User login

Atrial Fib: Surgical Beats Catheter Ablation

ORLANDO -- Minimally invasive surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation that is refractory to antiarrhythmic agents was significantly more effective than catheter ablation in the first-ever randomized trial comparing the two therapies.

The higher rate of freedom from left atrial arrhythmia that was achieved surgically came at a cost of more procedural complications, most of which were managed conservatively and without prolongation of hospitalization.

The clinical trial was conducted at two European medical centers. It involved 124 patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) who were deemed to be at high risk of having an unsuccessful catheter ablation procedure.

Two-thirds of participants were judged high risk because they had experienced a return of their AF after a prior catheter ablation, whereas the remaining patients were considered at high risk for an unsuccessful catheter ablation because of left atrial enlargement and hypertension, Dr. Lucas V.A. Boersma explained when presenting the results of the FAST (Ablation or Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation Treatment) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association.

Patients were randomized to pulmonary vein isolation by catheter ablation or to a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical ablation procedure pioneered at the University of Cincinnati (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130:797-802). Surgical ablation was performed under general anesthesia, but unlike catheter ablation it did not include fluoroscopy, noted Dr. Boersma, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

The primary efficacy end point was freedom from left atrial arrhythmia lasting longer than 30 seconds without antiarrhythmic drugs at 12 months post procedure; this was achieved in 66% of the surgical ablation group, compared with 37% of the catheter ablation group.

Adverse events occurred during the 12 months of follow-up in 34% of the surgical group, compared with 16% of the catheter ablation group. Most of the adverse events in the surgical group were procedural complications, mainly consisting of pneumothorax and bleeding.

Discussant Dr. A. Marc Gillinov, a cardiac surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, praised FAST as a well-designed, clearly focused study with important clinical implications, given that roughly one-fourth of Americans will eventually develop AF.

"The clear inference from this trial is that if catheter ablation fails and a patient comes to me, I will say to that patient, ‘We have many options, but we now have data to suggest we should discuss surgical ablation as one of those options because if you’ve had a catheter ablation and it failed, surgical ablation has a good chance of restoring you to sinus rhythm," he said.

"Most of the excess morbidity was related to chest drainage: retained fluid or air. I think it’s reasonable to state that those complications are not major and are probably preventable," he added.

The FAST trial was funded by St. Antonius Hospital and the University of Barcelona. Dr. Boersma disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Medtronic, and Dr. Gillinov serves as a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and AtriCure. ☐

ORLANDO -- Minimally invasive surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation that is refractory to antiarrhythmic agents was significantly more effective than catheter ablation in the first-ever randomized trial comparing the two therapies.

The higher rate of freedom from left atrial arrhythmia that was achieved surgically came at a cost of more procedural complications, most of which were managed conservatively and without prolongation of hospitalization.

The clinical trial was conducted at two European medical centers. It involved 124 patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) who were deemed to be at high risk of having an unsuccessful catheter ablation procedure.

Two-thirds of participants were judged high risk because they had experienced a return of their AF after a prior catheter ablation, whereas the remaining patients were considered at high risk for an unsuccessful catheter ablation because of left atrial enlargement and hypertension, Dr. Lucas V.A. Boersma explained when presenting the results of the FAST (Ablation or Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation Treatment) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association.

Patients were randomized to pulmonary vein isolation by catheter ablation or to a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical ablation procedure pioneered at the University of Cincinnati (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130:797-802). Surgical ablation was performed under general anesthesia, but unlike catheter ablation it did not include fluoroscopy, noted Dr. Boersma, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

The primary efficacy end point was freedom from left atrial arrhythmia lasting longer than 30 seconds without antiarrhythmic drugs at 12 months post procedure; this was achieved in 66% of the surgical ablation group, compared with 37% of the catheter ablation group.

Adverse events occurred during the 12 months of follow-up in 34% of the surgical group, compared with 16% of the catheter ablation group. Most of the adverse events in the surgical group were procedural complications, mainly consisting of pneumothorax and bleeding.

Discussant Dr. A. Marc Gillinov, a cardiac surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, praised FAST as a well-designed, clearly focused study with important clinical implications, given that roughly one-fourth of Americans will eventually develop AF.

"The clear inference from this trial is that if catheter ablation fails and a patient comes to me, I will say to that patient, ‘We have many options, but we now have data to suggest we should discuss surgical ablation as one of those options because if you’ve had a catheter ablation and it failed, surgical ablation has a good chance of restoring you to sinus rhythm," he said.

"Most of the excess morbidity was related to chest drainage: retained fluid or air. I think it’s reasonable to state that those complications are not major and are probably preventable," he added.

The FAST trial was funded by St. Antonius Hospital and the University of Barcelona. Dr. Boersma disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Medtronic, and Dr. Gillinov serves as a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and AtriCure. ☐

ORLANDO -- Minimally invasive surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation that is refractory to antiarrhythmic agents was significantly more effective than catheter ablation in the first-ever randomized trial comparing the two therapies.

The higher rate of freedom from left atrial arrhythmia that was achieved surgically came at a cost of more procedural complications, most of which were managed conservatively and without prolongation of hospitalization.

The clinical trial was conducted at two European medical centers. It involved 124 patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) who were deemed to be at high risk of having an unsuccessful catheter ablation procedure.

Two-thirds of participants were judged high risk because they had experienced a return of their AF after a prior catheter ablation, whereas the remaining patients were considered at high risk for an unsuccessful catheter ablation because of left atrial enlargement and hypertension, Dr. Lucas V.A. Boersma explained when presenting the results of the FAST (Ablation or Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation Treatment) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association.

Patients were randomized to pulmonary vein isolation by catheter ablation or to a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical ablation procedure pioneered at the University of Cincinnati (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130:797-802). Surgical ablation was performed under general anesthesia, but unlike catheter ablation it did not include fluoroscopy, noted Dr. Boersma, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

The primary efficacy end point was freedom from left atrial arrhythmia lasting longer than 30 seconds without antiarrhythmic drugs at 12 months post procedure; this was achieved in 66% of the surgical ablation group, compared with 37% of the catheter ablation group.

Adverse events occurred during the 12 months of follow-up in 34% of the surgical group, compared with 16% of the catheter ablation group. Most of the adverse events in the surgical group were procedural complications, mainly consisting of pneumothorax and bleeding.

Discussant Dr. A. Marc Gillinov, a cardiac surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, praised FAST as a well-designed, clearly focused study with important clinical implications, given that roughly one-fourth of Americans will eventually develop AF.

"The clear inference from this trial is that if catheter ablation fails and a patient comes to me, I will say to that patient, ‘We have many options, but we now have data to suggest we should discuss surgical ablation as one of those options because if you’ve had a catheter ablation and it failed, surgical ablation has a good chance of restoring you to sinus rhythm," he said.

"Most of the excess morbidity was related to chest drainage: retained fluid or air. I think it’s reasonable to state that those complications are not major and are probably preventable," he added.

The FAST trial was funded by St. Antonius Hospital and the University of Barcelona. Dr. Boersma disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Medtronic, and Dr. Gillinov serves as a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and AtriCure. ☐

Major Finding: A total of 66% of patients who were treated with minimally invasive surgical ablation achieved freedom from left atrial arrhythmia lasting longer than 30 seconds without antiarrhythmic drugs, compared with 37% treated with catheter ablation.

Data Source: A two-center randomized trial in 124 patients with "difficult" paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by St. Antonius Hospital and the University of Barcelona Thorax Institute. Dr. Boersma disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Medtronic, and Dr. Gillinov is a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences and AtriCure.

