User login

Annual recurrence rate of anaphylaxis in kids is nearly 30%

HOUSTON – The annual incidence of recurrent anaphylaxis in children was 29% in the first prospective study to examine the issue.

“That rate is higher than previously reported in retrospective studies,” Dr. Andrew O’Keefe said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

He presented a study conducted as part of the Cross-Canada Anaphylaxis Registry (C-CARE). In the prospective study, the parents of 266 children who presented with anaphylaxis to two Montreal hospitals were contacted annually thereafter and asked about subsequent allergic reactions.

The parents of 96 children participated. Twenty-five of these 96 children experienced a total of 42 recurrent episodes of anaphylaxis, with an annual recurrence rate of 29%. Three-quarters of recurrences were categorized by investigators as moderate in severity, meaning they entailed crampy abdominal pain, recurrent vomiting, diarrhea, a barky cough, stridor, hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, and/or moderate wheezing.

A striking study finding was that an epinephrine autoinjector was utilized prior to arrival at the hospital in only 52% of recurrences. That’s serious underutilization, commented Dr. O’Keefe, an allergist at Memorial University in St. Johns, Newfoundland.

“Physicians need to educate patients as to how to use the injectable epinephrine devices and encourage them to do so early during an episode of anaphylaxis, when they’re most effective,” he stressed in an interview.

Food was the principal trigger for 91% of recurrent episodes. Interestingly, children with recurrent anaphylaxis were 71% less likely to have peanut as a trigger, most likely because of extra vigilance regarding this notorious allergen, according to Dr. O’Keefe.

He noted a couple of significant study limitations. One is the small sample size. However, the study is being expanded to other academic medical centers across Canada, which will strengthen the findings.

The other limitation is the potential for bias introduced because parents whose child had severe anaphylaxis as the first episode were more than threefold more likely to participate in the prospective study. Still, the finding of a 29% annual recurrence rate among children in the Canadian study is not far afield from the results of some retrospective studies. For example, investigators at the Mayo Clinic reported as part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project a 21% incidence of a second anaphylactic event occurring at a median of 395 days after the first event in both child and adult residents of Olmsted County, Minn. (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;122:1161-5).

That study and others also suggest that the incidence of anaphylaxis is increasing. In Olmsted County, the rate rose from 46.9 cases/100,000 persons in 1990 to 58.9 cases/100,000 in 2000.

Asked why the prehospital use of injectable epinephrine was so low in the Montreal children, Dr. O’Keefe said there are several possible reasons.

“We know that the rates among physicians as well as parents and children are lower than what they should be. Some of the reasons include failure to identify anaphylaxis, not having the device with you, and, finally, patients have to know how to use it and be willing to. There’s a psychological hurdle involving fear of misusing the device or hurting their child or using it inappropriately that prevents people from using it,” he said.

The study was supported by research grants from AllerGen, Health Canada, and Sanofi.

HOUSTON – The annual incidence of recurrent anaphylaxis in children was 29% in the first prospective study to examine the issue.

“That rate is higher than previously reported in retrospective studies,” Dr. Andrew O’Keefe said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

He presented a study conducted as part of the Cross-Canada Anaphylaxis Registry (C-CARE). In the prospective study, the parents of 266 children who presented with anaphylaxis to two Montreal hospitals were contacted annually thereafter and asked about subsequent allergic reactions.

The parents of 96 children participated. Twenty-five of these 96 children experienced a total of 42 recurrent episodes of anaphylaxis, with an annual recurrence rate of 29%. Three-quarters of recurrences were categorized by investigators as moderate in severity, meaning they entailed crampy abdominal pain, recurrent vomiting, diarrhea, a barky cough, stridor, hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, and/or moderate wheezing.

A striking study finding was that an epinephrine autoinjector was utilized prior to arrival at the hospital in only 52% of recurrences. That’s serious underutilization, commented Dr. O’Keefe, an allergist at Memorial University in St. Johns, Newfoundland.

“Physicians need to educate patients as to how to use the injectable epinephrine devices and encourage them to do so early during an episode of anaphylaxis, when they’re most effective,” he stressed in an interview.

Food was the principal trigger for 91% of recurrent episodes. Interestingly, children with recurrent anaphylaxis were 71% less likely to have peanut as a trigger, most likely because of extra vigilance regarding this notorious allergen, according to Dr. O’Keefe.

He noted a couple of significant study limitations. One is the small sample size. However, the study is being expanded to other academic medical centers across Canada, which will strengthen the findings.

The other limitation is the potential for bias introduced because parents whose child had severe anaphylaxis as the first episode were more than threefold more likely to participate in the prospective study. Still, the finding of a 29% annual recurrence rate among children in the Canadian study is not far afield from the results of some retrospective studies. For example, investigators at the Mayo Clinic reported as part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project a 21% incidence of a second anaphylactic event occurring at a median of 395 days after the first event in both child and adult residents of Olmsted County, Minn. (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;122:1161-5).

That study and others also suggest that the incidence of anaphylaxis is increasing. In Olmsted County, the rate rose from 46.9 cases/100,000 persons in 1990 to 58.9 cases/100,000 in 2000.

Asked why the prehospital use of injectable epinephrine was so low in the Montreal children, Dr. O’Keefe said there are several possible reasons.

“We know that the rates among physicians as well as parents and children are lower than what they should be. Some of the reasons include failure to identify anaphylaxis, not having the device with you, and, finally, patients have to know how to use it and be willing to. There’s a psychological hurdle involving fear of misusing the device or hurting their child or using it inappropriately that prevents people from using it,” he said.

The study was supported by research grants from AllerGen, Health Canada, and Sanofi.

HOUSTON – The annual incidence of recurrent anaphylaxis in children was 29% in the first prospective study to examine the issue.

“That rate is higher than previously reported in retrospective studies,” Dr. Andrew O’Keefe said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

He presented a study conducted as part of the Cross-Canada Anaphylaxis Registry (C-CARE). In the prospective study, the parents of 266 children who presented with anaphylaxis to two Montreal hospitals were contacted annually thereafter and asked about subsequent allergic reactions.

The parents of 96 children participated. Twenty-five of these 96 children experienced a total of 42 recurrent episodes of anaphylaxis, with an annual recurrence rate of 29%. Three-quarters of recurrences were categorized by investigators as moderate in severity, meaning they entailed crampy abdominal pain, recurrent vomiting, diarrhea, a barky cough, stridor, hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, shortness of breath, and/or moderate wheezing.

A striking study finding was that an epinephrine autoinjector was utilized prior to arrival at the hospital in only 52% of recurrences. That’s serious underutilization, commented Dr. O’Keefe, an allergist at Memorial University in St. Johns, Newfoundland.

“Physicians need to educate patients as to how to use the injectable epinephrine devices and encourage them to do so early during an episode of anaphylaxis, when they’re most effective,” he stressed in an interview.

Food was the principal trigger for 91% of recurrent episodes. Interestingly, children with recurrent anaphylaxis were 71% less likely to have peanut as a trigger, most likely because of extra vigilance regarding this notorious allergen, according to Dr. O’Keefe.

He noted a couple of significant study limitations. One is the small sample size. However, the study is being expanded to other academic medical centers across Canada, which will strengthen the findings.

The other limitation is the potential for bias introduced because parents whose child had severe anaphylaxis as the first episode were more than threefold more likely to participate in the prospective study. Still, the finding of a 29% annual recurrence rate among children in the Canadian study is not far afield from the results of some retrospective studies. For example, investigators at the Mayo Clinic reported as part of the Rochester Epidemiology Project a 21% incidence of a second anaphylactic event occurring at a median of 395 days after the first event in both child and adult residents of Olmsted County, Minn. (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;122:1161-5).

That study and others also suggest that the incidence of anaphylaxis is increasing. In Olmsted County, the rate rose from 46.9 cases/100,000 persons in 1990 to 58.9 cases/100,000 in 2000.

Asked why the prehospital use of injectable epinephrine was so low in the Montreal children, Dr. O’Keefe said there are several possible reasons.

