college graduate (31%), and had never received a recommendation for HPV vaccination from a health care provider (75%).

“Health care providers should actively engage in discussions with parents about HPV and strongly recommend the vaccine to all eligible patients concurrently with other routinely administered vaccinations to dispel any potential negative assumptions or opinions regarding HPV vaccination, especially among girls,” Dr. Mohammed and his associates said.

Read more at (Prev Chronic Dis. 2017. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160314).

FROM PREVENTING CHRONIC DISEASE

It matters how you phrase a child’s flu vaccine recommendation

Vaccine hesitant parents were more likely to change their minds about flu vaccine for their children when pediatricians or pediatric nurse practitioners used a presumptive recommendation that their children get the vaccine, pursued the recommendation if the parent was resistant, and combined their recommendation for the flu vaccine with other childhood vaccines, said Annika M. Hofstetter, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates.

The researchers recruited 17 pediatricians and pediatric nurse practitioners from eight primary care pediatric practices in the Seattle area to take part in 50 videotaped visits with parents during the 2011-2012 and 2013-2014 flu seasons.

(83% vs. 33%; P less than .01), Dr. Hofstetter and her colleagues said. The various communication patterns did not appear to negatively affect the way parents rated their visit experiences.

Read more at Vaccine. 2017;35:2709-15.

Vaccine hesitant parents were more likely to change their minds about flu vaccine for their children when pediatricians or pediatric nurse practitioners used a presumptive recommendation that their children get the vaccine, pursued the recommendation if the parent was resistant, and combined their recommendation for the flu vaccine with other childhood vaccines, said Annika M. Hofstetter, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates.

The researchers recruited 17 pediatricians and pediatric nurse practitioners from eight primary care pediatric practices in the Seattle area to take part in 50 videotaped visits with parents during the 2011-2012 and 2013-2014 flu seasons.

(83% vs. 33%; P less than .01), Dr. Hofstetter and her colleagues said. The various communication patterns did not appear to negatively affect the way parents rated their visit experiences.

Read more at Vaccine. 2017;35:2709-15.

Vaccine hesitant parents were more likely to change their minds about flu vaccine for their children when pediatricians or pediatric nurse practitioners used a presumptive recommendation that their children get the vaccine, pursued the recommendation if the parent was resistant, and combined their recommendation for the flu vaccine with other childhood vaccines, said Annika M. Hofstetter, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her associates.

The researchers recruited 17 pediatricians and pediatric nurse practitioners from eight primary care pediatric practices in the Seattle area to take part in 50 videotaped visits with parents during the 2011-2012 and 2013-2014 flu seasons.

(83% vs. 33%; P less than .01), Dr. Hofstetter and her colleagues said. The various communication patterns did not appear to negatively affect the way parents rated their visit experiences.

Read more at Vaccine. 2017;35:2709-15.

FROM VACCINE

Immunization requirements, availability vary in U.S. universities

SAN FRANCISCO – in the enrollment process and vaccine availability through on-campus student health.

The policies of the institutions usually reflected the policies of the particular state or district.

The cross-sectional study surveyed two private and two publicly-funded 4-year degree-granting colleges or universities in each state and the District of Columbia – 216 institutions in total. The institutions were randomly selected to reflect the diversities in size, religious affiliations, and type of institution. The institutions’ websites were scrutinized for information on immunization requirements, vaccinations needed prior to enrollment, vaccination options available on-campus, and consequence of failure to obtain the necessary vaccinations.

A wide variation in vaccine requirements and on-campus availability was evident. MMR vaccination was an admission requirement of about 82% of the schools surveyed. Vaccination was best done prior to arrival on campus, as only 42% of the surveyed colleges and universities offered the vaccine through student health. Vaccination for hepatitis B was required by only 31% of colleges/universities, with 44% offering the vaccine through student health. Vaccination for hepatitis A was required by only about 1% of the surveyed institutions, although the vaccine was available on one-third of the campuses, Dr. Feemster said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccination was required by 25 schools, of which 6 (24%) had experienced MenB illness outbreaks. Of the 191 schools that did not have a requirement for MenB vaccination, only 4 (2.0%) had experienced a MenB outbreak.

