User login

MRSA coverage in cellulitis treatment

A 57-year-old man presents with pain and swelling in his leg. He has had low-grade fevers. He has a history of type 2 diabetes. On exam, his right lower extremity is warm, erythematous, and swollen to the midcalf. There is no purulence, fluctuance, or weeping skin. Labs are: WBC, 12,000; Na, 134; K, 5.2; BUN, 20; creatinine, 1.4.

What therapy would you recommend?

A) Ciprofloxacin.

B) Cefazolin.

C) Vancomycin.

D) Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Myth: Cellulitis treatment should include MRSA coverage.

Cellulitis is almost always caused by group A streptococcus. There are exceptional circumstances where other organisms must be considered; but for the most part, those situations are rare. With the growing concern for community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection (MRSA), more and more patients are receiving empiric coverage for MRSA for all skin infections. Is this coverage for MRSA in patients with cellulitis a new myth in evolution?

In a study by Dr. Arthur Jeng and colleagues, all patients admitted to one hospital over a 3-year period with diffuse cellulitis were studied (Medicine 2010;89:217-26). A total of 179 patients were enrolled in the study; all patients had serologic studies for exposure to streptococci and what antibiotics they received, and outcomes were recorded.

Almost all patients with positive antibodies to streptococci responded to beta-lactam antibiotics (97%). But 91% of the patients who did not develop streptococcal antibodies also responded to beta-lactam antibiotics, for an overall response rate of 95% for treatment with beta-lactam antibiotics.

The most recent clinical practice guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend treatment for infection with beta-hemolytic streptococci for outpatients with nonpurulent cellulitis (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:285-92). The addition of vancomycin is reserved for patients with purulence/evidence of abscess or exudate.

How common is it to prescribe antibiotics that cover MRSA in patients with cellulitis?

In a 2013 study, 61% of patients treated for cellulitis received antibiotics that included community-acquired MRSA coverage (Am. J. Med. 2013;126:1099-106).

A recent study looked at whether additional community-associated MRSA coverage with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in addition to beta-lactam therapy for cellulitis showed any benefit over therapy with only a beta-lactam (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;56:1754-62). The study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The experimental group received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and cephalexin, while the control group received cephalexin plus placebo.

There was no difference in outcome between the two groups, with the conclusion that addition of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to cephalexin did not lead to a better outcome than cephalexin alone in patients with nonpurulent cellulitis.

A study by Dr. Thana Khawcharoenporn and Dr. Alan Tice looked at whether cephalexin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin was superior for the treatment of outpatient cellulitis (Am. J. Med. 2010;123:942-50). They concluded that trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and clindamycin were better than cephalexin. However, more than 50% of patients in this study had abscesses or ulcers – clinical criteria that increase the possibility of MRSA.

The most commonly used oral antibiotic for the coverage of community-associated MRSA is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. This increasing use of TMP-sulfa has its risks, especially in elderly populations (Ann. Emerg. Med. 2014; 63:783-4). Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole can cause serious skin reactions and hyperkalemia (especially in the elderly and those with renal impairment), and the drug has a marked drug interaction with warfarin, leading to high risk of excessive anticoagulation.

These risks of TMP-sulfa use make it extremely important to have clear and worthwhile indications for its use.

The best evidence right now is that for simple cellulitis (no purulence, abscess, or exudate), treatment with a beta-lactam antibiotic is the best option. There is no need to add MRSA coverage to beta-lactam therapy.

If there is no response to treatment, then broadening coverage to include MRSA would be appropriate.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

A 57-year-old man presents with pain and swelling in his leg. He has had low-grade fevers. He has a history of type 2 diabetes. On exam, his right lower extremity is warm, erythematous, and swollen to the midcalf. There is no purulence, fluctuance, or weeping skin. Labs are: WBC, 12,000; Na, 134; K, 5.2; BUN, 20; creatinine, 1.4.

What therapy would you recommend?

A) Ciprofloxacin.

B) Cefazolin.

C) Vancomycin.

D) Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Myth: Cellulitis treatment should include MRSA coverage.

Cellulitis is almost always caused by group A streptococcus. There are exceptional circumstances where other organisms must be considered; but for the most part, those situations are rare. With the growing concern for community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection (MRSA), more and more patients are receiving empiric coverage for MRSA for all skin infections. Is this coverage for MRSA in patients with cellulitis a new myth in evolution?

In a study by Dr. Arthur Jeng and colleagues, all patients admitted to one hospital over a 3-year period with diffuse cellulitis were studied (Medicine 2010;89:217-26). A total of 179 patients were enrolled in the study; all patients had serologic studies for exposure to streptococci and what antibiotics they received, and outcomes were recorded.

Almost all patients with positive antibodies to streptococci responded to beta-lactam antibiotics (97%). But 91% of the patients who did not develop streptococcal antibodies also responded to beta-lactam antibiotics, for an overall response rate of 95% for treatment with beta-lactam antibiotics.

The most recent clinical practice guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend treatment for infection with beta-hemolytic streptococci for outpatients with nonpurulent cellulitis (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:285-92). The addition of vancomycin is reserved for patients with purulence/evidence of abscess or exudate.

How common is it to prescribe antibiotics that cover MRSA in patients with cellulitis?

In a 2013 study, 61% of patients treated for cellulitis received antibiotics that included community-acquired MRSA coverage (Am. J. Med. 2013;126:1099-106).

A recent study looked at whether additional community-associated MRSA coverage with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in addition to beta-lactam therapy for cellulitis showed any benefit over therapy with only a beta-lactam (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;56:1754-62). The study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The experimental group received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and cephalexin, while the control group received cephalexin plus placebo.

There was no difference in outcome between the two groups, with the conclusion that addition of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to cephalexin did not lead to a better outcome than cephalexin alone in patients with nonpurulent cellulitis.