“We know that the rates among physicians as well as parents and children are lower than what they should be. Some of the reasons include failure to identify anaphylaxis, not having the device with you, and, finally, patients have to know how to use it and be willing to. There’s a psychological hurdle involving fear of misusing the device or hurting their child or using it inappropriately that prevents people from using it,” he said.

The study was supported by research grants from AllerGen, Health Canada, and Sanofi.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: The risk of recurrent anaphylaxis in children who’ve experienced a first episode may be higher than previously recognized.

Major finding: The annual anaphylaxis recurrence rate was 29% in a group of prospectively followed Montreal children.

Data source: A prospective study of 96 children.

Disclosures: The study was supported by research grants from AllerGen, Health Canada, and Sanofi. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Reslizumab aces pivotal trials in asthma with eosinophilia

HOUSTON – Reslizumab, a next-generation molecular-based asthma therapy, achieved its primary and secondary endpoints and demonstrated favorable safety in patients with moderate to severe asthma and eosinophilia in two pivotal clinical trials.

“We believe that reslizumab is an effective therapy for controlling asthma in patients with elevated blood eosinophils who are inadequately controlled on medium to high dose inhaled corticosteroid–based regimens,” Dr. Mario Castro concluded in presenting the two phase III results at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The frequency of clinical asthma exacerbations was reduced by more than half in reslizumab-treated patients, compared with controls in the two year-long studies. In addition, the reslizumab group experienced an early improvement in lung function as expressed in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) that was sustained throughout the year-long trials, as well as improvements in other measures of asthma control, including quality of life, reported Dr. Castro, professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine and pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis.

Elevated blood and sputum levels of eosinophils define an asthma phenotype at increased risk for serious asthma exacerbations. Reslizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds circulating interleukin-5 and prevents binding to the IL-5 receptor, thereby disrupting eosinophil production and function.

Dr. Castro presented two identically designed phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-month studies totaling 953 adolescents and adults. They were randomized to intravenous reslizumab at 3 mg/kg or placebo every 4 weeks for a year.

The primary endpoint was frequency of clinical asthma exacerbations (CAEs), an independently adjudicated composite outcome which required an episode featuring an increase in corticosteroids, an asthma-related ER visit or unscheduled office visit, evidence of asthma worsening in the form of at least a 20% drop from baseline in FEV1 or a 30% reduction in peak expiratory flow rate on 2 consecutive days, and worsening clinical symptoms.

Participants averaged two CAEs during the year prior to enrollment. The placebo-treated controls maintained that event rate during the two year-long studies, while the reslizumab-treated patients experienced 50% and 59% reductions relative to controls (P < .0001).

Reslizumab also increased the time to first CAE. In the two trials, 61% and 73% of reslizumab-treated patients didn’t develop a single CAE during 52 weeks, compared with 44% and 52% of controls.

The more CAEs a patient had in the year prior to enrollment, the greater the magnitude of benefit with reslizumab. While the relative risk reduction was 54%, compared with placebo in the combined studies, it climbed to 64% in patients with four or more CAEs in the previous year.

FEV1 improved after the first dose of reslizumab. The benefit – placebo-subtracted gains of 0.126 L in one trial and 0.09 L in the other – was sustained throughout the 52 weeks.

The reslizumab group also outperformed controls in terms of Asthma Control Questionnaire scores and Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire scores. For example, 74% and 73% of reslizumab-treated patients in the two studies experienced at least a 0.5-point improvement in the AQLQ, which is considered the minimal clinically important difference, compared with 65% and 62% of controls, Dr. Castro continued.

Study discontinuation due to adverse events occurred in 2% of patients on reslizumab, with worsening asthma the No. 1 reason. Two patients on reslizumab experienced anaphylactoid reactions, neither requiring epinephrine. Three percent of reslizumab-treated patients developed low-titer, generally transient antidrug antibodies that didn’t affect eosinophil levels, which plunged with the first dose of reslizumab and stayed low throughout.

Reslizumab is one of a cluster of novel agents in development for severe or treatment-resistant asthma. These are targeted therapies directed at specific patient phenotypes. Biomarkers such as eosinophilia provide guidance as to the specific asthmatic inflammatory pathways involved.

Recent European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guidelines stress the major unmet need for new treatments for severe asthma (Eur. Respir. J. 2014;43:343-73).

In an interview, Dr. James E. Gern, who wasn’t involved in the reslizumab studies, said the various severe asthma phenotypes account for a relatively small proportion of the total asthma population, but a tremendously disproportionate amount of health care utilization.

“These new medications that are coming out are probably going to be indicated for a relatively small number of people. But for those people, it’ll make a huge difference because of the huge burden that severe asthma has on quality of life,” said Dr. Gern, professor of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The two pivotal reslizumab studies were sponsored by Teva. Dr. Castro is on the company’s speakers’ bureau and receives research grants from more than a dozen pharmaceutical and device companies as well as from the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Simultaneously with Dr. Castro’s presentation at AAAAI, the study results were published online (Lancet Respir. Med. 2015 [doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00042-9]).

HOUSTON – Reslizumab, a next-generation molecular-based asthma therapy, achieved its primary and secondary endpoints and demonstrated favorable safety in patients with moderate to severe asthma and eosinophilia in two pivotal clinical trials.

“We believe that reslizumab is an effective therapy for controlling asthma in patients with elevated blood eosinophils who are inadequately controlled on medium to high dose inhaled corticosteroid–based regimens,” Dr. Mario Castro concluded in presenting the two phase III results at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The frequency of clinical asthma exacerbations was reduced by more than half in reslizumab-treated patients, compared with controls in the two year-long studies. In addition, the reslizumab group experienced an early improvement in lung function as expressed in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) that was sustained throughout the year-long trials, as well as improvements in other measures of asthma control, including quality of life, reported Dr. Castro, professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine and pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis.

Elevated blood and sputum levels of eosinophils define an asthma phenotype at increased risk for serious asthma exacerbations. Reslizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds circulating interleukin-5 and prevents binding to the IL-5 receptor, thereby disrupting eosinophil production and function.

Dr. Castro presented two identically designed phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-month studies totaling 953 adolescents and adults. They were randomized to intravenous reslizumab at 3 mg/kg or placebo every 4 weeks for a year.

The primary endpoint was frequency of clinical asthma exacerbations (CAEs), an independently adjudicated composite outcome which required an episode featuring an increase in corticosteroids, an asthma-related ER visit or unscheduled office visit, evidence of asthma worsening in the form of at least a 20% drop from baseline in FEV1 or a 30% reduction in peak expiratory flow rate on 2 consecutive days, and worsening clinical symptoms.

Participants averaged two CAEs during the year prior to enrollment. The placebo-treated controls maintained that event rate during the two year-long studies, while the reslizumab-treated patients experienced 50% and 59% reductions relative to controls (P < .0001).

Reslizumab also increased the time to first CAE. In the two trials, 61% and 73% of reslizumab-treated patients didn’t develop a single CAE during 52 weeks, compared with 44% and 52% of controls.

The more CAEs a patient had in the year prior to enrollment, the greater the magnitude of benefit with reslizumab. While the relative risk reduction was 54%, compared with placebo in the combined studies, it climbed to 64% in patients with four or more CAEs in the previous year.

FEV1 improved after the first dose of reslizumab. The benefit – placebo-subtracted gains of 0.126 L in one trial and 0.09 L in the other – was sustained throughout the 52 weeks.

The reslizumab group also outperformed controls in terms of Asthma Control Questionnaire scores and Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire scores. For example, 74% and 73% of reslizumab-treated patients in the two studies experienced at least a 0.5-point improvement in the AQLQ, which is considered the minimal clinically important difference, compared with 65% and 62% of controls, Dr. Castro continued.

Study discontinuation due to adverse events occurred in 2% of patients on reslizumab, with worsening asthma the No. 1 reason. Two patients on reslizumab experienced anaphylactoid reactions, neither requiring epinephrine. Three percent of reslizumab-treated patients developed low-titer, generally transient antidrug antibodies that didn’t affect eosinophil levels, which plunged with the first dose of reslizumab and stayed low throughout.

Reslizumab is one of a cluster of novel agents in development for severe or treatment-resistant asthma. These are targeted therapies directed at specific patient phenotypes. Biomarkers such as eosinophilia provide guidance as to the specific asthmatic inflammatory pathways involved.