Of contemporary concern, vaccination for human papillomavirus was offered by one-third of the colleges/universities, but this vaccination was not a requirement for admission to any of the surveyed institutions. Vaccination for influenza, another disease with a high propensity to spread, also was not required by any school, with only 37% having influenza vaccination available as part of student health care.

Compliance with immunization requirements was enforced by 67% of the schools, with course registration not finalized until the necessary vaccinations had been received and documented. Of the 17% of schools that did not have an enforcement policy, 61% cited the vaccine requirements of their particular state, the assumption being that the incoming students from that state would have received the necessary vaccinations, reflecting a more reactive than proactive stance, according to Dr. Feemster. There was no difference in enforcement strategy between the public or private institutions.

Of the surveyed vaccines, at least some were available at just over 91% of the public institutions and at 76% of the private institutions

“The variation in requirements and enforcement suggest inconsistent vaccine uptake. Next steps include a mixed-methods study to measure attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to school vaccine policy among a national sample of college students and to identify facilitators and barriers to school vaccine policy implementation among school health administrators and providers,” said Dr. Feemster.

“The ultimate goal is to identify the best practices for implementation of college vaccine policies to optimize vaccine uptake and increase positive attitudes, beliefs, and future intentions about vaccines,” she added.

The sponsor of study was the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The study was not funded. Dr. Feemster had no conflicts to disclose.

SAN FRANCISCO – in the enrollment process and vaccine availability through on-campus student health.

The policies of the institutions usually reflected the policies of the particular state or district.

The cross-sectional study surveyed two private and two publicly-funded 4-year degree-granting colleges or universities in each state and the District of Columbia – 216 institutions in total. The institutions were randomly selected to reflect the diversities in size, religious affiliations, and type of institution. The institutions’ websites were scrutinized for information on immunization requirements, vaccinations needed prior to enrollment, vaccination options available on-campus, and consequence of failure to obtain the necessary vaccinations.

A wide variation in vaccine requirements and on-campus availability was evident. MMR vaccination was an admission requirement of about 82% of the schools surveyed. Vaccination was best done prior to arrival on campus, as only 42% of the surveyed colleges and universities offered the vaccine through student health. Vaccination for hepatitis B was required by only 31% of colleges/universities, with 44% offering the vaccine through student health. Vaccination for hepatitis A was required by only about 1% of the surveyed institutions, although the vaccine was available on one-third of the campuses, Dr. Feemster said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccination was required by 25 schools, of which 6 (24%) had experienced MenB illness outbreaks. Of the 191 schools that did not have a requirement for MenB vaccination, only 4 (2.0%) had experienced a MenB outbreak.

Of contemporary concern, vaccination for human papillomavirus was offered by one-third of the colleges/universities, but this vaccination was not a requirement for admission to any of the surveyed institutions. Vaccination for influenza, another disease with a high propensity to spread, also was not required by any school, with only 37% having influenza vaccination available as part of student health care.

Compliance with immunization requirements was enforced by 67% of the schools, with course registration not finalized until the necessary vaccinations had been received and documented. Of the 17% of schools that did not have an enforcement policy, 61% cited the vaccine requirements of their particular state, the assumption being that the incoming students from that state would have received the necessary vaccinations, reflecting a more reactive than proactive stance, according to Dr. Feemster. There was no difference in enforcement strategy between the public or private institutions.

Of the surveyed vaccines, at least some were available at just over 91% of the public institutions and at 76% of the private institutions

“The variation in requirements and enforcement suggest inconsistent vaccine uptake. Next steps include a mixed-methods study to measure attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to school vaccine policy among a national sample of college students and to identify facilitators and barriers to school vaccine policy implementation among school health administrators and providers,” said Dr. Feemster.

“The ultimate goal is to identify the best practices for implementation of college vaccine policies to optimize vaccine uptake and increase positive attitudes, beliefs, and future intentions about vaccines,” she added.

The sponsor of study was the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The study was not funded. Dr. Feemster had no conflicts to disclose.

SAN FRANCISCO – in the enrollment process and vaccine availability through on-campus student health.

The policies of the institutions usually reflected the policies of the particular state or district.

