User login

Plant-based or animal-based diet: Which is better?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Jain: I’m Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver. This is Dr. Christopher Gardner, a nutritional scientist at Stanford. He is the author of many publications, including the widely cited SWAP-MEAT study. He was also a presenter at the American Diabetes Association conference in San Diego in 2023.

We’ll be talking about his work and the presentation that he did classifying different kinds of diets as well as the pluses and minuses of a plant-based diet versus an animal-based diet. Welcome, Dr Gardner.

Dr. Gardner: Glad to be here.

Dr. Jain: Let’s get right into this. There’s obviously been a large amount of talk, both in the lay media and in the scientific literature, on plant-based diets versus animal-based diets.

Dr. Gardner: I think this is one of those false dichotomies. It’s really not all one or all the other. Two of my favorite sayings are “with what” and “instead of what.” You may be thinking, I’m really going to go for animal based. I know it’s low carb. I have diabetes. I know animal foods have few carbs in them.

That’s true. But think of some of the more and the less healthy animal foods. Yogurt is a great choice for an animal food. Fish is a great choice for an animal food with omega-3s. Chicken McNuggets, not so much.

Then, you switch to the plant side and say: “I’ve heard all these people talking about a whole-food, plant-based diet. That sounds great. I’m thinking broccoli and chickpeas.”

I know there’s somebody out there saying: “I just had a Coke. Isn’t that plant based? I just had a pastry. Isn’t that full of plants?” It doesn’t really take much to think about this, but it’s not as dichotomous as animal versus plant.

Dr. Jain: There is, obviously, a good understanding regarding what actually constitutes the diet. Initially, people were saying that animal-based diets are really bad from a cardiovascular perspective. But now, some studies are suggesting that it may not be true. What’s your take on that?

Dr. Gardner: Again, if you think “with what” or “instead of what,” microbiome is a super-hot topic. That’s really fiber and fermented food, which are only plants. Saturated fat, despite all the controversy, raises your blood cholesterol. It’s more prevalent in animal foods than in plant foods.

Are there any great nutrients in animal foods? Sure. There’s calcium in dairy products for osteoporosis. There’s iron. Actually, people can get too much iron, which can be a pro-oxidant in levels that are too high.

The American Heart Association, in particular, which I’m very involved with, came out with new guidelines in 2021. It was very plant focused. The top of the list was vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and protein. When it came to protein, it was mostly from lentils, beans, and grains.

Dr. Jain: That’s good to know. Let’s talk about protein. We often hear about how somebody on a plant-based diet only can never have all the essential amino acids and the amount of protein that one needs. Whether it’s for general everyday individuals or even more so for athletes or bodybuilders, you cannot get enough good-quality protein from a plant-based diet.

Is there any truth to that? If not, what would you suggest for everyday individuals on a plant-based diet?

Dr. Gardner: This one drives me nuts. Please stop obsessing about protein. This isn’t a very scientific answer, but go watch the documentary Game Changers, which is all about vegan athletes. There are some pretty hokey things in that film that are very unscientific.

Let’s go back to basics, since we only have a couple of minutes together. It is a myth that plants don’t have all the amino acids, including all nine essential amino acids. I have several YouTube rants about this if anybody wants to search “Gardner Stanford protein.” All plant foods have all nine essential amino acids and all 20 amino acids.

There is a modest difference. Grains tend to be a little low in lysine, and beans tend to be a little low in methionine. Part of this has to do with how much of a difference is a little low. If you go to protein requirements that were written up in 2005 by the Institute of Medicine, you’ll see that the estimated average requirement for adults is 0.66 g/kg of body weight.

If we recommended the estimated average requirement for everyone, and everyone got it, by definition, half the population would be deficient. We have recommended daily allowances. The recommended daily allowances include two standard deviations above the estimated average requirement. Why would we do that? It’s a population approach.

If that’s the goal and everybody got it, you’d actually still have the tail of the normal distribution that would be deficient, which would be about 2.5%. The flip side of that argument is how many would exceed their requirement? That’s 97.5% of the population who would exceed their requirement if they got the recommended daily allowance.

The recommended daily allowance translates to about 45 g of protein per day for women and about 55 g of protein per day for men. Today, men and women in the United States get 80 g, 90 g, and 100 g of protein per day. What I hear them say is: “I’m not sure if I need the recommended daily allowance. I feel like I’m extra special or I’m above the curve and I want to make sure I’m getting enough.”

The recommended daily allowance already has a safety buffer in it. It was designed that way.

Let’s flip to athletes just for a second. Athletes want to be more muscular and make sure they’re supporting their activity. Americans get 1.2-1.5 g of protein per kg of body weight per day, which is almost double.

Athletes don’t eat as many calories as the average American does. If they’re working out to be muscular, they’re not eating 2,000 or 2,500 calories per day. I have a Rose Bowl football player teaching assistant from a Human Nutrition class at Stanford. He logged what he was eating for his football workouts. He was eating 5,000 calories per day. He was getting 250 g of protein per day, without any supplements or shakes.

I really do think this whole protein thing is a myth. As long as you get a reasonable amount of variety in your diet, there is no problem meeting your protein needs. Vegetarians? Absolutely no problem because they’re getting dairy and some eggs and things. Even vegans are likely fine. They would have to pay a little more attention to this, but I know many very strong, healthy vegans.

Dr. Jain: This is so helpful, Dr Gardner. I know that many clinicians, including myself, will find this very helpful, including when we talk to our patients and counsel them on their requirements. Thanks for sharing that.

Final question for you. We know people who are on either side of the extreme: either completely plant based or completely animal based. For a majority of us that have some kind of a happy medium, what would your suggestions be as far as the macronutrient distribution that you would recommend from a mixed animal- and plant-based diet? What would be the ideal recommendations here?

Dr. Gardner: We did a huge weight loss study with people with prediabetes. It was as low in carbs as people could go and as low in fat as people could go. That didn’t end up being the ketogenic level or the low-fat, vegan level. That ended up being much more moderate.

We found that people were successful either on low carb or low fat. Interestingly, on both diets, protein was very similar. Let’s not get into that since we just did a lot of protein. The key was a healthy low carb or a healthy low fat. I actually think we have a lot of wiggle room there. Let me build on what you said just a moment ago.

I really don’t think you need to be vegan to be healthy. We prefer the term whole food, plant based. If you’re getting 70% or 80% of your food from plants, you’re fine. If you really want to get the last 5%, 10%, or 15% all from plants, the additional benefit is not going to be large. You might want to do that for the environment or animal rights and welfare, but from a health perspective, a whole-food, plant-based diet leaves room for some yogurt, fish, and maybe some eggs for breakfast instead of those silly high-carb breakfasts that most Americans eat.

I will say that animal foods have no fiber. Given what a hot topic the microbiome is these days, the higher and higher you get in animal food, it’s going to be really hard to get antioxidants, most of which are in plants, and very hard to get enough fiber, which is good for the microbiome.

That’s why I tend to follow along the lines of a whole-food, plant-based diet that leaves some room for meat and animal-sourced foods, which you could leave out and be fine. I wouldn’t go in the opposite direction to the all-animal side.

Dr. Jain: That was awesome. Thank you so much, Dr Gardner. Final pearl of wisdom here. When clinicians like us see patients with diabetes, what should be the final take-home message that we can counsel our patients about?

Dr. Gardner: That’s a great question. I don’t think it’s really so much animal or plants; it’s actually type of carbohydrate. There’s a great paper out of JAMA in 2019 or 2020 by Shan and colleagues. They looked at the proportion of calories from proteins, carbs, and fats over about 20 years, and they looked at the subtypes.

Very interestingly, protein from animal foods is about 10% of calories; from plants, about 5%; mono-, poly-, and saturated fats are all about 10% of calories; and high-quality carbohydrates are about 10% of calories. What’s left is 40% of calories from crappy carbohydrates. We eat so many calories from added sugars and refined grains, and those are plant-based. Added sugars and refined grains are plant-based.

In terms of a lower-carbohydrate diet, there is an immense amount of room for cutting back on that 40%. What would you do with that? Would you eat more animal food? Would you eat more plant food? This is where I think we have a large amount of wiggle room. If the patients could get rid of all or most of that 40%, they could pick some eggs, yogurt, fish, and some high-fat foods. They could pick avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil or they could have more broccoli, chickpeas, tempeh, and tofu.

There really is a large amount of wiggle room. The key – can we please get rid of the elephant in the room, which is plant food – is all that added sugar and refined grain.

