User login

One weird trick to fight burnout

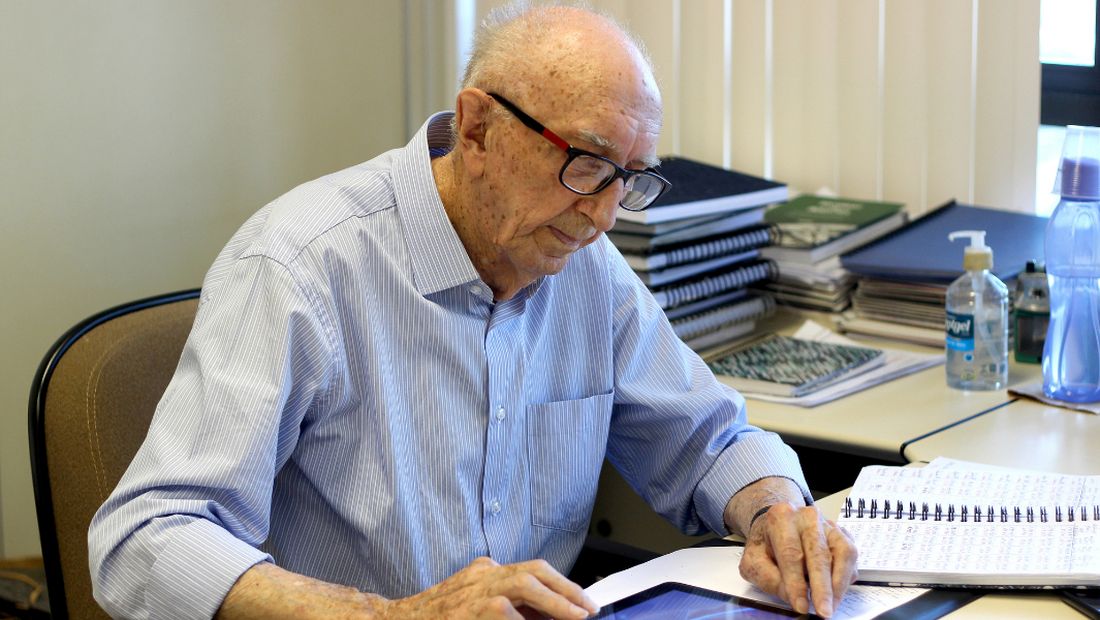

“Here and now is what counts. So, let’s go to work!” –Walter Orthmann, 100 years old

How long before you retire? If you know the answer in exact years, months, and days, you aren’t alone. For many good reasons, we doctors are more likely to be counting down the years until we retire rather than counting up the years since we started working. For me, if I’m to break the Guinness World Record, I have 69 more years, 3 months and 6 days left to go. That would surpass the current achievement for the longest career at one company, Mr. Walter Orthmann, who has been sitting at the same desk for 84 years. At 100 years old, Mr. Orthmann still shows up every Monday morning, as bright eyed and bushy tailed as a young squirrel. I’ll be 119 when I break his streak, which would also put me past Anthony Mancinelli, a New York barber who at 107 years of age was still brushing off his chair for the next customer. Unbelievable, I know! I wonder, what’s the one weird trick these guys are doing that keeps them going?

Of course, the job itself matters. Some jobs, like being a police officer, aren’t suitable for old people. Or are they? Officer L.C. “Buckshot” Smith was still keeping streets safe from his patrol car at 91 years old. After a bit of searching, I found pretty much any job you can think of has a very long-lasting Energizer Bunny story: A female surgeon who was operating at 90 years old, a 100-year-old rheumatologist who was still teaching at University of California, San Francisco, and a 105-year-old Japanese physician who was still seeing patients. There are plenty of geriatric lawyers, nurses, land surveyors, accountants, judges, you name it. So it seems it’s not the work, but the worker that matters. Why do some older workers recharge daily and carry on while many younger ones say the daily grind is burning them out? What makes the Greatest Generation so great?

We all know colleagues who hung up their white coats early. In my medical group, it’s often financially feasible to retire at 58 and many have chosen that option. Yet, we have loads of Partner Emeritus docs in their 70’s who still log on to EPIC and pitch in everyday.

“So, how do you keep going?” I asked my 105-year-old patient who still walks and manages his affairs. “Just stay healthy,” he advised. A circular argument, yet he’s right. You must both be lucky and also choose to be active mentally and physically. Mr. Mancinelli, who was barbering full time at 107 years old, had no aches and pains and all his teeth. He pruned his own bushes. The data are crystal clear that physical activity adds not only years of life, but also improves cognitive capabilities during those years.

As for beating burnout, it seems the one trick that these ultraworkers do is to focus only on the present. Mr. Orthmann’s pithy advice as quoted by NPR is, “You need to get busy with the present, not the past or the future.” These centenarian employees also frame their work not as stressful but rather as their daily series of problems to be solved.

When I asked my super-geriatric patient how he sleeps so well, he said, “I never worry when I get into bed, I just shut my eyes and sleep. I’ll think about tomorrow when I wake up.” Now if I can do that about 25,000 more times, I’ll have the record.

Dr. Jeff Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

“Here and now is what counts. So, let’s go to work!” –Walter Orthmann, 100 years old

How long before you retire? If you know the answer in exact years, months, and days, you aren’t alone. For many good reasons, we doctors are more likely to be counting down the years until we retire rather than counting up the years since we started working. For me, if I’m to break the Guinness World Record, I have 69 more years, 3 months and 6 days left to go. That would surpass the current achievement for the longest career at one company, Mr. Walter Orthmann, who has been sitting at the same desk for 84 years. At 100 years old, Mr. Orthmann still shows up every Monday morning, as bright eyed and bushy tailed as a young squirrel. I’ll be 119 when I break his streak, which would also put me past Anthony Mancinelli, a New York barber who at 107 years of age was still brushing off his chair for the next customer. Unbelievable, I know! I wonder, what’s the one weird trick these guys are doing that keeps them going?

Of course, the job itself matters. Some jobs, like being a police officer, aren’t suitable for old people. Or are they? Officer L.C. “Buckshot” Smith was still keeping streets safe from his patrol car at 91 years old. After a bit of searching, I found pretty much any job you can think of has a very long-lasting Energizer Bunny story: A female surgeon who was operating at 90 years old, a 100-year-old rheumatologist who was still teaching at University of California, San Francisco, and a 105-year-old Japanese physician who was still seeing patients. There are plenty of geriatric lawyers, nurses, land surveyors, accountants, judges, you name it. So it seems it’s not the work, but the worker that matters. Why do some older workers recharge daily and carry on while many younger ones say the daily grind is burning them out? What makes the Greatest Generation so great?

We all know colleagues who hung up their white coats early. In my medical group, it’s often financially feasible to retire at 58 and many have chosen that option. Yet, we have loads of Partner Emeritus docs in their 70’s who still log on to EPIC and pitch in everyday.

“So, how do you keep going?” I asked my 105-year-old patient who still walks and manages his affairs. “Just stay healthy,” he advised. A circular argument, yet he’s right. You must both be lucky and also choose to be active mentally and physically. Mr. Mancinelli, who was barbering full time at 107 years old, had no aches and pains and all his teeth. He pruned his own bushes. The data are crystal clear that physical activity adds not only years of life, but also improves cognitive capabilities during those years.

As for beating burnout, it seems the one trick that these ultraworkers do is to focus only on the present. Mr. Orthmann’s pithy advice as quoted by NPR is, “You need to get busy with the present, not the past or the future.” These centenarian employees also frame their work not as stressful but rather as their daily series of problems to be solved.

When I asked my super-geriatric patient how he sleeps so well, he said, “I never worry when I get into bed, I just shut my eyes and sleep. I’ll think about tomorrow when I wake up.” Now if I can do that about 25,000 more times, I’ll have the record.