A study by Dr. Thana Khawcharoenporn and Dr. Alan Tice looked at whether cephalexin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin was superior for the treatment of outpatient cellulitis (Am. J. Med. 2010;123:942-50). They concluded that trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and clindamycin were better than cephalexin. However, more than 50% of patients in this study had abscesses or ulcers – clinical criteria that increase the possibility of MRSA.

The most commonly used oral antibiotic for the coverage of community-associated MRSA is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. This increasing use of TMP-sulfa has its risks, especially in elderly populations (Ann. Emerg. Med. 2014; 63:783-4). Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole can cause serious skin reactions and hyperkalemia (especially in the elderly and those with renal impairment), and the drug has a marked drug interaction with warfarin, leading to high risk of excessive anticoagulation.

These risks of TMP-sulfa use make it extremely important to have clear and worthwhile indications for its use.

The best evidence right now is that for simple cellulitis (no purulence, abscess, or exudate), treatment with a beta-lactam antibiotic is the best option. There is no need to add MRSA coverage to beta-lactam therapy.

If there is no response to treatment, then broadening coverage to include MRSA would be appropriate.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

A 57-year-old man presents with pain and swelling in his leg. He has had low-grade fevers. He has a history of type 2 diabetes. On exam, his right lower extremity is warm, erythematous, and swollen to the midcalf. There is no purulence, fluctuance, or weeping skin. Labs are: WBC, 12,000; Na, 134; K, 5.2; BUN, 20; creatinine, 1.4.

What therapy would you recommend?

A) Ciprofloxacin.

B) Cefazolin.

C) Vancomycin.

D) Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Myth: Cellulitis treatment should include MRSA coverage.

Cellulitis is almost always caused by group A streptococcus. There are exceptional circumstances where other organisms must be considered; but for the most part, those situations are rare. With the growing concern for community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection (MRSA), more and more patients are receiving empiric coverage for MRSA for all skin infections. Is this coverage for MRSA in patients with cellulitis a new myth in evolution?

In a study by Dr. Arthur Jeng and colleagues, all patients admitted to one hospital over a 3-year period with diffuse cellulitis were studied (Medicine 2010;89:217-26). A total of 179 patients were enrolled in the study; all patients had serologic studies for exposure to streptococci and what antibiotics they received, and outcomes were recorded.

Almost all patients with positive antibodies to streptococci responded to beta-lactam antibiotics (97%). But 91% of the patients who did not develop streptococcal antibodies also responded to beta-lactam antibiotics, for an overall response rate of 95% for treatment with beta-lactam antibiotics.

The most recent clinical practice guidelines published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend treatment for infection with beta-hemolytic streptococci for outpatients with nonpurulent cellulitis (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:285-92). The addition of vancomycin is reserved for patients with purulence/evidence of abscess or exudate.

How common is it to prescribe antibiotics that cover MRSA in patients with cellulitis?

In a 2013 study, 61% of patients treated for cellulitis received antibiotics that included community-acquired MRSA coverage (Am. J. Med. 2013;126:1099-106).

A recent study looked at whether additional community-associated MRSA coverage with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in addition to beta-lactam therapy for cellulitis showed any benefit over therapy with only a beta-lactam (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;56:1754-62). The study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The experimental group received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and cephalexin, while the control group received cephalexin plus placebo.

There was no difference in outcome between the two groups, with the conclusion that addition of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to cephalexin did not lead to a better outcome than cephalexin alone in patients with nonpurulent cellulitis.

A study by Dr. Thana Khawcharoenporn and Dr. Alan Tice looked at whether cephalexin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or clindamycin was superior for the treatment of outpatient cellulitis (Am. J. Med. 2010;123:942-50). They concluded that trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and clindamycin were better than cephalexin. However, more than 50% of patients in this study had abscesses or ulcers – clinical criteria that increase the possibility of MRSA.

The most commonly used oral antibiotic for the coverage of community-associated MRSA is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. This increasing use of TMP-sulfa has its risks, especially in elderly populations (Ann. Emerg. Med. 2014; 63:783-4). Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole can cause serious skin reactions and hyperkalemia (especially in the elderly and those with renal impairment), and the drug has a marked drug interaction with warfarin, leading to high risk of excessive anticoagulation.

These risks of TMP-sulfa use make it extremely important to have clear and worthwhile indications for its use.

The best evidence right now is that for simple cellulitis (no purulence, abscess, or exudate), treatment with a beta-lactam antibiotic is the best option. There is no need to add MRSA coverage to beta-lactam therapy.

If there is no response to treatment, then broadening coverage to include MRSA would be appropriate.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

Avoiding metformin in renal insufficiency

A 47-year-old obese male with type 2 diabetes has been on metformin for the last 2 years with good effect (hemoglobin A1c of 6.8), and with exercise has been able to lose 5-10 pounds. His last two blood tests show creatinine levels of 1.5 and 1.6. What do you recommend?

A) Continue with metformin.

B) Stop metformin, start sulfonylurea.

C) Stop metformin, begin glargine.

D) Stop metformin, begin pioglitazone.

Myth: Metformin should not be used in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency because of an increased risk of lactic acidosis.

Metformin is the most commonly used oral agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the United States, but the FDA-approved drug label states that it is contraindicated in patients with an abnormal creatinine clearance or serum creatinine of 1.4 in women and 1.5 in men.<sup/>The concern is for development of lactic acidosis in patients because the renally excreted metformin may build up as a result of decreased renal function.

Metformin was approved for use in the United States in 1995, many years after the drug was introduced in Europe. The first drug in its class, phenformin, was removed from the United States and most European markets in 1977 because of a high incidence of lactic acidosis occurring at therapeutic doses. One in 4,000 patients taking phenformin develops lactic acidosis (J. Emerg. Med. 1998;16:881-6). Phenformin has been shown to cause type B lactic acidosis, without evidence of hypoxia or hypoperfusion, and lactic acidosis because of phenformin carried a 50% mortality rate.