Dr. Jain is an endocrinologist and clinical instructor University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Gardner is a professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Jain reported numerous conflicts of interest with various companies; Dr. Gardner reported receiving research funding from Beyond Meat.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Jain: I’m Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver. This is Dr. Christopher Gardner, a nutritional scientist at Stanford. He is the author of many publications, including the widely cited SWAP-MEAT study. He was also a presenter at the American Diabetes Association conference in San Diego in 2023.

We’ll be talking about his work and the presentation that he did classifying different kinds of diets as well as the pluses and minuses of a plant-based diet versus an animal-based diet. Welcome, Dr Gardner.

Dr. Gardner: Glad to be here.

Dr. Jain: Let’s get right into this. There’s obviously been a large amount of talk, both in the lay media and in the scientific literature, on plant-based diets versus animal-based diets.

Dr. Gardner: I think this is one of those false dichotomies. It’s really not all one or all the other. Two of my favorite sayings are “with what” and “instead of what.” You may be thinking, I’m really going to go for animal based. I know it’s low carb. I have diabetes. I know animal foods have few carbs in them.

That’s true. But think of some of the more and the less healthy animal foods. Yogurt is a great choice for an animal food. Fish is a great choice for an animal food with omega-3s. Chicken McNuggets, not so much.

Then, you switch to the plant side and say: “I’ve heard all these people talking about a whole-food, plant-based diet. That sounds great. I’m thinking broccoli and chickpeas.”

I know there’s somebody out there saying: “I just had a Coke. Isn’t that plant based? I just had a pastry. Isn’t that full of plants?” It doesn’t really take much to think about this, but it’s not as dichotomous as animal versus plant.

Dr. Jain: There is, obviously, a good understanding regarding what actually constitutes the diet. Initially, people were saying that animal-based diets are really bad from a cardiovascular perspective. But now, some studies are suggesting that it may not be true. What’s your take on that?

Dr. Gardner: Again, if you think “with what” or “instead of what,” microbiome is a super-hot topic. That’s really fiber and fermented food, which are only plants. Saturated fat, despite all the controversy, raises your blood cholesterol. It’s more prevalent in animal foods than in plant foods.

Are there any great nutrients in animal foods? Sure. There’s calcium in dairy products for osteoporosis. There’s iron. Actually, people can get too much iron, which can be a pro-oxidant in levels that are too high.

The American Heart Association, in particular, which I’m very involved with, came out with new guidelines in 2021. It was very plant focused. The top of the list was vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and protein. When it came to protein, it was mostly from lentils, beans, and grains.

Dr. Jain: That’s good to know. Let’s talk about protein. We often hear about how somebody on a plant-based diet only can never have all the essential amino acids and the amount of protein that one needs. Whether it’s for general everyday individuals or even more so for athletes or bodybuilders, you cannot get enough good-quality protein from a plant-based diet.

Is there any truth to that? If not, what would you suggest for everyday individuals on a plant-based diet?

Dr. Gardner: This one drives me nuts. Please stop obsessing about protein. This isn’t a very scientific answer, but go watch the documentary Game Changers, which is all about vegan athletes. There are some pretty hokey things in that film that are very unscientific.

Let’s go back to basics, since we only have a couple of minutes together. It is a myth that plants don’t have all the amino acids, including all nine essential amino acids. I have several YouTube rants about this if anybody wants to search “Gardner Stanford protein.” All plant foods have all nine essential amino acids and all 20 amino acids.

There is a modest difference. Grains tend to be a little low in lysine, and beans tend to be a little low in methionine. Part of this has to do with how much of a difference is a little low. If you go to protein requirements that were written up in 2005 by the Institute of Medicine, you’ll see that the estimated average requirement for adults is 0.66 g/kg of body weight.

If we recommended the estimated average requirement for everyone, and everyone got it, by definition, half the population would be deficient. We have recommended daily allowances. The recommended daily allowances include two standard deviations above the estimated average requirement. Why would we do that? It’s a population approach.

If that’s the goal and everybody got it, you’d actually still have the tail of the normal distribution that would be deficient, which would be about 2.5%. The flip side of that argument is how many would exceed their requirement? That’s 97.5% of the population who would exceed their requirement if they got the recommended daily allowance.

The recommended daily allowance translates to about 45 g of protein per day for women and about 55 g of protein per day for men. Today, men and women in the United States get 80 g, 90 g, and 100 g of protein per day. What I hear them say is: “I’m not sure if I need the recommended daily allowance. I feel like I’m extra special or I’m above the curve and I want to make sure I’m getting enough.”

The recommended daily allowance already has a safety buffer in it. It was designed that way.

Let’s flip to athletes just for a second. Athletes want to be more muscular and make sure they’re supporting their activity. Americans get 1.2-1.5 g of protein per kg of body weight per day, which is almost double.

Athletes don’t eat as many calories as the average American does. If they’re working out to be muscular, they’re not eating 2,000 or 2,500 calories per day. I have a Rose Bowl football player teaching assistant from a Human Nutrition class at Stanford. He logged what he was eating for his football workouts. He was eating 5,000 calories per day. He was getting 250 g of protein per day, without any supplements or shakes.

I really do think this whole protein thing is a myth. As long as you get a reasonable amount of variety in your diet, there is no problem meeting your protein needs. Vegetarians? Absolutely no problem because they’re getting dairy and some eggs and things. Even vegans are likely fine. They would have to pay a little more attention to this, but I know many very strong, healthy vegans.

Dr. Jain: This is so helpful, Dr Gardner. I know that many clinicians, including myself, will find this very helpful, including when we talk to our patients and counsel them on their requirements. Thanks for sharing that.

Final question for you. We know people who are on either side of the extreme: either completely plant based or completely animal based. For a majority of us that have some kind of a happy medium, what would your suggestions be as far as the macronutrient distribution that you would recommend from a mixed animal- and plant-based diet? What would be the ideal recommendations here?

Dr. Gardner: We did a huge weight loss study with people with prediabetes. It was as low in carbs as people could go and as low in fat as people could go. That didn’t end up being the ketogenic level or the low-fat, vegan level. That ended up being much more moderate.

We found that people were successful either on low carb or low fat. Interestingly, on both diets, protein was very similar. Let’s not get into that since we just did a lot of protein. The key was a healthy low carb or a healthy low fat. I actually think we have a lot of wiggle room there. Let me build on what you said just a moment ago.

I really don’t think you need to be vegan to be healthy. We prefer the term whole food, plant based. If you’re getting 70% or 80% of your food from plants, you’re fine. If you really want to get the last 5%, 10%, or 15% all from plants, the additional benefit is not going to be large. You might want to do that for the environment or animal rights and welfare, but from a health perspective, a whole-food, plant-based diet leaves room for some yogurt, fish, and maybe some eggs for breakfast instead of those silly high-carb breakfasts that most Americans eat.

I will say that animal foods have no fiber. Given what a hot topic the microbiome is these days, the higher and higher you get in animal food, it’s going to be really hard to get antioxidants, most of which are in plants, and very hard to get enough fiber, which is good for the microbiome.

That’s why I tend to follow along the lines of a whole-food, plant-based diet that leaves some room for meat and animal-sourced foods, which you could leave out and be fine. I wouldn’t go in the opposite direction to the all-animal side.

Dr. Jain: That was awesome. Thank you so much, Dr Gardner. Final pearl of wisdom here. When clinicians like us see patients with diabetes, what should be the final take-home message that we can counsel our patients about?

Dr. Gardner: That’s a great question. I don’t think it’s really so much animal or plants; it’s actually type of carbohydrate. There’s a great paper out of JAMA in 2019 or 2020 by Shan and colleagues. They looked at the proportion of calories from proteins, carbs, and fats over about 20 years, and they looked at the subtypes.

Very interestingly, protein from animal foods is about 10% of calories; from plants, about 5%; mono-, poly-, and saturated fats are all about 10% of calories; and high-quality carbohydrates are about 10% of calories. What’s left is 40% of calories from crappy carbohydrates. We eat so many calories from added sugars and refined grains, and those are plant-based. Added sugars and refined grains are plant-based.

In terms of a lower-carbohydrate diet, there is an immense amount of room for cutting back on that 40%. What would you do with that? Would you eat more animal food? Would you eat more plant food? This is where I think we have a large amount of wiggle room. If the patients could get rid of all or most of that 40%, they could pick some eggs, yogurt, fish, and some high-fat foods. They could pick avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil or they could have more broccoli, chickpeas, tempeh, and tofu.

There really is a large amount of wiggle room. The key – can we please get rid of the elephant in the room, which is plant food – is all that added sugar and refined grain.

