User login

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - August 2017

BY AYAN KUSARI AND CATALINA MATIZ, MD

The patient was diagnosed with eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHC). Treatment with a keratolytic, such as 12% lactic acid cream, was recommended. Hydrocortisone 2.5% once daily as needed also was recommended to treat the patient’s itch.

EVHC are benign middermal cysts characterized by epidermoid keratinization of the cyst wall, as well as lamellar keratin and vellus hairs within the cyst.1 The term “eruptive vellus hair cysts” was first used to describe a longstanding hyperpigmented, monomorphous papular eruption in two children by Esterly, Fretzin, and Pinkus in 1977.2 Clinically, EVHC present as 1- to 3-mm follicular, dome-shaped papules that are often skin-colored but also have been described as being brown, gray, green or black colored.3,4 They appear suddenly and sometimes are associated with mild tenderness and pruritus.1,5 EVHC most commonly present on the anterior chest but also can present on the upper and lower extremities, face, neck, axillae, and buttocks.4

Furthermore, although spontaneous resolution is possible through transepidermal elimination of cyst products, cases may persist for years in the absence of treatment.1

Accurate diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts is important to guide therapy.

Keratosis pilaris consists of follicular-based papules with variable erythema.4 It may be widespread – including over the anterior chest – but is most commonly seen on the cheeks, extensor surfaces of proximal upper extremities, and the anterior thighs.4 It is related to excessive keratinization, which leads to formation of horny plugs within hair-follicle orifices.1

Steatocystoma multiplex is typically characterized by firm, yellow-to-flesh–colored dermal cysts ranging from a few millimeters to 1 cm in size.1 They are sometimes clinically hard to distinguish from EVHC, and both are associated with keratin 17 gene mutations and type 2 pachyonychia congenita.1 Nonetheless, this patient’s lesions did not have any features – such as size or drainage – that would point toward steatocystoma multiplex or other skin findings suggestive of pachyonychia congenita.

Superficial folliculitis, also known as Bockhart’s impetigo, is an infection of the follicular ostium and typically presents with perifollicular pustules on an erythematous base that may be painful or pruritic and can occur throughout the corpus, including the anterior trunk.1

Acne vulgaris is a very common disease that involves the pilosebaceous unit and occurs most frequently on the face, back, upper arms, and chest. However, it is characterized by open and closed comedones, papules, and pustules and, in severe cases, nodules and cysts that may leave postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring. Tiny, hyperpigmented, dome-shaped macules occurring exclusively on the chest would not be characteristic.

Patients with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, also known as Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome, can present with EVHC. This condition is characterized by a triad of fair, sparse short hair; hyperthermia related to decreased sweating; and missing teeth.4 Although EVHC have been reported in association with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, this patient does not have any of the dysmorphic features associated with this syndrome.11

Patients with pachyonychia congenita (type 2) also may have EVHC as part of their presentation, but this patient does not have nail dystrophy, focal palmoplantar keratoderma, follicular keratoses, or multiple steatocysts which also are features of this condition.4

Treatment may be offered to patients who are distressed by the lesions or seek cosmesis. A 2012 review of 220 cases of EVHC found that topical retinoic acid, incision/excision, CO2 laser, erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser, needle evacuation, dermabrasion, and 10% urea cream were each associated with successful treatment in multiple cases.3

Forty years have passed since EVHC was identified as a distinct disease entity. Despite this, eruptive vellus hair cysts remains somewhat understudied, and further research is needed to determine an ideal treatment algorithm for patients with this condition. Our approach was to attempt noninvasive keratolytic therapy before considering retinoids or surgical options; we also recommended steroid treatment for symptom relief. Providers should keep EVHC in the differential for eruptions consisting of tiny papules so that appropriate treatment may be offered.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and an assistant clinical professor in the department of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego. Mr. Kusari is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Kusari said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. “Dermatology.” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders, 2012).

2. Arch Dermatol. 1977 Apr;113(4):500-3.

3. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Feb 1;13(1):19-28.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013 Jul;4(3):213-5.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980 Oct;3(4):425-9.

7. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997 Jun;19(3):250-3.

8. Hum Mol Genet. 1998 Jul;7(7):1143-8.

9. Dermatology. 1998;196(4):392-6.

BY AYAN KUSARI AND CATALINA MATIZ, MD

The patient was diagnosed with eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHC). Treatment with a keratolytic, such as 12% lactic acid cream, was recommended. Hydrocortisone 2.5% once daily as needed also was recommended to treat the patient’s itch.

EVHC are benign middermal cysts characterized by epidermoid keratinization of the cyst wall, as well as lamellar keratin and vellus hairs within the cyst.1 The term “eruptive vellus hair cysts” was first used to describe a longstanding hyperpigmented, monomorphous papular eruption in two children by Esterly, Fretzin, and Pinkus in 1977.2 Clinically, EVHC present as 1- to 3-mm follicular, dome-shaped papules that are often skin-colored but also have been described as being brown, gray, green or black colored.3,4 They appear suddenly and sometimes are associated with mild tenderness and pruritus.1,5 EVHC most commonly present on the anterior chest but also can present on the upper and lower extremities, face, neck, axillae, and buttocks.4

Furthermore, although spontaneous resolution is possible through transepidermal elimination of cyst products, cases may persist for years in the absence of treatment.1

Accurate diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts is important to guide therapy.

Keratosis pilaris consists of follicular-based papules with variable erythema.4 It may be widespread – including over the anterior chest – but is most commonly seen on the cheeks, extensor surfaces of proximal upper extremities, and the anterior thighs.4 It is related to excessive keratinization, which leads to formation of horny plugs within hair-follicle orifices.1

Steatocystoma multiplex is typically characterized by firm, yellow-to-flesh–colored dermal cysts ranging from a few millimeters to 1 cm in size.1 They are sometimes clinically hard to distinguish from EVHC, and both are associated with keratin 17 gene mutations and type 2 pachyonychia congenita.1 Nonetheless, this patient’s lesions did not have any features – such as size or drainage – that would point toward steatocystoma multiplex or other skin findings suggestive of pachyonychia congenita.

Superficial folliculitis, also known as Bockhart’s impetigo, is an infection of the follicular ostium and typically presents with perifollicular pustules on an erythematous base that may be painful or pruritic and can occur throughout the corpus, including the anterior trunk.1

Acne vulgaris is a very common disease that involves the pilosebaceous unit and occurs most frequently on the face, back, upper arms, and chest. However, it is characterized by open and closed comedones, papules, and pustules and, in severe cases, nodules and cysts that may leave postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring. Tiny, hyperpigmented, dome-shaped macules occurring exclusively on the chest would not be characteristic.