Dr. Jeff Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

“Here and now is what counts. So, let’s go to work!” –Walter Orthmann, 100 years old

How long before you retire? If you know the answer in exact years, months, and days, you aren’t alone. For many good reasons, we doctors are more likely to be counting down the years until we retire rather than counting up the years since we started working. For me, if I’m to break the Guinness World Record, I have 69 more years, 3 months and 6 days left to go. That would surpass the current achievement for the longest career at one company, Mr. Walter Orthmann, who has been sitting at the same desk for 84 years. At 100 years old, Mr. Orthmann still shows up every Monday morning, as bright eyed and bushy tailed as a young squirrel. I’ll be 119 when I break his streak, which would also put me past Anthony Mancinelli, a New York barber who at 107 years of age was still brushing off his chair for the next customer. Unbelievable, I know! I wonder, what’s the one weird trick these guys are doing that keeps them going?

Of course, the job itself matters. Some jobs, like being a police officer, aren’t suitable for old people. Or are they? Officer L.C. “Buckshot” Smith was still keeping streets safe from his patrol car at 91 years old. After a bit of searching, I found pretty much any job you can think of has a very long-lasting Energizer Bunny story: A female surgeon who was operating at 90 years old, a 100-year-old rheumatologist who was still teaching at University of California, San Francisco, and a 105-year-old Japanese physician who was still seeing patients. There are plenty of geriatric lawyers, nurses, land surveyors, accountants, judges, you name it. So it seems it’s not the work, but the worker that matters. Why do some older workers recharge daily and carry on while many younger ones say the daily grind is burning them out? What makes the Greatest Generation so great?

We all know colleagues who hung up their white coats early. In my medical group, it’s often financially feasible to retire at 58 and many have chosen that option. Yet, we have loads of Partner Emeritus docs in their 70’s who still log on to EPIC and pitch in everyday.

“So, how do you keep going?” I asked my 105-year-old patient who still walks and manages his affairs. “Just stay healthy,” he advised. A circular argument, yet he’s right. You must both be lucky and also choose to be active mentally and physically. Mr. Mancinelli, who was barbering full time at 107 years old, had no aches and pains and all his teeth. He pruned his own bushes. The data are crystal clear that physical activity adds not only years of life, but also improves cognitive capabilities during those years.

As for beating burnout, it seems the one trick that these ultraworkers do is to focus only on the present. Mr. Orthmann’s pithy advice as quoted by NPR is, “You need to get busy with the present, not the past or the future.” These centenarian employees also frame their work not as stressful but rather as their daily series of problems to be solved.

When I asked my super-geriatric patient how he sleeps so well, he said, “I never worry when I get into bed, I just shut my eyes and sleep. I’ll think about tomorrow when I wake up.” Now if I can do that about 25,000 more times, I’ll have the record.

Dr. Jeff Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

The work after work

Across the country, taxes unite us. Not that we all share the same, rather that we all have to do them. It was recently tax weekend in our house: The Saturday and Sunday that cap off weeks of hunting and gathering faded receipts and sorting through reams of credit card bills to find all the dollars we spent on work. The task is more tedious than all the Wednesdays of taking out trash bins combined, and equally as exciting. But wait, that’s not all.

This weekend I’ve been chatting with bots from a solar company trying to solve our drop in energy production and sat on terminal hold with apparently one person who answers the phone for Amazon. There’s also an homeowner’s association meeting to prepare for and research to be done on ceiling fans.

“Life admin” is a crisp phrase coined by Elizabeth Emens, JD, PhD, that captures the never-ending to-do list that comes with running a household. An accomplished law professor at Columbia University, New York, Dr. Emens noticed the negative impact this life admin has on our quality of life. Reading her book, “Life Admin: How I Learned to Do Less, Do Better, and Live More” (New York: HarperOne, 2019), your eyes widen as she magically makes salient all this hidden work that is stealing our time. Life admin, kidmin, mom and dadmin, just rattling them off feels like donning x-ray glasses allowing us to see how much work we do outside of our work. As doctors, I would add “family house calls,” as a contributing factor: Random family and friends who want to talk for a minute about their knee replacement or what drug the ICU should give Uncle Larry who is fighting COVID. (I only know ivermectin, but it would only help if he just had scabies).

By all accounts, the amount of life admin is growing insidiously, worsened by the great pandemic. There are events to plan and reply to, more DIY customer service to fix your own problems, more work to find a VRBO for a weekend getaway at the beach. (There are none on the entire coast of California this summer, so I just saved you time there. You’re welcome.)

There is no good time to do this work and combined with the heavy burden of our responsibilities as physicians, it can feel like fuel feeding the burnout fire.

Dr. Emens has some top tips to help. First up, know your admin type. Are you a super doer, reluctant doer, admin denier, or admin avoider? I’m mostly in the avoider quadrant, dropping into reluctant doer when consequences loom. Next, choose strategies that fit you. Instead of avoiding, there are some things I might deflect. For example, When your aunt in Peoria asks where she can get a COVID test, you can use LMGTFY.com to generate a link that will show them how to use Google to help with their question. Dr. Emens is joking, but the point rang true. We can lighten the load a bit if we delegate or push back the excessive or undue requests. For some tasks, we’d be better off paying someone to take it over. Last tip here, try doing life admin with a partner, be it spouse, friend, or colleague. This is particularly useful when your partner is a super doer, as mine is. Not only can they make the work lighter, but also less dreary.

We physicians are focused on fixing physician burnout. Maybe we should also be looking at what happens in the “second shift” at home. Tax season is over, but will be back soon.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Across the country, taxes unite us. Not that we all share the same, rather that we all have to do them. It was recently tax weekend in our house: The Saturday and Sunday that cap off weeks of hunting and gathering faded receipts and sorting through reams of credit card bills to find all the dollars we spent on work. The task is more tedious than all the Wednesdays of taking out trash bins combined, and equally as exciting. But wait, that’s not all.

This weekend I’ve been chatting with bots from a solar company trying to solve our drop in energy production and sat on terminal hold with apparently one person who answers the phone for Amazon. There’s also an homeowner’s association meeting to prepare for and research to be done on ceiling fans.

“Life admin” is a crisp phrase coined by Elizabeth Emens, JD, PhD, that captures the never-ending to-do list that comes with running a household. An accomplished law professor at Columbia University, New York, Dr. Emens noticed the negative impact this life admin has on our quality of life. Reading her book, “Life Admin: How I Learned to Do Less, Do Better, and Live More” (New York: HarperOne, 2019), your eyes widen as she magically makes salient all this hidden work that is stealing our time. Life admin, kidmin, mom and dadmin, just rattling them off feels like donning x-ray glasses allowing us to see how much work we do outside of our work. As doctors, I would add “family house calls,” as a contributing factor: Random family and friends who want to talk for a minute about their knee replacement or what drug the ICU should give Uncle Larry who is fighting COVID. (I only know ivermectin, but it would only help if he just had scabies).

By all accounts, the amount of life admin is growing insidiously, worsened by the great pandemic. There are events to plan and reply to, more DIY customer service to fix your own problems, more work to find a VRBO for a weekend getaway at the beach. (There are none on the entire coast of California this summer, so I just saved you time there. You’re welcome.)

There is no good time to do this work and combined with the heavy burden of our responsibilities as physicians, it can feel like fuel feeding the burnout fire.