Deep concern for the possibility of a similar problem with metformin played an important role in its delay of availability in the United States. It isn’t clear, however, that diabetes patients on metformin have a higher risk of developing lactic acidosis than diabetes patients who are not on metformin.

A Cochrane review of 347 studies, including 70,490 person-years of metformin use, compared with 55,451 person-years in the nonmetformin group, showed no cases of fatal or nonfatal lactic acidosis in either group (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Apr 14:CD002967). More than half the studies included (53%) allowed for the inclusion of patients with creatinine levels greater than 1.5. There were no differences in lactate levels between metformin-treated patients and patients who did not receive metformin.

In a study using the Saskatchewan Health administrative database, which involved 11,797 patients with 22,296 years of metformin exposure, there were two cases of lactic acidosis (Diabetes Care 1999;22:925-7). This calculates to a rate of 9 cases per 100,000 person years, the same rate as in patients with diabetes who are not taking metformin (9.7 cases per 100,000) (Diabetes Care 1998;21:1659-63).

A recent study looked at the incidence of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin with and without abnormalities in renal function (Diabetes Care 2014;37:2291-5). There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of lactic acidosis in patients who were on metformin with normal renal function, compared with those with varying degrees of renal insufficiency. The overall rate of lactic acidosis was 10.3 per 100,000 patient years, which is almost identical to the rates in the other studies mentioned, and there were no fatalities.

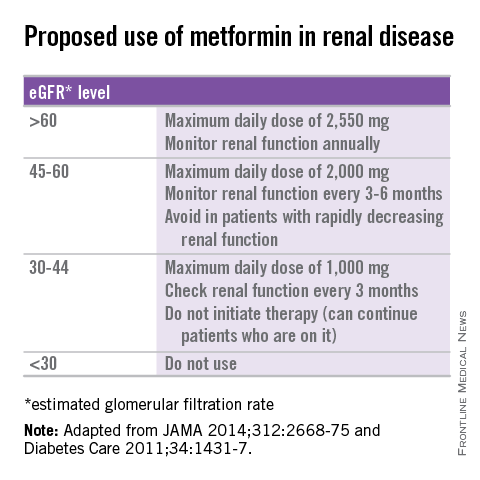

Several recommendations for using metformin in patients with renal insufficiency have been published (see table) (JAMA 2014;312:2668-75; Diabetes Care 2011;34:1431-7). Metformin has shown cardiovascular mortality benefits, compared with sulfonylureas, in the treatment of diabetes (Diabetes Care 2013;36:1304-11). Avoiding its use in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency in favor of other treatments that may not be as beneficial and may well lead to worse outcomes.

There is no evidence that metformin increases the lactic acidosis risk in patients with diabetes, but until there is a change in the FDA labeling, physicians will likely continue to be hesitant to use it in patients with renal insufficiency.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

A 47-year-old obese male with type 2 diabetes has been on metformin for the last 2 years with good effect (hemoglobin A1c of 6.8), and with exercise has been able to lose 5-10 pounds. His last two blood tests show creatinine levels of 1.5 and 1.6. What do you recommend?

A) Continue with metformin.

B) Stop metformin, start sulfonylurea.

C) Stop metformin, begin glargine.

D) Stop metformin, begin pioglitazone.

Myth: Metformin should not be used in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency because of an increased risk of lactic acidosis.

Metformin is the most commonly used oral agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the United States, but the FDA-approved drug label states that it is contraindicated in patients with an abnormal creatinine clearance or serum creatinine of 1.4 in women and 1.5 in men.<sup/>The concern is for development of lactic acidosis in patients because the renally excreted metformin may build up as a result of decreased renal function.

Metformin was approved for use in the United States in 1995, many years after the drug was introduced in Europe. The first drug in its class, phenformin, was removed from the United States and most European markets in 1977 because of a high incidence of lactic acidosis occurring at therapeutic doses. One in 4,000 patients taking phenformin develops lactic acidosis (J. Emerg. Med. 1998;16:881-6). Phenformin has been shown to cause type B lactic acidosis, without evidence of hypoxia or hypoperfusion, and lactic acidosis because of phenformin carried a 50% mortality rate.

Deep concern for the possibility of a similar problem with metformin played an important role in its delay of availability in the United States. It isn’t clear, however, that diabetes patients on metformin have a higher risk of developing lactic acidosis than diabetes patients who are not on metformin.

A Cochrane review of 347 studies, including 70,490 person-years of metformin use, compared with 55,451 person-years in the nonmetformin group, showed no cases of fatal or nonfatal lactic acidosis in either group (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Apr 14:CD002967). More than half the studies included (53%) allowed for the inclusion of patients with creatinine levels greater than 1.5. There were no differences in lactate levels between metformin-treated patients and patients who did not receive metformin.

In a study using the Saskatchewan Health administrative database, which involved 11,797 patients with 22,296 years of metformin exposure, there were two cases of lactic acidosis (Diabetes Care 1999;22:925-7). This calculates to a rate of 9 cases per 100,000 person years, the same rate as in patients with diabetes who are not taking metformin (9.7 cases per 100,000) (Diabetes Care 1998;21:1659-63).

A recent study looked at the incidence of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin with and without abnormalities in renal function (Diabetes Care 2014;37:2291-5). There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of lactic acidosis in patients who were on metformin with normal renal function, compared with those with varying degrees of renal insufficiency. The overall rate of lactic acidosis was 10.3 per 100,000 patient years, which is almost identical to the rates in the other studies mentioned, and there were no fatalities.