Patients with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, also known as Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome, can present with EVHC. This condition is characterized by a triad of fair, sparse short hair; hyperthermia related to decreased sweating; and missing teeth.4 Although EVHC have been reported in association with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, this patient does not have any of the dysmorphic features associated with this syndrome.11

Patients with pachyonychia congenita (type 2) also may have EVHC as part of their presentation, but this patient does not have nail dystrophy, focal palmoplantar keratoderma, follicular keratoses, or multiple steatocysts which also are features of this condition.4

Treatment may be offered to patients who are distressed by the lesions or seek cosmesis. A 2012 review of 220 cases of EVHC found that topical retinoic acid, incision/excision, CO2 laser, erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser, needle evacuation, dermabrasion, and 10% urea cream were each associated with successful treatment in multiple cases.3

Forty years have passed since EVHC was identified as a distinct disease entity. Despite this, eruptive vellus hair cysts remains somewhat understudied, and further research is needed to determine an ideal treatment algorithm for patients with this condition. Our approach was to attempt noninvasive keratolytic therapy before considering retinoids or surgical options; we also recommended steroid treatment for symptom relief. Providers should keep EVHC in the differential for eruptions consisting of tiny papules so that appropriate treatment may be offered.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and an assistant clinical professor in the department of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego. Mr. Kusari is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Kusari said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. “Dermatology.” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders, 2012).

2. Arch Dermatol. 1977 Apr;113(4):500-3.

3. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Feb 1;13(1):19-28.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013 Jul;4(3):213-5.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980 Oct;3(4):425-9.

7. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997 Jun;19(3):250-3.

8. Hum Mol Genet. 1998 Jul;7(7):1143-8.

9. Dermatology. 1998;196(4):392-6.

BY AYAN KUSARI AND CATALINA MATIZ, MD

The patient was diagnosed with eruptive vellus hair cysts (EVHC). Treatment with a keratolytic, such as 12% lactic acid cream, was recommended. Hydrocortisone 2.5% once daily as needed also was recommended to treat the patient’s itch.

EVHC are benign middermal cysts characterized by epidermoid keratinization of the cyst wall, as well as lamellar keratin and vellus hairs within the cyst.1 The term “eruptive vellus hair cysts” was first used to describe a longstanding hyperpigmented, monomorphous papular eruption in two children by Esterly, Fretzin, and Pinkus in 1977.2 Clinically, EVHC present as 1- to 3-mm follicular, dome-shaped papules that are often skin-colored but also have been described as being brown, gray, green or black colored.3,4 They appear suddenly and sometimes are associated with mild tenderness and pruritus.1,5 EVHC most commonly present on the anterior chest but also can present on the upper and lower extremities, face, neck, axillae, and buttocks.4

Furthermore, although spontaneous resolution is possible through transepidermal elimination of cyst products, cases may persist for years in the absence of treatment.1

Accurate diagnosis of eruptive vellus hair cysts is important to guide therapy.

Keratosis pilaris consists of follicular-based papules with variable erythema.4 It may be widespread – including over the anterior chest – but is most commonly seen on the cheeks, extensor surfaces of proximal upper extremities, and the anterior thighs.4 It is related to excessive keratinization, which leads to formation of horny plugs within hair-follicle orifices.1

Steatocystoma multiplex is typically characterized by firm, yellow-to-flesh–colored dermal cysts ranging from a few millimeters to 1 cm in size.1 They are sometimes clinically hard to distinguish from EVHC, and both are associated with keratin 17 gene mutations and type 2 pachyonychia congenita.1 Nonetheless, this patient’s lesions did not have any features – such as size or drainage – that would point toward steatocystoma multiplex or other skin findings suggestive of pachyonychia congenita.

Superficial folliculitis, also known as Bockhart’s impetigo, is an infection of the follicular ostium and typically presents with perifollicular pustules on an erythematous base that may be painful or pruritic and can occur throughout the corpus, including the anterior trunk.1

Acne vulgaris is a very common disease that involves the pilosebaceous unit and occurs most frequently on the face, back, upper arms, and chest. However, it is characterized by open and closed comedones, papules, and pustules and, in severe cases, nodules and cysts that may leave postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring. Tiny, hyperpigmented, dome-shaped macules occurring exclusively on the chest would not be characteristic.

Patients with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, also known as Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome, can present with EVHC. This condition is characterized by a triad of fair, sparse short hair; hyperthermia related to decreased sweating; and missing teeth.4 Although EVHC have been reported in association with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, this patient does not have any of the dysmorphic features associated with this syndrome.11

Patients with pachyonychia congenita (type 2) also may have EVHC as part of their presentation, but this patient does not have nail dystrophy, focal palmoplantar keratoderma, follicular keratoses, or multiple steatocysts which also are features of this condition.4

Treatment may be offered to patients who are distressed by the lesions or seek cosmesis. A 2012 review of 220 cases of EVHC found that topical retinoic acid, incision/excision, CO2 laser, erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser, needle evacuation, dermabrasion, and 10% urea cream were each associated with successful treatment in multiple cases.3

Forty years have passed since EVHC was identified as a distinct disease entity. Despite this, eruptive vellus hair cysts remains somewhat understudied, and further research is needed to determine an ideal treatment algorithm for patients with this condition. Our approach was to attempt noninvasive keratolytic therapy before considering retinoids or surgical options; we also recommended steroid treatment for symptom relief. Providers should keep EVHC in the differential for eruptions consisting of tiny papules so that appropriate treatment may be offered.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and an assistant clinical professor in the department of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at the University of California, San Diego. Mr. Kusari is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Kusari said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. “Dermatology.” 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders, 2012).

2. Arch Dermatol. 1977 Apr;113(4):500-3.

3. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Feb 1;13(1):19-28.

5. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013 Jul;4(3):213-5.

6. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980 Oct;3(4):425-9.

7. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997 Jun;19(3):250-3.

8. Hum Mol Genet. 1998 Jul;7(7):1143-8.

9. Dermatology. 1998;196(4):392-6.

A 6-year-old boy presents with bumps on his chest and lower abdomen that have been present for 6 months. The patient’s mother states that the bumps are occasionally pruritic but not painful. She reports that the bumps first appeared on the chest and subsequently spread downward to involve the upper abdomen.

The patient is otherwise healthy. No similar lesions are present beyond the trunk. The patient’s past medical history and developmental history are unremarkable aside from bilateral amblyopia and high myopia. The patient’s mother denies any other family members with similar lesions. There is no history of teeth or nail abnormalities.

On exam, you find symmetrically distributed, firm, nontender, tiny 1- to 2-mm hyperpigmented dome-shaped papules on the anterior chest with no similar lesions elsewhere on the body. The remainder of the physical exam discloses no abnormalities.

Florence A. Blanchfield: A Lifetime of Nursing Leadership

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

The U.S. Army hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, was named for army nurse, Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield—making it the only current army hospital named for a nurse.