The cross-sectional study surveyed two private and two publicly-funded 4-year degree-granting colleges or universities in each state and the District of Columbia – 216 institutions in total. The institutions were randomly selected to reflect the diversities in size, religious affiliations, and type of institution. The institutions’ websites were scrutinized for information on immunization requirements, vaccinations needed prior to enrollment, vaccination options available on-campus, and consequence of failure to obtain the necessary vaccinations.

A wide variation in vaccine requirements and on-campus availability was evident. MMR vaccination was an admission requirement of about 82% of the schools surveyed. Vaccination was best done prior to arrival on campus, as only 42% of the surveyed colleges and universities offered the vaccine through student health. Vaccination for hepatitis B was required by only 31% of colleges/universities, with 44% offering the vaccine through student health. Vaccination for hepatitis A was required by only about 1% of the surveyed institutions, although the vaccine was available on one-third of the campuses, Dr. Feemster said at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

Meningococcal B (MenB) vaccination was required by 25 schools, of which 6 (24%) had experienced MenB illness outbreaks. Of the 191 schools that did not have a requirement for MenB vaccination, only 4 (2.0%) had experienced a MenB outbreak.

Of contemporary concern, vaccination for human papillomavirus was offered by one-third of the colleges/universities, but this vaccination was not a requirement for admission to any of the surveyed institutions. Vaccination for influenza, another disease with a high propensity to spread, also was not required by any school, with only 37% having influenza vaccination available as part of student health care.

Compliance with immunization requirements was enforced by 67% of the schools, with course registration not finalized until the necessary vaccinations had been received and documented. Of the 17% of schools that did not have an enforcement policy, 61% cited the vaccine requirements of their particular state, the assumption being that the incoming students from that state would have received the necessary vaccinations, reflecting a more reactive than proactive stance, according to Dr. Feemster. There was no difference in enforcement strategy between the public or private institutions.

Of the surveyed vaccines, at least some were available at just over 91% of the public institutions and at 76% of the private institutions

“The variation in requirements and enforcement suggest inconsistent vaccine uptake. Next steps include a mixed-methods study to measure attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to school vaccine policy among a national sample of college students and to identify facilitators and barriers to school vaccine policy implementation among school health administrators and providers,” said Dr. Feemster.

“The ultimate goal is to identify the best practices for implementation of college vaccine policies to optimize vaccine uptake and increase positive attitudes, beliefs, and future intentions about vaccines,” she added.

The sponsor of study was the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The study was not funded. Dr. Feemster had no conflicts to disclose.

AT PAS 2017

Key clinical point: A survey of colleges and universities nationwide in the United States has revealed marked variation in vaccination requirements and vaccine availability.

Major finding: Of the two public and two private schools surveyed in each state and the District of Columbia, none require vaccination for human papillomavirus, with only one-third of schools having the vaccine available through student health.

Data source: Cross-sectional survey of 216 U.S. colleges and universities.

Disclosures: The sponsor of the study was the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The study was not funded. Dr. Feemster had no conflicts to disclose.

First trimester use of inactivated flu vaccine didn’t cause birth defects

, said Elyse Olshen Kharbanda, MD, of HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, and her associates.

Data from seven participating Vaccine Safety Datalink sites in six states were used to identify 52,856 women who received IIV in the first trimester of pregnancy (12% of the study total) and 373,088 not exposed to the flu vaccine in the first trimester (88%). A total of 865 women in the IIV-exposed group had an infant with 1 of the 50 selected major structural defects (1.6 per 100 live births), versus 5,730 in the unexposed group (1.5 per 100 live births).

Among the strengths of the study were the large population, which allowed the researchers to examine subgroups of major structural birth defects; their findings were consistent across all those subgroups. In addition, the investigators were able to exclude women at increased risk for major birth defects because of comorbidities such as diabetes, drug exposures, diagnosed chromosomal abnormalities, or congenital infections. Finally, the study authors were able to exclude women with potential exposure to teratogenic medications.

“Because IIV is currently recommended for all women who will be pregnant during periods of influenza circulation, these data should provide reassurance for women considering first trimester vaccination,” said Dr. Kharbanda and her associates.

Read more in the Journal of Pediatrics (2017 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.039).

, said Elyse Olshen Kharbanda, MD, of HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, and her associates.

