User login

Simplifying Allergic Contact Dermatitis Management with the Contact Allergen Management Program 2.0

Simplifying Allergic Contact Dermatitis Management with the Contact Allergen Management Program 2.0

While patch testing is the gold standard to diagnose type IV cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions, interpreting results can feel like trying to decipher a secret code, leaving patients feeling disempowered in avoiding their triggers. To truly manage allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), patients need comprehensive education on which allergens to avoid and ways to spot potential sources of exposure, including counseling, written guidelines, and lists of product alternatives.1 Patients who can recall and avoid their triggers experience greater improvement in clinical and quality-of-life scores.2 However, several studies have demonstrated that patients have difficulty recalling their allergens, even with longitudinal reminders.2-5 Quality-of-life and clinical outcomes also are not necessarily improved by successful allergen recall alone, as patients have reported limited success in actually avoiding allergens, highlighting the complexity of navigating exposures in daily life.2,6 To address these challenges, we examine common pitfalls patients encounter when avoiding allergens, highlight the benefits of utilizing safe lists and databases for allergen management, and introduce the updated Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) 2.0 as an optimal tool for long-term management of ACD.

Allergen Avoidance Pitfalls

Simply reading ingredient labels to avoid allergens is only marginally effective, as patients need to identify and interpret multiple chemical names as well as cross-reactors and related compounds to achieve success. Some allergens, such as fragrances or manufacturing impurities, are not explicitly identified on product labels. Even patients who can practice diligent label reading may struggle to find information on household or occupational products when full ingredient disclosure is not required.

Many of the allergens included in the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) Core 90 Series have alternative chemical aliases, and many have related compounds.6 For example, individuals with contact allergy to formaldehyde or a formaldehyde releaser usually need to avoid multiple other formaldehyde-releasing chemicals. Patients who test positive to amidoamine or dimethylaminopropylamine also must avoid the surfactant cocamidopropyl betaine—not because it is a cross-reactor, but because it is an impurity in the synthetic pathway.

Fragrance is one of the most common causes of ACD but can be challenging to avoid. Patients with allergies to fragrance or specific compounds (eg, limonene, linalool hydroperoxides) need to be savvy enough to navigate a broad spectrum of synthetic and botanical fragrance additives. Avoiding products that contain “fragrance” or “parfum” is simple enough, but patients also may need to recognize more than 3000 chemical names to identify individual fragrance ingredients that may be listed separately.7 Further, some fragrances are added for alternative purposes—preservative, medicinal, or emulsification—in which case products may deceptively tout themselves as being “fragrance free” yet still contain a fragrance allergen. This is made even more complex considering additional additives that commonly may cross-react with individual fragrance compounds; balsam of Peru, for example, is a botanical amalgam containing more than 250 compounds, including several fragrance components, making it an excellent indicator of fragrance allergy.8 While balsam of Peru and its fragrance constituents will almost never be listed on a product label, it cross-reacts with several benzyl derivatives commonly used in cosmetic formulations, such as benzyl alcohol, benzyl acetate, benzoic acid, benzyl benzoate, and benzyl cinnamate.9,10

Given that ACD is a common reason for patients to seek dermatologic care, it is crucial for clinicians to equip themselves with effective strategies to support patients after patch testing.11 This includes efficient translation of patch test results into practical advice while avoiding the oversimplified suggestion to read product labels; however, education alone cannot address the complexities of managing ACD, which is where contact allergen databases come into play.

