User login

Comprehensive Patch Testing: An Essential Tool for Care of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Comprehensive Patch Testing: An Essential Tool for Care of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a common skin condition affecting approximately 20% of the general population in the United States.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a unique disease in that there is an opportunity for complete cure through allergen avoidance; however, this requires proper identification of the offending allergen. When the culprit allergen is not identified or removed from the patient’s environment, chronic ACD can develop, leading to persistent inflammation and related symptoms, reduced quality of life, and greater economic burden for patients and the health care system.2,3

Patch testing (PT) is the only available diagnostic test for ACD, allowing for identification and subsequent avoidance of contact allergens. Patch testing involves applying allergens—typically chemicals that can be found in personal care products—onto the skin for 48 hours. Delayed readings are completed 72 to 168 hours after application. Interpretation of relevance and patient counseling, with resultant allergen avoidance, are required for a successful patient experience. Patch testing is considered safe in tested populations; rare risks associated with PT include active sensitization and anaphylaxis.4

There are many screening series available, with the number of screening allergens ranging from 35 (T.R.U.E. [Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous] test) to 90 (American Contact Dermatitis Society [ACDS] Core series). Comprehensive PT generally refers to the completion of PT for all potentially relevant and testable allergens for a given patient, which typically involves testing beyond a screening series. Currently in the United States, comprehensive PT typically includes testing for 80 to 90 allergens and any additional potentially relevant allergens based on the clinical history and patient exposures. A 2018 survey noted that, of 149 ACDS members, 82% always used a baseline screening series for PT, with 62% of these routinely testing 80 allergens and 18% routinely testing 70 allergens.5 Additionally, nearly 70% always or sometimes tested with supplemental or additional series. In other words, advanced patch testers were routinely testing 70 to 80 allergens in their screening series, and most were testing additional allergens to ensure the best care for their patients.

To account for emerging allergens, accommodate changes in allergen test concentrations recommended by ACDS and the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), and address the need for comprehensive PT for most patients, recommended screening series are regularly updated by patch test societies and expert panels such as the ACDS and the NACDG. When the ACDS Core series6 was introduced in 2013, it consisted of 80 recommended allergens.7 The panel was updated in 20178 and again in 2020,6 most recently with 90 allergens. The NACDG has collected patch test data since at least 19929 and revisits their recommended screening series on a 2-year cycle, evaluating test concentrations and adding and removing allergens based on allergen trends, allergen performance, patient need, and emergence of new allergens; the current NACDG series consists of 80 allergens. This article illustrates the clinical and public health value of comprehensive PT and the vital role of allergen access in the comprehensive patch test process, with the ultimate goal of optimizing care for patients with ACD.

Value of Comprehensive Patch Testing for ACD

Early PT represents the most cost-effective approach to the diagnosis and management of ACD. Lack of access to PT can lead to delayed diagnosis, resulting in continued exposure to the offending allergen, disease chronicity, and ultimately worse quality-of-life scores compared with patients who are diagnosed early.10 Earlier diagnosis also can minimize costs by avoiding unnecessary treatments. Without access to comprehensive PT, patients could potentially be erroneously diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and subsequently treated with expensive biologic therapies (eg, dupilumab, which costs approximately $4000 per dose or $104,000 per year11), when allergen avoidance would have been curative with minimal cost. The continued value of comprehensive PT, especially in the era of the atopic dermatitis therapeutic revolution, cannot be more strongly emphasized.

Among 140 patients with ACD, 87% found PT useful, 91% were able to avoid allergens, and 57% noted improvement or resolution of their dermatitis after avoidance of identified allergens.12 A multicenter prospective observational study demonstrated that PT improved dermatology-specific quality of life and reduced resources used for patients with ACD compared to non–patch tested individuals.13 Another study found that patients with ACD who underwent PT and were confirmed as having relevant positive contact allergens showed improvement in both perceived eczema severity and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores just 2 months after testing.14 This effect is attributed to the identification and subsequent avoidance of clinically relevant contact allergens. In a study of 519 patients with dermatitis, Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved significantly after PT regardless of whether the results were positive or negative, indicating benefits for the care and treatment of dermatitis, even in the setting of negative patch test results (P< .001).15 This could because they were still counseled on gentle skin care and management of their dermatitis at the PT visit. Improvements in disease severity also have been observed in adults and children after PT, with most patients having partial to complete clearance of their dermatitis.16,17 This is not surprising, as comprehensive PT allows clinicians to diagnose the cause of ACD by finding the exact allergen triggering the eruption and then guide patients through avoidance of these allergens to eventually clear their dermatitis.

Comprehensive Patch Testing Captures Allergen Trends

Dermatologists who perform PT in the United States currently have access to a diverse array of allergens, with more than 500 different allergens available. Access to and utilization of these allergens are essential for the comprehensive evaluation needed for our patients.

Comprehensive PT has uncovered emerging allergens such as dimethyl fumarate, the potent cause of sofa dermatitis18; isobornyl acrylate, which is found in wearable diabetic monitors19; and acetophenone azine, which can cause shin guard ACD in athletes.20 Increasing prevalence of ACD to these allergens would not have been identified without provider access to PT. Patch testing also has identified emerging allergen trends, such as the methylisothiazolinone allergy epidemic.21 All of these emerging allergens, identified through PT, have been named Contact Allergen of the Year by the ACDS due to their newfound relevance.18-20

In contrast, allergen prevalence can decrease over time, leading to removal from screening panels; examples include methyldibromo glutaronitrile, which is no longer widely present in consumer products, and thimerosal, which has frequent positive results but low relevance due to its infrequent use in personal care products. In response to comprehensive PT studies, allergen concentrations may be modified, as in the case of formaldehyde, which has notable irritant potential at higher tested concentrations but remains on the ACDS Core Allergen Series with a test concentration that optimizes the number of true positive reactions while decreasing irritant reactions.6 Likewise, nickel sulfate test concentrations were increased in the NACDG screening series due to evidence that testing at 5% identifies more nickel contact allergy than testing at 2.5% without considerably increasing irritant reactions.22

Allergen Choice and Flexibility are Key to Optimal Screening

Dermatologists who perform PT usually choose their screening series based on expert consensus and recommendations.6,23 Additional test allergens for comprehensive PT typically are chosen based on patient exposures, regional trends, and clinical expertise. This flexibility traditionally has allowed for the opportunity to identify culprit allergens that are relevant for the individual patient; for example, a hairdresser may have daily exposure to resorcinol, whereas a massage therapist may have regular exposure to essential oils. Testing only a standard screening series may miss the culprit allergen for both patients. For optimal patient outcomes, allergen choice and flexibility are key.

Currently, the 35-allergen T.R.U.E. test is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved patch test; however, multiple studies have shown that comprehensive PT, including supplemental allergens, considerably improves the diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes in ACD. A 6-year retrospective study found that using an extended screening series identified an additional 10.8% of patients (n=585) with positive tests who were negative to the T.R.U.E. test.24 Patch testing with the T.R.U.E. test alone would miss almost half of the positive reactions detected by the NACDG 80-panel screening series. Furthermore, an additional 21.1% of 3056 tested patients had at least one relevant reaction to a supplemental allergen that was not present in the NACDG screening series.23 In a retrospective study of 791 patients patch tested with the NACDG screening series and 2 supplemental series, 19.5% and 12.1% of patients, respectively, had positive reactions to supplemental allergens.25 This reinforces the importance of comprehensive PT beyond a more limited screening series. Testing more allergens identifies more causative allergens for patients.

Changes in Utilization May Affect Patient Care

Recent data have shown a shift in patch test utilization. An analysis of Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims for PT between 2010 and 2018 demonstrated that an increase in patch test utilization during this period was driven mainly by nonphysician providers and allergists.26 From 2012 to 2017, the number of patients patch tested by allergists grew by 20.3% compared to only 1.84% for dermatologists.27 Since dupilumab was approved in 2017 for the management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, claims data from 2017 to 2022 showed an exponential increase in its utilization, while patch test utilization has markedly decreased.28

Dermatologists are the predominant experts in ACD, but these concerning trends suggest decreasing utilization of PT by dermatologists, possibly due to lack of required residency training in PT, cost of patch test allergens and supplies with corresponding static reimbursement rates, staff time and training required for an excellent PT experience, comparative ease of biologic prescription vs the time-intensive process of comprehensive PT, and perceived high barrier of entry into PT. This may limit patient access to high-quality comprehensive PT and more importantly, a chance for our patients to experience resolution of their skin disease.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive PT is safe, effective, and readily available. Unfettered access to a wide range of allergens improves diagnostic accuracy and quality of life and reduces economic burden from sick leave, job loss, and treatment costs. Patch testing remains the one and only way to identify causative allergens for patients with ACD, and comprehensive PT is the most ideal approach for excellent patient care.

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Hand eczema. Lancet. 2024;404:2476-2486.

- Garg V, Brod B, Gaspari AA. Patch testing: uses, systems, risks/benefits, and its role in managing the patient with contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:580-590.

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Taylor J, Liu B, et al. Patch test practice patterns of members of the American Contact Dermatitis Society. Dermatitis. 2020;31:272-275.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 Update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series. Dermatitis. 2013;24:7-9.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2017 Update. Dermatitis. 2017;28:141-143.

