User login

Linearly Curved, Blackish Macule on the Wrist

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

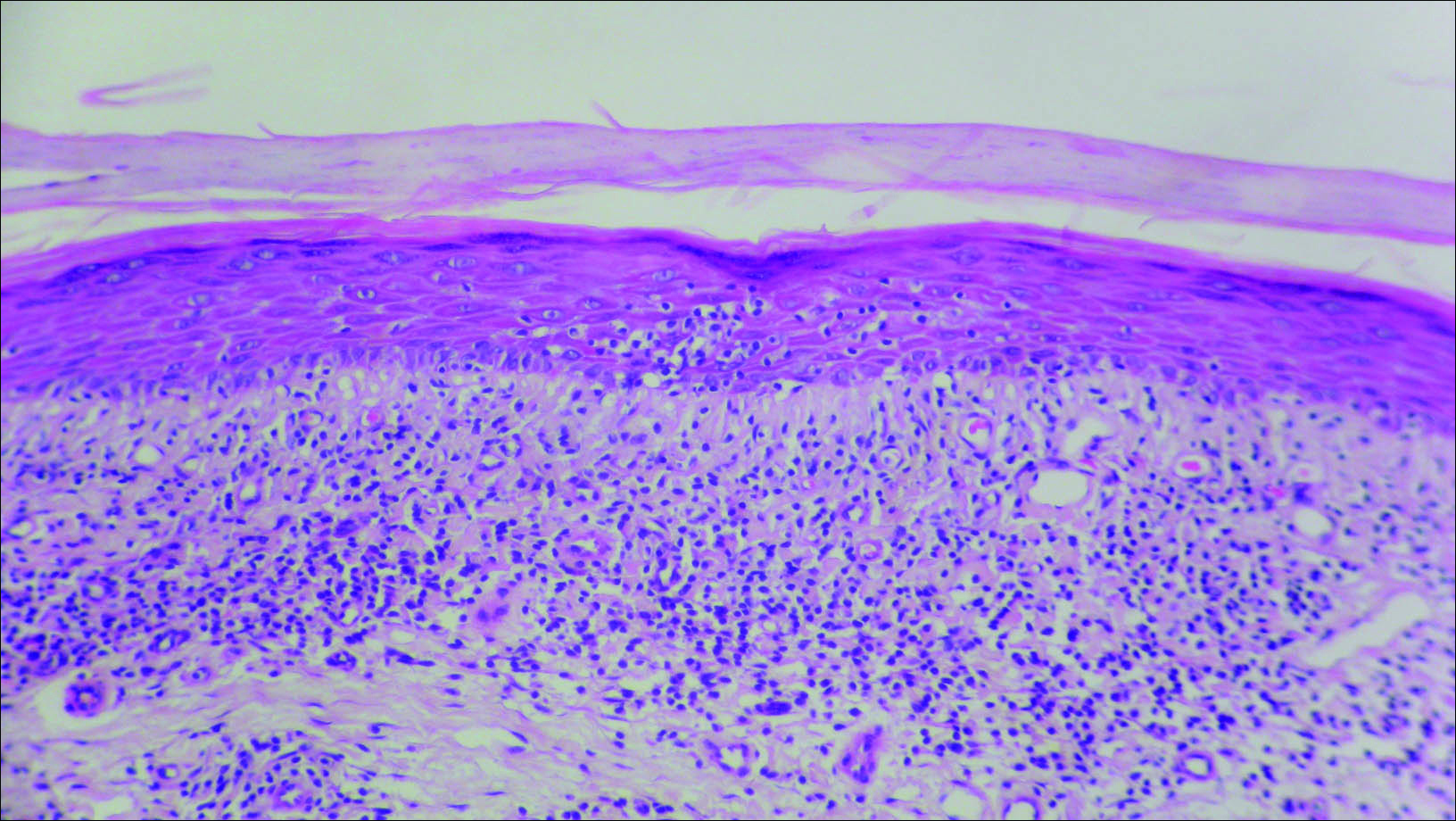

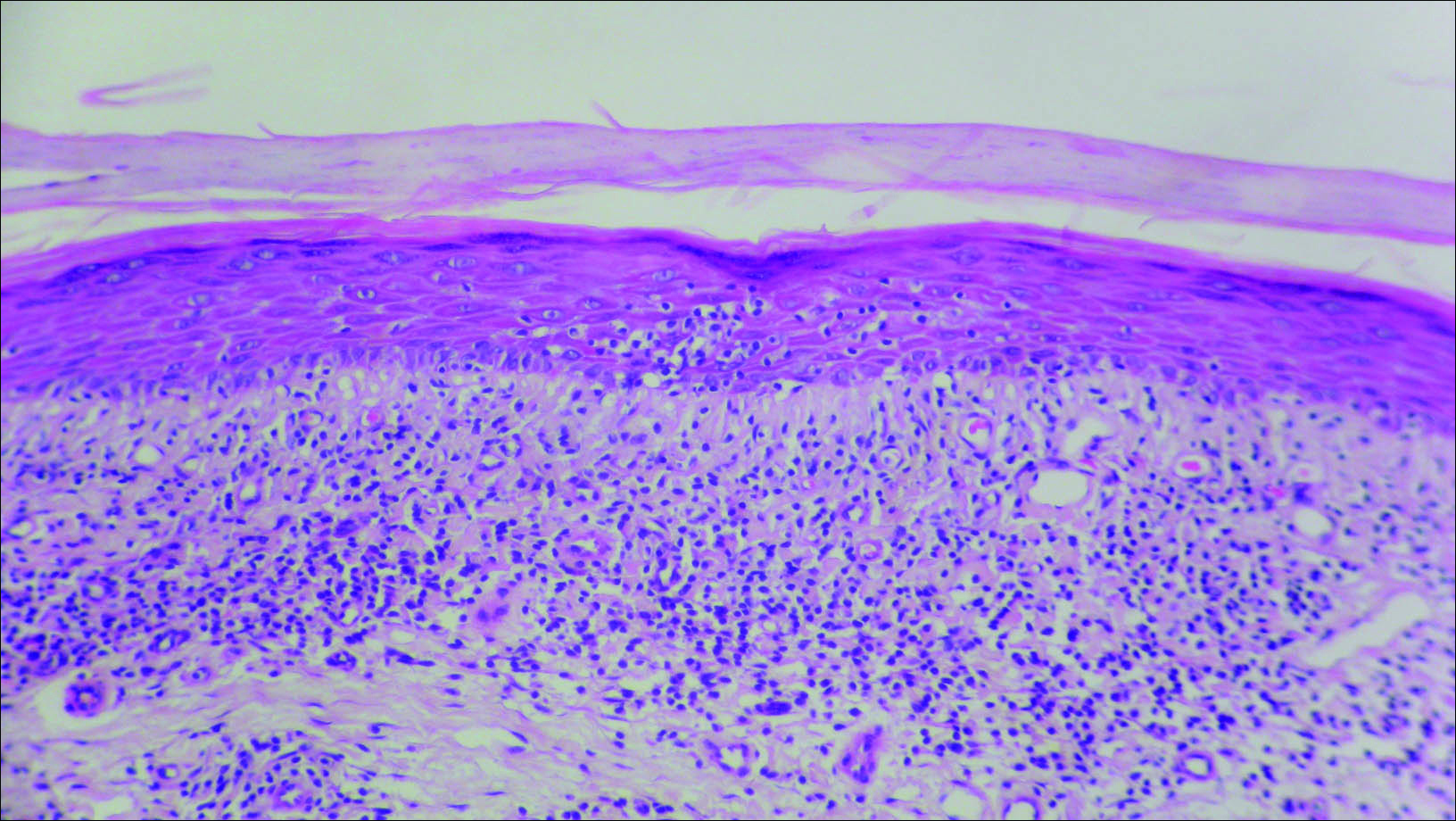

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

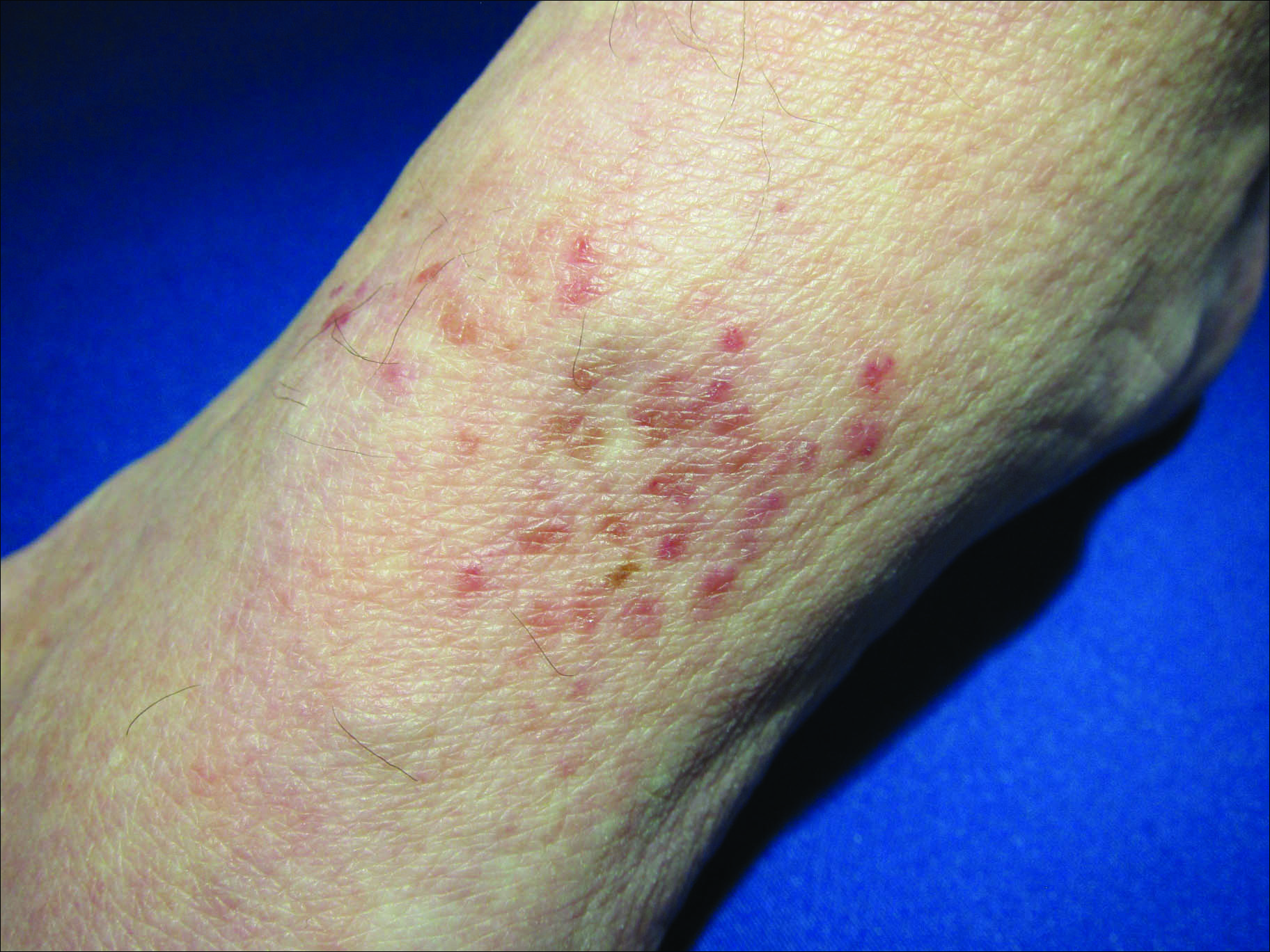

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

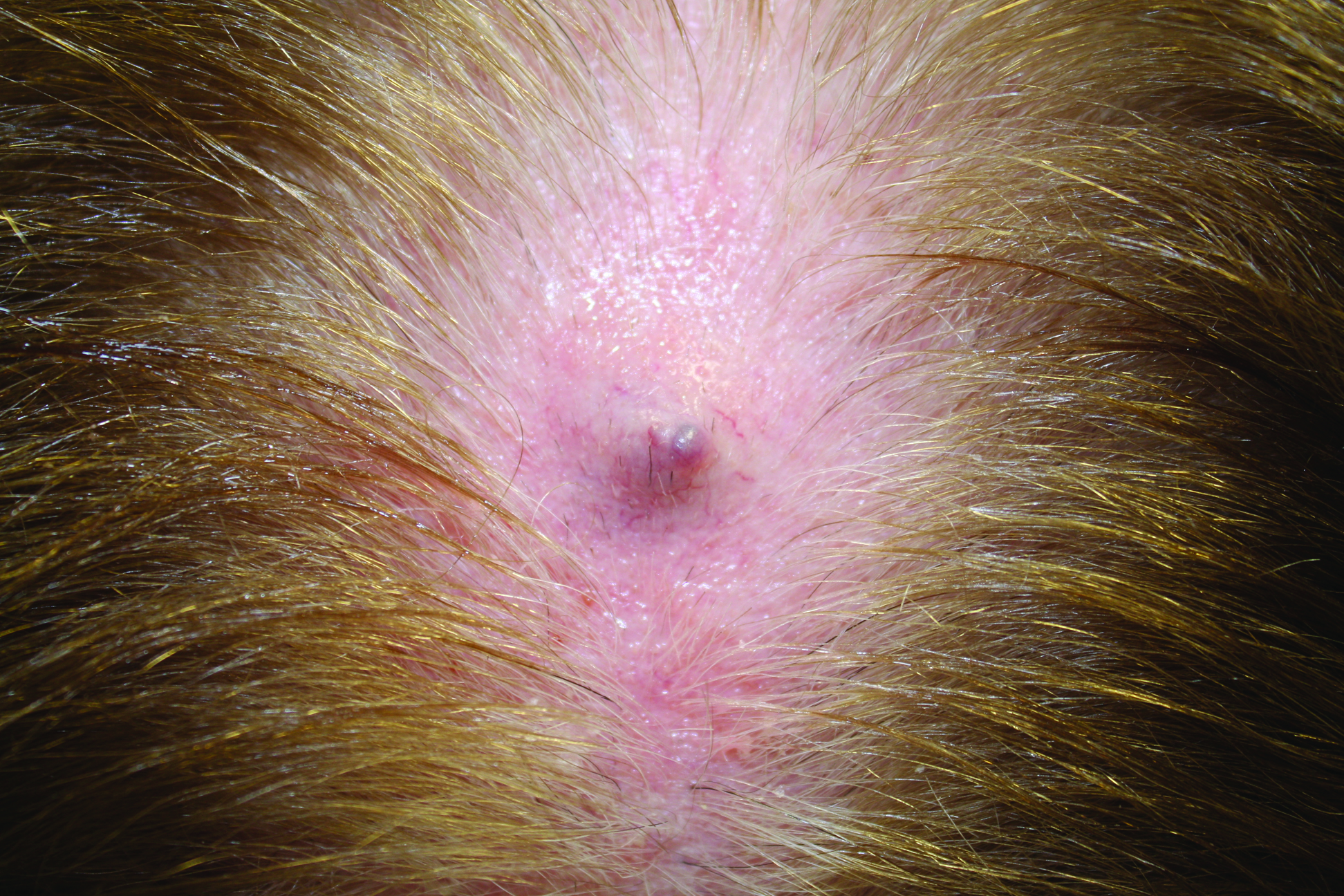

Firm Gray Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

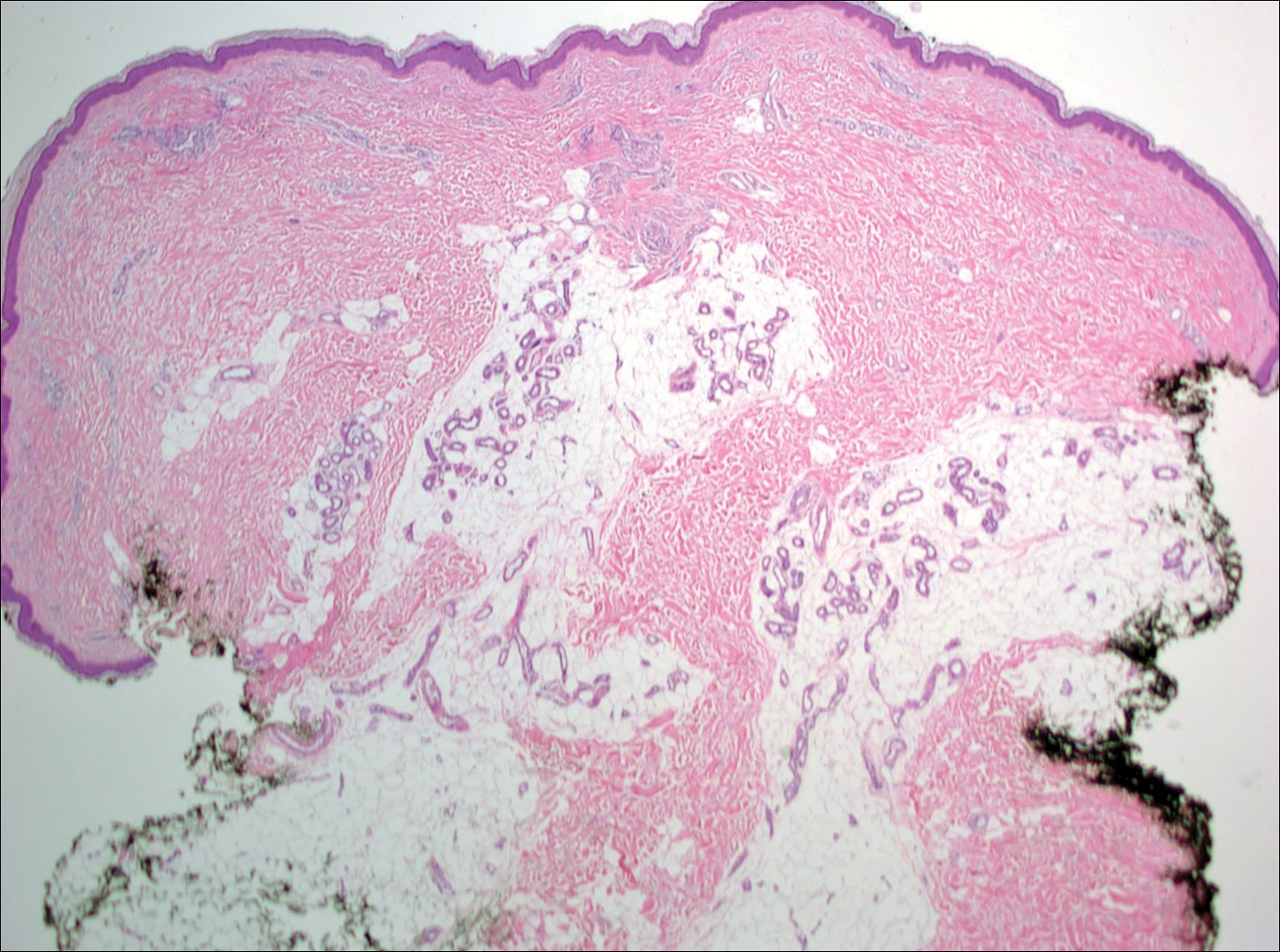

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

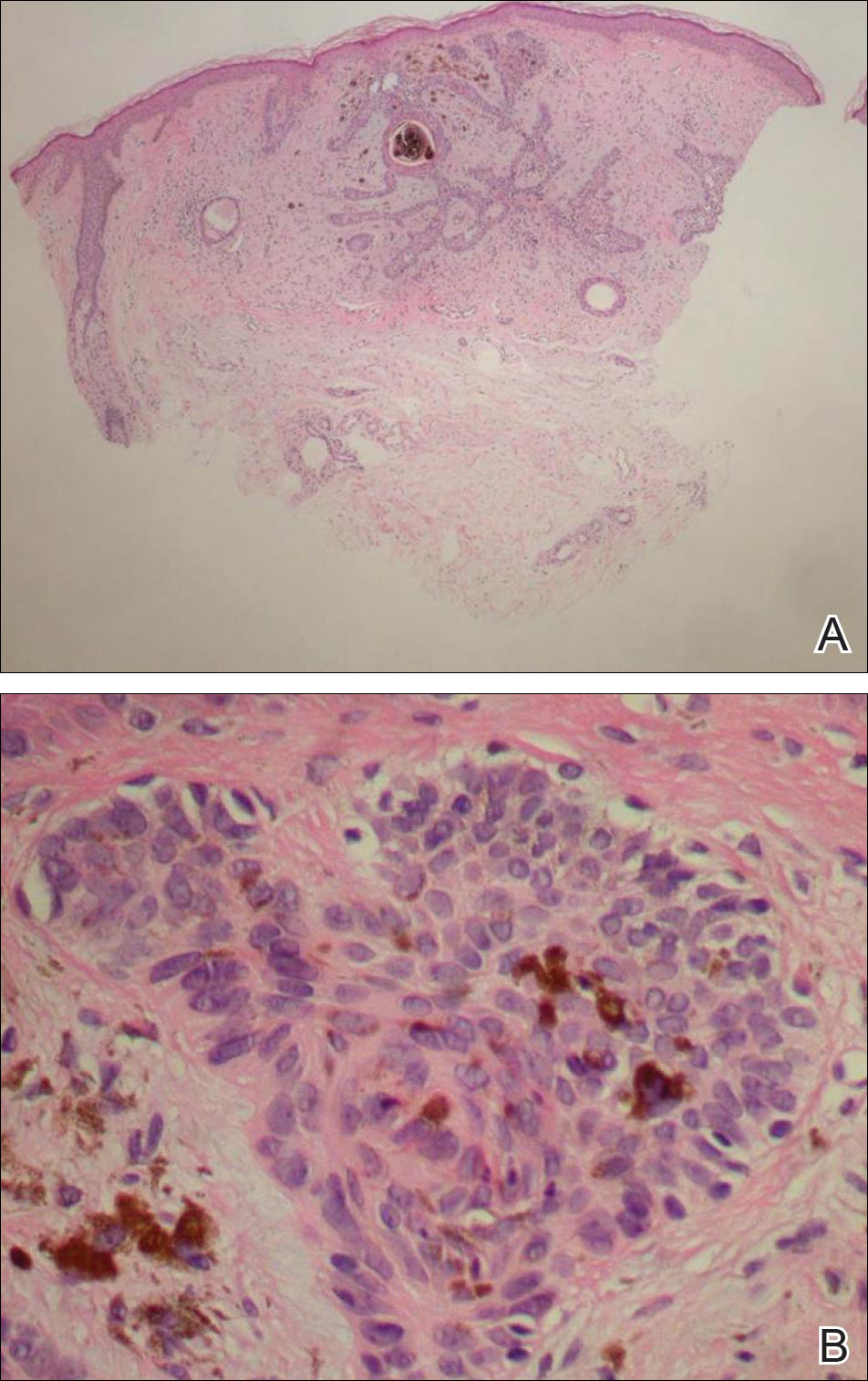