Atrial Fib: Surgical Beats Catheter Ablation

ORLANDO -- Minimally invasive surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation that is refractory to antiarrhythmic agents was significantly more effective than catheter ablation in the first-ever randomized trial comparing the two therapies.

The higher rate of freedom from left atrial arrhythmia that was achieved surgically came at a cost of more procedural complications, most of which were managed conservatively and without prolongation of hospitalization.

The clinical trial was conducted at two European medical centers. It involved 124 patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) who were deemed to be at high risk of having an unsuccessful catheter ablation procedure.

Two-thirds of participants were judged high risk because they had experienced a return of their AF after a prior catheter ablation, whereas the remaining patients were considered at high risk for an unsuccessful catheter ablation because of left atrial enlargement and hypertension, Dr. Lucas V.A. Boersma explained when presenting the results of the FAST (Ablation or Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation Treatment) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association.

Patients were randomized to pulmonary vein isolation by catheter ablation or to a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical ablation procedure pioneered at the University of Cincinnati (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130:797-802). Surgical ablation was performed under general anesthesia, but unlike catheter ablation it did not include fluoroscopy, noted Dr. Boersma, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

The primary efficacy end point was freedom from left atrial arrhythmia lasting longer than 30 seconds without antiarrhythmic drugs at 12 months post procedure; this was achieved in 66% of the surgical ablation group, compared with 37% of the catheter ablation group.

Adverse events occurred during the 12 months of follow-up in 34% of the surgical group, compared with 16% of the catheter ablation group. Most of the adverse events in the surgical group were procedural complications, mainly consisting of pneumothorax and bleeding.

Discussant Dr. A. Marc Gillinov, a cardiac surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, praised FAST as a well-designed, clearly focused study with important clinical implications, given that roughly one-fourth of Americans will eventually develop AF.

"The clear inference from this trial is that if catheter ablation fails and a patient comes to me, I will say to that patient, ‘We have many options, but we now have data to suggest we should discuss surgical ablation as one of those options because if you’ve had a catheter ablation and it failed, surgical ablation has a good chance of restoring you to sinus rhythm," he said.

"Most of the excess morbidity was related to chest drainage: retained fluid or air. I think it’s reasonable to state that those complications are not major and are probably preventable," he added.

The FAST trial was funded by St. Antonius Hospital and the University of Barcelona. Dr. Boersma disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Medtronic, and Dr. Gillinov serves as a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and AtriCure. ☐

ORLANDO -- Minimally invasive surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation that is refractory to antiarrhythmic agents was significantly more effective than catheter ablation in the first-ever randomized trial comparing the two therapies.

The higher rate of freedom from left atrial arrhythmia that was achieved surgically came at a cost of more procedural complications, most of which were managed conservatively and without prolongation of hospitalization.

The clinical trial was conducted at two European medical centers. It involved 124 patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) who were deemed to be at high risk of having an unsuccessful catheter ablation procedure.

Two-thirds of participants were judged high risk because they had experienced a return of their AF after a prior catheter ablation, whereas the remaining patients were considered at high risk for an unsuccessful catheter ablation because of left atrial enlargement and hypertension, Dr. Lucas V.A. Boersma explained when presenting the results of the FAST (Ablation or Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation Treatment) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association.

Patients were randomized to pulmonary vein isolation by catheter ablation or to a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical ablation procedure pioneered at the University of Cincinnati (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130:797-802). Surgical ablation was performed under general anesthesia, but unlike catheter ablation it did not include fluoroscopy, noted Dr. Boersma, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

The primary efficacy end point was freedom from left atrial arrhythmia lasting longer than 30 seconds without antiarrhythmic drugs at 12 months post procedure; this was achieved in 66% of the surgical ablation group, compared with 37% of the catheter ablation group.

Adverse events occurred during the 12 months of follow-up in 34% of the surgical group, compared with 16% of the catheter ablation group. Most of the adverse events in the surgical group were procedural complications, mainly consisting of pneumothorax and bleeding.

Discussant Dr. A. Marc Gillinov, a cardiac surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, praised FAST as a well-designed, clearly focused study with important clinical implications, given that roughly one-fourth of Americans will eventually develop AF.

"The clear inference from this trial is that if catheter ablation fails and a patient comes to me, I will say to that patient, ‘We have many options, but we now have data to suggest we should discuss surgical ablation as one of those options because if you’ve had a catheter ablation and it failed, surgical ablation has a good chance of restoring you to sinus rhythm," he said.

"Most of the excess morbidity was related to chest drainage: retained fluid or air. I think it’s reasonable to state that those complications are not major and are probably preventable," he added.

The FAST trial was funded by St. Antonius Hospital and the University of Barcelona. Dr. Boersma disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Medtronic, and Dr. Gillinov serves as a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and AtriCure. ☐

ORLANDO -- Minimally invasive surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation that is refractory to antiarrhythmic agents was significantly more effective than catheter ablation in the first-ever randomized trial comparing the two therapies.

The higher rate of freedom from left atrial arrhythmia that was achieved surgically came at a cost of more procedural complications, most of which were managed conservatively and without prolongation of hospitalization.

The clinical trial was conducted at two European medical centers. It involved 124 patients with drug-refractory paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation (AF) who were deemed to be at high risk of having an unsuccessful catheter ablation procedure.

Two-thirds of participants were judged high risk because they had experienced a return of their AF after a prior catheter ablation, whereas the remaining patients were considered at high risk for an unsuccessful catheter ablation because of left atrial enlargement and hypertension, Dr. Lucas V.A. Boersma explained when presenting the results of the FAST (Ablation or Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation Treatment) trial at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association.

Patients were randomized to pulmonary vein isolation by catheter ablation or to a video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical ablation procedure pioneered at the University of Cincinnati (J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005;130:797-802). Surgical ablation was performed under general anesthesia, but unlike catheter ablation it did not include fluoroscopy, noted Dr. Boersma, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

The primary efficacy end point was freedom from left atrial arrhythmia lasting longer than 30 seconds without antiarrhythmic drugs at 12 months post procedure; this was achieved in 66% of the surgical ablation group, compared with 37% of the catheter ablation group.

Adverse events occurred during the 12 months of follow-up in 34% of the surgical group, compared with 16% of the catheter ablation group. Most of the adverse events in the surgical group were procedural complications, mainly consisting of pneumothorax and bleeding.

Discussant Dr. A. Marc Gillinov, a cardiac surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, praised FAST as a well-designed, clearly focused study with important clinical implications, given that roughly one-fourth of Americans will eventually develop AF.

"The clear inference from this trial is that if catheter ablation fails and a patient comes to me, I will say to that patient, ‘We have many options, but we now have data to suggest we should discuss surgical ablation as one of those options because if you’ve had a catheter ablation and it failed, surgical ablation has a good chance of restoring you to sinus rhythm," he said.

"Most of the excess morbidity was related to chest drainage: retained fluid or air. I think it’s reasonable to state that those complications are not major and are probably preventable," he added.

The FAST trial was funded by St. Antonius Hospital and the University of Barcelona. Dr. Boersma disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Medtronic, and Dr. Gillinov serves as a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and AtriCure. ☐

Major Finding: A total of 66% of patients who were treated with minimally invasive surgical ablation achieved freedom from left atrial arrhythmia lasting longer than 30 seconds without antiarrhythmic drugs, compared with 37% treated with catheter ablation.