Dr. Jain is an endocrinologist and clinical instructor University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Gardner is a professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Jain reported numerous conflicts of interest with various companies; Dr. Gardner reported receiving research funding from Beyond Meat.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Jain: I’m Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver. This is Dr. Christopher Gardner, a nutritional scientist at Stanford. He is the author of many publications, including the widely cited SWAP-MEAT study. He was also a presenter at the American Diabetes Association conference in San Diego in 2023.

We’ll be talking about his work and the presentation that he did classifying different kinds of diets as well as the pluses and minuses of a plant-based diet versus an animal-based diet. Welcome, Dr Gardner.

Dr. Gardner: Glad to be here.

Dr. Jain: Let’s get right into this. There’s obviously been a large amount of talk, both in the lay media and in the scientific literature, on plant-based diets versus animal-based diets.

Dr. Gardner: I think this is one of those false dichotomies. It’s really not all one or all the other. Two of my favorite sayings are “with what” and “instead of what.” You may be thinking, I’m really going to go for animal based. I know it’s low carb. I have diabetes. I know animal foods have few carbs in them.

That’s true. But think of some of the more and the less healthy animal foods. Yogurt is a great choice for an animal food. Fish is a great choice for an animal food with omega-3s. Chicken McNuggets, not so much.

Then, you switch to the plant side and say: “I’ve heard all these people talking about a whole-food, plant-based diet. That sounds great. I’m thinking broccoli and chickpeas.”

I know there’s somebody out there saying: “I just had a Coke. Isn’t that plant based? I just had a pastry. Isn’t that full of plants?” It doesn’t really take much to think about this, but it’s not as dichotomous as animal versus plant.

Dr. Jain: There is, obviously, a good understanding regarding what actually constitutes the diet. Initially, people were saying that animal-based diets are really bad from a cardiovascular perspective. But now, some studies are suggesting that it may not be true. What’s your take on that?

Dr. Gardner: Again, if you think “with what” or “instead of what,” microbiome is a super-hot topic. That’s really fiber and fermented food, which are only plants. Saturated fat, despite all the controversy, raises your blood cholesterol. It’s more prevalent in animal foods than in plant foods.

Are there any great nutrients in animal foods? Sure. There’s calcium in dairy products for osteoporosis. There’s iron. Actually, people can get too much iron, which can be a pro-oxidant in levels that are too high.

The American Heart Association, in particular, which I’m very involved with, came out with new guidelines in 2021. It was very plant focused. The top of the list was vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and protein. When it came to protein, it was mostly from lentils, beans, and grains.

Dr. Jain: That’s good to know. Let’s talk about protein. We often hear about how somebody on a plant-based diet only can never have all the essential amino acids and the amount of protein that one needs. Whether it’s for general everyday individuals or even more so for athletes or bodybuilders, you cannot get enough good-quality protein from a plant-based diet.

Is there any truth to that? If not, what would you suggest for everyday individuals on a plant-based diet?

Dr. Gardner: This one drives me nuts. Please stop obsessing about protein. This isn’t a very scientific answer, but go watch the documentary Game Changers, which is all about vegan athletes. There are some pretty hokey things in that film that are very unscientific.

Let’s go back to basics, since we only have a couple of minutes together. It is a myth that plants don’t have all the amino acids, including all nine essential amino acids. I have several YouTube rants about this if anybody wants to search “Gardner Stanford protein.” All plant foods have all nine essential amino acids and all 20 amino acids.

There is a modest difference. Grains tend to be a little low in lysine, and beans tend to be a little low in methionine. Part of this has to do with how much of a difference is a little low. If you go to protein requirements that were written up in 2005 by the Institute of Medicine, you’ll see that the estimated average requirement for adults is 0.66 g/kg of body weight.

If we recommended the estimated average requirement for everyone, and everyone got it, by definition, half the population would be deficient. We have recommended daily allowances. The recommended daily allowances include two standard deviations above the estimated average requirement. Why would we do that? It’s a population approach.

If that’s the goal and everybody got it, you’d actually still have the tail of the normal distribution that would be deficient, which would be about 2.5%. The flip side of that argument is how many would exceed their requirement? That’s 97.5% of the population who would exceed their requirement if they got the recommended daily allowance.

The recommended daily allowance translates to about 45 g of protein per day for women and about 55 g of protein per day for men. Today, men and women in the United States get 80 g, 90 g, and 100 g of protein per day. What I hear them say is: “I’m not sure if I need the recommended daily allowance. I feel like I’m extra special or I’m above the curve and I want to make sure I’m getting enough.”

The recommended daily allowance already has a safety buffer in it. It was designed that way.

Let’s flip to athletes just for a second. Athletes want to be more muscular and make sure they’re supporting their activity. Americans get 1.2-1.5 g of protein per kg of body weight per day, which is almost double.

Athletes don’t eat as many calories as the average American does. If they’re working out to be muscular, they’re not eating 2,000 or 2,500 calories per day. I have a Rose Bowl football player teaching assistant from a Human Nutrition class at Stanford. He logged what he was eating for his football workouts. He was eating 5,000 calories per day. He was getting 250 g of protein per day, without any supplements or shakes.

I really do think this whole protein thing is a myth. As long as you get a reasonable amount of variety in your diet, there is no problem meeting your protein needs. Vegetarians? Absolutely no problem because they’re getting dairy and some eggs and things. Even vegans are likely fine. They would have to pay a little more attention to this, but I know many very strong, healthy vegans.

Dr. Jain: This is so helpful, Dr Gardner. I know that many clinicians, including myself, will find this very helpful, including when we talk to our patients and counsel them on their requirements. Thanks for sharing that.

Final question for you. We know people who are on either side of the extreme: either completely plant based or completely animal based. For a majority of us that have some kind of a happy medium, what would your suggestions be as far as the macronutrient distribution that you would recommend from a mixed animal- and plant-based diet? What would be the ideal recommendations here?

Dr. Gardner: We did a huge weight loss study with people with prediabetes. It was as low in carbs as people could go and as low in fat as people could go. That didn’t end up being the ketogenic level or the low-fat, vegan level. That ended up being much more moderate.

We found that people were successful either on low carb or low fat. Interestingly, on both diets, protein was very similar. Let’s not get into that since we just did a lot of protein. The key was a healthy low carb or a healthy low fat. I actually think we have a lot of wiggle room there. Let me build on what you said just a moment ago.

I really don’t think you need to be vegan to be healthy. We prefer the term whole food, plant based. If you’re getting 70% or 80% of your food from plants, you’re fine. If you really want to get the last 5%, 10%, or 15% all from plants, the additional benefit is not going to be large. You might want to do that for the environment or animal rights and welfare, but from a health perspective, a whole-food, plant-based diet leaves room for some yogurt, fish, and maybe some eggs for breakfast instead of those silly high-carb breakfasts that most Americans eat.

I will say that animal foods have no fiber. Given what a hot topic the microbiome is these days, the higher and higher you get in animal food, it’s going to be really hard to get antioxidants, most of which are in plants, and very hard to get enough fiber, which is good for the microbiome.

That’s why I tend to follow along the lines of a whole-food, plant-based diet that leaves some room for meat and animal-sourced foods, which you could leave out and be fine. I wouldn’t go in the opposite direction to the all-animal side.

Dr. Jain: That was awesome. Thank you so much, Dr Gardner. Final pearl of wisdom here. When clinicians like us see patients with diabetes, what should be the final take-home message that we can counsel our patients about?

Dr. Gardner: That’s a great question. I don’t think it’s really so much animal or plants; it’s actually type of carbohydrate. There’s a great paper out of JAMA in 2019 or 2020 by Shan and colleagues. They looked at the proportion of calories from proteins, carbs, and fats over about 20 years, and they looked at the subtypes.

Very interestingly, protein from animal foods is about 10% of calories; from plants, about 5%; mono-, poly-, and saturated fats are all about 10% of calories; and high-quality carbohydrates are about 10% of calories. What’s left is 40% of calories from crappy carbohydrates. We eat so many calories from added sugars and refined grains, and those are plant-based. Added sugars and refined grains are plant-based.

In terms of a lower-carbohydrate diet, there is an immense amount of room for cutting back on that 40%. What would you do with that? Would you eat more animal food? Would you eat more plant food? This is where I think we have a large amount of wiggle room. If the patients could get rid of all or most of that 40%, they could pick some eggs, yogurt, fish, and some high-fat foods. They could pick avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil or they could have more broccoli, chickpeas, tempeh, and tofu.

There really is a large amount of wiggle room. The key – can we please get rid of the elephant in the room, which is plant food – is all that added sugar and refined grain.