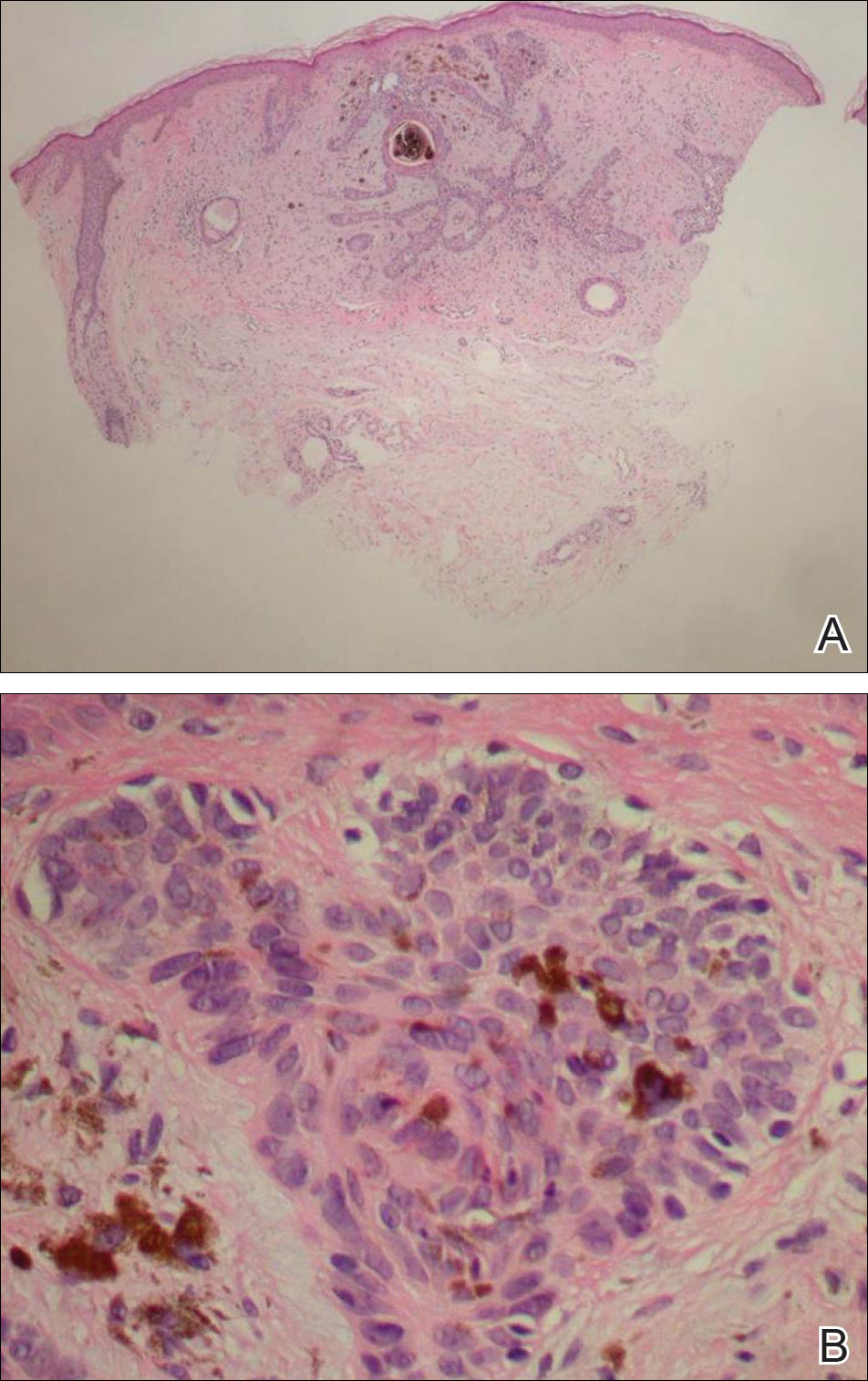

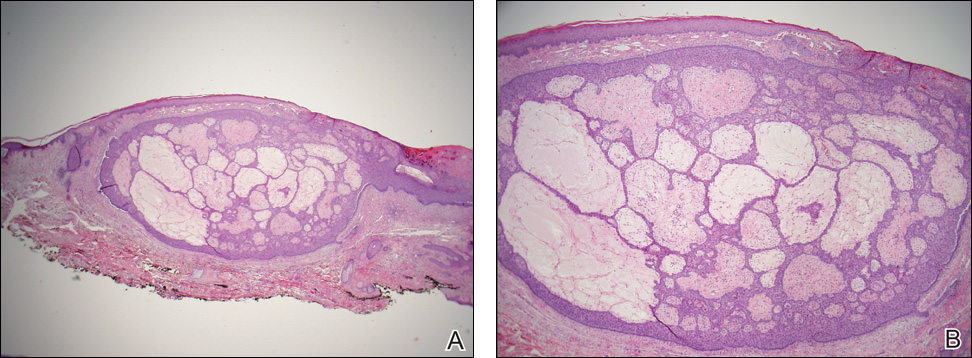

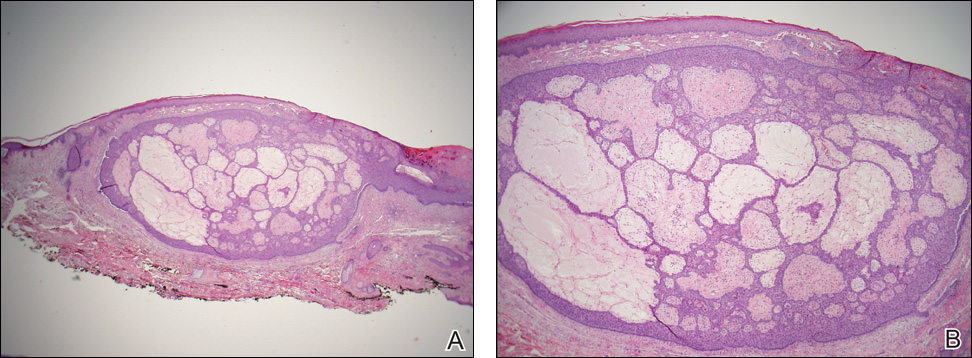

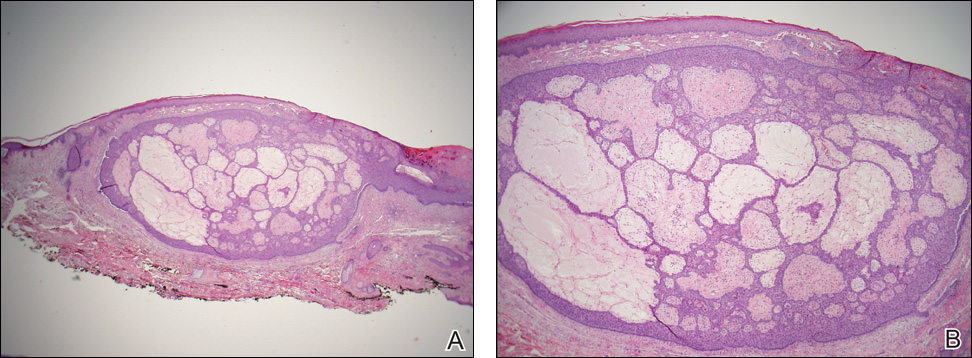

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma

Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is a rare tumor of the sweat glands that was first reported in 1952 by Lennox et al.1 These tumors are slow growing and have a predilection for the head and neck, with the eyelid being the most commonly reported location.2 In general, they present as erythematous asymptomatic nodules measuring less than 7 cm in diameter.2-4 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma tends to have a good prognosis with complete resection, but cases of metastasis and recurrence have been reported.2 Although there is no standard of care, treatment typically consists of surgical management, as the tumors are nonresponsive to chemotherapy or radiation.4 Kamalpour et al2 compared outcomes for Mohs micrographic surgery versus standard excision, the former showing a lower percentage of poor outcomes. Of note, there were fewer cases treated with Mohs surgery in this study; only more recently reported cases have been treated with Mohs surgery.