An Essential Tool: Patient Allergen Databases and Safe Lists

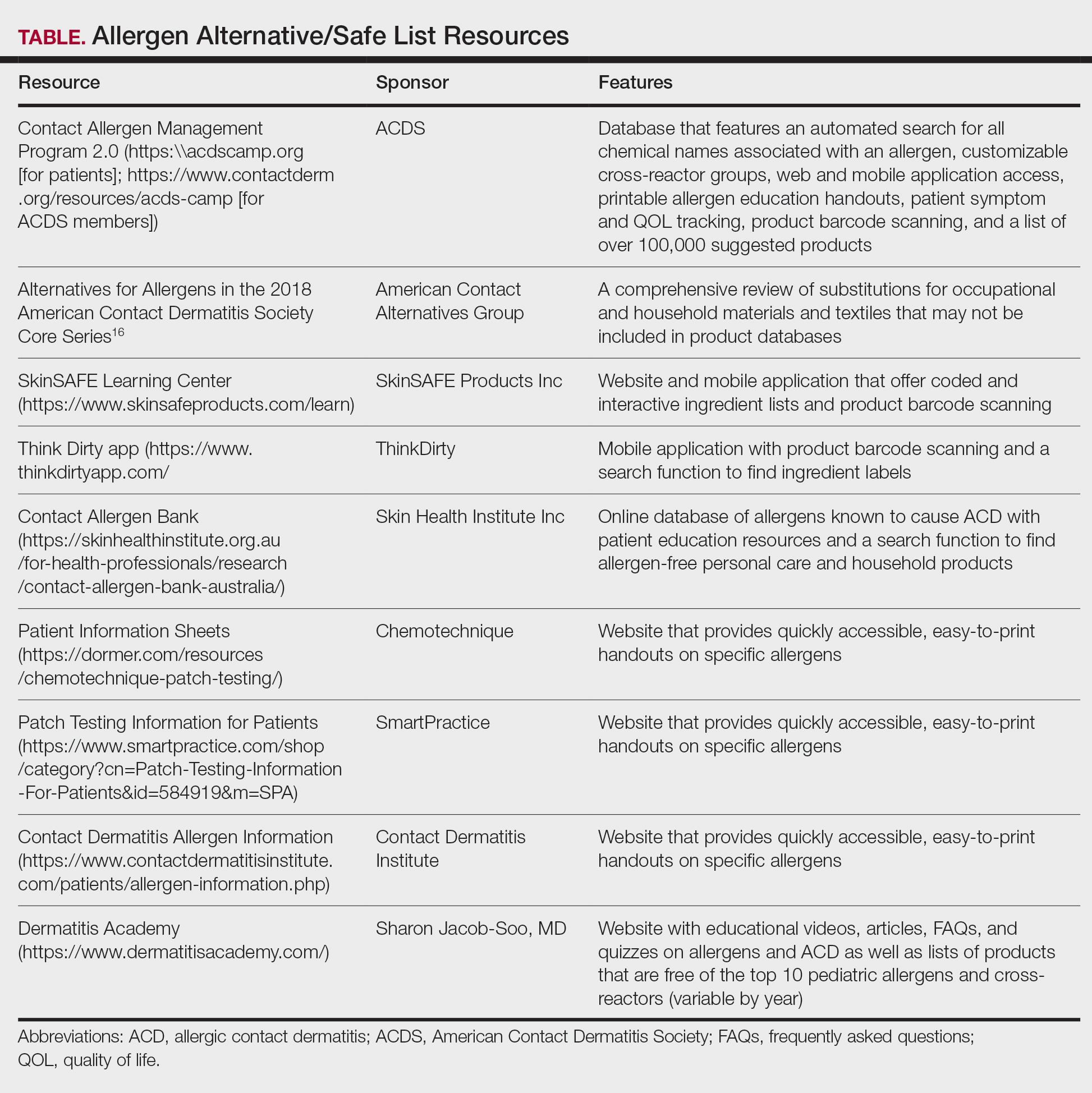

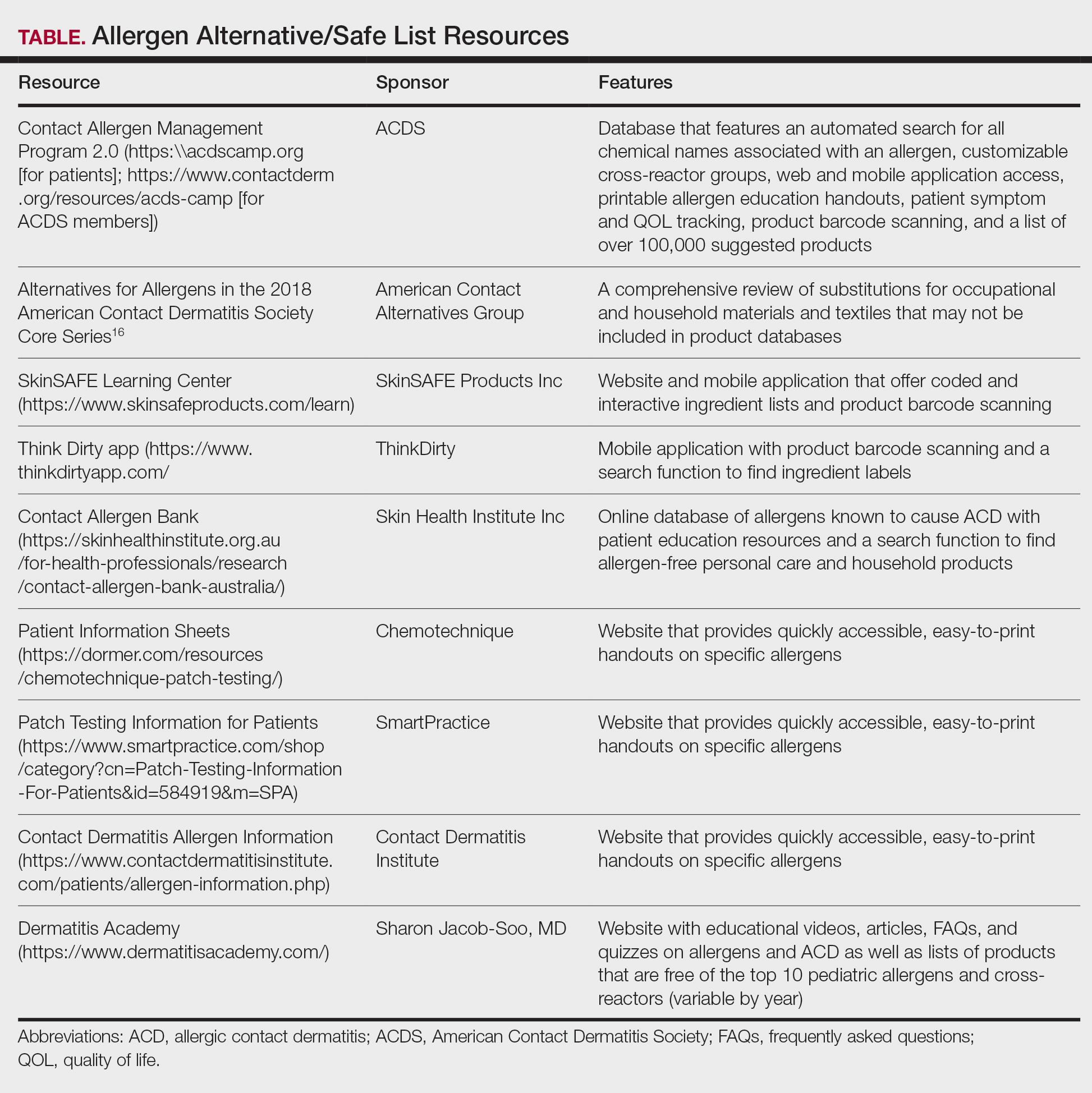

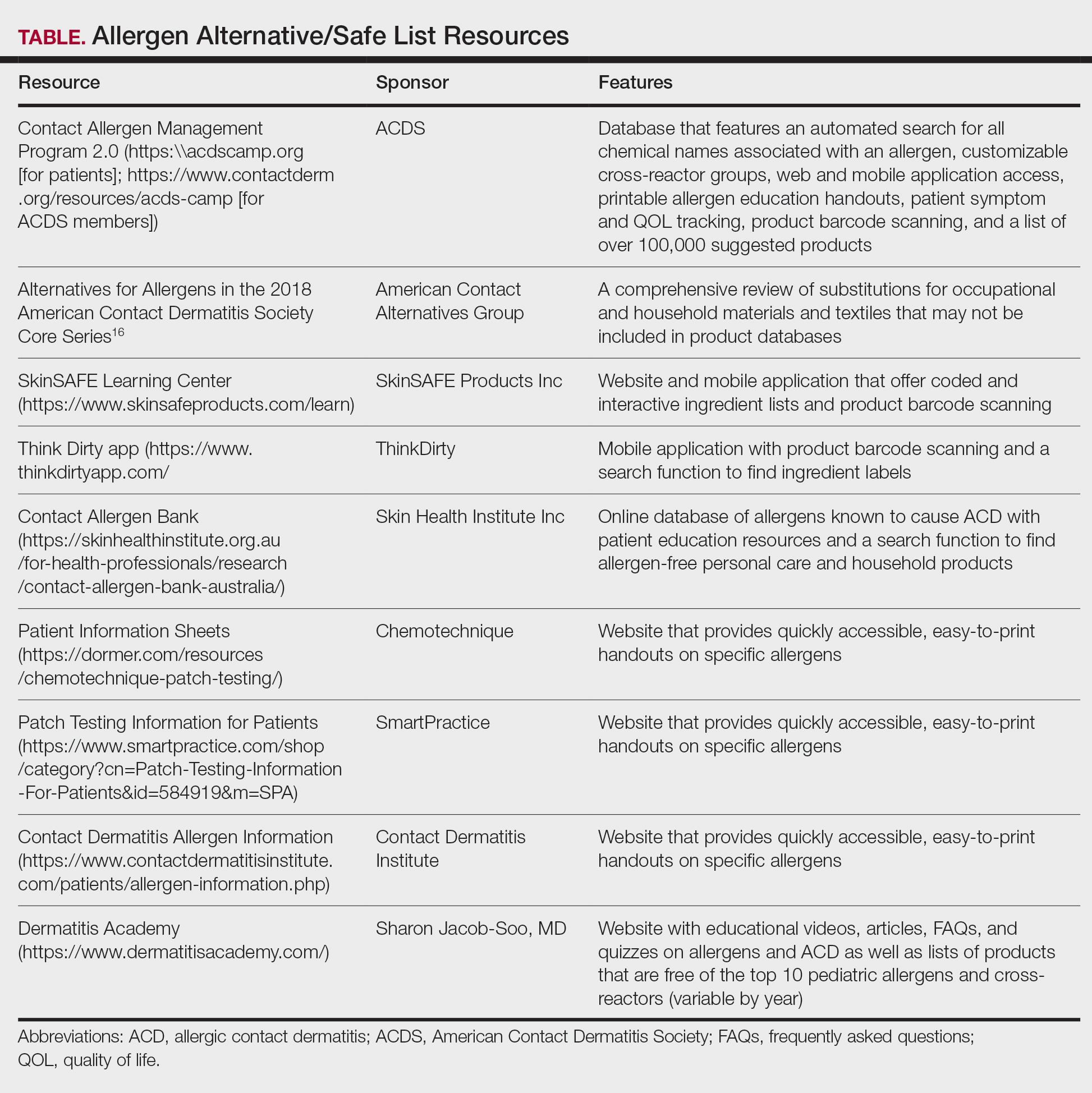

Contact allergen databases are like a trusty sidekick for patients and clinicians, providing easily accessible information and tools to support allergen avoidance and improve ACD outcomes. While there are several existing resources, the ACDS launched its CAMP database in 2011 for ACDS members and their patients.12 The CAMP allows clinicians to easily generate personalized safe lists for household, medicament, and personal care products, facilitating seamless patient access both online and via a mobile application. The database also includes allergen-specific handouts to guide patient education.13 A key highlight of the CAMP is automated management of cross-reactors, which allows patients to choose products without having to memorize complex cross-reactor algorithms and helps avoid overly restrictive safe lists (Table).12-15

Other databases and online resources provide similar features, such as resources for patient education or finding safe products. The 2018 Alternatives for Allergens report is a vital adjunctive resource for guiding patients to suitable allergen-free products not included in commonly accessible product databases such as occupational materials, medical adhesives, shoes, or textiles.16

Introduction of CAMP 2.0

The latest version, CAMP 2.0, was launched in late 2024. The fully revamped database has a catalog of more than 100,000 products and comes packed with features that address many of the limitations found in the original CAMP. How does CAMP 2.0 work? The clinician inputs the patient’s allergens and makes choices about cross-reactor groups, and CAMP 2.0 outputs a list of allergen-free products that the patient can use when shopping for personal care products and the clinician can use for prescribing medicaments. The new user experience is intended to be more informative and engaging for all parties.

The CAMP 2.0 interface offers frequent product updates and streamlined database navigation, including enhanced search functions, barcode scanning, and a new mobile application for Apple and Android users. The mobile application also allows patients to track their symptoms and quality of life over time. With this additional functionality, there also is an extensive section for frequently asked questions and tutorials to help patients understand and utilize these features effectively.