Data Source: A two-center randomized trial in 124 patients with "difficult" paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by St. Antonius Hospital and the University of Barcelona Thorax Institute. Dr. Boersma disclosed that he has served as a consultant to Medtronic, and Dr. Gillinov is a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences and AtriCure.

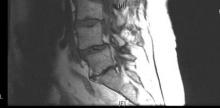

Surgery Brings Big Benefits in Lumbar Stenosis

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The unremitting natural history typical of the syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis makes surgery a particularly attractive therapeutic option for many patients with this common form of low back pain.

"Lumbar spinal stenosis patients, because of their age and comorbidities, face the highest risk from surgery, but they also have by far the most to gain because the natural history is so poor. So I spend a lot of time trying to get patients with low back pain due to a herniated disc to be patient, to use epidurals, to try a variety of different things to keep them out of the operating room. And I spend a lot of time helping the lumbar spinal stenosis patients overcome some of their fears and actually go ahead and elect surgery if they’re good candidates," Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz said at the symposium.

That being said, he added, there’s no rush. Rapid neurologic deterioration is rare in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS). Surgery usually can be deferred safely. About 20% of patients will experience symptomatic improvement over the course of a year, while a similar percentage will have symptomatic deterioration. The decision to undergo surgery should be based upon symptoms rather than on subtle neurologic deficits, which are highly unlikely to progress.

"Once people have well-established stenosis, things tend to sort of stay as they are," commented Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery Harvard Medical School, Boston, and professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Surgery for LSS competes against a poor natural history, as compared with that of lumbago, in which 90% of episodes are resolved with conservative therapy within 3 months, or sciatica caused by a herniated disc, in which 90% of affected patients are improved with nonsurgical management by 6 months and 50% are asymptomatic at 1 year.

Findings from the multicenter SPORT (Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial) study, the largest known randomized study of surgical vs. nonsurgical therapy for LSS, demonstrated an early and sustained outcome advantage favoring surgery through 2 years of follow-up (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:794-810).

Unfortunately, the randomized portion of SPORT was rendered uninterpretable because of the extremely high treatment crossover rates in both the surgical and nonsurgical groups. Nevertheless, the as-treated analysis of 654 patients in the combined randomized and observational cohorts showed that the surgery group had a mean 19.8-point improvement in Short Form-36 bodily pain scores at 6 weeks and a 26.9-point gain at 2 years over a baseline of 31.4, which are effect sizes roughly twice those seen with conservative therapy, Dr. Katz noted.

Predictors of worsened functional status following surgery for LSS include worse preoperative self-rated overall health, back pain in excess of leg pain, less-severe radiographic stenosis, and a greater number of comorbid conditions.

The 1-year rate of reoperation for recurrent stenosis in SPORT was just 1.3%, compared with reoperation rates of around 10% in studies of discectomy for low back pain from a herniated disc. That high reoperation rate is the major shortcoming of discectomy, and it’s particularly problematic in view of the fact that reoperation has an even higher failure rate than first-time surgery.

Nevertheless, more than 400,000 discectomies are performed per year in the United States, a rate 1.5- to 5-fold higher than in other developed countries.

"I think the increased surgery rate in the U.S. has more to do with patient preferences than surgeon aggressiveness," he noted.

Patients who want to pursue nonsurgical therapy for LSS need to understand that it’s largely anecdotal in nature rather than evidence based. The most common elements include education regarding good posture, abdominal strengthening exercises, analgesics ranging from NSAIDs to narcotics, and epidural corticosteroid injections, which tend to provide more improvement in leg than back pain.

"A lumbar corset can be very helpful, because many of these people have an accompanying spondylolisthesis and symptomatic instability," Dr. Katz observed.

Aerobic exercise is highly beneficial as well.

"These people are much more comfortable in flexion than extension. It’s problematic for these patients to walk a lot, but they can very often bicycle ad lib. That’s a very useful thing to offer to patients," he said.

Dr. Katz wasn’t involved in the SPORT trial, which was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He reported having no financial conflicts with regard to his presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The unremitting natural history typical of the syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis makes surgery a particularly attractive therapeutic option for many patients with this common form of low back pain.

"Lumbar spinal stenosis patients, because of their age and comorbidities, face the highest risk from surgery, but they also have by far the most to gain because the natural history is so poor. So I spend a lot of time trying to get patients with low back pain due to a herniated disc to be patient, to use epidurals, to try a variety of different things to keep them out of the operating room. And I spend a lot of time helping the lumbar spinal stenosis patients overcome some of their fears and actually go ahead and elect surgery if they’re good candidates," Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz said at the symposium.

That being said, he added, there’s no rush. Rapid neurologic deterioration is rare in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS). Surgery usually can be deferred safely. About 20% of patients will experience symptomatic improvement over the course of a year, while a similar percentage will have symptomatic deterioration. The decision to undergo surgery should be based upon symptoms rather than on subtle neurologic deficits, which are highly unlikely to progress.

"Once people have well-established stenosis, things tend to sort of stay as they are," commented Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery Harvard Medical School, Boston, and professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Surgery for LSS competes against a poor natural history, as compared with that of lumbago, in which 90% of episodes are resolved with conservative therapy within 3 months, or sciatica caused by a herniated disc, in which 90% of affected patients are improved with nonsurgical management by 6 months and 50% are asymptomatic at 1 year.

Findings from the multicenter SPORT (Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial) study, the largest known randomized study of surgical vs. nonsurgical therapy for LSS, demonstrated an early and sustained outcome advantage favoring surgery through 2 years of follow-up (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:794-810).

Unfortunately, the randomized portion of SPORT was rendered uninterpretable because of the extremely high treatment crossover rates in both the surgical and nonsurgical groups. Nevertheless, the as-treated analysis of 654 patients in the combined randomized and observational cohorts showed that the surgery group had a mean 19.8-point improvement in Short Form-36 bodily pain scores at 6 weeks and a 26.9-point gain at 2 years over a baseline of 31.4, which are effect sizes roughly twice those seen with conservative therapy, Dr. Katz noted.

Predictors of worsened functional status following surgery for LSS include worse preoperative self-rated overall health, back pain in excess of leg pain, less-severe radiographic stenosis, and a greater number of comorbid conditions.

The 1-year rate of reoperation for recurrent stenosis in SPORT was just 1.3%, compared with reoperation rates of around 10% in studies of discectomy for low back pain from a herniated disc. That high reoperation rate is the major shortcoming of discectomy, and it’s particularly problematic in view of the fact that reoperation has an even higher failure rate than first-time surgery.

Nevertheless, more than 400,000 discectomies are performed per year in the United States, a rate 1.5- to 5-fold higher than in other developed countries.

"I think the increased surgery rate in the U.S. has more to do with patient preferences than surgeon aggressiveness," he noted.

Patients who want to pursue nonsurgical therapy for LSS need to understand that it’s largely anecdotal in nature rather than evidence based. The most common elements include education regarding good posture, abdominal strengthening exercises, analgesics ranging from NSAIDs to narcotics, and epidural corticosteroid injections, which tend to provide more improvement in leg than back pain.

"A lumbar corset can be very helpful, because many of these people have an accompanying spondylolisthesis and symptomatic instability," Dr. Katz observed.

Aerobic exercise is highly beneficial as well.

"These people are much more comfortable in flexion than extension. It’s problematic for these patients to walk a lot, but they can very often bicycle ad lib. That’s a very useful thing to offer to patients," he said.

Dr. Katz wasn’t involved in the SPORT trial, which was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He reported having no financial conflicts with regard to his presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The unremitting natural history typical of the syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis makes surgery a particularly attractive therapeutic option for many patients with this common form of low back pain.