Histologically, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma is composed of cords, tubules, and lobules of epithelial cells floating in large pools of basophilic mucin, separated by thin fibrovascular septa.5 It can be difficult to distinguish a primary tumor from a mucinous carcinoma metastasis with histology alone, especially on the breasts and in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunohistochemistry can be helpful in determining the origin of the tumor. A homologue of p53, p63 expressed in basal and myoepithelial cells of the skin can aid in the confirmation of a primary tumor when present.6,7 Negative staining for cytokeratin 20 and positive staining for cytokeratin 7 also are helpful in distinguishing a primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma from a gastrointestinal tract metastasis.4,8

In our patient, no other symptoms were present that raised concern for an internal malignancy. Findings that supported a primary versus metastatic tumor included the clinicopathologic findings (Figure) as well as positive p63, cytokeratin 7, and negative cytokeratin 20 staining. The initial standard excision had tumor cells within 1 mm of the specimen margin; thus, a subsequent wider reexcision was performed. Reexcision was negative for tumor cells. Close follow-up with a primary care physician was recommended, with emphasis on colon and breast cancer screening. A follow-up mammogram was negative for breast cancer.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

- Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin: with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-880.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Papalas JA, Proia AD. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases and an update on recurrence rates. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1160-1165.

- Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrom K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-245.

- Walsh SN, Santa Cruz DJ. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. In: Rigel DS, Robinson JK, Ross M, et al, eds. Cancer of the Skin. 2nd ed. Beijing, China: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:140-149.

- Jo VY, Fletcher CD. p63 Immunohistochemical staining is limited in soft tissue tumors. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:762-766.

- Ivan D, Nash JW, Prieto VG, et al. Use of p63 expression in distinguishing primary and metastatic cutaneous adnexal neoplasms from metastatic adenocarcinoma to skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;34:478-489.

- Kazakov DV, Suster S, LeBoit PE, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the skin, primary, and secondary: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases with emphasis on the morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous forms: homologies with mucinous lesions in the breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:764-782.

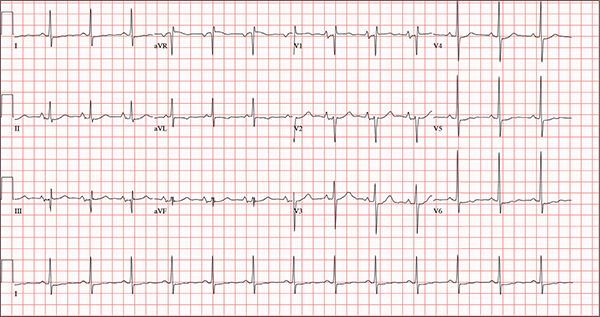

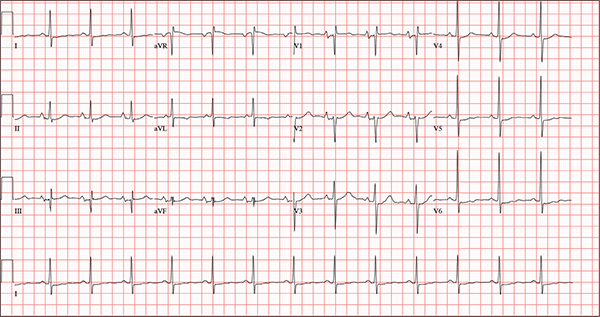

Persistent Cough, Peculiar Heart Sound

ANSWER

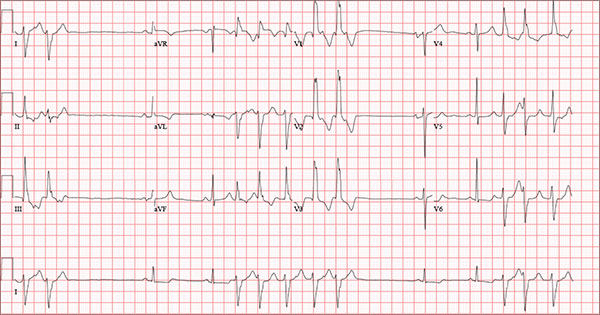

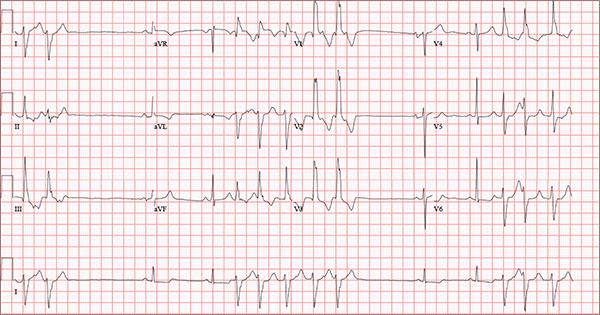

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, nonspecific ST-T wave abnormality, and an RSR’ or QR pattern in V1, suggestive of right ventricular conduction delay.

Biatrial enlargement by definition encompasses right atrial enlargement (criteria include P waves in leads II, III, and aVF measuring 2.5 mm or more) and left atrial enlargement (evidenced by P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms, and a biphasic, or “notched,” P wave with terminal negativity in lead V1).

Lead V1 may be interpreted as either an RSR’ or a QR pattern. However, the QRS duration of < 120 ms precludes this from meeting criteria for a right bundle branch block.

Finally, nonspecific ST-T wave changes were present in the precordial leads. These may be consistent with pulmonary disease.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, nonspecific ST-T wave abnormality, and an RSR’ or QR pattern in V1, suggestive of right ventricular conduction delay.

Biatrial enlargement by definition encompasses right atrial enlargement (criteria include P waves in leads II, III, and aVF measuring 2.5 mm or more) and left atrial enlargement (evidenced by P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms, and a biphasic, or “notched,” P wave with terminal negativity in lead V1).

Lead V1 may be interpreted as either an RSR’ or a QR pattern. However, the QRS duration of < 120 ms precludes this from meeting criteria for a right bundle branch block.

Finally, nonspecific ST-T wave changes were present in the precordial leads. These may be consistent with pulmonary disease.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, nonspecific ST-T wave abnormality, and an RSR’ or QR pattern in V1, suggestive of right ventricular conduction delay.

Biatrial enlargement by definition encompasses right atrial enlargement (criteria include P waves in leads II, III, and aVF measuring 2.5 mm or more) and left atrial enlargement (evidenced by P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms, and a biphasic, or “notched,” P wave with terminal negativity in lead V1).

Lead V1 may be interpreted as either an RSR’ or a QR pattern. However, the QRS duration of < 120 ms precludes this from meeting criteria for a right bundle branch block.

Finally, nonspecific ST-T wave changes were present in the precordial leads. These may be consistent with pulmonary disease.

A 54-year-old man presents with a four-day history of productive cough, low-grade fever, and malaise. The patient, a long-haul trucker, has been on the road for the past 30 days, traveling from Florida to California, and then to New Jersey. He first noticed a change in his cough after leaving Chicago. He says he’s tried OTC cough syrups to no avail, and he wants you to prescribe antibiotics so he can get back to work. He denies blood in his sputum; the specimen he provides on request is yellow, mucoid, and malodorous. You know this patient well: He has been in your patient panel for the past five years. His active problem list includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and heavy tobacco use. He is rarely compliant with any of the treatment regimens you prescribe, and he frequently misses scheduled appointments due to his job. The patient is divorced, with no children, and spends most of his time on the road. His family history is remarkable for diabetes and hypertension in both parents. He had a history of binge drinking in his early 20s but has never had a citation for driving under the influence. He denies current recreational drug use, but he admits to using amphetamines prior to his employer’s mandatory drug monitoring. He smokes 2 to 2.5 packs of cigarettes per day and always has one in his mouth. His surgical history includes appendectomy and cholecystectomy, as well as two laparoscopic procedures for abdominal adhesions. His current medication list includes an albuterol inhaler, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol, and metformin; however, he states he rarely takes any of them on a daily basis. He is allergic to tetracycline, which produces urticaria and a rash. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 168/114 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; O2 saturation, 92% on room air; and temperature, 101°F. The review of systems is positive for headaches, toothache in numbers 13 and 14, and bleeding hemorrhoids. The remainder of the review is noncontributory. The physical exam reveals a disheveled male who appears uncomfortable and diaphoretic. His weight is 314 lb and his height, 70 in. Pertinent physical findings include consolidation in the right lower chest that does not change with coughing. He has coarse respiratory sounds in all other lung fields. There are no murmurs or rubs; however, there is a fixed, split-second heart sound that you haven’t heard in previous exams. The patient’s abdomen is rotund and nontender, with wellhealed surgical scars. Two large, inflamed hemorrhoids are present, and a stool guaiac test is positive for blood. The peripheral exam reveals 2+ bilateral pitting edema. All pulses are full, and there are no focal neurologic abnormalities. Given your concern about the unfamiliar heart sound, you order an ECG in addition to laboratory bloodwork and chest x-ray. The white blood cell count measures 12.4 x 1,000 μL, and the chest xray is consistent with right lower lobe pneumonia. The ECG reveals a ventricular rate of 82 beats/min; PR interval, 148 ms; QRS duration, 82 ms; QT/QTc interval, 378/441 ms; P axis, 42°; R wave axis, 20°; and T axis, 96°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

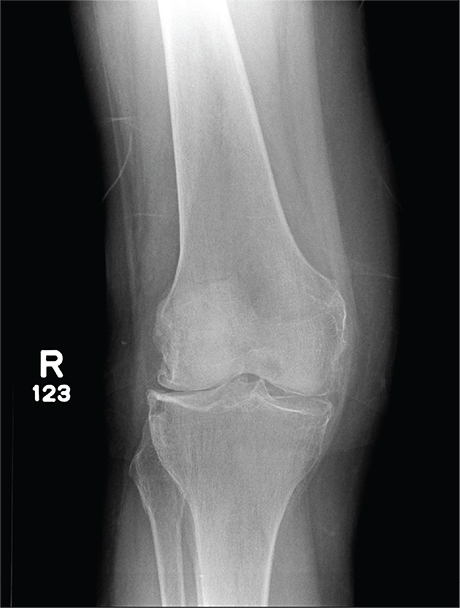

In Middle of Trip, Woman Falls

Answer

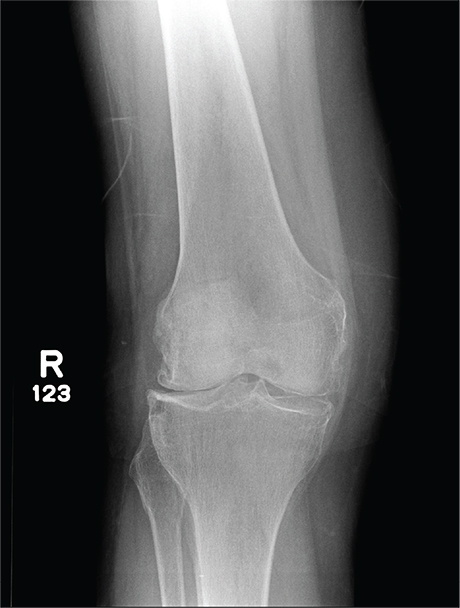

The radiograph has several findings, one of which is a nondisplaced proximal fibula fracture. In addition, there is a moderate suprapatellar joint effusion. The patient also has fairly advanced tricompartment degenerative arthrosis. (To review, the tricompartment comprises all three anatomic areas of the knee: the patellofemoral, lateral tibiofemoral, and medial tibiofemoral joints.)