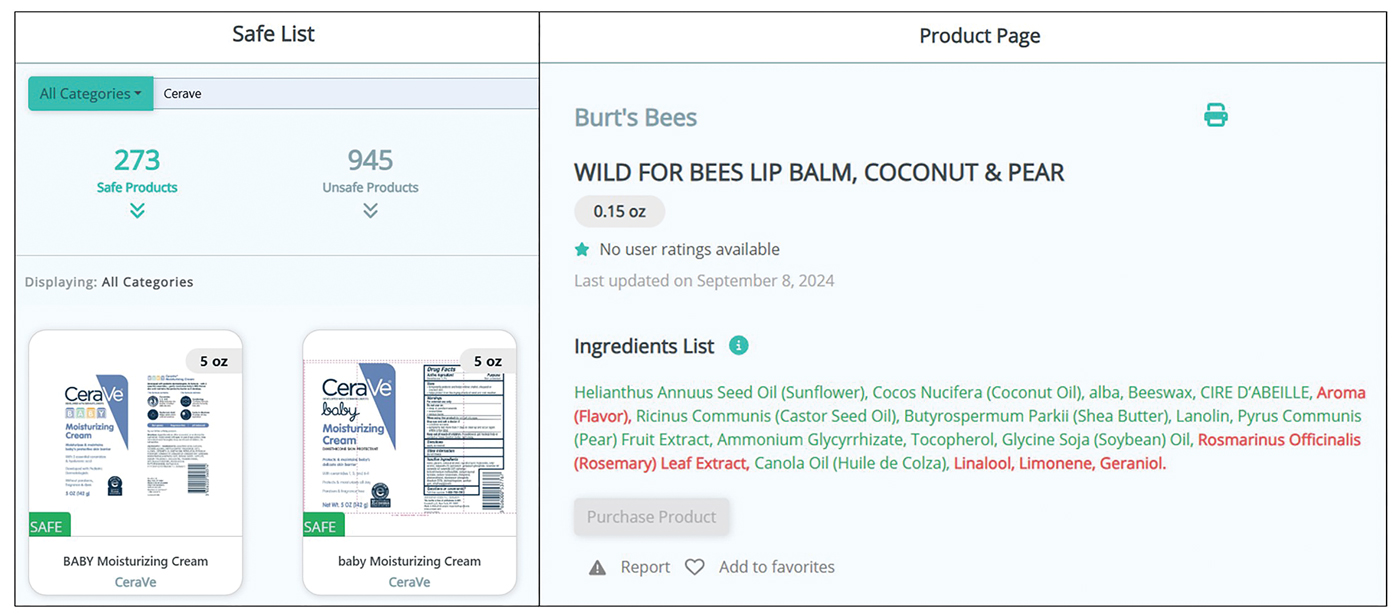

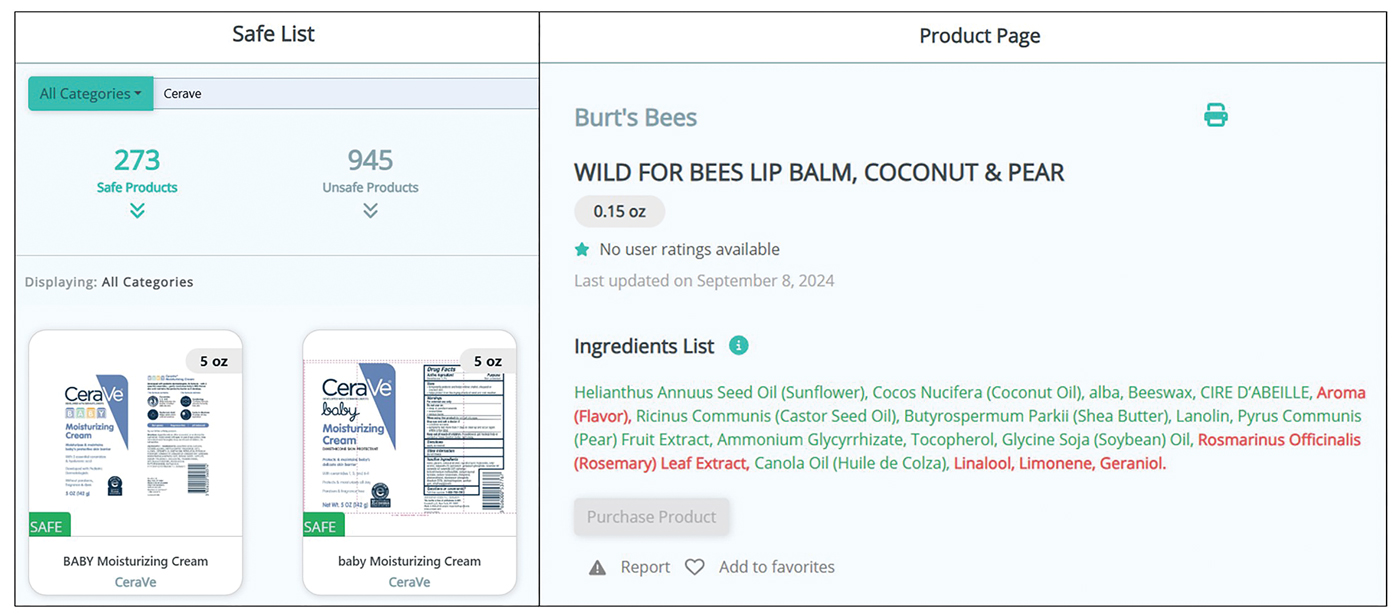

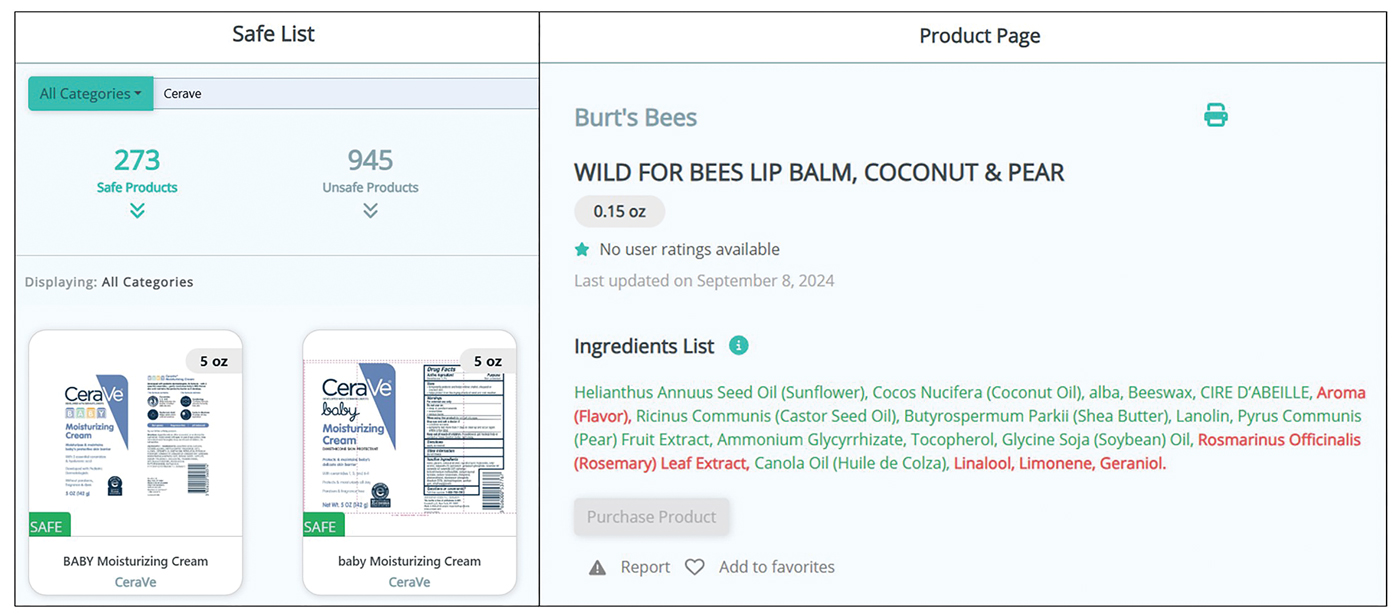

Patients no longer have to wonder if a product that is not listed on their safe list is actually unsafe or just missing from the database. Several new features, including color-coded ingredient lists and organization of search codes into “safe” and “unsafe” product lists (Figure 1), help increase product transparency. These features can facilitate patient recognition of allergen names and cross-reactors in selected products. Future updates will include product purchasing through the mobile application and more educational handouts, including Spanish translations and dietary guidelines for systemic contact dermatitis.