"Lumbar spinal stenosis patients, because of their age and comorbidities, face the highest risk from surgery, but they also have by far the most to gain because the natural history is so poor. So I spend a lot of time trying to get patients with low back pain due to a herniated disc to be patient, to use epidurals, to try a variety of different things to keep them out of the operating room. And I spend a lot of time helping the lumbar spinal stenosis patients overcome some of their fears and actually go ahead and elect surgery if they’re good candidates," Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz said at the symposium.

That being said, he added, there’s no rush. Rapid neurologic deterioration is rare in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS). Surgery usually can be deferred safely. About 20% of patients will experience symptomatic improvement over the course of a year, while a similar percentage will have symptomatic deterioration. The decision to undergo surgery should be based upon symptoms rather than on subtle neurologic deficits, which are highly unlikely to progress.

"Once people have well-established stenosis, things tend to sort of stay as they are," commented Dr. Katz, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery Harvard Medical School, Boston, and professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Surgery for LSS competes against a poor natural history, as compared with that of lumbago, in which 90% of episodes are resolved with conservative therapy within 3 months, or sciatica caused by a herniated disc, in which 90% of affected patients are improved with nonsurgical management by 6 months and 50% are asymptomatic at 1 year.

Findings from the multicenter SPORT (Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial) study, the largest known randomized study of surgical vs. nonsurgical therapy for LSS, demonstrated an early and sustained outcome advantage favoring surgery through 2 years of follow-up (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:794-810).

Unfortunately, the randomized portion of SPORT was rendered uninterpretable because of the extremely high treatment crossover rates in both the surgical and nonsurgical groups. Nevertheless, the as-treated analysis of 654 patients in the combined randomized and observational cohorts showed that the surgery group had a mean 19.8-point improvement in Short Form-36 bodily pain scores at 6 weeks and a 26.9-point gain at 2 years over a baseline of 31.4, which are effect sizes roughly twice those seen with conservative therapy, Dr. Katz noted.

Predictors of worsened functional status following surgery for LSS include worse preoperative self-rated overall health, back pain in excess of leg pain, less-severe radiographic stenosis, and a greater number of comorbid conditions.

The 1-year rate of reoperation for recurrent stenosis in SPORT was just 1.3%, compared with reoperation rates of around 10% in studies of discectomy for low back pain from a herniated disc. That high reoperation rate is the major shortcoming of discectomy, and it’s particularly problematic in view of the fact that reoperation has an even higher failure rate than first-time surgery.

Nevertheless, more than 400,000 discectomies are performed per year in the United States, a rate 1.5- to 5-fold higher than in other developed countries.

"I think the increased surgery rate in the U.S. has more to do with patient preferences than surgeon aggressiveness," he noted.

Patients who want to pursue nonsurgical therapy for LSS need to understand that it’s largely anecdotal in nature rather than evidence based. The most common elements include education regarding good posture, abdominal strengthening exercises, analgesics ranging from NSAIDs to narcotics, and epidural corticosteroid injections, which tend to provide more improvement in leg than back pain.

"A lumbar corset can be very helpful, because many of these people have an accompanying spondylolisthesis and symptomatic instability," Dr. Katz observed.

Aerobic exercise is highly beneficial as well.

"These people are much more comfortable in flexion than extension. It’s problematic for these patients to walk a lot, but they can very often bicycle ad lib. That’s a very useful thing to offer to patients," he said.

Dr. Katz wasn’t involved in the SPORT trial, which was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He reported having no financial conflicts with regard to his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A SYMPOSIUM SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Kidney Stones in Children Becoming More Common

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – Kidney stones, historically considered an adult malady, have become vastly more common among children during the past decade, in concert with the obesity epidemic.

Moreover, the clinical presentation of urolithiasis in children is often different than it is in adults. As a result, physicians are frequently caught off guard.

"The diagnosis of kidney stones is often not the first thing on the differential diagnosis list – or even on the list – for a child with abdominal pain," Dr. Beth A. Vogt observed at a meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The younger the child with a kidney stone, the more likely the clinical presentation will be nonspecific abdominal pain rather than the flank pain or renal colic typical in affected adults, according to Dr. Vogt, a pediatric nephrologist at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Thus, in the child with nonspecific abdominal pain, it’s important to add urolithiasis to the differential diagnosis list, which classically has included viral gastroenteritis, appendicitis, cholecystitis, intussusception, and food poisoning, she said.

Gross hematuria is present in 30%-40% of children who present with kidney stones. Dysuria is also common. In addition, asymptomatic kidney stones are frequently detected incidentally in children undergoing ultrasound or CT following traumatic injury.

The primary care physician’s role in pediatric urolithiasis is to make the diagnosis, begin acute management with hydration and pain control, hospitalize if necessary, and refer the patient to urology for intervention if the stone is so large it’s unlikely to pass.

Also, referral to a nephrologist is recommended after a first-ever stone has passed and the child has resumed normal activities. The nephrologist’s job is to figure out why the child is forming stones and to come up with a specific prevention plan (for example, a low-sodium diet in patients with hypercalciuria, or antibiotics in children with infection-related struvite stones), Dr. Vogt continued.

"In adults, the standard practice is to wait until they prove to be recurrent stone formers before doing a work-up. That’s not the case in children. Don’t wait until after a child has had several stones to refer to nephrology. We find something metabolically wrong in about 75% of the kids," she said.

The diagnosis of pediatric urolithiasis is suggested by the combination of abdominal or flank pain, hematuria on a urine dipstick test, and crystals in the urine upon microscopic examination. A couple of caveats, though: Recent studies indicate that up to 15% of kids with active stone disease have a negative urinalysis, so urolithiasis can’t be ruled out on the basis of a negative urine dipstick. Also, many children who don’t have kidney stone disease have crystals in their urine.

The best initial diagnostic imaging study is kidney ultrasound. It doesn’t involve radiation, which is an important advantage because some young patients will continue making stones and will therefore need to undergo imaging many times.

Ultrasound is very good at identifying stones in the renal parenchyma, but not ureteral stones or very small stones. So if the clinical picture and laboratory results suggest urolithiasis but the ultrasound is negative, it’s time to move on to CT without contrast, by far the most sensitive test. It is ordered by requesting a "CT stone protocol."

Acute management of stone disease entails oral or intravenous hydration to push the stone through the urinary tract. Pain medication is important. Tamsulosin (Flomax) is prescribed off label to induce ureteral relaxation and assist in the stone’s passage. It’s useful to have the patient use a urine-straining device to try to catch the stone for later analysis.

"The diagnosis of kidney stones is often not the first thing on the differential diagnosis list – or even on the list – for a child with abdominal pain."

Urologists consistently recommend a 4- to 6-week trial of spontaneous passage, provided the child doesn’t have a urinary tract infection, is able to hydrate orally, and obtains pain control with oral medications.

"When you tell that to parents, they say, ‘Are you kidding?’ That’s a long, long time. Parents don’t like it," Dr. Vogt said.

A stone larger than 10 mm is so unlikely to pass spontaneously that Dr. Vogt recommends going straight to urologic intervention. A stone less than 5 mm will usually pass spontaneously, even in a child.

Urologists will typically place a ureter-long stent in a patient with refractory nausea and vomiting or an infection. This allows urine to bypass an obstructive stone.

"It buys you time. It gets the patient out of the cycle of pain, vomiting, and renal colic," she explained.

A week or two later, the urologist will take out the stent and remove the stone, most often by ureteroscopy. This involves inserting the ureteroscope through the bladder and capturing the stone in a basket, sometimes after breaking it into fragments via laser lithotripsy.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, in which several thousand shock waves are directed at the stone, is still widely performed in adults. It is less popular in children because of the theoretical risk of damaging nearby healthy tissues, which might then result in hypertension or diabetes.