- Marks JG, Belsito DV, DeLeo VA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard tray patch test results (1992 to 1994). Am J Contact Dermat. 1995;6:160-165.

- Kadyk DL, McCarter K, Achen F, et al. Quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1037-1048.

- Dupixent® (dupilumab): pricing and insurance. Sanofi US. Updated June 2025. Accessed January 9, 2026. https://www.dupixent.com/support-savings/cost-insurance

- Woo PN, Hay IC, Ormerod AD. An audit of the value of patch testing and its effect on quality of life. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:244-247.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson R. Impact of patch testing on dermatology-specific quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:215-221.

- Thomson KF, Wilkinson SM, Sommer S, et al. Eczema: quality of life by body site and the effect of patch testing. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:627-630.

- Boonchai W, Charoenpipatsin N, Winayanuwattikun W, et al. Assessment of the quality of life (QoL) of patients with dermatitis and the impact of patch testing on QoL: a study of 519 patients diagnosed with dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:182-188.

- Johnson H, Rao M, Yu J. Improved or not improved, that is the question: patch testing outcomes from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Contact Dermatitis. 2024;90:324-327.

- George SE, Yu J. Patch testing outcomes in children at the Massachusetts General Hospital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:354-356.

- McNamara D. Dimethyl fumarate named 2011 allergen of the year.Int Med News. February 3, 2011. Accessed January 9, 2026. https://www.mdedge.com/internalmedicine/article/20401/dermatology/dimethyl-fumarate-named-2011-allergen-year

- Nath N, Reeder M, Atwater AR. Isobornyl acrylate and diabetic devices steal the show for the 2020 American Contact Dermatitis Societyallergen of the year. Cutis. 2020;105:283-285.

- Raison-Peyron N, Sasseville D. Acetophenone azine. Dermatitis. 2021;32:5-9.

- Castanedo-Tardana MP, Zug KA. Methylisothiazolinone. Dermatitis. 2013;24:2-6.

- Svedman C, Ale I, Goh CL, et al. Patch testing with nickel sulfate 5.0% traces significantly more contact allergy than 2.5%: a prospective study within the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Dermatitis. 2022;33:417-420.

- Houle MC, DeKoven JG, Atwater AR, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2021-2022. Dermatitis. 2025;36:464-476.

- Sundquist BK, Yang B, Pasha MA. Experience in patch testing: a 6-year retrospective review from a single academic allergy practice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:502-507.

- Atwater AR, Liu B, Walsh R, et al. Supplemental patch testing identifies allergens missed by standard screening series. Dermatitis. 2024;35:366-372.

- Ravishankar A, Freese RL, Parsons HM, et al. Trends in patch testing in the Medicare Part B fee-for-service population. Dermatitis. 2022;33:129-134.

- Cheraghlou S, Watsky KL, Cohen JM. Utilization, cost, and provider trends in patch testing among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States from 2012 to 2017. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1218-1226.

- Santiago Mangual KP, Rau A, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Increasing use of dupilumab and decreasing use of patch testing in medicare patients from 2017 to 2022: a claims database study. Dermatitis. 2025;36:538-540.

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a common skin condition affecting approximately 20% of the general population in the United States.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a unique disease in that there is an opportunity for complete cure through allergen avoidance; however, this requires proper identification of the offending allergen. When the culprit allergen is not identified or removed from the patient’s environment, chronic ACD can develop, leading to persistent inflammation and related symptoms, reduced quality of life, and greater economic burden for patients and the health care system.2,3

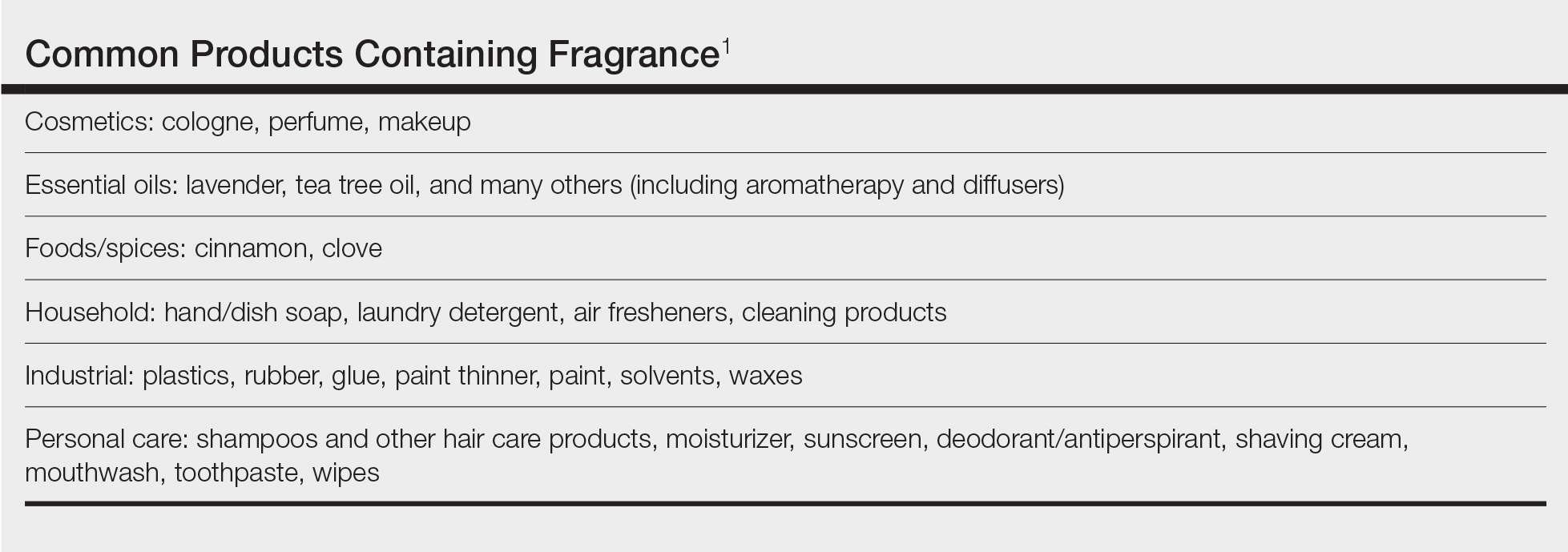

Patch testing (PT) is the only available diagnostic test for ACD, allowing for identification and subsequent avoidance of contact allergens. Patch testing involves applying allergens—typically chemicals that can be found in personal care products—onto the skin for 48 hours. Delayed readings are completed 72 to 168 hours after application. Interpretation of relevance and patient counseling, with resultant allergen avoidance, are required for a successful patient experience. Patch testing is considered safe in tested populations; rare risks associated with PT include active sensitization and anaphylaxis.4

There are many screening series available, with the number of screening allergens ranging from 35 (T.R.U.E. [Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous] test) to 90 (American Contact Dermatitis Society [ACDS] Core series). Comprehensive PT generally refers to the completion of PT for all potentially relevant and testable allergens for a given patient, which typically involves testing beyond a screening series. Currently in the United States, comprehensive PT typically includes testing for 80 to 90 allergens and any additional potentially relevant allergens based on the clinical history and patient exposures. A 2018 survey noted that, of 149 ACDS members, 82% always used a baseline screening series for PT, with 62% of these routinely testing 80 allergens and 18% routinely testing 70 allergens.5 Additionally, nearly 70% always or sometimes tested with supplemental or additional series. In other words, advanced patch testers were routinely testing 70 to 80 allergens in their screening series, and most were testing additional allergens to ensure the best care for their patients.

To account for emerging allergens, accommodate changes in allergen test concentrations recommended by ACDS and the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), and address the need for comprehensive PT for most patients, recommended screening series are regularly updated by patch test societies and expert panels such as the ACDS and the NACDG. When the ACDS Core series6 was introduced in 2013, it consisted of 80 recommended allergens.7 The panel was updated in 20178 and again in 2020,6 most recently with 90 allergens. The NACDG has collected patch test data since at least 19929 and revisits their recommended screening series on a 2-year cycle, evaluating test concentrations and adding and removing allergens based on allergen trends, allergen performance, patient need, and emergence of new allergens; the current NACDG series consists of 80 allergens. This article illustrates the clinical and public health value of comprehensive PT and the vital role of allergen access in the comprehensive patch test process, with the ultimate goal of optimizing care for patients with ACD.

Value of Comprehensive Patch Testing for ACD

Early PT represents the most cost-effective approach to the diagnosis and management of ACD. Lack of access to PT can lead to delayed diagnosis, resulting in continued exposure to the offending allergen, disease chronicity, and ultimately worse quality-of-life scores compared with patients who are diagnosed early.10 Earlier diagnosis also can minimize costs by avoiding unnecessary treatments. Without access to comprehensive PT, patients could potentially be erroneously diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and subsequently treated with expensive biologic therapies (eg, dupilumab, which costs approximately $4000 per dose or $104,000 per year11), when allergen avoidance would have been curative with minimal cost. The continued value of comprehensive PT, especially in the era of the atopic dermatitis therapeutic revolution, cannot be more strongly emphasized.