Patient Experience—Once patients complete patch testing with an ACDS member, they can access the CAMP 2.0 database for free via web-based or a mobile application. After setting up an account, patients gain immediate access to their allergen information, product database, and educational resources about ACD and CAMP 2.0. Patients can search for specific products using text or barcode scanning or browse through categorized lists of medical, household, and personal care items. Each product page contains the product name and brand along with a color-coded ingredient list to help patients identify safe and unsafe ingredients at a glance (Figure 1). Products not currently included in the database can be requested using the “Add Product” feature. Additional patient engagement features include options to mark favorite products, write reviews, and track quality of life over time.

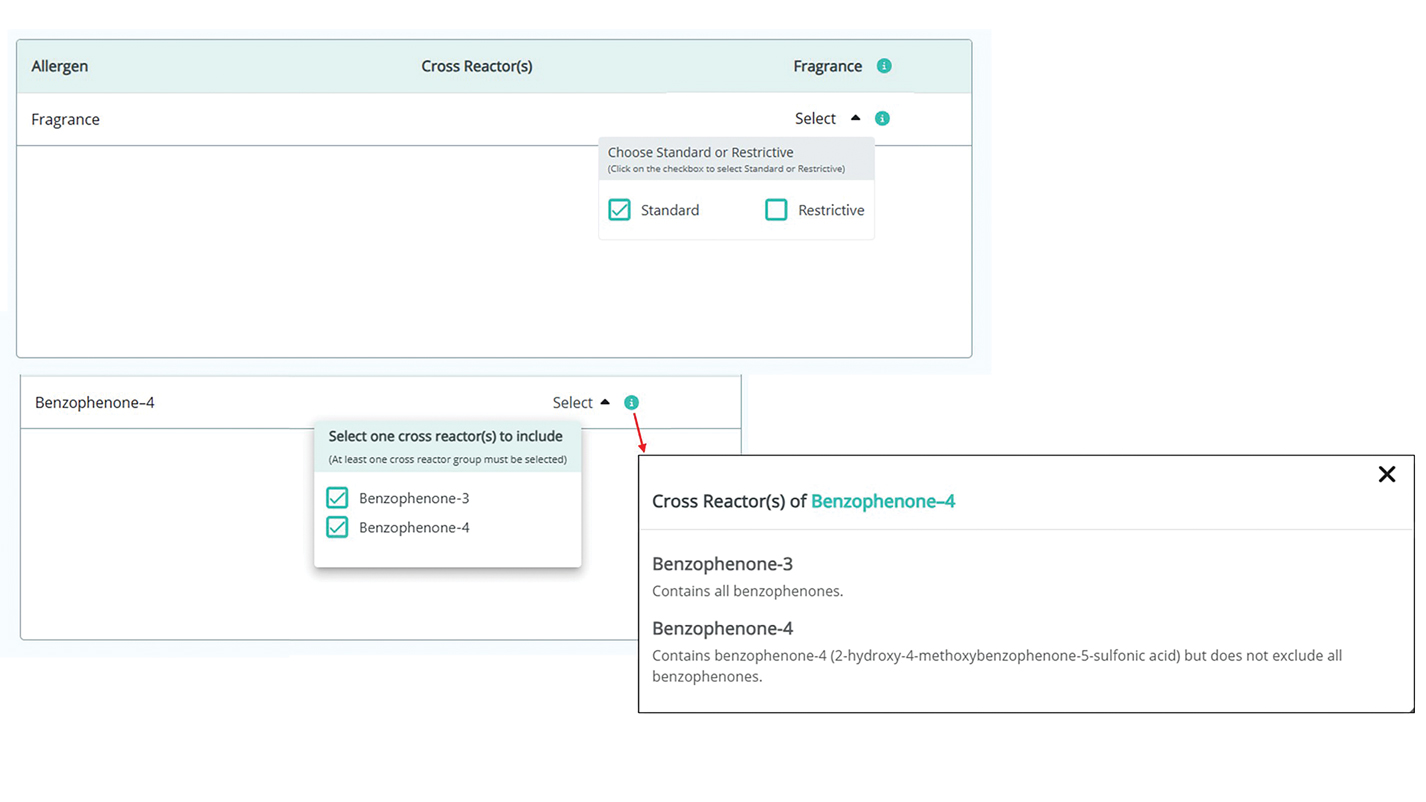

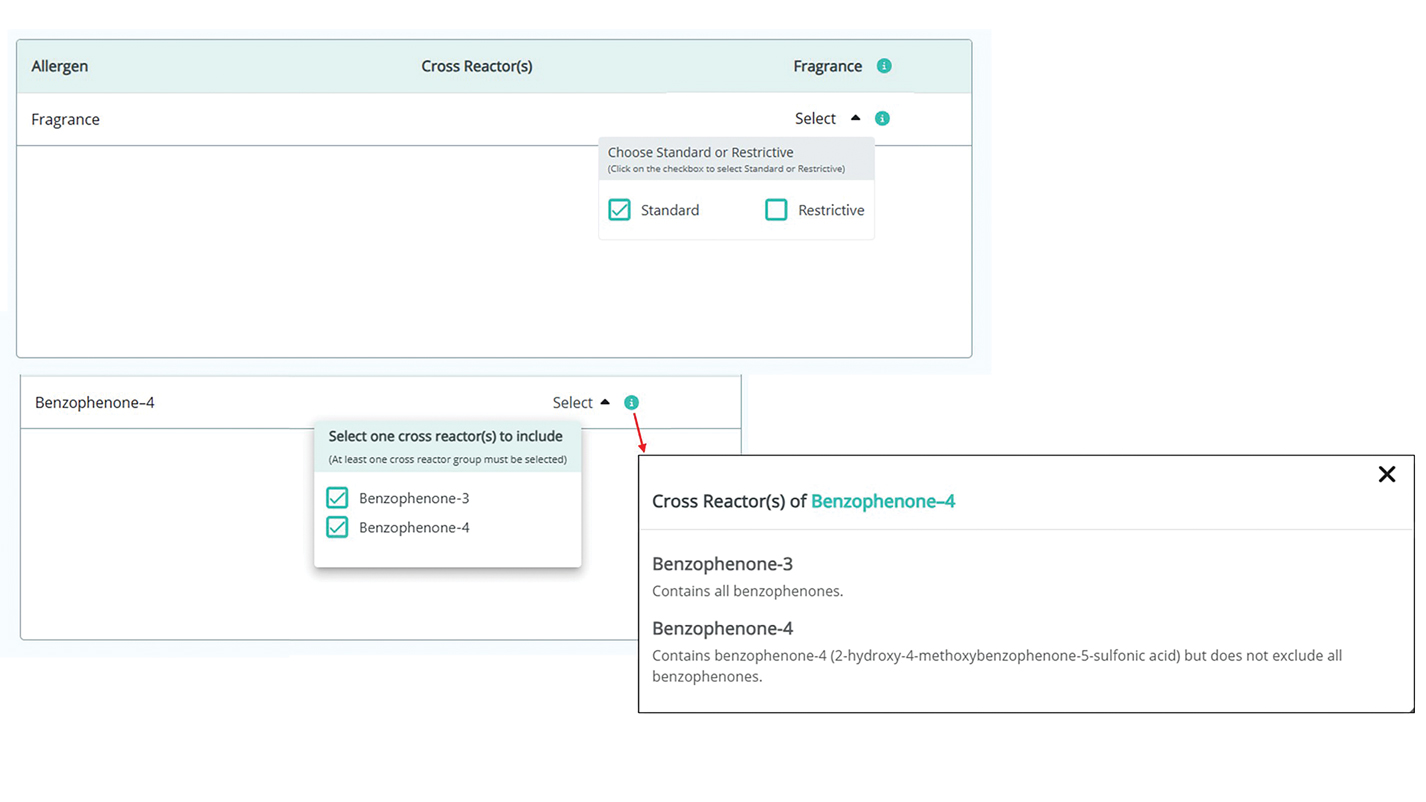

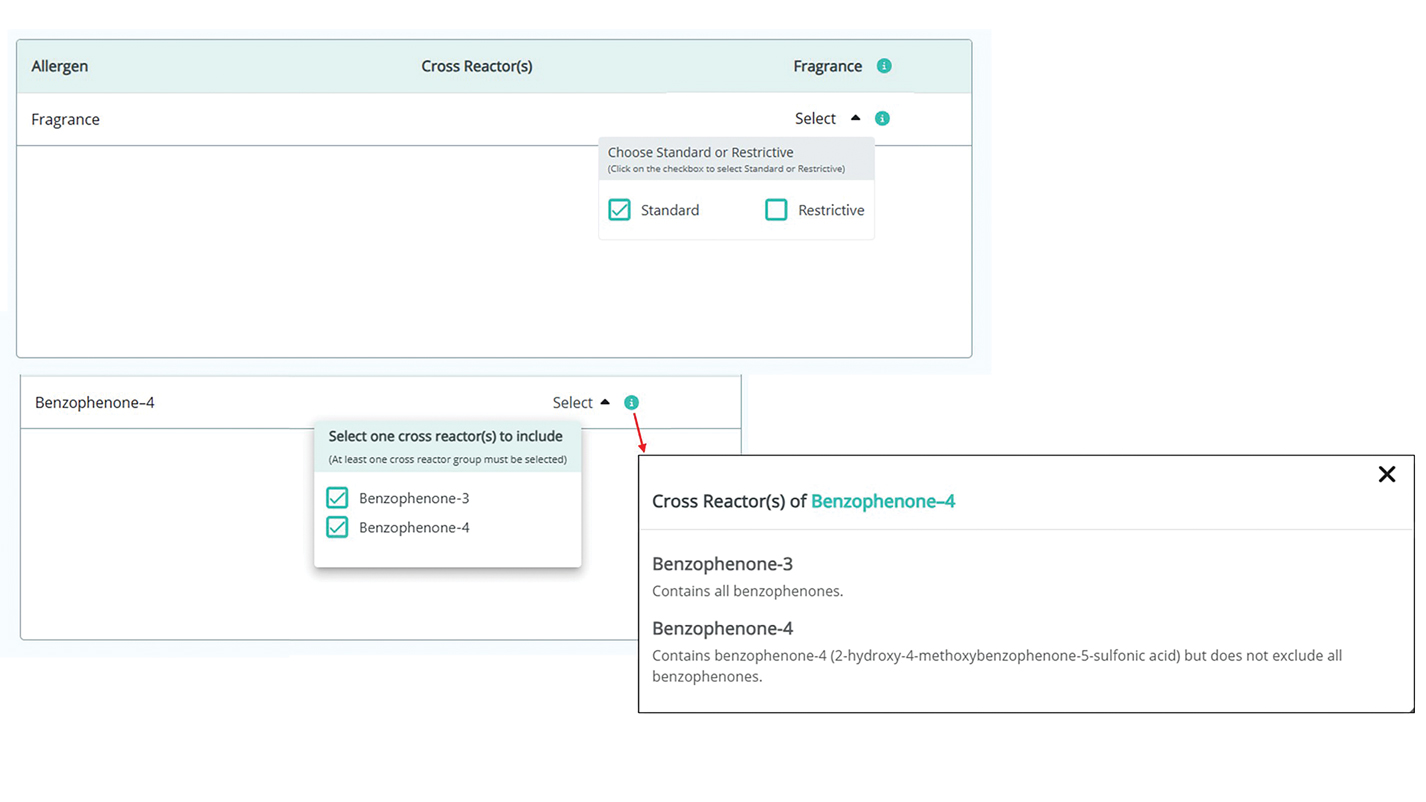

Physician Experience—The updated version includes several tutorials and frequently asked questions on how to improve ACD management and make the most of the new CAMP 2.0 tools and features. Generating patient allergen codes has been streamlined with an “Allergen Search” feature, allowing providers to quickly search and add or remove allergens to patients’ safe lists. Cross-reactor groups may be selectively added or removed for greater transparency and specificity in creating a patient safe list (Figure 2). Allergen codes now can be edited over time and are available for patient use via alphanumeric text or QR code format, which easily can be printed on a handout with instructions to help patients get acquainted with the system. For patient counseling, updated education handouts are available in the patient’s app and may be printed to provide supportive written educational material.

Approach to Long-Term Follow-up

When it comes to getting the most from patch testing, ongoing allergen avoidance is crucial. Patients may not see improvement unless they understand what ACD is and what needs to be done to improve it as well as become familiar with the names and common sources of their triggers.17 Clinicians can use CAMP 2.0 to facilitate patient improvement after patch testing, focusing on 3 key areas: continued patient education, patients’ ongoing progress in avoiding allergens, and monitored clinical improvement.

A solid understanding of ACD, such as its delayed (ie, 24-72 hours) onset after exposure, the need for allergen avoidance for at least 4 to 6 weeks before seeing improvement, and correlation of identified allergens with daily exposures, plays a major role in patient success. The CAMP 2.0 patch testing basics section is an excellent resource for patient-friendly explanations on patch testing and ACD. This resource, as well as allergen education handouts, may be reviewed at follow-up visits to continue to solidify patient learning.

Patients often have questions about allergen avoidance, such as occupational exposures, the suitability of specific products, or specific allergen names. These discussions are helpful for gauging how well patients are equipped to avoid their triggers as well as any hurdles they may be facing. If a patient still is experiencing flares after 6 to 8 weeks of safe-list adherence, it is important to take a thorough history of product use, daily exposures, and the patterns of distribution on the skin. Possible allergen exposures via topical medications also should be considered.18,19 Cross-checking products with a patient’s CAMP 2.0 safe list and correlating exposures with the continued ACD distribution are effective strategies to troubleshoot for unknown exposures to allergens.