Recent European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guidelines stress the major unmet need for new treatments for severe asthma (Eur. Respir. J. 2014;43:343-73).

In an interview, Dr. James E. Gern, who wasn’t involved in the reslizumab studies, said the various severe asthma phenotypes account for a relatively small proportion of the total asthma population, but a tremendously disproportionate amount of health care utilization.

“These new medications that are coming out are probably going to be indicated for a relatively small number of people. But for those people, it’ll make a huge difference because of the huge burden that severe asthma has on quality of life,” said Dr. Gern, professor of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The two pivotal reslizumab studies were sponsored by Teva. Dr. Castro is on the company’s speakers’ bureau and receives research grants from more than a dozen pharmaceutical and device companies as well as from the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Simultaneously with Dr. Castro’s presentation at AAAAI, the study results were published online (Lancet Respir. Med. 2015 [doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00042-9]).

HOUSTON – Reslizumab, a next-generation molecular-based asthma therapy, achieved its primary and secondary endpoints and demonstrated favorable safety in patients with moderate to severe asthma and eosinophilia in two pivotal clinical trials.

“We believe that reslizumab is an effective therapy for controlling asthma in patients with elevated blood eosinophils who are inadequately controlled on medium to high dose inhaled corticosteroid–based regimens,” Dr. Mario Castro concluded in presenting the two phase III results at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The frequency of clinical asthma exacerbations was reduced by more than half in reslizumab-treated patients, compared with controls in the two year-long studies. In addition, the reslizumab group experienced an early improvement in lung function as expressed in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) that was sustained throughout the year-long trials, as well as improvements in other measures of asthma control, including quality of life, reported Dr. Castro, professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine and pediatrics at Washington University in St. Louis.

Elevated blood and sputum levels of eosinophils define an asthma phenotype at increased risk for serious asthma exacerbations. Reslizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds circulating interleukin-5 and prevents binding to the IL-5 receptor, thereby disrupting eosinophil production and function.

Dr. Castro presented two identically designed phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-month studies totaling 953 adolescents and adults. They were randomized to intravenous reslizumab at 3 mg/kg or placebo every 4 weeks for a year.

The primary endpoint was frequency of clinical asthma exacerbations (CAEs), an independently adjudicated composite outcome which required an episode featuring an increase in corticosteroids, an asthma-related ER visit or unscheduled office visit, evidence of asthma worsening in the form of at least a 20% drop from baseline in FEV1 or a 30% reduction in peak expiratory flow rate on 2 consecutive days, and worsening clinical symptoms.

Participants averaged two CAEs during the year prior to enrollment. The placebo-treated controls maintained that event rate during the two year-long studies, while the reslizumab-treated patients experienced 50% and 59% reductions relative to controls (P < .0001).

Reslizumab also increased the time to first CAE. In the two trials, 61% and 73% of reslizumab-treated patients didn’t develop a single CAE during 52 weeks, compared with 44% and 52% of controls.

The more CAEs a patient had in the year prior to enrollment, the greater the magnitude of benefit with reslizumab. While the relative risk reduction was 54%, compared with placebo in the combined studies, it climbed to 64% in patients with four or more CAEs in the previous year.

FEV1 improved after the first dose of reslizumab. The benefit – placebo-subtracted gains of 0.126 L in one trial and 0.09 L in the other – was sustained throughout the 52 weeks.

The reslizumab group also outperformed controls in terms of Asthma Control Questionnaire scores and Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire scores. For example, 74% and 73% of reslizumab-treated patients in the two studies experienced at least a 0.5-point improvement in the AQLQ, which is considered the minimal clinically important difference, compared with 65% and 62% of controls, Dr. Castro continued.

Study discontinuation due to adverse events occurred in 2% of patients on reslizumab, with worsening asthma the No. 1 reason. Two patients on reslizumab experienced anaphylactoid reactions, neither requiring epinephrine. Three percent of reslizumab-treated patients developed low-titer, generally transient antidrug antibodies that didn’t affect eosinophil levels, which plunged with the first dose of reslizumab and stayed low throughout.

Reslizumab is one of a cluster of novel agents in development for severe or treatment-resistant asthma. These are targeted therapies directed at specific patient phenotypes. Biomarkers such as eosinophilia provide guidance as to the specific asthmatic inflammatory pathways involved.

Recent European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guidelines stress the major unmet need for new treatments for severe asthma (Eur. Respir. J. 2014;43:343-73).

In an interview, Dr. James E. Gern, who wasn’t involved in the reslizumab studies, said the various severe asthma phenotypes account for a relatively small proportion of the total asthma population, but a tremendously disproportionate amount of health care utilization.

“These new medications that are coming out are probably going to be indicated for a relatively small number of people. But for those people, it’ll make a huge difference because of the huge burden that severe asthma has on quality of life,” said Dr. Gern, professor of pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

The two pivotal reslizumab studies were sponsored by Teva. Dr. Castro is on the company’s speakers’ bureau and receives research grants from more than a dozen pharmaceutical and device companies as well as from the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Simultaneously with Dr. Castro’s presentation at AAAAI, the study results were published online (Lancet Respir. Med. 2015 [doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00042-9]).

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A monoclonal antibody against interleukin-5 significantly reduced the frequency of clinical asthma exacerbations in an important subset of asthma patients.

Major finding: Intravenous reslizumab given every 4 weeks reduced the annual rate of clinical asthma exacerbations by 50% and 59%, compared with placebo in two phase III trials.

Data source: The two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 1-year pivotal trials totaled 953 patients with moderate to severe asthma with elevated blood eosinophils inadequately controlled using inhaled corticosteroid–based regimens.

Disclosures: The studies were sponsored by Teva. The presenter is on the company’s speakers’ bureau and receives research grants from more than a dozen pharmaceutical and device companies.

Respiratory harm reversal seen in asthmatic smokers on e-cigarettes

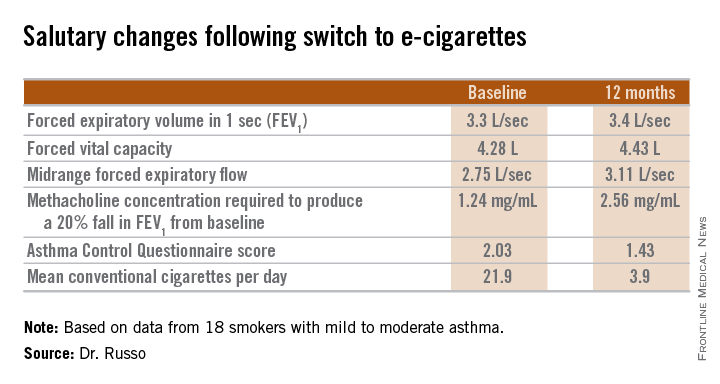

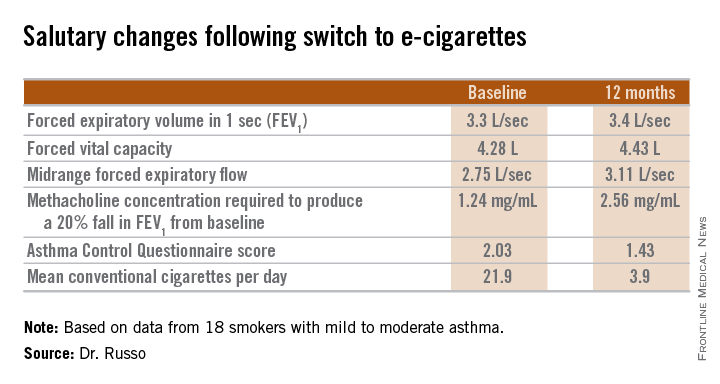

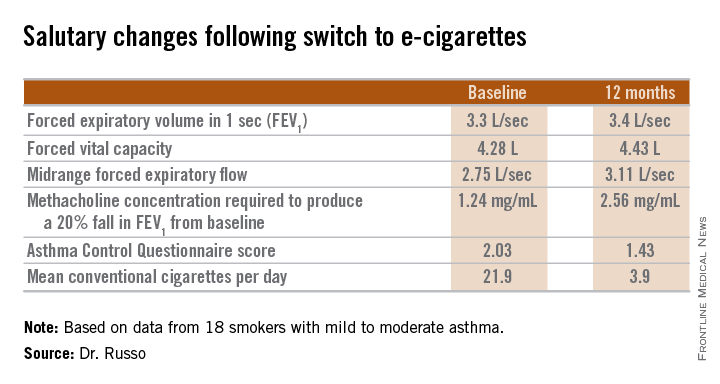

HOUSTON – Asthmatic smokers who switched to electronic cigarettes showed evidence suggestive of respiratory harm reversal in a retrospective pilot study.