Among 140 patients with ACD, 87% found PT useful, 91% were able to avoid allergens, and 57% noted improvement or resolution of their dermatitis after avoidance of identified allergens.12 A multicenter prospective observational study demonstrated that PT improved dermatology-specific quality of life and reduced resources used for patients with ACD compared to non–patch tested individuals.13 Another study found that patients with ACD who underwent PT and were confirmed as having relevant positive contact allergens showed improvement in both perceived eczema severity and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores just 2 months after testing.14 This effect is attributed to the identification and subsequent avoidance of clinically relevant contact allergens. In a study of 519 patients with dermatitis, Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved significantly after PT regardless of whether the results were positive or negative, indicating benefits for the care and treatment of dermatitis, even in the setting of negative patch test results (P< .001).15 This could because they were still counseled on gentle skin care and management of their dermatitis at the PT visit. Improvements in disease severity also have been observed in adults and children after PT, with most patients having partial to complete clearance of their dermatitis.16,17 This is not surprising, as comprehensive PT allows clinicians to diagnose the cause of ACD by finding the exact allergen triggering the eruption and then guide patients through avoidance of these allergens to eventually clear their dermatitis.

Comprehensive Patch Testing Captures Allergen Trends

Dermatologists who perform PT in the United States currently have access to a diverse array of allergens, with more than 500 different allergens available. Access to and utilization of these allergens are essential for the comprehensive evaluation needed for our patients.

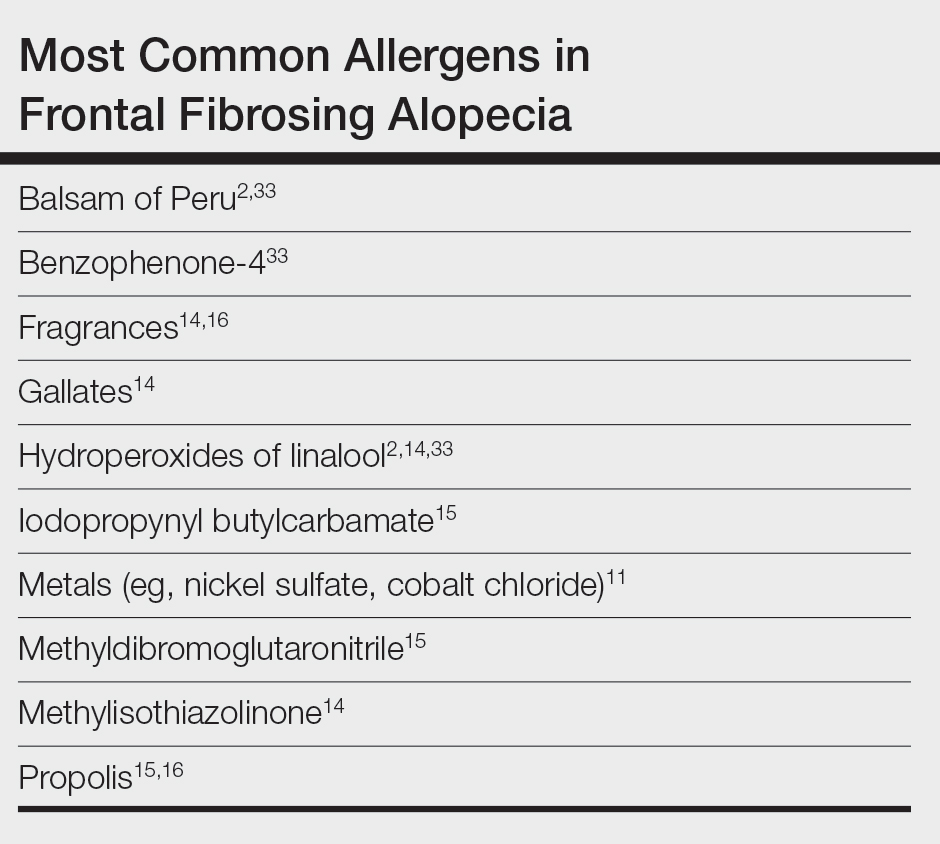

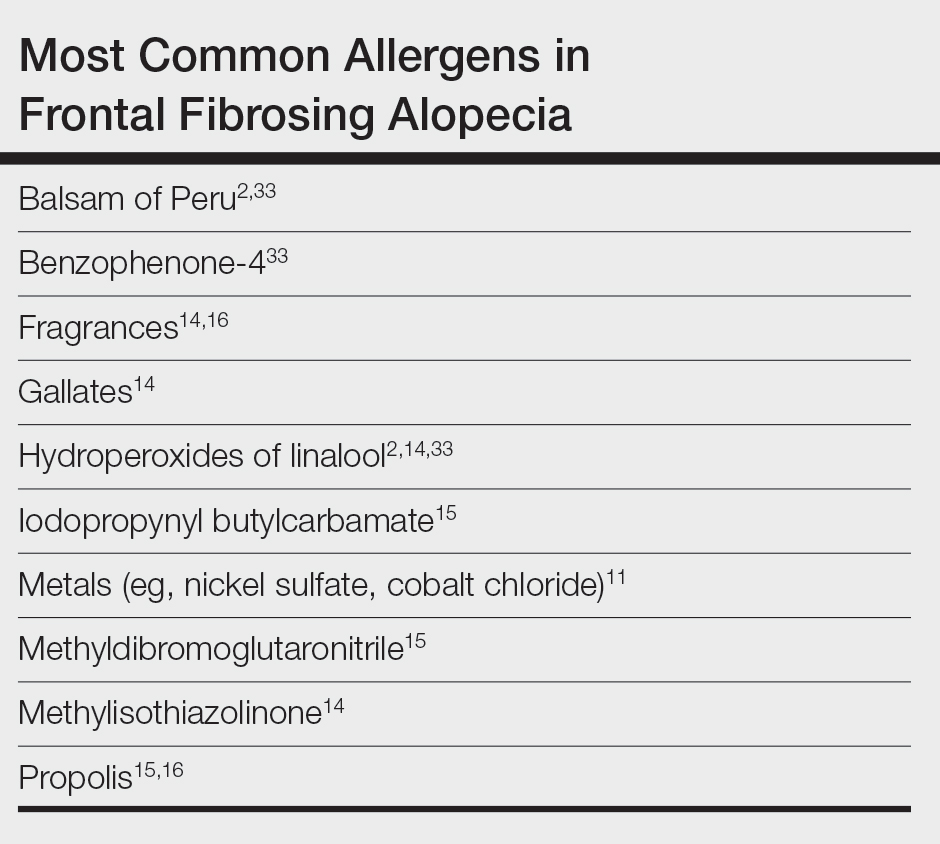

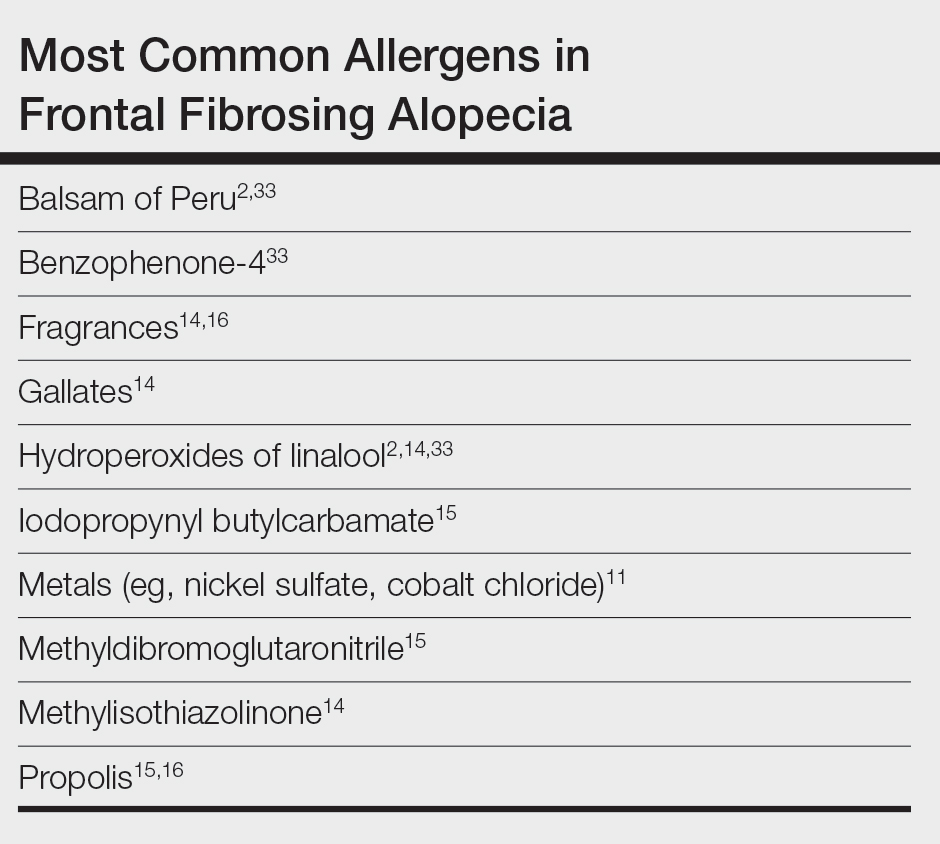

Comprehensive PT has uncovered emerging allergens such as dimethyl fumarate, the potent cause of sofa dermatitis18; isobornyl acrylate, which is found in wearable diabetic monitors19; and acetophenone azine, which can cause shin guard ACD in athletes.20 Increasing prevalence of ACD to these allergens would not have been identified without provider access to PT. Patch testing also has identified emerging allergen trends, such as the methylisothiazolinone allergy epidemic.21 All of these emerging allergens, identified through PT, have been named Contact Allergen of the Year by the ACDS due to their newfound relevance.18-20