Data from seven participating Vaccine Safety Datalink sites in six states were used to identify 52,856 women who received IIV in the first trimester of pregnancy (12% of the study total) and 373,088 not exposed to the flu vaccine in the first trimester (88%). A total of 865 women in the IIV-exposed group had an infant with 1 of the 50 selected major structural defects (1.6 per 100 live births), versus 5,730 in the unexposed group (1.5 per 100 live births).

Among the strengths of the study were the large population, which allowed the researchers to examine subgroups of major structural birth defects; their findings were consistent across all those subgroups. In addition, the investigators were able to exclude women at increased risk for major birth defects because of comorbidities such as diabetes, drug exposures, diagnosed chromosomal abnormalities, or congenital infections. Finally, the study authors were able to exclude women with potential exposure to teratogenic medications.

“Because IIV is currently recommended for all women who will be pregnant during periods of influenza circulation, these data should provide reassurance for women considering first trimester vaccination,” said Dr. Kharbanda and her associates.

Read more in the Journal of Pediatrics (2017 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.039).

, said Elyse Olshen Kharbanda, MD, of HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, and her associates.

Data from seven participating Vaccine Safety Datalink sites in six states were used to identify 52,856 women who received IIV in the first trimester of pregnancy (12% of the study total) and 373,088 not exposed to the flu vaccine in the first trimester (88%). A total of 865 women in the IIV-exposed group had an infant with 1 of the 50 selected major structural defects (1.6 per 100 live births), versus 5,730 in the unexposed group (1.5 per 100 live births).

Among the strengths of the study were the large population, which allowed the researchers to examine subgroups of major structural birth defects; their findings were consistent across all those subgroups. In addition, the investigators were able to exclude women at increased risk for major birth defects because of comorbidities such as diabetes, drug exposures, diagnosed chromosomal abnormalities, or congenital infections. Finally, the study authors were able to exclude women with potential exposure to teratogenic medications.

“Because IIV is currently recommended for all women who will be pregnant during periods of influenza circulation, these data should provide reassurance for women considering first trimester vaccination,” said Dr. Kharbanda and her associates.

Read more in the Journal of Pediatrics (2017 May 24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.039).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Cervical cancer screening adherence drops after HPV vaccination

SAN DIEGO – Young adult women who received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination were less likely to adhere to the recommended screening schedule for cervical cancer, according to a recent study.

In looking at a cohort of women who received at least two Pap smears during a 4-year study period, Daniel Terk, MD, and his colleagues saw a significant drop-off in screening visits after women received their HPV vaccinations. The group of women who received their vaccine midstudy were significantly less likely to come in for annual screening after their vaccination than before (n = 140, adjusted odds ratio 0.19, 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.49).

The retrospective chart review looked at rates of cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccination across 943 patient charts, beginning in 2006 when the HPV vaccine was released and ending in 2010. The inclusion criteria ensured that “participants were old enough to obtain cervical cancer screening and young enough to receive the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Terk and his collaborators wrote in the research abstract.

The drop-off in adherence for the subgroup who received their vaccines midstudy was an isolated finding, said Dr. Terk, noting that vaccination status did not affect adherence to the recommended screening schedule for the group as a whole.

Billing data and medical records were used to track HPV vaccination status and dates of administration, as well as the dates of testing and results for cervical cancer screening. Patients were included if they were born from 1980 to 1988, if they had two or more Pap smears during the study period, and if their HPV vaccination status could be verified. Patients with an initial abnormal Pap smear or a prior loop electrosurgical excision procedure were excluded, as were patients whose HPV vaccination status could not be confirmed.

In all, 943 patient charts were included in the review; 448 patients had no documented vaccination, with further review showing that 418 of these had, in fact, not been vaccinated, while the remaining 30 had actually had at least one HPV vaccine dose during the study period. Of the 495 patients with at least one documented vaccination, 175 had at least one Pap smear done before they were vaccinated, while 320 had their HPV vaccine before any documented cervical cancer screening.

Thus, there were two patient groups: 593 “unvaccinated” patients, who had at least one cervical cancer screening before receiving the vaccine, and 350 “vaccinated” patients, who had their HPV vaccine before any documented Pap smears.