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born into a large family in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in 1882. Her mother was a nurse, and her father was a mason and stonecutter. She grew up in Oranda, Virginia, and attended both public and private schools. Following in her mother’s footsteps to become a nurse, she attended Southside Hospital Training School in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated in 1906. She moved to Baltimore after graduation and worked with Howard Atwood Kelly, one of the “Big Four” along with William Osler, William Henry Welch, and William Stewart Halsted who were known as the founding physicians of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

After what must have been a remarkable experience with the innovative Kelly (inventor of many groundbreaking medical instruments and procedures, including the Kelly clamp), Blanchfield returned to Pittsburgh. She held positions of increasing responsibility over several years, including operating room supervisor at Southside Hospital and Montefiore Hospital and superintendent of the training school at Suburban General Hospital. Looking for adventure as well as service, she gave up her positions of leadership and headed to Panama in 1913 to become an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at Ancon Hospital in the U.S. Canal Zone.

As America prepared for its probable entry into World War I, Blanchfield joined the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) at age 35 to serve with the Medical School Unit of the University of Pittsburgh’s Base Hospital 27. She arrived in France in October 1917 and became acting chief nurse of Base Hospital 27 in Angers, Maine et Loire department. She also served as acting chief nurse of Camp Hospital 15 at Coëtquidan, Ille et Vil department.

Blanchfield returned to civilian life following World War I for a short period but returned to active duty in 1920. Over the next 15 years, she had several assignments within the continental U.S. and overseas in the Philippines and in Tianjin, China (formally known in English as Tientsin). In 1935, Blanchfield joined the Office of the Army Surgeon General in Washington, DC, where she was assigned to work on personnel matters in the office of the superintendent of the ANC. She became assistant superintendent in 1939, acting superintendent in 1942, and served as superintendent from June 1943 until September 1947. During World War II, she presided over the growth of the ANC from about 7,000 nurses on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked to more than 50,000 by the end of the war. She was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for her contributions and accomplishments during World War II.

Blanchfield, a long-time senior leader in the ANC, was instrumental in many of the significant changes that took place during and after World War II, including nurses gaining full rank and benefits. This was an incremental process that culminated with passage of the Army and Navy Nurse Corps Act of April 1947, with nurses being granted full commissioned status. As a result of this act, she became a lieutenant colonel and the first woman to receive a commission in the regular army.

Blanchfield remained active in national nursing affairs after her retirement from the U.S. Army. At a time when many believed that nurses did not need specialty training, she promoted the establishment of specialized courses of study. In 1951, she received the Florence Nightingale Medal of the International Red Cross.

Blanchfield died on May 12, 1971, and was buried in the nurse’s section of Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to memorialize Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. A successful letter writing campaign by army nurses inundated the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, which was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at fedprac@frontlinemedcom.com or on Facebook.

An ASCO 2017 recap: significant advances continue

As we head into vacation season and the dog days of summer, let’s reflect for a few minutes on some of the very important advances we heard about at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago. Nearly 40,000 individuals registered for the conference, an indication of both the interest and the excitement around the new agents and the emerging clinical trial data. Scientific sessions dedicated to the use of combination immunotherapy, the role of antibody drug conjugates, and targeting molecular aberrations with small molecules were among the most popular (p. e236).

In the setting of metastatic breast cancer, several trials produced highly significant results that will positively affect the duration and quality of life for our patients. The use of PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutated cancers has been shown to be effective in a few areas, particularly advanced ovarian cancer. The OlympiAD study evaluated olaparib monotherapy and a physician’s choice arm (capecitabine, eribulin, or vinorelbine) in BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. The 2:1 design enrolled 302 patients and demonstrated a 3-month improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) for olaparib compared with the control arm (7.0 vs 4.2 months, respectively; P = .0009). The patient population for this BRCA-mutated trial was relatively young, with a median age of 45 years, and 50% of the women were hormone positive and 30%, platinum resistant.

The CDK4/6 inhibitors continue to be impressive, with the recently reported results from the MONARCH 2 trial showing encouraging PFS and overall response rate results with the addition of the CDK4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib to fulvestrant, a selective estrogen-receptor degrader. In this study, hormone-positive, HER2-negative women who had progressed on previous endocrine therapy were randomized 2:1 to abemaciclib plus fulvestrant or placebo plus fulvestrant. A total of 669 patients were accrued, and after a median follow-up of 19 months, a highly significant PFS difference of 7 months between the abemaciclib–fulvestrant and fulvestrant–only groups was observed (16.4 vs 9.3 months, respectively; P < .0000001) along with an overall response rate of 48.1 months, compared with 21.3 months. Previous findings have demonstrated monotherapy activity for abemaciclib, and the comparisons with palbociclib and ribociclib will be forthcoming, although no comparative trials are underway. These agents will be extensively assessed in a variety of settings, including adjuvantly.

The results of the much anticipated APHINITY study, which evaluated the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab in the adjuvant HER2-positive setting, were met with mixed reviews. Patients were included if they had node-positive invasive breast cancer or node-negative tumors of >1.0 cm. A total of 4,804 patients (37% node negative) were enrolled in the study. The intent-to-treat primary endpoint of invasive disease-free survival (DFS) was statistically positive (P = .045), although the 3-year absolute percentages for the pertuzumab–trastuzumab and trastuzumab-only groups were 94.1% and 93.2%, respectively. It should be noted that the planned statistical assumption was for a delta of 2.6% – 91.8% and 89.2%, respectively. Thus, both arms actually did better than had been planned, which was based on historical comparisons, and the node-positive and hormone-negative subgroups trended toward a greater benefit with the addition of pertuzumab. There was, and will continue to be, much debate around the cost–benefit ratio and which patients should be offered the combination. The outstanding results with the addition of pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting will continue to be the setting in which the greatest absolute clinical benefit will be seen. It is unusual in this era to see trials this large planned to identify a small difference, and it is likely that resource constraints will make such studies a thing of the past.

The very active hormonal therapies, abiraterone and enzalutimide, for castrate-resistant prostate cancer remain of high interest in the area of clinical trials. The LATITUDE study evaluated a straightforward design that compared abiraterone with placebo in patients who were newly diagnosed with high-risk, metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancer. Patients in both arms received androgen-deprivation therapy and high risk was defined by having 2 of 3 criteria: a Gleason score of ≥8; 3 or more bone lesions; or visceral disease. Of note is that 1,199 patients were enrolled before publication of the CHAARTED or STAMPEDE results, which established docetaxel as a standard for these patients. The median age in the LATITUDE trial was 68 years, with 17% of patients having visceral disease and 48% having nodal disease, making it a similar patient population to those in the docetaxel studies. The results favoring abiraterone were strikingly positive, with a 38% reduction in the risk of death (P < .0001) and a 53% reduction in the risk of radiographic progression or death (P < .0001). The regimen was well tolerated overall, and it is clear that this option will be widely considered by physicians and their patients.

Two studies addressing the importance of managing symptoms and improving outcomes were also part of the plenary session. The IDEA Collaboration conducted a prospective pooled analysis of 6 phase 3 studies that assessed 3 and 6 months of oxaliplatin-based regimens for stage 3 colon cancer. FOLFOX and CAPOX given to 12,834 patients in 6 studies from the United States, European Union, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan were evaluated for DFS, treatment compliance, and adverse events. As would be anticipated, fewer side effects, particularly neurotoxicity, and greater compliance were observed in the 3-month group. Although DFS noninferiority for 3 months of therapy was not established statistically, the overall data led the investigators to issue a consensus statement advocating for a risk-based approach in deciding the duration of therapy and recommending 3 months of therapy for patients with stage 3, T1-3N1 disease, and consideration of 6 months therapy for T4 and/ or N2 disease. The investigators also acknowledged the leader and creator of IDEA, the late Daniel Sargent, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic, who passed away far too young after a brief illness last fall (1970-2016).