Several recommendations for using metformin in patients with renal insufficiency have been published (see table) (JAMA 2014;312:2668-75; Diabetes Care 2011;34:1431-7). Metformin has shown cardiovascular mortality benefits, compared with sulfonylureas, in the treatment of diabetes (Diabetes Care 2013;36:1304-11). Avoiding its use in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency in favor of other treatments that may not be as beneficial and may well lead to worse outcomes.

There is no evidence that metformin increases the lactic acidosis risk in patients with diabetes, but until there is a change in the FDA labeling, physicians will likely continue to be hesitant to use it in patients with renal insufficiency.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

A 47-year-old obese male with type 2 diabetes has been on metformin for the last 2 years with good effect (hemoglobin A1c of 6.8), and with exercise has been able to lose 5-10 pounds. His last two blood tests show creatinine levels of 1.5 and 1.6. What do you recommend?

A) Continue with metformin.

B) Stop metformin, start sulfonylurea.

C) Stop metformin, begin glargine.

D) Stop metformin, begin pioglitazone.

Myth: Metformin should not be used in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency because of an increased risk of lactic acidosis.

Metformin is the most commonly used oral agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the United States, but the FDA-approved drug label states that it is contraindicated in patients with an abnormal creatinine clearance or serum creatinine of 1.4 in women and 1.5 in men.<sup/>The concern is for development of lactic acidosis in patients because the renally excreted metformin may build up as a result of decreased renal function.

Metformin was approved for use in the United States in 1995, many years after the drug was introduced in Europe. The first drug in its class, phenformin, was removed from the United States and most European markets in 1977 because of a high incidence of lactic acidosis occurring at therapeutic doses. One in 4,000 patients taking phenformin develops lactic acidosis (J. Emerg. Med. 1998;16:881-6). Phenformin has been shown to cause type B lactic acidosis, without evidence of hypoxia or hypoperfusion, and lactic acidosis because of phenformin carried a 50% mortality rate.

Deep concern for the possibility of a similar problem with metformin played an important role in its delay of availability in the United States. It isn’t clear, however, that diabetes patients on metformin have a higher risk of developing lactic acidosis than diabetes patients who are not on metformin.

A Cochrane review of 347 studies, including 70,490 person-years of metformin use, compared with 55,451 person-years in the nonmetformin group, showed no cases of fatal or nonfatal lactic acidosis in either group (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 Apr 14:CD002967). More than half the studies included (53%) allowed for the inclusion of patients with creatinine levels greater than 1.5. There were no differences in lactate levels between metformin-treated patients and patients who did not receive metformin.

In a study using the Saskatchewan Health administrative database, which involved 11,797 patients with 22,296 years of metformin exposure, there were two cases of lactic acidosis (Diabetes Care 1999;22:925-7). This calculates to a rate of 9 cases per 100,000 person years, the same rate as in patients with diabetes who are not taking metformin (9.7 cases per 100,000) (Diabetes Care 1998;21:1659-63).

A recent study looked at the incidence of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin with and without abnormalities in renal function (Diabetes Care 2014;37:2291-5). There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of lactic acidosis in patients who were on metformin with normal renal function, compared with those with varying degrees of renal insufficiency. The overall rate of lactic acidosis was 10.3 per 100,000 patient years, which is almost identical to the rates in the other studies mentioned, and there were no fatalities.

Several recommendations for using metformin in patients with renal insufficiency have been published (see table) (JAMA 2014;312:2668-75; Diabetes Care 2011;34:1431-7). Metformin has shown cardiovascular mortality benefits, compared with sulfonylureas, in the treatment of diabetes (Diabetes Care 2013;36:1304-11). Avoiding its use in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency in favor of other treatments that may not be as beneficial and may well lead to worse outcomes.

There is no evidence that metformin increases the lactic acidosis risk in patients with diabetes, but until there is a change in the FDA labeling, physicians will likely continue to be hesitant to use it in patients with renal insufficiency.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

Is oral vitamin B12 therapy effective?

An 88-year-old Scandinavian man is seen for weakness and fatigue. Physical examination reveals a normal mental status and evidence of bilateral lower-extremity neuropathy. His hematocrit is 24%, with a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and a mean corpuscular value of 118 fL. The serum cobalamin level is 64 pg/mL (normal >200 pg/mL), and the plasma methylmalonic acid level is high. A diagnosis of pernicious anemia is made.

What do you recommend for treatment?

A) Intramuscular hydroxycobalamin 1,000-mcg load daily for 1 week, then 1,000 mcg monthly.

B) Intramuscular hydroxycobalamin 1,000 mcg monthly.

C) Vitamin B12 1,000 mcg orally.

Myth: Replacement of vitamin B12 deficiency because of pernicious anemia must not be done orally.

For decades, it has been taught that vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with pernicious anemia is due to poor B12 absorption caused by a lack of intrinsic factor, and that replacement must be given intramuscularly.

This belief was presented in the following statement of the USP Anti-Anemia Preparations Advisory Board: “In the management of a disease for which parenteral therapy with vitamin B12 is a completely adequate and wholly reliable form of therapy, it is unwise to employ a type of treatment which is, at best, unpredictably effective” (JAMA 1959;171:2092-4).

This belief is still being propagated, as this quote from an article published recently attests: “Pernicious anemia is caused by inadequate secretion of gastric intrinsic factor necessary for vitamin B12 absorption and thus cannot be treated with oral vitamin B12 supplements; rather, vitamin B12 must be administered parenterally” (Autoimmun. Rev. 2014;13:565-8).