Although the majority of cases of pediatric urolithiasis are managed on an outpatient basis, today roughly 1 in 1,000 pediatric hospitalizations is for kidney stones. The explanation for the increase in kidney stones in children over the past decade isn’t entirely clear. Increased consumption of salty, high-protein, processed foods and decreased water intake have been implicated.

General measures for prevention of stones in a stone-forming child include ample fluid intake – more than 2 L daily in teens – along with a healthy diet featuring liberal consumption of fruits and vegetables to increase excretion of stone-inhibiting citrate into the urine. Restriction of dietary calcium isn’t recommended, even in calcium stone formers.

"I usually tell patients to drink enough fluids that their urine looks very dilute. You don’t want dark yellow urine," Dr. Vogt said.

She reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – Kidney stones, historically considered an adult malady, have become vastly more common among children during the past decade, in concert with the obesity epidemic.

Moreover, the clinical presentation of urolithiasis in children is often different than it is in adults. As a result, physicians are frequently caught off guard.

"The diagnosis of kidney stones is often not the first thing on the differential diagnosis list – or even on the list – for a child with abdominal pain," Dr. Beth A. Vogt observed at a meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The younger the child with a kidney stone, the more likely the clinical presentation will be nonspecific abdominal pain rather than the flank pain or renal colic typical in affected adults, according to Dr. Vogt, a pediatric nephrologist at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Thus, in the child with nonspecific abdominal pain, it’s important to add urolithiasis to the differential diagnosis list, which classically has included viral gastroenteritis, appendicitis, cholecystitis, intussusception, and food poisoning, she said.

Gross hematuria is present in 30%-40% of children who present with kidney stones. Dysuria is also common. In addition, asymptomatic kidney stones are frequently detected incidentally in children undergoing ultrasound or CT following traumatic injury.

The primary care physician’s role in pediatric urolithiasis is to make the diagnosis, begin acute management with hydration and pain control, hospitalize if necessary, and refer the patient to urology for intervention if the stone is so large it’s unlikely to pass.

Also, referral to a nephrologist is recommended after a first-ever stone has passed and the child has resumed normal activities. The nephrologist’s job is to figure out why the child is forming stones and to come up with a specific prevention plan (for example, a low-sodium diet in patients with hypercalciuria, or antibiotics in children with infection-related struvite stones), Dr. Vogt continued.

"In adults, the standard practice is to wait until they prove to be recurrent stone formers before doing a work-up. That’s not the case in children. Don’t wait until after a child has had several stones to refer to nephrology. We find something metabolically wrong in about 75% of the kids," she said.

The diagnosis of pediatric urolithiasis is suggested by the combination of abdominal or flank pain, hematuria on a urine dipstick test, and crystals in the urine upon microscopic examination. A couple of caveats, though: Recent studies indicate that up to 15% of kids with active stone disease have a negative urinalysis, so urolithiasis can’t be ruled out on the basis of a negative urine dipstick. Also, many children who don’t have kidney stone disease have crystals in their urine.

The best initial diagnostic imaging study is kidney ultrasound. It doesn’t involve radiation, which is an important advantage because some young patients will continue making stones and will therefore need to undergo imaging many times.

Ultrasound is very good at identifying stones in the renal parenchyma, but not ureteral stones or very small stones. So if the clinical picture and laboratory results suggest urolithiasis but the ultrasound is negative, it’s time to move on to CT without contrast, by far the most sensitive test. It is ordered by requesting a "CT stone protocol."

Acute management of stone disease entails oral or intravenous hydration to push the stone through the urinary tract. Pain medication is important. Tamsulosin (Flomax) is prescribed off label to induce ureteral relaxation and assist in the stone’s passage. It’s useful to have the patient use a urine-straining device to try to catch the stone for later analysis.

"The diagnosis of kidney stones is often not the first thing on the differential diagnosis list – or even on the list – for a child with abdominal pain."

Urologists consistently recommend a 4- to 6-week trial of spontaneous passage, provided the child doesn’t have a urinary tract infection, is able to hydrate orally, and obtains pain control with oral medications.

"When you tell that to parents, they say, ‘Are you kidding?’ That’s a long, long time. Parents don’t like it," Dr. Vogt said.

A stone larger than 10 mm is so unlikely to pass spontaneously that Dr. Vogt recommends going straight to urologic intervention. A stone less than 5 mm will usually pass spontaneously, even in a child.

Urologists will typically place a ureter-long stent in a patient with refractory nausea and vomiting or an infection. This allows urine to bypass an obstructive stone.

"It buys you time. It gets the patient out of the cycle of pain, vomiting, and renal colic," she explained.

A week or two later, the urologist will take out the stent and remove the stone, most often by ureteroscopy. This involves inserting the ureteroscope through the bladder and capturing the stone in a basket, sometimes after breaking it into fragments via laser lithotripsy.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, in which several thousand shock waves are directed at the stone, is still widely performed in adults. It is less popular in children because of the theoretical risk of damaging nearby healthy tissues, which might then result in hypertension or diabetes.

Although the majority of cases of pediatric urolithiasis are managed on an outpatient basis, today roughly 1 in 1,000 pediatric hospitalizations is for kidney stones. The explanation for the increase in kidney stones in children over the past decade isn’t entirely clear. Increased consumption of salty, high-protein, processed foods and decreased water intake have been implicated.

General measures for prevention of stones in a stone-forming child include ample fluid intake – more than 2 L daily in teens – along with a healthy diet featuring liberal consumption of fruits and vegetables to increase excretion of stone-inhibiting citrate into the urine. Restriction of dietary calcium isn’t recommended, even in calcium stone formers.

"I usually tell patients to drink enough fluids that their urine looks very dilute. You don’t want dark yellow urine," Dr. Vogt said.

She reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – Kidney stones, historically considered an adult malady, have become vastly more common among children during the past decade, in concert with the obesity epidemic.

Moreover, the clinical presentation of urolithiasis in children is often different than it is in adults. As a result, physicians are frequently caught off guard.

"The diagnosis of kidney stones is often not the first thing on the differential diagnosis list – or even on the list – for a child with abdominal pain," Dr. Beth A. Vogt observed at a meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The younger the child with a kidney stone, the more likely the clinical presentation will be nonspecific abdominal pain rather than the flank pain or renal colic typical in affected adults, according to Dr. Vogt, a pediatric nephrologist at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Thus, in the child with nonspecific abdominal pain, it’s important to add urolithiasis to the differential diagnosis list, which classically has included viral gastroenteritis, appendicitis, cholecystitis, intussusception, and food poisoning, she said.

Gross hematuria is present in 30%-40% of children who present with kidney stones. Dysuria is also common. In addition, asymptomatic kidney stones are frequently detected incidentally in children undergoing ultrasound or CT following traumatic injury.

The primary care physician’s role in pediatric urolithiasis is to make the diagnosis, begin acute management with hydration and pain control, hospitalize if necessary, and refer the patient to urology for intervention if the stone is so large it’s unlikely to pass.

Also, referral to a nephrologist is recommended after a first-ever stone has passed and the child has resumed normal activities. The nephrologist’s job is to figure out why the child is forming stones and to come up with a specific prevention plan (for example, a low-sodium diet in patients with hypercalciuria, or antibiotics in children with infection-related struvite stones), Dr. Vogt continued.