Final Thoughts

Helping patients avoid allergens is essential to long-term management of ACD. The CAMP 2.0 safe list is an essential tool and a comprehensive reference for both patients and clinicians. With CAMP 2.0, allergen avoidance has never been more interactive or accessible.

- Tam I, Yu J. Allergic contact dermatitis in children: recommendations for patch testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:41. doi:10.1007 /s11882-020-00939-z

- Dizdarevic A, Troensegaard W, Uldahl A, et al. Intervention study to evaluate the importance of information given to patients with contact allergy: a randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:43-49. doi:10.1111/bjd.19119

- Jamil WN, Erikssohn I, Lindberg M. How well is the outcome of patch testing remembered by the patients? a 10-year follow-up of testing with the Swedish baseline series at the Department of Dermatology in Örebro, Sweden. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:215-220. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.02039.x

- Scalf LA, Genebriera J, Davis MDP, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the usefulness and outcome of patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:928-932. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.11.034

- Mossing K, Dizdarevic A, Svensson Å, et al. Impact on quality of life of an intervention providing additional information to patients with allergic contact dermatitis; a randomized clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:2166-2171. doi:10.1111/jdv.18412

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 Update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000621

- Ingredient Breakdown: Fragrance. Think Dirty® Shop Clean. Accessed January 9, 2025. https://www.thinkdirtyapp.com/ingredient-breakdown-fragrance-3a8ef28f296a/

- Guarneri F, Corazza M, Stingeni L, et al. Myroxylon pereirae (balsam of Peru): still worth testing? Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:269-273. doi:10.1111/cod.13839

- de Groot AC. Myroxylon pereirae resin (balsam of Peru)—a critical review of the literature and assessment of the significance of positive patch test reactions and the usefulness of restrictive diets. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:335-353. doi:10.1111/cod.13263

- Balsam of Peru: past and future. Allergic Contact Dermatitis Society; 2024. https://www.contactderm.org/UserFiles/members/Balsam_of_Peru___Past_and_Future.2.pdf

- Tramontana M, Hansel K, Bianchi L, et al. Advancing the understanding of allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to novel therapeutic approaches. Front Med. 2023;10. doi:10.3389 /fmed.2023.1184289

- McNamara D. ACDS launches Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP). Internal Med News. March 7, 2011. Accessed December 31, 2024. https://www.mdedge.com/content/acds-launches-contact-allergen-management-program-camp-0

- Haque MZ, Rehman R, Guan L, et al. Recommendations to optimize patient education for allergic contact dermatitis: our approach. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:423-424. doi:10.1111/cod.14269