Studies dating back to the 1950s showed that B12 could be absorbed orally in patients with pernicious anemia, and that two mechanisms of absorption of B12 exist: one involving intrinsic factor and one that does not (J. Clin. Invest. 1957;36:1551-7; N. Engl. J. Med. 1959;260:361-7). The earliest studies of vitamin B12 used low doses of vitamin B12, and some of the studies also used oral intrinsic factor. These studies failed to show adequate vitamin B12 absorption.

In the early 1960s, several studies showed that oral replacement with vitamin B12 could lead to correction of anemia (Acta Med. Scand. 1968;184:247-58; Arch. Intern. Med. 1960;106:280-92; Ann. Intern. Med. 1963;58:810-17). When doses of cyanocobalamin 300 mcg or greater were used, normalization of serum B12 levels was readily achievable. In one study, 64 patients receiving 500 mcg or 1,000 mcg of B12 orally daily for pernicious anemia all had normal serum B12 levels, normalization of hemoglobin levels, and no neurologic complications at follow-up through 5 years.

In a dose-finding trial in elderly patients with B12 deficiency, doses of 500 mcg or more were needed to normalize mild vitamin B12 deficiency (Arch. Intern. Med. 2005;165:1167-72) Using very high doses of daily oral vitamin B12 (1,000-2,000 mcg) leads to blood levels of vitamin B12 as high or higher than are achieved with monthly intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 (Acta Med. Scand. 1978;204:81-4; Blood 1998;92:1191-8; Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005;3:CD004655).

The cost of vitamin B12 replacement is comparable orally and parenterally. The cost of 100 tablets of 1,000 mcg of vitamin B12 is about $5-$10. Ten doses of B12 for injection (1,000 mcg) is about $15, but charges for administration either by clinic personnel or a visiting nurse dramatically increase the monthly cost. If patients are able to give themselves the B12 injection, the additional cost is the cost of the monthly syringe, needle, and alcohol wipes.

Given the evidence and the costs, why is oral vitamin B12 not widely used for replacement?

Most physicians do not believe that vitamin B12 can be replaced orally. In a survey of internists, 94% were not aware of an available, effective oral therapy for B12 replacement (JAMA 1991;265:94-5). In the same survey, 88% of the internists stated that an oral replacement form of B12 would be useful in their practice. These data are more than 20 years old, but physician knowledge in this area is slow to develop. When I lecture on the topic of medical myths and poll the audience about B12 replacement, 60%-80% still recommend intramuscular replacement instead of oral replacement.

This myth combines several features seen in medical myths.

First, it makes some sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint, as intrinsic factor is needed to absorb the small amounts of vitamin B12 in our usual diets. It is easy to understand why one would think that without intrinsic factor, vitamin B12 couldn’t be absorbed and would require intramuscular replacement.

In addition, the studies that refuted the myth were published at a time when high-dose oral vitamin B12 was not available in the United States, so oral replacement did not become standard practice.

Finally, the earliest studies on oral vitamin B12 replacement using low doses of vitamin B12 were failures, which gave evidence to the thinking that the only way vitamin B12 could be replaced would be via parenteral administration.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington Medical School. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

An 88-year-old Scandinavian man is seen for weakness and fatigue. Physical examination reveals a normal mental status and evidence of bilateral lower-extremity neuropathy. His hematocrit is 24%, with a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and a mean corpuscular value of 118 fL. The serum cobalamin level is 64 pg/mL (normal >200 pg/mL), and the plasma methylmalonic acid level is high. A diagnosis of pernicious anemia is made.

What do you recommend for treatment?

A) Intramuscular hydroxycobalamin 1,000-mcg load daily for 1 week, then 1,000 mcg monthly.

B) Intramuscular hydroxycobalamin 1,000 mcg monthly.

C) Vitamin B12 1,000 mcg orally.

Myth: Replacement of vitamin B12 deficiency because of pernicious anemia must not be done orally.

For decades, it has been taught that vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with pernicious anemia is due to poor B12 absorption caused by a lack of intrinsic factor, and that replacement must be given intramuscularly.

This belief was presented in the following statement of the USP Anti-Anemia Preparations Advisory Board: “In the management of a disease for which parenteral therapy with vitamin B12 is a completely adequate and wholly reliable form of therapy, it is unwise to employ a type of treatment which is, at best, unpredictably effective” (JAMA 1959;171:2092-4).

This belief is still being propagated, as this quote from an article published recently attests: “Pernicious anemia is caused by inadequate secretion of gastric intrinsic factor necessary for vitamin B12 absorption and thus cannot be treated with oral vitamin B12 supplements; rather, vitamin B12 must be administered parenterally” (Autoimmun. Rev. 2014;13:565-8).

Studies dating back to the 1950s showed that B12 could be absorbed orally in patients with pernicious anemia, and that two mechanisms of absorption of B12 exist: one involving intrinsic factor and one that does not (J. Clin. Invest. 1957;36:1551-7; N. Engl. J. Med. 1959;260:361-7). The earliest studies of vitamin B12 used low doses of vitamin B12, and some of the studies also used oral intrinsic factor. These studies failed to show adequate vitamin B12 absorption.

In the early 1960s, several studies showed that oral replacement with vitamin B12 could lead to correction of anemia (Acta Med. Scand. 1968;184:247-58; Arch. Intern. Med. 1960;106:280-92; Ann. Intern. Med. 1963;58:810-17). When doses of cyanocobalamin 300 mcg or greater were used, normalization of serum B12 levels was readily achievable. In one study, 64 patients receiving 500 mcg or 1,000 mcg of B12 orally daily for pernicious anemia all had normal serum B12 levels, normalization of hemoglobin levels, and no neurologic complications at follow-up through 5 years.

In a dose-finding trial in elderly patients with B12 deficiency, doses of 500 mcg or more were needed to normalize mild vitamin B12 deficiency (Arch. Intern. Med. 2005;165:1167-72) Using very high doses of daily oral vitamin B12 (1,000-2,000 mcg) leads to blood levels of vitamin B12 as high or higher than are achieved with monthly intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 (Acta Med. Scand. 1978;204:81-4; Blood 1998;92:1191-8; Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005;3:CD004655).