Dr. Terk and his colleagues considered a screening interval of 18 months or less appropriate, while a longer interval than that between Pap smears was considered inappropriate timing. Individual patients were considered adherent if 76%-100% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed, partially adherent if 50%-75% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed, and not adherent if less than 50% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed.

Of those receiving their vaccine midstudy, 116 (82.9%) were adherent before vaccination, while 69 (49.3%) were adherent after vaccination.

The HPV vaccine is highly effective at preventing infection with the strains of HPV that are primarily responsible for cervical cancer. At the same time, about 70% of the cervical cancer cases that occur are associated with missed screening or inappropriate screening intervals, so screening is still an important part of the strategy to prevent cervical cancers, said Dr. Terk, a 4th-year ob.gyn. resident at the University of Rochester, N.Y.

The ACOG guidelines for cervical cancer screening have shifted through the years. During the period from 2003 to 2009, annual Pap smears were recommended for women under the age of 30 years, beginning at age 21 or 3 years after first sexual intercourse. Women 30 years and older who were at low risk could have a less frequent screening interval. ACOG currently recommends Pap testing alone every 3 years for women aged 21-29 years; co-testing with a Pap test and an HPV test every 5 years in women aged 30-65 years, or a Pap test alone every 3 years.

The study had a large sample size, and adherence rates track with national data, Dr. Terk said. However, screening guidelines have shifted in recent years, and vaccinations are now happening at a much younger age, so the findings should be interpreted with some caution. Still, he said, clinicians should incorporate a strong message about the importance of cervical cancer screening in their HPV vaccination and well-woman counseling.

Dr. Terk reported having no relevant financial disclosures and reported no outside sources of funding.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

SAN DIEGO – Young adult women who received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination were less likely to adhere to the recommended screening schedule for cervical cancer, according to a recent study.

In looking at a cohort of women who received at least two Pap smears during a 4-year study period, Daniel Terk, MD, and his colleagues saw a significant drop-off in screening visits after women received their HPV vaccinations. The group of women who received their vaccine midstudy were significantly less likely to come in for annual screening after their vaccination than before (n = 140, adjusted odds ratio 0.19, 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.49).

The retrospective chart review looked at rates of cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccination across 943 patient charts, beginning in 2006 when the HPV vaccine was released and ending in 2010. The inclusion criteria ensured that “participants were old enough to obtain cervical cancer screening and young enough to receive the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Terk and his collaborators wrote in the research abstract.

The drop-off in adherence for the subgroup who received their vaccines midstudy was an isolated finding, said Dr. Terk, noting that vaccination status did not affect adherence to the recommended screening schedule for the group as a whole.

Billing data and medical records were used to track HPV vaccination status and dates of administration, as well as the dates of testing and results for cervical cancer screening. Patients were included if they were born from 1980 to 1988, if they had two or more Pap smears during the study period, and if their HPV vaccination status could be verified. Patients with an initial abnormal Pap smear or a prior loop electrosurgical excision procedure were excluded, as were patients whose HPV vaccination status could not be confirmed.

In all, 943 patient charts were included in the review; 448 patients had no documented vaccination, with further review showing that 418 of these had, in fact, not been vaccinated, while the remaining 30 had actually had at least one HPV vaccine dose during the study period. Of the 495 patients with at least one documented vaccination, 175 had at least one Pap smear done before they were vaccinated, while 320 had their HPV vaccine before any documented cervical cancer screening.

Thus, there were two patient groups: 593 “unvaccinated” patients, who had at least one cervical cancer screening before receiving the vaccine, and 350 “vaccinated” patients, who had their HPV vaccine before any documented Pap smears.

Dr. Terk and his colleagues considered a screening interval of 18 months or less appropriate, while a longer interval than that between Pap smears was considered inappropriate timing. Individual patients were considered adherent if 76%-100% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed, partially adherent if 50%-75% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed, and not adherent if less than 50% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed.

Of those receiving their vaccine midstudy, 116 (82.9%) were adherent before vaccination, while 69 (49.3%) were adherent after vaccination.