Dr. Emens has some top tips to help. First up, know your admin type. Are you a super doer, reluctant doer, admin denier, or admin avoider? I’m mostly in the avoider quadrant, dropping into reluctant doer when consequences loom. Next, choose strategies that fit you. Instead of avoiding, there are some things I might deflect. For example, When your aunt in Peoria asks where she can get a COVID test, you can use LMGTFY.com to generate a link that will show them how to use Google to help with their question. Dr. Emens is joking, but the point rang true. We can lighten the load a bit if we delegate or push back the excessive or undue requests. For some tasks, we’d be better off paying someone to take it over. Last tip here, try doing life admin with a partner, be it spouse, friend, or colleague. This is particularly useful when your partner is a super doer, as mine is. Not only can they make the work lighter, but also less dreary.

We physicians are focused on fixing physician burnout. Maybe we should also be looking at what happens in the “second shift” at home. Tax season is over, but will be back soon.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Across the country, taxes unite us. Not that we all share the same, rather that we all have to do them. It was recently tax weekend in our house: The Saturday and Sunday that cap off weeks of hunting and gathering faded receipts and sorting through reams of credit card bills to find all the dollars we spent on work. The task is more tedious than all the Wednesdays of taking out trash bins combined, and equally as exciting. But wait, that’s not all.

This weekend I’ve been chatting with bots from a solar company trying to solve our drop in energy production and sat on terminal hold with apparently one person who answers the phone for Amazon. There’s also an homeowner’s association meeting to prepare for and research to be done on ceiling fans.

“Life admin” is a crisp phrase coined by Elizabeth Emens, JD, PhD, that captures the never-ending to-do list that comes with running a household. An accomplished law professor at Columbia University, New York, Dr. Emens noticed the negative impact this life admin has on our quality of life. Reading her book, “Life Admin: How I Learned to Do Less, Do Better, and Live More” (New York: HarperOne, 2019), your eyes widen as she magically makes salient all this hidden work that is stealing our time. Life admin, kidmin, mom and dadmin, just rattling them off feels like donning x-ray glasses allowing us to see how much work we do outside of our work. As doctors, I would add “family house calls,” as a contributing factor: Random family and friends who want to talk for a minute about their knee replacement or what drug the ICU should give Uncle Larry who is fighting COVID. (I only know ivermectin, but it would only help if he just had scabies).

By all accounts, the amount of life admin is growing insidiously, worsened by the great pandemic. There are events to plan and reply to, more DIY customer service to fix your own problems, more work to find a VRBO for a weekend getaway at the beach. (There are none on the entire coast of California this summer, so I just saved you time there. You’re welcome.)

There is no good time to do this work and combined with the heavy burden of our responsibilities as physicians, it can feel like fuel feeding the burnout fire.

Dr. Emens has some top tips to help. First up, know your admin type. Are you a super doer, reluctant doer, admin denier, or admin avoider? I’m mostly in the avoider quadrant, dropping into reluctant doer when consequences loom. Next, choose strategies that fit you. Instead of avoiding, there are some things I might deflect. For example, When your aunt in Peoria asks where she can get a COVID test, you can use LMGTFY.com to generate a link that will show them how to use Google to help with their question. Dr. Emens is joking, but the point rang true. We can lighten the load a bit if we delegate or push back the excessive or undue requests. For some tasks, we’d be better off paying someone to take it over. Last tip here, try doing life admin with a partner, be it spouse, friend, or colleague. This is particularly useful when your partner is a super doer, as mine is. Not only can they make the work lighter, but also less dreary.

We physicians are focused on fixing physician burnout. Maybe we should also be looking at what happens in the “second shift” at home. Tax season is over, but will be back soon.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

‘We don’t want to be an inspiration’

Over 2.5 million people have fled the ghastly war in Ukraine for safety. But, not everyone is trying to leave. Shockingly, hundreds of thousands are actually flocking toward the danger in Ukraine right now. Many of them are women.

I was commuting to work when I first heard this story on a podcast. In astonishing numbers, women have chosen to return to or stay in Ukraine because they’re needed to fight and to protect their families. My reaction, like yours, was to be inspired. What amazing courage! Twitter and Instagram will swell with images of their balaclava masked faces standing in the breach once more. Like the women in medicine who armed themselves with surgical masks and face shields and babies on their backs to join the fight against COVID-19. They will be poster girls, blue sleeves rolled up and red polka dotted bandanas covering their hair.

But that’s not what they want. “We don’t want to be an inspiration,” said one fearless Ukrainian fighter in the story, “we want to be alive.”

At the time of this writing as we celebrate the brilliant accomplishments of women on March 8, International Women’s Day, I wonder if we don’t have it slightly wrong.

Although acknowledgment is appreciated, the women I work alongside don’t need me to be inspired by them. They need me to stand with them, to help them. . The “she-session” it’s been called, refers to the million women who have not rejoined the workforce since COVID-19. This is especially acute for us in medicine where women are significantly more likely than are men to report not working full time, or not working at all.

The truth is that even in 2022, the burdens of family life are still not borne equally. Bias against mothers in particular can be insidious. Take academia, where there is little sympathy for not publishing on schedule. Perhaps there are unexplained gaps, but where exactly on a CV does one put “recurrent pregnancy loss?” Do you know how many clinics or ORs a woman must cancel to attempt maddeningly unpredictable egg retrievals and embryo transfers? A lot. Not to mention the financial burden of doing so.

During the pandemic, female physicians were more likely to manage child care, schooling, and household duties, compared to male physicians.

And yet (perhaps even because of that?) women in medicine make less money. How much? About $80,000 less on average in dermatology. Inspired? Indeed. No thanks. Let’s #BreakTheBias rather.

I’m not a policy expert nor a sociologist. I don’t know what advice might be helpful here. I’d say raising our collective consciousness of the unfairness, highlighting discrepancies, and advocating for equality are good starts. But, International Women’s Day isn’t new. It’s old. Like over a hundred years old (since 1909 to be exact). We don’t just need a better hashtag, we need to do something. Give equity in pay. Offer opportunities for leadership that accommodate the extra duty women might have outside work. Create flexibility in schedules and without the penalty of having to pump at work or leave early to pick up a child. Not to mention all the opportunities we men have to do more of the household work that women currently do.

The gallant women of Ukraine don’t need our approbation. They need our aid and our prayers. Like the women in my department, at my medical center, in my community, they aren’t posing to be made into posters. There’s work to be done and they are flocking toward it right now.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Over 2.5 million people have fled the ghastly war in Ukraine for safety. But, not everyone is trying to leave. Shockingly, hundreds of thousands are actually flocking toward the danger in Ukraine right now. Many of them are women.

I was commuting to work when I first heard this story on a podcast. In astonishing numbers, women have chosen to return to or stay in Ukraine because they’re needed to fight and to protect their families. My reaction, like yours, was to be inspired. What amazing courage! Twitter and Instagram will swell with images of their balaclava masked faces standing in the breach once more. Like the women in medicine who armed themselves with surgical masks and face shields and babies on their backs to join the fight against COVID-19. They will be poster girls, blue sleeves rolled up and red polka dotted bandanas covering their hair.

But that’s not what they want. “We don’t want to be an inspiration,” said one fearless Ukrainian fighter in the story, “we want to be alive.”

At the time of this writing as we celebrate the brilliant accomplishments of women on March 8, International Women’s Day, I wonder if we don’t have it slightly wrong.

Although acknowledgment is appreciated, the women I work alongside don’t need me to be inspired by them. They need me to stand with them, to help them. . The “she-session” it’s been called, refers to the million women who have not rejoined the workforce since COVID-19. This is especially acute for us in medicine where women are significantly more likely than are men to report not working full time, or not working at all.

The truth is that even in 2022, the burdens of family life are still not borne equally. Bias against mothers in particular can be insidious. Take academia, where there is little sympathy for not publishing on schedule. Perhaps there are unexplained gaps, but where exactly on a CV does one put “recurrent pregnancy loss?” Do you know how many clinics or ORs a woman must cancel to attempt maddeningly unpredictable egg retrievals and embryo transfers? A lot. Not to mention the financial burden of doing so.