Dr. Jain is an endocrinologist and clinical instructor University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Gardner is a professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Jain reported numerous conflicts of interest with various companies; Dr. Gardner reported receiving research funding from Beyond Meat.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What AI can see in CT scans that humans can’t

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a CT scan of the chest might as well be Atlas Shrugged. When you think of the sheer information content in one of those scans, it becomes immediately clear that our usual method of CT scan interpretation must be leaving a lot on the table. After all, we can go through all that information and come out with simply “normal” and call it a day.

Of course, radiologists can glean a lot from a CT scan, but they are trained to look for abnormalities. They can find pneumonia, emboli, fractures, and pneumothoraces, but the presence or absence of life-threatening abnormalities is still just a fraction of the data contained within a CT scan.

Pulling out more data from those images – data that may not indicate disease per se, but nevertheless tell us something important about patients and their risks – might just fall to those entities that are primed to take a bunch of data and interpret it in new ways: artificial intelligence (AI).

I’m thinking about AI and CT scans this week thanks to this study, appearing in the journal Radiology, from Kaiwen Xu and colleagues at Vanderbilt.

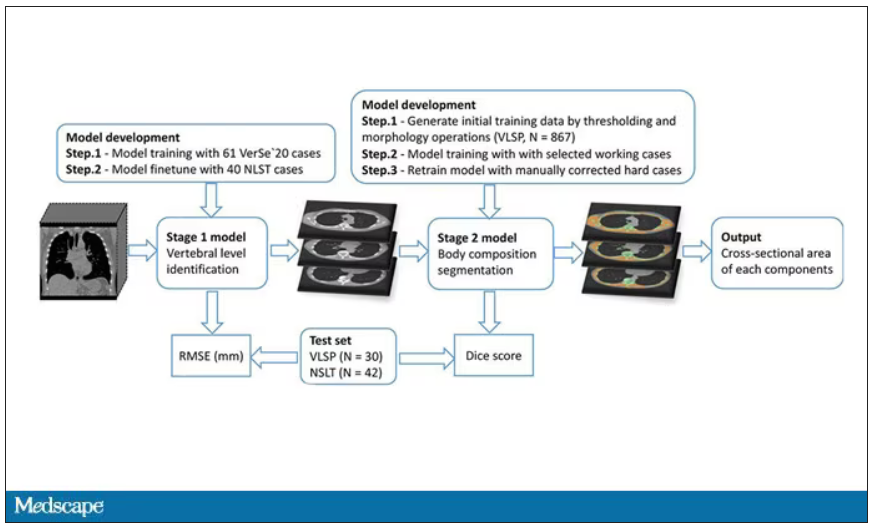

In a previous study, the team had developed an AI algorithm to take chest CT images and convert that data into information about body composition: skeletal muscle mass, fat mass, muscle lipid content – that sort of thing.

While the radiologists are busy looking for cancer or pneumonia, the AI can create a body composition report – two results from one data stream.

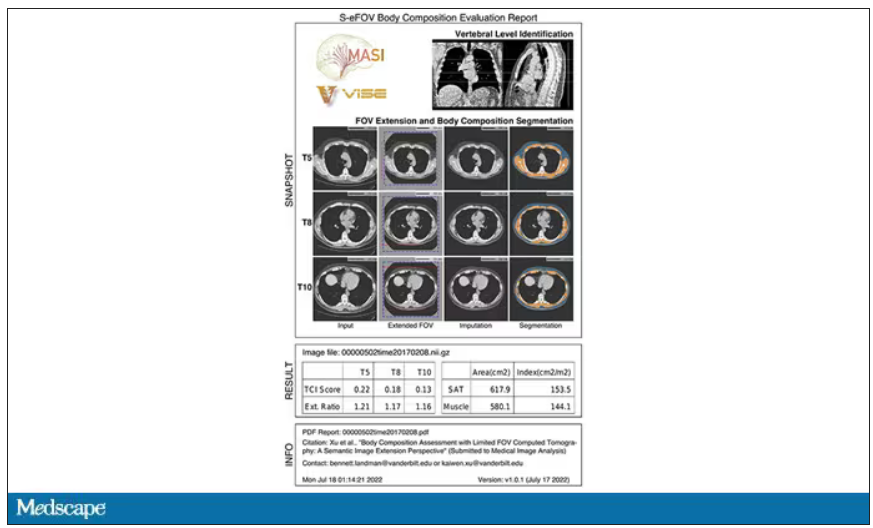

Here’s an example of a report generated from a CT scan from the authors’ GitHub page.

The cool thing here is that this is a clinically collected CT scan of the chest, not a special protocol designed to assess body composition. In fact, this comes from the low-dose lung cancer screening trial dataset.

As you may know, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends low-dose CT screening of the chest every year for those aged 50-80 with at least a 20 pack-year smoking history. These CT scans form an incredible dataset, actually, as they are all collected with nearly the same parameters. Obviously, the important thing to look for in these CT scans is whether there is early lung cancer. But the new paper asks, as long as we can get information about body composition from these scans, why don’t we? Can it help to risk-stratify these patients?

They took 20,768 individuals with CT scans done as part of the low-dose lung cancer screening trial and passed their scans through their automated data pipeline.

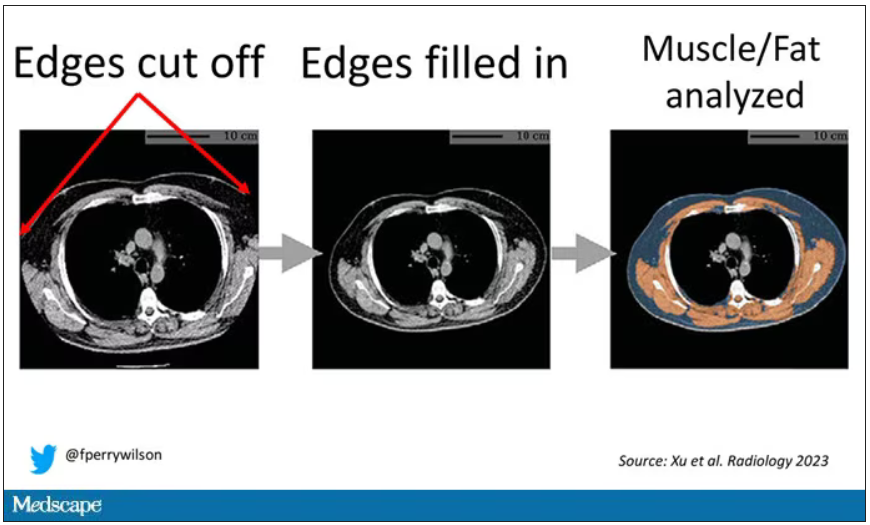

One cool feature here: Depending on body size, sometimes the edges of people in CT scans are not visible. That’s not a big deal for lung-cancer screening as long as you can see both lungs. But it does matter for assessment of muscle and body fat because that stuff lives on the edges of the thoracic cavity. The authors’ data pipeline actually accounts for this, extrapolating what the missing pieces look like from what is able to be seen. It’s quite clever.

On to some results. Would knowledge about the patient’s body composition help predict their ultimate outcome?

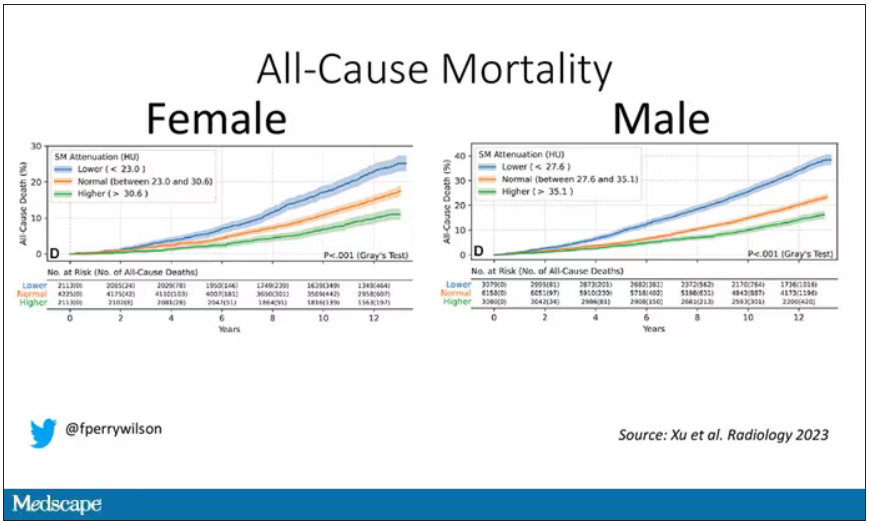

It would. And the best single predictor found was skeletal muscle attenuation – lower levels of skeletal muscle attenuation mean more fat infiltrating the muscle – so lower is worse here. You can see from these all-cause mortality curves that lower levels were associated with substantially worse life expectancy.