"In adults, the standard practice is to wait until they prove to be recurrent stone formers before doing a work-up. That’s not the case in children. Don’t wait until after a child has had several stones to refer to nephrology. We find something metabolically wrong in about 75% of the kids," she said.

The diagnosis of pediatric urolithiasis is suggested by the combination of abdominal or flank pain, hematuria on a urine dipstick test, and crystals in the urine upon microscopic examination. A couple of caveats, though: Recent studies indicate that up to 15% of kids with active stone disease have a negative urinalysis, so urolithiasis can’t be ruled out on the basis of a negative urine dipstick. Also, many children who don’t have kidney stone disease have crystals in their urine.

The best initial diagnostic imaging study is kidney ultrasound. It doesn’t involve radiation, which is an important advantage because some young patients will continue making stones and will therefore need to undergo imaging many times.

Ultrasound is very good at identifying stones in the renal parenchyma, but not ureteral stones or very small stones. So if the clinical picture and laboratory results suggest urolithiasis but the ultrasound is negative, it’s time to move on to CT without contrast, by far the most sensitive test. It is ordered by requesting a "CT stone protocol."

Acute management of stone disease entails oral or intravenous hydration to push the stone through the urinary tract. Pain medication is important. Tamsulosin (Flomax) is prescribed off label to induce ureteral relaxation and assist in the stone’s passage. It’s useful to have the patient use a urine-straining device to try to catch the stone for later analysis.

"The diagnosis of kidney stones is often not the first thing on the differential diagnosis list – or even on the list – for a child with abdominal pain."

Urologists consistently recommend a 4- to 6-week trial of spontaneous passage, provided the child doesn’t have a urinary tract infection, is able to hydrate orally, and obtains pain control with oral medications.

"When you tell that to parents, they say, ‘Are you kidding?’ That’s a long, long time. Parents don’t like it," Dr. Vogt said.

A stone larger than 10 mm is so unlikely to pass spontaneously that Dr. Vogt recommends going straight to urologic intervention. A stone less than 5 mm will usually pass spontaneously, even in a child.

Urologists will typically place a ureter-long stent in a patient with refractory nausea and vomiting or an infection. This allows urine to bypass an obstructive stone.

"It buys you time. It gets the patient out of the cycle of pain, vomiting, and renal colic," she explained.

A week or two later, the urologist will take out the stent and remove the stone, most often by ureteroscopy. This involves inserting the ureteroscope through the bladder and capturing the stone in a basket, sometimes after breaking it into fragments via laser lithotripsy.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, in which several thousand shock waves are directed at the stone, is still widely performed in adults. It is less popular in children because of the theoretical risk of damaging nearby healthy tissues, which might then result in hypertension or diabetes.

Although the majority of cases of pediatric urolithiasis are managed on an outpatient basis, today roughly 1 in 1,000 pediatric hospitalizations is for kidney stones. The explanation for the increase in kidney stones in children over the past decade isn’t entirely clear. Increased consumption of salty, high-protein, processed foods and decreased water intake have been implicated.

General measures for prevention of stones in a stone-forming child include ample fluid intake – more than 2 L daily in teens – along with a healthy diet featuring liberal consumption of fruits and vegetables to increase excretion of stone-inhibiting citrate into the urine. Restriction of dietary calcium isn’t recommended, even in calcium stone formers.

"I usually tell patients to drink enough fluids that their urine looks very dilute. You don’t want dark yellow urine," Dr. Vogt said.

She reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON PRACTICAL PEDIATRICS SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

A Spoonful of Frosting Helps the Clindamycin Go Down

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – Clindamycin is an effective and guideline-recommended treatment for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections that has one major shortcoming for use in children: The liquid pediatric formulation tastes and smells, well, awful.

"What we do instead of prescribing liquid clindamycin is we prescribe the capsule, crush it up, and put it into chocolate frosting. Usually you can get it into kids by doing that. It’s only going to be for 7-10 days. And it’s much better than trying to add flavors to liquid clindamycin," said Dr. Penelope H. Dennehy, professor and vice chair of pediatrics and director of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

She hit upon the chocolate frosting solution well before MRSA grew into the enormous problem it is today.

"I run a TB clinic, and INH [isonicotinic acid hydrazide] also tastes yucky," Dr. Dennehy said at the meeting.

"We make all our residents taste all the antibiotics. And I have to say, liquid clindamycin is about the worst-tasting antibiotic I’ve ever come across," she added.

Clindamycin is not recommended for treatment of MRSA infections in communities where the organism’s clindamycin-resistance rate exceeds 10%, so it’s important to know the local resistance pattern.

Dr. Dennehy reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – Clindamycin is an effective and guideline-recommended treatment for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections that has one major shortcoming for use in children: The liquid pediatric formulation tastes and smells, well, awful.

"What we do instead of prescribing liquid clindamycin is we prescribe the capsule, crush it up, and put it into chocolate frosting. Usually you can get it into kids by doing that. It’s only going to be for 7-10 days. And it’s much better than trying to add flavors to liquid clindamycin," said Dr. Penelope H. Dennehy, professor and vice chair of pediatrics and director of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

She hit upon the chocolate frosting solution well before MRSA grew into the enormous problem it is today.

"I run a TB clinic, and INH [isonicotinic acid hydrazide] also tastes yucky," Dr. Dennehy said at the meeting.

"We make all our residents taste all the antibiotics. And I have to say, liquid clindamycin is about the worst-tasting antibiotic I’ve ever come across," she added.

Clindamycin is not recommended for treatment of MRSA infections in communities where the organism’s clindamycin-resistance rate exceeds 10%, so it’s important to know the local resistance pattern.

Dr. Dennehy reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – Clindamycin is an effective and guideline-recommended treatment for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections that has one major shortcoming for use in children: The liquid pediatric formulation tastes and smells, well, awful.

"What we do instead of prescribing liquid clindamycin is we prescribe the capsule, crush it up, and put it into chocolate frosting. Usually you can get it into kids by doing that. It’s only going to be for 7-10 days. And it’s much better than trying to add flavors to liquid clindamycin," said Dr. Penelope H. Dennehy, professor and vice chair of pediatrics and director of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

She hit upon the chocolate frosting solution well before MRSA grew into the enormous problem it is today.

"I run a TB clinic, and INH [isonicotinic acid hydrazide] also tastes yucky," Dr. Dennehy said at the meeting.

"We make all our residents taste all the antibiotics. And I have to say, liquid clindamycin is about the worst-tasting antibiotic I’ve ever come across," she added.

Clindamycin is not recommended for treatment of MRSA infections in communities where the organism’s clindamycin-resistance rate exceeds 10%, so it’s important to know the local resistance pattern.

Dr. Dennehy reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

Distinguish Type 1 From Type 2 Diabetes in Obese Youth

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – New-onset type 1 diabetes in an obese youth cannot reliably be distinguished from pediatric type 2 diabetes on clinical grounds in this era of epidemic obesity.

"The only way to distinguish obese type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes is to measure diabetes autoantibodies. And those autoantibody panels are commercially available now. Signs and symptoms, diabetic ketoacidosis, family history – they don’t really help you. We get an autoantibody panel routinely in obese kids above age 10 presenting with new-onset diabetes," said Dr. Charlotte M. Boney, chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology and metabolism at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is widely thought of as incompatible with type 2 diabetes. Not true. Close to 20% of youth with type 2 diabetes present with DKA. Similarly, while a history of recent weight loss is considered a classic presenting symptom of type 1 diabetes, it’s also present in about one-quarter of young people presenting with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Boney noted.

The presence of pancreatic autoantibodies spells type 1 diabetes metabolically, even if the patient appears phenotypically to have type 2 disease.