The cost of vitamin B12 replacement is comparable orally and parenterally. The cost of 100 tablets of 1,000 mcg of vitamin B12 is about $5-$10. Ten doses of B12 for injection (1,000 mcg) is about $15, but charges for administration either by clinic personnel or a visiting nurse dramatically increase the monthly cost. If patients are able to give themselves the B12 injection, the additional cost is the cost of the monthly syringe, needle, and alcohol wipes.

Given the evidence and the costs, why is oral vitamin B12 not widely used for replacement?

Most physicians do not believe that vitamin B12 can be replaced orally. In a survey of internists, 94% were not aware of an available, effective oral therapy for B12 replacement (JAMA 1991;265:94-5). In the same survey, 88% of the internists stated that an oral replacement form of B12 would be useful in their practice. These data are more than 20 years old, but physician knowledge in this area is slow to develop. When I lecture on the topic of medical myths and poll the audience about B12 replacement, 60%-80% still recommend intramuscular replacement instead of oral replacement.

This myth combines several features seen in medical myths.

First, it makes some sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint, as intrinsic factor is needed to absorb the small amounts of vitamin B12 in our usual diets. It is easy to understand why one would think that without intrinsic factor, vitamin B12 couldn’t be absorbed and would require intramuscular replacement.

In addition, the studies that refuted the myth were published at a time when high-dose oral vitamin B12 was not available in the United States, so oral replacement did not become standard practice.

Finally, the earliest studies on oral vitamin B12 replacement using low doses of vitamin B12 were failures, which gave evidence to the thinking that the only way vitamin B12 could be replaced would be via parenteral administration.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington Medical School. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

An 88-year-old Scandinavian man is seen for weakness and fatigue. Physical examination reveals a normal mental status and evidence of bilateral lower-extremity neuropathy. His hematocrit is 24%, with a hemoglobin of 8 g/dL and a mean corpuscular value of 118 fL. The serum cobalamin level is 64 pg/mL (normal >200 pg/mL), and the plasma methylmalonic acid level is high. A diagnosis of pernicious anemia is made.

What do you recommend for treatment?

A) Intramuscular hydroxycobalamin 1,000-mcg load daily for 1 week, then 1,000 mcg monthly.

B) Intramuscular hydroxycobalamin 1,000 mcg monthly.

C) Vitamin B12 1,000 mcg orally.

Myth: Replacement of vitamin B12 deficiency because of pernicious anemia must not be done orally.

For decades, it has been taught that vitamin B12 deficiency in patients with pernicious anemia is due to poor B12 absorption caused by a lack of intrinsic factor, and that replacement must be given intramuscularly.

This belief was presented in the following statement of the USP Anti-Anemia Preparations Advisory Board: “In the management of a disease for which parenteral therapy with vitamin B12 is a completely adequate and wholly reliable form of therapy, it is unwise to employ a type of treatment which is, at best, unpredictably effective” (JAMA 1959;171:2092-4).

This belief is still being propagated, as this quote from an article published recently attests: “Pernicious anemia is caused by inadequate secretion of gastric intrinsic factor necessary for vitamin B12 absorption and thus cannot be treated with oral vitamin B12 supplements; rather, vitamin B12 must be administered parenterally” (Autoimmun. Rev. 2014;13:565-8).

Studies dating back to the 1950s showed that B12 could be absorbed orally in patients with pernicious anemia, and that two mechanisms of absorption of B12 exist: one involving intrinsic factor and one that does not (J. Clin. Invest. 1957;36:1551-7; N. Engl. J. Med. 1959;260:361-7). The earliest studies of vitamin B12 used low doses of vitamin B12, and some of the studies also used oral intrinsic factor. These studies failed to show adequate vitamin B12 absorption.

In the early 1960s, several studies showed that oral replacement with vitamin B12 could lead to correction of anemia (Acta Med. Scand. 1968;184:247-58; Arch. Intern. Med. 1960;106:280-92; Ann. Intern. Med. 1963;58:810-17). When doses of cyanocobalamin 300 mcg or greater were used, normalization of serum B12 levels was readily achievable. In one study, 64 patients receiving 500 mcg or 1,000 mcg of B12 orally daily for pernicious anemia all had normal serum B12 levels, normalization of hemoglobin levels, and no neurologic complications at follow-up through 5 years.

In a dose-finding trial in elderly patients with B12 deficiency, doses of 500 mcg or more were needed to normalize mild vitamin B12 deficiency (Arch. Intern. Med. 2005;165:1167-72) Using very high doses of daily oral vitamin B12 (1,000-2,000 mcg) leads to blood levels of vitamin B12 as high or higher than are achieved with monthly intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 (Acta Med. Scand. 1978;204:81-4; Blood 1998;92:1191-8; Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005;3:CD004655).

The cost of vitamin B12 replacement is comparable orally and parenterally. The cost of 100 tablets of 1,000 mcg of vitamin B12 is about $5-$10. Ten doses of B12 for injection (1,000 mcg) is about $15, but charges for administration either by clinic personnel or a visiting nurse dramatically increase the monthly cost. If patients are able to give themselves the B12 injection, the additional cost is the cost of the monthly syringe, needle, and alcohol wipes.

Given the evidence and the costs, why is oral vitamin B12 not widely used for replacement?

Most physicians do not believe that vitamin B12 can be replaced orally. In a survey of internists, 94% were not aware of an available, effective oral therapy for B12 replacement (JAMA 1991;265:94-5). In the same survey, 88% of the internists stated that an oral replacement form of B12 would be useful in their practice. These data are more than 20 years old, but physician knowledge in this area is slow to develop. When I lecture on the topic of medical myths and poll the audience about B12 replacement, 60%-80% still recommend intramuscular replacement instead of oral replacement.