Answer

The radiograph has several findings, one of which is a nondisplaced proximal fibula fracture. In addition, there is a moderate suprapatellar joint effusion. The patient also has fairly advanced tricompartment degenerative arthrosis. (To review, the tricompartment comprises all three anatomic areas of the knee: the patellofemoral, lateral tibiofemoral, and medial tibiofemoral joints.)

Answer

The radiograph has several findings, one of which is a nondisplaced proximal fibula fracture. In addition, there is a moderate suprapatellar joint effusion. The patient also has fairly advanced tricompartment degenerative arthrosis. (To review, the tricompartment comprises all three anatomic areas of the knee: the patellofemoral, lateral tibiofemoral, and medial tibiofemoral joints.)

A 70-year-old woman presents to your emergency department for evaluation of right knee pain secondary to a fall. She and her husband, in the process of driving from Florida to their home in California, stopped for the night in your town. The patient states that shortly after getting up this morning, she tripped, lost her balance, and fell. All her weight landed on her right knee; she says it is now “extremely painful” to bear weight on that leg. She also twisted her right ankle, causing additional discomfort. Her medical history is significant for hypertension, which is controlled by medication. On physical exam, you note an elderly female who is uncomfortable but in no obvious distress. Inspection of her right knee shows no obvious deformity but a moderate amount of swelling. The patient has limited range of motion secondary to the swelling. She also has moderate tenderness circumferentially around the knee. There is additional swelling and mild bruising on both the medial and lateral aspects of the right ankle. You obtain a radiograph of the right knee. What is your impression?

Moles: Their Role in Skin Cancer Diagnosis

ANSWER

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “d”). These lesions are all intradermal nevi, which have little, if any, risk for malignant transformation. Deeper nevi are considered quite safe, unless significant change has occurred. Despite the unlikelihood, however, it is risky to declare a 0% chance of skin cancer.

DISCUSSION

Slow growth and increased prominence are not the kinds of changes to look for in skin lesions. Rather, look for marked asymmetry (eg, the growth of a new, darker, macular component) or other change in color or consistency.

Hairs on these lesions are quite normal and are actually reassuring in confirming their benign nature. Skin cancers seldom support hair growth.

Most melanomas don’t come from moles. Instead, they are “de novo” lesions, literally coming from nothing, out of clear skin. It is true that the more moles someone has, the greater his or her risk for skin cancer, though not necessarily in one of the moles. When melanomas do develop from nevi (a collection of a certain type of melanocyte), this usually occurs in superficial types, such as compound or junctional nevi. From an objective standpoint, in this patient’s case, family history means nothing.

What does matter is to pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The more fair-skinned and sun-damaged (freckles, blue eyes, red hair) the patient is, the more worrisome a lesion can be.

This patient had none of those traits, and she will likely have one of her lesions surgically excised to ensure she’s satisfied with the resulting scar. Of course, the tissue sample will be sent for pathologic examination, as any specimen should be.

ANSWER

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “d”). These lesions are all intradermal nevi, which have little, if any, risk for malignant transformation. Deeper nevi are considered quite safe, unless significant change has occurred. Despite the unlikelihood, however, it is risky to declare a 0% chance of skin cancer.

DISCUSSION

Slow growth and increased prominence are not the kinds of changes to look for in skin lesions. Rather, look for marked asymmetry (eg, the growth of a new, darker, macular component) or other change in color or consistency.

Hairs on these lesions are quite normal and are actually reassuring in confirming their benign nature. Skin cancers seldom support hair growth.

Most melanomas don’t come from moles. Instead, they are “de novo” lesions, literally coming from nothing, out of clear skin. It is true that the more moles someone has, the greater his or her risk for skin cancer, though not necessarily in one of the moles. When melanomas do develop from nevi (a collection of a certain type of melanocyte), this usually occurs in superficial types, such as compound or junctional nevi. From an objective standpoint, in this patient’s case, family history means nothing.

What does matter is to pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The more fair-skinned and sun-damaged (freckles, blue eyes, red hair) the patient is, the more worrisome a lesion can be.

This patient had none of those traits, and she will likely have one of her lesions surgically excised to ensure she’s satisfied with the resulting scar. Of course, the tissue sample will be sent for pathologic examination, as any specimen should be.

ANSWER

The correct answer is none of the above (choice “d”). These lesions are all intradermal nevi, which have little, if any, risk for malignant transformation. Deeper nevi are considered quite safe, unless significant change has occurred. Despite the unlikelihood, however, it is risky to declare a 0% chance of skin cancer.

DISCUSSION

Slow growth and increased prominence are not the kinds of changes to look for in skin lesions. Rather, look for marked asymmetry (eg, the growth of a new, darker, macular component) or other change in color or consistency.

Hairs on these lesions are quite normal and are actually reassuring in confirming their benign nature. Skin cancers seldom support hair growth.

Most melanomas don’t come from moles. Instead, they are “de novo” lesions, literally coming from nothing, out of clear skin. It is true that the more moles someone has, the greater his or her risk for skin cancer, though not necessarily in one of the moles. When melanomas do develop from nevi (a collection of a certain type of melanocyte), this usually occurs in superficial types, such as compound or junctional nevi. From an objective standpoint, in this patient’s case, family history means nothing.

What does matter is to pay as much attention to the owner as to the lesion. The more fair-skinned and sun-damaged (freckles, blue eyes, red hair) the patient is, the more worrisome a lesion can be.

This patient had none of those traits, and she will likely have one of her lesions surgically excised to ensure she’s satisfied with the resulting scar. Of course, the tissue sample will be sent for pathologic examination, as any specimen should be.

A 39-year-old woman self-refers for evaluation of moles she’s had on her face “all her life.” They have become more prominent with age, and many now have hairs growing in them. They are often traumatized by contact with fingernails or clothing. The patient worries that they might “turn into cancer” the way her grandfather’s moles did. The patient looks her stated age, is moderately overweight, and has more than her share of moles (some of which exceed 6 mm in diameter.) For the most part, they are skin-colored, and several are hair-bearing. Further questioning reveals that her moles manifested during puberty and have not been present “all her life.” Her type II skin is otherwise unremarkable and free of sun damage.

Growing Subcutaneous Mass on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

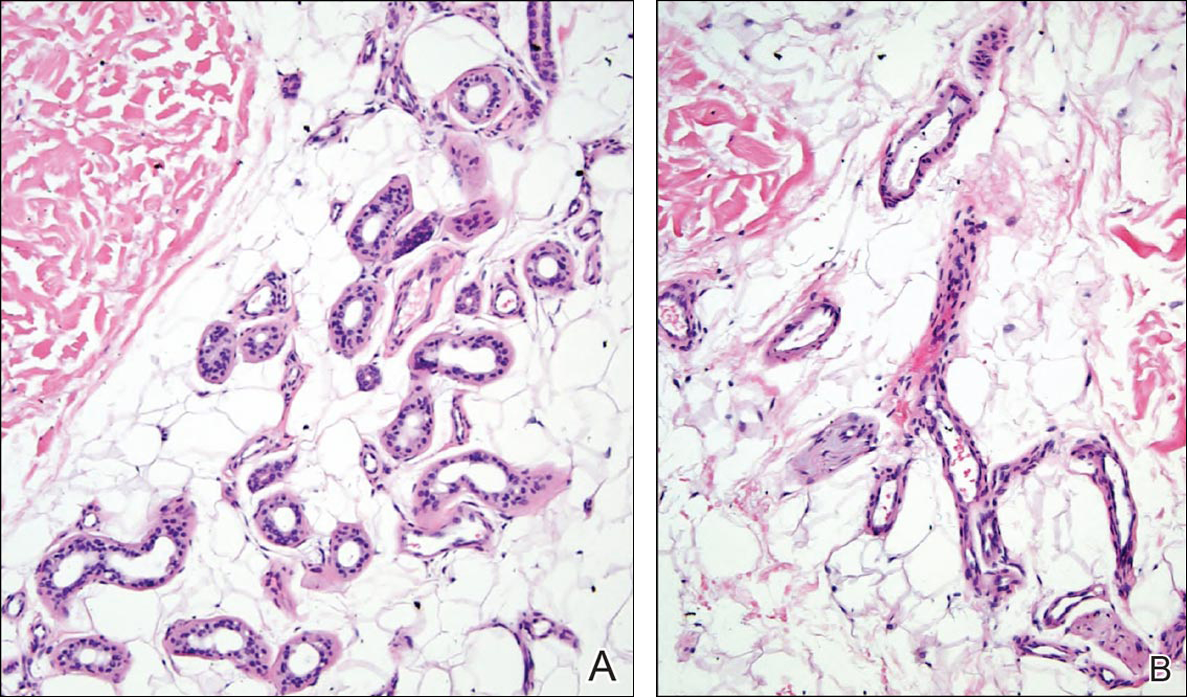

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.