“Electronic cigarette use improves respiratory physiology and subjective asthma outcomes in asthmatic smokers. E-cigarettes are a safer alternative to conventional cigarettes in this vulnerable population,” Dr. Cristina Russo declared at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

She said that her small retrospective study is the first to examine the respiratory health impact of a switch to e-cigarettes by asthmatic smokers.

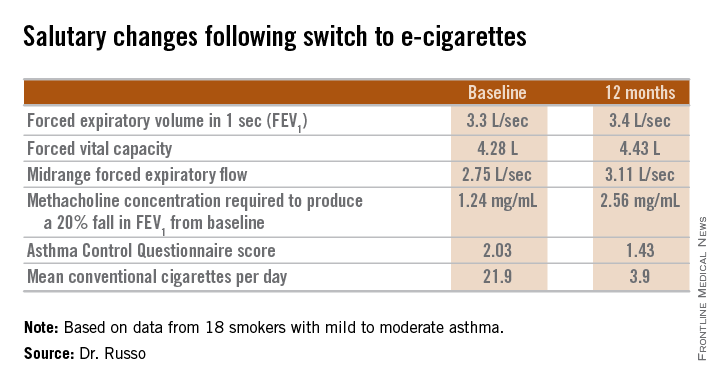

Every one of the objective and subjective measures of asthma status evaluated in the study showed statistically significant improvement 1 year after patients adopted e-cigarettes, and the e-cigarette users’ consumption of conventional cigarettes dropped precipitously, reported Dr. Russo of the University of Catania (Italy).

She and her colleagues in the university asthma clinic have taken to suggesting the use of battery-powered e-cigarettes to their asthmatic smokers who haven’t benefited from or aren’t interested in trying the more conventional approaches to smoking cessation or reduction, including medications. While abstinence from cigarette smoking is best, the available evidence indicates e-cigarettes are at least 95% less harmful than conventional cigarettes in the general population, she said.

The study included 18 smokers with mild to moderate asthma who switched to e-cigarettes and underwent spirometry and other testing at baseline and 6 and 12 months of follow-up. Ten patients switched over to e-cigarettes exclusively, while the other 8 used both conventional and e-cigarettes.

Among the highlights: The mid-range forced expiratory flow (25%-75%) showed a major, clinically important improvement, increasing from 2.75 L/sec to 3.11 L/sec. And patients’ mean self-reported conventional cigarette consumption dropped from 21.9 per day at baseline to 5 at 6 months and 3.9 per day at 12 months.

Among the group at large, no significant change was seen in the frequency of asthma exacerbations resulting in hospitalization. However, among the frequent exacerbators – the six patients with two or more exacerbations during the 6 months prior to baseline – exacerbation frequency was cut in half both 6 and 12 months following the switch to e-cigarettes.

Dr. Russo’s presentation sparked vigorous audience discussion. Several physicians cited a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warning about the unknowns regarding e-cigarette safety, and one allergist declared he didn’t think physicians should ever encourage patients to smoke anything. But others defended the “lesser of two evils” approach adopted by Dr. Russo and coworkers.

Dr. Russo noted that the prevalence of smoking among asthma patients is similar to that of the general population. She called smoking and asthma “a dangerous liaison.” Smoking accelerates asthma patients’ decline in lung function, worsens persistent airways obstruction, and increases insensitivity to corticosteroids.

Her study was supported by a university grant and the Italian League Against Smoking. She reported having no financial conflicts.

HOUSTON – Asthmatic smokers who switched to electronic cigarettes showed evidence suggestive of respiratory harm reversal in a retrospective pilot study.

“Electronic cigarette use improves respiratory physiology and subjective asthma outcomes in asthmatic smokers. E-cigarettes are a safer alternative to conventional cigarettes in this vulnerable population,” Dr. Cristina Russo declared at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

She said that her small retrospective study is the first to examine the respiratory health impact of a switch to e-cigarettes by asthmatic smokers.

Every one of the objective and subjective measures of asthma status evaluated in the study showed statistically significant improvement 1 year after patients adopted e-cigarettes, and the e-cigarette users’ consumption of conventional cigarettes dropped precipitously, reported Dr. Russo of the University of Catania (Italy).

She and her colleagues in the university asthma clinic have taken to suggesting the use of battery-powered e-cigarettes to their asthmatic smokers who haven’t benefited from or aren’t interested in trying the more conventional approaches to smoking cessation or reduction, including medications. While abstinence from cigarette smoking is best, the available evidence indicates e-cigarettes are at least 95% less harmful than conventional cigarettes in the general population, she said.

The study included 18 smokers with mild to moderate asthma who switched to e-cigarettes and underwent spirometry and other testing at baseline and 6 and 12 months of follow-up. Ten patients switched over to e-cigarettes exclusively, while the other 8 used both conventional and e-cigarettes.

Among the highlights: The mid-range forced expiratory flow (25%-75%) showed a major, clinically important improvement, increasing from 2.75 L/sec to 3.11 L/sec. And patients’ mean self-reported conventional cigarette consumption dropped from 21.9 per day at baseline to 5 at 6 months and 3.9 per day at 12 months.

Among the group at large, no significant change was seen in the frequency of asthma exacerbations resulting in hospitalization. However, among the frequent exacerbators – the six patients with two or more exacerbations during the 6 months prior to baseline – exacerbation frequency was cut in half both 6 and 12 months following the switch to e-cigarettes.

Dr. Russo’s presentation sparked vigorous audience discussion. Several physicians cited a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warning about the unknowns regarding e-cigarette safety, and one allergist declared he didn’t think physicians should ever encourage patients to smoke anything. But others defended the “lesser of two evils” approach adopted by Dr. Russo and coworkers.

Dr. Russo noted that the prevalence of smoking among asthma patients is similar to that of the general population. She called smoking and asthma “a dangerous liaison.” Smoking accelerates asthma patients’ decline in lung function, worsens persistent airways obstruction, and increases insensitivity to corticosteroids.

Her study was supported by a university grant and the Italian League Against Smoking. She reported having no financial conflicts.

HOUSTON – Asthmatic smokers who switched to electronic cigarettes showed evidence suggestive of respiratory harm reversal in a retrospective pilot study.

“Electronic cigarette use improves respiratory physiology and subjective asthma outcomes in asthmatic smokers. E-cigarettes are a safer alternative to conventional cigarettes in this vulnerable population,” Dr. Cristina Russo declared at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

She said that her small retrospective study is the first to examine the respiratory health impact of a switch to e-cigarettes by asthmatic smokers.

Every one of the objective and subjective measures of asthma status evaluated in the study showed statistically significant improvement 1 year after patients adopted e-cigarettes, and the e-cigarette users’ consumption of conventional cigarettes dropped precipitously, reported Dr. Russo of the University of Catania (Italy).

She and her colleagues in the university asthma clinic have taken to suggesting the use of battery-powered e-cigarettes to their asthmatic smokers who haven’t benefited from or aren’t interested in trying the more conventional approaches to smoking cessation or reduction, including medications. While abstinence from cigarette smoking is best, the available evidence indicates e-cigarettes are at least 95% less harmful than conventional cigarettes in the general population, she said.

The study included 18 smokers with mild to moderate asthma who switched to e-cigarettes and underwent spirometry and other testing at baseline and 6 and 12 months of follow-up. Ten patients switched over to e-cigarettes exclusively, while the other 8 used both conventional and e-cigarettes.

Among the highlights: The mid-range forced expiratory flow (25%-75%) showed a major, clinically important improvement, increasing from 2.75 L/sec to 3.11 L/sec. And patients’ mean self-reported conventional cigarette consumption dropped from 21.9 per day at baseline to 5 at 6 months and 3.9 per day at 12 months.