During the pandemic, female physicians were more likely to manage child care, schooling, and household duties, compared to male physicians.

And yet (perhaps even because of that?) women in medicine make less money. How much? About $80,000 less on average in dermatology. Inspired? Indeed. No thanks. Let’s #BreakTheBias rather.

I’m not a policy expert nor a sociologist. I don’t know what advice might be helpful here. I’d say raising our collective consciousness of the unfairness, highlighting discrepancies, and advocating for equality are good starts. But, International Women’s Day isn’t new. It’s old. Like over a hundred years old (since 1909 to be exact). We don’t just need a better hashtag, we need to do something. Give equity in pay. Offer opportunities for leadership that accommodate the extra duty women might have outside work. Create flexibility in schedules and without the penalty of having to pump at work or leave early to pick up a child. Not to mention all the opportunities we men have to do more of the household work that women currently do.

The gallant women of Ukraine don’t need our approbation. They need our aid and our prayers. Like the women in my department, at my medical center, in my community, they aren’t posing to be made into posters. There’s work to be done and they are flocking toward it right now.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Over 2.5 million people have fled the ghastly war in Ukraine for safety. But, not everyone is trying to leave. Shockingly, hundreds of thousands are actually flocking toward the danger in Ukraine right now. Many of them are women.

I was commuting to work when I first heard this story on a podcast. In astonishing numbers, women have chosen to return to or stay in Ukraine because they’re needed to fight and to protect their families. My reaction, like yours, was to be inspired. What amazing courage! Twitter and Instagram will swell with images of their balaclava masked faces standing in the breach once more. Like the women in medicine who armed themselves with surgical masks and face shields and babies on their backs to join the fight against COVID-19. They will be poster girls, blue sleeves rolled up and red polka dotted bandanas covering their hair.

But that’s not what they want. “We don’t want to be an inspiration,” said one fearless Ukrainian fighter in the story, “we want to be alive.”

At the time of this writing as we celebrate the brilliant accomplishments of women on March 8, International Women’s Day, I wonder if we don’t have it slightly wrong.

Although acknowledgment is appreciated, the women I work alongside don’t need me to be inspired by them. They need me to stand with them, to help them. . The “she-session” it’s been called, refers to the million women who have not rejoined the workforce since COVID-19. This is especially acute for us in medicine where women are significantly more likely than are men to report not working full time, or not working at all.

The truth is that even in 2022, the burdens of family life are still not borne equally. Bias against mothers in particular can be insidious. Take academia, where there is little sympathy for not publishing on schedule. Perhaps there are unexplained gaps, but where exactly on a CV does one put “recurrent pregnancy loss?” Do you know how many clinics or ORs a woman must cancel to attempt maddeningly unpredictable egg retrievals and embryo transfers? A lot. Not to mention the financial burden of doing so.

During the pandemic, female physicians were more likely to manage child care, schooling, and household duties, compared to male physicians.

And yet (perhaps even because of that?) women in medicine make less money. How much? About $80,000 less on average in dermatology. Inspired? Indeed. No thanks. Let’s #BreakTheBias rather.

I’m not a policy expert nor a sociologist. I don’t know what advice might be helpful here. I’d say raising our collective consciousness of the unfairness, highlighting discrepancies, and advocating for equality are good starts. But, International Women’s Day isn’t new. It’s old. Like over a hundred years old (since 1909 to be exact). We don’t just need a better hashtag, we need to do something. Give equity in pay. Offer opportunities for leadership that accommodate the extra duty women might have outside work. Create flexibility in schedules and without the penalty of having to pump at work or leave early to pick up a child. Not to mention all the opportunities we men have to do more of the household work that women currently do.

The gallant women of Ukraine don’t need our approbation. They need our aid and our prayers. Like the women in my department, at my medical center, in my community, they aren’t posing to be made into posters. There’s work to be done and they are flocking toward it right now.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

To a perfect day

Motionless, every Olympic skater starts off perfectly. Once the music starts, it’s up to them whether they will continue on perfectly or not. In this way, you’re just like an Olympic skater. Each day, a skating program. The music starts the moment your foot touches the floor in the morning. It’s up to you if the rest of the day will continue on flawlessly or not. To this point, I’ve yet to have a perfect day.

If I’m honest, my “perfect day” streak typically ends once I’ve made coffee. By then, I’ll have spilled a few grains of grounds or clinked mugs together when taking one from the cupboard. (D’oh!) Hardly ever can I make it to backing out of the driveway, let alone through a patient encounter. I’ve had a few procedures that when complete I’ve thought, “well, that looks great.” I can remember encounters that went brilliantly despite a high technical difficulty. I’ve also tagged a 7-iron shot 160 downwind yards to within inches of the cup. But I’ve hardly ever done anything in my life perfectly.

What does it mean to be perfect? Well, there have been 23 perfect baseball games. In 1972, the Miami Dolphins had the only perfect NFL season, 14-0 (although my 2007 Patriots went 18-0 before losing to the – ugh – Giants). Every year, several hundred students score a perfect 1600 on the SAT. In an underground vault somewhere in France is a perfect sphere, a perfectly spherical 1-kg mass of pure silicon. There are at least 51 perfect numbers. And model Bella Hadid’s exactly 1.62-ratioed face is said to be perfectly beautiful. But yet, U.S. skater Nathan Chen’s seemingly flawless 113.97-point short program in Beijing, still imperfect.

Attempting a perfect day or perfect surgery or a perfect pour over coffee is a fun game, but perfectionism has an insidious side. Some of us feel this way every day: We must do it exactly right, every time. Even an insignificant imperfection or error feels like failure. A 3.90 GPA is a fail. 515 on the MCAT, not nearly good enough. For them, the burden of perfection is crushing. It is hard for some to recognize that even if your performance could not be improved, the outcome can still be flawed. A chip in the ice, a patient showing up late, an interviewer with an agenda, a missed referee call can all flub up an otherwise flawless day. It isn’t necessary to abandon hope, all ye who live in the real world. Although achieving perfection is usually impossible, reward comes from the pursuit of perfection, not from holding it. It is called perfectionistic striving and in contrast to perfectionistic concerns, it is associated with resilience and positive mood. To do so you must combine giving your all with acceptance of whatever the outcome.

Keith Jarrett is one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time. He is a true perfectionist, precise in his standards and exacting in expectations. In 1975 in Cologne, Germany, he agreed to play at the behest of a teenage girl who arranged to have him perform at the opera house. Except, there was a miscommunication and only a small, broken rehearsal piano was available. As the story goes, she approached him as he waited to be taken back to his hotel, the concert was canceled and she somehow convinced him to play on the nearly unplayable instrument. The result is the Köln Concert, one of the greatest jazz performances in history. It was perfectly imperfect.

Yes, even the 1-kg sphere has femtogram quantities of other elements mixed in – the universal standard for perfect is itself, imperfect. It doesn’t matter. It’s the pursuit of such that makes life worthwhile. There’s always tomorrow. Have your coffee grinders ready.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Motionless, every Olympic skater starts off perfectly. Once the music starts, it’s up to them whether they will continue on perfectly or not. In this way, you’re just like an Olympic skater. Each day, a skating program. The music starts the moment your foot touches the floor in the morning. It’s up to you if the rest of the day will continue on flawlessly or not. To this point, I’ve yet to have a perfect day.