In contrast, allergen prevalence can decrease over time, leading to removal from screening panels; examples include methyldibromo glutaronitrile, which is no longer widely present in consumer products, and thimerosal, which has frequent positive results but low relevance due to its infrequent use in personal care products. In response to comprehensive PT studies, allergen concentrations may be modified, as in the case of formaldehyde, which has notable irritant potential at higher tested concentrations but remains on the ACDS Core Allergen Series with a test concentration that optimizes the number of true positive reactions while decreasing irritant reactions.6 Likewise, nickel sulfate test concentrations were increased in the NACDG screening series due to evidence that testing at 5% identifies more nickel contact allergy than testing at 2.5% without considerably increasing irritant reactions.22

Allergen Choice and Flexibility are Key to Optimal Screening

Dermatologists who perform PT usually choose their screening series based on expert consensus and recommendations.6,23 Additional test allergens for comprehensive PT typically are chosen based on patient exposures, regional trends, and clinical expertise. This flexibility traditionally has allowed for the opportunity to identify culprit allergens that are relevant for the individual patient; for example, a hairdresser may have daily exposure to resorcinol, whereas a massage therapist may have regular exposure to essential oils. Testing only a standard screening series may miss the culprit allergen for both patients. For optimal patient outcomes, allergen choice and flexibility are key.

Currently, the 35-allergen T.R.U.E. test is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved patch test; however, multiple studies have shown that comprehensive PT, including supplemental allergens, considerably improves the diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes in ACD. A 6-year retrospective study found that using an extended screening series identified an additional 10.8% of patients (n=585) with positive tests who were negative to the T.R.U.E. test.24 Patch testing with the T.R.U.E. test alone would miss almost half of the positive reactions detected by the NACDG 80-panel screening series. Furthermore, an additional 21.1% of 3056 tested patients had at least one relevant reaction to a supplemental allergen that was not present in the NACDG screening series.23 In a retrospective study of 791 patients patch tested with the NACDG screening series and 2 supplemental series, 19.5% and 12.1% of patients, respectively, had positive reactions to supplemental allergens.25 This reinforces the importance of comprehensive PT beyond a more limited screening series. Testing more allergens identifies more causative allergens for patients.

Changes in Utilization May Affect Patient Care

Recent data have shown a shift in patch test utilization. An analysis of Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims for PT between 2010 and 2018 demonstrated that an increase in patch test utilization during this period was driven mainly by nonphysician providers and allergists.26 From 2012 to 2017, the number of patients patch tested by allergists grew by 20.3% compared to only 1.84% for dermatologists.27 Since dupilumab was approved in 2017 for the management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, claims data from 2017 to 2022 showed an exponential increase in its utilization, while patch test utilization has markedly decreased.28

Dermatologists are the predominant experts in ACD, but these concerning trends suggest decreasing utilization of PT by dermatologists, possibly due to lack of required residency training in PT, cost of patch test allergens and supplies with corresponding static reimbursement rates, staff time and training required for an excellent PT experience, comparative ease of biologic prescription vs the time-intensive process of comprehensive PT, and perceived high barrier of entry into PT. This may limit patient access to high-quality comprehensive PT and more importantly, a chance for our patients to experience resolution of their skin disease.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive PT is safe, effective, and readily available. Unfettered access to a wide range of allergens improves diagnostic accuracy and quality of life and reduces economic burden from sick leave, job loss, and treatment costs. Patch testing remains the one and only way to identify causative allergens for patients with ACD, and comprehensive PT is the most ideal approach for excellent patient care.

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a common skin condition affecting approximately 20% of the general population in the United States.1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a unique disease in that there is an opportunity for complete cure through allergen avoidance; however, this requires proper identification of the offending allergen. When the culprit allergen is not identified or removed from the patient’s environment, chronic ACD can develop, leading to persistent inflammation and related symptoms, reduced quality of life, and greater economic burden for patients and the health care system.2,3

Patch testing (PT) is the only available diagnostic test for ACD, allowing for identification and subsequent avoidance of contact allergens. Patch testing involves applying allergens—typically chemicals that can be found in personal care products—onto the skin for 48 hours. Delayed readings are completed 72 to 168 hours after application. Interpretation of relevance and patient counseling, with resultant allergen avoidance, are required for a successful patient experience. Patch testing is considered safe in tested populations; rare risks associated with PT include active sensitization and anaphylaxis.4

There are many screening series available, with the number of screening allergens ranging from 35 (T.R.U.E. [Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous] test) to 90 (American Contact Dermatitis Society [ACDS] Core series). Comprehensive PT generally refers to the completion of PT for all potentially relevant and testable allergens for a given patient, which typically involves testing beyond a screening series. Currently in the United States, comprehensive PT typically includes testing for 80 to 90 allergens and any additional potentially relevant allergens based on the clinical history and patient exposures. A 2018 survey noted that, of 149 ACDS members, 82% always used a baseline screening series for PT, with 62% of these routinely testing 80 allergens and 18% routinely testing 70 allergens.5 Additionally, nearly 70% always or sometimes tested with supplemental or additional series. In other words, advanced patch testers were routinely testing 70 to 80 allergens in their screening series, and most were testing additional allergens to ensure the best care for their patients.

To account for emerging allergens, accommodate changes in allergen test concentrations recommended by ACDS and the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), and address the need for comprehensive PT for most patients, recommended screening series are regularly updated by patch test societies and expert panels such as the ACDS and the NACDG. When the ACDS Core series6 was introduced in 2013, it consisted of 80 recommended allergens.7 The panel was updated in 20178 and again in 2020,6 most recently with 90 allergens. The NACDG has collected patch test data since at least 19929 and revisits their recommended screening series on a 2-year cycle, evaluating test concentrations and adding and removing allergens based on allergen trends, allergen performance, patient need, and emergence of new allergens; the current NACDG series consists of 80 allergens. This article illustrates the clinical and public health value of comprehensive PT and the vital role of allergen access in the comprehensive patch test process, with the ultimate goal of optimizing care for patients with ACD.

Value of Comprehensive Patch Testing for ACD

Early PT represents the most cost-effective approach to the diagnosis and management of ACD. Lack of access to PT can lead to delayed diagnosis, resulting in continued exposure to the offending allergen, disease chronicity, and ultimately worse quality-of-life scores compared with patients who are diagnosed early.10 Earlier diagnosis also can minimize costs by avoiding unnecessary treatments. Without access to comprehensive PT, patients could potentially be erroneously diagnosed with atopic dermatitis and subsequently treated with expensive biologic therapies (eg, dupilumab, which costs approximately $4000 per dose or $104,000 per year11), when allergen avoidance would have been curative with minimal cost. The continued value of comprehensive PT, especially in the era of the atopic dermatitis therapeutic revolution, cannot be more strongly emphasized.

Among 140 patients with ACD, 87% found PT useful, 91% were able to avoid allergens, and 57% noted improvement or resolution of their dermatitis after avoidance of identified allergens.12 A multicenter prospective observational study demonstrated that PT improved dermatology-specific quality of life and reduced resources used for patients with ACD compared to non–patch tested individuals.13 Another study found that patients with ACD who underwent PT and were confirmed as having relevant positive contact allergens showed improvement in both perceived eczema severity and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores just 2 months after testing.14 This effect is attributed to the identification and subsequent avoidance of clinically relevant contact allergens. In a study of 519 patients with dermatitis, Dermatology Life Quality Index scores improved significantly after PT regardless of whether the results were positive or negative, indicating benefits for the care and treatment of dermatitis, even in the setting of negative patch test results (P< .001).15 This could because they were still counseled on gentle skin care and management of their dermatitis at the PT visit. Improvements in disease severity also have been observed in adults and children after PT, with most patients having partial to complete clearance of their dermatitis.16,17 This is not surprising, as comprehensive PT allows clinicians to diagnose the cause of ACD by finding the exact allergen triggering the eruption and then guide patients through avoidance of these allergens to eventually clear their dermatitis.

Comprehensive Patch Testing Captures Allergen Trends

Dermatologists who perform PT in the United States currently have access to a diverse array of allergens, with more than 500 different allergens available. Access to and utilization of these allergens are essential for the comprehensive evaluation needed for our patients.