The second symptom-based study was performed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York and designed by a group of investigators from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston; the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota; the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill; and MSKCC (p. e236). The hypothesis was simply that proactive symptom monitoring during chemotherapy would improve symptom management and lead to better outcomes. For the study, 766 patients with advanced solid tumors who were receiving outpatient chemotherapy were randomized to a control arm with standard follow-up or to the intervention arm, on which patients self-reported on 12 common symptoms before and between visits using a web-based tool and received weekly e-mail reminders and nursing alerts. At 6 months, and compared with baseline, the self-reporting patients in the intervention arm experienced an improved quality of life (P < .001). In addition, 7% fewer of the self-reporting patients visited the emergency department (P = .02), and they experienced longer survival by 5 months compared with the standard follow-up group (31.2 vs 26.0 months, respectively; P = .03). Although there are limitations to such a study, the growth in technological advances should create the opportunity to expand on this strategy in further trials and in practice. With such an emphasis in the Medicare Oncology Home Model on decreasing hospital admissions and visits to the emergency department, there should great motivation for all involved to consider incorporating self-reporting into their patterns of care.

A continued emphasis on molecular profiling, personalized and/or precision medicine, and identifying or matching the patient to the best possible therapy or the most appropriate clinical trial remains vital to improving outcomes. Just before the ASCO meeting, the US Food and Drug Administration approved pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and mismatch-repair deficient (dMMR) cancers, regardless of the site of origin. The approval was based on data from 149 patients with MSI-H or dMMR cancers, which showed a 40% response rate in this group of patients, two-thirds of whom had previously treated colon cancer. This landmark approval of a cancer therapy for a specific molecular profile and not the site of the disease, will certainly shape the future of oncology drug development. One of the highlighted stories at ASCO was the success of the larotrectinib (LOXO 101) tropomyosin receptor kinase inhibitor in patients with the TRK fusion mutations (p. e237). The data, including waterfall charts, swimmer plots, and computed-tomography scans, were impressive in this targeted population with a 76% response rate and a 91% duration of response at 6 months with a mild side effect profile.

In summary, across a variety of cancers, with treatment strategies of an equally diverse nature, we saw practice-changing data from the ASCO meeting that will benefit our patients. Continuing to seek out clinical trial options for patients will be critical in answering the many questions that have emerged and the substantial number of studies that are ongoing with combination immunotherapies, targeted small molecules, and a growing armamentarium of monoclonal antibodies.

As we head into vacation season and the dog days of summer, let’s reflect for a few minutes on some of the very important advances we heard about at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago. Nearly 40,000 individuals registered for the conference, an indication of both the interest and the excitement around the new agents and the emerging clinical trial data. Scientific sessions dedicated to the use of combination immunotherapy, the role of antibody drug conjugates, and targeting molecular aberrations with small molecules were among the most popular (p. e236).

In the setting of metastatic breast cancer, several trials produced highly significant results that will positively affect the duration and quality of life for our patients. The use of PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutated cancers has been shown to be effective in a few areas, particularly advanced ovarian cancer. The OlympiAD study evaluated olaparib monotherapy and a physician’s choice arm (capecitabine, eribulin, or vinorelbine) in BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. The 2:1 design enrolled 302 patients and demonstrated a 3-month improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) for olaparib compared with the control arm (7.0 vs 4.2 months, respectively; P = .0009). The patient population for this BRCA-mutated trial was relatively young, with a median age of 45 years, and 50% of the women were hormone positive and 30%, platinum resistant.

The CDK4/6 inhibitors continue to be impressive, with the recently reported results from the MONARCH 2 trial showing encouraging PFS and overall response rate results with the addition of the CDK4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib to fulvestrant, a selective estrogen-receptor degrader. In this study, hormone-positive, HER2-negative women who had progressed on previous endocrine therapy were randomized 2:1 to abemaciclib plus fulvestrant or placebo plus fulvestrant. A total of 669 patients were accrued, and after a median follow-up of 19 months, a highly significant PFS difference of 7 months between the abemaciclib–fulvestrant and fulvestrant–only groups was observed (16.4 vs 9.3 months, respectively; P < .0000001) along with an overall response rate of 48.1 months, compared with 21.3 months. Previous findings have demonstrated monotherapy activity for abemaciclib, and the comparisons with palbociclib and ribociclib will be forthcoming, although no comparative trials are underway. These agents will be extensively assessed in a variety of settings, including adjuvantly.

The results of the much anticipated APHINITY study, which evaluated the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab in the adjuvant HER2-positive setting, were met with mixed reviews. Patients were included if they had node-positive invasive breast cancer or node-negative tumors of >1.0 cm. A total of 4,804 patients (37% node negative) were enrolled in the study. The intent-to-treat primary endpoint of invasive disease-free survival (DFS) was statistically positive (P = .045), although the 3-year absolute percentages for the pertuzumab–trastuzumab and trastuzumab-only groups were 94.1% and 93.2%, respectively. It should be noted that the planned statistical assumption was for a delta of 2.6% – 91.8% and 89.2%, respectively. Thus, both arms actually did better than had been planned, which was based on historical comparisons, and the node-positive and hormone-negative subgroups trended toward a greater benefit with the addition of pertuzumab. There was, and will continue to be, much debate around the cost–benefit ratio and which patients should be offered the combination. The outstanding results with the addition of pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting will continue to be the setting in which the greatest absolute clinical benefit will be seen. It is unusual in this era to see trials this large planned to identify a small difference, and it is likely that resource constraints will make such studies a thing of the past.

The very active hormonal therapies, abiraterone and enzalutimide, for castrate-resistant prostate cancer remain of high interest in the area of clinical trials. The LATITUDE study evaluated a straightforward design that compared abiraterone with placebo in patients who were newly diagnosed with high-risk, metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancer. Patients in both arms received androgen-deprivation therapy and high risk was defined by having 2 of 3 criteria: a Gleason score of ≥8; 3 or more bone lesions; or visceral disease. Of note is that 1,199 patients were enrolled before publication of the CHAARTED or STAMPEDE results, which established docetaxel as a standard for these patients. The median age in the LATITUDE trial was 68 years, with 17% of patients having visceral disease and 48% having nodal disease, making it a similar patient population to those in the docetaxel studies. The results favoring abiraterone were strikingly positive, with a 38% reduction in the risk of death (P < .0001) and a 53% reduction in the risk of radiographic progression or death (P < .0001). The regimen was well tolerated overall, and it is clear that this option will be widely considered by physicians and their patients.