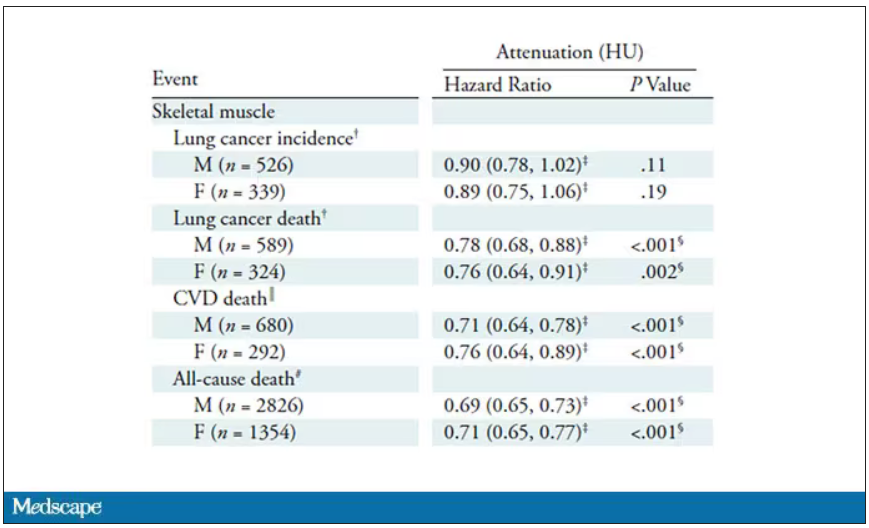

It’s worth noting that these are unadjusted curves. While AI prediction from CT images is very cool, we might be able to make similar predictions knowing, for example, the age of the patient. To account for this, the authors adjusted the findings for age, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and coronary calcium score (also calculated from those same CT scans). Even after adjustment, skeletal muscle attenuation was significantly associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and lung-cancer mortality – but not lung cancer incidence.

Those results tell us that there is likely a physiologic significance to skeletal muscle attenuation, and they provide a great proof-of-concept that automated data extraction techniques can be applied broadly to routinely collected radiology images.

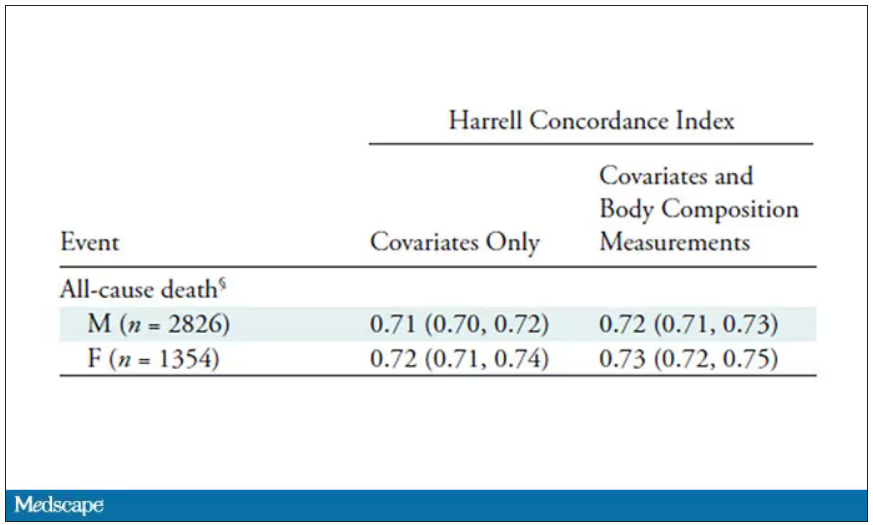

That said, it’s one thing to show that something is physiologically relevant. In terms of actually predicting outcomes, adding this information to a model that contains just those clinical factors like age and diabetes doesn’t actually improve things very much. We measure this with something called the concordance index. This tells us the probability, given two individuals, of how often we can identify the person who has the outcome of interest sooner – if at all. (You can probably guess that the worst possible score is thus 0.5 and the best is 1.) A model without the AI data gives a concordance index for all-cause mortality of 0.71 or 0.72, depending on sex. Adding in the body composition data bumps that up only by a percent or so.

This honestly feels a bit like a missed opportunity to me. The authors pass the imaging data through an AI to get body composition data and then see how that predicts death.

Why not skip the middleman? Train a model using the imaging data to predict death directly, using whatever signal the AI chooses: body composition, lung size, rib thickness – whatever.

I’d be very curious to see how that model might improve our ability to predict these outcomes. In the end, this is a space where AI can make some massive gains – not by trying to do radiologists’ jobs better than radiologists, but by extracting information that radiologists aren’t looking for in the first place.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a CT scan of the chest might as well be Atlas Shrugged. When you think of the sheer information content in one of those scans, it becomes immediately clear that our usual method of CT scan interpretation must be leaving a lot on the table. After all, we can go through all that information and come out with simply “normal” and call it a day.

Of course, radiologists can glean a lot from a CT scan, but they are trained to look for abnormalities. They can find pneumonia, emboli, fractures, and pneumothoraces, but the presence or absence of life-threatening abnormalities is still just a fraction of the data contained within a CT scan.

Pulling out more data from those images – data that may not indicate disease per se, but nevertheless tell us something important about patients and their risks – might just fall to those entities that are primed to take a bunch of data and interpret it in new ways: artificial intelligence (AI).

I’m thinking about AI and CT scans this week thanks to this study, appearing in the journal Radiology, from Kaiwen Xu and colleagues at Vanderbilt.

In a previous study, the team had developed an AI algorithm to take chest CT images and convert that data into information about body composition: skeletal muscle mass, fat mass, muscle lipid content – that sort of thing.

While the radiologists are busy looking for cancer or pneumonia, the AI can create a body composition report – two results from one data stream.

Here’s an example of a report generated from a CT scan from the authors’ GitHub page.

The cool thing here is that this is a clinically collected CT scan of the chest, not a special protocol designed to assess body composition. In fact, this comes from the low-dose lung cancer screening trial dataset.

As you may know, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends low-dose CT screening of the chest every year for those aged 50-80 with at least a 20 pack-year smoking history. These CT scans form an incredible dataset, actually, as they are all collected with nearly the same parameters. Obviously, the important thing to look for in these CT scans is whether there is early lung cancer. But the new paper asks, as long as we can get information about body composition from these scans, why don’t we? Can it help to risk-stratify these patients?

They took 20,768 individuals with CT scans done as part of the low-dose lung cancer screening trial and passed their scans through their automated data pipeline.

One cool feature here: Depending on body size, sometimes the edges of people in CT scans are not visible. That’s not a big deal for lung-cancer screening as long as you can see both lungs. But it does matter for assessment of muscle and body fat because that stuff lives on the edges of the thoracic cavity. The authors’ data pipeline actually accounts for this, extrapolating what the missing pieces look like from what is able to be seen. It’s quite clever.

On to some results. Would knowledge about the patient’s body composition help predict their ultimate outcome?

It would. And the best single predictor found was skeletal muscle attenuation – lower levels of skeletal muscle attenuation mean more fat infiltrating the muscle – so lower is worse here. You can see from these all-cause mortality curves that lower levels were associated with substantially worse life expectancy.

It’s worth noting that these are unadjusted curves. While AI prediction from CT images is very cool, we might be able to make similar predictions knowing, for example, the age of the patient. To account for this, the authors adjusted the findings for age, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and coronary calcium score (also calculated from those same CT scans). Even after adjustment, skeletal muscle attenuation was significantly associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and lung-cancer mortality – but not lung cancer incidence.

Those results tell us that there is likely a physiologic significance to skeletal muscle attenuation, and they provide a great proof-of-concept that automated data extraction techniques can be applied broadly to routinely collected radiology images.

That said, it’s one thing to show that something is physiologically relevant. In terms of actually predicting outcomes, adding this information to a model that contains just those clinical factors like age and diabetes doesn’t actually improve things very much. We measure this with something called the concordance index. This tells us the probability, given two individuals, of how often we can identify the person who has the outcome of interest sooner – if at all. (You can probably guess that the worst possible score is thus 0.5 and the best is 1.) A model without the AI data gives a concordance index for all-cause mortality of 0.71 or 0.72, depending on sex. Adding in the body composition data bumps that up only by a percent or so.

This honestly feels a bit like a missed opportunity to me. The authors pass the imaging data through an AI to get body composition data and then see how that predicts death.

Why not skip the middleman? Train a model using the imaging data to predict death directly, using whatever signal the AI chooses: body composition, lung size, rib thickness – whatever.