Comprehensive PT has uncovered emerging allergens such as dimethyl fumarate, the potent cause of sofa dermatitis18; isobornyl acrylate, which is found in wearable diabetic monitors19; and acetophenone azine, which can cause shin guard ACD in athletes.20 Increasing prevalence of ACD to these allergens would not have been identified without provider access to PT. Patch testing also has identified emerging allergen trends, such as the methylisothiazolinone allergy epidemic.21 All of these emerging allergens, identified through PT, have been named Contact Allergen of the Year by the ACDS due to their newfound relevance.18-20

In contrast, allergen prevalence can decrease over time, leading to removal from screening panels; examples include methyldibromo glutaronitrile, which is no longer widely present in consumer products, and thimerosal, which has frequent positive results but low relevance due to its infrequent use in personal care products. In response to comprehensive PT studies, allergen concentrations may be modified, as in the case of formaldehyde, which has notable irritant potential at higher tested concentrations but remains on the ACDS Core Allergen Series with a test concentration that optimizes the number of true positive reactions while decreasing irritant reactions.6 Likewise, nickel sulfate test concentrations were increased in the NACDG screening series due to evidence that testing at 5% identifies more nickel contact allergy than testing at 2.5% without considerably increasing irritant reactions.22

Allergen Choice and Flexibility are Key to Optimal Screening

Dermatologists who perform PT usually choose their screening series based on expert consensus and recommendations.6,23 Additional test allergens for comprehensive PT typically are chosen based on patient exposures, regional trends, and clinical expertise. This flexibility traditionally has allowed for the opportunity to identify culprit allergens that are relevant for the individual patient; for example, a hairdresser may have daily exposure to resorcinol, whereas a massage therapist may have regular exposure to essential oils. Testing only a standard screening series may miss the culprit allergen for both patients. For optimal patient outcomes, allergen choice and flexibility are key.

Currently, the 35-allergen T.R.U.E. test is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved patch test; however, multiple studies have shown that comprehensive PT, including supplemental allergens, considerably improves the diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes in ACD. A 6-year retrospective study found that using an extended screening series identified an additional 10.8% of patients (n=585) with positive tests who were negative to the T.R.U.E. test.24 Patch testing with the T.R.U.E. test alone would miss almost half of the positive reactions detected by the NACDG 80-panel screening series. Furthermore, an additional 21.1% of 3056 tested patients had at least one relevant reaction to a supplemental allergen that was not present in the NACDG screening series.23 In a retrospective study of 791 patients patch tested with the NACDG screening series and 2 supplemental series, 19.5% and 12.1% of patients, respectively, had positive reactions to supplemental allergens.25 This reinforces the importance of comprehensive PT beyond a more limited screening series. Testing more allergens identifies more causative allergens for patients.

Changes in Utilization May Affect Patient Care

Recent data have shown a shift in patch test utilization. An analysis of Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims for PT between 2010 and 2018 demonstrated that an increase in patch test utilization during this period was driven mainly by nonphysician providers and allergists.26 From 2012 to 2017, the number of patients patch tested by allergists grew by 20.3% compared to only 1.84% for dermatologists.27 Since dupilumab was approved in 2017 for the management of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, claims data from 2017 to 2022 showed an exponential increase in its utilization, while patch test utilization has markedly decreased.28

Dermatologists are the predominant experts in ACD, but these concerning trends suggest decreasing utilization of PT by dermatologists, possibly due to lack of required residency training in PT, cost of patch test allergens and supplies with corresponding static reimbursement rates, staff time and training required for an excellent PT experience, comparative ease of biologic prescription vs the time-intensive process of comprehensive PT, and perceived high barrier of entry into PT. This may limit patient access to high-quality comprehensive PT and more importantly, a chance for our patients to experience resolution of their skin disease.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive PT is safe, effective, and readily available. Unfettered access to a wide range of allergens improves diagnostic accuracy and quality of life and reduces economic burden from sick leave, job loss, and treatment costs. Patch testing remains the one and only way to identify causative allergens for patients with ACD, and comprehensive PT is the most ideal approach for excellent patient care.

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Hand eczema. Lancet. 2024;404:2476-2486.

- Garg V, Brod B, Gaspari AA. Patch testing: uses, systems, risks/benefits, and its role in managing the patient with contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:580-590.

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Taylor J, Liu B, et al. Patch test practice patterns of members of the American Contact Dermatitis Society. Dermatitis. 2020;31:272-275.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 Update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series. Dermatitis. 2013;24:7-9.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2017 Update. Dermatitis. 2017;28:141-143.

- Marks JG, Belsito DV, DeLeo VA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard tray patch test results (1992 to 1994). Am J Contact Dermat. 1995;6:160-165.

- Kadyk DL, McCarter K, Achen F, et al. Quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1037-1048.

- Dupixent® (dupilumab): pricing and insurance. Sanofi US. Updated June 2025. Accessed January 9, 2026. https://www.dupixent.com/support-savings/cost-insurance

- Woo PN, Hay IC, Ormerod AD. An audit of the value of patch testing and its effect on quality of life. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:244-247.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson R. Impact of patch testing on dermatology-specific quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:215-221.

- Thomson KF, Wilkinson SM, Sommer S, et al. Eczema: quality of life by body site and the effect of patch testing. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:627-630.

- Boonchai W, Charoenpipatsin N, Winayanuwattikun W, et al. Assessment of the quality of life (QoL) of patients with dermatitis and the impact of patch testing on QoL: a study of 519 patients diagnosed with dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:182-188.

- Johnson H, Rao M, Yu J. Improved or not improved, that is the question: patch testing outcomes from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Contact Dermatitis. 2024;90:324-327.

- George SE, Yu J. Patch testing outcomes in children at the Massachusetts General Hospital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:354-356.

- McNamara D. Dimethyl fumarate named 2011 allergen of the year.Int Med News. February 3, 2011. Accessed January 9, 2026. https://www.mdedge.com/internalmedicine/article/20401/dermatology/dimethyl-fumarate-named-2011-allergen-year

- Nath N, Reeder M, Atwater AR. Isobornyl acrylate and diabetic devices steal the show for the 2020 American Contact Dermatitis Societyallergen of the year. Cutis. 2020;105:283-285.

- Raison-Peyron N, Sasseville D. Acetophenone azine. Dermatitis. 2021;32:5-9.

- Castanedo-Tardana MP, Zug KA. Methylisothiazolinone. Dermatitis. 2013;24:2-6.

- Svedman C, Ale I, Goh CL, et al. Patch testing with nickel sulfate 5.0% traces significantly more contact allergy than 2.5%: a prospective study within the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Dermatitis. 2022;33:417-420.

- Houle MC, DeKoven JG, Atwater AR, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2021-2022. Dermatitis. 2025;36:464-476.

- Sundquist BK, Yang B, Pasha MA. Experience in patch testing: a 6-year retrospective review from a single academic allergy practice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:502-507.

- Atwater AR, Liu B, Walsh R, et al. Supplemental patch testing identifies allergens missed by standard screening series. Dermatitis. 2024;35:366-372.

- Ravishankar A, Freese RL, Parsons HM, et al. Trends in patch testing in the Medicare Part B fee-for-service population. Dermatitis. 2022;33:129-134.

- Cheraghlou S, Watsky KL, Cohen JM. Utilization, cost, and provider trends in patch testing among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States from 2012 to 2017. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1218-1226.

- Santiago Mangual KP, Rau A, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Increasing use of dupilumab and decreasing use of patch testing in medicare patients from 2017 to 2022: a claims database study. Dermatitis. 2025;36:538-540.

- Alinaghi F, Bennike NH, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence of contact allergy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:77-85.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Hand eczema. Lancet. 2024;404:2476-2486.

- Garg V, Brod B, Gaspari AA. Patch testing: uses, systems, risks/benefits, and its role in managing the patient with contact dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:580-590.

- Rodriguez-Homs LG, Taylor J, Liu B, et al. Patch test practice patterns of members of the American Contact Dermatitis Society. Dermatitis. 2020;31:272-275.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2020 Update. Dermatitis. 2020;31:279-282.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series. Dermatitis. 2013;24:7-9.

- Schalock PC, Dunnick CA, Nedorost S, et al. American Contact Dermatitis Society Core Allergen Series: 2017 Update. Dermatitis. 2017;28:141-143.

- Marks JG, Belsito DV, DeLeo VA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard tray patch test results (1992 to 1994). Am J Contact Dermat. 1995;6:160-165.

- Kadyk DL, McCarter K, Achen F, et al. Quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1037-1048.

- Dupixent® (dupilumab): pricing and insurance. Sanofi US. Updated June 2025. Accessed January 9, 2026. https://www.dupixent.com/support-savings/cost-insurance

- Woo PN, Hay IC, Ormerod AD. An audit of the value of patch testing and its effect on quality of life. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:244-247.

- Rajagopalan R, Anderson R. Impact of patch testing on dermatology-specific quality of life in patients with allergic contact dermatitis. Am J Contact Dermat. 1997;8:215-221.

- Thomson KF, Wilkinson SM, Sommer S, et al. Eczema: quality of life by body site and the effect of patch testing. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:627-630.

- Boonchai W, Charoenpipatsin N, Winayanuwattikun W, et al. Assessment of the quality of life (QoL) of patients with dermatitis and the impact of patch testing on QoL: a study of 519 patients diagnosed with dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:182-188.

- Johnson H, Rao M, Yu J. Improved or not improved, that is the question: patch testing outcomes from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Contact Dermatitis. 2024;90:324-327.

- George SE, Yu J. Patch testing outcomes in children at the Massachusetts General Hospital. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:354-356.