Two studies addressing the importance of managing symptoms and improving outcomes were also part of the plenary session. The IDEA Collaboration conducted a prospective pooled analysis of 6 phase 3 studies that assessed 3 and 6 months of oxaliplatin-based regimens for stage 3 colon cancer. FOLFOX and CAPOX given to 12,834 patients in 6 studies from the United States, European Union, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan were evaluated for DFS, treatment compliance, and adverse events. As would be anticipated, fewer side effects, particularly neurotoxicity, and greater compliance were observed in the 3-month group. Although DFS noninferiority for 3 months of therapy was not established statistically, the overall data led the investigators to issue a consensus statement advocating for a risk-based approach in deciding the duration of therapy and recommending 3 months of therapy for patients with stage 3, T1-3N1 disease, and consideration of 6 months therapy for T4 and/ or N2 disease. The investigators also acknowledged the leader and creator of IDEA, the late Daniel Sargent, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic, who passed away far too young after a brief illness last fall (1970-2016).

The second symptom-based study was performed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York and designed by a group of investigators from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston; the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota; the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill; and MSKCC (p. e236). The hypothesis was simply that proactive symptom monitoring during chemotherapy would improve symptom management and lead to better outcomes. For the study, 766 patients with advanced solid tumors who were receiving outpatient chemotherapy were randomized to a control arm with standard follow-up or to the intervention arm, on which patients self-reported on 12 common symptoms before and between visits using a web-based tool and received weekly e-mail reminders and nursing alerts. At 6 months, and compared with baseline, the self-reporting patients in the intervention arm experienced an improved quality of life (P < .001). In addition, 7% fewer of the self-reporting patients visited the emergency department (P = .02), and they experienced longer survival by 5 months compared with the standard follow-up group (31.2 vs 26.0 months, respectively; P = .03). Although there are limitations to such a study, the growth in technological advances should create the opportunity to expand on this strategy in further trials and in practice. With such an emphasis in the Medicare Oncology Home Model on decreasing hospital admissions and visits to the emergency department, there should great motivation for all involved to consider incorporating self-reporting into their patterns of care.

A continued emphasis on molecular profiling, personalized and/or precision medicine, and identifying or matching the patient to the best possible therapy or the most appropriate clinical trial remains vital to improving outcomes. Just before the ASCO meeting, the US Food and Drug Administration approved pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and mismatch-repair deficient (dMMR) cancers, regardless of the site of origin. The approval was based on data from 149 patients with MSI-H or dMMR cancers, which showed a 40% response rate in this group of patients, two-thirds of whom had previously treated colon cancer. This landmark approval of a cancer therapy for a specific molecular profile and not the site of the disease, will certainly shape the future of oncology drug development. One of the highlighted stories at ASCO was the success of the larotrectinib (LOXO 101) tropomyosin receptor kinase inhibitor in patients with the TRK fusion mutations (p. e237). The data, including waterfall charts, swimmer plots, and computed-tomography scans, were impressive in this targeted population with a 76% response rate and a 91% duration of response at 6 months with a mild side effect profile.

In summary, across a variety of cancers, with treatment strategies of an equally diverse nature, we saw practice-changing data from the ASCO meeting that will benefit our patients. Continuing to seek out clinical trial options for patients will be critical in answering the many questions that have emerged and the substantial number of studies that are ongoing with combination immunotherapies, targeted small molecules, and a growing armamentarium of monoclonal antibodies.

As we head into vacation season and the dog days of summer, let’s reflect for a few minutes on some of the very important advances we heard about at this year’s annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago. Nearly 40,000 individuals registered for the conference, an indication of both the interest and the excitement around the new agents and the emerging clinical trial data. Scientific sessions dedicated to the use of combination immunotherapy, the role of antibody drug conjugates, and targeting molecular aberrations with small molecules were among the most popular (p. e236).

In the setting of metastatic breast cancer, several trials produced highly significant results that will positively affect the duration and quality of life for our patients. The use of PARP inhibitors in BRCA-mutated cancers has been shown to be effective in a few areas, particularly advanced ovarian cancer. The OlympiAD study evaluated olaparib monotherapy and a physician’s choice arm (capecitabine, eribulin, or vinorelbine) in BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. The 2:1 design enrolled 302 patients and demonstrated a 3-month improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) for olaparib compared with the control arm (7.0 vs 4.2 months, respectively; P = .0009). The patient population for this BRCA-mutated trial was relatively young, with a median age of 45 years, and 50% of the women were hormone positive and 30%, platinum resistant.

The CDK4/6 inhibitors continue to be impressive, with the recently reported results from the MONARCH 2 trial showing encouraging PFS and overall response rate results with the addition of the CDK4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib to fulvestrant, a selective estrogen-receptor degrader. In this study, hormone-positive, HER2-negative women who had progressed on previous endocrine therapy were randomized 2:1 to abemaciclib plus fulvestrant or placebo plus fulvestrant. A total of 669 patients were accrued, and after a median follow-up of 19 months, a highly significant PFS difference of 7 months between the abemaciclib–fulvestrant and fulvestrant–only groups was observed (16.4 vs 9.3 months, respectively; P < .0000001) along with an overall response rate of 48.1 months, compared with 21.3 months. Previous findings have demonstrated monotherapy activity for abemaciclib, and the comparisons with palbociclib and ribociclib will be forthcoming, although no comparative trials are underway. These agents will be extensively assessed in a variety of settings, including adjuvantly.

The results of the much anticipated APHINITY study, which evaluated the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab in the adjuvant HER2-positive setting, were met with mixed reviews. Patients were included if they had node-positive invasive breast cancer or node-negative tumors of >1.0 cm. A total of 4,804 patients (37% node negative) were enrolled in the study. The intent-to-treat primary endpoint of invasive disease-free survival (DFS) was statistically positive (P = .045), although the 3-year absolute percentages for the pertuzumab–trastuzumab and trastuzumab-only groups were 94.1% and 93.2%, respectively. It should be noted that the planned statistical assumption was for a delta of 2.6% – 91.8% and 89.2%, respectively. Thus, both arms actually did better than had been planned, which was based on historical comparisons, and the node-positive and hormone-negative subgroups trended toward a greater benefit with the addition of pertuzumab. There was, and will continue to be, much debate around the cost–benefit ratio and which patients should be offered the combination. The outstanding results with the addition of pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting will continue to be the setting in which the greatest absolute clinical benefit will be seen. It is unusual in this era to see trials this large planned to identify a small difference, and it is likely that resource constraints will make such studies a thing of the past.

The very active hormonal therapies, abiraterone and enzalutimide, for castrate-resistant prostate cancer remain of high interest in the area of clinical trials. The LATITUDE study evaluated a straightforward design that compared abiraterone with placebo in patients who were newly diagnosed with high-risk, metastatic hormone-naïve prostate cancer. Patients in both arms received androgen-deprivation therapy and high risk was defined by having 2 of 3 criteria: a Gleason score of ≥8; 3 or more bone lesions; or visceral disease. Of note is that 1,199 patients were enrolled before publication of the CHAARTED or STAMPEDE results, which established docetaxel as a standard for these patients. The median age in the LATITUDE trial was 68 years, with 17% of patients having visceral disease and 48% having nodal disease, making it a similar patient population to those in the docetaxel studies. The results favoring abiraterone were strikingly positive, with a 38% reduction in the risk of death (P < .0001) and a 53% reduction in the risk of radiographic progression or death (P < .0001). The regimen was well tolerated overall, and it is clear that this option will be widely considered by physicians and their patients.