Erythematous Atrophic Plaque in the Inguinal Fold

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Slack Skin Disease

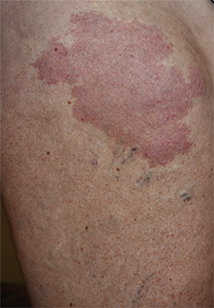

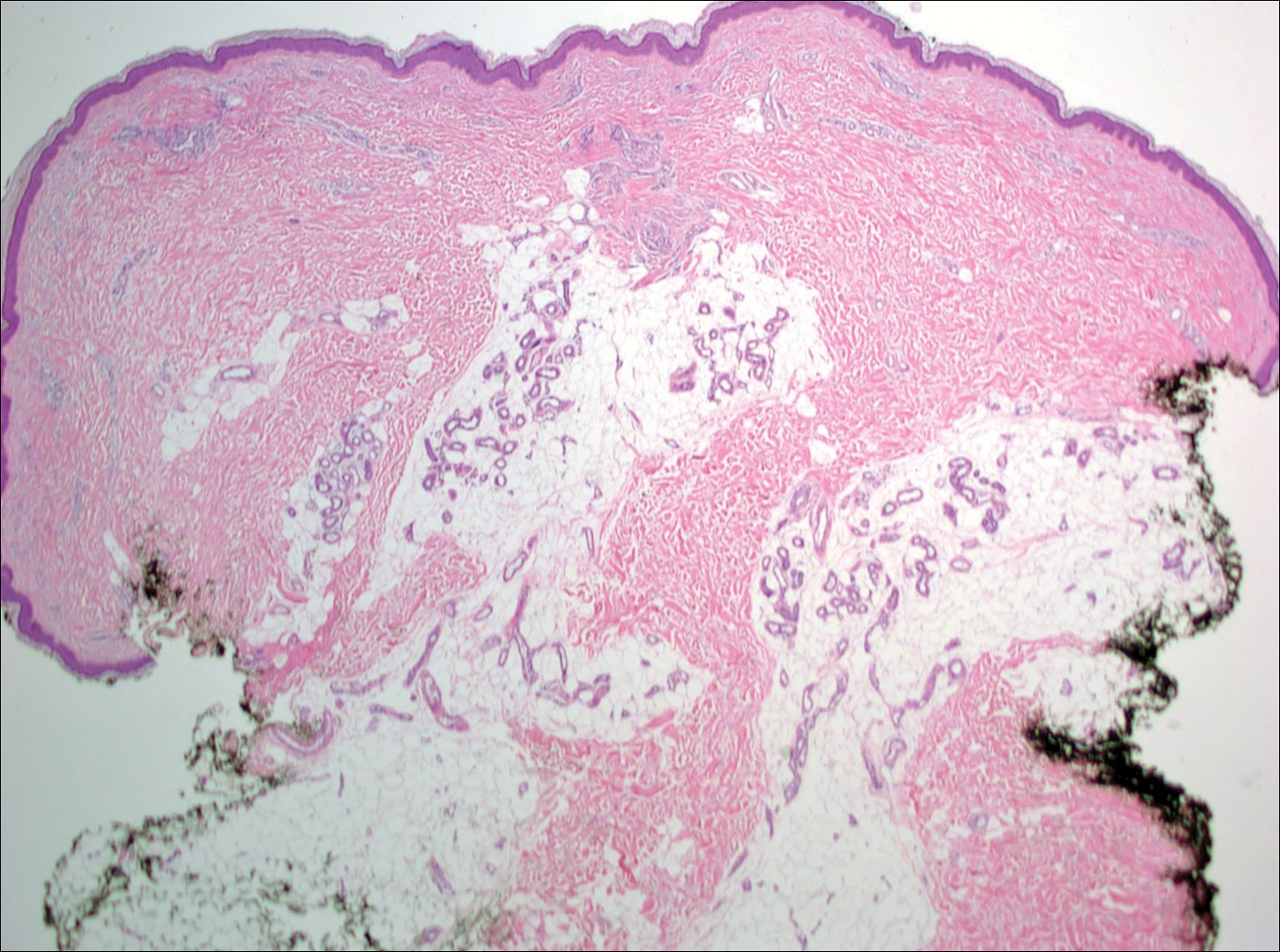

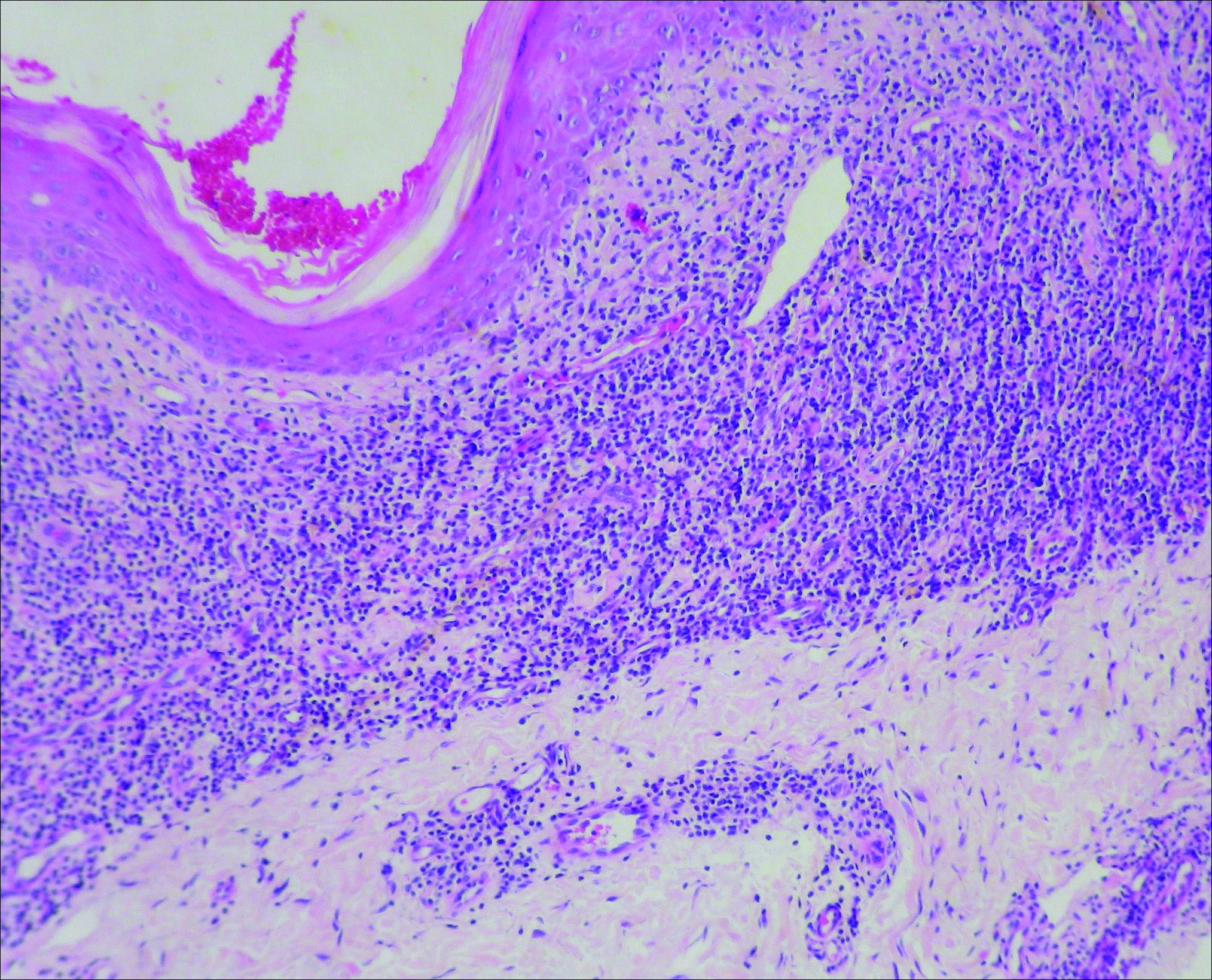

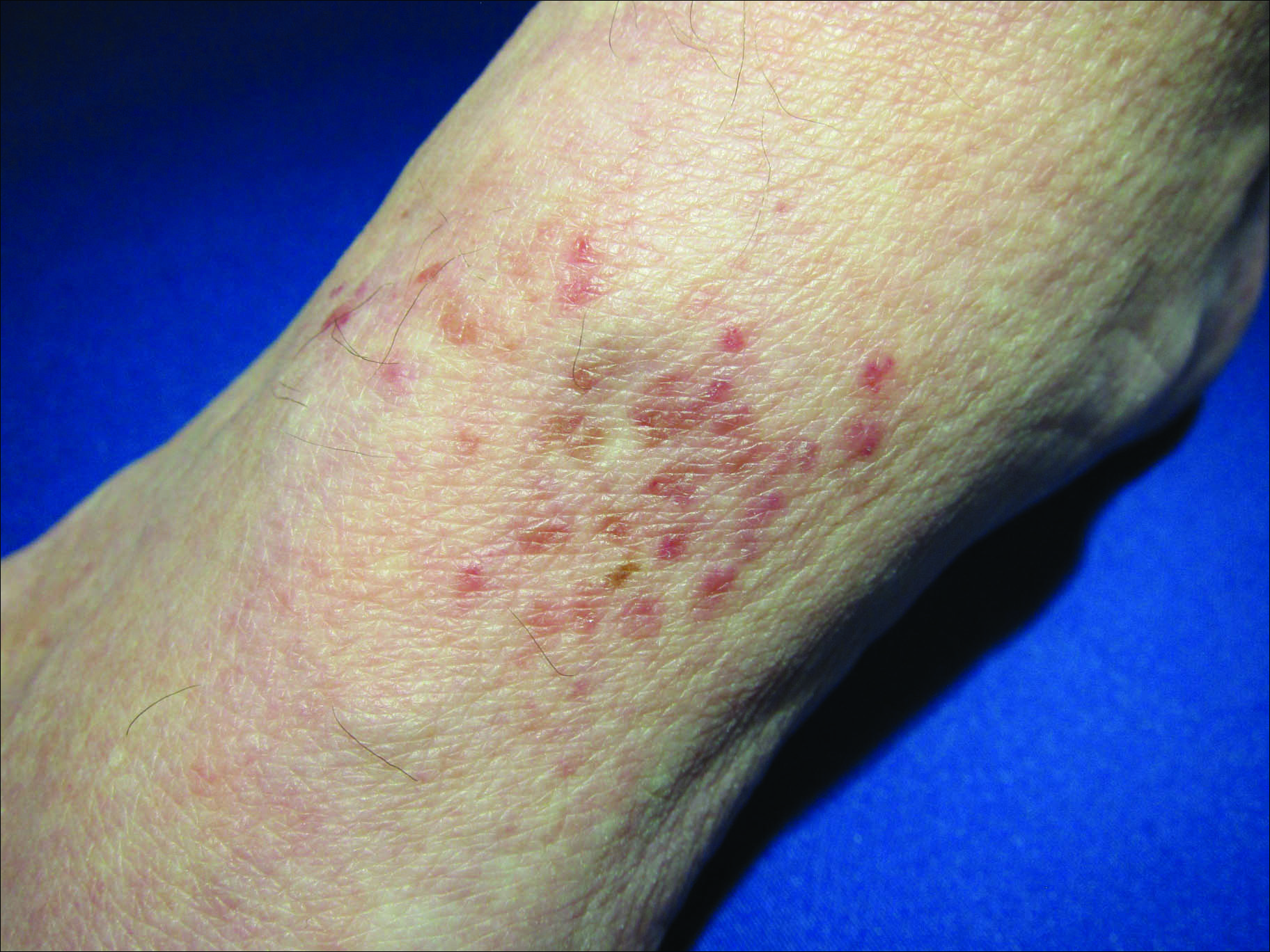

Initial biopsy revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered epidermotropism, papillary dermal sclerosis, and lymphocyte atypia (Figure 1). A repeat biopsy showed a lichenoid granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes and rare giant cells, superficially located in the dermis, without a deeper dense infiltration. Focal lymphocytic epidermotropism also was present (Figure 2). The infiltrate was CD3+CD4+ with a minority of cells also staining for CD8. An elastin stain demonstrated diminished elastin fibers in the superficial dermis. A clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement was identified by polymerase chain reaction. One group of pink and brown papules was present on the dorsal aspect of the right foot (Figure 3). A biopsy of this area showed similar findings. The patient was treated with a trial of carmustine 20-mg% ointment over the following year with some improvement of the mild pruritus but without notable change in the clinical findings.