- Kist JM, el-Azhary RA, Hentz JG, et al. The Contact Allergen Replacement Database and treatment of allergic contact dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1448-1450. doi:0.1001/archderm.140.12.1448

- El-Azhary RA, Yiannias JA. A new patient education approach in contact allergic dermatitis: the Contact Allergen Replacement Database (CARD). Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:278-280. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2004.01843.x

- Scheman A, Hylwa-Deufel S, Jacob SE, et al. Alternatives for allergens in the 2018 American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Series: report by the American Contact Alternatives Group. Dermatitis. 2019;30:87-105. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000453

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient management and education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1043-1054. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1144

- Ng A, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Contact allergy to topical medicaments, part 1: a double-edged sword. Cutis. 2021;108:271-275. doi:10.12788 /cutis.0390

- Nardelli A, D’Hooghe E, Drieghe J, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from fragrance components in specific topical pharmaceutical products in Belgium. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:303-313. doi:10.1111 /j.1600-0536.2009.01542.x

While patch testing is the gold standard to diagnose type IV cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions, interpreting results can feel like trying to decipher a secret code, leaving patients feeling disempowered in avoiding their triggers. To truly manage allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), patients need comprehensive education on which allergens to avoid and ways to spot potential sources of exposure, including counseling, written guidelines, and lists of product alternatives.1 Patients who can recall and avoid their triggers experience greater improvement in clinical and quality-of-life scores.2 However, several studies have demonstrated that patients have difficulty recalling their allergens, even with longitudinal reminders.2-5 Quality-of-life and clinical outcomes also are not necessarily improved by successful allergen recall alone, as patients have reported limited success in actually avoiding allergens, highlighting the complexity of navigating exposures in daily life.2,6 To address these challenges, we examine common pitfalls patients encounter when avoiding allergens, highlight the benefits of utilizing safe lists and databases for allergen management, and introduce the updated Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) 2.0 as an optimal tool for long-term management of ACD.

Allergen Avoidance Pitfalls

Simply reading ingredient labels to avoid allergens is only marginally effective, as patients need to identify and interpret multiple chemical names as well as cross-reactors and related compounds to achieve success. Some allergens, such as fragrances or manufacturing impurities, are not explicitly identified on product labels. Even patients who can practice diligent label reading may struggle to find information on household or occupational products when full ingredient disclosure is not required.

Many of the allergens included in the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) Core 90 Series have alternative chemical aliases, and many have related compounds.6 For example, individuals with contact allergy to formaldehyde or a formaldehyde releaser usually need to avoid multiple other formaldehyde-releasing chemicals. Patients who test positive to amidoamine or dimethylaminopropylamine also must avoid the surfactant cocamidopropyl betaine—not because it is a cross-reactor, but because it is an impurity in the synthetic pathway.

Fragrance is one of the most common causes of ACD but can be challenging to avoid. Patients with allergies to fragrance or specific compounds (eg, limonene, linalool hydroperoxides) need to be savvy enough to navigate a broad spectrum of synthetic and botanical fragrance additives. Avoiding products that contain “fragrance” or “parfum” is simple enough, but patients also may need to recognize more than 3000 chemical names to identify individual fragrance ingredients that may be listed separately.7 Further, some fragrances are added for alternative purposes—preservative, medicinal, or emulsification—in which case products may deceptively tout themselves as being “fragrance free” yet still contain a fragrance allergen. This is made even more complex considering additional additives that commonly may cross-react with individual fragrance compounds; balsam of Peru, for example, is a botanical amalgam containing more than 250 compounds, including several fragrance components, making it an excellent indicator of fragrance allergy.8 While balsam of Peru and its fragrance constituents will almost never be listed on a product label, it cross-reacts with several benzyl derivatives commonly used in cosmetic formulations, such as benzyl alcohol, benzyl acetate, benzoic acid, benzyl benzoate, and benzyl cinnamate.9,10

Given that ACD is a common reason for patients to seek dermatologic care, it is crucial for clinicians to equip themselves with effective strategies to support patients after patch testing.11 This includes efficient translation of patch test results into practical advice while avoiding the oversimplified suggestion to read product labels; however, education alone cannot address the complexities of managing ACD, which is where contact allergen databases come into play.

An Essential Tool: Patient Allergen Databases and Safe Lists

Contact allergen databases are like a trusty sidekick for patients and clinicians, providing easily accessible information and tools to support allergen avoidance and improve ACD outcomes. While there are several existing resources, the ACDS launched its CAMP database in 2011 for ACDS members and their patients.12 The CAMP allows clinicians to easily generate personalized safe lists for household, medicament, and personal care products, facilitating seamless patient access both online and via a mobile application. The database also includes allergen-specific handouts to guide patient education.13 A key highlight of the CAMP is automated management of cross-reactors, which allows patients to choose products without having to memorize complex cross-reactor algorithms and helps avoid overly restrictive safe lists (Table).12-15

Other databases and online resources provide similar features, such as resources for patient education or finding safe products. The 2018 Alternatives for Allergens report is a vital adjunctive resource for guiding patients to suitable allergen-free products not included in commonly accessible product databases such as occupational materials, medical adhesives, shoes, or textiles.16

Introduction of CAMP 2.0

The latest version, CAMP 2.0, was launched in late 2024. The fully revamped database has a catalog of more than 100,000 products and comes packed with features that address many of the limitations found in the original CAMP. How does CAMP 2.0 work? The clinician inputs the patient’s allergens and makes choices about cross-reactor groups, and CAMP 2.0 outputs a list of allergen-free products that the patient can use when shopping for personal care products and the clinician can use for prescribing medicaments. The new user experience is intended to be more informative and engaging for all parties.

The CAMP 2.0 interface offers frequent product updates and streamlined database navigation, including enhanced search functions, barcode scanning, and a new mobile application for Apple and Android users. The mobile application also allows patients to track their symptoms and quality of life over time. With this additional functionality, there also is an extensive section for frequently asked questions and tutorials to help patients understand and utilize these features effectively.

Patients no longer have to wonder if a product that is not listed on their safe list is actually unsafe or just missing from the database. Several new features, including color-coded ingredient lists and organization of search codes into “safe” and “unsafe” product lists (Figure 1), help increase product transparency. These features can facilitate patient recognition of allergen names and cross-reactors in selected products. Future updates will include product purchasing through the mobile application and more educational handouts, including Spanish translations and dietary guidelines for systemic contact dermatitis.

Patient Experience—Once patients complete patch testing with an ACDS member, they can access the CAMP 2.0 database for free via web-based or a mobile application. After setting up an account, patients gain immediate access to their allergen information, product database, and educational resources about ACD and CAMP 2.0. Patients can search for specific products using text or barcode scanning or browse through categorized lists of medical, household, and personal care items. Each product page contains the product name and brand along with a color-coded ingredient list to help patients identify safe and unsafe ingredients at a glance (Figure 1). Products not currently included in the database can be requested using the “Add Product” feature. Additional patient engagement features include options to mark favorite products, write reviews, and track quality of life over time.

Physician Experience—The updated version includes several tutorials and frequently asked questions on how to improve ACD management and make the most of the new CAMP 2.0 tools and features. Generating patient allergen codes has been streamlined with an “Allergen Search” feature, allowing providers to quickly search and add or remove allergens to patients’ safe lists. Cross-reactor groups may be selectively added or removed for greater transparency and specificity in creating a patient safe list (Figure 2). Allergen codes now can be edited over time and are available for patient use via alphanumeric text or QR code format, which easily can be printed on a handout with instructions to help patients get acquainted with the system. For patient counseling, updated education handouts are available in the patient’s app and may be printed to provide supportive written educational material.

Approach to Long-Term Follow-up

When it comes to getting the most from patch testing, ongoing allergen avoidance is crucial. Patients may not see improvement unless they understand what ACD is and what needs to be done to improve it as well as become familiar with the names and common sources of their triggers.17 Clinicians can use CAMP 2.0 to facilitate patient improvement after patch testing, focusing on 3 key areas: continued patient education, patients’ ongoing progress in avoiding allergens, and monitored clinical improvement.

A solid understanding of ACD, such as its delayed (ie, 24-72 hours) onset after exposure, the need for allergen avoidance for at least 4 to 6 weeks before seeing improvement, and correlation of identified allergens with daily exposures, plays a major role in patient success. The CAMP 2.0 patch testing basics section is an excellent resource for patient-friendly explanations on patch testing and ACD. This resource, as well as allergen education handouts, may be reviewed at follow-up visits to continue to solidify patient learning.