"Some pediatric endocrinologists call this ‘type one-and-a-half’ diabetes. No, no, no. Let’s not make things any weirder than they already are. They have autoimmune diabetes, which is clearly type 1 diabetes. It just happens to be a little more complicated in them because they also have the morbidity of obesity," she explained at the meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The obesity epidemic has muddied the diagnostic waters, because now 20%-30% of patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes are obese, as is a similar proportion of the general pediatric population. At the same time, the obesity epidemic has led to an increase in type 2 diabetes.

But it’s important to bear in mind that most youths with new-onset diabetes still have type 1 disease, she said.

In the landmark prospective The SEARCH For Diabetes In Youth study, nearly all children who presented under age 10 years had type 1 diabetes. Among 10- to 19-year-olds, the proportion with type 2 disease was 15% among whites, but considerably greater among racial minorities: 58% among African Americans, 46% in Hispanics, 70% in Asian/Pacific Islanders, and 86% among Native Americans (JAMA 2007;297:2716-24).

In the ongoing, multicenter, National Institutes of Health–sponsored Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) study, which enrolled 1,206 subjects with a presumptive diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, 9.8% proved to be positive for GAD-65and/or insulinoma-associated protein 2 autoantibodies. They had to be excluded from participation in the treatment phase (Diabetes Care 2010;33:1970-5).

As a practical approach to the initial therapy of young patients with new-onset diabetes, Dr. Boney urged that those with DKA and ketosis should be started on intravenous fluids and insulin, regardless of their age and body habitus. If they are over age 10 and obese, however, pancreatic autoimmunity should be ruled out before transitioning to long-term therapy. For autoantibody-negative patients whose clinical picture is consistent with type 2 diabetes, the treatment is metformin, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for children. Extensive experience shows that it’s a very safe drug, she said.

The TODAY trial is designed to determine whether the best treatment for type 2 diabetes in youth is metformin alone, metformin plus rosiglitazone, or metformin and an intensive lifestyle intervention aimed at achieving a 7%-10% weight loss.

The use of metformin to try to prevent diabetes in obese children with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome is the subject of large ongoing clinical trials. Until the results come in, Dr. Boney said she sees no role for off-label prescribing of metformin, given that weight loss and exercise are quite effective in improving insulin sensitivity.

Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young, or MODY, is worth considering in white youth who are pancreatic autoantibody–negative and have a strong history of parental non–type 1 diabetes. MODY is a single-gene disorder that causes diabetes and is inherited from a parent.

"There are a lot of experts in the MODY field that think we’re grossly underdiagnosing monogenic diabetes," said Dr. Boney.

The treatment for MODY is not insulin or metformin, but rather oral sulfonylureas, although those agents are not FDA-approved for use in children, she observed.

Dr. Boney reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – New-onset type 1 diabetes in an obese youth cannot reliably be distinguished from pediatric type 2 diabetes on clinical grounds in this era of epidemic obesity.

"The only way to distinguish obese type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes is to measure diabetes autoantibodies. And those autoantibody panels are commercially available now. Signs and symptoms, diabetic ketoacidosis, family history – they don’t really help you. We get an autoantibody panel routinely in obese kids above age 10 presenting with new-onset diabetes," said Dr. Charlotte M. Boney, chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology and metabolism at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is widely thought of as incompatible with type 2 diabetes. Not true. Close to 20% of youth with type 2 diabetes present with DKA. Similarly, while a history of recent weight loss is considered a classic presenting symptom of type 1 diabetes, it’s also present in about one-quarter of young people presenting with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Boney noted.

The presence of pancreatic autoantibodies spells type 1 diabetes metabolically, even if the patient appears phenotypically to have type 2 disease.

"Some pediatric endocrinologists call this ‘type one-and-a-half’ diabetes. No, no, no. Let’s not make things any weirder than they already are. They have autoimmune diabetes, which is clearly type 1 diabetes. It just happens to be a little more complicated in them because they also have the morbidity of obesity," she explained at the meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The obesity epidemic has muddied the diagnostic waters, because now 20%-30% of patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes are obese, as is a similar proportion of the general pediatric population. At the same time, the obesity epidemic has led to an increase in type 2 diabetes.

But it’s important to bear in mind that most youths with new-onset diabetes still have type 1 disease, she said.

In the landmark prospective The SEARCH For Diabetes In Youth study, nearly all children who presented under age 10 years had type 1 diabetes. Among 10- to 19-year-olds, the proportion with type 2 disease was 15% among whites, but considerably greater among racial minorities: 58% among African Americans, 46% in Hispanics, 70% in Asian/Pacific Islanders, and 86% among Native Americans (JAMA 2007;297:2716-24).

In the ongoing, multicenter, National Institutes of Health–sponsored Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) study, which enrolled 1,206 subjects with a presumptive diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, 9.8% proved to be positive for GAD-65and/or insulinoma-associated protein 2 autoantibodies. They had to be excluded from participation in the treatment phase (Diabetes Care 2010;33:1970-5).

As a practical approach to the initial therapy of young patients with new-onset diabetes, Dr. Boney urged that those with DKA and ketosis should be started on intravenous fluids and insulin, regardless of their age and body habitus. If they are over age 10 and obese, however, pancreatic autoimmunity should be ruled out before transitioning to long-term therapy. For autoantibody-negative patients whose clinical picture is consistent with type 2 diabetes, the treatment is metformin, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for children. Extensive experience shows that it’s a very safe drug, she said.

The TODAY trial is designed to determine whether the best treatment for type 2 diabetes in youth is metformin alone, metformin plus rosiglitazone, or metformin and an intensive lifestyle intervention aimed at achieving a 7%-10% weight loss.

The use of metformin to try to prevent diabetes in obese children with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome is the subject of large ongoing clinical trials. Until the results come in, Dr. Boney said she sees no role for off-label prescribing of metformin, given that weight loss and exercise are quite effective in improving insulin sensitivity.

Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young, or MODY, is worth considering in white youth who are pancreatic autoantibody–negative and have a strong history of parental non–type 1 diabetes. MODY is a single-gene disorder that causes diabetes and is inherited from a parent.

"There are a lot of experts in the MODY field that think we’re grossly underdiagnosing monogenic diabetes," said Dr. Boney.

The treatment for MODY is not insulin or metformin, but rather oral sulfonylureas, although those agents are not FDA-approved for use in children, she observed.

Dr. Boney reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – New-onset type 1 diabetes in an obese youth cannot reliably be distinguished from pediatric type 2 diabetes on clinical grounds in this era of epidemic obesity.

"The only way to distinguish obese type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes is to measure diabetes autoantibodies. And those autoantibody panels are commercially available now. Signs and symptoms, diabetic ketoacidosis, family history – they don’t really help you. We get an autoantibody panel routinely in obese kids above age 10 presenting with new-onset diabetes," said Dr. Charlotte M. Boney, chief of the division of pediatric endocrinology and metabolism at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I.

Diabetic ketoacidosis is widely thought of as incompatible with type 2 diabetes. Not true. Close to 20% of youth with type 2 diabetes present with DKA. Similarly, while a history of recent weight loss is considered a classic presenting symptom of type 1 diabetes, it’s also present in about one-quarter of young people presenting with type 2 diabetes, Dr. Boney noted.

The presence of pancreatic autoantibodies spells type 1 diabetes metabolically, even if the patient appears phenotypically to have type 2 disease.