Two studies addressing the importance of managing symptoms and improving outcomes were also part of the plenary session. The IDEA Collaboration conducted a prospective pooled analysis of 6 phase 3 studies that assessed 3 and 6 months of oxaliplatin-based regimens for stage 3 colon cancer. FOLFOX and CAPOX given to 12,834 patients in 6 studies from the United States, European Union, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan were evaluated for DFS, treatment compliance, and adverse events. As would be anticipated, fewer side effects, particularly neurotoxicity, and greater compliance were observed in the 3-month group. Although DFS noninferiority for 3 months of therapy was not established statistically, the overall data led the investigators to issue a consensus statement advocating for a risk-based approach in deciding the duration of therapy and recommending 3 months of therapy for patients with stage 3, T1-3N1 disease, and consideration of 6 months therapy for T4 and/ or N2 disease. The investigators also acknowledged the leader and creator of IDEA, the late Daniel Sargent, PhD, of the Mayo Clinic, who passed away far too young after a brief illness last fall (1970-2016).

The second symptom-based study was performed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York and designed by a group of investigators from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston; the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota; the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill; and MSKCC (p. e236). The hypothesis was simply that proactive symptom monitoring during chemotherapy would improve symptom management and lead to better outcomes. For the study, 766 patients with advanced solid tumors who were receiving outpatient chemotherapy were randomized to a control arm with standard follow-up or to the intervention arm, on which patients self-reported on 12 common symptoms before and between visits using a web-based tool and received weekly e-mail reminders and nursing alerts. At 6 months, and compared with baseline, the self-reporting patients in the intervention arm experienced an improved quality of life (P < .001). In addition, 7% fewer of the self-reporting patients visited the emergency department (P = .02), and they experienced longer survival by 5 months compared with the standard follow-up group (31.2 vs 26.0 months, respectively; P = .03). Although there are limitations to such a study, the growth in technological advances should create the opportunity to expand on this strategy in further trials and in practice. With such an emphasis in the Medicare Oncology Home Model on decreasing hospital admissions and visits to the emergency department, there should great motivation for all involved to consider incorporating self-reporting into their patterns of care.

A continued emphasis on molecular profiling, personalized and/or precision medicine, and identifying or matching the patient to the best possible therapy or the most appropriate clinical trial remains vital to improving outcomes. Just before the ASCO meeting, the US Food and Drug Administration approved pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients with high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and mismatch-repair deficient (dMMR) cancers, regardless of the site of origin. The approval was based on data from 149 patients with MSI-H or dMMR cancers, which showed a 40% response rate in this group of patients, two-thirds of whom had previously treated colon cancer. This landmark approval of a cancer therapy for a specific molecular profile and not the site of the disease, will certainly shape the future of oncology drug development. One of the highlighted stories at ASCO was the success of the larotrectinib (LOXO 101) tropomyosin receptor kinase inhibitor in patients with the TRK fusion mutations (p. e237). The data, including waterfall charts, swimmer plots, and computed-tomography scans, were impressive in this targeted population with a 76% response rate and a 91% duration of response at 6 months with a mild side effect profile.

In summary, across a variety of cancers, with treatment strategies of an equally diverse nature, we saw practice-changing data from the ASCO meeting that will benefit our patients. Continuing to seek out clinical trial options for patients will be critical in answering the many questions that have emerged and the substantial number of studies that are ongoing with combination immunotherapies, targeted small molecules, and a growing armamentarium of monoclonal antibodies.

Cartilage Restoration in the Patellofemoral Joint

Take-Home Points

- Careful evaluation is key in attributing knee pain to patellofemoral cartilage lesions-that is, in making a "diagnosis by exclusion".

- Initial treatment is nonoperative management focused on weight loss and extensive "core-to-floor" rehabilitation.

- Optimization of anatomy and biomechanics is crucial.

- Factors important in surgical decision-making incude defect location and size, subchondral bone status, unipolar vs bipolar lesions, and previous cartilage procedure.

- The most commonly used surgical procedures-autologous chondrocyte implantation, osteochondral autograft transfer, and osteochondral allograft-have demonstrated improved intermediate-term outcomes.

Patellofemoral (PF) pain is often a component of more general anterior knee pain. One source of PF pain is chondral lesions. As these lesions are commonly seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and during arthroscopy, it is necessary to differentiate incidental and symptomatic lesions.1 In addition, the correlation between symptoms and lesion presence and severity is poor.

PF pain is multifactorial (structural lesions, malalignment, deconditioning, muscle imbalance and overuse) and can coexist with other lesions in the knee (ligament tears, meniscal injuries, and cartilage lesions in other compartments). Therefore, careful evaluation is key in attributing knee pain to PF cartilage lesions—that is, in making a "diagnosis by exclusion."

From the start, it must be appreciated that the vast majority of patients will not require surgery, and many who require surgery for pain will not require cartilage restoration. One key to success with PF patients is a good working relationship with an experienced physical therapist.

Etiology

The primary causes of PF cartilage lesions are patellar instability, chronic maltracking without instability, direct trauma, repetitive microtrauma, and idiopathic.

Patellar Instability

Patients with patellar instability often present with underlying anatomical risk factors (eg, trochlear dysplasia, increased Q-angle/tibial tubercle-trochlear groove [TT-TG] distance, patella alta, and unbalanced medial and lateral soft tissues2). These factors should be addressed before surgery.

Patellar instability can cause cartilage damage during the dislocation event or by chronic subluxation. Cartilage becomes damaged in up to 96% of patellar dislocations.3 Most commonly, the damage consists of fissuring and/or fibrillation, but chondral and osteochondral fractures can occur as well. During dislocation, the medial patella strikes the lateral aspect of the femur, and, as the knee collapses into flexion, the lateral aspect of the proximal lateral femoral condyle (weight-bearing area) can sustain damage. In the patella, typically the injury is distal-medial (occasionally crossing the median ridge). A shear lesion may involve the chondral surface or be osteochondral (Figure 1A).

Chronic Maltracking Without Instability

Chronic maltracking is usually related to anatomical abnormalities, which include the same factors that can cause patellar instability. A common combination is trochlear dysplasia, increased TT-TG or TT-posterior cruciate ligament distance, and lateral soft-tissue contracture. These are often seen in PF joints that progress to lateral PF arthritis. As lateral PF arthritis progresses, lateral soft-tissue contracture worsens, compounding symptoms of laterally based pain. With respect to cartilage repair, these joints can be treated if recognized early; however, once osteoarthritis is fully established in the joint, facetectomy or PF replacement may be necessary.