This myth combines several features seen in medical myths.

First, it makes some sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint, as intrinsic factor is needed to absorb the small amounts of vitamin B12 in our usual diets. It is easy to understand why one would think that without intrinsic factor, vitamin B12 couldn’t be absorbed and would require intramuscular replacement.

In addition, the studies that refuted the myth were published at a time when high-dose oral vitamin B12 was not available in the United States, so oral replacement did not become standard practice.

Finally, the earliest studies on oral vitamin B12 replacement using low doses of vitamin B12 were failures, which gave evidence to the thinking that the only way vitamin B12 could be replaced would be via parenteral administration.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington Medical School. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

Never inject epinephrine in the fingers or toes?

A 30-year-old woman cuts her finger on a glass jar. She goes to the clinic and needs to have sutures on her right ring finger. What would you recommend for anesthesia to prepare the patient for repair?

A. 1% lidocaine.

B. 1% lidocaine with epinephrine.

C. Bupivacaine.

Myth: You should not use lidocaine with epinephrine on a digit.

Many of us were taught to avoid the use of epinephrine on digits because of the concern of precipitating digital ischemia. This was a common warning in emergency and surgical textbooks (J.C. Vance. Anesthesia. R.K. Roenigk, H.H. Roenigk [Eds.], Dermatologic Surgery, Principles and Practice [2nd ed.], Marcel Decker, New York, N.Y. [1996], pp. 31-52.).

Over the past 20 years, there has been a growing body of evidence that the concern is unwarranted and that there may be benefit to the addition of epinephrine.

Dr. Bradon J. Wilhelmi and his colleagues performed a randomized, double-blind trial comparing lidocaine with epinephrine (31 patients) and lidocaine (29 patients) in patients with traumatic injuries or elective procedures (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001;107:393-7). The need for control of bleeding required digital tourniquet use in 20 of 29 block procedures with plain lidocaine and in 9 of 31 procedures using lidocaine with epinephrine (P < .002). There were no complications in the patients who received lidocaine with epinephrine.

A retrospective study was done by Dr. Saeed Chowdhry and his colleagues of 1,111 patients who had hand surgery and received digital blocks (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010;126:2031-4). A total of 611 patients received lidocaine with epinephrine, and 500 patients received lidocaine alone. The concentration of lidocaine with epinephrine was 1:100,000, with an average dose of 4.33 cc.

There were no cases of digital gangrene or other complications because of the use of epinephrine in this retrospective study.

In a large, retrospective study of nine hand surgeons’ practices, looking at 3,110 cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in hands and fingers, there were no cases of digital tissue loss or need for phentolamine rescue (J. Hand Surg. Am. 2005;30:1061-7).

Several studies have been done using epinephrine digital injections of the toes. In a prospective, randomized, controlled trial, 44 patients undergoing phenolization matricectomy involving digital block injection of 70 toes received either anesthetic and epinephrine or anesthetic and digital tourniquet (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014 [doi:10.1111/jdv.12746]). The outcome measures were rate of recurrence, bleeding, pain, and duration of anesthetic effect.

There was no difference in recurrence rates, but postoperative bleeding was higher in the procedures done with digital tourniquet and no epinephrine (P = .001). Anesthetic effect as measured by less pain and duration of effect was superior in the patients receiving digital block with epinephrine (P = .001).

In another study looking at chemical matricectomy, Dr. Cevdet Altinyazar and his colleagues randomized patients to receive either 2% lidocaine or lidocaine with epinephrine for anesthesia for chemical matricectomy of ingrown toenails of the great toe (Dermatol. Surg. 2010;36:1568-71). There was less anesthetic needed in the patients who received lidocaine with epinephrine, and a statistically significant reduction in days of drainage following procedure in the lidocaine with epinephrine group (11.1 days +/- 2.5 days), compared with the lidocaine-only group (19.0 days +/- 3.8 days). There were no complications because of the use of epinephrine.

The belief in this myth is still quite common, despite the evidence from randomized, controlled trials and the experience of more than 3,500 patients who have received epinephrine in the fingers without any complications. The evidence from the podiatry literature on safety in use in the toes mirrors the evidence of safety in the fingers.

Dr. Paauw is a professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington Medical School. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

A 30-year-old woman cuts her finger on a glass jar. She goes to the clinic and needs to have sutures on her right ring finger. What would you recommend for anesthesia to prepare the patient for repair?

A. 1% lidocaine.

B. 1% lidocaine with epinephrine.

C. Bupivacaine.

Myth: You should not use lidocaine with epinephrine on a digit.

Many of us were taught to avoid the use of epinephrine on digits because of the concern of precipitating digital ischemia. This was a common warning in emergency and surgical textbooks (J.C. Vance. Anesthesia. R.K. Roenigk, H.H. Roenigk [Eds.], Dermatologic Surgery, Principles and Practice [2nd ed.], Marcel Decker, New York, N.Y. [1996], pp. 31-52.).

Over the past 20 years, there has been a growing body of evidence that the concern is unwarranted and that there may be benefit to the addition of epinephrine.

Dr. Bradon J. Wilhelmi and his colleagues performed a randomized, double-blind trial comparing lidocaine with epinephrine (31 patients) and lidocaine (29 patients) in patients with traumatic injuries or elective procedures (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001;107:393-7). The need for control of bleeding required digital tourniquet use in 20 of 29 block procedures with plain lidocaine and in 9 of 31 procedures using lidocaine with epinephrine (P < .002). There were no complications in the patients who received lidocaine with epinephrine.