If I’m honest, my “perfect day” streak typically ends once I’ve made coffee. By then, I’ll have spilled a few grains of grounds or clinked mugs together when taking one from the cupboard. (D’oh!) Hardly ever can I make it to backing out of the driveway, let alone through a patient encounter. I’ve had a few procedures that when complete I’ve thought, “well, that looks great.” I can remember encounters that went brilliantly despite a high technical difficulty. I’ve also tagged a 7-iron shot 160 downwind yards to within inches of the cup. But I’ve hardly ever done anything in my life perfectly.

What does it mean to be perfect? Well, there have been 23 perfect baseball games. In 1972, the Miami Dolphins had the only perfect NFL season, 14-0 (although my 2007 Patriots went 18-0 before losing to the – ugh – Giants). Every year, several hundred students score a perfect 1600 on the SAT. In an underground vault somewhere in France is a perfect sphere, a perfectly spherical 1-kg mass of pure silicon. There are at least 51 perfect numbers. And model Bella Hadid’s exactly 1.62-ratioed face is said to be perfectly beautiful. But yet, U.S. skater Nathan Chen’s seemingly flawless 113.97-point short program in Beijing, still imperfect.

Attempting a perfect day or perfect surgery or a perfect pour over coffee is a fun game, but perfectionism has an insidious side. Some of us feel this way every day: We must do it exactly right, every time. Even an insignificant imperfection or error feels like failure. A 3.90 GPA is a fail. 515 on the MCAT, not nearly good enough. For them, the burden of perfection is crushing. It is hard for some to recognize that even if your performance could not be improved, the outcome can still be flawed. A chip in the ice, a patient showing up late, an interviewer with an agenda, a missed referee call can all flub up an otherwise flawless day. It isn’t necessary to abandon hope, all ye who live in the real world. Although achieving perfection is usually impossible, reward comes from the pursuit of perfection, not from holding it. It is called perfectionistic striving and in contrast to perfectionistic concerns, it is associated with resilience and positive mood. To do so you must combine giving your all with acceptance of whatever the outcome.

Keith Jarrett is one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time. He is a true perfectionist, precise in his standards and exacting in expectations. In 1975 in Cologne, Germany, he agreed to play at the behest of a teenage girl who arranged to have him perform at the opera house. Except, there was a miscommunication and only a small, broken rehearsal piano was available. As the story goes, she approached him as he waited to be taken back to his hotel, the concert was canceled and she somehow convinced him to play on the nearly unplayable instrument. The result is the Köln Concert, one of the greatest jazz performances in history. It was perfectly imperfect.

Yes, even the 1-kg sphere has femtogram quantities of other elements mixed in – the universal standard for perfect is itself, imperfect. It doesn’t matter. It’s the pursuit of such that makes life worthwhile. There’s always tomorrow. Have your coffee grinders ready.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Motionless, every Olympic skater starts off perfectly. Once the music starts, it’s up to them whether they will continue on perfectly or not. In this way, you’re just like an Olympic skater. Each day, a skating program. The music starts the moment your foot touches the floor in the morning. It’s up to you if the rest of the day will continue on flawlessly or not. To this point, I’ve yet to have a perfect day.

If I’m honest, my “perfect day” streak typically ends once I’ve made coffee. By then, I’ll have spilled a few grains of grounds or clinked mugs together when taking one from the cupboard. (D’oh!) Hardly ever can I make it to backing out of the driveway, let alone through a patient encounter. I’ve had a few procedures that when complete I’ve thought, “well, that looks great.” I can remember encounters that went brilliantly despite a high technical difficulty. I’ve also tagged a 7-iron shot 160 downwind yards to within inches of the cup. But I’ve hardly ever done anything in my life perfectly.

What does it mean to be perfect? Well, there have been 23 perfect baseball games. In 1972, the Miami Dolphins had the only perfect NFL season, 14-0 (although my 2007 Patriots went 18-0 before losing to the – ugh – Giants). Every year, several hundred students score a perfect 1600 on the SAT. In an underground vault somewhere in France is a perfect sphere, a perfectly spherical 1-kg mass of pure silicon. There are at least 51 perfect numbers. And model Bella Hadid’s exactly 1.62-ratioed face is said to be perfectly beautiful. But yet, U.S. skater Nathan Chen’s seemingly flawless 113.97-point short program in Beijing, still imperfect.

Attempting a perfect day or perfect surgery or a perfect pour over coffee is a fun game, but perfectionism has an insidious side. Some of us feel this way every day: We must do it exactly right, every time. Even an insignificant imperfection or error feels like failure. A 3.90 GPA is a fail. 515 on the MCAT, not nearly good enough. For them, the burden of perfection is crushing. It is hard for some to recognize that even if your performance could not be improved, the outcome can still be flawed. A chip in the ice, a patient showing up late, an interviewer with an agenda, a missed referee call can all flub up an otherwise flawless day. It isn’t necessary to abandon hope, all ye who live in the real world. Although achieving perfection is usually impossible, reward comes from the pursuit of perfection, not from holding it. It is called perfectionistic striving and in contrast to perfectionistic concerns, it is associated with resilience and positive mood. To do so you must combine giving your all with acceptance of whatever the outcome.

Keith Jarrett is one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time. He is a true perfectionist, precise in his standards and exacting in expectations. In 1975 in Cologne, Germany, he agreed to play at the behest of a teenage girl who arranged to have him perform at the opera house. Except, there was a miscommunication and only a small, broken rehearsal piano was available. As the story goes, she approached him as he waited to be taken back to his hotel, the concert was canceled and she somehow convinced him to play on the nearly unplayable instrument. The result is the Köln Concert, one of the greatest jazz performances in history. It was perfectly imperfect.

Yes, even the 1-kg sphere has femtogram quantities of other elements mixed in – the universal standard for perfect is itself, imperfect. It doesn’t matter. It’s the pursuit of such that makes life worthwhile. There’s always tomorrow. Have your coffee grinders ready.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Is it OK to just be satisfied?

It is possible to talk to a patient for a brief moment and just know if he or she is a satisficer or a maximizer. A “satisficer” when presented with treatment options will invariably say: “I’ll do whatever you say, Doctor.” A “maximizer,” in contrast, would like a printed copy of treatment choices, then would seek a second opinion before ultimately buying an UpToDate subscription to research treatments for him or herself.

.

This notion that we have tendencies toward maximizing or satisficing is thanks to Nobel Memorial Prize winner and all-around smart guy, Herbert A. Simon, PhD. Dr. Simon recognized that, although each person might be expected to make optimal decisions to benefit himself or herself, this is practically impossible. To do so would require an infinite amount of time and energy. He found therefore that we actually exhibit “bounded rationality;” that is, we make the best decision given the limits of time, the price of acquiring information, and even our cognitive abilities. The amount of effort we give to make a decision also depends on the situation: You might be very invested in choosing the right spouse, but not at all invested in choosing soup or salad. (Although, we all have friends who are: “Um, is there any thyme in the soup?”)

You’ll certainly recognize that people have different set points on the spectrum between being a satisficer, one who will take the first option that meets a standard, and a maximizer, one who will seek and accept only the best, even if choosing is at great cost. There are risks and benefits of each. In getting the best job, maximizers might be more successful, but satisficers seem to be happier.

How much this extends into other spheres of life is unclear. It is clear, though, that the work of choosing can come at a cost.

The psychologist Barry Schwartz, PhD, believes that, in general, having more choices leads to more anxiety, not more contentment. For example, which Christmas tree lot would you rather visit: One with hundreds of trees of half a dozen varieties? Or one with just a few trees each of Balsam and Douglas Firs? Dr. Schwartz would argue that you might waste an entire afternoon in the first lot only to bring it home and have remorse when you realize it’s a little lopsided. Or let’s say your child applied to all the Ivy League and Public Ivy schools and also threw in all the top liberal arts colleges. The anxiety of selecting the best and the terror that the “best one” might not choose him or her could be overwhelming. A key lesson is that more in life is by chance than we realize, including how straight your tree is and who gets into Princeton this year. Yet, our expectation that things will work out perfectly if only we maximize is ubiquitous. That confidence in our ability to choose correctly is, however, unwarranted. Better to do your best and know that your tree will be festive and there are many colleges which would lead to a happy life than to fret in choosing and then suffer from dashed expectations. Sometimes good enough is good enough.