- McNamara D. Dimethyl fumarate named 2011 allergen of the year.Int Med News. February 3, 2011. Accessed January 9, 2026. https://www.mdedge.com/internalmedicine/article/20401/dermatology/dimethyl-fumarate-named-2011-allergen-year

- Nath N, Reeder M, Atwater AR. Isobornyl acrylate and diabetic devices steal the show for the 2020 American Contact Dermatitis Societyallergen of the year. Cutis. 2020;105:283-285.

- Raison-Peyron N, Sasseville D. Acetophenone azine. Dermatitis. 2021;32:5-9.

- Castanedo-Tardana MP, Zug KA. Methylisothiazolinone. Dermatitis. 2013;24:2-6.

- Svedman C, Ale I, Goh CL, et al. Patch testing with nickel sulfate 5.0% traces significantly more contact allergy than 2.5%: a prospective study within the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group. Dermatitis. 2022;33:417-420.

- Houle MC, DeKoven JG, Atwater AR, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2021-2022. Dermatitis. 2025;36:464-476.

- Sundquist BK, Yang B, Pasha MA. Experience in patch testing: a 6-year retrospective review from a single academic allergy practice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122:502-507.

- Atwater AR, Liu B, Walsh R, et al. Supplemental patch testing identifies allergens missed by standard screening series. Dermatitis. 2024;35:366-372.

- Ravishankar A, Freese RL, Parsons HM, et al. Trends in patch testing in the Medicare Part B fee-for-service population. Dermatitis. 2022;33:129-134.

- Cheraghlou S, Watsky KL, Cohen JM. Utilization, cost, and provider trends in patch testing among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States from 2012 to 2017. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1218-1226.

- Santiago Mangual KP, Rau A, Grant-Kels JM, et al. Increasing use of dupilumab and decreasing use of patch testing in medicare patients from 2017 to 2022: a claims database study. Dermatitis. 2025;36:538-540.

Comprehensive Patch Testing: An Essential Tool for Care of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Comprehensive Patch Testing: An Essential Tool for Care of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Practice Points

- Comprehensive patch testing refers to patch testing beyond a screening series to capture allergens that otherwise would be missed using a limited panel.

- Comprehensive patch testing can identify emerging allergens and shifting allergen trends.

- Recent changes in patch test utilization have the potential to negatively affect patient care.

Toluene-2,5-Diamine Sulfate: The 2025 American Contact Dermatitis Society Allergen of the Year

Toluene-2,5-Diamine Sulfate: The 2025 American Contact Dermatitis Society Allergen of the Year

The American Contact Dermatitis Society selected toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate (PTDS) as the 2025 Allergen of the Year.1 Widely used as an alternative to para-phenylenediamine (PPD) in oxidative and permanent/semipermanent hair dyes, PTDS has emerged as a potent contact allergen with substantial cross-reactivity to PPD. In this article, we discuss PTDS as both a PPD alternative and a contact allergen as well as the clinical features of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to PTDS and practical recommendations for management in at-risk populations.

Background

Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate is a compound formed by combining 2,5-diaminotoluene (PTD) with sulfuric acid, making it more water soluble and potentially less irritating than PTD alone.2 In this article, the terms PTDS and PTD will be used interchangeably due to their structural similarity.

Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate commonly is used in oxidative and permanent/semipermanent hair dyes as an alternative to PPD, the most common hair dye contact allergen.3 Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate also is a component used in color photography development and in dyes used for textiles, furs, leathers, and biologic stains.4 The prevalence of PTDS contact allergy likely is underreported due to its absence in routine patch test series such as the Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (Smart Practice) and the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 90 Series.

Cross-Reactivity Between PTDS and PPD

There is substantial cross-reactivity between PTDS and PPD, necessitating careful avoidance and alternative dye selection. The rate of cross-reactivity between these compounds is high, with some estimated to be more than 80% among patch tested individuals.5-9 In some cases, patients with a contact allergy to PPD are able to tolerate dyes containing PTDS. Studies conducted in Canada and Europe showed that 31.3% to 76.3% of patients with a contact allergy to PPD also had an allergy to PTDS or PTD.7,8,10 Stronger reactions to PPD also seem to be associated with an increased risk for cross-reaction.11

Clinical Manifestation of ACD to PTDS

In the literature, case reports of ACD caused by PTDS are rare. The clinical manifestations of PTDS-ACD will closely mirror those described in PPD-ACD or PTD-ACD, reflecting the cross-reactivity between these aromatic amines. Generally, ACD to components in hair dyes manifests as a pruritic, erythematous, edematous, eczematous rash that can affect the margins of the scalp, ears, face, and/or neck. Severe cases can extend beyond the initial area of contact, potentially resulting in widespread involvement and systemic symptoms.12 Notably, the scalp often is spared, which may be attributable to protection provided by sebum or the hair itself covering the scalp.13

Two case reports described ACD of the eyebrows after application of PTD-containing hair dye.14,15 One patient developed severe bullous ACD involving the eyebrows and eyelashes with concurrent conjunctivitis,14 and the other experienced erythema, edema, burning, itching, and exudation at and around the eyebrows.15 The latter patient had prior exposure to PPD from a black henna tattoo, which may have led to an initial sensitization and subsequent cross-reactivity to PTD in the hair dye.

Another case report described a patient with erythema, edema, and scaling of the face, neck, and arms within 1 week of exposure to a new hair dye at a salon.16 Patch testing revealed a positive reaction to PPD on day 3, despite it not being a component of the hair dye. On day 7, the patient showed a delayed reaction to PTD, which was confirmed to be present in the dye.16 The implications of these findings are twofold. First, delayed patch test readings beyond day 5 could provide more sensitive interpretation. Second, this case highlights the cross-reactivity between these related compounds.

Hairdressers and users of hair care products are most commonly affected by PTDS contact allergy. Though hairdressers generally are at a higher risk, prevalence for PTD sensitization in a European patch tested population showed rates of 20% in hairdressers and 30.8% in consumers.17 The North American Contact Dermatitis Group reported PTDS sensitization in fewer than 2% of 4121 patients patch tested across 13 North American centers over a period of 1 year.18 This suggests potential underutilization of the more specific panels that include PTDS.

Hairdressers are at an increased risk of contact allergy to PTDS due to occupational exposure and are at higher risk for hand dermatitis due to frequent exposure to water. In a review of epidemiologic studies published between 2000 and 2021, the pooled lifetime prevalence of hand eczema in hairdressers was 38.2% compared to an estimated lifetime prevalence of 14.5% in the general population.19 Higher risk for hand eczema can increase the risk for sensitization to contact allergens including PPD and PTDS due to impaired barrier function, allowing allergen penetration through disrupted skin.20

Strategies for Management and Avoidance

Patients with suspected contact allergy to PTDS should avoid this compound and related dye chemicals such as PPD due to the high risk for ACD and frequent cross-reactivity. While PTDS-allergic patients should avoid products containing PPD, some patients allergic to PPD may be able to tolerate exposure to PTD or PTDS.7,8,10 Regardless, any suspected contact allergy should be supported by patch testing with PTDS and PPD to confirm sensitization. Patch test readings for PTDS/PTD could be delayed beyond day 5 if clinical suspicion is high and early patch test reading is noncontributory; however, more studies are needed to establish that later readings are more reliable for PTDS.

Occupational risk reduction in hairdressers is essential. Hairdressers as well as at-home users of hair dyes should be properly informed by their dermatologist or other trained health care professional about PTDS and PTD as potent allergens and should be provided with information on potential alternatives. They also should be counseled on proper skin protection, including single-use gloves and careful hand care through gentle cleansing and use of barrier creams to protect skin integrity and prevent contact dermatitis. Nitrile rubber gloves offer the best protection when handling hair dyes. Polyvinyl chloride or natural latex rubber gloves also may be sufficient; however, polyethylene gloves should be avoided, as they have been shown to have the fastest time to penetration.21 Gloves should be properly sized, and reuse should be avoided.

Because PTDS and PTD frequently are used in semipermanent and permanent hair dyes, temporary hair dyes (eg, henna-based dyes) may be safer alternatives, as they infrequently contain these allergens. Food, Drug, and Cosmetics (FD&C) and Drug and Cosmetics (D&C) dyes also are used in some semipermanent hair dyes and seem to have low cross-reactivity to PPD; therefore, these may be used in patients allergic to PTDS or PTD.22 However, these dyes require frequent reapplication, which may be unfavorable to some patients. Gallic acid–based hair dyes have been shown to be safe alternatives in patients with contact allergy to PTDS or PTD, though pretesting is recommended with a repeat open application test.23 The PPD derivative 2-methoxymethyl-para-phenylenediamine (ME-PPD) has reduced sensitization potential. In simulated hair dye use conditions, cross-reactivity to ME-PPD in patients with PPD contact allergy was 30% compared with 84% for PPD.24 However, in an open-use test in 25 PPD-allergic individuals, ME-PPD was reactive in 84% (21/25) and ME-PPD 2% patch testing was positive in 48% (12/25), suggesting that ME-PPD could be a potential alternative but is not universally tolerated.25

It is important to note that products purporting to be natural or botanical are not inherently safe and may themselves be allergenic.25 Patients should attempt a repeat open application test or patch testing prior to use of an alternative dye.