A retrospective study was done by Dr. Saeed Chowdhry and his colleagues of 1,111 patients who had hand surgery and received digital blocks (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010;126:2031-4). A total of 611 patients received lidocaine with epinephrine, and 500 patients received lidocaine alone. The concentration of lidocaine with epinephrine was 1:100,000, with an average dose of 4.33 cc.

There were no cases of digital gangrene or other complications because of the use of epinephrine in this retrospective study.

In a large, retrospective study of nine hand surgeons’ practices, looking at 3,110 cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in hands and fingers, there were no cases of digital tissue loss or need for phentolamine rescue (J. Hand Surg. Am. 2005;30:1061-7).

Several studies have been done using epinephrine digital injections of the toes. In a prospective, randomized, controlled trial, 44 patients undergoing phenolization matricectomy involving digital block injection of 70 toes received either anesthetic and epinephrine or anesthetic and digital tourniquet (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014 [doi:10.1111/jdv.12746]). The outcome measures were rate of recurrence, bleeding, pain, and duration of anesthetic effect.

There was no difference in recurrence rates, but postoperative bleeding was higher in the procedures done with digital tourniquet and no epinephrine (P = .001). Anesthetic effect as measured by less pain and duration of effect was superior in the patients receiving digital block with epinephrine (P = .001).

In another study looking at chemical matricectomy, Dr. Cevdet Altinyazar and his colleagues randomized patients to receive either 2% lidocaine or lidocaine with epinephrine for anesthesia for chemical matricectomy of ingrown toenails of the great toe (Dermatol. Surg. 2010;36:1568-71). There was less anesthetic needed in the patients who received lidocaine with epinephrine, and a statistically significant reduction in days of drainage following procedure in the lidocaine with epinephrine group (11.1 days +/- 2.5 days), compared with the lidocaine-only group (19.0 days +/- 3.8 days). There were no complications because of the use of epinephrine.

The belief in this myth is still quite common, despite the evidence from randomized, controlled trials and the experience of more than 3,500 patients who have received epinephrine in the fingers without any complications. The evidence from the podiatry literature on safety in use in the toes mirrors the evidence of safety in the fingers.

Dr. Paauw is a professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington Medical School. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.

A 30-year-old woman cuts her finger on a glass jar. She goes to the clinic and needs to have sutures on her right ring finger. What would you recommend for anesthesia to prepare the patient for repair?

A. 1% lidocaine.

B. 1% lidocaine with epinephrine.

C. Bupivacaine.

Myth: You should not use lidocaine with epinephrine on a digit.

Many of us were taught to avoid the use of epinephrine on digits because of the concern of precipitating digital ischemia. This was a common warning in emergency and surgical textbooks (J.C. Vance. Anesthesia. R.K. Roenigk, H.H. Roenigk [Eds.], Dermatologic Surgery, Principles and Practice [2nd ed.], Marcel Decker, New York, N.Y. [1996], pp. 31-52.).

Over the past 20 years, there has been a growing body of evidence that the concern is unwarranted and that there may be benefit to the addition of epinephrine.

Dr. Bradon J. Wilhelmi and his colleagues performed a randomized, double-blind trial comparing lidocaine with epinephrine (31 patients) and lidocaine (29 patients) in patients with traumatic injuries or elective procedures (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2001;107:393-7). The need for control of bleeding required digital tourniquet use in 20 of 29 block procedures with plain lidocaine and in 9 of 31 procedures using lidocaine with epinephrine (P < .002). There were no complications in the patients who received lidocaine with epinephrine.

A retrospective study was done by Dr. Saeed Chowdhry and his colleagues of 1,111 patients who had hand surgery and received digital blocks (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010;126:2031-4). A total of 611 patients received lidocaine with epinephrine, and 500 patients received lidocaine alone. The concentration of lidocaine with epinephrine was 1:100,000, with an average dose of 4.33 cc.

There were no cases of digital gangrene or other complications because of the use of epinephrine in this retrospective study.

In a large, retrospective study of nine hand surgeons’ practices, looking at 3,110 cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine in hands and fingers, there were no cases of digital tissue loss or need for phentolamine rescue (J. Hand Surg. Am. 2005;30:1061-7).

Several studies have been done using epinephrine digital injections of the toes. In a prospective, randomized, controlled trial, 44 patients undergoing phenolization matricectomy involving digital block injection of 70 toes received either anesthetic and epinephrine or anesthetic and digital tourniquet (J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014 [doi:10.1111/jdv.12746]). The outcome measures were rate of recurrence, bleeding, pain, and duration of anesthetic effect.

There was no difference in recurrence rates, but postoperative bleeding was higher in the procedures done with digital tourniquet and no epinephrine (P = .001). Anesthetic effect as measured by less pain and duration of effect was superior in the patients receiving digital block with epinephrine (P = .001).

In another study looking at chemical matricectomy, Dr. Cevdet Altinyazar and his colleagues randomized patients to receive either 2% lidocaine or lidocaine with epinephrine for anesthesia for chemical matricectomy of ingrown toenails of the great toe (Dermatol. Surg. 2010;36:1568-71). There was less anesthetic needed in the patients who received lidocaine with epinephrine, and a statistically significant reduction in days of drainage following procedure in the lidocaine with epinephrine group (11.1 days +/- 2.5 days), compared with the lidocaine-only group (19.0 days +/- 3.8 days). There were no complications because of the use of epinephrine.

The belief in this myth is still quite common, despite the evidence from randomized, controlled trials and the experience of more than 3,500 patients who have received epinephrine in the fingers without any complications. The evidence from the podiatry literature on safety in use in the toes mirrors the evidence of safety in the fingers.

Dr. Paauw is a professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington Medical School. He is the Rathmann Family Foundation Chair in Patient-Centered Clinical Education. Contact Dr. Paauw at dpaauw@uw.edu.