Among the group at large, no significant change was seen in the frequency of asthma exacerbations resulting in hospitalization. However, among the frequent exacerbators – the six patients with two or more exacerbations during the 6 months prior to baseline – exacerbation frequency was cut in half both 6 and 12 months following the switch to e-cigarettes.

Dr. Russo’s presentation sparked vigorous audience discussion. Several physicians cited a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warning about the unknowns regarding e-cigarette safety, and one allergist declared he didn’t think physicians should ever encourage patients to smoke anything. But others defended the “lesser of two evils” approach adopted by Dr. Russo and coworkers.

Dr. Russo noted that the prevalence of smoking among asthma patients is similar to that of the general population. She called smoking and asthma “a dangerous liaison.” Smoking accelerates asthma patients’ decline in lung function, worsens persistent airways obstruction, and increases insensitivity to corticosteroids.

Her study was supported by a university grant and the Italian League Against Smoking. She reported having no financial conflicts.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Asthmatic smokers who adopted physician advice to switch to electronic cigarettes showed significant 1-year improvements in lung function, methacholine-provoked airway hyperresponsiveness, and asthma-related quality of life.

Major finding: Self-reported daily consumption of conventional cigarettes by asthmatic smokers who switched to e-cigarettes fell from a mean of 21.9 per day at baseline to 5.0 at 6 months and 3.9 at 12 months of follow-up.

Data source: This retrospective pilot study included 18 asthmatic smokers who switched to e-cigarettes.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a university grant and the Italian League Against Smoking. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

What’s new with methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Can an old rheumatoid arthritis drug – like an old dog – learn new tricks?

When that drug is methotrexate, the answer is definitely yes, according to Dr. Michael E. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinically important advances and refinements continue to be made in the use of this venerable drug, a treatment mainstay for RA since the mid-1980s.

“I had the pleasure of participating in a symposium on methotrexate organized by Dr. Joel Kremer at last year’s annual ACR meeting in Boston. This is the second one we’ve done, and I must tell you, the number of people in attendance was extraordinary. We probably filled one of the largest conference rooms for the second time in 2 years. And the questions went on forever. So even though methotrexate is an old drug, there still remains great interest in it,” he observed at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

Here’s what’s new:

Subcutaneous methotrexate for RA is finally legit.

Multiple studies over the past 15 years have established that at methotrexate doses above 15-20 mg/week, subcutaneous therapy achieves superior efficacy, compared with oral therapy. For this reason, rheumatologists have long used once-weekly subcutaneous injections of methotrexate in RA patients with an inadequate clinical response to oral therapy. However, as payers have often informed them, this has been off-label usage. Not any longer. Rheumatoid arthritis is now an FDA-approved indication for subcutaneous methotrexate. Moreover, two easy-to-use, single-dose, once-weekly, autoinjector formulations are now on the market, known as Otrexup and Rasuvo.

In a randomized, crossover study of various doses of oral methotrexate versus Otrexup in 49 RA patients, the systemic bioavailability of oral methotrexate plateaued at doses of 15 mg/week or above. In contrast, the systemic exposure of subcutaneous methotrexate continued to increase linearly out to 25 mg/week, the highest dose studied. And this greater bioavailability wasn’t associated with an increase in adverse events (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014;73:1549-51).

Split-dose oral therapy improves bioavailability.

When methotrexate was first prescribed for RA in the mid-1980s, it was given in a pulsed-dose regimen: 8 a.m., 8 p.m., and again at 8 a.m. the next morning. Three doses over a 24-hour period, once weekly.

“Over time, most of us shifted to a once-a-week regimen for convenience, ease-of-administration, and because of some concerns about liver exposure. We’ve come to appreciate, however, that if you dose-escalate methotrexate, a significant percentage of patients do not absorb the drug at doses above 15-20 mg once weekly. But pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated you get higher drug concentrations with a split dose,” according to the rheumatologist.

For example, a crossover study involving 10 patients on stable doses of oral methotrexate at 25-35 mg/week showed that splitting a dose into two halves given 8 hours apart resulted in 28% greater bioavailability, compared with the standard single dose. Indeed, the bioavailability with the oral split dose was comparable to that achieved with subcutaneous administration (J. Rheumatol. 2006;33:481-5).

“Many of us are now splitting the dose of methotrexate at doses above 17.5-20 mg/week. I would like to caution, however, that this does not mean you should give the drug on Mondays and Thursdays. This was studied 40 years ago at the [National Institutes of Health]. It caused more acute toxicity, including bone marrow suppression, and more chronic toxicity, such as liver disease. So the drug should only be administered over one 24-hour period per week,” Dr. Weinblatt advised.

Methotrexate: the next statin?

Four cohort studies over the past 10 years have reported that methotrexate appears to reduce cardiovascular mortality in RA patients. Registry data are also supportive. The evidence is sufficiently strong that a definitive randomized clinical trial is now well underway. This major study, known as the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial (CIRT), is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and led by renowned cardiologist Dr. Paul Ridker, the Eugene Braunwald Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. It will enroll 7,000 subjects – none with RA – at roughly 350 U.S. and Canadian sites.

Participants are high–cardiovascular risk patients with a history of acute MI within the previous 5 years plus type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome. They are being randomized to guideline-directed medical care plus either oral methotrexate at 10-20 mg/week or placebo for 2-4 years. The primary endpoint is cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or stroke.

The proposed mechanism of benefit is methotrexate’s anti-inflammatory effect. If the results of CIRT are positive, this low-cost generic drug with a thoroughly understood safety profile could transform preventive cardiology; lowering systemic inflammation would potentially join LDL lowering via statins as a cornerstone of disease prevention.

“This is one of the most exciting areas involving methotrexate,” commented Dr. Weinblatt, a participating investigator in CIRT.

Methotrexate boosts efficacy of selected biologics.

Concomitant methotrexate is known to increase the clinical efficacy of anti–tumor necrosis factor biologics and rituximab. Studies in patients on infliximab or adalimumab have shown that background methotrexate raises serum concentrations of the biologics by 20%-25%, which is presumably the explanation for the increased efficacy. Whether methotrexate enhances or attenuates the efficacy of the oral small-molecule JAK inhibitors is now under study.

One intriguing cohort study has shown that methotrexate reduces the immunogenicity of adalimumab in dose-dependent fashion; the higher the dose of methotrexate, the less ability patients had to develop blocking antibodies against adalimumab (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012;71:1914-5).

More recently, the randomized, double-blind CONCERTO trial conducted in 395 methotrexate- and biologic-naive RA patients extended this work. Participants were randomized to open-label adalimumab plus weekly blinded methotrexate at 2.5, 5, 10, or 20 mg. Clinical outcomes at 26 weeks as reflected in 28-joint count disease activity score and other measures were significantly better in patients on 10 or 20 mg/week of methotrexate. Serum adalimumab levels were higher in patients on those doses of methotrexate than in those on 2.5 or 5 mg/week as well (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204769]).

There’s an important lesson here for patient management: “If you’re going to dose-reduce your methotrexate in patients with low disease activity or in remission, there is a threshold at which you should probably stop reducing the methotrexate, at least when your patient is on this biologic,” according to Dr. Weinblatt.

In contrast, no methotrexate dose-threshold effect occurs with etanercept, he added.

Methotrexate and the liver.

A national observational cohort study of 659 military veterans over age 65 when they started methotrexate for RA or other rheumatic diseases found a 6% incidence of moderately elevated liver enzymes during a mean follow-up period of 7 months. The investigators identified a series of independent risk factors for liver function test abnormalities. Obesity was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk, a serum total cholesterol greater than 240 mg/dL conferred a 5.8-fold elevated risk, abnormal liver function tests premethotrexate was associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk, and lack of folic acid supplementation brought a 2.2-fold increase in risk (Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1159-66).

“This study confirms what a lot of us have been worried about,” Dr. Weinblatt commented. That is, the risk of methotrexate-related liver toxicity is particularly high in older patients with characteristics consistent with the metabolic syndrome, a condition that has reached epidemic proportions.