Given the prevalence of PTDS allergy, the fact that some PPD-allergic individuals may be able to tolerate hair dyes containing PTDS (assuming it tests negative), and the substantial quality of life and socioeconomic impacts of hair dye allergy, PTDS should be considered as an addition to standard patch test screening series.1

Final Thoughts

While initially popularized as an alternative to PPD in semipermanent and permanent hair dyes, PTDS now is emerging as a contact allergen with well-documented cross-reactivity to PPD. Dermatologists should consider patch testing for PTDS (and PPD) in individuals who regularly encounter this compound. This will guide further counseling and recommendations.

- Atwater AR, Botto N. Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate: allergen of the year 2025. Dermatitis. 2025;36:3-11. doi:10.1089/derm.2024.0384

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for 2,5-diamintoluene sulfate (CID 22856). Accessed Oct. 2, 2025. https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/2_5-Diaminotoluene-sulfate

- Søsted H, Rustemeyer T, Gonçalo M, et al. Contact allergy to common ingredients in hair dyes. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;69:32-39. doi:10.1111/cod.12077

- Burnett CL, Bergfeld WF, Belsito DV, et al. Final amended report of the safety assessment of toluene-2,5-diamine, toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate, and toluene-3,4-diamine as used in cosmetics. Int J Toxicol. 2010;29(3 suppl):61S-83S.

- Schmidt JD, Johansen JD, Nielsen MM, et al. Immune responses to hair dyes containing toluene-2,5-diamine. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:352-359. doi:10.1111/bjd.12676

- Yazar K, Boman A, Lidén C. Potent skin sensitizers in oxidative hair dye products on the Swedish market. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:269-275. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2009.01612.x

- Fautz R, Fuchs A, van der Walle H, et al. Hair dye-sensitized hairdressers: the cross-reaction pattern with new generation hair dyes. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;46:319-324. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.460601.x

- Vogel TA, Heijnen RW, Coenraads PJ, et al. Two decades of p-phenyl-enediamine and toluene-2,5-diamine patch testing—focus on co-sensitizations in the European baseline series and cross-reactions with chemically related substances. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76:81-88. doi:10.1111/cod.12619

- Skazik C, Grannemann S, Wilbers L, et al. Reactivity of in vitro activated human T lymphocytes to p-phenylenediamine and related substances. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:203-211. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01416.x

- LaBerge L, Pratt M, Fong B, et al. A 10-year review of p-phenylenediamine allergy and related para-amino compounds at the Ottawa Patch Test Clinic. Dermatitis. 2011;22:332. doi:10.2310/6620.2011.11044

- Thomas BR, White IR, McFadden JP, et al. Positive relationship—intensity of response to p-phenylenediamine on patch testing and cross-reactions with related allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:98-101. doi:10.1111/cod.12255

- Helaskoski E, Suojalehto H, Virtanen H, et al. Occupational asthma, rhinitis, and contact urticaria caused by oxidative hair dyes in hairdressers. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:46-52. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.10.002

- Mukkanna KS, Stone NM, Ingram JR. Para-phenylenediamine allergy: current perspectives on diagnosis and management. J Asthma Allergy. 2017;10:9-15. doi:10.2147/JAA.S90265

- Søsted H, Rastogi SC, Thomsen JS. Allergic contact dermatitis from toluene-2,5-diamine in a cream dye for eyelashes and eyebrows—quantitative exposure assessment. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:195-196. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01105.x

- Romita P, Foti C, Mascia P, et al. Eyebrow allergic contact dermatitis caused by m‐aminophenol and toluene‐2,5‐diamine secondary to a temporary black henna tattoo. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:51-52. doi:10.1111/cod.12987

- Bregnhøj A, Menne T. Primary sensitization to toluene-2,5-diamine giving rise to early positive patch reaction to p-phenylenediamine and late to toluene-2,5-diamine. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;59:189-190. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2008.01407.x

- Uter W, Hallmann S, Gefeller O, et al. Contact allergy to ingredients of hair cosmetics in female hairdressers and female consumers—an update based on IVDK data 2013-2020. Contact Dermatitis. 2023;89:161-170. doi:10.1111/cod.14363

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Reeder MJ, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2019-2020. Dermatitis. 2023;34:90-104. doi:10.1089/derm.2022.29017.jdk

- Havmose MS, Kezic S, Uter W, et al. Prevalence and incidence of hand eczema in hairdressers—a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the published literature from 2000–2021. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;86:254-265. doi:10.1111/cod.14048

- CDC. About skin exposures and effects. Published December 10, 2024. Accessed October 13, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/skin-exposure/about/index.html

- Havmose M, Thyssen JP, Zachariae C, et al. Use of protective gloves by hairdressers: a review of efficacy and potential adverse effects. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;83:75-82. doi:10.1111/cod.13561

- Fonacier L, Bernstein DI, Pacheco K, et al. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter–update 2015. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(3 suppl):S1-S39. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.02.009

- Choi Y, Lee JH, Kwon HB, et al. Skin testing of gallic acid-based hair dye in paraphenylenediamine/paratoluenediamine-reactive patients.J Dermatol. 2016;43:795-798. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13226

- Blömeke B, Pot LM, Coenraads PJ, et al. Cross-elicitation responses to 2-methoxymethyl-p-phenylenediamine under hair dye use conditions in p-phenylenediamine-allergic individuals. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:976-980. doi:10.1111/bjd.13412

- Schuttelaar ML, Dittmar D, Burgerhof JGM, et al. Cross-elicitation responses to 2-methoxymethyl-p-phenylenediamine in p-phenylenediamine-allergic individuals: results from open use testing and diagnostic patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;79:288-294. doi:10.1111/cod.13078

- Tran JM, Comstock JR, Reeder MJ. Natural is not always better: the prevalence of allergenic ingredients in "clean" beauty products. Dermatitis. 2022;33:215-219. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000863

The American Contact Dermatitis Society selected toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate (PTDS) as the 2025 Allergen of the Year.1 Widely used as an alternative to para-phenylenediamine (PPD) in oxidative and permanent/semipermanent hair dyes, PTDS has emerged as a potent contact allergen with substantial cross-reactivity to PPD. In this article, we discuss PTDS as both a PPD alternative and a contact allergen as well as the clinical features of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to PTDS and practical recommendations for management in at-risk populations.

Background

Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate is a compound formed by combining 2,5-diaminotoluene (PTD) with sulfuric acid, making it more water soluble and potentially less irritating than PTD alone.2 In this article, the terms PTDS and PTD will be used interchangeably due to their structural similarity.

Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate commonly is used in oxidative and permanent/semipermanent hair dyes as an alternative to PPD, the most common hair dye contact allergen.3 Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate also is a component used in color photography development and in dyes used for textiles, furs, leathers, and biologic stains.4 The prevalence of PTDS contact allergy likely is underreported due to its absence in routine patch test series such as the Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (Smart Practice) and the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 90 Series.

Cross-Reactivity Between PTDS and PPD

There is substantial cross-reactivity between PTDS and PPD, necessitating careful avoidance and alternative dye selection. The rate of cross-reactivity between these compounds is high, with some estimated to be more than 80% among patch tested individuals.5-9 In some cases, patients with a contact allergy to PPD are able to tolerate dyes containing PTDS. Studies conducted in Canada and Europe showed that 31.3% to 76.3% of patients with a contact allergy to PPD also had an allergy to PTDS or PTD.7,8,10 Stronger reactions to PPD also seem to be associated with an increased risk for cross-reaction.11

Clinical Manifestation of ACD to PTDS

In the literature, case reports of ACD caused by PTDS are rare. The clinical manifestations of PTDS-ACD will closely mirror those described in PPD-ACD or PTD-ACD, reflecting the cross-reactivity between these aromatic amines. Generally, ACD to components in hair dyes manifests as a pruritic, erythematous, edematous, eczematous rash that can affect the margins of the scalp, ears, face, and/or neck. Severe cases can extend beyond the initial area of contact, potentially resulting in widespread involvement and systemic symptoms.12 Notably, the scalp often is spared, which may be attributable to protection provided by sebum or the hair itself covering the scalp.13

Two case reports described ACD of the eyebrows after application of PTD-containing hair dye.14,15 One patient developed severe bullous ACD involving the eyebrows and eyelashes with concurrent conjunctivitis,14 and the other experienced erythema, edema, burning, itching, and exudation at and around the eyebrows.15 The latter patient had prior exposure to PPD from a black henna tattoo, which may have led to an initial sensitization and subsequent cross-reactivity to PTD in the hair dye.

Another case report described a patient with erythema, edema, and scaling of the face, neck, and arms within 1 week of exposure to a new hair dye at a salon.16 Patch testing revealed a positive reaction to PPD on day 3, despite it not being a component of the hair dye. On day 7, the patient showed a delayed reaction to PTD, which was confirmed to be present in the dye.16 The implications of these findings are twofold. First, delayed patch test readings beyond day 5 could provide more sensitive interpretation. Second, this case highlights the cross-reactivity between these related compounds.

Hairdressers and users of hair care products are most commonly affected by PTDS contact allergy. Though hairdressers generally are at a higher risk, prevalence for PTD sensitization in a European patch tested population showed rates of 20% in hairdressers and 30.8% in consumers.17 The North American Contact Dermatitis Group reported PTDS sensitization in fewer than 2% of 4121 patients patch tested across 13 North American centers over a period of 1 year.18 This suggests potential underutilization of the more specific panels that include PTDS.