The HPV vaccine is highly effective at preventing infection with the strains of HPV that are primarily responsible for cervical cancer. At the same time, about 70% of the cervical cancer cases that occur are associated with missed screening or inappropriate screening intervals, so screening is still an important part of the strategy to prevent cervical cancers, said Dr. Terk, a 4th-year ob.gyn. resident at the University of Rochester, N.Y.

The ACOG guidelines for cervical cancer screening have shifted through the years. During the period from 2003 to 2009, annual Pap smears were recommended for women under the age of 30 years, beginning at age 21 or 3 years after first sexual intercourse. Women 30 years and older who were at low risk could have a less frequent screening interval. ACOG currently recommends Pap testing alone every 3 years for women aged 21-29 years; co-testing with a Pap test and an HPV test every 5 years in women aged 30-65 years, or a Pap test alone every 3 years.

The study had a large sample size, and adherence rates track with national data, Dr. Terk said. However, screening guidelines have shifted in recent years, and vaccinations are now happening at a much younger age, so the findings should be interpreted with some caution. Still, he said, clinicians should incorporate a strong message about the importance of cervical cancer screening in their HPV vaccination and well-woman counseling.

Dr. Terk reported having no relevant financial disclosures and reported no outside sources of funding.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

SAN DIEGO – Young adult women who received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination were less likely to adhere to the recommended screening schedule for cervical cancer, according to a recent study.

In looking at a cohort of women who received at least two Pap smears during a 4-year study period, Daniel Terk, MD, and his colleagues saw a significant drop-off in screening visits after women received their HPV vaccinations. The group of women who received their vaccine midstudy were significantly less likely to come in for annual screening after their vaccination than before (n = 140, adjusted odds ratio 0.19, 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.49).

The retrospective chart review looked at rates of cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccination across 943 patient charts, beginning in 2006 when the HPV vaccine was released and ending in 2010. The inclusion criteria ensured that “participants were old enough to obtain cervical cancer screening and young enough to receive the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Terk and his collaborators wrote in the research abstract.

The drop-off in adherence for the subgroup who received their vaccines midstudy was an isolated finding, said Dr. Terk, noting that vaccination status did not affect adherence to the recommended screening schedule for the group as a whole.

Billing data and medical records were used to track HPV vaccination status and dates of administration, as well as the dates of testing and results for cervical cancer screening. Patients were included if they were born from 1980 to 1988, if they had two or more Pap smears during the study period, and if their HPV vaccination status could be verified. Patients with an initial abnormal Pap smear or a prior loop electrosurgical excision procedure were excluded, as were patients whose HPV vaccination status could not be confirmed.

In all, 943 patient charts were included in the review; 448 patients had no documented vaccination, with further review showing that 418 of these had, in fact, not been vaccinated, while the remaining 30 had actually had at least one HPV vaccine dose during the study period. Of the 495 patients with at least one documented vaccination, 175 had at least one Pap smear done before they were vaccinated, while 320 had their HPV vaccine before any documented cervical cancer screening.

Thus, there were two patient groups: 593 “unvaccinated” patients, who had at least one cervical cancer screening before receiving the vaccine, and 350 “vaccinated” patients, who had their HPV vaccine before any documented Pap smears.

Dr. Terk and his colleagues considered a screening interval of 18 months or less appropriate, while a longer interval than that between Pap smears was considered inappropriate timing. Individual patients were considered adherent if 76%-100% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed, partially adherent if 50%-75% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed, and not adherent if less than 50% of their Pap smears were appropriately timed.

Of those receiving their vaccine midstudy, 116 (82.9%) were adherent before vaccination, while 69 (49.3%) were adherent after vaccination.

The HPV vaccine is highly effective at preventing infection with the strains of HPV that are primarily responsible for cervical cancer. At the same time, about 70% of the cervical cancer cases that occur are associated with missed screening or inappropriate screening intervals, so screening is still an important part of the strategy to prevent cervical cancers, said Dr. Terk, a 4th-year ob.gyn. resident at the University of Rochester, N.Y.

The ACOG guidelines for cervical cancer screening have shifted through the years. During the period from 2003 to 2009, annual Pap smears were recommended for women under the age of 30 years, beginning at age 21 or 3 years after first sexual intercourse. Women 30 years and older who were at low risk could have a less frequent screening interval. ACOG currently recommends Pap testing alone every 3 years for women aged 21-29 years; co-testing with a Pap test and an HPV test every 5 years in women aged 30-65 years, or a Pap test alone every 3 years.