A strong take-home message from this study, he added, is that patients should not start on methotrexate if they have abnormal liver function tests. That guidance was included in the original guidelines for methotrexate in RA published back in the mid-1990s.

“I think rheumatologists have kind of lost sight of that. You probably should find out why those tests are elevated. In many cases you’ll find it may be related to NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” he said. “I actually think obesity is one of the greatest risk factors for methotrexate toxicity.”

Dr. Weinblatt reported receiving consulting fees or other remuneration from more than two dozen pharmaceutical companies.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Can an old rheumatoid arthritis drug – like an old dog – learn new tricks?

When that drug is methotrexate, the answer is definitely yes, according to Dr. Michael E. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinically important advances and refinements continue to be made in the use of this venerable drug, a treatment mainstay for RA since the mid-1980s.

“I had the pleasure of participating in a symposium on methotrexate organized by Dr. Joel Kremer at last year’s annual ACR meeting in Boston. This is the second one we’ve done, and I must tell you, the number of people in attendance was extraordinary. We probably filled one of the largest conference rooms for the second time in 2 years. And the questions went on forever. So even though methotrexate is an old drug, there still remains great interest in it,” he observed at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

Here’s what’s new:

Subcutaneous methotrexate for RA is finally legit.

Multiple studies over the past 15 years have established that at methotrexate doses above 15-20 mg/week, subcutaneous therapy achieves superior efficacy, compared with oral therapy. For this reason, rheumatologists have long used once-weekly subcutaneous injections of methotrexate in RA patients with an inadequate clinical response to oral therapy. However, as payers have often informed them, this has been off-label usage. Not any longer. Rheumatoid arthritis is now an FDA-approved indication for subcutaneous methotrexate. Moreover, two easy-to-use, single-dose, once-weekly, autoinjector formulations are now on the market, known as Otrexup and Rasuvo.

In a randomized, crossover study of various doses of oral methotrexate versus Otrexup in 49 RA patients, the systemic bioavailability of oral methotrexate plateaued at doses of 15 mg/week or above. In contrast, the systemic exposure of subcutaneous methotrexate continued to increase linearly out to 25 mg/week, the highest dose studied. And this greater bioavailability wasn’t associated with an increase in adverse events (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014;73:1549-51).

Split-dose oral therapy improves bioavailability.

When methotrexate was first prescribed for RA in the mid-1980s, it was given in a pulsed-dose regimen: 8 a.m., 8 p.m., and again at 8 a.m. the next morning. Three doses over a 24-hour period, once weekly.

“Over time, most of us shifted to a once-a-week regimen for convenience, ease-of-administration, and because of some concerns about liver exposure. We’ve come to appreciate, however, that if you dose-escalate methotrexate, a significant percentage of patients do not absorb the drug at doses above 15-20 mg once weekly. But pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated you get higher drug concentrations with a split dose,” according to the rheumatologist.

For example, a crossover study involving 10 patients on stable doses of oral methotrexate at 25-35 mg/week showed that splitting a dose into two halves given 8 hours apart resulted in 28% greater bioavailability, compared with the standard single dose. Indeed, the bioavailability with the oral split dose was comparable to that achieved with subcutaneous administration (J. Rheumatol. 2006;33:481-5).

“Many of us are now splitting the dose of methotrexate at doses above 17.5-20 mg/week. I would like to caution, however, that this does not mean you should give the drug on Mondays and Thursdays. This was studied 40 years ago at the [National Institutes of Health]. It caused more acute toxicity, including bone marrow suppression, and more chronic toxicity, such as liver disease. So the drug should only be administered over one 24-hour period per week,” Dr. Weinblatt advised.

Methotrexate: the next statin?

Four cohort studies over the past 10 years have reported that methotrexate appears to reduce cardiovascular mortality in RA patients. Registry data are also supportive. The evidence is sufficiently strong that a definitive randomized clinical trial is now well underway. This major study, known as the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial (CIRT), is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and led by renowned cardiologist Dr. Paul Ridker, the Eugene Braunwald Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. It will enroll 7,000 subjects – none with RA – at roughly 350 U.S. and Canadian sites.

Participants are high–cardiovascular risk patients with a history of acute MI within the previous 5 years plus type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome. They are being randomized to guideline-directed medical care plus either oral methotrexate at 10-20 mg/week or placebo for 2-4 years. The primary endpoint is cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or stroke.

The proposed mechanism of benefit is methotrexate’s anti-inflammatory effect. If the results of CIRT are positive, this low-cost generic drug with a thoroughly understood safety profile could transform preventive cardiology; lowering systemic inflammation would potentially join LDL lowering via statins as a cornerstone of disease prevention.

“This is one of the most exciting areas involving methotrexate,” commented Dr. Weinblatt, a participating investigator in CIRT.

Methotrexate boosts efficacy of selected biologics.

Concomitant methotrexate is known to increase the clinical efficacy of anti–tumor necrosis factor biologics and rituximab. Studies in patients on infliximab or adalimumab have shown that background methotrexate raises serum concentrations of the biologics by 20%-25%, which is presumably the explanation for the increased efficacy. Whether methotrexate enhances or attenuates the efficacy of the oral small-molecule JAK inhibitors is now under study.

One intriguing cohort study has shown that methotrexate reduces the immunogenicity of adalimumab in dose-dependent fashion; the higher the dose of methotrexate, the less ability patients had to develop blocking antibodies against adalimumab (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012;71:1914-5).

More recently, the randomized, double-blind CONCERTO trial conducted in 395 methotrexate- and biologic-naive RA patients extended this work. Participants were randomized to open-label adalimumab plus weekly blinded methotrexate at 2.5, 5, 10, or 20 mg. Clinical outcomes at 26 weeks as reflected in 28-joint count disease activity score and other measures were significantly better in patients on 10 or 20 mg/week of methotrexate. Serum adalimumab levels were higher in patients on those doses of methotrexate than in those on 2.5 or 5 mg/week as well (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204769]).

There’s an important lesson here for patient management: “If you’re going to dose-reduce your methotrexate in patients with low disease activity or in remission, there is a threshold at which you should probably stop reducing the methotrexate, at least when your patient is on this biologic,” according to Dr. Weinblatt.

In contrast, no methotrexate dose-threshold effect occurs with etanercept, he added.

Methotrexate and the liver.

A national observational cohort study of 659 military veterans over age 65 when they started methotrexate for RA or other rheumatic diseases found a 6% incidence of moderately elevated liver enzymes during a mean follow-up period of 7 months. The investigators identified a series of independent risk factors for liver function test abnormalities. Obesity was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk, a serum total cholesterol greater than 240 mg/dL conferred a 5.8-fold elevated risk, abnormal liver function tests premethotrexate was associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk, and lack of folic acid supplementation brought a 2.2-fold increase in risk (Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1159-66).

“This study confirms what a lot of us have been worried about,” Dr. Weinblatt commented. That is, the risk of methotrexate-related liver toxicity is particularly high in older patients with characteristics consistent with the metabolic syndrome, a condition that has reached epidemic proportions.

A strong take-home message from this study, he added, is that patients should not start on methotrexate if they have abnormal liver function tests. That guidance was included in the original guidelines for methotrexate in RA published back in the mid-1990s.

“I think rheumatologists have kind of lost sight of that. You probably should find out why those tests are elevated. In many cases you’ll find it may be related to NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” he said. “I actually think obesity is one of the greatest risk factors for methotrexate toxicity.”

Dr. Weinblatt reported receiving consulting fees or other remuneration from more than two dozen pharmaceutical companies.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Can an old rheumatoid arthritis drug – like an old dog – learn new tricks?

When that drug is methotrexate, the answer is definitely yes, according to Dr. Michael E. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinically important advances and refinements continue to be made in the use of this venerable drug, a treatment mainstay for RA since the mid-1980s.

“I had the pleasure of participating in a symposium on methotrexate organized by Dr. Joel Kremer at last year’s annual ACR meeting in Boston. This is the second one we’ve done, and I must tell you, the number of people in attendance was extraordinary. We probably filled one of the largest conference rooms for the second time in 2 years. And the questions went on forever. So even though methotrexate is an old drug, there still remains great interest in it,” he observed at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

Here’s what’s new:

Subcutaneous methotrexate for RA is finally legit.