Being a satisficer or maximizer is probably somewhat fixed, a personality trait, like being extroverted or conscientious. Yet, having insight can be helpful. If choosing a restaurant in Manhattan becomes an actual project for you with spreadsheets and your own statistical analysis, then go for it! Just know that if that process causes you angst and apprehension, then there is another way. Go to Eleven Madison Park, just because I say so. You might have the best dinner of your life or maybe not. At least by not choosing you’ll have the gift of time to spend picking out a tree instead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

It is possible to talk to a patient for a brief moment and just know if he or she is a satisficer or a maximizer. A “satisficer” when presented with treatment options will invariably say: “I’ll do whatever you say, Doctor.” A “maximizer,” in contrast, would like a printed copy of treatment choices, then would seek a second opinion before ultimately buying an UpToDate subscription to research treatments for him or herself.

.

This notion that we have tendencies toward maximizing or satisficing is thanks to Nobel Memorial Prize winner and all-around smart guy, Herbert A. Simon, PhD. Dr. Simon recognized that, although each person might be expected to make optimal decisions to benefit himself or herself, this is practically impossible. To do so would require an infinite amount of time and energy. He found therefore that we actually exhibit “bounded rationality;” that is, we make the best decision given the limits of time, the price of acquiring information, and even our cognitive abilities. The amount of effort we give to make a decision also depends on the situation: You might be very invested in choosing the right spouse, but not at all invested in choosing soup or salad. (Although, we all have friends who are: “Um, is there any thyme in the soup?”)

You’ll certainly recognize that people have different set points on the spectrum between being a satisficer, one who will take the first option that meets a standard, and a maximizer, one who will seek and accept only the best, even if choosing is at great cost. There are risks and benefits of each. In getting the best job, maximizers might be more successful, but satisficers seem to be happier.

How much this extends into other spheres of life is unclear. It is clear, though, that the work of choosing can come at a cost.

The psychologist Barry Schwartz, PhD, believes that, in general, having more choices leads to more anxiety, not more contentment. For example, which Christmas tree lot would you rather visit: One with hundreds of trees of half a dozen varieties? Or one with just a few trees each of Balsam and Douglas Firs? Dr. Schwartz would argue that you might waste an entire afternoon in the first lot only to bring it home and have remorse when you realize it’s a little lopsided. Or let’s say your child applied to all the Ivy League and Public Ivy schools and also threw in all the top liberal arts colleges. The anxiety of selecting the best and the terror that the “best one” might not choose him or her could be overwhelming. A key lesson is that more in life is by chance than we realize, including how straight your tree is and who gets into Princeton this year. Yet, our expectation that things will work out perfectly if only we maximize is ubiquitous. That confidence in our ability to choose correctly is, however, unwarranted. Better to do your best and know that your tree will be festive and there are many colleges which would lead to a happy life than to fret in choosing and then suffer from dashed expectations. Sometimes good enough is good enough.

Being a satisficer or maximizer is probably somewhat fixed, a personality trait, like being extroverted or conscientious. Yet, having insight can be helpful. If choosing a restaurant in Manhattan becomes an actual project for you with spreadsheets and your own statistical analysis, then go for it! Just know that if that process causes you angst and apprehension, then there is another way. Go to Eleven Madison Park, just because I say so. You might have the best dinner of your life or maybe not. At least by not choosing you’ll have the gift of time to spend picking out a tree instead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

It is possible to talk to a patient for a brief moment and just know if he or she is a satisficer or a maximizer. A “satisficer” when presented with treatment options will invariably say: “I’ll do whatever you say, Doctor.” A “maximizer,” in contrast, would like a printed copy of treatment choices, then would seek a second opinion before ultimately buying an UpToDate subscription to research treatments for him or herself.

.

This notion that we have tendencies toward maximizing or satisficing is thanks to Nobel Memorial Prize winner and all-around smart guy, Herbert A. Simon, PhD. Dr. Simon recognized that, although each person might be expected to make optimal decisions to benefit himself or herself, this is practically impossible. To do so would require an infinite amount of time and energy. He found therefore that we actually exhibit “bounded rationality;” that is, we make the best decision given the limits of time, the price of acquiring information, and even our cognitive abilities. The amount of effort we give to make a decision also depends on the situation: You might be very invested in choosing the right spouse, but not at all invested in choosing soup or salad. (Although, we all have friends who are: “Um, is there any thyme in the soup?”)

You’ll certainly recognize that people have different set points on the spectrum between being a satisficer, one who will take the first option that meets a standard, and a maximizer, one who will seek and accept only the best, even if choosing is at great cost. There are risks and benefits of each. In getting the best job, maximizers might be more successful, but satisficers seem to be happier.

How much this extends into other spheres of life is unclear. It is clear, though, that the work of choosing can come at a cost.

The psychologist Barry Schwartz, PhD, believes that, in general, having more choices leads to more anxiety, not more contentment. For example, which Christmas tree lot would you rather visit: One with hundreds of trees of half a dozen varieties? Or one with just a few trees each of Balsam and Douglas Firs? Dr. Schwartz would argue that you might waste an entire afternoon in the first lot only to bring it home and have remorse when you realize it’s a little lopsided. Or let’s say your child applied to all the Ivy League and Public Ivy schools and also threw in all the top liberal arts colleges. The anxiety of selecting the best and the terror that the “best one” might not choose him or her could be overwhelming. A key lesson is that more in life is by chance than we realize, including how straight your tree is and who gets into Princeton this year. Yet, our expectation that things will work out perfectly if only we maximize is ubiquitous. That confidence in our ability to choose correctly is, however, unwarranted. Better to do your best and know that your tree will be festive and there are many colleges which would lead to a happy life than to fret in choosing and then suffer from dashed expectations. Sometimes good enough is good enough.

Being a satisficer or maximizer is probably somewhat fixed, a personality trait, like being extroverted or conscientious. Yet, having insight can be helpful. If choosing a restaurant in Manhattan becomes an actual project for you with spreadsheets and your own statistical analysis, then go for it! Just know that if that process causes you angst and apprehension, then there is another way. Go to Eleven Madison Park, just because I say so. You might have the best dinner of your life or maybe not. At least by not choosing you’ll have the gift of time to spend picking out a tree instead.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Words from the wise

“When 900-years-old you reach, look as good you will not.” –Yoda

I’ve been on a roll lately: 100, 94, 90, 97, 94. These aren’t grades or even what I scratched on my scorecard for 18 holes (that’s more like 112), but rather patients I’ve seen.

Our oldest-old have been in COVID-19 protection for the last couple of years and only now feel safe to come out again. Many have skin cancers. Some of them have many. I’m grateful that for all their health problems, basal cell carcinomas at least I can cure. And

From a 94-year-old woman who was just discharged from the hospital for sepsis: First, sepsis can sneak up from behind and jump you when you’re 94. She was sitting in a waiting room for a routine exam when she passed out and woke up in the ICU. She made it home and is back on her feet, literally. When I asked her how she made it though, she was very matter of fact. Trust that the doctors know what’s right. Trust that someone will tell you what to do next. Trust that you know your own body and what you can and cannot do. Ask for help, then simply trust it will all work out. It usually does.