Direct Trauma

With the knee in flexion during a direct trauma over the patella (eg, fall or dashboard trauma), all zones of cartilage and subchondral bone in both patella and trochlea can be injured, leading to macrostructural damage, chondral/osteochondral fracture, or, with a subcritical force, microstructural damage and chondrocyte death, subsequently causing cartilage degeneration (cartilage may look normal initially; the matrix takes months to years to deteriorate). Direct trauma usually occurs with the knee flexed. Therefore, these lesions typically are located in the distal trochlea and superior pole of the patella.

Repetitive Microtrauma

Minor injuries, which by themselves do not immediately cause apparent chondral or osteochondral fractures, may eventually exceed the capacity of natural cartilage homeostasis and result in repetitive microtrauma. Common causes are repeated jumping (as in basketball and volleyball) and prolonged flexed-knee position (eg, what a baseball catcher experiences), which may also be associated with other lesions caused by extensor apparatus overload (eg, quadriceps tendon or patellar tendon tendinitis, and fat pad impingement syndrome).

Idiopathic

In a subset of patients with osteochondritis dissecans, the patella is the lesion site. In another subset, idiopathic lesions may be related to a genetic predisposition to osteoarthritis and may not be restricted to the PF joint. In some cases, the PF joint is the first compartment to degenerate and is the most symptomatic in a setting of truly tricompartmental disease. In these cases, treating only the PF lesion can result in functional failure, owing to disease progression in other compartments. Even mild disease in other compartments should be carefully evaluated.

History and Physical Examination

Patients often report a history of anterior knee pain that worsens with stair use, prolonged sitting, and flexed-knee activities (eg, squatting). Compared with pain alone, swelling, though not specific to cartilage disease, is more suspicious for a cartilage etiology. Identifying the cartilage defect as the sole source of pain is particularly difficult in patients with recurrent patellar instability. In these patients, pain and swelling, even between instability episodes, suggest that cartilage damage is at least a component of the symptomology.

Important diagnostic components of physical examination are gait analysis, tibiofemoral alignment, and patellar alignment in all 3 planes, both static and functional. Patella-specific measurements include medial-lateral position and quadrants of excursion, lateral tilt, and patella alta, as well as J-sign and subluxation with quadriceps contraction in extension.

It is also important to document effusion; crepitus; active and passive range of motion (spine, hips, knees); site of pain or tenderness to palpation (medial, lateral, distal, retropatellar) and whether it matches the complaints and the location of the cartilage lesion; results of the grind test (placing downward force on the patella during flexion and extension) and whether they match the flexion angle of the tenderness and the flexion angle in which the cartilage lesion has increased PF contact; ligamentous and soft-tissue stability or imbalance (tibiofemoral and patellar; apprehension test, glide test, tilt test); and muscle strength, flexibility, and atrophy of the core (abdomen, dorsal and hip muscles) and lower extremities (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius).

Imaging

Imaging should be used to evaluate both PF alignment and the cartilage lesions. For alignment, standard radiographs (weight-bearing knee sequence and axial view; full limb length when needed), computed tomography, and MRI can be used.

Meaningful evaluation requires MRI with cartilage-specific sequences, including standard spin-echo (SE) and gradient-recalled echo (GRE), fast SE, and, for cartilage morphology, T2-weighted fat suppression (FS) and 3-dimensional SE and GRE.5 For evaluation of cartilage function and metabolism, the collagen network, and proteoglycan content in the knee cartilage matrix, consideration should be given to compositional assessment techniques, such as T2 mapping, delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage, T1ρ imaging, sodium imaging, and diffusion-weighted sequences.5 Use of the latter functional sequences is still debatable, and these sequences are not widely available.

Treatment

In general, the initial approach is nonoperative management focused on weight loss and extensive core-to-floor rehabilitation, unless surgery is specifically indicated (eg, for loose body removal or osteochondral fracture reattachment). Rehabilitation focuses on achieving adequate range of motion of the spine, hips, and knees along with muscle strength and flexibility of the core (abdomen, dorsal and hip muscles) and lower limbs (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius). Rehabilitation is not defined by time but rather by development of an optimized soft-tissue envelope that decreases joint reactive forces. The full process can take 6 to 9 months, but there should be some improvement by 3 months.

Corticosteroid, hyaluronic acid,6 or platelet-rich plasma7 injections can provide temporary relief and facilitate rehabilitation in the setting of pain inhibition. As stand-alone treatment, injections are more suitable for more diffuse degenerative lesions in older and low-demand patients than for focal traumatic lesions in young and high-demand patients.

Surgery is indicated for full-thickness or nearly full-thickness lesions (International Cartilage Repair Society grade 3a or higher) >1 cm2 after failed conservative treatment.

Optimization of anatomy and biomechanics is crucial, as persistent abnormalities lead to high rates of failure of cartilage procedures, and correction of those factors results in outcomes similar to those of patients without such abnormal anatomy.8 The procedures most commonly used to improve patellar tracking or unloading in the PF compartment are lateral retinacular lengthening and TT transfer: medialization and/or distalization for correction of malalignment, and straight anteriorization or anteromedialization for unloading. These procedures can improve symptoms and function in lateral and distal patellar and trochlear lesions even without the addition of a cartilage restoration procedure.

Factors that are important in surgical decision-making include defect location and size, subchondral bone status, unipolar vs bipolar lesions, and previous cartilage procedure.

Location. The shapes of the patella and trochlea vary much more than the shapes of the condyles and plateaus. This variability complicates morphology matching, particularly with involvement of the central TG and median patellar ridge. Therefore, focal contained lesions of the patella and trochlea may be more technically amenable to cell therapy techniques than to osteochondral procedures, which require contour matching between donor and recipient

Size. Although small lesions in the femoral condyles can be considered for microfracture (MFx) or osteochondral autograft transfer (OAT), MFx is less suitable because of poor results in the PF joint, and OAT because of donor-site morbidity in the trochlea.

Subchondral bone status. When subchondral bone is compromised, such as with bone loss, cysts, or significant bone edema, the entire osteochondral unit should be treated. Here, OAT and osteochondral allograft (OCA) are the preferred treatments, depending on lesion size.

Unipolar vs bipolar lesions. Compared with unipolar lesions, bipolar lesions tend to have worse outcomes. Therefore, an associated unloading procedure (TT osteotomy) should be given special consideration. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) appears to have better outcomes than OCA for bipolar PF lesions.9,10

Previous surgery. Although a failed cartilage procedure can negatively affect ACI outcomes, particularly in the presence of intralesional osteophytes,11 it does not affect OCA outcomes.12 Therefore, after previous MFx, OCA instead of ACI may be considered.

Fragment Fixation

Viable fragments from traumatic lesions (direct trauma or patellar dislocation) or osteochondritis dissecans should be repaired if possible, particularly in young patients. In a fragment that contains a substantial amount of bone, compression screws provide stable fixation. More recently, it has been recognized that fixation of predominantly cartilaginous fragments can be successful13 (Figure 1B). Débridement of soft tissue in the lesion bed and on the fragment is important in facilitating healing, as is removal of sclerotic bone.