"Some pediatric endocrinologists call this ‘type one-and-a-half’ diabetes. No, no, no. Let’s not make things any weirder than they already are. They have autoimmune diabetes, which is clearly type 1 diabetes. It just happens to be a little more complicated in them because they also have the morbidity of obesity," she explained at the meeting on practical pediatrics sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The obesity epidemic has muddied the diagnostic waters, because now 20%-30% of patients with new-onset type 1 diabetes are obese, as is a similar proportion of the general pediatric population. At the same time, the obesity epidemic has led to an increase in type 2 diabetes.

But it’s important to bear in mind that most youths with new-onset diabetes still have type 1 disease, she said.

In the landmark prospective The SEARCH For Diabetes In Youth study, nearly all children who presented under age 10 years had type 1 diabetes. Among 10- to 19-year-olds, the proportion with type 2 disease was 15% among whites, but considerably greater among racial minorities: 58% among African Americans, 46% in Hispanics, 70% in Asian/Pacific Islanders, and 86% among Native Americans (JAMA 2007;297:2716-24).

In the ongoing, multicenter, National Institutes of Health–sponsored Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) study, which enrolled 1,206 subjects with a presumptive diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, 9.8% proved to be positive for GAD-65and/or insulinoma-associated protein 2 autoantibodies. They had to be excluded from participation in the treatment phase (Diabetes Care 2010;33:1970-5).

As a practical approach to the initial therapy of young patients with new-onset diabetes, Dr. Boney urged that those with DKA and ketosis should be started on intravenous fluids and insulin, regardless of their age and body habitus. If they are over age 10 and obese, however, pancreatic autoimmunity should be ruled out before transitioning to long-term therapy. For autoantibody-negative patients whose clinical picture is consistent with type 2 diabetes, the treatment is metformin, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved therapy for children. Extensive experience shows that it’s a very safe drug, she said.

The TODAY trial is designed to determine whether the best treatment for type 2 diabetes in youth is metformin alone, metformin plus rosiglitazone, or metformin and an intensive lifestyle intervention aimed at achieving a 7%-10% weight loss.

The use of metformin to try to prevent diabetes in obese children with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome is the subject of large ongoing clinical trials. Until the results come in, Dr. Boney said she sees no role for off-label prescribing of metformin, given that weight loss and exercise are quite effective in improving insulin sensitivity.

Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young, or MODY, is worth considering in white youth who are pancreatic autoantibody–negative and have a strong history of parental non–type 1 diabetes. MODY is a single-gene disorder that causes diabetes and is inherited from a parent.

"There are a lot of experts in the MODY field that think we’re grossly underdiagnosing monogenic diabetes," said Dr. Boney.

The treatment for MODY is not insulin or metformin, but rather oral sulfonylureas, although those agents are not FDA-approved for use in children, she observed.

Dr. Boney reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A MEETING ON PRACTICAL PEDIATRICS SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

LET Gel Eases Pediatric Wound Suturing

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – Make lidocaine, epinephrine, and tetracaine gel your choice for pain control when repairing lacerations in children, Dr. Steven M. Selbst said.

Adoption of LET gel for routine use in wound repair may be the single most important change in practice that physicians can make in terms of analgesia for children, said Dr. Steven M. Selbst, professor and vice chair of pediatrics at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia.

"Even if you don’t suture wounds in your office, I think it’s key to try to make sure that the emergency department near your office uses LET in wound repair for children. It’s an incredible agent. I’ve been using it for 20 years, and I know it has been around for longer than that. I’ve seen so many anxious kids who are scared to death of having a wound repair with suturing that have had a completely painless repair with LET without any injection whatsoever. To me it’s amazing that some hospitals still don’t use LET," said Dr. Selbst, who is chair of the executive committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

The advantages of pharmacist-compounded LET gel over commercially available anesthetic creams, such as eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) and lidocaine 4% (LMX-4), include much lower cost and a good anesthetic response within 20-30 minutes after LET is applied. In contrast, EMLA requires 60 minutes of contact, making it less practical for laceration repair. LET is as effective as tetracaine, adrenaline, and cocaine (TAC) solution, but it costs less and has less morbidity, he said at the meeting.

Once the treated site shows blanching due to LET’s vasoconstrictive activity, the physician can proceed with pain-free suturing, even on the face and scalp.

The gel formulation of LET contains 10 mL of injectable lidocaine 20%, 5 mL of racemic epinephrine, 12.5 mL of tetracaine hydrochloride 2%, 31.5 mg of sodium metabisulfite, and methylcellulose gel 5% added in sufficient quantity to bring the total volume to 50 mL. The ingredients are stirred or shaken until completely mixed, which takes about 2-3 minutes.

The LET gel remains stable for 4 weeks at room temperature or for 6 months if refrigerated.

"You can apply the gel directly to the wound or put it on cotton gauze and tape it to the wound. Use a generous amount," Dr. Selbst said.

Numerous studies have documented that inadequate pain control is far more common in children with painful conditions than in adults. Children with lower-extremity fractures, serious burns, or sickle cell crises were less than half as likely to get analgesics in the emergency department, compared with adults with the same conditions, according to an earlier study done by Dr. Selbst and a colleague. They also found that kids younger than 2 years got analgesics less frequently than older children (Ann. Emerg. Med. 1990;19:1010-3).

Recent studies indicate this gap has narrowed somewhat, although inadequate dosing of analgesics in children continues to be a problem. Possible explanations include the inability of infants and young children to verbalize, the disproved myth that babies don’t feel or remember pain, and fear of causing respiratory depression or addiction, although there is no evidence that giving a single dose of a narcotic for an acute painful condition is associated with an increased risk of addiction, Dr. Selbst emphasized.

He reported having no financial conflicts.

STEAMBOAT SPRINGS, COLO. – Make lidocaine, epinephrine, and tetracaine gel your choice for pain control when repairing lacerations in children, Dr. Steven M. Selbst said.

Adoption of LET gel for routine use in wound repair may be the single most important change in practice that physicians can make in terms of analgesia for children, said Dr. Steven M. Selbst, professor and vice chair of pediatrics at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia.

"Even if you don’t suture wounds in your office, I think it’s key to try to make sure that the emergency department near your office uses LET in wound repair for children. It’s an incredible agent. I’ve been using it for 20 years, and I know it has been around for longer than that. I’ve seen so many anxious kids who are scared to death of having a wound repair with suturing that have had a completely painless repair with LET without any injection whatsoever. To me it’s amazing that some hospitals still don’t use LET," said Dr. Selbst, who is chair of the executive committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Pediatric Emergency Medicine.

The advantages of pharmacist-compounded LET gel over commercially available anesthetic creams, such as eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) and lidocaine 4% (LMX-4), include much lower cost and a good anesthetic response within 20-30 minutes after LET is applied. In contrast, EMLA requires 60 minutes of contact, making it less practical for laceration repair. LET is as effective as tetracaine, adrenaline, and cocaine (TAC) solution, but it costs less and has less morbidity, he said at the meeting.

Once the treated site shows blanching due to LET’s vasoconstrictive activity, the physician can proceed with pain-free suturing, even on the face and scalp.

The gel formulation of LET contains 10 mL of injectable lidocaine 20%, 5 mL of racemic epinephrine, 12.5 mL of tetracaine hydrochloride 2%, 31.5 mg of sodium metabisulfite, and methylcellulose gel 5% added in sufficient quantity to bring the total volume to 50 mL. The ingredients are stirred or shaken until completely mixed, which takes about 2-3 minutes.

The LET gel remains stable for 4 weeks at room temperature or for 6 months if refrigerated.

"You can apply the gel directly to the wound or put it on cotton gauze and tape it to the wound. Use a generous amount," Dr. Selbst said.