Patients often have questions about allergen avoidance, such as occupational exposures, the suitability of specific products, or specific allergen names. These discussions are helpful for gauging how well patients are equipped to avoid their triggers as well as any hurdles they may be facing. If a patient still is experiencing flares after 6 to 8 weeks of safe-list adherence, it is important to take a thorough history of product use, daily exposures, and the patterns of distribution on the skin. Possible allergen exposures via topical medications also should be considered.18,19 Cross-checking products with a patient’s CAMP 2.0 safe list and correlating exposures with the continued ACD distribution are effective strategies to troubleshoot for unknown exposures to allergens.

Final Thoughts

Helping patients avoid allergens is essential to long-term management of ACD. The CAMP 2.0 safe list is an essential tool and a comprehensive reference for both patients and clinicians. With CAMP 2.0, allergen avoidance has never been more interactive or accessible.

While patch testing is the gold standard to diagnose type IV cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions, interpreting results can feel like trying to decipher a secret code, leaving patients feeling disempowered in avoiding their triggers. To truly manage allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), patients need comprehensive education on which allergens to avoid and ways to spot potential sources of exposure, including counseling, written guidelines, and lists of product alternatives.1 Patients who can recall and avoid their triggers experience greater improvement in clinical and quality-of-life scores.2 However, several studies have demonstrated that patients have difficulty recalling their allergens, even with longitudinal reminders.2-5 Quality-of-life and clinical outcomes also are not necessarily improved by successful allergen recall alone, as patients have reported limited success in actually avoiding allergens, highlighting the complexity of navigating exposures in daily life.2,6 To address these challenges, we examine common pitfalls patients encounter when avoiding allergens, highlight the benefits of utilizing safe lists and databases for allergen management, and introduce the updated Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) 2.0 as an optimal tool for long-term management of ACD.

Allergen Avoidance Pitfalls

Simply reading ingredient labels to avoid allergens is only marginally effective, as patients need to identify and interpret multiple chemical names as well as cross-reactors and related compounds to achieve success. Some allergens, such as fragrances or manufacturing impurities, are not explicitly identified on product labels. Even patients who can practice diligent label reading may struggle to find information on household or occupational products when full ingredient disclosure is not required.

Many of the allergens included in the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) Core 90 Series have alternative chemical aliases, and many have related compounds.6 For example, individuals with contact allergy to formaldehyde or a formaldehyde releaser usually need to avoid multiple other formaldehyde-releasing chemicals. Patients who test positive to amidoamine or dimethylaminopropylamine also must avoid the surfactant cocamidopropyl betaine—not because it is a cross-reactor, but because it is an impurity in the synthetic pathway.

Fragrance is one of the most common causes of ACD but can be challenging to avoid. Patients with allergies to fragrance or specific compounds (eg, limonene, linalool hydroperoxides) need to be savvy enough to navigate a broad spectrum of synthetic and botanical fragrance additives. Avoiding products that contain “fragrance” or “parfum” is simple enough, but patients also may need to recognize more than 3000 chemical names to identify individual fragrance ingredients that may be listed separately.7 Further, some fragrances are added for alternative purposes—preservative, medicinal, or emulsification—in which case products may deceptively tout themselves as being “fragrance free” yet still contain a fragrance allergen. This is made even more complex considering additional additives that commonly may cross-react with individual fragrance compounds; balsam of Peru, for example, is a botanical amalgam containing more than 250 compounds, including several fragrance components, making it an excellent indicator of fragrance allergy.8 While balsam of Peru and its fragrance constituents will almost never be listed on a product label, it cross-reacts with several benzyl derivatives commonly used in cosmetic formulations, such as benzyl alcohol, benzyl acetate, benzoic acid, benzyl benzoate, and benzyl cinnamate.9,10

Given that ACD is a common reason for patients to seek dermatologic care, it is crucial for clinicians to equip themselves with effective strategies to support patients after patch testing.11 This includes efficient translation of patch test results into practical advice while avoiding the oversimplified suggestion to read product labels; however, education alone cannot address the complexities of managing ACD, which is where contact allergen databases come into play.

An Essential Tool: Patient Allergen Databases and Safe Lists

Contact allergen databases are like a trusty sidekick for patients and clinicians, providing easily accessible information and tools to support allergen avoidance and improve ACD outcomes. While there are several existing resources, the ACDS launched its CAMP database in 2011 for ACDS members and their patients.12 The CAMP allows clinicians to easily generate personalized safe lists for household, medicament, and personal care products, facilitating seamless patient access both online and via a mobile application. The database also includes allergen-specific handouts to guide patient education.13 A key highlight of the CAMP is automated management of cross-reactors, which allows patients to choose products without having to memorize complex cross-reactor algorithms and helps avoid overly restrictive safe lists (Table).12-15

Other databases and online resources provide similar features, such as resources for patient education or finding safe products. The 2018 Alternatives for Allergens report is a vital adjunctive resource for guiding patients to suitable allergen-free products not included in commonly accessible product databases such as occupational materials, medical adhesives, shoes, or textiles.16

Introduction of CAMP 2.0

The latest version, CAMP 2.0, was launched in late 2024. The fully revamped database has a catalog of more than 100,000 products and comes packed with features that address many of the limitations found in the original CAMP. How does CAMP 2.0 work? The clinician inputs the patient’s allergens and makes choices about cross-reactor groups, and CAMP 2.0 outputs a list of allergen-free products that the patient can use when shopping for personal care products and the clinician can use for prescribing medicaments. The new user experience is intended to be more informative and engaging for all parties.

The CAMP 2.0 interface offers frequent product updates and streamlined database navigation, including enhanced search functions, barcode scanning, and a new mobile application for Apple and Android users. The mobile application also allows patients to track their symptoms and quality of life over time. With this additional functionality, there also is an extensive section for frequently asked questions and tutorials to help patients understand and utilize these features effectively.

Patients no longer have to wonder if a product that is not listed on their safe list is actually unsafe or just missing from the database. Several new features, including color-coded ingredient lists and organization of search codes into “safe” and “unsafe” product lists (Figure 1), help increase product transparency. These features can facilitate patient recognition of allergen names and cross-reactors in selected products. Future updates will include product purchasing through the mobile application and more educational handouts, including Spanish translations and dietary guidelines for systemic contact dermatitis.

Patient Experience—Once patients complete patch testing with an ACDS member, they can access the CAMP 2.0 database for free via web-based or a mobile application. After setting up an account, patients gain immediate access to their allergen information, product database, and educational resources about ACD and CAMP 2.0. Patients can search for specific products using text or barcode scanning or browse through categorized lists of medical, household, and personal care items. Each product page contains the product name and brand along with a color-coded ingredient list to help patients identify safe and unsafe ingredients at a glance (Figure 1). Products not currently included in the database can be requested using the “Add Product” feature. Additional patient engagement features include options to mark favorite products, write reviews, and track quality of life over time.

Physician Experience—The updated version includes several tutorials and frequently asked questions on how to improve ACD management and make the most of the new CAMP 2.0 tools and features. Generating patient allergen codes has been streamlined with an “Allergen Search” feature, allowing providers to quickly search and add or remove allergens to patients’ safe lists. Cross-reactor groups may be selectively added or removed for greater transparency and specificity in creating a patient safe list (Figure 2). Allergen codes now can be edited over time and are available for patient use via alphanumeric text or QR code format, which easily can be printed on a handout with instructions to help patients get acquainted with the system. For patient counseling, updated education handouts are available in the patient’s app and may be printed to provide supportive written educational material.

Approach to Long-Term Follow-up

When it comes to getting the most from patch testing, ongoing allergen avoidance is crucial. Patients may not see improvement unless they understand what ACD is and what needs to be done to improve it as well as become familiar with the names and common sources of their triggers.17 Clinicians can use CAMP 2.0 to facilitate patient improvement after patch testing, focusing on 3 key areas: continued patient education, patients’ ongoing progress in avoiding allergens, and monitored clinical improvement.

A solid understanding of ACD, such as its delayed (ie, 24-72 hours) onset after exposure, the need for allergen avoidance for at least 4 to 6 weeks before seeing improvement, and correlation of identified allergens with daily exposures, plays a major role in patient success. The CAMP 2.0 patch testing basics section is an excellent resource for patient-friendly explanations on patch testing and ACD. This resource, as well as allergen education handouts, may be reviewed at follow-up visits to continue to solidify patient learning.