From a 97-year-old fighter pilot who fought in the Korean War: Let regrets drop away and live to fight another day. He’s had multiple marriages, built and lost companies, been fired and fired at, and made some doozy mistakes, some that caused considerable pain and collateral damage. But each day is new and requires your best. He has lived long enough to love dozens of grandkids and give away more than what most people ever make. His bottom line, if you worry and fret and regret, you’ll make even more mistakes ahead. Look ahead, the ground never comes up from behind you.

From a 94-year-old whose son was killed in a car accident nearly 60 years ago: You can be both happy and sad. When she retold the story of how the police knocked on her door with the news that her son was dead, she started to cry. Even 60 years isn’t long enough to blunt such pain. She still thinks of him often and to this day sometimes finds it difficult to believe he’s gone. Such pain never leaves you. But she is still a happy person with countless joys and is still having such fun. If you live long enough, both will likely be true.

From a 90-year old who still played tennis: “Just one and one.” That is, one beer and one shot, every day. No more. No less. I daren’t say I recommend this one; however, it might also be the social aspect of drinking that matters. He also advised to be free with friendships. You’ll have many people come in and out of your life; be open to new ones all the time. Also sometimes let your friends win.

From a 100-year-old, I asked how he managed to get through the Great Depression, WWII, civil unrest of the 1950s, and the Vietnam War. His reply? “To be honest, I’ve never seen anything quite like this before.”

When there’s time, consider asking for advice from those elders who happen to have an appointment with you. Bring you wisdom, they will.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

“When 900-years-old you reach, look as good you will not.” –Yoda

I’ve been on a roll lately: 100, 94, 90, 97, 94. These aren’t grades or even what I scratched on my scorecard for 18 holes (that’s more like 112), but rather patients I’ve seen.

Our oldest-old have been in COVID-19 protection for the last couple of years and only now feel safe to come out again. Many have skin cancers. Some of them have many. I’m grateful that for all their health problems, basal cell carcinomas at least I can cure. And

From a 94-year-old woman who was just discharged from the hospital for sepsis: First, sepsis can sneak up from behind and jump you when you’re 94. She was sitting in a waiting room for a routine exam when she passed out and woke up in the ICU. She made it home and is back on her feet, literally. When I asked her how she made it though, she was very matter of fact. Trust that the doctors know what’s right. Trust that someone will tell you what to do next. Trust that you know your own body and what you can and cannot do. Ask for help, then simply trust it will all work out. It usually does.

From a 97-year-old fighter pilot who fought in the Korean War: Let regrets drop away and live to fight another day. He’s had multiple marriages, built and lost companies, been fired and fired at, and made some doozy mistakes, some that caused considerable pain and collateral damage. But each day is new and requires your best. He has lived long enough to love dozens of grandkids and give away more than what most people ever make. His bottom line, if you worry and fret and regret, you’ll make even more mistakes ahead. Look ahead, the ground never comes up from behind you.

From a 94-year-old whose son was killed in a car accident nearly 60 years ago: You can be both happy and sad. When she retold the story of how the police knocked on her door with the news that her son was dead, she started to cry. Even 60 years isn’t long enough to blunt such pain. She still thinks of him often and to this day sometimes finds it difficult to believe he’s gone. Such pain never leaves you. But she is still a happy person with countless joys and is still having such fun. If you live long enough, both will likely be true.

From a 90-year old who still played tennis: “Just one and one.” That is, one beer and one shot, every day. No more. No less. I daren’t say I recommend this one; however, it might also be the social aspect of drinking that matters. He also advised to be free with friendships. You’ll have many people come in and out of your life; be open to new ones all the time. Also sometimes let your friends win.

From a 100-year-old, I asked how he managed to get through the Great Depression, WWII, civil unrest of the 1950s, and the Vietnam War. His reply? “To be honest, I’ve never seen anything quite like this before.”

When there’s time, consider asking for advice from those elders who happen to have an appointment with you. Bring you wisdom, they will.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

“When 900-years-old you reach, look as good you will not.” –Yoda

I’ve been on a roll lately: 100, 94, 90, 97, 94. These aren’t grades or even what I scratched on my scorecard for 18 holes (that’s more like 112), but rather patients I’ve seen.

Our oldest-old have been in COVID-19 protection for the last couple of years and only now feel safe to come out again. Many have skin cancers. Some of them have many. I’m grateful that for all their health problems, basal cell carcinomas at least I can cure. And

From a 94-year-old woman who was just discharged from the hospital for sepsis: First, sepsis can sneak up from behind and jump you when you’re 94. She was sitting in a waiting room for a routine exam when she passed out and woke up in the ICU. She made it home and is back on her feet, literally. When I asked her how she made it though, she was very matter of fact. Trust that the doctors know what’s right. Trust that someone will tell you what to do next. Trust that you know your own body and what you can and cannot do. Ask for help, then simply trust it will all work out. It usually does.

From a 97-year-old fighter pilot who fought in the Korean War: Let regrets drop away and live to fight another day. He’s had multiple marriages, built and lost companies, been fired and fired at, and made some doozy mistakes, some that caused considerable pain and collateral damage. But each day is new and requires your best. He has lived long enough to love dozens of grandkids and give away more than what most people ever make. His bottom line, if you worry and fret and regret, you’ll make even more mistakes ahead. Look ahead, the ground never comes up from behind you.

From a 94-year-old whose son was killed in a car accident nearly 60 years ago: You can be both happy and sad. When she retold the story of how the police knocked on her door with the news that her son was dead, she started to cry. Even 60 years isn’t long enough to blunt such pain. She still thinks of him often and to this day sometimes finds it difficult to believe he’s gone. Such pain never leaves you. But she is still a happy person with countless joys and is still having such fun. If you live long enough, both will likely be true.

From a 90-year old who still played tennis: “Just one and one.” That is, one beer and one shot, every day. No more. No less. I daren’t say I recommend this one; however, it might also be the social aspect of drinking that matters. He also advised to be free with friendships. You’ll have many people come in and out of your life; be open to new ones all the time. Also sometimes let your friends win.

From a 100-year-old, I asked how he managed to get through the Great Depression, WWII, civil unrest of the 1950s, and the Vietnam War. His reply? “To be honest, I’ve never seen anything quite like this before.”

When there’s time, consider asking for advice from those elders who happen to have an appointment with you. Bring you wisdom, they will.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Timeless stories

Let me tell you a story. In 5 billion years the sun will run out of hydrogen, the fuel it is currently burning to power my solar panels amongst other things. At that time, the sun will no longer be able to keep its core contracted and will expand into a fiery, red giant, engulfing earth and obliterating any sign that we ever existed. No buildings. No blog posts. No mausoleums. No stories. Nothing of us will remain.

Well, here for a moment anyway, I’ve gotten you to think about something other than COVID. You’re welcome.

Fascinatingly, the image in your mind’s eye right now of a barren scorched landscape was put there by me. Simply by placing a few words together I have caused new thoughts in your head. You might even share this story with someone else – I would have actually changed your behavior through the power of language. This miraculous phenomenon seems to be unique to us humans; we are the only ones who can create whole worlds in another individual’s head just by making a few sounds. We in medicine have the privilege of experiencing this miracle every day.

Last week, a 97-year-old pale, frail, white man saw me for a basal cell carcinoma on his cheek. While performing a simple electrodesiccation and curettage, I asked if he remembers getting a lot of sunburns when he was young. He certainly remembered one. On a blustery sunny day, he fell asleep for hours on the deck of the USS West Virginia while in the Philippines. As a radio man, he was exhausted from days of conflict and he recalled how warm breezes lulled him asleep. He was so sunburned that for days he forgot how afraid he was of the Japanese.