MFx

Although MFx can have good outcomes in small contained femoral condyle lesions, in the PF joint treatment has been more challenging, and clinical outcomes have been poor (increased subchondral edema, increased effusion).14 In addition, deterioration becomes significant after 36 months. Therefore, MFx should be restricted to small (<2 cm2), well-contained trochlear defects, particularly in low-demand patients.

ACI and Matrix-Induced ACI

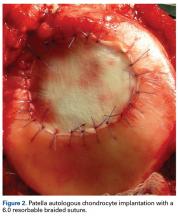

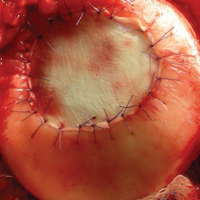

As stated, ACI (Figure 2) is suitable for PF joints because it intrinsically respects the complex anatomy.

OAT

As mentioned, donor-site morbidity may compromise final outcomes of harvest and implantation in the PF joint. Nonetheless, in carefully selected patients with small lesions that are limited to 1 facet (not including the patellar ridge or the TG) and that require only 1 plug (Figure 3), OAT can have good clinical results.16

OCA

Two techniques can be used with OCA in the PF joint. The dowel technique, in which circular plugs are implanted, is predominantly used for defects that do not cross the midline (those located in their entirety on the medial or lateral aspect of the patella or trochlea). Central defects, which can be treated with the dowel technique as well, are technically more challenging to match perfectly, because of the complex geometry of the median ridge and the TG (Figure 4).

Experimental and Emerging Technologies

Biocartilage

Biocartilage, a dehydrated, micronized allogeneic cartilage scaffold implanted with platelet-rich plasma and fibrin glue added over a contained MFx-treated defect, can be used in the patella and trochlea and has the same indications as MFx (small lesions, contained lesions). There are limited clinical studies of short- or long-term outcomes.

Fresh and Viable OCA

Fresh OCA (ProChondrix; AlloSource) and viable/cryopreserved OCA (Cartiform; Arthrex) are thin osteochondral scaffolds that contain viable chondrocytes and growth factors. They can be implanted alone or used with MFx, and are indicated for lesions measuring 1 cm2 to 3 cm2. Aside from a case report,17 there are no clinical studies on outcomes.

Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate Implantation

Bone marrow aspirate concentrate from centrifuged iliac crest–harvested aspirate containing mesenchymal stem cells with chondrogenic potential is applied under a synthetic scaffold. Indications are the same as for ACI. Medium-term follow-up studies in the PF joint have shown good results, similar to those obtained with matrix-induced ACI.18

Particulated Juvenile Allograft Cartilage

Particulated juvenile allograft cartilage (DeNovo NT Graft; Zimmer Biomet) is minced cartilage allograft (from juvenile donors) that has been cut into cubes (~1 mm3). Indications are for patellar and trochlear lesions 1 cm2 to 6 cm2. For both the trochlea and the patella, short-term outcomes have been good.19,20

Rehabilitation After Surgery

Isolated PF cartilage restoration generally does not require prolonged weight-bearing restrictions, and ambulation with the knee locked in full extension is permitted as tolerated. Concurrent TT osteotomy, however, requires protection with 4 to 6 weeks of toe-touch weight-bearing to minimize the risk of tibial fracture.

Conclusion

Comprehensive preoperative assessment is essential and should include a thorough core-to-floor physical examination as well as PF-specific imaging. Treatment of symptomatic chondral lesions in the PF joint requires specific technical and postoperative management, which differs significantly from management involving the condyles. Attending to all these details makes the outcomes of PF cartilage treatment reproducible. These outcomes may rival those of condylar treatment.

1. Curl WW, Krome J, Gordon ES, Rushing J, Smith BP, Poehling GG. Cartilage injuries: a review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(4):456-460.

2. Steensen RN, Bentley JC, Trinh TQ, Backes JR, Wiltfong RE. The prevalence and combined prevalences of anatomic factors associated with recurrent patellar dislocation: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):921-927.

3. Nomura E, Inoue M. Cartilage lesions of the patella in recurrent patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(2):498-502.

4. Vollnberg B, Koehlitz T, Jung T, et al. Prevalence of cartilage lesions and early osteoarthritis in patients with patellar dislocation. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(11):2347-2356.

5. Crema MD, Roemer FW, Marra MD, et al. Articular cartilage in the knee: current MR imaging techniques and applications in clinical practice and research. Radiographics. 2011;31(1):37-61.

6. Campbell KA, Erickson BJ, Saltzman BM, et al. Is local viscosupplementation injection clinically superior to other therapies in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):2036-2045.e14.

7. Saltzman BM, Jain A, Campbell KA, et al. Does the use of platelet-rich plasma at the time of surgery improve clinical outcomes in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair when compared with control cohorts? A systematic review of meta-analyses. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(5):906-918.

8. Gomoll AH, Gillogly SD, Cole BJ, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the patella: a multicenter experience. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1074-1081.

9. Meric G, Gracitelli GC, Gortz S, De Young AJ, Bugbee WD. Fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation for bipolar reciprocal osteochondral lesions of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):709-714.

10. Peterson L, Vasiliadis HS, Brittberg M, Lindahl A. Autologous chondrocyte implantation: a long-term follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(6):1117-1124.

11. Minas T, Gomoll AH, Rosenberger R, Royce RO, Bryant T. Increased failure rate of autologous chondrocyte implantation after previous treatment with marrow stimulation techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):902-908.

12. Gracitelli GC, Meric G, Briggs DT, et al. Fresh osteochondral allografts in the knee: comparison of primary transplantation versus transplantation after failure of previous subchondral marrow stimulation. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):885-891.

13. Anderson CN, Magnussen RA, Block JJ, Anderson AF, Spindler KP. Operative fixation of chondral loose bodies in osteochondritis dissecans in the knee: a report of 5 cases. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1(2):2325967113496546.

14. Kreuz PC, Steinwachs MR, Erggelet C, et al. Results after microfracture of full-thickness chondral defects in different compartments in the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(11):1119-1125.

15. Vasiliadis HS, Lindahl A, Georgoulis AD, Peterson L. Malalignment and cartilage lesions in the patellofemoral joint treated with autologous chondrocyte implantation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(3):452-457.

16. Astur DC, Arliani GG, Binz M, et al. Autologous osteochondral transplantation for treating patellar chondral injuries: evaluation, treatment, and outcomes of a two-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(10):816-823.

17. Hoffman JK, Geraghty S, Protzman NM. Articular cartilage repair using marrow simulation augmented with a viable chondral allograft: 9-month postoperative histological evaluation. Case Rep Orthop. 2015;2015:617365.

18. Gobbi A, Chaurasia S, Karnatzikos G, Nakamura N. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation versus multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large patellofemoral chondral lesions: a nonrandomized prospective trial. Cartilage. 2015;6(2):82-97.