I’d be very curious to see how that model might improve our ability to predict these outcomes. In the end, this is a space where AI can make some massive gains – not by trying to do radiologists’ jobs better than radiologists, but by extracting information that radiologists aren’t looking for in the first place.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a CT scan of the chest might as well be Atlas Shrugged. When you think of the sheer information content in one of those scans, it becomes immediately clear that our usual method of CT scan interpretation must be leaving a lot on the table. After all, we can go through all that information and come out with simply “normal” and call it a day.

Of course, radiologists can glean a lot from a CT scan, but they are trained to look for abnormalities. They can find pneumonia, emboli, fractures, and pneumothoraces, but the presence or absence of life-threatening abnormalities is still just a fraction of the data contained within a CT scan.

Pulling out more data from those images – data that may not indicate disease per se, but nevertheless tell us something important about patients and their risks – might just fall to those entities that are primed to take a bunch of data and interpret it in new ways: artificial intelligence (AI).

I’m thinking about AI and CT scans this week thanks to this study, appearing in the journal Radiology, from Kaiwen Xu and colleagues at Vanderbilt.

In a previous study, the team had developed an AI algorithm to take chest CT images and convert that data into information about body composition: skeletal muscle mass, fat mass, muscle lipid content – that sort of thing.

While the radiologists are busy looking for cancer or pneumonia, the AI can create a body composition report – two results from one data stream.

Here’s an example of a report generated from a CT scan from the authors’ GitHub page.

The cool thing here is that this is a clinically collected CT scan of the chest, not a special protocol designed to assess body composition. In fact, this comes from the low-dose lung cancer screening trial dataset.

As you may know, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends low-dose CT screening of the chest every year for those aged 50-80 with at least a 20 pack-year smoking history. These CT scans form an incredible dataset, actually, as they are all collected with nearly the same parameters. Obviously, the important thing to look for in these CT scans is whether there is early lung cancer. But the new paper asks, as long as we can get information about body composition from these scans, why don’t we? Can it help to risk-stratify these patients?

They took 20,768 individuals with CT scans done as part of the low-dose lung cancer screening trial and passed their scans through their automated data pipeline.

One cool feature here: Depending on body size, sometimes the edges of people in CT scans are not visible. That’s not a big deal for lung-cancer screening as long as you can see both lungs. But it does matter for assessment of muscle and body fat because that stuff lives on the edges of the thoracic cavity. The authors’ data pipeline actually accounts for this, extrapolating what the missing pieces look like from what is able to be seen. It’s quite clever.

On to some results. Would knowledge about the patient’s body composition help predict their ultimate outcome?

It would. And the best single predictor found was skeletal muscle attenuation – lower levels of skeletal muscle attenuation mean more fat infiltrating the muscle – so lower is worse here. You can see from these all-cause mortality curves that lower levels were associated with substantially worse life expectancy.

It’s worth noting that these are unadjusted curves. While AI prediction from CT images is very cool, we might be able to make similar predictions knowing, for example, the age of the patient. To account for this, the authors adjusted the findings for age, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and coronary calcium score (also calculated from those same CT scans). Even after adjustment, skeletal muscle attenuation was significantly associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and lung-cancer mortality – but not lung cancer incidence.

Those results tell us that there is likely a physiologic significance to skeletal muscle attenuation, and they provide a great proof-of-concept that automated data extraction techniques can be applied broadly to routinely collected radiology images.

That said, it’s one thing to show that something is physiologically relevant. In terms of actually predicting outcomes, adding this information to a model that contains just those clinical factors like age and diabetes doesn’t actually improve things very much. We measure this with something called the concordance index. This tells us the probability, given two individuals, of how often we can identify the person who has the outcome of interest sooner – if at all. (You can probably guess that the worst possible score is thus 0.5 and the best is 1.) A model without the AI data gives a concordance index for all-cause mortality of 0.71 or 0.72, depending on sex. Adding in the body composition data bumps that up only by a percent or so.

This honestly feels a bit like a missed opportunity to me. The authors pass the imaging data through an AI to get body composition data and then see how that predicts death.

Why not skip the middleman? Train a model using the imaging data to predict death directly, using whatever signal the AI chooses: body composition, lung size, rib thickness – whatever.

I’d be very curious to see how that model might improve our ability to predict these outcomes. In the end, this is a space where AI can make some massive gains – not by trying to do radiologists’ jobs better than radiologists, but by extracting information that radiologists aren’t looking for in the first place.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Time to end direct-to-consumer ads, says physician

One has to be living off the grid to not be bombarded with direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical advertising. Since 1997, when the Food and Drug Administration eased restrictions on this prohibition and allowed pharmaceutical companies to promote prescription-only medications to the public, there has been a deluge of ads in magazines, on the Internet, and, most annoying, on commercial television.

These television ads are quite formulaic:

We are initially introduced to a number of highly functioning patients (typically actors) who are engaged in rewarding pursuits. A voiceover narration then presents the pharmaceutical to be promoted, suggesting (not so subtly) to consumers that taking the advertised drug will improve one’s disease outlook or quality of life such that they too, just like the actors in the minidrama, can lead such highly productive lives.

The potential best-case scenarios of these new treatments may be stated. There then follows a litany of side effects – some of them life threatening – warnings, and contraindications. We’re again treated to another 5 or 10 seconds of patients leading “the good life,” and almost all of the ads end with the narrator concluding: “Ask your doctor (sometimes ‘provider’) if _____ is right for you.”

Americans spend more money on their prescriptions than do citizens of any other highly developed nation. I have personally heard from patients who get their prescriptions from other countries, where they are more affordable. These patients will also cut their pills in half or take a medication every other day instead of every day, to economize on drug costs.

Another “trick” they use to save money – and I have heard pharmacists and pharmaceutical reps themselves recommend this – is to ask for a higher dose of a medication, usually double, and then use a pill cutter to divide a tablet in half, thus making their prescription last twice as long. Why do Americans have to resort to such “workarounds”?

Many of the medications advertised are for relatively rare conditions, such as thyroid eye disease or myasthenia gravis (which affects up to about 60,000 patients in the United States). Why not spend these advertising dollars on programs to make drugs taken by the millions of Americans with common conditions (for example, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure) more affordable?

Very often the television ads contain medical jargon, such as: “If you have the EGFR mutation, or if your cancer is HER2 negative ...”

Do most patients truly understand what these terms mean? And what happens when a patient’s physician doesn’t prescribe a medication that a patient has seen on TV and asks for, or when the physician believes that a generic (nonadvertised) medication might work just as well? This creates conflict and potential discord, adversely affecting the doctor-patient relationship.

An oncologist colleague related to me that he often has to spend time correcting patients’ misperceptions of potential miracle cures offered by these ads, and that several patients have left his practice because he would not prescribe a drug they saw advertised.

Further, while these ads urge patients to try expensive “newest and latest” treatments, pharmacy benefit plans are working with health care insurance conglomerates to reduce costs of pharmaceuticals.

How does this juxtaposition of opposing forces make any sense?

It is time for us to put an end to DTC advertising, at least on television. It will require legislative action by our federal government to end this practice (legal, by the way, only in the United States and New Zealand), and hence the willingness of our politicians to get behind legislation to do so.

Just as a law was passed to prohibit tobacco advertising on television, so should a law be passed to regulate DTC pharmaceutical advertising.

The time to end DTC advertising has come!

Lloyd Alterman, MD, is a retired physician and chairman of the New Jersey Universal Healthcare Coalition. He disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One has to be living off the grid to not be bombarded with direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical advertising. Since 1997, when the Food and Drug Administration eased restrictions on this prohibition and allowed pharmaceutical companies to promote prescription-only medications to the public, there has been a deluge of ads in magazines, on the Internet, and, most annoying, on commercial television.

These television ads are quite formulaic:

We are initially introduced to a number of highly functioning patients (typically actors) who are engaged in rewarding pursuits. A voiceover narration then presents the pharmaceutical to be promoted, suggesting (not so subtly) to consumers that taking the advertised drug will improve one’s disease outlook or quality of life such that they too, just like the actors in the minidrama, can lead such highly productive lives.

The potential best-case scenarios of these new treatments may be stated. There then follows a litany of side effects – some of them life threatening – warnings, and contraindications. We’re again treated to another 5 or 10 seconds of patients leading “the good life,” and almost all of the ads end with the narrator concluding: “Ask your doctor (sometimes ‘provider’) if _____ is right for you.”

Americans spend more money on their prescriptions than do citizens of any other highly developed nation. I have personally heard from patients who get their prescriptions from other countries, where they are more affordable. These patients will also cut their pills in half or take a medication every other day instead of every day, to economize on drug costs.