Hairdressers are at an increased risk of contact allergy to PTDS due to occupational exposure and are at higher risk for hand dermatitis due to frequent exposure to water. In a review of epidemiologic studies published between 2000 and 2021, the pooled lifetime prevalence of hand eczema in hairdressers was 38.2% compared to an estimated lifetime prevalence of 14.5% in the general population.19 Higher risk for hand eczema can increase the risk for sensitization to contact allergens including PPD and PTDS due to impaired barrier function, allowing allergen penetration through disrupted skin.20

Strategies for Management and Avoidance

Patients with suspected contact allergy to PTDS should avoid this compound and related dye chemicals such as PPD due to the high risk for ACD and frequent cross-reactivity. While PTDS-allergic patients should avoid products containing PPD, some patients allergic to PPD may be able to tolerate exposure to PTD or PTDS.7,8,10 Regardless, any suspected contact allergy should be supported by patch testing with PTDS and PPD to confirm sensitization. Patch test readings for PTDS/PTD could be delayed beyond day 5 if clinical suspicion is high and early patch test reading is noncontributory; however, more studies are needed to establish that later readings are more reliable for PTDS.

Occupational risk reduction in hairdressers is essential. Hairdressers as well as at-home users of hair dyes should be properly informed by their dermatologist or other trained health care professional about PTDS and PTD as potent allergens and should be provided with information on potential alternatives. They also should be counseled on proper skin protection, including single-use gloves and careful hand care through gentle cleansing and use of barrier creams to protect skin integrity and prevent contact dermatitis. Nitrile rubber gloves offer the best protection when handling hair dyes. Polyvinyl chloride or natural latex rubber gloves also may be sufficient; however, polyethylene gloves should be avoided, as they have been shown to have the fastest time to penetration.21 Gloves should be properly sized, and reuse should be avoided.

Because PTDS and PTD frequently are used in semipermanent and permanent hair dyes, temporary hair dyes (eg, henna-based dyes) may be safer alternatives, as they infrequently contain these allergens. Food, Drug, and Cosmetics (FD&C) and Drug and Cosmetics (D&C) dyes also are used in some semipermanent hair dyes and seem to have low cross-reactivity to PPD; therefore, these may be used in patients allergic to PTDS or PTD.22 However, these dyes require frequent reapplication, which may be unfavorable to some patients. Gallic acid–based hair dyes have been shown to be safe alternatives in patients with contact allergy to PTDS or PTD, though pretesting is recommended with a repeat open application test.23 The PPD derivative 2-methoxymethyl-para-phenylenediamine (ME-PPD) has reduced sensitization potential. In simulated hair dye use conditions, cross-reactivity to ME-PPD in patients with PPD contact allergy was 30% compared with 84% for PPD.24 However, in an open-use test in 25 PPD-allergic individuals, ME-PPD was reactive in 84% (21/25) and ME-PPD 2% patch testing was positive in 48% (12/25), suggesting that ME-PPD could be a potential alternative but is not universally tolerated.25

It is important to note that products purporting to be natural or botanical are not inherently safe and may themselves be allergenic.25 Patients should attempt a repeat open application test or patch testing prior to use of an alternative dye.

Given the prevalence of PTDS allergy, the fact that some PPD-allergic individuals may be able to tolerate hair dyes containing PTDS (assuming it tests negative), and the substantial quality of life and socioeconomic impacts of hair dye allergy, PTDS should be considered as an addition to standard patch test screening series.1

Final Thoughts

While initially popularized as an alternative to PPD in semipermanent and permanent hair dyes, PTDS now is emerging as a contact allergen with well-documented cross-reactivity to PPD. Dermatologists should consider patch testing for PTDS (and PPD) in individuals who regularly encounter this compound. This will guide further counseling and recommendations.

The American Contact Dermatitis Society selected toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate (PTDS) as the 2025 Allergen of the Year.1 Widely used as an alternative to para-phenylenediamine (PPD) in oxidative and permanent/semipermanent hair dyes, PTDS has emerged as a potent contact allergen with substantial cross-reactivity to PPD. In this article, we discuss PTDS as both a PPD alternative and a contact allergen as well as the clinical features of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to PTDS and practical recommendations for management in at-risk populations.

Background

Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate is a compound formed by combining 2,5-diaminotoluene (PTD) with sulfuric acid, making it more water soluble and potentially less irritating than PTD alone.2 In this article, the terms PTDS and PTD will be used interchangeably due to their structural similarity.

Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate commonly is used in oxidative and permanent/semipermanent hair dyes as an alternative to PPD, the most common hair dye contact allergen.3 Toluene-2,5-diamine sulfate also is a component used in color photography development and in dyes used for textiles, furs, leathers, and biologic stains.4 The prevalence of PTDS contact allergy likely is underreported due to its absence in routine patch test series such as the Thin-Layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous (T.R.U.E.) test (Smart Practice) and the American Contact Dermatitis Society Core 90 Series.

Cross-Reactivity Between PTDS and PPD

There is substantial cross-reactivity between PTDS and PPD, necessitating careful avoidance and alternative dye selection. The rate of cross-reactivity between these compounds is high, with some estimated to be more than 80% among patch tested individuals.5-9 In some cases, patients with a contact allergy to PPD are able to tolerate dyes containing PTDS. Studies conducted in Canada and Europe showed that 31.3% to 76.3% of patients with a contact allergy to PPD also had an allergy to PTDS or PTD.7,8,10 Stronger reactions to PPD also seem to be associated with an increased risk for cross-reaction.11

Clinical Manifestation of ACD to PTDS

In the literature, case reports of ACD caused by PTDS are rare. The clinical manifestations of PTDS-ACD will closely mirror those described in PPD-ACD or PTD-ACD, reflecting the cross-reactivity between these aromatic amines. Generally, ACD to components in hair dyes manifests as a pruritic, erythematous, edematous, eczematous rash that can affect the margins of the scalp, ears, face, and/or neck. Severe cases can extend beyond the initial area of contact, potentially resulting in widespread involvement and systemic symptoms.12 Notably, the scalp often is spared, which may be attributable to protection provided by sebum or the hair itself covering the scalp.13

Two case reports described ACD of the eyebrows after application of PTD-containing hair dye.14,15 One patient developed severe bullous ACD involving the eyebrows and eyelashes with concurrent conjunctivitis,14 and the other experienced erythema, edema, burning, itching, and exudation at and around the eyebrows.15 The latter patient had prior exposure to PPD from a black henna tattoo, which may have led to an initial sensitization and subsequent cross-reactivity to PTD in the hair dye.

Another case report described a patient with erythema, edema, and scaling of the face, neck, and arms within 1 week of exposure to a new hair dye at a salon.16 Patch testing revealed a positive reaction to PPD on day 3, despite it not being a component of the hair dye. On day 7, the patient showed a delayed reaction to PTD, which was confirmed to be present in the dye.16 The implications of these findings are twofold. First, delayed patch test readings beyond day 5 could provide more sensitive interpretation. Second, this case highlights the cross-reactivity between these related compounds.

Hairdressers and users of hair care products are most commonly affected by PTDS contact allergy. Though hairdressers generally are at a higher risk, prevalence for PTD sensitization in a European patch tested population showed rates of 20% in hairdressers and 30.8% in consumers.17 The North American Contact Dermatitis Group reported PTDS sensitization in fewer than 2% of 4121 patients patch tested across 13 North American centers over a period of 1 year.18 This suggests potential underutilization of the more specific panels that include PTDS.

Hairdressers are at an increased risk of contact allergy to PTDS due to occupational exposure and are at higher risk for hand dermatitis due to frequent exposure to water. In a review of epidemiologic studies published between 2000 and 2021, the pooled lifetime prevalence of hand eczema in hairdressers was 38.2% compared to an estimated lifetime prevalence of 14.5% in the general population.19 Higher risk for hand eczema can increase the risk for sensitization to contact allergens including PPD and PTDS due to impaired barrier function, allowing allergen penetration through disrupted skin.20

Strategies for Management and Avoidance

Patients with suspected contact allergy to PTDS should avoid this compound and related dye chemicals such as PPD due to the high risk for ACD and frequent cross-reactivity. While PTDS-allergic patients should avoid products containing PPD, some patients allergic to PPD may be able to tolerate exposure to PTD or PTDS.7,8,10 Regardless, any suspected contact allergy should be supported by patch testing with PTDS and PPD to confirm sensitization. Patch test readings for PTDS/PTD could be delayed beyond day 5 if clinical suspicion is high and early patch test reading is noncontributory; however, more studies are needed to establish that later readings are more reliable for PTDS.

Occupational risk reduction in hairdressers is essential. Hairdressers as well as at-home users of hair dyes should be properly informed by their dermatologist or other trained health care professional about PTDS and PTD as potent allergens and should be provided with information on potential alternatives. They also should be counseled on proper skin protection, including single-use gloves and careful hand care through gentle cleansing and use of barrier creams to protect skin integrity and prevent contact dermatitis. Nitrile rubber gloves offer the best protection when handling hair dyes. Polyvinyl chloride or natural latex rubber gloves also may be sufficient; however, polyethylene gloves should be avoided, as they have been shown to have the fastest time to penetration.21 Gloves should be properly sized, and reuse should be avoided.