Patients often have questions about allergen avoidance, such as occupational exposures, the suitability of specific products, or specific allergen names. These discussions are helpful for gauging how well patients are equipped to avoid their triggers as well as any hurdles they may be facing. If a patient still is experiencing flares after 6 to 8 weeks of safe-list adherence, it is important to take a thorough history of product use, daily exposures, and the patterns of distribution on the skin. Possible allergen exposures via topical medications also should be considered.18,19 Cross-checking products with a patient’s CAMP 2.0 safe list and correlating exposures with the continued ACD distribution are effective strategies to troubleshoot for unknown exposures to allergens.

Final Thoughts

Helping patients avoid allergens is essential to long-term management of ACD. The CAMP 2.0 safe list is an essential tool and a comprehensive reference for both patients and clinicians. With CAMP 2.0, allergen avoidance has never been more interactive or accessible.

- Tam I, Yu J. Allergic contact dermatitis in children: recommendations for patch testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:41. doi:10.1007 /s11882-020-00939-z

- Dizdarevic A, Troensegaard W, Uldahl A, et al. Intervention study to evaluate the importance of information given to patients with contact allergy: a randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:43-49. doi:10.1111/bjd.19119

- Jamil WN, Erikssohn I, Lindberg M. How well is the outcome of patch testing remembered by the patients? a 10-year follow-up of testing with the Swedish baseline series at the Department of Dermatology in Örebro, Sweden. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:215-220. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.02039.x

- Scalf LA, Genebriera J, Davis MDP, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the usefulness and outcome of patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:928-932. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.11.034

- Mossing K, Dizdarevic A, Svensson Å, et al. Impact on quality of life of an intervention providing additional information to patients with allergic contact dermatitis; a randomized clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:2166-2171. doi:10.1111/jdv.18412

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 Update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000621

- Ingredient Breakdown: Fragrance. Think Dirty® Shop Clean. Accessed January 9, 2025. https://www.thinkdirtyapp.com/ingredient-breakdown-fragrance-3a8ef28f296a/

- Guarneri F, Corazza M, Stingeni L, et al. Myroxylon pereirae (balsam of Peru): still worth testing? Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:269-273. doi:10.1111/cod.13839

- de Groot AC. Myroxylon pereirae resin (balsam of Peru)—a critical review of the literature and assessment of the significance of positive patch test reactions and the usefulness of restrictive diets. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:335-353. doi:10.1111/cod.13263

- Balsam of Peru: past and future. Allergic Contact Dermatitis Society; 2024. https://www.contactderm.org/UserFiles/members/Balsam_of_Peru___Past_and_Future.2.pdf

- Tramontana M, Hansel K, Bianchi L, et al. Advancing the understanding of allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to novel therapeutic approaches. Front Med. 2023;10. doi:10.3389 /fmed.2023.1184289

- McNamara D. ACDS launches Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP). Internal Med News. March 7, 2011. Accessed December 31, 2024. https://www.mdedge.com/content/acds-launches-contact-allergen-management-program-camp-0

- Haque MZ, Rehman R, Guan L, et al. Recommendations to optimize patient education for allergic contact dermatitis: our approach. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:423-424. doi:10.1111/cod.14269

- Kist JM, el-Azhary RA, Hentz JG, et al. The Contact Allergen Replacement Database and treatment of allergic contact dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1448-1450. doi:0.1001/archderm.140.12.1448

- El-Azhary RA, Yiannias JA. A new patient education approach in contact allergic dermatitis: the Contact Allergen Replacement Database (CARD). Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:278-280. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2004.01843.x

- Scheman A, Hylwa-Deufel S, Jacob SE, et al. Alternatives for allergens in the 2018 American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Series: report by the American Contact Alternatives Group. Dermatitis. 2019;30:87-105. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000453

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient management and education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1043-1054. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1144

- Ng A, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Contact allergy to topical medicaments, part 1: a double-edged sword. Cutis. 2021;108:271-275. doi:10.12788 /cutis.0390

- Nardelli A, D’Hooghe E, Drieghe J, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from fragrance components in specific topical pharmaceutical products in Belgium. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:303-313. doi:10.1111 /j.1600-0536.2009.01542.x

- Tam I, Yu J. Allergic contact dermatitis in children: recommendations for patch testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20:41. doi:10.1007 /s11882-020-00939-z

- Dizdarevic A, Troensegaard W, Uldahl A, et al. Intervention study to evaluate the importance of information given to patients with contact allergy: a randomized, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:43-49. doi:10.1111/bjd.19119

- Jamil WN, Erikssohn I, Lindberg M. How well is the outcome of patch testing remembered by the patients? a 10-year follow-up of testing with the Swedish baseline series at the Department of Dermatology in Örebro, Sweden. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:215-220. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.02039.x

- Scalf LA, Genebriera J, Davis MDP, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the usefulness and outcome of patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:928-932. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.11.034

- Mossing K, Dizdarevic A, Svensson Å, et al. Impact on quality of life of an intervention providing additional information to patients with allergic contact dermatitis; a randomized clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:2166-2171. doi:10.1111/jdv.18412

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 Update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000621

- Ingredient Breakdown: Fragrance. Think Dirty® Shop Clean. Accessed January 9, 2025. https://www.thinkdirtyapp.com/ingredient-breakdown-fragrance-3a8ef28f296a/

- Guarneri F, Corazza M, Stingeni L, et al. Myroxylon pereirae (balsam of Peru): still worth testing? Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:269-273. doi:10.1111/cod.13839

- de Groot AC. Myroxylon pereirae resin (balsam of Peru)—a critical review of the literature and assessment of the significance of positive patch test reactions and the usefulness of restrictive diets. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:335-353. doi:10.1111/cod.13263

- Balsam of Peru: past and future. Allergic Contact Dermatitis Society; 2024. https://www.contactderm.org/UserFiles/members/Balsam_of_Peru___Past_and_Future.2.pdf

- Tramontana M, Hansel K, Bianchi L, et al. Advancing the understanding of allergic contact dermatitis: from pathophysiology to novel therapeutic approaches. Front Med. 2023;10. doi:10.3389 /fmed.2023.1184289

- McNamara D. ACDS launches Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP). Internal Med News. March 7, 2011. Accessed December 31, 2024. https://www.mdedge.com/content/acds-launches-contact-allergen-management-program-camp-0

- Haque MZ, Rehman R, Guan L, et al. Recommendations to optimize patient education for allergic contact dermatitis: our approach. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;88:423-424. doi:10.1111/cod.14269

- Kist JM, el-Azhary RA, Hentz JG, et al. The Contact Allergen Replacement Database and treatment of allergic contact dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1448-1450. doi:0.1001/archderm.140.12.1448

- El-Azhary RA, Yiannias JA. A new patient education approach in contact allergic dermatitis: the Contact Allergen Replacement Database (CARD). Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:278-280. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2004.01843.x

- Scheman A, Hylwa-Deufel S, Jacob SE, et al. Alternatives for allergens in the 2018 American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Series: report by the American Contact Alternatives Group. Dermatitis. 2019;30:87-105. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000453

- Mowad CM, Anderson B, Scheinman P, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis: patient management and education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1043-1054. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1144

- Ng A, Atwater AR, Reeder M. Contact allergy to topical medicaments, part 1: a double-edged sword. Cutis. 2021;108:271-275. doi:10.12788 /cutis.0390

- Nardelli A, D’Hooghe E, Drieghe J, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from fragrance components in specific topical pharmaceutical products in Belgium. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;60:303-313. doi:10.1111 /j.1600-0536.2009.01542.x

Simplifying Allergic Contact Dermatitis Management with the Contact Allergen Management Program 2.0

Simplifying Allergic Contact Dermatitis Management with the Contact Allergen Management Program 2.0

PRACTICE POINTS

- Comprehensive patient education is critical for appropriate allergen avoidance after patch testing, and allergen databases and product safe lists are invaluable tools to complement clinical guidance.

- The updated Contact Allergen Management Program 2.0 offers an updated approach to patient guidance, including a database of more than 100,000 products and an easy-to-use platform to find safe, allergen-free products.

- Interactive learning resources, product pages, and quality-of-life tracking tools can help equip patients with information to encourage further autonomy in allergen avoidance.