The study had a large sample size, and adherence rates track with national data, Dr. Terk said. However, screening guidelines have shifted in recent years, and vaccinations are now happening at a much younger age, so the findings should be interpreted with some caution. Still, he said, clinicians should incorporate a strong message about the importance of cervical cancer screening in their HPV vaccination and well-woman counseling.

Dr. Terk reported having no relevant financial disclosures and reported no outside sources of funding.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT ACOG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The odds ratio for adherence after immunization compared to before was 0.19 (95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.49).

Data source: Retrospective chart review of 495 women who received at least two Pap smears during the period from 2006 to 2010.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Oral HPV infections sharply lower for vaccinated youth

Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) appears to be highly effective at preventing oral infection with oncogenic types of the virus, based on the results of a cohort study of a nationally representative sample of more than 2,600 U.S. young adults.

“HPV-positive oropharynx cancer is the fastest rising cancer among young white men in the United States. Over 90% of these cancers are caused by HPV type 16,” said senior study author Maura L. Gillison, MD, PhD, who conducted the research at Ohio State University, Columbus. “HPV 16 is one of the types covered in currently recommended HPV vaccines that have been shown to be safe and effective in the prevention of anogenital infections and associated cancers.

Results of the study showed that only about a sixth of the young adults surveyed between 2011 and 2014 had received at least one dose of an HPV vaccine. But relative to peers who had not received any doses, these young adults had an 88% lower prevalence of oral infection with HPV types 16, 18, 6, and 11, which are covered by vaccines; in particular, prevalence was 100% lower, with complete absence of these infections, in vaccinated young men, compared with unvaccinated young men, Dr. Gillison said in a presscast leading up to the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Analyses further suggested that based on levels of vaccine uptake seen in 2014 in the population, the vaccine was preventing only about 17% of the total of approximately 927,000 preventable oral infections with these virus types in that year.

“Our data indicate that HPV vaccines have tremendous potential to prevent oral infection,” said Dr. Gillison, noting that they are already strongly recommended by numerous health and medical organizations. Unfortunately, at the time of the study, “low vaccine uptake limited the population impact of the vaccine.”

However, there is now “considerable optimism,” she said, because recent data have shown that 60% of girls and 40% of boys younger than 18 have received at least one dose of HPV vaccine, marking a major increase in uptake.

“We can’t say that this is cause effect, the impact of these vaccines on infection, because this isn’t a prospective clinical trial,” she acknowledged. “Nevertheless, we can conclude that HPV vaccination may have additional benefits beyond prevention of anogenital cancers.”

The findings are encouraging in that they suggest it will be possible to avert infection-induced oropharyngeal cancer, according to ASCO President-Elect Bruce E. Johnson, MD, who is also chief clinical research officer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“This certainly shows that in the target population to get vaccination, you can indeed prevent the infection, which is one of the first steps that would eventually potentially lead to cancer,” he said.

In the study, Dr. Gillison and her colleagues analyzed data from 2,627 men and women aged 18-33 years who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the years 2011-2014. Oral rinses were collected as part of the survey to assess HPV infection.

The results showed that 18% of the young adults overall reported having received at least one dose of HPV vaccine, although receipt was much higher among young women than among young men (29% vs. 7%).

The prevalence of oral infection with HPV types 16/18/6/11 was sharply lower for these vaccinated young adults, compared with unvaccinated peers in the cohort as a whole (0.11% vs. 1.6%; P = .008). In a sex-stratified analysis, the reduction was especially striking among men (0% vs. 2%, P = .007), reported Dr. Gillison, who is now professor of thoracic/head and neck medical oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

The vaccinated and unvaccinated groups did not differ significantly with respect to the combined prevalence of oral infection with 33 types of HPV that are not covered by vaccines.

When HPV vaccine uptake in the population in 2014 was considered, estimates suggested that vaccination was preventing only 17% of all vaccine-preventable oral HPV 16/18/6/11 infections in that year (25% in women and 7% in men).