Multiple studies over the past 15 years have established that at methotrexate doses above 15-20 mg/week, subcutaneous therapy achieves superior efficacy, compared with oral therapy. For this reason, rheumatologists have long used once-weekly subcutaneous injections of methotrexate in RA patients with an inadequate clinical response to oral therapy. However, as payers have often informed them, this has been off-label usage. Not any longer. Rheumatoid arthritis is now an FDA-approved indication for subcutaneous methotrexate. Moreover, two easy-to-use, single-dose, once-weekly, autoinjector formulations are now on the market, known as Otrexup and Rasuvo.

In a randomized, crossover study of various doses of oral methotrexate versus Otrexup in 49 RA patients, the systemic bioavailability of oral methotrexate plateaued at doses of 15 mg/week or above. In contrast, the systemic exposure of subcutaneous methotrexate continued to increase linearly out to 25 mg/week, the highest dose studied. And this greater bioavailability wasn’t associated with an increase in adverse events (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014;73:1549-51).

Split-dose oral therapy improves bioavailability.

When methotrexate was first prescribed for RA in the mid-1980s, it was given in a pulsed-dose regimen: 8 a.m., 8 p.m., and again at 8 a.m. the next morning. Three doses over a 24-hour period, once weekly.

“Over time, most of us shifted to a once-a-week regimen for convenience, ease-of-administration, and because of some concerns about liver exposure. We’ve come to appreciate, however, that if you dose-escalate methotrexate, a significant percentage of patients do not absorb the drug at doses above 15-20 mg once weekly. But pharmacokinetic studies have demonstrated you get higher drug concentrations with a split dose,” according to the rheumatologist.

For example, a crossover study involving 10 patients on stable doses of oral methotrexate at 25-35 mg/week showed that splitting a dose into two halves given 8 hours apart resulted in 28% greater bioavailability, compared with the standard single dose. Indeed, the bioavailability with the oral split dose was comparable to that achieved with subcutaneous administration (J. Rheumatol. 2006;33:481-5).

“Many of us are now splitting the dose of methotrexate at doses above 17.5-20 mg/week. I would like to caution, however, that this does not mean you should give the drug on Mondays and Thursdays. This was studied 40 years ago at the [National Institutes of Health]. It caused more acute toxicity, including bone marrow suppression, and more chronic toxicity, such as liver disease. So the drug should only be administered over one 24-hour period per week,” Dr. Weinblatt advised.

Methotrexate: the next statin?

Four cohort studies over the past 10 years have reported that methotrexate appears to reduce cardiovascular mortality in RA patients. Registry data are also supportive. The evidence is sufficiently strong that a definitive randomized clinical trial is now well underway. This major study, known as the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial (CIRT), is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and led by renowned cardiologist Dr. Paul Ridker, the Eugene Braunwald Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. It will enroll 7,000 subjects – none with RA – at roughly 350 U.S. and Canadian sites.

Participants are high–cardiovascular risk patients with a history of acute MI within the previous 5 years plus type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome. They are being randomized to guideline-directed medical care plus either oral methotrexate at 10-20 mg/week or placebo for 2-4 years. The primary endpoint is cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or stroke.

The proposed mechanism of benefit is methotrexate’s anti-inflammatory effect. If the results of CIRT are positive, this low-cost generic drug with a thoroughly understood safety profile could transform preventive cardiology; lowering systemic inflammation would potentially join LDL lowering via statins as a cornerstone of disease prevention.

“This is one of the most exciting areas involving methotrexate,” commented Dr. Weinblatt, a participating investigator in CIRT.

Methotrexate boosts efficacy of selected biologics.

Concomitant methotrexate is known to increase the clinical efficacy of anti–tumor necrosis factor biologics and rituximab. Studies in patients on infliximab or adalimumab have shown that background methotrexate raises serum concentrations of the biologics by 20%-25%, which is presumably the explanation for the increased efficacy. Whether methotrexate enhances or attenuates the efficacy of the oral small-molecule JAK inhibitors is now under study.

One intriguing cohort study has shown that methotrexate reduces the immunogenicity of adalimumab in dose-dependent fashion; the higher the dose of methotrexate, the less ability patients had to develop blocking antibodies against adalimumab (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012;71:1914-5).

More recently, the randomized, double-blind CONCERTO trial conducted in 395 methotrexate- and biologic-naive RA patients extended this work. Participants were randomized to open-label adalimumab plus weekly blinded methotrexate at 2.5, 5, 10, or 20 mg. Clinical outcomes at 26 weeks as reflected in 28-joint count disease activity score and other measures were significantly better in patients on 10 or 20 mg/week of methotrexate. Serum adalimumab levels were higher in patients on those doses of methotrexate than in those on 2.5 or 5 mg/week as well (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204769]).

There’s an important lesson here for patient management: “If you’re going to dose-reduce your methotrexate in patients with low disease activity or in remission, there is a threshold at which you should probably stop reducing the methotrexate, at least when your patient is on this biologic,” according to Dr. Weinblatt.

In contrast, no methotrexate dose-threshold effect occurs with etanercept, he added.

Methotrexate and the liver.

A national observational cohort study of 659 military veterans over age 65 when they started methotrexate for RA or other rheumatic diseases found a 6% incidence of moderately elevated liver enzymes during a mean follow-up period of 7 months. The investigators identified a series of independent risk factors for liver function test abnormalities. Obesity was associated with a 1.9-fold increased risk, a serum total cholesterol greater than 240 mg/dL conferred a 5.8-fold elevated risk, abnormal liver function tests premethotrexate was associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk, and lack of folic acid supplementation brought a 2.2-fold increase in risk (Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1159-66).

“This study confirms what a lot of us have been worried about,” Dr. Weinblatt commented. That is, the risk of methotrexate-related liver toxicity is particularly high in older patients with characteristics consistent with the metabolic syndrome, a condition that has reached epidemic proportions.

A strong take-home message from this study, he added, is that patients should not start on methotrexate if they have abnormal liver function tests. That guidance was included in the original guidelines for methotrexate in RA published back in the mid-1990s.

“I think rheumatologists have kind of lost sight of that. You probably should find out why those tests are elevated. In many cases you’ll find it may be related to NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis],” he said. “I actually think obesity is one of the greatest risk factors for methotrexate toxicity.”

Dr. Weinblatt reported receiving consulting fees or other remuneration from more than two dozen pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WINTER RHEUMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Rituximab for RA: Think like a European

SNOWMASS, COLO. – When it comes to prescribing rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, maybe it’s time to think like a European.

In response to a persuasive French study, rheumatologists across Europe have embraced a lower-dose rituximab regimen: Patients who achieve a moderate or good EULAR response to the standard initial induction dosing of two 1,000-mg doses given intravenously 2 weeks apart receive thereafter a single 1,000-mg dose every 6 months rather than the licensed maintenance dosing of two 1,000-mg IV injections every 6 months.

“They showed that one dose every 6 months is as good as two doses every 6 months. This is a strategy that our European colleagues have actively adopted. It’s a cost-effective strategy, and I think it’s actually an appropriate strategy to use and one we’re using routinely now in our rheumatoid patients after we’ve induced a response with the initial induction dosing,” Dr. Michael E. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

The French study was an open-label, prospective, multicenter, noninferiority study involving 225 rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents and a 6-month moderate or good EULAR response to rituximab (Rituxan) induction therapy coupled with methotrexate. They were randomized to rituximab retreatment at 6-month intervals at either a single 1,000-mg dose or the two 1,000-mg doses as described in the product labeling. At 104 weeks, disease activity as measured by the mean disease activity in 28 joints plus C-reactive protein level area under the curve was similar in the two treatment arms. So was the safety profile (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014;73:1508-14).

Dr. Weinblatt also provided an update on rituximab and infections. Two studies presented at last fall’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology in Boston shed new light on this perennially hot topic.