Granulomatous slack skin disease (GSSD) is a rare form of mycosis fungoides–type cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It usually presents as well-demarcated, atrophic, poikilodermatous patches and plaques with a predilection for the inguinal and axillary regions.1 The affected areas tend to be asymptomatic and enlarge gradually over years to become pendulous with lax skin and wrinkles. In contrast to other forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, extracutaneous spread is rare. The disease shows a slow progression over many years and by itself is not life threatening. However, affected patients have a risk for developing secondary lymphoproliferative neoplasms, which have been documented in approximately 50% of reported cases.2 These lymphoproliferative neoplasms may arise concurrently, precede, or follow the development of GSSD lesions. Hodgkin lymphoma, seen in 33% of cases, is the most common association, with others being non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, acute myeloid leukemia, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1-3

Histologically, GSSD is characterized by a dense, dermal, granulomatous proliferation of atypical T lymphocytes with scattered multinucleated giant cells.1,4 There is a loss of elastin fibers in the infiltrated areas, and occasional elastophagocytosis can be seen.1,2,4 Immunoprofiling of the infiltrate has shown CD3+CD4+CD45RO+ T-helper cells with occasional loss of CD5 and CD7.3 A clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement of the g and b genes frequently is described.1,4,5

At this time no treatment has been found to be reliably curative. Varying success in treating GSSD has been achieved with topical nitrogen mustard, carmustine, topical and systemic corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA, radiotherapy, azathioprine, IFN-g, and combinations of these agents.1-3,6-9 Excision of the diseased skin has been performed for cosmetically or functionally disturbing lesions, but in all but one case the lesions recurred within months.1,10 A consistently reliable treatment of GSSD has not been established; treatment should be tailored to the individual patient.

- Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

- Teixeira M, Alves R, Lima M, et al. Granulomatous slack skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:435-438.

- van Haselen CW, Toonstra J, van der Putte SJ, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: report of three patients with an updated review of the literature. Dermatology. 1998;196:382-391.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- LeBoit PE, Zackheim HS, White CR Jr. Granulomatous variants of cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: the histopathology of granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:83-95.

- Hultgren TL, Jones D, Duvic M. Topical nitrogen mustard for the treatment of granulomatous slack skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:51-54.

- Camacho FM, Burg G, Moreno JC, et al. Granulomatous slack skin in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:204-208.

- Liu Z, Huang C, Li J. Prednisone combined with interferon for the treatment of one case of generalized granulomatous slack skin. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolo Med Sci. 2005;25:617-618.

- Oberholzer PA, Cozzio A, Dummer R, et al. Granulomatous slack skin responds to UVA1 phototherapy. Dermatology. 2009;219:268-271.

- Clarijis M, Poot F, Laka A, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: treatment with extensive surgery and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2003;206:393-397.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Slack Skin Disease

Initial biopsy revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered epidermotropism, papillary dermal sclerosis, and lymphocyte atypia (Figure 1). A repeat biopsy showed a lichenoid granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes and rare giant cells, superficially located in the dermis, without a deeper dense infiltration. Focal lymphocytic epidermotropism also was present (Figure 2). The infiltrate was CD3+CD4+ with a minority of cells also staining for CD8. An elastin stain demonstrated diminished elastin fibers in the superficial dermis. A clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement was identified by polymerase chain reaction. One group of pink and brown papules was present on the dorsal aspect of the right foot (Figure 3). A biopsy of this area showed similar findings. The patient was treated with a trial of carmustine 20-mg% ointment over the following year with some improvement of the mild pruritus but without notable change in the clinical findings.

Granulomatous slack skin disease (GSSD) is a rare form of mycosis fungoides–type cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It usually presents as well-demarcated, atrophic, poikilodermatous patches and plaques with a predilection for the inguinal and axillary regions.1 The affected areas tend to be asymptomatic and enlarge gradually over years to become pendulous with lax skin and wrinkles. In contrast to other forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, extracutaneous spread is rare. The disease shows a slow progression over many years and by itself is not life threatening. However, affected patients have a risk for developing secondary lymphoproliferative neoplasms, which have been documented in approximately 50% of reported cases.2 These lymphoproliferative neoplasms may arise concurrently, precede, or follow the development of GSSD lesions. Hodgkin lymphoma, seen in 33% of cases, is the most common association, with others being non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, acute myeloid leukemia, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1-3

Histologically, GSSD is characterized by a dense, dermal, granulomatous proliferation of atypical T lymphocytes with scattered multinucleated giant cells.1,4 There is a loss of elastin fibers in the infiltrated areas, and occasional elastophagocytosis can be seen.1,2,4 Immunoprofiling of the infiltrate has shown CD3+CD4+CD45RO+ T-helper cells with occasional loss of CD5 and CD7.3 A clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement of the g and b genes frequently is described.1,4,5

At this time no treatment has been found to be reliably curative. Varying success in treating GSSD has been achieved with topical nitrogen mustard, carmustine, topical and systemic corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA, radiotherapy, azathioprine, IFN-g, and combinations of these agents.1-3,6-9 Excision of the diseased skin has been performed for cosmetically or functionally disturbing lesions, but in all but one case the lesions recurred within months.1,10 A consistently reliable treatment of GSSD has not been established; treatment should be tailored to the individual patient.

The Diagnosis: Granulomatous Slack Skin Disease

Initial biopsy revealed a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered epidermotropism, papillary dermal sclerosis, and lymphocyte atypia (Figure 1). A repeat biopsy showed a lichenoid granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes and rare giant cells, superficially located in the dermis, without a deeper dense infiltration. Focal lymphocytic epidermotropism also was present (Figure 2). The infiltrate was CD3+CD4+ with a minority of cells also staining for CD8. An elastin stain demonstrated diminished elastin fibers in the superficial dermis. A clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement was identified by polymerase chain reaction. One group of pink and brown papules was present on the dorsal aspect of the right foot (Figure 3). A biopsy of this area showed similar findings. The patient was treated with a trial of carmustine 20-mg% ointment over the following year with some improvement of the mild pruritus but without notable change in the clinical findings.

Granulomatous slack skin disease (GSSD) is a rare form of mycosis fungoides–type cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It usually presents as well-demarcated, atrophic, poikilodermatous patches and plaques with a predilection for the inguinal and axillary regions.1 The affected areas tend to be asymptomatic and enlarge gradually over years to become pendulous with lax skin and wrinkles. In contrast to other forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, extracutaneous spread is rare. The disease shows a slow progression over many years and by itself is not life threatening. However, affected patients have a risk for developing secondary lymphoproliferative neoplasms, which have been documented in approximately 50% of reported cases.2 These lymphoproliferative neoplasms may arise concurrently, precede, or follow the development of GSSD lesions. Hodgkin lymphoma, seen in 33% of cases, is the most common association, with others being non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, acute myeloid leukemia, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1-3

Histologically, GSSD is characterized by a dense, dermal, granulomatous proliferation of atypical T lymphocytes with scattered multinucleated giant cells.1,4 There is a loss of elastin fibers in the infiltrated areas, and occasional elastophagocytosis can be seen.1,2,4 Immunoprofiling of the infiltrate has shown CD3+CD4+CD45RO+ T-helper cells with occasional loss of CD5 and CD7.3 A clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement of the g and b genes frequently is described.1,4,5

At this time no treatment has been found to be reliably curative. Varying success in treating GSSD has been achieved with topical nitrogen mustard, carmustine, topical and systemic corticosteroids, psoralen plus UVA, radiotherapy, azathioprine, IFN-g, and combinations of these agents.1-3,6-9 Excision of the diseased skin has been performed for cosmetically or functionally disturbing lesions, but in all but one case the lesions recurred within months.1,10 A consistently reliable treatment of GSSD has not been established; treatment should be tailored to the individual patient.

- Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

- Teixeira M, Alves R, Lima M, et al. Granulomatous slack skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:435-438.

- van Haselen CW, Toonstra J, van der Putte SJ, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: report of three patients with an updated review of the literature. Dermatology. 1998;196:382-391.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- LeBoit PE, Zackheim HS, White CR Jr. Granulomatous variants of cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: the histopathology of granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:83-95.

- Hultgren TL, Jones D, Duvic M. Topical nitrogen mustard for the treatment of granulomatous slack skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:51-54.

- Camacho FM, Burg G, Moreno JC, et al. Granulomatous slack skin in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:204-208.

- Liu Z, Huang C, Li J. Prednisone combined with interferon for the treatment of one case of generalized granulomatous slack skin. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolo Med Sci. 2005;25:617-618.

- Oberholzer PA, Cozzio A, Dummer R, et al. Granulomatous slack skin responds to UVA1 phototherapy. Dermatology. 2009;219:268-271.

- Clarijis M, Poot F, Laka A, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: treatment with extensive surgery and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2003;206:393-397.

- Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

- Teixeira M, Alves R, Lima M, et al. Granulomatous slack skin. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:435-438.

- van Haselen CW, Toonstra J, van der Putte SJ, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: report of three patients with an updated review of the literature. Dermatology. 1998;196:382-391.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617.

- LeBoit PE, Zackheim HS, White CR Jr. Granulomatous variants of cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: the histopathology of granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:83-95.