After listening to his story, I had an image in my mind of palm trees swaying in the tropical winds while hundreds of hulking gray castles sat hidden in the vast surrounding oceans awaiting one of the greatest naval conflicts in history. I got to hear it from surely one of the last remaining people in existence to be able to tell that story. Listening to a patient’s tales is one of the benefits of being a physician. Not only do they help bond us with our patients, but also help lessen our burden of having to make diagnosis after diagnosis and write note after note for hours on end. Somehow performing yet another biopsy that day is made just a bit easier if I’m also learning about what it was like at the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Encouraging patients to talk more can be risky. No physician, not even allergists, can afford to be waylaid by a retiree with nothing else to do today. But meaningful encounters can not only be a vaccine against burnout, they also lead to better patient adherence and satisfaction. Sometimes, there is simply not time. But often there is a little window during a procedure or when you’re reasonably caught up and don’t expect delays ahead. And like every story, they literally transform us, the listener. In a true physical sense, their stories live on in me, and now that I’ve shared this one in writing, also with you for perpetuity. That is at least for the next 5 billion years when it, too, will be swallowed by the sun, leaving only a crispy, smoking rock where we once existed.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Let me tell you a story. In 5 billion years the sun will run out of hydrogen, the fuel it is currently burning to power my solar panels amongst other things. At that time, the sun will no longer be able to keep its core contracted and will expand into a fiery, red giant, engulfing earth and obliterating any sign that we ever existed. No buildings. No blog posts. No mausoleums. No stories. Nothing of us will remain.

Well, here for a moment anyway, I’ve gotten you to think about something other than COVID. You’re welcome.

Fascinatingly, the image in your mind’s eye right now of a barren scorched landscape was put there by me. Simply by placing a few words together I have caused new thoughts in your head. You might even share this story with someone else – I would have actually changed your behavior through the power of language. This miraculous phenomenon seems to be unique to us humans; we are the only ones who can create whole worlds in another individual’s head just by making a few sounds. We in medicine have the privilege of experiencing this miracle every day.

Last week, a 97-year-old pale, frail, white man saw me for a basal cell carcinoma on his cheek. While performing a simple electrodesiccation and curettage, I asked if he remembers getting a lot of sunburns when he was young. He certainly remembered one. On a blustery sunny day, he fell asleep for hours on the deck of the USS West Virginia while in the Philippines. As a radio man, he was exhausted from days of conflict and he recalled how warm breezes lulled him asleep. He was so sunburned that for days he forgot how afraid he was of the Japanese.

After listening to his story, I had an image in my mind of palm trees swaying in the tropical winds while hundreds of hulking gray castles sat hidden in the vast surrounding oceans awaiting one of the greatest naval conflicts in history. I got to hear it from surely one of the last remaining people in existence to be able to tell that story. Listening to a patient’s tales is one of the benefits of being a physician. Not only do they help bond us with our patients, but also help lessen our burden of having to make diagnosis after diagnosis and write note after note for hours on end. Somehow performing yet another biopsy that day is made just a bit easier if I’m also learning about what it was like at the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Encouraging patients to talk more can be risky. No physician, not even allergists, can afford to be waylaid by a retiree with nothing else to do today. But meaningful encounters can not only be a vaccine against burnout, they also lead to better patient adherence and satisfaction. Sometimes, there is simply not time. But often there is a little window during a procedure or when you’re reasonably caught up and don’t expect delays ahead. And like every story, they literally transform us, the listener. In a true physical sense, their stories live on in me, and now that I’ve shared this one in writing, also with you for perpetuity. That is at least for the next 5 billion years when it, too, will be swallowed by the sun, leaving only a crispy, smoking rock where we once existed.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Let me tell you a story. In 5 billion years the sun will run out of hydrogen, the fuel it is currently burning to power my solar panels amongst other things. At that time, the sun will no longer be able to keep its core contracted and will expand into a fiery, red giant, engulfing earth and obliterating any sign that we ever existed. No buildings. No blog posts. No mausoleums. No stories. Nothing of us will remain.

Well, here for a moment anyway, I’ve gotten you to think about something other than COVID. You’re welcome.

Fascinatingly, the image in your mind’s eye right now of a barren scorched landscape was put there by me. Simply by placing a few words together I have caused new thoughts in your head. You might even share this story with someone else – I would have actually changed your behavior through the power of language. This miraculous phenomenon seems to be unique to us humans; we are the only ones who can create whole worlds in another individual’s head just by making a few sounds. We in medicine have the privilege of experiencing this miracle every day.

Last week, a 97-year-old pale, frail, white man saw me for a basal cell carcinoma on his cheek. While performing a simple electrodesiccation and curettage, I asked if he remembers getting a lot of sunburns when he was young. He certainly remembered one. On a blustery sunny day, he fell asleep for hours on the deck of the USS West Virginia while in the Philippines. As a radio man, he was exhausted from days of conflict and he recalled how warm breezes lulled him asleep. He was so sunburned that for days he forgot how afraid he was of the Japanese.

After listening to his story, I had an image in my mind of palm trees swaying in the tropical winds while hundreds of hulking gray castles sat hidden in the vast surrounding oceans awaiting one of the greatest naval conflicts in history. I got to hear it from surely one of the last remaining people in existence to be able to tell that story. Listening to a patient’s tales is one of the benefits of being a physician. Not only do they help bond us with our patients, but also help lessen our burden of having to make diagnosis after diagnosis and write note after note for hours on end. Somehow performing yet another biopsy that day is made just a bit easier if I’m also learning about what it was like at the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Encouraging patients to talk more can be risky. No physician, not even allergists, can afford to be waylaid by a retiree with nothing else to do today. But meaningful encounters can not only be a vaccine against burnout, they also lead to better patient adherence and satisfaction. Sometimes, there is simply not time. But often there is a little window during a procedure or when you’re reasonably caught up and don’t expect delays ahead. And like every story, they literally transform us, the listener. In a true physical sense, their stories live on in me, and now that I’ve shared this one in writing, also with you for perpetuity. That is at least for the next 5 billion years when it, too, will be swallowed by the sun, leaving only a crispy, smoking rock where we once existed.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Noise in medicine

A 26-year-old woman who reports a history of acyclovir-resistant herpes complains of a recurring, stinging rash around her mouth. Topical tacrolimus made it worse, she said. On exam, she has somewhat grouped pustules on her cutaneous lip. I mentioned her to colleagues, saying: “I’ve a patient with acyclovir-resistant herpes who isn’t improving on high-dose Valtrex.” They proffered a few alternative diagnoses and treatment recommendations. I tried several to no avail.

(it is after all only one condition). Nobel Prize–winning economist Daniel Kahneman, PhD, with two other authors, has written a brilliant book about this cognitive unreliability called “Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment” (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2021).

Both bias and noise create trouble for us. Although biases get more attention, noise is both more prevalent and insidious. In a 2016 article, Dr. Kahneman and coauthors use a bathroom scale as an analogy to explain the difference. “We would say that the scale is biased if its readings are generally either too high or too low. A scale that consistently underestimates true weight by exactly 4 pounds is seriously biased but free of noise. A scale that gives two different readings when you step on it twice is noisy.” In the case presented, “measurements” by me and my colleagues were returning different “readings.” There is one true diagnosis and best treatment, yet because of noise, we waste time and resources by not getting it right the first time.

There is also evidence of bias in this case. For example, there’s probably some confirmation bias: The patient said she has a history of antiviral-resistant herpes; therefore, her rash might appear to be herpes. Also there might be salience bias: it’s easy to see how prominent pustules might be herpes simplex virus. Noise is an issue in many misdiagnoses, but trickier to see. In most instances, we don’t have the opportunity to get multiple assessments of the same case. When examined though, interrater reliability in medicine is often found to be shockingly low, an indication of how much noise there is in our clinical judgments. This leads to waste, frustration – and can even be dangerous when we’re trying to diagnose cancers such as melanoma, lung, or breast cancer.