In one, Dr. Kenneth G. Saag of the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and coinvestigators provided an update from the ongoing prospective, observational SUNSTONE cohort study, whose goal is to evaluate in a real-world setting the safety of rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients refractory to anti-TNF therapies. At a mean 4-year duration of follow-up in 938 patients who received a mean of four courses of rituximab, 17% of patients had experienced significant infections as defined either by the Food and Drug Administration serious adverse event criteria or need for intravenous antibiotics. The key finding from this intermediate analysis: The serious infection incidence rate did not increase with time and multiple courses of rituximab.

That’s reassuring, Dr. Weinblatt observed, and so is the finding that, in the 338 SUNSTONE participants who switched from rituximab to another biologic agent, there wasn’t any associated increased risk of serious infection.

All of the biologics carry an increased risk of infection. The one rituximab-associated infection that gives rheumatologists particular pause – and that has blunted the use of the anti-B-cell agent in the United States – is progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Indeed, rituximab is the only biologic agent or small molecule prescribed by rheumatologists that carries a warning label about PML, and the only one whose use is restricted to patients who’ve failed a first biologic.

“That means you have to – and should – discuss this with your patients,” Dr. Weinblatt noted.

At last November’s annual ACR meeting, Dr. Leonard H. Calabrese of the Cleveland Clinic and Dr. Eamonn Molloy of St. Vincent University Hospital, Dublin, provided an analysis of data released in response to their Freedom of Information Act request that the FDA provide information on all cases of PML recorded in the agency’s Adverse Event Reporting System through August 2012. In Dr. Weinblatt’s view, these data are reassuring.

“The rates are actually quite low. It’s a rare event. It’s clearly associated with rituximab, though,” he said.

Indeed, 30 confirmed cases of PML have been associated with biologic therapies for autoimmune rheumatic diseases, including 11 in patients with RA, 11 with systemic lupus erythematosus, and 5 with dermato/polymyositis. The median age was 53 years, and 25 of the 30 patients were women. Twenty-six cases occurred in patients who had most recently been on rituximab, the other four in patients who were on anti-TNF therapies at the time. Abatacept, belimumab, tocilizumab, and anakinra were not linked to PML.

PML developed after a median of two courses of rituximab. The median time interval was 15 months from the first rituximab infusion and 5 months from the last, but many confounders were present, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about causality. For example, four patients with PML had been on concomitant rituximab and cyclophosphamide, and another five had received cyclophosphamide prior to going on rituximab. Eighteen of 26 rituximab-treated patients were on one or more additional immunosuppressive agents at the time they were diagnosed with PML. Two patients had previously received cancer chemotherapy. Another five had significant lymphopenia.

Dr. Weinblatt reported receiving consulting fees or other remuneration from more than two dozen pharmaceutical companies, including Genentech, which markets rituximab.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – When it comes to prescribing rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, maybe it’s time to think like a European.

In response to a persuasive French study, rheumatologists across Europe have embraced a lower-dose rituximab regimen: Patients who achieve a moderate or good EULAR response to the standard initial induction dosing of two 1,000-mg doses given intravenously 2 weeks apart receive thereafter a single 1,000-mg dose every 6 months rather than the licensed maintenance dosing of two 1,000-mg IV injections every 6 months.

“They showed that one dose every 6 months is as good as two doses every 6 months. This is a strategy that our European colleagues have actively adopted. It’s a cost-effective strategy, and I think it’s actually an appropriate strategy to use and one we’re using routinely now in our rheumatoid patients after we’ve induced a response with the initial induction dosing,” Dr. Michael E. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

The French study was an open-label, prospective, multicenter, noninferiority study involving 225 rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents and a 6-month moderate or good EULAR response to rituximab (Rituxan) induction therapy coupled with methotrexate. They were randomized to rituximab retreatment at 6-month intervals at either a single 1,000-mg dose or the two 1,000-mg doses as described in the product labeling. At 104 weeks, disease activity as measured by the mean disease activity in 28 joints plus C-reactive protein level area under the curve was similar in the two treatment arms. So was the safety profile (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014;73:1508-14).

Dr. Weinblatt also provided an update on rituximab and infections. Two studies presented at last fall’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology in Boston shed new light on this perennially hot topic.

In one, Dr. Kenneth G. Saag of the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and coinvestigators provided an update from the ongoing prospective, observational SUNSTONE cohort study, whose goal is to evaluate in a real-world setting the safety of rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients refractory to anti-TNF therapies. At a mean 4-year duration of follow-up in 938 patients who received a mean of four courses of rituximab, 17% of patients had experienced significant infections as defined either by the Food and Drug Administration serious adverse event criteria or need for intravenous antibiotics. The key finding from this intermediate analysis: The serious infection incidence rate did not increase with time and multiple courses of rituximab.

That’s reassuring, Dr. Weinblatt observed, and so is the finding that, in the 338 SUNSTONE participants who switched from rituximab to another biologic agent, there wasn’t any associated increased risk of serious infection.

All of the biologics carry an increased risk of infection. The one rituximab-associated infection that gives rheumatologists particular pause – and that has blunted the use of the anti-B-cell agent in the United States – is progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Indeed, rituximab is the only biologic agent or small molecule prescribed by rheumatologists that carries a warning label about PML, and the only one whose use is restricted to patients who’ve failed a first biologic.

“That means you have to – and should – discuss this with your patients,” Dr. Weinblatt noted.

At last November’s annual ACR meeting, Dr. Leonard H. Calabrese of the Cleveland Clinic and Dr. Eamonn Molloy of St. Vincent University Hospital, Dublin, provided an analysis of data released in response to their Freedom of Information Act request that the FDA provide information on all cases of PML recorded in the agency’s Adverse Event Reporting System through August 2012. In Dr. Weinblatt’s view, these data are reassuring.

“The rates are actually quite low. It’s a rare event. It’s clearly associated with rituximab, though,” he said.

Indeed, 30 confirmed cases of PML have been associated with biologic therapies for autoimmune rheumatic diseases, including 11 in patients with RA, 11 with systemic lupus erythematosus, and 5 with dermato/polymyositis. The median age was 53 years, and 25 of the 30 patients were women. Twenty-six cases occurred in patients who had most recently been on rituximab, the other four in patients who were on anti-TNF therapies at the time. Abatacept, belimumab, tocilizumab, and anakinra were not linked to PML.

PML developed after a median of two courses of rituximab. The median time interval was 15 months from the first rituximab infusion and 5 months from the last, but many confounders were present, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about causality. For example, four patients with PML had been on concomitant rituximab and cyclophosphamide, and another five had received cyclophosphamide prior to going on rituximab. Eighteen of 26 rituximab-treated patients were on one or more additional immunosuppressive agents at the time they were diagnosed with PML. Two patients had previously received cancer chemotherapy. Another five had significant lymphopenia.

Dr. Weinblatt reported receiving consulting fees or other remuneration from more than two dozen pharmaceutical companies, including Genentech, which markets rituximab.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – When it comes to prescribing rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, maybe it’s time to think like a European.

In response to a persuasive French study, rheumatologists across Europe have embraced a lower-dose rituximab regimen: Patients who achieve a moderate or good EULAR response to the standard initial induction dosing of two 1,000-mg doses given intravenously 2 weeks apart receive thereafter a single 1,000-mg dose every 6 months rather than the licensed maintenance dosing of two 1,000-mg IV injections every 6 months.

“They showed that one dose every 6 months is as good as two doses every 6 months. This is a strategy that our European colleagues have actively adopted. It’s a cost-effective strategy, and I think it’s actually an appropriate strategy to use and one we’re using routinely now in our rheumatoid patients after we’ve induced a response with the initial induction dosing,” Dr. Michael E. Weinblatt, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

The French study was an open-label, prospective, multicenter, noninferiority study involving 225 rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents and a 6-month moderate or good EULAR response to rituximab (Rituxan) induction therapy coupled with methotrexate. They were randomized to rituximab retreatment at 6-month intervals at either a single 1,000-mg dose or the two 1,000-mg doses as described in the product labeling. At 104 weeks, disease activity as measured by the mean disease activity in 28 joints plus C-reactive protein level area under the curve was similar in the two treatment arms. So was the safety profile (Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014;73:1508-14).

Dr. Weinblatt also provided an update on rituximab and infections. Two studies presented at last fall’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology in Boston shed new light on this perennially hot topic.