- Hultgren TL, Jones D, Duvic M. Topical nitrogen mustard for the treatment of granulomatous slack skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:51-54.

- Camacho FM, Burg G, Moreno JC, et al. Granulomatous slack skin in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:204-208.

- Liu Z, Huang C, Li J. Prednisone combined with interferon for the treatment of one case of generalized granulomatous slack skin. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolo Med Sci. 2005;25:617-618.

- Oberholzer PA, Cozzio A, Dummer R, et al. Granulomatous slack skin responds to UVA1 phototherapy. Dermatology. 2009;219:268-271.

- Clarijis M, Poot F, Laka A, et al. Granulomatous slack skin: treatment with extensive surgery and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2003;206:393-397.

A 66-year-old man presented with a rash on the groin of more than 6 years’ duration. The eruption was asymptomatic, except for occasional pruritus during the summer months. Numerous over-the-counter ointments, creams, and powders, as well as prescription topical corticosteroids, had failed to provide improvement. An outside biopsy performed 1 year earlier was considered nondiagnostic. Physical examination revealed a pink to violaceous, pendulous, atrophic plaque with slight scale on the right side of the lower abdomen running just superior to the right inguinal fold; the left inguinal fold was unaffected. Inguinal lymph nodes were not palpable. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the plaque in the inguinal fold was performed.

Irregular, Smooth, Pink Plaque on the Back

The Diagnosis: Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP) was first described in 19531 and was thought to be premalignant as evidenced by the proposed name premalignant fibroepithelial tumor of the skin. This neoplasm now is largely believed to represent a rare form of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Typical presentation is a smooth, flesh-colored or pink plaque or nodule.2 Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus has a predilection for the lumbosacral back, though the groin also has been reported as a common site of incidence.1,3 Similar to other BCCs, it is seen in older individuals, typically those older than 50 years.3,4

Clinical diagnosis of FeP can be difficult. The differential diagnosis of FeP can include acrochordon, amelanotic melanoma, compound nevus, hemangioma, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceous, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.5 Dermoscopic evaluation can aid in the diagnosis. A vascular network composed of fine arborizing vessels with or without dotted vessels and white streaks are characteristic findings of FeP. Patients with pigment also demonstrate structureless gray-brown areas and gray-blue dots.6

Biopsy with subsequent histopathologic evaluation confirms the diagnosis of FeP. The characteristic microscopic findings of thin eosinophilic epithelial strands with eccrine ducts anastomosing in an abundant fibromyxoid stroma with collections of basophilic cells located at the ends of the epithelial strands were demonstrated in our patient’s histopathologic specimen (Figure). The histologic appearance is similar to syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro. Recognition of basaloid nests, which often demonstrate retraction, and mitotic activity can differentiate FeP from syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro.7

Treatment of FeP is largely the same as other BCCs including destruction by electrodesiccation and curettage or complete removal by surgical excision. Several studies have demonstrated effective treatment of nonaggressive BCCs with curettage alone and subjectively reported improved cosmesis compared to electrodesiccation and curettage.8-10 Although methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy has demonstrated some therapeutic efficacy for superficial and nodular BCCs,11 a case report utilizing the same modality for FeP did not provide adequate response.12 However, adequate data are not available to assess potential use of this less invasive therapy.

- Pinkus H. Premalignant fibroepithelial tumors of skin. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1953;67:598-615.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Barr RJ, Herten RJ, Stone OJ. Multiple premalignant fibroepitheliomas of Pinkus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 1978;21:335-337.

- Betti R, Inselvini E, Carducci M, et al. Age and site prevalence of histologic subtypes of basal cell carcinomas. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:174-176.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus presenting as a sessile thigh nodule. Skinmed. 2003;2:385-387.

- Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Broganelli P, et al. Dermoscopy patterns of fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1318-1322.

- Schadt CR, Boyd AS. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma with co-existent squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):71-74.

- Barlow JO, Zalla MJ, Kyle A, et al. Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with curettage alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1039-1045.

- McDaniel WE. Therapy for basal cell epitheliomas by curettage only. further study. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:901-903.

- Reymann F. 15 Years’ experience with treatment of basal cell carcinomas of the skin with curettage. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1985;120:56-59.

- Fai D, Arpaia N, Romano I, et al. Methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratoses and non-melanoma skin cancers: a retrospective analysis of response in 462 patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2009;144:281-285.

- Park MY, Kim YC. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus: poor response to topical photodynamic therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:133-134.

The Diagnosis: Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP) was first described in 19531 and was thought to be premalignant as evidenced by the proposed name premalignant fibroepithelial tumor of the skin. This neoplasm now is largely believed to represent a rare form of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Typical presentation is a smooth, flesh-colored or pink plaque or nodule.2 Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus has a predilection for the lumbosacral back, though the groin also has been reported as a common site of incidence.1,3 Similar to other BCCs, it is seen in older individuals, typically those older than 50 years.3,4

Clinical diagnosis of FeP can be difficult. The differential diagnosis of FeP can include acrochordon, amelanotic melanoma, compound nevus, hemangioma, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceous, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.5 Dermoscopic evaluation can aid in the diagnosis. A vascular network composed of fine arborizing vessels with or without dotted vessels and white streaks are characteristic findings of FeP. Patients with pigment also demonstrate structureless gray-brown areas and gray-blue dots.6

Biopsy with subsequent histopathologic evaluation confirms the diagnosis of FeP. The characteristic microscopic findings of thin eosinophilic epithelial strands with eccrine ducts anastomosing in an abundant fibromyxoid stroma with collections of basophilic cells located at the ends of the epithelial strands were demonstrated in our patient’s histopathologic specimen (Figure). The histologic appearance is similar to syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro. Recognition of basaloid nests, which often demonstrate retraction, and mitotic activity can differentiate FeP from syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro.7

Treatment of FeP is largely the same as other BCCs including destruction by electrodesiccation and curettage or complete removal by surgical excision. Several studies have demonstrated effective treatment of nonaggressive BCCs with curettage alone and subjectively reported improved cosmesis compared to electrodesiccation and curettage.8-10 Although methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy has demonstrated some therapeutic efficacy for superficial and nodular BCCs,11 a case report utilizing the same modality for FeP did not provide adequate response.12 However, adequate data are not available to assess potential use of this less invasive therapy.

The Diagnosis: Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP) was first described in 19531 and was thought to be premalignant as evidenced by the proposed name premalignant fibroepithelial tumor of the skin. This neoplasm now is largely believed to represent a rare form of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Typical presentation is a smooth, flesh-colored or pink plaque or nodule.2 Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus has a predilection for the lumbosacral back, though the groin also has been reported as a common site of incidence.1,3 Similar to other BCCs, it is seen in older individuals, typically those older than 50 years.3,4

Clinical diagnosis of FeP can be difficult. The differential diagnosis of FeP can include acrochordon, amelanotic melanoma, compound nevus, hemangioma, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceous, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.5 Dermoscopic evaluation can aid in the diagnosis. A vascular network composed of fine arborizing vessels with or without dotted vessels and white streaks are characteristic findings of FeP. Patients with pigment also demonstrate structureless gray-brown areas and gray-blue dots.6

Biopsy with subsequent histopathologic evaluation confirms the diagnosis of FeP. The characteristic microscopic findings of thin eosinophilic epithelial strands with eccrine ducts anastomosing in an abundant fibromyxoid stroma with collections of basophilic cells located at the ends of the epithelial strands were demonstrated in our patient’s histopathologic specimen (Figure). The histologic appearance is similar to syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro. Recognition of basaloid nests, which often demonstrate retraction, and mitotic activity can differentiate FeP from syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro.7

Treatment of FeP is largely the same as other BCCs including destruction by electrodesiccation and curettage or complete removal by surgical excision. Several studies have demonstrated effective treatment of nonaggressive BCCs with curettage alone and subjectively reported improved cosmesis compared to electrodesiccation and curettage.8-10 Although methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy has demonstrated some therapeutic efficacy for superficial and nodular BCCs,11 a case report utilizing the same modality for FeP did not provide adequate response.12 However, adequate data are not available to assess potential use of this less invasive therapy.

- Pinkus H. Premalignant fibroepithelial tumors of skin. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1953;67:598-615.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Barr RJ, Herten RJ, Stone OJ. Multiple premalignant fibroepitheliomas of Pinkus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 1978;21:335-337.

- Betti R, Inselvini E, Carducci M, et al. Age and site prevalence of histologic subtypes of basal cell carcinomas. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:174-176.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus presenting as a sessile thigh nodule. Skinmed. 2003;2:385-387.

- Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Broganelli P, et al. Dermoscopy patterns of fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1318-1322.

- Schadt CR, Boyd AS. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma with co-existent squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):71-74.

- Barlow JO, Zalla MJ, Kyle A, et al. Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with curettage alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1039-1045.

- McDaniel WE. Therapy for basal cell epitheliomas by curettage only. further study. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:901-903.

- Reymann F. 15 Years’ experience with treatment of basal cell carcinomas of the skin with curettage. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1985;120:56-59.

- Fai D, Arpaia N, Romano I, et al. Methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratoses and non-melanoma skin cancers: a retrospective analysis of response in 462 patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2009;144:281-285.

- Park MY, Kim YC. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus: poor response to topical photodynamic therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:133-134.

- Pinkus H. Premalignant fibroepithelial tumors of skin. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1953;67:598-615.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Barr RJ, Herten RJ, Stone OJ. Multiple premalignant fibroepitheliomas of Pinkus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 1978;21:335-337.

- Betti R, Inselvini E, Carducci M, et al. Age and site prevalence of histologic subtypes of basal cell carcinomas. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:174-176.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus presenting as a sessile thigh nodule. Skinmed. 2003;2:385-387.

- Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Broganelli P, et al. Dermoscopy patterns of fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1318-1322.

- Schadt CR, Boyd AS. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma with co-existent squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):71-74.

- Barlow JO, Zalla MJ, Kyle A, et al. Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with curettage alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1039-1045.

- McDaniel WE. Therapy for basal cell epitheliomas by curettage only. further study. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:901-903.

- Reymann F. 15 Years’ experience with treatment of basal cell carcinomas of the skin with curettage. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1985;120:56-59.

- Fai D, Arpaia N, Romano I, et al. Methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratoses and non-melanoma skin cancers: a retrospective analysis of response in 462 patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2009;144:281-285.

- Park MY, Kim YC. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus: poor response to topical photodynamic therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:133-134.

Is Postop Lethargy Cause for Concern?

Answer