Another “trick” they use to save money – and I have heard pharmacists and pharmaceutical reps themselves recommend this – is to ask for a higher dose of a medication, usually double, and then use a pill cutter to divide a tablet in half, thus making their prescription last twice as long. Why do Americans have to resort to such “workarounds”?

Many of the medications advertised are for relatively rare conditions, such as thyroid eye disease or myasthenia gravis (which affects up to about 60,000 patients in the United States). Why not spend these advertising dollars on programs to make drugs taken by the millions of Americans with common conditions (for example, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure) more affordable?

Very often the television ads contain medical jargon, such as: “If you have the EGFR mutation, or if your cancer is HER2 negative ...”

Do most patients truly understand what these terms mean? And what happens when a patient’s physician doesn’t prescribe a medication that a patient has seen on TV and asks for, or when the physician believes that a generic (nonadvertised) medication might work just as well? This creates conflict and potential discord, adversely affecting the doctor-patient relationship.

An oncologist colleague related to me that he often has to spend time correcting patients’ misperceptions of potential miracle cures offered by these ads, and that several patients have left his practice because he would not prescribe a drug they saw advertised.

Further, while these ads urge patients to try expensive “newest and latest” treatments, pharmacy benefit plans are working with health care insurance conglomerates to reduce costs of pharmaceuticals.

How does this juxtaposition of opposing forces make any sense?

It is time for us to put an end to DTC advertising, at least on television. It will require legislative action by our federal government to end this practice (legal, by the way, only in the United States and New Zealand), and hence the willingness of our politicians to get behind legislation to do so.

Just as a law was passed to prohibit tobacco advertising on television, so should a law be passed to regulate DTC pharmaceutical advertising.

The time to end DTC advertising has come!

Lloyd Alterman, MD, is a retired physician and chairman of the New Jersey Universal Healthcare Coalition. He disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One has to be living off the grid to not be bombarded with direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical advertising. Since 1997, when the Food and Drug Administration eased restrictions on this prohibition and allowed pharmaceutical companies to promote prescription-only medications to the public, there has been a deluge of ads in magazines, on the Internet, and, most annoying, on commercial television.

These television ads are quite formulaic:

We are initially introduced to a number of highly functioning patients (typically actors) who are engaged in rewarding pursuits. A voiceover narration then presents the pharmaceutical to be promoted, suggesting (not so subtly) to consumers that taking the advertised drug will improve one’s disease outlook or quality of life such that they too, just like the actors in the minidrama, can lead such highly productive lives.

The potential best-case scenarios of these new treatments may be stated. There then follows a litany of side effects – some of them life threatening – warnings, and contraindications. We’re again treated to another 5 or 10 seconds of patients leading “the good life,” and almost all of the ads end with the narrator concluding: “Ask your doctor (sometimes ‘provider’) if _____ is right for you.”

Americans spend more money on their prescriptions than do citizens of any other highly developed nation. I have personally heard from patients who get their prescriptions from other countries, where they are more affordable. These patients will also cut their pills in half or take a medication every other day instead of every day, to economize on drug costs.

Another “trick” they use to save money – and I have heard pharmacists and pharmaceutical reps themselves recommend this – is to ask for a higher dose of a medication, usually double, and then use a pill cutter to divide a tablet in half, thus making their prescription last twice as long. Why do Americans have to resort to such “workarounds”?

Many of the medications advertised are for relatively rare conditions, such as thyroid eye disease or myasthenia gravis (which affects up to about 60,000 patients in the United States). Why not spend these advertising dollars on programs to make drugs taken by the millions of Americans with common conditions (for example, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure) more affordable?

Very often the television ads contain medical jargon, such as: “If you have the EGFR mutation, or if your cancer is HER2 negative ...”

Do most patients truly understand what these terms mean? And what happens when a patient’s physician doesn’t prescribe a medication that a patient has seen on TV and asks for, or when the physician believes that a generic (nonadvertised) medication might work just as well? This creates conflict and potential discord, adversely affecting the doctor-patient relationship.

An oncologist colleague related to me that he often has to spend time correcting patients’ misperceptions of potential miracle cures offered by these ads, and that several patients have left his practice because he would not prescribe a drug they saw advertised.

Further, while these ads urge patients to try expensive “newest and latest” treatments, pharmacy benefit plans are working with health care insurance conglomerates to reduce costs of pharmaceuticals.

How does this juxtaposition of opposing forces make any sense?

It is time for us to put an end to DTC advertising, at least on television. It will require legislative action by our federal government to end this practice (legal, by the way, only in the United States and New Zealand), and hence the willingness of our politicians to get behind legislation to do so.

Just as a law was passed to prohibit tobacco advertising on television, so should a law be passed to regulate DTC pharmaceutical advertising.

The time to end DTC advertising has come!

Lloyd Alterman, MD, is a retired physician and chairman of the New Jersey Universal Healthcare Coalition. He disclosed having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

25 years of Viagra: A huge change in attitudes about ED

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Incredibly, 25 years ago, Bob Dole, a senator from Kansas at the time and former presidential candidate, went on national television in a commercial and discussed the fact that he was sexually impotent. You might be thinking, “What was happening then? Was this an early Jerry Springer experience or reality TV gone haywire?” No. Viagra was approved as a treatment 25 years ago this year.

Bob Dole was recruited by Pfizer, the manufacturer of Viagra, to do commercials in which he discussed his sexual dysfunction. He was recruited for a very specific set of reasons. First, he was a distinguished, prominent, respected national figure. Second, he was conservative.

For those of you who don’t remember, when 25 years ago Viagra first appeared, Pfizer was terrified that they would get attacked for promoting promiscuity by introducing a sex pill onto the market. Bob Dole was basically saying, “I have a medical problem. It’s tough to talk about, but there is a treatment. I’m going to discuss the fact that I, among many other men, could use this to help that problem.”

He was used in a way to deflect conservative or religious critics worried about the promotion of sex outside of marriage. Bob Dole was also well known to be married to Elizabeth Dole. This wasn’t somebody who was out on the dating market. Bob Dole was a family man, and his selection was no accident. For all these reasons, Bob Dole was the first spokesperson for Viagra.

Now, as it happens, I had a role to play with this drug. Pfizer called me up and asked me to come and do a consult with them about the ethics of this brand-new treatment. I had never been asked by a drug company to do anything like this. I didn’t know what I was doing. I thought about it and said: “I’ll do it if you let me sit in on discussions and meetings at your New York headquarters about this drug. I want open access.”

I assume they gave me open access. I went to many meetings before the Food and Drug Administration approved Viagra, and many discussions took place about how to roll it out. Once I got there, the one thing I insisted upon was that they had to be treating a disease. If they didn’t want to get involved in criticisms about this new miracle solution to the age-old problem of sexual dysfunction, impotence wouldn’t do. It wasn’t a medical diagnosis, and it was kind of a very undefined situation.

Erectile dysfunction was the answer. They met with urologists, sex experts, and individuals within the company and came up with the idea that if you were unable to have an erection after trying for 6 months or more, you suffered from erectile dysfunction, and that was the group for whom they should market Viagra. I fully agreed with that.

What happened was that probably hundreds of millions of men worldwide came forward for the first time and said, “I’m ashamed and guilty. I feel stigmatized. Now, with something that might help me, I’m going to say to my doctor, I have this problem.”

It’s a very important lesson because 25 years later, it’s still difficult for people – men and women – to discuss sexual problems, sexual dysfunction, and unhappiness with their sex life. I know we’ve gotten better at asking about this, but it’s still difficult for patients to go into it, bring it up, and talk about it. It’s something that we have to think hard about how we bring forward, honest, frank conversation and make people comfortable so they can tell us.

One thing that Viagra proved to the world is that not only is there a large amount of sexual dysfunction – some numbers as high as 35% of men over age 65 – but that sexual dysfunction is related to diseases. It’s caused by hypertension, hardening of the arteries, and diabetes. It may be caused by psychological anxiety or even just a poor relationship where things are falling apart.

I think it’s important that, when Viagra first appeared, what Pfizer tried to do and with the marketing oriented around it was treating it as a disease, trying to treat erectile dysfunction as a symptom, and then trying to explore the underlying possible causes for that symptom.

Sadly, if we look today, we have come a long way – and not always a good way – from where Viagra started. Viagra is easily available online. Many companies say, just get online and a doctor will talk with you about a prescription. They do, but they don’t explore the underlying causes anymore online of what might be causing the erectile dysfunction. They certainly may have a checkbox and ask somebody about this or that, but I’ve gone and tested the sites, and you can get a prescription in about 30 seconds.

It’s not really gone with the old medical model that accompanied the appearance of Viagra. We now treat it as a recreational drug or an aphrodisiac, none of which is true. If your body is working properly, blood will flow where it’s going to go. Taking Viagra or any of the other treatments will not help improve that or enhance that.

The other problem I see today with where we are with these impotence and erectile dysfunction drugs is that we still have not developed a full array of interventions for women. It’s true that men have Viagra, and it’s true that that’s often reimbursed. We still have women complaining that they have sexual dysfunction or loss of interest or whatever the problem might be, and we haven’t been able to develop drugs that will help them.

Since Viagra’s approval 25 years ago until the patent ran out in 2019, $40 billion worth of the drug has been sold. Its advertising has shifted so that

Doctors always need to be thinking about exploring that and trying to get a vision or a view of the health of their patients. It’s still hard for many people to speak up and say if they’re having problems in bed, and we want to make sure that we try our best to make that happen.

Overall, I think the approval of Viagra 25 years ago was a very good thing. It brought a terrible problem out into the open. It helped enhance the quality of life for many men. Despite where we are today, I think the introduction of that pill was actually a major achievement in pharmacology.

Dr. Kaplan is director, division of medical ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York. He reported conflicts of interest with Johnson & Johnson, Medscape, and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Incredibly, 25 years ago, Bob Dole, a senator from Kansas at the time and former presidential candidate, went on national television in a commercial and discussed the fact that he was sexually impotent. You might be thinking, “What was happening then? Was this an early Jerry Springer experience or reality TV gone haywire?” No. Viagra was approved as a treatment 25 years ago this year.

Bob Dole was recruited by Pfizer, the manufacturer of Viagra, to do commercials in which he discussed his sexual dysfunction. He was recruited for a very specific set of reasons. First, he was a distinguished, prominent, respected national figure. Second, he was conservative.

For those of you who don’t remember, when 25 years ago Viagra first appeared, Pfizer was terrified that they would get attacked for promoting promiscuity by introducing a sex pill onto the market. Bob Dole was basically saying, “I have a medical problem. It’s tough to talk about, but there is a treatment. I’m going to discuss the fact that I, among many other men, could use this to help that problem.”

He was used in a way to deflect conservative or religious critics worried about the promotion of sex outside of marriage. Bob Dole was also well known to be married to Elizabeth Dole. This wasn’t somebody who was out on the dating market. Bob Dole was a family man, and his selection was no accident. For all these reasons, Bob Dole was the first spokesperson for Viagra.

Now, as it happens, I had a role to play with this drug. Pfizer called me up and asked me to come and do a consult with them about the ethics of this brand-new treatment. I had never been asked by a drug company to do anything like this. I didn’t know what I was doing. I thought about it and said: “I’ll do it if you let me sit in on discussions and meetings at your New York headquarters about this drug. I want open access.”

I assume they gave me open access. I went to many meetings before the Food and Drug Administration approved Viagra, and many discussions took place about how to roll it out. Once I got there, the one thing I insisted upon was that they had to be treating a disease. If they didn’t want to get involved in criticisms about this new miracle solution to the age-old problem of sexual dysfunction, impotence wouldn’t do. It wasn’t a medical diagnosis, and it was kind of a very undefined situation.

Erectile dysfunction was the answer. They met with urologists, sex experts, and individuals within the company and came up with the idea that if you were unable to have an erection after trying for 6 months or more, you suffered from erectile dysfunction, and that was the group for whom they should market Viagra. I fully agreed with that.

What happened was that probably hundreds of millions of men worldwide came forward for the first time and said, “I’m ashamed and guilty. I feel stigmatized. Now, with something that might help me, I’m going to say to my doctor, I have this problem.”

It’s a very important lesson because 25 years later, it’s still difficult for people – men and women – to discuss sexual problems, sexual dysfunction, and unhappiness with their sex life. I know we’ve gotten better at asking about this, but it’s still difficult for patients to go into it, bring it up, and talk about it. It’s something that we have to think hard about how we bring forward, honest, frank conversation and make people comfortable so they can tell us.

One thing that Viagra proved to the world is that not only is there a large amount of sexual dysfunction – some numbers as high as 35% of men over age 65 – but that sexual dysfunction is related to diseases. It’s caused by hypertension, hardening of the arteries, and diabetes. It may be caused by psychological anxiety or even just a poor relationship where things are falling apart.

I think it’s important that, when Viagra first appeared, what Pfizer tried to do and with the marketing oriented around it was treating it as a disease, trying to treat erectile dysfunction as a symptom, and then trying to explore the underlying possible causes for that symptom.

Sadly, if we look today, we have come a long way – and not always a good way – from where Viagra started. Viagra is easily available online. Many companies say, just get online and a doctor will talk with you about a prescription. They do, but they don’t explore the underlying causes anymore online of what might be causing the erectile dysfunction. They certainly may have a checkbox and ask somebody about this or that, but I’ve gone and tested the sites, and you can get a prescription in about 30 seconds.

It’s not really gone with the old medical model that accompanied the appearance of Viagra. We now treat it as a recreational drug or an aphrodisiac, none of which is true. If your body is working properly, blood will flow where it’s going to go. Taking Viagra or any of the other treatments will not help improve that or enhance that.

The other problem I see today with where we are with these impotence and erectile dysfunction drugs is that we still have not developed a full array of interventions for women. It’s true that men have Viagra, and it’s true that that’s often reimbursed. We still have women complaining that they have sexual dysfunction or loss of interest or whatever the problem might be, and we haven’t been able to develop drugs that will help them.

Since Viagra’s approval 25 years ago until the patent ran out in 2019, $40 billion worth of the drug has been sold. Its advertising has shifted so that

Doctors always need to be thinking about exploring that and trying to get a vision or a view of the health of their patients. It’s still hard for many people to speak up and say if they’re having problems in bed, and we want to make sure that we try our best to make that happen.

Overall, I think the approval of Viagra 25 years ago was a very good thing. It brought a terrible problem out into the open. It helped enhance the quality of life for many men. Despite where we are today, I think the introduction of that pill was actually a major achievement in pharmacology.

Dr. Kaplan is director, division of medical ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York. He reported conflicts of interest with Johnson & Johnson, Medscape, and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Incredibly, 25 years ago, Bob Dole, a senator from Kansas at the time and former presidential candidate, went on national television in a commercial and discussed the fact that he was sexually impotent. You might be thinking, “What was happening then? Was this an early Jerry Springer experience or reality TV gone haywire?” No. Viagra was approved as a treatment 25 years ago this year.

Bob Dole was recruited by Pfizer, the manufacturer of Viagra, to do commercials in which he discussed his sexual dysfunction. He was recruited for a very specific set of reasons. First, he was a distinguished, prominent, respected national figure. Second, he was conservative.

For those of you who don’t remember, when 25 years ago Viagra first appeared, Pfizer was terrified that they would get attacked for promoting promiscuity by introducing a sex pill onto the market. Bob Dole was basically saying, “I have a medical problem. It’s tough to talk about, but there is a treatment. I’m going to discuss the fact that I, among many other men, could use this to help that problem.”

He was used in a way to deflect conservative or religious critics worried about the promotion of sex outside of marriage. Bob Dole was also well known to be married to Elizabeth Dole. This wasn’t somebody who was out on the dating market. Bob Dole was a family man, and his selection was no accident. For all these reasons, Bob Dole was the first spokesperson for Viagra.

Now, as it happens, I had a role to play with this drug. Pfizer called me up and asked me to come and do a consult with them about the ethics of this brand-new treatment. I had never been asked by a drug company to do anything like this. I didn’t know what I was doing. I thought about it and said: “I’ll do it if you let me sit in on discussions and meetings at your New York headquarters about this drug. I want open access.”

I assume they gave me open access. I went to many meetings before the Food and Drug Administration approved Viagra, and many discussions took place about how to roll it out. Once I got there, the one thing I insisted upon was that they had to be treating a disease. If they didn’t want to get involved in criticisms about this new miracle solution to the age-old problem of sexual dysfunction, impotence wouldn’t do. It wasn’t a medical diagnosis, and it was kind of a very undefined situation.

Erectile dysfunction was the answer. They met with urologists, sex experts, and individuals within the company and came up with the idea that if you were unable to have an erection after trying for 6 months or more, you suffered from erectile dysfunction, and that was the group for whom they should market Viagra. I fully agreed with that.

What happened was that probably hundreds of millions of men worldwide came forward for the first time and said, “I’m ashamed and guilty. I feel stigmatized. Now, with something that might help me, I’m going to say to my doctor, I have this problem.”